User login

Can CBT effectively treat adult insomnia disorder?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Three meta-analyses that included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) compared various CBT delivery methods with controls (wait-listed for treatment or general sleep hygiene education) to assess sleep outcomes for adults with insomnia.1-3 TABLE 11-3 summarizes the results.

CBT is comparable to pharmacotherapy

A 2002 comparative meta-analysis of 21 RCTs with a total of 470 patients examined the effectiveness of CBT (stimulus control and/or sleep restriction) compared with pharmacotherapy (benzodiazepines or benzodiazepine agonists) for treating primary insomnia of longer than one month’s duration in adults with no comorbid medical or psychiatric diagnoses.4 The CBT group received intervention over an average of 5 weeks, and the pharmacotherapy group received intervention over an average of 2 weeks.

CBT produced greater reductions in sleep onset latency than pharmacotherapy based on mean weighted effect size (1.05 vs 0.45 weighted effect size; 95% confidence interval, 0.17-1.04; P=.01). Although both CBT and pharmacotherapy improved sleep outcomes, no statistical differences were found in wake after sleep onset time, total sleep time, number of awakenings, or sleep quality ratings (TABLE 24).

Continue to: CBT has significant benefit for comorbid insomnia

CBT has significant benefit for comorbid insomnia

A 2015 meta-analysis of 23 studies enrolling a total of 1379 adults with a number of illnesses (chronic pain, alcohol dependence, breast cancer, psychiatric disorders, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, fibromyalgia) and comorbid insomnia investigated the qualitative effectiveness of individual or group CBT therapy.5 Subjects received at least 4 face-to-face sessions and at least 2 components of CBT.

The primary outcome showed that sleep quality improved, as measured by a 6.36-point reduction in the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; a 7-question scale on which 0=no insomnia and 28=severe insomnia) and a 3.3-point reduction in the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; a 7-category assessment tool on which 0=perfect quality and 21=poor quality). The effect size was large for both ISI and PSQI, as indicated by standard mean differences greater than 0.8 (1.22 and 0.88, respectively) and was sustained for as long as 18 months.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Physicians strongly recommends that all adult patients receive CBT as initial treatment for chronic insomnia disorder. It can be performed in multiple settings, including the primary care setting. Compared with hypnotics, CBT is unlikely to have any adverse effects.6

1. Trauer J, Qian M, Doyle J, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:191-204.

2. Koffel E, Koffel J, Gehrman P. A meta-analysis of group cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;19:6-16.

3. Ye Y, Chen N, Chen J, et al. Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (ICBT-i): a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010707.

4. Smith M, Perlis M, Park S, et al. Comparative meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy for persistent insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:5-11.

5. Geiger-Brown J, Rogers V, Liu W, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy in persons with comorbid insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;23:54-67.

6. Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea M, et al. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:125-133.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Three meta-analyses that included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) compared various CBT delivery methods with controls (wait-listed for treatment or general sleep hygiene education) to assess sleep outcomes for adults with insomnia.1-3 TABLE 11-3 summarizes the results.

CBT is comparable to pharmacotherapy

A 2002 comparative meta-analysis of 21 RCTs with a total of 470 patients examined the effectiveness of CBT (stimulus control and/or sleep restriction) compared with pharmacotherapy (benzodiazepines or benzodiazepine agonists) for treating primary insomnia of longer than one month’s duration in adults with no comorbid medical or psychiatric diagnoses.4 The CBT group received intervention over an average of 5 weeks, and the pharmacotherapy group received intervention over an average of 2 weeks.

CBT produced greater reductions in sleep onset latency than pharmacotherapy based on mean weighted effect size (1.05 vs 0.45 weighted effect size; 95% confidence interval, 0.17-1.04; P=.01). Although both CBT and pharmacotherapy improved sleep outcomes, no statistical differences were found in wake after sleep onset time, total sleep time, number of awakenings, or sleep quality ratings (TABLE 24).

Continue to: CBT has significant benefit for comorbid insomnia

CBT has significant benefit for comorbid insomnia

A 2015 meta-analysis of 23 studies enrolling a total of 1379 adults with a number of illnesses (chronic pain, alcohol dependence, breast cancer, psychiatric disorders, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, fibromyalgia) and comorbid insomnia investigated the qualitative effectiveness of individual or group CBT therapy.5 Subjects received at least 4 face-to-face sessions and at least 2 components of CBT.

