User login

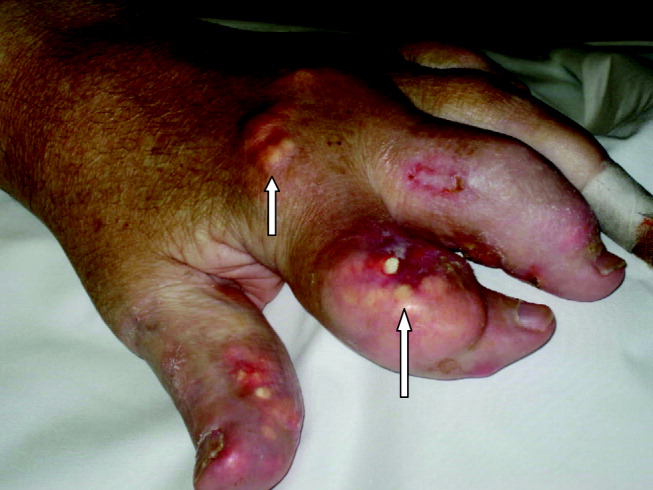

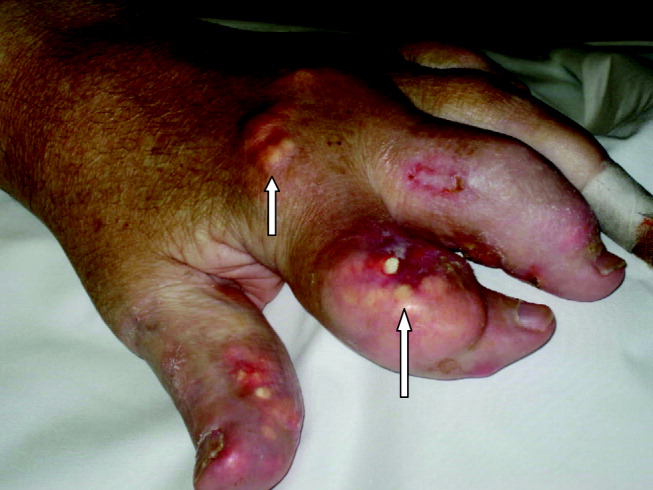

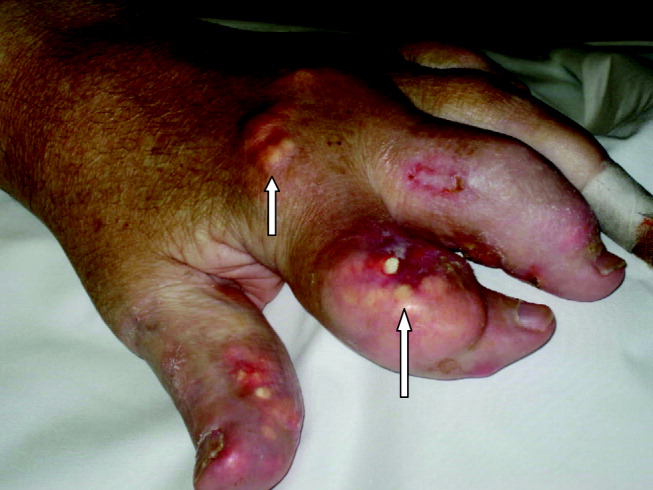

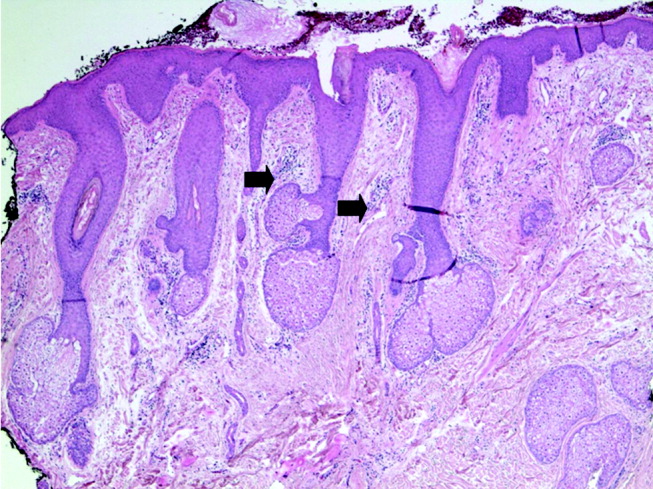

Paintball: Dermatologic Injuries

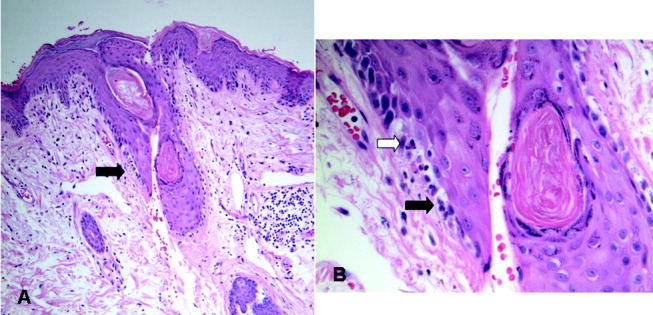

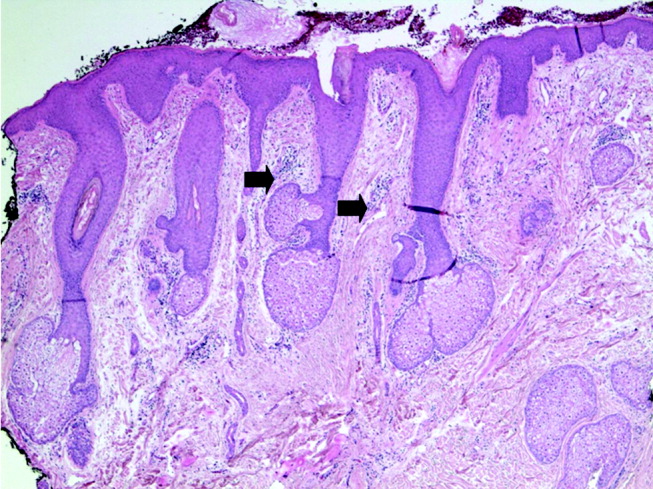

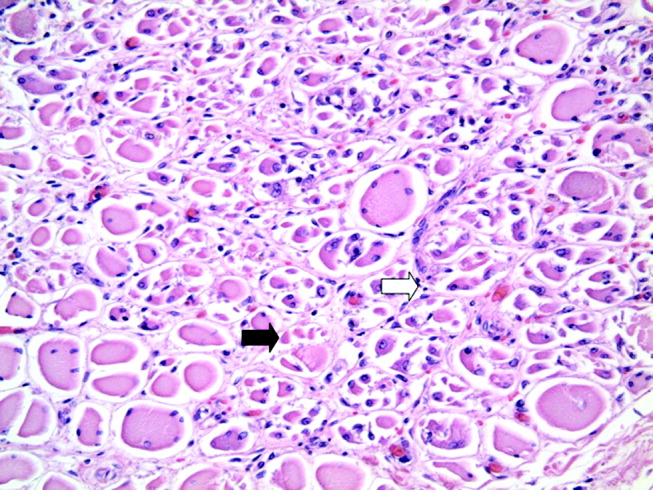

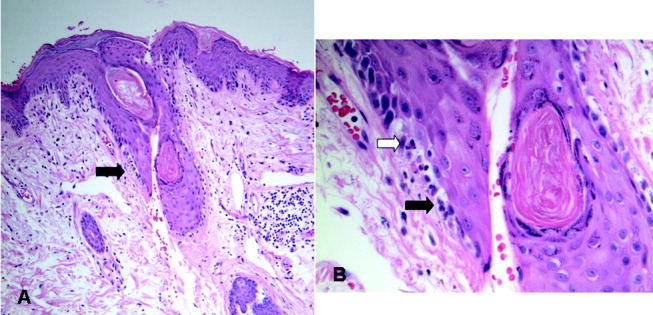

Blue Nevi: A Case Report and Review of the Literature

What's Eating You? Bees, Part 2: Venom Immunotherapy and Mastocytosis

Sun Sensitivity in 5 US Ethnoracial Groups

Want a bonus check? CMS has a program for you

Quality measures are reported on the CMS claim form just as any other service would be, except that no charge is billed for the reported measure. The time frame established for the reporting of these measures is July 1 through December 31 of this year. Although there are plans to continue the program in 2008, it is unclear whether funds will be available for a bonus in 2009, and the measures for 2008 will be different from those used in 2007.

To calculate the potential bonus amount when at least 3 measures are successfully reported, use your total Medicare income for the past 6 months. If you received $60,000 for treating Medicare patients from January 1 through May 31, for example, and Medicare income has been steady, expect a lump sum bonus of $900 in mid-2008.

How do I report an intervention?

Good news: You do not have to register to participate in PQRI; you need only report the selected quality measures each time you submit a claim for the patient service to which the quality measure applies. Criteria for reporting (and then receiving the bonus in mid-2008) for these quality measures are as follows:

- Select the quality measures that apply most often to your practice (see the TABLE)

- Enter the PQRI codes on block 24D of the CMS 1500 claim form with a $0.00 dollar amount; if your system does not allow this amount to be entered, change it to $0.01

- There must be a match between the acceptable CPT or ICD-9 code reported for the overall service with a CPT Category II or HCPCS “G” code designated as the quality measure, as listed in the Medicare specifications file (www.cms.hhs.gov/PQRI/15_MeasuresCodes.asp#TopOfPage)

- Apply any applicable allowed modifier that explains why the quality measure was not assessed:

- Measure title

- Description

- Instructions on reporting, including frequency, time frames, and applicability

- Numerator coding

- Definition of terms

- Coding instructions

The numerator part of the measure is represented by a CPT Category II code with or without a modifier. CPT code 1090F (presence or absence of urinary stress incontinence assessed) would be reported if the presence or absence of urinary incontinence was assessed, but a modifier 1P is placed in box 24E of the claim form if you have documented a medical reason why this was not assessed, or modifier 8P if it was not assessed but the reason was not documented.

