User login

Hypertrophic Scars and Keloids, Part 2: Newer and Investigational Therapies

Use of Bovine-Based Collagen Ointment in the Treatment of Plaque Psoriasis: An Open-Label, Pilot, Observational Clinical Study of 12 Patients

Cosmetic Aspects of Nail Products and Services

Soft Tissue Augmentation, Part 2: Hand Rejuvenation

Motivating Employees: Going Beyond Monetary Rewards

An Approach to Urticaria

The avoidant psychotherapy patient

CASE: Unexplained panic

Mr. J, age 35, is a married, unemployed musician who presents for outpatient treatment for panic attacks. He experienced his first panic attack at his oldest son’s baptism 12 years ago, but does not know why it occurred at that moment. He rarely has panic attacks now, but wants to continue medication management. He denies depressive symptoms, saying, “I’m the most optimistic person in the world.” Mr. J tried several medications for his panic attacks before clonazepam, 2 mg/d, proved effective, but always has been vehemently opposed to antidepressants. Despite his insistence that he needs only medication management, Mr. J chooses to enroll in a resident-run psychotherapy clinic.

In sessions, Mr. J describes his father, who also has panic disorder, as a powerful figure who is physically and emotionally abusive, but also charismatic, charming, and “impossible not to love.” However, Mr. J felt his father was impossible to live with, and moved out at age 18 to marry his high school sweetheart. They have 3 children, ages 12, 10, and 8. Mr. J worked for his father at his construction company, but was not able to satisfy him or live up to his standards so he quit because he was tired of being cut down and emasculated.

Mr. J’s parents divorced 15 years ago after his mother had an affair with her husband’s friend. His father learned of the affair and threatened his wife with a handgun. Although Mr. J and his mother were close before her affair, he has been unable to forgive or empathize with her, and rarely speaks to her. Mr. J’s mother could not protect him from his father’s abuse, and later compounded her failure by abandoning her husband and son through her sexual affair. Growing up with a father he did not respect or get comfort from and sharing a common fear and alliance with his mother likely made it difficult for Mr. J to navigate his Oedipal phase,1 and made her abandonment even more painful.

When Mr. J was 6 years old, he was molested by one of his father’s friends. His father stabbed the man in the shoulder when he found out about the molestation and received probation. Although Mr. J knows he was molested, he does not remember it and has repressed most of his childhood.

The authors’ observations

I (JF) wanted to discuss with Mr. J why his first panic attack occurred during such a symbolic occasion. His panic could be the result of a struggle between a murderous wish toward his father and paternal protective instinct toward his son. The baptism placed his son in a highly vulnerable position, which reminded Mr. J of his own vulnerability and impotent rage toward his father. Anxiety often results when an individual has 2 opposing wishes,2 and a murderous wish often is involved when anxiety progresses to panic. Getting to the root of this with Mr. J could allow for further psychological growth.3 His murderous wishes and fantasies are ego-dystonic, and panic could be a way of punishing himself for these thoughts. When Mr. J identified himself as his son during the baptism, he likely was flooded with thoughts that his defenses were no longer able to repress. Seeing his son submerged in the baptismal font brought back an aspect of his own life that he had completely split off from consciousness, and likely will take time to process. Considering the current therapeutic dynamic, I decided that it was not the best time to address this potential conflict; however, I could have chosen a manualized form of psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder.4 See Table 1 for an outline of the phases of psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder.

Although Mr. J’s initial willingness to discuss his past was encouraging, he refused to schedule more than 1 session every 4 weeks. He also began to keep the content of our sessions superficial, which caused me angst because he seemed to be withholding information and would not come more frequently. Although I was not proud of my feelings, I had to be honest with myself that I had started to dislike Mr. J.

Table 1

Psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder

| Phase | Comments |

|---|---|

| Treatment of acute panic | Therapy focuses on discovering the conscious and unconscious meaning of panic symptoms |

| Treatment of panic vulnerability | Core dynamic conflicts related to panic are understood and altered. Tasks include addressing the nature of the transference and working through them |

| Termination | The therapist directly addresses patients’ difficulties with separation and independence as they emerge in treatment. After treatment, patients may be better able to manage separations, anger, and independence |

| Source: Adapted from reference 4 | |

Countertransference reactions

Countertransference is a therapist's emotional reaction to a patient. Just as patients form reactions based on past relationships brought to present, therapists develop similar reactions.5 Noting one’s countertransference provides a window into how the patient’s thoughts and actions evoke feelings in others. It also can shed light on an aspect of the doctor-patient relationship that may have gone unnoticed.2

Countertransference hatred can occur when a therapist begins to dislike a patient. Typically, patients with borderline personality disorder, masochistic tendencies, or suicidality arouse strong countertransference reactions6; however, any patient can evoke these emotions. This type of hateful patient can precipitate antitherapeutic feelings such as aversion or malice that can be a major obstacle to treatment.7 Aversion leads the therapist to withdraw from the patient, and malice can trigger cruel impulses.

Maltsberger and Buie7 identified 5 defenses therapists may use to combat countertransference hatred (Table 2). When treating Mr. J, I used several of these defenses, including projection and turning against the self to protect myself from this challenging patient. In turning against the self, I became doubtful and critical of my skills and increasingly submissive to Mr. J. Additionally, I projected this countertransference hatred onto Mr. J, focusing on the negative transference that he brought to our therapeutic encounters. On an unconscious level, I may have feared retribution from Mr. J.

I became so frustrated with Mr. J that I reduced the frequency of our sessions to once every 6 weeks, which I realized could be evidence of my feelings regarding Mr. J’s minimization and avoidant style.

Table 2

Defenses against countertransference hate

| Defense mechanism | Description |

|---|---|

| Repression | Remaining unconscious of feelings of hate; may manifest as difficulty paying attention to what the patient is saying or feeling bored or tired |

| Turning against oneself | Doubting one’s capacity to help the patient; may feel inadequate, helpless, and hopeless. May lead to giving up on the patient because the therapist feels incompetent |

| Reaction formation | Turning hatred into the opposite emotion. The therapist may be too preoccupied with being helpful or overly concerned about the patient’s welfare and comfort |

| Projection | Feeling that the patient hates the therapist, leading to feelings of dread and fear |

| Distortion of reality | Devaluing the patient and seeing the patient as a hopeless case or a dangerous person. The therapist may feel indifference, pity, or anger toward the patient |

| Source: Reference 7 | |

TREATMENT: A breakthrough

Mr. J presents with obvious unease at the first visit after we had decreased the frequency of our sessions. At this point, Mr. J opens up to me. He says he has not been truthful with me, and has had worsening depression, anhedonia, and agoraphobia over the past year. He also reveals that he has homosexual fantasies that he cannot stop, which disturb him because he says he is heterosexual. He agrees to come once a week, and reluctantly admits that he desperately needs help.

Although Mr. J only takes clonazepam and citalopram, 20 mg/d, which I prescribed after he admitted to depression and anxiety, he has hyperlipidemia and a family history of heart disease. In addition to being a musician and working at his father’s construction company, he has worked as a security guard, bounty hunter, and computer technician. His careers have been solitary in nature, and, with the exception of computer work, permitted an outlet for aggression. However, he recently started taking online college classes and wants to become a music teacher because he feels he has a lot to offer children as a result of his life experiences. His fantasy of being a teacher shows considerably less aggression, and could be a sign of psychological growth.

Mr. J is struggling financially and his home is on the verge of foreclosure. Early in treatment he told me that he stopped paying his mortgage, but demonstrated blind optimism that things would “work out.” I asked if this was a wise decision, but he seemed confident and dismissive of my concerns. Although he now struggles with this situation, I consider this healthier than his constant pseudo-happy state, and a sign of psychological development.8 Despite his financial stressors, he wants to pursue his dream of being a famous musician, and says he “could never work a 9-to-5 job in a cubicle.”

