User login

Camp Discovery: A place for children to be comfortable in their own skin

The talent show, the grand finale of the 1-week camp, was nearly 7 years ago, but Emily Haygood of Houston, now 17 and about to start her senior year, remembers it in detail. She sang “Death of a Bachelor,” an R&B pop song and Billboard No. 1 hit at the time about a former bachelor who had happily married. These days, she said, if she watched the video of her 10-year-old singing self, “I would probably throw up.” But she still treasures the audience response, “having all those people I’d gotten close to cheer for me.”

Emily was at , but share one feature: they are the kind of dermatologic issues that can make doing everyday kid or teen activities like swimming difficult and can elicit mean comments from classmates and other would-be friends.

Emily was first diagnosed with atopic dermatitis at age 4, her mother, Amber Haygood, says. By age 9, it had become severe. Emily remembers being teased some in elementary school. “I did feel bad a lot of the time, when asked insensitive questions.” Her mother still bristles that adults often could be cruel, too.

But at Camp Discovery, those issues were nonexistent. “Camp was so cool,” Emily said. Besides the usual camp activities, it had things that “normal” camp didn’t, like other kids who didn’t stare at your skin condition or make fun of it.

30th anniversary season begins

This year is the 30th anniversary of Camp Discovery. Sessions began July 23 and continue through Aug. 18, with locations in Crosslake, Minn.; Hebron, Conn.; and Millville, Pa., in addition to Burton, Tex. About 300 campers will attend this year, according to the AAD, and 6,151 campers have attended from 1993 to 2022.

The 1-week camp accepts youth with conditions ranging from eczema and psoriasis to vitiligo, alopecia, epidermolysis bullosa, and ichthyosis, according to the academy. A dermatologist first refers a child, downloading and completing the referral form and sending it to the academy.

The 1-week session, including travel, is free for the campers, thanks to donors. As a nonprofit and membership-based organization, the AAD does not release the detailed financial information about the operating budget for the camp. Dermatologists, nurses, and counselors volunteer their time.

In his presidential address at the AAD’s annual meeting in March, outgoing president Mark D. Kaufmann, MD, of the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, referred to camp volunteering as an antidote to professional burnout. Remembering why as a dermatologist one entered the profession can be one solution, he said, and described his own recent 3-day volunteer stint at the camp.

“Those 3 magical days, being with kids as they discovered they weren’t alone in the world, sharing their experiences and ideas, reminded me why I became a physician in the first place,” he told the audience of meeting attendees. He vowed to expand the program, with a goal of having every dermatology resident attend Camp Discovery.

Mental health effects of skin conditions

Much research has focused on the mental health fallout from living with chronic skin conditions, and even young children can be adversely affected. In one review of the literature, researchers concluded that pediatric skin disease, including acne, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis, can affect quality of life, carry stigma, and lead to bullying and eventually even suicidal behavior. Another study, published earlier this year, found that atopic dermatitis affected children’s quality of life, impacting sleep and leading to feelings of being ashamed.

“It’s not necessarily about what their skin condition is and more about the psychosocial impact,’’ said Samantha Hill, MD, a pediatric and general dermatologist in Lynchburg, Va., who is the medical director of Camp Discovery in Minnesota this year.

Camp activities, reactions

The overriding theme of camp is allowing all the youth to be “just one of the kids at camp,” Dr. Hill said in an interview. “They come to do all kinds of things they don’t do in normal life because people don’t give them the credit to [be able to] do it.”

Every year, she said, “I tell my staff we are in the business of making things happen, so if there is a kid bandaged head to toe [because of a skin condition] and they want to go tubing and get in the lake, we figure out how to make it happen. We have done that multiple times.”

Newcomers are initially nervous, Dr. Hill acknowledged, but in time let their guard down. Returnees are a different story. “When kids who have been at camp before arrive, you can see them start breathing again, looking for their friends. You can see them relax right before your eyes.”

“The single most empowering thing is the realization you are not alone,” said Meena Julapalli, MD, a Houston dermatologist who is a medical team member and long-time volunteer at Camp Discovery. That, she said, and “You get to be a kid, and you don’t have to have people staring at you.”

Dr. Julapalli remembers one of her patients with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness (KID) syndrome. “She needed more than what I could offer,” she said. “She needed camp.” At camp, the organizers found a counselor who knew sign language to accompany her. At first, she was quiet and didn’t smile much. By the end of the week, as she was about to observe her birthday, things changed. After breakfast, she was led to the stage, where fellow campers began singing – and signing the song they had just learned.

Camp staff gets it

Allyson Garin, who was diagnosed with vitiligo at age 6 months, is a camp program director at Camp Discovery in Crosslake, Minn. She first went to camp in 1990 at age 11, returning until she “aged out” at 16, then worked as a counselor. She gets it when campers tell her they hear rude comments about their skin conditions.

“I remember being in swimming pools, in lines at fairgrounds or amusement parks,” she said in an interview, “and hearing people say, ‘Don’t touch her,’ ’’ fearing contagion, perhaps. “People would make jokes about cows, since they are spotted,” she said, or people would simply step back.

All those years ago, her mother found out about the camp and decided to figure out how to get her there. She got there, and she met a fellow camper with vitiligo, and they became pen pals. “We still talk,” she said.

Meeting someone with the same skin condition, she said, isn’t just about commiserating. “There is a lot of information sharing,” on topics such as best treatments, strategies, and other conversations.

Other lessons

While campers can feel comfortable around others who also have skin conditions, and understand, the lesson extends beyond that, Ms. Garin said. “It gave me a perspective,” she said of her camp experience. “I always felt, ‘Woe is me.’ ” But when she met others with, as she said, conditions “way worse than vitiligo, it really grounds you.”

Dr. Hill agreed. Campers get the benefit of others accepting and including them, but also practicing that same attitude toward fellow campers, she said. “It insures that we are providing this environment of inclusion, but that they are practicing it as well. They need to practice it like everyone else.”

Getting parents on board

The idea of camp, especially for those at the younger end of the 8- to 16-years age range accepted for Camp Discovery, can take some getting used to for some parents. Ms. Haygood, Emily’s mother, relates to that. Her daughter’s dermatologist at the time, who is now retired, had first suggested the camp. Her first reaction? “I am not sending my chronically ill child to camp with strangers.” She also acknowledged that she, like other parents of children with a chronic illness, can be a helicopter parent.

Then, she noticed that Emily seemed interested, so she got more information, finding out that it was staffed by doctors. It all sounded good, she said, and the social interaction, she knew, would be beneficial. “Then my husband was a no,” she said, concerned about their daughter being with strangers. “Eventually he came around,” Ms. Haygood said. All along, Emily said, “it seemed fun. I was probably trying to talk them into it.” She admits she was very nervous at first, but calmed down when she realized her own dermatologist was going to be there.

Vanessa Hadley of Spring, Tex., was on board the moment she heard about Camp Discovery. “I just thought it was amazing,” she said. Her daughter Isabelle, 13, has been to the camp. “She has alopecia areata and severe eczema,” Ms. Hadley said. Now, Isabelle is returning to camp and coaching her sister Penelope, 8, who has eczema and mild alopecia and is a first-timer this summer.

One tip the 8-year-old has learned so far: Turn to your counselor for support if you’re nervous. That worked, Isabelle said, the first year when she was wary of the zipline – then surprised herself and conquered it.

Dr. Hill and Dr. Julapalli have no disclosures.

The talent show, the grand finale of the 1-week camp, was nearly 7 years ago, but Emily Haygood of Houston, now 17 and about to start her senior year, remembers it in detail. She sang “Death of a Bachelor,” an R&B pop song and Billboard No. 1 hit at the time about a former bachelor who had happily married. These days, she said, if she watched the video of her 10-year-old singing self, “I would probably throw up.” But she still treasures the audience response, “having all those people I’d gotten close to cheer for me.”

Emily was at , but share one feature: they are the kind of dermatologic issues that can make doing everyday kid or teen activities like swimming difficult and can elicit mean comments from classmates and other would-be friends.

