User login

Study supports new gold standard for FL

PET-CT should be the new standard for response assessment in patients with follicular lymphoma (FL), according to researchers.

The group found evidence suggesting that PET-CT is more accurate than conventional CT in measuring treatment response and predicting survival in patients with FL.

“Our findings have important implications for patients with follicular lymphoma,” said study author Judith Trotman, MBChB, of the University of Sydney in Australia.

“Compared to conventional CT scanning, PET-CT is more accurate in mapping out the lymphoma and better identifies the majority of patients who have a prolonged remission after treatment.”

Dr Trotman and her colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet Haematology. The results will also be discussed at the International Workshop on PET in Lymphoma in Menton, France, which is taking place September 19-20.

By assessing imaging performed in 3 clinical trials, the researchers examined the link between PET-CT status and survival following first-line immunochemotherapy for advanced FL.

Independent, masked reviewers evaluated scans of 246 patients who underwent both PET-CT and traditional CT imaging within 3 months of their last dose of therapy. Patients were followed for a median of 54.8 months.

Seventeen percent of patients had a positive post-induction PET scan, according to a cutoff of 4 or higher on the 5PS.

When the researchers compared patients with a positive PET scan to those with a negative scan, the hazard ratio (HR) for progression-free survival (PFS) was 3.9 (P<0.0001). For overall survival, the HR was 6.7 (P=0.0002).

The 4-year PFS was 23.2% in patients with a positive PET scan and 63.4% in those who had a negative PET scan (P<0.0001). The 4-year overall survival was 87.2% and 97.1%, respectively (P<0.0001).

The researchers also discovered that conventional CT-based response—complete response or unconfirmed complete response compared to partial response—was weakly predictive of PFS. The HR was 1.7 (P=0.017).

“Our study shows that PET-CT is much better in evaluating treatment response and is an early predictor of survival,” Dr Trotman said. “This greater accuracy will assist physicians to more effectively monitor their patients.”

“We expect this research will result in PET-CT imaging replacing CT, becoming the new gold standard to evaluate patients with follicular lymphoma after treatment. Importantly, it will be a platform for future studies of response-adapted therapies aimed to improve the poor outcomes for those patients who remain PET-positive.”

This study may also pave the way for several new research opportunities, according to Bruce Cheson, MD, of Georgetown University in Washington DC, who wrote a comment article related to this study.

“One such possibility would be to assess if an early reaction to the PET scan result improves patient outcome,” he wrote. “Thus, patients with a positive PET scan after induction therapy could be randomly assigned to either deferred treatment until disease progression or immediate intervention.”

“A preferable alternative would be to introduce a unique agent at that time, such as the newly developed small molecules (eg, idelalisib, ibrutinib, or ABT-199) in a novel combination.” ![]()

PET-CT should be the new standard for response assessment in patients with follicular lymphoma (FL), according to researchers.

The group found evidence suggesting that PET-CT is more accurate than conventional CT in measuring treatment response and predicting survival in patients with FL.

“Our findings have important implications for patients with follicular lymphoma,” said study author Judith Trotman, MBChB, of the University of Sydney in Australia.

“Compared to conventional CT scanning, PET-CT is more accurate in mapping out the lymphoma and better identifies the majority of patients who have a prolonged remission after treatment.”

Dr Trotman and her colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet Haematology. The results will also be discussed at the International Workshop on PET in Lymphoma in Menton, France, which is taking place September 19-20.

By assessing imaging performed in 3 clinical trials, the researchers examined the link between PET-CT status and survival following first-line immunochemotherapy for advanced FL.

Independent, masked reviewers evaluated scans of 246 patients who underwent both PET-CT and traditional CT imaging within 3 months of their last dose of therapy. Patients were followed for a median of 54.8 months.

Seventeen percent of patients had a positive post-induction PET scan, according to a cutoff of 4 or higher on the 5PS.

When the researchers compared patients with a positive PET scan to those with a negative scan, the hazard ratio (HR) for progression-free survival (PFS) was 3.9 (P<0.0001). For overall survival, the HR was 6.7 (P=0.0002).

The 4-year PFS was 23.2% in patients with a positive PET scan and 63.4% in those who had a negative PET scan (P<0.0001). The 4-year overall survival was 87.2% and 97.1%, respectively (P<0.0001).

The researchers also discovered that conventional CT-based response—complete response or unconfirmed complete response compared to partial response—was weakly predictive of PFS. The HR was 1.7 (P=0.017).

“Our study shows that PET-CT is much better in evaluating treatment response and is an early predictor of survival,” Dr Trotman said. “This greater accuracy will assist physicians to more effectively monitor their patients.”

“We expect this research will result in PET-CT imaging replacing CT, becoming the new gold standard to evaluate patients with follicular lymphoma after treatment. Importantly, it will be a platform for future studies of response-adapted therapies aimed to improve the poor outcomes for those patients who remain PET-positive.”

This study may also pave the way for several new research opportunities, according to Bruce Cheson, MD, of Georgetown University in Washington DC, who wrote a comment article related to this study.

“One such possibility would be to assess if an early reaction to the PET scan result improves patient outcome,” he wrote. “Thus, patients with a positive PET scan after induction therapy could be randomly assigned to either deferred treatment until disease progression or immediate intervention.”

“A preferable alternative would be to introduce a unique agent at that time, such as the newly developed small molecules (eg, idelalisib, ibrutinib, or ABT-199) in a novel combination.” ![]()

PET-CT should be the new standard for response assessment in patients with follicular lymphoma (FL), according to researchers.

The group found evidence suggesting that PET-CT is more accurate than conventional CT in measuring treatment response and predicting survival in patients with FL.

“Our findings have important implications for patients with follicular lymphoma,” said study author Judith Trotman, MBChB, of the University of Sydney in Australia.

“Compared to conventional CT scanning, PET-CT is more accurate in mapping out the lymphoma and better identifies the majority of patients who have a prolonged remission after treatment.”

Dr Trotman and her colleagues reported these findings in The Lancet Haematology. The results will also be discussed at the International Workshop on PET in Lymphoma in Menton, France, which is taking place September 19-20.

By assessing imaging performed in 3 clinical trials, the researchers examined the link between PET-CT status and survival following first-line immunochemotherapy for advanced FL.

Independent, masked reviewers evaluated scans of 246 patients who underwent both PET-CT and traditional CT imaging within 3 months of their last dose of therapy. Patients were followed for a median of 54.8 months.

Seventeen percent of patients had a positive post-induction PET scan, according to a cutoff of 4 or higher on the 5PS.

When the researchers compared patients with a positive PET scan to those with a negative scan, the hazard ratio (HR) for progression-free survival (PFS) was 3.9 (P<0.0001). For overall survival, the HR was 6.7 (P=0.0002).

The 4-year PFS was 23.2% in patients with a positive PET scan and 63.4% in those who had a negative PET scan (P<0.0001). The 4-year overall survival was 87.2% and 97.1%, respectively (P<0.0001).

The researchers also discovered that conventional CT-based response—complete response or unconfirmed complete response compared to partial response—was weakly predictive of PFS. The HR was 1.7 (P=0.017).

“Our study shows that PET-CT is much better in evaluating treatment response and is an early predictor of survival,” Dr Trotman said. “This greater accuracy will assist physicians to more effectively monitor their patients.”

“We expect this research will result in PET-CT imaging replacing CT, becoming the new gold standard to evaluate patients with follicular lymphoma after treatment. Importantly, it will be a platform for future studies of response-adapted therapies aimed to improve the poor outcomes for those patients who remain PET-positive.”

This study may also pave the way for several new research opportunities, according to Bruce Cheson, MD, of Georgetown University in Washington DC, who wrote a comment article related to this study.

“One such possibility would be to assess if an early reaction to the PET scan result improves patient outcome,” he wrote. “Thus, patients with a positive PET scan after induction therapy could be randomly assigned to either deferred treatment until disease progression or immediate intervention.”

“A preferable alternative would be to introduce a unique agent at that time, such as the newly developed small molecules (eg, idelalisib, ibrutinib, or ABT-199) in a novel combination.” ![]()

Group investigates link between implants and ALCL

![]()

Credit: FDA

A newly published review provides insight into anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) associated with breast implants.

Previous reports have demonstrated a link between breast implants and ALCL, but the reasons why implants may contribute to this type of lymphoma have remained unclear.

