User login

“You have a pending query”

Specificity is essential in documentation and coding

Throughout medical training, you learn to write complete and detailed notes to communicate with other physicians. As a student and resident, you are praised when you succinctly analyze and address all patient problems while justifying your orders for the day. But notes do not exist just to document patient care; they are the template by which our actual quality of care is judged and our patients’ severity of illness is captured.

Like it or not, ICD-10 coding, documentation, denials, calls, and emails from administrators are integral parts of a hospitalist’s day-to-day job. Why? The specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses affect such metrics as hospital length of stay, mortality, and Case Mix Index documentation.

Good documentation can lead to better severity of illness (SOI) and risk of mortality (ROM) scores, better patient safety indicator (PSI) scores, better Healthgrades scores, better University Hospital Consortium (UHC) scores, and decreased Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) denials as well as appropriate reimbursement. Good documentation can even lead to improved patient care and better perceived treatment outcomes.

It is no surprise that many hospital administrators invest time and money in staff to support the proper usage of language in your notes. Of course, sometimes these well-meaning “queries” can throw you into emotional turmoil as you try to understand what was not clear in your excellent note about your patient’s heart failure exacerbation. In this article, we will try to help you take your specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses to the next level.

Basics of billing

Physicians do not need to become coders but it is helpful to have some understanding of what happens behind the scenes. Not everyone realizes that physician billing is completely different from hospital billing. Physician billing pertains to the care provided by the clinician, whereas hospital billing pertains to the overall care the patient received.

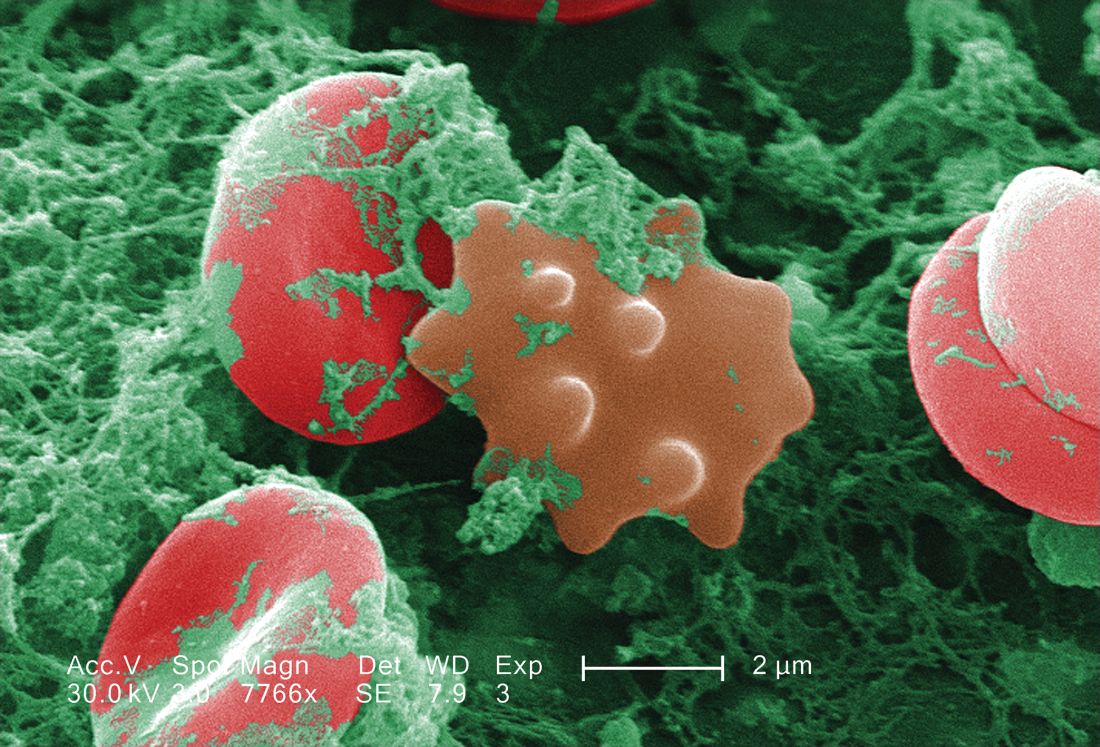

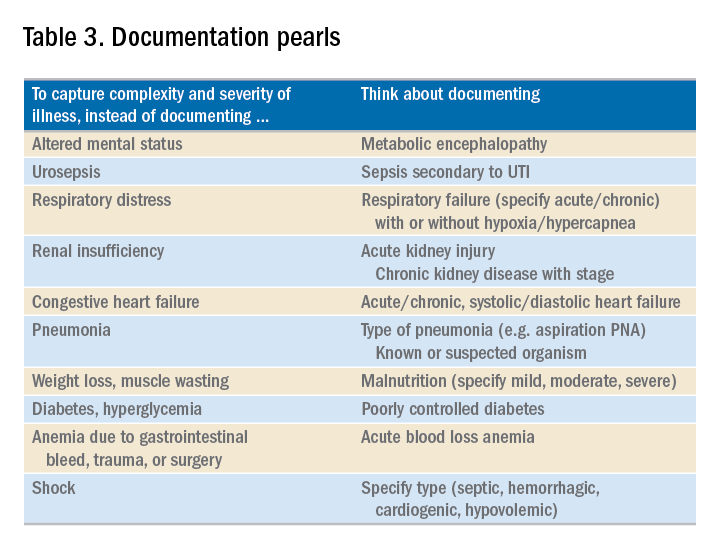

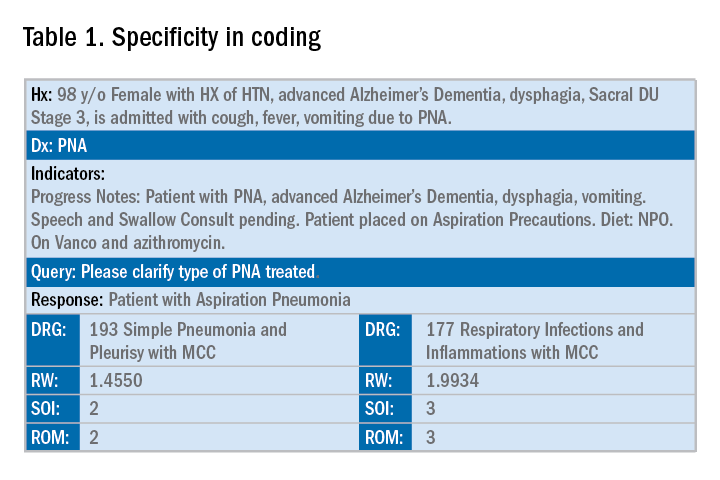

Below is an example of a case of pneumonia, (see Table 1) which shows the importance of specificity. Just by specifying ‘Aspiration’ for the type of pneumonia, we increased the SOI and the expected ROM appropriately. Also see a change in relative weight (RW): Each diagnosis-related group (DRG) is assigned a relative weight = estimated use of resources, and payment per case is based on estimated resource consumption = relative weight x “blended rate for each hospital.”

