User login

Gender bias and pediatric hospital medicine

Where do we go from here?

Autumn is a busy time for pediatric hospitalists, with this autumn being particularly eventful as the first American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) certifying exam for Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) will be offered on Nov. 12, 2019.

More than 1,600 med/peds and pediatric hospitalists applied to be eligible for the 2019 exam, 71% of whom were women. At least 3.9% of those applicants were denied eligibility for the 2019 exam.1 These denials resulted in discussions on the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM) email listserv related to unintentional gender bias.

PHM was first recognized as a subspecialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties in December 2015.2 Since that time, the ABP’s PHM sub-board developed eligibility criteria for practicing pediatric and med/peds hospitalists to apply for the exam. The sub-board identified three paths: a training pathway for applicants who had completed a 2-year PHM fellowship, a practice pathway for those satisfying ABP criteria for clinical activity in PHM, and a combined pathway for applicants who had completed PHM fellowships lasting less than 2 years.

Based on these pathways, 1,627 applicants applied for eligibility for the first PHM board certification exam.1 However, many concerns arose with the practice pathway eligibility criteria.

The PHM practice pathway initially included the following eligibility criteria:

• General pediatrics board certification.

• PHM practice “look back” period ends on or before June 30 of the exam year and starts 4 years earlier.

• More than 0.5 FTE professional PHM-related activities (patient-care, research, administration), defined as more than 900 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• More than 0.25 FTE direct patient care of hospitalized children, defined as more than 450 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Practice covers the full range of hospitalized children with regard to age, diagnoses, and complexity.

• Practice interruptions cannot exceed 3 months in the preceding 4 years, or 6 months in the preceding 5 years.

• Practice experience and hours were acquired in the United States and Canada.1,3

The start date and practice interruptions criteria in the practice pathway posed hurdles for many female applicants. Many women voiced concerns about feeling disadvantaged when applying for the PHM certifying exam and some of these women shared their concerns on the AAP SOHM email listserv. In response to these concerns, the PHM community called for increased transparency from the ABP related to denials, specifically related to unintentional gender bias against women applying for the exam.

David Skey, MD, and Jamee Walters, MD, pediatric hospitalists at Arnold Palmer Medical Center in Orlando, heard these concerns and decided to draft a petition with the help of legal counsel. The petition “demand[ed] immediate action,” and “request[ed] a formal response from the ABP regarding the practice pathway criteria.” The petition also stated that there was insufficient data to determine if the practice pathway “disadvantages women.” The petition asked the ABP to “facilitate a timely analysis to determine if gender bias” was present, or to perform an internal analysis and “release the findings publicly.”4

The petition was shared with the PHM community via the AAP SOHM listserv on July 29, 2019. Dr. Walters stated she was pleased by the response she and Dr. Skey received from the PHM community, on and off the AAP SOHM listserv. The petition was submitted to the ABP on Aug. 6, 2019, with 1,479 signatures.

On Aug. 29, 2019, the ABP’s response was shared on the AAP SOHM email listserv1 and was later published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine as a Special Announcement.5 In its response, the ABP stated that the gender bias allegation was “not supported by the facts” as there was “no significant difference between the percentage of women and men who were denied” eligibility.”5 In addressing the gender bias allegations and clarifying the practice pathway eligibility, the ABP removed the practice interruption criteria and modified the practice pathway criteria as follows:

• General pediatrics board certification.

• PHM practice started on or before July 2015 (for board eligibility in 2019).

• Professional PHM-related activities (patient-care, research, administration), defined as more than 900-1000 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Direct patient care of hospitalized children, defined as more than 450-500 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Practice covers the full range of hospitalized children with regard to age, diagnoses, and complexity.

• Practice experience and hours were acquired in the United States and Canada.1

Following the release of the ABP’s response, many members of the PHM community remain concerned about the ABP’s revised criteria. Arti Desai, MD, pediatric hospitalist at Seattle Children’s and senior author on a “Perspectives in Hospital Medicine” in the Journal of Hospital Medicine,6 was appreciative that the ABP chose to remove the practice interruptions criterion. However, she and her colleagues remain concerned about lingering gender bias in the ABP’s practice pathway eligibility criteria surrounding the “start date” criterion. The authors state that this criterion differentially affects women, as women may take time off during or after residency for maternity or family leave. Dr. Desai states that this criterion alone can affect a woman’s chance for being eligible for the practice pathway.

Other members of the PHM community also expressed concerns about the ABP’s response to the PHM petition. Beth C. Natt, MD, pediatric hospitalist and director of pediatric hospital medicine regional programs at Connecticut Children’s in Hartford, felt that the population may have been self-selected, as the ABP’s data were limited to individuals who applied for exam eligibility. She was concerned that the data excluded pediatric hospitalists who chose not to apply because of uncertainty about meeting eligibility criteria. Klint Schwenk, MD, pediatric hospitalist at Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Ky., stated that he wished the ABP had addressed the number of pediatric hospitalists who elected not to apply based on fear of ineligibility before concluding that there was no bias. He likened the ABP’s response to that of study authors omitting selection bias when discussing the limitations of their study.

Courtney Edgar-Zarate, MD, med/peds hospitalist and associate program director of the internal medicine/pediatrics residency at the University of Arkansas, expressed concerns that the ABP’s stringent clinical patient care hours criterion may unintentionally result in ineligibility for many mid-career or senior med/peds hospitalists. Dr. Edgar-Zarate also voiced concerns that graduating med/peds residents were electing not to pursue careers in hospital medicine because they would be required to complete a PHM fellowship to become a pediatric hospitalist, when a similar fellowship is not required to practice adult hospital medicine.

The Society of Hospital Medicine shared its position in regard to the ABP’s response in a Special Announcement in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.7 In it, SHM’s pediatric leaders recognized physicians for the excellent care they provide to hospitalized children. They stated that SHM would continue to support all hospitalists, independent of board eligibility status, and would continue to offer these hospitalists the merit-based Fellow designation. SHM’s pediatric leaders also proposed future directions for the ABP, including a Focused Practice Pathway in Hospital Medicine (FPHM), such as what the American Board of Internal Medicine and the American Board of Family Medicine have adopted for board recertification in internal medicine and family medicine. This maintenance of certification program that allows physicians primarily practicing in inpatient settings to focus their continuing education on inpatient practice, and is not a subspecialty.7

Dr. Edgar-Zarate fully supports the future directions for pediatric hospitalists outlined in SHM’s Special Announcement. She hopes that the ABP will support the FPHM. She feels the FPHM will encourage more med/peds physicians to practice med/peds hospital medicine. L. Nell Hodo, MD, a family medicine–trained pediatric hospitalist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, joins Dr. Edgar-Zarate in supporting an FPHM for PHM, and feels that it will open the door for hospitalists who are ineligible for the practice pathway to be able to focus their recertification on the inpatient setting.

Dr. Hodo and Dr. Desai hope that rather than excluding those who are not PHM board eligible/certified, institutions and professional organizations will consider all qualifications when hiring, mentoring, and promoting physicians who care for hospitalized children. Dr. Natt, Dr. Schwenk, Dr. Edgar-Zarate, and Dr. Hodo appreciate that SHM is leading the way, and will continue to allow all hospitalists who care for children to receive Fellow designation.

Dr. Kumar is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. The American Board of Pediatrics. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. https://www.abp.org/sites/abp/files/phm-petition-response.pdf. Published 2019.

2. Barrett DJ, McGuinness GA, Cunha CA, et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: A proposed new subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1823.

3. The American Board of Pediatrics. Pediatric Hospital Medicine Certification. https://www.abp.org/content/pediatric-hospital-medicine-certification. Published 2019.

4. Skey D. Pediatric Hospitalists, It’s time to take a stand on the PHM Boards Application Process! Five Dog Development, LLC.