Emily was first diagnosed with atopic dermatitis at age 4, her mother, Amber Haygood, says. By age 9, it had become severe. Emily remembers being teased some in elementary school. “I did feel bad a lot of the time, when asked insensitive questions.” Her mother still bristles that adults often could be cruel, too.

But at Camp Discovery, those issues were nonexistent. “Camp was so cool,” Emily said. Besides the usual camp activities, it had things that “normal” camp didn’t, like other kids who didn’t stare at your skin condition or make fun of it.

30th anniversary season begins

This year is the 30th anniversary of Camp Discovery. Sessions began July 23 and continue through Aug. 18, with locations in Crosslake, Minn.; Hebron, Conn.; and Millville, Pa., in addition to Burton, Tex. About 300 campers will attend this year, according to the AAD, and 6,151 campers have attended from 1993 to 2022.

The 1-week camp accepts youth with conditions ranging from eczema and psoriasis to vitiligo, alopecia, epidermolysis bullosa, and ichthyosis, according to the academy. A dermatologist first refers a child, downloading and completing the referral form and sending it to the academy.

The 1-week session, including travel, is free for the campers, thanks to donors. As a nonprofit and membership-based organization, the AAD does not release the detailed financial information about the operating budget for the camp. Dermatologists, nurses, and counselors volunteer their time.

In his presidential address at the AAD’s annual meeting in March, outgoing president Mark D. Kaufmann, MD, of the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, referred to camp volunteering as an antidote to professional burnout. Remembering why as a dermatologist one entered the profession can be one solution, he said, and described his own recent 3-day volunteer stint at the camp.

“Those 3 magical days, being with kids as they discovered they weren’t alone in the world, sharing their experiences and ideas, reminded me why I became a physician in the first place,” he told the audience of meeting attendees. He vowed to expand the program, with a goal of having every dermatology resident attend Camp Discovery.

Mental health effects of skin conditions

Much research has focused on the mental health fallout from living with chronic skin conditions, and even young children can be adversely affected. In one review of the literature, researchers concluded that pediatric skin disease, including acne, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis, can affect quality of life, carry stigma, and lead to bullying and eventually even suicidal behavior. Another study, published earlier this year, found that atopic dermatitis affected children’s quality of life, impacting sleep and leading to feelings of being ashamed.

“It’s not necessarily about what their skin condition is and more about the psychosocial impact,’’ said Samantha Hill, MD, a pediatric and general dermatologist in Lynchburg, Va., who is the medical director of Camp Discovery in Minnesota this year.

Camp activities, reactions

The overriding theme of camp is allowing all the youth to be “just one of the kids at camp,” Dr. Hill said in an interview. “They come to do all kinds of things they don’t do in normal life because people don’t give them the credit to [be able to] do it.”

Every year, she said, “I tell my staff we are in the business of making things happen, so if there is a kid bandaged head to toe [because of a skin condition] and they want to go tubing and get in the lake, we figure out how to make it happen. We have done that multiple times.”

Newcomers are initially nervous, Dr. Hill acknowledged, but in time let their guard down. Returnees are a different story. “When kids who have been at camp before arrive, you can see them start breathing again, looking for their friends. You can see them relax right before your eyes.”

“The single most empowering thing is the realization you are not alone,” said Meena Julapalli, MD, a Houston dermatologist who is a medical team member and long-time volunteer at Camp Discovery. That, she said, and “You get to be a kid, and you don’t have to have people staring at you.”

Dr. Julapalli remembers one of her patients with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness (KID) syndrome. “She needed more than what I could offer,” she said. “She needed camp.” At camp, the organizers found a counselor who knew sign language to accompany her. At first, she was quiet and didn’t smile much. By the end of the week, as she was about to observe her birthday, things changed. After breakfast, she was led to the stage, where fellow campers began singing – and signing the song they had just learned.

Camp staff gets it

Allyson Garin, who was diagnosed with vitiligo at age 6 months, is a camp program director at Camp Discovery in Crosslake, Minn. She first went to camp in 1990 at age 11, returning until she “aged out” at 16, then worked as a counselor. She gets it when campers tell her they hear rude comments about their skin conditions.

“I remember being in swimming pools, in lines at fairgrounds or amusement parks,” she said in an interview, “and hearing people say, ‘Don’t touch her,’ ’’ fearing contagion, perhaps. “People would make jokes about cows, since they are spotted,” she said, or people would simply step back.

All those years ago, her mother found out about the camp and decided to figure out how to get her there. She got there, and she met a fellow camper with vitiligo, and they became pen pals. “We still talk,” she said.

Meeting someone with the same skin condition, she said, isn’t just about commiserating. “There is a lot of information sharing,” on topics such as best treatments, strategies, and other conversations.

Other lessons

While campers can feel comfortable around others who also have skin conditions, and understand, the lesson extends beyond that, Ms. Garin said. “It gave me a perspective,” she said of her camp experience. “I always felt, ‘Woe is me.’ ” But when she met others with, as she said, conditions “way worse than vitiligo, it really grounds you.”

Dr. Hill agreed. Campers get the benefit of others accepting and including them, but also practicing that same attitude toward fellow campers, she said. “It insures that we are providing this environment of inclusion, but that they are practicing it as well. They need to practice it like everyone else.”

Getting parents on board

The idea of camp, especially for those at the younger end of the 8- to 16-years age range accepted for Camp Discovery, can take some getting used to for some parents. Ms. Haygood, Emily’s mother, relates to that. Her daughter’s dermatologist at the time, who is now retired, had first suggested the camp. Her first reaction? “I am not sending my chronically ill child to camp with strangers.” She also acknowledged that she, like other parents of children with a chronic illness, can be a helicopter parent.

Then, she noticed that Emily seemed interested, so she got more information, finding out that it was staffed by doctors. It all sounded good, she said, and the social interaction, she knew, would be beneficial. “Then my husband was a no,” she said, concerned about their daughter being with strangers. “Eventually he came around,” Ms. Haygood said. All along, Emily said, “it seemed fun. I was probably trying to talk them into it.” She admits she was very nervous at first, but calmed down when she realized her own dermatologist was going to be there.

Vanessa Hadley of Spring, Tex., was on board the moment she heard about Camp Discovery. “I just thought it was amazing,” she said. Her daughter Isabelle, 13, has been to the camp. “She has alopecia areata and severe eczema,” Ms. Hadley said. Now, Isabelle is returning to camp and coaching her sister Penelope, 8, who has eczema and mild alopecia and is a first-timer this summer.

One tip the 8-year-old has learned so far: Turn to your counselor for support if you’re nervous. That worked, Isabelle said, the first year when she was wary of the zipline – then surprised herself and conquered it.

Dr. Hill and Dr. Julapalli have no disclosures.

The talent show, the grand finale of the 1-week camp, was nearly 7 years ago, but Emily Haygood of Houston, now 17 and about to start her senior year, remembers it in detail. She sang “Death of a Bachelor,” an R&B pop song and Billboard No. 1 hit at the time about a former bachelor who had happily married. These days, she said, if she watched the video of her 10-year-old singing self, “I would probably throw up.” But she still treasures the audience response, “having all those people I’d gotten close to cheer for me.”

Emily was at , but share one feature: they are the kind of dermatologic issues that can make doing everyday kid or teen activities like swimming difficult and can elicit mean comments from classmates and other would-be friends.

Emily was first diagnosed with atopic dermatitis at age 4, her mother, Amber Haygood, says. By age 9, it had become severe. Emily remembers being teased some in elementary school. “I did feel bad a lot of the time, when asked insensitive questions.” Her mother still bristles that adults often could be cruel, too.

But at Camp Discovery, those issues were nonexistent. “Camp was so cool,” Emily said. Besides the usual camp activities, it had things that “normal” camp didn’t, like other kids who didn’t stare at your skin condition or make fun of it.

30th anniversary season begins

This year is the 30th anniversary of Camp Discovery. Sessions began July 23 and continue through Aug. 18, with locations in Crosslake, Minn.; Hebron, Conn.; and Millville, Pa., in addition to Burton, Tex. About 300 campers will attend this year, according to the AAD, and 6,151 campers have attended from 1993 to 2022.

