User login

Disseminated Erythema Induratum in a Patient With a History of Tuberculosis

To the Editor:

Erythema induratum, also known as nodular vasculitis, is a panniculitis that usually affects the lower extremities in middle-aged women. Classically, it has been described as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, also known as a tuberculid.1,2 Other infections, however, also have been implicated as causes of erythema induratum, including bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), the attenuated form of Mycobacterium bovis, which commonly is used for tuberculosis vaccination. Medications also may cause erythema induratum. The characteristic distribution of the nodules on the posterior calves helps to distinguish erythema induratum from other panniculitides. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term disseminated erythema induratum revealed few case reports documenting nodules on the arms, thighs, or chest, and only 1 case report of disseminated erythema induratum.3-8 We describe a rare combination of disseminated erythema induratum in a patient with remote exposure to tuberculosis and recent BCG exposure.

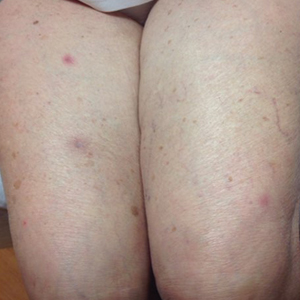

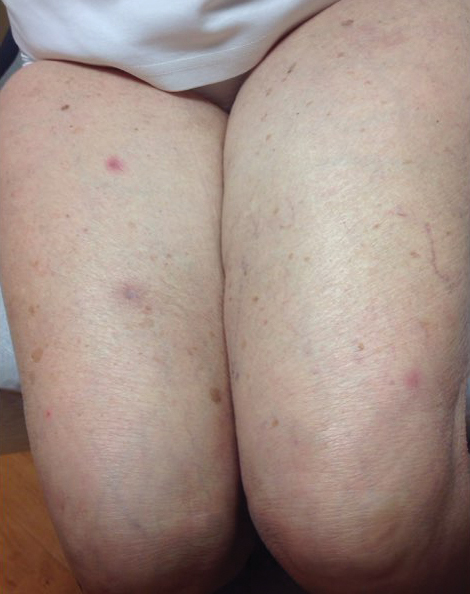

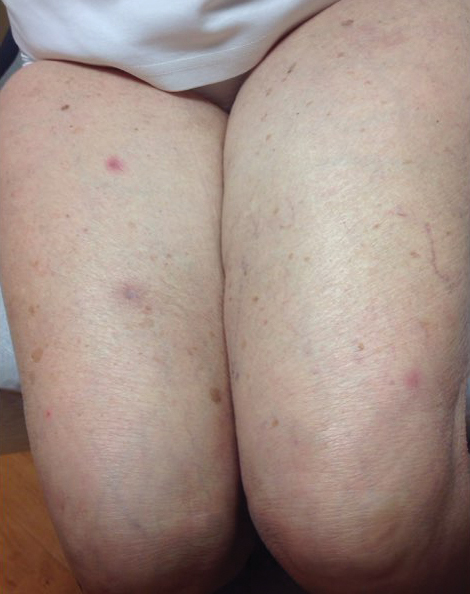

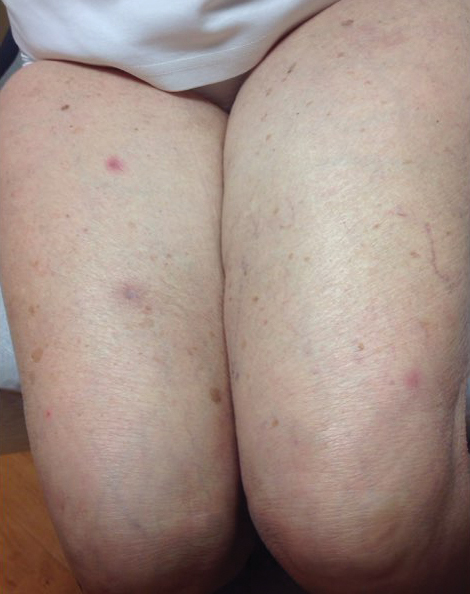

An 88-year-old woman presented for evaluation of violaceous, minimally tender, nonulcerated, subcutaneous nodules on the legs, arms, and trunk of several weeks’ duration (Figure 1). She had a remote history of tuberculosis as a child, prior to the advent of modern antituberculosis regimens. Her medical history also included hypertension, breast cancer treated with lymph node dissection, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and bladder cancer treated with intravesical BCG 10 years prior to the onset of the nodules. She reported minimal coughing and a 25-lb weight loss over the last year, but she denied night sweats, fever, or chills.

