User login

Is it flu, RSV, or COVID? Experts fear the ‘tripledemic’

Just when we thought this holiday season, finally, would be the back-to-normal one, some infectious disease experts are warning that a so-called “tripledemic” – influenza, COVID-19, and RSV – may be in the forecast.

The warning isn’t without basis.

The flu season has gotten an early start. As of Oct. 21, early increases in seasonal flu activity have been reported in most of the country, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said, with the southeast and south-central areas having the highest activity levels.

Children’s hospitals and EDs are seeing a surge in children with RSV.

COVID-19 cases are trending down, according to the CDC, but epidemiologists – scientists who study disease outbreaks – always have their eyes on emerging variants.

said Justin Lessler, PhD, a professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Lessler is on the coordinating team for the COVID-19 Scenario Modeling Hub, which aims to predict the course COVID-19, and the Flu Scenario Modeling Hub, which does the same for influenza.

For COVID-19, some models are predicting some spikes before Christmas, he said, and others see a new wave in 2023. For the flu, the model is predicting an earlier-than-usual start, as the CDC has reported.

While flu activity is relatively low, the CDC said, the season is off to an early start. For the week ending Oct. 21, 1,674 patients were hospitalized for flu, higher than in the summer months but fewer than the 2,675 hospitalizations for the week of May 15, 2022.

As of Oct. 20, COVID-19 cases have declined 12% over the last 2 weeks, nationwide. But hospitalizations are up 10% in much of the Northeast, The New York Times reports, and the improvement in cases and deaths has been slowing down.

As of Oct. 15, 15% of RSV tests reported nationwide were positive, compared with about 11% at that time in 2021, the CDC said. The surveillance collects information from 75 counties in 12 states.

Experts point out that the viruses – all three are respiratory viruses – are simply playing catchup.

“They spread the same way and along with lots of other viruses, and you tend to see an increase in them during the cold months,” said Timothy Brewer, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at UCLA.

The increase in all three viruses “is almost predictable at this point in the pandemic,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, a professor and chief of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of California Davis Health. “All the respiratory viruses are out of whack.”

Last year, RSV cases were up, too, and began to appear very early, he said, in the summer instead of in the cooler months. Flu also appeared early in 2021, as it has in 2022.

That contrasts with the flu season of 2020-2021, when COVID precautions were nearly universal, and cases were down. At UC Davis, “we didn’t have one pediatric admission due to influenza in the 2020-2021 [flu] season,” Dr. Blumberg said.

The number of pediatric flu deaths usually range from 37 to 199 per year, according to CDC records. But in the 2020-2021 season, the CDC recorded one pediatric flu death in the U.S.

Both children and adults have had less contact with others the past two seasons, Dr. Blumberg said, “and they don’t get the immunity they got with those infections [previously]. That’s why we are seeing out-of-season, early season [viruses].”

Eventually, he said, the cases of flu and RSV will return to previous levels. “It could be as soon as next year,” Dr. Blumberg said. And COVID-19, hopefully, will become like influenza, he said.

“RSV has always come around in the fall and winter,” said Elizabeth Murray, DO, a pediatric emergency medicine doctor at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics. In 2022, children are back in school and for the most part not masking. “It’s a perfect storm for all the germs to spread now. They’ve just been waiting for their opportunity to come back.”

Self-care vs. not

RSV can pose a risk for anyone, but most at risk are children under age 5, especially infants under age 1, and adults over age 65. There is no vaccine for it. Symptoms include a runny nose, decreased appetite, coughing, sneezing, fever, and wheezing. But in young infants, there may only be decreased activity, crankiness, and breathing issues, the CDC said.

Keep an eye on the breathing if RSV is suspected, Dr. Murray tells parents. If your child can’t breathe easily, is unable to lie down comfortably, can’t speak clearly, or is sucking in the chest muscles to breathe, get medical help. Most kids with RSV can stay home and recover, she said, but often will need to be checked by a medical professional.

She advises against getting an oximeter to measure oxygen levels for home use. “They are often not accurate,” she said. If in doubt about how serious your child’s symptoms are, “don’t wait it out,” and don’t hesitate to call 911.

Symptoms of flu, COVID, and RSV can overlap. But each can involve breathing problems, which can be an emergency.

“It’s important to seek medical attention for any concerning symptoms, but especially severe shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, as these could signal the need for supplemental oxygen or other emergency interventions,” said Mandy De Vries, a respiratory therapist and director of education at the American Association for Respiratory Care. Inhalation treatment or mechanical ventilation may be needed for severe respiratory issues.

Precautions

To avoid the tripledemic – or any single infection – Timothy Brewer, MD, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, suggests some familiar measures: “Stay home if you’re feeling sick. Make sure you are up to date on your vaccinations. Wear a mask indoors.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Just when we thought this holiday season, finally, would be the back-to-normal one, some infectious disease experts are warning that a so-called “tripledemic” – influenza, COVID-19, and RSV – may be in the forecast.

The warning isn’t without basis.

The flu season has gotten an early start. As of Oct. 21, early increases in seasonal flu activity have been reported in most of the country, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said, with the southeast and south-central areas having the highest activity levels.

Children’s hospitals and EDs are seeing a surge in children with RSV.

COVID-19 cases are trending down, according to the CDC, but epidemiologists – scientists who study disease outbreaks – always have their eyes on emerging variants.

said Justin Lessler, PhD, a professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Lessler is on the coordinating team for the COVID-19 Scenario Modeling Hub, which aims to predict the course COVID-19, and the Flu Scenario Modeling Hub, which does the same for influenza.

For COVID-19, some models are predicting some spikes before Christmas, he said, and others see a new wave in 2023. For the flu, the model is predicting an earlier-than-usual start, as the CDC has reported.

While flu activity is relatively low, the CDC said, the season is off to an early start. For the week ending Oct. 21, 1,674 patients were hospitalized for flu, higher than in the summer months but fewer than the 2,675 hospitalizations for the week of May 15, 2022.

As of Oct. 20, COVID-19 cases have declined 12% over the last 2 weeks, nationwide. But hospitalizations are up 10% in much of the Northeast, The New York Times reports, and the improvement in cases and deaths has been slowing down.

As of Oct. 15, 15% of RSV tests reported nationwide were positive, compared with about 11% at that time in 2021, the CDC said. The surveillance collects information from 75 counties in 12 states.

Experts point out that the viruses – all three are respiratory viruses – are simply playing catchup.

“They spread the same way and along with lots of other viruses, and you tend to see an increase in them during the cold months,” said Timothy Brewer, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at UCLA.

The increase in all three viruses “is almost predictable at this point in the pandemic,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, a professor and chief of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of California Davis Health. “All the respiratory viruses are out of whack.”

Last year, RSV cases were up, too, and began to appear very early, he said, in the summer instead of in the cooler months. Flu also appeared early in 2021, as it has in 2022.

That contrasts with the flu season of 2020-2021, when COVID precautions were nearly universal, and cases were down. At UC Davis, “we didn’t have one pediatric admission due to influenza in the 2020-2021 [flu] season,” Dr. Blumberg said.

The number of pediatric flu deaths usually range from 37 to 199 per year, according to CDC records. But in the 2020-2021 season, the CDC recorded one pediatric flu death in the U.S.

Both children and adults have had less contact with others the past two seasons, Dr. Blumberg said, “and they don’t get the immunity they got with those infections [previously]. That’s why we are seeing out-of-season, early season [viruses].”

Eventually, he said, the cases of flu and RSV will return to previous levels. “It could be as soon as next year,” Dr. Blumberg said. And COVID-19, hopefully, will become like influenza, he said.

“RSV has always come around in the fall and winter,” said Elizabeth Murray, DO, a pediatric emergency medicine doctor at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics. In 2022, children are back in school and for the most part not masking. “It’s a perfect storm for all the germs to spread now. They’ve just been waiting for their opportunity to come back.”

Self-care vs. not

RSV can pose a risk for anyone, but most at risk are children under age 5, especially infants under age 1, and adults over age 65. There is no vaccine for it. Symptoms include a runny nose, decreased appetite, coughing, sneezing, fever, and wheezing. But in young infants, there may only be decreased activity, crankiness, and breathing issues, the CDC said.

Keep an eye on the breathing if RSV is suspected, Dr. Murray tells parents. If your child can’t breathe easily, is unable to lie down comfortably, can’t speak clearly, or is sucking in the chest muscles to breathe, get medical help. Most kids with RSV can stay home and recover, she said, but often will need to be checked by a medical professional.

She advises against getting an oximeter to measure oxygen levels for home use. “They are often not accurate,” she said. If in doubt about how serious your child’s symptoms are, “don’t wait it out,” and don’t hesitate to call 911.

Symptoms of flu, COVID, and RSV can overlap. But each can involve breathing problems, which can be an emergency.

“It’s important to seek medical attention for any concerning symptoms, but especially severe shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, as these could signal the need for supplemental oxygen or other emergency interventions,” said Mandy De Vries, a respiratory therapist and director of education at the American Association for Respiratory Care. Inhalation treatment or mechanical ventilation may be needed for severe respiratory issues.

Precautions

To avoid the tripledemic – or any single infection – Timothy Brewer, MD, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, suggests some familiar measures: “Stay home if you’re feeling sick. Make sure you are up to date on your vaccinations. Wear a mask indoors.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Just when we thought this holiday season, finally, would be the back-to-normal one, some infectious disease experts are warning that a so-called “tripledemic” – influenza, COVID-19, and RSV – may be in the forecast.

The warning isn’t without basis.

The flu season has gotten an early start. As of Oct. 21, early increases in seasonal flu activity have been reported in most of the country, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said, with the southeast and south-central areas having the highest activity levels.

Children’s hospitals and EDs are seeing a surge in children with RSV.

