User login

Are Mortality Benefits from Bariatric Surgery Observed in a Nontraditional Surgical Population? Evidence from a VA Dataset

Study Overview

Objective. To determine the association between bariatric surgery and long-term mortality rates among patients with severe obesity.

Design. Retrospective cohort study.

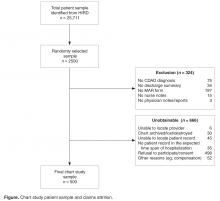

Setting and participants. This analysis relied upon data from Veteran’s Administration (VA) patients undergoing bariatric surgery between 2000 and 2011 and a group of matched controls. For this data-only study, a waiver of informed consent was obtained. Investigators first used the VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program (SQIP) dataset to identify all bariatric surgical procedures performed at VA hospitals between 2000 and the end of 2011, excluding patients who had any evidence of body mass index (BMI) less than 35 kg/m2 and those with certain baseline diagnoses that would be considered contraindications for surgery, as well as those who had prolonged inpatient stays immediately prior to their surgical date. No upper or lower age limits appear to have been specified, and no upper BMI limit appeared to have been set.

Once all surgical patients were identified, the investigators attempted to find a group of similar control patients who had not undergone surgery. Initially they pulled candidate matches for each surgical patient based on having the same sex, age-group (within 5 years), BMI category (35-40, 40-50, >50), diabetes status (present or absent), racial category, and VA region. From these candidates, they selected up to 3 of the closest matches on age, BMI, and a composite comorbidity score based on inpatient and outpatient claims in the year prior to surgery. The authors specified that controls could convert to surgical patients during the follow-up period, in which case their data was censored beginning with the surgical procedure. However, if a control patient underwent surgery during 2012 or 2013, censoring was not possible given that the dataset for identifying surgeries contained only procedures performed through the end of 2011.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome of interest was time to death (any cause) beginning at the date of surgery (or baseline date for nonsurgical controls) through the end of 2013. The investigators built Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate survival using multivariable models to adjust for baseline characteristics, including those involved in the matching process, as well as others that might have differentially impacted both likelihood of undergoing surgery and mortality risk. These included marital status, insurance markers of low income or disability, and a number of comorbid medical and psychiatric diagnoses.

In addition to the main analyses, the investigators also looked for effect modification of the surgery-mortality relationship by a patient’s sex and presence or absence of diabetes at the time of surgery, as well as the time period in which their surgery was conducted, dichotomized around the year 2006. This year was selected for several reasons, including that it was the year in which a VA-wide comprehensive weight management and surgical selection program was instituted.

Results. The surgical cohort was made up of 2500 patients, and there were 7462 matched controls. The surgical and control groups were similar with respect to matched baseline characteristics, tested using standardized differences (as opposed to t test or chi-square). Mean (SD) age was 52 (8.8) years for surgical patients versus 53 (8.7) years for controls. 74% of patients in both the surgical and control groups were men, and 81% in both groups were white (ethnicity not specified). Mean (SD) baseline BMI was 47 (7.9) kg/m2 in the surgical group and 46 (7.3) kg/m2 for controls.

Some between-group differences were present for baseline characteristics that had not been included in the matching protocol. More surgical patients than controls had diagnoses of hypertension (80% surgical vs. 70% control), dyslipidemia (61% vs. 52%), arthritis (27% vs. 15%), depression (44% vs. 32%), GERD (35% vs.19%), and fatty liver disease (6.6% vs. 0.6%). In contrast, more control patients than surgical patients had diagnoses of alcohol abuse (6.2% in controls vs. 3.9% in surgical) and schizophrenia (4.9% vs. 1.8%). Also, although a number of different surgical types were represented in the cohort, the vast majority of procedures were classified as Roux-en-Y gastric bypasses (RYGB). 53% of the procedures were open RYGB, 21% were laparoscopic RYGB, 10% were adjustable gastric bands (AGB), and 15% were vertical sleeve gastrectomies (VSG).

Mortality was lower among surgical patients than among matched controls during a mean follow-up time of 6.9 years for surgical patients and 6.6 years for controls. Namely, the 1-, 5- and 10-year cumulative mortality rates for surgical patients were: 2.4%, 6.4%, and 13.8%. Unadjusted mortality rates for nonsurgical controls were lower initially (1.7% at 1 year), but then much higher at years 5 (10.4%), and 10 (23.9%). In multivariable Cox models, the hazard ratio (HR) for mortality in bariatric patients versus controls was nonsignificant at 1 year of follow-up. However, between 1 and 5 years after surgery (or after baseline), multivariable models showed an HR (95% CI) of 0.45 (0.36–0.56) for mortality among surgical patients versus controls. For those with more than 5 years of follow up, the HR was similar (0.47, 95% CI 0.39–0.58) for death among surgical versus control patients. The investigators found that the year during which a patient underwent surgery (before or after 2006) did impact mortality during the first postoperative year, with those who had earlier procedures (2000-2005) exhibiting a significantly higher risk of death in that year relative to non-operative controls (HR 1.66, 95% CI 1.19–2.33). No significant sex or diabetes interactions were observed for the surgery-mortality relationship in multivariable Cox models. There was no information provided as to the breakdown of cause of death within the larger “all-cause mortality” outcome.

Conclusion. Bariatric surgery was associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality among surgical patients in the VA over a 5- to 14-year follow-up period compared with a group of severely obese VA patients who did not undergo surgery.

Commentary

Rates of severe obesity (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2) have risen at a faster pace than those of obesity in the United States over the past decade [1], driving clinicians, patients and payers to search for effective methods of treating this condition. Bariatric surgery has emerged as the most effective treatment for severe obesity; however, the existing surgical literature is predominated by studies with short- or medium-term postoperative follow-up and homogenous participant populations containing large numbers of younger non-Hispanic white women. Research from the Swedish Obesity Study (SOS), as well as smaller US-based studies, has suggested that severely obese patients who undergo bariatric surgery have better long-term survival than their nonsurgical counterparts [2,3].Counter to this finding, a previous medium-term study utilizing data from VA hospitals did not find that surgery conferred a mortality benefit among this largely male, older, and sicker patient population [4].The current study, by the same group of investigators, attempts to update the previous finding by including more recent surgical data and a longer follow-up period, to see whether or not a survival benefit appears to emerge for VA patients undergoing bariatric surgery.

A major strength of this study was the use of a large and comprehensive clinical dataset, a strength of many studies utilizing data from the VA. The availability of clinical data such as BMI, as well as diagnostic codes and sociodemographic variables, allowed the authors to match and adjust for a number of potential confounders of the surgery-mortality relationship. Another unique feature of VA data is that members of this health care system can often be followed regardless of their location, as the unified medical record transfers between states. This is in contrast to many claims-based or single-center studies of surgery, where patients are lost to follow-up if they move or transfer insurance providers. This study clearly benefited from this aspect of VA data, with a mean postoperative follow-up period of over 5 years in both study groups, much longer than is typically observed in bariatric surgical studies, and probably a necessary feature for examining more of a rare outcome such as mortality (as opposed to comparing weight loss or diabetes remission). Another clear contribution of this study is that it focused on a group of patients not typical of bariatric cohorts—this group was slightly older and sicker, with far more men than women, and therefore at a much higher risk of mortality than the typically younger females that are part of most studies.

