User login

Better ICU staff communication with family may improve end-of-life choices

A nurse-led support intervention for the families of critically ill patients did little to ease families’ psychological symptoms, but it did improve their perception of staff communication and family-centered care in the intensive care unit.

The length of ICU stay was also significantly shorter and the in-unit death rate higher among patients whose families received the intervention – a finding that suggests difficult end-of-life choices may have been eased, reported Douglas B. White, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75).

“The intervention resulted in significant improvements in markers of the quality of decision making, including the patient- and family-centeredness of care and the quality of clinician-family communication. Taken together, these findings suggest that the intervention allowed surrogates to transition a patient’s treatment to comfort-focused care when doing so aligned with the patient’s values,” wrote Dr. White of the University of Pittsburgh. “A previous study that was conducted in the context of advanced illness suggested that treatment that accords with the patient’s preferences may lead to shorter survival among those who prioritize comfort over longevity.”

The trial randomized 1,420 patients and their family surrogates in five ICUs to usual care, or to the multicomponent family-support intervention. The primary outcome was change in the surrogates’ scores on the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) at 6 months. The secondary outcomes were changes in Impact of Event Scale (IES; a measure of posttraumatic stress) the Quality of Communication (QOC) scale, quality of clinician-family communication measured by the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) scale and the mean length of ICU stay.

The intervention was delivered by nurses who received special training on communication and other skills needed to support the families of critically ill patients. Nurses met with families every day and arranged regular meetings with ICU clinicians. A quality improvement specialist incorporated the family support into daily work flow.

In a fully adjusted model, there was no significant between-group difference in the 6-month HADS scores (11.7 vs. 12 points). Likewise, there was no significant difference between the groups in the mean IES score at 6 months.

Family members in the active group did rate the quality of clinician-family communication as significantly better, and they also gave significantly higher ratings to the quality of patient- and family-centered care during the ICU stay.

The shorter length of stay was reflected in the time to death among patients who died during the stay (4.4 days in the intervention group vs. 6.8 days in the control group), although there was no significant difference in length of stay among patients who survived to discharge. Significantly more patients in the intervention group died in the ICU as well (36% vs. 28.5%); however, there was no significant difference in 6-month mortality (60.4% vs. 55.4%).

The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White reported having no financial disclosures

Although the results by White and colleagues “cannot be interpreted as clinically directive,” the study offers a glimpse of the path forward in improving the experience of families with critically ill loved ones, Daniela Lamas, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:2431-2).

The study didn’t meet its primary endpoint of reducing surrogates’ psychological symptoms at 6 months, but it did lead to an improved ICU experience, with better clinician communication. There was another finding that deserves a close look: In the intervention group, ICU length of stay was shorter and in-hospital mortality greater, although mortality among those who survived to discharge was similar at 6 months.

These findings suggest that the intervention did not lead to the premature death of patients who would have otherwise done well, but rather was associated with a shorter dying process for those who faced a dismal prognosis, according to Dr. Lamas.

“As we increasingly look beyond mortality as the primary outcome that matters, seeking to maximize quality of life and minimize suffering, this work represents an ‘end of the beginning’ by suggesting the next steps in moving closer to achieving these goals.”

Dr. Lamas is a pulmonary and critical care doctor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and on the faculty at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Although the results by White and colleagues “cannot be interpreted as clinically directive,” the study offers a glimpse of the path forward in improving the experience of families with critically ill loved ones, Daniela Lamas, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:2431-2).

The study didn’t meet its primary endpoint of reducing surrogates’ psychological symptoms at 6 months, but it did lead to an improved ICU experience, with better clinician communication. There was another finding that deserves a close look: In the intervention group, ICU length of stay was shorter and in-hospital mortality greater, although mortality among those who survived to discharge was similar at 6 months.

These findings suggest that the intervention did not lead to the premature death of patients who would have otherwise done well, but rather was associated with a shorter dying process for those who faced a dismal prognosis, according to Dr. Lamas.

“As we increasingly look beyond mortality as the primary outcome that matters, seeking to maximize quality of life and minimize suffering, this work represents an ‘end of the beginning’ by suggesting the next steps in moving closer to achieving these goals.”

Dr. Lamas is a pulmonary and critical care doctor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and on the faculty at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Although the results by White and colleagues “cannot be interpreted as clinically directive,” the study offers a glimpse of the path forward in improving the experience of families with critically ill loved ones, Daniela Lamas, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:2431-2).

The study didn’t meet its primary endpoint of reducing surrogates’ psychological symptoms at 6 months, but it did lead to an improved ICU experience, with better clinician communication. There was another finding that deserves a close look: In the intervention group, ICU length of stay was shorter and in-hospital mortality greater, although mortality among those who survived to discharge was similar at 6 months.

These findings suggest that the intervention did not lead to the premature death of patients who would have otherwise done well, but rather was associated with a shorter dying process for those who faced a dismal prognosis, according to Dr. Lamas.

“As we increasingly look beyond mortality as the primary outcome that matters, seeking to maximize quality of life and minimize suffering, this work represents an ‘end of the beginning’ by suggesting the next steps in moving closer to achieving these goals.”

Dr. Lamas is a pulmonary and critical care doctor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and on the faculty at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

A nurse-led support intervention for the families of critically ill patients did little to ease families’ psychological symptoms, but it did improve their perception of staff communication and family-centered care in the intensive care unit.

The length of ICU stay was also significantly shorter and the in-unit death rate higher among patients whose families received the intervention – a finding that suggests difficult end-of-life choices may have been eased, reported Douglas B. White, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75).

“The intervention resulted in significant improvements in markers of the quality of decision making, including the patient- and family-centeredness of care and the quality of clinician-family communication. Taken together, these findings suggest that the intervention allowed surrogates to transition a patient’s treatment to comfort-focused care when doing so aligned with the patient’s values,” wrote Dr. White of the University of Pittsburgh. “A previous study that was conducted in the context of advanced illness suggested that treatment that accords with the patient’s preferences may lead to shorter survival among those who prioritize comfort over longevity.”

The trial randomized 1,420 patients and their family surrogates in five ICUs to usual care, or to the multicomponent family-support intervention. The primary outcome was change in the surrogates’ scores on the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) at 6 months. The secondary outcomes were changes in Impact of Event Scale (IES; a measure of posttraumatic stress) the Quality of Communication (QOC) scale, quality of clinician-family communication measured by the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) scale and the mean length of ICU stay.

The intervention was delivered by nurses who received special training on communication and other skills needed to support the families of critically ill patients. Nurses met with families every day and arranged regular meetings with ICU clinicians. A quality improvement specialist incorporated the family support into daily work flow.

In a fully adjusted model, there was no significant between-group difference in the 6-month HADS scores (11.7 vs. 12 points). Likewise, there was no significant difference between the groups in the mean IES score at 6 months.

Family members in the active group did rate the quality of clinician-family communication as significantly better, and they also gave significantly higher ratings to the quality of patient- and family-centered care during the ICU stay.

The shorter length of stay was reflected in the time to death among patients who died during the stay (4.4 days in the intervention group vs. 6.8 days in the control group), although there was no significant difference in length of stay among patients who survived to discharge. Significantly more patients in the intervention group died in the ICU as well (36% vs. 28.5%); however, there was no significant difference in 6-month mortality (60.4% vs. 55.4%).

The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White reported having no financial disclosures

A nurse-led support intervention for the families of critically ill patients did little to ease families’ psychological symptoms, but it did improve their perception of staff communication and family-centered care in the intensive care unit.

The length of ICU stay was also significantly shorter and the in-unit death rate higher among patients whose families received the intervention – a finding that suggests difficult end-of-life choices may have been eased, reported Douglas B. White, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75).

“The intervention resulted in significant improvements in markers of the quality of decision making, including the patient- and family-centeredness of care and the quality of clinician-family communication. Taken together, these findings suggest that the intervention allowed surrogates to transition a patient’s treatment to comfort-focused care when doing so aligned with the patient’s values,” wrote Dr. White of the University of Pittsburgh. “A previous study that was conducted in the context of advanced illness suggested that treatment that accords with the patient’s preferences may lead to shorter survival among those who prioritize comfort over longevity.”

The trial randomized 1,420 patients and their family surrogates in five ICUs to usual care, or to the multicomponent family-support intervention. The primary outcome was change in the surrogates’ scores on the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) at 6 months. The secondary outcomes were changes in Impact of Event Scale (IES; a measure of posttraumatic stress) the Quality of Communication (QOC) scale, quality of clinician-family communication measured by the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) scale and the mean length of ICU stay.