5. Nichols DG, Woods SZ. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):586-8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3322.

6. Gold JM et al. Collective action and effective dialogue to address gender bias in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):630-2. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3331.

7. Chang WW et al. Society of Hospital Medicine position on the American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):589-90. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3326.

Where do we go from here?

Where do we go from here?

Autumn is a busy time for pediatric hospitalists, with this autumn being particularly eventful as the first American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) certifying exam for Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) will be offered on Nov. 12, 2019.

More than 1,600 med/peds and pediatric hospitalists applied to be eligible for the 2019 exam, 71% of whom were women. At least 3.9% of those applicants were denied eligibility for the 2019 exam.1 These denials resulted in discussions on the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM) email listserv related to unintentional gender bias.

PHM was first recognized as a subspecialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties in December 2015.2 Since that time, the ABP’s PHM sub-board developed eligibility criteria for practicing pediatric and med/peds hospitalists to apply for the exam. The sub-board identified three paths: a training pathway for applicants who had completed a 2-year PHM fellowship, a practice pathway for those satisfying ABP criteria for clinical activity in PHM, and a combined pathway for applicants who had completed PHM fellowships lasting less than 2 years.

Based on these pathways, 1,627 applicants applied for eligibility for the first PHM board certification exam.1 However, many concerns arose with the practice pathway eligibility criteria.

The PHM practice pathway initially included the following eligibility criteria:

• General pediatrics board certification.

• PHM practice “look back” period ends on or before June 30 of the exam year and starts 4 years earlier.

• More than 0.5 FTE professional PHM-related activities (patient-care, research, administration), defined as more than 900 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• More than 0.25 FTE direct patient care of hospitalized children, defined as more than 450 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Practice covers the full range of hospitalized children with regard to age, diagnoses, and complexity.

• Practice interruptions cannot exceed 3 months in the preceding 4 years, or 6 months in the preceding 5 years.

• Practice experience and hours were acquired in the United States and Canada.1,3

The start date and practice interruptions criteria in the practice pathway posed hurdles for many female applicants. Many women voiced concerns about feeling disadvantaged when applying for the PHM certifying exam and some of these women shared their concerns on the AAP SOHM email listserv. In response to these concerns, the PHM community called for increased transparency from the ABP related to denials, specifically related to unintentional gender bias against women applying for the exam.

David Skey, MD, and Jamee Walters, MD, pediatric hospitalists at Arnold Palmer Medical Center in Orlando, heard these concerns and decided to draft a petition with the help of legal counsel. The petition “demand[ed] immediate action,” and “request[ed] a formal response from the ABP regarding the practice pathway criteria.” The petition also stated that there was insufficient data to determine if the practice pathway “disadvantages women.” The petition asked the ABP to “facilitate a timely analysis to determine if gender bias” was present, or to perform an internal analysis and “release the findings publicly.”4

The petition was shared with the PHM community via the AAP SOHM listserv on July 29, 2019. Dr. Walters stated she was pleased by the response she and Dr. Skey received from the PHM community, on and off the AAP SOHM listserv. The petition was submitted to the ABP on Aug. 6, 2019, with 1,479 signatures.

On Aug. 29, 2019, the ABP’s response was shared on the AAP SOHM email listserv1 and was later published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine as a Special Announcement.5 In its response, the ABP stated that the gender bias allegation was “not supported by the facts” as there was “no significant difference between the percentage of women and men who were denied” eligibility.”5 In addressing the gender bias allegations and clarifying the practice pathway eligibility, the ABP removed the practice interruption criteria and modified the practice pathway criteria as follows:

• General pediatrics board certification.

• PHM practice started on or before July 2015 (for board eligibility in 2019).

• Professional PHM-related activities (patient-care, research, administration), defined as more than 900-1000 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Direct patient care of hospitalized children, defined as more than 450-500 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Practice covers the full range of hospitalized children with regard to age, diagnoses, and complexity.

• Practice experience and hours were acquired in the United States and Canada.1

Following the release of the ABP’s response, many members of the PHM community remain concerned about the ABP’s revised criteria. Arti Desai, MD, pediatric hospitalist at Seattle Children’s and senior author on a “Perspectives in Hospital Medicine” in the Journal of Hospital Medicine,6 was appreciative that the ABP chose to remove the practice interruptions criterion. However, she and her colleagues remain concerned about lingering gender bias in the ABP’s practice pathway eligibility criteria surrounding the “start date” criterion. The authors state that this criterion differentially affects women, as women may take time off during or after residency for maternity or family leave. Dr. Desai states that this criterion alone can affect a woman’s chance for being eligible for the practice pathway.

Other members of the PHM community also expressed concerns about the ABP’s response to the PHM petition. Beth C. Natt, MD, pediatric hospitalist and director of pediatric hospital medicine regional programs at Connecticut Children’s in Hartford, felt that the population may have been self-selected, as the ABP’s data were limited to individuals who applied for exam eligibility. She was concerned that the data excluded pediatric hospitalists who chose not to apply because of uncertainty about meeting eligibility criteria. Klint Schwenk, MD, pediatric hospitalist at Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Ky., stated that he wished the ABP had addressed the number of pediatric hospitalists who elected not to apply based on fear of ineligibility before concluding that there was no bias. He likened the ABP’s response to that of study authors omitting selection bias when discussing the limitations of their study.

Courtney Edgar-Zarate, MD, med/peds hospitalist and associate program director of the internal medicine/pediatrics residency at the University of Arkansas, expressed concerns that the ABP’s stringent clinical patient care hours criterion may unintentionally result in ineligibility for many mid-career or senior med/peds hospitalists. Dr. Edgar-Zarate also voiced concerns that graduating med/peds residents were electing not to pursue careers in hospital medicine because they would be required to complete a PHM fellowship to become a pediatric hospitalist, when a similar fellowship is not required to practice adult hospital medicine.

The Society of Hospital Medicine shared its position in regard to the ABP’s response in a Special Announcement in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.7 In it, SHM’s pediatric leaders recognized physicians for the excellent care they provide to hospitalized children. They stated that SHM would continue to support all hospitalists, independent of board eligibility status, and would continue to offer these hospitalists the merit-based Fellow designation. SHM’s pediatric leaders also proposed future directions for the ABP, including a Focused Practice Pathway in Hospital Medicine (FPHM), such as what the American Board of Internal Medicine and the American Board of Family Medicine have adopted for board recertification in internal medicine and family medicine. This maintenance of certification program that allows physicians primarily practicing in inpatient settings to focus their continuing education on inpatient practice, and is not a subspecialty.7

Dr. Edgar-Zarate fully supports the future directions for pediatric hospitalists outlined in SHM’s Special Announcement. She hopes that the ABP will support the FPHM. She feels the FPHM will encourage more med/peds physicians to practice med/peds hospital medicine. L. Nell Hodo, MD, a family medicine–trained pediatric hospitalist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, joins Dr. Edgar-Zarate in supporting an FPHM for PHM, and feels that it will open the door for hospitalists who are ineligible for the practice pathway to be able to focus their recertification on the inpatient setting.

Dr. Hodo and Dr. Desai hope that rather than excluding those who are not PHM board eligible/certified, institutions and professional organizations will consider all qualifications when hiring, mentoring, and promoting physicians who care for hospitalized children. Dr. Natt, Dr. Schwenk, Dr. Edgar-Zarate, and Dr. Hodo appreciate that SHM is leading the way, and will continue to allow all hospitalists who care for children to receive Fellow designation.

Dr. Kumar is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. The American Board of Pediatrics. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. https://www.abp.org/sites/abp/files/phm-petition-response.pdf. Published 2019.

2. Barrett DJ, McGuinness GA, Cunha CA, et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: A proposed new subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1823.

