User login

4 technology tools ObGyns can apply in practice

Over the past 15 years a technological tsunami has swept through the health care industry, and few physicians were prepared for the changes wrought by this tidal wave. It now is clear, however, that we are and will have to continue to navigate a future increasingly powered and populated by technology if we are to be successful clinicians. In addition, we must learn to take advantage of all that technology has to offer without compromising the quality of care and compassion we offer our patients. We are fortunate that technology has much to offer to enhance patient care.

One big change under way: Technology is leveling the playing field between doctors—once the high priests of medicine—and ordinary people. SMART (social, mobile, aware, and real-time) technologies such as cloud computing will broaden the setting of health care interventions from hospital rooms and doctors’ offices to patients’ everyday lives. Cloud computing involves the use of a network of remote servers hosted on the Internet to store, manage, and process data, rather than a local server or a desktop computer located in the doctor’s office. It is possible that, instead of being episodic, health care will be conducted continuously—and anywhere the patient wants it.

Without a doubt, the pace at which new technology affects our lives is increasing at lightning speeds. Today, 29% of Americans say their phone is the first and the last thing they look at each day, a telling sign of how dependent we are becoming on technology.1 In this article, we look at 4 technologies that can be effective in the clinical setting, attracting new patients and enhancing productivity, communication, and patient care.

1. A mobile-friendly Web site

According to Wikipedia, there are 327,577,529 mobile phones in the United States, give or take a few thousand. As of July 4, 2014, the US population was 318,881,992. That means there are more mobile phones in this country than there are people!2

Mobile phones are becoming more like personal assistants than phones. People are not just making calls, they’re buying movie tickets, checking the weather, sending and receiving emails, texting, making reservations, checking Web sites … and the list goes on.

According to a recent report from the Pew Research Center, almost two-thirds of Americans own a smartphone, and 62% of smartphone owners have used it to look up information on a health condition.3 Moreover, 15% of smartphone owners say they have a limited number of ways to access the Internet other than their cell phone.3

All the more reason for your Web site to be mobile-friendly. With a mobile- friendly site, the content is displayed in a more streamlined fashion on mobile phones, with larger type to make it more readable. See, for example, the FIGURE, which shows Dr. Baum’s regular Web site side by side with the mobile-friendly view.

There is another reason why you should ensure that your site is mobile-friendly: Google recently changed its algorithms so that, when someone searches for information on a mobile phone, only mobile- friendly sites make it into the top search results. Google wants mobile phone users to have a positive experience online. It is so adamant about this desire that it will lower your rankings or not show your Web site at all in search results if you fail to comply.

New patient acquisition is critical for any ObGyn practice, and we already know that just about everyone goes online to search for health information and solutions to their medical problems. If you want your practice to survive and thrive, you need to attract new patients online. If a visitor to your site cannot read the text and has to keep resizing the screen and scrolling left and right, you will lose that visitor in a hurry.

We all want to find what we are looking for quickly. In our experience, when we check Google Analytics reports for our ObGyn clients, we find that visitors to a nonresponsive site spend much less time there and do not visit as many pages as they do when a site is mobile-responsive.

To check your Web site’s mobile rating, go to http://www.google.com/webmasters/tools/mobile-friendly. Google also offers tips on making your site mobile-friendly at https://support.google.com/webmasters/answer/6001177?hl=en.

Once your site is up to snuff, you should test it from multiple devices to ensure that the pages are easily readable on all types of phones and computers.

2. Voice recognition software

Speech recognition is the ability of a machine or program to identify words and phrases in spoken language and convert them to a digital format. This tool can help you generate clinical notes and charting without having to stop and type into a computer. This can enhance your interactions with patients by freeing you from the computer during examinations and counseling and allows you to look at the patient and not at the computer.

According to data from June 2000, approximately 5% of physicians used speech recognition to generate text in their offices.4 A white paper from 2008 found that approximately 20% of physicians are using more advanced, more reliable voice recognition technology and saving both time and money.5 This report cited 2007 data showing that:

- 76% of clinicians who used “desktop speech recognition” (directly controlling an electronic health record [EHR] system via speech) reported faster turnaround time, better patient care, and quicker reimbursement

- Nearly 30% reported lower costs and increased productivity as benefits. The lower costs arise from reduced transcription and overhead expenses associated with billings and collection.5

The voice recognition software used in Dr. Neil Baum’s office is Dragon Medical Practice Edition 2 (www.dragonmedicalpractice.com). Dragon requires a good processor and a minimum of 4 gigabytes of RAM and will run with VMware, Boot Camp, Parallels, and other programs for Mac users. The software contains 80 subspecialty medical vocabularies and is easy to install. After a few minutes, the program learns how you speak and will understand you well with remarkable accuracy. However, to get the greatest benefit from the technology, you will need to invest in training, implementation, and workflow services to allow you to use the program to its full potential in record time.

Dr. Baum uses The Dragon People voice recognition software (www.thedragonpeople.com).

Although voice recognition software can reduce or eliminate transcription costs, improve documentation time, and boost the quality of medical notes, it is critical that you investigate how a particular program fits with your EHR prior to purchasing it—and a salesperson may try to gloss over this issue. In addition, the more you use voice recognition instead of checking off pull-down boxes for your clinical notes, the more difficult it will be to mine your data for quality metrics and pay-for-performance information. For that reason, voice recognition technology may be strongly discouraged by your employer or governing organization.

3. Online lab result reporting

TeleVox’s automated lab results (www .televox.com/lab-test-results-delivery) allow physicians or staff to assign lab result messages quickly and easily with the click of a mouse. Patients call an 800 number or use an Internet connection to retrieve their results, using a unique PIN to ensure privacy.

Practices that implement this technology see immediate improvements in 3 areas:

- Streamlined operations. This technology allows lab result messages to be assigned to patients with a few mouse clicks, saving time spent on phone calls and mailing coordination.

- Reduced costs. Automated lab result reporting reduces staff labor and mailing costs.

- Ease of access. Patients have round-the-clock access to their information—no more waiting for mail delivery or a phone call. Patients also can choose to be notified when their results are ready, which helps alleviate anxiety.

4. Automated wait-time notification

The most common complaint patients have about their health care experience is the excessive wait times they often experience. Now there are technologies that can provide automated information to let patients know how long they will have to wait to be seen.

A program such as MedWaitTime (www.medwaittime.com) can alert patients about the estimated wait time at a cost of approximately $50 per month per physician. Patients access the service for free.

In addition, many EHRs include practice management features to notify the staff and physician whether he or she is on time. These features may include a tie-in to alert patients as well.

The bottom line

Carefully selected technological tools have much to offer busy clinicians. By ensuring that your practice Web site is mobile- friendly, you stand to attract new patients. And the time you save with voice recognition software and computerized lab test result notification can allow you to spend more time with your patients. It can also help eliminate the lag in your patient schedule, keeping the women in your waiting room happy. Remember, a happy patient means a happy doctor!

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Your Wireless Life: Results of TIME’s Mobility Poll. http://content.time.com/time/interactive/0,31813,2122187,00.html. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Wikipedia: List of Countries by Number of Mobile Phones in Use. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_number_of_mobile_phones_in_use. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Smith A. US Smartphone Use in 2015. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/01/us-smartphone-use-in-2015. Published April 1, 2015. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Maisel JM, Wisnicki HJ. Documenting the medical encounter with speech recognition. Ophthalmol Times. 2002;27(5):38.

