User login

Bimekizumab approved in Europe for psoriasis treatment

, according to a statement from the manufacturer.

Bimekizumab (Bimzelx), a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody, is the first approved treatment for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis that selectively inhibits interleukin (IL)–17A and IL-17F, the statement from UCB said.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration is expected to make a decision on approval of bimekizumab for treating psoriasis on Oct. 15.

Approval in the EU was based on data from three phase 3 trials including a total of 1,480 adult patients with moderate to severe psoriasis, which found that those treated with bimekizumab experienced significantly greater skin clearance, compared with placebo, ustekinumab, and adalimumab, with a favorable safety profile, according to the company.

In all three studies (BE VIVID, BE READY, and BE SURE), more than 80% of patients treated with bimekizumab showed improved skin clearance after 16 weeks, significantly more than those treated with ustekinumab, placebo, or adalimumab, based on an improvement of at least 90% in the Psoriasis Area & Severity Index (PASI 90) and an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) response of clear or almost clear skin (IGA 0/1). In all three studies, these clinical responses persisted after 1 year.

The recommended dose of bimekizumab is 320 mg, given in two subcutaneous injections every 4 weeks to week 16, then every 8 weeks. However, for “some patients” weighing 120 kg or more who have not achieved complete skin clearance at 16 weeks, 320 mg every 4 weeks after that time may improve response to treatment, according to the company statement.

The most common treatment-related adverse events in the studies were upper respiratory tract infections (a majority of which were nasopharyngitis), reported by 14.5% of patients, followed by oral candidiasis, reported by 7.3%.

Results of BE READY and BE VIVID were published in The Lancet. Results of the BE SURE study were published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Bimekizumab is contraindicated for individuals with clinically important active infections such as tuberculosis, and for individuals with any hypersensitivity to the active substance. More details on bimekizumab are available on the website of the European Medicines Agency.

, according to a statement from the manufacturer.

Bimekizumab (Bimzelx), a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody, is the first approved treatment for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis that selectively inhibits interleukin (IL)–17A and IL-17F, the statement from UCB said.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration is expected to make a decision on approval of bimekizumab for treating psoriasis on Oct. 15.

Approval in the EU was based on data from three phase 3 trials including a total of 1,480 adult patients with moderate to severe psoriasis, which found that those treated with bimekizumab experienced significantly greater skin clearance, compared with placebo, ustekinumab, and adalimumab, with a favorable safety profile, according to the company.

In all three studies (BE VIVID, BE READY, and BE SURE), more than 80% of patients treated with bimekizumab showed improved skin clearance after 16 weeks, significantly more than those treated with ustekinumab, placebo, or adalimumab, based on an improvement of at least 90% in the Psoriasis Area & Severity Index (PASI 90) and an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) response of clear or almost clear skin (IGA 0/1). In all three studies, these clinical responses persisted after 1 year.

The recommended dose of bimekizumab is 320 mg, given in two subcutaneous injections every 4 weeks to week 16, then every 8 weeks. However, for “some patients” weighing 120 kg or more who have not achieved complete skin clearance at 16 weeks, 320 mg every 4 weeks after that time may improve response to treatment, according to the company statement.

The most common treatment-related adverse events in the studies were upper respiratory tract infections (a majority of which were nasopharyngitis), reported by 14.5% of patients, followed by oral candidiasis, reported by 7.3%.

Results of BE READY and BE VIVID were published in The Lancet. Results of the BE SURE study were published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Bimekizumab is contraindicated for individuals with clinically important active infections such as tuberculosis, and for individuals with any hypersensitivity to the active substance. More details on bimekizumab are available on the website of the European Medicines Agency.

, according to a statement from the manufacturer.

Bimekizumab (Bimzelx), a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody, is the first approved treatment for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis that selectively inhibits interleukin (IL)–17A and IL-17F, the statement from UCB said.

In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration is expected to make a decision on approval of bimekizumab for treating psoriasis on Oct. 15.

Approval in the EU was based on data from three phase 3 trials including a total of 1,480 adult patients with moderate to severe psoriasis, which found that those treated with bimekizumab experienced significantly greater skin clearance, compared with placebo, ustekinumab, and adalimumab, with a favorable safety profile, according to the company.

In all three studies (BE VIVID, BE READY, and BE SURE), more than 80% of patients treated with bimekizumab showed improved skin clearance after 16 weeks, significantly more than those treated with ustekinumab, placebo, or adalimumab, based on an improvement of at least 90% in the Psoriasis Area & Severity Index (PASI 90) and an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) response of clear or almost clear skin (IGA 0/1). In all three studies, these clinical responses persisted after 1 year.

The recommended dose of bimekizumab is 320 mg, given in two subcutaneous injections every 4 weeks to week 16, then every 8 weeks. However, for “some patients” weighing 120 kg or more who have not achieved complete skin clearance at 16 weeks, 320 mg every 4 weeks after that time may improve response to treatment, according to the company statement.

The most common treatment-related adverse events in the studies were upper respiratory tract infections (a majority of which were nasopharyngitis), reported by 14.5% of patients, followed by oral candidiasis, reported by 7.3%.

Results of BE READY and BE VIVID were published in The Lancet. Results of the BE SURE study were published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Bimekizumab is contraindicated for individuals with clinically important active infections such as tuberculosis, and for individuals with any hypersensitivity to the active substance. More details on bimekizumab are available on the website of the European Medicines Agency.

Psoriatic arthritis health care costs continue to rise over time

Annual health care costs for patients with psoriatic arthritis rose over recent 5-year periods across all categories of resource use to a significantly greater extent than among patients with psoriasis only or those without any psoriatic disease diagnoses, according to commercial insurance claims data.

Using an IBM MarketScan Commercial Database, researchers examined claims data for 208,434 patients with psoriasis, 47,274 with PsA, and 255,708 controls who had neither psoriasis nor PsA. Controls were matched for age and sex. Those with RA, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, or ulcerative colitis were excluded.

The investigators examined data for 2009-2020, following patients for 5 years within that period. They looked at hospitalizations, outpatient and pharmacy services, lab services, and office visits, Steven Peterson, director of market access for rheumatology at Janssen Pharmaceuticals, said in his presentation of the data at the Pan American League of Associations for Rheumatology 2021 annual meeting, held recently as a virtual event.

The research was also published online May 2, 2021, in Clinical Rheumatology.

Big differences between the groups were seen in the first year, when the average health care costs for the PsA group were $28,322, about half of which was outpatient drug costs. That compared with $12,039 for the psoriasis group and $6,672 for the control group.

The differences tended to widen over time. By the fifth year, average costs for the PsA group were $34,290, nearly 60% of which were drug costs. That compared with $12,877 for the psoriasis group and $8,569 for the control group. In each year examined, outpatient drug costs accounted for less than half of the expenses for the psoriasis group and about a quarter for the control group.

Researchers found that the PsA group needed 28.7 prescriptions per person per year, compared with 17.0 and 12.7 in the psoriasis and control groups, respectively, Mr. Peterson said. He also noted that patients with PsA and psoriasis tended to have higher rates of hypertension, depression, and anxiety.

“The cost and resource utilization disparity between these patient groups demonstrates the high remaining unmet medical need for patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis,” Mr. Peterson said during the virtual proceedings.

Do findings reflect treatment advances?

Elaine Husni, MD, MPH, director of the Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Center at the Cleveland Clinic, where she studies health outcomes in PsA, said the findings are helpful in pointing to a trend across a large sample. But she added it’s important to remember that the increasing costs could reflect recent advances in PsA treatment, which include costly biologic drugs.

“There’s a ton more treatments for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis than there were even just 5 years ago,” she said in an interview. She was not involved in the research.

Dr. Husni would like to see a more detailed look at the costs, from the categories of expenses to the patients who are incurring the highest costs.

“Is it just a couple of percent of really sick patients that are driving the psoriatic arthritis group?” she wondered.

She also pointed out that PsA is going to be more expensive by its very nature. PsA tends to develop 3-10 years after psoriasis, adding to the costs for someone who already has psoriasis and at a time when they are older and likely have higher health care costs because of comorbidities that develop with age.

Dr. Husni said she does think about treatment costs, in that a less expensive first-line drug might be more appropriate than going straight to a more expensive biologic, especially because they also tend to be safer. She said it’s not just a simple question of curbing costs.

“Is there a way that we can personalize medicine?” she asked. “Is there a way that we can be more accurate about which people may need the more expensive drugs, and which patients may need the less expensive drugs? Are we getting better at monitoring so we can avoid high-cost events?”

Mr. Peterson is an employee of Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Husni reported serving as a consultant to AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, UCB, Novartis, Lilly, and Pfizer.

* Update, 9/28/21: The headline and parts of this story were updated to better reflect the study on which it reports.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Annual health care costs for patients with psoriatic arthritis rose over recent 5-year periods across all categories of resource use to a significantly greater extent than among patients with psoriasis only or those without any psoriatic disease diagnoses, according to commercial insurance claims data.

Using an IBM MarketScan Commercial Database, researchers examined claims data for 208,434 patients with psoriasis, 47,274 with PsA, and 255,708 controls who had neither psoriasis nor PsA. Controls were matched for age and sex. Those with RA, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, or ulcerative colitis were excluded.

The investigators examined data for 2009-2020, following patients for 5 years within that period. They looked at hospitalizations, outpatient and pharmacy services, lab services, and office visits, Steven Peterson, director of market access for rheumatology at Janssen Pharmaceuticals, said in his presentation of the data at the Pan American League of Associations for Rheumatology 2021 annual meeting, held recently as a virtual event.

The research was also published online May 2, 2021, in Clinical Rheumatology.

Big differences between the groups were seen in the first year, when the average health care costs for the PsA group were $28,322, about half of which was outpatient drug costs. That compared with $12,039 for the psoriasis group and $6,672 for the control group.

The differences tended to widen over time. By the fifth year, average costs for the PsA group were $34,290, nearly 60% of which were drug costs. That compared with $12,877 for the psoriasis group and $8,569 for the control group. In each year examined, outpatient drug costs accounted for less than half of the expenses for the psoriasis group and about a quarter for the control group.

