User login

New HCV Diagnostic Tests Provide Accuracy and Low Costs

NEW YORK - Several hepatitis C virus core antigen (HCVcAg) tests accurately diagnose hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and could replace nucleic acid testing (NAT) in settings where HCV is prevalent, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis.

"Overall, several of the tests perform very well and while they are not equal to NAT, the lower costs may improve diagnostic capacity in the appropriate setting," Dr. J. Morgan Freiman from Boston Medical Center in Massachusetts told Reuters Health by email.

The current two-step diagnostic procedure for diagnosing HCV infection -- screening for antibodies to HCV followed by NAT for those with anti-HCV antibodies -- is a major bottleneck for addressing the HCV elimination strategy proposed by the World Health Organization. Currently, there are five tests for HCVcAg commercially available.

Dr. Freiman and colleagues evaluated the accuracy of diagnosis of active HCV infection among adults and children for these five commercially available tests compared with NAT in their systematic review and meta-analysis of 44 published reports.

The pooled sensitivity and specificity were 93.4% and 98.8% for the Abbott ARCHITECT assay, 93.2% and 99.2% for the Ortho HCV Ag ELISA, and 59.5% and 82.9% for the Hunan Jynda HCV Ag ELISA. There was insufficient information for a pooled analysis of the Eiken Lumispot HCV Ag and the Fujirebio Lumipulse Ortho HCV Ag assays.

Three reports showed that the HCVcAg correlated well with RNA when levels were at least 3000 IU/mL when the Abbott ARCHITECT assay was used, according to the June 21 Annals of Internal Medicine report.

"Although even tests with the highest performance are not as sensitive as NAT, well-performing HCVcAg tests with an analytic sensitivity reaching into the femtomolar range (equal to 3000 IU/mL) could replace NAT for HCV detection, particularly if a lower cost per test allows more patients to be served," the researchers conclude. "Therefore, HCVcAg should be explored for point-of-care (POC) testing to increase the number of patients diagnosed and streamline the HCV cascade of care."

"There is much more work to be done to determine at what sensitivity threshold a POC test would be clinically useful," Dr. Freiman said. "In settings with reliable access to centralized laboratory processing and higher diagnostic capacity, a POC test may still prove to be useful as a screening tool, but would be less likely to replace confirmatory nucleic acid testing (NAT)."

"We have the technology to detect circulating HCV RNA down to 15 IU/mL - amazing -- but how clinically relevant is that threshold when access to testing is equally as important as accuracy in resource limited settings?" he wondered.

Dr. Jose-Manuel Echevarria, from Carlos III Health Institute, Madrid, Spain, who recently reported that HCV core-specific antibody may represent occult HCV infection among blood donors, told Reuters Health by email, "Physicians should conclude from the report that HCVcAg testing provides trustful diagnostic results for the characterization of their anti-HCV positive patients as viremic or non-viremic before deciding about antiviral treatment."

"I would add that HCVcAg testing is particularly useful for the purpose of transfusion centers," he said. "Chronically infected blood donors are detected by anti-HCV screening, and HCVcAg will detect efficiently almost every blood unit obtained from donors experiencing the window period of the acute HCV infection, who test negative for anti-HCV."

"At present, high-resource settings will for sure use NAT testing because of its higher sensitivity, and because automatic equipment has reduced the chance for false-positive results because sample-to-sample contamination (is kept) to a minimum," Dr. Echevarria concluded. "However, HCVcAg testing is extremely useful and convenient for low-resource settings, and also for emergency units everywhere."

The National Institutes of Health funded this research. Three coauthors reported disclosures.

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/28LpRcU Ann Intern Med 2016.

NEW YORK - Several hepatitis C virus core antigen (HCVcAg) tests accurately diagnose hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and could replace nucleic acid testing (NAT) in settings where HCV is prevalent, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis.

"Overall, several of the tests perform very well and while they are not equal to NAT, the lower costs may improve diagnostic capacity in the appropriate setting," Dr. J. Morgan Freiman from Boston Medical Center in Massachusetts told Reuters Health by email.

The current two-step diagnostic procedure for diagnosing HCV infection -- screening for antibodies to HCV followed by NAT for those with anti-HCV antibodies -- is a major bottleneck for addressing the HCV elimination strategy proposed by the World Health Organization. Currently, there are five tests for HCVcAg commercially available.

Dr. Freiman and colleagues evaluated the accuracy of diagnosis of active HCV infection among adults and children for these five commercially available tests compared with NAT in their systematic review and meta-analysis of 44 published reports.

The pooled sensitivity and specificity were 93.4% and 98.8% for the Abbott ARCHITECT assay, 93.2% and 99.2% for the Ortho HCV Ag ELISA, and 59.5% and 82.9% for the Hunan Jynda HCV Ag ELISA. There was insufficient information for a pooled analysis of the Eiken Lumispot HCV Ag and the Fujirebio Lumipulse Ortho HCV Ag assays.

Three reports showed that the HCVcAg correlated well with RNA when levels were at least 3000 IU/mL when the Abbott ARCHITECT assay was used, according to the June 21 Annals of Internal Medicine report.

"Although even tests with the highest performance are not as sensitive as NAT, well-performing HCVcAg tests with an analytic sensitivity reaching into the femtomolar range (equal to 3000 IU/mL) could replace NAT for HCV detection, particularly if a lower cost per test allows more patients to be served," the researchers conclude. "Therefore, HCVcAg should be explored for point-of-care (POC) testing to increase the number of patients diagnosed and streamline the HCV cascade of care."

"There is much more work to be done to determine at what sensitivity threshold a POC test would be clinically useful," Dr. Freiman said. "In settings with reliable access to centralized laboratory processing and higher diagnostic capacity, a POC test may still prove to be useful as a screening tool, but would be less likely to replace confirmatory nucleic acid testing (NAT)."

"We have the technology to detect circulating HCV RNA down to 15 IU/mL - amazing -- but how clinically relevant is that threshold when access to testing is equally as important as accuracy in resource limited settings?" he wondered.

Dr. Jose-Manuel Echevarria, from Carlos III Health Institute, Madrid, Spain, who recently reported that HCV core-specific antibody may represent occult HCV infection among blood donors, told Reuters Health by email, "Physicians should conclude from the report that HCVcAg testing provides trustful diagnostic results for the characterization of their anti-HCV positive patients as viremic or non-viremic before deciding about antiviral treatment."

"I would add that HCVcAg testing is particularly useful for the purpose of transfusion centers," he said. "Chronically infected blood donors are detected by anti-HCV screening, and HCVcAg will detect efficiently almost every blood unit obtained from donors experiencing the window period of the acute HCV infection, who test negative for anti-HCV."

"At present, high-resource settings will for sure use NAT testing because of its higher sensitivity, and because automatic equipment has reduced the chance for false-positive results because sample-to-sample contamination (is kept) to a minimum," Dr. Echevarria concluded. "However, HCVcAg testing is extremely useful and convenient for low-resource settings, and also for emergency units everywhere."

The National Institutes of Health funded this research. Three coauthors reported disclosures.

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/28LpRcU Ann Intern Med 2016.

NEW YORK - Several hepatitis C virus core antigen (HCVcAg) tests accurately diagnose hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and could replace nucleic acid testing (NAT) in settings where HCV is prevalent, according to a systematic review and meta-analysis.

"Overall, several of the tests perform very well and while they are not equal to NAT, the lower costs may improve diagnostic capacity in the appropriate setting," Dr. J. Morgan Freiman from Boston Medical Center in Massachusetts told Reuters Health by email.

The current two-step diagnostic procedure for diagnosing HCV infection -- screening for antibodies to HCV followed by NAT for those with anti-HCV antibodies -- is a major bottleneck for addressing the HCV elimination strategy proposed by the World Health Organization. Currently, there are five tests for HCVcAg commercially available.

Dr. Freiman and colleagues evaluated the accuracy of diagnosis of active HCV infection among adults and children for these five commercially available tests compared with NAT in their systematic review and meta-analysis of 44 published reports.

The pooled sensitivity and specificity were 93.4% and 98.8% for the Abbott ARCHITECT assay, 93.2% and 99.2% for the Ortho HCV Ag ELISA, and 59.5% and 82.9% for the Hunan Jynda HCV Ag ELISA. There was insufficient information for a pooled analysis of the Eiken Lumispot HCV Ag and the Fujirebio Lumipulse Ortho HCV Ag assays.

