User login

Don't Let the Bedbugs Bite: An Unusual Presentation of Bedbug Infestation Resulting in Life-Threatening Anemia

To the Editor:

A 61-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a rash on the right leg, generalized pruritus, and chest pain. The patient described intermittent exertional pressure-like chest pain over the last few days but had no known prior cardiac history. He also noted worsening edema of the right leg with erythema. Three months prior he had been hospitalized for a similar presentation and was diagnosed with cellulitis of the right leg. The patient was treated with a course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and permethrin cream for presumed scabies and followed up with dermatology for the persistent generalized pruritic rash and cellulitis. At that time, he was diagnosed with stasis dermatitis with dermatitis neglecta and excoriations. He was educated on general hygiene and treated with triamcinolone, hydrophilic ointment, and pramoxine lotion for pruritus. He also was empirically treated again for scabies.

At the current presentation, preliminary investigation showed profound anemia with a hemoglobin level of 6.2 g/dL (baseline hemoglobin level 3 months prior, 13.1 g/dL). He was subsequently admitted to the general medicine ward for further investigation of severe symptomatic anemia. A medical history revealed moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, xerosis, and fracture of the right ankle following open reduction internal fixation 6 years prior to admission. There was no history of blood loss, antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulants. He was on disability and lived in a single-room occupancy hotel. He did not report any high-risk sexual behaviors or abuse of alcohol or drugs. He actively smoked 1.5 packs of cigarettes per day for the last 30 years. He denied any allergies.

