User login

The Development of an eHealth Tool Suite for Prostate Cancer Patients and Their Partners

Donna Van Bogaert, PhD

Abstract

Background

eHealth resources for people facing health crises must balance the expert knowledge and perspective of developers and clinicians against the very different needs and perspectives of prospective users. This formative study explores the information and support needs of posttreatment prostate cancer patients and their partners as a way to improve an existing eHealth information and support system called CHESS (Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System).

Methods

Focus groups with patient survivors and their partners were used to identify information gaps and information-seeking milestones.

Results

Both patients and partners expressed a need for assistance in decision making, connecting with experienced patients, and making sexual adjustments. Female partners of patients are more active in searching for cancer information. All partners have information and support needs distinct from those of the patient.

Conclusions

Findings were used to develop a series of interactive tools and navigational features for the CHESS prostate cancer computer-mediated system.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Donna Van Bogaert, PhD

Abstract

Background

eHealth resources for people facing health crises must balance the expert knowledge and perspective of developers and clinicians against the very different needs and perspectives of prospective users. This formative study explores the information and support needs of posttreatment prostate cancer patients and their partners as a way to improve an existing eHealth information and support system called CHESS (Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System).

Methods

Focus groups with patient survivors and their partners were used to identify information gaps and information-seeking milestones.

Results

Both patients and partners expressed a need for assistance in decision making, connecting with experienced patients, and making sexual adjustments. Female partners of patients are more active in searching for cancer information. All partners have information and support needs distinct from those of the patient.

Conclusions

Findings were used to develop a series of interactive tools and navigational features for the CHESS prostate cancer computer-mediated system.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Donna Van Bogaert, PhD

Abstract

Background

eHealth resources for people facing health crises must balance the expert knowledge and perspective of developers and clinicians against the very different needs and perspectives of prospective users. This formative study explores the information and support needs of posttreatment prostate cancer patients and their partners as a way to improve an existing eHealth information and support system called CHESS (Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System).

Methods

Focus groups with patient survivors and their partners were used to identify information gaps and information-seeking milestones.

Results

Both patients and partners expressed a need for assistance in decision making, connecting with experienced patients, and making sexual adjustments. Female partners of patients are more active in searching for cancer information. All partners have information and support needs distinct from those of the patient.

Conclusions

Findings were used to develop a series of interactive tools and navigational features for the CHESS prostate cancer computer-mediated system.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Can Counseling Add Value to an Exercise Intervention for Improving Quality of Life in Breast Cancer Survivors? A Feasibility Study

Fiona Naumann, PhD

Abstract

Background

Improved survivorship has led to increased recognition of the need to manage the side effects of cancer and its treatment. Exercise and psychological interventions benefit survivors; however, it is unknown if additional benefits can be gained by combining these two modalities.

Objective

Our purpose was to examine the feasibility of delivering an exercise and counseling intervention to 43 breast cancer survivors, to determine if counseling can add value to an exercise intervention for improving quality of life (QOL) in terms of physical and psychological function.

Methods

We compared exercise only (Ex), counseling only (C), exercise and counseling (ExC), and usual care (UsC) over an 8 week intervention.

Results

In all, 93% of participants completed the interventions, with no adverse effects documented. There were significant improvements in VO2max as well as upper body and lower body strength in the ExC and Ex groups compared to the C and UsC groups (P < .05). Significant improvements on the Beck Depression Inventory were observed in the ExC and Ex groups, compared with UsC (P < .04), with significant reduction in fatigue for the ExC group, compared with UsC, and no significant differences in QOL change between groups, although the ExC group had significant clinical improvement.

Limitations

Limitations included small subject number and study of only breast cancer survivors.

Conclusions

These preliminary results suggest that a combined exercise and psychological counseling program is both feasible and acceptable for breast cancer survivors and may improve QOL more than would a single-entity intervention.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Fiona Naumann, PhD

Abstract

Background

Improved survivorship has led to increased recognition of the need to manage the side effects of cancer and its treatment. Exercise and psychological interventions benefit survivors; however, it is unknown if additional benefits can be gained by combining these two modalities.

Objective

Our purpose was to examine the feasibility of delivering an exercise and counseling intervention to 43 breast cancer survivors, to determine if counseling can add value to an exercise intervention for improving quality of life (QOL) in terms of physical and psychological function.

Methods

We compared exercise only (Ex), counseling only (C), exercise and counseling (ExC), and usual care (UsC) over an 8 week intervention.

Results

In all, 93% of participants completed the interventions, with no adverse effects documented. There were significant improvements in VO2max as well as upper body and lower body strength in the ExC and Ex groups compared to the C and UsC groups (P < .05). Significant improvements on the Beck Depression Inventory were observed in the ExC and Ex groups, compared with UsC (P < .04), with significant reduction in fatigue for the ExC group, compared with UsC, and no significant differences in QOL change between groups, although the ExC group had significant clinical improvement.

Limitations

Limitations included small subject number and study of only breast cancer survivors.

Conclusions

These preliminary results suggest that a combined exercise and psychological counseling program is both feasible and acceptable for breast cancer survivors and may improve QOL more than would a single-entity intervention.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Fiona Naumann, PhD

Abstract

Background

Improved survivorship has led to increased recognition of the need to manage the side effects of cancer and its treatment. Exercise and psychological interventions benefit survivors; however, it is unknown if additional benefits can be gained by combining these two modalities.

Objective

Our purpose was to examine the feasibility of delivering an exercise and counseling intervention to 43 breast cancer survivors, to determine if counseling can add value to an exercise intervention for improving quality of life (QOL) in terms of physical and psychological function.

Methods

We compared exercise only (Ex), counseling only (C), exercise and counseling (ExC), and usual care (UsC) over an 8 week intervention.

Results

In all, 93% of participants completed the interventions, with no adverse effects documented. There were significant improvements in VO2max as well as upper body and lower body strength in the ExC and Ex groups compared to the C and UsC groups (P < .05). Significant improvements on the Beck Depression Inventory were observed in the ExC and Ex groups, compared with UsC (P < .04), with significant reduction in fatigue for the ExC group, compared with UsC, and no significant differences in QOL change between groups, although the ExC group had significant clinical improvement.

Limitations

Limitations included small subject number and study of only breast cancer survivors.

Conclusions

These preliminary results suggest that a combined exercise and psychological counseling program is both feasible and acceptable for breast cancer survivors and may improve QOL more than would a single-entity intervention.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

To Combat West Nile Virus, Emphasize Prevention

The best way to deal with the recent resurgence in West Nile virus is to emphasize prevention.

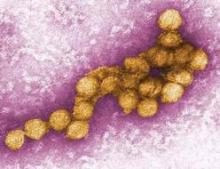

West Nile virus (WNV) is back with a vengeance this year. As of Sept. 4, 2012, there were 1,993 reported cases of WNV disease in people, including 1,069 with neuroinvasive disease and 87 deaths. My state, Texas, is leading the pack with a total of 888 cases, 443 neuroinvasive disease cases, and 35 deaths. Texas’ West Nile problem is clearly the worst in the country. The next-highest number of total cases is only 119, in South Dakota.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the total of 1,993 cases is the highest number of WNV disease cases reported to the CDC through the first week in September since the virus was first detected in the United States in 1999. It’s not clear why this resurgence is happening now, or why Texas has been so hard hit. Some say that rising temperatures have resulted in an increased mosquito population, but here in Texas there is also a drought and mosquitos need moisture, so I’m not sure about that.