The primary outcome showed that sleep quality improved, as measured by a 6.36-point reduction in the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; a 7-question scale on which 0=no insomnia and 28=severe insomnia) and a 3.3-point reduction in the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; a 7-category assessment tool on which 0=perfect quality and 21=poor quality). The effect size was large for both ISI and PSQI, as indicated by standard mean differences greater than 0.8 (1.22 and 0.88, respectively) and was sustained for as long as 18 months.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Physicians strongly recommends that all adult patients receive CBT as initial treatment for chronic insomnia disorder. It can be performed in multiple settings, including the primary care setting. Compared with hypnotics, CBT is unlikely to have any adverse effects.6

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Three meta-analyses that included only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) compared various CBT delivery methods with controls (wait-listed for treatment or general sleep hygiene education) to assess sleep outcomes for adults with insomnia.1-3 TABLE 11-3 summarizes the results.

CBT is comparable to pharmacotherapy

A 2002 comparative meta-analysis of 21 RCTs with a total of 470 patients examined the effectiveness of CBT (stimulus control and/or sleep restriction) compared with pharmacotherapy (benzodiazepines or benzodiazepine agonists) for treating primary insomnia of longer than one month’s duration in adults with no comorbid medical or psychiatric diagnoses.4 The CBT group received intervention over an average of 5 weeks, and the pharmacotherapy group received intervention over an average of 2 weeks.

CBT produced greater reductions in sleep onset latency than pharmacotherapy based on mean weighted effect size (1.05 vs 0.45 weighted effect size; 95% confidence interval, 0.17-1.04; P=.01). Although both CBT and pharmacotherapy improved sleep outcomes, no statistical differences were found in wake after sleep onset time, total sleep time, number of awakenings, or sleep quality ratings (TABLE 24).

Continue to: CBT has significant benefit for comorbid insomnia

CBT has significant benefit for comorbid insomnia

A 2015 meta-analysis of 23 studies enrolling a total of 1379 adults with a number of illnesses (chronic pain, alcohol dependence, breast cancer, psychiatric disorders, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, fibromyalgia) and comorbid insomnia investigated the qualitative effectiveness of individual or group CBT therapy.5 Subjects received at least 4 face-to-face sessions and at least 2 components of CBT.

The primary outcome showed that sleep quality improved, as measured by a 6.36-point reduction in the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; a 7-question scale on which 0=no insomnia and 28=severe insomnia) and a 3.3-point reduction in the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; a 7-category assessment tool on which 0=perfect quality and 21=poor quality). The effect size was large for both ISI and PSQI, as indicated by standard mean differences greater than 0.8 (1.22 and 0.88, respectively) and was sustained for as long as 18 months.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Physicians strongly recommends that all adult patients receive CBT as initial treatment for chronic insomnia disorder. It can be performed in multiple settings, including the primary care setting. Compared with hypnotics, CBT is unlikely to have any adverse effects.6

1. Trauer J, Qian M, Doyle J, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:191-204.

2. Koffel E, Koffel J, Gehrman P. A meta-analysis of group cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;19:6-16.

3. Ye Y, Chen N, Chen J, et al. Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (ICBT-i): a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010707.

4. Smith M, Perlis M, Park S, et al. Comparative meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy for persistent insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:5-11.

5. Geiger-Brown J, Rogers V, Liu W, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy in persons with comorbid insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;23:54-67.

6. Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea M, et al. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:125-133.

1. Trauer J, Qian M, Doyle J, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:191-204.

2. Koffel E, Koffel J, Gehrman P. A meta-analysis of group cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;19:6-16.

3. Ye Y, Chen N, Chen J, et al. Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (ICBT-i): a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010707.

4. Smith M, Perlis M, Park S, et al. Comparative meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy for persistent insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:5-11.

5. Geiger-Brown J, Rogers V, Liu W, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy in persons with comorbid insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;23:54-67.

6. Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea M, et al. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:125-133.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) administered individually, in a group setting, or on the internet is effective for treating insomnia in adults compared with control (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analyses).