Although the authors did adjust for many factors when comparing the surgical and nonsurgical groups, it is possible, as with any observational study, that unmeasured confounders may have been present. Psychosocial and behavioral features that may be linked both to a person’s likelihood of undergoing surgery, and to their mortality risk are of particular concern. It is worth noting, for example, that far more patients in the nonsurgical group were identified as schizophrenic, and that the rate of schizophrenia in that severely obese group was much higher than that of the general population. This pattern may have some relationship to the weight-gain promoting effect of antipsychotic medications and the unfortunate reality that patients with severe obesity and severe mental illness may not be as well equipped to seek out surgery (or viewed as acceptable candidates) as those without severe mental illness. One possible limitation mentioned by the authors was that control group patients who underwent surgery in 2012 or 2013 would not have been recognized (and thus had their data censored in this study), possibly leading to incorrect categorization of exposure category for some amount of person-time during follow-up. In general, though, there is a low likelihood of this phenomenon impacting the findings, given both the relative infrequency of crossover observed in the cohort prior to 2011, and the relatively short amount of person-time any later crossovers would have contributed in the later years of the study.

Although codes for baseline disease states were adjusted for in multivariable analyses, the surgical patients were in general a medically sicker group at baseline than control patients. As the authors point out, if anything, this should have biased the findings in favor of seeing higher mortality rate in the surgical group, the opposite of what was found. Further strengthening the finding of a correlation between survival and surgery is the mix of procedure types included in this study. Over half of the procedures were open RYGB surgeries, with far fewer of the more modern and lower risk procedures (eg, laparoscopic RYGB) represented. Again, this mix of procedures would be expected to result in an overestimation of mortality in surgical patients relative to what might be observed if all patients had been drawn from later years of the cohort, as surgical technique evolved.

Applications for Clinical Practice

This study adds to the evidence that patients with severe obesity who undergo bariatric surgery have a lower risk of death up to 10 years after their surgery compared with patients who do not have these procedures. The findings of this work should provide encouragement, particularly for managaing older adults with more longstanding comorbidities. Those who are strongly motivated to pursue weight loss surgery, and who are deemed good candidates by bariatric teams, may add years to their lives by undergoing one of these procedures. As always, however, the quality of life experienced by patients after surgery, and a realistic expectation of the ways in which surgery will fundamentally change their lifestyle, must be a critical part of the discussion.

—Kristina Lewis, MD, MPH

1. Sturm R, Hattori A. Morbid obesity rates continue to rise rapidly in the United States. Int J Obesity 2013;37:889-91.

2. Sjostrom L, Narbo K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2007;357:741–52.

3. Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2007;357:753–61.

4. Maciejewski ML, Livingston EH, Smith VA, et al. Survival among high-risk patients after bariatric surgery. JAMA 2011;305:2419–26.

Study Overview

Objective. To determine the association between bariatric surgery and long-term mortality rates among patients with severe obesity.

Design. Retrospective cohort study.

Setting and participants. This analysis relied upon data from Veteran’s Administration (VA) patients undergoing bariatric surgery between 2000 and 2011 and a group of matched controls. For this data-only study, a waiver of informed consent was obtained. Investigators first used the VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program (SQIP) dataset to identify all bariatric surgical procedures performed at VA hospitals between 2000 and the end of 2011, excluding patients who had any evidence of body mass index (BMI) less than 35 kg/m2 and those with certain baseline diagnoses that would be considered contraindications for surgery, as well as those who had prolonged inpatient stays immediately prior to their surgical date. No upper or lower age limits appear to have been specified, and no upper BMI limit appeared to have been set.

Once all surgical patients were identified, the investigators attempted to find a group of similar control patients who had not undergone surgery. Initially they pulled candidate matches for each surgical patient based on having the same sex, age-group (within 5 years), BMI category (35-40, 40-50, >50), diabetes status (present or absent), racial category, and VA region. From these candidates, they selected up to 3 of the closest matches on age, BMI, and a composite comorbidity score based on inpatient and outpatient claims in the year prior to surgery. The authors specified that controls could convert to surgical patients during the follow-up period, in which case their data was censored beginning with the surgical procedure. However, if a control patient underwent surgery during 2012 or 2013, censoring was not possible given that the dataset for identifying surgeries contained only procedures performed through the end of 2011.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome of interest was time to death (any cause) beginning at the date of surgery (or baseline date for nonsurgical controls) through the end of 2013. The investigators built Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate survival using multivariable models to adjust for baseline characteristics, including those involved in the matching process, as well as others that might have differentially impacted both likelihood of undergoing surgery and mortality risk. These included marital status, insurance markers of low income or disability, and a number of comorbid medical and psychiatric diagnoses.

In addition to the main analyses, the investigators also looked for effect modification of the surgery-mortality relationship by a patient’s sex and presence or absence of diabetes at the time of surgery, as well as the time period in which their surgery was conducted, dichotomized around the year 2006. This year was selected for several reasons, including that it was the year in which a VA-wide comprehensive weight management and surgical selection program was instituted.

Results. The surgical cohort was made up of 2500 patients, and there were 7462 matched controls. The surgical and control groups were similar with respect to matched baseline characteristics, tested using standardized differences (as opposed to t test or chi-square). Mean (SD) age was 52 (8.8) years for surgical patients versus 53 (8.7) years for controls. 74% of patients in both the surgical and control groups were men, and 81% in both groups were white (ethnicity not specified). Mean (SD) baseline BMI was 47 (7.9) kg/m2 in the surgical group and 46 (7.3) kg/m2 for controls.

Some between-group differences were present for baseline characteristics that had not been included in the matching protocol. More surgical patients than controls had diagnoses of hypertension (80% surgical vs. 70% control), dyslipidemia (61% vs. 52%), arthritis (27% vs. 15%), depression (44% vs. 32%), GERD (35% vs.19%), and fatty liver disease (6.6% vs. 0.6%). In contrast, more control patients than surgical patients had diagnoses of alcohol abuse (6.2% in controls vs. 3.9% in surgical) and schizophrenia (4.9% vs. 1.8%). Also, although a number of different surgical types were represented in the cohort, the vast majority of procedures were classified as Roux-en-Y gastric bypasses (RYGB). 53% of the procedures were open RYGB, 21% were laparoscopic RYGB, 10% were adjustable gastric bands (AGB), and 15% were vertical sleeve gastrectomies (VSG).

Mortality was lower among surgical patients than among matched controls during a mean follow-up time of 6.9 years for surgical patients and 6.6 years for controls. Namely, the 1-, 5- and 10-year cumulative mortality rates for surgical patients were: 2.4%, 6.4%, and 13.8%. Unadjusted mortality rates for nonsurgical controls were lower initially (1.7% at 1 year), but then much higher at years 5 (10.4%), and 10 (23.9%). In multivariable Cox models, the hazard ratio (HR) for mortality in bariatric patients versus controls was nonsignificant at 1 year of follow-up. However, between 1 and 5 years after surgery (or after baseline), multivariable models showed an HR (95% CI) of 0.45 (0.36–0.56) for mortality among surgical patients versus controls. For those with more than 5 years of follow up, the HR was similar (0.47, 95% CI 0.39–0.58) for death among surgical versus control patients. The investigators found that the year during which a patient underwent surgery (before or after 2006) did impact mortality during the first postoperative year, with those who had earlier procedures (2000-2005) exhibiting a significantly higher risk of death in that year relative to non-operative controls (HR 1.66, 95% CI 1.19–2.33). No significant sex or diabetes interactions were observed for the surgery-mortality relationship in multivariable Cox models. There was no information provided as to the breakdown of cause of death within the larger “all-cause mortality” outcome.

Conclusion. Bariatric surgery was associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality among surgical patients in the VA over a 5- to 14-year follow-up period compared with a group of severely obese VA patients who did not undergo surgery.