An arbovirus, WNV is usually transmitted to humans after a bite from an infected Culex mosquito. The transmission cycle is maintained between mosquito and vertebrate hosts, usually birds. Humans are actually an incidental and dead-end host. Though rare, person-to-person transmission has been documented through both blood transfusion and solid organ transplantation (N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:2196-203).

When speaking with your patients, it’s worth reemphasizing the methods for prevention. Parents should be instructed to apply one of the Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellents to their children before they go outside, using just enough to protect exposed skin. Products containing up to 30% DEET – but not higher – can be used in children older than 2 months of age. Products containing both DEET and a sunscreen should be avoided, since sunscreen needs to be applied more frequently.

Children should be covered up with clothing as much as possible when outside, and netting should be used over infant carriers. Outdoor exposure should be limited at dusk and dawn, when mosquitos are most active. Holes in screen doors should be repaired. Standing water, which attracts mosquitos, is a major hazard and should be avoided. Birdba ths and blow-up pools need to be emptied out often, and children should steer clear of puddles.

Here in Texas, the state health department has issued a statement preparing people for aerial spraying of chemicals to control the mosquitos. Each state most likely will develop its own recommendations, which should be available on the state health department website.

Routine screening of the U.S. blood supply was initiated in 2003, and no cases have been identified in donated blood since then. A single case of congenital infection also has been reported (MMWR 2002;51:1135-6). There are specific management guidelines for mother, fetus, and newborn if women are diagnosed with WNV during pregnancy (MMWR 2004;53:154-7).

Most people who become infected with WNV will be asymptomatic. About 1 in 5 who are infected will develop symptoms such as fever, headache, body aches, joint pains, vomiting, diarrhea, or rash after a 2-14 day incubation period. Less than 1% will develop neuroinvasive disease, but of those who do, about 10% are fatal.

It’s important to include WNV in your differential diagnosis for children who present with a febrile illness, meningitis, encephalitis, or acute flaccid paralysis, particularly if they’ve had exposure to mosquitos during the summer and early fall in endemic areas. The clinical presentation of neuroinvasive WNV is indistinguishable from those of other causes of viral meningitis and/or encephalitis. While the epidemiological characteristics of WNV disease in children are similar to those in adults, neuroinvasive disease due to WNV is more likely to manifest as meningitis in children than in older adults, who are more likely to develop encephalitis (Pediatrics 2009;123:e1084-9).

Because there is no specific treatment for WNV, and the majority of patients have a self-limited course, the diagnosis need not be made in every febrile patient. A definitive diagnosis should be sought in individuals with fever and acute neurologic symptoms who have recently been exposed to mosquitos, are solid organ transplant recipients, or are pregnant.

The presence of WNV-reactive IgM antibody in serum or cerebrospinal fluid supports a recent infection. However, anti-WNV IgM can persist up to a year in some people, so its presence may represent a prior infection. Moreover, if serum is tested within the first 10 days of illness, IgM antibody may not always be detected. Convalescent titers should be obtained 2-3 weeks following the onset of illness.

Treatment is supportive care. Standard precautions are recommended for hospitalized patients in the American Academy of Pediatrics Red Book on pages 792-5 (Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. L.K. Pickering, Ed. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics). Most people will recover from even the neuroinvasive manifestations of WNV, although symptoms may last for several weeks and those with severe cases may require hospitalization for supportive treatment. Serious sequelae can occur among those with underlying immune deficiencies.

For the most up-to-date information on WNV statistics from the CDC, click here.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at [email protected].

The best way to deal with the recent resurgence in West Nile virus is to emphasize prevention.

West Nile virus (WNV) is back with a vengeance this year. As of Sept. 4, 2012, there were 1,993 reported cases of WNV disease in people, including 1,069 with neuroinvasive disease and 87 deaths. My state, Texas, is leading the pack with a total of 888 cases, 443 neuroinvasive disease cases, and 35 deaths. Texas’ West Nile problem is clearly the worst in the country. The next-highest number of total cases is only 119, in South Dakota.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the total of 1,993 cases is the highest number of WNV disease cases reported to the CDC through the first week in September since the virus was first detected in the United States in 1999. It’s not clear why this resurgence is happening now, or why Texas has been so hard hit. Some say that rising temperatures have resulted in an increased mosquito population, but here in Texas there is also a drought and mosquitos need moisture, so I’m not sure about that.

An arbovirus, WNV is usually transmitted to humans after a bite from an infected Culex mosquito. The transmission cycle is maintained between mosquito and vertebrate hosts, usually birds. Humans are actually an incidental and dead-end host. Though rare, person-to-person transmission has been documented through both blood transfusion and solid organ transplantation (N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:2196-203).

When speaking with your patients, it’s worth reemphasizing the methods for prevention. Parents should be instructed to apply one of the Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellents to their children before they go outside, using just enough to protect exposed skin. Products containing up to 30% DEET – but not higher – can be used in children older than 2 months of age. Products containing both DEET and a sunscreen should be avoided, since sunscreen needs to be applied more frequently.

Children should be covered up with clothing as much as possible when outside, and netting should be used over infant carriers. Outdoor exposure should be limited at dusk and dawn, when mosquitos are most active. Holes in screen doors should be repaired. Standing water, which attracts mosquitos, is a major hazard and should be avoided. Birdba ths and blow-up pools need to be emptied out often, and children should steer clear of puddles.

Here in Texas, the state health department has issued a statement preparing people for aerial spraying of chemicals to control the mosquitos. Each state most likely will develop its own recommendations, which should be available on the state health department website.

Routine screening of the U.S. blood supply was initiated in 2003, and no cases have been identified in donated blood since then. A single case of congenital infection also has been reported (MMWR 2002;51:1135-6). There are specific management guidelines for mother, fetus, and newborn if women are diagnosed with WNV during pregnancy (MMWR 2004;53:154-7).

Most people who become infected with WNV will be asymptomatic. About 1 in 5 who are infected will develop symptoms such as fever, headache, body aches, joint pains, vomiting, diarrhea, or rash after a 2-14 day incubation period. Less than 1% will develop neuroinvasive disease, but of those who do, about 10% are fatal.

It’s important to include WNV in your differential diagnosis for children who present with a febrile illness, meningitis, encephalitis, or acute flaccid paralysis, particularly if they’ve had exposure to mosquitos during the summer and early fall in endemic areas. The clinical presentation of neuroinvasive WNV is indistinguishable from those of other causes of viral meningitis and/or encephalitis. While the epidemiological characteristics of WNV disease in children are similar to those in adults, neuroinvasive disease due to WNV is more likely to manifest as meningitis in children than in older adults, who are more likely to develop encephalitis (Pediatrics 2009;123:e1084-9).

Because there is no specific treatment for WNV, and the majority of patients have a self-limited course, the diagnosis need not be made in every febrile patient. A definitive diagnosis should be sought in individuals with fever and acute neurologic symptoms who have recently been exposed to mosquitos, are solid organ transplant recipients, or are pregnant.

The presence of WNV-reactive IgM antibody in serum or cerebrospinal fluid supports a recent infection. However, anti-WNV IgM can persist up to a year in some people, so its presence may represent a prior infection. Moreover, if serum is tested within the first 10 days of illness, IgM antibody may not always be detected. Convalescent titers should be obtained 2-3 weeks following the onset of illness.

