User login

Tumor Necrosis Factor α Inhibitor–Induced Lupuslike Syndrome in a Patient Prescribed Certolizumab Pegol

To the Editor:

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome (TAILS) is a newly described entity that refers to the onset of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) during drug therapy with TNF-α antagonists. The condition is unique because it is thought to occur via a separate pathophysiologic mechanism than all other agents implicated in the development of drug-induced lupus erythematosus (DILE). Infliximab and etanercept are the 2 most common TNF-α antagonists associated with TAILS. Although rare, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol have been reported to induce this state of autoimmunity. We report an uncommon presentation of TAILS in a patient taking certolizumab pegol with a brief discussion of the pathogenesis underlying TAILS.

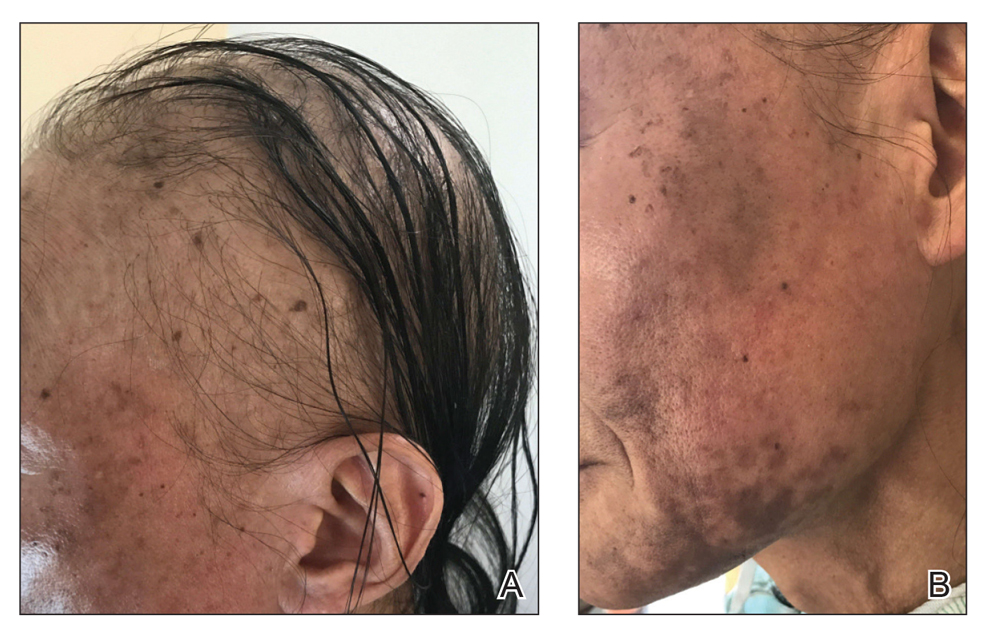

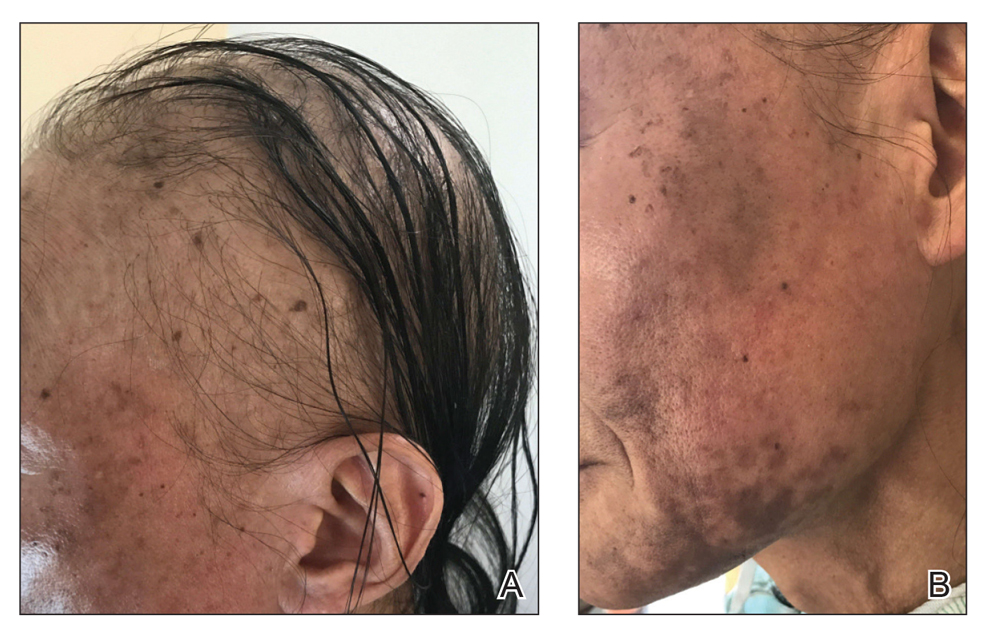

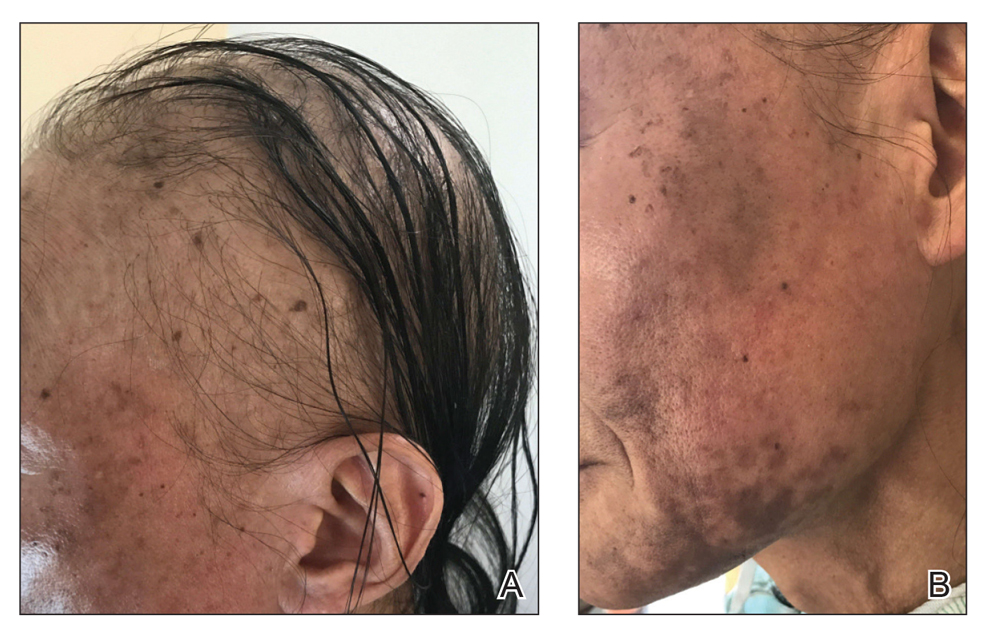

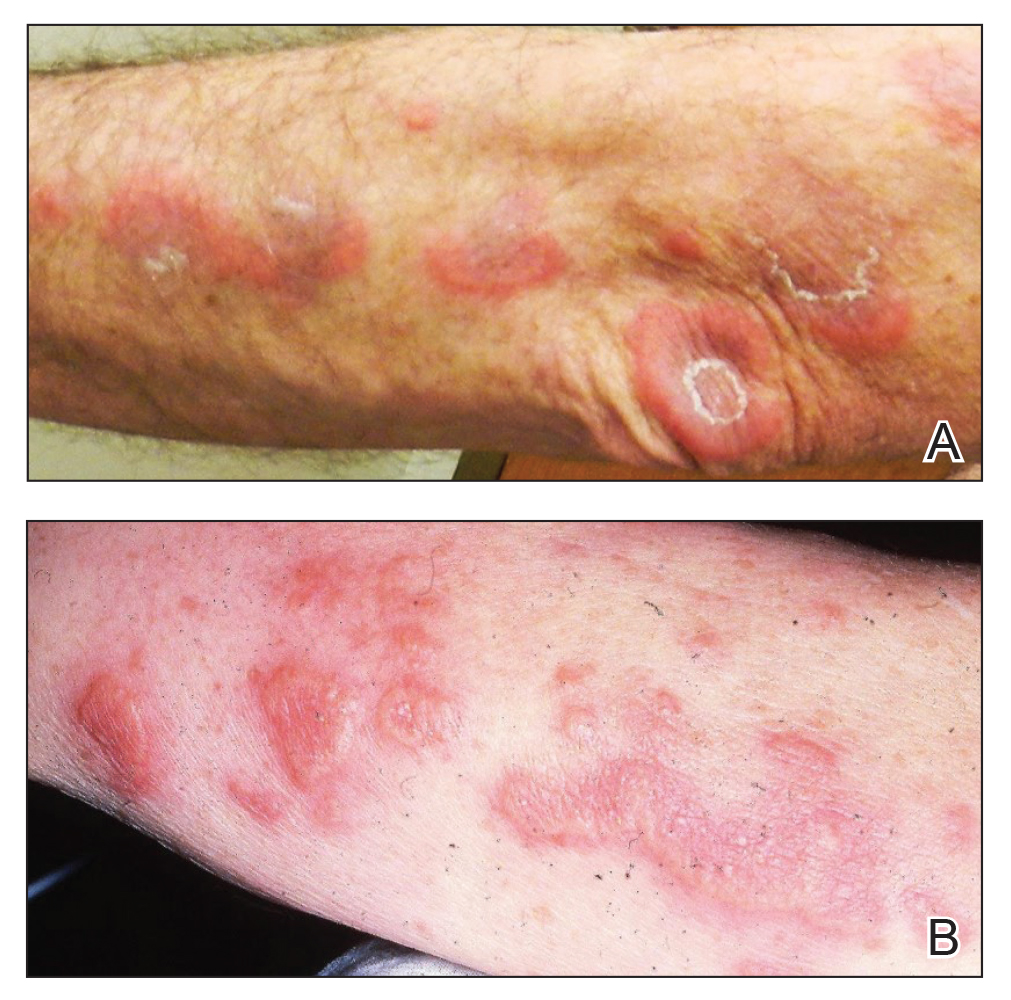

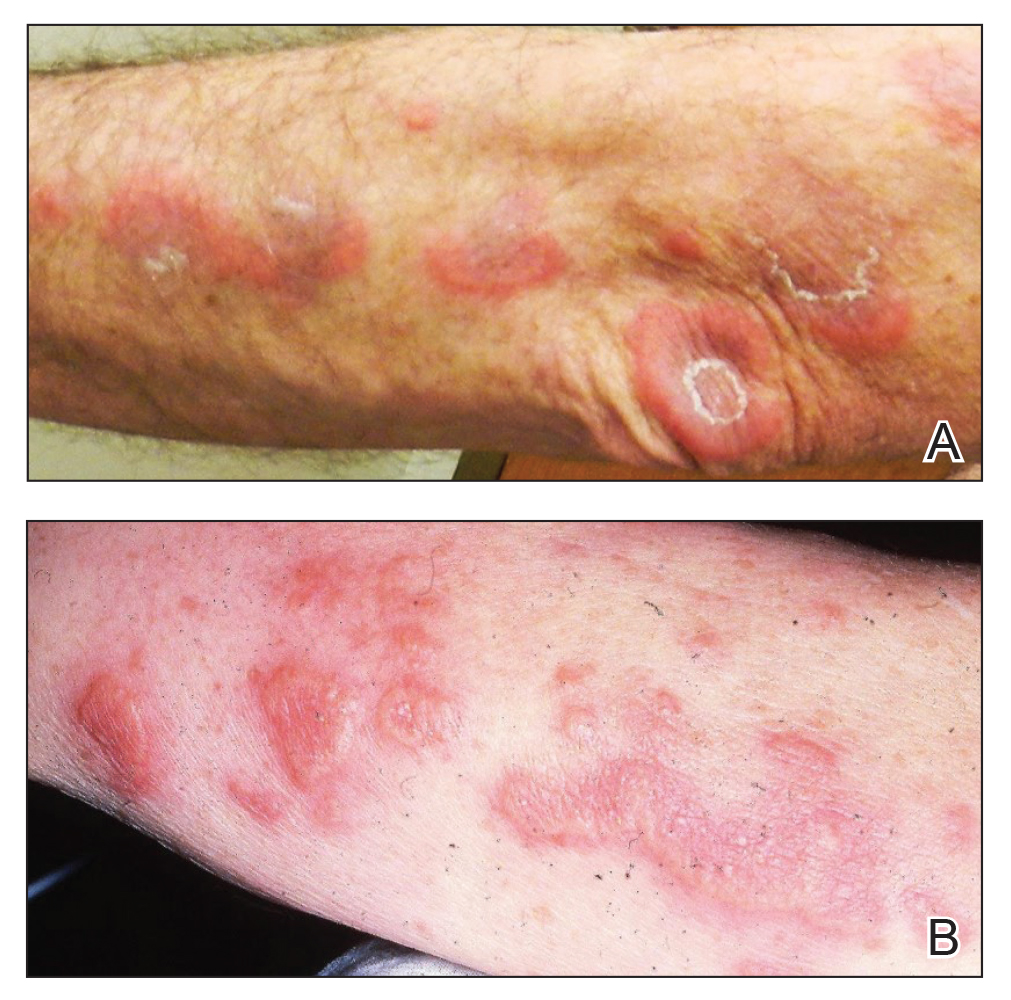

