User login

Inpatient Hypertension Review

Hypertension (HTN) is highly prevalent in the general adult population with recent estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of 29% in the United States.1, 2 The relationship between increasing levels of blood pressure (BP) and increasing risk for cardiovascular disease events and stroke is well established.3 However, while 64% of treated HTN patients have a BP <140/<90 mmHg, overall control rates for HTN in the adult population remain at approximately 44%.2 The 20% discrepancy in control rates between treated patients and the overall adult population reflects the fact that approximately 30% of patients are unaware of their HTN and that a substantial proportion of aware patients remain untreated. Historically, efforts to improve the recognition, treatment, and control of HTN have appropriately focused on the outpatient setting. However, programs to extend screening for HTN outside the clinic into the community, schools, and even dentists' offices have been around for some time.49

The potential also exists to improve the recognition, treatment, and control of HTN by focusing on hospitalized patients. Hospitalization is common in the U.S. with almost 35 million acute hospitalizations and more than 45,000 inpatient surgical procedures in 2006.10 Inpatient populations have increased in age and comorbidity over the past 3 decades whereas lengths of stay and continuity of care between the inpatient and outpatient arenas have diminished.10, 11 Multiple prior studies examining BP in different settings have noted that average BP among hospitalized patients is not systematically higher than that of outpatients.1214 Thus, patients with persistently elevated BP in the inpatient setting without mitigating factors may have HTN that will persist after hospital discharge. However, little information is available regarding the actual prevalence of HTN in the inpatient population and care patterns for inpatient HTN. Therefore, we performed a systematic review of the English‐language medical literature in order to describe the epidemiology of HTN observed in the inpatient setting.

Methods

Our search strategy was designed to identify randomized‐controlled trials, meta‐analyses, and observational studies that: (1) reported estimates of the prevalence of HTN in the inpatient setting, and (2) used HTN diagnosis or treatment as a primary focus. We performed an extensive review of the peer‐reviewed, English language medical literature in MEDLINE using a predetermined search algorithm. Search terms included HTN[Mesh] or BP[Mesh]. These results were cross‐referenced with the following search terms: Inpatients[Mesh] or Hospitalization[title/abstract] or Hospitalized[title/abstract]. Articles were further narrowed using the following terms: Prevalence[Mesh] or Epidemiology[Mesh] or Treatment[title/abstract] or Management [title/abstract]. Limits employed included limiting to humans and to adults 19 years‐of‐age and older. Studies published prior to 1976 were excluded because 1976 was the first year that the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High BP published consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HTN. We also excluded randomized, controlled trials that recorded measures of inpatient BP but whose focus was not HTN, because such trials would not answer the primary epidemiologic question of this review. We did include trials focused on subspecialty populations for which the diagnosis and inpatient management of HTN were key outcomes.

Next, the bibliographies of reviewed studies were investigated for additional relevant reports. Abstracts from the American Heart Association (AHA) were reviewed for the past 15 years for reports that were presented but not subsequently published and available in MEDLINE. We also searched for articles using the online Google search engine. One author (RNA) performed the preliminary MEDLINE search and abstract review with the assistance of a reference librarian (LC), and a second author (BME) also reviewed full‐text articles for potential inclusion. Ultimate decision for study inclusion was reached through discussion among authors. Finally, a list of potential articles was submitted to 2 experts in this field of study to determine whether other reports met our inclusion criteria for this systematic review but were overlooked.

Results

Search Results

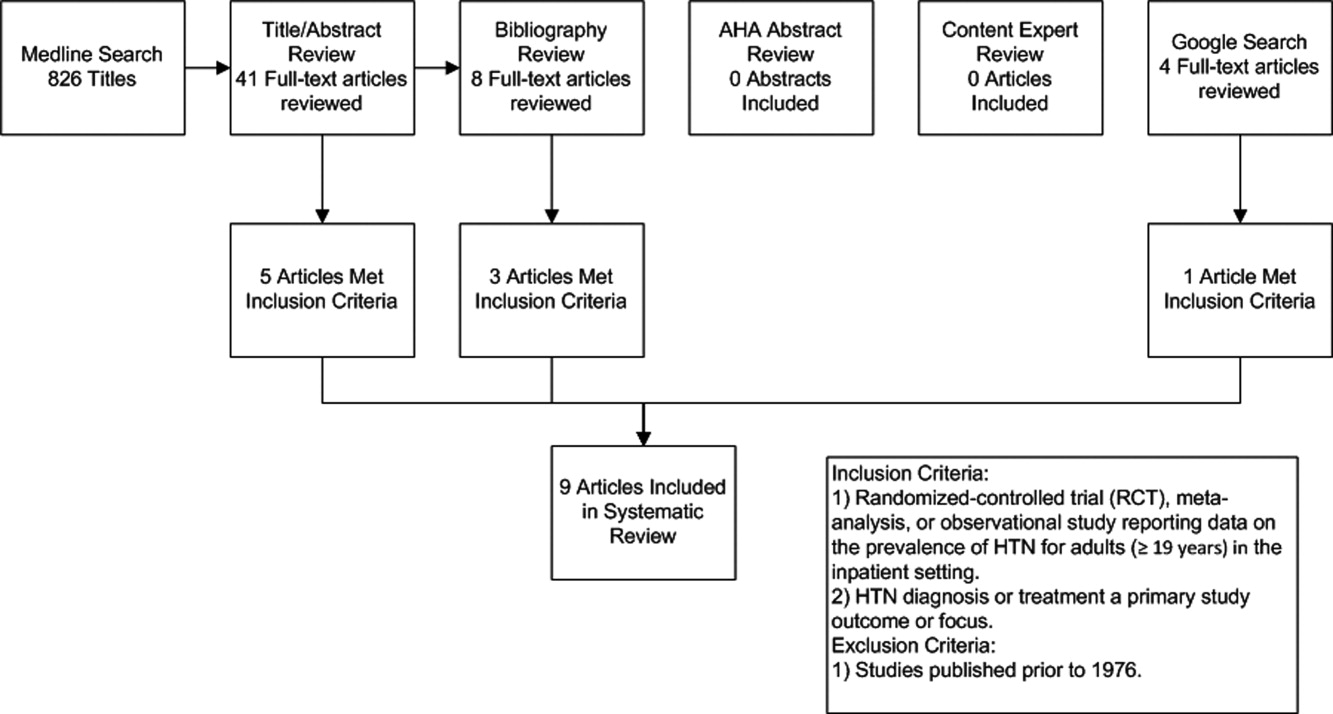

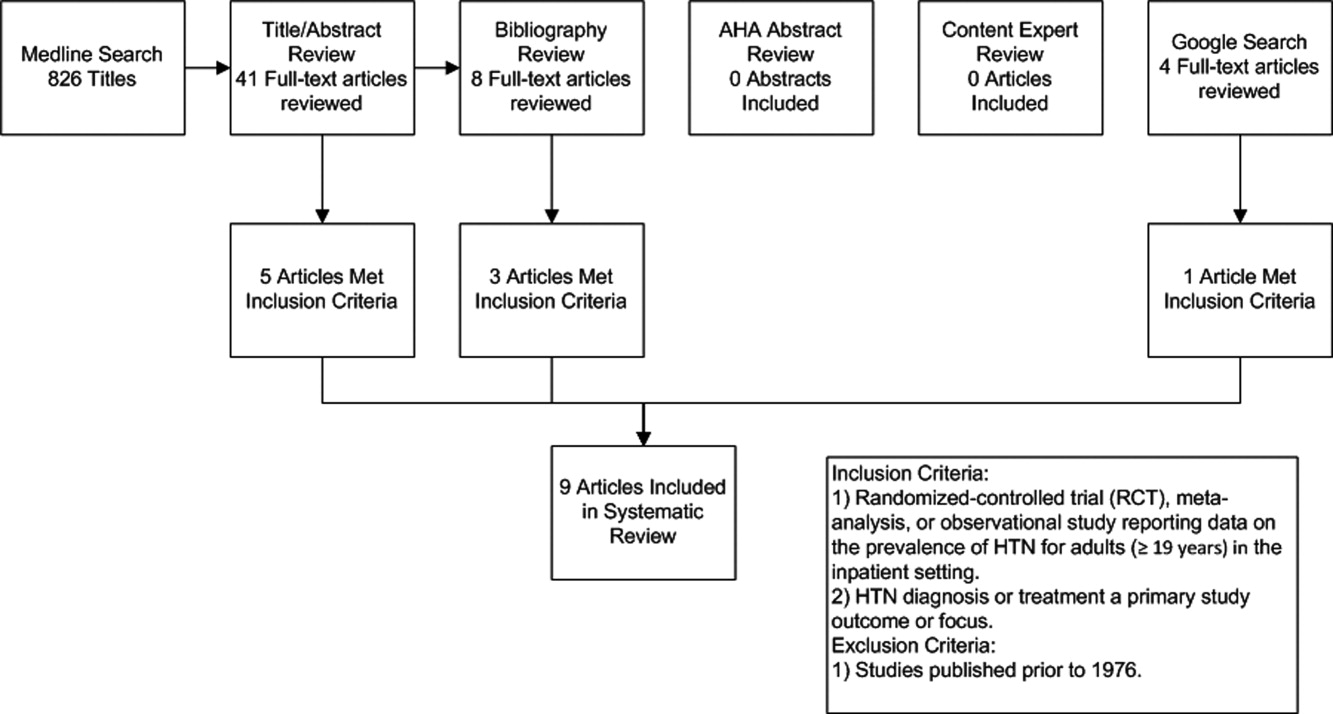

The initial MEDLINE search algorithm yielded a total of 826 articles. After title and abstract review, 41 full‐text articles were obtained for detailed review, and 5 met criteria for inclusion. Three additional articles were discovered through searching the bibliographies of the included studies. No AHA abstracts addressed this subject area. Experts were not aware of any additional studies. One article was located using a Google search. In all, 9 articles were deemed suitable for inclusion in this review. Search results at each stage are depicted in Figure 1.

