User login

Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis in a Patient With Multiple Inflammatory Disorders

First described in 2000 in a case series of 15 patients, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) is a rare scleroderma-like fibrosing skin condition associated with gadolinium exposure in end stage renal disease (ESRD).1 Patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) or ESRD are at the highest risk for this condition when exposed to gadolinium-based contrast dyes.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is a devastating and rapidly progressive condition, making its prevention in at-risk populations of utmost importance. In this article, the authors describe a case of a patient who developed NSF in the setting of gadolinium exposure and multiple inflammatory dermatologic conditions. This case illustrates the possible role of a pro-inflammatory state in predisposing to NSF, which may help further elucidate its mechanism of action.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old Hispanic male with a history of IV heroin use with ESRD secondary to membranous glomerulonephritis on hemodialysis and chronic hepatitis C infection presented to the West Los Angeles VAMC with fevers and night sweats that had persisted for 2 weeks. His physical examination was notable for diffuse tender palpable purpura and petechiae (including his palms and soles), altered mental status, and diffuse myoclonic jerks, which necessitated endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation for airway protection. Blood cultures were positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Laboratory results were notable for an elevated sedimentation rate of 53 mm/h (0-10 mm/h), C-reactive protein of 19.8 mg/L (< 0.744 mg/dL), and albumin of 1.2 g/dL (3.2-4.8 g/dL). An extensive rheumatologic workup was unrevealing, and a lumbar puncture was unremarkable. A biopsy of his skin lesions was consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

The patient’s prior hemodialysis access, a tunneled dialysis catheter in the right subclavian vein, was removed given concern for line infection and replaced with an internal jugular temporary hemodialysis line. Given his altered mental status and myoclonic jerks, the decision was made to pursue a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain and spine with gadolinium contrast to evaluate for cerebral vasculitis and/or septic emboli to the brain.

The patient received 15 mL of gadoversetamide contrast in accordance with hospital imaging protocol. The MRI revealed only chronic ischemic changes. The patient underwent hemodialysis about 18 hours later. The patient was treated with a 6-week course of IV penicillin G. His altered mental status and myoclonic jerks resolved without intervention, and he was then discharged to an acute rehabilitation unit.

Eight weeks after his initial presentation the patient developed a purulent wound on his right forearm (Figure 1)

The patient was discharged to continue physical and occupational therapy to preserve his functional mobility, as no other treatment options were available.

Discussion

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is a poorly understood inflammatory condition that produces diffuse fibrosis of the skin. Typically, the disease begins with progressive skin induration of the extremities. Systemic involvement may occur, leading to fibrosis of skeletal muscle, fascia, and multiple organs. Flexion contractures may develop that limit physical function. Fibrosis can become apparent within days to months after exposure to gadolinium contrast.

Beyond renal insufficiency, it is unclear what other risk factors predispose patients to developing this condition. Only a minority of patients with CKD stages 1 through 4 will develop NSF on exposure to gadolinium contrast. However, the incidence of NSF among patients with CKD stage 5 who are exposed to gadolinium has been estimated to be about 13.4% in a prospective study involving 18 patients.2

In a 2015 meta-analysis by Zhang and colleagues, the only clear risk factor identified for the development of NSF, aside from gadolinium exposure, was severe renal insufficiency with a glomerular filtration rate of < 30 mL/min/1.75m2.3 Due to the limited number of patients identified with this disease, it is difficult to identify other risk factors associated with the development of NSF. Based on in vitro studies, it has been postulated that a pro-inflammatory state predisposes patients to develop NSF.4,5 The proposed mechanism for NSF involves extravasation of gadolinium in the setting of vascular endothelial permeability.5,6 Gadolinium then interacts with tissue macrophages, which induce the release of inflammatory cytokines and the secretion of smooth muscle actin by dermal fibroblasts.6,7

Treatment of NSF has been largely unsuccessful. Multiple modalities of treatment that included topical and oral steroids, immunosuppression, plasmapheresis, and ultraviolent therapy have been attempted, none of which have been proven to consistently limit progression of the disease.8 The most effective intervention is early physical therapy to preserve functionality and prevent contracture formation. For patients who are eligible, early renal transplantation may offer the best chance of improved mobility. In a case series review by Cuffy and colleagues, 5 of 6 patients who underwent renal transplantation after the development of NSF experienced softening of the involved skin, and 2 patients had improved mobility of joints.9

Conclusion

The case presented here illustrates a possible association between a pro-inflammatory state and the development of NSF. This patient had multiple inflammatory conditions, including MSSA bacteremia, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and pyoderma gangrenosum (the latter 2 conditions were thought to be associated with his underlying chronic hepatitis C infection), which the authors believe predisposed him to endothelial permeability and risk for developing NSF. The risk of developing NSF in at-risk patients with each episode of gadolinium exposure is estimated around 2.4%, or an incidence of 4.3 cases per 1,000 patient-years, leading the American College of Radiologists to recommend against the administration of gadolinium-based contrast except in cases in which benefits clearly outweigh risks.10 However, an MRI with gadolinium contrast can offer high diagnostic yield in cases such as the one presented here in which a diagnosis remains elusive. Moreover, the use of linear gadolinium-based contrast agents such as gadoversetamide, as in this case, has been reported to be associated with higher incidence of NSF.5 Since this case, the West Los Angeles VAMC has switched to gadobutrol contrast for its MRI protocol, which has been purported to be a lower risk agent compared with that of linear gadolinium-based contrast agents (although several cases of NSF have been reported with gadobutrol in the literature).11

Providers weighing the decision to administer gadolinium contrast to patients with ESRD should discuss the risks and benefits thoroughly, especially in patients with preexisting inflammatory conditions. In addition, although it has not been shown to effectively reduce the risk of NSF after administration of gadolinium, hemodialysis is recommended 2 hours after contrast administration for individuals at risk (the study patient received hemodialysis approximately 18 hours after).12 Given the lack of effective treatment options for NSF, prevention is key. A deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of NSF and identification of its risk factors is paramount to the prevention of this devastating disease.

1. Cowper SE, Robin HS, Steinberg SM, Su LD, Gupta S, LeBoit PE. Scleromyxoedema-like cutaneous diseases in renal-dialysis patients. Lancet. 2000;356(9234):1000-1001.

2. Todd DJ, Kagan A, Chibnik LB, Kay J. Cutaneous changes of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(10):3433-3441.

3. Zhang B, Liang L, Chen W, Liang C, Zhang S. An updated study to determine association between gadolinium-based contrast agents and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129720.

4. Wermuth PJ, Del Galdo F, Jiménez SA. Induction of the expression of profibrotic cytokines and growth factors in normal human peripheral blood monocytes by gadolinium contrast agents. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(5):1508-1518.

5. Daftari Besheli L, Aran S, Shaqdan K, Kay J, Abujudeh H. Current status of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Clin Radiol. 2014;69(7):661-668.

6. Wagner B, Drel V, Gorin Y. Pathophysiology of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;31(1):F1-F11.

7. Idée JM, Fretellier N, Robic C, Corot C. The role of gadolinium chelates in the mechanism of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a critical update. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2014;44(10):895-913.

8. Mendoza FA, Artlett CM, Sandorfi N, Latinis K, Piera-Velazquez S, Jimenez SA. Description of 12 cases of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35(4):238-249.

9. Cuffy MC, Singh M, Formica R, et al. Renal transplantation for nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(3):1099-1109.

10. Deo A, Fogel M, Cowper SE. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a population study examining the relationship of disease development of gadolinium exposure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(2):264-267

11. Elmholdt TR, Jørgensen B, Ramsing M, Pedersen M, Olesen AB. Two cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after exposure to the macrocyclic compound gadobutrol. NDT Plus. 2010;3(3):285-287.

12. Abu-Alfa AK. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and gadolinium-based contrast agents. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2011;18(3);188-198.

First described in 2000 in a case series of 15 patients, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) is a rare scleroderma-like fibrosing skin condition associated with gadolinium exposure in end stage renal disease (ESRD).1 Patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) or ESRD are at the highest risk for this condition when exposed to gadolinium-based contrast dyes.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is a devastating and rapidly progressive condition, making its prevention in at-risk populations of utmost importance. In this article, the authors describe a case of a patient who developed NSF in the setting of gadolinium exposure and multiple inflammatory dermatologic conditions. This case illustrates the possible role of a pro-inflammatory state in predisposing to NSF, which may help further elucidate its mechanism of action.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old Hispanic male with a history of IV heroin use with ESRD secondary to membranous glomerulonephritis on hemodialysis and chronic hepatitis C infection presented to the West Los Angeles VAMC with fevers and night sweats that had persisted for 2 weeks. His physical examination was notable for diffuse tender palpable purpura and petechiae (including his palms and soles), altered mental status, and diffuse myoclonic jerks, which necessitated endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation for airway protection. Blood cultures were positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Laboratory results were notable for an elevated sedimentation rate of 53 mm/h (0-10 mm/h), C-reactive protein of 19.8 mg/L (< 0.744 mg/dL), and albumin of 1.2 g/dL (3.2-4.8 g/dL). An extensive rheumatologic workup was unrevealing, and a lumbar puncture was unremarkable. A biopsy of his skin lesions was consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

The patient’s prior hemodialysis access, a tunneled dialysis catheter in the right subclavian vein, was removed given concern for line infection and replaced with an internal jugular temporary hemodialysis line. Given his altered mental status and myoclonic jerks, the decision was made to pursue a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain and spine with gadolinium contrast to evaluate for cerebral vasculitis and/or septic emboli to the brain.

