User login

IMRT bests conventional radiation for soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities

ATLANTA – Intensity-modulated radiation therapy proved significantly better than conventional radiation for local control of soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities, according to new study results, investigators reported at the annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

The 5-year local control rate with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) was 92.4%, compared with 85% for external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT), said Dr. Kaled M. Alektiar, a radiation oncologist at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

The benefits of IMRT were seen despite a preponderance of higher risks in patients treated with IMRT. And, "the morbidity profile, especially for chronic lymphedema of grade 3 or higher, was significantly less," Dr. Alektiar said.

He and his coinvestigators looked at 320 patients who underwent definitive surgery and radiation therapy at Memorial Sloan-Kettering for primary, nonmetastatic soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities. Of this group, 155 received EBRT with a conventional technique, usually three-dimensional conformal radiation, and 165 patients received IMRT.

Most of the tumors (74.7%) were in the lower extremity, 45.6% were at least 10 cm in diameter, 92.2% were in deep tissue, 82.5% were high grade, and 40% had close or positive surgical margins. The majority of patients (75.9%) received adjuvant chemotherapy.

There were significantly more patients with positive or close margins in the IMRT group than in the conventional EBRT group (47.9% vs. 31.6%; P = .003), and more patients treated with IMRT had high-grade histology tumors, although this difference had only borderline significance (86.7% vs. 78.1%; P =.055).

Additionally, significantly more patients in the IMRT group received preoperative radiation (21.2% vs. 3.2%; P less than .001). Otherwise, the groups were balanced in terms of demographics, tumor size, depth, and use of CT in treatment planning.

The median follow-up was 49.5 months (42 months for patients treated with IMRT, and 87 months for those treated with EBRT). The 5-year local recurrence rates were 7.6% for IMRT and 15% for conventional EBRT. The median time to local recurrence was 18 months in each group.

Eight patients required amputations for salvage, including three in the IMRT cohort and five in the conventional radiation cohort.

In multivariate analysis, three factors that were significantly prognostic for local failure were IMRT (hazard ratio, 0.46; P = .02), age less than 50 years (HR, 0.44; P = .04), and a tumor size of 10 cm or less in the longest dimension (HR, 0.53; P = .05).

Overall survival at 5 years was 69.1% for IMRT and 75.6% for EBRT, a difference that was not significant.

Rates of grade 3 or 4 acute toxicities, including infected and noninfected wound complications and radiation dermatitis, were similar between the groups. Patients treated with IMRT had significantly shorter treatment interruptions, at a mean of 0.8 days, compared with 2.2 days for patients treated with conventional EBRT. Chronic grade 3 or higher lymphedema did not occur in any patients treated with IMRT, compared with four patients treated with conventional EBRT (P = .053).

The study was supported by a grant from the Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. Dr. Alektiar reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Intensity-modulated radiation therapy proved significantly better than conventional radiation for local control of soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities, according to new study results, investigators reported at the annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

The 5-year local control rate with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) was 92.4%, compared with 85% for external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT), said Dr. Kaled M. Alektiar, a radiation oncologist at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

The benefits of IMRT were seen despite a preponderance of higher risks in patients treated with IMRT. And, "the morbidity profile, especially for chronic lymphedema of grade 3 or higher, was significantly less," Dr. Alektiar said.

He and his coinvestigators looked at 320 patients who underwent definitive surgery and radiation therapy at Memorial Sloan-Kettering for primary, nonmetastatic soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities. Of this group, 155 received EBRT with a conventional technique, usually three-dimensional conformal radiation, and 165 patients received IMRT.

Most of the tumors (74.7%) were in the lower extremity, 45.6% were at least 10 cm in diameter, 92.2% were in deep tissue, 82.5% were high grade, and 40% had close or positive surgical margins. The majority of patients (75.9%) received adjuvant chemotherapy.

There were significantly more patients with positive or close margins in the IMRT group than in the conventional EBRT group (47.9% vs. 31.6%; P = .003), and more patients treated with IMRT had high-grade histology tumors, although this difference had only borderline significance (86.7% vs. 78.1%; P =.055).

Additionally, significantly more patients in the IMRT group received preoperative radiation (21.2% vs. 3.2%; P less than .001). Otherwise, the groups were balanced in terms of demographics, tumor size, depth, and use of CT in treatment planning.

The median follow-up was 49.5 months (42 months for patients treated with IMRT, and 87 months for those treated with EBRT). The 5-year local recurrence rates were 7.6% for IMRT and 15% for conventional EBRT. The median time to local recurrence was 18 months in each group.

Eight patients required amputations for salvage, including three in the IMRT cohort and five in the conventional radiation cohort.

In multivariate analysis, three factors that were significantly prognostic for local failure were IMRT (hazard ratio, 0.46; P = .02), age less than 50 years (HR, 0.44; P = .04), and a tumor size of 10 cm or less in the longest dimension (HR, 0.53; P = .05).

Overall survival at 5 years was 69.1% for IMRT and 75.6% for EBRT, a difference that was not significant.

Rates of grade 3 or 4 acute toxicities, including infected and noninfected wound complications and radiation dermatitis, were similar between the groups. Patients treated with IMRT had significantly shorter treatment interruptions, at a mean of 0.8 days, compared with 2.2 days for patients treated with conventional EBRT. Chronic grade 3 or higher lymphedema did not occur in any patients treated with IMRT, compared with four patients treated with conventional EBRT (P = .053).

The study was supported by a grant from the Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. Dr. Alektiar reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ATLANTA – Intensity-modulated radiation therapy proved significantly better than conventional radiation for local control of soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities, according to new study results, investigators reported at the annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology.

The 5-year local control rate with intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) was 92.4%, compared with 85% for external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT), said Dr. Kaled M. Alektiar, a radiation oncologist at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

The benefits of IMRT were seen despite a preponderance of higher risks in patients treated with IMRT. And, "the morbidity profile, especially for chronic lymphedema of grade 3 or higher, was significantly less," Dr. Alektiar said.

He and his coinvestigators looked at 320 patients who underwent definitive surgery and radiation therapy at Memorial Sloan-Kettering for primary, nonmetastatic soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities. Of this group, 155 received EBRT with a conventional technique, usually three-dimensional conformal radiation, and 165 patients received IMRT.

Most of the tumors (74.7%) were in the lower extremity, 45.6% were at least 10 cm in diameter, 92.2% were in deep tissue, 82.5% were high grade, and 40% had close or positive surgical margins. The majority of patients (75.9%) received adjuvant chemotherapy.

There were significantly more patients with positive or close margins in the IMRT group than in the conventional EBRT group (47.9% vs. 31.6%; P = .003), and more patients treated with IMRT had high-grade histology tumors, although this difference had only borderline significance (86.7% vs. 78.1%; P =.055).

Additionally, significantly more patients in the IMRT group received preoperative radiation (21.2% vs. 3.2%; P less than .001). Otherwise, the groups were balanced in terms of demographics, tumor size, depth, and use of CT in treatment planning.

The median follow-up was 49.5 months (42 months for patients treated with IMRT, and 87 months for those treated with EBRT). The 5-year local recurrence rates were 7.6% for IMRT and 15% for conventional EBRT. The median time to local recurrence was 18 months in each group.

Eight patients required amputations for salvage, including three in the IMRT cohort and five in the conventional radiation cohort.

In multivariate analysis, three factors that were significantly prognostic for local failure were IMRT (hazard ratio, 0.46; P = .02), age less than 50 years (HR, 0.44; P = .04), and a tumor size of 10 cm or less in the longest dimension (HR, 0.53; P = .05).

Overall survival at 5 years was 69.1% for IMRT and 75.6% for EBRT, a difference that was not significant.

Rates of grade 3 or 4 acute toxicities, including infected and noninfected wound complications and radiation dermatitis, were similar between the groups. Patients treated with IMRT had significantly shorter treatment interruptions, at a mean of 0.8 days, compared with 2.2 days for patients treated with conventional EBRT. Chronic grade 3 or higher lymphedema did not occur in any patients treated with IMRT, compared with four patients treated with conventional EBRT (P = .053).

