User login

Outcomes Discrepancy

A new study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine that reports insured hospitalized patients from ages 18-64 have 50% higher odds of surviving a heart attack or stroke than their uninsured counterparts should be a wake-up call to HM leaders looking to improve standards of care, one hospitalist says.

“It’s almost startling and embarrassing when you see the statistics on paper,” says Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSc, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of Boston-based Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s general medicine service. “If you’re going to assign a specialty to address the problem, it’s a hospital medicine problem.”

The researchers retrospectively analyzed 150,000 discharges among patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, or pneumonia (DOI: 10.1002/jhm.687). Compared with the privately insured, the study reported "in-hospital mortality among AMI and stroke patients was significantly higher for the uninsured (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.52, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.24-1.85 for AMI and 1.49 OR, 1.29-1.72 for stroke) and among pneumonia patients was significantly higher for Medicaid recipients (1.21 OR, 1.01-1.45)." The lead author was Omar Hasan, MBBS, MPH, an instructor at Harvard Medical School and a hospitalist at Brigham and Women’s.

Dr. Scheurer cautions that the subject raised by her colleague is a multidimensional problem with no easy solution. Physicians may unconsciously make triage decisions that feed into the difference of care, she says, while insured patients who more actively engage their doctors could also skew the numbers.

She thinks, however, that “systematically creating protocols, policies, and procedures” could result in clinical-care delivery that helps reduce the disparity.

“Part of [the importance of the study] is having an open dialogue,” Dr. Scheurer says. “This is real. There is this disparity.”

A new study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine that reports insured hospitalized patients from ages 18-64 have 50% higher odds of surviving a heart attack or stroke than their uninsured counterparts should be a wake-up call to HM leaders looking to improve standards of care, one hospitalist says.

“It’s almost startling and embarrassing when you see the statistics on paper,” says Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSc, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of Boston-based Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s general medicine service. “If you’re going to assign a specialty to address the problem, it’s a hospital medicine problem.”

The researchers retrospectively analyzed 150,000 discharges among patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, or pneumonia (DOI: 10.1002/jhm.687). Compared with the privately insured, the study reported "in-hospital mortality among AMI and stroke patients was significantly higher for the uninsured (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.52, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.24-1.85 for AMI and 1.49 OR, 1.29-1.72 for stroke) and among pneumonia patients was significantly higher for Medicaid recipients (1.21 OR, 1.01-1.45)." The lead author was Omar Hasan, MBBS, MPH, an instructor at Harvard Medical School and a hospitalist at Brigham and Women’s.

Dr. Scheurer cautions that the subject raised by her colleague is a multidimensional problem with no easy solution. Physicians may unconsciously make triage decisions that feed into the difference of care, she says, while insured patients who more actively engage their doctors could also skew the numbers.

She thinks, however, that “systematically creating protocols, policies, and procedures” could result in clinical-care delivery that helps reduce the disparity.

“Part of [the importance of the study] is having an open dialogue,” Dr. Scheurer says. “This is real. There is this disparity.”

A new study in the Journal of Hospital Medicine that reports insured hospitalized patients from ages 18-64 have 50% higher odds of surviving a heart attack or stroke than their uninsured counterparts should be a wake-up call to HM leaders looking to improve standards of care, one hospitalist says.

“It’s almost startling and embarrassing when you see the statistics on paper,” says Danielle Scheurer, MD, MSc, SFHM, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of Boston-based Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s general medicine service. “If you’re going to assign a specialty to address the problem, it’s a hospital medicine problem.”

The researchers retrospectively analyzed 150,000 discharges among patients hospitalized for acute myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, or pneumonia (DOI: 10.1002/jhm.687). Compared with the privately insured, the study reported "in-hospital mortality among AMI and stroke patients was significantly higher for the uninsured (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.52, 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.24-1.85 for AMI and 1.49 OR, 1.29-1.72 for stroke) and among pneumonia patients was significantly higher for Medicaid recipients (1.21 OR, 1.01-1.45)." The lead author was Omar Hasan, MBBS, MPH, an instructor at Harvard Medical School and a hospitalist at Brigham and Women’s.

Dr. Scheurer cautions that the subject raised by her colleague is a multidimensional problem with no easy solution. Physicians may unconsciously make triage decisions that feed into the difference of care, she says, while insured patients who more actively engage their doctors could also skew the numbers.

She thinks, however, that “systematically creating protocols, policies, and procedures” could result in clinical-care delivery that helps reduce the disparity.

“Part of [the importance of the study] is having an open dialogue,” Dr. Scheurer says. “This is real. There is this disparity.”

In the Literature: Research You Need to Know

Clinical question: What is the prevalence of silent pulmonary embolism (PE) in patients with deep venous thrombosis (DVT)?

Background: Pulmonary embolism was undiagnosed or unsuspected in approximately 80% to 93% patients antemortem who were found to have a PE at autopsy. The extent to which silent pulmonary embolism explains the undiagnosed or unsuspected pulmonary emboli at autopsy is not certain. Prior studies have demonstrated the association of silent PE in living patients with DVT.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: Published trials performed worldwide.

Synopsis: A systematic review of published trials addressing the prevalence of silent pulmonary embolism in patients with deep vein thrombosis was performed. Studies were included if methods of diagnosis of PE were described, if it was an asymptomatic PE, and if raw data were presented. Twenty-eight studies were identified and were stratified according to how the PE was diagnosed (Tier 1: high-probability VQ scan based on PIOPED criteria, CTA, angiography; Tier 2: VQ scans based on non-PIOPED criteria).

Among Tier 1 studies, silent PE was detected among 27% of patients with DVT. Among Tier 2 studies, silent PE was detected among 37% of patients with DVT. Combined, silent PE was diagnosed in 1,665 of 5,233 patients (32%) with DVT. Further analysis showed that the prevalence of silent PE in patients with proximal DVT was higher in those with distal DVT, and that there was a trend toward increased prevalence of silent PE with increased age.

A limitation of this study includes the heterogeneity in the methods used for diagnosis of silent pulmonary embolism.

Bottom line: Silent pulmonary embolism occurs in one-third of patients with deep venous thrombosis, and routine screening should be considered.

Citation: Stein P, Matta F, Musani MH, Diaczok B. Silent pulmonary embolism in patients with deep venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2010;123(5):426-431.

Reviewed for TH eWire by Alexander R. Carbo, MD, SFHM, Lauren Doctoroff, MD, John Fani Srour, MD, Matthew Hill, MD, Nancy Torres-Finnerty, MD, FHM, Anita Vanka, MD, Hospital Medicine Program, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

For more physician reviews of HM-related research, visit our website.

Clinical question: What is the prevalence of silent pulmonary embolism (PE) in patients with deep venous thrombosis (DVT)?

Background: Pulmonary embolism was undiagnosed or unsuspected in approximately 80% to 93% patients antemortem who were found to have a PE at autopsy. The extent to which silent pulmonary embolism explains the undiagnosed or unsuspected pulmonary emboli at autopsy is not certain. Prior studies have demonstrated the association of silent PE in living patients with DVT.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: Published trials performed worldwide.

Synopsis: A systematic review of published trials addressing the prevalence of silent pulmonary embolism in patients with deep vein thrombosis was performed. Studies were included if methods of diagnosis of PE were described, if it was an asymptomatic PE, and if raw data were presented. Twenty-eight studies were identified and were stratified according to how the PE was diagnosed (Tier 1: high-probability VQ scan based on PIOPED criteria, CTA, angiography; Tier 2: VQ scans based on non-PIOPED criteria).

Among Tier 1 studies, silent PE was detected among 27% of patients with DVT. Among Tier 2 studies, silent PE was detected among 37% of patients with DVT. Combined, silent PE was diagnosed in 1,665 of 5,233 patients (32%) with DVT. Further analysis showed that the prevalence of silent PE in patients with proximal DVT was higher in those with distal DVT, and that there was a trend toward increased prevalence of silent PE with increased age.

A limitation of this study includes the heterogeneity in the methods used for diagnosis of silent pulmonary embolism.

Bottom line: Silent pulmonary embolism occurs in one-third of patients with deep venous thrombosis, and routine screening should be considered.

Citation: Stein P, Matta F, Musani MH, Diaczok B. Silent pulmonary embolism in patients with deep venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2010;123(5):426-431.

Reviewed for TH eWire by Alexander R. Carbo, MD, SFHM, Lauren Doctoroff, MD, John Fani Srour, MD, Matthew Hill, MD, Nancy Torres-Finnerty, MD, FHM, Anita Vanka, MD, Hospital Medicine Program, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

For more physician reviews of HM-related research, visit our website.

Clinical question: What is the prevalence of silent pulmonary embolism (PE) in patients with deep venous thrombosis (DVT)?

Background: Pulmonary embolism was undiagnosed or unsuspected in approximately 80% to 93% patients antemortem who were found to have a PE at autopsy. The extent to which silent pulmonary embolism explains the undiagnosed or unsuspected pulmonary emboli at autopsy is not certain. Prior studies have demonstrated the association of silent PE in living patients with DVT.

Study design: Systematic review.

Setting: Published trials performed worldwide.

Synopsis: A systematic review of published trials addressing the prevalence of silent pulmonary embolism in patients with deep vein thrombosis was performed. Studies were included if methods of diagnosis of PE were described, if it was an asymptomatic PE, and if raw data were presented. Twenty-eight studies were identified and were stratified according to how the PE was diagnosed (Tier 1: high-probability VQ scan based on PIOPED criteria, CTA, angiography; Tier 2: VQ scans based on non-PIOPED criteria).