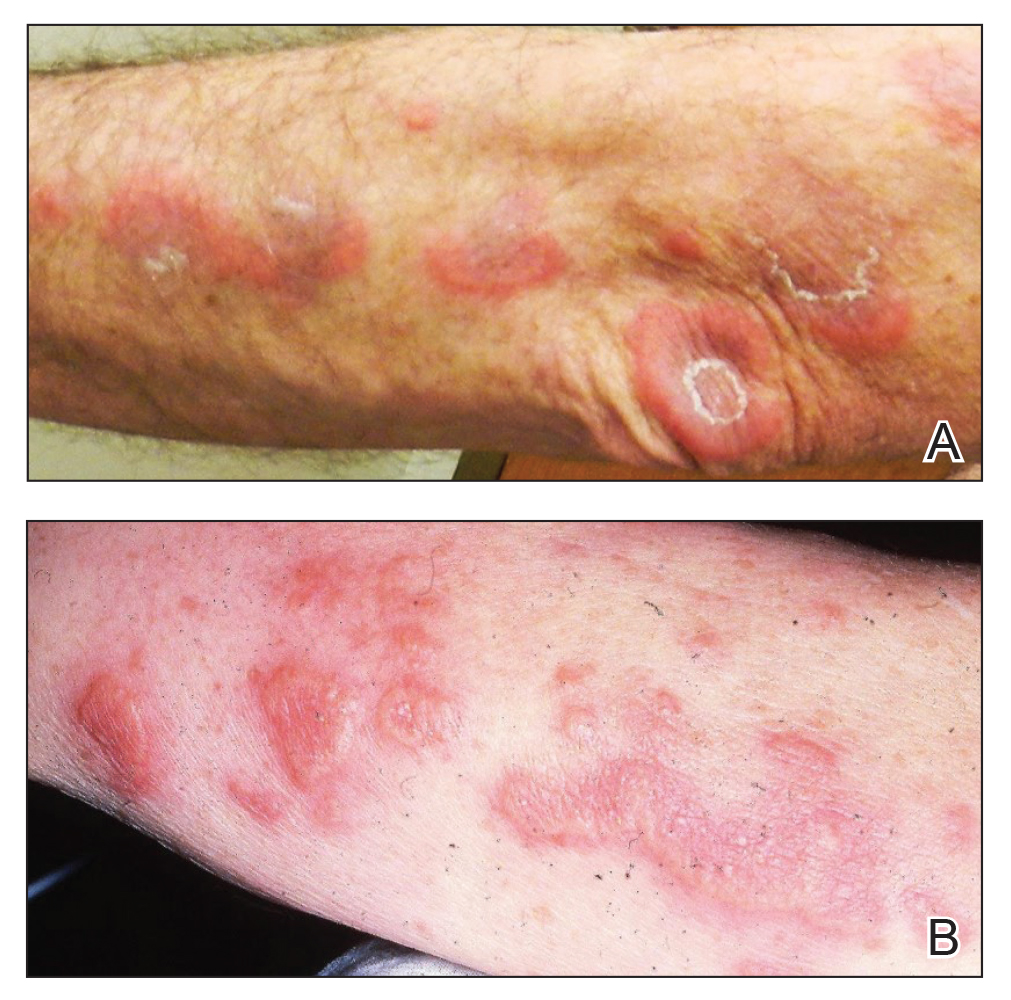

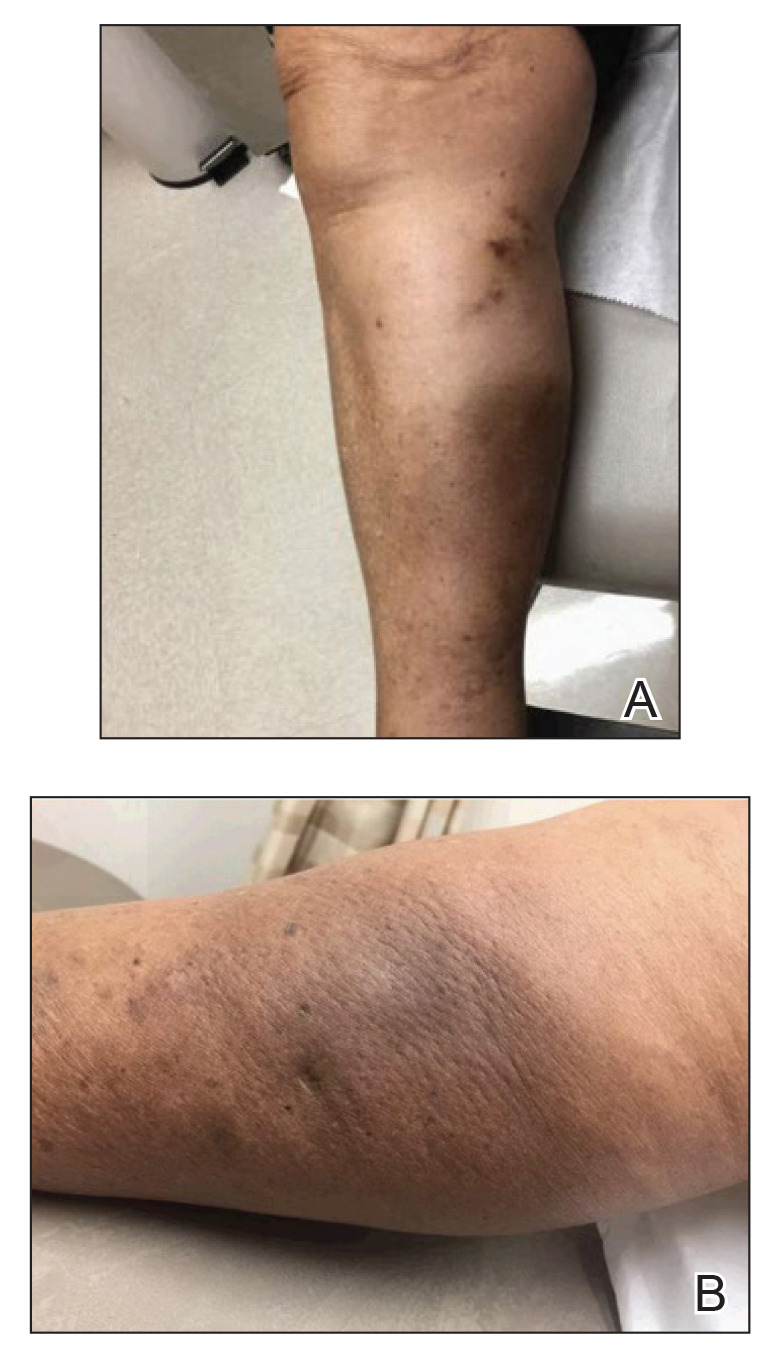

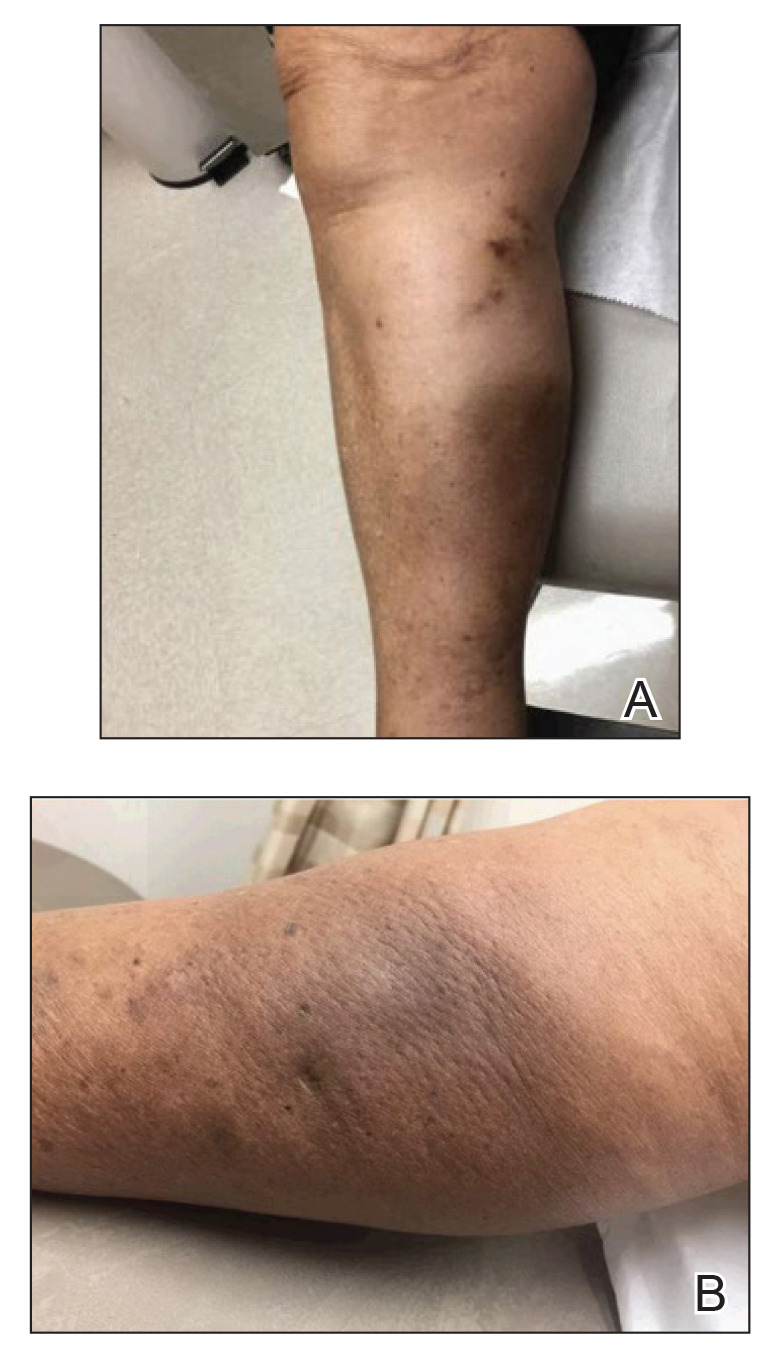

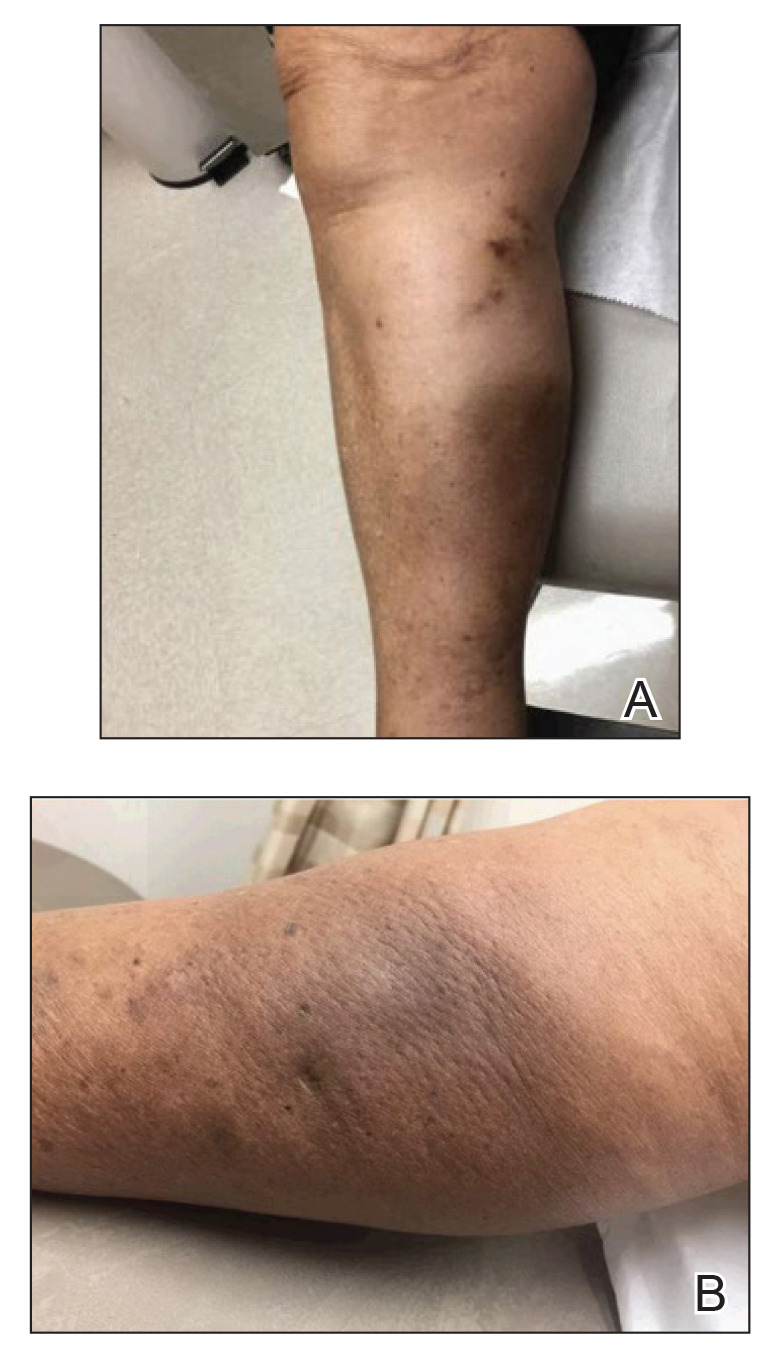

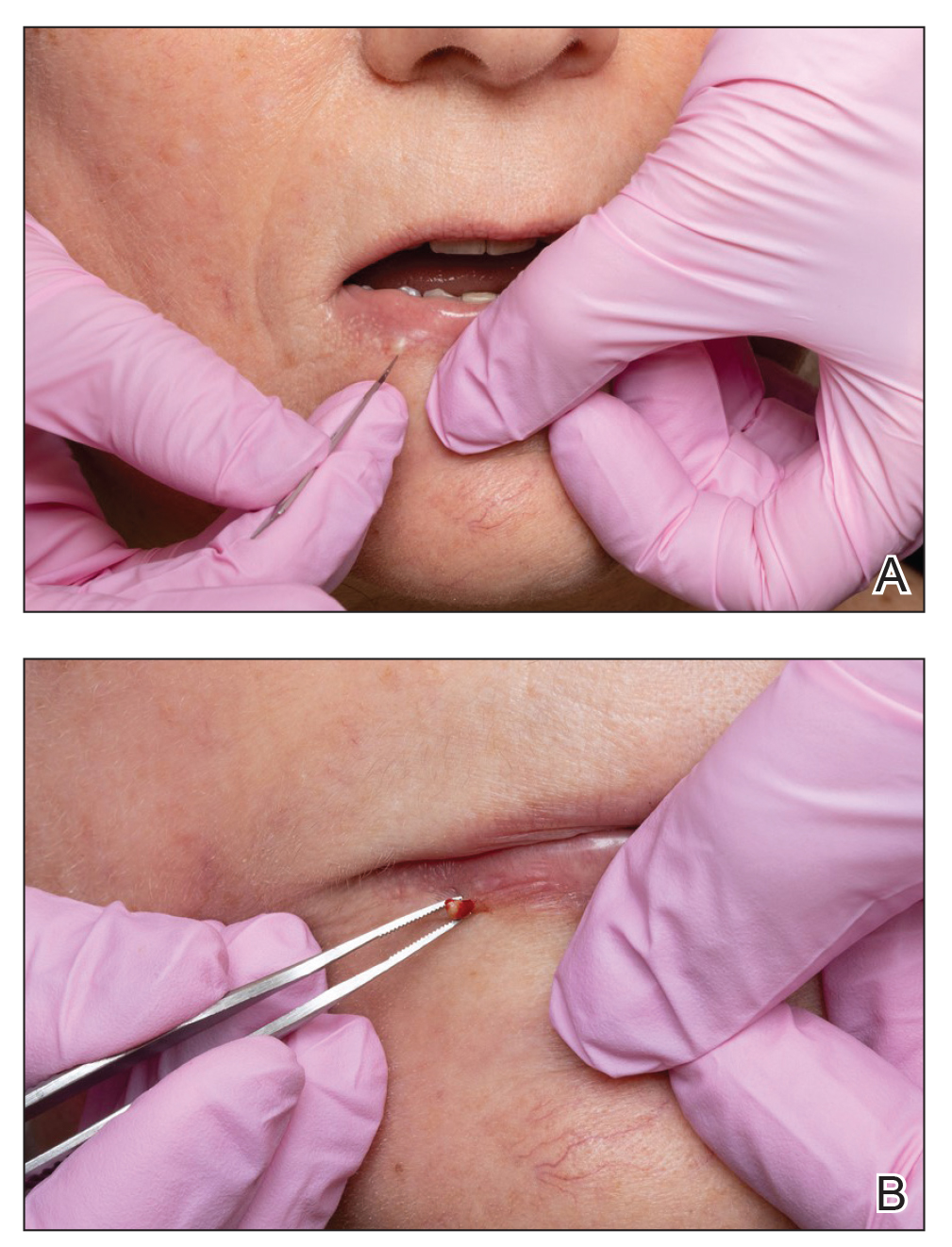

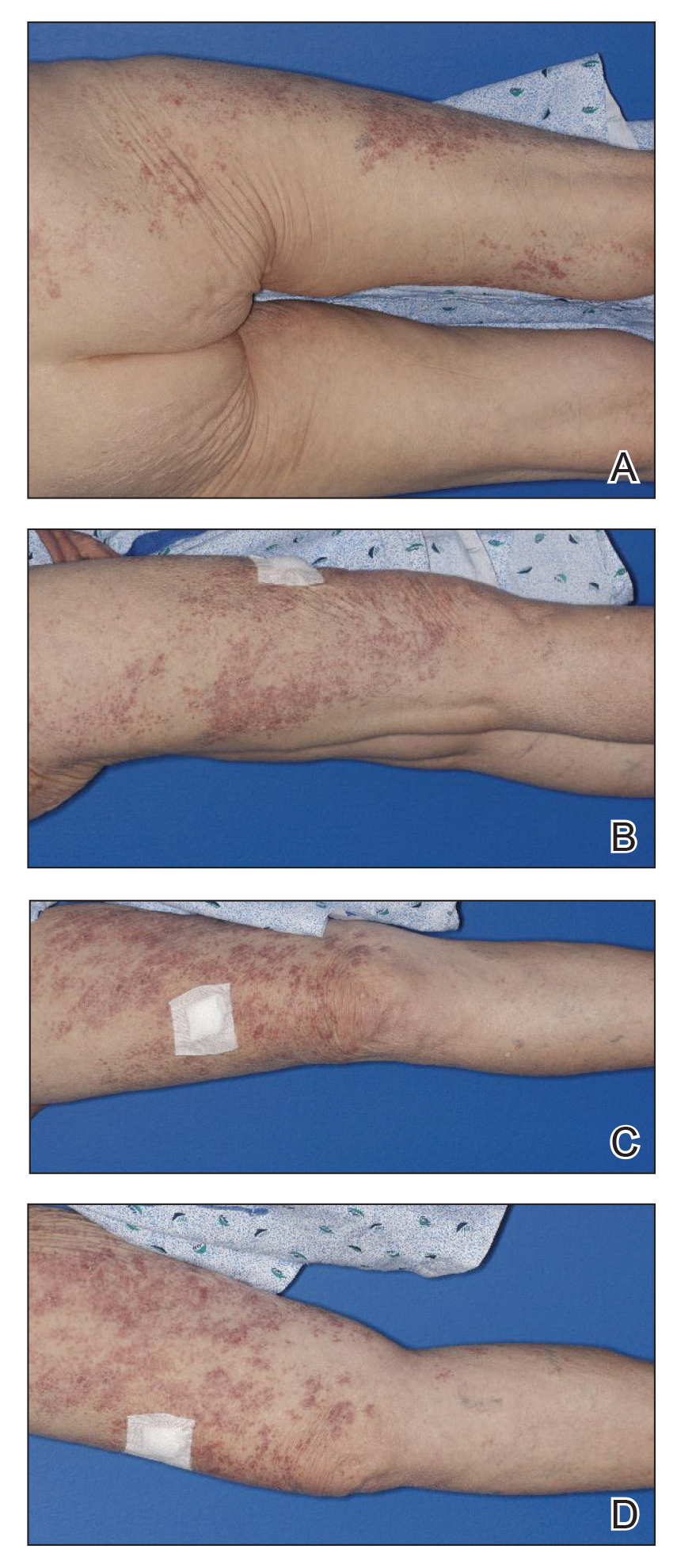

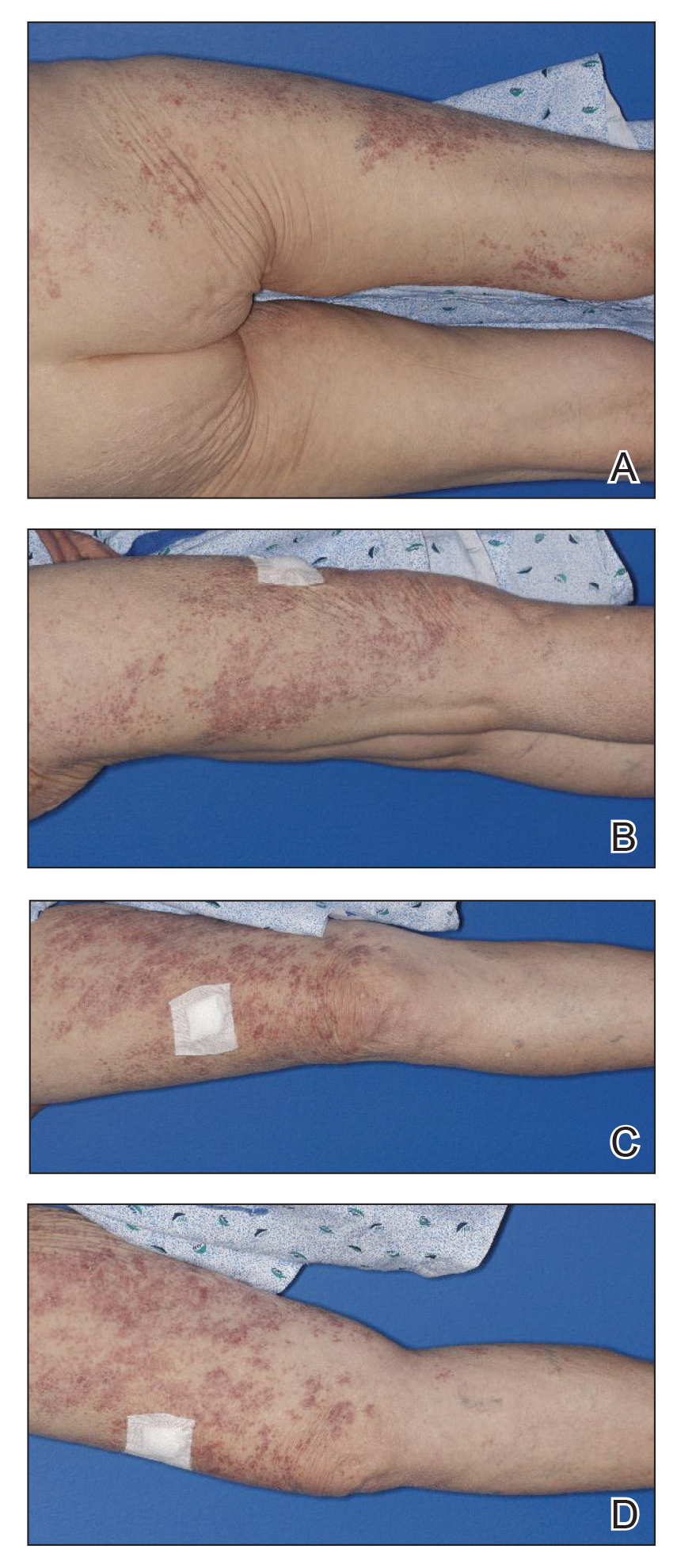

A 71-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash located on the arms, face, and trunk that she reported as having been present for months. She had a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and currently was receiving certolizumab pegol injections. Physical examination revealed erythematous patches and plaques with overlying scaling and evidence of atrophic scarring on sun-exposed areas of the body. The lesions predominantly were in a symmetrical distribution across the extensor surfaces of both outer arms as well as the posterior superior thoracic region extending anteriorly along the bilateral supraclavicular area (Figures 1 and 2). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent for histologic analysis, along with a sample of the patient’s serum for antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing.