So Suzanne Turner, PhD, of the University of Cambridge in the UK, and her colleagues evaluated the 71 recorded cases of implant-associated ALCL (iALCL).

The researchers recounted their findings in Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutations Research.

The team calculated that the absolute risk of developing iALCL is low, ranging from 1:500,000 to 1:3,000,000 patients with breast implants per year.

Among the 71 cases of iALCL, the average patient was 50 years of age. The average time from breast augmentation/reconstruction to iALCL diagnosis was 10 years.

Most of the cases presented in the capsule surrounding the implant, as part of the periprosthetic fluid or the capsule itself.

The majority of cases were ALK-negative but had a good prognosis. Of the 49 cases where information on the patients’ progress was available, there were 5 deaths.

Some patients received chemotherapy and radiotherapy, but many achieved remission once the implant and surrounding tissue were removed. This suggests it is the body’s abnormal immune response to the implant that is causing iALCL, the researchers said.

There is some evidence to suggest that having any type of prosthetic implant can increase the risk of lymphoma. And some researchers have suggested that lifestyle differences between patients with and without breast implants may be at the root of iALCL.

But Dr Turner and her colleagues said the biological features of lymphomas in the presence of implants, such as the lack of ALK and the proximity to the implant, suggest a real link.

“It’s becoming clear that implant-related ALCL is a distinct clinical entity in itself,” Dr Turner said. “There are still unanswered questions, and only by getting to the bottom of this very rare disease will we be able to find alternative ways to treat it.” ![]()

![]()

Credit: FDA

A newly published review provides insight into anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) associated with breast implants.

Previous reports have demonstrated a link between breast implants and ALCL, but the reasons why implants may contribute to this type of lymphoma have remained unclear.

So Suzanne Turner, PhD, of the University of Cambridge in the UK, and her colleagues evaluated the 71 recorded cases of implant-associated ALCL (iALCL).

The researchers recounted their findings in Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutations Research.

The team calculated that the absolute risk of developing iALCL is low, ranging from 1:500,000 to 1:3,000,000 patients with breast implants per year.

Among the 71 cases of iALCL, the average patient was 50 years of age. The average time from breast augmentation/reconstruction to iALCL diagnosis was 10 years.

Most of the cases presented in the capsule surrounding the implant, as part of the periprosthetic fluid or the capsule itself.

The majority of cases were ALK-negative but had a good prognosis. Of the 49 cases where information on the patients’ progress was available, there were 5 deaths.

Some patients received chemotherapy and radiotherapy, but many achieved remission once the implant and surrounding tissue were removed. This suggests it is the body’s abnormal immune response to the implant that is causing iALCL, the researchers said.

There is some evidence to suggest that having any type of prosthetic implant can increase the risk of lymphoma. And some researchers have suggested that lifestyle differences between patients with and without breast implants may be at the root of iALCL.

But Dr Turner and her colleagues said the biological features of lymphomas in the presence of implants, such as the lack of ALK and the proximity to the implant, suggest a real link.

“It’s becoming clear that implant-related ALCL is a distinct clinical entity in itself,” Dr Turner said. “There are still unanswered questions, and only by getting to the bottom of this very rare disease will we be able to find alternative ways to treat it.” ![]()

![]()

Credit: FDA

A newly published review provides insight into anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (ALCL) associated with breast implants.

Previous reports have demonstrated a link between breast implants and ALCL, but the reasons why implants may contribute to this type of lymphoma have remained unclear.

So Suzanne Turner, PhD, of the University of Cambridge in the UK, and her colleagues evaluated the 71 recorded cases of implant-associated ALCL (iALCL).

The researchers recounted their findings in Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutations Research.

The team calculated that the absolute risk of developing iALCL is low, ranging from 1:500,000 to 1:3,000,000 patients with breast implants per year.

Among the 71 cases of iALCL, the average patient was 50 years of age. The average time from breast augmentation/reconstruction to iALCL diagnosis was 10 years.

Most of the cases presented in the capsule surrounding the implant, as part of the periprosthetic fluid or the capsule itself.

The majority of cases were ALK-negative but had a good prognosis. Of the 49 cases where information on the patients’ progress was available, there were 5 deaths.

Some patients received chemotherapy and radiotherapy, but many achieved remission once the implant and surrounding tissue were removed. This suggests it is the body’s abnormal immune response to the implant that is causing iALCL, the researchers said.

There is some evidence to suggest that having any type of prosthetic implant can increase the risk of lymphoma. And some researchers have suggested that lifestyle differences between patients with and without breast implants may be at the root of iALCL.

But Dr Turner and her colleagues said the biological features of lymphomas in the presence of implants, such as the lack of ALK and the proximity to the implant, suggest a real link.

“It’s becoming clear that implant-related ALCL is a distinct clinical entity in itself,” Dr Turner said. “There are still unanswered questions, and only by getting to the bottom of this very rare disease will we be able to find alternative ways to treat it.” ![]()

Shorter duration of DAPT appears safe

Credit: Andre E.X. Brown

WASHINGTON, DC—New research indicates that patients may only need 6 months of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after receiving a second-generation drug-eluting stent.

Results of the SECURITY trial showed that patients had similar outcomes whether they received DAPT for 6 months or a full year.

The proportion of patients who met a composite endpoint of cardiac, thrombotic, and bleeding events was low among both treatment groups at the 12- and 24-month time points.

Antonio Colombo, MD, of San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan, Italy, and his colleagues reported these findings at TCT 2014 and in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

SECURITY was a randomized, multicenter study that aimed to address the need for prolonged use of DAPT following the implantation of a second-generation drug-eluting stent for patients without high-risk acute coronary syndromes.

Patients with a diagnosis of stable or unstable angina or documented silent ischemia undergoing revascularization with at least 1 second-generation drug-eluting stent were eligible for the study. The stents used were the Endeavor Resolute (Medtronic), Xience (Abbott), Promus (Boston Scientific), Nobori (Terumo Corporation), and the Biomatrix (Biosensors Europe SA).

Of 1399 patients, 682 were randomized to 6 months of DAPT, and 717 were randomized to 12 months of treatment. They received clopidogrel at 75 mg per day for at least 3 days before the procedure or a pre-procedural loading dose of a minimum of 300 mg of clopidogrel, if they were not on chronic clopidogrel therapy.

In the post-procedure period, patients received 75 mg of clopidogrel for 6 or 12 months, according to randomization. They also received aspirin indefinitely. And once the new antiplatelet compounds prasugrel and ticagrelor hit the market, they were allowed as treatment options in a protocol amendment.

At 12 months, the incidence of the primary endpoint—the composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, definite or probable stent thrombosis, or BARC type 3 or 5 bleeding—was 4.5% in the 6-month DAPT group and 3.7% in the 12-month DAPT group (P=0.469).

After 24 months, the 6-month and 12-month groups still showed similar incidences of cardiac death (0.9% vs 0.8%, P=0.925), MI (3.1% vs 2.6%, P=0.636), stroke (0.9% vs 0.4%, P=0.636), stent thrombosis (0.4% vs 0.4%, P=0.951), and BARC 3 or 5 bleeding (0.7% vs 1.1%, P=0.496).

Rates of the secondary endpoint—a composite of cardiac death, spontaneous MI, stroke, definite or probable stent thrombosis, or BARC type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding at 12 and 24 months—were also similar among the 6-month and 12-month treatment groups.

At 12 months, the incidence of the secondary composite endpoint was 5.3% in the 6-month group and 4.0% in the 12-month group (P=0.273). In the year that followed, both groups had lower incidences of secondary composite endpoints—1.5% and 2.2%, respectively (P=0.289).

A multivariable analysis showed that an age of 75 years or older, the type of stent used, the mean number of stents implanted, the mean stent length, and the mean stent size were all significant independent predictors of the primary endpoint.

The SECURITY trial was funded by grants from Medtronic and Terumo, makers of 2 brands of drug-eluting stents used in the study. ![]()

Credit: Andre E.X. Brown

WASHINGTON, DC—New research indicates that patients may only need 6 months of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after receiving a second-generation drug-eluting stent.

Results of the SECURITY trial showed that patients had similar outcomes whether they received DAPT for 6 months or a full year.

The proportion of patients who met a composite endpoint of cardiac, thrombotic, and bleeding events was low among both treatment groups at the 12- and 24-month time points.

