User login

Recurrence of a small gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor with high mitotic index

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common soft tissue sarcoma of the gastrointestinal tract, usually arising from the interstitial cells of Cajal or similar cells in the outer wall of the gastrointestinal tract.1,2 Most GISTs have an activating mutation in KIT or platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα). Tumor size, mitotic rate, and anatomic site are the most common pathological features used to risk stratify GIST tumors.3-10 It is important to note when using such risk calculators that preoperative imatinib before determining tumor characteristics (such as mitoses per 50 high-power fields [hpf]) often changes the relevant parameters so that the same risk calculations may not apply. Tumors with a mitotic rate ≤5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size ≤5 cm in greatest dimension have a lower recurrence rate after resection than tumors with a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size >10 cm, and larger tumors can have a recurrence rate of up to 86%.11,12 Findings from a large observational study have suggested that the prognosis of gastric GIST in Korea and Japan may be more favorable compared with that in Western countries.13

The primary treatment of a localized primary GIST is surgical excision, but a cure is limited by recurrence.14,15 Imatinib is useful in the treatment of metastatic or recurrent GIST, and adjuvant treatment with imatinib after surgery has been shown to improve progression-free and overall survival in some cases.3,16-18 Responses to adjuvant imatinib depend on tumor sensitivity to the drug and the risk of recurrence. Drug sensitivity is largely dependent on the presence of mutations in KIT or PDGFRα.3,18 Recurrence risk is highly dependent on tumor size, tumor site, tumor rupture, and mitotic index.1,3,5,6,8,9,18,19 Findings on the use of gene expression patterns to predict recurrence risk have also been reported.20-27 However, recurrence risk is poorly understood for categories in which there are few cases with known outcomes, such as very small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index. For example, few cases of gastric GIST have been reported with a tumor size ≤2 cm, a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf, and adequate clinical follow-up. In such cases, it is difficult to assess the risk of recurrence.6 We report here the long-term outcome of a patient with a 1.8-cm gastric GIST with a mitotic index of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf and a KIT exon 11 mutation.

Case Presentation and Summary

A 69-year-old man presented with periumbilical and epigastric pain of 6-month duration. His medical history was notable for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, coronary angioplasty, and spinal surgery. He had a 40 pack-year smoking history and consumed 2 to 4 alcoholic drinks per day. The results of a physical examination were unremarkable. A computed tomographic (CT) scan showed no abnormalities. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed gastric ulcers. He was treated successfully with omeprazole 20 mg by mouth daily.

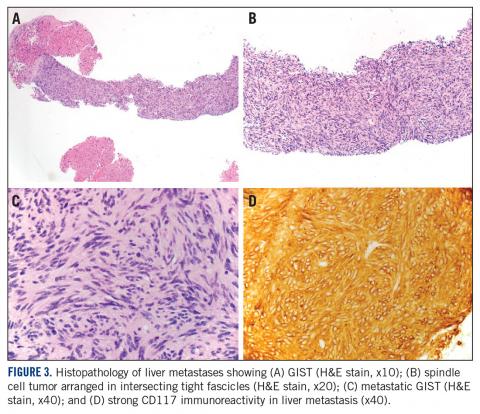

A month later, a follow-up EGD revealed a 1.8 x 1.5-cm submucosal mass 3 cm from the gastroesophageal junction. The patient underwent a fundus wedge resection, and a submucosal mass 1.8 cm in greatest dimension was removed. Pathologic examination revealed a GIST, spindle cell type, with a mitotic rate of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf with negative margins. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD117. An exon 11 deletion (KVV558-560NV) was present in KIT. The patient’s risk of recurrence was unclear, and his follow-up included CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis every 3 to 4 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for the next 2.5 years.

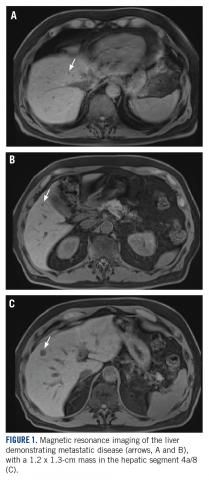

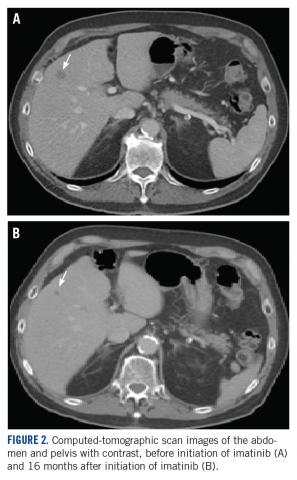

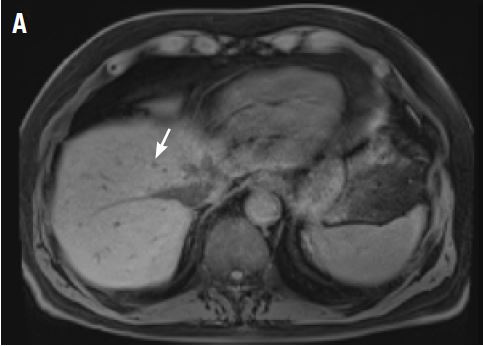

A CT scan about 3.5 years after primary resection revealed small nonspecific liver hypodensities that became more prominent during the next year. About 5 years after primary resection, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed several liver lesions, the largest of which measured 1.3 cm in greatest dimension. The patient’s liver metastases were readily identified by MRI (Figure 1) and CT imaging (Figure 2A).

Discussion

Small gastric GISTs are sometimes found by endoscopy performed for unrelated reasons. Recent data suggest that the incidence of gastric GIST may be higher than previously thought. In a Japanese study of patients with gastric cancer in which 100 stomachs were systematically examined pathologically, 50 microscopic GISTs were found in 35 patients.28 Most small gastric GISTs have a low mitotic index. Few cases have been described with a high mitotic index. In a study of 1765 cases of GIST of the stomach, 8 patients had a tumor size less than 2 cm and a mitotic index greater than 5. Of those, only 6 patients had long-term follow-up, and 3 were alive without disease at 2, 17, and 20 years of follow-up.7 These limited data make it impossible to predict outcomes in patients with small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index.

For patients who are at high risk of recurrence after surgery, 3 years of adjuvant imatinib treatment compared with 1 year has been shown to improve overall survival and is the current standard of care.10,17 A study comparing 5 and 3 years of imatinib is ongoing to establish whether a longer period of adjuvant treatment is warranted. In patients with metastatic GIST, lifelong imatinib until lack of benefit is considered optimal treatment.10 All patients should undergo KIT mutation analysis. Those with the PDGFRα D842V mutation, SDH (succinate dehydrogenase) deficiency, or neurofibromatosis-related GIST should not receive adjuvant imatinib.

This case has several unusual features. The small tumor size with a very high mitotic rate is rare. Such cases have not been reported in large numbers and have therefore not been reliably incorporated into risk prediction algorithms. In addition, despite a high mitotic index, the tumor was not FDG avid on PET imaging. The diagnosis of GIST is strongly supported by the KIT mutation and response to imatinib. This particular KIT mutation in larger GISTs is associated with aggressive disease. The present case adds to the data on the biology of small gastric GISTs with a high mitotic index and suggests the mitotic index in these tumors may be a more important predictor than size. TSJ

Acknowlegement

The authors thank Michael Franklin, MS, for editorial assistance, and Sabrina Porter for media edits.

aDepartment of Medicine, University of Minnesota Medical School; bDepartment of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Minnesota Medical School; and cMasonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Disclosures

The authors report no disclosures or conflicts of interest. This article was originally published in The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology JCSO. 2018;16(3):e163-e166. ©Frontline Medical Communications. doi:10.12788/jcso.0402. It is reproduced with permission from the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

1. Corless CL, Barnett CM, Heinrich MC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: origin and molecular oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(12):865-878.

2. Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, Hashimoto K, Nishida T, Ishiguro S, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279(5350):577-580.

3. Corless CL, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, Kolesnikova V, Maki RG, Pisters PW, et al. Pathologic and molecular features correlate with long-term outcome after adjuvant therapy of resected primary GI stromal tumor: the ACOSOG Z9001 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1563-1570.

4. Huang J, Zheng DL, Qin FS, Cheng N, Chen H, Wan BB, et al. Genetic and epigenetic silencing of SCARA5 may contribute to human hepatocellular carcinoma by activating FAK signaling. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(1):223-241.

5. Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimaki J, Nishida T, Steigen SE, Brabec P, et al. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):265-274.

6. Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(10):1466-1478.

7. Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(1):52-68.

8. Patel S. Navigating risk stratification systems for the management of patients with GIST. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(6):1698-1704.

9. Rossi S, Miceli R, Messerini L, Bearzi I, Mazzoleni G, Capella C, et al. Natural history of imatinib-naive GISTs: a retrospective analysis of 929 cases with long-term follow-up and development of a survival nomogram based on mitotic index and size as continuous variables. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(11):1646-1656.

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Sarcoma. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx#age. Accessed March 27, 2018.

11. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Int J Surg Pathol. 2002;10(2):81-89.

12. Huang HY, Li CF, Huang WW, Hu TH, Lin CN, Uen YH, et al. A modification of NIH consensus criteria to better distinguish the highly lethal subset of primary localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a subdivision of the original high-risk group on the basis of outcome. Surgery. 2007;141(6):748-756.

13. Kim MC, Yook JH, Yang HK, Lee HJ, Sohn TS, Hyung WJ, et al. Long-term surgical outcome of 1057 gastric GISTs according to 7th UICC/AJCC TNM system: multicenter observational study from Korea and Japan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(41):e1526.

14. Casali PG, Blay JY; ESMO/CONTICANET/EUROBONET Consensus Panel of experts. Soft tissue sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v198-v203.

15. Joensuu H, DeMatteo RP. The management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a model for targeted and multidisciplinary therapy of malignancy. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:247-258.

16. Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, Maki RG, Pisters PW, Demetri GD, et al. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1097-1104.

17. Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, Hartmann JT, Pink D, Schütte J, et al. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307(12):1265-1272.

18. Joensuu H, Rutkowski P, Nishida T, Steigen SE, Brabec P, Plank L, et al. KIT and PDGFRA mutations and the risk of GI stromal tumor recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):634-642.

19. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(5):459-465.

20. Antonescu CR, Viale A, Sarran L, Tschernyavsky SJ, Gonen M, Segal NH, et al. Gene expression in gastrointestinal stromal tumors is distinguished by KIT genotype and anatomic site. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(10):3282-3290.

21. Arne G, Kristiansson E, Nerman O, Kindblom LG, Ahlman H, Nilsson B, et al. Expression profiling of GIST: CD133 is associated with KIT exon 11 mutations, gastric location and poor prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(5):1149-1161.

22. Bertucci F, Finetti P, Ostrowski J, Kim WK, Kim H, Pantaleo MA, et al. Genomic Grade Index predicts postoperative clinical outcome of GIST. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(8):1433-1441.

23. Koon N, Schneider-Stock R, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Lasota J, Smolkin M, Petroni G, et al. Molecular targets for tumour progression in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Gut. 2004;53(2):235-240.

24. Lagarde P, Perot G, Kauffmann A, Brulard C, Dapremont V, Hostein I, et al. Mitotic checkpoints and chromosome instability are strong predictors of clinical outcome in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(3):826-838.

25. Skubitz KM, Geschwind K, Xu WW, Koopmeiners JS, Skubitz AP. Gene expression identifies heterogeneity of metastatic behavior among gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Transl Med. 2016;14:51.

26. Yamaguchi U, Nakayama R, Honda K, Ichikawa H, Haseqawa T, Shitashige M, et al. Distinct gene expression-defined classes of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4100-4108.

27. Ylipaa A, Hunt KK, Yang J, Lazar AJ, Torres KE, Lev DC, et al. Integrative genomic characterization and a genomic staging system for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer. 2011;117(2):380-389.

28. Kawanowa K, Sakuma Y, Sakurai S, Hishima T, Iwasaki Y, Saito K, et al. High incidence of microscopic gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(12):1527-1535.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common soft tissue sarcoma of the gastrointestinal tract, usually arising from the interstitial cells of Cajal or similar cells in the outer wall of the gastrointestinal tract.1,2 Most GISTs have an activating mutation in KIT or platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα). Tumor size, mitotic rate, and anatomic site are the most common pathological features used to risk stratify GIST tumors.3-10 It is important to note when using such risk calculators that preoperative imatinib before determining tumor characteristics (such as mitoses per 50 high-power fields [hpf]) often changes the relevant parameters so that the same risk calculations may not apply. Tumors with a mitotic rate ≤5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size ≤5 cm in greatest dimension have a lower recurrence rate after resection than tumors with a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size >10 cm, and larger tumors can have a recurrence rate of up to 86%.11,12 Findings from a large observational study have suggested that the prognosis of gastric GIST in Korea and Japan may be more favorable compared with that in Western countries.13

The primary treatment of a localized primary GIST is surgical excision, but a cure is limited by recurrence.14,15 Imatinib is useful in the treatment of metastatic or recurrent GIST, and adjuvant treatment with imatinib after surgery has been shown to improve progression-free and overall survival in some cases.3,16-18 Responses to adjuvant imatinib depend on tumor sensitivity to the drug and the risk of recurrence. Drug sensitivity is largely dependent on the presence of mutations in KIT or PDGFRα.3,18 Recurrence risk is highly dependent on tumor size, tumor site, tumor rupture, and mitotic index.1,3,5,6,8,9,18,19 Findings on the use of gene expression patterns to predict recurrence risk have also been reported.20-27 However, recurrence risk is poorly understood for categories in which there are few cases with known outcomes, such as very small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index. For example, few cases of gastric GIST have been reported with a tumor size ≤2 cm, a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf, and adequate clinical follow-up. In such cases, it is difficult to assess the risk of recurrence.6 We report here the long-term outcome of a patient with a 1.8-cm gastric GIST with a mitotic index of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf and a KIT exon 11 mutation.

Case Presentation and Summary

A 69-year-old man presented with periumbilical and epigastric pain of 6-month duration. His medical history was notable for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, coronary angioplasty, and spinal surgery. He had a 40 pack-year smoking history and consumed 2 to 4 alcoholic drinks per day. The results of a physical examination were unremarkable. A computed tomographic (CT) scan showed no abnormalities. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed gastric ulcers. He was treated successfully with omeprazole 20 mg by mouth daily.

A month later, a follow-up EGD revealed a 1.8 x 1.5-cm submucosal mass 3 cm from the gastroesophageal junction. The patient underwent a fundus wedge resection, and a submucosal mass 1.8 cm in greatest dimension was removed. Pathologic examination revealed a GIST, spindle cell type, with a mitotic rate of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf with negative margins. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD117. An exon 11 deletion (KVV558-560NV) was present in KIT. The patient’s risk of recurrence was unclear, and his follow-up included CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis every 3 to 4 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for the next 2.5 years.

A CT scan about 3.5 years after primary resection revealed small nonspecific liver hypodensities that became more prominent during the next year. About 5 years after primary resection, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed several liver lesions, the largest of which measured 1.3 cm in greatest dimension. The patient’s liver metastases were readily identified by MRI (Figure 1) and CT imaging (Figure 2A).

Discussion

Small gastric GISTs are sometimes found by endoscopy performed for unrelated reasons. Recent data suggest that the incidence of gastric GIST may be higher than previously thought. In a Japanese study of patients with gastric cancer in which 100 stomachs were systematically examined pathologically, 50 microscopic GISTs were found in 35 patients.28 Most small gastric GISTs have a low mitotic index. Few cases have been described with a high mitotic index. In a study of 1765 cases of GIST of the stomach, 8 patients had a tumor size less than 2 cm and a mitotic index greater than 5. Of those, only 6 patients had long-term follow-up, and 3 were alive without disease at 2, 17, and 20 years of follow-up.7 These limited data make it impossible to predict outcomes in patients with small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index.

For patients who are at high risk of recurrence after surgery, 3 years of adjuvant imatinib treatment compared with 1 year has been shown to improve overall survival and is the current standard of care.10,17 A study comparing 5 and 3 years of imatinib is ongoing to establish whether a longer period of adjuvant treatment is warranted. In patients with metastatic GIST, lifelong imatinib until lack of benefit is considered optimal treatment.10 All patients should undergo KIT mutation analysis. Those with the PDGFRα D842V mutation, SDH (succinate dehydrogenase) deficiency, or neurofibromatosis-related GIST should not receive adjuvant imatinib.

