User login

MI, stroke risk from HFrEF surpasses HFpEF

DALLAS – Patients newly diagnosed with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction had about an 8% incidence of MIs during the subsequent 9 months, and a 5% incidence of ischemic strokes in a retrospective review of more than 1,600 community-dwelling U.S. patients.

The MI and ischemic stroke incidence rates in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) were both significantly higher than in more than 4,000 patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, said while presenting a poster at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The findings suggest that greater attention is needed to reduce the risks for MI and stroke in HFrEF patients, suggested Dr. Fonarow, professor and cochief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and his associates in their poster.

The study used claims data collected during July 2009-September 2016 from more than 10 million people enrolled in the United Health Group, who received care at more than 650 hospitals and about 6,600 clinics. The study included all patients diagnosed with heart failure during a hospital or emergency room visit and who had no history of a heart failure diagnosis or episode during the preceding 18 months, a left ventricular ejection fraction measurement made close to the time of the index encounter, and no stroke or MI apparent at the time of the index event. The study included 1,622 patients with HFrEF, defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 40%, 4,288 with HFpEF, defined as an ejection fraction of 50% or more, and 1,095 with heart failure with a borderline ejection fraction of 40%-49%.

The HFrEF patients had an average ejection fraction of 28%, they averaged 72 years old, 36% were women, and 8% had a prior stroke. The HFpEF patients averaged 74 years old, their average ejection fraction was 61%, 55% were women, and 11% had a prior stroke. Follow-up data on all patients were available for an average of nearly 9 months following their index heart failure event, with some patients followed as long as 1 year.

During follow-up, the incidence of ischemic stroke was 5.4% in the HFrEF patients and 3.9% in those with HFpEF, a difference that worked out to a statistically significant 40% higher ischemic stroke rate in HFrEF patients after adjustment for baseline differences between the two patient groups, Dr. Fonarow reported. The patients with a borderline ejection fraction had a 3.7% stroke incidence that fell short of a significant difference, compared with the HFrEF patient.The rate of new MIs during follow-up was 7.5% in the HFrEF patients and 3.2% in the HFpEF patients, a statistically significant 2.5-fold relatively higher MI rate with HFrEF, a statistically significant difference after adjustments. The MI incidence in patients with a borderline ejection fraction was 5.9%

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

DALLAS – Patients newly diagnosed with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction had about an 8% incidence of MIs during the subsequent 9 months, and a 5% incidence of ischemic strokes in a retrospective review of more than 1,600 community-dwelling U.S. patients.

The MI and ischemic stroke incidence rates in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) were both significantly higher than in more than 4,000 patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, said while presenting a poster at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The findings suggest that greater attention is needed to reduce the risks for MI and stroke in HFrEF patients, suggested Dr. Fonarow, professor and cochief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and his associates in their poster.

The study used claims data collected during July 2009-September 2016 from more than 10 million people enrolled in the United Health Group, who received care at more than 650 hospitals and about 6,600 clinics. The study included all patients diagnosed with heart failure during a hospital or emergency room visit and who had no history of a heart failure diagnosis or episode during the preceding 18 months, a left ventricular ejection fraction measurement made close to the time of the index encounter, and no stroke or MI apparent at the time of the index event. The study included 1,622 patients with HFrEF, defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 40%, 4,288 with HFpEF, defined as an ejection fraction of 50% or more, and 1,095 with heart failure with a borderline ejection fraction of 40%-49%.

The HFrEF patients had an average ejection fraction of 28%, they averaged 72 years old, 36% were women, and 8% had a prior stroke. The HFpEF patients averaged 74 years old, their average ejection fraction was 61%, 55% were women, and 11% had a prior stroke. Follow-up data on all patients were available for an average of nearly 9 months following their index heart failure event, with some patients followed as long as 1 year.

During follow-up, the incidence of ischemic stroke was 5.4% in the HFrEF patients and 3.9% in those with HFpEF, a difference that worked out to a statistically significant 40% higher ischemic stroke rate in HFrEF patients after adjustment for baseline differences between the two patient groups, Dr. Fonarow reported. The patients with a borderline ejection fraction had a 3.7% stroke incidence that fell short of a significant difference, compared with the HFrEF patient.The rate of new MIs during follow-up was 7.5% in the HFrEF patients and 3.2% in the HFpEF patients, a statistically significant 2.5-fold relatively higher MI rate with HFrEF, a statistically significant difference after adjustments. The MI incidence in patients with a borderline ejection fraction was 5.9%

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

DALLAS – Patients newly diagnosed with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction had about an 8% incidence of MIs during the subsequent 9 months, and a 5% incidence of ischemic strokes in a retrospective review of more than 1,600 community-dwelling U.S. patients.

The MI and ischemic stroke incidence rates in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) were both significantly higher than in more than 4,000 patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, said while presenting a poster at the annual scientific meeting of the Heart Failure Society of America.

The findings suggest that greater attention is needed to reduce the risks for MI and stroke in HFrEF patients, suggested Dr. Fonarow, professor and cochief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and his associates in their poster.

The study used claims data collected during July 2009-September 2016 from more than 10 million people enrolled in the United Health Group, who received care at more than 650 hospitals and about 6,600 clinics. The study included all patients diagnosed with heart failure during a hospital or emergency room visit and who had no history of a heart failure diagnosis or episode during the preceding 18 months, a left ventricular ejection fraction measurement made close to the time of the index encounter, and no stroke or MI apparent at the time of the index event. The study included 1,622 patients with HFrEF, defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction of less than 40%, 4,288 with HFpEF, defined as an ejection fraction of 50% or more, and 1,095 with heart failure with a borderline ejection fraction of 40%-49%.

The HFrEF patients had an average ejection fraction of 28%, they averaged 72 years old, 36% were women, and 8% had a prior stroke. The HFpEF patients averaged 74 years old, their average ejection fraction was 61%, 55% were women, and 11% had a prior stroke. Follow-up data on all patients were available for an average of nearly 9 months following their index heart failure event, with some patients followed as long as 1 year.

During follow-up, the incidence of ischemic stroke was 5.4% in the HFrEF patients and 3.9% in those with HFpEF, a difference that worked out to a statistically significant 40% higher ischemic stroke rate in HFrEF patients after adjustment for baseline differences between the two patient groups, Dr. Fonarow reported. The patients with a borderline ejection fraction had a 3.7% stroke incidence that fell short of a significant difference, compared with the HFrEF patient.The rate of new MIs during follow-up was 7.5% in the HFrEF patients and 3.2% in the HFpEF patients, a statistically significant 2.5-fold relatively higher MI rate with HFrEF, a statistically significant difference after adjustments. The MI incidence in patients with a borderline ejection fraction was 5.9%

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE HFSA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: HFrEF patients had a 40% higher incidence of stroke and a 2.5-fold higher incidence of MI, compared with HFpEF patients.

Data source: Retrospective review of 7,005 U.S. patients newly diagnosed with heart failure.

Disclosures: The study was funded by Janssen. Dr. Fonarow had no relevant disclosures.

Hospitalists struggle with opioid epidemic’s rising toll

It’s the stuff of doctors’ nightmares. In a recent analysis of attitudes, beliefs, and practices regarding opioid prescribing, one hospitalist described how a patient had overdosed: “She crushed up the oxycodone we were giving her in the hospital and shot it up through her central line and died.”1

Susan Calcaterra, MD, MPH, of the department of family medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora; a hospitalist at Denver Health Hospital; and lead author of the recent study, says that the dramatic anecdotes don’t surprise her. “These are not uncommon events,” she said. “Across the country, you hear about overdose, you hear about people abusing fentanyl, and I think, when you have an addiction, your judgment of the dangers associated with your personal opioid use may be limited.”

Some critics have blamed the ubiquity of opioid prescriptions on the controversial movement to establish pain as a vital sign. Multiple investigations also have accused the pharmaceutical industry of aggressively promoting these prescription drugs while downplaying their risks. The CDC found that, in fact, so many opioid prescriptions were being written by 2012 that the 259 million scripts could have supplied every U.S. adult with his and her own bottle. In August 2017, President Trump declared the opioid crisis a national emergency, although opinions differ regarding the best ways forward.