3. The American Board of Pediatrics. Pediatric Hospital Medicine Certification. https://www.abp.org/content/pediatric-hospital-medicine-certification. Published 2019.

4. Skey D. Pediatric Hospitalists, It’s time to take a stand on the PHM Boards Application Process! Five Dog Development, LLC.

5. Nichols DG, Woods SZ. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):586-8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3322.

6. Gold JM et al. Collective action and effective dialogue to address gender bias in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):630-2. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3331.

7. Chang WW et al. Society of Hospital Medicine position on the American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):589-90. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3326.

Autumn is a busy time for pediatric hospitalists, with this autumn being particularly eventful as the first American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) certifying exam for Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) will be offered on Nov. 12, 2019.

More than 1,600 med/peds and pediatric hospitalists applied to be eligible for the 2019 exam, 71% of whom were women. At least 3.9% of those applicants were denied eligibility for the 2019 exam.1 These denials resulted in discussions on the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine (AAP SOHM) email listserv related to unintentional gender bias.

PHM was first recognized as a subspecialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties in December 2015.2 Since that time, the ABP’s PHM sub-board developed eligibility criteria for practicing pediatric and med/peds hospitalists to apply for the exam. The sub-board identified three paths: a training pathway for applicants who had completed a 2-year PHM fellowship, a practice pathway for those satisfying ABP criteria for clinical activity in PHM, and a combined pathway for applicants who had completed PHM fellowships lasting less than 2 years.

Based on these pathways, 1,627 applicants applied for eligibility for the first PHM board certification exam.1 However, many concerns arose with the practice pathway eligibility criteria.

The PHM practice pathway initially included the following eligibility criteria:

• General pediatrics board certification.

• PHM practice “look back” period ends on or before June 30 of the exam year and starts 4 years earlier.

• More than 0.5 FTE professional PHM-related activities (patient-care, research, administration), defined as more than 900 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• More than 0.25 FTE direct patient care of hospitalized children, defined as more than 450 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Practice covers the full range of hospitalized children with regard to age, diagnoses, and complexity.

• Practice interruptions cannot exceed 3 months in the preceding 4 years, or 6 months in the preceding 5 years.

• Practice experience and hours were acquired in the United States and Canada.1,3

The start date and practice interruptions criteria in the practice pathway posed hurdles for many female applicants. Many women voiced concerns about feeling disadvantaged when applying for the PHM certifying exam and some of these women shared their concerns on the AAP SOHM email listserv. In response to these concerns, the PHM community called for increased transparency from the ABP related to denials, specifically related to unintentional gender bias against women applying for the exam.

David Skey, MD, and Jamee Walters, MD, pediatric hospitalists at Arnold Palmer Medical Center in Orlando, heard these concerns and decided to draft a petition with the help of legal counsel. The petition “demand[ed] immediate action,” and “request[ed] a formal response from the ABP regarding the practice pathway criteria.” The petition also stated that there was insufficient data to determine if the practice pathway “disadvantages women.” The petition asked the ABP to “facilitate a timely analysis to determine if gender bias” was present, or to perform an internal analysis and “release the findings publicly.”4

The petition was shared with the PHM community via the AAP SOHM listserv on July 29, 2019. Dr. Walters stated she was pleased by the response she and Dr. Skey received from the PHM community, on and off the AAP SOHM listserv. The petition was submitted to the ABP on Aug. 6, 2019, with 1,479 signatures.

On Aug. 29, 2019, the ABP’s response was shared on the AAP SOHM email listserv1 and was later published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine as a Special Announcement.5 In its response, the ABP stated that the gender bias allegation was “not supported by the facts” as there was “no significant difference between the percentage of women and men who were denied” eligibility.”5 In addressing the gender bias allegations and clarifying the practice pathway eligibility, the ABP removed the practice interruption criteria and modified the practice pathway criteria as follows:

• General pediatrics board certification.

• PHM practice started on or before July 2015 (for board eligibility in 2019).

• Professional PHM-related activities (patient-care, research, administration), defined as more than 900-1000 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Direct patient care of hospitalized children, defined as more than 450-500 hours/year every year for the preceding 4 years.

• Practice covers the full range of hospitalized children with regard to age, diagnoses, and complexity.

• Practice experience and hours were acquired in the United States and Canada.1

Following the release of the ABP’s response, many members of the PHM community remain concerned about the ABP’s revised criteria. Arti Desai, MD, pediatric hospitalist at Seattle Children’s and senior author on a “Perspectives in Hospital Medicine” in the Journal of Hospital Medicine,6 was appreciative that the ABP chose to remove the practice interruptions criterion. However, she and her colleagues remain concerned about lingering gender bias in the ABP’s practice pathway eligibility criteria surrounding the “start date” criterion. The authors state that this criterion differentially affects women, as women may take time off during or after residency for maternity or family leave. Dr. Desai states that this criterion alone can affect a woman’s chance for being eligible for the practice pathway.

Other members of the PHM community also expressed concerns about the ABP’s response to the PHM petition. Beth C. Natt, MD, pediatric hospitalist and director of pediatric hospital medicine regional programs at Connecticut Children’s in Hartford, felt that the population may have been self-selected, as the ABP’s data were limited to individuals who applied for exam eligibility. She was concerned that the data excluded pediatric hospitalists who chose not to apply because of uncertainty about meeting eligibility criteria. Klint Schwenk, MD, pediatric hospitalist at Norton Children’s Hospital in Louisville, Ky., stated that he wished the ABP had addressed the number of pediatric hospitalists who elected not to apply based on fear of ineligibility before concluding that there was no bias. He likened the ABP’s response to that of study authors omitting selection bias when discussing the limitations of their study.

Courtney Edgar-Zarate, MD, med/peds hospitalist and associate program director of the internal medicine/pediatrics residency at the University of Arkansas, expressed concerns that the ABP’s stringent clinical patient care hours criterion may unintentionally result in ineligibility for many mid-career or senior med/peds hospitalists. Dr. Edgar-Zarate also voiced concerns that graduating med/peds residents were electing not to pursue careers in hospital medicine because they would be required to complete a PHM fellowship to become a pediatric hospitalist, when a similar fellowship is not required to practice adult hospital medicine.

The Society of Hospital Medicine shared its position in regard to the ABP’s response in a Special Announcement in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.7 In it, SHM’s pediatric leaders recognized physicians for the excellent care they provide to hospitalized children. They stated that SHM would continue to support all hospitalists, independent of board eligibility status, and would continue to offer these hospitalists the merit-based Fellow designation. SHM’s pediatric leaders also proposed future directions for the ABP, including a Focused Practice Pathway in Hospital Medicine (FPHM), such as what the American Board of Internal Medicine and the American Board of Family Medicine have adopted for board recertification in internal medicine and family medicine. This maintenance of certification program that allows physicians primarily practicing in inpatient settings to focus their continuing education on inpatient practice, and is not a subspecialty.7

Dr. Edgar-Zarate fully supports the future directions for pediatric hospitalists outlined in SHM’s Special Announcement. She hopes that the ABP will support the FPHM. She feels the FPHM will encourage more med/peds physicians to practice med/peds hospital medicine. L. Nell Hodo, MD, a family medicine–trained pediatric hospitalist at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York, joins Dr. Edgar-Zarate in supporting an FPHM for PHM, and feels that it will open the door for hospitalists who are ineligible for the practice pathway to be able to focus their recertification on the inpatient setting.

Dr. Hodo and Dr. Desai hope that rather than excluding those who are not PHM board eligible/certified, institutions and professional organizations will consider all qualifications when hiring, mentoring, and promoting physicians who care for hospitalized children. Dr. Natt, Dr. Schwenk, Dr. Edgar-Zarate, and Dr. Hodo appreciate that SHM is leading the way, and will continue to allow all hospitalists who care for children to receive Fellow designation.