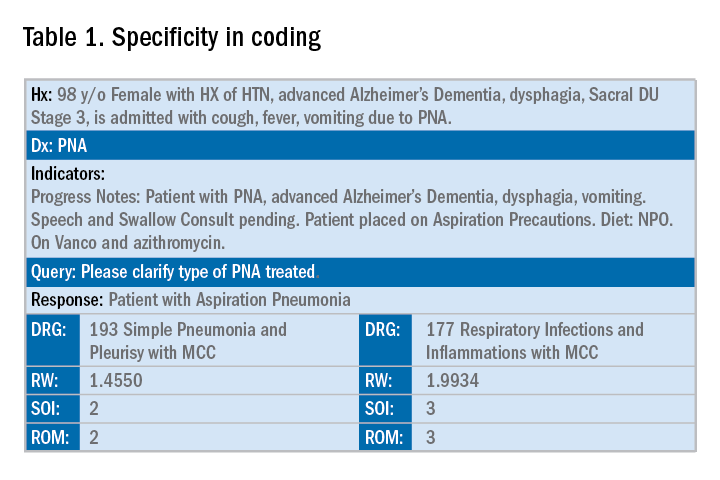

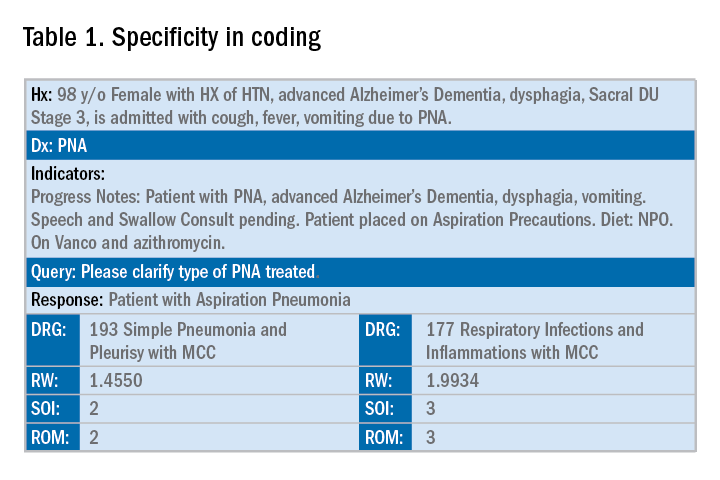

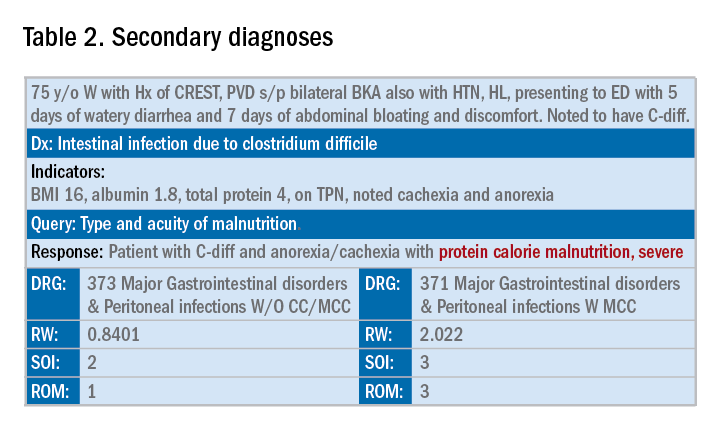

In addition to specificity, it is important to include all secondary diagnosis (know as cc/MCC – complication or comorbidity or a major complication or comorbidity – in the coding world). Table 2 is an example of using the correct terms and documenting secondary diagnosis. By documenting the type and severity of malnutrition we again increase the expected risk of mortality and the severity of illness.

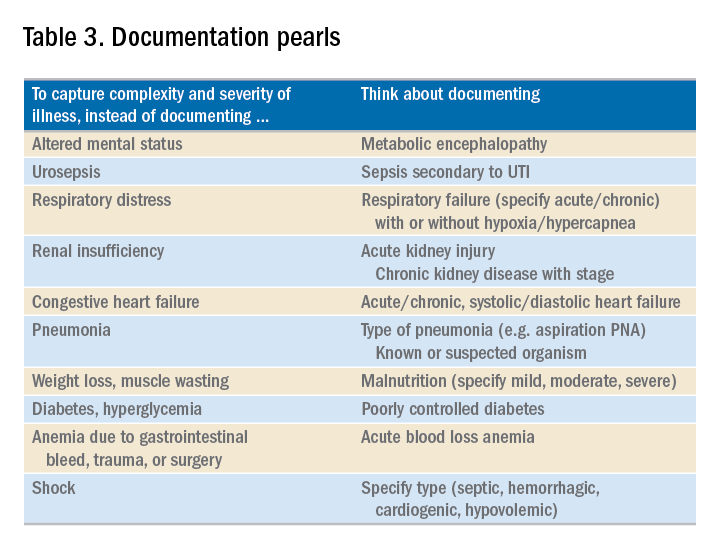

Physicians often do a lot more than what we record in the chart. Learning to document accurately to show the true clinical picture is an important skill set. Here are some tips to help understand and even avoid calls for better documentation.

- Use the terms “probable,” “possible,” “suspected,” or “likely” in documenting uncertain diagnoses (i.e., conditions for which physicians find clinical evidence that leads to a suspicion but not a definitive diagnosis). If conditions are ruled out or confirmed, clearly state so. If it remains uncertain, remember to carry this “possible” or “probable” diagnosis all the way through to the discharge summary or final progress note.

- Use linking of diagnoses when appropriate. For example, if the patient’s neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy are related to their uncontrolled insulin dependent diabetes, state “uncontrolled insulin-dependent DMII with A1c of 11 complicated with nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy.” The coders cannot link these diagnoses, and when you link them, you show a higher complexity of your patient. Remember to link the diagnoses only when they are truly related – this is where your medical knowledge and expertise come into play.

- Use the highest specificity of evidence that supports your medical decision making. You don’t need to be too verbose, all you need is evidence supporting your medical decision making and treatment plan. Think of it as demonstrating the logic of your diagnosis to another physician.

- Use Acuity (acute, chronic, acute on chronic, mild, moderate, severe, etc.) per diagnosis. For example, if you say heart failure exacerbation, it makes perfect sense to your medical colleagues, but in the coding world, it means nothing. Specify if it is acute, or acute on chronic, heart failure.

- Use status of each diagnosis. Is the condition improving, worsening, or resolved? Status does not have to be mentioned in all progress notes. Try to include this descriptor in the discharge summary and the day of the event.

- Always document the clinical significance of any abnormal laboratory, radiology reports, or pathology finding. Coders cannot use test results as a basis for coding unless a clinician has reviewed, interpreted, and documented the significance of the results in the progress note. Simply copying and pasting a report in the notes is not considered clinical acknowledgment. Shorthand notes like “Na=150, start hydration with 0.45% saline” is not acceptable. The actual diagnosis has to be written (i.e. “hypernatremia”). In addition, coders cannot code from nursing, dietitian, respiratory, and physical therapy notes. For example, if nursing documents that a patient has a pressure ulcer the clinician must still document the diagnosis of pressure ulcer, location, and stage. Although dietitian notes may state a body mass index greater than 40, coders cannot assume that patient is morbidly obese. Physician documentation is needed to support the obesity code assignment.

- Document all conditions that affect the patient’s stay, including complications and chronic conditions for which medications have been ordered. These secondary diagnoses paint the most accurate clinical picture and provide information needed to calculate important data, such as complexity and severity of patient illness and mortality risk. A patient with community-acquired pneumonia without other comorbidities requires fewer resources and has a greater chance of a good outcome than does the same patient with complications, such as acute heart failure.

- Downcoding brings losses, upcoding brings fines. Exaggerating the severity of patient conditions can lead to payer audits, reimbursement take backs, and charges of abuse and fraudulent billing. Never stretch the truth. Make sure you can support every diagnosis in the patient’s chart using clinical criteria.

You may be frustrated by the need to choose specific words about diagnoses that seem obvious to you without these descriptors. But accurate documentation can make a huge difference in your hospital’s bottom line and published metrics. Understanding the relative impact of changing your terminology can help you make these changes, until the language becomes second nature. Your hospital administrators will be grateful – and you just might cut down your queries!

Dr. Rajda is medical director of clinical documentation and quality improvement for Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and medical director for DRG appeals for the Mount Sinai Health System. She serves as assistant professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Fatemi is an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. She is director of documentation, coding, and billing for the division of hospital medicine at UNM. Dr. Reyna is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director for clinical documentation and quality improvement at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

Specificity is essential in documentation and coding

Specificity is essential in documentation and coding

Throughout medical training, you learn to write complete and detailed notes to communicate with other physicians. As a student and resident, you are praised when you succinctly analyze and address all patient problems while justifying your orders for the day. But notes do not exist just to document patient care; they are the template by which our actual quality of care is judged and our patients’ severity of illness is captured.

Like it or not, ICD-10 coding, documentation, denials, calls, and emails from administrators are integral parts of a hospitalist’s day-to-day job. Why? The specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses affect such metrics as hospital length of stay, mortality, and Case Mix Index documentation.

Good documentation can lead to better severity of illness (SOI) and risk of mortality (ROM) scores, better patient safety indicator (PSI) scores, better Healthgrades scores, better University Hospital Consortium (UHC) scores, and decreased Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) denials as well as appropriate reimbursement. Good documentation can even lead to improved patient care and better perceived treatment outcomes.

It is no surprise that many hospital administrators invest time and money in staff to support the proper usage of language in your notes. Of course, sometimes these well-meaning “queries” can throw you into emotional turmoil as you try to understand what was not clear in your excellent note about your patient’s heart failure exacerbation. In this article, we will try to help you take your specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses to the next level.

Basics of billing

Physicians do not need to become coders but it is helpful to have some understanding of what happens behind the scenes. Not everyone realizes that physician billing is completely different from hospital billing. Physician billing pertains to the care provided by the clinician, whereas hospital billing pertains to the overall care the patient received.

Below is an example of a case of pneumonia, (see Table 1) which shows the importance of specificity. Just by specifying ‘Aspiration’ for the type of pneumonia, we increased the SOI and the expected ROM appropriately. Also see a change in relative weight (RW): Each diagnosis-related group (DRG) is assigned a relative weight = estimated use of resources, and payment per case is based on estimated resource consumption = relative weight x “blended rate for each hospital.”

