User login

Transgender Care in the Primary Care Setting: A Review of Guidelines and Literature

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals face significant difficulties in obtaining high-quality,compassionate medical care, much of which has been attributed to inadequate provider knowledge. In this article, the authors present a transgender patient seen in primary care and discuss the knowledge gleaned to inform future care of this patient as well as the care of other similar patients.

The following case discussion and review of the literature also seeks to improve the practice of other primary care providers (PCPs) who are inexperienced in this arena. This article aims to review the basics to permit PCPs to venture into transgender care, including a review of basic terminology; a few interactive tips; and basics in medical and hormonal treatment, follow-up, contraindications, and risk. More details can be obtained through electronic consultation (Transgender eConsult) in the VA.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old patient who was assigned male sex at birth presented to the primary care clinic to discuss her desire to undergo male-to-female (MTF) transition. The patient stated that she had started taking female estrogen hormones 9 years previously purchased from craigslist without a prescription. She tried oral contraceptives as well as oral and injectable estradiol. While the patient was taking injectable estradiol she had breast growth, decreased anxiety, weight gain, and a feeling of peacefulness. The patient also reported that she had received several laser treatments for whole body hair removal, beginning 8 to 10 years before and more regularly in the past 2 to 3 years. She asked whether transition-related care could be provided, because she could no longer afford the hormones.

The patient wanted to transition because she felt that “Women are beautiful, the way they carry themselves, wear their hair, their nails, I want to be like that.” She also mentioned that when she watched TV, she envisioned herself as a woman. She reported that she enjoyed wearing her mother’s clothing since age 10, which made her feel more like herself. The patient noted that she had desired to remove her body hair since childhood but could not afford to do it until recently. She bought female clothing, shoes and makeup, and did her nails from a young age. The patient also reported that she did not “know what transgender was” until a decade ago.

The patient struggled with her identity growing up; however, she tried not to think about it or talk about it with anyone. She related that she was ashamed of her thoughts and that only recently had made peace with being transgender. Thus, she pursued talking to her medical provider about transitioning. The patient reported that she felt more energetic when taking female hormones and was better able to discuss the issue. Specifically, she noted that if she were not on estrogen now she would not be able to talk about transitioning.

The patient related that she has done extensive research about transitioning, including reading online about other transgender people. She noted that she was aware of “possible backlash with society,” but ultimately, she had decided that transitioning was the right decision for her.

She expressed a desire to have an orchiectomy and continue hormonal therapy to permit her “to have a more feminine face, soft skin, hairless body, big breasts, more fat around the hips, and a high-pitched voice.” She additionally related a desire to be in a stable relationship and be her true self. She also stated that she had not identified herself as a female to anyone yet but would like to soon. The patient reported a history of depression, especially during her military service when she wanted to be a woman but did not feel she understood what was going on or how to manage her feelings. She said that for the past 2 months she felt much happier since beginning to take estradiol 4 mg orally daily, which she had found online. She also tried to purchase anti-androgen medication but could not afford it. In addition, she said that she would like to eventually proceed with gender affirmation surgery.

She was currently having sex with men, primarily via anal receptive intercourse. She had no history of sexually transmitted infections but reported that she did not use condoms regularly. She had no history of physical or sexual abuse. The patient was offered referral to the HIV clinic to receive HIV preexposure prophylaxis therapy (emtricitabine + tenofovir), which she declined, but she was counseled on safe sex practice.

The patient was referred to psychiatry both for supportive mental health care and to clarify that her concomitant mental health issues would not preclude the prescription of gender-affirming hormone treatment. Based on the psychiatric evaluation, the patient was felt to be appropriate for treatment with feminizing hormone therapy. The psychiatric assessment also noted that although the patient had a history of psychosis, she was not exhibiting psychotic symptoms currently, and this would not be a contraindication to treatment.

After discussion of the risks and benefits of cross-sex hormone therapy, the patient was started on estradiol 4 mg orally daily, as well as spironolactone 50 mg daily. She was then switched to estradiol 10 mg intramuscular every 2 weeks with the aim of using a less thrombogenic route of administration.

Treatment Outcomes

The patient remains under care. She has had follow-up visits every 3 months to ensure appropriate signs of feminization and monitoring of adverse effects (AEs). The patient’s testosterone and estradiol levels are being checked every 3 months to ensure total testosterone is 1,2

After 12 months on therapy with estradiol and spironolactone, the patient notes that her mood has improved, she feels more energetic, she has gained some weight, and her skin is softer. Her voice pitch, with the help of speech therapy, is gradually changing to what she perceives as more feminine. Hormone levels and electrolytes are all in an acceptable range, and blood sugar and blood pressure (BP) are within normal range. The patient will be offered age-appropriate cancer screening at the appropriate time.

Discussion

The treatment of gender-nonconforming individuals has come a long way since Lili Elbe, the transgender artist depicted in The Danish Girl, underwent gender-affirmation surgery in the early 20th century. Lili and people like her paved the way for other transgender individuals by doggedly pursuing gender-affirming medical treatment although they faced rejection by society and forged a difficult path. In recent years, an increasing number of transgender individuals have begun to seek mainstream medical care; however, PCPs often lack the knowledge and training to properly interact with and care for transgender patients.3,4

Terminology

Although someone’s sex is typically assigned at birth based on the external appearance of their genitalia, gender identity refers to a person’s internal sense of self and how they fit in to the world. People often use these 2 terms interchangeably in everyday language, but these terms are different.1,2

Transgender refers to a person whose gender identity differs from the sex that was assigned at birth. A transgender man or transman, or female-to-male (FTM) transgender person, is an individual who is assigned female sex at birth but identifies as a male. A transgender woman, or transwoman or a male-to-female (MTF) transgender person, is an individual who is assigned male sex at birth but identifies as female. A nontransgender person may be referred to as cisgender.

Transsexual is a medical term and refers to a transgender individual who sought medical intervention to transition to their identified gender.

Sexual orientation describes sexual attraction only and is not related to gender identity. The sexual orientation of a transgender person is determined by emotional and/or physical attraction and not gender identity.

Gender dysphoria refers to the distress experienced by an individual when one’s gender identity and sex are not completely congruent.

Improving Patient Interaction

Transgender patients might avoid seeking care due to previous negative experiences or a fear of being judged. It is very important to create a safe environment where the patients feel comfortable. Meeting patients “where they are” without judgment will enhance the patient-physician relationship. It is necessary to train all clinic staff about the importance of transgender health issues. All staff should address the patient with the name, pronouns, and gender identity that the patient prefers. For patients with a gender identity that is not strictly male or female (nonbinary patients), gender-neutral pronouns, such as they/them/their, may be chosen. It is helpful to be direct in asking: What is your preferred name? When I speak about you to other providers, what pronouns do you prefer I use, he, she, they? This information can then be documented in the electronic health record (EHR) so that all staff know from visit to visit. Thank the patient for the clarification.

The physical examination can be uncomfortable for both the patient and the physician. Experience and familiarity with the current recommendations can help. The physical examination should be relevant to the anatomy that is present, regardless of the gender presentation. An anatomic survey of the organs currently present in an individual can be useful.1 The physician should be sensitive in examining and obtaining information from the patient, focusing on only those issues relevant to the presenting concern. Chest and genital examinations may be particularly distressing for patients. If a chest or genital examination is indicated, the provider and patient should have a discussion explaining the importance of the examination and how the patient’s comfort can be optimized.

Medical Treatment

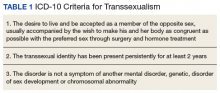

Gender-affirmation treatment should be multidisciplinary and include some or all of the following: diagnostic assessment, psychotherapy or counseling, real-life experience (RLE), hormone therapy, and surgical therapy..1,2,5 The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) has established internationally accepted Standards of Care (SOC) for the treatment of gender dysphoria that provide detailed expert opinion reviewing the background and guidance for care of transgender individuals. Most commonly, the diagnosis of gender dysphoria is made by a mental health professional (MHP) based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) criteria for gender dysphoria.1,2 The involvement of a MHP can be crucial in assessing potential psychological and social risk factors for unfavorable outcomes of medical interventions. In case of severe psychopathology, which can interfere with diagnosis and treatment, the psychopathology should be addressed first.1,2 The MHP also can confirm that the patient has the capacity to make an informed decision.

The 2017 Endocrine Society guidelines for the treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons emphasize the utility of evaluation of these patients by an expert MHP before starting the treatment.2 However, the guidelines from WPATH and the Center for Transgender Excellence at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) have stipulated that any provider who feels comfortable assessing the informed decision-making process with a patient can make this determination.