Dr. Kumar is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University and a pediatric hospitalist at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. She is the pediatric editor of The Hospitalist.

References

1. The American Board of Pediatrics. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. https://www.abp.org/sites/abp/files/phm-petition-response.pdf. Published 2019.

2. Barrett DJ, McGuinness GA, Cunha CA, et al. Pediatric hospital medicine: A proposed new subspecialty. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3). doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1823.

3. The American Board of Pediatrics. Pediatric Hospital Medicine Certification. https://www.abp.org/content/pediatric-hospital-medicine-certification. Published 2019.

4. Skey D. Pediatric Hospitalists, It’s time to take a stand on the PHM Boards Application Process! Five Dog Development, LLC.

5. Nichols DG, Woods SZ. The American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):586-8. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3322.

6. Gold JM et al. Collective action and effective dialogue to address gender bias in medicine. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):630-2. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3331.

7. Chang WW et al. Society of Hospital Medicine position on the American Board of Pediatrics response to the Pediatric Hospital Medicine petition. J Hosp Med. 2019 Oct;14(10):589-90. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3326.

Automated ventilation outperformed nurses in post-op cardiac care

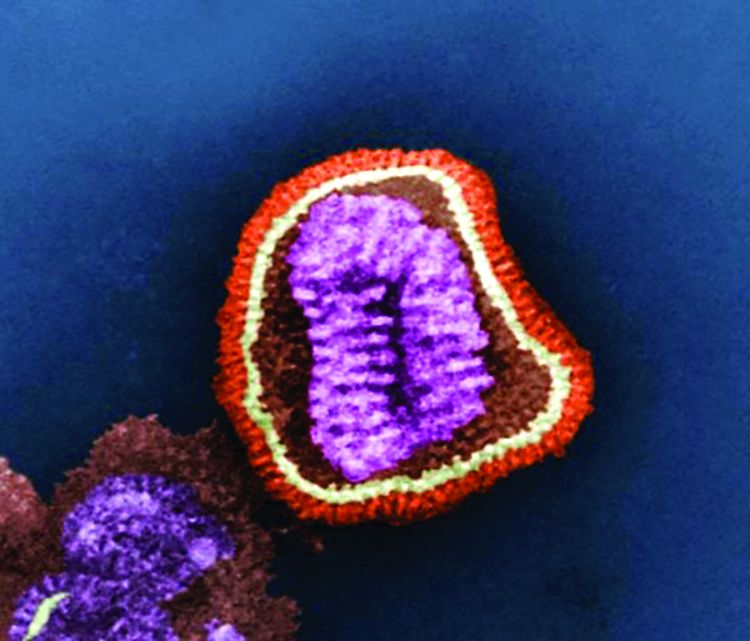

MADRID – In patients managed on mechanical ventilation in an intensive care unit following cardiac surgery, a fully automated system provides more reliable ventilatory support than highly experienced ICU nurses, suggest results of a randomized trial.

The study’s control group received usual care, which means that nurses adjusted mechanical ventilation manually in response to respiratory rate, tidal volume, positive end-respiratory pressure (PEEP), and other factors to maintain ventilation within parameters associated with safe respiration. The experimental group was managed with a fully automated closed-loop system to make these adjustments without any nurse intervention.

For those in the experimental group “the proportion of time in the optimal zone was increased and the proportion of time in the unsafe zone was decreased” relative to those randomized to conventional nursing care, Marcus J. Schultz, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Conducted at a hospital with an experienced ICU staff, the study had a control arm that was managed by “dedicated nurses who, I can tell you, are very eager to provide the best level of care possible,” said Dr. Schultz, professor of experimental intensive care, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands..

The investigator-initiated POSITiVE trial randomized 220 cardiac surgery patients scheduled to receive postoperative mechanical ventilation in the ICU. Exclusions included those with class III or higher chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a requirement for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), or a history of lung surgery.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of time spent in an optimal zone, an acceptable zone, or a dangerous zone of ventilation based on predefined values for tidal volume, maximum airway pressure, end-tidal CO2, and oxygen saturation (SpO2).

The greatest between-group difference was seen in the proportion of time spent in the optimal zone. This climbed from approximately 35% in the control arm to slightly more than 70% in the experimental arm, a significant difference. The proportion of time in the dangerous zone was reduced from approximately 6% in the control arm to 3% in the automated arm. On average nurse-managed patients spent nearly 60% of the time in the acceptable zone versus less than 30% of those in the automated experimental arm.

A heat map using green, yellow, and red to represent optimal, acceptable, and dangerous zones, respectively, for individual participants in the trial provided a more stark global impression. For the control group, the heat map was primarily yellow with scattered dashes of green and red. For the experimental group, the map was primarily green with dashes of yellow and a much smaller number of red dashes relative to the control group.

In addition, the time to spontaneous breathing was 38% shorter for those randomized to automated ventilation than to conventional care, a significant difference.

There are now many devices marketed for automated ventilation, according to Dr. Schultz. The device used in this study was the proprietary INTELLiVENT-ASV system, marketed by Hamilton Medical, which was selected based on prior satisfactory experience. Although not unique, this system has sophisticated software to adjust ventilation to reach targets set by the clinician on the basis of information it is receiving from physiologic sensors for such variables as respiratory rate, tidal volume, and inspiratory pressure.

“It is frequently adjusting the PEEP levels to reach the lowest driving pressure,” said Dr. Schultz. Among its many other features, it also “gives spontaneous breathing trials automatically.”

Uncomplicated patients were selected purposefully to test this system, but Dr. Schultz said that a second trial, called POSITiVE 2, is now being planned that will enroll more complex patients. Keeping complex patients within the optimal zone as defined by tidal volume and other critical variables has the potential to reduce the lung damage that is known to occur when these are not optimized.

“Applying safe ventilatory support in clinical practice remains a serious challenge and is extremely time consuming,” Dr. Schultz said. He reported that fully automated ventilation appears to be reliable, and “it takes out the human factor” in regard to diligence in monitoring and potential for error.

Overall, these results support the potential for a fully automated system to improve optimal ventilatory support, reduce risk of lung injury, and reduce staffing required for monitoring of mechanical ventilation, according to Dr. Schultz.

Relative costs were not evaluated in this analysis, but might be another factor relevant to the value of fully automated ventilation in ICU patients.

MADRID – In patients managed on mechanical ventilation in an intensive care unit following cardiac surgery, a fully automated system provides more reliable ventilatory support than highly experienced ICU nurses, suggest results of a randomized trial.

The study’s control group received usual care, which means that nurses adjusted mechanical ventilation manually in response to respiratory rate, tidal volume, positive end-respiratory pressure (PEEP), and other factors to maintain ventilation within parameters associated with safe respiration. The experimental group was managed with a fully automated closed-loop system to make these adjustments without any nurse intervention.

For those in the experimental group “the proportion of time in the optimal zone was increased and the proportion of time in the unsafe zone was decreased” relative to those randomized to conventional nursing care, Marcus J. Schultz, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Conducted at a hospital with an experienced ICU staff, the study had a control arm that was managed by “dedicated nurses who, I can tell you, are very eager to provide the best level of care possible,” said Dr. Schultz, professor of experimental intensive care, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands..

The investigator-initiated POSITiVE trial randomized 220 cardiac surgery patients scheduled to receive postoperative mechanical ventilation in the ICU. Exclusions included those with class III or higher chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a requirement for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), or a history of lung surgery.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of time spent in an optimal zone, an acceptable zone, or a dangerous zone of ventilation based on predefined values for tidal volume, maximum airway pressure, end-tidal CO2, and oxygen saturation (SpO2).