The study was supported by a grant from the Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. Dr. Alektiar reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ASTRO ANNUAL MEETING

Major finding: The 5-year local control rate with intensity-modulated radiation therapy was 92.4%, compared with 85% for conventional external-beam radiation therapy.

Data source: Retrospective study of 320 patients treated for soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a grant from the Clinical and Translational Science Center at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. Dr. Alektiar reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

ASDS 2013 Roundup with Dr. Kavita Mariwalla

Dr. Kavita Mariwalla, the 2013 ASDS annual meeting chair, provides a 3-minute summary of the hot topics discussed at the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery, held in Chicago. For more, visit http://www.skindandallergynews.com.

Dr. Kavita Mariwalla, the 2013 ASDS annual meeting chair, provides a 3-minute summary of the hot topics discussed at the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery, held in Chicago. For more, visit http://www.skindandallergynews.com.

Dr. Kavita Mariwalla, the 2013 ASDS annual meeting chair, provides a 3-minute summary of the hot topics discussed at the American Society of Dermatologic Surgery, held in Chicago. For more, visit http://www.skindandallergynews.com.

Collateral damage

Six and a half years ago, my malpractice insurer made a payment to settle a case against a company I once ran in a neighboring state. Nine years before that, a physician who worked for me had lasered a tattoo on a woman’s ankle. She claimed it got infected and then scarred, but refused to be examined at that time, or later.

This case wound its way slowly through the system. I drove to the nearby state to plot strategy with the insurer’s attorney for dealing with the $50,000 claim. "I can’t understand why anyone would take a case this small," said the attorney.

When we got to the courthouse that January day, we saw why. The plaintiff – whom I had never met – was accompanied by a lawyer. He and my attorney met with the judge.

"Settle this case," she ordered.

And so we did, for $22,500. The plaintiff stipulated that I "did not act negligently in any respect."

As we exited the courtroom into the hall, the plaintiff approached me. "My tattoo isn’t gone yet," she said. "Would you be able to treat it?"

My attorney’s jaw dropped. Not mine, though. I had her put her ankle up on a bench to look at it. There was no scarring, just the hypopigmentation one sees after laser treatment in that area.

"You know," I told her. "I’m all the way in the next state. "The doctor here in town who treated you – the one who was going to testify against me today? He would be perfect."

We smiled at each other, shook hands, and I went home.

Fast forward to last week. A registered letter came to my office from a local electrical union. It contained a flyer that read:

Don’t be in the DARK about your doctor. XYZ hospital continues to allow doctors with recent malpractice payments to treat patients, WHY?

DR. ALAN S. ROCKOFF MADE A MALPRACTICE PAYMENT.

What kind of DOCTOR do you want treating you and your loved ones?

The accompanying letter explained that, "We intend to distribute [the leaflet] in the near future to anyone entering or leaving your medical building, as well as residents and businesses in the surrounding community. We will also be publicizing the content on DrRockoffexposed.com and through social media including Facebook and Twitter."

They added, "We strive for accuracy in all of our leaflets and websites." I was given 1 week to let them know if I found "anything untruthful or inaccurate," to "kindly let me know."

I thought the "kindly" was a nice touch.

The leaflet included a lot of nasty innuendoes about hospital XYZ, where I have staff privileges.

Bewildered, I contacted my malpractice insurer, who helpfully told me there was nothing I could do, and suggested I contact the hospital, at whom the campaign was clearly intended. I did so. The people at the hospital expressed sympathy and outrage about the union’s letter, and told me to ignore it.

An attorney affiliated with my malpractice insurer did some digging, and he sent me a link to an article showing that his union had used similar tactics against a hospital north of town 2 years ago. Their motive, it appears, is to be sure their union secures contracts for work at the hospitals in question.

In other words, friends, this is what is known in Mafia movies as a shakedown. "Nice medical staff you’ve got there," says the leaflet, in so many words. "Be a shame if anything happened to it."

As a kid, I used to watch Elliot Ness in "The Untouchables," but I never thought I would be personally involved in anything I saw there. But if you live long enough, you never know what you’ll experience. Anyhow, any publicity is good publicity, and DrRockoffexposed.com does spell my name right, even if it’s not nearly as fun to see as what one could imagine at something like www.TweetingCongressmanExposed.com.

For better or worse, the time when doctors sat in their offices, wrote notes on 3x5 cards, and collected cash payments they stowed in their desk drawers are long gone. In the Olympian corridors of power far above our heads, powerful forces that dictate our lives hurl thunderbolts at each other as they vie for money, power, and control. The trick is to stay out of their way and avoid becoming collateral damage.

Easy to say. Less easy to do.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass. He is on the clinical faculty at Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Dr. Rockoff has contributed to the Under My Skin column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2002.

Six and a half years ago, my malpractice insurer made a payment to settle a case against a company I once ran in a neighboring state. Nine years before that, a physician who worked for me had lasered a tattoo on a woman’s ankle. She claimed it got infected and then scarred, but refused to be examined at that time, or later.

This case wound its way slowly through the system. I drove to the nearby state to plot strategy with the insurer’s attorney for dealing with the $50,000 claim. "I can’t understand why anyone would take a case this small," said the attorney.

When we got to the courthouse that January day, we saw why. The plaintiff – whom I had never met – was accompanied by a lawyer. He and my attorney met with the judge.

"Settle this case," she ordered.

And so we did, for $22,500. The plaintiff stipulated that I "did not act negligently in any respect."

As we exited the courtroom into the hall, the plaintiff approached me. "My tattoo isn’t gone yet," she said. "Would you be able to treat it?"

My attorney’s jaw dropped. Not mine, though. I had her put her ankle up on a bench to look at it. There was no scarring, just the hypopigmentation one sees after laser treatment in that area.

"You know," I told her. "I’m all the way in the next state. "The doctor here in town who treated you – the one who was going to testify against me today? He would be perfect."

We smiled at each other, shook hands, and I went home.

Fast forward to last week. A registered letter came to my office from a local electrical union. It contained a flyer that read:

Don’t be in the DARK about your doctor. XYZ hospital continues to allow doctors with recent malpractice payments to treat patients, WHY?

DR. ALAN S. ROCKOFF MADE A MALPRACTICE PAYMENT.

What kind of DOCTOR do you want treating you and your loved ones?

The accompanying letter explained that, "We intend to distribute [the leaflet] in the near future to anyone entering or leaving your medical building, as well as residents and businesses in the surrounding community. We will also be publicizing the content on DrRockoffexposed.com and through social media including Facebook and Twitter."

They added, "We strive for accuracy in all of our leaflets and websites." I was given 1 week to let them know if I found "anything untruthful or inaccurate," to "kindly let me know."

I thought the "kindly" was a nice touch.

The leaflet included a lot of nasty innuendoes about hospital XYZ, where I have staff privileges.

Bewildered, I contacted my malpractice insurer, who helpfully told me there was nothing I could do, and suggested I contact the hospital, at whom the campaign was clearly intended. I did so. The people at the hospital expressed sympathy and outrage about the union’s letter, and told me to ignore it.

An attorney affiliated with my malpractice insurer did some digging, and he sent me a link to an article showing that his union had used similar tactics against a hospital north of town 2 years ago. Their motive, it appears, is to be sure their union secures contracts for work at the hospitals in question.

In other words, friends, this is what is known in Mafia movies as a shakedown. "Nice medical staff you’ve got there," says the leaflet, in so many words. "Be a shame if anything happened to it."

As a kid, I used to watch Elliot Ness in "The Untouchables," but I never thought I would be personally involved in anything I saw there. But if you live long enough, you never know what you’ll experience. Anyhow, any publicity is good publicity, and DrRockoffexposed.com does spell my name right, even if it’s not nearly as fun to see as what one could imagine at something like www.TweetingCongressmanExposed.com.

For better or worse, the time when doctors sat in their offices, wrote notes on 3x5 cards, and collected cash payments they stowed in their desk drawers are long gone. In the Olympian corridors of power far above our heads, powerful forces that dictate our lives hurl thunderbolts at each other as they vie for money, power, and control. The trick is to stay out of their way and avoid becoming collateral damage.