The authors’ observations

I do not think it’s a coincidence that Mr. J stopped minimizing his symptoms when we decreased the frequency of his sessions. I had viewed our sessions as unproductive and blamed Mr. J for wasting both of our time with his resistance and minimization and had begun to dislike him. I felt impotent because he had been controlling each session with long, elaborate stories that had little relevance to his panic attacks, and I could not redirect him or get him to focus on pertinent issues. It was as if I was an audience for him, and provided nothing useful. However, I was interested in these superficial stories because Mr. J was charming and engaging. He likely reenacted his relationship with his father with me. Mr. J’s superficial relationship with me caused me to dislike him, and, similar to his father, reject him. This rejection likely was damaging because I was unable to anticipate his needs, which would have been to increase—rather than decrease—the frequency of our sessions. Just like his father, I was not able to take care of him.

Mr. J is deeply conflicted about his father. He states that his father “is a monster who instills fear and intimidation into everyone around him, but he’s charismatic, and I’ll always love him.” His view of his domineering father likely developed into a castration anxiety because he was afraid of competing for his mother’s love, contributing to a muddled sexual identity. This was intensified when Mr. J was sexually abused; he may have been stimulated by the molestation, adding to his confusion. Although Mr. J has repressed the abuse and split off most of his childhood, he suffers from shame, guilt, and depression because of his ego-dystonic homosexual fantasies. Homosexuality is at odds with his self-image and contributes to his anxiety and panic attacks. He cannot adequately discharge this dangerous libidinal energy, and as he becomes more conscious of it, his anxiety intensifies.

OUTCOME: Overcoming fear

As Mr. J sits crying in my office, he says he hasn’t cried in front of another man in years. I wonder aloud what his father would think of this situation. His states that his father does not respect any type of weakness and probably would “knock his teeth in.” Overcoming this fear of opening up will be a goal of Mr. J’s treatment. His unbridled optimism borders on pathologic, and is a defense against reality.8 Additionally, his reluctance to accept that he is suffering from depression, which he perceives as a weakness, will be a struggle throughout therapy. He likely will continue to minimize his symptoms when possible, making the true depths of his illness difficult to grasp.

Related Resources

- Waska R. Using countertransference: analytic contact, projective identification, and transference phantasy states. Am J Psychother. 2008;62(4):333-351.

- Gabbard GO, Litowitz BE, Williams P. Textbook of psychoanalysis. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2011.

Drug Brand Names

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Blos P. Son and father: before and beyond the Oedipus complex. New York NY: Free Press/Macmillan; 1985.

2. Ursano RJ, Sonnenberg SM, Lazar SG. Concise guide to psychodynamic psychotherapy. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004.

3. Akhtar S. Comprehensive dictionary of psychoanalysis. London United Kingdom: Kamac Books; 2009.

4. Busch FN, Milrod BL, Singer MB. Theory and technique in psychodynamic treatment of panic disorder. J Psychother Pract Res. 1999;8(3):234-242.

5. Freud S. The future prospects of psycho-analytic therapy. The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud volume XI (1910): five lectures on psycho-analysis, Leonardo da Vinci and other works. London, United Kingdom: Hogarth Press; 1957:139–152.

6. Winnicott DW. Hate in the counter-transference. J Psychother Pract Res. 1994;3(4):348-356.

7. Maltsberger JT, Buie DH. Countertransference hate in the treatment of suicidal patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974;30(5):625-633.

8. Akhtar S. “Someday…” and “if only…” fantasies: pathological optimism and inordinate nostalgia as related forms of idealization. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1996;44(3):723-753.

CASE: Unexplained panic

Mr. J, age 35, is a married, unemployed musician who presents for outpatient treatment for panic attacks. He experienced his first panic attack at his oldest son’s baptism 12 years ago, but does not know why it occurred at that moment. He rarely has panic attacks now, but wants to continue medication management. He denies depressive symptoms, saying, “I’m the most optimistic person in the world.” Mr. J tried several medications for his panic attacks before clonazepam, 2 mg/d, proved effective, but always has been vehemently opposed to antidepressants. Despite his insistence that he needs only medication management, Mr. J chooses to enroll in a resident-run psychotherapy clinic.

In sessions, Mr. J describes his father, who also has panic disorder, as a powerful figure who is physically and emotionally abusive, but also charismatic, charming, and “impossible not to love.” However, Mr. J felt his father was impossible to live with, and moved out at age 18 to marry his high school sweetheart. They have 3 children, ages 12, 10, and 8. Mr. J worked for his father at his construction company, but was not able to satisfy him or live up to his standards so he quit because he was tired of being cut down and emasculated.

Mr. J’s parents divorced 15 years ago after his mother had an affair with her husband’s friend. His father learned of the affair and threatened his wife with a handgun. Although Mr. J and his mother were close before her affair, he has been unable to forgive or empathize with her, and rarely speaks to her. Mr. J’s mother could not protect him from his father’s abuse, and later compounded her failure by abandoning her husband and son through her sexual affair. Growing up with a father he did not respect or get comfort from and sharing a common fear and alliance with his mother likely made it difficult for Mr. J to navigate his Oedipal phase,1 and made her abandonment even more painful.

When Mr. J was 6 years old, he was molested by one of his father’s friends. His father stabbed the man in the shoulder when he found out about the molestation and received probation. Although Mr. J knows he was molested, he does not remember it and has repressed most of his childhood.

The authors’ observations

I (JF) wanted to discuss with Mr. J why his first panic attack occurred during such a symbolic occasion. His panic could be the result of a struggle between a murderous wish toward his father and paternal protective instinct toward his son. The baptism placed his son in a highly vulnerable position, which reminded Mr. J of his own vulnerability and impotent rage toward his father. Anxiety often results when an individual has 2 opposing wishes,2 and a murderous wish often is involved when anxiety progresses to panic. Getting to the root of this with Mr. J could allow for further psychological growth.3 His murderous wishes and fantasies are ego-dystonic, and panic could be a way of punishing himself for these thoughts. When Mr. J identified himself as his son during the baptism, he likely was flooded with thoughts that his defenses were no longer able to repress. Seeing his son submerged in the baptismal font brought back an aspect of his own life that he had completely split off from consciousness, and likely will take time to process. Considering the current therapeutic dynamic, I decided that it was not the best time to address this potential conflict; however, I could have chosen a manualized form of psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder.4 See Table 1 for an outline of the phases of psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder.

Although Mr. J’s initial willingness to discuss his past was encouraging, he refused to schedule more than 1 session every 4 weeks. He also began to keep the content of our sessions superficial, which caused me angst because he seemed to be withholding information and would not come more frequently. Although I was not proud of my feelings, I had to be honest with myself that I had started to dislike Mr. J.

Table 1

Psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder

| Phase | Comments |

|---|---|

| Treatment of acute panic | Therapy focuses on discovering the conscious and unconscious meaning of panic symptoms |

| Treatment of panic vulnerability | Core dynamic conflicts related to panic are understood and altered. Tasks include addressing the nature of the transference and working through them |

| Termination | The therapist directly addresses patients’ difficulties with separation and independence as they emerge in treatment. After treatment, patients may be better able to manage separations, anger, and independence |

| Source: Adapted from reference 4 | |

Countertransference reactions

Countertransference is a therapist's emotional reaction to a patient. Just as patients form reactions based on past relationships brought to present, therapists develop similar reactions.5 Noting one’s countertransference provides a window into how the patient’s thoughts and actions evoke feelings in others. It also can shed light on an aspect of the doctor-patient relationship that may have gone unnoticed.2

Countertransference hatred can occur when a therapist begins to dislike a patient. Typically, patients with borderline personality disorder, masochistic tendencies, or suicidality arouse strong countertransference reactions6; however, any patient can evoke these emotions. This type of hateful patient can precipitate antitherapeutic feelings such as aversion or malice that can be a major obstacle to treatment.7 Aversion leads the therapist to withdraw from the patient, and malice can trigger cruel impulses.