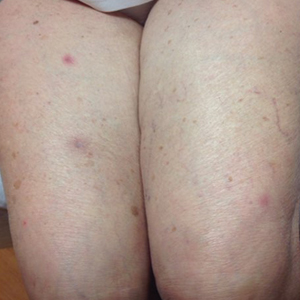

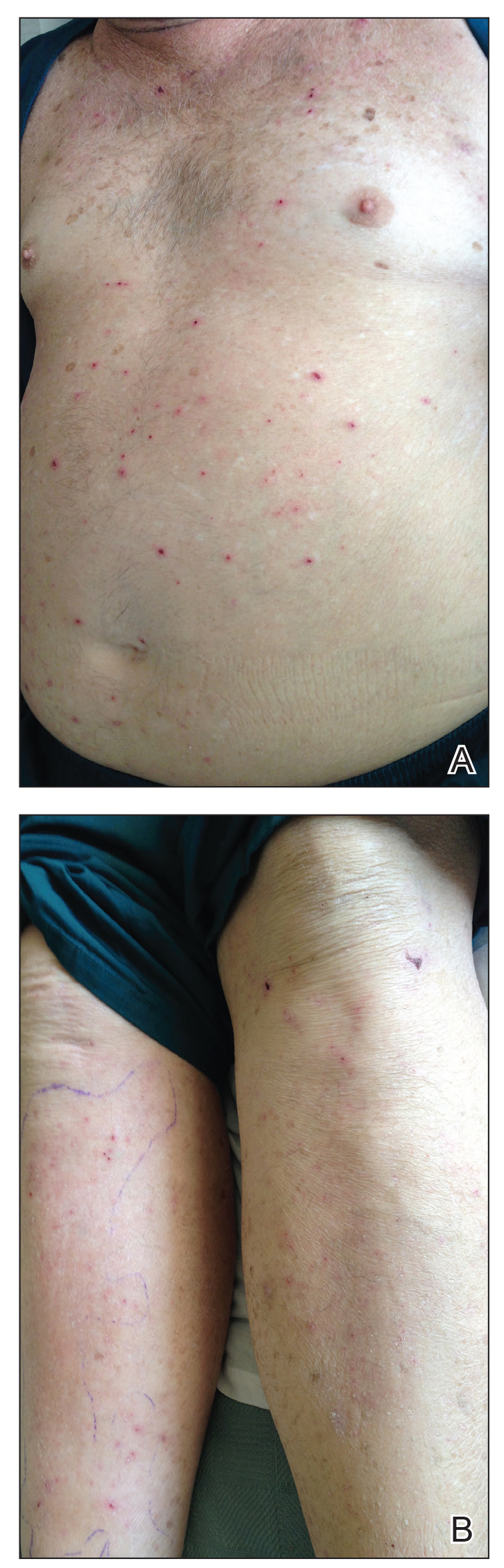

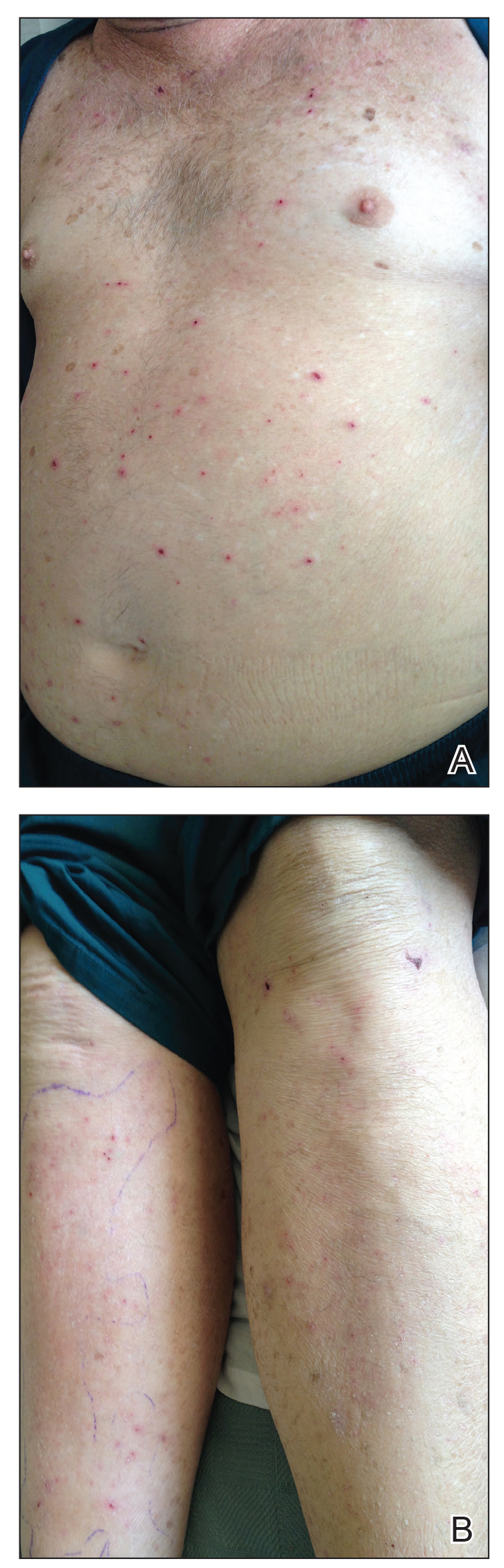

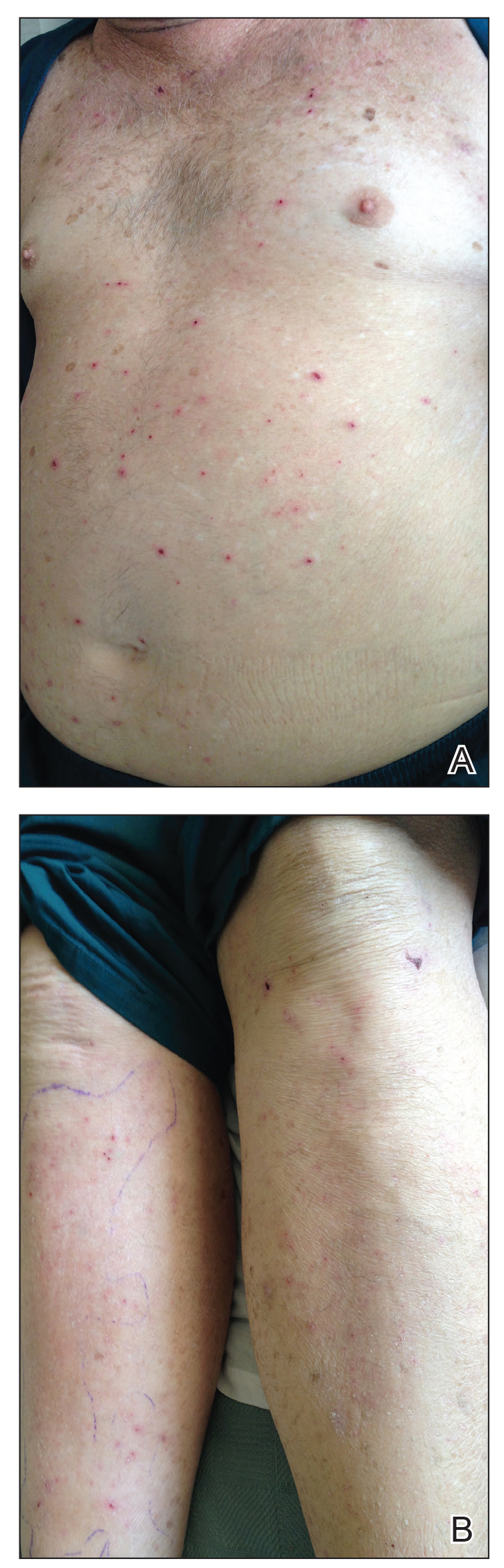

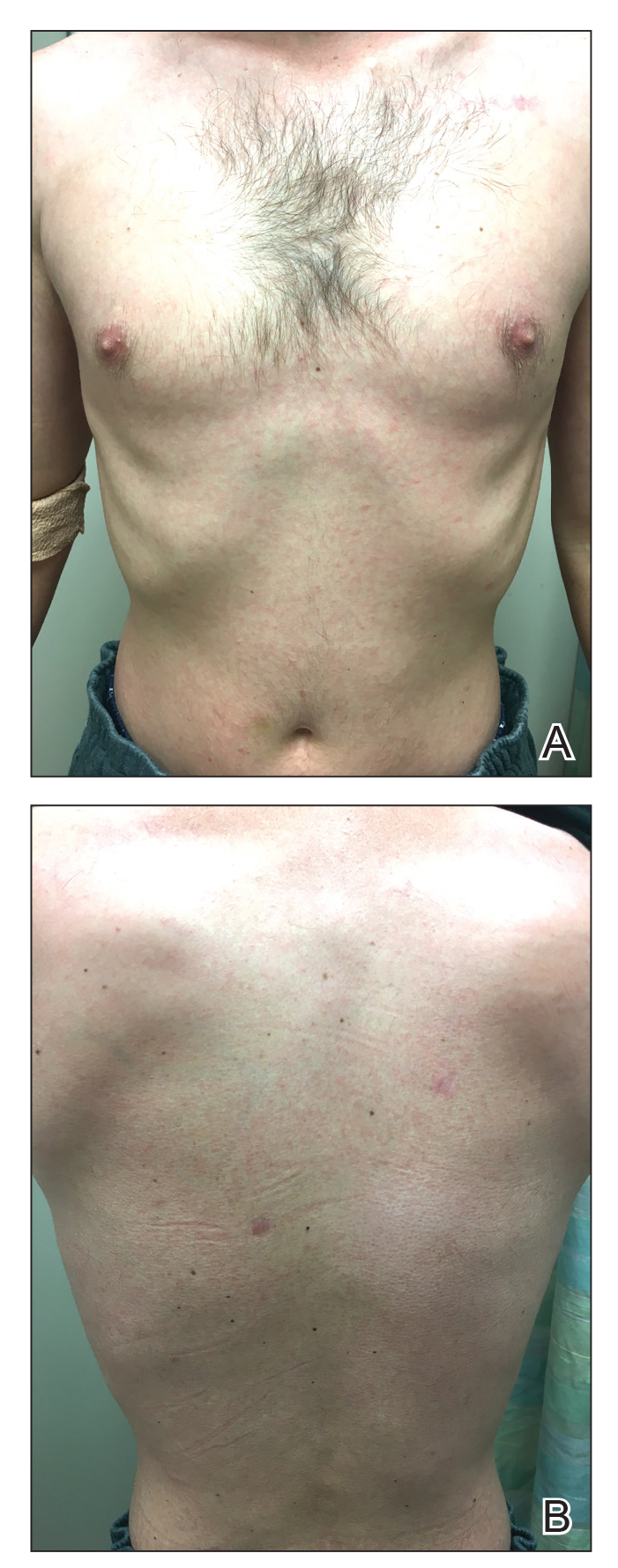

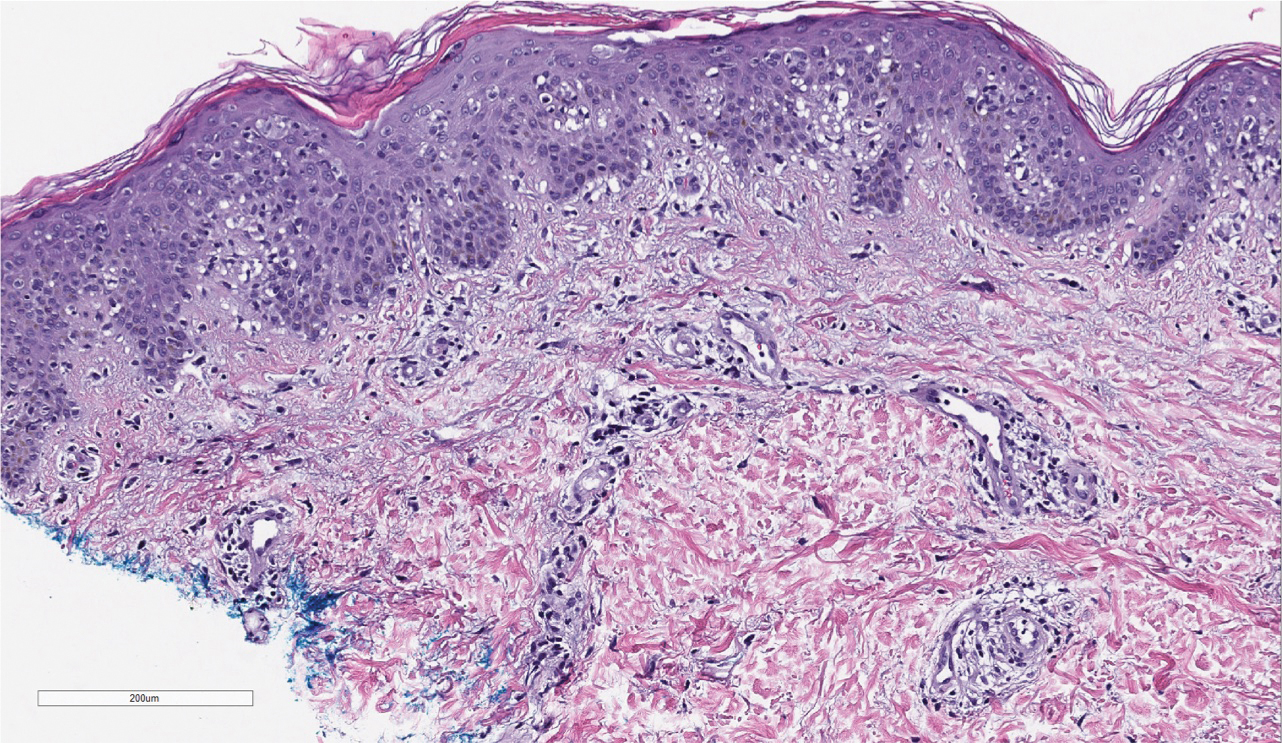

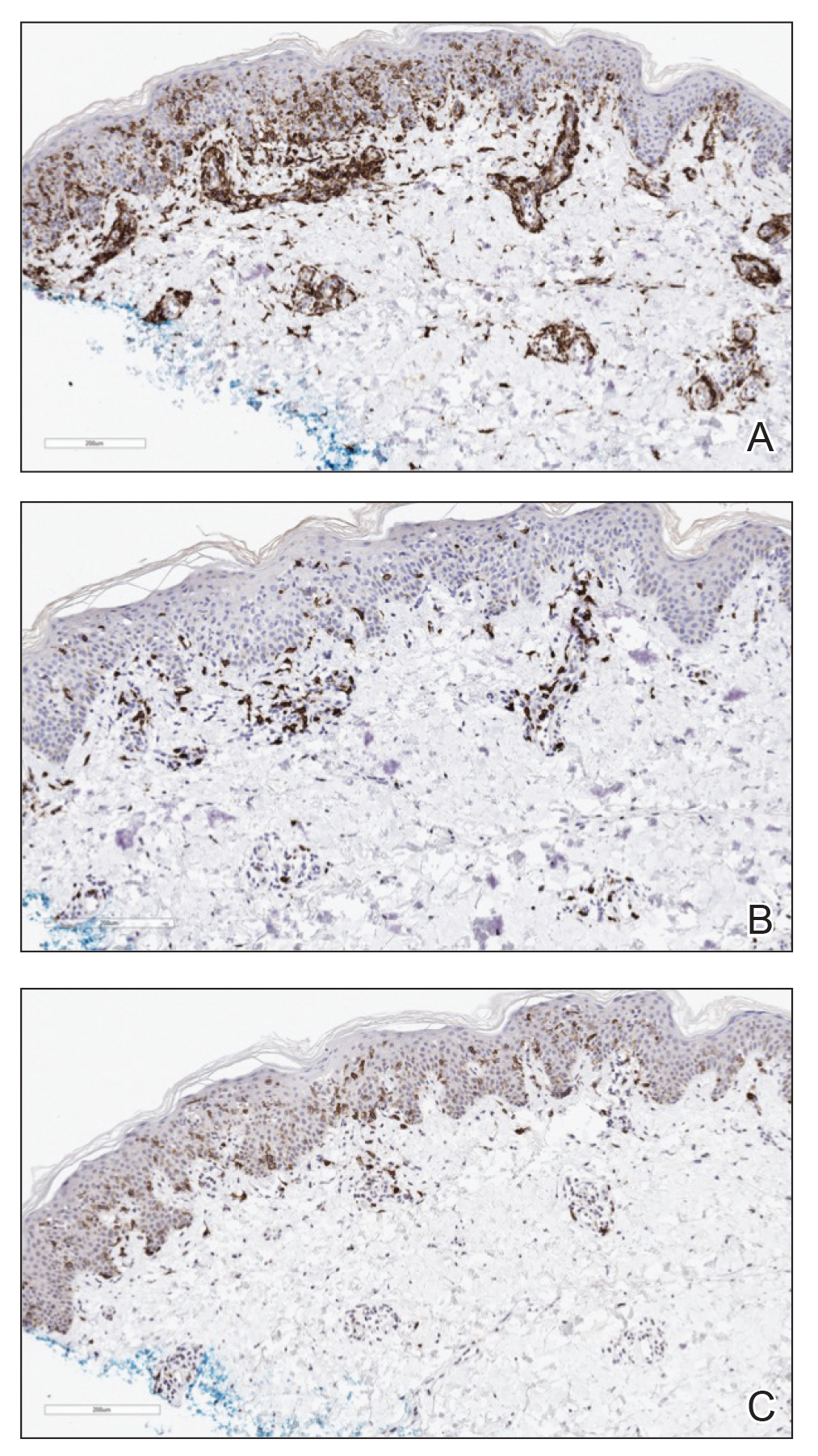

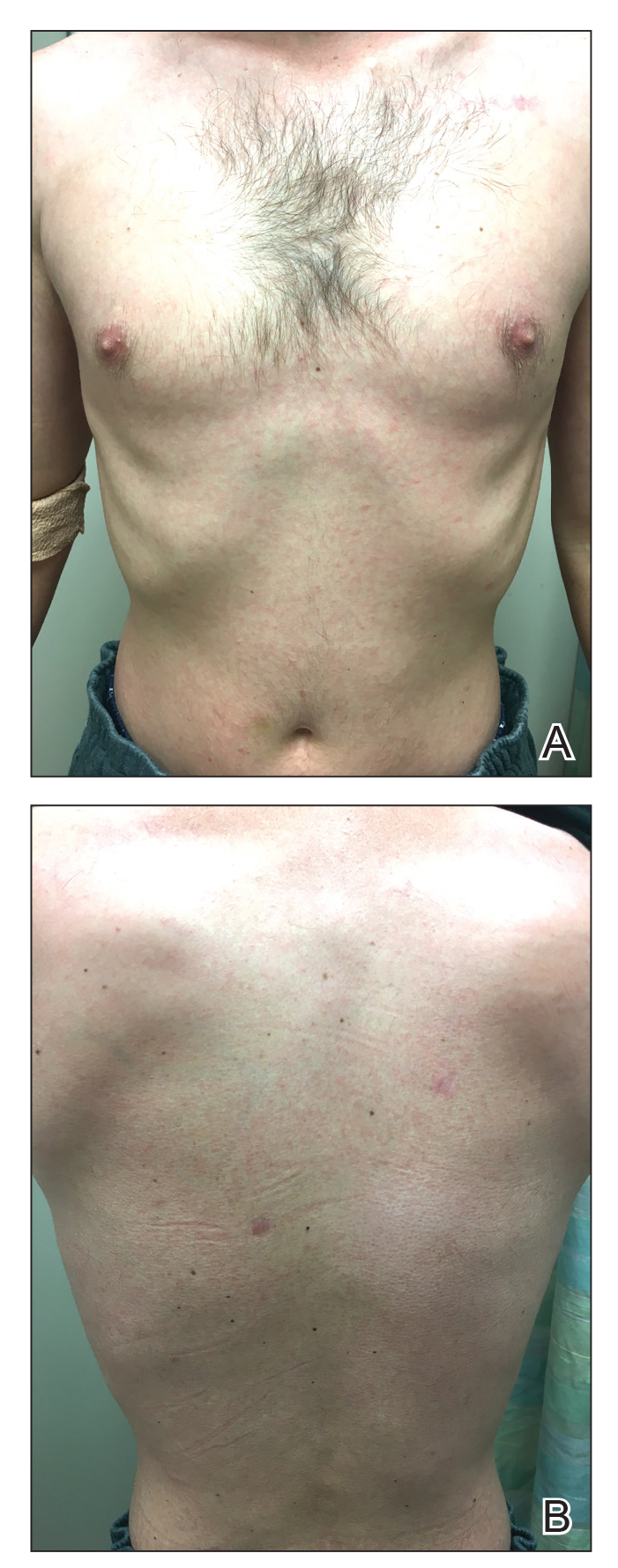

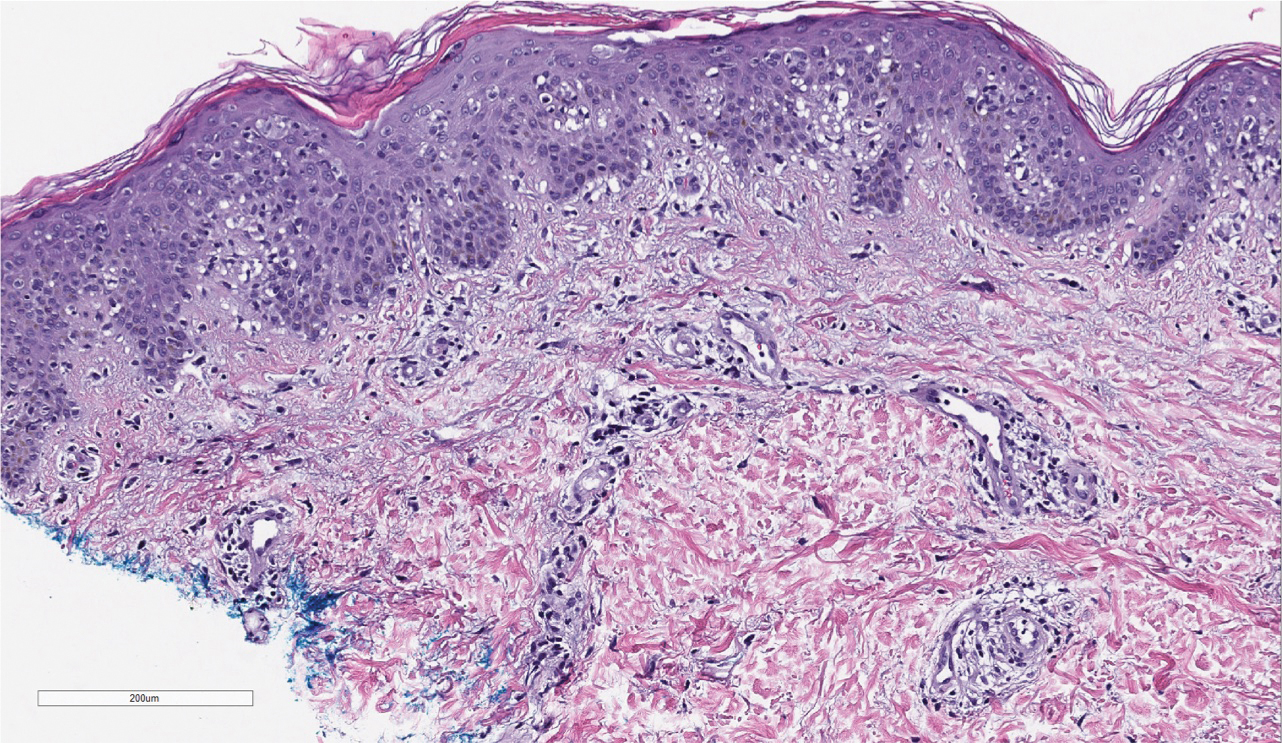

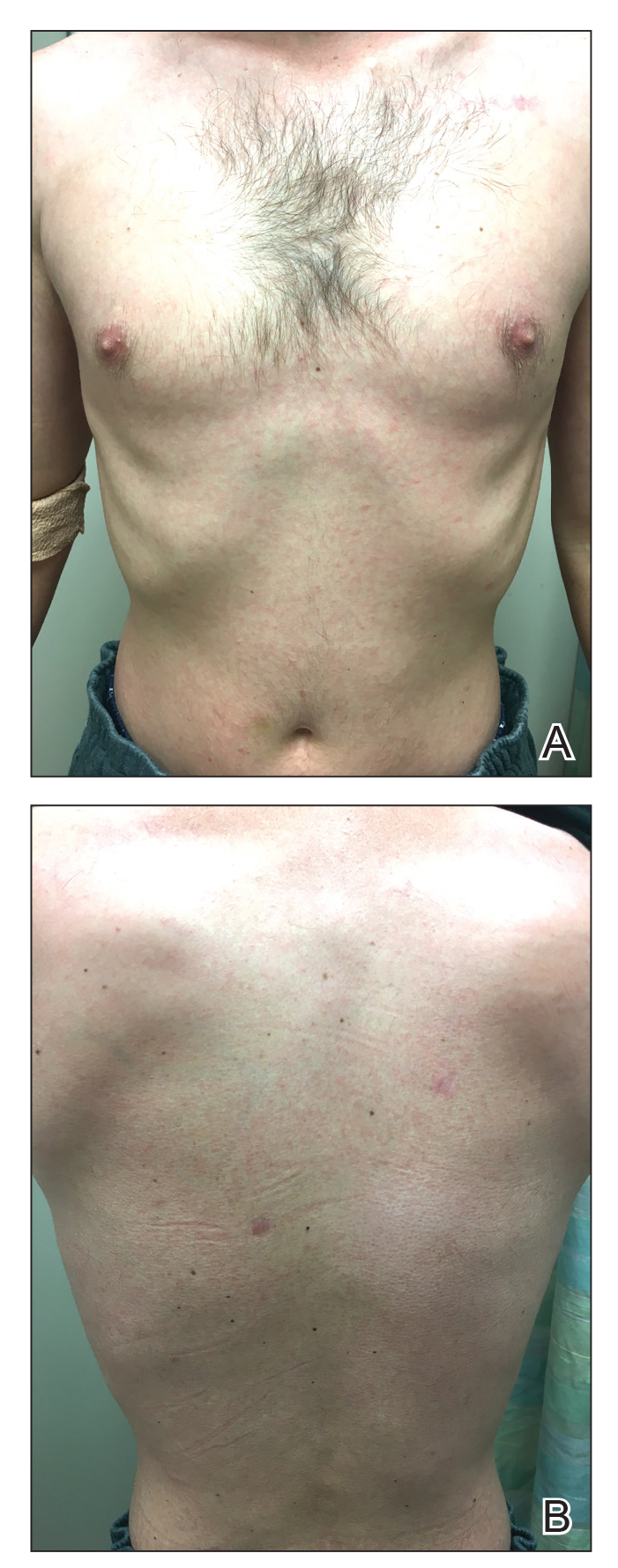

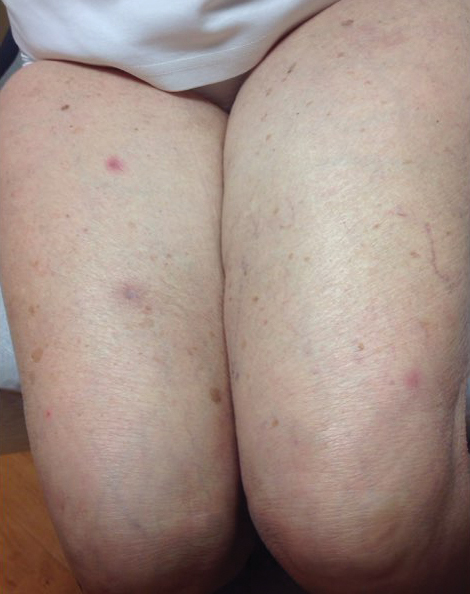

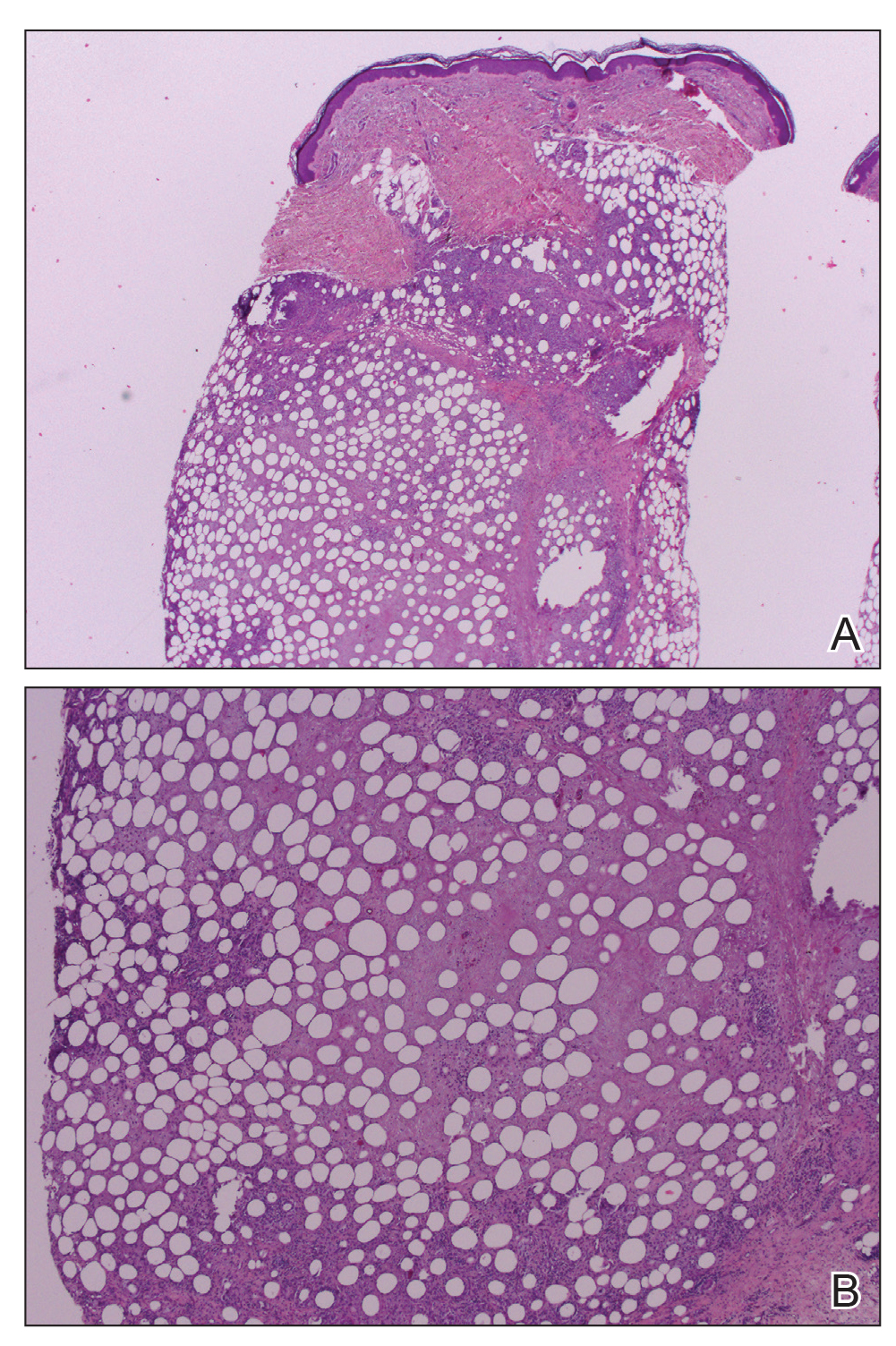

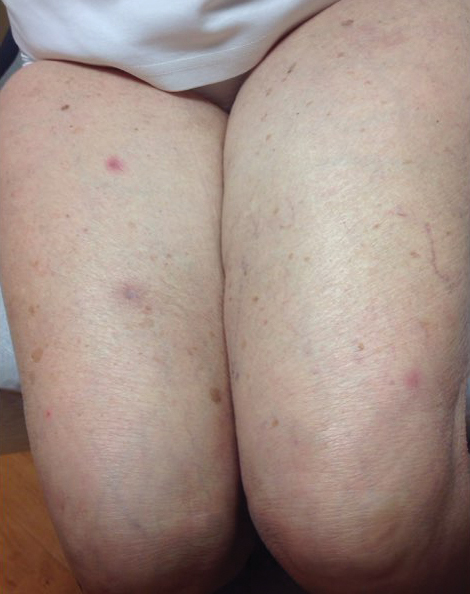

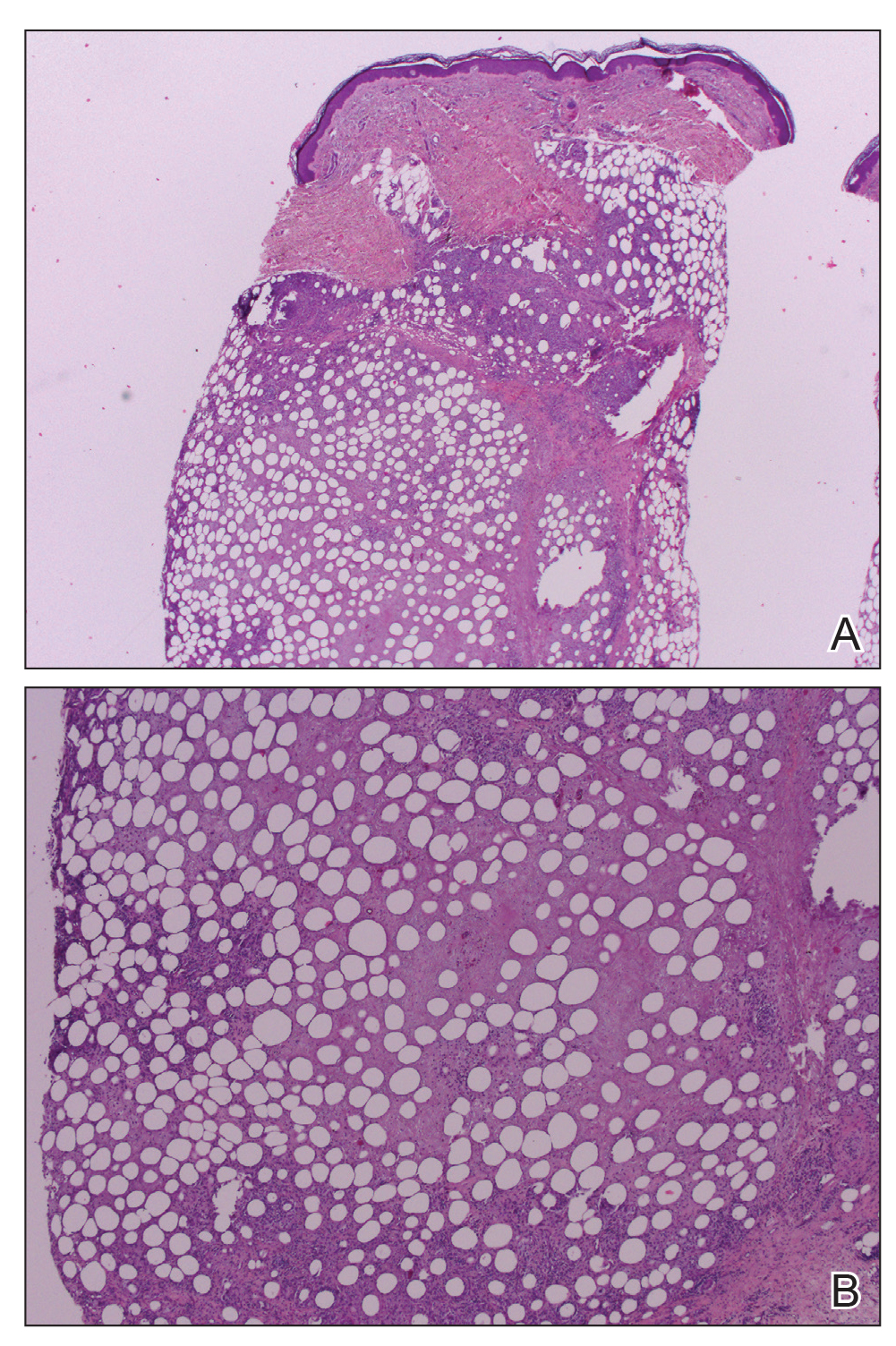

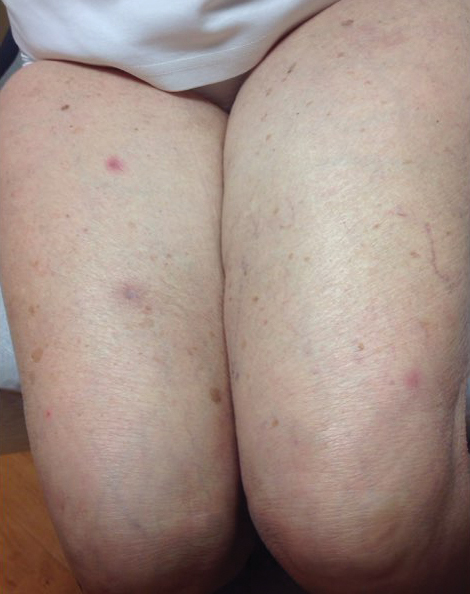

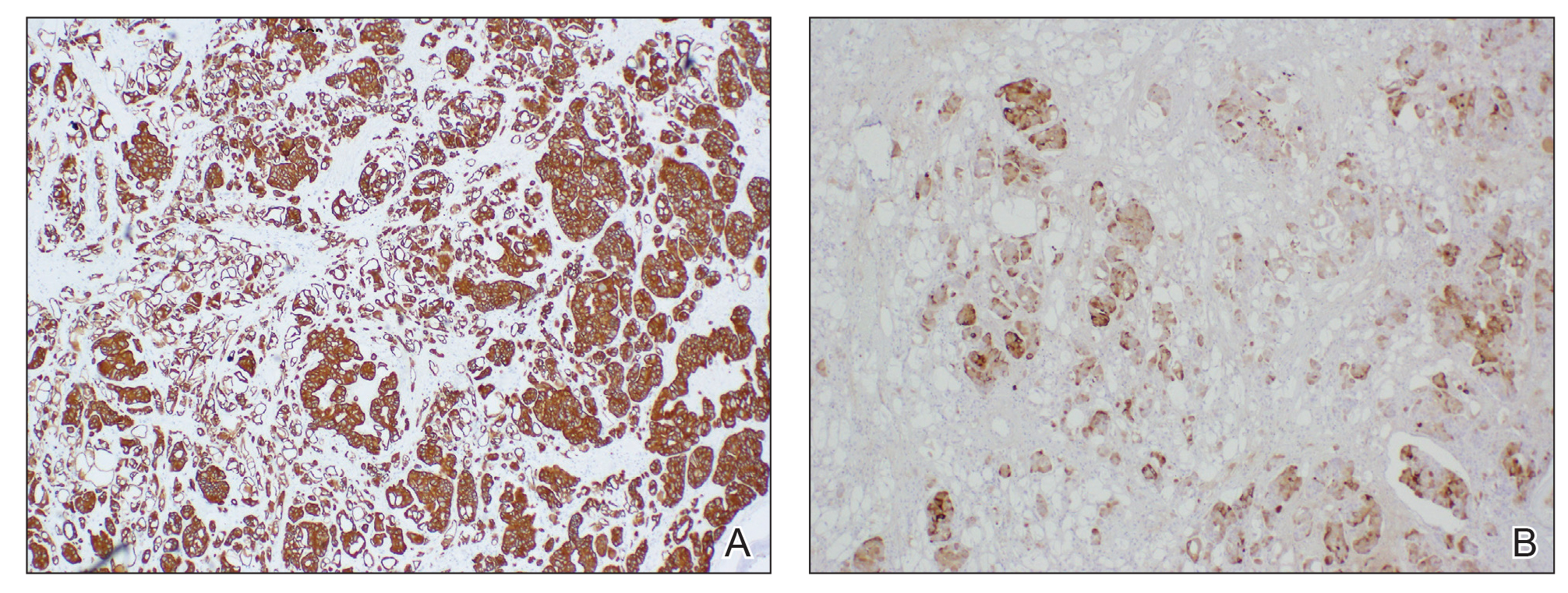

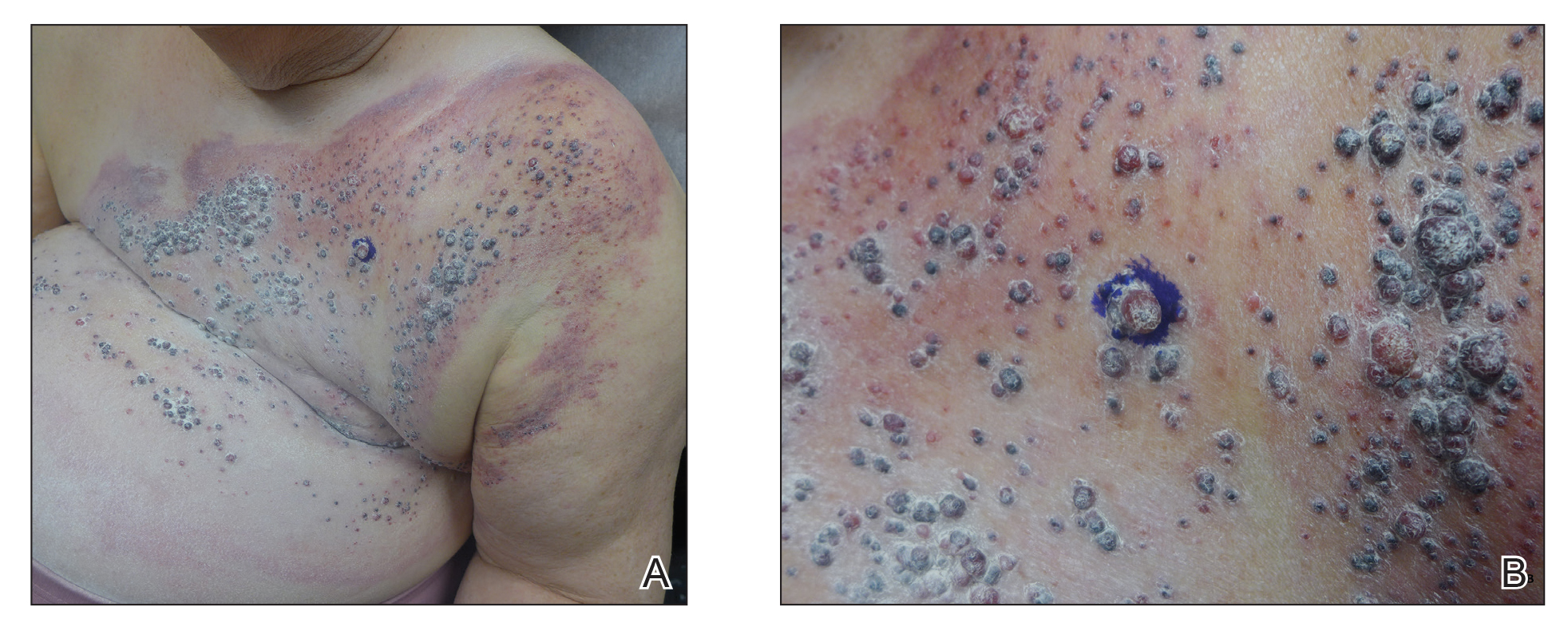

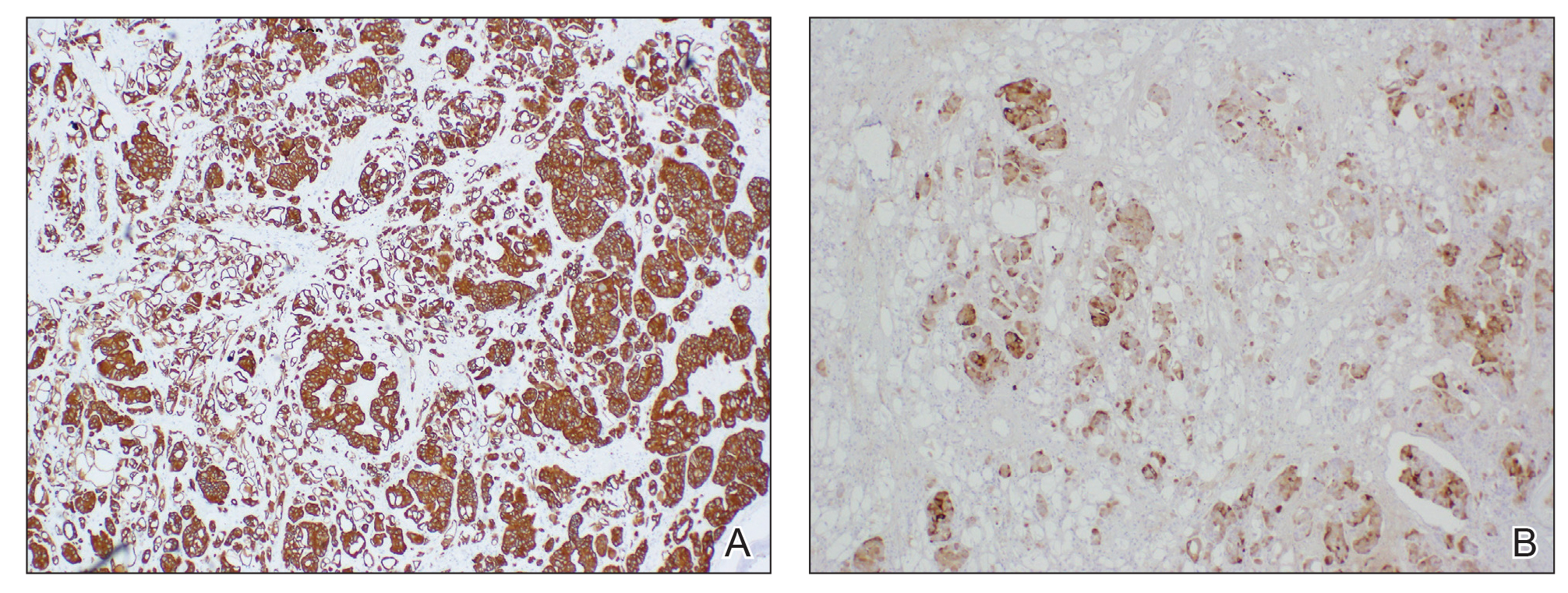

