User login

Pharmacotherapy for panic disorder: Clinical experience vs the literature

Clinical experiences sometimes contradict the psychiatric literature. For example, some of my patients with panic disorder (PD) benefit from adding benzodiazepines to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). However, 2 double-blind studies show that adding benzodiazepines to SSRIs does not help PD patients.1,2 Why are my patients different from those in the studies? Some of my patients may have been misusing benzodiazepines or were psychologically habituated to them, but I doubt that explains all of the improvement I observed.

A more relevant reason for the different responses seen in my patients and those in the 2 studies may be differences in the populations involved. For example, many of my PD patients had not responded to SSRIs alone. In contrast, none of the patients in the studies had been unresponsive to SSRIs.

Also, unlike patients in the studies, many of my patients with PD have severe psychiatric comorbidity—they also may have a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or depression. Comorbidity may affect the severity of PD and treatment response. For example, PD with recurrent comorbid depression has been shown to be more difficult to treat, suggesting the need for “combination treatment with SSRI and benzodiazepines or with pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavior therapy.”3

I am not suggesting that benzodiazepines should be added to SSRIs for every patient with PD and severe comorbidity. Some of my patients with PD and comorbid psychiatric disorders do quite well with SSRIs alone. I suggest that patients who do not respond to SSRIs may benefit from adjunctive benzodiazepines. Severe comorbidity may suggest the need for adding benzodiazepines; the lack of response to high doses of SSRIs also may be a determining factor.

Disclosure: Dr Wilf reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Pollack MH, Simon NM, Worthington JJ, et al. Combined paroxetine and clonazepam treatment strategies compared to paroxetine monotherapy for panic disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2003;17:276-282.

2. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:681-686.

3. Marchesi C, Cantoni A, Fonto S, et al. Predictors of symptom resolution in panic disorder after one year of pharmacological treatment: a naturalistic study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2006;39:60-65.

Clinical experiences sometimes contradict the psychiatric literature. For example, some of my patients with panic disorder (PD) benefit from adding benzodiazepines to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). However, 2 double-blind studies show that adding benzodiazepines to SSRIs does not help PD patients.1,2 Why are my patients different from those in the studies? Some of my patients may have been misusing benzodiazepines or were psychologically habituated to them, but I doubt that explains all of the improvement I observed.

A more relevant reason for the different responses seen in my patients and those in the 2 studies may be differences in the populations involved. For example, many of my PD patients had not responded to SSRIs alone. In contrast, none of the patients in the studies had been unresponsive to SSRIs.

Also, unlike patients in the studies, many of my patients with PD have severe psychiatric comorbidity—they also may have a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or depression. Comorbidity may affect the severity of PD and treatment response. For example, PD with recurrent comorbid depression has been shown to be more difficult to treat, suggesting the need for “combination treatment with SSRI and benzodiazepines or with pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavior therapy.”3

I am not suggesting that benzodiazepines should be added to SSRIs for every patient with PD and severe comorbidity. Some of my patients with PD and comorbid psychiatric disorders do quite well with SSRIs alone. I suggest that patients who do not respond to SSRIs may benefit from adjunctive benzodiazepines. Severe comorbidity may suggest the need for adding benzodiazepines; the lack of response to high doses of SSRIs also may be a determining factor.

Disclosure: Dr Wilf reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Clinical experiences sometimes contradict the psychiatric literature. For example, some of my patients with panic disorder (PD) benefit from adding benzodiazepines to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). However, 2 double-blind studies show that adding benzodiazepines to SSRIs does not help PD patients.1,2 Why are my patients different from those in the studies? Some of my patients may have been misusing benzodiazepines or were psychologically habituated to them, but I doubt that explains all of the improvement I observed.

A more relevant reason for the different responses seen in my patients and those in the 2 studies may be differences in the populations involved. For example, many of my PD patients had not responded to SSRIs alone. In contrast, none of the patients in the studies had been unresponsive to SSRIs.

Also, unlike patients in the studies, many of my patients with PD have severe psychiatric comorbidity—they also may have a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or depression. Comorbidity may affect the severity of PD and treatment response. For example, PD with recurrent comorbid depression has been shown to be more difficult to treat, suggesting the need for “combination treatment with SSRI and benzodiazepines or with pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavior therapy.”3

I am not suggesting that benzodiazepines should be added to SSRIs for every patient with PD and severe comorbidity. Some of my patients with PD and comorbid psychiatric disorders do quite well with SSRIs alone. I suggest that patients who do not respond to SSRIs may benefit from adjunctive benzodiazepines. Severe comorbidity may suggest the need for adding benzodiazepines; the lack of response to high doses of SSRIs also may be a determining factor.

Disclosure: Dr Wilf reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Pollack MH, Simon NM, Worthington JJ, et al. Combined paroxetine and clonazepam treatment strategies compared to paroxetine monotherapy for panic disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2003;17:276-282.

2. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:681-686.

3. Marchesi C, Cantoni A, Fonto S, et al. Predictors of symptom resolution in panic disorder after one year of pharmacological treatment: a naturalistic study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2006;39:60-65.

1. Pollack MH, Simon NM, Worthington JJ, et al. Combined paroxetine and clonazepam treatment strategies compared to paroxetine monotherapy for panic disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2003;17:276-282.

2. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:681-686.

3. Marchesi C, Cantoni A, Fonto S, et al. Predictors of symptom resolution in panic disorder after one year of pharmacological treatment: a naturalistic study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2006;39:60-65.

Precocious Thelarche or Adrenarche

First recognize that a child with precocious puberty might actually have a serious underlying medical condition that triggers puberty. It is appropriate for you to distinguish true precocious puberty from precocious puberty secondary to a general underlying medical condition if this is within your comfort zone.

Begin with a complete history and physical examination. If you see physical signs of puberty that are not simply caused by “early puberty,” consider looking for underlying thyroid disorders, ovarian tumors, central nervous system tumors, or even tumors of the adrenal gland.

Importantly, perform a complete evaluation before initiation of any “treatment.” Occasionally, a patient with premature vaginal bleeding undergoes a very thorough hormone evaluation only to find the cause of her bleeding is a foreign body. Therefore, inspect the vaginal cavity as part of your physical examination or include this in your gynecologist referral when a girl presents with vaginal bleeding and no other evident signs of puberty. You might spare the patient a full hormone work-up. Also refer the child to a gynecologist if you suspect an abnormality of the reproductive tract because of pelvic pain, vaginal discharge, and/or abnormal vaginal bleeding.

The treatment for precocious puberty is controversial itself. Administration of an injection that blocks gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion from the hypothalamus is the most commonly prescribed therapy (leuprolide acetate, Lupron Depot-PED). Consider referral of these patients because gynecologists and pediatric endocrinologists have the most experience with this medication.

Other medications and lifestyle modifications are not particularly effective at halting early puberty.

Optimally, I advocate a combined effort among the pediatrician, the pediatric endocrinologist, and the gynecologist with a special interest in children.

Consider ordering a bone age study during your initial evaluation. It is an easy-to-order test for early puberty. Determination of the bone age of the left wrist is particularly worthwhile and provides useful information should you decide to refer to a specialist. Referral is warranted if a child with precocious puberty has advanced bone age.

Although precocious puberty includes thelarche and adrenarche, some important differences exist. Breast development, the growth spurt, and menses are all under the control of one system, the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. Adrenarche, or secondary sexual hair, is primarily under the control of the adrenal gland, although the ovary is a major contributor to circulating androgens. Clinically, evaluate adrenal pathology more aggressively in cases of precocious adrenarche than in cases of thelarche.

