User login

Id Reaction Associated With Red Tattoo Ink

To the Editor:

Although relatively uncommon, hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos.1 Multiple adverse events have been described in association with tattoos, including inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic responses.2 An id reaction (also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization) develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. We describe a unique case of an id reaction and subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink.

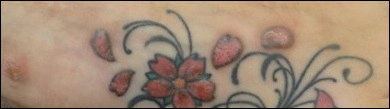

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the New York University Skin and Cancer Unit (New York, New York) for evaluation of a pruritic eruption arising on and near sites of tattooed skin on the right foot and right upper arm of 8 months’ duration. The patient reported that she had obtained a polychromatic tattoo on the right dorsal foot 9 months prior to the current presentation. Approximately 1 month later, she developed pruritic papulonodular lesions localized to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo. Concomitantly, the patient developed a similar eruption confined to areas of red pigment in a polychromatic tattoo on the right upper arm that she had obtained 10 years prior. She was treated with intralesional triamcinolone to several of the lesions on the right dorsal foot with some benefit; however, a few days later she developed a generalized, erythematous, pruritic eruption on the back, abdomen, arms, and legs. Her medical history was remarkable only for mild iron-deficiency anemia. She had no known drug allergies or history of atopy and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the eruption.

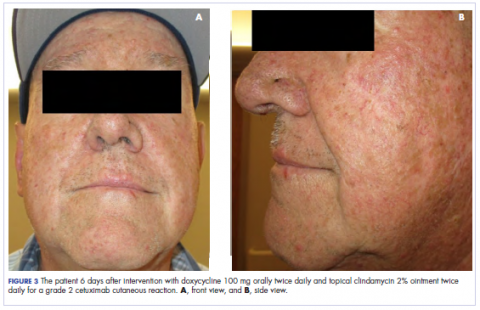

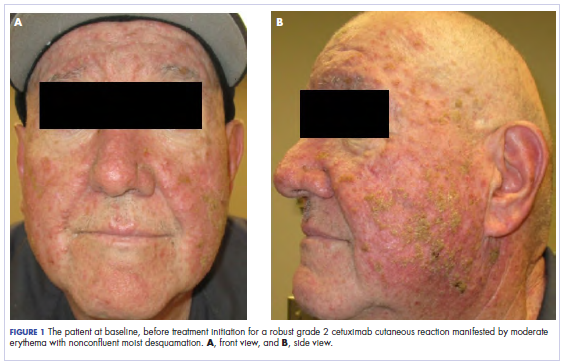

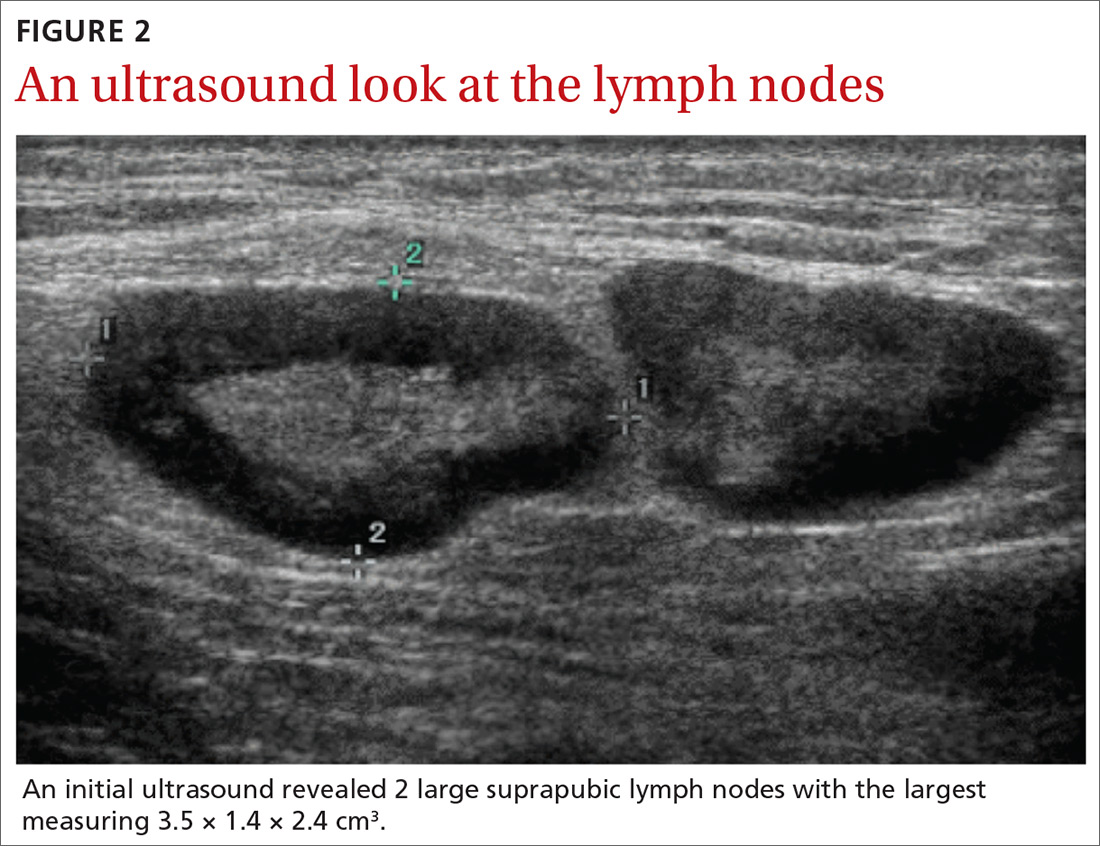

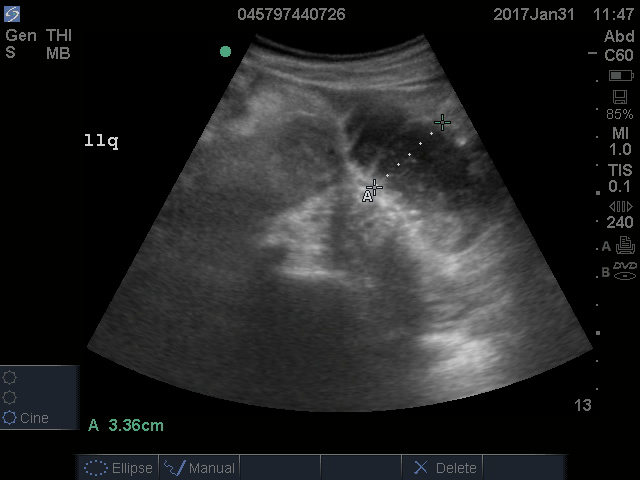

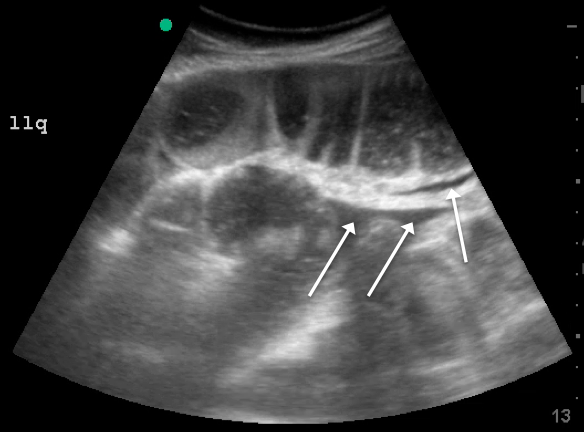

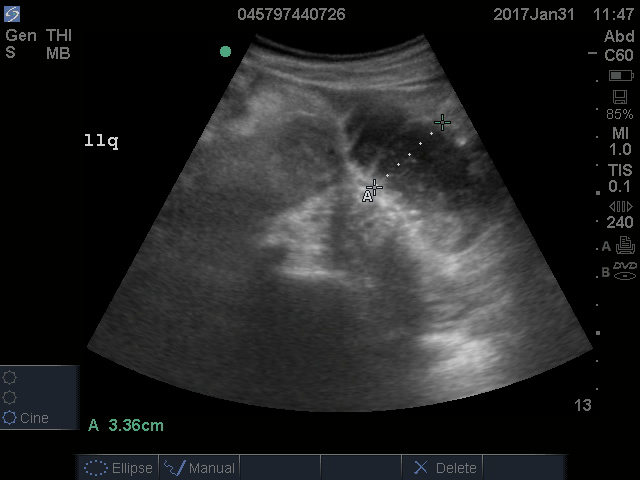

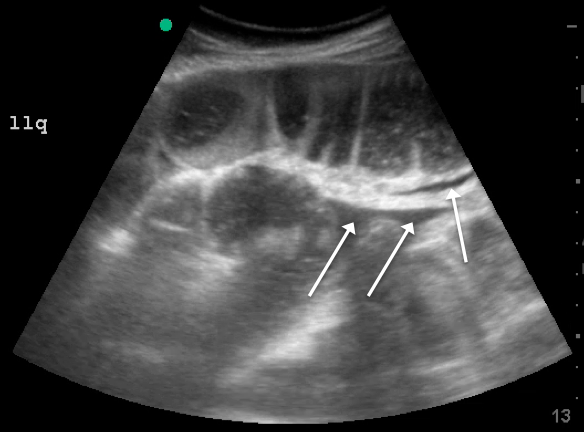

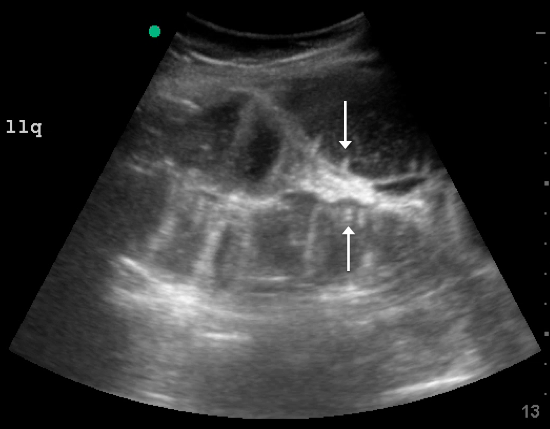

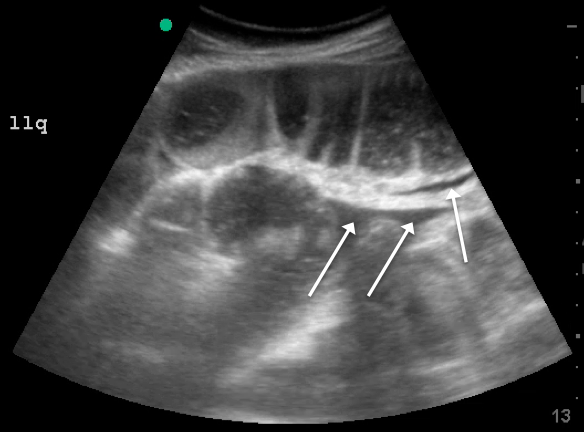

Skin examination revealed multiple, well-demarcated, eczematous papulonodules with surrounding erythema confined to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the right dorsal foot, with several similar lesions on the surrounding nontattooed skin (Figure 1). Linear, well-demarcated, eczematous, hyperpigmented plaques also were noted on the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the patient’s right upper arm (Figure 2). Eczematous plaques and scattered excoriations were noted on the back, abdomen, flanks, arms, and legs.