The greatest between-group difference was seen in the proportion of time spent in the optimal zone. This climbed from approximately 35% in the control arm to slightly more than 70% in the experimental arm, a significant difference. The proportion of time in the dangerous zone was reduced from approximately 6% in the control arm to 3% in the automated arm. On average nurse-managed patients spent nearly 60% of the time in the acceptable zone versus less than 30% of those in the automated experimental arm.

A heat map using green, yellow, and red to represent optimal, acceptable, and dangerous zones, respectively, for individual participants in the trial provided a more stark global impression. For the control group, the heat map was primarily yellow with scattered dashes of green and red. For the experimental group, the map was primarily green with dashes of yellow and a much smaller number of red dashes relative to the control group.

In addition, the time to spontaneous breathing was 38% shorter for those randomized to automated ventilation than to conventional care, a significant difference.

There are now many devices marketed for automated ventilation, according to Dr. Schultz. The device used in this study was the proprietary INTELLiVENT-ASV system, marketed by Hamilton Medical, which was selected based on prior satisfactory experience. Although not unique, this system has sophisticated software to adjust ventilation to reach targets set by the clinician on the basis of information it is receiving from physiologic sensors for such variables as respiratory rate, tidal volume, and inspiratory pressure.

“It is frequently adjusting the PEEP levels to reach the lowest driving pressure,” said Dr. Schultz. Among its many other features, it also “gives spontaneous breathing trials automatically.”

Uncomplicated patients were selected purposefully to test this system, but Dr. Schultz said that a second trial, called POSITiVE 2, is now being planned that will enroll more complex patients. Keeping complex patients within the optimal zone as defined by tidal volume and other critical variables has the potential to reduce the lung damage that is known to occur when these are not optimized.

“Applying safe ventilatory support in clinical practice remains a serious challenge and is extremely time consuming,” Dr. Schultz said. He reported that fully automated ventilation appears to be reliable, and “it takes out the human factor” in regard to diligence in monitoring and potential for error.

Overall, these results support the potential for a fully automated system to improve optimal ventilatory support, reduce risk of lung injury, and reduce staffing required for monitoring of mechanical ventilation, according to Dr. Schultz.

Relative costs were not evaluated in this analysis, but might be another factor relevant to the value of fully automated ventilation in ICU patients.

MADRID – In patients managed on mechanical ventilation in an intensive care unit following cardiac surgery, a fully automated system provides more reliable ventilatory support than highly experienced ICU nurses, suggest results of a randomized trial.

The study’s control group received usual care, which means that nurses adjusted mechanical ventilation manually in response to respiratory rate, tidal volume, positive end-respiratory pressure (PEEP), and other factors to maintain ventilation within parameters associated with safe respiration. The experimental group was managed with a fully automated closed-loop system to make these adjustments without any nurse intervention.

For those in the experimental group “the proportion of time in the optimal zone was increased and the proportion of time in the unsafe zone was decreased” relative to those randomized to conventional nursing care, Marcus J. Schultz, MD, reported at the annual congress of the European Respiratory Society.

Conducted at a hospital with an experienced ICU staff, the study had a control arm that was managed by “dedicated nurses who, I can tell you, are very eager to provide the best level of care possible,” said Dr. Schultz, professor of experimental intensive care, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands..

The investigator-initiated POSITiVE trial randomized 220 cardiac surgery patients scheduled to receive postoperative mechanical ventilation in the ICU. Exclusions included those with class III or higher chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a requirement for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), or a history of lung surgery.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of time spent in an optimal zone, an acceptable zone, or a dangerous zone of ventilation based on predefined values for tidal volume, maximum airway pressure, end-tidal CO2, and oxygen saturation (SpO2).

The greatest between-group difference was seen in the proportion of time spent in the optimal zone. This climbed from approximately 35% in the control arm to slightly more than 70% in the experimental arm, a significant difference. The proportion of time in the dangerous zone was reduced from approximately 6% in the control arm to 3% in the automated arm. On average nurse-managed patients spent nearly 60% of the time in the acceptable zone versus less than 30% of those in the automated experimental arm.

A heat map using green, yellow, and red to represent optimal, acceptable, and dangerous zones, respectively, for individual participants in the trial provided a more stark global impression. For the control group, the heat map was primarily yellow with scattered dashes of green and red. For the experimental group, the map was primarily green with dashes of yellow and a much smaller number of red dashes relative to the control group.

In addition, the time to spontaneous breathing was 38% shorter for those randomized to automated ventilation than to conventional care, a significant difference.

There are now many devices marketed for automated ventilation, according to Dr. Schultz. The device used in this study was the proprietary INTELLiVENT-ASV system, marketed by Hamilton Medical, which was selected based on prior satisfactory experience. Although not unique, this system has sophisticated software to adjust ventilation to reach targets set by the clinician on the basis of information it is receiving from physiologic sensors for such variables as respiratory rate, tidal volume, and inspiratory pressure.

“It is frequently adjusting the PEEP levels to reach the lowest driving pressure,” said Dr. Schultz. Among its many other features, it also “gives spontaneous breathing trials automatically.”

Uncomplicated patients were selected purposefully to test this system, but Dr. Schultz said that a second trial, called POSITiVE 2, is now being planned that will enroll more complex patients. Keeping complex patients within the optimal zone as defined by tidal volume and other critical variables has the potential to reduce the lung damage that is known to occur when these are not optimized.

“Applying safe ventilatory support in clinical practice remains a serious challenge and is extremely time consuming,” Dr. Schultz said. He reported that fully automated ventilation appears to be reliable, and “it takes out the human factor” in regard to diligence in monitoring and potential for error.

Overall, these results support the potential for a fully automated system to improve optimal ventilatory support, reduce risk of lung injury, and reduce staffing required for monitoring of mechanical ventilation, according to Dr. Schultz.

Relative costs were not evaluated in this analysis, but might be another factor relevant to the value of fully automated ventilation in ICU patients.

REPORTING FROM ERS 2019

Who makes the rules? CMS and IPPS

Major MS-DRG changes postponed

The introduction of the Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) through amendment of the Social Security Act in 1983 transformed hospital reimbursement in the United States. Under the IPPS, a new form of Medicare prospective payment that paid hospitals a fixed amount per discharge for inpatient services was created: the diagnosis-related group (DRG). This eliminated the preceding retrospective cost reimbursement system in an attempt to stop health care price inflation.

Each DRG represents a grouping of similar conditions and procedures for services provided during an inpatient hospitalization reimbursed under Medicare Part A. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services uses the Medicare Severity DRG (MS-DRG) system to account for severity of illness and resource consumption. There are three levels of severity based upon secondary diagnosis: major complication/comorbidity (MCC), complication/comorbidity (CC), and noncomplication/comorbidity (non-CC).

Payment rates are defined by base rates for operating costs and capital-related costs which are adjusted for relative weight (the average cost within a DRG, compared with the average Medicare case cost) and market condition adjustments. As the largest single health care payer in the United States, CMS’ annual changes to the IPPS have a major impact on hospital reimbursement.

In May 2019, CMS released its annual proposed rule for the Hospital IPPS suggesting extensive changes to MS-DRG reimbursements. Notably, CMS proposed changing the severity level of nearly 1,500 diagnosis codes by adjusting their categorization between MCC, CC, or non-CC. The majority of these changes included downgrading MCCs to CCs or non-CCs. In fact, 87% of the changes involved a downgrade from one of the higher severity levels to a non-CC level, while only 13% involved an upgrade from a lower severity level to MCC level.

The CMS derived these changes from an algorithmic review and input from their clinical advisors to determine each diagnoses impact on resource utilization. Multiple major groups of codes were included in the downgraded groups, including secondary cancer diagnoses, organ transplant status, and hip fracture.