The 1-week camp accepts youth with conditions ranging from eczema and psoriasis to vitiligo, alopecia, epidermolysis bullosa, and ichthyosis, according to the academy. A dermatologist first refers a child, downloading and completing the referral form and sending it to the academy.

The 1-week session, including travel, is free for the campers, thanks to donors. As a nonprofit and membership-based organization, the AAD does not release the detailed financial information about the operating budget for the camp. Dermatologists, nurses, and counselors volunteer their time.

In his presidential address at the AAD’s annual meeting in March, outgoing president Mark D. Kaufmann, MD, of the department of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, referred to camp volunteering as an antidote to professional burnout. Remembering why as a dermatologist one entered the profession can be one solution, he said, and described his own recent 3-day volunteer stint at the camp.

“Those 3 magical days, being with kids as they discovered they weren’t alone in the world, sharing their experiences and ideas, reminded me why I became a physician in the first place,” he told the audience of meeting attendees. He vowed to expand the program, with a goal of having every dermatology resident attend Camp Discovery.

Mental health effects of skin conditions

Much research has focused on the mental health fallout from living with chronic skin conditions, and even young children can be adversely affected. In one review of the literature, researchers concluded that pediatric skin disease, including acne, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis, can affect quality of life, carry stigma, and lead to bullying and eventually even suicidal behavior. Another study, published earlier this year, found that atopic dermatitis affected children’s quality of life, impacting sleep and leading to feelings of being ashamed.

“It’s not necessarily about what their skin condition is and more about the psychosocial impact,’’ said Samantha Hill, MD, a pediatric and general dermatologist in Lynchburg, Va., who is the medical director of Camp Discovery in Minnesota this year.

Camp activities, reactions

The overriding theme of camp is allowing all the youth to be “just one of the kids at camp,” Dr. Hill said in an interview. “They come to do all kinds of things they don’t do in normal life because people don’t give them the credit to [be able to] do it.”

Every year, she said, “I tell my staff we are in the business of making things happen, so if there is a kid bandaged head to toe [because of a skin condition] and they want to go tubing and get in the lake, we figure out how to make it happen. We have done that multiple times.”

Newcomers are initially nervous, Dr. Hill acknowledged, but in time let their guard down. Returnees are a different story. “When kids who have been at camp before arrive, you can see them start breathing again, looking for their friends. You can see them relax right before your eyes.”

“The single most empowering thing is the realization you are not alone,” said Meena Julapalli, MD, a Houston dermatologist who is a medical team member and long-time volunteer at Camp Discovery. That, she said, and “You get to be a kid, and you don’t have to have people staring at you.”

Dr. Julapalli remembers one of her patients with keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness (KID) syndrome. “She needed more than what I could offer,” she said. “She needed camp.” At camp, the organizers found a counselor who knew sign language to accompany her. At first, she was quiet and didn’t smile much. By the end of the week, as she was about to observe her birthday, things changed. After breakfast, she was led to the stage, where fellow campers began singing – and signing the song they had just learned.

Camp staff gets it

Allyson Garin, who was diagnosed with vitiligo at age 6 months, is a camp program director at Camp Discovery in Crosslake, Minn. She first went to camp in 1990 at age 11, returning until she “aged out” at 16, then worked as a counselor. She gets it when campers tell her they hear rude comments about their skin conditions.

“I remember being in swimming pools, in lines at fairgrounds or amusement parks,” she said in an interview, “and hearing people say, ‘Don’t touch her,’ ’’ fearing contagion, perhaps. “People would make jokes about cows, since they are spotted,” she said, or people would simply step back.

All those years ago, her mother found out about the camp and decided to figure out how to get her there. She got there, and she met a fellow camper with vitiligo, and they became pen pals. “We still talk,” she said.

Meeting someone with the same skin condition, she said, isn’t just about commiserating. “There is a lot of information sharing,” on topics such as best treatments, strategies, and other conversations.

Other lessons

While campers can feel comfortable around others who also have skin conditions, and understand, the lesson extends beyond that, Ms. Garin said. “It gave me a perspective,” she said of her camp experience. “I always felt, ‘Woe is me.’ ” But when she met others with, as she said, conditions “way worse than vitiligo, it really grounds you.”

Dr. Hill agreed. Campers get the benefit of others accepting and including them, but also practicing that same attitude toward fellow campers, she said. “It insures that we are providing this environment of inclusion, but that they are practicing it as well. They need to practice it like everyone else.”

Getting parents on board

The idea of camp, especially for those at the younger end of the 8- to 16-years age range accepted for Camp Discovery, can take some getting used to for some parents. Ms. Haygood, Emily’s mother, relates to that. Her daughter’s dermatologist at the time, who is now retired, had first suggested the camp. Her first reaction? “I am not sending my chronically ill child to camp with strangers.” She also acknowledged that she, like other parents of children with a chronic illness, can be a helicopter parent.

Then, she noticed that Emily seemed interested, so she got more information, finding out that it was staffed by doctors. It all sounded good, she said, and the social interaction, she knew, would be beneficial. “Then my husband was a no,” she said, concerned about their daughter being with strangers. “Eventually he came around,” Ms. Haygood said. All along, Emily said, “it seemed fun. I was probably trying to talk them into it.” She admits she was very nervous at first, but calmed down when she realized her own dermatologist was going to be there.

Vanessa Hadley of Spring, Tex., was on board the moment she heard about Camp Discovery. “I just thought it was amazing,” she said. Her daughter Isabelle, 13, has been to the camp. “She has alopecia areata and severe eczema,” Ms. Hadley said. Now, Isabelle is returning to camp and coaching her sister Penelope, 8, who has eczema and mild alopecia and is a first-timer this summer.

One tip the 8-year-old has learned so far: Turn to your counselor for support if you’re nervous. That worked, Isabelle said, the first year when she was wary of the zipline – then surprised herself and conquered it.

Dr. Hill and Dr. Julapalli have no disclosures.

Naltrexone is safe and beneficial in AUD with cirrhosis

VIENNA – , results of the first randomized controlled trial (RCT) show.

After 3 months, 64% of patients who received naltrexone were abstinent from alcohol, compared with 22% of patients who received placebo, Manasa Alla, MD, a hepatologist from the Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences (ILBS), New Delhi, said at the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) 2023, where she presented the study findings.

Importantly, naltrexone was found to be safe for patients with compensated cirrhosis. “This fragile population of patients has limited drugs to help them quit alcohol. Naltrexone can be a valuable addition to their measures to reduce craving and on their journey to reach de-addiction and abstinence,” Dr. Alla said.

Hepatotoxicity with naltrexone is rare and data are limited. The Food and Drug Administration previously placed a warning on its use for patients with alcoholic liver disease and underlying cirrhosis.

As a clinician constantly challenged with treating patients with AUD and cirrhosis, Dr. Alla wanted to explore the safety of naltrexone and to test its suitability for these patients who struggle to quit alcohol.

“Here we aimed to primarily test the safety of naltrexone in achieving abstinence and reducing alcohol cravings in patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis,” she said, adding, “The FDA black box warning has been removed, but it has never been tested in an RCT in patients with cirrhosis, so this is exactly what we did here.

“Naltrexone is a very good anti-alcohol-craving drug. If we can establish its safety in cirrhotic patients, it may have very good potential in reducing AUD and reducing the related complications of continued alcohol intake,” Dr. Alla said.

Safety, abstinence, lapse, and relapse assessed

The prospective, double-blind, single-center study at the ILBS in New Delhi, enrolled 100 patients with alcohol dependence and cirrhosis between 2020 and 2022. Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive naltrexone (50 mg/d) or placebo for 12 weeks. All participants attended regular counseling sessions with the resident psychiatrist. At baseline, the biochemical and drinking-related assessment scores between active and placebo groups of patients with compensated cirrhosis were matched.