Antonio Colombo, MD, of San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan, Italy, and his colleagues reported these findings at TCT 2014 and in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

SECURITY was a randomized, multicenter study that aimed to address the need for prolonged use of DAPT following the implantation of a second-generation drug-eluting stent for patients without high-risk acute coronary syndromes.

Patients with a diagnosis of stable or unstable angina or documented silent ischemia undergoing revascularization with at least 1 second-generation drug-eluting stent were eligible for the study. The stents used were the Endeavor Resolute (Medtronic), Xience (Abbott), Promus (Boston Scientific), Nobori (Terumo Corporation), and the Biomatrix (Biosensors Europe SA).

Of 1399 patients, 682 were randomized to 6 months of DAPT, and 717 were randomized to 12 months of treatment. They received clopidogrel at 75 mg per day for at least 3 days before the procedure or a pre-procedural loading dose of a minimum of 300 mg of clopidogrel, if they were not on chronic clopidogrel therapy.

In the post-procedure period, patients received 75 mg of clopidogrel for 6 or 12 months, according to randomization. They also received aspirin indefinitely. And once the new antiplatelet compounds prasugrel and ticagrelor hit the market, they were allowed as treatment options in a protocol amendment.

At 12 months, the incidence of the primary endpoint—the composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, definite or probable stent thrombosis, or BARC type 3 or 5 bleeding—was 4.5% in the 6-month DAPT group and 3.7% in the 12-month DAPT group (P=0.469).

After 24 months, the 6-month and 12-month groups still showed similar incidences of cardiac death (0.9% vs 0.8%, P=0.925), MI (3.1% vs 2.6%, P=0.636), stroke (0.9% vs 0.4%, P=0.636), stent thrombosis (0.4% vs 0.4%, P=0.951), and BARC 3 or 5 bleeding (0.7% vs 1.1%, P=0.496).

Rates of the secondary endpoint—a composite of cardiac death, spontaneous MI, stroke, definite or probable stent thrombosis, or BARC type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding at 12 and 24 months—were also similar among the 6-month and 12-month treatment groups.

At 12 months, the incidence of the secondary composite endpoint was 5.3% in the 6-month group and 4.0% in the 12-month group (P=0.273). In the year that followed, both groups had lower incidences of secondary composite endpoints—1.5% and 2.2%, respectively (P=0.289).

A multivariable analysis showed that an age of 75 years or older, the type of stent used, the mean number of stents implanted, the mean stent length, and the mean stent size were all significant independent predictors of the primary endpoint.

The SECURITY trial was funded by grants from Medtronic and Terumo, makers of 2 brands of drug-eluting stents used in the study. ![]()

Credit: Andre E.X. Brown

WASHINGTON, DC—New research indicates that patients may only need 6 months of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) after receiving a second-generation drug-eluting stent.

Results of the SECURITY trial showed that patients had similar outcomes whether they received DAPT for 6 months or a full year.

The proportion of patients who met a composite endpoint of cardiac, thrombotic, and bleeding events was low among both treatment groups at the 12- and 24-month time points.

Antonio Colombo, MD, of San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Milan, Italy, and his colleagues reported these findings at TCT 2014 and in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

SECURITY was a randomized, multicenter study that aimed to address the need for prolonged use of DAPT following the implantation of a second-generation drug-eluting stent for patients without high-risk acute coronary syndromes.

Patients with a diagnosis of stable or unstable angina or documented silent ischemia undergoing revascularization with at least 1 second-generation drug-eluting stent were eligible for the study. The stents used were the Endeavor Resolute (Medtronic), Xience (Abbott), Promus (Boston Scientific), Nobori (Terumo Corporation), and the Biomatrix (Biosensors Europe SA).

Of 1399 patients, 682 were randomized to 6 months of DAPT, and 717 were randomized to 12 months of treatment. They received clopidogrel at 75 mg per day for at least 3 days before the procedure or a pre-procedural loading dose of a minimum of 300 mg of clopidogrel, if they were not on chronic clopidogrel therapy.

In the post-procedure period, patients received 75 mg of clopidogrel for 6 or 12 months, according to randomization. They also received aspirin indefinitely. And once the new antiplatelet compounds prasugrel and ticagrelor hit the market, they were allowed as treatment options in a protocol amendment.

At 12 months, the incidence of the primary endpoint—the composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, definite or probable stent thrombosis, or BARC type 3 or 5 bleeding—was 4.5% in the 6-month DAPT group and 3.7% in the 12-month DAPT group (P=0.469).

After 24 months, the 6-month and 12-month groups still showed similar incidences of cardiac death (0.9% vs 0.8%, P=0.925), MI (3.1% vs 2.6%, P=0.636), stroke (0.9% vs 0.4%, P=0.636), stent thrombosis (0.4% vs 0.4%, P=0.951), and BARC 3 or 5 bleeding (0.7% vs 1.1%, P=0.496).

Rates of the secondary endpoint—a composite of cardiac death, spontaneous MI, stroke, definite or probable stent thrombosis, or BARC type 2, 3, or 5 bleeding at 12 and 24 months—were also similar among the 6-month and 12-month treatment groups.

At 12 months, the incidence of the secondary composite endpoint was 5.3% in the 6-month group and 4.0% in the 12-month group (P=0.273). In the year that followed, both groups had lower incidences of secondary composite endpoints—1.5% and 2.2%, respectively (P=0.289).

A multivariable analysis showed that an age of 75 years or older, the type of stent used, the mean number of stents implanted, the mean stent length, and the mean stent size were all significant independent predictors of the primary endpoint.

The SECURITY trial was funded by grants from Medtronic and Terumo, makers of 2 brands of drug-eluting stents used in the study. ![]()

Bivalirudin bests heparin in BRIGHT trial

Credit: Bill Branson

WASHINGTON, DC—The latest results from the BRIGHT trial suggest bivalirudin confers benefits over heparin monotherapy and heparin plus tirofiban for patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

Patients who received bivalirudin had a significantly lower incidence of net adverse clinical events (NACE), a composite of death from any cause, reinfarction, ischemia-driven target vessel revascularization, stroke, or any bleeding, both at 30 days and at 1 year.

Bivalirudin conferred a lower risk of bleeding at both time points as well.

However, there were no significant differences between the treatment arms with regard to stent thrombosis or major adverse cardiac and cerebral events (MACCE), a composite of death from any cause, reinfarction, ischemia-driven target vessel revascularization, or stroke.

Yaling Han, MD, of the General Hospital of Shenyang Military Region in China, presented these data at TCT 2014.

The BRIGHT trial included 2194 patients who had acute myocardial infarction and were eligible for emergency percutaneous coronary intervention. They were randomized to receive bivalirudin alone (n=735), heparin alone (n=729), or heparin plus tirofiban (n=730).

The primary endpoint was NACE at 30 days. Secondary endpoints were NACE at 1 year, any bleeding at 30 days and 1 year, and MACCE at 30 days and 1 year. Safety endpoints were thrombocytopenia at 30 days and stent thrombosis at 30 days and 1 year.

Bivalirudin was superior to both heparin monotherapy and heparin plus tirofiban in reducing the primary composite endpoint. At 30 days, NACE had occurred in 8.8%, 13.2%, and 17.0% of patients, respectively (P<0.001).

Bivalirudin was also superior with regard to bleeding at 30 days. Bleeding occurred in 4.1% of patients in the bivalirudin arm, 7.5% in the heparin arm, and 12.3% in the heparin-tirofiban arm (P<0.001).

However, there was no significant difference between the arms for the incidence of MACCE at 30 days—5.0%, 5.8%, and 4.9%, respectively (P=0.74). Likewise, there was no significant difference in the rate of stent thrombosis at 30 days—0.6%, 0.9%, and 0.7%, respectively (P=0.77).

There were differences between the arms in the 30-day thrombocytopenia rate, which was 0.1% in the bivalirudin arm, 0.7% in the heparin arm, and 1.1% in the heparin-tirofiban arm (P=0.04 for bivalirudin vs pooled heparin, P=0.12 for bivalirudin vs heparin, P=0.02 for bivalirudin vs heparin-tirofiban).

The differences between the treatment arms at 1 year were similar to those observed at the 30-day mark. Bivalirudin remained significantly superior when it came to NACE and bleeding, but there were no significant differences with regard to MACCE and stent thrombosis.

At 1-year, NACE had occurred in 12.8% of patients in the bivalirudin arm, 16.5% in the heparin arm, and 20.5% in the heparin-tirofiban arm (P<0.001). Bleeding had occurred in 6.3%, 9.9%, and 14.2% of patients, respectively (P<0.001).