Among Tier 1 studies, silent PE was detected among 27% of patients with DVT. Among Tier 2 studies, silent PE was detected among 37% of patients with DVT. Combined, silent PE was diagnosed in 1,665 of 5,233 patients (32%) with DVT. Further analysis showed that the prevalence of silent PE in patients with proximal DVT was higher in those with distal DVT, and that there was a trend toward increased prevalence of silent PE with increased age.

A limitation of this study includes the heterogeneity in the methods used for diagnosis of silent pulmonary embolism.

Bottom line: Silent pulmonary embolism occurs in one-third of patients with deep venous thrombosis, and routine screening should be considered.

Citation: Stein P, Matta F, Musani MH, Diaczok B. Silent pulmonary embolism in patients with deep venous thrombosis: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2010;123(5):426-431.

Reviewed for TH eWire by Alexander R. Carbo, MD, SFHM, Lauren Doctoroff, MD, John Fani Srour, MD, Matthew Hill, MD, Nancy Torres-Finnerty, MD, FHM, Anita Vanka, MD, Hospital Medicine Program, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

For more physician reviews of HM-related research, visit our website.

Age‐Specific CSF Protein Reference Values

Emergency department evaluation of a febrile neonate or young infant routinely includes lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis to diagnose meningitis or encephalitis. In addition to CSF Gram stain and culture, clinicians generally request a laboratory report for the CSF cell count, glucose content and protein concentration. Interpretation of these ancillary tests requires knowledge of normal reference values. In adult medicine, the accepted reference value for CSF protein concentration at the level of the lumbar spine is 15 mg/dL to45 mg/dL.1 There is general consensus among reference texts and published original studies dating back to Widell2 in 1958 that adult CSF protein reference values are not valid in the pediatric population. A healthy neonate's CSF protein concentration is normally twice to 3 times that of an adult, and declines with age from birth to early childhood. The most rapid rate of decline is thought to occur in the first 6 months of life as the infant's blood‐CSF barrier matures.3 However, published studies47 differ in the reported rate, timing, and magnitude of this decline; on close review these studies have significant limitations which call into question the appropriateness of using these values in clinical practice. Perhaps in recognition of the limited evidence, textbooks of general pediatrics,810 hospital medicine,1113 emergency medicine,14, 15 infectious diseases,16, 17 neonatology,18 and neurology19, 20 frequently publish norms for pediatric CSF protein concentration without reference to any original research studies.

Because ethical considerations prohibit subjecting young infants to a potentially painfully procedure (ie, lumbar puncture) before they are able to assent, we sought to define a study population that approximates a group of healthy infants. Our objectives were to quantify age‐related declines in CSF protein concentration and to determine accurate, age‐specific reference values for CSF protein concentration in a population of neonates and young infants who presented for medical care with an indication for lumbar puncture and were subsequently found to have no condition associated with elevated or depressed CSF protein concentration.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This cross‐sectional study was performed at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, PA), an urban, tertiary‐care children's hospital. The Committees for the Protection of Human Subjects approved this study with a waiver of informed consent.

Study Participants

Infants 56 days of age or younger were eligible for inclusion if they had a lumbar puncture performed as part of their emergency department evaluation between January 1, 2005 and June 30, 2007. Children in this age range were selected as they routinely undergo lumbar puncture when presenting with fever at our institution.21, 22 Patients undergoing lumbar puncture in the emergency department were identified using 2 different data sources to ensure accurate identification of all eligible infants: (1) Emergency department computerized order entry records identified all infants with CSF testing (including CSF Gram stain, culture, cell count, glucose, or protein) performed during the study period, and (2) Clinical Virology Laboratory records identified all infants in whom CSF herpes simplex virus or enterovirus testing was performed. Medical records of infants identified by these 2 sources were reviewed to determine study eligibility.

Subjects with conditions known or suspected to cause abnormal CSF protein concentration were systematically excluded from the final analysis. Exclusion criteria included traumatic lumbar puncture (defined as CSF sample with >500 red blood cells per mm3), serious bacterial infection (including meningitis, urinary tract infection, bacteremia, pneumonia, osteomyelitis, or septic arthritis), congenital infection, CSF positive for enterovirus by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, seizure prior to presentation, presence of a ventricular shunt device, elevated serum bilirubin, and absent CSF protein measurements or CSF red blood cell counts. The presence of lysed red blood cells in the CSF secondary to a traumatic lumbar puncture or subarachnoid hemorrhage alters the CSF protein.23 We also excluded subjects who had CSF assays done on samples drawn by accessing a ventricular shunt device, as there may be up to a 300% regional difference in CSF protein concentration between the cranial and caudal ends of the neuroaxis.1 Bilirubin in the CSF sample at a concentration of 5 mg/dL biases the CSF protein concentration measurement by an average of 13.7 mg/dL.24 Quantitative protein assay was performed on the institution's standard Vitros chemistry system; the protein assay is a modified biuret reaction.

Study Definitions

CSF pleocytosis was defined as a CSF white blood cell count (WBC) >22/mm3 (for infants age 28 days) or >15/mm3 (for infants 2956 days of age).25 Bacterial meningitis was defined as isolation of a bacterial pathogen from the CSF. Bacteremia was defined as isolation of a bacterial pathogen from blood culture, excluding isolates that reflected commensal skin flora. Bacterial pneumonia was defined as a new discrete infiltrate on chest radiograph as documented by an attending pediatric radiologist in conjunction with growth of a respiratory bacterial pathogen from blood culture. Urinary tract infection was defined as growth of a single known pathogen in culture as follows: (1) 1000 colony‐forming units/mL for cultures obtained by suprapubic aspiration, (2) 50,000 cfu/mL from a catheterized specimen, or (3) 10,000 cfu/mL from catheterized specimen in conjunction with a positive urinalysis.26 Positive urinalysis was defined as trace or greater leukocyte esterase by dip stick, or >9 WBC per high‐power filed on standard microscopic exam of centrifuged urine, or >10 WBC/mm3 by hemocytometer count of uncentrifuged urine.27, 28 We defined osteomyelitis as growth of pathogenic bacteria from blood, bone, or subperiosteal aspirate culture in a subject with fever and localized tenderness, edema or erythema at the site of bony infection, and compatible imaging; and septic arthritis as growth of pathogenic bacteria from synovial fluid or blood culture from a subject with purulent synovial fluid or positive Gram stain of synovial fluid.

A temperature 38.0C by any method qualified as fever. Prematurity was defined as a gestational age less than 37 weeks. Seizure included any clinical description of the event within 48 hours of presentation to the Emergency Department, or documented seizure activity on electroencephalogram. Enterovirus season was defined as June 1st to October 31st of each year.29

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

Information collected included the following: demographics, vital signs, history of present illness, birth history, clinical findings, results of laboratory testing and imaging within 48 hours of presentation, antibiotics administered, and duration of visit to the Emergency Department or admission to the hospital.

Categorical data were described using frequencies and percents, and continuous variables were described using mean, median, interquartile range, and 90th and 95th percentile values. Linear regression was used to determine the association between age and CSF protein concentration. Because the CSF protein concentrations had a skewed distribution (P < 0.001, Shapiro‐Wilk test), our analyses were performed using logarithmically transformed CSF protein values as the dependent variable. The resulting beta‐coefficients were transformed to reflect the percent change in CSF protein with increasing age. Two‐sample Wilcoxon rank‐sum tests were subsequently used to compare the distribution of CSF protein concentrations amongst four predefined age categories to facilitate implementation of our results into clinical practice: 014 days, 1528 days, 2942 days, and 4356 days. The analyses were repeated while excluding preterm infants, patients receiving antibiotics before lumbar puncture, and patients with CSF pleocytosis to determine the impact of these factors on CSF protein concentrations. Data were analyzed using STATA v10 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Two‐tailed P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

During the study period, 1064 infants age 56 days of age or younger underwent lumbar puncture in the emergency department. Of these, 689 (65%) met sequential exclusion criteria as follows: traumatic lumbar puncture (n = 330); transported from an outside medical facility (n = 90); bacterial meningitis (n = 6); noncentral nervous system serious bacterial infections (n = 135); CSF positive for herpes simplex virus by PCR (n = 2); CSF positive for enterovirus by PCR (n = 45); congenital syphilis (n = 1); seizures (n = 28); abnormal central nervous system imaging (n = 2); and ventricular shunt device (n = 1). An additional 44 patients had lumbar puncture and CSF testing but the protein assay was never done or never reported and 5 patients did not have a CSF red blood cell count available. No cases were excluded for elevated serum bilirubin. Infants may have met multiple exclusion criteria. The remaining 375 (35%) subjects were included in the final analysis. The median patient age was 36 days (interquartile range: 2247 days); 139 (37%) were 28 days of age or younger. Overall, 205 (55%) were male, 211 (56%) were black, and 145 (39%) presented during enterovirus season. Most (43 of 57) preterm infants were born between 34 weeks to 37 weeks gestation. Antibiotics were administered before lumbar puncture to 42 (11%) infants and 312 (83%) infants had fever.

