User login

Revisiting Tanning-Bed Legislation [editorial]

Recently Approved Systemic Therapies for Acne Vulgaris and Rosacea (See Erratum 2007;80:334)

What's Eating You? Saddleback Caterpillar (Acharia stimulea)

Talking to patients about screening colonoscopy—where conversations fall short

- When talking to patients about screening colonoscopy, make clear their risk of colorectal cancer. Also, be sure they know about such commonly overlooked details as insurance/scheduling issues, dietary and medication changes before the procedure, a companion to drive afterward, and possible colonoscopy complications.

- Consider recommending supplemental information sources such as telephone calls, letters, e-mails, Web sites, or videotapes to help patients understand the need for screening colonoscopy.

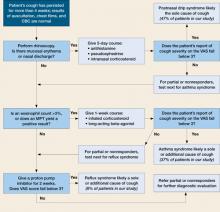

Abstract

Background A physician’s recommendation is a powerful motivator for a patient to undergo colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening, yet little is known about how physicians address this topic.

Methods We recruited 30 primary care physicians and physicians-in-training from 4 practices to counsel a “patient,” simulated by a researcher, regarding the need for screening colonoscopy. Audiotapes of the physician-patient encounters were transcribed. Preserving physician anonymity, we assessed each encounter for key informational points, positive or negative message framing, type of numeracy information, and use of colloquial or technical language.

Results Study physicians addressed a mean of 6.7 (standard deviation=1.8) of 13 key informational points. Most physicians (≥80%) discussed the benefits of colorectal cancer screening, the recognition of colonoscopy as a standard exploratory procedure, and the use of sedation. However, few (<20%) addressed the risks of colonoscopy, the nuances of scheduling, or the need for dietary and medication changes. Nearly all physicians (98%) used messages that focused on the positive aspects of screening (gain-framed messages), and many (67%) also used messages that focused on the risk of not screening (loss-framed messages). Numeracy information generally was expressed simply, but half of the physicians used statistical terms. Half used colloquial terms to describe the prep and procedure.

Conclusion Though most physicians used positive, simple terms to describe colonoscopy, they often omitted key information. Correcting for the areas of insufficient information found in our study—perhaps with supplementary educational sources—will help ensure that patients are adequately prepared for colonoscopy.

Colorectal cancer screening has the potential to reduce deaths from colorectal cancer by at least one third.1 Yet only half of eligible patients in the US who are age 50 or older have undergone screening.2 Patients often say they haven’t been screened because their physician didn’t recommend it.3-5

A physician’s recommendation is strongly predictive of whether a patient actually undergoes colorectal cancer screening, even after adjusting for multiple confounders.6-9 Yet several studies have found that, even after the physician has recommended or ordered an endoscopic study of the colon, many patients do not follow through.10-12 Successful completion of screening colonoscopy requires, in part, that a patient understand the need for the procedure and receive sufficient instruction about it. Thus, failure to undergo this test may reflect patient concerns or misunderstandings due to inadequate communication.13,14

In many settings, the primary care physician bears the responsibility for telling the patient about screening colonoscopy because the endoscopist meets the patient only at the time of the procedure. Supplementary educational programs can also play a role. Unfortunately, though, while these materials appear to reduce patient anxiety and increase adherence to screening recommendations,15-17 they are infrequently used.

Looking at physician communication with an eye toward improvement

Our goal in conducting this study was to evaluate the way in which physicians discuss the need for screening colonoscopy with their patients. Using a simulated patient scenario, we wanted to examine 4 dimensions of each discussion: completeness; type of messaging; type of numeracy information (ie, numerical and mathematical data); and use of colloquial vs technical language.

- Completeness reflected the number of key informational points addressed.

- Type of messaging focused on the use of loss- or gain-framed messages, both of which have been linked to increased patient intention to adopt a cancer prevention behavior or test.18-20 Gain-framed counseling emphasizes the positive aspects of screening; loss-framed, the risks of not screening.

- Type of numeracy information. Because poor numeracy skills are thought to impair the accuracy of patients’ perceptions of cancer risk,21 we categorized the type of numeracy information provided by physicians following an approach developed by Ahlers-Schmidt and colleagues.22

- Colloquial vs technical language. Because colonoscopy involves sensitive topics such as the bowels and feces, and because language choices may affect acceptance of care,23 we evaluated physicians’ use of terminology when describing the procedure.

We felt that by looking at these dimensions, we could help physicians to refine screening colonoscopy messages so that conversations with patients could be more clear, complete, and balanced.

Methods

13 key points regarding screening colonoscopy

We reviewed published literature and Internet sources to develop a preliminary list of topics a primary care physician could address when discussing colorectal cancer screening, especially screening colonoscopy. We used NLM Gateway and Medline databases and the following search terms: colonoscopy, patient education, patient instructions, guidelines, physician, colon cancer, counseling, and knowledge. A medical librarian directed the search. Despite having expert assistance, we did not find any publications that offered a peer-reviewed, validated list of topics to guide physicians’ discussions about screening colonoscopy.

We then conducted an Internet search using the terms colon cancer, colon cancer screening, colonoscopy, and colon cancer patient education. We categorized data from identified sites such as the American Gastroenterological Association, Up-to-Date, the American Cancer Society, and the National Library of Medicine, among others, into 13 common topics (TABLE 1). Three points addressed general information about colorectal cancer, and the rest dealt with colonoscopy specifically. A panel of 2 gastroenterologists and 3 internists from the same institution independently judged each item on the list for importance, relevance, and feasibility for discussion. Except for one panelist, all endorsed the need to address the 13 items.

TABLE 1

Percentage of physicians who covered key colorectal cancer screening points

| TOPIC | INFORMATIONAL POINT | PHYSICIANS ADDRESSING TOPIC (N=30), % |

|---|---|---|

| General colorectal prevention | ||

| 1. Standard preventive health care procedure | Recommended* as a standard screening test for those age 50 and older | 83 |

| 2. Value of screening | Can prevent cancer as well as detect cancer at a treatable stage | 83 |

| 3. Risk of colorectal cancer | Prevalence or incidence either nationally or regionally (family history)† | 43 |

| Specifics about colonoscopy | ||

| 4. Anesthesia | Sedation to reduce discomfort; risk information discussed or to be reviewed by anesthetist | 87 |

| 5. Gastrointestinal prep | Use of laxative, usual types used, and what patient can expect | 77 |

| 6. Abnormalities detected by colonoscopy | Finds growths (polyps) or cancer | 76 |

| 7. Description of procedure | Camera at the end of a flexible tube views the entire colon and tiny tweezers at the end sample or remove growths | 70 |

| 8. Follow-up after a negative test | Experts recommend screening after a negative test every 10 years | 67 |

| 9. Patient experience or knowledge‡ | Any personal or family/friend experience with colonoscopy or knowledge about the test | 64 |

| 10. Transportation | Another person must accompany the patient after procedure | 53 |

| 11. Insurance/scheduling | Insurance coverage, who arranges for the procedure, where test is performed | 13 |

| 12. Diet | Diet the day before and day of procedure, importance of hydration | 10 |

| 13. Risk of colonoscopy | Risk of bowel perforation or other complication | 10 |

| 14. Medications | Changes in medications for the procedure | 3 |

| *Recommendation by expert panels need not be specified. Physicians often just say, “We recommend.” | ||

| †Family history not necessary in this study because the patient was said to be at average risk for colorectal cancer. | ||

| ‡Point was not identified originally by the review and excluded from analysis. | ||

Physician sample

Of 135 providers practicing in 2 primary care and 1 geriatrics practice affiliated with the same urban academic medical center, we invited 30 physicians to participate. This sample was chosen to adequately represent female and minority physicians as well as physicians at different levels of training (TABLE 2). The physicians were invited to participate either by e-mail (N=19) or in person (N=11), and all invitees consented. Interviews were conducted alone in the physician’s office or in a practice conference room, and they were audiotaped with the physician’s consent.