COVID-19 cases are trending down, according to the CDC, but epidemiologists – scientists who study disease outbreaks – always have their eyes on emerging variants.

said Justin Lessler, PhD, a professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Lessler is on the coordinating team for the COVID-19 Scenario Modeling Hub, which aims to predict the course COVID-19, and the Flu Scenario Modeling Hub, which does the same for influenza.

For COVID-19, some models are predicting some spikes before Christmas, he said, and others see a new wave in 2023. For the flu, the model is predicting an earlier-than-usual start, as the CDC has reported.

While flu activity is relatively low, the CDC said, the season is off to an early start. For the week ending Oct. 21, 1,674 patients were hospitalized for flu, higher than in the summer months but fewer than the 2,675 hospitalizations for the week of May 15, 2022.

As of Oct. 20, COVID-19 cases have declined 12% over the last 2 weeks, nationwide. But hospitalizations are up 10% in much of the Northeast, The New York Times reports, and the improvement in cases and deaths has been slowing down.

As of Oct. 15, 15% of RSV tests reported nationwide were positive, compared with about 11% at that time in 2021, the CDC said. The surveillance collects information from 75 counties in 12 states.

Experts point out that the viruses – all three are respiratory viruses – are simply playing catchup.

“They spread the same way and along with lots of other viruses, and you tend to see an increase in them during the cold months,” said Timothy Brewer, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at UCLA.

The increase in all three viruses “is almost predictable at this point in the pandemic,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, a professor and chief of pediatric infectious diseases at the University of California Davis Health. “All the respiratory viruses are out of whack.”

Last year, RSV cases were up, too, and began to appear very early, he said, in the summer instead of in the cooler months. Flu also appeared early in 2021, as it has in 2022.

That contrasts with the flu season of 2020-2021, when COVID precautions were nearly universal, and cases were down. At UC Davis, “we didn’t have one pediatric admission due to influenza in the 2020-2021 [flu] season,” Dr. Blumberg said.

The number of pediatric flu deaths usually range from 37 to 199 per year, according to CDC records. But in the 2020-2021 season, the CDC recorded one pediatric flu death in the U.S.

Both children and adults have had less contact with others the past two seasons, Dr. Blumberg said, “and they don’t get the immunity they got with those infections [previously]. That’s why we are seeing out-of-season, early season [viruses].”

Eventually, he said, the cases of flu and RSV will return to previous levels. “It could be as soon as next year,” Dr. Blumberg said. And COVID-19, hopefully, will become like influenza, he said.

“RSV has always come around in the fall and winter,” said Elizabeth Murray, DO, a pediatric emergency medicine doctor at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center and a spokesperson for the American Academy of Pediatrics. In 2022, children are back in school and for the most part not masking. “It’s a perfect storm for all the germs to spread now. They’ve just been waiting for their opportunity to come back.”

Self-care vs. not

RSV can pose a risk for anyone, but most at risk are children under age 5, especially infants under age 1, and adults over age 65. There is no vaccine for it. Symptoms include a runny nose, decreased appetite, coughing, sneezing, fever, and wheezing. But in young infants, there may only be decreased activity, crankiness, and breathing issues, the CDC said.

Keep an eye on the breathing if RSV is suspected, Dr. Murray tells parents. If your child can’t breathe easily, is unable to lie down comfortably, can’t speak clearly, or is sucking in the chest muscles to breathe, get medical help. Most kids with RSV can stay home and recover, she said, but often will need to be checked by a medical professional.

She advises against getting an oximeter to measure oxygen levels for home use. “They are often not accurate,” she said. If in doubt about how serious your child’s symptoms are, “don’t wait it out,” and don’t hesitate to call 911.

Symptoms of flu, COVID, and RSV can overlap. But each can involve breathing problems, which can be an emergency.

“It’s important to seek medical attention for any concerning symptoms, but especially severe shortness of breath or difficulty breathing, as these could signal the need for supplemental oxygen or other emergency interventions,” said Mandy De Vries, a respiratory therapist and director of education at the American Association for Respiratory Care. Inhalation treatment or mechanical ventilation may be needed for severe respiratory issues.

Precautions

To avoid the tripledemic – or any single infection – Timothy Brewer, MD, a professor of medicine and epidemiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, suggests some familiar measures: “Stay home if you’re feeling sick. Make sure you are up to date on your vaccinations. Wear a mask indoors.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Ivermectin for COVID-19: Final nail in the coffin

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

It began in a petri dish.

Ivermectin, a widely available, cheap, and well-tolerated drug on the WHO’s list of essential medicines for its critical role in treating river blindness, was shown to dramatically reduce the proliferation of SARS-CoV-2 virus in cell culture.

You know the rest of the story. Despite the fact that the median inhibitory concentration in cell culture is about 100-fold higher than what one can achieve with oral dosing in humans, anecdotal reports of miraculous cures proliferated.

Cohort studies suggested that people who got ivermectin did very well in terms of COVID outcomes.

A narrative started to develop online – one that is still quite present today – that authorities were suppressing the good news about ivermectin in order to line their own pockets and those of the execs at Big Pharma. The official Twitter account of the Food and Drug Administration clapped back, reminding the populace that we are not horses or cows.

And every time a study came out that seemed like the nail in the coffin for the so-called horse paste, it rose again, vampire-like, feasting on the blood of social media outrage.

The truth is that, while excitement for ivermectin mounted online, it crashed quite quickly in scientific circles. Most randomized trials showed no effect of the drug. A couple of larger trials which seemed to show dramatic effects were subsequently shown to be fraudulent.