The incidence of MACCE was 6.7% in the bivalirudin arm, 7.3% in the heparin arm, and 6.8%, in the heparin-tirofiban arm. And stent thrombosis had occurred in 1.2%, 1.9%, and 1.2% of patients, respectively.

This research was funded by Salubris Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, makers of bivalirudin, and the National Key Science and Technology R&D project of the 12th Five-Year Plan. ![]()

Credit: Bill Branson

WASHINGTON, DC—The latest results from the BRIGHT trial suggest bivalirudin confers benefits over heparin monotherapy and heparin plus tirofiban for patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

Patients who received bivalirudin had a significantly lower incidence of net adverse clinical events (NACE), a composite of death from any cause, reinfarction, ischemia-driven target vessel revascularization, stroke, or any bleeding, both at 30 days and at 1 year.

Bivalirudin conferred a lower risk of bleeding at both time points as well.

However, there were no significant differences between the treatment arms with regard to stent thrombosis or major adverse cardiac and cerebral events (MACCE), a composite of death from any cause, reinfarction, ischemia-driven target vessel revascularization, or stroke.

Yaling Han, MD, of the General Hospital of Shenyang Military Region in China, presented these data at TCT 2014.

The BRIGHT trial included 2194 patients who had acute myocardial infarction and were eligible for emergency percutaneous coronary intervention. They were randomized to receive bivalirudin alone (n=735), heparin alone (n=729), or heparin plus tirofiban (n=730).

The primary endpoint was NACE at 30 days. Secondary endpoints were NACE at 1 year, any bleeding at 30 days and 1 year, and MACCE at 30 days and 1 year. Safety endpoints were thrombocytopenia at 30 days and stent thrombosis at 30 days and 1 year.

Bivalirudin was superior to both heparin monotherapy and heparin plus tirofiban in reducing the primary composite endpoint. At 30 days, NACE had occurred in 8.8%, 13.2%, and 17.0% of patients, respectively (P<0.001).

Bivalirudin was also superior with regard to bleeding at 30 days. Bleeding occurred in 4.1% of patients in the bivalirudin arm, 7.5% in the heparin arm, and 12.3% in the heparin-tirofiban arm (P<0.001).

However, there was no significant difference between the arms for the incidence of MACCE at 30 days—5.0%, 5.8%, and 4.9%, respectively (P=0.74). Likewise, there was no significant difference in the rate of stent thrombosis at 30 days—0.6%, 0.9%, and 0.7%, respectively (P=0.77).

There were differences between the arms in the 30-day thrombocytopenia rate, which was 0.1% in the bivalirudin arm, 0.7% in the heparin arm, and 1.1% in the heparin-tirofiban arm (P=0.04 for bivalirudin vs pooled heparin, P=0.12 for bivalirudin vs heparin, P=0.02 for bivalirudin vs heparin-tirofiban).

The differences between the treatment arms at 1 year were similar to those observed at the 30-day mark. Bivalirudin remained significantly superior when it came to NACE and bleeding, but there were no significant differences with regard to MACCE and stent thrombosis.

At 1-year, NACE had occurred in 12.8% of patients in the bivalirudin arm, 16.5% in the heparin arm, and 20.5% in the heparin-tirofiban arm (P<0.001). Bleeding had occurred in 6.3%, 9.9%, and 14.2% of patients, respectively (P<0.001).

The incidence of MACCE was 6.7% in the bivalirudin arm, 7.3% in the heparin arm, and 6.8%, in the heparin-tirofiban arm. And stent thrombosis had occurred in 1.2%, 1.9%, and 1.2% of patients, respectively.

This research was funded by Salubris Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, makers of bivalirudin, and the National Key Science and Technology R&D project of the 12th Five-Year Plan. ![]()

Credit: Bill Branson

WASHINGTON, DC—The latest results from the BRIGHT trial suggest bivalirudin confers benefits over heparin monotherapy and heparin plus tirofiban for patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention.

Patients who received bivalirudin had a significantly lower incidence of net adverse clinical events (NACE), a composite of death from any cause, reinfarction, ischemia-driven target vessel revascularization, stroke, or any bleeding, both at 30 days and at 1 year.

Bivalirudin conferred a lower risk of bleeding at both time points as well.

However, there were no significant differences between the treatment arms with regard to stent thrombosis or major adverse cardiac and cerebral events (MACCE), a composite of death from any cause, reinfarction, ischemia-driven target vessel revascularization, or stroke.

Yaling Han, MD, of the General Hospital of Shenyang Military Region in China, presented these data at TCT 2014.

The BRIGHT trial included 2194 patients who had acute myocardial infarction and were eligible for emergency percutaneous coronary intervention. They were randomized to receive bivalirudin alone (n=735), heparin alone (n=729), or heparin plus tirofiban (n=730).

The primary endpoint was NACE at 30 days. Secondary endpoints were NACE at 1 year, any bleeding at 30 days and 1 year, and MACCE at 30 days and 1 year. Safety endpoints were thrombocytopenia at 30 days and stent thrombosis at 30 days and 1 year.

Bivalirudin was superior to both heparin monotherapy and heparin plus tirofiban in reducing the primary composite endpoint. At 30 days, NACE had occurred in 8.8%, 13.2%, and 17.0% of patients, respectively (P<0.001).

Bivalirudin was also superior with regard to bleeding at 30 days. Bleeding occurred in 4.1% of patients in the bivalirudin arm, 7.5% in the heparin arm, and 12.3% in the heparin-tirofiban arm (P<0.001).

However, there was no significant difference between the arms for the incidence of MACCE at 30 days—5.0%, 5.8%, and 4.9%, respectively (P=0.74). Likewise, there was no significant difference in the rate of stent thrombosis at 30 days—0.6%, 0.9%, and 0.7%, respectively (P=0.77).

There were differences between the arms in the 30-day thrombocytopenia rate, which was 0.1% in the bivalirudin arm, 0.7% in the heparin arm, and 1.1% in the heparin-tirofiban arm (P=0.04 for bivalirudin vs pooled heparin, P=0.12 for bivalirudin vs heparin, P=0.02 for bivalirudin vs heparin-tirofiban).

The differences between the treatment arms at 1 year were similar to those observed at the 30-day mark. Bivalirudin remained significantly superior when it came to NACE and bleeding, but there were no significant differences with regard to MACCE and stent thrombosis.

At 1-year, NACE had occurred in 12.8% of patients in the bivalirudin arm, 16.5% in the heparin arm, and 20.5% in the heparin-tirofiban arm (P<0.001). Bleeding had occurred in 6.3%, 9.9%, and 14.2% of patients, respectively (P<0.001).

The incidence of MACCE was 6.7% in the bivalirudin arm, 7.3% in the heparin arm, and 6.8%, in the heparin-tirofiban arm. And stent thrombosis had occurred in 1.2%, 1.9%, and 1.2% of patients, respectively.

This research was funded by Salubris Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, makers of bivalirudin, and the National Key Science and Technology R&D project of the 12th Five-Year Plan. ![]()

Honey

Honeybees (Apis mellifera, A. cerana, A. dorsata, A. floria, A. andreniformis, A. koschevnikov, and A. laborisa) play a key role in propagating numerous plants, flower nectar, and flower pollen as well as in pollinating approximately one-third of common agricultural crops, including fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds (Time magazine; Proc. Biol. Sci. 2007;274[1608]:303-13). Indeed, the honeybee is the lone insect that produces food regularly consumed by human beings (Am. J. Ther. 2014;21:304-23). Honey, which contains more than 180 compounds, is produced by honeybees from flower nectar. This sweet food product is supersaturated in sugar, and also contains phenolic acids, flavonoids, ascorbic acid, alpha-tocopherol, carotenoids, the enzymes glucose oxidase and catalase, organic and amino acids, and proteins (J. Food Sci. 2008;73:R117-24). Honey has been used since ancient times in Ayurvedic medicine to treat diabetes and has long been used to treat infected wounds (Ayu 2012;33:178-82; Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:1541-9). Currently, honey is used in Ayurvedic medicine to treat acne, and it is incorporated in various cosmetic formulations such as facial washes, skin moisturizers, and hair conditioners (Ayu 2012;33:178-82).