It is also appropriate for a child without precocious puberty concerns to see a gynecologist in the early teenage years. This specialist can help you educate patients on reproductive health, including when Pap testing needs to be done and strategies to prevent pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection.

First recognize that a child with precocious puberty might actually have a serious underlying medical condition that triggers puberty. It is appropriate for you to distinguish true precocious puberty from precocious puberty secondary to a general underlying medical condition if this is within your comfort zone.

Begin with a complete history and physical examination. If you see physical signs of puberty that are not simply caused by “early puberty,” consider looking for underlying thyroid disorders, ovarian tumors, central nervous system tumors, or even tumors of the adrenal gland.

Importantly, perform a complete evaluation before initiation of any “treatment.” Occasionally, a patient with premature vaginal bleeding undergoes a very thorough hormone evaluation only to find the cause of her bleeding is a foreign body. Therefore, inspect the vaginal cavity as part of your physical examination or include this in your gynecologist referral when a girl presents with vaginal bleeding and no other evident signs of puberty. You might spare the patient a full hormone work-up. Also refer the child to a gynecologist if you suspect an abnormality of the reproductive tract because of pelvic pain, vaginal discharge, and/or abnormal vaginal bleeding.

The treatment for precocious puberty is controversial itself. Administration of an injection that blocks gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion from the hypothalamus is the most commonly prescribed therapy (leuprolide acetate, Lupron Depot-PED). Consider referral of these patients because gynecologists and pediatric endocrinologists have the most experience with this medication.

Other medications and lifestyle modifications are not particularly effective at halting early puberty.

Optimally, I advocate a combined effort among the pediatrician, the pediatric endocrinologist, and the gynecologist with a special interest in children.

Consider ordering a bone age study during your initial evaluation. It is an easy-to-order test for early puberty. Determination of the bone age of the left wrist is particularly worthwhile and provides useful information should you decide to refer to a specialist. Referral is warranted if a child with precocious puberty has advanced bone age.

Although precocious puberty includes thelarche and adrenarche, some important differences exist. Breast development, the growth spurt, and menses are all under the control of one system, the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. Adrenarche, or secondary sexual hair, is primarily under the control of the adrenal gland, although the ovary is a major contributor to circulating androgens. Clinically, evaluate adrenal pathology more aggressively in cases of precocious adrenarche than in cases of thelarche.

It is also appropriate for a child without precocious puberty concerns to see a gynecologist in the early teenage years. This specialist can help you educate patients on reproductive health, including when Pap testing needs to be done and strategies to prevent pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection.

First recognize that a child with precocious puberty might actually have a serious underlying medical condition that triggers puberty. It is appropriate for you to distinguish true precocious puberty from precocious puberty secondary to a general underlying medical condition if this is within your comfort zone.

Begin with a complete history and physical examination. If you see physical signs of puberty that are not simply caused by “early puberty,” consider looking for underlying thyroid disorders, ovarian tumors, central nervous system tumors, or even tumors of the adrenal gland.

Importantly, perform a complete evaluation before initiation of any “treatment.” Occasionally, a patient with premature vaginal bleeding undergoes a very thorough hormone evaluation only to find the cause of her bleeding is a foreign body. Therefore, inspect the vaginal cavity as part of your physical examination or include this in your gynecologist referral when a girl presents with vaginal bleeding and no other evident signs of puberty. You might spare the patient a full hormone work-up. Also refer the child to a gynecologist if you suspect an abnormality of the reproductive tract because of pelvic pain, vaginal discharge, and/or abnormal vaginal bleeding.

The treatment for precocious puberty is controversial itself. Administration of an injection that blocks gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion from the hypothalamus is the most commonly prescribed therapy (leuprolide acetate, Lupron Depot-PED). Consider referral of these patients because gynecologists and pediatric endocrinologists have the most experience with this medication.

Other medications and lifestyle modifications are not particularly effective at halting early puberty.

Optimally, I advocate a combined effort among the pediatrician, the pediatric endocrinologist, and the gynecologist with a special interest in children.

Consider ordering a bone age study during your initial evaluation. It is an easy-to-order test for early puberty. Determination of the bone age of the left wrist is particularly worthwhile and provides useful information should you decide to refer to a specialist. Referral is warranted if a child with precocious puberty has advanced bone age.

Although precocious puberty includes thelarche and adrenarche, some important differences exist. Breast development, the growth spurt, and menses are all under the control of one system, the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. Adrenarche, or secondary sexual hair, is primarily under the control of the adrenal gland, although the ovary is a major contributor to circulating androgens. Clinically, evaluate adrenal pathology more aggressively in cases of precocious adrenarche than in cases of thelarche.

It is also appropriate for a child without precocious puberty concerns to see a gynecologist in the early teenage years. This specialist can help you educate patients on reproductive health, including when Pap testing needs to be done and strategies to prevent pregnancy and sexually transmitted infection.

Are We Pandering to Peer Problems in Preschool?

www.CHADIS.com[email protected]

“The preschool just called for the second time about Jason's behavior! What can I do?” This plea to you the pediatrician makes your stomach turn upside down. “What am I supposed to do about that?” you ask yourself. You're not there to see what is happening, and the parent isn't either.

This scenario is made even more difficult because the parents can be desperate for advice and quick solutions. It is incredibly inconvenient when a child is thrown out of child care or preschool for bad behavior, especially for parents who both work. Parents may even get hysterical because they immediately envision their darling failing to get into Harvard based on an inability to interact properly in preschool.

The differential diagnosis of this complaint takes some good sleuthing, but can make a big difference in the life of a young child.

Young children deal with social interaction issues that also confront grown-ups, but without the skills to navigate and manage them.

Learning social skills is a major benefit of preschool and kindergarten, particularly for children with few siblings or siblings of much different ages. The poem “All I Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten” describes many of these social benefits, including learning to share, take turns, act kindly, and use manners. The poem does not mention some of the other less poetic skills developed at this age, however: learning how to tease successfully, pull your punches, stand tall when there is a bully, bounce back when people insult you or after you wet your pants, tell if someone is a real friend, and deal with a critical teacher who is screaming all the time.

Young children normally practice a social interaction known as “inclusion/exclusion,” where one day they say, “Oh, you're my best friend. Let's go have our secret club.” But the next day they say, “You're not my friend anymore. I've got a new best friend. You can't play with me.” In general, the best short- and long-term outcomes occur when children work out minor interaction problems on their own, with a little teacher support, but serious problems are handled privately by the adults.

Ask for specific information about one of the incidents from both the child and the parent. If a child comes home from school and says, “This kid called me names,” parents can ask, “What kind of names?” to distinguish normal teasing from a toxic environment that needs to be changed. Abnormal teasing is more vicious and adultlike, for example, a peer calling the child a “whore” or using a racial epithet.

Don't forget to suggest ways to pump up resilience such as getting sufficient sleep and proper nutrition.

Next, assess the child with problematic peer behavior for skill deficits. A child with a gap may act up to distract others from noticing, out of frustration or as result of discrimination the child experiences. Often children this age who are aggressive have shortcomings in language. They may speak a different language at home or still communicate only in two- or three-word phrases, and therefore are unable to keep up with others and feel – or actually are – left out. They don't have the repartee to negotiate social situations and can become the victim of taunting and teasing, a specialty of girls.

Children with gross motor skill deficits, particularly boys, also may experience difficulty keeping up with their peers. In some cases, they are rejected by the group for being unable to kick a soccer ball or to climb a jungle gym as well as others can, and they are angry as a result.