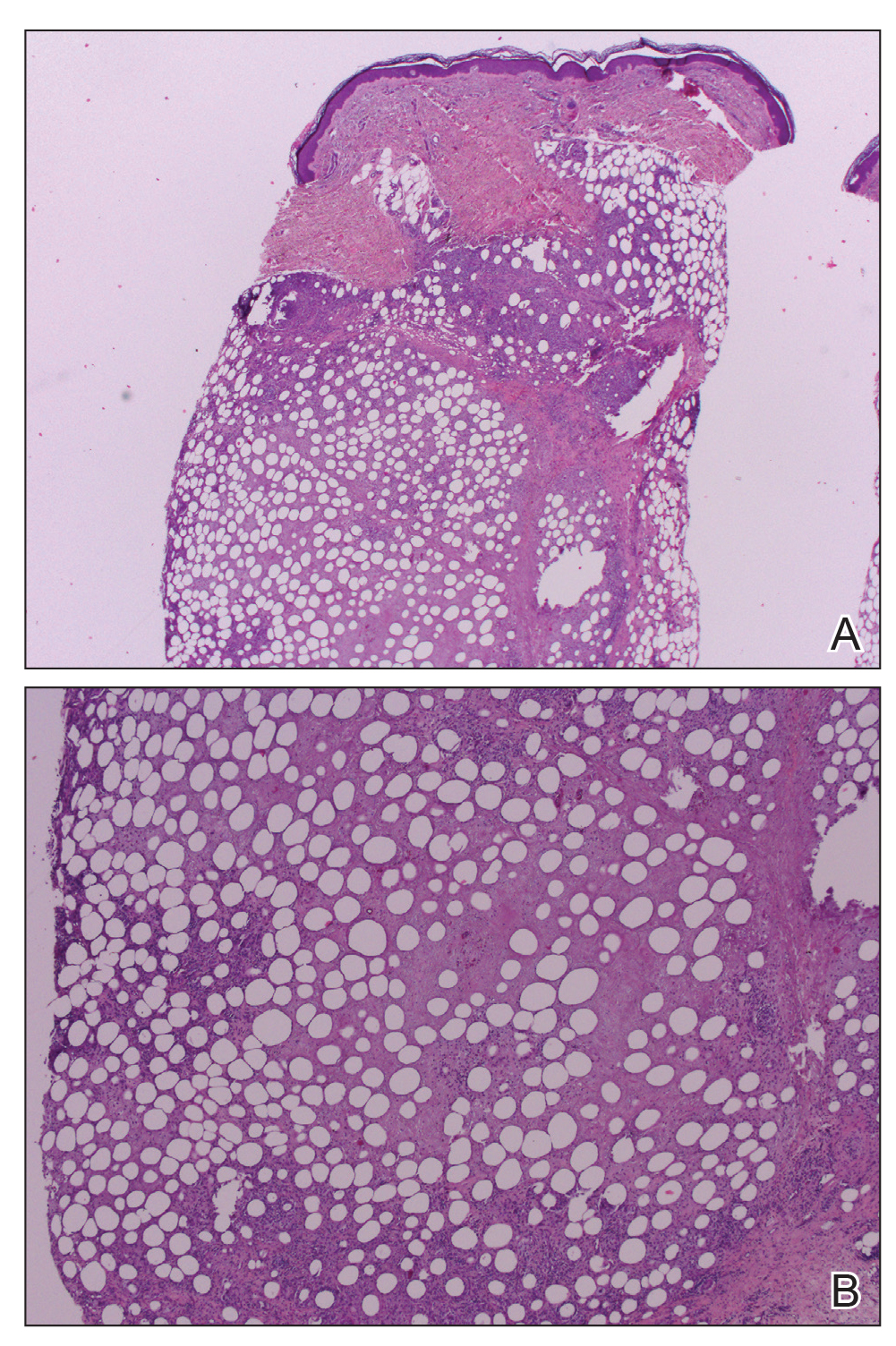

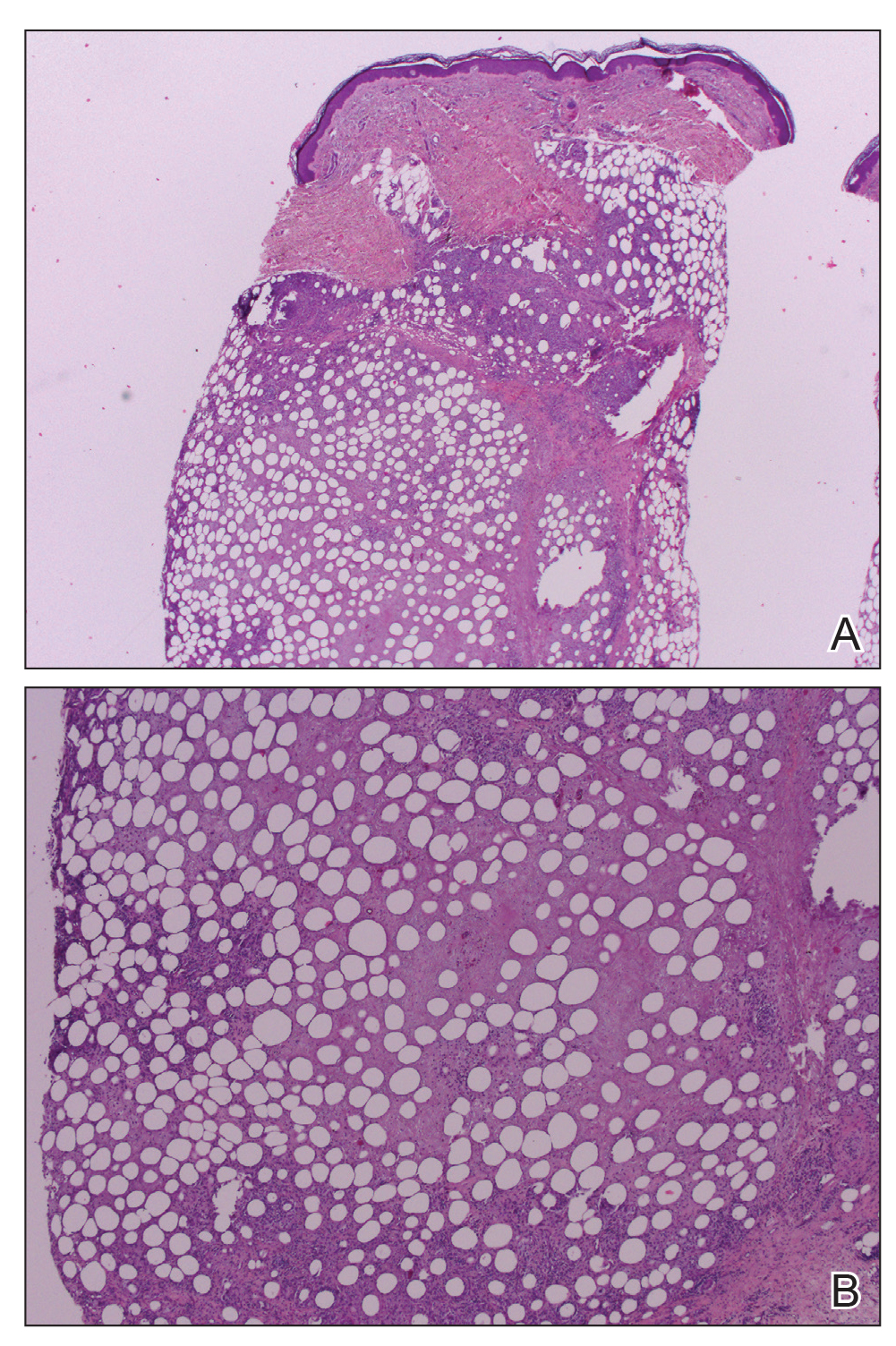

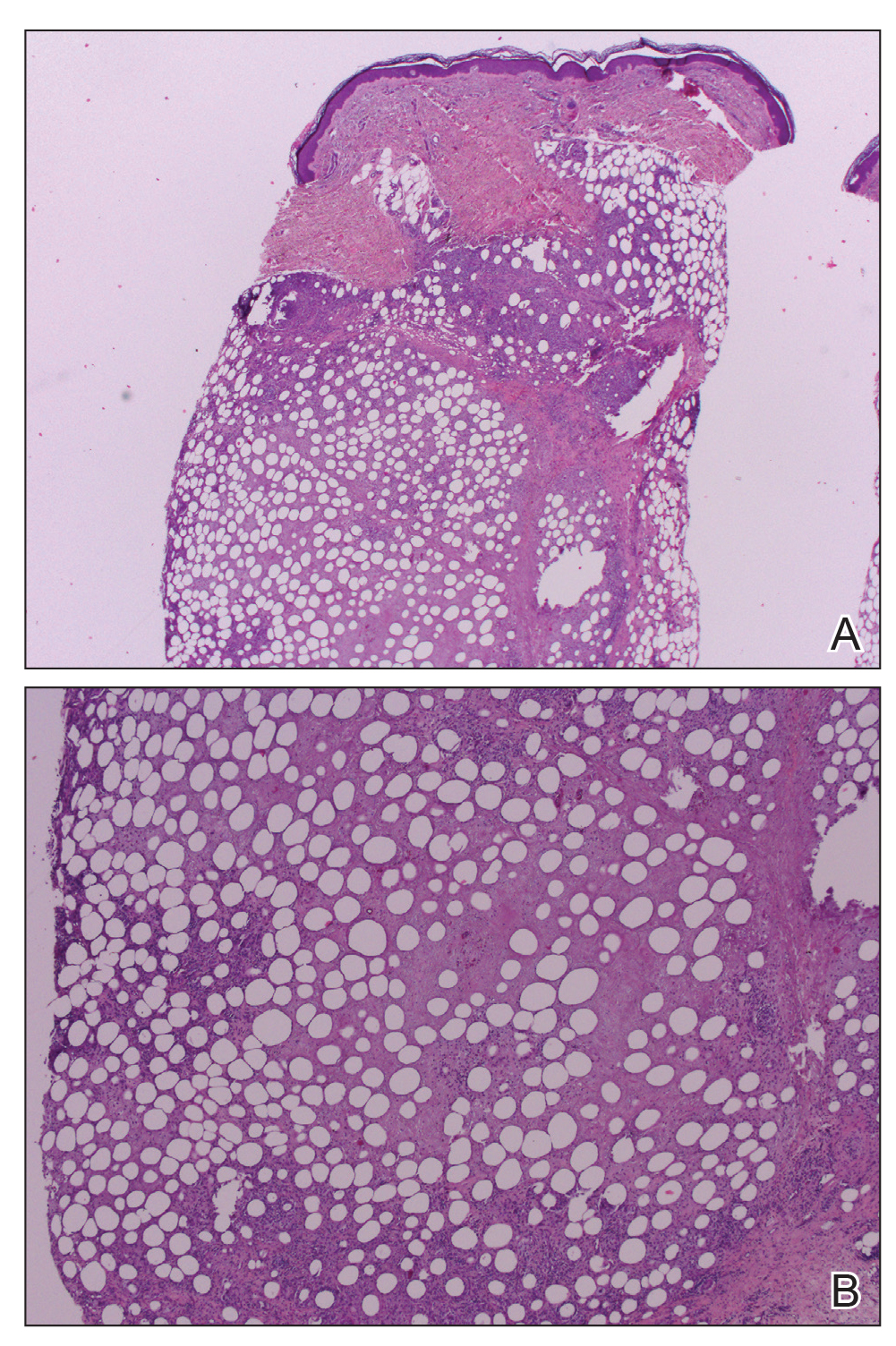

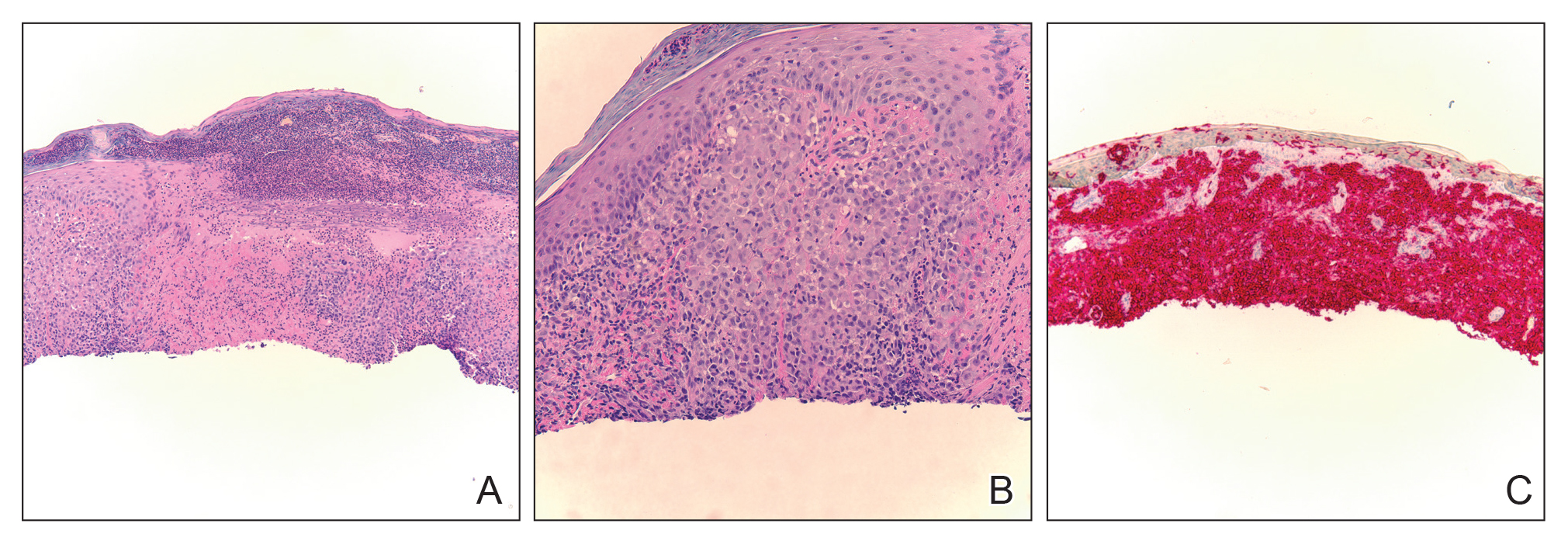

Workup included a biopsy, which showed a dense inflammatory infiltrate within the septae and lobules of the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2A). Foci of necrosis were seen within the fat lobules (Figure 2B). The histologic diagnosis was erythema induratum. Tissue cultures for bacteria, fungi, and atypical mycobacteria were negative. Mycobacterium tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis also was negative. An IFN-γ release assay test was positive for infection with M tuberculosis, suggesting that the erythema induratum was due to tuberculosis rather than BCG exposure. A chest radiograph demonstrated a 22-mm nodule in the left lung (unchanged from a prior film) and a new 10-mm nodule in the left upper lobe.

The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who concurred that the erythema induratum and the new lung nodule likely represented a reactivation of tuberculosis. Sputum samples were found to be smear and culture negative for mycobacteria, but due to high clinical suspicion, she was started on a 4-drug tuberculosis regimen of isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. Some lesions had started to improve prior to the institution of therapy; after initiation of treatment, all lesions resolved within 4 weeks of starting treatment without recurrence.

Erythema induratum was first described by Bazin9 in 1861. The disorder usually occurs in middle-aged women and is characterized by violaceous ulcerative plaques that classically present on the lower extremities, especially the calves. When the eruption occurs due to a nontuberculous etiology, the term nodular vasculitis is used.1,5 The distinction largely is historical, as most dermatologists today recognize erythema induratum and nodular vasculitis to be the same entity. Examples of nontuberculous causes include infections such as Nocardia, Pseudomonas, Fusarium, or other Mycobacterium species.10 Medications such as propylthiouracil also have been implicated.11 The classification of erythema induratum as a tuberculid suggests that the nodules are a reaction pattern rather than a primary infection, though the term tuberculid may be imprecise. The differential diagnosis of violaceous nodules on the lower extremities and trunk is broad and includes erythema nodosum, cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, pancreatic panniculitis, subcutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and lupus profundus.1,11,12

Histologically, lesions classically demonstrate a mostly lobular panniculitis with varying degrees of septal fibrosis and focal necrosis. Neutrophils may predominate early, while adipocyte necrosis, epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and lymphocytes may be found in older lesions. The presence of vasculitis as a requisite diagnostic criterion remains controversial.1,12

The incidence of erythema induratum has decreased since multidrug tuberculosis treatment has become more widespread.3 Our case displayed the disseminated variant of erythema induratum, an even rarer clinical entity.8 Interestingly, our patient had a history of tuberculosis and exposure to BCG prior to the development of lesions. Case reports have documented erythema induratum after BCG exposure but less frequently than in cases associated with tuberculosis.3,13

The use of BCG vaccines has necessitated the need for a more precise method of determining tuberculosis activity. The tuberculin skin test reacts positively with a history of BCG exposure, rendering it an inadequate test in a patient who is suspected of having an active or latent M tuberculosis infection.13,14 IFN-γ release assays are more specific in detecting latent or active tuberculosis than the tuberculin skin test. Such assays use early secretory antigenic target 6 and cultured filtrate protein 10 as antigens to determine sensitization to M tuberculosis.13,15 These antigens are not produced by BCG or Mycobacterium avium; however, other mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium marinum, Mycobacterium kansasii, and some strains of M bovis produce the aforementioned antigens, and exposure to these microbes may be confounding.13 Importantly, positive IFN-γ release assay results also have been documented after BCG exposure but occur at a much lower frequency than for tuberculosis.15 Thus, the combination of the positive IFN-γ release assay and new chest radiograph nodule in our patient provided strong evidence of reactivated tuberculosis as the precipitating cause of her skin disease.

Despite her negative PCR study, our patient’s presentation remains consistent with the diagnosis of disseminated erythema induratum.13,15 The value of PCR studies in establishing the diagnosis remains to be determined. Case reports have described positive PCR results detecting M tuberculosis in panniculitic nodules, suggesting that trace amounts of the organism are present in lesional tissue despite the negative culture result and immunostains.1 Tuberculid reactions, including lichen scrofulosorum, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and erythema induratum, historically are defined by the lack of positive cultures and immunostains, making positive PCR results difficult to reconcile pathophysiologically.1,13 Therefore, use of the term tuberculid altogether as a descriptor for pathogenesis of this disease may need to be avoided.16 Postulated explanations for the relationship of tuberculid diseases and negative cultures and immunostains include the presence of a small number of bacilli that escape routine laboratory detection, early destruction of organisms, or a reaction to circulating M tuberculosis fragments.2 Regardless, until the pathophysiology of erythema induratum has been fully elucidated, the value of PCR remains unclear.