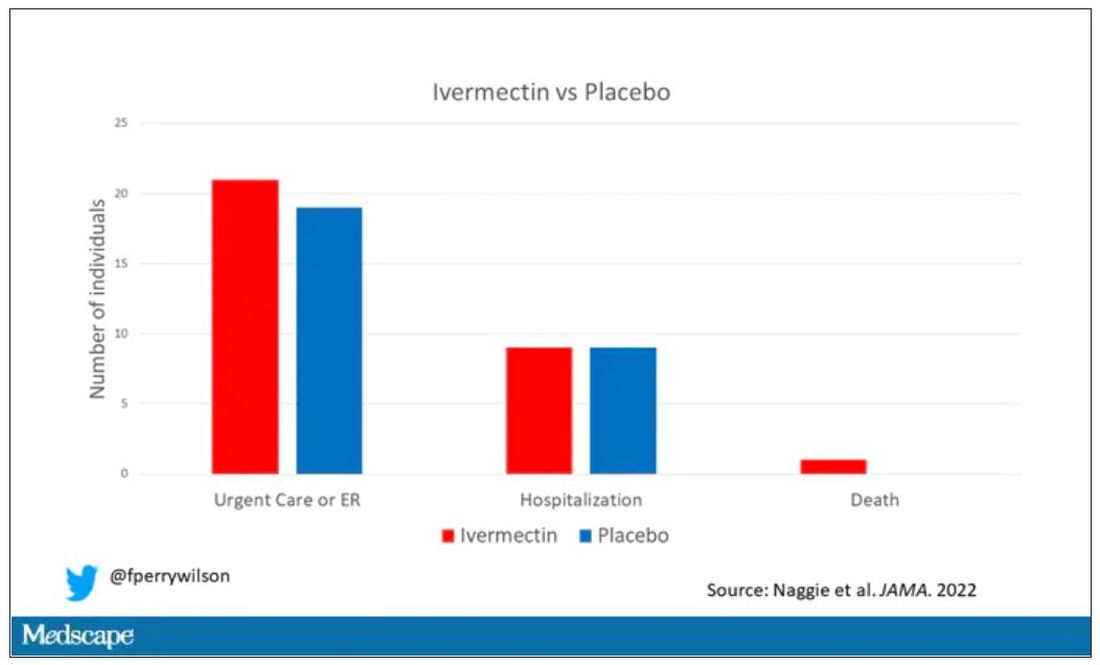

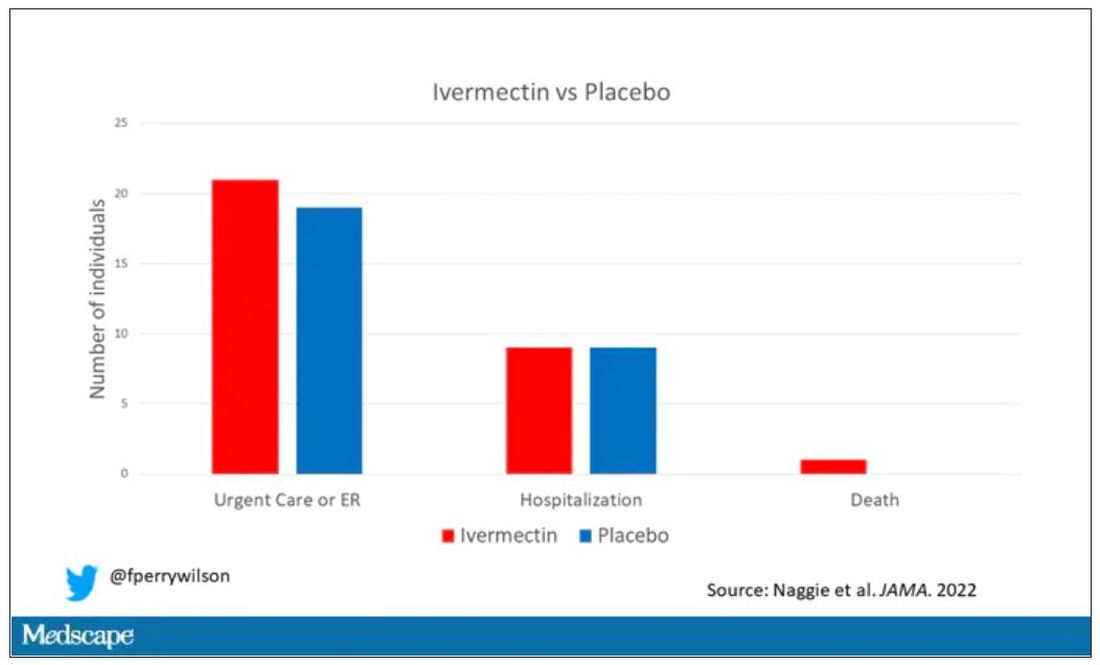

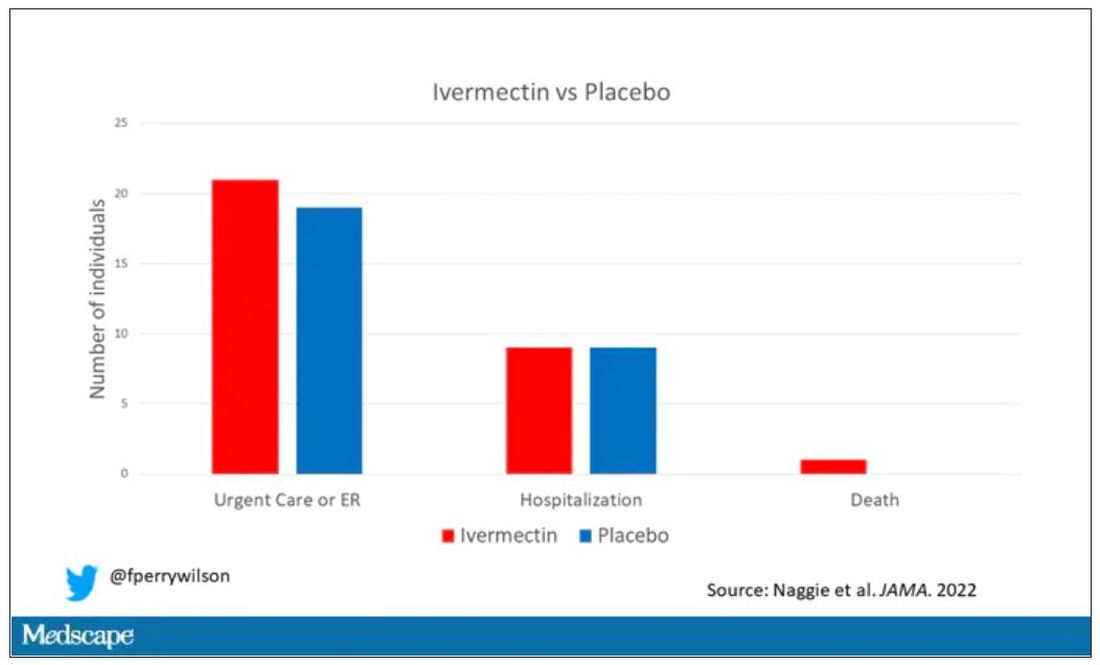

Then the TOGETHER trial was published. The 1,400-patient study from Brazil, which treated outpatients with COVID-19, found no significant difference in hospitalization or ER visits – the primary outcome – between those randomized to ivermectin vs. placebo or another therapy.

But still, Brazil. Different population than the United States. Different health systems. And very different rates of Strongyloides infections (this is a parasite that may be incidentally treated by ivermectin, leading to improvement independent of the drug’s effect on COVID). We all wanted a U.S. trial.

And now we have it. ACTIV-6 was published Oct. 21 in JAMA, a study randomizing outpatients with COVID-19 from 93 sites around the United States to ivermectin or placebo.

A total of 1,591 individuals – median age 47, 60% female – with confirmed symptomatic COVID-19 were randomized from June 2021 to February 2022. About half had been vaccinated.

The primary outcome was straightforward: time to clinical recovery. The time to recovery, defined as having three symptom-free days, was 12 days in the ivermectin group and 13 days in the placebo group – that’s within the margin of error.

But overall, everyone in the trial did fairly well. Serious outcomes, like death, hospitalization, urgent care, or ER visits, occurred in 32 people in the ivermectin group and 28 in the placebo group. Death itself was rare – just one occurred in the trial, in someone receiving ivermectin.OK, are we done with this drug yet? Is this nice U.S. randomized trial enough to convince people that results from a petri dish don’t always transfer to humans, regardless of the presence or absence of an evil pharmaceutical cabal?

No, of course not. At this point, I can predict the responses. The dose wasn’t high enough. It wasn’t given early enough. The patients weren’t sick enough, or they were too sick. This is motivated reasoning, plain and simple. It’s not to say that there isn’t a chance that this drug has some off-target effects on COVID that we haven’t adequately measured, but studies like ACTIV-6 effectively rule out the idea that it’s a miracle cure. And you know what? That’s OK. Miracle cures are vanishingly rare. Most things that work in medicine work OK; they make us a little better, and we learn why they do that and improve on them, and try again and again. It’s not flashy; it doesn’t have that allure of secret knowledge. But it’s what separates science from magic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator; his science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

It began in a petri dish.

Ivermectin, a widely available, cheap, and well-tolerated drug on the WHO’s list of essential medicines for its critical role in treating river blindness, was shown to dramatically reduce the proliferation of SARS-CoV-2 virus in cell culture.

You know the rest of the story. Despite the fact that the median inhibitory concentration in cell culture is about 100-fold higher than what one can achieve with oral dosing in humans, anecdotal reports of miraculous cures proliferated.

Cohort studies suggested that people who got ivermectin did very well in terms of COVID outcomes.

A narrative started to develop online – one that is still quite present today – that authorities were suppressing the good news about ivermectin in order to line their own pockets and those of the execs at Big Pharma. The official Twitter account of the Food and Drug Administration clapped back, reminding the populace that we are not horses or cows.

And every time a study came out that seemed like the nail in the coffin for the so-called horse paste, it rose again, vampire-like, feasting on the blood of social media outrage.

The truth is that, while excitement for ivermectin mounted online, it crashed quite quickly in scientific circles. Most randomized trials showed no effect of the drug. A couple of larger trials which seemed to show dramatic effects were subsequently shown to be fraudulent.

Then the TOGETHER trial was published. The 1,400-patient study from Brazil, which treated outpatients with COVID-19, found no significant difference in hospitalization or ER visits – the primary outcome – between those randomized to ivermectin vs. placebo or another therapy.

But still, Brazil. Different population than the United States. Different health systems. And very different rates of Strongyloides infections (this is a parasite that may be incidentally treated by ivermectin, leading to improvement independent of the drug’s effect on COVID). We all wanted a U.S. trial.

And now we have it. ACTIV-6 was published Oct. 21 in JAMA, a study randomizing outpatients with COVID-19 from 93 sites around the United States to ivermectin or placebo.

A total of 1,591 individuals – median age 47, 60% female – with confirmed symptomatic COVID-19 were randomized from June 2021 to February 2022. About half had been vaccinated.

The primary outcome was straightforward: time to clinical recovery. The time to recovery, defined as having three symptom-free days, was 12 days in the ivermectin group and 13 days in the placebo group – that’s within the margin of error.

But overall, everyone in the trial did fairly well. Serious outcomes, like death, hospitalization, urgent care, or ER visits, occurred in 32 people in the ivermectin group and 28 in the placebo group. Death itself was rare – just one occurred in the trial, in someone receiving ivermectin.OK, are we done with this drug yet? Is this nice U.S. randomized trial enough to convince people that results from a petri dish don’t always transfer to humans, regardless of the presence or absence of an evil pharmaceutical cabal?

No, of course not. At this point, I can predict the responses. The dose wasn’t high enough. It wasn’t given early enough. The patients weren’t sick enough, or they were too sick. This is motivated reasoning, plain and simple. It’s not to say that there isn’t a chance that this drug has some off-target effects on COVID that we haven’t adequately measured, but studies like ACTIV-6 effectively rule out the idea that it’s a miracle cure. And you know what? That’s OK. Miracle cures are vanishingly rare. Most things that work in medicine work OK; they make us a little better, and we learn why they do that and improve on them, and try again and again. It’s not flashy; it doesn’t have that allure of secret knowledge. But it’s what separates science from magic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator; his science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

It began in a petri dish.

Ivermectin, a widely available, cheap, and well-tolerated drug on the WHO’s list of essential medicines for its critical role in treating river blindness, was shown to dramatically reduce the proliferation of SARS-CoV-2 virus in cell culture.

You know the rest of the story. Despite the fact that the median inhibitory concentration in cell culture is about 100-fold higher than what one can achieve with oral dosing in humans, anecdotal reports of miraculous cures proliferated.

Cohort studies suggested that people who got ivermectin did very well in terms of COVID outcomes.

A narrative started to develop online – one that is still quite present today – that authorities were suppressing the good news about ivermectin in order to line their own pockets and those of the execs at Big Pharma. The official Twitter account of the Food and Drug Administration clapped back, reminding the populace that we are not horses or cows.

And every time a study came out that seemed like the nail in the coffin for the so-called horse paste, it rose again, vampire-like, feasting on the blood of social media outrage.

The truth is that, while excitement for ivermectin mounted online, it crashed quite quickly in scientific circles. Most randomized trials showed no effect of the drug. A couple of larger trials which seemed to show dramatic effects were subsequently shown to be fraudulent.

Then the TOGETHER trial was published. The 1,400-patient study from Brazil, which treated outpatients with COVID-19, found no significant difference in hospitalization or ER visits – the primary outcome – between those randomized to ivermectin vs. placebo or another therapy.

But still, Brazil. Different population than the United States. Different health systems. And very different rates of Strongyloides infections (this is a parasite that may be incidentally treated by ivermectin, leading to improvement independent of the drug’s effect on COVID). We all wanted a U.S. trial.

And now we have it. ACTIV-6 was published Oct. 21 in JAMA, a study randomizing outpatients with COVID-19 from 93 sites around the United States to ivermectin or placebo.

A total of 1,591 individuals – median age 47, 60% female – with confirmed symptomatic COVID-19 were randomized from June 2021 to February 2022. About half had been vaccinated.

The primary outcome was straightforward: time to clinical recovery. The time to recovery, defined as having three symptom-free days, was 12 days in the ivermectin group and 13 days in the placebo group – that’s within the margin of error.