Interviews lasted fewer than 15 minutes and did not intrude on patient care time. Study physicians read a vignette of a fictitious 51-year-old African American woman who was an established patient in their practice, without a family history of colon cancer but with arthritis and hypertension. We asked each physician to inform the patient (simulated by the interviewer) about colorectal cancer screening and colonoscopy, as well as the logistics of getting this test. To standardize the interaction, interviewers predefined the patient’s responses to questions. For example, if the physician asked about prior knowledge of colonoscopy, the simulated patient replied that she had none. Study physicians were not prompted in any way and, though not given time restrictions, all were brief and to the point.

TABLE 2

Study physician characteristics

| CHARACTERISTIC | PHYSICIANS WITH CHARACTERISTIC (N=30), % | INFORMATIONAL POINTS ADDRESSED,* MEAN (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 100 | 6.73 (1.84) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 66 | 6.70 (1.89) |

| Male | 34 | 6.80 (1.81) |

| Race | ||

| White | 80 | 6.84 (1.80) |

| Non-white | 20 | 6.20 (2.17) |

| Level of training | ||

| Attending | 63 | 6.84 (1.98) |

| Trainee | 37 | 6.54 (1.63) |

| Specialty | ||

| General Internal Medicine | 90 | 6.89 (1.83) |

| Geriatrics | 10 | 5.33 (1.53) |

| * All comparisons P >.05 | ||

Analysis

Interview transcripts were anonymous, identified only by a study number. The 2 study investigators coded transcribed interviews independently as to whether physicians addressed the 13 informational points. Inter-rater concordance in coding was 90%. We also independently evaluated the interviews according to the use of gain- or loss-framed messages (eg, detecting colon polyps early before cancer develops vs colorectal cancer being the second most common cause of cancer death). We independently classified types of numeracy information provided into 15 categories.22 We also independently examined audiotaped transcripts for examples of colloquial terms/slang or technical language. Because we are unaware of a validated approach to characterizing a physician’s language in this manner, we asked a layperson for assistance in identifying colloquial/slang terms.

To determine whether there were predictors of a physician addressing more of the informational points than his or her peers, we examined bivariate associations of the following demographic and professional data: gender, race (white vs non-white), academic advancement (attending vs trainee), and specialty (general internist vs geriatrician).

We analyzed data using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test because the data were not normally distributed. We used SAS Statistical Software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board approved the study. The project was supported by a grant from the Bach Fund of the Presbyterian Medical Center, University of Pennsylvania.

Results

How did the physicians talk to their patient?

The 30 study physicians were primarily women, one fifth were from under-represented minorities, and one third were either residents or fellows (TABLE 2). Of 13 key informational points endorsed by our physician panel (TABLE 1), the physician-subjects addressed a mean of 6.7 points (range, 3–10). Nearly all physician-subjects discussed the value of colorectal cancer screening, colonoscopy as a standard colorectal screening procedure, and sedation during the procedure. However, fewer than 20% addressed the following topics: insurance/scheduling, dietary changes, medication modification, and risks of colonoscopy. In this small sample, the number of topics mentioned did not differ significantly by physician characteristic (TABLE 2).

Two thirds of the physicians asked the simulated patient about her prior knowledge or experience with colonoscopy. Although this question was not among the original 13 informational points, it helped to guide the discussion by identifying specific preconceptions or prior knowledge of this test. Therefore, this post hoc 14th informational point was added to our list but not considered in our analyses.

Gain-framed messages used more than loss-framed messages

Nearly all physicians used gain-framed messages, and more than half also used loss-framed messages (TABLE 3). Only 1 physician offered only a loss-framed message. Overall, study physicians mentioned less than 2 gain- or loss-framed messages.

- The most common types of gain-framed messages were detecting cancer early, preventing cancer by taking out polyps, and screening at only a 10-year interval if the test result is negative.

- The most common loss-framed messages noted that colorectal cancer was the second most common cause of cancer death and that risk is increased with a family history of this cancer.

TABLE 3

Gain- and loss-framed messages and types of numeracy information used by study physicians

| TYPE OF MESSAGE OR NUMERACY | PHYSICIANS N (%) | OCCURRENCES IN INTERVIEWS, Total N (MEAN AMONG USERS, RANGE) |

|---|---|---|

| Message framing | ||

| Gain-framed | 29 (96) | 56 (1.9, 1–5) |

| Loss-framed | 20 (67) | 31 (1.6, 1–3) |

| Numeracy | ||

| Descriptive terms | 19 (63) | 36 (1.9, 1–3) |

| Statistical terms | 15 (50) | 30 (2.0, 1–5) |

| Temporal terms | 9 (30) | 11 (1.2, 1–2) |

| Proportions | 4 (13) | 5 (1.3, 1–2) |

| Fractions | 3 (10) | 3 (1.0, 1–1) |

Physicians avoided using numbers

Of the 15 types of numeracy information described by Ahlers-Schmit et al, our physicians used only 5. Nineteen physicians (63%) used descriptive terms such as “likely” or “increased,” and 15 (50%) used statistical concepts such as risk and second-most-common cause. Physicians avoided using numbers; 9 (30%) used temporal terms such as “early”; 4 (13%) cited a proportion; and only 3 (10%) used a fraction.

Colloquial language, or was it crude?

While reading the transcripts, we noted that some physicians used colloquial terms that could be regarded as crude. Other terms were probably too technical without an explanation. Some information was simply incorrect. We offer selected quotes to illustrate various types of language used.

About the prep:

- “Getting a colonoscopy is not the most fun experience…you have really bad diarrhea and you just empty out your guts.”

- “It’s basically Liquid Plumber for your bowels.”

- “Bowel prep…is kind of voluminous and associated with kind of massive bowel movements.”

- “Everybody hates the prep and you may be one of those and that’s just that.”

- “Generally you have to be up all night, sometimes, cleaning your bowels out.”

About the procedure:

- “It’s not the most comfortable screening exam in the world.”

- “It’s a test where they stick a lighted tube up your back-side.”

- “The stomach doctors put a camera up your bottom and look at the walls of your colon.”

- “They can go in with a microscope and look around and look at the colon itself.”

- “It’s a painless test.”

Word polyp is used, but not defined

Physicians often employed technical language when describing the pathology detected by colonoscopy. “Polyp” was mentioned by 20 physicians (67%) but rarely defined; “biopsy” by 5 (17%), and “lesion” by 6 (20%). Other technical terms were precancerous, symptomatic, and incapacitated.

Discussion

An informed patient is a willing patient

Our study physicians addressed only half of the 13 informational points, likely reflecting the time constraints of a typical office visit. Primary care physicians appear to expect that either the colonoscopist or other sources of information would fill in the gaps. As reported in several studies, unanswered questions can discourage patients from keeping their scheduled colonoscopy appointment.10,11 In one report of African-American church members, those with adequate knowledge about colorectal cancer screening were more likely to complete screening.24

Wolf and Becker suggested that discussions about cancer screening address 4 broad topics: the probability of developing the cancer, the operating characteristics of the screening test(s), the likelihood that screening will benefit the patient, and potential burdens of the test.25 Instead of a balanced and lengthy discussion, our study physicians generally emphasized the positives such as the value of avoiding colon cancer, the standard nature of this test, and the benefit of being sedated for the procedure. Thus, gain-framed messages about colorectal cancer were the norm for our study physicians.

Half of the physicians also offered loss-framed messages emphasizing the need to avoid the consequences of colorectal cancer and the increased threat associated with a family history of this malignancy. Research in mammography screening suggests that loss-framed messaging may be a more powerful motivator than gain-framed messaging,26 but it is not clear if this observation can be generalized to colorectal cancer screening.

