User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Inside the flawed White House testing scheme that did not protect Trump

The president has said others are tested before getting close to him, appearing to hold it as an iron shield of safety. He has largely eschewed mask-wearing and social distancing in meetings, travel and public events, while holding rallies for thousands of often maskless supporters.

The Trump administration has increasingly pinned its coronavirus testing strategy for the nation on antigen tests, which do not need a traditional lab for processing and quickly return results to patients. But the results are less accurate than those of the slower PCR tests.

An early antigen test used by the White House was woefully inaccurate. But the new antigen test the White House is using has not been independently evaluated for accuracy and reliability. Moreover, this is the kit the Trump administration is pushing out to thousands of nursing homes to test residents and staff.

Testing “isn’t a ‘get out of jail free card,’” said Dr. Alan Wells, medical director of clinical labs at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and creator of its test for the novel coronavirus. In general, antigen tests can miss up to half the cases that are detected by polymerase chain reaction tests, depending on the population of patients tested, he said.

The White House said the president’s diagnosis was confirmed with a PCR test but declined to say which test delivered his initial result. The White House has been using a new antigen test from Abbott Laboratories to screen its staff for COVID-19, according to two administration officials.

The test, known as BinaxNOW, received an emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration in August. It produces results in 15 minutes. Yet little is independently known about how effective it is. According to the company, the test is 97% accurate in detecting positives and 98.5% accurate in identifying those without disease. Abbott’s stated performance of its antigen test was based on examining people within 7 days of COVID symptoms appearing.

The president and first lady have both had symptoms, according to White House chief of staff Mark Meadows and the first lady’s Twitter account. The president was admitted to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center on Friday evening “out of an abundance of caution,” White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany said in a statement.

Vice President Mike Pence is also tested daily for the virus and tested negative, spokesperson Devin O’Malley said Friday, but he did not respond to a follow-up question about which test was used.

Trump heavily promoted another Abbott rapid testing device, the ID NOW, earlier this year. But that test relies on different technology than the newer Abbott antigen test.

“I have not seen any independent evaluation of the Binax assay in the literature or in the blogs,” Wells said. “It is an unknown.”

The Department of Health and Human Services announced in August that it had signed a $760 million contract with Abbott for 150 million BinaxNOW antigen tests, which are now being distributed to nursing homes and historically black colleges and universities, as well as to governors to help inform decisions about opening and closing schools. The Big Ten football conference has also pinned playing hopes on the deployment of antigen tests following Trump’s political pressure.

However, even senior federal officials concede that a test alone isn’t likely to stop the spread of a virus that has sickened more than 7 million Americans.

“Testing does not substitute for avoiding crowded indoor spaces, washing hands, or wearing a mask when you can’t physically distance; further, a negative test today does not mean that you won’t be positive tomorrow,” Adm. Brett Giroir, the senior HHS official helming the administration’s testing effort, said in a statement at the time.

Trump could be part of a “super-spreading event,” said Dr. Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota.

Given the timing of Trump’s positive test — which he announced on Twitter early Friday – his infection “likely happened 5 or more days ago,” Osterholm said. “If so, then he was widely infectious as early as Tuesday,” the day of the first presidential debate in Cleveland.

At least seven people who attended a Rose Garden announcement last Saturday, when Trump announced his nomination of Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, have since tested positive for the coronavirus. They include Trump’s former adviser Kellyanne Conway, Republican Sens. Mike Lee and Thom Tillis, and the president of the University of Notre Dame, the Rev. John Jenkins.

“Having that many infected people there all at one time, we’re still going to see transmission coming off that event for a couple days,” Osterholm said.

Osterholm notes that about 20% of infected people lead to 80% of COVID-19 cases, because “super spreaders” can infect so many people at once.

He notes that participants and audience members at Tuesday’s debate were separated by at least 6 feet. But 6 feet isn’t always enough to prevent infection, he said.

While many COVID-19 infections appear to be spread by respiratory droplets, which usually fall to the ground within 6 feet, people who are singing or speaking loudly can project virus much further. Evidence also suggests that the novel coronavirus can spread through aerosols, floating in the air like a speck of dust.

“I wonder how much virus was floating in that room that night,” Osterholm said.

Other experts say it’s too soon to say whether Trump was infected in a super-spreader event. “The president and his wife have had many exposures to many people in enclosed venues without protection,” so they could have been infected at any number of places, said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

Although Democratic presidential candidate and former Vice President Joe Biden tested negative for the virus with a PCR test Friday, experts note that false-negative results are common in the first few days after infection. Test results over the next several days will yield more useful information.

It can take more than a week for the virus to reproduce enough to be detected, Wells said: “You are probably not detectable for 3, 5, 7, even 10 days after you’re exposed.”

In Minnesota, where Trump held an outdoor campaign rally in Duluth with hundreds of attendees Wednesday, health officials warned that a 14-day quarantine is necessary, regardless of test results.

“Anyone who was a direct contact of President Trump or known COVID-19 cases needs to quarantine and should get tested,” the Minnesota Department of Health said.

Ongoing lapses in test result reporting could hamper efforts to track and isolate sick people. As of Sept. 10, 21 states and the District of Columbia were not reporting all antigen test results, according to a KHN investigation, a lapse in reporting that officials say leaves them blind to disease spread. Since then, public health departments in Arizona, North Carolina and South Dakota all have announced plans to add antigen testing to their case reporting.

Requests for comment to the D.C. Department of Health were referred to Mayor Muriel Bowser’s office, which did not respond. District health officials told KHN in early September that the White House does not report antigen test results to them – a potential violation of federal law under the CARES Act, which says any institution performing tests to diagnose COVID-19 must report all results to local or state public health departments.

Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security, said it’s not surprising that Trump tested positive, given that so many of his close associates – including his national security adviser and Secret Service officers – have also been infected by the virus.

“When you look at the number of social contacts and travel schedules, it’s not surprising,” Adalja said.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The president has said others are tested before getting close to him, appearing to hold it as an iron shield of safety. He has largely eschewed mask-wearing and social distancing in meetings, travel and public events, while holding rallies for thousands of often maskless supporters.

The Trump administration has increasingly pinned its coronavirus testing strategy for the nation on antigen tests, which do not need a traditional lab for processing and quickly return results to patients. But the results are less accurate than those of the slower PCR tests.

An early antigen test used by the White House was woefully inaccurate. But the new antigen test the White House is using has not been independently evaluated for accuracy and reliability. Moreover, this is the kit the Trump administration is pushing out to thousands of nursing homes to test residents and staff.

Testing “isn’t a ‘get out of jail free card,’” said Dr. Alan Wells, medical director of clinical labs at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and creator of its test for the novel coronavirus. In general, antigen tests can miss up to half the cases that are detected by polymerase chain reaction tests, depending on the population of patients tested, he said.

The White House said the president’s diagnosis was confirmed with a PCR test but declined to say which test delivered his initial result. The White House has been using a new antigen test from Abbott Laboratories to screen its staff for COVID-19, according to two administration officials.

The test, known as BinaxNOW, received an emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration in August. It produces results in 15 minutes. Yet little is independently known about how effective it is. According to the company, the test is 97% accurate in detecting positives and 98.5% accurate in identifying those without disease. Abbott’s stated performance of its antigen test was based on examining people within 7 days of COVID symptoms appearing.

The president and first lady have both had symptoms, according to White House chief of staff Mark Meadows and the first lady’s Twitter account. The president was admitted to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center on Friday evening “out of an abundance of caution,” White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany said in a statement.

Vice President Mike Pence is also tested daily for the virus and tested negative, spokesperson Devin O’Malley said Friday, but he did not respond to a follow-up question about which test was used.

Trump heavily promoted another Abbott rapid testing device, the ID NOW, earlier this year. But that test relies on different technology than the newer Abbott antigen test.

“I have not seen any independent evaluation of the Binax assay in the literature or in the blogs,” Wells said. “It is an unknown.”

The Department of Health and Human Services announced in August that it had signed a $760 million contract with Abbott for 150 million BinaxNOW antigen tests, which are now being distributed to nursing homes and historically black colleges and universities, as well as to governors to help inform decisions about opening and closing schools. The Big Ten football conference has also pinned playing hopes on the deployment of antigen tests following Trump’s political pressure.

However, even senior federal officials concede that a test alone isn’t likely to stop the spread of a virus that has sickened more than 7 million Americans.

“Testing does not substitute for avoiding crowded indoor spaces, washing hands, or wearing a mask when you can’t physically distance; further, a negative test today does not mean that you won’t be positive tomorrow,” Adm. Brett Giroir, the senior HHS official helming the administration’s testing effort, said in a statement at the time.

Trump could be part of a “super-spreading event,” said Dr. Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota.

Given the timing of Trump’s positive test — which he announced on Twitter early Friday – his infection “likely happened 5 or more days ago,” Osterholm said. “If so, then he was widely infectious as early as Tuesday,” the day of the first presidential debate in Cleveland.

At least seven people who attended a Rose Garden announcement last Saturday, when Trump announced his nomination of Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, have since tested positive for the coronavirus. They include Trump’s former adviser Kellyanne Conway, Republican Sens. Mike Lee and Thom Tillis, and the president of the University of Notre Dame, the Rev. John Jenkins.

“Having that many infected people there all at one time, we’re still going to see transmission coming off that event for a couple days,” Osterholm said.

Osterholm notes that about 20% of infected people lead to 80% of COVID-19 cases, because “super spreaders” can infect so many people at once.

He notes that participants and audience members at Tuesday’s debate were separated by at least 6 feet. But 6 feet isn’t always enough to prevent infection, he said.

While many COVID-19 infections appear to be spread by respiratory droplets, which usually fall to the ground within 6 feet, people who are singing or speaking loudly can project virus much further. Evidence also suggests that the novel coronavirus can spread through aerosols, floating in the air like a speck of dust.

“I wonder how much virus was floating in that room that night,” Osterholm said.

Other experts say it’s too soon to say whether Trump was infected in a super-spreader event. “The president and his wife have had many exposures to many people in enclosed venues without protection,” so they could have been infected at any number of places, said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

Although Democratic presidential candidate and former Vice President Joe Biden tested negative for the virus with a PCR test Friday, experts note that false-negative results are common in the first few days after infection. Test results over the next several days will yield more useful information.

It can take more than a week for the virus to reproduce enough to be detected, Wells said: “You are probably not detectable for 3, 5, 7, even 10 days after you’re exposed.”

In Minnesota, where Trump held an outdoor campaign rally in Duluth with hundreds of attendees Wednesday, health officials warned that a 14-day quarantine is necessary, regardless of test results.

“Anyone who was a direct contact of President Trump or known COVID-19 cases needs to quarantine and should get tested,” the Minnesota Department of Health said.

Ongoing lapses in test result reporting could hamper efforts to track and isolate sick people. As of Sept. 10, 21 states and the District of Columbia were not reporting all antigen test results, according to a KHN investigation, a lapse in reporting that officials say leaves them blind to disease spread. Since then, public health departments in Arizona, North Carolina and South Dakota all have announced plans to add antigen testing to their case reporting.

Requests for comment to the D.C. Department of Health were referred to Mayor Muriel Bowser’s office, which did not respond. District health officials told KHN in early September that the White House does not report antigen test results to them – a potential violation of federal law under the CARES Act, which says any institution performing tests to diagnose COVID-19 must report all results to local or state public health departments.

Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security, said it’s not surprising that Trump tested positive, given that so many of his close associates – including his national security adviser and Secret Service officers – have also been infected by the virus.

“When you look at the number of social contacts and travel schedules, it’s not surprising,” Adalja said.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

The president has said others are tested before getting close to him, appearing to hold it as an iron shield of safety. He has largely eschewed mask-wearing and social distancing in meetings, travel and public events, while holding rallies for thousands of often maskless supporters.

The Trump administration has increasingly pinned its coronavirus testing strategy for the nation on antigen tests, which do not need a traditional lab for processing and quickly return results to patients. But the results are less accurate than those of the slower PCR tests.

An early antigen test used by the White House was woefully inaccurate. But the new antigen test the White House is using has not been independently evaluated for accuracy and reliability. Moreover, this is the kit the Trump administration is pushing out to thousands of nursing homes to test residents and staff.

Testing “isn’t a ‘get out of jail free card,’” said Dr. Alan Wells, medical director of clinical labs at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and creator of its test for the novel coronavirus. In general, antigen tests can miss up to half the cases that are detected by polymerase chain reaction tests, depending on the population of patients tested, he said.

The White House said the president’s diagnosis was confirmed with a PCR test but declined to say which test delivered his initial result. The White House has been using a new antigen test from Abbott Laboratories to screen its staff for COVID-19, according to two administration officials.

The test, known as BinaxNOW, received an emergency use authorization from the Food and Drug Administration in August. It produces results in 15 minutes. Yet little is independently known about how effective it is. According to the company, the test is 97% accurate in detecting positives and 98.5% accurate in identifying those without disease. Abbott’s stated performance of its antigen test was based on examining people within 7 days of COVID symptoms appearing.

The president and first lady have both had symptoms, according to White House chief of staff Mark Meadows and the first lady’s Twitter account. The president was admitted to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center on Friday evening “out of an abundance of caution,” White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany said in a statement.

Vice President Mike Pence is also tested daily for the virus and tested negative, spokesperson Devin O’Malley said Friday, but he did not respond to a follow-up question about which test was used.

Trump heavily promoted another Abbott rapid testing device, the ID NOW, earlier this year. But that test relies on different technology than the newer Abbott antigen test.

“I have not seen any independent evaluation of the Binax assay in the literature or in the blogs,” Wells said. “It is an unknown.”

The Department of Health and Human Services announced in August that it had signed a $760 million contract with Abbott for 150 million BinaxNOW antigen tests, which are now being distributed to nursing homes and historically black colleges and universities, as well as to governors to help inform decisions about opening and closing schools. The Big Ten football conference has also pinned playing hopes on the deployment of antigen tests following Trump’s political pressure.

However, even senior federal officials concede that a test alone isn’t likely to stop the spread of a virus that has sickened more than 7 million Americans.

“Testing does not substitute for avoiding crowded indoor spaces, washing hands, or wearing a mask when you can’t physically distance; further, a negative test today does not mean that you won’t be positive tomorrow,” Adm. Brett Giroir, the senior HHS official helming the administration’s testing effort, said in a statement at the time.

Trump could be part of a “super-spreading event,” said Dr. Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota.

Given the timing of Trump’s positive test — which he announced on Twitter early Friday – his infection “likely happened 5 or more days ago,” Osterholm said. “If so, then he was widely infectious as early as Tuesday,” the day of the first presidential debate in Cleveland.

At least seven people who attended a Rose Garden announcement last Saturday, when Trump announced his nomination of Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, have since tested positive for the coronavirus. They include Trump’s former adviser Kellyanne Conway, Republican Sens. Mike Lee and Thom Tillis, and the president of the University of Notre Dame, the Rev. John Jenkins.

“Having that many infected people there all at one time, we’re still going to see transmission coming off that event for a couple days,” Osterholm said.

Osterholm notes that about 20% of infected people lead to 80% of COVID-19 cases, because “super spreaders” can infect so many people at once.

He notes that participants and audience members at Tuesday’s debate were separated by at least 6 feet. But 6 feet isn’t always enough to prevent infection, he said.

While many COVID-19 infections appear to be spread by respiratory droplets, which usually fall to the ground within 6 feet, people who are singing or speaking loudly can project virus much further. Evidence also suggests that the novel coronavirus can spread through aerosols, floating in the air like a speck of dust.

“I wonder how much virus was floating in that room that night,” Osterholm said.

Other experts say it’s too soon to say whether Trump was infected in a super-spreader event. “The president and his wife have had many exposures to many people in enclosed venues without protection,” so they could have been infected at any number of places, said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

Although Democratic presidential candidate and former Vice President Joe Biden tested negative for the virus with a PCR test Friday, experts note that false-negative results are common in the first few days after infection. Test results over the next several days will yield more useful information.

It can take more than a week for the virus to reproduce enough to be detected, Wells said: “You are probably not detectable for 3, 5, 7, even 10 days after you’re exposed.”

In Minnesota, where Trump held an outdoor campaign rally in Duluth with hundreds of attendees Wednesday, health officials warned that a 14-day quarantine is necessary, regardless of test results.

“Anyone who was a direct contact of President Trump or known COVID-19 cases needs to quarantine and should get tested,” the Minnesota Department of Health said.

Ongoing lapses in test result reporting could hamper efforts to track and isolate sick people. As of Sept. 10, 21 states and the District of Columbia were not reporting all antigen test results, according to a KHN investigation, a lapse in reporting that officials say leaves them blind to disease spread. Since then, public health departments in Arizona, North Carolina and South Dakota all have announced plans to add antigen testing to their case reporting.

Requests for comment to the D.C. Department of Health were referred to Mayor Muriel Bowser’s office, which did not respond. District health officials told KHN in early September that the White House does not report antigen test results to them – a potential violation of federal law under the CARES Act, which says any institution performing tests to diagnose COVID-19 must report all results to local or state public health departments.

Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security, said it’s not surprising that Trump tested positive, given that so many of his close associates – including his national security adviser and Secret Service officers – have also been infected by the virus.

“When you look at the number of social contacts and travel schedules, it’s not surprising,” Adalja said.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation), which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

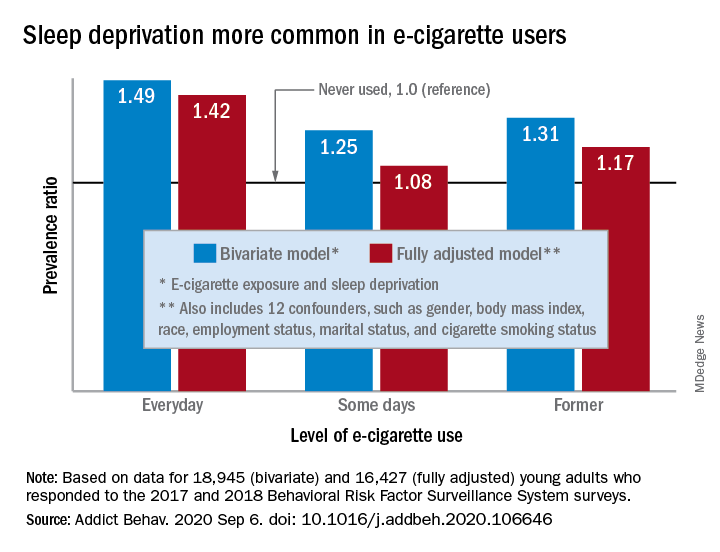

Use of e-cigarettes may be linked to sleep deprivation

compared with those who have never used e-cigarettes, according to the first study to evaluate the association in a large, nationally representative population of young adults.

“The e-cigarette use and sleep deprivation association seems to have a dose-response nature as the point estimate of the association increased with increased exposure to e-cigarette,” Sina Kianersi, DVM, and associates at Indiana University, Bloomington, said in Addictive Behaviors.

Sleep deprivation was 49% more prevalent among everyday users of e-cigarettes, compared with nonusers. Prevalence ratios for former users (1.31) and occasional users (1.25) also showed significantly higher sleep deprivation, compared with nonusers, they reported based on a bivariate analysis of data from young adults aged 18-24 years who participated in the 2017 and 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System surveys.

After adjustment for multiple confounders, young adults who currently used e-cigarettes every day were 42% more likely to report sleep deprivation than those who never used e-cigarettes, a difference that was statistically significant. The prevalence of sleep deprivation among those who used e-cigarettes on some days was not significantly higher (prevalence ratio, 1.08), but the ratio between former users and never users was a significant 1.17, the investigators said.

“The nicotine in the inhaled e-cigarette aerosols may have negative effects on sleep architecture and disturb the neurotransmitters that regulate sleep cycle,” they suggested, and since higher doses of nicotine produce greater reductions in sleep duration, “those who use e-cigarette on a daily basis might consume higher doses of nicotine, compared to some days, former, and never users, and therefore get fewer hours of sleep.”

Nicotine withdrawal, on the other hand, has been found to increase sleep duration in a dose-dependent manner, which “could explain the smaller [prevalence ratios] observed for the association between e-cigarette use and sleep deprivation among former and some days e-cigarette users,” Dr. Kianersi and associates added.

The bivariate analysis involved 18,945 survey respondents, of whom 16,427 were included in the fully adjusted model using 12 confounding factors.

SOURCE: Kianersi S et al. Addict Behav. 2020 Sep 6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106646.

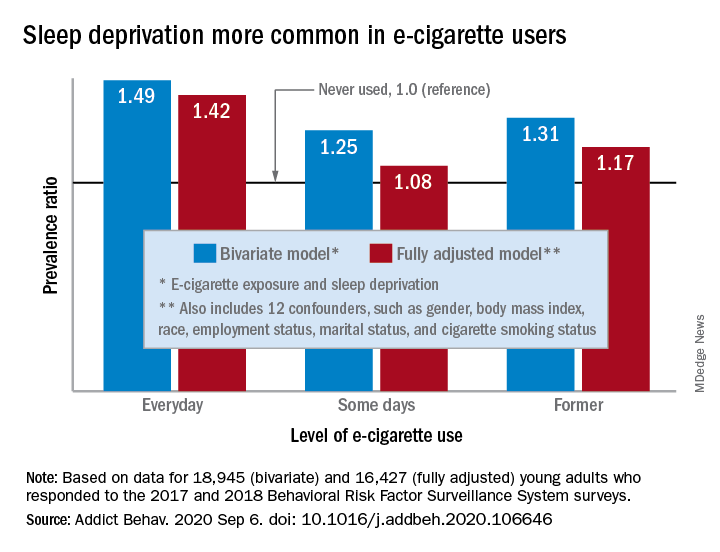

compared with those who have never used e-cigarettes, according to the first study to evaluate the association in a large, nationally representative population of young adults.

“The e-cigarette use and sleep deprivation association seems to have a dose-response nature as the point estimate of the association increased with increased exposure to e-cigarette,” Sina Kianersi, DVM, and associates at Indiana University, Bloomington, said in Addictive Behaviors.

Sleep deprivation was 49% more prevalent among everyday users of e-cigarettes, compared with nonusers. Prevalence ratios for former users (1.31) and occasional users (1.25) also showed significantly higher sleep deprivation, compared with nonusers, they reported based on a bivariate analysis of data from young adults aged 18-24 years who participated in the 2017 and 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System surveys.

After adjustment for multiple confounders, young adults who currently used e-cigarettes every day were 42% more likely to report sleep deprivation than those who never used e-cigarettes, a difference that was statistically significant. The prevalence of sleep deprivation among those who used e-cigarettes on some days was not significantly higher (prevalence ratio, 1.08), but the ratio between former users and never users was a significant 1.17, the investigators said.

“The nicotine in the inhaled e-cigarette aerosols may have negative effects on sleep architecture and disturb the neurotransmitters that regulate sleep cycle,” they suggested, and since higher doses of nicotine produce greater reductions in sleep duration, “those who use e-cigarette on a daily basis might consume higher doses of nicotine, compared to some days, former, and never users, and therefore get fewer hours of sleep.”

Nicotine withdrawal, on the other hand, has been found to increase sleep duration in a dose-dependent manner, which “could explain the smaller [prevalence ratios] observed for the association between e-cigarette use and sleep deprivation among former and some days e-cigarette users,” Dr. Kianersi and associates added.

The bivariate analysis involved 18,945 survey respondents, of whom 16,427 were included in the fully adjusted model using 12 confounding factors.

SOURCE: Kianersi S et al. Addict Behav. 2020 Sep 6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106646.

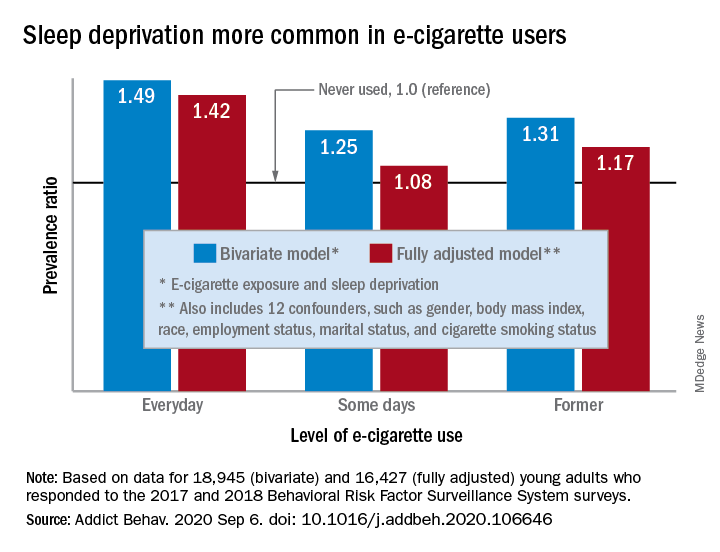

compared with those who have never used e-cigarettes, according to the first study to evaluate the association in a large, nationally representative population of young adults.

“The e-cigarette use and sleep deprivation association seems to have a dose-response nature as the point estimate of the association increased with increased exposure to e-cigarette,” Sina Kianersi, DVM, and associates at Indiana University, Bloomington, said in Addictive Behaviors.

Sleep deprivation was 49% more prevalent among everyday users of e-cigarettes, compared with nonusers. Prevalence ratios for former users (1.31) and occasional users (1.25) also showed significantly higher sleep deprivation, compared with nonusers, they reported based on a bivariate analysis of data from young adults aged 18-24 years who participated in the 2017 and 2018 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System surveys.

After adjustment for multiple confounders, young adults who currently used e-cigarettes every day were 42% more likely to report sleep deprivation than those who never used e-cigarettes, a difference that was statistically significant. The prevalence of sleep deprivation among those who used e-cigarettes on some days was not significantly higher (prevalence ratio, 1.08), but the ratio between former users and never users was a significant 1.17, the investigators said.

“The nicotine in the inhaled e-cigarette aerosols may have negative effects on sleep architecture and disturb the neurotransmitters that regulate sleep cycle,” they suggested, and since higher doses of nicotine produce greater reductions in sleep duration, “those who use e-cigarette on a daily basis might consume higher doses of nicotine, compared to some days, former, and never users, and therefore get fewer hours of sleep.”

Nicotine withdrawal, on the other hand, has been found to increase sleep duration in a dose-dependent manner, which “could explain the smaller [prevalence ratios] observed for the association between e-cigarette use and sleep deprivation among former and some days e-cigarette users,” Dr. Kianersi and associates added.

The bivariate analysis involved 18,945 survey respondents, of whom 16,427 were included in the fully adjusted model using 12 confounding factors.

SOURCE: Kianersi S et al. Addict Behav. 2020 Sep 6. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106646.

FROM ADDICTIVE BEHAVIORS

Mental illness tied to increased mortality in COVID-19

A psychiatric diagnosis for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 is linked to a significantly increased risk for death, new research shows.

Investigators found that patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 and who had been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder had a 50% increased risk for a COVID-related death in comparison with COVID-19 patients who had not received a psychiatric diagnosis.

“Pay attention and potentially address/treat a prior psychiatric diagnosis if a patient is hospitalized for COVID-19, as this risk factor can impact the patient’s outcome – death – while in the hospital,” lead investigator Luming Li, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry and associate medical director of quality improvement, Yale New Haven Psychiatric Hospital, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview.

The study was published Sept. 30 in JAMA Network Open.

Negative impact

“We were interested to learn more about the impact of psychiatric diagnoses on COVID-19 mortality, as prior large cohort studies included neurological and other medical conditions but did not assess for a priori psychiatric diagnoses,” said Dr. Li.

“We know from the literature that prior psychiatric diagnoses can have a negative impact on the outcomes of medical conditions, and therefore we tested our hypothesis on a cohort of patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19,” she added.

To investigate, the researchers analyzed data on 1,685 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 between Feb. 15 and April 25, 2020, and whose cases were followed to May 27, 2020. The patients (mean age, 65.2 years; 52.6% men) were drawn from the Yale New Haven Health System.

The median follow-up period was 8 days (interquartile range, 4-16 days) .

Of these patients, 28% had received a psychiatric diagnosis prior to hospitalization. (i.e., cancer, cerebrovascular disease, heart failure, diabetes, kidney disease, liver disease, MI, and/or HIV).

Psychiatric diagnoses were defined in accordance with ICD codes that included mental and behavioral health, Alzheimer’s disease, and self-injury.

Vulnerability to stress

In the unadjusted model, the risk for COVID-19–related hospital death was greater for those who had received any psychiatric diagnosis, compared with those had not (hazard ratio, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.8-2.9; P < .001).

In the adjusted model that controlled for demographic characteristics, other medical comorbidities, and hospital location, the mortality risk somewhat decreased but still remained significantly higher (HR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-1.9; P = .003).

Dr. Li noted a number of factors that might account for the higher mortality rate among psychiatric patients who had COVID-19 in comparison with COVD-19 patients who did not have a psychiatric disorder. These included “potential inflammatory and stress responses that the body experiences related to prior psychiatric conditions,” she said.

Having been previously diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder may also “reflect existing neurochemical differences, compared to those who do not have a prior psychiatric diagnosis, [and] these differences may make the population with the prior psychiatric diagnosis more vulnerable to respond to an acute stressor such as COVID-19,” she said.

Quality care

Harold Pincus, MD, professor and vice chair of the department of psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, said it “adds to the fairly well-known and well-established phenomenon that people with mental illnesses have a high risk of all sorts of morbidity and mortality for non–mental health conditions.”

The researchers “adjusted for various expected [mortality] risks that would be independent of the presence of COVID-19,” so “there was something else going on associated with mortality,” said Dr. Pincus, who is also codirector of the Irving Institute for Clinical and Translation Research. He was not involved with the study.

Beyond the possibility of “some basic immunologic process affected by the presence of a mental disorder,” it is possible that the vulnerability is “related to access to quality care for the comorbid general condition that is not being effectively treated,” he said.

“The take-home message is that people with mental disorders are at higher risk for death, and we need to make sure that, irrespective of COVID-19, they get adequate preventive and chronic-disease care, which would be the most effective way to intervene and protect the impact of a serious disease like COVID-19,” he noted. This would include being appropriately vaccinated and receiving preventive healthcare to reduce smoking and encourage weight loss.

No source of funding for the study was provided. Dr. Li reported receiving grants from a Health and Aging Policy Fellowship during the conduct of the study. Dr. Pincus reported no relevant financial relationships.

A psychiatric diagnosis for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 is linked to a significantly increased risk for death, new research shows.

Investigators found that patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 and who had been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder had a 50% increased risk for a COVID-related death in comparison with COVID-19 patients who had not received a psychiatric diagnosis.

“Pay attention and potentially address/treat a prior psychiatric diagnosis if a patient is hospitalized for COVID-19, as this risk factor can impact the patient’s outcome – death – while in the hospital,” lead investigator Luming Li, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry and associate medical director of quality improvement, Yale New Haven Psychiatric Hospital, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview.

The study was published Sept. 30 in JAMA Network Open.

Negative impact

“We were interested to learn more about the impact of psychiatric diagnoses on COVID-19 mortality, as prior large cohort studies included neurological and other medical conditions but did not assess for a priori psychiatric diagnoses,” said Dr. Li.

“We know from the literature that prior psychiatric diagnoses can have a negative impact on the outcomes of medical conditions, and therefore we tested our hypothesis on a cohort of patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19,” she added.

To investigate, the researchers analyzed data on 1,685 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 between Feb. 15 and April 25, 2020, and whose cases were followed to May 27, 2020. The patients (mean age, 65.2 years; 52.6% men) were drawn from the Yale New Haven Health System.

The median follow-up period was 8 days (interquartile range, 4-16 days) .

Of these patients, 28% had received a psychiatric diagnosis prior to hospitalization. (i.e., cancer, cerebrovascular disease, heart failure, diabetes, kidney disease, liver disease, MI, and/or HIV).

Psychiatric diagnoses were defined in accordance with ICD codes that included mental and behavioral health, Alzheimer’s disease, and self-injury.

Vulnerability to stress

In the unadjusted model, the risk for COVID-19–related hospital death was greater for those who had received any psychiatric diagnosis, compared with those had not (hazard ratio, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.8-2.9; P < .001).

In the adjusted model that controlled for demographic characteristics, other medical comorbidities, and hospital location, the mortality risk somewhat decreased but still remained significantly higher (HR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-1.9; P = .003).

Dr. Li noted a number of factors that might account for the higher mortality rate among psychiatric patients who had COVID-19 in comparison with COVD-19 patients who did not have a psychiatric disorder. These included “potential inflammatory and stress responses that the body experiences related to prior psychiatric conditions,” she said.

Having been previously diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder may also “reflect existing neurochemical differences, compared to those who do not have a prior psychiatric diagnosis, [and] these differences may make the population with the prior psychiatric diagnosis more vulnerable to respond to an acute stressor such as COVID-19,” she said.

Quality care

Harold Pincus, MD, professor and vice chair of the department of psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, said it “adds to the fairly well-known and well-established phenomenon that people with mental illnesses have a high risk of all sorts of morbidity and mortality for non–mental health conditions.”

The researchers “adjusted for various expected [mortality] risks that would be independent of the presence of COVID-19,” so “there was something else going on associated with mortality,” said Dr. Pincus, who is also codirector of the Irving Institute for Clinical and Translation Research. He was not involved with the study.

Beyond the possibility of “some basic immunologic process affected by the presence of a mental disorder,” it is possible that the vulnerability is “related to access to quality care for the comorbid general condition that is not being effectively treated,” he said.

“The take-home message is that people with mental disorders are at higher risk for death, and we need to make sure that, irrespective of COVID-19, they get adequate preventive and chronic-disease care, which would be the most effective way to intervene and protect the impact of a serious disease like COVID-19,” he noted. This would include being appropriately vaccinated and receiving preventive healthcare to reduce smoking and encourage weight loss.

No source of funding for the study was provided. Dr. Li reported receiving grants from a Health and Aging Policy Fellowship during the conduct of the study. Dr. Pincus reported no relevant financial relationships.

A psychiatric diagnosis for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 is linked to a significantly increased risk for death, new research shows.

Investigators found that patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 and who had been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder had a 50% increased risk for a COVID-related death in comparison with COVID-19 patients who had not received a psychiatric diagnosis.

“Pay attention and potentially address/treat a prior psychiatric diagnosis if a patient is hospitalized for COVID-19, as this risk factor can impact the patient’s outcome – death – while in the hospital,” lead investigator Luming Li, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry and associate medical director of quality improvement, Yale New Haven Psychiatric Hospital, New Haven, Conn., said in an interview.

The study was published Sept. 30 in JAMA Network Open.

Negative impact

“We were interested to learn more about the impact of psychiatric diagnoses on COVID-19 mortality, as prior large cohort studies included neurological and other medical conditions but did not assess for a priori psychiatric diagnoses,” said Dr. Li.

“We know from the literature that prior psychiatric diagnoses can have a negative impact on the outcomes of medical conditions, and therefore we tested our hypothesis on a cohort of patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19,” she added.

To investigate, the researchers analyzed data on 1,685 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 between Feb. 15 and April 25, 2020, and whose cases were followed to May 27, 2020. The patients (mean age, 65.2 years; 52.6% men) were drawn from the Yale New Haven Health System.

The median follow-up period was 8 days (interquartile range, 4-16 days) .

Of these patients, 28% had received a psychiatric diagnosis prior to hospitalization. (i.e., cancer, cerebrovascular disease, heart failure, diabetes, kidney disease, liver disease, MI, and/or HIV).

Psychiatric diagnoses were defined in accordance with ICD codes that included mental and behavioral health, Alzheimer’s disease, and self-injury.

Vulnerability to stress

In the unadjusted model, the risk for COVID-19–related hospital death was greater for those who had received any psychiatric diagnosis, compared with those had not (hazard ratio, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.8-2.9; P < .001).

In the adjusted model that controlled for demographic characteristics, other medical comorbidities, and hospital location, the mortality risk somewhat decreased but still remained significantly higher (HR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-1.9; P = .003).

Dr. Li noted a number of factors that might account for the higher mortality rate among psychiatric patients who had COVID-19 in comparison with COVD-19 patients who did not have a psychiatric disorder. These included “potential inflammatory and stress responses that the body experiences related to prior psychiatric conditions,” she said.

Having been previously diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder may also “reflect existing neurochemical differences, compared to those who do not have a prior psychiatric diagnosis, [and] these differences may make the population with the prior psychiatric diagnosis more vulnerable to respond to an acute stressor such as COVID-19,” she said.

Quality care

Harold Pincus, MD, professor and vice chair of the department of psychiatry at Columbia University, New York, said it “adds to the fairly well-known and well-established phenomenon that people with mental illnesses have a high risk of all sorts of morbidity and mortality for non–mental health conditions.”

The researchers “adjusted for various expected [mortality] risks that would be independent of the presence of COVID-19,” so “there was something else going on associated with mortality,” said Dr. Pincus, who is also codirector of the Irving Institute for Clinical and Translation Research. He was not involved with the study.

Beyond the possibility of “some basic immunologic process affected by the presence of a mental disorder,” it is possible that the vulnerability is “related to access to quality care for the comorbid general condition that is not being effectively treated,” he said.

“The take-home message is that people with mental disorders are at higher risk for death, and we need to make sure that, irrespective of COVID-19, they get adequate preventive and chronic-disease care, which would be the most effective way to intervene and protect the impact of a serious disease like COVID-19,” he noted. This would include being appropriately vaccinated and receiving preventive healthcare to reduce smoking and encourage weight loss.

No source of funding for the study was provided. Dr. Li reported receiving grants from a Health and Aging Policy Fellowship during the conduct of the study. Dr. Pincus reported no relevant financial relationships.

‘Celebration’ will be ‘short-lived’ if COVID vaccine rushed: Experts

on Wednesday.

The career staff of the Food and Drug Administration can be counted on to appropriately weigh whether a vaccine should be cleared for use in preventing COVID-19, witnesses, including Paul A. Offit, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s oversight and investigations panel.

FDA staffers would object to attempts by the Trump administration to rush a vaccine to the public without proper vetting, as would veteran federal researchers, including National Institutes of Health Director Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD, and Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Offit said.

“If COVID-19 vaccines are released before they’re ready to be released, you will hear from these people, and you will also hear from people like Dr. Francis Collins and Tony Fauci, both of whom are trusted by the American public, as well as many other academicians and researchers who wouldn’t stand for this,” he said.

“The public is already nervous about these vaccines,” said Offit, who serves on key FDA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention committees overseeing vaccine policy. “If trusted health officials stand up and decry a premature release, the celebration by the administration will be short-lived.”

Overly optimistic estimates about a potential approval can only serve to erode the public’s trust in these crucial vaccines, said another witness, Ashish K. Jha, MD, MPH, the dean of Brown University’s School of Public Health, in Providence, Rhode Island.

“All political leaders need to stop talking about things like time lines,” Jha told the lawmakers.

President Donald Trump has several times suggested that a COVID vaccine might be approved ahead of the November 3 election, where he faces a significant challenge from his Democratic rival, former Vice President Joe Biden.

In a Tuesday night debate with Biden, Trump again raised the idea of a quick approval. “Now we’re weeks away from a vaccine,” Trump said during the debate.

Trump’s estimates, though, are not in line with those offered by most firms involved with making vaccines. The most optimistic projections have come from Pfizer Inc. The drugmaker’s chief executive, Albert Bourla, has spoken about his company possibly having data to present to the FDA as early as late October about the safety and effectiveness of a vaccine.

In a September 8 interview with the Today show, Bourla said there was a 60% chance his company would meet that goal. In response to a question, he made it clear his comments applied to a potential Pfizer application, not an approval or release of a vaccine by that time.

In response to concerns about political pressures, the FDA in June issued guidance outlining what its staff would require for approval of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Pushback on politics

Another witness at the Wednesday hearing, Mark McClellan, MD, PhD, a former FDA commissioner (2002 – 2004), pushed back on objections to a potential release of further guidance from the agency.

“Some recent statements from the White House have implied that FDA’s plan to release additional written guidance on its expectations for emergency use authorization of a vaccine is unnecessarily raising the bar on regulatory standards for authorization,” said McClellan in his testimony for the House panel. “That is not the case.”

Instead, further FDA guidance would be a welcome form of feedback for the firms trying to develop COVID-19 vaccines, according to McClellan, who also serves on the board of directors for Johnson & Johnson. Johnson & Johnson is among the firms that have advanced a COVID-19 vaccine candidate to phase 3 testing. In his role as a director, he serves on the board’s regulatory compliance committee.

Along with politics, recent stumbles at FDA with emergency use authorizations (EUAs) of treatments for COVID-19 have eroded the public’s confidence in the agency, Jha told the House panel. The FDA approved hydroxychloroquine, a medicine promoted by Trump for use in COVID, under an EUA in March and then revoked this clearance in June.

Jha said the FDA’s most serious misstep was its handling of convalescent plasma, which was approved through an EUA on August 23 “in a highly advertised and widely televised announcement including the president.

“The announcement solidified in the public conversation the impression that, increasingly with this administration, politics are taking over trusted, nonpartisan scientific institutions,” he said in his testimony.

Approving a COVID-19 vaccine on the limited evidence through an EUA would mark a serious departure from FDA policy, according to Jha.

“While we sometimes accept a certain level of potential harm in experimental treatments for those who are severely ill, vaccines are given to healthy people and therefore need to have a substantially higher measure of safety and effectiveness,” he explained.

Jha said the FDA has only once before used this EUA approach for a vaccine. That was for a vaccine against inhaled anthrax and was mostly distributed to high-risk soldiers and civilians in war zones.

COVID-19, in contrast, is an infection that has changed lives around the world. The virus has contributed to more than 1 million deaths, including more than 200,000 in the United States, according to the World Health Organization.

Scientists are hoping vaccines will help curb this infection, although much of the future success of vaccines depends on how widely they are used, witnesses told the House panel.

Debate on approaches for vaccine effectiveness

In his testimony, Jha also noted concerns about COVID-19 vaccine trials. He included a reference to a Sept. 22 opinion article titled, “These Coronavirus Trials Don›t Answer the One Question We Need to Know,” which was written by Peter Doshi, PhD, of the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, in Baltimore, and Eric Topol, MD, a professor of molecular medicine at Scripps Research in La Jolla, Calif. Topol is also editor in chief of Medscape.

Topol and Doshi questioned why the firms Moderna, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca structured their competing trials such that “a vaccine could meet the companies’ benchmark for success if it lowered the risk of mild Covid-19, but was never shown to reduce moderate or severe forms of the disease, or the risk of hospitalization, admissions to the intensive care unit or death.”

“To say a vaccine works should mean that most people no longer run the risk of getting seriously sick,” Topol and Doshi wrote. “That’s not what these trials will determine.”

There was disagreement about this point at the hearing. U.S. Representative Morgan Griffith (R-Va.) read the section of the Doshi-Topol article quoted above and asked one witness, Offit, to weigh in.

“Do you agree with those concerns? And either way, tell me why,” Griffith asked.

“I don’t agree,” Offit responded.

“I think it’s actually much harder to prevent asymptomatic infection or mildly symptomatic infection,” he said. “If you can prevent that, you are much more likely to prevent moderate to severe disease. So I think they have it backwards.”

But other researchers also question the approaches used with the current crop of COVID-19 vaccines.

“With the current protocols, it is conceivable that a vaccine might be considered effective – and eventually approved – based primarily on its ability to prevent mild cases alone,” wrote William Haseltine, PhD, president of the nonprofit ACCESS Health International, in a September 22 opinion article in the Washington Post titled: “Beware of COVID-19 Vaccine Trials Designed to Succeed From the Start.”

In an interview with Medscape Medical News on Wednesday, Haseltine said he maintains these concerns about the tests. Earlier in his career, he was a leader in HIV research through his lab at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and he subsequently led a biotech company, Human Genome Sciences.

He fears consumers will not get what they might expect from the vaccines being tested.

“What people care about is if this is going to keep them out of the hospital and will it keep them alive. And that’s not even part of this protocol,” Haseltine said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

on Wednesday.

The career staff of the Food and Drug Administration can be counted on to appropriately weigh whether a vaccine should be cleared for use in preventing COVID-19, witnesses, including Paul A. Offit, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s oversight and investigations panel.

FDA staffers would object to attempts by the Trump administration to rush a vaccine to the public without proper vetting, as would veteran federal researchers, including National Institutes of Health Director Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD, and Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Offit said.

“If COVID-19 vaccines are released before they’re ready to be released, you will hear from these people, and you will also hear from people like Dr. Francis Collins and Tony Fauci, both of whom are trusted by the American public, as well as many other academicians and researchers who wouldn’t stand for this,” he said.

“The public is already nervous about these vaccines,” said Offit, who serves on key FDA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention committees overseeing vaccine policy. “If trusted health officials stand up and decry a premature release, the celebration by the administration will be short-lived.”

Overly optimistic estimates about a potential approval can only serve to erode the public’s trust in these crucial vaccines, said another witness, Ashish K. Jha, MD, MPH, the dean of Brown University’s School of Public Health, in Providence, Rhode Island.

“All political leaders need to stop talking about things like time lines,” Jha told the lawmakers.

President Donald Trump has several times suggested that a COVID vaccine might be approved ahead of the November 3 election, where he faces a significant challenge from his Democratic rival, former Vice President Joe Biden.

In a Tuesday night debate with Biden, Trump again raised the idea of a quick approval. “Now we’re weeks away from a vaccine,” Trump said during the debate.

Trump’s estimates, though, are not in line with those offered by most firms involved with making vaccines. The most optimistic projections have come from Pfizer Inc. The drugmaker’s chief executive, Albert Bourla, has spoken about his company possibly having data to present to the FDA as early as late October about the safety and effectiveness of a vaccine.

In a September 8 interview with the Today show, Bourla said there was a 60% chance his company would meet that goal. In response to a question, he made it clear his comments applied to a potential Pfizer application, not an approval or release of a vaccine by that time.

In response to concerns about political pressures, the FDA in June issued guidance outlining what its staff would require for approval of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Pushback on politics

Another witness at the Wednesday hearing, Mark McClellan, MD, PhD, a former FDA commissioner (2002 – 2004), pushed back on objections to a potential release of further guidance from the agency.

“Some recent statements from the White House have implied that FDA’s plan to release additional written guidance on its expectations for emergency use authorization of a vaccine is unnecessarily raising the bar on regulatory standards for authorization,” said McClellan in his testimony for the House panel. “That is not the case.”

Instead, further FDA guidance would be a welcome form of feedback for the firms trying to develop COVID-19 vaccines, according to McClellan, who also serves on the board of directors for Johnson & Johnson. Johnson & Johnson is among the firms that have advanced a COVID-19 vaccine candidate to phase 3 testing. In his role as a director, he serves on the board’s regulatory compliance committee.

Along with politics, recent stumbles at FDA with emergency use authorizations (EUAs) of treatments for COVID-19 have eroded the public’s confidence in the agency, Jha told the House panel. The FDA approved hydroxychloroquine, a medicine promoted by Trump for use in COVID, under an EUA in March and then revoked this clearance in June.

Jha said the FDA’s most serious misstep was its handling of convalescent plasma, which was approved through an EUA on August 23 “in a highly advertised and widely televised announcement including the president.

“The announcement solidified in the public conversation the impression that, increasingly with this administration, politics are taking over trusted, nonpartisan scientific institutions,” he said in his testimony.

Approving a COVID-19 vaccine on the limited evidence through an EUA would mark a serious departure from FDA policy, according to Jha.

“While we sometimes accept a certain level of potential harm in experimental treatments for those who are severely ill, vaccines are given to healthy people and therefore need to have a substantially higher measure of safety and effectiveness,” he explained.

Jha said the FDA has only once before used this EUA approach for a vaccine. That was for a vaccine against inhaled anthrax and was mostly distributed to high-risk soldiers and civilians in war zones.

COVID-19, in contrast, is an infection that has changed lives around the world. The virus has contributed to more than 1 million deaths, including more than 200,000 in the United States, according to the World Health Organization.

Scientists are hoping vaccines will help curb this infection, although much of the future success of vaccines depends on how widely they are used, witnesses told the House panel.

Debate on approaches for vaccine effectiveness

In his testimony, Jha also noted concerns about COVID-19 vaccine trials. He included a reference to a Sept. 22 opinion article titled, “These Coronavirus Trials Don›t Answer the One Question We Need to Know,” which was written by Peter Doshi, PhD, of the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, in Baltimore, and Eric Topol, MD, a professor of molecular medicine at Scripps Research in La Jolla, Calif. Topol is also editor in chief of Medscape.

Topol and Doshi questioned why the firms Moderna, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca structured their competing trials such that “a vaccine could meet the companies’ benchmark for success if it lowered the risk of mild Covid-19, but was never shown to reduce moderate or severe forms of the disease, or the risk of hospitalization, admissions to the intensive care unit or death.”

“To say a vaccine works should mean that most people no longer run the risk of getting seriously sick,” Topol and Doshi wrote. “That’s not what these trials will determine.”

There was disagreement about this point at the hearing. U.S. Representative Morgan Griffith (R-Va.) read the section of the Doshi-Topol article quoted above and asked one witness, Offit, to weigh in.

“Do you agree with those concerns? And either way, tell me why,” Griffith asked.

“I don’t agree,” Offit responded.

“I think it’s actually much harder to prevent asymptomatic infection or mildly symptomatic infection,” he said. “If you can prevent that, you are much more likely to prevent moderate to severe disease. So I think they have it backwards.”

But other researchers also question the approaches used with the current crop of COVID-19 vaccines.

“With the current protocols, it is conceivable that a vaccine might be considered effective – and eventually approved – based primarily on its ability to prevent mild cases alone,” wrote William Haseltine, PhD, president of the nonprofit ACCESS Health International, in a September 22 opinion article in the Washington Post titled: “Beware of COVID-19 Vaccine Trials Designed to Succeed From the Start.”

In an interview with Medscape Medical News on Wednesday, Haseltine said he maintains these concerns about the tests. Earlier in his career, he was a leader in HIV research through his lab at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and he subsequently led a biotech company, Human Genome Sciences.

He fears consumers will not get what they might expect from the vaccines being tested.

“What people care about is if this is going to keep them out of the hospital and will it keep them alive. And that’s not even part of this protocol,” Haseltine said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

on Wednesday.

The career staff of the Food and Drug Administration can be counted on to appropriately weigh whether a vaccine should be cleared for use in preventing COVID-19, witnesses, including Paul A. Offit, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s oversight and investigations panel.

FDA staffers would object to attempts by the Trump administration to rush a vaccine to the public without proper vetting, as would veteran federal researchers, including National Institutes of Health Director Francis S. Collins, MD, PhD, and Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Offit said.

“If COVID-19 vaccines are released before they’re ready to be released, you will hear from these people, and you will also hear from people like Dr. Francis Collins and Tony Fauci, both of whom are trusted by the American public, as well as many other academicians and researchers who wouldn’t stand for this,” he said.

“The public is already nervous about these vaccines,” said Offit, who serves on key FDA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention committees overseeing vaccine policy. “If trusted health officials stand up and decry a premature release, the celebration by the administration will be short-lived.”

Overly optimistic estimates about a potential approval can only serve to erode the public’s trust in these crucial vaccines, said another witness, Ashish K. Jha, MD, MPH, the dean of Brown University’s School of Public Health, in Providence, Rhode Island.

“All political leaders need to stop talking about things like time lines,” Jha told the lawmakers.

President Donald Trump has several times suggested that a COVID vaccine might be approved ahead of the November 3 election, where he faces a significant challenge from his Democratic rival, former Vice President Joe Biden.

In a Tuesday night debate with Biden, Trump again raised the idea of a quick approval. “Now we’re weeks away from a vaccine,” Trump said during the debate.

Trump’s estimates, though, are not in line with those offered by most firms involved with making vaccines. The most optimistic projections have come from Pfizer Inc. The drugmaker’s chief executive, Albert Bourla, has spoken about his company possibly having data to present to the FDA as early as late October about the safety and effectiveness of a vaccine.

In a September 8 interview with the Today show, Bourla said there was a 60% chance his company would meet that goal. In response to a question, he made it clear his comments applied to a potential Pfizer application, not an approval or release of a vaccine by that time.

In response to concerns about political pressures, the FDA in June issued guidance outlining what its staff would require for approval of a COVID-19 vaccine.

Pushback on politics

Another witness at the Wednesday hearing, Mark McClellan, MD, PhD, a former FDA commissioner (2002 – 2004), pushed back on objections to a potential release of further guidance from the agency.

“Some recent statements from the White House have implied that FDA’s plan to release additional written guidance on its expectations for emergency use authorization of a vaccine is unnecessarily raising the bar on regulatory standards for authorization,” said McClellan in his testimony for the House panel. “That is not the case.”

Instead, further FDA guidance would be a welcome form of feedback for the firms trying to develop COVID-19 vaccines, according to McClellan, who also serves on the board of directors for Johnson & Johnson. Johnson & Johnson is among the firms that have advanced a COVID-19 vaccine candidate to phase 3 testing. In his role as a director, he serves on the board’s regulatory compliance committee.

Along with politics, recent stumbles at FDA with emergency use authorizations (EUAs) of treatments for COVID-19 have eroded the public’s confidence in the agency, Jha told the House panel. The FDA approved hydroxychloroquine, a medicine promoted by Trump for use in COVID, under an EUA in March and then revoked this clearance in June.

Jha said the FDA’s most serious misstep was its handling of convalescent plasma, which was approved through an EUA on August 23 “in a highly advertised and widely televised announcement including the president.

“The announcement solidified in the public conversation the impression that, increasingly with this administration, politics are taking over trusted, nonpartisan scientific institutions,” he said in his testimony.

Approving a COVID-19 vaccine on the limited evidence through an EUA would mark a serious departure from FDA policy, according to Jha.

“While we sometimes accept a certain level of potential harm in experimental treatments for those who are severely ill, vaccines are given to healthy people and therefore need to have a substantially higher measure of safety and effectiveness,” he explained.

Jha said the FDA has only once before used this EUA approach for a vaccine. That was for a vaccine against inhaled anthrax and was mostly distributed to high-risk soldiers and civilians in war zones.

COVID-19, in contrast, is an infection that has changed lives around the world. The virus has contributed to more than 1 million deaths, including more than 200,000 in the United States, according to the World Health Organization.

Scientists are hoping vaccines will help curb this infection, although much of the future success of vaccines depends on how widely they are used, witnesses told the House panel.

Debate on approaches for vaccine effectiveness

In his testimony, Jha also noted concerns about COVID-19 vaccine trials. He included a reference to a Sept. 22 opinion article titled, “These Coronavirus Trials Don›t Answer the One Question We Need to Know,” which was written by Peter Doshi, PhD, of the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, in Baltimore, and Eric Topol, MD, a professor of molecular medicine at Scripps Research in La Jolla, Calif. Topol is also editor in chief of Medscape.

Topol and Doshi questioned why the firms Moderna, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca structured their competing trials such that “a vaccine could meet the companies’ benchmark for success if it lowered the risk of mild Covid-19, but was never shown to reduce moderate or severe forms of the disease, or the risk of hospitalization, admissions to the intensive care unit or death.”

“To say a vaccine works should mean that most people no longer run the risk of getting seriously sick,” Topol and Doshi wrote. “That’s not what these trials will determine.”