Check fine motor skills as well. A child with poor coordination may be slow to finish work and/or be ashamed of what they do produce. Children can be very self-critical at this age and even tear up their papers. If the teacher asks everyone to draw a truck, and another student pointedly says, 'That doesn't look like a truck,” the child might punch in return. The child is acting up in frustration.

While children at this age are just on the edge of acquiring “perspective taking” (considering another's point of view), in the most severe form, difficulty in doing this can be a sign of autism spectrum disorder. Peers quickly pick up on this and may tease them, call them names, and/or reject their awkward attempts to engage. Try telling them a joke or asking them to tell one, and you may see why.

You can help by addressing any detected skill deficits with language therapy or physical therapy. Importantly, suggest ways to build their skills while allowing them to bypass social humiliation. Let children who are not athletic skip recess, assigning them the task of getting out the snacks to avoid further humiliation. Then work on their motor skills through after-school karate instead.

Anxiety can spark aggression, too. If you are afraid, it seems better to strike first. If anxiety seems key, the parents and school will need to soften their handling of the child and help him or her put feelings into words to assist the child in not acting out.

Since some children will misbehave to get a teacher's attention, recommend that the parents drop in unannounced. Often the way a classroom appears (or is staffed) at 8 a.m. drop-off time is not the same way it operates at 10:30 a.m. Suggest a parent watch the part of the day their child complains about the most, which is frequently recess.

Even though there are bad situations and bad schools, most schools have great teachers and other professionals from whom parents can gain valuable information and advice.

Generally teachers can explain the timing of a child's troubles, for example, during circle time he cannot sit still or during craft time because his fine motor skills are not well developed. Having parents seek out these examples is the most efficient way to identify deficits in need of help.

Suggest parents speak to their child empathically instead of giving instructions. In this culture, boys especially are told to “keep a stiff upper lip” or “be a big soldier.” A better approach is to say, “Yes, it's tough when kids talk to you like that” or “I understand this really makes you sad and you feel like crying.”

It also helps when parents share a similar experience from their own childhood. For example, parents can say, “You know, when I was your age, I had an experience like this – I had a kid who was always on my case.”

Parents can promote social development as well. For example, role playing can clearly help a child develop appropriate socioemotional skills. Parents can use this strategy either before an incident – for example, to rehearse how a child might react to a bully in class – or afterward, to help the child determine what he or she might have said or done differently and prepare for the next time. Use of social stories can foster these skills (see www.socialstories.com

Parents who experienced a bad peer interaction as a preschooler or kindergartener may project their concerns on their child who may be doing just fine. The parents might be supersensitive to teasing, for example, and bring an otherwise minor incident to your attention and/or become overintrusive at school. Asking, “How was it for you when you were little? Did you ever run into anything like this?” may bring out past experiences as an important factor predisposing to overreaction. If they wet their pants in kindergarten and never got over it, realizing this connection makes it possible for them to back off and let the school and child handle the current problem.

Watch for red flags or warning signs that problematic behaviors are not within the range of normal stress. The child initially doing well at school who suddenly does not want to return is one example.

Sadly, you need to always consider whether there is abuse going on at school, including sexual abuse. Sudden adjustment problems at home, such as trouble sleeping, nightmares, or bed-wetting, also should raise your level of concern.

Also ask parents if their preschooler suddenly became more difficult to manage at home. Some children who experience negative peer interactions will cling to parents, but oppositional or defiant behavior is more common. Of course, 4-year-old children are notoriously brassy, so you cannot consider back talk a warning sign unless it is part of a sudden change in the normal flow of the child's behavior.

A child this stressed over school may need to be cared for at home or moved to a family day care situation

Unfortunately, the modern practice of grouping of kids of the same age together in a classroom increases the likelihood of interactions going badly. Ten 2-year-old children are not necessarily capable of peacefully spending hours together at a time. When a serious behavioral problem arises in this kind of setting, I frequently recommend family-based day care instead of center-based day care because children will be with others of different ages and different skill levels, and hopefully some of them will be more mature.

Support parents in deciding to pull the child out of a school if the situation is bad. If, for example, the school administration is unresponsive to or dismissive of a parent, removal of the child may be the best option. A new parent recently came to the parent group at our clinic. She reported that a teacher responded to her child's behavior problem by putting him in a closet, which would have been egregious enough, but the teacher also said that there were spiders and bugs in the closet that were going to get him before closing the door. I was flabbergasted. The school tried to defend the teacher for doing this, and my final advice was to “pull the kid.” Any school that ignorant of normal child development cannot be fixed.

www.CHADIS.com[email protected]

“The preschool just called for the second time about Jason's behavior! What can I do?” This plea to you the pediatrician makes your stomach turn upside down. “What am I supposed to do about that?” you ask yourself. You're not there to see what is happening, and the parent isn't either.

This scenario is made even more difficult because the parents can be desperate for advice and quick solutions. It is incredibly inconvenient when a child is thrown out of child care or preschool for bad behavior, especially for parents who both work. Parents may even get hysterical because they immediately envision their darling failing to get into Harvard based on an inability to interact properly in preschool.

The differential diagnosis of this complaint takes some good sleuthing, but can make a big difference in the life of a young child.

Young children deal with social interaction issues that also confront grown-ups, but without the skills to navigate and manage them.

Learning social skills is a major benefit of preschool and kindergarten, particularly for children with few siblings or siblings of much different ages. The poem “All I Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten” describes many of these social benefits, including learning to share, take turns, act kindly, and use manners. The poem does not mention some of the other less poetic skills developed at this age, however: learning how to tease successfully, pull your punches, stand tall when there is a bully, bounce back when people insult you or after you wet your pants, tell if someone is a real friend, and deal with a critical teacher who is screaming all the time.

Young children normally practice a social interaction known as “inclusion/exclusion,” where one day they say, “Oh, you're my best friend. Let's go have our secret club.” But the next day they say, “You're not my friend anymore. I've got a new best friend. You can't play with me.” In general, the best short- and long-term outcomes occur when children work out minor interaction problems on their own, with a little teacher support, but serious problems are handled privately by the adults.

Ask for specific information about one of the incidents from both the child and the parent. If a child comes home from school and says, “This kid called me names,” parents can ask, “What kind of names?” to distinguish normal teasing from a toxic environment that needs to be changed. Abnormal teasing is more vicious and adultlike, for example, a peer calling the child a “whore” or using a racial epithet.

Don't forget to suggest ways to pump up resilience such as getting sufficient sleep and proper nutrition.

Next, assess the child with problematic peer behavior for skill deficits. A child with a gap may act up to distract others from noticing, out of frustration or as result of discrimination the child experiences. Often children this age who are aggressive have shortcomings in language. They may speak a different language at home or still communicate only in two- or three-word phrases, and therefore are unable to keep up with others and feel – or actually are – left out. They don't have the repartee to negotiate social situations and can become the victim of taunting and teasing, a specialty of girls.

Children with gross motor skill deficits, particularly boys, also may experience difficulty keeping up with their peers. In some cases, they are rejected by the group for being unable to kick a soccer ball or to climb a jungle gym as well as others can, and they are angry as a result.

Check fine motor skills as well. A child with poor coordination may be slow to finish work and/or be ashamed of what they do produce. Children can be very self-critical at this age and even tear up their papers. If the teacher asks everyone to draw a truck, and another student pointedly says, 'That doesn't look like a truck,” the child might punch in return. The child is acting up in frustration.