Researchers found that the PsA group needed 28.7 prescriptions per person per year, compared with 17.0 and 12.7 in the psoriasis and control groups, respectively, Mr. Peterson said. He also noted that patients with PsA and psoriasis tended to have higher rates of hypertension, depression, and anxiety.

“The cost and resource utilization disparity between these patient groups demonstrates the high remaining unmet medical need for patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis,” Mr. Peterson said during the virtual proceedings.

Do findings reflect treatment advances?

Elaine Husni, MD, MPH, director of the Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Center at the Cleveland Clinic, where she studies health outcomes in PsA, said the findings are helpful in pointing to a trend across a large sample. But she added it’s important to remember that the increasing costs could reflect recent advances in PsA treatment, which include costly biologic drugs.

“There’s a ton more treatments for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis than there were even just 5 years ago,” she said in an interview. She was not involved in the research.

Dr. Husni would like to see a more detailed look at the costs, from the categories of expenses to the patients who are incurring the highest costs.

“Is it just a couple of percent of really sick patients that are driving the psoriatic arthritis group?” she wondered.

She also pointed out that PsA is going to be more expensive by its very nature. PsA tends to develop 3-10 years after psoriasis, adding to the costs for someone who already has psoriasis and at a time when they are older and likely have higher health care costs because of comorbidities that develop with age.

Dr. Husni said she does think about treatment costs, in that a less expensive first-line drug might be more appropriate than going straight to a more expensive biologic, especially because they also tend to be safer. She said it’s not just a simple question of curbing costs.

“Is there a way that we can personalize medicine?” she asked. “Is there a way that we can be more accurate about which people may need the more expensive drugs, and which patients may need the less expensive drugs? Are we getting better at monitoring so we can avoid high-cost events?”

Mr. Peterson is an employee of Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Husni reported serving as a consultant to AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, UCB, Novartis, Lilly, and Pfizer.

* Update, 9/28/21: The headline and parts of this story were updated to better reflect the study on which it reports.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Annual health care costs for patients with psoriatic arthritis rose over recent 5-year periods across all categories of resource use to a significantly greater extent than among patients with psoriasis only or those without any psoriatic disease diagnoses, according to commercial insurance claims data.

Using an IBM MarketScan Commercial Database, researchers examined claims data for 208,434 patients with psoriasis, 47,274 with PsA, and 255,708 controls who had neither psoriasis nor PsA. Controls were matched for age and sex. Those with RA, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, or ulcerative colitis were excluded.

The investigators examined data for 2009-2020, following patients for 5 years within that period. They looked at hospitalizations, outpatient and pharmacy services, lab services, and office visits, Steven Peterson, director of market access for rheumatology at Janssen Pharmaceuticals, said in his presentation of the data at the Pan American League of Associations for Rheumatology 2021 annual meeting, held recently as a virtual event.

The research was also published online May 2, 2021, in Clinical Rheumatology.

Big differences between the groups were seen in the first year, when the average health care costs for the PsA group were $28,322, about half of which was outpatient drug costs. That compared with $12,039 for the psoriasis group and $6,672 for the control group.

The differences tended to widen over time. By the fifth year, average costs for the PsA group were $34,290, nearly 60% of which were drug costs. That compared with $12,877 for the psoriasis group and $8,569 for the control group. In each year examined, outpatient drug costs accounted for less than half of the expenses for the psoriasis group and about a quarter for the control group.

Researchers found that the PsA group needed 28.7 prescriptions per person per year, compared with 17.0 and 12.7 in the psoriasis and control groups, respectively, Mr. Peterson said. He also noted that patients with PsA and psoriasis tended to have higher rates of hypertension, depression, and anxiety.

“The cost and resource utilization disparity between these patient groups demonstrates the high remaining unmet medical need for patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis,” Mr. Peterson said during the virtual proceedings.

Do findings reflect treatment advances?

Elaine Husni, MD, MPH, director of the Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Center at the Cleveland Clinic, where she studies health outcomes in PsA, said the findings are helpful in pointing to a trend across a large sample. But she added it’s important to remember that the increasing costs could reflect recent advances in PsA treatment, which include costly biologic drugs.

“There’s a ton more treatments for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis than there were even just 5 years ago,” she said in an interview. She was not involved in the research.

Dr. Husni would like to see a more detailed look at the costs, from the categories of expenses to the patients who are incurring the highest costs.

“Is it just a couple of percent of really sick patients that are driving the psoriatic arthritis group?” she wondered.

She also pointed out that PsA is going to be more expensive by its very nature. PsA tends to develop 3-10 years after psoriasis, adding to the costs for someone who already has psoriasis and at a time when they are older and likely have higher health care costs because of comorbidities that develop with age.

Dr. Husni said she does think about treatment costs, in that a less expensive first-line drug might be more appropriate than going straight to a more expensive biologic, especially because they also tend to be safer. She said it’s not just a simple question of curbing costs.

“Is there a way that we can personalize medicine?” she asked. “Is there a way that we can be more accurate about which people may need the more expensive drugs, and which patients may need the less expensive drugs? Are we getting better at monitoring so we can avoid high-cost events?”

Mr. Peterson is an employee of Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Husni reported serving as a consultant to AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, UCB, Novartis, Lilly, and Pfizer.

* Update, 9/28/21: The headline and parts of this story were updated to better reflect the study on which it reports.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Translating the 2019 AAD-NPF Guidelines of Care for Psoriasis With Attention to Comorbidities

Psoriasis is a chronic and relapsing systemic inflammatory disease that predisposes patients to a host of other conditions. It is believed that these widespread effects are due to chronic inflammation and cytokine activation, which affect multiple body processes and lead to the development of various comorbidities that need to be proactively managed.

In April 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released recommendation guidelines for managing psoriasis in adults with an emphasis on common disease comorbidities, including psoriatic arthritis (PsA), cardiovascular disease (CVD), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), metabolic syndrome, and mood disorders. Psychosocial wellness, mental health, and quality of life (QOL) measures in relation to psoriatic disease also were discussed.1