TABLE

The Physician Quality Reporting Initiative: 10 measures may apply to ObGyn practice in 2007

| MEASURE | CONSTRAINTS AND COMMENTS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| #20 Perioperative care: Timing of antibiotic prophylaxis—ordering physician |

| ||

| #21 Perioperative care: Selection of prophylactic antibiotic—first- or second-generation cephalosporin |

| ||

| #22 Perioperative care: Discontinuation of prophylactic antibiotic (non-cardiac procedures) |

| ||

| #23 Perioperative care: venous thromboembolism prophylaxis (when indicated in all patients) |

| ||

| #39 Screening or therapy for osteoporosis for women 65 years and older |

| ||

| #41 Osteoporosis: Pharmacotherapy |

| ||

| #42 Osteoporosis: Counseling for vitamin D and calcium intake, and exercise |

| ||

| #48 Assessment of presence or absence of urinary incontinence in women aged 65 years and older |

| ||

| #49 Characterization of urinary incontinence in women aged 65 years and older |

| ||

| #50 Plan of care for urinary incontinence in women aged 65 years and older |

| ||

Quality measures are reported on the CMS claim form just as any other service would be, except that no charge is billed for the reported measure. The time frame established for the reporting of these measures is July 1 through December 31 of this year. Although there are plans to continue the program in 2008, it is unclear whether funds will be available for a bonus in 2009, and the measures for 2008 will be different from those used in 2007.

To calculate the potential bonus amount when at least 3 measures are successfully reported, use your total Medicare income for the past 6 months. If you received $60,000 for treating Medicare patients from January 1 through May 31, for example, and Medicare income has been steady, expect a lump sum bonus of $900 in mid-2008.

How do I report an intervention?

Good news: You do not have to register to participate in PQRI; you need only report the selected quality measures each time you submit a claim for the patient service to which the quality measure applies. Criteria for reporting (and then receiving the bonus in mid-2008) for these quality measures are as follows:

- Select the quality measures that apply most often to your practice (see the TABLE)

- Enter the PQRI codes on block 24D of the CMS 1500 claim form with a $0.00 dollar amount; if your system does not allow this amount to be entered, change it to $0.01

- There must be a match between the acceptable CPT or ICD-9 code reported for the overall service with a CPT Category II or HCPCS “G” code designated as the quality measure, as listed in the Medicare specifications file (www.cms.hhs.gov/PQRI/15_MeasuresCodes.asp#TopOfPage)

- Apply any applicable allowed modifier that explains why the quality measure was not assessed:

- Measure title

- Description

- Instructions on reporting, including frequency, time frames, and applicability

- Numerator coding

- Definition of terms

- Coding instructions

The numerator part of the measure is represented by a CPT Category II code with or without a modifier. CPT code 1090F (presence or absence of urinary stress incontinence assessed) would be reported if the presence or absence of urinary incontinence was assessed, but a modifier 1P is placed in box 24E of the claim form if you have documented a medical reason why this was not assessed, or modifier 8P if it was not assessed but the reason was not documented.

TABLE

The Physician Quality Reporting Initiative: 10 measures may apply to ObGyn practice in 2007

| MEASURE | CONSTRAINTS AND COMMENTS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| #20 Perioperative care: Timing of antibiotic prophylaxis—ordering physician |

| ||

| #21 Perioperative care: Selection of prophylactic antibiotic—first- or second-generation cephalosporin |

| ||

| #22 Perioperative care: Discontinuation of prophylactic antibiotic (non-cardiac procedures) |

| ||

| #23 Perioperative care: venous thromboembolism prophylaxis (when indicated in all patients) |

| ||

| #39 Screening or therapy for osteoporosis for women 65 years and older |

| ||

| #41 Osteoporosis: Pharmacotherapy |

| ||

| #42 Osteoporosis: Counseling for vitamin D and calcium intake, and exercise |

| ||

| #48 Assessment of presence or absence of urinary incontinence in women aged 65 years and older |

| ||

| #49 Characterization of urinary incontinence in women aged 65 years and older |

| ||

| #50 Plan of care for urinary incontinence in women aged 65 years and older |

| ||

Quality measures are reported on the CMS claim form just as any other service would be, except that no charge is billed for the reported measure. The time frame established for the reporting of these measures is July 1 through December 31 of this year. Although there are plans to continue the program in 2008, it is unclear whether funds will be available for a bonus in 2009, and the measures for 2008 will be different from those used in 2007.

To calculate the potential bonus amount when at least 3 measures are successfully reported, use your total Medicare income for the past 6 months. If you received $60,000 for treating Medicare patients from January 1 through May 31, for example, and Medicare income has been steady, expect a lump sum bonus of $900 in mid-2008.

How do I report an intervention?

Good news: You do not have to register to participate in PQRI; you need only report the selected quality measures each time you submit a claim for the patient service to which the quality measure applies. Criteria for reporting (and then receiving the bonus in mid-2008) for these quality measures are as follows:

- Select the quality measures that apply most often to your practice (see the TABLE)

- Enter the PQRI codes on block 24D of the CMS 1500 claim form with a $0.00 dollar amount; if your system does not allow this amount to be entered, change it to $0.01

- There must be a match between the acceptable CPT or ICD-9 code reported for the overall service with a CPT Category II or HCPCS “G” code designated as the quality measure, as listed in the Medicare specifications file (www.cms.hhs.gov/PQRI/15_MeasuresCodes.asp#TopOfPage)

- Apply any applicable allowed modifier that explains why the quality measure was not assessed:

- Measure title

- Description

- Instructions on reporting, including frequency, time frames, and applicability

- Numerator coding

- Definition of terms

- Coding instructions

The numerator part of the measure is represented by a CPT Category II code with or without a modifier. CPT code 1090F (presence or absence of urinary stress incontinence assessed) would be reported if the presence or absence of urinary incontinence was assessed, but a modifier 1P is placed in box 24E of the claim form if you have documented a medical reason why this was not assessed, or modifier 8P if it was not assessed but the reason was not documented.

TABLE

The Physician Quality Reporting Initiative: 10 measures may apply to ObGyn practice in 2007

| MEASURE | CONSTRAINTS AND COMMENTS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| #20 Perioperative care: Timing of antibiotic prophylaxis—ordering physician |

| ||

| #21 Perioperative care: Selection of prophylactic antibiotic—first- or second-generation cephalosporin |

| ||

| #22 Perioperative care: Discontinuation of prophylactic antibiotic (non-cardiac procedures) |

| ||

| #23 Perioperative care: venous thromboembolism prophylaxis (when indicated in all patients) |

| ||

| #39 Screening or therapy for osteoporosis for women 65 years and older |

| ||

| #41 Osteoporosis: Pharmacotherapy |

| ||

| #42 Osteoporosis: Counseling for vitamin D and calcium intake, and exercise |

| ||

| #48 Assessment of presence or absence of urinary incontinence in women aged 65 years and older |

| ||

| #49 Characterization of urinary incontinence in women aged 65 years and older |

| ||

| #50 Plan of care for urinary incontinence in women aged 65 years and older |

| ||

Do our talks with patients meet their expectations?

- Patients want an attentive, friendly, frank and empathic doctor who listens well.

- To enhance quality of health care, consider asking patients at the end of a visit whether their communication preferences were met.

One physician has written that good patient-doctor communication, like jazz, calls for improvisation.1 We agree. And improvise we must when patients’ expectations for how we will communicate with them vary between visits and individuals.

For example, those who are ill may prefer that their doctor communicate with them in a way that is less important to those who are healthy. Patients with biomedical problems may have different preferences than persons with psychosocial problems. And older individuals may have communication desires that differ from those who are younger.2-4

Do patients want cure or care, or both?

Depending on the reason for a visit—eg, biomedical or psychosocial—patient preferences may fit either the cure or the care dimension.

Cure dimension. On one hand, patients expect their doctor to be task-oriented and to find a cure for what ails them. They want an explanation of what is wrong and advice about possible treatments, and they want the doctor to do whatever is needed to get answers.5

Care dimension. On the other hand, patients may feel anxious and want reassurance. They expect the doctor to listen to their story and encourage them to disclose all health problems, concerns, and worries. They also expect friendliness and empathy. They want to be taken seriously. The extent to which the doctor shows this affect-oriented (and patient-centered) behavior will determine how fulfilled patients feel in their preference for care.6,7

Why does it matter? Good communication serves a patient’s need to understand and to be understood.6,8,9 And communication aimed at matching patient preferences enhances satisfaction with care, compliance with medical instructions, and health status.10-13

How well do we assess patients’ communication preferences?

Patient-centered behavior is a necessary tool for discovering and fulfilling patients’ task-oriented (cure dimension) and affect-oriented (care dimension) communication preferences.14-17 It’s important to know how well primary-care physicians interpret patients’ preferences for clinical encounters and if they respond in a manner that satisfies those expectations.

Reassuringly, patients indicate on surveys that their physicians do a fairly good job of interpreting their communication preferences and acting accordingly.18-20 They also report that their desires and expectations from consultations are increasingly met.