Until recently, however, few studies had looked at how inpatient prescribing may be fueling a surging epidemic that already has exacted a staggering toll. So far, the early data paint a disturbing picture that suggests hospitals are both a part of the problem and a key to its solution.

Illuminating a ‘black box’

Changing the trajectory will be difficult. From 2002 to 2015, the nation’s overdose death rate from opioid analgesics, heroin, and synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, nearly tripled, and studies suggest that prescription painkillers have become major gateway drugs for heroin.2 In the last 3 years alone, fentanyl-related deaths soared by more than 500%, and annual mortality from all drug overdoses has blown by the peak of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in 1995, when nearly 51,000 died from the disease.3

Amid the ringing alarm bells, hospitals have remained a largely neglected “regulatory dead zone” for opioids, said Shoshana Herzig, MD, MPH, of the department of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of hospital medicine research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, also in Boston. In an editorial accompanying the recent study of hospitalist perspectives, Dr. Herzig called the inpatient setting an opioid prescribing “black box.”4

In a previous analysis of 1.1 million nonsurgical hospital admissions, however, she and colleagues found that opioids were prescribed to 51% of all patients.5 More than half of those with inpatient exposure were still taking opioids on their discharge day. With other studies suggesting that such practices may be contributing to chronic opioid use long after hospitalization, Dr. Herzig wrote, “reigning in inpatient prescribing may be a crucial step in curbing the opioid epidemic as a whole.”

A recent study led by Anupam Jena, MD, PhD, a health care policy expert at Harvard Medical School, echoes the refrain. “It’s kind of remarkable that the hospital setting hasn’t really been studied, and it’s an important setting,” he said. When he and colleagues did their own analysis of hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries, they found that 15% of previously opioid-naive patients were discharged with a prescription.6 Of those patients, more than 40% remained on opioids three months after discharge. The research also revealed a nearly two-fold variation in prescription rates across hospitals.

Some hospitalists have asserted that the increase in opioid prescriptions may partially be tied to pressure to reduce 30-day readmission rates; Dr. Jena and Dr. Karaca-Mandic’s work leaves open the possibility that such prescriptions may increase readmissions instead. The researchers, however, say a bigger driving force may be financial pressure tied to discharging patients earlier or scoring higher on quality measures that gauge factors, such as pain management. Hospitals that scored better on HCAHPS measures of inpatient pain control, their study found, were slightly more likely to discharge patients on opioids.

Keri Holmes-Maybank, MD, MSCR, FHM, an academic hospitalist at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, says a lack of clear evidence and guidelines, unrealistic expectations, and variable patient responses to opioids are compounding a “very frustrating and very scary” situation for hospital medicine. Hospitalists who conclude that a patient-requested antibiotic will do more harm than good, for example, usually feel comfortable saying no. “But a patient can talk you into an opioid,” she said. “It’s much harder to stand your ground with that, even though we need to be viewing it the same way.”

The pain paradox

The desire to alleviate pain, as doctors are discovering, often has replaced one harm with another inadvertently. Perhaps the single largest contributing factor, Dr. Herzig said, is the subjectivity of pain and the difficulty in discerning whether a patient’s self-reporting can be trusted. “We want to relieve suffering,” she said, “but we also don’t want to give a patient a drug to which they may develop an addiction or to which they may already be addicted, and so therein lies the conundrum.”

Some medical providers are also beginning to focus less on visual pain assessments and more on clinically meaningful functional improvements. “For example, instead of asking, ‘What level is your pain today?’ we might say, ‘Were you able to get up and work with physical therapy today?’ and ‘Were you able to get out of the bed to the chair while maintaining your pain at a tolerable level?’ ” Dr. Herzig said.

In addition, providers are recognizing that they should be clearer in telling patients that a complete absence of pain is not only unrealistic but also potentially harmful. “It takes time to have those discussions with patients, where you’re trying to explain to them, ‘Pain is the body’s way of telling you don’t do that, and you need to have some pain in order to know what your limitations are,’ ” Dr. Herzig said.

From talking with hospitalized patients, Dr. Mosher and her colleagues found that pain-related suffering can be manifested in or exacerbated by poor sleep or diet, boredom, physical discomfort, immobility, or inability to maintain comforting activities. In other words, how can the hospital improve sleeping conditions or address the understandable anxiety around health issues or being in a strange new environment and losing control? “One of the upsides of all this is that it may drive us to really think about, and make thoughtful investments in, changing the hospital to be a more therapeutic environment,” Dr. Mosher said.

Chronic use and discharge dilemmas

What about patients who already used opioids regularly before their hospital admission? In a 2014 study, Dr. Mosher and her colleagues found that among patients admitted to Veterans Affairs hospitals between 2009 and 2011, more than one in four were on chronic opioid therapy in the 6 months prior to their hospitalization.8 That subset of patients, the study suggested, was at greater risk for both 30-day readmission and death.

Determining whether an opioid prescription is appropriate or not, though, takes time. “Hospitalists are often terribly busy,” Dr. Mosher said. “There’s a lot of pressure to move people through the hospital. It’s a big ask to say, ‘How will hospitalists do what might be ideal?’ versus ‘What can we do?’ ” A workable solution, she said, may depend upon a cultural shift in recognizing that “pain is not something you measure by numbers,” but rather a part of a patient’s complex medical condition that may require consultations and coordination with specialists both within and beyond the hospital.

Sometimes, relatively simple questions can go a long way. When Dr. Mosher asks patients on opioids whether they help, she said, “I’ve had very few patients who will say it makes the pain go away.” Likewise, she contends that very few patients have been informed of potential side effects such as decreased muscle mass, osteoporosis, and endocrinopathy. Men on opioids can have a significant reduction in testosterone levels that negatively affects their sex life. When Dr. Mosher has talked to them about the downsides of long-term use, more than a few have requested her help in weaning them off the drugs.

If given the time to educate such patients and consider how their chronic pain and opioid use might be connected to the hospitalization, she said, “We can find opportunities to use that as a change moment.”

Discharging a patient with a well-considered opioid prescription can still present multiple challenges. The best-case scenario, Dr. Calcaterra said, is to coordinate a plan with the patient’s primary care provider. “A lot of patients that we take care of, though, don’t have a follow-up provider. They don’t have a primary care physician,” she said.

The opioid epidemic also has walloped many communities that lack sufficient resources for at-risk patients, whether it’s alternative pain therapy or a buprenorphine clinic. “If you look at access to medication-assisted therapies, the lights are out for a lot of America. There just isn’t access,” Dr. Mosher said. The limited options can set up a frustrating quandary: Hospitalists may be reluctant to wean patients off opioids and get them on buprenorphine if there’s no reliable resource to continue the therapy after a postdischarge handoff.

Until better safety nets and evidence-based protocols are woven together, hospitalists may need to make judgment calls based on their experience and available data and be creative in using existing resources to help their patients. Although electronic prescribing may help reduce the potential for tampering with a doctor’s script, Dr. Calcaterra said, diversion of opioid pills remains a “huge issue across the United States.” Several states now limit the amount of opioids that can be prescribed upon discharge, and hospitalists in many states can access prescription drug monitoring programs to determine whether patients are receiving opioids from other providers.

Pushing for proactive solutions

Kevin Vuernick, senior project manager of SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, said the society’s Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee is actively exploring plans to develop pain prescribing guidelines for hospitalized patients based on the input of hospitalists and other medical specialists. The society also hopes to set up a website that compiles available resources, such as its own well-received Reducing Adverse Drug Events related to Opioids Mentored Implementation Program.

Dr. Mosher said SHM and other professional organizations also could assume leadership roles in setting a research agenda, establishing priorities for quality improvement efforts, and evaluating the utility of intervention programs. She and others have said additional help is sorely needed in educating providers, most of whom have never received formal training in pain management.

Talented and skilled physicians with the right language and approach could serve as role models in teaching providers how to appropriately bring up sensitive topics, such as concerns that a patient may be misusing opioids or that the pain may be more psychological than physical in nature. “We need a common language,” Dr. Herzig said.

More broadly, hospital medicine practitioners could serve as institutional role models. Many already sit on safety and quality improvement committees, meaning that they can help develop standardized protocols and help inform decisions regarding both prescribing and oversight to improve the appropriateness and safety of opioid prescriptions.