Description of Included Studies

Characteristics of included studies are depicted in Table 1. Two older retrospective cohort studies reported HTN prevalence using earlier, less stringent diagnostic criteria. Shankar et al.15 abstracted data from more than 19,000 adults discharged alive from Maryland hospitals during 1978. Greenland et al.16 performed chart review for 536 medical and surgical inpatients in 1987 reporting information on the proportion of patients appropriately diagnosed as having HTN and the proportion with controlled BP on admission and at discharge based on then‐current JNC‐III criteria (HTN if BP > 160/90).

| Study | Design | Setting | Hypertension Prevalence | Diagnostic Criteria for HTN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Shankar et al.15 (1982) | Retrospective cohort | All hospital discharges in Maryland in 1978 | 23.8% (4571/19,259) | HTN diagnosis in record or diastolic BP 100 mm Hg |

| Greenland et al.16 (1987) | Retrospective cohort | Single University Center, U.S., medical/surgical patients | 28% (143/536 ) | HTN diagnosis in record or mean of first 4 hospital BP measures 160/90 mm Hg |

| Euroaspire I17 | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 9 European countries, coronary heart disease admissions | 57.8% (2553/4415) | Admission BP 140/90 mm Hg or on antihypertensive medications |

| Euroaspire II18 | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 15 European countries, coronary heart disease admissions | 50.5% (2806/5556) | Mean clinic BP at 618 months follow up of 140/90 mm Hg |

| Amar et al.20 (2002) | Retrospective cohort | 77 Cardiology centers, France, ischemic heart disease admissions | 58.5% (729/1247) | HTN diagnosis in record or admission BP 140/90 mm Hg |

| Onder et al.23 (2003) | Cross‐sectional | 81 Hospitals, Italy, elderly patients with known HTN | *86.9% (3304/3807) | HTN diagnosis in record AND admission BP 140/90 mm Hg |

| Jankowski et al.19 (2005) | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 3 University cardiology centers, Poland | 70.2% (593/845) | Mean clinic BP at 618 months follow up of 140/90 mm Hg |

| Conen et al.21 (2006) | Cross‐sectional | Single University Center, U.S., medical/surgical patients | 72.6% (228/314) | HTN diagnosis in record OR mean 24‐hour BP 125/80 mm Hg |

| Giantin et al.22 (2009) | Cross‐sectional | Single University Center, Italy, medical/surgical patients | 56.4% (141/250) | Mean 24‐hour BP 125/80 mm Hg |

| Clinical Question | Findings |

|---|---|

| |

| Accuracy of routine inpatient BP measurements | 56.4% to 72.6% of inpatients receiving 24 hour BP monitoring had HTN.21, 22 |

| 28% to 38% of HTN patients had masked HTN (identified by 24‐hour monitoring but not revealed by routine inpatient BP measures). | |

| Proportion of HTN patients uncontrolled on admission | 86.9% of patients with previously documented HTN were uncontrolled on admission.23 |

| Proportion of HTN patients uncontrolled at discharge | 37% to 77% of inpatients with HTN still had BP > 140/90 mm Hg at time of discharge.16, 20, 23 |

| Proportion of HTN patients without a recorded diagnosis at discharge | 8% to 44% of patients with elevated BP > 140/90 mmHg were discharged without a documented diagnosis of HTN.15, 16, 18, 19 |

| Proportion of uncontrolled HTN patients receiving intensification of therapy during index admission | 53.1% of patients with uncontrolled BP received additional antihypertensive medication upon discharge.23 |

| Proportion of HTN controlled at follow up | 50% of patients with HTN were controlled to <140/90 mm Hg at follow up.17 |

Four studies focused primarily on cardiac patients. The European Society of Cardiology survey of secondary prevention of coronary heart disease (EUROASPIRE I) and subsequent EUROASPIRE II studies used retrospective chart review and prospective follow up clinic visits with a focus on baseline patient characteristics and risk factor modification at post‐discharge follow up.17, 18 Jankowski et al.19 studied 845 similar cardiac patients discharged from 6 Polish centers. Amar et al.20 performed a retrospective cohort study using records from 77 French cardiology centers to assess the impact of BP control prior to discharge in patients with acute coronary syndromes on the prevention of subsequent nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiac death.

Two studies utilized 24‐hour BP monitoring to diagnose HTN among inpatients, and compared this to routine inpatient measurement techniques. Conen et al.21 performed 24‐hour BP monitoring on 314 consecutive stable medical and surgical inpatients admitted to a Swiss University hospital. Giantin et al.22 also performed 24‐hour monitoring on a cohort of elderly Italian outpatients and inpatients to determine the prevalence of masked and white coat HTN in different care settings. Finally, Onder et al.23 reported on rates of uncontrolled BP and HTN management among known hypertensives as part of a series of cross‐sectional surveys performed on elderly Italian inpatients.23

Inpatient HTN Prevalence

Overall, study authors reported an HTN prevalence among inpatients that ranged from 50.5% to 72%. Estimates varied somewhat based on HTN definitions, diagnostic standards utilized, measurement techniques, and patient populations. In earlier studies HTN prevalence was reported at 23.8% to 28%, but these likely represented significant underestimates by current diagnostic standards.15, 16 High estimates by Onder et al.23 (86.9%) stem from selection criteria that included a prior billing diagnosis of HTN coupled with elevated admission blood pressures. Estimates in the 50% to 70% prevalence range were seen in studies that focused on cardiac and general medical inpatients.1722 Additional findings of included studies are listed in Table 2.

Accuracy of Inpatient BP Measures

In two studies, 24‐hour BP monitors produced prevalence estimates ranging from 56.4% to 72.6%.21, 22 In both studies, a significant proportion of patients had masked HTN, or HTN detected by 24‐hour BP monitoring alone. Also, 28% to 38% of patients without a prior HTN diagnosis, who were not detected by routine measures, were found to be hypertensive by 24‐hour monitoring. Finally, Conen et al.21 retested a subset of hypertensives with 24‐hour monitoring one month after hospitalization, and 87.5% remained categorized as hypertensive on follow‐up. Of note, it is unclear how this subset of patients was selected.

Proportion of Controlled HTN on Admission and Discharge

Because most included studies established prevalence of HTN based in part upon uncontrolled BP at hospital admission, estimates for the proportion of hypertensive patients controlled on admission were not given. However, Onder et al.23 did examine patients with a prior International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD‐9) diagnosis of HTN and uncontrolled HTN (BP 140/90) on admission. At discharge, only 23.2% of this cohort was controlled with a BP < 140/90 mmHg. However, other estimates suggested that 37% to 44% of patients remained uncontrolled at discharge.16, 20

Proportion of Undiagnosed HTN

In 4 studies, the proportion of patients with elevated BP and/or a history of HTN who did not receive a diagnosis of HTN upon discharge ranged from 8.8% to 44% between cohorts.15, 16, 18, 19 Interpretation of these estimates, however, is difficult due to significant differences between the studies. For example, both earlier studies were performed during an era of higher thresholds for HTN diagnosis and lower overall HTN awareness.15, 16 Both studies of cardiac patients suggested lower rates of nondiagnosis than might have been found in general medical or surgical inpatients.18, 19 One of the 4 studies also suggested that surgical patients who were hypertensive during hospitalization were more likely than medical patients to be discharged without a HTN diagnosis (17% vs. 4%, P < 0.05); although, the overall number of patients was small (18/146 remained undiagnosed).16

Proportion Receiving Intensification of Therapy

In 3 studies, prescribing practices for hypertensive inpatients were discussed. Shankar et al.15 found that only 62% of patients with a recorded HTN diagnosis received antihypertensive medications during hospitalization. Unfortunately, no information was given on the proportion of patients prescribed antihypertensive medications at the time of discharge. However, Greenland et al.16 found no net increase in BP medication use at discharge compared to admission despite 44% of patients remaining uncontrolled to <160/90 mmHg at the time of discharge. Onder et al.23 determined that BP medication was intensified in only 53.1% of hypertensive patients during hospitalization. Younger age, fewer drugs on admission, lower comorbidity index, diagnosis of congestive heart failure, lengthy hospital stay, and increasing levels of BP (systolic and diastolic) were all associated with more aggressive prescribing practices. Interestingly, Jankowski et al.19 found that treatment with a BP lowering agent at discharge was associated with the lowest odds of nontreatment at follow up (odds ratio [OR] 0.08, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.030.19).

Proportion of HTN Controlled at Follow Up

In the EuroASPIRE 1 study, 50% of HTN patients had a systolic BP of < 140 mm Hg at follow up 6 months after hospitalization for MI.17 Jankowski et al.19 found that patients with documented inpatient HTN but without a recorded HTN diagnosis during index admission were 4 times more likely (19.2% vs. 4.5%, P < 0.0001) to be untreated for their HTN at 6 to 18 months postdischarge, and they were less likely to be controlled at <140/90 mmHg. In a separate cohort of cardiac patients, multivariable modeling identified uncontrolled isolated systolic HTN at hospital discharge as an independent predictor of subsequent cardiac death or nonfatal MI at 6 months follow up (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.153.36).20

Discussion

The present systematic review highlights the high prevalence of HTN with contemporary estimates ranging between 50% and 72% in general medical/surgical and cardiology populations. Furthermore, routine inpatient BP measurements may underestimate the prevalence of HTN among inpatients when compared to 24 hour BP monitoring; although there is no current diagnostic standard for HTN among inpatients. Among patients with uncontrolled BP on admission, BP typically remains above recommended levels at the time of discharge. Further, studies commenting on the prescribing practices at the time of discharge did not detect a strong tendency to intensify antihypertensive regimens in patients with uncontrolled inpatient HTN.16, 23 Most importantly, our data suggest that the medical literature is lacking: only 9 reports met our inclusion criteria for this review.

The validity of inpatient BP measures for making an HTN diagnosis remains a concern when asserting that the inpatient setting is appropriate for HTN screening and efforts to improve BP control. For example, BP measures might be inaccurate because of the inherent heterogeneity of patients with acute illness often with associated pain and nausea that might raise or lower BP. Inpatients often need to have their BP medications held for appropriate reasons, or they may have additional medications while hospitalized that also affect BP. Finally, BP measures in the inpatient setting are less commonly performed using standardized techniques or with accurate BP devices. However, both studies included in this review featuring follow up outpatient BP measures found high degrees of correlation between inpatient and outpatient measures.19, 21 Also, Giantin and colleagues reported that 28.6% of elderly patients who were normotensive based on routine BP measures, were actually hypertensive based on 24‐hour ambulatory BP monitoring.22

Some clinicians may have concerns about starting or titrating BP medications in dynamic hospitalized patients. Certainly, this should be done with caution and in appropriately selected patients. We would argue that achieving complete BP control during an index hospitalization as emphasized by Greenland and Amar is not always the most appropriate goal. However, appropriate recognition of persistently elevated BP does offer the opportunity to make an HTN diagnosis and to refer for future outpatient treatment or to communicate with existing primary care providers. The latter is especially important in this era of discontinuity between inpatient and outpatient care. Beginning or titrating BP medications in the hospital also has advantages for 2 reasons. First, medications started in the hospital tend to be the medications on which patients are sent home. Second, in the study by Jankowski et al.,19 the failure to prescribe an antihypertensive medication at the time of discharge was the single strongest predictor of nontreatment at 6 to 18 months follow‐up despite other follow up outpatient visits where BP medications might have been titrated.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that failure to appropriately manage HTN observed in the inpatient setting can impact subsequent medication use and disease outcomes for high‐risk patients. Amar et al.20 found that better controlled systolic BP on hospital discharge is associated with better outcomes in patients with ischemic heart disease. Only 35% of patients in one cohort admitted to the hospital with hypertensive urgency or emergency completed an outpatient follow up visit for HTN within 90 days. However, 37% were readmitted and 11% died during 3 month follow up.24 Predischarge initiation of a beta blocker in congestive heart failure patients has been associated with a nearly 18% absolute increase in rates of beta blocker use at 2 months follow‐up.25 Finally, prescription of antihypertensive medications is suboptimal for secondary stroke prevention despite a number needed to treat of 51 patients to prevent one stroke annually.26, 27

The primary limitation of this review is the paucity of published reports documenting the prevalence of inpatient HTN. It is possible that important articles were missed, but we did follow a prespecified systematic search strategy with the assistance of a trained reference librarian. Also, the definition of HTN varied significantly between studies. However, current consensus guidelines do not specifically address the diagnosis or management of HTN in the inpatient setting.28

In summary, available medical evidence suggests that HTN is a common problem observed in the hospital. Opportunities for the appropriate diagnosis of HTN and for the initiation or modification of HTN treatment are often missed. Future studies in this area are warranted to better understand the prevalence of HTN in the inpatient setting and the need to improve HTN detection, treatment, and control. Clearer diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for the detection and treatment of inpatient HTN could contribute to further improvements in control rates of all hypertensive patients, especially if coupled with improved care transitions between the inpatient and outpatient setting.