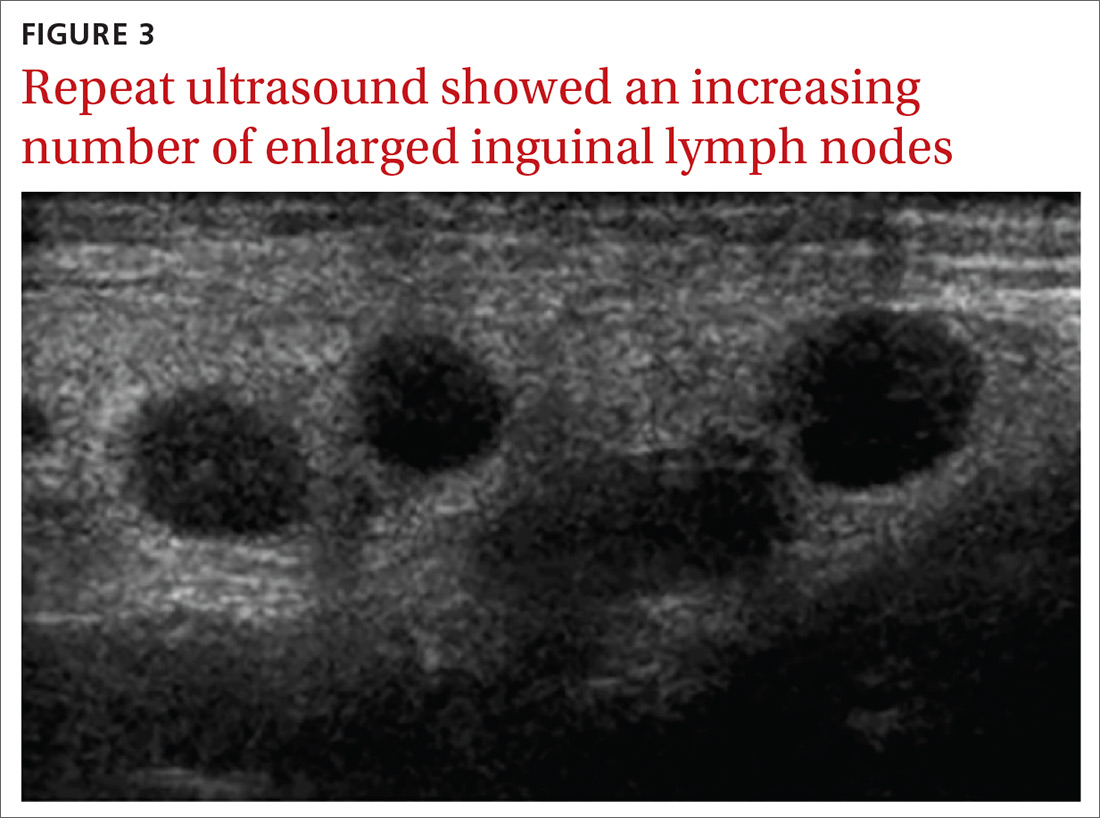

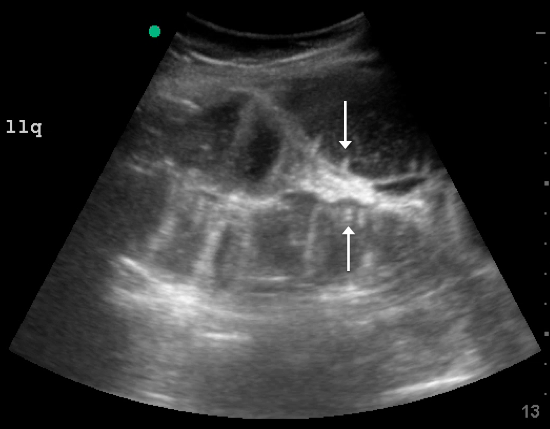

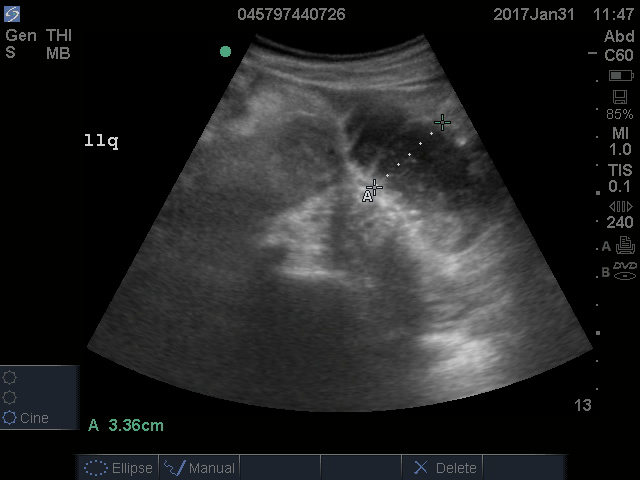

Patch testing with the North American Standard Series, metal series, and samples of the red pigments used in the tattoo on the foot were negative. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the dorsal right foot showed a psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining with diastase failed to reveal fungal hyphae. The histologic findings were consistent with allergic contact dermatitis. A punch biopsy of the eczematous reaction on nontattooed skin on the trunk demonstrated a perivascular dermatitis with eosinophils and subtle spongiosis consistent with an id reaction.

The patient was treated with fluocinonide ointment for several months with no effect. Subsequently, she received several short courses of oral prednisone, after which the affected areas of the tattoo on the arm and foot flattened and the id reaction resolved; however, after several months, the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the foot again became elevated and pruritic, and the patient developed widespread prurigo nodules on nontattooed skin on the trunk, arms, and legs. She was subsequently referred to a laser specialist for a trial of fractional laser treatment to cautiously remove the red tattoo pigment. After 2 treatments, the pruritus improved and the papular lesions appeared slightly flatter; however, the prurigo nodules remained. The tattoo on the patient’s foot was surgically removed; however, the prurigo nodules remained. Ultimately, the lesions cleared with a several-month course of mycophenolate mofetil.

Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity. An id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. Although the pathogenesis of this reaction is not certain, it has been hypothesized that autoimmunity to skin antigens might play a role.3 Autologous epidermal cells are thought to become antigenic in the presence of acute inflammation at the primary cutaneous site. These antigenic autologous epidermal cells are postulated to enter the circulation and cause secondary eczematous lesions at distant sites. This proposed mechanism is supported by the development of positive skin reactions to autologous extracts of epidermal scaling in patients with active id reaction.3

Hematogenous dissemination of cytokines has been implicated in id reactions.4 Keratinocytes produce cytokines in response to conditions that are known to trigger id reactions.5 Epidermal cytokines released from the primary site of sensitization are thought to heighten sensitivity at distant skin areas.4 These cytokines regulate both cell-mediated and humoral cutaneous immune responses. Increased levels of activated HLA-DR isotype–positive T cells in patients with active autoeczemization favors a cellular-mediated immune mechanism. The presence of activated antigen-specific T cells also supports the role of allergic contact dermatitis in triggering id reactions.6

Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common hypersensitivity reaction to tattoo ink, with red pigments representing the most common cause of tattoo-related allergic contact dermatitis. Historically, cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) has been the most common red pigment to cause allergic contact dermatitis.7 More recently, mercury-free organic pigments (eg, azo dyes) have been used in polychromatic tattoos due to their ability to retain color over long periods of time8; however, these organic red tattoo pigments also have been implicated in allergic reactions.8-11 The composition of these new organic red tattoo pigments varies, but chemical analysis has revealed a mixture of aromatic azo compounds (eg, quinacridone),10 heavy metals (eg, aluminum, lead, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, iron, titanium),9,12 and intermediate reactive compounds (eg, naphthalene, 2-naphthol, chlorobenzene, benzene).8 Allergic contact dermatitis to red tattoo ink is well documented8,13; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms tattoo and dermatitis, tattoo and allergy, tattoo and autosensitization, tattoo and id reaction, and tattoo and autoeczematization yielded only 3 other reports of a concomitant id reaction.11,14,15

The diagnosis of id reaction associated with allergic contact dermatitis is made on the basis of clinical history, physical examination, and histopathology. Patch testing usually is not positive in cases of tattoo allergy; it is thought that the allergen is a tattoo ink byproduct possibly caused by photoinduced or metabolic change of the tattoo pigment and a haptenization process.1,8,16 Histologically, variable reaction patterns, including eczematous, lichenoid, granulomatous, and pseudolymphomatous reactions have been reported in association with delayed-type inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigments, but the lichenoid pattern is most commonly observed.8

Treatment options for allergic contact dermatitis to tattoo ink include topical, intralesional, and oral steroids; topical calcineurin inhibitors; and surgical excision of the tattoo. Q-switched lasers—ruby, Nd:YAG, and alexandrite—are the gold standard for removing tattoo pigments17; however, these lasers remove tattoo pigment by selective photothermolysis, resulting in extracellular extravasation of pigment, which can precipitate a heightened immune response that can lead to localized and generalized allergic reactions.18 Therefore, Q-switched lasers should be avoided in the setting of an allergic reaction to tattoo ink. Fractional ablative laser resurfacing may be a safer alternative for removal of tattoos in the setting of an allergic reaction.17 Further studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of this modality for allergic tattoo ink removal.17,18

Our case illustrates a rare cause of id reaction and the subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink. We present this case to raise awareness of the potential health and iatrogenic risks associated with tattoo placement. Further investigation of these color additives is warranted to better elucidate ink components responsible for these cutaneous allergic reactions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Vitaly Terushkin, MD (West Orange, New Jersey, and New York, New York), and Arielle Kauvar, MD (New York, New York), for their contributions to the patient’s clinical care.