There is always the worry, though, that physicians in certain positions—eg, non-gatekeeper roles or positions involving only part-time clinical responsibilities—would be challenged to assess patient preferences as accurately as others.21

The aim of our study

While it’s encouraging that physicians by and large understand their patients and communicate with them meaningfully, we wondered whether communication could improve further. Our purpose in this study was to gain detailed insight into patients’ preferences in physician communication and, through patients’ subjective perspectives and observed real practice consultations, learn how well physicians communicate according to those preferences.

Methods

Design

We derived physician data from the Second Dutch National Survey of General Practice (2001). This study was carried out in practices representative of Dutch general practice.22 We asked patients for permission to videotape consultations with the general practitioner (GP), and asked them to sign a consent form. Collected data were kept private as per regulations.

We videotaped consultations of 142 GPs (76.1% male) and 2784 patients (41.2% male). The number of patients cared for by each GP ranged between 17 and 21 (mean=19.6). Each patient was videotaped just once. We rated roughly 15 patient-consultations per GP (13–15, mean=14.8), excluding the first 3 to correct for possible bias because of the video camera. Before and immediately after the consultation, patients 18 years of age and older answered a questionnaire. We used data from 1787 patient consultations.

Patients rate their communication preferences

The patient questionnaire covered demographic characteristics (gender, age, education); health problems (psychosocial or not [ICPC-coded]);23 overall health during the past 2 weeks (1=excellent, 2=very good, 3=good, 4=fair, 5=poor); and depressive feelings during the past 2 weeks (1=not at all, 2=slightly, 3=moderately, 4=quite a bit, 5=extremely) (COOP-WONCA charts24).

We defined communication preferences as “the extent of importance patients attach to communication aspects.”25 Patients’ preferences and the actual performance by the GP were measured using the conceptual framework of the QUOTE scale (quality of care through the patient’s eyes).5,25

Before consultation, patients recorded how important they considered different aspects of communication for the coming visit (1=not important, 2=rather important, 3=important, 4=utmost important). Following consultation, they rated the GP’s performance in meeting their expectations for these aspects (1=not, 2=really not, 3=really yes, 4=yes).

Factor analysis of both the pre- and post-visit lists of questions on preference and performance revealed 2 relevant subscales: an affect-oriented scale of 7 communication aspects and a task-oriented scale of 6 communication aspects (Cronbach’s alpha between 0.74 and 0.89).

We also used communication aspects from the original 4-point scale to present 4 new categories that compared and contrasted preferences and relevance. These categories included: important and performed; important and not performed; not important and performed; not important and not performed. In the multilevel analysis, we included the 2 subscales using the original 4-point scale.

Socio-demographic and practice variables were derived from the GP questionnaires in the Second Dutch National Survey of General Practice (2001).

Video observations

Nine observers measured verbal behavior during the videotaped visits using the Roter Method of Interaction Process Analysis (RIAS26), a well-documented, widely used system in the US and Netherlands. This observation system distinguishes both affect-oriented (socio-emotional) and task-oriented (instrumental) verbal behavior of doctors and patients, reflecting the care and cure dimensions, respectively. The RIAS categories are mutually exclusive and exhaustive.

Affect-oriented communication consists of personal remarks, agreements, concerns, reassurances, paraphrases, and disagreements.

Task-oriented talk includes asking questions, giving information, and (only GPs) counseling about medical/therapeutic and psychosocial, social context and lifestyle issues, and process-oriented talk (instructions, asking for understanding).

After finishing the RIAS-coding, we calculated the total numbers of affect-oriented and task-oriented verbal behaviors separately for GPs and patients.

The relevance and performance items and the RIAS-categories all measured the affect-oriented and task-oriented aspects.

We used the Noldus Observer-Video-Pro computer program for the observation study,27 including measurement of consultation length. The interobserver reliabilities were good to excellent: between r=0.80 to r=0.95 per category, except for personal remarks (0.72).

Patient-centeredness measured in 3 ways

The observers, using a 5-point scale, also rated the extent to which GPs communicated in a patient-centered way in 3 areas: patient’s involvement in the problem-defining process; patient’s involvement in the decision-making process; and doctor’s overall responsiveness to the patient.

Based on ratings in these 3 areas, we determined an overall magnitude of patient-centeredness (Cronbach’s alpha=0.75). Observers and the responsible researcher met weekly to validate the quality of rating. The same was done for the RIAS coding.

Controlling variables

For GPs, controlling variables were gender, age, and number of full-time equivalents (FTEs) working. For patients, GP and patient gender were included in the variable “gender-dyad”—male GPs/male patients, male GPs/female patients, female GPs/male patients, female GPs/female patients. Other patient variables were age; education (low=no/primary school, middle=secondary school, high=higher vocational training/university); health problems: somatic or psychosocial (ICPC chapters); overall physical health and mental health during the past 2 weeks; and consultation length.

Data analysis

We used descriptive and multilevel analyses. The intra-class correlations of the affect-oriented and task-oriented communication and patient-centeredness were significant (between .05 and 0.23), which made it clear that consultations of the same GP did indeed exhibit a greater degree of similarity than the consultations of different GPs. Therefore, multilevel analyses were necessary to account for the clustering of patients with the same GP.28 We applied a significance level of ≤0.05 (2-sided).

Results

Response rate

The overall patient response rate was 88%. Analysis of non-responders’ gender, age, and type of insurance showed no bias resulting from patients’ refusal.

GP response rate was 72.8%. Respondents were representative of all Dutch GPs with respect to gender, age, working hours, practice experience (mean=15.6 years, SD=8.3, range=1–32), and location (58% in an urban area). More GPs worked in a partnership or group practice than in a solo practice. We analyzed the influence of the practice type on doctor-patient communication and deemed it insignificant.

Study population

GP and patient characteristics appear in TABLE 1. Among patients, 22% had little education, 62% had an average education, and 16% had higher education. Nearly 10% had a psychosocial problem. GP-patient gender dyads were as follows: 32.1% male GP/male patient; 45.3% male GP/female patient; 6.9% female GP/male patient; 15.8% female GP/female patient.

TABLE 1

General practitioner and patient characteristics (N GPs=142, N patients=1787)

| MEAN | SD | RANGE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP characteristics | |||

| Age (yrs) | 46.9 | 6.2 | 32–62 |

| Full-time equivalents | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.2–1 |

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Age (yrs) | 49.5 | 17.4 | 18–95 |

| Psychosocial problem (1=yes) | 9.8% | — | — |

| Overall health (1=excellent, 5=poor) | 3.2 | 1.1 | 1–5 |

| Depressive feelings (1=not at all, 5=extremely) | 2.2 | 1.2 | 1–5 |

| Consultation length (min) | 10.1 | 4.8 | 1.3–33.0 |

| Patients’ preferences | |||

| Affect-oriented preference (1=not, 4=utmost important) | 3.2 | 0.5 | 1–4 |

| Task-oriented preference (1=not, 4=utmost important) | 3.1 | 0.6 | 1–4 |

Preference and performance of communication aspects

GPs good with affect-oriented communication aspects. Patients considered 6 of 7 affect-oriented communication aspects as very important (87%–96%, TABLE 2). The item “Doctor was empathic to me” was less important (61%) than items like “Doctor listened well to me” (96%) and “Doctor took enough time for me” (93%). We noted only a few discrepancies between preference and performance of the GPs’ affect-oriented behavior. If patients said beforehand that a communication aspect was important, the doctors nearly always performed that aspect. For instance, 87% wanted enough attention from the doctor and received it, while 99% of all patients received GP’s attention, whether it was important to them or not.

GPs less successful with task-oriented communication aspects. Many patients wanted information, explanations, advice, and help with their problems (85%–94%, TABLE 2). Knowing the diagnosis was less important (77%) than, say, receiving advice on what to do and having details of treatment explained.

GPs also performed most of the task-oriented aspects, if patients considered these aspects important.

Subjectively, preferences for GP task-oriented behavior and perceived performance often went together, though more discrepancies were visible than with affect-oriented behavior. One fifth of patients said their problems were not helped, though they had said this was important. Similarly, GPs did not give a diagnosis to nearly 15% of patients who considered it important.

TABLE 2

Care vs cure-centered communication: Physicians fared better on the care side (N=1787)

| AFFECT-ORIENTED ASPECTS (CARE DIMENSION) | PERFORMED | NOT PERFORMED | TOTAL* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N % | % | N | % | |

| Doctor gave me enough attention | ||||||

| Important | 1304 | 87.5 | 9 | 0.6 | 1313 | 88.1 |

| Not important | 174 | 11.7 | 4 | 0.3 | 178 | 11.9 |

| Doctor listened well to me | ||||||

| Important | 1456 | 95.3 | 10 | 0.7 | 1466 | 95.9 |

| Not important | 61 | 4.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 62 | 4.1 |

| Doctor took enough time for me | ||||||

| Important | 1412 | 92.3 | 11 | 0.7 | 1423 | 93.1 |

| Not important | 105 | 6.9 | 1 | 0.1 | 106 | 6.9 |

| Doctor was friendly | ||||||

| Important | 1331 | 87.2 | 3 | 0.2 | 1334 | 87.4 |

| Not important | 193 | 12.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 193 | 12.6 |