- ,,,,.Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999–2004.Hypertension.2007;49:69–75.

- ,,,.Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control‐continued disparities in adults: United States, 2005–2006.NCHS Data Brief.2008;3:1–8.

- ,,,,,Prospective Studies C.Age‐specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta‐analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies.Lancet.2002;360:1903–1913.

- ,,,,,.Blood pressure screening of school children in a multiracial school district: the Healthy Kids Project.Am J Hypertens.2009;22:351–356.

- ,,,,.Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Findings from a community screening program.Diabetes Educ.2004;30(2):196–198,200–202,220.

- .Screening for traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a review for oral health care providers.J Am Dent Assoc.2002;133:291–300.

- .Health screening in schools. Part II.J Pediatr.1985;107:653–661.

- ,,,.Experience with a community screening program for hypertension: results on 24,462 individuals.Eur J Cardiol.1978;7:487–497.

- .Screening for hypertension in the dental office.J Am Dent Assoc.1974;88:563–567.

- ,,,.2006 National Hospital Discharge Survey:National Center for Health Statistics;2008.

- ,,,,,.Continuity of outpatient and inpatient care by primary care physicians for hospitalized older adults.J Am Med Assoc.2009;301:1671–1680.

- ,,.Influence of hospitalization and placebo therapy on blood pressure and sympathetic function in essential hypertension.Hypertension.1981;3:113–118.

- ,,.Effect of hospitalization on conventional and 24‐hour blood pressure.Age Ageing.1995;24:25–29.

- ,,, et al.Spontaneous fall in blood pressure and reactivity of sympathetic nervous system in hospitalized patients with essential hypertension.Jpn J Med.1990;29:13–21.

- ,,,.Patterns of care for hypertension among hospitalized patients.Public Health Rep.1982;97:521–527.

- ,,.Hospitalization as an opportunity to improve hypertension recognition and control.Med Care.1987;25:717–723.

- EUROASPIRE.A European Society of Cardiology survey of secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: principal results. EUROASPIRE Study Group. European Action on Secondary Prevention through Intervention to Reduce Events.Eur Heart J.1997;18:1569–1582.

- Lifestyle and risk factor management and use of drug therapies in coronary patients from 15 countries; principal results from EUROASPIRE II Euro Heart Survey Programme.Eur Heart J.2001;22:554–572.

- ,,,.Determinants of poor hypertension management in patients with ischaemic heart disease.Blood Press.2005;14:284–292.

- ,,, et al.Hypertension control at hospital discharge after acute coronary event: influence on cardiovascular prognosis‐‐the PREVENIR study.Heart.2002;88:587–591.

- ,,,.High prevalence of newly detected hypertension in hospitalized patients: the value of in‐hospital 24‐h blood pressure measurement.J Hypertens2006;24:301–306.

- ,,, et al.Masked and white‐coat hypertension in two cohorts of elderly subjects, ambulatory and hospitalized patients.Arch Gerontol Geriatr.2009;49Suppl 1:125–128.

- ,,, et al.Impact of hospitalization on blood pressure control in Italy: results from the Italian Group of Pharmacoepidemiology in the Elderly (GIFA).Pharmacotherapy.2003;23:240–247.

- ,,, et al.Practice patterns, outcomes, and end‐organ dysfunction for patients with acute severe hypertension: The Studying the Treatment of Acute hyperTension (STAT) Registry.Am Heart J.2009;158:599–606.

- ,,,,.Predischarge initiation of carvedilol in patients hospitalized for decompensated heart failure: results of the Initiation Management Predischarge: Process for Assessment of Carvedilol Therapy in Heart Failure (IMPACT‐HF) trial.J Am Coll Cardiol.2004;43:1534–1541.

- ,,,.Antihypertensive medications prescribed at discharge after an acute ischemic cerebrovascular event.Stroke.2005;36:1944–1947.

- ,,.New Evidence for Stroke Prevention: Scientific Review.JAMA.2002;288:1388–1395.

- ,,,,.Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee.Hypertension.2003;42:1206–1252.

Hypertension (HTN) is highly prevalent in the general adult population with recent estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of 29% in the United States.1, 2 The relationship between increasing levels of blood pressure (BP) and increasing risk for cardiovascular disease events and stroke is well established.3 However, while 64% of treated HTN patients have a BP <140/<90 mmHg, overall control rates for HTN in the adult population remain at approximately 44%.2 The 20% discrepancy in control rates between treated patients and the overall adult population reflects the fact that approximately 30% of patients are unaware of their HTN and that a substantial proportion of aware patients remain untreated. Historically, efforts to improve the recognition, treatment, and control of HTN have appropriately focused on the outpatient setting. However, programs to extend screening for HTN outside the clinic into the community, schools, and even dentists' offices have been around for some time.49

The potential also exists to improve the recognition, treatment, and control of HTN by focusing on hospitalized patients. Hospitalization is common in the U.S. with almost 35 million acute hospitalizations and more than 45,000 inpatient surgical procedures in 2006.10 Inpatient populations have increased in age and comorbidity over the past 3 decades whereas lengths of stay and continuity of care between the inpatient and outpatient arenas have diminished.10, 11 Multiple prior studies examining BP in different settings have noted that average BP among hospitalized patients is not systematically higher than that of outpatients.1214 Thus, patients with persistently elevated BP in the inpatient setting without mitigating factors may have HTN that will persist after hospital discharge. However, little information is available regarding the actual prevalence of HTN in the inpatient population and care patterns for inpatient HTN. Therefore, we performed a systematic review of the English‐language medical literature in order to describe the epidemiology of HTN observed in the inpatient setting.

Methods

Our search strategy was designed to identify randomized‐controlled trials, meta‐analyses, and observational studies that: (1) reported estimates of the prevalence of HTN in the inpatient setting, and (2) used HTN diagnosis or treatment as a primary focus. We performed an extensive review of the peer‐reviewed, English language medical literature in MEDLINE using a predetermined search algorithm. Search terms included HTN[Mesh] or BP[Mesh]. These results were cross‐referenced with the following search terms: Inpatients[Mesh] or Hospitalization[title/abstract] or Hospitalized[title/abstract]. Articles were further narrowed using the following terms: Prevalence[Mesh] or Epidemiology[Mesh] or Treatment[title/abstract] or Management [title/abstract]. Limits employed included limiting to humans and to adults 19 years‐of‐age and older. Studies published prior to 1976 were excluded because 1976 was the first year that the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High BP published consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HTN. We also excluded randomized, controlled trials that recorded measures of inpatient BP but whose focus was not HTN, because such trials would not answer the primary epidemiologic question of this review. We did include trials focused on subspecialty populations for which the diagnosis and inpatient management of HTN were key outcomes.

Next, the bibliographies of reviewed studies were investigated for additional relevant reports. Abstracts from the American Heart Association (AHA) were reviewed for the past 15 years for reports that were presented but not subsequently published and available in MEDLINE. We also searched for articles using the online Google search engine. One author (RNA) performed the preliminary MEDLINE search and abstract review with the assistance of a reference librarian (LC), and a second author (BME) also reviewed full‐text articles for potential inclusion. Ultimate decision for study inclusion was reached through discussion among authors. Finally, a list of potential articles was submitted to 2 experts in this field of study to determine whether other reports met our inclusion criteria for this systematic review but were overlooked.

Results

Search Results

The initial MEDLINE search algorithm yielded a total of 826 articles. After title and abstract review, 41 full‐text articles were obtained for detailed review, and 5 met criteria for inclusion. Three additional articles were discovered through searching the bibliographies of the included studies. No AHA abstracts addressed this subject area. Experts were not aware of any additional studies. One article was located using a Google search. In all, 9 articles were deemed suitable for inclusion in this review. Search results at each stage are depicted in Figure 1.

Description of Included Studies

Characteristics of included studies are depicted in Table 1. Two older retrospective cohort studies reported HTN prevalence using earlier, less stringent diagnostic criteria. Shankar et al.15 abstracted data from more than 19,000 adults discharged alive from Maryland hospitals during 1978. Greenland et al.16 performed chart review for 536 medical and surgical inpatients in 1987 reporting information on the proportion of patients appropriately diagnosed as having HTN and the proportion with controlled BP on admission and at discharge based on then‐current JNC‐III criteria (HTN if BP > 160/90).

| Study | Design | Setting | Hypertension Prevalence | Diagnostic Criteria for HTN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Shankar et al.15 (1982) | Retrospective cohort | All hospital discharges in Maryland in 1978 | 23.8% (4571/19,259) | HTN diagnosis in record or diastolic BP 100 mm Hg |

| Greenland et al.16 (1987) | Retrospective cohort | Single University Center, U.S., medical/surgical patients | 28% (143/536 ) | HTN diagnosis in record or mean of first 4 hospital BP measures 160/90 mm Hg |

| Euroaspire I17 | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 9 European countries, coronary heart disease admissions | 57.8% (2553/4415) | Admission BP 140/90 mm Hg or on antihypertensive medications |

| Euroaspire II18 | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 15 European countries, coronary heart disease admissions | 50.5% (2806/5556) | Mean clinic BP at 618 months follow up of 140/90 mm Hg |

| Amar et al.20 (2002) | Retrospective cohort | 77 Cardiology centers, France, ischemic heart disease admissions | 58.5% (729/1247) | HTN diagnosis in record or admission BP 140/90 mm Hg |

| Onder et al.23 (2003) | Cross‐sectional | 81 Hospitals, Italy, elderly patients with known HTN | *86.9% (3304/3807) | HTN diagnosis in record AND admission BP 140/90 mm Hg |

| Jankowski et al.19 (2005) | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 3 University cardiology centers, Poland | 70.2% (593/845) | Mean clinic BP at 618 months follow up of 140/90 mm Hg |

| Conen et al.21 (2006) | Cross‐sectional | Single University Center, U.S., medical/surgical patients | 72.6% (228/314) | HTN diagnosis in record OR mean 24‐hour BP 125/80 mm Hg |

| Giantin et al.22 (2009) | Cross‐sectional | Single University Center, Italy, medical/surgical patients | 56.4% (141/250) | Mean 24‐hour BP 125/80 mm Hg |

| Clinical Question | Findings |

|---|---|

| |

| Accuracy of routine inpatient BP measurements | 56.4% to 72.6% of inpatients receiving 24 hour BP monitoring had HTN.21, 22 |

| 28% to 38% of HTN patients had masked HTN (identified by 24‐hour monitoring but not revealed by routine inpatient BP measures). | |

| Proportion of HTN patients uncontrolled on admission | 86.9% of patients with previously documented HTN were uncontrolled on admission.23 |

| Proportion of HTN patients uncontrolled at discharge | 37% to 77% of inpatients with HTN still had BP > 140/90 mm Hg at time of discharge.16, 20, 23 |

| Proportion of HTN patients without a recorded diagnosis at discharge | 8% to 44% of patients with elevated BP > 140/90 mmHg were discharged without a documented diagnosis of HTN.15, 16, 18, 19 |

| Proportion of uncontrolled HTN patients receiving intensification of therapy during index admission | 53.1% of patients with uncontrolled BP received additional antihypertensive medication upon discharge.23 |

| Proportion of HTN controlled at follow up | 50% of patients with HTN were controlled to <140/90 mm Hg at follow up.17 |

Four studies focused primarily on cardiac patients. The European Society of Cardiology survey of secondary prevention of coronary heart disease (EUROASPIRE I) and subsequent EUROASPIRE II studies used retrospective chart review and prospective follow up clinic visits with a focus on baseline patient characteristics and risk factor modification at post‐discharge follow up.17, 18 Jankowski et al.19 studied 845 similar cardiac patients discharged from 6 Polish centers. Amar et al.20 performed a retrospective cohort study using records from 77 French cardiology centers to assess the impact of BP control prior to discharge in patients with acute coronary syndromes on the prevention of subsequent nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiac death.