- Nuance Communications. Speech recognition: accelerating the adoption of electronic medical records. http://www.nuance.com/healthcare/pdf/wp_healthcareMDEMRadopt.pdf. Published 2008. Accessed July 30, 2015.

Over the past 15 years a technological tsunami has swept through the health care industry, and few physicians were prepared for the changes wrought by this tidal wave. It now is clear, however, that we are and will have to continue to navigate a future increasingly powered and populated by technology if we are to be successful clinicians. In addition, we must learn to take advantage of all that technology has to offer without compromising the quality of care and compassion we offer our patients. We are fortunate that technology has much to offer to enhance patient care.

One big change under way: Technology is leveling the playing field between doctors—once the high priests of medicine—and ordinary people. SMART (social, mobile, aware, and real-time) technologies such as cloud computing will broaden the setting of health care interventions from hospital rooms and doctors’ offices to patients’ everyday lives. Cloud computing involves the use of a network of remote servers hosted on the Internet to store, manage, and process data, rather than a local server or a desktop computer located in the doctor’s office. It is possible that, instead of being episodic, health care will be conducted continuously—and anywhere the patient wants it.

Without a doubt, the pace at which new technology affects our lives is increasing at lightning speeds. Today, 29% of Americans say their phone is the first and the last thing they look at each day, a telling sign of how dependent we are becoming on technology.1 In this article, we look at 4 technologies that can be effective in the clinical setting, attracting new patients and enhancing productivity, communication, and patient care.

1. A mobile-friendly Web site

According to Wikipedia, there are 327,577,529 mobile phones in the United States, give or take a few thousand. As of July 4, 2014, the US population was 318,881,992. That means there are more mobile phones in this country than there are people!2

Mobile phones are becoming more like personal assistants than phones. People are not just making calls, they’re buying movie tickets, checking the weather, sending and receiving emails, texting, making reservations, checking Web sites … and the list goes on.

According to a recent report from the Pew Research Center, almost two-thirds of Americans own a smartphone, and 62% of smartphone owners have used it to look up information on a health condition.3 Moreover, 15% of smartphone owners say they have a limited number of ways to access the Internet other than their cell phone.3

All the more reason for your Web site to be mobile-friendly. With a mobile- friendly site, the content is displayed in a more streamlined fashion on mobile phones, with larger type to make it more readable. See, for example, the FIGURE, which shows Dr. Baum’s regular Web site side by side with the mobile-friendly view.

There is another reason why you should ensure that your site is mobile-friendly: Google recently changed its algorithms so that, when someone searches for information on a mobile phone, only mobile- friendly sites make it into the top search results. Google wants mobile phone users to have a positive experience online. It is so adamant about this desire that it will lower your rankings or not show your Web site at all in search results if you fail to comply.

New patient acquisition is critical for any ObGyn practice, and we already know that just about everyone goes online to search for health information and solutions to their medical problems. If you want your practice to survive and thrive, you need to attract new patients online. If a visitor to your site cannot read the text and has to keep resizing the screen and scrolling left and right, you will lose that visitor in a hurry.

We all want to find what we are looking for quickly. In our experience, when we check Google Analytics reports for our ObGyn clients, we find that visitors to a nonresponsive site spend much less time there and do not visit as many pages as they do when a site is mobile-responsive.

To check your Web site’s mobile rating, go to http://www.google.com/webmasters/tools/mobile-friendly. Google also offers tips on making your site mobile-friendly at https://support.google.com/webmasters/answer/6001177?hl=en.

Once your site is up to snuff, you should test it from multiple devices to ensure that the pages are easily readable on all types of phones and computers.

2. Voice recognition software

Speech recognition is the ability of a machine or program to identify words and phrases in spoken language and convert them to a digital format. This tool can help you generate clinical notes and charting without having to stop and type into a computer. This can enhance your interactions with patients by freeing you from the computer during examinations and counseling and allows you to look at the patient and not at the computer.

According to data from June 2000, approximately 5% of physicians used speech recognition to generate text in their offices.4 A white paper from 2008 found that approximately 20% of physicians are using more advanced, more reliable voice recognition technology and saving both time and money.5 This report cited 2007 data showing that:

- 76% of clinicians who used “desktop speech recognition” (directly controlling an electronic health record [EHR] system via speech) reported faster turnaround time, better patient care, and quicker reimbursement

- Nearly 30% reported lower costs and increased productivity as benefits. The lower costs arise from reduced transcription and overhead expenses associated with billings and collection.5

The voice recognition software used in Dr. Neil Baum’s office is Dragon Medical Practice Edition 2 (www.dragonmedicalpractice.com). Dragon requires a good processor and a minimum of 4 gigabytes of RAM and will run with VMware, Boot Camp, Parallels, and other programs for Mac users. The software contains 80 subspecialty medical vocabularies and is easy to install. After a few minutes, the program learns how you speak and will understand you well with remarkable accuracy. However, to get the greatest benefit from the technology, you will need to invest in training, implementation, and workflow services to allow you to use the program to its full potential in record time.

Dr. Baum uses The Dragon People voice recognition software (www.thedragonpeople.com).

Although voice recognition software can reduce or eliminate transcription costs, improve documentation time, and boost the quality of medical notes, it is critical that you investigate how a particular program fits with your EHR prior to purchasing it—and a salesperson may try to gloss over this issue. In addition, the more you use voice recognition instead of checking off pull-down boxes for your clinical notes, the more difficult it will be to mine your data for quality metrics and pay-for-performance information. For that reason, voice recognition technology may be strongly discouraged by your employer or governing organization.

3. Online lab result reporting

TeleVox’s automated lab results (www .televox.com/lab-test-results-delivery) allow physicians or staff to assign lab result messages quickly and easily with the click of a mouse. Patients call an 800 number or use an Internet connection to retrieve their results, using a unique PIN to ensure privacy.

Practices that implement this technology see immediate improvements in 3 areas:

- Streamlined operations. This technology allows lab result messages to be assigned to patients with a few mouse clicks, saving time spent on phone calls and mailing coordination.

- Reduced costs. Automated lab result reporting reduces staff labor and mailing costs.

- Ease of access. Patients have round-the-clock access to their information—no more waiting for mail delivery or a phone call. Patients also can choose to be notified when their results are ready, which helps alleviate anxiety.

4. Automated wait-time notification

The most common complaint patients have about their health care experience is the excessive wait times they often experience. Now there are technologies that can provide automated information to let patients know how long they will have to wait to be seen.

A program such as MedWaitTime (www.medwaittime.com) can alert patients about the estimated wait time at a cost of approximately $50 per month per physician. Patients access the service for free.

In addition, many EHRs include practice management features to notify the staff and physician whether he or she is on time. These features may include a tie-in to alert patients as well.

The bottom line

Carefully selected technological tools have much to offer busy clinicians. By ensuring that your practice Web site is mobile- friendly, you stand to attract new patients. And the time you save with voice recognition software and computerized lab test result notification can allow you to spend more time with your patients. It can also help eliminate the lag in your patient schedule, keeping the women in your waiting room happy. Remember, a happy patient means a happy doctor!

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Over the past 15 years a technological tsunami has swept through the health care industry, and few physicians were prepared for the changes wrought by this tidal wave. It now is clear, however, that we are and will have to continue to navigate a future increasingly powered and populated by technology if we are to be successful clinicians. In addition, we must learn to take advantage of all that technology has to offer without compromising the quality of care and compassion we offer our patients. We are fortunate that technology has much to offer to enhance patient care.