CBT is comparable to pharmacotherapy for improving measures of sleep (SOR: A, comparative meta-analysis).

CBT produces sustainable improvements in subjective sleep quality for adults with comorbid insomnia (SOR: A, meta-analysis).

Does prophylactic azithromycin reduce the number of COPD exacerbations or hospitalizations?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A randomized, placebo-controlled trial including 1142 patients with COPD (forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1] <70%, postbronchodilator FEV1 <80%) found that daily azithromycin 250 mg reduced acute exacerbations more than placebo over one year.1 Researchers recruited patients who were using supplemental oxygen, had required glucocorticoids, or had been hospitalized for an acute exacerbation in the last year. Patients with asthma, resting heart rate >100 beats/min, prolonged QTc interval (or on prolonging medications), or hearing impairment were excluded.

Azithromycin increased the median time to first exacerbation (defined as increase or new onset of cough, sputum, wheeze, and chest tightness for 3 days requiring antibiotics or systemic steroids) compared with the placebo group (266 days vs 174 days; P<.001) and reduced the risk of an acute exacerbation per patient year (hazard ratio [HR]=0.73; 95% confidence [CI], 0.63-0.84). It also reduced the rate of acute exacerbations per patient year (1.83 vs 1.43; P=.01; rate ratio=0.83; 95% CI, 0.72-0.95). The number needed to treat to prevent one exacerbation was 2.86.

No differences in death from any cause (3% vs 4%; P=.87), death from respiratory cause (2% vs 1%; P=.48), or death from cardiovascular cause (0.2% vs 0.2%; P=1.0) were found between azithromycin and placebo. Nor did rates of hospitalizations for acute exacerbations differ.

The groups also showed no significant difference in serious adverse events leading to discontinuation of medication. Notably, more patients in the azithromycin group had audiogram-confirmed hearing loss (25% vs 20%; P=.04), although the authors state that their criteria for hearing loss may have been too stringent because hearing improved on repeat testing whether or not the study drug was discontinued. In addition, more patients in the placebo group developed nasopharyngeal colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (31% vs 12%; P<.001).

Older ex-smokers on long-term O2 benefit most from the antibiotic

A retrospective subgroup analysis of the RCT identified patients who benefited most from daily azithromycin therapy.2 Compared with placebo, azithromycin decreased the time to first exacerbation in patients >65 years (542 patients; HR=0.59; 95% CI, 0.47-0.74), but not patients ≤65 years (571 patients; HR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.68-1.04).

The azithromycin group also demonstrated decreased time to first exacerbation in ex-smokers (867 patients; HR=0.65; 95% CI, 0.55-0.77) and patients on long-term oxygen (659 patients; HR=0.66; 95% CI, 0.55-0.80) but not current smokers (246 patients; HR=0.99; 95% CI, 0.71-1.38) or patients not using long-term oxygen (454 patients; HR=0.80; 95% CI, 0.62-1.03).

Azithromycin administration decreased exacerbations in patients with GOLD stages II (292 patients; HR=0.55; 95% CI, 0.40-0.75) and III (451 patients; HR=0.71; 95% CI, 0.56-0.90), but not stage IV (370 patients; HR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.65-1.08). The significance of the results is limited because the study was not originally powered for this level of subgroup analysis.

Continue to: Smaller study shows similar results

Smaller study shows similar results

A smaller RCT of 92 patients that evaluated exacerbation rates with azithromycin and placebo recruited patients with at least 3 acute COPD exacerbations in the previous year.3

Compared with placebo, oral azithromycin 500 mg 3 times a week (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday) increased the time between exacerbations over a 12-month period (59 days vs 130 days; P=.001). It also reduced the exacerbation rate per person per year (1.94 vs 3.22; risk ratio=0.60; 95% CI, 0.43-0.84) but didn’t change the hospitalization rate (odds ratio=1.34; 95% CI, 0.67-2.7).

No difference in serious adverse events was found between the azithromycin and placebo groups (3 patients vs 5 patients; P=NS), but an increase in diarrhea (9 patients vs 1 patient; P=.015) was noted.

