User login

Most probable postsurgical VTEs diagnosed after hospital discharge

Among surgical patients treated in and discharged from VA hospitals, 49.4% of possible venous thromboembolism s and 47.8% of probable VTEs were diagnosed within 30 days after surgery, and 63.1% of possible VTEs and 62.9% of probable VTEs were diagnosed within 90 days after surgery, according to Dr. Richard E. Nelson of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

In a retrospective cohort study, researchers examined medical records from 468,515 operations on 383,551 patients who underwent surgery without prior VTE between Jan. 1, 2005 and Dec. 31, 2010. In total, VTE occurred in 1.3% of surgical admissions for VA patients in the 90 days after surgery. However, the researchers argued that presumed VTE diagnoses should not be monitored based on inpatient records alone.

“Reliable monitoring of postoperative VTE events should incorporate two aspects. First, it should use data sources that allow for extraction of information from unstructured medical records. Second, it should use data sources that have the ability to follow patients after discharge from the hospital,” they said.

Read the full article in Thrombosis Research.

Among surgical patients treated in and discharged from VA hospitals, 49.4% of possible venous thromboembolism s and 47.8% of probable VTEs were diagnosed within 30 days after surgery, and 63.1% of possible VTEs and 62.9% of probable VTEs were diagnosed within 90 days after surgery, according to Dr. Richard E. Nelson of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

In a retrospective cohort study, researchers examined medical records from 468,515 operations on 383,551 patients who underwent surgery without prior VTE between Jan. 1, 2005 and Dec. 31, 2010. In total, VTE occurred in 1.3% of surgical admissions for VA patients in the 90 days after surgery. However, the researchers argued that presumed VTE diagnoses should not be monitored based on inpatient records alone.

“Reliable monitoring of postoperative VTE events should incorporate two aspects. First, it should use data sources that allow for extraction of information from unstructured medical records. Second, it should use data sources that have the ability to follow patients after discharge from the hospital,” they said.

Read the full article in Thrombosis Research.

Among surgical patients treated in and discharged from VA hospitals, 49.4% of possible venous thromboembolism s and 47.8% of probable VTEs were diagnosed within 30 days after surgery, and 63.1% of possible VTEs and 62.9% of probable VTEs were diagnosed within 90 days after surgery, according to Dr. Richard E. Nelson of the University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

In a retrospective cohort study, researchers examined medical records from 468,515 operations on 383,551 patients who underwent surgery without prior VTE between Jan. 1, 2005 and Dec. 31, 2010. In total, VTE occurred in 1.3% of surgical admissions for VA patients in the 90 days after surgery. However, the researchers argued that presumed VTE diagnoses should not be monitored based on inpatient records alone.

“Reliable monitoring of postoperative VTE events should incorporate two aspects. First, it should use data sources that allow for extraction of information from unstructured medical records. Second, it should use data sources that have the ability to follow patients after discharge from the hospital,” they said.

Read the full article in Thrombosis Research.

Can we do less?

It is a busy night in the emergency department, and patients are lining up in the waiting room. The next patient is a 2-year-old boy with a cough, runny nose, and increased work of breathing. My stethoscope picks up a chorus of noises in his lungs, but no wheezes. The attending physician walks into the room with me, a pediatrics resident, and the mother looks on expectantly, hoping I will make her baby better.

The attending agrees with me, this child is doing poorly and needs to be admitted. Then the question comes: “What do you want to do for him?” A few minutes later, the patient is receiving an albuterol treatment. Unsurprisingly, he does not improve, but soon he disappears off to the floor and I move onto the next patient.

In medicine, the urge to help patients drives physicians every day. The true challenge comes when the only way to help patients is by doing less. In 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics released new bronchiolitis treatment guidelines. In this document, they cited numerous studies showing lack of benefit from albuterol or racemic epinephrine treatments, and they recommended against treatment trials in children with bronchiolitis. Additionally, they recommended against X-rays and steroids. This leaves pediatricians with the unsatisfying options of suctioning, watching, and waiting.

Physicians tend to be “fixers” by nature. Patients come to us to feel better, and we feel driven (internally and externally) to provide these cures. This desire can drive us to prescribe antibiotics for presumed viral infections, order imaging for minor head injuries, or offer trial bronchodilators in the setting of bronchiolitis. As medical trainees, we have the additional onus of answering to our attending physicians. Perhaps we are willing to watch a patient with bronchiolitis slowly evolve, but maybe some of our supervisors are not. How firmly do we stand our ground? What authority do we have?

Perhaps we have more to offer than we think. As trainees, we are exposed to education and updates from diverse fields of pediatrics, and this developing knowledge base can benefit our medical teams. We can utilize our knowledge of neurology to abort a seizure on the oncology floor. We can guide the evaluation for anemia while at an outpatient clinic. And we can apply our awareness of bronchiolitis guidelines to patients in the ED. By continuing to develop and apply an evidence base for our medical practice, we can provide meaningful insights about which interventions should (or should not) be done for our patients. Although uncomfortable at times, such situations provide us with the opportunity to improve medical practice while protecting our patients from unintended harms, gently remind our attending physicians which interventions should (or should not) be done for our patients. With education and a bit of spine, we can help our medical teams to follow that foremost of imperatives for the medical profession: Primum non nocere – First do no harm.

Dr. Sisk is a pediatrics resident at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. E-mail him at [email protected].

It is a busy night in the emergency department, and patients are lining up in the waiting room. The next patient is a 2-year-old boy with a cough, runny nose, and increased work of breathing. My stethoscope picks up a chorus of noises in his lungs, but no wheezes. The attending physician walks into the room with me, a pediatrics resident, and the mother looks on expectantly, hoping I will make her baby better.

The attending agrees with me, this child is doing poorly and needs to be admitted. Then the question comes: “What do you want to do for him?” A few minutes later, the patient is receiving an albuterol treatment. Unsurprisingly, he does not improve, but soon he disappears off to the floor and I move onto the next patient.

In medicine, the urge to help patients drives physicians every day. The true challenge comes when the only way to help patients is by doing less. In 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics released new bronchiolitis treatment guidelines. In this document, they cited numerous studies showing lack of benefit from albuterol or racemic epinephrine treatments, and they recommended against treatment trials in children with bronchiolitis. Additionally, they recommended against X-rays and steroids. This leaves pediatricians with the unsatisfying options of suctioning, watching, and waiting.

Physicians tend to be “fixers” by nature. Patients come to us to feel better, and we feel driven (internally and externally) to provide these cures. This desire can drive us to prescribe antibiotics for presumed viral infections, order imaging for minor head injuries, or offer trial bronchodilators in the setting of bronchiolitis. As medical trainees, we have the additional onus of answering to our attending physicians. Perhaps we are willing to watch a patient with bronchiolitis slowly evolve, but maybe some of our supervisors are not. How firmly do we stand our ground? What authority do we have?

Perhaps we have more to offer than we think. As trainees, we are exposed to education and updates from diverse fields of pediatrics, and this developing knowledge base can benefit our medical teams. We can utilize our knowledge of neurology to abort a seizure on the oncology floor. We can guide the evaluation for anemia while at an outpatient clinic. And we can apply our awareness of bronchiolitis guidelines to patients in the ED. By continuing to develop and apply an evidence base for our medical practice, we can provide meaningful insights about which interventions should (or should not) be done for our patients. Although uncomfortable at times, such situations provide us with the opportunity to improve medical practice while protecting our patients from unintended harms, gently remind our attending physicians which interventions should (or should not) be done for our patients. With education and a bit of spine, we can help our medical teams to follow that foremost of imperatives for the medical profession: Primum non nocere – First do no harm.

Dr. Sisk is a pediatrics resident at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. E-mail him at [email protected].