While children at this age are just on the edge of acquiring “perspective taking” (considering another's point of view), in the most severe form, difficulty in doing this can be a sign of autism spectrum disorder. Peers quickly pick up on this and may tease them, call them names, and/or reject their awkward attempts to engage. Try telling them a joke or asking them to tell one, and you may see why.

You can help by addressing any detected skill deficits with language therapy or physical therapy. Importantly, suggest ways to build their skills while allowing them to bypass social humiliation. Let children who are not athletic skip recess, assigning them the task of getting out the snacks to avoid further humiliation. Then work on their motor skills through after-school karate instead.

Anxiety can spark aggression, too. If you are afraid, it seems better to strike first. If anxiety seems key, the parents and school will need to soften their handling of the child and help him or her put feelings into words to assist the child in not acting out.

Since some children will misbehave to get a teacher's attention, recommend that the parents drop in unannounced. Often the way a classroom appears (or is staffed) at 8 a.m. drop-off time is not the same way it operates at 10:30 a.m. Suggest a parent watch the part of the day their child complains about the most, which is frequently recess.

Even though there are bad situations and bad schools, most schools have great teachers and other professionals from whom parents can gain valuable information and advice.

Generally teachers can explain the timing of a child's troubles, for example, during circle time he cannot sit still or during craft time because his fine motor skills are not well developed. Having parents seek out these examples is the most efficient way to identify deficits in need of help.

Suggest parents speak to their child empathically instead of giving instructions. In this culture, boys especially are told to “keep a stiff upper lip” or “be a big soldier.” A better approach is to say, “Yes, it's tough when kids talk to you like that” or “I understand this really makes you sad and you feel like crying.”

It also helps when parents share a similar experience from their own childhood. For example, parents can say, “You know, when I was your age, I had an experience like this – I had a kid who was always on my case.”

Parents can promote social development as well. For example, role playing can clearly help a child develop appropriate socioemotional skills. Parents can use this strategy either before an incident – for example, to rehearse how a child might react to a bully in class – or afterward, to help the child determine what he or she might have said or done differently and prepare for the next time. Use of social stories can foster these skills (see www.socialstories.com

Parents who experienced a bad peer interaction as a preschooler or kindergartener may project their concerns on their child who may be doing just fine. The parents might be supersensitive to teasing, for example, and bring an otherwise minor incident to your attention and/or become overintrusive at school. Asking, “How was it for you when you were little? Did you ever run into anything like this?” may bring out past experiences as an important factor predisposing to overreaction. If they wet their pants in kindergarten and never got over it, realizing this connection makes it possible for them to back off and let the school and child handle the current problem.

Watch for red flags or warning signs that problematic behaviors are not within the range of normal stress. The child initially doing well at school who suddenly does not want to return is one example.

Sadly, you need to always consider whether there is abuse going on at school, including sexual abuse. Sudden adjustment problems at home, such as trouble sleeping, nightmares, or bed-wetting, also should raise your level of concern.

Also ask parents if their preschooler suddenly became more difficult to manage at home. Some children who experience negative peer interactions will cling to parents, but oppositional or defiant behavior is more common. Of course, 4-year-old children are notoriously brassy, so you cannot consider back talk a warning sign unless it is part of a sudden change in the normal flow of the child's behavior.

A child this stressed over school may need to be cared for at home or moved to a family day care situation

Unfortunately, the modern practice of grouping of kids of the same age together in a classroom increases the likelihood of interactions going badly. Ten 2-year-old children are not necessarily capable of peacefully spending hours together at a time. When a serious behavioral problem arises in this kind of setting, I frequently recommend family-based day care instead of center-based day care because children will be with others of different ages and different skill levels, and hopefully some of them will be more mature.

Support parents in deciding to pull the child out of a school if the situation is bad. If, for example, the school administration is unresponsive to or dismissive of a parent, removal of the child may be the best option. A new parent recently came to the parent group at our clinic. She reported that a teacher responded to her child's behavior problem by putting him in a closet, which would have been egregious enough, but the teacher also said that there were spiders and bugs in the closet that were going to get him before closing the door. I was flabbergasted. The school tried to defend the teacher for doing this, and my final advice was to “pull the kid.” Any school that ignorant of normal child development cannot be fixed.

www.CHADIS.com[email protected]

“The preschool just called for the second time about Jason's behavior! What can I do?” This plea to you the pediatrician makes your stomach turn upside down. “What am I supposed to do about that?” you ask yourself. You're not there to see what is happening, and the parent isn't either.

This scenario is made even more difficult because the parents can be desperate for advice and quick solutions. It is incredibly inconvenient when a child is thrown out of child care or preschool for bad behavior, especially for parents who both work. Parents may even get hysterical because they immediately envision their darling failing to get into Harvard based on an inability to interact properly in preschool.

The differential diagnosis of this complaint takes some good sleuthing, but can make a big difference in the life of a young child.

Young children deal with social interaction issues that also confront grown-ups, but without the skills to navigate and manage them.

Learning social skills is a major benefit of preschool and kindergarten, particularly for children with few siblings or siblings of much different ages. The poem “All I Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten” describes many of these social benefits, including learning to share, take turns, act kindly, and use manners. The poem does not mention some of the other less poetic skills developed at this age, however: learning how to tease successfully, pull your punches, stand tall when there is a bully, bounce back when people insult you or after you wet your pants, tell if someone is a real friend, and deal with a critical teacher who is screaming all the time.

Young children normally practice a social interaction known as “inclusion/exclusion,” where one day they say, “Oh, you're my best friend. Let's go have our secret club.” But the next day they say, “You're not my friend anymore. I've got a new best friend. You can't play with me.” In general, the best short- and long-term outcomes occur when children work out minor interaction problems on their own, with a little teacher support, but serious problems are handled privately by the adults.

Ask for specific information about one of the incidents from both the child and the parent. If a child comes home from school and says, “This kid called me names,” parents can ask, “What kind of names?” to distinguish normal teasing from a toxic environment that needs to be changed. Abnormal teasing is more vicious and adultlike, for example, a peer calling the child a “whore” or using a racial epithet.

Don't forget to suggest ways to pump up resilience such as getting sufficient sleep and proper nutrition.

Next, assess the child with problematic peer behavior for skill deficits. A child with a gap may act up to distract others from noticing, out of frustration or as result of discrimination the child experiences. Often children this age who are aggressive have shortcomings in language. They may speak a different language at home or still communicate only in two- or three-word phrases, and therefore are unable to keep up with others and feel – or actually are – left out. They don't have the repartee to negotiate social situations and can become the victim of taunting and teasing, a specialty of girls.

Children with gross motor skill deficits, particularly boys, also may experience difficulty keeping up with their peers. In some cases, they are rejected by the group for being unable to kick a soccer ball or to climb a jungle gym as well as others can, and they are angry as a result.

Check fine motor skills as well. A child with poor coordination may be slow to finish work and/or be ashamed of what they do produce. Children can be very self-critical at this age and even tear up their papers. If the teacher asks everyone to draw a truck, and another student pointedly says, 'That doesn't look like a truck,” the child might punch in return. The child is acting up in frustration.

While children at this age are just on the edge of acquiring “perspective taking” (considering another's point of view), in the most severe form, difficulty in doing this can be a sign of autism spectrum disorder. Peers quickly pick up on this and may tease them, call them names, and/or reject their awkward attempts to engage. Try telling them a joke or asking them to tell one, and you may see why.

You can help by addressing any detected skill deficits with language therapy or physical therapy. Importantly, suggest ways to build their skills while allowing them to bypass social humiliation. Let children who are not athletic skip recess, assigning them the task of getting out the snacks to avoid further humiliation. Then work on their motor skills through after-school karate instead.

