User login

Team maps chromatin landscape in CLL

Researchers say they have performed the first large-scale analysis of the chromatin landscape in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

And, in doing so, they have identified shared gene regulatory networks as well as heterogeneity between patients and CLL subtypes.

The group says this work should enable deeper investigation into chromatin regulation in CLL and the identification of therapeutically relevant mechanisms of disease.

The work has been published in Nature Communications.

The researchers performed chromatin accessibility mapping—via the assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq)—on 88 CLL samples from 55 patients.

For 10 of the samples, the team also established histone profiles using ChIPmentation for 3 histone marks (H3K4me1, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3) and transcriptome profiles using RNA sequencing.

The researchers then developed a bioinformatic method for linking the chromatin profiles to clinical annotations and molecular diagnostics data, and they analyzed gene regulatory networks that underlie the major disease subtypes of CLL.

The work revealed a “shared core” of regulatory regions in CLL patients as well as variations between the samples.

Furthermore, the chromatin profiles and gene regulatory networks accurately predicted IGHV mutation status and pinpointed differences between IGVH-mutated and IGVH-unmutated CLL.

“Our study has been able to dissect the variability that exists in the epigenome of CLL patients and helped to identify disease-specific changes, which will hopefully be informative for distinguishing disease subtypes or identifying suitable treatments,” said study author Jonathan Strefford, PhD, of the University of Southampton in the UK.

“Epigenetics can offer a useful doorway into ways of improving disease diagnosis and more personalized treatment choices for patients.” ![]()

Researchers say they have performed the first large-scale analysis of the chromatin landscape in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

And, in doing so, they have identified shared gene regulatory networks as well as heterogeneity between patients and CLL subtypes.

The group says this work should enable deeper investigation into chromatin regulation in CLL and the identification of therapeutically relevant mechanisms of disease.

The work has been published in Nature Communications.

The researchers performed chromatin accessibility mapping—via the assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq)—on 88 CLL samples from 55 patients.

For 10 of the samples, the team also established histone profiles using ChIPmentation for 3 histone marks (H3K4me1, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3) and transcriptome profiles using RNA sequencing.

The researchers then developed a bioinformatic method for linking the chromatin profiles to clinical annotations and molecular diagnostics data, and they analyzed gene regulatory networks that underlie the major disease subtypes of CLL.

The work revealed a “shared core” of regulatory regions in CLL patients as well as variations between the samples.

Furthermore, the chromatin profiles and gene regulatory networks accurately predicted IGHV mutation status and pinpointed differences between IGVH-mutated and IGVH-unmutated CLL.

“Our study has been able to dissect the variability that exists in the epigenome of CLL patients and helped to identify disease-specific changes, which will hopefully be informative for distinguishing disease subtypes or identifying suitable treatments,” said study author Jonathan Strefford, PhD, of the University of Southampton in the UK.

“Epigenetics can offer a useful doorway into ways of improving disease diagnosis and more personalized treatment choices for patients.” ![]()

Researchers say they have performed the first large-scale analysis of the chromatin landscape in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

And, in doing so, they have identified shared gene regulatory networks as well as heterogeneity between patients and CLL subtypes.

The group says this work should enable deeper investigation into chromatin regulation in CLL and the identification of therapeutically relevant mechanisms of disease.

The work has been published in Nature Communications.

The researchers performed chromatin accessibility mapping—via the assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq)—on 88 CLL samples from 55 patients.

For 10 of the samples, the team also established histone profiles using ChIPmentation for 3 histone marks (H3K4me1, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3) and transcriptome profiles using RNA sequencing.

The researchers then developed a bioinformatic method for linking the chromatin profiles to clinical annotations and molecular diagnostics data, and they analyzed gene regulatory networks that underlie the major disease subtypes of CLL.

The work revealed a “shared core” of regulatory regions in CLL patients as well as variations between the samples.

Furthermore, the chromatin profiles and gene regulatory networks accurately predicted IGHV mutation status and pinpointed differences between IGVH-mutated and IGVH-unmutated CLL.

“Our study has been able to dissect the variability that exists in the epigenome of CLL patients and helped to identify disease-specific changes, which will hopefully be informative for distinguishing disease subtypes or identifying suitable treatments,” said study author Jonathan Strefford, PhD, of the University of Southampton in the UK.

“Epigenetics can offer a useful doorway into ways of improving disease diagnosis and more personalized treatment choices for patients.” ![]()

EBV-CTL product classified as ATMP

among uninfected cells (blue)

Image courtesy of Benjamin

Chaigne-Delalande

A cytotoxic T-lymphocyte product that targets Epstein-Barr virus (EBV-CTLs) has been classified as an advanced therapy medicinal product (ATMP) by the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

The EBV-CTLs are being developed by Atara Biotherapeutics, Inc., to treat patients with EBV post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (EBV-PTLD).

ATMP classification was established to regulate cell and gene therapy and tissue-engineered medicinal products, support the development of these products, and provide a benchmark for the level of quality compliance for pharmaceutical practices.

ATMP classification can provide developers with scientific regulatory guidance, help clarify the applicable regulatory framework and development path, and provide access to all relevant services and incentives offered by the EMA. It can also be advantageous when submitting clinical trial dossiers to national regulatory authorities within the European Union.

About EBV-CTLs

Atara Bio’s EBV-CTL product utilizes a technology in which T cells are collected from the blood of third-party donors and then exposed to EBV antigens. The activated T cells are then expanded, characterized, and stored for future use in a partially HLA-matched patient.

In the context of EBV-PTLD, the EBV-CTLs find the cancer cells expressing EBV and kill them.

Atara Bio’s EBV-CTL product is currently being studied in phase 2 trials of patients with EBV-associated cancers, including PTLD and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Results of a phase 1/2 study of EBV-CTLs were presented at the APHON 37th Annual Conference and Exhibit and the 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting.

Atara Bio’s EBV-CTL product has orphan designation in the European Union and the US, as well as breakthrough designation in the US. ![]()

among uninfected cells (blue)

Image courtesy of Benjamin

Chaigne-Delalande

A cytotoxic T-lymphocyte product that targets Epstein-Barr virus (EBV-CTLs) has been classified as an advanced therapy medicinal product (ATMP) by the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

The EBV-CTLs are being developed by Atara Biotherapeutics, Inc., to treat patients with EBV post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (EBV-PTLD).

ATMP classification was established to regulate cell and gene therapy and tissue-engineered medicinal products, support the development of these products, and provide a benchmark for the level of quality compliance for pharmaceutical practices.

ATMP classification can provide developers with scientific regulatory guidance, help clarify the applicable regulatory framework and development path, and provide access to all relevant services and incentives offered by the EMA. It can also be advantageous when submitting clinical trial dossiers to national regulatory authorities within the European Union.

About EBV-CTLs

Atara Bio’s EBV-CTL product utilizes a technology in which T cells are collected from the blood of third-party donors and then exposed to EBV antigens. The activated T cells are then expanded, characterized, and stored for future use in a partially HLA-matched patient.

In the context of EBV-PTLD, the EBV-CTLs find the cancer cells expressing EBV and kill them.

Atara Bio’s EBV-CTL product is currently being studied in phase 2 trials of patients with EBV-associated cancers, including PTLD and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Results of a phase 1/2 study of EBV-CTLs were presented at the APHON 37th Annual Conference and Exhibit and the 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting.

Atara Bio’s EBV-CTL product has orphan designation in the European Union and the US, as well as breakthrough designation in the US. ![]()

among uninfected cells (blue)

Image courtesy of Benjamin

Chaigne-Delalande

A cytotoxic T-lymphocyte product that targets Epstein-Barr virus (EBV-CTLs) has been classified as an advanced therapy medicinal product (ATMP) by the European Medicines Agency (EMA).

The EBV-CTLs are being developed by Atara Biotherapeutics, Inc., to treat patients with EBV post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (EBV-PTLD).

ATMP classification was established to regulate cell and gene therapy and tissue-engineered medicinal products, support the development of these products, and provide a benchmark for the level of quality compliance for pharmaceutical practices.

ATMP classification can provide developers with scientific regulatory guidance, help clarify the applicable regulatory framework and development path, and provide access to all relevant services and incentives offered by the EMA. It can also be advantageous when submitting clinical trial dossiers to national regulatory authorities within the European Union.

About EBV-CTLs

Atara Bio’s EBV-CTL product utilizes a technology in which T cells are collected from the blood of third-party donors and then exposed to EBV antigens. The activated T cells are then expanded, characterized, and stored for future use in a partially HLA-matched patient.

In the context of EBV-PTLD, the EBV-CTLs find the cancer cells expressing EBV and kill them.

