User login

Delivering Bad News in the Context of Culture: A Patient-Centered Approach

From the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the impact of culture on delivering bad news to patients and to describe a patient-centered approach physicians can use when delivering bad news.

- Methods: Descriptive report and discussion utilizing an illustrative case.

- Results: Physicians often find it challenging to deliver bad news in a culturally sensitive manner. Patients vary in their preferences for how they receive bad news, both within and across cultural groups. A strategy to address these preferences is presented that integrates the ethnographic Kleinman model and the SPIKES model.

- Conclusion: Delivering bad news is a challenging endeavor for many physicians. Strategies are available to guide clinicians through these conversations in a manner that is culturally sensitive and patient-centered.

A 52-year-old patient from Mexico is seeing his physician because he has been experiencing some fatigue and abdominal pain. The doctor asks the patient about his symptoms with the aid of an interpreter (in all the dialogues, a Spanish interpreter is present).

Doctor: How can I help you today?

Patient: I think it’s probably nothing, but my wife is worried and wanted me to see you. I don’t quite feel myself, just a little more tired than usual.

Doctor: Do you have any other symptoms?

Patient: Well, I have been having some pain in my stomach, just a little crampy feeling down low. My wife says I have lost some weight and she wanted me to see a doctor. I haven’t been eating as much as I usually do. I just don’t have much of an appetite, especially when I get the pain.

The doctor goes on to ask some additional questions and conducts a physical examination. He discovers the patient lost 20 pounds since his last visit 8 months ago. He is worried that the patient may have something serious going on, possibly colon cancer. He recommends some testing to the patient.

Doctor: I would like to do some tests to see what is going on.

Patient: What kind of tests?

Doctor: A few blood tests and a colonoscopy. Do you know what that is?

Patient: Yes, my brother had one a few years ago.

Doctor: Ok, my nurse will set that up and explain what you will need to do. We’ll schedule another appointment for you to come back to discuss the results. You mentioned your wife. Would you like her or anyone else to be with you at that appointment?

Patient: Yes, my wife and son. My son knows a lot more about medical things than I do, and I know he would want to come.

The Need for Culturally Sensitive Care

The concept of one’s culture encompasses a host of components including how an individual identifies oneself as well as the language, customs, beliefs, and value system one utilizes. Culture, in turn, profoundly affects patients’ belief systems regarding health and wellness, disease and illness, and the delivery of health care services, including the use of healers and alternative providers [1].In order to provide culturally sensitive and high-quality care to diverse patient populations, it is important for providers to gain an understanding and sensitivity to the influences of culture on patients’ beliefs and behaviors [2].

The ability to provide care to people of different cultures is more important than ever before. In 2011, the number of legal and unauthorized immigrants in the United States rose to 40.4 million (13% of the population) and between 2007 and 2011 alone, this number rose by 2.4 million [3].According to a 2010 census bureau report, in the last 30 years the number of individuals over the age of 5 who spoke a language other than English in their home more than doubled, an increase that was 4 times greater than the rate of population growth [4].In addition, in 2009 the United States resettled more refugees than any other nation (60,000+) and this number reached almost 70,000 in 2013 [5,6].Patient populations in the United States are becoming increasingly diverse, and providers must have the skills to communicate effectively with these groups. A one-size-fits-all approach is not sufficient for our changing population.

The Challenges of Delivering Bad News and the Impact of Culture

Perhaps one of the most challenging communication scenarios faced by physicians is the need to deliver bad news to a patient. “Bad news” can be described as any information that adversely alters one’s expectations for the future [7].Clinicians from nearly all specialties are confronted with the task of giving bad news [8],and this is particularly true regarding cancer care. Among oncologists, 60% reported the need to break bad news to patients between 5 to 20 times per month, with 14% reporting greater than 20 times per month [9].The concept of giving bad news is often viewed as stressful by clinicians [10], and clinicians must be able to balance a myriad of elements, including patients’ emotional responses, information needs, uncertainties of disease progression and treatments, patients’ preferred level of involvement in decision making, patient expectations, involvement of family members, and how to maintain hope, among others [9,11]. Indeed, it seems that clinicians find it difficult to take into account the full spectrum of patient needs [8]. While the descriptive literature indicates that patient satisfaction and psychological well-being is improved when a patient-centered approach is utilized that attends to the emotional needs of patients [12], clinicians often focus on biomedical information, with less focus on patients’ psychosocial needs and their level of understanding [13–15].

Further, the interaction of patient culture and context with the complexity of the “bad news” interaction can be daunting, and clinicians have noted their diminished level of comfort in adjusting to these cultural preferences [16].The ability of clinicians to “match” the patient’s preferred level of involvement in decision making is associated with higher patient satisfaction with decision making and lower depression after 3 months [11],yet clinicians often find it difficult to determine which patients want to be involved in the decision making to a greater or lesser extent [12].In addition, words have different meanings when used in medical settings or in lay contexts [8],not to mention the challenges of translation when dealing with non–English-speaking patients. Yet, the manner in which clinicians deliver bad news can affect patients’ understanding of their disease, treatment options, and patients’ adjustment to the diagnosis [8],as well as patients’ expected quality of life and intentions to adhere to recommendations [17].

Information Disclosure

One of the key areas impacted by culture relates to preferred disclosure of medical information. Walsh et al noted in their review that the majority of patients in English-speaking countries wanted relatively full disclosure regarding their illness in comparison to individuals from other countries [18].As a further distinction, Blackhall et al noted that African Americans and European Americans were more likely to believe that a patient should be told of a terminal diagnosis than Mexican and Korean Americans [19].In addition, Mexican and Korean Americans were more likely to believe that clinicians should not discuss death and dying with patients, as it could be harmful. Fujimori noted that Asians are less likely to prefer discussions of life expectancy in contrast to Westerners [20].In a survey of Albanian nationals, < 50% of patients wanted to know their true diagnosis; however, individuals who were male, urban, and educated demonstrated a significantly greater preference for disclosure [21].In the Middle East, the concept of disclosure is highly variable in terms of both provider and patient preferences [22].

Involvement of Family Members

A second important area relates to the involvement of family members. Fujimori noted high variability of patient preferences for having family members present when discussing bad news. Of Japanese patients, 78% preferred to be told with family members present, with the number decreasing for Portugal (61%), Australia (53%-57%), and Ireland (40%). Eighty-one percent of the US patients did not want anyone else present. However, almost all placed high value on physician expertise and honesty [20]. Blackhall noted that Mexican and Korean Americans were more likely to favor a family-centered approach to decision making [19]. In addition, Orona indicated that Mexican-American and Chinese-American families felt it was their duty to protect their relatives from a cancer diagnosis to keep the patient’s remaining time free of worry [23]. Haggerty found mixed evidence for patient preferences regarding disclosure of cancer prognosis to family members [24].

Given these variations and complexities, it is natural to try to develop a system for managing them, eg, a list of traits or attributes one can apply to certain groups. For example, patients of Asian origin prefer _______. However, there is an inherent danger in doing this, as it leads to stereotyping [25]. Cultural factors also may be given inappropriate meaning. Specifically, a well-meaning clinician might attribute certain characteristics to a patient when in fact it has little bearing on the patient’s perspective [25]. In addition, given the nature of communication, travel, and the fact that many individuals identify with more than one cultural group, it may be inappropriate to attribute a singular cultural identity to a group in contemporary society. As a result, Kleinman [25] proposed an ethnographic approach as opposed to a cultural approach. Specifically, this involves understanding a patient and his/her illness from an individual’s perspective as opposed to the cultural collective.

Communication Skills to Help Deliver Bad News

Set Up the Interview

Before meeting with the patient, it is important to review the medical data and have a plan in mind for delivering the bad news. Schedule adequate time for discussion and avoid interruptions. Meet in a quiet, private room that is large enough to accommodate family members or friends whom the patient may have brought. In our case example, the patient has brought his wife and son to the appointment.