- Vasold R, Engel E, Konig B, et al. Health risks of tattoo colors. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:9-13.

- Swigost AJ, Peltola J, Jacobson-Dunlop E, et al. Tattoo-related squamous proliferations: a specturm of reactive hyperplasia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:728-732.

- Cormia FE, Esplin BM. Autoeczematization; preliminary report. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;61:931-945.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Uchi H, Terao H, Koga T, et al. Cytokines and chemokines in the epidermis. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24(suppl 1):S29-S38.

- Kasteler JS, Petersen MJ, Vance JE, et al. Circulating activated T lymphocytes in autoeczematization. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:795-798.

- Mortimer NJ, Chave TA, Johnston GA. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Garcovich S, Carbone T, Avitabile S, et al. Lichenoid red tattoo reaction: histological and immunological perspectives. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:93-96.

- Sowden JM, Byrne JP, Smith AG, et al. Red tattoo reactions: x-ray microanalysis and patch-test studies. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:576-580.

- Bendsoe N, Hansson C, Sterner O. Inflammatory reactions from organic pigments in red tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:70-73.

- Greve B, Chytry R, Raulin C. Contact dermatitis from red tattoo pigment (quinacridone) with secondary spread. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:265-266.

- Cristaudo A, Forte G, Bocca B, et al. Permanent tattoos: evidence of pseudolymphoma in three patients and metal composition of the dyes. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:776-780.

- Wenzel SM, Welzel J, Hafner C, et al. Permanent make-up colorants may cause severe skin reactions. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:223-227.

- Goldberg HM. Tattoo allergy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1315-1316.

- Gamba CS, Smith FL, Wisell J, et al. Tattoo reactions in an HIV patient: autoeczematization and progressive allergic reaction to red ink after antiretroviral therapy initiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:395-398.

- Serup J, Hutton Carlsen K. Patch test study of 90 patients with tattoo reactions: negative outcome of allergy patch test to baseline batteries and culprit inks suggests allergen(s) are generated in the skin through haptenization. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:255-263.

- Ibrahimi OA, Syed Z, Sakamoto FH, et al. Treatment of tattoo allergy with ablative fractional resurfacing: a novel paradigm for tattoo removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1111-1114.

- Harper J, Losch AE, Otto SG, et al. New insight into the pathophysiology of tattoo reactions following laser tattoo removal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:313e-314e.

To the Editor:

Although relatively uncommon, hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos.1 Multiple adverse events have been described in association with tattoos, including inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic responses.2 An id reaction (also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization) develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. We describe a unique case of an id reaction and subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink.

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the New York University Skin and Cancer Unit (New York, New York) for evaluation of a pruritic eruption arising on and near sites of tattooed skin on the right foot and right upper arm of 8 months’ duration. The patient reported that she had obtained a polychromatic tattoo on the right dorsal foot 9 months prior to the current presentation. Approximately 1 month later, she developed pruritic papulonodular lesions localized to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo. Concomitantly, the patient developed a similar eruption confined to areas of red pigment in a polychromatic tattoo on the right upper arm that she had obtained 10 years prior. She was treated with intralesional triamcinolone to several of the lesions on the right dorsal foot with some benefit; however, a few days later she developed a generalized, erythematous, pruritic eruption on the back, abdomen, arms, and legs. Her medical history was remarkable only for mild iron-deficiency anemia. She had no known drug allergies or history of atopy and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the eruption.

Skin examination revealed multiple, well-demarcated, eczematous papulonodules with surrounding erythema confined to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the right dorsal foot, with several similar lesions on the surrounding nontattooed skin (Figure 1). Linear, well-demarcated, eczematous, hyperpigmented plaques also were noted on the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the patient’s right upper arm (Figure 2). Eczematous plaques and scattered excoriations were noted on the back, abdomen, flanks, arms, and legs.

Patch testing with the North American Standard Series, metal series, and samples of the red pigments used in the tattoo on the foot were negative. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the dorsal right foot showed a psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining with diastase failed to reveal fungal hyphae. The histologic findings were consistent with allergic contact dermatitis. A punch biopsy of the eczematous reaction on nontattooed skin on the trunk demonstrated a perivascular dermatitis with eosinophils and subtle spongiosis consistent with an id reaction.

The patient was treated with fluocinonide ointment for several months with no effect. Subsequently, she received several short courses of oral prednisone, after which the affected areas of the tattoo on the arm and foot flattened and the id reaction resolved; however, after several months, the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the foot again became elevated and pruritic, and the patient developed widespread prurigo nodules on nontattooed skin on the trunk, arms, and legs. She was subsequently referred to a laser specialist for a trial of fractional laser treatment to cautiously remove the red tattoo pigment. After 2 treatments, the pruritus improved and the papular lesions appeared slightly flatter; however, the prurigo nodules remained. The tattoo on the patient’s foot was surgically removed; however, the prurigo nodules remained. Ultimately, the lesions cleared with a several-month course of mycophenolate mofetil.

Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity. An id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. Although the pathogenesis of this reaction is not certain, it has been hypothesized that autoimmunity to skin antigens might play a role.3 Autologous epidermal cells are thought to become antigenic in the presence of acute inflammation at the primary cutaneous site. These antigenic autologous epidermal cells are postulated to enter the circulation and cause secondary eczematous lesions at distant sites. This proposed mechanism is supported by the development of positive skin reactions to autologous extracts of epidermal scaling in patients with active id reaction.3

Hematogenous dissemination of cytokines has been implicated in id reactions.4 Keratinocytes produce cytokines in response to conditions that are known to trigger id reactions.5 Epidermal cytokines released from the primary site of sensitization are thought to heighten sensitivity at distant skin areas.4 These cytokines regulate both cell-mediated and humoral cutaneous immune responses. Increased levels of activated HLA-DR isotype–positive T cells in patients with active autoeczemization favors a cellular-mediated immune mechanism. The presence of activated antigen-specific T cells also supports the role of allergic contact dermatitis in triggering id reactions.6

Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common hypersensitivity reaction to tattoo ink, with red pigments representing the most common cause of tattoo-related allergic contact dermatitis. Historically, cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) has been the most common red pigment to cause allergic contact dermatitis.7 More recently, mercury-free organic pigments (eg, azo dyes) have been used in polychromatic tattoos due to their ability to retain color over long periods of time8; however, these organic red tattoo pigments also have been implicated in allergic reactions.8-11 The composition of these new organic red tattoo pigments varies, but chemical analysis has revealed a mixture of aromatic azo compounds (eg, quinacridone),10 heavy metals (eg, aluminum, lead, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, iron, titanium),9,12 and intermediate reactive compounds (eg, naphthalene, 2-naphthol, chlorobenzene, benzene).8 Allergic contact dermatitis to red tattoo ink is well documented8,13; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms tattoo and dermatitis, tattoo and allergy, tattoo and autosensitization, tattoo and id reaction, and tattoo and autoeczematization yielded only 3 other reports of a concomitant id reaction.11,14,15

The diagnosis of id reaction associated with allergic contact dermatitis is made on the basis of clinical history, physical examination, and histopathology. Patch testing usually is not positive in cases of tattoo allergy; it is thought that the allergen is a tattoo ink byproduct possibly caused by photoinduced or metabolic change of the tattoo pigment and a haptenization process.1,8,16 Histologically, variable reaction patterns, including eczematous, lichenoid, granulomatous, and pseudolymphomatous reactions have been reported in association with delayed-type inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigments, but the lichenoid pattern is most commonly observed.8

Treatment options for allergic contact dermatitis to tattoo ink include topical, intralesional, and oral steroids; topical calcineurin inhibitors; and surgical excision of the tattoo. Q-switched lasers—ruby, Nd:YAG, and alexandrite—are the gold standard for removing tattoo pigments17; however, these lasers remove tattoo pigment by selective photothermolysis, resulting in extracellular extravasation of pigment, which can precipitate a heightened immune response that can lead to localized and generalized allergic reactions.18 Therefore, Q-switched lasers should be avoided in the setting of an allergic reaction to tattoo ink. Fractional ablative laser resurfacing may be a safer alternative for removal of tattoos in the setting of an allergic reaction.17 Further studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of this modality for allergic tattoo ink removal.17,18

Our case illustrates a rare cause of id reaction and the subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink. We present this case to raise awareness of the potential health and iatrogenic risks associated with tattoo placement. Further investigation of these color additives is warranted to better elucidate ink components responsible for these cutaneous allergic reactions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Vitaly Terushkin, MD (West Orange, New Jersey, and New York, New York), and Arielle Kauvar, MD (New York, New York), for their contributions to the patient’s clinical care.

To the Editor:

Although relatively uncommon, hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos.1 Multiple adverse events have been described in association with tattoos, including inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic responses.2 An id reaction (also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization) develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. We describe a unique case of an id reaction and subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink.

A 40-year-old woman was referred to the New York University Skin and Cancer Unit (New York, New York) for evaluation of a pruritic eruption arising on and near sites of tattooed skin on the right foot and right upper arm of 8 months’ duration. The patient reported that she had obtained a polychromatic tattoo on the right dorsal foot 9 months prior to the current presentation. Approximately 1 month later, she developed pruritic papulonodular lesions localized to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo. Concomitantly, the patient developed a similar eruption confined to areas of red pigment in a polychromatic tattoo on the right upper arm that she had obtained 10 years prior. She was treated with intralesional triamcinolone to several of the lesions on the right dorsal foot with some benefit; however, a few days later she developed a generalized, erythematous, pruritic eruption on the back, abdomen, arms, and legs. Her medical history was remarkable only for mild iron-deficiency anemia. She had no known drug allergies or history of atopy and was not taking any medications prior to the onset of the eruption.

Skin examination revealed multiple, well-demarcated, eczematous papulonodules with surrounding erythema confined to the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the right dorsal foot, with several similar lesions on the surrounding nontattooed skin (Figure 1). Linear, well-demarcated, eczematous, hyperpigmented plaques also were noted on the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the patient’s right upper arm (Figure 2). Eczematous plaques and scattered excoriations were noted on the back, abdomen, flanks, arms, and legs.