Evaluating codes based on coded resource use alone could have had a major negative impact on the clinical practice of hospitalists as it undervalues cognitive and clinical work associated with these secondary diagnoses. As an example, malignant neoplasm of head of pancreas (ICD-10, C25.0) was proposed to move to a non-CC. Under CMS’ proposed rule, if a patient was admitted with complications of pancreatic cancer such as cholangitis caused by biliary obstruction, the pancreatic cancer diagnosis would not serve as a CC since the primary condition for which the patient was hospitalized would be cholangitis. The anticipated increase in such a patient’s length of stay, severity of illness, and expected resource utilization would be grossly misrepresented in this case by CMS’ proposed rule changes. CMS also proposed to move major organ-transplant status (including heart, lung, kidney, and pancreas) from CC to non-CC status. Again, the cognitive work and resource utilization required to manage these patients would be underrepresented with this change, given the increased complexity of managing immunosuppressant medications or conducting an infectious diagnostic work-up in immunosuppressed patients.

The Society of Hospital Medicine Public Policy Committee provides comments annually to CMS on the IPPS, advocating for hospitalists and patients. After advocacy efforts from SHM and other groups, expressing concern about making such significant changes to the DRG system without further study, the IPPS final rule was released on August 2, 2019. SHM’s efforts paid off. The final rule excluded the proposed broad changes to the MS-DRG system that were in the proposed rule.

In deciding not to finalize the proposed severity level changes, CMS wrote that the adoption of these broad changes will be postponed in order “to fully consider the technical feedback provided” regarding the proposal. The final rule also describes making a “test GROUPER [software program] publicly available to allow for impact testing,” and allows for the possibility of phasing in changes and eliciting feedback. SHM is fully supportive of the decision to postpone major changes to the MS-DRG system in the IPPS until further review is obtained, and will continue to monitor this issue and provide appropriate input to CMS for our hospitalist members.

As hospitalists, it is important to understand the foundational role that public policy and CMS rule creation have on our work. Influencing change to the MS-DRG system is yet another example of how SHM’s work has impacted the policy domain, limiting negative effects on our members and advancing the practice of hospital medicine.

Dr. Biebelhausen is head of the section of hospital medicine at Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle. Dr. Cowart is a hospitalist at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. Dr. Hamilton is a hospitalist and associate chief quality officer at the Cleveland Clinic.

Major MS-DRG changes postponed

Major MS-DRG changes postponed

The introduction of the Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) through amendment of the Social Security Act in 1983 transformed hospital reimbursement in the United States. Under the IPPS, a new form of Medicare prospective payment that paid hospitals a fixed amount per discharge for inpatient services was created: the diagnosis-related group (DRG). This eliminated the preceding retrospective cost reimbursement system in an attempt to stop health care price inflation.

Each DRG represents a grouping of similar conditions and procedures for services provided during an inpatient hospitalization reimbursed under Medicare Part A. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services uses the Medicare Severity DRG (MS-DRG) system to account for severity of illness and resource consumption. There are three levels of severity based upon secondary diagnosis: major complication/comorbidity (MCC), complication/comorbidity (CC), and noncomplication/comorbidity (non-CC).

Payment rates are defined by base rates for operating costs and capital-related costs which are adjusted for relative weight (the average cost within a DRG, compared with the average Medicare case cost) and market condition adjustments. As the largest single health care payer in the United States, CMS’ annual changes to the IPPS have a major impact on hospital reimbursement.

In May 2019, CMS released its annual proposed rule for the Hospital IPPS suggesting extensive changes to MS-DRG reimbursements. Notably, CMS proposed changing the severity level of nearly 1,500 diagnosis codes by adjusting their categorization between MCC, CC, or non-CC. The majority of these changes included downgrading MCCs to CCs or non-CCs. In fact, 87% of the changes involved a downgrade from one of the higher severity levels to a non-CC level, while only 13% involved an upgrade from a lower severity level to MCC level.

The CMS derived these changes from an algorithmic review and input from their clinical advisors to determine each diagnoses impact on resource utilization. Multiple major groups of codes were included in the downgraded groups, including secondary cancer diagnoses, organ transplant status, and hip fracture.

Evaluating codes based on coded resource use alone could have had a major negative impact on the clinical practice of hospitalists as it undervalues cognitive and clinical work associated with these secondary diagnoses. As an example, malignant neoplasm of head of pancreas (ICD-10, C25.0) was proposed to move to a non-CC. Under CMS’ proposed rule, if a patient was admitted with complications of pancreatic cancer such as cholangitis caused by biliary obstruction, the pancreatic cancer diagnosis would not serve as a CC since the primary condition for which the patient was hospitalized would be cholangitis. The anticipated increase in such a patient’s length of stay, severity of illness, and expected resource utilization would be grossly misrepresented in this case by CMS’ proposed rule changes. CMS also proposed to move major organ-transplant status (including heart, lung, kidney, and pancreas) from CC to non-CC status. Again, the cognitive work and resource utilization required to manage these patients would be underrepresented with this change, given the increased complexity of managing immunosuppressant medications or conducting an infectious diagnostic work-up in immunosuppressed patients.

The Society of Hospital Medicine Public Policy Committee provides comments annually to CMS on the IPPS, advocating for hospitalists and patients. After advocacy efforts from SHM and other groups, expressing concern about making such significant changes to the DRG system without further study, the IPPS final rule was released on August 2, 2019. SHM’s efforts paid off. The final rule excluded the proposed broad changes to the MS-DRG system that were in the proposed rule.

In deciding not to finalize the proposed severity level changes, CMS wrote that the adoption of these broad changes will be postponed in order “to fully consider the technical feedback provided” regarding the proposal. The final rule also describes making a “test GROUPER [software program] publicly available to allow for impact testing,” and allows for the possibility of phasing in changes and eliciting feedback. SHM is fully supportive of the decision to postpone major changes to the MS-DRG system in the IPPS until further review is obtained, and will continue to monitor this issue and provide appropriate input to CMS for our hospitalist members.

As hospitalists, it is important to understand the foundational role that public policy and CMS rule creation have on our work. Influencing change to the MS-DRG system is yet another example of how SHM’s work has impacted the policy domain, limiting negative effects on our members and advancing the practice of hospital medicine.

Dr. Biebelhausen is head of the section of hospital medicine at Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle. Dr. Cowart is a hospitalist at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. Dr. Hamilton is a hospitalist and associate chief quality officer at the Cleveland Clinic.

The introduction of the Medicare Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) through amendment of the Social Security Act in 1983 transformed hospital reimbursement in the United States. Under the IPPS, a new form of Medicare prospective payment that paid hospitals a fixed amount per discharge for inpatient services was created: the diagnosis-related group (DRG). This eliminated the preceding retrospective cost reimbursement system in an attempt to stop health care price inflation.

Each DRG represents a grouping of similar conditions and procedures for services provided during an inpatient hospitalization reimbursed under Medicare Part A. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services uses the Medicare Severity DRG (MS-DRG) system to account for severity of illness and resource consumption. There are three levels of severity based upon secondary diagnosis: major complication/comorbidity (MCC), complication/comorbidity (CC), and noncomplication/comorbidity (non-CC).

Payment rates are defined by base rates for operating costs and capital-related costs which are adjusted for relative weight (the average cost within a DRG, compared with the average Medicare case cost) and market condition adjustments. As the largest single health care payer in the United States, CMS’ annual changes to the IPPS have a major impact on hospital reimbursement.

In May 2019, CMS released its annual proposed rule for the Hospital IPPS suggesting extensive changes to MS-DRG reimbursements. Notably, CMS proposed changing the severity level of nearly 1,500 diagnosis codes by adjusting their categorization between MCC, CC, or non-CC. The majority of these changes included downgrading MCCs to CCs or non-CCs. In fact, 87% of the changes involved a downgrade from one of the higher severity levels to a non-CC level, while only 13% involved an upgrade from a lower severity level to MCC level.

The CMS derived these changes from an algorithmic review and input from their clinical advisors to determine each diagnoses impact on resource utilization. Multiple major groups of codes were included in the downgraded groups, including secondary cancer diagnoses, organ transplant status, and hip fracture.

Evaluating codes based on coded resource use alone could have had a major negative impact on the clinical practice of hospitalists as it undervalues cognitive and clinical work associated with these secondary diagnoses. As an example, malignant neoplasm of head of pancreas (ICD-10, C25.0) was proposed to move to a non-CC. Under CMS’ proposed rule, if a patient was admitted with complications of pancreatic cancer such as cholangitis caused by biliary obstruction, the pancreatic cancer diagnosis would not serve as a CC since the primary condition for which the patient was hospitalized would be cholangitis. The anticipated increase in such a patient’s length of stay, severity of illness, and expected resource utilization would be grossly misrepresented in this case by CMS’ proposed rule changes. CMS also proposed to move major organ-transplant status (including heart, lung, kidney, and pancreas) from CC to non-CC status. Again, the cognitive work and resource utilization required to manage these patients would be underrepresented with this change, given the increased complexity of managing immunosuppressant medications or conducting an infectious diagnostic work-up in immunosuppressed patients.

The Society of Hospital Medicine Public Policy Committee provides comments annually to CMS on the IPPS, advocating for hospitalists and patients. After advocacy efforts from SHM and other groups, expressing concern about making such significant changes to the DRG system without further study, the IPPS final rule was released on August 2, 2019. SHM’s efforts paid off. The final rule excluded the proposed broad changes to the MS-DRG system that were in the proposed rule.

In deciding not to finalize the proposed severity level changes, CMS wrote that the adoption of these broad changes will be postponed in order “to fully consider the technical feedback provided” regarding the proposal. The final rule also describes making a “test GROUPER [software program] publicly available to allow for impact testing,” and allows for the possibility of phasing in changes and eliciting feedback. SHM is fully supportive of the decision to postpone major changes to the MS-DRG system in the IPPS until further review is obtained, and will continue to monitor this issue and provide appropriate input to CMS for our hospitalist members.

As hospitalists, it is important to understand the foundational role that public policy and CMS rule creation have on our work. Influencing change to the MS-DRG system is yet another example of how SHM’s work has impacted the policy domain, limiting negative effects on our members and advancing the practice of hospital medicine.

Dr. Biebelhausen is head of the section of hospital medicine at Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle. Dr. Cowart is a hospitalist at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla. Dr. Hamilton is a hospitalist and associate chief quality officer at the Cleveland Clinic.

CDC updates guidance on vaping-associated lung injury

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has released an updated interim clinical guidance for health providers for evaluating and treating patients with lung injury associated with e-cigarette use or vaping.

In a telebriefing, Anne Schuchat, MD, CDC principal deputy director, and her colleagues answered questions about the current investigation into the source of this lung injury outbreak and the updated clinical guidance. Dr. Schuchat said, “I can’t stress enough the seriousness of these injuries.” She added, “We are not seeing a drop in cases” but a continuation of the trend of hospitalization and deaths that started in August 2019.

Investigation update

The investigation to date has yielded some information about current cases of lung injury related to vaping:

• The acronym EVALI has been developed to refer to e-cigarette, or vaping products use associated lung injury;

• 1,299 EVALI cases have been reported as of Oct. 8;

• No single compound or ingredient has emerged as the cause of these injuries, and more than one substance may be involved;

• Among the 573 patients for whom data are available on vaping products used in the previous 90 days, 76% reported using THC-containing products; 58% reported using nicotine-containing products; 32% reported exclusive use of THC-containing products, and 13% reported exclusive use of nicotine-containing products;

• Of the 700+ samples sent to the CDC for analysis, most had little or no liquid remaining in the device, limiting content analysis. In 28 THC-containing samples, THC concentrations were found to be 13% - 77% (mean 41%).

• A “handful” of cases of readmission have been reported and the CDC is currently investigating whether these cases included patients who took up vaping again or had some other possible contributing factor.

• The CDC is currently developing an ICD-10 code relevant to EVALI.

Clinical guidance update

The CDC provided detailed guidance on evaluating and caring for patients with EVALI. The recommendations focus on patient history, lab testing, criteria for hospitalization, and follow-up of these patients.

Detailed history of patients presenting with suspected EVALI is especially important for this patient population, given the many unknowns surrounding this condition. The updated guidance states, “All health care providers evaluating patients for EVALI should ask about the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products and ideally should ask about types of substances used (e.g.,THC, cannabis [oil, dabs], nicotine, modified products or the addition of substances not intended by the manufacturer); product source, specific product brand and name; duration and frequency of use, time of last use; product delivery system, and method of use (aerosolization, dabbing, or dripping).” The approach recommended for soliciting accurate information is “empathetic, nonjudgmental” and, the guidelines say, patients should be questioned in private regarding sensitive information to assure confidentiality.

A respiratory virus panel is recommended for all suspected EVALI patients, although at this time, these tests cannot be used to distinguish EVALI from infectious etiologies. All patients should be considered for urine toxicology testing, including testing for THC.

Imaging guidance for suspected EVALI patients includes chest x-ray, with additional CT scan when the x-ray result does not correlate with clinical findings or to evaluate severe or worsening disease.

Recommended criteria for hospitalization of patients with suspected EVALI are those patients with decreased O2 saturation (less than 95%) on room air, are in respiratory distress, or have comorbidities that compromise pulmonary reserve. As of Oct. 8, 96% of patients with suspected EVALI reported to CDC have been hospitalized.

As for medical treatment of these patients, corticosteroids have been found helpful. The statement noted, “Among 140 cases reported nationally to CDC that received corticosteroids, 82% of patients improved

The natural progression of this injury is not known, however, and it is possible that patients might recover without corticosteroids. Given the unknown etiology of the disease and “because the diagnosis remains one of exclusion, aggressive empiric therapy with corticosteroids, antimicrobial, and antiviral therapy might be warranted for patients with severe illness. A range of corticosteroid doses, durations, and taper plans might be considered on a case-by-case basis.”

The report concludes with a strong recommendation that patients hospitalized with EVALI are followed closely with a visit 1-2 weeks after discharge and again with additional testing 1-2 months later. Health care providers are also advised to consult medical specialists, in particular pulmonologists, who can offer further evaluation, recommend empiric treatment, and review indications for bronchoscopy.

Mitch Zeller, JD, director, Center for Tobacco Products with the Food and Drug Administration emphasized the extraordinary complexity of the EVALI problem but noted that the FDA and CDC “will leave no stone unturned until we get to the bottom of it.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has released an updated interim clinical guidance for health providers for evaluating and treating patients with lung injury associated with e-cigarette use or vaping.

In a telebriefing, Anne Schuchat, MD, CDC principal deputy director, and her colleagues answered questions about the current investigation into the source of this lung injury outbreak and the updated clinical guidance. Dr. Schuchat said, “I can’t stress enough the seriousness of these injuries.” She added, “We are not seeing a drop in cases” but a continuation of the trend of hospitalization and deaths that started in August 2019.

Investigation update

The investigation to date has yielded some information about current cases of lung injury related to vaping:

• The acronym EVALI has been developed to refer to e-cigarette, or vaping products use associated lung injury;

• 1,299 EVALI cases have been reported as of Oct. 8;

• No single compound or ingredient has emerged as the cause of these injuries, and more than one substance may be involved;

• Among the 573 patients for whom data are available on vaping products used in the previous 90 days, 76% reported using THC-containing products; 58% reported using nicotine-containing products; 32% reported exclusive use of THC-containing products, and 13% reported exclusive use of nicotine-containing products;

• Of the 700+ samples sent to the CDC for analysis, most had little or no liquid remaining in the device, limiting content analysis. In 28 THC-containing samples, THC concentrations were found to be 13% - 77% (mean 41%).

