User login

For love or money: How do doctors choose their specialty?

Medical student loans top hundreds of thousands of dollars, so it’s understandable that physicians may want to select a specialty that pays well.

Moreover, most advised young doctors to follow their hearts rather than their wallets.

“There is no question that many young kids immediately think about money when deciding to pursue medicine, but the thought of a big paycheck will never sustain someone long enough to get them here,” says Sergio Alvarez, MD, a board-certified plastic surgeon based in Miami, Fla., and the CEO and medical director of Mia Aesthetics, which has several national locations.

“Getting into medicine is a long game, and there are many hurdles along the way that only the dedicated overcome,” says Dr. Alvarez.

Unfortunately, he says it may be late in that long game before some realize that the pay rate for certain specialties isn’t commensurate with the immense workload and responsibility they require.

“The short of it is that to become a happy doctor, medicine really needs to be a calling: a passion! There are far easier things to do to make money.”

Here is what physicians said about choosing between love or money.

The lowest-paying subspecialty in a low-paying specialty

Sophia Yen, MD, MPH, cofounder and CEO of Pandia Health, a women-founded, doctor-led birth control delivery service in Sunnyvale, Calif., and clinical associate professor at Stanford (Calif.) University, says you should pursue a specialty because you love the work.

“I chose the lowest-paying subspecialty (adolescent medicine) of a low-paying specialty (pediatrics), but I’d do it all again because I love the patient population – I love what I do.”

Dr. Yen says she chose adolescent medicine because she loves doing “outpatient gynecology” without going through the surgical training of a full ob.gyn. “I love the target population of young adults because you can talk to the patient versus in pediatrics, where you often talk to the parent. With young adults you can catch things – for example, teach a young person about consent, alcohol, marijuana’s effects on the growing brain, prevent unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections, instill healthy eating, and more.

“Do I wish that I got paid as much as a surgeon?” Dr. Yen says yes. “I hope that someday society will realize the time spent preventing future disease is worth it and pay us accordingly.”

Unfortunately, she says, since the health care system makes more money if you get pregnant, need a cardiac bypass, or need gastric surgery, those who deliver babies or do surgery get paid more than someone who prevents the need for those services.

Money doesn’t buy happiness

Stella Bard, MD, a rheumatologist in McKinney, Tex., says she eats, lives, and breathes rheumatology. “I never regret the decision of choosing this specialty for a single second,” says Dr. Bard. “I feel like it’s a rewarding experience with every single patient encounter.” Dr. Bard notes that money is no guarantee of happiness and that she feels blessed to wake up every morning doing what she loves.

Career or calling?

For Dr. Alvarez, inspiration came when watching his father help change people’s lives. “I saw how impactful a doctor is during a person’s most desperate moments, and that was enough to make medicine my life’s passion at the age of 10.”

He says once you’re in medical school, choosing a specialty is far easier than you think. “Each specialty requires a certain personality or specific characteristics, and some will call to you while others simply won’t.”

“For me, plastics was about finesse, art, and life-changing surgeries that affected people from kids to adults and involved every aspect of the human body. Changing someone’s outward appearance has a profoundly positive impact on their confidence and self-esteem, making plastic surgery a genuinely transformative experience.”

Patricia Celan, MD, a postgraduate psychiatry resident in Canada, also chose psychiatry for the love of the field. “I enjoy helping vulnerable people and exploring what makes a person tick, the source of their difficulties, and how to help people counteract and overcome the difficult cards they’ve been dealt in life.”

She says it’s incredibly rewarding to watch someone turn their life around from severe mental illness, especially those who have been victimized and traumatized, and learn to trust people again.

“I could have made more money in a higher-paying specialty, yes, but I’m not sure I would have felt as fulfilled as psychiatry can make me feel.”

Dr. Celan says everyone has their calling, and some lucky people find their deepest passion in higher-paying specialties. “My calling is psychiatry, and I am at peace with this no matter the money.”

For the love of surgery

“In my experience, most people don’t choose their specialty based on money,” says Nicole Aaronson, MD, MBA, an otolaryngologist and board-certified in the subspecialty of pediatric otolaryngology, an attending surgeon at Nemours Children’s Health of Delaware and clinical associate professor of otolaryngology and pediatrics at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia.

“The first decision point in medical school is usually figuring out if you are a surgery person or a medicine person. I knew very early that I wanted to be a surgeon and wanted to spend time in the OR fixing problems with my hands.”

Part of what attracted Dr. Aaronson to otolaryngology was the variety of conditions managed within the specialty, from head and neck cancer to voice problems to sleep disorders to sinus disease. “I chose my subspecialty because I enjoy working with children and making an impact that will help them live their best possible lives.”

She says a relatively simple surgery like placing ear tubes may help a child’s hearing and allow them to be more successful in school, opening up a new world of opportunities for the child’s future.

“While I don’t think most people choose their specialty based on prospective compensation, I do think all physicians want to be compensated fairly for their time, effort, and level of training,” says Dr. Aaronson.

Choosing a specialty for the money can lead to burnout and dissatisfaction

“For me, the decision to pursue gastroenterology went beyond financial considerations,” says Saurabh Sethi, MD, MPH, a gastroenterologist specializing in hepatology and interventional endoscopy. “While financial stability is undoubtedly important, no doctor enters this field solely for the love of money. The primary driving force for most medical professionals, myself included, is the passion to help people and make a positive difference in their lives.”

Dr. Sethi says the gratification that comes from providing quality care and witnessing patients’ improved well-being is priceless. Moreover, he believes that selecting a specialty based solely on financial gain is likely to lead to burnout and greater dissatisfaction over time.

“By following my love for gut health and prioritizing patient care, I have found a sense of fulfillment and purpose in my career. It has been a rewarding journey, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the well-being of my patients through my expertise in gastroenterology.”

Key takeaways: Love or money?

Multiple factors influence doctors’ specialty choices, including genuine love for the work and the future of the specialty. Others include job prospects, hands-on experience they receive, mentors, childhood dreams, parental expectations, complexity of cases, the lifestyle of each specialty, including office hours worked, on-call requirements, and autonomy.

Physicians also mentioned other factors they considered when choosing their specialty:

- Personal interest.

- Intellectual stimulation.

- Work-life balance.

- Patient populations.

- Future opportunities.

- Desire to make a difference.

- Passion.

- Financial stability.

- Being personally fulfilled.

Overwhelmingly, doctors say to pick a specialty you can envision yourself loving 40 years from now and you won’t go wrong.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medical student loans top hundreds of thousands of dollars, so it’s understandable that physicians may want to select a specialty that pays well.

Moreover, most advised young doctors to follow their hearts rather than their wallets.

“There is no question that many young kids immediately think about money when deciding to pursue medicine, but the thought of a big paycheck will never sustain someone long enough to get them here,” says Sergio Alvarez, MD, a board-certified plastic surgeon based in Miami, Fla., and the CEO and medical director of Mia Aesthetics, which has several national locations.

“Getting into medicine is a long game, and there are many hurdles along the way that only the dedicated overcome,” says Dr. Alvarez.

Unfortunately, he says it may be late in that long game before some realize that the pay rate for certain specialties isn’t commensurate with the immense workload and responsibility they require.

“The short of it is that to become a happy doctor, medicine really needs to be a calling: a passion! There are far easier things to do to make money.”

Here is what physicians said about choosing between love or money.

The lowest-paying subspecialty in a low-paying specialty

Sophia Yen, MD, MPH, cofounder and CEO of Pandia Health, a women-founded, doctor-led birth control delivery service in Sunnyvale, Calif., and clinical associate professor at Stanford (Calif.) University, says you should pursue a specialty because you love the work.

“I chose the lowest-paying subspecialty (adolescent medicine) of a low-paying specialty (pediatrics), but I’d do it all again because I love the patient population – I love what I do.”

