User login

Many people becoming reinfected as BA.5 dominates new COVID-19 cases

When the COVID-19 pandemic first began, the general thought was that once people were infected, they were then protected from the virus.

It’s hard to say how many. The ABC News analysis found at least 1.6 million reinfections in 24 states, but the actual number is probably a lot higher.

“These are not the real numbers because many people are not reporting cases,” Ali Mokdad, MD, an epidemiologist with the University of Washington, Seattle, told ABC.

The latest variant, BA.5, has become the dominant strain in the United States, making up more than 65% of all COVID-19 cases as of July 13, according to data from the CDC.

Prior infections and vaccines aren’t providing as much protection against the newly dominant BA.5 strain as they did against earlier variants.

But evidence doesn’t show this subvariant of Omicron to be more harmful than earlier, less transmissible versions.

Several factors are contributing to rising reinfections, experts say. For example, fewer people are wearing masks than in the first year or so of the pandemic. Dr. Mokdad said just 18% of Americans reported always wearing a mask in public at the end of May, down from 44% the year before.

The emergence of the Omicron variant, of which BA.5 is a subvariant, is indicating that less protection is being offered by prior infections.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

When the COVID-19 pandemic first began, the general thought was that once people were infected, they were then protected from the virus.

It’s hard to say how many. The ABC News analysis found at least 1.6 million reinfections in 24 states, but the actual number is probably a lot higher.

“These are not the real numbers because many people are not reporting cases,” Ali Mokdad, MD, an epidemiologist with the University of Washington, Seattle, told ABC.

The latest variant, BA.5, has become the dominant strain in the United States, making up more than 65% of all COVID-19 cases as of July 13, according to data from the CDC.

Prior infections and vaccines aren’t providing as much protection against the newly dominant BA.5 strain as they did against earlier variants.

But evidence doesn’t show this subvariant of Omicron to be more harmful than earlier, less transmissible versions.

Several factors are contributing to rising reinfections, experts say. For example, fewer people are wearing masks than in the first year or so of the pandemic. Dr. Mokdad said just 18% of Americans reported always wearing a mask in public at the end of May, down from 44% the year before.

The emergence of the Omicron variant, of which BA.5 is a subvariant, is indicating that less protection is being offered by prior infections.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

When the COVID-19 pandemic first began, the general thought was that once people were infected, they were then protected from the virus.

It’s hard to say how many. The ABC News analysis found at least 1.6 million reinfections in 24 states, but the actual number is probably a lot higher.

“These are not the real numbers because many people are not reporting cases,” Ali Mokdad, MD, an epidemiologist with the University of Washington, Seattle, told ABC.

The latest variant, BA.5, has become the dominant strain in the United States, making up more than 65% of all COVID-19 cases as of July 13, according to data from the CDC.

Prior infections and vaccines aren’t providing as much protection against the newly dominant BA.5 strain as they did against earlier variants.

But evidence doesn’t show this subvariant of Omicron to be more harmful than earlier, less transmissible versions.

Several factors are contributing to rising reinfections, experts say. For example, fewer people are wearing masks than in the first year or so of the pandemic. Dr. Mokdad said just 18% of Americans reported always wearing a mask in public at the end of May, down from 44% the year before.

The emergence of the Omicron variant, of which BA.5 is a subvariant, is indicating that less protection is being offered by prior infections.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Some have heavier periods after COVID vaccine

Many women who got a COVID-19 vaccine have reported heavier bleeding during their periods since they had the shots.

A team of researchers investigated the trend and set out to find out who among the vaccinated were more likely to experience the menstruation changes.

The researchers were led by Katharine M.N. Lee, PhD, MS, of the division of public health sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. Their findings were published ahead of print in Science Advances.

The investigators analyzed more than 139,000 responses from an online survey from both currently and formerly menstruating women.

They found that, among people who have regular periods, about the same percentage had heavier bleeding after they got a COVID vaccine as had no change in bleeding after the vaccine (44% vs. 42%, respectively).

“A much smaller portion had lighter periods,” they write.

The phenomenon has been difficult to study because questions about changes in menstruation are not a standard part of vaccine trials.

Date of last period is often tracked in clinical trials to make sure a participant is not pregnant, but the questions about periods often stop there.

Additionally, periods are different for everyone and can be influenced by all sorts of environmental factors, so making associations regarding exposures is problematic.

No changes found to fertility

The authors emphasized that, generally, changes to menstrual bleeding are not uncommon nor dangerous. They also emphasized that the changes in bleeding don’t mean changes to fertility.

The uterine reproductive system is flexible when the body is under stress, they note.

“We know that running a marathon may influence hormone concentrations in the short term while not rendering that person infertile,” the authors write.

However, they acknowledge that investigating these reports is critical in building trust in medicine.

This report includes information that hasn’t been available through the clinical trial follow-up process.

For instance, the authors write, “To the best of our knowledge, our work is the first to examine breakthrough bleeding after vaccination in either pre- or postmenopausal people.”

Reports of changes to periods after vaccination started emerging in 2021. But without data, reports were largely dismissed, fueling criticism from those waging campaigns against COVID vaccines.

Dr. Lee and colleagues gathered data from those who responded to the online survey and detailed some trends.

People who were bleeding more heavily after vaccination were more likely to be older, Hispanic, had vaccine side effects of fever and fatigue, had been pregnant at some point, or had given birth.

People with regular periods who had endometriosis, prolonged bleeding during their periods, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) or fibroids were also more likely to have increased bleeding after a COVID vaccine.

Breakthrough bleeding

For people who don’t menstruate, but have not reached menopause, breakthrough bleeding happened more often in women who had been pregnant and/or had given birth.

Among respondents who were postmenopausal, breakthrough bleeding happened more often in younger people and/or those who are Hispanic.

More than a third of the respondents (39%) who use gender-affirming hormones that eliminate menstruation reported breakthrough bleeding after vaccination.

The majority of premenopausal people on long-acting, reversible contraception (71%) and the majority of postmenopausal respondents (66%) had breakthrough bleeding as well.

The authors note that you can’t compare the percentages who report these experiences in the survey with the incidence of those who would experience changes in menstrual bleeding in the general population.

The nature of the online survey means it may be naturally biased because the people who responded may be more often those who noted some change in their own menstrual experiences, particularly if that involved discomfort, pain, or fear.

Researchers also acknowledge that Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and other respondents of color are underrepresented in this research and that represents a limitation in the work.

Alison Edelman, MD, MPH, with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, was not involved with Dr. Lee and associates’ study but has also studied the relationship between COVID vaccines and menstruation.

Her team’s study found that COVID vaccination is associated with a small change in time between periods but not length of periods.

She said about the work by Dr. Lee and colleagues, “This work really elevates the voices of the public and what they’re experiencing.”

The association makes sense, Dr. Edelman says, in that the reproductive system and the immune system talk to each other and inflammation in the immune system is going to be noticed by the system governing periods.

Lack of data on the relationship between exposures and menstruation didn’t start with COVID. “There has been a signal in the population before with other vaccines that’s been dismissed,” she said.

Tracking menstruation information in clinical trials can help physicians counsel women on what may be coming with any vaccine and alleviate fears and vaccine hesitancy, Dr. Edelman explained. It can also help vaccine developers know what to include in information about their product.

“When you are counseled about what to expect, it’s not as scary. That provides trust in the system,” she said. She likened it to original lack of data on whether COVID-19 vaccines would affect pregnancy.

“We have great science now that COVID vaccine does not affect fertility and [vaccine] does not impact pregnancy.”

Another important aspect of this paper is that it included subgroups not studied before regarding menstruation and breakthrough bleeding, such as those taking gender-affirming hormones, she added.

Menstruation has been often overlooked as important in clinical trial exposures but Dr. Edelman hopes this recent attention and question will escalate and prompt more research.

“I’m hoping with the immense outpouring from the public about how important this is, that future studies will look at this a little bit better,” she says.

She said when the National Institutes of Health opened up funding for trials on COVID-19 vaccines and menstruation, researchers got flooded with requests from women to share their stories.

“As a researcher – I’ve been doing research for over 20 years – that’s not something that usually happens. I would love to have that happen for every research project.”

The authors and Dr. Edelman declare that they have no competing interests. This research was supported in part by the University of Illinois Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, the University of Illinois Interdisciplinary Health Sciences Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital, and the Siteman Cancer Center.

Many women who got a COVID-19 vaccine have reported heavier bleeding during their periods since they had the shots.

A team of researchers investigated the trend and set out to find out who among the vaccinated were more likely to experience the menstruation changes.

The researchers were led by Katharine M.N. Lee, PhD, MS, of the division of public health sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. Their findings were published ahead of print in Science Advances.