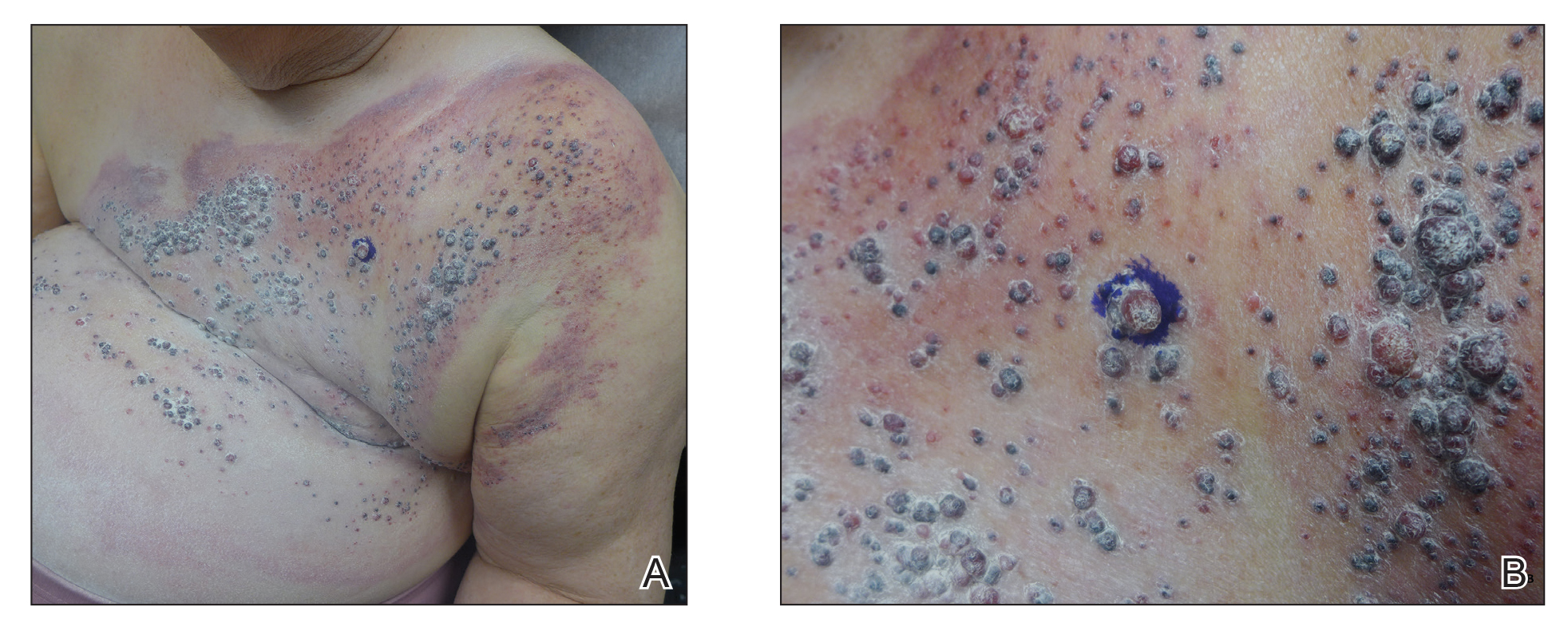

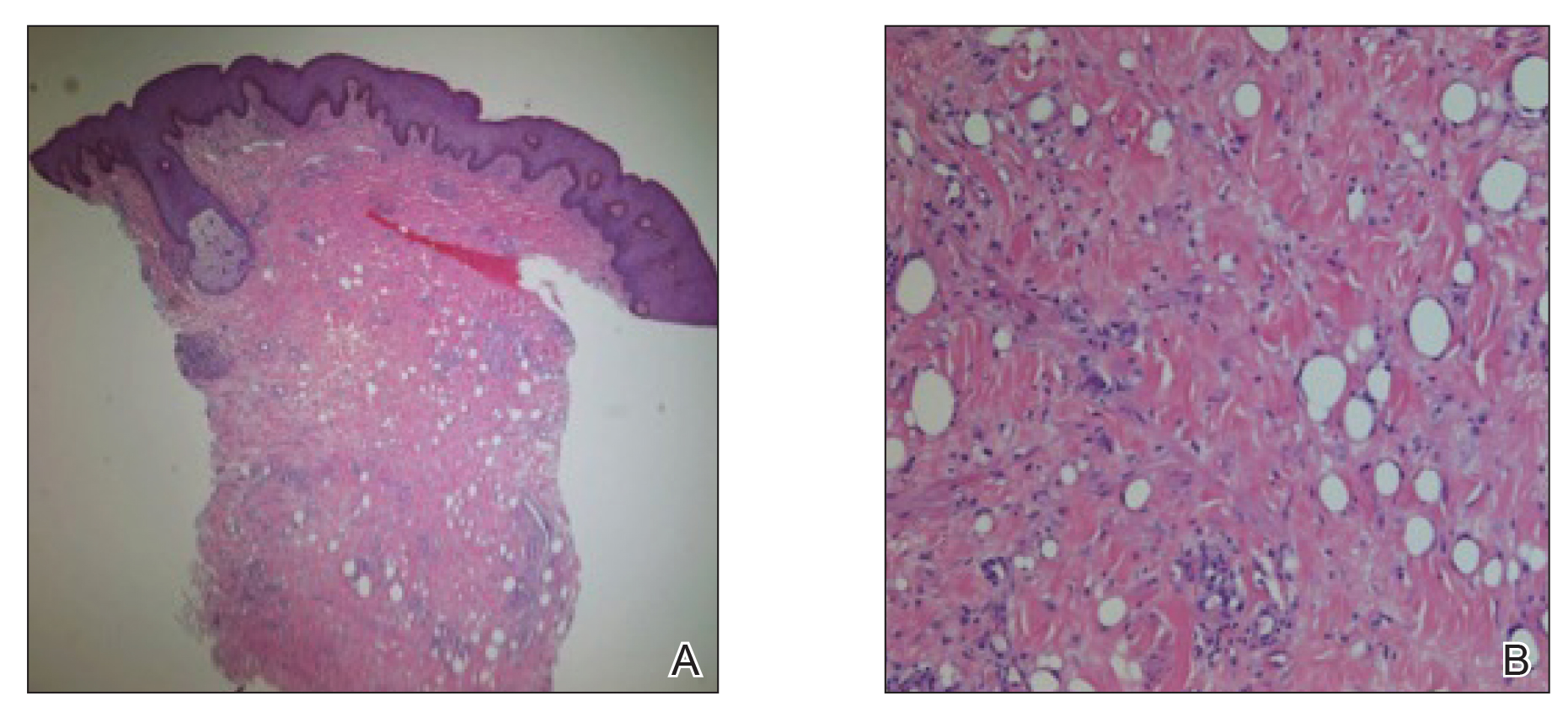

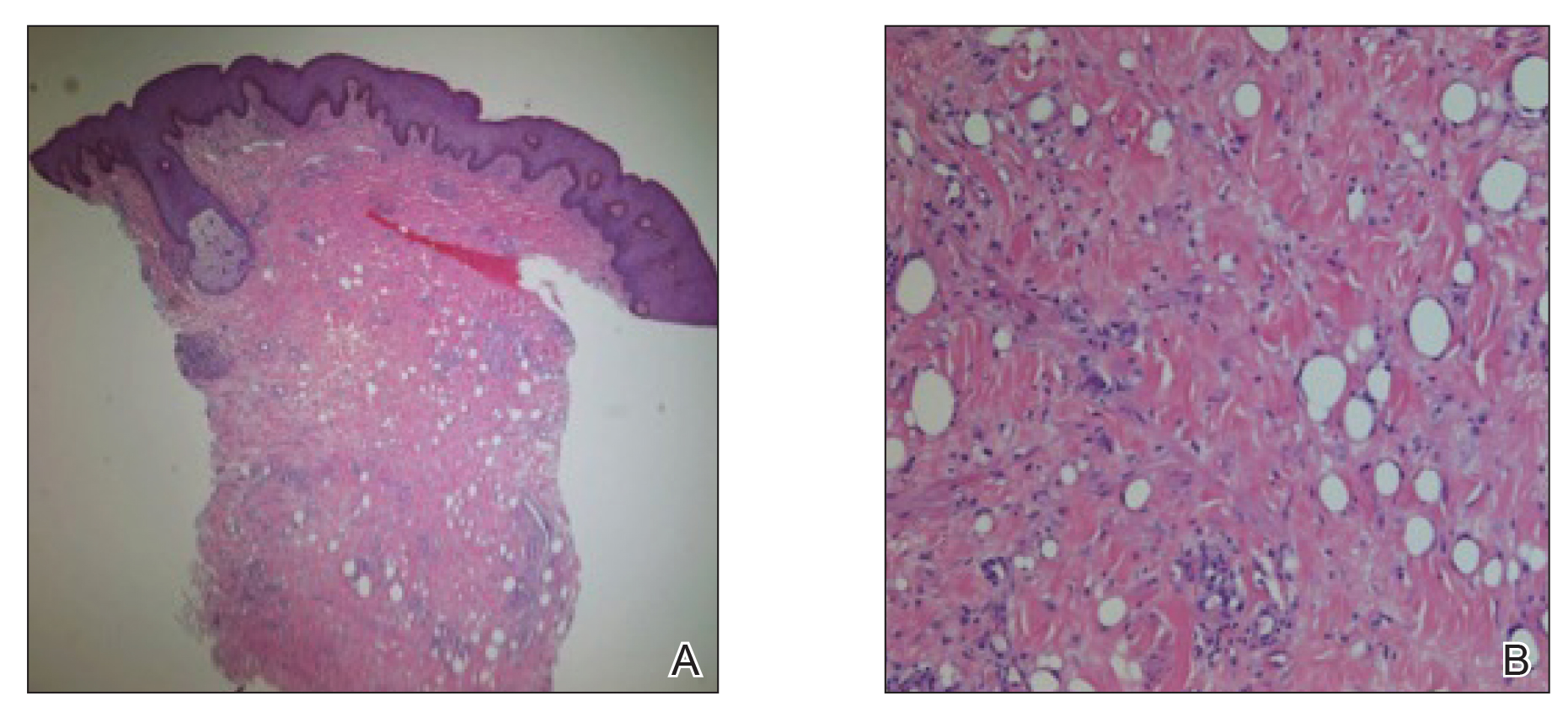

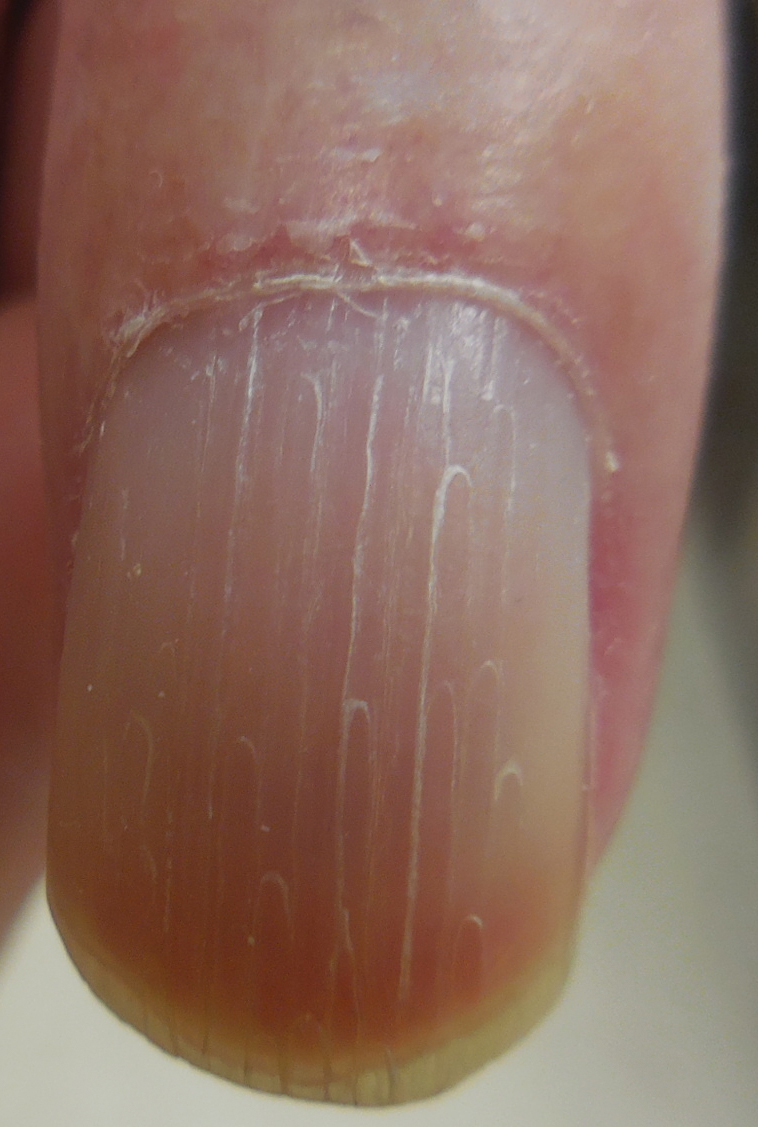

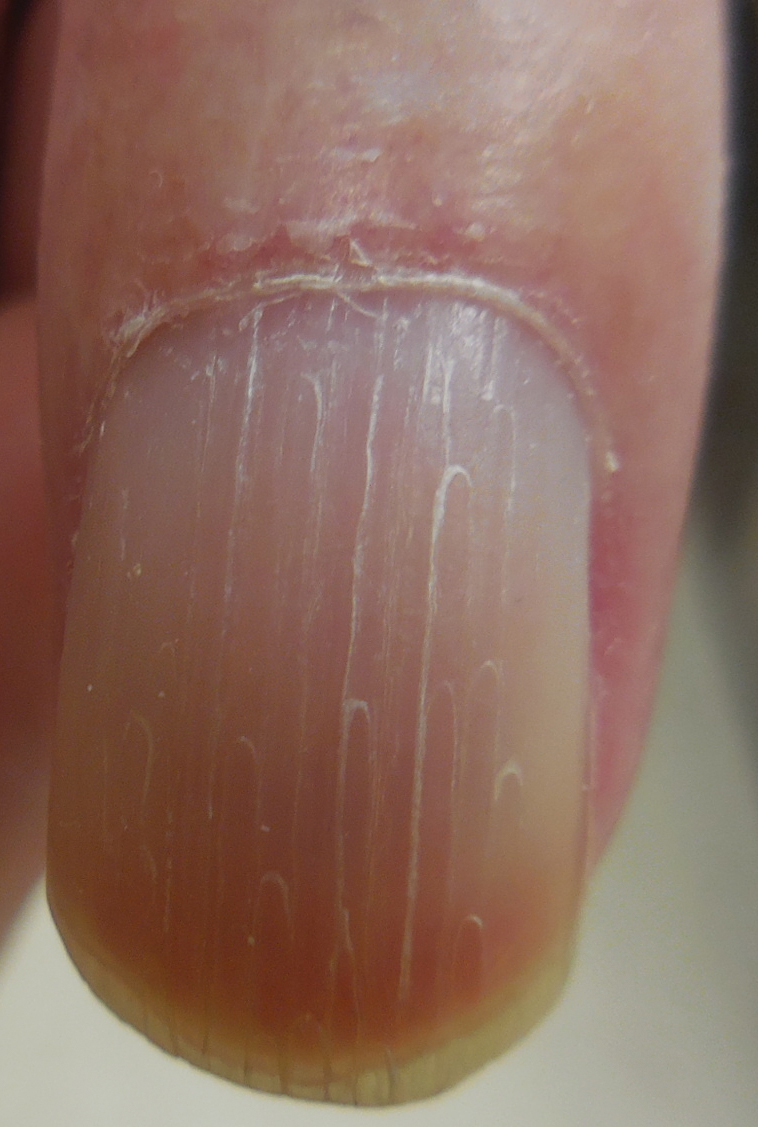

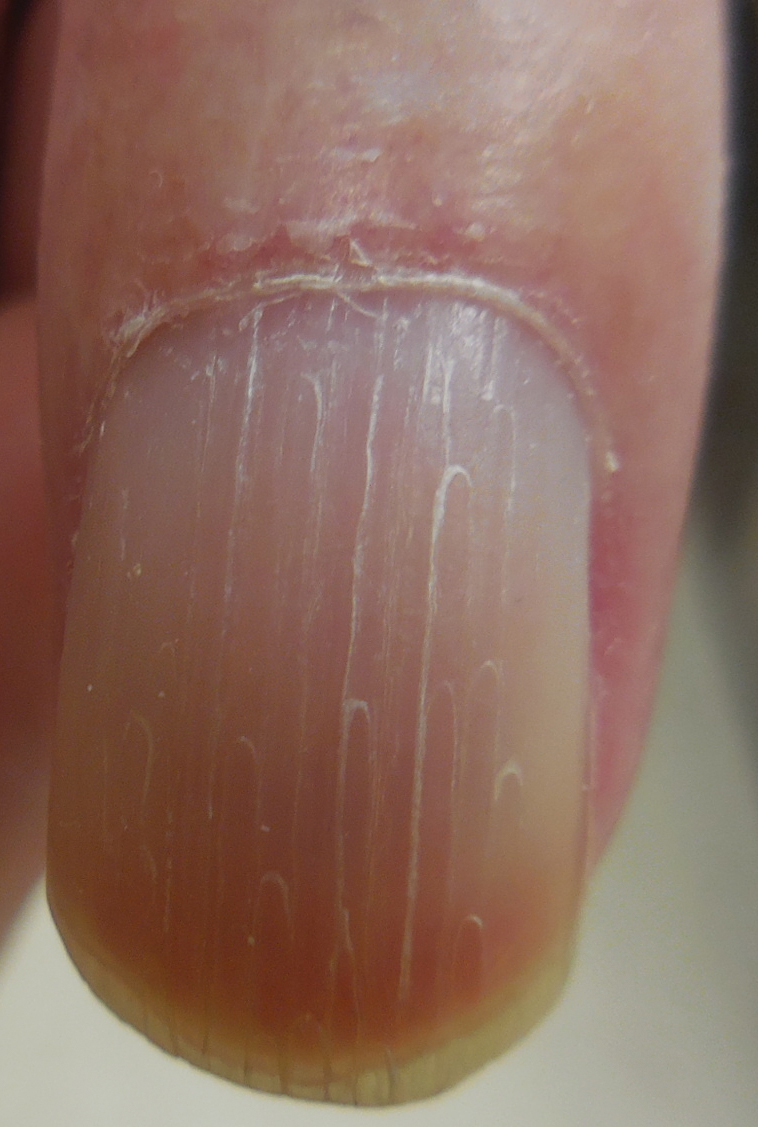

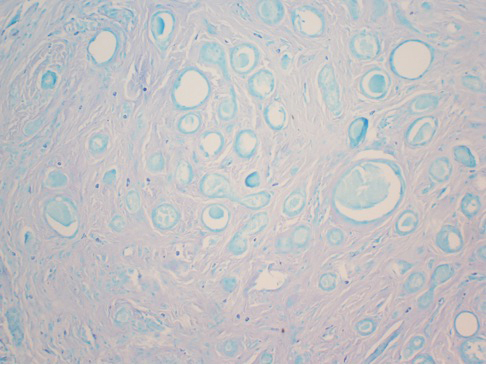

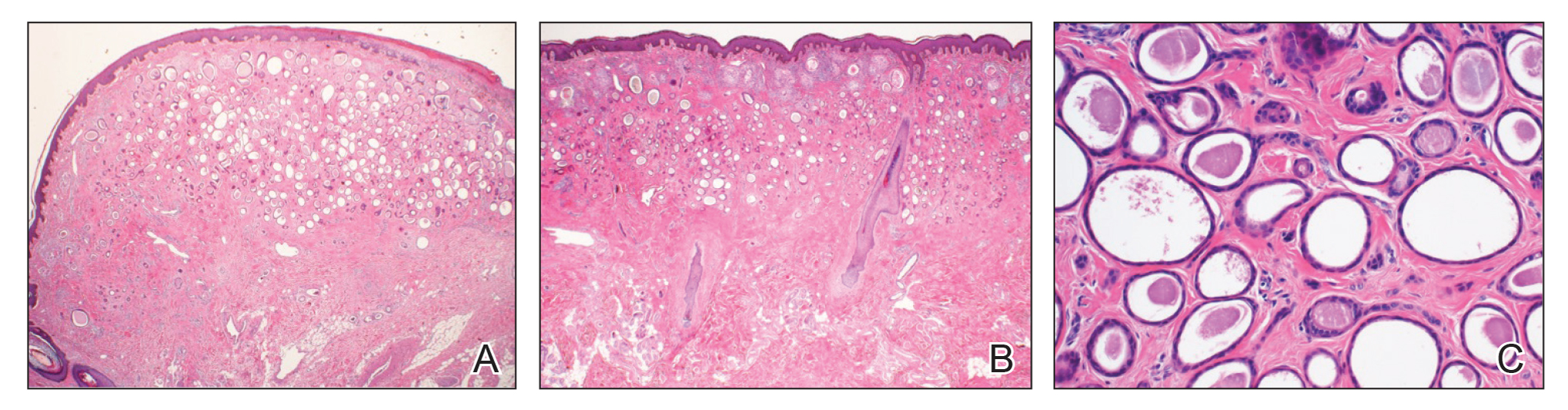

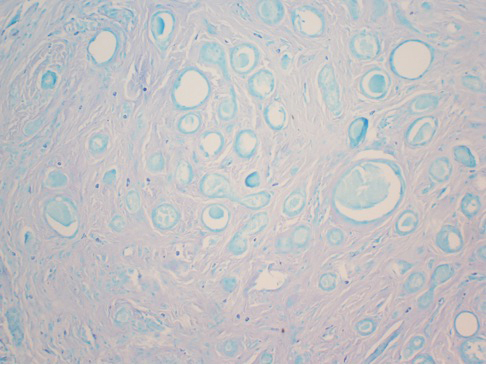

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile, nontoxic, disheveled, and in no acute distress. He had anicteric sclera and pale conjunctiva. The right leg appeared more erythematous and edematous compared to the left leg but without warmth or tenderness to palpation. He had innumerable 4- to 5-mm, erythematous, excoriated papules on the skin (Figure). His bed sheets were noted to have multiple rusty-black specks thought to be related to the crusted lesions. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable.

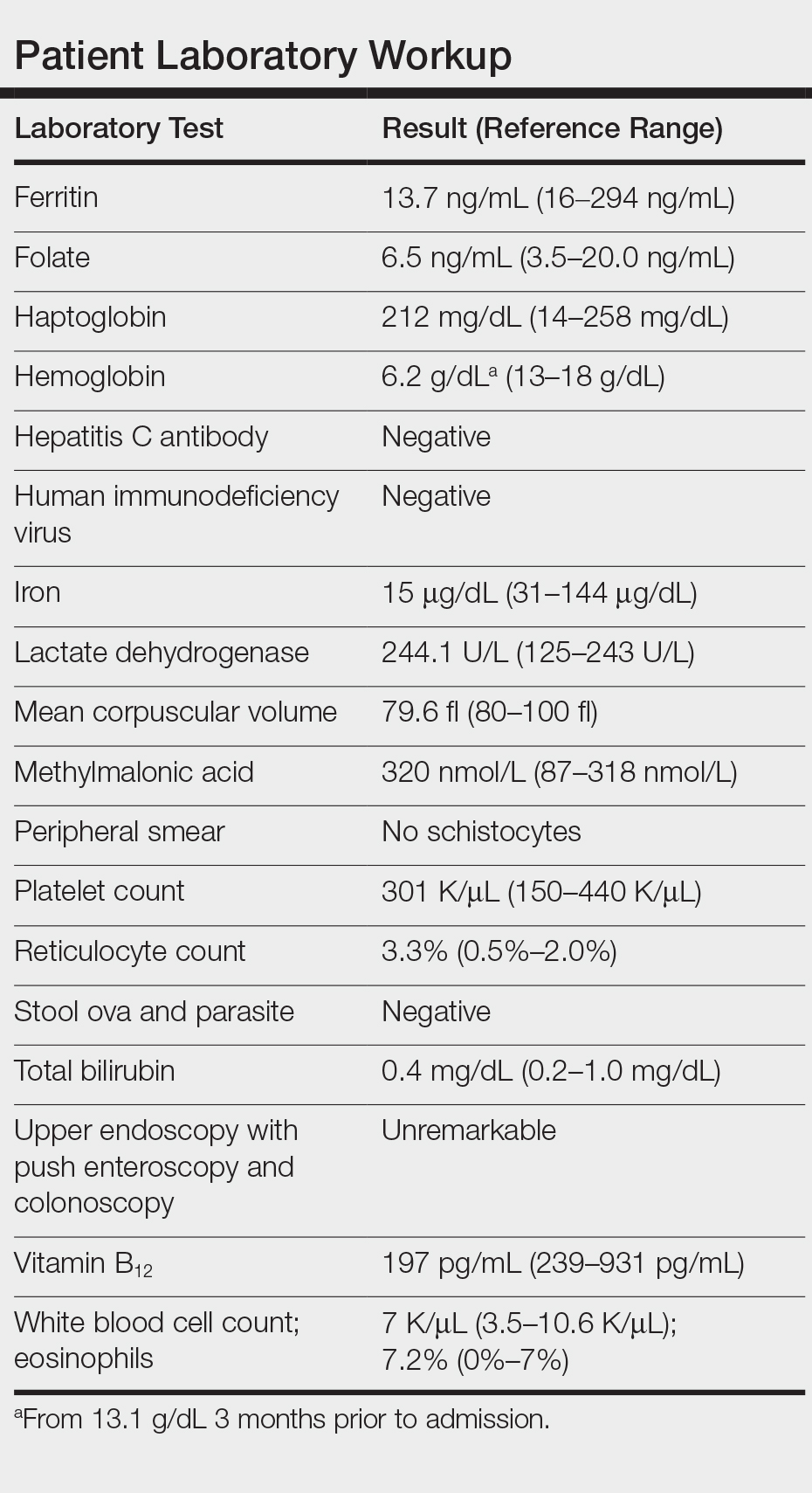

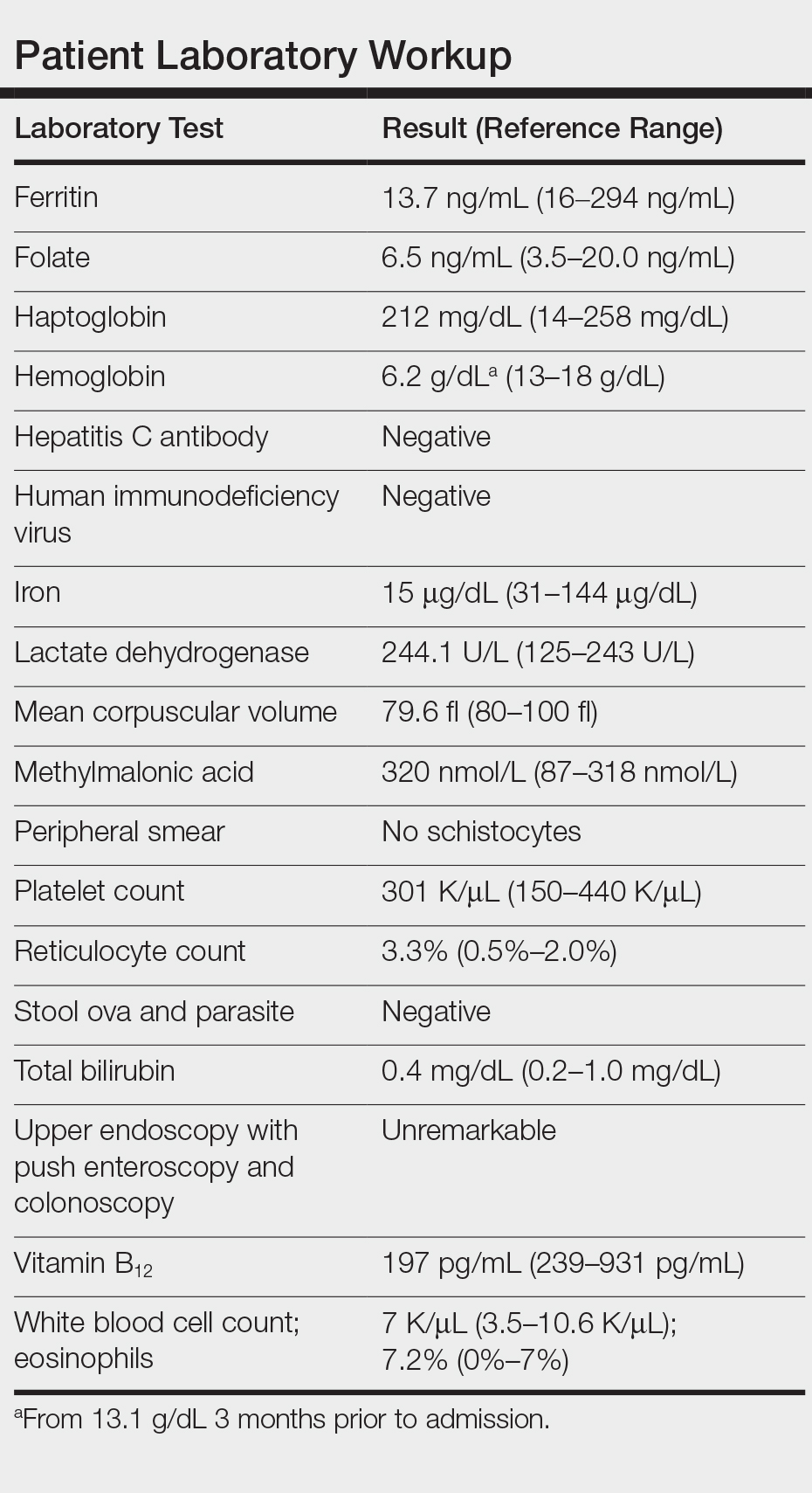

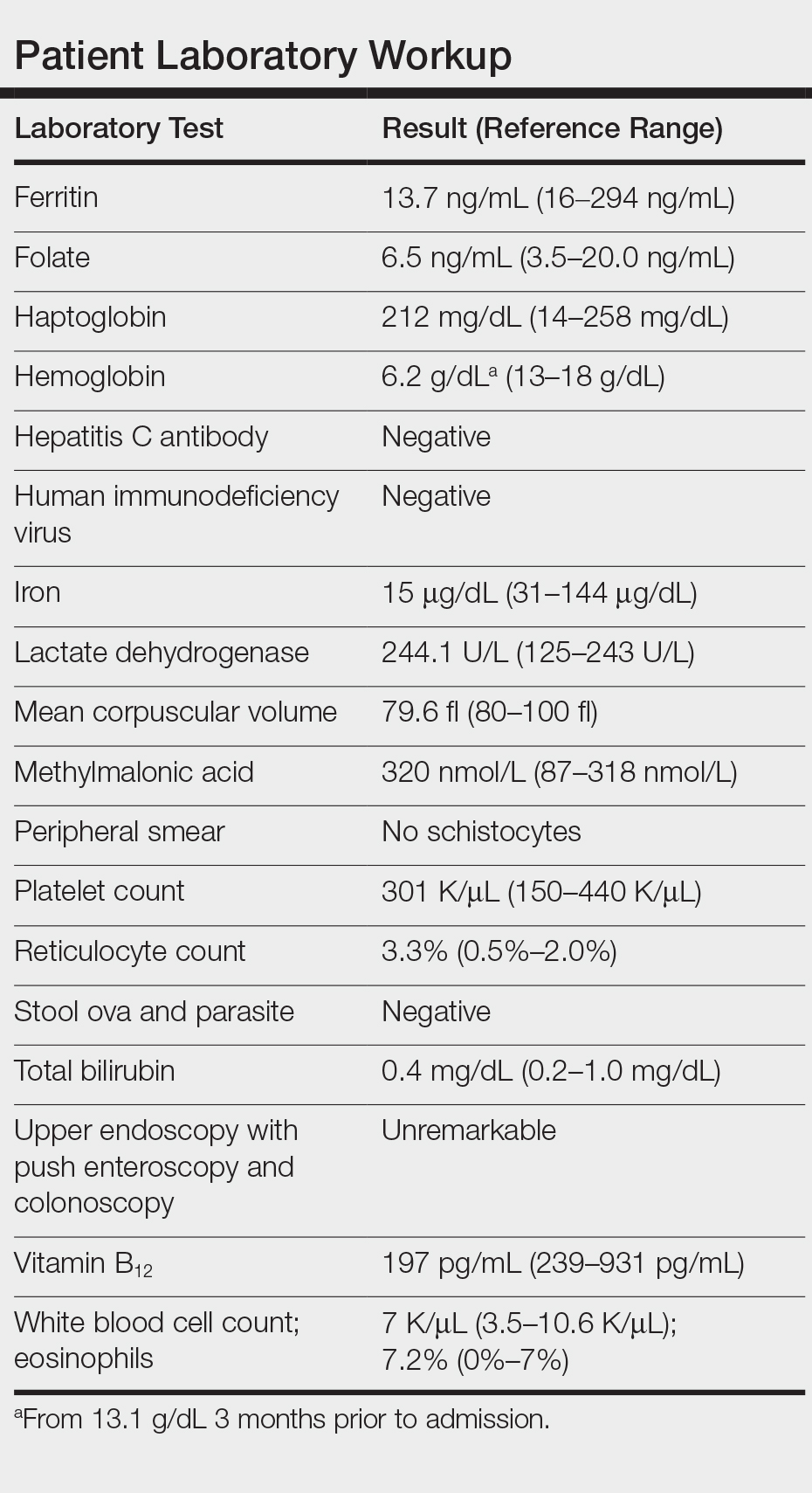

Laboratory workup revealed severe iron-deficiency anemia without any evidence of hemolysis, marrow suppression, infection, or immune compromise (Table). He had a vitamin B12 deficiency (197 pg/mL [reference range, 239-931 pg/mL]), but we felt it was very unlikely to be responsible for his profound, sudden-onset microcytic anemia. Further evaluation for occult bleeding revealed an unremarkable upper endoscopy with push enteroscopy and colonoscopy. An alternate etiology of the anemia could not be identified.

Subsequently, he reported multiple pruritic bug bites sustained at the hotel room where he resided and continued to note pruritus while hospitalized. Pest control inspected the hospital room and identified bedbugs, Cimex lectularius, among his belongings. Upon further review, his clothes and walker were found to be completely infested with these organisms in different stages of development. Treatment included blood transfusions, iron supplementation, and environmental control of the infested living space both in the hospital and at his residence, with subsequent resolution of symptoms and anemia. Two weeks following discharge, the patient no longer reported pruritus, and his hemoglobin level had returned to baseline.

Over the last decade there has been an exponential resurgence in C lectularius infestations in developed countries attributed to increasing global travel, growing pesticide resistance, lack of public awareness, and inadequate pest control programs. This re-emergence has resulted in a public health problem. Although bedbugs are not known to transmit infectious diseases, severe infestation can result in notable dermatitis, iron-deficiency anemia from chronic blood loss, superinfection, allergic reactions including anaphylaxis in rare cases, and psychologic distress.

Iron-deficiency anemia caused by excessive bedbug biting in infants and children has been documented as early as the 1960s.1 Our knowledge of severe anemia due to bedbug infestation is limited to only 4 cases in the literature, according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bedbugs anemia and cimex anemia.1-4 All cases reported bedbug infestations involving personal clothing, belongings, and/or living spaces. Patient concerns at presentation ranged from lethargy and fatigue with pruritic rash to chest pain and syncope with findings of severe microcytic or normocytic anemia (hemoglobin level, 5-8 g/dL). All cases were treated supportively with blood transfusion and iron supplementation, with hemoglobin recovery after several weeks. Environmental extermination also was required to prevent recurrence.1-4 Given that each bedbug blood meal is on average 7 mm3, one would have to incur a minimum of 143,000 bites to experience a blood loss of 1 L.3

The differential diagnosis for a patient with generalized pruritus should be broad and includes dermatologic conditions (eg, xerosis, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, urticaria, dermatophytosis, lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, scabies, pediculosis corporis and pubis, other arthropod bites, bullous pemphigoid), systemic disorders (eg, renal disease, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, cholestasis, human immunodeficiency virus), malignancy, connective tissue disease, medication side effects, and psychogenic and neuropathic itch.

The diagnosis of C lectularius infestation is confirmed by finding the wingless, reddish brown, flat and ovular arthropod, with adult lengths of 4 to 7 mm, approximately the size of an apple seed.5-11 Bedbugs typically are active at night and feed for 3 to 10 minutes. After their feed or during the day, bedbugs will return to their nest in furniture, mattresses, beds, walls, and floors. Bedbug bites appear as small clusters or lines of pruritic erythematous papules with a central hemorrhagic puncta. Other cutaneous symptoms include isolated pruritus, papules, nodules, and bullous eruptions.7 Additional signs of bedbug infestation include black fecal stains in areas of inhabitation as well as actual bedbugs feeding during the day due to overcrowding.

Treatment of pruritic localized cutaneous reactions is supportive and includes antipruritic agents, topical steroids, topical anesthetics, antihistamines, or topical or systemic antibiotics for secondary infections.5-11 Systemic reactions, including anaphylaxis, are treated with epinephrine, antihistamines, and/or corticosteroids, while severe anemia is treated supportively with blood transfusions and iron supplementation.5-11 To prevent reoccurrence, environmental control in the form of nonchemical and chemical treatments is crucial in controlling bedbug infestations.5-11

This case highlights the relevance of a rare but notable morbidity associated with bedbug infestation and the adverse effects of bedbugs on public health. This patient's living situation in a single-room occupancy hotel, poor hygiene, and possible cognitive impairment from his multiple medical conditions may have increased his risk for extreme bedbug infestation. With a good history, physical examination, proper inspection of the patient's belongings, and provider awareness of this epidemic, the severity of this patient's anemia may have been circumvented on the prior hospital admission and follow-up office visit. Once such an infestation is confirmed, a multidisciplinary approach including social work assistance, health services, and pest control is needed to appropriately treat the patient and the environment. Methods in preventing and managing this growing public health problem include improving hygiene, avoiding secondhand goods, and increasing awareness in the identification and proper elimination of bedbugs.5-7

- Venkatachalam PS, Belavady B. Loss of haemoglobin iron due to excessive biting by bed bugs. a possible aetiological factor in the iron deficiency anaemia of infants and children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1962;56:218-221.

- Pritchard MJ, Hwang SW. Severe anemia from bedbugs. CMAJ. 2009;181:287-288.

- Paulke-Korinek M, Széll M, Laferl H, et al. Bed bugs can cause severe anaemia in adults. Parasitol Res. 2012;110:2577-2579.

- Sabou M, Imperiale DG, Andrés E, et al. Bed bugs reproductive life cycle in the clothes of a patient suffering from Alzheimer's disease results in iron deficiency anemia. Parasite. 2013;20:16.

- Studdiford JS, Conniff KM, Trayes KP, et al. Bedbug infestation. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:653-658.

- Goddard J, deShazo R. Bed bugs (Cimex lectularis) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA. 2009;301:1358-1366.

- Bernardeschi C, Le Cleach L, Delaunay P, et al. Bed bug infestation. BMJ. 2013;346:f138.

- Silvia Munoz-Price L, Safdar N, Beier JC, et al. Bed bugs inhealthcare settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:1137-1142.

- Huntington MK. When bed bugs bite. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:384-388.

- Delaunay P, Blanc V, Del Giudice P, et al. Bedbugs and infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:200-212.

- Doggett SL, Dwyer DE, Penas PF, et al. Bed bugs: clinical relevance and control options. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:164-192.

To the Editor:

A 61-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a rash on the right leg, generalized pruritus, and chest pain. The patient described intermittent exertional pressure-like chest pain over the last few days but had no known prior cardiac history. He also noted worsening edema of the right leg with erythema. Three months prior he had been hospitalized for a similar presentation and was diagnosed with cellulitis of the right leg. The patient was treated with a course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and permethrin cream for presumed scabies and followed up with dermatology for the persistent generalized pruritic rash and cellulitis. At that time, he was diagnosed with stasis dermatitis with dermatitis neglecta and excoriations. He was educated on general hygiene and treated with triamcinolone, hydrophilic ointment, and pramoxine lotion for pruritus. He also was empirically treated again for scabies.

At the current presentation, preliminary investigation showed profound anemia with a hemoglobin level of 6.2 g/dL (baseline hemoglobin level 3 months prior, 13.1 g/dL). He was subsequently admitted to the general medicine ward for further investigation of severe symptomatic anemia. A medical history revealed moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, xerosis, and fracture of the right ankle following open reduction internal fixation 6 years prior to admission. There was no history of blood loss, antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulants. He was on disability and lived in a single-room occupancy hotel. He did not report any high-risk sexual behaviors or abuse of alcohol or drugs. He actively smoked 1.5 packs of cigarettes per day for the last 30 years. He denied any allergies.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile, nontoxic, disheveled, and in no acute distress. He had anicteric sclera and pale conjunctiva. The right leg appeared more erythematous and edematous compared to the left leg but without warmth or tenderness to palpation. He had innumerable 4- to 5-mm, erythematous, excoriated papules on the skin (Figure). His bed sheets were noted to have multiple rusty-black specks thought to be related to the crusted lesions. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable.

Laboratory workup revealed severe iron-deficiency anemia without any evidence of hemolysis, marrow suppression, infection, or immune compromise (Table). He had a vitamin B12 deficiency (197 pg/mL [reference range, 239-931 pg/mL]), but we felt it was very unlikely to be responsible for his profound, sudden-onset microcytic anemia. Further evaluation for occult bleeding revealed an unremarkable upper endoscopy with push enteroscopy and colonoscopy. An alternate etiology of the anemia could not be identified.

Subsequently, he reported multiple pruritic bug bites sustained at the hotel room where he resided and continued to note pruritus while hospitalized. Pest control inspected the hospital room and identified bedbugs, Cimex lectularius, among his belongings. Upon further review, his clothes and walker were found to be completely infested with these organisms in different stages of development. Treatment included blood transfusions, iron supplementation, and environmental control of the infested living space both in the hospital and at his residence, with subsequent resolution of symptoms and anemia. Two weeks following discharge, the patient no longer reported pruritus, and his hemoglobin level had returned to baseline.

Over the last decade there has been an exponential resurgence in C lectularius infestations in developed countries attributed to increasing global travel, growing pesticide resistance, lack of public awareness, and inadequate pest control programs. This re-emergence has resulted in a public health problem. Although bedbugs are not known to transmit infectious diseases, severe infestation can result in notable dermatitis, iron-deficiency anemia from chronic blood loss, superinfection, allergic reactions including anaphylaxis in rare cases, and psychologic distress.

Iron-deficiency anemia caused by excessive bedbug biting in infants and children has been documented as early as the 1960s.1 Our knowledge of severe anemia due to bedbug infestation is limited to only 4 cases in the literature, according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bedbugs anemia and cimex anemia.1-4 All cases reported bedbug infestations involving personal clothing, belongings, and/or living spaces. Patient concerns at presentation ranged from lethargy and fatigue with pruritic rash to chest pain and syncope with findings of severe microcytic or normocytic anemia (hemoglobin level, 5-8 g/dL). All cases were treated supportively with blood transfusion and iron supplementation, with hemoglobin recovery after several weeks. Environmental extermination also was required to prevent recurrence.1-4 Given that each bedbug blood meal is on average 7 mm3, one would have to incur a minimum of 143,000 bites to experience a blood loss of 1 L.3

The differential diagnosis for a patient with generalized pruritus should be broad and includes dermatologic conditions (eg, xerosis, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, urticaria, dermatophytosis, lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, scabies, pediculosis corporis and pubis, other arthropod bites, bullous pemphigoid), systemic disorders (eg, renal disease, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, cholestasis, human immunodeficiency virus), malignancy, connective tissue disease, medication side effects, and psychogenic and neuropathic itch.

The diagnosis of C lectularius infestation is confirmed by finding the wingless, reddish brown, flat and ovular arthropod, with adult lengths of 4 to 7 mm, approximately the size of an apple seed.5-11 Bedbugs typically are active at night and feed for 3 to 10 minutes. After their feed or during the day, bedbugs will return to their nest in furniture, mattresses, beds, walls, and floors. Bedbug bites appear as small clusters or lines of pruritic erythematous papules with a central hemorrhagic puncta. Other cutaneous symptoms include isolated pruritus, papules, nodules, and bullous eruptions.7 Additional signs of bedbug infestation include black fecal stains in areas of inhabitation as well as actual bedbugs feeding during the day due to overcrowding.

Treatment of pruritic localized cutaneous reactions is supportive and includes antipruritic agents, topical steroids, topical anesthetics, antihistamines, or topical or systemic antibiotics for secondary infections.5-11 Systemic reactions, including anaphylaxis, are treated with epinephrine, antihistamines, and/or corticosteroids, while severe anemia is treated supportively with blood transfusions and iron supplementation.5-11 To prevent reoccurrence, environmental control in the form of nonchemical and chemical treatments is crucial in controlling bedbug infestations.5-11

This case highlights the relevance of a rare but notable morbidity associated with bedbug infestation and the adverse effects of bedbugs on public health. This patient's living situation in a single-room occupancy hotel, poor hygiene, and possible cognitive impairment from his multiple medical conditions may have increased his risk for extreme bedbug infestation. With a good history, physical examination, proper inspection of the patient's belongings, and provider awareness of this epidemic, the severity of this patient's anemia may have been circumvented on the prior hospital admission and follow-up office visit. Once such an infestation is confirmed, a multidisciplinary approach including social work assistance, health services, and pest control is needed to appropriately treat the patient and the environment. Methods in preventing and managing this growing public health problem include improving hygiene, avoiding secondhand goods, and increasing awareness in the identification and proper elimination of bedbugs.5-7

To the Editor:

A 61-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a rash on the right leg, generalized pruritus, and chest pain. The patient described intermittent exertional pressure-like chest pain over the last few days but had no known prior cardiac history. He also noted worsening edema of the right leg with erythema. Three months prior he had been hospitalized for a similar presentation and was diagnosed with cellulitis of the right leg. The patient was treated with a course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and permethrin cream for presumed scabies and followed up with dermatology for the persistent generalized pruritic rash and cellulitis. At that time, he was diagnosed with stasis dermatitis with dermatitis neglecta and excoriations. He was educated on general hygiene and treated with triamcinolone, hydrophilic ointment, and pramoxine lotion for pruritus. He also was empirically treated again for scabies.

At the current presentation, preliminary investigation showed profound anemia with a hemoglobin level of 6.2 g/dL (baseline hemoglobin level 3 months prior, 13.1 g/dL). He was subsequently admitted to the general medicine ward for further investigation of severe symptomatic anemia. A medical history revealed moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, xerosis, and fracture of the right ankle following open reduction internal fixation 6 years prior to admission. There was no history of blood loss, antiplatelet agents, or anticoagulants. He was on disability and lived in a single-room occupancy hotel. He did not report any high-risk sexual behaviors or abuse of alcohol or drugs. He actively smoked 1.5 packs of cigarettes per day for the last 30 years. He denied any allergies.

Physical examination revealed the patient was afebrile, nontoxic, disheveled, and in no acute distress. He had anicteric sclera and pale conjunctiva. The right leg appeared more erythematous and edematous compared to the left leg but without warmth or tenderness to palpation. He had innumerable 4- to 5-mm, erythematous, excoriated papules on the skin (Figure). His bed sheets were noted to have multiple rusty-black specks thought to be related to the crusted lesions. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable.

Laboratory workup revealed severe iron-deficiency anemia without any evidence of hemolysis, marrow suppression, infection, or immune compromise (Table). He had a vitamin B12 deficiency (197 pg/mL [reference range, 239-931 pg/mL]), but we felt it was very unlikely to be responsible for his profound, sudden-onset microcytic anemia. Further evaluation for occult bleeding revealed an unremarkable upper endoscopy with push enteroscopy and colonoscopy. An alternate etiology of the anemia could not be identified.

Subsequently, he reported multiple pruritic bug bites sustained at the hotel room where he resided and continued to note pruritus while hospitalized. Pest control inspected the hospital room and identified bedbugs, Cimex lectularius, among his belongings. Upon further review, his clothes and walker were found to be completely infested with these organisms in different stages of development. Treatment included blood transfusions, iron supplementation, and environmental control of the infested living space both in the hospital and at his residence, with subsequent resolution of symptoms and anemia. Two weeks following discharge, the patient no longer reported pruritus, and his hemoglobin level had returned to baseline.

Over the last decade there has been an exponential resurgence in C lectularius infestations in developed countries attributed to increasing global travel, growing pesticide resistance, lack of public awareness, and inadequate pest control programs. This re-emergence has resulted in a public health problem. Although bedbugs are not known to transmit infectious diseases, severe infestation can result in notable dermatitis, iron-deficiency anemia from chronic blood loss, superinfection, allergic reactions including anaphylaxis in rare cases, and psychologic distress.

Iron-deficiency anemia caused by excessive bedbug biting in infants and children has been documented as early as the 1960s.1 Our knowledge of severe anemia due to bedbug infestation is limited to only 4 cases in the literature, according to a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms bedbugs anemia and cimex anemia.1-4 All cases reported bedbug infestations involving personal clothing, belongings, and/or living spaces. Patient concerns at presentation ranged from lethargy and fatigue with pruritic rash to chest pain and syncope with findings of severe microcytic or normocytic anemia (hemoglobin level, 5-8 g/dL). All cases were treated supportively with blood transfusion and iron supplementation, with hemoglobin recovery after several weeks. Environmental extermination also was required to prevent recurrence.1-4 Given that each bedbug blood meal is on average 7 mm3, one would have to incur a minimum of 143,000 bites to experience a blood loss of 1 L.3

The differential diagnosis for a patient with generalized pruritus should be broad and includes dermatologic conditions (eg, xerosis, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, urticaria, dermatophytosis, lichen simplex chronicus, psoriasis, scabies, pediculosis corporis and pubis, other arthropod bites, bullous pemphigoid), systemic disorders (eg, renal disease, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, cholestasis, human immunodeficiency virus), malignancy, connective tissue disease, medication side effects, and psychogenic and neuropathic itch.

The diagnosis of C lectularius infestation is confirmed by finding the wingless, reddish brown, flat and ovular arthropod, with adult lengths of 4 to 7 mm, approximately the size of an apple seed.5-11 Bedbugs typically are active at night and feed for 3 to 10 minutes. After their feed or during the day, bedbugs will return to their nest in furniture, mattresses, beds, walls, and floors. Bedbug bites appear as small clusters or lines of pruritic erythematous papules with a central hemorrhagic puncta. Other cutaneous symptoms include isolated pruritus, papules, nodules, and bullous eruptions.7 Additional signs of bedbug infestation include black fecal stains in areas of inhabitation as well as actual bedbugs feeding during the day due to overcrowding.

Treatment of pruritic localized cutaneous reactions is supportive and includes antipruritic agents, topical steroids, topical anesthetics, antihistamines, or topical or systemic antibiotics for secondary infections.5-11 Systemic reactions, including anaphylaxis, are treated with epinephrine, antihistamines, and/or corticosteroids, while severe anemia is treated supportively with blood transfusions and iron supplementation.5-11 To prevent reoccurrence, environmental control in the form of nonchemical and chemical treatments is crucial in controlling bedbug infestations.5-11

This case highlights the relevance of a rare but notable morbidity associated with bedbug infestation and the adverse effects of bedbugs on public health. This patient's living situation in a single-room occupancy hotel, poor hygiene, and possible cognitive impairment from his multiple medical conditions may have increased his risk for extreme bedbug infestation. With a good history, physical examination, proper inspection of the patient's belongings, and provider awareness of this epidemic, the severity of this patient's anemia may have been circumvented on the prior hospital admission and follow-up office visit. Once such an infestation is confirmed, a multidisciplinary approach including social work assistance, health services, and pest control is needed to appropriately treat the patient and the environment. Methods in preventing and managing this growing public health problem include improving hygiene, avoiding secondhand goods, and increasing awareness in the identification and proper elimination of bedbugs.5-7

- Venkatachalam PS, Belavady B. Loss of haemoglobin iron due to excessive biting by bed bugs. a possible aetiological factor in the iron deficiency anaemia of infants and children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1962;56:218-221.