Three reports showed that the HCVcAg correlated well with RNA when levels were at least 3000 IU/mL when the Abbott ARCHITECT assay was used, according to the June 21 Annals of Internal Medicine report.

"Although even tests with the highest performance are not as sensitive as NAT, well-performing HCVcAg tests with an analytic sensitivity reaching into the femtomolar range (equal to 3000 IU/mL) could replace NAT for HCV detection, particularly if a lower cost per test allows more patients to be served," the researchers conclude. "Therefore, HCVcAg should be explored for point-of-care (POC) testing to increase the number of patients diagnosed and streamline the HCV cascade of care."

"There is much more work to be done to determine at what sensitivity threshold a POC test would be clinically useful," Dr. Freiman said. "In settings with reliable access to centralized laboratory processing and higher diagnostic capacity, a POC test may still prove to be useful as a screening tool, but would be less likely to replace confirmatory nucleic acid testing (NAT)."

"We have the technology to detect circulating HCV RNA down to 15 IU/mL - amazing -- but how clinically relevant is that threshold when access to testing is equally as important as accuracy in resource limited settings?" he wondered.

Dr. Jose-Manuel Echevarria, from Carlos III Health Institute, Madrid, Spain, who recently reported that HCV core-specific antibody may represent occult HCV infection among blood donors, told Reuters Health by email, "Physicians should conclude from the report that HCVcAg testing provides trustful diagnostic results for the characterization of their anti-HCV positive patients as viremic or non-viremic before deciding about antiviral treatment."

"I would add that HCVcAg testing is particularly useful for the purpose of transfusion centers," he said. "Chronically infected blood donors are detected by anti-HCV screening, and HCVcAg will detect efficiently almost every blood unit obtained from donors experiencing the window period of the acute HCV infection, who test negative for anti-HCV."

"At present, high-resource settings will for sure use NAT testing because of its higher sensitivity, and because automatic equipment has reduced the chance for false-positive results because sample-to-sample contamination (is kept) to a minimum," Dr. Echevarria concluded. "However, HCVcAg testing is extremely useful and convenient for low-resource settings, and also for emergency units everywhere."

The National Institutes of Health funded this research. Three coauthors reported disclosures.

SOURCE: http://bit.ly/28LpRcU Ann Intern Med 2016.

Sign up now for the October Coding and Reimbursement Workshop

The Coding & Reimbursement for Vascular Surgeons Workshop will be held October 21-22, 2016 at the Millennium Knickerbocker Hotel in Chicago.

Vascular surgeons and their support staff need to maintain knowledge and competence for appropriate billing and coding procedures. The Coding and Reimbursement for Vascular Surgeons course is an intensive two-day program designed to address the 2016 updates including changes to endovascular stent placement outside the lower extremity and PQRS as well as coding for intravascular embolization and retrograde intrathoracic carotid stenting.

Additionally, the course will review the proposed updates for 2016 with a focus on reporting standards for interventional and open surgical procedures. The program also includes information about the global surgical package and how it impacts billing and reimbursement, along with the application of modifiers for streamlined reimbursement. This will be accomplished by using a multi-modality educational forum with didactic lectures, panel discussions, case studies, and question-answer sessions.

For further information and to sign up click here.

The Coding & Reimbursement for Vascular Surgeons Workshop will be held October 21-22, 2016 at the Millennium Knickerbocker Hotel in Chicago.

Vascular surgeons and their support staff need to maintain knowledge and competence for appropriate billing and coding procedures. The Coding and Reimbursement for Vascular Surgeons course is an intensive two-day program designed to address the 2016 updates including changes to endovascular stent placement outside the lower extremity and PQRS as well as coding for intravascular embolization and retrograde intrathoracic carotid stenting.

Additionally, the course will review the proposed updates for 2016 with a focus on reporting standards for interventional and open surgical procedures. The program also includes information about the global surgical package and how it impacts billing and reimbursement, along with the application of modifiers for streamlined reimbursement. This will be accomplished by using a multi-modality educational forum with didactic lectures, panel discussions, case studies, and question-answer sessions.

For further information and to sign up click here.

The Coding & Reimbursement for Vascular Surgeons Workshop will be held October 21-22, 2016 at the Millennium Knickerbocker Hotel in Chicago.

Vascular surgeons and their support staff need to maintain knowledge and competence for appropriate billing and coding procedures. The Coding and Reimbursement for Vascular Surgeons course is an intensive two-day program designed to address the 2016 updates including changes to endovascular stent placement outside the lower extremity and PQRS as well as coding for intravascular embolization and retrograde intrathoracic carotid stenting.

Additionally, the course will review the proposed updates for 2016 with a focus on reporting standards for interventional and open surgical procedures. The program also includes information about the global surgical package and how it impacts billing and reimbursement, along with the application of modifiers for streamlined reimbursement. This will be accomplished by using a multi-modality educational forum with didactic lectures, panel discussions, case studies, and question-answer sessions.

For further information and to sign up click here.

Raman Malhotra, MD

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Hand compression neuropathy: An assessment guide

› Use provocative testing to confirm a suspected diagnosis in a patient who presents with peripheral entrapment mononeuropathy. B

› Consider electrodiagnostic testing for help in diagnosing a challenging presentation, ruling out a competing diagnosis, or clarifying an atypical clinical picture or vague subjective history. A

› Evaluate any patient who presents with non-anatomic nerve distribution of symptoms—eg, burning, numbness, and tingling of the entire hand—for a metabolic, rather than an entrapment, neuropathy. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Neuropathic hand complaints—for which patients typically seek medical attention when the pain or paresthesia starts to interfere with their daily routine—are common and diverse. The ability to assess and accurately diagnose upper extremity compression neuropathies is critical for physicians in primary care.

Assessment starts, of course, with a thorough history of the present illness and past medical history, which helps define a broad differential diagnosis and identify comorbidities. Physical examination, including judicious use of provocative testing, allows you to objectively identify the pathologic deficit, evaluate function and coordination of multiple organ systems, and detect nerve dysfunction. The results determine whether additional tools, such as electrodiagnostic testing, are needed.

We’ve created this guide, detailed in the text, tables, and figures that follow, to help you hone your ability to accurately diagnose patients who present with compression neuropathies of the hand.

The medical history: Knowing what to ask

To clearly define a patient’s symptoms and disability, start with a thorough history of the presenting complaint.

Inquire about symptom onset and chronicity. Did the pain or paresthesia begin after an injury? Are the symptoms associated with repetitive use of the extremity? Do they occur at night?

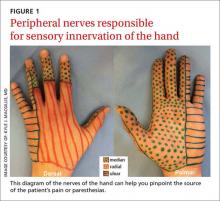

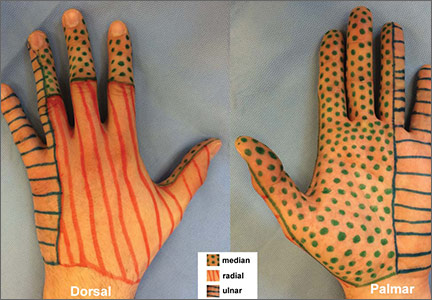

Pinpoint the location or distribution of pain or paresthesia. It is paramount to identify the affected nerve.1,2 Ask patients to complete a hand or upper extremity profile documenting location and/or type of numbness, tingling, or decreased sensation. A diagram of the peripheral nerves responsible for sensory innervation of the hand (FIGURE 1) is an effective way to screen individuals at high risk of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) or ulnar tunnel syndrome (UTS).1,2

A patient report such as, “My whole hand is numb,” calls for a follow-up question to determine whether the little finger is affected,3 which would indicate that the ulnar nerve, rather than just the median nerve, is involved. And if a patient reports feeling as if he or she is wearing gloves or mittens, it is essential to consider the possibility of a systemic neuropathy rather than a single peripheral neuropathy.3

Gather basic patient information. Inquire about hand dominance, occupation, and baseline function, any or all of which may be critical in the assessment and initiation of treatment.4,5

Review systemic conditions and medications

A broad range of comorbidities, such as cervical radiculopathy, diabetes, hypothyroidism, and vitamin deficiencies (TABLE 1),6,7 may be responsible for neuropathic hand complaints, and a thorough review of systemic complaints and past medical history is critical. Include a medication history and a review of prior procedures, such as post-traumatic surgeries of the hand or upper extremity or nerve decompression surgeries, which may provide additional insight into disease etiology.

Symptoms guide physical exam, provocative testing

A physical examination, including provocative testing, follows based on reported symptoms, medical history, and suspected source of nerve compression.

