User login

COVID nonvaccination linked with avoidable hospitalizations

A retrospective, population-based cohort study in Alberta, Edmonton, found that between late September 2021 and late January 2022, eligible unvaccinated patients with COVID-19 had a nearly 10-fold higher risk for hospitalization than did patients who were fully vaccinated with two doses. Unvaccinated patients had a nearly 21-fold higher risk than did patients who were boosted with three doses.

“We have shown that eligible nonvaccinated persons, especially in the age strata 50-79 years, accounted for 3,000-4,000 potentially avoidable hospitalizations, 35,000-40,000 avoidable bed-days, and $100–$110 million [Canadian dollars] in avoidable health care costs during a 120-day period coinciding with the fourth (Delta) and fifth (Omicron) COVID-19 waves, respectively,” wrote Sean M. Bagshaw, MD, chair of critical care medicine at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, and colleagues.

The findings were published in the Canadian Journal of Public Health.

‘Unsatisfactory’ vaccine uptake

While a previous study by Dr. Bagshaw and colleagues recently showed that higher vaccine uptake could have avoided significant intensive care unit admissions and costs, the researchers sought to expand their analysis to include non-ICU use.

The current study examined data from the government of Alberta and the Discharge Abstract Database to assess vaccination status and hospitalization with confirmed SARS-CoV-2. Secondary outcomes included avoidable hospitalizations, avoidable hospital bed-days, and the potential cost avoidance related to COVID-19.

During the study period, “societal factors contributed to an unsatisfactory voluntary vaccine uptake, particularly in the province of Alberta,” wrote the authors, adding that “only 63.7% and 2.7% of the eligible population in Alberta [had] received two (full) and three (boosted) COVID-19 vaccine doses as of September 27, 2021.”

The analysis found the highest number of hospitalizations among unvaccinated patients (n = 3,835), compared with vaccinated (n = 1,907) and boosted patients (n = 481). This finding yielded a risk ratio (RR) of hospitalization of 9.7 for unvaccinated patients, compared with fully vaccinated patients, and an RR of 20.6, compared with patients who were boosted. Unvaccinated patients aged 60-69 years had the highest RR for hospitalization, compared with vaccinated (RR, 16.4) and boosted patients (RR, 151.9).

The estimated number of avoidable hospitalizations for unvaccinated patients was 3,439 (total of 36,331 bed-days), compared with vaccinated patients, and 3,764 (total of 40,185 bed-days), compared with boosted patients.

The avoidable hospitalization-related costs for unvaccinated patients totaled $101.4 million (Canadian dollars) if they had been vaccinated and $110.24 million if they had been boosted.

“Moreover, strained hospital systems and the widespread adoption of crisis standards of care in response to surges in COVID-19 hospitalizations have contributed to unnecessary excess deaths,” wrote the authors. “These are preventable and missed public health opportunities that provoked massive health system disruptions and resource diversions, including deferral of routine health services (e.g., cancer and chronic disease screening and monitoring and scheduled vaccinations), postponement of scheduled procedures and surgeries, and redeployment of health care professionals.”

Dr. Bagshaw said in an interview that he was not surprised by the findings. “However, I wonder whether the public and those who direct policy and make decisions about the health system would be interested in better understanding the scope and sheer disruption the health system suffered due to COVID-19,” he said.

The current study suggests that “at least some of this could have been avoided,” said Dr. Bagshaw. “I hope we – that is the public, users of the health system, decision-makers and health care professionals – can learn from our experiences.” Studies such as the current analysis “will reinforce the importance of timely and clearly articulated public health promotion, education, and policy,” he added.

Economic benefit underestimated

Commenting on the study, David Fisman, MD, MPH, an epidemiologist and professor at the University of Toronto, said: “The approach these investigators have taken is clear and straightforward. It is easy to reproduce. It is also entirely consistent with what other scientific groups have been demonstrating for a couple of years now.” Dr. Fisman was not involved with the study.

A group led by Dr. Fisman as senior author has just completed a study examining the effectiveness of the Canadian pandemic response, compared with responses in four peer countries. In the as-yet unpublished paper, the researchers concluded that “relative to the United States, United Kingdom, and France, the Canadian pandemic response was estimated to have averted 94,492, 64,306, and 13,641 deaths, respectively, with more than 480,000 hospitalizations averted and 1 million QALY [quality-adjusted life-years] saved, relative to the United States. A United States pandemic response applied to Canada would have resulted in more than $40 billion in economic losses due to healthcare expenditures and lost QALY; losses relative to the United Kingdom and France would have been $21 billion and $5 billion, respectively. By contrast, an Australian pandemic response would have averted over 28,000 additional deaths and averted nearly $9 billion in costs in Canada.”

Dr. Fisman added that while the current researchers focused their study on the direct protective effects of vaccines, “we know that, even with initial waves of Omicron, vaccinated individuals continued to be protected against infection as well as disease, and even if they were infected, we know from household contact studies that they were less infectious to others. That means that even though the implicit estimate of cost savings that could have been achieved through better coverage are pretty high in this paper, the economic benefit of vaccination is underestimated in this analysis, because we can’t quantify the infections that never happened because of vaccination.”

The study was supported by the Strategic Clinical Networks, Alberta Health Services. Dr. Bagshaw declared no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Fisman has taken part in advisory boards for Seqirus, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, and Merck vaccines during the past 3 years.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A retrospective, population-based cohort study in Alberta, Edmonton, found that between late September 2021 and late January 2022, eligible unvaccinated patients with COVID-19 had a nearly 10-fold higher risk for hospitalization than did patients who were fully vaccinated with two doses. Unvaccinated patients had a nearly 21-fold higher risk than did patients who were boosted with three doses.

“We have shown that eligible nonvaccinated persons, especially in the age strata 50-79 years, accounted for 3,000-4,000 potentially avoidable hospitalizations, 35,000-40,000 avoidable bed-days, and $100–$110 million [Canadian dollars] in avoidable health care costs during a 120-day period coinciding with the fourth (Delta) and fifth (Omicron) COVID-19 waves, respectively,” wrote Sean M. Bagshaw, MD, chair of critical care medicine at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, and colleagues.

The findings were published in the Canadian Journal of Public Health.

‘Unsatisfactory’ vaccine uptake

While a previous study by Dr. Bagshaw and colleagues recently showed that higher vaccine uptake could have avoided significant intensive care unit admissions and costs, the researchers sought to expand their analysis to include non-ICU use.

The current study examined data from the government of Alberta and the Discharge Abstract Database to assess vaccination status and hospitalization with confirmed SARS-CoV-2. Secondary outcomes included avoidable hospitalizations, avoidable hospital bed-days, and the potential cost avoidance related to COVID-19.

During the study period, “societal factors contributed to an unsatisfactory voluntary vaccine uptake, particularly in the province of Alberta,” wrote the authors, adding that “only 63.7% and 2.7% of the eligible population in Alberta [had] received two (full) and three (boosted) COVID-19 vaccine doses as of September 27, 2021.”

The analysis found the highest number of hospitalizations among unvaccinated patients (n = 3,835), compared with vaccinated (n = 1,907) and boosted patients (n = 481). This finding yielded a risk ratio (RR) of hospitalization of 9.7 for unvaccinated patients, compared with fully vaccinated patients, and an RR of 20.6, compared with patients who were boosted. Unvaccinated patients aged 60-69 years had the highest RR for hospitalization, compared with vaccinated (RR, 16.4) and boosted patients (RR, 151.9).

The estimated number of avoidable hospitalizations for unvaccinated patients was 3,439 (total of 36,331 bed-days), compared with vaccinated patients, and 3,764 (total of 40,185 bed-days), compared with boosted patients.

The avoidable hospitalization-related costs for unvaccinated patients totaled $101.4 million (Canadian dollars) if they had been vaccinated and $110.24 million if they had been boosted.

“Moreover, strained hospital systems and the widespread adoption of crisis standards of care in response to surges in COVID-19 hospitalizations have contributed to unnecessary excess deaths,” wrote the authors. “These are preventable and missed public health opportunities that provoked massive health system disruptions and resource diversions, including deferral of routine health services (e.g., cancer and chronic disease screening and monitoring and scheduled vaccinations), postponement of scheduled procedures and surgeries, and redeployment of health care professionals.”

Dr. Bagshaw said in an interview that he was not surprised by the findings. “However, I wonder whether the public and those who direct policy and make decisions about the health system would be interested in better understanding the scope and sheer disruption the health system suffered due to COVID-19,” he said.

The current study suggests that “at least some of this could have been avoided,” said Dr. Bagshaw. “I hope we – that is the public, users of the health system, decision-makers and health care professionals – can learn from our experiences.” Studies such as the current analysis “will reinforce the importance of timely and clearly articulated public health promotion, education, and policy,” he added.

Economic benefit underestimated

Commenting on the study, David Fisman, MD, MPH, an epidemiologist and professor at the University of Toronto, said: “The approach these investigators have taken is clear and straightforward. It is easy to reproduce. It is also entirely consistent with what other scientific groups have been demonstrating for a couple of years now.” Dr. Fisman was not involved with the study.

A group led by Dr. Fisman as senior author has just completed a study examining the effectiveness of the Canadian pandemic response, compared with responses in four peer countries. In the as-yet unpublished paper, the researchers concluded that “relative to the United States, United Kingdom, and France, the Canadian pandemic response was estimated to have averted 94,492, 64,306, and 13,641 deaths, respectively, with more than 480,000 hospitalizations averted and 1 million QALY [quality-adjusted life-years] saved, relative to the United States. A United States pandemic response applied to Canada would have resulted in more than $40 billion in economic losses due to healthcare expenditures and lost QALY; losses relative to the United Kingdom and France would have been $21 billion and $5 billion, respectively. By contrast, an Australian pandemic response would have averted over 28,000 additional deaths and averted nearly $9 billion in costs in Canada.”

Dr. Fisman added that while the current researchers focused their study on the direct protective effects of vaccines, “we know that, even with initial waves of Omicron, vaccinated individuals continued to be protected against infection as well as disease, and even if they were infected, we know from household contact studies that they were less infectious to others. That means that even though the implicit estimate of cost savings that could have been achieved through better coverage are pretty high in this paper, the economic benefit of vaccination is underestimated in this analysis, because we can’t quantify the infections that never happened because of vaccination.”

The study was supported by the Strategic Clinical Networks, Alberta Health Services. Dr. Bagshaw declared no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Fisman has taken part in advisory boards for Seqirus, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, and Merck vaccines during the past 3 years.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A retrospective, population-based cohort study in Alberta, Edmonton, found that between late September 2021 and late January 2022, eligible unvaccinated patients with COVID-19 had a nearly 10-fold higher risk for hospitalization than did patients who were fully vaccinated with two doses. Unvaccinated patients had a nearly 21-fold higher risk than did patients who were boosted with three doses.

“We have shown that eligible nonvaccinated persons, especially in the age strata 50-79 years, accounted for 3,000-4,000 potentially avoidable hospitalizations, 35,000-40,000 avoidable bed-days, and $100–$110 million [Canadian dollars] in avoidable health care costs during a 120-day period coinciding with the fourth (Delta) and fifth (Omicron) COVID-19 waves, respectively,” wrote Sean M. Bagshaw, MD, chair of critical care medicine at the University of Alberta, Edmonton, and colleagues.