Abstinence from alcohol was assessed through self-reported mean number of standard drinks (12 g alcohol per day). Findings were corroborated through an interview with a family member. Serum ethyl glucuronide levels were measured in cases of discrepancy. A relapse was considered to be consumption of over four standard alcoholic drinks/month; a lapse was considered any other alcohol drinking event not classified as relapse.

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who achieved and maintained alcohol abstinence at 12 weeks; secondary outcomes were the proportion of patients who took naltrexone without a liver-related adverse effect compared with placebo at 12 weeks, the number of relapses and lapses, the difference in craving scores on the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (OCDS) between groups at 4, 8, and 12 weeks and at 6 months and 12 months, and the proportion of patients who achieved and maintained alcohol abstinence at 6 months.

Abstinence at 3 months

After 3 months, abstinence was noted in 64% of the study population who received naltrexone, compared to 22% of those who received placebo (P < .001). At 6 months, a higher proportion of patients in the naltrexone group achieved abstinence (22% vs. 8% with placebo; P = .09).

“We still need to look at the longer-term effects of naltrexone,” Dr. Alla said. “Here we gave the drug plus counseling for 3 months only, so despite encouraging findings, we need further studies to understand more.”

The researchers analyzed the predictors of abstinence at 3 months. They found that patients who consumed fewer than 17 drinks per month at baseline were more likely to achieve abstinence (sensitivity, 81%).

“Our study showed that patients who are consuming less alcohol at baseline can quit alcohol if adequately motivated. We need the motivation, as well as the drug,” she said.

Patient counseling was also very important and was provided for the 3 months of the study. “Even in the placebo arm, we had some patients who became abstinent [11/50 patients], but this dropped at 6 months [to 4/50],” Dr. Alla said.

At 12 weeks, 28% in the naltrexone group experienced relapse, vs. 72% in the placebo group (P < .001). Regarding the secondary outcome of craving scores and how they were affected by naltrexone, the mean OCDS-O (obsessive element) scores were 6.63, compared with 9.29 in naltrexone and placebo, respectively (P < .01). The mean OCDS-C (compulsive element) scores were 6.34 and 9.02, respectively (P < .01).

“Most important, was the safety of naltrexone in this study,” she said. There were no significant adverse events in either arm, and only one patient discontinued the drug in the naltrexone arm. Three patients in the naltrexone group who continued alcohol consumption developed jaundice, “so the jaundice can be attributed to continuous alcohol intake and may not be secondary to the naltrexone per se. We concluded that naltrexone is safe in a compensated cirrhotic patient,” Dr. Alla said.

Regarding other adverse events, 13.7% of patients experienced gastritis with naltrexone, vs. 3.7% among patients who received placebo. Nausea was more common in the placebo group, at 11.1% compared with 6.8% among patients who received naltrexone. Vomiting was more common in the naltrexone arm, at 10.3% vs. 7.4% with placebo. None of these differences reached statistical significance.

A longer-term study and comparisons to other drugs would provide valuable insights going forward.

Moderator Aleksander Krag, MD, professor and head of hepatology at the University of Southern Denmark and Odense University Hospital, Denmark, said: “Any intervention that can reduce or stop alcohol use in patients with cirrhosis and more advanced cirrhosis will improve outcome as well as reduce complications and mortality.

“In some cases, alcohol rehabilitation can completely revert the damaged liver. We have lots of data that show that continuous alcohol use at the more advanced stages can be devastating and reduction [in alcohol use] improves outcome. Therefore, any intervention that can help us to achieve this on behalf of all patients is most welcome,” he said.

Naltrexone (ADDTREX) and identical placebos were supplied by Rusan Pharma. Dr. Alla has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Krag has served as speaker for Norgine, Siemens, and Nordic Bioscience and has participated in advisory boards for Norgine and Siemens outside the submitted work. He receives royalties from Gyldendal and Echosens.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

VIENNA – , results of the first randomized controlled trial (RCT) show.

After 3 months, 64% of patients who received naltrexone were abstinent from alcohol, compared with 22% of patients who received placebo, Manasa Alla, MD, a hepatologist from the Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences (ILBS), New Delhi, said at the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) 2023, where she presented the study findings.

Importantly, naltrexone was found to be safe for patients with compensated cirrhosis. “This fragile population of patients has limited drugs to help them quit alcohol. Naltrexone can be a valuable addition to their measures to reduce craving and on their journey to reach de-addiction and abstinence,” Dr. Alla said.

Hepatotoxicity with naltrexone is rare and data are limited. The Food and Drug Administration previously placed a warning on its use for patients with alcoholic liver disease and underlying cirrhosis.

As a clinician constantly challenged with treating patients with AUD and cirrhosis, Dr. Alla wanted to explore the safety of naltrexone and to test its suitability for these patients who struggle to quit alcohol.

“Here we aimed to primarily test the safety of naltrexone in achieving abstinence and reducing alcohol cravings in patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis,” she said, adding, “The FDA black box warning has been removed, but it has never been tested in an RCT in patients with cirrhosis, so this is exactly what we did here.

“Naltrexone is a very good anti-alcohol-craving drug. If we can establish its safety in cirrhotic patients, it may have very good potential in reducing AUD and reducing the related complications of continued alcohol intake,” Dr. Alla said.

Safety, abstinence, lapse, and relapse assessed

The prospective, double-blind, single-center study at the ILBS in New Delhi, enrolled 100 patients with alcohol dependence and cirrhosis between 2020 and 2022. Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive naltrexone (50 mg/d) or placebo for 12 weeks. All participants attended regular counseling sessions with the resident psychiatrist. At baseline, the biochemical and drinking-related assessment scores between active and placebo groups of patients with compensated cirrhosis were matched.

Abstinence from alcohol was assessed through self-reported mean number of standard drinks (12 g alcohol per day). Findings were corroborated through an interview with a family member. Serum ethyl glucuronide levels were measured in cases of discrepancy. A relapse was considered to be consumption of over four standard alcoholic drinks/month; a lapse was considered any other alcohol drinking event not classified as relapse.

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who achieved and maintained alcohol abstinence at 12 weeks; secondary outcomes were the proportion of patients who took naltrexone without a liver-related adverse effect compared with placebo at 12 weeks, the number of relapses and lapses, the difference in craving scores on the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (OCDS) between groups at 4, 8, and 12 weeks and at 6 months and 12 months, and the proportion of patients who achieved and maintained alcohol abstinence at 6 months.

Abstinence at 3 months

After 3 months, abstinence was noted in 64% of the study population who received naltrexone, compared to 22% of those who received placebo (P < .001). At 6 months, a higher proportion of patients in the naltrexone group achieved abstinence (22% vs. 8% with placebo; P = .09).

“We still need to look at the longer-term effects of naltrexone,” Dr. Alla said. “Here we gave the drug plus counseling for 3 months only, so despite encouraging findings, we need further studies to understand more.”

The researchers analyzed the predictors of abstinence at 3 months. They found that patients who consumed fewer than 17 drinks per month at baseline were more likely to achieve abstinence (sensitivity, 81%).

“Our study showed that patients who are consuming less alcohol at baseline can quit alcohol if adequately motivated. We need the motivation, as well as the drug,” she said.

Patient counseling was also very important and was provided for the 3 months of the study. “Even in the placebo arm, we had some patients who became abstinent [11/50 patients], but this dropped at 6 months [to 4/50],” Dr. Alla said.

At 12 weeks, 28% in the naltrexone group experienced relapse, vs. 72% in the placebo group (P < .001). Regarding the secondary outcome of craving scores and how they were affected by naltrexone, the mean OCDS-O (obsessive element) scores were 6.63, compared with 9.29 in naltrexone and placebo, respectively (P < .01). The mean OCDS-C (compulsive element) scores were 6.34 and 9.02, respectively (P < .01).

“Most important, was the safety of naltrexone in this study,” she said. There were no significant adverse events in either arm, and only one patient discontinued the drug in the naltrexone arm. Three patients in the naltrexone group who continued alcohol consumption developed jaundice, “so the jaundice can be attributed to continuous alcohol intake and may not be secondary to the naltrexone per se. We concluded that naltrexone is safe in a compensated cirrhotic patient,” Dr. Alla said.