One big change under way: Technology is leveling the playing field between doctors—once the high priests of medicine—and ordinary people. SMART (social, mobile, aware, and real-time) technologies such as cloud computing will broaden the setting of health care interventions from hospital rooms and doctors’ offices to patients’ everyday lives. Cloud computing involves the use of a network of remote servers hosted on the Internet to store, manage, and process data, rather than a local server or a desktop computer located in the doctor’s office. It is possible that, instead of being episodic, health care will be conducted continuously—and anywhere the patient wants it.

Without a doubt, the pace at which new technology affects our lives is increasing at lightning speeds. Today, 29% of Americans say their phone is the first and the last thing they look at each day, a telling sign of how dependent we are becoming on technology.1 In this article, we look at 4 technologies that can be effective in the clinical setting, attracting new patients and enhancing productivity, communication, and patient care.

1. A mobile-friendly Web site

According to Wikipedia, there are 327,577,529 mobile phones in the United States, give or take a few thousand. As of July 4, 2014, the US population was 318,881,992. That means there are more mobile phones in this country than there are people!2

Mobile phones are becoming more like personal assistants than phones. People are not just making calls, they’re buying movie tickets, checking the weather, sending and receiving emails, texting, making reservations, checking Web sites … and the list goes on.

According to a recent report from the Pew Research Center, almost two-thirds of Americans own a smartphone, and 62% of smartphone owners have used it to look up information on a health condition.3 Moreover, 15% of smartphone owners say they have a limited number of ways to access the Internet other than their cell phone.3

All the more reason for your Web site to be mobile-friendly. With a mobile- friendly site, the content is displayed in a more streamlined fashion on mobile phones, with larger type to make it more readable. See, for example, the FIGURE, which shows Dr. Baum’s regular Web site side by side with the mobile-friendly view.

There is another reason why you should ensure that your site is mobile-friendly: Google recently changed its algorithms so that, when someone searches for information on a mobile phone, only mobile- friendly sites make it into the top search results. Google wants mobile phone users to have a positive experience online. It is so adamant about this desire that it will lower your rankings or not show your Web site at all in search results if you fail to comply.

New patient acquisition is critical for any ObGyn practice, and we already know that just about everyone goes online to search for health information and solutions to their medical problems. If you want your practice to survive and thrive, you need to attract new patients online. If a visitor to your site cannot read the text and has to keep resizing the screen and scrolling left and right, you will lose that visitor in a hurry.

We all want to find what we are looking for quickly. In our experience, when we check Google Analytics reports for our ObGyn clients, we find that visitors to a nonresponsive site spend much less time there and do not visit as many pages as they do when a site is mobile-responsive.

To check your Web site’s mobile rating, go to http://www.google.com/webmasters/tools/mobile-friendly. Google also offers tips on making your site mobile-friendly at https://support.google.com/webmasters/answer/6001177?hl=en.

Once your site is up to snuff, you should test it from multiple devices to ensure that the pages are easily readable on all types of phones and computers.

2. Voice recognition software

Speech recognition is the ability of a machine or program to identify words and phrases in spoken language and convert them to a digital format. This tool can help you generate clinical notes and charting without having to stop and type into a computer. This can enhance your interactions with patients by freeing you from the computer during examinations and counseling and allows you to look at the patient and not at the computer.

According to data from June 2000, approximately 5% of physicians used speech recognition to generate text in their offices.4 A white paper from 2008 found that approximately 20% of physicians are using more advanced, more reliable voice recognition technology and saving both time and money.5 This report cited 2007 data showing that:

- 76% of clinicians who used “desktop speech recognition” (directly controlling an electronic health record [EHR] system via speech) reported faster turnaround time, better patient care, and quicker reimbursement

- Nearly 30% reported lower costs and increased productivity as benefits. The lower costs arise from reduced transcription and overhead expenses associated with billings and collection.5

The voice recognition software used in Dr. Neil Baum’s office is Dragon Medical Practice Edition 2 (www.dragonmedicalpractice.com). Dragon requires a good processor and a minimum of 4 gigabytes of RAM and will run with VMware, Boot Camp, Parallels, and other programs for Mac users. The software contains 80 subspecialty medical vocabularies and is easy to install. After a few minutes, the program learns how you speak and will understand you well with remarkable accuracy. However, to get the greatest benefit from the technology, you will need to invest in training, implementation, and workflow services to allow you to use the program to its full potential in record time.

Dr. Baum uses The Dragon People voice recognition software (www.thedragonpeople.com).

Although voice recognition software can reduce or eliminate transcription costs, improve documentation time, and boost the quality of medical notes, it is critical that you investigate how a particular program fits with your EHR prior to purchasing it—and a salesperson may try to gloss over this issue. In addition, the more you use voice recognition instead of checking off pull-down boxes for your clinical notes, the more difficult it will be to mine your data for quality metrics and pay-for-performance information. For that reason, voice recognition technology may be strongly discouraged by your employer or governing organization.

3. Online lab result reporting

TeleVox’s automated lab results (www .televox.com/lab-test-results-delivery) allow physicians or staff to assign lab result messages quickly and easily with the click of a mouse. Patients call an 800 number or use an Internet connection to retrieve their results, using a unique PIN to ensure privacy.

Practices that implement this technology see immediate improvements in 3 areas:

- Streamlined operations. This technology allows lab result messages to be assigned to patients with a few mouse clicks, saving time spent on phone calls and mailing coordination.

- Reduced costs. Automated lab result reporting reduces staff labor and mailing costs.

- Ease of access. Patients have round-the-clock access to their information—no more waiting for mail delivery or a phone call. Patients also can choose to be notified when their results are ready, which helps alleviate anxiety.

4. Automated wait-time notification

The most common complaint patients have about their health care experience is the excessive wait times they often experience. Now there are technologies that can provide automated information to let patients know how long they will have to wait to be seen.

A program such as MedWaitTime (www.medwaittime.com) can alert patients about the estimated wait time at a cost of approximately $50 per month per physician. Patients access the service for free.

In addition, many EHRs include practice management features to notify the staff and physician whether he or she is on time. These features may include a tie-in to alert patients as well.

The bottom line

Carefully selected technological tools have much to offer busy clinicians. By ensuring that your practice Web site is mobile- friendly, you stand to attract new patients. And the time you save with voice recognition software and computerized lab test result notification can allow you to spend more time with your patients. It can also help eliminate the lag in your patient schedule, keeping the women in your waiting room happy. Remember, a happy patient means a happy doctor!

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Your Wireless Life: Results of TIME’s Mobility Poll. http://content.time.com/time/interactive/0,31813,2122187,00.html. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Wikipedia: List of Countries by Number of Mobile Phones in Use. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_number_of_mobile_phones_in_use. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Smith A. US Smartphone Use in 2015. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/01/us-smartphone-use-in-2015. Published April 1, 2015. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Maisel JM, Wisnicki HJ. Documenting the medical encounter with speech recognition. Ophthalmol Times. 2002;27(5):38.

- Nuance Communications. Speech recognition: accelerating the adoption of electronic medical records. http://www.nuance.com/healthcare/pdf/wp_healthcareMDEMRadopt.pdf. Published 2008. Accessed July 30, 2015.

- Your Wireless Life: Results of TIME’s Mobility Poll. http://content.time.com/time/interactive/0,31813,2122187,00.html. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Wikipedia: List of Countries by Number of Mobile Phones in Use. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_number_of_mobile_phones_in_use. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Smith A. US Smartphone Use in 2015. Pew Research Center. http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/01/us-smartphone-use-in-2015. Published April 1, 2015. Accessed July 29, 2015.