The findings were published in the Canadian Journal of Public Health.

‘Unsatisfactory’ vaccine uptake

While a previous study by Dr. Bagshaw and colleagues recently showed that higher vaccine uptake could have avoided significant intensive care unit admissions and costs, the researchers sought to expand their analysis to include non-ICU use.

The current study examined data from the government of Alberta and the Discharge Abstract Database to assess vaccination status and hospitalization with confirmed SARS-CoV-2. Secondary outcomes included avoidable hospitalizations, avoidable hospital bed-days, and the potential cost avoidance related to COVID-19.

During the study period, “societal factors contributed to an unsatisfactory voluntary vaccine uptake, particularly in the province of Alberta,” wrote the authors, adding that “only 63.7% and 2.7% of the eligible population in Alberta [had] received two (full) and three (boosted) COVID-19 vaccine doses as of September 27, 2021.”

The analysis found the highest number of hospitalizations among unvaccinated patients (n = 3,835), compared with vaccinated (n = 1,907) and boosted patients (n = 481). This finding yielded a risk ratio (RR) of hospitalization of 9.7 for unvaccinated patients, compared with fully vaccinated patients, and an RR of 20.6, compared with patients who were boosted. Unvaccinated patients aged 60-69 years had the highest RR for hospitalization, compared with vaccinated (RR, 16.4) and boosted patients (RR, 151.9).

The estimated number of avoidable hospitalizations for unvaccinated patients was 3,439 (total of 36,331 bed-days), compared with vaccinated patients, and 3,764 (total of 40,185 bed-days), compared with boosted patients.

The avoidable hospitalization-related costs for unvaccinated patients totaled $101.4 million (Canadian dollars) if they had been vaccinated and $110.24 million if they had been boosted.

“Moreover, strained hospital systems and the widespread adoption of crisis standards of care in response to surges in COVID-19 hospitalizations have contributed to unnecessary excess deaths,” wrote the authors. “These are preventable and missed public health opportunities that provoked massive health system disruptions and resource diversions, including deferral of routine health services (e.g., cancer and chronic disease screening and monitoring and scheduled vaccinations), postponement of scheduled procedures and surgeries, and redeployment of health care professionals.”

Dr. Bagshaw said in an interview that he was not surprised by the findings. “However, I wonder whether the public and those who direct policy and make decisions about the health system would be interested in better understanding the scope and sheer disruption the health system suffered due to COVID-19,” he said.

The current study suggests that “at least some of this could have been avoided,” said Dr. Bagshaw. “I hope we – that is the public, users of the health system, decision-makers and health care professionals – can learn from our experiences.” Studies such as the current analysis “will reinforce the importance of timely and clearly articulated public health promotion, education, and policy,” he added.

Economic benefit underestimated

Commenting on the study, David Fisman, MD, MPH, an epidemiologist and professor at the University of Toronto, said: “The approach these investigators have taken is clear and straightforward. It is easy to reproduce. It is also entirely consistent with what other scientific groups have been demonstrating for a couple of years now.” Dr. Fisman was not involved with the study.

A group led by Dr. Fisman as senior author has just completed a study examining the effectiveness of the Canadian pandemic response, compared with responses in four peer countries. In the as-yet unpublished paper, the researchers concluded that “relative to the United States, United Kingdom, and France, the Canadian pandemic response was estimated to have averted 94,492, 64,306, and 13,641 deaths, respectively, with more than 480,000 hospitalizations averted and 1 million QALY [quality-adjusted life-years] saved, relative to the United States. A United States pandemic response applied to Canada would have resulted in more than $40 billion in economic losses due to healthcare expenditures and lost QALY; losses relative to the United Kingdom and France would have been $21 billion and $5 billion, respectively. By contrast, an Australian pandemic response would have averted over 28,000 additional deaths and averted nearly $9 billion in costs in Canada.”

Dr. Fisman added that while the current researchers focused their study on the direct protective effects of vaccines, “we know that, even with initial waves of Omicron, vaccinated individuals continued to be protected against infection as well as disease, and even if they were infected, we know from household contact studies that they were less infectious to others. That means that even though the implicit estimate of cost savings that could have been achieved through better coverage are pretty high in this paper, the economic benefit of vaccination is underestimated in this analysis, because we can’t quantify the infections that never happened because of vaccination.”

The study was supported by the Strategic Clinical Networks, Alberta Health Services. Dr. Bagshaw declared no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Fisman has taken part in advisory boards for Seqirus, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, and Merck vaccines during the past 3 years.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM CANADIAN JOURNAL OF PUBLIC HEALTH

One in 10 people who had Omicron got long COVID: Study

About 10% of people infected with Omicron reported having long COVID, a lower percentage than estimated for people infected with earlier strains of the coronavirus, according to a study published in JAMA.

The research team looked at data from 8,646 adults infected with COVID-19 at different times of the pandemic and 1,118 who did not have COVID.

“Based on a subset of 2,231 patients in this analysis who had a first COVID-19 infection the National Institutes of Health said in a news release.

People who were unvaccinated or got COVID before Omicron were more likely to have long COVID and had more severe cases, the NIH said.

Previous studies have come up with higher figures than 10% for people who have long COVID.

For instance, in June 2022 the CDC said one in five Americans who had COVID reported having long COVID. And a University of Oxford study published in September 2021 found more than a third of patients had long COVID symptoms.

The scientists in the most recent study identified 12 symptoms that distinguished people who did and didn’t have COVID. The scientists developed a scoring system for the symptoms to set a threshold to identify people who had long COVID, the NIH said.

The symptoms were fatigue, brain fog, dizziness, stomach upset, heart palpitations, issues with sexual desire or capacity, loss of smell or taste, thirst, chronic coughing, chest pain, and abnormal movements. Another symptom was postexertional malaise, or worse symptoms after mental or physical exertion.

Scientists still have many questions about long COVID, such as how many people get it and why some people get it and others don’t.

The study was coordinated through the NIH’s RECOVER (Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery) initiative, which aims to find out how to define, detect, and treat long COVID.

“The researchers hope this study is the next step toward potential treatments for long COVID, which affects the health and wellbeing of millions of Americans,” the NIH said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

About 10% of people infected with Omicron reported having long COVID, a lower percentage than estimated for people infected with earlier strains of the coronavirus, according to a study published in JAMA.

The research team looked at data from 8,646 adults infected with COVID-19 at different times of the pandemic and 1,118 who did not have COVID.

“Based on a subset of 2,231 patients in this analysis who had a first COVID-19 infection the National Institutes of Health said in a news release.

People who were unvaccinated or got COVID before Omicron were more likely to have long COVID and had more severe cases, the NIH said.

Previous studies have come up with higher figures than 10% for people who have long COVID.

For instance, in June 2022 the CDC said one in five Americans who had COVID reported having long COVID. And a University of Oxford study published in September 2021 found more than a third of patients had long COVID symptoms.

The scientists in the most recent study identified 12 symptoms that distinguished people who did and didn’t have COVID. The scientists developed a scoring system for the symptoms to set a threshold to identify people who had long COVID, the NIH said.

The symptoms were fatigue, brain fog, dizziness, stomach upset, heart palpitations, issues with sexual desire or capacity, loss of smell or taste, thirst, chronic coughing, chest pain, and abnormal movements. Another symptom was postexertional malaise, or worse symptoms after mental or physical exertion.

Scientists still have many questions about long COVID, such as how many people get it and why some people get it and others don’t.

The study was coordinated through the NIH’s RECOVER (Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery) initiative, which aims to find out how to define, detect, and treat long COVID.

“The researchers hope this study is the next step toward potential treatments for long COVID, which affects the health and wellbeing of millions of Americans,” the NIH said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

About 10% of people infected with Omicron reported having long COVID, a lower percentage than estimated for people infected with earlier strains of the coronavirus, according to a study published in JAMA.

The research team looked at data from 8,646 adults infected with COVID-19 at different times of the pandemic and 1,118 who did not have COVID.

“Based on a subset of 2,231 patients in this analysis who had a first COVID-19 infection the National Institutes of Health said in a news release.

People who were unvaccinated or got COVID before Omicron were more likely to have long COVID and had more severe cases, the NIH said.

Previous studies have come up with higher figures than 10% for people who have long COVID.

For instance, in June 2022 the CDC said one in five Americans who had COVID reported having long COVID. And a University of Oxford study published in September 2021 found more than a third of patients had long COVID symptoms.

The scientists in the most recent study identified 12 symptoms that distinguished people who did and didn’t have COVID. The scientists developed a scoring system for the symptoms to set a threshold to identify people who had long COVID, the NIH said.

The symptoms were fatigue, brain fog, dizziness, stomach upset, heart palpitations, issues with sexual desire or capacity, loss of smell or taste, thirst, chronic coughing, chest pain, and abnormal movements. Another symptom was postexertional malaise, or worse symptoms after mental or physical exertion.

Scientists still have many questions about long COVID, such as how many people get it and why some people get it and others don’t.

The study was coordinated through the NIH’s RECOVER (Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery) initiative, which aims to find out how to define, detect, and treat long COVID.

“The researchers hope this study is the next step toward potential treatments for long COVID, which affects the health and wellbeing of millions of Americans,” the NIH said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM JAMA

Study finds COVID-19 boosters don’t increase miscarriage risk

COVID-19 boosters are not linked to an increased chance of miscarriage, according to a new study in JAMA Network Open.

Researchers were seeking to learn whether a booster in early pregnancy, before 20 weeks, was associated with greater likelihood of spontaneous abortion.

They examined more than 100,000 pregnancies at 6-19 weeks from eight health systems in the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD). They found that receiving a COVID-19 booster shot in a 28-day or 42-day exposure window did not increase the chances of miscarriage.

The VSD is a collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Immunization Safety Office and large health care systems. The “observational, case-control, surveillance study” was conducted from Nov. 1, 2021, to June 12, 2022.

“COVID infection during pregnancy increases risk of poor outcomes, yet many people who are pregnant or thinking about getting pregnant are hesitant to get a booster dose because of questions about safety,” said Elyse Kharbanda, MD, senior investigator at HealthPartners Institute and lead author of the study in a press release.

The University of Minnesota reported that “previous studies have shown COIVD-19 primary vaccination is safe in pregnancy and not associated with an increased risk for miscarriage. Several studies have also shown COVID-19 can be more severe in pregnancy and lead to worse outcomes for the mother.”

The study was funded by the CDC. Five study authors reported conflicts of interest with Pfizer, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, and Sanofi Pasteur.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 boosters are not linked to an increased chance of miscarriage, according to a new study in JAMA Network Open.

Researchers were seeking to learn whether a booster in early pregnancy, before 20 weeks, was associated with greater likelihood of spontaneous abortion.

They examined more than 100,000 pregnancies at 6-19 weeks from eight health systems in the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD). They found that receiving a COVID-19 booster shot in a 28-day or 42-day exposure window did not increase the chances of miscarriage.

The VSD is a collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Immunization Safety Office and large health care systems. The “observational, case-control, surveillance study” was conducted from Nov. 1, 2021, to June 12, 2022.

“COVID infection during pregnancy increases risk of poor outcomes, yet many people who are pregnant or thinking about getting pregnant are hesitant to get a booster dose because of questions about safety,” said Elyse Kharbanda, MD, senior investigator at HealthPartners Institute and lead author of the study in a press release.