Regarding other adverse events, 13.7% of patients experienced gastritis with naltrexone, vs. 3.7% among patients who received placebo. Nausea was more common in the placebo group, at 11.1% compared with 6.8% among patients who received naltrexone. Vomiting was more common in the naltrexone arm, at 10.3% vs. 7.4% with placebo. None of these differences reached statistical significance.

A longer-term study and comparisons to other drugs would provide valuable insights going forward.

Moderator Aleksander Krag, MD, professor and head of hepatology at the University of Southern Denmark and Odense University Hospital, Denmark, said: “Any intervention that can reduce or stop alcohol use in patients with cirrhosis and more advanced cirrhosis will improve outcome as well as reduce complications and mortality.

“In some cases, alcohol rehabilitation can completely revert the damaged liver. We have lots of data that show that continuous alcohol use at the more advanced stages can be devastating and reduction [in alcohol use] improves outcome. Therefore, any intervention that can help us to achieve this on behalf of all patients is most welcome,” he said.

Naltrexone (ADDTREX) and identical placebos were supplied by Rusan Pharma. Dr. Alla has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Krag has served as speaker for Norgine, Siemens, and Nordic Bioscience and has participated in advisory boards for Norgine and Siemens outside the submitted work. He receives royalties from Gyldendal and Echosens.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

VIENNA – , results of the first randomized controlled trial (RCT) show.

After 3 months, 64% of patients who received naltrexone were abstinent from alcohol, compared with 22% of patients who received placebo, Manasa Alla, MD, a hepatologist from the Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences (ILBS), New Delhi, said at the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) 2023, where she presented the study findings.

Importantly, naltrexone was found to be safe for patients with compensated cirrhosis. “This fragile population of patients has limited drugs to help them quit alcohol. Naltrexone can be a valuable addition to their measures to reduce craving and on their journey to reach de-addiction and abstinence,” Dr. Alla said.

Hepatotoxicity with naltrexone is rare and data are limited. The Food and Drug Administration previously placed a warning on its use for patients with alcoholic liver disease and underlying cirrhosis.

As a clinician constantly challenged with treating patients with AUD and cirrhosis, Dr. Alla wanted to explore the safety of naltrexone and to test its suitability for these patients who struggle to quit alcohol.

“Here we aimed to primarily test the safety of naltrexone in achieving abstinence and reducing alcohol cravings in patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis,” she said, adding, “The FDA black box warning has been removed, but it has never been tested in an RCT in patients with cirrhosis, so this is exactly what we did here.

“Naltrexone is a very good anti-alcohol-craving drug. If we can establish its safety in cirrhotic patients, it may have very good potential in reducing AUD and reducing the related complications of continued alcohol intake,” Dr. Alla said.

Safety, abstinence, lapse, and relapse assessed

The prospective, double-blind, single-center study at the ILBS in New Delhi, enrolled 100 patients with alcohol dependence and cirrhosis between 2020 and 2022. Participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive naltrexone (50 mg/d) or placebo for 12 weeks. All participants attended regular counseling sessions with the resident psychiatrist. At baseline, the biochemical and drinking-related assessment scores between active and placebo groups of patients with compensated cirrhosis were matched.

Abstinence from alcohol was assessed through self-reported mean number of standard drinks (12 g alcohol per day). Findings were corroborated through an interview with a family member. Serum ethyl glucuronide levels were measured in cases of discrepancy. A relapse was considered to be consumption of over four standard alcoholic drinks/month; a lapse was considered any other alcohol drinking event not classified as relapse.

The primary outcome was the proportion of patients who achieved and maintained alcohol abstinence at 12 weeks; secondary outcomes were the proportion of patients who took naltrexone without a liver-related adverse effect compared with placebo at 12 weeks, the number of relapses and lapses, the difference in craving scores on the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking Scale (OCDS) between groups at 4, 8, and 12 weeks and at 6 months and 12 months, and the proportion of patients who achieved and maintained alcohol abstinence at 6 months.

Abstinence at 3 months

After 3 months, abstinence was noted in 64% of the study population who received naltrexone, compared to 22% of those who received placebo (P < .001). At 6 months, a higher proportion of patients in the naltrexone group achieved abstinence (22% vs. 8% with placebo; P = .09).

“We still need to look at the longer-term effects of naltrexone,” Dr. Alla said. “Here we gave the drug plus counseling for 3 months only, so despite encouraging findings, we need further studies to understand more.”

The researchers analyzed the predictors of abstinence at 3 months. They found that patients who consumed fewer than 17 drinks per month at baseline were more likely to achieve abstinence (sensitivity, 81%).

“Our study showed that patients who are consuming less alcohol at baseline can quit alcohol if adequately motivated. We need the motivation, as well as the drug,” she said.

Patient counseling was also very important and was provided for the 3 months of the study. “Even in the placebo arm, we had some patients who became abstinent [11/50 patients], but this dropped at 6 months [to 4/50],” Dr. Alla said.

At 12 weeks, 28% in the naltrexone group experienced relapse, vs. 72% in the placebo group (P < .001). Regarding the secondary outcome of craving scores and how they were affected by naltrexone, the mean OCDS-O (obsessive element) scores were 6.63, compared with 9.29 in naltrexone and placebo, respectively (P < .01). The mean OCDS-C (compulsive element) scores were 6.34 and 9.02, respectively (P < .01).

“Most important, was the safety of naltrexone in this study,” she said. There were no significant adverse events in either arm, and only one patient discontinued the drug in the naltrexone arm. Three patients in the naltrexone group who continued alcohol consumption developed jaundice, “so the jaundice can be attributed to continuous alcohol intake and may not be secondary to the naltrexone per se. We concluded that naltrexone is safe in a compensated cirrhotic patient,” Dr. Alla said.

Regarding other adverse events, 13.7% of patients experienced gastritis with naltrexone, vs. 3.7% among patients who received placebo. Nausea was more common in the placebo group, at 11.1% compared with 6.8% among patients who received naltrexone. Vomiting was more common in the naltrexone arm, at 10.3% vs. 7.4% with placebo. None of these differences reached statistical significance.

A longer-term study and comparisons to other drugs would provide valuable insights going forward.

Moderator Aleksander Krag, MD, professor and head of hepatology at the University of Southern Denmark and Odense University Hospital, Denmark, said: “Any intervention that can reduce or stop alcohol use in patients with cirrhosis and more advanced cirrhosis will improve outcome as well as reduce complications and mortality.

“In some cases, alcohol rehabilitation can completely revert the damaged liver. We have lots of data that show that continuous alcohol use at the more advanced stages can be devastating and reduction [in alcohol use] improves outcome. Therefore, any intervention that can help us to achieve this on behalf of all patients is most welcome,” he said.

Naltrexone (ADDTREX) and identical placebos were supplied by Rusan Pharma. Dr. Alla has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Krag has served as speaker for Norgine, Siemens, and Nordic Bioscience and has participated in advisory boards for Norgine and Siemens outside the submitted work. He receives royalties from Gyldendal and Echosens.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

AT EASL CONGRESS 2023

Does timing of surgery affect rectal cancer outcomes?

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- A total of 1,506 patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who underwent neoadjuvant therapy followed by total mesorectal excision were divided into three groups based on the time interval between therapy and surgery: short (8 weeks), intermediate (> 8 to 12 weeks), and long (> 12 weeks).

- The primary outcome was pathologic complete response, and secondary outcomes included other histopathologic results, perioperative events, and survival outcomes.

- Median follow-up was 33 months.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, a pathologic complete response was observed in 255 patients (17.2%).

- Compared with the intermediate interval (reference) group, investigators found no association between time interval and pathologic complete response in the short-interval (odds ratio, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.55-1.01) or long-interval groups (OR, 1.07; P = .70).

- A long interval was significantly associated with a lower risk of a bad response as measured by tumor regression grade 2-3, compared with the reference category (OR, 0.47), but a higher risk of minor postoperative complications (OR, 1.43), conversion to open surgery (OR, 3.14), and longer operative time.