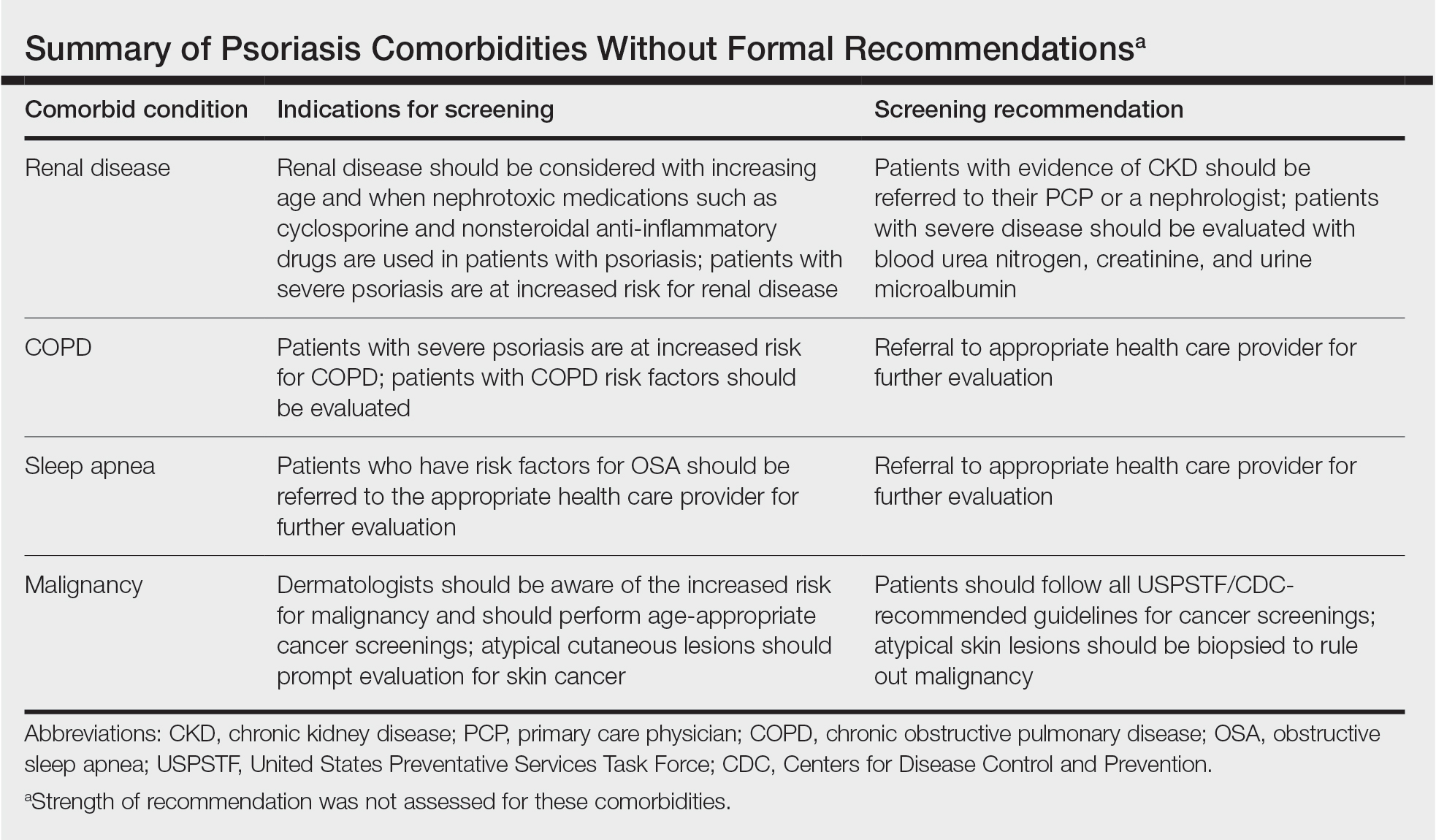

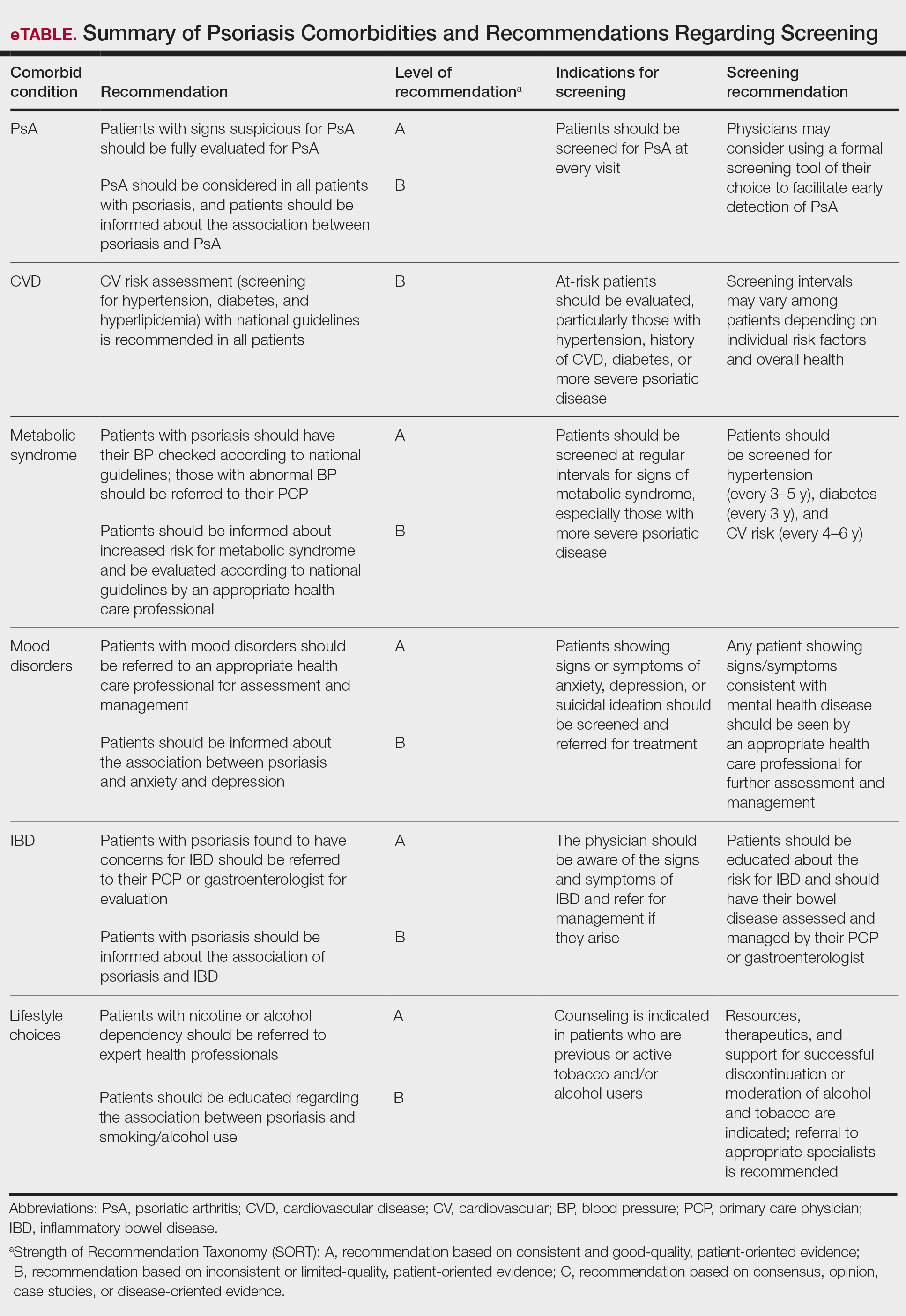

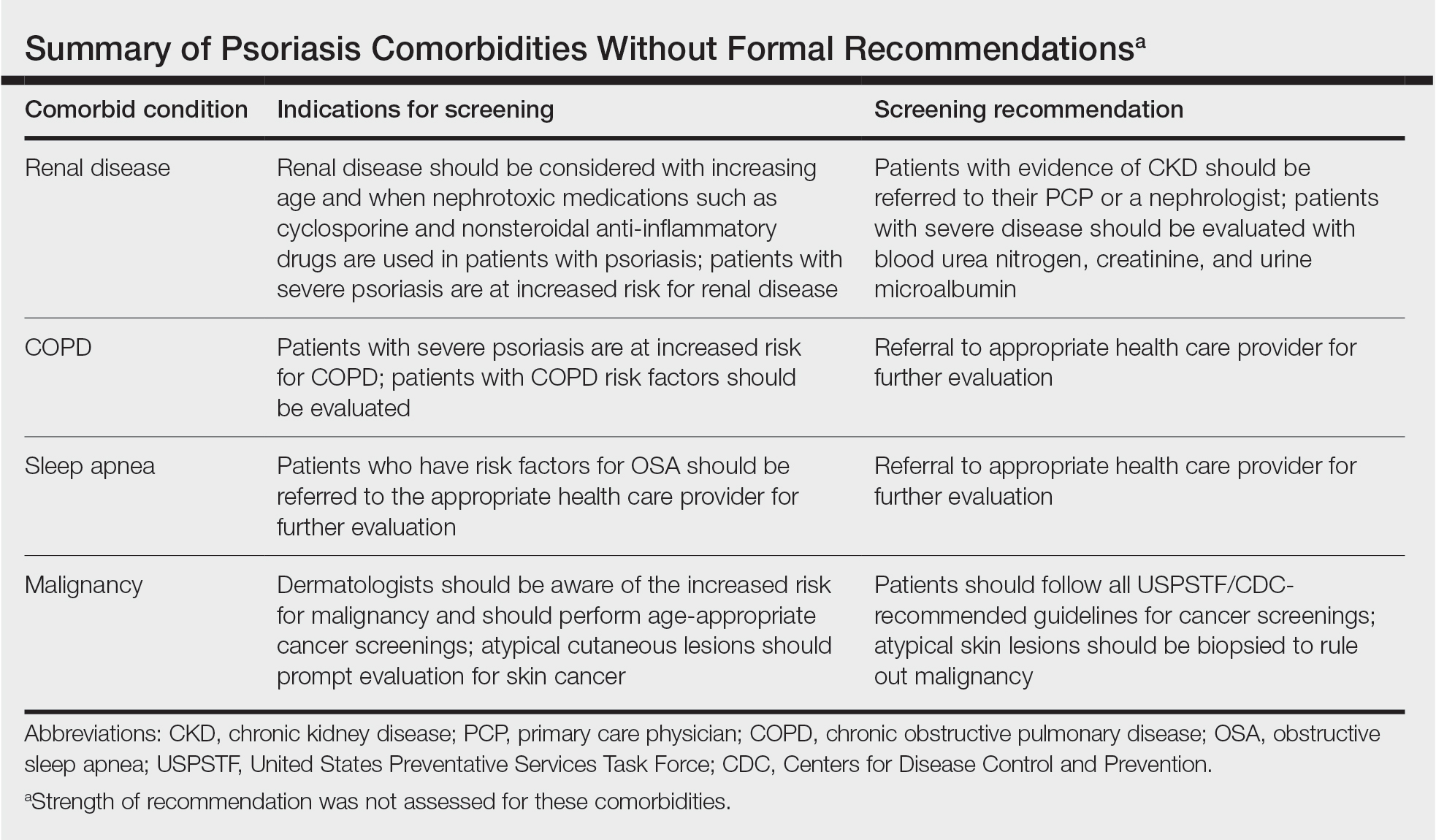

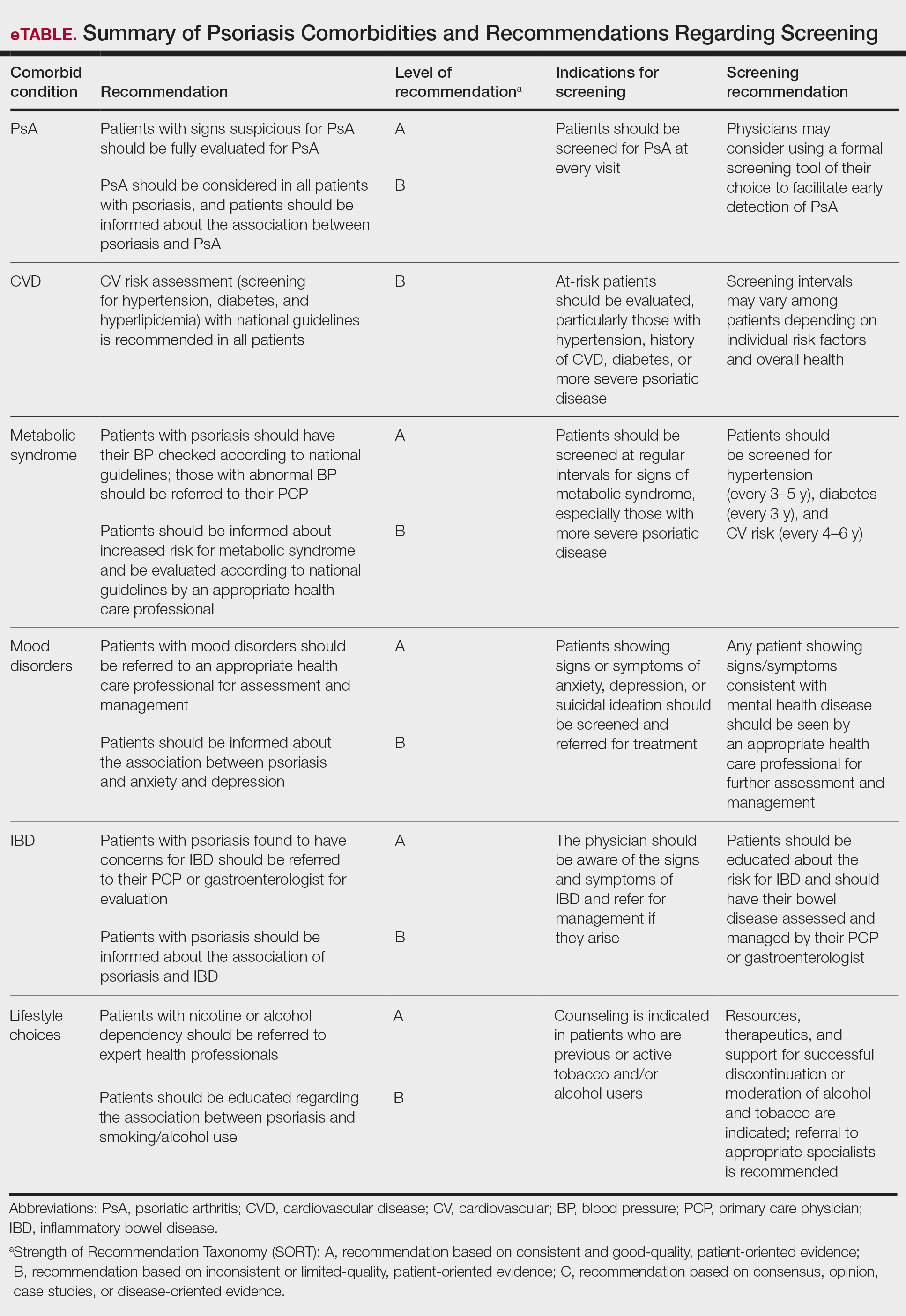

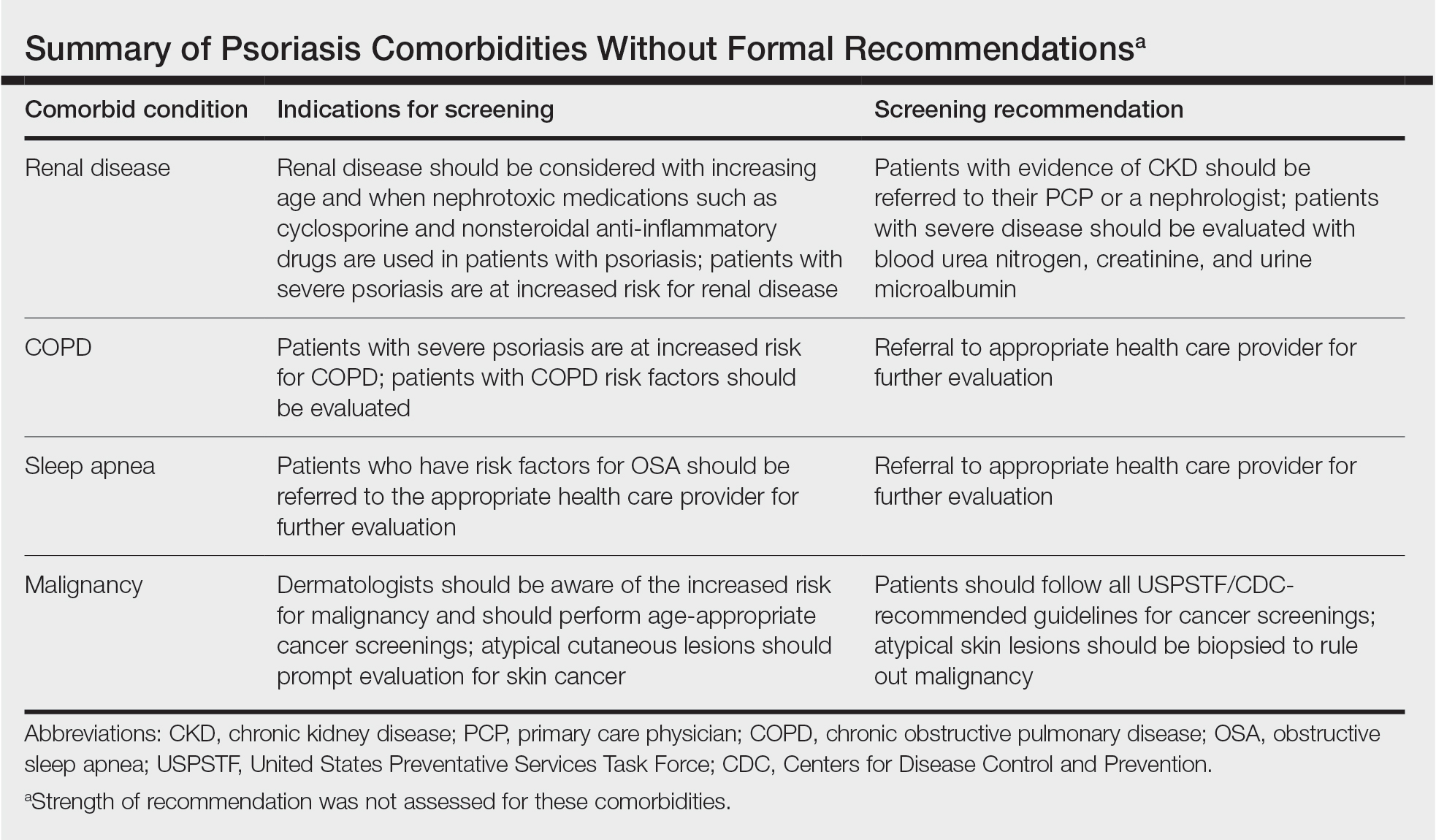

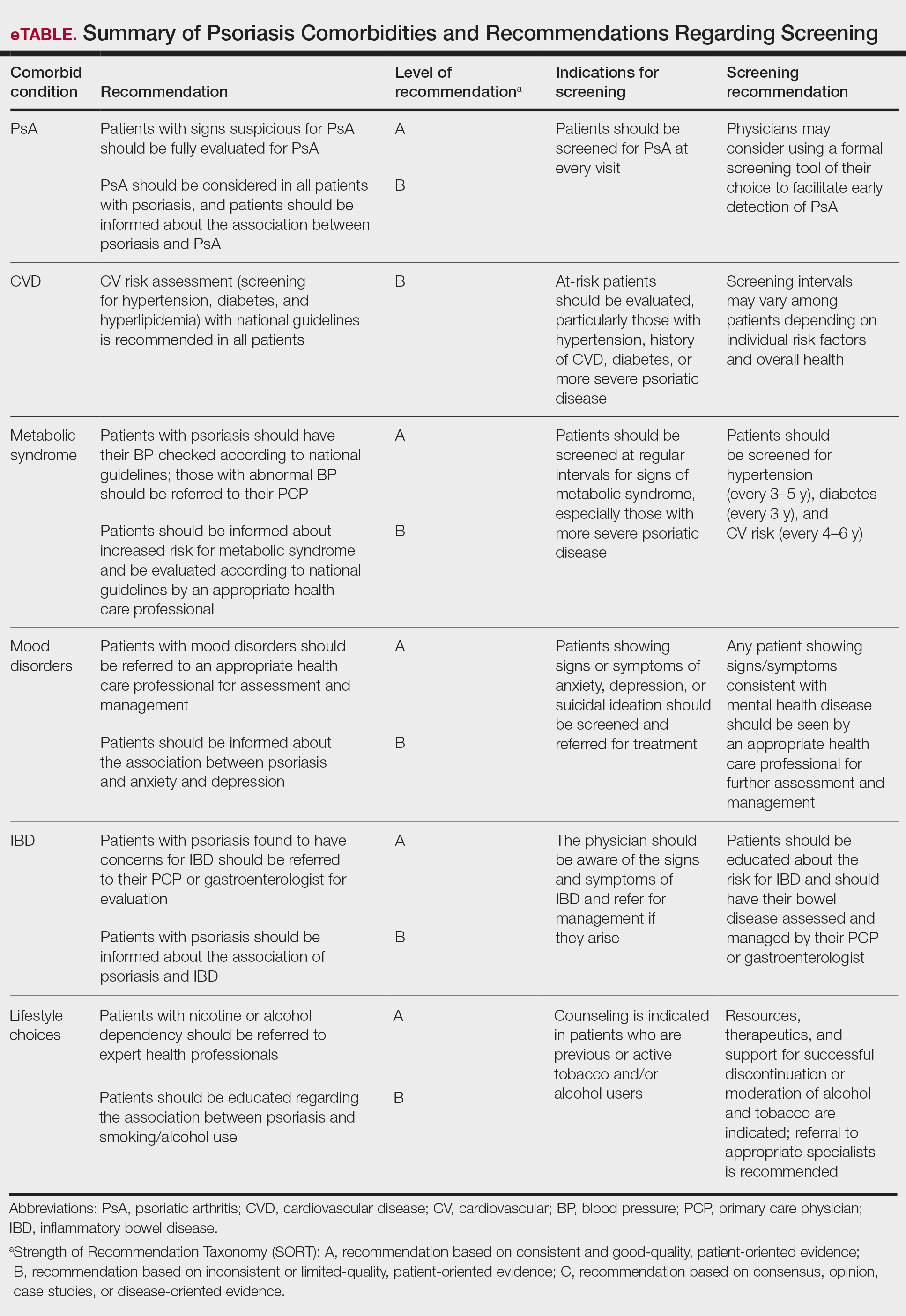

The AAD-NPF guidelines address current screening, monitoring, education, and treatment recommendations for the management of psoriatic comorbidities. The Table and eTable summarize the screening recommendations. These guidelines aim to assist dermatologists with comprehensive disease management by addressing potential extracutaneous manifestations of psoriasis in adults.

Screening and Risk Assessment

Patients with psoriasis should receive a thorough history and physical examination to assess disease severity and risk for potential comorbidities. Patients with greater disease severity—as measured by body surface area (BSA) involvement and type of therapy required—have a greater risk for other disease-related comorbidities, specifically metabolic syndrome, renal disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obstructive sleep apnea, uveitis, IBD, malignancy, and increased mortality.2 Because the likelihood of comorbidities is greatest with severe disease, more frequent monitoring is recommended for these patients.