It is a busy night in the emergency department, and patients are lining up in the waiting room. The next patient is a 2-year-old boy with a cough, runny nose, and increased work of breathing. My stethoscope picks up a chorus of noises in his lungs, but no wheezes. The attending physician walks into the room with me, a pediatrics resident, and the mother looks on expectantly, hoping I will make her baby better.

The attending agrees with me, this child is doing poorly and needs to be admitted. Then the question comes: “What do you want to do for him?” A few minutes later, the patient is receiving an albuterol treatment. Unsurprisingly, he does not improve, but soon he disappears off to the floor and I move onto the next patient.

In medicine, the urge to help patients drives physicians every day. The true challenge comes when the only way to help patients is by doing less. In 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics released new bronchiolitis treatment guidelines. In this document, they cited numerous studies showing lack of benefit from albuterol or racemic epinephrine treatments, and they recommended against treatment trials in children with bronchiolitis. Additionally, they recommended against X-rays and steroids. This leaves pediatricians with the unsatisfying options of suctioning, watching, and waiting.

Physicians tend to be “fixers” by nature. Patients come to us to feel better, and we feel driven (internally and externally) to provide these cures. This desire can drive us to prescribe antibiotics for presumed viral infections, order imaging for minor head injuries, or offer trial bronchodilators in the setting of bronchiolitis. As medical trainees, we have the additional onus of answering to our attending physicians. Perhaps we are willing to watch a patient with bronchiolitis slowly evolve, but maybe some of our supervisors are not. How firmly do we stand our ground? What authority do we have?

Perhaps we have more to offer than we think. As trainees, we are exposed to education and updates from diverse fields of pediatrics, and this developing knowledge base can benefit our medical teams. We can utilize our knowledge of neurology to abort a seizure on the oncology floor. We can guide the evaluation for anemia while at an outpatient clinic. And we can apply our awareness of bronchiolitis guidelines to patients in the ED. By continuing to develop and apply an evidence base for our medical practice, we can provide meaningful insights about which interventions should (or should not) be done for our patients. Although uncomfortable at times, such situations provide us with the opportunity to improve medical practice while protecting our patients from unintended harms, gently remind our attending physicians which interventions should (or should not) be done for our patients. With education and a bit of spine, we can help our medical teams to follow that foremost of imperatives for the medical profession: Primum non nocere – First do no harm.

Dr. Sisk is a pediatrics resident at St. Louis Children’s Hospital. E-mail him at [email protected].

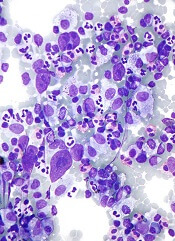

Drug produces ‘dramatic’ results in HL

The anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin can prolong progression-free survival (PFS) in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients who have undergone autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), results of the phase 3 AETHERA trial have shown.

The median PFS for patients who received brentuximab vedotin immediately after ASCT was nearly twice that of patients who received placebo—42.9 months and 24.1 months, respectively.

“No medication available today has had such dramatic results in patients with hard-to-treat Hodgkin lymphoma,” said Craig Moskowitz, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, New York.

Dr Moskowitz and his colleagues detailed these results in The Lancet. The results were previously presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting. The research was funded by Seattle Genetics, Inc., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, the companies developing brentuximab vedotin.

The AETHERA study included 329 HL patients age 18 or older who were thought to be at high risk of relapse or progression after ASCT. Patients were randomized to receive placebo or 16 cycles of brentuximab vedotin once every 3 weeks.

After a median observation time of 30 months (range, 0-50 months), the rate of PFS was significantly higher in the brentuximab vedotin arm than the placebo arm. The hazard ratio was 0.57 (P=0.0013), according to an independent review group.

The estimated 2-year PFS was 63% in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 51% in the placebo arm, according to the independent review group. But according to investigators, the estimated 2-year PFS was 65% in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 45% in the placebo arm.

“Nearly all of these patients who are progression-free at 2 years are likely to be cured, since relapse 2 years after a transplant is unlikely,” Dr Moskowitz noted.

An interim analysis revealed no significant difference between the treatment arms with regard to overall survival.

The researchers said brentuximab vedotin was generally well-tolerated. The most common adverse events were peripheral neuropathy—occurring in 67% of brentuximab vedotin-treated patients and 13% of placebo-treated patients—and neutropenia—occurring in 35% and 12%, respectively.

In all, 53 patients died, 17% of those in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 16% of those in the placebo arm. The proportion of patients who died from disease-related illness was the same in both arms—11%.

“The bottom line is that brentuximab vedotin is a very effective drug in poor-risk Hodgkin lymphoma, and it spares patients from the harmful effects of further traditional chemotherapy by breaking down inside the cell, resulting in less toxicity,” Dr Moskowitz said.

Writing in a linked comment article, Andreas Engert, MD, of the University Hospital of Cologne in Germany, discussed how best to define which patients are at high risk of relapse and should receive brentuximab vedotin.

“AETHERA is a positive study establishing a promising new treatment approach for patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma at high risk for relapse,” he wrote. “However, with a progression-free survival of about 50% at 24 months in the placebo group, whether this patient population is indeed high-risk could be debated.”

“An international consortium is currently reassessing the effect of risk factors in patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma to define a high-risk patient population in need of consolidation treatment. We look forward to a better definition of patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma who should receive consolidation treatment with brentuximab vedotin.” ![]()

The anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin can prolong progression-free survival (PFS) in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients who have undergone autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), results of the phase 3 AETHERA trial have shown.

The median PFS for patients who received brentuximab vedotin immediately after ASCT was nearly twice that of patients who received placebo—42.9 months and 24.1 months, respectively.

“No medication available today has had such dramatic results in patients with hard-to-treat Hodgkin lymphoma,” said Craig Moskowitz, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, New York.

Dr Moskowitz and his colleagues detailed these results in The Lancet. The results were previously presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting. The research was funded by Seattle Genetics, Inc., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, the companies developing brentuximab vedotin.

The AETHERA study included 329 HL patients age 18 or older who were thought to be at high risk of relapse or progression after ASCT. Patients were randomized to receive placebo or 16 cycles of brentuximab vedotin once every 3 weeks.

After a median observation time of 30 months (range, 0-50 months), the rate of PFS was significantly higher in the brentuximab vedotin arm than the placebo arm. The hazard ratio was 0.57 (P=0.0013), according to an independent review group.

The estimated 2-year PFS was 63% in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 51% in the placebo arm, according to the independent review group. But according to investigators, the estimated 2-year PFS was 65% in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 45% in the placebo arm.

“Nearly all of these patients who are progression-free at 2 years are likely to be cured, since relapse 2 years after a transplant is unlikely,” Dr Moskowitz noted.

An interim analysis revealed no significant difference between the treatment arms with regard to overall survival.

The researchers said brentuximab vedotin was generally well-tolerated. The most common adverse events were peripheral neuropathy—occurring in 67% of brentuximab vedotin-treated patients and 13% of placebo-treated patients—and neutropenia—occurring in 35% and 12%, respectively.

In all, 53 patients died, 17% of those in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 16% of those in the placebo arm. The proportion of patients who died from disease-related illness was the same in both arms—11%.

“The bottom line is that brentuximab vedotin is a very effective drug in poor-risk Hodgkin lymphoma, and it spares patients from the harmful effects of further traditional chemotherapy by breaking down inside the cell, resulting in less toxicity,” Dr Moskowitz said.

Writing in a linked comment article, Andreas Engert, MD, of the University Hospital of Cologne in Germany, discussed how best to define which patients are at high risk of relapse and should receive brentuximab vedotin.

“AETHERA is a positive study establishing a promising new treatment approach for patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma at high risk for relapse,” he wrote. “However, with a progression-free survival of about 50% at 24 months in the placebo group, whether this patient population is indeed high-risk could be debated.”

