User login

Study aims to determine prognostic factors for subset of thyroid cancer patients

CORONADO, CALIF. – In patients with radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer, those with target lesions less than 1.5 cm in size appeared to derive less benefit from sorafenib in terms of progression-free survival, results from an international study showed.

In addition, papillary histology was a positive predictive factor and a predictive factor for benefit from sorafenib.

“Patients with radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer have a poor prognosis, and there is a lack of effective treatments,” Dr. Martin Schlumberger said at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association. “The median survival for this subset is estimated to be 2.5-5 years.”

Sorafenib was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in November 2013 for the treatment of radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer based on results from the randomized, controlled, double-blind phase III DECISION trial (Lancet 2014;384:319-28). Investigators found that the use of sorafenib extended median progression-free survival by 5 months, compared with placebo (10.8 vs 5.8 months; P < .0001). The purpose of the current analysis was to determine which demographic baseline or disease-related characteristics are prognostic for better outcomes in this patient population. To do so, Dr. Schlumberger of the department of nuclear medicine and endocrine oncology at Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France, and his associates performed multivariate Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for treatment effect.

He reported findings from 417 patients. Of these, 210 were randomized to receive placebo and 207 were randomized to receive sorafenib. Variables found to be prognostic factors for progression-free survival in placebo patients, and in all patients when adjusted for sorafenib treatment, included papillary histology, lower targeted tumor size, baseline thyroglobulin less than 486 ng/mL, lower number of lesions, and residing in Asia vs. Europe and North America. Subgroup analyses of patients in the sorafenib arm revealed that the following baseline or disease-related variables were predictive of progression-free survival: papillary histology, tumor size of at least 1.5 cm, and having only lung metastases.

In a post-hoc exploratory analysis of progression-free survival by thyroid cancer symptoms among all 417 patients at study entry, the researchers found that both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients had improved progression-free survival following treatment with sorafenib.

On the basis of these findings, radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer patients with no progressive disease and a tumor size of less than 1.5 cm “appear to have a good prognosis and may be candidates for a ‘watch and wait’ approach before initiating treatment with sorafenib,” Dr. Schlumberger concluded.

Dr. Schlumberger is an adviser to AstraZeneca, Bayer, Eisai, Exelixis, and Genzyme. He has also received research support from Genzyme and Bayer.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

CORONADO, CALIF. – In patients with radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer, those with target lesions less than 1.5 cm in size appeared to derive less benefit from sorafenib in terms of progression-free survival, results from an international study showed.

In addition, papillary histology was a positive predictive factor and a predictive factor for benefit from sorafenib.

“Patients with radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer have a poor prognosis, and there is a lack of effective treatments,” Dr. Martin Schlumberger said at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association. “The median survival for this subset is estimated to be 2.5-5 years.”

Sorafenib was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in November 2013 for the treatment of radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer based on results from the randomized, controlled, double-blind phase III DECISION trial (Lancet 2014;384:319-28). Investigators found that the use of sorafenib extended median progression-free survival by 5 months, compared with placebo (10.8 vs 5.8 months; P < .0001). The purpose of the current analysis was to determine which demographic baseline or disease-related characteristics are prognostic for better outcomes in this patient population. To do so, Dr. Schlumberger of the department of nuclear medicine and endocrine oncology at Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France, and his associates performed multivariate Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for treatment effect.

He reported findings from 417 patients. Of these, 210 were randomized to receive placebo and 207 were randomized to receive sorafenib. Variables found to be prognostic factors for progression-free survival in placebo patients, and in all patients when adjusted for sorafenib treatment, included papillary histology, lower targeted tumor size, baseline thyroglobulin less than 486 ng/mL, lower number of lesions, and residing in Asia vs. Europe and North America. Subgroup analyses of patients in the sorafenib arm revealed that the following baseline or disease-related variables were predictive of progression-free survival: papillary histology, tumor size of at least 1.5 cm, and having only lung metastases.

In a post-hoc exploratory analysis of progression-free survival by thyroid cancer symptoms among all 417 patients at study entry, the researchers found that both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients had improved progression-free survival following treatment with sorafenib.

On the basis of these findings, radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer patients with no progressive disease and a tumor size of less than 1.5 cm “appear to have a good prognosis and may be candidates for a ‘watch and wait’ approach before initiating treatment with sorafenib,” Dr. Schlumberger concluded.

Dr. Schlumberger is an adviser to AstraZeneca, Bayer, Eisai, Exelixis, and Genzyme. He has also received research support from Genzyme and Bayer.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

CORONADO, CALIF. – In patients with radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer, those with target lesions less than 1.5 cm in size appeared to derive less benefit from sorafenib in terms of progression-free survival, results from an international study showed.

In addition, papillary histology was a positive predictive factor and a predictive factor for benefit from sorafenib.

“Patients with radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer have a poor prognosis, and there is a lack of effective treatments,” Dr. Martin Schlumberger said at the annual meeting of the American Thyroid Association. “The median survival for this subset is estimated to be 2.5-5 years.”

Sorafenib was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in November 2013 for the treatment of radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer based on results from the randomized, controlled, double-blind phase III DECISION trial (Lancet 2014;384:319-28). Investigators found that the use of sorafenib extended median progression-free survival by 5 months, compared with placebo (10.8 vs 5.8 months; P < .0001). The purpose of the current analysis was to determine which demographic baseline or disease-related characteristics are prognostic for better outcomes in this patient population. To do so, Dr. Schlumberger of the department of nuclear medicine and endocrine oncology at Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France, and his associates performed multivariate Cox proportional hazards models adjusted for treatment effect.

He reported findings from 417 patients. Of these, 210 were randomized to receive placebo and 207 were randomized to receive sorafenib. Variables found to be prognostic factors for progression-free survival in placebo patients, and in all patients when adjusted for sorafenib treatment, included papillary histology, lower targeted tumor size, baseline thyroglobulin less than 486 ng/mL, lower number of lesions, and residing in Asia vs. Europe and North America. Subgroup analyses of patients in the sorafenib arm revealed that the following baseline or disease-related variables were predictive of progression-free survival: papillary histology, tumor size of at least 1.5 cm, and having only lung metastases.

In a post-hoc exploratory analysis of progression-free survival by thyroid cancer symptoms among all 417 patients at study entry, the researchers found that both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients had improved progression-free survival following treatment with sorafenib.

On the basis of these findings, radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer patients with no progressive disease and a tumor size of less than 1.5 cm “appear to have a good prognosis and may be candidates for a ‘watch and wait’ approach before initiating treatment with sorafenib,” Dr. Schlumberger concluded.

Dr. Schlumberger is an adviser to AstraZeneca, Bayer, Eisai, Exelixis, and Genzyme. He has also received research support from Genzyme and Bayer.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

AT THE ATA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Radioactive iodine–refractory differentiated thyroid cancer patients with no progressive disease and a tumor size of less than 1.5 cm may be candidates for a “watch and wait” approach before initiating treatment with sorafenib.

Major finding: Baseline or disease-related variables found to be prognostic factors for progression-free survival in placebo patients and in all patients when adjusted for sorafenib treatment included papillary histology, lower targeted tumor size, baseline thyroglobulin less than 486 ng/mL, lower number of lesions, and residing in Asia versus Europe and North America.

Data source: An analysis of 417 patients from the randomized, controlled, double-blind, phase III DECISION trial.

Disclosures: Dr. Schlumberger is an adviser to AstraZeneca, Bayer, Eisai, Exelixis, and Genzyme. He has also received research support from Genzyme and Bayer.

Product News: 01 2015

Onexton

Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc, an-nounces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Onexton Gel (clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and benzoyl peroxide 3.75%) for the once-daily treatment of comedonal and inflammatory acne in patients 12 years and older. This dual-action topical therapy has a favorable cutaneous tolerability profile and contains no surfactants, alcohol, or preservatives. Onexton is expected to launch in early 2015. For more information, visit www.valeant.com.

Physical Eye UV Defense Sunscreen

SkinCeuticals presents Physical Eye UV Defense Sunscreen that provides broad-spectrum SPF 50 protection without migrating into or irritating the eyes. Physical Eye UV Defense unifies natural skin tone around the eye and provides a translucent universal tint. It should be applied around the entire eye area and is optimized for application under makeup. It also can be used following hyaluronic acid filler and botulinum toxin injections. SkinCeuticals products are physician dispensed. For more information, visit www.skinceuticals.com.

Refining Mineral Mask

Revision Skincare introduces the limited edition Refining Mineral Mask, a warming mask to reduce the appearance of pores and leave skin looking refined. It contains kaolin to purify the complexion, pumpkin enzymes to gently exfoliate skin, zeolite to provide an extra boost of radiance with its warming effect, and vitamin E microspheres to condition skin. Revision Skincare products are available exclusively through dermatologists, plastic surgeons, and medical spas. For more information, visit www.revisionskincare.com.

Resveratrol B E

SkinCeuticals launches Resveratrol B E, an intensive antioxidant night concentrate that boosts the skin’s endogenous antioxidant defense system, which loses efficiency with age and accumulated damage. It works by neutralizing age-accelerating internal free radicals, strength-ening functionality to resist new damage, and promoting skin’s natural repair to diminish the signs of accumulated damage. Resveratrol B E corrects signs of photodamage, loss of firmness and radiance, poor elasticity, and fine lines and wrinkles. SkinCeuticals products are physician dispensed. For more information, visit www.skinceuticals.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Onexton

Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc, an-nounces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Onexton Gel (clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and benzoyl peroxide 3.75%) for the once-daily treatment of comedonal and inflammatory acne in patients 12 years and older. This dual-action topical therapy has a favorable cutaneous tolerability profile and contains no surfactants, alcohol, or preservatives. Onexton is expected to launch in early 2015. For more information, visit www.valeant.com.

