User login

CDC issues new return-to-work guidelines

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is releasing new guidance on return-to-work rules for critical workers exposed to a COVID-19 case, or a suspected case, replacing previous guidance to stay home for 14 days.

“One of the most important things we can do is keep our critical workforce working,” CDC Director Robert Redfield said at a White House briefing on April 8. “In certain circumstances they can go back to work,” he said.

Neither Redfield nor the other governmental officials specified what counts as an essential worker, although it has generally referred to food-service and health care workers.

They must take their temperature before work, wear a facial mask at all times and practice social distancing when at work, the new guidance says. They cannot share headsets or other objects used near the face.

Employers must take the worker’s temperature and assess each one for symptoms before work starts, sending a worker home if he or she is sick. Employers must increase the cleaning of frequently used surfaces, increase air exchange in the building and test the use of face masks to be sure they do not interfere with workflow.

Pressed on whether he would reopen the country at the end of the 30-day Stop the Spread effort on April 30 — since one model has revised the U.S. death toll down from 100,000-240,000 to 61,000 — President Donald Trump said meetings will take place soon to discuss the decision and that he will ‘’rely very heavily” on health experts.

“We know now for sure that the mitigation we have been doing is having a positive effect,” said Anthony Fauci, MD, a coronavirus task force member and director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

This article first appeared on WebMD.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is releasing new guidance on return-to-work rules for critical workers exposed to a COVID-19 case, or a suspected case, replacing previous guidance to stay home for 14 days.

“One of the most important things we can do is keep our critical workforce working,” CDC Director Robert Redfield said at a White House briefing on April 8. “In certain circumstances they can go back to work,” he said.

Neither Redfield nor the other governmental officials specified what counts as an essential worker, although it has generally referred to food-service and health care workers.

They must take their temperature before work, wear a facial mask at all times and practice social distancing when at work, the new guidance says. They cannot share headsets or other objects used near the face.

Employers must take the worker’s temperature and assess each one for symptoms before work starts, sending a worker home if he or she is sick. Employers must increase the cleaning of frequently used surfaces, increase air exchange in the building and test the use of face masks to be sure they do not interfere with workflow.

Pressed on whether he would reopen the country at the end of the 30-day Stop the Spread effort on April 30 — since one model has revised the U.S. death toll down from 100,000-240,000 to 61,000 — President Donald Trump said meetings will take place soon to discuss the decision and that he will ‘’rely very heavily” on health experts.

“We know now for sure that the mitigation we have been doing is having a positive effect,” said Anthony Fauci, MD, a coronavirus task force member and director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

This article first appeared on WebMD.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is releasing new guidance on return-to-work rules for critical workers exposed to a COVID-19 case, or a suspected case, replacing previous guidance to stay home for 14 days.

“One of the most important things we can do is keep our critical workforce working,” CDC Director Robert Redfield said at a White House briefing on April 8. “In certain circumstances they can go back to work,” he said.

Neither Redfield nor the other governmental officials specified what counts as an essential worker, although it has generally referred to food-service and health care workers.

They must take their temperature before work, wear a facial mask at all times and practice social distancing when at work, the new guidance says. They cannot share headsets or other objects used near the face.

Employers must take the worker’s temperature and assess each one for symptoms before work starts, sending a worker home if he or she is sick. Employers must increase the cleaning of frequently used surfaces, increase air exchange in the building and test the use of face masks to be sure they do not interfere with workflow.

Pressed on whether he would reopen the country at the end of the 30-day Stop the Spread effort on April 30 — since one model has revised the U.S. death toll down from 100,000-240,000 to 61,000 — President Donald Trump said meetings will take place soon to discuss the decision and that he will ‘’rely very heavily” on health experts.

“We know now for sure that the mitigation we have been doing is having a positive effect,” said Anthony Fauci, MD, a coronavirus task force member and director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

This article first appeared on WebMD.

The 7 strategies of highly effective people facing the COVID-19 pandemic

A few weeks ago, I saw more than 60 responses to a post on Nextdoor.com entitled, “Toilet paper strategies?”

Asking for help is a great coping mechanism when one is struggling to find a strategy, even if it’s for toilet paper. What other kinds of coping strategies can help us through this historic and unprecedented time?

The late Stephen R. Covey, PhD, wrote about the coping strategies of highly effective people in his book, “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.”1 For, no matter how smart, perfect, or careful you may be, life will never be trouble free. When trouble comes, it’s important to have coping strategies that help you navigate through choppy waters. Whether you are a practitioner trying to help your patients or someone who wants to maximize their personal resilience during a worldwide pandemic, here are my conceptualizations of the seven top strategies highly effective people use when facing challenges.

Strategy #1: Begin with the end in mind

In 2007, this strategy helped me not only survive but thrive when I battled for my right to practice as a holistic psychiatrist against the Maryland Board of Physicians.2 From the first moment when I read the letter from the board, to the last when I read the administrative law judge’s dismissal, I turned to this strategy to help me cope with unrelenting stress.

I imagined myself remembering being the kind of person I wanted to be, wrote that script for myself, and created those memories for my future self. I wanted to remember myself as being brave, calm, strong, and grounded, so I behaved each day as if I were all of those things.

As Dr. Covey wrote, “ ‘Begin with the end in mind’ is based on the principle that all things are created twice. There’s a mental or first creation, and a physical or second creation to all things.” Imagine who you would like to remember yourself being a year or two down the road. Do you want to remember yourself showing good judgment and being positive and compassionate during this pandemic? Then, follow the script you’ve created in your mind and be that person now, knowing that you are forming memories for your future self. Your future self will look back at who you are right now with appreciation and satisfaction. Of course, this is a habit that you can apply to your entire life.

Strategy #2: Be proactive

Between the event and the outcome is you. You are the interpreter and transformer of the event, with the freedom to apply your will and intention on the event. Whether it is living through a pandemic or dealing with misplaced keys, every day you are revealing your nature through how you deal with life. To be proactive is different from being reactive. Within each of us there is a will, the drive, to rise above our difficult environments.

Dr. Covey wrote, “the ability to subordinate an impulse to a value is the essence of the proactive person.” A woman shared with me that she created an Excel spreadsheet with some of the things she plans to do with her free time while she stays in her NYC apartment. She doesn’t want to slip into a passive state and waste her time. That’s being proactive.

Strategy #3: Set proper priorities

Or, as Dr. Covey would say, “Put first things first.” During a pandemic, when the world seems to be precariously tilting at an angle, it’s easy to cling to outdated standards, expectations, and behavioral patterns. Doing so heightens our sense of regret, fear, and scarcity. Valuing gratitude will empower you to deal with financial loss differently because you can still remain grateful despite uncontrollable losses. We can choose “to have or to be” as psychoanalyst, Erich Fromm, PhD, would say.3 If your happiness is measured by how much money you have, then it would make sense that, when the amount shrinks, so does your happiness. However, if your happiness is a side effect of who you are, you will remain a mountain before the winds and tides of circumstance.

Strategy #4: Create a win/win mentality

This state of mind is built on character. Dr. Covey separates character into three categories: integrity, maturity, and abundance mentality. A lack of character resulted in the hoarding of toilet paper in many communities and the cry for help from Nextdoor.com. I noticed that, in the 60+ responses that included advice about using bidets, old towels, and even leaves, no one offered to share a bag of toilet paper. That’s because people experienced the fear of scarcity, in turn, causing the scarcity they feared.

During a pandemic, a highly effective person or company thinks beyond themselves to create a win/win scenario. At a grocery store in my neighborhood, a man stands at its entrance with a bottle of disinfectant spray in one hand for the shoppers and a sign on the sidewalk with guidelines for purchasing products to avoid hoarding. He tells you where the wipes are for the carts as you enter the store. People line up 6 feet apart, waiting to enter, to limit the number of shoppers inside the store, facilitating proper physical distancing. Instead of maximizing profits at the expense of everyone’s health and safety, the process is a win/win for everyone, from shoppers to employees.