Two studies utilized 24‐hour BP monitoring to diagnose HTN among inpatients, and compared this to routine inpatient measurement techniques. Conen et al.21 performed 24‐hour BP monitoring on 314 consecutive stable medical and surgical inpatients admitted to a Swiss University hospital. Giantin et al.22 also performed 24‐hour monitoring on a cohort of elderly Italian outpatients and inpatients to determine the prevalence of masked and white coat HTN in different care settings. Finally, Onder et al.23 reported on rates of uncontrolled BP and HTN management among known hypertensives as part of a series of cross‐sectional surveys performed on elderly Italian inpatients.23

Inpatient HTN Prevalence

Overall, study authors reported an HTN prevalence among inpatients that ranged from 50.5% to 72%. Estimates varied somewhat based on HTN definitions, diagnostic standards utilized, measurement techniques, and patient populations. In earlier studies HTN prevalence was reported at 23.8% to 28%, but these likely represented significant underestimates by current diagnostic standards.15, 16 High estimates by Onder et al.23 (86.9%) stem from selection criteria that included a prior billing diagnosis of HTN coupled with elevated admission blood pressures. Estimates in the 50% to 70% prevalence range were seen in studies that focused on cardiac and general medical inpatients.1722 Additional findings of included studies are listed in Table 2.

Accuracy of Inpatient BP Measures

In two studies, 24‐hour BP monitors produced prevalence estimates ranging from 56.4% to 72.6%.21, 22 In both studies, a significant proportion of patients had masked HTN, or HTN detected by 24‐hour BP monitoring alone. Also, 28% to 38% of patients without a prior HTN diagnosis, who were not detected by routine measures, were found to be hypertensive by 24‐hour monitoring. Finally, Conen et al.21 retested a subset of hypertensives with 24‐hour monitoring one month after hospitalization, and 87.5% remained categorized as hypertensive on follow‐up. Of note, it is unclear how this subset of patients was selected.

Proportion of Controlled HTN on Admission and Discharge

Because most included studies established prevalence of HTN based in part upon uncontrolled BP at hospital admission, estimates for the proportion of hypertensive patients controlled on admission were not given. However, Onder et al.23 did examine patients with a prior International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD‐9) diagnosis of HTN and uncontrolled HTN (BP 140/90) on admission. At discharge, only 23.2% of this cohort was controlled with a BP < 140/90 mmHg. However, other estimates suggested that 37% to 44% of patients remained uncontrolled at discharge.16, 20

Proportion of Undiagnosed HTN

In 4 studies, the proportion of patients with elevated BP and/or a history of HTN who did not receive a diagnosis of HTN upon discharge ranged from 8.8% to 44% between cohorts.15, 16, 18, 19 Interpretation of these estimates, however, is difficult due to significant differences between the studies. For example, both earlier studies were performed during an era of higher thresholds for HTN diagnosis and lower overall HTN awareness.15, 16 Both studies of cardiac patients suggested lower rates of nondiagnosis than might have been found in general medical or surgical inpatients.18, 19 One of the 4 studies also suggested that surgical patients who were hypertensive during hospitalization were more likely than medical patients to be discharged without a HTN diagnosis (17% vs. 4%, P < 0.05); although, the overall number of patients was small (18/146 remained undiagnosed).16

Proportion Receiving Intensification of Therapy

In 3 studies, prescribing practices for hypertensive inpatients were discussed. Shankar et al.15 found that only 62% of patients with a recorded HTN diagnosis received antihypertensive medications during hospitalization. Unfortunately, no information was given on the proportion of patients prescribed antihypertensive medications at the time of discharge. However, Greenland et al.16 found no net increase in BP medication use at discharge compared to admission despite 44% of patients remaining uncontrolled to <160/90 mmHg at the time of discharge. Onder et al.23 determined that BP medication was intensified in only 53.1% of hypertensive patients during hospitalization. Younger age, fewer drugs on admission, lower comorbidity index, diagnosis of congestive heart failure, lengthy hospital stay, and increasing levels of BP (systolic and diastolic) were all associated with more aggressive prescribing practices. Interestingly, Jankowski et al.19 found that treatment with a BP lowering agent at discharge was associated with the lowest odds of nontreatment at follow up (odds ratio [OR] 0.08, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.030.19).

Proportion of HTN Controlled at Follow Up

In the EuroASPIRE 1 study, 50% of HTN patients had a systolic BP of < 140 mm Hg at follow up 6 months after hospitalization for MI.17 Jankowski et al.19 found that patients with documented inpatient HTN but without a recorded HTN diagnosis during index admission were 4 times more likely (19.2% vs. 4.5%, P < 0.0001) to be untreated for their HTN at 6 to 18 months postdischarge, and they were less likely to be controlled at <140/90 mmHg. In a separate cohort of cardiac patients, multivariable modeling identified uncontrolled isolated systolic HTN at hospital discharge as an independent predictor of subsequent cardiac death or nonfatal MI at 6 months follow up (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.153.36).20

Discussion

The present systematic review highlights the high prevalence of HTN with contemporary estimates ranging between 50% and 72% in general medical/surgical and cardiology populations. Furthermore, routine inpatient BP measurements may underestimate the prevalence of HTN among inpatients when compared to 24 hour BP monitoring; although there is no current diagnostic standard for HTN among inpatients. Among patients with uncontrolled BP on admission, BP typically remains above recommended levels at the time of discharge. Further, studies commenting on the prescribing practices at the time of discharge did not detect a strong tendency to intensify antihypertensive regimens in patients with uncontrolled inpatient HTN.16, 23 Most importantly, our data suggest that the medical literature is lacking: only 9 reports met our inclusion criteria for this review.

The validity of inpatient BP measures for making an HTN diagnosis remains a concern when asserting that the inpatient setting is appropriate for HTN screening and efforts to improve BP control. For example, BP measures might be inaccurate because of the inherent heterogeneity of patients with acute illness often with associated pain and nausea that might raise or lower BP. Inpatients often need to have their BP medications held for appropriate reasons, or they may have additional medications while hospitalized that also affect BP. Finally, BP measures in the inpatient setting are less commonly performed using standardized techniques or with accurate BP devices. However, both studies included in this review featuring follow up outpatient BP measures found high degrees of correlation between inpatient and outpatient measures.19, 21 Also, Giantin and colleagues reported that 28.6% of elderly patients who were normotensive based on routine BP measures, were actually hypertensive based on 24‐hour ambulatory BP monitoring.22

Some clinicians may have concerns about starting or titrating BP medications in dynamic hospitalized patients. Certainly, this should be done with caution and in appropriately selected patients. We would argue that achieving complete BP control during an index hospitalization as emphasized by Greenland and Amar is not always the most appropriate goal. However, appropriate recognition of persistently elevated BP does offer the opportunity to make an HTN diagnosis and to refer for future outpatient treatment or to communicate with existing primary care providers. The latter is especially important in this era of discontinuity between inpatient and outpatient care. Beginning or titrating BP medications in the hospital also has advantages for 2 reasons. First, medications started in the hospital tend to be the medications on which patients are sent home. Second, in the study by Jankowski et al.,19 the failure to prescribe an antihypertensive medication at the time of discharge was the single strongest predictor of nontreatment at 6 to 18 months follow‐up despite other follow up outpatient visits where BP medications might have been titrated.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that failure to appropriately manage HTN observed in the inpatient setting can impact subsequent medication use and disease outcomes for high‐risk patients. Amar et al.20 found that better controlled systolic BP on hospital discharge is associated with better outcomes in patients with ischemic heart disease. Only 35% of patients in one cohort admitted to the hospital with hypertensive urgency or emergency completed an outpatient follow up visit for HTN within 90 days. However, 37% were readmitted and 11% died during 3 month follow up.24 Predischarge initiation of a beta blocker in congestive heart failure patients has been associated with a nearly 18% absolute increase in rates of beta blocker use at 2 months follow‐up.25 Finally, prescription of antihypertensive medications is suboptimal for secondary stroke prevention despite a number needed to treat of 51 patients to prevent one stroke annually.26, 27

The primary limitation of this review is the paucity of published reports documenting the prevalence of inpatient HTN. It is possible that important articles were missed, but we did follow a prespecified systematic search strategy with the assistance of a trained reference librarian. Also, the definition of HTN varied significantly between studies. However, current consensus guidelines do not specifically address the diagnosis or management of HTN in the inpatient setting.28

In summary, available medical evidence suggests that HTN is a common problem observed in the hospital. Opportunities for the appropriate diagnosis of HTN and for the initiation or modification of HTN treatment are often missed. Future studies in this area are warranted to better understand the prevalence of HTN in the inpatient setting and the need to improve HTN detection, treatment, and control. Clearer diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for the detection and treatment of inpatient HTN could contribute to further improvements in control rates of all hypertensive patients, especially if coupled with improved care transitions between the inpatient and outpatient setting.

Hypertension (HTN) is highly prevalent in the general adult population with recent estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) of 29% in the United States.1, 2 The relationship between increasing levels of blood pressure (BP) and increasing risk for cardiovascular disease events and stroke is well established.3 However, while 64% of treated HTN patients have a BP <140/<90 mmHg, overall control rates for HTN in the adult population remain at approximately 44%.2 The 20% discrepancy in control rates between treated patients and the overall adult population reflects the fact that approximately 30% of patients are unaware of their HTN and that a substantial proportion of aware patients remain untreated. Historically, efforts to improve the recognition, treatment, and control of HTN have appropriately focused on the outpatient setting. However, programs to extend screening for HTN outside the clinic into the community, schools, and even dentists' offices have been around for some time.49

The potential also exists to improve the recognition, treatment, and control of HTN by focusing on hospitalized patients. Hospitalization is common in the U.S. with almost 35 million acute hospitalizations and more than 45,000 inpatient surgical procedures in 2006.10 Inpatient populations have increased in age and comorbidity over the past 3 decades whereas lengths of stay and continuity of care between the inpatient and outpatient arenas have diminished.10, 11 Multiple prior studies examining BP in different settings have noted that average BP among hospitalized patients is not systematically higher than that of outpatients.1214 Thus, patients with persistently elevated BP in the inpatient setting without mitigating factors may have HTN that will persist after hospital discharge. However, little information is available regarding the actual prevalence of HTN in the inpatient population and care patterns for inpatient HTN. Therefore, we performed a systematic review of the English‐language medical literature in order to describe the epidemiology of HTN observed in the inpatient setting.

Methods

Our search strategy was designed to identify randomized‐controlled trials, meta‐analyses, and observational studies that: (1) reported estimates of the prevalence of HTN in the inpatient setting, and (2) used HTN diagnosis or treatment as a primary focus. We performed an extensive review of the peer‐reviewed, English language medical literature in MEDLINE using a predetermined search algorithm. Search terms included HTN[Mesh] or BP[Mesh]. These results were cross‐referenced with the following search terms: Inpatients[Mesh] or Hospitalization[title/abstract] or Hospitalized[title/abstract]. Articles were further narrowed using the following terms: Prevalence[Mesh] or Epidemiology[Mesh] or Treatment[title/abstract] or Management [title/abstract]. Limits employed included limiting to humans and to adults 19 years‐of‐age and older. Studies published prior to 1976 were excluded because 1976 was the first year that the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High BP published consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and management of HTN. We also excluded randomized, controlled trials that recorded measures of inpatient BP but whose focus was not HTN, because such trials would not answer the primary epidemiologic question of this review. We did include trials focused on subspecialty populations for which the diagnosis and inpatient management of HTN were key outcomes.