Disseminated erythema induratum, an exceptionally rare variant of panniculitis, may be seen in patients with a remote history of M tuberculosis exposure and/or recent therapeutic BCG exposure. It is imperative to rule out active tuberculosis, especially in elderly patients whose disease predated the advent of modern antituberculosis therapy. Using an IFN-γ release assay in addition to chest radiographs and other clinical stigmata allows differentiation of the etiology of erythema induratum in those patients with tuberculosis who also were treated with BCG.

- Mascaro JM, Basalga E. Erythema induratum of Bazin. Dermatol Clin. 2008;28:439-445.

- Lighter J, Tse DB, Li Y, et al. Erythema induratum of Bazin in a child: evidence for a cell-mediated hyper-response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:326-328.

- Inoue T, Fukumoto T, Ansai S, et al. Erythema induratum of Bazin in an infant after bacilli Calmette-Guerin vaccination. J Dermatol. 2006;33:268-272.

- Degonda Halter M, Nebiker P, Hug B, et al. Atypical erythema induratum Bazin with tuberculous osteomyelitis. Internist. 2006;47:853-856.

- Gilchrist H, Patterson JW. Erythema nodosum and erythema induratum (nodular vasculitis): diagnosis and management. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:320-327.

- Sharma S, Sehgal VN, Bhattacharya SN, et al. Clinicopathologic spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis: a retrospective analysis of 165 Indians. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:444-450.

- Sethuraman G, Ramesh V. Cutaneous tuberculosis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:7-16.

- Teramura K, Fujimoto N, Nakanishi G, et al. Disseminated erythema induratum of Bazin. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:697-698.

- Bazin E. Extrait des Lecons Théoretiques et Cliniques sur le Scrofule. 2nd ed. Paris, France: Delhaye; 1861.

- Campbell SM, Winkelmann RR, Sammons DL. Erythema induratum caused by Mycobacterium chelonei in an immunocompetent patient. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-40.

- Patterson JW. Panniculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. Barcelona, Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:1641-1662.

- Segura S, Pujol R, Trinidade F, et al. Vasculitis in erythema induratum of Bazin: a histopathologic study of 101 biopsy specimens from 86 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:839-851.

- Vera-Kellet C, Peters L, Elwood K, et al. Usefulness of interferon-γ release assays in the diagnosis of erythema induratum. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:949-952.

- Prajapati V, Steed M, Grewal P, et al. Erythema induratum: case series illustrating the utility of the interferon-γ release assay in determining the association with tuberculosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:S6-S11.

- Sim JH, Whang KU. Application of the QuantiFERON-Gold TB test in erythema induratum. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25:260-263.

- Wiebels D, Turnbull K, Steinkraus V, et al. Erythema induratum Bazin.”tuberculid” or tuberculosis? [in German]. Hautarzt. 2007;58:237-240.

To the Editor:

Erythema induratum, also known as nodular vasculitis, is a panniculitis that usually affects the lower extremities in middle-aged women. Classically, it has been described as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, also known as a tuberculid.1,2 Other infections, however, also have been implicated as causes of erythema induratum, including bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), the attenuated form of Mycobacterium bovis, which commonly is used for tuberculosis vaccination. Medications also may cause erythema induratum. The characteristic distribution of the nodules on the posterior calves helps to distinguish erythema induratum from other panniculitides. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term disseminated erythema induratum revealed few case reports documenting nodules on the arms, thighs, or chest, and only 1 case report of disseminated erythema induratum.3-8 We describe a rare combination of disseminated erythema induratum in a patient with remote exposure to tuberculosis and recent BCG exposure.

An 88-year-old woman presented for evaluation of violaceous, minimally tender, nonulcerated, subcutaneous nodules on the legs, arms, and trunk of several weeks’ duration (Figure 1). She had a remote history of tuberculosis as a child, prior to the advent of modern antituberculosis regimens. Her medical history also included hypertension, breast cancer treated with lymph node dissection, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and bladder cancer treated with intravesical BCG 10 years prior to the onset of the nodules. She reported minimal coughing and a 25-lb weight loss over the last year, but she denied night sweats, fever, or chills.

Workup included a biopsy, which showed a dense inflammatory infiltrate within the septae and lobules of the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2A). Foci of necrosis were seen within the fat lobules (Figure 2B). The histologic diagnosis was erythema induratum. Tissue cultures for bacteria, fungi, and atypical mycobacteria were negative. Mycobacterium tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis also was negative. An IFN-γ release assay test was positive for infection with M tuberculosis, suggesting that the erythema induratum was due to tuberculosis rather than BCG exposure. A chest radiograph demonstrated a 22-mm nodule in the left lung (unchanged from a prior film) and a new 10-mm nodule in the left upper lobe.

The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who concurred that the erythema induratum and the new lung nodule likely represented a reactivation of tuberculosis. Sputum samples were found to be smear and culture negative for mycobacteria, but due to high clinical suspicion, she was started on a 4-drug tuberculosis regimen of isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. Some lesions had started to improve prior to the institution of therapy; after initiation of treatment, all lesions resolved within 4 weeks of starting treatment without recurrence.

Erythema induratum was first described by Bazin9 in 1861. The disorder usually occurs in middle-aged women and is characterized by violaceous ulcerative plaques that classically present on the lower extremities, especially the calves. When the eruption occurs due to a nontuberculous etiology, the term nodular vasculitis is used.1,5 The distinction largely is historical, as most dermatologists today recognize erythema induratum and nodular vasculitis to be the same entity. Examples of nontuberculous causes include infections such as Nocardia, Pseudomonas, Fusarium, or other Mycobacterium species.10 Medications such as propylthiouracil also have been implicated.11 The classification of erythema induratum as a tuberculid suggests that the nodules are a reaction pattern rather than a primary infection, though the term tuberculid may be imprecise. The differential diagnosis of violaceous nodules on the lower extremities and trunk is broad and includes erythema nodosum, cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, pancreatic panniculitis, subcutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and lupus profundus.1,11,12

Histologically, lesions classically demonstrate a mostly lobular panniculitis with varying degrees of septal fibrosis and focal necrosis. Neutrophils may predominate early, while adipocyte necrosis, epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and lymphocytes may be found in older lesions. The presence of vasculitis as a requisite diagnostic criterion remains controversial.1,12

The incidence of erythema induratum has decreased since multidrug tuberculosis treatment has become more widespread.3 Our case displayed the disseminated variant of erythema induratum, an even rarer clinical entity.8 Interestingly, our patient had a history of tuberculosis and exposure to BCG prior to the development of lesions. Case reports have documented erythema induratum after BCG exposure but less frequently than in cases associated with tuberculosis.3,13

The use of BCG vaccines has necessitated the need for a more precise method of determining tuberculosis activity. The tuberculin skin test reacts positively with a history of BCG exposure, rendering it an inadequate test in a patient who is suspected of having an active or latent M tuberculosis infection.13,14 IFN-γ release assays are more specific in detecting latent or active tuberculosis than the tuberculin skin test. Such assays use early secretory antigenic target 6 and cultured filtrate protein 10 as antigens to determine sensitization to M tuberculosis.13,15 These antigens are not produced by BCG or Mycobacterium avium; however, other mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium marinum, Mycobacterium kansasii, and some strains of M bovis produce the aforementioned antigens, and exposure to these microbes may be confounding.13 Importantly, positive IFN-γ release assay results also have been documented after BCG exposure but occur at a much lower frequency than for tuberculosis.15 Thus, the combination of the positive IFN-γ release assay and new chest radiograph nodule in our patient provided strong evidence of reactivated tuberculosis as the precipitating cause of her skin disease.

Despite her negative PCR study, our patient’s presentation remains consistent with the diagnosis of disseminated erythema induratum.13,15 The value of PCR studies in establishing the diagnosis remains to be determined. Case reports have described positive PCR results detecting M tuberculosis in panniculitic nodules, suggesting that trace amounts of the organism are present in lesional tissue despite the negative culture result and immunostains.1 Tuberculid reactions, including lichen scrofulosorum, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and erythema induratum, historically are defined by the lack of positive cultures and immunostains, making positive PCR results difficult to reconcile pathophysiologically.1,13 Therefore, use of the term tuberculid altogether as a descriptor for pathogenesis of this disease may need to be avoided.16 Postulated explanations for the relationship of tuberculid diseases and negative cultures and immunostains include the presence of a small number of bacilli that escape routine laboratory detection, early destruction of organisms, or a reaction to circulating M tuberculosis fragments.2 Regardless, until the pathophysiology of erythema induratum has been fully elucidated, the value of PCR remains unclear.

Disseminated erythema induratum, an exceptionally rare variant of panniculitis, may be seen in patients with a remote history of M tuberculosis exposure and/or recent therapeutic BCG exposure. It is imperative to rule out active tuberculosis, especially in elderly patients whose disease predated the advent of modern antituberculosis therapy. Using an IFN-γ release assay in addition to chest radiographs and other clinical stigmata allows differentiation of the etiology of erythema induratum in those patients with tuberculosis who also were treated with BCG.

To the Editor:

Erythema induratum, also known as nodular vasculitis, is a panniculitis that usually affects the lower extremities in middle-aged women. Classically, it has been described as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, also known as a tuberculid.1,2 Other infections, however, also have been implicated as causes of erythema induratum, including bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG), the attenuated form of Mycobacterium bovis, which commonly is used for tuberculosis vaccination. Medications also may cause erythema induratum. The characteristic distribution of the nodules on the posterior calves helps to distinguish erythema induratum from other panniculitides. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the term disseminated erythema induratum revealed few case reports documenting nodules on the arms, thighs, or chest, and only 1 case report of disseminated erythema induratum.3-8 We describe a rare combination of disseminated erythema induratum in a patient with remote exposure to tuberculosis and recent BCG exposure.

An 88-year-old woman presented for evaluation of violaceous, minimally tender, nonulcerated, subcutaneous nodules on the legs, arms, and trunk of several weeks’ duration (Figure 1). She had a remote history of tuberculosis as a child, prior to the advent of modern antituberculosis regimens. Her medical history also included hypertension, breast cancer treated with lymph node dissection, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and bladder cancer treated with intravesical BCG 10 years prior to the onset of the nodules. She reported minimal coughing and a 25-lb weight loss over the last year, but she denied night sweats, fever, or chills.

Workup included a biopsy, which showed a dense inflammatory infiltrate within the septae and lobules of the subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2A). Foci of necrosis were seen within the fat lobules (Figure 2B). The histologic diagnosis was erythema induratum. Tissue cultures for bacteria, fungi, and atypical mycobacteria were negative. Mycobacterium tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis also was negative. An IFN-γ release assay test was positive for infection with M tuberculosis, suggesting that the erythema induratum was due to tuberculosis rather than BCG exposure. A chest radiograph demonstrated a 22-mm nodule in the left lung (unchanged from a prior film) and a new 10-mm nodule in the left upper lobe.

The patient was referred to an infectious disease specialist who concurred that the erythema induratum and the new lung nodule likely represented a reactivation of tuberculosis. Sputum samples were found to be smear and culture negative for mycobacteria, but due to high clinical suspicion, she was started on a 4-drug tuberculosis regimen of isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. Some lesions had started to improve prior to the institution of therapy; after initiation of treatment, all lesions resolved within 4 weeks of starting treatment without recurrence.