Doctor: Hello, Mr. Ruiz. (Turning to the patient’s wife and son) I am Dr. Simon.

Patient: Hello, Doctor. This is my wife, Maria, and son, Alejandro.

Doctor: Please have a seat. Are you comfortable?

Patient: Yes. We are anxious to hear the results of the tests.

Son: My father doesn’t always understand medical terms and I wanted to be here to help. I am very worried about him.

Doctor: I understand your concern and I will explain everything to you.

Assess the Patient’s Perception of the Problem

Before telling the patient the diagnosis, it is important to get an idea of the patient’s understanding of the problem, including what he calls it, what he thinks caused it, and how severe he thinks it is.

Doctor: Before I tell you the results, I would like to get a sense first of what you think is going on.

Patient: Well, I really don’t know for sure, but I know the pain is getting worse and I have been feeling weaker. The pain started right after my son’s wedding. There was a lot of food and I ate more than usual. Maybe it was something bad that I ate?

Doctor: (Turning to the wife and son) Do you have any thoughts about the illness?

Wife: I can see he is in pain a lot, even though he tries to hide it from me. I want to know what’s wrong. I am worried it could be something bad.

Obtain the Patient’s Invitation to Disclose the Information

It is important to know if the patient wants to be told the information about his or her diagnosis. Ideally, physicians should discuss this in general terms as part of routine care, before any bad news needs to be delivered. For example,

Doctor: There may come a time when I will need to tell you something bad about your health. Hopefully, that time will never come, but I want to know your preferences so I can honor them if the time does arise. Would you want to be told about this, or would you want someone else, perhaps someone in your family, to be told?

Patient: I appreciate your asking, Doctor. I haven’t really thought about it, but I get kind of nervous and upset when I hear bad news. I would rather you tell me when my wife and son can be there too.

Give Knowledge and Information to the Patient

It is important to provide information that is at a level that the patient can understand. Avoid the use of medical jargon. When speaking through an interpreter, the clinician may need to have a conversation with the interpreter before meeting the patient to explain the situation and the need to be sensitive. For example, if the clinician does not use the word “cancer” after determining from the patient or family the preference for an alternative word, be sure to inform the interpreter not to use the word “cancer.” Provide the information in small chunks and check in frequently to make sure the patient understands. Avoid language that takes away hope. If there is a family member who speaks English, there is a tendency to speak to that person rather than the patient directly. Avoid doing this unless the patient explicitly requests that the clinician speak directly to that individual. This is often the case with older patients. The following might take place at a subsequent appointment:

Doctor: Mr. Ruiz, you told me previously that you would like me to tell you the results of your tests, along with you wife and son. Unfortunately, I have some bad news to tell you. (Pause) The colonoscopy showed that you have a tumor in the colon, also called the large intestine. It is located in the part that we call the ascending colon (draws a picture to show them where this is). We will need to do some other scans to make sure that the tumor is just in the colon and has not spread. I am hopeful, though, that we have caught it fairly early and it has not spread. That would be the best situation. (Pause) Do you understand what I have told you so far?

Address the Patient’s and Family’s Emotions

Every patient will express their reactions to bad news differently, and their reactions may be different from what the physician might experience in a similar situation. Thus, the clinician should be self-aware and be prepared to respond to a variety of responses. It is important to express empathy and validate the patient’s and family reactions and emotions. If the patient does not express any emotion, the clinician should explore this carefully. It may require more than one visit for the patient to open up with his feelings.

Doctor: I am so sorry. I know that this must be a big shock for you.

Patient: I kind of figured it might be something bad, but it is still a shock. Even so, I am a religious man and I believe that I will get through this with the help of my wife and family.

Doctor: It sounds as if you have a great support system and get strength from your faith. You are lucky to have such a wonderful family and that will be a big help as we move forward.

Strategize and Summarize

Ask the patient if he or she is ready to have a discussion about treatment, including his or her goals of treatment. Continue to explore the patient’s knowledge, expectations and hopes. Always allow the patient to express his fears and concerns. Most importantly, let the patient know that you will share the responsibility of decision making with the patient and be there to support him.

Doctor: This is never easy and it’s a lot to take in. Would you like to discuss the next steps and possible treatments at this time or should we make another appointment after your CAT scan?

Patient: My wife is pretty upset and I think it might be better if we stop here for now. Is that ok?

Son: We want to come back as soon as we can after the CAT scan. In the meantime, can you provide me with some information or a good website to check out?

Doctor: Yes, of course. That sounds like a good plan.

Conclusion

The task of giving bad news is a necessity for physicians of most specialties and is often viewed as challenging and even stressful to some. However, the manner in which information is discussed with patients can impact patients’ satisfaction, understanding of their illness, adjustment to the diagnosis, expected quality of life, and intentions to adhere to recommendations [8,17]. Providing bad news in a culturally sensitive manner adds an additional level of complexity to an already challenging encounter. While an individual’s culture can strongly influence patient belief systems and utilization of care, there is an inherent danger when clinicians make assumptions about individuals’ culture and the role it plays in their lives. Instead of focusing on creating a mental list of cultural attributes, we recommend a patient-centered approach where few assumptions about the patient are made and instead, the clinician gains an understanding of each individual patient through queries and adjusts his/her approach and language according to each individual’s needs.

Corresponding author: Lisa K. Rollins, PhD, Dept. of Family Medicine, Univ.of Virginia, PO Box 800729, Charlottesville,VA 22908-0729, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Cultural competency – clear communication. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Accessed at www.nih.gov/clearcommunication/culturalcompetency.htm on 15 Jul 2014.

2. Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O. Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Pub Health Rep 2003;118:293–302.

3. PEW research: Hispanic trends project, a nation of immigrants. Accessed at www.pewhispanic.org/2013/01/29/a-nation-of-immigrants/ on 31 Jul 2014.

4. U.S. Census Bureau. New census bureau report analyzes nation’s linguistic diversity. Accessed at www.census/gov/newsroom/releases/archives/american_community_survey_acs/cb10-cn58.html on 31 Jul 2014.

5. Immigration Policy Center. Refugees: a fact sheet. Accessed at www.immigrationpolicy.org on 28 May 2014.

6. U.S. Department of State. U.S. welcomes record number of refugees. Accessed at iipdigital.usembassy.gov/st/english/article/2013/10/20131023285033.html?CP.rss=true#axzz3GtyMkFSe on 28 May 2014.

7. Barclay JS, Blackhall L J, Tulsky JA. Communication strategies and cultural issues in the delivery of bad news. J Palliative Med 2007;10:958–77.

8. Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet 2004;363;312–9.

9. Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES—A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist 2000;5:302–11.

10. Ptacek JT, McIntosh EG. Physician challenges in communicating bad news. J Behav Med 2009;32:380–7.

11. Vogel BA, Leonhart R, Helmes AW. Communication matters: the impact of communication and participation in decision making on breast cancer patients’ depression and quality of life. Patient Educ Couns 2009;77:391–7.

12. Hack TF, Degner LF, Parker PA. The communication goals and needs of cancer patients: a review. Psychooncology 2005;14:831–45.

13. Vail L, Sandhu H, Fisher J, et al. Hospital consultants breaking bad news with simulated patients: an analysis of communication using the roter interaction analysis system. Patient Educ Couns 2011;83:185–94.

14. Hack TF, Pickles T, Ruether JD, et al. Behind closed doors: systematic analysis of breast cancer consultation communication and predictors of satisfaction with communication.

Psychooncology 2010;19:626–36.

15. Cantwell BM, Ramirez A. Doctor-patient communication: a study of junior house officers. Med Educ 1997;31:17–21.

16. Rollins LK, Bradley EB, Hayden GF, et al. Responding to a changing nation: are faculty prepared for cross-cultural conversations and care? Fam Med 2013;45:736–9.