| Doctor was frank to me | ||||||

| Important | 1451 | 95.5 | 5 | 0.3 | 1456 | 95.8 |

| Not important | 63 | 4.15 | 0 | 0.0 | 63 | 4.2 |

| Doctor took my problem seriously | ||||||

| Important | 1455 | 95.8 | 7 | 0.5 | 1462 | 96.3 |

| Not important | 55 | 3.6 | 1 | 0.1 | 56 | 3.7 |

| Doctor was empathic to me | ||||||

| Important | 846 | 58.4 | 36 | 2.5 | 882 | 60.9 |

| Not important | 492 | 34.0 | 74 | 5.1 | 566 | 19.1 |

| TASK-ORIENTED ASPECTS (CURE DIMENSION) | ||||||

| Doctor diagnosed what’s wrong | ||||||

| Important | 921 | 62.8 | 209 | 14.2 | 1130 | 77.0 |

| Not important | 197 | 13.4 | 140 | 9.5 | 337 | 23.0 |

| Doctor explained well what’s wrong | ||||||

| Important | 1166 | 78.3 | 101 | 6.8 | 1267 | 85.0 |

| Not important | 175 | 11.7 | 48 | 3.2 | 223 | 15.0 |

| Doctor informed well on treatment | ||||||

| Important | 1304 | 86.6 | 109 | 7.2 | 1413 | 93.9 |

| Not important | 75 | 5.0 | 17 | 1.1 | 92 | 6.1 |

| Doctor gave advice on what to do | ||||||

| Important | 1294 | 85.9 | 121 | 8.0 | 1415 | 94.0 |

| Not important | 75 | 5.0 | 16 | 1.1 | 91 | 6.0 |

| Doctor helped me with my problem | ||||||

| Important | 1031 | 70.0 | 121 | 18.9 | 1152 | 88.9 |

| Not important | 94 | 6.4 | 16 | 4.7 | 110 | 11.1 |

| Doctor examined me | ||||||

| Important | 902 | 59.9 | 132 | 8.8 | 1034 | 62.8 |

| Not important | 228 | 15.1 | 244 | 16.2 | 472 | 27.2 |

| * Totals do not always add up to 1787 because of missing data. | ||||||

GP communication varies by doctor gender, patient characteristics

GPs engaged less in affect-oriented than in task-oriented communication (48.6 and 70.0 utterances on average, respectively, P≤.001).

The more patients regarded affect-oriented talk by GPs as important, the more the GPs actually showed affective and patient-centered behavior (TABLE 3). Preferences for task-oriented behavior (question-asking, information-giving, and counseling) were mirrored in their doctors’ talk.

When taking into account other GP and patient characteristics, female doctors were more often affect-oriented as well as task-oriented when communicating with patients than were male doctors, especially with female patients. In consultations with older patients and those in poor health, the doctors were more affective than in consultations with younger and healthy patients.

TABLE 3

On observation, physician communication corresponded to patient preferences (N GPs=142, N patients=1787)

| REGRESSION COEFFICIENTS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AFFECT-ORIENTED TALK GPs | TASK-ORIENTED TALK GPs | PATIENT-CENTEREDNESS | |

| GP characteristics | |||

| Age (yrs) | –0.20 | –0.37* | –0.01* |

| Full-time equivalents | –12.13* | 2.45 | 0.03 |

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Gender-dyad: | |||

| - Male/female | –0.89c | 0.17d | 0.01 |

| - Female/male | 9.40a,b,d | 6.24a,d | 0.10 |

| - Female/female | 5.73a,c | 6.85a,b,c | 0.02 |

| Age (yrs) | 0.09* | –0.15 | –0.00* |

| Education (1=low, 2=middle, 3=high) | –0.70 | 0.15 | 0.05 |

| Psychosocial problems (1=yes) | 7.93* | –4.62* | 0.13* |

| Overall health (1=excellent, 5=poor) | 1.13* | 0.96 | –0.01 |

| Depressive feelings (1=not at all, 5=extremely) | 0.78 | –0.72 | 0.01 |

| Consultation length (min) | 4.03* | 4.30* | 0.04* |

| Patients’ preferences | |||

| Affect-oriented preference (1=not, 4=utmost important) | 2.81* | –1.94 | 0.16* |

| Task-oriented preference (1=not, 4=utmost important) | –4.23 * | 3.62* | –0.15* |

| * P<.05 | |||

| a. Score differs significantly from score of male GP/male patient dyad (reference group). | |||

| b. Score differs significantly from score of male GP/female patient dyad. | |||

| c. Score differs significantly from score of female GP/male patient dyad. | |||

| d. Score differs significantly from score of female GP/female patient dyad. | |||

Discussion

Our study suggests most patients receive from their GPs the kind of communication they prefer in a consultation. In general, patients consider both affect- and task-oriented communication aspects important, and believe they are often performed. Our findings agree with most of the literature.5,14,20 Furthermore, patients’ preferences are for the greater part reflected in the GPs’ observed communication during the visit, which agrees with one earlier study18 but not with others.5,20

Patient preference for an affective doctor is very often met. GPs are generally considered attentive, friendly, frank, empathic, and good listeners. Patients seem satisfied in this respect. However, the task-oriented communication of the GPs is sometimes less satisfying. Contrary to patient preference, for example, GPs are not always able to make a diagnosis.

Observed physician behavior: patients usually get what they want. Looking at the relationship between preferences and actual GP communication, it appears that the more patients prefer an affective or caring doctor, the more they are likely to get an empathic, concerned, interested, and patient-centered doctor, especially when psychosocial problems are expressed. An affective GP was patient centered, involving patients in problem definition and decision making. This relationship between affective behavior and patient-centeredness was also found in earlier studies.22,29 However, Swenson found that not all patients wanted the doctor to exhibit a patient-centered approach.30

Likewise, the more patients prefer a task-oriented doctor, the better the chance they will have a doctor who explains things well, and who gives information and advice to their satisfaction. However, task-oriented doctors are usually less affective and less patient-centered when talking with patients. In view of the postulate that a doctor has to be curing as well as caring,6 doctors would be wise to give attention to both aspects.

GPs do improvise while communicating with patients. The study shows that GPs and patients working together can create the type of encounter both want. GPs are able to change their behavior in response to real-time cues they believe patients are giving in an encounter.

Physician gender often makes a difference. Our findings suggest that female doctors are more affective and task-oriented when talking with their patients than are male doctors, especially with female patients. In view of the steady increase of female doctors in general practice, this combined communication style may become more common in the future.

Psychosocial complaints prompt affective communication. Patients with a psychosocial problem are more likely to encounter an affective doctor than those with a biomedical problem. The growing number of psychosocial problems in the population may lead to a more affective communication.

Eventually the demand and the supply of affective communication may coincide. However, it is a challenge for every doctor to keep his or her mind open to both biomedical (task-oriented) and psychosocial (affective-oriented) information.31

Study caveats. Because we used scale scores for affect- and task-oriented preferences instead of the separate item scores for patient preferences, the reflection of preferences for GP communicative behavior might be somewhat overestimated. Likewise, we used total observation scores for affect- and task-oriented talk instead of the separate RIAS categories. More detailed measures of such communication aspects as empathy might give better insight into patient preferences.

Final thoughts on personal application. Primary care physicians would do well to take notice of patients’ preferences for communication. GPs in our study were often able to grasp what patients considered important to talk about, and there seemed to be only modest mismatches between patient expectations and physician behavior. To increase the quality of health care, consider asking patients at the end of a visit whether their preferences were met.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the participating general practitioners and patients, the observers of the videotaped consultations, and the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports for funding (for the greater part) the research project.

Correspondence

A. van den Brink-Muinen, PhD, NIVEL, PO Box 1568, 3500 BN Utrecht, The Netherlands; [email protected]

1. Haidet P. Jazz and the ‘Art’ of Medicine: Improvisation in the Medical Encounter. Ann Fam Med 2007;5:164-169.

2. Jung HP, Baerveldt C, Olesen F, Grol R, Wensing M. Patient characteristics as predictors of primary health care p: a systematic literature analysis. Health Expect 2003;6:160-181.

3. Bartholomew L, Schneiderman LJ. Attitudes of patients towards family care in a family practice group. J Fam Pract 1982;15:477-481.

4. Wetzels R, Geest TA, Wensing M, Lopes Ferreira P, Grol R, Baker R. GPs’ views on involvement of older patients: a European qualitative study. Pat Educ Couns 2004;53:183-188.

5. Brink-Muinen A, Verhaak PFM, Bensing JM, et al. Doctor-patient communication in different European health care systems: relevance and performance from the patients’ perspective. Pat Educ Counsel 2000;39:115-127.

6. Bensing JM, Dronkers J. Instrumental and affective aspects of physician behaviour. Med Care 1992;30:283-

7. Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. observational study of effect of patient centeredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice. BMJ 2001;323:908-911.

8. Roter DL, Hall JA. Doctors Talking with Patients/Patients Talking with Doctors: Improving Communication in Medical Visits Westport/London: Auburn House; 1992.

9. Roter DL, Stewart M, Putnam SM, Lipkin M, Stiles W, Inui TS. Communication patterns of primary care physicians. JAMA 1997;277:350-356.

10. Sixma H, Spreeuwenberg P, Pasch M van der. Patient satisfaction with the general practitioner: a two-level analysis. Med Care 1998;2:212-229.

11. Dulmen AM van, Bensing JM. The Effect of Context in Health Care: A Programming Study The Hague: RGO; 2001.

12. Wensing M, Baker R. Patient involvement in general practice care: a pragmatic framework. Eur J Gen Pract 2003;9:62-65.

13. Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract 2000;49:796-804.

14. Bensing JM, Langewitz W. Die ärztliche Konsultation. In: Uexkull: Psychosomatische Medizin. 2002:415-424.

15. Brown J, Stewart M, Ryan B. Assessing communication between patients and physicians: the measure of patient-centred communication (MPCC). London, Ontario, Canada: Centre for Studies in Family Medicine, 2001.