RECOMMENDATIONS

An evidence-based guideline by the American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society recommends long-term macrolide therapy to prevent acute exacerbations in patients >40 years with moderate or severe COPD and a history of ≥1 moderate or severe exacerbation in the previous year despite maximized inhaler therapy (Grade 2A, weak recommendation, high-quality evidence).4 The guideline also states that the duration and optimal dosages are unknown.

1. Albert RK, Connett J, Bailey WC, et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:689-698.

2. Han M, Tayob N, Murray S, et al. Predictors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation reduction in response to daily azithromycin therapy. Am J Resp Crit Care. 2014;189:1503-1508.

3. Pomares X, Montón C, Espasa M, et al. Long-term azithromycin therapy in patients with severe COPD and repeated exacerbations. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:449-456.

4. Criner GJ, Bourbeau J, Diekemper RL, et al. Prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD: American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society Guideline. Chest. 2015;147:894-942.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A randomized, placebo-controlled trial including 1142 patients with COPD (forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1] <70%, postbronchodilator FEV1 <80%) found that daily azithromycin 250 mg reduced acute exacerbations more than placebo over one year.1 Researchers recruited patients who were using supplemental oxygen, had required glucocorticoids, or had been hospitalized for an acute exacerbation in the last year. Patients with asthma, resting heart rate >100 beats/min, prolonged QTc interval (or on prolonging medications), or hearing impairment were excluded.

Azithromycin increased the median time to first exacerbation (defined as increase or new onset of cough, sputum, wheeze, and chest tightness for 3 days requiring antibiotics or systemic steroids) compared with the placebo group (266 days vs 174 days; P<.001) and reduced the risk of an acute exacerbation per patient year (hazard ratio [HR]=0.73; 95% confidence [CI], 0.63-0.84). It also reduced the rate of acute exacerbations per patient year (1.83 vs 1.43; P=.01; rate ratio=0.83; 95% CI, 0.72-0.95). The number needed to treat to prevent one exacerbation was 2.86.

No differences in death from any cause (3% vs 4%; P=.87), death from respiratory cause (2% vs 1%; P=.48), or death from cardiovascular cause (0.2% vs 0.2%; P=1.0) were found between azithromycin and placebo. Nor did rates of hospitalizations for acute exacerbations differ.

The groups also showed no significant difference in serious adverse events leading to discontinuation of medication. Notably, more patients in the azithromycin group had audiogram-confirmed hearing loss (25% vs 20%; P=.04), although the authors state that their criteria for hearing loss may have been too stringent because hearing improved on repeat testing whether or not the study drug was discontinued. In addition, more patients in the placebo group developed nasopharyngeal colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (31% vs 12%; P<.001).

Older ex-smokers on long-term O2 benefit most from the antibiotic

A retrospective subgroup analysis of the RCT identified patients who benefited most from daily azithromycin therapy.2 Compared with placebo, azithromycin decreased the time to first exacerbation in patients >65 years (542 patients; HR=0.59; 95% CI, 0.47-0.74), but not patients ≤65 years (571 patients; HR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.68-1.04).

The azithromycin group also demonstrated decreased time to first exacerbation in ex-smokers (867 patients; HR=0.65; 95% CI, 0.55-0.77) and patients on long-term oxygen (659 patients; HR=0.66; 95% CI, 0.55-0.80) but not current smokers (246 patients; HR=0.99; 95% CI, 0.71-1.38) or patients not using long-term oxygen (454 patients; HR=0.80; 95% CI, 0.62-1.03).

Azithromycin administration decreased exacerbations in patients with GOLD stages II (292 patients; HR=0.55; 95% CI, 0.40-0.75) and III (451 patients; HR=0.71; 95% CI, 0.56-0.90), but not stage IV (370 patients; HR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.65-1.08). The significance of the results is limited because the study was not originally powered for this level of subgroup analysis.

Continue to: Smaller study shows similar results

Smaller study shows similar results

A smaller RCT of 92 patients that evaluated exacerbation rates with azithromycin and placebo recruited patients with at least 3 acute COPD exacerbations in the previous year.3

Compared with placebo, oral azithromycin 500 mg 3 times a week (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday) increased the time between exacerbations over a 12-month period (59 days vs 130 days; P=.001). It also reduced the exacerbation rate per person per year (1.94 vs 3.22; risk ratio=0.60; 95% CI, 0.43-0.84) but didn’t change the hospitalization rate (odds ratio=1.34; 95% CI, 0.67-2.7).