“An international consortium is currently reassessing the effect of risk factors in patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma to define a high-risk patient population in need of consolidation treatment. We look forward to a better definition of patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma who should receive consolidation treatment with brentuximab vedotin.” ![]()

The anti-CD30 antibody-drug conjugate brentuximab vedotin can prolong progression-free survival (PFS) in Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) patients who have undergone autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), results of the phase 3 AETHERA trial have shown.

The median PFS for patients who received brentuximab vedotin immediately after ASCT was nearly twice that of patients who received placebo—42.9 months and 24.1 months, respectively.

“No medication available today has had such dramatic results in patients with hard-to-treat Hodgkin lymphoma,” said Craig Moskowitz, MD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York, New York.

Dr Moskowitz and his colleagues detailed these results in The Lancet. The results were previously presented at the 2014 ASH Annual Meeting. The research was funded by Seattle Genetics, Inc., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, the companies developing brentuximab vedotin.

The AETHERA study included 329 HL patients age 18 or older who were thought to be at high risk of relapse or progression after ASCT. Patients were randomized to receive placebo or 16 cycles of brentuximab vedotin once every 3 weeks.

After a median observation time of 30 months (range, 0-50 months), the rate of PFS was significantly higher in the brentuximab vedotin arm than the placebo arm. The hazard ratio was 0.57 (P=0.0013), according to an independent review group.

The estimated 2-year PFS was 63% in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 51% in the placebo arm, according to the independent review group. But according to investigators, the estimated 2-year PFS was 65% in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 45% in the placebo arm.

“Nearly all of these patients who are progression-free at 2 years are likely to be cured, since relapse 2 years after a transplant is unlikely,” Dr Moskowitz noted.

An interim analysis revealed no significant difference between the treatment arms with regard to overall survival.

The researchers said brentuximab vedotin was generally well-tolerated. The most common adverse events were peripheral neuropathy—occurring in 67% of brentuximab vedotin-treated patients and 13% of placebo-treated patients—and neutropenia—occurring in 35% and 12%, respectively.

In all, 53 patients died, 17% of those in the brentuximab vedotin arm and 16% of those in the placebo arm. The proportion of patients who died from disease-related illness was the same in both arms—11%.

“The bottom line is that brentuximab vedotin is a very effective drug in poor-risk Hodgkin lymphoma, and it spares patients from the harmful effects of further traditional chemotherapy by breaking down inside the cell, resulting in less toxicity,” Dr Moskowitz said.

Writing in a linked comment article, Andreas Engert, MD, of the University Hospital of Cologne in Germany, discussed how best to define which patients are at high risk of relapse and should receive brentuximab vedotin.

“AETHERA is a positive study establishing a promising new treatment approach for patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma at high risk for relapse,” he wrote. “However, with a progression-free survival of about 50% at 24 months in the placebo group, whether this patient population is indeed high-risk could be debated.”

“An international consortium is currently reassessing the effect of risk factors in patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma to define a high-risk patient population in need of consolidation treatment. We look forward to a better definition of patients with relapsed Hodgkin’s lymphoma who should receive consolidation treatment with brentuximab vedotin.” ![]()

Antidote can reverse effects of anticoagulant

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

SAN DIEGO—A factor Xa inhibitor antidote can reverse the anticoagulation activity of rivaroxaban (Xarelto) in healthy subjects, results of a phase 3 study suggest.

The antidote, andexanet alfa, reversed the anti-factor Xa activity of rivaroxaban, reduced the level of free rivaroxaban in the plasma, and restored thrombin generation to within the normal baseline range.

Subjects did not experience any severe or serious adverse events, and they did not develop antibodies to factor X or Xa.

Alexander Michael Gold, MD, of Portola Pharmaceuticals, and his colleagues presented these results at the American College of Cardiology’s 64th Annual Scientific Session (abstract 912-08*).

The study, ANNEXA-R, is sponsored by Portola Pharmaceuticals, the company developing andexanet alfa.

ANNEXA-R is a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study in which researchers are evaluating the safety and efficacy of andexanet alfa for reversing rivaroxaban-induced anticoagulation in healthy volunteers ages 50 to 75.

In the first part of the study, 41 subjects received rivaroxaban at 20 mg once daily for 4 days. They were then randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either an 800 mg IV bolus of andexanet alfa (n=27) or placebo (n=14).

Results showed that andexanet alfa reduced the anti-factor Xa activity of rivaroxaban from baseline to nadir by more than 90%, a statistically significant difference from placebo (P<0.0001).

Significantly more andexanet alfa-treated subjects (96%) than placebo-treated subjects (0%) had a 90% or greater reduction in anti-factor Xa activity from baseline to nadir (P<0.0001).

Andexanet alfa also reduced the free (unbound) rivaroxaban concentration significantly from baseline to nadir, compared with placebo (P<0.0001).

Endogenous thrombin potential significantly increased from baseline to peak in andexanet alfa-treated subjects compared with placebo-treated subjects (P<0.0001).

And 96% of andexanet alfa-treated subjects saw their thrombin generation return to the normal range within 10 minutes of completing treatment.

The researchers said andexanet alfa was well-tolerated. There were no serious or severe adverse events, no thrombotic events, and no antibodies to factor X or Xa.

For the second part of the ANNEXA-R study, researchers plan to treat 40 healthy volunteers with rivaroxaban at 20 mg once daily for 4 days.

Then, subjects will be randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either andexanet alfa administered as an 800 mg IV bolus followed by a continuous infusion of 8 mg/min for 120 minutes or to placebo. Data from this part of the study are expected in mid-2015. ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

SAN DIEGO—A factor Xa inhibitor antidote can reverse the anticoagulation activity of rivaroxaban (Xarelto) in healthy subjects, results of a phase 3 study suggest.

The antidote, andexanet alfa, reversed the anti-factor Xa activity of rivaroxaban, reduced the level of free rivaroxaban in the plasma, and restored thrombin generation to within the normal baseline range.

Subjects did not experience any severe or serious adverse events, and they did not develop antibodies to factor X or Xa.

Alexander Michael Gold, MD, of Portola Pharmaceuticals, and his colleagues presented these results at the American College of Cardiology’s 64th Annual Scientific Session (abstract 912-08*).

The study, ANNEXA-R, is sponsored by Portola Pharmaceuticals, the company developing andexanet alfa.

ANNEXA-R is a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study in which researchers are evaluating the safety and efficacy of andexanet alfa for reversing rivaroxaban-induced anticoagulation in healthy volunteers ages 50 to 75.

In the first part of the study, 41 subjects received rivaroxaban at 20 mg once daily for 4 days. They were then randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either an 800 mg IV bolus of andexanet alfa (n=27) or placebo (n=14).

Results showed that andexanet alfa reduced the anti-factor Xa activity of rivaroxaban from baseline to nadir by more than 90%, a statistically significant difference from placebo (P<0.0001).

Significantly more andexanet alfa-treated subjects (96%) than placebo-treated subjects (0%) had a 90% or greater reduction in anti-factor Xa activity from baseline to nadir (P<0.0001).

Andexanet alfa also reduced the free (unbound) rivaroxaban concentration significantly from baseline to nadir, compared with placebo (P<0.0001).

Endogenous thrombin potential significantly increased from baseline to peak in andexanet alfa-treated subjects compared with placebo-treated subjects (P<0.0001).

And 96% of andexanet alfa-treated subjects saw their thrombin generation return to the normal range within 10 minutes of completing treatment.

The researchers said andexanet alfa was well-tolerated. There were no serious or severe adverse events, no thrombotic events, and no antibodies to factor X or Xa.

For the second part of the ANNEXA-R study, researchers plan to treat 40 healthy volunteers with rivaroxaban at 20 mg once daily for 4 days.