History

For at least 2,700 years, traditional medical practice has included the use of topically applied honey for various conditions, with many modern researchers retrospectively attributing this usage to the antibacterial activity of honey (Am. J. Ther. 2014;21:304-23; Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;46:1677-82). Honey served as a potent anti-inflammatory and antibacterial agent in folk remedies in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, with written references to the medical application of bee products dating back to ancientEgypt, India, and China (Am. J. Ther. 2014;21:304-23; Cancer Res. 1993;53:1255-61; Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013;2013:697390)). For more than 4,000 years, honey has been used in Ayurvedic medicine, and its use has been traced to the Xin dynasty in China (Am. J. Ther. 2014;21:304-23). The antibacterial characteristics of honey were first reported in 1892 (IUBMB Life 2012;64:48-55). Russia and Germany used honey for wound treatment through World War I. The traditional medical application of honey began to subside with the advent of antibiotics in the 1940s(Burns 2013; 39:1514-25; Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007;61:1705-7).

Chemistry

Myriad biological functions are associated with honey (antibacterial, antioxidant, antitumor, anti-inflammatory, antibrowning, and antiviral) and ascribed mainly to its constituent phenolic compounds, such as flavonoids, including chrysin (J. Food Sci. 2008;73:R117-24). Indeed, medical grade honeys such as manuka honey (a monofloral honey derived from Leptospermum scoparium, a member of the Myrtaceae family, native to New Zealand) and Medihoney® (a standardized mix of Australian and New Zealand honeys) are rich in flavonoids (Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007;61:1705-7;J. Int. Acad. Periodontol. 2004;6:63-7; Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2009;6:165-73;J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:7229-37). Honey has a pH ranging from 3.2 to 4.5 and an acidity level that stymies the growth of many microorganisms (Burns 2013;39:1514-25; J. Clin. Nurs. 2008;17:2604-23; Nurs. Times. 2006;102:40-2; Br. J. Community Nurs. 2004;Suppl:S21-7 ).

Antibacterial activity

In 2008, Kwakman et al. found that within 24 hours, 10%-40% (vol/vol) medical grade honey (Revamil) destroyed antibiotic-susceptible and antibiotic-resistant isolates of Staphylococcus aureus,S. epidermidis, Enterococcus faecium, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter cloacae, and Klebsiella oxytoca. After 2 days of honey application, they also observed a 100-fold decrease in forearm skin colonization in healthy volunteers, with the number of positive skin cultures declining by 76%. The researchers concluded that Revamil exhibits significant potential to prevent or treat infections, including those spawned by multidrug-resistant bacteria (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;46:1677-82). Honey has been demonstrated to be clinically effective in treating several kinds of wound infections, reducing skin colonization of multiple bacteria, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;46:1677-82) and enhancing wound healing, without provoking adverse effects ( Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:1541-9). Manuka honey and Medihoney are the main forms of medical grade honey used in clinical practice. Nonmedical grade honey may contain viable bacterial spores (including clostridia), and manifest less predictable antibacterial properties (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:1541-9).

Honey is used in over-the-counter products as a moisturizing agent and in hair-conditioning products based on its strong humectant properties. It is also used in home remedies to treat burns, wounds, eczema, and dermatitis, especially in Asia (Ayu 2012;33:178-8).

Seborrheic dermatitis/dandruff

In 2001, Al-Waili assessed the potential of topically applied crude honey (90% honey diluted in warm water) to treat chronic seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp, face, and chest in 30 patients (20 males and 10 females, aged 15-60 years). Over the initial 4 weeks of treatment, honey was gently rubbed onto lesions every other day for 2-3 minutes at a time, with the ointment left on for 3 hours before gentle warm-water rinsing. Then, in a 6-month prophylactic phase, the participants were divided into a once-weekly treatment group and a control group. Skin lesions healed completely within 2 weeks in the treatment group, after significant reductions in itching and scaling in just the first week. Subjective improvements in hair loss were also reported. Relapse was observed in 12 of the 15 subjects in the control group within 2-4 months of therapy cessation and none in the treatment group. The author concluded that weekly use of crude honey significantly improves seborrheic dermatitis symptoms and related hair loss (Eur. J. Med. Res. 2001;6:306-8).

Wound healing

In February 2013, Jull published a review of 25 randomized and quasirandomized trials evaluating honey in the treatment of acute or chronic wounds, finding that honey might delay healing in partial- and full-thickness burns, compared with early excision and grafting, but it does not significantly enhance healing of chronic venous leg ulcers. They suggested that while honey may prove to be more effective than some conventional dressings for such ulcers, evidence is currently insufficient to support this claim ( Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013;2:CD005083). Later that year, Vandamme et al. identified 55 studies in a literature review suggesting that honey stimulates healing of burns, ulcers, and other wounds. They also found, despite some methodologic concerns, that honey exerts antibacterial activity in burn treatment and deodorizing, debridement, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic activity ( Burns 2013;39:1514-25).

Conclusion

Honey has a long history of traditional medicinal use and has been found to display significant biologic activity, including antibacterial, antioxidant, antitumor, anti-inflammatory, antibrowning, and antiviral. The antibacterial properties of honey are particularly compelling. While more research, in the form of randomized, controlled trials, is needed prior to incorporating bee products into the dermatologic armamentarium as first-line therapies, the potential of honey usage for skin care is promising.

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in Miami Beach. She founded the cosmetic dermatology center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (McGraw-Hill, April 2002), and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (Bantam, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2001. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Galderma, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy, Stiefel, Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

Honeybees (Apis mellifera, A. cerana, A. dorsata, A. floria, A. andreniformis, A. koschevnikov, and A. laborisa) play a key role in propagating numerous plants, flower nectar, and flower pollen as well as in pollinating approximately one-third of common agricultural crops, including fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds (Time magazine; Proc. Biol. Sci. 2007;274[1608]:303-13). Indeed, the honeybee is the lone insect that produces food regularly consumed by human beings (Am. J. Ther. 2014;21:304-23). Honey, which contains more than 180 compounds, is produced by honeybees from flower nectar. This sweet food product is supersaturated in sugar, and also contains phenolic acids, flavonoids, ascorbic acid, alpha-tocopherol, carotenoids, the enzymes glucose oxidase and catalase, organic and amino acids, and proteins (J. Food Sci. 2008;73:R117-24). Honey has been used since ancient times in Ayurvedic medicine to treat diabetes and has long been used to treat infected wounds (Ayu 2012;33:178-82; Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:1541-9). Currently, honey is used in Ayurvedic medicine to treat acne, and it is incorporated in various cosmetic formulations such as facial washes, skin moisturizers, and hair conditioners (Ayu 2012;33:178-82).

History

For at least 2,700 years, traditional medical practice has included the use of topically applied honey for various conditions, with many modern researchers retrospectively attributing this usage to the antibacterial activity of honey (Am. J. Ther. 2014;21:304-23; Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;46:1677-82). Honey served as a potent anti-inflammatory and antibacterial agent in folk remedies in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, with written references to the medical application of bee products dating back to ancientEgypt, India, and China (Am. J. Ther. 2014;21:304-23; Cancer Res. 1993;53:1255-61; Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013;2013:697390)). For more than 4,000 years, honey has been used in Ayurvedic medicine, and its use has been traced to the Xin dynasty in China (Am. J. Ther. 2014;21:304-23). The antibacterial characteristics of honey were first reported in 1892 (IUBMB Life 2012;64:48-55). Russia and Germany used honey for wound treatment through World War I. The traditional medical application of honey began to subside with the advent of antibiotics in the 1940s(Burns 2013; 39:1514-25; Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007;61:1705-7).

Chemistry

Myriad biological functions are associated with honey (antibacterial, antioxidant, antitumor, anti-inflammatory, antibrowning, and antiviral) and ascribed mainly to its constituent phenolic compounds, such as flavonoids, including chrysin (J. Food Sci. 2008;73:R117-24). Indeed, medical grade honeys such as manuka honey (a monofloral honey derived from Leptospermum scoparium, a member of the Myrtaceae family, native to New Zealand) and Medihoney® (a standardized mix of Australian and New Zealand honeys) are rich in flavonoids (Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007;61:1705-7;J. Int. Acad. Periodontol. 2004;6:63-7; Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2009;6:165-73;J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:7229-37). Honey has a pH ranging from 3.2 to 4.5 and an acidity level that stymies the growth of many microorganisms (Burns 2013;39:1514-25; J. Clin. Nurs. 2008;17:2604-23; Nurs. Times. 2006;102:40-2; Br. J. Community Nurs. 2004;Suppl:S21-7 ).