Physical Eye UV Defense Sunscreen

SkinCeuticals presents Physical Eye UV Defense Sunscreen that provides broad-spectrum SPF 50 protection without migrating into or irritating the eyes. Physical Eye UV Defense unifies natural skin tone around the eye and provides a translucent universal tint. It should be applied around the entire eye area and is optimized for application under makeup. It also can be used following hyaluronic acid filler and botulinum toxin injections. SkinCeuticals products are physician dispensed. For more information, visit www.skinceuticals.com.

Refining Mineral Mask

Revision Skincare introduces the limited edition Refining Mineral Mask, a warming mask to reduce the appearance of pores and leave skin looking refined. It contains kaolin to purify the complexion, pumpkin enzymes to gently exfoliate skin, zeolite to provide an extra boost of radiance with its warming effect, and vitamin E microspheres to condition skin. Revision Skincare products are available exclusively through dermatologists, plastic surgeons, and medical spas. For more information, visit www.revisionskincare.com.

Resveratrol B E

SkinCeuticals launches Resveratrol B E, an intensive antioxidant night concentrate that boosts the skin’s endogenous antioxidant defense system, which loses efficiency with age and accumulated damage. It works by neutralizing age-accelerating internal free radicals, strength-ening functionality to resist new damage, and promoting skin’s natural repair to diminish the signs of accumulated damage. Resveratrol B E corrects signs of photodamage, loss of firmness and radiance, poor elasticity, and fine lines and wrinkles. SkinCeuticals products are physician dispensed. For more information, visit www.skinceuticals.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Onexton

Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc, an-nounces US Food and Drug Administration approval of Onexton Gel (clindamycin phosphate 1.2% and benzoyl peroxide 3.75%) for the once-daily treatment of comedonal and inflammatory acne in patients 12 years and older. This dual-action topical therapy has a favorable cutaneous tolerability profile and contains no surfactants, alcohol, or preservatives. Onexton is expected to launch in early 2015. For more information, visit www.valeant.com.

Physical Eye UV Defense Sunscreen

SkinCeuticals presents Physical Eye UV Defense Sunscreen that provides broad-spectrum SPF 50 protection without migrating into or irritating the eyes. Physical Eye UV Defense unifies natural skin tone around the eye and provides a translucent universal tint. It should be applied around the entire eye area and is optimized for application under makeup. It also can be used following hyaluronic acid filler and botulinum toxin injections. SkinCeuticals products are physician dispensed. For more information, visit www.skinceuticals.com.

Refining Mineral Mask

Revision Skincare introduces the limited edition Refining Mineral Mask, a warming mask to reduce the appearance of pores and leave skin looking refined. It contains kaolin to purify the complexion, pumpkin enzymes to gently exfoliate skin, zeolite to provide an extra boost of radiance with its warming effect, and vitamin E microspheres to condition skin. Revision Skincare products are available exclusively through dermatologists, plastic surgeons, and medical spas. For more information, visit www.revisionskincare.com.

Resveratrol B E

SkinCeuticals launches Resveratrol B E, an intensive antioxidant night concentrate that boosts the skin’s endogenous antioxidant defense system, which loses efficiency with age and accumulated damage. It works by neutralizing age-accelerating internal free radicals, strength-ening functionality to resist new damage, and promoting skin’s natural repair to diminish the signs of accumulated damage. Resveratrol B E corrects signs of photodamage, loss of firmness and radiance, poor elasticity, and fine lines and wrinkles. SkinCeuticals products are physician dispensed. For more information, visit www.skinceuticals.com.

If you would like your product included in Product News, please e-mail a press release to the Editorial Office at [email protected].

Reduced Degree of Irritation During a Second Cycle of Ingenol Mebutate Gel 0.015% for the Treatment of Actinic Keratosis

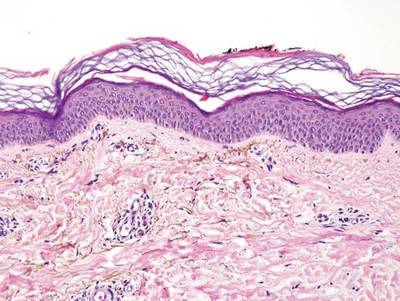

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are common skin lesions resulting from cumulative exposure to UV radiation and are associated with an increased risk for invasive squamous cell carcinoma1; therefore, diagnosis and treatment are important.2 Individual AKs are most frequently treated with cryosurgery, while topical agents including ingenol mebutate gel are used as field treatments on areas of confluent AKs of sun-damaged skin.2,3 Studies have shown that rates of complete clearance with topical therapy can be improved with more than a single treatment course.4-6

Although the mechanisms of action of ingenol mebutate on AKs are not fully understood, studies indicate that it induces cell death in proliferating keratinocytes, which suggests that it may act preferentially on AKs and not on healthy skin.7 The field treatment of AKs of the face and scalp using ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% involves a 3-day regimen,8 and clearance rates are similar to those observed with topical agents that are used for longer periods of time.3,9,10 Local skin reactions (LSRs) associated with application of ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% on the face and scalp generally are mild to moderate in intensity and resolve after 2 weeks without sequelae.3

The presumption that the cytotoxic actions of ingenol mebutate affect proliferating keratinocytes preferentially was the basis for this study. We hypothesized that application of a second sequential cycle of ingenol mebutate during AK treatment should produce lower LSR scores than the first application cycle due to the specific elimination of transformed keratinocytes from the treatment area. This open-label study compared the intensity of LSRs during 2 sequential cycles of treatment on the same site of the face or scalp using ingenol mebutate gel 0.015%.

Methods

Study Population

Eligible participants were adults with 4 to 8 clinically typical, visible, nonhypertrophic AKs in a 25-cm2 contiguous area of the face or scalp. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same as in the pivotal studies.3 The study was approved by the institutional review board at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (New York, New York). Enrollment took place from March 2013 to August 2013.

Study Design and Assessments

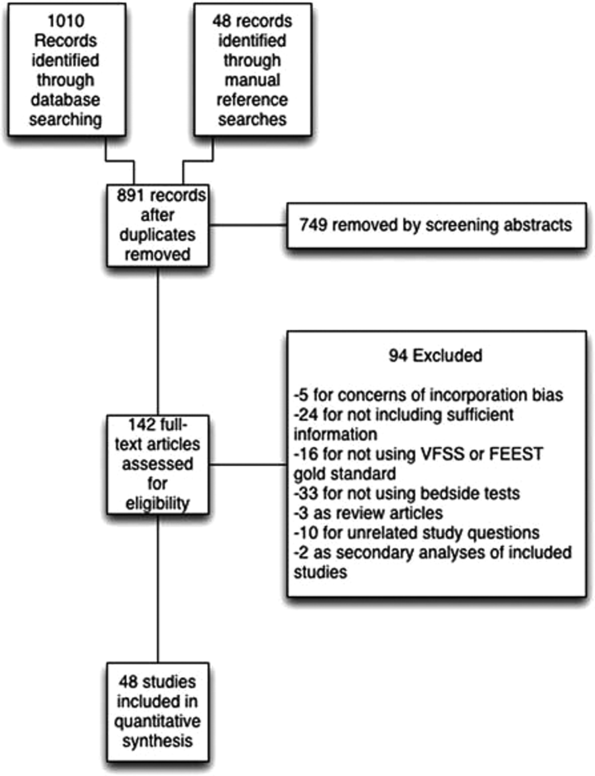

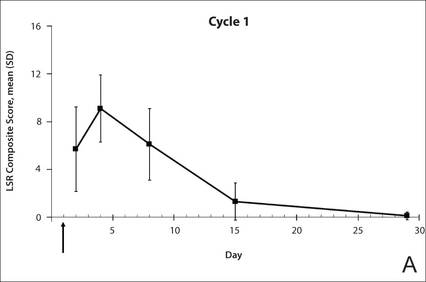

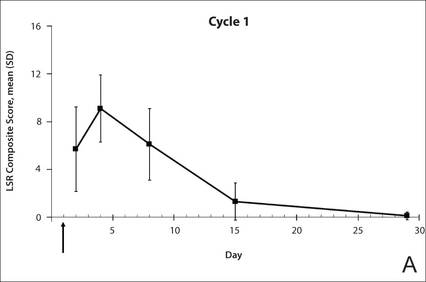

All participants were treated with 2 sequential 4-week cycles of ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% applied once daily for 3 consecutive days starting on the first day of each cycle (day 1 and day 29). Participants were evaluated at 11 visits (days 1, 2, 4, 8, 15, 29, 30, 32, 36, 43, and 56) during the 56-day study period (Figure 1). Eligibility, demographics, and medical history were assessed at day 1, and concomitant medications and adverse events (AEs) were evaluated at all visits. Using standardized photographic guides, 6 individual LSRs—erythema, flaking/scaling, crusting, swelling, vesiculation/pustulation, and erosion/ulceration—were assessed on a scale of 0 (none) to 4 (severe), with higher numbers indicating more severe reactions. For each participant, a composite score was calculated as the sum of the individual LSR scores.3 Throughout the study, 3 qualified evaluators assessed AK lesion count and graded the LSRs. The same evaluator assessed both treatment courses for each participant for the majority of assessments.

|

|

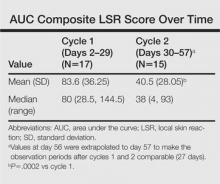

The primary end point of the study was to evaluate the degree of irritation in each of the 2 sequential cycles of ingenol mebutate treatment by assessing the mean area under the curve (AUC) of the composite LSR score over time following each of the 2 applications. Actinic keratoses were counted at baseline and at the end of each treatment cycle. The paired t test was used to compare AUCs of the composite LSR scores of the 2 cycles and to compare the changes in lesion counts from baseline to day 29 and from baseline to day 56. The complete clearance rates (number of participants with no AKs) at the end of cycles 1 and 2 were compared using a logistic regression model. Participant-perceived irritation and treatment satisfaction were evaluated using a 0 to 100 visual analog scale (VAS), with higher numbers indicating greater irritation and higher satisfaction. Participant-reported scores were summarized.