The intervention was delivered by nurses who received special training on communication and other skills needed to support the families of critically ill patients. Nurses met with families every day and arranged regular meetings with ICU clinicians. A quality improvement specialist incorporated the family support into daily work flow.

In a fully adjusted model, there was no significant between-group difference in the 6-month HADS scores (11.7 vs. 12 points). Likewise, there was no significant difference between the groups in the mean IES score at 6 months.

Family members in the active group did rate the quality of clinician-family communication as significantly better, and they also gave significantly higher ratings to the quality of patient- and family-centered care during the ICU stay.

The shorter length of stay was reflected in the time to death among patients who died during the stay (4.4 days in the intervention group vs. 6.8 days in the control group), although there was no significant difference in length of stay among patients who survived to discharge. Significantly more patients in the intervention group died in the ICU as well (36% vs. 28.5%); however, there was no significant difference in 6-month mortality (60.4% vs. 55.4%).

The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White reported having no financial disclosures

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: A family communication intervention didn’t improve 6-month psychological symptoms among those with loved ones in intensive care units.

Major finding: There was no significant difference on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale at 6 months (11.7 vs. 12 points).

Study details: The study randomized 1,420 ICU patients and surrogates to the intervention or to usual care.

Disclosures: The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White had no financial disclosures.

Source: White et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75.

Intranasal naloxone promising for type 1 hypoglycemia

ORLANDO –

“This has been a clinical problem for a very long time, and we see it all the time. A patient comes into my clinic, the nurses check their blood sugar, it’s 50 mg/dL, and they’re just sitting there without any symptoms,” said lead investigator Sandra Aleksic, MD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

As blood glucose in the brain drops, people get confused, and their behavioral defenses are compromised. They might crash if they’re driving. “If you have HAAF, it makes you prone to more hypoglycemia, which blunts your response even more. It’s a vicious cycle,” she said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Endogenous opioids are at least partly to blame. Hypoglycemia induces release of beta-endorphin, which in turn inhibits production of epinephrine. Einstein investigators have shown in previous small studies with healthy subjects that morphine blunts the response to induced hypoglycemia, and intravenous naloxone – an opioid blocker – prevents HAAF (Diabetes. 2017 Nov;66[11]:2764-73).

Intravenous naloxone, however, isn’t practical for outpatients, so the team wanted to see whether intranasal naloxone also prevented HAAF. The results “are very promising, but this is preliminary.” If it pans out, though, patients may one day carry intranasal naloxone along with their glucose pills and glucagon to treat hypoglycemia. “Any time they are getting low, they would take the spray,” Dr. Aleksic said.

The team used hypoglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamps to drop blood glucose levels in seven healthy subjects down to 54 mg/dL for 2 hours twice in one day and gave them hourly sprays of either intranasal saline or 4 mg of intranasal naloxone; hypoglycemia was induced again for 2 hours the following day. The 2-day experiment was repeated 5 weeks later.

Overall, there was no difference in peak epinephrine levels between the first hypoglycemic episode on day 1 and the third episode on day 2 in subjects randomized to naloxone (942 pg/mL plus or minus 190 versus 857 pg/mL plus or minus 134; P = .4). The third episode, meanwhile, placed placebo subjects into HAAF (first hypoglycemic episode 1,375 pg/mL plus or minus 182 versus 858 pg/mL plus or minus 235; P = .004). There was also a trend toward higher hepatic glucose production in the naloxone group.

“These findings suggest that HAAF can be prevented by acute blockade of opioid receptors during hypoglycemia. ... Acute self-administration of intranasal naloxone could be an effective and feasible real-world approach to ameliorate HAAF in type 1 diabetes,” the investigators concluded. A trial in patients with T1DM is being considered.

Dr. Aleksic estimated that patients with T1DM drop blood glucose below 54 mg/dL maybe three or four times a month, on average, depending on how well they manage the condition. For now, it’s unknown how long protection from naloxone would last.

The study subjects were men, 43 years old, on average, with a mean body mass index of 26 kg/m2.

The investigators didn’t have any disclosures, and there was no industry funding for the work.

SOURCE: Aleksic S et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 10-LB.

ORLANDO –

“This has been a clinical problem for a very long time, and we see it all the time. A patient comes into my clinic, the nurses check their blood sugar, it’s 50 mg/dL, and they’re just sitting there without any symptoms,” said lead investigator Sandra Aleksic, MD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

As blood glucose in the brain drops, people get confused, and their behavioral defenses are compromised. They might crash if they’re driving. “If you have HAAF, it makes you prone to more hypoglycemia, which blunts your response even more. It’s a vicious cycle,” she said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Endogenous opioids are at least partly to blame. Hypoglycemia induces release of beta-endorphin, which in turn inhibits production of epinephrine. Einstein investigators have shown in previous small studies with healthy subjects that morphine blunts the response to induced hypoglycemia, and intravenous naloxone – an opioid blocker – prevents HAAF (Diabetes. 2017 Nov;66[11]:2764-73).

Intravenous naloxone, however, isn’t practical for outpatients, so the team wanted to see whether intranasal naloxone also prevented HAAF. The results “are very promising, but this is preliminary.” If it pans out, though, patients may one day carry intranasal naloxone along with their glucose pills and glucagon to treat hypoglycemia. “Any time they are getting low, they would take the spray,” Dr. Aleksic said.

The team used hypoglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamps to drop blood glucose levels in seven healthy subjects down to 54 mg/dL for 2 hours twice in one day and gave them hourly sprays of either intranasal saline or 4 mg of intranasal naloxone; hypoglycemia was induced again for 2 hours the following day. The 2-day experiment was repeated 5 weeks later.

Overall, there was no difference in peak epinephrine levels between the first hypoglycemic episode on day 1 and the third episode on day 2 in subjects randomized to naloxone (942 pg/mL plus or minus 190 versus 857 pg/mL plus or minus 134; P = .4). The third episode, meanwhile, placed placebo subjects into HAAF (first hypoglycemic episode 1,375 pg/mL plus or minus 182 versus 858 pg/mL plus or minus 235; P = .004). There was also a trend toward higher hepatic glucose production in the naloxone group.

“These findings suggest that HAAF can be prevented by acute blockade of opioid receptors during hypoglycemia. ... Acute self-administration of intranasal naloxone could be an effective and feasible real-world approach to ameliorate HAAF in type 1 diabetes,” the investigators concluded. A trial in patients with T1DM is being considered.

Dr. Aleksic estimated that patients with T1DM drop blood glucose below 54 mg/dL maybe three or four times a month, on average, depending on how well they manage the condition. For now, it’s unknown how long protection from naloxone would last.

The study subjects were men, 43 years old, on average, with a mean body mass index of 26 kg/m2.

The investigators didn’t have any disclosures, and there was no industry funding for the work.

SOURCE: Aleksic S et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 10-LB.

ORLANDO –

“This has been a clinical problem for a very long time, and we see it all the time. A patient comes into my clinic, the nurses check their blood sugar, it’s 50 mg/dL, and they’re just sitting there without any symptoms,” said lead investigator Sandra Aleksic, MD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

As blood glucose in the brain drops, people get confused, and their behavioral defenses are compromised. They might crash if they’re driving. “If you have HAAF, it makes you prone to more hypoglycemia, which blunts your response even more. It’s a vicious cycle,” she said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Endogenous opioids are at least partly to blame. Hypoglycemia induces release of beta-endorphin, which in turn inhibits production of epinephrine. Einstein investigators have shown in previous small studies with healthy subjects that morphine blunts the response to induced hypoglycemia, and intravenous naloxone – an opioid blocker – prevents HAAF (Diabetes. 2017 Nov;66[11]:2764-73).

Intravenous naloxone, however, isn’t practical for outpatients, so the team wanted to see whether intranasal naloxone also prevented HAAF. The results “are very promising, but this is preliminary.” If it pans out, though, patients may one day carry intranasal naloxone along with their glucose pills and glucagon to treat hypoglycemia. “Any time they are getting low, they would take the spray,” Dr. Aleksic said.

The team used hypoglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamps to drop blood glucose levels in seven healthy subjects down to 54 mg/dL for 2 hours twice in one day and gave them hourly sprays of either intranasal saline or 4 mg of intranasal naloxone; hypoglycemia was induced again for 2 hours the following day. The 2-day experiment was repeated 5 weeks later.

Overall, there was no difference in peak epinephrine levels between the first hypoglycemic episode on day 1 and the third episode on day 2 in subjects randomized to naloxone (942 pg/mL plus or minus 190 versus 857 pg/mL plus or minus 134; P = .4). The third episode, meanwhile, placed placebo subjects into HAAF (first hypoglycemic episode 1,375 pg/mL plus or minus 182 versus 858 pg/mL plus or minus 235; P = .004). There was also a trend toward higher hepatic glucose production in the naloxone group.