The WPATH SOC states that RLE is essential to transition to the gender role that is congruent with the patient’s gender identity. The RLE is defined as the act of fully adopting a new or evolving gender role or gender presentation in everyday life. In the RLE, the person should fully experience life in the desired gender role before irreversible physical treatment is undertaken. Newer guidelines note that it may be too challenging to adopt the desired gender role without the benefit of feminizing or masculinizing treatment, and therefore, the treatment can be offered at the same time as adopting the new gender role.1

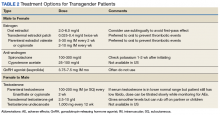

Medical treatment involves administration of masculinizing or feminizing hormone therapy. There are 2 major goals of this hormonal therapy.

For many transgender adults, genital reconstruction surgery and/or gonadectomy is a necessary step toward achieving their goal.

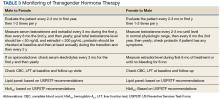

Pretreatment screening and appropriate medical monitoring is recommended for both FTM and MTF transgender patients during the endocrine transition and periodically thereafter.2 The physician should monitor the patient’s weight, BP, directed physical examinations, routine health questions focused on risk factors and medications, complete blood count, renal and liver functions, lipid and blood sugar.2

Physical Changes With Hormone Therapy

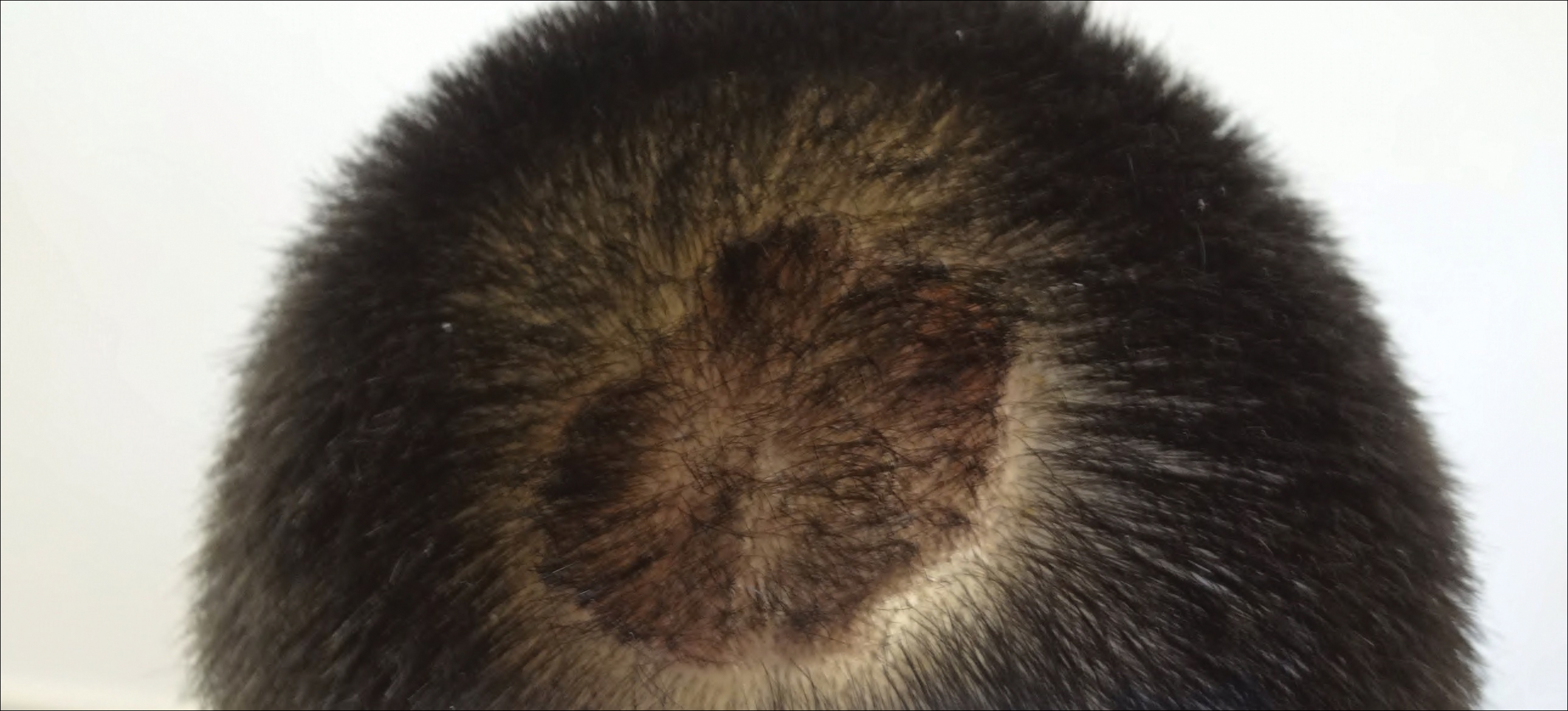

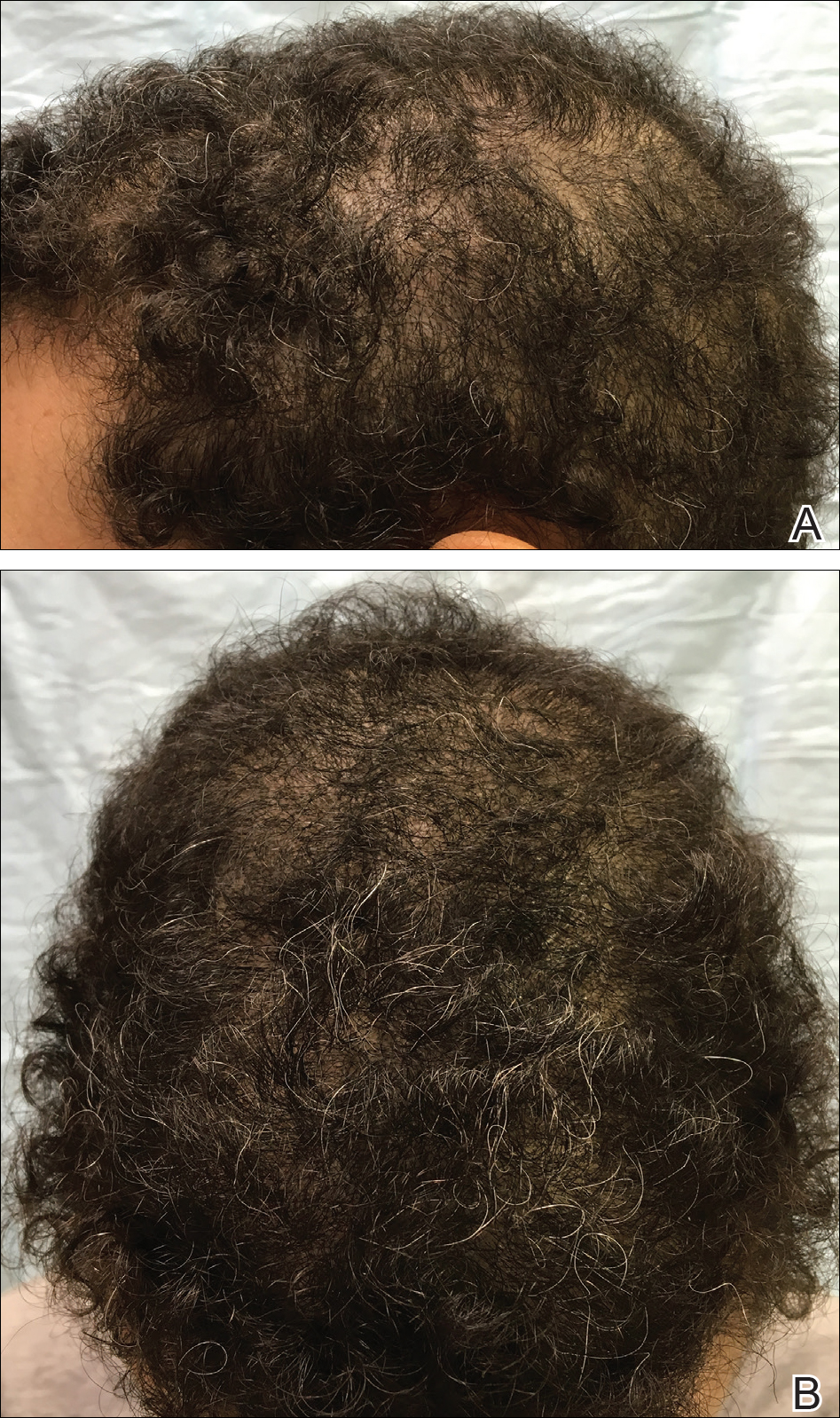

Transgender men. Physical changes that are expected to occur during the first 1 to 6 months of testosterone therapy include cessation of menses, increased sexual desire, increased facial and body hair, increased oiliness of skin, increased muscle, and redistribution of fat mass. Changes that occur within the first year of testosterone therapy include deepening of the voice, clitoromegaly, and male pattern hair loss (in some cases). Deepening of the voice, and clitoromegaly are not reversible with discontinuation of hormonal therapy.2

Transgender women. Physical changes that may occur in transgender females in the first 3 to 12 months of estrogen and anti-androgen therapy include decreased sexual desire, decreased spontaneous erections, decreased facial and body hair (usually mild), decreased oiliness of skin, increased breast tissue growth, and redistribution of fat mass. Breast development is generally maximal at 2 years after initiating estrogen, and it is irreversible.2 Effect on fertility may be permanent. Medical therapy has little effect on voice, and most transwomen will require speech therapy to achieve desired pitch.