Anxiety can spark aggression, too. If you are afraid, it seems better to strike first. If anxiety seems key, the parents and school will need to soften their handling of the child and help him or her put feelings into words to assist the child in not acting out.

Since some children will misbehave to get a teacher's attention, recommend that the parents drop in unannounced. Often the way a classroom appears (or is staffed) at 8 a.m. drop-off time is not the same way it operates at 10:30 a.m. Suggest a parent watch the part of the day their child complains about the most, which is frequently recess.

Even though there are bad situations and bad schools, most schools have great teachers and other professionals from whom parents can gain valuable information and advice.

Generally teachers can explain the timing of a child's troubles, for example, during circle time he cannot sit still or during craft time because his fine motor skills are not well developed. Having parents seek out these examples is the most efficient way to identify deficits in need of help.

Suggest parents speak to their child empathically instead of giving instructions. In this culture, boys especially are told to “keep a stiff upper lip” or “be a big soldier.” A better approach is to say, “Yes, it's tough when kids talk to you like that” or “I understand this really makes you sad and you feel like crying.”

It also helps when parents share a similar experience from their own childhood. For example, parents can say, “You know, when I was your age, I had an experience like this – I had a kid who was always on my case.”

Parents can promote social development as well. For example, role playing can clearly help a child develop appropriate socioemotional skills. Parents can use this strategy either before an incident – for example, to rehearse how a child might react to a bully in class – or afterward, to help the child determine what he or she might have said or done differently and prepare for the next time. Use of social stories can foster these skills (see www.socialstories.com

Parents who experienced a bad peer interaction as a preschooler or kindergartener may project their concerns on their child who may be doing just fine. The parents might be supersensitive to teasing, for example, and bring an otherwise minor incident to your attention and/or become overintrusive at school. Asking, “How was it for you when you were little? Did you ever run into anything like this?” may bring out past experiences as an important factor predisposing to overreaction. If they wet their pants in kindergarten and never got over it, realizing this connection makes it possible for them to back off and let the school and child handle the current problem.

Watch for red flags or warning signs that problematic behaviors are not within the range of normal stress. The child initially doing well at school who suddenly does not want to return is one example.

Sadly, you need to always consider whether there is abuse going on at school, including sexual abuse. Sudden adjustment problems at home, such as trouble sleeping, nightmares, or bed-wetting, also should raise your level of concern.

Also ask parents if their preschooler suddenly became more difficult to manage at home. Some children who experience negative peer interactions will cling to parents, but oppositional or defiant behavior is more common. Of course, 4-year-old children are notoriously brassy, so you cannot consider back talk a warning sign unless it is part of a sudden change in the normal flow of the child's behavior.

A child this stressed over school may need to be cared for at home or moved to a family day care situation

Unfortunately, the modern practice of grouping of kids of the same age together in a classroom increases the likelihood of interactions going badly. Ten 2-year-old children are not necessarily capable of peacefully spending hours together at a time. When a serious behavioral problem arises in this kind of setting, I frequently recommend family-based day care instead of center-based day care because children will be with others of different ages and different skill levels, and hopefully some of them will be more mature.

Support parents in deciding to pull the child out of a school if the situation is bad. If, for example, the school administration is unresponsive to or dismissive of a parent, removal of the child may be the best option. A new parent recently came to the parent group at our clinic. She reported that a teacher responded to her child's behavior problem by putting him in a closet, which would have been egregious enough, but the teacher also said that there were spiders and bugs in the closet that were going to get him before closing the door. I was flabbergasted. The school tried to defend the teacher for doing this, and my final advice was to “pull the kid.” Any school that ignorant of normal child development cannot be fixed.

Working When You're Sick: Symptom of a Larger Problem?

The phenomenon of physician presenteeism, doctors coming to work even if they themselves are sick, is an opportunity for residency directors to pull back on how they schedule physicians in training, one program head says.

A study last month found that 57.9% of residents reported working while sick at least once and 31.3% had done so in the previous year (JAMA 2010;304(11);1166-1168). In one outlier hospital, every resident surveyed reported working when sick.

"Hospitals have to learn not to schedule their people to the max," says Ethan Fried, MD, MS, FACP, assistant professor of clinical medicine at Columbia University, vice chair for education in the department of medicine and director of Graduate Medical Education at St. Luke's-Roosevelt in New York City. "Just because you can go 80 hours a week and take care of 10 patients doesn't mean you should go 80 hours a week and take care of 10 patients."

Dr. Fried, president of the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine (APDIM), says creating schedules with little or no flexibility can hamper a program's ability to handle inevitable sick calls. Larger programs might have "sick-call pools," which are used to cover staffing shortfalls, but smaller programs might not have that luxury, he adds.

Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, SFHM, FAAP, pediatric hospitalist with ELMO Pediatrics in New York City, says the culture of residencies is to "suck it up," and some physicians carry that attitude into private practice.

"The decision of whether or not to work sick is really related to the institutions' culture," Dr. Percelay, an SHM board member, writes in an e-mail interview. "If we are to discourage physicians from working when sick, some sort of sick leave benefit or backup system needs to be in place. ... It's a real Pandora's box. I don't want my colleagues to stay home with a runny nose, nor do I want them to come in and get IV fluids in the back room."

Dr. Fried notes that the issue is further complicated by rules on how much training time residents need to be considered competent. He says the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) recently gave program directors discretion in "granting credit for up to one month of missed time in a three-year period."

Still, presenteeism may be less of a problem with the current generation of residents than in the past because of culture changes tied to duty-hour rules. "We make such a big deal about working while fatigued, and that's now considered completely inappropriate," Dr. Fried says. "The trainees ... are much more willing to admit when they under the weather."

The phenomenon of physician presenteeism, doctors coming to work even if they themselves are sick, is an opportunity for residency directors to pull back on how they schedule physicians in training, one program head says.

A study last month found that 57.9% of residents reported working while sick at least once and 31.3% had done so in the previous year (JAMA 2010;304(11);1166-1168). In one outlier hospital, every resident surveyed reported working when sick.

"Hospitals have to learn not to schedule their people to the max," says Ethan Fried, MD, MS, FACP, assistant professor of clinical medicine at Columbia University, vice chair for education in the department of medicine and director of Graduate Medical Education at St. Luke's-Roosevelt in New York City. "Just because you can go 80 hours a week and take care of 10 patients doesn't mean you should go 80 hours a week and take care of 10 patients."

Dr. Fried, president of the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine (APDIM), says creating schedules with little or no flexibility can hamper a program's ability to handle inevitable sick calls. Larger programs might have "sick-call pools," which are used to cover staffing shortfalls, but smaller programs might not have that luxury, he adds.

Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, SFHM, FAAP, pediatric hospitalist with ELMO Pediatrics in New York City, says the culture of residencies is to "suck it up," and some physicians carry that attitude into private practice.

"The decision of whether or not to work sick is really related to the institutions' culture," Dr. Percelay, an SHM board member, writes in an e-mail interview. "If we are to discourage physicians from working when sick, some sort of sick leave benefit or backup system needs to be in place. ... It's a real Pandora's box. I don't want my colleagues to stay home with a runny nose, nor do I want them to come in and get IV fluids in the back room."

Dr. Fried notes that the issue is further complicated by rules on how much training time residents need to be considered competent. He says the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) recently gave program directors discretion in "granting credit for up to one month of missed time in a three-year period."