“These findings suggest that HAAF can be prevented by acute blockade of opioid receptors during hypoglycemia. ... Acute self-administration of intranasal naloxone could be an effective and feasible real-world approach to ameliorate HAAF in type 1 diabetes,” the investigators concluded. A trial in patients with T1DM is being considered.

Dr. Aleksic estimated that patients with T1DM drop blood glucose below 54 mg/dL maybe three or four times a month, on average, depending on how well they manage the condition. For now, it’s unknown how long protection from naloxone would last.

The study subjects were men, 43 years old, on average, with a mean body mass index of 26 kg/m2.

The investigators didn’t have any disclosures, and there was no industry funding for the work.

SOURCE: Aleksic S et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 10-LB.

REPORTING FROM ADA 2018

Key clinical point: Intranasal naloxone might be just the ticket to prevent hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure in type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Major finding: Overall, there was no difference in peak epinephrine levels between the first day 1 hypoglycemic episode and the third episode on day 2 in subjects randomized to naloxone (942 plus or minus 190 pg/mL versus 857 plus or minus 134 pg/mL; P = 0.4).

Study details: Randomized trial with seven healthy volunteers

Disclosures: There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

Source: Aleksic S et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 10-LB

What the (HM) world needs now

Practice compassion to rise to the challenges of HM

If you are in the business of health care – whether as a direct care provider who is doing their best in an increasingly complex system with an increasingly complex panel of patients; a hospital medicine group leader who is trying to keep a group afloat and lead people through this rocky terrain; or a hospital system leader or chief medical officer dealing with the arcane and ever-changing landscape – there is one universal truth: This business is hard.

You can call it “challenging.” You can say there are “opportunities for improvement.” You can put all kinds of sugar on top, but at times, it is a bitter drink to swallow.

So why, as hospitalists, do we keep doing this?

I always joke that I’m going to open a “fro-yo” stand on the beach, but of course, I never do. And that constancy is one huge reason why I love hospitalists. We are always trying to decode, unlock, and solve some of these seemingly unsolvable problems. But at the same time, this plethora of constant change and instability at all kinds of levels can be a bit, well, impossible.

How do we do it every day? You can change jobs, change patient panels, and change medical systems, but no matter what, you will be confronted on some level with a gap of clearly defined solutions to your “challenges.”

One thing in my arsenal of coping, beyond my fro-yo fantasy, is simply this: compassion. When one of your providers comes to you and is complaining about their workload, don’t tell them about how you used to see three times as many patients at your last job. Instead, put your hand on their shoulder, look them in the eye, and say “It is hard. It is.”

When the CEO of your hospital tells you that the already tiny margin of the hospital is shrinking, and she has to cut a service you feel is indispensable, reflect her pain. Believe me – she feels it.

To practice compassion in hospital medicine is to accept that medicine is hard on everyone. It’s not “us” versus “them.” It’s not just “us” that hurts and “them” that are immune. We all struggle.

We need – I need – to acknowledge the pain this profession often elicits. It can be burnout, resentment, overarching grief, or incredible frustration with broken systems and sometimes broken people. When we deny it, when we try to shove those feelings deep down, then people – good people who feel these things – perceive they are flawed or somehow not cut out for this profession. So they end up leaving. Or imploding.

Instead, if we practice compassion for ourselves and each other, we may find strength and restoration in these relationships with others. We will normalize these very normal responses to the challenges we face every day. And we may then survive all these “opportunities for improvement.”

I challenge everyone to practice this simple compassionate meditation. It will take less than five minutes. As you lay in bed at night, your mind racing, concentrate on feeling compassion for four different people. Start with the person you don’t know well, such as the person who works at the dry cleaner. Breathe deeply. Pick a sentence – a gift to give. I always think, “I wish you happy and healthy, wealthy and wise.” Do this for three or four deep breaths.

Next, using this same technique, choose someone that is hard to feel compassion for – perhaps that difficult family member, or the co-worker that gets under your skin.

Then feel that compassion. Breathe deeply – for yourself, with all your human frailties. You don’t have to be perfect to be loved or lovable. Feel that.

Finally, take a deep breath, feel your chest opening, expanding. Feel that compassion for the whole world – the whole crummy mixed-up world that’s just doing its best. The world needs our compassion, too.

While you were at HM18, I hope you were able to look into the eyes of the others you see. These are your fellow hospitalists. People who feel your joys, your frustrations. Some of those eyes will be bright and excited; others will be worn and tired. But revel in this shared and universal knowledge.

It is hard. But with compassion and understanding, we can make it a bit better. For all of us.

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Ms. Cardin, ACNP-BC, SFHM is vice president, Advanced Practice Providers, at Sound Physicians, and also serves on SHM’s Board of Directors.

Also in The Hospital Leader

- How Can Hospitalists Improve Their HCAHPS Scores? by Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM

- “Harper’s Index” of Hospital Medicine 2018 by Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM

- What’s a Cost, Charge, and Price? by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

Practice compassion to rise to the challenges of HM

Practice compassion to rise to the challenges of HM

If you are in the business of health care – whether as a direct care provider who is doing their best in an increasingly complex system with an increasingly complex panel of patients; a hospital medicine group leader who is trying to keep a group afloat and lead people through this rocky terrain; or a hospital system leader or chief medical officer dealing with the arcane and ever-changing landscape – there is one universal truth: This business is hard.

You can call it “challenging.” You can say there are “opportunities for improvement.” You can put all kinds of sugar on top, but at times, it is a bitter drink to swallow.

So why, as hospitalists, do we keep doing this?

I always joke that I’m going to open a “fro-yo” stand on the beach, but of course, I never do. And that constancy is one huge reason why I love hospitalists. We are always trying to decode, unlock, and solve some of these seemingly unsolvable problems. But at the same time, this plethora of constant change and instability at all kinds of levels can be a bit, well, impossible.

How do we do it every day? You can change jobs, change patient panels, and change medical systems, but no matter what, you will be confronted on some level with a gap of clearly defined solutions to your “challenges.”

One thing in my arsenal of coping, beyond my fro-yo fantasy, is simply this: compassion. When one of your providers comes to you and is complaining about their workload, don’t tell them about how you used to see three times as many patients at your last job. Instead, put your hand on their shoulder, look them in the eye, and say “It is hard. It is.”

When the CEO of your hospital tells you that the already tiny margin of the hospital is shrinking, and she has to cut a service you feel is indispensable, reflect her pain. Believe me – she feels it.

To practice compassion in hospital medicine is to accept that medicine is hard on everyone. It’s not “us” versus “them.” It’s not just “us” that hurts and “them” that are immune. We all struggle.

We need – I need – to acknowledge the pain this profession often elicits. It can be burnout, resentment, overarching grief, or incredible frustration with broken systems and sometimes broken people. When we deny it, when we try to shove those feelings deep down, then people – good people who feel these things – perceive they are flawed or somehow not cut out for this profession. So they end up leaving. Or imploding.

Instead, if we practice compassion for ourselves and each other, we may find strength and restoration in these relationships with others. We will normalize these very normal responses to the challenges we face every day. And we may then survive all these “opportunities for improvement.”

I challenge everyone to practice this simple compassionate meditation. It will take less than five minutes. As you lay in bed at night, your mind racing, concentrate on feeling compassion for four different people. Start with the person you don’t know well, such as the person who works at the dry cleaner. Breathe deeply. Pick a sentence – a gift to give. I always think, “I wish you happy and healthy, wealthy and wise.” Do this for three or four deep breaths.

Next, using this same technique, choose someone that is hard to feel compassion for – perhaps that difficult family member, or the co-worker that gets under your skin.

Then feel that compassion. Breathe deeply – for yourself, with all your human frailties. You don’t have to be perfect to be loved or lovable. Feel that.

Finally, take a deep breath, feel your chest opening, expanding. Feel that compassion for the whole world – the whole crummy mixed-up world that’s just doing its best. The world needs our compassion, too.

While you were at HM18, I hope you were able to look into the eyes of the others you see. These are your fellow hospitalists. People who feel your joys, your frustrations. Some of those eyes will be bright and excited; others will be worn and tired. But revel in this shared and universal knowledge.

It is hard. But with compassion and understanding, we can make it a bit better. For all of us.

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Ms. Cardin, ACNP-BC, SFHM is vice president, Advanced Practice Providers, at Sound Physicians, and also serves on SHM’s Board of Directors.

Also in The Hospital Leader

- How Can Hospitalists Improve Their HCAHPS Scores? by Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM

- “Harper’s Index” of Hospital Medicine 2018 by Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM

- What’s a Cost, Charge, and Price? by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

If you are in the business of health care – whether as a direct care provider who is doing their best in an increasingly complex system with an increasingly complex panel of patients; a hospital medicine group leader who is trying to keep a group afloat and lead people through this rocky terrain; or a hospital system leader or chief medical officer dealing with the arcane and ever-changing landscape – there is one universal truth: This business is hard.

You can call it “challenging.” You can say there are “opportunities for improvement.” You can put all kinds of sugar on top, but at times, it is a bitter drink to swallow.

So why, as hospitalists, do we keep doing this?

I always joke that I’m going to open a “fro-yo” stand on the beach, but of course, I never do. And that constancy is one huge reason why I love hospitalists. We are always trying to decode, unlock, and solve some of these seemingly unsolvable problems. But at the same time, this plethora of constant change and instability at all kinds of levels can be a bit, well, impossible.

How do we do it every day? You can change jobs, change patient panels, and change medical systems, but no matter what, you will be confronted on some level with a gap of clearly defined solutions to your “challenges.”

One thing in my arsenal of coping, beyond my fro-yo fantasy, is simply this: compassion. When one of your providers comes to you and is complaining about their workload, don’t tell them about how you used to see three times as many patients at your last job. Instead, put your hand on their shoulder, look them in the eye, and say “It is hard. It is.”

When the CEO of your hospital tells you that the already tiny margin of the hospital is shrinking, and she has to cut a service you feel is indispensable, reflect her pain. Believe me – she feels it.

To practice compassion in hospital medicine is to accept that medicine is hard on everyone. It’s not “us” versus “them.” It’s not just “us” that hurts and “them” that are immune. We all struggle.

We need – I need – to acknowledge the pain this profession often elicits. It can be burnout, resentment, overarching grief, or incredible frustration with broken systems and sometimes broken people. When we deny it, when we try to shove those feelings deep down, then people – good people who feel these things – perceive they are flawed or somehow not cut out for this profession. So they end up leaving. Or imploding.

Instead, if we practice compassion for ourselves and each other, we may find strength and restoration in these relationships with others. We will normalize these very normal responses to the challenges we face every day. And we may then survive all these “opportunities for improvement.”

I challenge everyone to practice this simple compassionate meditation. It will take less than five minutes. As you lay in bed at night, your mind racing, concentrate on feeling compassion for four different people. Start with the person you don’t know well, such as the person who works at the dry cleaner. Breathe deeply. Pick a sentence – a gift to give. I always think, “I wish you happy and healthy, wealthy and wise.” Do this for three or four deep breaths.

Next, using this same technique, choose someone that is hard to feel compassion for – perhaps that difficult family member, or the co-worker that gets under your skin.

Then feel that compassion. Breathe deeply – for yourself, with all your human frailties. You don’t have to be perfect to be loved or lovable. Feel that.

Finally, take a deep breath, feel your chest opening, expanding. Feel that compassion for the whole world – the whole crummy mixed-up world that’s just doing its best. The world needs our compassion, too.

While you were at HM18, I hope you were able to look into the eyes of the others you see. These are your fellow hospitalists. People who feel your joys, your frustrations. Some of those eyes will be bright and excited; others will be worn and tired. But revel in this shared and universal knowledge.

It is hard. But with compassion and understanding, we can make it a bit better. For all of us.

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Ms. Cardin, ACNP-BC, SFHM is vice president, Advanced Practice Providers, at Sound Physicians, and also serves on SHM’s Board of Directors.

Also in The Hospital Leader

- How Can Hospitalists Improve Their HCAHPS Scores? by Leslie Flores, MHA, SFHM

- “Harper’s Index” of Hospital Medicine 2018 by Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM

- What’s a Cost, Charge, and Price? by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

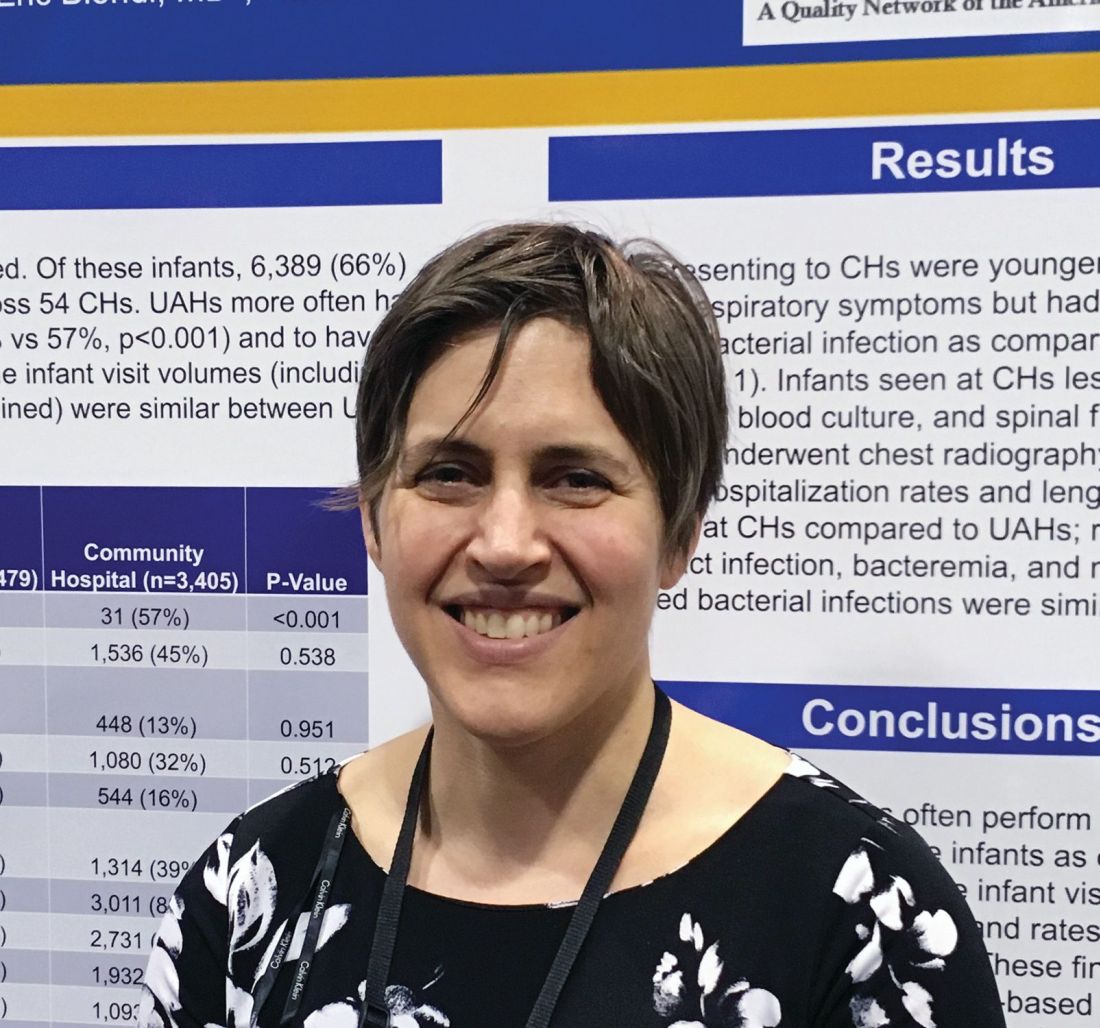

More testing of febrile infants at teaching vs. community hospitals, but similar outcomes

TORONTO – according to a study presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“The community hospitals are doing less procedures on the infants, but with basically the exact same outcomes,” said Beth C. Natt, MD, MPH, director of pediatric hospital medicine at Bridgeport (Conn.) Hospital.

Babies who presented to university-affiliated hospitals were more likely to be hospitalized (70% vs. 67%; P = .001) than were those at community hospitals, but had a similar likelihood of being diagnosed with bacteremia, meningitis, or urinary tract infection. The rates of missed bacterial infection were 0.8% for teaching hospitals and 1% for community hospitals (P = .346).

“There is some thought that in community settings, because we’re not completing the workup in the standard, protocolized way seen at teaching hospitals, we might be doing wrong by the children, but these data show we’re actually doing just fine,” Dr. Natt said in an interview.

She and her colleagues reviewed 9,884 febrile infant evaluations occurring at 132 hospitals participating in the Reducing Excessive Variation in the Infant Sepsis Evaluation (REVISE) quality improvement project. Two-thirds of the infants (n = 6,479) were evaluated across 78 university-affiliated hospitals and 3,405 (or 34%) were seen at 54 community hospitals. Hospital status was self-reported.

The teaching hospitals more often had at least one pediatric emergency medicine provider, compared with community hospitals (90% vs. 57%; P = .001) and were more likely to see babies between 7 and 30 days old (90% vs. 57%; P = .001). They also were more likely to obtain urine cultures (92% vs. 88%; P = 0.001), blood cultures (84% vs. 80%; P = .001), and cerebral spinal fluid cultures (62% vs. 57%; P = .001).

On the other hand, community hospitals were significantly more likely to see children presenting with respiratory symptoms (39% vs. 36% for teaching hospitals; P = .014), and were more likely to order chest x-rays on febrile infants (32% vs. 24% for university-affiliated hospitals; P = .001).

“As a community hospitalist, the results weren’t that surprising to me,” said Dr. Natt. “If anything was surprising it was how often we were doing chest x-rays, but I think that had to do with the fact that we had more children with respiratory symptoms coming to community hospitals.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for fever were written last in 1993, when I was in high school, so they are very due to be revised,” said Dr. Natt. “I suspect the new guidelines will have us doing fewer spinal taps in children and more watchful waiting.”

TORONTO – according to a study presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“The community hospitals are doing less procedures on the infants, but with basically the exact same outcomes,” said Beth C. Natt, MD, MPH, director of pediatric hospital medicine at Bridgeport (Conn.) Hospital.

Babies who presented to university-affiliated hospitals were more likely to be hospitalized (70% vs. 67%; P = .001) than were those at community hospitals, but had a similar likelihood of being diagnosed with bacteremia, meningitis, or urinary tract infection. The rates of missed bacterial infection were 0.8% for teaching hospitals and 1% for community hospitals (P = .346).

“There is some thought that in community settings, because we’re not completing the workup in the standard, protocolized way seen at teaching hospitals, we might be doing wrong by the children, but these data show we’re actually doing just fine,” Dr. Natt said in an interview.

She and her colleagues reviewed 9,884 febrile infant evaluations occurring at 132 hospitals participating in the Reducing Excessive Variation in the Infant Sepsis Evaluation (REVISE) quality improvement project. Two-thirds of the infants (n = 6,479) were evaluated across 78 university-affiliated hospitals and 3,405 (or 34%) were seen at 54 community hospitals. Hospital status was self-reported.

The teaching hospitals more often had at least one pediatric emergency medicine provider, compared with community hospitals (90% vs. 57%; P = .001) and were more likely to see babies between 7 and 30 days old (90% vs. 57%; P = .001). They also were more likely to obtain urine cultures (92% vs. 88%; P = 0.001), blood cultures (84% vs. 80%; P = .001), and cerebral spinal fluid cultures (62% vs. 57%; P = .001).

On the other hand, community hospitals were significantly more likely to see children presenting with respiratory symptoms (39% vs. 36% for teaching hospitals; P = .014), and were more likely to order chest x-rays on febrile infants (32% vs. 24% for university-affiliated hospitals; P = .001).

“As a community hospitalist, the results weren’t that surprising to me,” said Dr. Natt. “If anything was surprising it was how often we were doing chest x-rays, but I think that had to do with the fact that we had more children with respiratory symptoms coming to community hospitals.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for fever were written last in 1993, when I was in high school, so they are very due to be revised,” said Dr. Natt. “I suspect the new guidelines will have us doing fewer spinal taps in children and more watchful waiting.”

TORONTO – according to a study presented at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“The community hospitals are doing less procedures on the infants, but with basically the exact same outcomes,” said Beth C. Natt, MD, MPH, director of pediatric hospital medicine at Bridgeport (Conn.) Hospital.

Babies who presented to university-affiliated hospitals were more likely to be hospitalized (70% vs. 67%; P = .001) than were those at community hospitals, but had a similar likelihood of being diagnosed with bacteremia, meningitis, or urinary tract infection. The rates of missed bacterial infection were 0.8% for teaching hospitals and 1% for community hospitals (P = .346).

“There is some thought that in community settings, because we’re not completing the workup in the standard, protocolized way seen at teaching hospitals, we might be doing wrong by the children, but these data show we’re actually doing just fine,” Dr. Natt said in an interview.

She and her colleagues reviewed 9,884 febrile infant evaluations occurring at 132 hospitals participating in the Reducing Excessive Variation in the Infant Sepsis Evaluation (REVISE) quality improvement project. Two-thirds of the infants (n = 6,479) were evaluated across 78 university-affiliated hospitals and 3,405 (or 34%) were seen at 54 community hospitals. Hospital status was self-reported.

The teaching hospitals more often had at least one pediatric emergency medicine provider, compared with community hospitals (90% vs. 57%; P = .001) and were more likely to see babies between 7 and 30 days old (90% vs. 57%; P = .001). They also were more likely to obtain urine cultures (92% vs. 88%; P = 0.001), blood cultures (84% vs. 80%; P = .001), and cerebral spinal fluid cultures (62% vs. 57%; P = .001).

On the other hand, community hospitals were significantly more likely to see children presenting with respiratory symptoms (39% vs. 36% for teaching hospitals; P = .014), and were more likely to order chest x-rays on febrile infants (32% vs. 24% for university-affiliated hospitals; P = .001).

“As a community hospitalist, the results weren’t that surprising to me,” said Dr. Natt. “If anything was surprising it was how often we were doing chest x-rays, but I think that had to do with the fact that we had more children with respiratory symptoms coming to community hospitals.

“The American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for fever were written last in 1993, when I was in high school, so they are very due to be revised,” said Dr. Natt. “I suspect the new guidelines will have us doing fewer spinal taps in children and more watchful waiting.”

AT PAS 18

Key clinical point: University-affiliated hospitals do more invasive testing in febrile infants, but have outcomes similar to those of community hospitals.

Major finding: The rate of missed bacterial infection did not differ between hospital types: 0.8% for teaching hospitals and 1% for community hospitals (P = .346).

Study details: Review of 9,884 febrile infant evaluations occurring at 132 hospitals, 66% of which were university-affiliated hospitals and 34% of which were community hospitals.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

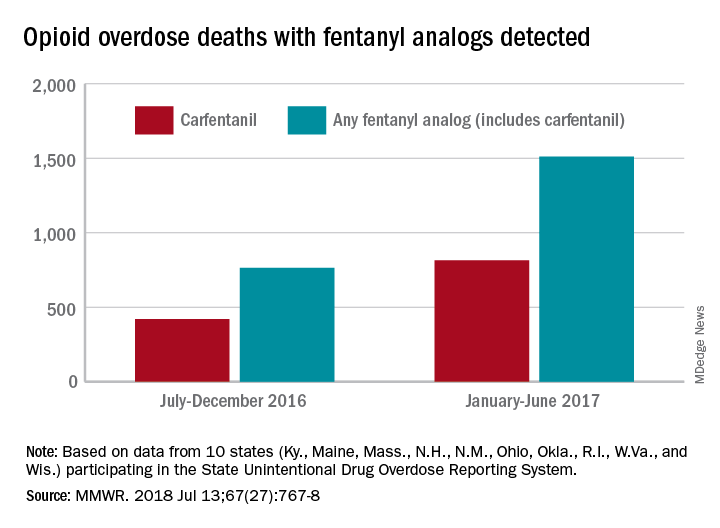

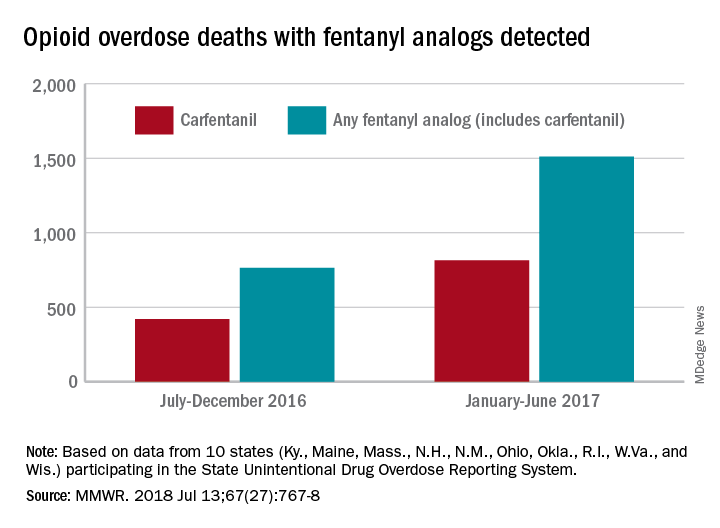

Fentanyl analogs nearly double their overdose death toll

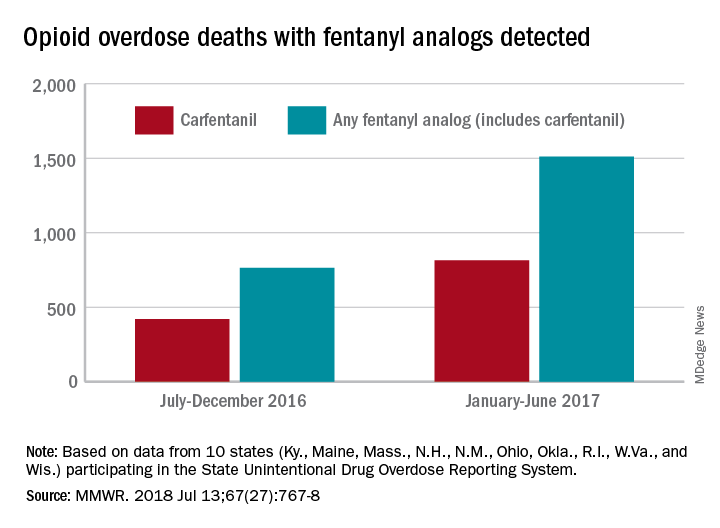

, according to preliminary data from 10 states.

During July 2016 to December 2016, there were 764 opioid overdose deaths that tested positive for any fentanyl analog, with carfentanil being the most common (421 deaths). From January 2017 to June 2017, the respective numbers increased by 98% (1,511) and 94% (815), wrote Julie O’Donnell, PhD, and her associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. The report was published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“The increasing array of fentanyl analogs highlights the need to build forensic toxicological testing capabilities to identify and report emerging threats, and to enhance capacity to rapidly respond to evolving drug trends,” Dr. O’Donnell and her associates said.

Along with carfentanil, 13 other analogs were detected in decedents during the 12-month period: 3-methylfentanyl, 4-fluorobutyrfentanyl, 4-fluorofentanyl, 4-fluoroisobutyrfentanyl, acetylfentanyl, acrylfentanyl, butyrylfentanyl, cyclopropylfentanyl, cyclopentylfentanyl, furanylethylfentanyl, furanylfentanyl, isobutyrylfentanyl, and tetrahydrofuranylfentanyl. Deaths may have involved “more than one analog, as well as ... other opioid and nonopioid substances,” they noted.

The 10 states reporting data to the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS) were Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Two other SUDORS-reporting states – Missouri and Pennsylvania – did not have their data ready in time to be included in this analysis.

The increasing availability of fentanyl analogs hit Ohio especially hard: More deaths occurred there than in the other 10 states combined. Of the 421 carfentanil-related deaths in July 2016 to December 2016, nearly 400 were in Ohio, and there were 218 Ohio deaths in April 2017 alone. A look at the bigger picture shows that 3 of the 10 states reported carfentanil-related overdose deaths in the second half of 2016, compared with 7 in the first half of 2017, the investigators said.

Carfentanil, which is the most potent of the 14 fentanyl analogs that have been detected so far, “is intended for sedation of large animals, and is estimated to have 10,000 times the potency of morphine,” Dr. O’Donnell and her associates wrote.

SOURCE: O’Donnell J et al. MMWR. 2018 Jul 13;67(27):767-8.

, according to preliminary data from 10 states.

During July 2016 to December 2016, there were 764 opioid overdose deaths that tested positive for any fentanyl analog, with carfentanil being the most common (421 deaths). From January 2017 to June 2017, the respective numbers increased by 98% (1,511) and 94% (815), wrote Julie O’Donnell, PhD, and her associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. The report was published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“The increasing array of fentanyl analogs highlights the need to build forensic toxicological testing capabilities to identify and report emerging threats, and to enhance capacity to rapidly respond to evolving drug trends,” Dr. O’Donnell and her associates said.

Along with carfentanil, 13 other analogs were detected in decedents during the 12-month period: 3-methylfentanyl, 4-fluorobutyrfentanyl, 4-fluorofentanyl, 4-fluoroisobutyrfentanyl, acetylfentanyl, acrylfentanyl, butyrylfentanyl, cyclopropylfentanyl, cyclopentylfentanyl, furanylethylfentanyl, furanylfentanyl, isobutyrylfentanyl, and tetrahydrofuranylfentanyl. Deaths may have involved “more than one analog, as well as ... other opioid and nonopioid substances,” they noted.

The 10 states reporting data to the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS) were Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Two other SUDORS-reporting states – Missouri and Pennsylvania – did not have their data ready in time to be included in this analysis.

The increasing availability of fentanyl analogs hit Ohio especially hard: More deaths occurred there than in the other 10 states combined. Of the 421 carfentanil-related deaths in July 2016 to December 2016, nearly 400 were in Ohio, and there were 218 Ohio deaths in April 2017 alone. A look at the bigger picture shows that 3 of the 10 states reported carfentanil-related overdose deaths in the second half of 2016, compared with 7 in the first half of 2017, the investigators said.

Carfentanil, which is the most potent of the 14 fentanyl analogs that have been detected so far, “is intended for sedation of large animals, and is estimated to have 10,000 times the potency of morphine,” Dr. O’Donnell and her associates wrote.

SOURCE: O’Donnell J et al. MMWR. 2018 Jul 13;67(27):767-8.

, according to preliminary data from 10 states.

During July 2016 to December 2016, there were 764 opioid overdose deaths that tested positive for any fentanyl analog, with carfentanil being the most common (421 deaths). From January 2017 to June 2017, the respective numbers increased by 98% (1,511) and 94% (815), wrote Julie O’Donnell, PhD, and her associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. The report was published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“The increasing array of fentanyl analogs highlights the need to build forensic toxicological testing capabilities to identify and report emerging threats, and to enhance capacity to rapidly respond to evolving drug trends,” Dr. O’Donnell and her associates said.

Along with carfentanil, 13 other analogs were detected in decedents during the 12-month period: 3-methylfentanyl, 4-fluorobutyrfentanyl, 4-fluorofentanyl, 4-fluoroisobutyrfentanyl, acetylfentanyl, acrylfentanyl, butyrylfentanyl, cyclopropylfentanyl, cyclopentylfentanyl, furanylethylfentanyl, furanylfentanyl, isobutyrylfentanyl, and tetrahydrofuranylfentanyl. Deaths may have involved “more than one analog, as well as ... other opioid and nonopioid substances,” they noted.

The 10 states reporting data to the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS) were Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Two other SUDORS-reporting states – Missouri and Pennsylvania – did not have their data ready in time to be included in this analysis.

The increasing availability of fentanyl analogs hit Ohio especially hard: More deaths occurred there than in the other 10 states combined. Of the 421 carfentanil-related deaths in July 2016 to December 2016, nearly 400 were in Ohio, and there were 218 Ohio deaths in April 2017 alone. A look at the bigger picture shows that 3 of the 10 states reported carfentanil-related overdose deaths in the second half of 2016, compared with 7 in the first half of 2017, the investigators said.

Carfentanil, which is the most potent of the 14 fentanyl analogs that have been detected so far, “is intended for sedation of large animals, and is estimated to have 10,000 times the potency of morphine,” Dr. O’Donnell and her associates wrote.

SOURCE: O’Donnell J et al. MMWR. 2018 Jul 13;67(27):767-8.

FROM MMWR

Pediatric inpatient seizures treated quickly with new intervention

TORONTO – Researchers at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in San Francisco implemented a novel intervention that leveraged existing in-room technology to expedite antiepileptic drug administration to inpatients having a seizure.

With the quality initiative, they were able to decrease median time from seizure onset to benzodiazepine (BZD) administration from 7 minutes (preintervention) to 2 minutes (post intervention) and reduce the median time from order to administration of second-phase non-BZDs from 28 minutes to 11 minutes.

“Leveraging existing patient room technology to mobilize pharmacy to the bedside expedited non-BZD administration by 60%,” reported principal investigator Arpi Bekmezian, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and medical director of quality and safety at Benioff Children’s Hospital. She presented the findings at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“Furthermore, the rapid-response seizure rescue process may have created an increased sense of urgency helping to expedite initial BZD administration by 70%. ... This may have prevented the need for second-phase therapy and progression to status epilepticus, potentially minimizing the risk of neuronal injury, and all without the additional resources of a Code team.”

Early and rapid escalation of treatment is critical to prevent neuronal injury in patients with status epilepticus. Guidelines recommend initial antiepileptic therapy at 5 minutes, with rapid escalation to second-phase therapy if the seizure persists.

Preintervention baseline data from UCSF Benioff Children’s indicated a 7-minute lag time from seizure onset to BZD therapy and a 28-minute lag from order to administration of non-BZDs (phenobarbital, phenytoin, levetiracetam, valproic acid). Other studies have shown significantly greater delays to antiepileptic treatment.