Matthew Jared, MD, a hospitalist at St. Anthony Hospital in Oklahoma City, said he and his colleagues have long worried about striking the right balance on opioids and about “trying to find an objective way to treat a subjective problem.” Because he and his hospitalist counterparts see 95% of St. Anthony’s inpatients, however, he said hospital medicine is uniquely positioned to help initiate a more holistic and consistent opioid management plan. “We’re key in the equation of trying to get this under control in a way that’s healthy and respectful to the patient and to the staff,” he said.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance writer in Seattle.

References

1. Calcaterra SL, Drabkin AD, Leslie SE, Doyle R, et al. The hospitalist perspective on opioid prescribing: A qualitative analysis. J Hosp Med. 2016 Aug;11(8):536-42.

2. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths – United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Dec;65(50-51):1445-52; and https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

3. Katz, J. The First Count of Fentanyl Deaths in 2016: Up 540% in Three Years. New York Times, Sept. 2, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/09/02/upshot/fentanyl-drug-overdose-deaths.html?mcubz=1&_r=0

4. Herzig SJ. Opening the black box of inpatient opioid prescribing. J Hosp Med. 2016 Aug;11(8):595-6.

5. Herzig SJ, Rothberg MB, Cheung M, et al. Opioid utilization and opioid-related adverse events in nonsurgical patients in U.S. hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):73-81.

6. Jena AB, Goldman D, Karaca-Mandic P. Hospital prescribing of opioids to Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 July;176(7):990-7.

7. Jena AB, Goldman D, Weaver L, Karaca-Mandic P. Opioid prescribing by multiple providers in Medicare: Retrospective observational study of insurance claims. BMJ. 2014;348:g1393.

8. Mosher HJ, Jiang L, Vaughan Sarrazin MS, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of hospitalized adults on chronic opioid therapy. J Hosp Med. 2014 Feb;9(2):82-7.

It’s the stuff of doctors’ nightmares. In a recent analysis of attitudes, beliefs, and practices regarding opioid prescribing, one hospitalist described how a patient had overdosed: “She crushed up the oxycodone we were giving her in the hospital and shot it up through her central line and died.”1

Susan Calcaterra, MD, MPH, of the department of family medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora; a hospitalist at Denver Health Hospital; and lead author of the recent study, says that the dramatic anecdotes don’t surprise her. “These are not uncommon events,” she said. “Across the country, you hear about overdose, you hear about people abusing fentanyl, and I think, when you have an addiction, your judgment of the dangers associated with your personal opioid use may be limited.”

Some critics have blamed the ubiquity of opioid prescriptions on the controversial movement to establish pain as a vital sign. Multiple investigations also have accused the pharmaceutical industry of aggressively promoting these prescription drugs while downplaying their risks. The CDC found that, in fact, so many opioid prescriptions were being written by 2012 that the 259 million scripts could have supplied every U.S. adult with his and her own bottle. In August 2017, President Trump declared the opioid crisis a national emergency, although opinions differ regarding the best ways forward.

Until recently, however, few studies had looked at how inpatient prescribing may be fueling a surging epidemic that already has exacted a staggering toll. So far, the early data paint a disturbing picture that suggests hospitals are both a part of the problem and a key to its solution.

Illuminating a ‘black box’

Changing the trajectory will be difficult. From 2002 to 2015, the nation’s overdose death rate from opioid analgesics, heroin, and synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, nearly tripled, and studies suggest that prescription painkillers have become major gateway drugs for heroin.2 In the last 3 years alone, fentanyl-related deaths soared by more than 500%, and annual mortality from all drug overdoses has blown by the peak of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in 1995, when nearly 51,000 died from the disease.3

Amid the ringing alarm bells, hospitals have remained a largely neglected “regulatory dead zone” for opioids, said Shoshana Herzig, MD, MPH, of the department of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of hospital medicine research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, also in Boston. In an editorial accompanying the recent study of hospitalist perspectives, Dr. Herzig called the inpatient setting an opioid prescribing “black box.”4

In a previous analysis of 1.1 million nonsurgical hospital admissions, however, she and colleagues found that opioids were prescribed to 51% of all patients.5 More than half of those with inpatient exposure were still taking opioids on their discharge day. With other studies suggesting that such practices may be contributing to chronic opioid use long after hospitalization, Dr. Herzig wrote, “reigning in inpatient prescribing may be a crucial step in curbing the opioid epidemic as a whole.”

A recent study led by Anupam Jena, MD, PhD, a health care policy expert at Harvard Medical School, echoes the refrain. “It’s kind of remarkable that the hospital setting hasn’t really been studied, and it’s an important setting,” he said. When he and colleagues did their own analysis of hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries, they found that 15% of previously opioid-naive patients were discharged with a prescription.6 Of those patients, more than 40% remained on opioids three months after discharge. The research also revealed a nearly two-fold variation in prescription rates across hospitals.

Some hospitalists have asserted that the increase in opioid prescriptions may partially be tied to pressure to reduce 30-day readmission rates; Dr. Jena and Dr. Karaca-Mandic’s work leaves open the possibility that such prescriptions may increase readmissions instead. The researchers, however, say a bigger driving force may be financial pressure tied to discharging patients earlier or scoring higher on quality measures that gauge factors, such as pain management. Hospitals that scored better on HCAHPS measures of inpatient pain control, their study found, were slightly more likely to discharge patients on opioids.

Keri Holmes-Maybank, MD, MSCR, FHM, an academic hospitalist at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, says a lack of clear evidence and guidelines, unrealistic expectations, and variable patient responses to opioids are compounding a “very frustrating and very scary” situation for hospital medicine. Hospitalists who conclude that a patient-requested antibiotic will do more harm than good, for example, usually feel comfortable saying no. “But a patient can talk you into an opioid,” she said. “It’s much harder to stand your ground with that, even though we need to be viewing it the same way.”

The pain paradox

The desire to alleviate pain, as doctors are discovering, often has replaced one harm with another inadvertently. Perhaps the single largest contributing factor, Dr. Herzig said, is the subjectivity of pain and the difficulty in discerning whether a patient’s self-reporting can be trusted. “We want to relieve suffering,” she said, “but we also don’t want to give a patient a drug to which they may develop an addiction or to which they may already be addicted, and so therein lies the conundrum.”

Some medical providers are also beginning to focus less on visual pain assessments and more on clinically meaningful functional improvements. “For example, instead of asking, ‘What level is your pain today?’ we might say, ‘Were you able to get up and work with physical therapy today?’ and ‘Were you able to get out of the bed to the chair while maintaining your pain at a tolerable level?’ ” Dr. Herzig said.

In addition, providers are recognizing that they should be clearer in telling patients that a complete absence of pain is not only unrealistic but also potentially harmful. “It takes time to have those discussions with patients, where you’re trying to explain to them, ‘Pain is the body’s way of telling you don’t do that, and you need to have some pain in order to know what your limitations are,’ ” Dr. Herzig said.

From talking with hospitalized patients, Dr. Mosher and her colleagues found that pain-related suffering can be manifested in or exacerbated by poor sleep or diet, boredom, physical discomfort, immobility, or inability to maintain comforting activities. In other words, how can the hospital improve sleeping conditions or address the understandable anxiety around health issues or being in a strange new environment and losing control? “One of the upsides of all this is that it may drive us to really think about, and make thoughtful investments in, changing the hospital to be a more therapeutic environment,” Dr. Mosher said.

Chronic use and discharge dilemmas

What about patients who already used opioids regularly before their hospital admission? In a 2014 study, Dr. Mosher and her colleagues found that among patients admitted to Veterans Affairs hospitals between 2009 and 2011, more than one in four were on chronic opioid therapy in the 6 months prior to their hospitalization.8 That subset of patients, the study suggested, was at greater risk for both 30-day readmission and death.

Determining whether an opioid prescription is appropriate or not, though, takes time. “Hospitalists are often terribly busy,” Dr. Mosher said. “There’s a lot of pressure to move people through the hospital. It’s a big ask to say, ‘How will hospitalists do what might be ideal?’ versus ‘What can we do?’ ” A workable solution, she said, may depend upon a cultural shift in recognizing that “pain is not something you measure by numbers,” but rather a part of a patient’s complex medical condition that may require consultations and coordination with specialists both within and beyond the hospital.