No difference in serious adverse events was found between the azithromycin and placebo groups (3 patients vs 5 patients; P=NS), but an increase in diarrhea (9 patients vs 1 patient; P=.015) was noted.

RECOMMENDATIONS

An evidence-based guideline by the American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society recommends long-term macrolide therapy to prevent acute exacerbations in patients >40 years with moderate or severe COPD and a history of ≥1 moderate or severe exacerbation in the previous year despite maximized inhaler therapy (Grade 2A, weak recommendation, high-quality evidence).4 The guideline also states that the duration and optimal dosages are unknown.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A randomized, placebo-controlled trial including 1142 patients with COPD (forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1] <70%, postbronchodilator FEV1 <80%) found that daily azithromycin 250 mg reduced acute exacerbations more than placebo over one year.1 Researchers recruited patients who were using supplemental oxygen, had required glucocorticoids, or had been hospitalized for an acute exacerbation in the last year. Patients with asthma, resting heart rate >100 beats/min, prolonged QTc interval (or on prolonging medications), or hearing impairment were excluded.

Azithromycin increased the median time to first exacerbation (defined as increase or new onset of cough, sputum, wheeze, and chest tightness for 3 days requiring antibiotics or systemic steroids) compared with the placebo group (266 days vs 174 days; P<.001) and reduced the risk of an acute exacerbation per patient year (hazard ratio [HR]=0.73; 95% confidence [CI], 0.63-0.84). It also reduced the rate of acute exacerbations per patient year (1.83 vs 1.43; P=.01; rate ratio=0.83; 95% CI, 0.72-0.95). The number needed to treat to prevent one exacerbation was 2.86.

No differences in death from any cause (3% vs 4%; P=.87), death from respiratory cause (2% vs 1%; P=.48), or death from cardiovascular cause (0.2% vs 0.2%; P=1.0) were found between azithromycin and placebo. Nor did rates of hospitalizations for acute exacerbations differ.

The groups also showed no significant difference in serious adverse events leading to discontinuation of medication. Notably, more patients in the azithromycin group had audiogram-confirmed hearing loss (25% vs 20%; P=.04), although the authors state that their criteria for hearing loss may have been too stringent because hearing improved on repeat testing whether or not the study drug was discontinued. In addition, more patients in the placebo group developed nasopharyngeal colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (31% vs 12%; P<.001).

Older ex-smokers on long-term O2 benefit most from the antibiotic

A retrospective subgroup analysis of the RCT identified patients who benefited most from daily azithromycin therapy.2 Compared with placebo, azithromycin decreased the time to first exacerbation in patients >65 years (542 patients; HR=0.59; 95% CI, 0.47-0.74), but not patients ≤65 years (571 patients; HR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.68-1.04).

The azithromycin group also demonstrated decreased time to first exacerbation in ex-smokers (867 patients; HR=0.65; 95% CI, 0.55-0.77) and patients on long-term oxygen (659 patients; HR=0.66; 95% CI, 0.55-0.80) but not current smokers (246 patients; HR=0.99; 95% CI, 0.71-1.38) or patients not using long-term oxygen (454 patients; HR=0.80; 95% CI, 0.62-1.03).

Azithromycin administration decreased exacerbations in patients with GOLD stages II (292 patients; HR=0.55; 95% CI, 0.40-0.75) and III (451 patients; HR=0.71; 95% CI, 0.56-0.90), but not stage IV (370 patients; HR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.65-1.08). The significance of the results is limited because the study was not originally powered for this level of subgroup analysis.

Continue to: Smaller study shows similar results

Smaller study shows similar results

A smaller RCT of 92 patients that evaluated exacerbation rates with azithromycin and placebo recruited patients with at least 3 acute COPD exacerbations in the previous year.3

Compared with placebo, oral azithromycin 500 mg 3 times a week (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday) increased the time between exacerbations over a 12-month period (59 days vs 130 days; P=.001). It also reduced the exacerbation rate per person per year (1.94 vs 3.22; risk ratio=0.60; 95% CI, 0.43-0.84) but didn’t change the hospitalization rate (odds ratio=1.34; 95% CI, 0.67-2.7).

