User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Q&A: What to know about the new BA 2.86 COVID variant

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization have dubbed the BA 2.86 variant of COVID-19 as a variant to watch.

So far, only 26 cases of “Pirola,” as the new variant is being called, have been identified: 10 in Denmark, four each in Sweden and the United States, three in South Africa, two in Portugal, and one each the United Kingdom, Israel, and Canada. BA 2.86 is a subvariant of Omicron, but according to reports from the CDC, the strain has many more mutations than the ones that came before it.

With so many facts still unknown about this new variant, this news organization asked experts what people need to be aware of as it continues to spread.

What is unique about the BA 2.86 variant?

“It is unique in that it has more than three mutations on the spike protein,” said Purvi S. Parikh, MD, an infectious disease expert at New York University’s Langone Health. The virus uses the spike proteins to enter our cells.

This “may mean it will be more transmissible, cause more severe disease, and/or our vaccines and treatments may not work as well, as compared to other variants,” she said.

What do we need to watch with BA 2.86 going forward?

“We don’t know if this variant will be associated with a change in the disease severity. We currently see increased numbers of cases in general, even though we don’t yet see the BA.2.86 in our system,” said Heba Mostafa, PhD, director of the molecular virology laboratory at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

“It is important to monitor BA.2.86 (and other variants) and understand how its evolution impacts the number of cases and disease outcomes,” she said. “We should all be aware of the current increase in cases, though, and try to get tested and be treated as soon as possible, as antivirals should be effective against the circulating variants.”

What should doctors know?

Dr. Parikh said doctors should generally expect more COVID cases in their clinics and make sure to screen patients even if their symptoms are mild.

“We have tools that can be used – antivirals like Paxlovid are still efficacious with current dominant strains such as EG.5,” she said. “And encourage your patients to get their boosters, mask, wash hands, and social distance.”

How well can our vaccines fight BA 2.86?

“Vaccine coverage for the BA.2.86 is an area of uncertainty right now,” said Dr. Mostafa.

In its report, the CDC said scientists are still figuring out how well the updated COVID vaccine works. It’s expected to be available in the fall, and for now, they believe the new shot will still make infections less severe, new variants and all.

Prior vaccinations and infections have created antibodies in many people, and that will likely provide some protection, Dr. Mostafa said. “When we experienced the Omicron wave in December 2021, even though the variant was distant from what circulated before its emergence and was associated with a very large increase in the number of cases, vaccinations were still protective against severe disease.”

What is the most important thing to keep track of when it comes to this variant?

According to Dr. Parikh, “it’s most important to monitor how transmissible [BA 2.86] is, how severe it is, and if our current treatments and vaccines work.”

Dr. Mostafa said how well the new variants escape existing antibody protection should also be studied and watched closely.

What does this stage of the virus mutation tell us about where we are in the pandemic?

The history of the coronavirus over the past few years shows that variants with many changes evolve and can spread very quickly, Dr. Mostafa said. “Now that the virus is endemic, it is essential to monitor, update vaccinations if necessary, diagnose, treat, and implement infection control measures when necessary.”

With the limited data we have so far, experts seem to agree that while the variant’s makeup raises some red flags, it is too soon to jump to any conclusions about how easy it is to catch it and the ways it may change how the virus impacts those who contract it.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization have dubbed the BA 2.86 variant of COVID-19 as a variant to watch.

So far, only 26 cases of “Pirola,” as the new variant is being called, have been identified: 10 in Denmark, four each in Sweden and the United States, three in South Africa, two in Portugal, and one each the United Kingdom, Israel, and Canada. BA 2.86 is a subvariant of Omicron, but according to reports from the CDC, the strain has many more mutations than the ones that came before it.

With so many facts still unknown about this new variant, this news organization asked experts what people need to be aware of as it continues to spread.

What is unique about the BA 2.86 variant?

“It is unique in that it has more than three mutations on the spike protein,” said Purvi S. Parikh, MD, an infectious disease expert at New York University’s Langone Health. The virus uses the spike proteins to enter our cells.

This “may mean it will be more transmissible, cause more severe disease, and/or our vaccines and treatments may not work as well, as compared to other variants,” she said.

What do we need to watch with BA 2.86 going forward?

“We don’t know if this variant will be associated with a change in the disease severity. We currently see increased numbers of cases in general, even though we don’t yet see the BA.2.86 in our system,” said Heba Mostafa, PhD, director of the molecular virology laboratory at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

“It is important to monitor BA.2.86 (and other variants) and understand how its evolution impacts the number of cases and disease outcomes,” she said. “We should all be aware of the current increase in cases, though, and try to get tested and be treated as soon as possible, as antivirals should be effective against the circulating variants.”

What should doctors know?

Dr. Parikh said doctors should generally expect more COVID cases in their clinics and make sure to screen patients even if their symptoms are mild.

“We have tools that can be used – antivirals like Paxlovid are still efficacious with current dominant strains such as EG.5,” she said. “And encourage your patients to get their boosters, mask, wash hands, and social distance.”

How well can our vaccines fight BA 2.86?

“Vaccine coverage for the BA.2.86 is an area of uncertainty right now,” said Dr. Mostafa.

In its report, the CDC said scientists are still figuring out how well the updated COVID vaccine works. It’s expected to be available in the fall, and for now, they believe the new shot will still make infections less severe, new variants and all.

Prior vaccinations and infections have created antibodies in many people, and that will likely provide some protection, Dr. Mostafa said. “When we experienced the Omicron wave in December 2021, even though the variant was distant from what circulated before its emergence and was associated with a very large increase in the number of cases, vaccinations were still protective against severe disease.”

What is the most important thing to keep track of when it comes to this variant?

According to Dr. Parikh, “it’s most important to monitor how transmissible [BA 2.86] is, how severe it is, and if our current treatments and vaccines work.”

Dr. Mostafa said how well the new variants escape existing antibody protection should also be studied and watched closely.

What does this stage of the virus mutation tell us about where we are in the pandemic?

The history of the coronavirus over the past few years shows that variants with many changes evolve and can spread very quickly, Dr. Mostafa said. “Now that the virus is endemic, it is essential to monitor, update vaccinations if necessary, diagnose, treat, and implement infection control measures when necessary.”

With the limited data we have so far, experts seem to agree that while the variant’s makeup raises some red flags, it is too soon to jump to any conclusions about how easy it is to catch it and the ways it may change how the virus impacts those who contract it.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization have dubbed the BA 2.86 variant of COVID-19 as a variant to watch.

So far, only 26 cases of “Pirola,” as the new variant is being called, have been identified: 10 in Denmark, four each in Sweden and the United States, three in South Africa, two in Portugal, and one each the United Kingdom, Israel, and Canada. BA 2.86 is a subvariant of Omicron, but according to reports from the CDC, the strain has many more mutations than the ones that came before it.

With so many facts still unknown about this new variant, this news organization asked experts what people need to be aware of as it continues to spread.

What is unique about the BA 2.86 variant?

“It is unique in that it has more than three mutations on the spike protein,” said Purvi S. Parikh, MD, an infectious disease expert at New York University’s Langone Health. The virus uses the spike proteins to enter our cells.

This “may mean it will be more transmissible, cause more severe disease, and/or our vaccines and treatments may not work as well, as compared to other variants,” she said.

What do we need to watch with BA 2.86 going forward?

“We don’t know if this variant will be associated with a change in the disease severity. We currently see increased numbers of cases in general, even though we don’t yet see the BA.2.86 in our system,” said Heba Mostafa, PhD, director of the molecular virology laboratory at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

“It is important to monitor BA.2.86 (and other variants) and understand how its evolution impacts the number of cases and disease outcomes,” she said. “We should all be aware of the current increase in cases, though, and try to get tested and be treated as soon as possible, as antivirals should be effective against the circulating variants.”

What should doctors know?

Dr. Parikh said doctors should generally expect more COVID cases in their clinics and make sure to screen patients even if their symptoms are mild.

“We have tools that can be used – antivirals like Paxlovid are still efficacious with current dominant strains such as EG.5,” she said. “And encourage your patients to get their boosters, mask, wash hands, and social distance.”

How well can our vaccines fight BA 2.86?

“Vaccine coverage for the BA.2.86 is an area of uncertainty right now,” said Dr. Mostafa.

In its report, the CDC said scientists are still figuring out how well the updated COVID vaccine works. It’s expected to be available in the fall, and for now, they believe the new shot will still make infections less severe, new variants and all.

Prior vaccinations and infections have created antibodies in many people, and that will likely provide some protection, Dr. Mostafa said. “When we experienced the Omicron wave in December 2021, even though the variant was distant from what circulated before its emergence and was associated with a very large increase in the number of cases, vaccinations were still protective against severe disease.”

What is the most important thing to keep track of when it comes to this variant?

According to Dr. Parikh, “it’s most important to monitor how transmissible [BA 2.86] is, how severe it is, and if our current treatments and vaccines work.”

Dr. Mostafa said how well the new variants escape existing antibody protection should also be studied and watched closely.

What does this stage of the virus mutation tell us about where we are in the pandemic?

The history of the coronavirus over the past few years shows that variants with many changes evolve and can spread very quickly, Dr. Mostafa said. “Now that the virus is endemic, it is essential to monitor, update vaccinations if necessary, diagnose, treat, and implement infection control measures when necessary.”

With the limited data we have so far, experts seem to agree that while the variant’s makeup raises some red flags, it is too soon to jump to any conclusions about how easy it is to catch it and the ways it may change how the virus impacts those who contract it.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

ADHD in older adults: A closer look

For many years, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was thought of as a disorder of childhood; however, it is now increasingly being recognized as a chronic, lifelong disorder that persists into adulthood in approximately two-thirds of patients.1 While our knowledge about ADHD in adults has increased, most research in this population focused on young or middle-aged adults; less is known about ADHD in older adults. Older adults with ADHD may be newly diagnosed at any point in their lives, or not at all.2 Because ADHD may present differently in older adults than in children or young adults, and because it may impair domains of life in different ways, a closer look at late-life ADHD is needed. This article summarizes the literature on the prevalence, impairment, diagnosis, and treatment of ADHD in adults age >60.

Challenges in determining the prevalence

Few studies have examined the age-specific prevalence of ADHD among older adults.3 Compared with childhood ADHD, adult ADHD is relatively neglected in epidemiological studies, largely due to the absence of well-established, validated diagnostic criteria.1,4 Some experts have noted that DSM-5’s ADHD criteria were designed for diagnosing children, and the children-focused symptom threshold may not be useful for adults because ADHD symptoms decline substantially with age.2 One study evaluating DSM-5 ADHD criteria in young adults (N = 4,000, age 18 to 19) found ADHD was better diagnosed when the required number of clinically relevant inattention and hyperactivity symptoms was reduced from 6 to 5 for each category.5 They also found the DSM-5 age-at-onset criterion of symptoms present before age 12 had a significant effect on ADHD prevalence, reducing the rate from 23.7% (95% CI, 22.38 to 25.02) to 5.4% (95% CI, 13.99 to 16.21).5 This suggests that strict usage of DSM-5 criteria may underestimate the prevalence of ADHD in adults, because ADHD symptoms may not be detected in childhood, or self-reporting of childhood ADHD symptoms in older adults may be unreliable due to aging processes that compromise memory and recall. These findings also indicate that fewer ADHD symptoms are needed to impair functioning in older age.

Determining the prevalence of ADHD among older adults is further complicated by individuals who report symptoms consistent with an ADHD diagnosis despite having never received this diagnosis during childhood.6-8 This may be due to the considerable number of children who meet ADHD criteria but do not get a diagnosis due to limited access to health care.9 Thus, many studies separately analyze the syndromatic (with a childhood onset) and symptomatic (regardless of childhood onset) persistence of ADHD. One epidemiological meta-analysis found the 2020 prevalence of syndromatic ADHD in adults age >60 was 0.77% and the prevalence of symptomatic ADHD was 4.51%, which translates to 7.91 million and 46.36 million affected older adults, respectively.8 Other research has reported higher rates among older adults.6,7,10 The variations among this research may be attributed to the use of different diagnostic tools/criteria, study populations, sampling methods, or DSM versions. Heterogeneity among this research also further supports the idea that the prevalence of ADHD is heavily dependent on how one defines and diagnoses the disorder.

Reasons for late-life ADHD diagnosis

There are many reasons a patient may not be diagnosed with ADHD until they are an older adult.11 In addition to socioeconomic barriers to health care access, members of different ethnic groups exhibit differences in help-seeking behaviors; children may belong to a culture that does not traditionally seek health care even when symptoms are evident.6,9 Therefore, individuals may not receive a diagnosis until adulthood. Some experts have discussed the similarity of ADHD to other neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder or social communication disorder, where ADHD symptoms may not manifest until stressors at critical points in life exceed an individual’s capacity to compensate.2

The life transition model contextualizes ADHD as being associated with demand/resource imbalances that come and go throughout life, resulting in variability in the degree of functional impairment ADHD symptoms cause in older adults.2,12 Hypothetically, events in late life—such as the death of a spouse or retirement—can remove essential support structures in the lives of high-functioning individuals with ADHD. As a result, such events surpass these individuals’ ability to cope, resulting in a late-life manifestation of ADHD.