Patch testing with the North American Standard Series, metal series, and samples of the red pigments used in the tattoo on the foot were negative. A punch biopsy of a lesion on the dorsal right foot showed a psoriasiform spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils (Figure 3). Periodic acid–Schiff staining with diastase failed to reveal fungal hyphae. The histologic findings were consistent with allergic contact dermatitis. A punch biopsy of the eczematous reaction on nontattooed skin on the trunk demonstrated a perivascular dermatitis with eosinophils and subtle spongiosis consistent with an id reaction.

The patient was treated with fluocinonide ointment for several months with no effect. Subsequently, she received several short courses of oral prednisone, after which the affected areas of the tattoo on the arm and foot flattened and the id reaction resolved; however, after several months, the red-pigmented areas of the tattoo on the foot again became elevated and pruritic, and the patient developed widespread prurigo nodules on nontattooed skin on the trunk, arms, and legs. She was subsequently referred to a laser specialist for a trial of fractional laser treatment to cautiously remove the red tattoo pigment. After 2 treatments, the pruritus improved and the papular lesions appeared slightly flatter; however, the prurigo nodules remained. The tattoo on the patient’s foot was surgically removed; however, the prurigo nodules remained. Ultimately, the lesions cleared with a several-month course of mycophenolate mofetil.

Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity. An id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization. Although the pathogenesis of this reaction is not certain, it has been hypothesized that autoimmunity to skin antigens might play a role.3 Autologous epidermal cells are thought to become antigenic in the presence of acute inflammation at the primary cutaneous site. These antigenic autologous epidermal cells are postulated to enter the circulation and cause secondary eczematous lesions at distant sites. This proposed mechanism is supported by the development of positive skin reactions to autologous extracts of epidermal scaling in patients with active id reaction.3

Hematogenous dissemination of cytokines has been implicated in id reactions.4 Keratinocytes produce cytokines in response to conditions that are known to trigger id reactions.5 Epidermal cytokines released from the primary site of sensitization are thought to heighten sensitivity at distant skin areas.4 These cytokines regulate both cell-mediated and humoral cutaneous immune responses. Increased levels of activated HLA-DR isotype–positive T cells in patients with active autoeczemization favors a cellular-mediated immune mechanism. The presence of activated antigen-specific T cells also supports the role of allergic contact dermatitis in triggering id reactions.6

Allergic contact dermatitis is the most common hypersensitivity reaction to tattoo ink, with red pigments representing the most common cause of tattoo-related allergic contact dermatitis. Historically, cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) has been the most common red pigment to cause allergic contact dermatitis.7 More recently, mercury-free organic pigments (eg, azo dyes) have been used in polychromatic tattoos due to their ability to retain color over long periods of time8; however, these organic red tattoo pigments also have been implicated in allergic reactions.8-11 The composition of these new organic red tattoo pigments varies, but chemical analysis has revealed a mixture of aromatic azo compounds (eg, quinacridone),10 heavy metals (eg, aluminum, lead, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, iron, titanium),9,12 and intermediate reactive compounds (eg, naphthalene, 2-naphthol, chlorobenzene, benzene).8 Allergic contact dermatitis to red tattoo ink is well documented8,13; however, a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms tattoo and dermatitis, tattoo and allergy, tattoo and autosensitization, tattoo and id reaction, and tattoo and autoeczematization yielded only 3 other reports of a concomitant id reaction.11,14,15

The diagnosis of id reaction associated with allergic contact dermatitis is made on the basis of clinical history, physical examination, and histopathology. Patch testing usually is not positive in cases of tattoo allergy; it is thought that the allergen is a tattoo ink byproduct possibly caused by photoinduced or metabolic change of the tattoo pigment and a haptenization process.1,8,16 Histologically, variable reaction patterns, including eczematous, lichenoid, granulomatous, and pseudolymphomatous reactions have been reported in association with delayed-type inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigments, but the lichenoid pattern is most commonly observed.8

Treatment options for allergic contact dermatitis to tattoo ink include topical, intralesional, and oral steroids; topical calcineurin inhibitors; and surgical excision of the tattoo. Q-switched lasers—ruby, Nd:YAG, and alexandrite—are the gold standard for removing tattoo pigments17; however, these lasers remove tattoo pigment by selective photothermolysis, resulting in extracellular extravasation of pigment, which can precipitate a heightened immune response that can lead to localized and generalized allergic reactions.18 Therefore, Q-switched lasers should be avoided in the setting of an allergic reaction to tattoo ink. Fractional ablative laser resurfacing may be a safer alternative for removal of tattoos in the setting of an allergic reaction.17 Further studies are needed to confirm the safety and efficacy of this modality for allergic tattoo ink removal.17,18

Our case illustrates a rare cause of id reaction and the subsequent development of prurigo nodules associated with contact allergy to red tattoo ink. We present this case to raise awareness of the potential health and iatrogenic risks associated with tattoo placement. Further investigation of these color additives is warranted to better elucidate ink components responsible for these cutaneous allergic reactions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Vitaly Terushkin, MD (West Orange, New Jersey, and New York, New York), and Arielle Kauvar, MD (New York, New York), for their contributions to the patient’s clinical care.

- Vasold R, Engel E, Konig B, et al. Health risks of tattoo colors. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:9-13.

- Swigost AJ, Peltola J, Jacobson-Dunlop E, et al. Tattoo-related squamous proliferations: a specturm of reactive hyperplasia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:728-732.

- Cormia FE, Esplin BM. Autoeczematization; preliminary report. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;61:931-945.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Uchi H, Terao H, Koga T, et al. Cytokines and chemokines in the epidermis. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24(suppl 1):S29-S38.

- Kasteler JS, Petersen MJ, Vance JE, et al. Circulating activated T lymphocytes in autoeczematization. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:795-798.

- Mortimer NJ, Chave TA, Johnston GA. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Garcovich S, Carbone T, Avitabile S, et al. Lichenoid red tattoo reaction: histological and immunological perspectives. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:93-96.

- Sowden JM, Byrne JP, Smith AG, et al. Red tattoo reactions: x-ray microanalysis and patch-test studies. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:576-580.

- Bendsoe N, Hansson C, Sterner O. Inflammatory reactions from organic pigments in red tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:70-73.

- Greve B, Chytry R, Raulin C. Contact dermatitis from red tattoo pigment (quinacridone) with secondary spread. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:265-266.

- Cristaudo A, Forte G, Bocca B, et al. Permanent tattoos: evidence of pseudolymphoma in three patients and metal composition of the dyes. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:776-780.

- Wenzel SM, Welzel J, Hafner C, et al. Permanent make-up colorants may cause severe skin reactions. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:223-227.

- Goldberg HM. Tattoo allergy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1315-1316.

- Gamba CS, Smith FL, Wisell J, et al. Tattoo reactions in an HIV patient: autoeczematization and progressive allergic reaction to red ink after antiretroviral therapy initiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:395-398.

- Serup J, Hutton Carlsen K. Patch test study of 90 patients with tattoo reactions: negative outcome of allergy patch test to baseline batteries and culprit inks suggests allergen(s) are generated in the skin through haptenization. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:255-263.

- Ibrahimi OA, Syed Z, Sakamoto FH, et al. Treatment of tattoo allergy with ablative fractional resurfacing: a novel paradigm for tattoo removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1111-1114.

- Harper J, Losch AE, Otto SG, et al. New insight into the pathophysiology of tattoo reactions following laser tattoo removal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:313e-314e.

- Vasold R, Engel E, Konig B, et al. Health risks of tattoo colors. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;391:9-13.

- Swigost AJ, Peltola J, Jacobson-Dunlop E, et al. Tattoo-related squamous proliferations: a specturm of reactive hyperplasia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:728-732.

- Cormia FE, Esplin BM. Autoeczematization; preliminary report. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1950;61:931-945.

- Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Uchi H, Terao H, Koga T, et al. Cytokines and chemokines in the epidermis. J Dermatol Sci. 2000;24(suppl 1):S29-S38.

- Kasteler JS, Petersen MJ, Vance JE, et al. Circulating activated T lymphocytes in autoeczematization. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:795-798.

- Mortimer NJ, Chave TA, Johnston GA. Red tattoo reactions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:508-510.

- Garcovich S, Carbone T, Avitabile S, et al. Lichenoid red tattoo reaction: histological and immunological perspectives. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:93-96.

- Sowden JM, Byrne JP, Smith AG, et al. Red tattoo reactions: x-ray microanalysis and patch-test studies. Br J Dermatol. 1991;124:576-580.

- Bendsoe N, Hansson C, Sterner O. Inflammatory reactions from organic pigments in red tattoos. Acta Derm Venereol. 1991;71:70-73.

- Greve B, Chytry R, Raulin C. Contact dermatitis from red tattoo pigment (quinacridone) with secondary spread. Contact Dermatitis. 2003;49:265-266.

- Cristaudo A, Forte G, Bocca B, et al. Permanent tattoos: evidence of pseudolymphoma in three patients and metal composition of the dyes. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:776-780.

- Wenzel SM, Welzel J, Hafner C, et al. Permanent make-up colorants may cause severe skin reactions. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;63:223-227.

- Goldberg HM. Tattoo allergy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:1315-1316.

- Gamba CS, Smith FL, Wisell J, et al. Tattoo reactions in an HIV patient: autoeczematization and progressive allergic reaction to red ink after antiretroviral therapy initiation. JAAD Case Rep. 2015;1:395-398.

- Serup J, Hutton Carlsen K. Patch test study of 90 patients with tattoo reactions: negative outcome of allergy patch test to baseline batteries and culprit inks suggests allergen(s) are generated in the skin through haptenization. Contact Dermatitis. 2014;71:255-263.

- Ibrahimi OA, Syed Z, Sakamoto FH, et al. Treatment of tattoo allergy with ablative fractional resurfacing: a novel paradigm for tattoo removal. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:1111-1114.

- Harper J, Losch AE, Otto SG, et al. New insight into the pathophysiology of tattoo reactions following laser tattoo removal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:313e-314e.

Practice Points

- Hypersensitivity reactions to tattoo pigment are on the rise due to the increasing popularity and prevalence of tattoos. Systemic allergic reactions to tattoo ink are rare but can cause considerable morbidity.

- Id reaction, also known as autoeczematization or autosensitization, is a reaction that develops distant to an initial site of infection or sensitization.

- Further investigation of color additives in tattoo pigments is warranted to better elucidate the components responsible for cutaneous allergic reactions associated with tattoo ink.