The patient received 15 mL of gadoversetamide contrast in accordance with hospital imaging protocol. The MRI revealed only chronic ischemic changes. The patient underwent hemodialysis about 18 hours later. The patient was treated with a 6-week course of IV penicillin G. His altered mental status and myoclonic jerks resolved without intervention, and he was then discharged to an acute rehabilitation unit.

Eight weeks after his initial presentation the patient developed a purulent wound on his right forearm (Figure 1)

The patient was discharged to continue physical and occupational therapy to preserve his functional mobility, as no other treatment options were available.

Discussion

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is a poorly understood inflammatory condition that produces diffuse fibrosis of the skin. Typically, the disease begins with progressive skin induration of the extremities. Systemic involvement may occur, leading to fibrosis of skeletal muscle, fascia, and multiple organs. Flexion contractures may develop that limit physical function. Fibrosis can become apparent within days to months after exposure to gadolinium contrast.

Beyond renal insufficiency, it is unclear what other risk factors predispose patients to developing this condition. Only a minority of patients with CKD stages 1 through 4 will develop NSF on exposure to gadolinium contrast. However, the incidence of NSF among patients with CKD stage 5 who are exposed to gadolinium has been estimated to be about 13.4% in a prospective study involving 18 patients.2

In a 2015 meta-analysis by Zhang and colleagues, the only clear risk factor identified for the development of NSF, aside from gadolinium exposure, was severe renal insufficiency with a glomerular filtration rate of < 30 mL/min/1.75m2.3 Due to the limited number of patients identified with this disease, it is difficult to identify other risk factors associated with the development of NSF. Based on in vitro studies, it has been postulated that a pro-inflammatory state predisposes patients to develop NSF.4,5 The proposed mechanism for NSF involves extravasation of gadolinium in the setting of vascular endothelial permeability.5,6 Gadolinium then interacts with tissue macrophages, which induce the release of inflammatory cytokines and the secretion of smooth muscle actin by dermal fibroblasts.6,7

Treatment of NSF has been largely unsuccessful. Multiple modalities of treatment that included topical and oral steroids, immunosuppression, plasmapheresis, and ultraviolent therapy have been attempted, none of which have been proven to consistently limit progression of the disease.8 The most effective intervention is early physical therapy to preserve functionality and prevent contracture formation. For patients who are eligible, early renal transplantation may offer the best chance of improved mobility. In a case series review by Cuffy and colleagues, 5 of 6 patients who underwent renal transplantation after the development of NSF experienced softening of the involved skin, and 2 patients had improved mobility of joints.9

Conclusion

The case presented here illustrates a possible association between a pro-inflammatory state and the development of NSF. This patient had multiple inflammatory conditions, including MSSA bacteremia, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and pyoderma gangrenosum (the latter 2 conditions were thought to be associated with his underlying chronic hepatitis C infection), which the authors believe predisposed him to endothelial permeability and risk for developing NSF. The risk of developing NSF in at-risk patients with each episode of gadolinium exposure is estimated around 2.4%, or an incidence of 4.3 cases per 1,000 patient-years, leading the American College of Radiologists to recommend against the administration of gadolinium-based contrast except in cases in which benefits clearly outweigh risks.10 However, an MRI with gadolinium contrast can offer high diagnostic yield in cases such as the one presented here in which a diagnosis remains elusive. Moreover, the use of linear gadolinium-based contrast agents such as gadoversetamide, as in this case, has been reported to be associated with higher incidence of NSF.5 Since this case, the West Los Angeles VAMC has switched to gadobutrol contrast for its MRI protocol, which has been purported to be a lower risk agent compared with that of linear gadolinium-based contrast agents (although several cases of NSF have been reported with gadobutrol in the literature).11

Providers weighing the decision to administer gadolinium contrast to patients with ESRD should discuss the risks and benefits thoroughly, especially in patients with preexisting inflammatory conditions. In addition, although it has not been shown to effectively reduce the risk of NSF after administration of gadolinium, hemodialysis is recommended 2 hours after contrast administration for individuals at risk (the study patient received hemodialysis approximately 18 hours after).12 Given the lack of effective treatment options for NSF, prevention is key. A deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of NSF and identification of its risk factors is paramount to the prevention of this devastating disease.

First described in 2000 in a case series of 15 patients, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF) is a rare scleroderma-like fibrosing skin condition associated with gadolinium exposure in end stage renal disease (ESRD).1 Patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (CKD) or ESRD are at the highest risk for this condition when exposed to gadolinium-based contrast dyes.

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is a devastating and rapidly progressive condition, making its prevention in at-risk populations of utmost importance. In this article, the authors describe a case of a patient who developed NSF in the setting of gadolinium exposure and multiple inflammatory dermatologic conditions. This case illustrates the possible role of a pro-inflammatory state in predisposing to NSF, which may help further elucidate its mechanism of action.

Case Presentation

A 61-year-old Hispanic male with a history of IV heroin use with ESRD secondary to membranous glomerulonephritis on hemodialysis and chronic hepatitis C infection presented to the West Los Angeles VAMC with fevers and night sweats that had persisted for 2 weeks. His physical examination was notable for diffuse tender palpable purpura and petechiae (including his palms and soles), altered mental status, and diffuse myoclonic jerks, which necessitated endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation for airway protection. Blood cultures were positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Laboratory results were notable for an elevated sedimentation rate of 53 mm/h (0-10 mm/h), C-reactive protein of 19.8 mg/L (< 0.744 mg/dL), and albumin of 1.2 g/dL (3.2-4.8 g/dL). An extensive rheumatologic workup was unrevealing, and a lumbar puncture was unremarkable. A biopsy of his skin lesions was consistent with leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

The patient’s prior hemodialysis access, a tunneled dialysis catheter in the right subclavian vein, was removed given concern for line infection and replaced with an internal jugular temporary hemodialysis line. Given his altered mental status and myoclonic jerks, the decision was made to pursue a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain and spine with gadolinium contrast to evaluate for cerebral vasculitis and/or septic emboli to the brain.

The patient received 15 mL of gadoversetamide contrast in accordance with hospital imaging protocol. The MRI revealed only chronic ischemic changes. The patient underwent hemodialysis about 18 hours later. The patient was treated with a 6-week course of IV penicillin G. His altered mental status and myoclonic jerks resolved without intervention, and he was then discharged to an acute rehabilitation unit.

Eight weeks after his initial presentation the patient developed a purulent wound on his right forearm (Figure 1)

The patient was discharged to continue physical and occupational therapy to preserve his functional mobility, as no other treatment options were available.

Discussion

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is a poorly understood inflammatory condition that produces diffuse fibrosis of the skin. Typically, the disease begins with progressive skin induration of the extremities. Systemic involvement may occur, leading to fibrosis of skeletal muscle, fascia, and multiple organs. Flexion contractures may develop that limit physical function. Fibrosis can become apparent within days to months after exposure to gadolinium contrast.

Beyond renal insufficiency, it is unclear what other risk factors predispose patients to developing this condition. Only a minority of patients with CKD stages 1 through 4 will develop NSF on exposure to gadolinium contrast. However, the incidence of NSF among patients with CKD stage 5 who are exposed to gadolinium has been estimated to be about 13.4% in a prospective study involving 18 patients.2

In a 2015 meta-analysis by Zhang and colleagues, the only clear risk factor identified for the development of NSF, aside from gadolinium exposure, was severe renal insufficiency with a glomerular filtration rate of < 30 mL/min/1.75m2.3 Due to the limited number of patients identified with this disease, it is difficult to identify other risk factors associated with the development of NSF. Based on in vitro studies, it has been postulated that a pro-inflammatory state predisposes patients to develop NSF.4,5 The proposed mechanism for NSF involves extravasation of gadolinium in the setting of vascular endothelial permeability.5,6 Gadolinium then interacts with tissue macrophages, which induce the release of inflammatory cytokines and the secretion of smooth muscle actin by dermal fibroblasts.6,7

Treatment of NSF has been largely unsuccessful. Multiple modalities of treatment that included topical and oral steroids, immunosuppression, plasmapheresis, and ultraviolent therapy have been attempted, none of which have been proven to consistently limit progression of the disease.8 The most effective intervention is early physical therapy to preserve functionality and prevent contracture formation. For patients who are eligible, early renal transplantation may offer the best chance of improved mobility. In a case series review by Cuffy and colleagues, 5 of 6 patients who underwent renal transplantation after the development of NSF experienced softening of the involved skin, and 2 patients had improved mobility of joints.9

Conclusion

The case presented here illustrates a possible association between a pro-inflammatory state and the development of NSF. This patient had multiple inflammatory conditions, including MSSA bacteremia, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and pyoderma gangrenosum (the latter 2 conditions were thought to be associated with his underlying chronic hepatitis C infection), which the authors believe predisposed him to endothelial permeability and risk for developing NSF. The risk of developing NSF in at-risk patients with each episode of gadolinium exposure is estimated around 2.4%, or an incidence of 4.3 cases per 1,000 patient-years, leading the American College of Radiologists to recommend against the administration of gadolinium-based contrast except in cases in which benefits clearly outweigh risks.10 However, an MRI with gadolinium contrast can offer high diagnostic yield in cases such as the one presented here in which a diagnosis remains elusive. Moreover, the use of linear gadolinium-based contrast agents such as gadoversetamide, as in this case, has been reported to be associated with higher incidence of NSF.5 Since this case, the West Los Angeles VAMC has switched to gadobutrol contrast for its MRI protocol, which has been purported to be a lower risk agent compared with that of linear gadolinium-based contrast agents (although several cases of NSF have been reported with gadobutrol in the literature).11

Providers weighing the decision to administer gadolinium contrast to patients with ESRD should discuss the risks and benefits thoroughly, especially in patients with preexisting inflammatory conditions. In addition, although it has not been shown to effectively reduce the risk of NSF after administration of gadolinium, hemodialysis is recommended 2 hours after contrast administration for individuals at risk (the study patient received hemodialysis approximately 18 hours after).12 Given the lack of effective treatment options for NSF, prevention is key. A deeper understanding of the pathophysiology of NSF and identification of its risk factors is paramount to the prevention of this devastating disease.

1. Cowper SE, Robin HS, Steinberg SM, Su LD, Gupta S, LeBoit PE. Scleromyxoedema-like cutaneous diseases in renal-dialysis patients. Lancet. 2000;356(9234):1000-1001.

2. Todd DJ, Kagan A, Chibnik LB, Kay J. Cutaneous changes of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(10):3433-3441.

3. Zhang B, Liang L, Chen W, Liang C, Zhang S. An updated study to determine association between gadolinium-based contrast agents and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129720.

4. Wermuth PJ, Del Galdo F, Jiménez SA. Induction of the expression of profibrotic cytokines and growth factors in normal human peripheral blood monocytes by gadolinium contrast agents. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(5):1508-1518.

5. Daftari Besheli L, Aran S, Shaqdan K, Kay J, Abujudeh H. Current status of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Clin Radiol. 2014;69(7):661-668.

6. Wagner B, Drel V, Gorin Y. Pathophysiology of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;31(1):F1-F11.

7. Idée JM, Fretellier N, Robic C, Corot C. The role of gadolinium chelates in the mechanism of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a critical update. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2014;44(10):895-913.

8. Mendoza FA, Artlett CM, Sandorfi N, Latinis K, Piera-Velazquez S, Jimenez SA. Description of 12 cases of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35(4):238-249.

9. Cuffy MC, Singh M, Formica R, et al. Renal transplantation for nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(3):1099-1109.

10. Deo A, Fogel M, Cowper SE. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a population study examining the relationship of disease development of gadolinium exposure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(2):264-267

11. Elmholdt TR, Jørgensen B, Ramsing M, Pedersen M, Olesen AB. Two cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after exposure to the macrocyclic compound gadobutrol. NDT Plus. 2010;3(3):285-287.

12. Abu-Alfa AK. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and gadolinium-based contrast agents. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2011;18(3);188-198.

1. Cowper SE, Robin HS, Steinberg SM, Su LD, Gupta S, LeBoit PE. Scleromyxoedema-like cutaneous diseases in renal-dialysis patients. Lancet. 2000;356(9234):1000-1001.

2. Todd DJ, Kagan A, Chibnik LB, Kay J. Cutaneous changes of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(10):3433-3441.

3. Zhang B, Liang L, Chen W, Liang C, Zhang S. An updated study to determine association between gadolinium-based contrast agents and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129720.

4. Wermuth PJ, Del Galdo F, Jiménez SA. Induction of the expression of profibrotic cytokines and growth factors in normal human peripheral blood monocytes by gadolinium contrast agents. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(5):1508-1518.

5. Daftari Besheli L, Aran S, Shaqdan K, Kay J, Abujudeh H. Current status of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Clin Radiol. 2014;69(7):661-668.

6. Wagner B, Drel V, Gorin Y. Pathophysiology of gadolinium-associated systemic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2016;31(1):F1-F11.

7. Idée JM, Fretellier N, Robic C, Corot C. The role of gadolinium chelates in the mechanism of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a critical update. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2014;44(10):895-913.

8. Mendoza FA, Artlett CM, Sandorfi N, Latinis K, Piera-Velazquez S, Jimenez SA. Description of 12 cases of nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35(4):238-249.

9. Cuffy MC, Singh M, Formica R, et al. Renal transplantation for nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a case report and review of the literature. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(3):1099-1109.

10. Deo A, Fogel M, Cowper SE. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a population study examining the relationship of disease development of gadolinium exposure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(2):264-267

11. Elmholdt TR, Jørgensen B, Ramsing M, Pedersen M, Olesen AB. Two cases of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis after exposure to the macrocyclic compound gadobutrol. NDT Plus. 2010;3(3):285-287.

12. Abu-Alfa AK. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis and gadolinium-based contrast agents. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2011;18(3);188-198.

Recurrence of a small gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor with high mitotic index

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common soft tissue sarcoma of the gastrointestinal tract, usually arising from the interstitial cells of Cajal or similar cells in the outer wall of the gastrointestinal tract.1,2 Most GISTs have an activating mutation in KIT or platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA). Tumor size, mitotic rate, and anatomic site are the most common pathological features used to risk stratify GIST tumors.3-10 It is important to note when using such risk calculators that preoperative imatinib before determining tumor characteristics (such as mitoses per 50 high-power fields [hpf]) often changes the relevant parameters so that the same risk calculations may not apply. Tumors with a mitotic rate ≤5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size ≤5 cm in greatest dimension have a lower recurrence rate after resection than tumors with a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size >10 cm, and larger tumors can have a recurrence rate of up to 86%.11,12 Findings from a large observational study have suggested that the prognosis of gastric GIST in Korea and Japan may be more favorable compared with that in Western countries.13

The primary treatment of a localized primary GIST is surgical excision, but a cure is limited by recurrence.14,15 Imatinib is useful in the treatment of metastatic or recurrent GIST, and adjuvant treatment with imatinib after surgery has been shown to improve progression-free and overall survival in some cases.3,16-18 Responses to adjuvant imatinib depend on tumor sensitivity to the drug and the risk of recurrence. Drug sensitivity is largely dependent on the presence of mutations in KIT or PDGFRA.3,18 Recurrence risk is highly dependent on tumor size, tumor site, tumor rupture, and mitotic index.1,3,5,6,8,9,18,19 Findings on the use of gene expression patterns to predict recurrence risk have also been reported.20-27 However, recurrence risk is poorly understood for categories in which there are few cases with known outcomes, such as very small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index. For example, few cases of gastric GIST have been reported with a tumor size ≤2 cm, a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf, and adequate clinical follow-up. In such cases, it is difficult to assess the risk of recurrence.6 We report here the long-term outcome of a patient with a 1.8 cm gastric GIST with a mitotic index of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf and a KIT exon 11 mutation.

Case presentation and summary

A 69-year-old man presented with periumbilical and epigastric pain of 6-month duration. His medical history was notable for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, coronary angioplasty, and spinal surgery. He had a 40 pack-year smoking history and consumed 2 to 4 alcoholic drinks per day. The results of a physical examination were unremarkable. A computedtomographic (CT) scan showed no abnormalities. An esophagoduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed gastric ulcers. He was treated successfully with omeprazole 20 mg by mouth daily.

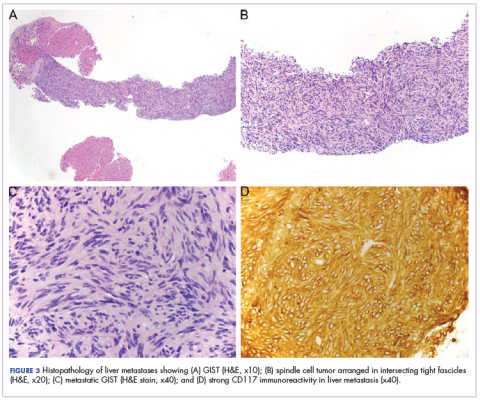

A month later, a follow-up EGD revealed a 1.8 × 1.5 cm submucosal mass 3 cm from the gastroesophageal junction. The patient underwent a fundus wedge resection, and a submucosal mass 1.8 cm in greatest dimension was removed. Pathologic examination revealed a GIST, spindle cell type, with a mitotic rate of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf with negative margins. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD117. An exon 11 deletion (KVV558-560NV) was present in KIT. The patient’s risk of recurrence was unclear, and his follow-up included CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis every 3 to 4 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for the next 2.5 years.

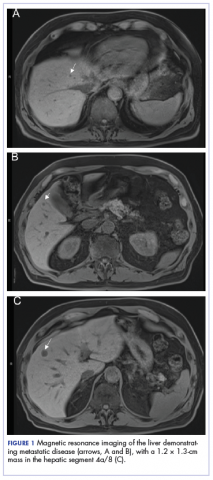

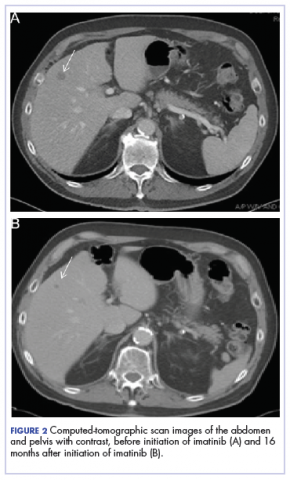

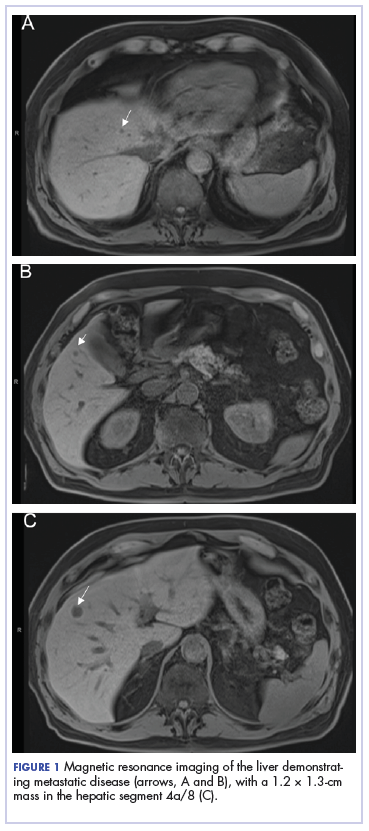

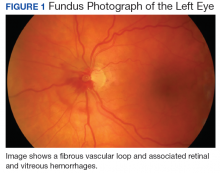

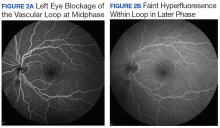

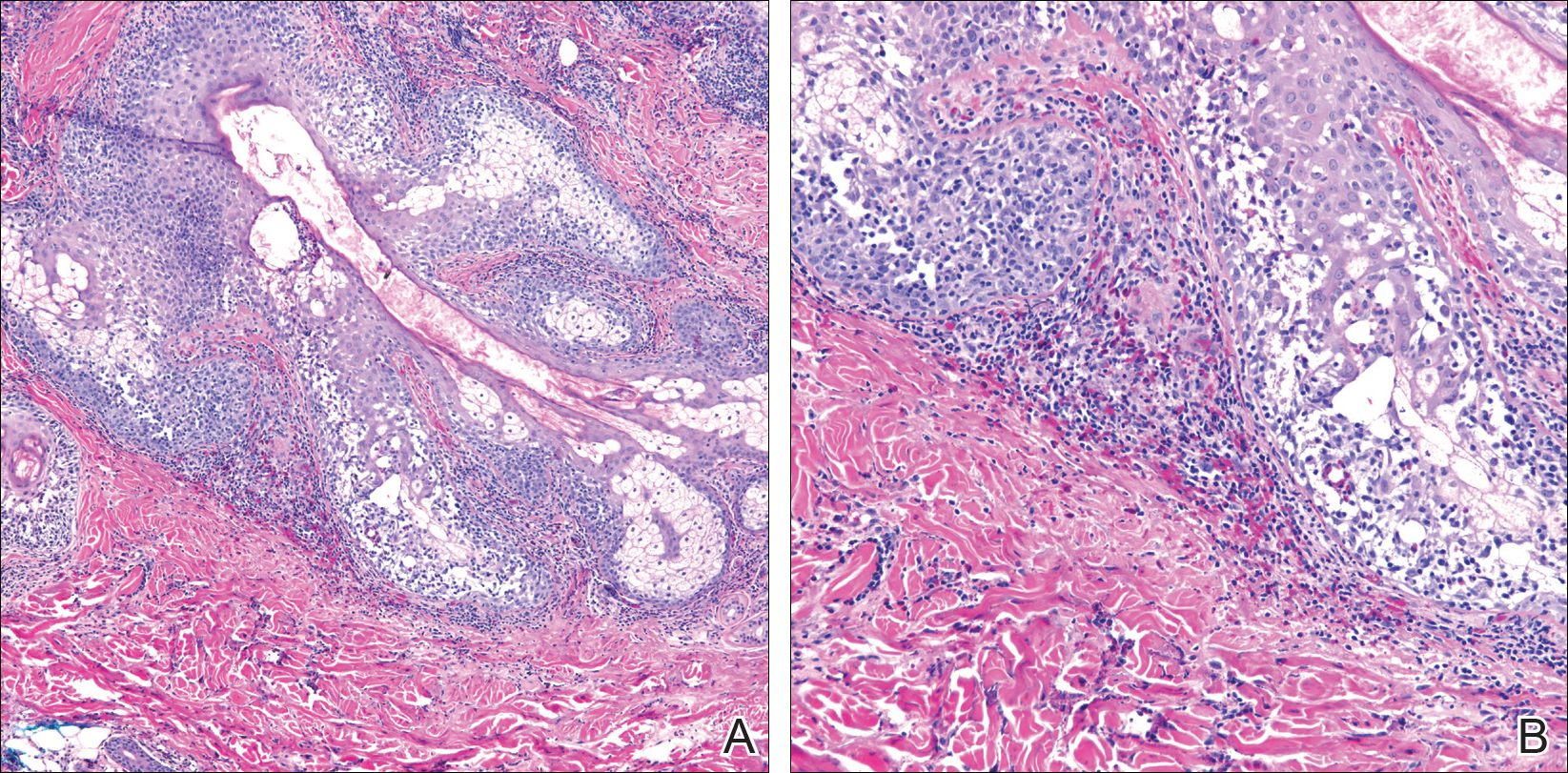

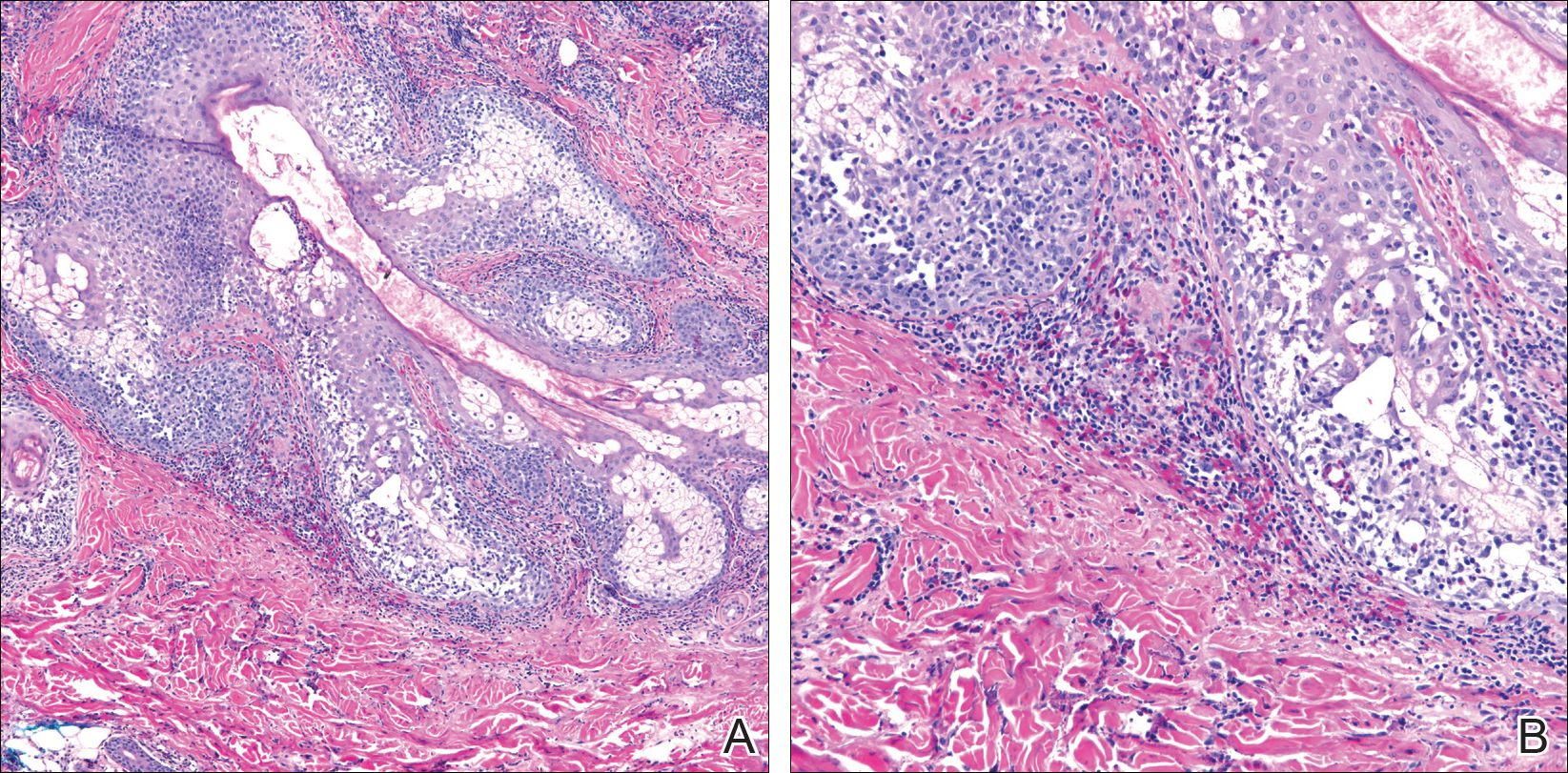

A CT scan about 3.5 years after primary resection revealed small nonspecific liver hypodensities that became more prominent during the next year. About 5 years after primary resection, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed several liver lesions, the largest of which measured at 1.3 cm in greatest dimension. The patient’s liver metastases were readily identified by MRI (Figure 1) and CT imaging (Figure 2A).

Discussion

Small gastric GISTs are sometimes found by endoscopy performed for unrelated reasons. Recent data suggest that the incidence of gastric GIST may be higher than previously thought. In a Japanese study of patients with gastric cancer in which 100 stomachs were systematically examined pathologically, 50 microscopic GISTs were found in 35 patients.28 Most small gastric GISTs have a low mitotic index. Few cases have been described with a high mitotic index. In a study of 1765 cases of GIST of the stomach, 8 patients had a tumor size less than 2 cm and a mitotic index greater than 5. Of those, only 6 patients had long-term follow-up, and 3 were alive without disease at 2, 17, and 20 years of follow-up.7 These limited data make it impossible to predict outcomes in patients with small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index.

For patients who are at high risk of recurrence after surgery, 3 years of adjuvant imatinib treatment compared with 1 year has been shown to improve overall survival and is the current standard of care.10,17 A study comparing 5 and 3 years of imatinib is ongoing to establish whether a longer period of adjuvant treatment is warranted. In patients with metastatic GIST, lifelong imatinib until lack of benefit is considered optimal treatment.10 All patients should undergo KIT mutation analysis. Those with the PDGFRA D842V mutation, SDH (succinate dehydrogenase) deficiency, or neurofibromatosis-related GIST should not receive adjuvant imatinib.

This case has several unusual features. The small tumor size with a very high mitotic rate is rare. Such cases have not been reported in large numbers and have therefore not been reliably incorporated into risk prediction algorithms. In addition, despite a high mitotic index, the tumor was not FDG avid on PET imaging. The diagnosis of GIST is strongly supported by the KIT mutation and response to imatinib. This particular KIT mutation in larger GISTs is associated with aggressive disease. The present case adds to the data on the biology of small gastric GISTs with a high mitotic index and suggests the mitotic index in these tumors may be a more important predictor than size.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Michael Franklin, MS, for editorial assistance, and Sabrina Porter for media edits.

1. Corless CL, Barnett CM, Heinrich MC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: origin and molecular oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(12):865-878.

2. Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279(5350):577-580.

3. Corless CL, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Pathologic and molecular features correlate with long-term outcome after adjuvant therapy of resected primary GI stromal tumor: the ACOSOG Z9001 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1563-1570.

4. Huang J, Zheng DL, Qin FS, et al. Genetic and epigenetic silencing of SCARA5 may contribute to human hepatocellular carcinoma by activating FAK signaling. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(1):223-241.

5. Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimaki J, et al. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):265-274.

6. Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(10):1466-1478.

7. Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(1):52-68.

8. Patel S. Navigating risk stratification systems for the management of patients with GIST. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(6):1698-1704.

9. Rossi S, Miceli R, Messerini L, et al. Natural history of imatinib-naive GISTs: a retrospective analysis of 929 cases with long-term follow-up and development of a survival nomogram based on mitotic index and size as continuous variables. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(11):1646-1656.

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Sarcoma. https://www.nccn.org. Accessed March 27, 2018.

11. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Int J Surg Pathol. 2002;10(2):81-89.

12. Huang HY, Li CF, Huang WW, et al. A modification of NIH consensus criteria to better distinguish the highly lethal subset of primary localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a subdivision of the original high-risk group on the basis of outcome. Surgery. 2007;141(6):748-756.

13. Kim MC, Yook JH, Yang HK, et al. Long-term surgical outcome of 1057 gastric GISTs according to 7th UICC/AJCC TNM system: multicenter observational study From Korea and Japan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(41):e1526.

14. Casali PG, Blay JY; ESMO/CONTICANET/EUROBONET Consensus Panel of experts. Soft tissue sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v198-v203.

15. Joensuu H, DeMatteo RP. The management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a model for targeted and multidisciplinary therapy of malignancy. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:247-258.

16. Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1097-1104.

17. Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, et al. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307(12):1265-1272.

18. Joensuu H, Rutkowski P, Nishida T, et al. KIT and PDGFRA mutations and the risk of GI stromal tumor recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):634-642.

19. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(5):459-465.

20. Antonescu CR, Viale A, Sarran L, et al. Gene expression in gastrointestinal stromal tumors is distinguished by KIT genotype and anatomic site. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(10):3282-3290.

21. Arne G, Kristiansson E, Nerman O, et al. Expression profiling of GIST: CD133 is associated with KIT exon 11 mutations, gastric location and poor prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(5):1149-1161.

22. Bertucci F, Finetti P, Ostrowski J, et al. Genomic Grade Index predicts postoperative clinical outcome of GIST. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(8):1433-1441.

23. Koon N, Schneider-Stock R, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Molecular targets for tumour progression in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Gut. 2004;53(2):235-240.

24. Lagarde P, Perot G, Kauffmann A, et al. Mitotic checkpoints and chromosome instability are strong predictors of clinical outcome in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(3):826-838.

25. Skubitz KM, Geschwind K, Xu WW, Koopmeiners JS, Skubitz AP. Gene expression identifies heterogeneity of metastatic behavior among gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Transl Med. 2016;14:51.

26. Yamaguchi U, Nakayama R, Honda K, et al. Distinct gene expression-defined classes of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4100-4108.

27. Ylipaa A, Hunt KK, Yang J, et al. Integrative genomic characterization and a genomic staging system for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer. 2011;117(2):380-389.

28. Kawanowa K, Sakuma Y, Sakurai S, et al. High incidence of microscopic gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(12):1527-1535.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common soft tissue sarcoma of the gastrointestinal tract, usually arising from the interstitial cells of Cajal or similar cells in the outer wall of the gastrointestinal tract.1,2 Most GISTs have an activating mutation in KIT or platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA). Tumor size, mitotic rate, and anatomic site are the most common pathological features used to risk stratify GIST tumors.3-10 It is important to note when using such risk calculators that preoperative imatinib before determining tumor characteristics (such as mitoses per 50 high-power fields [hpf]) often changes the relevant parameters so that the same risk calculations may not apply. Tumors with a mitotic rate ≤5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size ≤5 cm in greatest dimension have a lower recurrence rate after resection than tumors with a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size >10 cm, and larger tumors can have a recurrence rate of up to 86%.11,12 Findings from a large observational study have suggested that the prognosis of gastric GIST in Korea and Japan may be more favorable compared with that in Western countries.13

The primary treatment of a localized primary GIST is surgical excision, but a cure is limited by recurrence.14,15 Imatinib is useful in the treatment of metastatic or recurrent GIST, and adjuvant treatment with imatinib after surgery has been shown to improve progression-free and overall survival in some cases.3,16-18 Responses to adjuvant imatinib depend on tumor sensitivity to the drug and the risk of recurrence. Drug sensitivity is largely dependent on the presence of mutations in KIT or PDGFRA.3,18 Recurrence risk is highly dependent on tumor size, tumor site, tumor rupture, and mitotic index.1,3,5,6,8,9,18,19 Findings on the use of gene expression patterns to predict recurrence risk have also been reported.20-27 However, recurrence risk is poorly understood for categories in which there are few cases with known outcomes, such as very small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index. For example, few cases of gastric GIST have been reported with a tumor size ≤2 cm, a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf, and adequate clinical follow-up. In such cases, it is difficult to assess the risk of recurrence.6 We report here the long-term outcome of a patient with a 1.8 cm gastric GIST with a mitotic index of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf and a KIT exon 11 mutation.

Case presentation and summary

A 69-year-old man presented with periumbilical and epigastric pain of 6-month duration. His medical history was notable for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, coronary angioplasty, and spinal surgery. He had a 40 pack-year smoking history and consumed 2 to 4 alcoholic drinks per day. The results of a physical examination were unremarkable. A computedtomographic (CT) scan showed no abnormalities. An esophagoduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed gastric ulcers. He was treated successfully with omeprazole 20 mg by mouth daily.

A month later, a follow-up EGD revealed a 1.8 × 1.5 cm submucosal mass 3 cm from the gastroesophageal junction. The patient underwent a fundus wedge resection, and a submucosal mass 1.8 cm in greatest dimension was removed. Pathologic examination revealed a GIST, spindle cell type, with a mitotic rate of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf with negative margins. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD117. An exon 11 deletion (KVV558-560NV) was present in KIT. The patient’s risk of recurrence was unclear, and his follow-up included CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis every 3 to 4 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for the next 2.5 years.

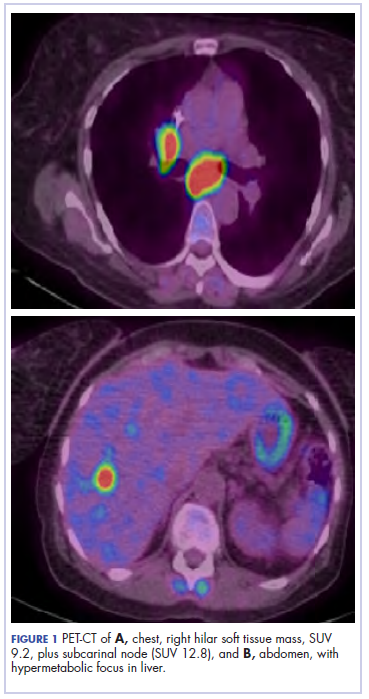

A CT scan about 3.5 years after primary resection revealed small nonspecific liver hypodensities that became more prominent during the next year. About 5 years after primary resection, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed several liver lesions, the largest of which measured at 1.3 cm in greatest dimension. The patient’s liver metastases were readily identified by MRI (Figure 1) and CT imaging (Figure 2A).

Discussion

Small gastric GISTs are sometimes found by endoscopy performed for unrelated reasons. Recent data suggest that the incidence of gastric GIST may be higher than previously thought. In a Japanese study of patients with gastric cancer in which 100 stomachs were systematically examined pathologically, 50 microscopic GISTs were found in 35 patients.28 Most small gastric GISTs have a low mitotic index. Few cases have been described with a high mitotic index. In a study of 1765 cases of GIST of the stomach, 8 patients had a tumor size less than 2 cm and a mitotic index greater than 5. Of those, only 6 patients had long-term follow-up, and 3 were alive without disease at 2, 17, and 20 years of follow-up.7 These limited data make it impossible to predict outcomes in patients with small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index.

For patients who are at high risk of recurrence after surgery, 3 years of adjuvant imatinib treatment compared with 1 year has been shown to improve overall survival and is the current standard of care.10,17 A study comparing 5 and 3 years of imatinib is ongoing to establish whether a longer period of adjuvant treatment is warranted. In patients with metastatic GIST, lifelong imatinib until lack of benefit is considered optimal treatment.10 All patients should undergo KIT mutation analysis. Those with the PDGFRA D842V mutation, SDH (succinate dehydrogenase) deficiency, or neurofibromatosis-related GIST should not receive adjuvant imatinib.

This case has several unusual features. The small tumor size with a very high mitotic rate is rare. Such cases have not been reported in large numbers and have therefore not been reliably incorporated into risk prediction algorithms. In addition, despite a high mitotic index, the tumor was not FDG avid on PET imaging. The diagnosis of GIST is strongly supported by the KIT mutation and response to imatinib. This particular KIT mutation in larger GISTs is associated with aggressive disease. The present case adds to the data on the biology of small gastric GISTs with a high mitotic index and suggests the mitotic index in these tumors may be a more important predictor than size.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Michael Franklin, MS, for editorial assistance, and Sabrina Porter for media edits.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is the most common soft tissue sarcoma of the gastrointestinal tract, usually arising from the interstitial cells of Cajal or similar cells in the outer wall of the gastrointestinal tract.1,2 Most GISTs have an activating mutation in KIT or platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA). Tumor size, mitotic rate, and anatomic site are the most common pathological features used to risk stratify GIST tumors.3-10 It is important to note when using such risk calculators that preoperative imatinib before determining tumor characteristics (such as mitoses per 50 high-power fields [hpf]) often changes the relevant parameters so that the same risk calculations may not apply. Tumors with a mitotic rate ≤5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size ≤5 cm in greatest dimension have a lower recurrence rate after resection than tumors with a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf and a size >10 cm, and larger tumors can have a recurrence rate of up to 86%.11,12 Findings from a large observational study have suggested that the prognosis of gastric GIST in Korea and Japan may be more favorable compared with that in Western countries.13

The primary treatment of a localized primary GIST is surgical excision, but a cure is limited by recurrence.14,15 Imatinib is useful in the treatment of metastatic or recurrent GIST, and adjuvant treatment with imatinib after surgery has been shown to improve progression-free and overall survival in some cases.3,16-18 Responses to adjuvant imatinib depend on tumor sensitivity to the drug and the risk of recurrence. Drug sensitivity is largely dependent on the presence of mutations in KIT or PDGFRA.3,18 Recurrence risk is highly dependent on tumor size, tumor site, tumor rupture, and mitotic index.1,3,5,6,8,9,18,19 Findings on the use of gene expression patterns to predict recurrence risk have also been reported.20-27 However, recurrence risk is poorly understood for categories in which there are few cases with known outcomes, such as very small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index. For example, few cases of gastric GIST have been reported with a tumor size ≤2 cm, a mitotic rate >5 mitoses per 50 hpf, and adequate clinical follow-up. In such cases, it is difficult to assess the risk of recurrence.6 We report here the long-term outcome of a patient with a 1.8 cm gastric GIST with a mitotic index of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf and a KIT exon 11 mutation.

Case presentation and summary

A 69-year-old man presented with periumbilical and epigastric pain of 6-month duration. His medical history was notable for hyperlipidemia, hypertension, coronary angioplasty, and spinal surgery. He had a 40 pack-year smoking history and consumed 2 to 4 alcoholic drinks per day. The results of a physical examination were unremarkable. A computedtomographic (CT) scan showed no abnormalities. An esophagoduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed gastric ulcers. He was treated successfully with omeprazole 20 mg by mouth daily.

A month later, a follow-up EGD revealed a 1.8 × 1.5 cm submucosal mass 3 cm from the gastroesophageal junction. The patient underwent a fundus wedge resection, and a submucosal mass 1.8 cm in greatest dimension was removed. Pathologic examination revealed a GIST, spindle cell type, with a mitotic rate of 36 mitoses per 50 hpf with negative margins. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD117. An exon 11 deletion (KVV558-560NV) was present in KIT. The patient’s risk of recurrence was unclear, and his follow-up included CT scans of the abdomen and pelvis every 3 to 4 months for the first 2 years, then every 6 months for the next 2.5 years.

A CT scan about 3.5 years after primary resection revealed small nonspecific liver hypodensities that became more prominent during the next year. About 5 years after primary resection, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed several liver lesions, the largest of which measured at 1.3 cm in greatest dimension. The patient’s liver metastases were readily identified by MRI (Figure 1) and CT imaging (Figure 2A).

Discussion

Small gastric GISTs are sometimes found by endoscopy performed for unrelated reasons. Recent data suggest that the incidence of gastric GIST may be higher than previously thought. In a Japanese study of patients with gastric cancer in which 100 stomachs were systematically examined pathologically, 50 microscopic GISTs were found in 35 patients.28 Most small gastric GISTs have a low mitotic index. Few cases have been described with a high mitotic index. In a study of 1765 cases of GIST of the stomach, 8 patients had a tumor size less than 2 cm and a mitotic index greater than 5. Of those, only 6 patients had long-term follow-up, and 3 were alive without disease at 2, 17, and 20 years of follow-up.7 These limited data make it impossible to predict outcomes in patients with small gastric GIST with a high mitotic index.

For patients who are at high risk of recurrence after surgery, 3 years of adjuvant imatinib treatment compared with 1 year has been shown to improve overall survival and is the current standard of care.10,17 A study comparing 5 and 3 years of imatinib is ongoing to establish whether a longer period of adjuvant treatment is warranted. In patients with metastatic GIST, lifelong imatinib until lack of benefit is considered optimal treatment.10 All patients should undergo KIT mutation analysis. Those with the PDGFRA D842V mutation, SDH (succinate dehydrogenase) deficiency, or neurofibromatosis-related GIST should not receive adjuvant imatinib.

This case has several unusual features. The small tumor size with a very high mitotic rate is rare. Such cases have not been reported in large numbers and have therefore not been reliably incorporated into risk prediction algorithms. In addition, despite a high mitotic index, the tumor was not FDG avid on PET imaging. The diagnosis of GIST is strongly supported by the KIT mutation and response to imatinib. This particular KIT mutation in larger GISTs is associated with aggressive disease. The present case adds to the data on the biology of small gastric GISTs with a high mitotic index and suggests the mitotic index in these tumors may be a more important predictor than size.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Michael Franklin, MS, for editorial assistance, and Sabrina Porter for media edits.

1. Corless CL, Barnett CM, Heinrich MC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: origin and molecular oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(12):865-878.

2. Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279(5350):577-580.

3. Corless CL, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Pathologic and molecular features correlate with long-term outcome after adjuvant therapy of resected primary GI stromal tumor: the ACOSOG Z9001 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1563-1570.

4. Huang J, Zheng DL, Qin FS, et al. Genetic and epigenetic silencing of SCARA5 may contribute to human hepatocellular carcinoma by activating FAK signaling. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(1):223-241.

5. Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimaki J, et al. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):265-274.

6. Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(10):1466-1478.

7. Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(1):52-68.

8. Patel S. Navigating risk stratification systems for the management of patients with GIST. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(6):1698-1704.

9. Rossi S, Miceli R, Messerini L, et al. Natural history of imatinib-naive GISTs: a retrospective analysis of 929 cases with long-term follow-up and development of a survival nomogram based on mitotic index and size as continuous variables. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(11):1646-1656.

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Sarcoma. https://www.nccn.org. Accessed March 27, 2018.

11. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Int J Surg Pathol. 2002;10(2):81-89.

12. Huang HY, Li CF, Huang WW, et al. A modification of NIH consensus criteria to better distinguish the highly lethal subset of primary localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a subdivision of the original high-risk group on the basis of outcome. Surgery. 2007;141(6):748-756.

13. Kim MC, Yook JH, Yang HK, et al. Long-term surgical outcome of 1057 gastric GISTs according to 7th UICC/AJCC TNM system: multicenter observational study From Korea and Japan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(41):e1526.

14. Casali PG, Blay JY; ESMO/CONTICANET/EUROBONET Consensus Panel of experts. Soft tissue sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v198-v203.

15. Joensuu H, DeMatteo RP. The management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a model for targeted and multidisciplinary therapy of malignancy. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:247-258.

16. Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1097-1104.

17. Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, et al. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307(12):1265-1272.

18. Joensuu H, Rutkowski P, Nishida T, et al. KIT and PDGFRA mutations and the risk of GI stromal tumor recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):634-642.

19. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(5):459-465.

20. Antonescu CR, Viale A, Sarran L, et al. Gene expression in gastrointestinal stromal tumors is distinguished by KIT genotype and anatomic site. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(10):3282-3290.

21. Arne G, Kristiansson E, Nerman O, et al. Expression profiling of GIST: CD133 is associated with KIT exon 11 mutations, gastric location and poor prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(5):1149-1161.

22. Bertucci F, Finetti P, Ostrowski J, et al. Genomic Grade Index predicts postoperative clinical outcome of GIST. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(8):1433-1441.

23. Koon N, Schneider-Stock R, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Molecular targets for tumour progression in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Gut. 2004;53(2):235-240.

24. Lagarde P, Perot G, Kauffmann A, et al. Mitotic checkpoints and chromosome instability are strong predictors of clinical outcome in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(3):826-838.

25. Skubitz KM, Geschwind K, Xu WW, Koopmeiners JS, Skubitz AP. Gene expression identifies heterogeneity of metastatic behavior among gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Transl Med. 2016;14:51.

26. Yamaguchi U, Nakayama R, Honda K, et al. Distinct gene expression-defined classes of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4100-4108.

27. Ylipaa A, Hunt KK, Yang J, et al. Integrative genomic characterization and a genomic staging system for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer. 2011;117(2):380-389.

28. Kawanowa K, Sakuma Y, Sakurai S, et al. High incidence of microscopic gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(12):1527-1535.

1. Corless CL, Barnett CM, Heinrich MC. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: origin and molecular oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(12):865-878.

2. Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279(5350):577-580.

3. Corless CL, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Pathologic and molecular features correlate with long-term outcome after adjuvant therapy of resected primary GI stromal tumor: the ACOSOG Z9001 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15):1563-1570.

4. Huang J, Zheng DL, Qin FS, et al. Genetic and epigenetic silencing of SCARA5 may contribute to human hepatocellular carcinoma by activating FAK signaling. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(1):223-241.

5. Joensuu H, Vehtari A, Riihimaki J, et al. Risk of recurrence of gastrointestinal stromal tumour after surgery: an analysis of pooled population-based cohorts. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):265-274.

6. Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130(10):1466-1478.

7. Miettinen M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(1):52-68.

8. Patel S. Navigating risk stratification systems for the management of patients with GIST. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(6):1698-1704.

9. Rossi S, Miceli R, Messerini L, et al. Natural history of imatinib-naive GISTs: a retrospective analysis of 929 cases with long-term follow-up and development of a survival nomogram based on mitotic index and size as continuous variables. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(11):1646-1656.

10. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Sarcoma. https://www.nccn.org. Accessed March 27, 2018.

11. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Int J Surg Pathol. 2002;10(2):81-89.

12. Huang HY, Li CF, Huang WW, et al. A modification of NIH consensus criteria to better distinguish the highly lethal subset of primary localized gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a subdivision of the original high-risk group on the basis of outcome. Surgery. 2007;141(6):748-756.

13. Kim MC, Yook JH, Yang HK, et al. Long-term surgical outcome of 1057 gastric GISTs according to 7th UICC/AJCC TNM system: multicenter observational study From Korea and Japan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(41):e1526.

14. Casali PG, Blay JY; ESMO/CONTICANET/EUROBONET Consensus Panel of experts. Soft tissue sarcomas: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v198-v203.

15. Joensuu H, DeMatteo RP. The management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a model for targeted and multidisciplinary therapy of malignancy. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:247-258.

16. Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, et al. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1097-1104.

17. Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, et al. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307(12):1265-1272.

18. Joensuu H, Rutkowski P, Nishida T, et al. KIT and PDGFRA mutations and the risk of GI stromal tumor recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):634-642.

19. Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(5):459-465.

20. Antonescu CR, Viale A, Sarran L, et al. Gene expression in gastrointestinal stromal tumors is distinguished by KIT genotype and anatomic site. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(10):3282-3290.

21. Arne G, Kristiansson E, Nerman O, et al. Expression profiling of GIST: CD133 is associated with KIT exon 11 mutations, gastric location and poor prognosis. Int J Cancer. 2011;129(5):1149-1161.

22. Bertucci F, Finetti P, Ostrowski J, et al. Genomic Grade Index predicts postoperative clinical outcome of GIST. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(8):1433-1441.

23. Koon N, Schneider-Stock R, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Molecular targets for tumour progression in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Gut. 2004;53(2):235-240.

24. Lagarde P, Perot G, Kauffmann A, et al. Mitotic checkpoints and chromosome instability are strong predictors of clinical outcome in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18(3):826-838.

25. Skubitz KM, Geschwind K, Xu WW, Koopmeiners JS, Skubitz AP. Gene expression identifies heterogeneity of metastatic behavior among gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Transl Med. 2016;14:51.

26. Yamaguchi U, Nakayama R, Honda K, et al. Distinct gene expression-defined classes of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(25):4100-4108.

27. Ylipaa A, Hunt KK, Yang J, et al. Integrative genomic characterization and a genomic staging system for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cancer. 2011;117(2):380-389.

28. Kawanowa K, Sakuma Y, Sakurai S, et al. High incidence of microscopic gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the stomach. Hum Pathol. 2006;37(12):1527-1535.

Striking rash in a patient with lung cancer on a checkpoint inhibitor

Lung cancer remains the most common cause of cancer death in the United States and worldwide.1 Despite advances in the treatment of the disease and development of targeted therapy, the 5-year overall survival in stage IV non–small-cell lung cancer remains poor, ranging from 6% to 10%.2 More recently, checkpoint inhibitors have had a major impact on the treatment of lung cancer. Nivolumab was the first program cell death protein-1 (PD-1) inhibitor approved for malignant melanoma.3 In July 2015, it was approved as a second-line treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the lung.4 Since then, the use of nivolumab has extended to other malignancies such as head and neck cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and the list continues to expand. In lung cancer, it demonstrated superior overall survival of 9 months, compared with 6 months with docetaxel.4 Other checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab5 and atezolizumab6 were subsequently developed, and are also used in the treatment of lung cancer.

Serious potential autoimmune complications arise in up to 30% of patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors. Dermatologic toxicity is the most common immune-related adverse event in these patients. In addition to vitiligo, most common is a reticular maculopapular rash on the trunk and extremities. Other adverse events, such as photosensitivity, alopecia, xerosis, and hair color changes, are reported less frequently.7 We report here a case of rash at an unusual location (auricular and periauricular) with skin exfoliation mimicking other common skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis.

Case presentation and summary

A 57-year-old woman with a history of cerebrovascular accident with residual left lower-leg paresis presented for acute onset expressive aphasia in the absence of other constitutional or neurological findings. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed a posterior, left parietal lobe lesion of 1.6 cm with intralesional hemorrhage and surrounding edema suggestive of brain metastasis. The patient had a 35 pack-year history of smoking. A staging work-up with computed-tomographic (CT) scans showed a spiculated enhancing nodule in the superior segment of the right lower lobe plus mediastinal adenopathy.

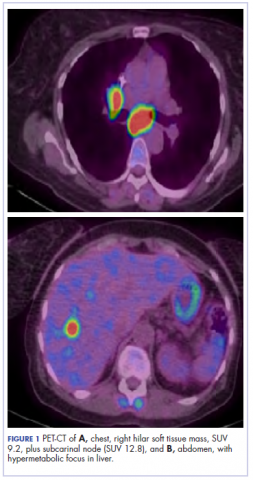

The patient underwent a CT-guided core biopsy of the spiculated nodule, which was found to be consistent with adenocarcinoma of the lung. It was negative for EGFR mutation or ALK rearrangement. She received stereotactic radiosurgery to the left posterior parietal lesion, and after completion of radiation, was started on systemic chemotherapy with cisplatin plus pemetrexed for adenocarcinoma of the lung. She received 4 cycles of chemotherapy. Repeat imaging with a PET-CT showed interval increase of the mediastinal hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy with new hypermetabolic pretracheal lymph nodes and interval development of multiple liver metastases in the right and left lobes of the liver (Figure 1). She was started on second-line therapy with nivolumab at a dose of 240 mg every 2 weeks. The treatment was complicated initially by new onset grade 2 papular pruritic rash after cycle 2 of therapy. The rash involved the upper and lower extremities, sparing the palms, soles, trunk, abdomen, and the back. It resolved with treatment delay and topical steroids.

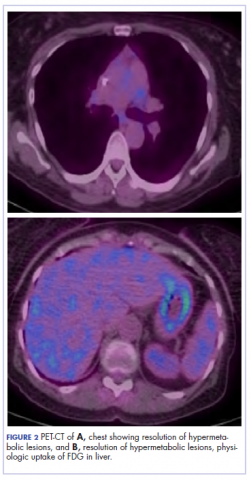

The patient resumed treatment with nivolumab after complete resolution of the rash. However, she developed grade 2 nephritis after cycle 5 with a creatinine level of 1.98 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6-1.2 mg/ dL). This was resolved after treatment with oral prednisone, at a starting dose of 1 mg/kg and tapered over 4 weeks. PET CT scans obtained after cycles 5 and 11 showed no metabolic activity in the mediastinum or the liver and markedly decreased uptake in the right lower lobe nodule, down to an SUV of 1.7 with no new nodules. An MRI of the brain was stable (Figure 2).

After cycle 16 of nivolumab, the patient developed a severe eczematous rash with excoriations at the base of both ears involving the periauricular and auricular areas bilaterally (Figure 3).

She completed 4 weeks of steroid therapy on a tapering schedule. Treatment with nivolumab was resumed afterward with no adverse autoimmune complications. At her last visit (25 months after initiating a PD-1 inhibitor), there was no clinical or radiologic evidence of lung cancer nor any of autoimmune adverse effects.

Discussion

Among multiple autoimmune complications, dermatologic toxicity is the most common immune-related adverse event, occuring in about 30% to 40% of patients7,8 and with an average onset of 3-4 weeks after initiating treatment with checkpoint inhibitors.9 In addition to vitiligo, the most common type of rash described is a reticular maculopapular rash on the trunk and extremities.10 Other findings, such as photosensitivity, alopecia, xerosis, and hair color changes, have been reported in smaller numbers. Skin exfoliation, as seen in the present case, has been reported in fewer than 1% of the cases.4 Perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates extending deep into the dermis are most likely to be seen if the lesions are biopsied. Both the location of the rash in our patient and its relapsing nature are rare and make it more interesting as it presents a diagnostic dilemma for treating physicians. Ear, nose, and throat surgeons are more likely to encounter such a complication with the expanded use of PD-1 and PD-ligand 1 inhibitors in advanced head and neck cancers. The differential diagnosis includes localized eczema, psoriatic rash, skin infection, or an autoimmune phenomenon.

The location of the rash was also of concern because there have been reports of autoimmune inner-ear disease related to immunotherapy.11 After the failure of treatment with empiric antibiotics and topical steroids, in addition to the development of a new rash on her abdomen, we concluded that this case might represent an unusual autoimmune skin complication. The resolution of the skin lesions in both locations (the ears and the abdomen) with the oral steroid therapy, supported our suspected diagnosis of autoimmune dermatitis.

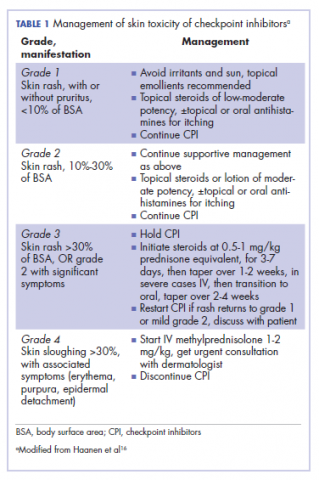

It is essential that these complications are detected early and misdiagnosis is avoided because timely treatment with steroids will prevent progression to more severe problems such as Steven-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis,12 or extension into the inner ear.11This case is part of a growing spectrum of other unusual cases seen with immunotherapy treatment, such as erythema nodosum-like reactions,13 bullous dermatitis,14 and psoriasiform eruptions.15 It highlights the need for an awareness of expanding dermatologic complications from immunotherapy beyond the reported common manifestations. Established guidelines and algorithms for the management of immune-related dermatologic toxicity are available to assist the physician in treatment (Table 1).16 Skin biopsy should be considered if the diagnosis remains uncertain, although starting empiric treatment with steroids is a widely acceptable approach. Reassessing the skin rash in 48 hours to 1 week after treatment initiation is crucial because steroid-refractory cases will need additional immunosuppression. Early termination of steroids is associated with higher recurrence rate, therefore tapering steroids over 4 weeks is highly recommended before resuming treatment with checkpoint inhibitors.

In summary, increased awareness among health care professionals of the common and unusual complications of immunotherapy agents is important and essential in patient care. In addition to oncologists, head and neck surgeons, pulmonologists, urologists, dermatologists, and general internists will encounter patients with immunotherapy-related complications. Patient education should be emphasized to ensure prompt investigation and treatment of complications. Finally, it is not yet clear whether the development of autoimmune reactions predicts disease response to treatment. In a series of 134 patients with lung cancer, the occurrence of autoimmune adverse events correlated with improved survival.17 More research is needed to identify prognostic and predictive biomarkers for response to immunotherapy.

Conclusion

This pattern of autoimmune dermatitis localizing to the ears is rare (<1% of cases of dermatitis). Nevertheless, it raises the awareness for dermatologic complications of immunotherapy beyond the classical reported manifestations. Prompt diagnosis and treatment is essential to avoid serious complications such as Steven-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, and potentially damage to the inner ear.

1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87-108.

2. Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (Eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:39-51.

3. Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320-330.

4. Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123-135.

5. Reck M, Rodriguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemo-therapy for PD- L1- positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1823- 1833.

6. Rittmeyer A, Barlesi F, Waterkamp D, et al. Atezolizumab versus docetaxel in patients with previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (OAK): a phase 3, open-label, multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:255-265.

7. Collins LK, Chapman MS, Carter JB, Samie FH. Cutaneous adverse events of the immune checkpoint inhibitors. Curr Prob Cancer. 2017;41:125-128.

8. Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(12):2375.

9. Weber JS, Kähler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2691-2697.

10. Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12-25.

11. Zibelman M, Pollak N, Olszanski AJ. Autoimmune inner ear disease in a melanoma patient treated with pembrolizumab. J Immunother Cancer. 2016;4:8.

12. Nayar N, Briscoe K, Penas PF. Toxic epidermal necrolysis-like reaction with severe satellite cell necrosis associated with nivolumab in a patient with ipilimumab refractory metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2016;39(3):149-152.

13. Tetzlaff MT, Jazaeri AA, Torres-Cabala CA, et al. Erythema nodosum-like panniculitis mimicking disease recurrence: a novel toxicity from immune checkpoint blockade therapy - report of 2 patients. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44(12):1080-1086.

14. Naidoo J, Schindler K, Querfeld C, et al. Autoimmune bullous skin disorders with immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting PD-1 and PD-L1. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4(5):383-389.

15. Ohtsuka M, Miura T, Mori T, Ishikawa M, Yamamoto T. Occurrence of psoriasiform eruption during nivolumab therapy for primary oral mucosal melanoma. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(7):797-799.

16. Haanen JBAG, Carbonnel F, Robert C, et al; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl 4):iv119-iv142.

17. Haratani K, Hayashi H, Chiba Y, et al. Association of immune-related adverse events with nivolumab efficacy in non-small-cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(3):374-378.

Lung cancer remains the most common cause of cancer death in the United States and worldwide.1 Despite advances in the treatment of the disease and development of targeted therapy, the 5-year overall survival in stage IV non–small-cell lung cancer remains poor, ranging from 6% to 10%.2 More recently, checkpoint inhibitors have had a major impact on the treatment of lung cancer. Nivolumab was the first program cell death protein-1 (PD-1) inhibitor approved for malignant melanoma.3 In July 2015, it was approved as a second-line treatment of squamous cell carcinoma of the lung.4 Since then, the use of nivolumab has extended to other malignancies such as head and neck cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and the list continues to expand. In lung cancer, it demonstrated superior overall survival of 9 months, compared with 6 months with docetaxel.4 Other checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab5 and atezolizumab6 were subsequently developed, and are also used in the treatment of lung cancer.

Serious potential autoimmune complications arise in up to 30% of patients treated with PD-1 inhibitors. Dermatologic toxicity is the most common immune-related adverse event in these patients. In addition to vitiligo, most common is a reticular maculopapular rash on the trunk and extremities. Other adverse events, such as photosensitivity, alopecia, xerosis, and hair color changes, are reported less frequently.7 We report here a case of rash at an unusual location (auricular and periauricular) with skin exfoliation mimicking other common skin conditions such as eczema and psoriasis.

Case presentation and summary

A 57-year-old woman with a history of cerebrovascular accident with residual left lower-leg paresis presented for acute onset expressive aphasia in the absence of other constitutional or neurological findings. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed a posterior, left parietal lobe lesion of 1.6 cm with intralesional hemorrhage and surrounding edema suggestive of brain metastasis. The patient had a 35 pack-year history of smoking. A staging work-up with computed-tomographic (CT) scans showed a spiculated enhancing nodule in the superior segment of the right lower lobe plus mediastinal adenopathy.

The patient underwent a CT-guided core biopsy of the spiculated nodule, which was found to be consistent with adenocarcinoma of the lung. It was negative for EGFR mutation or ALK rearrangement. She received stereotactic radiosurgery to the left posterior parietal lesion, and after completion of radiation, was started on systemic chemotherapy with cisplatin plus pemetrexed for adenocarcinoma of the lung. She received 4 cycles of chemotherapy. Repeat imaging with a PET-CT showed interval increase of the mediastinal hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy with new hypermetabolic pretracheal lymph nodes and interval development of multiple liver metastases in the right and left lobes of the liver (Figure 1). She was started on second-line therapy with nivolumab at a dose of 240 mg every 2 weeks. The treatment was complicated initially by new onset grade 2 papular pruritic rash after cycle 2 of therapy. The rash involved the upper and lower extremities, sparing the palms, soles, trunk, abdomen, and the back. It resolved with treatment delay and topical steroids.