The plausibility of late-onset ADHD

In recent years, many studies identifying ADHD in adults have been published,2,10,12-15 including some that discuss adult ADHD that spontaneously appears without childhood symptoms (ie, late-onset ADHD).2,4,12 Research of late-onset ADHD attracts attention because the data it presents challenge the current rationale that ADHD symptoms should be present before age 12, as defined by DSM-5 criteria. While most reports of late-onset ADHD pertain to younger adults, little evidence exists to reinforce the concept; to date just 1 study has reported cases of late-onset ADHD in older adults (n = 7, age 51 to 59).11 In this study, Sasaki et al11 acknowledged the strong possibility their cases may be late manifestations of long-standing ADHD. Late-onset ADHD is further challenged by findings that 95% of individuals initially diagnosed with late-onset ADHD can be excluded from the diagnosis with further detailed assessment that accounts for co-occurring mental disorders and substance use.16 This suggests false positive cases of late-onset ADHD may be a symptom of narrow clinical assessment that fails to encompass other aspects of a patient’s psychiatric profile, rather than an atypical ADHD presentation.

Comorbidity and psychosocial functioning

ADHD symptoms and diagnosis in older adults are associated with clinically relevant levels of depression and anxiety. The Dutch Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA) examined 1,494 older adults (age 55 to 85) using the Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults version 2.0.10 The 231 individuals identified as having symptoms of ADHD reported clinically relevant levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms. ADHD was significantly associated with these comorbid symptoms.

Continue to: Little is known regarding...

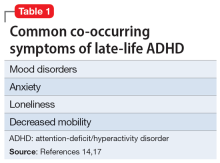

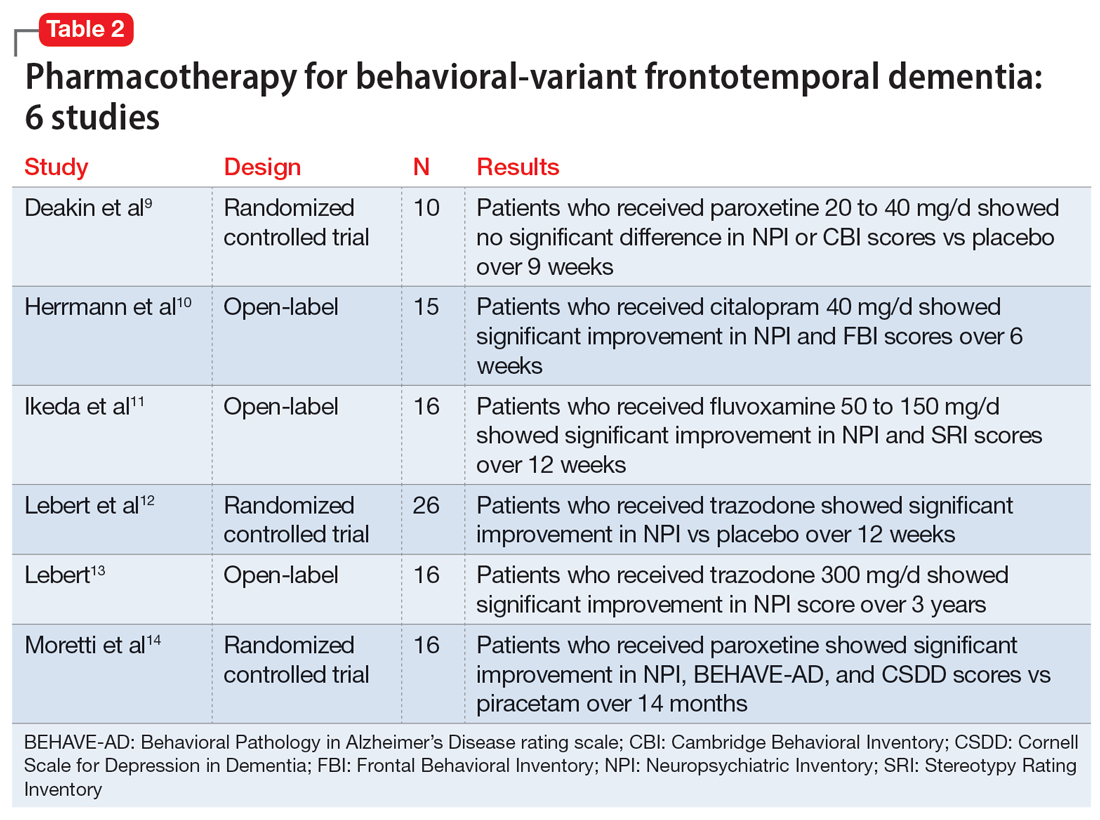

Little is known regarding the manifestation of symptoms of ADHD in older age and the difficulties these older adults face. Older adults with ADHD are more often divorced and report more loneliness than older adults without this disorder, which suggests loneliness in older age may be more pressing for the older ADHD population.17 ADHD in older adults has also been associated with poor quality-of-life measures, including moderate to severe problems in mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression (Table 114,17).

Qualitative research has described a domino effect of a lifetime of living with ADHD. In one American study, older adults with ADHD (N = 24, age 60 to 74) reported experiencing a tangible, accumulated impact from ADHD on their finances and long-term relationships with family, friends, and coworkers.13 Another study utilizing the Dutch LASA data examined how ADHD may impact patient’s lives among participants who were unaware of their diagnosis.18 One-half of patients reported low self-esteem, overstepping boundaries, and feeling different from others. When compared to younger adults with ADHD, older adults report significantly greater impairments in productivity and a worse life outlook.19

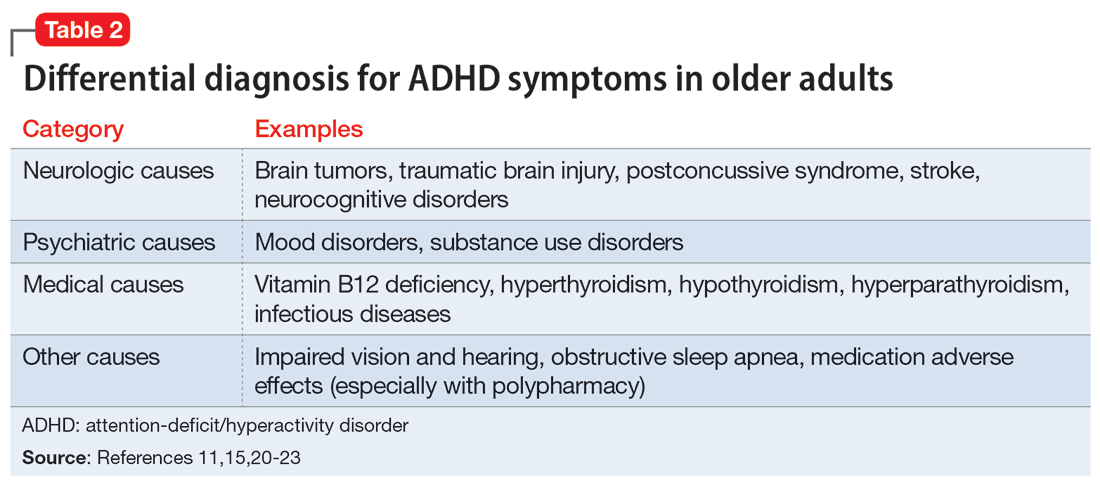

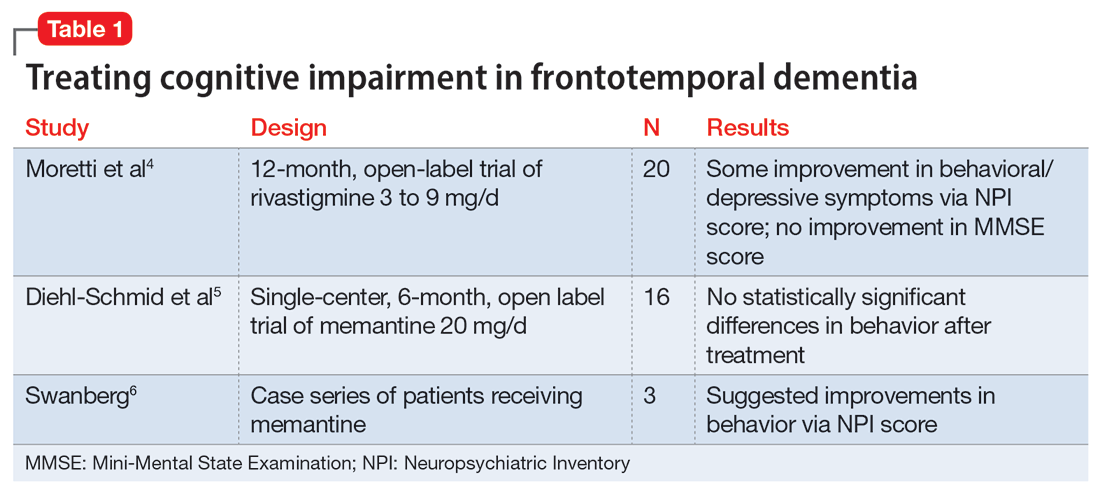

Differential diagnosis

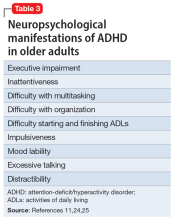

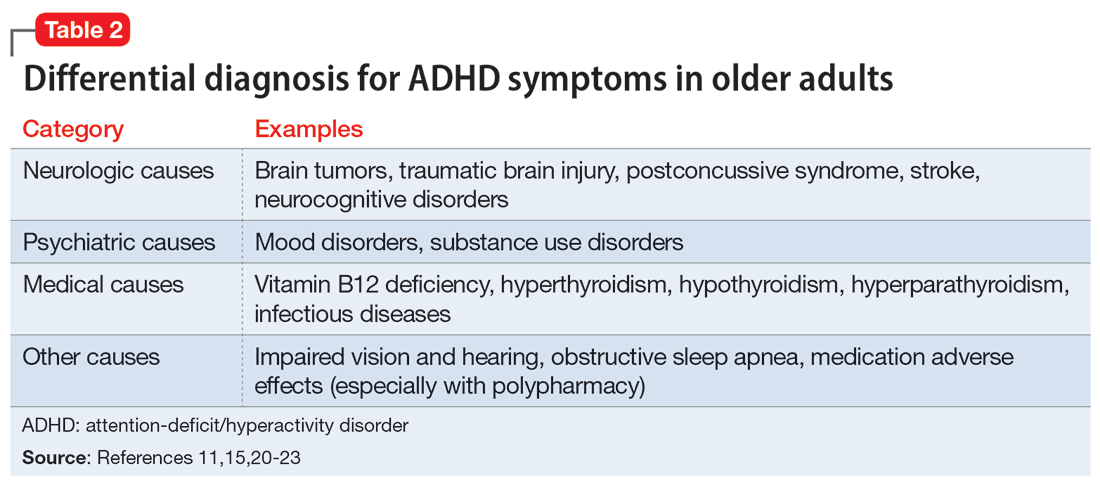

When assessing whether an older adult has ADHD, it is important to consider other potential causes of their symptoms (Table 211,15,20-23). The differential diagnosis includes impaired vision and hearing as well as medical illness (vitamin B12 deficiency, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, and infectious diseases such as herpes simplex virus or syphilis).