Carpal tunnel syndrome

CTS is the most common peripheral neuropathy.8 Patients often report nocturnal pain or paresthesia in the distal median nerve distribution, comprising the palmar surface of the thumb, index, middle, and radial half of the ring finger.

Researchers have identified 6 standardized clinical criteria for the diagnosis of CTS. Two criteria—numbness mostly in median nerve territory and nocturnal numbness—can be ascertained during the history of present illness.The other 4, detailed below, will be found during the physical exam.9

Thenar weakness or atrophy.9 Begin your evaluation by inspecting the thenar musculature for atrophic changes. Motor exam of intrinsic musculature innervated by the recurrent motor branch of the median nerve includes assessment of thumb abduction strength (assessed by applying resistance to the metacarpophalangeal joint [MCPJ] base towards the palm in the position of maximal abduction) and opposition strength (assessed by applying force to the MCPJ from the ulnar aspect).10

Positive Phalen’s test.9 Provocative testing for CTS includes Phalen’s test (sensitivity 43%-86%, specificity 48%-67%),11 which is an attempt to reproduce the numbness or tingling in the median nerve territory within 60 seconds of full wrist flexion. Ask the patient to hold his or her forearms vertically with elbows resting on the table (allowing gravity to flex the wrists),12 and to tell you if numbness or tingling occurs.

Positive Tinel’s sign.9 Tinel’s sign (sensitivity 45%-75%, specificity 48%-67%)11 is performed by lightly tapping the median nerve from the proximal to distal end over the carpal tunnel. The test is positive if paresthesia results. Provocative testing may also include Durkan’s test, also known as the carpal compression test. Durkan’s test (sensitivity 49%-89%, specificity 54%-96%)11 involves placing your thumb directly over the carpal tunnel and holding light compression for 60 seconds, or until paresthesia is reported.

Positive 2-point discrimination test.9 To assess CTS disease severity, use 2-point discrimination to evaluate the patient’s sensation qualitatively and quantitatively. Two-point discrimination can only be tested, however, if light touch sensation is intact. It is typically performed by lightly applying 2 caliper points at fixed distances sufficient to blanch the skin, but some clinicians have used other tools, such as a modified paperclip.13 The smallest distance at which the patient can detect 2 distinct stimuli is then recorded.

Researchers have reported an average of 3 to 5 mm for 2-point discrimination at the fingertipand a normal 2-point discrimination of 6 to 9 mm in the volar surface of the hand (TABLE 2).14,15

The scratch collapse test (sensitivity 64%, specificity 99%) is a supplemental exam that uses a different outcome measure to diagnose CTS.16 It involves lightly scratching the skin over the compressed carpal tunnel while the patient performs sustained resisted bilateral shoulder external rotation in an adducted position. A momentary loss of muscle resistance to external rotation indicates a positive test.

Pronator syndrome

Pronator syndrome (PS) is a proximal median neuropathy that may present in isolation or in combination with CTS as a double crush syndrome. Clinical symptoms include features of CTS and sensory paresthesias in the palm and distal forearm in the distribution of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. PS is commonly associated with volar proximal forearm pain exacerbated by repetitive activities involving pronation and supination.

PS is not easy to assess. Palpatory examination of a large supracondylar process at the distal humerus proximal to the medial epicondyle on its anteromedial aspect can be difficult, especially if the patient is overweight. And motor weakness is not a prominent feature. What’s more, power assessment of the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, and flexor digitorum superficialis may exacerbate symptoms.

Because the symptoms of PS and CTS may be the same, PS provocation maneuvers should be performed on patients with CTS symptoms and paresthesia involving the palm. Start by testing for Tinel’s sign over the pronator teres muscle, although this has been found to be positive in less than 50% of PS cases.17 Palpate the antecubital fossa and the proximal aspect of the pronator teres muscle to assess for discomfort or tenderness.

Pronator compression test. The pronator compression test has been found to be the most sensitive way to assess PS.18,19 This test involves direct compression of the proximal and radial edge of the pronator teres muscle belly along the proximal volar forearm with the thumb.20 It is performed bilaterally on supinated upper extremities, with the clinician applying pressure on each forearm simultaneously (FIGURE 2). If the symptoms in the hand are reproduced in ≤30 seconds, the test is positive. In a study of 10 patients with surgically confirmed PS, the pronator compression test was positive in every case.20,21

Resistance testing. You can also evaluate the pronator teres compression site by testing the patient’s ability to resist pronation with his or her elbow extended and the forearm in neutral position. To test for compression from the bicipital aponeurosis, ask the patient to flex the elbow to approximately 120° to 130° and apply active supinated resistance.22 Likewise, resistance of the long finger proximal interphalangeal joint (IPJ) to flexion—a maneuver performed with elbow fully extended—assesses compression from the fibrous arcade of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS).21 A positive resistance test will reproduce the reported symptoms.

Ulnar tunnel syndrome

Symptoms of UTS, which is much less common than CTS, include pain in the wrist and hand that is associated with paresthesia or numbness in the small finger and ulnar half of the ring finger. Patients may report difficulty with motor tasks involving grip and pinch strength or fatigue with prolonged action of the intrinsic muscles. Many also report an exacerbation of symptoms associated with increased wrist flexion or at night.

Evaluation of UTS requires a full assessment of the upper extremity, starting with observation of hand posture and muscle bulk to identify signs of chronic nerve compression. The contralateral extremity serves as a control to the neuropathic hand. Classically, chronic ulnar nerve compression leads to intrinsic muscle atrophy, evidenced by loss of topographical soft tissue bulk in the first dorsal web space, the palmar transverse metacarpal arch, and the hypothenar area.23 Ulnar motor nerve dysfunction is limited to the intrinsic muscles of the hand. The inverted pyramid sign, signified by atrophy of the transverse head of the adductor pollicis, is another visual aberrancy,24 as is clawing of the ring finger and small finger. The clawing, which involves hyperextension of the MCPJ and flexion of the proximal and distal IPJ, is commonly known as Duchenne’s sign. FIGURE 3 demonstrates hypothenar atrophy and the loss of muscle bulk in the first dorsal web space.

When you suspect UTS, palpate the wrist and hand in an attempt to locate a mass or area of tenderness. Not all patients with a volar ganglion cyst responsible for UTS present with a palpable mass, but tenderness along the radial aspect of the pisiform or an undefined fullness in this area may be noted.25 Any patient with a palpable mass should be tested for Tinel’s sign over the mass and undergo a thorough vascular assessment. Fracture of the hook of the hamate is indicated by tenderness in the region approximated by the intersection of Kaplan’s line and the proximal extension line from the ring finger.

Perform 2-point discrimination testing at the palmar distal aspect of the small finger and ulnar half of the ring finger. This tests the superficial sensory division of the ulnar nerve that travels within Guyon’s canal. Testing the dorsal ulnar cutaneous nerve involves the skin of the dorso-ulnar hand and dorsum of the long finger proximal to the IPJ. If this area is spared and the palmar distal ulnar digits are affected, compression within Guyon’s canal is likely. If both areas are affected, suspect a more proximal compression site at the cubital tunnel, as the dorsal ulnar cutaneous nerve branches proximal to Guyon’s canal.26

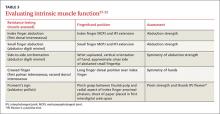

Ulnar motor nerve dysfunction in UTS is limited to the intrinsic muscles of the hand. Assessment of intrinsic muscle function is described in TABLE 3.27-32 It is important to become familiar with the tests and maneuvers described, but also to be aware that a comprehensive evaluation of ulnar nerve motor function requires a combination of tests.

Cubital tunnel syndrome

Cubital tunnel syndrome—the second most common peripheral neuropathy8—involves the proximal site of ulnar nerve compression in the upper extremity. Patients typically report symptoms similar to those of UTS, with sensory paresthesia in the ulnar digits and intrinsic weakness. To learn more about the symptoms, ask if the onset of pain or paresthesia is related to a particular elbow position, such as increased elbow flexion.

Notably, pain is usually not the initial complaint, unless the disease is advanced. This may be the reason atrophic intrinsic changes are 4 times more likely to be seen in patients with cubital tunnel syndrome than in those with CTS.33 You’re more likely to hear about vague motor problems, including hand clumsiness and difficulty with fine coordination of the fingers.34 Thus, it is important to evaluate patients for concurrent UTS and/or CTS, as well as for differentiation.