Psoriatic Arthritis

Patients with psoriasis need to be evaluated for PsA at every visit. Patients presenting with signs and symptoms suspicious for PsA—joint swelling, peripheral joint involvement, and joint inflammation—warrant further evaluation and consultation. Early detection and treatment of PsA is essential for preventing unnecessary suffering and progressive joint destruction.3

There are several PsA screening questionnaires currently available, including the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation, Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool, and Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen. No significant differences in sensitivity and specificity were found among these questionnaires when using the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis as the gold standard. All 3 questionnaires—the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation and the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool were developed for use in dermatology and rheumatology clinics, and the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen was developed for use in the primary care setting—were found to be effective in dermatology/rheumatology clinics and primary care clinics, respectively.3 False-positive results predominantly were seen in patients with degenerative joint disease or osteoarthritis. Dermatologists should conduct a thorough physical examination to distinguish PsA from degenerative joint disease. Imaging and laboratory tests to evaluate for signs of systemic inflammation (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) also can be helpful in distinguishing the 2 conditions; however, these metrics have not been shown to contribute to PsA diagnosis.1 Full rheumatologic consultation is warranted in challenging cases.

Cardiovascular Disease

Primary care physicians (PCPs) are recommended to screen patients for CVD risk factors using height, weight, blood pressure, blood glucose, hemoglobin A1C, lipid levels, abdominal circumference, and body mass index (BMI). Lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation, exercise, and dietary changes are encouraged to achieve and maintain a normal BMI.

Dermatologists also need to give special consideration to comorbidities when selecting medications and/or therapies for disease management. Patients on TNF inhibitors have a lower risk for MI compared with patients using topical medications, phototherapy, and other oral agents.10 Additionally, patients on TNF inhibitors have a lower risk for occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events compared with patients treated with methotrexate or phototherapy.11,12

Metabolic Syndrome

Numerous studies have demonstrated an association between psoriasis and metabolic syndrome. Patients with increased BSA involvement and

The association between psoriasis and weight loss has been analyzed in several studies. Weight loss, particularly in obese patients, has been shown to improve psoriasis severity, as measured by psoriasis area and severity index score and QOL measures.15 Another study found that gastric bypass was associated with a significant risk reduction in the development of psoriasis (P=.004) and the disease prognosis (P=.02 for severe psoriasis; P=.01 for PsA).16 Therefore, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to have their obesity status determined according to national guidelines. For patients with a BMI above 40 kg/m2 and standard weight-loss measures fail, bariatric surgery is recommended. Additionally, the impact of psoriasis medications on weight has been studied. Apremilast has been associated with weight loss, whereas etanercept and infliximab have been linked to weight gain.17,18

An association between psoriasis and hypertension also has been demonstrated by studies, especially among patients with severe disease. Therefore, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to have their blood pressure evaluated according to national guidelines, and those with a blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or higher should be referred to their PCP for assessment and treatment. Current evidence does not support restrictions on antihypertensive medications in patients with psoriasis. Physicians should be aware of the potential for cyclosporine to induce hypertension, which should be treated, specifically with amlodipine.19

Many studies have demonstrated an association between psoriasis and dyslipidemia, though the results are somewhat conflicting. In 2018, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology deemed psoriasis as an atherosclerotic CVD risk-enhancing condition, favoring early initiation of statin therapy. Because dyslipidemia plays a prominent role in atherosclerosis and CVD, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to undergo periodic screening with lipid tests (eg, fasting total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides).20 Patients with elevated fasting triglycerides or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol should be referred to their PCP for further management. Certain psoriasis medications also have been linked to dyslipidemia. Acitretin and cyclosporine are known to adversely affect lipid levels, so patients treated with either agent should undergo routine monitoring of serum lipid levels.

Psoriasis is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus. Because of the increased risk for diabetes in patients with severe disease, regular monitoring of fasting blood glucose and/or hemoglobin A1C levels in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis is recommended. Patients who meet criteria for prediabetes or diabetes should be referred to their PCP for further assessment and management.21,22

Mood Disorders

Psoriasis affects QOL and can have a major impact on patients’ interpersonal relationships. Studies have shown an association between psoriasis and mood disorders, specifically depression and anxiety. Unfortunately, patients with mood disorders are less likely to seek intervention for their skin disease, which poses a tremendous treatment barrier. Dermatologists should regularly monitor patients for psychiatric symptoms so that resources and treatments can be offered.

Certain psoriasis therapies have been shown to help alleviate associated depression and anxiety. Improvements in Beck Depression Inventory and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores were seen with etanercept.23 Adalimumab and ustekinumab showed improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index compared with placebo.24,25 Patients receiving Goeckerman treatment also had improvement in anxiety and depression scores compared with conventional therapy.26 Biologic medications had the largest impact on improving depression symptoms compared with conventional systemic therapy and phototherapy.27 The recommendations support use of biologics and the Goeckerman regimen for the concomitant treatment of mood disorders and psoriasis.

Renal Disease

Studies have supported an association between psoriasis and chronic kidney disease (CKD), independent of risk factors including vascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes. The prevalence of moderate to advanced CKD also has been found to be directly related to increasing BSA affected by psoriasis.28 Patients should receive testing of blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and urine microalbumin levels to assess for occult renal disease. In addition, physicians should be cautious when prescribing nephrotoxic drugs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclosporine) and renally excreted agents (methotrexate and apremilast) because of the risk for underlying renal disease in patients with psoriasis. If newly acquired renal disease is suspected, physicians should withhold the offending agents. Patients with psoriasis with CKD are recommended to follow up with their PCP or nephrologist for evaluation and management.

Pulmonary Disease

Psoriasis also has an independent association with COPD. Patients with psoriasis have a higher likelihood of developing COPD (hazard ratio, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.42-3.89; P<.01) than controls.29 The prevalence of COPD also was found to correlate with psoriasis severity. Dermatologists should educate patients about the association between smoking and psoriasis as well as advise patients to discontinue smoking to reduce their risk for developing COPD and cancer.

Patients with psoriasis also are at an increased risk for obstructive sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea should be considered in patients with risk factors including snoring, obesity, hypertension, or diabetes.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk for developing IBD. The prevalence ratios of both Crohn disease (2.49) and ulcerative colitis (1.64) are increased in patients with psoriasis relative to patients without psoriasis.30 Physicians need to be aware of the association between psoriasis and IBD and the effect that their coexistence may have on treatment choice for patients.

Adalimumab and infliximab are approved for the treatment of IBD, and certolizumab and ustekinumab are approved for Crohn disease. Use of TNF inhibitors in patients with IBD may cause psoriasiform lesions to develop.31 Nonetheless, treatment should be individualized and psoriasiform lesions treated with standard psoriasis measures. Psoriasis patients with IBD are recommended to avoid IL-17–inhibitor therapy, given its potential to worsen IBD flares.

Malignancy

Psoriasis patients aged 0 to 79 years have a greater overall risk for malignancy compared with patients without psoriasis.32 Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk for respiratory tract cancer, upper aerodigestive tract cancer, urinary tract cancer, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.33 A mild association exists between PsA and lymphoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), and lung cancer.34 More severe psoriasis is associated with greater risk for lymphoma and NMSC. Dermatologists are recommended to educate patients on their risk for certain malignancies and to refer patients to specialists upon suspicion of malignancy.

Risk for malignancy has been shown to be affected by psoriasis treatments. Patients treated with UVB have reduced overall cancer rates for all age groups (hazard ratio, 0.52; P=.3), while those treated with psoralen plus UVA have an increased incidence of

Lifestyle Choices and QOL

A crucial aspect of successful psoriasis management is patient education. The strongest recommendations support lifestyle changes, such as smoking cessation and limitation of alcohol use. A tactful discussion regarding substance use, work productivity, interpersonal relationships, and sexual function can address substantial effects of psoriasis on QOL so that support and resources can be provided.

Final Thoughts

Management of psoriasis is multifaceted and involves screening, education, monitoring, and collaboration with PCPs and specialists. Regular follow-up with a dermatologist and PCP is strongly recommended for patients with psoriasis given the systemic nature of the disease. The 2019 AAD-NPF recommendations provide important information for dermatologists to coordinate care for complicated psoriasis cases, but clinical judgment is paramount when making medical decisions. The consideration of comorbidities is critical for developing a comprehensive treatment approach, and this approach will lead to better health outcomes and improved QOL for patients with psoriasis.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113.

- Gelfand JM, Troxel AB, Lewis JD, et al. The risk of mortality in patients with psoriasis: results from a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1493-1499.

- Coates LC, Aslam T, Al Balushi F, et al. Comparison of three screening tools to detect psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis (CONTEST study). Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:802-807.

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3168-3209.

- Lerman JB, Joshi AA, Chaturvedi A, et al. Coronary plaque characterization in psoriasis reveals high-risk features that improve after treatment in a prospective observational study. Circulation. 2017;136:263-276.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Dunlay SM, Weston SA, Redfield MM, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and mortality in heart failure: a community study. Circulation. 2008;118:625-631.

- Russell SD, Saval MA, Robbins JL, et al. New York Heart Association functional class predicts exercise parameters in the current era. Am Heart J. 2009;158(4 suppl):S24-S30.

- Wu JJ, Poon K-YT, Channual JC, et al. Association between tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy and myocardial infarction risk in patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1244-1250.

- Wu JJ, Guerin A, Sundaram M, et al. Cardiovascular event risk assessment in psoriasis patients treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors versus methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:81-90.

- Wu JJ, Sundaram M, Cloutier M, et al. The risk of cardiovascular events in psoriasis patients treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors versus phototherapy: an observational cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:60-68.

- Gami AS, Witt BJ, Howard DE, et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular events and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:403-414.

- Langan SM, Seminara NM, Shin DB, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study in the United Kingdom. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:556-562.

- Jensen P, Zachariae C, Christensen R, et al. Effect of weight loss on the severity of psoriasis: a randomized clinical study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:795-801.