- Maisel JM, Wisnicki HJ. Documenting the medical encounter with speech recognition. Ophthalmol Times. 2002;27(5):38.

- Nuance Communications. Speech recognition: accelerating the adoption of electronic medical records. http://www.nuance.com/healthcare/pdf/wp_healthcareMDEMRadopt.pdf. Published 2008. Accessed July 30, 2015.

In this Article

- Voice recognition software lets you look at your patient

- Patients can retrieve online lab results

Which vaginal procedure is best for uterine prolapse?

More than one-third of women aged 45 years or older experience uterine prolapse, a condition that can impair physical, psychological, and sexual function. To compare vaginal vault suspension with hysterectomy, investigators at 4 large Dutch teaching hospitals from 2009 to 2012 randomly assigned women with uterine prolapse to sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSLF) or vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS). The primary outcome was recurrent stage 2 or greater prolapse (within 1 cm or more of the hymenal ring) with bothersome bulge symptoms or repeat surgery for prolapse by 12 months follow-up.

Details of the trialOne hundred two women assigned to SSLF (median age, 62.7 years) and 100 assigned to hysterectomy with ULS (median age, 61.9 years) were analyzed for the primary outcome. The patients ranged in age from 33 to 85 years.

Surgical failure rates and adverse events were similarMean hospital stay was 3 days in both groups and the occurrence of urinary retention was likewise similar (15% for SSLF and 11% for hysterectomy with ULS). At 12 months, 0 and 4 women in the SSLF and hysterectomy with ULS groups, respectively, met the primary outcome. Study participants were considered a “surgical failure” if any type of prolapse with bothersome symptoms or repeat surgery or pessary use occurred. Failures occurred in approximately one-half of the women in both groups.

Rates of serious adverse events were low, and none were related to type of surgery. Nine women experienced buttock pain following SSLF hysteropexy, a known complication of this surgery. This pain resolved within 6 weeks in 8 of these women. In the remaining woman, persistent pain led to release of the hysteropexy suture and vaginal hysterectomy 4 months after her initial procedure.

What this evidence means for practice

Advantages of hysterectomy at the time of vaginal vault suspension include prevention of endometrial and cervical cancers as well as elimination of uterine bleeding. However, data from published surveys indicate that many US women with prolapse prefer to avoid hysterectomy if effective alternate surgeries are available.1

In the previously published 2014 Barber and colleagues’ OPTIMAL trial,1,2 the efficacy of vaginal hysterectomy with either SSLF or USL was equivalent (63.1% versus 64.5%, respectively). The success rates are lower for both procedures in this trial by Detollenaere and colleagues.

Both SSLF and ULS may result in life-altering buttock or leg pain, necessitating removal of the offending sutures; however, the ULS procedure offers a more anatomically correct result. Although the short follow-up interval represents a limitation, these trial results suggest that sacrospinous fixation without hysterectomy represents a reasonable option for women with bothersome uterine prolapse who would like to avoid hysterectomy.

—Meadow M. Good, DO, and Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Korbly N, Kassis N, Good MM, et al. Patient preference for uterine preservation in women with pelvic organ prolapse: a fellow’s pelvic network research study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):470.e1−e6.

- Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse. The OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023–1034.

More than one-third of women aged 45 years or older experience uterine prolapse, a condition that can impair physical, psychological, and sexual function. To compare vaginal vault suspension with hysterectomy, investigators at 4 large Dutch teaching hospitals from 2009 to 2012 randomly assigned women with uterine prolapse to sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSLF) or vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS). The primary outcome was recurrent stage 2 or greater prolapse (within 1 cm or more of the hymenal ring) with bothersome bulge symptoms or repeat surgery for prolapse by 12 months follow-up.

Details of the trialOne hundred two women assigned to SSLF (median age, 62.7 years) and 100 assigned to hysterectomy with ULS (median age, 61.9 years) were analyzed for the primary outcome. The patients ranged in age from 33 to 85 years.

Surgical failure rates and adverse events were similarMean hospital stay was 3 days in both groups and the occurrence of urinary retention was likewise similar (15% for SSLF and 11% for hysterectomy with ULS). At 12 months, 0 and 4 women in the SSLF and hysterectomy with ULS groups, respectively, met the primary outcome. Study participants were considered a “surgical failure” if any type of prolapse with bothersome symptoms or repeat surgery or pessary use occurred. Failures occurred in approximately one-half of the women in both groups.

Rates of serious adverse events were low, and none were related to type of surgery. Nine women experienced buttock pain following SSLF hysteropexy, a known complication of this surgery. This pain resolved within 6 weeks in 8 of these women. In the remaining woman, persistent pain led to release of the hysteropexy suture and vaginal hysterectomy 4 months after her initial procedure.

What this evidence means for practice

Advantages of hysterectomy at the time of vaginal vault suspension include prevention of endometrial and cervical cancers as well as elimination of uterine bleeding. However, data from published surveys indicate that many US women with prolapse prefer to avoid hysterectomy if effective alternate surgeries are available.1

In the previously published 2014 Barber and colleagues’ OPTIMAL trial,1,2 the efficacy of vaginal hysterectomy with either SSLF or USL was equivalent (63.1% versus 64.5%, respectively). The success rates are lower for both procedures in this trial by Detollenaere and colleagues.

Both SSLF and ULS may result in life-altering buttock or leg pain, necessitating removal of the offending sutures; however, the ULS procedure offers a more anatomically correct result. Although the short follow-up interval represents a limitation, these trial results suggest that sacrospinous fixation without hysterectomy represents a reasonable option for women with bothersome uterine prolapse who would like to avoid hysterectomy.

—Meadow M. Good, DO, and Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

More than one-third of women aged 45 years or older experience uterine prolapse, a condition that can impair physical, psychological, and sexual function. To compare vaginal vault suspension with hysterectomy, investigators at 4 large Dutch teaching hospitals from 2009 to 2012 randomly assigned women with uterine prolapse to sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSLF) or vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension (ULS). The primary outcome was recurrent stage 2 or greater prolapse (within 1 cm or more of the hymenal ring) with bothersome bulge symptoms or repeat surgery for prolapse by 12 months follow-up.

Details of the trialOne hundred two women assigned to SSLF (median age, 62.7 years) and 100 assigned to hysterectomy with ULS (median age, 61.9 years) were analyzed for the primary outcome. The patients ranged in age from 33 to 85 years.

Surgical failure rates and adverse events were similarMean hospital stay was 3 days in both groups and the occurrence of urinary retention was likewise similar (15% for SSLF and 11% for hysterectomy with ULS). At 12 months, 0 and 4 women in the SSLF and hysterectomy with ULS groups, respectively, met the primary outcome. Study participants were considered a “surgical failure” if any type of prolapse with bothersome symptoms or repeat surgery or pessary use occurred. Failures occurred in approximately one-half of the women in both groups.

Rates of serious adverse events were low, and none were related to type of surgery. Nine women experienced buttock pain following SSLF hysteropexy, a known complication of this surgery. This pain resolved within 6 weeks in 8 of these women. In the remaining woman, persistent pain led to release of the hysteropexy suture and vaginal hysterectomy 4 months after her initial procedure.

What this evidence means for practice

Advantages of hysterectomy at the time of vaginal vault suspension include prevention of endometrial and cervical cancers as well as elimination of uterine bleeding. However, data from published surveys indicate that many US women with prolapse prefer to avoid hysterectomy if effective alternate surgeries are available.1

In the previously published 2014 Barber and colleagues’ OPTIMAL trial,1,2 the efficacy of vaginal hysterectomy with either SSLF or USL was equivalent (63.1% versus 64.5%, respectively). The success rates are lower for both procedures in this trial by Detollenaere and colleagues.