Treatment is supportive care. Standard precautions are recommended for hospitalized patients in the American Academy of Pediatrics Red Book on pages 792-5 (Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. L.K. Pickering, Ed. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics). Most people will recover from even the neuroinvasive manifestations of WNV, although symptoms may last for several weeks and those with severe cases may require hospitalization for supportive treatment. Serious sequelae can occur among those with underlying immune deficiencies.

For the most up-to-date information on WNV statistics from the CDC, click here.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at [email protected].

The best way to deal with the recent resurgence in West Nile virus is to emphasize prevention.

West Nile virus (WNV) is back with a vengeance this year. As of Sept. 4, 2012, there were 1,993 reported cases of WNV disease in people, including 1,069 with neuroinvasive disease and 87 deaths. My state, Texas, is leading the pack with a total of 888 cases, 443 neuroinvasive disease cases, and 35 deaths. Texas’ West Nile problem is clearly the worst in the country. The next-highest number of total cases is only 119, in South Dakota.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the total of 1,993 cases is the highest number of WNV disease cases reported to the CDC through the first week in September since the virus was first detected in the United States in 1999. It’s not clear why this resurgence is happening now, or why Texas has been so hard hit. Some say that rising temperatures have resulted in an increased mosquito population, but here in Texas there is also a drought and mosquitos need moisture, so I’m not sure about that.

An arbovirus, WNV is usually transmitted to humans after a bite from an infected Culex mosquito. The transmission cycle is maintained between mosquito and vertebrate hosts, usually birds. Humans are actually an incidental and dead-end host. Though rare, person-to-person transmission has been documented through both blood transfusion and solid organ transplantation (N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:2196-203).

When speaking with your patients, it’s worth reemphasizing the methods for prevention. Parents should be instructed to apply one of the Environmental Protection Agency–registered insect repellents to their children before they go outside, using just enough to protect exposed skin. Products containing up to 30% DEET – but not higher – can be used in children older than 2 months of age. Products containing both DEET and a sunscreen should be avoided, since sunscreen needs to be applied more frequently.

Children should be covered up with clothing as much as possible when outside, and netting should be used over infant carriers. Outdoor exposure should be limited at dusk and dawn, when mosquitos are most active. Holes in screen doors should be repaired. Standing water, which attracts mosquitos, is a major hazard and should be avoided. Birdba ths and blow-up pools need to be emptied out often, and children should steer clear of puddles.

Here in Texas, the state health department has issued a statement preparing people for aerial spraying of chemicals to control the mosquitos. Each state most likely will develop its own recommendations, which should be available on the state health department website.

Routine screening of the U.S. blood supply was initiated in 2003, and no cases have been identified in donated blood since then. A single case of congenital infection also has been reported (MMWR 2002;51:1135-6). There are specific management guidelines for mother, fetus, and newborn if women are diagnosed with WNV during pregnancy (MMWR 2004;53:154-7).

Most people who become infected with WNV will be asymptomatic. About 1 in 5 who are infected will develop symptoms such as fever, headache, body aches, joint pains, vomiting, diarrhea, or rash after a 2-14 day incubation period. Less than 1% will develop neuroinvasive disease, but of those who do, about 10% are fatal.

It’s important to include WNV in your differential diagnosis for children who present with a febrile illness, meningitis, encephalitis, or acute flaccid paralysis, particularly if they’ve had exposure to mosquitos during the summer and early fall in endemic areas. The clinical presentation of neuroinvasive WNV is indistinguishable from those of other causes of viral meningitis and/or encephalitis. While the epidemiological characteristics of WNV disease in children are similar to those in adults, neuroinvasive disease due to WNV is more likely to manifest as meningitis in children than in older adults, who are more likely to develop encephalitis (Pediatrics 2009;123:e1084-9).

Because there is no specific treatment for WNV, and the majority of patients have a self-limited course, the diagnosis need not be made in every febrile patient. A definitive diagnosis should be sought in individuals with fever and acute neurologic symptoms who have recently been exposed to mosquitos, are solid organ transplant recipients, or are pregnant.

The presence of WNV-reactive IgM antibody in serum or cerebrospinal fluid supports a recent infection. However, anti-WNV IgM can persist up to a year in some people, so its presence may represent a prior infection. Moreover, if serum is tested within the first 10 days of illness, IgM antibody may not always be detected. Convalescent titers should be obtained 2-3 weeks following the onset of illness.

Treatment is supportive care. Standard precautions are recommended for hospitalized patients in the American Academy of Pediatrics Red Book on pages 792-5 (Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. L.K. Pickering, Ed. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, Ill.: American Academy of Pediatrics). Most people will recover from even the neuroinvasive manifestations of WNV, although symptoms may last for several weeks and those with severe cases may require hospitalization for supportive treatment. Serious sequelae can occur among those with underlying immune deficiencies.

For the most up-to-date information on WNV statistics from the CDC, click here.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at [email protected].

Integrating Palliative Care in the Intensive Care Unit

Jacob J. Strand, MD

Abstract

The admission of cancer patients into intensive care units (ICUs) is on the rise. These patients are at high risk for physical and psychosocial suffering. Patients and their families often face difficult end-of-life decisions that highlight the importance of effective and empathetic communication. Palliative care teams are uniquely equipped to help care for cancer patients who are admitted to ICUs.

When utilized in the ICU, palliative care has the potential to improve a patient's symptoms, enhance the communication between care teams and families, and improve family-centered decision making. Within the context of this article, we will discuss how palliative care can be integrated into the care of ICU patients and how to enhance family-centered communication; we will also highlight the care of ICU patients at the end of life.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Jacob J. Strand, MD

Abstract

The admission of cancer patients into intensive care units (ICUs) is on the rise. These patients are at high risk for physical and psychosocial suffering. Patients and their families often face difficult end-of-life decisions that highlight the importance of effective and empathetic communication. Palliative care teams are uniquely equipped to help care for cancer patients who are admitted to ICUs.

When utilized in the ICU, palliative care has the potential to improve a patient's symptoms, enhance the communication between care teams and families, and improve family-centered decision making. Within the context of this article, we will discuss how palliative care can be integrated into the care of ICU patients and how to enhance family-centered communication; we will also highlight the care of ICU patients at the end of life.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Jacob J. Strand, MD

Abstract

The admission of cancer patients into intensive care units (ICUs) is on the rise. These patients are at high risk for physical and psychosocial suffering. Patients and their families often face difficult end-of-life decisions that highlight the importance of effective and empathetic communication. Palliative care teams are uniquely equipped to help care for cancer patients who are admitted to ICUs.

When utilized in the ICU, palliative care has the potential to improve a patient's symptoms, enhance the communication between care teams and families, and improve family-centered decision making. Within the context of this article, we will discuss how palliative care can be integrated into the care of ICU patients and how to enhance family-centered communication; we will also highlight the care of ICU patients at the end of life.

*For a PDF of the full article, click on the link to the left of this introduction.

Implementing the Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors

Kathleen Y. Wolin, ScD, Anna L. Schwartz, PhD, Charles E. Matthews, PhD, FACSM, Kerry S. Courneya, PhD, Kathryn H. Schmitz, PhD

Abstract

In 2009, the American College of Sports Medicine convened an expert roundtable to issue guidelines on exercise for cancer survivors. This multidisciplinary group evaluated the strength of the evidence for the safety and benefits of exercise as a therapeutic intervention for survivors. The panel concluded that exercise is safe and offers myriad benefits for survivors including improvements in physical function, strength, fatigue, quality of life, and possibly recurrence and survival. Recommendations for situations in which deviations from the US Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans are appropriate were provided. Here, we outline a process for implementing the guidelines in clinical practice and provide recommendations for how the oncology care provider can interface with the exercise and physical therapy community.