16. Sullivan M. The new subjective medicine: taking the patients’ view on health care and health. Soc Sci Med 2003;56:1995-1604.

17. Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centeredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:1087-1110.

18. Jung HP, Wensing M, Grol R. What makes a good general practitioner: do patients and doctors have different views? Br J Gen Pract 1997;47:805—809.

19. Wensing M, Jung HP, Mainz J, Olesen F, Grol R. A systematic review of the literature in patient priorities for general practice care. Part 1: description of the research domain. Soc Sci Med 1998;47:1573-1588.

20. Thorsen H, Witt K, Hollnagel H, Malterud K. The purpose of the general practice consultation from the patients’ perspective—theoretical aspects. Fam Pract 2001;18:638-643.

21. Brink-Muinen A, Verhaak PFM, Bensing JM, et al. Communication in general practice: differences between European countries. Fam Pract 2003;20:478-485.

22. Schellevis FG, Westert GP, Bakker DH de, Groenewegen PP, Zee J van der, Bensing JM. De tweede Nationale studie naar ziekten en verrichtingen in de huisartsenpraktijk: aanleiding en methoden [Second Dutch National Survey of general practice: background and methods]. H&W 2003;46:7-12.

23. Lamberts H, Wood M (eds). International Classification of Primary Care Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1987.

24. Weel C van, König-Zahn C, Touw-Otten FWMM, Duijn NP van, Meyboom-de Jong B. Measuring Functional Health Status with the COOP/WONCA Charts. A Manual WoNCA, ERGHo, NCH, university of Groningen, Netherlands; 1995.

25. Sixma HJ, Kerssens JJ, Campen C van, Peters L. Quality of care from the patients’ perspective: from theoretical concept to a new measurement instrument. Health Expect 1998;1:82-95.

26. Roter DL. The Roter Method of Interaction Process Analysis Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins University; 2001.

27. Noldus LP, Trienes RJ, Hendriksen AH, Janden H, Jansen RG. The observer video-Pro: new software for the collection, management and presentation of time-structured data from videotapes and digital media films. Behavioral Research Methods, Instruments & Computers 2000;32:197-206.

28. Leyland AH, Groenewegen PP. Multilevel modelling and public health policy. Scand J Public Health 2003;31:267-274

29. Jung HP, Horne F van, Wensing M, Hearnshaw H, Grol R. Which aspects of general practitioners’ behaviour determine patients’ evaluations of care? Soc Sci Med 1998;47:1077-1087.

30. Swenson SL, Buell S, Zettler P, White M, Ruston DC, Lo B. Patient-centred communication: do patients really prefer it? J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:1069-1079.

31. Epstein RM, Campbell TL, Cohen-Cole SA, MaWhinney IR, Smilkstein G. Perspectives on patient-doctor communication. J Fam Pract 1993;37:377-388.

- Patients want an attentive, friendly, frank and empathic doctor who listens well.

- To enhance quality of health care, consider asking patients at the end of a visit whether their communication preferences were met.

One physician has written that good patient-doctor communication, like jazz, calls for improvisation.1 We agree. And improvise we must when patients’ expectations for how we will communicate with them vary between visits and individuals.

For example, those who are ill may prefer that their doctor communicate with them in a way that is less important to those who are healthy. Patients with biomedical problems may have different preferences than persons with psychosocial problems. And older individuals may have communication desires that differ from those who are younger.2-4

Do patients want cure or care, or both?

Depending on the reason for a visit—eg, biomedical or psychosocial—patient preferences may fit either the cure or the care dimension.

Cure dimension. On one hand, patients expect their doctor to be task-oriented and to find a cure for what ails them. They want an explanation of what is wrong and advice about possible treatments, and they want the doctor to do whatever is needed to get answers.5

Care dimension. On the other hand, patients may feel anxious and want reassurance. They expect the doctor to listen to their story and encourage them to disclose all health problems, concerns, and worries. They also expect friendliness and empathy. They want to be taken seriously. The extent to which the doctor shows this affect-oriented (and patient-centered) behavior will determine how fulfilled patients feel in their preference for care.6,7

Why does it matter? Good communication serves a patient’s need to understand and to be understood.6,8,9 And communication aimed at matching patient preferences enhances satisfaction with care, compliance with medical instructions, and health status.10-13

How well do we assess patients’ communication preferences?

Patient-centered behavior is a necessary tool for discovering and fulfilling patients’ task-oriented (cure dimension) and affect-oriented (care dimension) communication preferences.14-17 It’s important to know how well primary-care physicians interpret patients’ preferences for clinical encounters and if they respond in a manner that satisfies those expectations.

Reassuringly, patients indicate on surveys that their physicians do a fairly good job of interpreting their communication preferences and acting accordingly.18-20 They also report that their desires and expectations from consultations are increasingly met.

There is always the worry, though, that physicians in certain positions—eg, non-gatekeeper roles or positions involving only part-time clinical responsibilities—would be challenged to assess patient preferences as accurately as others.21

The aim of our study

While it’s encouraging that physicians by and large understand their patients and communicate with them meaningfully, we wondered whether communication could improve further. Our purpose in this study was to gain detailed insight into patients’ preferences in physician communication and, through patients’ subjective perspectives and observed real practice consultations, learn how well physicians communicate according to those preferences.

Methods

Design

We derived physician data from the Second Dutch National Survey of General Practice (2001). This study was carried out in practices representative of Dutch general practice.22 We asked patients for permission to videotape consultations with the general practitioner (GP), and asked them to sign a consent form. Collected data were kept private as per regulations.

We videotaped consultations of 142 GPs (76.1% male) and 2784 patients (41.2% male). The number of patients cared for by each GP ranged between 17 and 21 (mean=19.6). Each patient was videotaped just once. We rated roughly 15 patient-consultations per GP (13–15, mean=14.8), excluding the first 3 to correct for possible bias because of the video camera. Before and immediately after the consultation, patients 18 years of age and older answered a questionnaire. We used data from 1787 patient consultations.

Patients rate their communication preferences

The patient questionnaire covered demographic characteristics (gender, age, education); health problems (psychosocial or not [ICPC-coded]);23 overall health during the past 2 weeks (1=excellent, 2=very good, 3=good, 4=fair, 5=poor); and depressive feelings during the past 2 weeks (1=not at all, 2=slightly, 3=moderately, 4=quite a bit, 5=extremely) (COOP-WONCA charts24).

We defined communication preferences as “the extent of importance patients attach to communication aspects.”25 Patients’ preferences and the actual performance by the GP were measured using the conceptual framework of the QUOTE scale (quality of care through the patient’s eyes).5,25

Before consultation, patients recorded how important they considered different aspects of communication for the coming visit (1=not important, 2=rather important, 3=important, 4=utmost important). Following consultation, they rated the GP’s performance in meeting their expectations for these aspects (1=not, 2=really not, 3=really yes, 4=yes).

Factor analysis of both the pre- and post-visit lists of questions on preference and performance revealed 2 relevant subscales: an affect-oriented scale of 7 communication aspects and a task-oriented scale of 6 communication aspects (Cronbach’s alpha between 0.74 and 0.89).

We also used communication aspects from the original 4-point scale to present 4 new categories that compared and contrasted preferences and relevance. These categories included: important and performed; important and not performed; not important and performed; not important and not performed. In the multilevel analysis, we included the 2 subscales using the original 4-point scale.

Socio-demographic and practice variables were derived from the GP questionnaires in the Second Dutch National Survey of General Practice (2001).

Video observations

Nine observers measured verbal behavior during the videotaped visits using the Roter Method of Interaction Process Analysis (RIAS26), a well-documented, widely used system in the US and Netherlands. This observation system distinguishes both affect-oriented (socio-emotional) and task-oriented (instrumental) verbal behavior of doctors and patients, reflecting the care and cure dimensions, respectively. The RIAS categories are mutually exclusive and exhaustive.

Affect-oriented communication consists of personal remarks, agreements, concerns, reassurances, paraphrases, and disagreements.

Task-oriented talk includes asking questions, giving information, and (only GPs) counseling about medical/therapeutic and psychosocial, social context and lifestyle issues, and process-oriented talk (instructions, asking for understanding).

After finishing the RIAS-coding, we calculated the total numbers of affect-oriented and task-oriented verbal behaviors separately for GPs and patients.

The relevance and performance items and the RIAS-categories all measured the affect-oriented and task-oriented aspects.

We used the Noldus Observer-Video-Pro computer program for the observation study,27 including measurement of consultation length. The interobserver reliabilities were good to excellent: between r=0.80 to r=0.95 per category, except for personal remarks (0.72).

Patient-centeredness measured in 3 ways

The observers, using a 5-point scale, also rated the extent to which GPs communicated in a patient-centered way in 3 areas: patient’s involvement in the problem-defining process; patient’s involvement in the decision-making process; and doctor’s overall responsiveness to the patient.

Based on ratings in these 3 areas, we determined an overall magnitude of patient-centeredness (Cronbach’s alpha=0.75). Observers and the responsible researcher met weekly to validate the quality of rating. The same was done for the RIAS coding.

Controlling variables

For GPs, controlling variables were gender, age, and number of full-time equivalents (FTEs) working. For patients, GP and patient gender were included in the variable “gender-dyad”—male GPs/male patients, male GPs/female patients, female GPs/male patients, female GPs/female patients. Other patient variables were age; education (low=no/primary school, middle=secondary school, high=higher vocational training/university); health problems: somatic or psychosocial (ICPC chapters); overall physical health and mental health during the past 2 weeks; and consultation length.

Data analysis

We used descriptive and multilevel analyses. The intra-class correlations of the affect-oriented and task-oriented communication and patient-centeredness were significant (between .05 and 0.23), which made it clear that consultations of the same GP did indeed exhibit a greater degree of similarity than the consultations of different GPs. Therefore, multilevel analyses were necessary to account for the clustering of patients with the same GP.28 We applied a significance level of ≤0.05 (2-sided).

Results

Response rate

The overall patient response rate was 88%. Analysis of non-responders’ gender, age, and type of insurance showed no bias resulting from patients’ refusal.

GP response rate was 72.8%. Respondents were representative of all Dutch GPs with respect to gender, age, working hours, practice experience (mean=15.6 years, SD=8.3, range=1–32), and location (58% in an urban area). More GPs worked in a partnership or group practice than in a solo practice. We analyzed the influence of the practice type on doctor-patient communication and deemed it insignificant.

Study population

GP and patient characteristics appear in TABLE 1. Among patients, 22% had little education, 62% had an average education, and 16% had higher education. Nearly 10% had a psychosocial problem. GP-patient gender dyads were as follows: 32.1% male GP/male patient; 45.3% male GP/female patient; 6.9% female GP/male patient; 15.8% female GP/female patient.

TABLE 1

General practitioner and patient characteristics (N GPs=142, N patients=1787)

| MEAN | SD | RANGE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP characteristics | |||

| Age (yrs) | 46.9 | 6.2 | 32–62 |

| Full-time equivalents | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.2–1 |

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Age (yrs) | 49.5 | 17.4 | 18–95 |

| Psychosocial problem (1=yes) | 9.8% | — | — |

| Overall health (1=excellent, 5=poor) | 3.2 | 1.1 | 1–5 |

| Depressive feelings (1=not at all, 5=extremely) | 2.2 | 1.2 | 1–5 |

| Consultation length (min) | 10.1 | 4.8 | 1.3–33.0 |

| Patients’ preferences | |||

| Affect-oriented preference (1=not, 4=utmost important) | 3.2 | 0.5 | 1–4 |

| Task-oriented preference (1=not, 4=utmost important) | 3.1 | 0.6 | 1–4 |

Preference and performance of communication aspects

GPs good with affect-oriented communication aspects. Patients considered 6 of 7 affect-oriented communication aspects as very important (87%–96%, TABLE 2). The item “Doctor was empathic to me” was less important (61%) than items like “Doctor listened well to me” (96%) and “Doctor took enough time for me” (93%). We noted only a few discrepancies between preference and performance of the GPs’ affect-oriented behavior. If patients said beforehand that a communication aspect was important, the doctors nearly always performed that aspect. For instance, 87% wanted enough attention from the doctor and received it, while 99% of all patients received GP’s attention, whether it was important to them or not.

GPs less successful with task-oriented communication aspects. Many patients wanted information, explanations, advice, and help with their problems (85%–94%, TABLE 2). Knowing the diagnosis was less important (77%) than, say, receiving advice on what to do and having details of treatment explained.

GPs also performed most of the task-oriented aspects, if patients considered these aspects important.

Subjectively, preferences for GP task-oriented behavior and perceived performance often went together, though more discrepancies were visible than with affect-oriented behavior. One fifth of patients said their problems were not helped, though they had said this was important. Similarly, GPs did not give a diagnosis to nearly 15% of patients who considered it important.

TABLE 2

Care vs cure-centered communication: Physicians fared better on the care side (N=1787)

| AFFECT-ORIENTED ASPECTS (CARE DIMENSION) | PERFORMED | NOT PERFORMED | TOTAL* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N % | % | N | % | |

| Doctor gave me enough attention | ||||||

| Important | 1304 | 87.5 | 9 | 0.6 | 1313 | 88.1 |

| Not important | 174 | 11.7 | 4 | 0.3 | 178 | 11.9 |

| Doctor listened well to me | ||||||

| Important | 1456 | 95.3 | 10 | 0.7 | 1466 | 95.9 |

| Not important | 61 | 4.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 62 | 4.1 |

| Doctor took enough time for me | ||||||

| Important | 1412 | 92.3 | 11 | 0.7 | 1423 | 93.1 |

| Not important | 105 | 6.9 | 1 | 0.1 | 106 | 6.9 |

| Doctor was friendly | ||||||

| Important | 1331 | 87.2 | 3 | 0.2 | 1334 | 87.4 |

| Not important | 193 | 12.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 193 | 12.6 |

| Doctor was frank to me | ||||||

| Important | 1451 | 95.5 | 5 | 0.3 | 1456 | 95.8 |

| Not important | 63 | 4.15 | 0 | 0.0 | 63 | 4.2 |

| Doctor took my problem seriously | ||||||

| Important | 1455 | 95.8 | 7 | 0.5 | 1462 | 96.3 |

| Not important | 55 | 3.6 | 1 | 0.1 | 56 | 3.7 |

| Doctor was empathic to me | ||||||

| Important | 846 | 58.4 | 36 | 2.5 | 882 | 60.9 |

| Not important | 492 | 34.0 | 74 | 5.1 | 566 | 19.1 |

| TASK-ORIENTED ASPECTS (CURE DIMENSION) | ||||||

| Doctor diagnosed what’s wrong | ||||||

| Important | 921 | 62.8 | 209 | 14.2 | 1130 | 77.0 |

| Not important | 197 | 13.4 | 140 | 9.5 | 337 | 23.0 |

| Doctor explained well what’s wrong | ||||||

| Important | 1166 | 78.3 | 101 | 6.8 | 1267 | 85.0 |

| Not important | 175 | 11.7 | 48 | 3.2 | 223 | 15.0 |

| Doctor informed well on treatment | ||||||

| Important | 1304 | 86.6 | 109 | 7.2 | 1413 | 93.9 |

| Not important | 75 | 5.0 | 17 | 1.1 | 92 | 6.1 |

| Doctor gave advice on what to do | ||||||

| Important | 1294 | 85.9 | 121 | 8.0 | 1415 | 94.0 |

| Not important | 75 | 5.0 | 16 | 1.1 | 91 | 6.0 |

| Doctor helped me with my problem | ||||||

| Important | 1031 | 70.0 | 121 | 18.9 | 1152 | 88.9 |

| Not important | 94 | 6.4 | 16 | 4.7 | 110 | 11.1 |

| Doctor examined me | ||||||

| Important | 902 | 59.9 | 132 | 8.8 | 1034 | 62.8 |

| Not important | 228 | 15.1 | 244 | 16.2 | 472 | 27.2 |

| * Totals do not always add up to 1787 because of missing data. | ||||||

GP communication varies by doctor gender, patient characteristics

GPs engaged less in affect-oriented than in task-oriented communication (48.6 and 70.0 utterances on average, respectively, P≤.001).

The more patients regarded affect-oriented talk by GPs as important, the more the GPs actually showed affective and patient-centered behavior (TABLE 3). Preferences for task-oriented behavior (question-asking, information-giving, and counseling) were mirrored in their doctors’ talk.

When taking into account other GP and patient characteristics, female doctors were more often affect-oriented as well as task-oriented when communicating with patients than were male doctors, especially with female patients. In consultations with older patients and those in poor health, the doctors were more affective than in consultations with younger and healthy patients.

TABLE 3

On observation, physician communication corresponded to patient preferences (N GPs=142, N patients=1787)

| REGRESSION COEFFICIENTS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AFFECT-ORIENTED TALK GPs | TASK-ORIENTED TALK GPs | PATIENT-CENTEREDNESS | |

| GP characteristics | |||

| Age (yrs) | –0.20 | –0.37* | –0.01* |

| Full-time equivalents | –12.13* | 2.45 | 0.03 |

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Gender-dyad: | |||

| - Male/female | –0.89c | 0.17d | 0.01 |

| - Female/male | 9.40a,b,d | 6.24a,d | 0.10 |

| - Female/female | 5.73a,c | 6.85a,b,c | 0.02 |

| Age (yrs) | 0.09* | –0.15 | –0.00* |

| Education (1=low, 2=middle, 3=high) | –0.70 | 0.15 | 0.05 |

| Psychosocial problems (1=yes) | 7.93* | –4.62* | 0.13* |

| Overall health (1=excellent, 5=poor) | 1.13* | 0.96 | –0.01 |

| Depressive feelings (1=not at all, 5=extremely) | 0.78 | –0.72 | 0.01 |

| Consultation length (min) | 4.03* | 4.30* | 0.04* |

| Patients’ preferences | |||

| Affect-oriented preference (1=not, 4=utmost important) | 2.81* | –1.94 | 0.16* |

| Task-oriented preference (1=not, 4=utmost important) | –4.23 * | 3.62* | –0.15* |

| * P<.05 | |||

| a. Score differs significantly from score of male GP/male patient dyad (reference group). | |||

| b. Score differs significantly from score of male GP/female patient dyad. | |||

| c. Score differs significantly from score of female GP/male patient dyad. | |||

| d. Score differs significantly from score of female GP/female patient dyad. | |||

Discussion

Our study suggests most patients receive from their GPs the kind of communication they prefer in a consultation. In general, patients consider both affect- and task-oriented communication aspects important, and believe they are often performed. Our findings agree with most of the literature.5,14,20 Furthermore, patients’ preferences are for the greater part reflected in the GPs’ observed communication during the visit, which agrees with one earlier study18 but not with others.5,20

Patient preference for an affective doctor is very often met. GPs are generally considered attentive, friendly, frank, empathic, and good listeners. Patients seem satisfied in this respect. However, the task-oriented communication of the GPs is sometimes less satisfying. Contrary to patient preference, for example, GPs are not always able to make a diagnosis.