The investigators analyzed more than 139,000 responses from an online survey from both currently and formerly menstruating women.

They found that, among people who have regular periods, about the same percentage had heavier bleeding after they got a COVID vaccine as had no change in bleeding after the vaccine (44% vs. 42%, respectively).

“A much smaller portion had lighter periods,” they write.

The phenomenon has been difficult to study because questions about changes in menstruation are not a standard part of vaccine trials.

Date of last period is often tracked in clinical trials to make sure a participant is not pregnant, but the questions about periods often stop there.

Additionally, periods are different for everyone and can be influenced by all sorts of environmental factors, so making associations regarding exposures is problematic.

No changes found to fertility

The authors emphasized that, generally, changes to menstrual bleeding are not uncommon nor dangerous. They also emphasized that the changes in bleeding don’t mean changes to fertility.

The uterine reproductive system is flexible when the body is under stress, they note.

“We know that running a marathon may influence hormone concentrations in the short term while not rendering that person infertile,” the authors write.

However, they acknowledge that investigating these reports is critical in building trust in medicine.

This report includes information that hasn’t been available through the clinical trial follow-up process.

For instance, the authors write, “To the best of our knowledge, our work is the first to examine breakthrough bleeding after vaccination in either pre- or postmenopausal people.”

Reports of changes to periods after vaccination started emerging in 2021. But without data, reports were largely dismissed, fueling criticism from those waging campaigns against COVID vaccines.

Dr. Lee and colleagues gathered data from those who responded to the online survey and detailed some trends.

People who were bleeding more heavily after vaccination were more likely to be older, Hispanic, had vaccine side effects of fever and fatigue, had been pregnant at some point, or had given birth.

People with regular periods who had endometriosis, prolonged bleeding during their periods, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) or fibroids were also more likely to have increased bleeding after a COVID vaccine.

Breakthrough bleeding

For people who don’t menstruate, but have not reached menopause, breakthrough bleeding happened more often in women who had been pregnant and/or had given birth.

Among respondents who were postmenopausal, breakthrough bleeding happened more often in younger people and/or those who are Hispanic.

More than a third of the respondents (39%) who use gender-affirming hormones that eliminate menstruation reported breakthrough bleeding after vaccination.

The majority of premenopausal people on long-acting, reversible contraception (71%) and the majority of postmenopausal respondents (66%) had breakthrough bleeding as well.

The authors note that you can’t compare the percentages who report these experiences in the survey with the incidence of those who would experience changes in menstrual bleeding in the general population.

The nature of the online survey means it may be naturally biased because the people who responded may be more often those who noted some change in their own menstrual experiences, particularly if that involved discomfort, pain, or fear.

Researchers also acknowledge that Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and other respondents of color are underrepresented in this research and that represents a limitation in the work.

Alison Edelman, MD, MPH, with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, was not involved with Dr. Lee and associates’ study but has also studied the relationship between COVID vaccines and menstruation.

Her team’s study found that COVID vaccination is associated with a small change in time between periods but not length of periods.

She said about the work by Dr. Lee and colleagues, “This work really elevates the voices of the public and what they’re experiencing.”

The association makes sense, Dr. Edelman says, in that the reproductive system and the immune system talk to each other and inflammation in the immune system is going to be noticed by the system governing periods.

Lack of data on the relationship between exposures and menstruation didn’t start with COVID. “There has been a signal in the population before with other vaccines that’s been dismissed,” she said.

Tracking menstruation information in clinical trials can help physicians counsel women on what may be coming with any vaccine and alleviate fears and vaccine hesitancy, Dr. Edelman explained. It can also help vaccine developers know what to include in information about their product.

“When you are counseled about what to expect, it’s not as scary. That provides trust in the system,” she said. She likened it to original lack of data on whether COVID-19 vaccines would affect pregnancy.

“We have great science now that COVID vaccine does not affect fertility and [vaccine] does not impact pregnancy.”

Another important aspect of this paper is that it included subgroups not studied before regarding menstruation and breakthrough bleeding, such as those taking gender-affirming hormones, she added.

Menstruation has been often overlooked as important in clinical trial exposures but Dr. Edelman hopes this recent attention and question will escalate and prompt more research.

“I’m hoping with the immense outpouring from the public about how important this is, that future studies will look at this a little bit better,” she says.

She said when the National Institutes of Health opened up funding for trials on COVID-19 vaccines and menstruation, researchers got flooded with requests from women to share their stories.

“As a researcher – I’ve been doing research for over 20 years – that’s not something that usually happens. I would love to have that happen for every research project.”

The authors and Dr. Edelman declare that they have no competing interests. This research was supported in part by the University of Illinois Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, the University of Illinois Interdisciplinary Health Sciences Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital, and the Siteman Cancer Center.

Many women who got a COVID-19 vaccine have reported heavier bleeding during their periods since they had the shots.

A team of researchers investigated the trend and set out to find out who among the vaccinated were more likely to experience the menstruation changes.

The researchers were led by Katharine M.N. Lee, PhD, MS, of the division of public health sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. Their findings were published ahead of print in Science Advances.

The investigators analyzed more than 139,000 responses from an online survey from both currently and formerly menstruating women.

They found that, among people who have regular periods, about the same percentage had heavier bleeding after they got a COVID vaccine as had no change in bleeding after the vaccine (44% vs. 42%, respectively).

“A much smaller portion had lighter periods,” they write.

The phenomenon has been difficult to study because questions about changes in menstruation are not a standard part of vaccine trials.

Date of last period is often tracked in clinical trials to make sure a participant is not pregnant, but the questions about periods often stop there.

Additionally, periods are different for everyone and can be influenced by all sorts of environmental factors, so making associations regarding exposures is problematic.

No changes found to fertility

The authors emphasized that, generally, changes to menstrual bleeding are not uncommon nor dangerous. They also emphasized that the changes in bleeding don’t mean changes to fertility.

The uterine reproductive system is flexible when the body is under stress, they note.

“We know that running a marathon may influence hormone concentrations in the short term while not rendering that person infertile,” the authors write.

However, they acknowledge that investigating these reports is critical in building trust in medicine.

This report includes information that hasn’t been available through the clinical trial follow-up process.

For instance, the authors write, “To the best of our knowledge, our work is the first to examine breakthrough bleeding after vaccination in either pre- or postmenopausal people.”

Reports of changes to periods after vaccination started emerging in 2021. But without data, reports were largely dismissed, fueling criticism from those waging campaigns against COVID vaccines.

Dr. Lee and colleagues gathered data from those who responded to the online survey and detailed some trends.

People who were bleeding more heavily after vaccination were more likely to be older, Hispanic, had vaccine side effects of fever and fatigue, had been pregnant at some point, or had given birth.

People with regular periods who had endometriosis, prolonged bleeding during their periods, polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) or fibroids were also more likely to have increased bleeding after a COVID vaccine.

Breakthrough bleeding

For people who don’t menstruate, but have not reached menopause, breakthrough bleeding happened more often in women who had been pregnant and/or had given birth.

Among respondents who were postmenopausal, breakthrough bleeding happened more often in younger people and/or those who are Hispanic.

More than a third of the respondents (39%) who use gender-affirming hormones that eliminate menstruation reported breakthrough bleeding after vaccination.

The majority of premenopausal people on long-acting, reversible contraception (71%) and the majority of postmenopausal respondents (66%) had breakthrough bleeding as well.

The authors note that you can’t compare the percentages who report these experiences in the survey with the incidence of those who would experience changes in menstrual bleeding in the general population.

The nature of the online survey means it may be naturally biased because the people who responded may be more often those who noted some change in their own menstrual experiences, particularly if that involved discomfort, pain, or fear.

Researchers also acknowledge that Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and other respondents of color are underrepresented in this research and that represents a limitation in the work.

Alison Edelman, MD, MPH, with the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, was not involved with Dr. Lee and associates’ study but has also studied the relationship between COVID vaccines and menstruation.

Her team’s study found that COVID vaccination is associated with a small change in time between periods but not length of periods.

She said about the work by Dr. Lee and colleagues, “This work really elevates the voices of the public and what they’re experiencing.”

The association makes sense, Dr. Edelman says, in that the reproductive system and the immune system talk to each other and inflammation in the immune system is going to be noticed by the system governing periods.

Lack of data on the relationship between exposures and menstruation didn’t start with COVID. “There has been a signal in the population before with other vaccines that’s been dismissed,” she said.

Tracking menstruation information in clinical trials can help physicians counsel women on what may be coming with any vaccine and alleviate fears and vaccine hesitancy, Dr. Edelman explained. It can also help vaccine developers know what to include in information about their product.