This case has several unusual features. The small tumor size with a very high mitotic rate is rare. Such cases have not been reported in large numbers and have therefore not been reliably incorporated into risk prediction algorithms. In addition, despite a high mitotic index, the tumor was not FDG avid on PET imaging. The diagnosis of GIST is strongly supported by the KIT mutation and response to imatinib. This particular KIT mutation in larger GISTs is associated with aggressive disease. The present case adds to the data on the biology of small gastric GISTs with a high mitotic index and suggests the mitotic index in these tumors may be a more important predictor than size. TSJ

Acknowlegement

The authors thank Michael Franklin, MS, for editorial assistance, and Sabrina Porter for media edits.

aDepartment of Medicine, University of Minnesota Medical School; bDepartment of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Minnesota Medical School; and cMasonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Disclosures

The authors report no disclosures or conflicts of interest. This article was originally published in The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology JCSO. 2018;16(3):e163-e166. ©Frontline Medical Communications. doi:10.12788/jcso.0402. It is reproduced with permission from the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common soft tissue sarcoma of the gastrointestinal tract, usually arising from the interstitial cells of Cajal or similar cells in the outer wall of the gastrointestinal tract.1,2 Most GISTs have an activating mutation in KIT or platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRα). Tumor size, mitotic rate, and anatomic site are the most common pathological features used to risk stratify GIST tumors.3-10 It is important to note when using such risk calculators that preoperative imatinib before determining tumor characteristics (such as mitoses per 50 high-power fields [hpf]) often changes the relevant parameters so that the same risk calculations may not apply. Tumors with a mitotic rate ≤5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size ≤5 cm in greatest dimension have a lower recurrence rate after resection than tumors with a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size >10 cm, and larger tumors can have a recurrence rate of up to 86%.11,12 Findings from a large observational study have suggested that the prognosis of gastric GIST in Korea and Japan may be more favorable compared with that in Western countries.13

The primary treatment of a localized primary GIST is surgical excision, but a cure is limited by recurrence.14,15 Imatinib is useful in the treatment of metastatic or recurrent GIST, and adjuvant treatment with imatinib after surgery has been shown to improve progression-free and overall survival in some cases.3,16-18 Responses to adjuvant imatinib depend on tumor sensitivity to the drug and the risk of recurrence. Drug sensitivity is largely dependent on the presence of mutations in KIT or PDGFRα.3,18 Recurrence risk is highly dependent on tumor size, tumor site, tumor rupture, and mitotic index.1,3,5,6,8,9,18,19 Findings on the use of gene expression patterns to predict recurrence risk have also been reported.20-27 However, recurrence risk is poorly understood for categories in which there are few cases with known outcomes, such as very small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index. For example, few cases of gastric GIST have been reported with a tumor size ≤2 cm, a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf, and adequate clinical follow-up. In such cases, it is difficult to assess the risk of recurrence.6 We report here the long-term outcome of a patient with a 1.8-cm gastric GIST with a mitotic index of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf and a KIT exon 11 mutation.

Case Presentation and Summary

A 69-year-old man presented with periumbilical and epigastric pain of 6-month duration. His medical history was notable for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, coronary angioplasty, and spinal surgery. He had a 40 pack-year smoking history and consumed 2 to 4 alcoholic drinks per day. The results of a physical examination were unremarkable. A computed tomographic (CT) scan showed no abnormalities. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed gastric ulcers. He was treated successfully with omeprazole 20 mg by mouth daily.

A month later, a follow-up EGD revealed a 1.8 x 1.5-cm submucosal mass 3 cm from the gastroesophageal junction. The patient underwent a fundus wedge resection, and a submucosal mass 1.8 cm in greatest dimension was removed. Pathologic examination revealed a GIST, spindle cell type, with a mitotic rate of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf with negative margins. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD117. An exon 11 deletion (KVV558-560NV) was present in KIT. The patient’s risk of recurrence was unclear, and his follow-up included CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis every 3 to 4 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for the next 2.5 years.

A CT scan about 3.5 years after primary resection revealed small nonspecific liver hypodensities that became more prominent during the next year. About 5 years after primary resection, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed several liver lesions, the largest of which measured 1.3 cm in greatest dimension. The patient’s liver metastases were readily identified by MRI (Figure 1) and CT imaging (Figure 2A).

Discussion

Small gastric GISTs are sometimes found by endoscopy performed for unrelated reasons. Recent data suggest that the incidence of gastric GIST may be higher than previously thought. In a Japanese study of patients with gastric cancer in which 100 stomachs were systematically examined pathologically, 50 microscopic GISTs were found in 35 patients.28 Most small gastric GISTs have a low mitotic index. Few cases have been described with a high mitotic index. In a study of 1765 cases of GIST of the stomach, 8 patients had a tumor size less than 2 cm and a mitotic index greater than 5. Of those, only 6 patients had long-term follow-up, and 3 were alive without disease at 2, 17, and 20 years of follow-up.7 These limited data make it impossible to predict outcomes in patients with small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index.

For patients who are at high risk of recurrence after surgery, 3 years of adjuvant imatinib treatment compared with 1 year has been shown to improve overall survival and is the current standard of care.10,17 A study comparing 5 and 3 years of imatinib is ongoing to establish whether a longer period of adjuvant treatment is warranted. In patients with metastatic GIST, lifelong imatinib until lack of benefit is considered optimal treatment.10 All patients should undergo KIT mutation analysis. Those with the PDGFRα D842V mutation, SDH (succinate dehydrogenase) deficiency, or neurofibromatosis-related GIST should not receive adjuvant imatinib.

This case has several unusual features. The small tumor size with a very high mitotic rate is rare. Such cases have not been reported in large numbers and have therefore not been reliably incorporated into risk prediction algorithms. In addition, despite a high mitotic index, the tumor was not FDG avid on PET imaging. The diagnosis of GIST is strongly supported by the KIT mutation and response to imatinib. This particular KIT mutation in larger GISTs is associated with aggressive disease. The present case adds to the data on the biology of small gastric GISTs with a high mitotic index and suggests the mitotic index in these tumors may be a more important predictor than size. TSJ

Acknowlegement

The authors thank Michael Franklin, MS, for editorial assistance, and Sabrina Porter for media edits.

aDepartment of Medicine, University of Minnesota Medical School; bDepartment of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, University of Minnesota Medical School; and cMasonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Disclosures

The authors report no disclosures or conflicts of interest. This article was originally published in The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology JCSO. 2018;16(3):e163-e166. ©Frontline Medical Communications. doi:10.12788/jcso.0402. It is reproduced with permission from the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

1. Corless CL, Barnett CM, Heinrich MC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: origin and molecular oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(12):865-878.

2. Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, Hashimoto K, Nishida T, Ishiguro S, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279(5350):577-580.

3. Corless CL, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, Kolesnikova V, Maki RG, Pisters PW, et al. Pathologic and molecular features correlate with long-term outcome after adjuvant therapy of resected primary GI stromal tumor: the ACOSOG Z9001 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1563-1570.

4. Huang J, Zheng DL, Qin FS, Cheng N, Chen H, Wan BB, et al. Genetic and epigenetic silencing of SCARA5 may contribute to human hepatocellular carcinoma by activating FAK signaling. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(1):223-241.

5. Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimaki J, Nishida T, Steigen SE, Brabec P, et al. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):265-274.

6. Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(10):1466-1478.

7. Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(1):52-68.

8. Patel S. Navigating risk stratification systems for the management of patients with GIST. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(6):1698-1704.

9. Rossi S, Miceli R, Messerini L, Bearzi I, Mazzoleni G, Capella C, et al. Natural history of imatinib-naive GISTs: a retrospective analysis of 929 cases with long-term follow-up and development of a survival nomogram based on mitotic index and size as continuous variables. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(11):1646-1656.

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Sarcoma. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx#age. Accessed March 27, 2018.

11. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Int J Surg Pathol. 2002;10(2):81-89.

12. Huang HY, Li CF, Huang WW, Hu TH, Lin CN, Uen YH, et al. A modification of NIH consensus criteria to better distinguish the highly lethal subset of primary localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a subdivision of the original high-risk group on the basis of outcome. Surgery. 2007;141(6):748-756.

13. Kim MC, Yook JH, Yang HK, Lee HJ, Sohn TS, Hyung WJ, et al. Long-term surgical outcome of 1057 gastric GISTs according to 7th UICC/AJCC TNM system: multicenter observational study from Korea and Japan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(41):e1526.

14. Casali PG, Blay JY; ESMO/CONTICANET/EUROBONET Consensus Panel of experts. Soft tissue sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v198-v203.

15. Joensuu H, DeMatteo RP. The management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a model for targeted and multidisciplinary therapy of malignancy. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:247-258.

16. Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, Maki RG, Pisters PW, Demetri GD, et al. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1097-1104.

17. Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, Hartmann JT, Pink D, Schütte J, et al. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307(12):1265-1272.

18. Joensuu H, Rutkowski P, Nishida T, Steigen SE, Brabec P, Plank L, et al. KIT and PDGFRA mutations and the risk of GI stromal tumor recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):634-642.

19. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(5):459-465.

20. Antonescu CR, Viale A, Sarran L, Tschernyavsky SJ, Gonen M, Segal NH, et al. Gene expression in gastrointestinal stromal tumors is distinguished by KIT genotype and anatomic site. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(10):3282-3290.

21. Arne G, Kristiansson E, Nerman O, Kindblom LG, Ahlman H, Nilsson B, et al. Expression profiling of GIST: CD133 is associated with KIT exon 11 mutations, gastric location and poor prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(5):1149-1161.

22. Bertucci F, Finetti P, Ostrowski J, Kim WK, Kim H, Pantaleo MA, et al. Genomic Grade Index predicts postoperative clinical outcome of GIST. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(8):1433-1441.

23. Koon N, Schneider-Stock R, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Lasota J, Smolkin M, Petroni G, et al. Molecular targets for tumour progression in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Gut. 2004;53(2):235-240.

24. Lagarde P, Perot G, Kauffmann A, Brulard C, Dapremont V, Hostein I, et al. Mitotic checkpoints and chromosome instability are strong predictors of clinical outcome in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(3):826-838.

25. Skubitz KM, Geschwind K, Xu WW, Koopmeiners JS, Skubitz AP. Gene expression identifies heterogeneity of metastatic behavior among gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Transl Med. 2016;14:51.

26. Yamaguchi U, Nakayama R, Honda K, Ichikawa H, Haseqawa T, Shitashige M, et al. Distinct gene expression-defined classes of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4100-4108.

27. Ylipaa A, Hunt KK, Yang J, Lazar AJ, Torres KE, Lev DC, et al. Integrative genomic characterization and a genomic staging system for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer. 2011;117(2):380-389.

28. Kawanowa K, Sakuma Y, Sakurai S, Hishima T, Iwasaki Y, Saito K, et al. High incidence of microscopic gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(12):1527-1535.

1. Corless CL, Barnett CM, Heinrich MC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: origin and molecular oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(12):865-878.

2. Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, Hashimoto K, Nishida T, Ishiguro S, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279(5350):577-580.

3. Corless CL, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, Kolesnikova V, Maki RG, Pisters PW, et al. Pathologic and molecular features correlate with long-term outcome after adjuvant therapy of resected primary GI stromal tumor: the ACOSOG Z9001 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1563-1570.

4. Huang J, Zheng DL, Qin FS, Cheng N, Chen H, Wan BB, et al. Genetic and epigenetic silencing of SCARA5 may contribute to human hepatocellular carcinoma by activating FAK signaling. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(1):223-241.

5. Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimaki J, Nishida T, Steigen SE, Brabec P, et al. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):265-274.

6. Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(10):1466-1478.

7. Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(1):52-68.

8. Patel S. Navigating risk stratification systems for the management of patients with GIST. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(6):1698-1704.

9. Rossi S, Miceli R, Messerini L, Bearzi I, Mazzoleni G, Capella C, et al. Natural history of imatinib-naive GISTs: a retrospective analysis of 929 cases with long-term follow-up and development of a survival nomogram based on mitotic index and size as continuous variables. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(11):1646-1656.

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Sarcoma. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx#age. Accessed March 27, 2018.

11. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Int J Surg Pathol. 2002;10(2):81-89.

12. Huang HY, Li CF, Huang WW, Hu TH, Lin CN, Uen YH, et al. A modification of NIH consensus criteria to better distinguish the highly lethal subset of primary localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a subdivision of the original high-risk group on the basis of outcome. Surgery. 2007;141(6):748-756.

13. Kim MC, Yook JH, Yang HK, Lee HJ, Sohn TS, Hyung WJ, et al. Long-term surgical outcome of 1057 gastric GISTs according to 7th UICC/AJCC TNM system: multicenter observational study from Korea and Japan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(41):e1526.

14. Casali PG, Blay JY; ESMO/CONTICANET/EUROBONET Consensus Panel of experts. Soft tissue sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v198-v203.

15. Joensuu H, DeMatteo RP. The management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a model for targeted and multidisciplinary therapy of malignancy. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:247-258.

16. Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, Maki RG, Pisters PW, Demetri GD, et al. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1097-1104.

17. Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, Hartmann JT, Pink D, Schütte J, et al. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307(12):1265-1272.

18. Joensuu H, Rutkowski P, Nishida T, Steigen SE, Brabec P, Plank L, et al. KIT and PDGFRA mutations and the risk of GI stromal tumor recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):634-642.

19. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(5):459-465.

20. Antonescu CR, Viale A, Sarran L, Tschernyavsky SJ, Gonen M, Segal NH, et al. Gene expression in gastrointestinal stromal tumors is distinguished by KIT genotype and anatomic site. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(10):3282-3290.

21. Arne G, Kristiansson E, Nerman O, Kindblom LG, Ahlman H, Nilsson B, et al. Expression profiling of GIST: CD133 is associated with KIT exon 11 mutations, gastric location and poor prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(5):1149-1161.

22. Bertucci F, Finetti P, Ostrowski J, Kim WK, Kim H, Pantaleo MA, et al. Genomic Grade Index predicts postoperative clinical outcome of GIST. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(8):1433-1441.

23. Koon N, Schneider-Stock R, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Lasota J, Smolkin M, Petroni G, et al. Molecular targets for tumour progression in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Gut. 2004;53(2):235-240.

24. Lagarde P, Perot G, Kauffmann A, Brulard C, Dapremont V, Hostein I, et al. Mitotic checkpoints and chromosome instability are strong predictors of clinical outcome in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(3):826-838.

25. Skubitz KM, Geschwind K, Xu WW, Koopmeiners JS, Skubitz AP. Gene expression identifies heterogeneity of metastatic behavior among gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Transl Med. 2016;14:51.

26. Yamaguchi U, Nakayama R, Honda K, Ichikawa H, Haseqawa T, Shitashige M, et al. Distinct gene expression-defined classes of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4100-4108.

27. Ylipaa A, Hunt KK, Yang J, Lazar AJ, Torres KE, Lev DC, et al. Integrative genomic characterization and a genomic staging system for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer. 2011;117(2):380-389.

28. Kawanowa K, Sakuma Y, Sakurai S, Hishima T, Iwasaki Y, Saito K, et al. High incidence of microscopic gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(12):1527-1535.

Abdominal Wall Schwannoma

Schwannomas are benign tumors exclusively composed of Schwann cells that arise from the peripheral nerve sheath; these tumors theoretically can present anywhere in the body where nerves reside. They tend to occur in the head and neck region (classically an acoustic neuroma) but also occur in other locations, including the retroperitoneal space and the extremities, particularly flexural surfaces. Patients with cutaneous schwannomas are most likely to present to their primary care provider’s office reporting skin findings or localized pain, and providers should be aware of schwannomas on the differential for painful nodular growths.

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to the primary care clinic for intermittent, sharp, localized left lower quadrant abdominal wall pain that was gradually progressive over the previous few months. The patient noticed the development of a small nodule 7 to 8 months prior to the visit, at which time the pain was less frequent and less severe. He reported no postprandial association of the pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, or other gastrointestinal symptoms.

Ten months prior to the presentation, he was involved in a low-impact motor vehicle collision as a pedestrian in which he fell face-first onto the hood of an oncoming car. At that time, he did not note any abdominal trauma or pain. Evaluation at a local emergency department did not reveal any major injuries. In the interim, he had self-administered insulin in his abdominal region, as he had without incident for the previous 2 years. He reported that he was not injecting near the site of the nodule since it had formed. He could not recall whether the location was a previous insulin administration site.

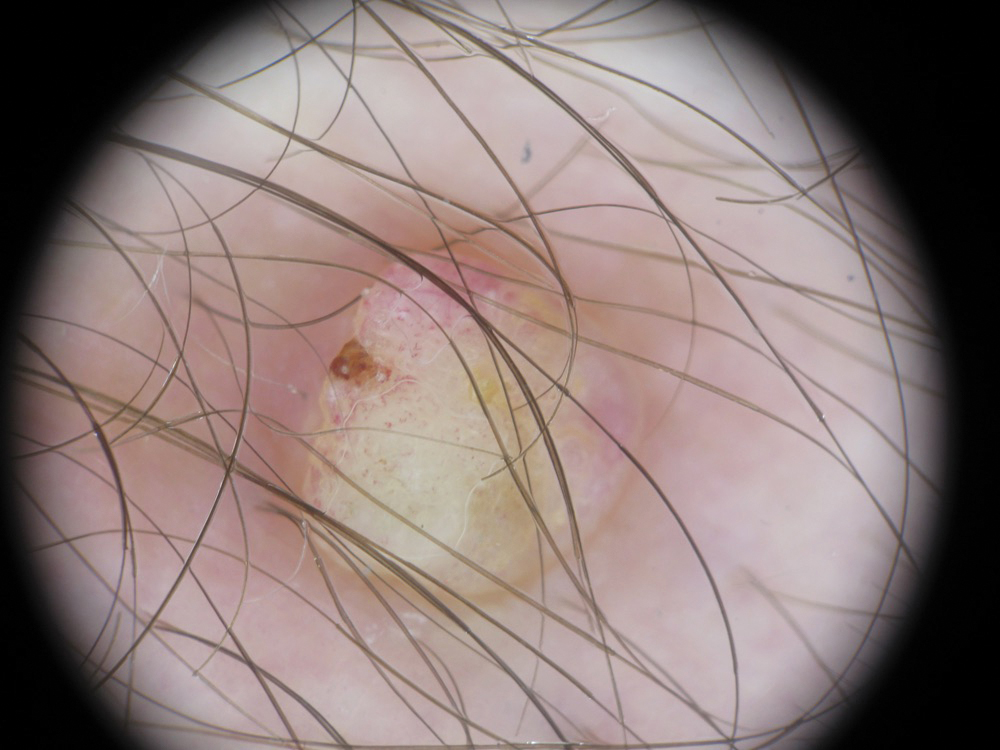

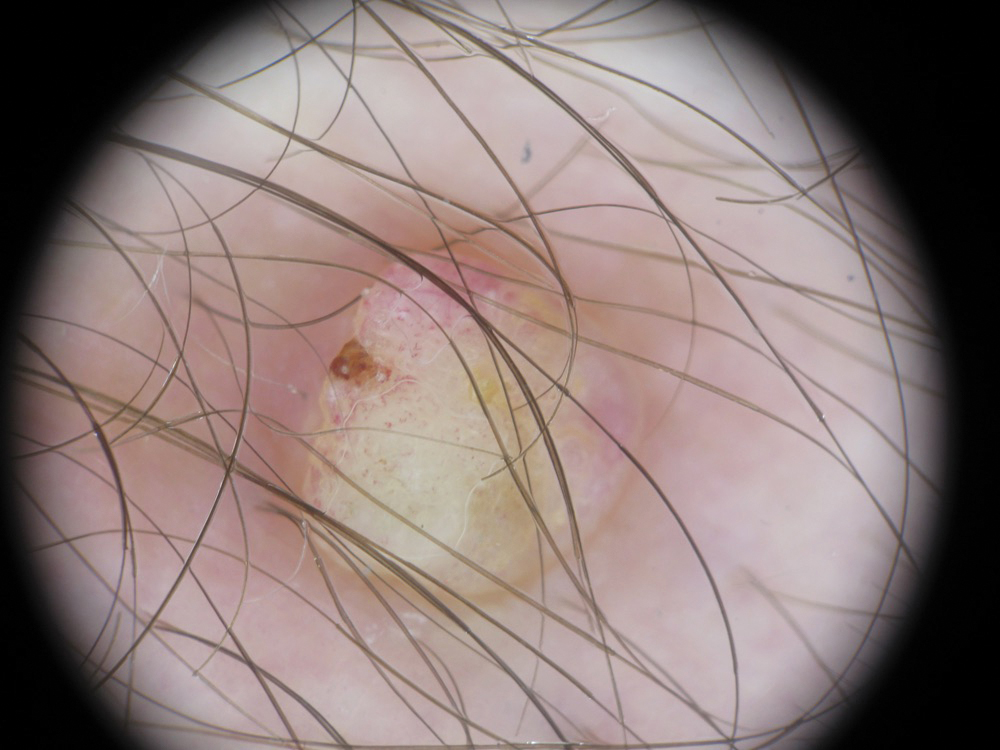

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were normal as were the cardiac and respiratory examinations. An abdominal exam revealed normal bowel sounds and no overlying skin changes or discoloration. Palpation revealed a 1.5 x 1 cm rubbery-to-firm, well-circumscribed subcutaneous nodule along his mid-left abdomen, about 7 cm lateral to the umbilicus. The nodule was sensitive to both light touch and deep pressure. It was firmer than expected for an abdominal wall lipoma. There was no central puncta or pore to suggest an epidermal inclusion cyst. There was no surrounding erythema or induration to suggest an abscess.