Atara Bio’s EBV-CTL product is currently being studied in phase 2 trials of patients with EBV-associated cancers, including PTLD and nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Results of a phase 1/2 study of EBV-CTLs were presented at the APHON 37th Annual Conference and Exhibit and the 2015 ASCO Annual Meeting.

Atara Bio’s EBV-CTL product has orphan designation in the European Union and the US, as well as breakthrough designation in the US. ![]()

P vivax evolving differently in different regions

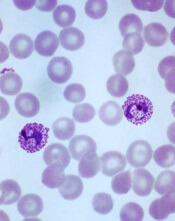

Plasmodium vivax

Image by Mae Melvin

Genomic research suggests the malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax is evolving rapidly to adapt to conditions in different geographic locations.

Researchers studied more than 200 parasite samples from across the Asia-Pacific region and found that P vivax has evolved differently in different areas.

The team identified substantial differences in the frequency of copy number variations (CNVs) in samples from western Thailand, western Cambodia, and Papua Indonesia.

They believe this is a result of the different antimalarial drugs used in these regions.

The researchers described this work in Nature Genetics.

“For so long, it’s not been possible to study P vivax genomes in detail, on a large-scale, but now we can, and we’re seeing the effect that drug use has on how parasites are evolving,” said study author Dominic Kwiatkowski, of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in the UK.

He and his colleagues studied the genomes of 228 parasite samples, identifying the strains carried by each patient and revealing their infection history. Most samples came from Southeast Asia (Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, and Malaysia) and Oceania (Papua Indonesia and Papua New Guinea), but the team also studied samples from China, India, Sri Lanka, Brazil, and Madagascar.

The researchers performed detailed population genetic analyses using 148 samples from western Thailand, western Cambodia, and Papua Indonesia. This revealed CNVs in 9 regions of the core genome, and the frequency of the 4 most common CNVs varied greatly according to geographical location.

The first common CNV was a 9-kb deletion on chromosome 8 that includes the first 3 exons of a gene encoding a cytoadherence-linked asexual protein. The CNV was present in 73% of Papua Indonesia samples, 6% of western Cambodia samples, and 3% of western Thailand samples.

The second common CNV was a 7-kb duplication on chromosome 6 that encompasses pvdbp, the gene that encodes the Duffy-binding protein, which mediates P vivax’s invasion of erythrocytes. It was present in 5% of Papua Indonesia samples, 35% of western Cambodia samples, and 25% of western Thailand samples.

The third common CNV was a 37-kb duplication on chromosome 10 that includes pvmdr1, which has been associated with resistance to mefloquine and is homologous to the pfmdr1 amplification responsible for mefloquine resistance in P falciparum. This CNV was only present in samples from western Thailand.

The fourth common CNV was a 3-kb duplication on chromosome 14 that includes the gene PVX_101445. It was found only in Papua Indonesia samples.

“Our study shows that the strongest evidence of evolution is in Papua, Indonesia, where resistance of P vivax to chloroquine is now rampant,” said Ric Price, MD, of the University of Oxford in the UK.

“These data provide crucial information from which we can start to identify the mechanisms of drug resistance in P vivax.”

“We can see in the genome that drug resistance is a huge driver for evolution,” added Richard Pearson, PhD, of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute.

“Intriguingly, in some places, this process appears to be happening in response to drugs used primarily to treat a different malaria parasite, P falciparum. Although the exact cause isn’t known, this is a worrying sign that drug resistance is becoming deeply entrenched in the parasite population.”

The researchers said there are a few possible reasons why P vivax may be evolving to evade drugs used against P falciparum.

Many people carry mixed infections of both species of parasite, so, in treating one species, the other automatically gets exposed to the drug. Another culprit may be unsupervised drug use—where many people take the most readily available, rather than the most suitable, antimalarial drug.

Another finding from this study was that, when the researchers identified patients who were carrying multiple strains of parasite, the genomic data made it possible to determine how closely the different strains were related to one another.

“This means that we can now start to pull apart the genetic complexity of individual Plasmodium vivax infections and work out whether the parasites came from one or more mosquito bites,” Kwiatkowski said. “It provides a way of addressing fundamental questions about how P vivax is transmitted and how it persists within a community and, in particular, about the biology of relapsing infections.” ![]()

Plasmodium vivax

Image by Mae Melvin

Genomic research suggests the malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax is evolving rapidly to adapt to conditions in different geographic locations.

Researchers studied more than 200 parasite samples from across the Asia-Pacific region and found that P vivax has evolved differently in different areas.

The team identified substantial differences in the frequency of copy number variations (CNVs) in samples from western Thailand, western Cambodia, and Papua Indonesia.

They believe this is a result of the different antimalarial drugs used in these regions.

The researchers described this work in Nature Genetics.

“For so long, it’s not been possible to study P vivax genomes in detail, on a large-scale, but now we can, and we’re seeing the effect that drug use has on how parasites are evolving,” said study author Dominic Kwiatkowski, of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in the UK.

He and his colleagues studied the genomes of 228 parasite samples, identifying the strains carried by each patient and revealing their infection history. Most samples came from Southeast Asia (Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, and Malaysia) and Oceania (Papua Indonesia and Papua New Guinea), but the team also studied samples from China, India, Sri Lanka, Brazil, and Madagascar.

The researchers performed detailed population genetic analyses using 148 samples from western Thailand, western Cambodia, and Papua Indonesia. This revealed CNVs in 9 regions of the core genome, and the frequency of the 4 most common CNVs varied greatly according to geographical location.

The first common CNV was a 9-kb deletion on chromosome 8 that includes the first 3 exons of a gene encoding a cytoadherence-linked asexual protein. The CNV was present in 73% of Papua Indonesia samples, 6% of western Cambodia samples, and 3% of western Thailand samples.

The second common CNV was a 7-kb duplication on chromosome 6 that encompasses pvdbp, the gene that encodes the Duffy-binding protein, which mediates P vivax’s invasion of erythrocytes. It was present in 5% of Papua Indonesia samples, 35% of western Cambodia samples, and 25% of western Thailand samples.

The third common CNV was a 37-kb duplication on chromosome 10 that includes pvmdr1, which has been associated with resistance to mefloquine and is homologous to the pfmdr1 amplification responsible for mefloquine resistance in P falciparum. This CNV was only present in samples from western Thailand.

The fourth common CNV was a 3-kb duplication on chromosome 14 that includes the gene PVX_101445. It was found only in Papua Indonesia samples.

“Our study shows that the strongest evidence of evolution is in Papua, Indonesia, where resistance of P vivax to chloroquine is now rampant,” said Ric Price, MD, of the University of Oxford in the UK.

“These data provide crucial information from which we can start to identify the mechanisms of drug resistance in P vivax.”

“We can see in the genome that drug resistance is a huge driver for evolution,” added Richard Pearson, PhD, of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute.

“Intriguingly, in some places, this process appears to be happening in response to drugs used primarily to treat a different malaria parasite, P falciparum. Although the exact cause isn’t known, this is a worrying sign that drug resistance is becoming deeply entrenched in the parasite population.”

The researchers said there are a few possible reasons why P vivax may be evolving to evade drugs used against P falciparum.

Many people carry mixed infections of both species of parasite, so, in treating one species, the other automatically gets exposed to the drug. Another culprit may be unsupervised drug use—where many people take the most readily available, rather than the most suitable, antimalarial drug.

Another finding from this study was that, when the researchers identified patients who were carrying multiple strains of parasite, the genomic data made it possible to determine how closely the different strains were related to one another.

“This means that we can now start to pull apart the genetic complexity of individual Plasmodium vivax infections and work out whether the parasites came from one or more mosquito bites,” Kwiatkowski said. “It provides a way of addressing fundamental questions about how P vivax is transmitted and how it persists within a community and, in particular, about the biology of relapsing infections.” ![]()

Plasmodium vivax

Image by Mae Melvin

Genomic research suggests the malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax is evolving rapidly to adapt to conditions in different geographic locations.

Researchers studied more than 200 parasite samples from across the Asia-Pacific region and found that P vivax has evolved differently in different areas.

The team identified substantial differences in the frequency of copy number variations (CNVs) in samples from western Thailand, western Cambodia, and Papua Indonesia.

They believe this is a result of the different antimalarial drugs used in these regions.

The researchers described this work in Nature Genetics.

“For so long, it’s not been possible to study P vivax genomes in detail, on a large-scale, but now we can, and we’re seeing the effect that drug use has on how parasites are evolving,” said study author Dominic Kwiatkowski, of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in the UK.

He and his colleagues studied the genomes of 228 parasite samples, identifying the strains carried by each patient and revealing their infection history. Most samples came from Southeast Asia (Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, and Malaysia) and Oceania (Papua Indonesia and Papua New Guinea), but the team also studied samples from China, India, Sri Lanka, Brazil, and Madagascar.