Dr. Yen says she chose adolescent medicine because she loves doing “outpatient gynecology” without going through the surgical training of a full ob.gyn. “I love the target population of young adults because you can talk to the patient versus in pediatrics, where you often talk to the parent. With young adults you can catch things – for example, teach a young person about consent, alcohol, marijuana’s effects on the growing brain, prevent unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections, instill healthy eating, and more.

“Do I wish that I got paid as much as a surgeon?” Dr. Yen says yes. “I hope that someday society will realize the time spent preventing future disease is worth it and pay us accordingly.”

Unfortunately, she says, since the health care system makes more money if you get pregnant, need a cardiac bypass, or need gastric surgery, those who deliver babies or do surgery get paid more than someone who prevents the need for those services.

Money doesn’t buy happiness

Stella Bard, MD, a rheumatologist in McKinney, Tex., says she eats, lives, and breathes rheumatology. “I never regret the decision of choosing this specialty for a single second,” says Dr. Bard. “I feel like it’s a rewarding experience with every single patient encounter.” Dr. Bard notes that money is no guarantee of happiness and that she feels blessed to wake up every morning doing what she loves.

Career or calling?

For Dr. Alvarez, inspiration came when watching his father help change people’s lives. “I saw how impactful a doctor is during a person’s most desperate moments, and that was enough to make medicine my life’s passion at the age of 10.”

He says once you’re in medical school, choosing a specialty is far easier than you think. “Each specialty requires a certain personality or specific characteristics, and some will call to you while others simply won’t.”

“For me, plastics was about finesse, art, and life-changing surgeries that affected people from kids to adults and involved every aspect of the human body. Changing someone’s outward appearance has a profoundly positive impact on their confidence and self-esteem, making plastic surgery a genuinely transformative experience.”

Patricia Celan, MD, a postgraduate psychiatry resident in Canada, also chose psychiatry for the love of the field. “I enjoy helping vulnerable people and exploring what makes a person tick, the source of their difficulties, and how to help people counteract and overcome the difficult cards they’ve been dealt in life.”

She says it’s incredibly rewarding to watch someone turn their life around from severe mental illness, especially those who have been victimized and traumatized, and learn to trust people again.

“I could have made more money in a higher-paying specialty, yes, but I’m not sure I would have felt as fulfilled as psychiatry can make me feel.”

Dr. Celan says everyone has their calling, and some lucky people find their deepest passion in higher-paying specialties. “My calling is psychiatry, and I am at peace with this no matter the money.”

For the love of surgery

“In my experience, most people don’t choose their specialty based on money,” says Nicole Aaronson, MD, MBA, an otolaryngologist and board-certified in the subspecialty of pediatric otolaryngology, an attending surgeon at Nemours Children’s Health of Delaware and clinical associate professor of otolaryngology and pediatrics at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia.

“The first decision point in medical school is usually figuring out if you are a surgery person or a medicine person. I knew very early that I wanted to be a surgeon and wanted to spend time in the OR fixing problems with my hands.”

Part of what attracted Dr. Aaronson to otolaryngology was the variety of conditions managed within the specialty, from head and neck cancer to voice problems to sleep disorders to sinus disease. “I chose my subspecialty because I enjoy working with children and making an impact that will help them live their best possible lives.”

She says a relatively simple surgery like placing ear tubes may help a child’s hearing and allow them to be more successful in school, opening up a new world of opportunities for the child’s future.

“While I don’t think most people choose their specialty based on prospective compensation, I do think all physicians want to be compensated fairly for their time, effort, and level of training,” says Dr. Aaronson.

Choosing a specialty for the money can lead to burnout and dissatisfaction

“For me, the decision to pursue gastroenterology went beyond financial considerations,” says Saurabh Sethi, MD, MPH, a gastroenterologist specializing in hepatology and interventional endoscopy. “While financial stability is undoubtedly important, no doctor enters this field solely for the love of money. The primary driving force for most medical professionals, myself included, is the passion to help people and make a positive difference in their lives.”

Dr. Sethi says the gratification that comes from providing quality care and witnessing patients’ improved well-being is priceless. Moreover, he believes that selecting a specialty based solely on financial gain is likely to lead to burnout and greater dissatisfaction over time.

“By following my love for gut health and prioritizing patient care, I have found a sense of fulfillment and purpose in my career. It has been a rewarding journey, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the well-being of my patients through my expertise in gastroenterology.”

Key takeaways: Love or money?

Multiple factors influence doctors’ specialty choices, including genuine love for the work and the future of the specialty. Others include job prospects, hands-on experience they receive, mentors, childhood dreams, parental expectations, complexity of cases, the lifestyle of each specialty, including office hours worked, on-call requirements, and autonomy.

Physicians also mentioned other factors they considered when choosing their specialty:

- Personal interest.

- Intellectual stimulation.

- Work-life balance.

- Patient populations.

- Future opportunities.

- Desire to make a difference.

- Passion.

- Financial stability.

- Being personally fulfilled.

Overwhelmingly, doctors say to pick a specialty you can envision yourself loving 40 years from now and you won’t go wrong.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medical student loans top hundreds of thousands of dollars, so it’s understandable that physicians may want to select a specialty that pays well.

Moreover, most advised young doctors to follow their hearts rather than their wallets.

“There is no question that many young kids immediately think about money when deciding to pursue medicine, but the thought of a big paycheck will never sustain someone long enough to get them here,” says Sergio Alvarez, MD, a board-certified plastic surgeon based in Miami, Fla., and the CEO and medical director of Mia Aesthetics, which has several national locations.

“Getting into medicine is a long game, and there are many hurdles along the way that only the dedicated overcome,” says Dr. Alvarez.

Unfortunately, he says it may be late in that long game before some realize that the pay rate for certain specialties isn’t commensurate with the immense workload and responsibility they require.

“The short of it is that to become a happy doctor, medicine really needs to be a calling: a passion! There are far easier things to do to make money.”

Here is what physicians said about choosing between love or money.

The lowest-paying subspecialty in a low-paying specialty

Sophia Yen, MD, MPH, cofounder and CEO of Pandia Health, a women-founded, doctor-led birth control delivery service in Sunnyvale, Calif., and clinical associate professor at Stanford (Calif.) University, says you should pursue a specialty because you love the work.

“I chose the lowest-paying subspecialty (adolescent medicine) of a low-paying specialty (pediatrics), but I’d do it all again because I love the patient population – I love what I do.”

Dr. Yen says she chose adolescent medicine because she loves doing “outpatient gynecology” without going through the surgical training of a full ob.gyn. “I love the target population of young adults because you can talk to the patient versus in pediatrics, where you often talk to the parent. With young adults you can catch things – for example, teach a young person about consent, alcohol, marijuana’s effects on the growing brain, prevent unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted infections, instill healthy eating, and more.

“Do I wish that I got paid as much as a surgeon?” Dr. Yen says yes. “I hope that someday society will realize the time spent preventing future disease is worth it and pay us accordingly.”

Unfortunately, she says, since the health care system makes more money if you get pregnant, need a cardiac bypass, or need gastric surgery, those who deliver babies or do surgery get paid more than someone who prevents the need for those services.

Money doesn’t buy happiness

Stella Bard, MD, a rheumatologist in McKinney, Tex., says she eats, lives, and breathes rheumatology. “I never regret the decision of choosing this specialty for a single second,” says Dr. Bard. “I feel like it’s a rewarding experience with every single patient encounter.” Dr. Bard notes that money is no guarantee of happiness and that she feels blessed to wake up every morning doing what she loves.

Career or calling?

For Dr. Alvarez, inspiration came when watching his father help change people’s lives. “I saw how impactful a doctor is during a person’s most desperate moments, and that was enough to make medicine my life’s passion at the age of 10.”

He says once you’re in medical school, choosing a specialty is far easier than you think. “Each specialty requires a certain personality or specific characteristics, and some will call to you while others simply won’t.”

“For me, plastics was about finesse, art, and life-changing surgeries that affected people from kids to adults and involved every aspect of the human body. Changing someone’s outward appearance has a profoundly positive impact on their confidence and self-esteem, making plastic surgery a genuinely transformative experience.”