The University of Minnesota reported that “previous studies have shown COIVD-19 primary vaccination is safe in pregnancy and not associated with an increased risk for miscarriage. Several studies have also shown COVID-19 can be more severe in pregnancy and lead to worse outcomes for the mother.”

The study was funded by the CDC. Five study authors reported conflicts of interest with Pfizer, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, and Sanofi Pasteur.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 boosters are not linked to an increased chance of miscarriage, according to a new study in JAMA Network Open.

Researchers were seeking to learn whether a booster in early pregnancy, before 20 weeks, was associated with greater likelihood of spontaneous abortion.

They examined more than 100,000 pregnancies at 6-19 weeks from eight health systems in the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD). They found that receiving a COVID-19 booster shot in a 28-day or 42-day exposure window did not increase the chances of miscarriage.

The VSD is a collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Immunization Safety Office and large health care systems. The “observational, case-control, surveillance study” was conducted from Nov. 1, 2021, to June 12, 2022.

“COVID infection during pregnancy increases risk of poor outcomes, yet many people who are pregnant or thinking about getting pregnant are hesitant to get a booster dose because of questions about safety,” said Elyse Kharbanda, MD, senior investigator at HealthPartners Institute and lead author of the study in a press release.

The University of Minnesota reported that “previous studies have shown COIVD-19 primary vaccination is safe in pregnancy and not associated with an increased risk for miscarriage. Several studies have also shown COVID-19 can be more severe in pregnancy and lead to worse outcomes for the mother.”

The study was funded by the CDC. Five study authors reported conflicts of interest with Pfizer, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, and Sanofi Pasteur.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

COVID boosters effective, but not for long

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

I am here today to talk about the effectiveness of COVID vaccine boosters in the midst of 2023. The reason I want to talk about this isn’t necessarily to dig into exactly how effective vaccines are. This is an area that’s been trod upon multiple times. But it does give me an opportunity to talk about a neat study design called the “test-negative case-control” design, which has some unique properties when you’re trying to evaluate the effect of something outside of the context of a randomized trial.

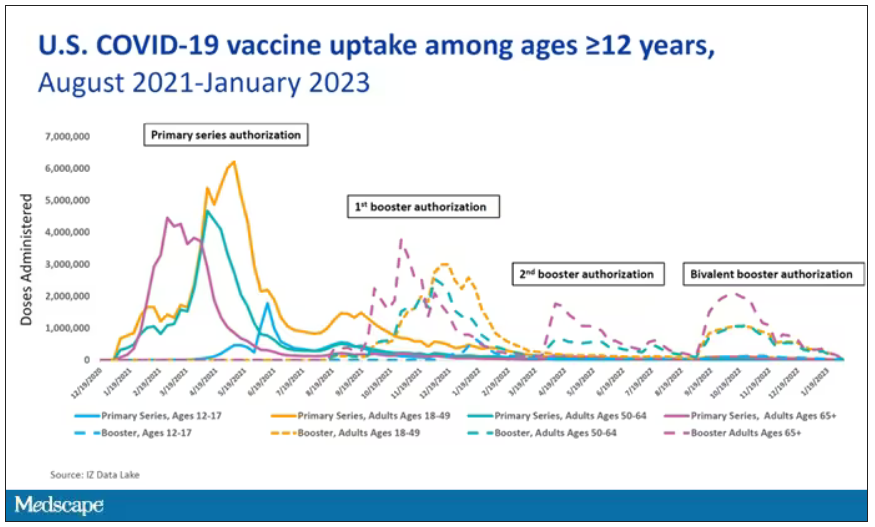

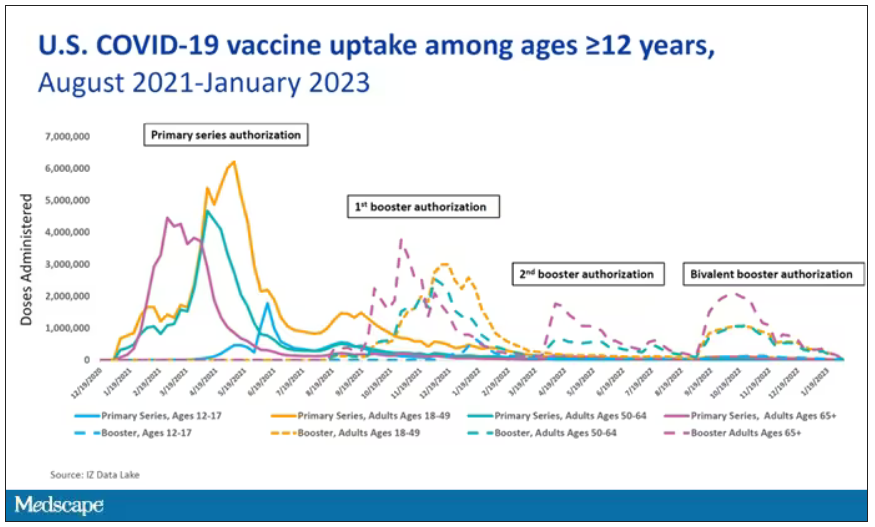

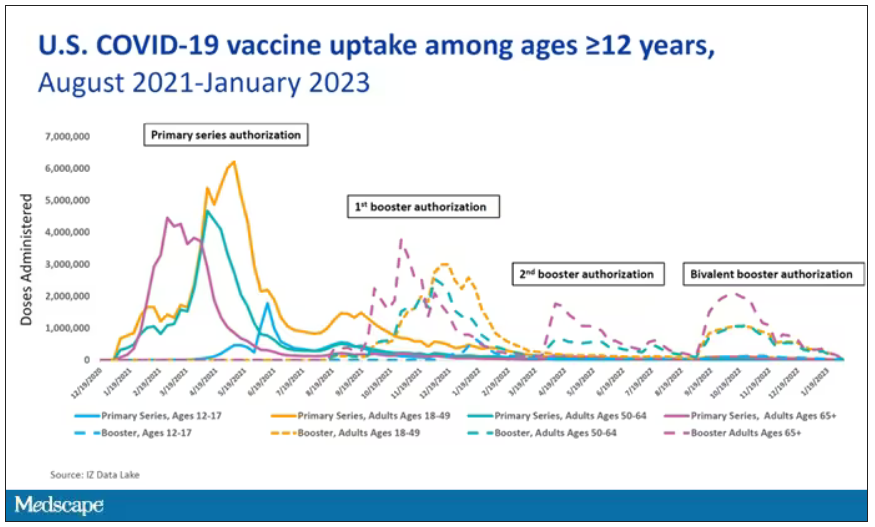

So, just a little bit of background to remind everyone where we are. These are the number of doses of COVID vaccines administered over time throughout the pandemic.

You can see that it’s stratified by age. The orange lines are adults ages 18-49, for example. You can see a big wave of vaccination when the vaccine first came out at the start of 2021. Then subsequently, you can see smaller waves after the first and second booster authorizations, and maybe a bit of a pickup, particularly among older adults, when the bivalent boosters were authorized. But still very little overall pickup of the bivalent booster, compared with the monovalent vaccines, which might suggest vaccine fatigue going on this far into the pandemic. But it’s important to try to understand exactly how effective those new boosters are, at least at this point in time.

I’m talking about Early Estimates of Bivalent mRNA Booster Dose Vaccine Effectiveness in Preventing Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection Attributable to Omicron BA.5– and XBB/XBB.1.5–Related Sublineages Among Immunocompetent Adults – Increasing Community Access to Testing Program, United States, December 2022–January 2023, which came out in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report very recently, which uses this test-negative case-control design to evaluate the ability of bivalent mRNA vaccines to prevent hospitalization.

The question is: Does receipt of a bivalent COVID vaccine booster prevent hospitalizations, ICU stay, or death? That may not be the question that is of interest to everyone. I know people are interested in symptoms, missed work, and transmission, but this paper was looking at hospitalization, ICU stay, and death.