In addition to specificity, it is important to include all secondary diagnosis (know as cc/MCC – complication or comorbidity or a major complication or comorbidity – in the coding world). Table 2 is an example of using the correct terms and documenting secondary diagnosis. By documenting the type and severity of malnutrition we again increase the expected risk of mortality and the severity of illness.

Physicians often do a lot more than what we record in the chart. Learning to document accurately to show the true clinical picture is an important skill set. Here are some tips to help understand and even avoid calls for better documentation.

- Use the terms “probable,” “possible,” “suspected,” or “likely” in documenting uncertain diagnoses (i.e., conditions for which physicians find clinical evidence that leads to a suspicion but not a definitive diagnosis). If conditions are ruled out or confirmed, clearly state so. If it remains uncertain, remember to carry this “possible” or “probable” diagnosis all the way through to the discharge summary or final progress note.

- Use linking of diagnoses when appropriate. For example, if the patient’s neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy are related to their uncontrolled insulin dependent diabetes, state “uncontrolled insulin-dependent DMII with A1c of 11 complicated with nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy.” The coders cannot link these diagnoses, and when you link them, you show a higher complexity of your patient. Remember to link the diagnoses only when they are truly related – this is where your medical knowledge and expertise come into play.

- Use the highest specificity of evidence that supports your medical decision making. You don’t need to be too verbose, all you need is evidence supporting your medical decision making and treatment plan. Think of it as demonstrating the logic of your diagnosis to another physician.

- Use Acuity (acute, chronic, acute on chronic, mild, moderate, severe, etc.) per diagnosis. For example, if you say heart failure exacerbation, it makes perfect sense to your medical colleagues, but in the coding world, it means nothing. Specify if it is acute, or acute on chronic, heart failure.

- Use status of each diagnosis. Is the condition improving, worsening, or resolved? Status does not have to be mentioned in all progress notes. Try to include this descriptor in the discharge summary and the day of the event.

- Always document the clinical significance of any abnormal laboratory, radiology reports, or pathology finding. Coders cannot use test results as a basis for coding unless a clinician has reviewed, interpreted, and documented the significance of the results in the progress note. Simply copying and pasting a report in the notes is not considered clinical acknowledgment. Shorthand notes like “Na=150, start hydration with 0.45% saline” is not acceptable. The actual diagnosis has to be written (i.e. “hypernatremia”). In addition, coders cannot code from nursing, dietitian, respiratory, and physical therapy notes. For example, if nursing documents that a patient has a pressure ulcer the clinician must still document the diagnosis of pressure ulcer, location, and stage. Although dietitian notes may state a body mass index greater than 40, coders cannot assume that patient is morbidly obese. Physician documentation is needed to support the obesity code assignment.

- Document all conditions that affect the patient’s stay, including complications and chronic conditions for which medications have been ordered. These secondary diagnoses paint the most accurate clinical picture and provide information needed to calculate important data, such as complexity and severity of patient illness and mortality risk. A patient with community-acquired pneumonia without other comorbidities requires fewer resources and has a greater chance of a good outcome than does the same patient with complications, such as acute heart failure.

- Downcoding brings losses, upcoding brings fines. Exaggerating the severity of patient conditions can lead to payer audits, reimbursement take backs, and charges of abuse and fraudulent billing. Never stretch the truth. Make sure you can support every diagnosis in the patient’s chart using clinical criteria.

You may be frustrated by the need to choose specific words about diagnoses that seem obvious to you without these descriptors. But accurate documentation can make a huge difference in your hospital’s bottom line and published metrics. Understanding the relative impact of changing your terminology can help you make these changes, until the language becomes second nature. Your hospital administrators will be grateful – and you just might cut down your queries!

Dr. Rajda is medical director of clinical documentation and quality improvement for Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and medical director for DRG appeals for the Mount Sinai Health System. She serves as assistant professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Fatemi is an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. She is director of documentation, coding, and billing for the division of hospital medicine at UNM. Dr. Reyna is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director for clinical documentation and quality improvement at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

Throughout medical training, you learn to write complete and detailed notes to communicate with other physicians. As a student and resident, you are praised when you succinctly analyze and address all patient problems while justifying your orders for the day. But notes do not exist just to document patient care; they are the template by which our actual quality of care is judged and our patients’ severity of illness is captured.

Like it or not, ICD-10 coding, documentation, denials, calls, and emails from administrators are integral parts of a hospitalist’s day-to-day job. Why? The specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses affect such metrics as hospital length of stay, mortality, and Case Mix Index documentation.

Good documentation can lead to better severity of illness (SOI) and risk of mortality (ROM) scores, better patient safety indicator (PSI) scores, better Healthgrades scores, better University Hospital Consortium (UHC) scores, and decreased Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) denials as well as appropriate reimbursement. Good documentation can even lead to improved patient care and better perceived treatment outcomes.

It is no surprise that many hospital administrators invest time and money in staff to support the proper usage of language in your notes. Of course, sometimes these well-meaning “queries” can throw you into emotional turmoil as you try to understand what was not clear in your excellent note about your patient’s heart failure exacerbation. In this article, we will try to help you take your specificity and comprehensiveness of diagnoses to the next level.

Basics of billing

Physicians do not need to become coders but it is helpful to have some understanding of what happens behind the scenes. Not everyone realizes that physician billing is completely different from hospital billing. Physician billing pertains to the care provided by the clinician, whereas hospital billing pertains to the overall care the patient received.

Below is an example of a case of pneumonia, (see Table 1) which shows the importance of specificity. Just by specifying ‘Aspiration’ for the type of pneumonia, we increased the SOI and the expected ROM appropriately. Also see a change in relative weight (RW): Each diagnosis-related group (DRG) is assigned a relative weight = estimated use of resources, and payment per case is based on estimated resource consumption = relative weight x “blended rate for each hospital.”

In addition to specificity, it is important to include all secondary diagnosis (know as cc/MCC – complication or comorbidity or a major complication or comorbidity – in the coding world). Table 2 is an example of using the correct terms and documenting secondary diagnosis. By documenting the type and severity of malnutrition we again increase the expected risk of mortality and the severity of illness.

Physicians often do a lot more than what we record in the chart. Learning to document accurately to show the true clinical picture is an important skill set. Here are some tips to help understand and even avoid calls for better documentation.

- Use the terms “probable,” “possible,” “suspected,” or “likely” in documenting uncertain diagnoses (i.e., conditions for which physicians find clinical evidence that leads to a suspicion but not a definitive diagnosis). If conditions are ruled out or confirmed, clearly state so. If it remains uncertain, remember to carry this “possible” or “probable” diagnosis all the way through to the discharge summary or final progress note.

- Use linking of diagnoses when appropriate. For example, if the patient’s neuropathy, nephropathy, and retinopathy are related to their uncontrolled insulin dependent diabetes, state “uncontrolled insulin-dependent DMII with A1c of 11 complicated with nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy.” The coders cannot link these diagnoses, and when you link them, you show a higher complexity of your patient. Remember to link the diagnoses only when they are truly related – this is where your medical knowledge and expertise come into play.

- Use the highest specificity of evidence that supports your medical decision making. You don’t need to be too verbose, all you need is evidence supporting your medical decision making and treatment plan. Think of it as demonstrating the logic of your diagnosis to another physician.

- Use Acuity (acute, chronic, acute on chronic, mild, moderate, severe, etc.) per diagnosis. For example, if you say heart failure exacerbation, it makes perfect sense to your medical colleagues, but in the coding world, it means nothing. Specify if it is acute, or acute on chronic, heart failure.

- Use status of each diagnosis. Is the condition improving, worsening, or resolved? Status does not have to be mentioned in all progress notes. Try to include this descriptor in the discharge summary and the day of the event.

- Always document the clinical significance of any abnormal laboratory, radiology reports, or pathology finding. Coders cannot use test results as a basis for coding unless a clinician has reviewed, interpreted, and documented the significance of the results in the progress note. Simply copying and pasting a report in the notes is not considered clinical acknowledgment. Shorthand notes like “Na=150, start hydration with 0.45% saline” is not acceptable. The actual diagnosis has to be written (i.e. “hypernatremia”). In addition, coders cannot code from nursing, dietitian, respiratory, and physical therapy notes. For example, if nursing documents that a patient has a pressure ulcer the clinician must still document the diagnosis of pressure ulcer, location, and stage. Although dietitian notes may state a body mass index greater than 40, coders cannot assume that patient is morbidly obese. Physician documentation is needed to support the obesity code assignment.

- Document all conditions that affect the patient’s stay, including complications and chronic conditions for which medications have been ordered. These secondary diagnoses paint the most accurate clinical picture and provide information needed to calculate important data, such as complexity and severity of patient illness and mortality risk. A patient with community-acquired pneumonia without other comorbidities requires fewer resources and has a greater chance of a good outcome than does the same patient with complications, such as acute heart failure.

- Downcoding brings losses, upcoding brings fines. Exaggerating the severity of patient conditions can lead to payer audits, reimbursement take backs, and charges of abuse and fraudulent billing. Never stretch the truth. Make sure you can support every diagnosis in the patient’s chart using clinical criteria.

You may be frustrated by the need to choose specific words about diagnoses that seem obvious to you without these descriptors. But accurate documentation can make a huge difference in your hospital’s bottom line and published metrics. Understanding the relative impact of changing your terminology can help you make these changes, until the language becomes second nature. Your hospital administrators will be grateful – and you just might cut down your queries!

Dr. Rajda is medical director of clinical documentation and quality improvement for Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, and medical director for DRG appeals for the Mount Sinai Health System. She serves as assistant professor of medicine at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Dr. Fatemi is an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico, Albuquerque. She is director of documentation, coding, and billing for the division of hospital medicine at UNM. Dr. Reyna is assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director for clinical documentation and quality improvement at Mount Sinai Medical Center.

Smartphone device beat Holter for post-stroke AF detection

MONTREAL – A smartphone-based method for quick and inexpensive monitoring for atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized for a recent acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack identified three times more patients with the arrhythmia than did 24-hour Holter monitoring of the same patients after their hospital discharge.

This high level of atrial fibrillation (AF) detection using a relatively cheap and noninvasive device suggests that this method is a good “complement” to conventional monitoring by a 24-hour Holter recording or an implanted loop recorder in recent stroke patients, as called for in current guidelines of the world’s cardiology societies.

In the study, 294 of 1,079 patients hospitalized for an acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) underwent Holter monitoring, which identified 8 patients (3%) with AF, compared with 25 of these 294 patients (9%) identified with AF while they were hospitalized using serial, 30-second monitoring with the AliveCor device for smartphone assessment of ECG measurement, Bernard Yan, MD, said at the World Stroke Congress. Seven of the eight patients identified with AF by Holter monitoring were also found to have AF by the AliveCor device.

Dr. Yan, an interventional neurologist at the Comprehensive Stroke Center at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, attributed the higher pick-up rate for AF by monitoring during hospitalization to the timing of screening, which was within days of the stroke or TIA, rather than waiting to run a Holter sometime after the patient left the hospital.

“I suspect the difference in timing explains the difference” in detection, he said in an interview. “The difference may be because we monitored patients [with the AliveCor device] much earlier, during their ‘hot’ period, right after their stroke.”

The SPOT-AF trial ran at several centers in Australia, China, and Hong Kong, and enrolled 1,079 patients hospitalized for acute ischemic stroke or TIA who all underwent AliveCor monitoring during their median 4-day stay in the hospital. Patients performed a 30-second heart rhythm check every time a nurse saw them for a routine vital-sign examination, usually three or four times a day. The current analysis focused on the 294 patients (27% of the 1,079 patients) who also underwent 24-hour Holter monitoring following hospital discharge when ordered by their personal physician. This 27% incidence of postdischarge Holter monitoring despite guidelines that call for AF screening in all recent ischemic stroke and TIA patients was consistent with a 2016 review of more than 17,000 stroke or TIA patients in Canada that showed 31% underwent 24-hour Holter monitoring for AF during the 30 days following their index event (Stroke. 2016 Aug;47[8]:1982-9).

Although AF screening with a smartphone-based device is inexpensive and easy, Dr. Yan stopped short of suggesting that it is time for this approach to replace a Holter monitor or an implanted loop recorder because that is what current guidelines call for. “To change the guidelines, we need a different study that compares these approaches head to head.”

SPOT-AF received partial funding from Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Yan has been a speaker on behalf of Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Stryker.

MONTREAL – A smartphone-based method for quick and inexpensive monitoring for atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized for a recent acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack identified three times more patients with the arrhythmia than did 24-hour Holter monitoring of the same patients after their hospital discharge.

This high level of atrial fibrillation (AF) detection using a relatively cheap and noninvasive device suggests that this method is a good “complement” to conventional monitoring by a 24-hour Holter recording or an implanted loop recorder in recent stroke patients, as called for in current guidelines of the world’s cardiology societies.

In the study, 294 of 1,079 patients hospitalized for an acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) underwent Holter monitoring, which identified 8 patients (3%) with AF, compared with 25 of these 294 patients (9%) identified with AF while they were hospitalized using serial, 30-second monitoring with the AliveCor device for smartphone assessment of ECG measurement, Bernard Yan, MD, said at the World Stroke Congress. Seven of the eight patients identified with AF by Holter monitoring were also found to have AF by the AliveCor device.

Dr. Yan, an interventional neurologist at the Comprehensive Stroke Center at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, attributed the higher pick-up rate for AF by monitoring during hospitalization to the timing of screening, which was within days of the stroke or TIA, rather than waiting to run a Holter sometime after the patient left the hospital.

“I suspect the difference in timing explains the difference” in detection, he said in an interview. “The difference may be because we monitored patients [with the AliveCor device] much earlier, during their ‘hot’ period, right after their stroke.”

The SPOT-AF trial ran at several centers in Australia, China, and Hong Kong, and enrolled 1,079 patients hospitalized for acute ischemic stroke or TIA who all underwent AliveCor monitoring during their median 4-day stay in the hospital. Patients performed a 30-second heart rhythm check every time a nurse saw them for a routine vital-sign examination, usually three or four times a day. The current analysis focused on the 294 patients (27% of the 1,079 patients) who also underwent 24-hour Holter monitoring following hospital discharge when ordered by their personal physician. This 27% incidence of postdischarge Holter monitoring despite guidelines that call for AF screening in all recent ischemic stroke and TIA patients was consistent with a 2016 review of more than 17,000 stroke or TIA patients in Canada that showed 31% underwent 24-hour Holter monitoring for AF during the 30 days following their index event (Stroke. 2016 Aug;47[8]:1982-9).

Although AF screening with a smartphone-based device is inexpensive and easy, Dr. Yan stopped short of suggesting that it is time for this approach to replace a Holter monitor or an implanted loop recorder because that is what current guidelines call for. “To change the guidelines, we need a different study that compares these approaches head to head.”

SPOT-AF received partial funding from Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Yan has been a speaker on behalf of Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Stryker.

MONTREAL – A smartphone-based method for quick and inexpensive monitoring for atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized for a recent acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack identified three times more patients with the arrhythmia than did 24-hour Holter monitoring of the same patients after their hospital discharge.

This high level of atrial fibrillation (AF) detection using a relatively cheap and noninvasive device suggests that this method is a good “complement” to conventional monitoring by a 24-hour Holter recording or an implanted loop recorder in recent stroke patients, as called for in current guidelines of the world’s cardiology societies.

In the study, 294 of 1,079 patients hospitalized for an acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) underwent Holter monitoring, which identified 8 patients (3%) with AF, compared with 25 of these 294 patients (9%) identified with AF while they were hospitalized using serial, 30-second monitoring with the AliveCor device for smartphone assessment of ECG measurement, Bernard Yan, MD, said at the World Stroke Congress. Seven of the eight patients identified with AF by Holter monitoring were also found to have AF by the AliveCor device.

Dr. Yan, an interventional neurologist at the Comprehensive Stroke Center at the Royal Melbourne Hospital, attributed the higher pick-up rate for AF by monitoring during hospitalization to the timing of screening, which was within days of the stroke or TIA, rather than waiting to run a Holter sometime after the patient left the hospital.

“I suspect the difference in timing explains the difference” in detection, he said in an interview. “The difference may be because we monitored patients [with the AliveCor device] much earlier, during their ‘hot’ period, right after their stroke.”

The SPOT-AF trial ran at several centers in Australia, China, and Hong Kong, and enrolled 1,079 patients hospitalized for acute ischemic stroke or TIA who all underwent AliveCor monitoring during their median 4-day stay in the hospital. Patients performed a 30-second heart rhythm check every time a nurse saw them for a routine vital-sign examination, usually three or four times a day. The current analysis focused on the 294 patients (27% of the 1,079 patients) who also underwent 24-hour Holter monitoring following hospital discharge when ordered by their personal physician. This 27% incidence of postdischarge Holter monitoring despite guidelines that call for AF screening in all recent ischemic stroke and TIA patients was consistent with a 2016 review of more than 17,000 stroke or TIA patients in Canada that showed 31% underwent 24-hour Holter monitoring for AF during the 30 days following their index event (Stroke. 2016 Aug;47[8]:1982-9).

Although AF screening with a smartphone-based device is inexpensive and easy, Dr. Yan stopped short of suggesting that it is time for this approach to replace a Holter monitor or an implanted loop recorder because that is what current guidelines call for. “To change the guidelines, we need a different study that compares these approaches head to head.”

SPOT-AF received partial funding from Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Yan has been a speaker on behalf of Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Stryker.

REPORTING FROM THE WORLD STROKE CONGRESS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Holter monitoring detected atrial fibrillation in 8 of 294 patients, while smartphone monitoring identified 25 with the arrhythmia.

Study details: SPOT-AF, a multicenter study with 1,079 total patients, including 294 who underwent Holter monitoring.

Disclosures: SPOT-AF received partial funding from Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. Yan has been a speaker on behalf of Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Stryker.

How much more proof do you need?

One piece of wisdom I was given in medical school was to never be the first nor the last to adopt a new treatment. The history of medicine is full of new discoveries that don’t work out as well as the first report. It also is full of long standing dogmas that later were proven false. This balancing act is part of being a professional and being an advocate for your patient. There is science behind this art. Everett Rogers identified innovators, early adopters, and laggards as new ideas are diffused into practice.1

A 2007 French study2 that investigated oral amoxicillin for early-onset group B streptococcal (GBS) disease is one of the few times in the past 3 decades in which I changed my practice based on a single article. It was a large, conclusive study with 222 patients, so it doesn’t need a meta-analysis like American research often requires. The research showed that most of what I had been taught about oral amoxicillin was false. Amoxicillin is absorbed well even at doses above 50 mg/kg per day. It is absorbed reliably by full term neonates, even mildly sick ones. It does adequately cross the blood-brain barrier. The French researchers measured serum levels and proved all this using both scientific principles and through a clinical trial.

I have used this oral protocol (10 days total after 2-3 days IV therapy) on two occasions to treat GBS sepsis when I had informed consent of the parents and buy-in from the primary care pediatrician to be early adopters. I expected the Red Book would update its recommendations. That didn’t happen.

Meanwhile, I have seen other babies kept for 10 days in the hospital for IV therapy with resultant wasted costs (about $20 million/year in the United States) and income loss for the parents. I’ve treated complications and readmissions caused by peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line issues. One baby at home got a syringe of gentamicin given as an IV push instead of a normal saline flush. Mistakes happen at home and in the hospital.

Because late-onset GBS can be acquired environmentally, there always will be recurrences. Unless you are practicing defensive medicine, the issue isn’t the rate of recurrence; it is whether the more invasive intervention of prolonged IV therapy reduces that rate. Then balance any measured reduction (which apparently is zero) against the adverse effects of the invasive intervention, such as PICC line infections. This Bayesian decision making is hard for some risk-averse humans to assimilate. (I’m part Borg.)

Coon et al.3 have confirmed, using big data, that prolonged IV therapy of uncomplicated, late-onset GBS bacteremia does not generate a clinically significant benefit. It certainly is possible to sow doubt by asking for proof in a variety of subpopulations. Even in the era of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, which has halved the incidence of GBS disease, GBS disease occurs in about 2,000 babies per year in the United States. However, most are treated in community hospitals and are not included in the database used in this new report. With fewer than 2-3 cases of GBS bacteremia per year per hospital, a multicenter, randomized controlled trial would be an unprecedented undertaking, is ethically problematic, and is not realistically happening soon. So these observational data, skillfully acquired and analyzed, are and will remain the best available data.

This new article is in the context of multiple articles over the past decade that have disproven the myth of the superiority of IV therapy. Given the known risks and costs of PICC lines and prolonged IV therapy, the default should be, absent a credible rationale to the contrary, that oral therapy at home is better.

Coon et al. show that, by 2015, 5 of 49 children’s hospitals (10%) were early adopters and had already made the switch to mostly using short treatment courses for uncomplicated GBS bacteremia; 14 of 49 (29%) hadn’t changed at all from the obsolete Red Book recommendation. Given this new analysis, what are you laggards4 waiting for?

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. “Diffusion of Innovations,” 5th ed. (New York: Free Press, 2003).

2. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007 Jul;63(7):657-62.

3. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5):e20180345.

4. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diffusion_of_innovations.

One piece of wisdom I was given in medical school was to never be the first nor the last to adopt a new treatment. The history of medicine is full of new discoveries that don’t work out as well as the first report. It also is full of long standing dogmas that later were proven false. This balancing act is part of being a professional and being an advocate for your patient. There is science behind this art. Everett Rogers identified innovators, early adopters, and laggards as new ideas are diffused into practice.1

A 2007 French study2 that investigated oral amoxicillin for early-onset group B streptococcal (GBS) disease is one of the few times in the past 3 decades in which I changed my practice based on a single article. It was a large, conclusive study with 222 patients, so it doesn’t need a meta-analysis like American research often requires. The research showed that most of what I had been taught about oral amoxicillin was false. Amoxicillin is absorbed well even at doses above 50 mg/kg per day. It is absorbed reliably by full term neonates, even mildly sick ones. It does adequately cross the blood-brain barrier. The French researchers measured serum levels and proved all this using both scientific principles and through a clinical trial.

I have used this oral protocol (10 days total after 2-3 days IV therapy) on two occasions to treat GBS sepsis when I had informed consent of the parents and buy-in from the primary care pediatrician to be early adopters. I expected the Red Book would update its recommendations. That didn’t happen.

Meanwhile, I have seen other babies kept for 10 days in the hospital for IV therapy with resultant wasted costs (about $20 million/year in the United States) and income loss for the parents. I’ve treated complications and readmissions caused by peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line issues. One baby at home got a syringe of gentamicin given as an IV push instead of a normal saline flush. Mistakes happen at home and in the hospital.

Because late-onset GBS can be acquired environmentally, there always will be recurrences. Unless you are practicing defensive medicine, the issue isn’t the rate of recurrence; it is whether the more invasive intervention of prolonged IV therapy reduces that rate. Then balance any measured reduction (which apparently is zero) against the adverse effects of the invasive intervention, such as PICC line infections. This Bayesian decision making is hard for some risk-averse humans to assimilate. (I’m part Borg.)

Coon et al.3 have confirmed, using big data, that prolonged IV therapy of uncomplicated, late-onset GBS bacteremia does not generate a clinically significant benefit. It certainly is possible to sow doubt by asking for proof in a variety of subpopulations. Even in the era of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, which has halved the incidence of GBS disease, GBS disease occurs in about 2,000 babies per year in the United States. However, most are treated in community hospitals and are not included in the database used in this new report. With fewer than 2-3 cases of GBS bacteremia per year per hospital, a multicenter, randomized controlled trial would be an unprecedented undertaking, is ethically problematic, and is not realistically happening soon. So these observational data, skillfully acquired and analyzed, are and will remain the best available data.

This new article is in the context of multiple articles over the past decade that have disproven the myth of the superiority of IV therapy. Given the known risks and costs of PICC lines and prolonged IV therapy, the default should be, absent a credible rationale to the contrary, that oral therapy at home is better.

Coon et al. show that, by 2015, 5 of 49 children’s hospitals (10%) were early adopters and had already made the switch to mostly using short treatment courses for uncomplicated GBS bacteremia; 14 of 49 (29%) hadn’t changed at all from the obsolete Red Book recommendation. Given this new analysis, what are you laggards4 waiting for?

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. “Diffusion of Innovations,” 5th ed. (New York: Free Press, 2003).

2. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007 Jul;63(7):657-62.

3. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5):e20180345.

4. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diffusion_of_innovations.

One piece of wisdom I was given in medical school was to never be the first nor the last to adopt a new treatment. The history of medicine is full of new discoveries that don’t work out as well as the first report. It also is full of long standing dogmas that later were proven false. This balancing act is part of being a professional and being an advocate for your patient. There is science behind this art. Everett Rogers identified innovators, early adopters, and laggards as new ideas are diffused into practice.1

A 2007 French study2 that investigated oral amoxicillin for early-onset group B streptococcal (GBS) disease is one of the few times in the past 3 decades in which I changed my practice based on a single article. It was a large, conclusive study with 222 patients, so it doesn’t need a meta-analysis like American research often requires. The research showed that most of what I had been taught about oral amoxicillin was false. Amoxicillin is absorbed well even at doses above 50 mg/kg per day. It is absorbed reliably by full term neonates, even mildly sick ones. It does adequately cross the blood-brain barrier. The French researchers measured serum levels and proved all this using both scientific principles and through a clinical trial.

I have used this oral protocol (10 days total after 2-3 days IV therapy) on two occasions to treat GBS sepsis when I had informed consent of the parents and buy-in from the primary care pediatrician to be early adopters. I expected the Red Book would update its recommendations. That didn’t happen.

Meanwhile, I have seen other babies kept for 10 days in the hospital for IV therapy with resultant wasted costs (about $20 million/year in the United States) and income loss for the parents. I’ve treated complications and readmissions caused by peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line issues. One baby at home got a syringe of gentamicin given as an IV push instead of a normal saline flush. Mistakes happen at home and in the hospital.

Because late-onset GBS can be acquired environmentally, there always will be recurrences. Unless you are practicing defensive medicine, the issue isn’t the rate of recurrence; it is whether the more invasive intervention of prolonged IV therapy reduces that rate. Then balance any measured reduction (which apparently is zero) against the adverse effects of the invasive intervention, such as PICC line infections. This Bayesian decision making is hard for some risk-averse humans to assimilate. (I’m part Borg.)

Coon et al.3 have confirmed, using big data, that prolonged IV therapy of uncomplicated, late-onset GBS bacteremia does not generate a clinically significant benefit. It certainly is possible to sow doubt by asking for proof in a variety of subpopulations. Even in the era of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, which has halved the incidence of GBS disease, GBS disease occurs in about 2,000 babies per year in the United States. However, most are treated in community hospitals and are not included in the database used in this new report. With fewer than 2-3 cases of GBS bacteremia per year per hospital, a multicenter, randomized controlled trial would be an unprecedented undertaking, is ethically problematic, and is not realistically happening soon. So these observational data, skillfully acquired and analyzed, are and will remain the best available data.

This new article is in the context of multiple articles over the past decade that have disproven the myth of the superiority of IV therapy. Given the known risks and costs of PICC lines and prolonged IV therapy, the default should be, absent a credible rationale to the contrary, that oral therapy at home is better.

Coon et al. show that, by 2015, 5 of 49 children’s hospitals (10%) were early adopters and had already made the switch to mostly using short treatment courses for uncomplicated GBS bacteremia; 14 of 49 (29%) hadn’t changed at all from the obsolete Red Book recommendation. Given this new analysis, what are you laggards4 waiting for?

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at [email protected].

References

1. “Diffusion of Innovations,” 5th ed. (New York: Free Press, 2003).

2. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007 Jul;63(7):657-62.

3. Pediatrics. 2018;142(5):e20180345.

4. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diffusion_of_innovations.

Protocol violations, missed transfusions among blood delivery errors

BOSTON – Even the most vigilant hospitals experience problems with blood storage and delivery on the patient floor, particularly in pediatric units, investigators cautioned.

A review of patient safety incidents that occurred surrounding more than 1 million transfusions in U.S. hospitals showed that pediatric transfusions were associated with a higher rate of safety problems compared with adult transfusions, with errors differing by age group.

“We just looked at units transfused [and] incidents that occurred during product administration and we found that the highest incident in the pediatric population is that the protocol is not being followed, and the highest incident in the adult population is that the transfusion is not performed, in error, at all,” said Sarah Vossoughi, MD, of Columbia University and New York–Presbyterian Hospital, New York.

In both settings, the investigators observed problems with product storage on the patient floor. “It’s very common for blood banks to find platelets in the refrigerator. It doesn’t matter how old you are or what type of hospital you’re at – everyone’s putting platelets in the fridge,” she said in an interview at AABB 2018, the annual meeting of the organization formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

Dr. Vossoughi and her colleagues in New York and at the University of Vermont in Burlington noted that the National Patient Safety Foundation, now a part of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, declared preventable medical harm to be a public health crisis. In a paper published in the BMJ in 2016, researchers estimated that medical errors were the third leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for more than 250,000 fatalities annually.

Dr. Vossoughi also pointed to a study suggesting that the incidence of nonlethal medical errors may be 10- to 20-fold higher than the number of fatal errors (J Patient Saf. 2013 Sep;9[3]:122-8).

To evaluate patient safety events related to blood transfusions, Dr. Vossoughi and her colleagues drew data on events reported by three children’s hospitals and 29 adult hospitals to either the AABB Center for Patient Safety or the medical center’s own adverse event reporting system from January 2010 through September 2017.

They identified a total of 1,806 reports associated with approximately 1,088.884 transfusions. Of these reports, 249 were associated with 99,064 pediatric transfusions, and 1,577 were reported in association with 989,820 adult transfusions.

In all, 31% of the pediatric events were failure to follow the transfusion protocol.

“In a lot of the pediatric hospitals, it’s kind of like the Wild West. People say, ‘well I know it’s the hospital policy, but this child is special, so I’m going to do it this way, this time.’ That seems to be a culture in pediatrics, whereas on the adult side [clinicians] seem to be much less likely to just deviate from the protocol,” Dr. Vossoughi said.

Among adults, 43% of the errors were “transfusion not performed,” which may occur because of a bungled patient hand-off during a shift change, or when a patient is being moved from one unit to another.

“The next day, they’ll check the patient’s CBC and realize that the patient didn’t respond to the infusion that it turned out they never got, and then the product will be found on the floor, expired,” Dr. Vossoughi said.

In all, 20% of pediatric errors and 24% of adult errors were associated with incorrect storage of blood products on the patient floor.

The information they presented could help inpatient blood management programs target education and interventions to providers who commit similar errors.

“If you know that a particular provider group has problems following the protocol, maybe you can make the protocol a little simpler to follow, or make the checklist less cumbersome, and then maybe they’ll follow them more often,” she said.

The study was supported by the AABB Center for Patient Safety and University of Vermont Medical Center. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Vossoughi S et al. AABB 2018, Abstract QT4.

BOSTON – Even the most vigilant hospitals experience problems with blood storage and delivery on the patient floor, particularly in pediatric units, investigators cautioned.

A review of patient safety incidents that occurred surrounding more than 1 million transfusions in U.S. hospitals showed that pediatric transfusions were associated with a higher rate of safety problems compared with adult transfusions, with errors differing by age group.

“We just looked at units transfused [and] incidents that occurred during product administration and we found that the highest incident in the pediatric population is that the protocol is not being followed, and the highest incident in the adult population is that the transfusion is not performed, in error, at all,” said Sarah Vossoughi, MD, of Columbia University and New York–Presbyterian Hospital, New York.

In both settings, the investigators observed problems with product storage on the patient floor. “It’s very common for blood banks to find platelets in the refrigerator. It doesn’t matter how old you are or what type of hospital you’re at – everyone’s putting platelets in the fridge,” she said in an interview at AABB 2018, the annual meeting of the organization formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

Dr. Vossoughi and her colleagues in New York and at the University of Vermont in Burlington noted that the National Patient Safety Foundation, now a part of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, declared preventable medical harm to be a public health crisis. In a paper published in the BMJ in 2016, researchers estimated that medical errors were the third leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for more than 250,000 fatalities annually.

Dr. Vossoughi also pointed to a study suggesting that the incidence of nonlethal medical errors may be 10- to 20-fold higher than the number of fatal errors (J Patient Saf. 2013 Sep;9[3]:122-8).

To evaluate patient safety events related to blood transfusions, Dr. Vossoughi and her colleagues drew data on events reported by three children’s hospitals and 29 adult hospitals to either the AABB Center for Patient Safety or the medical center’s own adverse event reporting system from January 2010 through September 2017.

They identified a total of 1,806 reports associated with approximately 1,088.884 transfusions. Of these reports, 249 were associated with 99,064 pediatric transfusions, and 1,577 were reported in association with 989,820 adult transfusions.

In all, 31% of the pediatric events were failure to follow the transfusion protocol.

“In a lot of the pediatric hospitals, it’s kind of like the Wild West. People say, ‘well I know it’s the hospital policy, but this child is special, so I’m going to do it this way, this time.’ That seems to be a culture in pediatrics, whereas on the adult side [clinicians] seem to be much less likely to just deviate from the protocol,” Dr. Vossoughi said.

Among adults, 43% of the errors were “transfusion not performed,” which may occur because of a bungled patient hand-off during a shift change, or when a patient is being moved from one unit to another.

“The next day, they’ll check the patient’s CBC and realize that the patient didn’t respond to the infusion that it turned out they never got, and then the product will be found on the floor, expired,” Dr. Vossoughi said.

In all, 20% of pediatric errors and 24% of adult errors were associated with incorrect storage of blood products on the patient floor.

The information they presented could help inpatient blood management programs target education and interventions to providers who commit similar errors.

“If you know that a particular provider group has problems following the protocol, maybe you can make the protocol a little simpler to follow, or make the checklist less cumbersome, and then maybe they’ll follow them more often,” she said.

The study was supported by the AABB Center for Patient Safety and University of Vermont Medical Center. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Vossoughi S et al. AABB 2018, Abstract QT4.

BOSTON – Even the most vigilant hospitals experience problems with blood storage and delivery on the patient floor, particularly in pediatric units, investigators cautioned.