Maltsberger and Buie7 identified 5 defenses therapists may use to combat countertransference hatred (Table 2). When treating Mr. J, I used several of these defenses, including projection and turning against the self to protect myself from this challenging patient. In turning against the self, I became doubtful and critical of my skills and increasingly submissive to Mr. J. Additionally, I projected this countertransference hatred onto Mr. J, focusing on the negative transference that he brought to our therapeutic encounters. On an unconscious level, I may have feared retribution from Mr. J.

I became so frustrated with Mr. J that I reduced the frequency of our sessions to once every 6 weeks, which I realized could be evidence of my feelings regarding Mr. J’s minimization and avoidant style.

Table 2

Defenses against countertransference hate

| Defense mechanism | Description |

|---|---|

| Repression | Remaining unconscious of feelings of hate; may manifest as difficulty paying attention to what the patient is saying or feeling bored or tired |

| Turning against oneself | Doubting one’s capacity to help the patient; may feel inadequate, helpless, and hopeless. May lead to giving up on the patient because the therapist feels incompetent |

| Reaction formation | Turning hatred into the opposite emotion. The therapist may be too preoccupied with being helpful or overly concerned about the patient’s welfare and comfort |

| Projection | Feeling that the patient hates the therapist, leading to feelings of dread and fear |

| Distortion of reality | Devaluing the patient and seeing the patient as a hopeless case or a dangerous person. The therapist may feel indifference, pity, or anger toward the patient |

| Source: Reference 7 | |

TREATMENT: A breakthrough

Mr. J presents with obvious unease at the first visit after we had decreased the frequency of our sessions. At this point, Mr. J opens up to me. He says he has not been truthful with me, and has had worsening depression, anhedonia, and agoraphobia over the past year. He also reveals that he has homosexual fantasies that he cannot stop, which disturb him because he says he is heterosexual. He agrees to come once a week, and reluctantly admits that he desperately needs help.

Although Mr. J only takes clonazepam and citalopram, 20 mg/d, which I prescribed after he admitted to depression and anxiety, he has hyperlipidemia and a family history of heart disease. In addition to being a musician and working at his father’s construction company, he has worked as a security guard, bounty hunter, and computer technician. His careers have been solitary in nature, and, with the exception of computer work, permitted an outlet for aggression. However, he recently started taking online college classes and wants to become a music teacher because he feels he has a lot to offer children as a result of his life experiences. His fantasy of being a teacher shows considerably less aggression, and could be a sign of psychological growth.

Mr. J is struggling financially and his home is on the verge of foreclosure. Early in treatment he told me that he stopped paying his mortgage, but demonstrated blind optimism that things would “work out.” I asked if this was a wise decision, but he seemed confident and dismissive of my concerns. Although he now struggles with this situation, I consider this healthier than his constant pseudo-happy state, and a sign of psychological development.8 Despite his financial stressors, he wants to pursue his dream of being a famous musician, and says he “could never work a 9-to-5 job in a cubicle.”

The authors’ observations

I do not think it’s a coincidence that Mr. J stopped minimizing his symptoms when we decreased the frequency of his sessions. I had viewed our sessions as unproductive and blamed Mr. J for wasting both of our time with his resistance and minimization and had begun to dislike him. I felt impotent because he had been controlling each session with long, elaborate stories that had little relevance to his panic attacks, and I could not redirect him or get him to focus on pertinent issues. It was as if I was an audience for him, and provided nothing useful. However, I was interested in these superficial stories because Mr. J was charming and engaging. He likely reenacted his relationship with his father with me. Mr. J’s superficial relationship with me caused me to dislike him, and, similar to his father, reject him. This rejection likely was damaging because I was unable to anticipate his needs, which would have been to increase—rather than decrease—the frequency of our sessions. Just like his father, I was not able to take care of him.

Mr. J is deeply conflicted about his father. He states that his father “is a monster who instills fear and intimidation into everyone around him, but he’s charismatic, and I’ll always love him.” His view of his domineering father likely developed into a castration anxiety because he was afraid of competing for his mother’s love, contributing to a muddled sexual identity. This was intensified when Mr. J was sexually abused; he may have been stimulated by the molestation, adding to his confusion. Although Mr. J has repressed the abuse and split off most of his childhood, he suffers from shame, guilt, and depression because of his ego-dystonic homosexual fantasies. Homosexuality is at odds with his self-image and contributes to his anxiety and panic attacks. He cannot adequately discharge this dangerous libidinal energy, and as he becomes more conscious of it, his anxiety intensifies.

OUTCOME: Overcoming fear

As Mr. J sits crying in my office, he says he hasn’t cried in front of another man in years. I wonder aloud what his father would think of this situation. His states that his father does not respect any type of weakness and probably would “knock his teeth in.” Overcoming this fear of opening up will be a goal of Mr. J’s treatment. His unbridled optimism borders on pathologic, and is a defense against reality.8 Additionally, his reluctance to accept that he is suffering from depression, which he perceives as a weakness, will be a struggle throughout therapy. He likely will continue to minimize his symptoms when possible, making the true depths of his illness difficult to grasp.

Related Resources

- Waska R. Using countertransference: analytic contact, projective identification, and transference phantasy states. Am J Psychother. 2008;62(4):333-351.

- Gabbard GO, Litowitz BE, Williams P. Textbook of psychoanalysis. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2011.

Drug Brand Names

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE: Unexplained panic

Mr. J, age 35, is a married, unemployed musician who presents for outpatient treatment for panic attacks. He experienced his first panic attack at his oldest son’s baptism 12 years ago, but does not know why it occurred at that moment. He rarely has panic attacks now, but wants to continue medication management. He denies depressive symptoms, saying, “I’m the most optimistic person in the world.” Mr. J tried several medications for his panic attacks before clonazepam, 2 mg/d, proved effective, but always has been vehemently opposed to antidepressants. Despite his insistence that he needs only medication management, Mr. J chooses to enroll in a resident-run psychotherapy clinic.

In sessions, Mr. J describes his father, who also has panic disorder, as a powerful figure who is physically and emotionally abusive, but also charismatic, charming, and “impossible not to love.” However, Mr. J felt his father was impossible to live with, and moved out at age 18 to marry his high school sweetheart. They have 3 children, ages 12, 10, and 8. Mr. J worked for his father at his construction company, but was not able to satisfy him or live up to his standards so he quit because he was tired of being cut down and emasculated.

Mr. J’s parents divorced 15 years ago after his mother had an affair with her husband’s friend. His father learned of the affair and threatened his wife with a handgun. Although Mr. J and his mother were close before her affair, he has been unable to forgive or empathize with her, and rarely speaks to her. Mr. J’s mother could not protect him from his father’s abuse, and later compounded her failure by abandoning her husband and son through her sexual affair. Growing up with a father he did not respect or get comfort from and sharing a common fear and alliance with his mother likely made it difficult for Mr. J to navigate his Oedipal phase,1 and made her abandonment even more painful.

When Mr. J was 6 years old, he was molested by one of his father’s friends. His father stabbed the man in the shoulder when he found out about the molestation and received probation. Although Mr. J knows he was molested, he does not remember it and has repressed most of his childhood.

The authors’ observations

I (JF) wanted to discuss with Mr. J why his first panic attack occurred during such a symbolic occasion. His panic could be the result of a struggle between a murderous wish toward his father and paternal protective instinct toward his son. The baptism placed his son in a highly vulnerable position, which reminded Mr. J of his own vulnerability and impotent rage toward his father. Anxiety often results when an individual has 2 opposing wishes,2 and a murderous wish often is involved when anxiety progresses to panic. Getting to the root of this with Mr. J could allow for further psychological growth.3 His murderous wishes and fantasies are ego-dystonic, and panic could be a way of punishing himself for these thoughts. When Mr. J identified himself as his son during the baptism, he likely was flooded with thoughts that his defenses were no longer able to repress. Seeing his son submerged in the baptismal font brought back an aspect of his own life that he had completely split off from consciousness, and likely will take time to process. Considering the current therapeutic dynamic, I decided that it was not the best time to address this potential conflict; however, I could have chosen a manualized form of psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder.4 See Table 1 for an outline of the phases of psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder.