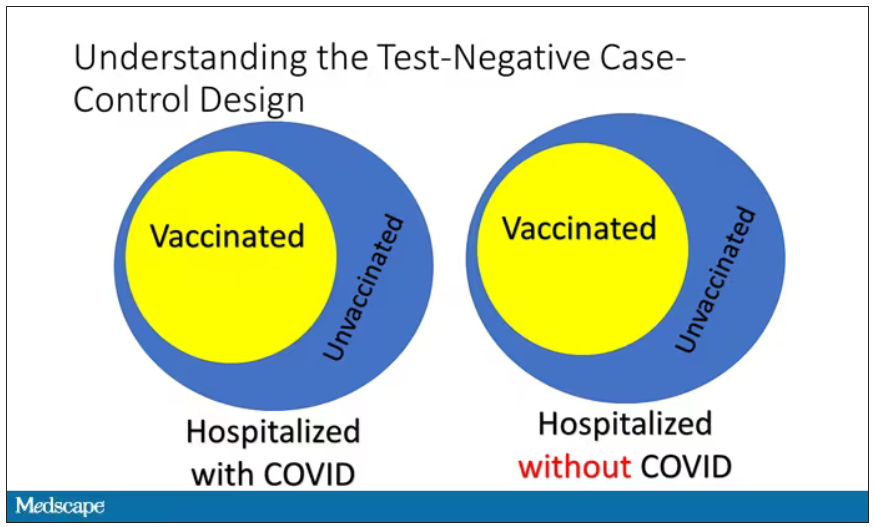

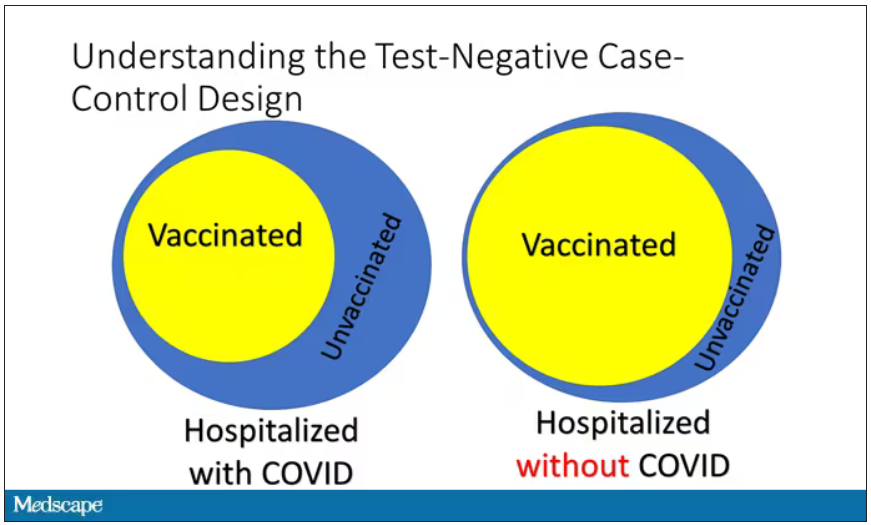

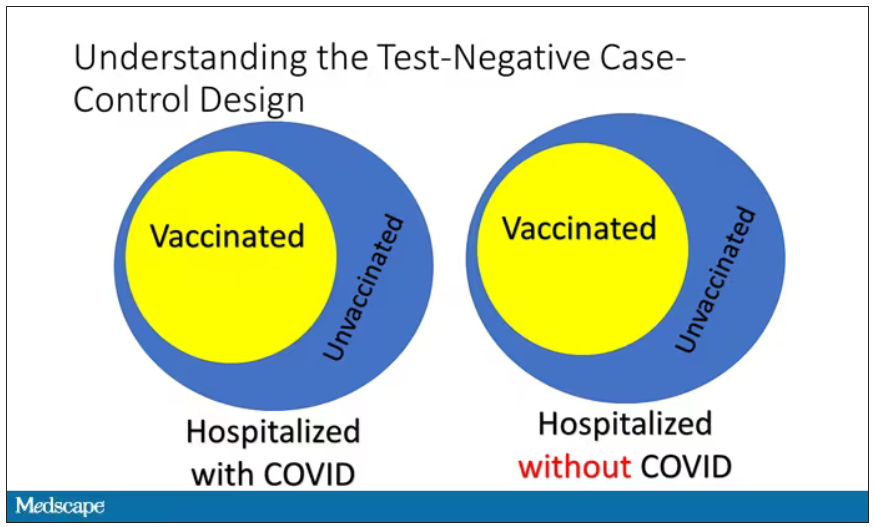

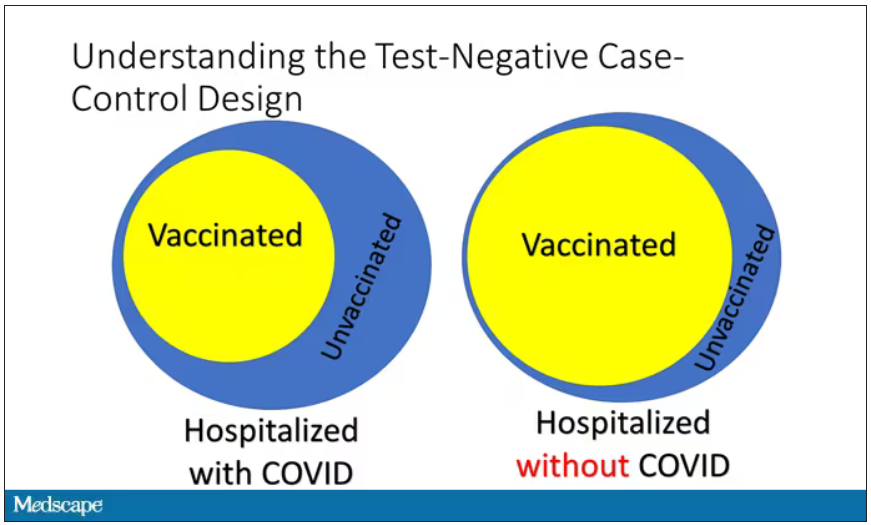

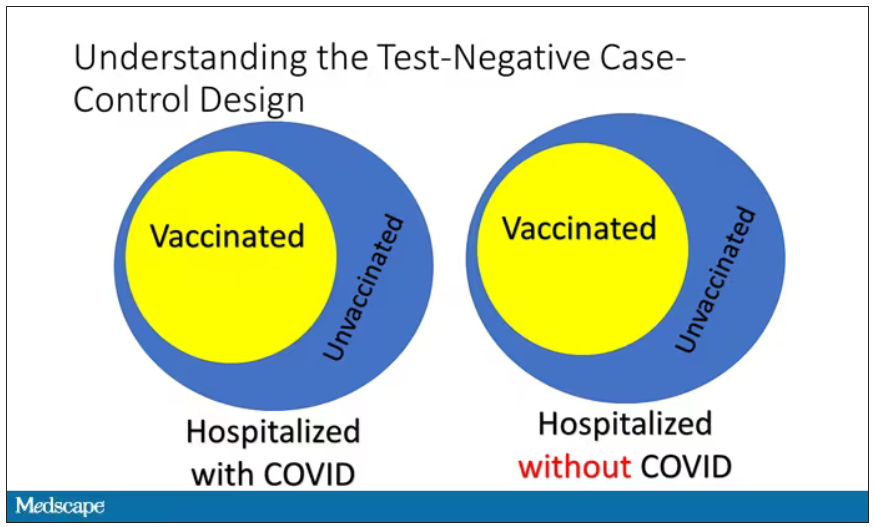

What’s kind of tricky here is that the data they’re using are in people who are hospitalized with various diseases. You might look at that on the surface and say: “Well, you can’t – that’s impossible.” But you can, actually, with this cool test-negative case-control design.

Here’s basically how it works. You take a population of people who are hospitalized and confirmed to have COVID. Some of them will be vaccinated and some of them will be unvaccinated. And the proportion of vaccinated and unvaccinated people doesn’t tell you very much because it depends on how that compares with the rates in the general population, for instance. Let me clarify this. If 100% of the population were vaccinated, then 100% of the people hospitalized with COVID would be vaccinated. That doesn’t mean vaccines are bad. Put another way, if 90% of the population were vaccinated and 60% of people hospitalized with COVID were vaccinated, that would actually show that the vaccines were working to some extent, all else being equal. So it’s not just the raw percentages that tell you anything. Some people are vaccinated, some people aren’t. You need to understand what the baseline rate is.

The test-negative case-control design looks at people who are hospitalized without COVID. Now who those people are (who the controls are, in this case) is something you really need to think about. In the case of this CDC study, they used people who were hospitalized with COVID-like illnesses – flu-like illnesses, respiratory illnesses, pneumonia, influenza, etc. This is a pretty good idea because it standardizes a little bit for people who have access to healthcare. They can get to a hospital and they’re the type of person who would go to a hospital when they’re feeling sick. That’s a better control than the general population overall, which is something I like about this design.

Some of those people who don’t have COVID (they’re in the hospital for flu or whatever) will have been vaccinated for COVID, and some will not have been vaccinated for COVID. And of course, we don’t expect COVID vaccines necessarily to protect against the flu or pneumonia, but that gives us a way to standardize.

If you look at these Venn diagrams, I’ve got vaccinated/unvaccinated being exactly the same proportion, which would suggest that you’re just as likely to be hospitalized with COVID if you’re vaccinated as you are to be hospitalized with some other respiratory illness, which suggests that the vaccine isn’t particularly effective.

However, if you saw something like this, looking at all those patients with flu and other non-COVID illnesses, a lot more of them had been vaccinated for COVID. What that tells you is that we’re seeing fewer vaccinated people hospitalized with COVID than we would expect because we have this standardization from other respiratory infections. We expect this many vaccinated people because that’s how many vaccinated people there are who show up with flu. But in the COVID population, there are fewer, and that would suggest that the vaccines are effective. So that is the test-negative case-control design. You can do the same thing with ICU stays and death.

There are some assumptions here which you might already be thinking about. The most important one is that vaccination status is not associated with the risk for the disease. I always think of older people in this context. During the pandemic, at least in the United States, older people were much more likely to be vaccinated but were also much more likely to contract COVID and be hospitalized with COVID. The test-negative design actually accounts for this in some sense, because older people are also more likely to be hospitalized for things like flu and pneumonia. So there’s some control there.

But to the extent that older people are uniquely susceptible to COVID compared with other respiratory illnesses, that would bias your results to make the vaccines look worse. So the standard approach here is to adjust for these things. I think the CDC adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and a few other things to settle down and see how effective the vaccines were.

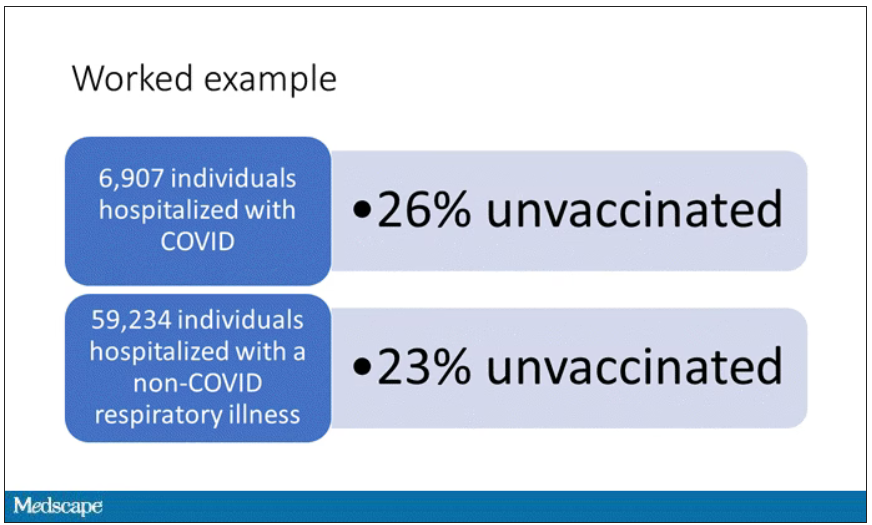

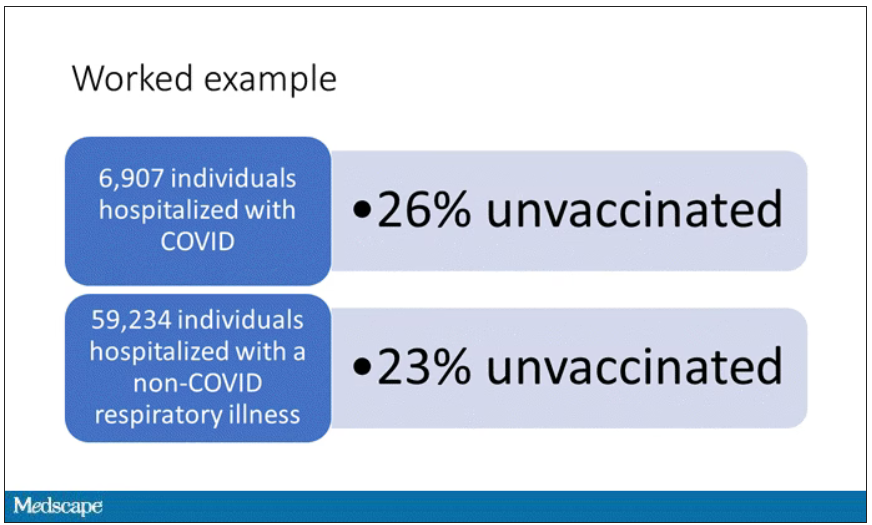

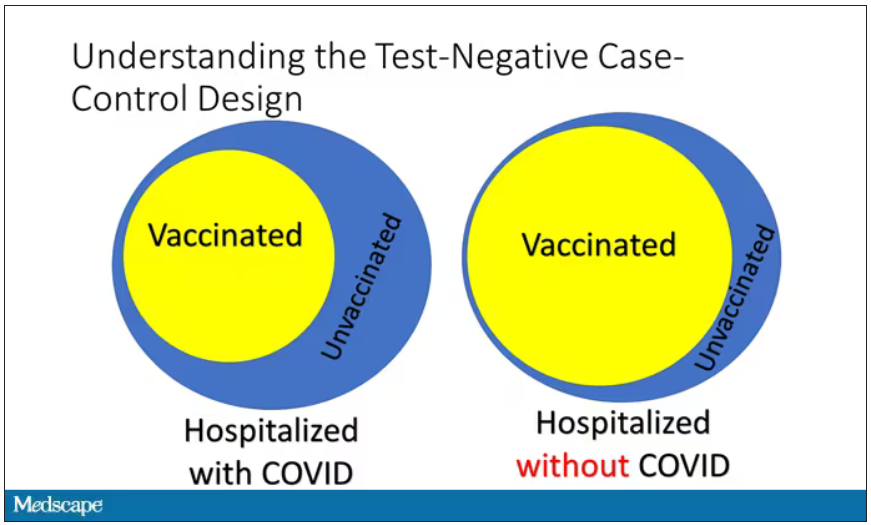

Let’s get to a worked example.