Patricia Celan, MD, a postgraduate psychiatry resident in Canada, also chose psychiatry for the love of the field. “I enjoy helping vulnerable people and exploring what makes a person tick, the source of their difficulties, and how to help people counteract and overcome the difficult cards they’ve been dealt in life.”

She says it’s incredibly rewarding to watch someone turn their life around from severe mental illness, especially those who have been victimized and traumatized, and learn to trust people again.

“I could have made more money in a higher-paying specialty, yes, but I’m not sure I would have felt as fulfilled as psychiatry can make me feel.”

Dr. Celan says everyone has their calling, and some lucky people find their deepest passion in higher-paying specialties. “My calling is psychiatry, and I am at peace with this no matter the money.”

For the love of surgery

“In my experience, most people don’t choose their specialty based on money,” says Nicole Aaronson, MD, MBA, an otolaryngologist and board-certified in the subspecialty of pediatric otolaryngology, an attending surgeon at Nemours Children’s Health of Delaware and clinical associate professor of otolaryngology and pediatrics at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Philadelphia.

“The first decision point in medical school is usually figuring out if you are a surgery person or a medicine person. I knew very early that I wanted to be a surgeon and wanted to spend time in the OR fixing problems with my hands.”

Part of what attracted Dr. Aaronson to otolaryngology was the variety of conditions managed within the specialty, from head and neck cancer to voice problems to sleep disorders to sinus disease. “I chose my subspecialty because I enjoy working with children and making an impact that will help them live their best possible lives.”

She says a relatively simple surgery like placing ear tubes may help a child’s hearing and allow them to be more successful in school, opening up a new world of opportunities for the child’s future.

“While I don’t think most people choose their specialty based on prospective compensation, I do think all physicians want to be compensated fairly for their time, effort, and level of training,” says Dr. Aaronson.

Choosing a specialty for the money can lead to burnout and dissatisfaction

“For me, the decision to pursue gastroenterology went beyond financial considerations,” says Saurabh Sethi, MD, MPH, a gastroenterologist specializing in hepatology and interventional endoscopy. “While financial stability is undoubtedly important, no doctor enters this field solely for the love of money. The primary driving force for most medical professionals, myself included, is the passion to help people and make a positive difference in their lives.”

Dr. Sethi says the gratification that comes from providing quality care and witnessing patients’ improved well-being is priceless. Moreover, he believes that selecting a specialty based solely on financial gain is likely to lead to burnout and greater dissatisfaction over time.

“By following my love for gut health and prioritizing patient care, I have found a sense of fulfillment and purpose in my career. It has been a rewarding journey, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the well-being of my patients through my expertise in gastroenterology.”

Key takeaways: Love or money?

Multiple factors influence doctors’ specialty choices, including genuine love for the work and the future of the specialty. Others include job prospects, hands-on experience they receive, mentors, childhood dreams, parental expectations, complexity of cases, the lifestyle of each specialty, including office hours worked, on-call requirements, and autonomy.

Physicians also mentioned other factors they considered when choosing their specialty:

- Personal interest.

- Intellectual stimulation.

- Work-life balance.

- Patient populations.

- Future opportunities.

- Desire to make a difference.

- Passion.

- Financial stability.

- Being personally fulfilled.

Overwhelmingly, doctors say to pick a specialty you can envision yourself loving 40 years from now and you won’t go wrong.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Interrupting radiotherapy for TNBC linked to worse survival

Topline

Methodology

- Clinicians sometimes give women with TNBC a break between radiation sessions so that their skin can heal.

- To gauge the impact, investigators reviewed data from the National Cancer Database on 35,845 patients with TNBC who were treated between 2010 and 2014.

- The researchers determined the number of interrupted radiation treatment days as the difference between the number of days women received radiotherapy versus the number of expected treatment days.

- The team then correlated treatment interruptions with overall survival.

Takeaway

- Longer duration of treatment was associated with worse overall survival (hazard ratio, 1.023).

- Compared with no days or just 1 day off, 2-5 interrupted days (HR, 1.069), 6-10 interrupted days (HR, 1.239), and 11-15 interrupted days (HR, 1.265) increased the likelihood of death in a stepwise fashion.

- More days between diagnosis and first cancer treatment of any kind (HR, 1.001) were associated with worse overall survival.

- Older age (HR, 1.014), Black race (HR, 1.278), race than other Black or White (HR, 1.337), grade II or III/IV tumors (HR, 1.471 and 1.743, respectively), and clinical N1-N3 stage (HR, 2.534, 3.729, 4.992, respectively) were also associated with worse overall survival.

In practice

“All reasonable efforts should be made to prevent any treatment interruptions,” including “prophylactic measures to reduce the severity of radiation dermatitis,” and consideration should be given to the use of hypofractionated regimens to shorten radiation schedules.

Source

The study was led by Ronald Chow, MS, of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and was published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Limitations

- The findings may not be applicable to less aggressive forms of breast cancer.

- Treatment interruptions may have been caused by poor performance status and other confounders that shorten survival.

Disclosures

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. The investigators had no disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Topline

Methodology

- Clinicians sometimes give women with TNBC a break between radiation sessions so that their skin can heal.

- To gauge the impact, investigators reviewed data from the National Cancer Database on 35,845 patients with TNBC who were treated between 2010 and 2014.

- The researchers determined the number of interrupted radiation treatment days as the difference between the number of days women received radiotherapy versus the number of expected treatment days.

- The team then correlated treatment interruptions with overall survival.

Takeaway

- Longer duration of treatment was associated with worse overall survival (hazard ratio, 1.023).

- Compared with no days or just 1 day off, 2-5 interrupted days (HR, 1.069), 6-10 interrupted days (HR, 1.239), and 11-15 interrupted days (HR, 1.265) increased the likelihood of death in a stepwise fashion.

- More days between diagnosis and first cancer treatment of any kind (HR, 1.001) were associated with worse overall survival.

- Older age (HR, 1.014), Black race (HR, 1.278), race than other Black or White (HR, 1.337), grade II or III/IV tumors (HR, 1.471 and 1.743, respectively), and clinical N1-N3 stage (HR, 2.534, 3.729, 4.992, respectively) were also associated with worse overall survival.

In practice

“All reasonable efforts should be made to prevent any treatment interruptions,” including “prophylactic measures to reduce the severity of radiation dermatitis,” and consideration should be given to the use of hypofractionated regimens to shorten radiation schedules.

Source

The study was led by Ronald Chow, MS, of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and was published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Limitations

- The findings may not be applicable to less aggressive forms of breast cancer.

- Treatment interruptions may have been caused by poor performance status and other confounders that shorten survival.

Disclosures

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. The investigators had no disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Topline

Methodology

- Clinicians sometimes give women with TNBC a break between radiation sessions so that their skin can heal.

- To gauge the impact, investigators reviewed data from the National Cancer Database on 35,845 patients with TNBC who were treated between 2010 and 2014.

- The researchers determined the number of interrupted radiation treatment days as the difference between the number of days women received radiotherapy versus the number of expected treatment days.

- The team then correlated treatment interruptions with overall survival.

Takeaway

- Longer duration of treatment was associated with worse overall survival (hazard ratio, 1.023).

- Compared with no days or just 1 day off, 2-5 interrupted days (HR, 1.069), 6-10 interrupted days (HR, 1.239), and 11-15 interrupted days (HR, 1.265) increased the likelihood of death in a stepwise fashion.

- More days between diagnosis and first cancer treatment of any kind (HR, 1.001) were associated with worse overall survival.

- Older age (HR, 1.014), Black race (HR, 1.278), race than other Black or White (HR, 1.337), grade II or III/IV tumors (HR, 1.471 and 1.743, respectively), and clinical N1-N3 stage (HR, 2.534, 3.729, 4.992, respectively) were also associated with worse overall survival.