Strategy #5: Develop empathy and understanding

Seeking to first understand and then be understood is one of the most powerful tools of effective people. In my holistic practice, every patient comes in with their own unique needs that evolve and transform over time. I must remain open, or I fail to deliver appropriately.

Learning to listen and then to clearly communicate ideas is essential to effective health care. During this time, it is critical that health care providers and political leaders first listen/understand and then communicate clearly to serve everyone in the best way possible.

In our brains, the frontal lobes (the adult in the room) manages our amygdala (the child in the room) when we get enough sleep, meditate, spend time in nature, exercise, and eat healthy food.4 Stress can interfere with the frontal lobe’s ability to maintain empathy, inhibit unhealthy impulses, and delay gratification. During the pandemic, we can help to shift from the stress response, or “fight-or-flight” response, driven by the sympathetic nervous system to a “rest-and-digest” response driven by the parasympathetic system through coherent breathing, taking slow, deep, relaxed breaths (6 seconds on inhalation and 6 seconds on exhalation). The vagus nerve connected to our diaphragm will help the heart return to a healthy rhythm.5

Strategy #6: Synergize and integrate

All of life is interdependent, each part no more or less important than any other. Is oxygen more important than hydrogen? Is H2O different from the oxygen and hydrogen atoms that make it?

During a pandemic, it’s important for us to appreciate each other’s contributions and work synergistically for the good of the whole. Our survival depends on valuing each other and our planet. This perspective informs the practice of physical distancing and staying home to minimize the spread of the virus and its impact on the health care system, regardless of whether an individual belongs in the high-risk group or not.

Many high-achieving people train in extremely competitive settings in which survival depends on individual performance rather than mutual cooperation. This training process encourages a disregard for others. Good leaders, however, understand that cooperation and mutual respect are essential to personal well-being.

Strategy #7: Practice self-care

There are five aspects of our lives that depend on our self-care: spiritual, mental, emotional, physical, and social. Unfortunately, many kind-hearted people are kinder to others than to themselves. There is really only one person who can truly take care of you properly, and that is yourself. In Seattle, where many suffered early in the pandemic, holistic psychiatrist David Kopacz, MD, is reminding people to nurture themselves in his post, “Nurture Yourself During the Pandemic: Try New Recipes!”6 Indeed, that is what many must do since eating out is not an option now. If you find yourself stuck at home with more time on your hands, take the opportunity to care for yourself. Ask yourself what you really need during this time, and make the effort to provide it to yourself.

After the pandemic is over, will you have grown from the experiences and become a better person from it? Despite our current circumstances, we can continue to grow as individuals and as a community, armed with strategies that can benefit all of us.

References

1. Covey SR. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1989.

2. Lee AW. Townsend Letter. 2009 Jun;311:22-3.

3. Fromm E. To Have or To Be? New York: Continuum International Publishing; 2005.

4. Rushlau K. Integrative Healthcare Symposium. 2020 Feb 21.

5. Gerbarg PL. Mind Body Practices for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Presentation at Integrative Medicine for Mental Health Conference. 2016 Sep.

6. Kopacz D. Nurture Yourself During the Pandemic: Try New Recipes! Being Fully Human. 2020 Mar 22.

Dr. Lee specializes in integrative and holistic psychiatry and has a private practice in Gaithersburg, Md. She has no disclosures.

A few weeks ago, I saw more than 60 responses to a post on Nextdoor.com entitled, “Toilet paper strategies?”

Asking for help is a great coping mechanism when one is struggling to find a strategy, even if it’s for toilet paper. What other kinds of coping strategies can help us through this historic and unprecedented time?

The late Stephen R. Covey, PhD, wrote about the coping strategies of highly effective people in his book, “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.”1 For, no matter how smart, perfect, or careful you may be, life will never be trouble free. When trouble comes, it’s important to have coping strategies that help you navigate through choppy waters. Whether you are a practitioner trying to help your patients or someone who wants to maximize their personal resilience during a worldwide pandemic, here are my conceptualizations of the seven top strategies highly effective people use when facing challenges.

Strategy #1: Begin with the end in mind

In 2007, this strategy helped me not only survive but thrive when I battled for my right to practice as a holistic psychiatrist against the Maryland Board of Physicians.2 From the first moment when I read the letter from the board, to the last when I read the administrative law judge’s dismissal, I turned to this strategy to help me cope with unrelenting stress.

I imagined myself remembering being the kind of person I wanted to be, wrote that script for myself, and created those memories for my future self. I wanted to remember myself as being brave, calm, strong, and grounded, so I behaved each day as if I were all of those things.

As Dr. Covey wrote, “ ‘Begin with the end in mind’ is based on the principle that all things are created twice. There’s a mental or first creation, and a physical or second creation to all things.” Imagine who you would like to remember yourself being a year or two down the road. Do you want to remember yourself showing good judgment and being positive and compassionate during this pandemic? Then, follow the script you’ve created in your mind and be that person now, knowing that you are forming memories for your future self. Your future self will look back at who you are right now with appreciation and satisfaction. Of course, this is a habit that you can apply to your entire life.

Strategy #2: Be proactive

Between the event and the outcome is you. You are the interpreter and transformer of the event, with the freedom to apply your will and intention on the event. Whether it is living through a pandemic or dealing with misplaced keys, every day you are revealing your nature through how you deal with life. To be proactive is different from being reactive. Within each of us there is a will, the drive, to rise above our difficult environments.

Dr. Covey wrote, “the ability to subordinate an impulse to a value is the essence of the proactive person.” A woman shared with me that she created an Excel spreadsheet with some of the things she plans to do with her free time while she stays in her NYC apartment. She doesn’t want to slip into a passive state and waste her time. That’s being proactive.

Strategy #3: Set proper priorities

Or, as Dr. Covey would say, “Put first things first.” During a pandemic, when the world seems to be precariously tilting at an angle, it’s easy to cling to outdated standards, expectations, and behavioral patterns. Doing so heightens our sense of regret, fear, and scarcity. Valuing gratitude will empower you to deal with financial loss differently because you can still remain grateful despite uncontrollable losses. We can choose “to have or to be” as psychoanalyst, Erich Fromm, PhD, would say.3 If your happiness is measured by how much money you have, then it would make sense that, when the amount shrinks, so does your happiness. However, if your happiness is a side effect of who you are, you will remain a mountain before the winds and tides of circumstance.

Strategy #4: Create a win/win mentality

This state of mind is built on character. Dr. Covey separates character into three categories: integrity, maturity, and abundance mentality. A lack of character resulted in the hoarding of toilet paper in many communities and the cry for help from Nextdoor.com. I noticed that, in the 60+ responses that included advice about using bidets, old towels, and even leaves, no one offered to share a bag of toilet paper. That’s because people experienced the fear of scarcity, in turn, causing the scarcity they feared.

During a pandemic, a highly effective person or company thinks beyond themselves to create a win/win scenario. At a grocery store in my neighborhood, a man stands at its entrance with a bottle of disinfectant spray in one hand for the shoppers and a sign on the sidewalk with guidelines for purchasing products to avoid hoarding. He tells you where the wipes are for the carts as you enter the store. People line up 6 feet apart, waiting to enter, to limit the number of shoppers inside the store, facilitating proper physical distancing. Instead of maximizing profits at the expense of everyone’s health and safety, the process is a win/win for everyone, from shoppers to employees.

Strategy #5: Develop empathy and understanding

Seeking to first understand and then be understood is one of the most powerful tools of effective people. In my holistic practice, every patient comes in with their own unique needs that evolve and transform over time. I must remain open, or I fail to deliver appropriately.

Learning to listen and then to clearly communicate ideas is essential to effective health care. During this time, it is critical that health care providers and political leaders first listen/understand and then communicate clearly to serve everyone in the best way possible.