No difference in serious adverse events was found between the azithromycin and placebo groups (3 patients vs 5 patients; P=NS), but an increase in diarrhea (9 patients vs 1 patient; P=.015) was noted.

RECOMMENDATIONS

An evidence-based guideline by the American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society recommends long-term macrolide therapy to prevent acute exacerbations in patients >40 years with moderate or severe COPD and a history of ≥1 moderate or severe exacerbation in the previous year despite maximized inhaler therapy (Grade 2A, weak recommendation, high-quality evidence).4 The guideline also states that the duration and optimal dosages are unknown.

1. Albert RK, Connett J, Bailey WC, et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:689-698.

2. Han M, Tayob N, Murray S, et al. Predictors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation reduction in response to daily azithromycin therapy. Am J Resp Crit Care. 2014;189:1503-1508.

3. Pomares X, Montón C, Espasa M, et al. Long-term azithromycin therapy in patients with severe COPD and repeated exacerbations. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:449-456.

4. Criner GJ, Bourbeau J, Diekemper RL, et al. Prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD: American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society Guideline. Chest. 2015;147:894-942.

1. Albert RK, Connett J, Bailey WC, et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:689-698.

2. Han M, Tayob N, Murray S, et al. Predictors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation reduction in response to daily azithromycin therapy. Am J Resp Crit Care. 2014;189:1503-1508.

3. Pomares X, Montón C, Espasa M, et al. Long-term azithromycin therapy in patients with severe COPD and repeated exacerbations. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:449-456.

4. Criner GJ, Bourbeau J, Diekemper RL, et al. Prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD: American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society Guideline. Chest. 2015;147:894-942.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes for exacerbations, no for hospitalizations. Prophylactic azithromycin reduces the number of exacerbations by about 25%. It also extends the time between exacerbations by approximately 90 days for patients with moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Azithromycin benefits patients who are >65 years, patients with Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage II or III COPD, former smokers, and patients using long-term oxygen; it doesn’t benefit patients ≤65 years, patients with GOLD stage IV COPD, current smokers, or patients not using oxygen (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Prophylactic azithromycin doesn’t reduce hospitalizations overall (SOR: B, single small RCT).

How effective and safe is fecal microbial transplant in preventing C difficile recurrence?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

An open-label RCT enrolled 41 immunocompetent older adults who had relapsed CDI after at least one course of antibiotic therapy.1 Investigators randomized patients to 3 treatment groups:

- vancomycin therapy, bowel lavage (with 4 L nasogastric polyethylene glycol solution), and nasogastric-infused fresh donor feces;

- vancomycin with nasogastric bowel lavage without donor feces; or

- vancomycin alone.

Researchers defined cure as the absence of diarrhea or 3 negative stool samples (if patients continued to have persistent diarrhea) at 10 weeks without relapse.

Thirteen of 16 patients (81%) in the donor feces infusion group were cured with the first infusion. Two of the 3 remaining patients were cured after a second donor transplant. FMT produced higher total cure rates than those of vancomycin (94% vs 27%; P<.001; number needed to treat [NNT]=2). Bowel lavage had no effect on outcome.

FMT cures more patients than vancomycin alone

An open-label RCT of 39 patients compared healthy-donor, fresh FMT given via colonoscopy with vancomycin alone for recurrent CDIs.2 Researchers recruited immunocompetent adults who had recurrent CDIs after at least one course of vancomycin or metronidazole.

Patients in the treatment group received a short course of vancomycin, followed by bowel cleansing and fecal transplant via colonoscopy. Clinicians repeated the fecal transplant every 3 days until resolution for patients with pseudomembranous colitis. Patients in the control group were treated with vancomycin for at least 3 weeks. Researchers defined cure as the absence of diarrhea or 2 negative stool samples (if patients continued to have diarrhea) at 10 weeks without relapse.

Thirteen of 20 patients in the FMT group (65%) achieved cure after the first fecal infusion. The 7 remaining patients received multiple infusions; 5 were cured. Overall, FMT cured more patients than vancomycin alone (90% vs 26%; odds ratio=25.2; 99.9% confidence interval [CI], 1.26-502; NNT=2).