The researchers performed detailed population genetic analyses using 148 samples from western Thailand, western Cambodia, and Papua Indonesia. This revealed CNVs in 9 regions of the core genome, and the frequency of the 4 most common CNVs varied greatly according to geographical location.

The first common CNV was a 9-kb deletion on chromosome 8 that includes the first 3 exons of a gene encoding a cytoadherence-linked asexual protein. The CNV was present in 73% of Papua Indonesia samples, 6% of western Cambodia samples, and 3% of western Thailand samples.

The second common CNV was a 7-kb duplication on chromosome 6 that encompasses pvdbp, the gene that encodes the Duffy-binding protein, which mediates P vivax’s invasion of erythrocytes. It was present in 5% of Papua Indonesia samples, 35% of western Cambodia samples, and 25% of western Thailand samples.

The third common CNV was a 37-kb duplication on chromosome 10 that includes pvmdr1, which has been associated with resistance to mefloquine and is homologous to the pfmdr1 amplification responsible for mefloquine resistance in P falciparum. This CNV was only present in samples from western Thailand.

The fourth common CNV was a 3-kb duplication on chromosome 14 that includes the gene PVX_101445. It was found only in Papua Indonesia samples.

“Our study shows that the strongest evidence of evolution is in Papua, Indonesia, where resistance of P vivax to chloroquine is now rampant,” said Ric Price, MD, of the University of Oxford in the UK.

“These data provide crucial information from which we can start to identify the mechanisms of drug resistance in P vivax.”

“We can see in the genome that drug resistance is a huge driver for evolution,” added Richard Pearson, PhD, of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute.

“Intriguingly, in some places, this process appears to be happening in response to drugs used primarily to treat a different malaria parasite, P falciparum. Although the exact cause isn’t known, this is a worrying sign that drug resistance is becoming deeply entrenched in the parasite population.”

The researchers said there are a few possible reasons why P vivax may be evolving to evade drugs used against P falciparum.

Many people carry mixed infections of both species of parasite, so, in treating one species, the other automatically gets exposed to the drug. Another culprit may be unsupervised drug use—where many people take the most readily available, rather than the most suitable, antimalarial drug.

Another finding from this study was that, when the researchers identified patients who were carrying multiple strains of parasite, the genomic data made it possible to determine how closely the different strains were related to one another.

“This means that we can now start to pull apart the genetic complexity of individual Plasmodium vivax infections and work out whether the parasites came from one or more mosquito bites,” Kwiatkowski said. “It provides a way of addressing fundamental questions about how P vivax is transmitted and how it persists within a community and, in particular, about the biology of relapsing infections.” ![]()

Immunotherapy drugs linked to rheumatic diseases

Photo by Bill Branson

Several case reports have suggested that cancer patients taking the immunotherapy drugs nivolumab and ipilimumab may have a higher-than-normal risk of developing rheumatic diseases.

Between 2012 and 2016, 13 patients at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center who were taking one or both drugs developed inflammatory arthritis or sicca syndrome, a set of autoimmune conditions causing dry eyes and mouth.

The cases were described in Annals of Rheumatic Diseases.

Nivolumab and ipilimumab are both designed to turn off the molecular “checkpoints” some cancers—including lymphoma—use to evade the immune system. When the drugs work, they allow the immune system to detect and attack tumor cells. However, they also turn up the activity of the immune system as a whole and can therefore trigger immune-related side effects.

Clinical trials of ipilimumab and nivolumab have indicated that the drugs confer an increased risk of inflammatory bowel diseases, lung inflammation, autoimmune thyroid disease, and pituitary gland inflammation.

However, those trials were designed primarily to determine efficacy against cancer and not to fully examine all features of rheumatologic side effects, said Laura C. Cappelli, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

With this in mind, she and her colleagues decided to take a closer look at 13 adults (older than 18) who were treated at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and reported rheumatologic symptoms after their treatment with nivolumab and/or ipilimumab.

Eight patients were taking both ipilimumab and nivolumab, and 5 were taking 1 of the 2 drugs. They were receiving the drugs to treat melanoma (n=6), non-small-cell lung cancer (n=5), small-cell lung cancer (n=1), and renal cell carcinoma (n=1).

Nine of the patients developed inflammatory arthritis—4 with synovitis confirmed via imaging and 4 with inflammatory synovial fluid—and the remaining 4 patients were diagnosed with sicca syndrome. Other immune-related adverse events included pneumonitis, colitis, interstitial nephritis, and thyroiditis.

The researchers said this is the largest published case series showing a link between checkpoint inhibitors and rheumatic diseases.

The patients described in this case report make up about 1.3% of all patients treated with the drugs—singly or in combination—at The Johns Hopkins Hospital from 2012 to 2016. However, the researchers believe that rate is likely an underestimation of how common rheumatic diseases are in patients taking immune checkpoint inhibitors.

“We keep having referrals coming in from our oncologists as more patients are treated with these drugs,” said Clifton Bingham, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“In particular, as more patients are treated with combinations of multiple immunotherapies, we expect the rate to go up.”

Dr Cappelli said she wants the case report to raise awareness among patients and clinicians that rheumatologic side effects may occur with checkpoint inhibitors.

“It is important when weighing the risk-benefit ratio of prescribing these drugs,” she said. “And it’s important for people to be on the lookout for symptoms so they can see a rheumatologist early in an effort to prevent or limit joint damage.”

Drs Cappelli and Bingham and their colleagues are planning further collaboration with Johns Hopkins oncologists to better track the incidence of rheumatic disease in patients taking immunotherapy drugs and determine whether any particular characteristics put cancer patients at higher risk of such complications. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

Several case reports have suggested that cancer patients taking the immunotherapy drugs nivolumab and ipilimumab may have a higher-than-normal risk of developing rheumatic diseases.

Between 2012 and 2016, 13 patients at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center who were taking one or both drugs developed inflammatory arthritis or sicca syndrome, a set of autoimmune conditions causing dry eyes and mouth.

The cases were described in Annals of Rheumatic Diseases.

Nivolumab and ipilimumab are both designed to turn off the molecular “checkpoints” some cancers—including lymphoma—use to evade the immune system. When the drugs work, they allow the immune system to detect and attack tumor cells. However, they also turn up the activity of the immune system as a whole and can therefore trigger immune-related side effects.

Clinical trials of ipilimumab and nivolumab have indicated that the drugs confer an increased risk of inflammatory bowel diseases, lung inflammation, autoimmune thyroid disease, and pituitary gland inflammation.

However, those trials were designed primarily to determine efficacy against cancer and not to fully examine all features of rheumatologic side effects, said Laura C. Cappelli, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

With this in mind, she and her colleagues decided to take a closer look at 13 adults (older than 18) who were treated at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and reported rheumatologic symptoms after their treatment with nivolumab and/or ipilimumab.

Eight patients were taking both ipilimumab and nivolumab, and 5 were taking 1 of the 2 drugs. They were receiving the drugs to treat melanoma (n=6), non-small-cell lung cancer (n=5), small-cell lung cancer (n=1), and renal cell carcinoma (n=1).

Nine of the patients developed inflammatory arthritis—4 with synovitis confirmed via imaging and 4 with inflammatory synovial fluid—and the remaining 4 patients were diagnosed with sicca syndrome. Other immune-related adverse events included pneumonitis, colitis, interstitial nephritis, and thyroiditis.

The researchers said this is the largest published case series showing a link between checkpoint inhibitors and rheumatic diseases.

The patients described in this case report make up about 1.3% of all patients treated with the drugs—singly or in combination—at The Johns Hopkins Hospital from 2012 to 2016. However, the researchers believe that rate is likely an underestimation of how common rheumatic diseases are in patients taking immune checkpoint inhibitors.

“We keep having referrals coming in from our oncologists as more patients are treated with these drugs,” said Clifton Bingham, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“In particular, as more patients are treated with combinations of multiple immunotherapies, we expect the rate to go up.”

Dr Cappelli said she wants the case report to raise awareness among patients and clinicians that rheumatologic side effects may occur with checkpoint inhibitors.

“It is important when weighing the risk-benefit ratio of prescribing these drugs,” she said. “And it’s important for people to be on the lookout for symptoms so they can see a rheumatologist early in an effort to prevent or limit joint damage.”

Drs Cappelli and Bingham and their colleagues are planning further collaboration with Johns Hopkins oncologists to better track the incidence of rheumatic disease in patients taking immunotherapy drugs and determine whether any particular characteristics put cancer patients at higher risk of such complications. ![]()

Photo by Bill Branson

Several case reports have suggested that cancer patients taking the immunotherapy drugs nivolumab and ipilimumab may have a higher-than-normal risk of developing rheumatic diseases.

Between 2012 and 2016, 13 patients at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center who were taking one or both drugs developed inflammatory arthritis or sicca syndrome, a set of autoimmune conditions causing dry eyes and mouth.