This is the actual data from the CDC paper. They had 6,907 individuals who were hospitalized with COVID, and 26% of them were unvaccinated. What’s the baseline rate that we would expect to be unvaccinated? A total of 59,234 individuals were hospitalized with a non-COVID respiratory illness, and 23% of them were unvaccinated. So you can see that there were more unvaccinated people than you would think in the COVID group. In other words, fewer vaccinated people, which suggests that the vaccine works to some degree because it’s keeping some people out of the hospital.

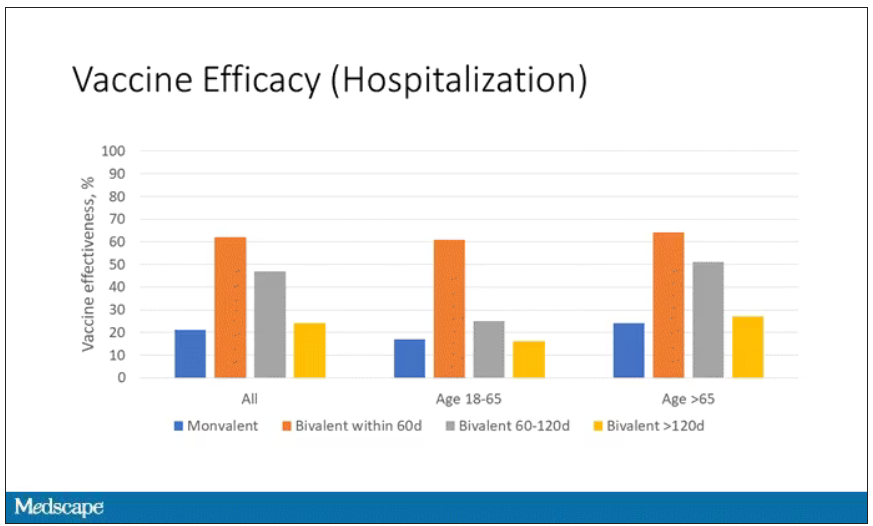

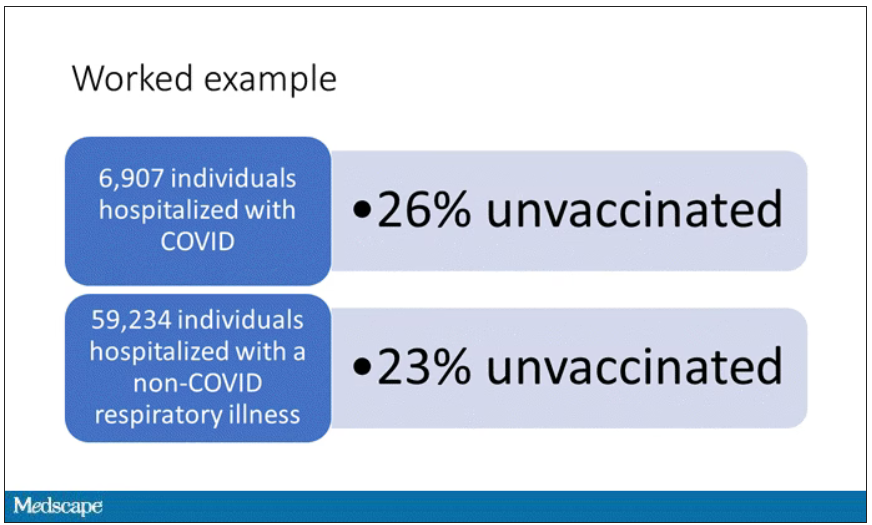

Now, 26% versus 23% is not a very impressive difference. But it gets more interesting when you break it down by the type of vaccine and how long ago the individual was vaccinated.

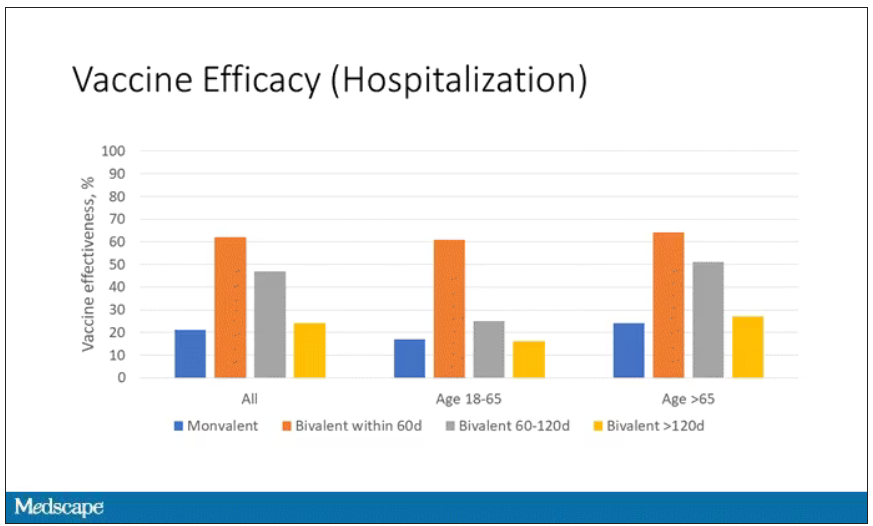

Let’s walk through the “all” group on this figure. What you can see is the calculated vaccine effectiveness. If you look at just the monovalent vaccine here, we see a 20% vaccine effectiveness. This means that you’re preventing 20% of hospitalizations basically due to COVID by people getting vaccinated. That’s okay but it’s certainly not anything to write home about. But we see much better vaccine effectiveness with the bivalent vaccine if it had been received within 60 days.

This compares people who received the bivalent vaccine within 60 days in the COVID group and the non-COVID group. The concern that the vaccine was given very recently affects both groups equally so it shouldn’t result in bias there. You see a step-off in vaccine effectiveness from 60 days, 60-120 days, and greater than 120 days. This is 4 months, and you’ve gone from 60% to 20%. When you break that down by age, you can see a similar pattern in the 18-to-65 group and potentially some more protection the greater than 65 age group.

Why is vaccine efficacy going down? The study doesn’t tell us, but we can hypothesize that this might be an immunologic effect – the antibodies or the protective T cells are waning over time. This could also reflect changes in the virus in the environment as the virus seeks to evade certain immune responses. But overall, this suggests that waiting a year between booster doses may leave you exposed for quite some time, although the take-home here is that bivalent vaccines in general are probably a good idea for the proportion of people who haven’t gotten them.

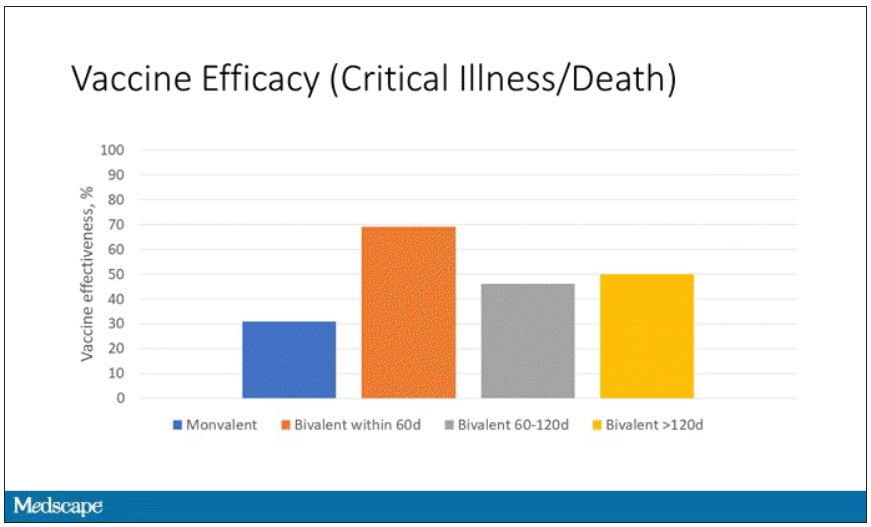

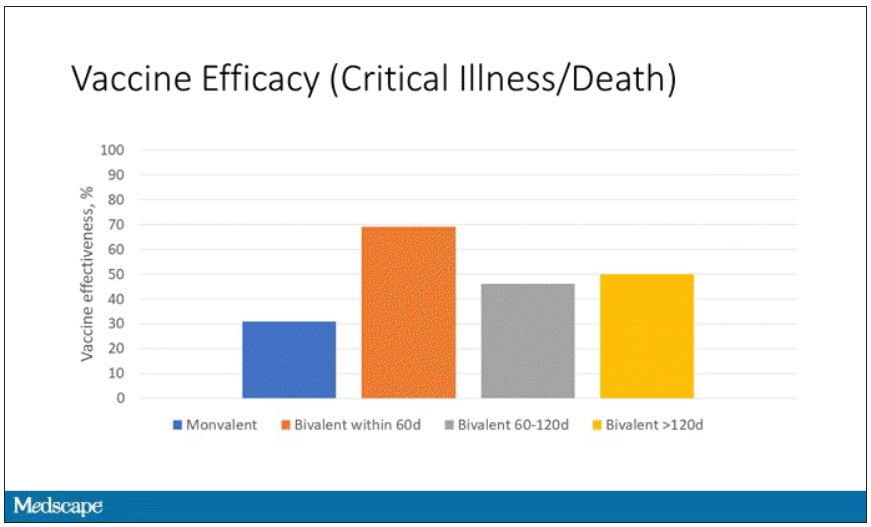

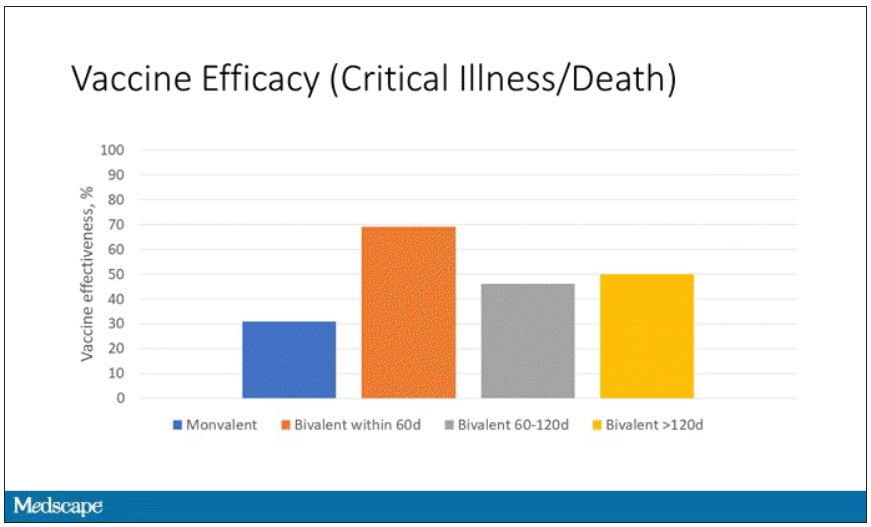

When we look at critical illness and death, the numbers look a little bit better.