Walking a fine line with the particulars of risk

Our study physicians rarely provided data on the probability of developing colorectal cancer. Physicians may avoid this topic because many patients have difficulty understanding information about the risk of colorectal cancer.11 In support of this approach, Lipkus and colleagues reported that various ways of informing patients about colorectal cancer risk did not affect their intention to be screened.27 Of concern, most of our physicians did not address the common misconception that colorectal cancer screening is unnecessary in the absence of symptoms.28

Overall, the level of numeracy information provided by study physicians required minimal patient understanding of mathematical and statistical concepts. Most information was descriptive, such as colonoscopy being “more thorough” than other tests. Though statistical concepts such as “risk” were often mentioned, few physicians offered probabilities or incidence data. Experts recommend providing such data,25 but Web sites have been criticized for offering excessive numerical cancer risk data.22 Therefore, physicians must walk a fine line between providing adequate information and offering data that require a high level of health numeracy for understanding.

6 key points physicians often overlook

Most physicians failed to mention dietary and medication changes, scheduling/insurance coverage issues, and risk of complications from colonoscopy. Nearly 60% failed to discuss the patient’s risk of colorectal cancer. Almost half did not mention the need for a companion to accompany the patient after the test. Scheduling challenges, in particular, are known to interfere with completing colonoscopy.11

Many neglect to describe the procedure

Thirty percent of physicians failed to describe the procedure itself, so it is not surprising that patients complain they have a poor understanding of test logistics.11,29,30 Denberg and colleagues have reported that mailing an informational brochure about colonoscopy can increase the number who keep their appointment.31

How language choices may affect understanding

Other researchers have identified additional patient barriers to colonoscopy, including fear of pain, concern for modesty, and desire to avoid the bowel prep.11,32 These concerns may be mitigated or heightened by the physician’s language. In our review of transcripts, physicians often used slang or colloquial language to describe the procedure, probably in an attempt to convey information in a familiar way. This language may be viewed as crude and potentially discouraging, but further research is needed to evaluate patient receptiveness to different ways of speaking about sensitive topics.

Additionally, physicians commonly used technical terms such as “polyp” and “biopsy” without explaining them. Technical language may increase racial disparities in adhering to scheduled colonoscopy. In a family medicine clinic, patients from minority groups had particular difficulty understanding medical terms and procedure names.28 Because little time is available for counseling about cancer screening tests, and because patients retain only a limited amount of information about procedures,33 supplementary informational sources are warranted.15-17,31 Options include brochures, telephone calls, letters, e-mails, Web site data, and videotapes, but it is unclear which sources optimally improve patient adherence to screening colonoscopy.34

Study limitations include simulated interaction

There were a number of limitations to this study. First, the investigators “simulated” the patient. Though study physicians were told to act as if they were speaking to a regular patient, they may still have unconsciously modified their usual approach to addressing this topic.

Second, we did not assess the effectiveness of these discussions in motivating actual patients to receive colonoscopy.

Other limitations included the following:

- We did not set a time period for these discussions, so they may have been even more limited in actual practice.

- We studied physicians from a single health care setting wherein colonoscopy appears to be the preferred approach to screen an average risk patient for colorectal cancer. In addition, in this health care system, this test is performed by a gastroenterologist, rather than a primary care physician.

- We did not determine whether patients regard our selected quotes as too colloquial or technical.

- This study did not address the important barrier of a physician forgetting to recommend colorectal cancer screening.35

Further research, next steps

Our study supports the hypothesis that physicians differ widely—but are generally deficient—when informing patients about screening colonoscopy. They generally emphasize the positives of colonoscopy and use terms that are colloquial, avoiding statistical concepts that may be hard for patients to understand. Future studies need to address the effectiveness of these approaches to discussing screening colonoscopy.

Given the central role of the primary care physician in motivating patients to undergo screening colonoscopy in a limited time period, it appears that additional supports are needed to supplement physician discussion about this important preventive care procedure.

Correspondence

Barbara J. Turner MD, MSEd, University of Pennsylvania, 1123 Blockley Hall/6021, 423 Guardian Drive, Philadelphia, PA 19104; [email protected]

1. Ries LA, Wingo PA, Miller DS, et al. The annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1997, with a special section on colorectal cancer. Cancer 2000;88:2398-2424.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Colorectal cancer test use among persons aged > or = 50 years—United States, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;52:193-196.

3. Wee CC, McCarthy EP, Phillips RS. Factors associated with colon cancer screening: the role of patient factors and physician counseling. Prev Med 2005;41:23-29.

4. Taylor V, Lessler D, Mertens K, et al. Colorectal cancer screening among African Americans: the importance of physician recommendations. J Natl Med Assoc 2003;95:806-812.

5. Brawarsky P, Brooks DR, Mucci LA, Wood PA. Effect of physician recommendation and patient adherence on rates of colorectal cancer testing. Cancer Detect Prevent 2004;28:260-268.

6. Holt WS, Jr. Factors affecting compliance with screening sigmoidoscopy. J Fam Pract 1991;32:585-589.

7. Brenes GA, Paskett ED. Predictors of stage of adoption for colorectal cancer screening. Prev Med 2000;31:410-416.

8. Myers RE, Turner B, Weinberg D, et al. Impact of a physician-oriented intervention on follow-up in colorectal cancer screening. Prev Med 2004;38:375-381.

9. Brawarsky P, Brooks DR, Mucci LA, Wood PA. Effect of physician recommendation and patient adherence on rates of colorectal cancer testing. Cancer Detect Prev 2004;28:260-268.

10. Turner BJ, Weiner M, Yang C, TenHave T. Predicting adherence to colonoscopy or flexible sigmoidoscopy on the basis of physician appointment-keeping behavior. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:528-532.

11. Denberg TD, Melhado TV, Coombes JM, et al. Predictors of nonadherence to screening colonoscopy. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:989-995.

12. Kelly RB, Shank JC. Adherence to screening flexible sigmoidoscopy in asymptomatic patients. Med Care 1992;30:1029-1042.

13. Janz NK, Wren PA, Schottenfeld D, Guire KE. Colorectal cancer screening attitudes and behavior: a population-based study. Prev Med 2003;37:627-634.

14. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:129-131.

15. Abuksis G, Mor M, Segal N, et al. A patient education program is cost-effective for preventing failure of endoscopic procedures in a gastroenterology department. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:1786-1790.

16. Pignone M, Harris R, Kinsinger L. Videotape-based decision aid for colon cancer screening. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2000;13:761-769.

17. Wardle J, Williamson S, McCaffery K, et al. Increasing attendance at colorectal cancer screening: testing the efficacy of a mailed, psychoeducational intervention in a community sample of older adults. Health Psychol 2003;22:99-105.

18. Detweiler JB, Bedell BT, Salovey P, et al. Message framing and sunscreen use: gain-framed messages motivate beach-goers. Health Psychol 1999;18:189-196.

19. Banks SM, Salovey P, Greener S, et al. The effects of message framing on mammography utilization. Health Psychol 1995;14:178-184.

20. Rivers SE, Salovey P, Pizarro DA, et al. Message framing and pap test utilization among women attending a community health clinic. J Health Psychol 2005;10:65-77.

21. Davids SL, Schapira MM, McAuliffe TL, Nattinger AB. Predictors of pessimistic breast cancer risk perceptions in a primary care population. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:310-315.

22. Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Golbeck AL, Paschal AM, et al. Breast cancer counts: numeracy in breast cancer information on the web. J Cancer Educ 2006;21:95-98.

23. Hodgson J, Hughes E, Lambert C. “SLANG”—Sensitive Language and the New Genetics—an exploratory study. J Genet Couns 2005;14:415-421.

24. Katz ML, James AS, Pignone MP, et al. Colorectal cancer screening among African American church members: a qualitative and quantitative study of patient-provider communication. BMC Public Health 2004;4:62.-

25. Wolf AM, Becker DM. Cancer screening and informed patient discussions. Truth and consequences. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:1069-1072.

26. Banks SM, Salovey P, Greener S, et al. The effects of message framing on mammography utilization. Health Psychol 1995;14:178-184.

27. Lipkus IM, Crawford Y, Fenn K, et al. Testing different formats for communicating colorectal cancer risk. J Health Commun 1999;4:311-324.

28. Shokar NK, Vernon SW, Weller SC. Cancer and colorectal cancer: knowledge, beliefs, and screening p of a diverse patient population. Fam Med 2005;37:341-347.