Both SSLF and ULS may result in life-altering buttock or leg pain, necessitating removal of the offending sutures; however, the ULS procedure offers a more anatomically correct result. Although the short follow-up interval represents a limitation, these trial results suggest that sacrospinous fixation without hysterectomy represents a reasonable option for women with bothersome uterine prolapse who would like to avoid hysterectomy.

—Meadow M. Good, DO, and Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Korbly N, Kassis N, Good MM, et al. Patient preference for uterine preservation in women with pelvic organ prolapse: a fellow’s pelvic network research study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):470.e1−e6.

- Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse. The OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023–1034.

- Korbly N, Kassis N, Good MM, et al. Patient preference for uterine preservation in women with pelvic organ prolapse: a fellow’s pelvic network research study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):470.e1−e6.

- Barber MD, Brubaker L, Burgio KL, et al. Comparison of 2 transvaginal surgical approaches and perioperative behavioral therapy for apical vaginal prolapse. The OPTIMAL randomized trial. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1023–1034.

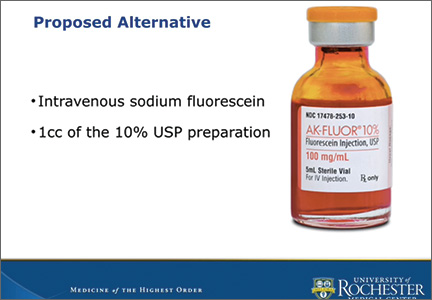

Sodium fluorescein as an alternative to indigo carmine during intraoperative cystoscopy

For more videos from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, click here

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

For more videos from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, click here

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

For more videos from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, click here

Visit the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons online: sgsonline.org

This video is brought to you by ![]()

ICD-10-CM documentation and coding for obstetric procedures

The countdown is on for the big coding switch. Last month I wrote about changes in International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes that will occur in relation to gynecologic services, but now it’s time to tackle obstetric services. For obstetricians, the changes will be all about definitions. And documentation of obstetric conditions will be more complicated due to several factors, including the need to report trimester information and gestational age, use of a placeholder code, more complex guidelines for certain conditions, chorionicity for multiple gestations, and use of a 7th digit to identify the fetus with a problem.

No one is expecting clinicians to instantly be fluent in code-speak, but in order for the most specific diagnoses to be reported, the clinical documentation must be spot on. Think of it this way: ICD-10-CM is not requiring you to document more, it’s requiring you to document more precisely.

How to get started

Figuring out where you are now goes a long way toward knowing where you need to be when the calendar changes to October 1—and the best way to do it is to perform a gap analysis. This analysis can be carried out by the clinician or a qualified practice staff person.

To begin, run a report of the distinct obstetric codes you have billed in 2015 by frequency. Then sort them in numeric order so that each individual code category is captured for all of the 5th digits (and the code then will be counted as a single code). Finally, review 5 medical records for each of the top 10 reported diagnosis categories and determine whether you could have reported a more specific ICD-10-CM code.

The information you gain will go a long way toward identifying potential weaknesses in the documentation, or, if you are currently using an electronic health record (EHR) to look up a code, it will point up any weak points in searching for the right code, based on your specific documentation at the encounter. Remember, practice makes perfect…eventually.

Well-trained staff can help

Not only must you, the clinician, learn about the part your clinical documentation will play in providing the most specific information that will lead to a very specific code, but your coding and billing staff will need training as well. They are the ones who should be checking your claims for accuracy from October 1 forward, as they will know the basic rules about which codes can be billed together, code order, place codes, and so on. In other words, while you as a clinician should be responsible for picking the more specific code in ICD-10-CM, your staff is your backup when you don’t.

Feedback from your staff on how the claims are being processed and, perhaps, the overuse of unspecified codes will keep you moving toward the goal of complete and precise clinical documentation and the reporting of diagnoses at the highest level possible given the documentation.

Highlights of ICD-10-CM obstetric coding

Given the complexity of obstetric coding, this article deals only with the most important changes. It will be up to each clinician to learn the rules that surround the diagnostic codes that you report most frequently. Here again, a trained staff can help by preparing specific coding tools for the most frequently used diagnoses, including notes about what must be in the record to report the most specific code.

Trimester, gestational age, and timing definitions

The majority of obstetric complication codes (these are the codes that start with the letter “O”) and the “Z” codes for supervision of a normal pregnancy require trimester information to be valid. In the outpatient setting, the trimester will be based on the gestational age at the date of the encounter. For inpatient admissions, the trimester will be based on the age at the time of admission; if the patient is hospitalized over more than one trimester, it is the admission trimester that continues to be recorded, not the discharge trimester.

Although there are codes that indicate an unspecified trimester, they should be reported rarely if this information is, in fact, available. Trimesters are defined as:

- first: less than 14 weeks, 0 days

- second: 14 weeks, 0 days to less than 28 weeks, 0 days

- third: 28 weeks, 0 days until delivery.

Examples of trimester codes include:

- O25.11Malnutrition in pregnancy, first trimester

- O14.02 Mild to moderate preeclampsia, second trimester

- O24.013 Preexisting diabetes mellitus, type 1, in pregnancy, third trimester.

However, definitions in ICD-10-CM go beyond this, and these definitions will have to be taken into account to provide sufficient documentation to report the condition. In ICD-9-CM, a missed abortion and early hemorrhage in pregnancy occurred prior to 22 completed weeks, but in ICD-10-CM that definition changes to prior to 20 completed weeks.

Additional definitions that may impact coding:

- preterm labor or delivery: 20 completed weeks to less than 37 completed weeks

- full-term labor or delivery: 37 completed weeks to 40 completed weeks

- postterm pregnancy: more than 40 completed weeks to 42 completed weeks

- prolonged pregnancy: more than 42 completed weeks.

You also will be required to include a code for gestational age any time you report an obstetric complication. This and the trimester information will change as the pregnancy advances, so always be sure that the code selected matches the gestational age on the flow sheet at the time of the encounter. The gestational age code is Z3A.__, with the final 2 digits representing the weeks of gestation (for instance, from 27 weeks, 0 days to 27 weeks, 6 days, the final 2 digits will be “27”).

ICD-10-CM also has different conventions when it comes to timing as it relates to conditions that are present during the episode in which the patient delivers. When this is the case, an “in childbirth” code must be selected instead of assigning the diagnosis by trimester, if one is available. There also are codes that are specific to “in the puer-perium,” and these generally will be reported after the patient has been discharged after delivery but also would be reported if there is no “in childbirth” code available at the time of delivery. The code categories to which this concept will apply are:

- preexisting hypertension

- diabetes mellitus

- malnutrition

- liver and biliary tract disorders

- subluxation of symphysis (pubis)

- obstetric embolism

- maternal infectious and parasitic diseases classifiable elsewhere

- other maternal diseases classifiable elsewhere

- maternal malignant neoplasms, traumatic injuries, and abuse classifiable elsewhere.

Taking time to read a code description from a search program or drop-down menu also will be important because some codes refer to “of the puerperium” versus “complicating the puerperium” or “in the puerperium.” The first reference means that the condition develops after delivery, while the second and third terms mean that it developed prior to delivery. For example, code O90.81, Anemia of the puerperium, refers to anemia that develops following delivery, while code O99.03 Anemia complicating the puerperium, denotes preexisting anemia that is still present in the postpartum period.