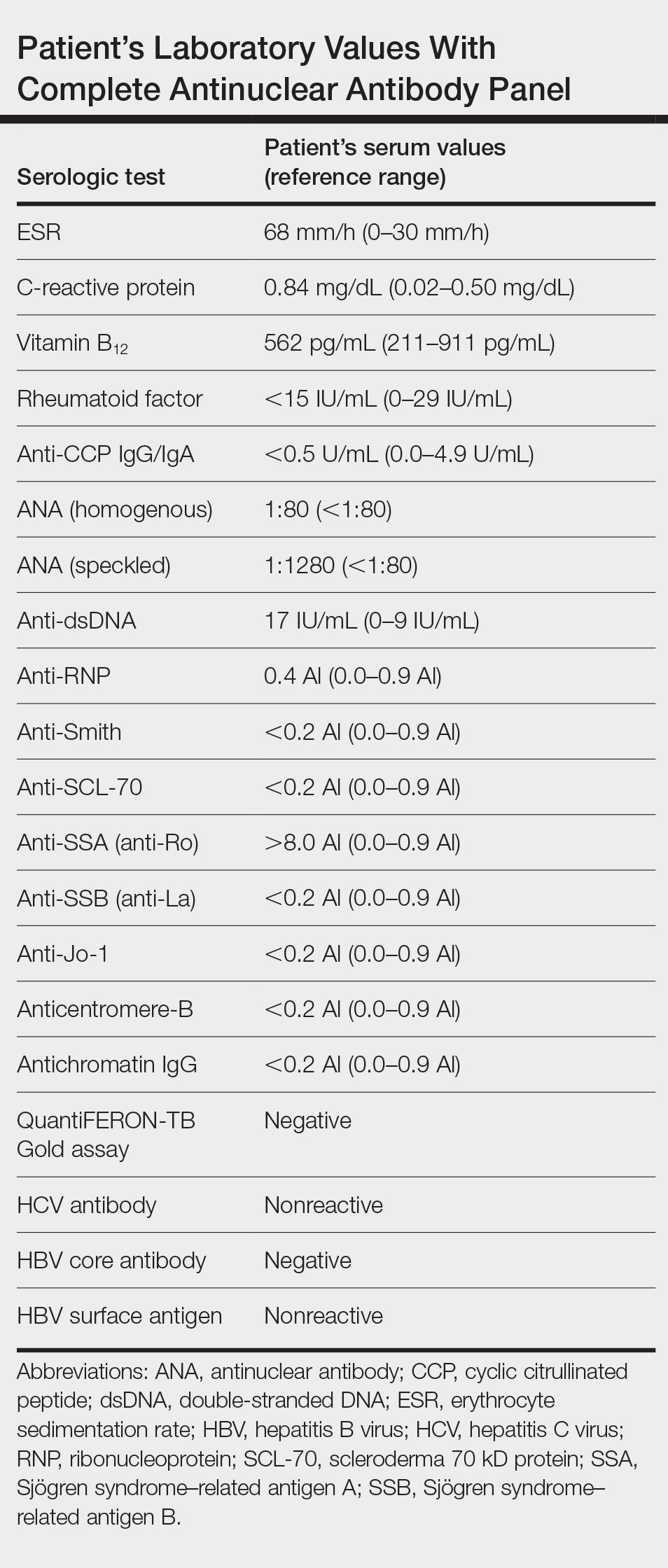

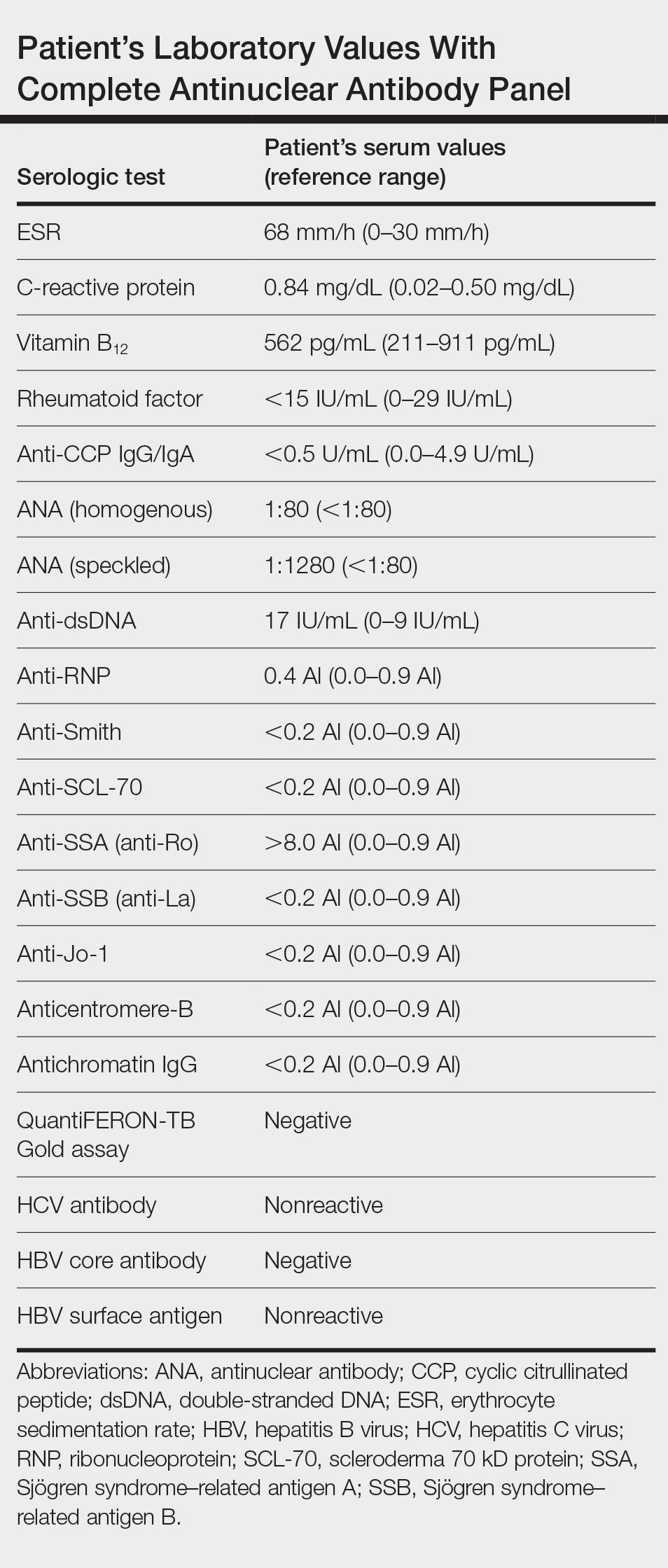

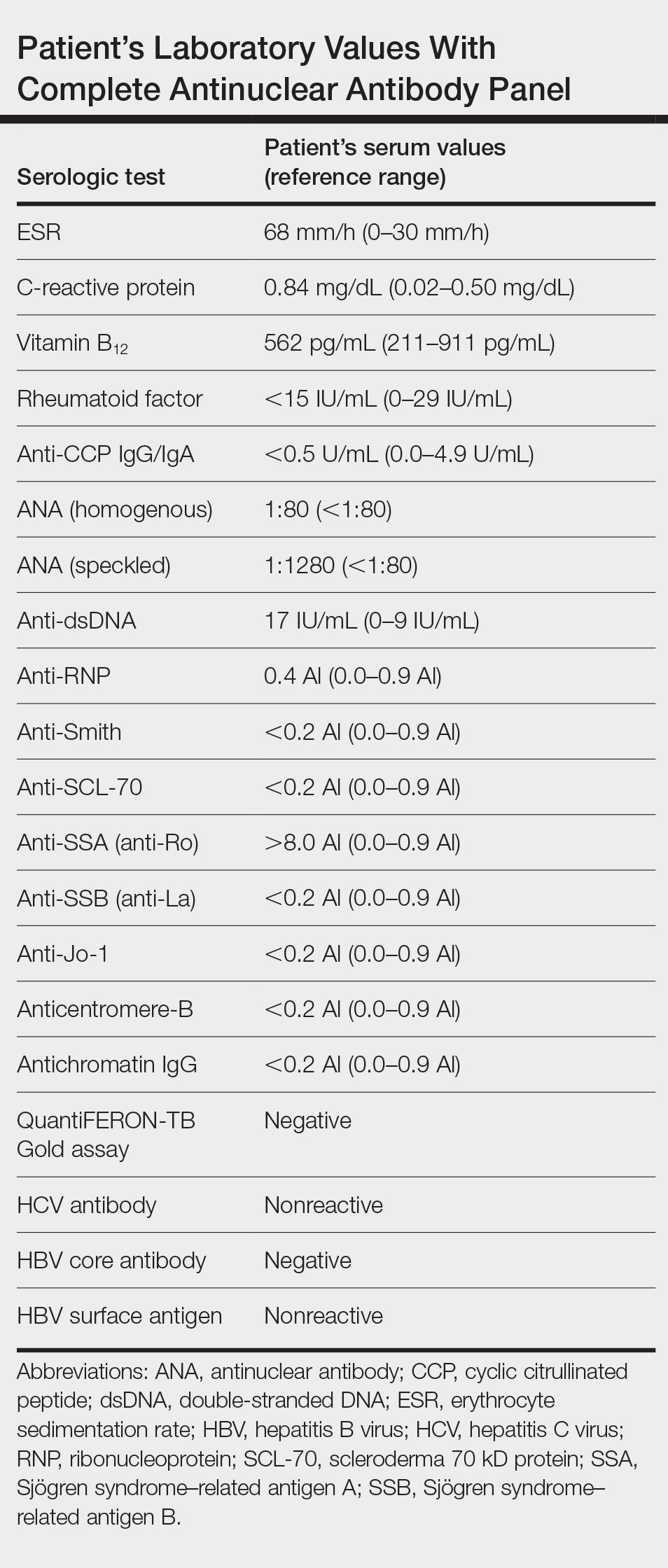

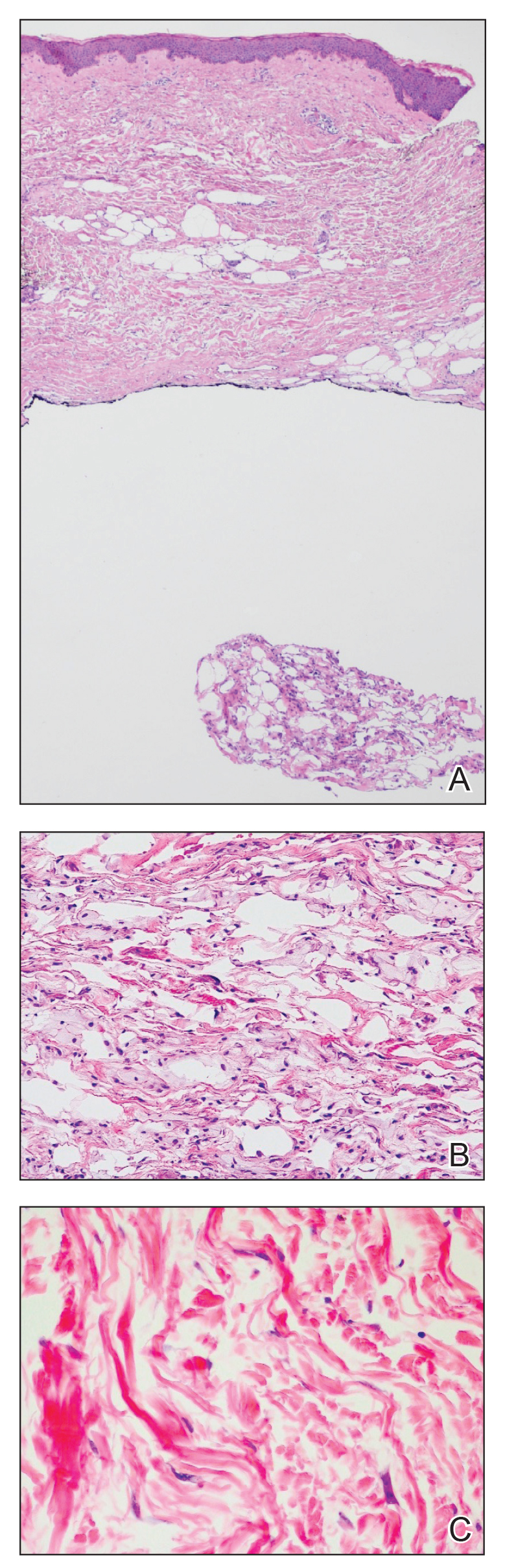

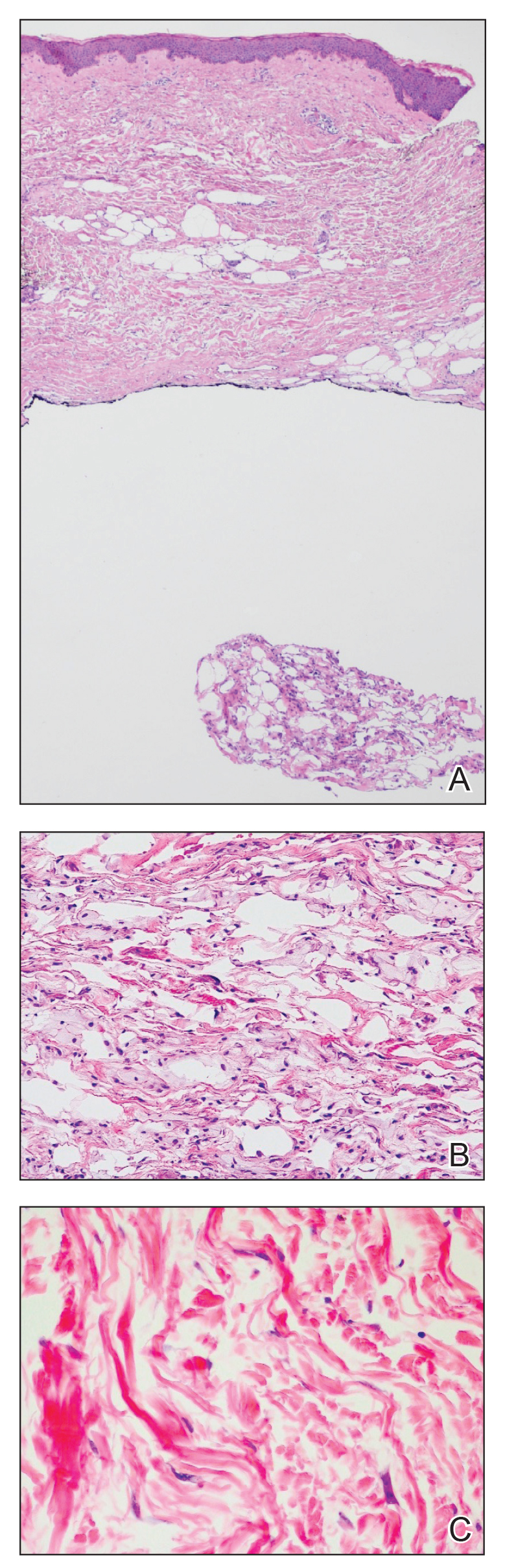

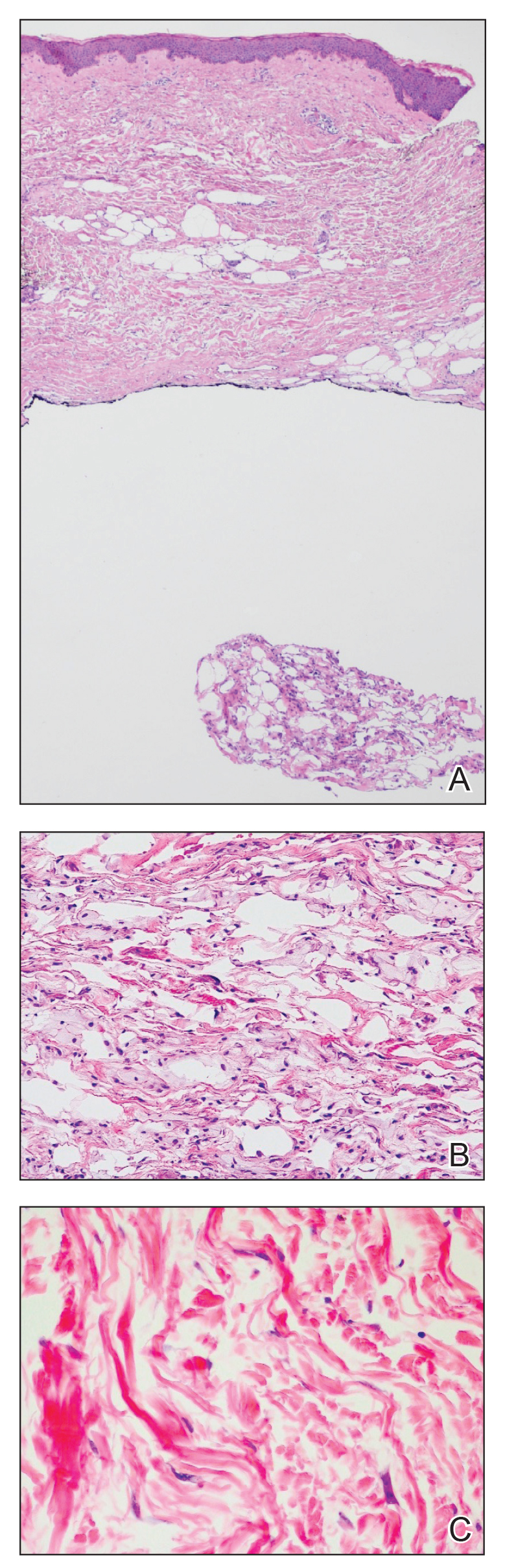

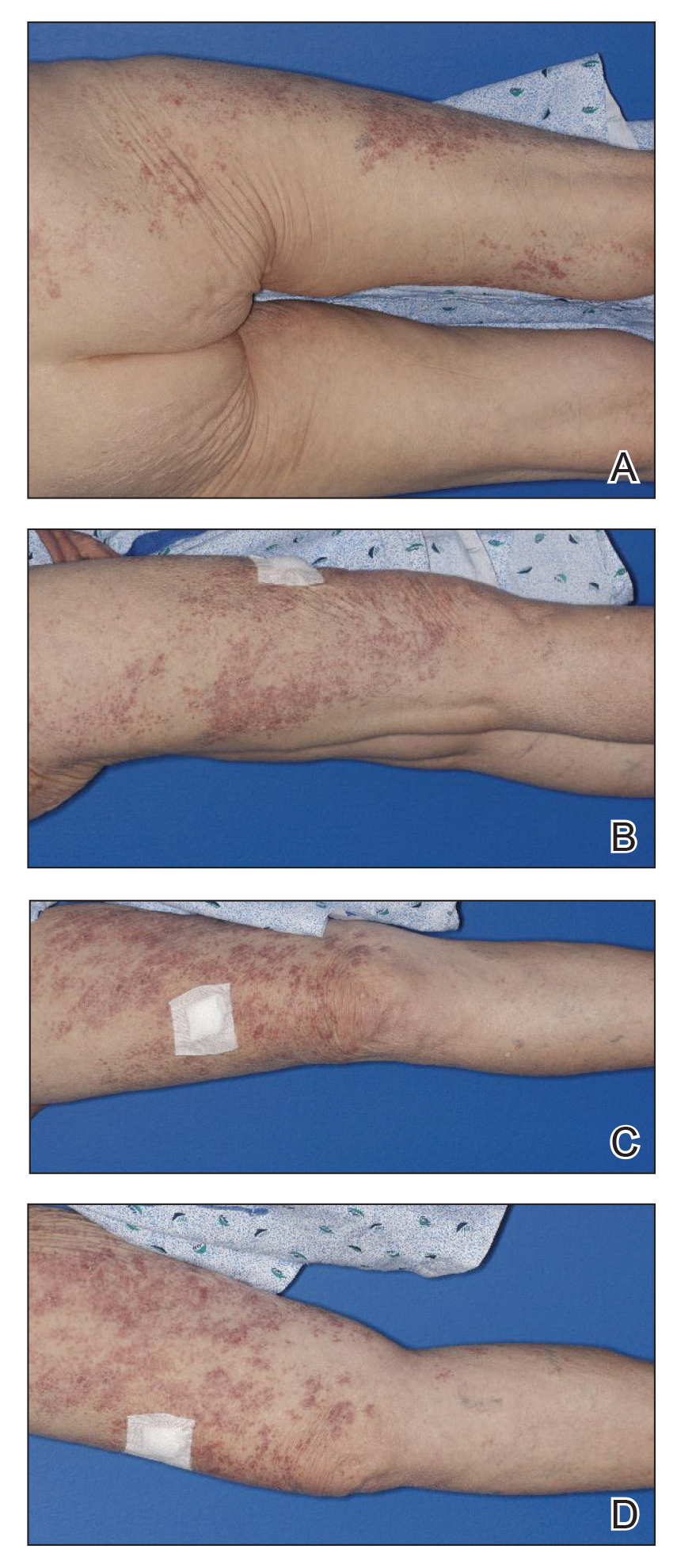

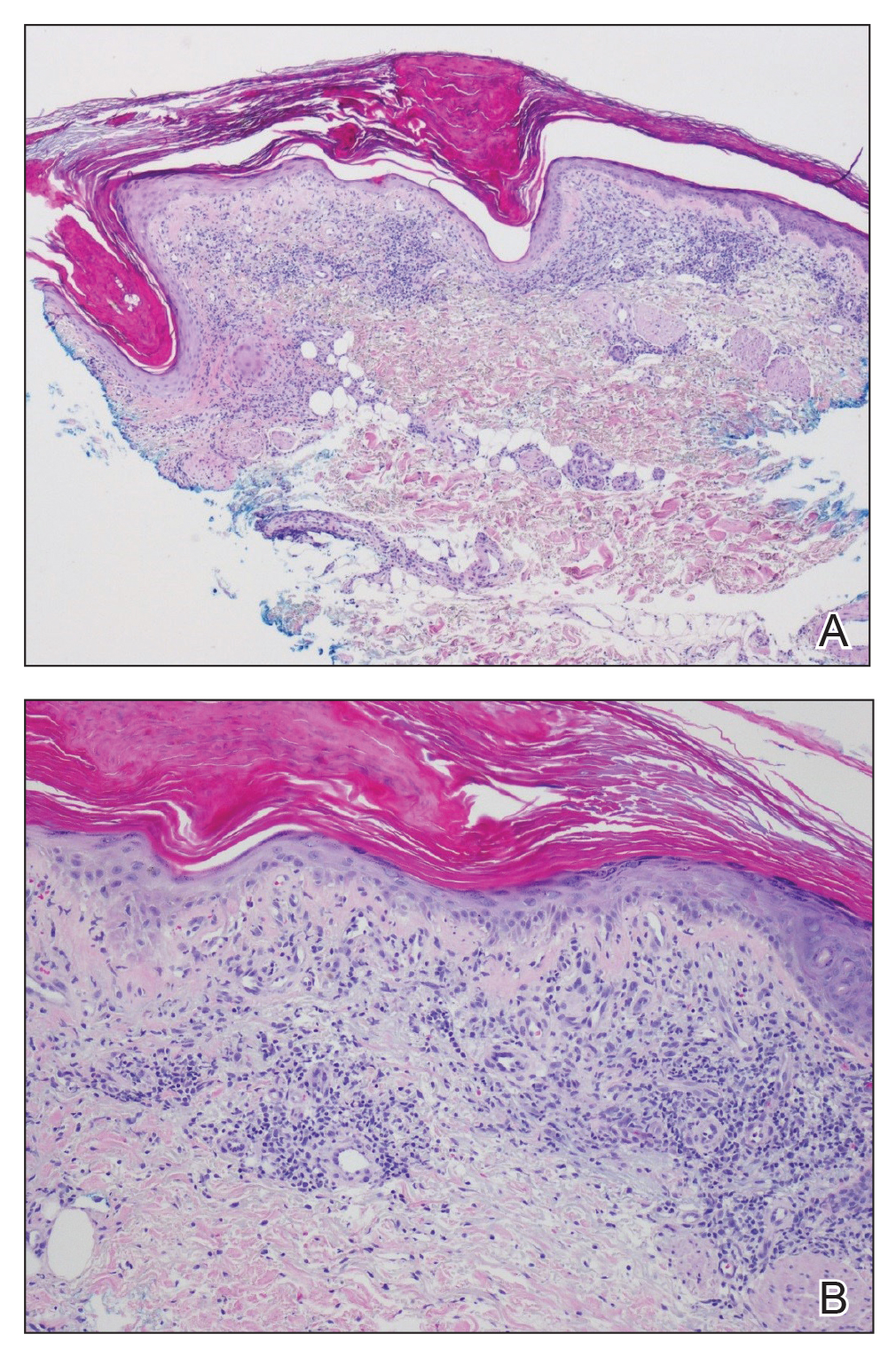

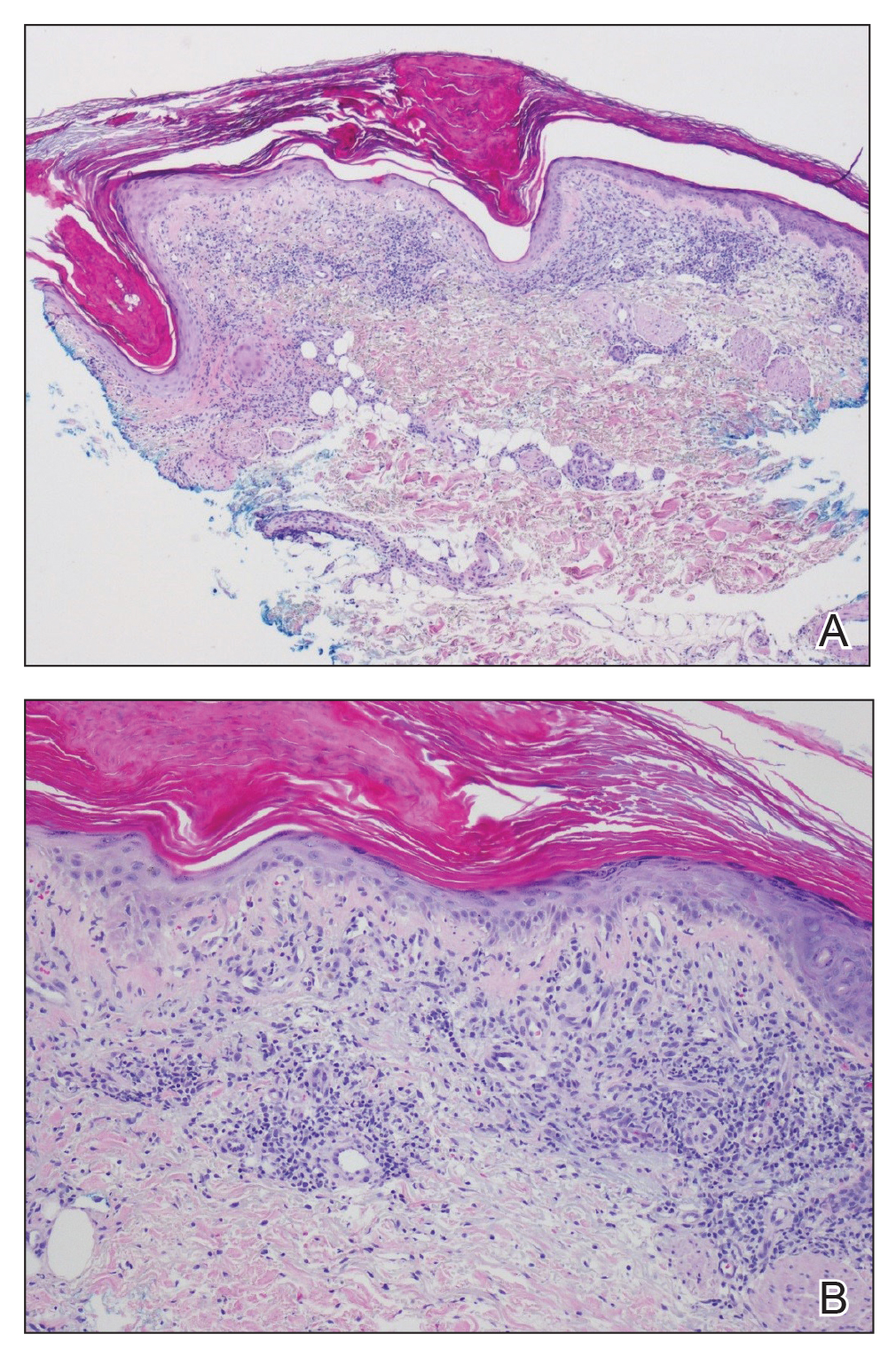

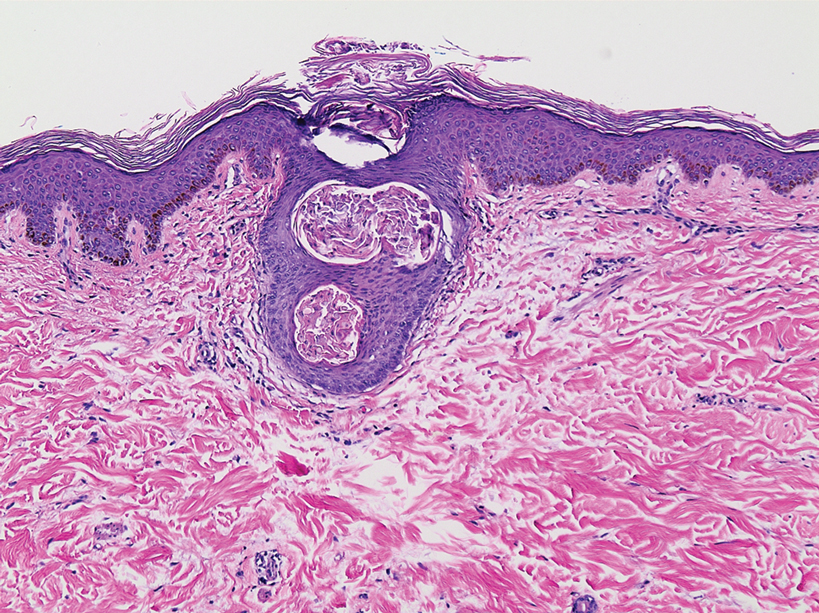

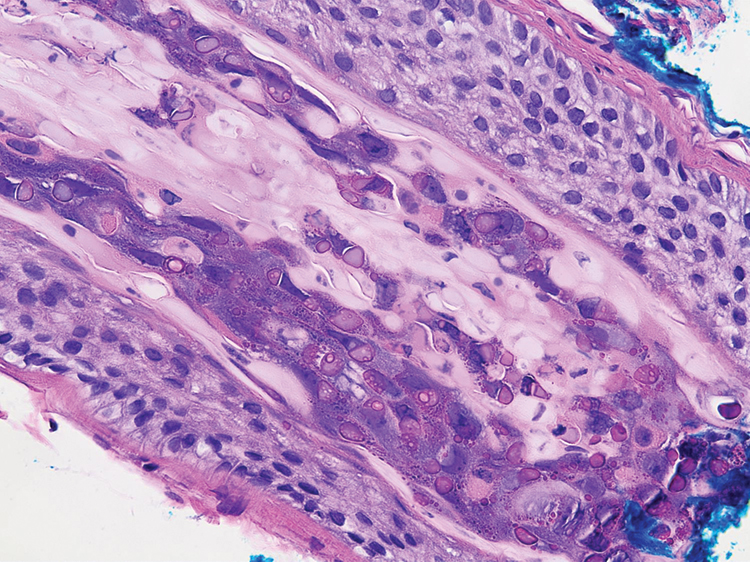

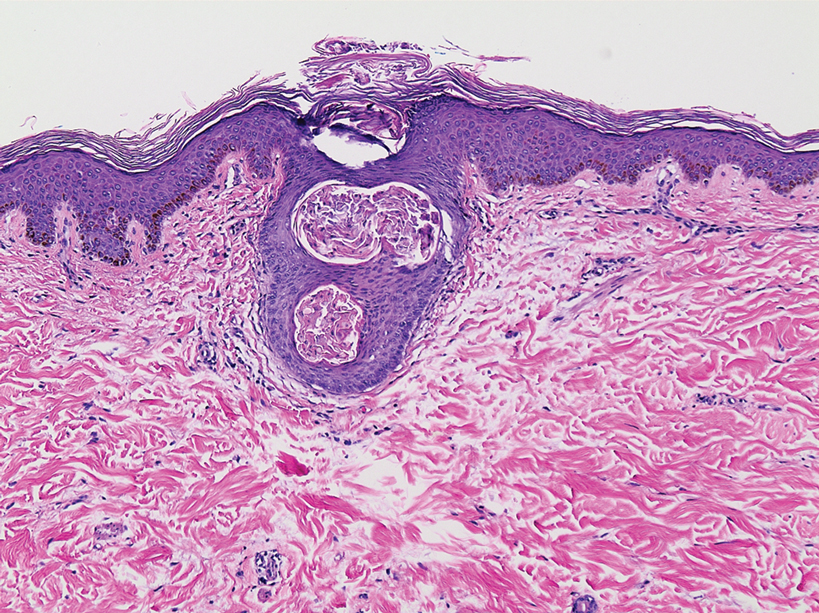

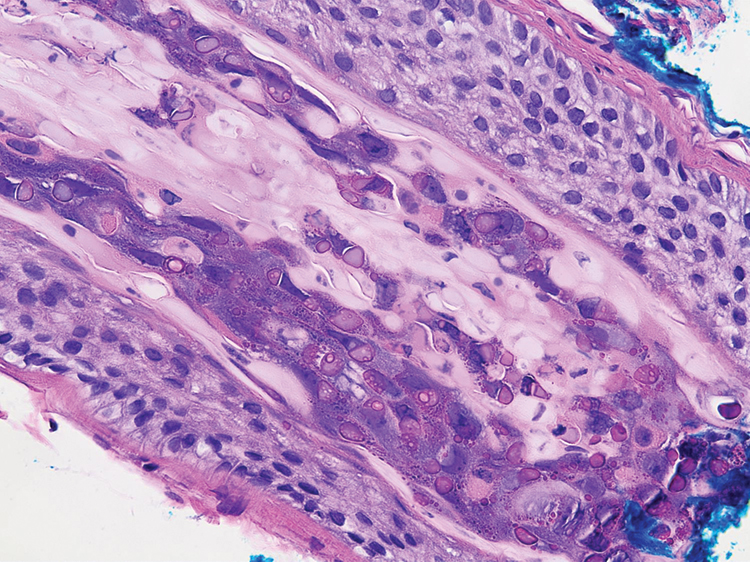

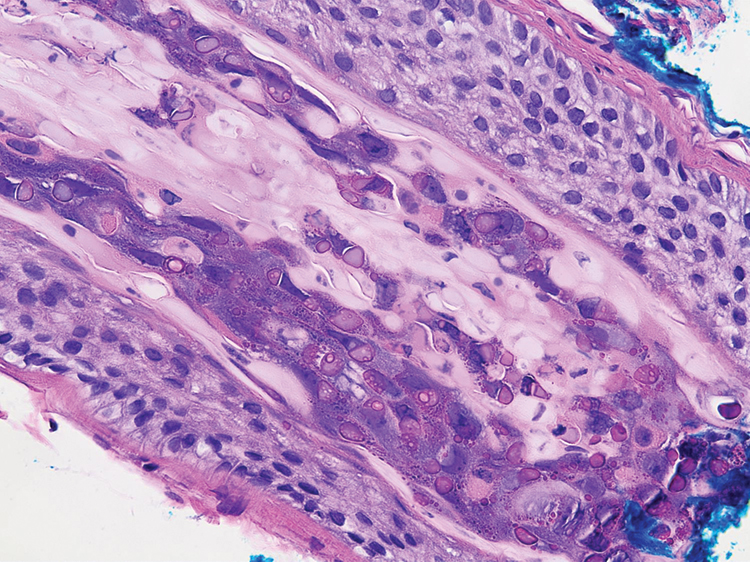

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained tissue sections of the right superior thoracic lesions revealed epidermal atrophy, hyperkeratosis, and vacuolar alteration of the basal layer with apoptosis, consistent with a lichenoid tissue reaction. In addition, both superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates were observed as well as increased dermal mucin. Serologic testing was performed with a comprehensive ANA panel of the patient’s serum (Table). Of note, there was a speckled ANA pattern (1:1280), with elevated anti–double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A (anti-SSA)(also called anti-Ro antibodies) levels. The patient’s rheumatologist was consulted; certolizumab pegol was removed from the current drug regimen and switched to a daily regimen of hydroxychloroquine and prednisone. Seven weeks after discontinuation of certolizumab pegol, the patient was symptom free and without any cutaneous involvement. Based on the histologic analysis, presence of anti-SSA (Ro) autoantibodies, and the resolution of symptoms following withdrawal of anti–TNF-α therapy, a diagnosis of TAILS was made.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, the most common subset of DILE, typically presents with annular polycyclic or papulosquamous skin eruptions on the legs; patients often test positive for anti-SSA/Ro and/or anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen B (also called anti-La) antibodies. Pharmaceutical agents linked to the development of SCLE are calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, thiazide diuretics, terbinafine, the chemotherapeutic agent gemcitabine, and TNF-α antagonists.1,2 Tumor necrosis factor α antagonists are biologic agents that commonly are used in the management of systemic inflammatory diseases such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, seronegative spondyloarthropathies, and rheumatoid arthritis. Among this family of therapeutics includes adalimumab (humanized monoclonal antibody), infliximab (chimeric monoclonal TNF-α antagonist), etanercept (soluble receptor fusion protein), certolizumab pegol (Fab fraction of a human IgG monoclonal antibody), and golimumab (humanized monoclonal antibody).