Next, the bibliographies of reviewed studies were investigated for additional relevant reports. Abstracts from the American Heart Association (AHA) were reviewed for the past 15 years for reports that were presented but not subsequently published and available in MEDLINE. We also searched for articles using the online Google search engine. One author (RNA) performed the preliminary MEDLINE search and abstract review with the assistance of a reference librarian (LC), and a second author (BME) also reviewed full‐text articles for potential inclusion. Ultimate decision for study inclusion was reached through discussion among authors. Finally, a list of potential articles was submitted to 2 experts in this field of study to determine whether other reports met our inclusion criteria for this systematic review but were overlooked.

Results

Search Results

The initial MEDLINE search algorithm yielded a total of 826 articles. After title and abstract review, 41 full‐text articles were obtained for detailed review, and 5 met criteria for inclusion. Three additional articles were discovered through searching the bibliographies of the included studies. No AHA abstracts addressed this subject area. Experts were not aware of any additional studies. One article was located using a Google search. In all, 9 articles were deemed suitable for inclusion in this review. Search results at each stage are depicted in Figure 1.

Description of Included Studies

Characteristics of included studies are depicted in Table 1. Two older retrospective cohort studies reported HTN prevalence using earlier, less stringent diagnostic criteria. Shankar et al.15 abstracted data from more than 19,000 adults discharged alive from Maryland hospitals during 1978. Greenland et al.16 performed chart review for 536 medical and surgical inpatients in 1987 reporting information on the proportion of patients appropriately diagnosed as having HTN and the proportion with controlled BP on admission and at discharge based on then‐current JNC‐III criteria (HTN if BP > 160/90).

| Study | Design | Setting | Hypertension Prevalence | Diagnostic Criteria for HTN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Shankar et al.15 (1982) | Retrospective cohort | All hospital discharges in Maryland in 1978 | 23.8% (4571/19,259) | HTN diagnosis in record or diastolic BP 100 mm Hg |

| Greenland et al.16 (1987) | Retrospective cohort | Single University Center, U.S., medical/surgical patients | 28% (143/536 ) | HTN diagnosis in record or mean of first 4 hospital BP measures 160/90 mm Hg |

| Euroaspire I17 | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 9 European countries, coronary heart disease admissions | 57.8% (2553/4415) | Admission BP 140/90 mm Hg or on antihypertensive medications |

| Euroaspire II18 | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 15 European countries, coronary heart disease admissions | 50.5% (2806/5556) | Mean clinic BP at 618 months follow up of 140/90 mm Hg |

| Amar et al.20 (2002) | Retrospective cohort | 77 Cardiology centers, France, ischemic heart disease admissions | 58.5% (729/1247) | HTN diagnosis in record or admission BP 140/90 mm Hg |

| Onder et al.23 (2003) | Cross‐sectional | 81 Hospitals, Italy, elderly patients with known HTN | *86.9% (3304/3807) | HTN diagnosis in record AND admission BP 140/90 mm Hg |

| Jankowski et al.19 (2005) | Retrospective cohort with prospective follow up | 3 University cardiology centers, Poland | 70.2% (593/845) | Mean clinic BP at 618 months follow up of 140/90 mm Hg |

| Conen et al.21 (2006) | Cross‐sectional | Single University Center, U.S., medical/surgical patients | 72.6% (228/314) | HTN diagnosis in record OR mean 24‐hour BP 125/80 mm Hg |

| Giantin et al.22 (2009) | Cross‐sectional | Single University Center, Italy, medical/surgical patients | 56.4% (141/250) | Mean 24‐hour BP 125/80 mm Hg |

| Clinical Question | Findings |

|---|---|

| |

| Accuracy of routine inpatient BP measurements | 56.4% to 72.6% of inpatients receiving 24 hour BP monitoring had HTN.21, 22 |

| 28% to 38% of HTN patients had masked HTN (identified by 24‐hour monitoring but not revealed by routine inpatient BP measures). | |

| Proportion of HTN patients uncontrolled on admission | 86.9% of patients with previously documented HTN were uncontrolled on admission.23 |

| Proportion of HTN patients uncontrolled at discharge | 37% to 77% of inpatients with HTN still had BP > 140/90 mm Hg at time of discharge.16, 20, 23 |

| Proportion of HTN patients without a recorded diagnosis at discharge | 8% to 44% of patients with elevated BP > 140/90 mmHg were discharged without a documented diagnosis of HTN.15, 16, 18, 19 |

| Proportion of uncontrolled HTN patients receiving intensification of therapy during index admission | 53.1% of patients with uncontrolled BP received additional antihypertensive medication upon discharge.23 |

| Proportion of HTN controlled at follow up | 50% of patients with HTN were controlled to <140/90 mm Hg at follow up.17 |

Four studies focused primarily on cardiac patients. The European Society of Cardiology survey of secondary prevention of coronary heart disease (EUROASPIRE I) and subsequent EUROASPIRE II studies used retrospective chart review and prospective follow up clinic visits with a focus on baseline patient characteristics and risk factor modification at post‐discharge follow up.17, 18 Jankowski et al.19 studied 845 similar cardiac patients discharged from 6 Polish centers. Amar et al.20 performed a retrospective cohort study using records from 77 French cardiology centers to assess the impact of BP control prior to discharge in patients with acute coronary syndromes on the prevention of subsequent nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiac death.

Two studies utilized 24‐hour BP monitoring to diagnose HTN among inpatients, and compared this to routine inpatient measurement techniques. Conen et al.21 performed 24‐hour BP monitoring on 314 consecutive stable medical and surgical inpatients admitted to a Swiss University hospital. Giantin et al.22 also performed 24‐hour monitoring on a cohort of elderly Italian outpatients and inpatients to determine the prevalence of masked and white coat HTN in different care settings. Finally, Onder et al.23 reported on rates of uncontrolled BP and HTN management among known hypertensives as part of a series of cross‐sectional surveys performed on elderly Italian inpatients.23

Inpatient HTN Prevalence

Overall, study authors reported an HTN prevalence among inpatients that ranged from 50.5% to 72%. Estimates varied somewhat based on HTN definitions, diagnostic standards utilized, measurement techniques, and patient populations. In earlier studies HTN prevalence was reported at 23.8% to 28%, but these likely represented significant underestimates by current diagnostic standards.15, 16 High estimates by Onder et al.23 (86.9%) stem from selection criteria that included a prior billing diagnosis of HTN coupled with elevated admission blood pressures. Estimates in the 50% to 70% prevalence range were seen in studies that focused on cardiac and general medical inpatients.1722 Additional findings of included studies are listed in Table 2.

Accuracy of Inpatient BP Measures

In two studies, 24‐hour BP monitors produced prevalence estimates ranging from 56.4% to 72.6%.21, 22 In both studies, a significant proportion of patients had masked HTN, or HTN detected by 24‐hour BP monitoring alone. Also, 28% to 38% of patients without a prior HTN diagnosis, who were not detected by routine measures, were found to be hypertensive by 24‐hour monitoring. Finally, Conen et al.21 retested a subset of hypertensives with 24‐hour monitoring one month after hospitalization, and 87.5% remained categorized as hypertensive on follow‐up. Of note, it is unclear how this subset of patients was selected.

Proportion of Controlled HTN on Admission and Discharge

Because most included studies established prevalence of HTN based in part upon uncontrolled BP at hospital admission, estimates for the proportion of hypertensive patients controlled on admission were not given. However, Onder et al.23 did examine patients with a prior International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD‐9) diagnosis of HTN and uncontrolled HTN (BP 140/90) on admission. At discharge, only 23.2% of this cohort was controlled with a BP < 140/90 mmHg. However, other estimates suggested that 37% to 44% of patients remained uncontrolled at discharge.16, 20

Proportion of Undiagnosed HTN

In 4 studies, the proportion of patients with elevated BP and/or a history of HTN who did not receive a diagnosis of HTN upon discharge ranged from 8.8% to 44% between cohorts.15, 16, 18, 19 Interpretation of these estimates, however, is difficult due to significant differences between the studies. For example, both earlier studies were performed during an era of higher thresholds for HTN diagnosis and lower overall HTN awareness.15, 16 Both studies of cardiac patients suggested lower rates of nondiagnosis than might have been found in general medical or surgical inpatients.18, 19 One of the 4 studies also suggested that surgical patients who were hypertensive during hospitalization were more likely than medical patients to be discharged without a HTN diagnosis (17% vs. 4%, P < 0.05); although, the overall number of patients was small (18/146 remained undiagnosed).16

Proportion Receiving Intensification of Therapy

In 3 studies, prescribing practices for hypertensive inpatients were discussed. Shankar et al.15 found that only 62% of patients with a recorded HTN diagnosis received antihypertensive medications during hospitalization. Unfortunately, no information was given on the proportion of patients prescribed antihypertensive medications at the time of discharge. However, Greenland et al.16 found no net increase in BP medication use at discharge compared to admission despite 44% of patients remaining uncontrolled to <160/90 mmHg at the time of discharge. Onder et al.23 determined that BP medication was intensified in only 53.1% of hypertensive patients during hospitalization. Younger age, fewer drugs on admission, lower comorbidity index, diagnosis of congestive heart failure, lengthy hospital stay, and increasing levels of BP (systolic and diastolic) were all associated with more aggressive prescribing practices. Interestingly, Jankowski et al.19 found that treatment with a BP lowering agent at discharge was associated with the lowest odds of nontreatment at follow up (odds ratio [OR] 0.08, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.030.19).

Proportion of HTN Controlled at Follow Up

In the EuroASPIRE 1 study, 50% of HTN patients had a systolic BP of < 140 mm Hg at follow up 6 months after hospitalization for MI.17 Jankowski et al.19 found that patients with documented inpatient HTN but without a recorded HTN diagnosis during index admission were 4 times more likely (19.2% vs. 4.5%, P < 0.0001) to be untreated for their HTN at 6 to 18 months postdischarge, and they were less likely to be controlled at <140/90 mmHg. In a separate cohort of cardiac patients, multivariable modeling identified uncontrolled isolated systolic HTN at hospital discharge as an independent predictor of subsequent cardiac death or nonfatal MI at 6 months follow up (OR, 1.96; 95% CI, 1.153.36).20

Discussion

The present systematic review highlights the high prevalence of HTN with contemporary estimates ranging between 50% and 72% in general medical/surgical and cardiology populations. Furthermore, routine inpatient BP measurements may underestimate the prevalence of HTN among inpatients when compared to 24 hour BP monitoring; although there is no current diagnostic standard for HTN among inpatients. Among patients with uncontrolled BP on admission, BP typically remains above recommended levels at the time of discharge. Further, studies commenting on the prescribing practices at the time of discharge did not detect a strong tendency to intensify antihypertensive regimens in patients with uncontrolled inpatient HTN.16, 23 Most importantly, our data suggest that the medical literature is lacking: only 9 reports met our inclusion criteria for this review.