Focus on the elbow. Whenever you suspect cubital tunnel syndrome, pay special attention to the elbow. Examine the carrying angle of the elbow in relation to the contralateral extremity. Deformity may provide clues to a history of trauma. Assess the ulnar nerve during active flexion and extension to identify a subluxatable nerve at the cubital tunnel. Examine the ulno-humeral joint for crepitus, and palpate the joint line for large osteophytes and/or ganglion cysts.

Motor examination of the ulnar nerve primarily focuses on the intrinsic muscles detailed in TABLE 3,27-32 although the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) and flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) to the ring finger and small finger are also innervated by the ulnar nerve. The FCU mediates the power grip, and can be tested by resisted wrist flexion and ulnar deviation. Ring finger and small finger FDP strength should be examined by resistance testing at the distal IPJ.

Provocative testing of cubital tunnel syndrome includes Tinel’s sign (performed over the cubital tunnel), the elbow flexion test (performed with elbow in maximum flexion and wrist at neutral position and held for 60 seconds), and the pressure provocation test (performed by applying pressure to the ulnar nerve just proximal to the cubital tunnel with your index and long fingers for 60 seconds while the patient’s elbow is at 20° flexion with the forearm supinated). For each test, eliciting distal paresthesia in ulnar nerve territory is a positive result. The sensitivity of these tests ranges from 70% (Tinel’s sign) to 98% (combined elbow flexion and pressure); specificity ranges from 95% to 99%.35

The scratch collapse test for cubital tunnel syndrome evaluation is similar to the version used to assess for CTS; the only difference is the location of the site that is scratched, in this case the cubital tunnel. The reported sensitivity and specificity are 69% and 99%, respectively.11

Wartenberg’s syndrome

When a patient reports paresthesia or pain along the radial aspect of the forearm that radiates into the dorsal thumb and index and middle fingers, consider Wartenberg’s syndrome—compression of the superficial radial nerve. The condition, also known as “cheiralgia paresthetica,” may exist anywhere along the course of the nerve in the forearm,36 but the compression typically occurs 9 cm proximal to the radial styloid.

Assess the skin over the forearm and hand for evidence of prior trauma, surgical scars, or external compression sources, such as a watch.37-39 Then use palpation to identify superficial or deep masses along the nerve.40 Perform Tinel’s sign by lightly tapping along the nerve course from proximal to distal in the forearm. The test is positive if paresthesias are provoked distally.41,42

Motor function of the extremity is unaffected in Wartenberg’s syndrome, unless a prior traumatic injury occurred or a comorbidity exists. Comorbidities to consider include de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, cervical radiculopathy, injury to the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve, and CTS.

Gross sensory testing usually is negative, but 2-point discrimination may show diminished responses. Testing distribution includes the dorsal radial wrist and hand, dorsal thumb skin proximal to the IPJ, and the dorsal surface of the index, middle, and radial half of the ring finger proximal to the IPJ.

Proceed with caution. Provocative testing with a pronated forearm and a flexed and ulnar-deviated wrist may exacerbate symptoms,12,42 and Finkelstein’s maneuver (isolated ulnar deviation at the wrist to elicit pain over the first dorsal wrist compartment) and Phalen’s test may elicit false-positive results. Upper motor neuron exams (ie, deep tendon reflexes) and Hoffman’s sign (reflexive flexion of the terminal phalanges of the thumb and index finger induced by flicking or tapping the distal phalanx of the long finger) should be symmetric to the contralateral extremity.

In patients with more than one compression injury, Spurling’s sign (neck extension and lateral rotation towards the affected extremity) may induce paresthesia when combined with axial compression, while the shoulder abduction test (shoulder 90° abduction, with external rotation) may diminish reported paresthesia. In those for whom Wartenberg’s syndrome is their only compression injury, however, these provocative maneuvers will be negative.

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome

A rare clinical entity that affects the anterior interosseous innervated muscles in the forearm, anterior interosseous nerve syndrome (AINS)’s etiology is unclear. But it is likely related to a spontaneous neuritis rather than a compressive etiology.43 Paresis or paralysis of the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) and the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) of the index and long finger is its hallmark, but patients may report vague forearm pain associated with weakness or absence of function.

Examination begins with a visual assessment and palpation of the forearm and hand for atrophy or a space-occupying lesion. Notably, sensory function of the hand should remain at baseline despite the motor dysfunction, as the anterior interosseous is purely a motor nerve.

Motor testing should focus on the median and anterior interosseous innervated muscles.

The FPL is tested by isolated thumb IPJ flexion and the Kiloh and Nevin sign—the inability to make an “OK” sign with the thumb and index finger.44 Assess pinch grasp with a maximally flexed thumb IPJ and distal IPJ of the index finger. Anterior interosseous nerve dysfunction results in a flattened pinch without IPJ or distal IPJ flexion, which increases the contact of the thumb and index finger pulp.45 In a series of 14 patients, researchers reported complete paralysis of FPL and FDP index finger in 5 patients, isolated paralysis of FPL in 7 patients, and isolated paralysis of FDP index and long fingers in 2 patients. None had isolated paralysis of the FDP long finger.46FIGURE 4 shows complete (A) and incomplete (B) paralysis.

Evaluation of AINS also includes assessment of FPL and FDP tendon integrity with passive tenodesis. The appearance of the hand at rest should reflect the natural digital cascade. In a completely relaxed or anesthetized hand, the forearm is placed in wrist supination and extension, allowing gravity to extend the wrist and placing the thumb MCPJ at 30° flexion, the index finger MCPJ at 40°, and the small finger MCPJ at 70°. The thumb IPJ should approximate the radial fingertip pulp of the index finger. The forearm is then pronated and flexed at the wrist, straightening the thumb MCPJ and producing a mild flexion cascade at the proximal and distal IPJ of the index, long, ring, and small fingers within 20° of full extension. This dynamic exercise is used to confirm that the patient has an intact tenodesis effect, thus excluding tendon lacerations or ruptures from the differential diagnosis. In one study, in 9 of 33 cases of partial or complete isolated index finger FPL or FDP, paralysis was initially diagnosed as tendon rupture.47

When to consider electrodiagnostic testing

Electrodiagnostic testing—a combination of electromyography and nerve conduction studies to assess the status of a peripheral nerve48—provides objective data that can help diagnose a challenging presentation, rule out a competing diagnosis, or clarify an atypical clinical picture or vague subjective history. This type of testing is also used to localize the entrapment site, identify a patient with polyneuropathy or brachial plexopathy, and assess the severity of nerve injury or presence of a double crush syndrome.49,50 Any patient with signs and symptoms of a compression neuropathy and supportive findings on physical exam should be referred for electrodiagnostic testing and/or to a surgeon specializing in treating these conditions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kyle J. MacGillis, MD, University of Illinois at Chicago, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, 835 South Wolcott Avenue, M/C 844, Chicago, IL 60612; [email protected].

1. Katz JN, Stirrat CR, Larson MG, et al. A self-administered hand symptom diagram for the diagnosis and epidemiologic study of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:1495-1498.

2. Werner RA, Chiodo T, Spiegelberg T, et al. Use of hand diagrams in screening for ulnar neuropathy: comparison with electrodiagnostic studies. Muscle Nerve. 2012;46:891-894.

3. Dellon AL. Patient evaluation and management considerations in nerve compression. Hand Clin. 1992;8:229-239.

4. Kaji H, Honma H, Usui M, et al. Hypothenar hammer syndrome in workers occupationally exposed to vibrating tools. J Hand Surg Br. 1993;18:761-766.

5. Blum J. Examination and interface with the musician. Hand Clin. 2003;19:223-230.

6. Azhary H, Farooq MU, Bhanushali M, et al. Peripheral neuropathy: differential diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:887-892.

7. Craig, AS, Richardson JK. Acquired peripheral neuropathy. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2003;14:365-386.

8. Latinovic R, Gulliford MC, Hughes RA. Incidence of common compressive neuropathies in primary care. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:263-265.

9. Graham B, Regehr G, Naglie G, et al. Development and validation of diagnostic criteria for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2006;31:919-924.

10. Foucher G, Malizos C, Sammut D, et al. Primary palmaris longus transfer as an opponensplasty in carpal tunnel release: a series of 73 cases. J Hand Surg Br. 1991;16:56-60.

11. Massy-Westropp N, Grimmer K, Bain G. A systematic review of the clinical diagnostic tests for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2000;25:120-127.