Erythema induratum was first described by Bazin9 in 1861. The disorder usually occurs in middle-aged women and is characterized by violaceous ulcerative plaques that classically present on the lower extremities, especially the calves. When the eruption occurs due to a nontuberculous etiology, the term nodular vasculitis is used.1,5 The distinction largely is historical, as most dermatologists today recognize erythema induratum and nodular vasculitis to be the same entity. Examples of nontuberculous causes include infections such as Nocardia, Pseudomonas, Fusarium, or other Mycobacterium species.10 Medications such as propylthiouracil also have been implicated.11 The classification of erythema induratum as a tuberculid suggests that the nodules are a reaction pattern rather than a primary infection, though the term tuberculid may be imprecise. The differential diagnosis of violaceous nodules on the lower extremities and trunk is broad and includes erythema nodosum, cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa, pancreatic panniculitis, subcutaneous T-cell lymphoma, and lupus profundus.1,11,12

Histologically, lesions classically demonstrate a mostly lobular panniculitis with varying degrees of septal fibrosis and focal necrosis. Neutrophils may predominate early, while adipocyte necrosis, epithelioid histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and lymphocytes may be found in older lesions. The presence of vasculitis as a requisite diagnostic criterion remains controversial.1,12

The incidence of erythema induratum has decreased since multidrug tuberculosis treatment has become more widespread.3 Our case displayed the disseminated variant of erythema induratum, an even rarer clinical entity.8 Interestingly, our patient had a history of tuberculosis and exposure to BCG prior to the development of lesions. Case reports have documented erythema induratum after BCG exposure but less frequently than in cases associated with tuberculosis.3,13

The use of BCG vaccines has necessitated the need for a more precise method of determining tuberculosis activity. The tuberculin skin test reacts positively with a history of BCG exposure, rendering it an inadequate test in a patient who is suspected of having an active or latent M tuberculosis infection.13,14 IFN-γ release assays are more specific in detecting latent or active tuberculosis than the tuberculin skin test. Such assays use early secretory antigenic target 6 and cultured filtrate protein 10 as antigens to determine sensitization to M tuberculosis.13,15 These antigens are not produced by BCG or Mycobacterium avium; however, other mycobacteria such as Mycobacterium marinum, Mycobacterium kansasii, and some strains of M bovis produce the aforementioned antigens, and exposure to these microbes may be confounding.13 Importantly, positive IFN-γ release assay results also have been documented after BCG exposure but occur at a much lower frequency than for tuberculosis.15 Thus, the combination of the positive IFN-γ release assay and new chest radiograph nodule in our patient provided strong evidence of reactivated tuberculosis as the precipitating cause of her skin disease.

Despite her negative PCR study, our patient’s presentation remains consistent with the diagnosis of disseminated erythema induratum.13,15 The value of PCR studies in establishing the diagnosis remains to be determined. Case reports have described positive PCR results detecting M tuberculosis in panniculitic nodules, suggesting that trace amounts of the organism are present in lesional tissue despite the negative culture result and immunostains.1 Tuberculid reactions, including lichen scrofulosorum, papulonecrotic tuberculid, and erythema induratum, historically are defined by the lack of positive cultures and immunostains, making positive PCR results difficult to reconcile pathophysiologically.1,13 Therefore, use of the term tuberculid altogether as a descriptor for pathogenesis of this disease may need to be avoided.16 Postulated explanations for the relationship of tuberculid diseases and negative cultures and immunostains include the presence of a small number of bacilli that escape routine laboratory detection, early destruction of organisms, or a reaction to circulating M tuberculosis fragments.2 Regardless, until the pathophysiology of erythema induratum has been fully elucidated, the value of PCR remains unclear.

Disseminated erythema induratum, an exceptionally rare variant of panniculitis, may be seen in patients with a remote history of M tuberculosis exposure and/or recent therapeutic BCG exposure. It is imperative to rule out active tuberculosis, especially in elderly patients whose disease predated the advent of modern antituberculosis therapy. Using an IFN-γ release assay in addition to chest radiographs and other clinical stigmata allows differentiation of the etiology of erythema induratum in those patients with tuberculosis who also were treated with BCG.

- Mascaro JM, Basalga E. Erythema induratum of Bazin. Dermatol Clin. 2008;28:439-445.

- Lighter J, Tse DB, Li Y, et al. Erythema induratum of Bazin in a child: evidence for a cell-mediated hyper-response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:326-328.

- Inoue T, Fukumoto T, Ansai S, et al. Erythema induratum of Bazin in an infant after bacilli Calmette-Guerin vaccination. J Dermatol. 2006;33:268-272.

- Degonda Halter M, Nebiker P, Hug B, et al. Atypical erythema induratum Bazin with tuberculous osteomyelitis. Internist. 2006;47:853-856.

- Gilchrist H, Patterson JW. Erythema nodosum and erythema induratum (nodular vasculitis): diagnosis and management. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:320-327.

- Sharma S, Sehgal VN, Bhattacharya SN, et al. Clinicopathologic spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis: a retrospective analysis of 165 Indians. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:444-450.

- Sethuraman G, Ramesh V. Cutaneous tuberculosis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:7-16.

- Teramura K, Fujimoto N, Nakanishi G, et al. Disseminated erythema induratum of Bazin. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:697-698.

- Bazin E. Extrait des Lecons Théoretiques et Cliniques sur le Scrofule. 2nd ed. Paris, France: Delhaye; 1861.

- Campbell SM, Winkelmann RR, Sammons DL. Erythema induratum caused by Mycobacterium chelonei in an immunocompetent patient. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-40.

- Patterson JW. Panniculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. Barcelona, Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:1641-1662.

- Segura S, Pujol R, Trinidade F, et al. Vasculitis in erythema induratum of Bazin: a histopathologic study of 101 biopsy specimens from 86 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:839-851.

- Vera-Kellet C, Peters L, Elwood K, et al. Usefulness of interferon-γ release assays in the diagnosis of erythema induratum. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:949-952.

- Prajapati V, Steed M, Grewal P, et al. Erythema induratum: case series illustrating the utility of the interferon-γ release assay in determining the association with tuberculosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:S6-S11.

- Sim JH, Whang KU. Application of the QuantiFERON-Gold TB test in erythema induratum. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25:260-263.

- Wiebels D, Turnbull K, Steinkraus V, et al. Erythema induratum Bazin.”tuberculid” or tuberculosis? [in German]. Hautarzt. 2007;58:237-240.

- Mascaro JM, Basalga E. Erythema induratum of Bazin. Dermatol Clin. 2008;28:439-445.

- Lighter J, Tse DB, Li Y, et al. Erythema induratum of Bazin in a child: evidence for a cell-mediated hyper-response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28:326-328.

- Inoue T, Fukumoto T, Ansai S, et al. Erythema induratum of Bazin in an infant after bacilli Calmette-Guerin vaccination. J Dermatol. 2006;33:268-272.

- Degonda Halter M, Nebiker P, Hug B, et al. Atypical erythema induratum Bazin with tuberculous osteomyelitis. Internist. 2006;47:853-856.

- Gilchrist H, Patterson JW. Erythema nodosum and erythema induratum (nodular vasculitis): diagnosis and management. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:320-327.

- Sharma S, Sehgal VN, Bhattacharya SN, et al. Clinicopathologic spectrum of cutaneous tuberculosis: a retrospective analysis of 165 Indians. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:444-450.

- Sethuraman G, Ramesh V. Cutaneous tuberculosis in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:7-16.

- Teramura K, Fujimoto N, Nakanishi G, et al. Disseminated erythema induratum of Bazin. Eur J Dermatol. 2014;24:697-698.

- Bazin E. Extrait des Lecons Théoretiques et Cliniques sur le Scrofule. 2nd ed. Paris, France: Delhaye; 1861.

- Campbell SM, Winkelmann RR, Sammons DL. Erythema induratum caused by Mycobacterium chelonei in an immunocompetent patient. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:38-40.

- Patterson JW. Panniculitis. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo J, Rapini RP, et al, eds. Dermatology. Barcelona, Spain: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:1641-1662.

- Segura S, Pujol R, Trinidade F, et al. Vasculitis in erythema induratum of Bazin: a histopathologic study of 101 biopsy specimens from 86 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:839-851.

- Vera-Kellet C, Peters L, Elwood K, et al. Usefulness of interferon-γ release assays in the diagnosis of erythema induratum. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:949-952.

- Prajapati V, Steed M, Grewal P, et al. Erythema induratum: case series illustrating the utility of the interferon-γ release assay in determining the association with tuberculosis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2013;17:S6-S11.

- Sim JH, Whang KU. Application of the QuantiFERON-Gold TB test in erythema induratum. J Dermatolog Treat. 2014;25:260-263.

- Wiebels D, Turnbull K, Steinkraus V, et al. Erythema induratum Bazin.”tuberculid” or tuberculosis? [in German]. Hautarzt. 2007;58:237-240.

Practice Points

- Erythema induratum is an uncommon panniculitis attributed to a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction, classically to Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

- The workup for such patients with exposure to both M tuberculosis and bacillus Calmette-Guérin should include IFN-11γ release assays.

- Clinicians should be aware of the disseminated variant of erythema induratum and the laboratory testing needed to establish a cause and help direct treatment.

Yellow-Brown Ulcerated Papule in a Newborn

The Diagnosis: Congenital Self-healing Reticulohistiocytosis

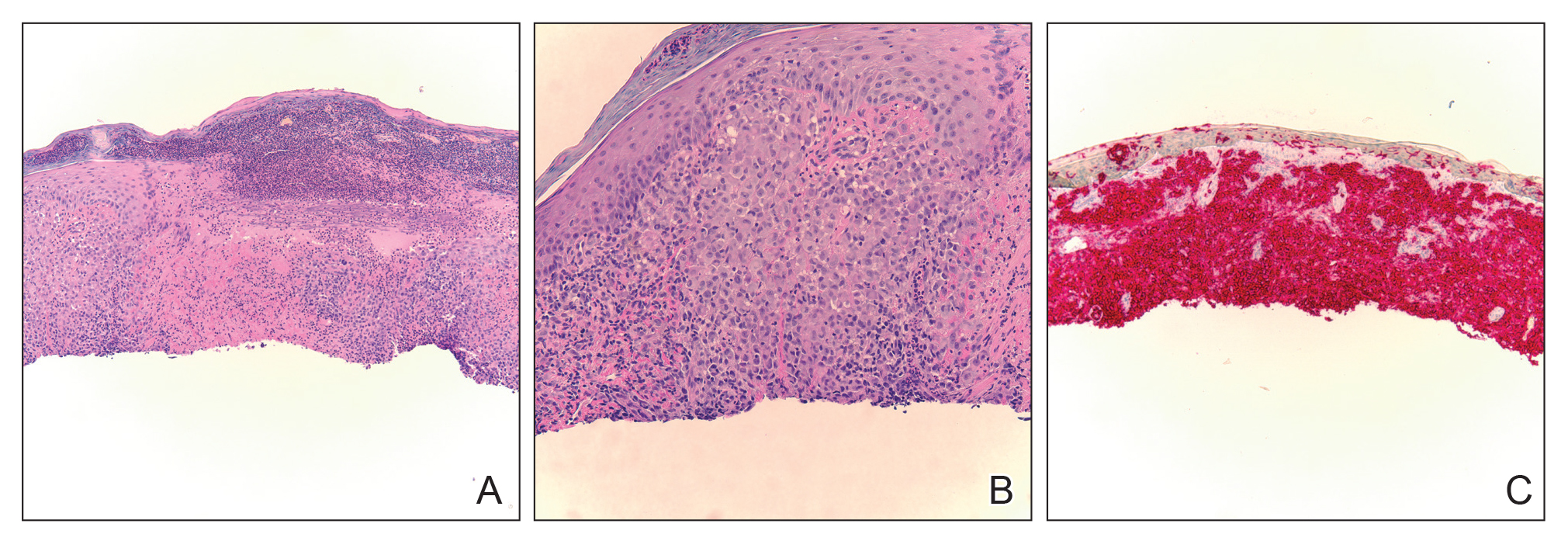

Biopsy of a representative lesion from this patient was consistent with congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, as shown in the Figure. Characteristic Langerhans cells were present in the dermis that stained CD1a positive, S-100 positive, and CD68 negative to confirm the diagnosis.

Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, or Hashimoto-Pritzker syndrome, is a rare benign form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. It is twice as common in males than females and typically noted at birth or early during the neonatal period. Lesions may present as pink, firm, asymptomatic papulonodular lesions that often ulcerate with possible residual hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation.1 The differential diagnosis includes congenital infectious and hematologic diseases typically associated with blueberry muffin baby. Thus, varicella, cytomegalovirus, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, rubella, neuroblastoma, leukemia cutis, and extramedullary hematopoiesis, among others, may be considered. Juvenile xanthogranuloma or urticaria pigmentosa also enter the differential diagnosis given the yellow-brown appearance. As a clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells, pathology reveals lesions that stain positive for CD1a and S-100.2

Although typically absent, evaluation for systemic involvement is warranted, which may be an early presentation of multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Continued monitoring is recommended given the risk of relapse and associated mortality. Our patient continues to do well. He will continue to be followed by our team and hematology/oncology during early childhood.

The treatment of congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis may include conservative monitoring, topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, tacrolimus, or psoralen plus UVA.3 Surgical excision may be considered for large lesions.

- Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555.

- Chen AJ, Jarrett P, Macfarlane S. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: the need for investigation. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:76-77.

- Gothwal S, Gupta AK, Choudhary R. Congenital self healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85:316-317.

The Diagnosis: Congenital Self-healing Reticulohistiocytosis

Biopsy of a representative lesion from this patient was consistent with congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, as shown in the Figure. Characteristic Langerhans cells were present in the dermis that stained CD1a positive, S-100 positive, and CD68 negative to confirm the diagnosis.

Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, or Hashimoto-Pritzker syndrome, is a rare benign form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. It is twice as common in males than females and typically noted at birth or early during the neonatal period. Lesions may present as pink, firm, asymptomatic papulonodular lesions that often ulcerate with possible residual hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation.1 The differential diagnosis includes congenital infectious and hematologic diseases typically associated with blueberry muffin baby. Thus, varicella, cytomegalovirus, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, rubella, neuroblastoma, leukemia cutis, and extramedullary hematopoiesis, among others, may be considered. Juvenile xanthogranuloma or urticaria pigmentosa also enter the differential diagnosis given the yellow-brown appearance. As a clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells, pathology reveals lesions that stain positive for CD1a and S-100.2

Although typically absent, evaluation for systemic involvement is warranted, which may be an early presentation of multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Continued monitoring is recommended given the risk of relapse and associated mortality. Our patient continues to do well. He will continue to be followed by our team and hematology/oncology during early childhood.

The treatment of congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis may include conservative monitoring, topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, tacrolimus, or psoralen plus UVA.3 Surgical excision may be considered for large lesions.

The Diagnosis: Congenital Self-healing Reticulohistiocytosis

Biopsy of a representative lesion from this patient was consistent with congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, as shown in the Figure. Characteristic Langerhans cells were present in the dermis that stained CD1a positive, S-100 positive, and CD68 negative to confirm the diagnosis.

Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis, or Hashimoto-Pritzker syndrome, is a rare benign form of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. It is twice as common in males than females and typically noted at birth or early during the neonatal period. Lesions may present as pink, firm, asymptomatic papulonodular lesions that often ulcerate with possible residual hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation.1 The differential diagnosis includes congenital infectious and hematologic diseases typically associated with blueberry muffin baby. Thus, varicella, cytomegalovirus, syphilis, toxoplasmosis, rubella, neuroblastoma, leukemia cutis, and extramedullary hematopoiesis, among others, may be considered. Juvenile xanthogranuloma or urticaria pigmentosa also enter the differential diagnosis given the yellow-brown appearance. As a clonal proliferation of Langerhans cells, pathology reveals lesions that stain positive for CD1a and S-100.2

Although typically absent, evaluation for systemic involvement is warranted, which may be an early presentation of multisystem Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Continued monitoring is recommended given the risk of relapse and associated mortality. Our patient continues to do well. He will continue to be followed by our team and hematology/oncology during early childhood.

The treatment of congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis may include conservative monitoring, topical steroids, topical nitrogen mustard, tacrolimus, or psoralen plus UVA.3 Surgical excision may be considered for large lesions.

- Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555.

- Chen AJ, Jarrett P, Macfarlane S. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: the need for investigation. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:76-77.

- Gothwal S, Gupta AK, Choudhary R. Congenital self healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85:316-317.

- Parimi LR, You J, Hong L, et al. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:553-555.

- Chen AJ, Jarrett P, Macfarlane S. Congenital self-healing reticulohistiocytosis: the need for investigation. Australas J Dermatol. 2016;57:76-77.

- Gothwal S, Gupta AK, Choudhary R. Congenital self healing Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Indian J Pediatr. 2018;85:316-317.

An 18-day-old infant boy presented with yellow-brown ulcerated papules on the left posterior leg (top) and left posterior shoulder (bottom). He was born via spontaneous vaginal delivery at 33 1/7 weeks' gestation complicated by preeclampsia. The lesions were unchanged during the infant's stay in the neonatal intensive care unit. However, his mother noted that one lesion crusted once home without an increase in size. His fraternal twin sister did not have any similar lesions. Jaundice and hepatosplenomegaly were absent. He was referred to hematology/oncology. A complete blood cell count revealed nonconcerning slight anemia. Liver function tests, coagulation studies, a chest radiograph, and a skeletal survey were ordered.

Discoid Lupus Erythematosus Following Herpes Zoster

Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can be classified as lupus-specific or lupus-nonspecific skin lesions. Lupus-specific lesions commonly are photodistributed, with involvement of the malar region, arms, and trunk. The development of discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) in areas of trauma, including sun-exposed skin, is not uncommon and may be associated with an isomorphic response. We present a rare case of an isomorphic response following herpes zoster (HZ) in a young woman undergoing treatment with immunosuppressive agents for SLE and DLE. Potential prophylactic therapy also is discussed.

Case Report

A 19-year-old woman initially presented to an outside dermatologist for evaluation of new-onset scarring alopecia, crusted erythematous plaques on the face and arms, and arthralgia. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the left arm demonstrated a lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with scattered necrotic keratinocytes, perifollicular inflammation, and focally thickened basement membrane at the dermoepidermal junction consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). A laboratory workup for SLE revealed 1:1280 antinuclear antibodies (reference range, negative <1:80) with elevated titers of double-stranded DNA, Smith, ribonucleoprotein, Sjögren syndrome A, and Sjögren syndrome B autoantibodies with low complement levels. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of SLE and DLE was made.

At that time, the patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily for SLE. Four days later she developed swelling in both hands and feet, and hydroxychloroquine was stopped due to a presumed adverse reaction; however, her symptoms subsequently were determined to be polyarthritis secondary to a lupus flare. Prednisone 10 mg once daily was then initiated. The patient was encouraged to restart hydroxychloroquine, but she declined.

Over the next 13 months, the patient developed severe photosensitivity, oral ulcers, Raynaud phenomenon, anemia, and nephrotic-range proteinuria. She ultimately was diagnosed by the nephrology department at our institution with mixed diffuse proliferative and membranous glomerulonephritis. Induction therapy with oral mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily and prednisone 60 mg once daily was started, followed by the addition of tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily. Despite immunosuppressive therapy, she continued to develop new discoid lesions on the face, chest, and arms. Th

After 4 weeks of treatment with mycophenolate mofetil, prednisone, and tacrolimus, the patient developed a painful vesicular rash on the left breast with extension over the left axilla and scapula in a T3 to T4 dermatomal distribution. A clinical diagnosis of HZ was made, and she was started on intravenous acyclovir 10 mg/kg in dextrose 5% every 8 hours for 4 days followed by oral valacyclovir 1000 mg every 8 hours for 14 days, which led to resolution of the eruption.