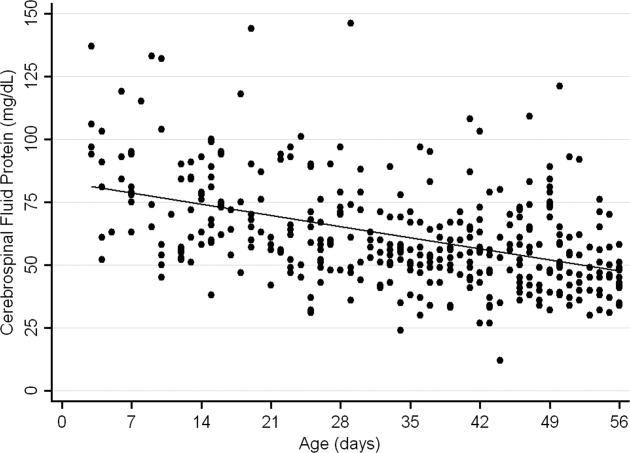

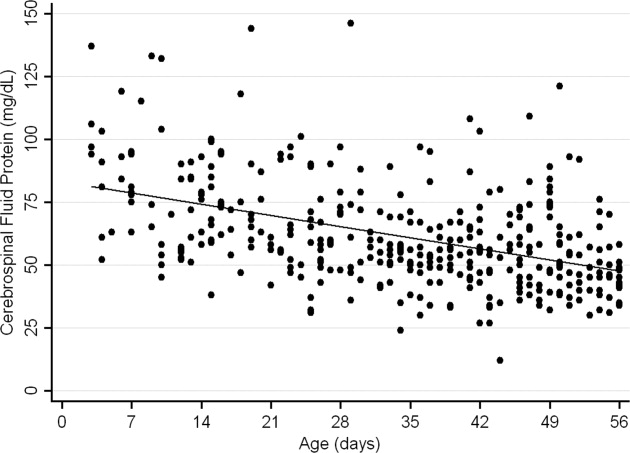

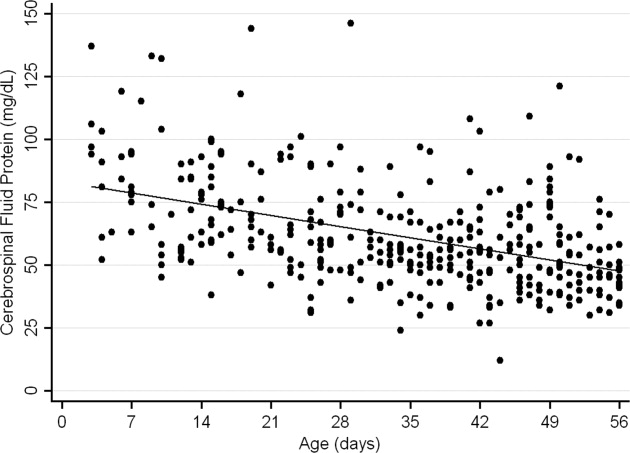

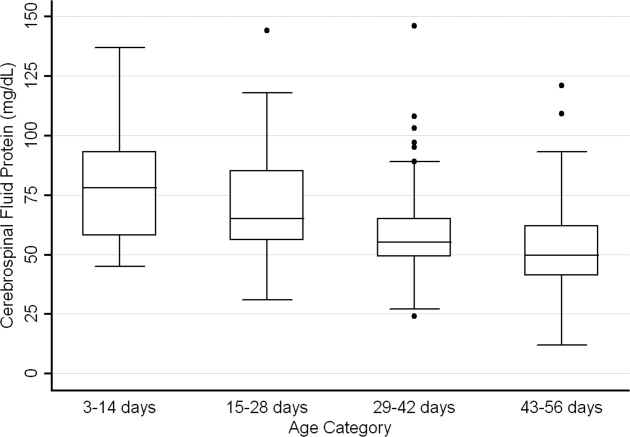

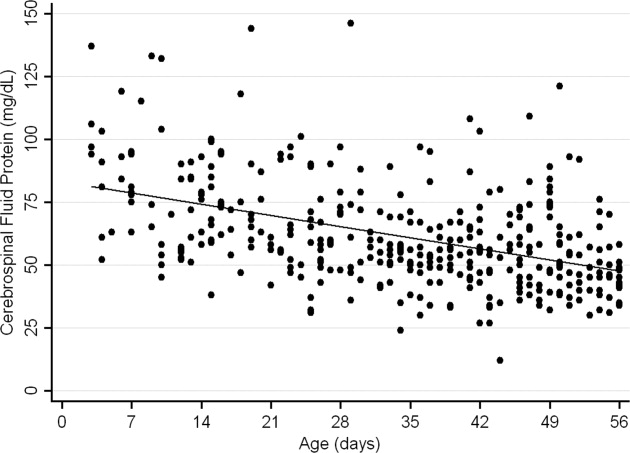

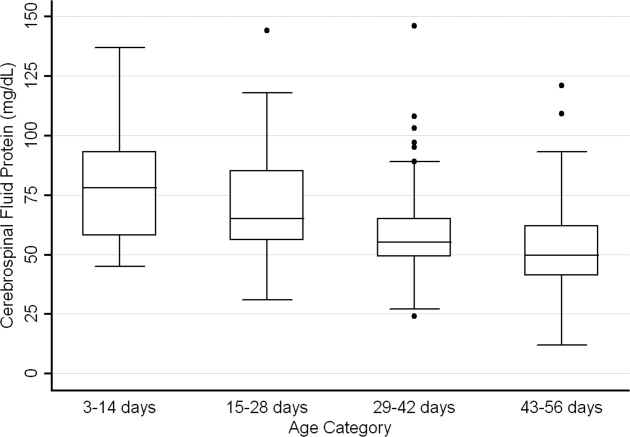

The median CSF protein value was 58 mg/dL (interquartile range: 4872 mg/dL). There was an age‐related declined in CSF protein concentration (Figure 1). In linear regression, the CSF protein concentration decreased 6.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.48.1%; P < 0.001) for each 1‐week increase in age.0

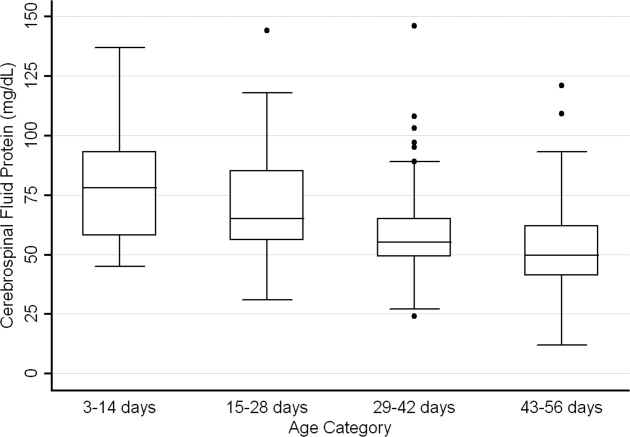

CSF protein concentrations were higher for infants 28 days of age than for infants 2956 days of age (P < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank‐sum test). The median CSF protein concentrations were 68 mg/dL (95th percentile value, 115 mg/dL) for infants 28 days of age and 54 mg/dL (95th percentile value, 89 mg/dL) for infants 2956 days. CSF protein concentrations by 2‐week age intervals are shown in Table 1. The 95th percentile CSF protein concentrations were as follows: ages 014 days, 132 mg/dL; ages 1528 days, 100 mg/dL; ages 2942 days, 89 mg/dL; and ages 4356 days, 83 mg/dL (Table 1). CSF protein concentration decreased significantly across each age interval when compared with infants in the next highest age category (P < 0.02 for all pair‐wise comparisons, Wilcoxon rank‐sum test).

| Value | 014 days (n = 52) | 1528 days (n = 87) | 2942 days (n = 110) | 4356 days (n = 126) | All Infants (n = 375) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Mean (SD) | 79 (23) | 69 (20) | 58 (17) | 53 (17) | 62 (21) |

| Median (IQR) | 78 (5893) | 65 (5685) | 55 (4965) | 50 (4162) | 58 (4872) |

| 90th percentile | 106 | 95 | 79 | 75 | 91 |

| 95th percentile | 132 | 100 | 89 | 83 | 99 |

| 95th percentile* | 132 | 101 | 89 | 82 | 97 |

| 95th percentile | 132 | 100 | 87 | 74 | 97 |

Age‐specific 95th percentile CSF protein values changed by <1% when infants receiving antibiotics before lumbar puncture were excluded (Table 1). Age‐specific CSF protein values changed minimally when preterm infants were excluded with the exception of infants 4356 days of age where the 95th percentile value was 9.7% lower than when all infants were included (Table 1); the 90th percentile values in this age group were more comparable at 75 mg/dL and 71 mg/dL, respectively, in the subgroups with and without preterm infants. Age‐specific 95th percentile CSF protein values changes by <1% when patients with CSF pleocytosis were excluded.

Discussion

We examined CSF protein values in neonates and young infants to establish reference values and to bring the literature up to date at a time when molecular tools are commonly used in clinical practice. We also quantified the age‐related decline in CSF protein concentrations over the first two months of life. Our findings provide age‐specific reference ranges for CSF protein concentrations in neonates and young infants. These findings are particularly important because a variety of infectious (eg, herpes simplex virus infection) and noninfectious (eg, subarachnoid or intraventricular hemorrhage) conditions may occur in the absence of appreciable elevations in the CSF WBC.

CSF protein concentrations depend on serum protein concentrations and on the permeability of the blood‐CSF barrier. Immaturity of the blood‐CSF barrier is thought to result in higher CSF protein concentrations for neonates and young infants compared with older children and adults. Though previous studies agree that CSF protein concentrations depend on age, the reported age‐specific values and rates of decline vary considerably.47, 3032 Additionally, these prior studies are limited by (1) small sample size, (2) variable inclusion and exclusion criteria, (3) variable laboratory techniques to quantify protein concentration in a CSF sample, and (4) presentation of mean, standard deviation, and range values rather than the 75th, 90th, or 95th percentile values necessary to define a clinically meaningful reference range.