Although Mr. J’s initial willingness to discuss his past was encouraging, he refused to schedule more than 1 session every 4 weeks. He also began to keep the content of our sessions superficial, which caused me angst because he seemed to be withholding information and would not come more frequently. Although I was not proud of my feelings, I had to be honest with myself that I had started to dislike Mr. J.

Table 1

Psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder

| Phase | Comments |

|---|---|

| Treatment of acute panic | Therapy focuses on discovering the conscious and unconscious meaning of panic symptoms |

| Treatment of panic vulnerability | Core dynamic conflicts related to panic are understood and altered. Tasks include addressing the nature of the transference and working through them |

| Termination | The therapist directly addresses patients’ difficulties with separation and independence as they emerge in treatment. After treatment, patients may be better able to manage separations, anger, and independence |

| Source: Adapted from reference 4 | |

Countertransference reactions

Countertransference is a therapist's emotional reaction to a patient. Just as patients form reactions based on past relationships brought to present, therapists develop similar reactions.5 Noting one’s countertransference provides a window into how the patient’s thoughts and actions evoke feelings in others. It also can shed light on an aspect of the doctor-patient relationship that may have gone unnoticed.2

Countertransference hatred can occur when a therapist begins to dislike a patient. Typically, patients with borderline personality disorder, masochistic tendencies, or suicidality arouse strong countertransference reactions6; however, any patient can evoke these emotions. This type of hateful patient can precipitate antitherapeutic feelings such as aversion or malice that can be a major obstacle to treatment.7 Aversion leads the therapist to withdraw from the patient, and malice can trigger cruel impulses.

Maltsberger and Buie7 identified 5 defenses therapists may use to combat countertransference hatred (Table 2). When treating Mr. J, I used several of these defenses, including projection and turning against the self to protect myself from this challenging patient. In turning against the self, I became doubtful and critical of my skills and increasingly submissive to Mr. J. Additionally, I projected this countertransference hatred onto Mr. J, focusing on the negative transference that he brought to our therapeutic encounters. On an unconscious level, I may have feared retribution from Mr. J.

I became so frustrated with Mr. J that I reduced the frequency of our sessions to once every 6 weeks, which I realized could be evidence of my feelings regarding Mr. J’s minimization and avoidant style.

Table 2

Defenses against countertransference hate

| Defense mechanism | Description |

|---|---|

| Repression | Remaining unconscious of feelings of hate; may manifest as difficulty paying attention to what the patient is saying or feeling bored or tired |

| Turning against oneself | Doubting one’s capacity to help the patient; may feel inadequate, helpless, and hopeless. May lead to giving up on the patient because the therapist feels incompetent |

| Reaction formation | Turning hatred into the opposite emotion. The therapist may be too preoccupied with being helpful or overly concerned about the patient’s welfare and comfort |

| Projection | Feeling that the patient hates the therapist, leading to feelings of dread and fear |

| Distortion of reality | Devaluing the patient and seeing the patient as a hopeless case or a dangerous person. The therapist may feel indifference, pity, or anger toward the patient |

| Source: Reference 7 | |

TREATMENT: A breakthrough

Mr. J presents with obvious unease at the first visit after we had decreased the frequency of our sessions. At this point, Mr. J opens up to me. He says he has not been truthful with me, and has had worsening depression, anhedonia, and agoraphobia over the past year. He also reveals that he has homosexual fantasies that he cannot stop, which disturb him because he says he is heterosexual. He agrees to come once a week, and reluctantly admits that he desperately needs help.

Although Mr. J only takes clonazepam and citalopram, 20 mg/d, which I prescribed after he admitted to depression and anxiety, he has hyperlipidemia and a family history of heart disease. In addition to being a musician and working at his father’s construction company, he has worked as a security guard, bounty hunter, and computer technician. His careers have been solitary in nature, and, with the exception of computer work, permitted an outlet for aggression. However, he recently started taking online college classes and wants to become a music teacher because he feels he has a lot to offer children as a result of his life experiences. His fantasy of being a teacher shows considerably less aggression, and could be a sign of psychological growth.

Mr. J is struggling financially and his home is on the verge of foreclosure. Early in treatment he told me that he stopped paying his mortgage, but demonstrated blind optimism that things would “work out.” I asked if this was a wise decision, but he seemed confident and dismissive of my concerns. Although he now struggles with this situation, I consider this healthier than his constant pseudo-happy state, and a sign of psychological development.8 Despite his financial stressors, he wants to pursue his dream of being a famous musician, and says he “could never work a 9-to-5 job in a cubicle.”

The authors’ observations

I do not think it’s a coincidence that Mr. J stopped minimizing his symptoms when we decreased the frequency of his sessions. I had viewed our sessions as unproductive and blamed Mr. J for wasting both of our time with his resistance and minimization and had begun to dislike him. I felt impotent because he had been controlling each session with long, elaborate stories that had little relevance to his panic attacks, and I could not redirect him or get him to focus on pertinent issues. It was as if I was an audience for him, and provided nothing useful. However, I was interested in these superficial stories because Mr. J was charming and engaging. He likely reenacted his relationship with his father with me. Mr. J’s superficial relationship with me caused me to dislike him, and, similar to his father, reject him. This rejection likely was damaging because I was unable to anticipate his needs, which would have been to increase—rather than decrease—the frequency of our sessions. Just like his father, I was not able to take care of him.

Mr. J is deeply conflicted about his father. He states that his father “is a monster who instills fear and intimidation into everyone around him, but he’s charismatic, and I’ll always love him.” His view of his domineering father likely developed into a castration anxiety because he was afraid of competing for his mother’s love, contributing to a muddled sexual identity. This was intensified when Mr. J was sexually abused; he may have been stimulated by the molestation, adding to his confusion. Although Mr. J has repressed the abuse and split off most of his childhood, he suffers from shame, guilt, and depression because of his ego-dystonic homosexual fantasies. Homosexuality is at odds with his self-image and contributes to his anxiety and panic attacks. He cannot adequately discharge this dangerous libidinal energy, and as he becomes more conscious of it, his anxiety intensifies.

OUTCOME: Overcoming fear

As Mr. J sits crying in my office, he says he hasn’t cried in front of another man in years. I wonder aloud what his father would think of this situation. His states that his father does not respect any type of weakness and probably would “knock his teeth in.” Overcoming this fear of opening up will be a goal of Mr. J’s treatment. His unbridled optimism borders on pathologic, and is a defense against reality.8 Additionally, his reluctance to accept that he is suffering from depression, which he perceives as a weakness, will be a struggle throughout therapy. He likely will continue to minimize his symptoms when possible, making the true depths of his illness difficult to grasp.

Related Resources

- Waska R. Using countertransference: analytic contact, projective identification, and transference phantasy states. Am J Psychother. 2008;62(4):333-351.

- Gabbard GO, Litowitz BE, Williams P. Textbook of psychoanalysis. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2011.

Drug Brand Names

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Blos P. Son and father: before and beyond the Oedipus complex. New York NY: Free Press/Macmillan; 1985.

2. Ursano RJ, Sonnenberg SM, Lazar SG. Concise guide to psychodynamic psychotherapy. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004.

3. Akhtar S. Comprehensive dictionary of psychoanalysis. London United Kingdom: Kamac Books; 2009.

4. Busch FN, Milrod BL, Singer MB. Theory and technique in psychodynamic treatment of panic disorder. J Psychother Pract Res. 1999;8(3):234-242.

5. Freud S. The future prospects of psycho-analytic therapy. The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud volume XI (1910): five lectures on psycho-analysis, Leonardo da Vinci and other works. London, United Kingdom: Hogarth Press; 1957:139–152.

6. Winnicott DW. Hate in the counter-transference. J Psychother Pract Res. 1994;3(4):348-356.

7. Maltsberger JT, Buie DH. Countertransference hate in the treatment of suicidal patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974;30(5):625-633.

8. Akhtar S. “Someday…” and “if only…” fantasies: pathological optimism and inordinate nostalgia as related forms of idealization. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1996;44(3):723-753.