In practice

“All reasonable efforts should be made to prevent any treatment interruptions,” including “prophylactic measures to reduce the severity of radiation dermatitis,” and consideration should be given to the use of hypofractionated regimens to shorten radiation schedules.

Source

The study was led by Ronald Chow, MS, of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and was published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Limitations

- The findings may not be applicable to less aggressive forms of breast cancer.

- Treatment interruptions may have been caused by poor performance status and other confounders that shorten survival.

Disclosures

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute. The investigators had no disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Fatigue after breast cancer radiotherapy: Who’s most at risk?

Topline

Many patients with breast cancer who receive radiotherapy can still experience fatigue years after treatment; risk factors, including pain, insomnia, depression, baseline fatigue, and endocrine therapy were associated with long-term fatigue, new data show.

Methodology

- Overall, 1,443 patients with breast cancer from the REQUITE study responded to the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory 20 (MFI-20) tool to assess five dimensions of fatigue: general, physical, and mental fatigue as well as reduced activity and motivation.

- Patients from France, Spain, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, and United States were assessed for characteristics, including age, body mass index (BMI), smoking, depression, pain, insomnia, fatigue, and therapy type, at baseline and at 24 months.

- Investigators identified factors associated with fatigue at 2 years post-radiotherapy among a total of 664 patients without chemotherapy and 324 with chemotherapy.

- General fatigue trajectories were classified as low, moderate, high, or decreasing.

Takeaways

- In general, levels of fatigue increased significantly from baseline to the end of radiotherapy for all fatigue dimensions (P < .05) and returned close to baseline levels after 1-2 years.

- About 24% of patients had high general fatigue trajectories and 25% had moderate, while 46% had low and 5% had decreasing fatigue trajectories.

- Factors such as age, BMI, global health status, insomnia, pain, dyspnea, depression, and baseline fatigue were each associated with multiple fatigue dimensions at 2 years; for instance, fatigue at baseline was associated with all five MFI-20 dimensions at 2 years regardless of chemotherapy status.

- Those with a combination of factors such as pain, insomnia, depression, younger age, and endocrine therapy were especially likely to develop high fatigue early and have it persist years after treatment.

In practice

the authors concluded.

Source

The study was led by Juan C. Rosas, with the German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg. It was published online July 5 in the International Journal of Cancer.

Limitations

About one-quarter of patients did not complete the 2-year follow-up. Some variables identified in the literature as possible fatigue predictors such as socioeconomic status, physical activity, and social support were not included.

Disclosures

The study had no commercial funding. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Topline

Many patients with breast cancer who receive radiotherapy can still experience fatigue years after treatment; risk factors, including pain, insomnia, depression, baseline fatigue, and endocrine therapy were associated with long-term fatigue, new data show.

Methodology

- Overall, 1,443 patients with breast cancer from the REQUITE study responded to the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory 20 (MFI-20) tool to assess five dimensions of fatigue: general, physical, and mental fatigue as well as reduced activity and motivation.

- Patients from France, Spain, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, and United States were assessed for characteristics, including age, body mass index (BMI), smoking, depression, pain, insomnia, fatigue, and therapy type, at baseline and at 24 months.

- Investigators identified factors associated with fatigue at 2 years post-radiotherapy among a total of 664 patients without chemotherapy and 324 with chemotherapy.

- General fatigue trajectories were classified as low, moderate, high, or decreasing.

Takeaways

- In general, levels of fatigue increased significantly from baseline to the end of radiotherapy for all fatigue dimensions (P < .05) and returned close to baseline levels after 1-2 years.

- About 24% of patients had high general fatigue trajectories and 25% had moderate, while 46% had low and 5% had decreasing fatigue trajectories.

- Factors such as age, BMI, global health status, insomnia, pain, dyspnea, depression, and baseline fatigue were each associated with multiple fatigue dimensions at 2 years; for instance, fatigue at baseline was associated with all five MFI-20 dimensions at 2 years regardless of chemotherapy status.

- Those with a combination of factors such as pain, insomnia, depression, younger age, and endocrine therapy were especially likely to develop high fatigue early and have it persist years after treatment.

In practice

the authors concluded.

Source

The study was led by Juan C. Rosas, with the German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg. It was published online July 5 in the International Journal of Cancer.

Limitations

About one-quarter of patients did not complete the 2-year follow-up. Some variables identified in the literature as possible fatigue predictors such as socioeconomic status, physical activity, and social support were not included.

Disclosures

The study had no commercial funding. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Topline

Many patients with breast cancer who receive radiotherapy can still experience fatigue years after treatment; risk factors, including pain, insomnia, depression, baseline fatigue, and endocrine therapy were associated with long-term fatigue, new data show.

Methodology

- Overall, 1,443 patients with breast cancer from the REQUITE study responded to the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory 20 (MFI-20) tool to assess five dimensions of fatigue: general, physical, and mental fatigue as well as reduced activity and motivation.

- Patients from France, Spain, Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom, and United States were assessed for characteristics, including age, body mass index (BMI), smoking, depression, pain, insomnia, fatigue, and therapy type, at baseline and at 24 months.

- Investigators identified factors associated with fatigue at 2 years post-radiotherapy among a total of 664 patients without chemotherapy and 324 with chemotherapy.

- General fatigue trajectories were classified as low, moderate, high, or decreasing.

Takeaways

- In general, levels of fatigue increased significantly from baseline to the end of radiotherapy for all fatigue dimensions (P < .05) and returned close to baseline levels after 1-2 years.

- About 24% of patients had high general fatigue trajectories and 25% had moderate, while 46% had low and 5% had decreasing fatigue trajectories.

- Factors such as age, BMI, global health status, insomnia, pain, dyspnea, depression, and baseline fatigue were each associated with multiple fatigue dimensions at 2 years; for instance, fatigue at baseline was associated with all five MFI-20 dimensions at 2 years regardless of chemotherapy status.

- Those with a combination of factors such as pain, insomnia, depression, younger age, and endocrine therapy were especially likely to develop high fatigue early and have it persist years after treatment.

In practice

the authors concluded.

Source

The study was led by Juan C. Rosas, with the German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg. It was published online July 5 in the International Journal of Cancer.

Limitations

About one-quarter of patients did not complete the 2-year follow-up. Some variables identified in the literature as possible fatigue predictors such as socioeconomic status, physical activity, and social support were not included.

Disclosures

The study had no commercial funding. The authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Cough and hemoptysis

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of combined small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Globally, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer incidence and mortality, accounting for an estimated 2 million new diagnoses and 1.76 million deaths per year. It consists of two major subtypes: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and SCLC. SCLC is unique in its presentation, imaging appearances, treatment, and prognosis. SCLC accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancers and is associated with an exceptionally high proliferative rate, strong predilection for early metastasis, and poor prognosis.

There are two subtypes of SCLC: oat cell carcinoma and combined SCLC. Combined SCLC is defined as SCLC with non-small cell components, such as squamous cell or adenocarcinoma. Men are affected more frequently than are women. Most presenting patients are older than 70 years and are either a current or former smoker. Patients frequently have multiple cardiovascular or pulmonary comorbidities.

In most cases, patients experience rapid onset of symptoms, normally beginning 8-12 weeks before presentation. Signs and symptoms vary depending on the location and bulk of the primary tumor, but may include cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis as well as weight loss, debility, and other signs of metastatic disease. Local intrathoracic tumor growth can affect the superior vena cava (leading to superior vena cava syndrome), chest wall, or esophagus. Neurologic problems, recurrent nerve pain, fatigue, and anorexia may result from extrapulmonary metastasis. Nearly 60% of patients present with metastatic disease, most commonly in the brain, liver, adrenal glands, bone, and bone marrow. If left untreated, SCLC tumors progress rapidly, with a median survival of 2-4 months.