The median and mean values found in this study were generally comparable to previously published values (Table 2). In addition, we have quantified the age‐related decline in CSF protein concentrations identified in previous studies. While our large sample size allowed us to define narrower reference intervals than most previous studies, direct comparison of values used to define reference ranges was hampered by lack of consistent reporting of data across studies. Ahmed et al.5 and Bonadio et al.4 reported only mean and standard deviation values. When data are skewed, as is the case for CSF protein values, the standard deviation will be grossly inflated, making extrapolation to percentile values unreliable. The 90th percentile value of 87 mg/dL reported by Wong et al.7 for infants 060 days of age was similar to the value of 91 mg/dL for infants 56 days of age and younger found in this study. Biou et al.6 reported the following 95th percentile values: ages 18 days, 108 mg/dL; ages 830 days, 90 mg/dL; and ages 12 months, 77 mg/dL. These values are lower than those reported in our study. The reason for such differences is not clear. The exclusion criteria were similar between the two studies though Biou et al.6 did not include preterm infants. When we excluded preterm infants from our analysis, no age‐specific result decreased by more than 5%, making the inclusion of this population an unlikely explanation for the differences between the two studies.

| Author | Year | Number of Infants | Age (days) | Median (mg/dL) | Mean SD (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Bonadio et al.4 | 1992 | 35 | 030 | 84 45 | |

| 40 | 3060 | 59 25 | |||

| Ahmed et al.5 | 1996 | 17 | 07 | 81 31 | |

| 33 | 814 | 69 23 | |||

| 25 | 1521 | 60 23 | |||

| 33 | 2230 | 54 16 | |||

| Biou et al.6 | 2000 | 26 | 18 | 71 | |

| 76 | 830 | 59 | |||

| 155 | 3060 | 47 | |||

| Wong et al.7 | 2000 | 99 | 060 | 60 | 59 21 |

CSF protein concentration is a method‐dependent value; the results depend a great deal on what technique the laboratory uses. Two common methods used in the past few decades are Biuret Colorimetry and Turbidimetric; reported values are approximately 25% higher with the Biuret method compared with the Turbidimetric method.33 A CSF protein reference value is only clinically useful if the method used to define the norm is specified and equivalent to currently used methods. Similar to our study, Biou et al.6 and Wong et al.7 used the Biuret (Vitros) method. The method of protein measurement was not specified by other studies.4, 5

This study had several limitations that could cause us to overestimate the upper bound of the reference range. First, spectrum bias is possible in this observational study. Individual physicians determined whether lumbar puncture was warranted, a limitation that could potentially lead to the disproportionate inclusion of infants with conditions associated with higher CSF protein concentrations. We do not believe that this limitation would meaningfully affect our results because febrile infants 56 days of age or younger routinely undergo lumbar puncture at our institution, regardless of illness severity, and patients diagnosed with conditions known or suspected to increase CSF protein concentrations were excluded. Second, infants with aseptic meningitisa condition that can be associated with elevated CSF protein concentrationsmay have been misclassified as uninfected. Though we excluded patients with positive CSF enteroviral PCR tests, some infants were not tested and other viruses (eg, parechoviruses)34 not detected by the enterovirus PCR may also cause aseptic meningitis. Third, certain antibiotics including ampicillin and vancomycin are known to interfere with the CSF protein assay used in our laboratory.24 Forty‐two of the 375 subjects included in our final analysis received antibiotics prior to lumbar puncture. When receiving antibiotics prior to lumbar puncture were excluded from analysis, the CSF protein concentrations were within 1% of the overall study population, suggesting that antibiotic administration before lumbar puncture did not influence our results in any meaningful way. We would not expect any of these limitations to disproportionately affect patients in 1 particular age category.

In conclusion, the CSF protein concentration values reported here represent the largest series to‐date for this young age group. Our study quantifies the age‐related decline in CSF protein concentration from birth to 56 days of life. Our work designing this study, specifically the exclusion criteria, refines the approach to defining normal CSF protein values in children. As CSF protein values decline steadily with increasing age, the selection of reference values is a balance of accuracy and convenience. Age‐specific reference values by 2‐week increments would be most accurate. However, considering reference values by month of age, as is the convention for CSF WBCs, is far more practical. The 95th percentile values by age category in our study were as follows: ages 014 days, 132 mg/dL; ages 1528 days, 100 mg/dL; ages 2942 days, 89 mg/dL; and ages 4356 days, 83 mg/dL. The 95th percentile values were 115 mg/dL for infants 28 days and 89 mg/dL for infants 2956 days. We feel that either approach is reasonable. These values can be used to accurately interpret the results of CSF studies in neonates and young infants.

- ,.Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods.21st ed.Philadelphia, PA:W.B. Saunders, Inc.;2006.

- .On the cerebrospinal fluid in normal children and in patients with acute abacterial meningo‐encephalitis.Acta Paediatr Suppl.1958;47(Suppl 115):1–102.

- ,.Development of the blood‐CSF barrier.Dev Med Child Neurol.1983;25(2):152–161.

- ,,,,.Reference values of normal cerebrospinal fluid composition in infants ages 0 to 8 weeks.Pediatr Infect Dis J.1992;11(7):589–591.

- ,,, et al.Cerebrospinal fluid values in the term neonate.Pediatr Infect Dis J.1996;15(4):298–303.

- ,,,,,.Cerebrospinal fluid protein concentrations in children: age‐related values in patients without disorders of the central nervous system.Clin Chem.2000;46(3):399–403.

- ,,,,.Cerebrospinal fluid protein concentration in pediatric patients: defining clinically relevant reference values.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2000;154(8):827–831.

- ,,.Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics.17th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Saunders;2004.

- ,,,.Oski's pediatrics : principles 2006.

- Robertson J, Shilkofski N, eds.Johns Hopkins: The Harriet Lane Handbook: A Manual for Pediatric House Officers.17 ed.Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier Mosby;2005.

- ,,,.The Philadelphia Guide: Inpatient Pediatrics.Philadelphia, PA:Lippincott Williams 2005.

- ,,,.Pediatric Hospital Medicine: Textbook of Inpatient Management.Philadelphia, PA:Lippincott Williams 2008.

- ,.Comprehensive pediatric hospital medicine.Philadelphia, PA:Mosby Elsevier;2007.

- ,,.Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine.5th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Lippincott Williams 2006.

- ,,,.Pediatric Emergency Medicine.Philadelphia, PA:Saunders Elsevier;2008.

- ,,,.Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases.5th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Saunders;2004.

- ,.Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant.6th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier Saunders;2006.

- ,.Avery's diseases of the newborn.7th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Saunders;1998.

- ,.Child Neurology.6th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Lippincott Williams 2000.

- ,.Pediatric Neurology: Principles and Practice.3rd ed.St. Louis, MO:Mosby;1999.

- ,.Unpredictability of serious bacterial illness in febrile infants from birth to 1 month of age.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.1999;153(5):508–511.

- ,,.The efficacy of routine outpatient management without antibiotics of fever in selected infants.Pediatrics.1999;103(3):627–631.

- ,,.Bacterial sepsis and meningitis. In: Remington JS, Klein JO, Wilson CB, Baker CJ, eds.Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant.6th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier, Inc.;2006:247–295.

- NCCLS.Interference testing in Clinical Chemistry, NCCLS Document EP7.Wayne, PA:NCCLS;1986.

- ,,,.Lack of cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis in young infants with enterovirus infections of the central nervous system.Pediatr Emerg Care.2010;26(2):77–81.

- ,,, et al.Clinical and demographic factors associated with urinary tract infection in young febrile infants.Pediatrics.2005;116(3):644–648.

- ,,,,.Enhanced urinalysis as a screening test for urinary tract infection.Pediatrics.1993;91(6):1196–1199.

- ,,,.Screening for urinary tract infection in infants in the emergency department: which test is best?Pediatrics.1998;101(6):E1.

- ,,,,,.Routine cerebrospinal fluid enterovirus polymerase chain reaction testing reduces hospitalization and antibiotic use for infants 90 days of age or younger.Pediatrics.2007;120(3):489–496.

- .The normal cerebro‐spinal fluid in children.Archf Dis Child.1928:96–108.

- .The cerebrospinal fluid in the healthy newborn infant.S Afr Med J.1968;42(35):933–935.

- ,,.Cerebrospinal fluid evaluation in neonates: comparison of high‐risk infants with and without meningitis.J Pediatr.1976;88(3):473–477.

- ,.Estimation of reference intervals for total protein in cerebrospinal fluid.Clin Chem.1989;35(8):1766–1770.

- ,,,,,.Severe neonatal parechovirus infection and similarity with enterovirus infection.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2008;27(3):241–245.

Emergency department evaluation of a febrile neonate or young infant routinely includes lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis to diagnose meningitis or encephalitis. In addition to CSF Gram stain and culture, clinicians generally request a laboratory report for the CSF cell count, glucose content and protein concentration. Interpretation of these ancillary tests requires knowledge of normal reference values. In adult medicine, the accepted reference value for CSF protein concentration at the level of the lumbar spine is 15 mg/dL to45 mg/dL.1 There is general consensus among reference texts and published original studies dating back to Widell2 in 1958 that adult CSF protein reference values are not valid in the pediatric population. A healthy neonate's CSF protein concentration is normally twice to 3 times that of an adult, and declines with age from birth to early childhood. The most rapid rate of decline is thought to occur in the first 6 months of life as the infant's blood‐CSF barrier matures.3 However, published studies47 differ in the reported rate, timing, and magnitude of this decline; on close review these studies have significant limitations which call into question the appropriateness of using these values in clinical practice. Perhaps in recognition of the limited evidence, textbooks of general pediatrics,810 hospital medicine,1113 emergency medicine,14, 15 infectious diseases,16, 17 neonatology,18 and neurology19, 20 frequently publish norms for pediatric CSF protein concentration without reference to any original research studies.