The cases were described in Annals of Rheumatic Diseases.

Nivolumab and ipilimumab are both designed to turn off the molecular “checkpoints” some cancers—including lymphoma—use to evade the immune system. When the drugs work, they allow the immune system to detect and attack tumor cells. However, they also turn up the activity of the immune system as a whole and can therefore trigger immune-related side effects.

Clinical trials of ipilimumab and nivolumab have indicated that the drugs confer an increased risk of inflammatory bowel diseases, lung inflammation, autoimmune thyroid disease, and pituitary gland inflammation.

However, those trials were designed primarily to determine efficacy against cancer and not to fully examine all features of rheumatologic side effects, said Laura C. Cappelli, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

With this in mind, she and her colleagues decided to take a closer look at 13 adults (older than 18) who were treated at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and reported rheumatologic symptoms after their treatment with nivolumab and/or ipilimumab.

Eight patients were taking both ipilimumab and nivolumab, and 5 were taking 1 of the 2 drugs. They were receiving the drugs to treat melanoma (n=6), non-small-cell lung cancer (n=5), small-cell lung cancer (n=1), and renal cell carcinoma (n=1).

Nine of the patients developed inflammatory arthritis—4 with synovitis confirmed via imaging and 4 with inflammatory synovial fluid—and the remaining 4 patients were diagnosed with sicca syndrome. Other immune-related adverse events included pneumonitis, colitis, interstitial nephritis, and thyroiditis.

The researchers said this is the largest published case series showing a link between checkpoint inhibitors and rheumatic diseases.

The patients described in this case report make up about 1.3% of all patients treated with the drugs—singly or in combination—at The Johns Hopkins Hospital from 2012 to 2016. However, the researchers believe that rate is likely an underestimation of how common rheumatic diseases are in patients taking immune checkpoint inhibitors.

“We keep having referrals coming in from our oncologists as more patients are treated with these drugs,” said Clifton Bingham, MD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“In particular, as more patients are treated with combinations of multiple immunotherapies, we expect the rate to go up.”

Dr Cappelli said she wants the case report to raise awareness among patients and clinicians that rheumatologic side effects may occur with checkpoint inhibitors.

“It is important when weighing the risk-benefit ratio of prescribing these drugs,” she said. “And it’s important for people to be on the lookout for symptoms so they can see a rheumatologist early in an effort to prevent or limit joint damage.”

Drs Cappelli and Bingham and their colleagues are planning further collaboration with Johns Hopkins oncologists to better track the incidence of rheumatic disease in patients taking immunotherapy drugs and determine whether any particular characteristics put cancer patients at higher risk of such complications. ![]()

ICU Transfer Delay and Outcome

Patients on hospital wards may become critically ill due to worsening of the underlying condition that was the cause of their admission or acquisition of a new hospital‐acquired illness. Once physiologic deterioration occurs, some patients are evaluated and quickly transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU), whereas others are left on the wards until further deterioration occurs. Because many critical illness syndromes benefit from early intervention, such as sepsis and respiratory failure, early transfer to the ICU for treatment may improve patient outcomes, and conversely, delays in ICU transfer may lead to increased mortality and length of stay (LOS) in critically ill ward patients.[1, 2] However, the timeliness of that transfer is dependent on numerous changing variables, such as ICU bed availability, clinician identification of the deterioration, and clinical judgment regarding the appropriate transfer thresholds.[2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] As a result, there is a large degree of heterogeneity in the severity of illness of patients at the time of ICU transfer and in patient outcomes.[6, 8]

Previous studies investigating the association between delayed ICU transfer and patient outcomes have typically utilized the time of consultation by the ICU team to denote the onset of critical illness.[5, 6, 9, 10] However, the decision to transfer a patient to the ICU is often subjective, and previous studies have found an alarmingly high rate of errors in diagnosis and management of critically ill ward patients, including the failure to call for help.[2, 11] Therefore, a more objective tool for quantifying critical illness is necessary for determining the onset of critical illness and quantifying the association of transfer delay with patient outcomes.

Early warning scores, which are designed to detect critical illness on the wards, represent objective measures of critical illness that can be easily calculated in ward patients.[12] The aim of this study was to utilize the electronic Cardiac Arrest Risk Triage (eCART) score, a previously published, statistically derived early warning score that utilizes demographic, vital sign, and laboratory data, as an objective measure of critical illness to estimate the effect of delayed ICU transfer on patient outcomes in a large, multicenter database.[13] We chose 6 hours as the cutoff for delay in this study a priori because it is a threshold noted to be an important time period in critical illness syndromes, such as sepsis.[14, 15]

METHODS

All patients admitted to the medical‐surgical wards at 5 hospitals between November 2008 and January 2013 were eligible for inclusion in this observational cohort study. Further details of the hospital populations have been previously described.[13] A waiver of consent was granted by NorthShore University HealthSystem (IRB #EH11‐258) and the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board (IRB #16995A) based on general impracticability and minimal harm. Collection of patient information was designed to comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) regulations.

Defining the Onset of Critical Illness

The eCART score, a statistically derived early warning score that is calculated based on patient demographic, vital sign, and laboratory data, was used as an objective measure of critical illness.[13] Score calculation was performed utilizing demographic information from administrative databases and time‐ and location‐stamped vital signs and laboratory results from data warehouses at the respective institutions. In this study, a score was calculated for each time‐stamped point in the entire dataset. Of note, eCART was not used in this population for patient care as this was a retrospective observational study. An eCART score at the 95% specificity cutoff for ICU transfer from the entire dataset defined a ward patient as critically ill, a definition created a priori and before any data analysis was performed.

Defining ICU Transfer Delay and Study Outcomes

The period of time from when a patient first reached this predefined eCART score to ICU transfer was calculated for each patient, up to a maximum of 24 hours. Transfer to the ICU greater than 6 hours after reaching the critical eCART score was defined a priori as a delayed transfer to allow comparisons between patients with nondelayed and delayed transfer. A patient who suffered a ward cardiac arrest with attempted resuscitation was counted as an ICU transfer at the time of arrest. If a patient experienced more than 1 ICU transfer during the admission, then only the first ward to ICU transfer was used. The primary outcome of the study was in‐hospital mortality, and secondary outcomes were ICU mortality and hospital LOS.

Statistical Analysis

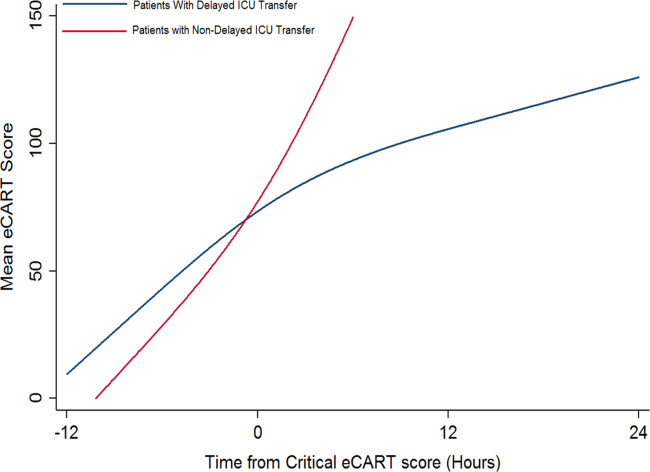

Patient characteristics were compared between patients who experienced delayed and nondelayed ICU transfers using t tests, Wilcoxon rank sums, and [2] tests, as appropriate. The association between length of transfer delay and in‐hospital mortality was calculated using logistic regression, with adjustment for age, sex, and surgical status. In a post hoc sensitivity analysis, additional adjustments were made using each patient's first eCART score on the ward, the individual vital signs and laboratory variables from eCART, and whether the ICU transfer was due to a cardiac arrest on the wards. In addition, an interaction term between time to transfer and the initial eCART on the ward was added to determine if the association between delay and mortality varied by baseline severity. The change in eCART score over time was plotted from 12 hours before the time of first reaching the critical value until ICU transfer for those in the delayed and nondelayed groups using restricted cubic splines to compare the trajectories of severity of illness between these 2 groups. In addition, a linear regression model was fit to investigate the association between the eCART slope in the 8 hours prior to the critical eCART value until ICU transfer and the timing of ICU transfer delay. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and all tests of significance used a 2‐sided P0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 269,999 admissions had documented vital signs on the hospital wards during the study period, including 11,995 patients who were either transferred from the wards to the ICU (n=11,636) or who suffered a cardiac arrest on the wards (n=359) during their initial ward stay. Of these patients, 3789 reached an eCART score at the 95% specificity cutoff (critical eCART score of 60) within 24 hours of transfer. The median time from first critical eCART value to ICU transfer was 5.4 hours (interquartile range (IQR), 214 hours; mean, 8 hours). Compared to patients without delayed ICU transfer, those with delayed transfer were slightly older (median age, 73 [IQR, 6083] years vs 71 [IQR, 5882] years; P=0.002), whereas all other characteristics were similar (Table 1). Table 2 shows comparisons of vital sign and laboratory results for delayed and nondelayed transfers at the time of ICU transfer. As shown, patients with delayed transfer had lower median respiratory rate, blood pressure, heart rate, and hemoglobin, but higher median white blood cell count and creatinine.