Then, subjects will be randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either andexanet alfa administered as an 800 mg IV bolus followed by a continuous infusion of 8 mg/min for 120 minutes or to placebo. Data from this part of the study are expected in mid-2015. ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

Image by Andre E.X. Brown

SAN DIEGO—A factor Xa inhibitor antidote can reverse the anticoagulation activity of rivaroxaban (Xarelto) in healthy subjects, results of a phase 3 study suggest.

The antidote, andexanet alfa, reversed the anti-factor Xa activity of rivaroxaban, reduced the level of free rivaroxaban in the plasma, and restored thrombin generation to within the normal baseline range.

Subjects did not experience any severe or serious adverse events, and they did not develop antibodies to factor X or Xa.

Alexander Michael Gold, MD, of Portola Pharmaceuticals, and his colleagues presented these results at the American College of Cardiology’s 64th Annual Scientific Session (abstract 912-08*).

The study, ANNEXA-R, is sponsored by Portola Pharmaceuticals, the company developing andexanet alfa.

ANNEXA-R is a randomized, double-blind, phase 3 study in which researchers are evaluating the safety and efficacy of andexanet alfa for reversing rivaroxaban-induced anticoagulation in healthy volunteers ages 50 to 75.

In the first part of the study, 41 subjects received rivaroxaban at 20 mg once daily for 4 days. They were then randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either an 800 mg IV bolus of andexanet alfa (n=27) or placebo (n=14).

Results showed that andexanet alfa reduced the anti-factor Xa activity of rivaroxaban from baseline to nadir by more than 90%, a statistically significant difference from placebo (P<0.0001).

Significantly more andexanet alfa-treated subjects (96%) than placebo-treated subjects (0%) had a 90% or greater reduction in anti-factor Xa activity from baseline to nadir (P<0.0001).

Andexanet alfa also reduced the free (unbound) rivaroxaban concentration significantly from baseline to nadir, compared with placebo (P<0.0001).

Endogenous thrombin potential significantly increased from baseline to peak in andexanet alfa-treated subjects compared with placebo-treated subjects (P<0.0001).

And 96% of andexanet alfa-treated subjects saw their thrombin generation return to the normal range within 10 minutes of completing treatment.

The researchers said andexanet alfa was well-tolerated. There were no serious or severe adverse events, no thrombotic events, and no antibodies to factor X or Xa.

For the second part of the ANNEXA-R study, researchers plan to treat 40 healthy volunteers with rivaroxaban at 20 mg once daily for 4 days.

Then, subjects will be randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either andexanet alfa administered as an 800 mg IV bolus followed by a continuous infusion of 8 mg/min for 120 minutes or to placebo. Data from this part of the study are expected in mid-2015. ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

Extended DAPT may not benefit patients with BMS

Photo by Frank C. Müller

Extended-duration dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) does not appear to confer any benefits for patients implanted with a bare-metal stent (BMS), according to a study published in JAMA.

An additional 18 months of DAPT among patients with a BMS did not result in significant differences in rates of stent thrombosis, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events, or moderate or severe bleeding, compared to patients who received placebo.

Study authors noted, however, that the sample of BMS patients studied was small, which makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions.

Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, of the Christ Hospital Heart and Vascular Center in Cincinnati, Ohio, and his colleagues conducted this research.

They analyzed 11,648 patients who received a BMS (n=1687) or drug-eluting stent (n=9961) and had completed 12 months of DAPT without bleeding or ischemic events.

The patients were randomized to continue DAPT—thienopyridine and aspirin—or receive placebo and aspirin for months 12 through 30.

Among the BMS patients, rates of stent thrombosis were 0.5% in the DAPT arm and 1.11% in the placebo arm (P=0.24).

Rates of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (a composite of death, heart attack, and stroke) were 4.04% and 4.69%, respectively (P=0.72). And rates of moderate/severe bleeding were 2.03% and 0.90%, respectively (P=0.07).

Among all the patients analyzed (both types of stent), the rates of stent thrombosis were 0.41% for patients who received DAPT and 1.32% for those who received placebo (P<0.001).

Rates of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events were 4.29% and 5.74%, respectively (P<0.001). And rates of moderate/severe bleeding were 2.45% and 1.47%, respectively (P<0.001).

Dr Kereiakes and his colleagues noted that fewer BMS patients were enrolled in this trial because of the prevailing use of drug-eluting stents in clinical practice.

So the study may have been underpowered to identify differences in adverse events among BMS patients, and additional trials are needed to confirm the results of this research. ![]()

Photo by Frank C. Müller

Extended-duration dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) does not appear to confer any benefits for patients implanted with a bare-metal stent (BMS), according to a study published in JAMA.

An additional 18 months of DAPT among patients with a BMS did not result in significant differences in rates of stent thrombosis, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events, or moderate or severe bleeding, compared to patients who received placebo.

Study authors noted, however, that the sample of BMS patients studied was small, which makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions.

Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, of the Christ Hospital Heart and Vascular Center in Cincinnati, Ohio, and his colleagues conducted this research.

They analyzed 11,648 patients who received a BMS (n=1687) or drug-eluting stent (n=9961) and had completed 12 months of DAPT without bleeding or ischemic events.

The patients were randomized to continue DAPT—thienopyridine and aspirin—or receive placebo and aspirin for months 12 through 30.

Among the BMS patients, rates of stent thrombosis were 0.5% in the DAPT arm and 1.11% in the placebo arm (P=0.24).

Rates of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (a composite of death, heart attack, and stroke) were 4.04% and 4.69%, respectively (P=0.72). And rates of moderate/severe bleeding were 2.03% and 0.90%, respectively (P=0.07).

Among all the patients analyzed (both types of stent), the rates of stent thrombosis were 0.41% for patients who received DAPT and 1.32% for those who received placebo (P<0.001).

Rates of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events were 4.29% and 5.74%, respectively (P<0.001). And rates of moderate/severe bleeding were 2.45% and 1.47%, respectively (P<0.001).

Dr Kereiakes and his colleagues noted that fewer BMS patients were enrolled in this trial because of the prevailing use of drug-eluting stents in clinical practice.

So the study may have been underpowered to identify differences in adverse events among BMS patients, and additional trials are needed to confirm the results of this research. ![]()

Photo by Frank C. Müller

Extended-duration dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) does not appear to confer any benefits for patients implanted with a bare-metal stent (BMS), according to a study published in JAMA.

An additional 18 months of DAPT among patients with a BMS did not result in significant differences in rates of stent thrombosis, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events, or moderate or severe bleeding, compared to patients who received placebo.

Study authors noted, however, that the sample of BMS patients studied was small, which makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions.

Dean J. Kereiakes, MD, of the Christ Hospital Heart and Vascular Center in Cincinnati, Ohio, and his colleagues conducted this research.

They analyzed 11,648 patients who received a BMS (n=1687) or drug-eluting stent (n=9961) and had completed 12 months of DAPT without bleeding or ischemic events.

The patients were randomized to continue DAPT—thienopyridine and aspirin—or receive placebo and aspirin for months 12 through 30.

Among the BMS patients, rates of stent thrombosis were 0.5% in the DAPT arm and 1.11% in the placebo arm (P=0.24).

Rates of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (a composite of death, heart attack, and stroke) were 4.04% and 4.69%, respectively (P=0.72). And rates of moderate/severe bleeding were 2.03% and 0.90%, respectively (P=0.07).

Among all the patients analyzed (both types of stent), the rates of stent thrombosis were 0.41% for patients who received DAPT and 1.32% for those who received placebo (P<0.001).

Rates of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events were 4.29% and 5.74%, respectively (P<0.001). And rates of moderate/severe bleeding were 2.45% and 1.47%, respectively (P<0.001).

Dr Kereiakes and his colleagues noted that fewer BMS patients were enrolled in this trial because of the prevailing use of drug-eluting stents in clinical practice.