29. Katz ML, Ruzek SB, Miller SM, Legos P. Gender differences in patients needs and concerns to diagnostic tests for possible cancer. J Cancer Educ 2004;19:227-231.

30. Dube CE, Fuller BK, Rosen RK, et al. Men’s experiences of physical exams and cancer screening tests: a qualitative study. Prev Med 2005;40:628-635.

31. Denberg TD, Coombes JM, Byers TE, et al. Effect of a mailed brochure on appointment-keeping for screening colonoscopy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:895-900.

32. Harewood GC, Wiersema MJ, Melton LJ, 3rd. A prospective, controlled assessment of factors influencing acceptance of screening colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:3186-3194.

33. Godwin Y. Do they listen? A review of information retained by patients following consent for reduction mammoplasty. Br J Plastic Surgery 2000;53:121-125.

34. Greisinger A, Hawley ST, Bettencourt JL, et al. Primary care patients’ understanding of colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Detect Prev 2006;30:67-74.

35. Dulai GS, Farmer MM, Ganz PA, et al. Primary care physician perceptions of barriers to and facilitators of colorectal cancer screening in a managed care setting. Cancer 2004;100:1843-1852.

- When talking to patients about screening colonoscopy, make clear their risk of colorectal cancer. Also, be sure they know about such commonly overlooked details as insurance/scheduling issues, dietary and medication changes before the procedure, a companion to drive afterward, and possible colonoscopy complications.

- Consider recommending supplemental information sources such as telephone calls, letters, e-mails, Web sites, or videotapes to help patients understand the need for screening colonoscopy.

Abstract

Background A physician’s recommendation is a powerful motivator for a patient to undergo colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening, yet little is known about how physicians address this topic.

Methods We recruited 30 primary care physicians and physicians-in-training from 4 practices to counsel a “patient,” simulated by a researcher, regarding the need for screening colonoscopy. Audiotapes of the physician-patient encounters were transcribed. Preserving physician anonymity, we assessed each encounter for key informational points, positive or negative message framing, type of numeracy information, and use of colloquial or technical language.

Results Study physicians addressed a mean of 6.7 (standard deviation=1.8) of 13 key informational points. Most physicians (≥80%) discussed the benefits of colorectal cancer screening, the recognition of colonoscopy as a standard exploratory procedure, and the use of sedation. However, few (<20%) addressed the risks of colonoscopy, the nuances of scheduling, or the need for dietary and medication changes. Nearly all physicians (98%) used messages that focused on the positive aspects of screening (gain-framed messages), and many (67%) also used messages that focused on the risk of not screening (loss-framed messages). Numeracy information generally was expressed simply, but half of the physicians used statistical terms. Half used colloquial terms to describe the prep and procedure.

Conclusion Though most physicians used positive, simple terms to describe colonoscopy, they often omitted key information. Correcting for the areas of insufficient information found in our study—perhaps with supplementary educational sources—will help ensure that patients are adequately prepared for colonoscopy.

Colorectal cancer screening has the potential to reduce deaths from colorectal cancer by at least one third.1 Yet only half of eligible patients in the US who are age 50 or older have undergone screening.2 Patients often say they haven’t been screened because their physician didn’t recommend it.3-5

A physician’s recommendation is strongly predictive of whether a patient actually undergoes colorectal cancer screening, even after adjusting for multiple confounders.6-9 Yet several studies have found that, even after the physician has recommended or ordered an endoscopic study of the colon, many patients do not follow through.10-12 Successful completion of screening colonoscopy requires, in part, that a patient understand the need for the procedure and receive sufficient instruction about it. Thus, failure to undergo this test may reflect patient concerns or misunderstandings due to inadequate communication.13,14

In many settings, the primary care physician bears the responsibility for telling the patient about screening colonoscopy because the endoscopist meets the patient only at the time of the procedure. Supplementary educational programs can also play a role. Unfortunately, though, while these materials appear to reduce patient anxiety and increase adherence to screening recommendations,15-17 they are infrequently used.

Looking at physician communication with an eye toward improvement

Our goal in conducting this study was to evaluate the way in which physicians discuss the need for screening colonoscopy with their patients. Using a simulated patient scenario, we wanted to examine 4 dimensions of each discussion: completeness; type of messaging; type of numeracy information (ie, numerical and mathematical data); and use of colloquial vs technical language.

- Completeness reflected the number of key informational points addressed.

- Type of messaging focused on the use of loss- or gain-framed messages, both of which have been linked to increased patient intention to adopt a cancer prevention behavior or test.18-20 Gain-framed counseling emphasizes the positive aspects of screening; loss-framed, the risks of not screening.

- Type of numeracy information. Because poor numeracy skills are thought to impair the accuracy of patients’ perceptions of cancer risk,21 we categorized the type of numeracy information provided by physicians following an approach developed by Ahlers-Schmidt and colleagues.22

- Colloquial vs technical language. Because colonoscopy involves sensitive topics such as the bowels and feces, and because language choices may affect acceptance of care,23 we evaluated physicians’ use of terminology when describing the procedure.

We felt that by looking at these dimensions, we could help physicians to refine screening colonoscopy messages so that conversations with patients could be more clear, complete, and balanced.

Methods

13 key points regarding screening colonoscopy

We reviewed published literature and Internet sources to develop a preliminary list of topics a primary care physician could address when discussing colorectal cancer screening, especially screening colonoscopy. We used NLM Gateway and Medline databases and the following search terms: colonoscopy, patient education, patient instructions, guidelines, physician, colon cancer, counseling, and knowledge. A medical librarian directed the search. Despite having expert assistance, we did not find any publications that offered a peer-reviewed, validated list of topics to guide physicians’ discussions about screening colonoscopy.

We then conducted an Internet search using the terms colon cancer, colon cancer screening, colonoscopy, and colon cancer patient education. We categorized data from identified sites such as the American Gastroenterological Association, Up-to-Date, the American Cancer Society, and the National Library of Medicine, among others, into 13 common topics (TABLE 1). Three points addressed general information about colorectal cancer, and the rest dealt with colonoscopy specifically. A panel of 2 gastroenterologists and 3 internists from the same institution independently judged each item on the list for importance, relevance, and feasibility for discussion. Except for one panelist, all endorsed the need to address the 13 items.

TABLE 1

Percentage of physicians who covered key colorectal cancer screening points

| TOPIC | INFORMATIONAL POINT | PHYSICIANS ADDRESSING TOPIC (N=30), % |

|---|---|---|

| General colorectal prevention | ||

| 1. Standard preventive health care procedure | Recommended* as a standard screening test for those age 50 and older | 83 |

| 2. Value of screening | Can prevent cancer as well as detect cancer at a treatable stage | 83 |

| 3. Risk of colorectal cancer | Prevalence or incidence either nationally or regionally (family history)† | 43 |

| Specifics about colonoscopy | ||

| 4. Anesthesia | Sedation to reduce discomfort; risk information discussed or to be reviewed by anesthetist | 87 |

| 5. Gastrointestinal prep | Use of laxative, usual types used, and what patient can expect | 77 |

| 6. Abnormalities detected by colonoscopy | Finds growths (polyps) or cancer | 76 |

| 7. Description of procedure | Camera at the end of a flexible tube views the entire colon and tiny tweezers at the end sample or remove growths | 70 |

| 8. Follow-up after a negative test | Experts recommend screening after a negative test every 10 years | 67 |

| 9. Patient experience or knowledge‡ | Any personal or family/friend experience with colonoscopy or knowledge about the test | 64 |

| 10. Transportation | Another person must accompany the patient after procedure | 53 |

| 11. Insurance/scheduling | Insurance coverage, who arranges for the procedure, where test is performed | 13 |

| 12. Diet | Diet the day before and day of procedure, importance of hydration | 10 |

| 13. Risk of colonoscopy | Risk of bowel perforation or other complication | 10 |

| 14. Medications | Changes in medications for the procedure | 3 |

| *Recommendation by expert panels need not be specified. Physicians often just say, “We recommend.” | ||

| †Family history not necessary in this study because the patient was said to be at average risk for colorectal cancer. | ||

| ‡Point was not identified originally by the review and excluded from analysis. | ||

Physician sample

Of 135 providers practicing in 2 primary care and 1 geriatrics practice affiliated with the same urban academic medical center, we invited 30 physicians to participate. This sample was chosen to adequately represent female and minority physicians as well as physicians at different levels of training (TABLE 2). The physicians were invited to participate either by e-mail (N=19) or in person (N=11), and all invitees consented. Interviews were conducted alone in the physician’s office or in a practice conference room, and they were audiotaped with the physician’s consent.