12. Dellon AL, Mackinnon SE. Radial sensory nerve entrapment in the forearm. J Hand Surg Am. 1986;11:199-205.

13. Mackinnon SE, Dellon AL. Two-point discrimination tester. J Hand Surg (Am). 1985;10:906-907.

14. Louis DS, Greene TL, Jacobson KE, et al. Evaluation of normal values for stationary and moving two-point discrimination in the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1984;9:552-555.

15. Omer GE Jr. Physical diagnosis of peripheral nerve injuries. Orthop Clin North Am. 1981;12:207-228.

16. Cheng CJ, Mackinnon-Patterson B, Beck JL, et al. Scratch collapse test for evaluation of carpal and cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:1518-1524.

17. Haussmann P, Patel MR. Intraepineurial constriction of nerve fascicles in pronator syndrome and anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. Orthop Clin North Am. 1996;27:339-344.

18. Lee AK, Khorsandi M, Nurbhai N, et al. Endoscopically assisted decompression for pronator syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37:1173-1179.

19. Lee MJ, LaStayo PC. Pronator syndrome and other nerve compressions that mimic carpal tunnel syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:601-609.

20. Gainor BJ. The pronator compression test revisited: a forgotten physical sign. Orthop Rev. 1990;19:888-892.

21. Rehak DC. Pronator syndrome. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20:531-540.

22. Eversmann WW. Compression and entrapment neuropathies of the upper extremity. J Hand Surg Am. 1983;8:759-766.

23. Masse L. Contribution a l’etude de l’achon des interosseus. J Med (Bordeaux). 1916;46:198-200.

24. Draeger RW, Stern PJ. The inverted pyramid sign and other eponymous signs of ulnar nerve palsy. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39:2517-2520.

25. Wang B, Zhao Y, Lu A, et al. Ulnar nerve deep branch compression by a ganglion: a review of nine cases. Injury. 2014;45:1126-1130.

26. Polatsch DB, Melone CP, Beldner S, et al. Ulnar nerve anatomy. Hand Clin. 2007;23:283-289.

27. Buschbacher R. Side-to-side confrontational strength-testing for weakness of the intrinsic muscles of the hand. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:401-405.

28. Wartenberg R. A sign of ulnar palsy. JAMA. 1939;112:1688.

29. Earle A, Vlastou C. Crossed fingers and other tests of ulnar nerve motor function. J Hand Surg Am. 1980;5:560-565.

30. Tsujino A, Macnicol M. Finger flexion sign for ulnar neuropathy. J Hand Surg Br. 1998;23:240-241.

31. Mannerfelt L. Studies on the hand in ulnar nerve paralysis: a clinical-experimental investigation in normal and anomalous innervations. Acta Orthop Scand. 1966;87(Suppl):S118-S129.

32. Froment J. La prehension dans les paralysies du nerf cubital et Le Signe du Pouce. Presse Med. 1915;23:409.

33. Mallette P, Zhao M, Zurakowski D, et al. Muscle atrophy at diagnosis of carpal and cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32:855-858.

34. Huang JH, Samadani U, Zagar EL. Ulnar nerve entrapment neuropathy at the elbow: simple decompression. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:1150-1153.

35. Novak CB, Lee GW, Mackinnon SE, et al. Provocative testing for cubital tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1994;19:817-820.

36. Auerbach DM, Collins ED, Kunkle KL, et al. The radial sensory nerve. an anatomic study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;308:241-249.

37. Braidwood AS. Superficial radial neuropathy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1975;57:380-383.

38. Bierman HR. Nerve compression due to a tight watchband. N Engl J Med. 1959;261:237-238.

39. Linscheid RL. Injuries to radial nerve at wrist. Arch Surg. 1965;91:942-946.

40. Hermansdorfer JD, Greider JL, Dell PC. A case report of a compressive neuropathy of the radial sensory nerve caused by a ganglion cyst at the elbow. Orthopedics. 1986;9:1005-1006.

41. Poppinchalk SP, Schaffer AA. Physical examination of the upper extremity compressive neuropathies. Orthop Clin N Am. 2012;43:417-430.

42. Posner MA. Compressive neuropathies of the median and radial nerves at the elbow. Clin Sports Med. 1990;9:343-363.

43. Dang AC, Rodner CM. Unusual compression neuropathies of the forearm. Part II: median nerve. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34A:1915-1920.

44. Kiloh LG, Nevin S. Isolated neuritis of the anterior interosseous nerve. Br Med J. 1952;1:850-851.

45. Park IJ, Roh YT, Jeong C, et al. Spontaneous anterior interosseous nerve syndrome: clinical analysis and eleven surgical cases. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2013;47:519-523.

46. Ulrich D, Piatkowski A, Pallua N. Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome: retrospective analysis of 14 patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2011;131:1561-1565.

47. Hill NA, Howard FM, Huffer BR. The incomplete anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1985;10:4-16.

48. Bergquist ER, Hammert WC. Timing and appropriate use of electrodiagnostic studies. Hand Clin. 2013;29:363-370.

49. Lo JK, Finestone HM, Gilbert K, et al. Community-based referrals for electrodiagnostic studies in patients with possible carpal tunnel syndrome: what is the diagnosis? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:598-603.

50. Kane NM, Oware A. Nerve conduction and electromyography studies. J Neurol. 2012;259:1502-1508.

› Use provocative testing to confirm a suspected diagnosis in a patient who presents with peripheral entrapment mononeuropathy. B

› Consider electrodiagnostic testing for help in diagnosing a challenging presentation, ruling out a competing diagnosis, or clarifying an atypical clinical picture or vague subjective history. A

› Evaluate any patient who presents with non-anatomic nerve distribution of symptoms—eg, burning, numbness, and tingling of the entire hand—for a metabolic, rather than an entrapment, neuropathy. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Neuropathic hand complaints—for which patients typically seek medical attention when the pain or paresthesia starts to interfere with their daily routine—are common and diverse. The ability to assess and accurately diagnose upper extremity compression neuropathies is critical for physicians in primary care.

Assessment starts, of course, with a thorough history of the present illness and past medical history, which helps define a broad differential diagnosis and identify comorbidities. Physical examination, including judicious use of provocative testing, allows you to objectively identify the pathologic deficit, evaluate function and coordination of multiple organ systems, and detect nerve dysfunction. The results determine whether additional tools, such as electrodiagnostic testing, are needed.

We’ve created this guide, detailed in the text, tables, and figures that follow, to help you hone your ability to accurately diagnose patients who present with compression neuropathies of the hand.

The medical history: Knowing what to ask

To clearly define a patient’s symptoms and disability, start with a thorough history of the presenting complaint.

Inquire about symptom onset and chronicity. Did the pain or paresthesia begin after an injury? Are the symptoms associated with repetitive use of the extremity? Do they occur at night?

Pinpoint the location or distribution of pain or paresthesia. It is paramount to identify the affected nerve.1,2 Ask patients to complete a hand or upper extremity profile documenting location and/or type of numbness, tingling, or decreased sensation. A diagram of the peripheral nerves responsible for sensory innervation of the hand (FIGURE 1) is an effective way to screen individuals at high risk of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) or ulnar tunnel syndrome (UTS).1,2

A patient report such as, “My whole hand is numb,” calls for a follow-up question to determine whether the little finger is affected,3 which would indicate that the ulnar nerve, rather than just the median nerve, is involved. And if a patient reports feeling as if he or she is wearing gloves or mittens, it is essential to consider the possibility of a systemic neuropathy rather than a single peripheral neuropathy.3

Gather basic patient information. Inquire about hand dominance, occupation, and baseline function, any or all of which may be critical in the assessment and initiation of treatment.4,5

Review systemic conditions and medications

A broad range of comorbidities, such as cervical radiculopathy, diabetes, hypothyroidism, and vitamin deficiencies (TABLE 1),6,7 may be responsible for neuropathic hand complaints, and a thorough review of systemic complaints and past medical history is critical. Include a medication history and a review of prior procedures, such as post-traumatic surgeries of the hand or upper extremity or nerve decompression surgeries, which may provide additional insight into disease etiology.

Symptoms guide physical exam, provocative testing

A physical examination, including provocative testing, follows based on reported symptoms, medical history, and suspected source of nerve compression.

Carpal tunnel syndrome

CTS is the most common peripheral neuropathy.8 Patients often report nocturnal pain or paresthesia in the distal median nerve distribution, comprising the palmar surface of the thumb, index, middle, and radial half of the ring finger.