“That was just too long, and it matched our clinical experience of being at the bedside of a seizing patient and wondering why the medication was taking so long to arrive from the pharmacy.”

The researchers set out to reduce time to BZD administration from 7 minutes to 5 minutes or less and to reduce time to second-phase non-BZD administration to less than 10 minutes. To accomplish this, a multidisciplinary team that included leadership from physicians, pharmacy, and nursing defined primary and secondary drivers of efficiency, with interventions targeting both team communication and medication delivery.

The intervention period lasted 16 months, during which time there were 61 seizure events requiring urgent antiepileptic treatment. Complete data were available for 57 seizures.

Among the interventions they implemented was to stock all medication-dispensing stations with intranasal/buccal BZD available on “nursing override” for easy access and administration.

Because non-BZDs require pharmacy compounding, and the main pharmacy receives many STAT orders with competing priorities, they developed a hospitalwide “seizure rescue” (SR) process by using patient-room staff terminals to activate a dedicated individual from the pharmacy, who would then report to the bedside with a backpack stocked with non-BZDs ready to compound. Nurses were trained to press the SR button for any seizure that may require urgent therapy.

“We didn’t want nurses to waste time on the phone [calling pharmacy], and we considered calling a Code, but we couldn’t really justify the resource utilization as most of these patients didn’t have respiratory compromise, and they didn’t need the whole Code team,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that her hospital strongly discourages bedside compounding by nursing staff.

Instead, they realized they could easily reprogram the patient-room electronic staff terminals to have a dedicated SR button that would directly alert a dedicated pharmacist carrying the SR phone. The pharmacist could then swipe and confirm that they received the alert and let the nurse know they were on the way, “and this would free up the nurse to go ahead and obtain the benzodiazepines and administer them as pharmacy made their way to the room.”

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to report expediting antiepileptic drug delivery to patients in the hospital,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that less than 50% of cases actually required pharmacist response, “but the pharmacy staff chose to be activated earlier in the management algorithm to avoid delays in treatment.”

UCSF Children’s Hospital San Francisco campus is a 183-bed, tertiary care, teaching children’s hospital that has pediatric, neonatal, and cardiac intensive care units and set-down units. They provide liver, bone marrow, kidney, and cardiac transplantation and have more than 10,000 annual admissions.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bekmezian A et al. PAS 2018. Abstract 3545.3.

TORONTO – Researchers at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in San Francisco implemented a novel intervention that leveraged existing in-room technology to expedite antiepileptic drug administration to inpatients having a seizure.

With the quality initiative, they were able to decrease median time from seizure onset to benzodiazepine (BZD) administration from 7 minutes (preintervention) to 2 minutes (post intervention) and reduce the median time from order to administration of second-phase non-BZDs from 28 minutes to 11 minutes.

“Leveraging existing patient room technology to mobilize pharmacy to the bedside expedited non-BZD administration by 60%,” reported principal investigator Arpi Bekmezian, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and medical director of quality and safety at Benioff Children’s Hospital. She presented the findings at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“Furthermore, the rapid-response seizure rescue process may have created an increased sense of urgency helping to expedite initial BZD administration by 70%. ... This may have prevented the need for second-phase therapy and progression to status epilepticus, potentially minimizing the risk of neuronal injury, and all without the additional resources of a Code team.”

Early and rapid escalation of treatment is critical to prevent neuronal injury in patients with status epilepticus. Guidelines recommend initial antiepileptic therapy at 5 minutes, with rapid escalation to second-phase therapy if the seizure persists.

Preintervention baseline data from UCSF Benioff Children’s indicated a 7-minute lag time from seizure onset to BZD therapy and a 28-minute lag from order to administration of non-BZDs (phenobarbital, phenytoin, levetiracetam, valproic acid). Other studies have shown significantly greater delays to antiepileptic treatment.

“That was just too long, and it matched our clinical experience of being at the bedside of a seizing patient and wondering why the medication was taking so long to arrive from the pharmacy.”

The researchers set out to reduce time to BZD administration from 7 minutes to 5 minutes or less and to reduce time to second-phase non-BZD administration to less than 10 minutes. To accomplish this, a multidisciplinary team that included leadership from physicians, pharmacy, and nursing defined primary and secondary drivers of efficiency, with interventions targeting both team communication and medication delivery.

The intervention period lasted 16 months, during which time there were 61 seizure events requiring urgent antiepileptic treatment. Complete data were available for 57 seizures.

Among the interventions they implemented was to stock all medication-dispensing stations with intranasal/buccal BZD available on “nursing override” for easy access and administration.

Because non-BZDs require pharmacy compounding, and the main pharmacy receives many STAT orders with competing priorities, they developed a hospitalwide “seizure rescue” (SR) process by using patient-room staff terminals to activate a dedicated individual from the pharmacy, who would then report to the bedside with a backpack stocked with non-BZDs ready to compound. Nurses were trained to press the SR button for any seizure that may require urgent therapy.

“We didn’t want nurses to waste time on the phone [calling pharmacy], and we considered calling a Code, but we couldn’t really justify the resource utilization as most of these patients didn’t have respiratory compromise, and they didn’t need the whole Code team,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that her hospital strongly discourages bedside compounding by nursing staff.

Instead, they realized they could easily reprogram the patient-room electronic staff terminals to have a dedicated SR button that would directly alert a dedicated pharmacist carrying the SR phone. The pharmacist could then swipe and confirm that they received the alert and let the nurse know they were on the way, “and this would free up the nurse to go ahead and obtain the benzodiazepines and administer them as pharmacy made their way to the room.”

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to report expediting antiepileptic drug delivery to patients in the hospital,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that less than 50% of cases actually required pharmacist response, “but the pharmacy staff chose to be activated earlier in the management algorithm to avoid delays in treatment.”

UCSF Children’s Hospital San Francisco campus is a 183-bed, tertiary care, teaching children’s hospital that has pediatric, neonatal, and cardiac intensive care units and set-down units. They provide liver, bone marrow, kidney, and cardiac transplantation and have more than 10,000 annual admissions.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bekmezian A et al. PAS 2018. Abstract 3545.3.

TORONTO – Researchers at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in San Francisco implemented a novel intervention that leveraged existing in-room technology to expedite antiepileptic drug administration to inpatients having a seizure.

With the quality initiative, they were able to decrease median time from seizure onset to benzodiazepine (BZD) administration from 7 minutes (preintervention) to 2 minutes (post intervention) and reduce the median time from order to administration of second-phase non-BZDs from 28 minutes to 11 minutes.

“Leveraging existing patient room technology to mobilize pharmacy to the bedside expedited non-BZD administration by 60%,” reported principal investigator Arpi Bekmezian, MD, a pediatric hospitalist and medical director of quality and safety at Benioff Children’s Hospital. She presented the findings at the Pediatric Academic Societies annual meeting.

“Furthermore, the rapid-response seizure rescue process may have created an increased sense of urgency helping to expedite initial BZD administration by 70%. ... This may have prevented the need for second-phase therapy and progression to status epilepticus, potentially minimizing the risk of neuronal injury, and all without the additional resources of a Code team.”

Early and rapid escalation of treatment is critical to prevent neuronal injury in patients with status epilepticus. Guidelines recommend initial antiepileptic therapy at 5 minutes, with rapid escalation to second-phase therapy if the seizure persists.

Preintervention baseline data from UCSF Benioff Children’s indicated a 7-minute lag time from seizure onset to BZD therapy and a 28-minute lag from order to administration of non-BZDs (phenobarbital, phenytoin, levetiracetam, valproic acid). Other studies have shown significantly greater delays to antiepileptic treatment.

“That was just too long, and it matched our clinical experience of being at the bedside of a seizing patient and wondering why the medication was taking so long to arrive from the pharmacy.”

The researchers set out to reduce time to BZD administration from 7 minutes to 5 minutes or less and to reduce time to second-phase non-BZD administration to less than 10 minutes. To accomplish this, a multidisciplinary team that included leadership from physicians, pharmacy, and nursing defined primary and secondary drivers of efficiency, with interventions targeting both team communication and medication delivery.

The intervention period lasted 16 months, during which time there were 61 seizure events requiring urgent antiepileptic treatment. Complete data were available for 57 seizures.

Among the interventions they implemented was to stock all medication-dispensing stations with intranasal/buccal BZD available on “nursing override” for easy access and administration.

Because non-BZDs require pharmacy compounding, and the main pharmacy receives many STAT orders with competing priorities, they developed a hospitalwide “seizure rescue” (SR) process by using patient-room staff terminals to activate a dedicated individual from the pharmacy, who would then report to the bedside with a backpack stocked with non-BZDs ready to compound. Nurses were trained to press the SR button for any seizure that may require urgent therapy.