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome most commonly occurs in women in the fifth decade of life, and it is seen more often in those using infliximab or entanercept.3 Although reports do exist, TAILS rarely complicates treatment with adalimumab, golimumab, or certolizumab.4,5 Due to the lack of reports, there are no diagnostic criteria nor an acceptable theory regarding the pathogenesis. In one study in France, the estimated incidence was thought to be 0.19% for infliximab and 0.18% for etanercept.6 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome is unique in that it is thought to occur by a different mechanism than that of other known offending agents in the development of DILE. Molecular mimicry, direct cytotoxicity, altered T-cell gene expression, and disruption of central immune tolerance have all been hypothesized to cause drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus, SCLE, and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, are postulated to cause the induction of SCLE via an independent route separate from not only other drugs that cause SCLE but also all forms of DILE as a whole, making it a distinctive player within the realm of agents known to cause a lupuslike syndrome. The following hypotheses may explain this occurrence:

1. Increased humoral autoimmunity: Under normal circumstances, TNF-α activation leads to upregulation in the production of cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes. The upregulation of CD8+ T lymphocytes concurrently leads to a simultaneous suppression of B lymphocytes. Inhibiting the effects of TNF-α on the other hand promotes cytotoxic T-lymphocyte suppression, leading to an increased synthesis of B cells and subsequently a state of increased humoral autoimmunity.7

2. Infection: The immunosuppressive effects of TNF-α inhibitors are well known, and the propensity to develop microbial infections, such as tuberculosis, is markedly increased on the use of these agents. Infections brought on by TNF-α inhibitor usage are hypothesized to induce a widespread activation of polyclonal B lymphocytes, eventually leading to the formation of antibodies against these polyclonal B lymphocytes and subsequently SCLE.8

3. Helper T cell (TH2) response: The inhibition of TH1 CD4+ lymphocytes by TNF-α inversely leads to an increased production of TH2 CD4+ lymphocytes. This increase in the levels of circulating TH2 CD4+ lymphocytes brought on by the action of anti–TNF-α agents is thought to promote the development of SCLE.9,10

4. Apoptosis theory: Molecules of TNF-α inhibitors are capable of binding to TNF-α receptors on the cell surface. In doing so, cellular apoptosis is triggered, resulting in the release of nucleosomal autoantigens from the apoptotic cells. In susceptible individuals, autoantibodies then begin to form against the nucleosomal autoantigens, leading to an autoimmune reaction that is characterized by SCLE.11,12

Major histone compatibility (MHC) antigen testing performed by Sontheimer et al12 established the presence of the HLA class I, HLA-B8, and/or HLA-DR3 haplotypes in patients with SCLE.13,14 Furthermore, there is a well-known association between the antinuclear profile of known SCLE patients and the presence of anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies.13 Therefore, we propose that in susceptible individuals, such as those with the HLA class I, HLA-B8, or HLA-DR3 haplotypes, the initiation of a TNF-α inhibitor causes cellular apoptosis with the subsequent release of nucleosomal and cytoplasmic components (namely that of the Ro autoantigens), inducing a state of autoimmunity. An ensuing immunogenic response is then initiated in predisposed individuals for which anti-SSA (Ro) autoantibodies are produced against these previously mentioned autoantigens.

Drug-induced SCLE is most common in females (71%), with a median age of 58 years. The most common site of cutaneous manifestations is the legs.15 Although our patient was in the eighth decade of life with predominant cutaneous involvement of the upper extremity, the erythematous plaques with a symmetric, annular, polycyclic appearance in photosensitive regions raised a heightened suspicion for lupus erythematosus. Histology classically involves an interface dermatitis with vacuolar or hydropic change and lymphocytic infiltrates,16 consistent with the analysis of tissue sections from our patient. Moreover, the speckled ANA profile with positive anti-dsDNA and anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies in the absence of a negative rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies strongly favored the diagnosis of SCLE over alternative diagnoses.2

The supraclavicular rash in our patient raises clinical suspicion for the shawl sign of dermatomyositis, which also is associated with musculoskeletal pain and photosensitivity. In addition, skin biopsy revealed vacuolar alteration of the basement membrane zoneand dermal mucin in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis; therefore, skin biopsy is of little use in distinguishing the 2 conditions, and antibody testing must be performed. Although anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies commonly are associated with SCLE, there are reports involving positivity for the extractable nuclear antigen in cases of dermatomyositis.17 Based on our patient’s current drug regimen, including that of a known offending agent for SCLE, a presumptive diagnosis of TAILS was made. Following withdrawal of certolizumab pegol injections and subsequent resolution of the skin lesions, our patient was given a definitive diagnosis of TAILS based on clinical and pathological assessments.

The clinical diagnosis of TAILS should be made according to the triad of at least 1 serologic and 1 nonserologic American College of Rheumatology criteria, such as anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies and a photosensitive rash, respectively, as well as a relationship between the onset of symptoms and TNF-α inhibitor therapy.18 Both the definitive diagnosis and the treatment of TAILS can be made via withdrawal of the TNF-α inhibitor, which was true in our case whereby chronologically the onset of use with a TNF-α inhibitor was associated with disease onset. Furthermore, withdrawal led to complete improvement of all signs and symptoms, collectively supporting a diagnosis of TAILS. Notably, switching to a different TNF-α inhibitor has been shown to be safe and effective.19

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Crosti C. Drug-induced lupus: an update on its dermatological aspects. Lupus. 2009;18:935-940.

- Wiznia LE, Subtil A, Choi JN. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced by chemotherapy: gemcitabine as a causative agent. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1071-1075.

- Williams VL, Cohen PR. TNF alpha antagonist-induced lupus-like syndrome: report and review of the literature with implications for treatment with alternative TNF alpha antagonists. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:619-625.

- Pasut G. Pegylation of biological molecules and potential benefits: pharmacological properties of certolizumab pegol. Bio Drugs. 2014;28(suppl 1):15-23.

- Mudduluru BM, Shah S, Shamah S. et al. TNF-alpha antagonist induced lupus on three different agents. Postgrad Med. 2017;129:304-306.

- De Bandt M. Anti-TNF-alpha-induced lupus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:235.

- Costa MF, Said NR, Zimmermann B. Drug-induced lupus due to anti-tumor necrosis factor alfa agents. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;37:381-387.

- Caramaschi P, Biasi D, Colombatti M. Anti-TNF alpha therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmunity. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:209-214.

- Yung RL, Quddus J, Chrisp CE, et al. Mechanism of drug-induced lupus. I. cloned Th2 cells modified with DNA methylation inhibitors in vitro cause autoimmunity in vivo. J Immunol. 1995;154:3025-3035.

- Yung R, Powers D, Johnson K, et al. Mechanisms of drug-induced lupus. II. T cells overexpressing lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 become autoreactive and cause a lupuslike disease in syngeneic mice. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2866-2871.

- Sontheimer RD, Stastny P, Gilliam JN. Human histocompatibility antigen associations in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1981;67:312-316.

- Sontheimer RD, Maddison PJ, Reichlin M, et al. Serologic and HLA associations in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, a clinical subset of lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97:664-671.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

- Deutscher SL, Harley JB, Keene JD. Molecular analysis of the 60-kDa human Ro ribonucleoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:9479-9483.

- DalleVedove C, Simon JC, Girolomoni G. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus with emphasis on skin manifestations and the role of anti-TNFα agents [article in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:889-897.

- Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:391-404.

- Schulte-Pelkum J, Fritzler M, Mahler M. Latest update on the Ro/SS-A autoantibody system. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:632-637.

- De Bandt M, Sibilia J, Le Loët X, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus induced by anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapy: a French national survey. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R545-R551.

- Lupu A, Tieranu C, Constantinescu CL, et al. TNFα inhibitor induced lupus-like syndrome (TAILS) in a patient with IBD. Current Health Sci J. 2014;40:285-288.

To the Editor:

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome (TAILS) is a newly described entity that refers to the onset of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) during drug therapy with TNF-α antagonists. The condition is unique because it is thought to occur via a separate pathophysiologic mechanism than all other agents implicated in the development of drug-induced lupus erythematosus (DILE). Infliximab and etanercept are the 2 most common TNF-α antagonists associated with TAILS. Although rare, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol have been reported to induce this state of autoimmunity. We report an uncommon presentation of TAILS in a patient taking certolizumab pegol with a brief discussion of the pathogenesis underlying TAILS.

A 71-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash located on the arms, face, and trunk that she reported as having been present for months. She had a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and currently was receiving certolizumab pegol injections. Physical examination revealed erythematous patches and plaques with overlying scaling and evidence of atrophic scarring on sun-exposed areas of the body. The lesions predominantly were in a symmetrical distribution across the extensor surfaces of both outer arms as well as the posterior superior thoracic region extending anteriorly along the bilateral supraclavicular area (Figures 1 and 2). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent for histologic analysis, along with a sample of the patient’s serum for antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing.

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained tissue sections of the right superior thoracic lesions revealed epidermal atrophy, hyperkeratosis, and vacuolar alteration of the basal layer with apoptosis, consistent with a lichenoid tissue reaction. In addition, both superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates were observed as well as increased dermal mucin. Serologic testing was performed with a comprehensive ANA panel of the patient’s serum (Table). Of note, there was a speckled ANA pattern (1:1280), with elevated anti–double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A (anti-SSA)(also called anti-Ro antibodies) levels. The patient’s rheumatologist was consulted; certolizumab pegol was removed from the current drug regimen and switched to a daily regimen of hydroxychloroquine and prednisone. Seven weeks after discontinuation of certolizumab pegol, the patient was symptom free and without any cutaneous involvement. Based on the histologic analysis, presence of anti-SSA (Ro) autoantibodies, and the resolution of symptoms following withdrawal of anti–TNF-α therapy, a diagnosis of TAILS was made.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, the most common subset of DILE, typically presents with annular polycyclic or papulosquamous skin eruptions on the legs; patients often test positive for anti-SSA/Ro and/or anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen B (also called anti-La) antibodies. Pharmaceutical agents linked to the development of SCLE are calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, thiazide diuretics, terbinafine, the chemotherapeutic agent gemcitabine, and TNF-α antagonists.1,2 Tumor necrosis factor α antagonists are biologic agents that commonly are used in the management of systemic inflammatory diseases such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, seronegative spondyloarthropathies, and rheumatoid arthritis. Among this family of therapeutics includes adalimumab (humanized monoclonal antibody), infliximab (chimeric monoclonal TNF-α antagonist), etanercept (soluble receptor fusion protein), certolizumab pegol (Fab fraction of a human IgG monoclonal antibody), and golimumab (humanized monoclonal antibody).

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome most commonly occurs in women in the fifth decade of life, and it is seen more often in those using infliximab or entanercept.3 Although reports do exist, TAILS rarely complicates treatment with adalimumab, golimumab, or certolizumab.4,5 Due to the lack of reports, there are no diagnostic criteria nor an acceptable theory regarding the pathogenesis. In one study in France, the estimated incidence was thought to be 0.19% for infliximab and 0.18% for etanercept.6 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome is unique in that it is thought to occur by a different mechanism than that of other known offending agents in the development of DILE. Molecular mimicry, direct cytotoxicity, altered T-cell gene expression, and disruption of central immune tolerance have all been hypothesized to cause drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus, SCLE, and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, are postulated to cause the induction of SCLE via an independent route separate from not only other drugs that cause SCLE but also all forms of DILE as a whole, making it a distinctive player within the realm of agents known to cause a lupuslike syndrome. The following hypotheses may explain this occurrence:

1. Increased humoral autoimmunity: Under normal circumstances, TNF-α activation leads to upregulation in the production of cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes. The upregulation of CD8+ T lymphocytes concurrently leads to a simultaneous suppression of B lymphocytes. Inhibiting the effects of TNF-α on the other hand promotes cytotoxic T-lymphocyte suppression, leading to an increased synthesis of B cells and subsequently a state of increased humoral autoimmunity.7

2. Infection: The immunosuppressive effects of TNF-α inhibitors are well known, and the propensity to develop microbial infections, such as tuberculosis, is markedly increased on the use of these agents. Infections brought on by TNF-α inhibitor usage are hypothesized to induce a widespread activation of polyclonal B lymphocytes, eventually leading to the formation of antibodies against these polyclonal B lymphocytes and subsequently SCLE.8

3. Helper T cell (TH2) response: The inhibition of TH1 CD4+ lymphocytes by TNF-α inversely leads to an increased production of TH2 CD4+ lymphocytes. This increase in the levels of circulating TH2 CD4+ lymphocytes brought on by the action of anti–TNF-α agents is thought to promote the development of SCLE.9,10

4. Apoptosis theory: Molecules of TNF-α inhibitors are capable of binding to TNF-α receptors on the cell surface. In doing so, cellular apoptosis is triggered, resulting in the release of nucleosomal autoantigens from the apoptotic cells. In susceptible individuals, autoantibodies then begin to form against the nucleosomal autoantigens, leading to an autoimmune reaction that is characterized by SCLE.11,12

Major histone compatibility (MHC) antigen testing performed by Sontheimer et al12 established the presence of the HLA class I, HLA-B8, and/or HLA-DR3 haplotypes in patients with SCLE.13,14 Furthermore, there is a well-known association between the antinuclear profile of known SCLE patients and the presence of anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies.13 Therefore, we propose that in susceptible individuals, such as those with the HLA class I, HLA-B8, or HLA-DR3 haplotypes, the initiation of a TNF-α inhibitor causes cellular apoptosis with the subsequent release of nucleosomal and cytoplasmic components (namely that of the Ro autoantigens), inducing a state of autoimmunity. An ensuing immunogenic response is then initiated in predisposed individuals for which anti-SSA (Ro) autoantibodies are produced against these previously mentioned autoantigens.

Drug-induced SCLE is most common in females (71%), with a median age of 58 years. The most common site of cutaneous manifestations is the legs.15 Although our patient was in the eighth decade of life with predominant cutaneous involvement of the upper extremity, the erythematous plaques with a symmetric, annular, polycyclic appearance in photosensitive regions raised a heightened suspicion for lupus erythematosus. Histology classically involves an interface dermatitis with vacuolar or hydropic change and lymphocytic infiltrates,16 consistent with the analysis of tissue sections from our patient. Moreover, the speckled ANA profile with positive anti-dsDNA and anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies in the absence of a negative rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies strongly favored the diagnosis of SCLE over alternative diagnoses.2

The supraclavicular rash in our patient raises clinical suspicion for the shawl sign of dermatomyositis, which also is associated with musculoskeletal pain and photosensitivity. In addition, skin biopsy revealed vacuolar alteration of the basement membrane zoneand dermal mucin in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis; therefore, skin biopsy is of little use in distinguishing the 2 conditions, and antibody testing must be performed. Although anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies commonly are associated with SCLE, there are reports involving positivity for the extractable nuclear antigen in cases of dermatomyositis.17 Based on our patient’s current drug regimen, including that of a known offending agent for SCLE, a presumptive diagnosis of TAILS was made. Following withdrawal of certolizumab pegol injections and subsequent resolution of the skin lesions, our patient was given a definitive diagnosis of TAILS based on clinical and pathological assessments.

The clinical diagnosis of TAILS should be made according to the triad of at least 1 serologic and 1 nonserologic American College of Rheumatology criteria, such as anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies and a photosensitive rash, respectively, as well as a relationship between the onset of symptoms and TNF-α inhibitor therapy.18 Both the definitive diagnosis and the treatment of TAILS can be made via withdrawal of the TNF-α inhibitor, which was true in our case whereby chronologically the onset of use with a TNF-α inhibitor was associated with disease onset. Furthermore, withdrawal led to complete improvement of all signs and symptoms, collectively supporting a diagnosis of TAILS. Notably, switching to a different TNF-α inhibitor has been shown to be safe and effective.19

To the Editor:

Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome (TAILS) is a newly described entity that refers to the onset of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) during drug therapy with TNF-α antagonists. The condition is unique because it is thought to occur via a separate pathophysiologic mechanism than all other agents implicated in the development of drug-induced lupus erythematosus (DILE). Infliximab and etanercept are the 2 most common TNF-α antagonists associated with TAILS. Although rare, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol have been reported to induce this state of autoimmunity. We report an uncommon presentation of TAILS in a patient taking certolizumab pegol with a brief discussion of the pathogenesis underlying TAILS.

A 71-year-old woman presented to the dermatology clinic with a rash located on the arms, face, and trunk that she reported as having been present for months. She had a medical history of rheumatoid arthritis and currently was receiving certolizumab pegol injections. Physical examination revealed erythematous patches and plaques with overlying scaling and evidence of atrophic scarring on sun-exposed areas of the body. The lesions predominantly were in a symmetrical distribution across the extensor surfaces of both outer arms as well as the posterior superior thoracic region extending anteriorly along the bilateral supraclavicular area (Figures 1 and 2). A 4-mm punch biopsy was obtained and sent for histologic analysis, along with a sample of the patient’s serum for antinuclear antibody (ANA) testing.

Hematoxylin and eosin–stained tissue sections of the right superior thoracic lesions revealed epidermal atrophy, hyperkeratosis, and vacuolar alteration of the basal layer with apoptosis, consistent with a lichenoid tissue reaction. In addition, both superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrates were observed as well as increased dermal mucin. Serologic testing was performed with a comprehensive ANA panel of the patient’s serum (Table). Of note, there was a speckled ANA pattern (1:1280), with elevated anti–double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) and anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen A (anti-SSA)(also called anti-Ro antibodies) levels. The patient’s rheumatologist was consulted; certolizumab pegol was removed from the current drug regimen and switched to a daily regimen of hydroxychloroquine and prednisone. Seven weeks after discontinuation of certolizumab pegol, the patient was symptom free and without any cutaneous involvement. Based on the histologic analysis, presence of anti-SSA (Ro) autoantibodies, and the resolution of symptoms following withdrawal of anti–TNF-α therapy, a diagnosis of TAILS was made.

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, the most common subset of DILE, typically presents with annular polycyclic or papulosquamous skin eruptions on the legs; patients often test positive for anti-SSA/Ro and/or anti–Sjögren syndrome–related antigen B (also called anti-La) antibodies. Pharmaceutical agents linked to the development of SCLE are calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, thiazide diuretics, terbinafine, the chemotherapeutic agent gemcitabine, and TNF-α antagonists.1,2 Tumor necrosis factor α antagonists are biologic agents that commonly are used in the management of systemic inflammatory diseases such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, seronegative spondyloarthropathies, and rheumatoid arthritis. Among this family of therapeutics includes adalimumab (humanized monoclonal antibody), infliximab (chimeric monoclonal TNF-α antagonist), etanercept (soluble receptor fusion protein), certolizumab pegol (Fab fraction of a human IgG monoclonal antibody), and golimumab (humanized monoclonal antibody).

Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome most commonly occurs in women in the fifth decade of life, and it is seen more often in those using infliximab or entanercept.3 Although reports do exist, TAILS rarely complicates treatment with adalimumab, golimumab, or certolizumab.4,5 Due to the lack of reports, there are no diagnostic criteria nor an acceptable theory regarding the pathogenesis. In one study in France, the estimated incidence was thought to be 0.19% for infliximab and 0.18% for etanercept.6 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome is unique in that it is thought to occur by a different mechanism than that of other known offending agents in the development of DILE. Molecular mimicry, direct cytotoxicity, altered T-cell gene expression, and disruption of central immune tolerance have all been hypothesized to cause drug-induced systemic lupus erythematosus, SCLE, and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors, are postulated to cause the induction of SCLE via an independent route separate from not only other drugs that cause SCLE but also all forms of DILE as a whole, making it a distinctive player within the realm of agents known to cause a lupuslike syndrome. The following hypotheses may explain this occurrence:

1. Increased humoral autoimmunity: Under normal circumstances, TNF-α activation leads to upregulation in the production of cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes. The upregulation of CD8+ T lymphocytes concurrently leads to a simultaneous suppression of B lymphocytes. Inhibiting the effects of TNF-α on the other hand promotes cytotoxic T-lymphocyte suppression, leading to an increased synthesis of B cells and subsequently a state of increased humoral autoimmunity.7

2. Infection: The immunosuppressive effects of TNF-α inhibitors are well known, and the propensity to develop microbial infections, such as tuberculosis, is markedly increased on the use of these agents. Infections brought on by TNF-α inhibitor usage are hypothesized to induce a widespread activation of polyclonal B lymphocytes, eventually leading to the formation of antibodies against these polyclonal B lymphocytes and subsequently SCLE.8

3. Helper T cell (TH2) response: The inhibition of TH1 CD4+ lymphocytes by TNF-α inversely leads to an increased production of TH2 CD4+ lymphocytes. This increase in the levels of circulating TH2 CD4+ lymphocytes brought on by the action of anti–TNF-α agents is thought to promote the development of SCLE.9,10

4. Apoptosis theory: Molecules of TNF-α inhibitors are capable of binding to TNF-α receptors on the cell surface. In doing so, cellular apoptosis is triggered, resulting in the release of nucleosomal autoantigens from the apoptotic cells. In susceptible individuals, autoantibodies then begin to form against the nucleosomal autoantigens, leading to an autoimmune reaction that is characterized by SCLE.11,12

Major histone compatibility (MHC) antigen testing performed by Sontheimer et al12 established the presence of the HLA class I, HLA-B8, and/or HLA-DR3 haplotypes in patients with SCLE.13,14 Furthermore, there is a well-known association between the antinuclear profile of known SCLE patients and the presence of anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies.13 Therefore, we propose that in susceptible individuals, such as those with the HLA class I, HLA-B8, or HLA-DR3 haplotypes, the initiation of a TNF-α inhibitor causes cellular apoptosis with the subsequent release of nucleosomal and cytoplasmic components (namely that of the Ro autoantigens), inducing a state of autoimmunity. An ensuing immunogenic response is then initiated in predisposed individuals for which anti-SSA (Ro) autoantibodies are produced against these previously mentioned autoantigens.

Drug-induced SCLE is most common in females (71%), with a median age of 58 years. The most common site of cutaneous manifestations is the legs.15 Although our patient was in the eighth decade of life with predominant cutaneous involvement of the upper extremity, the erythematous plaques with a symmetric, annular, polycyclic appearance in photosensitive regions raised a heightened suspicion for lupus erythematosus. Histology classically involves an interface dermatitis with vacuolar or hydropic change and lymphocytic infiltrates,16 consistent with the analysis of tissue sections from our patient. Moreover, the speckled ANA profile with positive anti-dsDNA and anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies in the absence of a negative rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies strongly favored the diagnosis of SCLE over alternative diagnoses.2

The supraclavicular rash in our patient raises clinical suspicion for the shawl sign of dermatomyositis, which also is associated with musculoskeletal pain and photosensitivity. In addition, skin biopsy revealed vacuolar alteration of the basement membrane zoneand dermal mucin in both lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis; therefore, skin biopsy is of little use in distinguishing the 2 conditions, and antibody testing must be performed. Although anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies commonly are associated with SCLE, there are reports involving positivity for the extractable nuclear antigen in cases of dermatomyositis.17 Based on our patient’s current drug regimen, including that of a known offending agent for SCLE, a presumptive diagnosis of TAILS was made. Following withdrawal of certolizumab pegol injections and subsequent resolution of the skin lesions, our patient was given a definitive diagnosis of TAILS based on clinical and pathological assessments.

The clinical diagnosis of TAILS should be made according to the triad of at least 1 serologic and 1 nonserologic American College of Rheumatology criteria, such as anti-SSA (Ro) antibodies and a photosensitive rash, respectively, as well as a relationship between the onset of symptoms and TNF-α inhibitor therapy.18 Both the definitive diagnosis and the treatment of TAILS can be made via withdrawal of the TNF-α inhibitor, which was true in our case whereby chronologically the onset of use with a TNF-α inhibitor was associated with disease onset. Furthermore, withdrawal led to complete improvement of all signs and symptoms, collectively supporting a diagnosis of TAILS. Notably, switching to a different TNF-α inhibitor has been shown to be safe and effective.19

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Crosti C. Drug-induced lupus: an update on its dermatological aspects. Lupus. 2009;18:935-940.

- Wiznia LE, Subtil A, Choi JN. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced by chemotherapy: gemcitabine as a causative agent. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1071-1075.

- Williams VL, Cohen PR. TNF alpha antagonist-induced lupus-like syndrome: report and review of the literature with implications for treatment with alternative TNF alpha antagonists. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:619-625.

- Pasut G. Pegylation of biological molecules and potential benefits: pharmacological properties of certolizumab pegol. Bio Drugs. 2014;28(suppl 1):15-23.

- Mudduluru BM, Shah S, Shamah S. et al. TNF-alpha antagonist induced lupus on three different agents. Postgrad Med. 2017;129:304-306.

- De Bandt M. Anti-TNF-alpha-induced lupus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:235.

- Costa MF, Said NR, Zimmermann B. Drug-induced lupus due to anti-tumor necrosis factor alfa agents. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;37:381-387.

- Caramaschi P, Biasi D, Colombatti M. Anti-TNF alpha therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmunity. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:209-214.

- Yung RL, Quddus J, Chrisp CE, et al. Mechanism of drug-induced lupus. I. cloned Th2 cells modified with DNA methylation inhibitors in vitro cause autoimmunity in vivo. J Immunol. 1995;154:3025-3035.

- Yung R, Powers D, Johnson K, et al. Mechanisms of drug-induced lupus. II. T cells overexpressing lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 become autoreactive and cause a lupuslike disease in syngeneic mice. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2866-2871.

- Sontheimer RD, Stastny P, Gilliam JN. Human histocompatibility antigen associations in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1981;67:312-316.

- Sontheimer RD, Maddison PJ, Reichlin M, et al. Serologic and HLA associations in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, a clinical subset of lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97:664-671.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

- Deutscher SL, Harley JB, Keene JD. Molecular analysis of the 60-kDa human Ro ribonucleoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:9479-9483.

- DalleVedove C, Simon JC, Girolomoni G. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus with emphasis on skin manifestations and the role of anti-TNFα agents [article in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:889-897.

- Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:391-404.

- Schulte-Pelkum J, Fritzler M, Mahler M. Latest update on the Ro/SS-A autoantibody system. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:632-637.

- De Bandt M, Sibilia J, Le Loët X, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus induced by anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapy: a French national survey. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R545-R551.

- Lupu A, Tieranu C, Constantinescu CL, et al. TNFα inhibitor induced lupus-like syndrome (TAILS) in a patient with IBD. Current Health Sci J. 2014;40:285-288.

- Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, Crosti C. Drug-induced lupus: an update on its dermatological aspects. Lupus. 2009;18:935-940.

- Wiznia LE, Subtil A, Choi JN. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus induced by chemotherapy: gemcitabine as a causative agent. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1071-1075.

- Williams VL, Cohen PR. TNF alpha antagonist-induced lupus-like syndrome: report and review of the literature with implications for treatment with alternative TNF alpha antagonists. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:619-625.

- Pasut G. Pegylation of biological molecules and potential benefits: pharmacological properties of certolizumab pegol. Bio Drugs. 2014;28(suppl 1):15-23.

- Mudduluru BM, Shah S, Shamah S. et al. TNF-alpha antagonist induced lupus on three different agents. Postgrad Med. 2017;129:304-306.

- De Bandt M. Anti-TNF-alpha-induced lupus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21:235.

- Costa MF, Said NR, Zimmermann B. Drug-induced lupus due to anti-tumor necrosis factor alfa agents. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;37:381-387.

- Caramaschi P, Biasi D, Colombatti M. Anti-TNF alpha therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and autoimmunity. Rheumatol Int. 2006;26:209-214.

- Yung RL, Quddus J, Chrisp CE, et al. Mechanism of drug-induced lupus. I. cloned Th2 cells modified with DNA methylation inhibitors in vitro cause autoimmunity in vivo. J Immunol. 1995;154:3025-3035.

- Yung R, Powers D, Johnson K, et al. Mechanisms of drug-induced lupus. II. T cells overexpressing lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1 become autoreactive and cause a lupuslike disease in syngeneic mice. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2866-2871.

- Sontheimer RD, Stastny P, Gilliam JN. Human histocompatibility antigen associations in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Clin Invest. 1981;67:312-316.

- Sontheimer RD, Maddison PJ, Reichlin M, et al. Serologic and HLA associations in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, a clinical subset of lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97:664-671.

- Lee LA, Roberts CM, Frank MB, et al. The autoantibody response to Ro/SSA in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:1262-1268.

- Deutscher SL, Harley JB, Keene JD. Molecular analysis of the 60-kDa human Ro ribonucleoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:9479-9483.

- DalleVedove C, Simon JC, Girolomoni G. Drug-induced lupus erythematosus with emphasis on skin manifestations and the role of anti-TNFα agents [article in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2012;10:889-897.

- Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:391-404.

- Schulte-Pelkum J, Fritzler M, Mahler M. Latest update on the Ro/SS-A autoantibody system. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:632-637.

- De Bandt M, Sibilia J, Le Loët X, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus induced by anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapy: a French national survey. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R545-R551.

- Lupu A, Tieranu C, Constantinescu CL, et al. TNFα inhibitor induced lupus-like syndrome (TAILS) in a patient with IBD. Current Health Sci J. 2014;40:285-288.

Practice Points

- Tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitor–induced lupuslike syndrome (TAILS) is a form of drug-induced lupus specific to patients on anti–TNF-α therapy.

- The underlying mechanism of disease development is unique compared to other types of drug-induced lupus.

- TAILS most commonly is associated with the use of infliximab and etanercept but also has been reported with adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol.

Nodules on the Anterior Neck Following Poly-L-lactic Acid Injection

Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) is a synthetic biologic polymer that is suspended in solution and can be injected for soft-tissue augmentation. The stimulatory molecule functions to increase collagen synthesis as a by-product of its degradation.1 Poly-L-lactic acid measures 40 to 63 μm and is irregularly shaped, which inhibits product mobility and allows for precise tissue augmentation.2 Clinical trials of injectable PLLA have proven its safety with no reported cases of infection, allergies, or serious adverse reactions.3-5 The most common patient concerns generally are transient in nature, such as swelling, tenderness, pain, bruising, and bleeding. Persistent adverse events of PLLA primarily are papule and nodule formation.6 Clinical trials showed a variable incidence of papule/nodule formation between 6% and 44%.2 Nodule formation remains a major challenge to achieving optimal results from injectable PLLA. We present a case in which a hyperdiluted formulation of PLLA produced a relatively acute (3-week) onset of multiple nodule formations dispersed on the anterior neck. The nodules were resistant to less-invasive treatment modalities and were further requested to be surgically excised.

Case Report

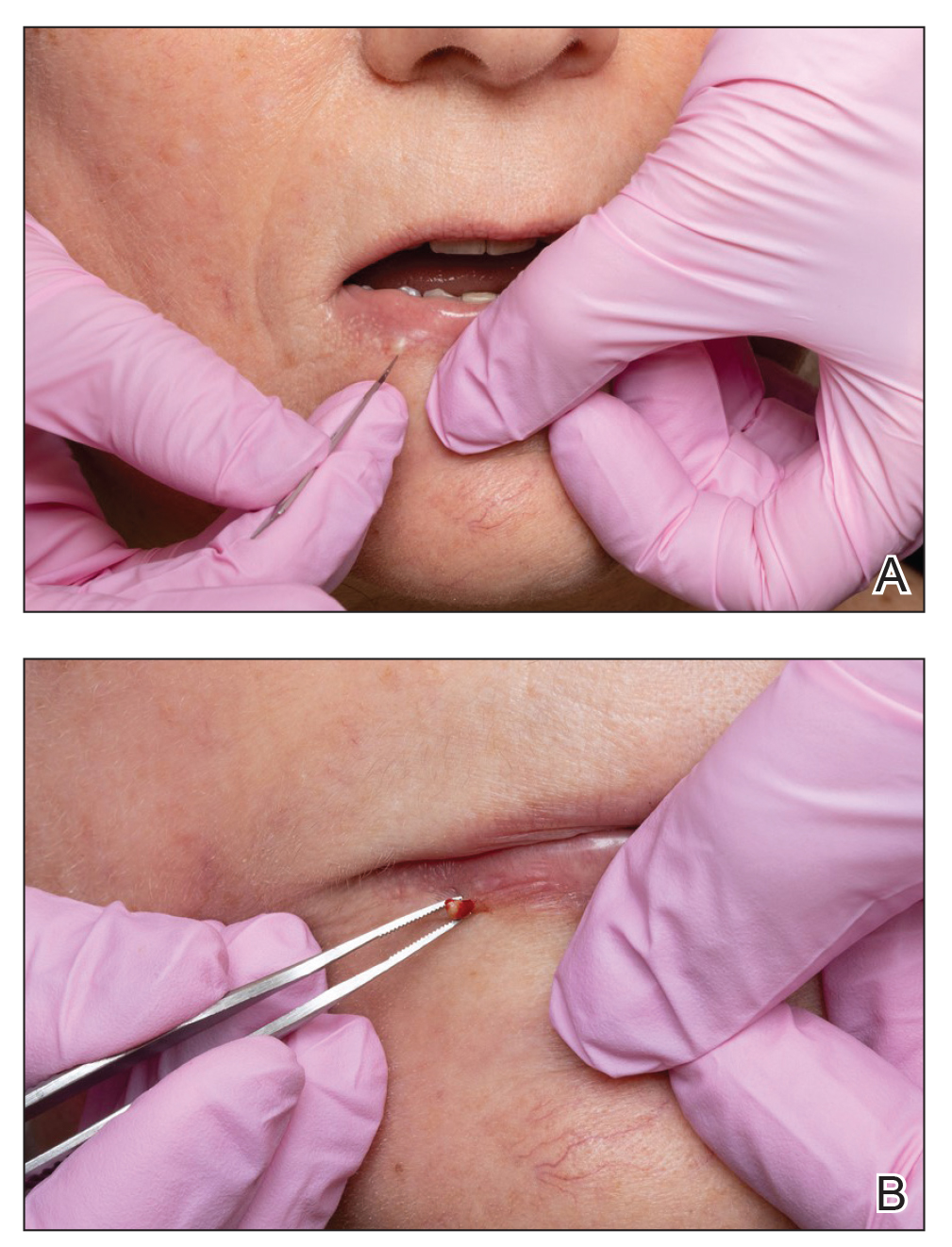

A 38-year-old woman presented for soft-tissue augmentation of the anterior neck using PLLA to achieve correction of skin laxity and static rhytides. She had a history of successful PLLA injections in the temples, knees, chest, and buttocks over a 5-year period. Forty-eight hours prior to injection, 1 PLLA vial was hydrated with 7 cc bacteriostatic water by using a continuous rotation suspension method over the 48 hours. On the day of injection, the PLLA was further hyperdiluted with 2 cc of 2% lidocaine and an additional 7 cc of bacteriostatic water, for a total of 16 cc diluent. The product was injected using a cannula in the anterior and lateral neck. According to the patient, 3 weeks after the procedure she noticed that some nodules began to form at the cannula insertion sites, while others formed distant from those sites; a total of 10 nodules had formed on the anterior neck (Figure 1).