In our brains, the frontal lobes (the adult in the room) manages our amygdala (the child in the room) when we get enough sleep, meditate, spend time in nature, exercise, and eat healthy food.4 Stress can interfere with the frontal lobe’s ability to maintain empathy, inhibit unhealthy impulses, and delay gratification. During the pandemic, we can help to shift from the stress response, or “fight-or-flight” response, driven by the sympathetic nervous system to a “rest-and-digest” response driven by the parasympathetic system through coherent breathing, taking slow, deep, relaxed breaths (6 seconds on inhalation and 6 seconds on exhalation). The vagus nerve connected to our diaphragm will help the heart return to a healthy rhythm.5

Strategy #6: Synergize and integrate

All of life is interdependent, each part no more or less important than any other. Is oxygen more important than hydrogen? Is H2O different from the oxygen and hydrogen atoms that make it?

During a pandemic, it’s important for us to appreciate each other’s contributions and work synergistically for the good of the whole. Our survival depends on valuing each other and our planet. This perspective informs the practice of physical distancing and staying home to minimize the spread of the virus and its impact on the health care system, regardless of whether an individual belongs in the high-risk group or not.

Many high-achieving people train in extremely competitive settings in which survival depends on individual performance rather than mutual cooperation. This training process encourages a disregard for others. Good leaders, however, understand that cooperation and mutual respect are essential to personal well-being.

Strategy #7: Practice self-care

There are five aspects of our lives that depend on our self-care: spiritual, mental, emotional, physical, and social. Unfortunately, many kind-hearted people are kinder to others than to themselves. There is really only one person who can truly take care of you properly, and that is yourself. In Seattle, where many suffered early in the pandemic, holistic psychiatrist David Kopacz, MD, is reminding people to nurture themselves in his post, “Nurture Yourself During the Pandemic: Try New Recipes!”6 Indeed, that is what many must do since eating out is not an option now. If you find yourself stuck at home with more time on your hands, take the opportunity to care for yourself. Ask yourself what you really need during this time, and make the effort to provide it to yourself.

After the pandemic is over, will you have grown from the experiences and become a better person from it? Despite our current circumstances, we can continue to grow as individuals and as a community, armed with strategies that can benefit all of us.

References

1. Covey SR. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1989.

2. Lee AW. Townsend Letter. 2009 Jun;311:22-3.

3. Fromm E. To Have or To Be? New York: Continuum International Publishing; 2005.

4. Rushlau K. Integrative Healthcare Symposium. 2020 Feb 21.

5. Gerbarg PL. Mind Body Practices for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Presentation at Integrative Medicine for Mental Health Conference. 2016 Sep.

6. Kopacz D. Nurture Yourself During the Pandemic: Try New Recipes! Being Fully Human. 2020 Mar 22.

Dr. Lee specializes in integrative and holistic psychiatry and has a private practice in Gaithersburg, Md. She has no disclosures.

A few weeks ago, I saw more than 60 responses to a post on Nextdoor.com entitled, “Toilet paper strategies?”

Asking for help is a great coping mechanism when one is struggling to find a strategy, even if it’s for toilet paper. What other kinds of coping strategies can help us through this historic and unprecedented time?

The late Stephen R. Covey, PhD, wrote about the coping strategies of highly effective people in his book, “The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People.”1 For, no matter how smart, perfect, or careful you may be, life will never be trouble free. When trouble comes, it’s important to have coping strategies that help you navigate through choppy waters. Whether you are a practitioner trying to help your patients or someone who wants to maximize their personal resilience during a worldwide pandemic, here are my conceptualizations of the seven top strategies highly effective people use when facing challenges.

Strategy #1: Begin with the end in mind

In 2007, this strategy helped me not only survive but thrive when I battled for my right to practice as a holistic psychiatrist against the Maryland Board of Physicians.2 From the first moment when I read the letter from the board, to the last when I read the administrative law judge’s dismissal, I turned to this strategy to help me cope with unrelenting stress.

I imagined myself remembering being the kind of person I wanted to be, wrote that script for myself, and created those memories for my future self. I wanted to remember myself as being brave, calm, strong, and grounded, so I behaved each day as if I were all of those things.

As Dr. Covey wrote, “ ‘Begin with the end in mind’ is based on the principle that all things are created twice. There’s a mental or first creation, and a physical or second creation to all things.” Imagine who you would like to remember yourself being a year or two down the road. Do you want to remember yourself showing good judgment and being positive and compassionate during this pandemic? Then, follow the script you’ve created in your mind and be that person now, knowing that you are forming memories for your future self. Your future self will look back at who you are right now with appreciation and satisfaction. Of course, this is a habit that you can apply to your entire life.

Strategy #2: Be proactive

Between the event and the outcome is you. You are the interpreter and transformer of the event, with the freedom to apply your will and intention on the event. Whether it is living through a pandemic or dealing with misplaced keys, every day you are revealing your nature through how you deal with life. To be proactive is different from being reactive. Within each of us there is a will, the drive, to rise above our difficult environments.

Dr. Covey wrote, “the ability to subordinate an impulse to a value is the essence of the proactive person.” A woman shared with me that she created an Excel spreadsheet with some of the things she plans to do with her free time while she stays in her NYC apartment. She doesn’t want to slip into a passive state and waste her time. That’s being proactive.

Strategy #3: Set proper priorities

Or, as Dr. Covey would say, “Put first things first.” During a pandemic, when the world seems to be precariously tilting at an angle, it’s easy to cling to outdated standards, expectations, and behavioral patterns. Doing so heightens our sense of regret, fear, and scarcity. Valuing gratitude will empower you to deal with financial loss differently because you can still remain grateful despite uncontrollable losses. We can choose “to have or to be” as psychoanalyst, Erich Fromm, PhD, would say.3 If your happiness is measured by how much money you have, then it would make sense that, when the amount shrinks, so does your happiness. However, if your happiness is a side effect of who you are, you will remain a mountain before the winds and tides of circumstance.

Strategy #4: Create a win/win mentality

This state of mind is built on character. Dr. Covey separates character into three categories: integrity, maturity, and abundance mentality. A lack of character resulted in the hoarding of toilet paper in many communities and the cry for help from Nextdoor.com. I noticed that, in the 60+ responses that included advice about using bidets, old towels, and even leaves, no one offered to share a bag of toilet paper. That’s because people experienced the fear of scarcity, in turn, causing the scarcity they feared.

During a pandemic, a highly effective person or company thinks beyond themselves to create a win/win scenario. At a grocery store in my neighborhood, a man stands at its entrance with a bottle of disinfectant spray in one hand for the shoppers and a sign on the sidewalk with guidelines for purchasing products to avoid hoarding. He tells you where the wipes are for the carts as you enter the store. People line up 6 feet apart, waiting to enter, to limit the number of shoppers inside the store, facilitating proper physical distancing. Instead of maximizing profits at the expense of everyone’s health and safety, the process is a win/win for everyone, from shoppers to employees.

Strategy #5: Develop empathy and understanding

Seeking to first understand and then be understood is one of the most powerful tools of effective people. In my holistic practice, every patient comes in with their own unique needs that evolve and transform over time. I must remain open, or I fail to deliver appropriately.

Learning to listen and then to clearly communicate ideas is essential to effective health care. During this time, it is critical that health care providers and political leaders first listen/understand and then communicate clearly to serve everyone in the best way possible.

In our brains, the frontal lobes (the adult in the room) manages our amygdala (the child in the room) when we get enough sleep, meditate, spend time in nature, exercise, and eat healthy food.4 Stress can interfere with the frontal lobe’s ability to maintain empathy, inhibit unhealthy impulses, and delay gratification. During the pandemic, we can help to shift from the stress response, or “fight-or-flight” response, driven by the sympathetic nervous system to a “rest-and-digest” response driven by the parasympathetic system through coherent breathing, taking slow, deep, relaxed breaths (6 seconds on inhalation and 6 seconds on exhalation). The vagus nerve connected to our diaphragm will help the heart return to a healthy rhythm.5

Strategy #6: Synergize and integrate

All of life is interdependent, each part no more or less important than any other. Is oxygen more important than hydrogen? Is H2O different from the oxygen and hydrogen atoms that make it?

During a pandemic, it’s important for us to appreciate each other’s contributions and work synergistically for the good of the whole. Our survival depends on valuing each other and our planet. This perspective informs the practice of physical distancing and staying home to minimize the spread of the virus and its impact on the health care system, regardless of whether an individual belongs in the high-risk group or not.