Researchers have identified 6 standardized clinical criteria for the diagnosis of CTS. Two criteria—numbness mostly in median nerve territory and nocturnal numbness—can be ascertained during the history of present illness.The other 4, detailed below, will be found during the physical exam.9

Thenar weakness or atrophy.9 Begin your evaluation by inspecting the thenar musculature for atrophic changes. Motor exam of intrinsic musculature innervated by the recurrent motor branch of the median nerve includes assessment of thumb abduction strength (assessed by applying resistance to the metacarpophalangeal joint [MCPJ] base towards the palm in the position of maximal abduction) and opposition strength (assessed by applying force to the MCPJ from the ulnar aspect).10

Positive Phalen’s test.9 Provocative testing for CTS includes Phalen’s test (sensitivity 43%-86%, specificity 48%-67%),11 which is an attempt to reproduce the numbness or tingling in the median nerve territory within 60 seconds of full wrist flexion. Ask the patient to hold his or her forearms vertically with elbows resting on the table (allowing gravity to flex the wrists),12 and to tell you if numbness or tingling occurs.

Positive Tinel’s sign.9 Tinel’s sign (sensitivity 45%-75%, specificity 48%-67%)11 is performed by lightly tapping the median nerve from the proximal to distal end over the carpal tunnel. The test is positive if paresthesia results. Provocative testing may also include Durkan’s test, also known as the carpal compression test. Durkan’s test (sensitivity 49%-89%, specificity 54%-96%)11 involves placing your thumb directly over the carpal tunnel and holding light compression for 60 seconds, or until paresthesia is reported.

Positive 2-point discrimination test.9 To assess CTS disease severity, use 2-point discrimination to evaluate the patient’s sensation qualitatively and quantitatively. Two-point discrimination can only be tested, however, if light touch sensation is intact. It is typically performed by lightly applying 2 caliper points at fixed distances sufficient to blanch the skin, but some clinicians have used other tools, such as a modified paperclip.13 The smallest distance at which the patient can detect 2 distinct stimuli is then recorded.

Researchers have reported an average of 3 to 5 mm for 2-point discrimination at the fingertipand a normal 2-point discrimination of 6 to 9 mm in the volar surface of the hand (TABLE 2).14,15

The scratch collapse test (sensitivity 64%, specificity 99%) is a supplemental exam that uses a different outcome measure to diagnose CTS.16 It involves lightly scratching the skin over the compressed carpal tunnel while the patient performs sustained resisted bilateral shoulder external rotation in an adducted position. A momentary loss of muscle resistance to external rotation indicates a positive test.

Pronator syndrome

Pronator syndrome (PS) is a proximal median neuropathy that may present in isolation or in combination with CTS as a double crush syndrome. Clinical symptoms include features of CTS and sensory paresthesias in the palm and distal forearm in the distribution of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. PS is commonly associated with volar proximal forearm pain exacerbated by repetitive activities involving pronation and supination.

PS is not easy to assess. Palpatory examination of a large supracondylar process at the distal humerus proximal to the medial epicondyle on its anteromedial aspect can be difficult, especially if the patient is overweight. And motor weakness is not a prominent feature. What’s more, power assessment of the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, and flexor digitorum superficialis may exacerbate symptoms.

Because the symptoms of PS and CTS may be the same, PS provocation maneuvers should be performed on patients with CTS symptoms and paresthesia involving the palm. Start by testing for Tinel’s sign over the pronator teres muscle, although this has been found to be positive in less than 50% of PS cases.17 Palpate the antecubital fossa and the proximal aspect of the pronator teres muscle to assess for discomfort or tenderness.

Pronator compression test. The pronator compression test has been found to be the most sensitive way to assess PS.18,19 This test involves direct compression of the proximal and radial edge of the pronator teres muscle belly along the proximal volar forearm with the thumb.20 It is performed bilaterally on supinated upper extremities, with the clinician applying pressure on each forearm simultaneously (FIGURE 2). If the symptoms in the hand are reproduced in ≤30 seconds, the test is positive. In a study of 10 patients with surgically confirmed PS, the pronator compression test was positive in every case.20,21

Resistance testing. You can also evaluate the pronator teres compression site by testing the patient’s ability to resist pronation with his or her elbow extended and the forearm in neutral position. To test for compression from the bicipital aponeurosis, ask the patient to flex the elbow to approximately 120° to 130° and apply active supinated resistance.22 Likewise, resistance of the long finger proximal interphalangeal joint (IPJ) to flexion—a maneuver performed with elbow fully extended—assesses compression from the fibrous arcade of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS).21 A positive resistance test will reproduce the reported symptoms.

Ulnar tunnel syndrome

Symptoms of UTS, which is much less common than CTS, include pain in the wrist and hand that is associated with paresthesia or numbness in the small finger and ulnar half of the ring finger. Patients may report difficulty with motor tasks involving grip and pinch strength or fatigue with prolonged action of the intrinsic muscles. Many also report an exacerbation of symptoms associated with increased wrist flexion or at night.

Evaluation of UTS requires a full assessment of the upper extremity, starting with observation of hand posture and muscle bulk to identify signs of chronic nerve compression. The contralateral extremity serves as a control to the neuropathic hand. Classically, chronic ulnar nerve compression leads to intrinsic muscle atrophy, evidenced by loss of topographical soft tissue bulk in the first dorsal web space, the palmar transverse metacarpal arch, and the hypothenar area.23 Ulnar motor nerve dysfunction is limited to the intrinsic muscles of the hand. The inverted pyramid sign, signified by atrophy of the transverse head of the adductor pollicis, is another visual aberrancy,24 as is clawing of the ring finger and small finger. The clawing, which involves hyperextension of the MCPJ and flexion of the proximal and distal IPJ, is commonly known as Duchenne’s sign. FIGURE 3 demonstrates hypothenar atrophy and the loss of muscle bulk in the first dorsal web space.

When you suspect UTS, palpate the wrist and hand in an attempt to locate a mass or area of tenderness. Not all patients with a volar ganglion cyst responsible for UTS present with a palpable mass, but tenderness along the radial aspect of the pisiform or an undefined fullness in this area may be noted.25 Any patient with a palpable mass should be tested for Tinel’s sign over the mass and undergo a thorough vascular assessment. Fracture of the hook of the hamate is indicated by tenderness in the region approximated by the intersection of Kaplan’s line and the proximal extension line from the ring finger.

Perform 2-point discrimination testing at the palmar distal aspect of the small finger and ulnar half of the ring finger. This tests the superficial sensory division of the ulnar nerve that travels within Guyon’s canal. Testing the dorsal ulnar cutaneous nerve involves the skin of the dorso-ulnar hand and dorsum of the long finger proximal to the IPJ. If this area is spared and the palmar distal ulnar digits are affected, compression within Guyon’s canal is likely. If both areas are affected, suspect a more proximal compression site at the cubital tunnel, as the dorsal ulnar cutaneous nerve branches proximal to Guyon’s canal.26

Ulnar motor nerve dysfunction in UTS is limited to the intrinsic muscles of the hand. Assessment of intrinsic muscle function is described in TABLE 3.27-32 It is important to become familiar with the tests and maneuvers described, but also to be aware that a comprehensive evaluation of ulnar nerve motor function requires a combination of tests.

Cubital tunnel syndrome

Cubital tunnel syndrome—the second most common peripheral neuropathy8—involves the proximal site of ulnar nerve compression in the upper extremity. Patients typically report symptoms similar to those of UTS, with sensory paresthesia in the ulnar digits and intrinsic weakness. To learn more about the symptoms, ask if the onset of pain or paresthesia is related to a particular elbow position, such as increased elbow flexion.

Notably, pain is usually not the initial complaint, unless the disease is advanced. This may be the reason atrophic intrinsic changes are 4 times more likely to be seen in patients with cubital tunnel syndrome than in those with CTS.33 You’re more likely to hear about vague motor problems, including hand clumsiness and difficulty with fine coordination of the fingers.34 Thus, it is important to evaluate patients for concurrent UTS and/or CTS, as well as for differentiation.

Focus on the elbow. Whenever you suspect cubital tunnel syndrome, pay special attention to the elbow. Examine the carrying angle of the elbow in relation to the contralateral extremity. Deformity may provide clues to a history of trauma. Assess the ulnar nerve during active flexion and extension to identify a subluxatable nerve at the cubital tunnel. Examine the ulno-humeral joint for crepitus, and palpate the joint line for large osteophytes and/or ganglion cysts.