- Pritchard MJ, Hwang SW. Severe anemia from bedbugs. CMAJ. 2009;181:287-288.

- Paulke-Korinek M, Széll M, Laferl H, et al. Bed bugs can cause severe anaemia in adults. Parasitol Res. 2012;110:2577-2579.

- Sabou M, Imperiale DG, Andrés E, et al. Bed bugs reproductive life cycle in the clothes of a patient suffering from Alzheimer's disease results in iron deficiency anemia. Parasite. 2013;20:16.

- Studdiford JS, Conniff KM, Trayes KP, et al. Bedbug infestation. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:653-658.

- Goddard J, deShazo R. Bed bugs (Cimex lectularis) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA. 2009;301:1358-1366.

- Bernardeschi C, Le Cleach L, Delaunay P, et al. Bed bug infestation. BMJ. 2013;346:f138.

- Silvia Munoz-Price L, Safdar N, Beier JC, et al. Bed bugs inhealthcare settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:1137-1142.

- Huntington MK. When bed bugs bite. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:384-388.

- Delaunay P, Blanc V, Del Giudice P, et al. Bedbugs and infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:200-212.

- Doggett SL, Dwyer DE, Penas PF, et al. Bed bugs: clinical relevance and control options. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:164-192.

- Venkatachalam PS, Belavady B. Loss of haemoglobin iron due to excessive biting by bed bugs. a possible aetiological factor in the iron deficiency anaemia of infants and children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1962;56:218-221.

- Pritchard MJ, Hwang SW. Severe anemia from bedbugs. CMAJ. 2009;181:287-288.

- Paulke-Korinek M, Széll M, Laferl H, et al. Bed bugs can cause severe anaemia in adults. Parasitol Res. 2012;110:2577-2579.

- Sabou M, Imperiale DG, Andrés E, et al. Bed bugs reproductive life cycle in the clothes of a patient suffering from Alzheimer's disease results in iron deficiency anemia. Parasite. 2013;20:16.

- Studdiford JS, Conniff KM, Trayes KP, et al. Bedbug infestation. Am Fam Physician. 2012;86:653-658.

- Goddard J, deShazo R. Bed bugs (Cimex lectularis) and clinical consequences of their bites. JAMA. 2009;301:1358-1366.

- Bernardeschi C, Le Cleach L, Delaunay P, et al. Bed bug infestation. BMJ. 2013;346:f138.

- Silvia Munoz-Price L, Safdar N, Beier JC, et al. Bed bugs inhealthcare settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33:1137-1142.

- Huntington MK. When bed bugs bite. J Fam Pract. 2012;61:384-388.

- Delaunay P, Blanc V, Del Giudice P, et al. Bedbugs and infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:200-212.

- Doggett SL, Dwyer DE, Penas PF, et al. Bed bugs: clinical relevance and control options. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:164-192.

Practice Points

- There has been a resurgence in bedbug (Cimex lectularius) infestations in developed countries.

- Although rare, anemia due to bedbug infestation should be considered in patients presenting with anemia and a widespread pruritic papular eruption.

- A thorough history and physical examination are essential to prevent a delay in diagnosis and avoid a costly and unnecessary workup.

- Successful treatment requires a multidisciplinary approach, which includes medical management, social services, and pest control.

Raynaud Phenomenon of the Nipple Successfully Treated With Nifedipine and Gabapentin

To the Editor:

Raynaud phenomenon is characterized by vasospasm of arterioles causing intermittent ischemia of the digits. The characteristic triphasic color change presents first as a dramatic change in skin color from normal to white, as the vasoconstriction causes pallor secondary to ischemia. This change is followed by a blue appearance, as cyanosis results from the deoxygenated venous blood. Finally, reflex vasodilation and reperfusion manifest as a red color from erythema. Several cases have been reported describing Raynaud phenomenon affecting the nipples of breastfeeding women.1-5 This vasospasm results in episodic nipple pain manifesting from breastfeeding and exposure to cold. If it is not appropriately treated, the pain’s severity causes affected women to stop breastfeeding. We report a case of vasospasm of the nipple in which the patient experienced nipple pain and a separate lancinating pain that radiated through the breasts.

A 36-year-old woman presented with excruciating nipple and breast pain 3 weeks after delivering her first child. She had no history of smoking or Raynaud phenomenon. The nipple pain was triggered upon breastfeeding and exposure to cold. During these episodes, the nipples would initially blanch white, then turn purple and finally a deep red. The patient also experienced an episodic excruciating lancinating pain of the breast that would randomly and spontaneously radiate through either breast several times per day for 15 to 30 seconds. A workup including an antinuclear antibody test, complete blood cell count with differential, and comprehensive metabolic panel all were within reference range.

The patient was diagnosed with nipple vasospasm. Partial relief of nipple pain occurred after treatment with 30 mg daily of nifedipine; 60 mg daily resulted in complete control, allowing the patient to breastfeed without discomfort, but the lancinating pain continued unabated. The patient could not discontinue breastfeeding because her child was intolerant to formula. She became despondent, as she could find no relief from the pain that she found to be intolerable. Because the patient’s description was reminiscent of the lancinating pain seen in postherpetic neuralgia, a trial of pregabalin was prescribed. A dosage of 75 mg twice daily resulted in near-complete resolution of the pain. After 3 months, the patient successfully weaned her child from breast milk to formula, and the nipple and breast pain promptly resolved. The baby experienced no adverse effects from the patient’s use of pregabalin.

This condition was first described by Gunther1 in 1970 as initial blanching of the nipple followed by a mulberry color. It was termed psychosomatic sore nipples.1 Lawlor-Smith and Lawlor-Smith2 described the condition in 1997 and termed it vasospasm of the nipple. They reported 5 patients who experienced debilitating nipple pain as well as the triphasic color change of Raynaud phenomenon or a biphasic color change (white and blue). Two patients had a history of Raynaud phenomenon affecting the digits before their first pregnancy.2 Anderson et al3 presented 12 breastfeeding women with Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple; only 1 patient had a history of Raynaud phenomenon. In this series, all 6 women who chose to try nifedipine responded well to the drug.3

Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple also has been reported to be associated with the use of labetalol.4 In this case, the patient had a history of Raynaud phenomenon affecting the toes and nipples on cold days. In 2 subsequent pregnancies she was treated with labetalol for pregnancy-induced hypertension, which resulted in severe nipple pain with each pregnancy unrelated to cold weather. Unlike other cases, this patient experienced antenatal symptoms in addition to the typical postnatal symptoms. The nipple pain resolved with discontinuation of the labetalol.4

Barrett et al5 conducted a retrospective review of medical records of 88 breastfeeding mothers who presented with nipple pain and dermatitis. They defined the criteria for Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple as chronic deep breast pain (in general lasting >4 weeks) that responded to therapy for the condition and had at least 2 of the following characteristics: (1) observed or self-reported color changes of the nipple, especially with cold exposure (white, blue, or red); (2) cold sensitivity or color changes of the hands or feet with cold exposure; or (3) failed therapy with oral antifungals. Using these criteria, they diagnosed 22 women (25%) with Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple; 20 (91%) reported a history of cold sensitivity or color change of acral surfaces. Of 12 patients who received and tolerated nifedipine use, 10 (83%) reported decreased pain or complete resolution. This series described breast or nipple pain, whereas other reported cases only described nipple pain. The authors described a sharp, shooting, or stabbing pain—qualifications not previously noted.5 Our patient experienced both nipple pain and a lancinating breast pain consistent with the cases reported by Barrett et al.5

The nipple pain and treatment response in our patient was typical of previously reported cases of vasospasm of the nipple in breastfeeding women; however, Barrett et al5 did not describe individual patients who exhibited the dual nature of the pain described in our patient. The nipple pain experienced during breastfeeding in our patient was successfully treated with nifedipine. We report the successful treatment of the separate lancinating pain with pregabalin.

- Gunther M. Infant Feeding. London, United Kingdom: Methuen; 1970.

- Lawlor-Smith L, Lawlor-Smith C. Vasospasm of the nipple—a manifestation of Raynaud’s phenomenon: case reports. BMJ. 1997;314:644-645.

- Anderson JE, Held N, Wright K. Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple: a treatable cause of painful breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2004;113:360-364.

- McGuinness N, Cording V. Raynaud’s phenomenon of the nipple associated with labetalol use. J Hum Lact. 2013;29:17-19.

- Barrett ME, Heller MM, Stone HF, et al. Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple in breastfeeding mothers: an underdiagnosed cause of nipple pain. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:300-306.

To the Editor:

Raynaud phenomenon is characterized by vasospasm of arterioles causing intermittent ischemia of the digits. The characteristic triphasic color change presents first as a dramatic change in skin color from normal to white, as the vasoconstriction causes pallor secondary to ischemia. This change is followed by a blue appearance, as cyanosis results from the deoxygenated venous blood. Finally, reflex vasodilation and reperfusion manifest as a red color from erythema. Several cases have been reported describing Raynaud phenomenon affecting the nipples of breastfeeding women.1-5 This vasospasm results in episodic nipple pain manifesting from breastfeeding and exposure to cold. If it is not appropriately treated, the pain’s severity causes affected women to stop breastfeeding. We report a case of vasospasm of the nipple in which the patient experienced nipple pain and a separate lancinating pain that radiated through the breasts.

A 36-year-old woman presented with excruciating nipple and breast pain 3 weeks after delivering her first child. She had no history of smoking or Raynaud phenomenon. The nipple pain was triggered upon breastfeeding and exposure to cold. During these episodes, the nipples would initially blanch white, then turn purple and finally a deep red. The patient also experienced an episodic excruciating lancinating pain of the breast that would randomly and spontaneously radiate through either breast several times per day for 15 to 30 seconds. A workup including an antinuclear antibody test, complete blood cell count with differential, and comprehensive metabolic panel all were within reference range.

The patient was diagnosed with nipple vasospasm. Partial relief of nipple pain occurred after treatment with 30 mg daily of nifedipine; 60 mg daily resulted in complete control, allowing the patient to breastfeed without discomfort, but the lancinating pain continued unabated. The patient could not discontinue breastfeeding because her child was intolerant to formula. She became despondent, as she could find no relief from the pain that she found to be intolerable. Because the patient’s description was reminiscent of the lancinating pain seen in postherpetic neuralgia, a trial of pregabalin was prescribed. A dosage of 75 mg twice daily resulted in near-complete resolution of the pain. After 3 months, the patient successfully weaned her child from breast milk to formula, and the nipple and breast pain promptly resolved. The baby experienced no adverse effects from the patient’s use of pregabalin.

This condition was first described by Gunther1 in 1970 as initial blanching of the nipple followed by a mulberry color. It was termed psychosomatic sore nipples.1 Lawlor-Smith and Lawlor-Smith2 described the condition in 1997 and termed it vasospasm of the nipple. They reported 5 patients who experienced debilitating nipple pain as well as the triphasic color change of Raynaud phenomenon or a biphasic color change (white and blue). Two patients had a history of Raynaud phenomenon affecting the digits before their first pregnancy.2 Anderson et al3 presented 12 breastfeeding women with Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple; only 1 patient had a history of Raynaud phenomenon. In this series, all 6 women who chose to try nifedipine responded well to the drug.3

Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple also has been reported to be associated with the use of labetalol.4 In this case, the patient had a history of Raynaud phenomenon affecting the toes and nipples on cold days. In 2 subsequent pregnancies she was treated with labetalol for pregnancy-induced hypertension, which resulted in severe nipple pain with each pregnancy unrelated to cold weather. Unlike other cases, this patient experienced antenatal symptoms in addition to the typical postnatal symptoms. The nipple pain resolved with discontinuation of the labetalol.4

Barrett et al5 conducted a retrospective review of medical records of 88 breastfeeding mothers who presented with nipple pain and dermatitis. They defined the criteria for Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple as chronic deep breast pain (in general lasting >4 weeks) that responded to therapy for the condition and had at least 2 of the following characteristics: (1) observed or self-reported color changes of the nipple, especially with cold exposure (white, blue, or red); (2) cold sensitivity or color changes of the hands or feet with cold exposure; or (3) failed therapy with oral antifungals. Using these criteria, they diagnosed 22 women (25%) with Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple; 20 (91%) reported a history of cold sensitivity or color change of acral surfaces. Of 12 patients who received and tolerated nifedipine use, 10 (83%) reported decreased pain or complete resolution. This series described breast or nipple pain, whereas other reported cases only described nipple pain. The authors described a sharp, shooting, or stabbing pain—qualifications not previously noted.5 Our patient experienced both nipple pain and a lancinating breast pain consistent with the cases reported by Barrett et al.5

The nipple pain and treatment response in our patient was typical of previously reported cases of vasospasm of the nipple in breastfeeding women; however, Barrett et al5 did not describe individual patients who exhibited the dual nature of the pain described in our patient. The nipple pain experienced during breastfeeding in our patient was successfully treated with nifedipine. We report the successful treatment of the separate lancinating pain with pregabalin.

To the Editor:

Raynaud phenomenon is characterized by vasospasm of arterioles causing intermittent ischemia of the digits. The characteristic triphasic color change presents first as a dramatic change in skin color from normal to white, as the vasoconstriction causes pallor secondary to ischemia. This change is followed by a blue appearance, as cyanosis results from the deoxygenated venous blood. Finally, reflex vasodilation and reperfusion manifest as a red color from erythema. Several cases have been reported describing Raynaud phenomenon affecting the nipples of breastfeeding women.1-5 This vasospasm results in episodic nipple pain manifesting from breastfeeding and exposure to cold. If it is not appropriately treated, the pain’s severity causes affected women to stop breastfeeding. We report a case of vasospasm of the nipple in which the patient experienced nipple pain and a separate lancinating pain that radiated through the breasts.

A 36-year-old woman presented with excruciating nipple and breast pain 3 weeks after delivering her first child. She had no history of smoking or Raynaud phenomenon. The nipple pain was triggered upon breastfeeding and exposure to cold. During these episodes, the nipples would initially blanch white, then turn purple and finally a deep red. The patient also experienced an episodic excruciating lancinating pain of the breast that would randomly and spontaneously radiate through either breast several times per day for 15 to 30 seconds. A workup including an antinuclear antibody test, complete blood cell count with differential, and comprehensive metabolic panel all were within reference range.

The patient was diagnosed with nipple vasospasm. Partial relief of nipple pain occurred after treatment with 30 mg daily of nifedipine; 60 mg daily resulted in complete control, allowing the patient to breastfeed without discomfort, but the lancinating pain continued unabated. The patient could not discontinue breastfeeding because her child was intolerant to formula. She became despondent, as she could find no relief from the pain that she found to be intolerable. Because the patient’s description was reminiscent of the lancinating pain seen in postherpetic neuralgia, a trial of pregabalin was prescribed. A dosage of 75 mg twice daily resulted in near-complete resolution of the pain. After 3 months, the patient successfully weaned her child from breast milk to formula, and the nipple and breast pain promptly resolved. The baby experienced no adverse effects from the patient’s use of pregabalin.

This condition was first described by Gunther1 in 1970 as initial blanching of the nipple followed by a mulberry color. It was termed psychosomatic sore nipples.1 Lawlor-Smith and Lawlor-Smith2 described the condition in 1997 and termed it vasospasm of the nipple. They reported 5 patients who experienced debilitating nipple pain as well as the triphasic color change of Raynaud phenomenon or a biphasic color change (white and blue). Two patients had a history of Raynaud phenomenon affecting the digits before their first pregnancy.2 Anderson et al3 presented 12 breastfeeding women with Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple; only 1 patient had a history of Raynaud phenomenon. In this series, all 6 women who chose to try nifedipine responded well to the drug.3

Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple also has been reported to be associated with the use of labetalol.4 In this case, the patient had a history of Raynaud phenomenon affecting the toes and nipples on cold days. In 2 subsequent pregnancies she was treated with labetalol for pregnancy-induced hypertension, which resulted in severe nipple pain with each pregnancy unrelated to cold weather. Unlike other cases, this patient experienced antenatal symptoms in addition to the typical postnatal symptoms. The nipple pain resolved with discontinuation of the labetalol.4

Barrett et al5 conducted a retrospective review of medical records of 88 breastfeeding mothers who presented with nipple pain and dermatitis. They defined the criteria for Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple as chronic deep breast pain (in general lasting >4 weeks) that responded to therapy for the condition and had at least 2 of the following characteristics: (1) observed or self-reported color changes of the nipple, especially with cold exposure (white, blue, or red); (2) cold sensitivity or color changes of the hands or feet with cold exposure; or (3) failed therapy with oral antifungals. Using these criteria, they diagnosed 22 women (25%) with Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple; 20 (91%) reported a history of cold sensitivity or color change of acral surfaces. Of 12 patients who received and tolerated nifedipine use, 10 (83%) reported decreased pain or complete resolution. This series described breast or nipple pain, whereas other reported cases only described nipple pain. The authors described a sharp, shooting, or stabbing pain—qualifications not previously noted.5 Our patient experienced both nipple pain and a lancinating breast pain consistent with the cases reported by Barrett et al.5

The nipple pain and treatment response in our patient was typical of previously reported cases of vasospasm of the nipple in breastfeeding women; however, Barrett et al5 did not describe individual patients who exhibited the dual nature of the pain described in our patient. The nipple pain experienced during breastfeeding in our patient was successfully treated with nifedipine. We report the successful treatment of the separate lancinating pain with pregabalin.

- Gunther M. Infant Feeding. London, United Kingdom: Methuen; 1970.

- Lawlor-Smith L, Lawlor-Smith C. Vasospasm of the nipple—a manifestation of Raynaud’s phenomenon: case reports. BMJ. 1997;314:644-645.

- Anderson JE, Held N, Wright K. Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple: a treatable cause of painful breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2004;113:360-364.

- McGuinness N, Cording V. Raynaud’s phenomenon of the nipple associated with labetalol use. J Hum Lact. 2013;29:17-19.

- Barrett ME, Heller MM, Stone HF, et al. Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple in breastfeeding mothers: an underdiagnosed cause of nipple pain. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:300-306.

- Gunther M. Infant Feeding. London, United Kingdom: Methuen; 1970.

- Lawlor-Smith L, Lawlor-Smith C. Vasospasm of the nipple—a manifestation of Raynaud’s phenomenon: case reports. BMJ. 1997;314:644-645.

- Anderson JE, Held N, Wright K. Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple: a treatable cause of painful breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2004;113:360-364.

- McGuinness N, Cording V. Raynaud’s phenomenon of the nipple associated with labetalol use. J Hum Lact. 2013;29:17-19.

- Barrett ME, Heller MM, Stone HF, et al. Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple in breastfeeding mothers: an underdiagnosed cause of nipple pain. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:300-306.

Practice Points

- Raynaud phenomenon of the nipple may be accompanied by lancinating pain of the breast in addition to nipple pain reminiscent of postherpetic neuralgia.

- Associated breast pain is particularly distressing for breastfeeding women, particularly primiparous mothers with children intolerant to formula.

- In women with Raynaud phenomenon accompanied by lancinating breast pain, consider a trial of pregabalin.

Radiation Recall Dermatitis Triggered by Prednisone

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman presented to the allergy clinic for evaluation of a rash on the left breast. The patient had a history of breast cancer that was treated with a lumpectomy followed by external beam radiation therapy (total dose, 6000 cGy) to the lateral aspect of the left breast approximately 4 years prior. She developed acute breast dermatitis from the radiation, which was self-treated with over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream. The patient subsequently developed a blistering skin eruption over the area where she applied the cream. She did not recall the subtype of hydrocortisone she used (butyrate and acetate are available over-the-counter). She discontinued the hydrocortisone and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1%, which was well tolerated, and the rash resolved.