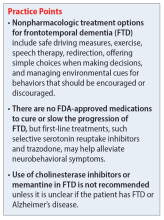

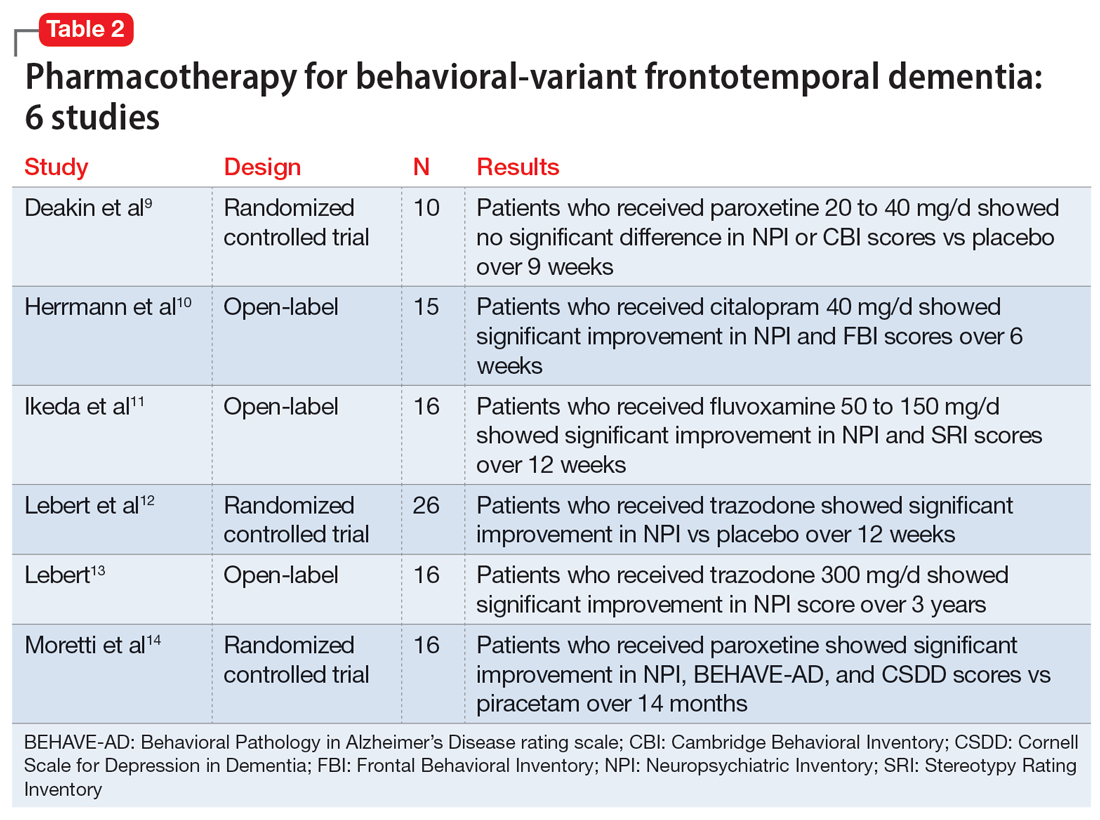

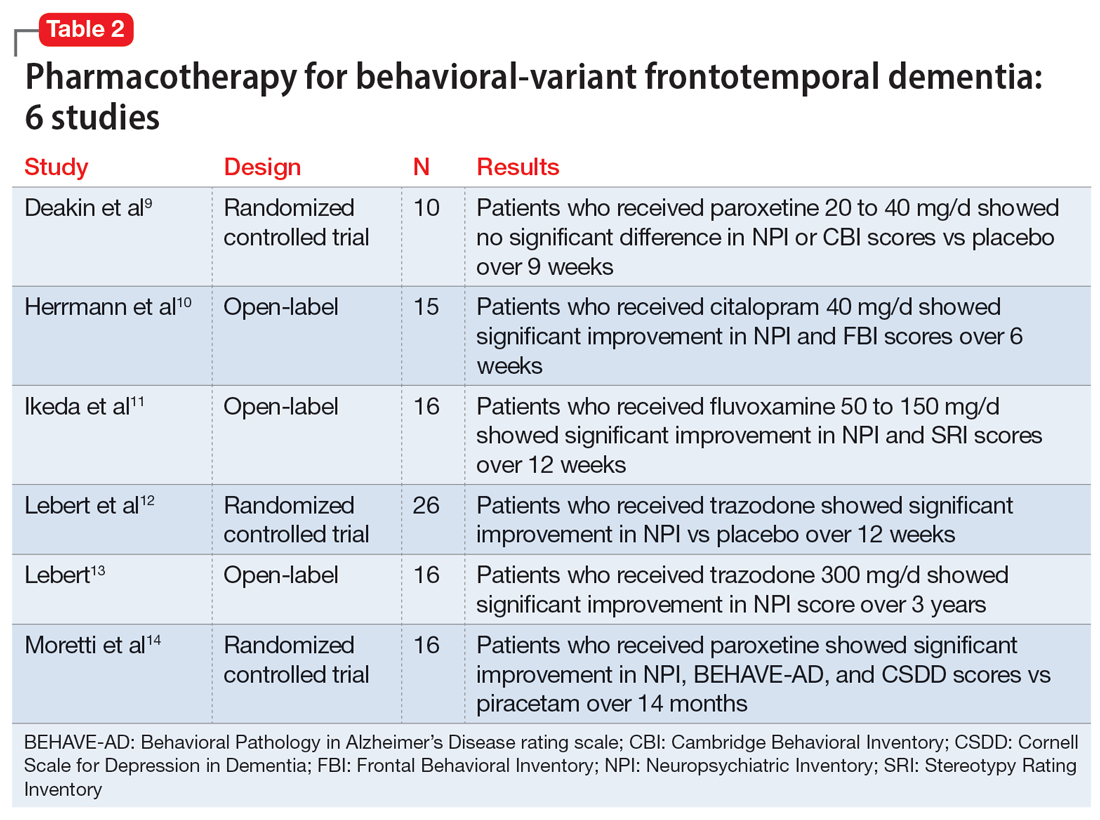

In older adults, ADHD symptoms include frontal-executive impairments, inattentiveness, difficulty with organization or multitasking, forgetfulness, and challenges involving activities of daily living or socialization that can appear to be a mild or major neurocognitive disorder (Table 311,24,25). This includes major neurocognitive disorder due to Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body disease, and vascular disease.2,26 However, frontotemporal lobar degeneration is reported to have more symptom overlap with ADHD.21,22,26,27 A way to differentiate between neurocognitive disorders and ADHD in older adults is to consider that patients with neurocognitive disorders often progress to visual hallucinations and more extreme personality changes than would be expected in ADHD.11 Each disease also has its own identifiable characteristics. Extreme changes in memory are often Alzheimer’s disease, personality changes suggest frontotemporal lobar degeneration, stepwise decline is classic for vascular disease, and parkinsonian features may indicate dementia with Lewy bodies.21 In addition, the onset of ADHD usually occurs in childhood and can be traced throughout the lifespan,2 whereas neurocognitive diseases usually appear for the first time in later life.2,28 There are nuances in the nature of forgetfulness that can distinguish ADHD from neurocognitive disorders. For instance, the forgetfulness in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease involves “the lack of episodic memories,” while in contrast ADHD is thought to be “forgetfulness due to inadvertence.”11 Furthermore, patients with neurocognitive disorders are reported to have more severe symptoms and an inability to explain why, whereas those with ADHD have a steady level of symptoms and can provide a more comprehensive story.24 Two recent studies have shown that weak performance on language tests is more indicative of a neurodegenerative process than of ADHD.29,30 Research has suggested that if an older adult shows a sudden, acute onset of ADHD-like symptoms, this is most likely reflective of cognitive decline or a mood disorder such as depression.2,15,24