Many high-achieving people train in extremely competitive settings in which survival depends on individual performance rather than mutual cooperation. This training process encourages a disregard for others. Good leaders, however, understand that cooperation and mutual respect are essential to personal well-being.

Strategy #7: Practice self-care

There are five aspects of our lives that depend on our self-care: spiritual, mental, emotional, physical, and social. Unfortunately, many kind-hearted people are kinder to others than to themselves. There is really only one person who can truly take care of you properly, and that is yourself. In Seattle, where many suffered early in the pandemic, holistic psychiatrist David Kopacz, MD, is reminding people to nurture themselves in his post, “Nurture Yourself During the Pandemic: Try New Recipes!”6 Indeed, that is what many must do since eating out is not an option now. If you find yourself stuck at home with more time on your hands, take the opportunity to care for yourself. Ask yourself what you really need during this time, and make the effort to provide it to yourself.

After the pandemic is over, will you have grown from the experiences and become a better person from it? Despite our current circumstances, we can continue to grow as individuals and as a community, armed with strategies that can benefit all of us.

References

1. Covey SR. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1989.

2. Lee AW. Townsend Letter. 2009 Jun;311:22-3.

3. Fromm E. To Have or To Be? New York: Continuum International Publishing; 2005.

4. Rushlau K. Integrative Healthcare Symposium. 2020 Feb 21.

5. Gerbarg PL. Mind Body Practices for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Presentation at Integrative Medicine for Mental Health Conference. 2016 Sep.

6. Kopacz D. Nurture Yourself During the Pandemic: Try New Recipes! Being Fully Human. 2020 Mar 22.

Dr. Lee specializes in integrative and holistic psychiatry and has a private practice in Gaithersburg, Md. She has no disclosures.

CDC: Screen nearly all adults, including pregnant women, for HCV

In the latest issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended hepatitis C virus screening for all adults and all pregnant women – during each of their pregnancies – in areas where prevalence of the infection is 0.1% or greater.

That’s essentially the entire United States; there’s no state with a statewide adult prevalence below 0.1%, and “few settings are known to exist” otherwise, the CDC noted (MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020 Apr 10;69(2):1-17).

The agency encouraged providers to consult state or local health departments or the CDC directly to determine local HCV prevalence. “As a general guide ... approximately 59% of anti-HCV positive persons are HCV RNA positive,” indicating active infection, the agency noted.

The advice was an expansion from the CDC’s last universal screening recommendation in 2012, which was limited to people born from 1945 to 1965; the incidence of acute infections has climbed since then and is highest now among younger people, so the guideline needed to be revisited, explained authors led by Sarah Schillie, MD, of the CDC’s Division of Viral Hepatitis, Atlanta.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force also recently recommended universal adult screening after previously limiting it to baby boomers.

As for pregnancy, the CDC’s past advice was to screen pregnant women with known risk factors, but that needed to be revisited as well. For one thing, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America have since recommended testing all pregnant women.

But also, the CDC said, it’s an opportune time for screening because “many women only have access to health care during pregnancy and the immediate postpartum period,” when treatment, if needed, can be started. Plus, HCV status is important for management decisions, such as using amniocentesis in positive women instead of chorionic villus sampling.

The rest of CDC’s 2012 recommendations stand, including screening all people with risk factors and repeating screening while they persist. Also, “any person who requests hepatitis C testing should receive it, regardless of disclosure of risk,” because people might be reluctant to report things like IV drug use, the authors said.

Screening in the guidelines means an HCV antibody test, followed by a nucleic acid test to check for active infection. The CDC encouraged automatic reflex testing, meaning immediately checking antibody positive samples for HCV RNA. RNA in the blood indicates active, replicating virus.

The new recommendations penciled out in modeling, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for universal adult screening of approximately $36,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained, and an ICER of approximately $15,000 per QALY gained for pregnancy screening, where HCV prevalence is 0.1%; the 0.1% cost/benefit cutpoint was one of the reasons it was chosen as the prevalence threshold. An ICER under $50,000 is the conservative benchmark for cost-effectiveness, the authors noted.

There was no external funding, and the authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Schillie S et al. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020 Apr 10;69[2]:1-17).

In the latest issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended hepatitis C virus screening for all adults and all pregnant women – during each of their pregnancies – in areas where prevalence of the infection is 0.1% or greater.

That’s essentially the entire United States; there’s no state with a statewide adult prevalence below 0.1%, and “few settings are known to exist” otherwise, the CDC noted (MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020 Apr 10;69(2):1-17).

The agency encouraged providers to consult state or local health departments or the CDC directly to determine local HCV prevalence. “As a general guide ... approximately 59% of anti-HCV positive persons are HCV RNA positive,” indicating active infection, the agency noted.

The advice was an expansion from the CDC’s last universal screening recommendation in 2012, which was limited to people born from 1945 to 1965; the incidence of acute infections has climbed since then and is highest now among younger people, so the guideline needed to be revisited, explained authors led by Sarah Schillie, MD, of the CDC’s Division of Viral Hepatitis, Atlanta.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force also recently recommended universal adult screening after previously limiting it to baby boomers.

As for pregnancy, the CDC’s past advice was to screen pregnant women with known risk factors, but that needed to be revisited as well. For one thing, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America have since recommended testing all pregnant women.

But also, the CDC said, it’s an opportune time for screening because “many women only have access to health care during pregnancy and the immediate postpartum period,” when treatment, if needed, can be started. Plus, HCV status is important for management decisions, such as using amniocentesis in positive women instead of chorionic villus sampling.

The rest of CDC’s 2012 recommendations stand, including screening all people with risk factors and repeating screening while they persist. Also, “any person who requests hepatitis C testing should receive it, regardless of disclosure of risk,” because people might be reluctant to report things like IV drug use, the authors said.

Screening in the guidelines means an HCV antibody test, followed by a nucleic acid test to check for active infection. The CDC encouraged automatic reflex testing, meaning immediately checking antibody positive samples for HCV RNA. RNA in the blood indicates active, replicating virus.

The new recommendations penciled out in modeling, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for universal adult screening of approximately $36,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained, and an ICER of approximately $15,000 per QALY gained for pregnancy screening, where HCV prevalence is 0.1%; the 0.1% cost/benefit cutpoint was one of the reasons it was chosen as the prevalence threshold. An ICER under $50,000 is the conservative benchmark for cost-effectiveness, the authors noted.

There was no external funding, and the authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Schillie S et al. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020 Apr 10;69[2]:1-17).

In the latest issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended hepatitis C virus screening for all adults and all pregnant women – during each of their pregnancies – in areas where prevalence of the infection is 0.1% or greater.

That’s essentially the entire United States; there’s no state with a statewide adult prevalence below 0.1%, and “few settings are known to exist” otherwise, the CDC noted (MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020 Apr 10;69(2):1-17).

The agency encouraged providers to consult state or local health departments or the CDC directly to determine local HCV prevalence. “As a general guide ... approximately 59% of anti-HCV positive persons are HCV RNA positive,” indicating active infection, the agency noted.

The advice was an expansion from the CDC’s last universal screening recommendation in 2012, which was limited to people born from 1945 to 1965; the incidence of acute infections has climbed since then and is highest now among younger people, so the guideline needed to be revisited, explained authors led by Sarah Schillie, MD, of the CDC’s Division of Viral Hepatitis, Atlanta.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force also recently recommended universal adult screening after previously limiting it to baby boomers.

As for pregnancy, the CDC’s past advice was to screen pregnant women with known risk factors, but that needed to be revisited as well. For one thing, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the Infectious Diseases Society of America have since recommended testing all pregnant women.

But also, the CDC said, it’s an opportune time for screening because “many women only have access to health care during pregnancy and the immediate postpartum period,” when treatment, if needed, can be started. Plus, HCV status is important for management decisions, such as using amniocentesis in positive women instead of chorionic villus sampling.

The rest of CDC’s 2012 recommendations stand, including screening all people with risk factors and repeating screening while they persist. Also, “any person who requests hepatitis C testing should receive it, regardless of disclosure of risk,” because people might be reluctant to report things like IV drug use, the authors said.

Screening in the guidelines means an HCV antibody test, followed by a nucleic acid test to check for active infection. The CDC encouraged automatic reflex testing, meaning immediately checking antibody positive samples for HCV RNA. RNA in the blood indicates active, replicating virus.

The new recommendations penciled out in modeling, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for universal adult screening of approximately $36,000 per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained, and an ICER of approximately $15,000 per QALY gained for pregnancy screening, where HCV prevalence is 0.1%; the 0.1% cost/benefit cutpoint was one of the reasons it was chosen as the prevalence threshold. An ICER under $50,000 is the conservative benchmark for cost-effectiveness, the authors noted.

There was no external funding, and the authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Schillie S et al. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020 Apr 10;69[2]:1-17).

Almost 90% of COVID-19 admissions involve comorbidities

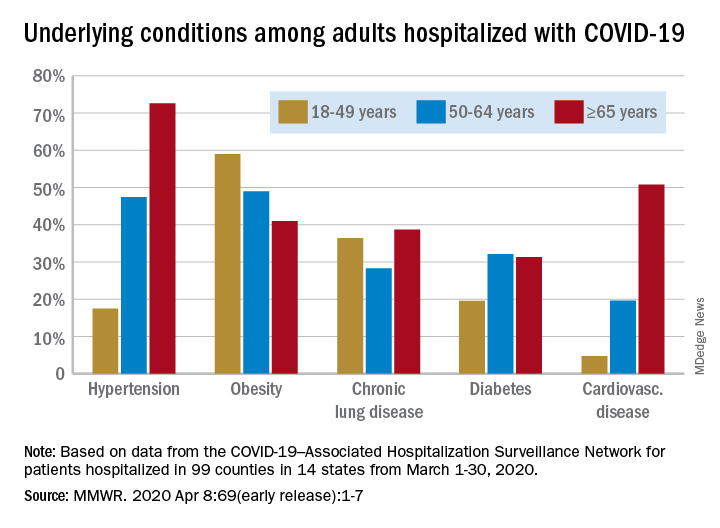

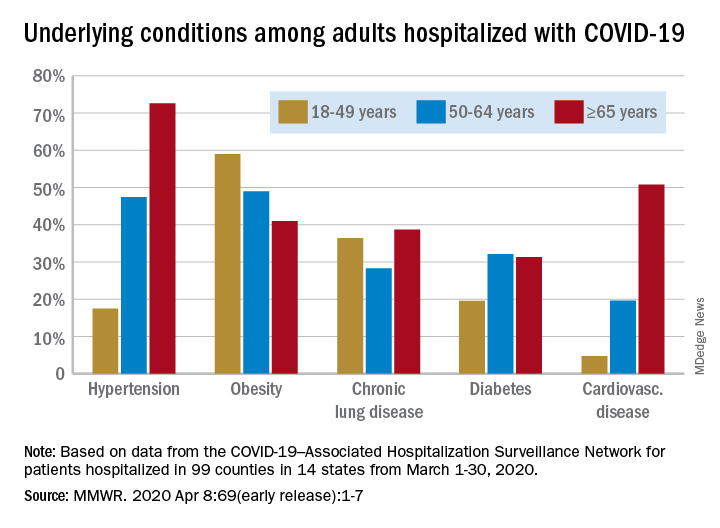

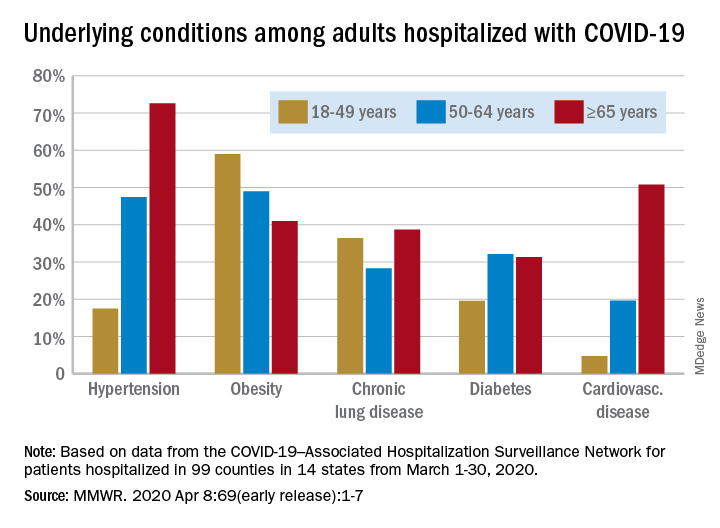

The hospitalization rate for COVID-19 is 4.6 per 100,000 population, and almost 90% of hospitalized patients have some type of underlying condition, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Data collected by the newly created COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET) put the exact prevalence of underlying conditions at 89.3% for patients hospitalized during March 1-30, 2020, Shikha Garg, MD, of the CDC’s COVID-NET team and associates wrote in the MMWR.

The hospitalization rate, based on COVID-NET data for March 1-28, increased with patient age. Those aged 65 years and older were admitted at a rate of 13.8 per 100,000, with 50- to 64-year-olds next at 7.4 per 100,000 and 18- to 49-year-olds at 2.5, they wrote.

The patients aged 65 years and older also were the most likely to have one or more underlying conditions, at 94.4%, compared with 86.4% of those aged 50-64 years and 85.4% of individuals who were aged 18-44 years, the investigators reported.

Hypertension was the most common comorbidity among the oldest patients, with a prevalence of 72.6%, followed by cardiovascular disease at 50.8% and obesity at 41%. In the two younger groups, obesity was the condition most often seen in COVID-19 patients, with prevalences of 49% in 50- to 64-year-olds and 59% in those aged 18-49, Dr. Garg and associates wrote.

“These findings underscore the importance of preventive measures (e.g., social distancing, respiratory hygiene, and wearing face coverings in public settings where social distancing measures are difficult to maintain) to protect older adults and persons with underlying medical conditions,” the investigators wrote.

COVID-NET surveillance includes laboratory-confirmed hospitalizations in 99 counties in 14 states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Tennessee, and Utah. Those counties represent about 10% of the U.S. population.

SOURCE: Garg S et al. MMWR. 2020 Apr 8;69(early release):1-7.

The hospitalization rate for COVID-19 is 4.6 per 100,000 population, and almost 90% of hospitalized patients have some type of underlying condition, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Data collected by the newly created COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET) put the exact prevalence of underlying conditions at 89.3% for patients hospitalized during March 1-30, 2020, Shikha Garg, MD, of the CDC’s COVID-NET team and associates wrote in the MMWR.

The hospitalization rate, based on COVID-NET data for March 1-28, increased with patient age. Those aged 65 years and older were admitted at a rate of 13.8 per 100,000, with 50- to 64-year-olds next at 7.4 per 100,000 and 18- to 49-year-olds at 2.5, they wrote.

The patients aged 65 years and older also were the most likely to have one or more underlying conditions, at 94.4%, compared with 86.4% of those aged 50-64 years and 85.4% of individuals who were aged 18-44 years, the investigators reported.

Hypertension was the most common comorbidity among the oldest patients, with a prevalence of 72.6%, followed by cardiovascular disease at 50.8% and obesity at 41%. In the two younger groups, obesity was the condition most often seen in COVID-19 patients, with prevalences of 49% in 50- to 64-year-olds and 59% in those aged 18-49, Dr. Garg and associates wrote.

“These findings underscore the importance of preventive measures (e.g., social distancing, respiratory hygiene, and wearing face coverings in public settings where social distancing measures are difficult to maintain) to protect older adults and persons with underlying medical conditions,” the investigators wrote.

COVID-NET surveillance includes laboratory-confirmed hospitalizations in 99 counties in 14 states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Tennessee, and Utah. Those counties represent about 10% of the U.S. population.

SOURCE: Garg S et al. MMWR. 2020 Apr 8;69(early release):1-7.