So the study may have been underpowered to identify differences in adverse events among BMS patients, and additional trials are needed to confirm the results of this research. ![]()

Study supports short-term DAPT in patients with DES

Results of a meta-analysis support short-term dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for most patients who have a drug-eluting stent (DES), according to investigators.

The research showed that shorter-duration DAPT was associated with a decrease in all-cause mortality and major bleeding.

On the other hand, patients who received DAPT for a shorter period also had an increase in myocardial infarction (MI) and definite or probable stent thrombosis.

The results appear in The Lancet.

Study investigators examined 31,666 patients with DES from 10 randomized trials that compared different durations of DAPT. DAPT duration was categorized in each study as “shorter” vs “longer,” and ≤6 months vs 1 year vs >1 year.

The study’s primary endpoint was all-cause mortality. Secondary pre-specified endpoints included cardiac death, non-cardiac death, MI, stroke, stent thrombosis (definite or probable), major bleeding, and any bleeding.

A shorter DAPT duration was associated with significantly lower rates of all-cause mortality compared to longer DAPT (hazard ratio [HR]=0.82, P=0.02).

This difference was driven by a significant reduction in non-cardiac mortality with shorter DAPT (HR=0.67, P=0.006). There was no significant difference in cardiac mortality between the shorter and longer strategies (HR=0.93, P=0.52).

“[L]onger DAPT was associated with a 22% increased rate of all-cause mortality due to a 49% increased rate in non-cardiac mortality . . . ,” said study author Gregg W. Stone, MD, of Columbia University Medical Center in New York, New York.

“These results support a short-term (3 or 6 months) DAPT strategy in most patients, especially those at low risk of recurrent coronary events and stent thrombosis, and at high risk of bleeding.”

“However, an extended DAPT strategy (longer than 1 year) may still be appropriate in selected patients in whom prevention of stent- and non-stent-related coronary events are likely to offset the adverse events associated with extended-duration antiplatelet therapy.”

Dr Stone and his colleagues found that shorter-duration DAPT was associated with significantly lower rates of major bleeding (HR=0.58, P<0.0001) and any bleeding (HR=0.56, P<0.0001) compared to longer-duration DAPT.

However, shorter DAPT was also associated with significantly higher rates of MI (HR=1.51, P<0.0001) and definite or probable stent thrombosis (HR=2.04, P<0.0001), with moderate heterogeneity across trials. Stroke rates did not vary significantly with DAPT duration (HR=1.03, P=0.86).

Additional subgroup analyses showed that patients treated with DAPT for 6 months or less and those treated for 1 year had a higher risk of MI and stent thrombosis but a lower risk of mortality than patients who received DAPT for more than 1 year.

Patients treated with DAPT for 6 months or less had similar rates of mortality, MI, and stent thrombosis as patients who received DAPT for 1 year. But the 6-months-or-less patients had lower rates of major bleeding.

“Establishing the optimal duration of DAPT after DES implantation is extremely important in balancing the risks of ischemic and bleeding complications,” Dr Stone said. “Therefore, an individualized approach in which the benefit-risk profile for each patient should be carefully considered.”

“Further studies are required to model the demographic, laboratory-based, and genetic variables that affect the benefit-vs-risk balance of prolonged DAPT that might remove the guesswork from this equation.” ![]()

Results of a meta-analysis support short-term dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for most patients who have a drug-eluting stent (DES), according to investigators.

The research showed that shorter-duration DAPT was associated with a decrease in all-cause mortality and major bleeding.

On the other hand, patients who received DAPT for a shorter period also had an increase in myocardial infarction (MI) and definite or probable stent thrombosis.

The results appear in The Lancet.

Study investigators examined 31,666 patients with DES from 10 randomized trials that compared different durations of DAPT. DAPT duration was categorized in each study as “shorter” vs “longer,” and ≤6 months vs 1 year vs >1 year.

The study’s primary endpoint was all-cause mortality. Secondary pre-specified endpoints included cardiac death, non-cardiac death, MI, stroke, stent thrombosis (definite or probable), major bleeding, and any bleeding.

A shorter DAPT duration was associated with significantly lower rates of all-cause mortality compared to longer DAPT (hazard ratio [HR]=0.82, P=0.02).

This difference was driven by a significant reduction in non-cardiac mortality with shorter DAPT (HR=0.67, P=0.006). There was no significant difference in cardiac mortality between the shorter and longer strategies (HR=0.93, P=0.52).

“[L]onger DAPT was associated with a 22% increased rate of all-cause mortality due to a 49% increased rate in non-cardiac mortality . . . ,” said study author Gregg W. Stone, MD, of Columbia University Medical Center in New York, New York.

“These results support a short-term (3 or 6 months) DAPT strategy in most patients, especially those at low risk of recurrent coronary events and stent thrombosis, and at high risk of bleeding.”

“However, an extended DAPT strategy (longer than 1 year) may still be appropriate in selected patients in whom prevention of stent- and non-stent-related coronary events are likely to offset the adverse events associated with extended-duration antiplatelet therapy.”

Dr Stone and his colleagues found that shorter-duration DAPT was associated with significantly lower rates of major bleeding (HR=0.58, P<0.0001) and any bleeding (HR=0.56, P<0.0001) compared to longer-duration DAPT.

However, shorter DAPT was also associated with significantly higher rates of MI (HR=1.51, P<0.0001) and definite or probable stent thrombosis (HR=2.04, P<0.0001), with moderate heterogeneity across trials. Stroke rates did not vary significantly with DAPT duration (HR=1.03, P=0.86).

Additional subgroup analyses showed that patients treated with DAPT for 6 months or less and those treated for 1 year had a higher risk of MI and stent thrombosis but a lower risk of mortality than patients who received DAPT for more than 1 year.

Patients treated with DAPT for 6 months or less had similar rates of mortality, MI, and stent thrombosis as patients who received DAPT for 1 year. But the 6-months-or-less patients had lower rates of major bleeding.

“Establishing the optimal duration of DAPT after DES implantation is extremely important in balancing the risks of ischemic and bleeding complications,” Dr Stone said. “Therefore, an individualized approach in which the benefit-risk profile for each patient should be carefully considered.”

“Further studies are required to model the demographic, laboratory-based, and genetic variables that affect the benefit-vs-risk balance of prolonged DAPT that might remove the guesswork from this equation.” ![]()

Results of a meta-analysis support short-term dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for most patients who have a drug-eluting stent (DES), according to investigators.

The research showed that shorter-duration DAPT was associated with a decrease in all-cause mortality and major bleeding.

On the other hand, patients who received DAPT for a shorter period also had an increase in myocardial infarction (MI) and definite or probable stent thrombosis.

The results appear in The Lancet.

Study investigators examined 31,666 patients with DES from 10 randomized trials that compared different durations of DAPT. DAPT duration was categorized in each study as “shorter” vs “longer,” and ≤6 months vs 1 year vs >1 year.

The study’s primary endpoint was all-cause mortality. Secondary pre-specified endpoints included cardiac death, non-cardiac death, MI, stroke, stent thrombosis (definite or probable), major bleeding, and any bleeding.

A shorter DAPT duration was associated with significantly lower rates of all-cause mortality compared to longer DAPT (hazard ratio [HR]=0.82, P=0.02).

This difference was driven by a significant reduction in non-cardiac mortality with shorter DAPT (HR=0.67, P=0.006). There was no significant difference in cardiac mortality between the shorter and longer strategies (HR=0.93, P=0.52).

“[L]onger DAPT was associated with a 22% increased rate of all-cause mortality due to a 49% increased rate in non-cardiac mortality . . . ,” said study author Gregg W. Stone, MD, of Columbia University Medical Center in New York, New York.

“These results support a short-term (3 or 6 months) DAPT strategy in most patients, especially those at low risk of recurrent coronary events and stent thrombosis, and at high risk of bleeding.”