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 20 participants were enrolled in the study. At the completion of the study, 2 participants withdrew consent but allowed use of data from their completed assessments. Consequently, a total of 18 patients completed the entire study. The mean age was 75.35 years (median, 77.5 years; age range, 49–87 years). Most of the participants (15/20 [75%]) were men. All participants were white, and 2 were of Hispanic ethnicity. Of the 20 participants, 19 (95%) were Fitzpatrick skin type II, and 1 (5%) was Fitzpatrick skin type I. Most of the participants (16/20 [80%]) received treatment of lesions on the face. With the exception of 2 (10%) participants, all had received prior treatment of AKs, including cryosurgery (16/20 [80%]), imiquimod (5/20 [25%]), fluorouracil (2/20 [10%]), diclofenac (2/20 [10%]), and photodynamic therapy (2/20 [10%]); 8 (40%) participants had received more than 1 type of treatment.

LSRs in Cycles 1 and 2

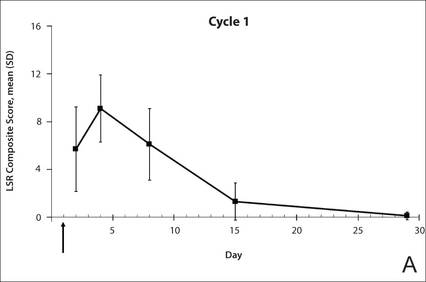

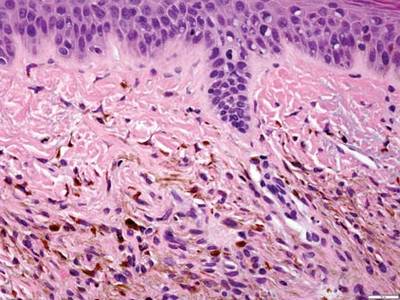

The time course for the development and resolution of LSRs during both treatment cycles was similar. Local skin reactions were evident on day 2 in each cycle, peaked at 3 days after the application of the first dose, declined rapidly by the 15th day of the cycle, and returned to baseline by the end of each 4-week cycle (Figure 1). The mean (standard deviation [SD]) composite LSR score at 3 days after application of the first dose was higher in cycle 1 than in cycle 2 (9.1 [2.83] vs 5.0 [3.24])(Figure 1). The composite LSR score assessed over time based on the mean (SD) AUC was significantly lower in cycle 2 than in cycle 1 (40.5 [28.05] vs 83.6 [36.25])(P=.0002)(Table). Statistical differences in scores for individual reactions between the 2 cycles were not determined because of the risk for a spurious indication of significance from multiple comparisons in such a limited patient sample.

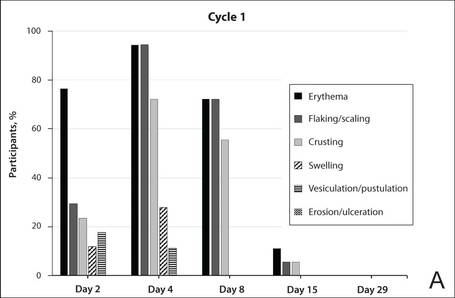

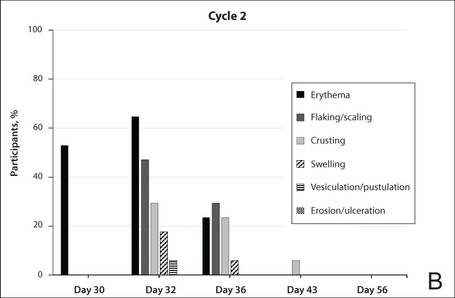

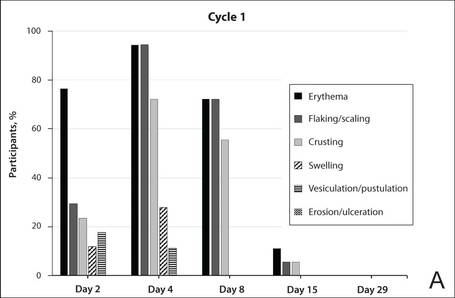

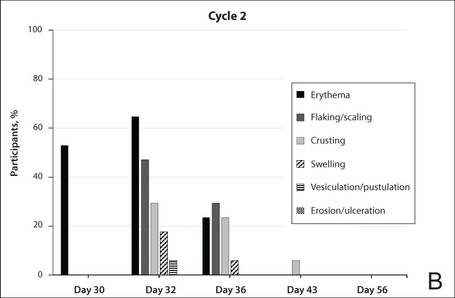

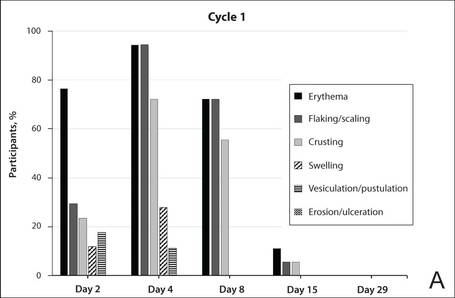

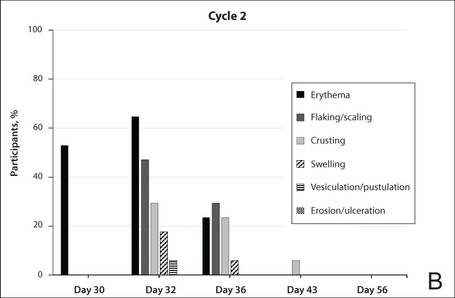

The percentage of participants who had a score greater than 1 for any of the 6 components of the LSR assessment was lower in cycle 2 than in cycle 1 at all of the assessed time points (Figure 2). In both cycles, the percentage of participants with an LSR score greater than 1 was highest 3 days after the application of the first dose in the cycle (day 4 or day 32, respectively). Erythema, flaking/scaling, and crusting were the most freq-uently observed reactions. At day 29, there were no participants with an LSR score greater than 1 in any of the 6 components. At day 29 and day 56, 94% (17/18) and 100% (18/18) of participants, respectively, had a score of 0 for all reactions.