1. Blos P. Son and father: before and beyond the Oedipus complex. New York NY: Free Press/Macmillan; 1985.

2. Ursano RJ, Sonnenberg SM, Lazar SG. Concise guide to psychodynamic psychotherapy. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2004.

3. Akhtar S. Comprehensive dictionary of psychoanalysis. London United Kingdom: Kamac Books; 2009.

4. Busch FN, Milrod BL, Singer MB. Theory and technique in psychodynamic treatment of panic disorder. J Psychother Pract Res. 1999;8(3):234-242.

5. Freud S. The future prospects of psycho-analytic therapy. The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud volume XI (1910): five lectures on psycho-analysis, Leonardo da Vinci and other works. London, United Kingdom: Hogarth Press; 1957:139–152.

6. Winnicott DW. Hate in the counter-transference. J Psychother Pract Res. 1994;3(4):348-356.

7. Maltsberger JT, Buie DH. Countertransference hate in the treatment of suicidal patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1974;30(5):625-633.

8. Akhtar S. “Someday…” and “if only…” fantasies: pathological optimism and inordinate nostalgia as related forms of idealization. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 1996;44(3):723-753.

Prolonged delivery: child with CP awarded $70M … and more

AFTER MORE THAN 4 HOURS of second-stage labor followed by prolonged pushing and crowning, the baby was born depressed. Later, the child was found to have cerebral palsy.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in failing to perform an episiotomy, not attempting vacuum extraction, and not using forceps to assist delivery. Although fetal heart-rate monitoring results deteriorated, the ObGyn did not assess contractions for 30 minutes at one point. Hospital staff members were unable to adequately intubate or ventilate the newborn. The hospital staff disposed of the baby’s cord blood. Records were altered.

The parents’ counsel proposed that the defendants’ insurance company refused all settlement efforts prior to trial because the case venue was known to be conservative regarding jury verdicts.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The hospital and the ObGyn were not negligent; the mother and baby received proper care. Hospital staff acted appropriately.

VERDICT During the trial, the hospital settled for an undisclosed amount. An additional $2 million was offered on behalf of the ObGyn later in the trial, but the parents refused settlement at that time.

A California jury returned a $74.525 million verdict against the ObGyn. The child was awarded $70.725 million for medical expenses, lost earnings, and damages. The parents were awarded $3.8 million for emotional distress.

Was ectopic pregnancy missed?

A WOMAN IN SEVERE ABDOMINAL PAIN saw her internist. CT scans revealed a right ovarian cyst. When pain continued, she saw her ObGyn 3 weeks later, and her bowel was full of hard stool. Ultrasonography (US) showed a multicystic right ovary and a thin endometrial stripe. She was taking birth control pills and her husband had a vasectomy. She was told her abdominal pain was from constipation and ovarian cysts. A week later, she had laparoscopic surgery to remove an ectopic pregnancy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn did not perform a pregnancy test, and did not diagnose an ectopic pregnancy in a timely manner. An earlier diagnosis would have allowed medical rather than surgical resolution.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE It was too early to determine if the pregnancy was intrauterine or ectopic. An earlier diagnosis would have resulted in laparoscopic surgery rather than medical treatment, as the medication (methotrexate) can cause increased pain.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Foreshortened vagina inhibits intercourse

A 65-YEAR-OLD WOMAN underwent anterior and posterior colphorrhaphy to repair a cystocele and rectocele, sacrospinous ligament fixation for vaginal prolapse, and a TVT mid-urethral suspension procedure to correct stress urinary incontinence. During two follow-up visits, the gynecologist determined that she was healing normally.

Within the next few weeks, the patient came to believe that her vagina had been sewn shut. She did not return to her gynecologist, but sought treatment with another physician 6 months later. It was determined that she had a stenotic and foreshortened vagina.

PATIENT’S CLAIM Too much vaginal tissue was removed during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The stenotic and foreshortened vagina was an unexpected result of the healing process after surgery.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Hydrocephalus in utero not seen until too late

A WOMAN HAD PRENATAL TREATMENT at a federally funded health clinic. A certified nurse midwife (CNM) ordered second-trimester US, with normal results. During the third trimester, the mother switched to a private ObGyn who ordered testing. US indicated the fetus was hydrocephalic. The child was born with cognitive disabilities and will need lifelong care.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The CNM ordered US too early in the pregnancy to be of diagnostic value; no further testing was undertaken. When hydrocephalus was seen, an abortion was not legally available because of fetal age.

DEFENDANT’S DEFENSE Even if US had been performed later in the second trimester, the defect would not have shown.

VERDICT A $4 million New Jersey settlement was reached.

WHEN SHOULDER DYSTOCIA WAS ENCOUNTERED, the ObGyn used standard maneuvers to deliver the child. The baby suffered a severe brachial plexus injury with rupture of C7 nerve and avulsions at C8 and T1.

Nerve-graft surgery at 6 months and tendon transfer surgery at 2 years resulted in recovery of good shoulder and elbow function, but the child has inadequate use of his wrist and hand. Additional surgeries are planned.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn did not inform the mother that she was at risk for shoulder dystocia, nor did he discuss cesarean delivery. The mother’s risk factors included short stature, gestational diabetes, excessive weight gain during pregnancy, and two previous deliveries that involved vacuum assistance and a broken clavicle. The ObGyn applied excessive traction to the fetal head during delivery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The mother’s risk factors were not severe enough to consider the chance of shoulder dystocia. The baby’s injuries were due to the normal forces of labor. Traction placed on the baby’s head during delivery was gentle and appropriate.

VERDICT A $5.5 million Iowa verdict was returned.

Faulty testing: baby has Down syndrome

AT 13 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a 34-year-old woman underwent chorionic villus sampling (CVS) at a maternal-fetal medicine center. Results showed a normal chromosomal profile. Later, two sonograms indicated possible Down syndrome. The parents were assured that the baby did not have a genetic disorder; amniocentesis was never suggested.

A week before the baby’s birth, the parents were told the child has Down syndrome.

PARENTS’ CLAIM Maternal tissue, not fetal tissue, had been removed and tested during CVS. The parents would have aborted the fetus had they known she had Down syndrome.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE CVS was properly administered.

VERDICT A $3 million Missouri verdict was returned against the center where the testing was performed.

Why did the uterus seem to be growing?

A 52-YEAR-OLD WOMAN’S UTERUS was larger than normal in February 2007. By November 2008, her uterus was the size of a 14-week gestation. In September 2009, she complained of abdominal discomfort. Her uterus was larger than at the previous visit. The gynecologist suggested a hysterectomy, but nothing was scheduled.

In November 2009, she reported increasing pelvic pressure; her uterus was the size of an 18-week gestation. US and MRI showed large masses on both ovaries although the uterus had no masses or fibroids within it. A gynecologic oncologist performed abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and bilateral peri-aortic lymph node dissection. Pathology returned a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. The patient underwent chemotherapy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The gynecologist was negligent in not ordering testing in 2007 when the larger-than-normal uterus was first detected, or in subsequent visits through September 2009. A more timely reaction would have given her an opportunity to treat the cancer at an earlier stage.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The case was settled before trial.

VERDICT A $650,000 Maryland settlement was reached.

Erb’s palsy after shoulder dystocia

DURING VAGINAL DELIVERY, the ObGyn encountered shoulder dystocia. The child suffered a brachial plexus injury and has Erb’s palsy. There was some improvement after two operations, but she still has muscle weakness, arm-length discrepancy, and limited range of motion.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn applied excessive downward traction on the baby’s head when her left shoulder could not pass under the pubic bone.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The injury was caused by uterine contractions and maternal pushing. Proper maneuvers and gentle pressure were used.