You can see that bivalent is better than monovalent – certainly pretty good if you’ve received it within 60 days. It does tend to wane a little bit, but not nearly as much. You’ve still got about 50% vaccine efficacy beyond 120 days when we’re looking at critical illness, which is stays in the ICU and death.

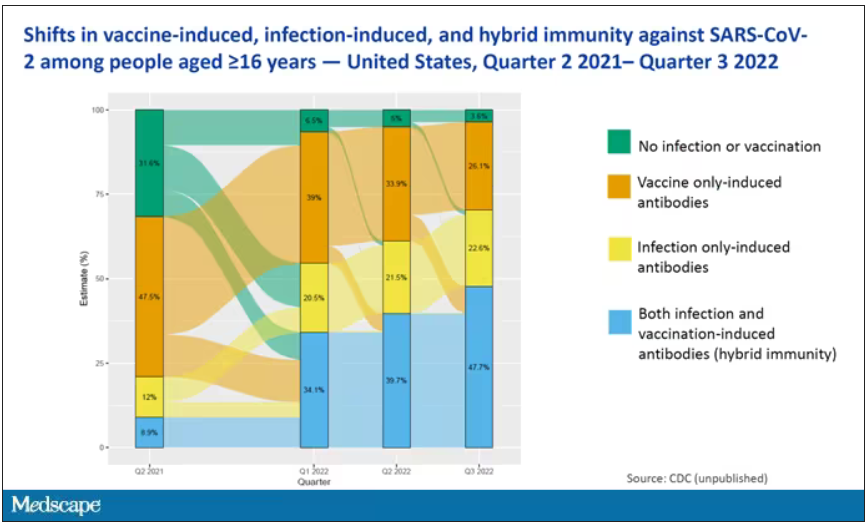

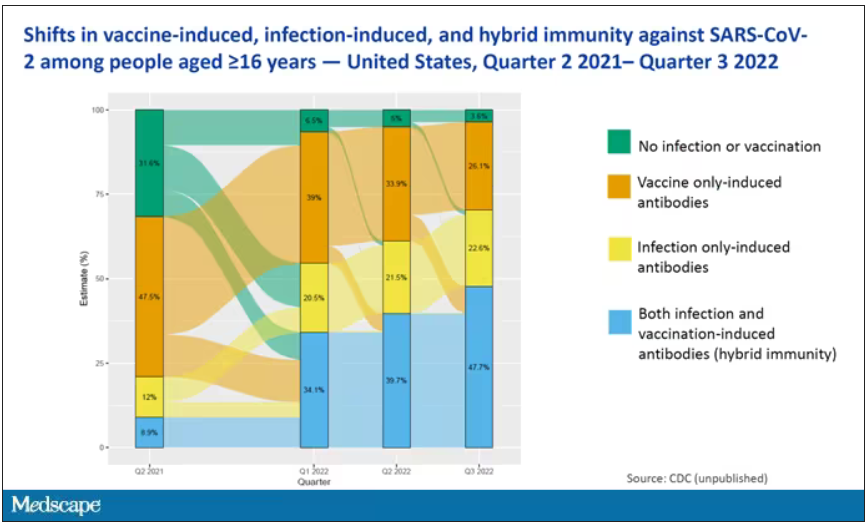

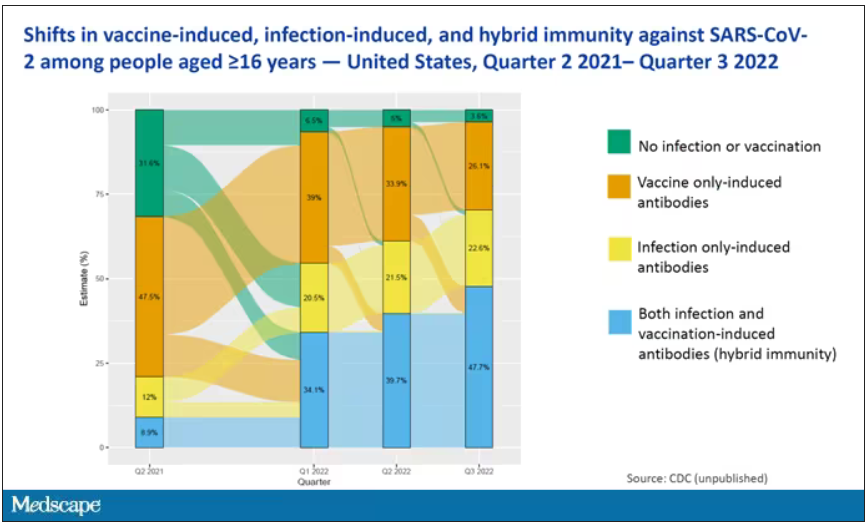

The overriding thing to think about when we think about vaccine policy is that the way you get immunized against COVID is either by vaccine or by getting infected with COVID, or both.

This really interesting graph from the CDC (although it’s updated only through quarter three of 2022) shows the proportion of Americans, based on routine lab tests, who have varying degrees of protection against COVID. What you can see is that, by quarter three of 2022, just 3.6% of people who had blood drawn at a commercial laboratory had no evidence of infection or vaccination. In other words, almost no one was totally naive. Then 26% of people had never been infected – they only have vaccine antibodies – plus 22% of people had only been infected but had never been vaccinated. And then 50% of people had both. So there’s a tremendous amount of existing immunity out there.

The really interesting question about future vaccination and future booster doses is, how does it work on the background of this pattern? The CDC study doesn’t tell us, and I don’t think they have the data to tell us the vaccine efficacy in these different groups. Is it more effective in people who have only had an infection, for example? Is it more effective in people who have only had vaccination versus people who had both, or people who have no protection whatsoever? Those are the really interesting questions that need to be answered going forward as vaccine policy gets developed in the future.

I hope this was a helpful primer on how the test-negative case-control design can answer questions that seem a little bit unanswerable.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

I am here today to talk about the effectiveness of COVID vaccine boosters in the midst of 2023. The reason I want to talk about this isn’t necessarily to dig into exactly how effective vaccines are. This is an area that’s been trod upon multiple times. But it does give me an opportunity to talk about a neat study design called the “test-negative case-control” design, which has some unique properties when you’re trying to evaluate the effect of something outside of the context of a randomized trial.

So, just a little bit of background to remind everyone where we are. These are the number of doses of COVID vaccines administered over time throughout the pandemic.

You can see that it’s stratified by age. The orange lines are adults ages 18-49, for example. You can see a big wave of vaccination when the vaccine first came out at the start of 2021. Then subsequently, you can see smaller waves after the first and second booster authorizations, and maybe a bit of a pickup, particularly among older adults, when the bivalent boosters were authorized. But still very little overall pickup of the bivalent booster, compared with the monovalent vaccines, which might suggest vaccine fatigue going on this far into the pandemic. But it’s important to try to understand exactly how effective those new boosters are, at least at this point in time.

I’m talking about Early Estimates of Bivalent mRNA Booster Dose Vaccine Effectiveness in Preventing Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection Attributable to Omicron BA.5– and XBB/XBB.1.5–Related Sublineages Among Immunocompetent Adults – Increasing Community Access to Testing Program, United States, December 2022–January 2023, which came out in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report very recently, which uses this test-negative case-control design to evaluate the ability of bivalent mRNA vaccines to prevent hospitalization.

The question is: Does receipt of a bivalent COVID vaccine booster prevent hospitalizations, ICU stay, or death? That may not be the question that is of interest to everyone. I know people are interested in symptoms, missed work, and transmission, but this paper was looking at hospitalization, ICU stay, and death.

What’s kind of tricky here is that the data they’re using are in people who are hospitalized with various diseases. You might look at that on the surface and say: “Well, you can’t – that’s impossible.” But you can, actually, with this cool test-negative case-control design.

Here’s basically how it works. You take a population of people who are hospitalized and confirmed to have COVID. Some of them will be vaccinated and some of them will be unvaccinated. And the proportion of vaccinated and unvaccinated people doesn’t tell you very much because it depends on how that compares with the rates in the general population, for instance. Let me clarify this. If 100% of the population were vaccinated, then 100% of the people hospitalized with COVID would be vaccinated. That doesn’t mean vaccines are bad. Put another way, if 90% of the population were vaccinated and 60% of people hospitalized with COVID were vaccinated, that would actually show that the vaccines were working to some extent, all else being equal. So it’s not just the raw percentages that tell you anything. Some people are vaccinated, some people aren’t. You need to understand what the baseline rate is.

The test-negative case-control design looks at people who are hospitalized without COVID. Now who those people are (who the controls are, in this case) is something you really need to think about. In the case of this CDC study, they used people who were hospitalized with COVID-like illnesses – flu-like illnesses, respiratory illnesses, pneumonia, influenza, etc. This is a pretty good idea because it standardizes a little bit for people who have access to healthcare. They can get to a hospital and they’re the type of person who would go to a hospital when they’re feeling sick. That’s a better control than the general population overall, which is something I like about this design.

Some of those people who don’t have COVID (they’re in the hospital for flu or whatever) will have been vaccinated for COVID, and some will not have been vaccinated for COVID. And of course, we don’t expect COVID vaccines necessarily to protect against the flu or pneumonia, but that gives us a way to standardize.

If you look at these Venn diagrams, I’ve got vaccinated/unvaccinated being exactly the same proportion, which would suggest that you’re just as likely to be hospitalized with COVID if you’re vaccinated as you are to be hospitalized with some other respiratory illness, which suggests that the vaccine isn’t particularly effective.

However, if you saw something like this, looking at all those patients with flu and other non-COVID illnesses, a lot more of them had been vaccinated for COVID. What that tells you is that we’re seeing fewer vaccinated people hospitalized with COVID than we would expect because we have this standardization from other respiratory infections. We expect this many vaccinated people because that’s how many vaccinated people there are who show up with flu. But in the COVID population, there are fewer, and that would suggest that the vaccines are effective. So that is the test-negative case-control design. You can do the same thing with ICU stays and death.

There are some assumptions here which you might already be thinking about. The most important one is that vaccination status is not associated with the risk for the disease. I always think of older people in this context. During the pandemic, at least in the United States, older people were much more likely to be vaccinated but were also much more likely to contract COVID and be hospitalized with COVID. The test-negative design actually accounts for this in some sense, because older people are also more likely to be hospitalized for things like flu and pneumonia. So there’s some control there.

But to the extent that older people are uniquely susceptible to COVID compared with other respiratory illnesses, that would bias your results to make the vaccines look worse. So the standard approach here is to adjust for these things. I think the CDC adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and a few other things to settle down and see how effective the vaccines were.

Let’s get to a worked example.

This is the actual data from the CDC paper. They had 6,907 individuals who were hospitalized with COVID, and 26% of them were unvaccinated. What’s the baseline rate that we would expect to be unvaccinated? A total of 59,234 individuals were hospitalized with a non-COVID respiratory illness, and 23% of them were unvaccinated. So you can see that there were more unvaccinated people than you would think in the COVID group. In other words, fewer vaccinated people, which suggests that the vaccine works to some degree because it’s keeping some people out of the hospital.