*For a PDF of the full article and accompanying commentary by Nicole Stout, click on the links to the left of this introduction.

Kathleen Y. Wolin, ScD, Anna L. Schwartz, PhD, Charles E. Matthews, PhD, FACSM, Kerry S. Courneya, PhD, Kathryn H. Schmitz, PhD

Abstract

In 2009, the American College of Sports Medicine convened an expert roundtable to issue guidelines on exercise for cancer survivors. This multidisciplinary group evaluated the strength of the evidence for the safety and benefits of exercise as a therapeutic intervention for survivors. The panel concluded that exercise is safe and offers myriad benefits for survivors including improvements in physical function, strength, fatigue, quality of life, and possibly recurrence and survival. Recommendations for situations in which deviations from the US Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans are appropriate were provided. Here, we outline a process for implementing the guidelines in clinical practice and provide recommendations for how the oncology care provider can interface with the exercise and physical therapy community.

*For a PDF of the full article and accompanying commentary by Nicole Stout, click on the links to the left of this introduction.

Kathleen Y. Wolin, ScD, Anna L. Schwartz, PhD, Charles E. Matthews, PhD, FACSM, Kerry S. Courneya, PhD, Kathryn H. Schmitz, PhD

Abstract

In 2009, the American College of Sports Medicine convened an expert roundtable to issue guidelines on exercise for cancer survivors. This multidisciplinary group evaluated the strength of the evidence for the safety and benefits of exercise as a therapeutic intervention for survivors. The panel concluded that exercise is safe and offers myriad benefits for survivors including improvements in physical function, strength, fatigue, quality of life, and possibly recurrence and survival. Recommendations for situations in which deviations from the US Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans are appropriate were provided. Here, we outline a process for implementing the guidelines in clinical practice and provide recommendations for how the oncology care provider can interface with the exercise and physical therapy community.

*For a PDF of the full article and accompanying commentary by Nicole Stout, click on the links to the left of this introduction.

Speak Up: Getting Hospitalists to Voice Dissatisfaction Isn’t Easy

“There is that hesitation to be looked upon as weak,” Dr. Bowman says. “Before, it was, ‘I’m the strongest guy; I can take on anything.’ As a leader, you’ve got to be in tune to that.”

Dr. Bowman says it takes a lot of courage for a hospitalist to express dissatisfaction to their supervisor. When a hospitalist says they need a moment to talk in private, “they’ve thought about it for weeks, if not months.”

Often, it’s the leader who has to bring up the topic of job satisfaction, says Dr. Scarpinato. “I don’t think [leaders] are that open, actually. I think they need to be educated,” he says. “I think that’s why leadership is so important. We have to be sensitive as leaders to be aware of the fact that this might be on the table.”

Meaningful discussions during group meetings and annual performance evaluations are vital; they help group leaders can pick up on signs of dissatisfaction. Common examples are hospitalists who say they want to pursue another degree or complain about the job.

—Len Scarpinato, DO, MS, SFHM. The chief medical officer of clinical development for Brentwood, Tenn.-based Cogent-HMG

“During this session,” he says, “I can usually tell.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer based in South Florida.

“There is that hesitation to be looked upon as weak,” Dr. Bowman says. “Before, it was, ‘I’m the strongest guy; I can take on anything.’ As a leader, you’ve got to be in tune to that.”

Dr. Bowman says it takes a lot of courage for a hospitalist to express dissatisfaction to their supervisor. When a hospitalist says they need a moment to talk in private, “they’ve thought about it for weeks, if not months.”

Often, it’s the leader who has to bring up the topic of job satisfaction, says Dr. Scarpinato. “I don’t think [leaders] are that open, actually. I think they need to be educated,” he says. “I think that’s why leadership is so important. We have to be sensitive as leaders to be aware of the fact that this might be on the table.”

Meaningful discussions during group meetings and annual performance evaluations are vital; they help group leaders can pick up on signs of dissatisfaction. Common examples are hospitalists who say they want to pursue another degree or complain about the job.

—Len Scarpinato, DO, MS, SFHM. The chief medical officer of clinical development for Brentwood, Tenn.-based Cogent-HMG

“During this session,” he says, “I can usually tell.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer based in South Florida.

“There is that hesitation to be looked upon as weak,” Dr. Bowman says. “Before, it was, ‘I’m the strongest guy; I can take on anything.’ As a leader, you’ve got to be in tune to that.”

Dr. Bowman says it takes a lot of courage for a hospitalist to express dissatisfaction to their supervisor. When a hospitalist says they need a moment to talk in private, “they’ve thought about it for weeks, if not months.”

Often, it’s the leader who has to bring up the topic of job satisfaction, says Dr. Scarpinato. “I don’t think [leaders] are that open, actually. I think they need to be educated,” he says. “I think that’s why leadership is so important. We have to be sensitive as leaders to be aware of the fact that this might be on the table.”

Meaningful discussions during group meetings and annual performance evaluations are vital; they help group leaders can pick up on signs of dissatisfaction. Common examples are hospitalists who say they want to pursue another degree or complain about the job.

—Len Scarpinato, DO, MS, SFHM. The chief medical officer of clinical development for Brentwood, Tenn.-based Cogent-HMG

“During this session,” he says, “I can usually tell.”

Tom Collins is a freelance writer based in South Florida.

Social Media: The Basics

Yesterday, 526 million people went on Facebook. Why? What happened yesterday? Nothing happened. A half-billion people visit Facebook every day.

In fact, when this article went to print, Facebook was on the cusp of reaching more than 1 billion users. Chances are you’re one of them. But are you using Facebook to help build your practice? If you’re like many of our colleagues, you know you need to be using social media, but you may find it to be overwhelming, and you don’t know where to begin. I’m here to help.

I’ve been writing about, speaking about, and participating in social media for the last 5 years. I have had over 4 million visits to my blog; I have over 15,000 followers on Twitter; and my videos on YouTube have been viewed almost 100,000 times. I don’t do all of this to build my practice (I work at an HMO), or to make more money (I’m paid a set salary regardless of the number of patients I see); rather, I do it because it is becoming an integral part of practicing medicine and will be a requisite skill for successful dermatologists.

I’m on social media daily, where I listen, respond, engage, and teach, because that’s where our patients are: Three-quarters of all Internet searches are health related, and one in five people on Facebook is looking for health care information. And it’s my hope to inspire and support you in doing the same, and to help you pursue your own social media goals.

So for this inaugural column, let’s start with the basics: What are social media, and why do you need to use them?

Social media refer to web-based and mobile technologies that allow people to connect and share information with one another. Think of them as ways to have digital conversations. People flock to Facebook because sociability is a core human characteristic. Humans are compelled to interact with others.

Connecting with people at meetings, parties, and meals is what we’ve always done. Now, powerful technologies, such as Facebook and Twitter, make that connection easier than ever. Instead of sharing stories with your family on special occasions, you can share stories and photos with them anytime, anywhere, instantaneously. That’s why Facebook will soon have more than 1 billion subscribers.

Why is this important for your dermatology practice? Word of mouth has always been the most valuable way dermatologists have built their practices. But now, technologies such as Yelp and DrScore enable patients to spread word of mouth far beyond what was previously possible. Rating sites like these are fundamentally social media sites – places where patients connect and share information (in this case, information about you).