Interviews lasted fewer than 15 minutes and did not intrude on patient care time. Study physicians read a vignette of a fictitious 51-year-old African American woman who was an established patient in their practice, without a family history of colon cancer but with arthritis and hypertension. We asked each physician to inform the patient (simulated by the interviewer) about colorectal cancer screening and colonoscopy, as well as the logistics of getting this test. To standardize the interaction, interviewers predefined the patient’s responses to questions. For example, if the physician asked about prior knowledge of colonoscopy, the simulated patient replied that she had none. Study physicians were not prompted in any way and, though not given time restrictions, all were brief and to the point.

TABLE 2

Study physician characteristics

| CHARACTERISTIC | PHYSICIANS WITH CHARACTERISTIC (N=30), % | INFORMATIONAL POINTS ADDRESSED,* MEAN (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 100 | 6.73 (1.84) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 66 | 6.70 (1.89) |

| Male | 34 | 6.80 (1.81) |

| Race | ||

| White | 80 | 6.84 (1.80) |

| Non-white | 20 | 6.20 (2.17) |

| Level of training | ||

| Attending | 63 | 6.84 (1.98) |

| Trainee | 37 | 6.54 (1.63) |

| Specialty | ||

| General Internal Medicine | 90 | 6.89 (1.83) |

| Geriatrics | 10 | 5.33 (1.53) |

| * All comparisons P >.05 | ||

Analysis

Interview transcripts were anonymous, identified only by a study number. The 2 study investigators coded transcribed interviews independently as to whether physicians addressed the 13 informational points. Inter-rater concordance in coding was 90%. We also independently evaluated the interviews according to the use of gain- or loss-framed messages (eg, detecting colon polyps early before cancer develops vs colorectal cancer being the second most common cause of cancer death). We independently classified types of numeracy information provided into 15 categories.22 We also independently examined audiotaped transcripts for examples of colloquial terms/slang or technical language. Because we are unaware of a validated approach to characterizing a physician’s language in this manner, we asked a layperson for assistance in identifying colloquial/slang terms.

To determine whether there were predictors of a physician addressing more of the informational points than his or her peers, we examined bivariate associations of the following demographic and professional data: gender, race (white vs non-white), academic advancement (attending vs trainee), and specialty (general internist vs geriatrician).

We analyzed data using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test because the data were not normally distributed. We used SAS Statistical Software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board approved the study. The project was supported by a grant from the Bach Fund of the Presbyterian Medical Center, University of Pennsylvania.

Results

How did the physicians talk to their patient?

The 30 study physicians were primarily women, one fifth were from under-represented minorities, and one third were either residents or fellows (TABLE 2). Of 13 key informational points endorsed by our physician panel (TABLE 1), the physician-subjects addressed a mean of 6.7 points (range, 3–10). Nearly all physician-subjects discussed the value of colorectal cancer screening, colonoscopy as a standard colorectal screening procedure, and sedation during the procedure. However, fewer than 20% addressed the following topics: insurance/scheduling, dietary changes, medication modification, and risks of colonoscopy. In this small sample, the number of topics mentioned did not differ significantly by physician characteristic (TABLE 2).

Two thirds of the physicians asked the simulated patient about her prior knowledge or experience with colonoscopy. Although this question was not among the original 13 informational points, it helped to guide the discussion by identifying specific preconceptions or prior knowledge of this test. Therefore, this post hoc 14th informational point was added to our list but not considered in our analyses.

Gain-framed messages used more than loss-framed messages

Nearly all physicians used gain-framed messages, and more than half also used loss-framed messages (TABLE 3). Only 1 physician offered only a loss-framed message. Overall, study physicians mentioned less than 2 gain- or loss-framed messages.

- The most common types of gain-framed messages were detecting cancer early, preventing cancer by taking out polyps, and screening at only a 10-year interval if the test result is negative.

- The most common loss-framed messages noted that colorectal cancer was the second most common cause of cancer death and that risk is increased with a family history of this cancer.

TABLE 3

Gain- and loss-framed messages and types of numeracy information used by study physicians

| TYPE OF MESSAGE OR NUMERACY | PHYSICIANS N (%) | OCCURRENCES IN INTERVIEWS, Total N (MEAN AMONG USERS, RANGE) |

|---|---|---|

| Message framing | ||

| Gain-framed | 29 (96) | 56 (1.9, 1–5) |

| Loss-framed | 20 (67) | 31 (1.6, 1–3) |

| Numeracy | ||

| Descriptive terms | 19 (63) | 36 (1.9, 1–3) |

| Statistical terms | 15 (50) | 30 (2.0, 1–5) |

| Temporal terms | 9 (30) | 11 (1.2, 1–2) |

| Proportions | 4 (13) | 5 (1.3, 1–2) |

| Fractions | 3 (10) | 3 (1.0, 1–1) |

Physicians avoided using numbers

Of the 15 types of numeracy information described by Ahlers-Schmit et al, our physicians used only 5. Nineteen physicians (63%) used descriptive terms such as “likely” or “increased,” and 15 (50%) used statistical concepts such as risk and second-most-common cause. Physicians avoided using numbers; 9 (30%) used temporal terms such as “early”; 4 (13%) cited a proportion; and only 3 (10%) used a fraction.

Colloquial language, or was it crude?

While reading the transcripts, we noted that some physicians used colloquial terms that could be regarded as crude. Other terms were probably too technical without an explanation. Some information was simply incorrect. We offer selected quotes to illustrate various types of language used.

About the prep:

- “Getting a colonoscopy is not the most fun experience…you have really bad diarrhea and you just empty out your guts.”

- “It’s basically Liquid Plumber for your bowels.”

- “Bowel prep…is kind of voluminous and associated with kind of massive bowel movements.”

- “Everybody hates the prep and you may be one of those and that’s just that.”

- “Generally you have to be up all night, sometimes, cleaning your bowels out.”

About the procedure:

- “It’s not the most comfortable screening exam in the world.”

- “It’s a test where they stick a lighted tube up your back-side.”

- “The stomach doctors put a camera up your bottom and look at the walls of your colon.”

- “They can go in with a microscope and look around and look at the colon itself.”

- “It’s a painless test.”

Word polyp is used, but not defined

Physicians often employed technical language when describing the pathology detected by colonoscopy. “Polyp” was mentioned by 20 physicians (67%) but rarely defined; “biopsy” by 5 (17%), and “lesion” by 6 (20%). Other technical terms were precancerous, symptomatic, and incapacitated.

Discussion

An informed patient is a willing patient

Our study physicians addressed only half of the 13 informational points, likely reflecting the time constraints of a typical office visit. Primary care physicians appear to expect that either the colonoscopist or other sources of information would fill in the gaps. As reported in several studies, unanswered questions can discourage patients from keeping their scheduled colonoscopy appointment.10,11 In one report of African-American church members, those with adequate knowledge about colorectal cancer screening were more likely to complete screening.24

Wolf and Becker suggested that discussions about cancer screening address 4 broad topics: the probability of developing the cancer, the operating characteristics of the screening test(s), the likelihood that screening will benefit the patient, and potential burdens of the test.25 Instead of a balanced and lengthy discussion, our study physicians generally emphasized the positives such as the value of avoiding colon cancer, the standard nature of this test, and the benefit of being sedated for the procedure. Thus, gain-framed messages about colorectal cancer were the norm for our study physicians.