A review of patient safety incidents that occurred surrounding more than 1 million transfusions in U.S. hospitals showed that pediatric transfusions were associated with a higher rate of safety problems compared with adult transfusions, with errors differing by age group.

“We just looked at units transfused [and] incidents that occurred during product administration and we found that the highest incident in the pediatric population is that the protocol is not being followed, and the highest incident in the adult population is that the transfusion is not performed, in error, at all,” said Sarah Vossoughi, MD, of Columbia University and New York–Presbyterian Hospital, New York.

In both settings, the investigators observed problems with product storage on the patient floor. “It’s very common for blood banks to find platelets in the refrigerator. It doesn’t matter how old you are or what type of hospital you’re at – everyone’s putting platelets in the fridge,” she said in an interview at AABB 2018, the annual meeting of the organization formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks.

Dr. Vossoughi and her colleagues in New York and at the University of Vermont in Burlington noted that the National Patient Safety Foundation, now a part of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, declared preventable medical harm to be a public health crisis. In a paper published in the BMJ in 2016, researchers estimated that medical errors were the third leading cause of death in the United States, accounting for more than 250,000 fatalities annually.

Dr. Vossoughi also pointed to a study suggesting that the incidence of nonlethal medical errors may be 10- to 20-fold higher than the number of fatal errors (J Patient Saf. 2013 Sep;9[3]:122-8).

To evaluate patient safety events related to blood transfusions, Dr. Vossoughi and her colleagues drew data on events reported by three children’s hospitals and 29 adult hospitals to either the AABB Center for Patient Safety or the medical center’s own adverse event reporting system from January 2010 through September 2017.

They identified a total of 1,806 reports associated with approximately 1,088.884 transfusions. Of these reports, 249 were associated with 99,064 pediatric transfusions, and 1,577 were reported in association with 989,820 adult transfusions.

In all, 31% of the pediatric events were failure to follow the transfusion protocol.

“In a lot of the pediatric hospitals, it’s kind of like the Wild West. People say, ‘well I know it’s the hospital policy, but this child is special, so I’m going to do it this way, this time.’ That seems to be a culture in pediatrics, whereas on the adult side [clinicians] seem to be much less likely to just deviate from the protocol,” Dr. Vossoughi said.

Among adults, 43% of the errors were “transfusion not performed,” which may occur because of a bungled patient hand-off during a shift change, or when a patient is being moved from one unit to another.

“The next day, they’ll check the patient’s CBC and realize that the patient didn’t respond to the infusion that it turned out they never got, and then the product will be found on the floor, expired,” Dr. Vossoughi said.

In all, 20% of pediatric errors and 24% of adult errors were associated with incorrect storage of blood products on the patient floor.

The information they presented could help inpatient blood management programs target education and interventions to providers who commit similar errors.

“If you know that a particular provider group has problems following the protocol, maybe you can make the protocol a little simpler to follow, or make the checklist less cumbersome, and then maybe they’ll follow them more often,” she said.

The study was supported by the AABB Center for Patient Safety and University of Vermont Medical Center. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Vossoughi S et al. AABB 2018, Abstract QT4.

REPORTING FROM AABB 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In all, 31% of pediatric errors were due to protocol violation, and 43% of adult errors were due to an ordered transfusion not being performed.

Study details: Descriptive study of data from 32 U.S. hospitals that reported transfusion safety events.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the AABB Center for Patient Safety and University of Vermont. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Vossoughi S et al. AABB 2018, Abstract QT4.

NAIP to SHM: The importance of a name

Defining the hospitalist ‘brand’

The National Association of Inpatient Physicians (NAIP) “opened its doors” in the spring of 1998, welcoming the first 300 hospitalists. The term “hospitalist” was first coined in Bob Wachter’s 1996 New England Journal of Medicine article,1 although hospitalists were relatively few at that time, and the term not infrequently evoked controversy.

Having full-time hospital-based physicians was highly disruptive to the traditional culture of medicine, where hospital rounds were an integral part of a primary care physicians’ practice, professional identity, and referral patterns. Additionally, many hospital-based specialists were beginning to fill the hospitalist role.

The decision to include “inpatient physician” rather than “hospitalist” in the name was carefully considered and was intended to be inclusive, without alienating potential allies. Virtually any doctor working in a hospital could identify themselves as an inpatient physician, and all who wanted to participate were welcomed. It also was evident early on that this young specialty was going to comprise many different disciplines, including internal medicine, family practice, and pediatrics to name a few, and reaching out to all potential stakeholders was an urgent priority.

During its’ first 5 years, the field of hospital medicine grew rapidly, with NAIP membership nearing 2,000 members. The bimonthly newsletter The Hospitalist provided a vehicle to reach out to members and other stakeholders, and the annual meeting gave hospitalists a forum to gather, learn from each other, and enjoy camaraderie. Early research efforts focused on patient safety and, just as importantly, in 2002, the publication of the first Productivity and Compensation Survey (which is now known as SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine Report) and the initial development of The Hospitalist Core Competencies (first published in 2006, and now in its’ 2017 revision) all helped define the young specialty and gain acceptance.2,3

The term hospitalist became mainstream and accepted, and the name of our field, hospital medicine, has now become widely recognized.

Though the term “inpatient physician” had focused on physicians as a primary constituency, the successful growth of hospital medicine now increasingly depended upon other important constituencies and their understanding of the hospital medicine specialty and the role of hospitalists. These stakeholders included virtually all health care professionals and administrators, government officials at the federal, state, and local levels, patients, and the American public.

As NAIP leadership, it was our belief and intent that having a name that accurately portrayed hospitalists and hospital medicine would define our “brand” in an understandable way. This was especially important given the breadth and depth of the responsibilities that NAIP and its’ members were increasingly taking on in a rapidly changing health care system. Additionally, it was a top priority to find a name that would inspire confidence and passion among our members, stir a sense of loyalty and pride, and continue to be inclusive.

With this in mind, the NAIP board undertook a process to search for a new name in the spring of 2002. As NAIP President-Elect, stewarding the name change process was my responsibility.

In approaching this challenge, we initially evaluated the components of other professional organizations’ names, including academy, college, and society among others, and whether the specialist name or professional field was included. We then held focus groups among regional hospitalists, invited feedback from all NAIP members, and solicited leadership feedback from other professional organizations. All of these data were taken into our fall 2002 board meeting in St. Louis.

Prior to the meeting, it was agreed that making a name change would require a supermajority of two-thirds of the 11 voting board members (though only 10 ultimately attended the meeting). Also participating in the discussion were the nonvoting four ex-officio board members and the NAIP CEO. The initial discussion included presentations arguing for Hospital Medicine versus Hospitalist as part of the name. We then discussed and voted on the primary professional component of the name, with “Society” finally being chosen. After further discussion and a series of ballots, we arrived at the name “Society of Hospital Medicine.” In the final ballot, 7 out of 10 cast their votes in favor of this finalist, and our organization became The Society of Hospital Medicine. Our abbreviation SHM was to become our logo, which was developed in advance of our 2003 annual meeting.

In the 15 years since, the Society of Hospital Medicine has become well known to our constituents and stakeholders. SHM is recognized for its staunch advocacy, particularly at the federal level, with recent establishment of a Medicare specialty code designation for hospitalists, and support for endeavors such as Project Boost, which focused on patient transitions from hospital discharge to home.4,5,6 Hospitalists throughout the United States routinely manage hospitalized patients, and now have their specialty expertise recognized via Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (Internal Medicine and Family Practice), and future specialty training and certification for pediatric hospitalists.7,8,9

The Journal of Hospital Medicine now highlights accomplishments in hospital medicine research and knowledge.10 Hospitalist leaders frequently are developed through the SHM Leadership Academy,11 and hospitalists increasingly fill diverse health care responsibilities in education, research, informatics, palliative care, performance improvement, administration, among many others. Of note, SHM membership currently exceeds 17,000 members, and now offers membership that includes nurse practitioners, physician assistants, fellows, residents, students, and practice administrators, among others.12

These achievements and many more have been driven by the efforts of past and present Society of Hospital Medicine members and staff, and like-minded, invested professionals and organizations. The name Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) is highly familiar and well regarded by virtually all our stakeholders and is recognized for its proven leadership in continuing to define our brand, hospital medicine.

Dr. Dichter is an intensivist and associate professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical Center, Minneapolis.

References

1. Wachter RM et al. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Eng J Med. 1996 Aug 15;335(7):514-7.

2. SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine Report 2018. Fall 2018.

3. Satyen N et al. Core competencies in hospital medicine 2017 Revision. J Hosp Med. 2017 Apr;12:S1.

4. Society of Hospital Medicine website, Policy & Advocacy homepage (accessed July 26, 2018).

5. CMS manual system, Oct. 28, 2016 (accessed July 26, 2018).

6. Society of Hospital Medicine website, Clinical Topics: Advancing successful care transitions to improve outcomes (accessed July 26, 2018).