Commentary

Rates of severe obesity (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2) have risen at a faster pace than those of obesity in the United States over the past decade [1], driving clinicians, patients and payers to search for effective methods of treating this condition. Bariatric surgery has emerged as the most effective treatment for severe obesity; however, the existing surgical literature is predominated by studies with short- or medium-term postoperative follow-up and homogenous participant populations containing large numbers of younger non-Hispanic white women. Research from the Swedish Obesity Study (SOS), as well as smaller US-based studies, has suggested that severely obese patients who undergo bariatric surgery have better long-term survival than their nonsurgical counterparts [2,3].Counter to this finding, a previous medium-term study utilizing data from VA hospitals did not find that surgery conferred a mortality benefit among this largely male, older, and sicker patient population [4].The current study, by the same group of investigators, attempts to update the previous finding by including more recent surgical data and a longer follow-up period, to see whether or not a survival benefit appears to emerge for VA patients undergoing bariatric surgery.

A major strength of this study was the use of a large and comprehensive clinical dataset, a strength of many studies utilizing data from the VA. The availability of clinical data such as BMI, as well as diagnostic codes and sociodemographic variables, allowed the authors to match and adjust for a number of potential confounders of the surgery-mortality relationship. Another unique feature of VA data is that members of this health care system can often be followed regardless of their location, as the unified medical record transfers between states. This is in contrast to many claims-based or single-center studies of surgery, where patients are lost to follow-up if they move or transfer insurance providers. This study clearly benefited from this aspect of VA data, with a mean postoperative follow-up period of over 5 years in both study groups, much longer than is typically observed in bariatric surgical studies, and probably a necessary feature for examining more of a rare outcome such as mortality (as opposed to comparing weight loss or diabetes remission). Another clear contribution of this study is that it focused on a group of patients not typical of bariatric cohorts—this group was slightly older and sicker, with far more men than women, and therefore at a much higher risk of mortality than the typically younger females that are part of most studies.

Although the authors did adjust for many factors when comparing the surgical and nonsurgical groups, it is possible, as with any observational study, that unmeasured confounders may have been present. Psychosocial and behavioral features that may be linked both to a person’s likelihood of undergoing surgery, and to their mortality risk are of particular concern. It is worth noting, for example, that far more patients in the nonsurgical group were identified as schizophrenic, and that the rate of schizophrenia in that severely obese group was much higher than that of the general population. This pattern may have some relationship to the weight-gain promoting effect of antipsychotic medications and the unfortunate reality that patients with severe obesity and severe mental illness may not be as well equipped to seek out surgery (or viewed as acceptable candidates) as those without severe mental illness. One possible limitation mentioned by the authors was that control group patients who underwent surgery in 2012 or 2013 would not have been recognized (and thus had their data censored in this study), possibly leading to incorrect categorization of exposure category for some amount of person-time during follow-up. In general, though, there is a low likelihood of this phenomenon impacting the findings, given both the relative infrequency of crossover observed in the cohort prior to 2011, and the relatively short amount of person-time any later crossovers would have contributed in the later years of the study.

Although codes for baseline disease states were adjusted for in multivariable analyses, the surgical patients were in general a medically sicker group at baseline than control patients. As the authors point out, if anything, this should have biased the findings in favor of seeing higher mortality rate in the surgical group, the opposite of what was found. Further strengthening the finding of a correlation between survival and surgery is the mix of procedure types included in this study. Over half of the procedures were open RYGB surgeries, with far fewer of the more modern and lower risk procedures (eg, laparoscopic RYGB) represented. Again, this mix of procedures would be expected to result in an overestimation of mortality in surgical patients relative to what might be observed if all patients had been drawn from later years of the cohort, as surgical technique evolved.

Applications for Clinical Practice

This study adds to the evidence that patients with severe obesity who undergo bariatric surgery have a lower risk of death up to 10 years after their surgery compared with patients who do not have these procedures. The findings of this work should provide encouragement, particularly for managaing older adults with more longstanding comorbidities. Those who are strongly motivated to pursue weight loss surgery, and who are deemed good candidates by bariatric teams, may add years to their lives by undergoing one of these procedures. As always, however, the quality of life experienced by patients after surgery, and a realistic expectation of the ways in which surgery will fundamentally change their lifestyle, must be a critical part of the discussion.

—Kristina Lewis, MD, MPH

Study Overview

Objective. To determine the association between bariatric surgery and long-term mortality rates among patients with severe obesity.

Design. Retrospective cohort study.

Setting and participants. This analysis relied upon data from Veteran’s Administration (VA) patients undergoing bariatric surgery between 2000 and 2011 and a group of matched controls. For this data-only study, a waiver of informed consent was obtained. Investigators first used the VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program (SQIP) dataset to identify all bariatric surgical procedures performed at VA hospitals between 2000 and the end of 2011, excluding patients who had any evidence of body mass index (BMI) less than 35 kg/m2 and those with certain baseline diagnoses that would be considered contraindications for surgery, as well as those who had prolonged inpatient stays immediately prior to their surgical date. No upper or lower age limits appear to have been specified, and no upper BMI limit appeared to have been set.

Once all surgical patients were identified, the investigators attempted to find a group of similar control patients who had not undergone surgery. Initially they pulled candidate matches for each surgical patient based on having the same sex, age-group (within 5 years), BMI category (35-40, 40-50, >50), diabetes status (present or absent), racial category, and VA region. From these candidates, they selected up to 3 of the closest matches on age, BMI, and a composite comorbidity score based on inpatient and outpatient claims in the year prior to surgery. The authors specified that controls could convert to surgical patients during the follow-up period, in which case their data was censored beginning with the surgical procedure. However, if a control patient underwent surgery during 2012 or 2013, censoring was not possible given that the dataset for identifying surgeries contained only procedures performed through the end of 2011.

Main outcome measures. The primary outcome of interest was time to death (any cause) beginning at the date of surgery (or baseline date for nonsurgical controls) through the end of 2013. The investigators built Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate survival using multivariable models to adjust for baseline characteristics, including those involved in the matching process, as well as others that might have differentially impacted both likelihood of undergoing surgery and mortality risk. These included marital status, insurance markers of low income or disability, and a number of comorbid medical and psychiatric diagnoses.

In addition to the main analyses, the investigators also looked for effect modification of the surgery-mortality relationship by a patient’s sex and presence or absence of diabetes at the time of surgery, as well as the time period in which their surgery was conducted, dichotomized around the year 2006. This year was selected for several reasons, including that it was the year in which a VA-wide comprehensive weight management and surgical selection program was instituted.

Results. The surgical cohort was made up of 2500 patients, and there were 7462 matched controls. The surgical and control groups were similar with respect to matched baseline characteristics, tested using standardized differences (as opposed to t test or chi-square). Mean (SD) age was 52 (8.8) years for surgical patients versus 53 (8.7) years for controls. 74% of patients in both the surgical and control groups were men, and 81% in both groups were white (ethnicity not specified). Mean (SD) baseline BMI was 47 (7.9) kg/m2 in the surgical group and 46 (7.3) kg/m2 for controls.