17. Burgers C, Beukeboom CJ, Sparks L. How the doc should (not) talk: when breaking bad news with negations influences patients’ immediate responses and medical adherence intentions. Patient Educ Couns 2012;89:267–73.

18. Walsh RA, Girgis A, Sanson-Fisher RW. Breaking bad news 2: what evidence is available to guide clinicians? Behav Med 1998;24:61–73.

19. Blackhall LJ, Murphy ST, Frank G, et al. Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. JAMA 1995;274:820–5.

20. Fujimori M, Uchitomi Y. Preferences of cancer patients regarding communication of bad news: a systematic literature review. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2009;39:201–16.

21. Beqiri A, Toci E, Sallaku A, et al. Breaking bad news in a southeast european population: a survey among cancer patients in Albania. J Palliat Med 2012;15:1100–5.

22. Khalil RB. Attitudes, beliefs and perceptions regarding truth disclosure of cancer-related information in the Middle East: a review. Palliat Supp Care 2013;11:69–78.

23. Orona CJ, Koenig BA, Davis AJ. Cultural aspects of nondisclosure. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 1994;3:338–46.

24. Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, et al. Communicating prognosis in cancer care: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Oncol 2005;16:1005–53.

25. Kleinman A, Benson P. Anthropology in the clinic: the problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. PLoS Med 2006;3:1673–6.

From the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the impact of culture on delivering bad news to patients and to describe a patient-centered approach physicians can use when delivering bad news.

- Methods: Descriptive report and discussion utilizing an illustrative case.

- Results: Physicians often find it challenging to deliver bad news in a culturally sensitive manner. Patients vary in their preferences for how they receive bad news, both within and across cultural groups. A strategy to address these preferences is presented that integrates the ethnographic Kleinman model and the SPIKES model.

- Conclusion: Delivering bad news is a challenging endeavor for many physicians. Strategies are available to guide clinicians through these conversations in a manner that is culturally sensitive and patient-centered.

A 52-year-old patient from Mexico is seeing his physician because he has been experiencing some fatigue and abdominal pain. The doctor asks the patient about his symptoms with the aid of an interpreter (in all the dialogues, a Spanish interpreter is present).

Doctor: How can I help you today?

Patient: I think it’s probably nothing, but my wife is worried and wanted me to see you. I don’t quite feel myself, just a little more tired than usual.

Doctor: Do you have any other symptoms?

Patient: Well, I have been having some pain in my stomach, just a little crampy feeling down low. My wife says I have lost some weight and she wanted me to see a doctor. I haven’t been eating as much as I usually do. I just don’t have much of an appetite, especially when I get the pain.

The doctor goes on to ask some additional questions and conducts a physical examination. He discovers the patient lost 20 pounds since his last visit 8 months ago. He is worried that the patient may have something serious going on, possibly colon cancer. He recommends some testing to the patient.

Doctor: I would like to do some tests to see what is going on.

Patient: What kind of tests?

Doctor: A few blood tests and a colonoscopy. Do you know what that is?

Patient: Yes, my brother had one a few years ago.

Doctor: Ok, my nurse will set that up and explain what you will need to do. We’ll schedule another appointment for you to come back to discuss the results. You mentioned your wife. Would you like her or anyone else to be with you at that appointment?

Patient: Yes, my wife and son. My son knows a lot more about medical things than I do, and I know he would want to come.

The Need for Culturally Sensitive Care

The concept of one’s culture encompasses a host of components including how an individual identifies oneself as well as the language, customs, beliefs, and value system one utilizes. Culture, in turn, profoundly affects patients’ belief systems regarding health and wellness, disease and illness, and the delivery of health care services, including the use of healers and alternative providers [1].In order to provide culturally sensitive and high-quality care to diverse patient populations, it is important for providers to gain an understanding and sensitivity to the influences of culture on patients’ beliefs and behaviors [2].

The ability to provide care to people of different cultures is more important than ever before. In 2011, the number of legal and unauthorized immigrants in the United States rose to 40.4 million (13% of the population) and between 2007 and 2011 alone, this number rose by 2.4 million [3].According to a 2010 census bureau report, in the last 30 years the number of individuals over the age of 5 who spoke a language other than English in their home more than doubled, an increase that was 4 times greater than the rate of population growth [4].In addition, in 2009 the United States resettled more refugees than any other nation (60,000+) and this number reached almost 70,000 in 2013 [5,6].Patient populations in the United States are becoming increasingly diverse, and providers must have the skills to communicate effectively with these groups. A one-size-fits-all approach is not sufficient for our changing population.

The Challenges of Delivering Bad News and the Impact of Culture

Perhaps one of the most challenging communication scenarios faced by physicians is the need to deliver bad news to a patient. “Bad news” can be described as any information that adversely alters one’s expectations for the future [7].Clinicians from nearly all specialties are confronted with the task of giving bad news [8],and this is particularly true regarding cancer care. Among oncologists, 60% reported the need to break bad news to patients between 5 to 20 times per month, with 14% reporting greater than 20 times per month [9].The concept of giving bad news is often viewed as stressful by clinicians [10], and clinicians must be able to balance a myriad of elements, including patients’ emotional responses, information needs, uncertainties of disease progression and treatments, patients’ preferred level of involvement in decision making, patient expectations, involvement of family members, and how to maintain hope, among others [9,11]. Indeed, it seems that clinicians find it difficult to take into account the full spectrum of patient needs [8]. While the descriptive literature indicates that patient satisfaction and psychological well-being is improved when a patient-centered approach is utilized that attends to the emotional needs of patients [12], clinicians often focus on biomedical information, with less focus on patients’ psychosocial needs and their level of understanding [13–15].

Further, the interaction of patient culture and context with the complexity of the “bad news” interaction can be daunting, and clinicians have noted their diminished level of comfort in adjusting to these cultural preferences [16].The ability of clinicians to “match” the patient’s preferred level of involvement in decision making is associated with higher patient satisfaction with decision making and lower depression after 3 months [11],yet clinicians often find it difficult to determine which patients want to be involved in the decision making to a greater or lesser extent [12].In addition, words have different meanings when used in medical settings or in lay contexts [8],not to mention the challenges of translation when dealing with non–English-speaking patients. Yet, the manner in which clinicians deliver bad news can affect patients’ understanding of their disease, treatment options, and patients’ adjustment to the diagnosis [8],as well as patients’ expected quality of life and intentions to adhere to recommendations [17].

Information Disclosure

One of the key areas impacted by culture relates to preferred disclosure of medical information. Walsh et al noted in their review that the majority of patients in English-speaking countries wanted relatively full disclosure regarding their illness in comparison to individuals from other countries [18].As a further distinction, Blackhall et al noted that African Americans and European Americans were more likely to believe that a patient should be told of a terminal diagnosis than Mexican and Korean Americans [19].In addition, Mexican and Korean Americans were more likely to believe that clinicians should not discuss death and dying with patients, as it could be harmful. Fujimori noted that Asians are less likely to prefer discussions of life expectancy in contrast to Westerners [20].In a survey of Albanian nationals, < 50% of patients wanted to know their true diagnosis; however, individuals who were male, urban, and educated demonstrated a significantly greater preference for disclosure [21].In the Middle East, the concept of disclosure is highly variable in terms of both provider and patient preferences [22].