VERDICT A $1.34 million New Jersey verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

AFTER MORE THAN 4 HOURS of second-stage labor followed by prolonged pushing and crowning, the baby was born depressed. Later, the child was found to have cerebral palsy.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in failing to perform an episiotomy, not attempting vacuum extraction, and not using forceps to assist delivery. Although fetal heart-rate monitoring results deteriorated, the ObGyn did not assess contractions for 30 minutes at one point. Hospital staff members were unable to adequately intubate or ventilate the newborn. The hospital staff disposed of the baby’s cord blood. Records were altered.

The parents’ counsel proposed that the defendants’ insurance company refused all settlement efforts prior to trial because the case venue was known to be conservative regarding jury verdicts.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The hospital and the ObGyn were not negligent; the mother and baby received proper care. Hospital staff acted appropriately.

VERDICT During the trial, the hospital settled for an undisclosed amount. An additional $2 million was offered on behalf of the ObGyn later in the trial, but the parents refused settlement at that time.

A California jury returned a $74.525 million verdict against the ObGyn. The child was awarded $70.725 million for medical expenses, lost earnings, and damages. The parents were awarded $3.8 million for emotional distress.

Was ectopic pregnancy missed?

A WOMAN IN SEVERE ABDOMINAL PAIN saw her internist. CT scans revealed a right ovarian cyst. When pain continued, she saw her ObGyn 3 weeks later, and her bowel was full of hard stool. Ultrasonography (US) showed a multicystic right ovary and a thin endometrial stripe. She was taking birth control pills and her husband had a vasectomy. She was told her abdominal pain was from constipation and ovarian cysts. A week later, she had laparoscopic surgery to remove an ectopic pregnancy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn did not perform a pregnancy test, and did not diagnose an ectopic pregnancy in a timely manner. An earlier diagnosis would have allowed medical rather than surgical resolution.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE It was too early to determine if the pregnancy was intrauterine or ectopic. An earlier diagnosis would have resulted in laparoscopic surgery rather than medical treatment, as the medication (methotrexate) can cause increased pain.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Foreshortened vagina inhibits intercourse

A 65-YEAR-OLD WOMAN underwent anterior and posterior colphorrhaphy to repair a cystocele and rectocele, sacrospinous ligament fixation for vaginal prolapse, and a TVT mid-urethral suspension procedure to correct stress urinary incontinence. During two follow-up visits, the gynecologist determined that she was healing normally.

Within the next few weeks, the patient came to believe that her vagina had been sewn shut. She did not return to her gynecologist, but sought treatment with another physician 6 months later. It was determined that she had a stenotic and foreshortened vagina.

PATIENT’S CLAIM Too much vaginal tissue was removed during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The stenotic and foreshortened vagina was an unexpected result of the healing process after surgery.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Hydrocephalus in utero not seen until too late

A WOMAN HAD PRENATAL TREATMENT at a federally funded health clinic. A certified nurse midwife (CNM) ordered second-trimester US, with normal results. During the third trimester, the mother switched to a private ObGyn who ordered testing. US indicated the fetus was hydrocephalic. The child was born with cognitive disabilities and will need lifelong care.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The CNM ordered US too early in the pregnancy to be of diagnostic value; no further testing was undertaken. When hydrocephalus was seen, an abortion was not legally available because of fetal age.

DEFENDANT’S DEFENSE Even if US had been performed later in the second trimester, the defect would not have shown.

VERDICT A $4 million New Jersey settlement was reached.

WHEN SHOULDER DYSTOCIA WAS ENCOUNTERED, the ObGyn used standard maneuvers to deliver the child. The baby suffered a severe brachial plexus injury with rupture of C7 nerve and avulsions at C8 and T1.

Nerve-graft surgery at 6 months and tendon transfer surgery at 2 years resulted in recovery of good shoulder and elbow function, but the child has inadequate use of his wrist and hand. Additional surgeries are planned.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn did not inform the mother that she was at risk for shoulder dystocia, nor did he discuss cesarean delivery. The mother’s risk factors included short stature, gestational diabetes, excessive weight gain during pregnancy, and two previous deliveries that involved vacuum assistance and a broken clavicle. The ObGyn applied excessive traction to the fetal head during delivery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The mother’s risk factors were not severe enough to consider the chance of shoulder dystocia. The baby’s injuries were due to the normal forces of labor. Traction placed on the baby’s head during delivery was gentle and appropriate.

VERDICT A $5.5 million Iowa verdict was returned.

Faulty testing: baby has Down syndrome

AT 13 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a 34-year-old woman underwent chorionic villus sampling (CVS) at a maternal-fetal medicine center. Results showed a normal chromosomal profile. Later, two sonograms indicated possible Down syndrome. The parents were assured that the baby did not have a genetic disorder; amniocentesis was never suggested.

A week before the baby’s birth, the parents were told the child has Down syndrome.

PARENTS’ CLAIM Maternal tissue, not fetal tissue, had been removed and tested during CVS. The parents would have aborted the fetus had they known she had Down syndrome.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE CVS was properly administered.

VERDICT A $3 million Missouri verdict was returned against the center where the testing was performed.

Why did the uterus seem to be growing?

A 52-YEAR-OLD WOMAN’S UTERUS was larger than normal in February 2007. By November 2008, her uterus was the size of a 14-week gestation. In September 2009, she complained of abdominal discomfort. Her uterus was larger than at the previous visit. The gynecologist suggested a hysterectomy, but nothing was scheduled.

In November 2009, she reported increasing pelvic pressure; her uterus was the size of an 18-week gestation. US and MRI showed large masses on both ovaries although the uterus had no masses or fibroids within it. A gynecologic oncologist performed abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and bilateral peri-aortic lymph node dissection. Pathology returned a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. The patient underwent chemotherapy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The gynecologist was negligent in not ordering testing in 2007 when the larger-than-normal uterus was first detected, or in subsequent visits through September 2009. A more timely reaction would have given her an opportunity to treat the cancer at an earlier stage.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The case was settled before trial.

VERDICT A $650,000 Maryland settlement was reached.

Erb’s palsy after shoulder dystocia

DURING VAGINAL DELIVERY, the ObGyn encountered shoulder dystocia. The child suffered a brachial plexus injury and has Erb’s palsy. There was some improvement after two operations, but she still has muscle weakness, arm-length discrepancy, and limited range of motion.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn applied excessive downward traction on the baby’s head when her left shoulder could not pass under the pubic bone.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The injury was caused by uterine contractions and maternal pushing. Proper maneuvers and gentle pressure were used.

VERDICT A $1.34 million New Jersey verdict was returned.

AFTER MORE THAN 4 HOURS of second-stage labor followed by prolonged pushing and crowning, the baby was born depressed. Later, the child was found to have cerebral palsy.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn was negligent in failing to perform an episiotomy, not attempting vacuum extraction, and not using forceps to assist delivery. Although fetal heart-rate monitoring results deteriorated, the ObGyn did not assess contractions for 30 minutes at one point. Hospital staff members were unable to adequately intubate or ventilate the newborn. The hospital staff disposed of the baby’s cord blood. Records were altered.

The parents’ counsel proposed that the defendants’ insurance company refused all settlement efforts prior to trial because the case venue was known to be conservative regarding jury verdicts.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE The hospital and the ObGyn were not negligent; the mother and baby received proper care. Hospital staff acted appropriately.

VERDICT During the trial, the hospital settled for an undisclosed amount. An additional $2 million was offered on behalf of the ObGyn later in the trial, but the parents refused settlement at that time.

A California jury returned a $74.525 million verdict against the ObGyn. The child was awarded $70.725 million for medical expenses, lost earnings, and damages. The parents were awarded $3.8 million for emotional distress.

Was ectopic pregnancy missed?