Routine Health Maintenance

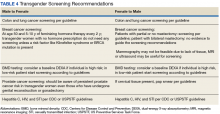

Breast Cancer Screening

Although there are limited data, it is thought that gender-affirming hormone therapy has similar risks as sex hormone replacement therapy in nontransgender males and females. Most AEs arise from use of supraphysiologic doses or inadequate doses.2 Therefore, regular clinical and laboratory monitoring is essential to cross-sex hormone therapy. Treatment with exogenous estrogen and anti-androgens result in transgender women developing breast tissue with ducts, lobules, and acini that is histologically identical to breast tissue in nontransgender females.6

Breast cancer is a concern in transgender women due to prolonged exposure to estrogen. However, the relationship between breast cancer and cross-sex hormone therapy is controversial.

Many factors contribute to breast cancer risk in patients of all genders. Studies of premenopausal and menopausal women taking exogenous estrogen alone have not shown an increase in breast cancer risk. However, the combination of estrogen and progesterone has shown an association with a significant increase in the incidence of breast cancer in postmenopausal women.2,7-10

A study of 5,136 veterans showed a statistically insignificant increased incidence of breast cancer in transgender women compared with data collected from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, although the sample size and duration of the observation were limiting factors.8 A European cohort study found decreased incidence of breast cancer in both MTF and FTM transgender patients, but these patients were an overall younger cohort with decreased risk in general. A cohort of 2,236 MTF individuals in the Netherlands in 1997 showed no increase in all-cause mortality related to hormone therapy at 30-year follow-up. Patients were exposed to exogenous estrogen from 2 months to 41 years.9 A follow-up of this study published in 2013, which included 2,307 MTF individuals taking estrogen for 5 years to > 30 years, revealed only 2 cases of breast cancer, which was the same incidence rate (4.1 per 100,000 person-years) as that of nontransgender women.10

In general, the incidence of breast cancer is rare in nontransgender men, and therefore there have not been a lot of clinical studies to assess risk factors and detection methods. The following risk factors can increase the risk of breast cancer in nontransgender patients: known presence of BRCA mutation, estrogen exposure/androgen insufficiency, Klinefelter syndrome, liver cirrhosis, and obesity.11

Guidelines from the Endocrine Society, WPATH, and UCSF suggest that MTF transgender individuals who have a known increased risk for breast cancer should follow screening guidelines recommended for nontransgender women if they are aged > 50 years and have had more than 5 years of hormone use.2 For FTM patients who have not had chest surgery, screening guidelines should follow those for nontransgender women. For those patients who have had chest reconstruction, small residual amounts of breast tissue may remain. Screening guidelines for these patients do not exist. For these patients, mammography can be technically difficult. Clinical chest wall examination, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and/or ultrasound may be helpful modalities. An individual risk vs benefit discussion with the patient is recommended.

Prostate Cancer Screening

Although the prostate gland will undergo atrophy with extended treatment with feminizing hormone therapy, there are case reports of prostate cancer in transgender women.12,13 Usually these patients have started hormone treatment after age 50 years. Therefore, prostate cancer screening is recommended in transgender women as per general guidelines. Because the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level is expected to be reduced, a PSA > 1.0 should be considered abnormal.1

Cervical Cancer Screening

When a transgender man has a pap smear, it is essential to make it clear to the laboratory that the sample is a cervical pap smear (especially if the gender is marked as male) to avoid the sample being run incorrectly as an anal pap. Also, it is essential to indicate on the pap smear request form that the patient is on testosterone therapy and amenorrhea is present, because the lack of the female hormone can cause atrophy of cervix. This population has a high rate of inadequate specimens. Pretreatment with 1 to 2 weeks of vaginal estrogen can improve the success rate of inadequate specimens. Transgender women who have undergone vaginoplasty do not have a cervix, therefore, cervical cancer screening is not recommended. The anatomy of the neovagina has a more posterior orientation, and an anoscope is a more appropriate tool to examine the neovagina when necessary.

Hematology Health

Transgender women on cross-sex hormone therapy with estrogens may be at increased risk for a venous thromboembolism (VTE). In 2 European studies, patients treated with oral ethinyl estradiol as well as the anti-androgen cyproterone acetate were found to have up to 20 times increased risk of VTE. However, in later studies, oral ethinyl estradiol was changed to either oral conjugated estrogens or transdermal/intramuscular estradiol, and these studies did not show a significant increase in VTE risk.14-16 Tobacco use in combination with estrogen therapy is associated with an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT).1 All transgender women who smoke should be counseled on tobacco risks and cessation options at every visit.1 The transgender individuals who are not willing to quit smoking may be offered transdermal estrogen, which has lower risk of DVT.14-16

Sexual Health

Clinicians should assess the risks for sexually transmitted infection (STIs) or HIV for transgender patients based on current anatomy and sexual behaviors. Presentations of STIs can be atypical due to varied sexual practices and gender-affirming surgeries. Thus, providers must remain vigilant for symptoms consistent with common STIs and screen for asymptomatic STIs on the basis of behavior history and sexual practices.17 Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV should be considered when appropriate. Serologic screening recommendations for transgender people (eg, HIV, hepatitis B and C, syphilis) do not differ in recommendations from those for nontransgender people.

Cardiovascular Health

The effect of cross-hormone treatment on cardiovascular (CV) health is still unknown. There are no randomized controlled trials that have investigated the relationship between cross-hormone treatment and CV health. Evidence from several studies suggests that CV risk is unchanged among transgender men using testosterone compared with that of nontransgender women.18,19 There is conflicting evidence for transgender women with respect to CV risk and cross-sex hormone treatment.1,18,19 The current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline advises using the ASCVD risk calculator to determine the need for aspirin and statin treatment based on race, age, gender, and risk factors. There is no guideline on whether to use natal sex or affirmed gender while using the ASCVD calculator. It is reasonable to use the calculator based on natal sex if the cross-hormone treatment has started later in life, but if the cross-sex hormone treatment started at a young age, then one should consider using the affirmed gender to calculate the risk.

As with all patients, life style modifications, including smoking cessation, weight loss, physical activity, and management of BP and blood sugar, are important for CV health. For transgender women with CV risk factors or known CV disease, transdermal route of estrogen is preferred due to lower rates of VTE.18,19

Conclusion

In recent years, an increased number of transgender individuals are seeking mainstream medical care. However, PCPs often lack the knowledge and training to properly interact with and care for transgender patients. It is critical that clinicians understand the difference between sex, gender, and sexuality. For patients who desire transgender care, providers must be able to comfortably ask the patient about their preferred name and prior care, know the basics in cross-sex hormone therapy, including appropriate follow-up of hormonal levels as well as laboratory tests that delineate risk, and know possible complications and AEs. The VA offers significant resources, including electronic transgender care consultation for cases where the provider does not have adequate expertise in the care of these patients.

Both medical schools and residency training programs are starting to incorporate curricula regarding LGBT care. For those who have already completed training, this article serves as a brief guide to terminology, interactive tips, and management of this growing and underserved group of individuals.

1. Deutsch MB. Guidelines for the primary and gender-affirming care of transgender and gender nonbinary people. http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/protocols. Updated June 17, 2016. Accessed June 13, 2018.

2. Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoria/gender-incongruent persons: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3869-3903.

3. Buchholz L. Transgender care moves into the mainstream. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1785-1787.

4. Sobralske M. Primary care needs of patients who have undergone gender reassignment. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005;17(4):133-138.

5. Unger CA. Hormone therapy for transgender patients. Transl Androl Urol. 2016;5(6):877-884.

6. Kanhai RC, Hage JJ, van Diest PJ, Bloemena E, Mulder JW. Short-term and long-term histologic effects of castration and estrogen treatment on breast tissue of 14 male-to-female transsexuals in comparison with two chemically castrated men. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(1):74-80.

7. Braun H, Nash R, Tangpricha V, Brockman J, Ward K, Goodman M. Cancer in transgender people: evidence and methodological consideration. Epidemiol Rev. 2017;39(1):93-107.

8. Brown GR, Jones KT. Incidence of breast cancer in a cohort of 5,135 transgender veterans. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149(1):191-198.

9. Van Kesteren PJ, Asscheman H, Megens JA, Gooren LJ. Mortality and morbidity in transsexual subjects treated with cross-sex hormones. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1997;47(3):337-342.

10. Gooren LJ, van Trotsenburg MA, Giltay EJ, van Diest PJ. Breast cancer development in transsexual subjects receiving cross-sex hormone treatment. J Sex Med. 2013;10(12):3129-3134.

11. Johansen Taber KA, Morisy LR, Osbahr AJ III, Dickinson BD. Male breast cancer: risk factors, diagnosis and management (review). Oncol Rep. 2010;24(5):1115-1120.

12. Miksad RA, Bubley G, Church P, et al. Prostate cancer in a transgender woman, 41 years after initiation of feminization. JAMA. 2006;296(19):2316-2317.

13. Turo R, Jallad S, Prescott S, Cross WR. Metastatic prostate cancer in transsexual diagnosed after three decades of estrogen therapy. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7(7-8):E544-E546.

14. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 556: postmenopausal estrogen therapy: route of administration and risk of venous thromboembolism. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(4):887-890.

15. Asscheman H, Gooren LJ, Eklund PL. Mortality and morbidity in transsexual patients with cross-gender treatment. Metabolism. 1989;38(9):869-873.

16. Asscheman H, Giltay EJ, Megens JA, de Ronde WP, van Trotsenburg MA, Gooren LJ. A long-term follow-up study of mortality in transsexuals receiving treatment with cross-sex hormones. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164(4):635-642.

17. Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1-137.

18. Gooren LJ, Wierckx K, Giltay EJ. Cardiovascular disease in transsexual persons treated with cross-sex hormones: reversal of the traditional sex difference in cardiovascular disease pattern. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;170(6):809-819.

19. Streed CG Jr, Harfouch O, Marvel F, Blumenthal RS, Martin SS, Mukherjee M. Cardiovascular disease among transgender adults receiving hormone therapy: a narrative review. Ann Int Med. 2017;167(4):256-267.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals face significant difficulties in obtaining high-quality,compassionate medical care, much of which has been attributed to inadequate provider knowledge. In this article, the authors present a transgender patient seen in primary care and discuss the knowledge gleaned to inform future care of this patient as well as the care of other similar patients.

The following case discussion and review of the literature also seeks to improve the practice of other primary care providers (PCPs) who are inexperienced in this arena. This article aims to review the basics to permit PCPs to venture into transgender care, including a review of basic terminology; a few interactive tips; and basics in medical and hormonal treatment, follow-up, contraindications, and risk. More details can be obtained through electronic consultation (Transgender eConsult) in the VA.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old patient who was assigned male sex at birth presented to the primary care clinic to discuss her desire to undergo male-to-female (MTF) transition. The patient stated that she had started taking female estrogen hormones 9 years previously purchased from craigslist without a prescription. She tried oral contraceptives as well as oral and injectable estradiol. While the patient was taking injectable estradiol she had breast growth, decreased anxiety, weight gain, and a feeling of peacefulness. The patient also reported that she had received several laser treatments for whole body hair removal, beginning 8 to 10 years before and more regularly in the past 2 to 3 years. She asked whether transition-related care could be provided, because she could no longer afford the hormones.

The patient wanted to transition because she felt that “Women are beautiful, the way they carry themselves, wear their hair, their nails, I want to be like that.” She also mentioned that when she watched TV, she envisioned herself as a woman. She reported that she enjoyed wearing her mother’s clothing since age 10, which made her feel more like herself. The patient noted that she had desired to remove her body hair since childhood but could not afford to do it until recently. She bought female clothing, shoes and makeup, and did her nails from a young age. The patient also reported that she did not “know what transgender was” until a decade ago.

The patient struggled with her identity growing up; however, she tried not to think about it or talk about it with anyone. She related that she was ashamed of her thoughts and that only recently had made peace with being transgender. Thus, she pursued talking to her medical provider about transitioning. The patient reported that she felt more energetic when taking female hormones and was better able to discuss the issue. Specifically, she noted that if she were not on estrogen now she would not be able to talk about transitioning.

The patient related that she has done extensive research about transitioning, including reading online about other transgender people. She noted that she was aware of “possible backlash with society,” but ultimately, she had decided that transitioning was the right decision for her.

She expressed a desire to have an orchiectomy and continue hormonal therapy to permit her “to have a more feminine face, soft skin, hairless body, big breasts, more fat around the hips, and a high-pitched voice.” She additionally related a desire to be in a stable relationship and be her true self. She also stated that she had not identified herself as a female to anyone yet but would like to soon. The patient reported a history of depression, especially during her military service when she wanted to be a woman but did not feel she understood what was going on or how to manage her feelings. She said that for the past 2 months she felt much happier since beginning to take estradiol 4 mg orally daily, which she had found online. She also tried to purchase anti-androgen medication but could not afford it. In addition, she said that she would like to eventually proceed with gender affirmation surgery.

She was currently having sex with men, primarily via anal receptive intercourse. She had no history of sexually transmitted infections but reported that she did not use condoms regularly. She had no history of physical or sexual abuse. The patient was offered referral to the HIV clinic to receive HIV preexposure prophylaxis therapy (emtricitabine + tenofovir), which she declined, but she was counseled on safe sex practice.

The patient was referred to psychiatry both for supportive mental health care and to clarify that her concomitant mental health issues would not preclude the prescription of gender-affirming hormone treatment. Based on the psychiatric evaluation, the patient was felt to be appropriate for treatment with feminizing hormone therapy. The psychiatric assessment also noted that although the patient had a history of psychosis, she was not exhibiting psychotic symptoms currently, and this would not be a contraindication to treatment.

After discussion of the risks and benefits of cross-sex hormone therapy, the patient was started on estradiol 4 mg orally daily, as well as spironolactone 50 mg daily. She was then switched to estradiol 10 mg intramuscular every 2 weeks with the aim of using a less thrombogenic route of administration.

Treatment Outcomes

The patient remains under care. She has had follow-up visits every 3 months to ensure appropriate signs of feminization and monitoring of adverse effects (AEs). The patient’s testosterone and estradiol levels are being checked every 3 months to ensure total testosterone is 1,2

After 12 months on therapy with estradiol and spironolactone, the patient notes that her mood has improved, she feels more energetic, she has gained some weight, and her skin is softer. Her voice pitch, with the help of speech therapy, is gradually changing to what she perceives as more feminine. Hormone levels and electrolytes are all in an acceptable range, and blood sugar and blood pressure (BP) are within normal range. The patient will be offered age-appropriate cancer screening at the appropriate time.

Discussion

The treatment of gender-nonconforming individuals has come a long way since Lili Elbe, the transgender artist depicted in The Danish Girl, underwent gender-affirmation surgery in the early 20th century. Lili and people like her paved the way for other transgender individuals by doggedly pursuing gender-affirming medical treatment although they faced rejection by society and forged a difficult path. In recent years, an increasing number of transgender individuals have begun to seek mainstream medical care; however, PCPs often lack the knowledge and training to properly interact with and care for transgender patients.3,4

Terminology

Although someone’s sex is typically assigned at birth based on the external appearance of their genitalia, gender identity refers to a person’s internal sense of self and how they fit in to the world. People often use these 2 terms interchangeably in everyday language, but these terms are different.1,2

Transgender refers to a person whose gender identity differs from the sex that was assigned at birth. A transgender man or transman, or female-to-male (FTM) transgender person, is an individual who is assigned female sex at birth but identifies as a male. A transgender woman, or transwoman or a male-to-female (MTF) transgender person, is an individual who is assigned male sex at birth but identifies as female. A nontransgender person may be referred to as cisgender.

Transsexual is a medical term and refers to a transgender individual who sought medical intervention to transition to their identified gender.

Sexual orientation describes sexual attraction only and is not related to gender identity. The sexual orientation of a transgender person is determined by emotional and/or physical attraction and not gender identity.

Gender dysphoria refers to the distress experienced by an individual when one’s gender identity and sex are not completely congruent.

Improving Patient Interaction

Transgender patients might avoid seeking care due to previous negative experiences or a fear of being judged. It is very important to create a safe environment where the patients feel comfortable. Meeting patients “where they are” without judgment will enhance the patient-physician relationship. It is necessary to train all clinic staff about the importance of transgender health issues. All staff should address the patient with the name, pronouns, and gender identity that the patient prefers. For patients with a gender identity that is not strictly male or female (nonbinary patients), gender-neutral pronouns, such as they/them/their, may be chosen. It is helpful to be direct in asking: What is your preferred name? When I speak about you to other providers, what pronouns do you prefer I use, he, she, they? This information can then be documented in the electronic health record (EHR) so that all staff know from visit to visit. Thank the patient for the clarification.

The physical examination can be uncomfortable for both the patient and the physician. Experience and familiarity with the current recommendations can help. The physical examination should be relevant to the anatomy that is present, regardless of the gender presentation. An anatomic survey of the organs currently present in an individual can be useful.1 The physician should be sensitive in examining and obtaining information from the patient, focusing on only those issues relevant to the presenting concern. Chest and genital examinations may be particularly distressing for patients. If a chest or genital examination is indicated, the provider and patient should have a discussion explaining the importance of the examination and how the patient’s comfort can be optimized.

Medical Treatment

Gender-affirmation treatment should be multidisciplinary and include some or all of the following: diagnostic assessment, psychotherapy or counseling, real-life experience (RLE), hormone therapy, and surgical therapy..1,2,5 The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) has established internationally accepted Standards of Care (SOC) for the treatment of gender dysphoria that provide detailed expert opinion reviewing the background and guidance for care of transgender individuals. Most commonly, the diagnosis of gender dysphoria is made by a mental health professional (MHP) based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) criteria for gender dysphoria.1,2 The involvement of a MHP can be crucial in assessing potential psychological and social risk factors for unfavorable outcomes of medical interventions. In case of severe psychopathology, which can interfere with diagnosis and treatment, the psychopathology should be addressed first.1,2 The MHP also can confirm that the patient has the capacity to make an informed decision.

The 2017 Endocrine Society guidelines for the treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons emphasize the utility of evaluation of these patients by an expert MHP before starting the treatment.2 However, the guidelines from WPATH and the Center for Transgender Excellence at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) have stipulated that any provider who feels comfortable assessing the informed decision-making process with a patient can make this determination.

The WPATH SOC states that RLE is essential to transition to the gender role that is congruent with the patient’s gender identity. The RLE is defined as the act of fully adopting a new or evolving gender role or gender presentation in everyday life. In the RLE, the person should fully experience life in the desired gender role before irreversible physical treatment is undertaken. Newer guidelines note that it may be too challenging to adopt the desired gender role without the benefit of feminizing or masculinizing treatment, and therefore, the treatment can be offered at the same time as adopting the new gender role.1

Medical treatment involves administration of masculinizing or feminizing hormone therapy. There are 2 major goals of this hormonal therapy.

For many transgender adults, genital reconstruction surgery and/or gonadectomy is a necessary step toward achieving their goal.

Pretreatment screening and appropriate medical monitoring is recommended for both FTM and MTF transgender patients during the endocrine transition and periodically thereafter.2 The physician should monitor the patient’s weight, BP, directed physical examinations, routine health questions focused on risk factors and medications, complete blood count, renal and liver functions, lipid and blood sugar.2

Physical Changes With Hormone Therapy

Transgender men. Physical changes that are expected to occur during the first 1 to 6 months of testosterone therapy include cessation of menses, increased sexual desire, increased facial and body hair, increased oiliness of skin, increased muscle, and redistribution of fat mass. Changes that occur within the first year of testosterone therapy include deepening of the voice, clitoromegaly, and male pattern hair loss (in some cases). Deepening of the voice, and clitoromegaly are not reversible with discontinuation of hormonal therapy.2

Transgender women. Physical changes that may occur in transgender females in the first 3 to 12 months of estrogen and anti-androgen therapy include decreased sexual desire, decreased spontaneous erections, decreased facial and body hair (usually mild), decreased oiliness of skin, increased breast tissue growth, and redistribution of fat mass. Breast development is generally maximal at 2 years after initiating estrogen, and it is irreversible.2 Effect on fertility may be permanent. Medical therapy has little effect on voice, and most transwomen will require speech therapy to achieve desired pitch.

Routine Health Maintenance

Breast Cancer Screening

Although there are limited data, it is thought that gender-affirming hormone therapy has similar risks as sex hormone replacement therapy in nontransgender males and females. Most AEs arise from use of supraphysiologic doses or inadequate doses.2 Therefore, regular clinical and laboratory monitoring is essential to cross-sex hormone therapy. Treatment with exogenous estrogen and anti-androgens result in transgender women developing breast tissue with ducts, lobules, and acini that is histologically identical to breast tissue in nontransgender females.6

Breast cancer is a concern in transgender women due to prolonged exposure to estrogen. However, the relationship between breast cancer and cross-sex hormone therapy is controversial.

Many factors contribute to breast cancer risk in patients of all genders. Studies of premenopausal and menopausal women taking exogenous estrogen alone have not shown an increase in breast cancer risk. However, the combination of estrogen and progesterone has shown an association with a significant increase in the incidence of breast cancer in postmenopausal women.2,7-10

A study of 5,136 veterans showed a statistically insignificant increased incidence of breast cancer in transgender women compared with data collected from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, although the sample size and duration of the observation were limiting factors.8 A European cohort study found decreased incidence of breast cancer in both MTF and FTM transgender patients, but these patients were an overall younger cohort with decreased risk in general. A cohort of 2,236 MTF individuals in the Netherlands in 1997 showed no increase in all-cause mortality related to hormone therapy at 30-year follow-up. Patients were exposed to exogenous estrogen from 2 months to 41 years.9 A follow-up of this study published in 2013, which included 2,307 MTF individuals taking estrogen for 5 years to > 30 years, revealed only 2 cases of breast cancer, which was the same incidence rate (4.1 per 100,000 person-years) as that of nontransgender women.10

In general, the incidence of breast cancer is rare in nontransgender men, and therefore there have not been a lot of clinical studies to assess risk factors and detection methods. The following risk factors can increase the risk of breast cancer in nontransgender patients: known presence of BRCA mutation, estrogen exposure/androgen insufficiency, Klinefelter syndrome, liver cirrhosis, and obesity.11

Guidelines from the Endocrine Society, WPATH, and UCSF suggest that MTF transgender individuals who have a known increased risk for breast cancer should follow screening guidelines recommended for nontransgender women if they are aged > 50 years and have had more than 5 years of hormone use.2 For FTM patients who have not had chest surgery, screening guidelines should follow those for nontransgender women. For those patients who have had chest reconstruction, small residual amounts of breast tissue may remain. Screening guidelines for these patients do not exist. For these patients, mammography can be technically difficult. Clinical chest wall examination, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and/or ultrasound may be helpful modalities. An individual risk vs benefit discussion with the patient is recommended.

Prostate Cancer Screening

Although the prostate gland will undergo atrophy with extended treatment with feminizing hormone therapy, there are case reports of prostate cancer in transgender women.12,13 Usually these patients have started hormone treatment after age 50 years. Therefore, prostate cancer screening is recommended in transgender women as per general guidelines. Because the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level is expected to be reduced, a PSA > 1.0 should be considered abnormal.1

Cervical Cancer Screening

When a transgender man has a pap smear, it is essential to make it clear to the laboratory that the sample is a cervical pap smear (especially if the gender is marked as male) to avoid the sample being run incorrectly as an anal pap. Also, it is essential to indicate on the pap smear request form that the patient is on testosterone therapy and amenorrhea is present, because the lack of the female hormone can cause atrophy of cervix. This population has a high rate of inadequate specimens. Pretreatment with 1 to 2 weeks of vaginal estrogen can improve the success rate of inadequate specimens. Transgender women who have undergone vaginoplasty do not have a cervix, therefore, cervical cancer screening is not recommended. The anatomy of the neovagina has a more posterior orientation, and an anoscope is a more appropriate tool to examine the neovagina when necessary.

Hematology Health

Transgender women on cross-sex hormone therapy with estrogens may be at increased risk for a venous thromboembolism (VTE). In 2 European studies, patients treated with oral ethinyl estradiol as well as the anti-androgen cyproterone acetate were found to have up to 20 times increased risk of VTE. However, in later studies, oral ethinyl estradiol was changed to either oral conjugated estrogens or transdermal/intramuscular estradiol, and these studies did not show a significant increase in VTE risk.14-16 Tobacco use in combination with estrogen therapy is associated with an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT).1 All transgender women who smoke should be counseled on tobacco risks and cessation options at every visit.1 The transgender individuals who are not willing to quit smoking may be offered transdermal estrogen, which has lower risk of DVT.14-16

Sexual Health

Clinicians should assess the risks for sexually transmitted infection (STIs) or HIV for transgender patients based on current anatomy and sexual behaviors. Presentations of STIs can be atypical due to varied sexual practices and gender-affirming surgeries. Thus, providers must remain vigilant for symptoms consistent with common STIs and screen for asymptomatic STIs on the basis of behavior history and sexual practices.17 Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV should be considered when appropriate. Serologic screening recommendations for transgender people (eg, HIV, hepatitis B and C, syphilis) do not differ in recommendations from those for nontransgender people.