“We didn’t want nurses to waste time on the phone [calling pharmacy], and we considered calling a Code, but we couldn’t really justify the resource utilization as most of these patients didn’t have respiratory compromise, and they didn’t need the whole Code team,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that her hospital strongly discourages bedside compounding by nursing staff.

Instead, they realized they could easily reprogram the patient-room electronic staff terminals to have a dedicated SR button that would directly alert a dedicated pharmacist carrying the SR phone. The pharmacist could then swipe and confirm that they received the alert and let the nurse know they were on the way, “and this would free up the nurse to go ahead and obtain the benzodiazepines and administer them as pharmacy made their way to the room.”

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to report expediting antiepileptic drug delivery to patients in the hospital,” said Dr. Bekmezian. She noted that less than 50% of cases actually required pharmacist response, “but the pharmacy staff chose to be activated earlier in the management algorithm to avoid delays in treatment.”

UCSF Children’s Hospital San Francisco campus is a 183-bed, tertiary care, teaching children’s hospital that has pediatric, neonatal, and cardiac intensive care units and set-down units. They provide liver, bone marrow, kidney, and cardiac transplantation and have more than 10,000 annual admissions.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bekmezian A et al. PAS 2018. Abstract 3545.3.

AT PAS 2018

Key clinical point: An intervention to speed delivery of antiepileptic drugs significantly reduced time to treatment.

Major finding: Median time from seizure onset to benzodiazepine (BZD) administration fell from 7 minutes preintervention to 2 minutes post intervention, and median time from order to administration of non-BZDs dropped from 28 minutes to 11 minutes.

Study details: A prospective, multicenter study of 57 seizure events during a 16-month period.

Disclosures: The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Bekmezian A et al. PAS 2018. Abstract 3545.3.

Benefits, drawbacks when hospitalists expand roles

Hospitalists can’t ‘fill all the cracks’ in primary care

As vice chair of the hospital medicine service at Northwell Health, Nick Fitterman, MD, FACP, SFHM, oversees 16 HM groups at 15 hospitals in New York. He says the duties of his hospitalist staff, like those of most U.S. hospitalists, are similar to what they have traditionally been – clinical care on the wards, teaching, comanagement of surgery, quality improvement, committee work, and research. But he has noticed a trend of late: rapid expansion of the hospitalist’s role.

Speaking at an education session at HM18 in Orlando, Dr. Fitterman said the role of the hospitalist is growing to include tasks that might not be as common, but are becoming more familiar all the time: working at infusion centers, caring for patients in skilled nursing facilities, specializing in electronic health record use, colocating in psychiatric hospitals, even being deployed to natural disasters. His list went on, and it was much longer than the list of traditional hospitalist responsibilities.

“Where do we draw the line and say, ‘Wait a minute, our primary site is going to suffer if we continue to get spread this thin. Can we really do it all?” Dr. Fitterman said. As the number of hats hospitalists wear grows ever bigger, he said more thought must be placed into how expansion happens.

The preop clinic

Efren Manjarrez, MD, SFHM, former chief of hospital medicine at the University of Miami, told a cautionary tale about a preoperative clinic staffed by hospitalists that appeared to provide a financial benefit to a hospital – helping to avoid costly last-minute cancellations of surgeries – but that ultimately was shuttered. The hospital, he said, loses $8,000-$10,000 for each case that gets canceled on the same day.

“Think about that just for a minute,” Dr. Manjarrez said. “If 100 cases are canceled during the year at the last minute, that’s a lot of money.”

A preoperative clinic seemed like a worthwhile role for hospitalists – the program was started in Miami by the same doctor who initiated a similar program at Cleveland Clinic. “Surgical cases are what support the hospital [financially], and we’re here to help them along,” Dr. Manjarrez said. “The purpose of hospitalists is to make sure that patients are medically optimized.”

The preop program concept, used in U.S. medicine since the 1990s, was originally started by anesthesiologists, but they may not always be the best fit to staff such programs.

“Anesthesiologists do not manage all beta blockers,” Dr. Manjarrez said. “They don’t manage ACE inhibitors by mouth. They don’t manage all oral diabetes agents, and they sure as heck don’t manage pills that are anticoagulants. That’s the domain of internal medicine. And as patients have become more complex, that’s where hospitalists who [work in] preop clinics have stepped in.”

Studies have found that hospitalists staffing preop clinics have improved quality metrics and some clinical outcomes, including lowering cancellation rates and more appropriate use of beta blockers, he said.

In the Miami program described by Dr. Manjarrez, hospitalists in the preop clinic at first saw only patients who’d been financially cleared as able to pay. But ultimately, a tiered system was developed, and hospitalists saw only patients who were higher risk – those with COPD or stroke patients, for example – without regard to ability to pay.

“The hospital would have to make up any financial deficit at the very end,” Dr. Manjarrez said. This meant there were no longer efficient 5-minute encounters with patients. Instead, visits lasted about 45 minutes, so fewer patients were seen.

The program was successful, in that the same-day cancellation rate for surgeries dropped to less than 0.1% – fewer than 1 in 1,000 – with the preop clinic up and running, Dr. Manjarrez. Still, the hospital decided to end the program. “The hospital no longer wanted to reimburse us,” he said.

A takeaway from this experience for Dr. Manjarrez was that hospitalists need to do a better job of showing the financial benefits in their expanding roles, if they want them to endure.

“At the end of the day, hospitalists do provide value in preoperative clinics,” he said. “But unfortunately, we’re not doing a great job of publishing our data and showing our value.”

At-home care

At Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, hospitalists have demonstrated good results with a program to provide care at home rather than in the hospital.

David Levine, MD, MPH, MA, clinician and investigator at Brigham and Women’s and an instructor in medicine at Harvard Medical School, said that the structure of inpatient care has generally not changed much over decades, despite advances in technology.

“We round on them once a day – if they’re lucky, twice,” he said. “The medicines have changed and imaging has changed, but we really haven’t changed the structure of how we take care of acutely ill adults for almost a hundred years.”

Hospitalizing patients brings unintended consequences. Twenty percent of older adults will become delirious during their stay, 1 out of 3 will lose a level of functional status in the hospital that they’ll never regain, and 1 out of 10 hospitalized patients will experience an adverse event, like an infection or a medication error.

Brigham and Women’s program of at-home care involves “admitting” patients to their homes after being treated in the emergency department. The goal is to reduce costs by 20%, while maintaining quality and safety and improving patients’ quality of life and experience.

Researchers are studying their results. They randomized patients, after the ED determined they required admission, either to admission to the hospital or to their home. The decision on whether to admit was made before the study investigators became involved with the patients, Dr. Levine said.

The program is also intended to improve access to hospitals. Brigham and Women’s is often over 100% capacity in the general medical ward.

Patients in the study needed to live within a 5-mile radius of either Brigham and Women’s Hospital, or Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital, a nearby community hospital. A physician and a registered nurse form the core team; they assess patient needs and ratchet care either up or down, perhaps adding a home health aide or social worker.

The home care team takes advantage of technology: Portable equipment allows a basic metabolic panel to be performed on the spot – for example, a hemoglobin and hematocrit can be produced within 2 minutes. Also, portable ultrasounds and x-rays are used. Doctors keep a “tackle box” of urgent medications such as antibiotics and diuretics.

“We showed a direct cost reduction taking care of patients at home,” Dr. Levine said. There was also a reduction in utilization of care, and an increase in patient activity, with patients taking about 1,800 steps at home, compared with 180 in the hospital. There were no significant changes in safety, quality, or patient experience, he said.

Postdischarge clinics

Lauren Doctoroff, MD, FHM – a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconness Medical Center in Boston and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School – explained another hospitalist-staffed project meant to improve access to care: her center’s postdischarge clinic, which was started in 2009 but is no longer operating.

The clinic tackled the problem of what to do with patients when you discharge them, Dr. Doctoroff said, and its goal was to foster more cooperation between hospitalists and the faculty primary care practice, as well as to improve postdischarge access for patients from that practice.

A dedicated group of hospitalists staffed the clinics, handling medication reconciliation, symptom management, pending tests, and other services the patients were supposed to be getting after discharge, Dr. Doctoroff said.

“We greatly improved access so that when you came to see us you generally saw a hospitalist a week before you would have seen your primary care doctor,” she said. “And that was mostly because we created open access in a clinic that did not have open access. So if a doctor discharging a patient really thought that the patient needed to be seen after discharge, they would often see us.”

Hospitalists considering starting such a clinic have several key questions to consider, Dr. Doctoroff said.

“You need to focus on who the patient population is, the clinic structure, how you plan to staff the clinic, and what your outcomes are – mainly how you will measure performance,” she said.