Now, 26% versus 23% is not a very impressive difference. But it gets more interesting when you break it down by the type of vaccine and how long ago the individual was vaccinated.

Let’s walk through the “all” group on this figure. What you can see is the calculated vaccine effectiveness. If you look at just the monovalent vaccine here, we see a 20% vaccine effectiveness. This means that you’re preventing 20% of hospitalizations basically due to COVID by people getting vaccinated. That’s okay but it’s certainly not anything to write home about. But we see much better vaccine effectiveness with the bivalent vaccine if it had been received within 60 days.

This compares people who received the bivalent vaccine within 60 days in the COVID group and the non-COVID group. The concern that the vaccine was given very recently affects both groups equally so it shouldn’t result in bias there. You see a step-off in vaccine effectiveness from 60 days, 60-120 days, and greater than 120 days. This is 4 months, and you’ve gone from 60% to 20%. When you break that down by age, you can see a similar pattern in the 18-to-65 group and potentially some more protection the greater than 65 age group.

Why is vaccine efficacy going down? The study doesn’t tell us, but we can hypothesize that this might be an immunologic effect – the antibodies or the protective T cells are waning over time. This could also reflect changes in the virus in the environment as the virus seeks to evade certain immune responses. But overall, this suggests that waiting a year between booster doses may leave you exposed for quite some time, although the take-home here is that bivalent vaccines in general are probably a good idea for the proportion of people who haven’t gotten them.

When we look at critical illness and death, the numbers look a little bit better.

You can see that bivalent is better than monovalent – certainly pretty good if you’ve received it within 60 days. It does tend to wane a little bit, but not nearly as much. You’ve still got about 50% vaccine efficacy beyond 120 days when we’re looking at critical illness, which is stays in the ICU and death.

The overriding thing to think about when we think about vaccine policy is that the way you get immunized against COVID is either by vaccine or by getting infected with COVID, or both.

This really interesting graph from the CDC (although it’s updated only through quarter three of 2022) shows the proportion of Americans, based on routine lab tests, who have varying degrees of protection against COVID. What you can see is that, by quarter three of 2022, just 3.6% of people who had blood drawn at a commercial laboratory had no evidence of infection or vaccination. In other words, almost no one was totally naive. Then 26% of people had never been infected – they only have vaccine antibodies – plus 22% of people had only been infected but had never been vaccinated. And then 50% of people had both. So there’s a tremendous amount of existing immunity out there.

The really interesting question about future vaccination and future booster doses is, how does it work on the background of this pattern? The CDC study doesn’t tell us, and I don’t think they have the data to tell us the vaccine efficacy in these different groups. Is it more effective in people who have only had an infection, for example? Is it more effective in people who have only had vaccination versus people who had both, or people who have no protection whatsoever? Those are the really interesting questions that need to be answered going forward as vaccine policy gets developed in the future.

I hope this was a helpful primer on how the test-negative case-control design can answer questions that seem a little bit unanswerable.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

I am here today to talk about the effectiveness of COVID vaccine boosters in the midst of 2023. The reason I want to talk about this isn’t necessarily to dig into exactly how effective vaccines are. This is an area that’s been trod upon multiple times. But it does give me an opportunity to talk about a neat study design called the “test-negative case-control” design, which has some unique properties when you’re trying to evaluate the effect of something outside of the context of a randomized trial.

So, just a little bit of background to remind everyone where we are. These are the number of doses of COVID vaccines administered over time throughout the pandemic.

You can see that it’s stratified by age. The orange lines are adults ages 18-49, for example. You can see a big wave of vaccination when the vaccine first came out at the start of 2021. Then subsequently, you can see smaller waves after the first and second booster authorizations, and maybe a bit of a pickup, particularly among older adults, when the bivalent boosters were authorized. But still very little overall pickup of the bivalent booster, compared with the monovalent vaccines, which might suggest vaccine fatigue going on this far into the pandemic. But it’s important to try to understand exactly how effective those new boosters are, at least at this point in time.

I’m talking about Early Estimates of Bivalent mRNA Booster Dose Vaccine Effectiveness in Preventing Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection Attributable to Omicron BA.5– and XBB/XBB.1.5–Related Sublineages Among Immunocompetent Adults – Increasing Community Access to Testing Program, United States, December 2022–January 2023, which came out in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report very recently, which uses this test-negative case-control design to evaluate the ability of bivalent mRNA vaccines to prevent hospitalization.

The question is: Does receipt of a bivalent COVID vaccine booster prevent hospitalizations, ICU stay, or death? That may not be the question that is of interest to everyone. I know people are interested in symptoms, missed work, and transmission, but this paper was looking at hospitalization, ICU stay, and death.

What’s kind of tricky here is that the data they’re using are in people who are hospitalized with various diseases. You might look at that on the surface and say: “Well, you can’t – that’s impossible.” But you can, actually, with this cool test-negative case-control design.

Here’s basically how it works. You take a population of people who are hospitalized and confirmed to have COVID. Some of them will be vaccinated and some of them will be unvaccinated. And the proportion of vaccinated and unvaccinated people doesn’t tell you very much because it depends on how that compares with the rates in the general population, for instance. Let me clarify this. If 100% of the population were vaccinated, then 100% of the people hospitalized with COVID would be vaccinated. That doesn’t mean vaccines are bad. Put another way, if 90% of the population were vaccinated and 60% of people hospitalized with COVID were vaccinated, that would actually show that the vaccines were working to some extent, all else being equal. So it’s not just the raw percentages that tell you anything. Some people are vaccinated, some people aren’t. You need to understand what the baseline rate is.

The test-negative case-control design looks at people who are hospitalized without COVID. Now who those people are (who the controls are, in this case) is something you really need to think about. In the case of this CDC study, they used people who were hospitalized with COVID-like illnesses – flu-like illnesses, respiratory illnesses, pneumonia, influenza, etc. This is a pretty good idea because it standardizes a little bit for people who have access to healthcare. They can get to a hospital and they’re the type of person who would go to a hospital when they’re feeling sick. That’s a better control than the general population overall, which is something I like about this design.

Some of those people who don’t have COVID (they’re in the hospital for flu or whatever) will have been vaccinated for COVID, and some will not have been vaccinated for COVID. And of course, we don’t expect COVID vaccines necessarily to protect against the flu or pneumonia, but that gives us a way to standardize.

If you look at these Venn diagrams, I’ve got vaccinated/unvaccinated being exactly the same proportion, which would suggest that you’re just as likely to be hospitalized with COVID if you’re vaccinated as you are to be hospitalized with some other respiratory illness, which suggests that the vaccine isn’t particularly effective.

However, if you saw something like this, looking at all those patients with flu and other non-COVID illnesses, a lot more of them had been vaccinated for COVID. What that tells you is that we’re seeing fewer vaccinated people hospitalized with COVID than we would expect because we have this standardization from other respiratory infections. We expect this many vaccinated people because that’s how many vaccinated people there are who show up with flu. But in the COVID population, there are fewer, and that would suggest that the vaccines are effective. So that is the test-negative case-control design. You can do the same thing with ICU stays and death.

There are some assumptions here which you might already be thinking about. The most important one is that vaccination status is not associated with the risk for the disease. I always think of older people in this context. During the pandemic, at least in the United States, older people were much more likely to be vaccinated but were also much more likely to contract COVID and be hospitalized with COVID. The test-negative design actually accounts for this in some sense, because older people are also more likely to be hospitalized for things like flu and pneumonia. So there’s some control there.

But to the extent that older people are uniquely susceptible to COVID compared with other respiratory illnesses, that would bias your results to make the vaccines look worse. So the standard approach here is to adjust for these things. I think the CDC adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and a few other things to settle down and see how effective the vaccines were.

Let’s get to a worked example.

This is the actual data from the CDC paper. They had 6,907 individuals who were hospitalized with COVID, and 26% of them were unvaccinated. What’s the baseline rate that we would expect to be unvaccinated? A total of 59,234 individuals were hospitalized with a non-COVID respiratory illness, and 23% of them were unvaccinated. So you can see that there were more unvaccinated people than you would think in the COVID group. In other words, fewer vaccinated people, which suggests that the vaccine works to some degree because it’s keeping some people out of the hospital.

Now, 26% versus 23% is not a very impressive difference. But it gets more interesting when you break it down by the type of vaccine and how long ago the individual was vaccinated.

Let’s walk through the “all” group on this figure. What you can see is the calculated vaccine effectiveness. If you look at just the monovalent vaccine here, we see a 20% vaccine effectiveness. This means that you’re preventing 20% of hospitalizations basically due to COVID by people getting vaccinated. That’s okay but it’s certainly not anything to write home about. But we see much better vaccine effectiveness with the bivalent vaccine if it had been received within 60 days.

This compares people who received the bivalent vaccine within 60 days in the COVID group and the non-COVID group. The concern that the vaccine was given very recently affects both groups equally so it shouldn’t result in bias there. You see a step-off in vaccine effectiveness from 60 days, 60-120 days, and greater than 120 days. This is 4 months, and you’ve gone from 60% to 20%. When you break that down by age, you can see a similar pattern in the 18-to-65 group and potentially some more protection the greater than 65 age group.

Why is vaccine efficacy going down? The study doesn’t tell us, but we can hypothesize that this might be an immunologic effect – the antibodies or the protective T cells are waning over time. This could also reflect changes in the virus in the environment as the virus seeks to evade certain immune responses. But overall, this suggests that waiting a year between booster doses may leave you exposed for quite some time, although the take-home here is that bivalent vaccines in general are probably a good idea for the proportion of people who haven’t gotten them.

When we look at critical illness and death, the numbers look a little bit better.

You can see that bivalent is better than monovalent – certainly pretty good if you’ve received it within 60 days. It does tend to wane a little bit, but not nearly as much. You’ve still got about 50% vaccine efficacy beyond 120 days when we’re looking at critical illness, which is stays in the ICU and death.

The overriding thing to think about when we think about vaccine policy is that the way you get immunized against COVID is either by vaccine or by getting infected with COVID, or both.

This really interesting graph from the CDC (although it’s updated only through quarter three of 2022) shows the proportion of Americans, based on routine lab tests, who have varying degrees of protection against COVID. What you can see is that, by quarter three of 2022, just 3.6% of people who had blood drawn at a commercial laboratory had no evidence of infection or vaccination. In other words, almost no one was totally naive. Then 26% of people had never been infected – they only have vaccine antibodies – plus 22% of people had only been infected but had never been vaccinated. And then 50% of people had both. So there’s a tremendous amount of existing immunity out there.

The really interesting question about future vaccination and future booster doses is, how does it work on the background of this pattern? The CDC study doesn’t tell us, and I don’t think they have the data to tell us the vaccine efficacy in these different groups. Is it more effective in people who have only had an infection, for example? Is it more effective in people who have only had vaccination versus people who had both, or people who have no protection whatsoever? Those are the really interesting questions that need to be answered going forward as vaccine policy gets developed in the future.

I hope this was a helpful primer on how the test-negative case-control design can answer questions that seem a little bit unanswerable.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Review supports continued mask-wearing in health care visits

A new study urges people to continue wearing protective masks in medical settings, even though the U.S. public health emergency declaration around COVID-19 has expired.