Easy to say. Less easy to do.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass. He is on the clinical faculty at Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Dr. Rockoff has contributed to the Under My Skin column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2002.

Six and a half years ago, my malpractice insurer made a payment to settle a case against a company I once ran in a neighboring state. Nine years before that, a physician who worked for me had lasered a tattoo on a woman’s ankle. She claimed it got infected and then scarred, but refused to be examined at that time, or later.

This case wound its way slowly through the system. I drove to the nearby state to plot strategy with the insurer’s attorney for dealing with the $50,000 claim. "I can’t understand why anyone would take a case this small," said the attorney.

When we got to the courthouse that January day, we saw why. The plaintiff – whom I had never met – was accompanied by a lawyer. He and my attorney met with the judge.

"Settle this case," she ordered.

And so we did, for $22,500. The plaintiff stipulated that I "did not act negligently in any respect."

As we exited the courtroom into the hall, the plaintiff approached me. "My tattoo isn’t gone yet," she said. "Would you be able to treat it?"

My attorney’s jaw dropped. Not mine, though. I had her put her ankle up on a bench to look at it. There was no scarring, just the hypopigmentation one sees after laser treatment in that area.

"You know," I told her. "I’m all the way in the next state. "The doctor here in town who treated you – the one who was going to testify against me today? He would be perfect."

We smiled at each other, shook hands, and I went home.

Fast forward to last week. A registered letter came to my office from a local electrical union. It contained a flyer that read:

Don’t be in the DARK about your doctor. XYZ hospital continues to allow doctors with recent malpractice payments to treat patients, WHY?

DR. ALAN S. ROCKOFF MADE A MALPRACTICE PAYMENT.

What kind of DOCTOR do you want treating you and your loved ones?

The accompanying letter explained that, "We intend to distribute [the leaflet] in the near future to anyone entering or leaving your medical building, as well as residents and businesses in the surrounding community. We will also be publicizing the content on DrRockoffexposed.com and through social media including Facebook and Twitter."

They added, "We strive for accuracy in all of our leaflets and websites." I was given 1 week to let them know if I found "anything untruthful or inaccurate," to "kindly let me know."

I thought the "kindly" was a nice touch.

The leaflet included a lot of nasty innuendoes about hospital XYZ, where I have staff privileges.

Bewildered, I contacted my malpractice insurer, who helpfully told me there was nothing I could do, and suggested I contact the hospital, at whom the campaign was clearly intended. I did so. The people at the hospital expressed sympathy and outrage about the union’s letter, and told me to ignore it.

An attorney affiliated with my malpractice insurer did some digging, and he sent me a link to an article showing that his union had used similar tactics against a hospital north of town 2 years ago. Their motive, it appears, is to be sure their union secures contracts for work at the hospitals in question.

In other words, friends, this is what is known in Mafia movies as a shakedown. "Nice medical staff you’ve got there," says the leaflet, in so many words. "Be a shame if anything happened to it."

As a kid, I used to watch Elliot Ness in "The Untouchables," but I never thought I would be personally involved in anything I saw there. But if you live long enough, you never know what you’ll experience. Anyhow, any publicity is good publicity, and DrRockoffexposed.com does spell my name right, even if it’s not nearly as fun to see as what one could imagine at something like www.TweetingCongressmanExposed.com.

For better or worse, the time when doctors sat in their offices, wrote notes on 3x5 cards, and collected cash payments they stowed in their desk drawers are long gone. In the Olympian corridors of power far above our heads, powerful forces that dictate our lives hurl thunderbolts at each other as they vie for money, power, and control. The trick is to stay out of their way and avoid becoming collateral damage.

Easy to say. Less easy to do.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass. He is on the clinical faculty at Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Dr. Rockoff has contributed to the Under My Skin column in Skin & Allergy News since January 2002.

Predicting Safe Physician Workloads

Attending physician workload may be compromising patient safety and quality of care. Recent studies show hospitalists, intensivists, and surgeons report that excessive attending physician workload has a negative impact on patient care.[1, 2, 3] Because physician teams and hospitals differ in composition, function, and setting, it is difficult to directly compare one service to another within or between institutions. Identifying physician, team, and hospital characteristics associated with clinicians' impressions of unsafe workload provides physician leaders, hospital administrators, and policymakers with potential risk factors and specific targets for interventions.[4] In this study, we use a national survey of hospitalists to identify the physician, team, and hospital factors associated with physician report of an unsafe workload.

METHODS

We electronically surveyed 890 self‐identified hospitalists enrolled in

RESULTS

Of the 890 physicians contacted, 506 (57%) responded. Full characteristics of respondents are reported elsewhere.[1] Forty percent of physicians (n=202) indicated that their typical inpatient census exceeded safe levels at least monthly. A descriptive comparison of the lower and higher reporters of unsafe levels is provided (Table 1). Higher frequency of reporting an unsafe census was associated with higher percentages of clinical (P=0.004) and inpatient responsibilities (P0.001) and more time seeing patients without midlevel or housestaff assistance (P=0.001) (Table 1). On the other hand, lower reported unsafe census was associated with more years in practice (P=0.02), greater percentage of personal time (P=0.02), and the presence of any system for census control (patient caps, fixed bed capacity, staffing augmentation plans) (P=0.007) (Table 1). Fixed census caps decreased the odds of reporting an unsafe census by 34% and was the only statistically significant workload control mechanism (odds ratio: 0.66; 95% confidence interval: 0.43‐0.99; P=0.04). There was no association between reported unsafe census and physician age (P=0.42), practice area (P=0.63), organization type (P=0.98), or compensation (salary [P=0.23], bonus [P=0.61], or total [P=0.54]).

| Characteristic | Report of Unsafe Workloada | Univariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Reported Effect on Unsafe Workload Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Higher | |||

| ||||

| Percentage of total work hours devoted to patient care, median [IQR] | 95 [80100] | 100 [90100] | 1.13b (1.041.23)c | Increased |

| Percentage of clinical care that is inpatient, median [IQR] | 75 [5085] | 80 [7090] | 1.21b (1.131.34)d | |

| Percentage of clinical work performed with no assistance from housestaff or midlevels, median [IQR] | 80 [25100] | 90 [50100] | 1.08b (1.031.14)c | |

| Years in practice, median [IQR] | 6 [311] | 5 [310] | 0.85e (0.750.98)f | Decreased |

| Percentage of workday allotted for personal time, median [IQR] | 5 [07] | 3 [05] | 0.50b (0.380.92)f | |

| Systems for increased patient volume, No. (%) | ||||

| Fixed census cap | 87 (30) | 45 (22) | 0.66 (0.430.99)f | |

| Fixed bed capacity | 36 (13) | 24 (12) | 0.94 (0.541.63) | |

| Staffing augmentation | 88 (31) | 58 (29) | 0.91 (0.611.35) | |

| Any system | 217 (76) | 130 (64) | 0.58 (0.390.86)g | |

| Primary practice area of hospital medicine, No. (%) | ||||

| Adult | 211 (73) | 173 (86) | 1 | Equivocal |

| Pediatric | 7 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.24 (0.032.10) | |

| Combined, adult and pediatric | 5 (2) | 3 (1) | 0.73 (0.173.10) | |

| Primary role, No. (%) | ||||

| Clinical | 242 (83) | 186 (92) | 1 | |

| Research | 5 (2) | 4 (2) | 1.04 (0.283.93) | |

| Administrative | 14 (5) | 6 (3) | 0.56 (0.211.48) | |

| Physician age, median [IQR], y | 36 [3242] | 37 [3342] | 0.96e (0.861.07) | |

| Compensation, median [IQR], thousands of dollars | ||||

| Salary only | 180 [130200] | 180 [150200] | 0.97h (0.981.05) | |

| Incentive pay only | 10 [025] | 10 [020] | 0.99h (0.941.04) | |

| Total | 190 [140220] | 196 [165220] | 0.99h (0.981.03) | |

| Practice area, No. (%) | ||||

| Urban | 128 (45) | 98 (49) | 1 | |

| Suburban | 126 (44) | 81 (41) | 0.84 (0.571.23) | |

| Rural | 33 (11) | 21 (10) | 0.83 (0.451.53) | |

| Practice location, No. (%) | ||||

| Academic | 82 (29) | 54 (27) | 1 | |

| Community | 153 (53) | 110 (55) | 1.09 (0.721.66) | |

| Veterans hospital | 7 (2) | 4 (2) | 0.87 (0.243.10) | |

| Group | 32 (11) | 25 (13) | 1.19 (0.632.21) | |

| Physician group size, median [IQR] | 12 [620] | 12 [822] | 0.99i (0.981.03) | |