The patient was referred for surgery and underwent excisional biopsy of the mass. Pathology revealed a well-circumscribed vascular/spindle-cell lesion consistent with a schwannoma. His postoperative course was uncomplicated. At 4-week follow-up the incision had healed completely and the patient was pain free.

Discussion

Soft-tissue nodules are common—about two-thirds of soft-tissue tumors are classified into 7 diagnostic categories: lipoma and lipoma variants (16%), fibrous histiocytoma (13%), nodular fasciitis (11%), hemangioma (8%), fibromatosis (7%), neurofibroma (5%), and schwannoma (5%).1 Peripheral nerve tumors (schwannomas, neurofibromas) can be associated with pain or paresthesias, and less commonly, neurologic deficits, such as motor weakness. Peripheral nerve tumors have several classifications, such as nonneoplastic vs neoplastic, benign vs malignant, and sheath vs nonsheath origins. Schwannomas are considered part of the neoplastic subset due to their growth; otherwise, they are benign with a sheath origin. In contrast to neurofibromas, benign schwannomas have a slower rate of progression, lower association with pain, and fewer neurologic symptoms.2

The neural sheath is made up of 3 types of cells: the fibroblast, the Schwann cell, and the perineural cell, which lacks a basement membrane. It is the Schwann cell that can give rise to the 3 main types of cutaneous nerve tumors: neuromas, neurofibromas, and schwannomas.3 A nerve that is both entering and exiting a mass is a classic presentation for a peripheral nerve sheath tumor. If the nerve is eccentric to the lesion, then it is consistent with a schwannoma (not a neurofibroma).4 Schwannomas are made exclusively of Schwann cells that arise from the nerve sheath, whereas neurofibromas are made up of all the different cell types that constitute a nerve. Bilateral vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas) are virtually pathognomonic of neurofibromatosis 2 (NF-2), which can manifest as hearing loss, tinnitus, and equilibrium problems. In contrast, neurofibromatosis 1 (NF-1) is more common, characterized by multiple café au lait spots, freckling in the axillary and groin regions, increased risk of cancers overall, and development of pedunculated skin growths, brain, or organ-based neurofibromas.

Diagnosis

A workup generally includes a thorough history and examination as well as imaging. In cases of superficial subcutaneous lesions, an ultrasound is often the imaging modality of choice. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans are frequently used for more deep-seated lesions. There can be significant differences between malignant and benign neural lesions on MRI and CT in terms of contrast-uptake and heterogeneity of tissue, but the visual features are not consistent. Best estimates for MRI suggest 61% sensitivity and 90% specificity for the diagnosis of high-grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors based on imaging alone.5

Definitive diagnosis requires surgical excision. Fine-needle aspiration can be used to diagnose subcutaneous nodules, but there is a possibility that degenerative changes and nuclear atypia seen on a smaller sample may be confused with a more aggressive sarcoma. For example, long-standing schwannomas are often called ancient, meaning that they break down over time, and the atypia they display is a regressive phenomenon.6 Therefore, a small or limited tissue sampling may not be representative of the entire lesion.7 As such, patients will likely need referral for surgical removal to determine the exact nature of the growth.

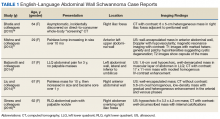

Although schwannomas are uncommon overall, the highest incidence is in the fourth decade of life with a slight predominance in females. They are often incidentally found as a palpable mass but can be symptomatic with paresthesias, pain, or neurologic changes—particularly when identified in the retroperitoneum or along joints. Schwannomas are most commonly found in the retroperitoneum (32%), mediastinum (23%), head and neck (18%), and extremities (16%).8 The majority of cases (about 90%) are sporadic; whereas 2% are related to NF-2.9 The abdominal wall schwannoma is rare. Our review of English-language literature in PubMed and EMBASE found only 5 other case reports (Table 1).

On physical examination, superficial lesions are freely movable except for a single point of attachment, which is generally along the long axis of the nerve.