| Characteristic | Transferred Within 6 Hours, n=2,055 | Transfer Delayed, n=1,734 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 71 (5882) | 73 (6083) | 0.002 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 1,018 (49.5) | 847 (48.8) | 0.67 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.72 | ||

| Black | 467 (22.7) | 374 (21.6) | |

| White | 1,141 (55.5) | 971 (56.0) | |

| Other/unknown | 447 (21.8) | 389 (22.4) | |

| Surgical patient, n (%) | 572 (27.8) | 438 (25.2) | 0.07 |

| Hospital LOS prior to first critical eCART, median (IQR), d | 1.5 (0.33.7) | 1.6 (0.43.9) | 0.04 |

| Total hospital LOS, median (IQR), d* | 11 (719) | 13 (821) | 0.001 |

| Died during admission, n (%) | 503 (24.5) | 576 (33.2) | 0.001 |

| Transferred Within 6 Hours, n=2,055 | Transfer Delayed, n=1,734 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 23 (1830) | 22 (1828) | 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 111 (92134) | 109 (92128) | 0.002 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 61 (5075) | 59 (4971) | 0.001 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 106 (88124) | 101 (85117) | 0.001 |

| Oxygen saturation, median (IQR), % | 97 (9499) | 97 (9599) | 0.15 |

| Temperature, F | 98.0 (97.299.1) | 98.0 (97.199.0) | 0.001 |

| Alert mental status, number of observations (%) | 1,749 (85%) | 1,431 (83%) | 0.001 |

| eCART score at time of ICU transfer | 61 (26122) | 48 (21121) | 0.914 |

| WBC | 10.3 (7.514.5) | 11.7 (8.117.0) | 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin | 10.7 (9.312.0) | 10.3 (9.111.6) | 0.001 |