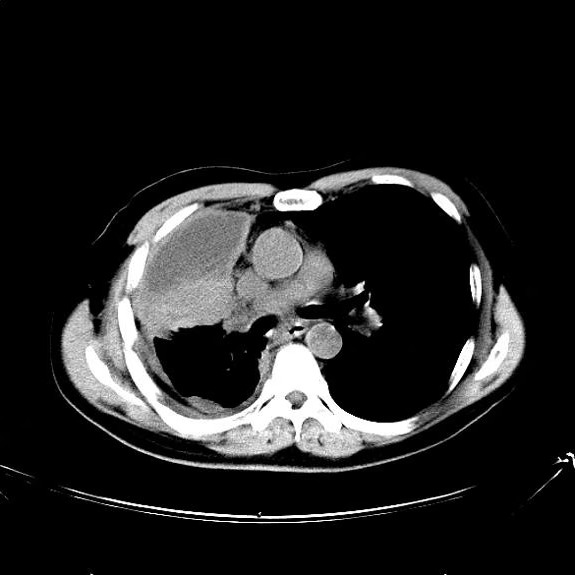

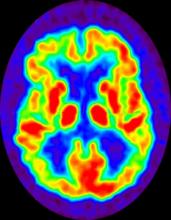

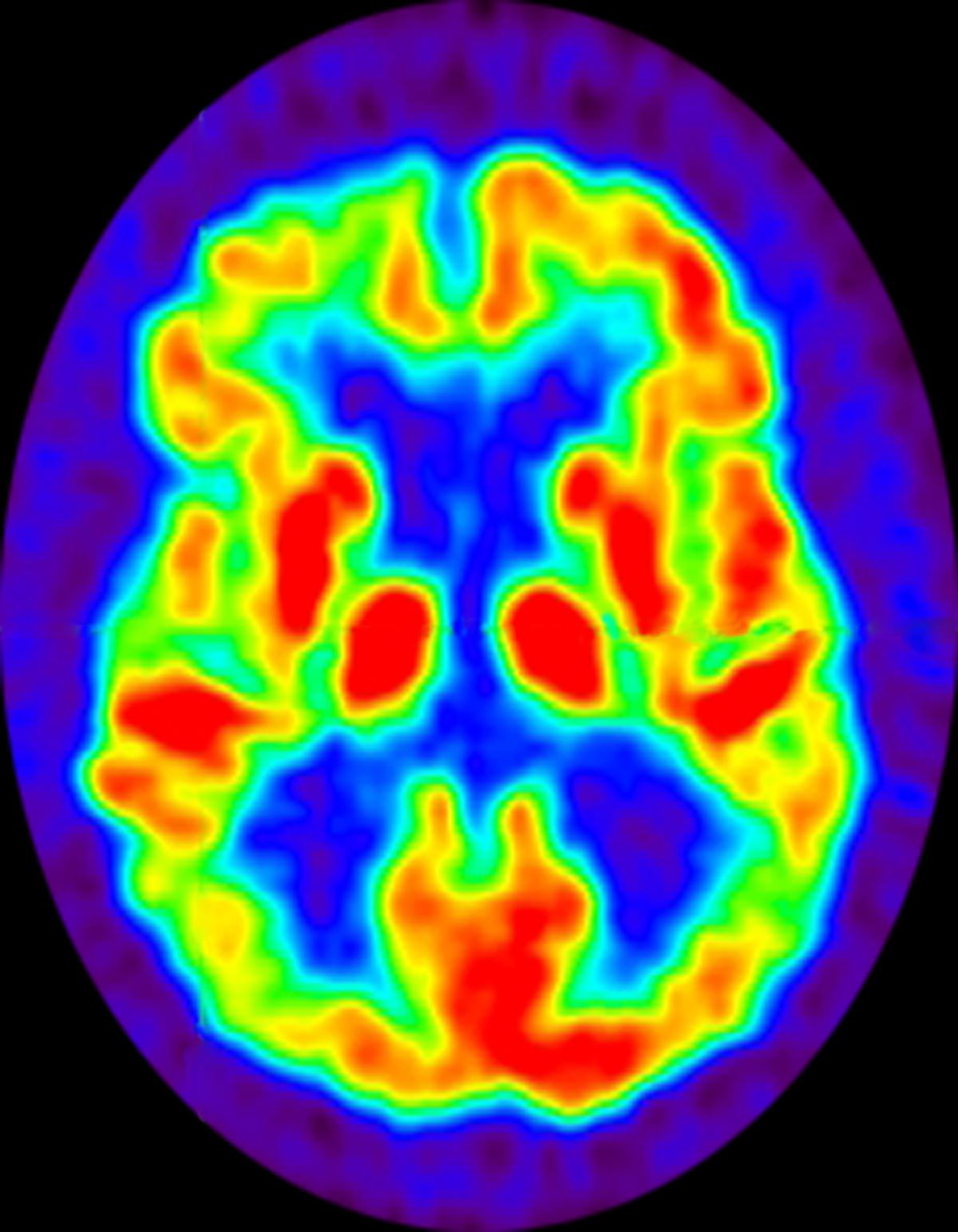

All patients with SCLC require a thorough staging workup to evaluate the extent of disease because stage plays a central role in treatment selection. The initial imaging workup includes plain film radiography and contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and upper abdomen, brain MRI, and PET-CT. Laboratory studies to evaluate for the presence of neoplastic syndromes include complete blood count, electrolytes, calcium, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, and creatinine. Biopsy is usually obtained via CT-guided biopsy or transbronchial biopsy, though this can vary depending on the location of the tumor.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), most patients with limited-stage SCLC are not eligible for surgery or stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR). Surgery is only recommended for select patients with stage I–IIA SCLC (about 5% of patients). Concurrent chemoradiation or SABR is recommended for patients with limited stage I-IIA (T1-2,N0) SCLC who are ineligible for or do not want to pursue surgical resection. The majority of patients with SCLC have extensive-stage disease, and treatment with systemic therapy alone (with or without palliative radiotherapy) is recommended. Preferred cytotoxic and immunotherapeutic agents can be found in the NCCN guidelines.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of combined small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Globally, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer incidence and mortality, accounting for an estimated 2 million new diagnoses and 1.76 million deaths per year. It consists of two major subtypes: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and SCLC. SCLC is unique in its presentation, imaging appearances, treatment, and prognosis. SCLC accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancers and is associated with an exceptionally high proliferative rate, strong predilection for early metastasis, and poor prognosis.

There are two subtypes of SCLC: oat cell carcinoma and combined SCLC. Combined SCLC is defined as SCLC with non-small cell components, such as squamous cell or adenocarcinoma. Men are affected more frequently than are women. Most presenting patients are older than 70 years and are either a current or former smoker. Patients frequently have multiple cardiovascular or pulmonary comorbidities.

In most cases, patients experience rapid onset of symptoms, normally beginning 8-12 weeks before presentation. Signs and symptoms vary depending on the location and bulk of the primary tumor, but may include cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis as well as weight loss, debility, and other signs of metastatic disease. Local intrathoracic tumor growth can affect the superior vena cava (leading to superior vena cava syndrome), chest wall, or esophagus. Neurologic problems, recurrent nerve pain, fatigue, and anorexia may result from extrapulmonary metastasis. Nearly 60% of patients present with metastatic disease, most commonly in the brain, liver, adrenal glands, bone, and bone marrow. If left untreated, SCLC tumors progress rapidly, with a median survival of 2-4 months.

All patients with SCLC require a thorough staging workup to evaluate the extent of disease because stage plays a central role in treatment selection. The initial imaging workup includes plain film radiography and contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and upper abdomen, brain MRI, and PET-CT. Laboratory studies to evaluate for the presence of neoplastic syndromes include complete blood count, electrolytes, calcium, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, and creatinine. Biopsy is usually obtained via CT-guided biopsy or transbronchial biopsy, though this can vary depending on the location of the tumor.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), most patients with limited-stage SCLC are not eligible for surgery or stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR). Surgery is only recommended for select patients with stage I–IIA SCLC (about 5% of patients). Concurrent chemoradiation or SABR is recommended for patients with limited stage I-IIA (T1-2,N0) SCLC who are ineligible for or do not want to pursue surgical resection. The majority of patients with SCLC have extensive-stage disease, and treatment with systemic therapy alone (with or without palliative radiotherapy) is recommended. Preferred cytotoxic and immunotherapeutic agents can be found in the NCCN guidelines.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The history and findings in this case are suggestive of combined small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Globally, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer incidence and mortality, accounting for an estimated 2 million new diagnoses and 1.76 million deaths per year. It consists of two major subtypes: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and SCLC. SCLC is unique in its presentation, imaging appearances, treatment, and prognosis. SCLC accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancers and is associated with an exceptionally high proliferative rate, strong predilection for early metastasis, and poor prognosis.