Sometimes, relatively simple questions can go a long way. When Dr. Mosher asks patients on opioids whether they help, she said, “I’ve had very few patients who will say it makes the pain go away.” Likewise, she contends that very few patients have been informed of potential side effects such as decreased muscle mass, osteoporosis, and endocrinopathy. Men on opioids can have a significant reduction in testosterone levels that negatively affects their sex life. When Dr. Mosher has talked to them about the downsides of long-term use, more than a few have requested her help in weaning them off the drugs.

If given the time to educate such patients and consider how their chronic pain and opioid use might be connected to the hospitalization, she said, “We can find opportunities to use that as a change moment.”

Discharging a patient with a well-considered opioid prescription can still present multiple challenges. The best-case scenario, Dr. Calcaterra said, is to coordinate a plan with the patient’s primary care provider. “A lot of patients that we take care of, though, don’t have a follow-up provider. They don’t have a primary care physician,” she said.

The opioid epidemic also has walloped many communities that lack sufficient resources for at-risk patients, whether it’s alternative pain therapy or a buprenorphine clinic. “If you look at access to medication-assisted therapies, the lights are out for a lot of America. There just isn’t access,” Dr. Mosher said. The limited options can set up a frustrating quandary: Hospitalists may be reluctant to wean patients off opioids and get them on buprenorphine if there’s no reliable resource to continue the therapy after a postdischarge handoff.

Until better safety nets and evidence-based protocols are woven together, hospitalists may need to make judgment calls based on their experience and available data and be creative in using existing resources to help their patients. Although electronic prescribing may help reduce the potential for tampering with a doctor’s script, Dr. Calcaterra said, diversion of opioid pills remains a “huge issue across the United States.” Several states now limit the amount of opioids that can be prescribed upon discharge, and hospitalists in many states can access prescription drug monitoring programs to determine whether patients are receiving opioids from other providers.

Pushing for proactive solutions

Kevin Vuernick, senior project manager of SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, said the society’s Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee is actively exploring plans to develop pain prescribing guidelines for hospitalized patients based on the input of hospitalists and other medical specialists. The society also hopes to set up a website that compiles available resources, such as its own well-received Reducing Adverse Drug Events related to Opioids Mentored Implementation Program.

Dr. Mosher said SHM and other professional organizations also could assume leadership roles in setting a research agenda, establishing priorities for quality improvement efforts, and evaluating the utility of intervention programs. She and others have said additional help is sorely needed in educating providers, most of whom have never received formal training in pain management.

Talented and skilled physicians with the right language and approach could serve as role models in teaching providers how to appropriately bring up sensitive topics, such as concerns that a patient may be misusing opioids or that the pain may be more psychological than physical in nature. “We need a common language,” Dr. Herzig said.

More broadly, hospital medicine practitioners could serve as institutional role models. Many already sit on safety and quality improvement committees, meaning that they can help develop standardized protocols and help inform decisions regarding both prescribing and oversight to improve the appropriateness and safety of opioid prescriptions.

Matthew Jared, MD, a hospitalist at St. Anthony Hospital in Oklahoma City, said he and his colleagues have long worried about striking the right balance on opioids and about “trying to find an objective way to treat a subjective problem.” Because he and his hospitalist counterparts see 95% of St. Anthony’s inpatients, however, he said hospital medicine is uniquely positioned to help initiate a more holistic and consistent opioid management plan. “We’re key in the equation of trying to get this under control in a way that’s healthy and respectful to the patient and to the staff,” he said.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance writer in Seattle.

References

1. Calcaterra SL, Drabkin AD, Leslie SE, Doyle R, et al. The hospitalist perspective on opioid prescribing: A qualitative analysis. J Hosp Med. 2016 Aug;11(8):536-42.

2. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths – United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Dec;65(50-51):1445-52; and https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

3. Katz, J. The First Count of Fentanyl Deaths in 2016: Up 540% in Three Years. New York Times, Sept. 2, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/09/02/upshot/fentanyl-drug-overdose-deaths.html?mcubz=1&_r=0

4. Herzig SJ. Opening the black box of inpatient opioid prescribing. J Hosp Med. 2016 Aug;11(8):595-6.

5. Herzig SJ, Rothberg MB, Cheung M, et al. Opioid utilization and opioid-related adverse events in nonsurgical patients in U.S. hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):73-81.

6. Jena AB, Goldman D, Karaca-Mandic P. Hospital prescribing of opioids to Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 July;176(7):990-7.

7. Jena AB, Goldman D, Weaver L, Karaca-Mandic P. Opioid prescribing by multiple providers in Medicare: Retrospective observational study of insurance claims. BMJ. 2014;348:g1393.

8. Mosher HJ, Jiang L, Vaughan Sarrazin MS, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of hospitalized adults on chronic opioid therapy. J Hosp Med. 2014 Feb;9(2):82-7.

It’s the stuff of doctors’ nightmares. In a recent analysis of attitudes, beliefs, and practices regarding opioid prescribing, one hospitalist described how a patient had overdosed: “She crushed up the oxycodone we were giving her in the hospital and shot it up through her central line and died.”1

Susan Calcaterra, MD, MPH, of the department of family medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora; a hospitalist at Denver Health Hospital; and lead author of the recent study, says that the dramatic anecdotes don’t surprise her. “These are not uncommon events,” she said. “Across the country, you hear about overdose, you hear about people abusing fentanyl, and I think, when you have an addiction, your judgment of the dangers associated with your personal opioid use may be limited.”

Some critics have blamed the ubiquity of opioid prescriptions on the controversial movement to establish pain as a vital sign. Multiple investigations also have accused the pharmaceutical industry of aggressively promoting these prescription drugs while downplaying their risks. The CDC found that, in fact, so many opioid prescriptions were being written by 2012 that the 259 million scripts could have supplied every U.S. adult with his and her own bottle. In August 2017, President Trump declared the opioid crisis a national emergency, although opinions differ regarding the best ways forward.

Until recently, however, few studies had looked at how inpatient prescribing may be fueling a surging epidemic that already has exacted a staggering toll. So far, the early data paint a disturbing picture that suggests hospitals are both a part of the problem and a key to its solution.

Illuminating a ‘black box’

Changing the trajectory will be difficult. From 2002 to 2015, the nation’s overdose death rate from opioid analgesics, heroin, and synthetic opioids, such as fentanyl, nearly tripled, and studies suggest that prescription painkillers have become major gateway drugs for heroin.2 In the last 3 years alone, fentanyl-related deaths soared by more than 500%, and annual mortality from all drug overdoses has blown by the peak of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in 1995, when nearly 51,000 died from the disease.3

Amid the ringing alarm bells, hospitals have remained a largely neglected “regulatory dead zone” for opioids, said Shoshana Herzig, MD, MPH, of the department of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and director of hospital medicine research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, also in Boston. In an editorial accompanying the recent study of hospitalist perspectives, Dr. Herzig called the inpatient setting an opioid prescribing “black box.”4

In a previous analysis of 1.1 million nonsurgical hospital admissions, however, she and colleagues found that opioids were prescribed to 51% of all patients.5 More than half of those with inpatient exposure were still taking opioids on their discharge day. With other studies suggesting that such practices may be contributing to chronic opioid use long after hospitalization, Dr. Herzig wrote, “reigning in inpatient prescribing may be a crucial step in curbing the opioid epidemic as a whole.”

A recent study led by Anupam Jena, MD, PhD, a health care policy expert at Harvard Medical School, echoes the refrain. “It’s kind of remarkable that the hospital setting hasn’t really been studied, and it’s an important setting,” he said. When he and colleagues did their own analysis of hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries, they found that 15% of previously opioid-naive patients were discharged with a prescription.6 Of those patients, more than 40% remained on opioids three months after discharge. The research also revealed a nearly two-fold variation in prescription rates across hospitals.

Some hospitalists have asserted that the increase in opioid prescriptions may partially be tied to pressure to reduce 30-day readmission rates; Dr. Jena and Dr. Karaca-Mandic’s work leaves open the possibility that such prescriptions may increase readmissions instead. The researchers, however, say a bigger driving force may be financial pressure tied to discharging patients earlier or scoring higher on quality measures that gauge factors, such as pain management. Hospitals that scored better on HCAHPS measures of inpatient pain control, their study found, were slightly more likely to discharge patients on opioids.