The patient had a history of a similar reaction to hydrocortisone butyrate after blepharoplasty approximately 10 years prior to the current presentation, characterized by facial erythema, pruritus, and blistering. A patch test confirmed reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and tixocortol pivalate. However, a skin-prick test for hydrocortisone acetate cream 1% was negative.

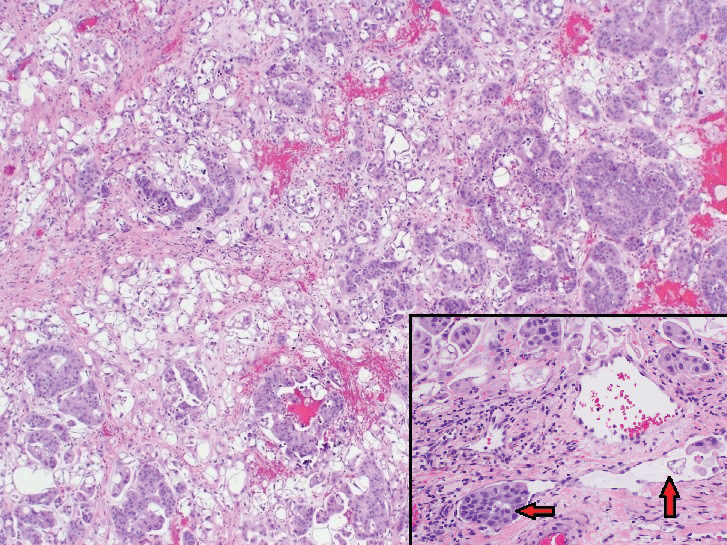

Subsequently, the patient developed acute-onset dyspepsia, gnawing epigastric pain, regurgitation, and bloating. A diagnosis of eosinophilic gastritis was established via biopsy, which found increased eosinophils in the lamina propria (>50 eosinophils per high-power field). Helicobacter pylori was not identified. She was started on the proton-pump inhibitor dexlansoprazole but symptoms did not improve. Her other medications included benazepril, alprazolam as needed, vitamin D, and magnesium. The patient subsequently was started on a trial of oral prednisone 40 mg/d. Three days after initiation, she developed an erythematous macular rash over the left breast.

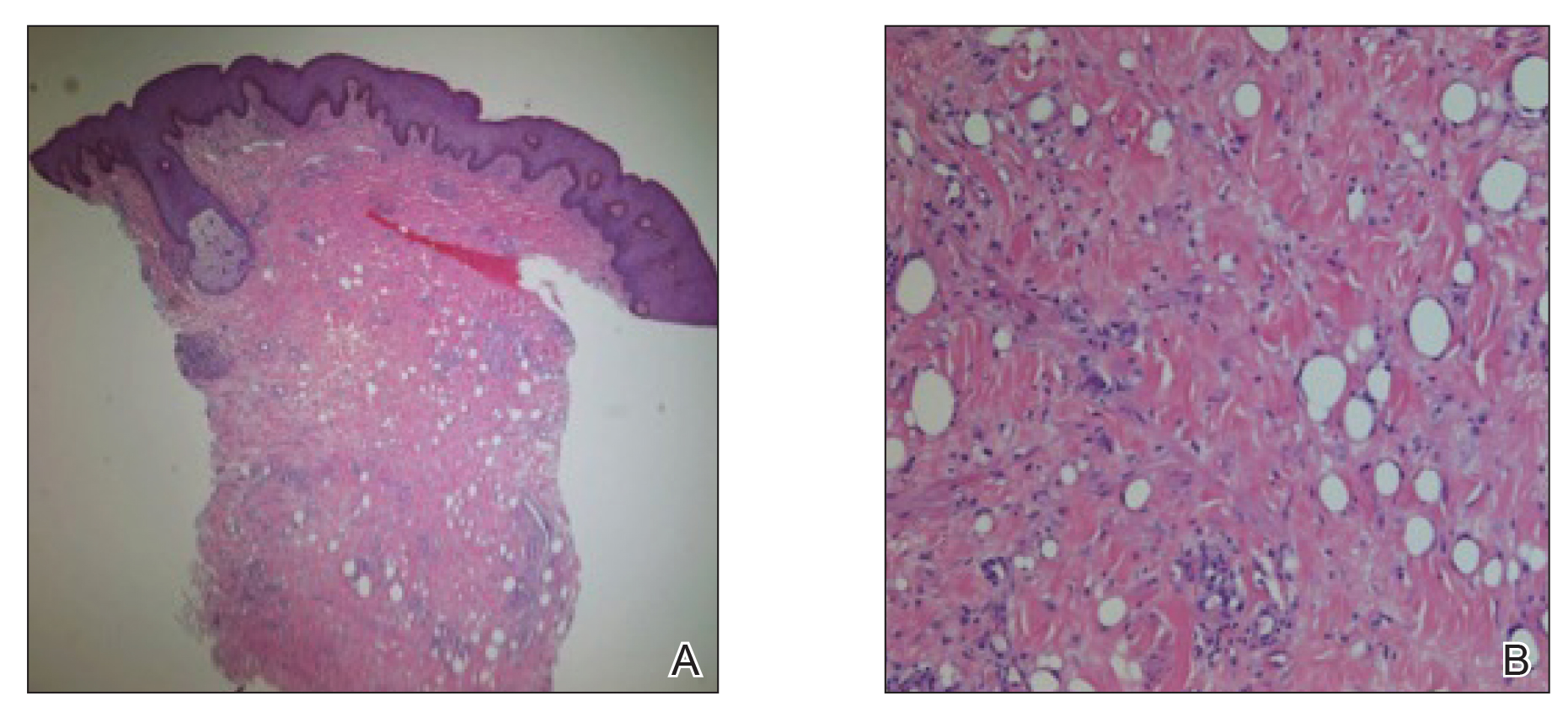

The next day she presented to the allergy clinic. Physical examination of the left breast revealed a 20×10-cm, nipple-sparing patch of well-demarcated erythema without fluctuance or overlying lesions. The area of erythema overlapped with the prior radiation field based on radiation marker tattoos and the lumpectomy scar (Figure). There was no evidence to suggest inflammation of deeper tissue or the pectoral muscles. Vital signs were normal, and the remainder of the examination was unremarkable, including breast, lymph node, and complete skin examinations.

At evaluation, the differential diagnosis included contact dermatitis, fixed drug eruption, infection, tumor recurrence with overlying skin changes, and radiation recall dermatitis. Given that the dermatitis had developed at the site of previously irradiated skin in the absence of fever or an associated mass, the presentation was thought to be most consistent with radiation recall dermatitis.

Oral prednisone was discontinued, and the dermatitis spontaneously improved in a few weeks. Given the patient’s test results and prior tolerance to triamcinolone, eosinophilic gastroenteritis was treated with triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg via intramuscular injection, which was well tolerated.

Radiation recall dermatitis is an acute inflammatory reaction over an area of skin that was previously irradiated. It is most often triggered by chemotherapy agents and occurs in as many as 9% of patients who receive chemotherapy after radiation.1 Commonly implicated chemotherapy agents include anthracyclines, taxanes, antimetabolites, and alkylating agents. Newer targeted cancer treatments also have been reported to trigger radiation recall dermatitis, including epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors, and anti–programmed cell death protein 1 monoclonal antibodies.2-5 Radiation recall dermatitis also has been reported to be triggered by intravenous contrast dye.6

The clinical presentation of radiation recall dermatitis ranges from mild rash to skin necrosis and desquamation. Patients often report pruritus or pain in the affected area. The US National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) includes a 5-point scale for grading the severity of radiation recall dermatitis: grade 1, faint erythema or dry desquamation; grade 2, moderate to brisk erythema or patchy moist desquamation, mostly confined to skin folds and creases; grade 3, moist desquamation in areas other than skin folds and creases, with bleeding induced by minor trauma or abrasion; grade 4, skin necrosis or ulceration of full-thickness dermis, with spontaneous bleeding; grade 5, death.7 Based on these criteria, our patient had grade 2 radiation recall dermatitis.

In addition to cutaneous inflammation, additional sites can be inflamed, including the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and oral mucosa. Cases of myocarditis, sialadenitis, and cystitis also have been reported.⁷

Radiation recall dermatitis can occur even if dermatitis did not occur upon initial treatment. The inflammatory reaction can occur weeks or years after initial irradiation. A study evaluating targeted chemotherapy agents found the median time from initiation of chemotherapy to radiation recall dermatitis was 16.9 weeks (range, 1–86.9 weeks). Inflammation usually lasts approximately 1 to 2 weeks but has been reported to persist as long as 14 weeks.8 Withdrawal of the offending agent in addition to administration of corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents typically results in clinical improvement. Histology on skin biopsy is nonspecific and can reveal mixed infiltrates.7

The pathophysiology of radiation recall dermatitis remains unknown; the condition might be an idiosyncratic drug reaction. It has been hypothesized that prior radiation lowers the threshold for an inflammatory reaction, an example of Ruocco immunocompromised cutaneous districts, in which a prior injury at a cutaneous site increases the likelihood of opportunistic infection, tumor, and immune reactions.9 Because radiation can induce expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, platelet-derived growth factor β, and tumor necrosis factor α, cells in irradiated areas can continue to secrete low levels of these cytokines after radiation therapy, thus priming an inflammatory reaction in the future.10 An alternative theory is that radiation induces mutations within surviving stem cells, rendering them unable to tolerate or unusually sensitive to subsequent chemotherapy and cytotoxic drugs. However, this premise would not explain how noncytotoxic drugs also can trigger radiation recall dermatitis, as described in our case.11

Prednisone-triggered radiation recall dermatitis is curious, as corticosteroids are used to treat the condition. Corticosteroids are classified by their chemical structure, and patch testing can be used to distinguish allergies across the various classes. Hydrocortisone acetate,

In contrast, triamcinolone is a class B steroid, which has a C16,17-cis-diol or -ketal. Other than budesonide, which can cross-react with D2 steroids, class B steroids do not cross-react with hydrocortisone or prednisone. Triamcinolone does not usually cross-react with D2 corticosteroids, which likely explains why our patient was later able to tolerate triamcinolone to treat eosinophilic gastrointestinal tract disease.

In summary, we present a case of radiation recall dermatitis triggered by prednisone. Radiation can prime an area for a future inflammatory response by upregulating proinflammatory cytokines or triggering stem cell mutation. In our case, clinical reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and sensitization to tixocortol pivalate via patch testing could have increased the likelihood of a reaction with prednisone use due to cross-reactivity. This case instructs dermatologists, allergists, and oncologists to be aware of prednisone as a potential trigger of radiation recall dermatitis.

- Kodym E, Kalinska R, Ehringfeld C, et al. Frequency of radiation recall dermatitis in adult cancer patients. Onkologie. 2005;28:18-21.

- Seidel C, Janssen S, Karstens JH, et al. Recall pneumonitis during systemic treatment with sunitinib. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2119-2120.

- Togashi Y, Masago K, Mishima M, et al. A case of radiation recall pneumonitis induced by erlotinib, which can be related to high plasma concentration. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:924-925.

- Bourgier C, Massard C, Moldovan C, et al. Total recall of radiotherapy with mTOR inhibitors: a novel and potentially frequent side-effect? Ann Oncol. 2011;22:485-486.

- Korman AM, Tyler KH, Kaffenberger BH. Radiation recall dermatitis associated with nivolumab for metastatic malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e75-e77.

- Lau SKM, Rahimi A. Radiation recall precipitated by iodinated nonionic contrast. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2015;5:263-266.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic

_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf. Published November 27, 2017. Accessed June 10, 2020.] - Levy A, Hollebecque A, Bourgier C, et al. Targeted therapy-induced radiation recall. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1662-1668.

- Piccolo V, Baroni A, Russo T, et al. Ruocco’s immunocompromised cutaneous district. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:135-141.

- Johnson CJ, Piedboeuf P, Rubin P, et al. Early and persistent alterations in the expression of interleukin-1 alpha, interleukin-1 beta and tumour necrosis factor alpha mRNA levels in fibrosis-resistant and sensitive mice after thoracic irradiation. Radiat Res. 1996;145:762-767.

- Azira D, Magné N, Zouhair A, et al. Radiation recall: a well recognized but neglected phenomenon. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:555-570.

- Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: a quick reference guide including patch test substances and cross-reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723-727.

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman presented to the allergy clinic for evaluation of a rash on the left breast. The patient had a history of breast cancer that was treated with a lumpectomy followed by external beam radiation therapy (total dose, 6000 cGy) to the lateral aspect of the left breast approximately 4 years prior. She developed acute breast dermatitis from the radiation, which was self-treated with over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream. The patient subsequently developed a blistering skin eruption over the area where she applied the cream. She did not recall the subtype of hydrocortisone she used (butyrate and acetate are available over-the-counter). She discontinued the hydrocortisone and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1%, which was well tolerated, and the rash resolved.

The patient had a history of a similar reaction to hydrocortisone butyrate after blepharoplasty approximately 10 years prior to the current presentation, characterized by facial erythema, pruritus, and blistering. A patch test confirmed reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and tixocortol pivalate. However, a skin-prick test for hydrocortisone acetate cream 1% was negative.

Subsequently, the patient developed acute-onset dyspepsia, gnawing epigastric pain, regurgitation, and bloating. A diagnosis of eosinophilic gastritis was established via biopsy, which found increased eosinophils in the lamina propria (>50 eosinophils per high-power field). Helicobacter pylori was not identified. She was started on the proton-pump inhibitor dexlansoprazole but symptoms did not improve. Her other medications included benazepril, alprazolam as needed, vitamin D, and magnesium. The patient subsequently was started on a trial of oral prednisone 40 mg/d. Three days after initiation, she developed an erythematous macular rash over the left breast.

The next day she presented to the allergy clinic. Physical examination of the left breast revealed a 20×10-cm, nipple-sparing patch of well-demarcated erythema without fluctuance or overlying lesions. The area of erythema overlapped with the prior radiation field based on radiation marker tattoos and the lumpectomy scar (Figure). There was no evidence to suggest inflammation of deeper tissue or the pectoral muscles. Vital signs were normal, and the remainder of the examination was unremarkable, including breast, lymph node, and complete skin examinations.

At evaluation, the differential diagnosis included contact dermatitis, fixed drug eruption, infection, tumor recurrence with overlying skin changes, and radiation recall dermatitis. Given that the dermatitis had developed at the site of previously irradiated skin in the absence of fever or an associated mass, the presentation was thought to be most consistent with radiation recall dermatitis.

Oral prednisone was discontinued, and the dermatitis spontaneously improved in a few weeks. Given the patient’s test results and prior tolerance to triamcinolone, eosinophilic gastroenteritis was treated with triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg via intramuscular injection, which was well tolerated.

Radiation recall dermatitis is an acute inflammatory reaction over an area of skin that was previously irradiated. It is most often triggered by chemotherapy agents and occurs in as many as 9% of patients who receive chemotherapy after radiation.1 Commonly implicated chemotherapy agents include anthracyclines, taxanes, antimetabolites, and alkylating agents. Newer targeted cancer treatments also have been reported to trigger radiation recall dermatitis, including epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors, and anti–programmed cell death protein 1 monoclonal antibodies.2-5 Radiation recall dermatitis also has been reported to be triggered by intravenous contrast dye.6

The clinical presentation of radiation recall dermatitis ranges from mild rash to skin necrosis and desquamation. Patients often report pruritus or pain in the affected area. The US National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) includes a 5-point scale for grading the severity of radiation recall dermatitis: grade 1, faint erythema or dry desquamation; grade 2, moderate to brisk erythema or patchy moist desquamation, mostly confined to skin folds and creases; grade 3, moist desquamation in areas other than skin folds and creases, with bleeding induced by minor trauma or abrasion; grade 4, skin necrosis or ulceration of full-thickness dermis, with spontaneous bleeding; grade 5, death.7 Based on these criteria, our patient had grade 2 radiation recall dermatitis.

In addition to cutaneous inflammation, additional sites can be inflamed, including the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and oral mucosa. Cases of myocarditis, sialadenitis, and cystitis also have been reported.⁷

Radiation recall dermatitis can occur even if dermatitis did not occur upon initial treatment. The inflammatory reaction can occur weeks or years after initial irradiation. A study evaluating targeted chemotherapy agents found the median time from initiation of chemotherapy to radiation recall dermatitis was 16.9 weeks (range, 1–86.9 weeks). Inflammation usually lasts approximately 1 to 2 weeks but has been reported to persist as long as 14 weeks.8 Withdrawal of the offending agent in addition to administration of corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents typically results in clinical improvement. Histology on skin biopsy is nonspecific and can reveal mixed infiltrates.7

The pathophysiology of radiation recall dermatitis remains unknown; the condition might be an idiosyncratic drug reaction. It has been hypothesized that prior radiation lowers the threshold for an inflammatory reaction, an example of Ruocco immunocompromised cutaneous districts, in which a prior injury at a cutaneous site increases the likelihood of opportunistic infection, tumor, and immune reactions.9 Because radiation can induce expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, platelet-derived growth factor β, and tumor necrosis factor α, cells in irradiated areas can continue to secrete low levels of these cytokines after radiation therapy, thus priming an inflammatory reaction in the future.10 An alternative theory is that radiation induces mutations within surviving stem cells, rendering them unable to tolerate or unusually sensitive to subsequent chemotherapy and cytotoxic drugs. However, this premise would not explain how noncytotoxic drugs also can trigger radiation recall dermatitis, as described in our case.11

Prednisone-triggered radiation recall dermatitis is curious, as corticosteroids are used to treat the condition. Corticosteroids are classified by their chemical structure, and patch testing can be used to distinguish allergies across the various classes. Hydrocortisone acetate,

In contrast, triamcinolone is a class B steroid, which has a C16,17-cis-diol or -ketal. Other than budesonide, which can cross-react with D2 steroids, class B steroids do not cross-react with hydrocortisone or prednisone. Triamcinolone does not usually cross-react with D2 corticosteroids, which likely explains why our patient was later able to tolerate triamcinolone to treat eosinophilic gastrointestinal tract disease.

In summary, we present a case of radiation recall dermatitis triggered by prednisone. Radiation can prime an area for a future inflammatory response by upregulating proinflammatory cytokines or triggering stem cell mutation. In our case, clinical reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and sensitization to tixocortol pivalate via patch testing could have increased the likelihood of a reaction with prednisone use due to cross-reactivity. This case instructs dermatologists, allergists, and oncologists to be aware of prednisone as a potential trigger of radiation recall dermatitis.

To the Editor:

A 69-year-old woman presented to the allergy clinic for evaluation of a rash on the left breast. The patient had a history of breast cancer that was treated with a lumpectomy followed by external beam radiation therapy (total dose, 6000 cGy) to the lateral aspect of the left breast approximately 4 years prior. She developed acute breast dermatitis from the radiation, which was self-treated with over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream. The patient subsequently developed a blistering skin eruption over the area where she applied the cream. She did not recall the subtype of hydrocortisone she used (butyrate and acetate are available over-the-counter). She discontinued the hydrocortisone and was started on triamcinolone cream 0.1%, which was well tolerated, and the rash resolved.

The patient had a history of a similar reaction to hydrocortisone butyrate after blepharoplasty approximately 10 years prior to the current presentation, characterized by facial erythema, pruritus, and blistering. A patch test confirmed reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and tixocortol pivalate. However, a skin-prick test for hydrocortisone acetate cream 1% was negative.

Subsequently, the patient developed acute-onset dyspepsia, gnawing epigastric pain, regurgitation, and bloating. A diagnosis of eosinophilic gastritis was established via biopsy, which found increased eosinophils in the lamina propria (>50 eosinophils per high-power field). Helicobacter pylori was not identified. She was started on the proton-pump inhibitor dexlansoprazole but symptoms did not improve. Her other medications included benazepril, alprazolam as needed, vitamin D, and magnesium. The patient subsequently was started on a trial of oral prednisone 40 mg/d. Three days after initiation, she developed an erythematous macular rash over the left breast.