The hospitalization rate for COVID-19 is 4.6 per 100,000 population, and almost 90% of hospitalized patients have some type of underlying condition, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Data collected by the newly created COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET) put the exact prevalence of underlying conditions at 89.3% for patients hospitalized during March 1-30, 2020, Shikha Garg, MD, of the CDC’s COVID-NET team and associates wrote in the MMWR.

The hospitalization rate, based on COVID-NET data for March 1-28, increased with patient age. Those aged 65 years and older were admitted at a rate of 13.8 per 100,000, with 50- to 64-year-olds next at 7.4 per 100,000 and 18- to 49-year-olds at 2.5, they wrote.

The patients aged 65 years and older also were the most likely to have one or more underlying conditions, at 94.4%, compared with 86.4% of those aged 50-64 years and 85.4% of individuals who were aged 18-44 years, the investigators reported.

Hypertension was the most common comorbidity among the oldest patients, with a prevalence of 72.6%, followed by cardiovascular disease at 50.8% and obesity at 41%. In the two younger groups, obesity was the condition most often seen in COVID-19 patients, with prevalences of 49% in 50- to 64-year-olds and 59% in those aged 18-49, Dr. Garg and associates wrote.

“These findings underscore the importance of preventive measures (e.g., social distancing, respiratory hygiene, and wearing face coverings in public settings where social distancing measures are difficult to maintain) to protect older adults and persons with underlying medical conditions,” the investigators wrote.

COVID-NET surveillance includes laboratory-confirmed hospitalizations in 99 counties in 14 states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Tennessee, and Utah. Those counties represent about 10% of the U.S. population.

SOURCE: Garg S et al. MMWR. 2020 Apr 8;69(early release):1-7.

FROM THE MMWR

The wide-ranging impact of hospital closures

Clinicians struggle to balance priorities

On June 26, 2019, American Academic Health System and Philadelphia Academic Health System announced that Hahnemann University Hospital, a 496-bed tertiary care center in North Philadelphia in operation for over 170 years, would close that September.

The emergency department closed 52 days after the announcement, leaving little time for physicians and staff to coordinate care for patients and secure new employment. The announcement was also made right at the beginning of the new academic year, which meant residents and fellows were forced to find new training programs. In total, 2,500 workers at Hahnemann, including more than 570 hospitalists and physicians training as residents and fellows, were displaced as the hospital closed – the largest such closing in U.S. history.

For most of its existence, Hahnemann was a teaching hospital. While trainees were all eventually placed in new programs thanks to efforts from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), some of the permanent staff at Hahnemann weren’t so lucky. A month after the announcement, Drexel University’s president told university employees that 40% of the staff who worked at Hahnemann would be cut as a result of the closing. Drexel, also based in Philadelphia, had long had an academic affiliation agreement for training Drexel’s medical school students as a primary academic partner. Overall, Drexel’s entire clinical staff at Hahnemann was let go, and Tower Health Medical Group is expected to hire about 60% of the former Hahnemann staff.

Kevin D’Mello, MD, FACP, FHM, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at Drexel University, said residents during Hahnemann’s closure were essentially teaching themselves how to swim. “There were just no laws, no rules,” he said.

The vast majority of programs accepting applications from residents at Hahnemann were sympathetic and accommodating, he said, but a few programs applied “pressure tactics” to some of the residents offered a transfer position, despite graduate medical education rules in place to prevent such a situation from happening. “The resident says: ‘Oh, well, I’m waiting to hear from this other program,’ ” said Dr. D’Mello. “They’d say: ‘Okay, well, we’re giving you a position now. You have 12 hours to answer.’ ”

Decision makers at the hospital also were not very forthcoming with information to residents, fellows and program directors, according to a recent paper written by Thomas J. Nasca, MD, current president and CEO of ACGME, and colleagues in the journal Academic Medicine (Nasca T et al. Acad Med. 2019 Dec 17. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003133). When Dr. Nasca and colleagues went to investigate the situation at Hahnemann firsthand, “the team found that residents, fellows, and program directors alike considered their voices to have been ignored in decision making and deemed themselves ‘out of the loop’ of important information that would affect their career transitions.”

While the hospital closed in September 2019, the effects are still being felt. In Pennsylvania, the Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error Act requires that hospitals and providers have malpractice insurance, including tail insurance for when a doctor’s insurance policy expires. American Academic announced it would not be paying tail insurance for claims made while physicians were at Hahnemann. This meant residents, fellows and physicians who worked at Hahnemann during the closure would be on the hook for paying their own malpractice insurance.

“On one hand, the risk is very low for the house staff. Lawsuits that come up later for house staff are generally dropped at some point,” said William W. Pinsky, MD, FAAP, FACC, president and CEO of the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG). “But who wants to take that risk going forward? It’s an issue that’s still not resolved.”

The American Medical Association, Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the Philadelphia County Medical Society, and other medical societies have collectively put pressure on Hahnemann’s owners to pay for tail coverage. Beyond a Feb. 10, 2020 deadline, former Hahnemann physicians were still expected to cover their own tail insurance.

To further complicate matters, American Academic attempted to auction more than 570 residency slots at Hahnemann. The slots were sold to a consortium of six health systems in the area – Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals, Einstein Healthcare Network, Temple University Health System, Main Line Health, Cooper University Health Care, and Christiana Care Health System – for $55 million. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services opposed the sale, arguing that the slots are a contract that hospitals enter into with CMS, rather than an asset to be sold. An appeal is currently pending.

The case is being watched by former physicians at Hahnemann. “American Academic said, ‘If we don’t get this $55 million, we’re not going to be able to cover this tail insurance.’ They’re kind of linking the two things,” said Dr. D’Mello. “To me, it’s almost like putting pressure to allow the sale to happen.”

Urban hospital closures disrupt health system balance

When an urban hospital like Hahnemann University Hospital closes, there is a major disruption to patient care. Patients need to relocate to other nearby centers, and they may not always be able to follow their physician to the next health center.

If patients have comorbidities, are being tracked across multiple care points, or change physicians during a hospital closure, details can be missed and care can become more complicated for physicians who end up seeing the patient at a new center. For example, a patient receiving obstetrics care at a hospital that closes will have to reschedule their delivery at another health center, noted Dr. Pinsky.

“Where patients get lost is when there’s not a physician or an individual can keep track of all that, coordinate, and help to be sure that the patient follows through,” he said.

Patients at a closing hospital need to go somewhere else for care, and patient volume naturally increases at other nearby centers, potentially causing problems for systems without the resources to handle the spike in traffic.

“I’m a service director of quality improvement and patient safety for Drexel internal medicine. I know that those sort of jumps and volumes are what increases medical errors and potentially could create some adverse outcomes,” said Dr. D’Mello. “That’s something I’m particularly worried about.”

Physicians are also reconciling their own personal situations during a hospital closure, attempting to figure out their next step while at the same time helping patients figure out theirs. In the case of international medical graduates on J-1 or H1-B visas, who are dependent on hospital positions and training programs to remain in the United States, the situation can be even more dire.

During Hahnemann’s closure, Dr. Pinsky said that the ECFMG, which represents 11,000 individuals with J-1 visas across the country, reached out to the 55 individuals on J-1 visas at the hospital and offered them assistance, including working with the Department of State to ensure they aren’t in jeopardy of deportation before they secure another training program position.

The ECFMG, AMA, AAMC, and ACGME also offered funding to help J-1 visa holders who needed to relocate outside Philadelphia. “Many of them spent a lot of their money or all their money just coming over here,” said Dr. Pinsky. “This was a way to help defray some immediate costs that they might have.”

Education and research, of which hospitalists and residents play a large role, are likewise affected during a hospital closure, Dr. Pinsky said. “Education and research in the hospital is an important contributor to the community, health care and medical education nationally overall. When it’s not considered, there can be a significant asset that is lost in the process, which is hard to ever regain.

“The hospitalists have an integral role in medical education. In most hospitals where there is graduate medical education, particularly in internal medicine or pediatrics, and where there is a hospitalist program, it’s the hospitalists that do the majority of the in-hospital or inpatient training and education,” he added.