Half of the physicians also offered loss-framed messages emphasizing the need to avoid the consequences of colorectal cancer and the increased threat associated with a family history of this malignancy. Research in mammography screening suggests that loss-framed messaging may be a more powerful motivator than gain-framed messaging,26 but it is not clear if this observation can be generalized to colorectal cancer screening.

Walking a fine line with the particulars of risk

Our study physicians rarely provided data on the probability of developing colorectal cancer. Physicians may avoid this topic because many patients have difficulty understanding information about the risk of colorectal cancer.11 In support of this approach, Lipkus and colleagues reported that various ways of informing patients about colorectal cancer risk did not affect their intention to be screened.27 Of concern, most of our physicians did not address the common misconception that colorectal cancer screening is unnecessary in the absence of symptoms.28

Overall, the level of numeracy information provided by study physicians required minimal patient understanding of mathematical and statistical concepts. Most information was descriptive, such as colonoscopy being “more thorough” than other tests. Though statistical concepts such as “risk” were often mentioned, few physicians offered probabilities or incidence data. Experts recommend providing such data,25 but Web sites have been criticized for offering excessive numerical cancer risk data.22 Therefore, physicians must walk a fine line between providing adequate information and offering data that require a high level of health numeracy for understanding.

6 key points physicians often overlook

Most physicians failed to mention dietary and medication changes, scheduling/insurance coverage issues, and risk of complications from colonoscopy. Nearly 60% failed to discuss the patient’s risk of colorectal cancer. Almost half did not mention the need for a companion to accompany the patient after the test. Scheduling challenges, in particular, are known to interfere with completing colonoscopy.11

Many neglect to describe the procedure

Thirty percent of physicians failed to describe the procedure itself, so it is not surprising that patients complain they have a poor understanding of test logistics.11,29,30 Denberg and colleagues have reported that mailing an informational brochure about colonoscopy can increase the number who keep their appointment.31

How language choices may affect understanding

Other researchers have identified additional patient barriers to colonoscopy, including fear of pain, concern for modesty, and desire to avoid the bowel prep.11,32 These concerns may be mitigated or heightened by the physician’s language. In our review of transcripts, physicians often used slang or colloquial language to describe the procedure, probably in an attempt to convey information in a familiar way. This language may be viewed as crude and potentially discouraging, but further research is needed to evaluate patient receptiveness to different ways of speaking about sensitive topics.

Additionally, physicians commonly used technical terms such as “polyp” and “biopsy” without explaining them. Technical language may increase racial disparities in adhering to scheduled colonoscopy. In a family medicine clinic, patients from minority groups had particular difficulty understanding medical terms and procedure names.28 Because little time is available for counseling about cancer screening tests, and because patients retain only a limited amount of information about procedures,33 supplementary informational sources are warranted.15-17,31 Options include brochures, telephone calls, letters, e-mails, Web site data, and videotapes, but it is unclear which sources optimally improve patient adherence to screening colonoscopy.34

Study limitations include simulated interaction

There were a number of limitations to this study. First, the investigators “simulated” the patient. Though study physicians were told to act as if they were speaking to a regular patient, they may still have unconsciously modified their usual approach to addressing this topic.

Second, we did not assess the effectiveness of these discussions in motivating actual patients to receive colonoscopy.

Other limitations included the following:

- We did not set a time period for these discussions, so they may have been even more limited in actual practice.

- We studied physicians from a single health care setting wherein colonoscopy appears to be the preferred approach to screen an average risk patient for colorectal cancer. In addition, in this health care system, this test is performed by a gastroenterologist, rather than a primary care physician.

- We did not determine whether patients regard our selected quotes as too colloquial or technical.

- This study did not address the important barrier of a physician forgetting to recommend colorectal cancer screening.35

Further research, next steps

Our study supports the hypothesis that physicians differ widely—but are generally deficient—when informing patients about screening colonoscopy. They generally emphasize the positives of colonoscopy and use terms that are colloquial, avoiding statistical concepts that may be hard for patients to understand. Future studies need to address the effectiveness of these approaches to discussing screening colonoscopy.

Given the central role of the primary care physician in motivating patients to undergo screening colonoscopy in a limited time period, it appears that additional supports are needed to supplement physician discussion about this important preventive care procedure.

Correspondence

Barbara J. Turner MD, MSEd, University of Pennsylvania, 1123 Blockley Hall/6021, 423 Guardian Drive, Philadelphia, PA 19104; [email protected]

- When talking to patients about screening colonoscopy, make clear their risk of colorectal cancer. Also, be sure they know about such commonly overlooked details as insurance/scheduling issues, dietary and medication changes before the procedure, a companion to drive afterward, and possible colonoscopy complications.

- Consider recommending supplemental information sources such as telephone calls, letters, e-mails, Web sites, or videotapes to help patients understand the need for screening colonoscopy.

Abstract

Background A physician’s recommendation is a powerful motivator for a patient to undergo colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening, yet little is known about how physicians address this topic.

Methods We recruited 30 primary care physicians and physicians-in-training from 4 practices to counsel a “patient,” simulated by a researcher, regarding the need for screening colonoscopy. Audiotapes of the physician-patient encounters were transcribed. Preserving physician anonymity, we assessed each encounter for key informational points, positive or negative message framing, type of numeracy information, and use of colloquial or technical language.

Results Study physicians addressed a mean of 6.7 (standard deviation=1.8) of 13 key informational points. Most physicians (≥80%) discussed the benefits of colorectal cancer screening, the recognition of colonoscopy as a standard exploratory procedure, and the use of sedation. However, few (<20%) addressed the risks of colonoscopy, the nuances of scheduling, or the need for dietary and medication changes. Nearly all physicians (98%) used messages that focused on the positive aspects of screening (gain-framed messages), and many (67%) also used messages that focused on the risk of not screening (loss-framed messages). Numeracy information generally was expressed simply, but half of the physicians used statistical terms. Half used colloquial terms to describe the prep and procedure.

Conclusion Though most physicians used positive, simple terms to describe colonoscopy, they often omitted key information. Correcting for the areas of insufficient information found in our study—perhaps with supplementary educational sources—will help ensure that patients are adequately prepared for colonoscopy.

Colorectal cancer screening has the potential to reduce deaths from colorectal cancer by at least one third.1 Yet only half of eligible patients in the US who are age 50 or older have undergone screening.2 Patients often say they haven’t been screened because their physician didn’t recommend it.3-5

A physician’s recommendation is strongly predictive of whether a patient actually undergoes colorectal cancer screening, even after adjusting for multiple confounders.6-9 Yet several studies have found that, even after the physician has recommended or ordered an endoscopic study of the colon, many patients do not follow through.10-12 Successful completion of screening colonoscopy requires, in part, that a patient understand the need for the procedure and receive sufficient instruction about it. Thus, failure to undergo this test may reflect patient concerns or misunderstandings due to inadequate communication.13,14

In many settings, the primary care physician bears the responsibility for telling the patient about screening colonoscopy because the endoscopist meets the patient only at the time of the procedure. Supplementary educational programs can also play a role. Unfortunately, though, while these materials appear to reduce patient anxiety and increase adherence to screening recommendations,15-17 they are infrequently used.

Looking at physician communication with an eye toward improvement

Our goal in conducting this study was to evaluate the way in which physicians discuss the need for screening colonoscopy with their patients. Using a simulated patient scenario, we wanted to examine 4 dimensions of each discussion: completeness; type of messaging; type of numeracy information (ie, numerical and mathematical data); and use of colloquial vs technical language.

- Completeness reflected the number of key informational points addressed.

- Type of messaging focused on the use of loss- or gain-framed messages, both of which have been linked to increased patient intention to adopt a cancer prevention behavior or test.18-20 Gain-framed counseling emphasizes the positive aspects of screening; loss-framed, the risks of not screening.

- Type of numeracy information. Because poor numeracy skills are thought to impair the accuracy of patients’ perceptions of cancer risk,21 we categorized the type of numeracy information provided by physicians following an approach developed by Ahlers-Schmidt and colleagues.22

- Colloquial vs technical language. Because colonoscopy involves sensitive topics such as the bowels and feces, and because language choices may affect acceptance of care,23 we evaluated physicians’ use of terminology when describing the procedure.