Pathology

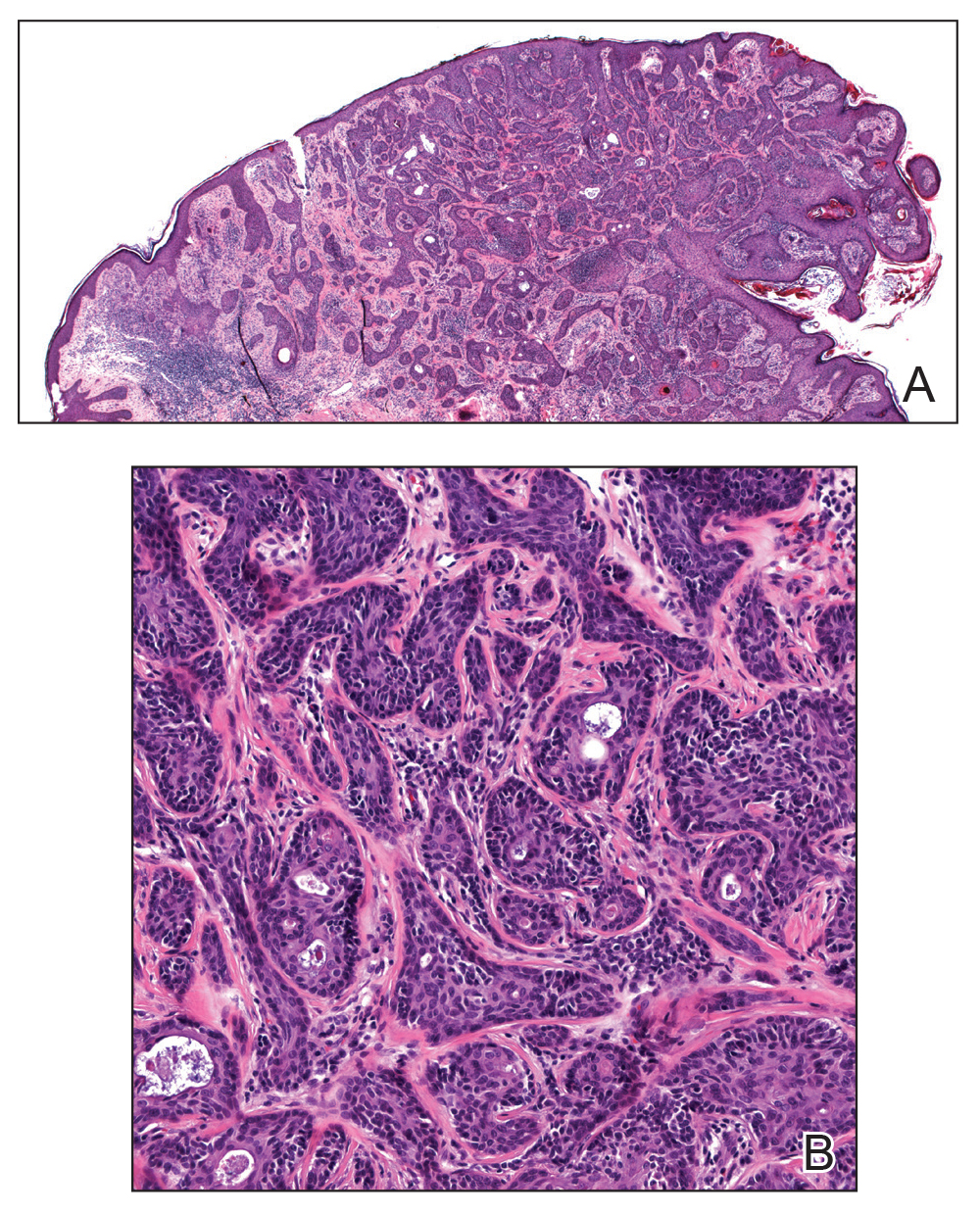

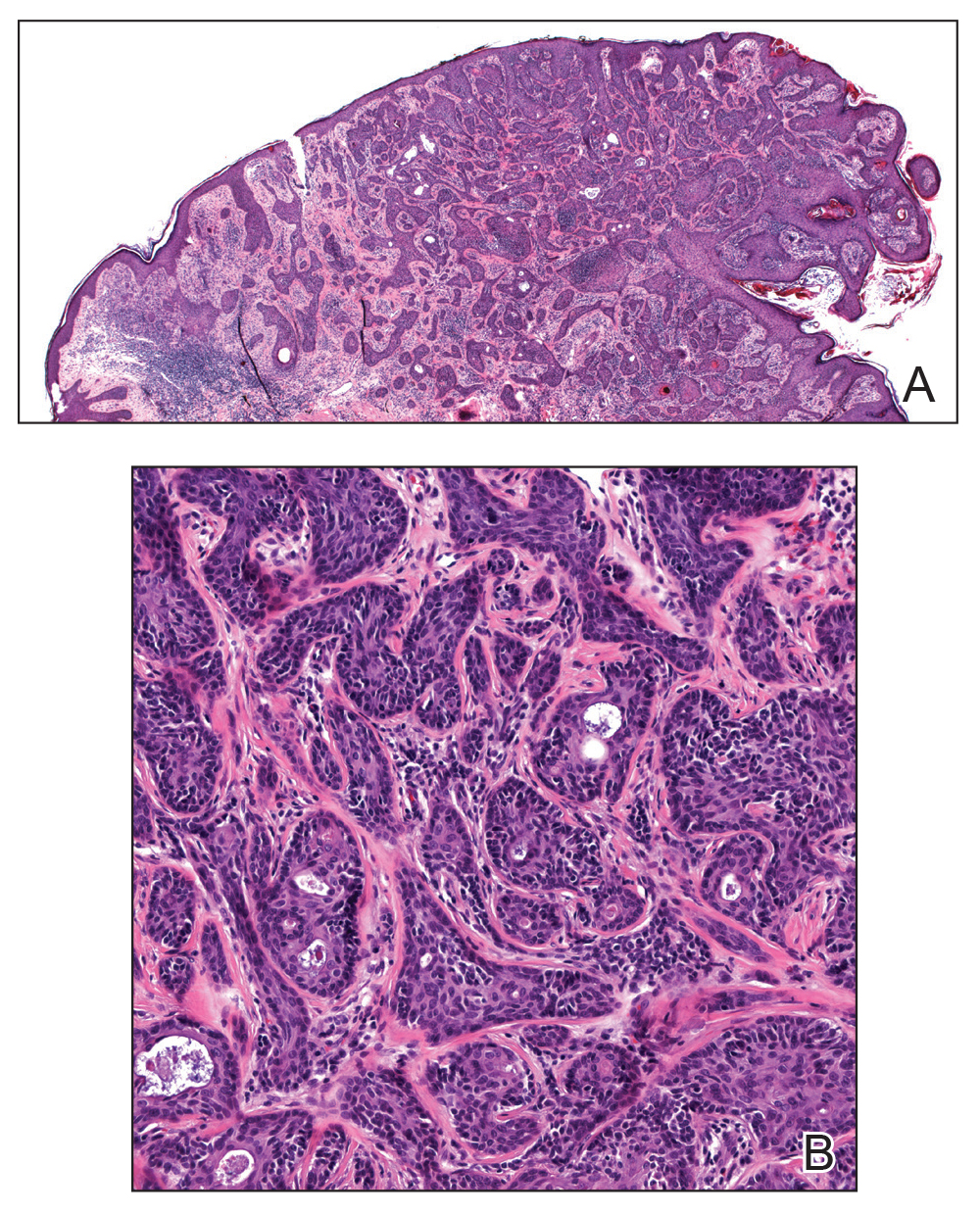

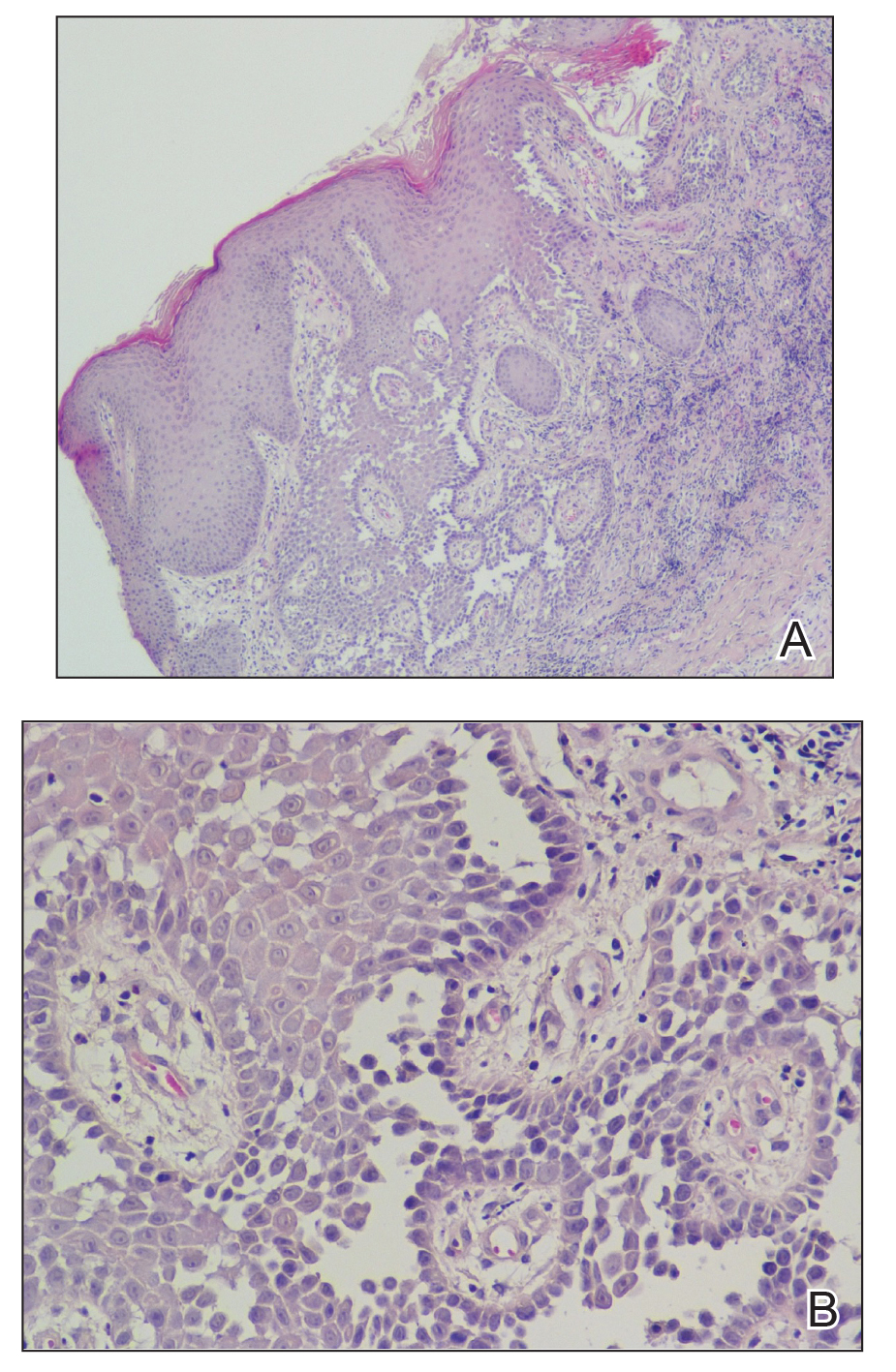

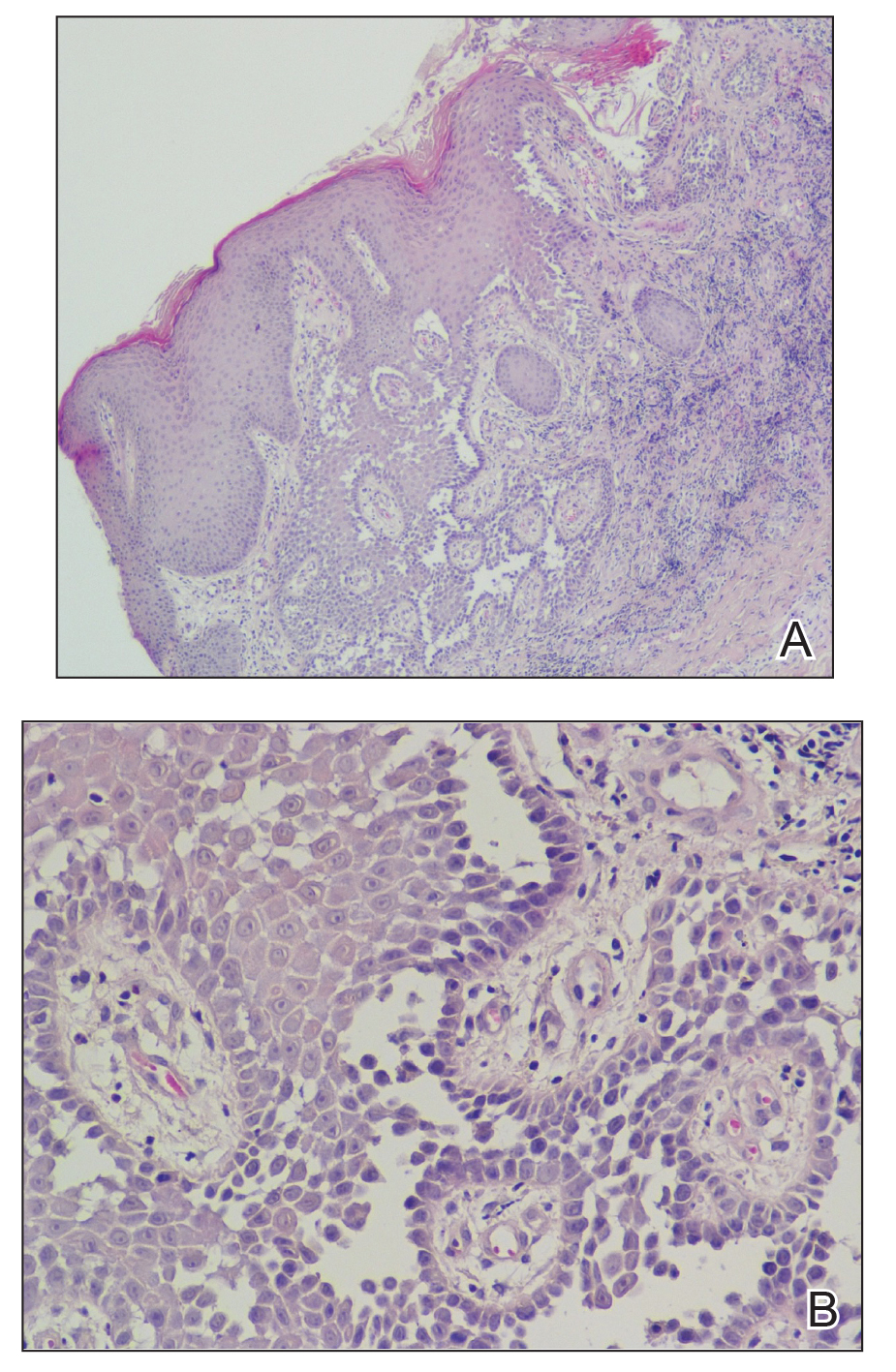

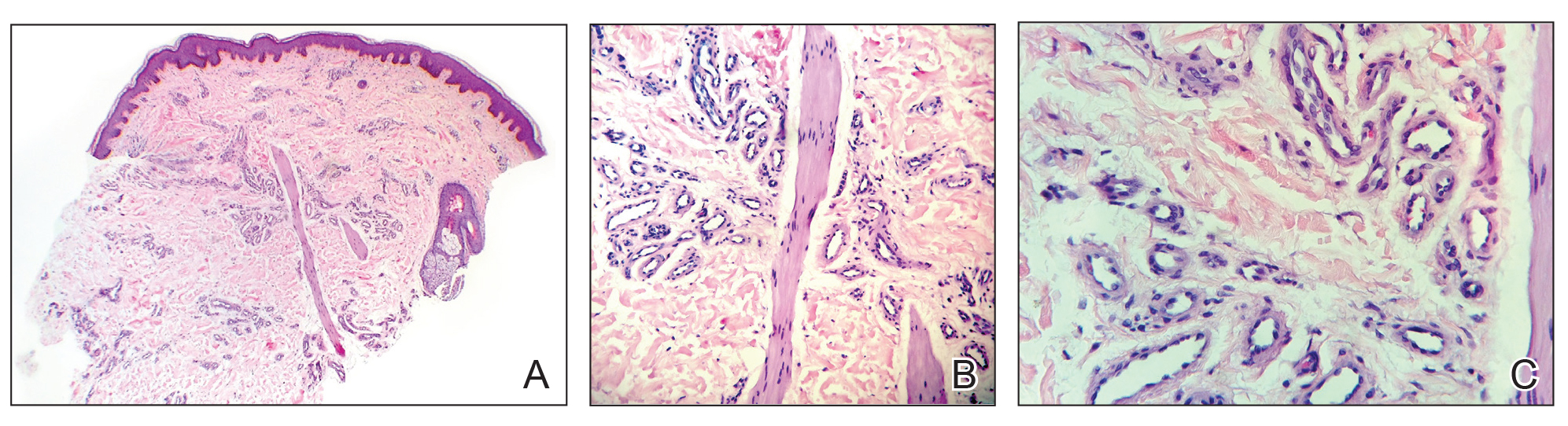

On gross pathology examination, schwannomas have a well-circumscribed smooth external surface. On microscopy, schwannomas are truly encapsulated, uninodular, spindle-cell proliferations arranged in a streaming pattern within a background of thick, hyalinized blood vessels. Classic schwannomas typically exhibit a biphasic pattern of alternating areas of high and low cellularity and are named for Swedish neurologist Nils Antoni. The more cellular regions are referred to as Antoni A areas and consist of streaming fascicles of compact spindle cells that often palisade around acellular eosinophilic areas of fibrillary processes known as Verocay bodies.