Rural hospital closures affect access to care

Since 2005, 163 rural hospitals have closed in the United States. When rural hospitals close, the situation for hospitalists and other physicians is different. In communities where a larger health system owns a hospital, such as when Vidant Health closed Pungo District Hospital in Belhaven, N.C., in 2014 before reopening a nonemergency clinic in the area in 2016, health care services for the community may have limited interruption.

However, if there isn’t a nearby system to join, many doctors will end up leaving the area. More than half of rural hospitals that close end up not providing any kind of supplementary health care service, according to the NC Rural Health Research Program.

“A lot of the hospitals that have closed have not been owned by a system,” said George H. Pink, PhD, deputy director of the NC Rural Health Research Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “They’ve been independent, freestanding, and that perhaps is one of the reasons why they’re closing, is because they haven’t been able to find a system that would buy them out and inject capital into the community.”

This can also have an effect on the number of health care providers in the area, Dr. Pink said. “Their ability to refer patients and treat patients locally may be affected. That’s why, in many towns where hospitals have closed, we see a drop in the number of providers, particularly primary care doctors who actually live in the community.”

Politicians and federal entities have proposed a number of solutions to help protect rural hospitals from closure. Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa), Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), and Sen. Cory Gardener (R-Colo.) have sponsored bills in the Senate, while Rep. Sam Graves (R-Mo.) has introduced legislation in the House. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission has proposed two models of rural hospital care, and there are additional models proposed by the Kansas Hospital Association. A pilot program in Pennsylvania, the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model, is testing how a global budget by CMS for all inpatient and hospital-based outcomes might help rural hospitals.

“What we haven’t had a lot of action on is actually testing these models out and seeing whether they will work, and in what kinds of communities they will work,” Dr. Pink said.

Hospitalists as community advocates

Dr. D’Mello, who wrote an article for the Journal of Hospital Medicine on Hahnemann’s ownership by a private equity firm (doi: 10.12788/jhm.3378), said that the inherent nature of a for-profit entity trying to make a hospital profitable is a bad sign for a hospital and not necessarily what is in the best interest for an academic institution or for doctors who train there.

“I don’t know if I could blame the private equity firm completely, but in retrospect, the private equity firms stepping in was like the death knell of the hospital,” he said of Hahnemann’s closure.

“I think what the community needs to know – what the health care community, patient community, the hospitalist community need to know – is that there’s got to be more attention paid to these types of issues during mergers and acquisitions to prevent this from happening,” Dr. Pinsky said.

One larger issue was Hahnemann’s position as a safety net hospital, which partly played into American Academic’s lack of success in making the hospital as profitable as they wanted it to be, Dr. D’Mello noted. Hahnemann’s patient population consisted mostly of minority patients on Medicare, Medicaid, and charity care insurance, while recent studies have shown that hospitals are more likely to succeed when they have a larger proportion of patients with private insurance.

“Studies show that, to [make more] money from private insurance, you really have to have this huge footprint, because then you’ve got a better ability to negotiate with these private insurance companies,” Dr. D’Mello said. “Whether that’s actually good for health care is a different issue.”

Despite their own situations, it is not unusual for hospitalists and hospital physicians to step up during a hospital closure and advocate for their patients on behalf of the community, Dr. Pink said.

“When hospitals are in financial difficulty and there’s the risk of closure, typically, the medical staff are among the first to step up and warn the community: ‘We’re at risk of losing our service. We need some help,’ ” he said. “Generally speaking, the local physicians have been at the forefront of helping to keep access to hospital care available in some of these small communities – unfortunately, not always successfully.”

Dr. D’Mello, Dr. Pinsky, and Dr. Pink report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Clinicians struggle to balance priorities

Clinicians struggle to balance priorities

On June 26, 2019, American Academic Health System and Philadelphia Academic Health System announced that Hahnemann University Hospital, a 496-bed tertiary care center in North Philadelphia in operation for over 170 years, would close that September.

The emergency department closed 52 days after the announcement, leaving little time for physicians and staff to coordinate care for patients and secure new employment. The announcement was also made right at the beginning of the new academic year, which meant residents and fellows were forced to find new training programs. In total, 2,500 workers at Hahnemann, including more than 570 hospitalists and physicians training as residents and fellows, were displaced as the hospital closed – the largest such closing in U.S. history.

For most of its existence, Hahnemann was a teaching hospital. While trainees were all eventually placed in new programs thanks to efforts from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), some of the permanent staff at Hahnemann weren’t so lucky. A month after the announcement, Drexel University’s president told university employees that 40% of the staff who worked at Hahnemann would be cut as a result of the closing. Drexel, also based in Philadelphia, had long had an academic affiliation agreement for training Drexel’s medical school students as a primary academic partner. Overall, Drexel’s entire clinical staff at Hahnemann was let go, and Tower Health Medical Group is expected to hire about 60% of the former Hahnemann staff.

Kevin D’Mello, MD, FACP, FHM, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at Drexel University, said residents during Hahnemann’s closure were essentially teaching themselves how to swim. “There were just no laws, no rules,” he said.

The vast majority of programs accepting applications from residents at Hahnemann were sympathetic and accommodating, he said, but a few programs applied “pressure tactics” to some of the residents offered a transfer position, despite graduate medical education rules in place to prevent such a situation from happening. “The resident says: ‘Oh, well, I’m waiting to hear from this other program,’ ” said Dr. D’Mello. “They’d say: ‘Okay, well, we’re giving you a position now. You have 12 hours to answer.’ ”

Decision makers at the hospital also were not very forthcoming with information to residents, fellows and program directors, according to a recent paper written by Thomas J. Nasca, MD, current president and CEO of ACGME, and colleagues in the journal Academic Medicine (Nasca T et al. Acad Med. 2019 Dec 17. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003133). When Dr. Nasca and colleagues went to investigate the situation at Hahnemann firsthand, “the team found that residents, fellows, and program directors alike considered their voices to have been ignored in decision making and deemed themselves ‘out of the loop’ of important information that would affect their career transitions.”

While the hospital closed in September 2019, the effects are still being felt. In Pennsylvania, the Medical Care Availability and Reduction of Error Act requires that hospitals and providers have malpractice insurance, including tail insurance for when a doctor’s insurance policy expires. American Academic announced it would not be paying tail insurance for claims made while physicians were at Hahnemann. This meant residents, fellows and physicians who worked at Hahnemann during the closure would be on the hook for paying their own malpractice insurance.

“On one hand, the risk is very low for the house staff. Lawsuits that come up later for house staff are generally dropped at some point,” said William W. Pinsky, MD, FAAP, FACC, president and CEO of the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG). “But who wants to take that risk going forward? It’s an issue that’s still not resolved.”

The American Medical Association, Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the Philadelphia County Medical Society, and other medical societies have collectively put pressure on Hahnemann’s owners to pay for tail coverage. Beyond a Feb. 10, 2020 deadline, former Hahnemann physicians were still expected to cover their own tail insurance.

To further complicate matters, American Academic attempted to auction more than 570 residency slots at Hahnemann. The slots were sold to a consortium of six health systems in the area – Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals, Einstein Healthcare Network, Temple University Health System, Main Line Health, Cooper University Health Care, and Christiana Care Health System – for $55 million. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services opposed the sale, arguing that the slots are a contract that hospitals enter into with CMS, rather than an asset to be sold. An appeal is currently pending.

The case is being watched by former physicians at Hahnemann. “American Academic said, ‘If we don’t get this $55 million, we’re not going to be able to cover this tail insurance.’ They’re kind of linking the two things,” said Dr. D’Mello. “To me, it’s almost like putting pressure to allow the sale to happen.”

Urban hospital closures disrupt health system balance

When an urban hospital like Hahnemann University Hospital closes, there is a major disruption to patient care. Patients need to relocate to other nearby centers, and they may not always be able to follow their physician to the next health center.