“When you are counseled about what to expect, it’s not as scary. That provides trust in the system,” she said. She likened it to original lack of data on whether COVID-19 vaccines would affect pregnancy.

“We have great science now that COVID vaccine does not affect fertility and [vaccine] does not impact pregnancy.”

Another important aspect of this paper is that it included subgroups not studied before regarding menstruation and breakthrough bleeding, such as those taking gender-affirming hormones, she added.

Menstruation has been often overlooked as important in clinical trial exposures but Dr. Edelman hopes this recent attention and question will escalate and prompt more research.

“I’m hoping with the immense outpouring from the public about how important this is, that future studies will look at this a little bit better,” she says.

She said when the National Institutes of Health opened up funding for trials on COVID-19 vaccines and menstruation, researchers got flooded with requests from women to share their stories.

“As a researcher – I’ve been doing research for over 20 years – that’s not something that usually happens. I would love to have that happen for every research project.”

The authors and Dr. Edelman declare that they have no competing interests. This research was supported in part by the University of Illinois Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, the University of Illinois Interdisciplinary Health Sciences Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital, and the Siteman Cancer Center.

FROM SCIENCE ADVANCES

Cancer drug significantly cuts risk for COVID-19 death

, an interim analysis of a phase 3 placebo-controlled trial found.

Sabizabulin treatment consistently and significantly reduced deaths across patient subgroups “regardless of standard of care treatment received, baseline World Health Organization scores, age, comorbidities, vaccination status, COVID-19 variant, or geography,” study investigator Mitchell Steiner, MD, chairman, president, and CEO of Veru, said in a news release.

The company has submitted an emergency use authorization request to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to use sabizabulin to treat COVID-19.

The analysis was published online in NEJM Evidence.

Sabizabulin, originally developed to treat metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, is a novel, investigational, oral microtubule disruptor with dual antiviral and anti-inflammatory activities. Given the drug’s mechanism, researchers at Veru thought that sabizabulin could help treat lung inflammation in patients with COVID-19 as well.

Findings of the interim analysis are based on 150 adults hospitalized with moderate to severe COVID-19 at high risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome and death. The patients were randomly allocated to receive 9 mg oral sabizabulin (n = 98) or placebo (n = 52) once daily for up to 21 days.

Overall, the mortality rate was 20.2% in the sabizabulin group vs. 45.1% in the placebo group. Compared with placebo, treatment with sabizabulin led to a 24.9–percentage point absolute reduction and a 55.2% relative reduction in death (odds ratio, 3.23; P = .0042).

The key secondary endpoint of mortality through day 29 also favored sabizabulin over placebo, with a mortality rate of 17% vs. 35.3%. In this scenario, treatment with sabizabulin resulted in an absolute reduction in deaths of 18.3 percentage points and a relative reduction of 51.8%.

Sabizabulin led to a significant 43% relative reduction in ICU days, a 49% relative reduction in days on mechanical ventilation, and a 26% relative reduction in days in the hospital, compared with placebo.

Adverse and serious adverse events were also lower in the sabizabulin group (61.5%) than the placebo group (78.3%).

The data are “pretty impressive and in a group of patients that we really have limited things to offer,” Aaron Glatt, MD, a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America and chief of infectious diseases and hospital epidemiologist at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, N.Y., said in an interview. “This is an interim analysis and obviously we’d like to see more data, but it certainly is something that is novel and quite interesting.”

David Boulware, MD, MPH, an infectious disease expert at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, told the New York Times that the large number of deaths in the placebo group seemed “rather high” and that the final analysis might reveal a more modest benefit for sabizabulin.

“I would be skeptical” that the reduced risk for death remains 55%, he noted.

The study was funded by Veru Pharmaceuticals. Several authors are employed by the company or have financial relationships with the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, an interim analysis of a phase 3 placebo-controlled trial found.

Sabizabulin treatment consistently and significantly reduced deaths across patient subgroups “regardless of standard of care treatment received, baseline World Health Organization scores, age, comorbidities, vaccination status, COVID-19 variant, or geography,” study investigator Mitchell Steiner, MD, chairman, president, and CEO of Veru, said in a news release.

The company has submitted an emergency use authorization request to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to use sabizabulin to treat COVID-19.

The analysis was published online in NEJM Evidence.

Sabizabulin, originally developed to treat metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, is a novel, investigational, oral microtubule disruptor with dual antiviral and anti-inflammatory activities. Given the drug’s mechanism, researchers at Veru thought that sabizabulin could help treat lung inflammation in patients with COVID-19 as well.

Findings of the interim analysis are based on 150 adults hospitalized with moderate to severe COVID-19 at high risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome and death. The patients were randomly allocated to receive 9 mg oral sabizabulin (n = 98) or placebo (n = 52) once daily for up to 21 days.

Overall, the mortality rate was 20.2% in the sabizabulin group vs. 45.1% in the placebo group. Compared with placebo, treatment with sabizabulin led to a 24.9–percentage point absolute reduction and a 55.2% relative reduction in death (odds ratio, 3.23; P = .0042).

The key secondary endpoint of mortality through day 29 also favored sabizabulin over placebo, with a mortality rate of 17% vs. 35.3%. In this scenario, treatment with sabizabulin resulted in an absolute reduction in deaths of 18.3 percentage points and a relative reduction of 51.8%.

Sabizabulin led to a significant 43% relative reduction in ICU days, a 49% relative reduction in days on mechanical ventilation, and a 26% relative reduction in days in the hospital, compared with placebo.

Adverse and serious adverse events were also lower in the sabizabulin group (61.5%) than the placebo group (78.3%).

The data are “pretty impressive and in a group of patients that we really have limited things to offer,” Aaron Glatt, MD, a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America and chief of infectious diseases and hospital epidemiologist at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, N.Y., said in an interview. “This is an interim analysis and obviously we’d like to see more data, but it certainly is something that is novel and quite interesting.”

David Boulware, MD, MPH, an infectious disease expert at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, told the New York Times that the large number of deaths in the placebo group seemed “rather high” and that the final analysis might reveal a more modest benefit for sabizabulin.

“I would be skeptical” that the reduced risk for death remains 55%, he noted.

The study was funded by Veru Pharmaceuticals. Several authors are employed by the company or have financial relationships with the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, an interim analysis of a phase 3 placebo-controlled trial found.

Sabizabulin treatment consistently and significantly reduced deaths across patient subgroups “regardless of standard of care treatment received, baseline World Health Organization scores, age, comorbidities, vaccination status, COVID-19 variant, or geography,” study investigator Mitchell Steiner, MD, chairman, president, and CEO of Veru, said in a news release.

The company has submitted an emergency use authorization request to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to use sabizabulin to treat COVID-19.

The analysis was published online in NEJM Evidence.

Sabizabulin, originally developed to treat metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, is a novel, investigational, oral microtubule disruptor with dual antiviral and anti-inflammatory activities. Given the drug’s mechanism, researchers at Veru thought that sabizabulin could help treat lung inflammation in patients with COVID-19 as well.

Findings of the interim analysis are based on 150 adults hospitalized with moderate to severe COVID-19 at high risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome and death. The patients were randomly allocated to receive 9 mg oral sabizabulin (n = 98) or placebo (n = 52) once daily for up to 21 days.

Overall, the mortality rate was 20.2% in the sabizabulin group vs. 45.1% in the placebo group. Compared with placebo, treatment with sabizabulin led to a 24.9–percentage point absolute reduction and a 55.2% relative reduction in death (odds ratio, 3.23; P = .0042).

The key secondary endpoint of mortality through day 29 also favored sabizabulin over placebo, with a mortality rate of 17% vs. 35.3%. In this scenario, treatment with sabizabulin resulted in an absolute reduction in deaths of 18.3 percentage points and a relative reduction of 51.8%.

Sabizabulin led to a significant 43% relative reduction in ICU days, a 49% relative reduction in days on mechanical ventilation, and a 26% relative reduction in days in the hospital, compared with placebo.

Adverse and serious adverse events were also lower in the sabizabulin group (61.5%) than the placebo group (78.3%).

The data are “pretty impressive and in a group of patients that we really have limited things to offer,” Aaron Glatt, MD, a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America and chief of infectious diseases and hospital epidemiologist at Mount Sinai South Nassau in Oceanside, N.Y., said in an interview. “This is an interim analysis and obviously we’d like to see more data, but it certainly is something that is novel and quite interesting.”

David Boulware, MD, MPH, an infectious disease expert at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, told the New York Times that the large number of deaths in the placebo group seemed “rather high” and that the final analysis might reveal a more modest benefit for sabizabulin.