Some between-group differences were present for baseline characteristics that had not been included in the matching protocol. More surgical patients than controls had diagnoses of hypertension (80% surgical vs. 70% control), dyslipidemia (61% vs. 52%), arthritis (27% vs. 15%), depression (44% vs. 32%), GERD (35% vs.19%), and fatty liver disease (6.6% vs. 0.6%). In contrast, more control patients than surgical patients had diagnoses of alcohol abuse (6.2% in controls vs. 3.9% in surgical) and schizophrenia (4.9% vs. 1.8%). Also, although a number of different surgical types were represented in the cohort, the vast majority of procedures were classified as Roux-en-Y gastric bypasses (RYGB). 53% of the procedures were open RYGB, 21% were laparoscopic RYGB, 10% were adjustable gastric bands (AGB), and 15% were vertical sleeve gastrectomies (VSG).

Mortality was lower among surgical patients than among matched controls during a mean follow-up time of 6.9 years for surgical patients and 6.6 years for controls. Namely, the 1-, 5- and 10-year cumulative mortality rates for surgical patients were: 2.4%, 6.4%, and 13.8%. Unadjusted mortality rates for nonsurgical controls were lower initially (1.7% at 1 year), but then much higher at years 5 (10.4%), and 10 (23.9%). In multivariable Cox models, the hazard ratio (HR) for mortality in bariatric patients versus controls was nonsignificant at 1 year of follow-up. However, between 1 and 5 years after surgery (or after baseline), multivariable models showed an HR (95% CI) of 0.45 (0.36–0.56) for mortality among surgical patients versus controls. For those with more than 5 years of follow up, the HR was similar (0.47, 95% CI 0.39–0.58) for death among surgical versus control patients. The investigators found that the year during which a patient underwent surgery (before or after 2006) did impact mortality during the first postoperative year, with those who had earlier procedures (2000-2005) exhibiting a significantly higher risk of death in that year relative to non-operative controls (HR 1.66, 95% CI 1.19–2.33). No significant sex or diabetes interactions were observed for the surgery-mortality relationship in multivariable Cox models. There was no information provided as to the breakdown of cause of death within the larger “all-cause mortality” outcome.

Conclusion. Bariatric surgery was associated with significantly lower all-cause mortality among surgical patients in the VA over a 5- to 14-year follow-up period compared with a group of severely obese VA patients who did not undergo surgery.

Commentary

Rates of severe obesity (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2) have risen at a faster pace than those of obesity in the United States over the past decade [1], driving clinicians, patients and payers to search for effective methods of treating this condition. Bariatric surgery has emerged as the most effective treatment for severe obesity; however, the existing surgical literature is predominated by studies with short- or medium-term postoperative follow-up and homogenous participant populations containing large numbers of younger non-Hispanic white women. Research from the Swedish Obesity Study (SOS), as well as smaller US-based studies, has suggested that severely obese patients who undergo bariatric surgery have better long-term survival than their nonsurgical counterparts [2,3].Counter to this finding, a previous medium-term study utilizing data from VA hospitals did not find that surgery conferred a mortality benefit among this largely male, older, and sicker patient population [4].The current study, by the same group of investigators, attempts to update the previous finding by including more recent surgical data and a longer follow-up period, to see whether or not a survival benefit appears to emerge for VA patients undergoing bariatric surgery.

A major strength of this study was the use of a large and comprehensive clinical dataset, a strength of many studies utilizing data from the VA. The availability of clinical data such as BMI, as well as diagnostic codes and sociodemographic variables, allowed the authors to match and adjust for a number of potential confounders of the surgery-mortality relationship. Another unique feature of VA data is that members of this health care system can often be followed regardless of their location, as the unified medical record transfers between states. This is in contrast to many claims-based or single-center studies of surgery, where patients are lost to follow-up if they move or transfer insurance providers. This study clearly benefited from this aspect of VA data, with a mean postoperative follow-up period of over 5 years in both study groups, much longer than is typically observed in bariatric surgical studies, and probably a necessary feature for examining more of a rare outcome such as mortality (as opposed to comparing weight loss or diabetes remission). Another clear contribution of this study is that it focused on a group of patients not typical of bariatric cohorts—this group was slightly older and sicker, with far more men than women, and therefore at a much higher risk of mortality than the typically younger females that are part of most studies.

Although the authors did adjust for many factors when comparing the surgical and nonsurgical groups, it is possible, as with any observational study, that unmeasured confounders may have been present. Psychosocial and behavioral features that may be linked both to a person’s likelihood of undergoing surgery, and to their mortality risk are of particular concern. It is worth noting, for example, that far more patients in the nonsurgical group were identified as schizophrenic, and that the rate of schizophrenia in that severely obese group was much higher than that of the general population. This pattern may have some relationship to the weight-gain promoting effect of antipsychotic medications and the unfortunate reality that patients with severe obesity and severe mental illness may not be as well equipped to seek out surgery (or viewed as acceptable candidates) as those without severe mental illness. One possible limitation mentioned by the authors was that control group patients who underwent surgery in 2012 or 2013 would not have been recognized (and thus had their data censored in this study), possibly leading to incorrect categorization of exposure category for some amount of person-time during follow-up. In general, though, there is a low likelihood of this phenomenon impacting the findings, given both the relative infrequency of crossover observed in the cohort prior to 2011, and the relatively short amount of person-time any later crossovers would have contributed in the later years of the study.

Although codes for baseline disease states were adjusted for in multivariable analyses, the surgical patients were in general a medically sicker group at baseline than control patients. As the authors point out, if anything, this should have biased the findings in favor of seeing higher mortality rate in the surgical group, the opposite of what was found. Further strengthening the finding of a correlation between survival and surgery is the mix of procedure types included in this study. Over half of the procedures were open RYGB surgeries, with far fewer of the more modern and lower risk procedures (eg, laparoscopic RYGB) represented. Again, this mix of procedures would be expected to result in an overestimation of mortality in surgical patients relative to what might be observed if all patients had been drawn from later years of the cohort, as surgical technique evolved.

Applications for Clinical Practice

This study adds to the evidence that patients with severe obesity who undergo bariatric surgery have a lower risk of death up to 10 years after their surgery compared with patients who do not have these procedures. The findings of this work should provide encouragement, particularly for managaing older adults with more longstanding comorbidities. Those who are strongly motivated to pursue weight loss surgery, and who are deemed good candidates by bariatric teams, may add years to their lives by undergoing one of these procedures. As always, however, the quality of life experienced by patients after surgery, and a realistic expectation of the ways in which surgery will fundamentally change their lifestyle, must be a critical part of the discussion.

—Kristina Lewis, MD, MPH

1. Sturm R, Hattori A. Morbid obesity rates continue to rise rapidly in the United States. Int J Obesity 2013;37:889-91.

2. Sjostrom L, Narbo K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2007;357:741–52.

3. Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2007;357:753–61.

4. Maciejewski ML, Livingston EH, Smith VA, et al. Survival among high-risk patients after bariatric surgery. JAMA 2011;305:2419–26.

1. Sturm R, Hattori A. Morbid obesity rates continue to rise rapidly in the United States. Int J Obesity 2013;37:889-91.

2. Sjostrom L, Narbo K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2007;357:741–52.

3. Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2007;357:753–61.

4. Maciejewski ML, Livingston EH, Smith VA, et al. Survival among high-risk patients after bariatric surgery. JAMA 2011;305:2419–26.

Perfect Depression Care Spread: The Traction of Zero Suicides

From The Menninger Clinic, Houston, TX.

Abstract

- Objective: To summarize the Perfect Depression Care initiative and describe recent work to spread this quality improvement initiative.

- Methods: We summarize the background and methodology of the Perfect Depression Care initiative within the specialty behavioral health care setting and then describe the application of this methodology to 2 examples of spreading Perfect Depression Care to general medical settings: primary care and general hospitals.

