User login

Is brain damage an ‘inevitable consequence or an avoidable risk’ of American football?

More research is needed to better understand and prevent traumatic brain injury such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy in American football players, Chad A. Asplund and Dr. Thomas M. Best wrote in an editorial published March 24 in BMJ.

Currently, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) can be formally diagnosed only at autopsy.

Though the National Football League denies a relationship between football and CTE, all confirmed cases of the disease in American football players to date were in those with a history of repetitive blows to the head. Athletes who began playing football before 12 years of age show greater cognitive impairment in older age than do those who started later, according to the authors.

“Further work into risk mitigation, paralleled with increased research into the pathophysiology of both concussion and CTE, is needed,” the authors wrote. “For now, it seems that the more we learn about CTE, the more questions are left unanswered – it still remains unclear if brain damage is an inevitable consequence or an avoidable risk of American football.”

Read the full article here: BMJ 2015;349:h1381 (doi:10.1136/bmj.h1381).

More research is needed to better understand and prevent traumatic brain injury such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy in American football players, Chad A. Asplund and Dr. Thomas M. Best wrote in an editorial published March 24 in BMJ.

Currently, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) can be formally diagnosed only at autopsy.

Though the National Football League denies a relationship between football and CTE, all confirmed cases of the disease in American football players to date were in those with a history of repetitive blows to the head. Athletes who began playing football before 12 years of age show greater cognitive impairment in older age than do those who started later, according to the authors.

“Further work into risk mitigation, paralleled with increased research into the pathophysiology of both concussion and CTE, is needed,” the authors wrote. “For now, it seems that the more we learn about CTE, the more questions are left unanswered – it still remains unclear if brain damage is an inevitable consequence or an avoidable risk of American football.”

Read the full article here: BMJ 2015;349:h1381 (doi:10.1136/bmj.h1381).

More research is needed to better understand and prevent traumatic brain injury such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy in American football players, Chad A. Asplund and Dr. Thomas M. Best wrote in an editorial published March 24 in BMJ.

Currently, chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) can be formally diagnosed only at autopsy.

Though the National Football League denies a relationship between football and CTE, all confirmed cases of the disease in American football players to date were in those with a history of repetitive blows to the head. Athletes who began playing football before 12 years of age show greater cognitive impairment in older age than do those who started later, according to the authors.

“Further work into risk mitigation, paralleled with increased research into the pathophysiology of both concussion and CTE, is needed,” the authors wrote. “For now, it seems that the more we learn about CTE, the more questions are left unanswered – it still remains unclear if brain damage is an inevitable consequence or an avoidable risk of American football.”

Read the full article here: BMJ 2015;349:h1381 (doi:10.1136/bmj.h1381).

Dos and don’ts for handling common sling complications

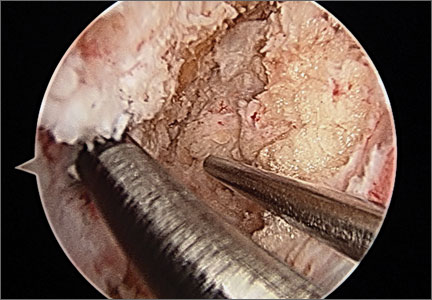

Large-scale randomized trials have not only documented the efficacy of minimally invasive midurethral slings for stress urinary continence, they have also provided more adequate data on the incidence of complications. In practice, meanwhile, we are seeing more complications as the number of midurethral sling placements increases.

Often times, complications can be significantly more impactful than the original urinary incontinence. It is important to take the complications of sling placement seriously. Let patients know that their symptoms matter, and that there are ways to manage complications.

With more long-term data and experience, we have learned more about what to do, and what not to do, to prevent, diagnose, and manage the complications associated with midurethral slings. Here is my approach to the complications most commonly encountered, including bladder perforation, voiding dysfunction, erosion, pain, and recurrent stress urinary incontinence.

I will not address vascular injury in this article, but certainly, this is a surgical emergency that needs to be handled as such. As described in the February 2015 edition of Master Class on midurethral sling technique, accurate visualization toward the ipsilateral shoulder during needle passage is an essential part of preventing vascular injuries during retropubic sling placement.

Bladder perforation

Bladder perforation has consistently been shown to be significantly more common with retropubic slings than with transobturator slings. Reported incidence has ranged from 0.8% to 34% for tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedures, with the higher rates seen mainly in teaching institutions. Most commonly, the reported incidence is less than 10%.

Bladder perforation has no effect on the efficacy of the treatment, and no apparent long-term consequences, as long as the injury is identified. Especially with a retropubic sling, cystoscopy should be performed after both needles are placed but prior to advancing the needles all the way through the retropubic space. Simply withdrawing a needle will cause little bladder injury while retracting deployed mesh is significantly more consequential.

I recommend filling the bladder to approximately 300 cc, or to the point where you can see evidence of full distension such as flattened urethral orifices. This confirms that the bladder is under enough distension to preclude any mucosal wrinkles or folds that can hide a trocar injury.

The first step upon recognition of a perforation is to stay calm. In the vast majority of cases, simply withdrawing the needle, replacing it, and verifying correct replacement will prevent any long-term consequences. On the other hand, you must be fully alert to the possibility that the needle wandered away from the pubic bone, and consequently may have entered a space such as the peritoneum. Suspicion for visceral injury should be increased.

Resist the temptation to replace the needle more laterally. This course correction is often an unhelpful instinct, because a more lateral replacement will not move the needle farther from the bladder; it will instead bring it closer to the iliac vessels. Vascular injuries resulting from the surgeon’s attempts at needle replacement are unfortunate, as a minor complication becomes a major one. The key is to be as distal as possible – as close to the pubic bone as possible – and not to replace the needles more laterally.

Postoperative drainage for 1-2 days may be considered, but there is nothing in the literature to require this, and many surgeons do not employ any sort of extra catheterization after surgery where perforation has been observed.

Voiding dysfunction

Some degree of voiding dysfunction is not uncommon in the short term, but when a patient is still unable to void normally or completely after several days, an evaluation is warranted. As with bladder perforation, reported incidence of voiding dysfunction has varied widely, from 2% to 45% with the newer midurethral slings. Generally, the need for surgical revision is about 2%.

There are two reasons for urinary retention: Insufficient contraction force in the bladder or too much resistance. If retention persists beyond a week – in the 7-10 day postop time period – I assess whether the problem is resulting from too much obstruction from the sling, some form of hypotonic bladder, other surgery performed in conjunction with sling placement, medications, or something else.

Difficulty in passing a small urethra catheter in the office may indicate excessive obstruction, for instance, and there may be indications on vaginal examination or through cystoscopy that the sling is too tight. A midurethral “speed bump,” or elevation at the midpoint, with either catheterization or the scope is consistent with over-correction.

Do not dilate or pull down on the sling with any kind of urethra dilator. The sling is more robust than the urethral mucosa, and we now appreciate that this practice is associated with urethral erosion.

If the problem is deemed to be excessive obstruction or over-resistance, and it is fewer than 10 days postop, the patient may be offered a minor revision; the original incision is reopened, the sling material is identified, and the sling arms (lateral to the urethra) are grasped with clamps. Gentle downward traction can loosen the sling.

The sling should be grasped laterally and not at the midpoint; some sling materials will stretch and fracture where the force is applied. A little bit of gentle downward traction (3-5 mm) will often give you the needed amount of space for relieving some of the obstruction.

Beyond 10 days postop, tissue in-growth makes such a sling adjustment difficult, if not impossible. At this point, I recommend transecting the entire sling in the midline.There is differing opinion about whether a portion of the mesh should be resected; I believe that such a resection is usually unnecessary, and that a simple midline release procedure is the best approach.