Every physician has a social media presence. Don’t believe me? Google yourself. Many of the links that are on your first page will lead to some type of social media site. You can choose to remain an object of other people’s conversations, or you can become an active participant in them instead.

Engaging in social media can mean having a practice Facebook page, a video channel, and perhaps even a blog or Twitter account. These tools will help you to engage and educate patients and prospective patients about yourself, to market and build your practice, and to protect your online reputation. Social media sites can also help you to build and maintain relationships with other physicians, learn from colleagues, and engage in continuing medical education.

As with learning a new surgical technique, the beginning is always the hardest part.

In columns to come, I hope to help you understand the fundamentals of web-based technologies, because once you understand the basic concepts, you can choose which media to use based on your needs and the needs of your practice.

Just as you can’t contract out CME, you can’t contract out social media. The tools are just technological enhancements of real person-to-person interactions. Your patients know and like you because they’ve built a relationship with you in your office. Similarly, your online presence will need to be genuine, or people will quickly realize it’s not actually you.

Learning social media isn’t difficult, but it can be time consuming. I look forward to your questions, feedback, and discussion as we all boldly go forth into the future of medical practice.

Dr. Benabio is in private practice in San Diego. Visit his consumer health blog; connect with him on Twitter (@Dermdoc) and on Facebook (DermDoc).

Yesterday, 526 million people went on Facebook. Why? What happened yesterday? Nothing happened. A half-billion people visit Facebook every day.

In fact, when this article went to print, Facebook was on the cusp of reaching more than 1 billion users. Chances are you’re one of them. But are you using Facebook to help build your practice? If you’re like many of our colleagues, you know you need to be using social media, but you may find it to be overwhelming, and you don’t know where to begin. I’m here to help.

I’ve been writing about, speaking about, and participating in social media for the last 5 years. I have had over 4 million visits to my blog; I have over 15,000 followers on Twitter; and my videos on YouTube have been viewed almost 100,000 times. I don’t do all of this to build my practice (I work at an HMO), or to make more money (I’m paid a set salary regardless of the number of patients I see); rather, I do it because it is becoming an integral part of practicing medicine and will be a requisite skill for successful dermatologists.

I’m on social media daily, where I listen, respond, engage, and teach, because that’s where our patients are: Three-quarters of all Internet searches are health related, and one in five people on Facebook is looking for health care information. And it’s my hope to inspire and support you in doing the same, and to help you pursue your own social media goals.

So for this inaugural column, let’s start with the basics: What are social media, and why do you need to use them?

Social media refer to web-based and mobile technologies that allow people to connect and share information with one another. Think of them as ways to have digital conversations. People flock to Facebook because sociability is a core human characteristic. Humans are compelled to interact with others.

Connecting with people at meetings, parties, and meals is what we’ve always done. Now, powerful technologies, such as Facebook and Twitter, make that connection easier than ever. Instead of sharing stories with your family on special occasions, you can share stories and photos with them anytime, anywhere, instantaneously. That’s why Facebook will soon have more than 1 billion subscribers.

Why is this important for your dermatology practice? Word of mouth has always been the most valuable way dermatologists have built their practices. But now, technologies such as Yelp and DrScore enable patients to spread word of mouth far beyond what was previously possible. Rating sites like these are fundamentally social media sites – places where patients connect and share information (in this case, information about you).

Every physician has a social media presence. Don’t believe me? Google yourself. Many of the links that are on your first page will lead to some type of social media site. You can choose to remain an object of other people’s conversations, or you can become an active participant in them instead.

Engaging in social media can mean having a practice Facebook page, a video channel, and perhaps even a blog or Twitter account. These tools will help you to engage and educate patients and prospective patients about yourself, to market and build your practice, and to protect your online reputation. Social media sites can also help you to build and maintain relationships with other physicians, learn from colleagues, and engage in continuing medical education.

As with learning a new surgical technique, the beginning is always the hardest part.

In columns to come, I hope to help you understand the fundamentals of web-based technologies, because once you understand the basic concepts, you can choose which media to use based on your needs and the needs of your practice.

Just as you can’t contract out CME, you can’t contract out social media. The tools are just technological enhancements of real person-to-person interactions. Your patients know and like you because they’ve built a relationship with you in your office. Similarly, your online presence will need to be genuine, or people will quickly realize it’s not actually you.

Learning social media isn’t difficult, but it can be time consuming. I look forward to your questions, feedback, and discussion as we all boldly go forth into the future of medical practice.

Dr. Benabio is in private practice in San Diego. Visit his consumer health blog; connect with him on Twitter (@Dermdoc) and on Facebook (DermDoc).

Yesterday, 526 million people went on Facebook. Why? What happened yesterday? Nothing happened. A half-billion people visit Facebook every day.

In fact, when this article went to print, Facebook was on the cusp of reaching more than 1 billion users. Chances are you’re one of them. But are you using Facebook to help build your practice? If you’re like many of our colleagues, you know you need to be using social media, but you may find it to be overwhelming, and you don’t know where to begin. I’m here to help.

I’ve been writing about, speaking about, and participating in social media for the last 5 years. I have had over 4 million visits to my blog; I have over 15,000 followers on Twitter; and my videos on YouTube have been viewed almost 100,000 times. I don’t do all of this to build my practice (I work at an HMO), or to make more money (I’m paid a set salary regardless of the number of patients I see); rather, I do it because it is becoming an integral part of practicing medicine and will be a requisite skill for successful dermatologists.

I’m on social media daily, where I listen, respond, engage, and teach, because that’s where our patients are: Three-quarters of all Internet searches are health related, and one in five people on Facebook is looking for health care information. And it’s my hope to inspire and support you in doing the same, and to help you pursue your own social media goals.

So for this inaugural column, let’s start with the basics: What are social media, and why do you need to use them?

Social media refer to web-based and mobile technologies that allow people to connect and share information with one another. Think of them as ways to have digital conversations. People flock to Facebook because sociability is a core human characteristic. Humans are compelled to interact with others.

Connecting with people at meetings, parties, and meals is what we’ve always done. Now, powerful technologies, such as Facebook and Twitter, make that connection easier than ever. Instead of sharing stories with your family on special occasions, you can share stories and photos with them anytime, anywhere, instantaneously. That’s why Facebook will soon have more than 1 billion subscribers.

Why is this important for your dermatology practice? Word of mouth has always been the most valuable way dermatologists have built their practices. But now, technologies such as Yelp and DrScore enable patients to spread word of mouth far beyond what was previously possible. Rating sites like these are fundamentally social media sites – places where patients connect and share information (in this case, information about you).

Every physician has a social media presence. Don’t believe me? Google yourself. Many of the links that are on your first page will lead to some type of social media site. You can choose to remain an object of other people’s conversations, or you can become an active participant in them instead.

Engaging in social media can mean having a practice Facebook page, a video channel, and perhaps even a blog or Twitter account. These tools will help you to engage and educate patients and prospective patients about yourself, to market and build your practice, and to protect your online reputation. Social media sites can also help you to build and maintain relationships with other physicians, learn from colleagues, and engage in continuing medical education.

As with learning a new surgical technique, the beginning is always the hardest part.

In columns to come, I hope to help you understand the fundamentals of web-based technologies, because once you understand the basic concepts, you can choose which media to use based on your needs and the needs of your practice.

Just as you can’t contract out CME, you can’t contract out social media. The tools are just technological enhancements of real person-to-person interactions. Your patients know and like you because they’ve built a relationship with you in your office. Similarly, your online presence will need to be genuine, or people will quickly realize it’s not actually you.