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: an elusive diagnosis with challenging management

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVBCL) is an aggressive and systemically disseminated disease that affects the elderly, with a median age of diagnosis around 70 years and no gender predilection. It is a rare subtype of extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) characterized by selective growth of neoplastic cells within blood vessel lumen without any obvious extravascular tumor mass. Hence, an absence of marked lymphadenopathy and heterogeneous clinical presentation make it difficult to diagnose accurately and timely, with roughly half of the cases found postmortem in previous case reports.1,2 The exact incidence of this disease is not known, but more recently, the accuracy of diagnosis of this type of lymphoma has improved with random skin and bone marrow biopsy.1,2 We present here a clinical case of this disease with an atypical presentation followed by a detailed review of its clinical aspects.

Case presentation and summary

A 43-year-old white woman with a history of hypothyroidism and recurrent ovarian cysts presented to clinic with 3 months of loss of appetite, abdominal distension, pelvic pain, and progressive lower-extremity swelling. A physical examination was notable for marked abdominal distension, diffuse lower abdominal tenderness, and pitting lower-extremity edema. No skin rash or any other cutaneous abnormality was noted on exam. Laboratory test results revealed a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level of 1652 U/L and a CA-125 level of 50 U/mL (reference range, 0-35 U/mL). No significant beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and alpha-fetoprotein levels were detected. Computed-tomographic (CT) imaging revealed small bilateral pleural effusions and gallbladder wall thickening with abdominal wall edema, but it was otherwise unrevealing. An echocardiogram showed normal cardiac structure and function, with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 60%. No protein was detected in the patient’s urine, and thyroid function tests were unrevealing. Doppler ultrasound studies of her lower extremities and abdomen revealed no thrombosis. Given the patient’s continued pelvic pain, history of ovarian cysts, and elevation in CA-125, she underwent a laparoscopic total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingoopherectomy.

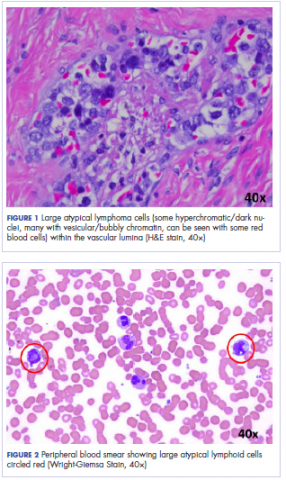

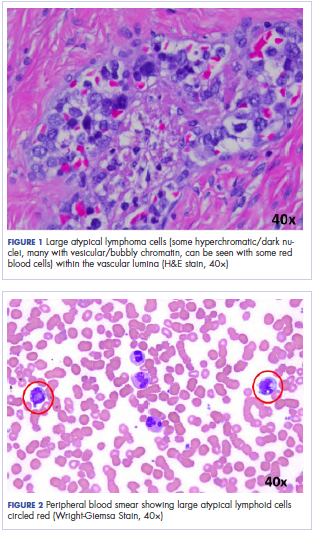

Histologic examination revealed neoplastic cells involving only the vascular lumina of the cervix, endomyometrium, bilateral fallopian tubes, and bilateral ovaries (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry stains were positive for CD5, CD20, PAX-5, CD45, BCL-2, and BCL-6 and focally positive for CD10. Peripheral smear showed pseudo-Pelger–Huet cells with 5% atypical lymphoma cells (Figure 2). Complete staging with positron-emission and CT (PET–CT) imaging revealed no metabolic activity, and a bone marrow biopsy showed trilineage hematopoiesis with adequate maturation and less than 5% of the marrow involved with large B-cell lymphoma cells. A diagnosis of IVBCL was made.

Further work-up to rule out involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) included magnetic-resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cytology and flow cytometry, which were negative.

Our patient underwent treatment with 6 cycles of infusional, dose-adjusted R-EPOCH (rituximab, etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) and 6 doses of prophylactic intrathecal chemotherapy with alternating methotrexate and cytarabine (Ara-C), and initial and subsequent CSF sampling showed no disease involvement. Consolidation with high-dose chemotherapy with R-BEAM (rituximab, carmustine, etoposide, Ara-C [cytarabine], melphalan) followed by rescue autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) was performed, and the patient has remained in clinical and hematologic remission for the past 24 months.

Discussion

Clinical presentation

The clinical manifestation of this disease is highly variable, and virtually any organ can be involved. Besides causing constitutional symptoms, including fatigue, B symptoms, and decline in performance status, heterogeneity of the clinical presentation depends on the organ system involved. One of the exceptional features of this disease is the difference in clinical presentation based on the geographical origin of the patient.2-4

Western-variant IVBCL has a higher frequency of CNS and skin involvement, whereas Asian-variant IVBCL shows preferential involvement of bone marrow with hemophagocytosis, hepatosplenomegaly, and thrombocytopenia. However, these 2 clinical variants have no difference in clinical outcome, except with the cutaneous-variant kind.24 A retrospective case series of 38 Western-variant IVBCL cases showed that 55% of patients had B symptoms with poor performance status.3 Brain and skin were the organs that were most frequently involved, with 68% of patients having involvement of at least 1 of those organs. Ten patients in this case series had disease that was exclusively limited to the skin and described as a “cutaneous variant” of IVBCL.3

Similarly, a retrospective case series of 96 cases of Asian-variant IVBCL showed B symptoms in 76% of patients, with predominant bone marrow involvement in 75% of patients, accompanied by hemophagocytosis in 66% and hepatosplenomegaly and anemia/thrombocytopenia in 77% and 84% of the patients, respectively.4 This difference in clinical presentation might have existed as a result of ethnic difference associated with production of inflammatory cytokines, including interferon gamma, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interlukin-1 beta, and soluble interlukin-2 receptor, with levels of soluble interlukin-2 receptor found to be significantly higher in Asian patients than non-Asian patients.2

Diagnosis

Involved organ biopsy is mandatory for establishing the diagnosis of IVBCL. Laboratory findings are nonspecific, with the most common abnormality being increased serum LDH and beta-2 microglobulin levels observed in 80% to 90% or more of patients. Despite its intravascular growth pattern, IVBCL was associated with peripheral blood involvement in only 5% to 9% of patients.1

Staging

Clinical staging work-up suggested for IVBCL patients by International Extranodal lymphoma study group in 2005 included physical examination (with emphasis on nervous system and skin), routine blood studies, peripheral blood smear, total body CT scan with contrast or PET–CT scan, MRI brain with contrast, CSF cytology, and bone marrow or organ biopsy.1 The role of fluorodeoxyglucose-PET scan is controversial but can be helpful to detect unexpected locations for biopsy and to assess treatment response.5,6

Morphology and immunophenotyping

In general, IVBCL histopathology shows large neoplastic lymphoid cells with large nuclei along with one or more nucleoli and scant cytoplasm within blood vessel lumen. Immunophenotypically, IVBCL cells mostly express nongerminal B-cell–associated markers with CD79a (100%), CD20 (96%), MUM-IRF4 (95%), CD5 (38%), and CD10 (12%) expressions. IVBCL cells have been demonstrated to lack cell surface protein CD29 and CD54 critical to transvascular migration. Similarly, aberrant expression of proteins such as CD11a and CXCR3 allows lymphoma cells to be attracted to endothelial cells, which might explain their intravascular confinement.7

Genetics

No pathognomic cytogenetic abnormalities have been reported in IVBCL to date, and the genetic features of this disease are not yet completely understood.2,7

Management

IVBCL is considered a stage IV disseminated disease with an International Prognostic Index score of high-intermediate to high in most cases. Half of the patients with IVBCL who were treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy relapsed and died within 18 months of diagnosis. One third of the relapses involved the CNS, thereby highlighting the importance of prophylactic CNS-directed Intrathecal therapy in an induction treatment regimen.2-4 Ferreri and colleagues reported in their case series response rates of about 60%, with an overall survival (OS) of 3 years of 30% in patients who were treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy. A multivariate analysis of the entire series showed cutaneous variant of the disease to be an independent favorable prognostic factor for OS.3

In the Murase and colleagues case series, the authors reported 67% response rates and a median OS of 13 months with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, prednisone) or CHOP-like regimens. Multivariate analysis showed older age, thrombocytopenia, and absence of anthracycline-based chemotherapy to be an independent negative prognostic factor for OS.4 Another retrospective analysis by Shimada and colleagues of 106 patients with IVBCL showed improved outcome with the addition of rituximab to CHOP-based chemotherapy (R-CHOP). Complete response rate (CR), 2-year progression-free survival, and OS were significantly higher for patients in rituximab-chemotherapy group than for those in the chemotherapy-alone group (CR, 82% vs 51%, respectively, P = .001; PFS, 56% vs 27%; OS, 66% vs 46%, P = .001), thereby establishing rituximab with CHOP-based therapy as induction therapy for IVBCL patients.8

The role of high-dose chemotherapy followed by ASCT could also be used as consolidation therapy to improve clinical outcomes as reported in 7 patients, showing durable remission after transplant in these 2 case series.3,4 Another retrospective analysis of 6 patients with IVBCL who were treated with 6 cycles of R-CHOP as induction therapy and consolidated with ASCT reported all patients to be alive and in complete remission after a median follow-up of 56 months.9 Based on the retrospective case series data by Kato and colleagues and considering that more than 80% of the patients with IVBCL were in the high-risk International Prognostic Index group, ASCT in first remission might be a useful treatment option for durable remission; however, because the median age for the diagnosis of IVBCL is about 70 years, ASCT may not be a realistic option for all patients.

Conclusions

IVBCL is a rare, aggressive, and distinct type of DLBCL with complex constellations of symptoms requiring strong clinical suspicion to establish this challenging diagnosis. Rituximab with anthracycline-based therapy along with prophylactic CNS-directed therapy followed by consolidative ASCT may lead to long-term remission. More research is needed into the genetic features of this disease to better understand its pathogenesis and potential targets for treatment.

1. Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJ, Campo E, et al. Definition, diagnosis, and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: proposals and perspectives from an international consensus meeting. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(21):3168-3173.

2. Shimada K, Kinoshita T, Naoe T, Nakamura S. Presentation and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(9):895-902.

3. Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Seymour JF, et al. Intravascular lymphoma: clinical presentation, natural history, management and prognostic factors in a series of 38 cases, with special emphasis on the ‘cutaneous variant’. Br J Haematol. 2004;127(2):173-183.