|

|

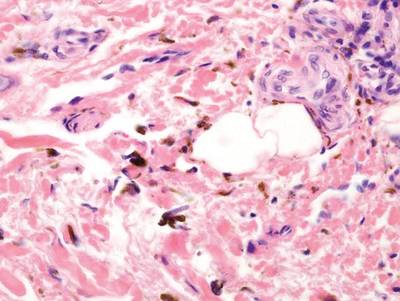

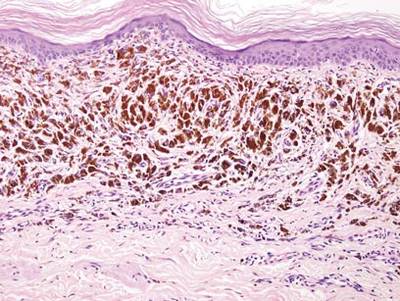

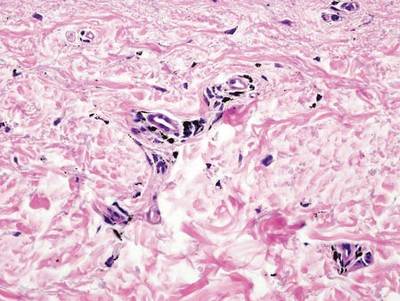

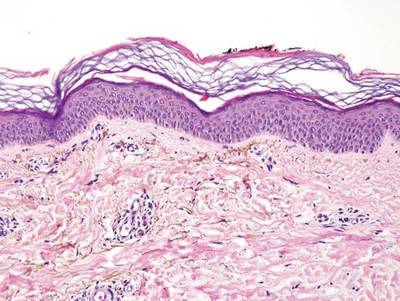

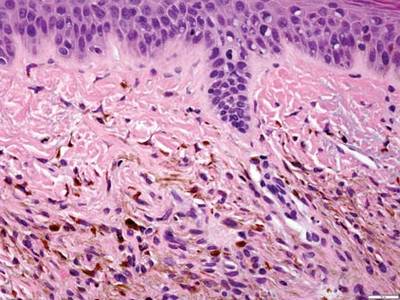

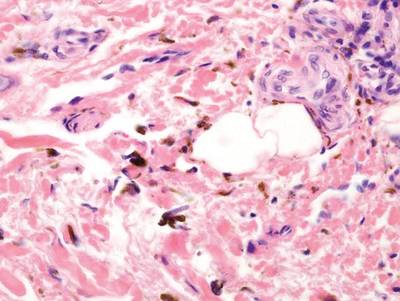

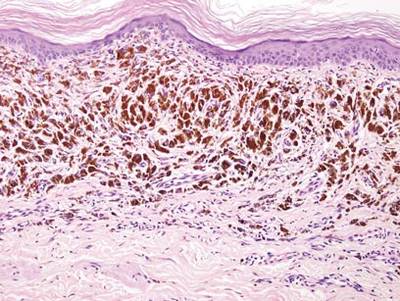

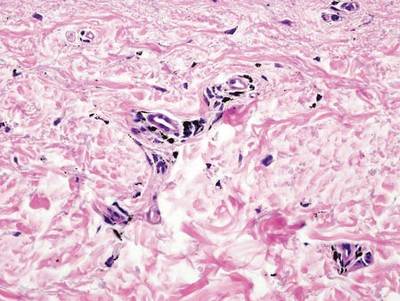

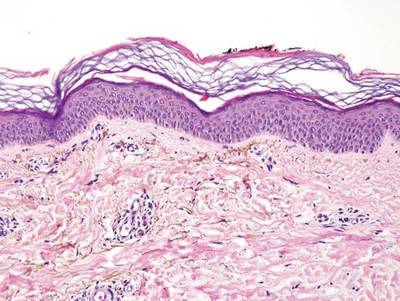

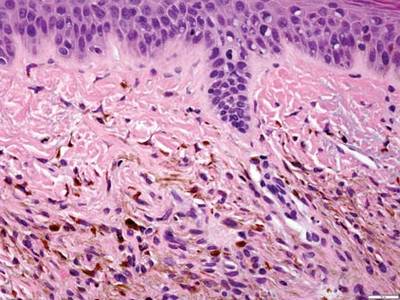

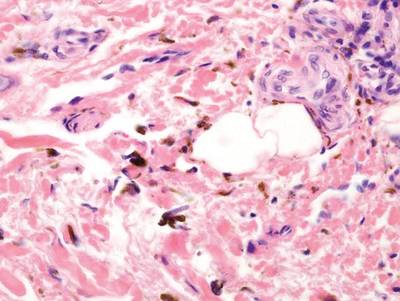

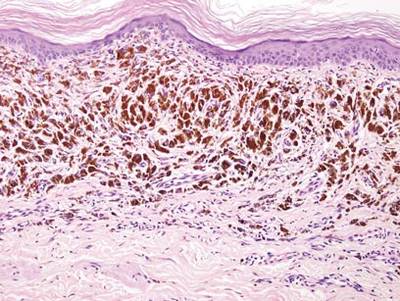

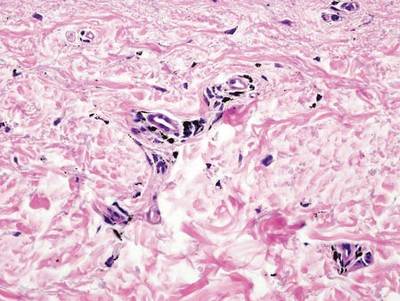

The photographs in Figure 3, taken 7 days after the application of the first dose of ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% in each cycle of treatment of AK lesions on the face, show that there was less flaking/scaling and crusting in cycle 2 than in cycle 1. A review of participant photographs from the third treatment day of each cycle showed that the areas of erythema were the same in both cycles. The other 5 LSRs—flaking/scaling, crusting, swelling, vesiculation/pustulation, and erosion/ulceration—were observed in different areas of the treated field in the 2 cycles when applicable.

Adverse Events

The few AEs that were reported were considered to be mild in severity. The AEs included application-site pain (n=5), application-site pruritus (n=3), and nasopharyngitis (n=1). No serious AEs were reported. After the first treatment cycle, 1 participant experienced hypopigmentation at the treatment site that persisted as faint hypopigmentation at the last study visit (day 56).

AK Lesion Count

The lesion count in all participants at baseline ranged from 4 to 8, with a mean (SD) of 5.9 (1.55). Mean lesion count was substantially reduced at the end of cycle 1 (0.9 [1.39]) and cycle 2 (0.3 [0.57]). The change in lesion count from baseline to day 56 was greater than the change from baseline to day 29 (-5.7 [1.61] vs -5.0 [1.57])(P=.0137). Complete clearance at day 29 and day 56 was achieved in 55.6% (10/18) and 77.8% (14/18) of participants, respectively. The difference in the clearance rate between day 29 and day 56 did not reach statistical significance, most likely due to the small sample size.

Participant-Reported Outcomes

|

|

Visual analog scale scores for participant-perceived irritation were less than 50 on a scale of 0 to 100 during both application cycles. At 1 day and 3 days after application of the first dose of ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% in cycle 1, the mean (SD) VAS scores for irritation were 31.8 (37.06) and 37.9 (30.77), respectively. At the same time points in cycle 2, VAS scores were 44.2 (32.45) and 49.6 (26.90), respectively. No information was available regarding resolution of participant-perceived irritation, as irritation data were not collected after day 4 of each treatment cycle; therefore, P values were not determined. Participant satisfaction with treatment was high and nearly the same at the end of cycles 1 and 2 (VAS scores: 83.7 [12.73] and 83.8 [20.46], respectively).

Comment

Our findings show that a second course of treatment with ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% on the same site on the face or scalp produced a less intense inflammatory reaction than the first course of treatment. Composite LSR scores at each time point after the start of treatment were lower in cycle 2 than in cycle 1. The percentage of participants who demonstrated a severity score greater than 1 for any of the 6 components of the LSR assessment also was lower at time points in cycle 2 than in cycle 1. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the activity of ingenol mebutate includes a mechanism that specifically targets transformed keratinocytes, which are reduced by the start of a second cycle of treatment.

The mechanism for the clinical efficacy of ingenol mebutate has not been fully described. Studies in preclinical models suggest at least 2 components, including direct cytotoxic effects on tumor cells and a localized inflammatory reaction that includes protein kinase C activation.11 Ingenol mebutate preferentially induces death in tumor cells and in proliferating undifferentiated keratinocytes.7,12 Cell death and protein kinase C activation lead to an inflammatory response dominated by neutrophils and other immunocompetent cells that add to the destruction of transformed cells.11

The reduced inflammatory response observed in participants during the second cycle of treatment in this study is consistent with the theory of a preferential action on transformed keratinocytes by ingenol mebutate. Once transformed keratinocytes are substantially cleared in cycle 1, fewer target cells remain, and therefore the inflammatory response is less intense in cycle 2. If ingenol mebutate were uniformly cytotoxic and inflammatory to all cells, the LSR scores in both cycles would be expected to be similar.

Assessment of participant-perceived irritation supplemented the measurement of the 6 visible manifestations of inflammation over each 4-week cycle. Participant-perceived irritation was recorded early in the cycles at 1 and 3 days after the first dose. Although it is difficult to standardize patient perceptions, VAS scores for irritation in cycle 2 were higher than those reported in cycle 1, which suggests an increased perception of irritation. The clinical relevance of this perception is not certain and may be due to the small number of participants and/or the time interval between the 2 treatment courses.

The results of this study were limited by the small patient sample. Additionally, LSR assessments were limited by the quality of the photographs. However, LSRs and AK clearance rates were similar to the pooled findings seen in the phase 3 studies of ingenol mebutate.3 Adverse events were predominantly conditions that occurred at the application site, as in phase 3 studies.3 Similarly, the time course of LSR development and resolution followed the same pattern as in those trials. The peak composite LSR score for the face and scalp was approximately 9 in both the present study (cycle 1) and in the pooled phase 3 studies.3

Conclusion

Ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% may specifically target and remove transformed proliferating keratinocytes, cumulatively reducing the burden of sun-damaged skin over the course of 2 treatment cycles. Patients may experience fewer LSRs on reapplication of ingenol mebutate to a previously treated site.

Acknowledgment

Editorial support was provided by Tanya MacNeil, PhD, of p-value communications, LLC, Cedar Knolls, New Jersey.

1. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530.

2. Berman B, Cohen DE, Amini S. What is the role of field-directed therapy in the treatment of actinic keratosis? part 1: overview and investigational topical agents. Cutis. 2012;89:241-250.

3. Lebwohl M, Swanson N, Anderson LL, et al. Ingenol mebutate gel for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1010-1019.

4. Alomar A, Bichel J, McRae S. Vehicle-controlled, randomized, double-blind study to assess safety and efficacy of imiquimod 5% cream applied once daily 3 days per week in one or two courses of treatment of actinic keratoses on the head. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:133-141.

5. Jorizzo J, Dinehart S, Matheson R, et al. Vehicle-controlled, double-blind, randomized study of imiquimod 5% cream applied 3 days per week in one or two courses of treatment for actinic keratoses on the head. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:265-268.

6. Del Rosso JQ, Sofen H, Leshin B, et al. Safety and efficacy of multiple 16-week courses of topical imiquimod for the treatment of large areas of skin involved with actinic keratoses. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:20-28.

7. Stahlhut M, Bertelsen M, Hoyer-Hansen M, et al. Ingenol mebutate: induced cell death patterns in normal and cancer epithelial cells. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1181-1192.

8. Picato gel 0.015%, 0.05% [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: LEO Pharma; 2013.

9. Rivers JK, Arlette J, Shear N, et al. Topical treatment of actinic keratoses with 3.0% diclofenac in 2.5% hyaluronan gel. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:94-100.

10. Swanson N, Abramovits W, Berman B, et al. Imiquimod 2.5% and 3.75% for the treatment of actinic keratoses: results of two placebo-controlled studies of daily application to the face and balding scalp for two 2-week cycles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:582-590.

11. Challacombe JM, Suhrbier A, Parsons PG, et al. Neutrophils are a key component of the antitumor efficacy of topical chemotherapy with ingenol-3-angelate. J Immunol. 2006;177:8123-8132.

12. Ogbourne SM, Suhrbier A, Jones B, et al. Antitumor activity of 3-ingenyl angelate: plasma membrane and mitochondrial disruption and necrotic cell death. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2833-2839.