- Egeberg A, Sørensen JA, Gislason GH, et al. Incidence and prognosis of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:344-349.

- Crowley J, Thaçi D, Joly P, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of apremilast in patients with psoriasis: pooled safety analysis for ≥156 weeks from 2 phase 3, randomized, controlled trials (ESTEEM 1 and 2). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:310-317.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.052

- Gisondi P, Del Giglio M, Di Francesco V, et al. Weight loss improves the response of obese patients with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis to low-dose cyclosporine therapy: a randomized, controlled, investigator-blinded clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1242-1247.

- Leenen FHH, Coletta E, Davies RA. Prevention of renal dysfunction and hypertension by amlodipine after heart transplant. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:531-535.

- Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennet G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2014;129(suppl 2):S49-S73.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(suppl 1):S14-S80.

- Ratner RE, Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. An update on the diabetes prevention program. Endocr Pract. 2006;12(suppl 1):20-24.

- Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, et al. Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2006;367:29-35.

- Kimball AB, Edson-Heredia E, Zhu B, et al. Understanding the relationship between pruritus severity and work productivity in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: sleep problems are a mediating factor. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:183-188.

- Langley RG, Tsai T-F, Flavin S, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis who have an inadequate response to ustekinumab: results of the randomized, double-blind, phase III NAVIGATE trial. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:114-123.

- Chern E, Yau D, Ho J-C, et al. Positive effect of modified Goeckerman regimen on quality of life and psychosocial distress in moderate and severe psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:447-451.

- Strober B, Gooderham M, de Jong EMGJ, et al. Depressive symptoms, depression, and the effect of biologic therapy among patients in Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:70-80.

- Wan J, Wang S, Haynes K, et al. Risk of moderate to advanced kidney disease in patients with psoriasis: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2013;347:f5961. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5961

- Chiang Y-Y, Lin H-W. Association between psoriasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based study in Taiwan. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:59-65.

- Cohen AD, Dreiher J, Birkenfeld S. Psoriasis associated with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:561-565.

- Denadai R, Teixeira FV, Saad-Hossne R. The onset of psoriasis during the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases with infliximab: should biological therapy be suspended? Arq Gastroenterol. 2012;49:172-176.

- Chen Y-J, Wu C-Y, Chen T-J, et al. The risk of cancer in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:84-91.

- Pouplard C, Brenaut E, Horreau C, et al. Risk of cancer in psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(suppl 3):36-46.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Shin DB, Ogdie Beatty A, et al. The risk of cancer in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the health improvement network. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:282-290.

- Burmester GR, Panaccione R, Gordon KB, et al. Adalimumab: long-term safety in 23 458 patients from global clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn’s disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:517-524.

- Dommasch ED, Abuabara K, Shin DB, et al. The risk of infection and malignancy with tumor necrosis factor antagonists in adults with psoriatic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1035-1050.

- Gordon KB, Papp KA, Langley RG, et al. Long-term safety experience of ustekinumab in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis (part II of II): results from analyses of infections and malignancy from pooled phase II and III clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:742-751.

Psoriasis is a chronic and relapsing systemic inflammatory disease that predisposes patients to a host of other conditions. It is believed that these widespread effects are due to chronic inflammation and cytokine activation, which affect multiple body processes and lead to the development of various comorbidities that need to be proactively managed.

In April 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released recommendation guidelines for managing psoriasis in adults with an emphasis on common disease comorbidities, including psoriatic arthritis (PsA), cardiovascular disease (CVD), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), metabolic syndrome, and mood disorders. Psychosocial wellness, mental health, and quality of life (QOL) measures in relation to psoriatic disease also were discussed.1

The AAD-NPF guidelines address current screening, monitoring, education, and treatment recommendations for the management of psoriatic comorbidities. The Table and eTable summarize the screening recommendations. These guidelines aim to assist dermatologists with comprehensive disease management by addressing potential extracutaneous manifestations of psoriasis in adults.

Screening and Risk Assessment

Patients with psoriasis should receive a thorough history and physical examination to assess disease severity and risk for potential comorbidities. Patients with greater disease severity—as measured by body surface area (BSA) involvement and type of therapy required—have a greater risk for other disease-related comorbidities, specifically metabolic syndrome, renal disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obstructive sleep apnea, uveitis, IBD, malignancy, and increased mortality.2 Because the likelihood of comorbidities is greatest with severe disease, more frequent monitoring is recommended for these patients.

Psoriatic Arthritis

Patients with psoriasis need to be evaluated for PsA at every visit. Patients presenting with signs and symptoms suspicious for PsA—joint swelling, peripheral joint involvement, and joint inflammation—warrant further evaluation and consultation. Early detection and treatment of PsA is essential for preventing unnecessary suffering and progressive joint destruction.3

There are several PsA screening questionnaires currently available, including the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation, Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool, and Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen. No significant differences in sensitivity and specificity were found among these questionnaires when using the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis as the gold standard. All 3 questionnaires—the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation and the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool were developed for use in dermatology and rheumatology clinics, and the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen was developed for use in the primary care setting—were found to be effective in dermatology/rheumatology clinics and primary care clinics, respectively.3 False-positive results predominantly were seen in patients with degenerative joint disease or osteoarthritis. Dermatologists should conduct a thorough physical examination to distinguish PsA from degenerative joint disease. Imaging and laboratory tests to evaluate for signs of systemic inflammation (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) also can be helpful in distinguishing the 2 conditions; however, these metrics have not been shown to contribute to PsA diagnosis.1 Full rheumatologic consultation is warranted in challenging cases.

Cardiovascular Disease

Primary care physicians (PCPs) are recommended to screen patients for CVD risk factors using height, weight, blood pressure, blood glucose, hemoglobin A1C, lipid levels, abdominal circumference, and body mass index (BMI). Lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation, exercise, and dietary changes are encouraged to achieve and maintain a normal BMI.

Dermatologists also need to give special consideration to comorbidities when selecting medications and/or therapies for disease management. Patients on TNF inhibitors have a lower risk for MI compared with patients using topical medications, phototherapy, and other oral agents.10 Additionally, patients on TNF inhibitors have a lower risk for occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events compared with patients treated with methotrexate or phototherapy.11,12

Metabolic Syndrome

Numerous studies have demonstrated an association between psoriasis and metabolic syndrome. Patients with increased BSA involvement and

The association between psoriasis and weight loss has been analyzed in several studies. Weight loss, particularly in obese patients, has been shown to improve psoriasis severity, as measured by psoriasis area and severity index score and QOL measures.15 Another study found that gastric bypass was associated with a significant risk reduction in the development of psoriasis (P=.004) and the disease prognosis (P=.02 for severe psoriasis; P=.01 for PsA).16 Therefore, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to have their obesity status determined according to national guidelines. For patients with a BMI above 40 kg/m2 and standard weight-loss measures fail, bariatric surgery is recommended. Additionally, the impact of psoriasis medications on weight has been studied. Apremilast has been associated with weight loss, whereas etanercept and infliximab have been linked to weight gain.17,18

An association between psoriasis and hypertension also has been demonstrated by studies, especially among patients with severe disease. Therefore, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to have their blood pressure evaluated according to national guidelines, and those with a blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or higher should be referred to their PCP for assessment and treatment. Current evidence does not support restrictions on antihypertensive medications in patients with psoriasis. Physicians should be aware of the potential for cyclosporine to induce hypertension, which should be treated, specifically with amlodipine.19

Many studies have demonstrated an association between psoriasis and dyslipidemia, though the results are somewhat conflicting. In 2018, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology deemed psoriasis as an atherosclerotic CVD risk-enhancing condition, favoring early initiation of statin therapy. Because dyslipidemia plays a prominent role in atherosclerosis and CVD, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to undergo periodic screening with lipid tests (eg, fasting total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides).20 Patients with elevated fasting triglycerides or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol should be referred to their PCP for further management. Certain psoriasis medications also have been linked to dyslipidemia. Acitretin and cyclosporine are known to adversely affect lipid levels, so patients treated with either agent should undergo routine monitoring of serum lipid levels.

Psoriasis is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus. Because of the increased risk for diabetes in patients with severe disease, regular monitoring of fasting blood glucose and/or hemoglobin A1C levels in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis is recommended. Patients who meet criteria for prediabetes or diabetes should be referred to their PCP for further assessment and management.21,22

Mood Disorders

Psoriasis affects QOL and can have a major impact on patients’ interpersonal relationships. Studies have shown an association between psoriasis and mood disorders, specifically depression and anxiety. Unfortunately, patients with mood disorders are less likely to seek intervention for their skin disease, which poses a tremendous treatment barrier. Dermatologists should regularly monitor patients for psychiatric symptoms so that resources and treatments can be offered.

Certain psoriasis therapies have been shown to help alleviate associated depression and anxiety. Improvements in Beck Depression Inventory and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores were seen with etanercept.23 Adalimumab and ustekinumab showed improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index compared with placebo.24,25 Patients receiving Goeckerman treatment also had improvement in anxiety and depression scores compared with conventional therapy.26 Biologic medications had the largest impact on improving depression symptoms compared with conventional systemic therapy and phototherapy.27 The recommendations support use of biologics and the Goeckerman regimen for the concomitant treatment of mood disorders and psoriasis.

Renal Disease

Studies have supported an association between psoriasis and chronic kidney disease (CKD), independent of risk factors including vascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes. The prevalence of moderate to advanced CKD also has been found to be directly related to increasing BSA affected by psoriasis.28 Patients should receive testing of blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and urine microalbumin levels to assess for occult renal disease. In addition, physicians should be cautious when prescribing nephrotoxic drugs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclosporine) and renally excreted agents (methotrexate and apremilast) because of the risk for underlying renal disease in patients with psoriasis. If newly acquired renal disease is suspected, physicians should withhold the offending agents. Patients with psoriasis with CKD are recommended to follow up with their PCP or nephrologist for evaluation and management.

Pulmonary Disease

Psoriasis also has an independent association with COPD. Patients with psoriasis have a higher likelihood of developing COPD (hazard ratio, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.42-3.89; P<.01) than controls.29 The prevalence of COPD also was found to correlate with psoriasis severity. Dermatologists should educate patients about the association between smoking and psoriasis as well as advise patients to discontinue smoking to reduce their risk for developing COPD and cancer.

Patients with psoriasis also are at an increased risk for obstructive sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea should be considered in patients with risk factors including snoring, obesity, hypertension, or diabetes.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk for developing IBD. The prevalence ratios of both Crohn disease (2.49) and ulcerative colitis (1.64) are increased in patients with psoriasis relative to patients without psoriasis.30 Physicians need to be aware of the association between psoriasis and IBD and the effect that their coexistence may have on treatment choice for patients.

Adalimumab and infliximab are approved for the treatment of IBD, and certolizumab and ustekinumab are approved for Crohn disease. Use of TNF inhibitors in patients with IBD may cause psoriasiform lesions to develop.31 Nonetheless, treatment should be individualized and psoriasiform lesions treated with standard psoriasis measures. Psoriasis patients with IBD are recommended to avoid IL-17–inhibitor therapy, given its potential to worsen IBD flares.

Malignancy

Psoriasis patients aged 0 to 79 years have a greater overall risk for malignancy compared with patients without psoriasis.32 Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk for respiratory tract cancer, upper aerodigestive tract cancer, urinary tract cancer, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.33 A mild association exists between PsA and lymphoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), and lung cancer.34 More severe psoriasis is associated with greater risk for lymphoma and NMSC. Dermatologists are recommended to educate patients on their risk for certain malignancies and to refer patients to specialists upon suspicion of malignancy.

Risk for malignancy has been shown to be affected by psoriasis treatments. Patients treated with UVB have reduced overall cancer rates for all age groups (hazard ratio, 0.52; P=.3), while those treated with psoralen plus UVA have an increased incidence of

Lifestyle Choices and QOL

A crucial aspect of successful psoriasis management is patient education. The strongest recommendations support lifestyle changes, such as smoking cessation and limitation of alcohol use. A tactful discussion regarding substance use, work productivity, interpersonal relationships, and sexual function can address substantial effects of psoriasis on QOL so that support and resources can be provided.

Final Thoughts

Management of psoriasis is multifaceted and involves screening, education, monitoring, and collaboration with PCPs and specialists. Regular follow-up with a dermatologist and PCP is strongly recommended for patients with psoriasis given the systemic nature of the disease. The 2019 AAD-NPF recommendations provide important information for dermatologists to coordinate care for complicated psoriasis cases, but clinical judgment is paramount when making medical decisions. The consideration of comorbidities is critical for developing a comprehensive treatment approach, and this approach will lead to better health outcomes and improved QOL for patients with psoriasis.

Psoriasis is a chronic and relapsing systemic inflammatory disease that predisposes patients to a host of other conditions. It is believed that these widespread effects are due to chronic inflammation and cytokine activation, which affect multiple body processes and lead to the development of various comorbidities that need to be proactively managed.

In April 2019, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) released recommendation guidelines for managing psoriasis in adults with an emphasis on common disease comorbidities, including psoriatic arthritis (PsA), cardiovascular disease (CVD), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), metabolic syndrome, and mood disorders. Psychosocial wellness, mental health, and quality of life (QOL) measures in relation to psoriatic disease also were discussed.1

The AAD-NPF guidelines address current screening, monitoring, education, and treatment recommendations for the management of psoriatic comorbidities. The Table and eTable summarize the screening recommendations. These guidelines aim to assist dermatologists with comprehensive disease management by addressing potential extracutaneous manifestations of psoriasis in adults.

Screening and Risk Assessment

Patients with psoriasis should receive a thorough history and physical examination to assess disease severity and risk for potential comorbidities. Patients with greater disease severity—as measured by body surface area (BSA) involvement and type of therapy required—have a greater risk for other disease-related comorbidities, specifically metabolic syndrome, renal disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), obstructive sleep apnea, uveitis, IBD, malignancy, and increased mortality.2 Because the likelihood of comorbidities is greatest with severe disease, more frequent monitoring is recommended for these patients.

Psoriatic Arthritis

Patients with psoriasis need to be evaluated for PsA at every visit. Patients presenting with signs and symptoms suspicious for PsA—joint swelling, peripheral joint involvement, and joint inflammation—warrant further evaluation and consultation. Early detection and treatment of PsA is essential for preventing unnecessary suffering and progressive joint destruction.3

There are several PsA screening questionnaires currently available, including the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation, Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool, and Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen. No significant differences in sensitivity and specificity were found among these questionnaires when using the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis as the gold standard. All 3 questionnaires—the Psoriatic Arthritis Screening Evaluation and the Psoriasis Epidemiology Screening Tool were developed for use in dermatology and rheumatology clinics, and the Toronto Psoriatic Arthritis Screen was developed for use in the primary care setting—were found to be effective in dermatology/rheumatology clinics and primary care clinics, respectively.3 False-positive results predominantly were seen in patients with degenerative joint disease or osteoarthritis. Dermatologists should conduct a thorough physical examination to distinguish PsA from degenerative joint disease. Imaging and laboratory tests to evaluate for signs of systemic inflammation (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) also can be helpful in distinguishing the 2 conditions; however, these metrics have not been shown to contribute to PsA diagnosis.1 Full rheumatologic consultation is warranted in challenging cases.

Cardiovascular Disease

Primary care physicians (PCPs) are recommended to screen patients for CVD risk factors using height, weight, blood pressure, blood glucose, hemoglobin A1C, lipid levels, abdominal circumference, and body mass index (BMI). Lifestyle modifications such as smoking cessation, exercise, and dietary changes are encouraged to achieve and maintain a normal BMI.

Dermatologists also need to give special consideration to comorbidities when selecting medications and/or therapies for disease management. Patients on TNF inhibitors have a lower risk for MI compared with patients using topical medications, phototherapy, and other oral agents.10 Additionally, patients on TNF inhibitors have a lower risk for occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events compared with patients treated with methotrexate or phototherapy.11,12

Metabolic Syndrome

Numerous studies have demonstrated an association between psoriasis and metabolic syndrome. Patients with increased BSA involvement and

The association between psoriasis and weight loss has been analyzed in several studies. Weight loss, particularly in obese patients, has been shown to improve psoriasis severity, as measured by psoriasis area and severity index score and QOL measures.15 Another study found that gastric bypass was associated with a significant risk reduction in the development of psoriasis (P=.004) and the disease prognosis (P=.02 for severe psoriasis; P=.01 for PsA).16 Therefore, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to have their obesity status determined according to national guidelines. For patients with a BMI above 40 kg/m2 and standard weight-loss measures fail, bariatric surgery is recommended. Additionally, the impact of psoriasis medications on weight has been studied. Apremilast has been associated with weight loss, whereas etanercept and infliximab have been linked to weight gain.17,18

An association between psoriasis and hypertension also has been demonstrated by studies, especially among patients with severe disease. Therefore, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to have their blood pressure evaluated according to national guidelines, and those with a blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or higher should be referred to their PCP for assessment and treatment. Current evidence does not support restrictions on antihypertensive medications in patients with psoriasis. Physicians should be aware of the potential for cyclosporine to induce hypertension, which should be treated, specifically with amlodipine.19

Many studies have demonstrated an association between psoriasis and dyslipidemia, though the results are somewhat conflicting. In 2018, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology deemed psoriasis as an atherosclerotic CVD risk-enhancing condition, favoring early initiation of statin therapy. Because dyslipidemia plays a prominent role in atherosclerosis and CVD, patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are recommended to undergo periodic screening with lipid tests (eg, fasting total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides).20 Patients with elevated fasting triglycerides or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol should be referred to their PCP for further management. Certain psoriasis medications also have been linked to dyslipidemia. Acitretin and cyclosporine are known to adversely affect lipid levels, so patients treated with either agent should undergo routine monitoring of serum lipid levels.

Psoriasis is strongly associated with diabetes mellitus. Because of the increased risk for diabetes in patients with severe disease, regular monitoring of fasting blood glucose and/or hemoglobin A1C levels in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis is recommended. Patients who meet criteria for prediabetes or diabetes should be referred to their PCP for further assessment and management.21,22

Mood Disorders

Psoriasis affects QOL and can have a major impact on patients’ interpersonal relationships. Studies have shown an association between psoriasis and mood disorders, specifically depression and anxiety. Unfortunately, patients with mood disorders are less likely to seek intervention for their skin disease, which poses a tremendous treatment barrier. Dermatologists should regularly monitor patients for psychiatric symptoms so that resources and treatments can be offered.

Certain psoriasis therapies have been shown to help alleviate associated depression and anxiety. Improvements in Beck Depression Inventory and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores were seen with etanercept.23 Adalimumab and ustekinumab showed improvement in Dermatology Life Quality Index compared with placebo.24,25 Patients receiving Goeckerman treatment also had improvement in anxiety and depression scores compared with conventional therapy.26 Biologic medications had the largest impact on improving depression symptoms compared with conventional systemic therapy and phototherapy.27 The recommendations support use of biologics and the Goeckerman regimen for the concomitant treatment of mood disorders and psoriasis.

Renal Disease

Studies have supported an association between psoriasis and chronic kidney disease (CKD), independent of risk factors including vascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes. The prevalence of moderate to advanced CKD also has been found to be directly related to increasing BSA affected by psoriasis.28 Patients should receive testing of blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and urine microalbumin levels to assess for occult renal disease. In addition, physicians should be cautious when prescribing nephrotoxic drugs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclosporine) and renally excreted agents (methotrexate and apremilast) because of the risk for underlying renal disease in patients with psoriasis. If newly acquired renal disease is suspected, physicians should withhold the offending agents. Patients with psoriasis with CKD are recommended to follow up with their PCP or nephrologist for evaluation and management.