| Localization of patients, No. (%) | ||||

| Multiple units | 179 (61) | 124 (61) | 1 | |

| Single or adjacent unit(s) | 87 (30) | 58 (29) | 0.96 (0.641.44) | |

| Multiple hospitals | 25 (9) | 20 (10) | 1.15 (0.612.17) | |

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to our knowledge to describe factors associated with provider reports of unsafe workload and identifies potential targets for intervention. By identifying modifiable factors affecting workload, such as different team structures with housestaff or midlevels, it may be possible to improve workload, efficiency, and perhaps safety.[5, 6] Less experience, decreased housestaff or midlevel assistance, higher percentages of inpatient and clinical responsibilities, and lack of systems for census control were strongly associated with reports of unsafe workload.

Having any system in place to address increased patient volumes reduced the odds of reporting an unsafe workload. However, only fixed patient census caps were statistically significant. A system that incorporates fixed service or admitting caps may provide greater control on workload but may also result in back‐ups and delays in the emergency room. Similarly, fixed caps may require overflow of patients to less experienced or willing services or increase the number of handoffs, which may adversely affect the quality of patient care. Use of separate admitting teams has the potential to increase efficiency, but is also subject to fluctuations in patient volume and increases the number of handoffs. Each institution should use a multidisciplinary systems approach to address patient throughput and enforce manageable workload such as through the creation of patient flow teams.[7]

Limitations of the study include the relatively small sample of hospitalists and self‐reporting of safety. Because of the diverse characteristics and structures of the individual programs, even if a predictor variable was not missing, if a particular value for that predictor occurred very infrequently, it generated very wide effect estimates. This limited our ability to effectively explore potential confounders and interactions. To our knowledge, this study is the first to explore potential predictors of unsafe attending physician workload. Large national surveys of physicians with greater statistical power can expand upon this initial work and further explore the association between, and interaction of, workload factors and varying perceptions of providers.[4] The most important limitation of this work is that we relied on self‐reporting to define a safe census. We do not have any measured clinical outcomes that can serve to validate the self‐reported impressions. We recognize, however, that adverse events in healthcare require multiple weaknesses to align, and typically, multiple barriers exist to prevent such events. This often makes it difficult to show direct causal links. Additionally, self‐reporting of safety may also be subject to recall bias, because adverse patient outcomes are often particularly memorable. However, high‐reliability organizations recognize the importance of front‐line provider input, such as on the sensitivity of operations (working conditions) and by deferring to expertise (insights and recommendations from providers most knowledgeable of conditions, regardless of seniority).[8]

We acknowledge that several workload factors, such as hospital setting, may not be readily modifiable. However, we also report factors that can be intervened upon, such as assistance[5, 6] or geographic localization of patients.[9, 10] An understanding of both modifiable and fixed factors in healthcare delivery is essential for improving patient care.

This study has significant research implications. It suggests that team structure and physician experience may be used to improve workload safety. Also, particularly if these self‐reported findings are verified using clinical outcomes, providing hospitalists with greater staffing assistance and systems responsive to census fluctuations may improve the safety, quality, and flow of patient care. Future research may identify the association of physician, team, and hospital factors with outcomes and objectively assess targeted interventions to improve both the efficiency and quality of care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Johns Hopkins Clinical Research Network Hospitalists, General Internal Medicine Research in Progress Physicians, and Hospitalist Directors for the Maryland/District of Columbia region for sharing their models of care and comments on the survey content. They also thank Michael Paskavitz, BA (Editor‐in‐Chief) and Brian Driscoll, BA (Managing Editor) from Quantia Communications for all of their technical assistance in administering the survey.

Disclosures: Drs. Michtalik and Brotman had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Michtalik, Pronovost, Brotman. Analysis, interpretation of data: Michtalik, Pronovost, Marsteller, Spetz, Brotman. Drafting of the manuscript: Michtalik, Brotman. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Michtalik, Pronovost, Marsteller, Spetz, Brotman. Dr. Brotman has received compensation from Quantia Communications, not exceeding $10,000 annually, for developing educational content. Dr. Michtalik was supported by NIH grant T32 HP10025‐17‐00 and NIH/Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research KL2 Award 5KL2RR025006. The Johns Hopkins Hospitalist Scholars Fund provided funding for survey implementation and data acquisition by Quantia Communications. The funders had no role in the design, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , . Impact of attending physician workload on patient care: a survey of hospitalists. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(5):375–377.

- , , , et al. Does surgeon workload per day affect outcomes after pulmonary lobectomies? Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94(3):966–972.

- , , , . Perceived effects of attending physician workload in academic medical intensive care units: a national survey of training program directors. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):400–405.

- , , , , . Developing a model for attending physician workload and outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(11):1026–1028.

- , , , et al. A comparison of outcomes of general medical inpatient care provided by a hospitalist‐physician assistant model vs a traditional resident‐based model. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):122–130.

- , , , et al. Implementation of a physician assistant/hospitalist service in an academic medical center: impact on efficiency and patient outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):361–368.

- , , , . Improving patient flow and reducing emergency department crowding: a guide for hospitals. AHRQ publication no. 11(12)−0094. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

- , , , et al. Becoming a high reliability organization: operational advice for hospital leaders. AHRQ publication no. 08–0022. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008.

- , , , et al. Impact of localizing general medical teams to a single nursing unit. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(7):551–556.

- , , , et al. Impact of localizing physicians to hospital units on nurse‐physician communication and agreement on the plan of care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(11):1223–1227.

Attending physician workload may be compromising patient safety and quality of care. Recent studies show hospitalists, intensivists, and surgeons report that excessive attending physician workload has a negative impact on patient care.[1, 2, 3] Because physician teams and hospitals differ in composition, function, and setting, it is difficult to directly compare one service to another within or between institutions. Identifying physician, team, and hospital characteristics associated with clinicians' impressions of unsafe workload provides physician leaders, hospital administrators, and policymakers with potential risk factors and specific targets for interventions.[4] In this study, we use a national survey of hospitalists to identify the physician, team, and hospital factors associated with physician report of an unsafe workload.

METHODS

We electronically surveyed 890 self‐identified hospitalists enrolled in

RESULTS

Of the 890 physicians contacted, 506 (57%) responded. Full characteristics of respondents are reported elsewhere.[1] Forty percent of physicians (n=202) indicated that their typical inpatient census exceeded safe levels at least monthly. A descriptive comparison of the lower and higher reporters of unsafe levels is provided (Table 1). Higher frequency of reporting an unsafe census was associated with higher percentages of clinical (P=0.004) and inpatient responsibilities (P0.001) and more time seeing patients without midlevel or housestaff assistance (P=0.001) (Table 1). On the other hand, lower reported unsafe census was associated with more years in practice (P=0.02), greater percentage of personal time (P=0.02), and the presence of any system for census control (patient caps, fixed bed capacity, staffing augmentation plans) (P=0.007) (Table 1). Fixed census caps decreased the odds of reporting an unsafe census by 34% and was the only statistically significant workload control mechanism (odds ratio: 0.66; 95% confidence interval: 0.43‐0.99; P=0.04). There was no association between reported unsafe census and physician age (P=0.42), practice area (P=0.63), organization type (P=0.98), or compensation (salary [P=0.23], bonus [P=0.61], or total [P=0.54]).