“However, an extended DAPT strategy (longer than 1 year) may still be appropriate in selected patients in whom prevention of stent- and non-stent-related coronary events are likely to offset the adverse events associated with extended-duration antiplatelet therapy.”

Dr Stone and his colleagues found that shorter-duration DAPT was associated with significantly lower rates of major bleeding (HR=0.58, P<0.0001) and any bleeding (HR=0.56, P<0.0001) compared to longer-duration DAPT.

However, shorter DAPT was also associated with significantly higher rates of MI (HR=1.51, P<0.0001) and definite or probable stent thrombosis (HR=2.04, P<0.0001), with moderate heterogeneity across trials. Stroke rates did not vary significantly with DAPT duration (HR=1.03, P=0.86).

Additional subgroup analyses showed that patients treated with DAPT for 6 months or less and those treated for 1 year had a higher risk of MI and stent thrombosis but a lower risk of mortality than patients who received DAPT for more than 1 year.

Patients treated with DAPT for 6 months or less had similar rates of mortality, MI, and stent thrombosis as patients who received DAPT for 1 year. But the 6-months-or-less patients had lower rates of major bleeding.

“Establishing the optimal duration of DAPT after DES implantation is extremely important in balancing the risks of ischemic and bleeding complications,” Dr Stone said. “Therefore, an individualized approach in which the benefit-risk profile for each patient should be carefully considered.”

“Further studies are required to model the demographic, laboratory-based, and genetic variables that affect the benefit-vs-risk balance of prolonged DAPT that might remove the guesswork from this equation.” ![]()

Mobility Sensors for Hospital Patients

Functional impairment, such as difficulty with activities of daily living or limited mobility,[1] is common among hospitalized patients and correlated with important outcomes: approximately 50% of hospitalized Medicare seniors have some level of impairment that correlates with higher rates of readmission,[2] long‐term care placement,[3] and even death.[4]

Lack of consistent, accurate, and reliable data on functional mobility during hospitalization poses an important barrier for programs seeking to improve functional outcomes in hospitalized patients.[5, 6] More accurate mobility data could improve current hospital practices to diagnose mobility problems, target mobility interventions, and measure interventions' effectiveness. Although wearable mobility sensors (small, wireless accelerometers placed on patients' wrists, ankles, or waists) hold promise in overcoming these barriers and improving current practice, existing data are from small samples of focused populations and have not integrated sensor data into patient care.[7, 8]

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Sallis and colleagues used mobility sensors to study 777 hospitalized patients.[9] This article has several strengths that make it unique among the handful of articles in this area: it is the largest to date, the first to consider patients on both medical and surgical units, and the first to correlate sensor data with clinical assessments of mobility by providers (nurses). The authors found that, regardless of length of stay, patients averaged 1100 steps during the final 24 hours of their hospitalization. Older patients had slightly fewer steps on average (982 per 24 hours), but, taken collectively, these findings led the authors to postulate that 1000 steps per day might be a good normative value for discharge readiness in terms of patient mobility.

This idea of a normative value for steps taken by inpatients prior to discharge raises several interesting questions. First, could numbers of steps become a value that hospital providers routinely use to optimize care of hospitalized patients similar to other values such as blood pressure or blood sugar? Such a threshold could be used to define strategies that target tight mobility control for patients at high risk for decline, and others might be managed with a more traditional ad lib approach. Alternatively, perhaps physicians should focus more on improvement in mobility regardless of a population‐defined threshold. In this case, the measure would be progress toward a patient‐centered or patient‐defined goal. Second, it is important to note that Sallis and colleagues found that patients whose nurses documented their estimated mobility more frequently in the medical record also had substantially higher sensor step counts. This raises the question of whether more data from sensors can assist front‐line inpatient providers to more effectively engage patients in mobilizing to avoid functional deconditioning during hospitalization. Often we tell our patients to try to get out of bed todaygo for a walk around the unit, but we are rarely specific about how far they should walk, and patients do not get feedback on their daily progress toward a specific mobility goal. Perhaps data on the number of steps from mobility sensors could be shown to both patients and providers so as to encourage patients to reach their goal, whether that is the normative 1000 steps per day or slightly more or less.

This article also has limitations, which raise important questions for future research. First, patients in this study were ambulatory and relatively healthy (85% had Charlson scores 0 or 1) at the time of admission, making it difficult to determine whether the approach used or threshold defined are valid in higher‐risk populations, such as those with preexisting functional limitations. Second, lack of clinical outcomes data is another important limitation in this study, which is shared by many, but not all, inpatient sensor studies. For example, a recent study correlated discharge location (skilled nursing facility vs home) to levels of step mobility; however, the authors were unable to determine the degree to which their step measures were simply mirroring clinical decision making.[10] Another recent study demonstrated that decreased inpatient step counts are associated with early mortality; however, more proximal outcomes such as postdischarge function were not measured.[11] Moreover, future studies will need to assess whether mobility sensors can reliably predict postdischarge function, and even be used to improve mobility or reduce functional impairment in hospital populations that include sicker patients.

Ultimately, the results by Sallis et al. are a useful step in the right direction, but much more work is needed to determine the clinical utility of mobility sensors as part of larger efforts to harness the potential of mobile health (mHealth) efforts to improve care for hospitalized patients.[12] The future of mobility sensors in healthcare is likely about how well patients and providers can use them to successfully guide and support behavior change. This will require a strong health‐adopter focus in coaching patients to use mobility sensors and their mobile, patient‐facing applications.[13] Ultimately, the goal must be to embed these mHealth approaches into larger behavior management and health system redesign so that clinical goals such as improved function after hospital discharge are met.[14]

Disclosures

Nothing to report.

- , , . Hospitalization‐associated disability: "She was probably able to ambulate, but I'm not sure." JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782–1793.

- , , , . Functional impairment and readmissions in Medicare seniors [published online ahead of print February 2, 2015]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7756.

- , , , et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451–458.

- , , , et al. Prediction of recovery, dependence or death in elders who become disabled during hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):261–268.

- , . Functional status—an important but overlooked variable in the readmissions equation. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):330–331.

- , , , , , . Association of impaired functional status at hospital discharge and subsequent rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):277–282.

- , , , . The under‐recognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1660–1665.

- , , , et al. Twenty‐four‐hour mobility during acute hospitalization in older medical patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(3):331–337.

- , , , et al. Stepping towards discharge: level of ambulation in hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):358–363.

- , , , , . Functional recovery in the elderly after major surgery: assessment of mobility recovery using wireless technology. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(3):1057–1061.

- , , , et al. Mobility activity and its value as a prognostic indicator of survival in hospitalized older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(4):551–557.

- . Wearables are totally failing the people who need them most. Wired. Available at: http://www.wired.com/2014/11/where‐fitness‐trackers‐fail. Published November 6, 2014. Accessed January 21, 2015.

- , , . Wearable devices as facilitators, not drivers, of health behavior change. JAMA. 2015;313(5):459–460.

- , , . Digital medical tools and sensors. JAMA. 2015;313(4):353–354.

Functional impairment, such as difficulty with activities of daily living or limited mobility,[1] is common among hospitalized patients and correlated with important outcomes: approximately 50% of hospitalized Medicare seniors have some level of impairment that correlates with higher rates of readmission,[2] long‐term care placement,[3] and even death.[4]

Lack of consistent, accurate, and reliable data on functional mobility during hospitalization poses an important barrier for programs seeking to improve functional outcomes in hospitalized patients.[5, 6] More accurate mobility data could improve current hospital practices to diagnose mobility problems, target mobility interventions, and measure interventions' effectiveness. Although wearable mobility sensors (small, wireless accelerometers placed on patients' wrists, ankles, or waists) hold promise in overcoming these barriers and improving current practice, existing data are from small samples of focused populations and have not integrated sensor data into patient care.[7, 8]

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Sallis and colleagues used mobility sensors to study 777 hospitalized patients.[9] This article has several strengths that make it unique among the handful of articles in this area: it is the largest to date, the first to consider patients on both medical and surgical units, and the first to correlate sensor data with clinical assessments of mobility by providers (nurses). The authors found that, regardless of length of stay, patients averaged 1100 steps during the final 24 hours of their hospitalization. Older patients had slightly fewer steps on average (982 per 24 hours), but, taken collectively, these findings led the authors to postulate that 1000 steps per day might be a good normative value for discharge readiness in terms of patient mobility.