7. American Board of Internal Medicine website, MOC requirements: Focused practice in hospital medicine (accessed July 26, 2018).

8. American Board of Family Medicine website, Designation of practice in hospital medicine (accessed July 26, 2018).

9. The American Board of Pediatrics website, Pediatric hospital medicine certification (accessed July 26, 2018).

10. Journal of Hospital Medicine official website (accessed July 26, 2018).

11. SHM Leadership Academy website (accessed July 26, 2018).

12. Society of Hospital Medicine website, About SHM membership (accessed July 26, 2018).

Defining the hospitalist ‘brand’

Defining the hospitalist ‘brand’

The National Association of Inpatient Physicians (NAIP) “opened its doors” in the spring of 1998, welcoming the first 300 hospitalists. The term “hospitalist” was first coined in Bob Wachter’s 1996 New England Journal of Medicine article,1 although hospitalists were relatively few at that time, and the term not infrequently evoked controversy.

Having full-time hospital-based physicians was highly disruptive to the traditional culture of medicine, where hospital rounds were an integral part of a primary care physicians’ practice, professional identity, and referral patterns. Additionally, many hospital-based specialists were beginning to fill the hospitalist role.

The decision to include “inpatient physician” rather than “hospitalist” in the name was carefully considered and was intended to be inclusive, without alienating potential allies. Virtually any doctor working in a hospital could identify themselves as an inpatient physician, and all who wanted to participate were welcomed. It also was evident early on that this young specialty was going to comprise many different disciplines, including internal medicine, family practice, and pediatrics to name a few, and reaching out to all potential stakeholders was an urgent priority.

During its’ first 5 years, the field of hospital medicine grew rapidly, with NAIP membership nearing 2,000 members. The bimonthly newsletter The Hospitalist provided a vehicle to reach out to members and other stakeholders, and the annual meeting gave hospitalists a forum to gather, learn from each other, and enjoy camaraderie. Early research efforts focused on patient safety and, just as importantly, in 2002, the publication of the first Productivity and Compensation Survey (which is now known as SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine Report) and the initial development of The Hospitalist Core Competencies (first published in 2006, and now in its’ 2017 revision) all helped define the young specialty and gain acceptance.2,3

The term hospitalist became mainstream and accepted, and the name of our field, hospital medicine, has now become widely recognized.

Though the term “inpatient physician” had focused on physicians as a primary constituency, the successful growth of hospital medicine now increasingly depended upon other important constituencies and their understanding of the hospital medicine specialty and the role of hospitalists. These stakeholders included virtually all health care professionals and administrators, government officials at the federal, state, and local levels, patients, and the American public.

As NAIP leadership, it was our belief and intent that having a name that accurately portrayed hospitalists and hospital medicine would define our “brand” in an understandable way. This was especially important given the breadth and depth of the responsibilities that NAIP and its’ members were increasingly taking on in a rapidly changing health care system. Additionally, it was a top priority to find a name that would inspire confidence and passion among our members, stir a sense of loyalty and pride, and continue to be inclusive.

With this in mind, the NAIP board undertook a process to search for a new name in the spring of 2002. As NAIP President-Elect, stewarding the name change process was my responsibility.

In approaching this challenge, we initially evaluated the components of other professional organizations’ names, including academy, college, and society among others, and whether the specialist name or professional field was included. We then held focus groups among regional hospitalists, invited feedback from all NAIP members, and solicited leadership feedback from other professional organizations. All of these data were taken into our fall 2002 board meeting in St. Louis.

Prior to the meeting, it was agreed that making a name change would require a supermajority of two-thirds of the 11 voting board members (though only 10 ultimately attended the meeting). Also participating in the discussion were the nonvoting four ex-officio board members and the NAIP CEO. The initial discussion included presentations arguing for Hospital Medicine versus Hospitalist as part of the name. We then discussed and voted on the primary professional component of the name, with “Society” finally being chosen. After further discussion and a series of ballots, we arrived at the name “Society of Hospital Medicine.” In the final ballot, 7 out of 10 cast their votes in favor of this finalist, and our organization became The Society of Hospital Medicine. Our abbreviation SHM was to become our logo, which was developed in advance of our 2003 annual meeting.

In the 15 years since, the Society of Hospital Medicine has become well known to our constituents and stakeholders. SHM is recognized for its staunch advocacy, particularly at the federal level, with recent establishment of a Medicare specialty code designation for hospitalists, and support for endeavors such as Project Boost, which focused on patient transitions from hospital discharge to home.4,5,6 Hospitalists throughout the United States routinely manage hospitalized patients, and now have their specialty expertise recognized via Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine (Internal Medicine and Family Practice), and future specialty training and certification for pediatric hospitalists.7,8,9

The Journal of Hospital Medicine now highlights accomplishments in hospital medicine research and knowledge.10 Hospitalist leaders frequently are developed through the SHM Leadership Academy,11 and hospitalists increasingly fill diverse health care responsibilities in education, research, informatics, palliative care, performance improvement, administration, among many others. Of note, SHM membership currently exceeds 17,000 members, and now offers membership that includes nurse practitioners, physician assistants, fellows, residents, students, and practice administrators, among others.12

These achievements and many more have been driven by the efforts of past and present Society of Hospital Medicine members and staff, and like-minded, invested professionals and organizations. The name Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) is highly familiar and well regarded by virtually all our stakeholders and is recognized for its proven leadership in continuing to define our brand, hospital medicine.

Dr. Dichter is an intensivist and associate professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical Center, Minneapolis.

References

1. Wachter RM et al. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Eng J Med. 1996 Aug 15;335(7):514-7.

2. SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine Report 2018. Fall 2018.

3. Satyen N et al. Core competencies in hospital medicine 2017 Revision. J Hosp Med. 2017 Apr;12:S1.

4. Society of Hospital Medicine website, Policy & Advocacy homepage (accessed July 26, 2018).

5. CMS manual system, Oct. 28, 2016 (accessed July 26, 2018).

6. Society of Hospital Medicine website, Clinical Topics: Advancing successful care transitions to improve outcomes (accessed July 26, 2018).

7. American Board of Internal Medicine website, MOC requirements: Focused practice in hospital medicine (accessed July 26, 2018).

8. American Board of Family Medicine website, Designation of practice in hospital medicine (accessed July 26, 2018).

9. The American Board of Pediatrics website, Pediatric hospital medicine certification (accessed July 26, 2018).

10. Journal of Hospital Medicine official website (accessed July 26, 2018).

11. SHM Leadership Academy website (accessed July 26, 2018).

12. Society of Hospital Medicine website, About SHM membership (accessed July 26, 2018).

The National Association of Inpatient Physicians (NAIP) “opened its doors” in the spring of 1998, welcoming the first 300 hospitalists. The term “hospitalist” was first coined in Bob Wachter’s 1996 New England Journal of Medicine article,1 although hospitalists were relatively few at that time, and the term not infrequently evoked controversy.

Having full-time hospital-based physicians was highly disruptive to the traditional culture of medicine, where hospital rounds were an integral part of a primary care physicians’ practice, professional identity, and referral patterns. Additionally, many hospital-based specialists were beginning to fill the hospitalist role.

The decision to include “inpatient physician” rather than “hospitalist” in the name was carefully considered and was intended to be inclusive, without alienating potential allies. Virtually any doctor working in a hospital could identify themselves as an inpatient physician, and all who wanted to participate were welcomed. It also was evident early on that this young specialty was going to comprise many different disciplines, including internal medicine, family practice, and pediatrics to name a few, and reaching out to all potential stakeholders was an urgent priority.

During its’ first 5 years, the field of hospital medicine grew rapidly, with NAIP membership nearing 2,000 members. The bimonthly newsletter The Hospitalist provided a vehicle to reach out to members and other stakeholders, and the annual meeting gave hospitalists a forum to gather, learn from each other, and enjoy camaraderie. Early research efforts focused on patient safety and, just as importantly, in 2002, the publication of the first Productivity and Compensation Survey (which is now known as SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine Report) and the initial development of The Hospitalist Core Competencies (first published in 2006, and now in its’ 2017 revision) all helped define the young specialty and gain acceptance.2,3

The term hospitalist became mainstream and accepted, and the name of our field, hospital medicine, has now become widely recognized.

Though the term “inpatient physician” had focused on physicians as a primary constituency, the successful growth of hospital medicine now increasingly depended upon other important constituencies and their understanding of the hospital medicine specialty and the role of hospitalists. These stakeholders included virtually all health care professionals and administrators, government officials at the federal, state, and local levels, patients, and the American public.