Observed physician behavior: patients usually get what they want. Looking at the relationship between preferences and actual GP communication, it appears that the more patients prefer an affective or caring doctor, the more they are likely to get an empathic, concerned, interested, and patient-centered doctor, especially when psychosocial problems are expressed. An affective GP was patient centered, involving patients in problem definition and decision making. This relationship between affective behavior and patient-centeredness was also found in earlier studies.22,29 However, Swenson found that not all patients wanted the doctor to exhibit a patient-centered approach.30

Likewise, the more patients prefer a task-oriented doctor, the better the chance they will have a doctor who explains things well, and who gives information and advice to their satisfaction. However, task-oriented doctors are usually less affective and less patient-centered when talking with patients. In view of the postulate that a doctor has to be curing as well as caring,6 doctors would be wise to give attention to both aspects.

GPs do improvise while communicating with patients. The study shows that GPs and patients working together can create the type of encounter both want. GPs are able to change their behavior in response to real-time cues they believe patients are giving in an encounter.

Physician gender often makes a difference. Our findings suggest that female doctors are more affective and task-oriented when talking with their patients than are male doctors, especially with female patients. In view of the steady increase of female doctors in general practice, this combined communication style may become more common in the future.

Psychosocial complaints prompt affective communication. Patients with a psychosocial problem are more likely to encounter an affective doctor than those with a biomedical problem. The growing number of psychosocial problems in the population may lead to a more affective communication.

Eventually the demand and the supply of affective communication may coincide. However, it is a challenge for every doctor to keep his or her mind open to both biomedical (task-oriented) and psychosocial (affective-oriented) information.31

Study caveats. Because we used scale scores for affect- and task-oriented preferences instead of the separate item scores for patient preferences, the reflection of preferences for GP communicative behavior might be somewhat overestimated. Likewise, we used total observation scores for affect- and task-oriented talk instead of the separate RIAS categories. More detailed measures of such communication aspects as empathy might give better insight into patient preferences.

Final thoughts on personal application. Primary care physicians would do well to take notice of patients’ preferences for communication. GPs in our study were often able to grasp what patients considered important to talk about, and there seemed to be only modest mismatches between patient expectations and physician behavior. To increase the quality of health care, consider asking patients at the end of a visit whether their preferences were met.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the participating general practitioners and patients, the observers of the videotaped consultations, and the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports for funding (for the greater part) the research project.

Correspondence

A. van den Brink-Muinen, PhD, NIVEL, PO Box 1568, 3500 BN Utrecht, The Netherlands; [email protected]

- Patients want an attentive, friendly, frank and empathic doctor who listens well.

- To enhance quality of health care, consider asking patients at the end of a visit whether their communication preferences were met.

One physician has written that good patient-doctor communication, like jazz, calls for improvisation.1 We agree. And improvise we must when patients’ expectations for how we will communicate with them vary between visits and individuals.

For example, those who are ill may prefer that their doctor communicate with them in a way that is less important to those who are healthy. Patients with biomedical problems may have different preferences than persons with psychosocial problems. And older individuals may have communication desires that differ from those who are younger.2-4

Do patients want cure or care, or both?

Depending on the reason for a visit—eg, biomedical or psychosocial—patient preferences may fit either the cure or the care dimension.

Cure dimension. On one hand, patients expect their doctor to be task-oriented and to find a cure for what ails them. They want an explanation of what is wrong and advice about possible treatments, and they want the doctor to do whatever is needed to get answers.5

Care dimension. On the other hand, patients may feel anxious and want reassurance. They expect the doctor to listen to their story and encourage them to disclose all health problems, concerns, and worries. They also expect friendliness and empathy. They want to be taken seriously. The extent to which the doctor shows this affect-oriented (and patient-centered) behavior will determine how fulfilled patients feel in their preference for care.6,7

Why does it matter? Good communication serves a patient’s need to understand and to be understood.6,8,9 And communication aimed at matching patient preferences enhances satisfaction with care, compliance with medical instructions, and health status.10-13

How well do we assess patients’ communication preferences?

Patient-centered behavior is a necessary tool for discovering and fulfilling patients’ task-oriented (cure dimension) and affect-oriented (care dimension) communication preferences.14-17 It’s important to know how well primary-care physicians interpret patients’ preferences for clinical encounters and if they respond in a manner that satisfies those expectations.

Reassuringly, patients indicate on surveys that their physicians do a fairly good job of interpreting their communication preferences and acting accordingly.18-20 They also report that their desires and expectations from consultations are increasingly met.

There is always the worry, though, that physicians in certain positions—eg, non-gatekeeper roles or positions involving only part-time clinical responsibilities—would be challenged to assess patient preferences as accurately as others.21

The aim of our study

While it’s encouraging that physicians by and large understand their patients and communicate with them meaningfully, we wondered whether communication could improve further. Our purpose in this study was to gain detailed insight into patients’ preferences in physician communication and, through patients’ subjective perspectives and observed real practice consultations, learn how well physicians communicate according to those preferences.

Methods

Design

We derived physician data from the Second Dutch National Survey of General Practice (2001). This study was carried out in practices representative of Dutch general practice.22 We asked patients for permission to videotape consultations with the general practitioner (GP), and asked them to sign a consent form. Collected data were kept private as per regulations.

We videotaped consultations of 142 GPs (76.1% male) and 2784 patients (41.2% male). The number of patients cared for by each GP ranged between 17 and 21 (mean=19.6). Each patient was videotaped just once. We rated roughly 15 patient-consultations per GP (13–15, mean=14.8), excluding the first 3 to correct for possible bias because of the video camera. Before and immediately after the consultation, patients 18 years of age and older answered a questionnaire. We used data from 1787 patient consultations.

Patients rate their communication preferences

The patient questionnaire covered demographic characteristics (gender, age, education); health problems (psychosocial or not [ICPC-coded]);23 overall health during the past 2 weeks (1=excellent, 2=very good, 3=good, 4=fair, 5=poor); and depressive feelings during the past 2 weeks (1=not at all, 2=slightly, 3=moderately, 4=quite a bit, 5=extremely) (COOP-WONCA charts24).

We defined communication preferences as “the extent of importance patients attach to communication aspects.”25 Patients’ preferences and the actual performance by the GP were measured using the conceptual framework of the QUOTE scale (quality of care through the patient’s eyes).5,25

Before consultation, patients recorded how important they considered different aspects of communication for the coming visit (1=not important, 2=rather important, 3=important, 4=utmost important). Following consultation, they rated the GP’s performance in meeting their expectations for these aspects (1=not, 2=really not, 3=really yes, 4=yes).

Factor analysis of both the pre- and post-visit lists of questions on preference and performance revealed 2 relevant subscales: an affect-oriented scale of 7 communication aspects and a task-oriented scale of 6 communication aspects (Cronbach’s alpha between 0.74 and 0.89).

We also used communication aspects from the original 4-point scale to present 4 new categories that compared and contrasted preferences and relevance. These categories included: important and performed; important and not performed; not important and performed; not important and not performed. In the multilevel analysis, we included the 2 subscales using the original 4-point scale.

Socio-demographic and practice variables were derived from the GP questionnaires in the Second Dutch National Survey of General Practice (2001).

Video observations

Nine observers measured verbal behavior during the videotaped visits using the Roter Method of Interaction Process Analysis (RIAS26), a well-documented, widely used system in the US and Netherlands. This observation system distinguishes both affect-oriented (socio-emotional) and task-oriented (instrumental) verbal behavior of doctors and patients, reflecting the care and cure dimensions, respectively. The RIAS categories are mutually exclusive and exhaustive.

Affect-oriented communication consists of personal remarks, agreements, concerns, reassurances, paraphrases, and disagreements.

Task-oriented talk includes asking questions, giving information, and (only GPs) counseling about medical/therapeutic and psychosocial, social context and lifestyle issues, and process-oriented talk (instructions, asking for understanding).

After finishing the RIAS-coding, we calculated the total numbers of affect-oriented and task-oriented verbal behaviors separately for GPs and patients.

The relevance and performance items and the RIAS-categories all measured the affect-oriented and task-oriented aspects.

We used the Noldus Observer-Video-Pro computer program for the observation study,27 including measurement of consultation length. The interobserver reliabilities were good to excellent: between r=0.80 to r=0.95 per category, except for personal remarks (0.72).

Patient-centeredness measured in 3 ways

The observers, using a 5-point scale, also rated the extent to which GPs communicated in a patient-centered way in 3 areas: patient’s involvement in the problem-defining process; patient’s involvement in the decision-making process; and doctor’s overall responsiveness to the patient.

Based on ratings in these 3 areas, we determined an overall magnitude of patient-centeredness (Cronbach’s alpha=0.75). Observers and the responsible researcher met weekly to validate the quality of rating. The same was done for the RIAS coding.

Controlling variables

For GPs, controlling variables were gender, age, and number of full-time equivalents (FTEs) working. For patients, GP and patient gender were included in the variable “gender-dyad”—male GPs/male patients, male GPs/female patients, female GPs/male patients, female GPs/female patients. Other patient variables were age; education (low=no/primary school, middle=secondary school, high=higher vocational training/university); health problems: somatic or psychosocial (ICPC chapters); overall physical health and mental health during the past 2 weeks; and consultation length.