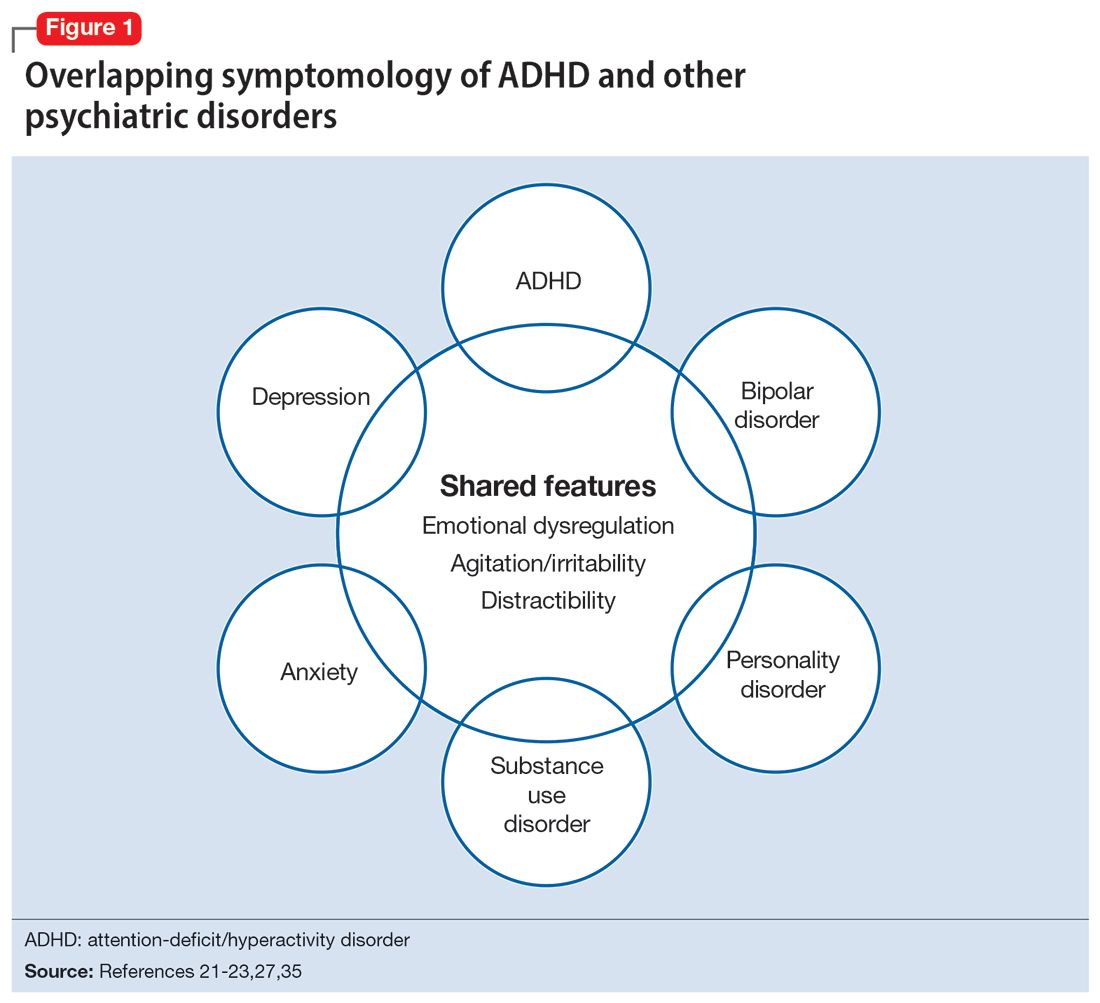

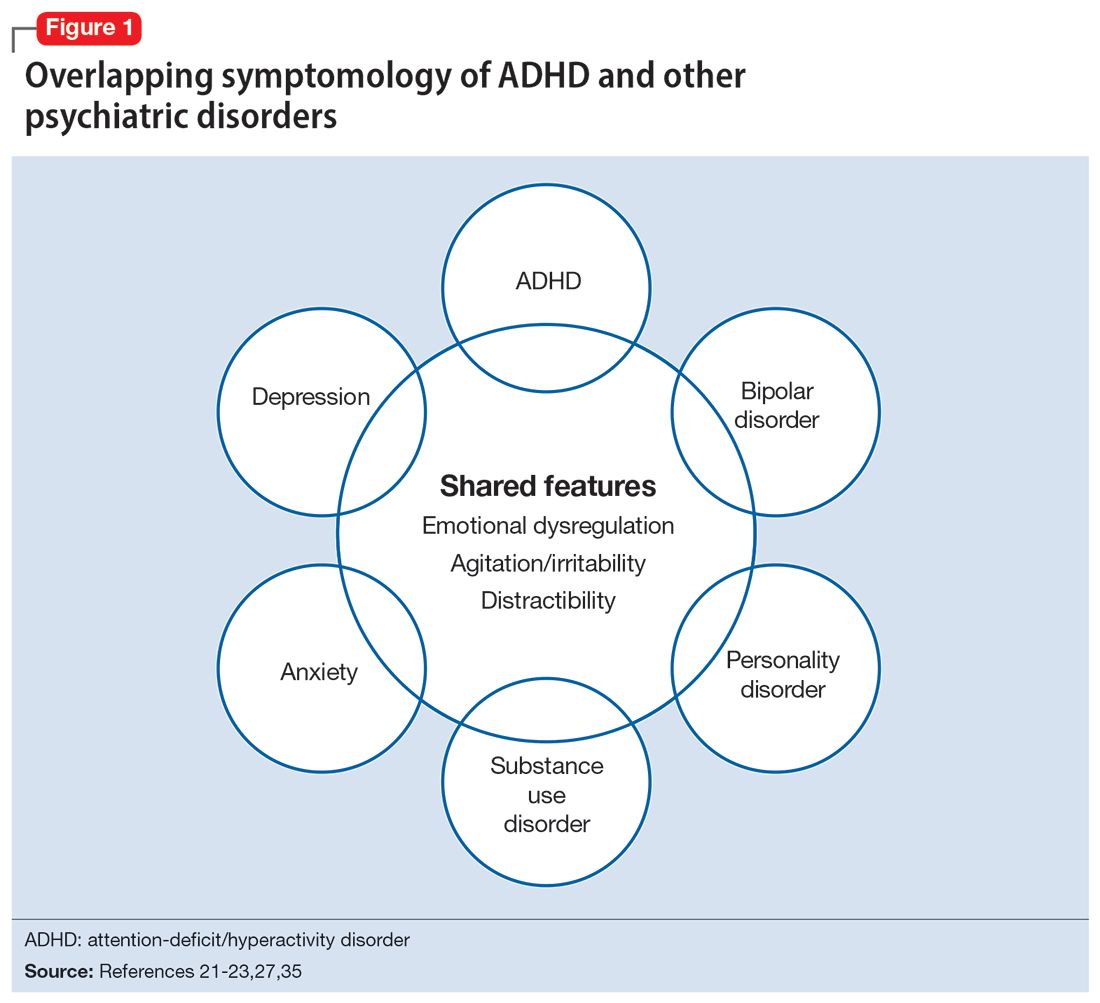

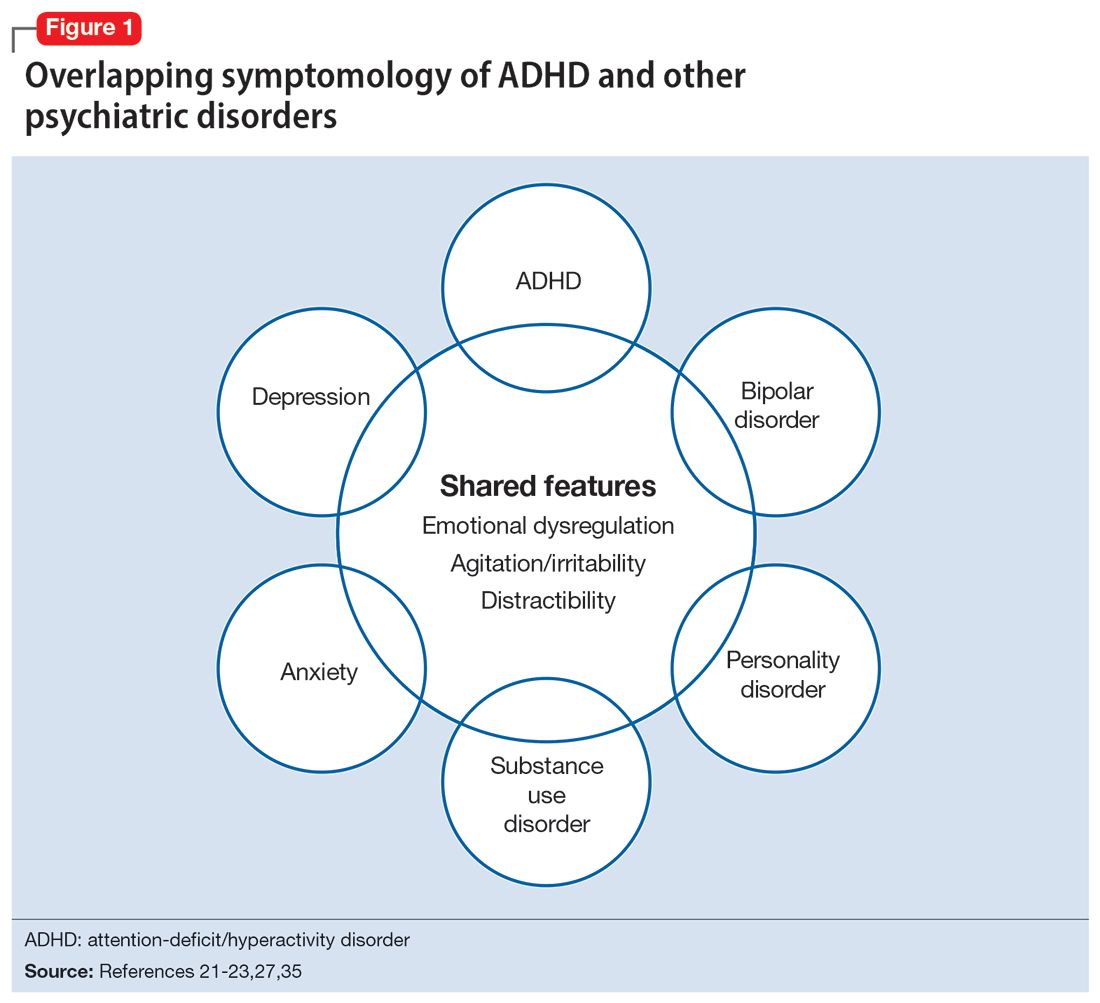

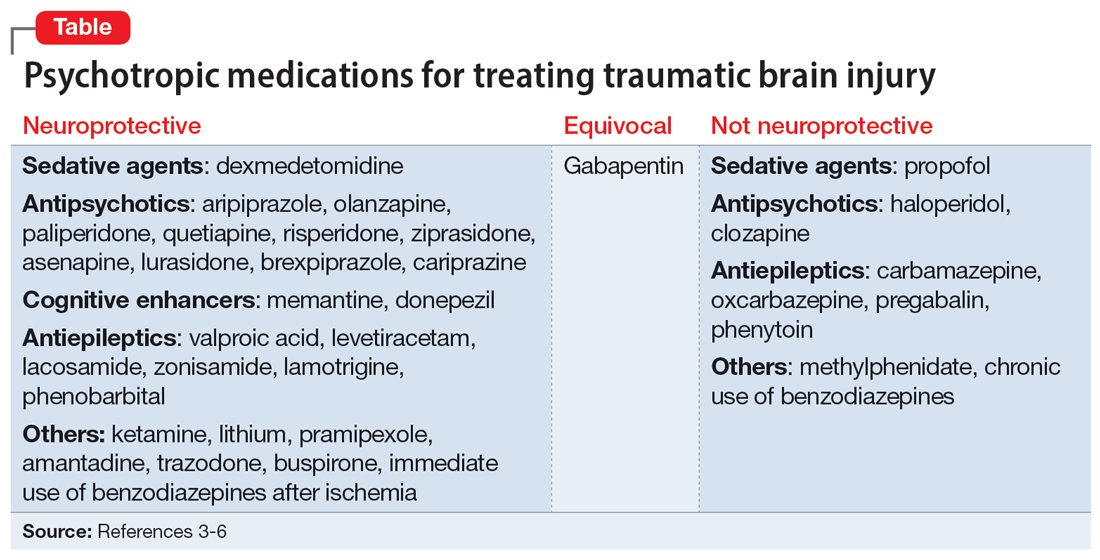

Several other psychiatric conditions share many symptoms with ADHD. Overlapping symptomology between ADHD and mood and anxiety disorders presents challenges.27 Emotional dysregulation is a feature of adult ADHD, and this often causes a mood disorder to be diagnosed without considering other possible explanations.21,22,27,31-34 Features of mania can overlap with ADHD symptoms, including psychomotor agitation, talkativeness, and distractibility.27 Several other disorders also include distractibility, such as depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders.35 Depression and anxiety can be an outcome of untreated ADHD, or can co-occur with ADHD.21-23,27 ADHD can also co-occur with bipolar disorder (BD), substance use disorders, and personality disorders (borderline and antisocial personality disorder) (Figure 121-23,27,35). One suggested method of establishing an appropriate diagnosis is to study the efficacy of the treatment retrospectively. For example, if a patient is presumed to have depression and they do not respond to several selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, this may be undetected ADHD.27 In addition, the argument about the chronicity of the symptoms should also be considered. ADHD symptoms are pervasive whereas BD symptoms are episodic.35 Depression can be chronic; however, there are often discrete major depressive episodes. It is important to have a clear timeline of the patient’s symptoms. Ask about age of onset, because in theory, ADHD is supposed to start in childhood.22 It is sometimes difficult to ascertain this information because many older adults grew up during a time where ADHD was not a recognized diagnosis.21

Continue to: Diagnosis and workup

Diagnosis and workup

The key aspects of diagnosing ADHD are the interview based on DSM-5 criteria, exclusion of other diagnoses, and collateral information. Research has shown that clinical interviews and longitudinal family histories provide critical information that can differentiate ADHD from other psychiatric conditions.35 DSM-5 criteria are adjusted for adults: 5 out of 9 criteria for inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity must be fulfilled, as opposed to 6 out of 9 in children age <17.21,31,36 However, no criteria are specific for older adults.37 Since the differential diagnosis involves multiple entities, it is important to follow DSM-5 criteria for ADHD, which include eliminating other conditions that can explain these symptoms.15 Additionally, in DSM-5, the age-of-onset threshold for ADHD diagnosis was increased from 7 and younger to 12 and younger, addressing criticism that the previous cutoff was too restrictive.24,31 The age of onset of childhood symptoms can be challenging to verify in older adults. Older patients can have unreliable memories and their childhood records are not always available.2,20 In this population, childhood symptoms are mainly underreported but sometimes overreported.10,38 However, to establish a diagnosis, the patient should have experienced some symptoms of the disorder within their first 50 years of life, including having impaired functionality in multiple settings.15,26 The goal is to establish the chronicity of this condition to distinguish it from other psychiatric conditions.22 Overall, using DSM-5 criteria without any modifications may lead to underdiagnosis of ADHD in adults.23 At this time, however, DSM-5 remains the main criteria used to make a diagnosis.

While tools to assist in screening and diagnosing ADHD have been validated in adults, none have been validated specifically for older adults.22 Structured diagnostic interviews to diagnose ADHD include39:

- Adult ADHD Clinical Diagnostic Scale version 1.2

- ADHD Lifespan Functioning interview

- Conners’ Adult ADHD Diagnostic interview for DSM-IV

- Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults version 2.0

- Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5.

ADHD symptom measures that can be used for screening and to look at treatment response include39:

- ADHD Rating Scale 5

- Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale Symptom Checklist

- Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale IV

- Barkley Quick-Check for Adult ADHD Diagnosis

- Young ADHD Questionnaire

- RATE Scales.

Adult ADHD inventories consider problems that adults with ADHD face. These include39:

- Brown Attention Deficit Disorders Scales—Adult version

- Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales

- Wender-Reimherr Adult Attention Deficit Disorder Scale.

Since these scales were not designed for older adults, they may miss nuances in this population.40

Continue to: It can be particularly...

It can be particularly perplexing to diagnose ADHD in older adults because the other possible causes of the symptoms are vast. During the interview, it is important to ask questions that may rule out other psychiatric, neurologic, and medical conditions.21 Screen for other diagnoses, and include questions about a patient’s sleep history to rule out obstructive sleep apnea.21 To screen for other psychiatric conditions, the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview 5.0.0 may be used.22 Other tools include the Saint Louis University AMSAD screen for depression, the Geriatric Depression Scale, and the Beck Anxiety Inventory.28,41 To screen for cognitive functioning, the Saint Louis University Mental Status Exam, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, or Mini-Mental State Examination can be used.22,28,42,43 Once screening is performed, a physical and neurologic examination is the best next step.26 Additionally, laboratory data and imaging can rule out other conditions; however, these are not routinely performed to diagnose ADHD.

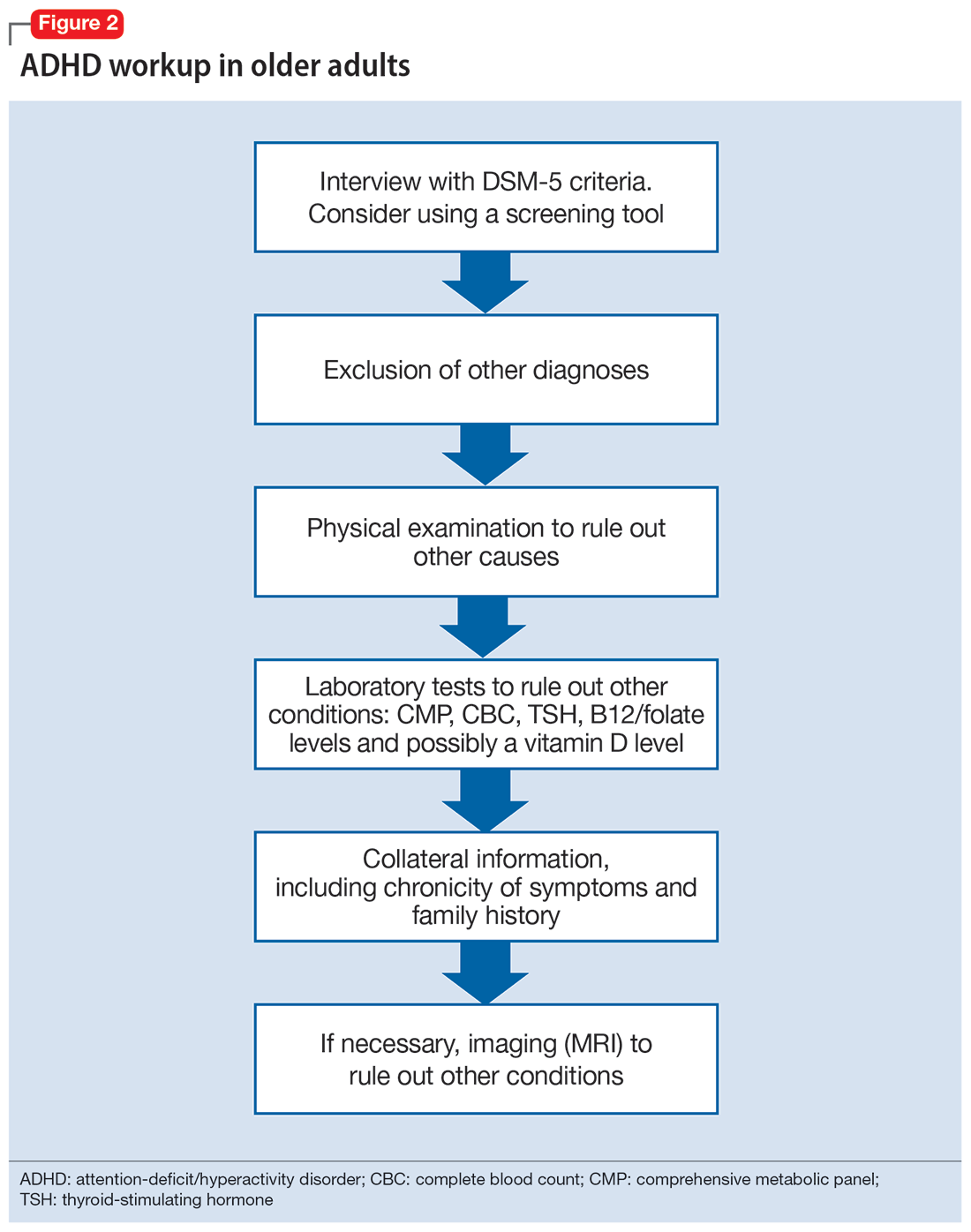

Laboratory tests should include a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone level, B12/folate level, and possibly a vitamin D level.11,36 These tests cover several conditions that may mimic ADHD. Brain MRI is not routinely recommended for diagnosing ADHD, though it may be useful because some research has found brain structural differences in individuals with ADHD.28,44,45 Neurocognitive disorders have notable MRI findings that distinguish them from ADHD and each other.24 If there is significant concern for neurocognitive disorders, more specific tests can be employed, such as CSF studies, to look for phosphorylated tau and beta amyloid markers.11