Cardiovascular Health

The effect of cross-hormone treatment on cardiovascular (CV) health is still unknown. There are no randomized controlled trials that have investigated the relationship between cross-hormone treatment and CV health. Evidence from several studies suggests that CV risk is unchanged among transgender men using testosterone compared with that of nontransgender women.18,19 There is conflicting evidence for transgender women with respect to CV risk and cross-sex hormone treatment.1,18,19 The current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline advises using the ASCVD risk calculator to determine the need for aspirin and statin treatment based on race, age, gender, and risk factors. There is no guideline on whether to use natal sex or affirmed gender while using the ASCVD calculator. It is reasonable to use the calculator based on natal sex if the cross-hormone treatment has started later in life, but if the cross-sex hormone treatment started at a young age, then one should consider using the affirmed gender to calculate the risk.

As with all patients, life style modifications, including smoking cessation, weight loss, physical activity, and management of BP and blood sugar, are important for CV health. For transgender women with CV risk factors or known CV disease, transdermal route of estrogen is preferred due to lower rates of VTE.18,19

Conclusion

In recent years, an increased number of transgender individuals are seeking mainstream medical care. However, PCPs often lack the knowledge and training to properly interact with and care for transgender patients. It is critical that clinicians understand the difference between sex, gender, and sexuality. For patients who desire transgender care, providers must be able to comfortably ask the patient about their preferred name and prior care, know the basics in cross-sex hormone therapy, including appropriate follow-up of hormonal levels as well as laboratory tests that delineate risk, and know possible complications and AEs. The VA offers significant resources, including electronic transgender care consultation for cases where the provider does not have adequate expertise in the care of these patients.

Both medical schools and residency training programs are starting to incorporate curricula regarding LGBT care. For those who have already completed training, this article serves as a brief guide to terminology, interactive tips, and management of this growing and underserved group of individuals.

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals face significant difficulties in obtaining high-quality,compassionate medical care, much of which has been attributed to inadequate provider knowledge. In this article, the authors present a transgender patient seen in primary care and discuss the knowledge gleaned to inform future care of this patient as well as the care of other similar patients.

The following case discussion and review of the literature also seeks to improve the practice of other primary care providers (PCPs) who are inexperienced in this arena. This article aims to review the basics to permit PCPs to venture into transgender care, including a review of basic terminology; a few interactive tips; and basics in medical and hormonal treatment, follow-up, contraindications, and risk. More details can be obtained through electronic consultation (Transgender eConsult) in the VA.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old patient who was assigned male sex at birth presented to the primary care clinic to discuss her desire to undergo male-to-female (MTF) transition. The patient stated that she had started taking female estrogen hormones 9 years previously purchased from craigslist without a prescription. She tried oral contraceptives as well as oral and injectable estradiol. While the patient was taking injectable estradiol she had breast growth, decreased anxiety, weight gain, and a feeling of peacefulness. The patient also reported that she had received several laser treatments for whole body hair removal, beginning 8 to 10 years before and more regularly in the past 2 to 3 years. She asked whether transition-related care could be provided, because she could no longer afford the hormones.

The patient wanted to transition because she felt that “Women are beautiful, the way they carry themselves, wear their hair, their nails, I want to be like that.” She also mentioned that when she watched TV, she envisioned herself as a woman. She reported that she enjoyed wearing her mother’s clothing since age 10, which made her feel more like herself. The patient noted that she had desired to remove her body hair since childhood but could not afford to do it until recently. She bought female clothing, shoes and makeup, and did her nails from a young age. The patient also reported that she did not “know what transgender was” until a decade ago.

The patient struggled with her identity growing up; however, she tried not to think about it or talk about it with anyone. She related that she was ashamed of her thoughts and that only recently had made peace with being transgender. Thus, she pursued talking to her medical provider about transitioning. The patient reported that she felt more energetic when taking female hormones and was better able to discuss the issue. Specifically, she noted that if she were not on estrogen now she would not be able to talk about transitioning.

The patient related that she has done extensive research about transitioning, including reading online about other transgender people. She noted that she was aware of “possible backlash with society,” but ultimately, she had decided that transitioning was the right decision for her.

She expressed a desire to have an orchiectomy and continue hormonal therapy to permit her “to have a more feminine face, soft skin, hairless body, big breasts, more fat around the hips, and a high-pitched voice.” She additionally related a desire to be in a stable relationship and be her true self. She also stated that she had not identified herself as a female to anyone yet but would like to soon. The patient reported a history of depression, especially during her military service when she wanted to be a woman but did not feel she understood what was going on or how to manage her feelings. She said that for the past 2 months she felt much happier since beginning to take estradiol 4 mg orally daily, which she had found online. She also tried to purchase anti-androgen medication but could not afford it. In addition, she said that she would like to eventually proceed with gender affirmation surgery.

She was currently having sex with men, primarily via anal receptive intercourse. She had no history of sexually transmitted infections but reported that she did not use condoms regularly. She had no history of physical or sexual abuse. The patient was offered referral to the HIV clinic to receive HIV preexposure prophylaxis therapy (emtricitabine + tenofovir), which she declined, but she was counseled on safe sex practice.

The patient was referred to psychiatry both for supportive mental health care and to clarify that her concomitant mental health issues would not preclude the prescription of gender-affirming hormone treatment. Based on the psychiatric evaluation, the patient was felt to be appropriate for treatment with feminizing hormone therapy. The psychiatric assessment also noted that although the patient had a history of psychosis, she was not exhibiting psychotic symptoms currently, and this would not be a contraindication to treatment.

After discussion of the risks and benefits of cross-sex hormone therapy, the patient was started on estradiol 4 mg orally daily, as well as spironolactone 50 mg daily. She was then switched to estradiol 10 mg intramuscular every 2 weeks with the aim of using a less thrombogenic route of administration.

Treatment Outcomes

The patient remains under care. She has had follow-up visits every 3 months to ensure appropriate signs of feminization and monitoring of adverse effects (AEs). The patient’s testosterone and estradiol levels are being checked every 3 months to ensure total testosterone is 1,2

After 12 months on therapy with estradiol and spironolactone, the patient notes that her mood has improved, she feels more energetic, she has gained some weight, and her skin is softer. Her voice pitch, with the help of speech therapy, is gradually changing to what she perceives as more feminine. Hormone levels and electrolytes are all in an acceptable range, and blood sugar and blood pressure (BP) are within normal range. The patient will be offered age-appropriate cancer screening at the appropriate time.

Discussion

The treatment of gender-nonconforming individuals has come a long way since Lili Elbe, the transgender artist depicted in The Danish Girl, underwent gender-affirmation surgery in the early 20th century. Lili and people like her paved the way for other transgender individuals by doggedly pursuing gender-affirming medical treatment although they faced rejection by society and forged a difficult path. In recent years, an increasing number of transgender individuals have begun to seek mainstream medical care; however, PCPs often lack the knowledge and training to properly interact with and care for transgender patients.3,4

Terminology

Although someone’s sex is typically assigned at birth based on the external appearance of their genitalia, gender identity refers to a person’s internal sense of self and how they fit in to the world. People often use these 2 terms interchangeably in everyday language, but these terms are different.1,2

Transgender refers to a person whose gender identity differs from the sex that was assigned at birth. A transgender man or transman, or female-to-male (FTM) transgender person, is an individual who is assigned female sex at birth but identifies as a male. A transgender woman, or transwoman or a male-to-female (MTF) transgender person, is an individual who is assigned male sex at birth but identifies as female. A nontransgender person may be referred to as cisgender.

Transsexual is a medical term and refers to a transgender individual who sought medical intervention to transition to their identified gender.

Sexual orientation describes sexual attraction only and is not related to gender identity. The sexual orientation of a transgender person is determined by emotional and/or physical attraction and not gender identity.

Gender dysphoria refers to the distress experienced by an individual when one’s gender identity and sex are not completely congruent.