4. Murase T, Yamaguchi M, Suzuki R, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL): a clinicopathologic study of 96 cases with special reference to the immunophenotypic heterogeneity of CD5. Blood. 2007;109(2):478-485.

5. Miura Y, Tsudo M. Fluorodeoxyglucose-PET/CT for diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(8):e56-e57.

6. Shimada K, Kosugi H, Shimada S, et al. Evaluation of organ involvement in intravascular large B-cell lymphoma by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Int J Hematol. 2008;88(2):149-153.

7. Orwat DE, Batalis NI. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(3):333-338.

8. Shimada K, Matsue K, Yamamoto K, et al. Retrospective analysis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab-containing chemotherapy as reported by the IVL study group in Japan. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(19):3189-3195.

9. Kato K, Ohno Y, Kamimura T, et al. Long-term remission after high-dose chemotherapy followed by auto-SCT as consolidation for intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(12):1543-1544.

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVBCL) is an aggressive and systemically disseminated disease that affects the elderly, with a median age of diagnosis around 70 years and no gender predilection. It is a rare subtype of extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) characterized by selective growth of neoplastic cells within blood vessel lumen without any obvious extravascular tumor mass. Hence, an absence of marked lymphadenopathy and heterogeneous clinical presentation make it difficult to diagnose accurately and timely, with roughly half of the cases found postmortem in previous case reports.1,2 The exact incidence of this disease is not known, but more recently, the accuracy of diagnosis of this type of lymphoma has improved with random skin and bone marrow biopsy.1,2 We present here a clinical case of this disease with an atypical presentation followed by a detailed review of its clinical aspects.

Case presentation and summary

A 43-year-old white woman with a history of hypothyroidism and recurrent ovarian cysts presented to clinic with 3 months of loss of appetite, abdominal distension, pelvic pain, and progressive lower-extremity swelling. A physical examination was notable for marked abdominal distension, diffuse lower abdominal tenderness, and pitting lower-extremity edema. No skin rash or any other cutaneous abnormality was noted on exam. Laboratory test results revealed a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level of 1652 U/L and a CA-125 level of 50 U/mL (reference range, 0-35 U/mL). No significant beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and alpha-fetoprotein levels were detected. Computed-tomographic (CT) imaging revealed small bilateral pleural effusions and gallbladder wall thickening with abdominal wall edema, but it was otherwise unrevealing. An echocardiogram showed normal cardiac structure and function, with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 60%. No protein was detected in the patient’s urine, and thyroid function tests were unrevealing. Doppler ultrasound studies of her lower extremities and abdomen revealed no thrombosis. Given the patient’s continued pelvic pain, history of ovarian cysts, and elevation in CA-125, she underwent a laparoscopic total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingoopherectomy.

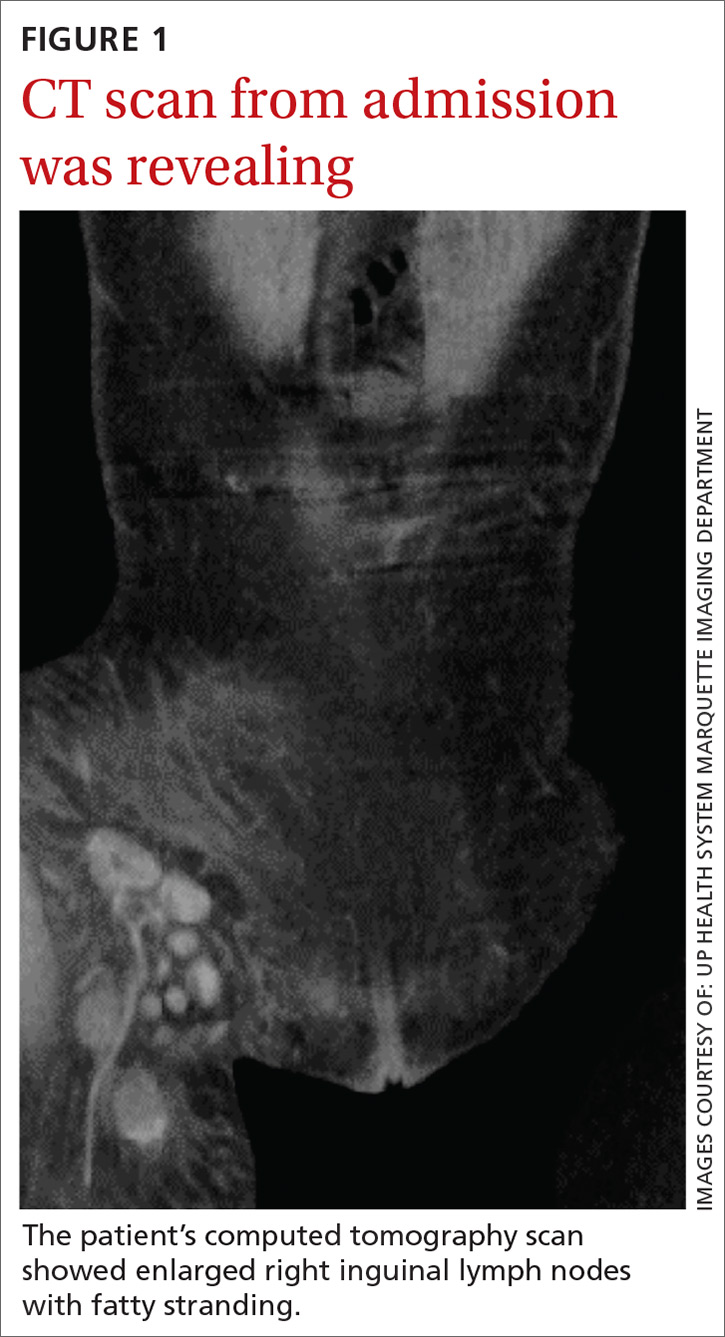

Histologic examination revealed neoplastic cells involving only the vascular lumina of the cervix, endomyometrium, bilateral fallopian tubes, and bilateral ovaries (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry stains were positive for CD5, CD20, PAX-5, CD45, BCL-2, and BCL-6 and focally positive for CD10. Peripheral smear showed pseudo-Pelger–Huet cells with 5% atypical lymphoma cells (Figure 2). Complete staging with positron-emission and CT (PET–CT) imaging revealed no metabolic activity, and a bone marrow biopsy showed trilineage hematopoiesis with adequate maturation and less than 5% of the marrow involved with large B-cell lymphoma cells. A diagnosis of IVBCL was made.

Further work-up to rule out involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) included magnetic-resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cytology and flow cytometry, which were negative.

Our patient underwent treatment with 6 cycles of infusional, dose-adjusted R-EPOCH (rituximab, etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) and 6 doses of prophylactic intrathecal chemotherapy with alternating methotrexate and cytarabine (Ara-C), and initial and subsequent CSF sampling showed no disease involvement. Consolidation with high-dose chemotherapy with R-BEAM (rituximab, carmustine, etoposide, Ara-C [cytarabine], melphalan) followed by rescue autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) was performed, and the patient has remained in clinical and hematologic remission for the past 24 months.

Discussion

Clinical presentation

The clinical manifestation of this disease is highly variable, and virtually any organ can be involved. Besides causing constitutional symptoms, including fatigue, B symptoms, and decline in performance status, heterogeneity of the clinical presentation depends on the organ system involved. One of the exceptional features of this disease is the difference in clinical presentation based on the geographical origin of the patient.2-4

Western-variant IVBCL has a higher frequency of CNS and skin involvement, whereas Asian-variant IVBCL shows preferential involvement of bone marrow with hemophagocytosis, hepatosplenomegaly, and thrombocytopenia. However, these 2 clinical variants have no difference in clinical outcome, except with the cutaneous-variant kind.24 A retrospective case series of 38 Western-variant IVBCL cases showed that 55% of patients had B symptoms with poor performance status.3 Brain and skin were the organs that were most frequently involved, with 68% of patients having involvement of at least 1 of those organs. Ten patients in this case series had disease that was exclusively limited to the skin and described as a “cutaneous variant” of IVBCL.3

Similarly, a retrospective case series of 96 cases of Asian-variant IVBCL showed B symptoms in 76% of patients, with predominant bone marrow involvement in 75% of patients, accompanied by hemophagocytosis in 66% and hepatosplenomegaly and anemia/thrombocytopenia in 77% and 84% of the patients, respectively.4 This difference in clinical presentation might have existed as a result of ethnic difference associated with production of inflammatory cytokines, including interferon gamma, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interlukin-1 beta, and soluble interlukin-2 receptor, with levels of soluble interlukin-2 receptor found to be significantly higher in Asian patients than non-Asian patients.2

Diagnosis

Involved organ biopsy is mandatory for establishing the diagnosis of IVBCL. Laboratory findings are nonspecific, with the most common abnormality being increased serum LDH and beta-2 microglobulin levels observed in 80% to 90% or more of patients. Despite its intravascular growth pattern, IVBCL was associated with peripheral blood involvement in only 5% to 9% of patients.1

Staging

Clinical staging work-up suggested for IVBCL patients by International Extranodal lymphoma study group in 2005 included physical examination (with emphasis on nervous system and skin), routine blood studies, peripheral blood smear, total body CT scan with contrast or PET–CT scan, MRI brain with contrast, CSF cytology, and bone marrow or organ biopsy.1 The role of fluorodeoxyglucose-PET scan is controversial but can be helpful to detect unexpected locations for biopsy and to assess treatment response.5,6

Morphology and immunophenotyping

In general, IVBCL histopathology shows large neoplastic lymphoid cells with large nuclei along with one or more nucleoli and scant cytoplasm within blood vessel lumen. Immunophenotypically, IVBCL cells mostly express nongerminal B-cell–associated markers with CD79a (100%), CD20 (96%), MUM-IRF4 (95%), CD5 (38%), and CD10 (12%) expressions. IVBCL cells have been demonstrated to lack cell surface protein CD29 and CD54 critical to transvascular migration. Similarly, aberrant expression of proteins such as CD11a and CXCR3 allows lymphoma cells to be attracted to endothelial cells, which might explain their intravascular confinement.7

Genetics

No pathognomic cytogenetic abnormalities have been reported in IVBCL to date, and the genetic features of this disease are not yet completely understood.2,7