- The long-interval group was associated with a significantly reduced risk of systemic recurrence, compared with the reference group (hazard ratio, 0.59; P = .04), but not improved overall survival (HR, 1.38; P = .11) or locoregional recurrence (HR, 0.53; P = .18); no significant findings occurred for the short versus intermediate group.

IN PRACTICE:

“Findings suggest that delaying surgery may improve tumor regression and decrease risk of distant metastasis but increase surgical complexity,” the authors conclude. “Nonetheless, the reported improvements in tumor regression and systemic recurrence in the long-interval group were unexpectedly not followed by improved [overall survival].”

SOURCE:

F. Borja de Lacy, MD, PhD, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, University of Barcelona, led the study, published online in JAMA Surgery, with an accompanying editorial.

LIMITATIONS:

- The study’s main limitation was its retrospective design, which could have resulted in missing or inconsistent data, as well as the short follow-up time.

- Decisions about time interval were based more on professional preference rather than specific tumor characteristics.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. de Lacy has reported no relevant financial relationships. No outside funding source was disclosed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- A total of 1,506 patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who underwent neoadjuvant therapy followed by total mesorectal excision were divided into three groups based on the time interval between therapy and surgery: short (8 weeks), intermediate (> 8 to 12 weeks), and long (> 12 weeks).

- The primary outcome was pathologic complete response, and secondary outcomes included other histopathologic results, perioperative events, and survival outcomes.

- Median follow-up was 33 months.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, a pathologic complete response was observed in 255 patients (17.2%).

- Compared with the intermediate interval (reference) group, investigators found no association between time interval and pathologic complete response in the short-interval (odds ratio, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.55-1.01) or long-interval groups (OR, 1.07; P = .70).

- A long interval was significantly associated with a lower risk of a bad response as measured by tumor regression grade 2-3, compared with the reference category (OR, 0.47), but a higher risk of minor postoperative complications (OR, 1.43), conversion to open surgery (OR, 3.14), and longer operative time.

- The long-interval group was associated with a significantly reduced risk of systemic recurrence, compared with the reference group (hazard ratio, 0.59; P = .04), but not improved overall survival (HR, 1.38; P = .11) or locoregional recurrence (HR, 0.53; P = .18); no significant findings occurred for the short versus intermediate group.

IN PRACTICE:

“Findings suggest that delaying surgery may improve tumor regression and decrease risk of distant metastasis but increase surgical complexity,” the authors conclude. “Nonetheless, the reported improvements in tumor regression and systemic recurrence in the long-interval group were unexpectedly not followed by improved [overall survival].”

SOURCE:

F. Borja de Lacy, MD, PhD, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, University of Barcelona, led the study, published online in JAMA Surgery, with an accompanying editorial.

LIMITATIONS:

- The study’s main limitation was its retrospective design, which could have resulted in missing or inconsistent data, as well as the short follow-up time.

- Decisions about time interval were based more on professional preference rather than specific tumor characteristics.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. de Lacy has reported no relevant financial relationships. No outside funding source was disclosed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- A total of 1,506 patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who underwent neoadjuvant therapy followed by total mesorectal excision were divided into three groups based on the time interval between therapy and surgery: short (8 weeks), intermediate (> 8 to 12 weeks), and long (> 12 weeks).

- The primary outcome was pathologic complete response, and secondary outcomes included other histopathologic results, perioperative events, and survival outcomes.

- Median follow-up was 33 months.

TAKEAWAY:

- Overall, a pathologic complete response was observed in 255 patients (17.2%).

- Compared with the intermediate interval (reference) group, investigators found no association between time interval and pathologic complete response in the short-interval (odds ratio, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.55-1.01) or long-interval groups (OR, 1.07; P = .70).

- A long interval was significantly associated with a lower risk of a bad response as measured by tumor regression grade 2-3, compared with the reference category (OR, 0.47), but a higher risk of minor postoperative complications (OR, 1.43), conversion to open surgery (OR, 3.14), and longer operative time.

- The long-interval group was associated with a significantly reduced risk of systemic recurrence, compared with the reference group (hazard ratio, 0.59; P = .04), but not improved overall survival (HR, 1.38; P = .11) or locoregional recurrence (HR, 0.53; P = .18); no significant findings occurred for the short versus intermediate group.

IN PRACTICE:

“Findings suggest that delaying surgery may improve tumor regression and decrease risk of distant metastasis but increase surgical complexity,” the authors conclude. “Nonetheless, the reported improvements in tumor regression and systemic recurrence in the long-interval group were unexpectedly not followed by improved [overall survival].”

SOURCE:

F. Borja de Lacy, MD, PhD, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, University of Barcelona, led the study, published online in JAMA Surgery, with an accompanying editorial.

LIMITATIONS:

- The study’s main limitation was its retrospective design, which could have resulted in missing or inconsistent data, as well as the short follow-up time.

- Decisions about time interval were based more on professional preference rather than specific tumor characteristics.

DISCLOSURES:

Dr. de Lacy has reported no relevant financial relationships. No outside funding source was disclosed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Postmenopausal screening mammogram

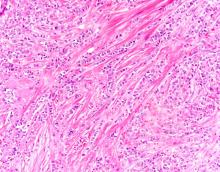

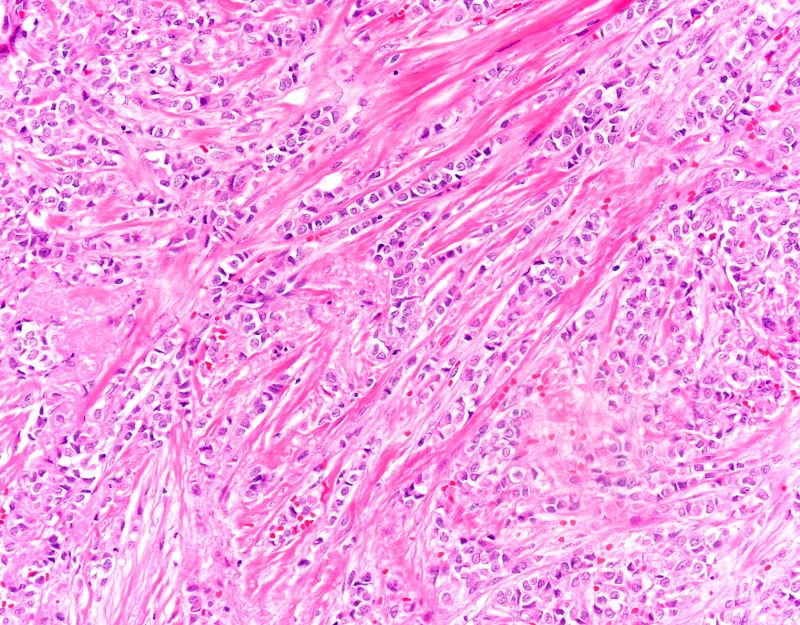

The findings in this case are suggestive of invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC).

Globally, breast cancer remains the most common life-threatening cancer diagnosed and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women. In the United States, approximately 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022 and 43,250 deaths were attributed to breast cancer in the same year. Worldwide, approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 breast cancer-related deaths were reported in 2020.

ILC is one of the leading histologic types of invasive carcinoma, second in incidence only to invasive carcinoma of no special type. ILC accounts for 5%-15% of all invasive breast cancers, and its incidence has been steadily increasing — particularly among postmenopausal women — over the past two decades. ILC has distinct molecular and histopathologic features, including the loss of cell-cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin, resulting in small, discohesive cells proliferating in single-file strands; positivity for both the estrogen and progesterone receptor; and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negativity.

The diagnosis of ILC can be challenging, as it is difficult to detect both on physical examination and with standard imaging techniques. Patients are often diagnosed with late-stage disease, characterized by large tumors and lymph node involvement. The signs of ILC are often vague, such as skin thickening or dimpling. In addition, measuring the extent of ILC can be challenging, as traditional screening methods (eg, mammography and ultrasonography) have a low sensitivity for detecting ILC compared with other invasive breast tumors. This difficulty is usually ascribed to the diffuse infiltrative growth pattern of ILC. MRI has a greater sensitivity for detecting ILC.