Multiple gestation coding and the 7th digit

The first thing you will notice here is that several code categories require a 7th numeric character of 0 or 1 through 9. This rule will apply to the following categories:

- complications specific to multiple gestation

- maternal care for malpresentation of fetus

- maternal care for disproportion

- maternal care for known or suspected fetal abnormality and damage

- maternal care for other fetal problems

- polyhydramnios

- other disorders of amniotic fluid and membranes

- preterm labor with preterm delivery

- term delivery with preterm labor

- obstructed labor due to malposition and malpresentation of fetus

- labor and delivery with umbilical cord complications.

A 7th character of 0 will be reported if this is a singleton pregnancy, and the numbers 1 through 5 and 9 refer to which fetus of the multiple gestation has the problem. The number 9 would indicate any fetus that was not labeled as 1 to 5.

The trick in documentation will be identifying the fetus with the problem consistently while still recognizing that, in some cases, such as fetal position, twins may switch places. On the other hand, if one fetus is small for dates, chances are good that this fetus will remain so during pregnancy when twins are present.

A code will be denied as invalid without this 7th digit, so it will be good practice for the clinician to document this information at each visit.

Additional information in regard to multiple gestations will be the chorionicity of the pregnancy, if known, but there will also be an “unable to determine” and an “unspecified” code available if that better fits the documentation for the visit. Note, however, that there is no code for a trichorionic/ triamniotic pregnancy; therefore, only the unspecified code would be reported in that case. In addition, if there is a continuing pregnancy after fetal loss, the cause must be identified within the code (that is, fetal reduction, fetal demise [and retained], or spontaneous abortion).

Documentation requirements for certain conditions

If you plan on reporting any complication of pregnancy at the time of the encounter, information about that condition needs to be part of the antepartum flow sheet comments. If, at the time of the encounter, a condition the patient has is not addressed and the entire visit involves only routine care, you would report the code for routine supervision of preg- nancy rather than the complication code. If the complication is again addressed at a later visit, the complication code would be reported again for that visit. The routine supervision code and the complication code cannot be reported on the record for the same encounter under ICD-10-CM rules.

Hypertension. Documentation needs to state whether the hypertension is preexisting or gestational. If it is preexisting, it needs to be identified as essential or secondary. If the patient also has hypertensive heart disease or chronic kidney disease, this information should be included, as different codes must be selected.

Diabetes. The documentation needs to state whether it is preexisting or gestational. If preexisting, you must document whether it is type 1 or type 2. If it is type 2, you must report an additional code for long-term insulin use, if applicable. The assumption for a woman with type 1 diabetes is that she is always insulin-dependent, so long-term use is not reported separately. Note, however, that neither metformin nor glyburide is considered insulin and there is no mechanism for reporting control with these medications.

If diabetes is gestational, you must indicate whether the patient’s blood glucose level is controlled by diet or insulin. If both, report only the insulin. There is no code for the use of other medications for the control of gestational diabetes, so you would have to report an unspecified code in that case.

Also note that ICD-10-CM differentiates between an abnormal 1-hour glucose tolerance test (GTT) and gestational diabetes. Unless a 3-specimen or 4-specimen GTT has been performed and results are abnormal, a diagnosis of gestational diabetes should not be reported.

An additional code outside of the obstetric complication chapter is required to denote any manifestations of diabetes. If there are none, then a diabetes uncomplicated manifestation code must be reported.

Preterm labor and delivery. Your documentation must clearly indicate whether the patient has preterm labor with preterm delivery or whether the delivery is term in addition to the trimester. For instance, if you document that Mary presents with preterm labor at 27 weeks, 2 days and delivers a girl at 28 weeks, 6 days, your code will describe Preterm labor second trimester with preterm delivery third trimester. However, if Susan presents with preterm labor at 30 weeks, 2 days and is managed until 37 weeks, 1 day, when she delivers a baby boy, your code would describe Term delivery with preterm labor, third trimester.

New coding options

Among the new coding options under ICD-10-CM:

- Abnormal findings on antenatal screening. These would be reported when the antenatal test is abnormal but you have not yet determined a definitive diagnosis.

- Alcohol, drug, and tobacco use during pregnancy. If you report any of these codes, you must also report a manifestation code for the patient’s condition. If the use is uncomplicated, you would report that code instead.

- Abuse of the pregnant patient. You can report sexual, physical, or psychological abuse, but you also must report a code for any applicable injury to the patient and identify the abuser, if known.

- Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy

- Retained intrauterine contraceptive device in pregnancy

- Maternal care due to uterine scar from other previous surgery. This would mean a surgery other than a previous cesarean delivery.

- Maternal care for (suspected) damage to the fetus by other medical procedures

- Maternal care for hydrops fetalis

- Maternal care for viable fetus in abdominal pregnancy

- Malignant neoplasm complicating pregnancy

- Failed attempt at vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery

- Supervision of high-risk pregnancy due to social problems (for instance, a homeless patient)

- Rh incompatibility status (when you lack confirmation of serum antibodies and are giving prophylactic Rho[D] immune globulin).

CMS takes steps to ease transition to ICD-10-CM

To help health care providers get “up to speed” on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM), which takes effect October 1, 2015, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has launched a new series for specialists. A guide tailored to ObGyns is available at http://roadto10.org/example-practice-obgyn. The guide includes:

Parting words

ICD-10-CM may seem like the end of the world, but its difficulty is exaggerated. If you fail to prepare, you will fail, and money coming in the door may be affected. If you prepare with training and practice, you will have a short learning curve. I wish you all the best. If you have specific questions about your practice, don’t hesitate to let us know so they can be addressed early.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The countdown is on for the big coding switch. Last month I wrote about changes in International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes that will occur in relation to gynecologic services, but now it’s time to tackle obstetric services. For obstetricians, the changes will be all about definitions. And documentation of obstetric conditions will be more complicated due to several factors, including the need to report trimester information and gestational age, use of a placeholder code, more complex guidelines for certain conditions, chorionicity for multiple gestations, and use of a 7th digit to identify the fetus with a problem.

No one is expecting clinicians to instantly be fluent in code-speak, but in order for the most specific diagnoses to be reported, the clinical documentation must be spot on. Think of it this way: ICD-10-CM is not requiring you to document more, it’s requiring you to document more precisely.

How to get started

Figuring out where you are now goes a long way toward knowing where you need to be when the calendar changes to October 1—and the best way to do it is to perform a gap analysis. This analysis can be carried out by the clinician or a qualified practice staff person.

To begin, run a report of the distinct obstetric codes you have billed in 2015 by frequency. Then sort them in numeric order so that each individual code category is captured for all of the 5th digits (and the code then will be counted as a single code). Finally, review 5 medical records for each of the top 10 reported diagnosis categories and determine whether you could have reported a more specific ICD-10-CM code.

The information you gain will go a long way toward identifying potential weaknesses in the documentation, or, if you are currently using an electronic health record (EHR) to look up a code, it will point up any weak points in searching for the right code, based on your specific documentation at the encounter. Remember, practice makes perfect…eventually.

Well-trained staff can help

Not only must you, the clinician, learn about the part your clinical documentation will play in providing the most specific information that will lead to a very specific code, but your coding and billing staff will need training as well. They are the ones who should be checking your claims for accuracy from October 1 forward, as they will know the basic rules about which codes can be billed together, code order, place codes, and so on. In other words, while you as a clinician should be responsible for picking the more specific code in ICD-10-CM, your staff is your backup when you don’t.