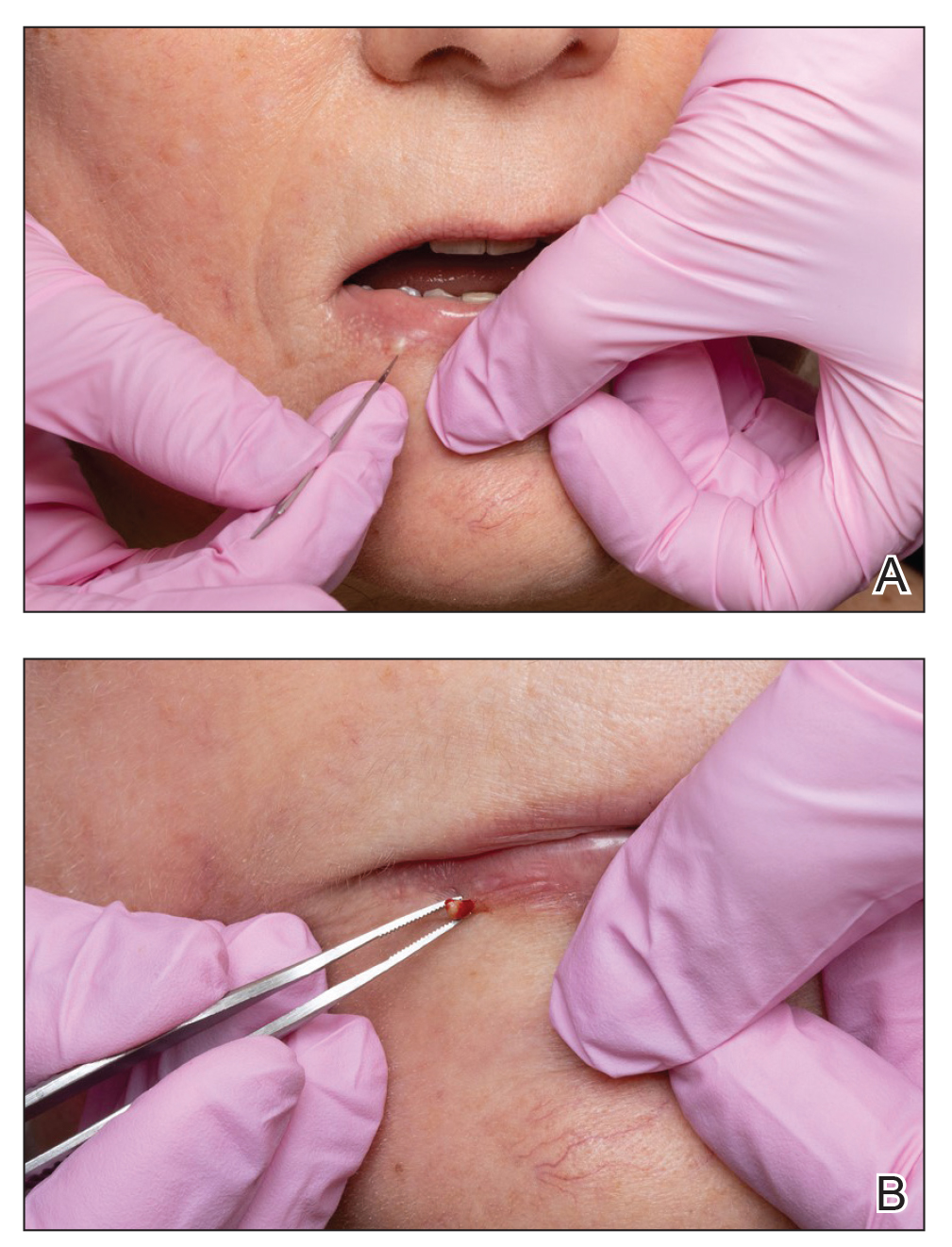

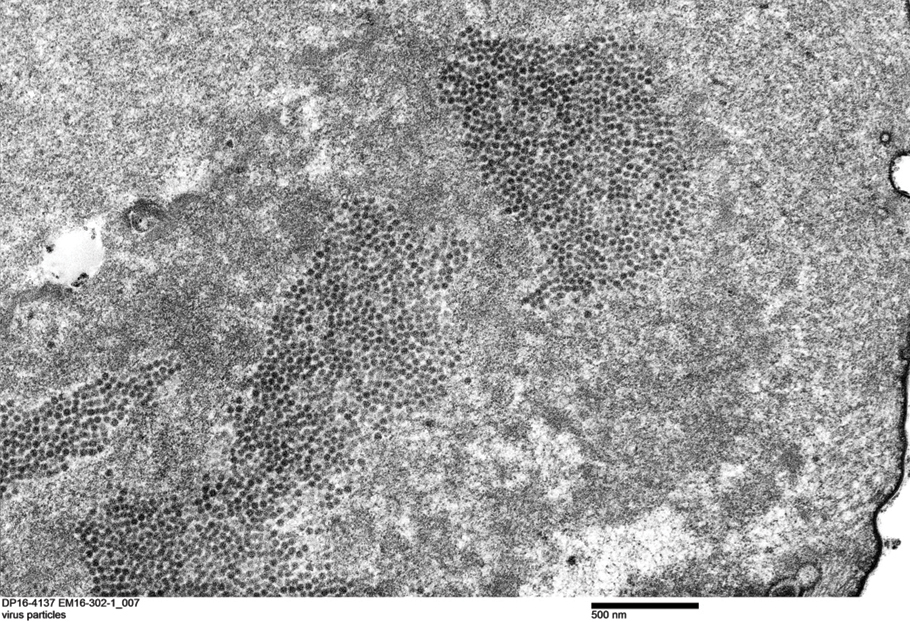

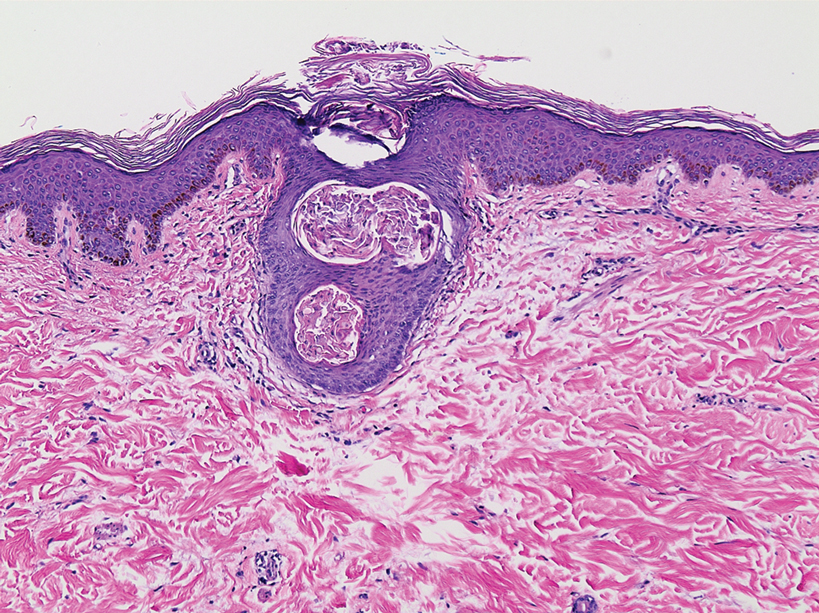

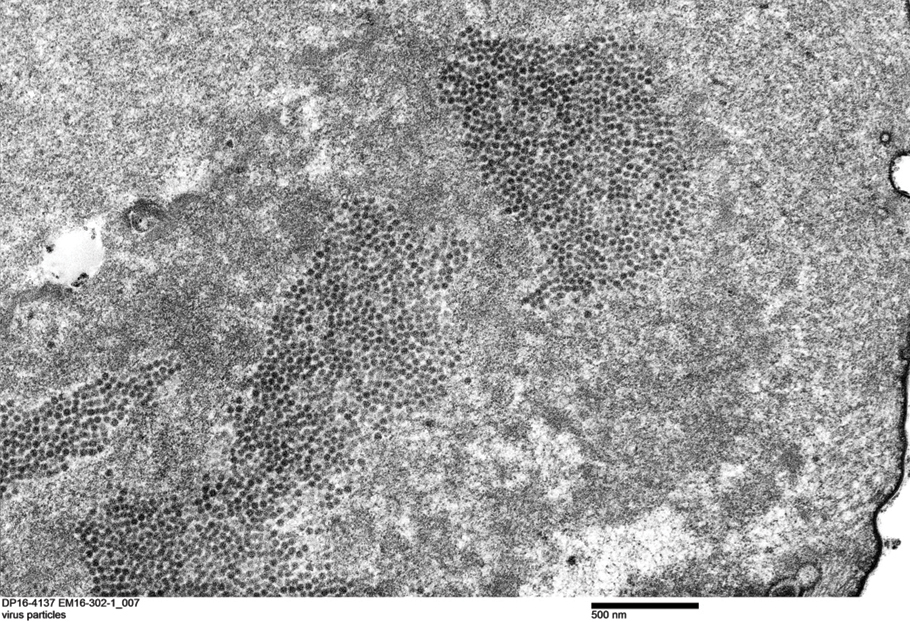

The bacteriostatic water, lidocaine, and PLLA vial were all confirmed not to be expired. The manufacturer was contacted, and no other adverse reactions have been reported with this particular lot number of PLLA. The nodules initially were treated with injections of large boluses of bacteriostatic saline, which was ineffective. Treatment was then attempted using injections of a solution containing 1.0 mL of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) 50 mg/mL, 0.4 mL of dexamethasone 4 mg/mL, 0.1 mL of triamcinolone 10 mg/mL, and 0.3 mL hyaluronidase. A series of 4 injections was performed in 2- to 4-week intervals. Two of the nodules resolved completely with this treatment. The remaining 8 nodules subjectively improved in size and softened to palpation but did not resolve completely. At 2 of the injection sites, treatment was complicated with steroid atrophy of the overlying skin. At the patient’s request, the remaining nodules were surgically excised (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed exogenous foreign material consistent with dermal filler (Figure 3).

Comment

Causes of Nodule Formation—Two factors that could contribute to nodule formation are inadequate dispersion of molecules and an insufficient volume of dilution. One study demonstrated that hydration for at least 24 hours is required for adequate PLLA dispersion. Furthermore, sonification for 5 minutes after a 2-hour hydration disperses molecules similarly to the 48-hour hydration.7 The PLLA in the current case was hydrated for 48 hours using a continuous rotation suspension method. Therefore, this likely did not play a role in our patient’s nodule formation. The volume of dilution has been shown to impact the incidence of nodule formation.8 At present, most injectors (60.4%) reconstitute each vial of PLLA with 9 to 10 mL of diluent.9 The PLLA in our patient was reconstituted with 16 mL; therefore, we believe that the anatomic location was the main contributor of nodule formation.

Fillers should be injected in the subcutaneous or deep dermal plane of tissue.10 The platysma is a superficial muscle that is intimately involved with the overlying skin of the anterior neck, and injections in this area could inadvertently be intramuscular. Intramuscular injections have a higher incidence of nodule formation.1 Our patient had prior PLLA injections without adverse reactions in numerous other sites, supporting the claim that the anterior neck is prone to nodule formation from PLLA injections.

Management of Noninflammatory Nodules—Initial treatment of nodules with injections of saline was ineffective. This treatment can be used in an attempt to disperse the product. Treatment was then attempted with injections of a solution containing 5-FU, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and hyaluronidase. Combination steroid therapy may be superior to monotherapy.11 Dexamethasone may exhibit a cytoprotective effect on cells such as fibroblasts when used in combination with triamcinolone; monotherapy steroid use with triamcinolone alone induced fibroblast apoptosis at a much higher level.12 Hyaluronidase works by breaking cross-links in hyaluronic acid, a glycosaminoglycan polysaccharide prevalent in the skin and connective tissue, which increases tissue permeability and aids in delivery of the other injected fluids.13 5-Fluorouracil is an antimetabolite that may aid in treating nodules by discouraging additional fibroblast activity and fibrosis.14

The combination of 5-FU, dexamethasone, and triamcinolone has been shown to be successful in treating noninflammatory nodules in as few as 1 treatment.14 In our patient, hyaluronidase also was used in an attempt to aid delivery of the other injected fluids. If nodules do not resolve with 1 injection, it is recommended to wait at least 8 weeks before repeating the injection to prevent steroid atrophy of the overlying skin. In our patient, the intramuscular placement of the filler contributed to the nodules being resistant to this treatment. During excision, the nodules were tightly embedded in the underlying tissue, which may have prevented the solution from being delivered to the nodule (Figure 2).

Conclusion

Injectable PLLA is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for soft-tissue augmentation of deep nasolabial folds and facial wrinkles. Off-label use of this product may cause higher incidence of nodule formation. Injectors should be cautious of injecting into the anterior neck. If nodules do form, treatment can be attempted with injections of saline. If that treatment fails, another treatment option is injection(s) of a mixture of 5-FU, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and hyaluronidase separated by 8-week intervals. Finally, surgical excision is a viable treatment option, as presented in our case.

- Bartus C, William HC, Daro-Kaftan E. A decade of experience with injectable poly-L-lactic acid: a focus on safety. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:698-705.

- Engelhard P, Humble G, Mest D. Safety of Sculptra: a review of clinical trial data. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2005;7:201-205.

- Mest DR, Humble G. Safety and efficacy of poly-L-lactic acid injections in persons with HIV-associated lipoatrophy: the US experience. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1336-1345.

- Burgess CM, Quiroga RM. Assessment of the safety and efficacy of poly-L-lactic acid for the treatment of HIV associated facial lipoatrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:233-239.

- Cattelan AM, Bauer U, Trevenzoli M, et al. Use of polylactic acid implants to correct facial lipoatrophy in human immunodeficiency virus 1-positive individuals receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:329-334.

- Sculptra. Package insert. sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC; 2009.

- Li CN, Wang CC, Huang CC, et al. A novel, optimized method to accelerate the preparation of injectable poly-L-lactic acid by sonication. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:894-898.

- Rossner F, Rossner M, Hartmann V, et al. Decrease of reported adverse events to injectable polylactic acid after recommending an increased dilution: 8-year results from the Injectable Filler Safety study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8:14-18.

- Lin MJ, Dubin DP, Goldberg DJ, et al. Practices in the usage and reconstitution of poly-L-lactic acid. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:880-886.

- Sieber DA, Scheuer JF 3rd, Villanueva NL, et al. Review of 3-dimensional facial anatomy: injecting fillers and neuromodulators. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(12 suppl Anatomy and Safety in Cosmetic Medicine: Cosmetic Bootcamp):E1166.

- Syed F, Singh S, Bayat A. Superior effect of combination vs. single steroid therapy in keloid disease: a comparative in vitro analysis of glucocorticoids. Wound Repair Regen. 2013;21:88-102.

- Brody HJ. Use of hyaluronidase in the treatment of granulomatous hyaluronic acid reactions or unwanted hyaluronic acid misplacement. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:893-897.

- Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin Cosm Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:295-316.

- Aguilera SB, Aristizabal M, Reed A. Successful treatment of calcium hydroxylapatite nodules with intralesional 5-fluorouracil, dexamethasone, and triamcinolone. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:1142-1143.

Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) is a synthetic biologic polymer that is suspended in solution and can be injected for soft-tissue augmentation. The stimulatory molecule functions to increase collagen synthesis as a by-product of its degradation.1 Poly-L-lactic acid measures 40 to 63 μm and is irregularly shaped, which inhibits product mobility and allows for precise tissue augmentation.2 Clinical trials of injectable PLLA have proven its safety with no reported cases of infection, allergies, or serious adverse reactions.3-5 The most common patient concerns generally are transient in nature, such as swelling, tenderness, pain, bruising, and bleeding. Persistent adverse events of PLLA primarily are papule and nodule formation.6 Clinical trials showed a variable incidence of papule/nodule formation between 6% and 44%.2 Nodule formation remains a major challenge to achieving optimal results from injectable PLLA. We present a case in which a hyperdiluted formulation of PLLA produced a relatively acute (3-week) onset of multiple nodule formations dispersed on the anterior neck. The nodules were resistant to less-invasive treatment modalities and were further requested to be surgically excised.

Case Report

A 38-year-old woman presented for soft-tissue augmentation of the anterior neck using PLLA to achieve correction of skin laxity and static rhytides. She had a history of successful PLLA injections in the temples, knees, chest, and buttocks over a 5-year period. Forty-eight hours prior to injection, 1 PLLA vial was hydrated with 7 cc bacteriostatic water by using a continuous rotation suspension method over the 48 hours. On the day of injection, the PLLA was further hyperdiluted with 2 cc of 2% lidocaine and an additional 7 cc of bacteriostatic water, for a total of 16 cc diluent. The product was injected using a cannula in the anterior and lateral neck. According to the patient, 3 weeks after the procedure she noticed that some nodules began to form at the cannula insertion sites, while others formed distant from those sites; a total of 10 nodules had formed on the anterior neck (Figure 1).

The bacteriostatic water, lidocaine, and PLLA vial were all confirmed not to be expired. The manufacturer was contacted, and no other adverse reactions have been reported with this particular lot number of PLLA. The nodules initially were treated with injections of large boluses of bacteriostatic saline, which was ineffective. Treatment was then attempted using injections of a solution containing 1.0 mL of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) 50 mg/mL, 0.4 mL of dexamethasone 4 mg/mL, 0.1 mL of triamcinolone 10 mg/mL, and 0.3 mL hyaluronidase. A series of 4 injections was performed in 2- to 4-week intervals. Two of the nodules resolved completely with this treatment. The remaining 8 nodules subjectively improved in size and softened to palpation but did not resolve completely. At 2 of the injection sites, treatment was complicated with steroid atrophy of the overlying skin. At the patient’s request, the remaining nodules were surgically excised (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed exogenous foreign material consistent with dermal filler (Figure 3).

Comment

Causes of Nodule Formation—Two factors that could contribute to nodule formation are inadequate dispersion of molecules and an insufficient volume of dilution. One study demonstrated that hydration for at least 24 hours is required for adequate PLLA dispersion. Furthermore, sonification for 5 minutes after a 2-hour hydration disperses molecules similarly to the 48-hour hydration.7 The PLLA in the current case was hydrated for 48 hours using a continuous rotation suspension method. Therefore, this likely did not play a role in our patient’s nodule formation. The volume of dilution has been shown to impact the incidence of nodule formation.8 At present, most injectors (60.4%) reconstitute each vial of PLLA with 9 to 10 mL of diluent.9 The PLLA in our patient was reconstituted with 16 mL; therefore, we believe that the anatomic location was the main contributor of nodule formation.

Fillers should be injected in the subcutaneous or deep dermal plane of tissue.10 The platysma is a superficial muscle that is intimately involved with the overlying skin of the anterior neck, and injections in this area could inadvertently be intramuscular. Intramuscular injections have a higher incidence of nodule formation.1 Our patient had prior PLLA injections without adverse reactions in numerous other sites, supporting the claim that the anterior neck is prone to nodule formation from PLLA injections.

Management of Noninflammatory Nodules—Initial treatment of nodules with injections of saline was ineffective. This treatment can be used in an attempt to disperse the product. Treatment was then attempted with injections of a solution containing 5-FU, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and hyaluronidase. Combination steroid therapy may be superior to monotherapy.11 Dexamethasone may exhibit a cytoprotective effect on cells such as fibroblasts when used in combination with triamcinolone; monotherapy steroid use with triamcinolone alone induced fibroblast apoptosis at a much higher level.12 Hyaluronidase works by breaking cross-links in hyaluronic acid, a glycosaminoglycan polysaccharide prevalent in the skin and connective tissue, which increases tissue permeability and aids in delivery of the other injected fluids.13 5-Fluorouracil is an antimetabolite that may aid in treating nodules by discouraging additional fibroblast activity and fibrosis.14

The combination of 5-FU, dexamethasone, and triamcinolone has been shown to be successful in treating noninflammatory nodules in as few as 1 treatment.14 In our patient, hyaluronidase also was used in an attempt to aid delivery of the other injected fluids. If nodules do not resolve with 1 injection, it is recommended to wait at least 8 weeks before repeating the injection to prevent steroid atrophy of the overlying skin. In our patient, the intramuscular placement of the filler contributed to the nodules being resistant to this treatment. During excision, the nodules were tightly embedded in the underlying tissue, which may have prevented the solution from being delivered to the nodule (Figure 2).

Conclusion

Injectable PLLA is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for soft-tissue augmentation of deep nasolabial folds and facial wrinkles. Off-label use of this product may cause higher incidence of nodule formation. Injectors should be cautious of injecting into the anterior neck. If nodules do form, treatment can be attempted with injections of saline. If that treatment fails, another treatment option is injection(s) of a mixture of 5-FU, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and hyaluronidase separated by 8-week intervals. Finally, surgical excision is a viable treatment option, as presented in our case.

Poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) is a synthetic biologic polymer that is suspended in solution and can be injected for soft-tissue augmentation. The stimulatory molecule functions to increase collagen synthesis as a by-product of its degradation.1 Poly-L-lactic acid measures 40 to 63 μm and is irregularly shaped, which inhibits product mobility and allows for precise tissue augmentation.2 Clinical trials of injectable PLLA have proven its safety with no reported cases of infection, allergies, or serious adverse reactions.3-5 The most common patient concerns generally are transient in nature, such as swelling, tenderness, pain, bruising, and bleeding. Persistent adverse events of PLLA primarily are papule and nodule formation.6 Clinical trials showed a variable incidence of papule/nodule formation between 6% and 44%.2 Nodule formation remains a major challenge to achieving optimal results from injectable PLLA. We present a case in which a hyperdiluted formulation of PLLA produced a relatively acute (3-week) onset of multiple nodule formations dispersed on the anterior neck. The nodules were resistant to less-invasive treatment modalities and were further requested to be surgically excised.