Pulmonary Disease

Psoriasis also has an independent association with COPD. Patients with psoriasis have a higher likelihood of developing COPD (hazard ratio, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.42-3.89; P<.01) than controls.29 The prevalence of COPD also was found to correlate with psoriasis severity. Dermatologists should educate patients about the association between smoking and psoriasis as well as advise patients to discontinue smoking to reduce their risk for developing COPD and cancer.

Patients with psoriasis also are at an increased risk for obstructive sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea should be considered in patients with risk factors including snoring, obesity, hypertension, or diabetes.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk for developing IBD. The prevalence ratios of both Crohn disease (2.49) and ulcerative colitis (1.64) are increased in patients with psoriasis relative to patients without psoriasis.30 Physicians need to be aware of the association between psoriasis and IBD and the effect that their coexistence may have on treatment choice for patients.

Adalimumab and infliximab are approved for the treatment of IBD, and certolizumab and ustekinumab are approved for Crohn disease. Use of TNF inhibitors in patients with IBD may cause psoriasiform lesions to develop.31 Nonetheless, treatment should be individualized and psoriasiform lesions treated with standard psoriasis measures. Psoriasis patients with IBD are recommended to avoid IL-17–inhibitor therapy, given its potential to worsen IBD flares.

Malignancy

Psoriasis patients aged 0 to 79 years have a greater overall risk for malignancy compared with patients without psoriasis.32 Patients with psoriasis have an increased risk for respiratory tract cancer, upper aerodigestive tract cancer, urinary tract cancer, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.33 A mild association exists between PsA and lymphoma, nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), and lung cancer.34 More severe psoriasis is associated with greater risk for lymphoma and NMSC. Dermatologists are recommended to educate patients on their risk for certain malignancies and to refer patients to specialists upon suspicion of malignancy.

Risk for malignancy has been shown to be affected by psoriasis treatments. Patients treated with UVB have reduced overall cancer rates for all age groups (hazard ratio, 0.52; P=.3), while those treated with psoralen plus UVA have an increased incidence of

Lifestyle Choices and QOL

A crucial aspect of successful psoriasis management is patient education. The strongest recommendations support lifestyle changes, such as smoking cessation and limitation of alcohol use. A tactful discussion regarding substance use, work productivity, interpersonal relationships, and sexual function can address substantial effects of psoriasis on QOL so that support and resources can be provided.

Final Thoughts

Management of psoriasis is multifaceted and involves screening, education, monitoring, and collaboration with PCPs and specialists. Regular follow-up with a dermatologist and PCP is strongly recommended for patients with psoriasis given the systemic nature of the disease. The 2019 AAD-NPF recommendations provide important information for dermatologists to coordinate care for complicated psoriasis cases, but clinical judgment is paramount when making medical decisions. The consideration of comorbidities is critical for developing a comprehensive treatment approach, and this approach will lead to better health outcomes and improved QOL for patients with psoriasis.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113.

- Gelfand JM, Troxel AB, Lewis JD, et al. The risk of mortality in patients with psoriasis: results from a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1493-1499.

- Coates LC, Aslam T, Al Balushi F, et al. Comparison of three screening tools to detect psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis (CONTEST study). Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:802-807.

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3168-3209.

- Lerman JB, Joshi AA, Chaturvedi A, et al. Coronary plaque characterization in psoriasis reveals high-risk features that improve after treatment in a prospective observational study. Circulation. 2017;136:263-276.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Dunlay SM, Weston SA, Redfield MM, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and mortality in heart failure: a community study. Circulation. 2008;118:625-631.

- Russell SD, Saval MA, Robbins JL, et al. New York Heart Association functional class predicts exercise parameters in the current era. Am Heart J. 2009;158(4 suppl):S24-S30.

- Wu JJ, Poon K-YT, Channual JC, et al. Association between tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy and myocardial infarction risk in patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1244-1250.

- Wu JJ, Guerin A, Sundaram M, et al. Cardiovascular event risk assessment in psoriasis patients treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors versus methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:81-90.

- Wu JJ, Sundaram M, Cloutier M, et al. The risk of cardiovascular events in psoriasis patients treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors versus phototherapy: an observational cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:60-68.

- Gami AS, Witt BJ, Howard DE, et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular events and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:403-414.

- Langan SM, Seminara NM, Shin DB, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study in the United Kingdom. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:556-562.

- Jensen P, Zachariae C, Christensen R, et al. Effect of weight loss on the severity of psoriasis: a randomized clinical study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:795-801.

- Egeberg A, Sørensen JA, Gislason GH, et al. Incidence and prognosis of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:344-349.

- Crowley J, Thaçi D, Joly P, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of apremilast in patients with psoriasis: pooled safety analysis for ≥156 weeks from 2 phase 3, randomized, controlled trials (ESTEEM 1 and 2). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:310-317.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.052

- Gisondi P, Del Giglio M, Di Francesco V, et al. Weight loss improves the response of obese patients with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis to low-dose cyclosporine therapy: a randomized, controlled, investigator-blinded clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1242-1247.

- Leenen FHH, Coletta E, Davies RA. Prevention of renal dysfunction and hypertension by amlodipine after heart transplant. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:531-535.

- Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennet G, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk. Circulation. 2014;129(suppl 2):S49-S73.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(suppl 1):S14-S80.

- Ratner RE, Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. An update on the diabetes prevention program. Endocr Pract. 2006;12(suppl 1):20-24.

- Tyring S, Gottlieb A, Papp K, et al. Etanercept and clinical outcomes, fatigue, and depression in psoriasis: double-blind placebo-controlled randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2006;367:29-35.

- Kimball AB, Edson-Heredia E, Zhu B, et al. Understanding the relationship between pruritus severity and work productivity in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: sleep problems are a mediating factor. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:183-188.

- Langley RG, Tsai T-F, Flavin S, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with psoriasis who have an inadequate response to ustekinumab: results of the randomized, double-blind, phase III NAVIGATE trial. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:114-123.

- Chern E, Yau D, Ho J-C, et al. Positive effect of modified Goeckerman regimen on quality of life and psychosocial distress in moderate and severe psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:447-451.

- Strober B, Gooderham M, de Jong EMGJ, et al. Depressive symptoms, depression, and the effect of biologic therapy among patients in Psoriasis Longitudinal Assessment and Registry (PSOLAR). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:70-80.

- Wan J, Wang S, Haynes K, et al. Risk of moderate to advanced kidney disease in patients with psoriasis: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2013;347:f5961. doi:10.1136/bmj.f5961

- Chiang Y-Y, Lin H-W. Association between psoriasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based study in Taiwan. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:59-65.

- Cohen AD, Dreiher J, Birkenfeld S. Psoriasis associated with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:561-565.

- Denadai R, Teixeira FV, Saad-Hossne R. The onset of psoriasis during the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases with infliximab: should biological therapy be suspended? Arq Gastroenterol. 2012;49:172-176.

- Chen Y-J, Wu C-Y, Chen T-J, et al. The risk of cancer in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:84-91.

- Pouplard C, Brenaut E, Horreau C, et al. Risk of cancer in psoriasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27(suppl 3):36-46.

- Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Shin DB, Ogdie Beatty A, et al. The risk of cancer in patients with psoriasis: a population-based cohort study in the health improvement network. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:282-290.

- Burmester GR, Panaccione R, Gordon KB, et al. Adalimumab: long-term safety in 23 458 patients from global clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn’s disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:517-524.

- Dommasch ED, Abuabara K, Shin DB, et al. The risk of infection and malignancy with tumor necrosis factor antagonists in adults with psoriatic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1035-1050.

- Gordon KB, Papp KA, Langley RG, et al. Long-term safety experience of ustekinumab in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis (part II of II): results from analyses of infections and malignancy from pooled phase II and III clinical trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:742-751.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113.

- Gelfand JM, Troxel AB, Lewis JD, et al. The risk of mortality in patients with psoriasis: results from a population-based study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1493-1499.

- Coates LC, Aslam T, Al Balushi F, et al. Comparison of three screening tools to detect psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis (CONTEST study). Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:802-807.

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3168-3209.

- Lerman JB, Joshi AA, Chaturvedi A, et al. Coronary plaque characterization in psoriasis reveals high-risk features that improve after treatment in a prospective observational study. Circulation. 2017;136:263-276.

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735-1741.

- Gelfand JM, Dommasch ED, Shin DB, et al. The risk of stroke in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2411-2418.

- Dunlay SM, Weston SA, Redfield MM, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and mortality in heart failure: a community study. Circulation. 2008;118:625-631.

- Russell SD, Saval MA, Robbins JL, et al. New York Heart Association functional class predicts exercise parameters in the current era. Am Heart J. 2009;158(4 suppl):S24-S30.

- Wu JJ, Poon K-YT, Channual JC, et al. Association between tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy and myocardial infarction risk in patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:1244-1250.

- Wu JJ, Guerin A, Sundaram M, et al. Cardiovascular event risk assessment in psoriasis patients treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors versus methotrexate. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:81-90.

- Wu JJ, Sundaram M, Cloutier M, et al. The risk of cardiovascular events in psoriasis patients treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors versus phototherapy: an observational cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:60-68.

- Gami AS, Witt BJ, Howard DE, et al. Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular events and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:403-414.

- Langan SM, Seminara NM, Shin DB, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study in the United Kingdom. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:556-562.

- Jensen P, Zachariae C, Christensen R, et al. Effect of weight loss on the severity of psoriasis: a randomized clinical study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:795-801.

- Egeberg A, Sørensen JA, Gislason GH, et al. Incidence and prognosis of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:344-349.

- Crowley J, Thaçi D, Joly P, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of apremilast in patients with psoriasis: pooled safety analysis for ≥156 weeks from 2 phase 3, randomized, controlled trials (ESTEEM 1 and 2). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:310-317.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.052

- Gisondi P, Del Giglio M, Di Francesco V, et al. Weight loss improves the response of obese patients with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis to low-dose cyclosporine therapy: a randomized, controlled, investigator-blinded clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1242-1247.