Feedback from your staff on how the claims are being processed and, perhaps, the overuse of unspecified codes will keep you moving toward the goal of complete and precise clinical documentation and the reporting of diagnoses at the highest level possible given the documentation.

Highlights of ICD-10-CM obstetric coding

Given the complexity of obstetric coding, this article deals only with the most important changes. It will be up to each clinician to learn the rules that surround the diagnostic codes that you report most frequently. Here again, a trained staff can help by preparing specific coding tools for the most frequently used diagnoses, including notes about what must be in the record to report the most specific code.

Trimester, gestational age, and timing definitions

The majority of obstetric complication codes (these are the codes that start with the letter “O”) and the “Z” codes for supervision of a normal pregnancy require trimester information to be valid. In the outpatient setting, the trimester will be based on the gestational age at the date of the encounter. For inpatient admissions, the trimester will be based on the age at the time of admission; if the patient is hospitalized over more than one trimester, it is the admission trimester that continues to be recorded, not the discharge trimester.

Although there are codes that indicate an unspecified trimester, they should be reported rarely if this information is, in fact, available. Trimesters are defined as:

- first: less than 14 weeks, 0 days

- second: 14 weeks, 0 days to less than 28 weeks, 0 days

- third: 28 weeks, 0 days until delivery.

Examples of trimester codes include:

- O25.11Malnutrition in pregnancy, first trimester

- O14.02 Mild to moderate preeclampsia, second trimester

- O24.013 Preexisting diabetes mellitus, type 1, in pregnancy, third trimester.

However, definitions in ICD-10-CM go beyond this, and these definitions will have to be taken into account to provide sufficient documentation to report the condition. In ICD-9-CM, a missed abortion and early hemorrhage in pregnancy occurred prior to 22 completed weeks, but in ICD-10-CM that definition changes to prior to 20 completed weeks.

Additional definitions that may impact coding:

- preterm labor or delivery: 20 completed weeks to less than 37 completed weeks

- full-term labor or delivery: 37 completed weeks to 40 completed weeks

- postterm pregnancy: more than 40 completed weeks to 42 completed weeks

- prolonged pregnancy: more than 42 completed weeks.

You also will be required to include a code for gestational age any time you report an obstetric complication. This and the trimester information will change as the pregnancy advances, so always be sure that the code selected matches the gestational age on the flow sheet at the time of the encounter. The gestational age code is Z3A.__, with the final 2 digits representing the weeks of gestation (for instance, from 27 weeks, 0 days to 27 weeks, 6 days, the final 2 digits will be “27”).

ICD-10-CM also has different conventions when it comes to timing as it relates to conditions that are present during the episode in which the patient delivers. When this is the case, an “in childbirth” code must be selected instead of assigning the diagnosis by trimester, if one is available. There also are codes that are specific to “in the puer-perium,” and these generally will be reported after the patient has been discharged after delivery but also would be reported if there is no “in childbirth” code available at the time of delivery. The code categories to which this concept will apply are:

- preexisting hypertension

- diabetes mellitus

- malnutrition

- liver and biliary tract disorders

- subluxation of symphysis (pubis)

- obstetric embolism

- maternal infectious and parasitic diseases classifiable elsewhere

- other maternal diseases classifiable elsewhere

- maternal malignant neoplasms, traumatic injuries, and abuse classifiable elsewhere.

Taking time to read a code description from a search program or drop-down menu also will be important because some codes refer to “of the puerperium” versus “complicating the puerperium” or “in the puerperium.” The first reference means that the condition develops after delivery, while the second and third terms mean that it developed prior to delivery. For example, code O90.81, Anemia of the puerperium, refers to anemia that develops following delivery, while code O99.03 Anemia complicating the puerperium, denotes preexisting anemia that is still present in the postpartum period.

Multiple gestation coding and the 7th digit

The first thing you will notice here is that several code categories require a 7th numeric character of 0 or 1 through 9. This rule will apply to the following categories:

- complications specific to multiple gestation

- maternal care for malpresentation of fetus

- maternal care for disproportion

- maternal care for known or suspected fetal abnormality and damage

- maternal care for other fetal problems

- polyhydramnios

- other disorders of amniotic fluid and membranes

- preterm labor with preterm delivery

- term delivery with preterm labor

- obstructed labor due to malposition and malpresentation of fetus

- labor and delivery with umbilical cord complications.

A 7th character of 0 will be reported if this is a singleton pregnancy, and the numbers 1 through 5 and 9 refer to which fetus of the multiple gestation has the problem. The number 9 would indicate any fetus that was not labeled as 1 to 5.

The trick in documentation will be identifying the fetus with the problem consistently while still recognizing that, in some cases, such as fetal position, twins may switch places. On the other hand, if one fetus is small for dates, chances are good that this fetus will remain so during pregnancy when twins are present.

A code will be denied as invalid without this 7th digit, so it will be good practice for the clinician to document this information at each visit.

Additional information in regard to multiple gestations will be the chorionicity of the pregnancy, if known, but there will also be an “unable to determine” and an “unspecified” code available if that better fits the documentation for the visit. Note, however, that there is no code for a trichorionic/ triamniotic pregnancy; therefore, only the unspecified code would be reported in that case. In addition, if there is a continuing pregnancy after fetal loss, the cause must be identified within the code (that is, fetal reduction, fetal demise [and retained], or spontaneous abortion).

Documentation requirements for certain conditions

If you plan on reporting any complication of pregnancy at the time of the encounter, information about that condition needs to be part of the antepartum flow sheet comments. If, at the time of the encounter, a condition the patient has is not addressed and the entire visit involves only routine care, you would report the code for routine supervision of preg- nancy rather than the complication code. If the complication is again addressed at a later visit, the complication code would be reported again for that visit. The routine supervision code and the complication code cannot be reported on the record for the same encounter under ICD-10-CM rules.

Hypertension. Documentation needs to state whether the hypertension is preexisting or gestational. If it is preexisting, it needs to be identified as essential or secondary. If the patient also has hypertensive heart disease or chronic kidney disease, this information should be included, as different codes must be selected.

Diabetes. The documentation needs to state whether it is preexisting or gestational. If preexisting, you must document whether it is type 1 or type 2. If it is type 2, you must report an additional code for long-term insulin use, if applicable. The assumption for a woman with type 1 diabetes is that she is always insulin-dependent, so long-term use is not reported separately. Note, however, that neither metformin nor glyburide is considered insulin and there is no mechanism for reporting control with these medications.

If diabetes is gestational, you must indicate whether the patient’s blood glucose level is controlled by diet or insulin. If both, report only the insulin. There is no code for the use of other medications for the control of gestational diabetes, so you would have to report an unspecified code in that case.

Also note that ICD-10-CM differentiates between an abnormal 1-hour glucose tolerance test (GTT) and gestational diabetes. Unless a 3-specimen or 4-specimen GTT has been performed and results are abnormal, a diagnosis of gestational diabetes should not be reported.

An additional code outside of the obstetric complication chapter is required to denote any manifestations of diabetes. If there are none, then a diabetes uncomplicated manifestation code must be reported.

Preterm labor and delivery. Your documentation must clearly indicate whether the patient has preterm labor with preterm delivery or whether the delivery is term in addition to the trimester. For instance, if you document that Mary presents with preterm labor at 27 weeks, 2 days and delivers a girl at 28 weeks, 6 days, your code will describe Preterm labor second trimester with preterm delivery third trimester. However, if Susan presents with preterm labor at 30 weeks, 2 days and is managed until 37 weeks, 1 day, when she delivers a baby boy, your code would describe Term delivery with preterm labor, third trimester.