Still, presenteeism may be less of a problem with the current generation of residents than in the past because of culture changes tied to duty-hour rules. "We make such a big deal about working while fatigued, and that's now considered completely inappropriate," Dr. Fried says. "The trainees ... are much more willing to admit when they under the weather."

The phenomenon of physician presenteeism, doctors coming to work even if they themselves are sick, is an opportunity for residency directors to pull back on how they schedule physicians in training, one program head says.

A study last month found that 57.9% of residents reported working while sick at least once and 31.3% had done so in the previous year (JAMA 2010;304(11);1166-1168). In one outlier hospital, every resident surveyed reported working when sick.

"Hospitals have to learn not to schedule their people to the max," says Ethan Fried, MD, MS, FACP, assistant professor of clinical medicine at Columbia University, vice chair for education in the department of medicine and director of Graduate Medical Education at St. Luke's-Roosevelt in New York City. "Just because you can go 80 hours a week and take care of 10 patients doesn't mean you should go 80 hours a week and take care of 10 patients."

Dr. Fried, president of the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine (APDIM), says creating schedules with little or no flexibility can hamper a program's ability to handle inevitable sick calls. Larger programs might have "sick-call pools," which are used to cover staffing shortfalls, but smaller programs might not have that luxury, he adds.

Jack Percelay, MD, MPH, SFHM, FAAP, pediatric hospitalist with ELMO Pediatrics in New York City, says the culture of residencies is to "suck it up," and some physicians carry that attitude into private practice.

"The decision of whether or not to work sick is really related to the institutions' culture," Dr. Percelay, an SHM board member, writes in an e-mail interview. "If we are to discourage physicians from working when sick, some sort of sick leave benefit or backup system needs to be in place. ... It's a real Pandora's box. I don't want my colleagues to stay home with a runny nose, nor do I want them to come in and get IV fluids in the back room."

Dr. Fried notes that the issue is further complicated by rules on how much training time residents need to be considered competent. He says the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) recently gave program directors discretion in "granting credit for up to one month of missed time in a three-year period."

Still, presenteeism may be less of a problem with the current generation of residents than in the past because of culture changes tied to duty-hour rules. "We make such a big deal about working while fatigued, and that's now considered completely inappropriate," Dr. Fried says. "The trainees ... are much more willing to admit when they under the weather."

Technology, Follow-Up Care Concern Hospitalists

Hospitalists at the "Management of the Hospitalized Patient" conference, Oct. 14-16 in San Francisco, expressed frustrations during an interactive presentation on how to reduce preventable rehospitalizations.

Participants described the challenges of high-risk patients who lack insurance coverage and a relationship with a primary care physician (PCP), which can negate streamlined outreach to PCPs at the time of discharge. “The people who least need follow-up, I'm able to call their physician. But it seems like the ones who most need follow-up care are the hardest to reach a PCP," one hospitalist observed ruefully. Participants also acknowledged steep learning curves for electronic medical records, even though they hope these could facilitate better discharge processes in the long run.

And careful patient education might not help with cases like the 75-year-old heart failure patient described in the July 28, 2009, issue of The Wall Street Journal, cited by the presenters as a typical example of readmission risk. Despite targeted education on the need to reduce her sodium intake, the patient insisted on eating a hot dog at a Fourth of July picnic and was readmitted to the hospital the following day.

Presenter Michelle Mourad, MD, medical director of CHF and Oncology Hospitalist Services at the University of California at San Francisco, which sponsors the annual conference, challenged hospitalists to identify readmission risk factors for their patients, including diagnoses of heart failure, pneumonia and COPD, high-risk medications and polypharmacy, poor health literacy, poor social support, and advanced age. Patients at risk could then become the focus of strategies designed to minimize rehospitalizations, including follow-up phone calls post-discharge and scheduling a visit to a PCP before the patient leaves the hospital.

Hospitalists have an important role in improving the quality of discharges at their hospitals, Dr. Mourad said. They can start by convening a multidisciplinary team of stakeholders that assesses current practice and designs process improvements.

“At UCSF, our discharge process was broken,” she says. A new QI process led to implementing patient teachback strategies, a hotline phone number discharged patients could call, and "core measures" of discharge quality, as well as designing new discharge folders with a user-friendly yellow medication card for patients to bring home.

Hospitalists at the "Management of the Hospitalized Patient" conference, Oct. 14-16 in San Francisco, expressed frustrations during an interactive presentation on how to reduce preventable rehospitalizations.

Participants described the challenges of high-risk patients who lack insurance coverage and a relationship with a primary care physician (PCP), which can negate streamlined outreach to PCPs at the time of discharge. “The people who least need follow-up, I'm able to call their physician. But it seems like the ones who most need follow-up care are the hardest to reach a PCP," one hospitalist observed ruefully. Participants also acknowledged steep learning curves for electronic medical records, even though they hope these could facilitate better discharge processes in the long run.

And careful patient education might not help with cases like the 75-year-old heart failure patient described in the July 28, 2009, issue of The Wall Street Journal, cited by the presenters as a typical example of readmission risk. Despite targeted education on the need to reduce her sodium intake, the patient insisted on eating a hot dog at a Fourth of July picnic and was readmitted to the hospital the following day.

Presenter Michelle Mourad, MD, medical director of CHF and Oncology Hospitalist Services at the University of California at San Francisco, which sponsors the annual conference, challenged hospitalists to identify readmission risk factors for their patients, including diagnoses of heart failure, pneumonia and COPD, high-risk medications and polypharmacy, poor health literacy, poor social support, and advanced age. Patients at risk could then become the focus of strategies designed to minimize rehospitalizations, including follow-up phone calls post-discharge and scheduling a visit to a PCP before the patient leaves the hospital.

Hospitalists have an important role in improving the quality of discharges at their hospitals, Dr. Mourad said. They can start by convening a multidisciplinary team of stakeholders that assesses current practice and designs process improvements.

“At UCSF, our discharge process was broken,” she says. A new QI process led to implementing patient teachback strategies, a hotline phone number discharged patients could call, and "core measures" of discharge quality, as well as designing new discharge folders with a user-friendly yellow medication card for patients to bring home.

Hospitalists at the "Management of the Hospitalized Patient" conference, Oct. 14-16 in San Francisco, expressed frustrations during an interactive presentation on how to reduce preventable rehospitalizations.

Participants described the challenges of high-risk patients who lack insurance coverage and a relationship with a primary care physician (PCP), which can negate streamlined outreach to PCPs at the time of discharge. “The people who least need follow-up, I'm able to call their physician. But it seems like the ones who most need follow-up care are the hardest to reach a PCP," one hospitalist observed ruefully. Participants also acknowledged steep learning curves for electronic medical records, even though they hope these could facilitate better discharge processes in the long run.

And careful patient education might not help with cases like the 75-year-old heart failure patient described in the July 28, 2009, issue of The Wall Street Journal, cited by the presenters as a typical example of readmission risk. Despite targeted education on the need to reduce her sodium intake, the patient insisted on eating a hot dog at a Fourth of July picnic and was readmitted to the hospital the following day.

Presenter Michelle Mourad, MD, medical director of CHF and Oncology Hospitalist Services at the University of California at San Francisco, which sponsors the annual conference, challenged hospitalists to identify readmission risk factors for their patients, including diagnoses of heart failure, pneumonia and COPD, high-risk medications and polypharmacy, poor health literacy, poor social support, and advanced age. Patients at risk could then become the focus of strategies designed to minimize rehospitalizations, including follow-up phone calls post-discharge and scheduling a visit to a PCP before the patient leaves the hospital.