- Results: In the primary care setting, Perfect Depression Care spread successfully in association with the development and implementation of a practice guideline for managing the potentially suicidal patient. In the general hospital setting, Perfect Depression Care is spreading successfully in association with the development and implementation of a simple and efficient tool to screen not for suicide risk specifically, but for common psychiatric conditions associated with increased risk of suicide.

- Conclusion: Both examples of spreading Perfect Depression Care to general medical settings illustrate the social traction of “zero suicides,” the audacious and transformative goal of the Perfect Depression Care Initiative.

Each year depression affects roughly 10% of adults in the United States [1]. The leading cause of disability in developed countries, depression results in substantial medical care expenditures, lost productivity, and absenteeism [1]. It is a chronic condition, and one that is associated with tremendous comorbidity from multiple chronic general medical conditions, including congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, and diabetes [2]. Moreover, the presence of depression has deleterious effects on the outcomes of those comorbid conditions [2]. Untreated or poorly treated, depression can be deadly—each year as many as 10% of patients with major depression die from suicide [1].

In 1999 the Behavioral Health Services (BHS) division of Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, Michigan, set out to eliminate suicide among all patients with depression in our HMO network. This audacious goal was a key lever in a broader aim, which was to build a system of perfect depression care. We aimed to achieve breakthrough improvement in quality and safety by completely redesigning the delivery of depression care using the 6 aims and 10 new rules set forth in the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) report Crossing the Quality Chasm [3]. To communicate our bold vision, we called the initiative Perfect Depression Care. Today, we can report a dramatic and sustained reduction in suicide that is unprecedented in the clinical and quality improvement literature [4].

In the Chasm report, the IOM cast a spotlight on behavioral health care, placing depression and anxiety disorders on the short list of priority conditions for immediate national attention and improvement. Importantly, the IOM called for a focus on not only behavioral health care benefits and coverage, but access and quality of care for all persons with depression. Finding inspiration from our success in the specialty behavioral health care setting, we decided to answer the IOM’s call. We set out to build a system of depression care that is not confined to the specialty behavioral health care setting, a system that delivers perfect care to every patient with depression, regardless of general medical comorbidity or care setting. We called this work Perfect Depression Care Spread.

In this article, we first summarize the background and methodology of the Perfect Depression Care initiative. We then describe the application of this methodology to spreading Perfect Depression Care into 2 nonspecialty care settings—primary care and general hospitals. Finally, we review some of the challenges and lessons learned from our efforts to sustain this important work.

Building a System of Perfect Depression Care

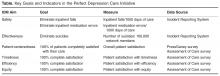

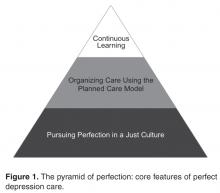

One example of the transformative power of a “zero defects” approach is the case of the Effectiveness aim. Our team engaged in vigorous debate about the goal for this aim. While some team members eagerly embraced the “zero defects” ambition and argued that truly perfect care could only mean “no suicides,” others challenged it, viewing it as lofty but unrealistic. After all, we had been taught that for some number of individuals with depression, suicide was the tragic yet inevitable outcome of their illness. How could it be possible to eliminate every single suicide? The debate was ultimately resolved when one team member asked, “If zero isn’t the right number of suicides, then what is? Two? Four? Forty?” The answer was obvious and undeniable. It was at that moment that setting “zero suicides” as the goal became a galvanizing force within BHS for the Perfect Depression Care initiative.

The pursuit of zero defects must take place within a “just culture,” an organizational environment in which frontline staff feel comfortable disclosing errors, especially their own, while still maintaining professional accountability [6]. Without a just culture, good but imperfect performance can breed disengagement and resentment. By contrast, within a just culture, it becomes possible to implement specific strategies and tactics to pursue perfection. Along the way, each step towards “zero defects” is celebrated because each defect that does occur is identified as an opportunity for learning.

One core strategy for Perfect Depression Care was organizing care according to the planned care model, a locally tailored version of the chronic care model [7]. We developed a clear vision for how each patient’s care would change in a system of Perfect Depression Care. We partnered with patients to ensure their voice in the redesign of our depression care services. We then conceptualized, designed, and tested strategies for improvement in 4 high-leverage domains (patient partnership, clinical practice, access to care, and information systems), which were identified through mapping our current care processes. Once this new model of care was in place, we implemented relevant measures of care quality and began continually assessing progress and then adjusting the plan as needed (ie, following the Model for Improvement).

Spread to Primary Care

The spread to primary care began in 2005, about 5 years after the initial launch of Perfect Depression Care in BHS. (There had been some previous work done aimed at integrating depression screening into a small number of specialty chronic disease management initiatives, although that work was not sustained.) We based the overall clinical structure on the IMPACT model of integrated behavioral health care [10]. Primary care providers collaborated with depression care managers, typically nurses, who had been trained to provide education to primary care providers and problem solving therapy to patients. The care managers were supervised by a project leader (a full-time clinical psychologist) and supported by 2 full-time psychiatric nurse practitioners who were embedded in each clinic during the early phases of implementation. An electronic medical record (EMR) was comfortably in place and facilitated the delivery of evidence-based depression care, as well as the collection of relevant process and outcome measures, which were fed back to the care teams on a regular basis. And, importantly, the primary care leadership team formally sanctioned depression care to be spread to all 27 primary care clinics.

Overcoming the Challenges of the Primary Care Visits

From 2005 to 2010, the model was spread tenuously to 5 primary care clinics. At that rate (1 clinic per year), it would have taken over 20 years to spread depression care through all 27 primary care clinics. Not satisfied with this progress, we stepped back to consider why adoption was happening so slowly. First, we spoke with leaders. Although the project was on a shoestring budget, our leaders understood the business case for integrating some version of depression care into the primary care setting [11]. They advised limiting the scope of the project to focus only on adults with 1 of 6 chronic diseases: diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, and chronic kidney disease. This narrower focus was aimed at using the project’s limited resources more effectively on behalf of patients who were more frequent utilizers of care and statistically more likely to have a comorbid depressive illness. Through the use of time studies, however, we learned that the time consumed discerning which patients each day were eligible for depression screening created delays in clinic workflow that were untenable. It turned out that the process of screening all patients was far more efficient that the process of identifying which patients “should” be screened and then screening only those who were identified. This pragmatic approach to daily workflow in the clinics was a key driver of successful spread.

Next, we spoke to patients. In an effort to assess patient engagement, we reviewed the records of 830 patients who had been seen in one of the clinics where depression care was up and running. Among this group, less than 1% had declined to receive depression screening. In fact, during informal discussions with patients and clinic staff, patients were thanking their primary care providers for talking with them about depression. When it came to spreading depression care, patient engagement was not the problem.

Finally, we spoke with primary care providers, physicians who were viewed as leaders in their clinics. They described trepidation among their teams about adopting an innovation that would lead to patients being identified as at risk for suicide. Their concern was not that integrating depression care was not the right thing to do in the primary care setting; indeed, they had a strong and genuine desire to provide better depression care for their patients. Their concern was that the primary care clinic was not equipped to manage a suicidal patient safely and effectively. This concern was real, and it was pervasive. After all, the typical primary care office visit was already replete with problem lists too long to be managed effectively in the diminishing amount of time allotted to each visit. Screening for depression would only make matters worse [12]. Furthermore, identifying a patient at risk for suicide was not uncommon in our primary care setting. Between 2006 and 2012, an average of 16% of primary care patients screened each year had reported some degree of suicidal ideation (as measures by a positive response on question 9 of the PHQ-9). These discussions showed us that the model of depression care we were trying to spread into primary care was not designed with an explicit and confident approach to suicide—it was not Perfect Depression Care.