A study we performed more than a decade ago on surgical release of TVT showed that persistent post-TVT voiding dysfunction can be successfully managed with a simple midline release. Of 1,175 women who underwent TVT placement for stress urinary incontinence and/or intrinsic sphincter deficiency, 23 (1.9%) had persistent voiding dysfunction. All cases of impaired emptying were completely resolved with a release of the tape, and the majority remained cured in terms of their continence or went from “cured” to “improved” over baseline. Three patients (13%) had recurrence of stress incontinence (Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;100:898-902).

We used to wait longer before revising the sling out of fear of losing the entire benefit of the sling. As it turns out, a simple midline release (leaving most, if not all, of the mesh in place) is usually just enough to treat the new complaint while still providing enough lateral support so that the patient retains most or all of the continence achieved with the sling.

Complaints of de novo urge incontinence, or overactive bladder, should be taken seriously. Urge incontinence has even more significant associations with depression and poor quality of life than stress incontinence. In the absence of retention, usual first-line therapies for overactive bladder can be employed, including anticholinergic medications, behavioral therapies, and physical therapy. Failing these interventions, my assessment for this complaint will be similar to that for retention; I’ll look for evidence of too much resistance, such as difficulty in passing a catheter, a “speed bump” cystoscopically, or an elevated pDet on pressure-flow studies, for instance.

If any of these are present, I usually offer sling release first. If, on the other hand, there is no evidence of over resistance in a patient who has de novo urge incontinence or overactive bladder and is refractory to conservative measures, a trial of sacral neuromodulation or botox injections is considered the next step.

Erosion

Erosion remains a difficult complication to understand. Long-term follow-up data show that it occurs after 3%-4% of sling placements, rather than 1% as originally believed. Data are inconsistent, but there probably is a slightly higher incidence of vaginal erosion with a transobturator sling, given more contact between the sling and the anterior vaginal wall.

There are hints in the literature that erosion may be related to technique – perhaps to the depth of dissection during surgery – but this is difficult to quantify. Moreover, many of the reported cases of erosion occur several years, or longer, after surgery. It is hard to blame surgical technique for such delayed erosion.

As we’ve seen with previous generations of mesh, there does not appear to be any window of time after which erosion is no longer a risk. We need to recognize that there is a medium- and long-term risk of erosion and appreciate its presenting symptoms: Recurrent urinary tract infection, pain with voiding, urgency, urinary incontinence, and microscopic hematuria of new onset.

Prevention may well entail preoperative estrogenization. The science looking at the effect of estrogen on sling placement is becoming more robust. While there are uncertainties, I believe that studies likely will show that topical estrogen in the preoperative and perioperative phases plays an important role in preventing erosion from occurring. Personally, I am using it much more than I was 10 years ago.

I like the convenience of the Vagifem tablet (Novo Nordisk Inc., Plainsboro, N.J.), and am reassured by data on systemic absorption with the 10-mcg dose, but any vaginal cream or compounded suppository can be used. I usually advise 4-6 weeks of preoperative preparation, with nightly use for 2 weeks followed by 2-3 nights per week thereafter. Smoking is also a likely risk factor. Data are not entirely consistent, but I believe we should provide counseling and encourage smoking cessation before the implant of mesh.

Management is dependent on when the erosion occurs or is recognized. When erosion occurs within 6 weeks post operatively, primary repair is an option. When erosion is detected after the 6-week window and is causing symptoms, a conservative trim of bristles poking through the vaginal mucosa is worth a try. I do not advise more than one such conservative trim, however, as repeated attempts and series of small resections can make the sling exceedingly difficult to remove if more complete resection is ultimately needed. After one unsuccessful trim, I usually remove the whole sling belly, or most of the vaginal part of the sling.

For slings made of type 1 macroporous mesh, resection of the retropubic or transobturator portions of the mesh usually is not required. In the more rare situation where those pelvic areas of the mesh are associated with pain, I favor a laparoscopic approach to the retropubic space to facilitate minimally invasive removal.

Postop pain, sling failure

Groin pain, or thigh pain, sometimes occurs after placement of a transobturator sling. As I discussed in the previous Master Class on midurethral sling technique, I have seen a significant decrease in groin pain in my patients – without any reduction in benefit – with the use of a shorter transobturator sling that does not leave mesh in the adductor compartment of the thigh and groin.

For persistent groin pain, I favor the use of trigger point injection. Sometimes one injection will impact the inflammatory cycle such that the patient derives long-term benefit. At other times, the trigger point injection will serve as a diagnostic; if pain returns after a period of benefit, I am inclined to resect that part of the mesh.

Pain inside the pelvis, especially on the pelvic sidewall (obturator or puborectalis complex) usually is related to mechanical tension. In my experience, this type of discomfort is slightly more likely to occur with the transobturator slings, which penetrate through the muscular pelvic sidewall and lead to more fibrosis and scar tissue formation.

In most cases of pain and discomfort, attempting to reproduce the patient’s symptoms by putting tension on particular parts of the sling during the office exam helps guide management. If I find that palpating or putting the sling on tension recreates her complaints, and conservative injections have provided temporary or inadequate relief, I usually advocate resecting the vaginal portion of the mesh to relieve that tension.

In cases of recurrent stress urinary incontinence (when the sling has failed), a TVT or repeat TVT is often warranted. The TVT sling has been demonstrated to work after nearly every other previous kind of anti-incontinence procedure, even after a previous retropubic sling. There is little data on mesh removal in such cases. I believe that unless a previously placed but failed sling is causing symptoms, there is no need to resect it. Mesh removal is significantly more traumatic than mesh placement, and in most cases it is not necessary.

Dr. Rardin reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

Large-scale randomized trials have not only documented the efficacy of minimally invasive midurethral slings for stress urinary continence, they have also provided more adequate data on the incidence of complications. In practice, meanwhile, we are seeing more complications as the number of midurethral sling placements increases.

Often times, complications can be significantly more impactful than the original urinary incontinence. It is important to take the complications of sling placement seriously. Let patients know that their symptoms matter, and that there are ways to manage complications.

With more long-term data and experience, we have learned more about what to do, and what not to do, to prevent, diagnose, and manage the complications associated with midurethral slings. Here is my approach to the complications most commonly encountered, including bladder perforation, voiding dysfunction, erosion, pain, and recurrent stress urinary incontinence.

I will not address vascular injury in this article, but certainly, this is a surgical emergency that needs to be handled as such. As described in the February 2015 edition of Master Class on midurethral sling technique, accurate visualization toward the ipsilateral shoulder during needle passage is an essential part of preventing vascular injuries during retropubic sling placement.

Bladder perforation

Bladder perforation has consistently been shown to be significantly more common with retropubic slings than with transobturator slings. Reported incidence has ranged from 0.8% to 34% for tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedures, with the higher rates seen mainly in teaching institutions. Most commonly, the reported incidence is less than 10%.

Bladder perforation has no effect on the efficacy of the treatment, and no apparent long-term consequences, as long as the injury is identified. Especially with a retropubic sling, cystoscopy should be performed after both needles are placed but prior to advancing the needles all the way through the retropubic space. Simply withdrawing a needle will cause little bladder injury while retracting deployed mesh is significantly more consequential.

I recommend filling the bladder to approximately 300 cc, or to the point where you can see evidence of full distension such as flattened urethral orifices. This confirms that the bladder is under enough distension to preclude any mucosal wrinkles or folds that can hide a trocar injury.

The first step upon recognition of a perforation is to stay calm. In the vast majority of cases, simply withdrawing the needle, replacing it, and verifying correct replacement will prevent any long-term consequences. On the other hand, you must be fully alert to the possibility that the needle wandered away from the pubic bone, and consequently may have entered a space such as the peritoneum. Suspicion for visceral injury should be increased.