We felt that by looking at these dimensions, we could help physicians to refine screening colonoscopy messages so that conversations with patients could be more clear, complete, and balanced.

Methods

13 key points regarding screening colonoscopy

We reviewed published literature and Internet sources to develop a preliminary list of topics a primary care physician could address when discussing colorectal cancer screening, especially screening colonoscopy. We used NLM Gateway and Medline databases and the following search terms: colonoscopy, patient education, patient instructions, guidelines, physician, colon cancer, counseling, and knowledge. A medical librarian directed the search. Despite having expert assistance, we did not find any publications that offered a peer-reviewed, validated list of topics to guide physicians’ discussions about screening colonoscopy.

We then conducted an Internet search using the terms colon cancer, colon cancer screening, colonoscopy, and colon cancer patient education. We categorized data from identified sites such as the American Gastroenterological Association, Up-to-Date, the American Cancer Society, and the National Library of Medicine, among others, into 13 common topics (TABLE 1). Three points addressed general information about colorectal cancer, and the rest dealt with colonoscopy specifically. A panel of 2 gastroenterologists and 3 internists from the same institution independently judged each item on the list for importance, relevance, and feasibility for discussion. Except for one panelist, all endorsed the need to address the 13 items.

TABLE 1

Percentage of physicians who covered key colorectal cancer screening points

| TOPIC | INFORMATIONAL POINT | PHYSICIANS ADDRESSING TOPIC (N=30), % |

|---|---|---|

| General colorectal prevention | ||

| 1. Standard preventive health care procedure | Recommended* as a standard screening test for those age 50 and older | 83 |

| 2. Value of screening | Can prevent cancer as well as detect cancer at a treatable stage | 83 |

| 3. Risk of colorectal cancer | Prevalence or incidence either nationally or regionally (family history)† | 43 |

| Specifics about colonoscopy | ||

| 4. Anesthesia | Sedation to reduce discomfort; risk information discussed or to be reviewed by anesthetist | 87 |

| 5. Gastrointestinal prep | Use of laxative, usual types used, and what patient can expect | 77 |

| 6. Abnormalities detected by colonoscopy | Finds growths (polyps) or cancer | 76 |

| 7. Description of procedure | Camera at the end of a flexible tube views the entire colon and tiny tweezers at the end sample or remove growths | 70 |

| 8. Follow-up after a negative test | Experts recommend screening after a negative test every 10 years | 67 |

| 9. Patient experience or knowledge‡ | Any personal or family/friend experience with colonoscopy or knowledge about the test | 64 |

| 10. Transportation | Another person must accompany the patient after procedure | 53 |

| 11. Insurance/scheduling | Insurance coverage, who arranges for the procedure, where test is performed | 13 |

| 12. Diet | Diet the day before and day of procedure, importance of hydration | 10 |

| 13. Risk of colonoscopy | Risk of bowel perforation or other complication | 10 |

| 14. Medications | Changes in medications for the procedure | 3 |

| *Recommendation by expert panels need not be specified. Physicians often just say, “We recommend.” | ||

| †Family history not necessary in this study because the patient was said to be at average risk for colorectal cancer. | ||

| ‡Point was not identified originally by the review and excluded from analysis. | ||

Physician sample

Of 135 providers practicing in 2 primary care and 1 geriatrics practice affiliated with the same urban academic medical center, we invited 30 physicians to participate. This sample was chosen to adequately represent female and minority physicians as well as physicians at different levels of training (TABLE 2). The physicians were invited to participate either by e-mail (N=19) or in person (N=11), and all invitees consented. Interviews were conducted alone in the physician’s office or in a practice conference room, and they were audiotaped with the physician’s consent.

Interviews lasted fewer than 15 minutes and did not intrude on patient care time. Study physicians read a vignette of a fictitious 51-year-old African American woman who was an established patient in their practice, without a family history of colon cancer but with arthritis and hypertension. We asked each physician to inform the patient (simulated by the interviewer) about colorectal cancer screening and colonoscopy, as well as the logistics of getting this test. To standardize the interaction, interviewers predefined the patient’s responses to questions. For example, if the physician asked about prior knowledge of colonoscopy, the simulated patient replied that she had none. Study physicians were not prompted in any way and, though not given time restrictions, all were brief and to the point.

TABLE 2

Study physician characteristics

| CHARACTERISTIC | PHYSICIANS WITH CHARACTERISTIC (N=30), % | INFORMATIONAL POINTS ADDRESSED,* MEAN (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 100 | 6.73 (1.84) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 66 | 6.70 (1.89) |

| Male | 34 | 6.80 (1.81) |

| Race | ||

| White | 80 | 6.84 (1.80) |

| Non-white | 20 | 6.20 (2.17) |

| Level of training | ||

| Attending | 63 | 6.84 (1.98) |

| Trainee | 37 | 6.54 (1.63) |

| Specialty | ||

| General Internal Medicine | 90 | 6.89 (1.83) |

| Geriatrics | 10 | 5.33 (1.53) |

| * All comparisons P >.05 | ||

Analysis

Interview transcripts were anonymous, identified only by a study number. The 2 study investigators coded transcribed interviews independently as to whether physicians addressed the 13 informational points. Inter-rater concordance in coding was 90%. We also independently evaluated the interviews according to the use of gain- or loss-framed messages (eg, detecting colon polyps early before cancer develops vs colorectal cancer being the second most common cause of cancer death). We independently classified types of numeracy information provided into 15 categories.22 We also independently examined audiotaped transcripts for examples of colloquial terms/slang or technical language. Because we are unaware of a validated approach to characterizing a physician’s language in this manner, we asked a layperson for assistance in identifying colloquial/slang terms.

To determine whether there were predictors of a physician addressing more of the informational points than his or her peers, we examined bivariate associations of the following demographic and professional data: gender, race (white vs non-white), academic advancement (attending vs trainee), and specialty (general internist vs geriatrician).

We analyzed data using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test because the data were not normally distributed. We used SAS Statistical Software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board approved the study. The project was supported by a grant from the Bach Fund of the Presbyterian Medical Center, University of Pennsylvania.

Results

How did the physicians talk to their patient?

The 30 study physicians were primarily women, one fifth were from under-represented minorities, and one third were either residents or fellows (TABLE 2). Of 13 key informational points endorsed by our physician panel (TABLE 1), the physician-subjects addressed a mean of 6.7 points (range, 3–10). Nearly all physician-subjects discussed the value of colorectal cancer screening, colonoscopy as a standard colorectal screening procedure, and sedation during the procedure. However, fewer than 20% addressed the following topics: insurance/scheduling, dietary changes, medication modification, and risks of colonoscopy. In this small sample, the number of topics mentioned did not differ significantly by physician characteristic (TABLE 2).

Two thirds of the physicians asked the simulated patient about her prior knowledge or experience with colonoscopy. Although this question was not among the original 13 informational points, it helped to guide the discussion by identifying specific preconceptions or prior knowledge of this test. Therefore, this post hoc 14th informational point was added to our list but not considered in our analyses.

Gain-framed messages used more than loss-framed messages

Nearly all physicians used gain-framed messages, and more than half also used loss-framed messages (TABLE 3). Only 1 physician offered only a loss-framed message. Overall, study physicians mentioned less than 2 gain- or loss-framed messages.

- The most common types of gain-framed messages were detecting cancer early, preventing cancer by taking out polyps, and screening at only a 10-year interval if the test result is negative.

- The most common loss-framed messages noted that colorectal cancer was the second most common cause of cancer death and that risk is increased with a family history of this cancer.