Keri Holmes-Maybank, MD, MSCR, FHM, an academic hospitalist at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, says a lack of clear evidence and guidelines, unrealistic expectations, and variable patient responses to opioids are compounding a “very frustrating and very scary” situation for hospital medicine. Hospitalists who conclude that a patient-requested antibiotic will do more harm than good, for example, usually feel comfortable saying no. “But a patient can talk you into an opioid,” she said. “It’s much harder to stand your ground with that, even though we need to be viewing it the same way.”

The pain paradox

The desire to alleviate pain, as doctors are discovering, often has replaced one harm with another inadvertently. Perhaps the single largest contributing factor, Dr. Herzig said, is the subjectivity of pain and the difficulty in discerning whether a patient’s self-reporting can be trusted. “We want to relieve suffering,” she said, “but we also don’t want to give a patient a drug to which they may develop an addiction or to which they may already be addicted, and so therein lies the conundrum.”

Some medical providers are also beginning to focus less on visual pain assessments and more on clinically meaningful functional improvements. “For example, instead of asking, ‘What level is your pain today?’ we might say, ‘Were you able to get up and work with physical therapy today?’ and ‘Were you able to get out of the bed to the chair while maintaining your pain at a tolerable level?’ ” Dr. Herzig said.

In addition, providers are recognizing that they should be clearer in telling patients that a complete absence of pain is not only unrealistic but also potentially harmful. “It takes time to have those discussions with patients, where you’re trying to explain to them, ‘Pain is the body’s way of telling you don’t do that, and you need to have some pain in order to know what your limitations are,’ ” Dr. Herzig said.

From talking with hospitalized patients, Dr. Mosher and her colleagues found that pain-related suffering can be manifested in or exacerbated by poor sleep or diet, boredom, physical discomfort, immobility, or inability to maintain comforting activities. In other words, how can the hospital improve sleeping conditions or address the understandable anxiety around health issues or being in a strange new environment and losing control? “One of the upsides of all this is that it may drive us to really think about, and make thoughtful investments in, changing the hospital to be a more therapeutic environment,” Dr. Mosher said.

Chronic use and discharge dilemmas

What about patients who already used opioids regularly before their hospital admission? In a 2014 study, Dr. Mosher and her colleagues found that among patients admitted to Veterans Affairs hospitals between 2009 and 2011, more than one in four were on chronic opioid therapy in the 6 months prior to their hospitalization.8 That subset of patients, the study suggested, was at greater risk for both 30-day readmission and death.

Determining whether an opioid prescription is appropriate or not, though, takes time. “Hospitalists are often terribly busy,” Dr. Mosher said. “There’s a lot of pressure to move people through the hospital. It’s a big ask to say, ‘How will hospitalists do what might be ideal?’ versus ‘What can we do?’ ” A workable solution, she said, may depend upon a cultural shift in recognizing that “pain is not something you measure by numbers,” but rather a part of a patient’s complex medical condition that may require consultations and coordination with specialists both within and beyond the hospital.

Sometimes, relatively simple questions can go a long way. When Dr. Mosher asks patients on opioids whether they help, she said, “I’ve had very few patients who will say it makes the pain go away.” Likewise, she contends that very few patients have been informed of potential side effects such as decreased muscle mass, osteoporosis, and endocrinopathy. Men on opioids can have a significant reduction in testosterone levels that negatively affects their sex life. When Dr. Mosher has talked to them about the downsides of long-term use, more than a few have requested her help in weaning them off the drugs.

If given the time to educate such patients and consider how their chronic pain and opioid use might be connected to the hospitalization, she said, “We can find opportunities to use that as a change moment.”

Discharging a patient with a well-considered opioid prescription can still present multiple challenges. The best-case scenario, Dr. Calcaterra said, is to coordinate a plan with the patient’s primary care provider. “A lot of patients that we take care of, though, don’t have a follow-up provider. They don’t have a primary care physician,” she said.

The opioid epidemic also has walloped many communities that lack sufficient resources for at-risk patients, whether it’s alternative pain therapy or a buprenorphine clinic. “If you look at access to medication-assisted therapies, the lights are out for a lot of America. There just isn’t access,” Dr. Mosher said. The limited options can set up a frustrating quandary: Hospitalists may be reluctant to wean patients off opioids and get them on buprenorphine if there’s no reliable resource to continue the therapy after a postdischarge handoff.

Until better safety nets and evidence-based protocols are woven together, hospitalists may need to make judgment calls based on their experience and available data and be creative in using existing resources to help their patients. Although electronic prescribing may help reduce the potential for tampering with a doctor’s script, Dr. Calcaterra said, diversion of opioid pills remains a “huge issue across the United States.” Several states now limit the amount of opioids that can be prescribed upon discharge, and hospitalists in many states can access prescription drug monitoring programs to determine whether patients are receiving opioids from other providers.

Pushing for proactive solutions

Kevin Vuernick, senior project manager of SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, said the society’s Hospital Quality and Patient Safety Committee is actively exploring plans to develop pain prescribing guidelines for hospitalized patients based on the input of hospitalists and other medical specialists. The society also hopes to set up a website that compiles available resources, such as its own well-received Reducing Adverse Drug Events related to Opioids Mentored Implementation Program.

Dr. Mosher said SHM and other professional organizations also could assume leadership roles in setting a research agenda, establishing priorities for quality improvement efforts, and evaluating the utility of intervention programs. She and others have said additional help is sorely needed in educating providers, most of whom have never received formal training in pain management.

Talented and skilled physicians with the right language and approach could serve as role models in teaching providers how to appropriately bring up sensitive topics, such as concerns that a patient may be misusing opioids or that the pain may be more psychological than physical in nature. “We need a common language,” Dr. Herzig said.

More broadly, hospital medicine practitioners could serve as institutional role models. Many already sit on safety and quality improvement committees, meaning that they can help develop standardized protocols and help inform decisions regarding both prescribing and oversight to improve the appropriateness and safety of opioid prescriptions.

Matthew Jared, MD, a hospitalist at St. Anthony Hospital in Oklahoma City, said he and his colleagues have long worried about striking the right balance on opioids and about “trying to find an objective way to treat a subjective problem.” Because he and his hospitalist counterparts see 95% of St. Anthony’s inpatients, however, he said hospital medicine is uniquely positioned to help initiate a more holistic and consistent opioid management plan. “We’re key in the equation of trying to get this under control in a way that’s healthy and respectful to the patient and to the staff,” he said.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance writer in Seattle.

References

1. Calcaterra SL, Drabkin AD, Leslie SE, Doyle R, et al. The hospitalist perspective on opioid prescribing: A qualitative analysis. J Hosp Med. 2016 Aug;11(8):536-42.

2. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths – United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Dec;65(50-51):1445-52; and https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates.

3. Katz, J. The First Count of Fentanyl Deaths in 2016: Up 540% in Three Years. New York Times, Sept. 2, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/09/02/upshot/fentanyl-drug-overdose-deaths.html?mcubz=1&_r=0

4. Herzig SJ. Opening the black box of inpatient opioid prescribing. J Hosp Med. 2016 Aug;11(8):595-6.

5. Herzig SJ, Rothberg MB, Cheung M, et al. Opioid utilization and opioid-related adverse events in nonsurgical patients in U.S. hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):73-81.

6. Jena AB, Goldman D, Karaca-Mandic P. Hospital prescribing of opioids to Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016 July;176(7):990-7.

7. Jena AB, Goldman D, Weaver L, Karaca-Mandic P. Opioid prescribing by multiple providers in Medicare: Retrospective observational study of insurance claims. BMJ. 2014;348:g1393.

8. Mosher HJ, Jiang L, Vaughan Sarrazin MS, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of hospitalized adults on chronic opioid therapy. J Hosp Med. 2014 Feb;9(2):82-7.

Ideal intubation position still unknown

In critically ill adults undergoing endotracheal intubation, the ramped position does not significantly improve oxygenation compared with the sniffing position, according to results of a multicenter, randomized trial of 260 patients treated in an intensive care unit.