| Characteristic | Report of Unsafe Workloada | Univariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Reported Effect on Unsafe Workload Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Higher | |||

| ||||

| Percentage of total work hours devoted to patient care, median [IQR] | 95 [80100] | 100 [90100] | 1.13b (1.041.23)c | Increased |

| Percentage of clinical care that is inpatient, median [IQR] | 75 [5085] | 80 [7090] | 1.21b (1.131.34)d | |

| Percentage of clinical work performed with no assistance from housestaff or midlevels, median [IQR] | 80 [25100] | 90 [50100] | 1.08b (1.031.14)c | |

| Years in practice, median [IQR] | 6 [311] | 5 [310] | 0.85e (0.750.98)f | Decreased |

| Percentage of workday allotted for personal time, median [IQR] | 5 [07] | 3 [05] | 0.50b (0.380.92)f | |

| Systems for increased patient volume, No. (%) | ||||

| Fixed census cap | 87 (30) | 45 (22) | 0.66 (0.430.99)f | |

| Fixed bed capacity | 36 (13) | 24 (12) | 0.94 (0.541.63) | |

| Staffing augmentation | 88 (31) | 58 (29) | 0.91 (0.611.35) | |

| Any system | 217 (76) | 130 (64) | 0.58 (0.390.86)g | |

| Primary practice area of hospital medicine, No. (%) | ||||

| Adult | 211 (73) | 173 (86) | 1 | Equivocal |

| Pediatric | 7 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.24 (0.032.10) | |

| Combined, adult and pediatric | 5 (2) | 3 (1) | 0.73 (0.173.10) | |

| Primary role, No. (%) | ||||

| Clinical | 242 (83) | 186 (92) | 1 | |

| Research | 5 (2) | 4 (2) | 1.04 (0.283.93) | |

| Administrative | 14 (5) | 6 (3) | 0.56 (0.211.48) | |

| Physician age, median [IQR], y | 36 [3242] | 37 [3342] | 0.96e (0.861.07) | |

| Compensation, median [IQR], thousands of dollars | ||||

| Salary only | 180 [130200] | 180 [150200] | 0.97h (0.981.05) | |

| Incentive pay only | 10 [025] | 10 [020] | 0.99h (0.941.04) | |

| Total | 190 [140220] | 196 [165220] | 0.99h (0.981.03) | |

| Practice area, No. (%) | ||||

| Urban | 128 (45) | 98 (49) | 1 | |

| Suburban | 126 (44) | 81 (41) | 0.84 (0.571.23) | |

| Rural | 33 (11) | 21 (10) | 0.83 (0.451.53) | |

| Practice location, No. (%) | ||||

| Academic | 82 (29) | 54 (27) | 1 | |

| Community | 153 (53) | 110 (55) | 1.09 (0.721.66) | |

| Veterans hospital | 7 (2) | 4 (2) | 0.87 (0.243.10) | |

| Group | 32 (11) | 25 (13) | 1.19 (0.632.21) | |

| Physician group size, median [IQR] | 12 [620] | 12 [822] | 0.99i (0.981.03) | |

| Localization of patients, No. (%) | ||||

| Multiple units | 179 (61) | 124 (61) | 1 | |

| Single or adjacent unit(s) | 87 (30) | 58 (29) | 0.96 (0.641.44) | |

| Multiple hospitals | 25 (9) | 20 (10) | 1.15 (0.612.17) | |

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to our knowledge to describe factors associated with provider reports of unsafe workload and identifies potential targets for intervention. By identifying modifiable factors affecting workload, such as different team structures with housestaff or midlevels, it may be possible to improve workload, efficiency, and perhaps safety.[5, 6] Less experience, decreased housestaff or midlevel assistance, higher percentages of inpatient and clinical responsibilities, and lack of systems for census control were strongly associated with reports of unsafe workload.

Having any system in place to address increased patient volumes reduced the odds of reporting an unsafe workload. However, only fixed patient census caps were statistically significant. A system that incorporates fixed service or admitting caps may provide greater control on workload but may also result in back‐ups and delays in the emergency room. Similarly, fixed caps may require overflow of patients to less experienced or willing services or increase the number of handoffs, which may adversely affect the quality of patient care. Use of separate admitting teams has the potential to increase efficiency, but is also subject to fluctuations in patient volume and increases the number of handoffs. Each institution should use a multidisciplinary systems approach to address patient throughput and enforce manageable workload such as through the creation of patient flow teams.[7]

Limitations of the study include the relatively small sample of hospitalists and self‐reporting of safety. Because of the diverse characteristics and structures of the individual programs, even if a predictor variable was not missing, if a particular value for that predictor occurred very infrequently, it generated very wide effect estimates. This limited our ability to effectively explore potential confounders and interactions. To our knowledge, this study is the first to explore potential predictors of unsafe attending physician workload. Large national surveys of physicians with greater statistical power can expand upon this initial work and further explore the association between, and interaction of, workload factors and varying perceptions of providers.[4] The most important limitation of this work is that we relied on self‐reporting to define a safe census. We do not have any measured clinical outcomes that can serve to validate the self‐reported impressions. We recognize, however, that adverse events in healthcare require multiple weaknesses to align, and typically, multiple barriers exist to prevent such events. This often makes it difficult to show direct causal links. Additionally, self‐reporting of safety may also be subject to recall bias, because adverse patient outcomes are often particularly memorable. However, high‐reliability organizations recognize the importance of front‐line provider input, such as on the sensitivity of operations (working conditions) and by deferring to expertise (insights and recommendations from providers most knowledgeable of conditions, regardless of seniority).[8]

We acknowledge that several workload factors, such as hospital setting, may not be readily modifiable. However, we also report factors that can be intervened upon, such as assistance[5, 6] or geographic localization of patients.[9, 10] An understanding of both modifiable and fixed factors in healthcare delivery is essential for improving patient care.

This study has significant research implications. It suggests that team structure and physician experience may be used to improve workload safety. Also, particularly if these self‐reported findings are verified using clinical outcomes, providing hospitalists with greater staffing assistance and systems responsive to census fluctuations may improve the safety, quality, and flow of patient care. Future research may identify the association of physician, team, and hospital factors with outcomes and objectively assess targeted interventions to improve both the efficiency and quality of care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Johns Hopkins Clinical Research Network Hospitalists, General Internal Medicine Research in Progress Physicians, and Hospitalist Directors for the Maryland/District of Columbia region for sharing their models of care and comments on the survey content. They also thank Michael Paskavitz, BA (Editor‐in‐Chief) and Brian Driscoll, BA (Managing Editor) from Quantia Communications for all of their technical assistance in administering the survey.

Disclosures: Drs. Michtalik and Brotman had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Michtalik, Pronovost, Brotman. Analysis, interpretation of data: Michtalik, Pronovost, Marsteller, Spetz, Brotman. Drafting of the manuscript: Michtalik, Brotman. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Michtalik, Pronovost, Marsteller, Spetz, Brotman. Dr. Brotman has received compensation from Quantia Communications, not exceeding $10,000 annually, for developing educational content. Dr. Michtalik was supported by NIH grant T32 HP10025‐17‐00 and NIH/Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research KL2 Award 5KL2RR025006. The Johns Hopkins Hospitalist Scholars Fund provided funding for survey implementation and data acquisition by Quantia Communications. The funders had no role in the design, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Attending physician workload may be compromising patient safety and quality of care. Recent studies show hospitalists, intensivists, and surgeons report that excessive attending physician workload has a negative impact on patient care.[1, 2, 3] Because physician teams and hospitals differ in composition, function, and setting, it is difficult to directly compare one service to another within or between institutions. Identifying physician, team, and hospital characteristics associated with clinicians' impressions of unsafe workload provides physician leaders, hospital administrators, and policymakers with potential risk factors and specific targets for interventions.[4] In this study, we use a national survey of hospitalists to identify the physician, team, and hospital factors associated with physician report of an unsafe workload.