But overall, everyone in the trial did fairly well. Serious outcomes, like death, hospitalization, urgent care, or ER visits, occurred in 32 people in the ivermectin group and 28 in the placebo group. Death itself was rare – just one occurred in the trial, in someone receiving ivermectin.OK, are we done with this drug yet? Is this nice U.S. randomized trial enough to convince people that results from a petri dish don’t always transfer to humans, regardless of the presence or absence of an evil pharmaceutical cabal?

No, of course not. At this point, I can predict the responses. The dose wasn’t high enough. It wasn’t given early enough. The patients weren’t sick enough, or they were too sick. This is motivated reasoning, plain and simple. It’s not to say that there isn’t a chance that this drug has some off-target effects on COVID that we haven’t adequately measured, but studies like ACTIV-6 effectively rule out the idea that it’s a miracle cure. And you know what? That’s OK. Miracle cures are vanishingly rare. Most things that work in medicine work OK; they make us a little better, and we learn why they do that and improve on them, and try again and again. It’s not flashy; it doesn’t have that allure of secret knowledge. But it’s what separates science from magic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator; his science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Side effects from COVID vaccine show its effectiveness

It means your body had a greater antibody response than people who had just a little pain or rash at the injection site, or no reaction at all.

That’s according to new research published in the journal JAMA Network Open .

“These findings support reframing postvaccination symptoms as signals of vaccine effectiveness and reinforce guidelines for vaccine boosters in older adults,” researchers from Columbia University in New York, the University of Vermont, and Boston University wrote.

The vaccines provided strong protection regardless of the level of reaction, researchers said. Almost all the study’s 928 adult participants had a positive antibody response after receiving two doses of vaccine.

“I don’t want a patient to tell me that, ‘Golly, I didn’t get any reaction, my arm wasn’t sore, I didn’t have fever. The vaccine didn’t work.’ I don’t want that conclusion to be out there,” William Schaffner, MD, a professor in the division of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., told CNN.

“This is more to reassure people who have had a reaction that that’s their immune system responding, actually in a rather good way, to the vaccine, even though it has caused them some discomfort,” said Dr. Schaffner, who was not involved in the study.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It means your body had a greater antibody response than people who had just a little pain or rash at the injection site, or no reaction at all.

That’s according to new research published in the journal JAMA Network Open .

“These findings support reframing postvaccination symptoms as signals of vaccine effectiveness and reinforce guidelines for vaccine boosters in older adults,” researchers from Columbia University in New York, the University of Vermont, and Boston University wrote.

The vaccines provided strong protection regardless of the level of reaction, researchers said. Almost all the study’s 928 adult participants had a positive antibody response after receiving two doses of vaccine.

“I don’t want a patient to tell me that, ‘Golly, I didn’t get any reaction, my arm wasn’t sore, I didn’t have fever. The vaccine didn’t work.’ I don’t want that conclusion to be out there,” William Schaffner, MD, a professor in the division of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., told CNN.

“This is more to reassure people who have had a reaction that that’s their immune system responding, actually in a rather good way, to the vaccine, even though it has caused them some discomfort,” said Dr. Schaffner, who was not involved in the study.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

It means your body had a greater antibody response than people who had just a little pain or rash at the injection site, or no reaction at all.

That’s according to new research published in the journal JAMA Network Open .

“These findings support reframing postvaccination symptoms as signals of vaccine effectiveness and reinforce guidelines for vaccine boosters in older adults,” researchers from Columbia University in New York, the University of Vermont, and Boston University wrote.

The vaccines provided strong protection regardless of the level of reaction, researchers said. Almost all the study’s 928 adult participants had a positive antibody response after receiving two doses of vaccine.

“I don’t want a patient to tell me that, ‘Golly, I didn’t get any reaction, my arm wasn’t sore, I didn’t have fever. The vaccine didn’t work.’ I don’t want that conclusion to be out there,” William Schaffner, MD, a professor in the division of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., told CNN.

“This is more to reassure people who have had a reaction that that’s their immune system responding, actually in a rather good way, to the vaccine, even though it has caused them some discomfort,” said Dr. Schaffner, who was not involved in the study.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Children and COVID: Weekly cases fall to lowest level in over a year

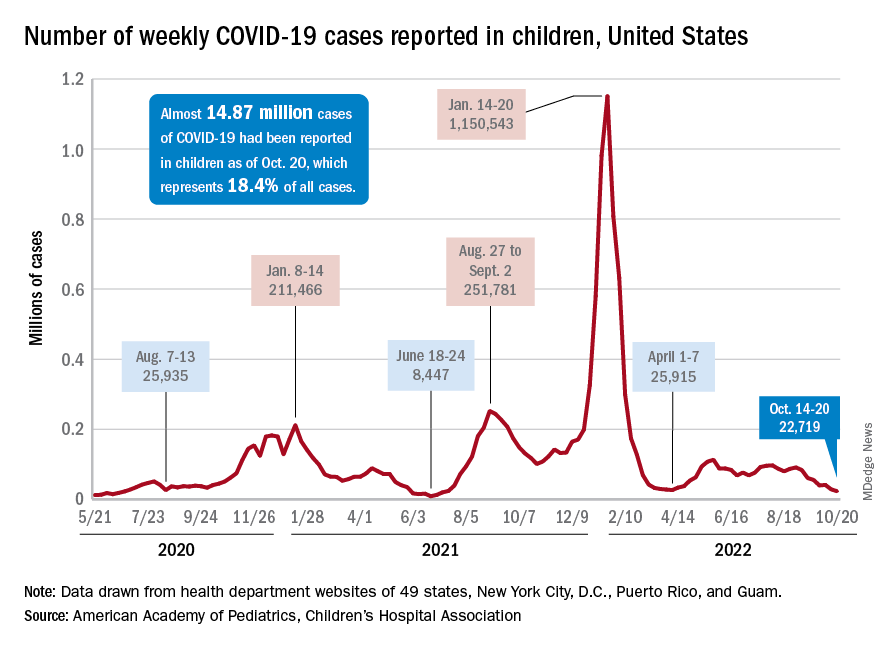

With the third autumn of the COVID era now upon us, the discussion has turned again to a possible influenza/COVID twindemic, as well as the new-for-2022 influenza/COVID/respiratory syncytial virus tripledemic. It appears, however, that COVID may have missed the memo.

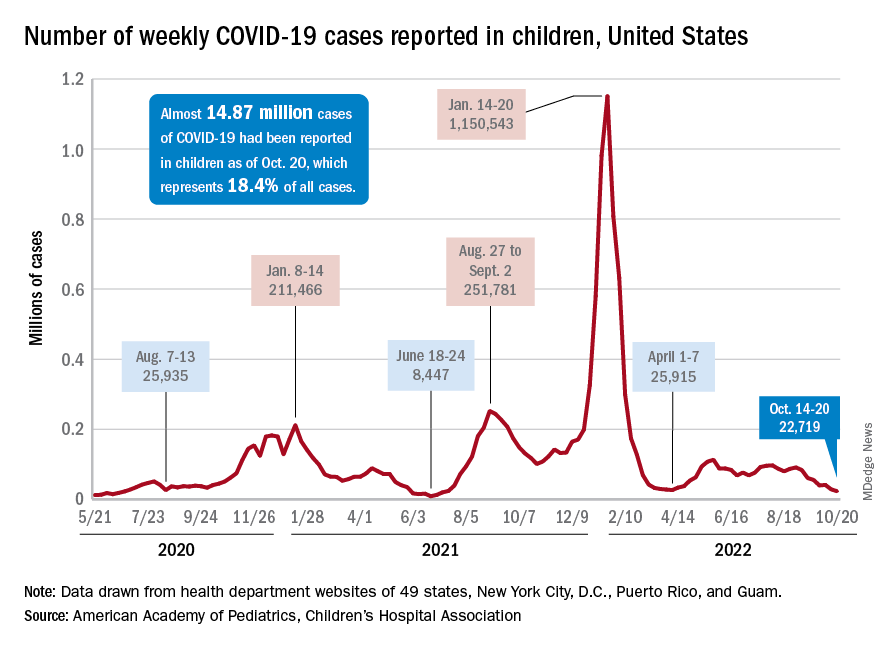

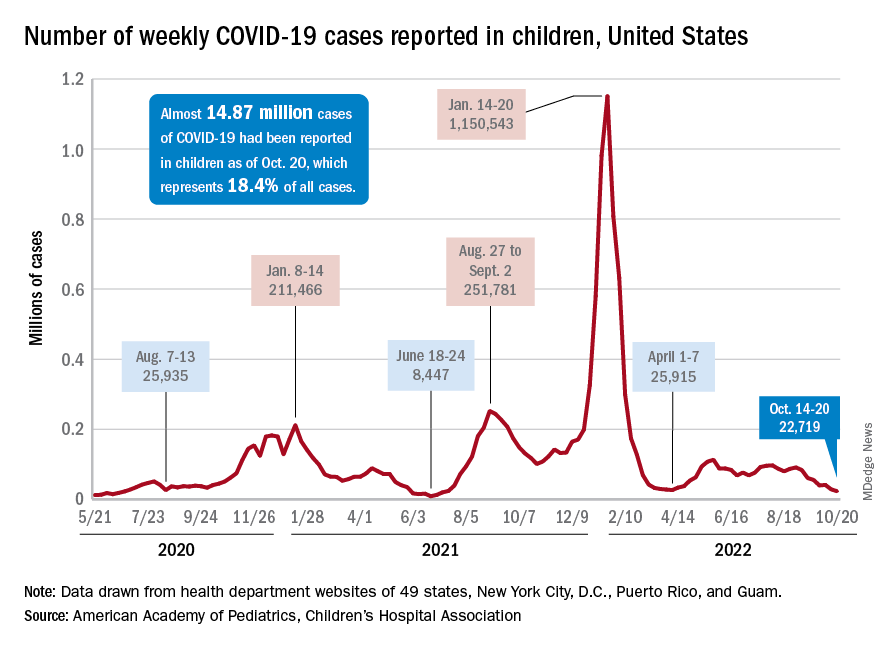

For the sixth time in the last 7 weeks, the number of new COVID cases in children fell, with just under 23,000 reported during the week of Oct. 14-20, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association. That is the lowest weekly count so far this year, and the lowest since early July of 2021, just as the Delta surge was starting. New pediatric cases had dipped to 8,500, the lowest for any week during the pandemic, a couple of weeks before that, the AAP/CHA data show.