Improving Patient Interaction

Transgender patients might avoid seeking care due to previous negative experiences or a fear of being judged. It is very important to create a safe environment where the patients feel comfortable. Meeting patients “where they are” without judgment will enhance the patient-physician relationship. It is necessary to train all clinic staff about the importance of transgender health issues. All staff should address the patient with the name, pronouns, and gender identity that the patient prefers. For patients with a gender identity that is not strictly male or female (nonbinary patients), gender-neutral pronouns, such as they/them/their, may be chosen. It is helpful to be direct in asking: What is your preferred name? When I speak about you to other providers, what pronouns do you prefer I use, he, she, they? This information can then be documented in the electronic health record (EHR) so that all staff know from visit to visit. Thank the patient for the clarification.

The physical examination can be uncomfortable for both the patient and the physician. Experience and familiarity with the current recommendations can help. The physical examination should be relevant to the anatomy that is present, regardless of the gender presentation. An anatomic survey of the organs currently present in an individual can be useful.1 The physician should be sensitive in examining and obtaining information from the patient, focusing on only those issues relevant to the presenting concern. Chest and genital examinations may be particularly distressing for patients. If a chest or genital examination is indicated, the provider and patient should have a discussion explaining the importance of the examination and how the patient’s comfort can be optimized.

Medical Treatment

Gender-affirmation treatment should be multidisciplinary and include some or all of the following: diagnostic assessment, psychotherapy or counseling, real-life experience (RLE), hormone therapy, and surgical therapy..1,2,5 The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) has established internationally accepted Standards of Care (SOC) for the treatment of gender dysphoria that provide detailed expert opinion reviewing the background and guidance for care of transgender individuals. Most commonly, the diagnosis of gender dysphoria is made by a mental health professional (MHP) based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) criteria for gender dysphoria.1,2 The involvement of a MHP can be crucial in assessing potential psychological and social risk factors for unfavorable outcomes of medical interventions. In case of severe psychopathology, which can interfere with diagnosis and treatment, the psychopathology should be addressed first.1,2 The MHP also can confirm that the patient has the capacity to make an informed decision.

The 2017 Endocrine Society guidelines for the treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons emphasize the utility of evaluation of these patients by an expert MHP before starting the treatment.2 However, the guidelines from WPATH and the Center for Transgender Excellence at University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) have stipulated that any provider who feels comfortable assessing the informed decision-making process with a patient can make this determination.

The WPATH SOC states that RLE is essential to transition to the gender role that is congruent with the patient’s gender identity. The RLE is defined as the act of fully adopting a new or evolving gender role or gender presentation in everyday life. In the RLE, the person should fully experience life in the desired gender role before irreversible physical treatment is undertaken. Newer guidelines note that it may be too challenging to adopt the desired gender role without the benefit of feminizing or masculinizing treatment, and therefore, the treatment can be offered at the same time as adopting the new gender role.1

Medical treatment involves administration of masculinizing or feminizing hormone therapy. There are 2 major goals of this hormonal therapy.

For many transgender adults, genital reconstruction surgery and/or gonadectomy is a necessary step toward achieving their goal.

Pretreatment screening and appropriate medical monitoring is recommended for both FTM and MTF transgender patients during the endocrine transition and periodically thereafter.2 The physician should monitor the patient’s weight, BP, directed physical examinations, routine health questions focused on risk factors and medications, complete blood count, renal and liver functions, lipid and blood sugar.2

Physical Changes With Hormone Therapy

Transgender men. Physical changes that are expected to occur during the first 1 to 6 months of testosterone therapy include cessation of menses, increased sexual desire, increased facial and body hair, increased oiliness of skin, increased muscle, and redistribution of fat mass. Changes that occur within the first year of testosterone therapy include deepening of the voice, clitoromegaly, and male pattern hair loss (in some cases). Deepening of the voice, and clitoromegaly are not reversible with discontinuation of hormonal therapy.2

Transgender women. Physical changes that may occur in transgender females in the first 3 to 12 months of estrogen and anti-androgen therapy include decreased sexual desire, decreased spontaneous erections, decreased facial and body hair (usually mild), decreased oiliness of skin, increased breast tissue growth, and redistribution of fat mass. Breast development is generally maximal at 2 years after initiating estrogen, and it is irreversible.2 Effect on fertility may be permanent. Medical therapy has little effect on voice, and most transwomen will require speech therapy to achieve desired pitch.

Routine Health Maintenance

Breast Cancer Screening

Although there are limited data, it is thought that gender-affirming hormone therapy has similar risks as sex hormone replacement therapy in nontransgender males and females. Most AEs arise from use of supraphysiologic doses or inadequate doses.2 Therefore, regular clinical and laboratory monitoring is essential to cross-sex hormone therapy. Treatment with exogenous estrogen and anti-androgens result in transgender women developing breast tissue with ducts, lobules, and acini that is histologically identical to breast tissue in nontransgender females.6

Breast cancer is a concern in transgender women due to prolonged exposure to estrogen. However, the relationship between breast cancer and cross-sex hormone therapy is controversial.

Many factors contribute to breast cancer risk in patients of all genders. Studies of premenopausal and menopausal women taking exogenous estrogen alone have not shown an increase in breast cancer risk. However, the combination of estrogen and progesterone has shown an association with a significant increase in the incidence of breast cancer in postmenopausal women.2,7-10

A study of 5,136 veterans showed a statistically insignificant increased incidence of breast cancer in transgender women compared with data collected from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database, although the sample size and duration of the observation were limiting factors.8 A European cohort study found decreased incidence of breast cancer in both MTF and FTM transgender patients, but these patients were an overall younger cohort with decreased risk in general. A cohort of 2,236 MTF individuals in the Netherlands in 1997 showed no increase in all-cause mortality related to hormone therapy at 30-year follow-up. Patients were exposed to exogenous estrogen from 2 months to 41 years.9 A follow-up of this study published in 2013, which included 2,307 MTF individuals taking estrogen for 5 years to > 30 years, revealed only 2 cases of breast cancer, which was the same incidence rate (4.1 per 100,000 person-years) as that of nontransgender women.10

In general, the incidence of breast cancer is rare in nontransgender men, and therefore there have not been a lot of clinical studies to assess risk factors and detection methods. The following risk factors can increase the risk of breast cancer in nontransgender patients: known presence of BRCA mutation, estrogen exposure/androgen insufficiency, Klinefelter syndrome, liver cirrhosis, and obesity.11

Guidelines from the Endocrine Society, WPATH, and UCSF suggest that MTF transgender individuals who have a known increased risk for breast cancer should follow screening guidelines recommended for nontransgender women if they are aged > 50 years and have had more than 5 years of hormone use.2 For FTM patients who have not had chest surgery, screening guidelines should follow those for nontransgender women. For those patients who have had chest reconstruction, small residual amounts of breast tissue may remain. Screening guidelines for these patients do not exist. For these patients, mammography can be technically difficult. Clinical chest wall examination, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and/or ultrasound may be helpful modalities. An individual risk vs benefit discussion with the patient is recommended.

Prostate Cancer Screening

Although the prostate gland will undergo atrophy with extended treatment with feminizing hormone therapy, there are case reports of prostate cancer in transgender women.12,13 Usually these patients have started hormone treatment after age 50 years. Therefore, prostate cancer screening is recommended in transgender women as per general guidelines. Because the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level is expected to be reduced, a PSA > 1.0 should be considered abnormal.1

Cervical Cancer Screening

When a transgender man has a pap smear, it is essential to make it clear to the laboratory that the sample is a cervical pap smear (especially if the gender is marked as male) to avoid the sample being run incorrectly as an anal pap. Also, it is essential to indicate on the pap smear request form that the patient is on testosterone therapy and amenorrhea is present, because the lack of the female hormone can cause atrophy of cervix. This population has a high rate of inadequate specimens. Pretreatment with 1 to 2 weeks of vaginal estrogen can improve the success rate of inadequate specimens. Transgender women who have undergone vaginoplasty do not have a cervix, therefore, cervical cancer screening is not recommended. The anatomy of the neovagina has a more posterior orientation, and an anoscope is a more appropriate tool to examine the neovagina when necessary.

Hematology Health

Transgender women on cross-sex hormone therapy with estrogens may be at increased risk for a venous thromboembolism (VTE). In 2 European studies, patients treated with oral ethinyl estradiol as well as the anti-androgen cyproterone acetate were found to have up to 20 times increased risk of VTE. However, in later studies, oral ethinyl estradiol was changed to either oral conjugated estrogens or transdermal/intramuscular estradiol, and these studies did not show a significant increase in VTE risk.14-16 Tobacco use in combination with estrogen therapy is associated with an increased risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT).1 All transgender women who smoke should be counseled on tobacco risks and cessation options at every visit.1 The transgender individuals who are not willing to quit smoking may be offered transdermal estrogen, which has lower risk of DVT.14-16

Sexual Health

Clinicians should assess the risks for sexually transmitted infection (STIs) or HIV for transgender patients based on current anatomy and sexual behaviors. Presentations of STIs can be atypical due to varied sexual practices and gender-affirming surgeries. Thus, providers must remain vigilant for symptoms consistent with common STIs and screen for asymptomatic STIs on the basis of behavior history and sexual practices.17 Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV should be considered when appropriate. Serologic screening recommendations for transgender people (eg, HIV, hepatitis B and C, syphilis) do not differ in recommendations from those for nontransgender people.