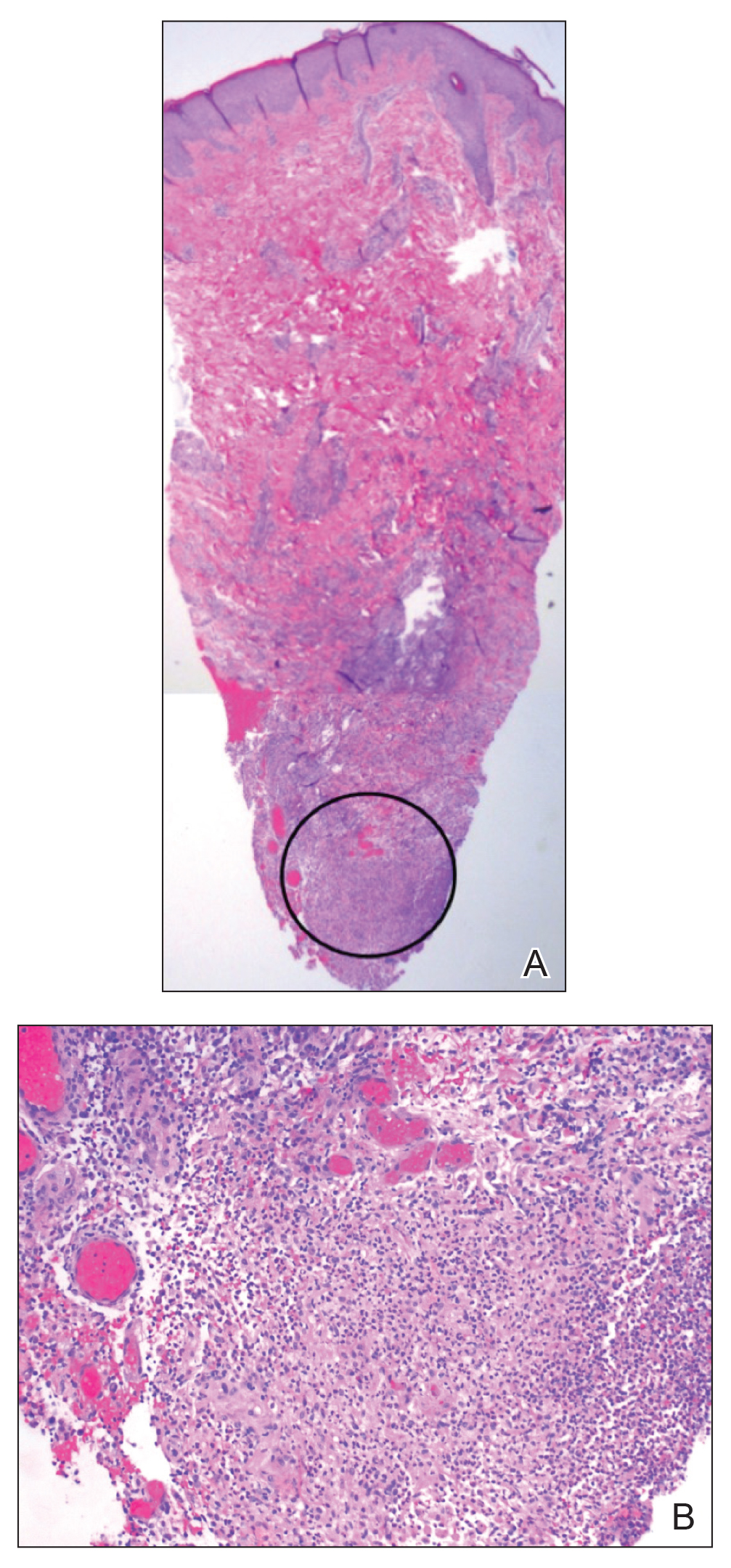

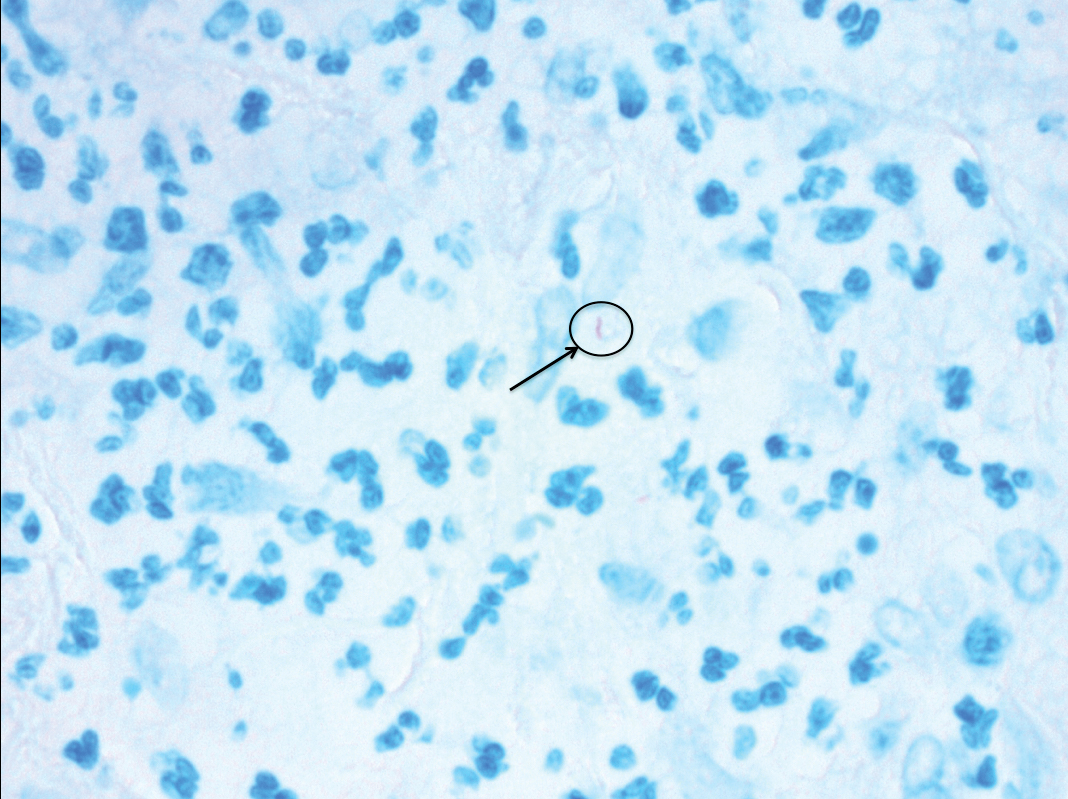

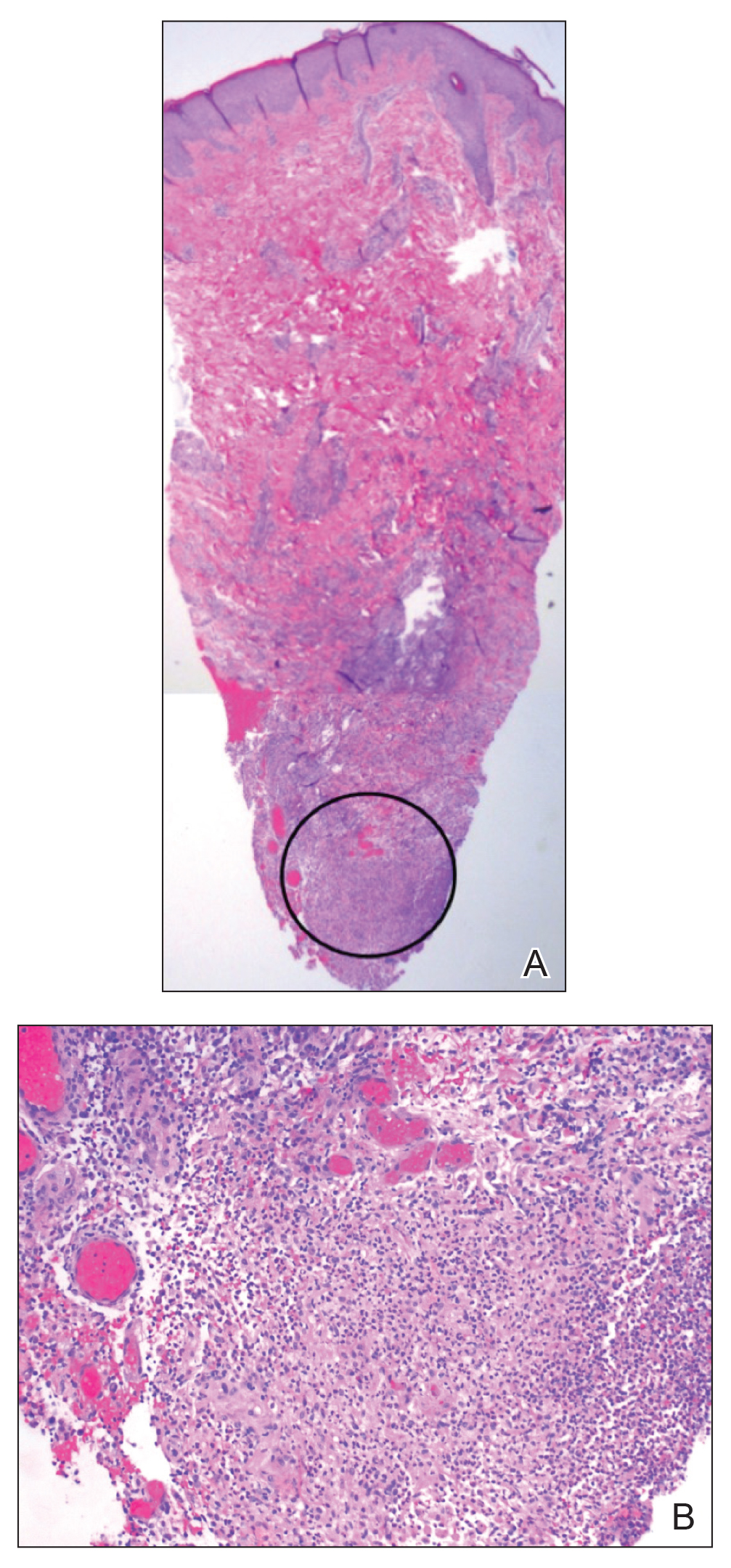

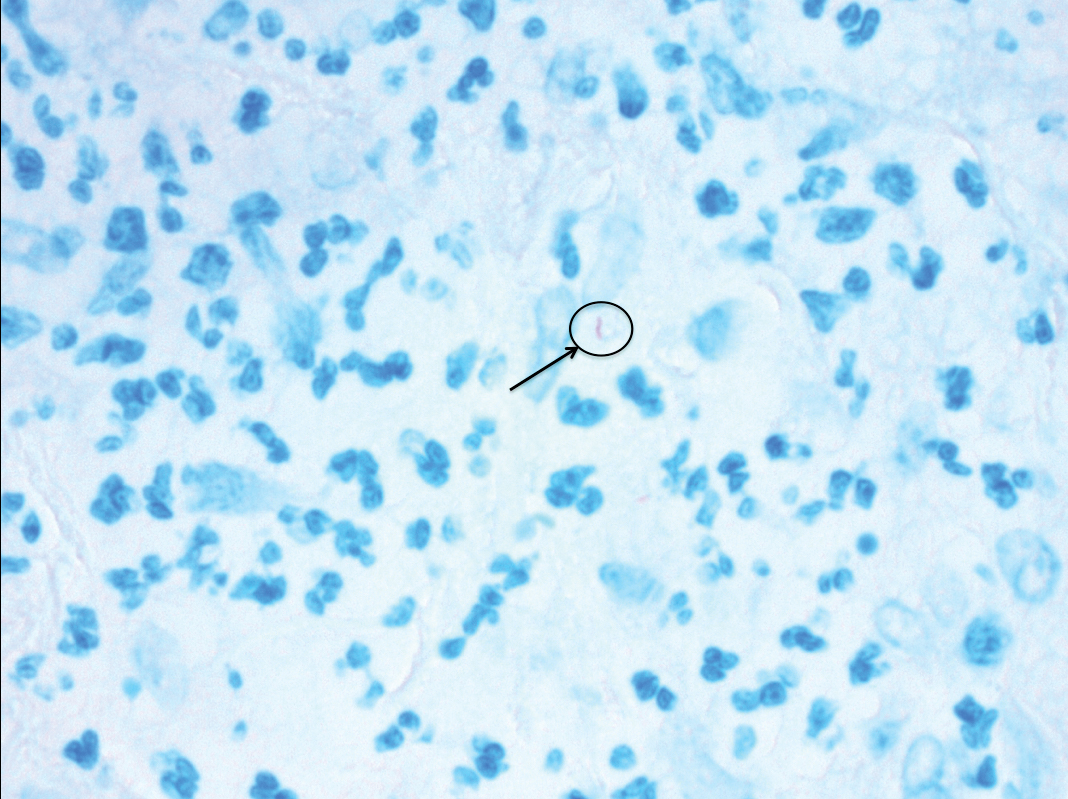

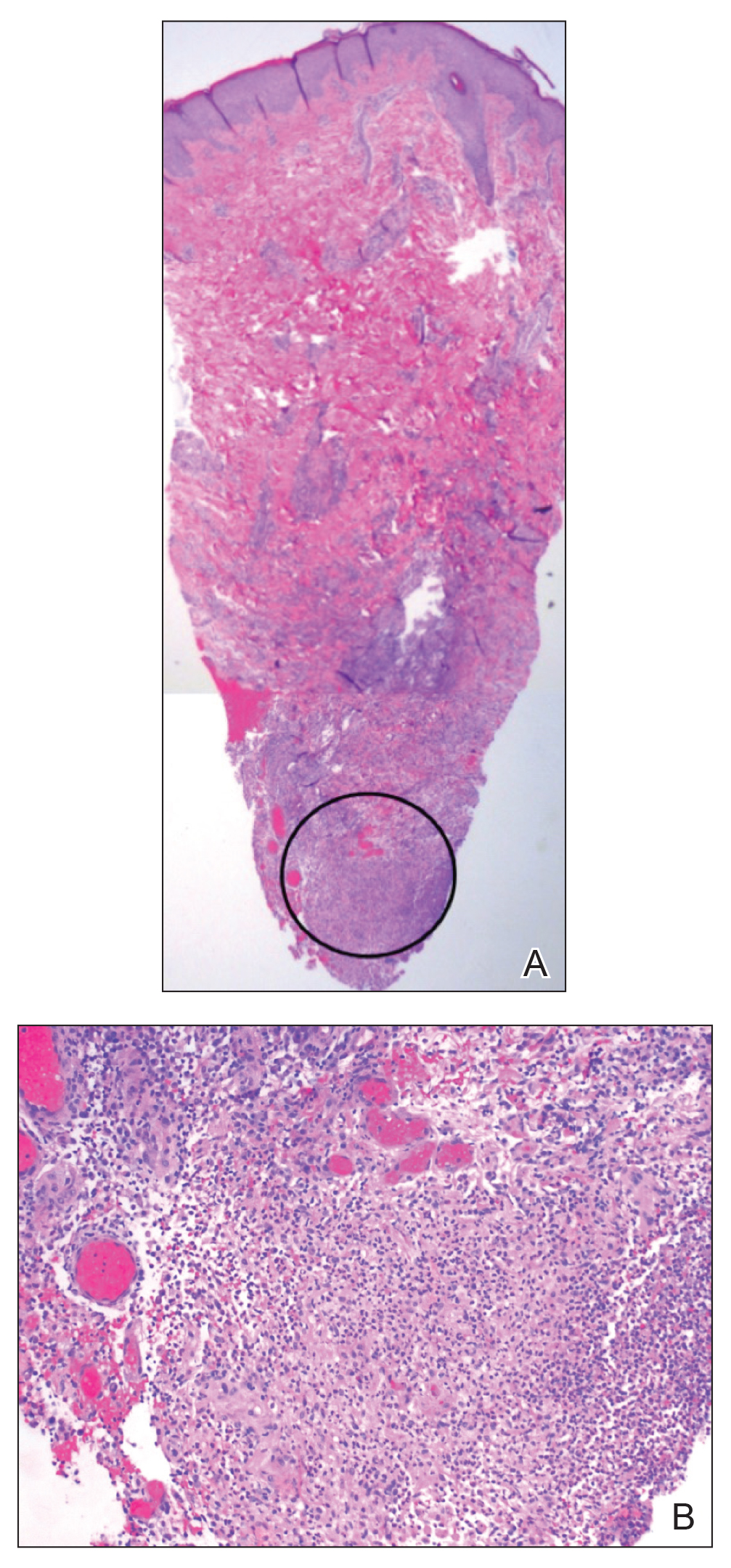

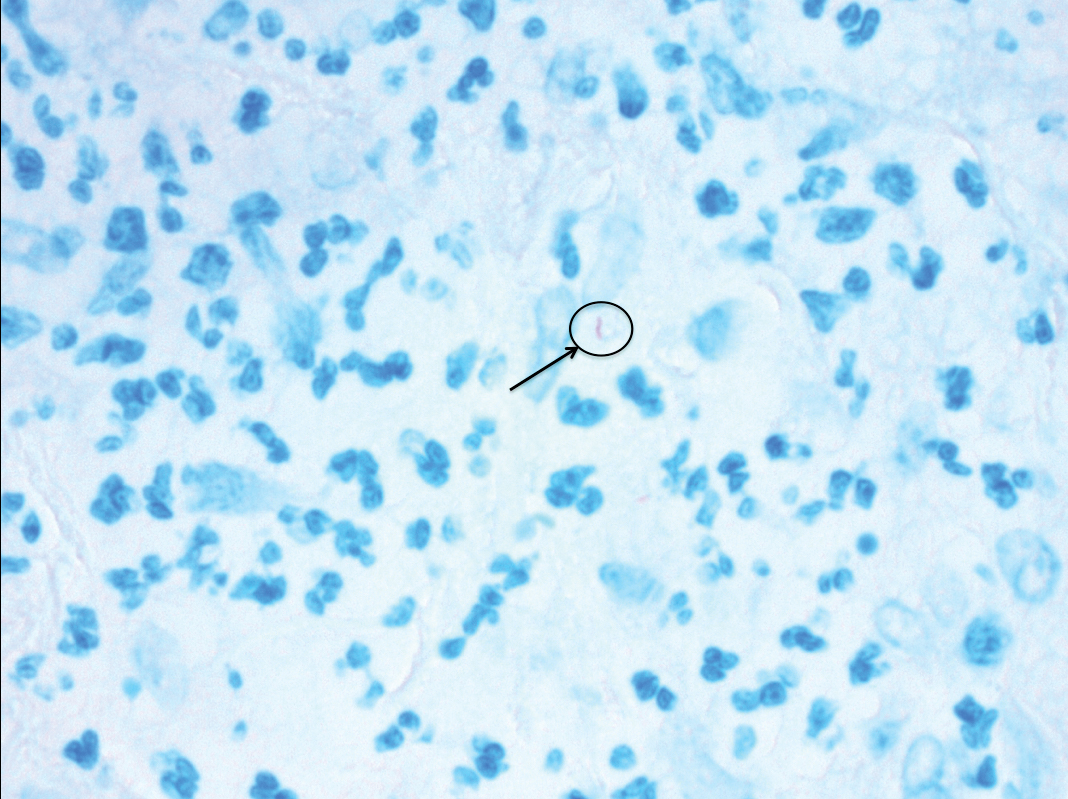

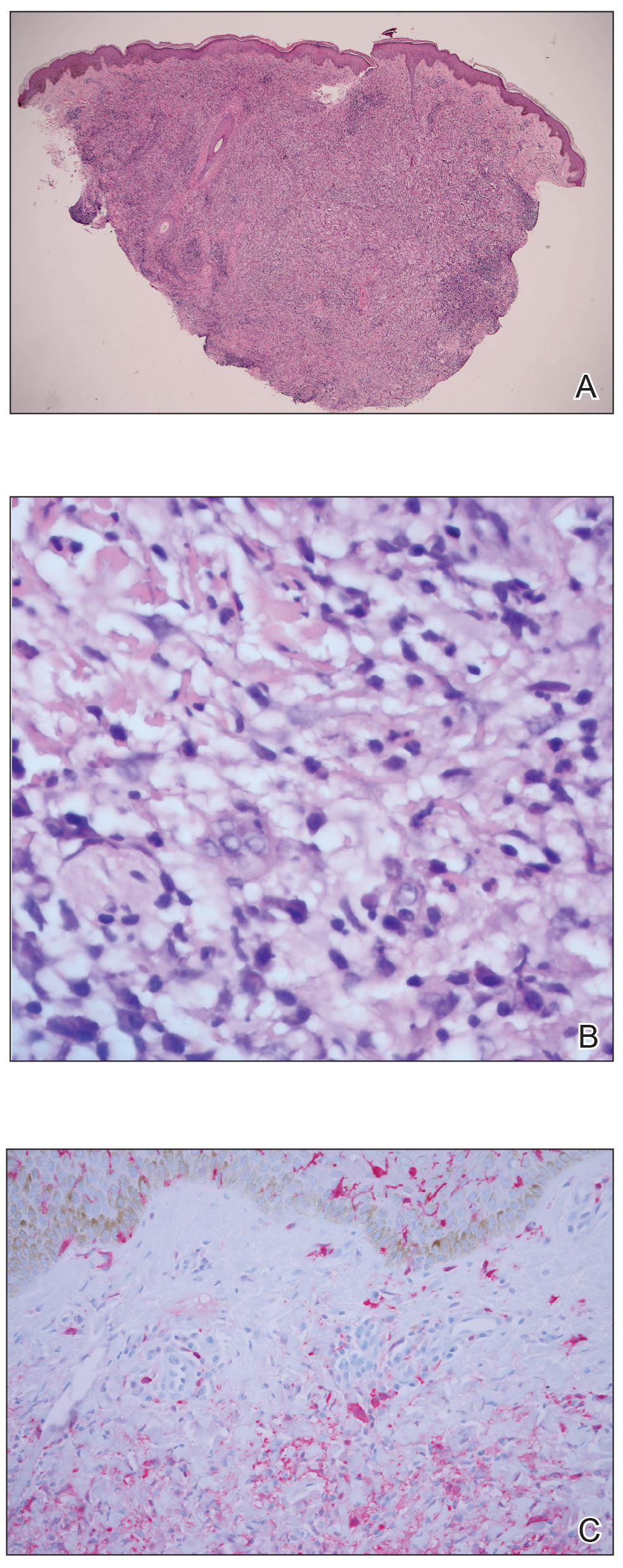

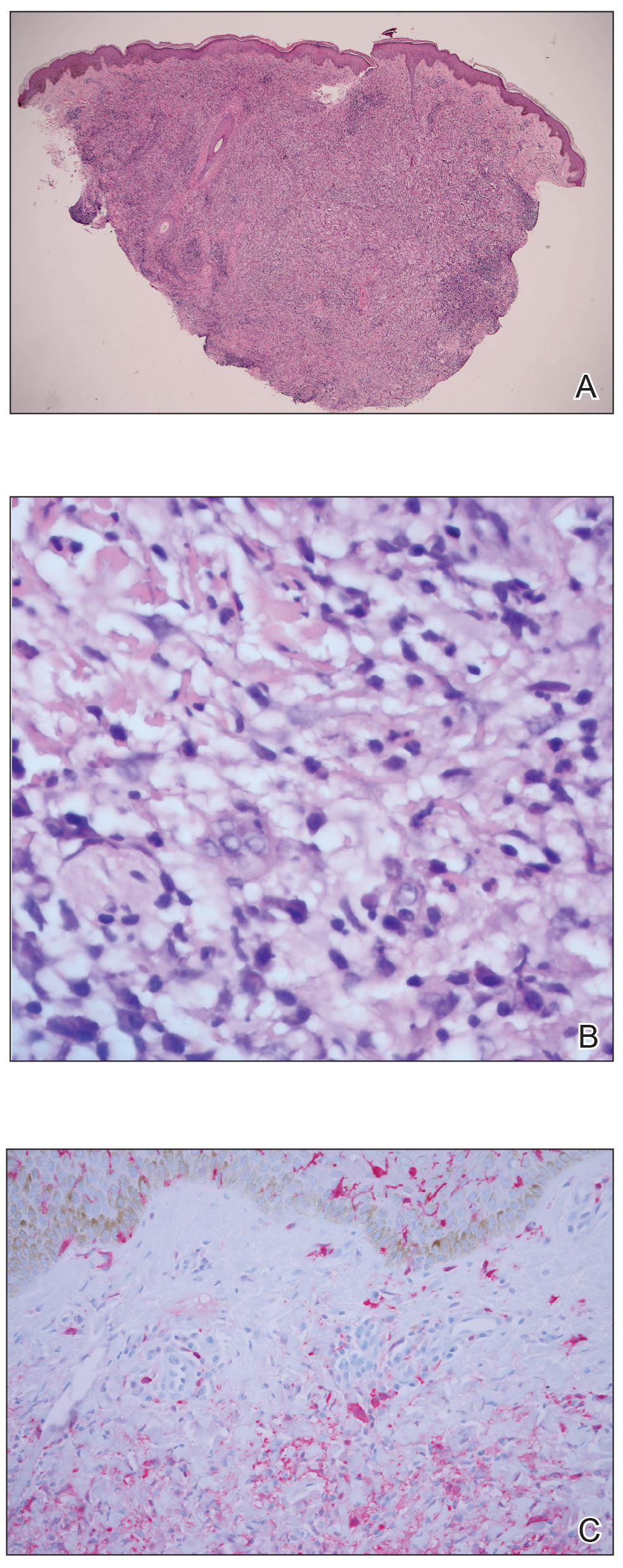

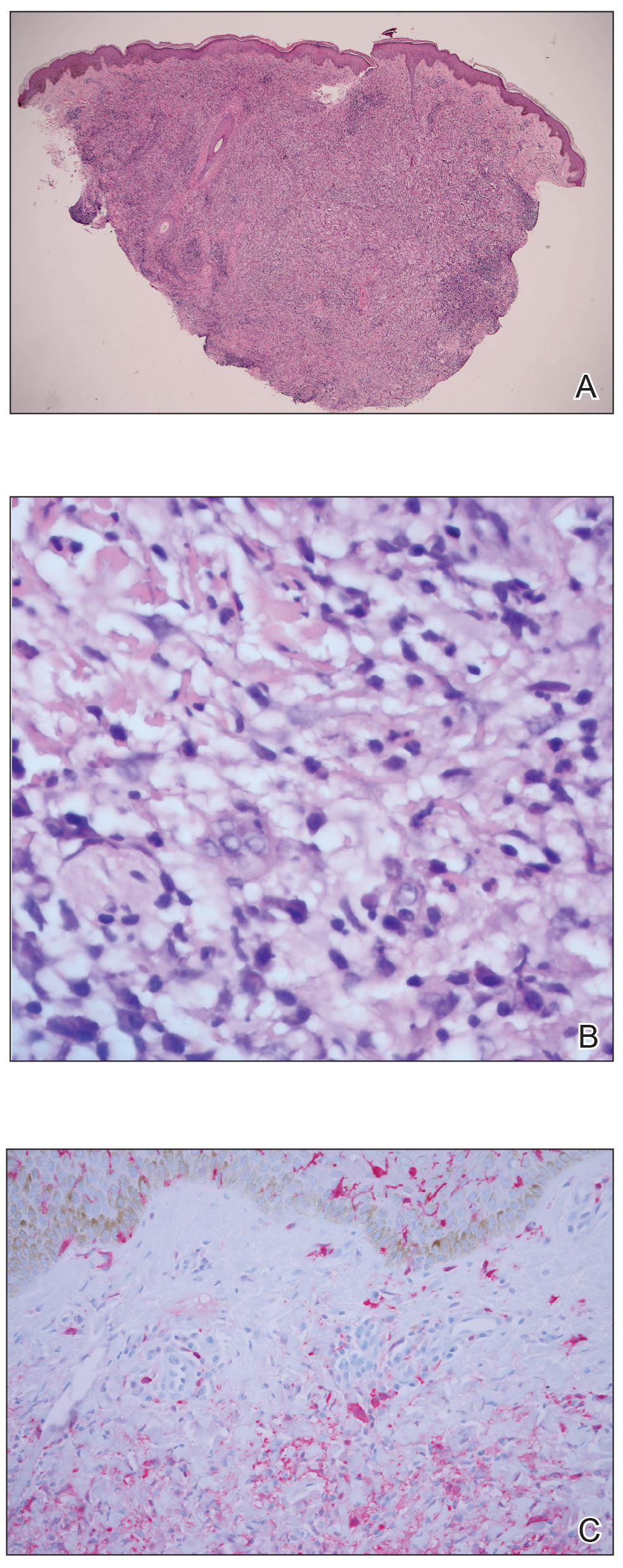

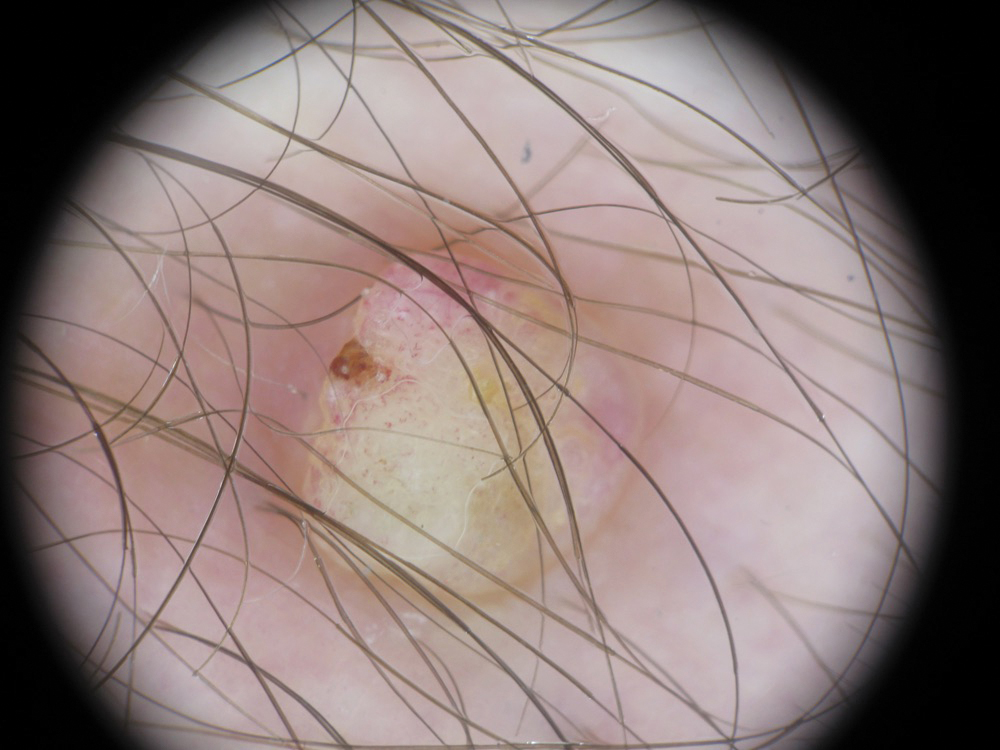

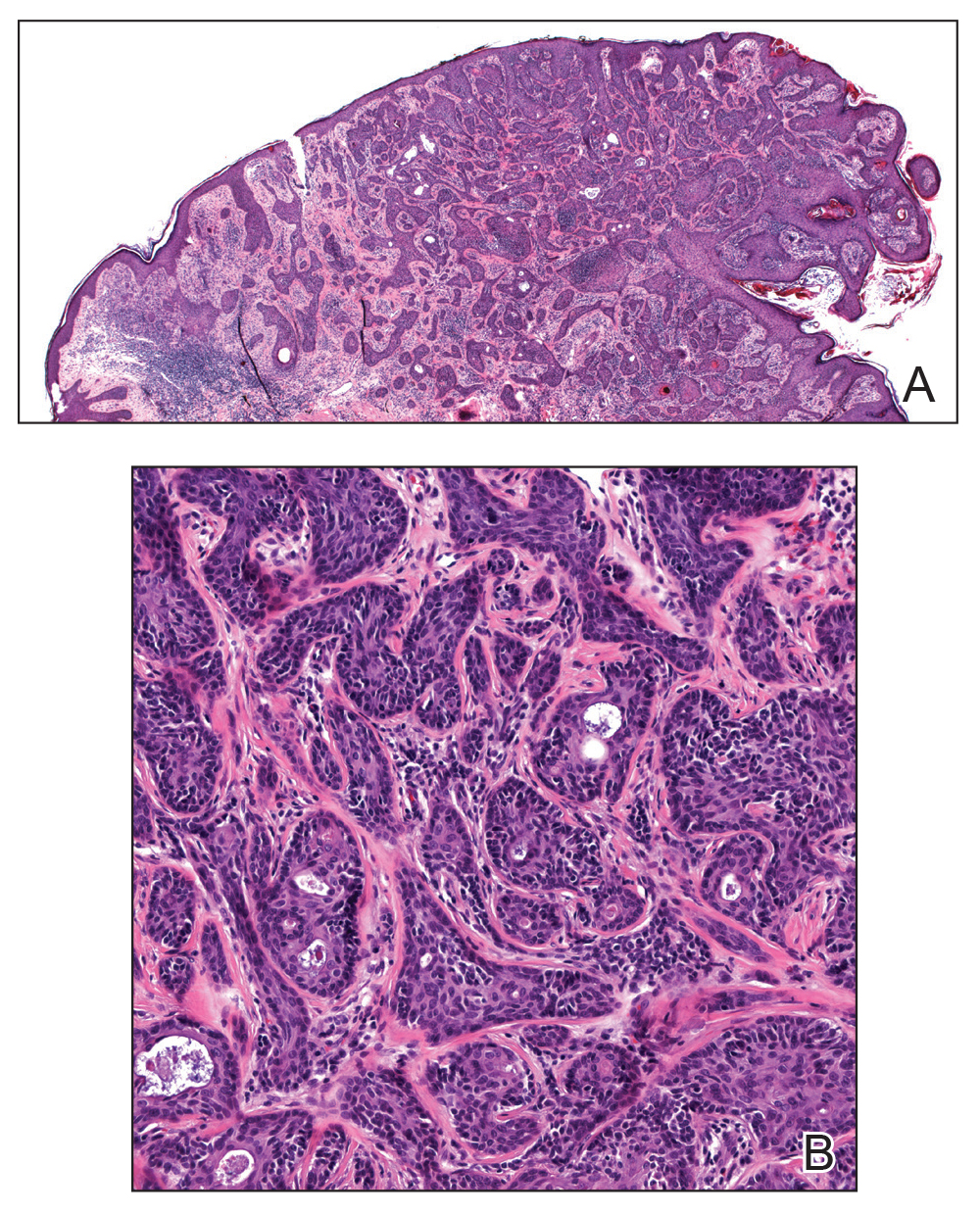

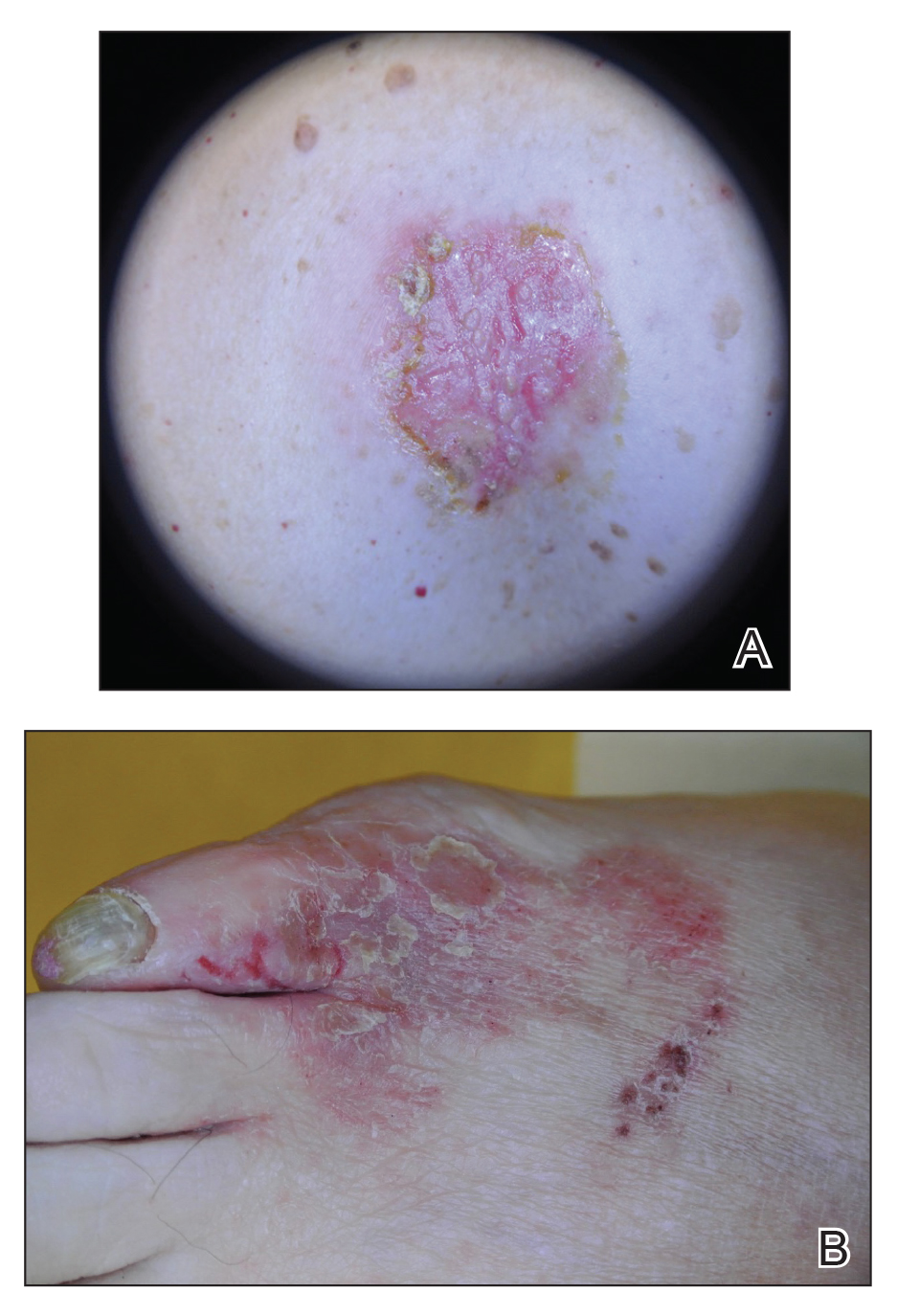

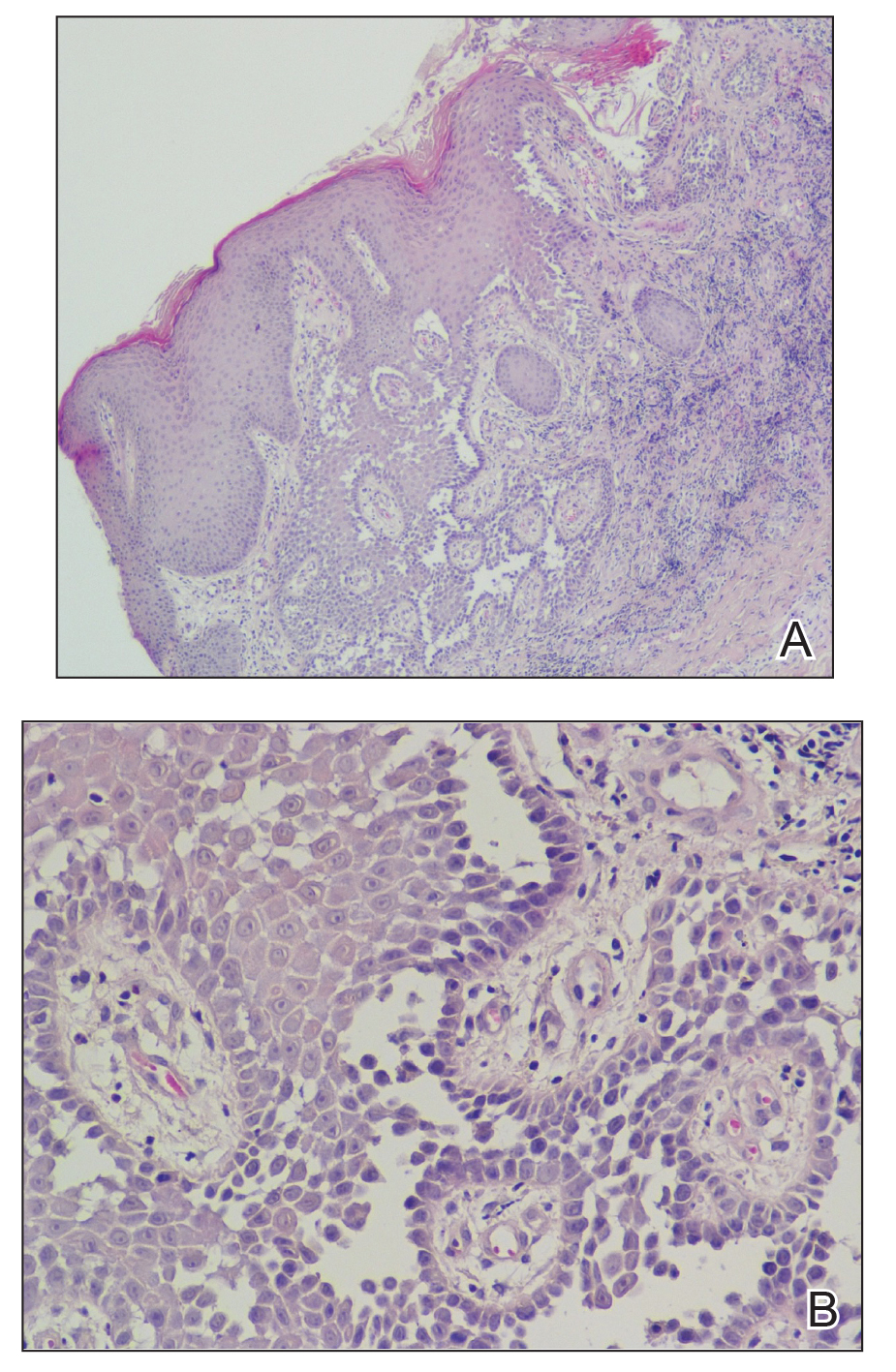

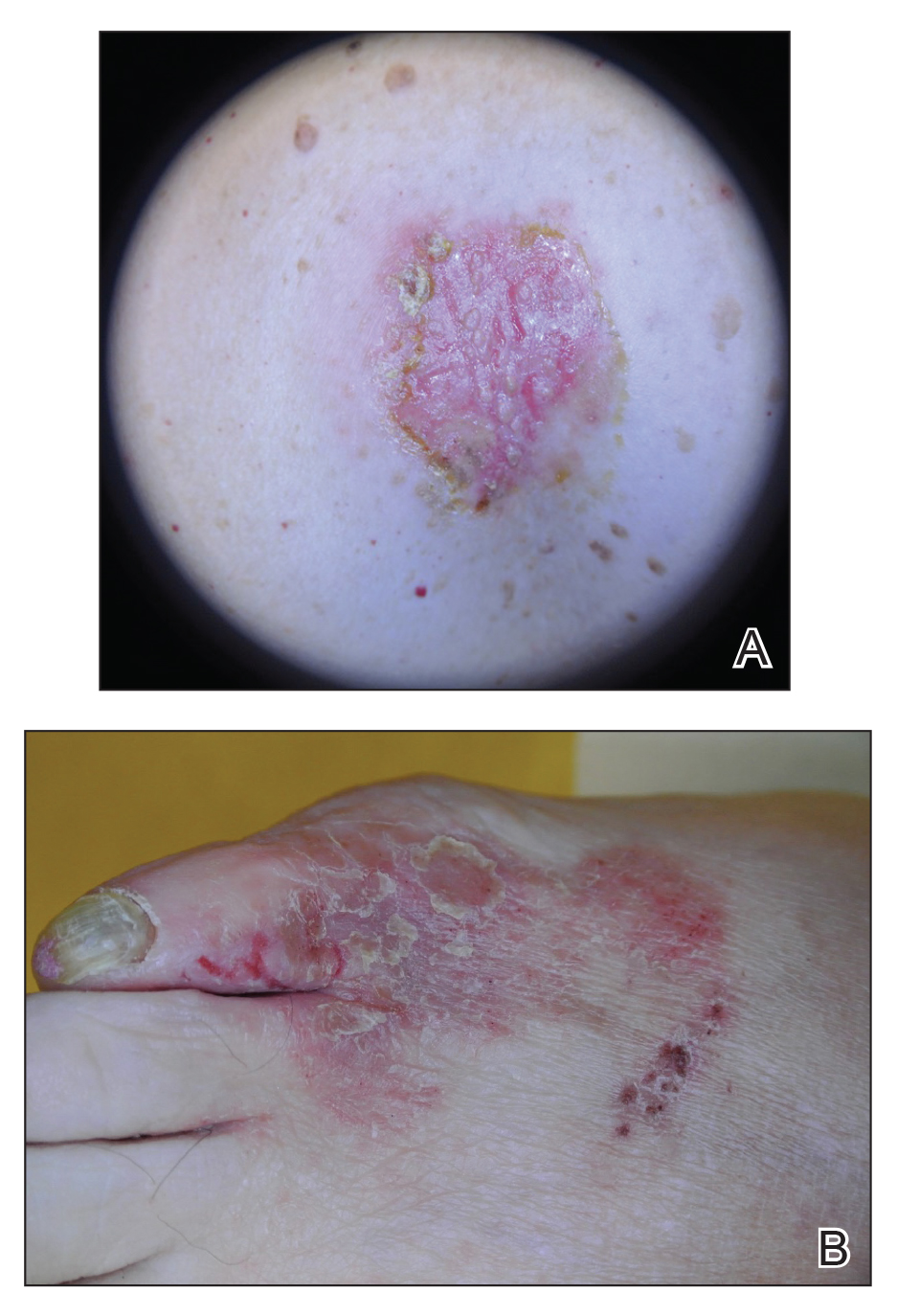

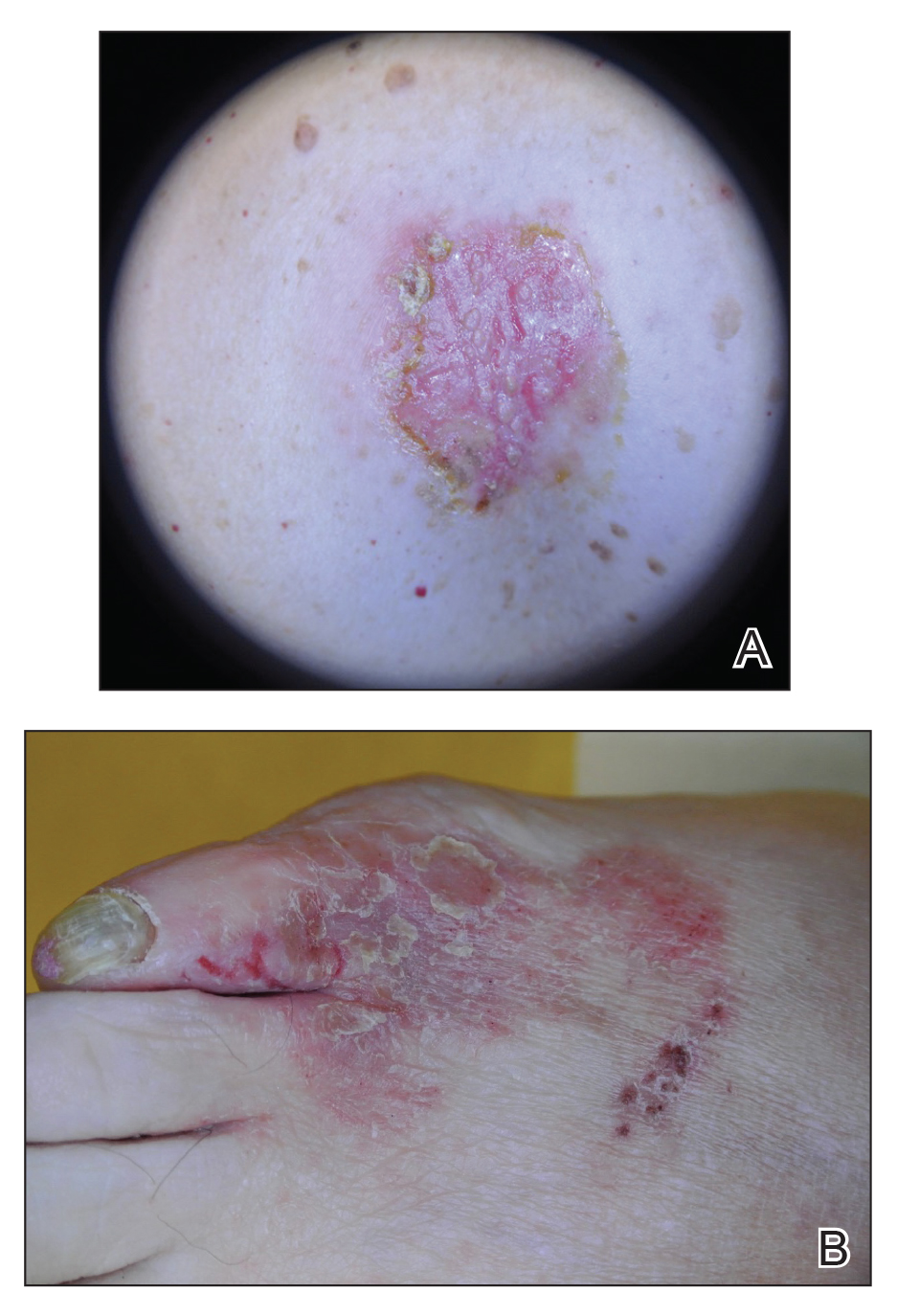

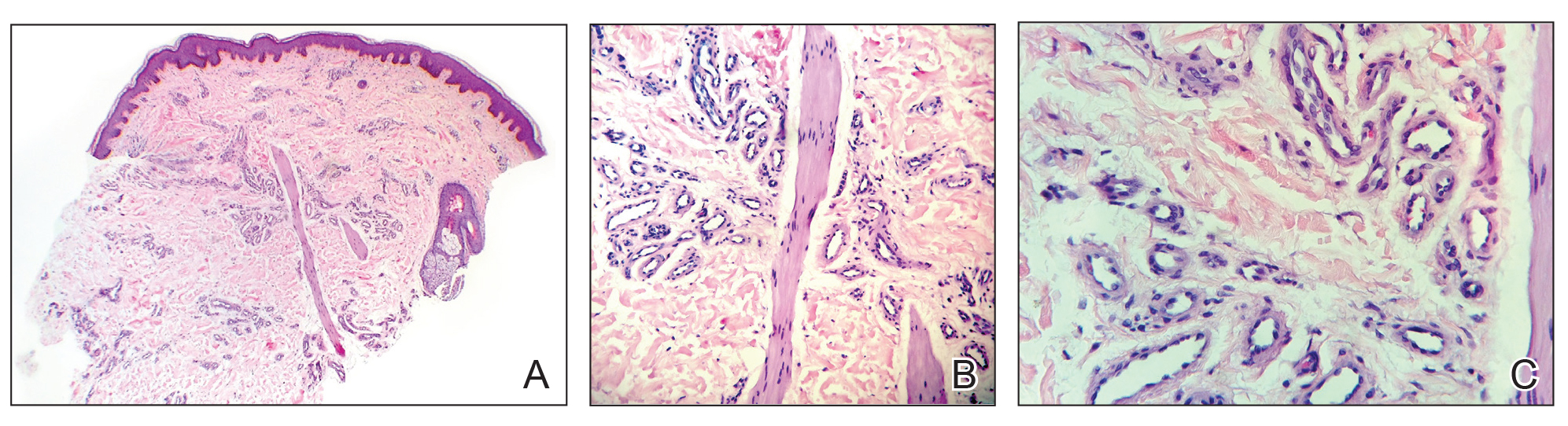

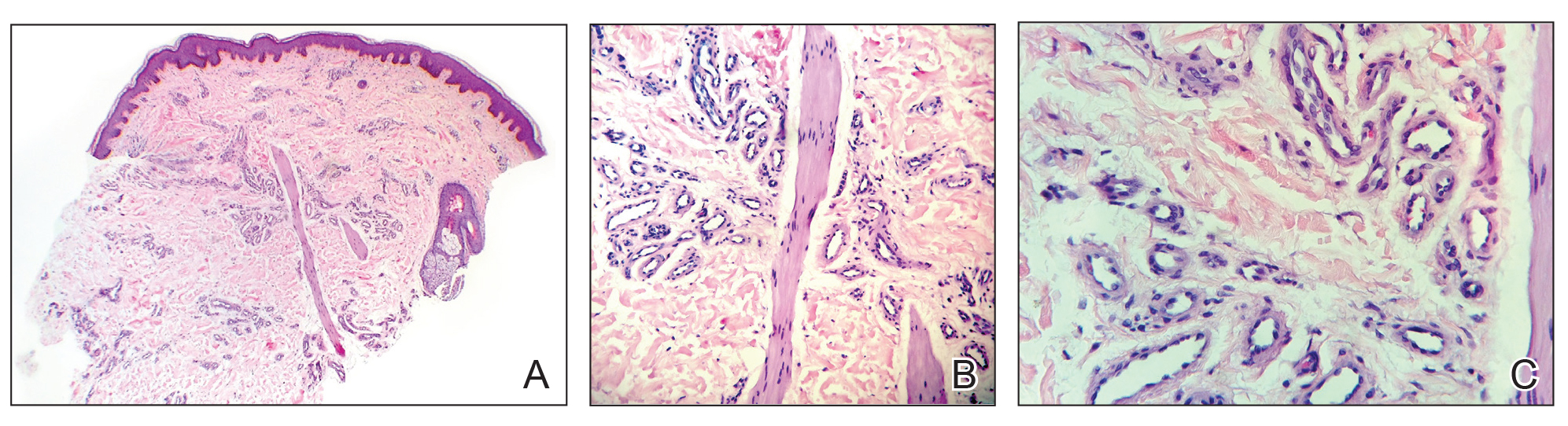

In contrast, the lower cellularity regions (Antoni B areas) consist of multipolar, loosely textured cells with abundant cytoplasm, haphazardly arranged processes, and an overall myxoid appearance.11 Schwannomas are known to have widely variable proportions of Antoni A and Antoni B areas; in this case, the excised specimen was noted to have predominately Antoni A areas without well-defined Verocay bodies and only scattered foci showing some suggestion of the hypocellular Antoni B architecture (Figure 2).9,12

Immunohistochemical stains for S100 and SOX10 (used to identify cells derived from a neural crest lineage) were strongly positive, which is characteristic of schwannomas.13 Although there have only been rare reports of extracranial schwannomas undergoing malignant transformation, it is critical to rule out the possibility of a de novo malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST).13 In general, MPNSTs tend to be more cellular, have brisk mitotic activity, areas of necrosis, hyperchromatic nuclei, and conspicuous pleomorphism. Mitotic figures, which can be concerning for malignant potential if present in high number, were noted occasionally in our patient; however, occasional mitosis may be seen in classic schwannomas. Clinically, MPNSTs have a poor prognosis. Based on case reports, disease-specific survival at 10 years is 31.6% for localized disease and only 7.5% for metastatic disease.14 In this case, there was no evidence of any of the high-grade features of a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, thus supporting the diagnosis of schwannoma (neurilemmoma).

Treatment

Schwannomas are exclusively treated by excision. Prognosis is good with low recurrence rates. It is unknown what the recurrence rates are for completely resected abdominal wall schwannomas since there are so few reports in the literature. For other well-known entities, such as vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuromas), the recurrence rates are generally 2% to 3%.15 Transformation of schwannomas into MPNSTs are so unusual that they are only described in single case reports.

Conclusion

Soft-tissue masses are a common complaint. Most are benign and do not require excision unless it interferes with the quality of life of the patient or if the diagnosis is uncertain. It is important to be aware of schwannomas in the differential diagnosis of soft-tissue masses. Diagnosis may be achieved through the combination of imaging and biopsy, but the definitive diagnosis is made on complete excision of the mass.

Acknowledgments

Contributors: Michael Lewis, MD, Department of Pathology, VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. Written permission also was obtained from the patient.

1. Kransdorf MJ. Benign soft-tissue tumors in a large referral population: distribution of specific diagnoses by age, sex, and location. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164(2):395-402.

2. Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ismaili N, Bastuji-Garin S, et al. Symptoms associated with malignancy of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: a retrospective study of 69 patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(1):79-82.

3. Patterson JW. Neural and neuroendocrine tumors. In: Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1042-1049.

4. Balzarotti R, Rondelli F, Barizzi J, Cartolari R. Symptomatic schwannoma of the abdominal wall: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(3):1095-1098.