Moreover, “[ramped] position appeared to worsen glottic view and increase the number of attempts required for successful intubation,” wrote Matthew W. Semler, MD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and his coauthors (Chest. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.061).

The ramped and sniffing positions are the two most common patient positions used during emergent intubation, according to investigators. The sniffing position is characterized by supine torso, neck flexed forward, and head extended, while ramped position involves elevating the torso and head.

Some believe the ramped position may offer superior anatomic alignment of the upper airway; however, only a few observational studies suggest it is associated with fewer complications than the sniffing position, the authors wrote.

Accordingly, they conducted a multicenter randomized trial with a primary endpoint of lowest arterial oxygen saturation, hypothesizing that the endpoint would be higher for the ramped position: “Our primary outcome of lowest arterial oxygen saturation is an established endpoint in ICU intubation trials, and is linked to periprocedural cardiac arrest and death,” they wrote.

The investigators instead found that median lowest arterial oxygen saturation was not statistically different between groups, at 93% for the ramped position, and 92% for the sniffing position (P = 0.27), published data show.

Further results showed that the ramped position appeared to be associated with poor glottic view and more difficult intubation. The incidence of grade III (only epiglottis) or grade IV (no visible glottis structures) views were 25.4% for ramped vs. 11.5% for sniffing (P = .01), while the rate of first-attempt intubation was 76.2% for ramped vs 85.4% for sniffing (P = .02).

While the findings are compelling, the authors were forthcoming about the potential limitations of the study and differences compared with earlier investigations. Notably, they said, all prior controlled trials of patient positioning during endotracheal intubation were conducted in the operating room, rather than in the ICU.

Also, the operators’ skill levels may further explain differences in this study’s outcomes from those of similar studies, the researchers noted. Earlier studies included patients intubated by one or two senior anesthesiologists from one center, while this trial involved 30 operators across multiple centers, with the average operator having performed 60 previous intubations. “Thus, our findings may generalize to settings in which airway management is performed by trainees, but whether results would be similar among expert operators remains unknown,” the investigators noted.

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest. One coauthor reported serving on an advisory board for Avisa Pharma.

Editorialists praised the multicenter, randomized design of this study, and its total recruitment of 260 patients. They also noted several limitations of the study that “could shed some light” on the group’s conclusions (Chest. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.002).

“The results diverge from [operating room] literature of the past 15 years that suggest that the ramped position is the preferred intubation position for obese patients or those with an anticipated difficult airway.” This may have been caused by shortcomings of this study’s design and differences between it and other research exploring the topic of patient positioning during endotracheal intubation, they wrote.

The study lacked a prespecified algorithm for preoxygenation and the operators had relatively low amounts of experience with intubations. Finally, the beds used in this study could contribute to the divergences between this intensive care unit experience and the operating room literature. The operating room table is narrower, firmer, and more stable, while by contrast, the ICU bed is wider and softer, they noted. This “may make initial positioning, maintenance of positioning, and accessing the patient’s head more difficult.”

Nevertheless, “[this] important study provides ideas for further study of optimal positioning in the ICU and adds valuable data to the sparse literature on the subject in the ICU setting,” they concluded.

James Aaron Scott, DO, Jens Matthias Walz, MD, FCCP, and Stephen O. Heard, MD, FCCP, are in the department of anesthesiology and perioperative medicine, UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, Mass. The authors reported no conflicts of interest. These comments are based on their editorial.

Editorialists praised the multicenter, randomized design of this study, and its total recruitment of 260 patients. They also noted several limitations of the study that “could shed some light” on the group’s conclusions (Chest. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.002).

“The results diverge from [operating room] literature of the past 15 years that suggest that the ramped position is the preferred intubation position for obese patients or those with an anticipated difficult airway.” This may have been caused by shortcomings of this study’s design and differences between it and other research exploring the topic of patient positioning during endotracheal intubation, they wrote.

The study lacked a prespecified algorithm for preoxygenation and the operators had relatively low amounts of experience with intubations. Finally, the beds used in this study could contribute to the divergences between this intensive care unit experience and the operating room literature. The operating room table is narrower, firmer, and more stable, while by contrast, the ICU bed is wider and softer, they noted. This “may make initial positioning, maintenance of positioning, and accessing the patient’s head more difficult.”

Nevertheless, “[this] important study provides ideas for further study of optimal positioning in the ICU and adds valuable data to the sparse literature on the subject in the ICU setting,” they concluded.

James Aaron Scott, DO, Jens Matthias Walz, MD, FCCP, and Stephen O. Heard, MD, FCCP, are in the department of anesthesiology and perioperative medicine, UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, Mass. The authors reported no conflicts of interest. These comments are based on their editorial.

Editorialists praised the multicenter, randomized design of this study, and its total recruitment of 260 patients. They also noted several limitations of the study that “could shed some light” on the group’s conclusions (Chest. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.002).

“The results diverge from [operating room] literature of the past 15 years that suggest that the ramped position is the preferred intubation position for obese patients or those with an anticipated difficult airway.” This may have been caused by shortcomings of this study’s design and differences between it and other research exploring the topic of patient positioning during endotracheal intubation, they wrote.

The study lacked a prespecified algorithm for preoxygenation and the operators had relatively low amounts of experience with intubations. Finally, the beds used in this study could contribute to the divergences between this intensive care unit experience and the operating room literature. The operating room table is narrower, firmer, and more stable, while by contrast, the ICU bed is wider and softer, they noted. This “may make initial positioning, maintenance of positioning, and accessing the patient’s head more difficult.”

Nevertheless, “[this] important study provides ideas for further study of optimal positioning in the ICU and adds valuable data to the sparse literature on the subject in the ICU setting,” they concluded.

James Aaron Scott, DO, Jens Matthias Walz, MD, FCCP, and Stephen O. Heard, MD, FCCP, are in the department of anesthesiology and perioperative medicine, UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, Mass. The authors reported no conflicts of interest. These comments are based on their editorial.

In critically ill adults undergoing endotracheal intubation, the ramped position does not significantly improve oxygenation compared with the sniffing position, according to results of a multicenter, randomized trial of 260 patients treated in an intensive care unit.

Moreover, “[ramped] position appeared to worsen glottic view and increase the number of attempts required for successful intubation,” wrote Matthew W. Semler, MD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and his coauthors (Chest. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.061).

The ramped and sniffing positions are the two most common patient positions used during emergent intubation, according to investigators. The sniffing position is characterized by supine torso, neck flexed forward, and head extended, while ramped position involves elevating the torso and head.

Some believe the ramped position may offer superior anatomic alignment of the upper airway; however, only a few observational studies suggest it is associated with fewer complications than the sniffing position, the authors wrote.

Accordingly, they conducted a multicenter randomized trial with a primary endpoint of lowest arterial oxygen saturation, hypothesizing that the endpoint would be higher for the ramped position: “Our primary outcome of lowest arterial oxygen saturation is an established endpoint in ICU intubation trials, and is linked to periprocedural cardiac arrest and death,” they wrote.

The investigators instead found that median lowest arterial oxygen saturation was not statistically different between groups, at 93% for the ramped position, and 92% for the sniffing position (P = 0.27), published data show.

Further results showed that the ramped position appeared to be associated with poor glottic view and more difficult intubation. The incidence of grade III (only epiglottis) or grade IV (no visible glottis structures) views were 25.4% for ramped vs. 11.5% for sniffing (P = .01), while the rate of first-attempt intubation was 76.2% for ramped vs 85.4% for sniffing (P = .02).

While the findings are compelling, the authors were forthcoming about the potential limitations of the study and differences compared with earlier investigations. Notably, they said, all prior controlled trials of patient positioning during endotracheal intubation were conducted in the operating room, rather than in the ICU.

Also, the operators’ skill levels may further explain differences in this study’s outcomes from those of similar studies, the researchers noted. Earlier studies included patients intubated by one or two senior anesthesiologists from one center, while this trial involved 30 operators across multiple centers, with the average operator having performed 60 previous intubations. “Thus, our findings may generalize to settings in which airway management is performed by trainees, but whether results would be similar among expert operators remains unknown,” the investigators noted.

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest. One coauthor reported serving on an advisory board for Avisa Pharma.