Motor examination of the ulnar nerve primarily focuses on the intrinsic muscles detailed in TABLE 3,27-32 although the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) and flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) to the ring finger and small finger are also innervated by the ulnar nerve. The FCU mediates the power grip, and can be tested by resisted wrist flexion and ulnar deviation. Ring finger and small finger FDP strength should be examined by resistance testing at the distal IPJ.

Provocative testing of cubital tunnel syndrome includes Tinel’s sign (performed over the cubital tunnel), the elbow flexion test (performed with elbow in maximum flexion and wrist at neutral position and held for 60 seconds), and the pressure provocation test (performed by applying pressure to the ulnar nerve just proximal to the cubital tunnel with your index and long fingers for 60 seconds while the patient’s elbow is at 20° flexion with the forearm supinated). For each test, eliciting distal paresthesia in ulnar nerve territory is a positive result. The sensitivity of these tests ranges from 70% (Tinel’s sign) to 98% (combined elbow flexion and pressure); specificity ranges from 95% to 99%.35

The scratch collapse test for cubital tunnel syndrome evaluation is similar to the version used to assess for CTS; the only difference is the location of the site that is scratched, in this case the cubital tunnel. The reported sensitivity and specificity are 69% and 99%, respectively.11

Wartenberg’s syndrome

When a patient reports paresthesia or pain along the radial aspect of the forearm that radiates into the dorsal thumb and index and middle fingers, consider Wartenberg’s syndrome—compression of the superficial radial nerve. The condition, also known as “cheiralgia paresthetica,” may exist anywhere along the course of the nerve in the forearm,36 but the compression typically occurs 9 cm proximal to the radial styloid.

Assess the skin over the forearm and hand for evidence of prior trauma, surgical scars, or external compression sources, such as a watch.37-39 Then use palpation to identify superficial or deep masses along the nerve.40 Perform Tinel’s sign by lightly tapping along the nerve course from proximal to distal in the forearm. The test is positive if paresthesias are provoked distally.41,42

Motor function of the extremity is unaffected in Wartenberg’s syndrome, unless a prior traumatic injury occurred or a comorbidity exists. Comorbidities to consider include de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, cervical radiculopathy, injury to the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve, and CTS.

Gross sensory testing usually is negative, but 2-point discrimination may show diminished responses. Testing distribution includes the dorsal radial wrist and hand, dorsal thumb skin proximal to the IPJ, and the dorsal surface of the index, middle, and radial half of the ring finger proximal to the IPJ.

Proceed with caution. Provocative testing with a pronated forearm and a flexed and ulnar-deviated wrist may exacerbate symptoms,12,42 and Finkelstein’s maneuver (isolated ulnar deviation at the wrist to elicit pain over the first dorsal wrist compartment) and Phalen’s test may elicit false-positive results. Upper motor neuron exams (ie, deep tendon reflexes) and Hoffman’s sign (reflexive flexion of the terminal phalanges of the thumb and index finger induced by flicking or tapping the distal phalanx of the long finger) should be symmetric to the contralateral extremity.

In patients with more than one compression injury, Spurling’s sign (neck extension and lateral rotation towards the affected extremity) may induce paresthesia when combined with axial compression, while the shoulder abduction test (shoulder 90° abduction, with external rotation) may diminish reported paresthesia. In those for whom Wartenberg’s syndrome is their only compression injury, however, these provocative maneuvers will be negative.

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome

A rare clinical entity that affects the anterior interosseous innervated muscles in the forearm, anterior interosseous nerve syndrome (AINS)’s etiology is unclear. But it is likely related to a spontaneous neuritis rather than a compressive etiology.43 Paresis or paralysis of the flexor pollicis longus (FPL) and the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) of the index and long finger is its hallmark, but patients may report vague forearm pain associated with weakness or absence of function.

Examination begins with a visual assessment and palpation of the forearm and hand for atrophy or a space-occupying lesion. Notably, sensory function of the hand should remain at baseline despite the motor dysfunction, as the anterior interosseous is purely a motor nerve.

Motor testing should focus on the median and anterior interosseous innervated muscles.

The FPL is tested by isolated thumb IPJ flexion and the Kiloh and Nevin sign—the inability to make an “OK” sign with the thumb and index finger.44 Assess pinch grasp with a maximally flexed thumb IPJ and distal IPJ of the index finger. Anterior interosseous nerve dysfunction results in a flattened pinch without IPJ or distal IPJ flexion, which increases the contact of the thumb and index finger pulp.45 In a series of 14 patients, researchers reported complete paralysis of FPL and FDP index finger in 5 patients, isolated paralysis of FPL in 7 patients, and isolated paralysis of FDP index and long fingers in 2 patients. None had isolated paralysis of the FDP long finger.46FIGURE 4 shows complete (A) and incomplete (B) paralysis.

Evaluation of AINS also includes assessment of FPL and FDP tendon integrity with passive tenodesis. The appearance of the hand at rest should reflect the natural digital cascade. In a completely relaxed or anesthetized hand, the forearm is placed in wrist supination and extension, allowing gravity to extend the wrist and placing the thumb MCPJ at 30° flexion, the index finger MCPJ at 40°, and the small finger MCPJ at 70°. The thumb IPJ should approximate the radial fingertip pulp of the index finger. The forearm is then pronated and flexed at the wrist, straightening the thumb MCPJ and producing a mild flexion cascade at the proximal and distal IPJ of the index, long, ring, and small fingers within 20° of full extension. This dynamic exercise is used to confirm that the patient has an intact tenodesis effect, thus excluding tendon lacerations or ruptures from the differential diagnosis. In one study, in 9 of 33 cases of partial or complete isolated index finger FPL or FDP, paralysis was initially diagnosed as tendon rupture.47

When to consider electrodiagnostic testing

Electrodiagnostic testing—a combination of electromyography and nerve conduction studies to assess the status of a peripheral nerve48—provides objective data that can help diagnose a challenging presentation, rule out a competing diagnosis, or clarify an atypical clinical picture or vague subjective history. This type of testing is also used to localize the entrapment site, identify a patient with polyneuropathy or brachial plexopathy, and assess the severity of nerve injury or presence of a double crush syndrome.49,50 Any patient with signs and symptoms of a compression neuropathy and supportive findings on physical exam should be referred for electrodiagnostic testing and/or to a surgeon specializing in treating these conditions.

CORRESPONDENCE

Kyle J. MacGillis, MD, University of Illinois at Chicago, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, 835 South Wolcott Avenue, M/C 844, Chicago, IL 60612; [email protected].

› Use provocative testing to confirm a suspected diagnosis in a patient who presents with peripheral entrapment mononeuropathy. B

› Consider electrodiagnostic testing for help in diagnosing a challenging presentation, ruling out a competing diagnosis, or clarifying an atypical clinical picture or vague subjective history. A

› Evaluate any patient who presents with non-anatomic nerve distribution of symptoms—eg, burning, numbness, and tingling of the entire hand—for a metabolic, rather than an entrapment, neuropathy. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Neuropathic hand complaints—for which patients typically seek medical attention when the pain or paresthesia starts to interfere with their daily routine—are common and diverse. The ability to assess and accurately diagnose upper extremity compression neuropathies is critical for physicians in primary care.

Assessment starts, of course, with a thorough history of the present illness and past medical history, which helps define a broad differential diagnosis and identify comorbidities. Physical examination, including judicious use of provocative testing, allows you to objectively identify the pathologic deficit, evaluate function and coordination of multiple organ systems, and detect nerve dysfunction. The results determine whether additional tools, such as electrodiagnostic testing, are needed.

We’ve created this guide, detailed in the text, tables, and figures that follow, to help you hone your ability to accurately diagnose patients who present with compression neuropathies of the hand.

The medical history: Knowing what to ask

To clearly define a patient’s symptoms and disability, start with a thorough history of the presenting complaint.

Inquire about symptom onset and chronicity. Did the pain or paresthesia begin after an injury? Are the symptoms associated with repetitive use of the extremity? Do they occur at night?