Resist the temptation to replace the needle more laterally. This course correction is often an unhelpful instinct, because a more lateral replacement will not move the needle farther from the bladder; it will instead bring it closer to the iliac vessels. Vascular injuries resulting from the surgeon’s attempts at needle replacement are unfortunate, as a minor complication becomes a major one. The key is to be as distal as possible – as close to the pubic bone as possible – and not to replace the needles more laterally.

Postoperative drainage for 1-2 days may be considered, but there is nothing in the literature to require this, and many surgeons do not employ any sort of extra catheterization after surgery where perforation has been observed.

Voiding dysfunction

Some degree of voiding dysfunction is not uncommon in the short term, but when a patient is still unable to void normally or completely after several days, an evaluation is warranted. As with bladder perforation, reported incidence of voiding dysfunction has varied widely, from 2% to 45% with the newer midurethral slings. Generally, the need for surgical revision is about 2%.

There are two reasons for urinary retention: Insufficient contraction force in the bladder or too much resistance. If retention persists beyond a week – in the 7-10 day postop time period – I assess whether the problem is resulting from too much obstruction from the sling, some form of hypotonic bladder, other surgery performed in conjunction with sling placement, medications, or something else.

Difficulty in passing a small urethra catheter in the office may indicate excessive obstruction, for instance, and there may be indications on vaginal examination or through cystoscopy that the sling is too tight. A midurethral “speed bump,” or elevation at the midpoint, with either catheterization or the scope is consistent with over-correction.

Do not dilate or pull down on the sling with any kind of urethra dilator. The sling is more robust than the urethral mucosa, and we now appreciate that this practice is associated with urethral erosion.

If the problem is deemed to be excessive obstruction or over-resistance, and it is fewer than 10 days postop, the patient may be offered a minor revision; the original incision is reopened, the sling material is identified, and the sling arms (lateral to the urethra) are grasped with clamps. Gentle downward traction can loosen the sling.

The sling should be grasped laterally and not at the midpoint; some sling materials will stretch and fracture where the force is applied. A little bit of gentle downward traction (3-5 mm) will often give you the needed amount of space for relieving some of the obstruction.

Beyond 10 days postop, tissue in-growth makes such a sling adjustment difficult, if not impossible. At this point, I recommend transecting the entire sling in the midline.There is differing opinion about whether a portion of the mesh should be resected; I believe that such a resection is usually unnecessary, and that a simple midline release procedure is the best approach.

A study we performed more than a decade ago on surgical release of TVT showed that persistent post-TVT voiding dysfunction can be successfully managed with a simple midline release. Of 1,175 women who underwent TVT placement for stress urinary incontinence and/or intrinsic sphincter deficiency, 23 (1.9%) had persistent voiding dysfunction. All cases of impaired emptying were completely resolved with a release of the tape, and the majority remained cured in terms of their continence or went from “cured” to “improved” over baseline. Three patients (13%) had recurrence of stress incontinence (Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;100:898-902).

We used to wait longer before revising the sling out of fear of losing the entire benefit of the sling. As it turns out, a simple midline release (leaving most, if not all, of the mesh in place) is usually just enough to treat the new complaint while still providing enough lateral support so that the patient retains most or all of the continence achieved with the sling.

Complaints of de novo urge incontinence, or overactive bladder, should be taken seriously. Urge incontinence has even more significant associations with depression and poor quality of life than stress incontinence. In the absence of retention, usual first-line therapies for overactive bladder can be employed, including anticholinergic medications, behavioral therapies, and physical therapy. Failing these interventions, my assessment for this complaint will be similar to that for retention; I’ll look for evidence of too much resistance, such as difficulty in passing a catheter, a “speed bump” cystoscopically, or an elevated pDet on pressure-flow studies, for instance.

If any of these are present, I usually offer sling release first. If, on the other hand, there is no evidence of over resistance in a patient who has de novo urge incontinence or overactive bladder and is refractory to conservative measures, a trial of sacral neuromodulation or botox injections is considered the next step.

Erosion

Erosion remains a difficult complication to understand. Long-term follow-up data show that it occurs after 3%-4% of sling placements, rather than 1% as originally believed. Data are inconsistent, but there probably is a slightly higher incidence of vaginal erosion with a transobturator sling, given more contact between the sling and the anterior vaginal wall.

There are hints in the literature that erosion may be related to technique – perhaps to the depth of dissection during surgery – but this is difficult to quantify. Moreover, many of the reported cases of erosion occur several years, or longer, after surgery. It is hard to blame surgical technique for such delayed erosion.

As we’ve seen with previous generations of mesh, there does not appear to be any window of time after which erosion is no longer a risk. We need to recognize that there is a medium- and long-term risk of erosion and appreciate its presenting symptoms: Recurrent urinary tract infection, pain with voiding, urgency, urinary incontinence, and microscopic hematuria of new onset.

Prevention may well entail preoperative estrogenization. The science looking at the effect of estrogen on sling placement is becoming more robust. While there are uncertainties, I believe that studies likely will show that topical estrogen in the preoperative and perioperative phases plays an important role in preventing erosion from occurring. Personally, I am using it much more than I was 10 years ago.

I like the convenience of the Vagifem tablet (Novo Nordisk Inc., Plainsboro, N.J.), and am reassured by data on systemic absorption with the 10-mcg dose, but any vaginal cream or compounded suppository can be used. I usually advise 4-6 weeks of preoperative preparation, with nightly use for 2 weeks followed by 2-3 nights per week thereafter. Smoking is also a likely risk factor. Data are not entirely consistent, but I believe we should provide counseling and encourage smoking cessation before the implant of mesh.

Management is dependent on when the erosion occurs or is recognized. When erosion occurs within 6 weeks post operatively, primary repair is an option. When erosion is detected after the 6-week window and is causing symptoms, a conservative trim of bristles poking through the vaginal mucosa is worth a try. I do not advise more than one such conservative trim, however, as repeated attempts and series of small resections can make the sling exceedingly difficult to remove if more complete resection is ultimately needed. After one unsuccessful trim, I usually remove the whole sling belly, or most of the vaginal part of the sling.

For slings made of type 1 macroporous mesh, resection of the retropubic or transobturator portions of the mesh usually is not required. In the more rare situation where those pelvic areas of the mesh are associated with pain, I favor a laparoscopic approach to the retropubic space to facilitate minimally invasive removal.

Postop pain, sling failure

Groin pain, or thigh pain, sometimes occurs after placement of a transobturator sling. As I discussed in the previous Master Class on midurethral sling technique, I have seen a significant decrease in groin pain in my patients – without any reduction in benefit – with the use of a shorter transobturator sling that does not leave mesh in the adductor compartment of the thigh and groin.

For persistent groin pain, I favor the use of trigger point injection. Sometimes one injection will impact the inflammatory cycle such that the patient derives long-term benefit. At other times, the trigger point injection will serve as a diagnostic; if pain returns after a period of benefit, I am inclined to resect that part of the mesh.

Pain inside the pelvis, especially on the pelvic sidewall (obturator or puborectalis complex) usually is related to mechanical tension. In my experience, this type of discomfort is slightly more likely to occur with the transobturator slings, which penetrate through the muscular pelvic sidewall and lead to more fibrosis and scar tissue formation.

In most cases of pain and discomfort, attempting to reproduce the patient’s symptoms by putting tension on particular parts of the sling during the office exam helps guide management. If I find that palpating or putting the sling on tension recreates her complaints, and conservative injections have provided temporary or inadequate relief, I usually advocate resecting the vaginal portion of the mesh to relieve that tension.

In cases of recurrent stress urinary incontinence (when the sling has failed), a TVT or repeat TVT is often warranted. The TVT sling has been demonstrated to work after nearly every other previous kind of anti-incontinence procedure, even after a previous retropubic sling. There is little data on mesh removal in such cases. I believe that unless a previously placed but failed sling is causing symptoms, there is no need to resect it. Mesh removal is significantly more traumatic than mesh placement, and in most cases it is not necessary.