| Platelet | 215 (137275) | 195 (120269) | 0.017 |

| Sodium | 137 (134140) | 137 (134141) | 0.70 |

| K+ | 4.1 (3.84.6) | 4.2 (3.84.7) | 0.006 |

| Anion Gap | 10 (813) | 10 (814) | 0.001 |

| CO2 | 24 (2026) | 23 (1826) | 0.001 |

| BUN | 24 (1640) | 32 (1853) | 0.001 |

| Cr | 1.2 (0.92.0) | 1.5 (1.02.7) | 0.001 |

| GFR | 70 (7070) | 70 (5170) | 0.001 |

| Glucose | 123 (106161) | 129 (105164) | 0.48 |

| Calcium | 8.5 (7.98.8) | 8.2 (7.78.7) | 0.001 |

| SGOT | 26 (2635) | 26 (2644) | 0.001 |

| SGPT | 21 (2127) | 21 (2033) | 0.002 |

| Total bilirubin | 0.7 (0.71.0) | 0.7 (0.71.3) | 0.001 |

| Alk phos | 80 (8096) | 80 (79111) | 0.175 |

| Albumin | 3.0 (2.73.0) | 3.0 (2.43.0) | 0.001 |

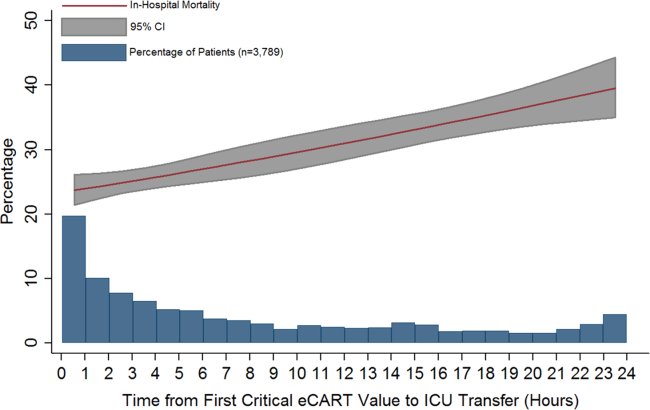

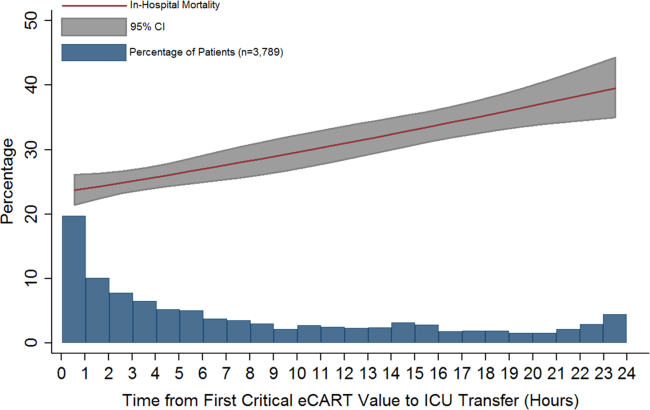

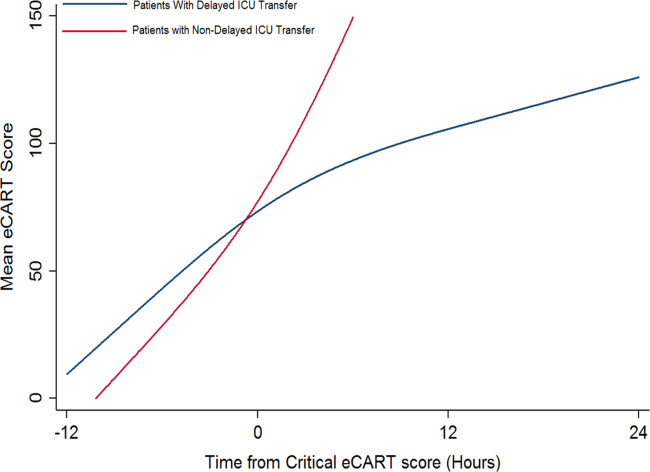

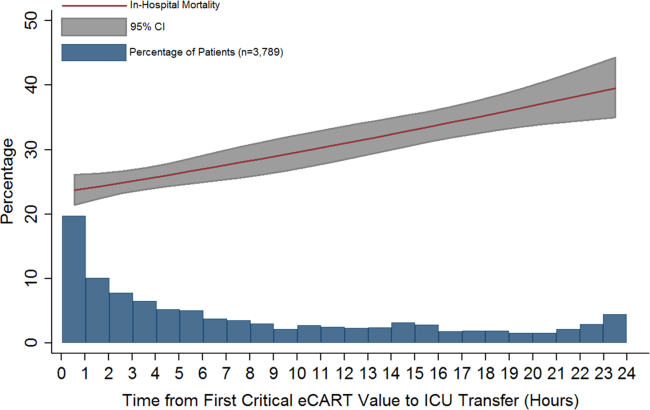

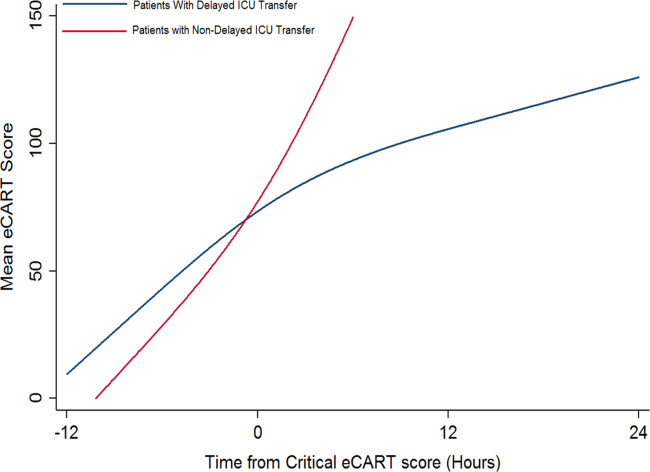

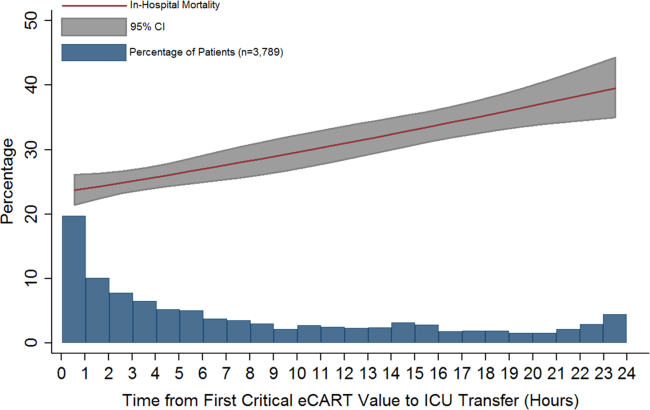

Delayed transfer occurred in 46% of patients (n=1734) and was associated with increased in‐hospital mortality (33.2% vs 24.5%, P0.001). This relationship was linear, with each 1‐hour increase in transfer delay associated with a 3% increase in the odds of in‐hospital death (P0.001) (Figure 1). The association between length of transfer delay and hospital mortality remained unchanged after controlling for age, sex, surgical status, initial eCART score on the wards, vital signs, laboratory values, and whether the ICU transfer was due to a cardiac arrest (3% increase per hour, P0.001). This association did not vary based on the initial eCART score on the wards (P=0.71 for interaction). Additionally, despite having similar median hospital lengths of stay prior to first critical eCART score (1.6 vs 1.5 days, P=0.04), patients experiencing delayed ICU transfer who survived to discharge had a longer median hospital LOS by 2 days compared to those with nondelayed transfer who survived to discharge (median LOS, 13 (821) days vs 11 (719) days, P=0.01). The change in eCART score over time in the 12 hours before first reaching the critical eCART score until ICU transfer is shown in Figure 2 for patients with delayed and nondelayed transfer. As shown, patients transferred within 6 hours had a more rapid rise in eCART score prior to ICU transfer compared to those with a delayed transfer. This difference in trajectories between delayed and nondelayed patients was similar in patients with low (13), intermediate (1359), and high (60) initial eCART scores on the wards. A regression model investigating the association between eCART slope prior to ICU transfer and time to ICU transfer demonstrated that a steeper slope was significantly associated with a decreased time to ICU transfer (P0.01).

DISCUSSION

We found that a delay in transfer to the ICU after reaching a predefined objective threshold of critical illness was associated with a significant increase in hospital mortality and hospital LOS. We also discovered a significant association between critical illness trajectory and delays in transfer, suggesting that caregivers may not recognize more subtle trends in critical illness. This work highlights the importance of timely transfer to the ICU for critically ill ward patients, which can be affected by several factors such as ICU bed availability and caregiver recognition and triage decisions. Our findings have significant implications for patient safety on the wards and provide further evidence for implementing early warning scores into practice to aid with clinical decision making.

Our findings of increased mortality with delayed ICU transfer are consistent with previous studies.[1, 5, 9] For example, Young et al. compared ICU mortality between delayed and nondelayed transfers in 91 consecutive patients with noncardiac diagnoses at a community hospital.[1] They also used predefined criteria for critical illness, and found that delayed transfers had a higher ICU mortality than nondelayed patients (41% vs 11%). However, their criteria for critical illness only had a specificity of 13% for predicting ICU transfer, compared to 95% in our study, suggesting that our threshold is more consistent with critical illness. Another study, by Cardoso and colleagues, investigated the impact of delayed ICU admission due to bed shortages on ICU mortality in 401 patients at a university hospital.[9] Of those patients deemed appropriate for transfer to the ICU but who had to wait for a bed to become available, the median wait time for a bed was 18 hours. They found that each hour of waiting was associated with a 1.5% increase in ICU death. A similar study by Robert and colleagues investigated the impact of delayed or refused ICU admission due to a lack of bed availability.[5] Patients deemed too sick (or too well) to benefit from ICU transfer were excluded. Twenty‐eightday and 60‐day mortality were higher in the admitted group compared to those not admitted, although this finding was not statistically significant. In addition, patients later admitted to the ICU once a bed became available (median wait time, 6 hours; n=89) had higher 28‐day mortality than those admitted immediately (adjusted odds ratio, 1.78; P=0.05). Several other studies have investigated the impact of ICU refusal for reasons that included bed shortages, and found increased mortality in those not admitted to the ICU.[16, 17] However, many of these studies included patients deemed too sick or too well to be transferred to the ICU in the group of nonadmitted patients. Our study adds to this literature by utilizing a highly specific objective measure of critical illness and by including all patients on the wards who reached this threshold, rather than only those for whom a consult was requested.

There are several potential explanations for our finding of increased mortality with delayed ICU transfer. First, those with delayed transfer might be different in some way from those transferred immediately. For example, we found that those with delayed transfer were older. The finding that increasing age is associated with a delay in ICU transfer is interesting, and may reflect physiologic differences in older patients compared to younger ones. For example, older patients have a lower maximum heart rate and thus may not develop the same level of vital sign abnormalities that younger patients do, causing them to be inappropriately left on the wards for too long.[18] In addition, patients with delayed transfer had more deranged renal function and lower blood pressure. It is unknown whether these organ dysfunctions would have been prevented by earlier transfer and to what degree they were related to chronic conditions. However, delayed transfer was still associated with increased mortality even after controlling for age, vital sign and laboratory values, and eCART on ward admission. It may also be possible that patients with delayed transfer received early and appropriate treatment on the wards but failed to improve and thus required ICU transfer. We did not have access to orders in this large database, so this theory will need to be investigated in future work. Finally, the most likely explanation for our findings is that earlier identification and treatment improves outcomes of critically ill patients on the wards, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies.[1, 5, 9, 10] Our study demonstrates that early identification of critical illness is crucial, and that delayed treatment can rapidly lead to increased mortality and LOS.

Our comparison of eCART score trajectory showed that patients transferred within 6 hours of onset of critical illness had a more rapid rise in eCART score over the preceding time period, whereas patients who experienced transfer delay showed a slower increase in eCART score. One explanation for this finding is that patients who decompensate more rapidly are in turn more readily recognizable to providers, whereas patients who experience a more insidious clinical deterioration are recognized later in the process, which then leads to a delay in escalation of care. This hypothesis underlines the importance of utilizing an objective marker of illness that is calculated longitudinally and in real time, as opposed to relying upon provider recognition alone. In fact, we have recently demonstrated that eCART is more accurate and identifies patients earlier than standard rapid response team activation.[19]

There are several important implications of our findings. First, it highlights the potential impact that early warning scores, particular those that are evidence based, can have on the outcomes of hospitalized patients. Second, it suggests that it is important to include age in early warning scores. Previous studies have been mixed as to whether the inclusion of age improves detection of outcomes on the wards, although the method of inclusion of age has been variable in terms of its weighting.[20, 21, 22] Our study found that older patients were more likely to be left on the wards longer prior to ICU transfer after becoming critically ill. By incorporating age into early warning scores, both accuracy and early recognition of critical illness may be improved. Finally, our finding that the trends of the eCART score differed among patients who were immediately transferred to the ICU, and who had a delay in their transfer, suggests that adding vital sign trends to early warning scores may further improve their accuracy and ability to serve as clinical decision support tools.

Our study is unique in that we used an objective measure of critical illness and then examined outcomes after patients reached this threshold on the wards. This overcomes the subjectivity of using evaluation by the ICU team or rapid response team as the starting point, as previous studies have shown a failure to call for help when patients become critically ill on the wards.[2, 11, 23] By using the eCART score, which contains commonly collected electronic health record data and can be calculated electronically in real time, we were able to calculate the score for patients on the wards and in the ICU. This allowed us to examine trends in the eCART score over time to find clues as to why some patients are transferred late to the ICU and why these late transfers have worse outcomes than those transferred earlier. Another strength is the large multicenter database used for the analysis, which included an urban tertiary care hospital, suburban teaching hospitals, and a community nonteaching hospital.

Our study has several limitations. First, we utilized just 1 of many potential measures of critical illness and a cutoff that only included one‐third of patients ultimately transferred to the ICU. However, by using the eCART score, we were able to track a patient's physiologic status over time and remove the variability that comes with using subjective definitions of critical illness. Furthermore, we utilized a high‐specificity cutoff for eCART to ensure that transferred patients had significantly deranged physiology and to avoid including planned transfers to the ICU. It is likely that some patients who were critically ill with less deranged physiology that would have benefitted from earlier transfer were excluded from the study. Second, we were unable to determine the cause of physiologic deterioration for patients in our study due to the large number of included patients. In addition, we did not have code status, comorbidities, or reason for ICU admission available in the dataset. It is likely that the impact of delayed transfer varies by the indication for ICU admission and chronic disease burden. It is also possible that controlling for these unmeasured factors could negate the beneficial association seen for earlier ICU admission. However, our finding of such a strong relationship between time to transfer and mortality after controlling for several important variables suggests that early recognition of critical illness is beneficial to many patients on the wards. Third, due to its observational nature, our study cannot estimate the true impact of timely ICU transfer on critically ill ward patient outcomes. Future clinical trials will be needed to determine the impact of electronic early warning scores on patient outcomes.