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are common skin lesions resulting from cumulative exposure to UV radiation and are associated with an increased risk for invasive squamous cell carcinoma1; therefore, diagnosis and treatment are important.2 Individual AKs are most frequently treated with cryosurgery, while topical agents including ingenol mebutate gel are used as field treatments on areas of confluent AKs of sun-damaged skin.2,3 Studies have shown that rates of complete clearance with topical therapy can be improved with more than a single treatment course.4-6

Although the mechanisms of action of ingenol mebutate on AKs are not fully understood, studies indicate that it induces cell death in proliferating keratinocytes, which suggests that it may act preferentially on AKs and not on healthy skin.7 The field treatment of AKs of the face and scalp using ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% involves a 3-day regimen,8 and clearance rates are similar to those observed with topical agents that are used for longer periods of time.3,9,10 Local skin reactions (LSRs) associated with application of ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% on the face and scalp generally are mild to moderate in intensity and resolve after 2 weeks without sequelae.3

The presumption that the cytotoxic actions of ingenol mebutate affect proliferating keratinocytes preferentially was the basis for this study. We hypothesized that application of a second sequential cycle of ingenol mebutate during AK treatment should produce lower LSR scores than the first application cycle due to the specific elimination of transformed keratinocytes from the treatment area. This open-label study compared the intensity of LSRs during 2 sequential cycles of treatment on the same site of the face or scalp using ingenol mebutate gel 0.015%.

Methods

Study Population

Eligible participants were adults with 4 to 8 clinically typical, visible, nonhypertrophic AKs in a 25-cm2 contiguous area of the face or scalp. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same as in the pivotal studies.3 The study was approved by the institutional review board at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (New York, New York). Enrollment took place from March 2013 to August 2013.

Study Design and Assessments

All participants were treated with 2 sequential 4-week cycles of ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% applied once daily for 3 consecutive days starting on the first day of each cycle (day 1 and day 29). Participants were evaluated at 11 visits (days 1, 2, 4, 8, 15, 29, 30, 32, 36, 43, and 56) during the 56-day study period (Figure 1). Eligibility, demographics, and medical history were assessed at day 1, and concomitant medications and adverse events (AEs) were evaluated at all visits. Using standardized photographic guides, 6 individual LSRs—erythema, flaking/scaling, crusting, swelling, vesiculation/pustulation, and erosion/ulceration—were assessed on a scale of 0 (none) to 4 (severe), with higher numbers indicating more severe reactions. For each participant, a composite score was calculated as the sum of the individual LSR scores.3 Throughout the study, 3 qualified evaluators assessed AK lesion count and graded the LSRs. The same evaluator assessed both treatment courses for each participant for the majority of assessments.

|

|

The primary end point of the study was to evaluate the degree of irritation in each of the 2 sequential cycles of ingenol mebutate treatment by assessing the mean area under the curve (AUC) of the composite LSR score over time following each of the 2 applications. Actinic keratoses were counted at baseline and at the end of each treatment cycle. The paired t test was used to compare AUCs of the composite LSR scores of the 2 cycles and to compare the changes in lesion counts from baseline to day 29 and from baseline to day 56. The complete clearance rates (number of participants with no AKs) at the end of cycles 1 and 2 were compared using a logistic regression model. Participant-perceived irritation and treatment satisfaction were evaluated using a 0 to 100 visual analog scale (VAS), with higher numbers indicating greater irritation and higher satisfaction. Participant-reported scores were summarized.

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 20 participants were enrolled in the study. At the completion of the study, 2 participants withdrew consent but allowed use of data from their completed assessments. Consequently, a total of 18 patients completed the entire study. The mean age was 75.35 years (median, 77.5 years; age range, 49–87 years). Most of the participants (15/20 [75%]) were men. All participants were white, and 2 were of Hispanic ethnicity. Of the 20 participants, 19 (95%) were Fitzpatrick skin type II, and 1 (5%) was Fitzpatrick skin type I. Most of the participants (16/20 [80%]) received treatment of lesions on the face. With the exception of 2 (10%) participants, all had received prior treatment of AKs, including cryosurgery (16/20 [80%]), imiquimod (5/20 [25%]), fluorouracil (2/20 [10%]), diclofenac (2/20 [10%]), and photodynamic therapy (2/20 [10%]); 8 (40%) participants had received more than 1 type of treatment.

LSRs in Cycles 1 and 2

The time course for the development and resolution of LSRs during both treatment cycles was similar. Local skin reactions were evident on day 2 in each cycle, peaked at 3 days after the application of the first dose, declined rapidly by the 15th day of the cycle, and returned to baseline by the end of each 4-week cycle (Figure 1). The mean (standard deviation [SD]) composite LSR score at 3 days after application of the first dose was higher in cycle 1 than in cycle 2 (9.1 [2.83] vs 5.0 [3.24])(Figure 1). The composite LSR score assessed over time based on the mean (SD) AUC was significantly lower in cycle 2 than in cycle 1 (40.5 [28.05] vs 83.6 [36.25])(P=.0002)(Table). Statistical differences in scores for individual reactions between the 2 cycles were not determined because of the risk for a spurious indication of significance from multiple comparisons in such a limited patient sample.

The percentage of participants who had a score greater than 1 for any of the 6 components of the LSR assessment was lower in cycle 2 than in cycle 1 at all of the assessed time points (Figure 2). In both cycles, the percentage of participants with an LSR score greater than 1 was highest 3 days after the application of the first dose in the cycle (day 4 or day 32, respectively). Erythema, flaking/scaling, and crusting were the most freq-uently observed reactions. At day 29, there were no participants with an LSR score greater than 1 in any of the 6 components. At day 29 and day 56, 94% (17/18) and 100% (18/18) of participants, respectively, had a score of 0 for all reactions.

|

|

The photographs in Figure 3, taken 7 days after the application of the first dose of ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% in each cycle of treatment of AK lesions on the face, show that there was less flaking/scaling and crusting in cycle 2 than in cycle 1. A review of participant photographs from the third treatment day of each cycle showed that the areas of erythema were the same in both cycles. The other 5 LSRs—flaking/scaling, crusting, swelling, vesiculation/pustulation, and erosion/ulceration—were observed in different areas of the treated field in the 2 cycles when applicable.

Adverse Events

The few AEs that were reported were considered to be mild in severity. The AEs included application-site pain (n=5), application-site pruritus (n=3), and nasopharyngitis (n=1). No serious AEs were reported. After the first treatment cycle, 1 participant experienced hypopigmentation at the treatment site that persisted as faint hypopigmentation at the last study visit (day 56).

AK Lesion Count

The lesion count in all participants at baseline ranged from 4 to 8, with a mean (SD) of 5.9 (1.55). Mean lesion count was substantially reduced at the end of cycle 1 (0.9 [1.39]) and cycle 2 (0.3 [0.57]). The change in lesion count from baseline to day 56 was greater than the change from baseline to day 29 (-5.7 [1.61] vs -5.0 [1.57])(P=.0137). Complete clearance at day 29 and day 56 was achieved in 55.6% (10/18) and 77.8% (14/18) of participants, respectively. The difference in the clearance rate between day 29 and day 56 did not reach statistical significance, most likely due to the small sample size.

Participant-Reported Outcomes

|

|

Visual analog scale scores for participant-perceived irritation were less than 50 on a scale of 0 to 100 during both application cycles. At 1 day and 3 days after application of the first dose of ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% in cycle 1, the mean (SD) VAS scores for irritation were 31.8 (37.06) and 37.9 (30.77), respectively. At the same time points in cycle 2, VAS scores were 44.2 (32.45) and 49.6 (26.90), respectively. No information was available regarding resolution of participant-perceived irritation, as irritation data were not collected after day 4 of each treatment cycle; therefore, P values were not determined. Participant satisfaction with treatment was high and nearly the same at the end of cycles 1 and 2 (VAS scores: 83.7 [12.73] and 83.8 [20.46], respectively).

Comment

Our findings show that a second course of treatment with ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% on the same site on the face or scalp produced a less intense inflammatory reaction than the first course of treatment. Composite LSR scores at each time point after the start of treatment were lower in cycle 2 than in cycle 1. The percentage of participants who demonstrated a severity score greater than 1 for any of the 6 components of the LSR assessment also was lower at time points in cycle 2 than in cycle 1. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the activity of ingenol mebutate includes a mechanism that specifically targets transformed keratinocytes, which are reduced by the start of a second cycle of treatment.

The mechanism for the clinical efficacy of ingenol mebutate has not been fully described. Studies in preclinical models suggest at least 2 components, including direct cytotoxic effects on tumor cells and a localized inflammatory reaction that includes protein kinase C activation.11 Ingenol mebutate preferentially induces death in tumor cells and in proliferating undifferentiated keratinocytes.7,12 Cell death and protein kinase C activation lead to an inflammatory response dominated by neutrophils and other immunocompetent cells that add to the destruction of transformed cells.11

The reduced inflammatory response observed in participants during the second cycle of treatment in this study is consistent with the theory of a preferential action on transformed keratinocytes by ingenol mebutate. Once transformed keratinocytes are substantially cleared in cycle 1, fewer target cells remain, and therefore the inflammatory response is less intense in cycle 2. If ingenol mebutate were uniformly cytotoxic and inflammatory to all cells, the LSR scores in both cycles would be expected to be similar.