Continue to: Fresh and frozen stool are equally effective

Fresh and frozen stool are equally effective

A randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial compared the effectiveness of frozen and thawed FMT with that of fresh FMT in 219 patients ≥18 years of age with recurrent or refractory CDIs.3 Researchers prescribed suppressive antibiotics, which were discontinued within 24 to 48 hours of FMT, and then administered 50 mL of either fresh or frozen stool by enema. They repeated the FMT with the same donor stool if symptoms didn’t improve within 4 days. Any patient still unresponsive was offered repeat FMT or antibiotic therapy.

Researchers defined a 15% difference in outcome as a clinically important effect. Intention-to-treat analysis yielded no significant difference in clinical resolution between groups (75% frozen vs 70.3% fresh; P=.01 for noninferiority).

Nasogastric delivery works as well as colonoscopy

An open-label RCT (not included in the reviews described previously) evaluated the effectiveness of colonoscopically administered FMT compared with that of nasogastric administration in 20 patients with recurrent or refractory CDIs.4 Patients had experienced either a minimum of 3 episodes of mild-to-moderate CDI with a failed 6- to 8-week taper of vancomycin or 2 episodes of severe CDI resulting in hospitalization. Researchers offered patients from both groups a second FMT if symptoms didn’t improve with the initial administration.

Eight patients in the colonoscopy group and 6 in the nasogastric group were cured (all symptoms resolved) after the first FMT. One patient in the nasogastric group refused subsequent administration. All 5 remaining participants chose to have subsequent nasogastric administration (80% cure rate). Both methods of administering FMT produced comparable cure rates (80% in the initial nasogastric group vs 100% in the initial colonoscopy group; P=.53).

Continue to: A third of patients suffer adverse effects, but serious harms are rare

A third of patients suffer adverse effects, but serious harms are rare

A systematic review analyzed 50 trials (16 case series, 9 case reports, 4 RCTs, 21 unreported type; 1089 FMT-treated patients) for adverse effects of FMT.5 Most patients (831) had CDIs, 235 had inflammatory bowel disease, and 106 had both conditions. Donor screening tests for FMT included viral screenings (hepatitis A, B, and C; Epstein-Barr virus; human immunodeficiency virus; Treponema pallidum; and cytomegalovirus), stool tests for C difficile toxin, and routine bacterial culture for enteric pathogens (Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Campylobacter), ova, and parasites.

Overall, 28.5% of patients receiving FMT experienced adverse events. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) administration resulted in more total adverse events than did lower GI delivery (43.6% vs 20.6%; P value not given), mostly abdominal discomfort. However, upper GI delivery was associated with fewer serious adverse events than was lower GI delivery (2% vs 6%; P value not given). FMT possibly or probably produced serious infections in 0.7% of patients, and there was one colonoscopy-associated death caused by aspiration (0.1% mortality).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Guidelines published by the American College of Gastroenterology in 2013 listed FMT as a treatment option for patients who have had 3 episodes of CDI and vancomycin therapy (based on moderate quality evidence).6

1. van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407-415.

2. Cammarota G, Masucci L, Ianiro G, et al. Randomised clinical trial: faecal microbiota transplantation by colonoscopy vs. vancomycin for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:835-843.

3. Lee CH, Steiner T, Petrof EO, et al. Frozen vs fresh fecal microbiota transplantation and clinical resolution of diarrhea in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. JAMA. 2016;315:142-149.

4. Youngster I, Sauk J, Pindar C, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection using a frozen inoculum from unrelated donors: a randomized, open-label, controlled pilot study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1515-1522.

5. Wang S, Xu M, Wang W, et al. Systematic review: adverse events of fecal microbiota transplantation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161174.

6. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:478-498.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

An open-label RCT enrolled 41 immunocompetent older adults who had relapsed CDI after at least one course of antibiotic therapy.1 Investigators randomized patients to 3 treatment groups:

- vancomycin therapy, bowel lavage (with 4 L nasogastric polyethylene glycol solution), and nasogastric-infused fresh donor feces;

- vancomycin with nasogastric bowel lavage without donor feces; or

- vancomycin alone.