Because ethical considerations prohibit subjecting young infants to a potentially painfully procedure (ie, lumbar puncture) before they are able to assent, we sought to define a study population that approximates a group of healthy infants. Our objectives were to quantify age‐related declines in CSF protein concentration and to determine accurate, age‐specific reference values for CSF protein concentration in a population of neonates and young infants who presented for medical care with an indication for lumbar puncture and were subsequently found to have no condition associated with elevated or depressed CSF protein concentration.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This cross‐sectional study was performed at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, PA), an urban, tertiary‐care children's hospital. The Committees for the Protection of Human Subjects approved this study with a waiver of informed consent.

Study Participants

Infants 56 days of age or younger were eligible for inclusion if they had a lumbar puncture performed as part of their emergency department evaluation between January 1, 2005 and June 30, 2007. Children in this age range were selected as they routinely undergo lumbar puncture when presenting with fever at our institution.21, 22 Patients undergoing lumbar puncture in the emergency department were identified using 2 different data sources to ensure accurate identification of all eligible infants: (1) Emergency department computerized order entry records identified all infants with CSF testing (including CSF Gram stain, culture, cell count, glucose, or protein) performed during the study period, and (2) Clinical Virology Laboratory records identified all infants in whom CSF herpes simplex virus or enterovirus testing was performed. Medical records of infants identified by these 2 sources were reviewed to determine study eligibility.

Subjects with conditions known or suspected to cause abnormal CSF protein concentration were systematically excluded from the final analysis. Exclusion criteria included traumatic lumbar puncture (defined as CSF sample with >500 red blood cells per mm3), serious bacterial infection (including meningitis, urinary tract infection, bacteremia, pneumonia, osteomyelitis, or septic arthritis), congenital infection, CSF positive for enterovirus by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, seizure prior to presentation, presence of a ventricular shunt device, elevated serum bilirubin, and absent CSF protein measurements or CSF red blood cell counts. The presence of lysed red blood cells in the CSF secondary to a traumatic lumbar puncture or subarachnoid hemorrhage alters the CSF protein.23 We also excluded subjects who had CSF assays done on samples drawn by accessing a ventricular shunt device, as there may be up to a 300% regional difference in CSF protein concentration between the cranial and caudal ends of the neuroaxis.1 Bilirubin in the CSF sample at a concentration of 5 mg/dL biases the CSF protein concentration measurement by an average of 13.7 mg/dL.24 Quantitative protein assay was performed on the institution's standard Vitros chemistry system; the protein assay is a modified biuret reaction.

Study Definitions

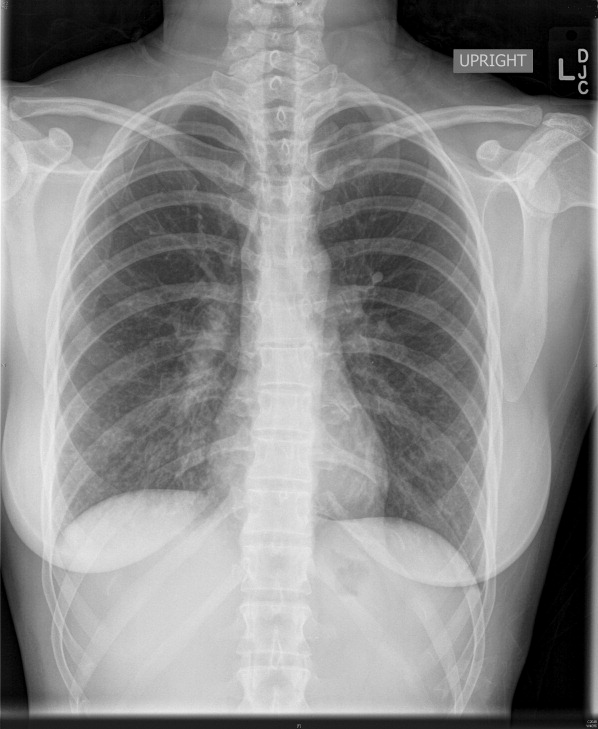

CSF pleocytosis was defined as a CSF white blood cell count (WBC) >22/mm3 (for infants age 28 days) or >15/mm3 (for infants 2956 days of age).25 Bacterial meningitis was defined as isolation of a bacterial pathogen from the CSF. Bacteremia was defined as isolation of a bacterial pathogen from blood culture, excluding isolates that reflected commensal skin flora. Bacterial pneumonia was defined as a new discrete infiltrate on chest radiograph as documented by an attending pediatric radiologist in conjunction with growth of a respiratory bacterial pathogen from blood culture. Urinary tract infection was defined as growth of a single known pathogen in culture as follows: (1) 1000 colony‐forming units/mL for cultures obtained by suprapubic aspiration, (2) 50,000 cfu/mL from a catheterized specimen, or (3) 10,000 cfu/mL from catheterized specimen in conjunction with a positive urinalysis.26 Positive urinalysis was defined as trace or greater leukocyte esterase by dip stick, or >9 WBC per high‐power filed on standard microscopic exam of centrifuged urine, or >10 WBC/mm3 by hemocytometer count of uncentrifuged urine.27, 28 We defined osteomyelitis as growth of pathogenic bacteria from blood, bone, or subperiosteal aspirate culture in a subject with fever and localized tenderness, edema or erythema at the site of bony infection, and compatible imaging; and septic arthritis as growth of pathogenic bacteria from synovial fluid or blood culture from a subject with purulent synovial fluid or positive Gram stain of synovial fluid.

A temperature 38.0C by any method qualified as fever. Prematurity was defined as a gestational age less than 37 weeks. Seizure included any clinical description of the event within 48 hours of presentation to the Emergency Department, or documented seizure activity on electroencephalogram. Enterovirus season was defined as June 1st to October 31st of each year.29

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

Information collected included the following: demographics, vital signs, history of present illness, birth history, clinical findings, results of laboratory testing and imaging within 48 hours of presentation, antibiotics administered, and duration of visit to the Emergency Department or admission to the hospital.

Categorical data were described using frequencies and percents, and continuous variables were described using mean, median, interquartile range, and 90th and 95th percentile values. Linear regression was used to determine the association between age and CSF protein concentration. Because the CSF protein concentrations had a skewed distribution (P < 0.001, Shapiro‐Wilk test), our analyses were performed using logarithmically transformed CSF protein values as the dependent variable. The resulting beta‐coefficients were transformed to reflect the percent change in CSF protein with increasing age. Two‐sample Wilcoxon rank‐sum tests were subsequently used to compare the distribution of CSF protein concentrations amongst four predefined age categories to facilitate implementation of our results into clinical practice: 014 days, 1528 days, 2942 days, and 4356 days. The analyses were repeated while excluding preterm infants, patients receiving antibiotics before lumbar puncture, and patients with CSF pleocytosis to determine the impact of these factors on CSF protein concentrations. Data were analyzed using STATA v10 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Two‐tailed P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

During the study period, 1064 infants age 56 days of age or younger underwent lumbar puncture in the emergency department. Of these, 689 (65%) met sequential exclusion criteria as follows: traumatic lumbar puncture (n = 330); transported from an outside medical facility (n = 90); bacterial meningitis (n = 6); noncentral nervous system serious bacterial infections (n = 135); CSF positive for herpes simplex virus by PCR (n = 2); CSF positive for enterovirus by PCR (n = 45); congenital syphilis (n = 1); seizures (n = 28); abnormal central nervous system imaging (n = 2); and ventricular shunt device (n = 1). An additional 44 patients had lumbar puncture and CSF testing but the protein assay was never done or never reported and 5 patients did not have a CSF red blood cell count available. No cases were excluded for elevated serum bilirubin. Infants may have met multiple exclusion criteria. The remaining 375 (35%) subjects were included in the final analysis. The median patient age was 36 days (interquartile range: 2247 days); 139 (37%) were 28 days of age or younger. Overall, 205 (55%) were male, 211 (56%) were black, and 145 (39%) presented during enterovirus season. Most (43 of 57) preterm infants were born between 34 weeks to 37 weeks gestation. Antibiotics were administered before lumbar puncture to 42 (11%) infants and 312 (83%) infants had fever.