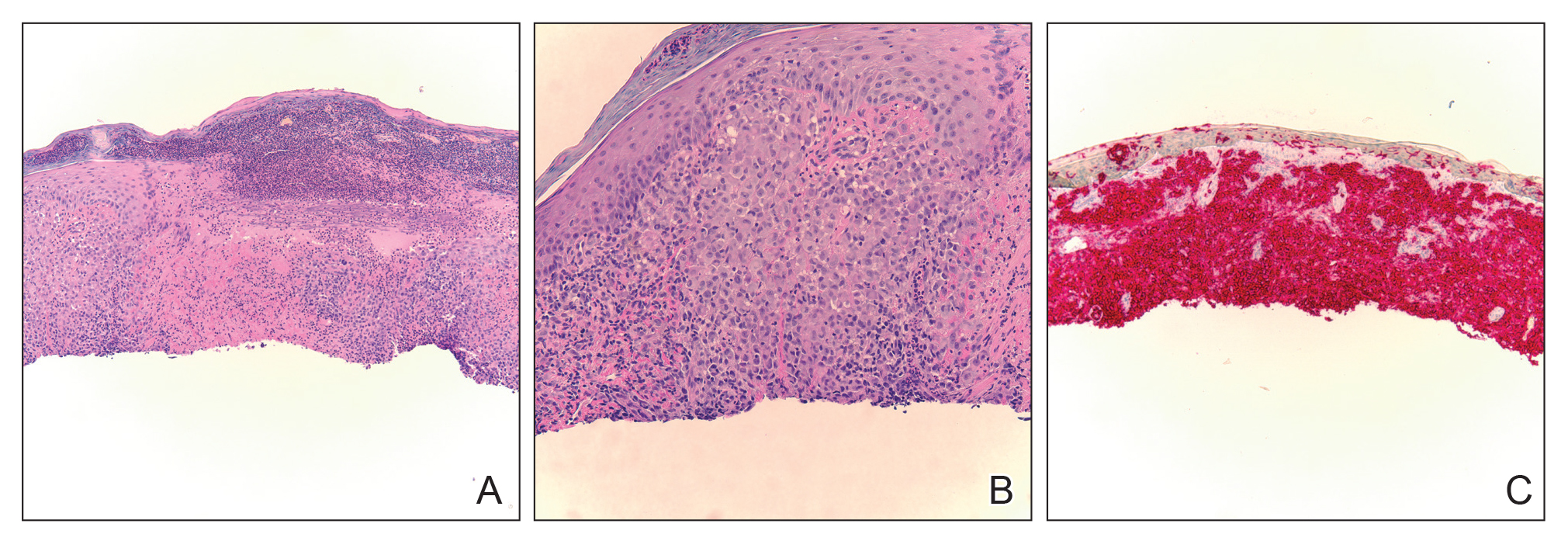

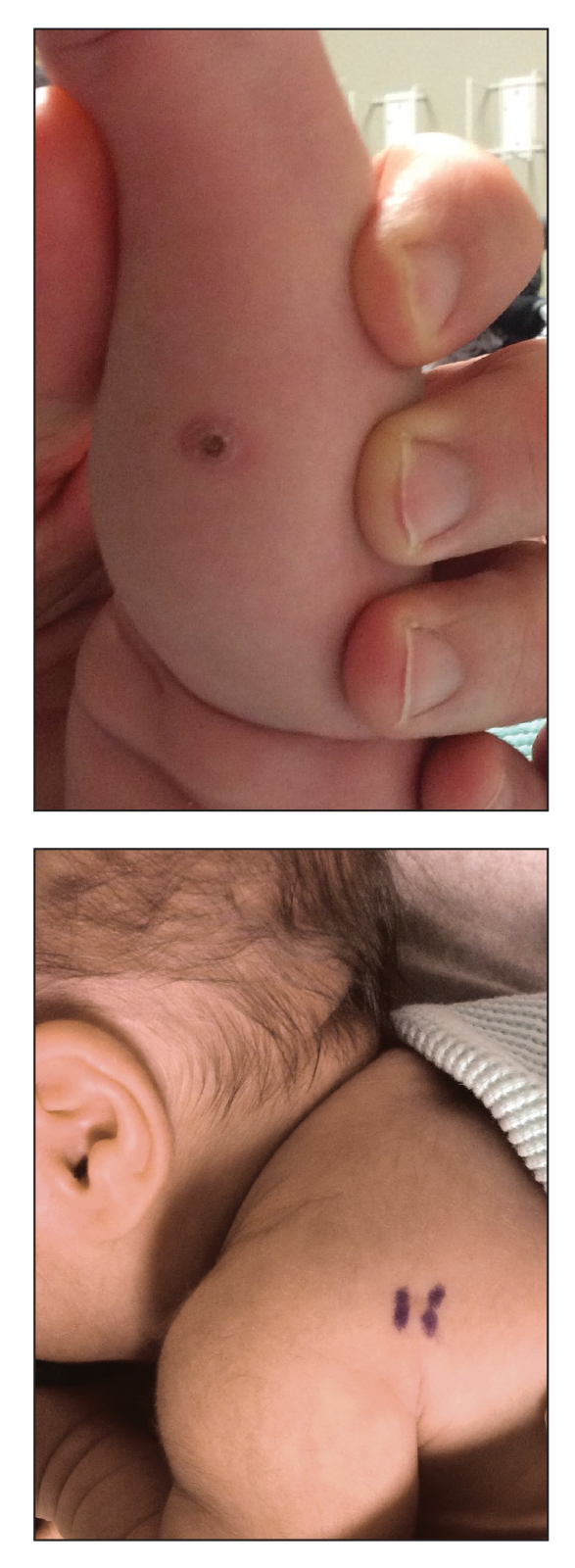

Over the next 4 months, the patient continued to experience pain confined to the same dermatomal area as the HZ, which was consistent with postherpetic neuralgia. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued after she developed acute liver toxicity attributed to the drug. Upon discontinuation, the patient developed a new pruritic rash on both arms and the back. Physical examination by the dermatology department at our institution revealed diffuse, scaly, hyperpigmented papules and annular plaques with central pink hypopigmentation on the face, ears, anterior chest, arms, hands, and back. On the left anterior chest and back, the distribution was strikingly unilateral and multidermatomal (Figure 1). Upon further questioning, the patient confirmed that the areas of the new rash coincided with areas previously affected by HZ. Histologic examination of a representative lesion from the left lateral breast revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, a patchy lichenoid and perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate, and pigment incontinence (Figure 2A). These histologic features were subtle and were not diagnostic for lupus; however, direct immunofluorescence demonstrated a continuous granular band of IgG and C3 along the dermoepidermal junction, confirming the diagnosis of DLE (Figure 2B). The histologic findings and clinical presentation were consistent with the development of DLE in areas of previous trauma from HZ. The patient continues to follow-up with the rheumatology and nephrology departments but was lost to dermatology follow-up.

Comment

The pathogenesis of DLE is poorly understood but is thought to be multifactorial, involving genetics, sun exposure, and immune dysregulation.1 Development of DLE lesions in skin traumatized by tattoos, scratches, scars, and prolonged heat exposure has been reported.2 Clarification of the mechanism(s) underlying these traumatized areas may provide insight into the pathophysiology of DLE.

The isomorphic response, also known as the Köbner phenomenon, is the development of a preexisting skin condition at a site of trauma. This phenomenon has been observed in several dermatologic conditions including psoriasis, lichen planus, systemic sclerosis, dermatomyositis, sarcoidosis, vitiligo, and DLE.3 Koebnerization may result from trauma to the skin caused by scratches, sun exposure, radiography, prolonged heat and cold exposure, pressure, tattoos, scars, and inflammatory dermatoses.2,4 Ueki4 suggested that localized trauma to the skin stimulates an immune response that makes the traumatized site a target for a preexisting skin condition. Inflammatory mediators such as IL-1, tumor necrosis factor α, IL-6, and interferon γ have been implicated in the pathophysiology of the isomorphic response.4

Wolf isotopic response is a similar entity that refers to the development of a novel skin condition at the site of a distinct, previously resolved skin disorder. This phenomenon was described by Wolf et al5 in 1995, and since then over 170 cases have been reported.5-7 In most cases the initial skin condition is HZ, although herpes simplex virus has also been implicated. The common resulting skin conditions include granulomatous reactions, malignant tumors, lichen planus, morphea, and infections. The notion that the antecedent skin disease alters the affected site and causes it to be more susceptible to autoimmunity has been proposed as a mechanism for the isotopic response.7,8 While one might consider our presentation of DLE following HZ to be an isotopic response, we believe this case is best classified as an isomorphic response, as the patient already had an established diagnosis of DLE.

The development of DLE at the site of a previous HZ eruption has been described in 2 other cases of young women with SLE.9,10 Unique to our case is the development of a multidermatomal eruption, which may be an indication of her degree of immunosuppression, as immunosuppressed patients are more likely to present with multidermatomal reactivation of varicella zoster virus and postherpetic neuralgia.11 The similarities between our case and the 2 prior reports—including the patients’ age, sex, history of SLE, and degree of immunosuppression—are noteworthy in that they may represent a subset of SLE patients who are predisposed to developing koebnerization following HZ. Physicians should be aware of this phenomenon and consider being proactive in preventing long-term damage.

When feasible, physicians should consider administering the HZ vaccine to reduce the course and severity of HZ before prescribing immunosuppressive agents. When HZ presents in young, immunosuppressed women with a history of SLE, we suggest monitoring the affected sites closely for any evidence of DLE. Topical corticosteroids should be applied to involved areas of the face or body at the earliest appearance of such lesions, which may prevent the isomorphic response and its potentially scarring DLE lesions. This will be our therapeutic approach if we encounter a similar clinical situation in the future. Fur

Acknowledgment

We thank Carolyn E. Grotkowski, MD, from the Department of Pathology, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, New Jersey, for her assistance in photographing the pathology slides.

- Lin JH, Dutz JP, Sontheimer RD, et al. Pathophysiology of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol. 2007;33:85-106.

- Ueki H. Köbner phenomenon in lupus erythematosus [in German]. Hautarzt. 1994;45:154-160.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. The isomorphic response of Koebner. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:401-410.

- Ueki H. Koebner phenomenon in lupus erythematosus with special consideration of clinical findings. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:219-223.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Ruocco V, Brunetti G, Puca RV, et al. The immunocompromised district: a unifying concept for lymphoedematous, herpes-infected and otherwise damaged sites. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1364-1373.

- Martires KJ, Baird K, Citrin DE, et al. Localization of sclerotic-type chronic graft-vs-host disease to sites of skin injury. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1081-1086.

- Lee NY, Daniel AS, Dasher DA, et al. Cutaneous lupus after herpes zoster: isomorphic, isotopic, or both [published online May 29, 2012]? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:e110-e113.

- Longhi BS, Centeville M, Marini R, et al. Koebner’s phenomenon in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1403-1405.

- Failla V, Jacques J, Castronovo C, et al. Herpes zoster in patients treated with biologicals. Dermatology. 2012;224:251-256.

Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can be classified as lupus-specific or lupus-nonspecific skin lesions. Lupus-specific lesions commonly are photodistributed, with involvement of the malar region, arms, and trunk. The development of discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) in areas of trauma, including sun-exposed skin, is not uncommon and may be associated with an isomorphic response. We present a rare case of an isomorphic response following herpes zoster (HZ) in a young woman undergoing treatment with immunosuppressive agents for SLE and DLE. Potential prophylactic therapy also is discussed.

Case Report

A 19-year-old woman initially presented to an outside dermatologist for evaluation of new-onset scarring alopecia, crusted erythematous plaques on the face and arms, and arthralgia. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the left arm demonstrated a lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with scattered necrotic keratinocytes, perifollicular inflammation, and focally thickened basement membrane at the dermoepidermal junction consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). A laboratory workup for SLE revealed 1:1280 antinuclear antibodies (reference range, negative <1:80) with elevated titers of double-stranded DNA, Smith, ribonucleoprotein, Sjögren syndrome A, and Sjögren syndrome B autoantibodies with low complement levels. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of SLE and DLE was made.

At that time, the patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily for SLE. Four days later she developed swelling in both hands and feet, and hydroxychloroquine was stopped due to a presumed adverse reaction; however, her symptoms subsequently were determined to be polyarthritis secondary to a lupus flare. Prednisone 10 mg once daily was then initiated. The patient was encouraged to restart hydroxychloroquine, but she declined.

Over the next 13 months, the patient developed severe photosensitivity, oral ulcers, Raynaud phenomenon, anemia, and nephrotic-range proteinuria. She ultimately was diagnosed by the nephrology department at our institution with mixed diffuse proliferative and membranous glomerulonephritis. Induction therapy with oral mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily and prednisone 60 mg once daily was started, followed by the addition of tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily. Despite immunosuppressive therapy, she continued to develop new discoid lesions on the face, chest, and arms. Th

After 4 weeks of treatment with mycophenolate mofetil, prednisone, and tacrolimus, the patient developed a painful vesicular rash on the left breast with extension over the left axilla and scapula in a T3 to T4 dermatomal distribution. A clinical diagnosis of HZ was made, and she was started on intravenous acyclovir 10 mg/kg in dextrose 5% every 8 hours for 4 days followed by oral valacyclovir 1000 mg every 8 hours for 14 days, which led to resolution of the eruption.

Over the next 4 months, the patient continued to experience pain confined to the same dermatomal area as the HZ, which was consistent with postherpetic neuralgia. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued after she developed acute liver toxicity attributed to the drug. Upon discontinuation, the patient developed a new pruritic rash on both arms and the back. Physical examination by the dermatology department at our institution revealed diffuse, scaly, hyperpigmented papules and annular plaques with central pink hypopigmentation on the face, ears, anterior chest, arms, hands, and back. On the left anterior chest and back, the distribution was strikingly unilateral and multidermatomal (Figure 1). Upon further questioning, the patient confirmed that the areas of the new rash coincided with areas previously affected by HZ. Histologic examination of a representative lesion from the left lateral breast revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, a patchy lichenoid and perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate, and pigment incontinence (Figure 2A). These histologic features were subtle and were not diagnostic for lupus; however, direct immunofluorescence demonstrated a continuous granular band of IgG and C3 along the dermoepidermal junction, confirming the diagnosis of DLE (Figure 2B). The histologic findings and clinical presentation were consistent with the development of DLE in areas of previous trauma from HZ. The patient continues to follow-up with the rheumatology and nephrology departments but was lost to dermatology follow-up.

Comment

The pathogenesis of DLE is poorly understood but is thought to be multifactorial, involving genetics, sun exposure, and immune dysregulation.1 Development of DLE lesions in skin traumatized by tattoos, scratches, scars, and prolonged heat exposure has been reported.2 Clarification of the mechanism(s) underlying these traumatized areas may provide insight into the pathophysiology of DLE.