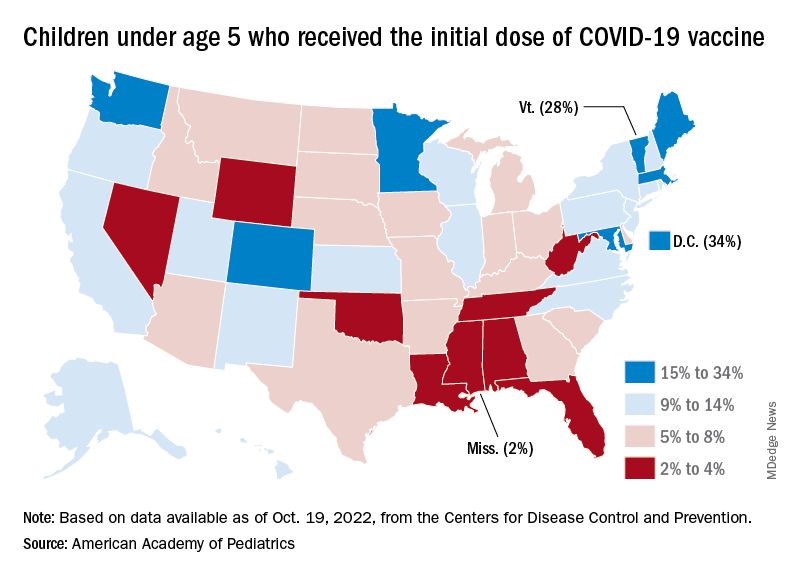

Weekly cases have fallen by almost 75% since over 90,000 were reported for the week of Aug. 26 to Sept. 1, even as children have returned to school and vaccine uptake remains slow in the youngest age groups. Rates of emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID also have continued to drop, as have new admissions, and both are nearing their 2021 lows, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

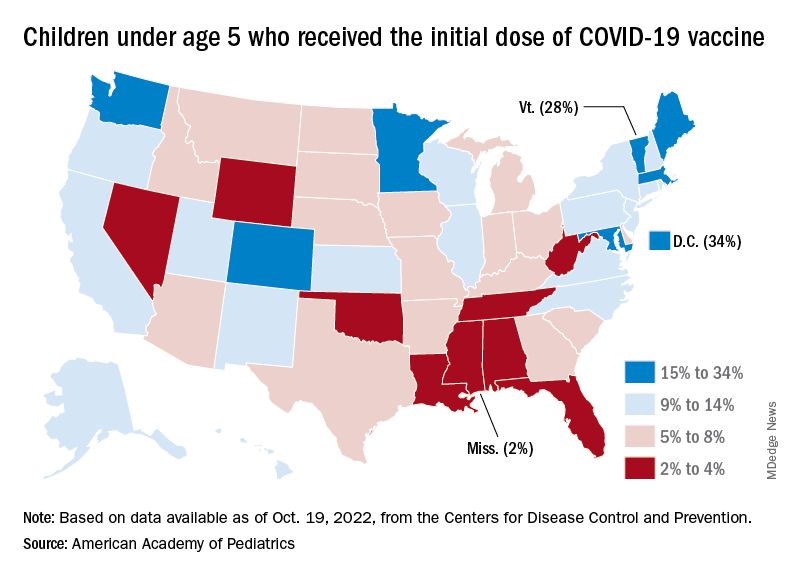

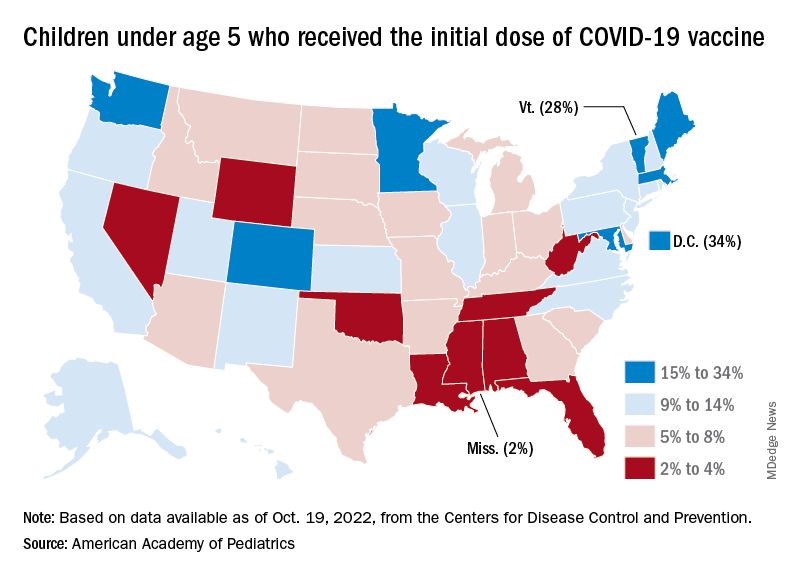

New vaccinations in children under age 5 years were up slightly for the most recent week (Oct. 13-19), but total uptake for that age group is only 7.1% for an initial dose and 2.9% for full vaccination. Among children aged 5-11 years, 38.7% have received at least one dose and 31.6% have completed the primary series, with corresponding figures of 71.2% and 60.9% for those aged 12-17, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Despite the low overall numbers, though, the youngest children are, in one respect, punching above their weight when it comes to vaccinations. In the 2 weeks from Oct. 6 to Oct. 19, children under 5 years of age, who represent 5.9% of the U.S. population, received 9.2% of the initial vaccine doses administered. Children aged 5-11 years, who represent 8.7% of the total population, got just 4.2% of all first doses over those same 2 weeks, while 12- to 17-year-olds, who make up 7.6% of the population, got 3.4% of the vaccine doses, the CDC reported.

On the vaccine-approval front, the Food and Drug Administration recently announced that the new bivalent COVID-19 vaccines are now included in the emergency use authorizations for children who have completed primary or booster vaccination. The Moderna vaccine is authorized as a single-dose booster for children as young as 6 years and the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine can be given as a single booster dose in children as young as 5 years, the FDA said.

“These bivalent COVID-19 vaccines include an mRNA component of the original strain to provide an immune response that is broadly protective against COVID-19 and an mRNA component in common between the omicron variant BA.4 and BA.5 lineages,” the FDA said.

With the third autumn of the COVID era now upon us, the discussion has turned again to a possible influenza/COVID twindemic, as well as the new-for-2022 influenza/COVID/respiratory syncytial virus tripledemic. It appears, however, that COVID may have missed the memo.

For the sixth time in the last 7 weeks, the number of new COVID cases in children fell, with just under 23,000 reported during the week of Oct. 14-20, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association. That is the lowest weekly count so far this year, and the lowest since early July of 2021, just as the Delta surge was starting. New pediatric cases had dipped to 8,500, the lowest for any week during the pandemic, a couple of weeks before that, the AAP/CHA data show.

Weekly cases have fallen by almost 75% since over 90,000 were reported for the week of Aug. 26 to Sept. 1, even as children have returned to school and vaccine uptake remains slow in the youngest age groups. Rates of emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID also have continued to drop, as have new admissions, and both are nearing their 2021 lows, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New vaccinations in children under age 5 years were up slightly for the most recent week (Oct. 13-19), but total uptake for that age group is only 7.1% for an initial dose and 2.9% for full vaccination. Among children aged 5-11 years, 38.7% have received at least one dose and 31.6% have completed the primary series, with corresponding figures of 71.2% and 60.9% for those aged 12-17, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Despite the low overall numbers, though, the youngest children are, in one respect, punching above their weight when it comes to vaccinations. In the 2 weeks from Oct. 6 to Oct. 19, children under 5 years of age, who represent 5.9% of the U.S. population, received 9.2% of the initial vaccine doses administered. Children aged 5-11 years, who represent 8.7% of the total population, got just 4.2% of all first doses over those same 2 weeks, while 12- to 17-year-olds, who make up 7.6% of the population, got 3.4% of the vaccine doses, the CDC reported.

On the vaccine-approval front, the Food and Drug Administration recently announced that the new bivalent COVID-19 vaccines are now included in the emergency use authorizations for children who have completed primary or booster vaccination. The Moderna vaccine is authorized as a single-dose booster for children as young as 6 years and the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine can be given as a single booster dose in children as young as 5 years, the FDA said.

“These bivalent COVID-19 vaccines include an mRNA component of the original strain to provide an immune response that is broadly protective against COVID-19 and an mRNA component in common between the omicron variant BA.4 and BA.5 lineages,” the FDA said.

With the third autumn of the COVID era now upon us, the discussion has turned again to a possible influenza/COVID twindemic, as well as the new-for-2022 influenza/COVID/respiratory syncytial virus tripledemic. It appears, however, that COVID may have missed the memo.

For the sixth time in the last 7 weeks, the number of new COVID cases in children fell, with just under 23,000 reported during the week of Oct. 14-20, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association. That is the lowest weekly count so far this year, and the lowest since early July of 2021, just as the Delta surge was starting. New pediatric cases had dipped to 8,500, the lowest for any week during the pandemic, a couple of weeks before that, the AAP/CHA data show.

Weekly cases have fallen by almost 75% since over 90,000 were reported for the week of Aug. 26 to Sept. 1, even as children have returned to school and vaccine uptake remains slow in the youngest age groups. Rates of emergency department visits with diagnosed COVID also have continued to drop, as have new admissions, and both are nearing their 2021 lows, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

New vaccinations in children under age 5 years were up slightly for the most recent week (Oct. 13-19), but total uptake for that age group is only 7.1% for an initial dose and 2.9% for full vaccination. Among children aged 5-11 years, 38.7% have received at least one dose and 31.6% have completed the primary series, with corresponding figures of 71.2% and 60.9% for those aged 12-17, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Despite the low overall numbers, though, the youngest children are, in one respect, punching above their weight when it comes to vaccinations. In the 2 weeks from Oct. 6 to Oct. 19, children under 5 years of age, who represent 5.9% of the U.S. population, received 9.2% of the initial vaccine doses administered. Children aged 5-11 years, who represent 8.7% of the total population, got just 4.2% of all first doses over those same 2 weeks, while 12- to 17-year-olds, who make up 7.6% of the population, got 3.4% of the vaccine doses, the CDC reported.

On the vaccine-approval front, the Food and Drug Administration recently announced that the new bivalent COVID-19 vaccines are now included in the emergency use authorizations for children who have completed primary or booster vaccination. The Moderna vaccine is authorized as a single-dose booster for children as young as 6 years and the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine can be given as a single booster dose in children as young as 5 years, the FDA said.

“These bivalent COVID-19 vaccines include an mRNA component of the original strain to provide an immune response that is broadly protective against COVID-19 and an mRNA component in common between the omicron variant BA.4 and BA.5 lineages,” the FDA said.

Myocarditis after COVID vax rare and mild in teens

New data from Israel provide further evidence that myocarditis is a rare adverse event of vaccination with the Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in adolescents – one that predominantly occurs in males and typically after the second dose.

The new data also indicate a “mild and benign” clinical course of myocarditis after vaccination, with “favorable” long-term prognosis based on cardiac imaging findings.

Guy Witberg, MD, MPH, Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel, and colleagues report their latest observations in correspondence in The New England Journal of Medicine, online.

The group previously reported in December 2021 that the incidence of myocarditis in Israel after receipt of the Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine was highest among males between the ages of 16 and 29 (10.7 cases per 100,000).

The vaccine has since been approved for adolescents aged 12-15. Initial evidence for this age group, reported by Dr. Witberg and colleagues in March 2022, suggests a similar low incidence and mild course of myocarditis, although follow-up was limited to 30 days.

In their latest report, with follow-up out to 6 months, Dr. Witberg and colleagues identified nine probable or definite cases of myocarditis among 182,605 Israeli adolescents aged 12-15 who received the Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA vaccine – an incidence of 4.8 cases per 100,000.

Eight cases occurred after the second vaccine dose. All nine cases were mild.

Cardiac and inflammatory markers were elevated in all adolescent patients and electrocardiographic results were abnormal in two-thirds.

Eight patients had a normal ejection fraction, and four had a pericardial effusion. The patients spent 2-4 days hospitalized, and the in-hospital course was uneventful.

Echocardiographic findings were available a median of 10 days after discharge for eight patients. All echocardiograms showed a normal ejection fraction and resolution of pericardial effusion.

Five patients underwent cardiac MRI, including three scans performed at a median of 104 days after discharge. The scans showed “minimal evidence” of myocardial scarring or fibrosis, with evidence of late gadolinium enhancement ranging from 0% to 2%.

At a median of 206 days following discharge, all of the patients were alive, and none had been readmitted to the hospital, Dr. Witberg and colleagues report.

This research had no specific funding. Five authors have received research grants from Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New data from Israel provide further evidence that myocarditis is a rare adverse event of vaccination with the Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in adolescents – one that predominantly occurs in males and typically after the second dose.

The new data also indicate a “mild and benign” clinical course of myocarditis after vaccination, with “favorable” long-term prognosis based on cardiac imaging findings.

Guy Witberg, MD, MPH, Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel, and colleagues report their latest observations in correspondence in The New England Journal of Medicine, online.

The group previously reported in December 2021 that the incidence of myocarditis in Israel after receipt of the Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine was highest among males between the ages of 16 and 29 (10.7 cases per 100,000).

The vaccine has since been approved for adolescents aged 12-15. Initial evidence for this age group, reported by Dr. Witberg and colleagues in March 2022, suggests a similar low incidence and mild course of myocarditis, although follow-up was limited to 30 days.

In their latest report, with follow-up out to 6 months, Dr. Witberg and colleagues identified nine probable or definite cases of myocarditis among 182,605 Israeli adolescents aged 12-15 who received the Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA vaccine – an incidence of 4.8 cases per 100,000.

Eight cases occurred after the second vaccine dose. All nine cases were mild.

Cardiac and inflammatory markers were elevated in all adolescent patients and electrocardiographic results were abnormal in two-thirds.

Eight patients had a normal ejection fraction, and four had a pericardial effusion. The patients spent 2-4 days hospitalized, and the in-hospital course was uneventful.

Echocardiographic findings were available a median of 10 days after discharge for eight patients. All echocardiograms showed a normal ejection fraction and resolution of pericardial effusion.

Five patients underwent cardiac MRI, including three scans performed at a median of 104 days after discharge. The scans showed “minimal evidence” of myocardial scarring or fibrosis, with evidence of late gadolinium enhancement ranging from 0% to 2%.

At a median of 206 days following discharge, all of the patients were alive, and none had been readmitted to the hospital, Dr. Witberg and colleagues report.

This research had no specific funding. Five authors have received research grants from Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New data from Israel provide further evidence that myocarditis is a rare adverse event of vaccination with the Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in adolescents – one that predominantly occurs in males and typically after the second dose.

The new data also indicate a “mild and benign” clinical course of myocarditis after vaccination, with “favorable” long-term prognosis based on cardiac imaging findings.

Guy Witberg, MD, MPH, Rabin Medical Center, Petah Tikva, Israel, and colleagues report their latest observations in correspondence in The New England Journal of Medicine, online.

The group previously reported in December 2021 that the incidence of myocarditis in Israel after receipt of the Pfizer/BioNTech BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine was highest among males between the ages of 16 and 29 (10.7 cases per 100,000).

The vaccine has since been approved for adolescents aged 12-15. Initial evidence for this age group, reported by Dr. Witberg and colleagues in March 2022, suggests a similar low incidence and mild course of myocarditis, although follow-up was limited to 30 days.

In their latest report, with follow-up out to 6 months, Dr. Witberg and colleagues identified nine probable or definite cases of myocarditis among 182,605 Israeli adolescents aged 12-15 who received the Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA vaccine – an incidence of 4.8 cases per 100,000.

Eight cases occurred after the second vaccine dose. All nine cases were mild.

Cardiac and inflammatory markers were elevated in all adolescent patients and electrocardiographic results were abnormal in two-thirds.

Eight patients had a normal ejection fraction, and four had a pericardial effusion. The patients spent 2-4 days hospitalized, and the in-hospital course was uneventful.

Echocardiographic findings were available a median of 10 days after discharge for eight patients. All echocardiograms showed a normal ejection fraction and resolution of pericardial effusion.

Five patients underwent cardiac MRI, including three scans performed at a median of 104 days after discharge. The scans showed “minimal evidence” of myocardial scarring or fibrosis, with evidence of late gadolinium enhancement ranging from 0% to 2%.

At a median of 206 days following discharge, all of the patients were alive, and none had been readmitted to the hospital, Dr. Witberg and colleagues report.

This research had no specific funding. Five authors have received research grants from Pfizer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Updated Moderna booster shows greater activity against COVID in adults

WASHINGTON –

The bivalent booster was superior regardless of age and whether a person had previously been infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Additionally, no new safety concerns emerged.

Spyros Chalkias, MD, senior medical director of clinical development at Moderna, presented the data during an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

In the phase 2/3 trial, participants received either 50 mcg of the bivalent vaccine mRNA-1273.214 (25 mcg each of the original Wuhan-Hu-1 and Omicron BA.1 spike mRNAs) or 50 mcg of the standard authorized mRNA-1273. The doses were given as second boosters in adults who had previously received a two-dose primary series and a first booster at least 3 months before.

The model-based geometric mean titers (GMTs) ratio of the enhanced booster compared with the standard booster was 1.74 (1.49-2.04), meeting the prespecified bar for superiority against Omicron BA.1.

In participants without prior SARS-CoV-2 infection who received updated booster doses and those who received standard boosters, the neutralizing antibody GMTs against Omicron BA.1 were 2372.4 and 1473.5, respectively.

Additionally, the updated booster elicited higher GMTs (727.4) than the standard booster (492.1) against Omicron subvariants BA.4/BA.5. Safety and reactogenicity were similar for both vaccine groups.

“By the end of this year, we expect to also have clinical trial data from our BA.4/BA.5 bivalent booster,” Dr. Chalkias said.

In the interim, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently granted emergency use authorization for Moderna’s BA.4/BA.5 Omicron-targeting bivalent COVID-19 booster vaccine in children and adolescents aged 6-17 years.

Pfizer/BioNTech also has recently issued an announcement that their COVID-19 booster, adapted for the BA.4 and the BA.5 Omicron subvariants, generated a strong immune response and was well tolerated in human tests.

Pfizer/BioNTech said data from roughly 80 adult patients showed that the booster led to a substantial increase in neutralizing antibody levels against the BA.4/BA.5 variants after 1 week.

Separate study of causes of severe breakthrough infections in early vaccine formulations

Though COVID vaccines reduce the incidence of severe outcomes, there are reports of breakthrough infections in persons who received the original vaccines, and some of these have been serious.

In a separate study, also presented at the meeting, researchers led by first author Austin D. Vo, BS, with the VA Boston Healthcare System, used data collected from Dec. 15, 2020, through Feb. 28, 2022, in a U.S. veteran population to assess those at highest risk for severe disease despite vaccination.

Results of the large, nationwide retrospective study were simultaneously published in JAMA Network Open.

The primary outcome was development of severe COVID, defined as a hospitalization within 14 days of a confirmed positive SARS-CoV-2 test, receipt of supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation, or death within 28 days.

Among 110,760 participants with severe disease after primary vaccination, 13% (14,690) were hospitalized with severe COVID-19 or died.

The strongest risk factor for severe disease despite vaccination was age, the researchers found.

Presenting author Westyn Branch-Elliman, MD, associate professor of medicine with VA Boston Healthcare System, said, “We found that age greater than 50 was associated with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.42 for every 5-year increase.”

To put that in perspective, she said, “compared to patients who are 45 to 50, those over 80 had an adjusted odds ratio of 16 for hospitalization or death following breakthrough infection.”

Priya Nori, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Montefiore Medical Center in New York, said in an interview that the evidence that age is a strong risk factor for severe disease – even after vaccination – confirms that attention should be focused on those in the highest age groups, particularly those 80 years and older.

Other top risk factors included having immunocompromising conditions; having received cytotoxic chemotherapy within 6 months (adjusted odds ratio, 2.69; 95% confidence interval, 2.25-3.21); having leukemias/lymphomas (aOR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.59-2.14); and having chronic conditions associated with end-organ disease.

“We also found that receipt of an additional booster dose of vaccine was associated with a 50% reduction in adjusted odds of severe disease,” noted Dr. Branch-Elliman.

Dr. Nori emphasized that, given these data, emphatic messaging is needed to encourage uptake of the updated Omicron-targeted vaccines for these high-risk age groups.

The study by Dr. Chalkias and colleagues was funded by Moderna. Dr. Chalkias and several coauthors are employed by Moderna. One coauthor has relationships with DLA Piper/Medtronic, and Gilead Pharmaceuticals, and one has relationships with Celgene/Bristol-Myers Squibb, ChemoCentryx, Gilead, and Kiniksa. Dr. Nori has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON –

The bivalent booster was superior regardless of age and whether a person had previously been infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Additionally, no new safety concerns emerged.

Spyros Chalkias, MD, senior medical director of clinical development at Moderna, presented the data during an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

In the phase 2/3 trial, participants received either 50 mcg of the bivalent vaccine mRNA-1273.214 (25 mcg each of the original Wuhan-Hu-1 and Omicron BA.1 spike mRNAs) or 50 mcg of the standard authorized mRNA-1273. The doses were given as second boosters in adults who had previously received a two-dose primary series and a first booster at least 3 months before.

The model-based geometric mean titers (GMTs) ratio of the enhanced booster compared with the standard booster was 1.74 (1.49-2.04), meeting the prespecified bar for superiority against Omicron BA.1.

In participants without prior SARS-CoV-2 infection who received updated booster doses and those who received standard boosters, the neutralizing antibody GMTs against Omicron BA.1 were 2372.4 and 1473.5, respectively.

Additionally, the updated booster elicited higher GMTs (727.4) than the standard booster (492.1) against Omicron subvariants BA.4/BA.5. Safety and reactogenicity were similar for both vaccine groups.

“By the end of this year, we expect to also have clinical trial data from our BA.4/BA.5 bivalent booster,” Dr. Chalkias said.

In the interim, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently granted emergency use authorization for Moderna’s BA.4/BA.5 Omicron-targeting bivalent COVID-19 booster vaccine in children and adolescents aged 6-17 years.

Pfizer/BioNTech also has recently issued an announcement that their COVID-19 booster, adapted for the BA.4 and the BA.5 Omicron subvariants, generated a strong immune response and was well tolerated in human tests.

Pfizer/BioNTech said data from roughly 80 adult patients showed that the booster led to a substantial increase in neutralizing antibody levels against the BA.4/BA.5 variants after 1 week.

Separate study of causes of severe breakthrough infections in early vaccine formulations

Though COVID vaccines reduce the incidence of severe outcomes, there are reports of breakthrough infections in persons who received the original vaccines, and some of these have been serious.

In a separate study, also presented at the meeting, researchers led by first author Austin D. Vo, BS, with the VA Boston Healthcare System, used data collected from Dec. 15, 2020, through Feb. 28, 2022, in a U.S. veteran population to assess those at highest risk for severe disease despite vaccination.

Results of the large, nationwide retrospective study were simultaneously published in JAMA Network Open.

The primary outcome was development of severe COVID, defined as a hospitalization within 14 days of a confirmed positive SARS-CoV-2 test, receipt of supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation, or death within 28 days.

Among 110,760 participants with severe disease after primary vaccination, 13% (14,690) were hospitalized with severe COVID-19 or died.

The strongest risk factor for severe disease despite vaccination was age, the researchers found.

Presenting author Westyn Branch-Elliman, MD, associate professor of medicine with VA Boston Healthcare System, said, “We found that age greater than 50 was associated with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.42 for every 5-year increase.”

To put that in perspective, she said, “compared to patients who are 45 to 50, those over 80 had an adjusted odds ratio of 16 for hospitalization or death following breakthrough infection.”

Priya Nori, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Montefiore Medical Center in New York, said in an interview that the evidence that age is a strong risk factor for severe disease – even after vaccination – confirms that attention should be focused on those in the highest age groups, particularly those 80 years and older.

Other top risk factors included having immunocompromising conditions; having received cytotoxic chemotherapy within 6 months (adjusted odds ratio, 2.69; 95% confidence interval, 2.25-3.21); having leukemias/lymphomas (aOR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.59-2.14); and having chronic conditions associated with end-organ disease.

“We also found that receipt of an additional booster dose of vaccine was associated with a 50% reduction in adjusted odds of severe disease,” noted Dr. Branch-Elliman.

Dr. Nori emphasized that, given these data, emphatic messaging is needed to encourage uptake of the updated Omicron-targeted vaccines for these high-risk age groups.

The study by Dr. Chalkias and colleagues was funded by Moderna. Dr. Chalkias and several coauthors are employed by Moderna. One coauthor has relationships with DLA Piper/Medtronic, and Gilead Pharmaceuticals, and one has relationships with Celgene/Bristol-Myers Squibb, ChemoCentryx, Gilead, and Kiniksa. Dr. Nori has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON –

The bivalent booster was superior regardless of age and whether a person had previously been infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Additionally, no new safety concerns emerged.

Spyros Chalkias, MD, senior medical director of clinical development at Moderna, presented the data during an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases.

In the phase 2/3 trial, participants received either 50 mcg of the bivalent vaccine mRNA-1273.214 (25 mcg each of the original Wuhan-Hu-1 and Omicron BA.1 spike mRNAs) or 50 mcg of the standard authorized mRNA-1273. The doses were given as second boosters in adults who had previously received a two-dose primary series and a first booster at least 3 months before.

The model-based geometric mean titers (GMTs) ratio of the enhanced booster compared with the standard booster was 1.74 (1.49-2.04), meeting the prespecified bar for superiority against Omicron BA.1.

In participants without prior SARS-CoV-2 infection who received updated booster doses and those who received standard boosters, the neutralizing antibody GMTs against Omicron BA.1 were 2372.4 and 1473.5, respectively.

Additionally, the updated booster elicited higher GMTs (727.4) than the standard booster (492.1) against Omicron subvariants BA.4/BA.5. Safety and reactogenicity were similar for both vaccine groups.

“By the end of this year, we expect to also have clinical trial data from our BA.4/BA.5 bivalent booster,” Dr. Chalkias said.

In the interim, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recently granted emergency use authorization for Moderna’s BA.4/BA.5 Omicron-targeting bivalent COVID-19 booster vaccine in children and adolescents aged 6-17 years.

Pfizer/BioNTech also has recently issued an announcement that their COVID-19 booster, adapted for the BA.4 and the BA.5 Omicron subvariants, generated a strong immune response and was well tolerated in human tests.

Pfizer/BioNTech said data from roughly 80 adult patients showed that the booster led to a substantial increase in neutralizing antibody levels against the BA.4/BA.5 variants after 1 week.

Separate study of causes of severe breakthrough infections in early vaccine formulations

Though COVID vaccines reduce the incidence of severe outcomes, there are reports of breakthrough infections in persons who received the original vaccines, and some of these have been serious.

In a separate study, also presented at the meeting, researchers led by first author Austin D. Vo, BS, with the VA Boston Healthcare System, used data collected from Dec. 15, 2020, through Feb. 28, 2022, in a U.S. veteran population to assess those at highest risk for severe disease despite vaccination.

Results of the large, nationwide retrospective study were simultaneously published in JAMA Network Open.

The primary outcome was development of severe COVID, defined as a hospitalization within 14 days of a confirmed positive SARS-CoV-2 test, receipt of supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation, or death within 28 days.

Among 110,760 participants with severe disease after primary vaccination, 13% (14,690) were hospitalized with severe COVID-19 or died.

The strongest risk factor for severe disease despite vaccination was age, the researchers found.

Presenting author Westyn Branch-Elliman, MD, associate professor of medicine with VA Boston Healthcare System, said, “We found that age greater than 50 was associated with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.42 for every 5-year increase.”

To put that in perspective, she said, “compared to patients who are 45 to 50, those over 80 had an adjusted odds ratio of 16 for hospitalization or death following breakthrough infection.”

Priya Nori, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Montefiore Medical Center in New York, said in an interview that the evidence that age is a strong risk factor for severe disease – even after vaccination – confirms that attention should be focused on those in the highest age groups, particularly those 80 years and older.

Other top risk factors included having immunocompromising conditions; having received cytotoxic chemotherapy within 6 months (adjusted odds ratio, 2.69; 95% confidence interval, 2.25-3.21); having leukemias/lymphomas (aOR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.59-2.14); and having chronic conditions associated with end-organ disease.

“We also found that receipt of an additional booster dose of vaccine was associated with a 50% reduction in adjusted odds of severe disease,” noted Dr. Branch-Elliman.

Dr. Nori emphasized that, given these data, emphatic messaging is needed to encourage uptake of the updated Omicron-targeted vaccines for these high-risk age groups.

The study by Dr. Chalkias and colleagues was funded by Moderna. Dr. Chalkias and several coauthors are employed by Moderna. One coauthor has relationships with DLA Piper/Medtronic, and Gilead Pharmaceuticals, and one has relationships with Celgene/Bristol-Myers Squibb, ChemoCentryx, Gilead, and Kiniksa. Dr. Nori has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT IDWEEK 2022

More data suggest preexisting statin use improves COVID outcomes

Compared with patients who didn’t take statins, statin users had better health outcomes. For those who used these medications, the researchers saw lower mortality, lower clinical severity, and shorter hospital stays, aligning with previous observational studies, said lead author Ettore Crimi, MD, of the University of Central Florida, Orlando, and colleagues in their abstract, which was part of the agenda for the Anesthesiology annual meeting.

They attributed these clinical improvements to the pleiotropic – non–cholesterol lowering – effects of statins.

“[These] benefits of statins have been reported since the 1990s,” Dr. Crimi said in an interview. “Statin treatment has been associated with a marked reduction of markers of inflammation, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), ferritin, and white blood cell count, among others.”

He noted that these effects have been studied in an array of conditions, including cancer, autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammatory disease, and in the perioperative setting, and with infectious diseases, including COVID-19.

In those previous studies, “preexisting statin use was protective among hospitalized COVID-19 patients, but a large, multicenter cohort study has not been reported in the United States,” Dr. Crimi and his colleagues wrote in their abstract.

To address this knowledge gap, they turned to electronic medical records from 38,875 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 from January to September 2020. Almost one-third of the population (n = 11,533) were using statins prior to hospitalization, while the remainder (n = 27,342) were nonusers.

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included death from COVID-19, along with a variety of severe complications. While the analysis did account for a range of potentially confounding variables, the effects of different SARS-CoV-2 variants and new therapeutics were not considered. Vaccines were not yet available at the time the data were collected.

Statin users had a 31% lower rate of all-cause mortality (odds ratio, 0.69; 95% confidence interval, 0.64-0.75; P = .001) and a 37% reduced rate of death from COVID-19 (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.58-0.69; P = .001).

A litany of other secondary variables also favored statin users, including reduced rates of discharge to hospice (OR, 0.79), ICU admission (OR, 0.69), severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDs; OR, 0.72), critical ARDs (OR, 0.57), mechanical ventilation (OR, 0.60), severe sepsis with septic shock (OR, 0.66), and thrombosis (OR, 0.46). Statin users also had, on average, shorter hospital stays and briefer mechanical ventilation.

“Our study showed a strong association between preexisting statin use and reduced mortality and morbidity rates in hospitalized COVID-19 patients,” the investigators concluded. “Pleiotropic benefits of statins could be repurposed for COVID-19 illness.”

Prospective studies needed before practice changes

How to best use statins against COVID-19, if at all, remains unclear, Dr. Crimi said, as initiation upon infection has generated mixed results in other studies, possibly because of statin pharmacodynamics. Cholesterol normalization can take about 6 weeks, so other benefits may track a similar timeline.

“The delayed onset of statins’ pleiotropic effects may likely fail to keep pace with the rapidly progressive, devastating COVID-19 disease,” Dr. Crimi said. “Therefore, initiating statins for an acute disease may not be an ideal first-line treatment.”

Stronger data are on the horizon, he added, noting that 19 federally funded prospective trials are underway to better understand the relationship between statins and COVID-19.

Daniel Rader, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the present findings are “not especially notable” because they “mostly confirm previous studies, but in a large U.S. cohort.”

Dr. Rader, who wrote about the potential repurposing of statins for COVID-19 back in the first year of the pandemic (Cell Metab. 2020 Aug 4;32[2]:145-7), agreed with the investigators that recommending changes to clinical practice would be imprudent until randomized controlled data confirm the benefits of initiating statins in patients with active COVID-19.

“More research on the impact of cellular cholesterol metabolism on SARS-CoV-2 infection of cells and generation of inflammation would also be of interest,” he added.

The investigators disclosed no competing interests. Dr. Rader disclosed relationships with Novartis, Pfizer, Verve, and others.

Compared with patients who didn’t take statins, statin users had better health outcomes. For those who used these medications, the researchers saw lower mortality, lower clinical severity, and shorter hospital stays, aligning with previous observational studies, said lead author Ettore Crimi, MD, of the University of Central Florida, Orlando, and colleagues in their abstract, which was part of the agenda for the Anesthesiology annual meeting.

They attributed these clinical improvements to the pleiotropic – non–cholesterol lowering – effects of statins.

“[These] benefits of statins have been reported since the 1990s,” Dr. Crimi said in an interview. “Statin treatment has been associated with a marked reduction of markers of inflammation, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), ferritin, and white blood cell count, among others.”

He noted that these effects have been studied in an array of conditions, including cancer, autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammatory disease, and in the perioperative setting, and with infectious diseases, including COVID-19.

In those previous studies, “preexisting statin use was protective among hospitalized COVID-19 patients, but a large, multicenter cohort study has not been reported in the United States,” Dr. Crimi and his colleagues wrote in their abstract.

To address this knowledge gap, they turned to electronic medical records from 38,875 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 from January to September 2020. Almost one-third of the population (n = 11,533) were using statins prior to hospitalization, while the remainder (n = 27,342) were nonusers.

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included death from COVID-19, along with a variety of severe complications. While the analysis did account for a range of potentially confounding variables, the effects of different SARS-CoV-2 variants and new therapeutics were not considered. Vaccines were not yet available at the time the data were collected.

Statin users had a 31% lower rate of all-cause mortality (odds ratio, 0.69; 95% confidence interval, 0.64-0.75; P = .001) and a 37% reduced rate of death from COVID-19 (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.58-0.69; P = .001).

A litany of other secondary variables also favored statin users, including reduced rates of discharge to hospice (OR, 0.79), ICU admission (OR, 0.69), severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDs; OR, 0.72), critical ARDs (OR, 0.57), mechanical ventilation (OR, 0.60), severe sepsis with septic shock (OR, 0.66), and thrombosis (OR, 0.46). Statin users also had, on average, shorter hospital stays and briefer mechanical ventilation.

“Our study showed a strong association between preexisting statin use and reduced mortality and morbidity rates in hospitalized COVID-19 patients,” the investigators concluded. “Pleiotropic benefits of statins could be repurposed for COVID-19 illness.”

Prospective studies needed before practice changes

How to best use statins against COVID-19, if at all, remains unclear, Dr. Crimi said, as initiation upon infection has generated mixed results in other studies, possibly because of statin pharmacodynamics. Cholesterol normalization can take about 6 weeks, so other benefits may track a similar timeline.

“The delayed onset of statins’ pleiotropic effects may likely fail to keep pace with the rapidly progressive, devastating COVID-19 disease,” Dr. Crimi said. “Therefore, initiating statins for an acute disease may not be an ideal first-line treatment.”

Stronger data are on the horizon, he added, noting that 19 federally funded prospective trials are underway to better understand the relationship between statins and COVID-19.

Daniel Rader, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said the present findings are “not especially notable” because they “mostly confirm previous studies, but in a large U.S. cohort.”

Dr. Rader, who wrote about the potential repurposing of statins for COVID-19 back in the first year of the pandemic (Cell Metab. 2020 Aug 4;32[2]:145-7), agreed with the investigators that recommending changes to clinical practice would be imprudent until randomized controlled data confirm the benefits of initiating statins in patients with active COVID-19.

“More research on the impact of cellular cholesterol metabolism on SARS-CoV-2 infection of cells and generation of inflammation would also be of interest,” he added.

The investigators disclosed no competing interests. Dr. Rader disclosed relationships with Novartis, Pfizer, Verve, and others.

Compared with patients who didn’t take statins, statin users had better health outcomes. For those who used these medications, the researchers saw lower mortality, lower clinical severity, and shorter hospital stays, aligning with previous observational studies, said lead author Ettore Crimi, MD, of the University of Central Florida, Orlando, and colleagues in their abstract, which was part of the agenda for the Anesthesiology annual meeting.

They attributed these clinical improvements to the pleiotropic – non–cholesterol lowering – effects of statins.

“[These] benefits of statins have been reported since the 1990s,” Dr. Crimi said in an interview. “Statin treatment has been associated with a marked reduction of markers of inflammation, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), ferritin, and white blood cell count, among others.”

He noted that these effects have been studied in an array of conditions, including cancer, autoimmune diseases, chronic inflammatory disease, and in the perioperative setting, and with infectious diseases, including COVID-19.

In those previous studies, “preexisting statin use was protective among hospitalized COVID-19 patients, but a large, multicenter cohort study has not been reported in the United States,” Dr. Crimi and his colleagues wrote in their abstract.

To address this knowledge gap, they turned to electronic medical records from 38,875 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 from January to September 2020. Almost one-third of the population (n = 11,533) were using statins prior to hospitalization, while the remainder (n = 27,342) were nonusers.

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included death from COVID-19, along with a variety of severe complications. While the analysis did account for a range of potentially confounding variables, the effects of different SARS-CoV-2 variants and new therapeutics were not considered. Vaccines were not yet available at the time the data were collected.

Statin users had a 31% lower rate of all-cause mortality (odds ratio, 0.69; 95% confidence interval, 0.64-0.75; P = .001) and a 37% reduced rate of death from COVID-19 (OR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.58-0.69; P = .001).

A litany of other secondary variables also favored statin users, including reduced rates of discharge to hospice (OR, 0.79), ICU admission (OR, 0.69), severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDs; OR, 0.72), critical ARDs (OR, 0.57), mechanical ventilation (OR, 0.60), severe sepsis with septic shock (OR, 0.66), and thrombosis (OR, 0.46). Statin users also had, on average, shorter hospital stays and briefer mechanical ventilation.