The median CSF protein value was 58 mg/dL (interquartile range: 4872 mg/dL). There was an age‐related declined in CSF protein concentration (Figure 1). In linear regression, the CSF protein concentration decreased 6.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.48.1%; P < 0.001) for each 1‐week increase in age.0

CSF protein concentrations were higher for infants 28 days of age than for infants 2956 days of age (P < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank‐sum test). The median CSF protein concentrations were 68 mg/dL (95th percentile value, 115 mg/dL) for infants 28 days of age and 54 mg/dL (95th percentile value, 89 mg/dL) for infants 2956 days. CSF protein concentrations by 2‐week age intervals are shown in Table 1. The 95th percentile CSF protein concentrations were as follows: ages 014 days, 132 mg/dL; ages 1528 days, 100 mg/dL; ages 2942 days, 89 mg/dL; and ages 4356 days, 83 mg/dL (Table 1). CSF protein concentration decreased significantly across each age interval when compared with infants in the next highest age category (P < 0.02 for all pair‐wise comparisons, Wilcoxon rank‐sum test).

| Value | 014 days (n = 52) | 1528 days (n = 87) | 2942 days (n = 110) | 4356 days (n = 126) | All Infants (n = 375) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Mean (SD) | 79 (23) | 69 (20) | 58 (17) | 53 (17) | 62 (21) |

| Median (IQR) | 78 (5893) | 65 (5685) | 55 (4965) | 50 (4162) | 58 (4872) |

| 90th percentile | 106 | 95 | 79 | 75 | 91 |

| 95th percentile | 132 | 100 | 89 | 83 | 99 |

| 95th percentile* | 132 | 101 | 89 | 82 | 97 |

| 95th percentile | 132 | 100 | 87 | 74 | 97 |

Age‐specific 95th percentile CSF protein values changed by <1% when infants receiving antibiotics before lumbar puncture were excluded (Table 1). Age‐specific CSF protein values changed minimally when preterm infants were excluded with the exception of infants 4356 days of age where the 95th percentile value was 9.7% lower than when all infants were included (Table 1); the 90th percentile values in this age group were more comparable at 75 mg/dL and 71 mg/dL, respectively, in the subgroups with and without preterm infants. Age‐specific 95th percentile CSF protein values changes by <1% when patients with CSF pleocytosis were excluded.

Discussion

We examined CSF protein values in neonates and young infants to establish reference values and to bring the literature up to date at a time when molecular tools are commonly used in clinical practice. We also quantified the age‐related decline in CSF protein concentrations over the first two months of life. Our findings provide age‐specific reference ranges for CSF protein concentrations in neonates and young infants. These findings are particularly important because a variety of infectious (eg, herpes simplex virus infection) and noninfectious (eg, subarachnoid or intraventricular hemorrhage) conditions may occur in the absence of appreciable elevations in the CSF WBC.

CSF protein concentrations depend on serum protein concentrations and on the permeability of the blood‐CSF barrier. Immaturity of the blood‐CSF barrier is thought to result in higher CSF protein concentrations for neonates and young infants compared with older children and adults. Though previous studies agree that CSF protein concentrations depend on age, the reported age‐specific values and rates of decline vary considerably.47, 3032 Additionally, these prior studies are limited by (1) small sample size, (2) variable inclusion and exclusion criteria, (3) variable laboratory techniques to quantify protein concentration in a CSF sample, and (4) presentation of mean, standard deviation, and range values rather than the 75th, 90th, or 95th percentile values necessary to define a clinically meaningful reference range.

The median and mean values found in this study were generally comparable to previously published values (Table 2). In addition, we have quantified the age‐related decline in CSF protein concentrations identified in previous studies. While our large sample size allowed us to define narrower reference intervals than most previous studies, direct comparison of values used to define reference ranges was hampered by lack of consistent reporting of data across studies. Ahmed et al.5 and Bonadio et al.4 reported only mean and standard deviation values. When data are skewed, as is the case for CSF protein values, the standard deviation will be grossly inflated, making extrapolation to percentile values unreliable. The 90th percentile value of 87 mg/dL reported by Wong et al.7 for infants 060 days of age was similar to the value of 91 mg/dL for infants 56 days of age and younger found in this study. Biou et al.6 reported the following 95th percentile values: ages 18 days, 108 mg/dL; ages 830 days, 90 mg/dL; and ages 12 months, 77 mg/dL. These values are lower than those reported in our study. The reason for such differences is not clear. The exclusion criteria were similar between the two studies though Biou et al.6 did not include preterm infants. When we excluded preterm infants from our analysis, no age‐specific result decreased by more than 5%, making the inclusion of this population an unlikely explanation for the differences between the two studies.

| Author | Year | Number of Infants | Age (days) | Median (mg/dL) | Mean SD (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Bonadio et al.4 | 1992 | 35 | 030 | 84 45 | |

| 40 | 3060 | 59 25 | |||

| Ahmed et al.5 | 1996 | 17 | 07 | 81 31 | |

| 33 | 814 | 69 23 | |||

| 25 | 1521 | 60 23 | |||

| 33 | 2230 | 54 16 | |||

| Biou et al.6 | 2000 | 26 | 18 | 71 | |

| 76 | 830 | 59 | |||

| 155 | 3060 | 47 | |||

| Wong et al.7 | 2000 | 99 | 060 | 60 | 59 21 |

CSF protein concentration is a method‐dependent value; the results depend a great deal on what technique the laboratory uses. Two common methods used in the past few decades are Biuret Colorimetry and Turbidimetric; reported values are approximately 25% higher with the Biuret method compared with the Turbidimetric method.33 A CSF protein reference value is only clinically useful if the method used to define the norm is specified and equivalent to currently used methods. Similar to our study, Biou et al.6 and Wong et al.7 used the Biuret (Vitros) method. The method of protein measurement was not specified by other studies.4, 5

This study had several limitations that could cause us to overestimate the upper bound of the reference range. First, spectrum bias is possible in this observational study. Individual physicians determined whether lumbar puncture was warranted, a limitation that could potentially lead to the disproportionate inclusion of infants with conditions associated with higher CSF protein concentrations. We do not believe that this limitation would meaningfully affect our results because febrile infants 56 days of age or younger routinely undergo lumbar puncture at our institution, regardless of illness severity, and patients diagnosed with conditions known or suspected to increase CSF protein concentrations were excluded. Second, infants with aseptic meningitisa condition that can be associated with elevated CSF protein concentrationsmay have been misclassified as uninfected. Though we excluded patients with positive CSF enteroviral PCR tests, some infants were not tested and other viruses (eg, parechoviruses)34 not detected by the enterovirus PCR may also cause aseptic meningitis. Third, certain antibiotics including ampicillin and vancomycin are known to interfere with the CSF protein assay used in our laboratory.24 Forty‐two of the 375 subjects included in our final analysis received antibiotics prior to lumbar puncture. When receiving antibiotics prior to lumbar puncture were excluded from analysis, the CSF protein concentrations were within 1% of the overall study population, suggesting that antibiotic administration before lumbar puncture did not influence our results in any meaningful way. We would not expect any of these limitations to disproportionately affect patients in 1 particular age category.

In conclusion, the CSF protein concentration values reported here represent the largest series to‐date for this young age group. Our study quantifies the age‐related decline in CSF protein concentration from birth to 56 days of life. Our work designing this study, specifically the exclusion criteria, refines the approach to defining normal CSF protein values in children. As CSF protein values decline steadily with increasing age, the selection of reference values is a balance of accuracy and convenience. Age‐specific reference values by 2‐week increments would be most accurate. However, considering reference values by month of age, as is the convention for CSF WBCs, is far more practical. The 95th percentile values by age category in our study were as follows: ages 014 days, 132 mg/dL; ages 1528 days, 100 mg/dL; ages 2942 days, 89 mg/dL; and ages 4356 days, 83 mg/dL. The 95th percentile values were 115 mg/dL for infants 28 days and 89 mg/dL for infants 2956 days. We feel that either approach is reasonable. These values can be used to accurately interpret the results of CSF studies in neonates and young infants.

Emergency department evaluation of a febrile neonate or young infant routinely includes lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis to diagnose meningitis or encephalitis. In addition to CSF Gram stain and culture, clinicians generally request a laboratory report for the CSF cell count, glucose content and protein concentration. Interpretation of these ancillary tests requires knowledge of normal reference values. In adult medicine, the accepted reference value for CSF protein concentration at the level of the lumbar spine is 15 mg/dL to45 mg/dL.1 There is general consensus among reference texts and published original studies dating back to Widell2 in 1958 that adult CSF protein reference values are not valid in the pediatric population. A healthy neonate's CSF protein concentration is normally twice to 3 times that of an adult, and declines with age from birth to early childhood. The most rapid rate of decline is thought to occur in the first 6 months of life as the infant's blood‐CSF barrier matures.3 However, published studies47 differ in the reported rate, timing, and magnitude of this decline; on close review these studies have significant limitations which call into question the appropriateness of using these values in clinical practice. Perhaps in recognition of the limited evidence, textbooks of general pediatrics,810 hospital medicine,1113 emergency medicine,14, 15 infectious diseases,16, 17 neonatology,18 and neurology19, 20 frequently publish norms for pediatric CSF protein concentration without reference to any original research studies.

Because ethical considerations prohibit subjecting young infants to a potentially painfully procedure (ie, lumbar puncture) before they are able to assent, we sought to define a study population that approximates a group of healthy infants. Our objectives were to quantify age‐related declines in CSF protein concentration and to determine accurate, age‐specific reference values for CSF protein concentration in a population of neonates and young infants who presented for medical care with an indication for lumbar puncture and were subsequently found to have no condition associated with elevated or depressed CSF protein concentration.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

This cross‐sectional study was performed at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, PA), an urban, tertiary‐care children's hospital. The Committees for the Protection of Human Subjects approved this study with a waiver of informed consent.

Study Participants

Infants 56 days of age or younger were eligible for inclusion if they had a lumbar puncture performed as part of their emergency department evaluation between January 1, 2005 and June 30, 2007. Children in this age range were selected as they routinely undergo lumbar puncture when presenting with fever at our institution.21, 22 Patients undergoing lumbar puncture in the emergency department were identified using 2 different data sources to ensure accurate identification of all eligible infants: (1) Emergency department computerized order entry records identified all infants with CSF testing (including CSF Gram stain, culture, cell count, glucose, or protein) performed during the study period, and (2) Clinical Virology Laboratory records identified all infants in whom CSF herpes simplex virus or enterovirus testing was performed. Medical records of infants identified by these 2 sources were reviewed to determine study eligibility.