The isomorphic response, also known as the Köbner phenomenon, is the development of a preexisting skin condition at a site of trauma. This phenomenon has been observed in several dermatologic conditions including psoriasis, lichen planus, systemic sclerosis, dermatomyositis, sarcoidosis, vitiligo, and DLE.3 Koebnerization may result from trauma to the skin caused by scratches, sun exposure, radiography, prolonged heat and cold exposure, pressure, tattoos, scars, and inflammatory dermatoses.2,4 Ueki4 suggested that localized trauma to the skin stimulates an immune response that makes the traumatized site a target for a preexisting skin condition. Inflammatory mediators such as IL-1, tumor necrosis factor α, IL-6, and interferon γ have been implicated in the pathophysiology of the isomorphic response.4

Wolf isotopic response is a similar entity that refers to the development of a novel skin condition at the site of a distinct, previously resolved skin disorder. This phenomenon was described by Wolf et al5 in 1995, and since then over 170 cases have been reported.5-7 In most cases the initial skin condition is HZ, although herpes simplex virus has also been implicated. The common resulting skin conditions include granulomatous reactions, malignant tumors, lichen planus, morphea, and infections. The notion that the antecedent skin disease alters the affected site and causes it to be more susceptible to autoimmunity has been proposed as a mechanism for the isotopic response.7,8 While one might consider our presentation of DLE following HZ to be an isotopic response, we believe this case is best classified as an isomorphic response, as the patient already had an established diagnosis of DLE.

The development of DLE at the site of a previous HZ eruption has been described in 2 other cases of young women with SLE.9,10 Unique to our case is the development of a multidermatomal eruption, which may be an indication of her degree of immunosuppression, as immunosuppressed patients are more likely to present with multidermatomal reactivation of varicella zoster virus and postherpetic neuralgia.11 The similarities between our case and the 2 prior reports—including the patients’ age, sex, history of SLE, and degree of immunosuppression—are noteworthy in that they may represent a subset of SLE patients who are predisposed to developing koebnerization following HZ. Physicians should be aware of this phenomenon and consider being proactive in preventing long-term damage.

When feasible, physicians should consider administering the HZ vaccine to reduce the course and severity of HZ before prescribing immunosuppressive agents. When HZ presents in young, immunosuppressed women with a history of SLE, we suggest monitoring the affected sites closely for any evidence of DLE. Topical corticosteroids should be applied to involved areas of the face or body at the earliest appearance of such lesions, which may prevent the isomorphic response and its potentially scarring DLE lesions. This will be our therapeutic approach if we encounter a similar clinical situation in the future. Fur

Acknowledgment

We thank Carolyn E. Grotkowski, MD, from the Department of Pathology, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, New Jersey, for her assistance in photographing the pathology slides.

Cutaneous manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can be classified as lupus-specific or lupus-nonspecific skin lesions. Lupus-specific lesions commonly are photodistributed, with involvement of the malar region, arms, and trunk. The development of discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) in areas of trauma, including sun-exposed skin, is not uncommon and may be associated with an isomorphic response. We present a rare case of an isomorphic response following herpes zoster (HZ) in a young woman undergoing treatment with immunosuppressive agents for SLE and DLE. Potential prophylactic therapy also is discussed.

Case Report

A 19-year-old woman initially presented to an outside dermatologist for evaluation of new-onset scarring alopecia, crusted erythematous plaques on the face and arms, and arthralgia. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the left arm demonstrated a lichenoid and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with scattered necrotic keratinocytes, perifollicular inflammation, and focally thickened basement membrane at the dermoepidermal junction consistent with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). A laboratory workup for SLE revealed 1:1280 antinuclear antibodies (reference range, negative <1:80) with elevated titers of double-stranded DNA, Smith, ribonucleoprotein, Sjögren syndrome A, and Sjögren syndrome B autoantibodies with low complement levels. Based on these findings, a diagnosis of SLE and DLE was made.

At that time, the patient was started on hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily for SLE. Four days later she developed swelling in both hands and feet, and hydroxychloroquine was stopped due to a presumed adverse reaction; however, her symptoms subsequently were determined to be polyarthritis secondary to a lupus flare. Prednisone 10 mg once daily was then initiated. The patient was encouraged to restart hydroxychloroquine, but she declined.

Over the next 13 months, the patient developed severe photosensitivity, oral ulcers, Raynaud phenomenon, anemia, and nephrotic-range proteinuria. She ultimately was diagnosed by the nephrology department at our institution with mixed diffuse proliferative and membranous glomerulonephritis. Induction therapy with oral mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily and prednisone 60 mg once daily was started, followed by the addition of tacrolimus 1 mg twice daily. Despite immunosuppressive therapy, she continued to develop new discoid lesions on the face, chest, and arms. Th

After 4 weeks of treatment with mycophenolate mofetil, prednisone, and tacrolimus, the patient developed a painful vesicular rash on the left breast with extension over the left axilla and scapula in a T3 to T4 dermatomal distribution. A clinical diagnosis of HZ was made, and she was started on intravenous acyclovir 10 mg/kg in dextrose 5% every 8 hours for 4 days followed by oral valacyclovir 1000 mg every 8 hours for 14 days, which led to resolution of the eruption.

Over the next 4 months, the patient continued to experience pain confined to the same dermatomal area as the HZ, which was consistent with postherpetic neuralgia. Mycophenolate mofetil was discontinued after she developed acute liver toxicity attributed to the drug. Upon discontinuation, the patient developed a new pruritic rash on both arms and the back. Physical examination by the dermatology department at our institution revealed diffuse, scaly, hyperpigmented papules and annular plaques with central pink hypopigmentation on the face, ears, anterior chest, arms, hands, and back. On the left anterior chest and back, the distribution was strikingly unilateral and multidermatomal (Figure 1). Upon further questioning, the patient confirmed that the areas of the new rash coincided with areas previously affected by HZ. Histologic examination of a representative lesion from the left lateral breast revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, a patchy lichenoid and perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrate, and pigment incontinence (Figure 2A). These histologic features were subtle and were not diagnostic for lupus; however, direct immunofluorescence demonstrated a continuous granular band of IgG and C3 along the dermoepidermal junction, confirming the diagnosis of DLE (Figure 2B). The histologic findings and clinical presentation were consistent with the development of DLE in areas of previous trauma from HZ. The patient continues to follow-up with the rheumatology and nephrology departments but was lost to dermatology follow-up.

Comment

The pathogenesis of DLE is poorly understood but is thought to be multifactorial, involving genetics, sun exposure, and immune dysregulation.1 Development of DLE lesions in skin traumatized by tattoos, scratches, scars, and prolonged heat exposure has been reported.2 Clarification of the mechanism(s) underlying these traumatized areas may provide insight into the pathophysiology of DLE.

The isomorphic response, also known as the Köbner phenomenon, is the development of a preexisting skin condition at a site of trauma. This phenomenon has been observed in several dermatologic conditions including psoriasis, lichen planus, systemic sclerosis, dermatomyositis, sarcoidosis, vitiligo, and DLE.3 Koebnerization may result from trauma to the skin caused by scratches, sun exposure, radiography, prolonged heat and cold exposure, pressure, tattoos, scars, and inflammatory dermatoses.2,4 Ueki4 suggested that localized trauma to the skin stimulates an immune response that makes the traumatized site a target for a preexisting skin condition. Inflammatory mediators such as IL-1, tumor necrosis factor α, IL-6, and interferon γ have been implicated in the pathophysiology of the isomorphic response.4

Wolf isotopic response is a similar entity that refers to the development of a novel skin condition at the site of a distinct, previously resolved skin disorder. This phenomenon was described by Wolf et al5 in 1995, and since then over 170 cases have been reported.5-7 In most cases the initial skin condition is HZ, although herpes simplex virus has also been implicated. The common resulting skin conditions include granulomatous reactions, malignant tumors, lichen planus, morphea, and infections. The notion that the antecedent skin disease alters the affected site and causes it to be more susceptible to autoimmunity has been proposed as a mechanism for the isotopic response.7,8 While one might consider our presentation of DLE following HZ to be an isotopic response, we believe this case is best classified as an isomorphic response, as the patient already had an established diagnosis of DLE.

The development of DLE at the site of a previous HZ eruption has been described in 2 other cases of young women with SLE.9,10 Unique to our case is the development of a multidermatomal eruption, which may be an indication of her degree of immunosuppression, as immunosuppressed patients are more likely to present with multidermatomal reactivation of varicella zoster virus and postherpetic neuralgia.11 The similarities between our case and the 2 prior reports—including the patients’ age, sex, history of SLE, and degree of immunosuppression—are noteworthy in that they may represent a subset of SLE patients who are predisposed to developing koebnerization following HZ. Physicians should be aware of this phenomenon and consider being proactive in preventing long-term damage.

When feasible, physicians should consider administering the HZ vaccine to reduce the course and severity of HZ before prescribing immunosuppressive agents. When HZ presents in young, immunosuppressed women with a history of SLE, we suggest monitoring the affected sites closely for any evidence of DLE. Topical corticosteroids should be applied to involved areas of the face or body at the earliest appearance of such lesions, which may prevent the isomorphic response and its potentially scarring DLE lesions. This will be our therapeutic approach if we encounter a similar clinical situation in the future. Fur

Acknowledgment

We thank Carolyn E. Grotkowski, MD, from the Department of Pathology, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, New Jersey, for her assistance in photographing the pathology slides.

- Lin JH, Dutz JP, Sontheimer RD, et al. Pathophysiology of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol. 2007;33:85-106.

- Ueki H. Köbner phenomenon in lupus erythematosus [in German]. Hautarzt. 1994;45:154-160.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. The isomorphic response of Koebner. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:401-410.

- Ueki H. Koebner phenomenon in lupus erythematosus with special consideration of clinical findings. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:219-223.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Ruocco V, Brunetti G, Puca RV, et al. The immunocompromised district: a unifying concept for lymphoedematous, herpes-infected and otherwise damaged sites. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1364-1373.

- Martires KJ, Baird K, Citrin DE, et al. Localization of sclerotic-type chronic graft-vs-host disease to sites of skin injury. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1081-1086.

- Lee NY, Daniel AS, Dasher DA, et al. Cutaneous lupus after herpes zoster: isomorphic, isotopic, or both [published online May 29, 2012]? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:e110-e113.

- Longhi BS, Centeville M, Marini R, et al. Koebner’s phenomenon in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1403-1405.

- Failla V, Jacques J, Castronovo C, et al. Herpes zoster in patients treated with biologicals. Dermatology. 2012;224:251-256.

- Lin JH, Dutz JP, Sontheimer RD, et al. Pathophysiology of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol. 2007;33:85-106.

- Ueki H. Köbner phenomenon in lupus erythematosus [in German]. Hautarzt. 1994;45:154-160.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. The isomorphic response of Koebner. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:401-410.

- Ueki H. Koebner phenomenon in lupus erythematosus with special consideration of clinical findings. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:219-223.

- Wolf R, Brenner S, Ruocco V, et al. Isotopic response. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:341-348.

- Wolf R, Wolf D, Ruocco E, et al. Wolf’s isotopic response. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:237-240.

- Ruocco V, Brunetti G, Puca RV, et al. The immunocompromised district: a unifying concept for lymphoedematous, herpes-infected and otherwise damaged sites. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1364-1373.

- Martires KJ, Baird K, Citrin DE, et al. Localization of sclerotic-type chronic graft-vs-host disease to sites of skin injury. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1081-1086.

- Lee NY, Daniel AS, Dasher DA, et al. Cutaneous lupus after herpes zoster: isomorphic, isotopic, or both [published online May 29, 2012]? Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:e110-e113.

- Longhi BS, Centeville M, Marini R, et al. Koebner’s phenomenon in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1403-1405.

- Failla V, Jacques J, Castronovo C, et al. Herpes zoster in patients treated with biologicals. Dermatology. 2012;224:251-256.

Practice Points

- Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) most commonly presents as scaling and crusted plaques in sun-exposed areas of the face and arms. It also may present in skin traumatized by tattoos, scratches, scars, prolonged heat exposure, andherpes zoster (HZ).

- Patients with a history of DLE who subsequently develop HZ should be followed closely for the development of DLE in HZ-affected dermatomes.

- Following resolution of HZ, topical corticosteroids may have a role in prevention of DLE in HZ-affected dermatomes.