Learning social media isn’t difficult, but it can be time consuming. I look forward to your questions, feedback, and discussion as we all boldly go forth into the future of medical practice.

Dr. Benabio is in private practice in San Diego. Visit his consumer health blog; connect with him on Twitter (@Dermdoc) and on Facebook (DermDoc).

ITL: Physician Reviews of HM-Relevant Research

Clinical question: Does treatment with drotrecogin alfa (activated) reduce mortality in patients with septic shock?

Background: Recombinant human activated protein C, or drotrecogin alfa (activated) (DrotAA), was approved for the treatment of patients with severe sepsis in 2001 on the basis of the Prospective Recombinant Human Activated Protein C Worldwide Evaluation in Severe Sepsis (PROWESS) study. Since its approval, conflicting reports about its efficacy have surfaced.

Study design: Double-blind, randomized-controlled trial.

Setting: Multicenter, multinational trial.

Synopsis: This trial enrolled 1,697 patients with septic shock to receive either DrotAA or placebo. At 28 days, 223 of 846 patients (26.4%) in the DrotAA group and 202 of 834 (24.2%) in the placebo group had died (relative risk in the DrotAA group, 1.09; 95% confidence interval, 0.92 to 1.28; P=0.31). At 90 days, there was still no significant difference in mortality. Mortality was also unchanged in patients with severe protein C deficiency at baseline. This lack of mortality benefit with either therapy persisted across all predefined subgroups in this study.

The incidence of nonserious bleeding was more common among patients who received DrotAA than among those in the placebo group (8.6% vs. 4.8%, P=0.002), but the incidence of serious bleeding events was similar in both groups. This study was appropriately powered after adjusting the sample size when aggregate mortality was found to be lower than anticipated.

Bottom line: DrotAA does not significantly reduce mortality at 28 or 90 days in patients with septic shock.

Citation: Ranieri VM, Thompson BT, Barie PS, et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in adults with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2055-2064.

Read more of our physician reviews of recent, HM-relevant literature.

Clinical question: Does treatment with drotrecogin alfa (activated) reduce mortality in patients with septic shock?

Background: Recombinant human activated protein C, or drotrecogin alfa (activated) (DrotAA), was approved for the treatment of patients with severe sepsis in 2001 on the basis of the Prospective Recombinant Human Activated Protein C Worldwide Evaluation in Severe Sepsis (PROWESS) study. Since its approval, conflicting reports about its efficacy have surfaced.

Study design: Double-blind, randomized-controlled trial.

Setting: Multicenter, multinational trial.

Synopsis: This trial enrolled 1,697 patients with septic shock to receive either DrotAA or placebo. At 28 days, 223 of 846 patients (26.4%) in the DrotAA group and 202 of 834 (24.2%) in the placebo group had died (relative risk in the DrotAA group, 1.09; 95% confidence interval, 0.92 to 1.28; P=0.31). At 90 days, there was still no significant difference in mortality. Mortality was also unchanged in patients with severe protein C deficiency at baseline. This lack of mortality benefit with either therapy persisted across all predefined subgroups in this study.

The incidence of nonserious bleeding was more common among patients who received DrotAA than among those in the placebo group (8.6% vs. 4.8%, P=0.002), but the incidence of serious bleeding events was similar in both groups. This study was appropriately powered after adjusting the sample size when aggregate mortality was found to be lower than anticipated.

Bottom line: DrotAA does not significantly reduce mortality at 28 or 90 days in patients with septic shock.

Citation: Ranieri VM, Thompson BT, Barie PS, et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in adults with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2055-2064.

Read more of our physician reviews of recent, HM-relevant literature.

Clinical question: Does treatment with drotrecogin alfa (activated) reduce mortality in patients with septic shock?

Background: Recombinant human activated protein C, or drotrecogin alfa (activated) (DrotAA), was approved for the treatment of patients with severe sepsis in 2001 on the basis of the Prospective Recombinant Human Activated Protein C Worldwide Evaluation in Severe Sepsis (PROWESS) study. Since its approval, conflicting reports about its efficacy have surfaced.

Study design: Double-blind, randomized-controlled trial.

Setting: Multicenter, multinational trial.

Synopsis: This trial enrolled 1,697 patients with septic shock to receive either DrotAA or placebo. At 28 days, 223 of 846 patients (26.4%) in the DrotAA group and 202 of 834 (24.2%) in the placebo group had died (relative risk in the DrotAA group, 1.09; 95% confidence interval, 0.92 to 1.28; P=0.31). At 90 days, there was still no significant difference in mortality. Mortality was also unchanged in patients with severe protein C deficiency at baseline. This lack of mortality benefit with either therapy persisted across all predefined subgroups in this study.

The incidence of nonserious bleeding was more common among patients who received DrotAA than among those in the placebo group (8.6% vs. 4.8%, P=0.002), but the incidence of serious bleeding events was similar in both groups. This study was appropriately powered after adjusting the sample size when aggregate mortality was found to be lower than anticipated.

Bottom line: DrotAA does not significantly reduce mortality at 28 or 90 days in patients with septic shock.

Citation: Ranieri VM, Thompson BT, Barie PS, et al. Drotrecogin alfa (activated) in adults with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2055-2064.

Read more of our physician reviews of recent, HM-relevant literature.

Digesting Advice on Kids' Vitamins and Supplements

Most pediatricians manage children and adolescents with mild to moderate nutritional deficiencies appropriately in the primary care setting. However, some of your patients with more complex clinical concerns can benefit from consultation with a subspecialty colleague.

It can be challenging to digest all the information, advice, and trends regarding vitamins and nutritional supplements, but staying up to date is important. This awareness will help you formulate an opinion before a patient or family member asks about a new "miracle" modality or "megadose" supplement cure.

Some supplementation advice for well children is old, well known, and time honored, such as vitamin K supplementation at birth and vitamin D supplementation for breastfeeding infants during their first 6 months of life.

The American Academy of Pediatrics is your best source of guidance on newer ideas and more recent developments. The academy also provides dependable guidance and thoughtful recommendations on overall nutritional supplementation. Stick with their evidence-based practice guidelines and policies whenever possible.

Also, consult their online publication resources often, as the academy updates their guidance frequently.

The website not only is a perfect entry point for accessing comprehensive practice advice, including the Bright Futures program and other recommended sources, but also features advice for parents.

The Pediatric Nutrition Handbook is a useful offline reference. This wonderful resource has been prepared by the AAP Committee on Nutrition and is now in its sixth edition.

Patient and family counseling to optimize vitamin and supplement intake is important. Compared with prescription and over-the-counter medicines, vitamins and supplements are marketed with surprising freedom in the United States, although the Food and Drug Administration assumes some monitoring responsibilities once they are available to consumers. The agency’s involvement is surprisingly limited.

Your guidance, therefore, is crucial because vitamins, even the most familiar ones, are not harmless. Vitamins are sold openly in "health stores" and people assume they are safe. However, high doses of many vitamins can cause effects from discomfort to even life-threatening events. For example, too much vitamin A can damage the liver, and excess vitamin D can be toxic. Unfortunately, megadoses of most vitamins are not simply excreted in the urine, as is vitamin C.

Herbal supplements are even more mysterious, and there is simply not enough research to separate chaff from grain or to confidently advise patients on the benefits and harm.