Assessment of participant-perceived irritation supplemented the measurement of the 6 visible manifestations of inflammation over each 4-week cycle. Participant-perceived irritation was recorded early in the cycles at 1 and 3 days after the first dose. Although it is difficult to standardize patient perceptions, VAS scores for irritation in cycle 2 were higher than those reported in cycle 1, which suggests an increased perception of irritation. The clinical relevance of this perception is not certain and may be due to the small number of participants and/or the time interval between the 2 treatment courses.

The results of this study were limited by the small patient sample. Additionally, LSR assessments were limited by the quality of the photographs. However, LSRs and AK clearance rates were similar to the pooled findings seen in the phase 3 studies of ingenol mebutate.3 Adverse events were predominantly conditions that occurred at the application site, as in phase 3 studies.3 Similarly, the time course of LSR development and resolution followed the same pattern as in those trials. The peak composite LSR score for the face and scalp was approximately 9 in both the present study (cycle 1) and in the pooled phase 3 studies.3

Conclusion

Ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% may specifically target and remove transformed proliferating keratinocytes, cumulatively reducing the burden of sun-damaged skin over the course of 2 treatment cycles. Patients may experience fewer LSRs on reapplication of ingenol mebutate to a previously treated site.

Acknowledgment

Editorial support was provided by Tanya MacNeil, PhD, of p-value communications, LLC, Cedar Knolls, New Jersey.

Actinic keratoses (AKs) are common skin lesions resulting from cumulative exposure to UV radiation and are associated with an increased risk for invasive squamous cell carcinoma1; therefore, diagnosis and treatment are important.2 Individual AKs are most frequently treated with cryosurgery, while topical agents including ingenol mebutate gel are used as field treatments on areas of confluent AKs of sun-damaged skin.2,3 Studies have shown that rates of complete clearance with topical therapy can be improved with more than a single treatment course.4-6

Although the mechanisms of action of ingenol mebutate on AKs are not fully understood, studies indicate that it induces cell death in proliferating keratinocytes, which suggests that it may act preferentially on AKs and not on healthy skin.7 The field treatment of AKs of the face and scalp using ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% involves a 3-day regimen,8 and clearance rates are similar to those observed with topical agents that are used for longer periods of time.3,9,10 Local skin reactions (LSRs) associated with application of ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% on the face and scalp generally are mild to moderate in intensity and resolve after 2 weeks without sequelae.3

The presumption that the cytotoxic actions of ingenol mebutate affect proliferating keratinocytes preferentially was the basis for this study. We hypothesized that application of a second sequential cycle of ingenol mebutate during AK treatment should produce lower LSR scores than the first application cycle due to the specific elimination of transformed keratinocytes from the treatment area. This open-label study compared the intensity of LSRs during 2 sequential cycles of treatment on the same site of the face or scalp using ingenol mebutate gel 0.015%.

Methods

Study Population

Eligible participants were adults with 4 to 8 clinically typical, visible, nonhypertrophic AKs in a 25-cm2 contiguous area of the face or scalp. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same as in the pivotal studies.3 The study was approved by the institutional review board at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (New York, New York). Enrollment took place from March 2013 to August 2013.

Study Design and Assessments

All participants were treated with 2 sequential 4-week cycles of ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% applied once daily for 3 consecutive days starting on the first day of each cycle (day 1 and day 29). Participants were evaluated at 11 visits (days 1, 2, 4, 8, 15, 29, 30, 32, 36, 43, and 56) during the 56-day study period (Figure 1). Eligibility, demographics, and medical history were assessed at day 1, and concomitant medications and adverse events (AEs) were evaluated at all visits. Using standardized photographic guides, 6 individual LSRs—erythema, flaking/scaling, crusting, swelling, vesiculation/pustulation, and erosion/ulceration—were assessed on a scale of 0 (none) to 4 (severe), with higher numbers indicating more severe reactions. For each participant, a composite score was calculated as the sum of the individual LSR scores.3 Throughout the study, 3 qualified evaluators assessed AK lesion count and graded the LSRs. The same evaluator assessed both treatment courses for each participant for the majority of assessments.

|

|

The primary end point of the study was to evaluate the degree of irritation in each of the 2 sequential cycles of ingenol mebutate treatment by assessing the mean area under the curve (AUC) of the composite LSR score over time following each of the 2 applications. Actinic keratoses were counted at baseline and at the end of each treatment cycle. The paired t test was used to compare AUCs of the composite LSR scores of the 2 cycles and to compare the changes in lesion counts from baseline to day 29 and from baseline to day 56. The complete clearance rates (number of participants with no AKs) at the end of cycles 1 and 2 were compared using a logistic regression model. Participant-perceived irritation and treatment satisfaction were evaluated using a 0 to 100 visual analog scale (VAS), with higher numbers indicating greater irritation and higher satisfaction. Participant-reported scores were summarized.

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 20 participants were enrolled in the study. At the completion of the study, 2 participants withdrew consent but allowed use of data from their completed assessments. Consequently, a total of 18 patients completed the entire study. The mean age was 75.35 years (median, 77.5 years; age range, 49–87 years). Most of the participants (15/20 [75%]) were men. All participants were white, and 2 were of Hispanic ethnicity. Of the 20 participants, 19 (95%) were Fitzpatrick skin type II, and 1 (5%) was Fitzpatrick skin type I. Most of the participants (16/20 [80%]) received treatment of lesions on the face. With the exception of 2 (10%) participants, all had received prior treatment of AKs, including cryosurgery (16/20 [80%]), imiquimod (5/20 [25%]), fluorouracil (2/20 [10%]), diclofenac (2/20 [10%]), and photodynamic therapy (2/20 [10%]); 8 (40%) participants had received more than 1 type of treatment.

LSRs in Cycles 1 and 2

The time course for the development and resolution of LSRs during both treatment cycles was similar. Local skin reactions were evident on day 2 in each cycle, peaked at 3 days after the application of the first dose, declined rapidly by the 15th day of the cycle, and returned to baseline by the end of each 4-week cycle (Figure 1). The mean (standard deviation [SD]) composite LSR score at 3 days after application of the first dose was higher in cycle 1 than in cycle 2 (9.1 [2.83] vs 5.0 [3.24])(Figure 1). The composite LSR score assessed over time based on the mean (SD) AUC was significantly lower in cycle 2 than in cycle 1 (40.5 [28.05] vs 83.6 [36.25])(P=.0002)(Table). Statistical differences in scores for individual reactions between the 2 cycles were not determined because of the risk for a spurious indication of significance from multiple comparisons in such a limited patient sample.

The percentage of participants who had a score greater than 1 for any of the 6 components of the LSR assessment was lower in cycle 2 than in cycle 1 at all of the assessed time points (Figure 2). In both cycles, the percentage of participants with an LSR score greater than 1 was highest 3 days after the application of the first dose in the cycle (day 4 or day 32, respectively). Erythema, flaking/scaling, and crusting were the most freq-uently observed reactions. At day 29, there were no participants with an LSR score greater than 1 in any of the 6 components. At day 29 and day 56, 94% (17/18) and 100% (18/18) of participants, respectively, had a score of 0 for all reactions.

|

|

The photographs in Figure 3, taken 7 days after the application of the first dose of ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% in each cycle of treatment of AK lesions on the face, show that there was less flaking/scaling and crusting in cycle 2 than in cycle 1. A review of participant photographs from the third treatment day of each cycle showed that the areas of erythema were the same in both cycles. The other 5 LSRs—flaking/scaling, crusting, swelling, vesiculation/pustulation, and erosion/ulceration—were observed in different areas of the treated field in the 2 cycles when applicable.

Adverse Events

The few AEs that were reported were considered to be mild in severity. The AEs included application-site pain (n=5), application-site pruritus (n=3), and nasopharyngitis (n=1). No serious AEs were reported. After the first treatment cycle, 1 participant experienced hypopigmentation at the treatment site that persisted as faint hypopigmentation at the last study visit (day 56).

AK Lesion Count

The lesion count in all participants at baseline ranged from 4 to 8, with a mean (SD) of 5.9 (1.55). Mean lesion count was substantially reduced at the end of cycle 1 (0.9 [1.39]) and cycle 2 (0.3 [0.57]). The change in lesion count from baseline to day 56 was greater than the change from baseline to day 29 (-5.7 [1.61] vs -5.0 [1.57])(P=.0137). Complete clearance at day 29 and day 56 was achieved in 55.6% (10/18) and 77.8% (14/18) of participants, respectively. The difference in the clearance rate between day 29 and day 56 did not reach statistical significance, most likely due to the small sample size.

Participant-Reported Outcomes

|

|

Visual analog scale scores for participant-perceived irritation were less than 50 on a scale of 0 to 100 during both application cycles. At 1 day and 3 days after application of the first dose of ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% in cycle 1, the mean (SD) VAS scores for irritation were 31.8 (37.06) and 37.9 (30.77), respectively. At the same time points in cycle 2, VAS scores were 44.2 (32.45) and 49.6 (26.90), respectively. No information was available regarding resolution of participant-perceived irritation, as irritation data were not collected after day 4 of each treatment cycle; therefore, P values were not determined. Participant satisfaction with treatment was high and nearly the same at the end of cycles 1 and 2 (VAS scores: 83.7 [12.73] and 83.8 [20.46], respectively).

Comment

Our findings show that a second course of treatment with ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% on the same site on the face or scalp produced a less intense inflammatory reaction than the first course of treatment. Composite LSR scores at each time point after the start of treatment were lower in cycle 2 than in cycle 1. The percentage of participants who demonstrated a severity score greater than 1 for any of the 6 components of the LSR assessment also was lower at time points in cycle 2 than in cycle 1. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that the activity of ingenol mebutate includes a mechanism that specifically targets transformed keratinocytes, which are reduced by the start of a second cycle of treatment.