Bullous Pemphigoid Associated With a Lymphoepithelial Cyst of the Pancreas

Bullous pemphigoid (BP) is an acquired, autoimmune, subepidermal blistering disease that is more common in elderly patients.1 An association with internal neoplasms and BP has been established; however, there is debate regarding the precise nature of the relationship.2 Several gastrointestinal tract tumors have been associated with BP, including adenocarcinoma of the colon, adenosquamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the stomach, adenocarcinoma of the rectum, and liver and bile duct malignancies.3-5 Association with pancreatic neoplasms (eg, carcinoma of the pancreas) rarely has been reported.5-7 We present an unusual case of a lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas in a patient with BP.

Case Report

A 67-year-old man presented with erythematous crusted plaques and pink scars over the chest, back, arms, and legs (Figure 1). A 1.5-cm tense bullous lesion was observed on the right knee. The patient’s medical history was notable for biopsy-proven BP of 8 months’ duration as well as diabetes mellitus and hypothyroidism. The patient was being followed by his surgeon for a 1.9-cm soft-tissue lesion in the pancreatic tail and was awaiting surgical excision at the time of the current presentation. The pancreatic lesion was discovered incidentally on magnetic resonance imaging performed following urologic concerns. At the current presentation, the patient’s medications included nifedipine, hydralazine, metoprolol, torsemide, aspirin, levothyroxine, atorvastatin, insulin lispro, and insulin glargine. He had previously been treated for BP with prednisone at a maximum dosage of 60 mg daily, clobetasol propionate cream 0.05%, and mupirocin ointment 2% without improvement. Because of substantial weight gain and poorly controlled diabetes, prednisone was discontinued.

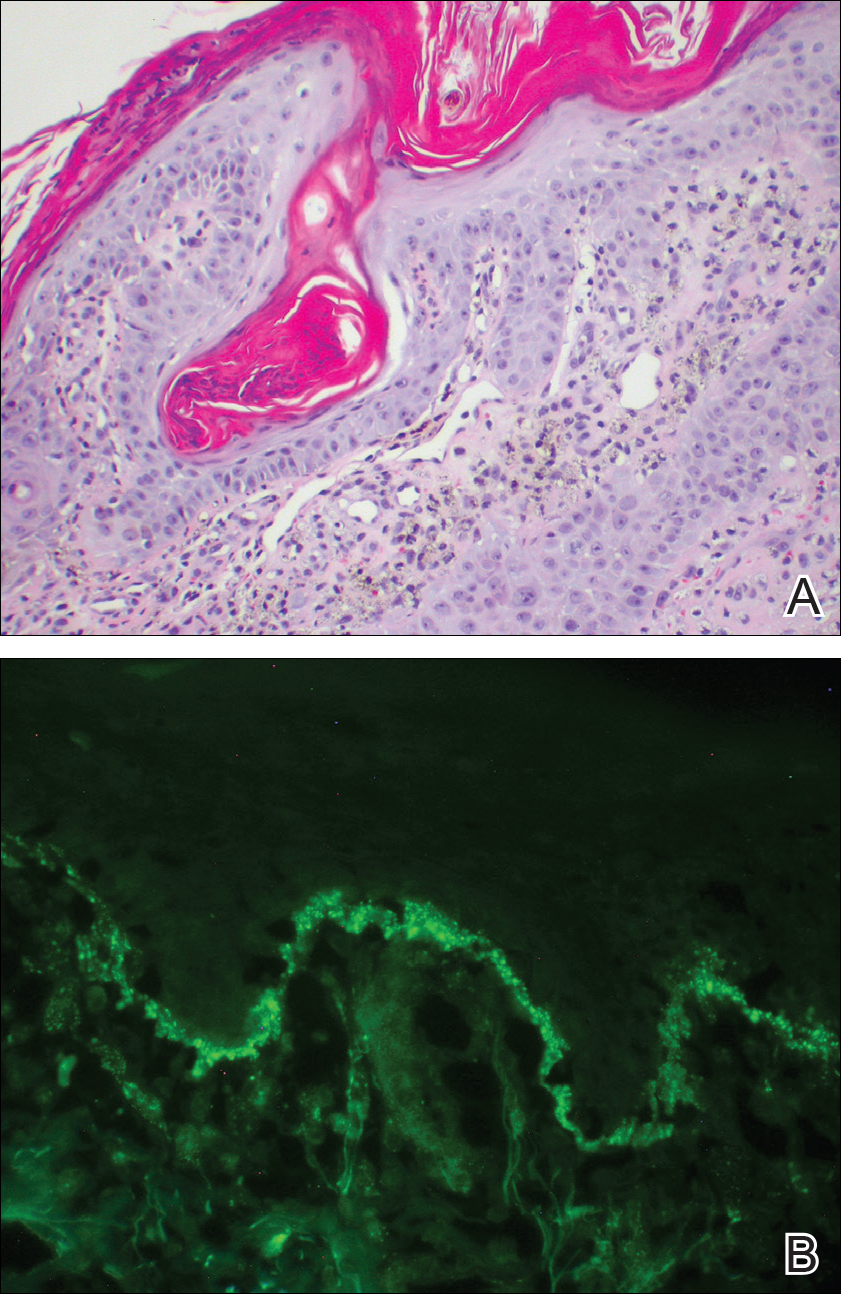

Bullous pemphigoid had been diagnosed histopathologically by a prior dermatologist. Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrated a subepidermal separation with eosinophils within the perivascular infiltrate (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence was noted in a linear pattern at the dermoepidermal junction with IgG and C3. Bullous pemphigoid antigen antibodies 1 and 2 were obtained via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with a positive BP-1 antigen antibody of 19 U/mL (positive, >15 U/mL) and a normal BP-2 antigen antibody of less than 9 U/mL (reference range, <9 U/mL). The glucagon level was elevated at 245 pg/mL (reference range, ≤134 pg/mL).

The patient was prescribed minocycline 100 mg twice daily and niacinamide 500 mg 3 times daily. Topical treatment with clobetasol and mupirocin was continued. One month later, the patient returned with an increase in disease activity. Changes to his therapeutic regimen were deferred until after excision of the pancreatic lesion based on the decision not to start immunosuppressive therapy until the precise nature of the pancreatic lesion was determined.

The patient underwent excision of the pancreatic lesion approximately 3 months later, which proved to be a benign lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas. Histology of the cyst consisted of dense fibrous tissue with a squamous epithelial lining focally infiltrated by lymphocytes (Figure 3A). Immunoperoxidase staining of the cyst revealed focal linear areas of C3d staining along the basement membrane of the stratified squamous epithelium (Figure 3B).

The patient stated that his skin started to improve virtually immediately following the excision without systemic treatment for BP. On follow-up examination 3 weeks postoperatively, no bullae were observed and there was a notable decrease in erythematous crusted plaques (Figure 4).

Comment

Paraneoplastic BP has been documented; however, lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas in association with BP are rare. We propose that the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas provided the immunologic stimulus for the development of cutaneous BP based on the observation that our patient’s condition remarkably improved with resection of the tumor.

There are fewer than 100 cases of lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas reported in the literature.8 The histologic appearance is consistent with a true cyst exhibiting a well-differentiated stratified squamous epithelium, often with keratinization, surrounded by lymphoid tissue. These tumors are most commonly seen in middle-aged men and are frequently found incidentally,8-10 as was the case with our patient. Although histologically similar, lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas are considered distinct from lymphoepithelial cysts of the parotid gland or head and neck region.10 Lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas are unrelated to elevated glucagon levels; it is likely that our patient’s glucagon levels were associated with his history of diabetes.11

The diagnosis of BP is characteristically confirmed by direct immunofluorescence. Although it was performed for our patient’s cutaneous lesions, it was not obtained for the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas. Once the diagnosis of the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas was established, as direct immunofluorescence could not be performed in formalin-fixed tissue, immunoperoxidase staining with C3d was obtained. C3 has a well-established role in activation of complement and as a marker in BP. Deposition of C3d is a result of deactivation of C3b, a cleavage product of C3. In a study of 6 autoimmune blistering disorders that included 32 patients with BP, Pfaltz et al12 found positive immunoperoxidase staining for C3d in 31 of 32 patients, which translated to a sensitivity of 97%, a positive predictive value of 100%, and a negative predictive value of 98% among the blistering diseases being studied. Similarly, Magro and Dyrsen13 had positive staining of C3d in 17 of 17 (100%) patients with BP.

In theory, any process that involves deposition of C3 should be positive for C3d on immunoperoxidase staining. Other dermatologic inflammatory conditions stain positively with C3d, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, discoid lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and dermatomysositis.13 The staining for these diseases correlates with the site of the associated inflammatory component seen on hematoxylin and eosin staining. The staining of C3d along the basement membrane of stratified squamous epithelium in the lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas seen in our patient closely resembles the staining seen in cutaneous BP.

A proposed mechanism for BP in our patient would be exposure of BP-1 antigen in the pancreatic cyst leading to antibody recognition and C3 deposition along the basement membrane in the cyst, as evidenced by C3d immunoperoxidase staining. The IgG and C3 deposition along the cutaneous basement membrane would then represent a systemic response to the antigen exposure in the cyst. Thus, the lymphoepithelial cyst provided the immunologic stimulus for the development of the cutaneous BP. This theory is based on the observation of our patient’s rapid improvement without a change in his treatment regimen immediately after surgical excision of the cyst.

Despite the plausibility of our hypothesis, several questions remain regarding the validity of our assumptions. Although sensitive for C3 deposition, C3d immunoperoxidase staining is not specific for BP. If the proposed mechanism for causation is true, one might have expected that a subepithelial cleft along the basement membrane of the pancreatic cyst would be observed, which was not seen. A repeat BP antigen antibody was not obtained, which would have been helpful in determining if there was clearance of the antibody that would have correlated with the clinical resolution of the BP lesions.

Conclusion

Our case suggests that paraneoplastic BP is a genuine entity. Indeed, the primary tumor itself may be the immunologic stimulus in the development of BP. Recalcitrant BP should raise the question of a neoplastic process that is exposing the BP antigen. If a thorough review of systems accompanied by corroborating laboratory studies suggests a neoplastic process, the suspect lesion should be further evaluated and surgically excised if clinically indicated. Further evaluation of neoplasms with advanced staining methods may aid in establishing the causative nature of tumors in the development of BP.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to John Stanley, MD, and Aimee Payne, MD (both from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania), for theirinsights into this case.

- Charneux J, Lorin J, Vitry F, et al. Usefulness of BP230 and BP180-NC16a enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays in the initial diagnosis of bullous pemphigoid. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:286-291.

- Patel M, Sniha AA, Gilbert E. Bullous pemphigoid associated with renal cell carcinoma and invasive squamous cell carcinoma. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:234-238.

- Song HJ, Han SH, Hong WK, et al. Paraneoplastic bullous pemphigoid: clinical disease activity correlated with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay index for NC16A domain of BP180. J Dermatol. 2009;36:66-68.

- Muramatsu T, Iida T, Tada H, et al. Bullous pemphigoid associated with internal malignancies: identification of 180-kDa antigen by Western immunoblotting. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:782-784.

- Ogawa H, Sakuma M, Morioka S, et al. The incidence of internal malignancies in pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid in Japan. J Dermatol Sci. 1995;9:136-141.

- Boyd RV. Pemphigoid and carcinoma of the pancreas. Br Med J. 1964;1:1092.

- Eustace S, Morrow G, O’Loughlin S, et al. The role of computed tomography and sonography in acute bullous pemphigoid. Ir J Med Sci. 1993;162:401-404.

- Clemente G, Sarno G, De Rose AM, et al. Lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas: case report and review of the literature. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2011;74:343-346.

- Frezza E, Wachtel MS. Lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas tail. case report and review of the literature. JOP. 2008;9:46-49.