Masks continue to lower the risk of catching the virus during medical visits, according to the study, published in Annals of Internal Medicine. And there was not much difference between wearing surgical masks and N95 respirators in health care settings.

The researchers reviewed 3 randomized trials and 21 observational studies to compare the effectiveness of those and cloth masks in reducing COVID-19 transmission.

Tara N. Palmore, MD, of George Washington University, Washington, and David K. Henderson, MD, of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., wrote in an opinion article accompanying the study.

“In our enthusiasm to return to the appearance and feeling of normalcy, and as institutions decide which mitigation strategies to discontinue, we strongly advocate not discarding this important lesson learned for the sake of our patients’ safety,” Dr. Palmore and Dr. Henderson wrote.

Surgical masks limit the spread of aerosols and droplets from people who have the flu, coronaviruses or other respiratory viruses, CNN reported. And while masks are not 100% effective, they substantially lower the amount of virus put into the air via coughing and talking.

The study said one reason people should wear masks to medical settings is because “health care personnel are notorious for coming to work while ill.” Transmission from patient to staff and staff to patient is still possible, but rare, when both are masked.

The review authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Palmore has received grants from the NIH, Rigel, Gilead, and AbbVie, and Dr. Henderson is a past president of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A new study urges people to continue wearing protective masks in medical settings, even though the U.S. public health emergency declaration around COVID-19 has expired.

Masks continue to lower the risk of catching the virus during medical visits, according to the study, published in Annals of Internal Medicine. And there was not much difference between wearing surgical masks and N95 respirators in health care settings.

The researchers reviewed 3 randomized trials and 21 observational studies to compare the effectiveness of those and cloth masks in reducing COVID-19 transmission.

Tara N. Palmore, MD, of George Washington University, Washington, and David K. Henderson, MD, of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., wrote in an opinion article accompanying the study.

“In our enthusiasm to return to the appearance and feeling of normalcy, and as institutions decide which mitigation strategies to discontinue, we strongly advocate not discarding this important lesson learned for the sake of our patients’ safety,” Dr. Palmore and Dr. Henderson wrote.

Surgical masks limit the spread of aerosols and droplets from people who have the flu, coronaviruses or other respiratory viruses, CNN reported. And while masks are not 100% effective, they substantially lower the amount of virus put into the air via coughing and talking.

The study said one reason people should wear masks to medical settings is because “health care personnel are notorious for coming to work while ill.” Transmission from patient to staff and staff to patient is still possible, but rare, when both are masked.

The review authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Palmore has received grants from the NIH, Rigel, Gilead, and AbbVie, and Dr. Henderson is a past president of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

A new study urges people to continue wearing protective masks in medical settings, even though the U.S. public health emergency declaration around COVID-19 has expired.

Masks continue to lower the risk of catching the virus during medical visits, according to the study, published in Annals of Internal Medicine. And there was not much difference between wearing surgical masks and N95 respirators in health care settings.

The researchers reviewed 3 randomized trials and 21 observational studies to compare the effectiveness of those and cloth masks in reducing COVID-19 transmission.

Tara N. Palmore, MD, of George Washington University, Washington, and David K. Henderson, MD, of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md., wrote in an opinion article accompanying the study.

“In our enthusiasm to return to the appearance and feeling of normalcy, and as institutions decide which mitigation strategies to discontinue, we strongly advocate not discarding this important lesson learned for the sake of our patients’ safety,” Dr. Palmore and Dr. Henderson wrote.

Surgical masks limit the spread of aerosols and droplets from people who have the flu, coronaviruses or other respiratory viruses, CNN reported. And while masks are not 100% effective, they substantially lower the amount of virus put into the air via coughing and talking.

The study said one reason people should wear masks to medical settings is because “health care personnel are notorious for coming to work while ill.” Transmission from patient to staff and staff to patient is still possible, but rare, when both are masked.

The review authors reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Palmore has received grants from the NIH, Rigel, Gilead, and AbbVie, and Dr. Henderson is a past president of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Could vitamin D supplementation help in long COVID?

, in a retrospective, case-matched study.

The lower levels of vitamin D in patients with long COVID were most notable in those with brain fog.

These findings, by Luigi di Filippo, MD, and colleagues, were recently presented at the European Congress of Endocrinology and published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“Our data suggest that vitamin D levels should be evaluated in COVID-19 patients after hospital discharge,” wrote the researchers, from San Raffaele Hospital, Milan.

“The role of vitamin D supplementation as a preventive strategy of COVID-19 sequelae should be tested in randomized controlled trials,” they urged.

The researchers also stressed that this was a controlled study in a homogeneous population, it included multiple signs and symptoms of long COVID, and it had a longer follow-up than most previous studies (6 vs. 3 months).

“The highly controlled nature of our study helps us better understand the role of vitamin D deficiency in long COVID and establish that there is likely a link between vitamin D deficiency and long COVID,” senior author Andrea Giustina, MD, said in a press release from the ECE.

“Our study shows that COVID-19 patients with low vitamin D levels are more likely to develop long COVID, but it is not yet known whether vitamin D supplements could improve the symptoms or reduce this risk altogether,” he cautioned.

“If confirmed in large, interventional, randomized controlled trials, [our data suggest] that vitamin D supplementation could represent a possible preventive strategy in reducing the burden of COVID-19 sequelae,” Dr. Giustina and colleagues wrote.

Reasonable to test vitamin D levels, consider supplementation

Invited to comment, Amiel Dror, MD, PhD, who led a related study that showed that people with a vitamin D deficiency were more likely to have severe COVID-19, agreed.

“The novelty and significance of this [new] study lie in the fact that it expands on our current understanding of the interplay between vitamin D and COVID-19, taking it beyond the acute phase of the disease,” said Dr. Dror, from Bar-Ilan University, Safed, Israel.

“It’s striking to see how vitamin D levels continue to influence patients’ health even after recovery from the initial infection,” he noted.

“The findings certainly add weight to the argument for conducting a randomized control trial [RCT],” he continued, which “would enable us to conclusively determine whether vitamin D supplementation can effectively reduce the risk or severity of long COVID.”

“In the interim,” Dr. Dror said, “given the safety profile of vitamin D and its broad health benefits, it could be reasonable to test for vitamin D levels in patients admitted with COVID-19. If levels are found to be low, supplementation could be considered.”

“However, it’s important to note that this should be done under medical supervision,” he cautioned, “and further studies are needed to establish the optimal timing and dosage of supplementation.”

“I anticipate that we’ll see more RCTs [of this] in the future,” he speculated.

Low vitamin D and risk of long COVID

Long COVID is an emerging syndrome that affects 50%-70% of COVID-19 survivors.

Low levels of vitamin D have been associated with increased likelihood of needing mechanical ventilation and worse survival in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, but the risk of long COVID associated with vitamin D has not been known.

Researchers analyzed data from adults aged 18 and older hospitalized at San Raffaele Hospital with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 and discharged during the first pandemic wave, from March to May 2020, and then seen 6-months later for follow-up.

Patients were excluded if they had been admitted to the intensive care unit during hospitalization or had missing medical data or blood samples available to determine (OH) vitamin D levels, at admission and the 6-month follow-up.

Long COVID-19 was defined based on the U.K. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines as the concomitant presence of at least two or more of 17 signs and symptoms that were absent prior to the COVID-19 infection and could only be attributed to that acute disease.

Researchers identified 50 patients with long COVID at the 6-month follow-up and matched them with 50 patients without long COVID at that time point, based on age, sex, concomitant comorbidities, need for noninvasive mechanical ventilation, and week of evaluation.

Patients were a mean age of 61 years (range, 51-73) and 56% were men; 28% had been on a ventilator during hospitalization for COVID-19.

The most frequent signs and symptoms at 6 months in the patients with long COVID were asthenia (weakness, 38% of patients), dysgeusia (bad taste in the mouth, 34%), dyspnea (shortness of breath, 34%), and anosmia (loss of sense of smell, 24%).

Most symptoms were related to the cardiorespiratory system (42%), the feeling of well-being (42%), or the senses (36%), and fewer patients had symptoms related to neurocognitive impairment (headache or brain fog, 14%), or ear, nose, and throat (12%), or gastrointestinal system (4%).

Patients with long COVID had lower mean 25(OH) vitamin D levels than patients without long COVID (20.1 vs 23.2 ng/mL; P = .03). However, actual vitamin D deficiency levels were similar in both groups.

Two-thirds of patients with low vitamin D levels at hospital admission still presented with low levels at the 6-month follow-up.

Vitamin D levels were significantly lower in patients with neurocognitive symptoms at follow-up (n = 7) than in those without such symptoms (n = 93) (14.6 vs. 20.6 ng/mL; P = .042).

In patients with vitamin D deficiency (< 20 ng/mL) at admission and at follow-up (n = 42), those with long COVID (n = 22) had lower vitamin D levels at follow-up than those without long COVID (n = 20) (12.7 vs. 15.2 ng/mL; P = .041).

And in multiple regression analyses, a lower 25(OH) vitamin D level at follow-up was the only variable that was significantly associated with long COVID (odds ratio, 1.09; 95% confidence interval, 1.01-1.16; P = .008).

The findings “strongly reinforce the clinical usefulness of 25(OH) vitamin D evaluation as a possible modifiable pathophysiological factor underlying this emerging worldwide critical health issue,” the researchers concluded.

The study was supported by Abiogen Pharma. One study author is an employee at Abiogen. Dr. Giustina has reported being a consultant for Abiogen and Takeda and receiving a research grant to his institution from Takeda. Dr. Di Filippo and the other authors reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, in a retrospective, case-matched study.

The lower levels of vitamin D in patients with long COVID were most notable in those with brain fog.

These findings, by Luigi di Filippo, MD, and colleagues, were recently presented at the European Congress of Endocrinology and published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

“Our data suggest that vitamin D levels should be evaluated in COVID-19 patients after hospital discharge,” wrote the researchers, from San Raffaele Hospital, Milan.

“The role of vitamin D supplementation as a preventive strategy of COVID-19 sequelae should be tested in randomized controlled trials,” they urged.

The researchers also stressed that this was a controlled study in a homogeneous population, it included multiple signs and symptoms of long COVID, and it had a longer follow-up than most previous studies (6 vs. 3 months).

“The highly controlled nature of our study helps us better understand the role of vitamin D deficiency in long COVID and establish that there is likely a link between vitamin D deficiency and long COVID,” senior author Andrea Giustina, MD, said in a press release from the ECE.

“Our study shows that COVID-19 patients with low vitamin D levels are more likely to develop long COVID, but it is not yet known whether vitamin D supplements could improve the symptoms or reduce this risk altogether,” he cautioned.

“If confirmed in large, interventional, randomized controlled trials, [our data suggest] that vitamin D supplementation could represent a possible preventive strategy in reducing the burden of COVID-19 sequelae,” Dr. Giustina and colleagues wrote.

Reasonable to test vitamin D levels, consider supplementation

Invited to comment, Amiel Dror, MD, PhD, who led a related study that showed that people with a vitamin D deficiency were more likely to have severe COVID-19, agreed.

“The novelty and significance of this [new] study lie in the fact that it expands on our current understanding of the interplay between vitamin D and COVID-19, taking it beyond the acute phase of the disease,” said Dr. Dror, from Bar-Ilan University, Safed, Israel.