Dr. Rardin reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

Large-scale randomized trials have not only documented the efficacy of minimally invasive midurethral slings for stress urinary continence, they have also provided more adequate data on the incidence of complications. In practice, meanwhile, we are seeing more complications as the number of midurethral sling placements increases.

Often times, complications can be significantly more impactful than the original urinary incontinence. It is important to take the complications of sling placement seriously. Let patients know that their symptoms matter, and that there are ways to manage complications.

With more long-term data and experience, we have learned more about what to do, and what not to do, to prevent, diagnose, and manage the complications associated with midurethral slings. Here is my approach to the complications most commonly encountered, including bladder perforation, voiding dysfunction, erosion, pain, and recurrent stress urinary incontinence.

I will not address vascular injury in this article, but certainly, this is a surgical emergency that needs to be handled as such. As described in the February 2015 edition of Master Class on midurethral sling technique, accurate visualization toward the ipsilateral shoulder during needle passage is an essential part of preventing vascular injuries during retropubic sling placement.

Bladder perforation

Bladder perforation has consistently been shown to be significantly more common with retropubic slings than with transobturator slings. Reported incidence has ranged from 0.8% to 34% for tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedures, with the higher rates seen mainly in teaching institutions. Most commonly, the reported incidence is less than 10%.

Bladder perforation has no effect on the efficacy of the treatment, and no apparent long-term consequences, as long as the injury is identified. Especially with a retropubic sling, cystoscopy should be performed after both needles are placed but prior to advancing the needles all the way through the retropubic space. Simply withdrawing a needle will cause little bladder injury while retracting deployed mesh is significantly more consequential.

I recommend filling the bladder to approximately 300 cc, or to the point where you can see evidence of full distension such as flattened urethral orifices. This confirms that the bladder is under enough distension to preclude any mucosal wrinkles or folds that can hide a trocar injury.

The first step upon recognition of a perforation is to stay calm. In the vast majority of cases, simply withdrawing the needle, replacing it, and verifying correct replacement will prevent any long-term consequences. On the other hand, you must be fully alert to the possibility that the needle wandered away from the pubic bone, and consequently may have entered a space such as the peritoneum. Suspicion for visceral injury should be increased.

Resist the temptation to replace the needle more laterally. This course correction is often an unhelpful instinct, because a more lateral replacement will not move the needle farther from the bladder; it will instead bring it closer to the iliac vessels. Vascular injuries resulting from the surgeon’s attempts at needle replacement are unfortunate, as a minor complication becomes a major one. The key is to be as distal as possible – as close to the pubic bone as possible – and not to replace the needles more laterally.

Postoperative drainage for 1-2 days may be considered, but there is nothing in the literature to require this, and many surgeons do not employ any sort of extra catheterization after surgery where perforation has been observed.

Voiding dysfunction

Some degree of voiding dysfunction is not uncommon in the short term, but when a patient is still unable to void normally or completely after several days, an evaluation is warranted. As with bladder perforation, reported incidence of voiding dysfunction has varied widely, from 2% to 45% with the newer midurethral slings. Generally, the need for surgical revision is about 2%.

There are two reasons for urinary retention: Insufficient contraction force in the bladder or too much resistance. If retention persists beyond a week – in the 7-10 day postop time period – I assess whether the problem is resulting from too much obstruction from the sling, some form of hypotonic bladder, other surgery performed in conjunction with sling placement, medications, or something else.

Difficulty in passing a small urethra catheter in the office may indicate excessive obstruction, for instance, and there may be indications on vaginal examination or through cystoscopy that the sling is too tight. A midurethral “speed bump,” or elevation at the midpoint, with either catheterization or the scope is consistent with over-correction.

Do not dilate or pull down on the sling with any kind of urethra dilator. The sling is more robust than the urethral mucosa, and we now appreciate that this practice is associated with urethral erosion.

If the problem is deemed to be excessive obstruction or over-resistance, and it is fewer than 10 days postop, the patient may be offered a minor revision; the original incision is reopened, the sling material is identified, and the sling arms (lateral to the urethra) are grasped with clamps. Gentle downward traction can loosen the sling.

The sling should be grasped laterally and not at the midpoint; some sling materials will stretch and fracture where the force is applied. A little bit of gentle downward traction (3-5 mm) will often give you the needed amount of space for relieving some of the obstruction.

Beyond 10 days postop, tissue in-growth makes such a sling adjustment difficult, if not impossible. At this point, I recommend transecting the entire sling in the midline.There is differing opinion about whether a portion of the mesh should be resected; I believe that such a resection is usually unnecessary, and that a simple midline release procedure is the best approach.

A study we performed more than a decade ago on surgical release of TVT showed that persistent post-TVT voiding dysfunction can be successfully managed with a simple midline release. Of 1,175 women who underwent TVT placement for stress urinary incontinence and/or intrinsic sphincter deficiency, 23 (1.9%) had persistent voiding dysfunction. All cases of impaired emptying were completely resolved with a release of the tape, and the majority remained cured in terms of their continence or went from “cured” to “improved” over baseline. Three patients (13%) had recurrence of stress incontinence (Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;100:898-902).

We used to wait longer before revising the sling out of fear of losing the entire benefit of the sling. As it turns out, a simple midline release (leaving most, if not all, of the mesh in place) is usually just enough to treat the new complaint while still providing enough lateral support so that the patient retains most or all of the continence achieved with the sling.

Complaints of de novo urge incontinence, or overactive bladder, should be taken seriously. Urge incontinence has even more significant associations with depression and poor quality of life than stress incontinence. In the absence of retention, usual first-line therapies for overactive bladder can be employed, including anticholinergic medications, behavioral therapies, and physical therapy. Failing these interventions, my assessment for this complaint will be similar to that for retention; I’ll look for evidence of too much resistance, such as difficulty in passing a catheter, a “speed bump” cystoscopically, or an elevated pDet on pressure-flow studies, for instance.

If any of these are present, I usually offer sling release first. If, on the other hand, there is no evidence of over resistance in a patient who has de novo urge incontinence or overactive bladder and is refractory to conservative measures, a trial of sacral neuromodulation or botox injections is considered the next step.

Erosion

Erosion remains a difficult complication to understand. Long-term follow-up data show that it occurs after 3%-4% of sling placements, rather than 1% as originally believed. Data are inconsistent, but there probably is a slightly higher incidence of vaginal erosion with a transobturator sling, given more contact between the sling and the anterior vaginal wall.

There are hints in the literature that erosion may be related to technique – perhaps to the depth of dissection during surgery – but this is difficult to quantify. Moreover, many of the reported cases of erosion occur several years, or longer, after surgery. It is hard to blame surgical technique for such delayed erosion.

As we’ve seen with previous generations of mesh, there does not appear to be any window of time after which erosion is no longer a risk. We need to recognize that there is a medium- and long-term risk of erosion and appreciate its presenting symptoms: Recurrent urinary tract infection, pain with voiding, urgency, urinary incontinence, and microscopic hematuria of new onset.

Prevention may well entail preoperative estrogenization. The science looking at the effect of estrogen on sling placement is becoming more robust. While there are uncertainties, I believe that studies likely will show that topical estrogen in the preoperative and perioperative phases plays an important role in preventing erosion from occurring. Personally, I am using it much more than I was 10 years ago.

I like the convenience of the Vagifem tablet (Novo Nordisk Inc., Plainsboro, N.J.), and am reassured by data on systemic absorption with the 10-mcg dose, but any vaginal cream or compounded suppository can be used. I usually advise 4-6 weeks of preoperative preparation, with nightly use for 2 weeks followed by 2-3 nights per week thereafter. Smoking is also a likely risk factor. Data are not entirely consistent, but I believe we should provide counseling and encourage smoking cessation before the implant of mesh.