In critically ill adults undergoing endotracheal intubation, the ramped position does not significantly improve oxygenation compared with the sniffing position, according to results of a multicenter, randomized trial of 260 patients treated in an intensive care unit.

Moreover, “[ramped] position appeared to worsen glottic view and increase the number of attempts required for successful intubation,” wrote Matthew W. Semler, MD, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and his coauthors (Chest. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.061).

The ramped and sniffing positions are the two most common patient positions used during emergent intubation, according to investigators. The sniffing position is characterized by supine torso, neck flexed forward, and head extended, while ramped position involves elevating the torso and head.

Some believe the ramped position may offer superior anatomic alignment of the upper airway; however, only a few observational studies suggest it is associated with fewer complications than the sniffing position, the authors wrote.

Accordingly, they conducted a multicenter randomized trial with a primary endpoint of lowest arterial oxygen saturation, hypothesizing that the endpoint would be higher for the ramped position: “Our primary outcome of lowest arterial oxygen saturation is an established endpoint in ICU intubation trials, and is linked to periprocedural cardiac arrest and death,” they wrote.

The investigators instead found that median lowest arterial oxygen saturation was not statistically different between groups, at 93% for the ramped position, and 92% for the sniffing position (P = 0.27), published data show.

Further results showed that the ramped position appeared to be associated with poor glottic view and more difficult intubation. The incidence of grade III (only epiglottis) or grade IV (no visible glottis structures) views were 25.4% for ramped vs. 11.5% for sniffing (P = .01), while the rate of first-attempt intubation was 76.2% for ramped vs 85.4% for sniffing (P = .02).

While the findings are compelling, the authors were forthcoming about the potential limitations of the study and differences compared with earlier investigations. Notably, they said, all prior controlled trials of patient positioning during endotracheal intubation were conducted in the operating room, rather than in the ICU.

Also, the operators’ skill levels may further explain differences in this study’s outcomes from those of similar studies, the researchers noted. Earlier studies included patients intubated by one or two senior anesthesiologists from one center, while this trial involved 30 operators across multiple centers, with the average operator having performed 60 previous intubations. “Thus, our findings may generalize to settings in which airway management is performed by trainees, but whether results would be similar among expert operators remains unknown,” the investigators noted.

The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest. One coauthor reported serving on an advisory board for Avisa Pharma.

FROM CHEST

Key clinical point: During endotracheal intubation of critically ill adults, use of the ramped position did not significantly improve oxygenation compared with the sniffing position, and it increased the number of attempts needed to achieve successful intubation.

Major finding: The median lowest arterial oxygen saturation was 93% for the ramped position and 92% for the sniffing position (P = .27).

Data source: Multicenter, randomized trial of 260 critically ill adults undergoing endotracheal intubation.

Disclosures: The authors reported no potential conflicts of interest. One coauthor reported serving on an advisory board for Avisa Pharma.

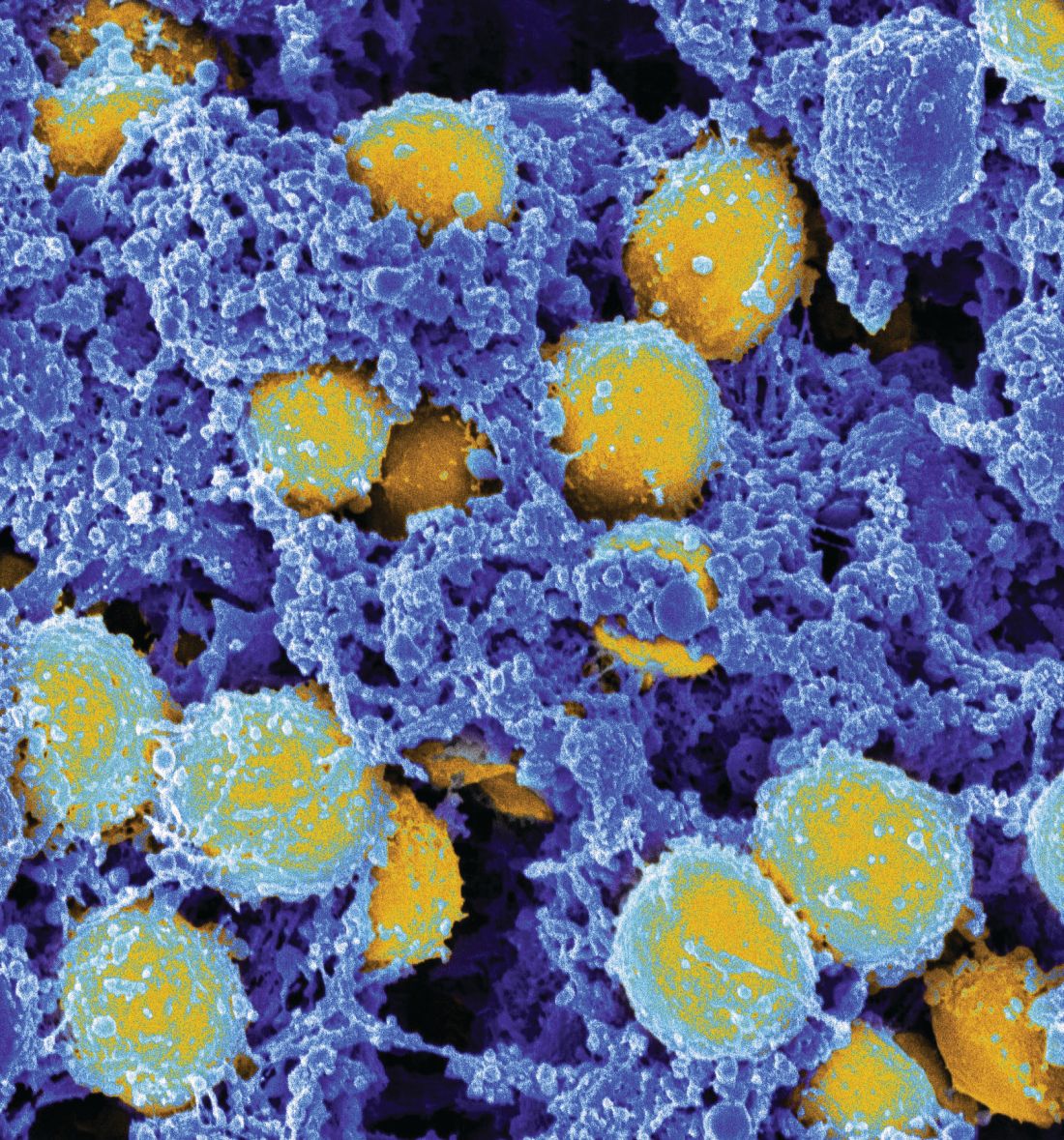

CDC data show decline in some hospital-acquired infections

SAN DIEGO – There was an encouraging 22% reduction in hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) after adjustment for clinical variables when 2015 and 2011 data from national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention hospital surveys were compared.

“The data suggest that national efforts toward preventing HAIs are succeeding,” reported Shelley S. Magill, MD, PhD, a medical epidemiologist in the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion at the CDC who summarized the data at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases .

The comparative data were drawn from point prevalence surveys conducted in 2011 and 2015 as part of the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program. In this type of survey, the data are collected over 1 day, providing a snapshot in time among selected hospitals. The analysis presented by Dr. Magill was restricted to the 148 hospitals that participated in both the 2011 and 2015 surveys, although the 2015 survey included a total of 199 hospitals, of which other data analyses are planned.

Due to the change in incidence, the rank order of HAIs was different in 2015 relative to 2011. While surgical site infections (SSIs) represented the most frequent HAI in 2011, they fell to the third most frequent HAI in 2015; pneumonia and gastrointestinal (GI) infections assumed the first and second spots, respectively. The GI HAI infection category includes Clostridium difficile infection.

The incidence of SSI HAI among all hospitalized patients in the survey fell by 41% between 2011 and 2015 (from 1.00% to 0.59%; P = .001). The other big contributor to the overall reduction in HAIs was the fall in the incidence of urinary tract infections, which fell 36% (from 0.55% to 0.35%; P = .04). The decrease in pneumonia (from 0.97% to 0.89%) was not significant, nor was the even more modest reduction in bloodstream HAI (from 0.45% to 0.43%). There was a modest increase in GI/Clostridium difficile infections (from 0.56% to 0.59%).