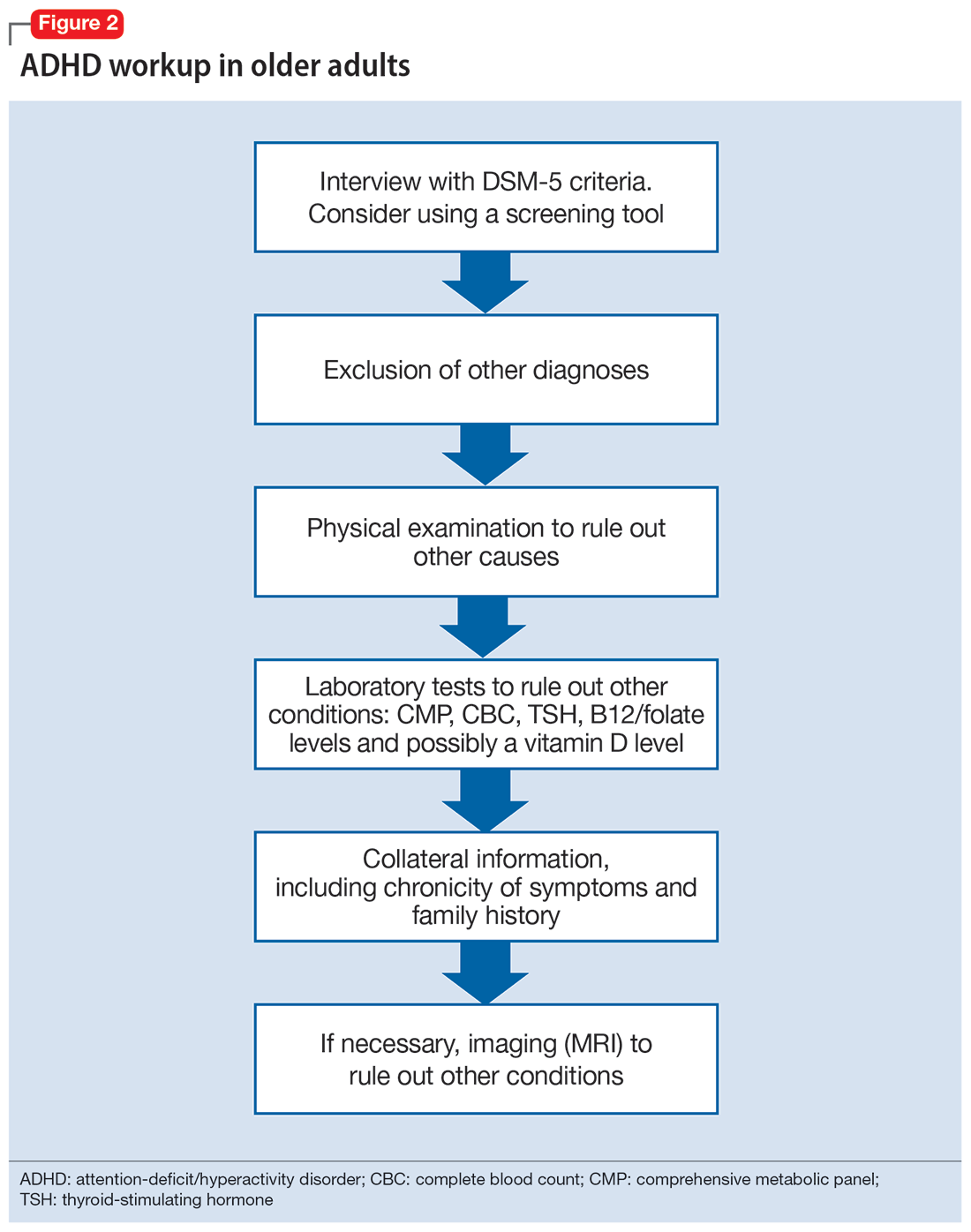

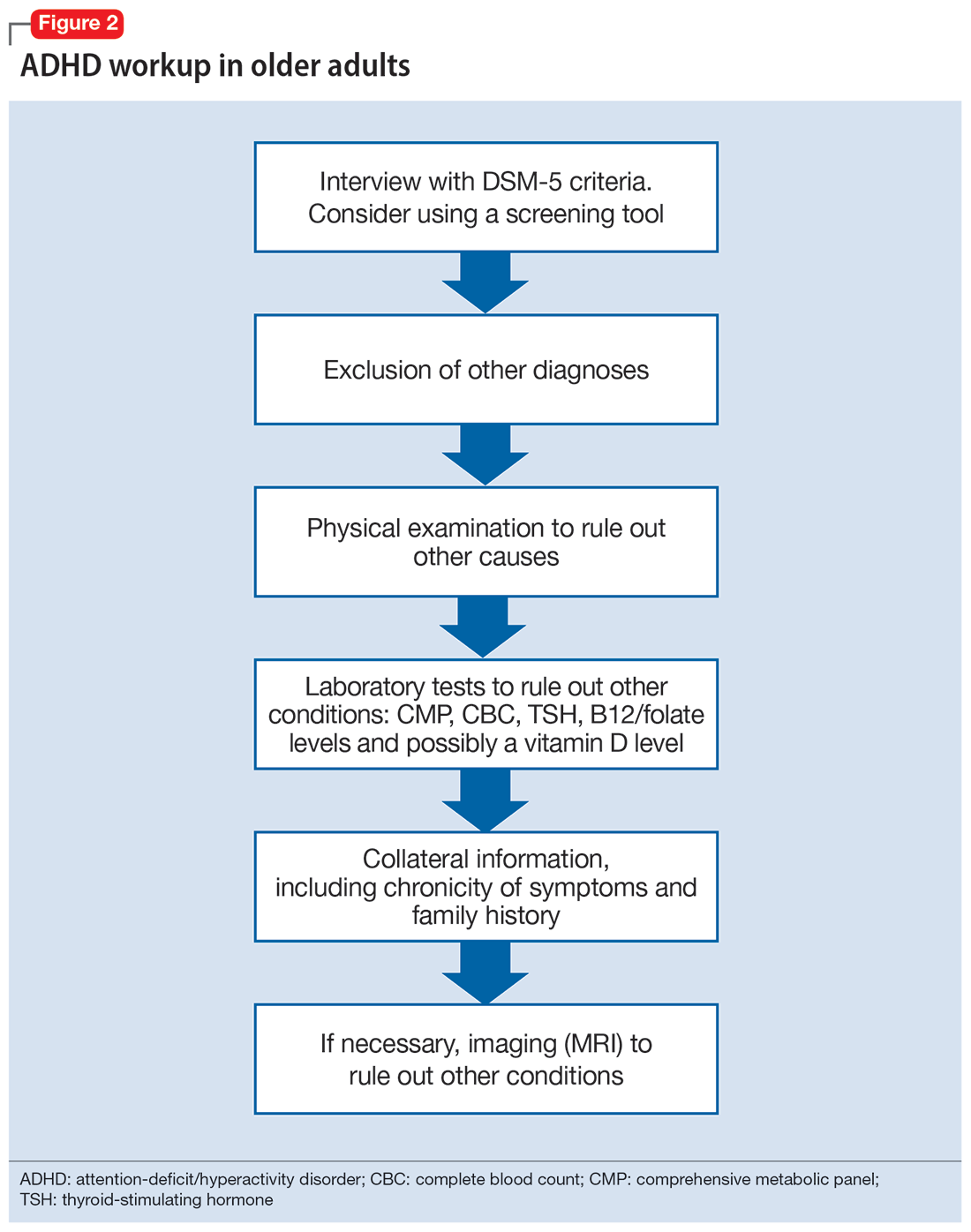

Ask about family history (first-degree relative with ADHD) and obtain collateral information to make sure no other diagnoses are overlooked. Family history can help diagnose this disorder in older adults because there is evidence that ADHD runs in families.2,25 This evidence would ideally come from someone who has known the patient their entire life, such as a sibling or parent.24 The collateral information will be especially helpful to discern the chronicity of the patient’s symptoms, which would point toward a diagnosis of ADHD. To summarize (Figure 2):

- obtain a thorough interview that may be supported by a screening tool

- rule out other conditions

- conduct a physical examination

- obtain laboratory results

- collect collateral information

- obtain neuroimaging if necessary.

Treatment

ADHD symptoms can be treated with medications and psychotherapy. Research has shown the efficacy of ADHD medications in older adults, demonstrating that treatment leads to better functioning in multiple settings and decreases the risk for developing comorbid psychiatric conditions (mood disorder, substance use disorders).25,27 Symptoms that improve with medication include attention, concentration, self-efficacy, functioning, self-esteem, psychomotor agitation, mood, energy, and procrastination.21,31,46 If a patient with ADHD also has other psychiatric diagnoses, treat the most impairing disorder first.22 This often means mood disorders and substance use disorders must be remedied before ADHD is treated.21

Medication options include stimulants and nonstimulants. First-line treatments are stimulant medications, including methylphenidate, amphetamines, and mixed amphetamine salts.12,22,27,31,35 Stimulants have shown significant efficacy in older adults, although the American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria list stimulants as potentially inappropriate for older adults.33 Adults show significant improvement with methylphenidate.21,23,47 In an observational study, Michielsen et al46 found stimulants were safe and efficacious in older adults if patients are carefully monitored for adverse effects, especially cardiovascular changes. Second-line treatments include the nonstimulant atomoxetine.12,22,27,31 Clonidine and guanfacine are FDA-approved for treating ADHD in children, but not approved for adults.26 There is little evidence for other treatments, such as bupropion.12,22,27 All of these medications have adverse effects, which are especially important to consider in older adults, who experience age-related physiological changes.

Continue to: Medications for ADHD symptoms...

Medications for ADHD symptoms are thought to act via catecholaminergic mechanisms.21 As a result, adverse effects of stimulants can include headache, appetite suppression, nausea, difficulty sleeping, tremor, blurred vision, agitation, psychosis, increased heart rate, arrhythmia, and hypertension.22,27,32-34 Especially in older adults, adverse effects such as reduced appetite, disrupted sleep, or increased blood pressure or heart rate may be harmful.21,23 Using caffeine or pseudoephedrine can exacerbate these adverse effects.21 Atomoxetine’s adverse effects include appetite suppression, insomnia, dizziness, anxiety, agitation, fatigue, dry mouth, constipation, nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, and increased heart rate or blood pressure.27,32,35 Genitourinary adverse effects have also been reported, including priapism (rare), decreased libido, and urinary hesitancy and retention.26,32 Before any medication is initiated, it is important to conduct a physical and neurologic examination and a detailed clinical interview.

Before starting medication, as with any medical treatment, conduct a risk vs benefit analysis. Record baseline values for the patient’s heart rate, blood pressure, and weight.23,26,27,31 During the interview, screen for family and personal cardiovascular conditions,27,33 and obtain an electrocardiogram for any patient with cardiovascular risks.23,26,27,31 Once the patient is deemed to be an appropriate candidate for pharmacologic treatment, begin with low doses and titrate the medication slowly until reaching a therapeutic level.23,48

Medications should be combined with psychotherapy (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy or dialectical behavioral therapy) and other lifestyle changes (exercise, mindfulness, support groups).18,22,23,27,31,49 Psychotherapy can help patients come to terms with receiving an ADHD diagnosis later in life and help with organization and socialization.12,50 Pharmacologic treatments are thought to be helpful with attention challenges and emotional instability.50 Taken together, medications and behavioral interventions can help individuals experience an improved quality of life.

Future directions

Given the relatively recent interest in ADHD in older adults, there are several areas that need further research. For future editions of DSM, it may be prudent to consider establishing ADHD criteria specific to older adults. Research has also shown the need for clear diagnostic and validated tools for older adults.8 Few analyses have been undertaken regarding pharmacotherapy for this population. Randomized controlled clinical trials are needed.23,37,48 More research about the relative utility of psychotherapy and behavioral interventions would also be useful, given their potential to improve the quality of life for older adults with ADHD.