Hospitalists have an important role in improving the quality of discharges at their hospitals, Dr. Mourad said. They can start by convening a multidisciplinary team of stakeholders that assesses current practice and designs process improvements.

“At UCSF, our discharge process was broken,” she says. A new QI process led to implementing patient teachback strategies, a hotline phone number discharged patients could call, and "core measures" of discharge quality, as well as designing new discharge folders with a user-friendly yellow medication card for patients to bring home.

Hospitalists Should Expect More HIV Patients

Advances in treatment and ever-growing life expectancies for patients diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are likely to push more HIV-positive patients into the censuses of HM groups, according to a specialist at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City.

“Hospitalists … are going to be doing more and more of the HIV care because we have a growing population of aging patients who are in care or identify as being HIV-positive, and they’re not coming in with exotic or unusual opportunistic infections,” says Rich MacKay, MD, director of the inpatient HIV service at Mount Sinai Medial Center in New York. “They are coming in with the things that other 50-, 60-, 70-year-olds are coming in with, though they may have more of those.”

Dr. MacKay, who is an assistant professor and splits his time between admitted patients and an outpatient clinic, spoke to more than 100 attendees at the fifth annual Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium last weekend in New York. He says hospitalists who familiarize themselves with HIV indicators could press for earlier identification of HIV in patients.

“If you screen people and you’re testing them on the day of their hospitalization, I think that’s huge,” Dr. MacKay says. “Finding somebody who is early in the disease and linking them in to care, so that they don’t fall off the cliff, so that they don’t come in five years later with PCP [pneumocystis pneumonia] and die from it—I think that’s a huge part for the hospitalist.”

Dr. MacKay further notes that just being aware of HIV symptoms can provide the cognizance necessary to consider alternative diagnoses. That can be particularly relevant for cases in which standard treatments might be effective for a few days (e.g. a steroid regimen) but not actually resolve the underlying problem, he adds.

“Maybe [a patient] is coming in with what looks like an exacerbation of COPD, but they’ve only got 50 T-cells and in fact what you’re seeing is PCP,” he says. “It’s not always clear.”

Advances in treatment and ever-growing life expectancies for patients diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are likely to push more HIV-positive patients into the censuses of HM groups, according to a specialist at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City.

“Hospitalists … are going to be doing more and more of the HIV care because we have a growing population of aging patients who are in care or identify as being HIV-positive, and they’re not coming in with exotic or unusual opportunistic infections,” says Rich MacKay, MD, director of the inpatient HIV service at Mount Sinai Medial Center in New York. “They are coming in with the things that other 50-, 60-, 70-year-olds are coming in with, though they may have more of those.”

Dr. MacKay, who is an assistant professor and splits his time between admitted patients and an outpatient clinic, spoke to more than 100 attendees at the fifth annual Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium last weekend in New York. He says hospitalists who familiarize themselves with HIV indicators could press for earlier identification of HIV in patients.

“If you screen people and you’re testing them on the day of their hospitalization, I think that’s huge,” Dr. MacKay says. “Finding somebody who is early in the disease and linking them in to care, so that they don’t fall off the cliff, so that they don’t come in five years later with PCP [pneumocystis pneumonia] and die from it—I think that’s a huge part for the hospitalist.”

Dr. MacKay further notes that just being aware of HIV symptoms can provide the cognizance necessary to consider alternative diagnoses. That can be particularly relevant for cases in which standard treatments might be effective for a few days (e.g. a steroid regimen) but not actually resolve the underlying problem, he adds.

“Maybe [a patient] is coming in with what looks like an exacerbation of COPD, but they’ve only got 50 T-cells and in fact what you’re seeing is PCP,” he says. “It’s not always clear.”

Advances in treatment and ever-growing life expectancies for patients diagnosed with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are likely to push more HIV-positive patients into the censuses of HM groups, according to a specialist at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City.

“Hospitalists … are going to be doing more and more of the HIV care because we have a growing population of aging patients who are in care or identify as being HIV-positive, and they’re not coming in with exotic or unusual opportunistic infections,” says Rich MacKay, MD, director of the inpatient HIV service at Mount Sinai Medial Center in New York. “They are coming in with the things that other 50-, 60-, 70-year-olds are coming in with, though they may have more of those.”

Dr. MacKay, who is an assistant professor and splits his time between admitted patients and an outpatient clinic, spoke to more than 100 attendees at the fifth annual Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium last weekend in New York. He says hospitalists who familiarize themselves with HIV indicators could press for earlier identification of HIV in patients.

“If you screen people and you’re testing them on the day of their hospitalization, I think that’s huge,” Dr. MacKay says. “Finding somebody who is early in the disease and linking them in to care, so that they don’t fall off the cliff, so that they don’t come in five years later with PCP [pneumocystis pneumonia] and die from it—I think that’s a huge part for the hospitalist.”

Dr. MacKay further notes that just being aware of HIV symptoms can provide the cognizance necessary to consider alternative diagnoses. That can be particularly relevant for cases in which standard treatments might be effective for a few days (e.g. a steroid regimen) but not actually resolve the underlying problem, he adds.

“Maybe [a patient] is coming in with what looks like an exacerbation of COPD, but they’ve only got 50 T-cells and in fact what you’re seeing is PCP,” he says. “It’s not always clear.”

In the Literature: Research You Need to Know

Clinical question: What is the prevalence of silent pulmonary embolism (PE) in patients with DVT?

Background: PE was undiagnosed or unsuspected in approximately 80% to 93% patients antemortem who were found to have a PE at autopsy. The extent to which silent PE explains the undiagnosed or unsuspected pulmonary emboli at autopsy is not certain. Prior studies have demonstrated the association of silent PE in living patients with DVT.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: Published trials performed worldwide.

Synopsis: Researchers performed a systematic review of all published trials addressing the prevalence of silent PE in patients with DVT. Studies were included if the methods of PE diagnosis were described, if it was an asymptomatic PE, and if raw data were presented. Twenty-eight studies were identified and were stratified according to how the PE was diagnosed (Tier 1: high-probability VQ scan based on PIOPED criteria, computerized tomographic angiography [CTA], angiography; Tier 2: VQ scans based on non-PIOPED criteria).

Among Tier 1 studies, silent PE was detected in 27% of patients with DVT. Among Tier 2 studies, silent PE was detected among 37% of patients with DVT. Combined, silent PE was diagnosed in 1,665 of 5,233 patients (32%) with DVT.

Further analysis showed that the prevalence of silent PE in patients with proximal DVT was higher in those with distal DVT and that there was a trend toward increased prevalence of silent PE with increased age.

A limitation of this study includes the heterogeneity in the methods used for diagnosis of silent PE.

Bottom line: Silent PE occurs in a third of patients with DVT, and routine screening should be considered.

Citation: Stein PD, Matta F, Musani MH, Diaczok B. Silent pulmonary embolism in patients with deep venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2010;123(5):426-431.

Reviewed for TH eWireby Alexander R. Carbo, MD, SFHM, Lauren Doctoroff, MD, John Fani Srour, MD, Matthew Hill, MD, Nancy Torres-Finnerty, MD, FHM, and Anita Vanka, MD, Hospital Medicine Program, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

For more physician reviews of literature, visit our website.

Clinical question: What is the prevalence of silent pulmonary embolism (PE) in patients with DVT?

Background: PE was undiagnosed or unsuspected in approximately 80% to 93% patients antemortem who were found to have a PE at autopsy. The extent to which silent PE explains the undiagnosed or unsuspected pulmonary emboli at autopsy is not certain. Prior studies have demonstrated the association of silent PE in living patients with DVT.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: Published trials performed worldwide.