The surveys do not permit the reduction in HAI rates to be attributed to any specific prevention practices, but Dr. Magill pointed out that the overall reductions correlate with reduced use of urinary catheters and central lines; reductions of both have been advocated as a means for improved infection control. Of several factors that might contribute to a reduction in SSI HAI, Dr. Magill speculated that better adherence to guidelines and more rigorous steps at preoperative infection control strategies might be among them.

Detailed analyses of the data collected from all of the hospitals that participated in the 2015 survey are planned, including an evaluation of which antibiotics were used to treat the HAIs found in this survey. Although the findings so far encourage speculation that infection control practices, such as prudent use of urinary catheters, are having a positive effect, Dr. Magill said that the data also point out the challenges.

“Given that pneumonia continues to represent a large proportion of HAIs in hospitals, more work is needed to identify risk factors; understand the factors that are preventable, particularly in the nonventilated patients; and develop better preventive approaches,” Dr. Magill said.

Dr. Magill reported no financial relationships relevant to this study.

SAN DIEGO – There was an encouraging 22% reduction in hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) after adjustment for clinical variables when 2015 and 2011 data from national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention hospital surveys were compared.

“The data suggest that national efforts toward preventing HAIs are succeeding,” reported Shelley S. Magill, MD, PhD, a medical epidemiologist in the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion at the CDC who summarized the data at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases .

The comparative data were drawn from point prevalence surveys conducted in 2011 and 2015 as part of the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program. In this type of survey, the data are collected over 1 day, providing a snapshot in time among selected hospitals. The analysis presented by Dr. Magill was restricted to the 148 hospitals that participated in both the 2011 and 2015 surveys, although the 2015 survey included a total of 199 hospitals, of which other data analyses are planned.

Due to the change in incidence, the rank order of HAIs was different in 2015 relative to 2011. While surgical site infections (SSIs) represented the most frequent HAI in 2011, they fell to the third most frequent HAI in 2015; pneumonia and gastrointestinal (GI) infections assumed the first and second spots, respectively. The GI HAI infection category includes Clostridium difficile infection.

The incidence of SSI HAI among all hospitalized patients in the survey fell by 41% between 2011 and 2015 (from 1.00% to 0.59%; P = .001). The other big contributor to the overall reduction in HAIs was the fall in the incidence of urinary tract infections, which fell 36% (from 0.55% to 0.35%; P = .04). The decrease in pneumonia (from 0.97% to 0.89%) was not significant, nor was the even more modest reduction in bloodstream HAI (from 0.45% to 0.43%). There was a modest increase in GI/Clostridium difficile infections (from 0.56% to 0.59%).

The surveys do not permit the reduction in HAI rates to be attributed to any specific prevention practices, but Dr. Magill pointed out that the overall reductions correlate with reduced use of urinary catheters and central lines; reductions of both have been advocated as a means for improved infection control. Of several factors that might contribute to a reduction in SSI HAI, Dr. Magill speculated that better adherence to guidelines and more rigorous steps at preoperative infection control strategies might be among them.

Detailed analyses of the data collected from all of the hospitals that participated in the 2015 survey are planned, including an evaluation of which antibiotics were used to treat the HAIs found in this survey. Although the findings so far encourage speculation that infection control practices, such as prudent use of urinary catheters, are having a positive effect, Dr. Magill said that the data also point out the challenges.

“Given that pneumonia continues to represent a large proportion of HAIs in hospitals, more work is needed to identify risk factors; understand the factors that are preventable, particularly in the nonventilated patients; and develop better preventive approaches,” Dr. Magill said.

Dr. Magill reported no financial relationships relevant to this study.

SAN DIEGO – There was an encouraging 22% reduction in hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) after adjustment for clinical variables when 2015 and 2011 data from national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention hospital surveys were compared.

“The data suggest that national efforts toward preventing HAIs are succeeding,” reported Shelley S. Magill, MD, PhD, a medical epidemiologist in the Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion at the CDC who summarized the data at an annual scientific meeting on infectious diseases .

The comparative data were drawn from point prevalence surveys conducted in 2011 and 2015 as part of the CDC’s Emerging Infections Program. In this type of survey, the data are collected over 1 day, providing a snapshot in time among selected hospitals. The analysis presented by Dr. Magill was restricted to the 148 hospitals that participated in both the 2011 and 2015 surveys, although the 2015 survey included a total of 199 hospitals, of which other data analyses are planned.

Due to the change in incidence, the rank order of HAIs was different in 2015 relative to 2011. While surgical site infections (SSIs) represented the most frequent HAI in 2011, they fell to the third most frequent HAI in 2015; pneumonia and gastrointestinal (GI) infections assumed the first and second spots, respectively. The GI HAI infection category includes Clostridium difficile infection.

The incidence of SSI HAI among all hospitalized patients in the survey fell by 41% between 2011 and 2015 (from 1.00% to 0.59%; P = .001). The other big contributor to the overall reduction in HAIs was the fall in the incidence of urinary tract infections, which fell 36% (from 0.55% to 0.35%; P = .04). The decrease in pneumonia (from 0.97% to 0.89%) was not significant, nor was the even more modest reduction in bloodstream HAI (from 0.45% to 0.43%). There was a modest increase in GI/Clostridium difficile infections (from 0.56% to 0.59%).

The surveys do not permit the reduction in HAI rates to be attributed to any specific prevention practices, but Dr. Magill pointed out that the overall reductions correlate with reduced use of urinary catheters and central lines; reductions of both have been advocated as a means for improved infection control. Of several factors that might contribute to a reduction in SSI HAI, Dr. Magill speculated that better adherence to guidelines and more rigorous steps at preoperative infection control strategies might be among them.

Detailed analyses of the data collected from all of the hospitals that participated in the 2015 survey are planned, including an evaluation of which antibiotics were used to treat the HAIs found in this survey. Although the findings so far encourage speculation that infection control practices, such as prudent use of urinary catheters, are having a positive effect, Dr. Magill said that the data also point out the challenges.

“Given that pneumonia continues to represent a large proportion of HAIs in hospitals, more work is needed to identify risk factors; understand the factors that are preventable, particularly in the nonventilated patients; and develop better preventive approaches,” Dr. Magill said.

Dr. Magill reported no financial relationships relevant to this study.

AT ID WEEK 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: In two point prevalence surveys conducted in the same hospitals, the rate of HAI was 22% lower in 2015 (P = .001), compared with 2011.

Data source: CDC national surveys of HAIs in 148 hospitals in two different years (2011 and 2015) were compared.

Disclosures: Dr. Magill reported no financial relationships relevant to this study.

Bringing critical care training to hospitalists

It’s 9 p.m., and the ER calls you to admit a 60-year-old woman with COPD and multilobar pneumonia. She’s hypoxemic, intubated, and hypotensive after 3 L of crystalloid.

You’re asked to evaluate a patient who has developed stridor after an anterior cervical decompression and fusion. He seems to have responded to racemic epinephrine. Is he okay or not? What should you do next?

A patient develops dyspnea and chest pain after a total knee replacement. Chest CT shows extensive bilateral PE and a dilated right ventricle. She’s normotensive, but tachycardic and tachypneic. Now what?

Recognizing this growing phenomenon, SHM convened a task force of hospitalists and intensivists to quantify the problem and to develop tools and curricula to support hospitalists who provide critical care services. Our mission is make sure that every hospitalist who cares for critically ill patients has the skills and knowledge necessary to do so safely and competently. We’re working to define the scale and scope of the problem, advocate for hospitalists who provide critical care services, and develop educational content to fill gaps in knowledge and skill. We hope to offer a comprehensive but flexible critical care curriculum to meet the needs of hospitalists across the range of knowledge and skills.

When we can, we’ll leverage existing critical care courses and content and build that into our curriculum. When we can’t find material that is appropriate for hospitalists, we’ll develop our own. As a first step, we have produced targeted CME-eligible web-based education modules on the SHM Learning Portal covering high-risk clinical scenarios that hospitalists commonly encounter:

• Airway management for the hospitalist