In conclusion, delayed ICU transfer is associated with significantly increased hospital LOS and mortality. This association highlights the need for ongoing work toward both the implementation of an evidence‐based risk stratification tool as well as development of effective critical care outreach resources for patients decompensating on the wards. Real‐time use of a validated early warning score, such as eCART, could potentially lead to more timely ICU transfer for critically ill patients and reduced rates of preventable in‐hospital death.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Timothy Holper, Justin Lakeman, and Contessa Hsu for assistance with data extraction and technical support; Poome Chamnankit, MS, CNP, Kelly Bhatia, MSN, ACNP, and Audrey Seitman, MSN, ACNP for performing manual chart review of cardiac arrest patients; and Nicole Twu for administrative support.

Disclosures: This research was funded in part by an institutional Clinical and Translational Science Award grant (UL1 RR024999, PI: Dr. Julian Solway). Dr. Churpek is supported by a career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08 HL121080). Drs. Churpek and Edelson have a patent pending (ARCD. P0535US.P2) for risk stratification algorithms for hospitalized patients. In addition, Dr. Edelson has received research support from Philips Healthcare (Andover, MA), the American Heart Association (Dallas, TX), and Laerdal Medical (Stavanger, Norway). She has ownership interest in Quant HC (Chicago, IL), which is developing products for risk stratification of hospitalized patients. Drs. Churpek and Wendlandt had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Preliminary versions of these data were presented at the 2015 meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine (March 31, 2015, National Harbor, MD).

- , , , , . Inpatient transfers to the intensive care unit: delays are associated with increased mortality and morbidity. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(2):77–83.

- , , , et al. Confidential inquiry into quality of care before admission to intensive care. BMJ. 1998;316(7148):1853–1858.

- , , , , , . Relationship between ICU bed availability, ICU readmission, and cardiac arrest in the general wards. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(9):2037–2041.

- , , , et al. Survival of critically ill patients hospitalized in and out of intensive care units under paucity of intensive care unit beds. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(8):1654–1661.

- , , , et al. Refusal of intensive care unit admission due to a full unit: impact on mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(10):1081–1087.

- , , , et al. Evaluation of triage decisions for intensive care admission. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(6):1073–1079.

- , , , et al. Predictors of intensive care unit refusal in French intensive care units: a multiple‐center study. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(4):750–755.

- , , , . Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV: hospital mortality assessment for today's critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(5):1297–1310.

- , , , et al. Impact of delayed admission to intensive care units on mortality of critically ill patients: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2011;15(1):R28.

- , , , et al. Reasons for refusal of admission to intensive care and impact on mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(10):1772–1779.

- , , , et al. Incidence, location and reasons for avoidable in‐hospital cardiac arrest in a district general hospital. Resuscitation. 2002;54(2):115–123.

- , , . Risk stratification of hospitalized patients on the wards. Chest. 2013;143(6):1758–1765.

- , , , et al. Multicenter development and validation of a risk stratification tool for ward patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(6):649–655.

- , , , et al. Early goal‐directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1368–1377.

- , , , et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(2):580–637.

- , , , et al. Outcomes of patients considered for, but not admitted to, the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(3):812–817.

- , , . Mortality among appropriately referred patients refused admission to intensive‐care units. Lancet. 1997;350(9070):7–11.

- , , , , . Differences in vital signs between elderly and nonelderly patients prior to ward cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(4):816–822.

- , , , , , . Real‐time risk prediction on the wards: a feasibility study [published April 13, 2016]. Crit Care Med. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001716.

- , , , et al. Should age be included as a component of track and trigger systems used to identify sick adult patients? Resuscitation. 2008;78(2):109–115.

- , , , et al. Worthing physiological scoring system: derivation and validation of a physiological early‐warning system for medical admissions. An observational, population‐based single‐centre study. Br J Anaesth. 2007;98(6):769–774.

- , , , . Validation of a modified Early Warning Score in medical admissions. QJM. 2001;94(10):521–526.

- , , , et al. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9477):2091–2097.

Patients on hospital wards may become critically ill due to worsening of the underlying condition that was the cause of their admission or acquisition of a new hospital‐acquired illness. Once physiologic deterioration occurs, some patients are evaluated and quickly transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU), whereas others are left on the wards until further deterioration occurs. Because many critical illness syndromes benefit from early intervention, such as sepsis and respiratory failure, early transfer to the ICU for treatment may improve patient outcomes, and conversely, delays in ICU transfer may lead to increased mortality and length of stay (LOS) in critically ill ward patients.[1, 2] However, the timeliness of that transfer is dependent on numerous changing variables, such as ICU bed availability, clinician identification of the deterioration, and clinical judgment regarding the appropriate transfer thresholds.[2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] As a result, there is a large degree of heterogeneity in the severity of illness of patients at the time of ICU transfer and in patient outcomes.[6, 8]

Previous studies investigating the association between delayed ICU transfer and patient outcomes have typically utilized the time of consultation by the ICU team to denote the onset of critical illness.[5, 6, 9, 10] However, the decision to transfer a patient to the ICU is often subjective, and previous studies have found an alarmingly high rate of errors in diagnosis and management of critically ill ward patients, including the failure to call for help.[2, 11] Therefore, a more objective tool for quantifying critical illness is necessary for determining the onset of critical illness and quantifying the association of transfer delay with patient outcomes.

Early warning scores, which are designed to detect critical illness on the wards, represent objective measures of critical illness that can be easily calculated in ward patients.[12] The aim of this study was to utilize the electronic Cardiac Arrest Risk Triage (eCART) score, a previously published, statistically derived early warning score that utilizes demographic, vital sign, and laboratory data, as an objective measure of critical illness to estimate the effect of delayed ICU transfer on patient outcomes in a large, multicenter database.[13] We chose 6 hours as the cutoff for delay in this study a priori because it is a threshold noted to be an important time period in critical illness syndromes, such as sepsis.[14, 15]

METHODS

All patients admitted to the medical‐surgical wards at 5 hospitals between November 2008 and January 2013 were eligible for inclusion in this observational cohort study. Further details of the hospital populations have been previously described.[13] A waiver of consent was granted by NorthShore University HealthSystem (IRB #EH11‐258) and the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board (IRB #16995A) based on general impracticability and minimal harm. Collection of patient information was designed to comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) regulations.

Defining the Onset of Critical Illness

The eCART score, a statistically derived early warning score that is calculated based on patient demographic, vital sign, and laboratory data, was used as an objective measure of critical illness.[13] Score calculation was performed utilizing demographic information from administrative databases and time‐ and location‐stamped vital signs and laboratory results from data warehouses at the respective institutions. In this study, a score was calculated for each time‐stamped point in the entire dataset. Of note, eCART was not used in this population for patient care as this was a retrospective observational study. An eCART score at the 95% specificity cutoff for ICU transfer from the entire dataset defined a ward patient as critically ill, a definition created a priori and before any data analysis was performed.

Defining ICU Transfer Delay and Study Outcomes

The period of time from when a patient first reached this predefined eCART score to ICU transfer was calculated for each patient, up to a maximum of 24 hours. Transfer to the ICU greater than 6 hours after reaching the critical eCART score was defined a priori as a delayed transfer to allow comparisons between patients with nondelayed and delayed transfer. A patient who suffered a ward cardiac arrest with attempted resuscitation was counted as an ICU transfer at the time of arrest. If a patient experienced more than 1 ICU transfer during the admission, then only the first ward to ICU transfer was used. The primary outcome of the study was in‐hospital mortality, and secondary outcomes were ICU mortality and hospital LOS.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics were compared between patients who experienced delayed and nondelayed ICU transfers using t tests, Wilcoxon rank sums, and [2] tests, as appropriate. The association between length of transfer delay and in‐hospital mortality was calculated using logistic regression, with adjustment for age, sex, and surgical status. In a post hoc sensitivity analysis, additional adjustments were made using each patient's first eCART score on the ward, the individual vital signs and laboratory variables from eCART, and whether the ICU transfer was due to a cardiac arrest on the wards. In addition, an interaction term between time to transfer and the initial eCART on the ward was added to determine if the association between delay and mortality varied by baseline severity. The change in eCART score over time was plotted from 12 hours before the time of first reaching the critical value until ICU transfer for those in the delayed and nondelayed groups using restricted cubic splines to compare the trajectories of severity of illness between these 2 groups. In addition, a linear regression model was fit to investigate the association between the eCART slope in the 8 hours prior to the critical eCART value until ICU transfer and the timing of ICU transfer delay. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and all tests of significance used a 2‐sided P0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 269,999 admissions had documented vital signs on the hospital wards during the study period, including 11,995 patients who were either transferred from the wards to the ICU (n=11,636) or who suffered a cardiac arrest on the wards (n=359) during their initial ward stay. Of these patients, 3789 reached an eCART score at the 95% specificity cutoff (critical eCART score of 60) within 24 hours of transfer. The median time from first critical eCART value to ICU transfer was 5.4 hours (interquartile range (IQR), 214 hours; mean, 8 hours). Compared to patients without delayed ICU transfer, those with delayed transfer were slightly older (median age, 73 [IQR, 6083] years vs 71 [IQR, 5882] years; P=0.002), whereas all other characteristics were similar (Table 1). Table 2 shows comparisons of vital sign and laboratory results for delayed and nondelayed transfers at the time of ICU transfer. As shown, patients with delayed transfer had lower median respiratory rate, blood pressure, heart rate, and hemoglobin, but higher median white blood cell count and creatinine.