Leveraging Suicide As a Driver of Spread

When we realized that the anxiety surrounding the management of a suicidal patient was the biggest obstacle to Perfect Depression Care spread to primary care, we decided to turn this obstacle into an opportunity. First, an interdisciplinary team developed a practice guideline for managing the suicidal patient in general medical settings. The guideline was based on the World Health Organization’s evidence-based guidelines for addressing mental health disorders in nonspecialized health settings [13] and modified into a single page to make it easy to adopt. Following the guideline was not at all a requirement, but doing so made it very easy to identify patients at potential risk for suicide and to refer them safely and seamlessly to the next most appropriate level of care.

Second, and most importantly, BHS made a formal commitment to provide immediate access for any patient referred by a primary care provider following the practice guideline. BHS pledged to perform the evaluation on the same day as the referral was made and without any questions asked. Delivering on this promise required BHS to develop and implement reliable processes for its ambulatory centers to receive same-day referrals from any one of 27 primary care clinics. Success meant delighting our customers in primary care while obviating the expense and trauma associated with sending patients to local emergency departments. This work was hard. And it was made possible by the culture within BHS of pursuing perfection.

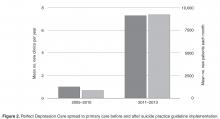

During this time of successful spread, project resources remained similar, no new or additional financial support was provided, and no new leadership directives had been communicated. The only new features of Perfect Depression Care spread were a 1-page practice guideline and a promise. Making suicide an explicit target of the intervention, and doing so in a ruthlessly practical way, created the conditions for the intervention to diffuse and be adopted more readily.

Spread to General Hospitals

In 2006, the Joint Commission established National Patient Safety Goal (NPSG) 15.01.01 for hospitals and health care facilities “to identify patients at risk for suicide” [14]. NPSG 15.01.01 applies not just to patients in psychiatric hospitals, but to all patients “being treated for emotional or behavioral disorders in general hospitals,” including emergency departments. As a measure of safety, suicide is the second most common sentinel event among hospitalized patients—only wrong-site surgery occurs more often. And when a suicide does take place in a hospital, the impact on patients, families, health care workers, and administrators is profound.

Still, completed suicide among hospitalized patients is statistically a very rare event. As a result, general hospitals find it challenging to meet the expectations set forth in NPSG 15.01.01, which seemingly asks hospitals to search for a needle in a haystack. Is it really valuable to ask a patient about suicide when that patient is a 16-year-old teenager who presented to the emergency department for minor scrapes and bruises sustained while skateboarding? Should all patients with “do not resuscitate” orders receive a mandatory, comprehensive suicide risk assessment? In 2010, general hospitals in our organization enlisted our Perfect Depression Care team to help them develop a meaningful approach to NPSG 15.01.01, and so Perfect Depression Care spread to general hospitals began.

The goal of NPSG 15.01.01 is “to identify patients at risk for suicide.” To accomplish this goal, hospital care teams need simple, efficient, evidence-based tools for identifying such patients and responding appropriately to the identified risk. In a general hospital setting, implementing targeted suicide risk assessments is simply not feasible. Assessing every single hospitalized patient for suicide risk seems clinically unnecessary, if not wasteful, and yet the processes needed to identify reliably which patients ought to be assessed end up taking far longer than simply screening everybody. With these considerations in mind, our Perfect Depression Care team took a different approach.

The DAPS Tool

We developed a simple and easy tool to screen, not for suicide risk specifically, but for common psychiatric conditions associated with increased risk of suicide. The Depression, Anxiety, Polysubstance Use, and Suicide screen (DAPS) [15] consists of 7 questions coming from 5 individual evidence-based screening measures: the PHQ-2 for depression, the GAD-2 for anxiety, question 9 from the PHQ-9 for suicidal ideation, the SASQ for problem alcohol use, and a single drug use question for substance use. Each of these questionnaires has been validated as a sensitive screening measure for the psychiatric condition of interest (eg, major depression, generalized anxiety, current problem drinking). Some of them have been validated specifically in general medical settings or among general medical patient populations. Moreover, each questionnaire is valid whether clinician-administered or self-completed. Some have also been validated in languages other than English.

The DAPS tool bundles together these separate screening measures into one easy to use and efficient tool. As a bundle, the DAPS tool offers 3 major advantages over traditional screening tools. First, the tool takes a broader approach to suicide risk with the aim of increasing utility. Suicide is a statistically rare event, especially in general medical settings. On the other hand, psychiatric conditions that themselves increase people’s risk of suicide are quite common, particularly in hospital settings. Rather than screening exclusively for suicidal thoughts and behavior, the DAPS tool screens for psychiatric conditions associated with an increased risk of suicide that are common in general medical settings. This approach to suicide screening is novel. It allows for the recognition of higher number of patients who may benefit from behavioral health interventions, whether or not they are “actively suicidal” at that moment. By not including extensive assessments of numerous suicide risk factors, the DAPS tool offers practical utility without losing much specificity. After all, persons in general hospital settings who at acutely increased risk of suicide (eg, a person admitted to the hospital following a suicide attempt via overdose) are already being identified.

The second advantage of the DAPS tool is that the information it obtains is actionable. Suicide screening tools, whether brief or comprehensive, are not immediately predictive and arrive at essentially the same conclusion—the person screened is deemed to fall into some risk stratification (eg, high, medium, low risk; acute vs non-acute risk). In general hospital settings, the responses to these stratifications are limited (eg, order a sitter, call a psychiatry consultation) and not specific to the level of risk. Furthermore, persons with psychiatric disorders may be at increased risk of suicide even if they deny having suicidal thoughts. The DAPS tool allows for the recognition of these persons, thus identifying opportunities for intervention. For example, a person who screens positive on the PHQ-2 portion of the DAPS but who denies having recent suicidal thoughts or behavior may not benefit from an immediate safety measure (eg, ordering a sitter) but may benefit from an evaluation and, if indicated, treatment for depression. Treating that person’s depression would decrease the longitudinal risk of suicide. If another person screens negative on the PHQ-2 but positive on the SASQ, then that person may benefit most from interventions targeting problem alcohol use, such as the initiation of a CIWA protocol in order to prevent the emergence of alcohol withdrawal during the hospitalization, but not necessarily from depression treatment.

The third main advantage of the DAPS tool is its ease of use. There are a limited number of psychiatrists and other mental health care workers in general hospitals, and that number is not adequate to have all psychiatric screens and assessments in performed by a specialist. The DAPS tool consists of scripted questions that any health care provider can read and follow. This type of instruction may be especially beneficial to health care providers who are unsure or uncomfortable about how to screen patients for suicide or psychiatric disorders. The DAPS tool provides these clinicians with language they can use comfortably when talking with patients. Alternatively, patients themselves can complete the DAPS questions, which frees up valuable time for providers to deliver other types of care. During a pilot project at one of our general hospitals, 20 general floor nurses were asked to implement the DAPS with their patients after receiving only a very brief set of instructions. On average, it took a nurse less than 4 minutes to complete the DAPS. Ninety percent of the nurses stated the DAPS tool would take “less time” or “no additional time” compared with the behavioral health questions in the current nursing admission assessment they were required to complete on every patient. Eighty-five percent found the tool “easy” or “very easy” to use.