Bottom Line

Although generally thought of as a disorder of childhood, attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has substantial effects in older adults. When the condition is appropriately diagnosed, pharmacologic treatment and psychotherapy are associated with improved quality of life for older patients with ADHD.

Related Resources

- Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Living with ADHD: A lifespan disorder. https://chadd.org/for-adults/living-with-adhd-a-lifespan-disorder/

- Attention Deficit Disorder Association. Support groups for adults. https://add.org/adhd-support-groups/

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine/dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Atomoxetine • Straterra

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Clonidine • Catapres

Guanfacine • Intuniv

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

1. Sibley MH, Mitchell JT, Becker SP. Method of adult diagnosis influences estimated persistence of childhood ADHD: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(12):1157-1165. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30190-0

2. Sharma MJ, Lavoie S, Callahan BL. A call for research on the validity of the age-of-onset criterion application in older adults being evaluated for ADHD: a review of the literature in clinical and cognitive psychology. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(7):669-678. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2020.10.016

3. Biederman J, Petty CR, Evans M, et al. How persistent is ADHD? A controlled 10-year follow-up study of boys with ADHD. Psychiatry Res. 2010;177(3):299-304. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.12.010

4. McGough JJ, Barkley RA. Diagnostic controversies in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):1948-1956. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.1948

5. Matte B, Anselmi L, Salum GA, et al. ADHD in DSM-5: a field trial in a large, representative sample of 18- to 19-year-old adults. Psychol Med. 2015;45(2):361-373. doi:10.1017/S0033291714001470

6. Chung W, Jiang SF, Paksarian D, et al. Trends in the prevalence and incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults and children of different racial and ethnic groups. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1914344. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14344

7. Guldberg-Kjär T, Johansson B. Old people reporting childhood AD/HD symptoms: retrospectively self-rated AD/HD symptoms in a population-based Swedish sample aged 65-80. Nord J Psychiatry. 2009;63(5):375-382. doi:10.1080/08039480902818238

8. Song P, Zha M, Yang Q, et al. The prevalence of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2021;11:04009. doi:10.7189/jogh.11.04009

9. Russell AE, Ford T, Williams R, et al. The association between socioeconomic disadvantage and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2016;47(3):440-458. doi:10.1007/s10578/-015-0578-3

10. Michielsen M, Semeijn E, Comijs HC, et al. Prevalence of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in older adults in The Netherlands. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201(4):298-305. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.111.101196

11. Sasaki H, Jono T, Fukuhara R, et al. Late-manifestation of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in older adults: an observational study. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):354. doi:10.1186/s12888-022-03978-0

12. Turgay A, Goodman DW, Asherson P, et al. Lifespan persistence of ADHD: the life transition model and its application. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(2):192-201. doi:10.4088/JCP.10m06628

13. Brod M, Schmitt E, Goodwin M, et al. ADHD burden of illness in older adults: a life course perspective. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(5):795-799. doi:10.1007/s1136-011-9981-9

14. Thorell LB, Holst Y, Sjöwall D. Quality of life in older adults with ADHD: links to ADHD symptom levels and executive functioning deficits. Nord J Psychiatry. 2019;73(7):409-416. doi:10.1080/08039488.2019.1646804

15. Sibley MH. Diagnosing ADHD in older adults: critical next steps for research. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(7):679-681. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2020.11.012

16. Sibley MH, Rohde LA, Swanson JM, et al. Late-onset ADHD reconsidered with comprehensive repeated assessments between ages 10 and 25. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(2):140-149. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17030298

17. Michielsen M, Comijs HC, Aartsen MJ, et al. The relationships between ADHD and social functioning and participation in older adults in a population-based study. J Atten Disord. 2015;19(5):368-379. doi:10.1177/1087054713515748

18. Michielsen M, de Kruif JTCM, Comijs HC, et al. The burden of ADHD in older adults: a qualitative study. J Atten Disord. 2018;22(6):591-600. doi:10.1177/1087054715610001

19. Lensing MB, Zeiner P, Sandvik L, et al. Quality of life in adults aged 50+ with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2015;19(5):405-413. doi:10.1177/1087054713480035

20. Fischer BL, Gunter-Hunt G, Steinhafel CH, et al. The identification and assessment of late-life ADHD in memory clinics. J Atten Disord. 2012;16(4):333-338. doi:10.1177/1087054711398886

21. Goodman DW, Mitchell S, Rhodewalt L, et al. Clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in older adults: a review of the evidence and its implications for clinical care. Drugs Aging. 2016;33(1):27-36. doi:10.1007/s40266-015-0327-0

22. Kooij JJ, Michielsen M, Kruithof H, et al. ADHD in old age: a review of the literature and proposal for assessment and treatment. Expert Rev Neurother. 2016;16(12):1371-1381. doi:10.1080/14737175.2016.1204914

23. Torgersen T, Gjervan B, Lensing MB, et al. Optimal management of ADHD in older adults. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:79-87. doi:10.2147/NDT.S59271

24. Callahan BL, Bierstone D, Stuss DT, et al. Adult ADHD: risk factor for dementia or phenotypic mimic? Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:260. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2017.00260

25. Mendonca F, Sudo FK, Santiago-Bravo G, et al. Mild cognitive impairment or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in older adults? A cross sectional study. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:737357. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.737357

26. De Crescenzo F, Cortese S, Adamo N, et al. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment of adults with ADHD: a meta-review. Evid Based Ment Health. 2017;20(1):4-11. doi:10.1136/eb-2016-102415

27. Katzman MA, Bilkey TS, Chokka PR, et al. Adult ADHD and comorbid disorders: clinical implications of a dimensional approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):302. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1463-3

28. Klein M, Silva MA, Belizario GO, et al. Longitudinal neuropsychological assessment in two elderly adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: case report. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1119. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01119

29. Prentice JL, Schaeffer MJ, Wall AK, et al. A systematic review and comparison of neurocognitive features of late-life attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and dementia with Lewy bodies. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2021;34(5):466-481. doi:10.1177/0891988720944251

30. Callahan BL, Ramakrishnan N, Shammi P, et al. Cognitive and neuroimaging profiles of older adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder presenting to a memory clinic. J Atten Disord. 2022;26(8):1118-1129. doi:10.1177/10870547211060546

31. Ramos-Quiroga, JA, Nasillo V, Fernández-Aranda, et al. Addressing the lack of studies in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. Expert Rev Neurother. 2014;14(5):553-567. doi:10.1586/14737175.2014.908708

32. Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology: Prescriber’s Guide. 6th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2017.

33. Latronica JR, Clegg TJ, Tuan WJ, et al. Are amphetamines associated with adverse cardiovascular events among elderly individuals? J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(6):1074-1081. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2021.06.210228

34. Garcia-Argibay M, du Rietz E, Lu Y, et al. The role of ADHD genetic risk in mid-to-late life somatic health conditions. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12(1):152. doi:10.1038/s41398-022-01919-9

35. Jain R, Jain S, Montano CB, Addressing diagnosis and treatment gaps in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2017;19(5):17nr02153. doi:10.4088/PCC.17nr02153

36. Sasaki H, Jono T, Fukuhara R, et al. Late-onset attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder as a differential diagnosis of dementia: a case report. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):550. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02949-7

37. Surman CBH, Goodman DW. Is ADHD a valid diagnosis in older adults? Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2017;9(3):161-168. doi:10.1007/s12402-017-0217-x

38. Semeijn EJ, Michielsen M, Comijs HC, et al. Criterion validity of an attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) screening list for screening ADHD in older adults aged 60-94 years. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(7):631-635. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2012.08.003

39. Ramsay JR. Assessment and monitoring of treatment response in adult ADHD patients: current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:221-232. doi:10.2147/NDT.S104706

40. Das D, Cherbuin N, Easteal S, et al. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and cognitive abilities in the late-life cohort of the PATH through life study. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86552. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086552

41. Kaya D, Isik AT, Usarel C, et al. The Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination is better than the Mini-Mental State Examination to determine the cognitive impairment in Turkish elderly people. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(4):370.e11-370.e3.7E15. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2015.12.093

42. Michielsen M, Comijs HC, Semeijn EJ, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and personality characteristics in older adults in the general Dutch population. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(12):1623-1632. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2014.02.005

43. Khoury R, Chakkamparambil B, Chibnall J, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the SLU AMSAD scale for depression in older adults without dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(5):665-668. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2019.09.011

44. Çavuşoğlu Ç, Demirkol ME, Tamam L. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in the elderly. Current Approaches in Psychiatry. 2020;12(2):182-194. doi:10.18863/pgy.548052

45. Klein M, Souza-Duran FL, Menezes AKPM, et al. Gray matter volume in elderly adults with ADHD: associations of symptoms and comorbidities with brain structures. J Atten Disord. 2021;25(6):829-838. doi:10.1177/1087054719855683

46. Michielsen M, Kleef D, Bijlenga D, et al. Response and side effects using stimulant medication in older adults with ADHD: an observational archive study. J Atten Disord. 2021;25(12):1712-1719. doi:10.1177/1087054720925884

47. Manor I, Rozen S, Zemishlani Z, et al. When does it end? Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the middle aged and older populations. Clin Neuropharmacol, 2011;34(4):148-154. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e3182206dc1

48. Deshmukh P, Patel D. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and its treatment in geriatrics. Curr Dev Disord Rep. 2020;7(3):79-84.

49. Barkley RA. The important role of executive functioning and self-regulation in ADHD. 2010. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://www.russellbarkley.org/factsheets/ADHD_EF_and_SR.pdf

50. Corbisiero S, Bitto H, Newark P, et al. A comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy alone in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)-a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:571. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00571

For many years, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was thought of as a disorder of childhood; however, it is now increasingly being recognized as a chronic, lifelong disorder that persists into adulthood in approximately two-thirds of patients.1 While our knowledge about ADHD in adults has increased, most research in this population focused on young or middle-aged adults; less is known about ADHD in older adults. Older adults with ADHD may be newly diagnosed at any point in their lives, or not at all.2 Because ADHD may present differently in older adults than in children or young adults, and because it may impair domains of life in different ways, a closer look at late-life ADHD is needed. This article summarizes the literature on the prevalence, impairment, diagnosis, and treatment of ADHD in adults age >60.

Challenges in determining the prevalence

Few studies have examined the age-specific prevalence of ADHD among older adults.3 Compared with childhood ADHD, adult ADHD is relatively neglected in epidemiological studies, largely due to the absence of well-established, validated diagnostic criteria.1,4 Some experts have noted that DSM-5’s ADHD criteria were designed for diagnosing children, and the children-focused symptom threshold may not be useful for adults because ADHD symptoms decline substantially with age.2 One study evaluating DSM-5 ADHD criteria in young adults (N = 4,000, age 18 to 19) found ADHD was better diagnosed when the required number of clinically relevant inattention and hyperactivity symptoms was reduced from 6 to 5 for each category.5 They also found the DSM-5 age-at-onset criterion of symptoms present before age 12 had a significant effect on ADHD prevalence, reducing the rate from 23.7% (95% CI, 22.38 to 25.02) to 5.4% (95% CI, 13.99 to 16.21).5 This suggests that strict usage of DSM-5 criteria may underestimate the prevalence of ADHD in adults, because ADHD symptoms may not be detected in childhood, or self-reporting of childhood ADHD symptoms in older adults may be unreliable due to aging processes that compromise memory and recall. These findings also indicate that fewer ADHD symptoms are needed to impair functioning in older age.

Determining the prevalence of ADHD among older adults is further complicated by individuals who report symptoms consistent with an ADHD diagnosis despite having never received this diagnosis during childhood.6-8 This may be due to the considerable number of children who meet ADHD criteria but do not get a diagnosis due to limited access to health care.9 Thus, many studies separately analyze the syndromatic (with a childhood onset) and symptomatic (regardless of childhood onset) persistence of ADHD. One epidemiological meta-analysis found the 2020 prevalence of syndromatic ADHD in adults age >60 was 0.77% and the prevalence of symptomatic ADHD was 4.51%, which translates to 7.91 million and 46.36 million affected older adults, respectively.8 Other research has reported higher rates among older adults.6,7,10 The variations among this research may be attributed to the use of different diagnostic tools/criteria, study populations, sampling methods, or DSM versions. Heterogeneity among this research also further supports the idea that the prevalence of ADHD is heavily dependent on how one defines and diagnoses the disorder.

Reasons for late-life ADHD diagnosis

There are many reasons a patient may not be diagnosed with ADHD until they are an older adult.11 In addition to socioeconomic barriers to health care access, members of different ethnic groups exhibit differences in help-seeking behaviors; children may belong to a culture that does not traditionally seek health care even when symptoms are evident.6,9 Therefore, individuals may not receive a diagnosis until adulthood. Some experts have discussed the similarity of ADHD to other neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder or social communication disorder, where ADHD symptoms may not manifest until stressors at critical points in life exceed an individual’s capacity to compensate.2

The life transition model contextualizes ADHD as being associated with demand/resource imbalances that come and go throughout life, resulting in variability in the degree of functional impairment ADHD symptoms cause in older adults.2,12 Hypothetically, events in late life—such as the death of a spouse or retirement—can remove essential support structures in the lives of high-functioning individuals with ADHD. As a result, such events surpass these individuals’ ability to cope, resulting in a late-life manifestation of ADHD.

The plausibility of late-onset ADHD

In recent years, many studies identifying ADHD in adults have been published,2,10,12-15 including some that discuss adult ADHD that spontaneously appears without childhood symptoms (ie, late-onset ADHD).2,4,12 Research of late-onset ADHD attracts attention because the data it presents challenge the current rationale that ADHD symptoms should be present before age 12, as defined by DSM-5 criteria. While most reports of late-onset ADHD pertain to younger adults, little evidence exists to reinforce the concept; to date just 1 study has reported cases of late-onset ADHD in older adults (n = 7, age 51 to 59).11 In this study, Sasaki et al11 acknowledged the strong possibility their cases may be late manifestations of long-standing ADHD. Late-onset ADHD is further challenged by findings that 95% of individuals initially diagnosed with late-onset ADHD can be excluded from the diagnosis with further detailed assessment that accounts for co-occurring mental disorders and substance use.16 This suggests false positive cases of late-onset ADHD may be a symptom of narrow clinical assessment that fails to encompass other aspects of a patient’s psychiatric profile, rather than an atypical ADHD presentation.

Comorbidity and psychosocial functioning

ADHD symptoms and diagnosis in older adults are associated with clinically relevant levels of depression and anxiety. The Dutch Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA) examined 1,494 older adults (age 55 to 85) using the Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults version 2.0.10 The 231 individuals identified as having symptoms of ADHD reported clinically relevant levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms. ADHD was significantly associated with these comorbid symptoms.

Continue to: Little is known regarding...

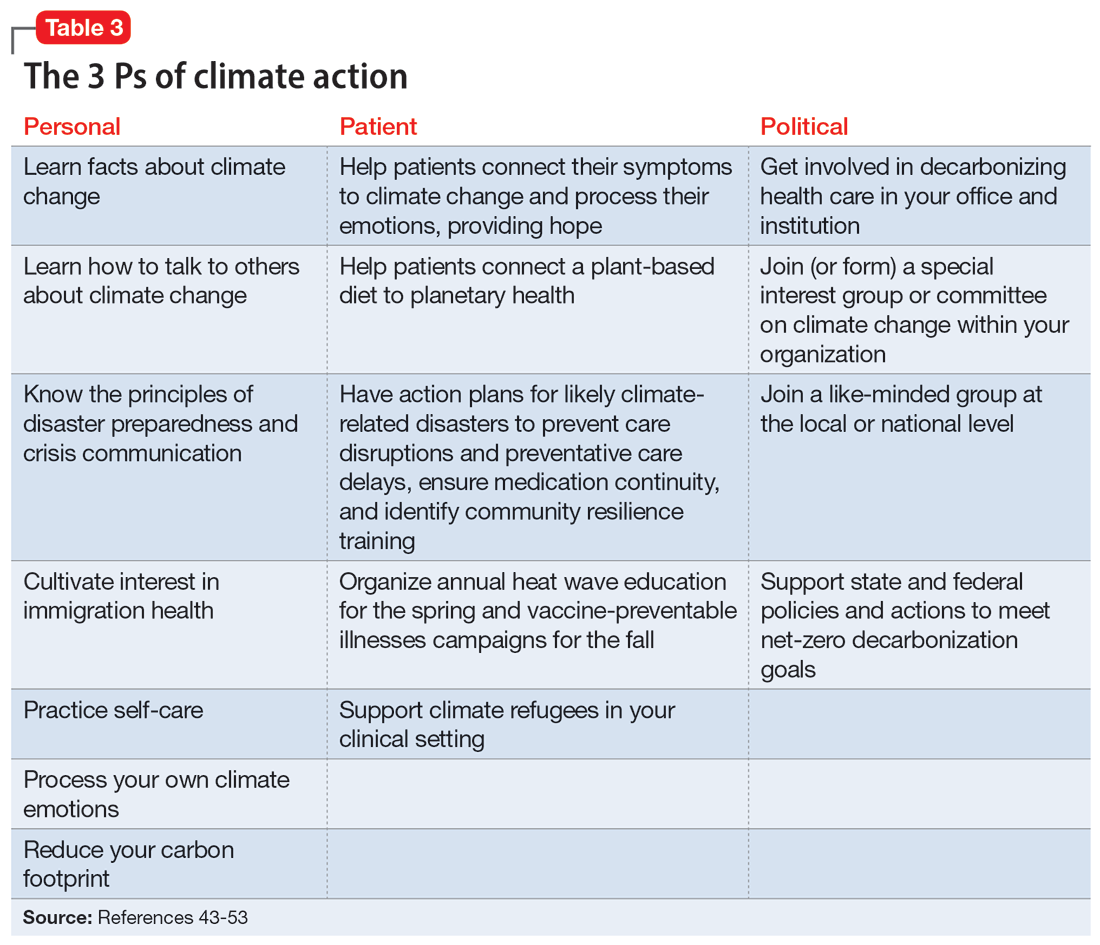

Little is known regarding the manifestation of symptoms of ADHD in older age and the difficulties these older adults face. Older adults with ADHD are more often divorced and report more loneliness than older adults without this disorder, which suggests loneliness in older age may be more pressing for the older ADHD population.17 ADHD in older adults has also been associated with poor quality-of-life measures, including moderate to severe problems in mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression (Table 114,17).

Qualitative research has described a domino effect of a lifetime of living with ADHD. In one American study, older adults with ADHD (N = 24, age 60 to 74) reported experiencing a tangible, accumulated impact from ADHD on their finances and long-term relationships with family, friends, and coworkers.13 Another study utilizing the Dutch LASA data examined how ADHD may impact patient’s lives among participants who were unaware of their diagnosis.18 One-half of patients reported low self-esteem, overstepping boundaries, and feeling different from others. When compared to younger adults with ADHD, older adults report significantly greater impairments in productivity and a worse life outlook.19

Differential diagnosis

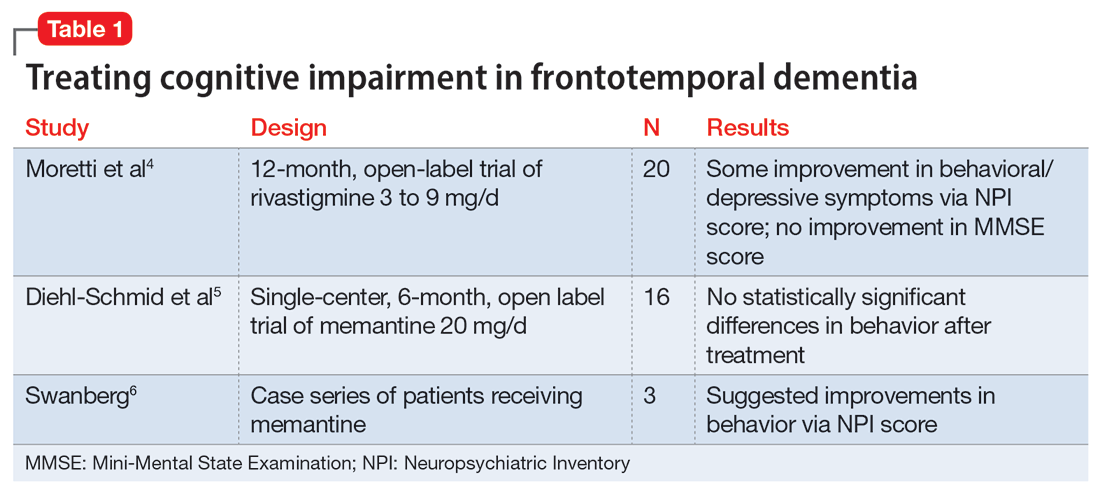

When assessing whether an older adult has ADHD, it is important to consider other potential causes of their symptoms (Table 211,15,20-23). The differential diagnosis includes impaired vision and hearing as well as medical illness (vitamin B12 deficiency, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, and infectious diseases such as herpes simplex virus or syphilis).

In older adults, ADHD symptoms include frontal-executive impairments, inattentiveness, difficulty with organization or multitasking, forgetfulness, and challenges involving activities of daily living or socialization that can appear to be a mild or major neurocognitive disorder (Table 311,24,25). This includes major neurocognitive disorder due to Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body disease, and vascular disease.2,26 However, frontotemporal lobar degeneration is reported to have more symptom overlap with ADHD.21,22,26,27 A way to differentiate between neurocognitive disorders and ADHD in older adults is to consider that patients with neurocognitive disorders often progress to visual hallucinations and more extreme personality changes than would be expected in ADHD.11 Each disease also has its own identifiable characteristics. Extreme changes in memory are often Alzheimer’s disease, personality changes suggest frontotemporal lobar degeneration, stepwise decline is classic for vascular disease, and parkinsonian features may indicate dementia with Lewy bodies.21 In addition, the onset of ADHD usually occurs in childhood and can be traced throughout the lifespan,2 whereas neurocognitive diseases usually appear for the first time in later life.2,28 There are nuances in the nature of forgetfulness that can distinguish ADHD from neurocognitive disorders. For instance, the forgetfulness in early-onset Alzheimer’s disease involves “the lack of episodic memories,” while in contrast ADHD is thought to be “forgetfulness due to inadvertence.”11 Furthermore, patients with neurocognitive disorders are reported to have more severe symptoms and an inability to explain why, whereas those with ADHD have a steady level of symptoms and can provide a more comprehensive story.24 Two recent studies have shown that weak performance on language tests is more indicative of a neurodegenerative process than of ADHD.29,30 Research has suggested that if an older adult shows a sudden, acute onset of ADHD-like symptoms, this is most likely reflective of cognitive decline or a mood disorder such as depression.2,15,24

Several other psychiatric conditions share many symptoms with ADHD. Overlapping symptomology between ADHD and mood and anxiety disorders presents challenges.27 Emotional dysregulation is a feature of adult ADHD, and this often causes a mood disorder to be diagnosed without considering other possible explanations.21,22,27,31-34 Features of mania can overlap with ADHD symptoms, including psychomotor agitation, talkativeness, and distractibility.27 Several other disorders also include distractibility, such as depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders.35 Depression and anxiety can be an outcome of untreated ADHD, or can co-occur with ADHD.21-23,27 ADHD can also co-occur with bipolar disorder (BD), substance use disorders, and personality disorders (borderline and antisocial personality disorder) (Figure 121-23,27,35). One suggested method of establishing an appropriate diagnosis is to study the efficacy of the treatment retrospectively. For example, if a patient is presumed to have depression and they do not respond to several selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, this may be undetected ADHD.27 In addition, the argument about the chronicity of the symptoms should also be considered. ADHD symptoms are pervasive whereas BD symptoms are episodic.35 Depression can be chronic; however, there are often discrete major depressive episodes. It is important to have a clear timeline of the patient’s symptoms. Ask about age of onset, because in theory, ADHD is supposed to start in childhood.22 It is sometimes difficult to ascertain this information because many older adults grew up during a time where ADHD was not a recognized diagnosis.21

Continue to: Diagnosis and workup

Diagnosis and workup

The key aspects of diagnosing ADHD are the interview based on DSM-5 criteria, exclusion of other diagnoses, and collateral information. Research has shown that clinical interviews and longitudinal family histories provide critical information that can differentiate ADHD from other psychiatric conditions.35 DSM-5 criteria are adjusted for adults: 5 out of 9 criteria for inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity must be fulfilled, as opposed to 6 out of 9 in children age <17.21,31,36 However, no criteria are specific for older adults.37 Since the differential diagnosis involves multiple entities, it is important to follow DSM-5 criteria for ADHD, which include eliminating other conditions that can explain these symptoms.15 Additionally, in DSM-5, the age-of-onset threshold for ADHD diagnosis was increased from 7 and younger to 12 and younger, addressing criticism that the previous cutoff was too restrictive.24,31 The age of onset of childhood symptoms can be challenging to verify in older adults. Older patients can have unreliable memories and their childhood records are not always available.2,20 In this population, childhood symptoms are mainly underreported but sometimes overreported.10,38 However, to establish a diagnosis, the patient should have experienced some symptoms of the disorder within their first 50 years of life, including having impaired functionality in multiple settings.15,26 The goal is to establish the chronicity of this condition to distinguish it from other psychiatric conditions.22 Overall, using DSM-5 criteria without any modifications may lead to underdiagnosis of ADHD in adults.23 At this time, however, DSM-5 remains the main criteria used to make a diagnosis.

While tools to assist in screening and diagnosing ADHD have been validated in adults, none have been validated specifically for older adults.22 Structured diagnostic interviews to diagnose ADHD include39:

- Adult ADHD Clinical Diagnostic Scale version 1.2

- ADHD Lifespan Functioning interview

- Conners’ Adult ADHD Diagnostic interview for DSM-IV

- Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults version 2.0

- Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5.

ADHD symptom measures that can be used for screening and to look at treatment response include39:

- ADHD Rating Scale 5

- Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale Symptom Checklist

- Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale IV

- Barkley Quick-Check for Adult ADHD Diagnosis

- Young ADHD Questionnaire

- RATE Scales.

Adult ADHD inventories consider problems that adults with ADHD face. These include39:

- Brown Attention Deficit Disorders Scales—Adult version

- Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales

- Wender-Reimherr Adult Attention Deficit Disorder Scale.

Since these scales were not designed for older adults, they may miss nuances in this population.40

Continue to: It can be particularly...

It can be particularly perplexing to diagnose ADHD in older adults because the other possible causes of the symptoms are vast. During the interview, it is important to ask questions that may rule out other psychiatric, neurologic, and medical conditions.21 Screen for other diagnoses, and include questions about a patient’s sleep history to rule out obstructive sleep apnea.21 To screen for other psychiatric conditions, the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview 5.0.0 may be used.22 Other tools include the Saint Louis University AMSAD screen for depression, the Geriatric Depression Scale, and the Beck Anxiety Inventory.28,41 To screen for cognitive functioning, the Saint Louis University Mental Status Exam, Montreal Cognitive Assessment, or Mini-Mental State Examination can be used.22,28,42,43 Once screening is performed, a physical and neurologic examination is the best next step.26 Additionally, laboratory data and imaging can rule out other conditions; however, these are not routinely performed to diagnose ADHD.

Laboratory tests should include a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count, thyroid-stimulating hormone level, B12/folate level, and possibly a vitamin D level.11,36 These tests cover several conditions that may mimic ADHD. Brain MRI is not routinely recommended for diagnosing ADHD, though it may be useful because some research has found brain structural differences in individuals with ADHD.28,44,45 Neurocognitive disorders have notable MRI findings that distinguish them from ADHD and each other.24 If there is significant concern for neurocognitive disorders, more specific tests can be employed, such as CSF studies, to look for phosphorylated tau and beta amyloid markers.11

Ask about family history (first-degree relative with ADHD) and obtain collateral information to make sure no other diagnoses are overlooked. Family history can help diagnose this disorder in older adults because there is evidence that ADHD runs in families.2,25 This evidence would ideally come from someone who has known the patient their entire life, such as a sibling or parent.24 The collateral information will be especially helpful to discern the chronicity of the patient’s symptoms, which would point toward a diagnosis of ADHD. To summarize (Figure 2):

- obtain a thorough interview that may be supported by a screening tool

- rule out other conditions

- conduct a physical examination

- obtain laboratory results

- collect collateral information

- obtain neuroimaging if necessary.

Treatment

ADHD symptoms can be treated with medications and psychotherapy. Research has shown the efficacy of ADHD medications in older adults, demonstrating that treatment leads to better functioning in multiple settings and decreases the risk for developing comorbid psychiatric conditions (mood disorder, substance use disorders).25,27 Symptoms that improve with medication include attention, concentration, self-efficacy, functioning, self-esteem, psychomotor agitation, mood, energy, and procrastination.21,31,46 If a patient with ADHD also has other psychiatric diagnoses, treat the most impairing disorder first.22 This often means mood disorders and substance use disorders must be remedied before ADHD is treated.21

Medication options include stimulants and nonstimulants. First-line treatments are stimulant medications, including methylphenidate, amphetamines, and mixed amphetamine salts.12,22,27,31,35 Stimulants have shown significant efficacy in older adults, although the American Geriatrics Society’s Beers Criteria list stimulants as potentially inappropriate for older adults.33 Adults show significant improvement with methylphenidate.21,23,47 In an observational study, Michielsen et al46 found stimulants were safe and efficacious in older adults if patients are carefully monitored for adverse effects, especially cardiovascular changes. Second-line treatments include the nonstimulant atomoxetine.12,22,27,31 Clonidine and guanfacine are FDA-approved for treating ADHD in children, but not approved for adults.26 There is little evidence for other treatments, such as bupropion.12,22,27 All of these medications have adverse effects, which are especially important to consider in older adults, who experience age-related physiological changes.

Continue to: Medications for ADHD symptoms...

Medications for ADHD symptoms are thought to act via catecholaminergic mechanisms.21 As a result, adverse effects of stimulants can include headache, appetite suppression, nausea, difficulty sleeping, tremor, blurred vision, agitation, psychosis, increased heart rate, arrhythmia, and hypertension.22,27,32-34 Especially in older adults, adverse effects such as reduced appetite, disrupted sleep, or increased blood pressure or heart rate may be harmful.21,23 Using caffeine or pseudoephedrine can exacerbate these adverse effects.21 Atomoxetine’s adverse effects include appetite suppression, insomnia, dizziness, anxiety, agitation, fatigue, dry mouth, constipation, nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, and increased heart rate or blood pressure.27,32,35 Genitourinary adverse effects have also been reported, including priapism (rare), decreased libido, and urinary hesitancy and retention.26,32 Before any medication is initiated, it is important to conduct a physical and neurologic examination and a detailed clinical interview.

Before starting medication, as with any medical treatment, conduct a risk vs benefit analysis. Record baseline values for the patient’s heart rate, blood pressure, and weight.23,26,27,31 During the interview, screen for family and personal cardiovascular conditions,27,33 and obtain an electrocardiogram for any patient with cardiovascular risks.23,26,27,31 Once the patient is deemed to be an appropriate candidate for pharmacologic treatment, begin with low doses and titrate the medication slowly until reaching a therapeutic level.23,48

Medications should be combined with psychotherapy (eg, cognitive-behavioral therapy or dialectical behavioral therapy) and other lifestyle changes (exercise, mindfulness, support groups).18,22,23,27,31,49 Psychotherapy can help patients come to terms with receiving an ADHD diagnosis later in life and help with organization and socialization.12,50 Pharmacologic treatments are thought to be helpful with attention challenges and emotional instability.50 Taken together, medications and behavioral interventions can help individuals experience an improved quality of life.

Future directions

Given the relatively recent interest in ADHD in older adults, there are several areas that need further research. For future editions of DSM, it may be prudent to consider establishing ADHD criteria specific to older adults. Research has also shown the need for clear diagnostic and validated tools for older adults.8 Few analyses have been undertaken regarding pharmacotherapy for this population. Randomized controlled clinical trials are needed.23,37,48 More research about the relative utility of psychotherapy and behavioral interventions would also be useful, given their potential to improve the quality of life for older adults with ADHD.

Bottom Line

Although generally thought of as a disorder of childhood, attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has substantial effects in older adults. When the condition is appropriately diagnosed, pharmacologic treatment and psychotherapy are associated with improved quality of life for older patients with ADHD.

Related Resources

- Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Living with ADHD: A lifespan disorder. https://chadd.org/for-adults/living-with-adhd-a-lifespan-disorder/

- Attention Deficit Disorder Association. Support groups for adults. https://add.org/adhd-support-groups/

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine/dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Atomoxetine • Straterra

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Clonidine • Catapres

Guanfacine • Intuniv

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

For many years, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was thought of as a disorder of childhood; however, it is now increasingly being recognized as a chronic, lifelong disorder that persists into adulthood in approximately two-thirds of patients.1 While our knowledge about ADHD in adults has increased, most research in this population focused on young or middle-aged adults; less is known about ADHD in older adults. Older adults with ADHD may be newly diagnosed at any point in their lives, or not at all.2 Because ADHD may present differently in older adults than in children or young adults, and because it may impair domains of life in different ways, a closer look at late-life ADHD is needed. This article summarizes the literature on the prevalence, impairment, diagnosis, and treatment of ADHD in adults age >60.

Challenges in determining the prevalence

Few studies have examined the age-specific prevalence of ADHD among older adults.3 Compared with childhood ADHD, adult ADHD is relatively neglected in epidemiological studies, largely due to the absence of well-established, validated diagnostic criteria.1,4 Some experts have noted that DSM-5’s ADHD criteria were designed for diagnosing children, and the children-focused symptom threshold may not be useful for adults because ADHD symptoms decline substantially with age.2 One study evaluating DSM-5 ADHD criteria in young adults (N = 4,000, age 18 to 19) found ADHD was better diagnosed when the required number of clinically relevant inattention and hyperactivity symptoms was reduced from 6 to 5 for each category.5 They also found the DSM-5 age-at-onset criterion of symptoms present before age 12 had a significant effect on ADHD prevalence, reducing the rate from 23.7% (95% CI, 22.38 to 25.02) to 5.4% (95% CI, 13.99 to 16.21).5 This suggests that strict usage of DSM-5 criteria may underestimate the prevalence of ADHD in adults, because ADHD symptoms may not be detected in childhood, or self-reporting of childhood ADHD symptoms in older adults may be unreliable due to aging processes that compromise memory and recall. These findings also indicate that fewer ADHD symptoms are needed to impair functioning in older age.

Determining the prevalence of ADHD among older adults is further complicated by individuals who report symptoms consistent with an ADHD diagnosis despite having never received this diagnosis during childhood.6-8 This may be due to the considerable number of children who meet ADHD criteria but do not get a diagnosis due to limited access to health care.9 Thus, many studies separately analyze the syndromatic (with a childhood onset) and symptomatic (regardless of childhood onset) persistence of ADHD. One epidemiological meta-analysis found the 2020 prevalence of syndromatic ADHD in adults age >60 was 0.77% and the prevalence of symptomatic ADHD was 4.51%, which translates to 7.91 million and 46.36 million affected older adults, respectively.8 Other research has reported higher rates among older adults.6,7,10 The variations among this research may be attributed to the use of different diagnostic tools/criteria, study populations, sampling methods, or DSM versions. Heterogeneity among this research also further supports the idea that the prevalence of ADHD is heavily dependent on how one defines and diagnoses the disorder.

Reasons for late-life ADHD diagnosis

There are many reasons a patient may not be diagnosed with ADHD until they are an older adult.11 In addition to socioeconomic barriers to health care access, members of different ethnic groups exhibit differences in help-seeking behaviors; children may belong to a culture that does not traditionally seek health care even when symptoms are evident.6,9 Therefore, individuals may not receive a diagnosis until adulthood. Some experts have discussed the similarity of ADHD to other neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder or social communication disorder, where ADHD symptoms may not manifest until stressors at critical points in life exceed an individual’s capacity to compensate.2

The life transition model contextualizes ADHD as being associated with demand/resource imbalances that come and go throughout life, resulting in variability in the degree of functional impairment ADHD symptoms cause in older adults.2,12 Hypothetically, events in late life—such as the death of a spouse or retirement—can remove essential support structures in the lives of high-functioning individuals with ADHD. As a result, such events surpass these individuals’ ability to cope, resulting in a late-life manifestation of ADHD.

The plausibility of late-onset ADHD

In recent years, many studies identifying ADHD in adults have been published,2,10,12-15 including some that discuss adult ADHD that spontaneously appears without childhood symptoms (ie, late-onset ADHD).2,4,12 Research of late-onset ADHD attracts attention because the data it presents challenge the current rationale that ADHD symptoms should be present before age 12, as defined by DSM-5 criteria. While most reports of late-onset ADHD pertain to younger adults, little evidence exists to reinforce the concept; to date just 1 study has reported cases of late-onset ADHD in older adults (n = 7, age 51 to 59).11 In this study, Sasaki et al11 acknowledged the strong possibility their cases may be late manifestations of long-standing ADHD. Late-onset ADHD is further challenged by findings that 95% of individuals initially diagnosed with late-onset ADHD can be excluded from the diagnosis with further detailed assessment that accounts for co-occurring mental disorders and substance use.16 This suggests false positive cases of late-onset ADHD may be a symptom of narrow clinical assessment that fails to encompass other aspects of a patient’s psychiatric profile, rather than an atypical ADHD presentation.

Comorbidity and psychosocial functioning

ADHD symptoms and diagnosis in older adults are associated with clinically relevant levels of depression and anxiety. The Dutch Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA) examined 1,494 older adults (age 55 to 85) using the Diagnostic Interview for ADHD in Adults version 2.0.10 The 231 individuals identified as having symptoms of ADHD reported clinically relevant levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms. ADHD was significantly associated with these comorbid symptoms.

Continue to: Little is known regarding...

Little is known regarding the manifestation of symptoms of ADHD in older age and the difficulties these older adults face. Older adults with ADHD are more often divorced and report more loneliness than older adults without this disorder, which suggests loneliness in older age may be more pressing for the older ADHD population.17 ADHD in older adults has also been associated with poor quality-of-life measures, including moderate to severe problems in mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression (Table 114,17).

Qualitative research has described a domino effect of a lifetime of living with ADHD. In one American study, older adults with ADHD (N = 24, age 60 to 74) reported experiencing a tangible, accumulated impact from ADHD on their finances and long-term relationships with family, friends, and coworkers.13 Another study utilizing the Dutch LASA data examined how ADHD may impact patient’s lives among participants who were unaware of their diagnosis.18 One-half of patients reported low self-esteem, overstepping boundaries, and feeling different from others. When compared to younger adults with ADHD, older adults report significantly greater impairments in productivity and a worse life outlook.19

Differential diagnosis

When assessing whether an older adult has ADHD, it is important to consider other potential causes of their symptoms (Table 211,15,20-23). The differential diagnosis includes impaired vision and hearing as well as medical illness (vitamin B12 deficiency, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, and infectious diseases such as herpes simplex virus or syphilis).