A WOMAN IN SEVERE ABDOMINAL PAIN saw her internist. CT scans revealed a right ovarian cyst. When pain continued, she saw her ObGyn 3 weeks later, and her bowel was full of hard stool. Ultrasonography (US) showed a multicystic right ovary and a thin endometrial stripe. She was taking birth control pills and her husband had a vasectomy. She was told her abdominal pain was from constipation and ovarian cysts. A week later, she had laparoscopic surgery to remove an ectopic pregnancy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The ObGyn did not perform a pregnancy test, and did not diagnose an ectopic pregnancy in a timely manner. An earlier diagnosis would have allowed medical rather than surgical resolution.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE It was too early to determine if the pregnancy was intrauterine or ectopic. An earlier diagnosis would have resulted in laparoscopic surgery rather than medical treatment, as the medication (methotrexate) can cause increased pain.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Foreshortened vagina inhibits intercourse

A 65-YEAR-OLD WOMAN underwent anterior and posterior colphorrhaphy to repair a cystocele and rectocele, sacrospinous ligament fixation for vaginal prolapse, and a TVT mid-urethral suspension procedure to correct stress urinary incontinence. During two follow-up visits, the gynecologist determined that she was healing normally.

Within the next few weeks, the patient came to believe that her vagina had been sewn shut. She did not return to her gynecologist, but sought treatment with another physician 6 months later. It was determined that she had a stenotic and foreshortened vagina.

PATIENT’S CLAIM Too much vaginal tissue was removed during surgery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The stenotic and foreshortened vagina was an unexpected result of the healing process after surgery.

VERDICT An Illinois defense verdict was returned.

Hydrocephalus in utero not seen until too late

A WOMAN HAD PRENATAL TREATMENT at a federally funded health clinic. A certified nurse midwife (CNM) ordered second-trimester US, with normal results. During the third trimester, the mother switched to a private ObGyn who ordered testing. US indicated the fetus was hydrocephalic. The child was born with cognitive disabilities and will need lifelong care.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The CNM ordered US too early in the pregnancy to be of diagnostic value; no further testing was undertaken. When hydrocephalus was seen, an abortion was not legally available because of fetal age.

DEFENDANT’S DEFENSE Even if US had been performed later in the second trimester, the defect would not have shown.

VERDICT A $4 million New Jersey settlement was reached.

WHEN SHOULDER DYSTOCIA WAS ENCOUNTERED, the ObGyn used standard maneuvers to deliver the child. The baby suffered a severe brachial plexus injury with rupture of C7 nerve and avulsions at C8 and T1.

Nerve-graft surgery at 6 months and tendon transfer surgery at 2 years resulted in recovery of good shoulder and elbow function, but the child has inadequate use of his wrist and hand. Additional surgeries are planned.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn did not inform the mother that she was at risk for shoulder dystocia, nor did he discuss cesarean delivery. The mother’s risk factors included short stature, gestational diabetes, excessive weight gain during pregnancy, and two previous deliveries that involved vacuum assistance and a broken clavicle. The ObGyn applied excessive traction to the fetal head during delivery.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The mother’s risk factors were not severe enough to consider the chance of shoulder dystocia. The baby’s injuries were due to the normal forces of labor. Traction placed on the baby’s head during delivery was gentle and appropriate.

VERDICT A $5.5 million Iowa verdict was returned.

Faulty testing: baby has Down syndrome

AT 13 WEEKS’ GESTATION, a 34-year-old woman underwent chorionic villus sampling (CVS) at a maternal-fetal medicine center. Results showed a normal chromosomal profile. Later, two sonograms indicated possible Down syndrome. The parents were assured that the baby did not have a genetic disorder; amniocentesis was never suggested.

A week before the baby’s birth, the parents were told the child has Down syndrome.

PARENTS’ CLAIM Maternal tissue, not fetal tissue, had been removed and tested during CVS. The parents would have aborted the fetus had they known she had Down syndrome.

DEFENDANTS’ DEFENSE CVS was properly administered.

VERDICT A $3 million Missouri verdict was returned against the center where the testing was performed.

Why did the uterus seem to be growing?

A 52-YEAR-OLD WOMAN’S UTERUS was larger than normal in February 2007. By November 2008, her uterus was the size of a 14-week gestation. In September 2009, she complained of abdominal discomfort. Her uterus was larger than at the previous visit. The gynecologist suggested a hysterectomy, but nothing was scheduled.

In November 2009, she reported increasing pelvic pressure; her uterus was the size of an 18-week gestation. US and MRI showed large masses on both ovaries although the uterus had no masses or fibroids within it. A gynecologic oncologist performed abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and bilateral peri-aortic lymph node dissection. Pathology returned a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. The patient underwent chemotherapy.

PATIENT’S CLAIM The gynecologist was negligent in not ordering testing in 2007 when the larger-than-normal uterus was first detected, or in subsequent visits through September 2009. A more timely reaction would have given her an opportunity to treat the cancer at an earlier stage.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The case was settled before trial.

VERDICT A $650,000 Maryland settlement was reached.

Erb’s palsy after shoulder dystocia

DURING VAGINAL DELIVERY, the ObGyn encountered shoulder dystocia. The child suffered a brachial plexus injury and has Erb’s palsy. There was some improvement after two operations, but she still has muscle weakness, arm-length discrepancy, and limited range of motion.

PARENTS’ CLAIM The ObGyn applied excessive downward traction on the baby’s head when her left shoulder could not pass under the pubic bone.

PHYSICIAN’S DEFENSE The injury was caused by uterine contractions and maternal pushing. Proper maneuvers and gentle pressure were used.

VERDICT A $1.34 million New Jersey verdict was returned.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

These cases were selected by the editors of OBG Management from Medical Malpractice Verdicts, Settlements & Experts, with permission of the editor, Lewis Laska (www.verdictslaska.com). The information available to the editors about the cases presented here is sometimes incomplete. Moreover, the cases may or may not have merit. Nevertheless, these cases represent the types of clinical situations that typically result in litigation and are meant to illustrate nationwide variation in jury verdicts and awards.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Does mediolateral episiotomy reduce the risk of anal sphincter injury in operative vaginal delivery?

Stop performing median episiotomy!

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, April 2012)

Episiotomy is an incision into the perineal body that is made during the second stage of labor to expedite delivery. Despite guidelines recommending restrictions on its use, episiotomy is still performed in more than 25% of vaginal deliveries in the United States. Suggested benefits include a shortened second stage of labor, the substitution of a straight surgical incision for a ragged spontaneous tear, and a reduced incidence of severe perineal injury and resultant pelvic floor dysfunction. Few data support these assertions, however.

Episiotomy is no OASIS

Absolute indications for episiotomy have yet to be established. Although there is general agreement that episiotomy may be indicated in select circumstances (such as to expedite delivery in the setting of nonreassuring fetal testing in the second stage of labor, shoulder dystocia, or at the time of operative vaginal delivery), routine use is discouraged.1,2 Besides the lack of data showing its benefit, episiotomy is associated with several potential complications, including increased blood loss, fetal injury, and localized pain. In contrast to the stated goal of reducing perineal trauma, episiotomy is associated with an increased incidence of third- or fourth-degree perineal lacerations,3,4 referred to in this study as obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS).

Third- or fourth-degree tears are identified clinically at the time of vaginal delivery in 0.6% to 9% of patients.4 Studies using two-dimensional endoanal ultrasonography suggest that the true incidence of rectal injury is probably closer to 11%.5 Such injuries are associated with an increased risk of subsequent urinary or fecal incontinence (or both) and pelvic organ prolapse.

If episiotomy is indicated, how should it be performed?

There are two main types of episiotomy: median (favored in the United States) and mediolateral episiotomy. Complications—especially OASIS—are more common with median episiotomy,3,6,7 which involves a vertical midline incision from the posterior fourchette toward the rectum. Mediolateral episiotomy (favored in Europe), refers to an incision performed at a 45° angle from the posterior fourchette. OASIS is more common after median episiotomy, compared with the mediolateral approach.4,6 What is not yet clear is whether mediolateral episiotomy actually protects against OASIS.

Details of the study

de Vogel and colleagues evaluated the frequency of OASIS in women at high risk—specifically, those undergoing operative vaginal delivery; they also sought to determine whether mediolateral episiotomy is protective against OASIS. To this end, they performed a retrospective analysis of 2,861 consecutive women who delivered a singleton liveborn infant at term by vacuum, forceps, or both, from 2001–2009. Women were identified through the Netherlands Perinatal Registry, a voluntary reporting national database that includes approximately 96% of the 190,000 births that occur after 16 weeks’ gestation each year in the Netherlands. Exclusion criteria included multiple gestation, breech presentation, and use of median episiotomy.