There was disagreement about this point at the hearing. U.S. Representative Morgan Griffith (R-Va.) read the section of the Doshi-Topol article quoted above and asked one witness, Offit, to weigh in.

“Do you agree with those concerns? And either way, tell me why,” Griffith asked.

“I don’t agree,” Offit responded.

“I think it’s actually much harder to prevent asymptomatic infection or mildly symptomatic infection,” he said. “If you can prevent that, you are much more likely to prevent moderate to severe disease. So I think they have it backwards.”

But other researchers also question the approaches used with the current crop of COVID-19 vaccines.

“With the current protocols, it is conceivable that a vaccine might be considered effective – and eventually approved – based primarily on its ability to prevent mild cases alone,” wrote William Haseltine, PhD, president of the nonprofit ACCESS Health International, in a September 22 opinion article in the Washington Post titled: “Beware of COVID-19 Vaccine Trials Designed to Succeed From the Start.”

In an interview with Medscape Medical News on Wednesday, Haseltine said he maintains these concerns about the tests. Earlier in his career, he was a leader in HIV research through his lab at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and he subsequently led a biotech company, Human Genome Sciences.

He fears consumers will not get what they might expect from the vaccines being tested.

“What people care about is if this is going to keep them out of the hospital and will it keep them alive. And that’s not even part of this protocol,” Haseltine said.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

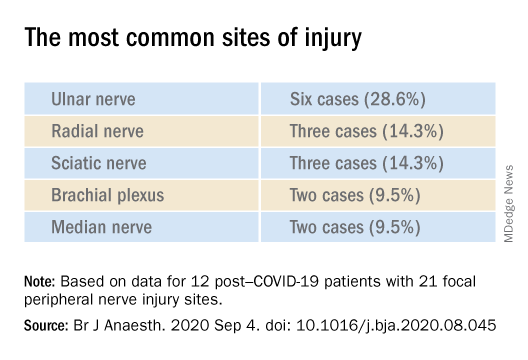

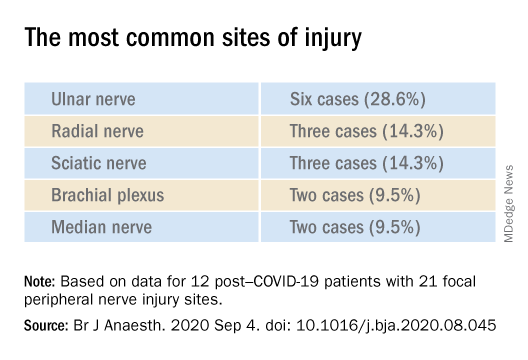

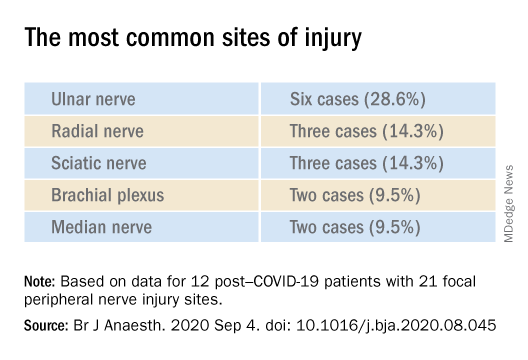

Nerve damage linked to prone positioning in COVID-19

A new case series describes peripheral nerve injuries associated with this type of positioning and suggests ways to minimize the potential damage.

“Physicians should remain aware of increased susceptibility to peripheral nerve damage in patients with severe COVID-19 after prone positioning, since it is surprisingly common among these patients, and should refine standard protocols accordingly to reduce that risk,” said senior author Colin Franz, MD, PhD, director of the Electrodiagnostic Laboratory, Shirley Ryan AbilityLab, Chicago.

The article was published online Sept. 4 in the British Journal of Anaesthesiology.

Unique type of nerve injury

Many patients who are admitted to the intensive care unit with COVID-19 undergo invasive mechanical ventilation because of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Clinical guidelines recommend that such patients lie in the prone position 12-16 hours per day.

“Prone positioning for up to 16 hours is a therapy we use for patients with more severe forms of ARDS, and high-level evidence points to mortality benefit in patients with moderate to severe ARDS if [mechanical] ventilation occurs,” said study coauthor James McCauley Walter, MD, of the pulmonary division at Northwestern University, Chicago.

With a “significant number of COVID-19 patients flooding the ICU, we quickly started to prone a lot of them, but if you are in a specific position for multiple hours a day, coupled with the neurotoxic effects of the SARS-CoV-2 virus itself, you may be exposed to a unique type of nerve injury,” he said.

Dr. Walter said that the “incidence of asymmetric neuropathies seems out of proportion to what has been reported in non–COVID-19 settings, which is what caught our attention.”

Many of these patients are discharged to rehabilitation hospitals, and “what we noticed, which was unique about COVID-19 patients coming to our rehab hospital, was that, compared with other patients who had been critically ill with a long hospital stay, there was a significantly higher percentage of COVID-19 patients who had peripheral nerve damage,” Dr. Franz said.

The authors described 12 of these patients who were admitted between April 24 and June 30, 2020 (mean age, 60.3 years; range, 23-80 years). The sample included White, Black, and Hispanic individuals. Eleven of the 12 post–COVID-19 patients with peripheral nerve damage had experienced prone positioning during acute management.

The average number of days patients received mechanical ventilation was 33.6 (range, 12-62 days). The average number of proning sessions was 4.5 (range, 1-16) with an average of 81.2 hours (range, 16-252 hours) spent prone.

A major contributor

Dr. Franz suggested that prone positioning is likely not the only cause of peripheral nerve damage but “may play a big role in these patients who are vulnerable because of viral infection and the critical illness that causes damage and nerve injuries.”

“The first component of lifesaving care for the critically ill in the ICU is intravenous fluids, mechanical ventilation, steroids, and antibiotics for infection,” said Dr. Walter.

“We are trying to come up with ways to place patients in prone position in safer ways, to pay attention to pressure points and areas of injury that we have seen and try to offload them, to see if we can decrease the rate of these injuries,” he added.

The researchers’ article includes a heat map diagram as a “template for where to focus the most efforts, in terms of decreasing pressure,” Dr. Walter said.

“The nerves are accepting too much force for gravely ill COVID-19 patients to handle, so we suggest using the template to determine where extra padding might be needed, or a protocol that might include changes in positioning,” he added.

Dr. Franz described the interventions used for COVID-19 patients with prone positioning–related peripheral nerve damage. “The first step is trying to address the problems one by one, either trying to solve them through exercise or teaching new skills, new ways to compensate, beginning with basic activities, such as getting out of bed and self-care,” he said.

Long-term recovery of nerve injuries depends on how severe the injuries are. Some nerves can slowly regenerate – possibly at the rate of 1 inch per month – which can be a long process, taking between a year and 18 months.

Dr. Franz said that therapies for this condition are “extrapolated from clinical trial work” on promoting nerve regeneration after surgery using electrical stimulation to enable nerves to regrow at a faster rate.

“Regeneration is not only slow, but it may not happen completely, leaving the patient with permanent nerve damage – in fact, based on our experience and what has been reported, the percentage of patients with full recovery is only 10%,” he said.

The most common symptomatic complaint other than lack of movement or feeling is neuropathic pain, “which may require medication to take the edge off the pain,” Dr. Franz added.

Irreversible damage?

Commenting on the study, Tae Chung, MD, of the departments of physical medicine, rehabilitation, and neurology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said the study “provides one of the first and the largest description of peripheral nerve injury associated with prone positioning for management of ARDS from COVID-19.”

Dr. Chung, who was not involved in the research, noted that “various neurological complications from COVID-19 have been reported, and some of them may result in irreversible neurological damage or delay the recovery from COVID-19 infection,” so “accurate and timely diagnosis of such neurological complications is critical for rehabilitation of the COVID-19 survivors.”

The study received no funding. Dr. Franz, Dr. Walter, study coauthors, and Dr. Chung report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

A new case series describes peripheral nerve injuries associated with this type of positioning and suggests ways to minimize the potential damage.