5. Wasa J, Nishida Y, Tsukushi S, et al. MRI features in the differentiation of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and neurofibromas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(6):1568-1574.

6. Dodd LG, Marom EM, Dash RC, Matthews MR, McLendon RE. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of “ancient” schwannoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;20(5):307-311.

7. Powers CN, Berardo MD, Frable WJ. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy: pitfalls in the diagnosis of spindle-cell lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;10(3):232-240; discussion 241.

8. White W, Shiu MH, Rosenblum MK, Erlandson RA, Woodruff JM. Cellular schwannoma: a clinicopathologic study of 57 patients and 58 tumors. Cancer. 1990;66(6):1266-1275.

9. Goldblum JR, Weiss SW, Folpe AL. Benign tumors of peripheral nerves. In: Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014:813-828.

10. Naversen DN, Trask DM, Watson FH, Burket JM. Painful tumors of the skin: “LEND AN EGG.” J Am Acad Deramatol. 1993;28(2, pt 2):298-300.

11. Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. Diagnostic Pathology: Neuropathology. 1st ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys; 2012.

12. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, eds. World Health Organization Histological Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Vol. 1. Paris, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2016.

13. Woodruff JM, Selig AM, Crowley K, Allen PW. Schwannoma (neurilemoma) with malignant transformation. A rare, distinctive peripheral nerve tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18(9)82-895.

14. Zou C, Smith KD, Liu J, et al. Clinical, pathological, and molecular variables predictive of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor outcome. Ann Surg. 2009;249(6):1014-1022.

15. Ahmad RA, Sivalingam S, Topsakal V, Russo A, Taibah A, Sanna M. Rate of recurrent vestibular schwannoma after total removal via different surgical approaches. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2012;121(3):156-161.

16. Bhatia RK, Banerjea A, Ram M, Lovett BE. Benign ancient schwannoma of the abdominal wall: an unwanted birthday present. BMC Surg. 2010;10:1-5.

17. Mishra A, Hamadto M, Azzabi M, Elfagieh M. Abdominal wall schwannoma: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Radiol. 2013;2013:456863.

18. Liu Y, Chen X, Wang T, Wang Z. Imaging observations of a schwannoma of low malignant potential in the anterior abdominal wall: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(3):1159-1162.

19. Ginesu GC, Puledda M, Feo CF et al. Abdominal wall schwannoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(10):1781-1783.

Schwannomas are benign tumors exclusively composed of Schwann cells that arise from the peripheral nerve sheath; these tumors theoretically can present anywhere in the body where nerves reside. They tend to occur in the head and neck region (classically an acoustic neuroma) but also occur in other locations, including the retroperitoneal space and the extremities, particularly flexural surfaces. Patients with cutaneous schwannomas are most likely to present to their primary care provider’s office reporting skin findings or localized pain, and providers should be aware of schwannomas on the differential for painful nodular growths.

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to the primary care clinic for intermittent, sharp, localized left lower quadrant abdominal wall pain that was gradually progressive over the previous few months. The patient noticed the development of a small nodule 7 to 8 months prior to the visit, at which time the pain was less frequent and less severe. He reported no postprandial association of the pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, or other gastrointestinal symptoms.

Ten months prior to the presentation, he was involved in a low-impact motor vehicle collision as a pedestrian in which he fell face-first onto the hood of an oncoming car. At that time, he did not note any abdominal trauma or pain. Evaluation at a local emergency department did not reveal any major injuries. In the interim, he had self-administered insulin in his abdominal region, as he had without incident for the previous 2 years. He reported that he was not injecting near the site of the nodule since it had formed. He could not recall whether the location was a previous insulin administration site.