At the time of publication of this article, one of our general hospitals is set to roll out DAPS screening hospital wide with the goal of prospectively identifying patients who might benefit from some form of behavioral health intervention and thus reducing length of stay. Another of our general hospitals is already using the DAPS to reduce hospital readmissions [15]. What started out as an initiative simply to meet a regulatory requirement turned into a novel and efficient means to bring mental health care services to hospitalized patients.

Lessons Learned

Our goal in the Perfect Depression Care initiative was to eliminate suicide, and we have come remarkably close to achieving that goal. Our determination to strive for perfection rather than incremental goals had a powerful effect on our results. To move to a different order of performance required us to challenge our most basic assumptions and required new learning and new behavior.

This social aspect of our improvement work was fundamental to every effort made to spread Perfect Depression Care outside of the specialty behavioral health care setting. Indeed, the diffusion of all innovation occurs within a social context [16]. Ideas do not spread by themselves—they are spread from one person (the messenger) to another (the adopter). Successful spread, therefore, depends in large part on the communication between messenger and adopter.

Implementing Perfect Depression Care within BHS involved like-minded messengers and adopters from the same department, whereas spreading the initiative to the general medical setting involved messengers from one specialty and adopters from another. The nature of such a social system demands that the goals of the messenger be aligned with the incentives of the adopter. In health service organizations, such alignment requires effective leadership, not just local champions [17]. For example, spreading the initiative to the primary care setting really only became possible when our departmental leaders made a public promise to the leaders of primary care that BHS would see any patient referred from primary care on the same day of referral with no questions asked. And while it is true that operationalizing that promise was a more arduous task than articulating it, the promise itself is what created a social space within which the innovation could diffuse.

Even if leaders are successful at aligning the messenger’s goals and the adopter’s incentives, spread still must actually occur locally between 2 people. This social context means that a “good” idea in the mind of the messenger must be a “better” idea in the mind of the adopter. In other words, an idea or innovation is more likely to be adopted if it is better than the status quo [18]. And it is the adopter’s definition of “better” that matters. For example, our organization’s primary care clinics agreed that improving their depression care was a good idea. However, specific interventions were not adopted (or adoptable) until they became a way to make daily life easier for the front-line clinic staff (eg, by facilitating more efficient referrals to BHS). Furthermore, because daily life in each clinic was a little bit different, the specific interventions adopted were allowed to vary. Similarly, in the general hospital setting, DAPS screening was nothing more than a good idea until the nurses learned that it took less time and yielded more actionable results than the long list of behavioral health screening questions they were currently required to complete on every patient being admitted. When replacing those questions with the DAPS screen saved time and added value, the DAPS became better than the status quo, a tipping point was reached, and spread took place.

Future Spread

The 2 examples of Perfect Depression Care Spread described herein are testaments to the social traction of “zero suicides.” Importantly, the success of each effort has hinged on its creative, practical approach to suicide, even though there is scant scientific evidence to support suicide prevention initiatives in general medical settings [19].

As it turns out, there is also little scientific knowledge about how innovations in health service organizations are successfully sustained [16]. It is our hope that the 15 years of Perfect Depression Care shed some light on this question, and that the initiative can continue to be sustained in today’s turbulent and increasingly austere health care environment. We are confident that we will keep improving as long as we keep learning.

In addition, we find tremendous inspiration in the many others who are learning and improving with us. In 2012, for instance, the US Surgeon General promoted the adoption “zero suicides” as a national strategic objective [1]. And in 2015, the Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom called for the adoption of “zero suicides” across the entire National Health Service [20]. As the Perfect Depression Care team continues to grow, the pursuit of perfection becomes even more stirring.

Acknowledgment: The author acknowledges Brian K. Ahmedani, PhD, Charles E. Coffey, MD, MS, C. Edward Coffey, MD, Terri Robertson, PhD, and the entire Perfect Depression Care team.

Corresponding author: M. Justin Coffey, MD, The Menninger Clinic, 12301 S. Main St., Houston, TX 77035, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of the Surgeon General and National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention. 2012 National Strategy for Suicide Prevention: goals and objectives for action. Washington, DC: HHS; 2012.

2. Druss BG, Walker ER. Mental disorders and medical comorbidity: research synthesis report no. 21. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation 2011.

3. Committee on Quality Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

4. Coffey CE, Coffey MJ, Ahmedani BK. An update on Perfect Depression Care. Psychiatric Services 2013;64:396.

5. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Pursuing Perfection: Raising the bar in health care performance. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2014.

6. Marx D. Patient safety and the “just culture”: a primer for health care executives. New York: Columbia University; 2001.

7. Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, Wagner EH. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millennium. Health Aff 2009;28:75–85.

8. Coffey CE. Building a system of perfect depression care in behavioral health. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2007;33:193–9.

9. Hampton T. Depression care effort brings dramatic drop in large HMO population’s suicide rate. JAMA 2010;303: 1903–5.

10. Unützer J, Powers D, Katon W, Langston C. From establishing an evidence-based practice to implementation in real-world settings: IMPACT as a case study. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2005;28:1079–92.

11. Melek SP, Norris DT, Paulus J. Economic impact of integrated medical-behavioral healthcare: implications for psychiatry. Milliman; 2014.

12. Schmitt MR, Miller MJ, Harrison DL, Touchet BK. Relationship of depression screening and physician office visit duration in a national sample. Psych Svc 2010;61:1126–31.

13. mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings: Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP). World Health Organization; 2010.

14. National Patient Safety Goals 2008. The Joint Commission. Oakbrook, IL.

15. Coffey CE, Johns J, Veliz S, Coffey MJ. The DAPS tool: an actionable screen for psychiatric risk factors for rehospitalization. J Hosp Med 2012;7(suppl 2):S100–101.

16. Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q 2004;82:581–629.

17. Berwick DM. Disseminating innovations in health care. JAMA 2003;289:1969–75.

18. Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 4th ed. New York: The Free Press; 1995.

19. LeFevre MF. Screening for suicide risk in adolescents, adults, and older adults in primary care: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:719–26.

20. Clegg N. Speech at mental health conference. Available at www.gov.uk/government/speeches/nick-clegg-at-mental-health-conference.

From The Menninger Clinic, Houston, TX.

Abstract

- Objective: To summarize the Perfect Depression Care initiative and describe recent work to spread this quality improvement initiative.

- Methods: We summarize the background and methodology of the Perfect Depression Care initiative within the specialty behavioral health care setting and then describe the application of this methodology to 2 examples of spreading Perfect Depression Care to general medical settings: primary care and general hospitals.

- Results: In the primary care setting, Perfect Depression Care spread successfully in association with the development and implementation of a practice guideline for managing the potentially suicidal patient. In the general hospital setting, Perfect Depression Care is spreading successfully in association with the development and implementation of a simple and efficient tool to screen not for suicide risk specifically, but for common psychiatric conditions associated with increased risk of suicide.

- Conclusion: Both examples of spreading Perfect Depression Care to general medical settings illustrate the social traction of “zero suicides,” the audacious and transformative goal of the Perfect Depression Care Initiative.

Each year depression affects roughly 10% of adults in the United States [1]. The leading cause of disability in developed countries, depression results in substantial medical care expenditures, lost productivity, and absenteeism [1]. It is a chronic condition, and one that is associated with tremendous comorbidity from multiple chronic general medical conditions, including congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, and diabetes [2]. Moreover, the presence of depression has deleterious effects on the outcomes of those comorbid conditions [2]. Untreated or poorly treated, depression can be deadly—each year as many as 10% of patients with major depression die from suicide [1].