Involvement of Family Members

A second important area relates to the involvement of family members. Fujimori noted high variability of patient preferences for having family members present when discussing bad news. Of Japanese patients, 78% preferred to be told with family members present, with the number decreasing for Portugal (61%), Australia (53%-57%), and Ireland (40%). Eighty-one percent of the US patients did not want anyone else present. However, almost all placed high value on physician expertise and honesty [20]. Blackhall noted that Mexican and Korean Americans were more likely to favor a family-centered approach to decision making [19]. In addition, Orona indicated that Mexican-American and Chinese-American families felt it was their duty to protect their relatives from a cancer diagnosis to keep the patient’s remaining time free of worry [23]. Haggerty found mixed evidence for patient preferences regarding disclosure of cancer prognosis to family members [24].

Given these variations and complexities, it is natural to try to develop a system for managing them, eg, a list of traits or attributes one can apply to certain groups. For example, patients of Asian origin prefer _______. However, there is an inherent danger in doing this, as it leads to stereotyping [25]. Cultural factors also may be given inappropriate meaning. Specifically, a well-meaning clinician might attribute certain characteristics to a patient when in fact it has little bearing on the patient’s perspective [25]. In addition, given the nature of communication, travel, and the fact that many individuals identify with more than one cultural group, it may be inappropriate to attribute a singular cultural identity to a group in contemporary society. As a result, Kleinman [25] proposed an ethnographic approach as opposed to a cultural approach. Specifically, this involves understanding a patient and his/her illness from an individual’s perspective as opposed to the cultural collective.

Communication Skills to Help Deliver Bad News

Set Up the Interview

Before meeting with the patient, it is important to review the medical data and have a plan in mind for delivering the bad news. Schedule adequate time for discussion and avoid interruptions. Meet in a quiet, private room that is large enough to accommodate family members or friends whom the patient may have brought. In our case example, the patient has brought his wife and son to the appointment.

Doctor: Hello, Mr. Ruiz. (Turning to the patient’s wife and son) I am Dr. Simon.

Patient: Hello, Doctor. This is my wife, Maria, and son, Alejandro.

Doctor: Please have a seat. Are you comfortable?

Patient: Yes. We are anxious to hear the results of the tests.

Son: My father doesn’t always understand medical terms and I wanted to be here to help. I am very worried about him.

Doctor: I understand your concern and I will explain everything to you.

Assess the Patient’s Perception of the Problem

Before telling the patient the diagnosis, it is important to get an idea of the patient’s understanding of the problem, including what he calls it, what he thinks caused it, and how severe he thinks it is.

Doctor: Before I tell you the results, I would like to get a sense first of what you think is going on.

Patient: Well, I really don’t know for sure, but I know the pain is getting worse and I have been feeling weaker. The pain started right after my son’s wedding. There was a lot of food and I ate more than usual. Maybe it was something bad that I ate?

Doctor: (Turning to the wife and son) Do you have any thoughts about the illness?

Wife: I can see he is in pain a lot, even though he tries to hide it from me. I want to know what’s wrong. I am worried it could be something bad.

Obtain the Patient’s Invitation to Disclose the Information

It is important to know if the patient wants to be told the information about his or her diagnosis. Ideally, physicians should discuss this in general terms as part of routine care, before any bad news needs to be delivered. For example,

Doctor: There may come a time when I will need to tell you something bad about your health. Hopefully, that time will never come, but I want to know your preferences so I can honor them if the time does arise. Would you want to be told about this, or would you want someone else, perhaps someone in your family, to be told?

Patient: I appreciate your asking, Doctor. I haven’t really thought about it, but I get kind of nervous and upset when I hear bad news. I would rather you tell me when my wife and son can be there too.

Give Knowledge and Information to the Patient

It is important to provide information that is at a level that the patient can understand. Avoid the use of medical jargon. When speaking through an interpreter, the clinician may need to have a conversation with the interpreter before meeting the patient to explain the situation and the need to be sensitive. For example, if the clinician does not use the word “cancer” after determining from the patient or family the preference for an alternative word, be sure to inform the interpreter not to use the word “cancer.” Provide the information in small chunks and check in frequently to make sure the patient understands. Avoid language that takes away hope. If there is a family member who speaks English, there is a tendency to speak to that person rather than the patient directly. Avoid doing this unless the patient explicitly requests that the clinician speak directly to that individual. This is often the case with older patients. The following might take place at a subsequent appointment:

Doctor: Mr. Ruiz, you told me previously that you would like me to tell you the results of your tests, along with you wife and son. Unfortunately, I have some bad news to tell you. (Pause) The colonoscopy showed that you have a tumor in the colon, also called the large intestine. It is located in the part that we call the ascending colon (draws a picture to show them where this is). We will need to do some other scans to make sure that the tumor is just in the colon and has not spread. I am hopeful, though, that we have caught it fairly early and it has not spread. That would be the best situation. (Pause) Do you understand what I have told you so far?

Address the Patient’s and Family’s Emotions

Every patient will express their reactions to bad news differently, and their reactions may be different from what the physician might experience in a similar situation. Thus, the clinician should be self-aware and be prepared to respond to a variety of responses. It is important to express empathy and validate the patient’s and family reactions and emotions. If the patient does not express any emotion, the clinician should explore this carefully. It may require more than one visit for the patient to open up with his feelings.

Doctor: I am so sorry. I know that this must be a big shock for you.

Patient: I kind of figured it might be something bad, but it is still a shock. Even so, I am a religious man and I believe that I will get through this with the help of my wife and family.

Doctor: It sounds as if you have a great support system and get strength from your faith. You are lucky to have such a wonderful family and that will be a big help as we move forward.

Strategize and Summarize

Ask the patient if he or she is ready to have a discussion about treatment, including his or her goals of treatment. Continue to explore the patient’s knowledge, expectations and hopes. Always allow the patient to express his fears and concerns. Most importantly, let the patient know that you will share the responsibility of decision making with the patient and be there to support him.

Doctor: This is never easy and it’s a lot to take in. Would you like to discuss the next steps and possible treatments at this time or should we make another appointment after your CAT scan?

Patient: My wife is pretty upset and I think it might be better if we stop here for now. Is that ok?

Son: We want to come back as soon as we can after the CAT scan. In the meantime, can you provide me with some information or a good website to check out?

Doctor: Yes, of course. That sounds like a good plan.

Conclusion

The task of giving bad news is a necessity for physicians of most specialties and is often viewed as challenging and even stressful to some. However, the manner in which information is discussed with patients can impact patients’ satisfaction, understanding of their illness, adjustment to the diagnosis, expected quality of life, and intentions to adhere to recommendations [8,17]. Providing bad news in a culturally sensitive manner adds an additional level of complexity to an already challenging encounter. While an individual’s culture can strongly influence patient belief systems and utilization of care, there is an inherent danger when clinicians make assumptions about individuals’ culture and the role it plays in their lives. Instead of focusing on creating a mental list of cultural attributes, we recommend a patient-centered approach where few assumptions about the patient are made and instead, the clinician gains an understanding of each individual patient through queries and adjusts his/her approach and language according to each individual’s needs.

Corresponding author: Lisa K. Rollins, PhD, Dept. of Family Medicine, Univ.of Virginia, PO Box 800729, Charlottesville,VA 22908-0729, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville, VA.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the impact of culture on delivering bad news to patients and to describe a patient-centered approach physicians can use when delivering bad news.

- Methods: Descriptive report and discussion utilizing an illustrative case.

- Results: Physicians often find it challenging to deliver bad news in a culturally sensitive manner. Patients vary in their preferences for how they receive bad news, both within and across cultural groups. A strategy to address these preferences is presented that integrates the ethnographic Kleinman model and the SPIKES model.

- Conclusion: Delivering bad news is a challenging endeavor for many physicians. Strategies are available to guide clinicians through these conversations in a manner that is culturally sensitive and patient-centered.

A 52-year-old patient from Mexico is seeing his physician because he has been experiencing some fatigue and abdominal pain. The doctor asks the patient about his symptoms with the aid of an interpreter (in all the dialogues, a Spanish interpreter is present).

Doctor: How can I help you today?