There are two subtypes of SCLC: oat cell carcinoma and combined SCLC. Combined SCLC is defined as SCLC with non-small cell components, such as squamous cell or adenocarcinoma. Men are affected more frequently than are women. Most presenting patients are older than 70 years and are either a current or former smoker. Patients frequently have multiple cardiovascular or pulmonary comorbidities.

In most cases, patients experience rapid onset of symptoms, normally beginning 8-12 weeks before presentation. Signs and symptoms vary depending on the location and bulk of the primary tumor, but may include cough, wheezing, and hemoptysis as well as weight loss, debility, and other signs of metastatic disease. Local intrathoracic tumor growth can affect the superior vena cava (leading to superior vena cava syndrome), chest wall, or esophagus. Neurologic problems, recurrent nerve pain, fatigue, and anorexia may result from extrapulmonary metastasis. Nearly 60% of patients present with metastatic disease, most commonly in the brain, liver, adrenal glands, bone, and bone marrow. If left untreated, SCLC tumors progress rapidly, with a median survival of 2-4 months.

All patients with SCLC require a thorough staging workup to evaluate the extent of disease because stage plays a central role in treatment selection. The initial imaging workup includes plain film radiography and contrast-enhanced CT of the chest and upper abdomen, brain MRI, and PET-CT. Laboratory studies to evaluate for the presence of neoplastic syndromes include complete blood count, electrolytes, calcium, alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, and creatinine. Biopsy is usually obtained via CT-guided biopsy or transbronchial biopsy, though this can vary depending on the location of the tumor.

According to 2023 guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), most patients with limited-stage SCLC are not eligible for surgery or stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR). Surgery is only recommended for select patients with stage I–IIA SCLC (about 5% of patients). Concurrent chemoradiation or SABR is recommended for patients with limited stage I-IIA (T1-2,N0) SCLC who are ineligible for or do not want to pursue surgical resection. The majority of patients with SCLC have extensive-stage disease, and treatment with systemic therapy alone (with or without palliative radiotherapy) is recommended. Preferred cytotoxic and immunotherapeutic agents can be found in the NCCN guidelines.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston; Medical Director, Department of Oncology and Hematology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Peabody, Massachusetts.

Karl J. D'Silva, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 74-year-old man presents to the emergency department with reports of cough, hemoptysis, and unintentional weight loss of approximately 8 weeks' duration. The patient has a 35-year history of smoking (35 pack years). The patient's vital signs include temperature of 98.4 °F, BP of 135/80 mm Hg, and pulse oximeter reading of 94%. Physical examination reveals rales over the left side of the chest and decreased breath sounds in bilateral bases of the lungs. The patient appears cachexic. He is 6 ft 2 in and weighs 163 lb.

A chest radiograph reveals a mass in the right lung field. A subsequent CT of the chest reveals multiple pulmonary nodules and extensive mediastinal nodal metastases. Histopathology reveals small, uniform, poorly differentiated necrotic cancers and adenocarcinoma with papillary and acinar features.

Anxiety screening

Anxiety symptoms in children are common, ranging from a toddler’s fear of the dark to an adolescent worrying about a major exam. The good news is that, if they are detected early and treated appropriately, they are curable. Unfortunately, they are often silent, or present with misleading symptoms. Screening for anxiety disorders, especially in the presence of the most common presenting concerns, can illuminate the true nature of a child’s challenge and point the way forward. In this month’s article, we will provide details on the prevalence of anxiety disorders in children, how they typically present, and how best to screen for them. We will offer some strategies for speaking about them with your patients and their parents, as well as introduce some of the strategies that can improve mild to moderate anxiety disorders. We will follow up with another piece on the evidence-based treatments for these common disorders, how to find appropriate referrals, and what you can do in your office to get treatment started.

Anxiety disorders: Common and treatable

Anxiety disorders – including separation anxiety disorder, social phobia, simple phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and PTSD – affect between 15% and 20% of children before the age of 18, with some recent estimates as high as 31.9% of youth being affected. Indeed, the mean age of onset for most anxiety disorders (excluding panic disorder and PTSD) is between 5 and 9 years of age. Despite being so common, many anxiety disorders in childhood are never properly diagnosed, and most (as many as 80%) do not receive treatment from a mental health professional. With early diagnosis and evidence-based treatment, most anxiety disorders can be “cured” and no longer impair functioning. Untreated, anxiety disorders usually have a chronic course, causing significant behavioral problems and disruption of a child’s critical social, emotional, and identity development and their academic function. Untreated, they are frequently complicated in adolescence by mood, substance use, and eating disorders. With the passage of time, developmental consequences and comorbid illnesses, a curable childhood anxiety disorder can become a complex and entrenched psychiatric syndrome in young adulthood.

One of the reasons these illnesses frequently go unrecognized is that states of fearful distress, such as separation anxiety or social anxiety, are developmentally normal at different stages of childhood, and it can be difficult to discriminate between normal and pathological anxiety. Anxiety itself is an “internalizing” symptom, and is invisible except for the behaviors that can accompany it. Some behaviors suggest anxiety, such as fearful expressions, clinginess, excessive need for reassurance, or avoidance. But anxiety can also lead to obstinate refusal to do certain things. It might lead to explosive tantrums when a child is pushed to do something that makes them intensely anxious. It can lead to irritability and moody tantrums for a child exhausted after a long school day spent managing high levels of anxiety by themselves. Anxious children often appear inattentive in school. Anxiety disorders frequently disrupt restful sleep, leading to children who are irritable and moody as well as inattentive. These children may present to the pediatrician with frustrated parents concerned that they are oppositional or explosive, or because their teachers are concerned about ADHD, when the culprit is actually anxiety.

While anxiety is uncomfortable, these children are unlikely to experience their anxiety as unusual and foreign, like a sudden toothache. Instead, it feels to them like they are fearful for good reason, responding appropriately to something real. These children are more likely to respond to a novel or uncertain situation with worry rather than curiosity, and to a new challenge as a threat. For children who are managing their anxiety more internally, their parents are often unaware of their degree of distress. Indeed, these children are often careful, thoughtful, and attentive to detail. Parents and teachers may think they are doing wonderfully. They are typically very sensitive to physical discomforts, which are heightened by an anxious state. These are likely to present to the pediatrician’s office with parents very worried about a cluster of vague physical complaints (stomach ache, headache, “just not feeling good”), which coincides with a change, challenge, or anxious stimulus. In this situation, the parents may dismiss the possibility of anxiety, and the child may not even be aware of it. But it will get worse if they are pushed to bear the source of anxiety (going to school, sports practice, etc.).

Anxiety screening and treatment

When a child presents for a sick visit with vague symptoms, or a negative workup for specific ones, you should screen them for an anxiety disorder. When they present with concerns about inattention, insomnia, moodiness, obstinacy, and even explosive behaviors, you should screen them for an anxiety disorder. This is especially true if they are prepubertal, when anxiety disorders are far more common than mood disorders. But you should consider anxiety disorders alongside mood disorders in adolescents presenting with these complaints. While parents may be unaware of the presence of anxiety in their child, explain to them that anxiety disorders are very common and treatable in childhood to help them understand the value of screening. Asking children directly about their internal experience can also be helpful. Avoid asking about “anxiety,” instead asking if they ever worry about specific things, such as “talking to kids you don’t know at recess,” “being alone at home,” “getting robbed or kidnapped,” or “something bad happening to your parents.” Just asking helps children pay attention to their thoughts and feelings, and is a powerful screening instrument.