The validity of inpatient BP measures for making an HTN diagnosis remains a concern when asserting that the inpatient setting is appropriate for HTN screening and efforts to improve BP control. For example, BP measures might be inaccurate because of the inherent heterogeneity of patients with acute illness often with associated pain and nausea that might raise or lower BP. Inpatients often need to have their BP medications held for appropriate reasons, or they may have additional medications while hospitalized that also affect BP. Finally, BP measures in the inpatient setting are less commonly performed using standardized techniques or with accurate BP devices. However, both studies included in this review featuring follow up outpatient BP measures found high degrees of correlation between inpatient and outpatient measures.19, 21 Also, Giantin and colleagues reported that 28.6% of elderly patients who were normotensive based on routine BP measures, were actually hypertensive based on 24‐hour ambulatory BP monitoring.22

Some clinicians may have concerns about starting or titrating BP medications in dynamic hospitalized patients. Certainly, this should be done with caution and in appropriately selected patients. We would argue that achieving complete BP control during an index hospitalization as emphasized by Greenland and Amar is not always the most appropriate goal. However, appropriate recognition of persistently elevated BP does offer the opportunity to make an HTN diagnosis and to refer for future outpatient treatment or to communicate with existing primary care providers. The latter is especially important in this era of discontinuity between inpatient and outpatient care. Beginning or titrating BP medications in the hospital also has advantages for 2 reasons. First, medications started in the hospital tend to be the medications on which patients are sent home. Second, in the study by Jankowski et al.,19 the failure to prescribe an antihypertensive medication at the time of discharge was the single strongest predictor of nontreatment at 6 to 18 months follow‐up despite other follow up outpatient visits where BP medications might have been titrated.

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that failure to appropriately manage HTN observed in the inpatient setting can impact subsequent medication use and disease outcomes for high‐risk patients. Amar et al.20 found that better controlled systolic BP on hospital discharge is associated with better outcomes in patients with ischemic heart disease. Only 35% of patients in one cohort admitted to the hospital with hypertensive urgency or emergency completed an outpatient follow up visit for HTN within 90 days. However, 37% were readmitted and 11% died during 3 month follow up.24 Predischarge initiation of a beta blocker in congestive heart failure patients has been associated with a nearly 18% absolute increase in rates of beta blocker use at 2 months follow‐up.25 Finally, prescription of antihypertensive medications is suboptimal for secondary stroke prevention despite a number needed to treat of 51 patients to prevent one stroke annually.26, 27

The primary limitation of this review is the paucity of published reports documenting the prevalence of inpatient HTN. It is possible that important articles were missed, but we did follow a prespecified systematic search strategy with the assistance of a trained reference librarian. Also, the definition of HTN varied significantly between studies. However, current consensus guidelines do not specifically address the diagnosis or management of HTN in the inpatient setting.28

In summary, available medical evidence suggests that HTN is a common problem observed in the hospital. Opportunities for the appropriate diagnosis of HTN and for the initiation or modification of HTN treatment are often missed. Future studies in this area are warranted to better understand the prevalence of HTN in the inpatient setting and the need to improve HTN detection, treatment, and control. Clearer diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for the detection and treatment of inpatient HTN could contribute to further improvements in control rates of all hypertensive patients, especially if coupled with improved care transitions between the inpatient and outpatient setting.

- ,,,,.Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999–2004.Hypertension.2007;49:69–75.

- ,,,.Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control‐continued disparities in adults: United States, 2005–2006.NCHS Data Brief.2008;3:1–8.

- ,,,,,Prospective Studies C.Age‐specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta‐analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies.Lancet.2002;360:1903–1913.

- ,,,,,.Blood pressure screening of school children in a multiracial school district: the Healthy Kids Project.Am J Hypertens.2009;22:351–356.

- ,,,,.Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Findings from a community screening program.Diabetes Educ.2004;30(2):196–198,200–202,220.

- .Screening for traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a review for oral health care providers.J Am Dent Assoc.2002;133:291–300.

- .Health screening in schools. Part II.J Pediatr.1985;107:653–661.

- ,,,.Experience with a community screening program for hypertension: results on 24,462 individuals.Eur J Cardiol.1978;7:487–497.

- .Screening for hypertension in the dental office.J Am Dent Assoc.1974;88:563–567.

- ,,,.2006 National Hospital Discharge Survey:National Center for Health Statistics;2008.

- ,,,,,.Continuity of outpatient and inpatient care by primary care physicians for hospitalized older adults.J Am Med Assoc.2009;301:1671–1680.

- ,,.Influence of hospitalization and placebo therapy on blood pressure and sympathetic function in essential hypertension.Hypertension.1981;3:113–118.

- ,,.Effect of hospitalization on conventional and 24‐hour blood pressure.Age Ageing.1995;24:25–29.

- ,,, et al.Spontaneous fall in blood pressure and reactivity of sympathetic nervous system in hospitalized patients with essential hypertension.Jpn J Med.1990;29:13–21.

- ,,,.Patterns of care for hypertension among hospitalized patients.Public Health Rep.1982;97:521–527.

- ,,.Hospitalization as an opportunity to improve hypertension recognition and control.Med Care.1987;25:717–723.

- EUROASPIRE.A European Society of Cardiology survey of secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: principal results. EUROASPIRE Study Group. European Action on Secondary Prevention through Intervention to Reduce Events.Eur Heart J.1997;18:1569–1582.

- Lifestyle and risk factor management and use of drug therapies in coronary patients from 15 countries; principal results from EUROASPIRE II Euro Heart Survey Programme.Eur Heart J.2001;22:554–572.

- ,,,.Determinants of poor hypertension management in patients with ischaemic heart disease.Blood Press.2005;14:284–292.

- ,,, et al.Hypertension control at hospital discharge after acute coronary event: influence on cardiovascular prognosis‐‐the PREVENIR study.Heart.2002;88:587–591.

- ,,,.High prevalence of newly detected hypertension in hospitalized patients: the value of in‐hospital 24‐h blood pressure measurement.J Hypertens2006;24:301–306.

- ,,, et al.Masked and white‐coat hypertension in two cohorts of elderly subjects, ambulatory and hospitalized patients.Arch Gerontol Geriatr.2009;49Suppl 1:125–128.

- ,,, et al.Impact of hospitalization on blood pressure control in Italy: results from the Italian Group of Pharmacoepidemiology in the Elderly (GIFA).Pharmacotherapy.2003;23:240–247.

- ,,, et al.Practice patterns, outcomes, and end‐organ dysfunction for patients with acute severe hypertension: The Studying the Treatment of Acute hyperTension (STAT) Registry.Am Heart J.2009;158:599–606.

- ,,,,.Predischarge initiation of carvedilol in patients hospitalized for decompensated heart failure: results of the Initiation Management Predischarge: Process for Assessment of Carvedilol Therapy in Heart Failure (IMPACT‐HF) trial.J Am Coll Cardiol.2004;43:1534–1541.

- ,,,.Antihypertensive medications prescribed at discharge after an acute ischemic cerebrovascular event.Stroke.2005;36:1944–1947.

- ,,.New Evidence for Stroke Prevention: Scientific Review.JAMA.2002;288:1388–1395.

- ,,,,.Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee.Hypertension.2003;42:1206–1252.

- ,,,,.Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension among United States adults 1999–2004.Hypertension.2007;49:69–75.

- ,,,.Hypertension awareness, treatment, and control‐continued disparities in adults: United States, 2005–2006.NCHS Data Brief.2008;3:1–8.

- ,,,,,Prospective Studies C.Age‐specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta‐analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies.Lancet.2002;360:1903–1913.

- ,,,,,.Blood pressure screening of school children in a multiracial school district: the Healthy Kids Project.Am J Hypertens.2009;22:351–356.

- ,,,,.Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Findings from a community screening program.Diabetes Educ.2004;30(2):196–198,200–202,220.

- .Screening for traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a review for oral health care providers.J Am Dent Assoc.2002;133:291–300.

- .Health screening in schools. Part II.J Pediatr.1985;107:653–661.

- ,,,.Experience with a community screening program for hypertension: results on 24,462 individuals.Eur J Cardiol.1978;7:487–497.

- .Screening for hypertension in the dental office.J Am Dent Assoc.1974;88:563–567.

- ,,,.2006 National Hospital Discharge Survey:National Center for Health Statistics;2008.

- ,,,,,.Continuity of outpatient and inpatient care by primary care physicians for hospitalized older adults.J Am Med Assoc.2009;301:1671–1680.

- ,,.Influence of hospitalization and placebo therapy on blood pressure and sympathetic function in essential hypertension.Hypertension.1981;3:113–118.

- ,,.Effect of hospitalization on conventional and 24‐hour blood pressure.Age Ageing.1995;24:25–29.

- ,,, et al.Spontaneous fall in blood pressure and reactivity of sympathetic nervous system in hospitalized patients with essential hypertension.Jpn J Med.1990;29:13–21.

- ,,,.Patterns of care for hypertension among hospitalized patients.Public Health Rep.1982;97:521–527.

- ,,.Hospitalization as an opportunity to improve hypertension recognition and control.Med Care.1987;25:717–723.

- EUROASPIRE.A European Society of Cardiology survey of secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: principal results. EUROASPIRE Study Group. European Action on Secondary Prevention through Intervention to Reduce Events.Eur Heart J.1997;18:1569–1582.

- Lifestyle and risk factor management and use of drug therapies in coronary patients from 15 countries; principal results from EUROASPIRE II Euro Heart Survey Programme.Eur Heart J.2001;22:554–572.

- ,,,.Determinants of poor hypertension management in patients with ischaemic heart disease.Blood Press.2005;14:284–292.

- ,,, et al.Hypertension control at hospital discharge after acute coronary event: influence on cardiovascular prognosis‐‐the PREVENIR study.Heart.2002;88:587–591.

- ,,,.High prevalence of newly detected hypertension in hospitalized patients: the value of in‐hospital 24‐h blood pressure measurement.J Hypertens2006;24:301–306.

- ,,, et al.Masked and white‐coat hypertension in two cohorts of elderly subjects, ambulatory and hospitalized patients.Arch Gerontol Geriatr.2009;49Suppl 1:125–128.

- ,,, et al.Impact of hospitalization on blood pressure control in Italy: results from the Italian Group of Pharmacoepidemiology in the Elderly (GIFA).Pharmacotherapy.2003;23:240–247.

- ,,, et al.Practice patterns, outcomes, and end‐organ dysfunction for patients with acute severe hypertension: The Studying the Treatment of Acute hyperTension (STAT) Registry.Am Heart J.2009;158:599–606.

- ,,,,.Predischarge initiation of carvedilol in patients hospitalized for decompensated heart failure: results of the Initiation Management Predischarge: Process for Assessment of Carvedilol Therapy in Heart Failure (IMPACT‐HF) trial.J Am Coll Cardiol.2004;43:1534–1541.

- ,,,.Antihypertensive medications prescribed at discharge after an acute ischemic cerebrovascular event.Stroke.2005;36:1944–1947.

- ,,.New Evidence for Stroke Prevention: Scientific Review.JAMA.2002;288:1388–1395.

- ,,,,.Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee.Hypertension.2003;42:1206–1252.