Antibacterial activity

In 2008, Kwakman et al. found that within 24 hours, 10%-40% (vol/vol) medical grade honey (Revamil) destroyed antibiotic-susceptible and antibiotic-resistant isolates of Staphylococcus aureus,S. epidermidis, Enterococcus faecium, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter cloacae, and Klebsiella oxytoca. After 2 days of honey application, they also observed a 100-fold decrease in forearm skin colonization in healthy volunteers, with the number of positive skin cultures declining by 76%. The researchers concluded that Revamil exhibits significant potential to prevent or treat infections, including those spawned by multidrug-resistant bacteria (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;46:1677-82). Honey has been demonstrated to be clinically effective in treating several kinds of wound infections, reducing skin colonization of multiple bacteria, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;46:1677-82) and enhancing wound healing, without provoking adverse effects ( Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:1541-9). Manuka honey and Medihoney are the main forms of medical grade honey used in clinical practice. Nonmedical grade honey may contain viable bacterial spores (including clostridia), and manifest less predictable antibacterial properties (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:1541-9).

Honey is used in over-the-counter products as a moisturizing agent and in hair-conditioning products based on its strong humectant properties. It is also used in home remedies to treat burns, wounds, eczema, and dermatitis, especially in Asia (Ayu 2012;33:178-8).

Seborrheic dermatitis/dandruff

In 2001, Al-Waili assessed the potential of topically applied crude honey (90% honey diluted in warm water) to treat chronic seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp, face, and chest in 30 patients (20 males and 10 females, aged 15-60 years). Over the initial 4 weeks of treatment, honey was gently rubbed onto lesions every other day for 2-3 minutes at a time, with the ointment left on for 3 hours before gentle warm-water rinsing. Then, in a 6-month prophylactic phase, the participants were divided into a once-weekly treatment group and a control group. Skin lesions healed completely within 2 weeks in the treatment group, after significant reductions in itching and scaling in just the first week. Subjective improvements in hair loss were also reported. Relapse was observed in 12 of the 15 subjects in the control group within 2-4 months of therapy cessation and none in the treatment group. The author concluded that weekly use of crude honey significantly improves seborrheic dermatitis symptoms and related hair loss (Eur. J. Med. Res. 2001;6:306-8).

Wound healing

In February 2013, Jull published a review of 25 randomized and quasirandomized trials evaluating honey in the treatment of acute or chronic wounds, finding that honey might delay healing in partial- and full-thickness burns, compared with early excision and grafting, but it does not significantly enhance healing of chronic venous leg ulcers. They suggested that while honey may prove to be more effective than some conventional dressings for such ulcers, evidence is currently insufficient to support this claim ( Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013;2:CD005083). Later that year, Vandamme et al. identified 55 studies in a literature review suggesting that honey stimulates healing of burns, ulcers, and other wounds. They also found, despite some methodologic concerns, that honey exerts antibacterial activity in burn treatment and deodorizing, debridement, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic activity ( Burns 2013;39:1514-25).

Conclusion

Honey has a long history of traditional medicinal use and has been found to display significant biologic activity, including antibacterial, antioxidant, antitumor, anti-inflammatory, antibrowning, and antiviral. The antibacterial properties of honey are particularly compelling. While more research, in the form of randomized, controlled trials, is needed prior to incorporating bee products into the dermatologic armamentarium as first-line therapies, the potential of honey usage for skin care is promising.

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in Miami Beach. She founded the cosmetic dermatology center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (McGraw-Hill, April 2002), and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (Bantam, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2001. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Galderma, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy, Stiefel, Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

Honeybees (Apis mellifera, A. cerana, A. dorsata, A. floria, A. andreniformis, A. koschevnikov, and A. laborisa) play a key role in propagating numerous plants, flower nectar, and flower pollen as well as in pollinating approximately one-third of common agricultural crops, including fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds (Time magazine; Proc. Biol. Sci. 2007;274[1608]:303-13). Indeed, the honeybee is the lone insect that produces food regularly consumed by human beings (Am. J. Ther. 2014;21:304-23). Honey, which contains more than 180 compounds, is produced by honeybees from flower nectar. This sweet food product is supersaturated in sugar, and also contains phenolic acids, flavonoids, ascorbic acid, alpha-tocopherol, carotenoids, the enzymes glucose oxidase and catalase, organic and amino acids, and proteins (J. Food Sci. 2008;73:R117-24). Honey has been used since ancient times in Ayurvedic medicine to treat diabetes and has long been used to treat infected wounds (Ayu 2012;33:178-82; Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:1541-9). Currently, honey is used in Ayurvedic medicine to treat acne, and it is incorporated in various cosmetic formulations such as facial washes, skin moisturizers, and hair conditioners (Ayu 2012;33:178-82).

History

For at least 2,700 years, traditional medical practice has included the use of topically applied honey for various conditions, with many modern researchers retrospectively attributing this usage to the antibacterial activity of honey (Am. J. Ther. 2014;21:304-23; Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;46:1677-82). Honey served as a potent anti-inflammatory and antibacterial agent in folk remedies in ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, with written references to the medical application of bee products dating back to ancientEgypt, India, and China (Am. J. Ther. 2014;21:304-23; Cancer Res. 1993;53:1255-61; Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2013;2013:697390)). For more than 4,000 years, honey has been used in Ayurvedic medicine, and its use has been traced to the Xin dynasty in China (Am. J. Ther. 2014;21:304-23). The antibacterial characteristics of honey were first reported in 1892 (IUBMB Life 2012;64:48-55). Russia and Germany used honey for wound treatment through World War I. The traditional medical application of honey began to subside with the advent of antibiotics in the 1940s(Burns 2013; 39:1514-25; Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007;61:1705-7).

Chemistry

Myriad biological functions are associated with honey (antibacterial, antioxidant, antitumor, anti-inflammatory, antibrowning, and antiviral) and ascribed mainly to its constituent phenolic compounds, such as flavonoids, including chrysin (J. Food Sci. 2008;73:R117-24). Indeed, medical grade honeys such as manuka honey (a monofloral honey derived from Leptospermum scoparium, a member of the Myrtaceae family, native to New Zealand) and Medihoney® (a standardized mix of Australian and New Zealand honeys) are rich in flavonoids (Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007;61:1705-7;J. Int. Acad. Periodontol. 2004;6:63-7; Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2009;6:165-73;J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:7229-37). Honey has a pH ranging from 3.2 to 4.5 and an acidity level that stymies the growth of many microorganisms (Burns 2013;39:1514-25; J. Clin. Nurs. 2008;17:2604-23; Nurs. Times. 2006;102:40-2; Br. J. Community Nurs. 2004;Suppl:S21-7 ).

Antibacterial activity

In 2008, Kwakman et al. found that within 24 hours, 10%-40% (vol/vol) medical grade honey (Revamil) destroyed antibiotic-susceptible and antibiotic-resistant isolates of Staphylococcus aureus,S. epidermidis, Enterococcus faecium, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter cloacae, and Klebsiella oxytoca. After 2 days of honey application, they also observed a 100-fold decrease in forearm skin colonization in healthy volunteers, with the number of positive skin cultures declining by 76%. The researchers concluded that Revamil exhibits significant potential to prevent or treat infections, including those spawned by multidrug-resistant bacteria (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;46:1677-82). Honey has been demonstrated to be clinically effective in treating several kinds of wound infections, reducing skin colonization of multiple bacteria, including methicillin-resistant S. aureus (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;46:1677-82) and enhancing wound healing, without provoking adverse effects ( Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:1541-9). Manuka honey and Medihoney are the main forms of medical grade honey used in clinical practice. Nonmedical grade honey may contain viable bacterial spores (including clostridia), and manifest less predictable antibacterial properties (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;49:1541-9).

Honey is used in over-the-counter products as a moisturizing agent and in hair-conditioning products based on its strong humectant properties. It is also used in home remedies to treat burns, wounds, eczema, and dermatitis, especially in Asia (Ayu 2012;33:178-8).