There’s another issue: It does not occur to some families that supplements – especially the herbal ones – could be of interest to their medical doctor. They think of supplements in a domain that is separate from that of medical care, and forget or neglect to mention their use. In some cases, families will not disclose their use of herbal supplements because they fear your disapproval. This is a particular problem if anxiety about a child’s condition motivates parents to seek alternative therapies or unproven methods.

The best and perhaps only way of overcoming these hurdles is to ask the question about herbal supplements directly. Ideally, you already have a safe and trusting relationship with the family, one in which the family feels that you are interested and willing to listen with an open mind, and to research the subject on their behalf. If trust is established early on, before disagreements crop up, then the family knows everyone is on the same side – that is, on the child’s side – even if a disagreement does come up.

Although the issues surrounding supplementation can be complex, start with the basics. Diagnose and manage your patients who have nutritional issues by taking comprehensive histories and performing skillful physical examinations.

Signs and symptoms elicited by your evaluation drive your diagnostic work-up. No screening battery is specifically designed to catch undiagnosed nutritional deficiencies in the primary care of well children. Health maintenance guidelines support a complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel as being sufficient to screen healthy children. These panels also provide a good starting point to work up any nutritional deficiencies and growth problems.

Other children require special consideration, but the general rule is the same. Tailor any diagnostic work-up beyond established well-child primary care guidelines to your individual patient’s underlying condition, history, and physical examination.

Some of your patients will be at high risk for nutritional deficiency. Chronic kidney disease; growth issues related to failure to thrive; feeding challenges stemming from a neurodevelopmental disability; and deficiencies because of poverty or homelessness are examples. Because these conditions can inhibit the intake, absorption, or metabolism of nutrients, consider referral and comanagement of children with a subspecialist colleague.

In some more-acute situations, hospitalization might be indicated. For example, the initial feeding of a severely malnourished child or the rectifying of a profound and long-lasting deficiency can cause complications such as refeeding syndrome or electrolyte imbalances. Programs that are specialized for failure to thrive cases can help when the etiology is multifactorial and complicated by psychological, social, and/or economic problems. These cases require long-term management by multidisciplinary teams, and often take too much time and resources for the regular pediatric office.

Dr. Bishku is an attending physician and vice president of medical affairs at La Rabida Children’s Hospital in Chicago. She had no relevant financial disclosures.

Most pediatricians manage children and adolescents with mild to moderate nutritional deficiencies appropriately in the primary care setting. However, some of your patients with more complex clinical concerns can benefit from consultation with a subspecialty colleague.

It can be challenging to digest all the information, advice, and trends regarding vitamins and nutritional supplements, but staying up to date is important. This awareness will help you formulate an opinion before a patient or family member asks about a new "miracle" modality or "megadose" supplement cure.

Some supplementation advice for well children is old, well known, and time honored, such as vitamin K supplementation at birth and vitamin D supplementation for breastfeeding infants during their first 6 months of life.

The American Academy of Pediatrics is your best source of guidance on newer ideas and more recent developments. The academy also provides dependable guidance and thoughtful recommendations on overall nutritional supplementation. Stick with their evidence-based practice guidelines and policies whenever possible.

Also, consult their online publication resources often, as the academy updates their guidance frequently.

The website not only is a perfect entry point for accessing comprehensive practice advice, including the Bright Futures program and other recommended sources, but also features advice for parents.

The Pediatric Nutrition Handbook is a useful offline reference. This wonderful resource has been prepared by the AAP Committee on Nutrition and is now in its sixth edition.

Patient and family counseling to optimize vitamin and supplement intake is important. Compared with prescription and over-the-counter medicines, vitamins and supplements are marketed with surprising freedom in the United States, although the Food and Drug Administration assumes some monitoring responsibilities once they are available to consumers. The agency’s involvement is surprisingly limited.

Your guidance, therefore, is crucial because vitamins, even the most familiar ones, are not harmless. Vitamins are sold openly in "health stores" and people assume they are safe. However, high doses of many vitamins can cause effects from discomfort to even life-threatening events. For example, too much vitamin A can damage the liver, and excess vitamin D can be toxic. Unfortunately, megadoses of most vitamins are not simply excreted in the urine, as is vitamin C.

Herbal supplements are even more mysterious, and there is simply not enough research to separate chaff from grain or to confidently advise patients on the benefits and harm.

There’s another issue: It does not occur to some families that supplements – especially the herbal ones – could be of interest to their medical doctor. They think of supplements in a domain that is separate from that of medical care, and forget or neglect to mention their use. In some cases, families will not disclose their use of herbal supplements because they fear your disapproval. This is a particular problem if anxiety about a child’s condition motivates parents to seek alternative therapies or unproven methods.

The best and perhaps only way of overcoming these hurdles is to ask the question about herbal supplements directly. Ideally, you already have a safe and trusting relationship with the family, one in which the family feels that you are interested and willing to listen with an open mind, and to research the subject on their behalf. If trust is established early on, before disagreements crop up, then the family knows everyone is on the same side – that is, on the child’s side – even if a disagreement does come up.

Although the issues surrounding supplementation can be complex, start with the basics. Diagnose and manage your patients who have nutritional issues by taking comprehensive histories and performing skillful physical examinations.

Signs and symptoms elicited by your evaluation drive your diagnostic work-up. No screening battery is specifically designed to catch undiagnosed nutritional deficiencies in the primary care of well children. Health maintenance guidelines support a complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel as being sufficient to screen healthy children. These panels also provide a good starting point to work up any nutritional deficiencies and growth problems.

Other children require special consideration, but the general rule is the same. Tailor any diagnostic work-up beyond established well-child primary care guidelines to your individual patient’s underlying condition, history, and physical examination.

Some of your patients will be at high risk for nutritional deficiency. Chronic kidney disease; growth issues related to failure to thrive; feeding challenges stemming from a neurodevelopmental disability; and deficiencies because of poverty or homelessness are examples. Because these conditions can inhibit the intake, absorption, or metabolism of nutrients, consider referral and comanagement of children with a subspecialist colleague.

In some more-acute situations, hospitalization might be indicated. For example, the initial feeding of a severely malnourished child or the rectifying of a profound and long-lasting deficiency can cause complications such as refeeding syndrome or electrolyte imbalances. Programs that are specialized for failure to thrive cases can help when the etiology is multifactorial and complicated by psychological, social, and/or economic problems. These cases require long-term management by multidisciplinary teams, and often take too much time and resources for the regular pediatric office.

Dr. Bishku is an attending physician and vice president of medical affairs at La Rabida Children’s Hospital in Chicago. She had no relevant financial disclosures.

Most pediatricians manage children and adolescents with mild to moderate nutritional deficiencies appropriately in the primary care setting. However, some of your patients with more complex clinical concerns can benefit from consultation with a subspecialty colleague.

It can be challenging to digest all the information, advice, and trends regarding vitamins and nutritional supplements, but staying up to date is important. This awareness will help you formulate an opinion before a patient or family member asks about a new "miracle" modality or "megadose" supplement cure.

Some supplementation advice for well children is old, well known, and time honored, such as vitamin K supplementation at birth and vitamin D supplementation for breastfeeding infants during their first 6 months of life.

The American Academy of Pediatrics is your best source of guidance on newer ideas and more recent developments. The academy also provides dependable guidance and thoughtful recommendations on overall nutritional supplementation. Stick with their evidence-based practice guidelines and policies whenever possible.

Also, consult their online publication resources often, as the academy updates their guidance frequently.