Patient: I think it’s probably nothing, but my wife is worried and wanted me to see you. I don’t quite feel myself, just a little more tired than usual.

Doctor: Do you have any other symptoms?

Patient: Well, I have been having some pain in my stomach, just a little crampy feeling down low. My wife says I have lost some weight and she wanted me to see a doctor. I haven’t been eating as much as I usually do. I just don’t have much of an appetite, especially when I get the pain.

The doctor goes on to ask some additional questions and conducts a physical examination. He discovers the patient lost 20 pounds since his last visit 8 months ago. He is worried that the patient may have something serious going on, possibly colon cancer. He recommends some testing to the patient.

Doctor: I would like to do some tests to see what is going on.

Patient: What kind of tests?

Doctor: A few blood tests and a colonoscopy. Do you know what that is?

Patient: Yes, my brother had one a few years ago.

Doctor: Ok, my nurse will set that up and explain what you will need to do. We’ll schedule another appointment for you to come back to discuss the results. You mentioned your wife. Would you like her or anyone else to be with you at that appointment?

Patient: Yes, my wife and son. My son knows a lot more about medical things than I do, and I know he would want to come.

The Need for Culturally Sensitive Care

The concept of one’s culture encompasses a host of components including how an individual identifies oneself as well as the language, customs, beliefs, and value system one utilizes. Culture, in turn, profoundly affects patients’ belief systems regarding health and wellness, disease and illness, and the delivery of health care services, including the use of healers and alternative providers [1].In order to provide culturally sensitive and high-quality care to diverse patient populations, it is important for providers to gain an understanding and sensitivity to the influences of culture on patients’ beliefs and behaviors [2].

The ability to provide care to people of different cultures is more important than ever before. In 2011, the number of legal and unauthorized immigrants in the United States rose to 40.4 million (13% of the population) and between 2007 and 2011 alone, this number rose by 2.4 million [3].According to a 2010 census bureau report, in the last 30 years the number of individuals over the age of 5 who spoke a language other than English in their home more than doubled, an increase that was 4 times greater than the rate of population growth [4].In addition, in 2009 the United States resettled more refugees than any other nation (60,000+) and this number reached almost 70,000 in 2013 [5,6].Patient populations in the United States are becoming increasingly diverse, and providers must have the skills to communicate effectively with these groups. A one-size-fits-all approach is not sufficient for our changing population.

The Challenges of Delivering Bad News and the Impact of Culture

Perhaps one of the most challenging communication scenarios faced by physicians is the need to deliver bad news to a patient. “Bad news” can be described as any information that adversely alters one’s expectations for the future [7].Clinicians from nearly all specialties are confronted with the task of giving bad news [8],and this is particularly true regarding cancer care. Among oncologists, 60% reported the need to break bad news to patients between 5 to 20 times per month, with 14% reporting greater than 20 times per month [9].The concept of giving bad news is often viewed as stressful by clinicians [10], and clinicians must be able to balance a myriad of elements, including patients’ emotional responses, information needs, uncertainties of disease progression and treatments, patients’ preferred level of involvement in decision making, patient expectations, involvement of family members, and how to maintain hope, among others [9,11]. Indeed, it seems that clinicians find it difficult to take into account the full spectrum of patient needs [8]. While the descriptive literature indicates that patient satisfaction and psychological well-being is improved when a patient-centered approach is utilized that attends to the emotional needs of patients [12], clinicians often focus on biomedical information, with less focus on patients’ psychosocial needs and their level of understanding [13–15].

Further, the interaction of patient culture and context with the complexity of the “bad news” interaction can be daunting, and clinicians have noted their diminished level of comfort in adjusting to these cultural preferences [16].The ability of clinicians to “match” the patient’s preferred level of involvement in decision making is associated with higher patient satisfaction with decision making and lower depression after 3 months [11],yet clinicians often find it difficult to determine which patients want to be involved in the decision making to a greater or lesser extent [12].In addition, words have different meanings when used in medical settings or in lay contexts [8],not to mention the challenges of translation when dealing with non–English-speaking patients. Yet, the manner in which clinicians deliver bad news can affect patients’ understanding of their disease, treatment options, and patients’ adjustment to the diagnosis [8],as well as patients’ expected quality of life and intentions to adhere to recommendations [17].

Information Disclosure

One of the key areas impacted by culture relates to preferred disclosure of medical information. Walsh et al noted in their review that the majority of patients in English-speaking countries wanted relatively full disclosure regarding their illness in comparison to individuals from other countries [18].As a further distinction, Blackhall et al noted that African Americans and European Americans were more likely to believe that a patient should be told of a terminal diagnosis than Mexican and Korean Americans [19].In addition, Mexican and Korean Americans were more likely to believe that clinicians should not discuss death and dying with patients, as it could be harmful. Fujimori noted that Asians are less likely to prefer discussions of life expectancy in contrast to Westerners [20].In a survey of Albanian nationals, < 50% of patients wanted to know their true diagnosis; however, individuals who were male, urban, and educated demonstrated a significantly greater preference for disclosure [21].In the Middle East, the concept of disclosure is highly variable in terms of both provider and patient preferences [22].

Involvement of Family Members

A second important area relates to the involvement of family members. Fujimori noted high variability of patient preferences for having family members present when discussing bad news. Of Japanese patients, 78% preferred to be told with family members present, with the number decreasing for Portugal (61%), Australia (53%-57%), and Ireland (40%). Eighty-one percent of the US patients did not want anyone else present. However, almost all placed high value on physician expertise and honesty [20]. Blackhall noted that Mexican and Korean Americans were more likely to favor a family-centered approach to decision making [19]. In addition, Orona indicated that Mexican-American and Chinese-American families felt it was their duty to protect their relatives from a cancer diagnosis to keep the patient’s remaining time free of worry [23]. Haggerty found mixed evidence for patient preferences regarding disclosure of cancer prognosis to family members [24].

Given these variations and complexities, it is natural to try to develop a system for managing them, eg, a list of traits or attributes one can apply to certain groups. For example, patients of Asian origin prefer _______. However, there is an inherent danger in doing this, as it leads to stereotyping [25]. Cultural factors also may be given inappropriate meaning. Specifically, a well-meaning clinician might attribute certain characteristics to a patient when in fact it has little bearing on the patient’s perspective [25]. In addition, given the nature of communication, travel, and the fact that many individuals identify with more than one cultural group, it may be inappropriate to attribute a singular cultural identity to a group in contemporary society. As a result, Kleinman [25] proposed an ethnographic approach as opposed to a cultural approach. Specifically, this involves understanding a patient and his/her illness from an individual’s perspective as opposed to the cultural collective.

Communication Skills to Help Deliver Bad News

Set Up the Interview

Before meeting with the patient, it is important to review the medical data and have a plan in mind for delivering the bad news. Schedule adequate time for discussion and avoid interruptions. Meet in a quiet, private room that is large enough to accommodate family members or friends whom the patient may have brought. In our case example, the patient has brought his wife and son to the appointment.

Doctor: Hello, Mr. Ruiz. (Turning to the patient’s wife and son) I am Dr. Simon.

Patient: Hello, Doctor. This is my wife, Maria, and son, Alejandro.

Doctor: Please have a seat. Are you comfortable?

Patient: Yes. We are anxious to hear the results of the tests.

Son: My father doesn’t always understand medical terms and I wanted to be here to help. I am very worried about him.

Doctor: I understand your concern and I will explain everything to you.

Assess the Patient’s Perception of the Problem

Before telling the patient the diagnosis, it is important to get an idea of the patient’s understanding of the problem, including what he calls it, what he thinks caused it, and how severe he thinks it is.

Doctor: Before I tell you the results, I would like to get a sense first of what you think is going on.