Synopsis: Researchers performed a systematic review of all published trials addressing the prevalence of silent PE in patients with DVT. Studies were included if the methods of PE diagnosis were described, if it was an asymptomatic PE, and if raw data were presented. Twenty-eight studies were identified and were stratified according to how the PE was diagnosed (Tier 1: high-probability VQ scan based on PIOPED criteria, computerized tomographic angiography [CTA], angiography; Tier 2: VQ scans based on non-PIOPED criteria).

Among Tier 1 studies, silent PE was detected in 27% of patients with DVT. Among Tier 2 studies, silent PE was detected among 37% of patients with DVT. Combined, silent PE was diagnosed in 1,665 of 5,233 patients (32%) with DVT.

Further analysis showed that the prevalence of silent PE in patients with proximal DVT was higher in those with distal DVT and that there was a trend toward increased prevalence of silent PE with increased age.

A limitation of this study includes the heterogeneity in the methods used for diagnosis of silent PE.

Bottom line: Silent PE occurs in a third of patients with DVT, and routine screening should be considered.

Citation: Stein PD, Matta F, Musani MH, Diaczok B. Silent pulmonary embolism in patients with deep venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2010;123(5):426-431.

Reviewed for TH eWireby Alexander R. Carbo, MD, SFHM, Lauren Doctoroff, MD, John Fani Srour, MD, Matthew Hill, MD, Nancy Torres-Finnerty, MD, FHM, and Anita Vanka, MD, Hospital Medicine Program, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

For more physician reviews of literature, visit our website.

Clinical question: What is the prevalence of silent pulmonary embolism (PE) in patients with DVT?

Background: PE was undiagnosed or unsuspected in approximately 80% to 93% patients antemortem who were found to have a PE at autopsy. The extent to which silent PE explains the undiagnosed or unsuspected pulmonary emboli at autopsy is not certain. Prior studies have demonstrated the association of silent PE in living patients with DVT.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: Published trials performed worldwide.

Synopsis: Researchers performed a systematic review of all published trials addressing the prevalence of silent PE in patients with DVT. Studies were included if the methods of PE diagnosis were described, if it was an asymptomatic PE, and if raw data were presented. Twenty-eight studies were identified and were stratified according to how the PE was diagnosed (Tier 1: high-probability VQ scan based on PIOPED criteria, computerized tomographic angiography [CTA], angiography; Tier 2: VQ scans based on non-PIOPED criteria).

Among Tier 1 studies, silent PE was detected in 27% of patients with DVT. Among Tier 2 studies, silent PE was detected among 37% of patients with DVT. Combined, silent PE was diagnosed in 1,665 of 5,233 patients (32%) with DVT.

Further analysis showed that the prevalence of silent PE in patients with proximal DVT was higher in those with distal DVT and that there was a trend toward increased prevalence of silent PE with increased age.

A limitation of this study includes the heterogeneity in the methods used for diagnosis of silent PE.

Bottom line: Silent PE occurs in a third of patients with DVT, and routine screening should be considered.

Citation: Stein PD, Matta F, Musani MH, Diaczok B. Silent pulmonary embolism in patients with deep venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2010;123(5):426-431.

Reviewed for TH eWireby Alexander R. Carbo, MD, SFHM, Lauren Doctoroff, MD, John Fani Srour, MD, Matthew Hill, MD, Nancy Torres-Finnerty, MD, FHM, and Anita Vanka, MD, Hospital Medicine Program, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

For more physician reviews of literature, visit our website.

FDA approves dabigatran for AF patients

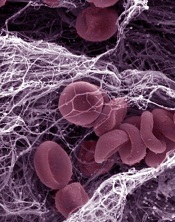

Credit: Kevin MacKenzie

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) to prevent strokes and thrombosis in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

Dabigatran is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor that can be administered at a fixed oral dose, with no need for coagulation monitoring.

“Unlike warfarin, which requires patients to undergo periodic monitoring with blood tests, such monitoring is not necessary for Pradaxa,” said Norman Stockbridge, MD, PhD, director of the Division of Cardiovascular and Renal Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The FDA has approved dabigatran based on results of the RE-LY trial, in which investigators compared dabigatran to warfarin in more than 18,000 AF patients.

Results suggested that, overall, dabigatran is noninferior to warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolism. And, at a 150 mg dose, dabigatran is actually more effective than warfarin.

Bleeding, including life-threatening and fatal bleeding, was among the most common adverse events observed in patients treated with dabigatran. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including dyspepsia, stomach pain, nausea, heartburn, and bloating were reported as well.

Dabigatran was approved with a medication guide that informs patients of the risk of serious bleeding. The guide will be distributed each time a patient fills a prescription for the medication.

Dabigatran will be marketed as Pradaxa by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. It will be available in 75 mg and 150 mg capsules. ![]()

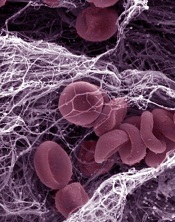

Credit: Kevin MacKenzie

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) to prevent strokes and thrombosis in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

Dabigatran is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor that can be administered at a fixed oral dose, with no need for coagulation monitoring.

“Unlike warfarin, which requires patients to undergo periodic monitoring with blood tests, such monitoring is not necessary for Pradaxa,” said Norman Stockbridge, MD, PhD, director of the Division of Cardiovascular and Renal Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The FDA has approved dabigatran based on results of the RE-LY trial, in which investigators compared dabigatran to warfarin in more than 18,000 AF patients.

Results suggested that, overall, dabigatran is noninferior to warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolism. And, at a 150 mg dose, dabigatran is actually more effective than warfarin.

Bleeding, including life-threatening and fatal bleeding, was among the most common adverse events observed in patients treated with dabigatran. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including dyspepsia, stomach pain, nausea, heartburn, and bloating were reported as well.

Dabigatran was approved with a medication guide that informs patients of the risk of serious bleeding. The guide will be distributed each time a patient fills a prescription for the medication.

Dabigatran will be marketed as Pradaxa by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. It will be available in 75 mg and 150 mg capsules. ![]()

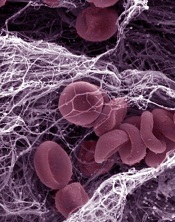

Credit: Kevin MacKenzie

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) to prevent strokes and thrombosis in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

Dabigatran is an oral direct thrombin inhibitor that can be administered at a fixed oral dose, with no need for coagulation monitoring.

“Unlike warfarin, which requires patients to undergo periodic monitoring with blood tests, such monitoring is not necessary for Pradaxa,” said Norman Stockbridge, MD, PhD, director of the Division of Cardiovascular and Renal Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

The FDA has approved dabigatran based on results of the RE-LY trial, in which investigators compared dabigatran to warfarin in more than 18,000 AF patients.

Results suggested that, overall, dabigatran is noninferior to warfarin for preventing stroke and systemic embolism. And, at a 150 mg dose, dabigatran is actually more effective than warfarin.

Bleeding, including life-threatening and fatal bleeding, was among the most common adverse events observed in patients treated with dabigatran. Gastrointestinal symptoms, including dyspepsia, stomach pain, nausea, heartburn, and bloating were reported as well.

Dabigatran was approved with a medication guide that informs patients of the risk of serious bleeding. The guide will be distributed each time a patient fills a prescription for the medication.

Dabigatran will be marketed as Pradaxa by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. It will be available in 75 mg and 150 mg capsules. ![]()