In 1999 the Behavioral Health Services (BHS) division of Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, Michigan, set out to eliminate suicide among all patients with depression in our HMO network. This audacious goal was a key lever in a broader aim, which was to build a system of perfect depression care. We aimed to achieve breakthrough improvement in quality and safety by completely redesigning the delivery of depression care using the 6 aims and 10 new rules set forth in the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) report Crossing the Quality Chasm [3]. To communicate our bold vision, we called the initiative Perfect Depression Care. Today, we can report a dramatic and sustained reduction in suicide that is unprecedented in the clinical and quality improvement literature [4].

In the Chasm report, the IOM cast a spotlight on behavioral health care, placing depression and anxiety disorders on the short list of priority conditions for immediate national attention and improvement. Importantly, the IOM called for a focus on not only behavioral health care benefits and coverage, but access and quality of care for all persons with depression. Finding inspiration from our success in the specialty behavioral health care setting, we decided to answer the IOM’s call. We set out to build a system of depression care that is not confined to the specialty behavioral health care setting, a system that delivers perfect care to every patient with depression, regardless of general medical comorbidity or care setting. We called this work Perfect Depression Care Spread.

In this article, we first summarize the background and methodology of the Perfect Depression Care initiative. We then describe the application of this methodology to spreading Perfect Depression Care into 2 nonspecialty care settings—primary care and general hospitals. Finally, we review some of the challenges and lessons learned from our efforts to sustain this important work.

Building a System of Perfect Depression Care

One example of the transformative power of a “zero defects” approach is the case of the Effectiveness aim. Our team engaged in vigorous debate about the goal for this aim. While some team members eagerly embraced the “zero defects” ambition and argued that truly perfect care could only mean “no suicides,” others challenged it, viewing it as lofty but unrealistic. After all, we had been taught that for some number of individuals with depression, suicide was the tragic yet inevitable outcome of their illness. How could it be possible to eliminate every single suicide? The debate was ultimately resolved when one team member asked, “If zero isn’t the right number of suicides, then what is? Two? Four? Forty?” The answer was obvious and undeniable. It was at that moment that setting “zero suicides” as the goal became a galvanizing force within BHS for the Perfect Depression Care initiative.

The pursuit of zero defects must take place within a “just culture,” an organizational environment in which frontline staff feel comfortable disclosing errors, especially their own, while still maintaining professional accountability [6]. Without a just culture, good but imperfect performance can breed disengagement and resentment. By contrast, within a just culture, it becomes possible to implement specific strategies and tactics to pursue perfection. Along the way, each step towards “zero defects” is celebrated because each defect that does occur is identified as an opportunity for learning.

One core strategy for Perfect Depression Care was organizing care according to the planned care model, a locally tailored version of the chronic care model [7]. We developed a clear vision for how each patient’s care would change in a system of Perfect Depression Care. We partnered with patients to ensure their voice in the redesign of our depression care services. We then conceptualized, designed, and tested strategies for improvement in 4 high-leverage domains (patient partnership, clinical practice, access to care, and information systems), which were identified through mapping our current care processes. Once this new model of care was in place, we implemented relevant measures of care quality and began continually assessing progress and then adjusting the plan as needed (ie, following the Model for Improvement).

Spread to Primary Care

The spread to primary care began in 2005, about 5 years after the initial launch of Perfect Depression Care in BHS. (There had been some previous work done aimed at integrating depression screening into a small number of specialty chronic disease management initiatives, although that work was not sustained.) We based the overall clinical structure on the IMPACT model of integrated behavioral health care [10]. Primary care providers collaborated with depression care managers, typically nurses, who had been trained to provide education to primary care providers and problem solving therapy to patients. The care managers were supervised by a project leader (a full-time clinical psychologist) and supported by 2 full-time psychiatric nurse practitioners who were embedded in each clinic during the early phases of implementation. An electronic medical record (EMR) was comfortably in place and facilitated the delivery of evidence-based depression care, as well as the collection of relevant process and outcome measures, which were fed back to the care teams on a regular basis. And, importantly, the primary care leadership team formally sanctioned depression care to be spread to all 27 primary care clinics.

Overcoming the Challenges of the Primary Care Visits

From 2005 to 2010, the model was spread tenuously to 5 primary care clinics. At that rate (1 clinic per year), it would have taken over 20 years to spread depression care through all 27 primary care clinics. Not satisfied with this progress, we stepped back to consider why adoption was happening so slowly. First, we spoke with leaders. Although the project was on a shoestring budget, our leaders understood the business case for integrating some version of depression care into the primary care setting [11]. They advised limiting the scope of the project to focus only on adults with 1 of 6 chronic diseases: diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, and chronic kidney disease. This narrower focus was aimed at using the project’s limited resources more effectively on behalf of patients who were more frequent utilizers of care and statistically more likely to have a comorbid depressive illness. Through the use of time studies, however, we learned that the time consumed discerning which patients each day were eligible for depression screening created delays in clinic workflow that were untenable. It turned out that the process of screening all patients was far more efficient that the process of identifying which patients “should” be screened and then screening only those who were identified. This pragmatic approach to daily workflow in the clinics was a key driver of successful spread.

Next, we spoke to patients. In an effort to assess patient engagement, we reviewed the records of 830 patients who had been seen in one of the clinics where depression care was up and running. Among this group, less than 1% had declined to receive depression screening. In fact, during informal discussions with patients and clinic staff, patients were thanking their primary care providers for talking with them about depression. When it came to spreading depression care, patient engagement was not the problem.

Finally, we spoke with primary care providers, physicians who were viewed as leaders in their clinics. They described trepidation among their teams about adopting an innovation that would lead to patients being identified as at risk for suicide. Their concern was not that integrating depression care was not the right thing to do in the primary care setting; indeed, they had a strong and genuine desire to provide better depression care for their patients. Their concern was that the primary care clinic was not equipped to manage a suicidal patient safely and effectively. This concern was real, and it was pervasive. After all, the typical primary care office visit was already replete with problem lists too long to be managed effectively in the diminishing amount of time allotted to each visit. Screening for depression would only make matters worse [12]. Furthermore, identifying a patient at risk for suicide was not uncommon in our primary care setting. Between 2006 and 2012, an average of 16% of primary care patients screened each year had reported some degree of suicidal ideation (as measures by a positive response on question 9 of the PHQ-9). These discussions showed us that the model of depression care we were trying to spread into primary care was not designed with an explicit and confident approach to suicide—it was not Perfect Depression Care.

Leveraging Suicide As a Driver of Spread

When we realized that the anxiety surrounding the management of a suicidal patient was the biggest obstacle to Perfect Depression Care spread to primary care, we decided to turn this obstacle into an opportunity. First, an interdisciplinary team developed a practice guideline for managing the suicidal patient in general medical settings. The guideline was based on the World Health Organization’s evidence-based guidelines for addressing mental health disorders in nonspecialized health settings [13] and modified into a single page to make it easy to adopt. Following the guideline was not at all a requirement, but doing so made it very easy to identify patients at potential risk for suicide and to refer them safely and seamlessly to the next most appropriate level of care.

Second, and most importantly, BHS made a formal commitment to provide immediate access for any patient referred by a primary care provider following the practice guideline. BHS pledged to perform the evaluation on the same day as the referral was made and without any questions asked. Delivering on this promise required BHS to develop and implement reliable processes for its ambulatory centers to receive same-day referrals from any one of 27 primary care clinics. Success meant delighting our customers in primary care while obviating the expense and trauma associated with sending patients to local emergency departments. This work was hard. And it was made possible by the culture within BHS of pursuing perfection.