METHODS

We electronically surveyed 890 self‐identified hospitalists enrolled in

RESULTS

Of the 890 physicians contacted, 506 (57%) responded. Full characteristics of respondents are reported elsewhere.[1] Forty percent of physicians (n=202) indicated that their typical inpatient census exceeded safe levels at least monthly. A descriptive comparison of the lower and higher reporters of unsafe levels is provided (Table 1). Higher frequency of reporting an unsafe census was associated with higher percentages of clinical (P=0.004) and inpatient responsibilities (P0.001) and more time seeing patients without midlevel or housestaff assistance (P=0.001) (Table 1). On the other hand, lower reported unsafe census was associated with more years in practice (P=0.02), greater percentage of personal time (P=0.02), and the presence of any system for census control (patient caps, fixed bed capacity, staffing augmentation plans) (P=0.007) (Table 1). Fixed census caps decreased the odds of reporting an unsafe census by 34% and was the only statistically significant workload control mechanism (odds ratio: 0.66; 95% confidence interval: 0.43‐0.99; P=0.04). There was no association between reported unsafe census and physician age (P=0.42), practice area (P=0.63), organization type (P=0.98), or compensation (salary [P=0.23], bonus [P=0.61], or total [P=0.54]).

| Characteristic | Report of Unsafe Workloada | Univariate Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Reported Effect on Unsafe Workload Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Higher | |||

| ||||

| Percentage of total work hours devoted to patient care, median [IQR] | 95 [80100] | 100 [90100] | 1.13b (1.041.23)c | Increased |

| Percentage of clinical care that is inpatient, median [IQR] | 75 [5085] | 80 [7090] | 1.21b (1.131.34)d | |

| Percentage of clinical work performed with no assistance from housestaff or midlevels, median [IQR] | 80 [25100] | 90 [50100] | 1.08b (1.031.14)c | |

| Years in practice, median [IQR] | 6 [311] | 5 [310] | 0.85e (0.750.98)f | Decreased |

| Percentage of workday allotted for personal time, median [IQR] | 5 [07] | 3 [05] | 0.50b (0.380.92)f | |

| Systems for increased patient volume, No. (%) | ||||

| Fixed census cap | 87 (30) | 45 (22) | 0.66 (0.430.99)f | |

| Fixed bed capacity | 36 (13) | 24 (12) | 0.94 (0.541.63) | |

| Staffing augmentation | 88 (31) | 58 (29) | 0.91 (0.611.35) | |

| Any system | 217 (76) | 130 (64) | 0.58 (0.390.86)g | |

| Primary practice area of hospital medicine, No. (%) | ||||

| Adult | 211 (73) | 173 (86) | 1 | Equivocal |

| Pediatric | 7 (2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.24 (0.032.10) | |

| Combined, adult and pediatric | 5 (2) | 3 (1) | 0.73 (0.173.10) | |

| Primary role, No. (%) | ||||

| Clinical | 242 (83) | 186 (92) | 1 | |

| Research | 5 (2) | 4 (2) | 1.04 (0.283.93) | |

| Administrative | 14 (5) | 6 (3) | 0.56 (0.211.48) | |

| Physician age, median [IQR], y | 36 [3242] | 37 [3342] | 0.96e (0.861.07) | |

| Compensation, median [IQR], thousands of dollars | ||||

| Salary only | 180 [130200] | 180 [150200] | 0.97h (0.981.05) | |

| Incentive pay only | 10 [025] | 10 [020] | 0.99h (0.941.04) | |

| Total | 190 [140220] | 196 [165220] | 0.99h (0.981.03) | |

| Practice area, No. (%) | ||||

| Urban | 128 (45) | 98 (49) | 1 | |

| Suburban | 126 (44) | 81 (41) | 0.84 (0.571.23) | |

| Rural | 33 (11) | 21 (10) | 0.83 (0.451.53) | |

| Practice location, No. (%) | ||||

| Academic | 82 (29) | 54 (27) | 1 | |

| Community | 153 (53) | 110 (55) | 1.09 (0.721.66) | |

| Veterans hospital | 7 (2) | 4 (2) | 0.87 (0.243.10) | |

| Group | 32 (11) | 25 (13) | 1.19 (0.632.21) | |

| Physician group size, median [IQR] | 12 [620] | 12 [822] | 0.99i (0.981.03) | |

| Localization of patients, No. (%) | ||||

| Multiple units | 179 (61) | 124 (61) | 1 | |

| Single or adjacent unit(s) | 87 (30) | 58 (29) | 0.96 (0.641.44) | |

| Multiple hospitals | 25 (9) | 20 (10) | 1.15 (0.612.17) | |

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to our knowledge to describe factors associated with provider reports of unsafe workload and identifies potential targets for intervention. By identifying modifiable factors affecting workload, such as different team structures with housestaff or midlevels, it may be possible to improve workload, efficiency, and perhaps safety.[5, 6] Less experience, decreased housestaff or midlevel assistance, higher percentages of inpatient and clinical responsibilities, and lack of systems for census control were strongly associated with reports of unsafe workload.

Having any system in place to address increased patient volumes reduced the odds of reporting an unsafe workload. However, only fixed patient census caps were statistically significant. A system that incorporates fixed service or admitting caps may provide greater control on workload but may also result in back‐ups and delays in the emergency room. Similarly, fixed caps may require overflow of patients to less experienced or willing services or increase the number of handoffs, which may adversely affect the quality of patient care. Use of separate admitting teams has the potential to increase efficiency, but is also subject to fluctuations in patient volume and increases the number of handoffs. Each institution should use a multidisciplinary systems approach to address patient throughput and enforce manageable workload such as through the creation of patient flow teams.[7]

Limitations of the study include the relatively small sample of hospitalists and self‐reporting of safety. Because of the diverse characteristics and structures of the individual programs, even if a predictor variable was not missing, if a particular value for that predictor occurred very infrequently, it generated very wide effect estimates. This limited our ability to effectively explore potential confounders and interactions. To our knowledge, this study is the first to explore potential predictors of unsafe attending physician workload. Large national surveys of physicians with greater statistical power can expand upon this initial work and further explore the association between, and interaction of, workload factors and varying perceptions of providers.[4] The most important limitation of this work is that we relied on self‐reporting to define a safe census. We do not have any measured clinical outcomes that can serve to validate the self‐reported impressions. We recognize, however, that adverse events in healthcare require multiple weaknesses to align, and typically, multiple barriers exist to prevent such events. This often makes it difficult to show direct causal links. Additionally, self‐reporting of safety may also be subject to recall bias, because adverse patient outcomes are often particularly memorable. However, high‐reliability organizations recognize the importance of front‐line provider input, such as on the sensitivity of operations (working conditions) and by deferring to expertise (insights and recommendations from providers most knowledgeable of conditions, regardless of seniority).[8]

We acknowledge that several workload factors, such as hospital setting, may not be readily modifiable. However, we also report factors that can be intervened upon, such as assistance[5, 6] or geographic localization of patients.[9, 10] An understanding of both modifiable and fixed factors in healthcare delivery is essential for improving patient care.

This study has significant research implications. It suggests that team structure and physician experience may be used to improve workload safety. Also, particularly if these self‐reported findings are verified using clinical outcomes, providing hospitalists with greater staffing assistance and systems responsive to census fluctuations may improve the safety, quality, and flow of patient care. Future research may identify the association of physician, team, and hospital factors with outcomes and objectively assess targeted interventions to improve both the efficiency and quality of care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Johns Hopkins Clinical Research Network Hospitalists, General Internal Medicine Research in Progress Physicians, and Hospitalist Directors for the Maryland/District of Columbia region for sharing their models of care and comments on the survey content. They also thank Michael Paskavitz, BA (Editor‐in‐Chief) and Brian Driscoll, BA (Managing Editor) from Quantia Communications for all of their technical assistance in administering the survey.

Disclosures: Drs. Michtalik and Brotman had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Michtalik, Pronovost, Brotman. Analysis, interpretation of data: Michtalik, Pronovost, Marsteller, Spetz, Brotman. Drafting of the manuscript: Michtalik, Brotman. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Michtalik, Pronovost, Marsteller, Spetz, Brotman. Dr. Brotman has received compensation from Quantia Communications, not exceeding $10,000 annually, for developing educational content. Dr. Michtalik was supported by NIH grant T32 HP10025‐17‐00 and NIH/Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research KL2 Award 5KL2RR025006. The Johns Hopkins Hospitalist Scholars Fund provided funding for survey implementation and data acquisition by Quantia Communications. The funders had no role in the design, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , . Impact of attending physician workload on patient care: a survey of hospitalists. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(5):375–377.