There are also real screening instruments that you might use routinely for sick visits in prepubertal children or when anxiety should be in the differential. These instruments can be prone to recall bias, but generally make it easier for (anxious) children to accurately describe their internal experience. An instrument like the GAD7 is brief, free, and sensitive, but not very specific. If it is positive, you can then offer a longer screen such as the SCARED, also free, which indicates likely diagnoses such as generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social phobia. There is a parent version and a self-report, and it is validated for youths 8-18 years old and takes approximately 20 minutes to complete and score.

A positive screen should lead to a more nuanced conversation with your patient and their parents about their anxiety symptoms. You may feel comfortable doing a more extensive interview to make the likely diagnosis or may prefer to refer to a psychiatrist or psychologist to assist with diagnosis and treatment recommendations. In either case, you can offer your patient and their parents meaningful reassurance that the intense discomfort of their anxiety will get better with effective treatment. In this visit, you can get treatment started by identifying what parents and their children can do right away to begin addressing anxiety symptoms. Offer strategies to protect and promote restful sleep and daily vigorous exercise, both of which can directly improve mild to moderate anxiety symptoms. Suggest to parents that they should help their children to notice what they are feeling, rather than rushing in to remove a source of anxiety. These measures can help their child to identify what is a thought, a feeling, a physical sensation, or a fact. They can offer support and validation around how uncomfortable these feelings are, but just being curious will reassure their child that they will be able to manage and master this feeling. This “practice” is akin to what their child will do in most effective treatments, and will have the added benefit of helping them to build skills that all children need to manage the challenges and worries that are a normal, but difficult part of growing up and of adult life. Finally, you can tell them that anxious temperaments come with advantages also, such as great powers of observation, attention to detail, and thoroughness, high levels of empathy, drive, and tenacity. By learning to manage anxiety early, these children can grow up to be engaged, resilient, successful, and satisfied adults.

Once identified, the range of effective treatments available include cognitive-behavioral therapy, graduated exposure, mindfulness/relaxation techniques, and medication, and we will discuss these in our next article.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

Reference

Beesdo K et al. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002.

Anxiety symptoms in children are common, ranging from a toddler’s fear of the dark to an adolescent worrying about a major exam. The good news is that, if they are detected early and treated appropriately, they are curable. Unfortunately, they are often silent, or present with misleading symptoms. Screening for anxiety disorders, especially in the presence of the most common presenting concerns, can illuminate the true nature of a child’s challenge and point the way forward. In this month’s article, we will provide details on the prevalence of anxiety disorders in children, how they typically present, and how best to screen for them. We will offer some strategies for speaking about them with your patients and their parents, as well as introduce some of the strategies that can improve mild to moderate anxiety disorders. We will follow up with another piece on the evidence-based treatments for these common disorders, how to find appropriate referrals, and what you can do in your office to get treatment started.

Anxiety disorders: Common and treatable

Anxiety disorders – including separation anxiety disorder, social phobia, simple phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and PTSD – affect between 15% and 20% of children before the age of 18, with some recent estimates as high as 31.9% of youth being affected. Indeed, the mean age of onset for most anxiety disorders (excluding panic disorder and PTSD) is between 5 and 9 years of age. Despite being so common, many anxiety disorders in childhood are never properly diagnosed, and most (as many as 80%) do not receive treatment from a mental health professional. With early diagnosis and evidence-based treatment, most anxiety disorders can be “cured” and no longer impair functioning. Untreated, anxiety disorders usually have a chronic course, causing significant behavioral problems and disruption of a child’s critical social, emotional, and identity development and their academic function. Untreated, they are frequently complicated in adolescence by mood, substance use, and eating disorders. With the passage of time, developmental consequences and comorbid illnesses, a curable childhood anxiety disorder can become a complex and entrenched psychiatric syndrome in young adulthood.

One of the reasons these illnesses frequently go unrecognized is that states of fearful distress, such as separation anxiety or social anxiety, are developmentally normal at different stages of childhood, and it can be difficult to discriminate between normal and pathological anxiety. Anxiety itself is an “internalizing” symptom, and is invisible except for the behaviors that can accompany it. Some behaviors suggest anxiety, such as fearful expressions, clinginess, excessive need for reassurance, or avoidance. But anxiety can also lead to obstinate refusal to do certain things. It might lead to explosive tantrums when a child is pushed to do something that makes them intensely anxious. It can lead to irritability and moody tantrums for a child exhausted after a long school day spent managing high levels of anxiety by themselves. Anxious children often appear inattentive in school. Anxiety disorders frequently disrupt restful sleep, leading to children who are irritable and moody as well as inattentive. These children may present to the pediatrician with frustrated parents concerned that they are oppositional or explosive, or because their teachers are concerned about ADHD, when the culprit is actually anxiety.

While anxiety is uncomfortable, these children are unlikely to experience their anxiety as unusual and foreign, like a sudden toothache. Instead, it feels to them like they are fearful for good reason, responding appropriately to something real. These children are more likely to respond to a novel or uncertain situation with worry rather than curiosity, and to a new challenge as a threat. For children who are managing their anxiety more internally, their parents are often unaware of their degree of distress. Indeed, these children are often careful, thoughtful, and attentive to detail. Parents and teachers may think they are doing wonderfully. They are typically very sensitive to physical discomforts, which are heightened by an anxious state. These are likely to present to the pediatrician’s office with parents very worried about a cluster of vague physical complaints (stomach ache, headache, “just not feeling good”), which coincides with a change, challenge, or anxious stimulus. In this situation, the parents may dismiss the possibility of anxiety, and the child may not even be aware of it. But it will get worse if they are pushed to bear the source of anxiety (going to school, sports practice, etc.).

Anxiety screening and treatment

When a child presents for a sick visit with vague symptoms, or a negative workup for specific ones, you should screen them for an anxiety disorder. When they present with concerns about inattention, insomnia, moodiness, obstinacy, and even explosive behaviors, you should screen them for an anxiety disorder. This is especially true if they are prepubertal, when anxiety disorders are far more common than mood disorders. But you should consider anxiety disorders alongside mood disorders in adolescents presenting with these complaints. While parents may be unaware of the presence of anxiety in their child, explain to them that anxiety disorders are very common and treatable in childhood to help them understand the value of screening. Asking children directly about their internal experience can also be helpful. Avoid asking about “anxiety,” instead asking if they ever worry about specific things, such as “talking to kids you don’t know at recess,” “being alone at home,” “getting robbed or kidnapped,” or “something bad happening to your parents.” Just asking helps children pay attention to their thoughts and feelings, and is a powerful screening instrument.

There are also real screening instruments that you might use routinely for sick visits in prepubertal children or when anxiety should be in the differential. These instruments can be prone to recall bias, but generally make it easier for (anxious) children to accurately describe their internal experience. An instrument like the GAD7 is brief, free, and sensitive, but not very specific. If it is positive, you can then offer a longer screen such as the SCARED, also free, which indicates likely diagnoses such as generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social phobia. There is a parent version and a self-report, and it is validated for youths 8-18 years old and takes approximately 20 minutes to complete and score.

A positive screen should lead to a more nuanced conversation with your patient and their parents about their anxiety symptoms. You may feel comfortable doing a more extensive interview to make the likely diagnosis or may prefer to refer to a psychiatrist or psychologist to assist with diagnosis and treatment recommendations. In either case, you can offer your patient and their parents meaningful reassurance that the intense discomfort of their anxiety will get better with effective treatment. In this visit, you can get treatment started by identifying what parents and their children can do right away to begin addressing anxiety symptoms. Offer strategies to protect and promote restful sleep and daily vigorous exercise, both of which can directly improve mild to moderate anxiety symptoms. Suggest to parents that they should help their children to notice what they are feeling, rather than rushing in to remove a source of anxiety. These measures can help their child to identify what is a thought, a feeling, a physical sensation, or a fact. They can offer support and validation around how uncomfortable these feelings are, but just being curious will reassure their child that they will be able to manage and master this feeling. This “practice” is akin to what their child will do in most effective treatments, and will have the added benefit of helping them to build skills that all children need to manage the challenges and worries that are a normal, but difficult part of growing up and of adult life. Finally, you can tell them that anxious temperaments come with advantages also, such as great powers of observation, attention to detail, and thoroughness, high levels of empathy, drive, and tenacity. By learning to manage anxiety early, these children can grow up to be engaged, resilient, successful, and satisfied adults.