The overall frequency of OASIS was 5.7% (162 cases among 2,861 deliveries). After logistic-regression modeling, a number of variables were significantly associated with OASIS, all of which have been identified previously: forceps delivery, occiput posterior position, primiparity, and epidural anesthesia. Women with a mediolateral episiotomy were at a significantly lower risk for OASIS, compared with women without mediolateral episiotomy (3.5% vs 15.6%, respectively; P<.001). Further analysis suggested that 8.6 mediolateral episiotomies would be needed to prevent one OASIS during vacuum extraction, whereas 5.2 procedures would be necessary to prevent one OASIS during forceps delivery. de Vogel and colleagues concluded that mediolateral episiotomy should be performed during all operative vaginal deliveries to reduce the incidence of OASIS.

Although this study included a large sample from a well-established and validated dataset (collected prospectively), it was, by design, retrospective. There was no standardization of when or how to cut the mediolateral episiotomy. However, many of these uncontrolled variables (such as cutting an episiotomy that is more median than mediolateral or cutting an episiotomy only in women who appear to be at imminent risk of sustaining a perineal laceration) would increase—not decrease—the risk of severe perineal injury. This fact suggests that the protective effect of mediolateral episiotomy may be even more dramatic than the sixfold protection reported in this study.

This study focused on women who underwent operative vaginal delivery. It remains controversial whether mediolateral episiotomy is protective in women who have a spontaneous (noninstrumental) vaginal delivery.

The study also lacks follow-up data on how many women with OASIS went on to develop fecal or urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse. However, a third- or fourth-degree perineal laceration is serious enough that it can serve as an acceptable primary outcome measure even in the absence of long-term functional data.

In this study, use of median episiotomy was an exclusion, mostly likely because it is rarely performed in Europe.

While the battle over “to cut or not to cut” continues to rage, one fact is clear: median episiotomy should be abandoned. If you are going to perform episiotomy, make it mediolateral. According to this report, accoucheurs should consider cutting a mediolateral episiotomy for perineal protection each time they perform operative vaginal delivery.

ERROL R. NORWITZ, MD, PHD

After reading this article, and Dr. Barbieri’s April Editorial, we want to know if these articles have changed your practice. If you were faced with a difficult vaginal delivery, would you use a median or mediolateral episiotomy incision? Why?

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Hartmann K, Viswanathan M, Palmieri R, Gartlehner G, Thorp J, Lohr KN. Outcomes of routine episiotomy: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293(17):2141-2148.

2. Carroli G, Mignini L. Episiotomy for vaginal birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD000081.-

3. Helwig JT, Thorp JM, Jr, Bowes WA, Jr. Does midline episiotomy increase the risk of third- and fourth-degree lacerations in operative vaginal deliveries? Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82(2):276-279.

4. Dudding TC, Vaizey C, Kamm MA. Obstetric anal sphincter injury: incidence, risk factors, and management. Ann Surg. 2008;247(2):224-237.

5. Williams AB, Bartram CI, Halligan S, Spencer JA, Nicholls RJ, Kmiot WA. Anal sphincter damage after vaginal delivery using three-dimensional endosonography. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(5 Pt 1):770-775.

6. Coats PM, Chan KK, Wilkins M, Beard RJ. A comparison between midline and mediolateral episiotomies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1980;87(5):408-412.

7. Kudish B, Blackwell S, McNeeley SG, et al. Operative vaginal delivery and midline episiotomy: a bad combination for the perineum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(3):749-754.

Stop performing median episiotomy!

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, April 2012)

Episiotomy is an incision into the perineal body that is made during the second stage of labor to expedite delivery. Despite guidelines recommending restrictions on its use, episiotomy is still performed in more than 25% of vaginal deliveries in the United States. Suggested benefits include a shortened second stage of labor, the substitution of a straight surgical incision for a ragged spontaneous tear, and a reduced incidence of severe perineal injury and resultant pelvic floor dysfunction. Few data support these assertions, however.

Episiotomy is no OASIS

Absolute indications for episiotomy have yet to be established. Although there is general agreement that episiotomy may be indicated in select circumstances (such as to expedite delivery in the setting of nonreassuring fetal testing in the second stage of labor, shoulder dystocia, or at the time of operative vaginal delivery), routine use is discouraged.1,2 Besides the lack of data showing its benefit, episiotomy is associated with several potential complications, including increased blood loss, fetal injury, and localized pain. In contrast to the stated goal of reducing perineal trauma, episiotomy is associated with an increased incidence of third- or fourth-degree perineal lacerations,3,4 referred to in this study as obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS).

Third- or fourth-degree tears are identified clinically at the time of vaginal delivery in 0.6% to 9% of patients.4 Studies using two-dimensional endoanal ultrasonography suggest that the true incidence of rectal injury is probably closer to 11%.5 Such injuries are associated with an increased risk of subsequent urinary or fecal incontinence (or both) and pelvic organ prolapse.

If episiotomy is indicated, how should it be performed?

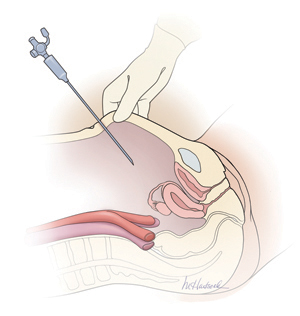

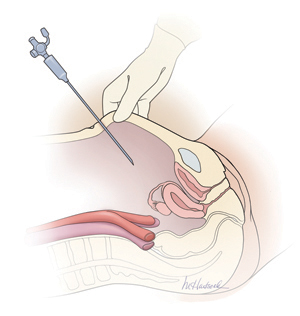

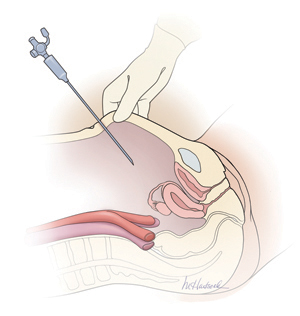

There are two main types of episiotomy: median (favored in the United States) and mediolateral episiotomy. Complications—especially OASIS—are more common with median episiotomy,3,6,7 which involves a vertical midline incision from the posterior fourchette toward the rectum. Mediolateral episiotomy (favored in Europe), refers to an incision performed at a 45° angle from the posterior fourchette. OASIS is more common after median episiotomy, compared with the mediolateral approach.4,6 What is not yet clear is whether mediolateral episiotomy actually protects against OASIS.

Details of the study

de Vogel and colleagues evaluated the frequency of OASIS in women at high risk—specifically, those undergoing operative vaginal delivery; they also sought to determine whether mediolateral episiotomy is protective against OASIS. To this end, they performed a retrospective analysis of 2,861 consecutive women who delivered a singleton liveborn infant at term by vacuum, forceps, or both, from 2001–2009. Women were identified through the Netherlands Perinatal Registry, a voluntary reporting national database that includes approximately 96% of the 190,000 births that occur after 16 weeks’ gestation each year in the Netherlands. Exclusion criteria included multiple gestation, breech presentation, and use of median episiotomy.

The overall frequency of OASIS was 5.7% (162 cases among 2,861 deliveries). After logistic-regression modeling, a number of variables were significantly associated with OASIS, all of which have been identified previously: forceps delivery, occiput posterior position, primiparity, and epidural anesthesia. Women with a mediolateral episiotomy were at a significantly lower risk for OASIS, compared with women without mediolateral episiotomy (3.5% vs 15.6%, respectively; P<.001). Further analysis suggested that 8.6 mediolateral episiotomies would be needed to prevent one OASIS during vacuum extraction, whereas 5.2 procedures would be necessary to prevent one OASIS during forceps delivery. de Vogel and colleagues concluded that mediolateral episiotomy should be performed during all operative vaginal deliveries to reduce the incidence of OASIS.