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were normal as were the cardiac and respiratory examinations. An abdominal exam revealed normal bowel sounds and no overlying skin changes or discoloration. Palpation revealed a 1.5 x 1 cm rubbery-to-firm, well-circumscribed subcutaneous nodule along his mid-left abdomen, about 7 cm lateral to the umbilicus. The nodule was sensitive to both light touch and deep pressure. It was firmer than expected for an abdominal wall lipoma. There was no central puncta or pore to suggest an epidermal inclusion cyst. There was no surrounding erythema or induration to suggest an abscess.

The patient was referred for surgery and underwent excisional biopsy of the mass. Pathology revealed a well-circumscribed vascular/spindle-cell lesion consistent with a schwannoma. His postoperative course was uncomplicated. At 4-week follow-up the incision had healed completely and the patient was pain free.

Discussion

Soft-tissue nodules are common—about two-thirds of soft-tissue tumors are classified into 7 diagnostic categories: lipoma and lipoma variants (16%), fibrous histiocytoma (13%), nodular fasciitis (11%), hemangioma (8%), fibromatosis (7%), neurofibroma (5%), and schwannoma (5%).1 Peripheral nerve tumors (schwannomas, neurofibromas) can be associated with pain or paresthesias, and less commonly, neurologic deficits, such as motor weakness. Peripheral nerve tumors have several classifications, such as nonneoplastic vs neoplastic, benign vs malignant, and sheath vs nonsheath origins. Schwannomas are considered part of the neoplastic subset due to their growth; otherwise, they are benign with a sheath origin. In contrast to neurofibromas, benign schwannomas have a slower rate of progression, lower association with pain, and fewer neurologic symptoms.2

The neural sheath is made up of 3 types of cells: the fibroblast, the Schwann cell, and the perineural cell, which lacks a basement membrane. It is the Schwann cell that can give rise to the 3 main types of cutaneous nerve tumors: neuromas, neurofibromas, and schwannomas.3 A nerve that is both entering and exiting a mass is a classic presentation for a peripheral nerve sheath tumor. If the nerve is eccentric to the lesion, then it is consistent with a schwannoma (not a neurofibroma).4 Schwannomas are made exclusively of Schwann cells that arise from the nerve sheath, whereas neurofibromas are made up of all the different cell types that constitute a nerve. Bilateral vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas) are virtually pathognomonic of neurofibromatosis 2 (NF-2), which can manifest as hearing loss, tinnitus, and equilibrium problems. In contrast, neurofibromatosis 1 (NF-1) is more common, characterized by multiple café au lait spots, freckling in the axillary and groin regions, increased risk of cancers overall, and development of pedunculated skin growths, brain, or organ-based neurofibromas.

Diagnosis

A workup generally includes a thorough history and examination as well as imaging. In cases of superficial subcutaneous lesions, an ultrasound is often the imaging modality of choice. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans are frequently used for more deep-seated lesions. There can be significant differences between malignant and benign neural lesions on MRI and CT in terms of contrast-uptake and heterogeneity of tissue, but the visual features are not consistent. Best estimates for MRI suggest 61% sensitivity and 90% specificity for the diagnosis of high-grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors based on imaging alone.5

Definitive diagnosis requires surgical excision. Fine-needle aspiration can be used to diagnose subcutaneous nodules, but there is a possibility that degenerative changes and nuclear atypia seen on a smaller sample may be confused with a more aggressive sarcoma. For example, long-standing schwannomas are often called ancient, meaning that they break down over time, and the atypia they display is a regressive phenomenon.6 Therefore, a small or limited tissue sampling may not be representative of the entire lesion.7 As such, patients will likely need referral for surgical removal to determine the exact nature of the growth.