Risk factors for the development of ILC have been identified and include:

• Alcohol consumption

• Use of combined hormone replacement therapy

• Early menarche (menarche before the age of 12 years)

• Late-onset menopause (menopause after the age of 55 years)

• Nulliparity/low parity (defined by World Health Organization as fewer than five pregnancies with gestation periods of ≥ 20 weeks)

• Late age at birth (> 30 years)

• Family history (eg, hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome)

• Genetics (eg, CDH1 mutations)

Treatment protocols for ILC align with those used in other breast cancer subtypes and typically involve a multidisciplinary approach comprising surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic therapies. Cancers that are deemed resectable will typically be managed surgically upfront, although some patients may require neoadjuvant therapy to reduce tumor burden and facilitate surgical intervention. Breast-conserving surgery using a wide local excision can frequently be performed; however, in up to 65% of cases, a second surgery will be required (re-excision or mastectomy). Axillary lymph node status is a crucial factor in the prognosis of all breast cancers and affects surgical planning. Sentinel node biopsy is the standard method of assessing the axilla.

Systemic therapy is an integral part of the multidisciplinary approach to treating breast cancer and usually involves the use of chemotherapy. However, because of the unique molecular biology of ILC, treatment response to chemotherapy is often poor, resulting in lower rates of complete pathologic response and higher rates of mastectomy. Conversely, ILC has been shown to respond well to endocrine therapy, making it the optimal treatment choice. Novel therapeutic approaches are under investigation.

Detailed guidance on the treatment of ILC is available from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The findings in this case are suggestive of invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC).

Globally, breast cancer remains the most common life-threatening cancer diagnosed and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women. In the United States, approximately 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022 and 43,250 deaths were attributed to breast cancer in the same year. Worldwide, approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 breast cancer-related deaths were reported in 2020.

ILC is one of the leading histologic types of invasive carcinoma, second in incidence only to invasive carcinoma of no special type. ILC accounts for 5%-15% of all invasive breast cancers, and its incidence has been steadily increasing — particularly among postmenopausal women — over the past two decades. ILC has distinct molecular and histopathologic features, including the loss of cell-cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin, resulting in small, discohesive cells proliferating in single-file strands; positivity for both the estrogen and progesterone receptor; and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negativity.

The diagnosis of ILC can be challenging, as it is difficult to detect both on physical examination and with standard imaging techniques. Patients are often diagnosed with late-stage disease, characterized by large tumors and lymph node involvement. The signs of ILC are often vague, such as skin thickening or dimpling. In addition, measuring the extent of ILC can be challenging, as traditional screening methods (eg, mammography and ultrasonography) have a low sensitivity for detecting ILC compared with other invasive breast tumors. This difficulty is usually ascribed to the diffuse infiltrative growth pattern of ILC. MRI has a greater sensitivity for detecting ILC.

Risk factors for the development of ILC have been identified and include:

• Alcohol consumption

• Use of combined hormone replacement therapy

• Early menarche (menarche before the age of 12 years)

• Late-onset menopause (menopause after the age of 55 years)

• Nulliparity/low parity (defined by World Health Organization as fewer than five pregnancies with gestation periods of ≥ 20 weeks)

• Late age at birth (> 30 years)

• Family history (eg, hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome)

• Genetics (eg, CDH1 mutations)

Treatment protocols for ILC align with those used in other breast cancer subtypes and typically involve a multidisciplinary approach comprising surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic therapies. Cancers that are deemed resectable will typically be managed surgically upfront, although some patients may require neoadjuvant therapy to reduce tumor burden and facilitate surgical intervention. Breast-conserving surgery using a wide local excision can frequently be performed; however, in up to 65% of cases, a second surgery will be required (re-excision or mastectomy). Axillary lymph node status is a crucial factor in the prognosis of all breast cancers and affects surgical planning. Sentinel node biopsy is the standard method of assessing the axilla.

Systemic therapy is an integral part of the multidisciplinary approach to treating breast cancer and usually involves the use of chemotherapy. However, because of the unique molecular biology of ILC, treatment response to chemotherapy is often poor, resulting in lower rates of complete pathologic response and higher rates of mastectomy. Conversely, ILC has been shown to respond well to endocrine therapy, making it the optimal treatment choice. Novel therapeutic approaches are under investigation.

Detailed guidance on the treatment of ILC is available from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

The findings in this case are suggestive of invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC).

Globally, breast cancer remains the most common life-threatening cancer diagnosed and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women. In the United States, approximately 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer were diagnosed in 2022 and 43,250 deaths were attributed to breast cancer in the same year. Worldwide, approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and 685,000 breast cancer-related deaths were reported in 2020.

ILC is one of the leading histologic types of invasive carcinoma, second in incidence only to invasive carcinoma of no special type. ILC accounts for 5%-15% of all invasive breast cancers, and its incidence has been steadily increasing — particularly among postmenopausal women — over the past two decades. ILC has distinct molecular and histopathologic features, including the loss of cell-cell adhesion molecule E-cadherin, resulting in small, discohesive cells proliferating in single-file strands; positivity for both the estrogen and progesterone receptor; and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negativity.

The diagnosis of ILC can be challenging, as it is difficult to detect both on physical examination and with standard imaging techniques. Patients are often diagnosed with late-stage disease, characterized by large tumors and lymph node involvement. The signs of ILC are often vague, such as skin thickening or dimpling. In addition, measuring the extent of ILC can be challenging, as traditional screening methods (eg, mammography and ultrasonography) have a low sensitivity for detecting ILC compared with other invasive breast tumors. This difficulty is usually ascribed to the diffuse infiltrative growth pattern of ILC. MRI has a greater sensitivity for detecting ILC.

Risk factors for the development of ILC have been identified and include:

• Alcohol consumption

• Use of combined hormone replacement therapy

• Early menarche (menarche before the age of 12 years)

• Late-onset menopause (menopause after the age of 55 years)

• Nulliparity/low parity (defined by World Health Organization as fewer than five pregnancies with gestation periods of ≥ 20 weeks)

• Late age at birth (> 30 years)

• Family history (eg, hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome)

• Genetics (eg, CDH1 mutations)

Treatment protocols for ILC align with those used in other breast cancer subtypes and typically involve a multidisciplinary approach comprising surgery, radiotherapy, and systemic therapies. Cancers that are deemed resectable will typically be managed surgically upfront, although some patients may require neoadjuvant therapy to reduce tumor burden and facilitate surgical intervention. Breast-conserving surgery using a wide local excision can frequently be performed; however, in up to 65% of cases, a second surgery will be required (re-excision or mastectomy). Axillary lymph node status is a crucial factor in the prognosis of all breast cancers and affects surgical planning. Sentinel node biopsy is the standard method of assessing the axilla.

Systemic therapy is an integral part of the multidisciplinary approach to treating breast cancer and usually involves the use of chemotherapy. However, because of the unique molecular biology of ILC, treatment response to chemotherapy is often poor, resulting in lower rates of complete pathologic response and higher rates of mastectomy. Conversely, ILC has been shown to respond well to endocrine therapy, making it the optimal treatment choice. Novel therapeutic approaches are under investigation.

Detailed guidance on the treatment of ILC is available from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, Assistant Member, Department of Breast Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center, University of South Florida, Tampa, FL.

Avan J. Armaghani, MD, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

A 58-year-old postmenopausal woman presents for screening mammography. The patient's last mammogram was 18 months ago and showed dense breast tissue with no abnormalities. The patient states that she has no breast symptoms. She is 5 ft 3 in and weighs 196 lb (BMI 34.7). Her previous medical history is unremarkable. There is a family history of breast cancer (two maternal cousins) and colon cancer (paternal grandmother). Bilateral mammography reveals an irregular mass that is approximately 2.4 cm and calcifications in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast. Physical examination reveals no palpable abnormalities. The patient undergoes a stereotactic breast biopsy. Pathology findings include malignant monomorphic cells that form loosely dispersed linear columns encircling the mammary ducts and infiltrating breast tissue and fat.