Patient: Well, I really don’t know for sure, but I know the pain is getting worse and I have been feeling weaker. The pain started right after my son’s wedding. There was a lot of food and I ate more than usual. Maybe it was something bad that I ate?

Doctor: (Turning to the wife and son) Do you have any thoughts about the illness?

Wife: I can see he is in pain a lot, even though he tries to hide it from me. I want to know what’s wrong. I am worried it could be something bad.

Obtain the Patient’s Invitation to Disclose the Information

It is important to know if the patient wants to be told the information about his or her diagnosis. Ideally, physicians should discuss this in general terms as part of routine care, before any bad news needs to be delivered. For example,

Doctor: There may come a time when I will need to tell you something bad about your health. Hopefully, that time will never come, but I want to know your preferences so I can honor them if the time does arise. Would you want to be told about this, or would you want someone else, perhaps someone in your family, to be told?

Patient: I appreciate your asking, Doctor. I haven’t really thought about it, but I get kind of nervous and upset when I hear bad news. I would rather you tell me when my wife and son can be there too.

Give Knowledge and Information to the Patient

It is important to provide information that is at a level that the patient can understand. Avoid the use of medical jargon. When speaking through an interpreter, the clinician may need to have a conversation with the interpreter before meeting the patient to explain the situation and the need to be sensitive. For example, if the clinician does not use the word “cancer” after determining from the patient or family the preference for an alternative word, be sure to inform the interpreter not to use the word “cancer.” Provide the information in small chunks and check in frequently to make sure the patient understands. Avoid language that takes away hope. If there is a family member who speaks English, there is a tendency to speak to that person rather than the patient directly. Avoid doing this unless the patient explicitly requests that the clinician speak directly to that individual. This is often the case with older patients. The following might take place at a subsequent appointment:

Doctor: Mr. Ruiz, you told me previously that you would like me to tell you the results of your tests, along with you wife and son. Unfortunately, I have some bad news to tell you. (Pause) The colonoscopy showed that you have a tumor in the colon, also called the large intestine. It is located in the part that we call the ascending colon (draws a picture to show them where this is). We will need to do some other scans to make sure that the tumor is just in the colon and has not spread. I am hopeful, though, that we have caught it fairly early and it has not spread. That would be the best situation. (Pause) Do you understand what I have told you so far?

Address the Patient’s and Family’s Emotions

Every patient will express their reactions to bad news differently, and their reactions may be different from what the physician might experience in a similar situation. Thus, the clinician should be self-aware and be prepared to respond to a variety of responses. It is important to express empathy and validate the patient’s and family reactions and emotions. If the patient does not express any emotion, the clinician should explore this carefully. It may require more than one visit for the patient to open up with his feelings.

Doctor: I am so sorry. I know that this must be a big shock for you.

Patient: I kind of figured it might be something bad, but it is still a shock. Even so, I am a religious man and I believe that I will get through this with the help of my wife and family.

Doctor: It sounds as if you have a great support system and get strength from your faith. You are lucky to have such a wonderful family and that will be a big help as we move forward.

Strategize and Summarize

Ask the patient if he or she is ready to have a discussion about treatment, including his or her goals of treatment. Continue to explore the patient’s knowledge, expectations and hopes. Always allow the patient to express his fears and concerns. Most importantly, let the patient know that you will share the responsibility of decision making with the patient and be there to support him.

Doctor: This is never easy and it’s a lot to take in. Would you like to discuss the next steps and possible treatments at this time or should we make another appointment after your CAT scan?

Patient: My wife is pretty upset and I think it might be better if we stop here for now. Is that ok?

Son: We want to come back as soon as we can after the CAT scan. In the meantime, can you provide me with some information or a good website to check out?

Doctor: Yes, of course. That sounds like a good plan.

Conclusion

The task of giving bad news is a necessity for physicians of most specialties and is often viewed as challenging and even stressful to some. However, the manner in which information is discussed with patients can impact patients’ satisfaction, understanding of their illness, adjustment to the diagnosis, expected quality of life, and intentions to adhere to recommendations [8,17]. Providing bad news in a culturally sensitive manner adds an additional level of complexity to an already challenging encounter. While an individual’s culture can strongly influence patient belief systems and utilization of care, there is an inherent danger when clinicians make assumptions about individuals’ culture and the role it plays in their lives. Instead of focusing on creating a mental list of cultural attributes, we recommend a patient-centered approach where few assumptions about the patient are made and instead, the clinician gains an understanding of each individual patient through queries and adjusts his/her approach and language according to each individual’s needs.

Corresponding author: Lisa K. Rollins, PhD, Dept. of Family Medicine, Univ.of Virginia, PO Box 800729, Charlottesville,VA 22908-0729, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Cultural competency – clear communication. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Accessed at www.nih.gov/clearcommunication/culturalcompetency.htm on 15 Jul 2014.

2. Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O. Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Pub Health Rep 2003;118:293–302.

3. PEW research: Hispanic trends project, a nation of immigrants. Accessed at www.pewhispanic.org/2013/01/29/a-nation-of-immigrants/ on 31 Jul 2014.

4. U.S. Census Bureau. New census bureau report analyzes nation’s linguistic diversity. Accessed at www.census/gov/newsroom/releases/archives/american_community_survey_acs/cb10-cn58.html on 31 Jul 2014.

5. Immigration Policy Center. Refugees: a fact sheet. Accessed at www.immigrationpolicy.org on 28 May 2014.

6. U.S. Department of State. U.S. welcomes record number of refugees. Accessed at iipdigital.usembassy.gov/st/english/article/2013/10/20131023285033.html?CP.rss=true#axzz3GtyMkFSe on 28 May 2014.

7. Barclay JS, Blackhall L J, Tulsky JA. Communication strategies and cultural issues in the delivery of bad news. J Palliative Med 2007;10:958–77.

8. Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet 2004;363;312–9.

9. Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES—A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist 2000;5:302–11.

10. Ptacek JT, McIntosh EG. Physician challenges in communicating bad news. J Behav Med 2009;32:380–7.

11. Vogel BA, Leonhart R, Helmes AW. Communication matters: the impact of communication and participation in decision making on breast cancer patients’ depression and quality of life. Patient Educ Couns 2009;77:391–7.

12. Hack TF, Degner LF, Parker PA. The communication goals and needs of cancer patients: a review. Psychooncology 2005;14:831–45.

13. Vail L, Sandhu H, Fisher J, et al. Hospital consultants breaking bad news with simulated patients: an analysis of communication using the roter interaction analysis system. Patient Educ Couns 2011;83:185–94.

14. Hack TF, Pickles T, Ruether JD, et al. Behind closed doors: systematic analysis of breast cancer consultation communication and predictors of satisfaction with communication.

Psychooncology 2010;19:626–36.

15. Cantwell BM, Ramirez A. Doctor-patient communication: a study of junior house officers. Med Educ 1997;31:17–21.

16. Rollins LK, Bradley EB, Hayden GF, et al. Responding to a changing nation: are faculty prepared for cross-cultural conversations and care? Fam Med 2013;45:736–9.

17. Burgers C, Beukeboom CJ, Sparks L. How the doc should (not) talk: when breaking bad news with negations influences patients’ immediate responses and medical adherence intentions. Patient Educ Couns 2012;89:267–73.

18. Walsh RA, Girgis A, Sanson-Fisher RW. Breaking bad news 2: what evidence is available to guide clinicians? Behav Med 1998;24:61–73.

19. Blackhall LJ, Murphy ST, Frank G, et al. Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. JAMA 1995;274:820–5.

20. Fujimori M, Uchitomi Y. Preferences of cancer patients regarding communication of bad news: a systematic literature review. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2009;39:201–16.

21. Beqiri A, Toci E, Sallaku A, et al. Breaking bad news in a southeast european population: a survey among cancer patients in Albania. J Palliat Med 2012;15:1100–5.