Management is dependent on when the erosion occurs or is recognized. When erosion occurs within 6 weeks post operatively, primary repair is an option. When erosion is detected after the 6-week window and is causing symptoms, a conservative trim of bristles poking through the vaginal mucosa is worth a try. I do not advise more than one such conservative trim, however, as repeated attempts and series of small resections can make the sling exceedingly difficult to remove if more complete resection is ultimately needed. After one unsuccessful trim, I usually remove the whole sling belly, or most of the vaginal part of the sling.

For slings made of type 1 macroporous mesh, resection of the retropubic or transobturator portions of the mesh usually is not required. In the more rare situation where those pelvic areas of the mesh are associated with pain, I favor a laparoscopic approach to the retropubic space to facilitate minimally invasive removal.

Postop pain, sling failure

Groin pain, or thigh pain, sometimes occurs after placement of a transobturator sling. As I discussed in the previous Master Class on midurethral sling technique, I have seen a significant decrease in groin pain in my patients – without any reduction in benefit – with the use of a shorter transobturator sling that does not leave mesh in the adductor compartment of the thigh and groin.

For persistent groin pain, I favor the use of trigger point injection. Sometimes one injection will impact the inflammatory cycle such that the patient derives long-term benefit. At other times, the trigger point injection will serve as a diagnostic; if pain returns after a period of benefit, I am inclined to resect that part of the mesh.

Pain inside the pelvis, especially on the pelvic sidewall (obturator or puborectalis complex) usually is related to mechanical tension. In my experience, this type of discomfort is slightly more likely to occur with the transobturator slings, which penetrate through the muscular pelvic sidewall and lead to more fibrosis and scar tissue formation.

In most cases of pain and discomfort, attempting to reproduce the patient’s symptoms by putting tension on particular parts of the sling during the office exam helps guide management. If I find that palpating or putting the sling on tension recreates her complaints, and conservative injections have provided temporary or inadequate relief, I usually advocate resecting the vaginal portion of the mesh to relieve that tension.

In cases of recurrent stress urinary incontinence (when the sling has failed), a TVT or repeat TVT is often warranted. The TVT sling has been demonstrated to work after nearly every other previous kind of anti-incontinence procedure, even after a previous retropubic sling. There is little data on mesh removal in such cases. I believe that unless a previously placed but failed sling is causing symptoms, there is no need to resect it. Mesh removal is significantly more traumatic than mesh placement, and in most cases it is not necessary.

Dr. Rardin reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

Tackling midurethral sling complications

Over the past 2 decades, midurethral slings, both via a retropubic and a transobturator approach have become the first-line therapy for the surgical correction of female stress urinary incontinence. Not only are cure rates excellent for both techniques, but the incidence of complications are low.

Intraoperatively, major concerns include vascular lesions, nerve injuries, and injuries to the bowel. More minor concerns are related to the bladder.

Perioperative complications include retropubic hematoma, blood loss, urinary tract infection, and spondylitis. Postoperative risks include transient versus permanent urinary retention, vaginal versus urethral erosion, de novo urgency, bladder erosion, and urethral obstruction.

In this edition of Master Class in gynecologic surgery, I am pleased to solicit the help of Dr. Charles Rardin, who will make recommendations regarding the management of some of the most common complications related to midurethral sling procedures.

Dr. Rardin is the director of the Robotic Surgery Program at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, in Providence; a surgeon in Women & Infants’ division of urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery; and is the director of the hospital’s fellowship urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller is a consultant and on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon.

Over the past 2 decades, midurethral slings, both via a retropubic and a transobturator approach have become the first-line therapy for the surgical correction of female stress urinary incontinence. Not only are cure rates excellent for both techniques, but the incidence of complications are low.

Intraoperatively, major concerns include vascular lesions, nerve injuries, and injuries to the bowel. More minor concerns are related to the bladder.

Perioperative complications include retropubic hematoma, blood loss, urinary tract infection, and spondylitis. Postoperative risks include transient versus permanent urinary retention, vaginal versus urethral erosion, de novo urgency, bladder erosion, and urethral obstruction.

In this edition of Master Class in gynecologic surgery, I am pleased to solicit the help of Dr. Charles Rardin, who will make recommendations regarding the management of some of the most common complications related to midurethral sling procedures.

Dr. Rardin is the director of the Robotic Surgery Program at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, in Providence; a surgeon in Women & Infants’ division of urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery; and is the director of the hospital’s fellowship urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller is a consultant and on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon.

Over the past 2 decades, midurethral slings, both via a retropubic and a transobturator approach have become the first-line therapy for the surgical correction of female stress urinary incontinence. Not only are cure rates excellent for both techniques, but the incidence of complications are low.

Intraoperatively, major concerns include vascular lesions, nerve injuries, and injuries to the bowel. More minor concerns are related to the bladder.

Perioperative complications include retropubic hematoma, blood loss, urinary tract infection, and spondylitis. Postoperative risks include transient versus permanent urinary retention, vaginal versus urethral erosion, de novo urgency, bladder erosion, and urethral obstruction.

In this edition of Master Class in gynecologic surgery, I am pleased to solicit the help of Dr. Charles Rardin, who will make recommendations regarding the management of some of the most common complications related to midurethral sling procedures.

Dr. Rardin is the director of the Robotic Surgery Program at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island, in Providence; a surgeon in Women & Infants’ division of urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery; and is the director of the hospital’s fellowship urogynecology and reconstructive pelvic surgery.

Dr. Miller is clinical associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, immediate past president of the International Society for Gynecologic Endoscopy (ISGE), and a past president of the AAGL. He is a reproductive endocrinologist and minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in private practice in Naperville, Ill., and Schaumburg, Ill.; the director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery and the director of the AAGL/SRS fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, Ill.; and the medical editor of this column, Master Class. Dr. Miller is a consultant and on the speaker’s bureau for Ethicon.

Hospitalist Continuity Doesn’t Affect Adverse Events among Inpatients

Hospitalist continuity does not appear to be associated with the incidence of adverse events (AEs), according to a new report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Authors used two methods to measure continuity: the Number of Physicians Index (NPI) represented the total number of unique hospitalists caring for a patient, while the Usual Provider of Care (UPC) Index was the proportion of encounters with the most frequently encountered hospitalist.

Researchers reported that, in unadjusted models, each one-unit increase in the NPI—meaning less continuity—was significantly associated with the incidence of one or more AEs (odds ratio, 1.75; P<0.001). In addition, UPC was not associated with incidence of AEs. Across all adjusted models, neither index was "significantly associated" with the incidence of AEs.

Lead author Kevin O'Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, of Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, says that the data could be used to help determine how best to structure handoffs.

"Where I think this has a major impact is that a whole lot of groups [are] trying to figure out how long should our rotation length be," Dr. O'Leary says. "All of those programs that are really trying to maximize continuity because they think it's the safest thing and best thing for patient outcomes, they can probably relax a little bit and swing the pendulum a little bit further toward what they think is the right model for the work-life balance of their hospitalist. [They can] worry a little bit less about the impact on the patients because there doesn't seem to be much." TH

Visit our website for more information on transitions of care.

Hospitalist continuity does not appear to be associated with the incidence of adverse events (AEs), according to a new report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Authors used two methods to measure continuity: the Number of Physicians Index (NPI) represented the total number of unique hospitalists caring for a patient, while the Usual Provider of Care (UPC) Index was the proportion of encounters with the most frequently encountered hospitalist.

Researchers reported that, in unadjusted models, each one-unit increase in the NPI—meaning less continuity—was significantly associated with the incidence of one or more AEs (odds ratio, 1.75; P<0.001). In addition, UPC was not associated with incidence of AEs. Across all adjusted models, neither index was "significantly associated" with the incidence of AEs.