Seborrheic dermatitis/dandruff

In 2001, Al-Waili assessed the potential of topically applied crude honey (90% honey diluted in warm water) to treat chronic seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp, face, and chest in 30 patients (20 males and 10 females, aged 15-60 years). Over the initial 4 weeks of treatment, honey was gently rubbed onto lesions every other day for 2-3 minutes at a time, with the ointment left on for 3 hours before gentle warm-water rinsing. Then, in a 6-month prophylactic phase, the participants were divided into a once-weekly treatment group and a control group. Skin lesions healed completely within 2 weeks in the treatment group, after significant reductions in itching and scaling in just the first week. Subjective improvements in hair loss were also reported. Relapse was observed in 12 of the 15 subjects in the control group within 2-4 months of therapy cessation and none in the treatment group. The author concluded that weekly use of crude honey significantly improves seborrheic dermatitis symptoms and related hair loss (Eur. J. Med. Res. 2001;6:306-8).

Wound healing

In February 2013, Jull published a review of 25 randomized and quasirandomized trials evaluating honey in the treatment of acute or chronic wounds, finding that honey might delay healing in partial- and full-thickness burns, compared with early excision and grafting, but it does not significantly enhance healing of chronic venous leg ulcers. They suggested that while honey may prove to be more effective than some conventional dressings for such ulcers, evidence is currently insufficient to support this claim ( Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013;2:CD005083). Later that year, Vandamme et al. identified 55 studies in a literature review suggesting that honey stimulates healing of burns, ulcers, and other wounds. They also found, despite some methodologic concerns, that honey exerts antibacterial activity in burn treatment and deodorizing, debridement, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic activity ( Burns 2013;39:1514-25).

Conclusion

Honey has a long history of traditional medicinal use and has been found to display significant biologic activity, including antibacterial, antioxidant, antitumor, anti-inflammatory, antibrowning, and antiviral. The antibacterial properties of honey are particularly compelling. While more research, in the form of randomized, controlled trials, is needed prior to incorporating bee products into the dermatologic armamentarium as first-line therapies, the potential of honey usage for skin care is promising.

Dr. Baumann is chief executive officer of the Baumann Cosmetic & Research Institute in Miami Beach. She founded the cosmetic dermatology center at the University of Miami in 1997. Dr. Baumann wrote the textbook “Cosmetic Dermatology: Principles and Practice” (McGraw-Hill, April 2002), and a book for consumers, “The Skin Type Solution” (Bantam, 2006). She has contributed to the Cosmeceutical Critique column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2001. Dr. Baumann has received funding for clinical grants from Allergan, Aveeno, Avon Products, Galderma, Mary Kay, Medicis Pharmaceuticals, Neutrogena, Philosophy, Stiefel, Topix Pharmaceuticals, and Unilever.

Depressed, suicidal, and brittle in her bones

CASE Broken down

Ms. E, age 20, is a college student who has had major depressive disorder for several years and a genetic bone disease (osteogenesis imperfecta, mixed type III and IV). She presents with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. She reports recent worsening of her depressive symptoms, including anhedonia, excessive sleep, difficulty concentrating, and feeling overwhelmed, hopeless, and worthless. She also describes frequent thoughts of suicide with the plan of putting herself in oncoming traffic, although she has no history of suicide attempts.

Previously, her primary care physician prescribed lorazepam, 0.5 mg, as needed for anxiety, and sertraline, 100 mg/d, for depression and anxiety. She experienced only partial improvement in symptoms, however.

In addition to depressive symptoms, Ms. E describes manic symptoms lasting for as long as 3 to 5 days, including decreased need for sleep, increased energy, pressured speech, racing thoughts, distractibility, spending excessive money on cosmetics, and risking her safety—given her skeletal disorder— by participating in high-impact stage-combat classes. She denies auditory and visual hallucinations, homicidal ideation, and delusions.

The medical history is significant for osteogenesis imperfecta, which has caused 62 fractures and required 16 surgeries. Ms. E is a theater major who, despite her short stature and wheelchair use, reports enjoying her acting career and says she does not feel demoralized by her medical condition. She describes overcoming her physical disabilities with pride and confidence. However, her recent worsening mood symptoms have left her unable to concentrate and feeling overwhelmed with school.

Ms. E is voluntarily admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder with rapid cycling, most recent episode mixed. Because of her bone fragility, the treatment team considers what would be an appropriate course of drug treatment to control bipolar symptoms while minimizing risk of bone loss.

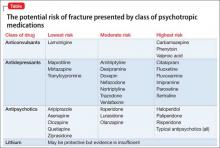

Which medications are associated with decreased bone mineral density?

a) citalopram

b) haloperidol

c) carbamazepine

d) paliperidone

e) all of the above

The authors’ observations

Osteogenesis imperfecta is a genetic condition caused by mutations in genes implicated in collagen production. As a result, bones are brittle and prone to fracture. Different classes of psychotropics have been shown to increase risk of bone fractures through a variety of mechanisms. Clinicians often must choose appropriate pharmacotherapy for patients at high risk of fracture, including postmenopausal women, older patients, malnourished persons, and those with hormonal deficiencies leading to osteoporosis.

To assist our clinical decision-making, we reviewed the literature to establish appropriate management of a patient with increased bone fragility and new-onset bipolar disorder. We considered all classes of medications used to treat bipolar disorder, including antipsychotics, antidepressants, lithium, and anticonvulsants.

Antipsychotics

In population-based studies, prolactin-elevating antipsychotics have been associated with decreased bone mineral density and increased risk of fracture.1 Additional studies on geriatric and non-geriatric populations have supported these findings.2,3

The mechanism through which fracture risk is increased likely is related to antipsychotics’ effect on serum prolactin and cortisol levels. Antipsychotics act as antagonists on D2 receptors in the hypothalamic tubero-infundibular pathway, therefore preventing inhibition of prolactin. Long-term elevation in serum prolactin can cause loss of bone mineral density through secondary hypogonadism and direct effects on target tissues. Additional modifying factors include smoking and estrogen use.

The degree to which antipsychotics increase fracture risk might be related to the degree of serum prolactin elevation.4 Antipsychotics previously have been grouped by the degree of prolactin elevation, categorizing them as high, medium, and low or no potential to elevate serum prolactin.4 Based on this classification, typical antipsychotics, risperidone, and paliperidone have the highest potential to elevate prolactin. Accordingly, antipsychotics with the lowest fracture risk are those that have the lowest risk of serum prolactin elevation: ziprasidone, asenapine, quetiapine, and clozapine. Aripiprazole may lower prolactin in some patients. This is supported by studies noting reduced bone mineral density5,6 and increased risk of fracture1 with high-potential vs low- or no-potential antipsychotics. Because of these findings, it is crucial to consider the potential risk of prolactin elevation when treating patients at increased risk of fracture. Providers should consider low/no potential antipsychotic medications before considering those with medium or high potential (Table).

Antidepressants

In a meta-analysis, antidepressants were shown to increase fracture risk by 70% to 90%.2 However, the relative risk varies by antidepressant class. Several studies have shown that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are associated with a higher risk of fracture compared with tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs).7 In addition, antidepressants with a high affinity for the serotonin transporter, including citalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, sertraline, and imipramine, have been associated with greater risk of osteoporotic fracture compared with those with low affinity.8

The mechanisms by which antidepressants increase fracture risk are complex, although the strongest evidence implicates a direct effect on bone metabolism via the 5-HTT receptor. This receptor, found on osteoblasts and osteoclasts, plays an important role in bone metabolism; it is through this receptor that SSRIs might inhibit osteoblasts and promote osteoclast activity, thereby disrupting bone microarchitecture. Additional studies are needed to further describe the mechanism of the association among antidepressants, bone mineral density, and fracture risk.

Fracture risk is associated with duration of use rather than dosage. Population-based studies show a higher fracture risk for new users of TCAs compared with continuous users, and the risk of fracture with SSRIs seems to increase slightly over time.9 No association has been identified between fracture risk and antidepressant dosage. According to the literature, drugs with low affinity for the serotonin transporter, such as maprotiline and mirtazapine, likely are the safest antidepressants for patients at increased risk of fracture. Options also include other TCAs and any antidepressant with low affinity for the serotonin receptor.7,8

Lithium

Studies on lithium and bone mineral density have shown mixed results. Older studies found that lithium had a negative or no effect on bone mineral density or the parathyroid hormone level.10 More recent investigations, however, suggest that the drug has a protective effect on bone mineral density, although this has not been replicated in all studies.

In a mouse model, lithium has been shown to enhance bone formation and improve bone mass, at least in part by activation of the Wnt signaling pathway through an inhibitory effect on glycogen synthase kinase-3β.11 In humans, lithium-treated adults had lower serum alkaline phosphate, osteocalcin, and C-telopeptide levels compared with controls, suggesting a state of decreased bone remodeling and increased turnover.12 There is a paucity of clinical data on the effect of lithium on fracture risk. Additional studies are necessary to elucidate lithium’s mechanism on bone mineral density and determine the magnitude of the clinical effect.