Data analysis

We used descriptive and multilevel analyses. The intra-class correlations of the affect-oriented and task-oriented communication and patient-centeredness were significant (between .05 and 0.23), which made it clear that consultations of the same GP did indeed exhibit a greater degree of similarity than the consultations of different GPs. Therefore, multilevel analyses were necessary to account for the clustering of patients with the same GP.28 We applied a significance level of ≤0.05 (2-sided).

Results

Response rate

The overall patient response rate was 88%. Analysis of non-responders’ gender, age, and type of insurance showed no bias resulting from patients’ refusal.

GP response rate was 72.8%. Respondents were representative of all Dutch GPs with respect to gender, age, working hours, practice experience (mean=15.6 years, SD=8.3, range=1–32), and location (58% in an urban area). More GPs worked in a partnership or group practice than in a solo practice. We analyzed the influence of the practice type on doctor-patient communication and deemed it insignificant.

Study population

GP and patient characteristics appear in TABLE 1. Among patients, 22% had little education, 62% had an average education, and 16% had higher education. Nearly 10% had a psychosocial problem. GP-patient gender dyads were as follows: 32.1% male GP/male patient; 45.3% male GP/female patient; 6.9% female GP/male patient; 15.8% female GP/female patient.

TABLE 1

General practitioner and patient characteristics (N GPs=142, N patients=1787)

| MEAN | SD | RANGE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP characteristics | |||

| Age (yrs) | 46.9 | 6.2 | 32–62 |

| Full-time equivalents | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.2–1 |

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Age (yrs) | 49.5 | 17.4 | 18–95 |

| Psychosocial problem (1=yes) | 9.8% | — | — |

| Overall health (1=excellent, 5=poor) | 3.2 | 1.1 | 1–5 |

| Depressive feelings (1=not at all, 5=extremely) | 2.2 | 1.2 | 1–5 |

| Consultation length (min) | 10.1 | 4.8 | 1.3–33.0 |

| Patients’ preferences | |||

| Affect-oriented preference (1=not, 4=utmost important) | 3.2 | 0.5 | 1–4 |

| Task-oriented preference (1=not, 4=utmost important) | 3.1 | 0.6 | 1–4 |

Preference and performance of communication aspects

GPs good with affect-oriented communication aspects. Patients considered 6 of 7 affect-oriented communication aspects as very important (87%–96%, TABLE 2). The item “Doctor was empathic to me” was less important (61%) than items like “Doctor listened well to me” (96%) and “Doctor took enough time for me” (93%). We noted only a few discrepancies between preference and performance of the GPs’ affect-oriented behavior. If patients said beforehand that a communication aspect was important, the doctors nearly always performed that aspect. For instance, 87% wanted enough attention from the doctor and received it, while 99% of all patients received GP’s attention, whether it was important to them or not.

GPs less successful with task-oriented communication aspects. Many patients wanted information, explanations, advice, and help with their problems (85%–94%, TABLE 2). Knowing the diagnosis was less important (77%) than, say, receiving advice on what to do and having details of treatment explained.

GPs also performed most of the task-oriented aspects, if patients considered these aspects important.

Subjectively, preferences for GP task-oriented behavior and perceived performance often went together, though more discrepancies were visible than with affect-oriented behavior. One fifth of patients said their problems were not helped, though they had said this was important. Similarly, GPs did not give a diagnosis to nearly 15% of patients who considered it important.

TABLE 2

Care vs cure-centered communication: Physicians fared better on the care side (N=1787)

| AFFECT-ORIENTED ASPECTS (CARE DIMENSION) | PERFORMED | NOT PERFORMED | TOTAL* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N % | % | N | % | |

| Doctor gave me enough attention | ||||||

| Important | 1304 | 87.5 | 9 | 0.6 | 1313 | 88.1 |

| Not important | 174 | 11.7 | 4 | 0.3 | 178 | 11.9 |

| Doctor listened well to me | ||||||

| Important | 1456 | 95.3 | 10 | 0.7 | 1466 | 95.9 |

| Not important | 61 | 4.0 | 1 | 0.1 | 62 | 4.1 |

| Doctor took enough time for me | ||||||

| Important | 1412 | 92.3 | 11 | 0.7 | 1423 | 93.1 |

| Not important | 105 | 6.9 | 1 | 0.1 | 106 | 6.9 |

| Doctor was friendly | ||||||

| Important | 1331 | 87.2 | 3 | 0.2 | 1334 | 87.4 |

| Not important | 193 | 12.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 193 | 12.6 |

| Doctor was frank to me | ||||||

| Important | 1451 | 95.5 | 5 | 0.3 | 1456 | 95.8 |

| Not important | 63 | 4.15 | 0 | 0.0 | 63 | 4.2 |

| Doctor took my problem seriously | ||||||

| Important | 1455 | 95.8 | 7 | 0.5 | 1462 | 96.3 |

| Not important | 55 | 3.6 | 1 | 0.1 | 56 | 3.7 |

| Doctor was empathic to me | ||||||

| Important | 846 | 58.4 | 36 | 2.5 | 882 | 60.9 |

| Not important | 492 | 34.0 | 74 | 5.1 | 566 | 19.1 |

| TASK-ORIENTED ASPECTS (CURE DIMENSION) | ||||||

| Doctor diagnosed what’s wrong | ||||||

| Important | 921 | 62.8 | 209 | 14.2 | 1130 | 77.0 |

| Not important | 197 | 13.4 | 140 | 9.5 | 337 | 23.0 |

| Doctor explained well what’s wrong | ||||||

| Important | 1166 | 78.3 | 101 | 6.8 | 1267 | 85.0 |

| Not important | 175 | 11.7 | 48 | 3.2 | 223 | 15.0 |

| Doctor informed well on treatment | ||||||

| Important | 1304 | 86.6 | 109 | 7.2 | 1413 | 93.9 |

| Not important | 75 | 5.0 | 17 | 1.1 | 92 | 6.1 |

| Doctor gave advice on what to do | ||||||

| Important | 1294 | 85.9 | 121 | 8.0 | 1415 | 94.0 |

| Not important | 75 | 5.0 | 16 | 1.1 | 91 | 6.0 |

| Doctor helped me with my problem | ||||||

| Important | 1031 | 70.0 | 121 | 18.9 | 1152 | 88.9 |

| Not important | 94 | 6.4 | 16 | 4.7 | 110 | 11.1 |

| Doctor examined me | ||||||

| Important | 902 | 59.9 | 132 | 8.8 | 1034 | 62.8 |

| Not important | 228 | 15.1 | 244 | 16.2 | 472 | 27.2 |

| * Totals do not always add up to 1787 because of missing data. | ||||||

GP communication varies by doctor gender, patient characteristics

GPs engaged less in affect-oriented than in task-oriented communication (48.6 and 70.0 utterances on average, respectively, P≤.001).

The more patients regarded affect-oriented talk by GPs as important, the more the GPs actually showed affective and patient-centered behavior (TABLE 3). Preferences for task-oriented behavior (question-asking, information-giving, and counseling) were mirrored in their doctors’ talk.

When taking into account other GP and patient characteristics, female doctors were more often affect-oriented as well as task-oriented when communicating with patients than were male doctors, especially with female patients. In consultations with older patients and those in poor health, the doctors were more affective than in consultations with younger and healthy patients.

TABLE 3

On observation, physician communication corresponded to patient preferences (N GPs=142, N patients=1787)

| REGRESSION COEFFICIENTS | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| AFFECT-ORIENTED TALK GPs | TASK-ORIENTED TALK GPs | PATIENT-CENTEREDNESS | |

| GP characteristics | |||

| Age (yrs) | –0.20 | –0.37* | –0.01* |

| Full-time equivalents | –12.13* | 2.45 | 0.03 |

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Gender-dyad: | |||

| - Male/female | –0.89c | 0.17d | 0.01 |

| - Female/male | 9.40a,b,d | 6.24a,d | 0.10 |

| - Female/female | 5.73a,c | 6.85a,b,c | 0.02 |

| Age (yrs) | 0.09* | –0.15 | –0.00* |

| Education (1=low, 2=middle, 3=high) | –0.70 | 0.15 | 0.05 |

| Psychosocial problems (1=yes) | 7.93* | –4.62* | 0.13* |

| Overall health (1=excellent, 5=poor) | 1.13* | 0.96 | –0.01 |

| Depressive feelings (1=not at all, 5=extremely) | 0.78 | –0.72 | 0.01 |

| Consultation length (min) | 4.03* | 4.30* | 0.04* |

| Patients’ preferences | |||

| Affect-oriented preference (1=not, 4=utmost important) | 2.81* | –1.94 | 0.16* |

| Task-oriented preference (1=not, 4=utmost important) | –4.23 * | 3.62* | –0.15* |

| * P<.05 | |||

| a. Score differs significantly from score of male GP/male patient dyad (reference group). | |||

| b. Score differs significantly from score of male GP/female patient dyad. | |||

| c. Score differs significantly from score of female GP/male patient dyad. | |||

| d. Score differs significantly from score of female GP/female patient dyad. | |||

Discussion

Our study suggests most patients receive from their GPs the kind of communication they prefer in a consultation. In general, patients consider both affect- and task-oriented communication aspects important, and believe they are often performed. Our findings agree with most of the literature.5,14,20 Furthermore, patients’ preferences are for the greater part reflected in the GPs’ observed communication during the visit, which agrees with one earlier study18 but not with others.5,20

Patient preference for an affective doctor is very often met. GPs are generally considered attentive, friendly, frank, empathic, and good listeners. Patients seem satisfied in this respect. However, the task-oriented communication of the GPs is sometimes less satisfying. Contrary to patient preference, for example, GPs are not always able to make a diagnosis.