WHO declares aspartame as possible carcinogen

Although this means aspartame might cause cancer in humans, the Group 2B classification from the IARC means the evidence is “limited.” A summary of the working group’s evaluation, also published in The Lancet Oncology, explained that the classification was based on data from three studies assessing the link between aspartame intake and primary liver cancer.

Using that evidence, the World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives confirmed its existing stance that aspartame consumption of up to 40 mg/kg of body weight per day – the amount found in 9-14 diet soft drinks – is safe.

The decision, which was anticipated by Reuters in late June, drew praise from an array of experts who weighed in on the study results via the U.K.-based Science Media Centre. Many emphasized the lack of data showing a causal relationship between the low-calorie artificial sweetener and sought to temper any alarmism related to the decision.

“In short the evidence that aspartame causes primary liver cancer, or any other cancer in humans, is very weak,” said Paul Pharoah, MD, PhD, a professor of cancer epidemiology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. “Group 2B is a very conservative classification in that almost any evidence of carcinogenicity, however flawed, will put a chemical in that category or above.”

Other examples of substances classified as Group 2B are extract of aloe vera, diesel oil, and caffeic acid found in coffee and tea, Dr. Pharoah explained, adding that “this is reflected in the view of the [JECFA] who concluded that there was no convincing evidence from experimental animal or human data that aspartame has adverse effects after ingestion.”

“The general public should not be worried about the risk of cancer associated with a chemical classed as Group 2B by IARC,” he stressed.

Alan Boobis, OBE, PhD, similarly noted that the Group 2B classification “reflects a lack of confidence that the data from experimental animals or from humans is sufficiently convincing to reach a clear conclusion that aspartame is carcinogenic.”

“Hence, exposure at current levels would not be anticipated to have any detrimental effects,” added Dr. Boobis, emeritus professor of toxicology, Imperial College London.

The IARC/JECFA opinion is “very welcome” and “ends the speculation about the safety of aspartame,” added Gunter Kuhnle, Dr. rer. nat., a professor of nutrition and food science at the University of Reading (England).

“It is unfortunate that leaking some information might have created unnecessary uncertainty and concern as consumers might be rightfully worried if they are told that something that is in many foods could cause cancer,” Dr. Kuhnle said. “The published opinion puts this into perspective and makes it very clear that there is no cause for concern when consumed at the current amounts.”

The data reviewed by the IARC Working Group included three studies, comprising four prospective cohorts, that “assessed the association of artificially sweetened beverage consumption with liver cancer risk,” the group reported.

The cohort studies – including one conducted within 10 European countries, one that pooled data from two large U.S. cohorts, and a prospective study also conducted in the United States – each “showed positive associations between artificially sweetened beverage consumption and cancer incidence or cancer mortality” in the overall study population or in relevant subgroups.

Although the studies were of “high quality and controlled for many potential confounders,” the Working Group concluded that “chance, bias, or confounding could not be ruled out with reasonable confidence.” Thus, the evidence for cancer in humans was deemed “limited” for hepatocellular carcinoma and “inadequate” for other cancer types.”

Dr. Pharoah and Dr. Kuhnle disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Boobis is a member of a number of advisory committees in the public and private sectors, including the International Life Science Institute and The Center for Research on Ingredient Safety at Michigan State University.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although this means aspartame might cause cancer in humans, the Group 2B classification from the IARC means the evidence is “limited.” A summary of the working group’s evaluation, also published in The Lancet Oncology, explained that the classification was based on data from three studies assessing the link between aspartame intake and primary liver cancer.

Using that evidence, the World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives confirmed its existing stance that aspartame consumption of up to 40 mg/kg of body weight per day – the amount found in 9-14 diet soft drinks – is safe.

The decision, which was anticipated by Reuters in late June, drew praise from an array of experts who weighed in on the study results via the U.K.-based Science Media Centre. Many emphasized the lack of data showing a causal relationship between the low-calorie artificial sweetener and sought to temper any alarmism related to the decision.

“In short the evidence that aspartame causes primary liver cancer, or any other cancer in humans, is very weak,” said Paul Pharoah, MD, PhD, a professor of cancer epidemiology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. “Group 2B is a very conservative classification in that almost any evidence of carcinogenicity, however flawed, will put a chemical in that category or above.”

Other examples of substances classified as Group 2B are extract of aloe vera, diesel oil, and caffeic acid found in coffee and tea, Dr. Pharoah explained, adding that “this is reflected in the view of the [JECFA] who concluded that there was no convincing evidence from experimental animal or human data that aspartame has adverse effects after ingestion.”

“The general public should not be worried about the risk of cancer associated with a chemical classed as Group 2B by IARC,” he stressed.

Alan Boobis, OBE, PhD, similarly noted that the Group 2B classification “reflects a lack of confidence that the data from experimental animals or from humans is sufficiently convincing to reach a clear conclusion that aspartame is carcinogenic.”

“Hence, exposure at current levels would not be anticipated to have any detrimental effects,” added Dr. Boobis, emeritus professor of toxicology, Imperial College London.

The IARC/JECFA opinion is “very welcome” and “ends the speculation about the safety of aspartame,” added Gunter Kuhnle, Dr. rer. nat., a professor of nutrition and food science at the University of Reading (England).

“It is unfortunate that leaking some information might have created unnecessary uncertainty and concern as consumers might be rightfully worried if they are told that something that is in many foods could cause cancer,” Dr. Kuhnle said. “The published opinion puts this into perspective and makes it very clear that there is no cause for concern when consumed at the current amounts.”

The data reviewed by the IARC Working Group included three studies, comprising four prospective cohorts, that “assessed the association of artificially sweetened beverage consumption with liver cancer risk,” the group reported.

The cohort studies – including one conducted within 10 European countries, one that pooled data from two large U.S. cohorts, and a prospective study also conducted in the United States – each “showed positive associations between artificially sweetened beverage consumption and cancer incidence or cancer mortality” in the overall study population or in relevant subgroups.

Although the studies were of “high quality and controlled for many potential confounders,” the Working Group concluded that “chance, bias, or confounding could not be ruled out with reasonable confidence.” Thus, the evidence for cancer in humans was deemed “limited” for hepatocellular carcinoma and “inadequate” for other cancer types.”

Dr. Pharoah and Dr. Kuhnle disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Boobis is a member of a number of advisory committees in the public and private sectors, including the International Life Science Institute and The Center for Research on Ingredient Safety at Michigan State University.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although this means aspartame might cause cancer in humans, the Group 2B classification from the IARC means the evidence is “limited.” A summary of the working group’s evaluation, also published in The Lancet Oncology, explained that the classification was based on data from three studies assessing the link between aspartame intake and primary liver cancer.

Using that evidence, the World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives confirmed its existing stance that aspartame consumption of up to 40 mg/kg of body weight per day – the amount found in 9-14 diet soft drinks – is safe.

The decision, which was anticipated by Reuters in late June, drew praise from an array of experts who weighed in on the study results via the U.K.-based Science Media Centre. Many emphasized the lack of data showing a causal relationship between the low-calorie artificial sweetener and sought to temper any alarmism related to the decision.

“In short the evidence that aspartame causes primary liver cancer, or any other cancer in humans, is very weak,” said Paul Pharoah, MD, PhD, a professor of cancer epidemiology at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. “Group 2B is a very conservative classification in that almost any evidence of carcinogenicity, however flawed, will put a chemical in that category or above.”

Other examples of substances classified as Group 2B are extract of aloe vera, diesel oil, and caffeic acid found in coffee and tea, Dr. Pharoah explained, adding that “this is reflected in the view of the [JECFA] who concluded that there was no convincing evidence from experimental animal or human data that aspartame has adverse effects after ingestion.”

“The general public should not be worried about the risk of cancer associated with a chemical classed as Group 2B by IARC,” he stressed.