Anticonvulsants

The association among anticonvulsants, decreased bone mineral density, and increased risk of fracture is well-established in the literature.13 However, causality is difficult to determine, because many studies were of patients with a seizure disorder, who often have additional risk factors for fracture, including seizure-related trauma, drowsiness, and slowed reflexes.

Mechanisms through which anticonvulsants increase fracture risk include increased bone resorption, secondary hypoparathyroidism, and pseudohypoparathyroidism. Markers of bone resorption were elevated in patients receiving an antiepileptic.14 This effect might be enhanced by co-administration of cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants and CYP450 enzyme-inhibiting medications, such as valproate. Long-term treatment with valproate may produce reduction of bone mass and increased risk of fractures; however, other studies disagree with this finding.15

In addition to CYP450-inducing effects, phenytoin, carbamezapine, and phenobarbital can increase catabolism of vitamin D, which is associated with osteomalacia.14 This results in decreased intestinal absorption of calcium, hypocalcemia, and secondary hyperparathyroidism, which also increases fracture risk. Anticonvulsants also might increase resistance to pseudohypoparathyroidism and inhibit calcitonin secretion.

Lamotrigine has not been shown to interfere with bone accrual16 and may be a safer mood stabilizer for patients at high risk of fracture. For patients at increased risk of fracture, it is important to select an anticonvulsant wisely to minimize fracture risk.

How would you treat Ms. E during her hospitalization for bipolar disorder?

a) carbamazepine

b) lithium

c) risperidone

d) mirtazapine

TREATMENT Minimizing polypharmacy

Because many pharmacotherapeutic options for managing bipolar disorder can increase the risk of fracture, clinicians must be aware of the relative risk of each class of medication and each individual drug. We initiated lithium, 300 mg, 3 times a day, to stabilize Ms. E’s mood. Although clinical data are inconclusive regarding lithium’s effect on fracture risk, we felt that the benefit of acute mood stabilization outweighed the risk of decreased bone mineral index.

We selected aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, as an adjunctive treatment because of its minimal effect on serum prolactin levels.4 We considered prescribing an antidepressant but decided against it because we were concerned about manic switching.

Polypharmacy is another important consideration for Ms. E. Several studies have identified polypharmacy, particularly with antipsychotics, as an independent risk factor for fracture.3 Therefore, we sought to minimize the number of medications Ms. E receives. Although lithium monotherapy is an option, we thought that her mood symptoms were severe enough that the risk of inadequately treating her bipolar symptoms outweighed the additional risk of fracture from dual therapy with lithium and aripiprazole. Untreated or inadequately treated depression is associated with a higher fracture risk. Therefore, we avoided prescribing >2 medications to mitigate any excessive risk of fracture from polypharmacy.

Bottom Line

Different classes of medications—antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and lithium—used for treating bipolar disorder have been shown to increase risk of bone fracture through a variety of mechanisms. Anticonvulsants and prolactin-elevating antipsychotics are associated with increased fracture risk; evidence on lithium is mixed. Fracture risk with antidepressants is associated with duration of use, rather than dosage.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Howard L, Kirkwood G, Leese M. Risk of hip fracture in patients with a history of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:129-134.

2. Takkouche B, Montes-Martínez A, Gill SS, et al. Psychotropic medications and the risk of fracture: a meta-analysis. Drug Saf. 2007;30(2):171-184.

3. Sørensen HJ, Jensen SO, Nielsen J. Schizophrenia, antipsychotics and risk of hip fracture: a population-based analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(8):872-878.

4. Rahman T, Clevenger CV, Kaklamani V, et al. Antipsychotic treatment in breast cancer patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(6):616-621.

5. Bilici M, Cakirbay H, Guler M, et al. Classical and atypical neuroleptics, and bone mineral density, in patients with schizophrenia. Int J Neurosci. 2002;112(7):817-828.

6. Becker D, Liver O, Mester R, et al. Risperidone, but not olanzapine, decreases bone mineral density in female premenopausal schizophrenia patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(7):761-766.

7. Bolton JM, Metge C, Lix L, et al. Fracture risk from psychotropic medications: a population-based analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(4):384-391.

8. Verdel BM, Souverein PC, Egberts TC, et al. Use of antidepressant drugs and risk of osteoporotic and non-osteoporotic fractures. Bone. 2010;47(3):604-609.

9. Diem SJ, Ruppert K, Cauley JA. Rates of bone loss among women initiating antidepressant medication use in midlife. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;(11):4355-4363.

10. Plenge P, Rafaelsen OJ. Lithium effects on calcium, magnesium and phosphate in man: effects on balance, bone mineral content, faecal and urinary excretion. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1982;66(5):361-373.

11. Clément-Lacroix P, Ai M, Morvan F, et al. Lrp5-independent activation of Wnt signaling by lithium chloride increases bone formation and bone mass in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(48):17406-17411.

12. Zamani A, Omrani GR, Nasab MM. Lithium’s effect on bone mineral density. Bone. 2009;44(2):331-334.

13. Swanton J, Simister R, Altmann D, et al. Bone mineral density in institutionalised patients with refractory epilepsy. Seizure. 2007;16(6):538-541.

14. Pack AM, Morrell MJ. Epilepsy and bone health in adults. Epilepsy Behav. 2004;5(suppl 2):S24-S29.

15. Pack AM. Bone disease in epilepsy. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2004;4(4):329-334.

16. Sheth RD, Hermann BP. Bone mineral density with lamotrigine monotherapy for epilepsy. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;37(4):250-254.

CASE Broken down

Ms. E, age 20, is a college student who has had major depressive disorder for several years and a genetic bone disease (osteogenesis imperfecta, mixed type III and IV). She presents with depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. She reports recent worsening of her depressive symptoms, including anhedonia, excessive sleep, difficulty concentrating, and feeling overwhelmed, hopeless, and worthless. She also describes frequent thoughts of suicide with the plan of putting herself in oncoming traffic, although she has no history of suicide attempts.

Previously, her primary care physician prescribed lorazepam, 0.5 mg, as needed for anxiety, and sertraline, 100 mg/d, for depression and anxiety. She experienced only partial improvement in symptoms, however.

In addition to depressive symptoms, Ms. E describes manic symptoms lasting for as long as 3 to 5 days, including decreased need for sleep, increased energy, pressured speech, racing thoughts, distractibility, spending excessive money on cosmetics, and risking her safety—given her skeletal disorder— by participating in high-impact stage-combat classes. She denies auditory and visual hallucinations, homicidal ideation, and delusions.

The medical history is significant for osteogenesis imperfecta, which has caused 62 fractures and required 16 surgeries. Ms. E is a theater major who, despite her short stature and wheelchair use, reports enjoying her acting career and says she does not feel demoralized by her medical condition. She describes overcoming her physical disabilities with pride and confidence. However, her recent worsening mood symptoms have left her unable to concentrate and feeling overwhelmed with school.

Ms. E is voluntarily admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder with rapid cycling, most recent episode mixed. Because of her bone fragility, the treatment team considers what would be an appropriate course of drug treatment to control bipolar symptoms while minimizing risk of bone loss.

Which medications are associated with decreased bone mineral density?

a) citalopram

b) haloperidol

c) carbamazepine

d) paliperidone

e) all of the above

The authors’ observations

Osteogenesis imperfecta is a genetic condition caused by mutations in genes implicated in collagen production. As a result, bones are brittle and prone to fracture. Different classes of psychotropics have been shown to increase risk of bone fractures through a variety of mechanisms. Clinicians often must choose appropriate pharmacotherapy for patients at high risk of fracture, including postmenopausal women, older patients, malnourished persons, and those with hormonal deficiencies leading to osteoporosis.

To assist our clinical decision-making, we reviewed the literature to establish appropriate management of a patient with increased bone fragility and new-onset bipolar disorder. We considered all classes of medications used to treat bipolar disorder, including antipsychotics, antidepressants, lithium, and anticonvulsants.

Antipsychotics

In population-based studies, prolactin-elevating antipsychotics have been associated with decreased bone mineral density and increased risk of fracture.1 Additional studies on geriatric and non-geriatric populations have supported these findings.2,3