Lead author Kevin O'Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, of Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, says that the data could be used to help determine how best to structure handoffs.

"Where I think this has a major impact is that a whole lot of groups [are] trying to figure out how long should our rotation length be," Dr. O'Leary says. "All of those programs that are really trying to maximize continuity because they think it's the safest thing and best thing for patient outcomes, they can probably relax a little bit and swing the pendulum a little bit further toward what they think is the right model for the work-life balance of their hospitalist. [They can] worry a little bit less about the impact on the patients because there doesn't seem to be much." TH

Visit our website for more information on transitions of care.

Hospitalist continuity does not appear to be associated with the incidence of adverse events (AEs), according to a new report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.

Authors used two methods to measure continuity: the Number of Physicians Index (NPI) represented the total number of unique hospitalists caring for a patient, while the Usual Provider of Care (UPC) Index was the proportion of encounters with the most frequently encountered hospitalist.

Researchers reported that, in unadjusted models, each one-unit increase in the NPI—meaning less continuity—was significantly associated with the incidence of one or more AEs (odds ratio, 1.75; P<0.001). In addition, UPC was not associated with incidence of AEs. Across all adjusted models, neither index was "significantly associated" with the incidence of AEs.

Lead author Kevin O'Leary, MD, MS, SFHM, of Northwestern University's Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, says that the data could be used to help determine how best to structure handoffs.

"Where I think this has a major impact is that a whole lot of groups [are] trying to figure out how long should our rotation length be," Dr. O'Leary says. "All of those programs that are really trying to maximize continuity because they think it's the safest thing and best thing for patient outcomes, they can probably relax a little bit and swing the pendulum a little bit further toward what they think is the right model for the work-life balance of their hospitalist. [They can] worry a little bit less about the impact on the patients because there doesn't seem to be much." TH

Visit our website for more information on transitions of care.

Perioperative Hyperglycemia Increases Risk of Poor Outcomes in Nondiabetics

Clinical question: How does perioperative hyperglycemia affect the risk of adverse events in diabetic patients compared to nondiabetic patients?

Background: Perioperative hyperglycemia is associated with increased rates of infection, myocardial infarction, stroke, and death. Recent studies suggest that nondiabetics are more prone to hyperglycemia-related complications than diabetics. This study sought to analyze the effect and mechanism by which nondiabetics may be at increased risk for such complications.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Fifty-three hospitals in Washington.

Synopsis: Among 40,836 patients who underwent surgery, diabetics had a higher rate of perioperative adverse events overall compared to nondiabetics (12% versus 9%, P<0.001). Perioperative hyperglycemia, defined as blood glucose 180 or greater, was also associated with an increased rate of adverse events. Ironically, this association was more significant in nondiabetic patients (odds ratio, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3–2.1) than in diabetic patients (odds ratio, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.6–1.0). Although the exact reason for this is unknown, existing theories include the following:

- Diabetics are more apt to receive insulin for perioperative hyperglycemia than nondiabetics (P<0.001);

- Hyperglycemia in diabetics may be a less-reliable marker of surgical stress than in nondiabetics; and

- Diabetics may be better adapted to hyperglycemia than nondiabetics.

Bottom line: Perioperative hyperglycemia leads to an increased risk of adverse events; this relationship is more pronounced in nondiabetic patients than in diabetic patients.

Citation: Kotagal M, Symons RG, Hirsch IB, et al. Perioperative hyperglycemia and risk of adverse events among patients with and without diabetes. Ann Surg. 2015;261(1):97–103. TH

Visit our website for more physician reviews of hospitalist-focused literature.

Clinical question: How does perioperative hyperglycemia affect the risk of adverse events in diabetic patients compared to nondiabetic patients?

Background: Perioperative hyperglycemia is associated with increased rates of infection, myocardial infarction, stroke, and death. Recent studies suggest that nondiabetics are more prone to hyperglycemia-related complications than diabetics. This study sought to analyze the effect and mechanism by which nondiabetics may be at increased risk for such complications.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Fifty-three hospitals in Washington.

Synopsis: Among 40,836 patients who underwent surgery, diabetics had a higher rate of perioperative adverse events overall compared to nondiabetics (12% versus 9%, P<0.001). Perioperative hyperglycemia, defined as blood glucose 180 or greater, was also associated with an increased rate of adverse events. Ironically, this association was more significant in nondiabetic patients (odds ratio, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3–2.1) than in diabetic patients (odds ratio, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.6–1.0). Although the exact reason for this is unknown, existing theories include the following:

- Diabetics are more apt to receive insulin for perioperative hyperglycemia than nondiabetics (P<0.001);

- Hyperglycemia in diabetics may be a less-reliable marker of surgical stress than in nondiabetics; and

- Diabetics may be better adapted to hyperglycemia than nondiabetics.

Bottom line: Perioperative hyperglycemia leads to an increased risk of adverse events; this relationship is more pronounced in nondiabetic patients than in diabetic patients.

Citation: Kotagal M, Symons RG, Hirsch IB, et al. Perioperative hyperglycemia and risk of adverse events among patients with and without diabetes. Ann Surg. 2015;261(1):97–103. TH

Visit our website for more physician reviews of hospitalist-focused literature.

Clinical question: How does perioperative hyperglycemia affect the risk of adverse events in diabetic patients compared to nondiabetic patients?

Background: Perioperative hyperglycemia is associated with increased rates of infection, myocardial infarction, stroke, and death. Recent studies suggest that nondiabetics are more prone to hyperglycemia-related complications than diabetics. This study sought to analyze the effect and mechanism by which nondiabetics may be at increased risk for such complications.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Fifty-three hospitals in Washington.

Synopsis: Among 40,836 patients who underwent surgery, diabetics had a higher rate of perioperative adverse events overall compared to nondiabetics (12% versus 9%, P<0.001). Perioperative hyperglycemia, defined as blood glucose 180 or greater, was also associated with an increased rate of adverse events. Ironically, this association was more significant in nondiabetic patients (odds ratio, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.3–2.1) than in diabetic patients (odds ratio, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.6–1.0). Although the exact reason for this is unknown, existing theories include the following:

- Diabetics are more apt to receive insulin for perioperative hyperglycemia than nondiabetics (P<0.001);

- Hyperglycemia in diabetics may be a less-reliable marker of surgical stress than in nondiabetics; and

- Diabetics may be better adapted to hyperglycemia than nondiabetics.

Bottom line: Perioperative hyperglycemia leads to an increased risk of adverse events; this relationship is more pronounced in nondiabetic patients than in diabetic patients.

Citation: Kotagal M, Symons RG, Hirsch IB, et al. Perioperative hyperglycemia and risk of adverse events among patients with and without diabetes. Ann Surg. 2015;261(1):97–103. TH

Visit our website for more physician reviews of hospitalist-focused literature.