IRIS Presenting as Acute Pericarditis

Although antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)‐infected patients reduces viral load dramatically and improves immune function, some patients experience a clinical deterioration within the first few months of therapy because of an exuberant and dysregulated immune responsethe immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). The exaggerated immune response associated with this syndrome can be stimulated by either antigens from infectious agents (typically a mycobacterium or cryptococcus) or from autoantigens, giving rise to a heterogeneous range of clinical manifestations.1 IRIS may present as an inflammatory reaction that unmasks a previously untreated infection or as a paradoxical worsening of an infection that is being treated appropriately. Although most cases of IRIS are mild and self‐limited, some patients require aggressive treatment.1

Case Report

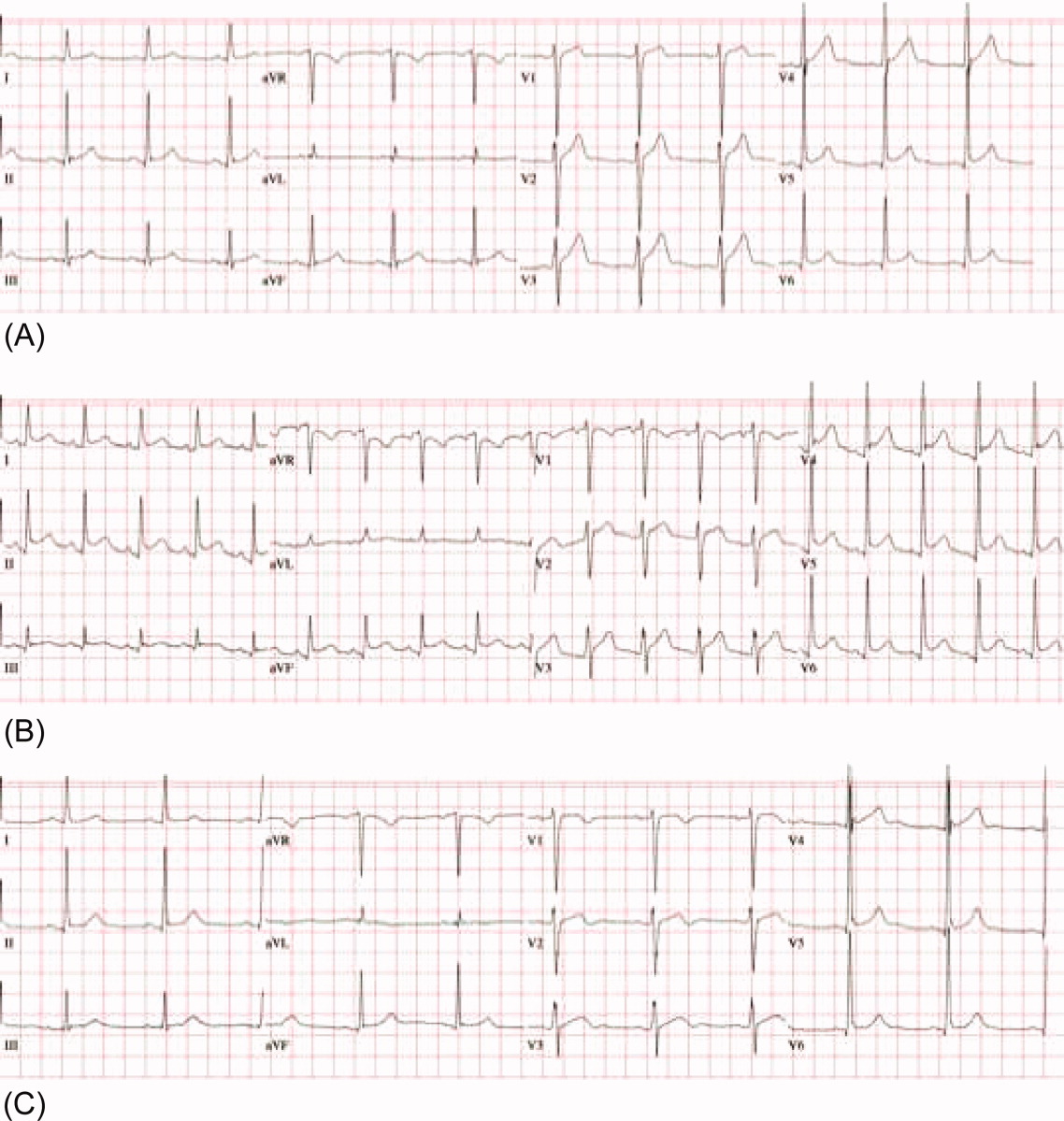

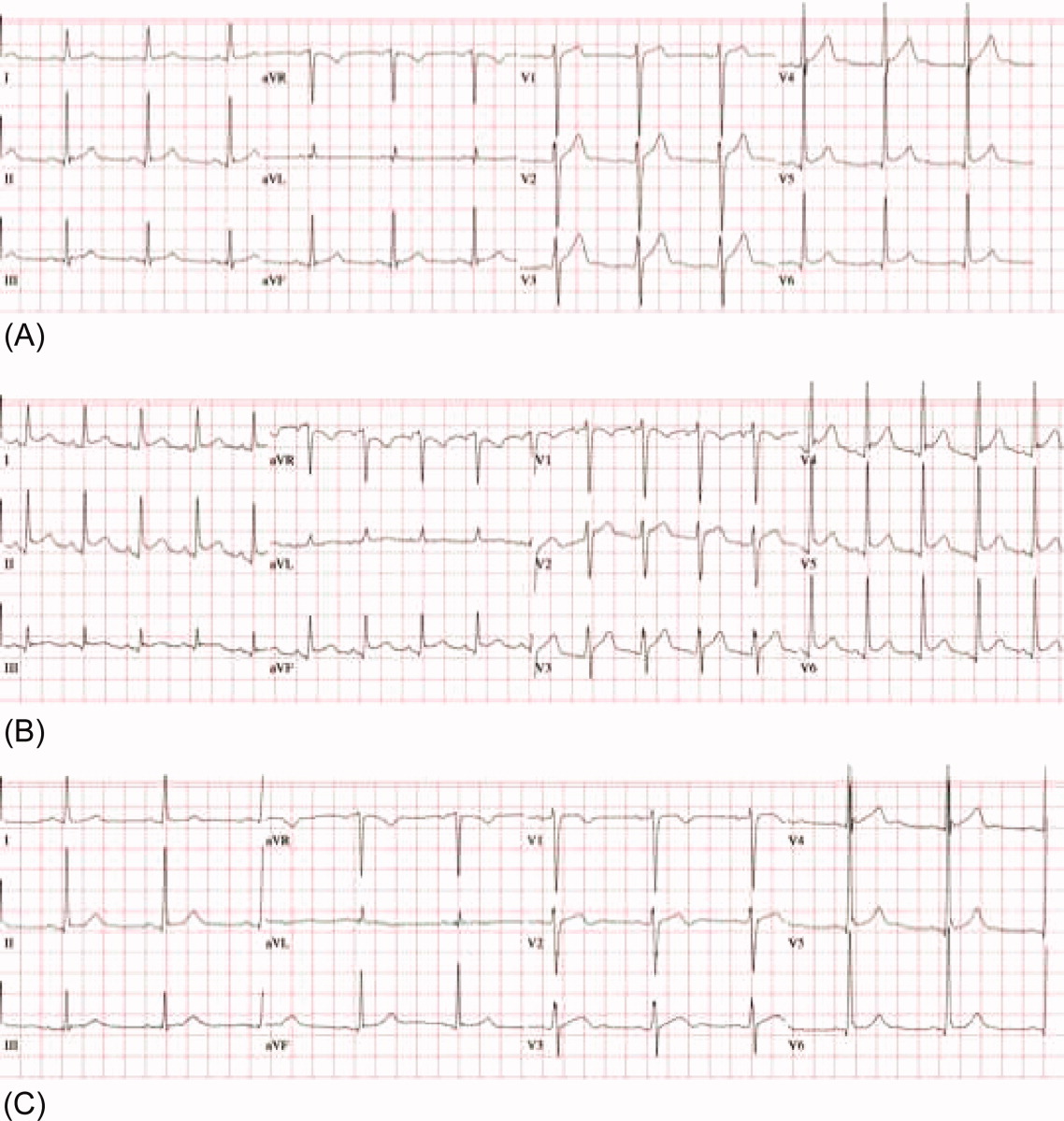

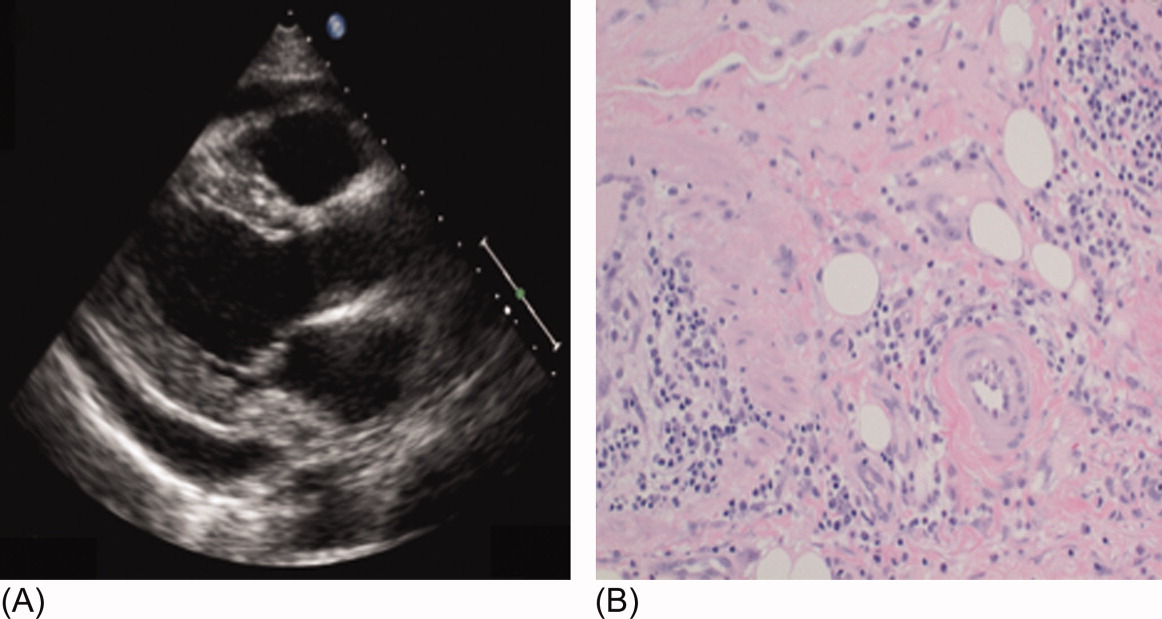

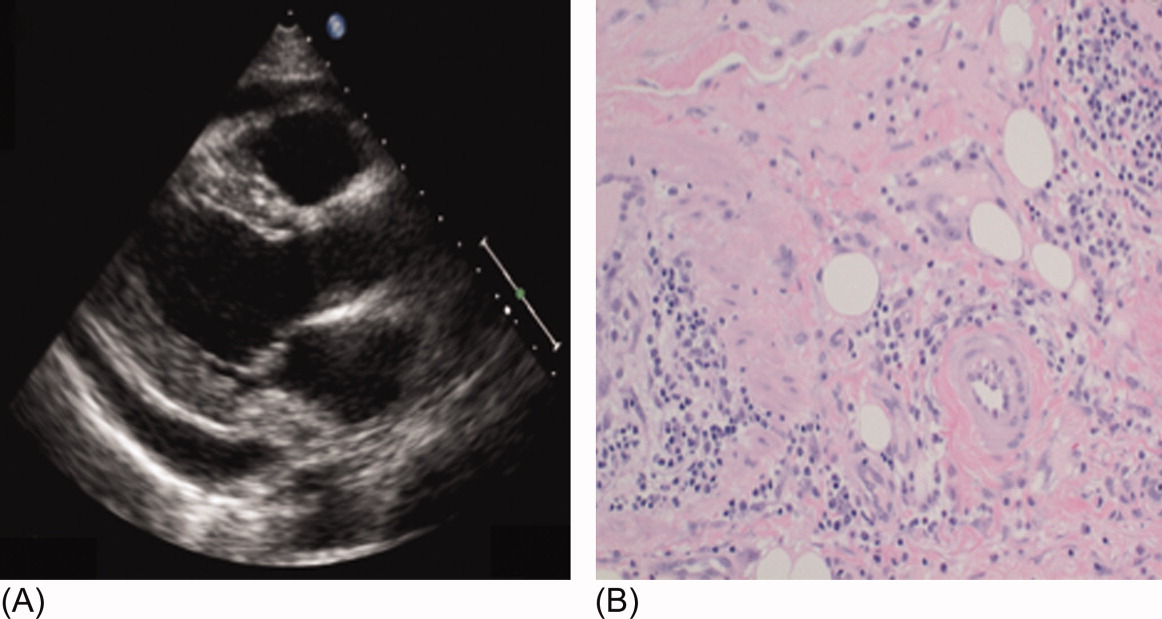

A 53‐year‐old man was evaluated for a 5‐day history of intermittent chest pain. He had been diagnosed with HIV/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) 11 years ago but he had not been compliant with therapy. Seven years earlier he had been treated for 9 months with isoniazid for a positive tuberculin skin test. Three months before admission, he developed methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin abscesses and was found to have a CD4 count of 1/L and a HIV viral load of over 400,000 copies/mL. He finished a course of vancomycin, and was started on lopinavir, ritonavir, abacavir, lamivudine, and zidovudine. Five days before admission, he was evaluated in the emergency department for intermittent chest pain and described using cocaine. There was only J‐point elevation on the electrocardiogram (Figure 1A), serial cardiac enzymes were negative, and he was discharged home. However, despite discontinuation of cocaine use, his chest pain worsened, became pleuritic, and was associated with dyspnea, which prompted this admission. Physical examination was remarkable only for tachycardia, although the electrocardiogram now revealed diffuse ST segment (ST) elevation and PR segment (PR) depression, consistent with acute pericarditis (Figure 1B). Serial cardiac enzymes, viral studies, and bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial blood cultures were negative. His CD4 count was 16/L, and the HIV viral load was 870 copies/mL.

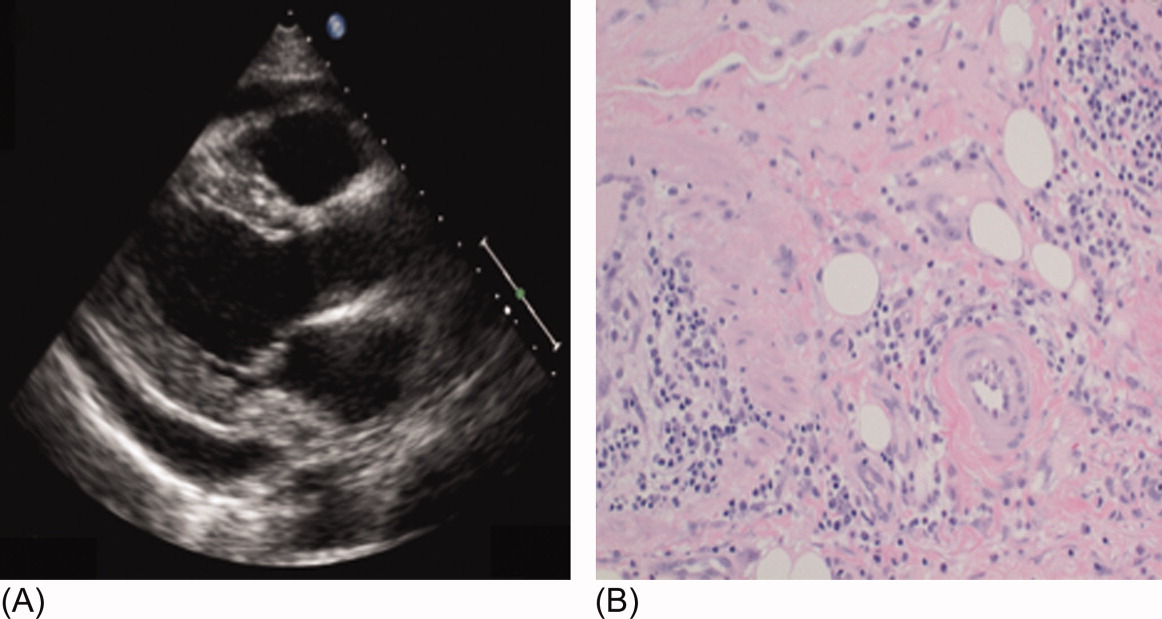

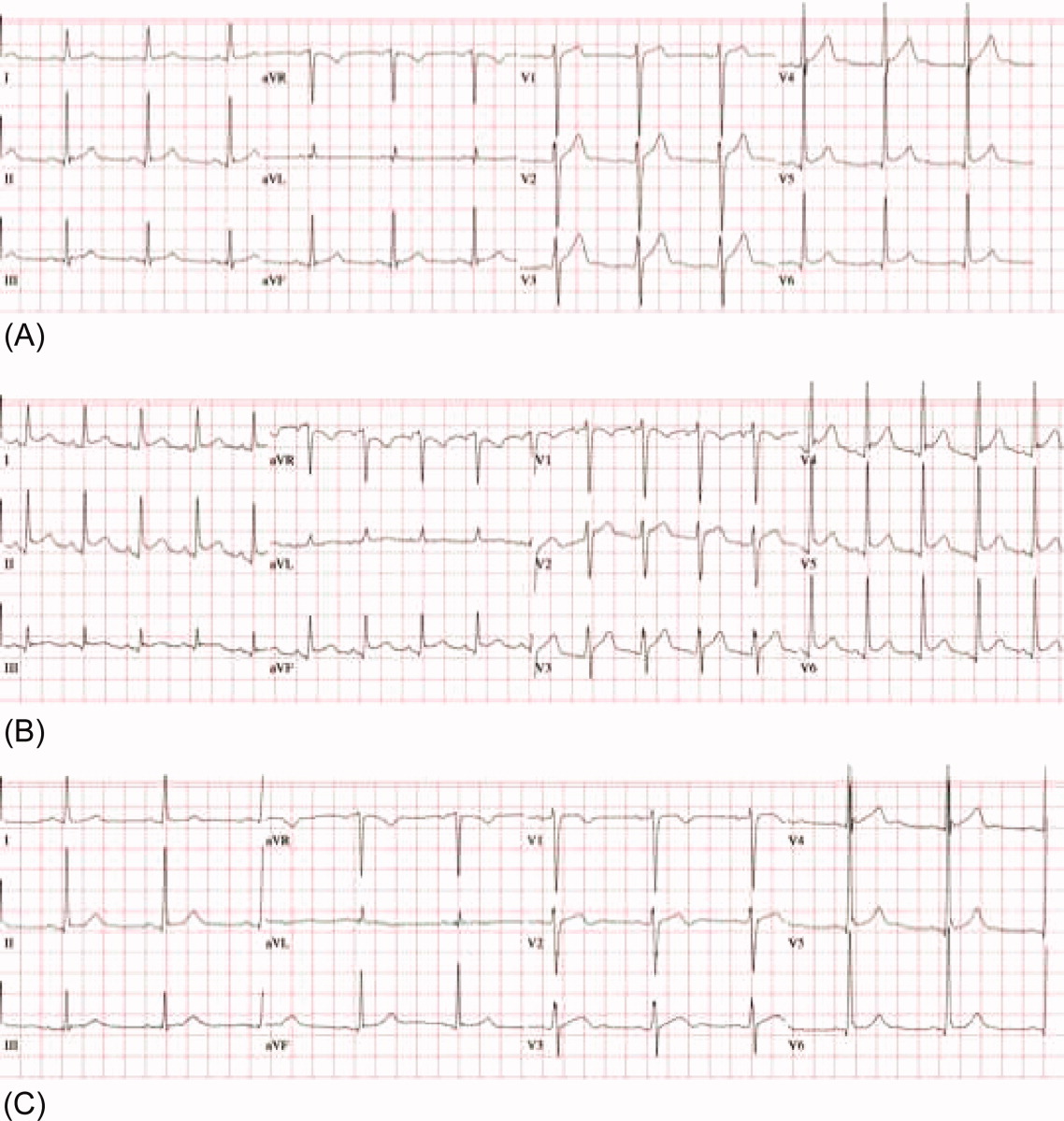