TABLE 3

Gain- and loss-framed messages and types of numeracy information used by study physicians

| TYPE OF MESSAGE OR NUMERACY | PHYSICIANS N (%) | OCCURRENCES IN INTERVIEWS, Total N (MEAN AMONG USERS, RANGE) |

|---|---|---|

| Message framing | ||

| Gain-framed | 29 (96) | 56 (1.9, 1–5) |

| Loss-framed | 20 (67) | 31 (1.6, 1–3) |

| Numeracy | ||

| Descriptive terms | 19 (63) | 36 (1.9, 1–3) |

| Statistical terms | 15 (50) | 30 (2.0, 1–5) |

| Temporal terms | 9 (30) | 11 (1.2, 1–2) |

| Proportions | 4 (13) | 5 (1.3, 1–2) |

| Fractions | 3 (10) | 3 (1.0, 1–1) |

Physicians avoided using numbers

Of the 15 types of numeracy information described by Ahlers-Schmit et al, our physicians used only 5. Nineteen physicians (63%) used descriptive terms such as “likely” or “increased,” and 15 (50%) used statistical concepts such as risk and second-most-common cause. Physicians avoided using numbers; 9 (30%) used temporal terms such as “early”; 4 (13%) cited a proportion; and only 3 (10%) used a fraction.

Colloquial language, or was it crude?

While reading the transcripts, we noted that some physicians used colloquial terms that could be regarded as crude. Other terms were probably too technical without an explanation. Some information was simply incorrect. We offer selected quotes to illustrate various types of language used.

About the prep:

- “Getting a colonoscopy is not the most fun experience…you have really bad diarrhea and you just empty out your guts.”

- “It’s basically Liquid Plumber for your bowels.”

- “Bowel prep…is kind of voluminous and associated with kind of massive bowel movements.”

- “Everybody hates the prep and you may be one of those and that’s just that.”

- “Generally you have to be up all night, sometimes, cleaning your bowels out.”

About the procedure:

- “It’s not the most comfortable screening exam in the world.”

- “It’s a test where they stick a lighted tube up your back-side.”

- “The stomach doctors put a camera up your bottom and look at the walls of your colon.”

- “They can go in with a microscope and look around and look at the colon itself.”

- “It’s a painless test.”

Word polyp is used, but not defined

Physicians often employed technical language when describing the pathology detected by colonoscopy. “Polyp” was mentioned by 20 physicians (67%) but rarely defined; “biopsy” by 5 (17%), and “lesion” by 6 (20%). Other technical terms were precancerous, symptomatic, and incapacitated.

Discussion

An informed patient is a willing patient

Our study physicians addressed only half of the 13 informational points, likely reflecting the time constraints of a typical office visit. Primary care physicians appear to expect that either the colonoscopist or other sources of information would fill in the gaps. As reported in several studies, unanswered questions can discourage patients from keeping their scheduled colonoscopy appointment.10,11 In one report of African-American church members, those with adequate knowledge about colorectal cancer screening were more likely to complete screening.24

Wolf and Becker suggested that discussions about cancer screening address 4 broad topics: the probability of developing the cancer, the operating characteristics of the screening test(s), the likelihood that screening will benefit the patient, and potential burdens of the test.25 Instead of a balanced and lengthy discussion, our study physicians generally emphasized the positives such as the value of avoiding colon cancer, the standard nature of this test, and the benefit of being sedated for the procedure. Thus, gain-framed messages about colorectal cancer were the norm for our study physicians.

Half of the physicians also offered loss-framed messages emphasizing the need to avoid the consequences of colorectal cancer and the increased threat associated with a family history of this malignancy. Research in mammography screening suggests that loss-framed messaging may be a more powerful motivator than gain-framed messaging,26 but it is not clear if this observation can be generalized to colorectal cancer screening.

Walking a fine line with the particulars of risk

Our study physicians rarely provided data on the probability of developing colorectal cancer. Physicians may avoid this topic because many patients have difficulty understanding information about the risk of colorectal cancer.11 In support of this approach, Lipkus and colleagues reported that various ways of informing patients about colorectal cancer risk did not affect their intention to be screened.27 Of concern, most of our physicians did not address the common misconception that colorectal cancer screening is unnecessary in the absence of symptoms.28

Overall, the level of numeracy information provided by study physicians required minimal patient understanding of mathematical and statistical concepts. Most information was descriptive, such as colonoscopy being “more thorough” than other tests. Though statistical concepts such as “risk” were often mentioned, few physicians offered probabilities or incidence data. Experts recommend providing such data,25 but Web sites have been criticized for offering excessive numerical cancer risk data.22 Therefore, physicians must walk a fine line between providing adequate information and offering data that require a high level of health numeracy for understanding.

6 key points physicians often overlook

Most physicians failed to mention dietary and medication changes, scheduling/insurance coverage issues, and risk of complications from colonoscopy. Nearly 60% failed to discuss the patient’s risk of colorectal cancer. Almost half did not mention the need for a companion to accompany the patient after the test. Scheduling challenges, in particular, are known to interfere with completing colonoscopy.11

Many neglect to describe the procedure

Thirty percent of physicians failed to describe the procedure itself, so it is not surprising that patients complain they have a poor understanding of test logistics.11,29,30 Denberg and colleagues have reported that mailing an informational brochure about colonoscopy can increase the number who keep their appointment.31

How language choices may affect understanding

Other researchers have identified additional patient barriers to colonoscopy, including fear of pain, concern for modesty, and desire to avoid the bowel prep.11,32 These concerns may be mitigated or heightened by the physician’s language. In our review of transcripts, physicians often used slang or colloquial language to describe the procedure, probably in an attempt to convey information in a familiar way. This language may be viewed as crude and potentially discouraging, but further research is needed to evaluate patient receptiveness to different ways of speaking about sensitive topics.

Additionally, physicians commonly used technical terms such as “polyp” and “biopsy” without explaining them. Technical language may increase racial disparities in adhering to scheduled colonoscopy. In a family medicine clinic, patients from minority groups had particular difficulty understanding medical terms and procedure names.28 Because little time is available for counseling about cancer screening tests, and because patients retain only a limited amount of information about procedures,33 supplementary informational sources are warranted.15-17,31 Options include brochures, telephone calls, letters, e-mails, Web site data, and videotapes, but it is unclear which sources optimally improve patient adherence to screening colonoscopy.34

Study limitations include simulated interaction

There were a number of limitations to this study. First, the investigators “simulated” the patient. Though study physicians were told to act as if they were speaking to a regular patient, they may still have unconsciously modified their usual approach to addressing this topic.

Second, we did not assess the effectiveness of these discussions in motivating actual patients to receive colonoscopy.

Other limitations included the following:

- We did not set a time period for these discussions, so they may have been even more limited in actual practice.

- We studied physicians from a single health care setting wherein colonoscopy appears to be the preferred approach to screen an average risk patient for colorectal cancer. In addition, in this health care system, this test is performed by a gastroenterologist, rather than a primary care physician.

- We did not determine whether patients regard our selected quotes as too colloquial or technical.

- This study did not address the important barrier of a physician forgetting to recommend colorectal cancer screening.35

Further research, next steps

Our study supports the hypothesis that physicians differ widely—but are generally deficient—when informing patients about screening colonoscopy. They generally emphasize the positives of colonoscopy and use terms that are colloquial, avoiding statistical concepts that may be hard for patients to understand. Future studies need to address the effectiveness of these approaches to discussing screening colonoscopy.

Given the central role of the primary care physician in motivating patients to undergo screening colonoscopy in a limited time period, it appears that additional supports are needed to supplement physician discussion about this important preventive care procedure.

Correspondence

Barbara J. Turner MD, MSEd, University of Pennsylvania, 1123 Blockley Hall/6021, 423 Guardian Drive, Philadelphia, PA 19104; [email protected]

1. Ries LA, Wingo PA, Miller DS, et al. The annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1997, with a special section on colorectal cancer. Cancer 2000;88:2398-2424.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Colorectal cancer test use among persons aged > or = 50 years—United States, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;52:193-196.

3. Wee CC, McCarthy EP, Phillips RS. Factors associated with colon cancer screening: the role of patient factors and physician counseling. Prev Med 2005;41:23-29.

4. Taylor V, Lessler D, Mertens K, et al. Colorectal cancer screening among African Americans: the importance of physician recommendations. J Natl Med Assoc 2003;95:806-812.