Subjects with conditions known or suspected to cause abnormal CSF protein concentration were systematically excluded from the final analysis. Exclusion criteria included traumatic lumbar puncture (defined as CSF sample with >500 red blood cells per mm3), serious bacterial infection (including meningitis, urinary tract infection, bacteremia, pneumonia, osteomyelitis, or septic arthritis), congenital infection, CSF positive for enterovirus by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing, seizure prior to presentation, presence of a ventricular shunt device, elevated serum bilirubin, and absent CSF protein measurements or CSF red blood cell counts. The presence of lysed red blood cells in the CSF secondary to a traumatic lumbar puncture or subarachnoid hemorrhage alters the CSF protein.23 We also excluded subjects who had CSF assays done on samples drawn by accessing a ventricular shunt device, as there may be up to a 300% regional difference in CSF protein concentration between the cranial and caudal ends of the neuroaxis.1 Bilirubin in the CSF sample at a concentration of 5 mg/dL biases the CSF protein concentration measurement by an average of 13.7 mg/dL.24 Quantitative protein assay was performed on the institution's standard Vitros chemistry system; the protein assay is a modified biuret reaction.

Study Definitions

CSF pleocytosis was defined as a CSF white blood cell count (WBC) >22/mm3 (for infants age 28 days) or >15/mm3 (for infants 2956 days of age).25 Bacterial meningitis was defined as isolation of a bacterial pathogen from the CSF. Bacteremia was defined as isolation of a bacterial pathogen from blood culture, excluding isolates that reflected commensal skin flora. Bacterial pneumonia was defined as a new discrete infiltrate on chest radiograph as documented by an attending pediatric radiologist in conjunction with growth of a respiratory bacterial pathogen from blood culture. Urinary tract infection was defined as growth of a single known pathogen in culture as follows: (1) 1000 colony‐forming units/mL for cultures obtained by suprapubic aspiration, (2) 50,000 cfu/mL from a catheterized specimen, or (3) 10,000 cfu/mL from catheterized specimen in conjunction with a positive urinalysis.26 Positive urinalysis was defined as trace or greater leukocyte esterase by dip stick, or >9 WBC per high‐power filed on standard microscopic exam of centrifuged urine, or >10 WBC/mm3 by hemocytometer count of uncentrifuged urine.27, 28 We defined osteomyelitis as growth of pathogenic bacteria from blood, bone, or subperiosteal aspirate culture in a subject with fever and localized tenderness, edema or erythema at the site of bony infection, and compatible imaging; and septic arthritis as growth of pathogenic bacteria from synovial fluid or blood culture from a subject with purulent synovial fluid or positive Gram stain of synovial fluid.

A temperature 38.0C by any method qualified as fever. Prematurity was defined as a gestational age less than 37 weeks. Seizure included any clinical description of the event within 48 hours of presentation to the Emergency Department, or documented seizure activity on electroencephalogram. Enterovirus season was defined as June 1st to October 31st of each year.29

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

Information collected included the following: demographics, vital signs, history of present illness, birth history, clinical findings, results of laboratory testing and imaging within 48 hours of presentation, antibiotics administered, and duration of visit to the Emergency Department or admission to the hospital.

Categorical data were described using frequencies and percents, and continuous variables were described using mean, median, interquartile range, and 90th and 95th percentile values. Linear regression was used to determine the association between age and CSF protein concentration. Because the CSF protein concentrations had a skewed distribution (P < 0.001, Shapiro‐Wilk test), our analyses were performed using logarithmically transformed CSF protein values as the dependent variable. The resulting beta‐coefficients were transformed to reflect the percent change in CSF protein with increasing age. Two‐sample Wilcoxon rank‐sum tests were subsequently used to compare the distribution of CSF protein concentrations amongst four predefined age categories to facilitate implementation of our results into clinical practice: 014 days, 1528 days, 2942 days, and 4356 days. The analyses were repeated while excluding preterm infants, patients receiving antibiotics before lumbar puncture, and patients with CSF pleocytosis to determine the impact of these factors on CSF protein concentrations. Data were analyzed using STATA v10 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). Two‐tailed P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

During the study period, 1064 infants age 56 days of age or younger underwent lumbar puncture in the emergency department. Of these, 689 (65%) met sequential exclusion criteria as follows: traumatic lumbar puncture (n = 330); transported from an outside medical facility (n = 90); bacterial meningitis (n = 6); noncentral nervous system serious bacterial infections (n = 135); CSF positive for herpes simplex virus by PCR (n = 2); CSF positive for enterovirus by PCR (n = 45); congenital syphilis (n = 1); seizures (n = 28); abnormal central nervous system imaging (n = 2); and ventricular shunt device (n = 1). An additional 44 patients had lumbar puncture and CSF testing but the protein assay was never done or never reported and 5 patients did not have a CSF red blood cell count available. No cases were excluded for elevated serum bilirubin. Infants may have met multiple exclusion criteria. The remaining 375 (35%) subjects were included in the final analysis. The median patient age was 36 days (interquartile range: 2247 days); 139 (37%) were 28 days of age or younger. Overall, 205 (55%) were male, 211 (56%) were black, and 145 (39%) presented during enterovirus season. Most (43 of 57) preterm infants were born between 34 weeks to 37 weeks gestation. Antibiotics were administered before lumbar puncture to 42 (11%) infants and 312 (83%) infants had fever.

The median CSF protein value was 58 mg/dL (interquartile range: 4872 mg/dL). There was an age‐related declined in CSF protein concentration (Figure 1). In linear regression, the CSF protein concentration decreased 6.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], 5.48.1%; P < 0.001) for each 1‐week increase in age.0

CSF protein concentrations were higher for infants 28 days of age than for infants 2956 days of age (P < 0.001, Wilcoxon rank‐sum test). The median CSF protein concentrations were 68 mg/dL (95th percentile value, 115 mg/dL) for infants 28 days of age and 54 mg/dL (95th percentile value, 89 mg/dL) for infants 2956 days. CSF protein concentrations by 2‐week age intervals are shown in Table 1. The 95th percentile CSF protein concentrations were as follows: ages 014 days, 132 mg/dL; ages 1528 days, 100 mg/dL; ages 2942 days, 89 mg/dL; and ages 4356 days, 83 mg/dL (Table 1). CSF protein concentration decreased significantly across each age interval when compared with infants in the next highest age category (P < 0.02 for all pair‐wise comparisons, Wilcoxon rank‐sum test).

| Value | 014 days (n = 52) | 1528 days (n = 87) | 2942 days (n = 110) | 4356 days (n = 126) | All Infants (n = 375) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Mean (SD) | 79 (23) | 69 (20) | 58 (17) | 53 (17) | 62 (21) |

| Median (IQR) | 78 (5893) | 65 (5685) | 55 (4965) | 50 (4162) | 58 (4872) |

| 90th percentile | 106 | 95 | 79 | 75 | 91 |

| 95th percentile | 132 | 100 | 89 | 83 | 99 |

| 95th percentile* | 132 | 101 | 89 | 82 | 97 |

| 95th percentile | 132 | 100 | 87 | 74 | 97 |

Age‐specific 95th percentile CSF protein values changed by <1% when infants receiving antibiotics before lumbar puncture were excluded (Table 1). Age‐specific CSF protein values changed minimally when preterm infants were excluded with the exception of infants 4356 days of age where the 95th percentile value was 9.7% lower than when all infants were included (Table 1); the 90th percentile values in this age group were more comparable at 75 mg/dL and 71 mg/dL, respectively, in the subgroups with and without preterm infants. Age‐specific 95th percentile CSF protein values changes by <1% when patients with CSF pleocytosis were excluded.

Discussion

We examined CSF protein values in neonates and young infants to establish reference values and to bring the literature up to date at a time when molecular tools are commonly used in clinical practice. We also quantified the age‐related decline in CSF protein concentrations over the first two months of life. Our findings provide age‐specific reference ranges for CSF protein concentrations in neonates and young infants. These findings are particularly important because a variety of infectious (eg, herpes simplex virus infection) and noninfectious (eg, subarachnoid or intraventricular hemorrhage) conditions may occur in the absence of appreciable elevations in the CSF WBC.

CSF protein concentrations depend on serum protein concentrations and on the permeability of the blood‐CSF barrier. Immaturity of the blood‐CSF barrier is thought to result in higher CSF protein concentrations for neonates and young infants compared with older children and adults. Though previous studies agree that CSF protein concentrations depend on age, the reported age‐specific values and rates of decline vary considerably.47, 3032 Additionally, these prior studies are limited by (1) small sample size, (2) variable inclusion and exclusion criteria, (3) variable laboratory techniques to quantify protein concentration in a CSF sample, and (4) presentation of mean, standard deviation, and range values rather than the 75th, 90th, or 95th percentile values necessary to define a clinically meaningful reference range.