Cardiovascular Health

The effect of cross-hormone treatment on cardiovascular (CV) health is still unknown. There are no randomized controlled trials that have investigated the relationship between cross-hormone treatment and CV health. Evidence from several studies suggests that CV risk is unchanged among transgender men using testosterone compared with that of nontransgender women.18,19 There is conflicting evidence for transgender women with respect to CV risk and cross-sex hormone treatment.1,18,19 The current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guideline advises using the ASCVD risk calculator to determine the need for aspirin and statin treatment based on race, age, gender, and risk factors. There is no guideline on whether to use natal sex or affirmed gender while using the ASCVD calculator. It is reasonable to use the calculator based on natal sex if the cross-hormone treatment has started later in life, but if the cross-sex hormone treatment started at a young age, then one should consider using the affirmed gender to calculate the risk.

As with all patients, life style modifications, including smoking cessation, weight loss, physical activity, and management of BP and blood sugar, are important for CV health. For transgender women with CV risk factors or known CV disease, transdermal route of estrogen is preferred due to lower rates of VTE.18,19

Conclusion

In recent years, an increased number of transgender individuals are seeking mainstream medical care. However, PCPs often lack the knowledge and training to properly interact with and care for transgender patients. It is critical that clinicians understand the difference between sex, gender, and sexuality. For patients who desire transgender care, providers must be able to comfortably ask the patient about their preferred name and prior care, know the basics in cross-sex hormone therapy, including appropriate follow-up of hormonal levels as well as laboratory tests that delineate risk, and know possible complications and AEs. The VA offers significant resources, including electronic transgender care consultation for cases where the provider does not have adequate expertise in the care of these patients.

Both medical schools and residency training programs are starting to incorporate curricula regarding LGBT care. For those who have already completed training, this article serves as a brief guide to terminology, interactive tips, and management of this growing and underserved group of individuals.

1. Deutsch MB. Guidelines for the primary and gender-affirming care of transgender and gender nonbinary people. http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/protocols. Updated June 17, 2016. Accessed June 13, 2018.

2. Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoria/gender-incongruent persons: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3869-3903.

3. Buchholz L. Transgender care moves into the mainstream. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1785-1787.

4. Sobralske M. Primary care needs of patients who have undergone gender reassignment. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005;17(4):133-138.

5. Unger CA. Hormone therapy for transgender patients. Transl Androl Urol. 2016;5(6):877-884.

6. Kanhai RC, Hage JJ, van Diest PJ, Bloemena E, Mulder JW. Short-term and long-term histologic effects of castration and estrogen treatment on breast tissue of 14 male-to-female transsexuals in comparison with two chemically castrated men. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(1):74-80.

7. Braun H, Nash R, Tangpricha V, Brockman J, Ward K, Goodman M. Cancer in transgender people: evidence and methodological consideration. Epidemiol Rev. 2017;39(1):93-107.

8. Brown GR, Jones KT. Incidence of breast cancer in a cohort of 5,135 transgender veterans. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149(1):191-198.

9. Van Kesteren PJ, Asscheman H, Megens JA, Gooren LJ. Mortality and morbidity in transsexual subjects treated with cross-sex hormones. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1997;47(3):337-342.

10. Gooren LJ, van Trotsenburg MA, Giltay EJ, van Diest PJ. Breast cancer development in transsexual subjects receiving cross-sex hormone treatment. J Sex Med. 2013;10(12):3129-3134.

11. Johansen Taber KA, Morisy LR, Osbahr AJ III, Dickinson BD. Male breast cancer: risk factors, diagnosis and management (review). Oncol Rep. 2010;24(5):1115-1120.

12. Miksad RA, Bubley G, Church P, et al. Prostate cancer in a transgender woman, 41 years after initiation of feminization. JAMA. 2006;296(19):2316-2317.

13. Turo R, Jallad S, Prescott S, Cross WR. Metastatic prostate cancer in transsexual diagnosed after three decades of estrogen therapy. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7(7-8):E544-E546.

14. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 556: postmenopausal estrogen therapy: route of administration and risk of venous thromboembolism. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(4):887-890.

15. Asscheman H, Gooren LJ, Eklund PL. Mortality and morbidity in transsexual patients with cross-gender treatment. Metabolism. 1989;38(9):869-873.

16. Asscheman H, Giltay EJ, Megens JA, de Ronde WP, van Trotsenburg MA, Gooren LJ. A long-term follow-up study of mortality in transsexuals receiving treatment with cross-sex hormones. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164(4):635-642.

17. Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1-137.

18. Gooren LJ, Wierckx K, Giltay EJ. Cardiovascular disease in transsexual persons treated with cross-sex hormones: reversal of the traditional sex difference in cardiovascular disease pattern. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;170(6):809-819.

19. Streed CG Jr, Harfouch O, Marvel F, Blumenthal RS, Martin SS, Mukherjee M. Cardiovascular disease among transgender adults receiving hormone therapy: a narrative review. Ann Int Med. 2017;167(4):256-267.

1. Deutsch MB. Guidelines for the primary and gender-affirming care of transgender and gender nonbinary people. http://transhealth.ucsf.edu/protocols. Updated June 17, 2016. Accessed June 13, 2018.

2. Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoria/gender-incongruent persons: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(11):3869-3903.

3. Buchholz L. Transgender care moves into the mainstream. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1785-1787.

4. Sobralske M. Primary care needs of patients who have undergone gender reassignment. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005;17(4):133-138.

5. Unger CA. Hormone therapy for transgender patients. Transl Androl Urol. 2016;5(6):877-884.

6. Kanhai RC, Hage JJ, van Diest PJ, Bloemena E, Mulder JW. Short-term and long-term histologic effects of castration and estrogen treatment on breast tissue of 14 male-to-female transsexuals in comparison with two chemically castrated men. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(1):74-80.

7. Braun H, Nash R, Tangpricha V, Brockman J, Ward K, Goodman M. Cancer in transgender people: evidence and methodological consideration. Epidemiol Rev. 2017;39(1):93-107.

8. Brown GR, Jones KT. Incidence of breast cancer in a cohort of 5,135 transgender veterans. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149(1):191-198.

9. Van Kesteren PJ, Asscheman H, Megens JA, Gooren LJ. Mortality and morbidity in transsexual subjects treated with cross-sex hormones. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1997;47(3):337-342.

10. Gooren LJ, van Trotsenburg MA, Giltay EJ, van Diest PJ. Breast cancer development in transsexual subjects receiving cross-sex hormone treatment. J Sex Med. 2013;10(12):3129-3134.

11. Johansen Taber KA, Morisy LR, Osbahr AJ III, Dickinson BD. Male breast cancer: risk factors, diagnosis and management (review). Oncol Rep. 2010;24(5):1115-1120.

12. Miksad RA, Bubley G, Church P, et al. Prostate cancer in a transgender woman, 41 years after initiation of feminization. JAMA. 2006;296(19):2316-2317.

13. Turo R, Jallad S, Prescott S, Cross WR. Metastatic prostate cancer in transsexual diagnosed after three decades of estrogen therapy. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7(7-8):E544-E546.

14. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 556: postmenopausal estrogen therapy: route of administration and risk of venous thromboembolism. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(4):887-890.

15. Asscheman H, Gooren LJ, Eklund PL. Mortality and morbidity in transsexual patients with cross-gender treatment. Metabolism. 1989;38(9):869-873.

16. Asscheman H, Giltay EJ, Megens JA, de Ronde WP, van Trotsenburg MA, Gooren LJ. A long-term follow-up study of mortality in transsexuals receiving treatment with cross-sex hormones. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164(4):635-642.

17. Workowski KA, Bolan GA; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(RR-03):1-137.

18. Gooren LJ, Wierckx K, Giltay EJ. Cardiovascular disease in transsexual persons treated with cross-sex hormones: reversal of the traditional sex difference in cardiovascular disease pattern. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;170(6):809-819.

19. Streed CG Jr, Harfouch O, Marvel F, Blumenthal RS, Martin SS, Mukherjee M. Cardiovascular disease among transgender adults receiving hormone therapy: a narrative review. Ann Int Med. 2017;167(4):256-267.

Not Another Missed Spinal Epidural Abscess