| Characteristic | Transferred Within 6 Hours, n=2,055 | Transfer Delayed, n=1,734 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 71 (5882) | 73 (6083) | 0.002 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 1,018 (49.5) | 847 (48.8) | 0.67 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.72 | ||

| Black | 467 (22.7) | 374 (21.6) | |

| White | 1,141 (55.5) | 971 (56.0) | |

| Other/unknown | 447 (21.8) | 389 (22.4) | |

| Surgical patient, n (%) | 572 (27.8) | 438 (25.2) | 0.07 |

| Hospital LOS prior to first critical eCART, median (IQR), d | 1.5 (0.33.7) | 1.6 (0.43.9) | 0.04 |

| Total hospital LOS, median (IQR), d* | 11 (719) | 13 (821) | 0.001 |

| Died during admission, n (%) | 503 (24.5) | 576 (33.2) | 0.001 |

| Transferred Within 6 Hours, n=2,055 | Transfer Delayed, n=1,734 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min | 23 (1830) | 22 (1828) | 0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 111 (92134) | 109 (92128) | 0.002 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 61 (5075) | 59 (4971) | 0.001 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 106 (88124) | 101 (85117) | 0.001 |

| Oxygen saturation, median (IQR), % | 97 (9499) | 97 (9599) | 0.15 |

| Temperature, F | 98.0 (97.299.1) | 98.0 (97.199.0) | 0.001 |

| Alert mental status, number of observations (%) | 1,749 (85%) | 1,431 (83%) | 0.001 |

| eCART score at time of ICU transfer | 61 (26122) | 48 (21121) | 0.914 |

| WBC | 10.3 (7.514.5) | 11.7 (8.117.0) | 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin | 10.7 (9.312.0) | 10.3 (9.111.6) | 0.001 |

| Platelet | 215 (137275) | 195 (120269) | 0.017 |

| Sodium | 137 (134140) | 137 (134141) | 0.70 |

| K+ | 4.1 (3.84.6) | 4.2 (3.84.7) | 0.006 |

| Anion Gap | 10 (813) | 10 (814) | 0.001 |

| CO2 | 24 (2026) | 23 (1826) | 0.001 |

| BUN | 24 (1640) | 32 (1853) | 0.001 |

| Cr | 1.2 (0.92.0) | 1.5 (1.02.7) | 0.001 |

| GFR | 70 (7070) | 70 (5170) | 0.001 |

| Glucose | 123 (106161) | 129 (105164) | 0.48 |

| Calcium | 8.5 (7.98.8) | 8.2 (7.78.7) | 0.001 |

| SGOT | 26 (2635) | 26 (2644) | 0.001 |

| SGPT | 21 (2127) | 21 (2033) | 0.002 |

| Total bilirubin | 0.7 (0.71.0) | 0.7 (0.71.3) | 0.001 |

| Alk phos | 80 (8096) | 80 (79111) | 0.175 |

| Albumin | 3.0 (2.73.0) | 3.0 (2.43.0) | 0.001 |

Delayed transfer occurred in 46% of patients (n=1734) and was associated with increased in‐hospital mortality (33.2% vs 24.5%, P0.001). This relationship was linear, with each 1‐hour increase in transfer delay associated with a 3% increase in the odds of in‐hospital death (P0.001) (Figure 1). The association between length of transfer delay and hospital mortality remained unchanged after controlling for age, sex, surgical status, initial eCART score on the wards, vital signs, laboratory values, and whether the ICU transfer was due to a cardiac arrest (3% increase per hour, P0.001). This association did not vary based on the initial eCART score on the wards (P=0.71 for interaction). Additionally, despite having similar median hospital lengths of stay prior to first critical eCART score (1.6 vs 1.5 days, P=0.04), patients experiencing delayed ICU transfer who survived to discharge had a longer median hospital LOS by 2 days compared to those with nondelayed transfer who survived to discharge (median LOS, 13 (821) days vs 11 (719) days, P=0.01). The change in eCART score over time in the 12 hours before first reaching the critical eCART score until ICU transfer is shown in Figure 2 for patients with delayed and nondelayed transfer. As shown, patients transferred within 6 hours had a more rapid rise in eCART score prior to ICU transfer compared to those with a delayed transfer. This difference in trajectories between delayed and nondelayed patients was similar in patients with low (13), intermediate (1359), and high (60) initial eCART scores on the wards. A regression model investigating the association between eCART slope prior to ICU transfer and time to ICU transfer demonstrated that a steeper slope was significantly associated with a decreased time to ICU transfer (P0.01).

DISCUSSION

We found that a delay in transfer to the ICU after reaching a predefined objective threshold of critical illness was associated with a significant increase in hospital mortality and hospital LOS. We also discovered a significant association between critical illness trajectory and delays in transfer, suggesting that caregivers may not recognize more subtle trends in critical illness. This work highlights the importance of timely transfer to the ICU for critically ill ward patients, which can be affected by several factors such as ICU bed availability and caregiver recognition and triage decisions. Our findings have significant implications for patient safety on the wards and provide further evidence for implementing early warning scores into practice to aid with clinical decision making.

Our findings of increased mortality with delayed ICU transfer are consistent with previous studies.[1, 5, 9] For example, Young et al. compared ICU mortality between delayed and nondelayed transfers in 91 consecutive patients with noncardiac diagnoses at a community hospital.[1] They also used predefined criteria for critical illness, and found that delayed transfers had a higher ICU mortality than nondelayed patients (41% vs 11%). However, their criteria for critical illness only had a specificity of 13% for predicting ICU transfer, compared to 95% in our study, suggesting that our threshold is more consistent with critical illness. Another study, by Cardoso and colleagues, investigated the impact of delayed ICU admission due to bed shortages on ICU mortality in 401 patients at a university hospital.[9] Of those patients deemed appropriate for transfer to the ICU but who had to wait for a bed to become available, the median wait time for a bed was 18 hours. They found that each hour of waiting was associated with a 1.5% increase in ICU death. A similar study by Robert and colleagues investigated the impact of delayed or refused ICU admission due to a lack of bed availability.[5] Patients deemed too sick (or too well) to benefit from ICU transfer were excluded. Twenty‐eightday and 60‐day mortality were higher in the admitted group compared to those not admitted, although this finding was not statistically significant. In addition, patients later admitted to the ICU once a bed became available (median wait time, 6 hours; n=89) had higher 28‐day mortality than those admitted immediately (adjusted odds ratio, 1.78; P=0.05). Several other studies have investigated the impact of ICU refusal for reasons that included bed shortages, and found increased mortality in those not admitted to the ICU.[16, 17] However, many of these studies included patients deemed too sick or too well to be transferred to the ICU in the group of nonadmitted patients. Our study adds to this literature by utilizing a highly specific objective measure of critical illness and by including all patients on the wards who reached this threshold, rather than only those for whom a consult was requested.

There are several potential explanations for our finding of increased mortality with delayed ICU transfer. First, those with delayed transfer might be different in some way from those transferred immediately. For example, we found that those with delayed transfer were older. The finding that increasing age is associated with a delay in ICU transfer is interesting, and may reflect physiologic differences in older patients compared to younger ones. For example, older patients have a lower maximum heart rate and thus may not develop the same level of vital sign abnormalities that younger patients do, causing them to be inappropriately left on the wards for too long.[18] In addition, patients with delayed transfer had more deranged renal function and lower blood pressure. It is unknown whether these organ dysfunctions would have been prevented by earlier transfer and to what degree they were related to chronic conditions. However, delayed transfer was still associated with increased mortality even after controlling for age, vital sign and laboratory values, and eCART on ward admission. It may also be possible that patients with delayed transfer received early and appropriate treatment on the wards but failed to improve and thus required ICU transfer. We did not have access to orders in this large database, so this theory will need to be investigated in future work. Finally, the most likely explanation for our findings is that earlier identification and treatment improves outcomes of critically ill patients on the wards, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies.[1, 5, 9, 10] Our study demonstrates that early identification of critical illness is crucial, and that delayed treatment can rapidly lead to increased mortality and LOS.