“I would be skeptical” that the reduced risk for death remains 55%, he noted.

The study was funded by Veru Pharmaceuticals. Several authors are employed by the company or have financial relationships with the company.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NEJM EVIDENCE

FDA grants emergency authorization for Novavax COVID vaccine

on July 13.

The vaccine is authorized for adults only. Should the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention follow suit and approve its use, Novavax would join Moderna, Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson on the U.S. market. A CDC panel of advisors is expected to consider the new entry on July 19.

The Novavax vaccine is only for those who have not yet been vaccinated at all.

“Today’s authorization offers adults in the United States who have not yet received a COVID-19 vaccine another option that meets the FDA’s rigorous standards for safety, effectiveness and manufacturing quality needed to support emergency use authorization,” FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, said in a statement. “COVID-19 vaccines remain the best preventive measure against severe disease caused by COVID-19 and I encourage anyone who is eligible for, but has not yet received a COVID-19 vaccine, to consider doing so.”

The Novavax vaccine is protein-based, making it different than mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna. It contains harmless elements of actual coronavirus spike protein and an ingredient known as a adjuvant that enhances the patient’s immune response.

Clinical trials found the vaccine to be 90.4% effective in preventing mild, moderate or severe COVID-19. Only 17 patients out of 17,200 developed COVID-19 after receiving both doses.

The FDA said, however, that Novavax’s vaccine did show evidence of increased risk of myocarditis – inflammation of the heart – and pericarditis, inflammation of tissue surrounding the heart. In most people both disorders began within 10 days.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

on July 13.

The vaccine is authorized for adults only. Should the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention follow suit and approve its use, Novavax would join Moderna, Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson on the U.S. market. A CDC panel of advisors is expected to consider the new entry on July 19.

The Novavax vaccine is only for those who have not yet been vaccinated at all.

“Today’s authorization offers adults in the United States who have not yet received a COVID-19 vaccine another option that meets the FDA’s rigorous standards for safety, effectiveness and manufacturing quality needed to support emergency use authorization,” FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, said in a statement. “COVID-19 vaccines remain the best preventive measure against severe disease caused by COVID-19 and I encourage anyone who is eligible for, but has not yet received a COVID-19 vaccine, to consider doing so.”

The Novavax vaccine is protein-based, making it different than mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna. It contains harmless elements of actual coronavirus spike protein and an ingredient known as a adjuvant that enhances the patient’s immune response.

Clinical trials found the vaccine to be 90.4% effective in preventing mild, moderate or severe COVID-19. Only 17 patients out of 17,200 developed COVID-19 after receiving both doses.

The FDA said, however, that Novavax’s vaccine did show evidence of increased risk of myocarditis – inflammation of the heart – and pericarditis, inflammation of tissue surrounding the heart. In most people both disorders began within 10 days.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

on July 13.

The vaccine is authorized for adults only. Should the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention follow suit and approve its use, Novavax would join Moderna, Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson on the U.S. market. A CDC panel of advisors is expected to consider the new entry on July 19.

The Novavax vaccine is only for those who have not yet been vaccinated at all.

“Today’s authorization offers adults in the United States who have not yet received a COVID-19 vaccine another option that meets the FDA’s rigorous standards for safety, effectiveness and manufacturing quality needed to support emergency use authorization,” FDA Commissioner Robert Califf, MD, said in a statement. “COVID-19 vaccines remain the best preventive measure against severe disease caused by COVID-19 and I encourage anyone who is eligible for, but has not yet received a COVID-19 vaccine, to consider doing so.”

The Novavax vaccine is protein-based, making it different than mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna. It contains harmless elements of actual coronavirus spike protein and an ingredient known as a adjuvant that enhances the patient’s immune response.

Clinical trials found the vaccine to be 90.4% effective in preventing mild, moderate or severe COVID-19. Only 17 patients out of 17,200 developed COVID-19 after receiving both doses.

The FDA said, however, that Novavax’s vaccine did show evidence of increased risk of myocarditis – inflammation of the heart – and pericarditis, inflammation of tissue surrounding the heart. In most people both disorders began within 10 days.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