The patient was treated with high‐dose ibuprofen and colchicine, but mild chest pain and electrocardiogram changes persisted, and he developed a friction rub. A chest computed tomography (CT) scan was negative for pulmonary embolism and revealed no significant intra‐thoracic pathology, except for a moderate pericardial effusion that was confirmed by transthoracic echocardiogram (Figure 2A). There was no echocardiographic evidence of tamponade. He underwent thoracoscopic pericardial and mediastinal lymph node biopsy, along with drainage of the pericardial effusion. Pericardial biopsy showed acute on chronic inflammation consistent with pericarditis (Figure 2B) and culture was positive for Mycobacterium Avium Complex (MAC). He was treated with clarithromycin, ethambutol, and prednisone, and his antiretroviral medications were continued. At 2, 6, and 12 months follow‐up, he was asymptomatic, the electrocardiogram had normalized (Figure 1C), and the echocardiogram showed no effusion or evidence of pericardial constriction.

Discussion

This case demonstrates a unique manifestation of the IRIS associated with MAC infection, which more typically presents as peripheral, pulmonary, or intra‐abdominal lymphadenopathy.2, 3 It usually responds to MAC therapy, although intra‐abdominal disease portends a poor prognosis.3, 4 This patient has two significant risk factors for the development of IRIS: low CD4 count at the time of antiretroviral therapy and rapid viral clearance.5, 6 While his CD4 count response is lower than expected for IRIS, previous studies have shown that functional immune recovery usually precedes quantitative CD4 count recovery, and that IRIS could happen at low CD4 count.1, 7 Finally, we believe that the use of corticosteroids accounted for his rapid clinical improvement and favorable long‐term outcome, consistent with previous experience of corticosteroid use in MAC‐associated IRIS.3, 4 To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of MAC‐associated IRIS presenting as isolated acute pericarditis and pericardial effusion. In conclusion, our case illustrates that IRIS can present as an abnormal immune response to an opportunistic infection in an unusual location. Clinicians must be aware that after starting antiretroviral therapy, new symptoms, including chest pain, might represent 1 of the IRISs, and that corticosteroids might be beneficial when inflammation is severe.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Arthur Evans for his comments.

- ,,,,.Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in HIV‐infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy.Drugs.2008;68:191–208.

- ,,,,.The imaging features of nontuberculous mycobacterial immune reconstitution syndrome.J Comput Assist Tomogr.2009;33:242–246.

- ,,, et al.Nontuberculous mycobacterial immune reconstitution syndrome in HIV‐infected patients: spectrum of disease and long‐term follow‐up.Clin Infect Dis.2005;41:1483–1497.

- ,,,,,.Mycobacterium avium complex immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: long term outcomes.J Transl Med.2007;5:50–56.

- ,,, et al.Incidence and risk factors for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome during highly active antiretroviral therapy.AIDS.2005;19:399–406.