The website not only is a perfect entry point for accessing comprehensive practice advice, including the Bright Futures program and other recommended sources, but also features advice for parents.

The Pediatric Nutrition Handbook is a useful offline reference. This wonderful resource has been prepared by the AAP Committee on Nutrition and is now in its sixth edition.

Patient and family counseling to optimize vitamin and supplement intake is important. Compared with prescription and over-the-counter medicines, vitamins and supplements are marketed with surprising freedom in the United States, although the Food and Drug Administration assumes some monitoring responsibilities once they are available to consumers. The agency’s involvement is surprisingly limited.

Your guidance, therefore, is crucial because vitamins, even the most familiar ones, are not harmless. Vitamins are sold openly in "health stores" and people assume they are safe. However, high doses of many vitamins can cause effects from discomfort to even life-threatening events. For example, too much vitamin A can damage the liver, and excess vitamin D can be toxic. Unfortunately, megadoses of most vitamins are not simply excreted in the urine, as is vitamin C.

Herbal supplements are even more mysterious, and there is simply not enough research to separate chaff from grain or to confidently advise patients on the benefits and harm.

There’s another issue: It does not occur to some families that supplements – especially the herbal ones – could be of interest to their medical doctor. They think of supplements in a domain that is separate from that of medical care, and forget or neglect to mention their use. In some cases, families will not disclose their use of herbal supplements because they fear your disapproval. This is a particular problem if anxiety about a child’s condition motivates parents to seek alternative therapies or unproven methods.

The best and perhaps only way of overcoming these hurdles is to ask the question about herbal supplements directly. Ideally, you already have a safe and trusting relationship with the family, one in which the family feels that you are interested and willing to listen with an open mind, and to research the subject on their behalf. If trust is established early on, before disagreements crop up, then the family knows everyone is on the same side – that is, on the child’s side – even if a disagreement does come up.

Although the issues surrounding supplementation can be complex, start with the basics. Diagnose and manage your patients who have nutritional issues by taking comprehensive histories and performing skillful physical examinations.

Signs and symptoms elicited by your evaluation drive your diagnostic work-up. No screening battery is specifically designed to catch undiagnosed nutritional deficiencies in the primary care of well children. Health maintenance guidelines support a complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel as being sufficient to screen healthy children. These panels also provide a good starting point to work up any nutritional deficiencies and growth problems.

Other children require special consideration, but the general rule is the same. Tailor any diagnostic work-up beyond established well-child primary care guidelines to your individual patient’s underlying condition, history, and physical examination.

Some of your patients will be at high risk for nutritional deficiency. Chronic kidney disease; growth issues related to failure to thrive; feeding challenges stemming from a neurodevelopmental disability; and deficiencies because of poverty or homelessness are examples. Because these conditions can inhibit the intake, absorption, or metabolism of nutrients, consider referral and comanagement of children with a subspecialist colleague.

In some more-acute situations, hospitalization might be indicated. For example, the initial feeding of a severely malnourished child or the rectifying of a profound and long-lasting deficiency can cause complications such as refeeding syndrome or electrolyte imbalances. Programs that are specialized for failure to thrive cases can help when the etiology is multifactorial and complicated by psychological, social, and/or economic problems. These cases require long-term management by multidisciplinary teams, and often take too much time and resources for the regular pediatric office.

Dr. Bishku is an attending physician and vice president of medical affairs at La Rabida Children’s Hospital in Chicago. She had no relevant financial disclosures.

Teaching Scripts and Faculty Development

Patient complexity,1 productivity, and documentation pressures have increased substantially over the past 2 decades. Within this environment, time for teaching is often limited. The same pressures which limit faculty members' teaching time also limit their availability to learn how to teach; faculty development efforts need to be both effective and efficient.

In a seminal study of exemplary clinical teachers, Irby discovered that expert teachers often developed and utilized teaching scripts for commonly encountered teachable moments.2 Teaching scripts consist of a trigger, key teaching points, and teaching strategies.2 A trigger may be a specific clinical situation or a learner knowledge gap identified by the teacher. The trigger prompts the teacher to select key teaching points about the topic (the content), and utilize strategies for making these teaching points comprehensible (the process).2 Through a reflective process, these expert teachers evaluated the effectiveness of each teaching session and honed their scripts over time.2 While additional reports have described the use of teaching scripts,35 we found no studies evaluating the impact of collaboratively developing teaching scripts. In the present study, we sought to understand faculty members' early experiences with a program of collaboratively developing teaching scripts and the impact on their self‐efficacy with teaching about commonly encountered clinical conditions on attending rounds.

METHODS

Participants were the 22 internal medicine, or combined internal medicine and pediatrics (med‐peds), hospitalists in a 750‐bed university teaching hospital in upstate New York. Nine hospitalists worked for only 1 year (eg, chief residents and recent graduates awaiting fellowship training), and were present for half of the program year. All hospitalists conducted daily bedside attending rounds, lasting 1.52 hours, with a dual purpose of teaching the residents and students, and making management decisions for their shared patients.

Hospitalists were surveyed to identify 10 commonly encountered diagnoses about which they wanted to learn how to teach. The faculty development director (V.J.L.) conducted a 1‐hour workshop to introduce the concept of teaching scripts, and role‐play a teaching script. Nine hospitalists volunteered to write scripts for the remaining target diagnoses. They were provided with a template; example teaching script (see Supporting Information, Supplemental Content 1, in the online version of this article); and guidelines on writing scripts which highlighted effective clinical teaching principles for hospitalists, including: managing time with short scripts and high‐yield teaching points, knowledge acquisition with evidence‐based resources, self‐reflection/emnsight, patient‐centered teaching (identifying triggers among commonly encountered situations), and learner‐centered teaching (identifying common misconceptions and strategies for engaging all levels of learners) (Figure 1).2, 6 Faculty were encouraged to practice their scripts on attending rounds, using lessons learned to refine and write the script for presentation. Each script was presented verbally and on paper at a monthly 1‐hour interactive workshop where lunch was provided. Authors received feedback and incorporated suggestions for teaching strategies from the other hospitalists. Revised scripts were distributed electronically.

Baseline surveys measured prior teaching and faculty development experience, and self‐efficacy with teaching about the 10 target diagnoses, ranging from Not confident at all to Very confident on a 4‐point Likert scale. Using open‐ended surveys, we asked all of the hospitalists about their experiences with presenting scripts and participating in peer feedback, and the impact of the program on their teaching skills and patient care.

Because the learning objectives for each teaching script were determined by each script's author and were not known prior to the program, we were unable to assess changes in residents' and students' knowledge directly. As a surrogate measure, we surveyed students, residents, and faculty regarding how often the hospitalist taught about the 10 target diagnoses and whether teaching points were applicable to current or future patients. We administered the surveys online weekly for 8 weeks before and after the program. Residents and students were notified that participation had no impact on their evaluations. They received a $2.50 coffee gift card for each survey. The study received an exemption from the university's Institutional Review Board.

The number of teaching episodes per week related to the target diagnoses was averaged across survey weeks. Student t tests were used to compare results before versus after the intervention, and 95% confidence interval (CI) calculated. We considered P 0.05 to be statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC).

Qualitative data were analyzed by coding each statement, then developing themes using an iterative process. Three investigators independently developed themes, and met twice to review the categorization of each statement until consensus was achieved. Two of the investigators were involved in the program (V.J.L. and A.B.) and one did not participate in the workshops (C.G.).

RESULTS