• A “handful” of cases of readmission have been reported and the CDC is currently investigating whether these cases included patients who took up vaping again or had some other possible contributing factor.

• The CDC is currently developing an ICD-10 code relevant to EVALI.

Clinical guidance update

The CDC provided detailed guidance on evaluating and caring for patients with EVALI. The recommendations focus on patient history, lab testing, criteria for hospitalization, and follow-up of these patients.

Detailed history of patients presenting with suspected EVALI is especially important for this patient population, given the many unknowns surrounding this condition. The updated guidance states, “All health care providers evaluating patients for EVALI should ask about the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products and ideally should ask about types of substances used (e.g.,THC, cannabis [oil, dabs], nicotine, modified products or the addition of substances not intended by the manufacturer); product source, specific product brand and name; duration and frequency of use, time of last use; product delivery system, and method of use (aerosolization, dabbing, or dripping).” The approach recommended for soliciting accurate information is “empathetic, nonjudgmental” and, the guidelines say, patients should be questioned in private regarding sensitive information to assure confidentiality.

A respiratory virus panel is recommended for all suspected EVALI patients, although at this time, these tests cannot be used to distinguish EVALI from infectious etiologies. All patients should be considered for urine toxicology testing, including testing for THC.

Imaging guidance for suspected EVALI patients includes chest x-ray, with additional CT scan when the x-ray result does not correlate with clinical findings or to evaluate severe or worsening disease.

Recommended criteria for hospitalization of patients with suspected EVALI are those patients with decreased O2 saturation (less than 95%) on room air, are in respiratory distress, or have comorbidities that compromise pulmonary reserve. As of Oct. 8, 96% of patients with suspected EVALI reported to CDC have been hospitalized.

As for medical treatment of these patients, corticosteroids have been found helpful. The statement noted, “Among 140 cases reported nationally to CDC that received corticosteroids, 82% of patients improved

The natural progression of this injury is not known, however, and it is possible that patients might recover without corticosteroids. Given the unknown etiology of the disease and “because the diagnosis remains one of exclusion, aggressive empiric therapy with corticosteroids, antimicrobial, and antiviral therapy might be warranted for patients with severe illness. A range of corticosteroid doses, durations, and taper plans might be considered on a case-by-case basis.”

The report concludes with a strong recommendation that patients hospitalized with EVALI are followed closely with a visit 1-2 weeks after discharge and again with additional testing 1-2 months later. Health care providers are also advised to consult medical specialists, in particular pulmonologists, who can offer further evaluation, recommend empiric treatment, and review indications for bronchoscopy.

Mitch Zeller, JD, director, Center for Tobacco Products with the Food and Drug Administration emphasized the extraordinary complexity of the EVALI problem but noted that the FDA and CDC “will leave no stone unturned until we get to the bottom of it.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has released an updated interim clinical guidance for health providers for evaluating and treating patients with lung injury associated with e-cigarette use or vaping.

In a telebriefing, Anne Schuchat, MD, CDC principal deputy director, and her colleagues answered questions about the current investigation into the source of this lung injury outbreak and the updated clinical guidance. Dr. Schuchat said, “I can’t stress enough the seriousness of these injuries.” She added, “We are not seeing a drop in cases” but a continuation of the trend of hospitalization and deaths that started in August 2019.

Investigation update

The investigation to date has yielded some information about current cases of lung injury related to vaping:

• The acronym EVALI has been developed to refer to e-cigarette, or vaping products use associated lung injury;

• 1,299 EVALI cases have been reported as of Oct. 8;

• No single compound or ingredient has emerged as the cause of these injuries, and more than one substance may be involved;

• Among the 573 patients for whom data are available on vaping products used in the previous 90 days, 76% reported using THC-containing products; 58% reported using nicotine-containing products; 32% reported exclusive use of THC-containing products, and 13% reported exclusive use of nicotine-containing products;

• Of the 700+ samples sent to the CDC for analysis, most had little or no liquid remaining in the device, limiting content analysis. In 28 THC-containing samples, THC concentrations were found to be 13% - 77% (mean 41%).

• A “handful” of cases of readmission have been reported and the CDC is currently investigating whether these cases included patients who took up vaping again or had some other possible contributing factor.

• The CDC is currently developing an ICD-10 code relevant to EVALI.

Clinical guidance update

The CDC provided detailed guidance on evaluating and caring for patients with EVALI. The recommendations focus on patient history, lab testing, criteria for hospitalization, and follow-up of these patients.

Detailed history of patients presenting with suspected EVALI is especially important for this patient population, given the many unknowns surrounding this condition. The updated guidance states, “All health care providers evaluating patients for EVALI should ask about the use of e-cigarette, or vaping, products and ideally should ask about types of substances used (e.g.,THC, cannabis [oil, dabs], nicotine, modified products or the addition of substances not intended by the manufacturer); product source, specific product brand and name; duration and frequency of use, time of last use; product delivery system, and method of use (aerosolization, dabbing, or dripping).” The approach recommended for soliciting accurate information is “empathetic, nonjudgmental” and, the guidelines say, patients should be questioned in private regarding sensitive information to assure confidentiality.

A respiratory virus panel is recommended for all suspected EVALI patients, although at this time, these tests cannot be used to distinguish EVALI from infectious etiologies. All patients should be considered for urine toxicology testing, including testing for THC.

Imaging guidance for suspected EVALI patients includes chest x-ray, with additional CT scan when the x-ray result does not correlate with clinical findings or to evaluate severe or worsening disease.

Recommended criteria for hospitalization of patients with suspected EVALI are those patients with decreased O2 saturation (less than 95%) on room air, are in respiratory distress, or have comorbidities that compromise pulmonary reserve. As of Oct. 8, 96% of patients with suspected EVALI reported to CDC have been hospitalized.

As for medical treatment of these patients, corticosteroids have been found helpful. The statement noted, “Among 140 cases reported nationally to CDC that received corticosteroids, 82% of patients improved

The natural progression of this injury is not known, however, and it is possible that patients might recover without corticosteroids. Given the unknown etiology of the disease and “because the diagnosis remains one of exclusion, aggressive empiric therapy with corticosteroids, antimicrobial, and antiviral therapy might be warranted for patients with severe illness. A range of corticosteroid doses, durations, and taper plans might be considered on a case-by-case basis.”

The report concludes with a strong recommendation that patients hospitalized with EVALI are followed closely with a visit 1-2 weeks after discharge and again with additional testing 1-2 months later. Health care providers are also advised to consult medical specialists, in particular pulmonologists, who can offer further evaluation, recommend empiric treatment, and review indications for bronchoscopy.

Mitch Zeller, JD, director, Center for Tobacco Products with the Food and Drug Administration emphasized the extraordinary complexity of the EVALI problem but noted that the FDA and CDC “will leave no stone unturned until we get to the bottom of it.”

REPORTING FROM A CDC TELEBRIEFING

Short-term statin use linked to risk of skin and soft tissue infections

according to a sequence symmetry analysis of prescription claims over a 10-year period reported in the British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology.

In the study, statin use for as little as 91 days was linked with elevated risks of SSTIs and diabetes. However, the increased risk of infection was seen in individuals who did and did not develop diabetes, wrote Humphrey Ko, of the school of pharmacy and biomedical sciences, Curtin University, Perth, Australia, and colleagues.

The current literature on the impact of statins on SSTIs is conflicted, they noted. Previous research shows that statins “may reduce the risk of community-acquired [Staphylococcus aureus] bacteremia and exert antibacterial effects against S. aureus,” and therefore may have potential for reducing SSTI risk “or evolve into promising novel treatments for SSTIs,” the researchers said; they noted, however, that other data show that statins may induce new-onset diabetes.