This idea of a normative value for steps taken by inpatients prior to discharge raises several interesting questions. First, could numbers of steps become a value that hospital providers routinely use to optimize care of hospitalized patients similar to other values such as blood pressure or blood sugar? Such a threshold could be used to define strategies that target tight mobility control for patients at high risk for decline, and others might be managed with a more traditional ad lib approach. Alternatively, perhaps physicians should focus more on improvement in mobility regardless of a population‐defined threshold. In this case, the measure would be progress toward a patient‐centered or patient‐defined goal. Second, it is important to note that Sallis and colleagues found that patients whose nurses documented their estimated mobility more frequently in the medical record also had substantially higher sensor step counts. This raises the question of whether more data from sensors can assist front‐line inpatient providers to more effectively engage patients in mobilizing to avoid functional deconditioning during hospitalization. Often we tell our patients to try to get out of bed todaygo for a walk around the unit, but we are rarely specific about how far they should walk, and patients do not get feedback on their daily progress toward a specific mobility goal. Perhaps data on the number of steps from mobility sensors could be shown to both patients and providers so as to encourage patients to reach their goal, whether that is the normative 1000 steps per day or slightly more or less.

This article also has limitations, which raise important questions for future research. First, patients in this study were ambulatory and relatively healthy (85% had Charlson scores 0 or 1) at the time of admission, making it difficult to determine whether the approach used or threshold defined are valid in higher‐risk populations, such as those with preexisting functional limitations. Second, lack of clinical outcomes data is another important limitation in this study, which is shared by many, but not all, inpatient sensor studies. For example, a recent study correlated discharge location (skilled nursing facility vs home) to levels of step mobility; however, the authors were unable to determine the degree to which their step measures were simply mirroring clinical decision making.[10] Another recent study demonstrated that decreased inpatient step counts are associated with early mortality; however, more proximal outcomes such as postdischarge function were not measured.[11] Moreover, future studies will need to assess whether mobility sensors can reliably predict postdischarge function, and even be used to improve mobility or reduce functional impairment in hospital populations that include sicker patients.

Ultimately, the results by Sallis et al. are a useful step in the right direction, but much more work is needed to determine the clinical utility of mobility sensors as part of larger efforts to harness the potential of mobile health (mHealth) efforts to improve care for hospitalized patients.[12] The future of mobility sensors in healthcare is likely about how well patients and providers can use them to successfully guide and support behavior change. This will require a strong health‐adopter focus in coaching patients to use mobility sensors and their mobile, patient‐facing applications.[13] Ultimately, the goal must be to embed these mHealth approaches into larger behavior management and health system redesign so that clinical goals such as improved function after hospital discharge are met.[14]

Disclosures

Nothing to report.

Functional impairment, such as difficulty with activities of daily living or limited mobility,[1] is common among hospitalized patients and correlated with important outcomes: approximately 50% of hospitalized Medicare seniors have some level of impairment that correlates with higher rates of readmission,[2] long‐term care placement,[3] and even death.[4]

Lack of consistent, accurate, and reliable data on functional mobility during hospitalization poses an important barrier for programs seeking to improve functional outcomes in hospitalized patients.[5, 6] More accurate mobility data could improve current hospital practices to diagnose mobility problems, target mobility interventions, and measure interventions' effectiveness. Although wearable mobility sensors (small, wireless accelerometers placed on patients' wrists, ankles, or waists) hold promise in overcoming these barriers and improving current practice, existing data are from small samples of focused populations and have not integrated sensor data into patient care.[7, 8]

In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Sallis and colleagues used mobility sensors to study 777 hospitalized patients.[9] This article has several strengths that make it unique among the handful of articles in this area: it is the largest to date, the first to consider patients on both medical and surgical units, and the first to correlate sensor data with clinical assessments of mobility by providers (nurses). The authors found that, regardless of length of stay, patients averaged 1100 steps during the final 24 hours of their hospitalization. Older patients had slightly fewer steps on average (982 per 24 hours), but, taken collectively, these findings led the authors to postulate that 1000 steps per day might be a good normative value for discharge readiness in terms of patient mobility.

This idea of a normative value for steps taken by inpatients prior to discharge raises several interesting questions. First, could numbers of steps become a value that hospital providers routinely use to optimize care of hospitalized patients similar to other values such as blood pressure or blood sugar? Such a threshold could be used to define strategies that target tight mobility control for patients at high risk for decline, and others might be managed with a more traditional ad lib approach. Alternatively, perhaps physicians should focus more on improvement in mobility regardless of a population‐defined threshold. In this case, the measure would be progress toward a patient‐centered or patient‐defined goal. Second, it is important to note that Sallis and colleagues found that patients whose nurses documented their estimated mobility more frequently in the medical record also had substantially higher sensor step counts. This raises the question of whether more data from sensors can assist front‐line inpatient providers to more effectively engage patients in mobilizing to avoid functional deconditioning during hospitalization. Often we tell our patients to try to get out of bed todaygo for a walk around the unit, but we are rarely specific about how far they should walk, and patients do not get feedback on their daily progress toward a specific mobility goal. Perhaps data on the number of steps from mobility sensors could be shown to both patients and providers so as to encourage patients to reach their goal, whether that is the normative 1000 steps per day or slightly more or less.

This article also has limitations, which raise important questions for future research. First, patients in this study were ambulatory and relatively healthy (85% had Charlson scores 0 or 1) at the time of admission, making it difficult to determine whether the approach used or threshold defined are valid in higher‐risk populations, such as those with preexisting functional limitations. Second, lack of clinical outcomes data is another important limitation in this study, which is shared by many, but not all, inpatient sensor studies. For example, a recent study correlated discharge location (skilled nursing facility vs home) to levels of step mobility; however, the authors were unable to determine the degree to which their step measures were simply mirroring clinical decision making.[10] Another recent study demonstrated that decreased inpatient step counts are associated with early mortality; however, more proximal outcomes such as postdischarge function were not measured.[11] Moreover, future studies will need to assess whether mobility sensors can reliably predict postdischarge function, and even be used to improve mobility or reduce functional impairment in hospital populations that include sicker patients.

Ultimately, the results by Sallis et al. are a useful step in the right direction, but much more work is needed to determine the clinical utility of mobility sensors as part of larger efforts to harness the potential of mobile health (mHealth) efforts to improve care for hospitalized patients.[12] The future of mobility sensors in healthcare is likely about how well patients and providers can use them to successfully guide and support behavior change. This will require a strong health‐adopter focus in coaching patients to use mobility sensors and their mobile, patient‐facing applications.[13] Ultimately, the goal must be to embed these mHealth approaches into larger behavior management and health system redesign so that clinical goals such as improved function after hospital discharge are met.[14]

Disclosures

Nothing to report.

- , , . Hospitalization‐associated disability: "She was probably able to ambulate, but I'm not sure." JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782–1793.

- , , , . Functional impairment and readmissions in Medicare seniors [published online ahead of print February 2, 2015]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7756.

- , , , et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451–458.

- , , , et al. Prediction of recovery, dependence or death in elders who become disabled during hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):261–268.

- , . Functional status—an important but overlooked variable in the readmissions equation. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):330–331.