Although schwannomas are uncommon overall, the highest incidence is in the fourth decade of life with a slight predominance in females. They are often incidentally found as a palpable mass but can be symptomatic with paresthesias, pain, or neurologic changes—particularly when identified in the retroperitoneum or along joints. Schwannomas are most commonly found in the retroperitoneum (32%), mediastinum (23%), head and neck (18%), and extremities (16%).8 The majority of cases (about 90%) are sporadic; whereas 2% are related to NF-2.9 The abdominal wall schwannoma is rare. Our review of English-language literature in PubMed and EMBASE found only 5 other case reports (Table 1).

On physical examination, superficial lesions are freely movable except for a single point of attachment, which is generally along the long axis of the nerve.

Pathology

On gross pathology examination, schwannomas have a well-circumscribed smooth external surface. On microscopy, schwannomas are truly encapsulated, uninodular, spindle-cell proliferations arranged in a streaming pattern within a background of thick, hyalinized blood vessels. Classic schwannomas typically exhibit a biphasic pattern of alternating areas of high and low cellularity and are named for Swedish neurologist Nils Antoni. The more cellular regions are referred to as Antoni A areas and consist of streaming fascicles of compact spindle cells that often palisade around acellular eosinophilic areas of fibrillary processes known as Verocay bodies.

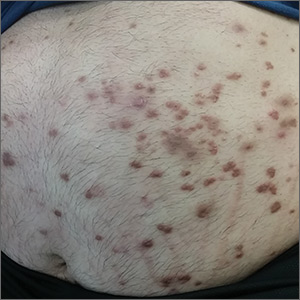

In contrast, the lower cellularity regions (Antoni B areas) consist of multipolar, loosely textured cells with abundant cytoplasm, haphazardly arranged processes, and an overall myxoid appearance.11 Schwannomas are known to have widely variable proportions of Antoni A and Antoni B areas; in this case, the excised specimen was noted to have predominately Antoni A areas without well-defined Verocay bodies and only scattered foci showing some suggestion of the hypocellular Antoni B architecture (Figure 2).9,12

Immunohistochemical stains for S100 and SOX10 (used to identify cells derived from a neural crest lineage) were strongly positive, which is characteristic of schwannomas.13 Although there have only been rare reports of extracranial schwannomas undergoing malignant transformation, it is critical to rule out the possibility of a de novo malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST).13 In general, MPNSTs tend to be more cellular, have brisk mitotic activity, areas of necrosis, hyperchromatic nuclei, and conspicuous pleomorphism. Mitotic figures, which can be concerning for malignant potential if present in high number, were noted occasionally in our patient; however, occasional mitosis may be seen in classic schwannomas. Clinically, MPNSTs have a poor prognosis. Based on case reports, disease-specific survival at 10 years is 31.6% for localized disease and only 7.5% for metastatic disease.14 In this case, there was no evidence of any of the high-grade features of a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, thus supporting the diagnosis of schwannoma (neurilemmoma).

Treatment

Schwannomas are exclusively treated by excision. Prognosis is good with low recurrence rates. It is unknown what the recurrence rates are for completely resected abdominal wall schwannomas since there are so few reports in the literature. For other well-known entities, such as vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuromas), the recurrence rates are generally 2% to 3%.15 Transformation of schwannomas into MPNSTs are so unusual that they are only described in single case reports.

Conclusion

Soft-tissue masses are a common complaint. Most are benign and do not require excision unless it interferes with the quality of life of the patient or if the diagnosis is uncertain. It is important to be aware of schwannomas in the differential diagnosis of soft-tissue masses. Diagnosis may be achieved through the combination of imaging and biopsy, but the definitive diagnosis is made on complete excision of the mass.

Acknowledgments

Contributors: Michael Lewis, MD, Department of Pathology, VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. Written permission also was obtained from the patient.

Schwannomas are benign tumors exclusively composed of Schwann cells that arise from the peripheral nerve sheath; these tumors theoretically can present anywhere in the body where nerves reside. They tend to occur in the head and neck region (classically an acoustic neuroma) but also occur in other locations, including the retroperitoneal space and the extremities, particularly flexural surfaces. Patients with cutaneous schwannomas are most likely to present to their primary care provider’s office reporting skin findings or localized pain, and providers should be aware of schwannomas on the differential for painful nodular growths.

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to the primary care clinic for intermittent, sharp, localized left lower quadrant abdominal wall pain that was gradually progressive over the previous few months. The patient noticed the development of a small nodule 7 to 8 months prior to the visit, at which time the pain was less frequent and less severe. He reported no postprandial association of the pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, or other gastrointestinal symptoms.

Ten months prior to the presentation, he was involved in a low-impact motor vehicle collision as a pedestrian in which he fell face-first onto the hood of an oncoming car. At that time, he did not note any abdominal trauma or pain. Evaluation at a local emergency department did not reveal any major injuries. In the interim, he had self-administered insulin in his abdominal region, as he had without incident for the previous 2 years. He reported that he was not injecting near the site of the nodule since it had formed. He could not recall whether the location was a previous insulin administration site.

On examination, the patient’s vital signs were normal as were the cardiac and respiratory examinations. An abdominal exam revealed normal bowel sounds and no overlying skin changes or discoloration. Palpation revealed a 1.5 x 1 cm rubbery-to-firm, well-circumscribed subcutaneous nodule along his mid-left abdomen, about 7 cm lateral to the umbilicus. The nodule was sensitive to both light touch and deep pressure. It was firmer than expected for an abdominal wall lipoma. There was no central puncta or pore to suggest an epidermal inclusion cyst. There was no surrounding erythema or induration to suggest an abscess.

The patient was referred for surgery and underwent excisional biopsy of the mass. Pathology revealed a well-circumscribed vascular/spindle-cell lesion consistent with a schwannoma. His postoperative course was uncomplicated. At 4-week follow-up the incision had healed completely and the patient was pain free.

Discussion

Soft-tissue nodules are common—about two-thirds of soft-tissue tumors are classified into 7 diagnostic categories: lipoma and lipoma variants (16%), fibrous histiocytoma (13%), nodular fasciitis (11%), hemangioma (8%), fibromatosis (7%), neurofibroma (5%), and schwannoma (5%).1 Peripheral nerve tumors (schwannomas, neurofibromas) can be associated with pain or paresthesias, and less commonly, neurologic deficits, such as motor weakness. Peripheral nerve tumors have several classifications, such as nonneoplastic vs neoplastic, benign vs malignant, and sheath vs nonsheath origins. Schwannomas are considered part of the neoplastic subset due to their growth; otherwise, they are benign with a sheath origin. In contrast to neurofibromas, benign schwannomas have a slower rate of progression, lower association with pain, and fewer neurologic symptoms.2

The neural sheath is made up of 3 types of cells: the fibroblast, the Schwann cell, and the perineural cell, which lacks a basement membrane. It is the Schwann cell that can give rise to the 3 main types of cutaneous nerve tumors: neuromas, neurofibromas, and schwannomas.3 A nerve that is both entering and exiting a mass is a classic presentation for a peripheral nerve sheath tumor. If the nerve is eccentric to the lesion, then it is consistent with a schwannoma (not a neurofibroma).4 Schwannomas are made exclusively of Schwann cells that arise from the nerve sheath, whereas neurofibromas are made up of all the different cell types that constitute a nerve. Bilateral vestibular schwannomas (acoustic neuromas) are virtually pathognomonic of neurofibromatosis 2 (NF-2), which can manifest as hearing loss, tinnitus, and equilibrium problems. In contrast, neurofibromatosis 1 (NF-1) is more common, characterized by multiple café au lait spots, freckling in the axillary and groin regions, increased risk of cancers overall, and development of pedunculated skin growths, brain, or organ-based neurofibromas.

Diagnosis

A workup generally includes a thorough history and examination as well as imaging. In cases of superficial subcutaneous lesions, an ultrasound is often the imaging modality of choice. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans are frequently used for more deep-seated lesions. There can be significant differences between malignant and benign neural lesions on MRI and CT in terms of contrast-uptake and heterogeneity of tissue, but the visual features are not consistent. Best estimates for MRI suggest 61% sensitivity and 90% specificity for the diagnosis of high-grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors based on imaging alone.5

Definitive diagnosis requires surgical excision. Fine-needle aspiration can be used to diagnose subcutaneous nodules, but there is a possibility that degenerative changes and nuclear atypia seen on a smaller sample may be confused with a more aggressive sarcoma. For example, long-standing schwannomas are often called ancient, meaning that they break down over time, and the atypia they display is a regressive phenomenon.6 Therefore, a small or limited tissue sampling may not be representative of the entire lesion.7 As such, patients will likely need referral for surgical removal to determine the exact nature of the growth.

Although schwannomas are uncommon overall, the highest incidence is in the fourth decade of life with a slight predominance in females. They are often incidentally found as a palpable mass but can be symptomatic with paresthesias, pain, or neurologic changes—particularly when identified in the retroperitoneum or along joints. Schwannomas are most commonly found in the retroperitoneum (32%), mediastinum (23%), head and neck (18%), and extremities (16%).8 The majority of cases (about 90%) are sporadic; whereas 2% are related to NF-2.9 The abdominal wall schwannoma is rare. Our review of English-language literature in PubMed and EMBASE found only 5 other case reports (Table 1).

On physical examination, superficial lesions are freely movable except for a single point of attachment, which is generally along the long axis of the nerve.

Pathology

On gross pathology examination, schwannomas have a well-circumscribed smooth external surface. On microscopy, schwannomas are truly encapsulated, uninodular, spindle-cell proliferations arranged in a streaming pattern within a background of thick, hyalinized blood vessels. Classic schwannomas typically exhibit a biphasic pattern of alternating areas of high and low cellularity and are named for Swedish neurologist Nils Antoni. The more cellular regions are referred to as Antoni A areas and consist of streaming fascicles of compact spindle cells that often palisade around acellular eosinophilic areas of fibrillary processes known as Verocay bodies.

In contrast, the lower cellularity regions (Antoni B areas) consist of multipolar, loosely textured cells with abundant cytoplasm, haphazardly arranged processes, and an overall myxoid appearance.11 Schwannomas are known to have widely variable proportions of Antoni A and Antoni B areas; in this case, the excised specimen was noted to have predominately Antoni A areas without well-defined Verocay bodies and only scattered foci showing some suggestion of the hypocellular Antoni B architecture (Figure 2).9,12

Immunohistochemical stains for S100 and SOX10 (used to identify cells derived from a neural crest lineage) were strongly positive, which is characteristic of schwannomas.13 Although there have only been rare reports of extracranial schwannomas undergoing malignant transformation, it is critical to rule out the possibility of a de novo malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST).13 In general, MPNSTs tend to be more cellular, have brisk mitotic activity, areas of necrosis, hyperchromatic nuclei, and conspicuous pleomorphism. Mitotic figures, which can be concerning for malignant potential if present in high number, were noted occasionally in our patient; however, occasional mitosis may be seen in classic schwannomas. Clinically, MPNSTs have a poor prognosis. Based on case reports, disease-specific survival at 10 years is 31.6% for localized disease and only 7.5% for metastatic disease.14 In this case, there was no evidence of any of the high-grade features of a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, thus supporting the diagnosis of schwannoma (neurilemmoma).

Treatment

Schwannomas are exclusively treated by excision. Prognosis is good with low recurrence rates. It is unknown what the recurrence rates are for completely resected abdominal wall schwannomas since there are so few reports in the literature. For other well-known entities, such as vestibular schwannoma (acoustic neuromas), the recurrence rates are generally 2% to 3%.15 Transformation of schwannomas into MPNSTs are so unusual that they are only described in single case reports.

Conclusion

Soft-tissue masses are a common complaint. Most are benign and do not require excision unless it interferes with the quality of life of the patient or if the diagnosis is uncertain. It is important to be aware of schwannomas in the differential diagnosis of soft-tissue masses. Diagnosis may be achieved through the combination of imaging and biopsy, but the definitive diagnosis is made on complete excision of the mass.

Acknowledgments

Contributors: Michael Lewis, MD, Department of Pathology, VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. Written permission also was obtained from the patient.

1. Kransdorf MJ. Benign soft-tissue tumors in a large referral population: distribution of specific diagnoses by age, sex, and location. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164(2):395-402.

2. Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ismaili N, Bastuji-Garin S, et al. Symptoms associated with malignancy of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: a retrospective study of 69 patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(1):79-82.

3. Patterson JW. Neural and neuroendocrine tumors. In: Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1042-1049.

4. Balzarotti R, Rondelli F, Barizzi J, Cartolari R. Symptomatic schwannoma of the abdominal wall: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(3):1095-1098.

5. Wasa J, Nishida Y, Tsukushi S, et al. MRI features in the differentiation of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and neurofibromas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(6):1568-1574.

6. Dodd LG, Marom EM, Dash RC, Matthews MR, McLendon RE. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of “ancient” schwannoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;20(5):307-311.

7. Powers CN, Berardo MD, Frable WJ. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy: pitfalls in the diagnosis of spindle-cell lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;10(3):232-240; discussion 241.

8. White W, Shiu MH, Rosenblum MK, Erlandson RA, Woodruff JM. Cellular schwannoma: a clinicopathologic study of 57 patients and 58 tumors. Cancer. 1990;66(6):1266-1275.

9. Goldblum JR, Weiss SW, Folpe AL. Benign tumors of peripheral nerves. In: Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014:813-828.

10. Naversen DN, Trask DM, Watson FH, Burket JM. Painful tumors of the skin: “LEND AN EGG.” J Am Acad Deramatol. 1993;28(2, pt 2):298-300.

11. Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. Diagnostic Pathology: Neuropathology. 1st ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys; 2012.

12. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, eds. World Health Organization Histological Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Vol. 1. Paris, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2016.

13. Woodruff JM, Selig AM, Crowley K, Allen PW. Schwannoma (neurilemoma) with malignant transformation. A rare, distinctive peripheral nerve tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18(9)82-895.

14. Zou C, Smith KD, Liu J, et al. Clinical, pathological, and molecular variables predictive of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor outcome. Ann Surg. 2009;249(6):1014-1022.

15. Ahmad RA, Sivalingam S, Topsakal V, Russo A, Taibah A, Sanna M. Rate of recurrent vestibular schwannoma after total removal via different surgical approaches. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2012;121(3):156-161.

16. Bhatia RK, Banerjea A, Ram M, Lovett BE. Benign ancient schwannoma of the abdominal wall: an unwanted birthday present. BMC Surg. 2010;10:1-5.

17. Mishra A, Hamadto M, Azzabi M, Elfagieh M. Abdominal wall schwannoma: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Radiol. 2013;2013:456863.

18. Liu Y, Chen X, Wang T, Wang Z. Imaging observations of a schwannoma of low malignant potential in the anterior abdominal wall: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(3):1159-1162.

19. Ginesu GC, Puledda M, Feo CF et al. Abdominal wall schwannoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20(10):1781-1783.

1. Kransdorf MJ. Benign soft-tissue tumors in a large referral population: distribution of specific diagnoses by age, sex, and location. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164(2):395-402.

2. Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ismaili N, Bastuji-Garin S, et al. Symptoms associated with malignancy of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: a retrospective study of 69 patients with neurofibromatosis 1. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(1):79-82.

3. Patterson JW. Neural and neuroendocrine tumors. In: Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2016:1042-1049.

4. Balzarotti R, Rondelli F, Barizzi J, Cartolari R. Symptomatic schwannoma of the abdominal wall: a case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;9(3):1095-1098.

5. Wasa J, Nishida Y, Tsukushi S, et al. MRI features in the differentiation of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors and neurofibromas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194(6):1568-1574.

6. Dodd LG, Marom EM, Dash RC, Matthews MR, McLendon RE. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of “ancient” schwannoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1999;20(5):307-311.

7. Powers CN, Berardo MD, Frable WJ. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy: pitfalls in the diagnosis of spindle-cell lesions. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;10(3):232-240; discussion 241.

8. White W, Shiu MH, Rosenblum MK, Erlandson RA, Woodruff JM. Cellular schwannoma: a clinicopathologic study of 57 patients and 58 tumors. Cancer. 1990;66(6):1266-1275.

9. Goldblum JR, Weiss SW, Folpe AL. Benign tumors of peripheral nerves. In: Enzinger and Weiss’s Soft Tissue Tumors. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2014:813-828.

10. Naversen DN, Trask DM, Watson FH, Burket JM. Painful tumors of the skin: “LEND AN EGG.” J Am Acad Deramatol. 1993;28(2, pt 2):298-300.

11. Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. Diagnostic Pathology: Neuropathology. 1st ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys; 2012.

12. Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK, eds. World Health Organization Histological Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Vol. 1. Paris, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2016.

13. Woodruff JM, Selig AM, Crowley K, Allen PW. Schwannoma (neurilemoma) with malignant transformation. A rare, distinctive peripheral nerve tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18(9)82-895.

14. Zou C, Smith KD, Liu J, et al. Clinical, pathological, and molecular variables predictive of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor outcome. Ann Surg. 2009;249(6):1014-1022.

15. Ahmad RA, Sivalingam S, Topsakal V, Russo A, Taibah A, Sanna M. Rate of recurrent vestibular schwannoma after total removal via different surgical approaches. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2012;121(3):156-161.

16. Bhatia RK, Banerjea A, Ram M, Lovett BE. Benign ancient schwannoma of the abdominal wall: an unwanted birthday present. BMC Surg. 2010;10:1-5.

17. Mishra A, Hamadto M, Azzabi M, Elfagieh M. Abdominal wall schwannoma: case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Radiol. 2013;2013:456863.

18. Liu Y, Chen X, Wang T, Wang Z. Imaging observations of a schwannoma of low malignant potential in the anterior abdominal wall: a case report. Oncol Lett. 2014;8(3):1159-1162.