Greater Auricular Nerve Palsy After Arthroscopic Anterior-Inferior and Posterior-Inferior Labral Tear Repair Using Beach-Chair Positioning and a Standard Universal Headrest

Anterior-inferior and posterior-inferior labral tears are common injuries treated with arthroscopic surgery1 typically performed with beach-chair2,3 or lateral decubitus1,2 positioning and variable headrest positioning. Iatrogenic nerve damage that occurs after arthroscopic shoulder surgery—including damage to the suprascapular, axillary, musculocutaneous, subscapular, and spinal accessory nerves—has recently been reported to be more common than previously recognized.2,4

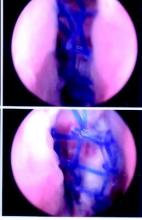

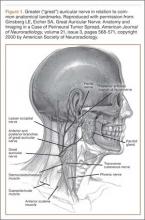

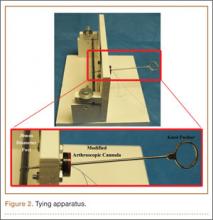

Although iatrogenic nerve injuries are in general being recognized,1,2,4 reports of greater auricular nerve injuries are limited. The greater auricular nerve is a superficial cutaneous nerve that arises from the cervical plexus at the C2 and C3 spinal nerves, obliquely crosses the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and splits into anterior and posterior portions that innervate the skin over the mastoid process and parotid gland.5,6 In particular, as illustrated by Ginsberg and Eicher6 (Figure 1), its superficial anatomy lies very near where a headrest is positioned during arthroscopic surgery, and increased pressure on the nerve throughout arthroscopic shoulder surgery may lead to neurapraxia.6,7 In 2 case series, authors reported on a total of 5 patients who had greater auricular nerve palsy after uncomplicated shoulder surgery using beach-chair positioning and a horseshoe headrest.7,8 The authors attributed these palsies to the horseshoe headrest, which they believed was compressing the greater auricular nerve during the entire surgery.7,8 However, standard universal headrests, which are thought to distribute pressures that would theoretically place the greater auricular nerve at risk for palsy, previously had not been described as contributing to palsy of the greater auricular nerve.

In this article, we report on a case of greater auricular nerve palsy that occurred after the patient’s anterior-inferior and posterior-inferior labral tear was arthroscopically repaired using beach-chair positioning and a standard universal headrest. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

An 18-year-old right-hand–dominant high school American football player was referred for orthopedic evaluation of left chronic glenohumeral instability after 6 months of physical therapy. Physical examination revealed a positive apprehension test with the shoulder abducted and externally rotated at 90° and a positive relocation test. The patient complained of pain and instability when his arm was placed in a cross-chest adducted position and a posteroinferiorly directed axial load was applied. Magnetic resonance arthrogram showed an anterior-inferior labral Bankart tear with a small Hill-Sachs lesion to the humeral head but did not clearly reveal the posterior-inferior labral tear. Because of persistent left shoulder instability with most overhead activities and continued pain, the patient decided to undergo left shoulder arthroscopic Bankart repair with inferior capsular shift and posterior-inferior labral repair with capsulorraphy. He had no significant past medical history or known drug allergies.

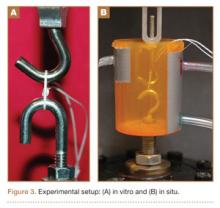

The patient was placed in the standard beach-chair position: upright at 45° to the floor, hips flexed at 60°, knees flexed at 30°.1 Pneumatic compression devices were placed on his lower extremities. His head was secured in neutral position to a standard universal headrest (model A-90026; Allen Medical Systems, Acton, Massachusetts) (Figures 2, 3). Care was taken to protect the deep neurovascular structures and bony prominences throughout. The patient was in this position for 122 minutes of the operation, from positioning and draping to wound closure and dressing application. Before draping, the anesthesiologist, head nurse, and circulating nurse ensured that head and neck were in neutral position. The anesthesiologist monitored positioning throughout the perioperative period to ensure head and neck were in neutral, and the head did not need to be repositioned during surgery. Standard preoperative intravenous antibiotics were given.

General anesthesia and postoperative interscalene block were used. Standard preparation and draping were performed. Three standard arthroscopic portal incisions were used: posterior, anterior, and anterosuperolateral. Findings included extensive labral pathology, small bony Hill-Sachs lesion to humeral head, small bony anterior glenoid deficiency, and deficient anterior-inferior and posterior-inferior labral remnant. These were repaired arthroscopically in a standard fashion using bioabsorbable suture anchors. There were no arthroscopic complications. After surgery, a standard well-fitted shoulder immobilizer was placed. The anesthesiologist provided interscalene regional analgesia (15 mL of bupivacaine 0.5%) in the recovery area after surgery.

Postoperative neurovascular examination in the recovery room revealed no discomfort. The patient was discharged the same day. At a scheduled 1-week follow-up, he complained of numbness and dysesthesia on the left side of the greater auricular nerve distribution. A diagnosis of greater auricular nerve palsy was made by physical examination; the symptoms were along the classic greater auricular nerve distribution affecting the lower face and ear (Figure 4). The patient had no pain, skin lesions, or soft-tissue swelling. Otolaryngology confirmed the diagnosis and recommended observation-only treatment of symptoms. Symptoms lessened over the next 3 months, and the altered sensation resolved without deficit by 6 months. In addition, by 6 months the patient had returned to full activities (including collision sports) pain-free and with normal left shoulder function. Because symptoms continued to improve, the patient was followed with clinical observation, and a formal work-up was not necessary.

Discussion

The most important finding in this case is the greater auricular nerve palsy that occurred after arthroscopic anterior-inferior and posterior-inferior labral repairs in beach-chair positioning. This greater auricular nerve palsy was the first encountered by Dr. Foad, who over 17 years in a primarily shoulder practice setting has used beach-chair positioning exclusively. Previous reports have described a palsy occurring after arthroscopic shoulder surgery using beach-chair positioning and a horseshoe headrest.7,8 Ng and Page7 discontinued and recommended against use of this headrest because of the complications of the palsy, and Park and Kim8 recommended a headrest redesign. We think the present case report is the first to describe a greater auricular nerve palsy that occurred after arthroscopic surgery using a standard universal headrest, which theoretically should prevent compression of the greater auricular nerve. Increased awareness of the possibility of greater auricular nerve palsy, even when proper precautions are taken,1 is therefore warranted.

Based on the location of our patient’s palsy, we think his paralysis was most likely the result of nerve compression by the headrest during the shoulder surgery. Other factors, though unlikely, may have played a role. These include operative time (increases duration of nerve compression) and head positioning. However, 122 minutes is not unusually long for a patient’s head to be in this position during a procedure, and over the past 10 years the same anesthesiologist, head nurse, and circulating nurse have routinely used the same beach-chair positioning and headrest for Dr. Foad’s patients. Second, the postoperative interscalene block theoretically could have caused the palsy, but we think this is unlikely, as the block is placed lower on the neck, at the C6 level, and the greater auricular nerve branches off the C2–C3 spinal nerves. As described by Rains and colleagues,9 other authors have reported transient neuropathies to the brachial plexus, which originates in the C5–C8 region, but not to the greater auricular nerve. Last, it cannot be ruled out that a variant of the greater auricular nerve could have played a role, given the variation in the greater auricular nerve.10,11 However, Brennan and colleagues10 reported that 2 of 25 neck dissections involved a variant in which the anterior division of the greater auricular nerve passed into the submandibular triangle and joined the mandibular region of the facial nerve. Stimulation of this nerve resulted in activity of the depressor of the lower lip, which was not the location of our patient’s palsy. In addition, our patient’s symptoms followed a classic nerve distribution of the greater auricular nerve (Figures 1, 4), which would seem to decrease the likelihood that a variant was the source of the palsy.

The superficial nature of the greater auricular nerve, which runs roughly parallel with the sternocleidomastoid muscle and innervates much of the superficial region of the skin over the mastoid, parotid gland, and mandible,5-7 theoretically places the nerve at risk for compressive forces from the headrest during arthroscopic shoulder surgery. Skyhar and colleagues3 first described beach-chair positioning as an alternative to lateral decubitus positioning, which had been reported to result in neurologic injury in about 10% of surgical cases.9 The theoretical advantages of beach-chair positioning are lack of traction needed and ease of setup, which would therefore decrease the possibility of neuropathy.1,3 However, as seen in this and other case reports,7,8 greater auricular nerve neuropathy should still be considered a possible complication, even when using beach-chair positioning.