22. Khalil RB. Attitudes, beliefs and perceptions regarding truth disclosure of cancer-related information in the Middle East: a review. Palliat Supp Care 2013;11:69–78.

23. Orona CJ, Koenig BA, Davis AJ. Cultural aspects of nondisclosure. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 1994;3:338–46.

24. Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, et al. Communicating prognosis in cancer care: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Oncol 2005;16:1005–53.

25. Kleinman A, Benson P. Anthropology in the clinic: the problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. PLoS Med 2006;3:1673–6.

1. Cultural competency – clear communication. National Institutes of Health (NIH). Accessed at www.nih.gov/clearcommunication/culturalcompetency.htm on 15 Jul 2014.

2. Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O. Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Pub Health Rep 2003;118:293–302.

3. PEW research: Hispanic trends project, a nation of immigrants. Accessed at www.pewhispanic.org/2013/01/29/a-nation-of-immigrants/ on 31 Jul 2014.

4. U.S. Census Bureau. New census bureau report analyzes nation’s linguistic diversity. Accessed at www.census/gov/newsroom/releases/archives/american_community_survey_acs/cb10-cn58.html on 31 Jul 2014.

5. Immigration Policy Center. Refugees: a fact sheet. Accessed at www.immigrationpolicy.org on 28 May 2014.

6. U.S. Department of State. U.S. welcomes record number of refugees. Accessed at iipdigital.usembassy.gov/st/english/article/2013/10/20131023285033.html?CP.rss=true#axzz3GtyMkFSe on 28 May 2014.

7. Barclay JS, Blackhall L J, Tulsky JA. Communication strategies and cultural issues in the delivery of bad news. J Palliative Med 2007;10:958–77.

8. Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet 2004;363;312–9.

9. Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES—A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist 2000;5:302–11.

10. Ptacek JT, McIntosh EG. Physician challenges in communicating bad news. J Behav Med 2009;32:380–7.

11. Vogel BA, Leonhart R, Helmes AW. Communication matters: the impact of communication and participation in decision making on breast cancer patients’ depression and quality of life. Patient Educ Couns 2009;77:391–7.

12. Hack TF, Degner LF, Parker PA. The communication goals and needs of cancer patients: a review. Psychooncology 2005;14:831–45.

13. Vail L, Sandhu H, Fisher J, et al. Hospital consultants breaking bad news with simulated patients: an analysis of communication using the roter interaction analysis system. Patient Educ Couns 2011;83:185–94.

14. Hack TF, Pickles T, Ruether JD, et al. Behind closed doors: systematic analysis of breast cancer consultation communication and predictors of satisfaction with communication.

Psychooncology 2010;19:626–36.

15. Cantwell BM, Ramirez A. Doctor-patient communication: a study of junior house officers. Med Educ 1997;31:17–21.

16. Rollins LK, Bradley EB, Hayden GF, et al. Responding to a changing nation: are faculty prepared for cross-cultural conversations and care? Fam Med 2013;45:736–9.

17. Burgers C, Beukeboom CJ, Sparks L. How the doc should (not) talk: when breaking bad news with negations influences patients’ immediate responses and medical adherence intentions. Patient Educ Couns 2012;89:267–73.

18. Walsh RA, Girgis A, Sanson-Fisher RW. Breaking bad news 2: what evidence is available to guide clinicians? Behav Med 1998;24:61–73.

19. Blackhall LJ, Murphy ST, Frank G, et al. Ethnicity and attitudes toward patient autonomy. JAMA 1995;274:820–5.

20. Fujimori M, Uchitomi Y. Preferences of cancer patients regarding communication of bad news: a systematic literature review. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2009;39:201–16.

21. Beqiri A, Toci E, Sallaku A, et al. Breaking bad news in a southeast european population: a survey among cancer patients in Albania. J Palliat Med 2012;15:1100–5.

22. Khalil RB. Attitudes, beliefs and perceptions regarding truth disclosure of cancer-related information in the Middle East: a review. Palliat Supp Care 2013;11:69–78.

23. Orona CJ, Koenig BA, Davis AJ. Cultural aspects of nondisclosure. Camb Q Healthc Ethics 1994;3:338–46.

24. Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, et al. Communicating prognosis in cancer care: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Oncol 2005;16:1005–53.

25. Kleinman A, Benson P. Anthropology in the clinic: the problem of cultural competency and how to fix it. PLoS Med 2006;3:1673–6.

Emotional Distress, Barriers to Care, and Health-Related Quality of Life in Sickle Cell Disease

From the UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland, Oakland, CA

Abstract

- Objective: Emotional distress may adversely affect the course and complicate treatment for individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD). We evaluated variables associated with physical and mental components of health-related quality of life (HRQL) in SCD in the context of a biobehavioral model.

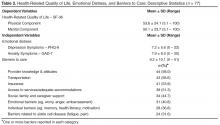

- Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional cohort study of 77 adults with SCD (18–69 years; 60% female; 73% Hgb SS) attending an urban, academic medical center. We measured emotional distress (Patient Health Questionnaire–9, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale), clinical complications and utilization, barriers to health care, sociodemo-graphics and HRQL (SF-36 Health Survey). We developed models predictive of physical and mental HRQL by conducting stepwise regression analyses.

- Results: Sample prevalence of moderate to severe depression and anxiety symptoms was 33% and 36%, respectively; prevalence of impaired physical and mental HRQL was 17% and 16%, respectively. Increased symptoms of depression, older age, and ≥ 3 emergency department visits in the previous 12 months were independently associated with lower ratings of physical HRQL, controlling for anxiety and sex. Increased symptoms of depression were independently associated with lower ratings of mental HRQL, controlling for barriers to care, insurance status, lifetime complications of SCD, and sex.

- Conclusion: Emotional distress is an important contributor to both physical and mental HRQL for adults with SCD, although sociodemographic variables and barriers to care must also be considered. Innovative approaches that integrate mental health interventions with SCD clinical care are needed.

Emotional distress, including symptoms of depression and anxiety, may adversely affect the course and complicate the treatment of chronic physical conditions [1]. For patients with sickle cell disease (SCD), a group of inherited red blood cell conditions, symptoms of depression and anxiety are more prevalent compared with rates found in the general population [2–8]. The most common symptom of SCD is acute pain events, and other complications range from mild to life-threatening, including anemia, increased risk of infection, acute chest syndrome, stroke, skin ulcers, and pulmonary hypertension [9]. Depression in adults with SCD has been associated with increased sickle cell vaso-occlusive pain events, poor pain control, multiple blood transfusions, and prescription of the disease-modifying therapy hydroxyurea [4]. Adults with SCD and comorbid depression and anxiety had more daily pain and greater distress and interference from pain compared with those who did not have comorbid depression or anxiety [10]. Patients have linked emotional distress and episodes of illness [11], and research has found a relation between pain episodes and depression [12]. In a diary study, negative mood was significantly higher on pain days compared with non-pain days [13].

Studies examining the consequences of emotional distress on health-related quality of life (HRQL) for patients with SCD are emerging. Depressed adults with SCD rated their quality of life on the SF-36 Health Survey [14] as significantly poorer in all areas compared with non-depressed adults with SCD [15]. In regression models, depression was a stronger predictor of SF-36 scores than demographics, hemoglobin type, and pain measures. In a multi-site study [16], 1046 adults with SCD completed the SF-36. Increasing age was associated with significantly lower scores on all subscales except mental health, while female sex additionally contributed to diminished physical function and vitality scale scores in multivariate models [16]. The presence of a mood disorder was associated with bodily pain, and diminished vitality, social functioning, emotional role, and the mental component of HRQL. Medical complications other than pain were not associated with impaired HRQL. Anie and colleagues [17,18] have highlighted the contributions of sickle cell–related pain to diminished mood and HRQL, both in the acute hospital phase and 1 week post discharge.