Pinpoint the location or distribution of pain or paresthesia. It is paramount to identify the affected nerve.1,2 Ask patients to complete a hand or upper extremity profile documenting location and/or type of numbness, tingling, or decreased sensation. A diagram of the peripheral nerves responsible for sensory innervation of the hand (FIGURE 1) is an effective way to screen individuals at high risk of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) or ulnar tunnel syndrome (UTS).1,2

A patient report such as, “My whole hand is numb,” calls for a follow-up question to determine whether the little finger is affected,3 which would indicate that the ulnar nerve, rather than just the median nerve, is involved. And if a patient reports feeling as if he or she is wearing gloves or mittens, it is essential to consider the possibility of a systemic neuropathy rather than a single peripheral neuropathy.3

Gather basic patient information. Inquire about hand dominance, occupation, and baseline function, any or all of which may be critical in the assessment and initiation of treatment.4,5

Review systemic conditions and medications

A broad range of comorbidities, such as cervical radiculopathy, diabetes, hypothyroidism, and vitamin deficiencies (TABLE 1),6,7 may be responsible for neuropathic hand complaints, and a thorough review of systemic complaints and past medical history is critical. Include a medication history and a review of prior procedures, such as post-traumatic surgeries of the hand or upper extremity or nerve decompression surgeries, which may provide additional insight into disease etiology.

Symptoms guide physical exam, provocative testing

A physical examination, including provocative testing, follows based on reported symptoms, medical history, and suspected source of nerve compression.

Carpal tunnel syndrome

CTS is the most common peripheral neuropathy.8 Patients often report nocturnal pain or paresthesia in the distal median nerve distribution, comprising the palmar surface of the thumb, index, middle, and radial half of the ring finger.

Researchers have identified 6 standardized clinical criteria for the diagnosis of CTS. Two criteria—numbness mostly in median nerve territory and nocturnal numbness—can be ascertained during the history of present illness.The other 4, detailed below, will be found during the physical exam.9

Thenar weakness or atrophy.9 Begin your evaluation by inspecting the thenar musculature for atrophic changes. Motor exam of intrinsic musculature innervated by the recurrent motor branch of the median nerve includes assessment of thumb abduction strength (assessed by applying resistance to the metacarpophalangeal joint [MCPJ] base towards the palm in the position of maximal abduction) and opposition strength (assessed by applying force to the MCPJ from the ulnar aspect).10

Positive Phalen’s test.9 Provocative testing for CTS includes Phalen’s test (sensitivity 43%-86%, specificity 48%-67%),11 which is an attempt to reproduce the numbness or tingling in the median nerve territory within 60 seconds of full wrist flexion. Ask the patient to hold his or her forearms vertically with elbows resting on the table (allowing gravity to flex the wrists),12 and to tell you if numbness or tingling occurs.

Positive Tinel’s sign.9 Tinel’s sign (sensitivity 45%-75%, specificity 48%-67%)11 is performed by lightly tapping the median nerve from the proximal to distal end over the carpal tunnel. The test is positive if paresthesia results. Provocative testing may also include Durkan’s test, also known as the carpal compression test. Durkan’s test (sensitivity 49%-89%, specificity 54%-96%)11 involves placing your thumb directly over the carpal tunnel and holding light compression for 60 seconds, or until paresthesia is reported.

Positive 2-point discrimination test.9 To assess CTS disease severity, use 2-point discrimination to evaluate the patient’s sensation qualitatively and quantitatively. Two-point discrimination can only be tested, however, if light touch sensation is intact. It is typically performed by lightly applying 2 caliper points at fixed distances sufficient to blanch the skin, but some clinicians have used other tools, such as a modified paperclip.13 The smallest distance at which the patient can detect 2 distinct stimuli is then recorded.

Researchers have reported an average of 3 to 5 mm for 2-point discrimination at the fingertipand a normal 2-point discrimination of 6 to 9 mm in the volar surface of the hand (TABLE 2).14,15

The scratch collapse test (sensitivity 64%, specificity 99%) is a supplemental exam that uses a different outcome measure to diagnose CTS.16 It involves lightly scratching the skin over the compressed carpal tunnel while the patient performs sustained resisted bilateral shoulder external rotation in an adducted position. A momentary loss of muscle resistance to external rotation indicates a positive test.

Pronator syndrome

Pronator syndrome (PS) is a proximal median neuropathy that may present in isolation or in combination with CTS as a double crush syndrome. Clinical symptoms include features of CTS and sensory paresthesias in the palm and distal forearm in the distribution of the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. PS is commonly associated with volar proximal forearm pain exacerbated by repetitive activities involving pronation and supination.

PS is not easy to assess. Palpatory examination of a large supracondylar process at the distal humerus proximal to the medial epicondyle on its anteromedial aspect can be difficult, especially if the patient is overweight. And motor weakness is not a prominent feature. What’s more, power assessment of the pronator teres, flexor carpi radialis, and flexor digitorum superficialis may exacerbate symptoms.

Because the symptoms of PS and CTS may be the same, PS provocation maneuvers should be performed on patients with CTS symptoms and paresthesia involving the palm. Start by testing for Tinel’s sign over the pronator teres muscle, although this has been found to be positive in less than 50% of PS cases.17 Palpate the antecubital fossa and the proximal aspect of the pronator teres muscle to assess for discomfort or tenderness.

Pronator compression test. The pronator compression test has been found to be the most sensitive way to assess PS.18,19 This test involves direct compression of the proximal and radial edge of the pronator teres muscle belly along the proximal volar forearm with the thumb.20 It is performed bilaterally on supinated upper extremities, with the clinician applying pressure on each forearm simultaneously (FIGURE 2). If the symptoms in the hand are reproduced in ≤30 seconds, the test is positive. In a study of 10 patients with surgically confirmed PS, the pronator compression test was positive in every case.20,21

Resistance testing. You can also evaluate the pronator teres compression site by testing the patient’s ability to resist pronation with his or her elbow extended and the forearm in neutral position. To test for compression from the bicipital aponeurosis, ask the patient to flex the elbow to approximately 120° to 130° and apply active supinated resistance.22 Likewise, resistance of the long finger proximal interphalangeal joint (IPJ) to flexion—a maneuver performed with elbow fully extended—assesses compression from the fibrous arcade of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS).21 A positive resistance test will reproduce the reported symptoms.

Ulnar tunnel syndrome

Symptoms of UTS, which is much less common than CTS, include pain in the wrist and hand that is associated with paresthesia or numbness in the small finger and ulnar half of the ring finger. Patients may report difficulty with motor tasks involving grip and pinch strength or fatigue with prolonged action of the intrinsic muscles. Many also report an exacerbation of symptoms associated with increased wrist flexion or at night.

Evaluation of UTS requires a full assessment of the upper extremity, starting with observation of hand posture and muscle bulk to identify signs of chronic nerve compression. The contralateral extremity serves as a control to the neuropathic hand. Classically, chronic ulnar nerve compression leads to intrinsic muscle atrophy, evidenced by loss of topographical soft tissue bulk in the first dorsal web space, the palmar transverse metacarpal arch, and the hypothenar area.23 Ulnar motor nerve dysfunction is limited to the intrinsic muscles of the hand. The inverted pyramid sign, signified by atrophy of the transverse head of the adductor pollicis, is another visual aberrancy,24 as is clawing of the ring finger and small finger. The clawing, which involves hyperextension of the MCPJ and flexion of the proximal and distal IPJ, is commonly known as Duchenne’s sign. FIGURE 3 demonstrates hypothenar atrophy and the loss of muscle bulk in the first dorsal web space.

When you suspect UTS, palpate the wrist and hand in an attempt to locate a mass or area of tenderness. Not all patients with a volar ganglion cyst responsible for UTS present with a palpable mass, but tenderness along the radial aspect of the pisiform or an undefined fullness in this area may be noted.25 Any patient with a palpable mass should be tested for Tinel’s sign over the mass and undergo a thorough vascular assessment. Fracture of the hook of the hamate is indicated by tenderness in the region approximated by the intersection of Kaplan’s line and the proximal extension line from the ring finger.

Perform 2-point discrimination testing at the palmar distal aspect of the small finger and ulnar half of the ring finger. This tests the superficial sensory division of the ulnar nerve that travels within Guyon’s canal. Testing the dorsal ulnar cutaneous nerve involves the skin of the dorso-ulnar hand and dorsum of the long finger proximal to the IPJ. If this area is spared and the palmar distal ulnar digits are affected, compression within Guyon’s canal is likely. If both areas are affected, suspect a more proximal compression site at the cubital tunnel, as the dorsal ulnar cutaneous nerve branches proximal to Guyon’s canal.26

Ulnar motor nerve dysfunction in UTS is limited to the intrinsic muscles of the hand. Assessment of intrinsic muscle function is described in TABLE 3.27-32 It is important to become familiar with the tests and maneuvers described, but also to be aware that a comprehensive evaluation of ulnar nerve motor function requires a combination of tests.

Cubital tunnel syndrome