- , , , et al. Does surgeon workload per day affect outcomes after pulmonary lobectomies? Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94(3):966–972.

- , , , . Perceived effects of attending physician workload in academic medical intensive care units: a national survey of training program directors. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):400–405.

- , , , , . Developing a model for attending physician workload and outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(11):1026–1028.

- , , , et al. A comparison of outcomes of general medical inpatient care provided by a hospitalist‐physician assistant model vs a traditional resident‐based model. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):122–130.

- , , , et al. Implementation of a physician assistant/hospitalist service in an academic medical center: impact on efficiency and patient outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):361–368.

- , , , . Improving patient flow and reducing emergency department crowding: a guide for hospitals. AHRQ publication no. 11(12)−0094. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

- , , , et al. Becoming a high reliability organization: operational advice for hospital leaders. AHRQ publication no. 08–0022. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008.

- , , , et al. Impact of localizing general medical teams to a single nursing unit. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(7):551–556.

- , , , et al. Impact of localizing physicians to hospital units on nurse‐physician communication and agreement on the plan of care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(11):1223–1227.

- , , , . Impact of attending physician workload on patient care: a survey of hospitalists. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(5):375–377.

- , , , et al. Does surgeon workload per day affect outcomes after pulmonary lobectomies? Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94(3):966–972.

- , , , . Perceived effects of attending physician workload in academic medical intensive care units: a national survey of training program directors. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(2):400–405.

- , , , , . Developing a model for attending physician workload and outcomes. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(11):1026–1028.

- , , , et al. A comparison of outcomes of general medical inpatient care provided by a hospitalist‐physician assistant model vs a traditional resident‐based model. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(3):122–130.

- , , , et al. Implementation of a physician assistant/hospitalist service in an academic medical center: impact on efficiency and patient outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2008;3(5):361–368.

- , , , . Improving patient flow and reducing emergency department crowding: a guide for hospitals. AHRQ publication no. 11(12)−0094. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

- , , , et al. Becoming a high reliability organization: operational advice for hospital leaders. AHRQ publication no. 08–0022. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008.

- , , , et al. Impact of localizing general medical teams to a single nursing unit. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(7):551–556.

- , , , et al. Impact of localizing physicians to hospital units on nurse‐physician communication and agreement on the plan of care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(11):1223–1227.

Use of the JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor ruxolitinib in the treatment of patients with myelofibrosis

Myelofibrosis (MF), including primary MF and MF secondary to polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia, is a chronic, clinically heterogeneous hematologic malignancy characterized by inefficient hematopoiesis, bone marrow fibrosis, and shortened survival. Typical clinical manifestations include progressive splenomegaly, debilitating symptoms, and anemia. MF is associated with dysregulation of Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway affecting hematopoiesis and inflammation. Ruxolitinib, an oral JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, was approved for the treatment of patients with intermediate or high-risk MF based on the results of 2 phase 3 studies (Controlled MyeloFibrosis Study with Oral JAK Inhibitor Treatment [COMFORT]-I and COMFORT-II). In these trials, ruxolitinib treatment was associated with reductions in spleen size and symptom burden, and improvements in quality of life. The most common adverse events were dose-dependent cytopenias, which were managed by dose modifications, treatment interruptions, and red blood cell transfusions (for anemia). Ruxolitinib was effective regardless of MF type, risk status, or JAK2V617F mutation status, and across various other MF subpopulations. Two-year follow-up data from the COMFORT trials also demonstrate that ruxolitinib has durable efficacy and may be associated with a survival advantage relative to placebo and best available therapy. Preliminary data from ongoing studies support possible dosing strategies for patients with low platelet counts.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Myelofibrosis (MF), including primary MF and MF secondary to polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia, is a chronic, clinically heterogeneous hematologic malignancy characterized by inefficient hematopoiesis, bone marrow fibrosis, and shortened survival. Typical clinical manifestations include progressive splenomegaly, debilitating symptoms, and anemia. MF is associated with dysregulation of Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway affecting hematopoiesis and inflammation. Ruxolitinib, an oral JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, was approved for the treatment of patients with intermediate or high-risk MF based on the results of 2 phase 3 studies (Controlled MyeloFibrosis Study with Oral JAK Inhibitor Treatment [COMFORT]-I and COMFORT-II). In these trials, ruxolitinib treatment was associated with reductions in spleen size and symptom burden, and improvements in quality of life. The most common adverse events were dose-dependent cytopenias, which were managed by dose modifications, treatment interruptions, and red blood cell transfusions (for anemia). Ruxolitinib was effective regardless of MF type, risk status, or JAK2V617F mutation status, and across various other MF subpopulations. Two-year follow-up data from the COMFORT trials also demonstrate that ruxolitinib has durable efficacy and may be associated with a survival advantage relative to placebo and best available therapy. Preliminary data from ongoing studies support possible dosing strategies for patients with low platelet counts.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Myelofibrosis (MF), including primary MF and MF secondary to polycythemia vera or essential thrombocythemia, is a chronic, clinically heterogeneous hematologic malignancy characterized by inefficient hematopoiesis, bone marrow fibrosis, and shortened survival. Typical clinical manifestations include progressive splenomegaly, debilitating symptoms, and anemia. MF is associated with dysregulation of Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway affecting hematopoiesis and inflammation. Ruxolitinib, an oral JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor, was approved for the treatment of patients with intermediate or high-risk MF based on the results of 2 phase 3 studies (Controlled MyeloFibrosis Study with Oral JAK Inhibitor Treatment [COMFORT]-I and COMFORT-II). In these trials, ruxolitinib treatment was associated with reductions in spleen size and symptom burden, and improvements in quality of life. The most common adverse events were dose-dependent cytopenias, which were managed by dose modifications, treatment interruptions, and red blood cell transfusions (for anemia). Ruxolitinib was effective regardless of MF type, risk status, or JAK2V617F mutation status, and across various other MF subpopulations. Two-year follow-up data from the COMFORT trials also demonstrate that ruxolitinib has durable efficacy and may be associated with a survival advantage relative to placebo and best available therapy. Preliminary data from ongoing studies support possible dosing strategies for patients with low platelet counts.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Pediatric Parvovirus B19: Spectrum of Clinical Manifestations

Test your knowledge on pediatric parvovirus with MD-IQ: the medical intelligence quiz. Click here to answer 5 questions.

Botanical Briefs: Cashew Apple (Anacardium occidentale)

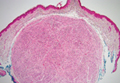

Palisaded Encapsulated Neuroma

Drug gets orphan designation for MDS

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation to an investigational drug for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The drug, CPI-613, targets metabolic changes that are thought to occur in many cancer cells.

It has demonstrated activity and tolerability in a phase 1 trial of patients with advanced, relapsed/refractory hematologic malignancies.

CPI-613 previously received orphan designation for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and pancreatic carcinoma.

Orphan designation is granted for drugs intended to treat diseases that affect fewer than 200,000 individuals in the US. This designation gives the makers of CPI-613, Cornerstone Pharmaceuticals, 7 years of US marketing exclusivity once the drug is approved.

The designation also allows the company to apply for government funding to defray trial costs, tax credits for clinical research expenses, and a potential waiver of the FDA’s application user fee.

CPI-613: Mechanism and phase 1 results

CPI-613 induces cancer-specific inhibition of the mitochondrial enzymes pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and alpha ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (KGDH).

Disrupting the function of PDH and KGDH disrupts tumor mitochondrial metabolism. As a result, tumor cells are starved of energy and biosynthetic intermediates, which leads to cell death.

Researchers evaluated CPI-613 in a phase 1 study of patients with advanced, relapsed/refractory hematologic malignancies.

The team, led by Timothy S. Pardee, MD, of Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, presented the results at the 2013 ASCO Annual Meeting as abstract 2516. (Information in the abstract differs slightly from that presented at the meeting.)

The trial was designed to determine the maximum tolerated dose, safety, and anticancer activity of CPI-613 as a single agent.

Twenty-one evaluable patients received CPI-613 on days 1 and 4 for 3 weeks every 28 days. Ten patients received more than 1 cycle of therapy.