A comprehensive literature review of patient-reported outcomes for adults with SCD revealed broad categories of the impact of SCD and its treatment on the lives of adults [19]. Categories included pain and pain management, emotional distress, poor social role functioning, diminished overall quality of life, and poor quality of care. Follow-up individual and group interviews with adults with SCD (n = 122) as well as individual interviews with their providers (n = 15) revealed findings consistent with the literature review on the major effects of pain on the lives of adults with SCD, interwoven with emotional distress, poor quality of care, and stigmatization [19].

In the present study, our goal was to describe variables associated with physical and mental HRQL in SCD within the context of the recently published comprehensive conceptual model of broad clinical and life effects associated with SCD [19]. The present analysis uses an existing clinical database and evaluates the effects of the relations between clinical complications of SCD, emotional distress, health care utilization, and HRQL. Our model includes barriers to health care that might prevent vulnerable patients from accessing needed health care services. Sociodemographic variables including ethnic and racial minority status and lower socioeconomic status and educational attainment may create barriers to health care for patients with SCD, as they do for individuals with other chronic conditions [20–23]. Over 60% of patients with SCD are on public insurance [24] and can have difficulties with accessing quality health care [25]. Negative provider attitudes and stigmatization when patients are seeking care for acute pain episodes have been highlighted by patients as major barriers to seeking health care [19,26–28]. In a qualitative study, 45 youth with SCD reported that competing school or peer-group activities, “feeling good,” poor patient-provider relationships, adverse clinic experiences, and forgetting were barriers to clinic attendance [29]. Limited research suggests that barriers to accessing health care are associated with poorer HRQL [30,31]; however no studies were identified that directly evaluated the relation between barriers to care and HRQL for populations with SCD.

We hypothesized that clinical complications of SCD, including pain, and barriers to accessing health care would be independently associated with the physical component of HRQL for adult patients with SCD, controlling for demographic variables. Further, we hypothesized that emotional distress, clinical complications of SCD, and barriers to accessing health care would be independently associated with the mental component of HRQL for adult patients with SCD, controlling for demographic variables.

Methods

Patient Recruitment

Participants were 18 years and older and were a subgroup selected from a larger prospective cohort enrolled in the Sickle Cell Disease Treatment Demonstration Program (SCDTDP) funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). As 1 of 7 SCDTDP grantees, our network collected common demographic, disease-related, and HRQL data as the other grantees to examine sickle cell health and health care [32]. Enrollment at our site was n = 115 from birth through adult, with data collection occurring at baseline in 2010 and annually through 2014. Participants were eligible for enrollment if they had any confirmed diagnosis of SCD and if they were seen at any facility treating SCD in the San Francisco Bay Area region. Interpreter services were available where English was a second language; however, no participant requested those services. The data collection site was an urban comprehensive sickle cell center. Participants were recruited through mailings, posted flyers, or were introduced to the project by their clinical providers. The institutional review boards of the sponsoring hospitals approved all procedures. This report describes analyses from the baseline data collected in 2010 and excludes pediatric patients under the age of 18 years, as we developed our conceptual model based on the adult SCD literature.

Procedures

Patients directly contacted the project coordinator or were introduced by their health care provider. The project coordinator explained the study in more detail, and if the patient agreed to participate, the project coordinator obtained thier informed consent. Participants completed the study materials in a private space in the clinic immediately after or were scheduled for a separate visit at a convenient time and location. Participants with known or observed difficulties with reading completed the questionnaires as an interview. We allowed participants who were unable to complete the forms in one visit to take them home or schedule a follow-up visit to complete them. We asked participants who took the questionnaires home to return them within 2 business days and provided them with a stamped addressed envelope. Participants were compensated with gift cards for their involvement.

Measures

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Participants completed an Individual Utilization Questionnaire created for the SCDTDP grantees [32], either as an interview or in paper and pencil format. Participants indicated their age, race and ethnicity, education level, type of insurance, and annual household income. They indicated the type of SCD, number of hospital days and emergency department (ED) visits in the previous 12 months, disease-modifying therapies including hydroxyurea or transfusions, and lifetime incidence of sickle cell–related complications. Complications included pain, acute chest syndrome, fever, severe infection, stroke, kidney damage, gallbladder attack, spleen problems and priapism. Medical data was verified by reviewing medical records when possible; the clinical databases in the hematology/oncology department at the sponsoring hospital are maintained using Microsoft SQL Server, a relational database management system designed for the enterprise environment. However, not all of the participating institutions were linked via this common clinical database or by an electronic health record at the time the study was conducted.

Barriers to Care

We modified a checklist of barriers to accessing health care for patients with a range of chronic conditions [33] to create a SCD-specific checklist [34]. The final checklist consists of 53 items organized into 8 categories including insurance, transportation, accommodations and accessibility, provider knowledge and attitudes, social support, individual barriers such as forgetting or difficulties understanding instructions, emotional barriers such as fear or anger, and barriers posed by SCD itself (eg, pain, fatigue). Participants check off any applicable barrier, yielding a total score ranging from 0 to 53. The checklist overall has demonstrated face validity and test-retest reliability (Pearson r = 0.74, P < 0.05).

Depressive Symptoms

Adults with SCD completed the PHQ-9, the 9-item depression scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire [35]. The PHQ-9 is a tool for assisting primary care clinicians in assessing symptoms of depression, based on criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 4th edition (DSM-IV [36]). The PHQ-9 asks about such symptoms as sleep disturbance and difficulty concentrating over the past 2 weeks with scores ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (Every day). The total symptom count is based on the number of items in which the respondent answered as “more than half of days” or greater, and scores are categorized as reflecting no (< 10), mild (10–14), moderate (15–19) or severe (≥ 20) symptoms of depression. Respondents indicate how difficult the symptoms make it for them to engage in daily activities from 0 (Not difficult at all) to 3 (Extremely difficult). The sensitivity and diagnostic and criterion validity of the PHQ-9 have been established [37]. The internal consistency of the PHQ-9 is high, with α > 0.85 in several studies and 48-hour test-retest reliability of 0.84. The PHQ has been used widely, including with African-American and Hispanic populations, and with individuals with chronic conditions [38].

Symptoms of Anxiety

Participants completed the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) questionnaire for screening and measuring severity of generalized anxiety disorder [39]. The GAD-7 asks about such symptoms as feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge over the past two weeks. Scores from all 7 items are added to obtain a total score [40]. Cut-points of 5, 10, and 15 represent mild, moderate, and severe levels of anxiety symptoms. Respondents indicate how difficult the symptoms make it for them to engage in daily activities from 0 (Not difficult at all) to 3 (Extremely difficult). The internal consistency of the GAD-7 is excellent (α = 0.92). Test-retest reliability is also good (Pearson r = 0.83) as is procedural validity (intraclass correlation = 0.83). The GAD-7 has excellent sensitivity and specificity to identify generalized anxiety disorder [41].

Health-Related Quality of Life

Participants completed the SF-36, which asks about the patient’s health status in the past week [14]. Eight subscales include physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional and mental health. Two summary measures, the Physical Component Summary and the Mental Component Summary, are calculated from 4 scales each. Use of the summary measures has been shown to increase the reliability of scores and improve the validity of scores in discriminating between physical and psychosocial outcomes [14]. Higher scores represent better HRQL, with a mean score of 50 (SD = 50) for the general population. Internal consistency estimates for the component summary scores are α > 0.89, item discriminant validity estimates are greater than 92.5% and 2-week test-retest reliability was excellent. Scores on the SF-36 have been divided into categories of HRQL functioning [42,43]. Participants in the impaired to very impaired category have scores ≤ mean – 1 SD while participants with average to above average functioning have scores > mean – 1 SD.