Management

IVBCL is considered a stage IV disseminated disease with an International Prognostic Index score of high-intermediate to high in most cases. Half of the patients with IVBCL who were treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy relapsed and died within 18 months of diagnosis. One third of the relapses involved the CNS, thereby highlighting the importance of prophylactic CNS-directed Intrathecal therapy in an induction treatment regimen.2-4 Ferreri and colleagues reported in their case series response rates of about 60%, with an overall survival (OS) of 3 years of 30% in patients who were treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy. A multivariate analysis of the entire series showed cutaneous variant of the disease to be an independent favorable prognostic factor for OS.3

In the Murase and colleagues case series, the authors reported 67% response rates and a median OS of 13 months with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, prednisone) or CHOP-like regimens. Multivariate analysis showed older age, thrombocytopenia, and absence of anthracycline-based chemotherapy to be an independent negative prognostic factor for OS.4 Another retrospective analysis by Shimada and colleagues of 106 patients with IVBCL showed improved outcome with the addition of rituximab to CHOP-based chemotherapy (R-CHOP). Complete response rate (CR), 2-year progression-free survival, and OS were significantly higher for patients in rituximab-chemotherapy group than for those in the chemotherapy-alone group (CR, 82% vs 51%, respectively, P = .001; PFS, 56% vs 27%; OS, 66% vs 46%, P = .001), thereby establishing rituximab with CHOP-based therapy as induction therapy for IVBCL patients.8

The role of high-dose chemotherapy followed by ASCT could also be used as consolidation therapy to improve clinical outcomes as reported in 7 patients, showing durable remission after transplant in these 2 case series.3,4 Another retrospective analysis of 6 patients with IVBCL who were treated with 6 cycles of R-CHOP as induction therapy and consolidated with ASCT reported all patients to be alive and in complete remission after a median follow-up of 56 months.9 Based on the retrospective case series data by Kato and colleagues and considering that more than 80% of the patients with IVBCL were in the high-risk International Prognostic Index group, ASCT in first remission might be a useful treatment option for durable remission; however, because the median age for the diagnosis of IVBCL is about 70 years, ASCT may not be a realistic option for all patients.

Conclusions

IVBCL is a rare, aggressive, and distinct type of DLBCL with complex constellations of symptoms requiring strong clinical suspicion to establish this challenging diagnosis. Rituximab with anthracycline-based therapy along with prophylactic CNS-directed therapy followed by consolidative ASCT may lead to long-term remission. More research is needed into the genetic features of this disease to better understand its pathogenesis and potential targets for treatment.

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVBCL) is an aggressive and systemically disseminated disease that affects the elderly, with a median age of diagnosis around 70 years and no gender predilection. It is a rare subtype of extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) characterized by selective growth of neoplastic cells within blood vessel lumen without any obvious extravascular tumor mass. Hence, an absence of marked lymphadenopathy and heterogeneous clinical presentation make it difficult to diagnose accurately and timely, with roughly half of the cases found postmortem in previous case reports.1,2 The exact incidence of this disease is not known, but more recently, the accuracy of diagnosis of this type of lymphoma has improved with random skin and bone marrow biopsy.1,2 We present here a clinical case of this disease with an atypical presentation followed by a detailed review of its clinical aspects.

Case presentation and summary

A 43-year-old white woman with a history of hypothyroidism and recurrent ovarian cysts presented to clinic with 3 months of loss of appetite, abdominal distension, pelvic pain, and progressive lower-extremity swelling. A physical examination was notable for marked abdominal distension, diffuse lower abdominal tenderness, and pitting lower-extremity edema. No skin rash or any other cutaneous abnormality was noted on exam. Laboratory test results revealed a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level of 1652 U/L and a CA-125 level of 50 U/mL (reference range, 0-35 U/mL). No significant beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and alpha-fetoprotein levels were detected. Computed-tomographic (CT) imaging revealed small bilateral pleural effusions and gallbladder wall thickening with abdominal wall edema, but it was otherwise unrevealing. An echocardiogram showed normal cardiac structure and function, with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 60%. No protein was detected in the patient’s urine, and thyroid function tests were unrevealing. Doppler ultrasound studies of her lower extremities and abdomen revealed no thrombosis. Given the patient’s continued pelvic pain, history of ovarian cysts, and elevation in CA-125, she underwent a laparoscopic total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingoopherectomy.

Histologic examination revealed neoplastic cells involving only the vascular lumina of the cervix, endomyometrium, bilateral fallopian tubes, and bilateral ovaries (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry stains were positive for CD5, CD20, PAX-5, CD45, BCL-2, and BCL-6 and focally positive for CD10. Peripheral smear showed pseudo-Pelger–Huet cells with 5% atypical lymphoma cells (Figure 2). Complete staging with positron-emission and CT (PET–CT) imaging revealed no metabolic activity, and a bone marrow biopsy showed trilineage hematopoiesis with adequate maturation and less than 5% of the marrow involved with large B-cell lymphoma cells. A diagnosis of IVBCL was made.

Further work-up to rule out involvement of the central nervous system (CNS) included magnetic-resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cytology and flow cytometry, which were negative.

Our patient underwent treatment with 6 cycles of infusional, dose-adjusted R-EPOCH (rituximab, etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride) and 6 doses of prophylactic intrathecal chemotherapy with alternating methotrexate and cytarabine (Ara-C), and initial and subsequent CSF sampling showed no disease involvement. Consolidation with high-dose chemotherapy with R-BEAM (rituximab, carmustine, etoposide, Ara-C [cytarabine], melphalan) followed by rescue autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) was performed, and the patient has remained in clinical and hematologic remission for the past 24 months.

Discussion

Clinical presentation

The clinical manifestation of this disease is highly variable, and virtually any organ can be involved. Besides causing constitutional symptoms, including fatigue, B symptoms, and decline in performance status, heterogeneity of the clinical presentation depends on the organ system involved. One of the exceptional features of this disease is the difference in clinical presentation based on the geographical origin of the patient.2-4

Western-variant IVBCL has a higher frequency of CNS and skin involvement, whereas Asian-variant IVBCL shows preferential involvement of bone marrow with hemophagocytosis, hepatosplenomegaly, and thrombocytopenia. However, these 2 clinical variants have no difference in clinical outcome, except with the cutaneous-variant kind.24 A retrospective case series of 38 Western-variant IVBCL cases showed that 55% of patients had B symptoms with poor performance status.3 Brain and skin were the organs that were most frequently involved, with 68% of patients having involvement of at least 1 of those organs. Ten patients in this case series had disease that was exclusively limited to the skin and described as a “cutaneous variant” of IVBCL.3

Similarly, a retrospective case series of 96 cases of Asian-variant IVBCL showed B symptoms in 76% of patients, with predominant bone marrow involvement in 75% of patients, accompanied by hemophagocytosis in 66% and hepatosplenomegaly and anemia/thrombocytopenia in 77% and 84% of the patients, respectively.4 This difference in clinical presentation might have existed as a result of ethnic difference associated with production of inflammatory cytokines, including interferon gamma, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interlukin-1 beta, and soluble interlukin-2 receptor, with levels of soluble interlukin-2 receptor found to be significantly higher in Asian patients than non-Asian patients.2

Diagnosis

Involved organ biopsy is mandatory for establishing the diagnosis of IVBCL. Laboratory findings are nonspecific, with the most common abnormality being increased serum LDH and beta-2 microglobulin levels observed in 80% to 90% or more of patients. Despite its intravascular growth pattern, IVBCL was associated with peripheral blood involvement in only 5% to 9% of patients.1

Staging

Clinical staging work-up suggested for IVBCL patients by International Extranodal lymphoma study group in 2005 included physical examination (with emphasis on nervous system and skin), routine blood studies, peripheral blood smear, total body CT scan with contrast or PET–CT scan, MRI brain with contrast, CSF cytology, and bone marrow or organ biopsy.1 The role of fluorodeoxyglucose-PET scan is controversial but can be helpful to detect unexpected locations for biopsy and to assess treatment response.5,6

Morphology and immunophenotyping

In general, IVBCL histopathology shows large neoplastic lymphoid cells with large nuclei along with one or more nucleoli and scant cytoplasm within blood vessel lumen. Immunophenotypically, IVBCL cells mostly express nongerminal B-cell–associated markers with CD79a (100%), CD20 (96%), MUM-IRF4 (95%), CD5 (38%), and CD10 (12%) expressions. IVBCL cells have been demonstrated to lack cell surface protein CD29 and CD54 critical to transvascular migration. Similarly, aberrant expression of proteins such as CD11a and CXCR3 allows lymphoma cells to be attracted to endothelial cells, which might explain their intravascular confinement.7

Genetics

No pathognomic cytogenetic abnormalities have been reported in IVBCL to date, and the genetic features of this disease are not yet completely understood.2,7

Management

IVBCL is considered a stage IV disseminated disease with an International Prognostic Index score of high-intermediate to high in most cases. Half of the patients with IVBCL who were treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy relapsed and died within 18 months of diagnosis. One third of the relapses involved the CNS, thereby highlighting the importance of prophylactic CNS-directed Intrathecal therapy in an induction treatment regimen.2-4 Ferreri and colleagues reported in their case series response rates of about 60%, with an overall survival (OS) of 3 years of 30% in patients who were treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy. A multivariate analysis of the entire series showed cutaneous variant of the disease to be an independent favorable prognostic factor for OS.3

In the Murase and colleagues case series, the authors reported 67% response rates and a median OS of 13 months with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride, vincristine sulfate, prednisone) or CHOP-like regimens. Multivariate analysis showed older age, thrombocytopenia, and absence of anthracycline-based chemotherapy to be an independent negative prognostic factor for OS.4 Another retrospective analysis by Shimada and colleagues of 106 patients with IVBCL showed improved outcome with the addition of rituximab to CHOP-based chemotherapy (R-CHOP). Complete response rate (CR), 2-year progression-free survival, and OS were significantly higher for patients in rituximab-chemotherapy group than for those in the chemotherapy-alone group (CR, 82% vs 51%, respectively, P = .001; PFS, 56% vs 27%; OS, 66% vs 46%, P = .001), thereby establishing rituximab with CHOP-based therapy as induction therapy for IVBCL patients.8

The role of high-dose chemotherapy followed by ASCT could also be used as consolidation therapy to improve clinical outcomes as reported in 7 patients, showing durable remission after transplant in these 2 case series.3,4 Another retrospective analysis of 6 patients with IVBCL who were treated with 6 cycles of R-CHOP as induction therapy and consolidated with ASCT reported all patients to be alive and in complete remission after a median follow-up of 56 months.9 Based on the retrospective case series data by Kato and colleagues and considering that more than 80% of the patients with IVBCL were in the high-risk International Prognostic Index group, ASCT in first remission might be a useful treatment option for durable remission; however, because the median age for the diagnosis of IVBCL is about 70 years, ASCT may not be a realistic option for all patients.