The median and mean values found in this study were generally comparable to previously published values (Table 2). In addition, we have quantified the age‐related decline in CSF protein concentrations identified in previous studies. While our large sample size allowed us to define narrower reference intervals than most previous studies, direct comparison of values used to define reference ranges was hampered by lack of consistent reporting of data across studies. Ahmed et al.5 and Bonadio et al.4 reported only mean and standard deviation values. When data are skewed, as is the case for CSF protein values, the standard deviation will be grossly inflated, making extrapolation to percentile values unreliable. The 90th percentile value of 87 mg/dL reported by Wong et al.7 for infants 060 days of age was similar to the value of 91 mg/dL for infants 56 days of age and younger found in this study. Biou et al.6 reported the following 95th percentile values: ages 18 days, 108 mg/dL; ages 830 days, 90 mg/dL; and ages 12 months, 77 mg/dL. These values are lower than those reported in our study. The reason for such differences is not clear. The exclusion criteria were similar between the two studies though Biou et al.6 did not include preterm infants. When we excluded preterm infants from our analysis, no age‐specific result decreased by more than 5%, making the inclusion of this population an unlikely explanation for the differences between the two studies.

| Author | Year | Number of Infants | Age (days) | Median (mg/dL) | Mean SD (mg/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Bonadio et al.4 | 1992 | 35 | 030 | 84 45 | |

| 40 | 3060 | 59 25 | |||

| Ahmed et al.5 | 1996 | 17 | 07 | 81 31 | |

| 33 | 814 | 69 23 | |||

| 25 | 1521 | 60 23 | |||

| 33 | 2230 | 54 16 | |||

| Biou et al.6 | 2000 | 26 | 18 | 71 | |

| 76 | 830 | 59 | |||

| 155 | 3060 | 47 | |||

| Wong et al.7 | 2000 | 99 | 060 | 60 | 59 21 |

CSF protein concentration is a method‐dependent value; the results depend a great deal on what technique the laboratory uses. Two common methods used in the past few decades are Biuret Colorimetry and Turbidimetric; reported values are approximately 25% higher with the Biuret method compared with the Turbidimetric method.33 A CSF protein reference value is only clinically useful if the method used to define the norm is specified and equivalent to currently used methods. Similar to our study, Biou et al.6 and Wong et al.7 used the Biuret (Vitros) method. The method of protein measurement was not specified by other studies.4, 5

This study had several limitations that could cause us to overestimate the upper bound of the reference range. First, spectrum bias is possible in this observational study. Individual physicians determined whether lumbar puncture was warranted, a limitation that could potentially lead to the disproportionate inclusion of infants with conditions associated with higher CSF protein concentrations. We do not believe that this limitation would meaningfully affect our results because febrile infants 56 days of age or younger routinely undergo lumbar puncture at our institution, regardless of illness severity, and patients diagnosed with conditions known or suspected to increase CSF protein concentrations were excluded. Second, infants with aseptic meningitisa condition that can be associated with elevated CSF protein concentrationsmay have been misclassified as uninfected. Though we excluded patients with positive CSF enteroviral PCR tests, some infants were not tested and other viruses (eg, parechoviruses)34 not detected by the enterovirus PCR may also cause aseptic meningitis. Third, certain antibiotics including ampicillin and vancomycin are known to interfere with the CSF protein assay used in our laboratory.24 Forty‐two of the 375 subjects included in our final analysis received antibiotics prior to lumbar puncture. When receiving antibiotics prior to lumbar puncture were excluded from analysis, the CSF protein concentrations were within 1% of the overall study population, suggesting that antibiotic administration before lumbar puncture did not influence our results in any meaningful way. We would not expect any of these limitations to disproportionately affect patients in 1 particular age category.

In conclusion, the CSF protein concentration values reported here represent the largest series to‐date for this young age group. Our study quantifies the age‐related decline in CSF protein concentration from birth to 56 days of life. Our work designing this study, specifically the exclusion criteria, refines the approach to defining normal CSF protein values in children. As CSF protein values decline steadily with increasing age, the selection of reference values is a balance of accuracy and convenience. Age‐specific reference values by 2‐week increments would be most accurate. However, considering reference values by month of age, as is the convention for CSF WBCs, is far more practical. The 95th percentile values by age category in our study were as follows: ages 014 days, 132 mg/dL; ages 1528 days, 100 mg/dL; ages 2942 days, 89 mg/dL; and ages 4356 days, 83 mg/dL. The 95th percentile values were 115 mg/dL for infants 28 days and 89 mg/dL for infants 2956 days. We feel that either approach is reasonable. These values can be used to accurately interpret the results of CSF studies in neonates and young infants.

- ,.Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods.21st ed.Philadelphia, PA:W.B. Saunders, Inc.;2006.

- .On the cerebrospinal fluid in normal children and in patients with acute abacterial meningo‐encephalitis.Acta Paediatr Suppl.1958;47(Suppl 115):1–102.

- ,.Development of the blood‐CSF barrier.Dev Med Child Neurol.1983;25(2):152–161.

- ,,,,.Reference values of normal cerebrospinal fluid composition in infants ages 0 to 8 weeks.Pediatr Infect Dis J.1992;11(7):589–591.

- ,,, et al.Cerebrospinal fluid values in the term neonate.Pediatr Infect Dis J.1996;15(4):298–303.

- ,,,,,.Cerebrospinal fluid protein concentrations in children: age‐related values in patients without disorders of the central nervous system.Clin Chem.2000;46(3):399–403.

- ,,,,.Cerebrospinal fluid protein concentration in pediatric patients: defining clinically relevant reference values.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2000;154(8):827–831.

- ,,.Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics.17th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Saunders;2004.

- ,,,.Oski's pediatrics : principles 2006.

- Robertson J, Shilkofski N, eds.Johns Hopkins: The Harriet Lane Handbook: A Manual for Pediatric House Officers.17 ed.Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier Mosby;2005.

- ,,,.The Philadelphia Guide: Inpatient Pediatrics.Philadelphia, PA:Lippincott Williams 2005.

- ,,,.Pediatric Hospital Medicine: Textbook of Inpatient Management.Philadelphia, PA:Lippincott Williams 2008.

- ,.Comprehensive pediatric hospital medicine.Philadelphia, PA:Mosby Elsevier;2007.

- ,,.Textbook of Pediatric Emergency Medicine.5th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Lippincott Williams 2006.

- ,,,.Pediatric Emergency Medicine.Philadelphia, PA:Saunders Elsevier;2008.

- ,,,.Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases.5th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Saunders;2004.

- ,.Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant.6th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier Saunders;2006.

- ,.Avery's diseases of the newborn.7th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Saunders;1998.

- ,.Child Neurology.6th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Lippincott Williams 2000.

- ,.Pediatric Neurology: Principles and Practice.3rd ed.St. Louis, MO:Mosby;1999.

- ,.Unpredictability of serious bacterial illness in febrile infants from birth to 1 month of age.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.1999;153(5):508–511.

- ,,.The efficacy of routine outpatient management without antibiotics of fever in selected infants.Pediatrics.1999;103(3):627–631.

- ,,.Bacterial sepsis and meningitis. In: Remington JS, Klein JO, Wilson CB, Baker CJ, eds.Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn Infant.6th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier, Inc.;2006:247–295.

- NCCLS.Interference testing in Clinical Chemistry, NCCLS Document EP7.Wayne, PA:NCCLS;1986.

- ,,,.Lack of cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis in young infants with enterovirus infections of the central nervous system.Pediatr Emerg Care.2010;26(2):77–81.

- ,,, et al.Clinical and demographic factors associated with urinary tract infection in young febrile infants.Pediatrics.2005;116(3):644–648.

- ,,,,.Enhanced urinalysis as a screening test for urinary tract infection.Pediatrics.1993;91(6):1196–1199.

- ,,,.Screening for urinary tract infection in infants in the emergency department: which test is best?Pediatrics.1998;101(6):E1.

- ,,,,,.Routine cerebrospinal fluid enterovirus polymerase chain reaction testing reduces hospitalization and antibiotic use for infants 90 days of age or younger.Pediatrics.2007;120(3):489–496.

- .The normal cerebro‐spinal fluid in children.Archf Dis Child.1928:96–108.

- .The cerebrospinal fluid in the healthy newborn infant.S Afr Med J.1968;42(35):933–935.

- ,,.Cerebrospinal fluid evaluation in neonates: comparison of high‐risk infants with and without meningitis.J Pediatr.1976;88(3):473–477.

- ,.Estimation of reference intervals for total protein in cerebrospinal fluid.Clin Chem.1989;35(8):1766–1770.

- ,,,,,.Severe neonatal parechovirus infection and similarity with enterovirus infection.Pediatr Infect Dis J.2008;27(3):241–245.

- ,.Henry's Clinical Diagnosis and Management by Laboratory Methods.21st ed.Philadelphia, PA:W.B. Saunders, Inc.;2006.

- .On the cerebrospinal fluid in normal children and in patients with acute abacterial meningo‐encephalitis.Acta Paediatr Suppl.1958;47(Suppl 115):1–102.

- ,.Development of the blood‐CSF barrier.Dev Med Child Neurol.1983;25(2):152–161.

- ,,,,.Reference values of normal cerebrospinal fluid composition in infants ages 0 to 8 weeks.Pediatr Infect Dis J.1992;11(7):589–591.

- ,,, et al.Cerebrospinal fluid values in the term neonate.Pediatr Infect Dis J.1996;15(4):298–303.

- ,,,,,.Cerebrospinal fluid protein concentrations in children: age‐related values in patients without disorders of the central nervous system.Clin Chem.2000;46(3):399–403.

- ,,,,.Cerebrospinal fluid protein concentration in pediatric patients: defining clinically relevant reference values.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2000;154(8):827–831.

- ,,.Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics.17th ed.Philadelphia, PA:Saunders;2004.

- ,,,.Oski's pediatrics : principles 2006.

- Robertson J, Shilkofski N, eds.Johns Hopkins: The Harriet Lane Handbook: A Manual for Pediatric House Officers.17 ed.Philadelphia, PA:Elsevier Mosby;2005.

- ,,,.The Philadelphia Guide: Inpatient Pediatrics.Philadelphia, PA:Lippincott Williams 2005.

- ,,,.Pediatric Hospital Medicine: Textbook of Inpatient Management.Philadelphia, PA:Lippincott Williams 2008.