The starting dose was 420 mg/m2. Treatment could be continued if the patient experienced clinical benefit. Doses were escalated to a final dose of 3780 mg/m2.

CPI-613 was generally well-tolerated when infused over 2 hours. Patients did not experience worsening cytopenias at any dose level. However, 1-hour infusions led to grade 3 renal failure in 2 patients.

At a dose of 3780 mg/m2, 1 patient had prolonged grade 3 nausea, and 1 patient had grade 3 renal failure. Six patients received a 2-hour infusion of 2940 mg/m2 without dose-limiting toxicities, so the researchers considered this the maximum tolerated dose.

Of the 21 patients, 9 achieved a response of stable disease or better. One MDS patient achieved a complete remission and maintained it over 23 cycles. One AML patient achieved a morphologic leukemia-free state.

A Burkitt lymphoma patient and a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma patient maintained partial responses over 16 and 15 cycles, respectively. Two multiple myeloma patients, 2 MDS patients, and 1 AML patient had stable disease.

“We are very encouraged by the tolerability and signals of activity seen in several patients in this phase 1 study for whom there is no available therapy shown to provide clinical benefit,” Dr Pardee said.

“We look forward to further evaluating CPI-613 in the early relapsed/refractory AML patient setting when administered in combination with a standard chemotherapeutic regimen, as well as in early relapsed or refractory MDS patients, with the hope of improving the outcomes and the quality of life for these patients through the combined use of this mechanistically novel agent.”

The AML study is a phase 1 trial investigating CPI-613 in combination with high-dose cytarabine and mitoxantrone, and the MDS study is a phase 2 trial investigating single-agent CPI-613. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation to an investigational drug for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The drug, CPI-613, targets metabolic changes that are thought to occur in many cancer cells.

It has demonstrated activity and tolerability in a phase 1 trial of patients with advanced, relapsed/refractory hematologic malignancies.

CPI-613 previously received orphan designation for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and pancreatic carcinoma.

Orphan designation is granted for drugs intended to treat diseases that affect fewer than 200,000 individuals in the US. This designation gives the makers of CPI-613, Cornerstone Pharmaceuticals, 7 years of US marketing exclusivity once the drug is approved.

The designation also allows the company to apply for government funding to defray trial costs, tax credits for clinical research expenses, and a potential waiver of the FDA’s application user fee.

CPI-613: Mechanism and phase 1 results

CPI-613 induces cancer-specific inhibition of the mitochondrial enzymes pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and alpha ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (KGDH).

Disrupting the function of PDH and KGDH disrupts tumor mitochondrial metabolism. As a result, tumor cells are starved of energy and biosynthetic intermediates, which leads to cell death.

Researchers evaluated CPI-613 in a phase 1 study of patients with advanced, relapsed/refractory hematologic malignancies.

The team, led by Timothy S. Pardee, MD, of Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, presented the results at the 2013 ASCO Annual Meeting as abstract 2516. (Information in the abstract differs slightly from that presented at the meeting.)

The trial was designed to determine the maximum tolerated dose, safety, and anticancer activity of CPI-613 as a single agent.

Twenty-one evaluable patients received CPI-613 on days 1 and 4 for 3 weeks every 28 days. Ten patients received more than 1 cycle of therapy.

The starting dose was 420 mg/m2. Treatment could be continued if the patient experienced clinical benefit. Doses were escalated to a final dose of 3780 mg/m2.

CPI-613 was generally well-tolerated when infused over 2 hours. Patients did not experience worsening cytopenias at any dose level. However, 1-hour infusions led to grade 3 renal failure in 2 patients.

At a dose of 3780 mg/m2, 1 patient had prolonged grade 3 nausea, and 1 patient had grade 3 renal failure. Six patients received a 2-hour infusion of 2940 mg/m2 without dose-limiting toxicities, so the researchers considered this the maximum tolerated dose.

Of the 21 patients, 9 achieved a response of stable disease or better. One MDS patient achieved a complete remission and maintained it over 23 cycles. One AML patient achieved a morphologic leukemia-free state.

A Burkitt lymphoma patient and a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma patient maintained partial responses over 16 and 15 cycles, respectively. Two multiple myeloma patients, 2 MDS patients, and 1 AML patient had stable disease.

“We are very encouraged by the tolerability and signals of activity seen in several patients in this phase 1 study for whom there is no available therapy shown to provide clinical benefit,” Dr Pardee said.

“We look forward to further evaluating CPI-613 in the early relapsed/refractory AML patient setting when administered in combination with a standard chemotherapeutic regimen, as well as in early relapsed or refractory MDS patients, with the hope of improving the outcomes and the quality of life for these patients through the combined use of this mechanistically novel agent.”

The AML study is a phase 1 trial investigating CPI-613 in combination with high-dose cytarabine and mitoxantrone, and the MDS study is a phase 2 trial investigating single-agent CPI-613. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation to an investigational drug for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS).

The drug, CPI-613, targets metabolic changes that are thought to occur in many cancer cells.

It has demonstrated activity and tolerability in a phase 1 trial of patients with advanced, relapsed/refractory hematologic malignancies.

CPI-613 previously received orphan designation for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and pancreatic carcinoma.

Orphan designation is granted for drugs intended to treat diseases that affect fewer than 200,000 individuals in the US. This designation gives the makers of CPI-613, Cornerstone Pharmaceuticals, 7 years of US marketing exclusivity once the drug is approved.

The designation also allows the company to apply for government funding to defray trial costs, tax credits for clinical research expenses, and a potential waiver of the FDA’s application user fee.

CPI-613: Mechanism and phase 1 results

CPI-613 induces cancer-specific inhibition of the mitochondrial enzymes pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and alpha ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (KGDH).

Disrupting the function of PDH and KGDH disrupts tumor mitochondrial metabolism. As a result, tumor cells are starved of energy and biosynthetic intermediates, which leads to cell death.

Researchers evaluated CPI-613 in a phase 1 study of patients with advanced, relapsed/refractory hematologic malignancies.

The team, led by Timothy S. Pardee, MD, of Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, presented the results at the 2013 ASCO Annual Meeting as abstract 2516. (Information in the abstract differs slightly from that presented at the meeting.)

The trial was designed to determine the maximum tolerated dose, safety, and anticancer activity of CPI-613 as a single agent.

Twenty-one evaluable patients received CPI-613 on days 1 and 4 for 3 weeks every 28 days. Ten patients received more than 1 cycle of therapy.

The starting dose was 420 mg/m2. Treatment could be continued if the patient experienced clinical benefit. Doses were escalated to a final dose of 3780 mg/m2.

CPI-613 was generally well-tolerated when infused over 2 hours. Patients did not experience worsening cytopenias at any dose level. However, 1-hour infusions led to grade 3 renal failure in 2 patients.

At a dose of 3780 mg/m2, 1 patient had prolonged grade 3 nausea, and 1 patient had grade 3 renal failure. Six patients received a 2-hour infusion of 2940 mg/m2 without dose-limiting toxicities, so the researchers considered this the maximum tolerated dose.

Of the 21 patients, 9 achieved a response of stable disease or better. One MDS patient achieved a complete remission and maintained it over 23 cycles. One AML patient achieved a morphologic leukemia-free state.

A Burkitt lymphoma patient and a cutaneous T-cell lymphoma patient maintained partial responses over 16 and 15 cycles, respectively. Two multiple myeloma patients, 2 MDS patients, and 1 AML patient had stable disease.

“We are very encouraged by the tolerability and signals of activity seen in several patients in this phase 1 study for whom there is no available therapy shown to provide clinical benefit,” Dr Pardee said.

“We look forward to further evaluating CPI-613 in the early relapsed/refractory AML patient setting when administered in combination with a standard chemotherapeutic regimen, as well as in early relapsed or refractory MDS patients, with the hope of improving the outcomes and the quality of life for these patients through the combined use of this mechanistically novel agent.”

The AML study is a phase 1 trial investigating CPI-613 in combination with high-dose cytarabine and mitoxantrone, and the MDS study is a phase 2 trial investigating single-agent CPI-613. ![]()

Vendor CPOE for Renal Impairment