New coding options

Among the new coding options under ICD-10-CM:

- Abnormal findings on antenatal screening. These would be reported when the antenatal test is abnormal but you have not yet determined a definitive diagnosis.

- Alcohol, drug, and tobacco use during pregnancy. If you report any of these codes, you must also report a manifestation code for the patient’s condition. If the use is uncomplicated, you would report that code instead.

- Abuse of the pregnant patient. You can report sexual, physical, or psychological abuse, but you also must report a code for any applicable injury to the patient and identify the abuser, if known.

- Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy

- Retained intrauterine contraceptive device in pregnancy

- Maternal care due to uterine scar from other previous surgery. This would mean a surgery other than a previous cesarean delivery.

- Maternal care for (suspected) damage to the fetus by other medical procedures

- Maternal care for hydrops fetalis

- Maternal care for viable fetus in abdominal pregnancy

- Malignant neoplasm complicating pregnancy

- Failed attempt at vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery

- Supervision of high-risk pregnancy due to social problems (for instance, a homeless patient)

- Rh incompatibility status (when you lack confirmation of serum antibodies and are giving prophylactic Rho[D] immune globulin).

CMS takes steps to ease transition to ICD-10-CM

To help health care providers get “up to speed” on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM), which takes effect October 1, 2015, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has launched a new series for specialists. A guide tailored to ObGyns is available at http://roadto10.org/example-practice-obgyn. The guide includes:

Parting words

ICD-10-CM may seem like the end of the world, but its difficulty is exaggerated. If you fail to prepare, you will fail, and money coming in the door may be affected. If you prepare with training and practice, you will have a short learning curve. I wish you all the best. If you have specific questions about your practice, don’t hesitate to let us know so they can be addressed early.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The countdown is on for the big coding switch. Last month I wrote about changes in International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes that will occur in relation to gynecologic services, but now it’s time to tackle obstetric services. For obstetricians, the changes will be all about definitions. And documentation of obstetric conditions will be more complicated due to several factors, including the need to report trimester information and gestational age, use of a placeholder code, more complex guidelines for certain conditions, chorionicity for multiple gestations, and use of a 7th digit to identify the fetus with a problem.

No one is expecting clinicians to instantly be fluent in code-speak, but in order for the most specific diagnoses to be reported, the clinical documentation must be spot on. Think of it this way: ICD-10-CM is not requiring you to document more, it’s requiring you to document more precisely.

How to get started

Figuring out where you are now goes a long way toward knowing where you need to be when the calendar changes to October 1—and the best way to do it is to perform a gap analysis. This analysis can be carried out by the clinician or a qualified practice staff person.

To begin, run a report of the distinct obstetric codes you have billed in 2015 by frequency. Then sort them in numeric order so that each individual code category is captured for all of the 5th digits (and the code then will be counted as a single code). Finally, review 5 medical records for each of the top 10 reported diagnosis categories and determine whether you could have reported a more specific ICD-10-CM code.

The information you gain will go a long way toward identifying potential weaknesses in the documentation, or, if you are currently using an electronic health record (EHR) to look up a code, it will point up any weak points in searching for the right code, based on your specific documentation at the encounter. Remember, practice makes perfect…eventually.

Well-trained staff can help

Not only must you, the clinician, learn about the part your clinical documentation will play in providing the most specific information that will lead to a very specific code, but your coding and billing staff will need training as well. They are the ones who should be checking your claims for accuracy from October 1 forward, as they will know the basic rules about which codes can be billed together, code order, place codes, and so on. In other words, while you as a clinician should be responsible for picking the more specific code in ICD-10-CM, your staff is your backup when you don’t.

Feedback from your staff on how the claims are being processed and, perhaps, the overuse of unspecified codes will keep you moving toward the goal of complete and precise clinical documentation and the reporting of diagnoses at the highest level possible given the documentation.

Highlights of ICD-10-CM obstetric coding

Given the complexity of obstetric coding, this article deals only with the most important changes. It will be up to each clinician to learn the rules that surround the diagnostic codes that you report most frequently. Here again, a trained staff can help by preparing specific coding tools for the most frequently used diagnoses, including notes about what must be in the record to report the most specific code.

Trimester, gestational age, and timing definitions

The majority of obstetric complication codes (these are the codes that start with the letter “O”) and the “Z” codes for supervision of a normal pregnancy require trimester information to be valid. In the outpatient setting, the trimester will be based on the gestational age at the date of the encounter. For inpatient admissions, the trimester will be based on the age at the time of admission; if the patient is hospitalized over more than one trimester, it is the admission trimester that continues to be recorded, not the discharge trimester.

Although there are codes that indicate an unspecified trimester, they should be reported rarely if this information is, in fact, available. Trimesters are defined as:

- first: less than 14 weeks, 0 days

- second: 14 weeks, 0 days to less than 28 weeks, 0 days

- third: 28 weeks, 0 days until delivery.

Examples of trimester codes include:

- O25.11Malnutrition in pregnancy, first trimester

- O14.02 Mild to moderate preeclampsia, second trimester

- O24.013 Preexisting diabetes mellitus, type 1, in pregnancy, third trimester.

However, definitions in ICD-10-CM go beyond this, and these definitions will have to be taken into account to provide sufficient documentation to report the condition. In ICD-9-CM, a missed abortion and early hemorrhage in pregnancy occurred prior to 22 completed weeks, but in ICD-10-CM that definition changes to prior to 20 completed weeks.

Additional definitions that may impact coding:

- preterm labor or delivery: 20 completed weeks to less than 37 completed weeks

- full-term labor or delivery: 37 completed weeks to 40 completed weeks

- postterm pregnancy: more than 40 completed weeks to 42 completed weeks

- prolonged pregnancy: more than 42 completed weeks.

You also will be required to include a code for gestational age any time you report an obstetric complication. This and the trimester information will change as the pregnancy advances, so always be sure that the code selected matches the gestational age on the flow sheet at the time of the encounter. The gestational age code is Z3A.__, with the final 2 digits representing the weeks of gestation (for instance, from 27 weeks, 0 days to 27 weeks, 6 days, the final 2 digits will be “27”).

ICD-10-CM also has different conventions when it comes to timing as it relates to conditions that are present during the episode in which the patient delivers. When this is the case, an “in childbirth” code must be selected instead of assigning the diagnosis by trimester, if one is available. There also are codes that are specific to “in the puer-perium,” and these generally will be reported after the patient has been discharged after delivery but also would be reported if there is no “in childbirth” code available at the time of delivery. The code categories to which this concept will apply are:

- preexisting hypertension

- diabetes mellitus

- malnutrition

- liver and biliary tract disorders

- subluxation of symphysis (pubis)

- obstetric embolism

- maternal infectious and parasitic diseases classifiable elsewhere

- other maternal diseases classifiable elsewhere

- maternal malignant neoplasms, traumatic injuries, and abuse classifiable elsewhere.

Taking time to read a code description from a search program or drop-down menu also will be important because some codes refer to “of the puerperium” versus “complicating the puerperium” or “in the puerperium.” The first reference means that the condition develops after delivery, while the second and third terms mean that it developed prior to delivery. For example, code O90.81, Anemia of the puerperium, refers to anemia that develops following delivery, while code O99.03 Anemia complicating the puerperium, denotes preexisting anemia that is still present in the postpartum period.