Once identified, the range of effective treatments available include cognitive-behavioral therapy, graduated exposure, mindfulness/relaxation techniques, and medication, and we will discuss these in our next article.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

Reference

Beesdo K et al. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002.

Anxiety symptoms in children are common, ranging from a toddler’s fear of the dark to an adolescent worrying about a major exam. The good news is that, if they are detected early and treated appropriately, they are curable. Unfortunately, they are often silent, or present with misleading symptoms. Screening for anxiety disorders, especially in the presence of the most common presenting concerns, can illuminate the true nature of a child’s challenge and point the way forward. In this month’s article, we will provide details on the prevalence of anxiety disorders in children, how they typically present, and how best to screen for them. We will offer some strategies for speaking about them with your patients and their parents, as well as introduce some of the strategies that can improve mild to moderate anxiety disorders. We will follow up with another piece on the evidence-based treatments for these common disorders, how to find appropriate referrals, and what you can do in your office to get treatment started.

Anxiety disorders: Common and treatable

Anxiety disorders – including separation anxiety disorder, social phobia, simple phobias, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and PTSD – affect between 15% and 20% of children before the age of 18, with some recent estimates as high as 31.9% of youth being affected. Indeed, the mean age of onset for most anxiety disorders (excluding panic disorder and PTSD) is between 5 and 9 years of age. Despite being so common, many anxiety disorders in childhood are never properly diagnosed, and most (as many as 80%) do not receive treatment from a mental health professional. With early diagnosis and evidence-based treatment, most anxiety disorders can be “cured” and no longer impair functioning. Untreated, anxiety disorders usually have a chronic course, causing significant behavioral problems and disruption of a child’s critical social, emotional, and identity development and their academic function. Untreated, they are frequently complicated in adolescence by mood, substance use, and eating disorders. With the passage of time, developmental consequences and comorbid illnesses, a curable childhood anxiety disorder can become a complex and entrenched psychiatric syndrome in young adulthood.

One of the reasons these illnesses frequently go unrecognized is that states of fearful distress, such as separation anxiety or social anxiety, are developmentally normal at different stages of childhood, and it can be difficult to discriminate between normal and pathological anxiety. Anxiety itself is an “internalizing” symptom, and is invisible except for the behaviors that can accompany it. Some behaviors suggest anxiety, such as fearful expressions, clinginess, excessive need for reassurance, or avoidance. But anxiety can also lead to obstinate refusal to do certain things. It might lead to explosive tantrums when a child is pushed to do something that makes them intensely anxious. It can lead to irritability and moody tantrums for a child exhausted after a long school day spent managing high levels of anxiety by themselves. Anxious children often appear inattentive in school. Anxiety disorders frequently disrupt restful sleep, leading to children who are irritable and moody as well as inattentive. These children may present to the pediatrician with frustrated parents concerned that they are oppositional or explosive, or because their teachers are concerned about ADHD, when the culprit is actually anxiety.

While anxiety is uncomfortable, these children are unlikely to experience their anxiety as unusual and foreign, like a sudden toothache. Instead, it feels to them like they are fearful for good reason, responding appropriately to something real. These children are more likely to respond to a novel or uncertain situation with worry rather than curiosity, and to a new challenge as a threat. For children who are managing their anxiety more internally, their parents are often unaware of their degree of distress. Indeed, these children are often careful, thoughtful, and attentive to detail. Parents and teachers may think they are doing wonderfully. They are typically very sensitive to physical discomforts, which are heightened by an anxious state. These are likely to present to the pediatrician’s office with parents very worried about a cluster of vague physical complaints (stomach ache, headache, “just not feeling good”), which coincides with a change, challenge, or anxious stimulus. In this situation, the parents may dismiss the possibility of anxiety, and the child may not even be aware of it. But it will get worse if they are pushed to bear the source of anxiety (going to school, sports practice, etc.).

Anxiety screening and treatment

When a child presents for a sick visit with vague symptoms, or a negative workup for specific ones, you should screen them for an anxiety disorder. When they present with concerns about inattention, insomnia, moodiness, obstinacy, and even explosive behaviors, you should screen them for an anxiety disorder. This is especially true if they are prepubertal, when anxiety disorders are far more common than mood disorders. But you should consider anxiety disorders alongside mood disorders in adolescents presenting with these complaints. While parents may be unaware of the presence of anxiety in their child, explain to them that anxiety disorders are very common and treatable in childhood to help them understand the value of screening. Asking children directly about their internal experience can also be helpful. Avoid asking about “anxiety,” instead asking if they ever worry about specific things, such as “talking to kids you don’t know at recess,” “being alone at home,” “getting robbed or kidnapped,” or “something bad happening to your parents.” Just asking helps children pay attention to their thoughts and feelings, and is a powerful screening instrument.

There are also real screening instruments that you might use routinely for sick visits in prepubertal children or when anxiety should be in the differential. These instruments can be prone to recall bias, but generally make it easier for (anxious) children to accurately describe their internal experience. An instrument like the GAD7 is brief, free, and sensitive, but not very specific. If it is positive, you can then offer a longer screen such as the SCARED, also free, which indicates likely diagnoses such as generalized anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social phobia. There is a parent version and a self-report, and it is validated for youths 8-18 years old and takes approximately 20 minutes to complete and score.

A positive screen should lead to a more nuanced conversation with your patient and their parents about their anxiety symptoms. You may feel comfortable doing a more extensive interview to make the likely diagnosis or may prefer to refer to a psychiatrist or psychologist to assist with diagnosis and treatment recommendations. In either case, you can offer your patient and their parents meaningful reassurance that the intense discomfort of their anxiety will get better with effective treatment. In this visit, you can get treatment started by identifying what parents and their children can do right away to begin addressing anxiety symptoms. Offer strategies to protect and promote restful sleep and daily vigorous exercise, both of which can directly improve mild to moderate anxiety symptoms. Suggest to parents that they should help their children to notice what they are feeling, rather than rushing in to remove a source of anxiety. These measures can help their child to identify what is a thought, a feeling, a physical sensation, or a fact. They can offer support and validation around how uncomfortable these feelings are, but just being curious will reassure their child that they will be able to manage and master this feeling. This “practice” is akin to what their child will do in most effective treatments, and will have the added benefit of helping them to build skills that all children need to manage the challenges and worries that are a normal, but difficult part of growing up and of adult life. Finally, you can tell them that anxious temperaments come with advantages also, such as great powers of observation, attention to detail, and thoroughness, high levels of empathy, drive, and tenacity. By learning to manage anxiety early, these children can grow up to be engaged, resilient, successful, and satisfied adults.

Once identified, the range of effective treatments available include cognitive-behavioral therapy, graduated exposure, mindfulness/relaxation techniques, and medication, and we will discuss these in our next article.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at [email protected].

Reference

Beesdo K et al. Anxiety and anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: developmental issues and implications for DSM-V. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2009 Sep. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2009.06.002.

Metachronous CRC risk after colonoscopy for positive FIT

TOPLINE:

a study suggests.

,

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators conducted a retrospective analysis of 253,833 colonoscopies performed after FIT-positive screens in a Dutch CRC screening program.

- A Cox regression analysis assessed the association between the findings at baseline colonoscopy and metachronous CRC risk.

- Investigators categorized patients into subgroups based on removed polyp subtypes and used groups without polyps as a reference.