- , , , , , . Association of impaired functional status at hospital discharge and subsequent rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):277–282.

- , , , . The under‐recognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1660–1665.

- , , , et al. Twenty‐four‐hour mobility during acute hospitalization in older medical patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(3):331–337.

- , , , et al. Stepping towards discharge: level of ambulation in hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):358–363.

- , , , , . Functional recovery in the elderly after major surgery: assessment of mobility recovery using wireless technology. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(3):1057–1061.

- , , , et al. Mobility activity and its value as a prognostic indicator of survival in hospitalized older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(4):551–557.

- . Wearables are totally failing the people who need them most. Wired. Available at: http://www.wired.com/2014/11/where‐fitness‐trackers‐fail. Published November 6, 2014. Accessed January 21, 2015.

- , , . Wearable devices as facilitators, not drivers, of health behavior change. JAMA. 2015;313(5):459–460.

- , , . Digital medical tools and sensors. JAMA. 2015;313(4):353–354.

- , , . Hospitalization‐associated disability: "She was probably able to ambulate, but I'm not sure." JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782–1793.

- , , , . Functional impairment and readmissions in Medicare seniors [published online ahead of print February 2, 2015]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7756.

- , , , et al. Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: increased vulnerability with age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):451–458.

- , , , et al. Prediction of recovery, dependence or death in elders who become disabled during hospitalization. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):261–268.

- , . Functional status—an important but overlooked variable in the readmissions equation. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):330–331.

- , , , , , . Association of impaired functional status at hospital discharge and subsequent rehospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(5):277–282.

- , , , . The under‐recognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1660–1665.

- , , , et al. Twenty‐four‐hour mobility during acute hospitalization in older medical patients. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68(3):331–337.

- , , , et al. Stepping towards discharge: level of ambulation in hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(6):358–363.

- , , , , . Functional recovery in the elderly after major surgery: assessment of mobility recovery using wireless technology. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(3):1057–1061.

- , , , et al. Mobility activity and its value as a prognostic indicator of survival in hospitalized older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(4):551–557.

- . Wearables are totally failing the people who need them most. Wired. Available at: http://www.wired.com/2014/11/where‐fitness‐trackers‐fail. Published November 6, 2014. Accessed January 21, 2015.

- , , . Wearable devices as facilitators, not drivers, of health behavior change. JAMA. 2015;313(5):459–460.

- , , . Digital medical tools and sensors. JAMA. 2015;313(4):353–354.

Brentuximab doubles PFS in Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients

Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) increased progression-free survival to 43 months when given to adults with hard-to-treat Hodgkin’s lymphoma immediately after stem cell transplant, compared to 24 months for placebo, according to research published online March 18 in The Lancet.

As part of the AETHERA phase III trial, 329 patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma who were at high risk of relapse or progression after autologous stem cell transplant were given brentuximab vedotin infusions or placebo every 3 weeks for up to 16 cycles. After a 2-year follow-up, the cancer had not progressed in 65% of the patients in the treatment group, compared with 45% in the placebo group.

The most common side effects were peripheral neuropathy (67% vs. 13% placebo) and neutropenia (35% vs. 12% placebo), noted Dr. Craig Moskowitz of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and his associates.

Read the full article here.

Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) increased progression-free survival to 43 months when given to adults with hard-to-treat Hodgkin’s lymphoma immediately after stem cell transplant, compared to 24 months for placebo, according to research published online March 18 in The Lancet.

As part of the AETHERA phase III trial, 329 patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma who were at high risk of relapse or progression after autologous stem cell transplant were given brentuximab vedotin infusions or placebo every 3 weeks for up to 16 cycles. After a 2-year follow-up, the cancer had not progressed in 65% of the patients in the treatment group, compared with 45% in the placebo group.

The most common side effects were peripheral neuropathy (67% vs. 13% placebo) and neutropenia (35% vs. 12% placebo), noted Dr. Craig Moskowitz of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and his associates.

Read the full article here.

Brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris) increased progression-free survival to 43 months when given to adults with hard-to-treat Hodgkin’s lymphoma immediately after stem cell transplant, compared to 24 months for placebo, according to research published online March 18 in The Lancet.

As part of the AETHERA phase III trial, 329 patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma who were at high risk of relapse or progression after autologous stem cell transplant were given brentuximab vedotin infusions or placebo every 3 weeks for up to 16 cycles. After a 2-year follow-up, the cancer had not progressed in 65% of the patients in the treatment group, compared with 45% in the placebo group.

The most common side effects were peripheral neuropathy (67% vs. 13% placebo) and neutropenia (35% vs. 12% placebo), noted Dr. Craig Moskowitz of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and his associates.

Read the full article here.

ACP: Avoid ECG, MPI cardiac screening in low-risk patients

Clinicians should not screen for cardiac disease in asymptomatic, low-risk adults using resting or stress electrocardiography, stress echocardiography, or stress myocardial perfusion imaging , according to new guidelines from the American College of Physicians.

“There is no evidence that cardiac screening of low-risk adults with resting or stress ECG, stress echocardiography, or stress MPI improves outcomes, but it is associated with increased costs and potential harms,” wrote the guideline’s author, Dr. Roger Chou, associate professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

The recommendation is based on a systematic literature review, recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, and American College of Cardiology guidelines. The new ACP clinical guideline was published March 17 in Annals of Internal Medicine (doi: 10.7326/M14-1225).

“What we are saying here is that, as physicians, we have responsibility to understand what the pretest probability is, and what the likelihood is that someone actually has disease – and if it’s low enough, then doing the screening test is going to cause a lot more false positives than true positives,” Dr. Robert Centor, regional dean of the Huntsville Medical Campus of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, explained in an interview.

“Even if it is a true positive, there is no evidence that we can find that finding that heart disease will do anything other than lead someone to do a procedure that we have no evidence will improve their outcomes,” added Dr. Centor, chair of the ACP Board of Regents.

Despite existing recommendations to the contrary, physicians are increasingly performing these tests on low-risk patients, the ACP cautioned.

For example, a Consumer Reports survey found that “39% of asymptomatic adults without high blood pressure or a high cholesterol level reported having ECG within the past 5 years, and 12% reported undergoing exercise ECG,” Dr. Chou wrote in his report on behalf of the ACP High Value Care Task Force. More than half of those patients said their physicians recommended the tests as part of their routine health care.

The rise in the use of such tests is likely the result of a combination of factors, Dr. Centor said. Those factors include money (patients see no out-of-pocket cost and thus don’t consider the cost of tests in their decision making), direct-to-consumer advertising, fear on behalf of physicians that they might miss a diagnosis, and a lack of understanding by patients on the adverse effects of screening if they are at low risk for heart disease.

Dr. Chou identified a number of potential harms related to unnecessary screenings, including sudden death or hospitalization during stress tests; adverse events from pharmacologics used to induce stress; radiation exposure from myocardial perfusion imaging; false positive results that, in turn, lead to anxiety by the patient and additional unnecessary tests and treatments; disease labeling; and downstream harms from follow-up testing and interventions.

“To be most effective, efforts to reduce the use of imaging should be multifocal and should address clinician behavior, patient expectations, direct-to-consumer screening programs, and financial incentives,” Dr. Chou explained.

In low-risk patients, physicians instead should “focus on treating modifiable risk factors (such as smoking, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and overweight) and encouraging healthy levels of exercise,” according to the guideline.

Clinicians should not screen for cardiac disease in asymptomatic, low-risk adults using resting or stress electrocardiography, stress echocardiography, or stress myocardial perfusion imaging , according to new guidelines from the American College of Physicians.

“There is no evidence that cardiac screening of low-risk adults with resting or stress ECG, stress echocardiography, or stress MPI improves outcomes, but it is associated with increased costs and potential harms,” wrote the guideline’s author, Dr. Roger Chou, associate professor of medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.