Conclusions

IVBCL is a rare, aggressive, and distinct type of DLBCL with complex constellations of symptoms requiring strong clinical suspicion to establish this challenging diagnosis. Rituximab with anthracycline-based therapy along with prophylactic CNS-directed therapy followed by consolidative ASCT may lead to long-term remission. More research is needed into the genetic features of this disease to better understand its pathogenesis and potential targets for treatment.

1. Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJ, Campo E, et al. Definition, diagnosis, and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: proposals and perspectives from an international consensus meeting. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(21):3168-3173.

2. Shimada K, Kinoshita T, Naoe T, Nakamura S. Presentation and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(9):895-902.

3. Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Seymour JF, et al. Intravascular lymphoma: clinical presentation, natural history, management and prognostic factors in a series of 38 cases, with special emphasis on the ‘cutaneous variant’. Br J Haematol. 2004;127(2):173-183.

4. Murase T, Yamaguchi M, Suzuki R, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL): a clinicopathologic study of 96 cases with special reference to the immunophenotypic heterogeneity of CD5. Blood. 2007;109(2):478-485.

5. Miura Y, Tsudo M. Fluorodeoxyglucose-PET/CT for diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(8):e56-e57.

6. Shimada K, Kosugi H, Shimada S, et al. Evaluation of organ involvement in intravascular large B-cell lymphoma by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Int J Hematol. 2008;88(2):149-153.

7. Orwat DE, Batalis NI. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(3):333-338.

8. Shimada K, Matsue K, Yamamoto K, et al. Retrospective analysis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab-containing chemotherapy as reported by the IVL study group in Japan. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(19):3189-3195.

9. Kato K, Ohno Y, Kamimura T, et al. Long-term remission after high-dose chemotherapy followed by auto-SCT as consolidation for intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(12):1543-1544.

1. Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJ, Campo E, et al. Definition, diagnosis, and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: proposals and perspectives from an international consensus meeting. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(21):3168-3173.

2. Shimada K, Kinoshita T, Naoe T, Nakamura S. Presentation and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(9):895-902.

3. Ferreri AJ, Campo E, Seymour JF, et al. Intravascular lymphoma: clinical presentation, natural history, management and prognostic factors in a series of 38 cases, with special emphasis on the ‘cutaneous variant’. Br J Haematol. 2004;127(2):173-183.

4. Murase T, Yamaguchi M, Suzuki R, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL): a clinicopathologic study of 96 cases with special reference to the immunophenotypic heterogeneity of CD5. Blood. 2007;109(2):478-485.

5. Miura Y, Tsudo M. Fluorodeoxyglucose-PET/CT for diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(8):e56-e57.

6. Shimada K, Kosugi H, Shimada S, et al. Evaluation of organ involvement in intravascular large B-cell lymphoma by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Int J Hematol. 2008;88(2):149-153.

7. Orwat DE, Batalis NI. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(3):333-338.

8. Shimada K, Matsue K, Yamamoto K, et al. Retrospective analysis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab-containing chemotherapy as reported by the IVL study group in Japan. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(19):3189-3195.

9. Kato K, Ohno Y, Kamimura T, et al. Long-term remission after high-dose chemotherapy followed by auto-SCT as consolidation for intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49(12):1543-1544.

Elevated liver function tests in a patient on palbociclib and fulvestrant

About 12.4% of women in the United States will be diagnosed with breast cancer at some point in their lifetime.1 A percentage of these women will develop metastatic disease and are estimated to have a 5-year survival rate of 22%.2 There have been meaningful improvements in su

However, endocrine resistance inevitably occurs, and a great deal of research has been focused on developing strategies to combat resistance. One mechanism of endocrine resistance is though the Cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 (CDK4/6) complexes. Among the most promising of the strategies to prevent resistance are the CDK4/6 inhibitors. There are now 3 approved CDK4/6 inhibitor drugs that can be used in combination with endocrine therapy, 1 of which can also be used as a single agent. When used in combination with endocrine therapy, the use of CDK 4/6 inhibitors has significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with hormone-sensitive HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer by inhibiting cellular division and growth.3 In postmenopausal women, endocrine therapy plus CDK4/6 inhibitors are the preferred first-line regimen for metastatic disease.

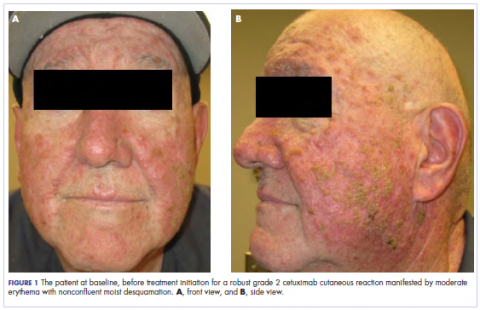

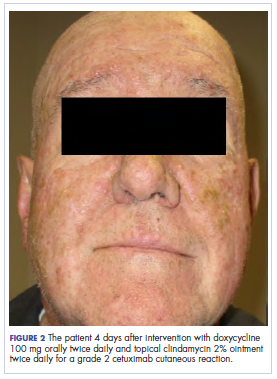

Since the approval of palbociclib by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2015, the most common hematologic lab abnormalities are anemia, leukopenia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia. The most common nonhematologic adverse events (AEs) are fatigue, infection, nausea, and stomatitis. Hepatic toxicity has not been commonly observed. We report here the case of a 57-year-old woman on palbociclib and fulvestrant who developed significant elevation of liver function tests after starting palbociclib, suggesting a possible drug-induced liver injury from palbociclib.

Case presentation and summary

A 57-year-old woman with history of hypothyroidism and hypertension presented in May 2016 with a lump in her right breast and back pain. The lump was biopsied and revealed invasive ductal carcinoma, moderately differentiated, estrogen receptor (ER) positive 100%, progesterone receptor (PR) positive 95%, and HER2 negative. A positron emission tomography (PET)–computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging showed bone metastasis at several vertebral levels, and the results of a bone biopsy confirmed metastatic adenocarcinoma of breast origin, ER positive 60%, PR positive 40%, and HER2 negative. No liver lesions were seen on imaging, but there was suggestion of fatty liver. She was started on letrozole 2.5 mg daily in July 2016 while undergoing kyphoplasty and subsequent radiation. A restaging PET scan revealed progression of disease on letrozole, with possible new rib lesion and progression in the breast. No liver disease was noted. Therapy was changed to fulvestrant and palbociclib. Fulvestrant was started in March 2017 with standard dosing of 500 mg intramuscular on days 1, 15, and 29, and then once a month thereafter. Her first cycle of palbociclib was started on April 5, dosed at 125 mg by mouth daily for 21 days, followed by 7 days off, repeated every 28 days (all dates hereinafter fell within 2017, unless otherwise stipulated).

Labs checked on April 28 and May 26 were unremarkable. A restaging CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was done on June 21 after completion of 3 cycles of fulvestrant and palbociclib. There was no evidence of liver metastases, only the fatty infiltration of the liver that had been seen previously. On June 23, 2017, lab results showed a transaminitis with an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 446 IU/L (reference range 10-33 IU/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of 183 IU/L (reference range 0-32 IU/L).

The patient’s liver enzyme levels continued to increase and peaked on July 3 at ALT >700 IU/L and AST at 421 IU/L. Her total bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels remained within normal limits. She had received her final dose of fulvestrant on May 31 and had taken her last dose of palbociclib on June 20, 2017. She had no history of elevated liver enzymes or liver disease, although the initial PET scan done at diagnosis had suggested hepatic steatosis. She said she had not recently used antibiotics, alcohol, or over-the-counter medications or supplements. There was no family history of liver problems, inflammatory bowel disease, or gastrointestinal malignancy. The only other medications she had taken recently were denosumab, levothyroxine for hypothyroidism, and amlodipine for hypertension. She was seen by hepatology for evaluation of acute hepatitis. Other etiologies for her elevated liver enzymes were ruled out, and she was diagnosed with a drug-induced liver injury from one of her anticancer medications. Her treatments with fulvestrant and palbociclib were held, and the results of her liver function tests normalized by September 2017.

Fulvestrant was restarted on August 24, and her lab results remained normal through November of that year, when restaging scans showed progression with new axillary adenopathy suspicious for metastasis. Imaging also showed a 1.6-cm hepatic lesion suggestive of a focal area of fat deposition or atypical hemangioma without definitive evidence of metastasis. Follow-up imaging was recommended. She was therefore rechallenged with palbociclib at a reduced dose of 100 mg by mouth daily and received the first dose on November 30. On December 8, repeat labs again showed elevated liver function tests (ALT, 285 IU/L; AST, 112 IU/L). Treatment with palbociclib was discontinued on December 10. Because the patient was not able to tolerate palbociclib, and fulvestrant alone was not controlling the disease, she was started on an alternate endocrine therapy with tamoxifen on December 26. The patient’s liver function tests normalized again by January 2018.

Discussion

The use of targeted therapies has changed the landscape of oncologic treatments. Several studies have evaluated the safety and efficacy of palbociclib in combination with endocrine therapy. The Palbociclib Ongoing Trials in the Management of Breast Cancer (PALOMA)-1 study, an open-label, randomized, phase-2 trial involving patients with newly diagnosed metastatic hormone sensitive HER2-negative breast cancer, demonstrated that palbociclib in combination with letrozole was associated with significantly longer PFS than letrozole alone.4 These results were later confirmed in the larger PALOMA-2 study, a randomized, double-blind, phase-3 trial that evaluated 666 postmenopausal patients with no prior systemic therapy. In that study, median PFS for the palbociclib–letrozole group was 24.8 months, compared with 14.5 months for the letrozole-alone group (hazard ratio [HR] for disease progression or death, 0.58 [0.46–0.72], P < .001).5 The most recent PALOMA-3 study, a phase-3 trial involving 521 patients with advanced hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer that had progressed during initial endocrine therapy, evaluated the efficacy of combined palbociclib and fulvestrant in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. The result was that the palbociclib–fulvestrant combination resulted in longer median PFS of 9.2 months, compared with 3.8 months with fulvestrant alone (P < .001).6