The mechanism for the clinical efficacy of ingenol mebutate has not been fully described. Studies in preclinical models suggest at least 2 components, including direct cytotoxic effects on tumor cells and a localized inflammatory reaction that includes protein kinase C activation.11 Ingenol mebutate preferentially induces death in tumor cells and in proliferating undifferentiated keratinocytes.7,12 Cell death and protein kinase C activation lead to an inflammatory response dominated by neutrophils and other immunocompetent cells that add to the destruction of transformed cells.11

The reduced inflammatory response observed in participants during the second cycle of treatment in this study is consistent with the theory of a preferential action on transformed keratinocytes by ingenol mebutate. Once transformed keratinocytes are substantially cleared in cycle 1, fewer target cells remain, and therefore the inflammatory response is less intense in cycle 2. If ingenol mebutate were uniformly cytotoxic and inflammatory to all cells, the LSR scores in both cycles would be expected to be similar.

Assessment of participant-perceived irritation supplemented the measurement of the 6 visible manifestations of inflammation over each 4-week cycle. Participant-perceived irritation was recorded early in the cycles at 1 and 3 days after the first dose. Although it is difficult to standardize patient perceptions, VAS scores for irritation in cycle 2 were higher than those reported in cycle 1, which suggests an increased perception of irritation. The clinical relevance of this perception is not certain and may be due to the small number of participants and/or the time interval between the 2 treatment courses.

The results of this study were limited by the small patient sample. Additionally, LSR assessments were limited by the quality of the photographs. However, LSRs and AK clearance rates were similar to the pooled findings seen in the phase 3 studies of ingenol mebutate.3 Adverse events were predominantly conditions that occurred at the application site, as in phase 3 studies.3 Similarly, the time course of LSR development and resolution followed the same pattern as in those trials. The peak composite LSR score for the face and scalp was approximately 9 in both the present study (cycle 1) and in the pooled phase 3 studies.3

Conclusion

Ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% may specifically target and remove transformed proliferating keratinocytes, cumulatively reducing the burden of sun-damaged skin over the course of 2 treatment cycles. Patients may experience fewer LSRs on reapplication of ingenol mebutate to a previously treated site.

Acknowledgment

Editorial support was provided by Tanya MacNeil, PhD, of p-value communications, LLC, Cedar Knolls, New Jersey.

1. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530.

2. Berman B, Cohen DE, Amini S. What is the role of field-directed therapy in the treatment of actinic keratosis? part 1: overview and investigational topical agents. Cutis. 2012;89:241-250.

3. Lebwohl M, Swanson N, Anderson LL, et al. Ingenol mebutate gel for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1010-1019.

4. Alomar A, Bichel J, McRae S. Vehicle-controlled, randomized, double-blind study to assess safety and efficacy of imiquimod 5% cream applied once daily 3 days per week in one or two courses of treatment of actinic keratoses on the head. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:133-141.

5. Jorizzo J, Dinehart S, Matheson R, et al. Vehicle-controlled, double-blind, randomized study of imiquimod 5% cream applied 3 days per week in one or two courses of treatment for actinic keratoses on the head. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:265-268.

6. Del Rosso JQ, Sofen H, Leshin B, et al. Safety and efficacy of multiple 16-week courses of topical imiquimod for the treatment of large areas of skin involved with actinic keratoses. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:20-28.

7. Stahlhut M, Bertelsen M, Hoyer-Hansen M, et al. Ingenol mebutate: induced cell death patterns in normal and cancer epithelial cells. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1181-1192.

8. Picato gel 0.015%, 0.05% [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: LEO Pharma; 2013.

9. Rivers JK, Arlette J, Shear N, et al. Topical treatment of actinic keratoses with 3.0% diclofenac in 2.5% hyaluronan gel. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:94-100.

10. Swanson N, Abramovits W, Berman B, et al. Imiquimod 2.5% and 3.75% for the treatment of actinic keratoses: results of two placebo-controlled studies of daily application to the face and balding scalp for two 2-week cycles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:582-590.

11. Challacombe JM, Suhrbier A, Parsons PG, et al. Neutrophils are a key component of the antitumor efficacy of topical chemotherapy with ingenol-3-angelate. J Immunol. 2006;177:8123-8132.

12. Ogbourne SM, Suhrbier A, Jones B, et al. Antitumor activity of 3-ingenyl angelate: plasma membrane and mitochondrial disruption and necrotic cell death. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2833-2839.

1. Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, et al. Actinic keratoses: natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial. Cancer. 2009;115:2523-2530.

2. Berman B, Cohen DE, Amini S. What is the role of field-directed therapy in the treatment of actinic keratosis? part 1: overview and investigational topical agents. Cutis. 2012;89:241-250.

3. Lebwohl M, Swanson N, Anderson LL, et al. Ingenol mebutate gel for actinic keratosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1010-1019.

4. Alomar A, Bichel J, McRae S. Vehicle-controlled, randomized, double-blind study to assess safety and efficacy of imiquimod 5% cream applied once daily 3 days per week in one or two courses of treatment of actinic keratoses on the head. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:133-141.

5. Jorizzo J, Dinehart S, Matheson R, et al. Vehicle-controlled, double-blind, randomized study of imiquimod 5% cream applied 3 days per week in one or two courses of treatment for actinic keratoses on the head. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:265-268.

6. Del Rosso JQ, Sofen H, Leshin B, et al. Safety and efficacy of multiple 16-week courses of topical imiquimod for the treatment of large areas of skin involved with actinic keratoses. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2009;2:20-28.

7. Stahlhut M, Bertelsen M, Hoyer-Hansen M, et al. Ingenol mebutate: induced cell death patterns in normal and cancer epithelial cells. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:1181-1192.

8. Picato gel 0.015%, 0.05% [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ: LEO Pharma; 2013.

9. Rivers JK, Arlette J, Shear N, et al. Topical treatment of actinic keratoses with 3.0% diclofenac in 2.5% hyaluronan gel. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:94-100.

10. Swanson N, Abramovits W, Berman B, et al. Imiquimod 2.5% and 3.75% for the treatment of actinic keratoses: results of two placebo-controlled studies of daily application to the face and balding scalp for two 2-week cycles. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:582-590.

11. Challacombe JM, Suhrbier A, Parsons PG, et al. Neutrophils are a key component of the antitumor efficacy of topical chemotherapy with ingenol-3-angelate. J Immunol. 2006;177:8123-8132.

12. Ogbourne SM, Suhrbier A, Jones B, et al. Antitumor activity of 3-ingenyl angelate: plasma membrane and mitochondrial disruption and necrotic cell death. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2833-2839.

Practice Points

- Reapplication of ingenol mebutate gel 0.015% to the same treatment area on the face or scalp produced a less intense inflammatory reaction than the first treatment course.

- Ingenol mebutate may specifically target and remove transformed proliferating keratinocytes, cumulatively reducing the burden of sun-damaged skin over 2 treatment cycles.

- Almost all patients were either clear or almost clear of actinic keratosis lesions by 4 weeks following the second application of ingenol mebutate.

Survey reveals cancer survivors’ unmet needs

patient and her father

Credit: Rhoda Baer

New research shows that, even decades after being cured, many cancer survivors face challenges resulting from their disease and its treatment.

A survey of more than 1500 cancer survivors revealed 16 themes of challenges or unmet needs, such as physical dysfunction, financial problems, a lack of education about cancer survival, and anxiety about cancer recurrence.

Mary Ann Burg, PhD, of the University of Central Florida in Orlando, and her colleagues reported these findings in Cancer.

To assess the unmet needs of cancer survivors, the researchers evaluated responses from an American Cancer Society survey in which subjects responded to the open-ended question, “Please tell us about any needs you have now as a cancer survivor that are not being met to your satisfaction.”

There were a total of 1514 respondents who were 2, 5, or 10 years from cancer diagnosis. They were 24 to 97 years of age, 65.4% were female, and 24.8% were racial/ethnic minorities (black and Hispanic/Latino).

“This study was unique in that it gave a very large sample of cancer survivors a real voice to express their needs and concerns,” Dr Burg said.

The researchers found that the number and type of challenges/unmet needs were not associated with a subject’s time since cancer treatment, although older cancer survivors tended to report fewer unmet needs than younger survivors.

Sixteen themes of challenges/unmet needs emerged from respondents’ answers, with physical issues being the most common. About 38% of respondents reported physical issues, such as pain, symptoms, and sexual dysfunction.

About 20% reported financial problems, such as issues with insurance and the affordability of needed services and products. About 20% also said they had needs related to unanswered questions and a lack of knowledge about what to expect as a cancer survivor, including guidance on follow-up care and cancer risks, causes, and prevention.

About 16% of respondents cited issues relating to personal control (a lack of physical and social autonomy). And about 16% described flaws and constraints in the healthcare system that affected early detection, diagnosis, treatment, follow-up care, and continuity of care.

About 14% of respondents reported a lack of resources (such as supplies, equipment, and medications), and about 14% cited emotional and mental health issues (such as fear of cancer recurrence, depression, and anxiety).

About 13% of respondents said they lacked social support (such as access to support groups), and 10% reported issues relating to societal perceptions of cancer survivors (such as discrimination and misinformation).

About 9% of respondents expressed the need to talk about or explain the cancer experience with their physician, friends, and family. And about 9% cited a lack of trust in healthcare providers.

Other themes included the wish for more effective cancer treatments (3.5%), body image issues such as feeling unattractive or losing trust in the body (3.5%), issues with the “survivor” identity (3.1%), trouble obtaining or maintaining appropriate employment (2.3%), and existential issues, such as finding meaning in the cancer experience (0.6%).