If patients have comorbidities, are being tracked across multiple care points, or change physicians during a hospital closure, details can be missed and care can become more complicated for physicians who end up seeing the patient at a new center. For example, a patient receiving obstetrics care at a hospital that closes will have to reschedule their delivery at another health center, noted Dr. Pinsky.

“Where patients get lost is when there’s not a physician or an individual can keep track of all that, coordinate, and help to be sure that the patient follows through,” he said.

Patients at a closing hospital need to go somewhere else for care, and patient volume naturally increases at other nearby centers, potentially causing problems for systems without the resources to handle the spike in traffic.

“I’m a service director of quality improvement and patient safety for Drexel internal medicine. I know that those sort of jumps and volumes are what increases medical errors and potentially could create some adverse outcomes,” said Dr. D’Mello. “That’s something I’m particularly worried about.”

Physicians are also reconciling their own personal situations during a hospital closure, attempting to figure out their next step while at the same time helping patients figure out theirs. In the case of international medical graduates on J-1 or H1-B visas, who are dependent on hospital positions and training programs to remain in the United States, the situation can be even more dire.

During Hahnemann’s closure, Dr. Pinsky said that the ECFMG, which represents 11,000 individuals with J-1 visas across the country, reached out to the 55 individuals on J-1 visas at the hospital and offered them assistance, including working with the Department of State to ensure they aren’t in jeopardy of deportation before they secure another training program position.

The ECFMG, AMA, AAMC, and ACGME also offered funding to help J-1 visa holders who needed to relocate outside Philadelphia. “Many of them spent a lot of their money or all their money just coming over here,” said Dr. Pinsky. “This was a way to help defray some immediate costs that they might have.”

Education and research, of which hospitalists and residents play a large role, are likewise affected during a hospital closure, Dr. Pinsky said. “Education and research in the hospital is an important contributor to the community, health care and medical education nationally overall. When it’s not considered, there can be a significant asset that is lost in the process, which is hard to ever regain.

“The hospitalists have an integral role in medical education. In most hospitals where there is graduate medical education, particularly in internal medicine or pediatrics, and where there is a hospitalist program, it’s the hospitalists that do the majority of the in-hospital or inpatient training and education,” he added.

Rural hospital closures affect access to care

Since 2005, 163 rural hospitals have closed in the United States. When rural hospitals close, the situation for hospitalists and other physicians is different. In communities where a larger health system owns a hospital, such as when Vidant Health closed Pungo District Hospital in Belhaven, N.C., in 2014 before reopening a nonemergency clinic in the area in 2016, health care services for the community may have limited interruption.

However, if there isn’t a nearby system to join, many doctors will end up leaving the area. More than half of rural hospitals that close end up not providing any kind of supplementary health care service, according to the NC Rural Health Research Program.

“A lot of the hospitals that have closed have not been owned by a system,” said George H. Pink, PhD, deputy director of the NC Rural Health Research Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “They’ve been independent, freestanding, and that perhaps is one of the reasons why they’re closing, is because they haven’t been able to find a system that would buy them out and inject capital into the community.”

This can also have an effect on the number of health care providers in the area, Dr. Pink said. “Their ability to refer patients and treat patients locally may be affected. That’s why, in many towns where hospitals have closed, we see a drop in the number of providers, particularly primary care doctors who actually live in the community.”

Politicians and federal entities have proposed a number of solutions to help protect rural hospitals from closure. Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa), Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), and Sen. Cory Gardener (R-Colo.) have sponsored bills in the Senate, while Rep. Sam Graves (R-Mo.) has introduced legislation in the House. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission has proposed two models of rural hospital care, and there are additional models proposed by the Kansas Hospital Association. A pilot program in Pennsylvania, the Pennsylvania Rural Health Model, is testing how a global budget by CMS for all inpatient and hospital-based outcomes might help rural hospitals.

“What we haven’t had a lot of action on is actually testing these models out and seeing whether they will work, and in what kinds of communities they will work,” Dr. Pink said.

Hospitalists as community advocates

Dr. D’Mello, who wrote an article for the Journal of Hospital Medicine on Hahnemann’s ownership by a private equity firm (doi: 10.12788/jhm.3378), said that the inherent nature of a for-profit entity trying to make a hospital profitable is a bad sign for a hospital and not necessarily what is in the best interest for an academic institution or for doctors who train there.

“I don’t know if I could blame the private equity firm completely, but in retrospect, the private equity firms stepping in was like the death knell of the hospital,” he said of Hahnemann’s closure.

“I think what the community needs to know – what the health care community, patient community, the hospitalist community need to know – is that there’s got to be more attention paid to these types of issues during mergers and acquisitions to prevent this from happening,” Dr. Pinsky said.

One larger issue was Hahnemann’s position as a safety net hospital, which partly played into American Academic’s lack of success in making the hospital as profitable as they wanted it to be, Dr. D’Mello noted. Hahnemann’s patient population consisted mostly of minority patients on Medicare, Medicaid, and charity care insurance, while recent studies have shown that hospitals are more likely to succeed when they have a larger proportion of patients with private insurance.

“Studies show that, to [make more] money from private insurance, you really have to have this huge footprint, because then you’ve got a better ability to negotiate with these private insurance companies,” Dr. D’Mello said. “Whether that’s actually good for health care is a different issue.”

Despite their own situations, it is not unusual for hospitalists and hospital physicians to step up during a hospital closure and advocate for their patients on behalf of the community, Dr. Pink said.

“When hospitals are in financial difficulty and there’s the risk of closure, typically, the medical staff are among the first to step up and warn the community: ‘We’re at risk of losing our service. We need some help,’ ” he said. “Generally speaking, the local physicians have been at the forefront of helping to keep access to hospital care available in some of these small communities – unfortunately, not always successfully.”

Dr. D’Mello, Dr. Pinsky, and Dr. Pink report no relevant conflicts of interest.

On June 26, 2019, American Academic Health System and Philadelphia Academic Health System announced that Hahnemann University Hospital, a 496-bed tertiary care center in North Philadelphia in operation for over 170 years, would close that September.

The emergency department closed 52 days after the announcement, leaving little time for physicians and staff to coordinate care for patients and secure new employment. The announcement was also made right at the beginning of the new academic year, which meant residents and fellows were forced to find new training programs. In total, 2,500 workers at Hahnemann, including more than 570 hospitalists and physicians training as residents and fellows, were displaced as the hospital closed – the largest such closing in U.S. history.

For most of its existence, Hahnemann was a teaching hospital. While trainees were all eventually placed in new programs thanks to efforts from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), some of the permanent staff at Hahnemann weren’t so lucky. A month after the announcement, Drexel University’s president told university employees that 40% of the staff who worked at Hahnemann would be cut as a result of the closing. Drexel, also based in Philadelphia, had long had an academic affiliation agreement for training Drexel’s medical school students as a primary academic partner. Overall, Drexel’s entire clinical staff at Hahnemann was let go, and Tower Health Medical Group is expected to hire about 60% of the former Hahnemann staff.

Kevin D’Mello, MD, FACP, FHM, a hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine at Drexel University, said residents during Hahnemann’s closure were essentially teaching themselves how to swim. “There were just no laws, no rules,” he said.

The vast majority of programs accepting applications from residents at Hahnemann were sympathetic and accommodating, he said, but a few programs applied “pressure tactics” to some of the residents offered a transfer position, despite graduate medical education rules in place to prevent such a situation from happening. “The resident says: ‘Oh, well, I’m waiting to hear from this other program,’ ” said Dr. D’Mello. “They’d say: ‘Okay, well, we’re giving you a position now. You have 12 hours to answer.’ ”

Decision makers at the hospital also were not very forthcoming with information to residents, fellows and program directors, according to a recent paper written by Thomas J. Nasca, MD, current president and CEO of ACGME, and colleagues in the journal Academic Medicine (Nasca T et al. Acad Med. 2019 Dec 17. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003133). When Dr. Nasca and colleagues went to investigate the situation at Hahnemann firsthand, “the team found that residents, fellows, and program directors alike considered their voices to have been ignored in decision making and deemed themselves ‘out of the loop’ of important information that would affect their career transitions.”