Besides neuropathy after arthroscopic shoulder surgery, as described in previous case reports7,8 and in the present report, greater auricular nerve injury has been described as arising from other stimuli. Greater auricular nerve injury has arisen after perineural tumor metastasis,6 neuroma of greater auricular nerve after endolympathic shunt surgery,12 internal fixation of mandibular condyle,13 and carotid endarterectomy.14,15 Given the superficial nature of the greater auricular nerve, it may not be all that surprising that a palsy could also develop after headrest compression during arthroscopic shoulder surgery.

This case report brings to light a possible complication of greater auricular nerve palsy during arthroscopic shoulder surgery using beach-chair positioning and a standard universal headrest. Studies should now investigate whether greater auricular nerve palsy is more common than realized, especially with regard to specific headrests in beach-chair positioning. For now, though, Dr. Foad’s intention is not to change to a different headrest or discontinue beach-chair positioning but to draw attention to this rare complication. Additional attention should be given to the location of the headrest in relation to the greater auricular nerve, especially in cases in which operative time may be longer.

Conclusion

We have reported a greater auricular nerve palsy that occurred after arthroscopic shoulder surgery for an anterior-inferior and posterior-inferior labral tear. This is the first report of a greater auricular nerve palsy occurring with beach-chair positioning and a standard universal headrest. Symptoms resolved within 6 months. New studies should investigate the incidence of greater auricular nerve palsy after arthroscopic shoulder surgery.

1. Paxton ES, Backus J, Keener J, Brophy RH. Shoulder arthroscopy: basic principles of positioning, anesthesia, and portal anatomy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(6):332-342.

2. Scully WF, Wilson DJ, Parada SA, Arrington ED. Iatrogenic nerve injuries in shoulder surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(12):717-726.

3. Skyhar MJ, Altchek DW, Warren RF, Wickiewicz TL, O’Brien SJ. Shoulder arthroscopy with the patient in the beach-chair position. Arthroscopy. 1988;4(4):256-259.

4. Zhang J, Moore AE, Stringer MD. Iatrogenic upper limb nerve injuries: a systematic review. ANZ J Surg. 2011;81(4):227-236.

5. Alberti PW. The greater auricular nerve. Donor for facial nerve grafts: a note on its topographical anatomy. Arch Otolaryngol. 1962;76:422-424.

6. Ginsberg LE, Eicher SA. Great auricular nerve: anatomy and imaging in a case of perineural tumor spread. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21(3):568-571.

7. Ng AK, Page RS. Greater auricular nerve neuropraxia with beach chair positioning during shoulder surgery. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2010;4(2):48-50.

8. Park TS, Kim YS. Neuropraxia of the cutaneous nerve of the cervical plexus after shoulder arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(5):631.e1-e3.

9. Rains DD, Rooke GA, Wahl CJ. Pathomechanisms and complications related to patient positioning and anesthesia during shoulder arthroscopy. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(4):532-541.

10. Brennan PA, Al Gholmy M, Ounnas H, Zaki GA, Puxeddu R, Standring S. Communication of the anterior branch of the great auricular nerve with the marginal mandibular nerve: a prospective study of 25 neck dissections. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;48(6):431-433.

11. Sand T, Becser N. Neurophysiological and anatomical variability of the greater auricular nerve. Acta Neurol Scand. 1998;98(5):333-339.

12. Vorobeichik L, Fallucco MA, Hagan RR. Chronic daily headaches secondary to greater auricular and lesser occipital neuromas following endolymphatic shunt surgery. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. pii: bcr-2012-007189. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-007189.

13. Sverzut CE, Trivellato AE, Serra EC, Ferraz EP, Sverzut AT. Frey’s syndrome after condylar fracture: case report. Braz Dent J. 2004;15(2):159-162.

14. AbuRahma AF, Choueiri MA. Cranial and cervical nerve injuries after repeat carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32(4):649-654.

15. Ballotta E, Da Giau G, Renon L, et al. Cranial and cervical nerve injuries after carotid endarterectomy: a prospective study. Surgery. 1999;125(1):85-91.

Anterior-inferior and posterior-inferior labral tears are common injuries treated with arthroscopic surgery1 typically performed with beach-chair2,3 or lateral decubitus1,2 positioning and variable headrest positioning. Iatrogenic nerve damage that occurs after arthroscopic shoulder surgery—including damage to the suprascapular, axillary, musculocutaneous, subscapular, and spinal accessory nerves—has recently been reported to be more common than previously recognized.2,4

Although iatrogenic nerve injuries are in general being recognized,1,2,4 reports of greater auricular nerve injuries are limited. The greater auricular nerve is a superficial cutaneous nerve that arises from the cervical plexus at the C2 and C3 spinal nerves, obliquely crosses the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and splits into anterior and posterior portions that innervate the skin over the mastoid process and parotid gland.5,6 In particular, as illustrated by Ginsberg and Eicher6 (Figure 1), its superficial anatomy lies very near where a headrest is positioned during arthroscopic surgery, and increased pressure on the nerve throughout arthroscopic shoulder surgery may lead to neurapraxia.6,7 In 2 case series, authors reported on a total of 5 patients who had greater auricular nerve palsy after uncomplicated shoulder surgery using beach-chair positioning and a horseshoe headrest.7,8 The authors attributed these palsies to the horseshoe headrest, which they believed was compressing the greater auricular nerve during the entire surgery.7,8 However, standard universal headrests, which are thought to distribute pressures that would theoretically place the greater auricular nerve at risk for palsy, previously had not been described as contributing to palsy of the greater auricular nerve.

In this article, we report on a case of greater auricular nerve palsy that occurred after the patient’s anterior-inferior and posterior-inferior labral tear was arthroscopically repaired using beach-chair positioning and a standard universal headrest. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

An 18-year-old right-hand–dominant high school American football player was referred for orthopedic evaluation of left chronic glenohumeral instability after 6 months of physical therapy. Physical examination revealed a positive apprehension test with the shoulder abducted and externally rotated at 90° and a positive relocation test. The patient complained of pain and instability when his arm was placed in a cross-chest adducted position and a posteroinferiorly directed axial load was applied. Magnetic resonance arthrogram showed an anterior-inferior labral Bankart tear with a small Hill-Sachs lesion to the humeral head but did not clearly reveal the posterior-inferior labral tear. Because of persistent left shoulder instability with most overhead activities and continued pain, the patient decided to undergo left shoulder arthroscopic Bankart repair with inferior capsular shift and posterior-inferior labral repair with capsulorraphy. He had no significant past medical history or known drug allergies.

The patient was placed in the standard beach-chair position: upright at 45° to the floor, hips flexed at 60°, knees flexed at 30°.1 Pneumatic compression devices were placed on his lower extremities. His head was secured in neutral position to a standard universal headrest (model A-90026; Allen Medical Systems, Acton, Massachusetts) (Figures 2, 3). Care was taken to protect the deep neurovascular structures and bony prominences throughout. The patient was in this position for 122 minutes of the operation, from positioning and draping to wound closure and dressing application. Before draping, the anesthesiologist, head nurse, and circulating nurse ensured that head and neck were in neutral position. The anesthesiologist monitored positioning throughout the perioperative period to ensure head and neck were in neutral, and the head did not need to be repositioned during surgery. Standard preoperative intravenous antibiotics were given.

General anesthesia and postoperative interscalene block were used. Standard preparation and draping were performed. Three standard arthroscopic portal incisions were used: posterior, anterior, and anterosuperolateral. Findings included extensive labral pathology, small bony Hill-Sachs lesion to humeral head, small bony anterior glenoid deficiency, and deficient anterior-inferior and posterior-inferior labral remnant. These were repaired arthroscopically in a standard fashion using bioabsorbable suture anchors. There were no arthroscopic complications. After surgery, a standard well-fitted shoulder immobilizer was placed. The anesthesiologist provided interscalene regional analgesia (15 mL of bupivacaine 0.5%) in the recovery area after surgery.