The next day she presented to the allergy clinic. Physical examination of the left breast revealed a 20×10-cm, nipple-sparing patch of well-demarcated erythema without fluctuance or overlying lesions. The area of erythema overlapped with the prior radiation field based on radiation marker tattoos and the lumpectomy scar (Figure). There was no evidence to suggest inflammation of deeper tissue or the pectoral muscles. Vital signs were normal, and the remainder of the examination was unremarkable, including breast, lymph node, and complete skin examinations.

At evaluation, the differential diagnosis included contact dermatitis, fixed drug eruption, infection, tumor recurrence with overlying skin changes, and radiation recall dermatitis. Given that the dermatitis had developed at the site of previously irradiated skin in the absence of fever or an associated mass, the presentation was thought to be most consistent with radiation recall dermatitis.

Oral prednisone was discontinued, and the dermatitis spontaneously improved in a few weeks. Given the patient’s test results and prior tolerance to triamcinolone, eosinophilic gastroenteritis was treated with triamcinolone acetonide 40 mg via intramuscular injection, which was well tolerated.

Radiation recall dermatitis is an acute inflammatory reaction over an area of skin that was previously irradiated. It is most often triggered by chemotherapy agents and occurs in as many as 9% of patients who receive chemotherapy after radiation.1 Commonly implicated chemotherapy agents include anthracyclines, taxanes, antimetabolites, and alkylating agents. Newer targeted cancer treatments also have been reported to trigger radiation recall dermatitis, including epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitors, mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors, and anti–programmed cell death protein 1 monoclonal antibodies.2-5 Radiation recall dermatitis also has been reported to be triggered by intravenous contrast dye.6

The clinical presentation of radiation recall dermatitis ranges from mild rash to skin necrosis and desquamation. Patients often report pruritus or pain in the affected area. The US National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) includes a 5-point scale for grading the severity of radiation recall dermatitis: grade 1, faint erythema or dry desquamation; grade 2, moderate to brisk erythema or patchy moist desquamation, mostly confined to skin folds and creases; grade 3, moist desquamation in areas other than skin folds and creases, with bleeding induced by minor trauma or abrasion; grade 4, skin necrosis or ulceration of full-thickness dermis, with spontaneous bleeding; grade 5, death.7 Based on these criteria, our patient had grade 2 radiation recall dermatitis.

In addition to cutaneous inflammation, additional sites can be inflamed, including the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, and oral mucosa. Cases of myocarditis, sialadenitis, and cystitis also have been reported.⁷

Radiation recall dermatitis can occur even if dermatitis did not occur upon initial treatment. The inflammatory reaction can occur weeks or years after initial irradiation. A study evaluating targeted chemotherapy agents found the median time from initiation of chemotherapy to radiation recall dermatitis was 16.9 weeks (range, 1–86.9 weeks). Inflammation usually lasts approximately 1 to 2 weeks but has been reported to persist as long as 14 weeks.8 Withdrawal of the offending agent in addition to administration of corticosteroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents typically results in clinical improvement. Histology on skin biopsy is nonspecific and can reveal mixed infiltrates.7

The pathophysiology of radiation recall dermatitis remains unknown; the condition might be an idiosyncratic drug reaction. It has been hypothesized that prior radiation lowers the threshold for an inflammatory reaction, an example of Ruocco immunocompromised cutaneous districts, in which a prior injury at a cutaneous site increases the likelihood of opportunistic infection, tumor, and immune reactions.9 Because radiation can induce expression of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, platelet-derived growth factor β, and tumor necrosis factor α, cells in irradiated areas can continue to secrete low levels of these cytokines after radiation therapy, thus priming an inflammatory reaction in the future.10 An alternative theory is that radiation induces mutations within surviving stem cells, rendering them unable to tolerate or unusually sensitive to subsequent chemotherapy and cytotoxic drugs. However, this premise would not explain how noncytotoxic drugs also can trigger radiation recall dermatitis, as described in our case.11

Prednisone-triggered radiation recall dermatitis is curious, as corticosteroids are used to treat the condition. Corticosteroids are classified by their chemical structure, and patch testing can be used to distinguish allergies across the various classes. Hydrocortisone acetate,

In contrast, triamcinolone is a class B steroid, which has a C16,17-cis-diol or -ketal. Other than budesonide, which can cross-react with D2 steroids, class B steroids do not cross-react with hydrocortisone or prednisone. Triamcinolone does not usually cross-react with D2 corticosteroids, which likely explains why our patient was later able to tolerate triamcinolone to treat eosinophilic gastrointestinal tract disease.

In summary, we present a case of radiation recall dermatitis triggered by prednisone. Radiation can prime an area for a future inflammatory response by upregulating proinflammatory cytokines or triggering stem cell mutation. In our case, clinical reactivity to hydrocortisone-17-butyrate and sensitization to tixocortol pivalate via patch testing could have increased the likelihood of a reaction with prednisone use due to cross-reactivity. This case instructs dermatologists, allergists, and oncologists to be aware of prednisone as a potential trigger of radiation recall dermatitis.

- Kodym E, Kalinska R, Ehringfeld C, et al. Frequency of radiation recall dermatitis in adult cancer patients. Onkologie. 2005;28:18-21.

- Seidel C, Janssen S, Karstens JH, et al. Recall pneumonitis during systemic treatment with sunitinib. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2119-2120.

- Togashi Y, Masago K, Mishima M, et al. A case of radiation recall pneumonitis induced by erlotinib, which can be related to high plasma concentration. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:924-925.

- Bourgier C, Massard C, Moldovan C, et al. Total recall of radiotherapy with mTOR inhibitors: a novel and potentially frequent side-effect? Ann Oncol. 2011;22:485-486.

- Korman AM, Tyler KH, Kaffenberger BH. Radiation recall dermatitis associated with nivolumab for metastatic malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e75-e77.

- Lau SKM, Rahimi A. Radiation recall precipitated by iodinated nonionic contrast. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2015;5:263-266.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic

_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf. Published November 27, 2017. Accessed June 10, 2020.] - Levy A, Hollebecque A, Bourgier C, et al. Targeted therapy-induced radiation recall. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1662-1668.

- Piccolo V, Baroni A, Russo T, et al. Ruocco’s immunocompromised cutaneous district. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:135-141.

- Johnson CJ, Piedboeuf P, Rubin P, et al. Early and persistent alterations in the expression of interleukin-1 alpha, interleukin-1 beta and tumour necrosis factor alpha mRNA levels in fibrosis-resistant and sensitive mice after thoracic irradiation. Radiat Res. 1996;145:762-767.

- Azira D, Magné N, Zouhair A, et al. Radiation recall: a well recognized but neglected phenomenon. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:555-570.

- Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: a quick reference guide including patch test substances and cross-reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723-727.

- Kodym E, Kalinska R, Ehringfeld C, et al. Frequency of radiation recall dermatitis in adult cancer patients. Onkologie. 2005;28:18-21.

- Seidel C, Janssen S, Karstens JH, et al. Recall pneumonitis during systemic treatment with sunitinib. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2119-2120.

- Togashi Y, Masago K, Mishima M, et al. A case of radiation recall pneumonitis induced by erlotinib, which can be related to high plasma concentration. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:924-925.

- Bourgier C, Massard C, Moldovan C, et al. Total recall of radiotherapy with mTOR inhibitors: a novel and potentially frequent side-effect? Ann Oncol. 2011;22:485-486.

- Korman AM, Tyler KH, Kaffenberger BH. Radiation recall dermatitis associated with nivolumab for metastatic malignant melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:e75-e77.

- Lau SKM, Rahimi A. Radiation recall precipitated by iodinated nonionic contrast. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2015;5:263-266.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 5.0. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic

_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf. Published November 27, 2017. Accessed June 10, 2020.] - Levy A, Hollebecque A, Bourgier C, et al. Targeted therapy-induced radiation recall. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1662-1668.

- Piccolo V, Baroni A, Russo T, et al. Ruocco’s immunocompromised cutaneous district. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:135-141.

- Johnson CJ, Piedboeuf P, Rubin P, et al. Early and persistent alterations in the expression of interleukin-1 alpha, interleukin-1 beta and tumour necrosis factor alpha mRNA levels in fibrosis-resistant and sensitive mice after thoracic irradiation. Radiat Res. 1996;145:762-767.

- Azira D, Magné N, Zouhair A, et al. Radiation recall: a well recognized but neglected phenomenon. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:555-570.

- Jacob SE, Steele T. Corticosteroid classes: a quick reference guide including patch test substances and cross-reactivity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:723-727.

Practice Points

- Consider the diagnosis of radiation recall dermatitis for a skin eruption that occurs in the same location as prior radiation exposure.

- Prednisone may be a trigger for radiation recall dermatitis in patients with sensitization to cross-reactive topical steroids such as tixocortol pivalate.

- Radiation therapy may prime the skin for a future inflammatory response by upregulating proinflammatory cytokines that persist after the conclusion of treatment.

Mycosis Fungoides Manifesting as a Morbilliform Eruption Mimicking a Viral Exanthem

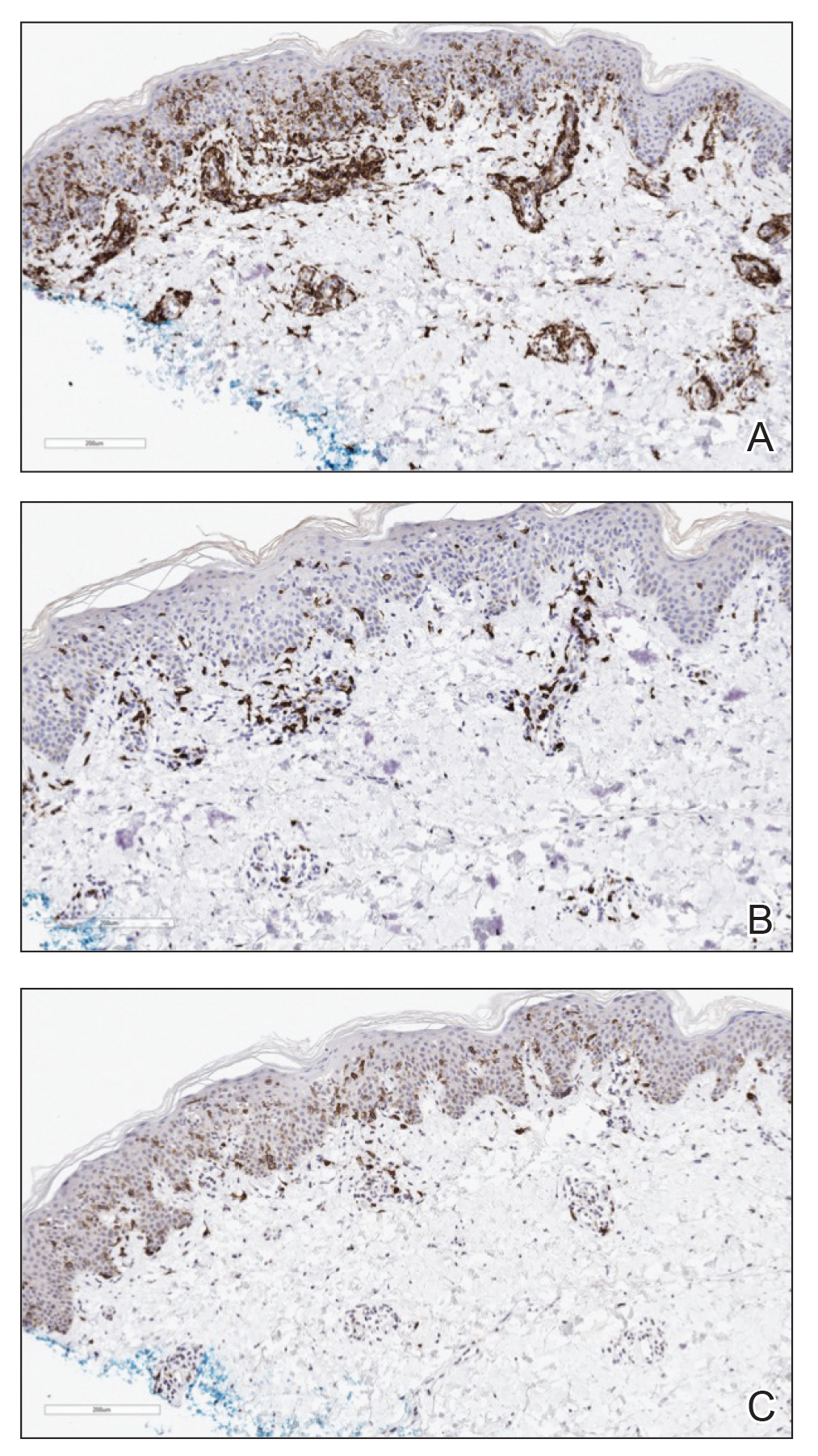

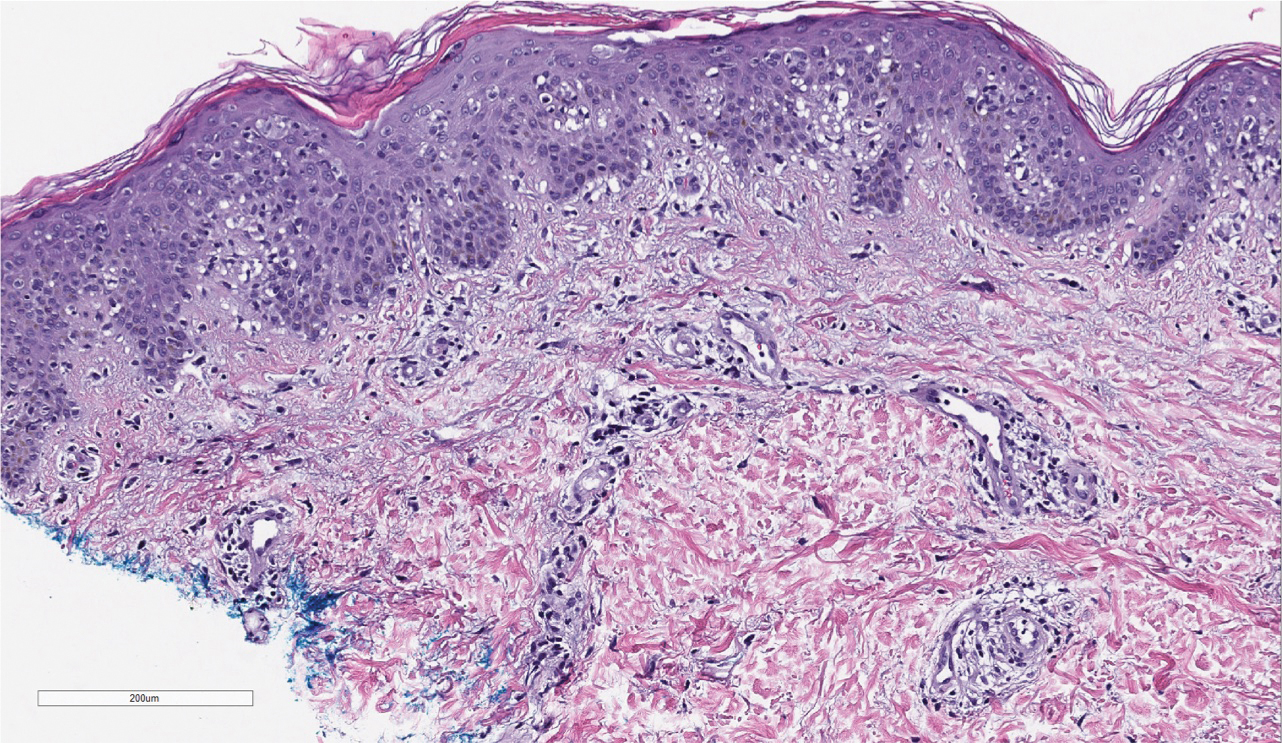

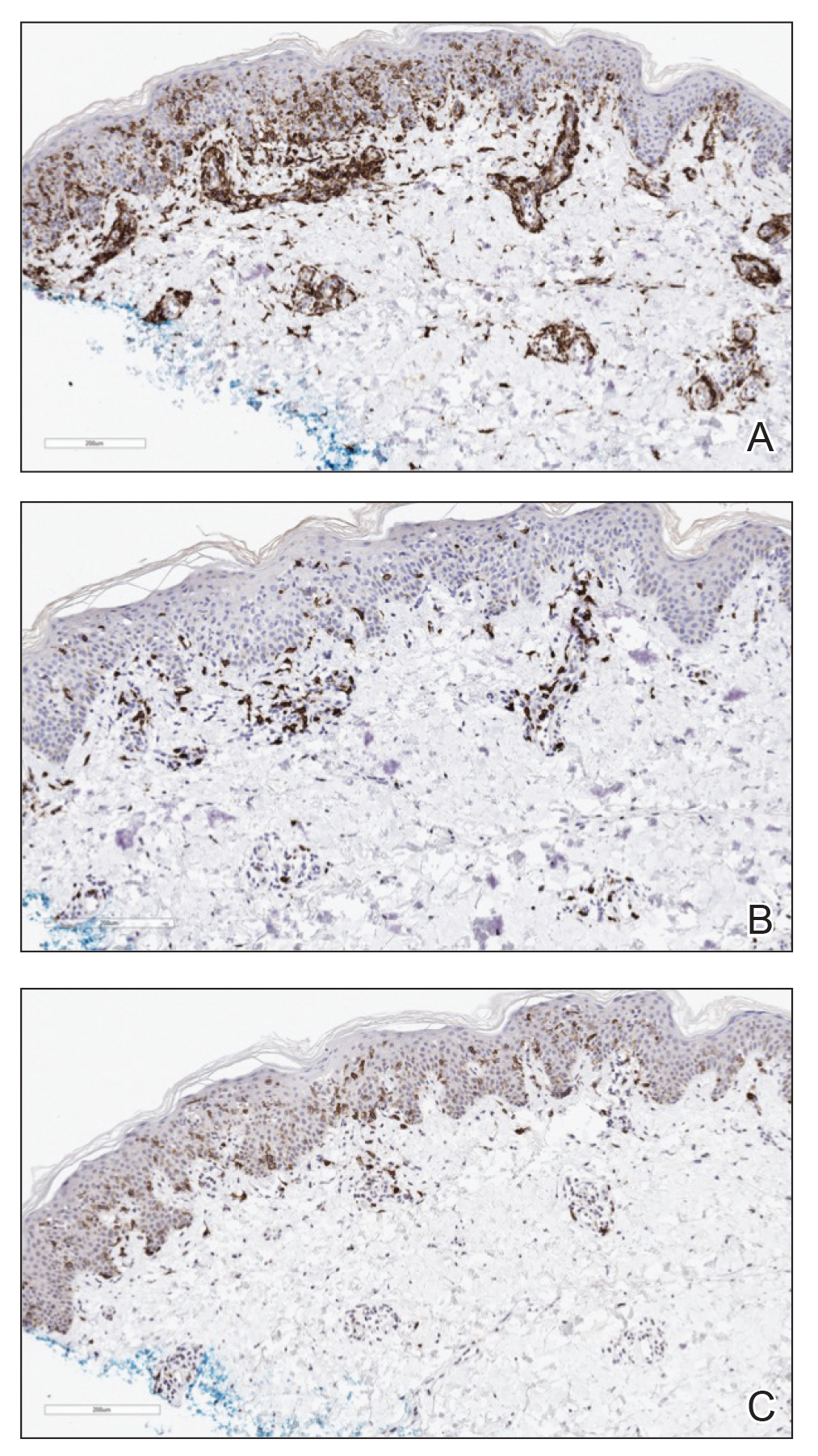

To the Editor:

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of primary cutaneous lymphoma, occurring in approximately 4 of 1 million individuals per year in the United States.1 It classically occurs in patch, plaque, and tumor stages with lesions preferentially occurring on regions of the body spared from sun exposure2; however, MF is known to have variable presentations and has been reported to imitate at least 25 other dermatoses.3 This case describes MF as a morbilliform eruption mimicking a viral exanthem.