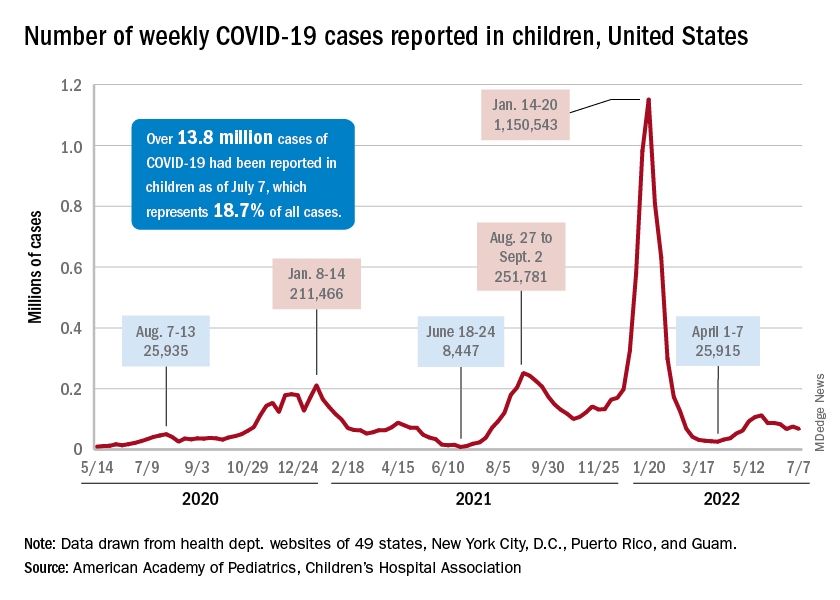

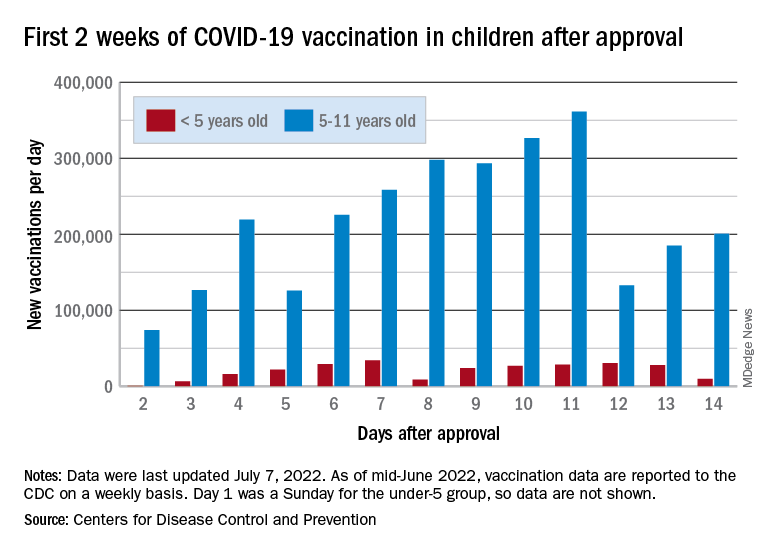

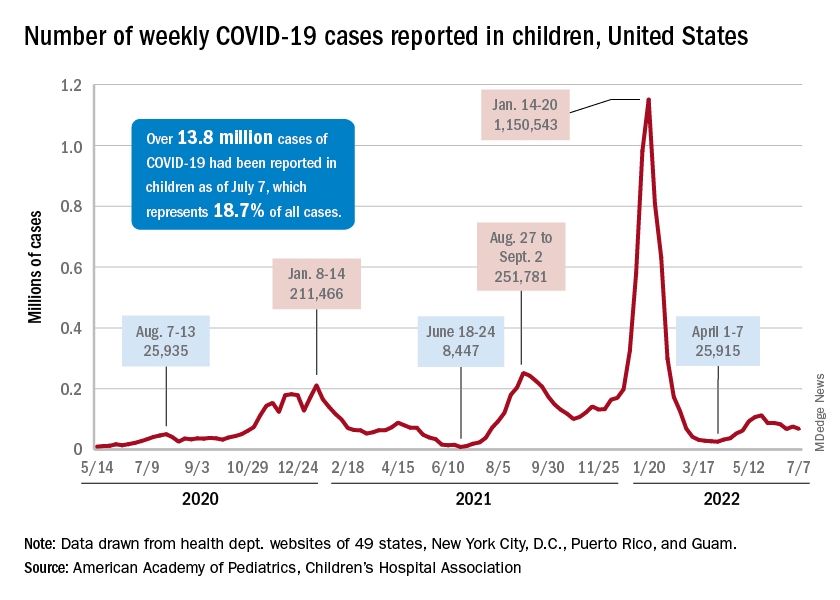

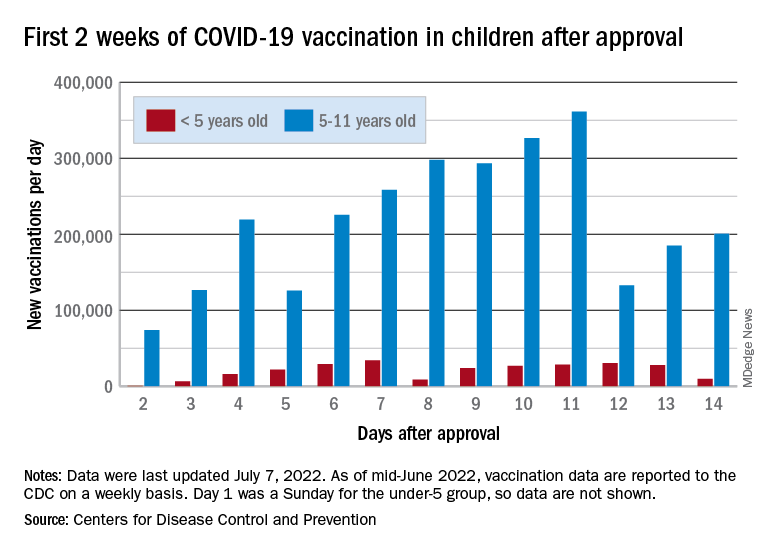

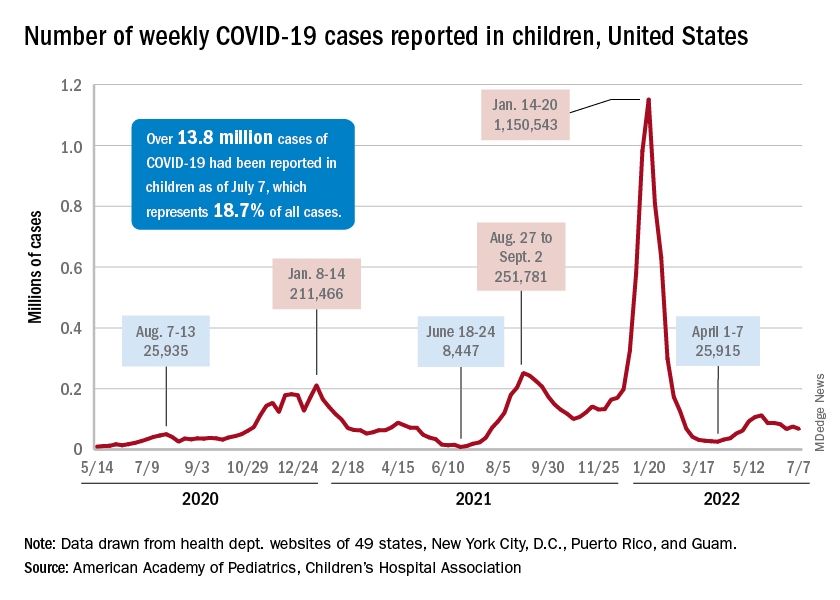

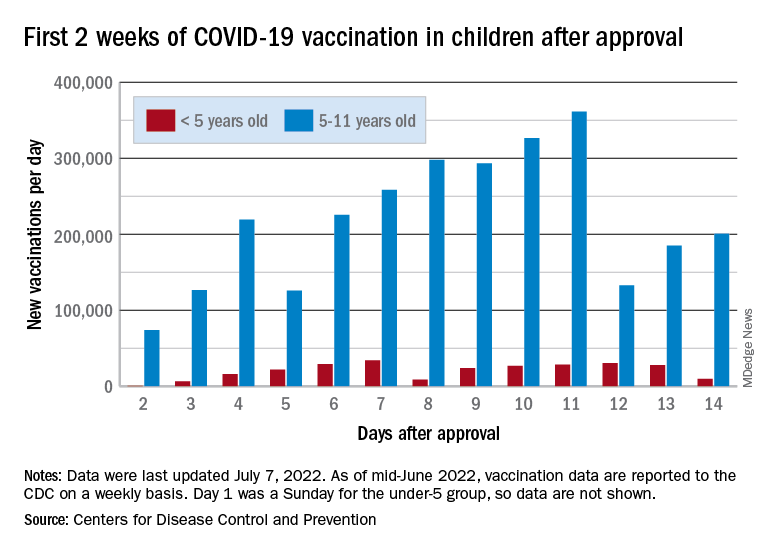

Children and COVID: Vaccination a harder sell in the summer

The COVID-19 vaccination effort in the youngest children has begun much more slowly than the most recent rollout for older children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

in early November of 2021, based on CDC data last updated on July 7.

That approval, of course, came between the Delta and Omicron surges, when awareness was higher. The low initial uptake among those under age 5, however, was not unexpected by the Biden administration. “That number in and of itself is very much in line with our expectation, and we’re eager to continue working closely with partners to build on this start,” a senior administration official told ABC News.

With approval of the vaccine occurring after the school year was over, parents’ thoughts have been focused more on vacations and less on vaccinations. “Even before these vaccines officially became available, this was going to be a different rollout; it was going to take more time,” the official explained.

Incidence measures continue on different paths

New COVID-19 cases dropped during the latest reporting week (July 1-7), returning to the downward trend that began in late May and then stopped for 1 week (June 24-30), when cases were up by 12.4%, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Children also represent a smaller share of cases, probably because of underreporting. “There has been a notable decline in the portion of reported weekly COVID-19 cases that are children,” the two groups said in their weekly COVID report. Although “cases are likely increasingly underreported for all age groups, this decline indicates that children are disproportionately undercounted in reported COVID-19 cases.”

Other measures, however, have been rising slowly but steadily since the spring. New admissions of patients aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID, which were down to 0.13 per 100,000 population in early April, had climbed to 0.39 per 100,000 by July 7, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Emergency department visits continue to show the same upward trend, despite a small decline in early June. A COVID diagnosis was involved in just 0.5% of ED visits in children aged 0-11 years on March 26, but by July 6 the rate was 4.7%. Increases were not as high among older children: From 0.3% on March 26 to 2.5% on July 6 for those aged 12-15 and from 0.3% to 2.4% for 16- and 17-year-olds, according to the CDC.

The COVID-19 vaccination effort in the youngest children has begun much more slowly than the most recent rollout for older children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

in early November of 2021, based on CDC data last updated on July 7.

That approval, of course, came between the Delta and Omicron surges, when awareness was higher. The low initial uptake among those under age 5, however, was not unexpected by the Biden administration. “That number in and of itself is very much in line with our expectation, and we’re eager to continue working closely with partners to build on this start,” a senior administration official told ABC News.

With approval of the vaccine occurring after the school year was over, parents’ thoughts have been focused more on vacations and less on vaccinations. “Even before these vaccines officially became available, this was going to be a different rollout; it was going to take more time,” the official explained.

Incidence measures continue on different paths

New COVID-19 cases dropped during the latest reporting week (July 1-7), returning to the downward trend that began in late May and then stopped for 1 week (June 24-30), when cases were up by 12.4%, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Children also represent a smaller share of cases, probably because of underreporting. “There has been a notable decline in the portion of reported weekly COVID-19 cases that are children,” the two groups said in their weekly COVID report. Although “cases are likely increasingly underreported for all age groups, this decline indicates that children are disproportionately undercounted in reported COVID-19 cases.”

Other measures, however, have been rising slowly but steadily since the spring. New admissions of patients aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID, which were down to 0.13 per 100,000 population in early April, had climbed to 0.39 per 100,000 by July 7, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Emergency department visits continue to show the same upward trend, despite a small decline in early June. A COVID diagnosis was involved in just 0.5% of ED visits in children aged 0-11 years on March 26, but by July 6 the rate was 4.7%. Increases were not as high among older children: From 0.3% on March 26 to 2.5% on July 6 for those aged 12-15 and from 0.3% to 2.4% for 16- and 17-year-olds, according to the CDC.

The COVID-19 vaccination effort in the youngest children has begun much more slowly than the most recent rollout for older children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

in early November of 2021, based on CDC data last updated on July 7.

That approval, of course, came between the Delta and Omicron surges, when awareness was higher. The low initial uptake among those under age 5, however, was not unexpected by the Biden administration. “That number in and of itself is very much in line with our expectation, and we’re eager to continue working closely with partners to build on this start,” a senior administration official told ABC News.

With approval of the vaccine occurring after the school year was over, parents’ thoughts have been focused more on vacations and less on vaccinations. “Even before these vaccines officially became available, this was going to be a different rollout; it was going to take more time,” the official explained.

Incidence measures continue on different paths

New COVID-19 cases dropped during the latest reporting week (July 1-7), returning to the downward trend that began in late May and then stopped for 1 week (June 24-30), when cases were up by 12.4%, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

Children also represent a smaller share of cases, probably because of underreporting. “There has been a notable decline in the portion of reported weekly COVID-19 cases that are children,” the two groups said in their weekly COVID report. Although “cases are likely increasingly underreported for all age groups, this decline indicates that children are disproportionately undercounted in reported COVID-19 cases.”

Other measures, however, have been rising slowly but steadily since the spring. New admissions of patients aged 0-17 years with confirmed COVID, which were down to 0.13 per 100,000 population in early April, had climbed to 0.39 per 100,000 by July 7, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Emergency department visits continue to show the same upward trend, despite a small decline in early June. A COVID diagnosis was involved in just 0.5% of ED visits in children aged 0-11 years on March 26, but by July 6 the rate was 4.7%. Increases were not as high among older children: From 0.3% on March 26 to 2.5% on July 6 for those aged 12-15 and from 0.3% to 2.4% for 16- and 17-year-olds, according to the CDC.

BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants are more evasive of antibodies, but not of cellular immunity

The picture around the BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants of Omicron has been really confusing in that the pair is driving up cases but global COVID-19 deaths remain at their lowest level since the beginning of the pandemic. Explaining the two components of the immune response – antibodies versus cellular immune responses – can help us understand where we are in the pandemic and future booster options.

These two subvariants of Omicron, as of July 5, make up more than half of the COVID-19 strains in the United States and are expected to keep increasing. One of two reasons can lead to a variant or subvariant becoming dominant strain: increased transmissibility or evasion of antibodies.

Although BA.4 and BA.5 could be more transmissible than other subvariants of Omicron (which is already very transmissible), this has not yet been established in experiments showing increased affinity for the human receptor or in animal models. What we do know is that BA.4 and BA.5 seem to evade neutralizing antibodies conferred by the vaccines or even prior BA.1 infection (an earlier subvariant of Omicron), which could be the reason we are seeing so many reinfections now. Of note, BA.1 infection conferred antibodies that protected against subsequent BA.2 infection, so we did not see the same spike in cases in the United States with BA.2 (after a large BA.1 spike over the winter) earlier this spring.

Okay, so isn’t evasion of antibodies a bad thing? Of course it is but, luckily, our immune system is “redundant” and doesn›t just rely on antibodies to protect us from infection. In fact, antibodies (such as IgA, which is the mucosal antibody most prevalent in the nose and mouth, and IgG, which is the most prevalent antibody in the bloodstream) are our first line of COVID-19 defense in the nasal mucosa. Therefore, mild upper respiratory infections will be common as BA.4/BA.5 evade our nasal antibodies. Luckily, the rate of severe disease is remaining low throughout the world, probably because of the high amounts of cellular immunity to the virus. B and T cells are our protectors from severe disease.

For instance, two-dose vaccines are still conferring high rates of protection from severe disease with the BA.4 and BA.5 variants, with 87% protection against hospitalization per South Africa data. This is probably attributable to the fact that T-cell immunity from the vaccines remains protective across variants “from Alpha to Omicron,” as described by a recent and elegant paper.

Data from Qatar show that natural infection (even occurring up to 14 months ago) remains very protective (97.3%) against severe disease with the current circulating subvariants, including BA.4 and BA.5. Again, this is probably attributable to T cells which specifically amplify in response to a piece of the virus and help recruit cells to attack the pathogen directly.

The original BA.1 subvariant of Omicron has 26-32 mutations along its spike protein that differ from the “ancestral strain,” and BA.4 and BA.5 variants have a few more. Our T-cell response, even across a mutated spike protein, is so robust that we have not seen Omicron yet able to evade the many T cells (which we produce from the vaccines or infection) that descend upon the mutated virus to fight severe disease. Antibody-producing memory B cells, generated by the vaccines (or prior infection), have been shown to actually adapt their immune response to the variant to which they are exposed.

Therefore, the story of the BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants seems to remain about antibodies vs. cellular immunity. Our immunity in the United States is growing and is from both vaccination and natural infection, with 78.3% of the population having had at least one dose of the vaccine and at least 60% of adults (and 75% of children 0-18) having been exposed to the virus by February 2022, per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (with exposure probably much higher now in July 2022 after subsequent Omicron subvariants waves).

So, what about Omicron-specific boosters? A booster shot will just raise antibodies temporarily, but their effectiveness wanes several months later. Moreover, a booster shot against the ancestral strain is not very effective in neutralizing BA.4 and BA.5 (with a prior BA.1 Omicron infection being more effective than a booster). Luckily, Pfizer has promised a BA.4/BA.5-specific mRNA vaccine by October, and Moderna has promised a bivalent vaccine containing BA.4/BA.5 mRNA sequences around the same time. A vaccine that specifically increases antibodies against the most prevalent circulating strain should be important as a booster for those who are predisposed to severe breakthrough infections (for example, those with immunocompromise or older individuals with multiple comorbidities). Moreover, BA.4/BA.5–specific booster vaccines may help prevent mild infections for many individuals. Finally, any booster (or exposure) should diversify and broaden T-cell responses to the virus, and a booster shot will also expand the potency of B cells, making them better able to respond to the newest subvariants as we continue to live with COVID-19.

Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, is an infectious diseases doctor, professor of medicine, and associate chief in the division of HIV, infectious diseases, and global medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The picture around the BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants of Omicron has been really confusing in that the pair is driving up cases but global COVID-19 deaths remain at their lowest level since the beginning of the pandemic. Explaining the two components of the immune response – antibodies versus cellular immune responses – can help us understand where we are in the pandemic and future booster options.

These two subvariants of Omicron, as of July 5, make up more than half of the COVID-19 strains in the United States and are expected to keep increasing. One of two reasons can lead to a variant or subvariant becoming dominant strain: increased transmissibility or evasion of antibodies.

Although BA.4 and BA.5 could be more transmissible than other subvariants of Omicron (which is already very transmissible), this has not yet been established in experiments showing increased affinity for the human receptor or in animal models. What we do know is that BA.4 and BA.5 seem to evade neutralizing antibodies conferred by the vaccines or even prior BA.1 infection (an earlier subvariant of Omicron), which could be the reason we are seeing so many reinfections now. Of note, BA.1 infection conferred antibodies that protected against subsequent BA.2 infection, so we did not see the same spike in cases in the United States with BA.2 (after a large BA.1 spike over the winter) earlier this spring.

Okay, so isn’t evasion of antibodies a bad thing? Of course it is but, luckily, our immune system is “redundant” and doesn›t just rely on antibodies to protect us from infection. In fact, antibodies (such as IgA, which is the mucosal antibody most prevalent in the nose and mouth, and IgG, which is the most prevalent antibody in the bloodstream) are our first line of COVID-19 defense in the nasal mucosa. Therefore, mild upper respiratory infections will be common as BA.4/BA.5 evade our nasal antibodies. Luckily, the rate of severe disease is remaining low throughout the world, probably because of the high amounts of cellular immunity to the virus. B and T cells are our protectors from severe disease.

For instance, two-dose vaccines are still conferring high rates of protection from severe disease with the BA.4 and BA.5 variants, with 87% protection against hospitalization per South Africa data. This is probably attributable to the fact that T-cell immunity from the vaccines remains protective across variants “from Alpha to Omicron,” as described by a recent and elegant paper.

Data from Qatar show that natural infection (even occurring up to 14 months ago) remains very protective (97.3%) against severe disease with the current circulating subvariants, including BA.4 and BA.5. Again, this is probably attributable to T cells which specifically amplify in response to a piece of the virus and help recruit cells to attack the pathogen directly.

The original BA.1 subvariant of Omicron has 26-32 mutations along its spike protein that differ from the “ancestral strain,” and BA.4 and BA.5 variants have a few more. Our T-cell response, even across a mutated spike protein, is so robust that we have not seen Omicron yet able to evade the many T cells (which we produce from the vaccines or infection) that descend upon the mutated virus to fight severe disease. Antibody-producing memory B cells, generated by the vaccines (or prior infection), have been shown to actually adapt their immune response to the variant to which they are exposed.

Therefore, the story of the BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants seems to remain about antibodies vs. cellular immunity. Our immunity in the United States is growing and is from both vaccination and natural infection, with 78.3% of the population having had at least one dose of the vaccine and at least 60% of adults (and 75% of children 0-18) having been exposed to the virus by February 2022, per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (with exposure probably much higher now in July 2022 after subsequent Omicron subvariants waves).

So, what about Omicron-specific boosters? A booster shot will just raise antibodies temporarily, but their effectiveness wanes several months later. Moreover, a booster shot against the ancestral strain is not very effective in neutralizing BA.4 and BA.5 (with a prior BA.1 Omicron infection being more effective than a booster). Luckily, Pfizer has promised a BA.4/BA.5-specific mRNA vaccine by October, and Moderna has promised a bivalent vaccine containing BA.4/BA.5 mRNA sequences around the same time. A vaccine that specifically increases antibodies against the most prevalent circulating strain should be important as a booster for those who are predisposed to severe breakthrough infections (for example, those with immunocompromise or older individuals with multiple comorbidities). Moreover, BA.4/BA.5–specific booster vaccines may help prevent mild infections for many individuals. Finally, any booster (or exposure) should diversify and broaden T-cell responses to the virus, and a booster shot will also expand the potency of B cells, making them better able to respond to the newest subvariants as we continue to live with COVID-19.

Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, is an infectious diseases doctor, professor of medicine, and associate chief in the division of HIV, infectious diseases, and global medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The picture around the BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants of Omicron has been really confusing in that the pair is driving up cases but global COVID-19 deaths remain at their lowest level since the beginning of the pandemic. Explaining the two components of the immune response – antibodies versus cellular immune responses – can help us understand where we are in the pandemic and future booster options.

These two subvariants of Omicron, as of July 5, make up more than half of the COVID-19 strains in the United States and are expected to keep increasing. One of two reasons can lead to a variant or subvariant becoming dominant strain: increased transmissibility or evasion of antibodies.

Although BA.4 and BA.5 could be more transmissible than other subvariants of Omicron (which is already very transmissible), this has not yet been established in experiments showing increased affinity for the human receptor or in animal models. What we do know is that BA.4 and BA.5 seem to evade neutralizing antibodies conferred by the vaccines or even prior BA.1 infection (an earlier subvariant of Omicron), which could be the reason we are seeing so many reinfections now. Of note, BA.1 infection conferred antibodies that protected against subsequent BA.2 infection, so we did not see the same spike in cases in the United States with BA.2 (after a large BA.1 spike over the winter) earlier this spring.

Okay, so isn’t evasion of antibodies a bad thing? Of course it is but, luckily, our immune system is “redundant” and doesn›t just rely on antibodies to protect us from infection. In fact, antibodies (such as IgA, which is the mucosal antibody most prevalent in the nose and mouth, and IgG, which is the most prevalent antibody in the bloodstream) are our first line of COVID-19 defense in the nasal mucosa. Therefore, mild upper respiratory infections will be common as BA.4/BA.5 evade our nasal antibodies. Luckily, the rate of severe disease is remaining low throughout the world, probably because of the high amounts of cellular immunity to the virus. B and T cells are our protectors from severe disease.

For instance, two-dose vaccines are still conferring high rates of protection from severe disease with the BA.4 and BA.5 variants, with 87% protection against hospitalization per South Africa data. This is probably attributable to the fact that T-cell immunity from the vaccines remains protective across variants “from Alpha to Omicron,” as described by a recent and elegant paper.

Data from Qatar show that natural infection (even occurring up to 14 months ago) remains very protective (97.3%) against severe disease with the current circulating subvariants, including BA.4 and BA.5. Again, this is probably attributable to T cells which specifically amplify in response to a piece of the virus and help recruit cells to attack the pathogen directly.

The original BA.1 subvariant of Omicron has 26-32 mutations along its spike protein that differ from the “ancestral strain,” and BA.4 and BA.5 variants have a few more. Our T-cell response, even across a mutated spike protein, is so robust that we have not seen Omicron yet able to evade the many T cells (which we produce from the vaccines or infection) that descend upon the mutated virus to fight severe disease. Antibody-producing memory B cells, generated by the vaccines (or prior infection), have been shown to actually adapt their immune response to the variant to which they are exposed.

Therefore, the story of the BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants seems to remain about antibodies vs. cellular immunity. Our immunity in the United States is growing and is from both vaccination and natural infection, with 78.3% of the population having had at least one dose of the vaccine and at least 60% of adults (and 75% of children 0-18) having been exposed to the virus by February 2022, per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (with exposure probably much higher now in July 2022 after subsequent Omicron subvariants waves).

So, what about Omicron-specific boosters? A booster shot will just raise antibodies temporarily, but their effectiveness wanes several months later. Moreover, a booster shot against the ancestral strain is not very effective in neutralizing BA.4 and BA.5 (with a prior BA.1 Omicron infection being more effective than a booster). Luckily, Pfizer has promised a BA.4/BA.5-specific mRNA vaccine by October, and Moderna has promised a bivalent vaccine containing BA.4/BA.5 mRNA sequences around the same time. A vaccine that specifically increases antibodies against the most prevalent circulating strain should be important as a booster for those who are predisposed to severe breakthrough infections (for example, those with immunocompromise or older individuals with multiple comorbidities). Moreover, BA.4/BA.5–specific booster vaccines may help prevent mild infections for many individuals. Finally, any booster (or exposure) should diversify and broaden T-cell responses to the virus, and a booster shot will also expand the potency of B cells, making them better able to respond to the newest subvariants as we continue to live with COVID-19.

Monica Gandhi, MD, MPH, is an infectious diseases doctor, professor of medicine, and associate chief in the division of HIV, infectious diseases, and global medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Obesity links to faster fading of COVID vaccine protection

Researchers published the study covered in this summary on medRxiv.org as a preprint that has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaways

- The study results suggest that

- The findings documented evidence of reduced neutralizing antibody capacity 6 months after primary vaccination in people with severe obesity.

- This was a large study involving about more than 3.5 million people who had received at least two doses of COVID-19 vaccine, including more than 650,000 with obesity.

Why this matters

- Obesity is associated with comorbidities that independently increase the risk for severe COVID-19, including type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure.

- The authors concluded that additional or more frequent booster doses are likely to be required to maintain protection among people with obesity against COVID-19.

Study design

- Prospective longitudinal study of the incidence and severity of COVID-19 infections and immune responses in a cohort of more than 3.5 million adults from a Scottish healthcare database who received two or three doses of COVID-19 vaccine. The data came from the study, centered at the University of Edinburgh.

- About 16% had obesity with a body mass index of 30-39.9 kg/m2, and an additional 3% had severe obesity with a BMI of 40 or greater.

- Although not specified in this preprint, another said that the vaccines administered in Scotland have been the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca formulations.

Key results

- Between Sept. 14, 2020, and March 19, 2022, 10,983 people (0.3% of the total cohort; 6.0 events per 1,000 person-years) had severe COVID-19, consisting of 9,733 who were hospitalized and 2,207 who died (957 of those hospitalized also died).

- People with obesity or severe obesity were at higher risk of hospitalization or death from COVID-19 after both a second and third (booster) dose of vaccine.

- Compared with those with normal weight, those with severe obesity (BMI higher than 40) were at significantly increased risk for severe COVID-19 after a second vaccine dose, with an adjusted rate ratio 1.76, whereas those with standard obesity (BMI, 30-40) were at a modestly but significantly increased risk with an adjusted rate ratio of 1.11.

- Breakthrough infections after the second dose for those with severe obesity, obesity, and normal weight occurred on average at 10 weeks, 15 weeks, and 20 weeks, respectively.

- Interaction testing showed that vaccine effectiveness significantly diminished over time across BMI groups, and protection waned more rapidly as BMI increased.

- Results from immunophenotyping studies run in a subgroup of several dozen subjects with severe obesity or normal weight showed significant decrements in the robustness of antibody responses in those with severe obesity 6 months after a second or third vaccine dose.

Limitations

- The authors did not specify any limitations.

Disclosures

- The study received no commercial funding.

- One author received funding from Wellcome.

This is a summary of a preprint research study , “Accelerated waning of the humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in obesity,” published by researchers primarily at the University of Cambridge (England), on medRxiv. This study has not yet been peer reviewed. The full text of the study can be found on medRxiv.org.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers published the study covered in this summary on medRxiv.org as a preprint that has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaways

- The study results suggest that

- The findings documented evidence of reduced neutralizing antibody capacity 6 months after primary vaccination in people with severe obesity.

- This was a large study involving about more than 3.5 million people who had received at least two doses of COVID-19 vaccine, including more than 650,000 with obesity.

Why this matters

- Obesity is associated with comorbidities that independently increase the risk for severe COVID-19, including type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure.

- The authors concluded that additional or more frequent booster doses are likely to be required to maintain protection among people with obesity against COVID-19.

Study design

- Prospective longitudinal study of the incidence and severity of COVID-19 infections and immune responses in a cohort of more than 3.5 million adults from a Scottish healthcare database who received two or three doses of COVID-19 vaccine. The data came from the study, centered at the University of Edinburgh.

- About 16% had obesity with a body mass index of 30-39.9 kg/m2, and an additional 3% had severe obesity with a BMI of 40 or greater.

- Although not specified in this preprint, another said that the vaccines administered in Scotland have been the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca formulations.

Key results

- Between Sept. 14, 2020, and March 19, 2022, 10,983 people (0.3% of the total cohort; 6.0 events per 1,000 person-years) had severe COVID-19, consisting of 9,733 who were hospitalized and 2,207 who died (957 of those hospitalized also died).

- People with obesity or severe obesity were at higher risk of hospitalization or death from COVID-19 after both a second and third (booster) dose of vaccine.

- Compared with those with normal weight, those with severe obesity (BMI higher than 40) were at significantly increased risk for severe COVID-19 after a second vaccine dose, with an adjusted rate ratio 1.76, whereas those with standard obesity (BMI, 30-40) were at a modestly but significantly increased risk with an adjusted rate ratio of 1.11.

- Breakthrough infections after the second dose for those with severe obesity, obesity, and normal weight occurred on average at 10 weeks, 15 weeks, and 20 weeks, respectively.

- Interaction testing showed that vaccine effectiveness significantly diminished over time across BMI groups, and protection waned more rapidly as BMI increased.

- Results from immunophenotyping studies run in a subgroup of several dozen subjects with severe obesity or normal weight showed significant decrements in the robustness of antibody responses in those with severe obesity 6 months after a second or third vaccine dose.

Limitations

- The authors did not specify any limitations.

Disclosures

- The study received no commercial funding.

- One author received funding from Wellcome.

This is a summary of a preprint research study , “Accelerated waning of the humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in obesity,” published by researchers primarily at the University of Cambridge (England), on medRxiv. This study has not yet been peer reviewed. The full text of the study can be found on medRxiv.org.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers published the study covered in this summary on medRxiv.org as a preprint that has not yet been peer reviewed.

Key takeaways

- The study results suggest that

- The findings documented evidence of reduced neutralizing antibody capacity 6 months after primary vaccination in people with severe obesity.

- This was a large study involving about more than 3.5 million people who had received at least two doses of COVID-19 vaccine, including more than 650,000 with obesity.

Why this matters

- Obesity is associated with comorbidities that independently increase the risk for severe COVID-19, including type 2 diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and heart failure.

- The authors concluded that additional or more frequent booster doses are likely to be required to maintain protection among people with obesity against COVID-19.

Study design

- Prospective longitudinal study of the incidence and severity of COVID-19 infections and immune responses in a cohort of more than 3.5 million adults from a Scottish healthcare database who received two or three doses of COVID-19 vaccine. The data came from the study, centered at the University of Edinburgh.

- About 16% had obesity with a body mass index of 30-39.9 kg/m2, and an additional 3% had severe obesity with a BMI of 40 or greater.

- Although not specified in this preprint, another said that the vaccines administered in Scotland have been the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca formulations.

Key results

- Between Sept. 14, 2020, and March 19, 2022, 10,983 people (0.3% of the total cohort; 6.0 events per 1,000 person-years) had severe COVID-19, consisting of 9,733 who were hospitalized and 2,207 who died (957 of those hospitalized also died).

- People with obesity or severe obesity were at higher risk of hospitalization or death from COVID-19 after both a second and third (booster) dose of vaccine.

- Compared with those with normal weight, those with severe obesity (BMI higher than 40) were at significantly increased risk for severe COVID-19 after a second vaccine dose, with an adjusted rate ratio 1.76, whereas those with standard obesity (BMI, 30-40) were at a modestly but significantly increased risk with an adjusted rate ratio of 1.11.

- Breakthrough infections after the second dose for those with severe obesity, obesity, and normal weight occurred on average at 10 weeks, 15 weeks, and 20 weeks, respectively.

- Interaction testing showed that vaccine effectiveness significantly diminished over time across BMI groups, and protection waned more rapidly as BMI increased.

- Results from immunophenotyping studies run in a subgroup of several dozen subjects with severe obesity or normal weight showed significant decrements in the robustness of antibody responses in those with severe obesity 6 months after a second or third vaccine dose.

Limitations

- The authors did not specify any limitations.

Disclosures

- The study received no commercial funding.

- One author received funding from Wellcome.

This is a summary of a preprint research study , “Accelerated waning of the humoral response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in obesity,” published by researchers primarily at the University of Cambridge (England), on medRxiv. This study has not yet been peer reviewed. The full text of the study can be found on medRxiv.org.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Long COVID-19 in children and adolescents: What do we know?

Among scientists, the existence of long COVID-19 in children and adolescents has been the subject of debate.

Published by a Mexican multidisciplinary group in Scientific Reports, the first study is a systematic review and meta-analysis. It identified mood symptoms as the most prevalent clinical manifestations of long COVID-19 in children and adolescents. These symptoms included sadness, tension, anger, depression, and anxiety (16.50%); fatigue (9.66%); and sleep disorders (8.42%).

The second study, LongCOVIDKidsDK, was conducted in Denmark. It compared 11,000 children younger than 14 years who had tested positive for COVID-19 with 33,000 children who had no history of COVID-19. The study was published in The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health.

Definitions are changing

In their meta-analysis, the researchers estimated the prevalence and counted signs and symptoms of long COVID-19, as defined by the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Long COVID-19 was defined as the presence of one or more symptoms more than 4 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection. For search terms, the researchers used “COVID-19,” “COVID,” “SARSCOV-2,” “coronavirus,” “long COVID,” “postCOVID,” “PASC,” “long-haulers,” “prolonged,” “post-acute,” “persistent,” “convalescent,” “sequelae,” and “postviral.”

Of the 8,373 citations returned by the search as of Feb. 10, 2022, 21 prospective studies, 2 of them on preprint servers, met the authors’ selection criteria. Those studies included a total of 80,071 children and adolescents younger than 18 years.

In the meta-analysis, the prevalence of long COVID-19 among children and adolescents was reported to be 25.24% (95% confidence interval, 18.17-33.02; I2, 99.61%), regardless of whether the case had been asymptomatic, mild, moderate, severe, or serious. For patients who had been hospitalized, the prevalence was 29.19% (95% CI, 17.83-41.98; I2, 80.84%).

These numbers, while striking, are not the focus of the study, according to first author Sandra Lopez-Leon, MD, PhD, associate professor of pharmacoepidemiology at Rutgers University, New Brunswick, N.J. “It’s important that we don’t focus on that 25%,” she said in an interview. “It’s a disease that we’re learning about, we’re at a time when the definitions are still changing, and, depending on when it is measured, a different number will be given. The message we want to give is that long COVID-19 exists, it’s happening in children and adolescents, and patients need this recognition. And also to show that it can affect the whole body.”

The study showed that the children and adolescents who presented with SARS-CoV-2 infection were at higher risk of subsequent long dyspnea, anosmia/ageusia, or fever, compared with control persons.

In total, in the studies that were included, more than 40 long-term clinical manifestations associated with COVID-19 in the pediatric population were identified.

The most common symptoms among children aged 0-3 years were mood swings, skin rashes, and stomachaches. In 4- to 11-year-olds, the most common symptoms were mood swings, trouble remembering or concentrating, and skin rashes. In 12- to 14-year-olds, they were fatigue, mood swings, and trouble remembering or concentrating. These data are based on parent responses.

The list of signs and symptoms also includes headache, respiratory symptoms, cognitive symptoms (such as decreased concentration, learning difficulties, confusion, and memory loss), loss of appetite, and smell disorder (hyposmia, anosmia, hyperosmia, parosmia, and phantom smell).

In the studies, the prevalence of the following symptoms was less than 5%: hyperhidrosis, chest pain, dizziness, cough, myalgia/arthralgia, changes in body weight, taste disorder, otalgia (tinnitus, ear pain, vertigo), ophthalmologic symptoms (conjunctivitis, dry eye, blurred vision, photophobia, pain), dermatologic symptoms (dry skin, itchy skin, rashes, hives, hair loss), urinary symptoms, abdominal pain, throat pain, chest tightness, variations in heart rate, palpitations, constipation, dysphonia, fever, diarrhea, vomiting/nausea, menstrual changes, neurological abnormalities, speech disorders, and dysphagia.

The authors made it clear that the frequency and severity of these symptoms can fluctuate from one patient to another.