Case Report

A 38-year-old woman presented for soft-tissue augmentation of the anterior neck using PLLA to achieve correction of skin laxity and static rhytides. She had a history of successful PLLA injections in the temples, knees, chest, and buttocks over a 5-year period. Forty-eight hours prior to injection, 1 PLLA vial was hydrated with 7 cc bacteriostatic water by using a continuous rotation suspension method over the 48 hours. On the day of injection, the PLLA was further hyperdiluted with 2 cc of 2% lidocaine and an additional 7 cc of bacteriostatic water, for a total of 16 cc diluent. The product was injected using a cannula in the anterior and lateral neck. According to the patient, 3 weeks after the procedure she noticed that some nodules began to form at the cannula insertion sites, while others formed distant from those sites; a total of 10 nodules had formed on the anterior neck (Figure 1).

The bacteriostatic water, lidocaine, and PLLA vial were all confirmed not to be expired. The manufacturer was contacted, and no other adverse reactions have been reported with this particular lot number of PLLA. The nodules initially were treated with injections of large boluses of bacteriostatic saline, which was ineffective. Treatment was then attempted using injections of a solution containing 1.0 mL of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) 50 mg/mL, 0.4 mL of dexamethasone 4 mg/mL, 0.1 mL of triamcinolone 10 mg/mL, and 0.3 mL hyaluronidase. A series of 4 injections was performed in 2- to 4-week intervals. Two of the nodules resolved completely with this treatment. The remaining 8 nodules subjectively improved in size and softened to palpation but did not resolve completely. At 2 of the injection sites, treatment was complicated with steroid atrophy of the overlying skin. At the patient’s request, the remaining nodules were surgically excised (Figure 2). Histopathology revealed exogenous foreign material consistent with dermal filler (Figure 3).

Comment

Causes of Nodule Formation—Two factors that could contribute to nodule formation are inadequate dispersion of molecules and an insufficient volume of dilution. One study demonstrated that hydration for at least 24 hours is required for adequate PLLA dispersion. Furthermore, sonification for 5 minutes after a 2-hour hydration disperses molecules similarly to the 48-hour hydration.7 The PLLA in the current case was hydrated for 48 hours using a continuous rotation suspension method. Therefore, this likely did not play a role in our patient’s nodule formation. The volume of dilution has been shown to impact the incidence of nodule formation.8 At present, most injectors (60.4%) reconstitute each vial of PLLA with 9 to 10 mL of diluent.9 The PLLA in our patient was reconstituted with 16 mL; therefore, we believe that the anatomic location was the main contributor of nodule formation.

Fillers should be injected in the subcutaneous or deep dermal plane of tissue.10 The platysma is a superficial muscle that is intimately involved with the overlying skin of the anterior neck, and injections in this area could inadvertently be intramuscular. Intramuscular injections have a higher incidence of nodule formation.1 Our patient had prior PLLA injections without adverse reactions in numerous other sites, supporting the claim that the anterior neck is prone to nodule formation from PLLA injections.

Management of Noninflammatory Nodules—Initial treatment of nodules with injections of saline was ineffective. This treatment can be used in an attempt to disperse the product. Treatment was then attempted with injections of a solution containing 5-FU, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and hyaluronidase. Combination steroid therapy may be superior to monotherapy.11 Dexamethasone may exhibit a cytoprotective effect on cells such as fibroblasts when used in combination with triamcinolone; monotherapy steroid use with triamcinolone alone induced fibroblast apoptosis at a much higher level.12 Hyaluronidase works by breaking cross-links in hyaluronic acid, a glycosaminoglycan polysaccharide prevalent in the skin and connective tissue, which increases tissue permeability and aids in delivery of the other injected fluids.13 5-Fluorouracil is an antimetabolite that may aid in treating nodules by discouraging additional fibroblast activity and fibrosis.14

The combination of 5-FU, dexamethasone, and triamcinolone has been shown to be successful in treating noninflammatory nodules in as few as 1 treatment.14 In our patient, hyaluronidase also was used in an attempt to aid delivery of the other injected fluids. If nodules do not resolve with 1 injection, it is recommended to wait at least 8 weeks before repeating the injection to prevent steroid atrophy of the overlying skin. In our patient, the intramuscular placement of the filler contributed to the nodules being resistant to this treatment. During excision, the nodules were tightly embedded in the underlying tissue, which may have prevented the solution from being delivered to the nodule (Figure 2).

Conclusion

Injectable PLLA is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for soft-tissue augmentation of deep nasolabial folds and facial wrinkles. Off-label use of this product may cause higher incidence of nodule formation. Injectors should be cautious of injecting into the anterior neck. If nodules do form, treatment can be attempted with injections of saline. If that treatment fails, another treatment option is injection(s) of a mixture of 5-FU, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and hyaluronidase separated by 8-week intervals. Finally, surgical excision is a viable treatment option, as presented in our case.

- Bartus C, William HC, Daro-Kaftan E. A decade of experience with injectable poly-L-lactic acid: a focus on safety. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:698-705.

- Engelhard P, Humble G, Mest D. Safety of Sculptra: a review of clinical trial data. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2005;7:201-205.

- Mest DR, Humble G. Safety and efficacy of poly-L-lactic acid injections in persons with HIV-associated lipoatrophy: the US experience. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1336-1345.

- Burgess CM, Quiroga RM. Assessment of the safety and efficacy of poly-L-lactic acid for the treatment of HIV associated facial lipoatrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:233-239.

- Cattelan AM, Bauer U, Trevenzoli M, et al. Use of polylactic acid implants to correct facial lipoatrophy in human immunodeficiency virus 1-positive individuals receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:329-334.

- Sculptra. Package insert. sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC; 2009.

- Li CN, Wang CC, Huang CC, et al. A novel, optimized method to accelerate the preparation of injectable poly-L-lactic acid by sonication. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:894-898.

- Rossner F, Rossner M, Hartmann V, et al. Decrease of reported adverse events to injectable polylactic acid after recommending an increased dilution: 8-year results from the Injectable Filler Safety study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8:14-18.

- Lin MJ, Dubin DP, Goldberg DJ, et al. Practices in the usage and reconstitution of poly-L-lactic acid. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:880-886.

- Sieber DA, Scheuer JF 3rd, Villanueva NL, et al. Review of 3-dimensional facial anatomy: injecting fillers and neuromodulators. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(12 suppl Anatomy and Safety in Cosmetic Medicine: Cosmetic Bootcamp):E1166.

- Syed F, Singh S, Bayat A. Superior effect of combination vs. single steroid therapy in keloid disease: a comparative in vitro analysis of glucocorticoids. Wound Repair Regen. 2013;21:88-102.

- Brody HJ. Use of hyaluronidase in the treatment of granulomatous hyaluronic acid reactions or unwanted hyaluronic acid misplacement. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:893-897.

- Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin Cosm Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:295-316.

- Aguilera SB, Aristizabal M, Reed A. Successful treatment of calcium hydroxylapatite nodules with intralesional 5-fluorouracil, dexamethasone, and triamcinolone. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:1142-1143.

- Bartus C, William HC, Daro-Kaftan E. A decade of experience with injectable poly-L-lactic acid: a focus on safety. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:698-705.

- Engelhard P, Humble G, Mest D. Safety of Sculptra: a review of clinical trial data. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2005;7:201-205.

- Mest DR, Humble G. Safety and efficacy of poly-L-lactic acid injections in persons with HIV-associated lipoatrophy: the US experience. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1336-1345.

- Burgess CM, Quiroga RM. Assessment of the safety and efficacy of poly-L-lactic acid for the treatment of HIV associated facial lipoatrophy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:233-239.

- Cattelan AM, Bauer U, Trevenzoli M, et al. Use of polylactic acid implants to correct facial lipoatrophy in human immunodeficiency virus 1-positive individuals receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:329-334.

- Sculptra. Package insert. sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC; 2009.

- Li CN, Wang CC, Huang CC, et al. A novel, optimized method to accelerate the preparation of injectable poly-L-lactic acid by sonication. J Drugs Dermatol. 2018;17:894-898.

- Rossner F, Rossner M, Hartmann V, et al. Decrease of reported adverse events to injectable polylactic acid after recommending an increased dilution: 8-year results from the Injectable Filler Safety study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8:14-18.

- Lin MJ, Dubin DP, Goldberg DJ, et al. Practices in the usage and reconstitution of poly-L-lactic acid. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:880-886.

- Sieber DA, Scheuer JF 3rd, Villanueva NL, et al. Review of 3-dimensional facial anatomy: injecting fillers and neuromodulators. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(12 suppl Anatomy and Safety in Cosmetic Medicine: Cosmetic Bootcamp):E1166.

- Syed F, Singh S, Bayat A. Superior effect of combination vs. single steroid therapy in keloid disease: a comparative in vitro analysis of glucocorticoids. Wound Repair Regen. 2013;21:88-102.

- Brody HJ. Use of hyaluronidase in the treatment of granulomatous hyaluronic acid reactions or unwanted hyaluronic acid misplacement. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:893-897.

- Funt D, Pavicic T. Dermal fillers in aesthetics: an overview of adverse events and treatment approaches. Clin Cosm Investig Dermatol. 2013;6:295-316.

- Aguilera SB, Aristizabal M, Reed A. Successful treatment of calcium hydroxylapatite nodules with intralesional 5-fluorouracil, dexamethasone, and triamcinolone. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:1142-1143.

Practice Points

- Injecting poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) into the anterior neck is an off-label procedure and may cause a higher incidence of nodule formation.

- Most nodules from PLLA can be treated with injections of 5-fluorouracil, dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and hyaluronidase separated by 8-week intervals.

- Treatment-resistant nodules may require surgical excision.

Acute Alopecia Associated With Albendazole Toxicosis

To the Editor:

Albendazole is a commonly prescribed anthelmintic that typically is well tolerated. Its broadest application is in developing countries that have a high rate of endemic nematode infection.1,2 Albendazole belongs to the benzimidazole class of anthelmintic chemotherapeutic agents that function by inhibiting microtubule dynamics, resulting in cytotoxic antimitotic effects.3 Benzimidazoles (eg, albendazole, mebendazole) have a binding affinity for helminthic β-tubulin that is 25- to 400-times greater than their binding affinity for the mammalian counterpart.4 Consequently, benzimidazoles generally are afforded a very broad therapeutic index for helminthic infection.

A 53-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) after an episode of syncope and sudden hair loss. At presentation he had a fever (temperature, 103 °F [39.4 °C]), a heart rate of 120 bpm, and pancytopenia (white blood cell count, 0.4×103/μL [reference range, 4.0–10.0×103/μL]; hemoglobin, 7.0 g/dL [reference range, 11.2–15.7 g/dL]; platelet count, 100

The patient reported severe gastrointestinal (GI) distress and diarrhea for the last year as well as a 25-lb weight loss. He discussed his belief that his GI symptoms were due to a parasite he had acquired the year prior; however, he reported that an exhaustive outpatient GI workup had been negative. Two weeks before presentation to our ED, the patient presented to another ED with stomach upset and was given a dose of albendazole. Perceiving alleviation of his symptoms, he purchased 2 bottles of veterinary albendazole online and consumed 113,000 mg—approximately 300 times the standard dose of 400 mg.

A dermatologic examination in our ED demonstrated reticulated violaceous patches on the face and severe alopecia with preferential sparing of the occipital scalp (Figure 1). Photographs taken by the patient on his phone from a week prior to presentation showed no facial dyschromia or signs of hair loss. A punch biopsy of the chin demonstrated perivascular and perifollicular dermatitis with eosinophils, most consistent with a drug reaction.

The patient received broad-spectrum antibiotics and supportive care. Blood count parameters normalized, and his hair began to regrow within 2 weeks after albendazole discontinuation (Figure 2).

Our patient exhibited symptoms of tachycardia, pancytopenia, and acute massive hair loss with preferential sparing of the occipital and posterior hair line; this pattern of hair loss is classic in men with chemotherapy-induced anagen effluvium.5 Conventional chemotherapeutics include taxanes and Vinca alkaloids, both of which bind mammalian β-tubulin and commonly induce anagen effluvium.

Our patient’s toxicosis syndrome was strikingly similar to common adverse effects in patients treated with conventional chemotherapeutics, including aplastic anemia with severe neutropenia and anagen effluvium.6,7 This adverse effect profile suggests that albendazole exerts an effect on mammalian β-tubulin that is similar to conventional chemotherapy when albendazole is ingested in a massive quantity.

Other reports of albendazole-induced alopecia describe an idiosyncratic, dose-dependent telogen effluvium.8-10 Conventional chemotherapy uncommonly might induce telogen effluvium when given below a threshold necessary to induce anagen effluvium. In those cases, follicular matrix keratinocytes are disrupted without complete follicular fracture and attempt to repair the damaged elongating follicle before entering the telogen phase.7 This observed phenomenon and the inherent susceptibility of matrix keratinocytes to antimicrotubule agents might explain why a therapeutic dose of albendazole has been associated with telogen effluvium in certain individuals.

Our case of albendazole-related toxicosis of this magnitude is unique. Ghias et al11 reported a case of abendazole-induced anagen effluvium. Future reports might clarify whether this toxicosis syndrome is typical or atypical in massive albendazole overdose.

- Keiser J, Utzinger J. Efficacy of current drugs against soil-transmitted helminth infections: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;299:1937-1948. doi:10.1001/jama.299.16.1937

- Bethony J, Brooker S, Albonico M, et al. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm. Lancet. 2006;367:1521-1532. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68653-4

- Lanusse CE, Prichard RK. Clinical pharmacokinetics and metabolism of benzimidazole anthelmintics in ruminants. Drug Metab Rev. 1993;25:235-279. doi:10.3109/03602539308993977

- Page SW. Antiparasitic drugs. In: Maddison JE, Church DB, Page SW, eds. Small Animal Clinical Pharmacology. 2nd ed. W.B. Saunders; 2008:198-260.

- Yun SJ, Kim S-J. Hair loss pattern due to chemotherapy-induced anagen effluvium: a cross-sectional observation. Dermatology. 2007;215:36-40. doi:10.1159/000102031

- de Weger VA, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM. Cellular and clinical pharmacology of the taxanes docetaxel and paclitaxel—a review. Anticancer Drugs. 2014;25:488-494. doi:10.1097/CAD.0000000000000093

- Paus R, Haslam IS, Sharov AA, et al. Pathobiology of chemotherapy-induced hair loss. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:E50-E59. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70553-3

- Imamkuliev KD, Alekseev VG, Dovgalev AS, et al. A case of alopecia in a patient with hydatid disease treated with Nemozole (albendazole)[in Russian]. Med Parazitol (Mosk). 2013:48-50.

- Tas A, Köklü S, Celik H. Loss of body hair as a side effect of albendazole. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124:220. doi:10.1007/s00508-011-0112-y

- Pilar García-Muret M, Sitjas D, Tuneu L, et al. Telogen effluvium associated with albendazole therapy. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:669-670. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1990.tb02597.x

- Ghias M, Amin B, Kutner A. Albendazole-induced anagen effluvium. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:54-56.

To the Editor:

Albendazole is a commonly prescribed anthelmintic that typically is well tolerated. Its broadest application is in developing countries that have a high rate of endemic nematode infection.1,2 Albendazole belongs to the benzimidazole class of anthelmintic chemotherapeutic agents that function by inhibiting microtubule dynamics, resulting in cytotoxic antimitotic effects.3 Benzimidazoles (eg, albendazole, mebendazole) have a binding affinity for helminthic β-tubulin that is 25- to 400-times greater than their binding affinity for the mammalian counterpart.4 Consequently, benzimidazoles generally are afforded a very broad therapeutic index for helminthic infection.

A 53-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) after an episode of syncope and sudden hair loss. At presentation he had a fever (temperature, 103 °F [39.4 °C]), a heart rate of 120 bpm, and pancytopenia (white blood cell count, 0.4×103/μL [reference range, 4.0–10.0×103/μL]; hemoglobin, 7.0 g/dL [reference range, 11.2–15.7 g/dL]; platelet count, 100

The patient reported severe gastrointestinal (GI) distress and diarrhea for the last year as well as a 25-lb weight loss. He discussed his belief that his GI symptoms were due to a parasite he had acquired the year prior; however, he reported that an exhaustive outpatient GI workup had been negative. Two weeks before presentation to our ED, the patient presented to another ED with stomach upset and was given a dose of albendazole. Perceiving alleviation of his symptoms, he purchased 2 bottles of veterinary albendazole online and consumed 113,000 mg—approximately 300 times the standard dose of 400 mg.

A dermatologic examination in our ED demonstrated reticulated violaceous patches on the face and severe alopecia with preferential sparing of the occipital scalp (Figure 1). Photographs taken by the patient on his phone from a week prior to presentation showed no facial dyschromia or signs of hair loss. A punch biopsy of the chin demonstrated perivascular and perifollicular dermatitis with eosinophils, most consistent with a drug reaction.

The patient received broad-spectrum antibiotics and supportive care. Blood count parameters normalized, and his hair began to regrow within 2 weeks after albendazole discontinuation (Figure 2).

Our patient exhibited symptoms of tachycardia, pancytopenia, and acute massive hair loss with preferential sparing of the occipital and posterior hair line; this pattern of hair loss is classic in men with chemotherapy-induced anagen effluvium.5 Conventional chemotherapeutics include taxanes and Vinca alkaloids, both of which bind mammalian β-tubulin and commonly induce anagen effluvium.

Our patient’s toxicosis syndrome was strikingly similar to common adverse effects in patients treated with conventional chemotherapeutics, including aplastic anemia with severe neutropenia and anagen effluvium.6,7 This adverse effect profile suggests that albendazole exerts an effect on mammalian β-tubulin that is similar to conventional chemotherapy when albendazole is ingested in a massive quantity.

Other reports of albendazole-induced alopecia describe an idiosyncratic, dose-dependent telogen effluvium.8-10 Conventional chemotherapy uncommonly might induce telogen effluvium when given below a threshold necessary to induce anagen effluvium. In those cases, follicular matrix keratinocytes are disrupted without complete follicular fracture and attempt to repair the damaged elongating follicle before entering the telogen phase.7 This observed phenomenon and the inherent susceptibility of matrix keratinocytes to antimicrotubule agents might explain why a therapeutic dose of albendazole has been associated with telogen effluvium in certain individuals.

Our case of albendazole-related toxicosis of this magnitude is unique. Ghias et al11 reported a case of abendazole-induced anagen effluvium. Future reports might clarify whether this toxicosis syndrome is typical or atypical in massive albendazole overdose.

To the Editor: