User login

Acrodermatitis Enteropathica From Zinc-Deficient Total Parenteral Nutrition

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with a pruritic and slightly painful skin eruption that began perinasally and progressed over 1 week to involve the labial commissures, finger webs, dorsal surfaces of the feet, heels, and bilateral gluteal folds. In addition, the eruption involved the left thigh at the donor site of a prior skin graft. She received no relief after an intramuscular steroid injection and hydrocortisone cream 1% prescribed by a primary care physician who diagnosed the rash as poison ivy contact dermatitis despite no exposure to plants. Review of systems was negative and she denied any new medication use. Her medical history was notable for extensive mesenteric injury secondary to a motor vehicle accident. She subsequently had multiple enterocutaneous fistulas that resulted in a complete small bowel enterectomy 10 months prior to presentation, which caused her to become dependent on total parenteral nutrition (TPN).

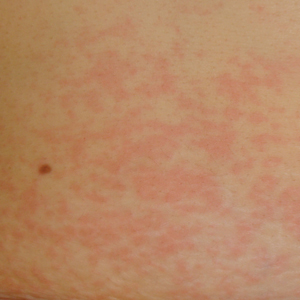

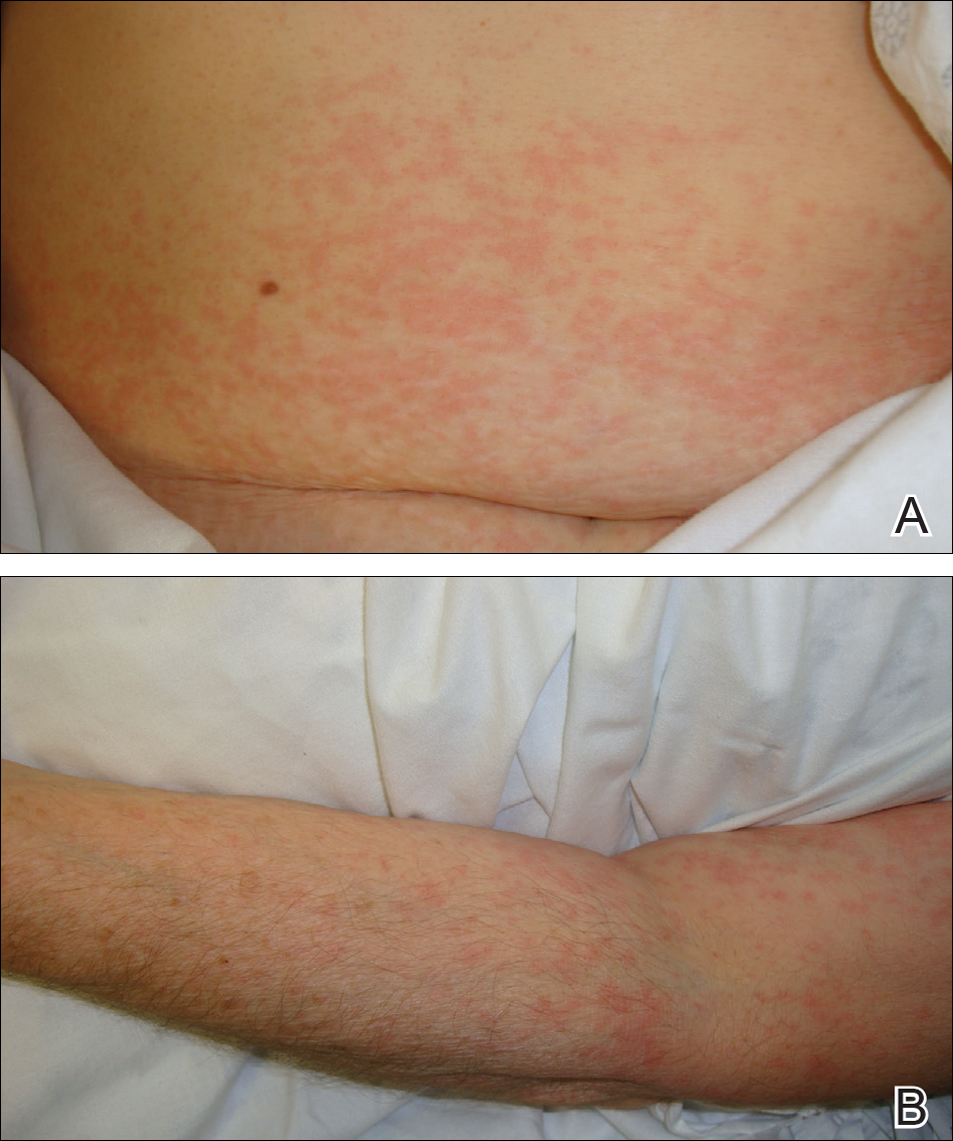

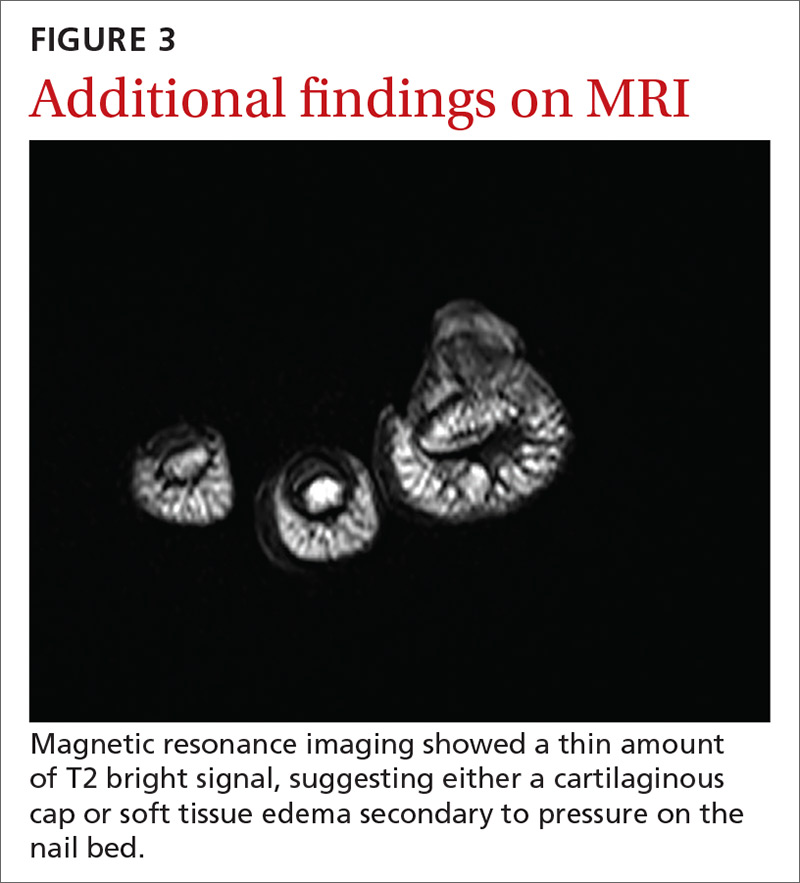

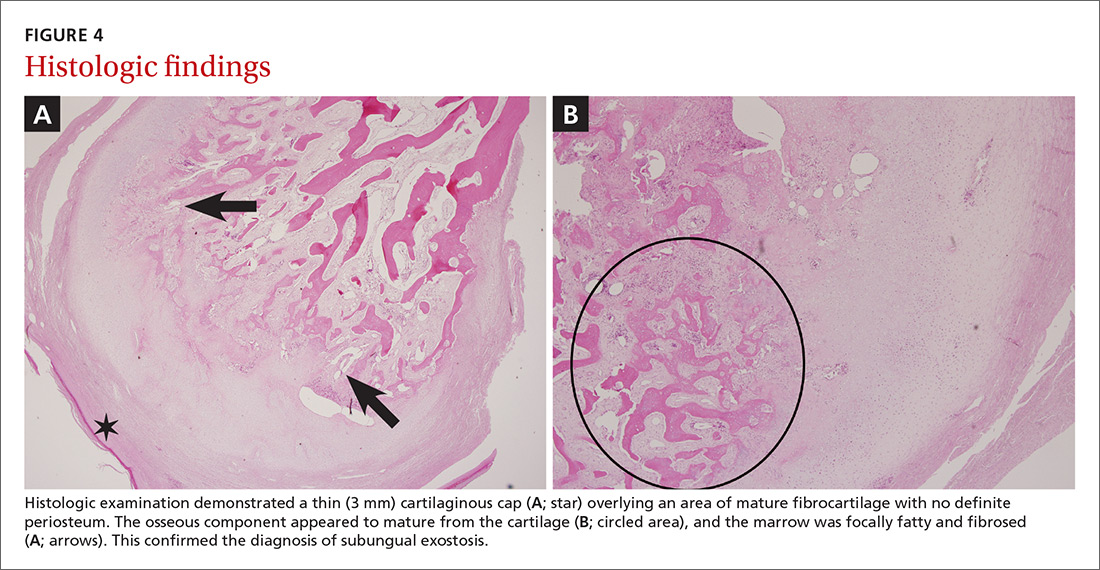

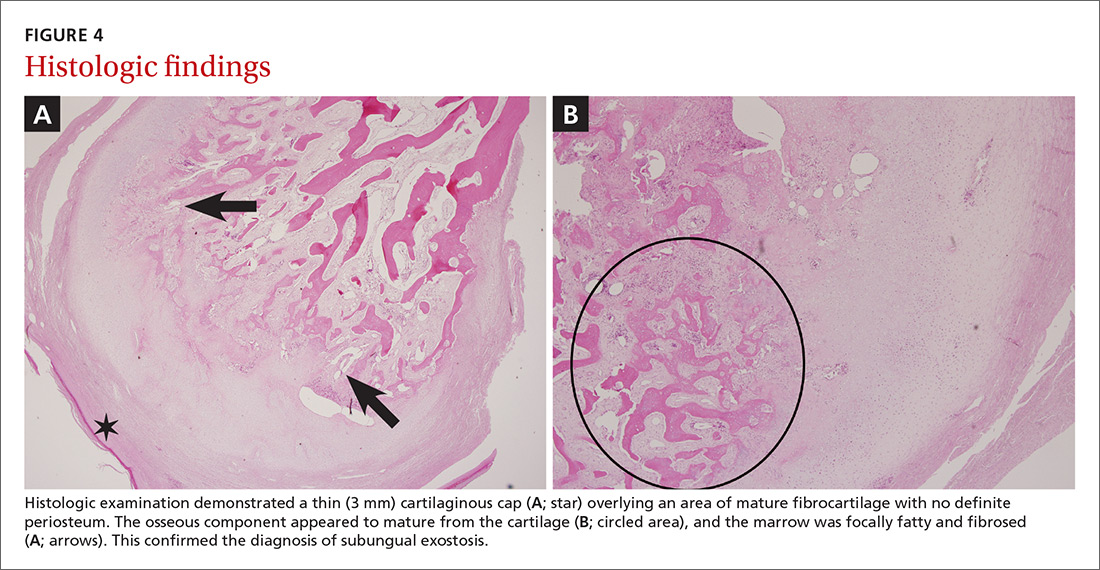

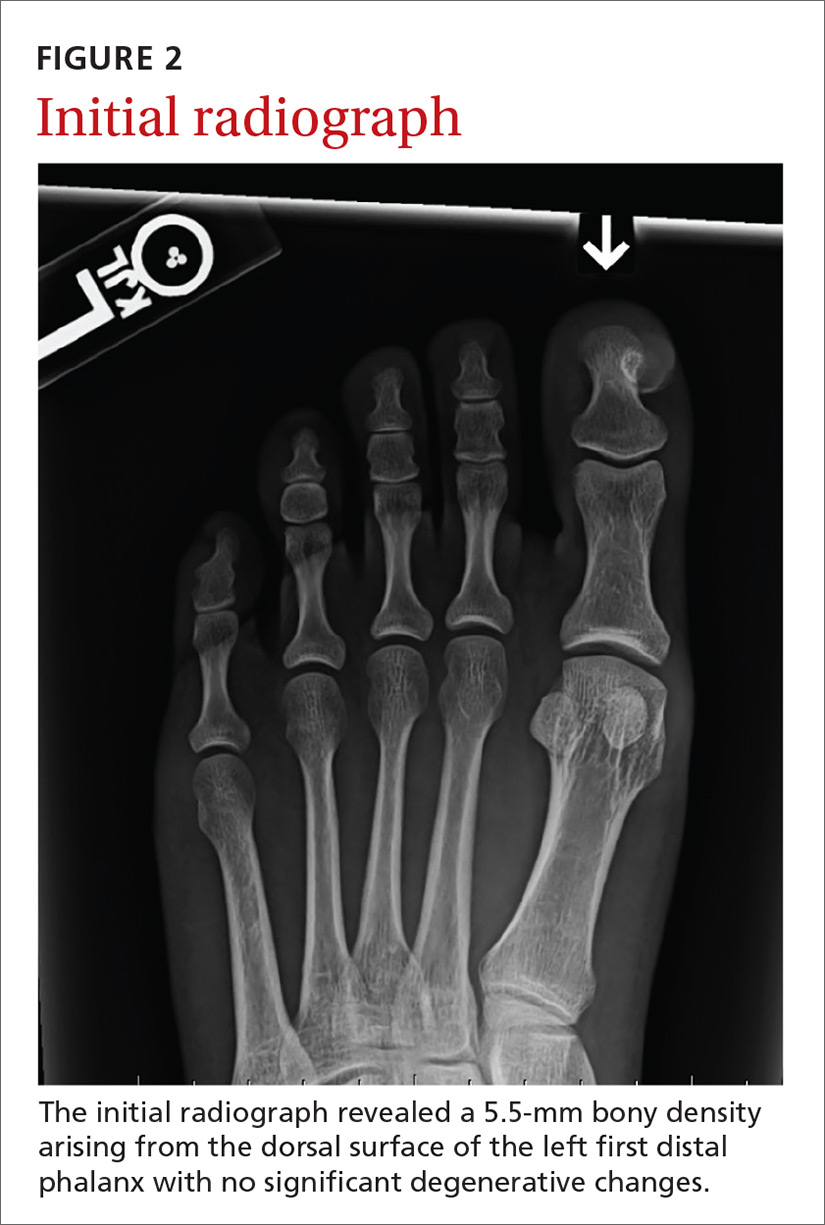

Physical examination revealed sharply demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques perinasally, periorally, and on the bilateral gluteal folds (Figure 1). There were sharply demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques on the right and left finger webs, dorsal surface of the right foot, and left upper thigh. Hemorrhagic bullae were appreciated on the left finger webs. Large flaccid bullae were present on the bilateral heels and dorsum of the right foot (Figure 2).

Suspecting a diagnosis of acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE), laboratory testing included a serum zinc level, which was 42 µg/dL (reference range, 70–130 µg/dL). The copper and selenium levels also were low with values of 71 µg/dL (reference range, 80–155 µg/dL) and 31 µg/dL (reference range, 79–326 µg/dL), respectively. No additional vitamin or mineral deficiencies were discovered. A complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were performed and showed no abnormalities other than a mildly elevated sodium level of 147 mEq/L (reference range, 136–142 mEq/L).

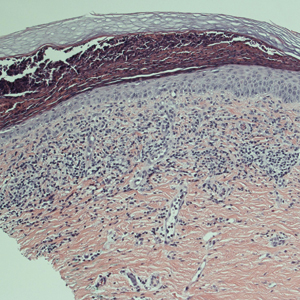

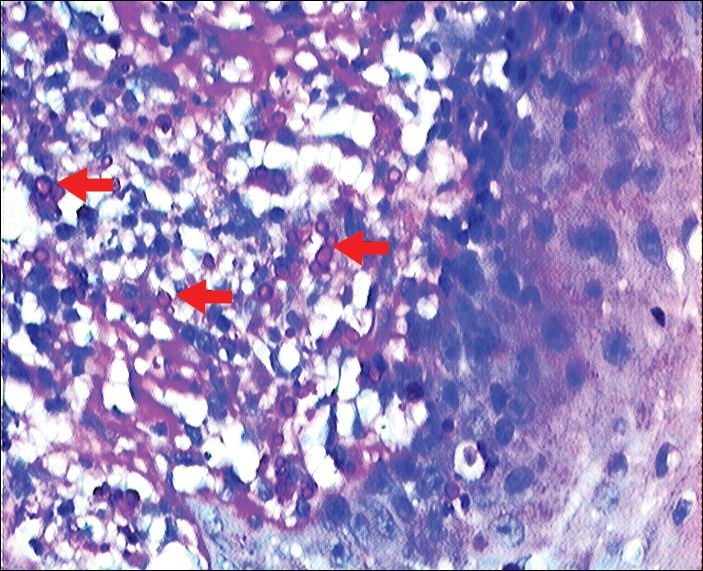

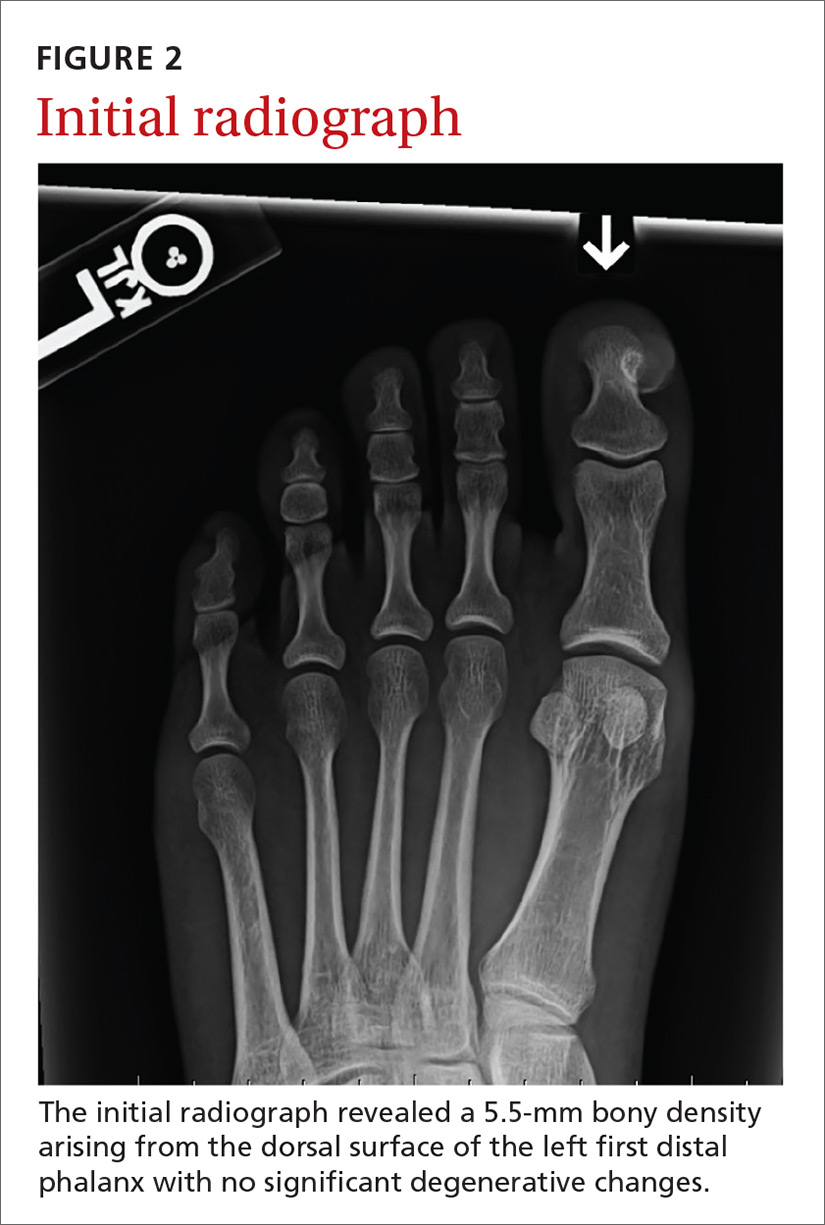

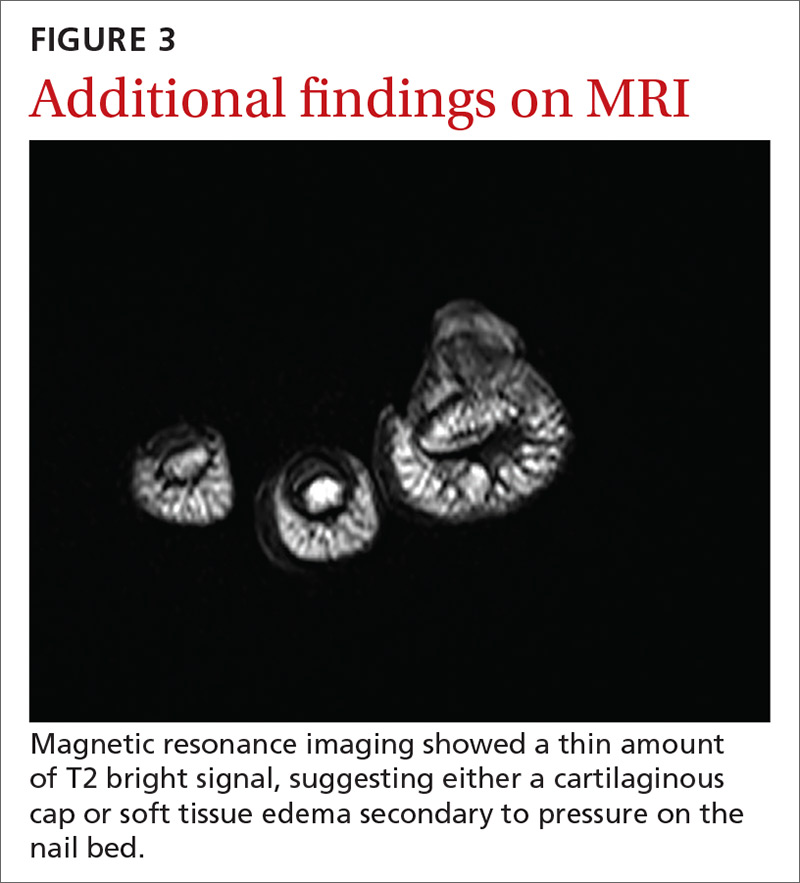

A punch biopsy was performed. Histopathology revealed subcorneal neutrophils and neutrophilic crust, mild spongiosis, and a dense upper dermal mixed neutrophilic and lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. The specimen also exhibited mild intercellular edema and prominent capillaries (Figure 3).

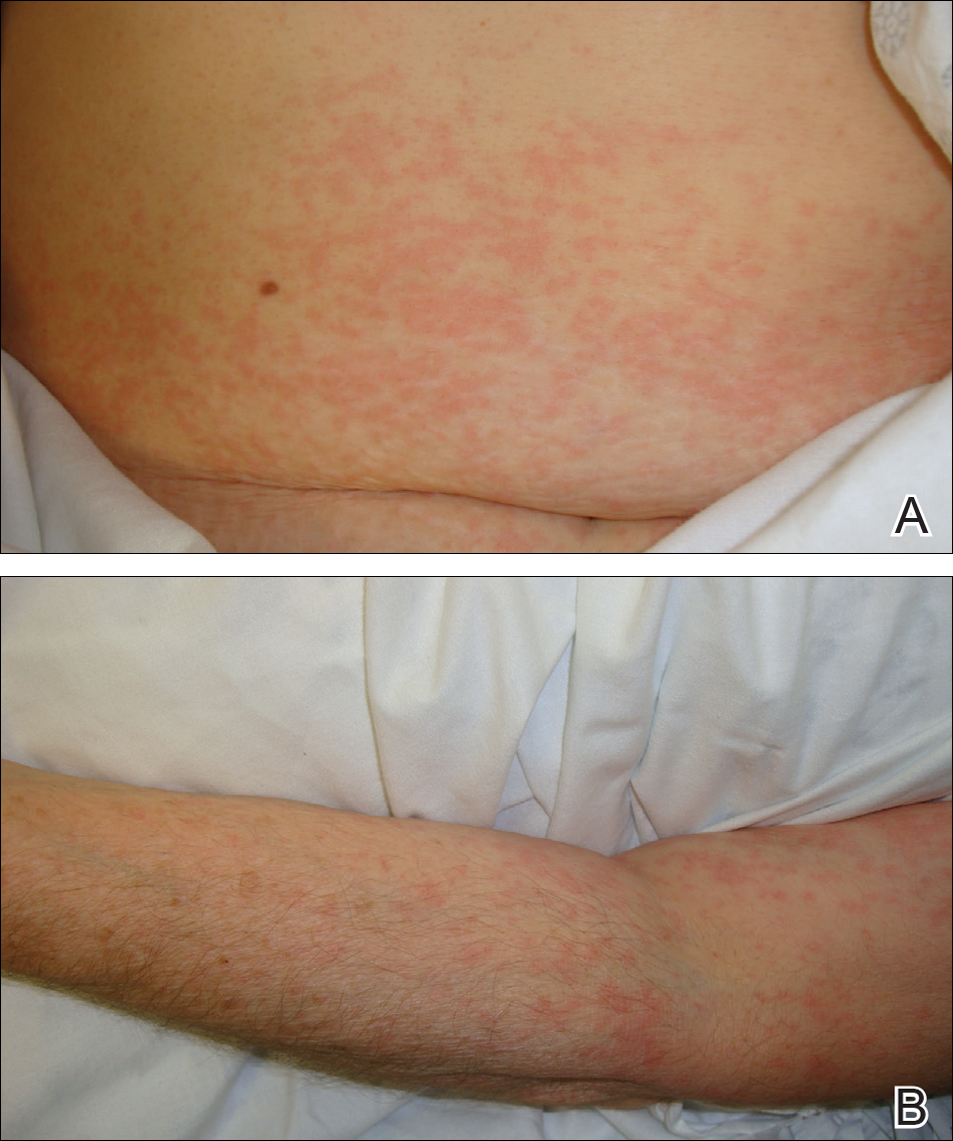

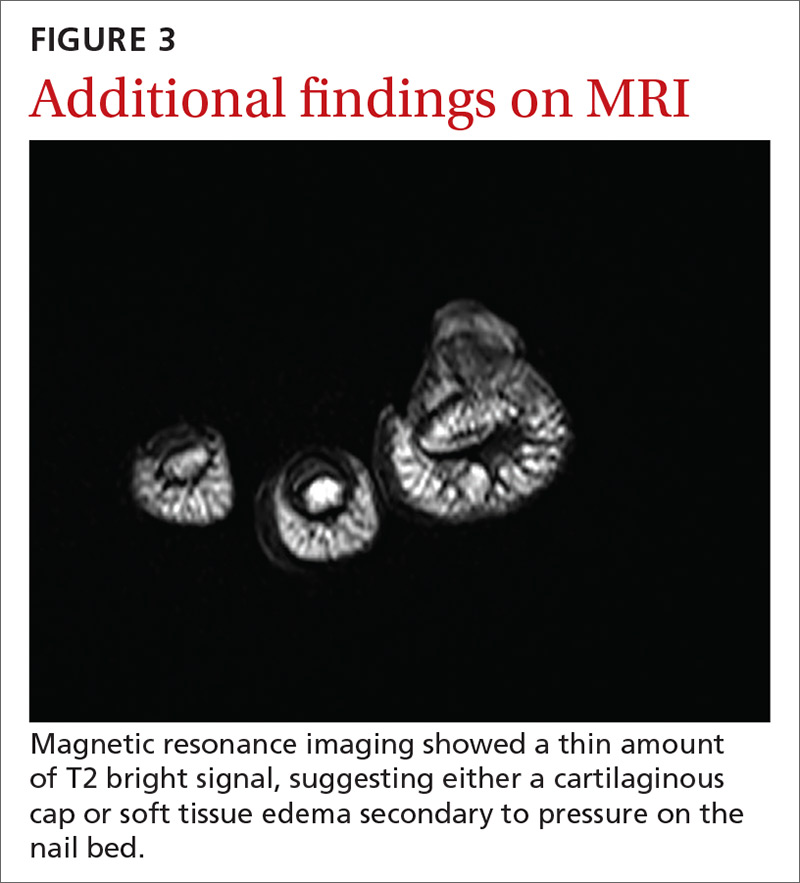

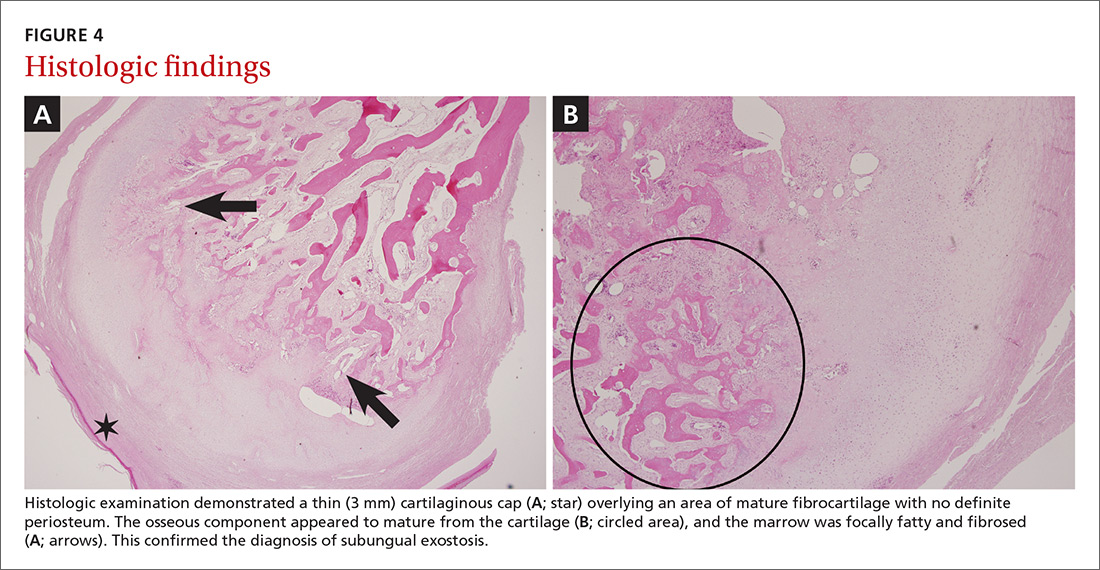

After further investigation, the company providing the patient’s TPN confirmed that zinc had been removed several weeks prior to the onset of symptoms due to a critical national shortage of trace element additives. Zinc was supplemented at 15 mg daily to the TPN solution. Three days later a skin examination revealed dramatic changes with notable improvement of the finger web plaques and complete resolution of the facial lesions. The plaques and bullae on the lower extremities also had resolved (Figure 4).

Comment

Background

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder of zinc metabolism characterized by skin lesions predominantly distributed in acral and periorificial sites as well as alopecia and diarrhea. Acrodermatitis enteropathica was first described by Brandt1 in 1936 and later characterized by Danbolt and Closs2 in 1942 as a unique and often fatal disease of unknown etiology. More than 30 years later, the link between zinc deficiency and AE was illustrated by Moynahan3 who demonstrated clinical improvement with zinc supplementation. It was not until 2002 that the molecular pathogenesis of hypozincemia in patients with inherited AE was described. Küry et al4 identified a mutation in the SLC39A4 gene responsible for encoding the Zip4 protein, a zinc transporter found on enterocytes, particularly in the proximal small intestine.5,6 Classically, patients with inherited AE are children who present within days of birth or days to weeks after being weaned from breast milk to cow’s milk. The zinc in bovine milk is less bioavailable than breast milk, though both have similar total zinc concentrations, which results in the decreased plasma zinc levels seen in children with inherited AE.5-8 Occasionally, children present before weaning due to decreased maternal mammary zinc secretion (lactogenic AE).9,10

Clinical Presentation

Similar clinical findings are seen in patients with noninherited forms of zinc deficiency known as acquired AE. Acquired zinc deficiency may be broadly categorized as being from inadequate intake, deficient absorption, excess demand, or overexcretion.8 Such disturbances of zinc balance are most frequently seen in patients with restrictive diets, anorexia nervosa, intestinal bypass procedures, Crohn disease, pancreatic insufficiency, alcoholism, human immunodeficiency virus, and extensive cutaneous burns. Premature infants, mothers who are breastfeeding, and those dependent on TPN are at risk for developing acquired zinc deficiency.7-9,11

Differentiating Characteristics

Both acquired and inherited AE present as erythematous or pink eczematous scaly plaques with the variable presence of vesicular or bullous lesions involving periorificial, acral, and anogenital regions. Early manifestations of AE may include angular cheilitis and paronychia. Alopecia and diarrhea are characteristics of later disease. In fact, the complete triad of dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea is seen in only 20% of cases.7 Without treatment, patients may develop blepharitis, conjunctivitis, photophobia, irritability, anorexia, apathy, growth retardation, hypogonadism, hypogeusia, and mental slowing. Skin lesions frequently become secondarily infected with Candida albicans and/or bacteria.5,7,11

Histopathology

Histopathologic examination of skin biopsy specimens from AE lesions demonstrates nonspecific findings similar to other deficiency dermatoses, such as pellagra and glucagonoma-associated necrolytic migratory erythema. Histology typically reveals cytoplasmic pallor with vacuolization and ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes, followed by confluent keratinocyte necrosis within the stratum granulosum and stratum spinosum of the epidermis.5 Confluent parakeratosis with hypogranulosis variably associated with neutrophil crust also is seen. Scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes may be found within all levels of the epidermis. In resolving or chronic AE lesions, psoriasiform hyperplasia is prevalent, though necrolysis may be minimal or absent.5,11

Diagnosis

Evaluation includes measurement of plasma zinc levels. Zinc levels less than 50 µg/dL are suggestive but not diagnostic of AE.5 Although plasma zinc measurement is the most useful indicator of zinc status, its utility in assessing the true total body store of zinc is limited. Plasma zinc is tightly regulated and only represents 0.1% of body stores.5,6 Additionally, zinc levels may decrease in proinflammatory states.12 Beyond zinc measurement, evaluation of alkaline phosphatase, a zinc-dependent enzyme, can provide useful diagnostic information.5,6

Zinc and TPN

Patients on TPN are at a unique risk for developing zinc and other nutritional deficiencies. Because the daily recommended dietary allowance for zinc is low (8 mg daily for adult women and 11 mg daily for adult men)5 and the element is found in a wide variety of foods, maintaining adequate zinc levels is easily achieved in healthy individuals with normal diets. Kay et al13 described 4 patients on parenteral nutrition who developed hypozincemia and an AE-like syndrome within weeks of TPN induction. The authors described rapid and drastic clinical improvement after initiating zinc supplementation, accentuating the importance of including zinc as a component of TPN.13,14 Brazin et al15 also reported a case of an AE-like syndrome from zinc-deficient hyperalimentation in a patient receiving TPN for short bowel syndrome. Chun et al16 described another case of acquired AE in a patient on TPN for acute pancreatitis. Both cases demonstrated prompt improvement of skin lesions after treatment with zinc supplementation. Other nutrient deficiencies may reveal themselves through similar dermatologic manifestations. For example, cases of scaly dermatitis secondary to the development of essential fatty acid deficiency from TPN formulations lacking adequate quantities of linoleic acid have been reported.Similar to our case, the resolution of skin lesions was seen after TPN was supplemented with the deficient nutrient.17 These cases exemplify the importance in considering deficiency dermatoses in the TPN-dependent patient population.

Conclusion

In our case, the development of skin lesions directly coincided with a recent removal of zinc from the patient’s TPN, which provided us with a unique opportunity to observe the causal relationship between decreased zinc intake and the development of clinical signs of acquired AE. This association was further elucidated by laboratory confirmation of low serum zinc levels and rapid improvement in all skin lesions after zinc supplementation was initiated.

- Brandt T. Dermatitis in children with disturbances of general condition and absorption of food. Acta Derm Venereol. 1936;17:513-537.

- Danbolt N, Closs K. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. Acta Derm Venereol. 1942;23:127-169.

- Moynahan E. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: a lethal inherited human zinc deficiency disorder. Lancet. 1974;2:299-400.

- Küry S, Dréno B, Bézieau S, et al. Identification of SLC39A4, a gene involved in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Nat Genet. 2002;31:238-240.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease: part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:211.e1-211.e33; quiz 244-246.

- Perafán-Riveros C, França LF, Alves AC, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- Kumar P, Ranjan NR, Mondal AK. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Saritha M, Gupta D, Chandrashekar L, et al. Acquired zinc deficiency in an adult female. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:492-494.

- Neldner K, Hambidge K, Walravens P. Acrodermatitis enteropathica.Int J Dermatol. 1978;17:380-387.

- Gehrig K, Dinulos J. Acrodermatitis due to nutritional deficiency. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:107-112.

- Liuzzi JP, Lichten LA, Rivera S, et al. Interleukin-6 regulates the zinc transporter Zip14 in liver and contributes to hypozincemia of the acute-phase response. Proct Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6843-6848.

- Kay RG, Tasman-Jones C, Pybus J, et al. A syndrome of acute zinc deficiency during total parenteral nutrition in man. Ann Surg. 1976;183:331-340.

- Jeejeebhoy K. Zinc: an essential trace element for parenteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(5 suppl):S7-S12.

- Brazin SA, Johnson WT, Abramson LJ. The acrodermatitis enteropathica-like syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:597-599.

- Chun JH, Baek JH, Chung NG. Development of bullous acrodermatitis enteropathica during the course of chemotherapy for acute lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S326-S328.

- Roongpisuthipong W, Phanachet P, Roongpisuthipong C, et al. Essential fatty acid deficiency while a patient receiving fat regimen total parenteral nutrition [published June 14, 2012]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2011.4475.

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with a pruritic and slightly painful skin eruption that began perinasally and progressed over 1 week to involve the labial commissures, finger webs, dorsal surfaces of the feet, heels, and bilateral gluteal folds. In addition, the eruption involved the left thigh at the donor site of a prior skin graft. She received no relief after an intramuscular steroid injection and hydrocortisone cream 1% prescribed by a primary care physician who diagnosed the rash as poison ivy contact dermatitis despite no exposure to plants. Review of systems was negative and she denied any new medication use. Her medical history was notable for extensive mesenteric injury secondary to a motor vehicle accident. She subsequently had multiple enterocutaneous fistulas that resulted in a complete small bowel enterectomy 10 months prior to presentation, which caused her to become dependent on total parenteral nutrition (TPN).

Physical examination revealed sharply demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques perinasally, periorally, and on the bilateral gluteal folds (Figure 1). There were sharply demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques on the right and left finger webs, dorsal surface of the right foot, and left upper thigh. Hemorrhagic bullae were appreciated on the left finger webs. Large flaccid bullae were present on the bilateral heels and dorsum of the right foot (Figure 2).

Suspecting a diagnosis of acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE), laboratory testing included a serum zinc level, which was 42 µg/dL (reference range, 70–130 µg/dL). The copper and selenium levels also were low with values of 71 µg/dL (reference range, 80–155 µg/dL) and 31 µg/dL (reference range, 79–326 µg/dL), respectively. No additional vitamin or mineral deficiencies were discovered. A complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were performed and showed no abnormalities other than a mildly elevated sodium level of 147 mEq/L (reference range, 136–142 mEq/L).

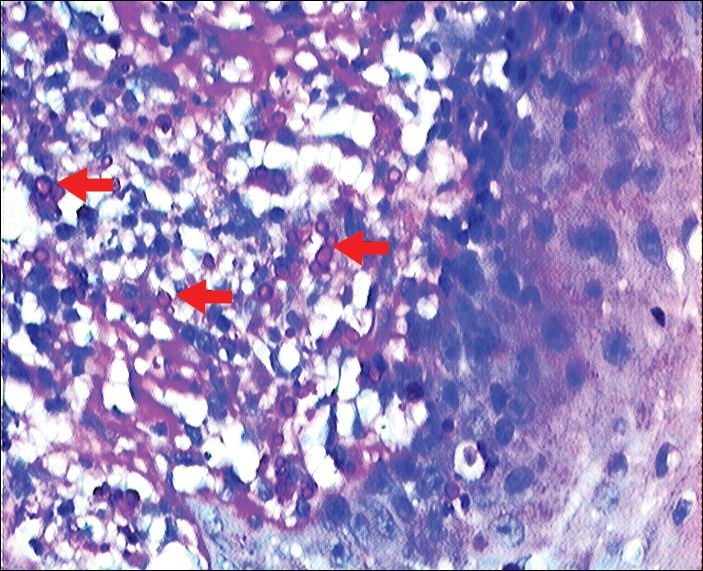

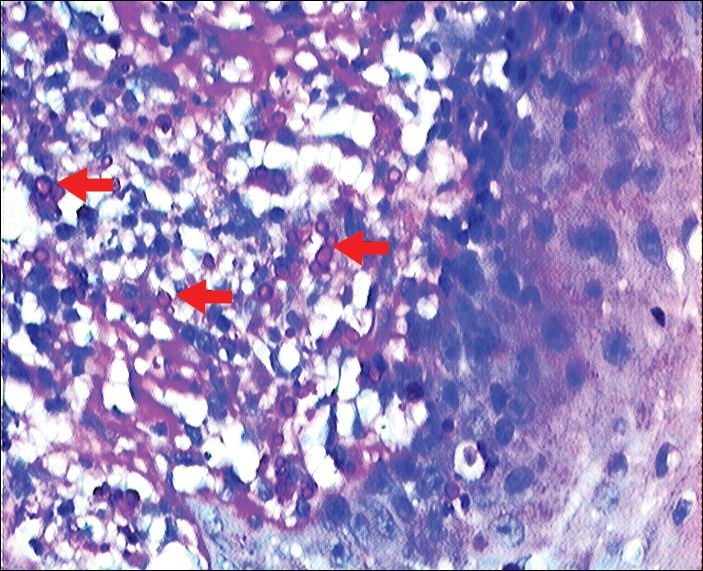

A punch biopsy was performed. Histopathology revealed subcorneal neutrophils and neutrophilic crust, mild spongiosis, and a dense upper dermal mixed neutrophilic and lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. The specimen also exhibited mild intercellular edema and prominent capillaries (Figure 3).

After further investigation, the company providing the patient’s TPN confirmed that zinc had been removed several weeks prior to the onset of symptoms due to a critical national shortage of trace element additives. Zinc was supplemented at 15 mg daily to the TPN solution. Three days later a skin examination revealed dramatic changes with notable improvement of the finger web plaques and complete resolution of the facial lesions. The plaques and bullae on the lower extremities also had resolved (Figure 4).

Comment

Background

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder of zinc metabolism characterized by skin lesions predominantly distributed in acral and periorificial sites as well as alopecia and diarrhea. Acrodermatitis enteropathica was first described by Brandt1 in 1936 and later characterized by Danbolt and Closs2 in 1942 as a unique and often fatal disease of unknown etiology. More than 30 years later, the link between zinc deficiency and AE was illustrated by Moynahan3 who demonstrated clinical improvement with zinc supplementation. It was not until 2002 that the molecular pathogenesis of hypozincemia in patients with inherited AE was described. Küry et al4 identified a mutation in the SLC39A4 gene responsible for encoding the Zip4 protein, a zinc transporter found on enterocytes, particularly in the proximal small intestine.5,6 Classically, patients with inherited AE are children who present within days of birth or days to weeks after being weaned from breast milk to cow’s milk. The zinc in bovine milk is less bioavailable than breast milk, though both have similar total zinc concentrations, which results in the decreased plasma zinc levels seen in children with inherited AE.5-8 Occasionally, children present before weaning due to decreased maternal mammary zinc secretion (lactogenic AE).9,10

Clinical Presentation

Similar clinical findings are seen in patients with noninherited forms of zinc deficiency known as acquired AE. Acquired zinc deficiency may be broadly categorized as being from inadequate intake, deficient absorption, excess demand, or overexcretion.8 Such disturbances of zinc balance are most frequently seen in patients with restrictive diets, anorexia nervosa, intestinal bypass procedures, Crohn disease, pancreatic insufficiency, alcoholism, human immunodeficiency virus, and extensive cutaneous burns. Premature infants, mothers who are breastfeeding, and those dependent on TPN are at risk for developing acquired zinc deficiency.7-9,11

Differentiating Characteristics

Both acquired and inherited AE present as erythematous or pink eczematous scaly plaques with the variable presence of vesicular or bullous lesions involving periorificial, acral, and anogenital regions. Early manifestations of AE may include angular cheilitis and paronychia. Alopecia and diarrhea are characteristics of later disease. In fact, the complete triad of dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea is seen in only 20% of cases.7 Without treatment, patients may develop blepharitis, conjunctivitis, photophobia, irritability, anorexia, apathy, growth retardation, hypogonadism, hypogeusia, and mental slowing. Skin lesions frequently become secondarily infected with Candida albicans and/or bacteria.5,7,11

Histopathology

Histopathologic examination of skin biopsy specimens from AE lesions demonstrates nonspecific findings similar to other deficiency dermatoses, such as pellagra and glucagonoma-associated necrolytic migratory erythema. Histology typically reveals cytoplasmic pallor with vacuolization and ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes, followed by confluent keratinocyte necrosis within the stratum granulosum and stratum spinosum of the epidermis.5 Confluent parakeratosis with hypogranulosis variably associated with neutrophil crust also is seen. Scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes may be found within all levels of the epidermis. In resolving or chronic AE lesions, psoriasiform hyperplasia is prevalent, though necrolysis may be minimal or absent.5,11

Diagnosis

Evaluation includes measurement of plasma zinc levels. Zinc levels less than 50 µg/dL are suggestive but not diagnostic of AE.5 Although plasma zinc measurement is the most useful indicator of zinc status, its utility in assessing the true total body store of zinc is limited. Plasma zinc is tightly regulated and only represents 0.1% of body stores.5,6 Additionally, zinc levels may decrease in proinflammatory states.12 Beyond zinc measurement, evaluation of alkaline phosphatase, a zinc-dependent enzyme, can provide useful diagnostic information.5,6

Zinc and TPN

Patients on TPN are at a unique risk for developing zinc and other nutritional deficiencies. Because the daily recommended dietary allowance for zinc is low (8 mg daily for adult women and 11 mg daily for adult men)5 and the element is found in a wide variety of foods, maintaining adequate zinc levels is easily achieved in healthy individuals with normal diets. Kay et al13 described 4 patients on parenteral nutrition who developed hypozincemia and an AE-like syndrome within weeks of TPN induction. The authors described rapid and drastic clinical improvement after initiating zinc supplementation, accentuating the importance of including zinc as a component of TPN.13,14 Brazin et al15 also reported a case of an AE-like syndrome from zinc-deficient hyperalimentation in a patient receiving TPN for short bowel syndrome. Chun et al16 described another case of acquired AE in a patient on TPN for acute pancreatitis. Both cases demonstrated prompt improvement of skin lesions after treatment with zinc supplementation. Other nutrient deficiencies may reveal themselves through similar dermatologic manifestations. For example, cases of scaly dermatitis secondary to the development of essential fatty acid deficiency from TPN formulations lacking adequate quantities of linoleic acid have been reported.Similar to our case, the resolution of skin lesions was seen after TPN was supplemented with the deficient nutrient.17 These cases exemplify the importance in considering deficiency dermatoses in the TPN-dependent patient population.

Conclusion

In our case, the development of skin lesions directly coincided with a recent removal of zinc from the patient’s TPN, which provided us with a unique opportunity to observe the causal relationship between decreased zinc intake and the development of clinical signs of acquired AE. This association was further elucidated by laboratory confirmation of low serum zinc levels and rapid improvement in all skin lesions after zinc supplementation was initiated.

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with a pruritic and slightly painful skin eruption that began perinasally and progressed over 1 week to involve the labial commissures, finger webs, dorsal surfaces of the feet, heels, and bilateral gluteal folds. In addition, the eruption involved the left thigh at the donor site of a prior skin graft. She received no relief after an intramuscular steroid injection and hydrocortisone cream 1% prescribed by a primary care physician who diagnosed the rash as poison ivy contact dermatitis despite no exposure to plants. Review of systems was negative and she denied any new medication use. Her medical history was notable for extensive mesenteric injury secondary to a motor vehicle accident. She subsequently had multiple enterocutaneous fistulas that resulted in a complete small bowel enterectomy 10 months prior to presentation, which caused her to become dependent on total parenteral nutrition (TPN).

Physical examination revealed sharply demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques perinasally, periorally, and on the bilateral gluteal folds (Figure 1). There were sharply demarcated, erythematous, scaly plaques on the right and left finger webs, dorsal surface of the right foot, and left upper thigh. Hemorrhagic bullae were appreciated on the left finger webs. Large flaccid bullae were present on the bilateral heels and dorsum of the right foot (Figure 2).

Suspecting a diagnosis of acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE), laboratory testing included a serum zinc level, which was 42 µg/dL (reference range, 70–130 µg/dL). The copper and selenium levels also were low with values of 71 µg/dL (reference range, 80–155 µg/dL) and 31 µg/dL (reference range, 79–326 µg/dL), respectively. No additional vitamin or mineral deficiencies were discovered. A complete blood cell count and comprehensive metabolic panel were performed and showed no abnormalities other than a mildly elevated sodium level of 147 mEq/L (reference range, 136–142 mEq/L).

A punch biopsy was performed. Histopathology revealed subcorneal neutrophils and neutrophilic crust, mild spongiosis, and a dense upper dermal mixed neutrophilic and lymphohistiocytic infiltrate. The specimen also exhibited mild intercellular edema and prominent capillaries (Figure 3).

After further investigation, the company providing the patient’s TPN confirmed that zinc had been removed several weeks prior to the onset of symptoms due to a critical national shortage of trace element additives. Zinc was supplemented at 15 mg daily to the TPN solution. Three days later a skin examination revealed dramatic changes with notable improvement of the finger web plaques and complete resolution of the facial lesions. The plaques and bullae on the lower extremities also had resolved (Figure 4).

Comment

Background

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is a rare autosomal-recessive disorder of zinc metabolism characterized by skin lesions predominantly distributed in acral and periorificial sites as well as alopecia and diarrhea. Acrodermatitis enteropathica was first described by Brandt1 in 1936 and later characterized by Danbolt and Closs2 in 1942 as a unique and often fatal disease of unknown etiology. More than 30 years later, the link between zinc deficiency and AE was illustrated by Moynahan3 who demonstrated clinical improvement with zinc supplementation. It was not until 2002 that the molecular pathogenesis of hypozincemia in patients with inherited AE was described. Küry et al4 identified a mutation in the SLC39A4 gene responsible for encoding the Zip4 protein, a zinc transporter found on enterocytes, particularly in the proximal small intestine.5,6 Classically, patients with inherited AE are children who present within days of birth or days to weeks after being weaned from breast milk to cow’s milk. The zinc in bovine milk is less bioavailable than breast milk, though both have similar total zinc concentrations, which results in the decreased plasma zinc levels seen in children with inherited AE.5-8 Occasionally, children present before weaning due to decreased maternal mammary zinc secretion (lactogenic AE).9,10

Clinical Presentation

Similar clinical findings are seen in patients with noninherited forms of zinc deficiency known as acquired AE. Acquired zinc deficiency may be broadly categorized as being from inadequate intake, deficient absorption, excess demand, or overexcretion.8 Such disturbances of zinc balance are most frequently seen in patients with restrictive diets, anorexia nervosa, intestinal bypass procedures, Crohn disease, pancreatic insufficiency, alcoholism, human immunodeficiency virus, and extensive cutaneous burns. Premature infants, mothers who are breastfeeding, and those dependent on TPN are at risk for developing acquired zinc deficiency.7-9,11

Differentiating Characteristics

Both acquired and inherited AE present as erythematous or pink eczematous scaly plaques with the variable presence of vesicular or bullous lesions involving periorificial, acral, and anogenital regions. Early manifestations of AE may include angular cheilitis and paronychia. Alopecia and diarrhea are characteristics of later disease. In fact, the complete triad of dermatitis, alopecia, and diarrhea is seen in only 20% of cases.7 Without treatment, patients may develop blepharitis, conjunctivitis, photophobia, irritability, anorexia, apathy, growth retardation, hypogonadism, hypogeusia, and mental slowing. Skin lesions frequently become secondarily infected with Candida albicans and/or bacteria.5,7,11

Histopathology

Histopathologic examination of skin biopsy specimens from AE lesions demonstrates nonspecific findings similar to other deficiency dermatoses, such as pellagra and glucagonoma-associated necrolytic migratory erythema. Histology typically reveals cytoplasmic pallor with vacuolization and ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes, followed by confluent keratinocyte necrosis within the stratum granulosum and stratum spinosum of the epidermis.5 Confluent parakeratosis with hypogranulosis variably associated with neutrophil crust also is seen. Scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes may be found within all levels of the epidermis. In resolving or chronic AE lesions, psoriasiform hyperplasia is prevalent, though necrolysis may be minimal or absent.5,11

Diagnosis

Evaluation includes measurement of plasma zinc levels. Zinc levels less than 50 µg/dL are suggestive but not diagnostic of AE.5 Although plasma zinc measurement is the most useful indicator of zinc status, its utility in assessing the true total body store of zinc is limited. Plasma zinc is tightly regulated and only represents 0.1% of body stores.5,6 Additionally, zinc levels may decrease in proinflammatory states.12 Beyond zinc measurement, evaluation of alkaline phosphatase, a zinc-dependent enzyme, can provide useful diagnostic information.5,6

Zinc and TPN

Patients on TPN are at a unique risk for developing zinc and other nutritional deficiencies. Because the daily recommended dietary allowance for zinc is low (8 mg daily for adult women and 11 mg daily for adult men)5 and the element is found in a wide variety of foods, maintaining adequate zinc levels is easily achieved in healthy individuals with normal diets. Kay et al13 described 4 patients on parenteral nutrition who developed hypozincemia and an AE-like syndrome within weeks of TPN induction. The authors described rapid and drastic clinical improvement after initiating zinc supplementation, accentuating the importance of including zinc as a component of TPN.13,14 Brazin et al15 also reported a case of an AE-like syndrome from zinc-deficient hyperalimentation in a patient receiving TPN for short bowel syndrome. Chun et al16 described another case of acquired AE in a patient on TPN for acute pancreatitis. Both cases demonstrated prompt improvement of skin lesions after treatment with zinc supplementation. Other nutrient deficiencies may reveal themselves through similar dermatologic manifestations. For example, cases of scaly dermatitis secondary to the development of essential fatty acid deficiency from TPN formulations lacking adequate quantities of linoleic acid have been reported.Similar to our case, the resolution of skin lesions was seen after TPN was supplemented with the deficient nutrient.17 These cases exemplify the importance in considering deficiency dermatoses in the TPN-dependent patient population.

Conclusion

In our case, the development of skin lesions directly coincided with a recent removal of zinc from the patient’s TPN, which provided us with a unique opportunity to observe the causal relationship between decreased zinc intake and the development of clinical signs of acquired AE. This association was further elucidated by laboratory confirmation of low serum zinc levels and rapid improvement in all skin lesions after zinc supplementation was initiated.

- Brandt T. Dermatitis in children with disturbances of general condition and absorption of food. Acta Derm Venereol. 1936;17:513-537.

- Danbolt N, Closs K. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. Acta Derm Venereol. 1942;23:127-169.

- Moynahan E. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: a lethal inherited human zinc deficiency disorder. Lancet. 1974;2:299-400.

- Küry S, Dréno B, Bézieau S, et al. Identification of SLC39A4, a gene involved in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Nat Genet. 2002;31:238-240.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease: part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:211.e1-211.e33; quiz 244-246.

- Perafán-Riveros C, França LF, Alves AC, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- Kumar P, Ranjan NR, Mondal AK. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Saritha M, Gupta D, Chandrashekar L, et al. Acquired zinc deficiency in an adult female. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:492-494.

- Neldner K, Hambidge K, Walravens P. Acrodermatitis enteropathica.Int J Dermatol. 1978;17:380-387.

- Gehrig K, Dinulos J. Acrodermatitis due to nutritional deficiency. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:107-112.

- Liuzzi JP, Lichten LA, Rivera S, et al. Interleukin-6 regulates the zinc transporter Zip14 in liver and contributes to hypozincemia of the acute-phase response. Proct Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6843-6848.

- Kay RG, Tasman-Jones C, Pybus J, et al. A syndrome of acute zinc deficiency during total parenteral nutrition in man. Ann Surg. 1976;183:331-340.

- Jeejeebhoy K. Zinc: an essential trace element for parenteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(5 suppl):S7-S12.

- Brazin SA, Johnson WT, Abramson LJ. The acrodermatitis enteropathica-like syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:597-599.

- Chun JH, Baek JH, Chung NG. Development of bullous acrodermatitis enteropathica during the course of chemotherapy for acute lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S326-S328.

- Roongpisuthipong W, Phanachet P, Roongpisuthipong C, et al. Essential fatty acid deficiency while a patient receiving fat regimen total parenteral nutrition [published June 14, 2012]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2011.4475.

- Brandt T. Dermatitis in children with disturbances of general condition and absorption of food. Acta Derm Venereol. 1936;17:513-537.

- Danbolt N, Closs K. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. Acta Derm Venereol. 1942;23:127-169.

- Moynahan E. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: a lethal inherited human zinc deficiency disorder. Lancet. 1974;2:299-400.

- Küry S, Dréno B, Bézieau S, et al. Identification of SLC39A4, a gene involved in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Nat Genet. 2002;31:238-240.

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116-124.

- Thrash B, Patel M, Shah KR, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of gastrointestinal disease: part II. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:211.e1-211.e33; quiz 244-246.

- Perafán-Riveros C, França LF, Alves AC, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426-431.

- Kumar P, Ranjan NR, Mondal AK. Zinc and skin: a brief summary. Dermatol Online J. 2012;18:1.

- Saritha M, Gupta D, Chandrashekar L, et al. Acquired zinc deficiency in an adult female. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:492-494.

- Neldner K, Hambidge K, Walravens P. Acrodermatitis enteropathica.Int J Dermatol. 1978;17:380-387.

- Gehrig K, Dinulos J. Acrodermatitis due to nutritional deficiency. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22:107-112.

- Liuzzi JP, Lichten LA, Rivera S, et al. Interleukin-6 regulates the zinc transporter Zip14 in liver and contributes to hypozincemia of the acute-phase response. Proct Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:6843-6848.

- Kay RG, Tasman-Jones C, Pybus J, et al. A syndrome of acute zinc deficiency during total parenteral nutrition in man. Ann Surg. 1976;183:331-340.

- Jeejeebhoy K. Zinc: an essential trace element for parenteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(5 suppl):S7-S12.

- Brazin SA, Johnson WT, Abramson LJ. The acrodermatitis enteropathica-like syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:597-599.

- Chun JH, Baek JH, Chung NG. Development of bullous acrodermatitis enteropathica during the course of chemotherapy for acute lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23(suppl 3):S326-S328.

- Roongpisuthipong W, Phanachet P, Roongpisuthipong C, et al. Essential fatty acid deficiency while a patient receiving fat regimen total parenteral nutrition [published June 14, 2012]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr.07.2011.4475.

Practice Points

- Acrodermatitis enteropathica (AE) may be acquired or due to a rare autosomal-recessive disorder of zinc absorption.

- Hereditary AE typically becomes symptomatic during infancy, while acquired AE may develop during hypozincemia in patients of any age.

- Both acquired and hereditary AE improve with zinc supplementation.

Uncommon Presentation of Chromoblastomycosis

Case Report

A 25-year-old man who was a dairy farmer in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, India, presented with a history of slowly growing, occasionally itchy lesions on both cheeks of 20 years’ duration. Most of the right cheek was covered by a well-defined, lobulated, gray-brown verrucous mass with a cerebriform surface (Figure 1). The left cheek was covered with a gray-brown infiltrated plaque surrounded by brown-tinged monomorphic papules.

Routine investigations were normal at presentation. Tests for purified protein derivative (tuberculin) and antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus were negative. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed soft tissue thickening with ulcerations involving the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and underlying facial muscles of the right cheek.

On histopathology, a hematoxylin and eosin–stained section showed hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and follicular plugs in the epidermis, as well as a mixed cellular infiltrate with Langhans giant cells and sclerotic bodies in the dermis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and methenamine silver special stains revealed sclerotic bodies.

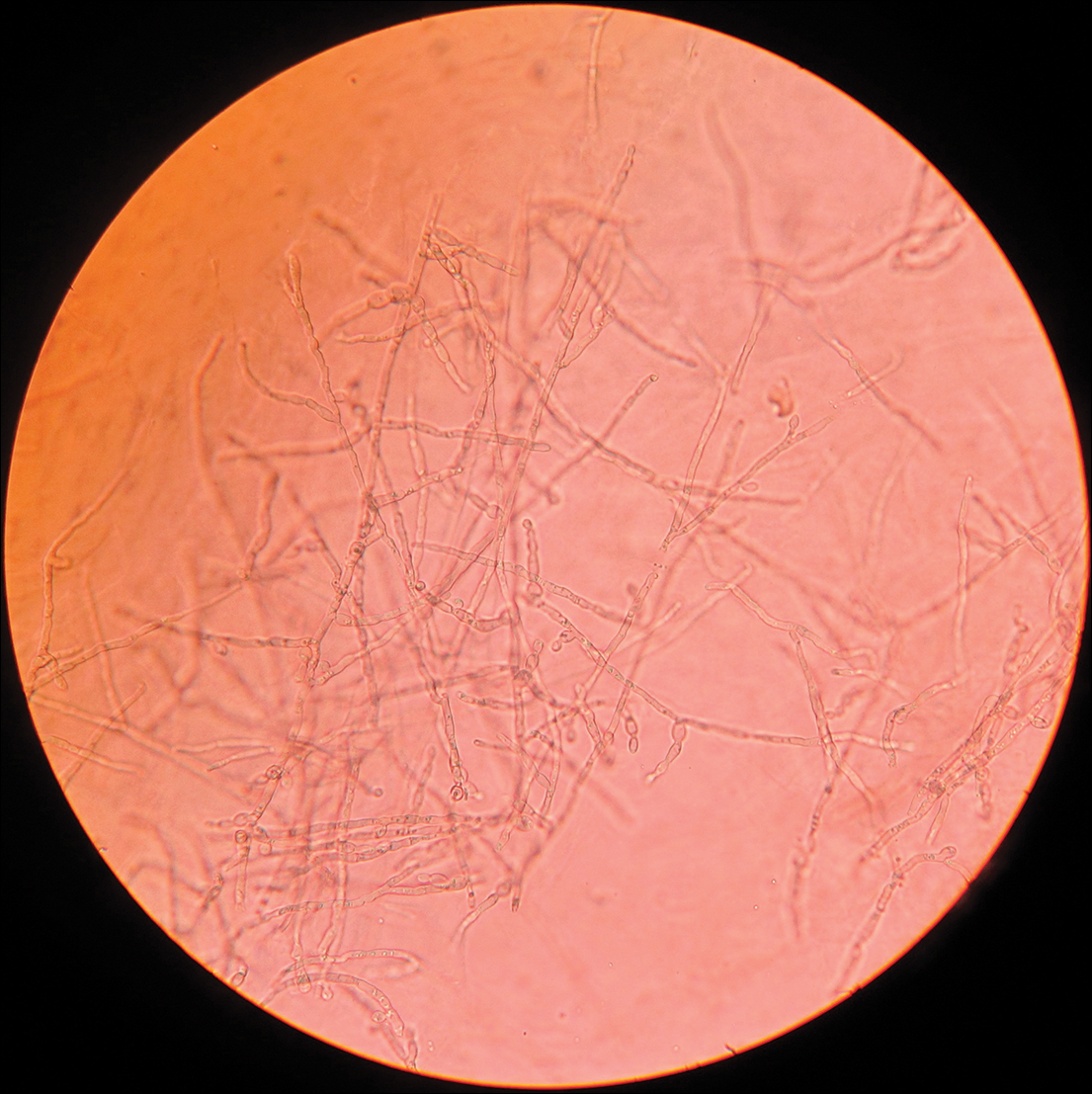

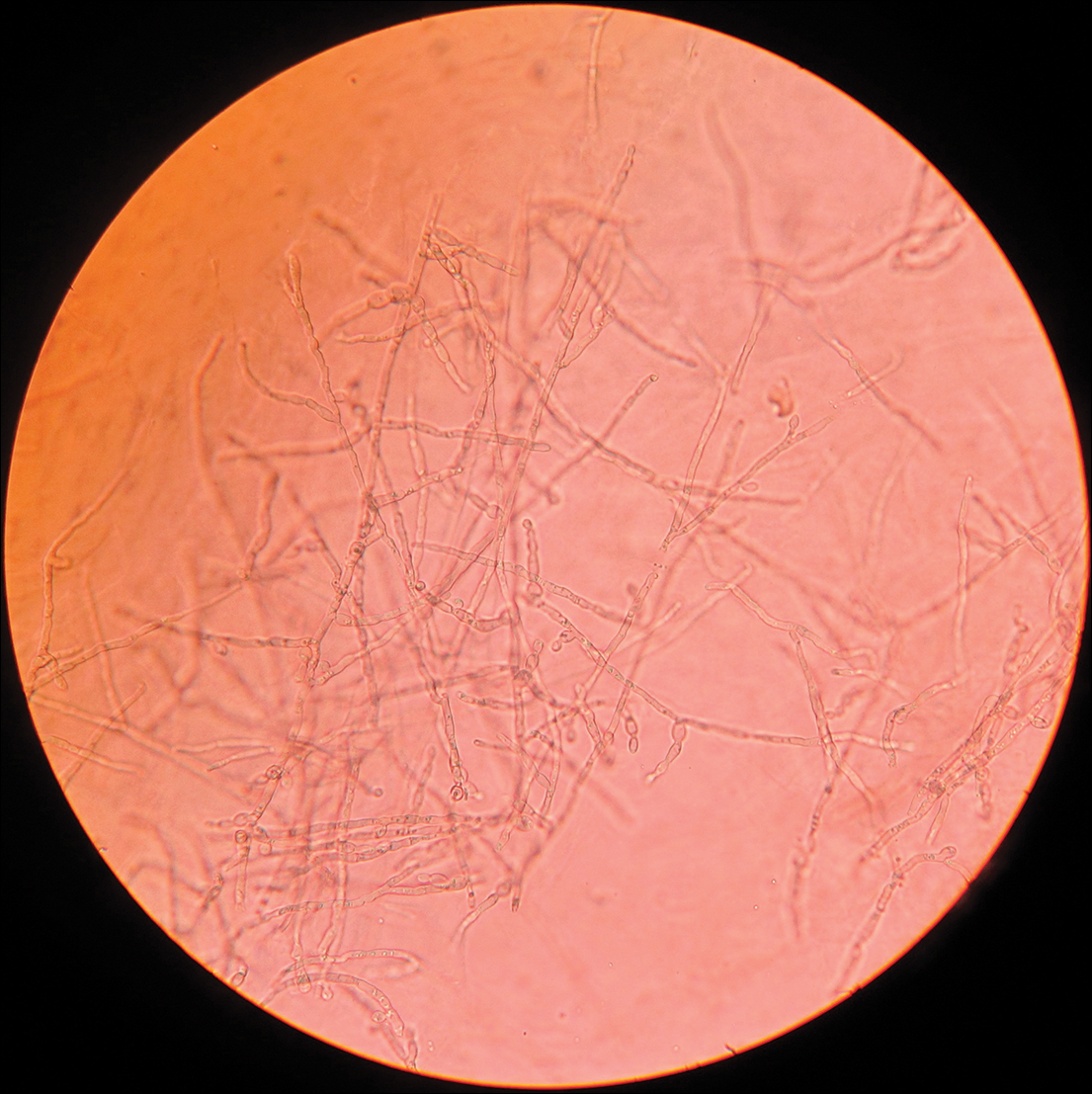

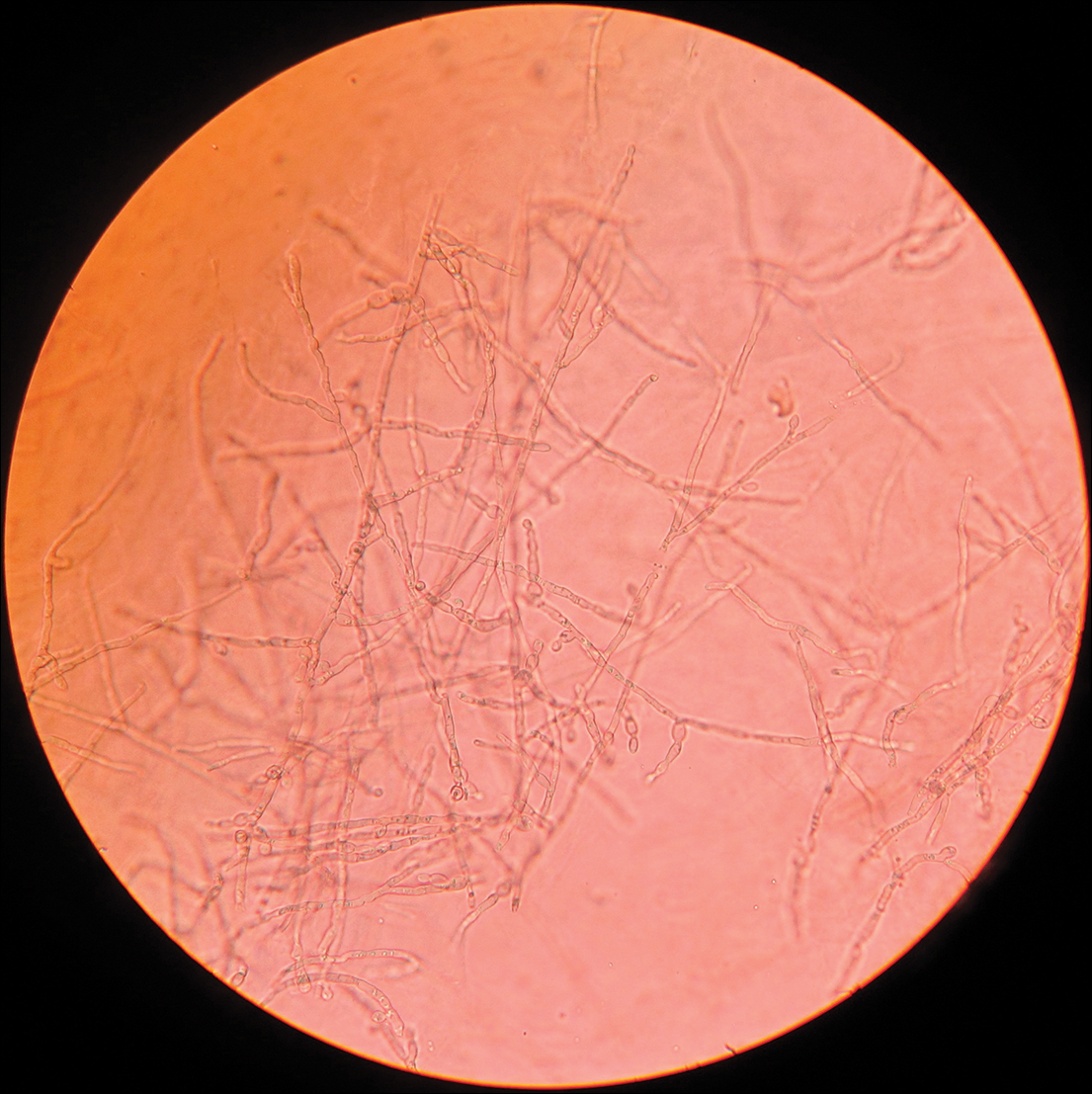

Fungal culture on Sabouraud dextrose agar at 25°C and 37°C grew olive green, rugose, velvety, leathery colonies within 48 hours, with pigmentation front and reverse (Figure 3). A panfungal polymerase chain reaction assay was positive. Direct microscopic examination of a 10% potassium hydroxide mount of the colonies showed mycelia with dematiaceous septate hyphae (Figure 4), apical branching, branching conidiophores, elliptical conidia in long chains, and pathognomonic round yeastlike bodies resembling copper pennies known as sclerotic cells (also called muriform cells and medlar bodies).1,2 The causative organism was identified as Cladosporium carrionii. A final diagnosis of chromoblastomycosis was made.

After 2 months of treatment with oral itraconazole 400 mg daily, there was no notable clinical improvement and fungal elements were still seen on culture. Four treatment cycles of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B 50 mg daily (1 mg/kg daily) for 15 days followed by itraconazole 200 mg daily for another 15 days caused substantial reduction and flattening of the lesion on the right side and resolution of the lesions on the left side. Healing was accompanied by central erythema and depigmentation (Figure 5). With a suspicion of continuing C carrionii activity on the right cheek, intralesional liposomal amphotericin B 0.2 mL (in a dilution of 5 mg in 1 mL) was given weekly in the peripheral hyperpigmented raised margin, which resulted in further flattening and reduction in tissue resistance. Fungal elements were absent on repeat biopsy and culture after 4 weeks.

Six months after negative culture, further cosmetic correction of the scar on the right cheek was performed with a patterned full-thickness graft for the upper half and excision with approximation of the edges for the lower half (Figure 6). Cultures have been negative for the last 20 months; as of this writing, there has been no recurrence of lesions.

Comment

Distribution

Chromoblastomycosis, also known as chromomycosis and verrucous dermatitis,3 is a chronic subcutaneous mycosis found in tropical and subtropical regions.3,4 It is caused by traumatic inoculation of any of several members of a specific group of dematiaceous fungi through the skin.2,3 Common causative organisms include Fonsecaea pedrosoi, C carrionii, Fonsecaea compacta, and Phialophora verrucosa, all of which are saprophytes in soil and plants. Fonsecaea pedrosoi is the most common causative agent worldwide (70%–90% of cases).2Cladosporium carrionii tends to be the predominant pathogen isolated in patients who present in drier climates, with F pedrosoi in humid forests.1-4

In India, chromoblastomycosis has been reported from the sub-Himalayan belt and western and eastern coasts.1,5 Our patient resided in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, India, which has a predominantly hot and dry climate. The history might include vegetational trauma, such as a thorn prick. Time between inoculation and development of disease is believed to be years.

Clinical Presentation

Chromoblastomycosis is characterized by a slowly enlarging lesion at the site of inoculation. Five morphological variants are known: nodular, tumoral, verrucous, plaque, and cicatricial; verrucous and nodular types are most common.3,4

The disease is limited to the skin and subcutaneous tissue, growing in extent rather than in depth and not directly invading muscle or bone.4 Lymphatic and hematogenous dissemination can occur.3,4 Secondary bacterial infection is common. The most common affected site is the lower limb, especially the foot.1,3 The upper limb and rarely the ear, trunk, face, and breast can be affected.

Diagnosis

Routine laboratory investigations are usually within reference range. Diagnosis is made by histopathological and mycological studies. Preferably, scrapings or biopsy material are taken from lesions that are covered with what is described as “black dots” (an area of transepidermal elimination of the fungus) where there is a better diagnostic yield.2-4 Routine histopathology shows hyperkeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis, a mixed granulomatous neutrophil response with multinucleated giant cells and neutrophil abscesses, refractile fungal spores, typical sclerotic cells around abscesses or granulomas, and a dense fibrous response in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue.

Extensive fibrosis, coupled with a chronic inflammatory infiltrate and increased susceptibility to secondary infection, leads to obstruction of lymphatic flow and lymphedema below the affected site.2-4 Periodic acid–Schiff and Gomori methenamine silver stains confirm the presence of fungus. Direct microscopic examination of a 10% potassium hydroxide mount of scrapings reveals spherical, thick-walled, darkly pigmented, multiseptate sclerotic cells known as medlar bodies, copper pennies, and muriform cells that are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis.1-4Cladosporium carrionii culture on Sabouraud dextrose agar at 37°C shows olive green, dark, rugose, smooth, hairy, leathery or velvety colonies with pigmentation front and reverse. Direct microscopic examination of the colonies shows dematiaceous septate hyphae and sparsely branching conidiophores bearing ellipsoidal, smooth-walled conidia in long acropetal chains.1,4

Treatment

Treatment options for chromoblastomycosis can be divided into antifungal agents and physical methods.Antifungal agents include itraconazole (200–400 mg daily),3 terbinafine (250–500 mg daily),3 5-fluorocytosine (100–150 mg/kg daily),3 amphotericin B (intravenous/intralesional), and others (eg, fluconazole, ketoconazole, posaconazole [800 mg daily],6,7 potassium iodide, voriconazole). Physical methods include CO2 laser, cryosurgery, local heat therapy, Mohs micrographic surgery, and standard surgery.3 There is no evidence-based treatment protocol. Itraconazole and terbinafine are considered drugs of first choice1,8; however, combination therapy is the best option.9

- Ajanta S, Naba KH, Deepak G. Chromoblastomycosis in sub-tropical regions of India. Mycopathologia. 2010;169:381-386.

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

- Flavio QT, Phillippe E, Maigualida PB, et al. Chromoblastomycosis: an overview of clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Med Mycol. 2009;47:3-15.

- López Martínez R, Méndez Tovar LJ. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:188-194.

- Pradhan SV, Talwar OP, Ghosh A, et al. Chromoblastomycosis in Nepal: a study of 13 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:176-178.

- Krzys´ciak PM, Pindycka-Piaszczys´ska M, Piaszczys´ski M. Chromoblastomycosis [published online October 22, 2014]. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:310-321.

- Negroni R, Tobón A, Bustamante B, et al. Posaconazole treatment of refractory eumycetoma and chromoblastomycosis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2005;47:339-346.

- Mohanty L, Mohanty P, Padhi T, et al. Verrucous growth on leg. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:399-400.

- Najafzadeh MJ, Rezusta A, Cameo MI, et al. Successful treatment of chromoblastomycosis of 36 years duration caused by Fonsecaea monophora. Med Mycol. 2010;48:390-393.

Case Report

A 25-year-old man who was a dairy farmer in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, India, presented with a history of slowly growing, occasionally itchy lesions on both cheeks of 20 years’ duration. Most of the right cheek was covered by a well-defined, lobulated, gray-brown verrucous mass with a cerebriform surface (Figure 1). The left cheek was covered with a gray-brown infiltrated plaque surrounded by brown-tinged monomorphic papules.

Routine investigations were normal at presentation. Tests for purified protein derivative (tuberculin) and antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus were negative. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed soft tissue thickening with ulcerations involving the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and underlying facial muscles of the right cheek.

On histopathology, a hematoxylin and eosin–stained section showed hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and follicular plugs in the epidermis, as well as a mixed cellular infiltrate with Langhans giant cells and sclerotic bodies in the dermis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and methenamine silver special stains revealed sclerotic bodies.

Fungal culture on Sabouraud dextrose agar at 25°C and 37°C grew olive green, rugose, velvety, leathery colonies within 48 hours, with pigmentation front and reverse (Figure 3). A panfungal polymerase chain reaction assay was positive. Direct microscopic examination of a 10% potassium hydroxide mount of the colonies showed mycelia with dematiaceous septate hyphae (Figure 4), apical branching, branching conidiophores, elliptical conidia in long chains, and pathognomonic round yeastlike bodies resembling copper pennies known as sclerotic cells (also called muriform cells and medlar bodies).1,2 The causative organism was identified as Cladosporium carrionii. A final diagnosis of chromoblastomycosis was made.

After 2 months of treatment with oral itraconazole 400 mg daily, there was no notable clinical improvement and fungal elements were still seen on culture. Four treatment cycles of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B 50 mg daily (1 mg/kg daily) for 15 days followed by itraconazole 200 mg daily for another 15 days caused substantial reduction and flattening of the lesion on the right side and resolution of the lesions on the left side. Healing was accompanied by central erythema and depigmentation (Figure 5). With a suspicion of continuing C carrionii activity on the right cheek, intralesional liposomal amphotericin B 0.2 mL (in a dilution of 5 mg in 1 mL) was given weekly in the peripheral hyperpigmented raised margin, which resulted in further flattening and reduction in tissue resistance. Fungal elements were absent on repeat biopsy and culture after 4 weeks.

Six months after negative culture, further cosmetic correction of the scar on the right cheek was performed with a patterned full-thickness graft for the upper half and excision with approximation of the edges for the lower half (Figure 6). Cultures have been negative for the last 20 months; as of this writing, there has been no recurrence of lesions.

Comment

Distribution

Chromoblastomycosis, also known as chromomycosis and verrucous dermatitis,3 is a chronic subcutaneous mycosis found in tropical and subtropical regions.3,4 It is caused by traumatic inoculation of any of several members of a specific group of dematiaceous fungi through the skin.2,3 Common causative organisms include Fonsecaea pedrosoi, C carrionii, Fonsecaea compacta, and Phialophora verrucosa, all of which are saprophytes in soil and plants. Fonsecaea pedrosoi is the most common causative agent worldwide (70%–90% of cases).2Cladosporium carrionii tends to be the predominant pathogen isolated in patients who present in drier climates, with F pedrosoi in humid forests.1-4

In India, chromoblastomycosis has been reported from the sub-Himalayan belt and western and eastern coasts.1,5 Our patient resided in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, India, which has a predominantly hot and dry climate. The history might include vegetational trauma, such as a thorn prick. Time between inoculation and development of disease is believed to be years.

Clinical Presentation

Chromoblastomycosis is characterized by a slowly enlarging lesion at the site of inoculation. Five morphological variants are known: nodular, tumoral, verrucous, plaque, and cicatricial; verrucous and nodular types are most common.3,4

The disease is limited to the skin and subcutaneous tissue, growing in extent rather than in depth and not directly invading muscle or bone.4 Lymphatic and hematogenous dissemination can occur.3,4 Secondary bacterial infection is common. The most common affected site is the lower limb, especially the foot.1,3 The upper limb and rarely the ear, trunk, face, and breast can be affected.

Diagnosis

Routine laboratory investigations are usually within reference range. Diagnosis is made by histopathological and mycological studies. Preferably, scrapings or biopsy material are taken from lesions that are covered with what is described as “black dots” (an area of transepidermal elimination of the fungus) where there is a better diagnostic yield.2-4 Routine histopathology shows hyperkeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis, a mixed granulomatous neutrophil response with multinucleated giant cells and neutrophil abscesses, refractile fungal spores, typical sclerotic cells around abscesses or granulomas, and a dense fibrous response in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue.

Extensive fibrosis, coupled with a chronic inflammatory infiltrate and increased susceptibility to secondary infection, leads to obstruction of lymphatic flow and lymphedema below the affected site.2-4 Periodic acid–Schiff and Gomori methenamine silver stains confirm the presence of fungus. Direct microscopic examination of a 10% potassium hydroxide mount of scrapings reveals spherical, thick-walled, darkly pigmented, multiseptate sclerotic cells known as medlar bodies, copper pennies, and muriform cells that are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis.1-4Cladosporium carrionii culture on Sabouraud dextrose agar at 37°C shows olive green, dark, rugose, smooth, hairy, leathery or velvety colonies with pigmentation front and reverse. Direct microscopic examination of the colonies shows dematiaceous septate hyphae and sparsely branching conidiophores bearing ellipsoidal, smooth-walled conidia in long acropetal chains.1,4

Treatment

Treatment options for chromoblastomycosis can be divided into antifungal agents and physical methods.Antifungal agents include itraconazole (200–400 mg daily),3 terbinafine (250–500 mg daily),3 5-fluorocytosine (100–150 mg/kg daily),3 amphotericin B (intravenous/intralesional), and others (eg, fluconazole, ketoconazole, posaconazole [800 mg daily],6,7 potassium iodide, voriconazole). Physical methods include CO2 laser, cryosurgery, local heat therapy, Mohs micrographic surgery, and standard surgery.3 There is no evidence-based treatment protocol. Itraconazole and terbinafine are considered drugs of first choice1,8; however, combination therapy is the best option.9

Case Report

A 25-year-old man who was a dairy farmer in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, India, presented with a history of slowly growing, occasionally itchy lesions on both cheeks of 20 years’ duration. Most of the right cheek was covered by a well-defined, lobulated, gray-brown verrucous mass with a cerebriform surface (Figure 1). The left cheek was covered with a gray-brown infiltrated plaque surrounded by brown-tinged monomorphic papules.

Routine investigations were normal at presentation. Tests for purified protein derivative (tuberculin) and antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus were negative. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed soft tissue thickening with ulcerations involving the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and underlying facial muscles of the right cheek.

On histopathology, a hematoxylin and eosin–stained section showed hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and follicular plugs in the epidermis, as well as a mixed cellular infiltrate with Langhans giant cells and sclerotic bodies in the dermis (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff and methenamine silver special stains revealed sclerotic bodies.

Fungal culture on Sabouraud dextrose agar at 25°C and 37°C grew olive green, rugose, velvety, leathery colonies within 48 hours, with pigmentation front and reverse (Figure 3). A panfungal polymerase chain reaction assay was positive. Direct microscopic examination of a 10% potassium hydroxide mount of the colonies showed mycelia with dematiaceous septate hyphae (Figure 4), apical branching, branching conidiophores, elliptical conidia in long chains, and pathognomonic round yeastlike bodies resembling copper pennies known as sclerotic cells (also called muriform cells and medlar bodies).1,2 The causative organism was identified as Cladosporium carrionii. A final diagnosis of chromoblastomycosis was made.

After 2 months of treatment with oral itraconazole 400 mg daily, there was no notable clinical improvement and fungal elements were still seen on culture. Four treatment cycles of intravenous liposomal amphotericin B 50 mg daily (1 mg/kg daily) for 15 days followed by itraconazole 200 mg daily for another 15 days caused substantial reduction and flattening of the lesion on the right side and resolution of the lesions on the left side. Healing was accompanied by central erythema and depigmentation (Figure 5). With a suspicion of continuing C carrionii activity on the right cheek, intralesional liposomal amphotericin B 0.2 mL (in a dilution of 5 mg in 1 mL) was given weekly in the peripheral hyperpigmented raised margin, which resulted in further flattening and reduction in tissue resistance. Fungal elements were absent on repeat biopsy and culture after 4 weeks.

Six months after negative culture, further cosmetic correction of the scar on the right cheek was performed with a patterned full-thickness graft for the upper half and excision with approximation of the edges for the lower half (Figure 6). Cultures have been negative for the last 20 months; as of this writing, there has been no recurrence of lesions.

Comment

Distribution

Chromoblastomycosis, also known as chromomycosis and verrucous dermatitis,3 is a chronic subcutaneous mycosis found in tropical and subtropical regions.3,4 It is caused by traumatic inoculation of any of several members of a specific group of dematiaceous fungi through the skin.2,3 Common causative organisms include Fonsecaea pedrosoi, C carrionii, Fonsecaea compacta, and Phialophora verrucosa, all of which are saprophytes in soil and plants. Fonsecaea pedrosoi is the most common causative agent worldwide (70%–90% of cases).2Cladosporium carrionii tends to be the predominant pathogen isolated in patients who present in drier climates, with F pedrosoi in humid forests.1-4

In India, chromoblastomycosis has been reported from the sub-Himalayan belt and western and eastern coasts.1,5 Our patient resided in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra, India, which has a predominantly hot and dry climate. The history might include vegetational trauma, such as a thorn prick. Time between inoculation and development of disease is believed to be years.

Clinical Presentation

Chromoblastomycosis is characterized by a slowly enlarging lesion at the site of inoculation. Five morphological variants are known: nodular, tumoral, verrucous, plaque, and cicatricial; verrucous and nodular types are most common.3,4

The disease is limited to the skin and subcutaneous tissue, growing in extent rather than in depth and not directly invading muscle or bone.4 Lymphatic and hematogenous dissemination can occur.3,4 Secondary bacterial infection is common. The most common affected site is the lower limb, especially the foot.1,3 The upper limb and rarely the ear, trunk, face, and breast can be affected.

Diagnosis

Routine laboratory investigations are usually within reference range. Diagnosis is made by histopathological and mycological studies. Preferably, scrapings or biopsy material are taken from lesions that are covered with what is described as “black dots” (an area of transepidermal elimination of the fungus) where there is a better diagnostic yield.2-4 Routine histopathology shows hyperkeratosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis, a mixed granulomatous neutrophil response with multinucleated giant cells and neutrophil abscesses, refractile fungal spores, typical sclerotic cells around abscesses or granulomas, and a dense fibrous response in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue.

Extensive fibrosis, coupled with a chronic inflammatory infiltrate and increased susceptibility to secondary infection, leads to obstruction of lymphatic flow and lymphedema below the affected site.2-4 Periodic acid–Schiff and Gomori methenamine silver stains confirm the presence of fungus. Direct microscopic examination of a 10% potassium hydroxide mount of scrapings reveals spherical, thick-walled, darkly pigmented, multiseptate sclerotic cells known as medlar bodies, copper pennies, and muriform cells that are pathognomonic for chromoblastomycosis.1-4Cladosporium carrionii culture on Sabouraud dextrose agar at 37°C shows olive green, dark, rugose, smooth, hairy, leathery or velvety colonies with pigmentation front and reverse. Direct microscopic examination of the colonies shows dematiaceous septate hyphae and sparsely branching conidiophores bearing ellipsoidal, smooth-walled conidia in long acropetal chains.1,4

Treatment

Treatment options for chromoblastomycosis can be divided into antifungal agents and physical methods.Antifungal agents include itraconazole (200–400 mg daily),3 terbinafine (250–500 mg daily),3 5-fluorocytosine (100–150 mg/kg daily),3 amphotericin B (intravenous/intralesional), and others (eg, fluconazole, ketoconazole, posaconazole [800 mg daily],6,7 potassium iodide, voriconazole). Physical methods include CO2 laser, cryosurgery, local heat therapy, Mohs micrographic surgery, and standard surgery.3 There is no evidence-based treatment protocol. Itraconazole and terbinafine are considered drugs of first choice1,8; however, combination therapy is the best option.9

- Ajanta S, Naba KH, Deepak G. Chromoblastomycosis in sub-tropical regions of India. Mycopathologia. 2010;169:381-386.

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

- Flavio QT, Phillippe E, Maigualida PB, et al. Chromoblastomycosis: an overview of clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Med Mycol. 2009;47:3-15.

- López Martínez R, Méndez Tovar LJ. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:188-194.

- Pradhan SV, Talwar OP, Ghosh A, et al. Chromoblastomycosis in Nepal: a study of 13 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:176-178.

- Krzys´ciak PM, Pindycka-Piaszczys´ska M, Piaszczys´ski M. Chromoblastomycosis [published online October 22, 2014]. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:310-321.

- Negroni R, Tobón A, Bustamante B, et al. Posaconazole treatment of refractory eumycetoma and chromoblastomycosis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2005;47:339-346.

- Mohanty L, Mohanty P, Padhi T, et al. Verrucous growth on leg. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:399-400.

- Najafzadeh MJ, Rezusta A, Cameo MI, et al. Successful treatment of chromoblastomycosis of 36 years duration caused by Fonsecaea monophora. Med Mycol. 2010;48:390-393.

- Ajanta S, Naba KH, Deepak G. Chromoblastomycosis in sub-tropical regions of India. Mycopathologia. 2010;169:381-386.

- Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

- Flavio QT, Phillippe E, Maigualida PB, et al. Chromoblastomycosis: an overview of clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Med Mycol. 2009;47:3-15.

- López Martínez R, Méndez Tovar LJ. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:188-194.

- Pradhan SV, Talwar OP, Ghosh A, et al. Chromoblastomycosis in Nepal: a study of 13 cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:176-178.

- Krzys´ciak PM, Pindycka-Piaszczys´ska M, Piaszczys´ski M. Chromoblastomycosis [published online October 22, 2014]. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2014;31:310-321.

- Negroni R, Tobón A, Bustamante B, et al. Posaconazole treatment of refractory eumycetoma and chromoblastomycosis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2005;47:339-346.

- Mohanty L, Mohanty P, Padhi T, et al. Verrucous growth on leg. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:399-400.

- Najafzadeh MJ, Rezusta A, Cameo MI, et al. Successful treatment of chromoblastomycosis of 36 years duration caused by Fonsecaea monophora. Med Mycol. 2010;48:390-393.

Practice Points

- Chromoblastomycosis is limited to skin and subcutaneous tissue, most commonly of the lower limb, especially the foot; it does not directly invade muscle or bone. Secondary bacterial infection is common.

- Chromoblastomycosis is a therapeutic challenge due to its recalcitrant nature. Itraconazole and terbinafine are considered drugs of first choice, but consensus and evidence are lacking on a standard of care.

Delayed Cutaneous Reactions to Iodinated Contrast

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman with a history of allergic rhinitis presented in the spring with a pruritic eruption of 2 days’ duration that began on the abdomen and spread to the chest, back, and bilateral arms. Six days prior to the onset of the symptoms she underwent computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis to evaluate abdominal pain and peripheral eosinophilia. Two iodinated contrast (IC) agents were used: intravenous iohexol and oral diatrizoate meglumine–diatrizoate sodium. The eruption was not preceded by fever, malaise, sore throat, rhinorrhea, cough, arthralgia, headache, diarrhea, or new medication or supplement use. The patient denied any history of drug allergy or cutaneous eruptions. Her current medications, which she had been taking long-term, were aspirin, lisinopril, diltiazem, levothyroxine, esomeprazole, paroxetine, gabapentin, and diphenhydramine.

Physical examination was notable for erythematous, blanchable, nontender macules coalescing into patches on the trunk and bilateral arms (Figure). There was slight erythema on the nasolabial folds and ears. The mucosal surfaces and distal legs were clear. The patient was afebrile. Her white blood cell count was 12.5×109/L with 32.3% eosinophils (baseline: white blood cell count, 14.8×109/L; 22% eosinophils)(reference range, 4.8–10.8×109/L; 1%–4% eosinophils). Her comprehensive metabolic panel was within reference range. The human immunodeficiency virus 1/2 antibody immunoassay was nonreactive.

The patient was diagnosed with an exanthematous eruption caused by IC and was treated with oral hydroxyzine and triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1%. The eruption resolved within 2 weeks without recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

Comment

Del

Clinical Presentation of Delayed Reactions

Most delayed cutaneous reactions to IC present as exanthematous eruptions in the week following a contrast-enhanced CT scan or coronary angiogram.2,12 The reactions tend to resolve within 2 weeks of onset, and the treatment is largely supportive with antihistamines and/or corticosteroids for the associated pruritus.2,5,6 In a study of 98 patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC, delayed-onset urticaria and angioedema also have been reported with incidence rates of 19% and 24%, respectively.2 Other reactions are less common. In the same study, 7% of patients developed palpable purpura; acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; bullous, flexural, or psoriasislike exanthema; exfoliative eruptions; or purpura and a maculopapular eruption combined with eosinophilia.2 There also have been reports of IC-induced erythema multiforme,3 fixed drug eruptions,10,11 symmetrical drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema,13 cutaneous vasculitis,14 drug reactions with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms,15 Stevens-Johnson syndrome/TEN,7,8,16,17 and iododerma.18

IC Agents

Virtually all delayed cutaneous reactions to IC reportedly are due to intravascular rather than oral agents,1,2,19 with the exception of iododerma18 and 1 reported case of TEN.17 Intravenous iohexol was most likely the offending drug in our case. In a prospective cohort study of 539 patients undergoing CT scans, the absolute risk for developing a delayed cutaneous reaction (defined as rash, itching, or skin redness or swelling) to intravascular iohexol was 9.4%.20 Randomized, double-blind studies have found that the risk for delayed cutaneous eruptions is similar among various types of IC, except for iodixanol, which confers a higher risk.5,6,21

Risk Factors

Interestingly, analyses have shown that delayed reactions to IC are more common in atopic patients and during high pollen season.22 Our patient displayed these risk factors, as she had allergic rhinitis and presented for evaluation in late spring when local pollen counts were high. Additionally, patients who develop delayed reactions to IC are notably more likely than controls to have a history of other cutaneous drug reactions, serum creatinine levels greater than 2.0 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL),3 or history of treatment with recombinant interleukin 2.19

Patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC are not at increased risk for immediate reactions and vice versa.2,3 This finding is consistent with the evidence that delayed and immediate reactions to IC are mechanistically unrelated.23 Additionally, seafood allergy is not a risk factor for either immediate or delayed reactions to IC, despite a common misconception among physicians and patients because seafood is iodinated.24,25

Reexposure to IC

Patients who have had delayed cutaneous reactions to IC are at risk for similar eruptions upon reexposure. Although the reactions are believed to be cell mediated, skin testing with IC is not sensitive enough to reliably identify tolerable alternatives.12 Consequently, gadolinium-based agents have been recommended in patients with a history of reactions to IC if additional contrast-enhanced studies are needed.13,26 Iodinated and gadolinium-based contrast agents do not cross-react, and gadolinium is compatible with studies other than magnetic resonance imaging.1,27

Premedication

Despite the absence of cross-reactivity, the American College of Radiology considers patients with hypersensitivity reactions to IC to be at increased risk for reactions to gadolinium but does not make specific recommendations regarding premedication given the dearth of data.1 As a result, premedication may be considered prior to gadolinium administration depending on the severity of the delayed reaction to IC. Additionally, premedication may be beneficial in cases in which gadolinium is contraindicated and IC must be reused. In a retrospective study, all patients with suspected delayed reactions to IC tolerated IC or gadolinium contrast when pretreated with corticosteroids with or without antihistamines.28 Regimens with corticosteroids and either cyclosporine or intravenous immunoglobulin also have prevented the recurrence of IC-induced exanthematous eruptions and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.29,30 Despite these reports, delayed cutaneous reactions to IC have recurred in other patients receiving corticosteroids, antihistamines, and/or cyclosporine for premedication or concurrent treatment of an underlying condition.16,29-31

Conclusion

It is important for dermatologists to recognize IC as a cause of delayed drug reactions. Current awareness is limited, and as a result, patients often are reexposed to the offending contrast agents unsuspectingly. In addition to diagnosing these eruptions, dermatologists may help prevent their recurrence if future contrast-enhanced studies are required by recommending gadolinium-based agents and/or premedication.

- Cohan RH, Davenport MS, Dillman JR, et al; ACR Committee on Drugs and Contrast Media. ACR Manual on Contrast Media. 9th ed. Reston, VA: American College of Radiology; 2013.

- Brockow K, Romano A, Aberer W, et al; European Network of Drug Allergy and the EAACI Interest Group on Drug Hypersensitivity. Skin testing in patients with hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media—a European multicenter study. Allergy. 2009;64:234-241.

Hosoya T, Yamaguchi K, Akutsu T, et al. Delayed adverse reactions to iodinated contrast media and their risk factors. Radiat Med. 2000;18:39-45. - Rydberg J, Charles J, Aspelin P. Frequency of late allergy-like adverse reactions following injection of intravascular non-ionic contrast media: a retrospective study comparing a non-ionic monomeric contrast medium with a non-ionic dimeric contrast medium. Acta Radiol. 1998;39:219-222.

- Sutton AG, Finn P, Grech ED, et al. Early and late reactions after the use of iopamidol 340, ioxaglate 320, and iodixanol 320 in cardiac catheterization. Am Heart J. 2001;141:677-683.

- Sutton AG, Finn P, Campbell PG, et al. Early and late reactions following the use of iopamidol 340, iomeprol 350 and iodixanol 320 in cardiac catheterization. J Invasive Cardiol. 2003;15:133-138.

- Brown M, Yowler C, Brandt C. Recurrent toxic epidermal necrolysis secondary to iopromide contrast. J Burn Care Res. 2013;34:E53-E56.

- Rosado A, Canto G, Veleiro B, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis after repeated injections of iohexol. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:262-263.

- Peterson A, Katzberg RW, Fung MA, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis as a delayed dermatotoxic reaction to IV-administered nonionic contrast media. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W198-W201.

- Good AE, Novak E, Sonda LP III. Fixed eruption and fever after urography. South Med J. 1980;73:948-949.

- Benson PM, Giblin WJ, Douglas DM. Transient, nonpigmenting fixed drug eruption caused by radiopaque contrast media. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(2, pt 2):379-381.

- Torres MJ, Gomez F, Doña I, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of patients with nonimmediate cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Allergy. 2012;67:929-935.

- Scherer K, Harr T, Bach S, et al. The role of iodine in hypersensitivity reactions to radio contrast media. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40:468-475.

- Reynolds NJ, Wallington TB, Burton JL. Hydralazine predisposes to acute cutaneous vasculitis following urography with iopamidol. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129:82-85.

- Belhadjali H, Bouzgarrou L, Youssef M, et al. DRESS syndrome induced by sodium meglumine ioxitalamate. Allergy. 2008;63:786-787.

- Baldwin BT, Lien MH, Khan H, et al. Case of fatal toxic epidermal necrolysis due to cardiac catheterization dye. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:837-840.

- Schmidt BJ, Foley WD, Bohorfoush AG. Toxic epidermal necrolysis related to oral administration of diluted diatrizoate meglumine and diatrizoate sodium. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1215-1216.

- Young AL, Grossman ME. Acute iododerma secondary to iodinated contrast media. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1377-1379.

- Choyke PL, Miller DL, Lotze MT, et al. Delayed reactions to contrast media after interleukin-2 immunotherapy. Radiology. 1992;183:111-114.

- Loh S, Bagheri S, Katzberg RW, et al. Delayed adverse reaction to contrast-enhanced CT: a prospective single-center study comparison to control group without enhancement. Radiology. 2010;255:764-771.

- Bertrand P, Delhommais A, Alison D, et al. Immediate and delayed tolerance of iohexol and ioxaglate in lower limb phlebography: a double-blind comparative study in humans. Acad Radiol. 1995;2:683-686.

- Munechika H, Hiramatsu Y, Kudo S, et al. A prospective survey of delayed adverse reactions to iohexol in urography and computed tomography. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:185-194.

- Guéant-Rodriguez RM, Romano A, Barbaud A, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:3359-3372.

- H

uang SW. Seafood and iodine: an analysis of a medical myth. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2005;26:468-469. - B

aig M, Farag A, Sajid J, et al. Shellfish allergy and relation to iodinated contrast media: United Kingdom survey. World J Cardiol. 2014;6:107-111. - B

öhm I, Schild HH. A practical guide to diagnose lesser-known immediate and delayed contrast media-induced adverse cutaneous reactions. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1570-1579. - Ose K, Doue T, Zen K, et al. “Gadolinium” as an alternative to iodinated contrast media for X-ray angiography in patients with severe allergy. Circ J. 2005;69:507-509.

- Ji

ngu A, Fukuda J, Taketomi-Takahashi A, et al. Breakthrough reactions of iodinated and gadolinium contrast media after oral steroid premedication protocol. BMC Med Imaging. 2014;14:34. - Ro

mano A, Artesani MC, Andriolo M, et al. Effective prophylactic protocol in delayed hypersensitivity to contrast media: report of a case involving lymphocyte transformation studies with different compounds. Radiology. 2002;225:466-470. - He

bert AA, Bogle MA. Intravenous immunoglobulin prophylaxis for recurrent Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:286-288. - Ha

sdenteufel F, Waton J, Cordebar V, et al. Delayed hypersensitivity reactions caused by iodixanol: an assessment of cross-reactivity in 22 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:1356-1357.

Case Report

A 67-year-old woman with a history of allergic rhinitis presented in the spring with a pruritic eruption of 2 days’ duration that began on the abdomen and spread to the chest, back, and bilateral arms. Six days prior to the onset of the symptoms she underwent computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis to evaluate abdominal pain and peripheral eosinophilia. Two iodinated contrast (IC) agents were used: intravenous iohexol and oral diatrizoate meglumine–diatrizoate sodium. The eruption was not preceded by fever, malaise, sore throat, rhinorrhea, cough, arthralgia, headache, diarrhea, or new medication or supplement use. The patient denied any history of drug allergy or cutaneous eruptions. Her current medications, which she had been taking long-term, were aspirin, lisinopril, diltiazem, levothyroxine, esomeprazole, paroxetine, gabapentin, and diphenhydramine.

Physical examination was notable for erythematous, blanchable, nontender macules coalescing into patches on the trunk and bilateral arms (Figure). There was slight erythema on the nasolabial folds and ears. The mucosal surfaces and distal legs were clear. The patient was afebrile. Her white blood cell count was 12.5×109/L with 32.3% eosinophils (baseline: white blood cell count, 14.8×109/L; 22% eosinophils)(reference range, 4.8–10.8×109/L; 1%–4% eosinophils). Her comprehensive metabolic panel was within reference range. The human immunodeficiency virus 1/2 antibody immunoassay was nonreactive.

The patient was diagnosed with an exanthematous eruption caused by IC and was treated with oral hydroxyzine and triamcinolone acetonide cream 0.1%. The eruption resolved within 2 weeks without recurrence at 3-month follow-up.

Comment

Del

Clinical Presentation of Delayed Reactions

Most delayed cutaneous reactions to IC present as exanthematous eruptions in the week following a contrast-enhanced CT scan or coronary angiogram.2,12 The reactions tend to resolve within 2 weeks of onset, and the treatment is largely supportive with antihistamines and/or corticosteroids for the associated pruritus.2,5,6 In a study of 98 patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC, delayed-onset urticaria and angioedema also have been reported with incidence rates of 19% and 24%, respectively.2 Other reactions are less common. In the same study, 7% of patients developed palpable purpura; acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; bullous, flexural, or psoriasislike exanthema; exfoliative eruptions; or purpura and a maculopapular eruption combined with eosinophilia.2 There also have been reports of IC-induced erythema multiforme,3 fixed drug eruptions,10,11 symmetrical drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema,13 cutaneous vasculitis,14 drug reactions with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms,15 Stevens-Johnson syndrome/TEN,7,8,16,17 and iododerma.18

IC Agents

Virtually all delayed cutaneous reactions to IC reportedly are due to intravascular rather than oral agents,1,2,19 with the exception of iododerma18 and 1 reported case of TEN.17 Intravenous iohexol was most likely the offending drug in our case. In a prospective cohort study of 539 patients undergoing CT scans, the absolute risk for developing a delayed cutaneous reaction (defined as rash, itching, or skin redness or swelling) to intravascular iohexol was 9.4%.20 Randomized, double-blind studies have found that the risk for delayed cutaneous eruptions is similar among various types of IC, except for iodixanol, which confers a higher risk.5,6,21

Risk Factors

Interestingly, analyses have shown that delayed reactions to IC are more common in atopic patients and during high pollen season.22 Our patient displayed these risk factors, as she had allergic rhinitis and presented for evaluation in late spring when local pollen counts were high. Additionally, patients who develop delayed reactions to IC are notably more likely than controls to have a history of other cutaneous drug reactions, serum creatinine levels greater than 2.0 mg/dL (reference range, 0.6–1.2 mg/dL),3 or history of treatment with recombinant interleukin 2.19

Patients with a history of delayed reactions to IC are not at increased risk for immediate reactions and vice versa.2,3 This finding is consistent with the evidence that delayed and immediate reactions to IC are mechanistically unrelated.23 Additionally, seafood allergy is not a risk factor for either immediate or delayed reactions to IC, despite a common misconception among physicians and patients because seafood is iodinated.24,25

Reexposure to IC

Patients who have had delayed cutaneous reactions to IC are at risk for similar eruptions upon reexposure. Although the reactions are believed to be cell mediated, skin testing with IC is not sensitive enough to reliably identify tolerable alternatives.12 Consequently, gadolinium-based agents have been recommended in patients with a history of reactions to IC if additional contrast-enhanced studies are needed.13,26 Iodinated and gadolinium-based contrast agents do not cross-react, and gadolinium is compatible with studies other than magnetic resonance imaging.1,27

Premedication

Despite the absence of cross-reactivity, the American College of Radiology considers patients with hypersensitivity reactions to IC to be at increased risk for reactions to gadolinium but does not make specific recommendations regarding premedication given the dearth of data.1 As a result, premedication may be considered prior to gadolinium administration depending on the severity of the delayed reaction to IC. Additionally, premedication may be beneficial in cases in which gadolinium is contraindicated and IC must be reused. In a retrospective study, all patients with suspected delayed reactions to IC tolerated IC or gadolinium contrast when pretreated with corticosteroids with or without antihistamines.28 Regimens with corticosteroids and either cyclosporine or intravenous immunoglobulin also have prevented the recurrence of IC-induced exanthematous eruptions and Stevens-Johnson syndrome.29,30 Despite these reports, delayed cutaneous reactions to IC have recurred in other patients receiving corticosteroids, antihistamines, and/or cyclosporine for premedication or concurrent treatment of an underlying condition.16,29-31

Conclusion