“Overall, we found that cancer survivors are often caught off guard by the lingering problems they experience after cancer treatment,” Dr Burg said. “In the wake of cancer, many survivors feel they have lost a sense of personal control, have reduced quality of life, and are frustrated that these problems are not sufficiently addressed within the medical care system.”

She added that this study points to several areas in which we might work to improve the situation, including raising public awareness of cancer survivors’ problems, promoting honest professional communication about the side effects of cancer and its treatment, and coordinating medical care resources to help survivors and their families cope with lingering challenges. ![]()

patient and her father

Credit: Rhoda Baer

New research shows that, even decades after being cured, many cancer survivors face challenges resulting from their disease and its treatment.

A survey of more than 1500 cancer survivors revealed 16 themes of challenges or unmet needs, such as physical dysfunction, financial problems, a lack of education about cancer survival, and anxiety about cancer recurrence.

Mary Ann Burg, PhD, of the University of Central Florida in Orlando, and her colleagues reported these findings in Cancer.

To assess the unmet needs of cancer survivors, the researchers evaluated responses from an American Cancer Society survey in which subjects responded to the open-ended question, “Please tell us about any needs you have now as a cancer survivor that are not being met to your satisfaction.”

There were a total of 1514 respondents who were 2, 5, or 10 years from cancer diagnosis. They were 24 to 97 years of age, 65.4% were female, and 24.8% were racial/ethnic minorities (black and Hispanic/Latino).

“This study was unique in that it gave a very large sample of cancer survivors a real voice to express their needs and concerns,” Dr Burg said.

The researchers found that the number and type of challenges/unmet needs were not associated with a subject’s time since cancer treatment, although older cancer survivors tended to report fewer unmet needs than younger survivors.

Sixteen themes of challenges/unmet needs emerged from respondents’ answers, with physical issues being the most common. About 38% of respondents reported physical issues, such as pain, symptoms, and sexual dysfunction.

About 20% reported financial problems, such as issues with insurance and the affordability of needed services and products. About 20% also said they had needs related to unanswered questions and a lack of knowledge about what to expect as a cancer survivor, including guidance on follow-up care and cancer risks, causes, and prevention.

About 16% of respondents cited issues relating to personal control (a lack of physical and social autonomy). And about 16% described flaws and constraints in the healthcare system that affected early detection, diagnosis, treatment, follow-up care, and continuity of care.

About 14% of respondents reported a lack of resources (such as supplies, equipment, and medications), and about 14% cited emotional and mental health issues (such as fear of cancer recurrence, depression, and anxiety).

About 13% of respondents said they lacked social support (such as access to support groups), and 10% reported issues relating to societal perceptions of cancer survivors (such as discrimination and misinformation).

About 9% of respondents expressed the need to talk about or explain the cancer experience with their physician, friends, and family. And about 9% cited a lack of trust in healthcare providers.

Other themes included the wish for more effective cancer treatments (3.5%), body image issues such as feeling unattractive or losing trust in the body (3.5%), issues with the “survivor” identity (3.1%), trouble obtaining or maintaining appropriate employment (2.3%), and existential issues, such as finding meaning in the cancer experience (0.6%).

“Overall, we found that cancer survivors are often caught off guard by the lingering problems they experience after cancer treatment,” Dr Burg said. “In the wake of cancer, many survivors feel they have lost a sense of personal control, have reduced quality of life, and are frustrated that these problems are not sufficiently addressed within the medical care system.”

She added that this study points to several areas in which we might work to improve the situation, including raising public awareness of cancer survivors’ problems, promoting honest professional communication about the side effects of cancer and its treatment, and coordinating medical care resources to help survivors and their families cope with lingering challenges. ![]()

patient and her father

Credit: Rhoda Baer

New research shows that, even decades after being cured, many cancer survivors face challenges resulting from their disease and its treatment.

A survey of more than 1500 cancer survivors revealed 16 themes of challenges or unmet needs, such as physical dysfunction, financial problems, a lack of education about cancer survival, and anxiety about cancer recurrence.

Mary Ann Burg, PhD, of the University of Central Florida in Orlando, and her colleagues reported these findings in Cancer.

To assess the unmet needs of cancer survivors, the researchers evaluated responses from an American Cancer Society survey in which subjects responded to the open-ended question, “Please tell us about any needs you have now as a cancer survivor that are not being met to your satisfaction.”

There were a total of 1514 respondents who were 2, 5, or 10 years from cancer diagnosis. They were 24 to 97 years of age, 65.4% were female, and 24.8% were racial/ethnic minorities (black and Hispanic/Latino).

“This study was unique in that it gave a very large sample of cancer survivors a real voice to express their needs and concerns,” Dr Burg said.

The researchers found that the number and type of challenges/unmet needs were not associated with a subject’s time since cancer treatment, although older cancer survivors tended to report fewer unmet needs than younger survivors.

Sixteen themes of challenges/unmet needs emerged from respondents’ answers, with physical issues being the most common. About 38% of respondents reported physical issues, such as pain, symptoms, and sexual dysfunction.

About 20% reported financial problems, such as issues with insurance and the affordability of needed services and products. About 20% also said they had needs related to unanswered questions and a lack of knowledge about what to expect as a cancer survivor, including guidance on follow-up care and cancer risks, causes, and prevention.

About 16% of respondents cited issues relating to personal control (a lack of physical and social autonomy). And about 16% described flaws and constraints in the healthcare system that affected early detection, diagnosis, treatment, follow-up care, and continuity of care.

About 14% of respondents reported a lack of resources (such as supplies, equipment, and medications), and about 14% cited emotional and mental health issues (such as fear of cancer recurrence, depression, and anxiety).

About 13% of respondents said they lacked social support (such as access to support groups), and 10% reported issues relating to societal perceptions of cancer survivors (such as discrimination and misinformation).

About 9% of respondents expressed the need to talk about or explain the cancer experience with their physician, friends, and family. And about 9% cited a lack of trust in healthcare providers.

Other themes included the wish for more effective cancer treatments (3.5%), body image issues such as feeling unattractive or losing trust in the body (3.5%), issues with the “survivor” identity (3.1%), trouble obtaining or maintaining appropriate employment (2.3%), and existential issues, such as finding meaning in the cancer experience (0.6%).

“Overall, we found that cancer survivors are often caught off guard by the lingering problems they experience after cancer treatment,” Dr Burg said. “In the wake of cancer, many survivors feel they have lost a sense of personal control, have reduced quality of life, and are frustrated that these problems are not sufficiently addressed within the medical care system.”

She added that this study points to several areas in which we might work to improve the situation, including raising public awareness of cancer survivors’ problems, promoting honest professional communication about the side effects of cancer and its treatment, and coordinating medical care resources to help survivors and their families cope with lingering challenges. ![]()

‘Mother of bone marrow transplantation’ dies

husband, E. Donnall Thomas,

at a 2005 reunion of transplant

patients in Seattle

Photo by Jim Linna

Dorothy “Dottie” Thomas, the wife and research partner of 1990 Nobel laureate E. Donnall “Don” Thomas, MD, passed away on January 9 at the age of 92.

Don, pioneer of the bone marrow transplant (BMT), preceded Dottie in passing away himself on October 20, 2012, also at the age of 92.

The Thomases formed the core of a team that proved BMT could cure leukemias and other hematologic malignancies, work that spanned several decades.

Dottie may have gotten the name “the mother of bone marrow transplantation,” from the late George Santos, MD, a BMT expert at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, and a colleague.

“If Dr Thomas is the father of bone marrow transplantation, then Dottie Thomas is the mother,” he once said.

“Dottie’s life had a profound impact, not just on those who knew her personally, but also countless patients,” said Gary Gilliland, MD, PhD, president and director of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, who became friends with the Thomases when he and Don served on the advisory board of the José Carreras Leukemia Foundation.

“She and Don were amazing together in both what they accomplished and the way they cared for each other. They were so sweet together. Now, their legacy continues through the many whose lives have been saved by bone marrow transplant and those who will be saved in the future. Dottie truly helped change the future of medicine. All of us at Fred Hutch are part of her legacy.”

A romantic partnership becomes a professional one

A snowball to the face during a rare Texas snowfall in 1940 precipitated a partnership in love and work between Don and Dottie that spanned 70 years.

“I was a senior at the University of Texas when she was a freshman,” Don told The Seattle Times in a 1999 interview. “I was waiting tables at the girls dormitory, which is how I got my food.”

“It snowed in Texas, which is very unusual. And I came out of the dormitory after we’d finished serving breakfast, and there was about 6 inches of snow. This girl whacked me in the face with a snowball. She still claims she was throwing it at another fellow and hit me by mistake. One thing led to another, and we seemed to hit it off.”

The couple married in December 1942. Dottie was a journalism major in college when, in March 1943, Don was admitted to Harvard University Medical School under a US Army program. Dottie got a job as a secretary with the Navy while Don attended medical school.

“Dottie and I talked it over, and we decided that if we were going to spend time together, which it turned out we liked to do, that she probably ought to change her profession,” Don told The Seattle Times. “She’d taken a lot of science in her time in school, much more than most journalists. She liked science.”

So Dottie left her Navy job and enrolled in the medical technology training program at New England Deaconess Hospital.

“Because Dottie was a hematology technician, we used to look at smears and bone marrow together when we were students,” Don said.

She worked as a medical technician for some doctors in Boston until Don had his own laboratory. Then, she began to work with him. She worked part-time when their children were small, but, otherwise, she was in the lab full-time with her husband.