Researchers defined cure as the absence of diarrhea or 3 negative stool samples (if patients continued to have persistent diarrhea) at 10 weeks without relapse.

Thirteen of 16 patients (81%) in the donor feces infusion group were cured with the first infusion. Two of the 3 remaining patients were cured after a second donor transplant. FMT produced higher total cure rates than those of vancomycin (94% vs 27%; P<.001; number needed to treat [NNT]=2). Bowel lavage had no effect on outcome.

FMT cures more patients than vancomycin alone

An open-label RCT of 39 patients compared healthy-donor, fresh FMT given via colonoscopy with vancomycin alone for recurrent CDIs.2 Researchers recruited immunocompetent adults who had recurrent CDIs after at least one course of vancomycin or metronidazole.

Patients in the treatment group received a short course of vancomycin, followed by bowel cleansing and fecal transplant via colonoscopy. Clinicians repeated the fecal transplant every 3 days until resolution for patients with pseudomembranous colitis. Patients in the control group were treated with vancomycin for at least 3 weeks. Researchers defined cure as the absence of diarrhea or 2 negative stool samples (if patients continued to have diarrhea) at 10 weeks without relapse.

Thirteen of 20 patients in the FMT group (65%) achieved cure after the first fecal infusion. The 7 remaining patients received multiple infusions; 5 were cured. Overall, FMT cured more patients than vancomycin alone (90% vs 26%; odds ratio=25.2; 99.9% confidence interval [CI], 1.26-502; NNT=2).

Continue to: Fresh and frozen stool are equally effective

Fresh and frozen stool are equally effective

A randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial compared the effectiveness of frozen and thawed FMT with that of fresh FMT in 219 patients ≥18 years of age with recurrent or refractory CDIs.3 Researchers prescribed suppressive antibiotics, which were discontinued within 24 to 48 hours of FMT, and then administered 50 mL of either fresh or frozen stool by enema. They repeated the FMT with the same donor stool if symptoms didn’t improve within 4 days. Any patient still unresponsive was offered repeat FMT or antibiotic therapy.

Researchers defined a 15% difference in outcome as a clinically important effect. Intention-to-treat analysis yielded no significant difference in clinical resolution between groups (75% frozen vs 70.3% fresh; P=.01 for noninferiority).

Nasogastric delivery works as well as colonoscopy

An open-label RCT (not included in the reviews described previously) evaluated the effectiveness of colonoscopically administered FMT compared with that of nasogastric administration in 20 patients with recurrent or refractory CDIs.4 Patients had experienced either a minimum of 3 episodes of mild-to-moderate CDI with a failed 6- to 8-week taper of vancomycin or 2 episodes of severe CDI resulting in hospitalization. Researchers offered patients from both groups a second FMT if symptoms didn’t improve with the initial administration.

Eight patients in the colonoscopy group and 6 in the nasogastric group were cured (all symptoms resolved) after the first FMT. One patient in the nasogastric group refused subsequent administration. All 5 remaining participants chose to have subsequent nasogastric administration (80% cure rate). Both methods of administering FMT produced comparable cure rates (80% in the initial nasogastric group vs 100% in the initial colonoscopy group; P=.53).

Continue to: A third of patients suffer adverse effects, but serious harms are rare

A third of patients suffer adverse effects, but serious harms are rare

A systematic review analyzed 50 trials (16 case series, 9 case reports, 4 RCTs, 21 unreported type; 1089 FMT-treated patients) for adverse effects of FMT.5 Most patients (831) had CDIs, 235 had inflammatory bowel disease, and 106 had both conditions. Donor screening tests for FMT included viral screenings (hepatitis A, B, and C; Epstein-Barr virus; human immunodeficiency virus; Treponema pallidum; and cytomegalovirus), stool tests for C difficile toxin, and routine bacterial culture for enteric pathogens (Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Campylobacter), ova, and parasites.

Overall, 28.5% of patients receiving FMT experienced adverse events. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) administration resulted in more total adverse events than did lower GI delivery (43.6% vs 20.6%; P value not given), mostly abdominal discomfort. However, upper GI delivery was associated with fewer serious adverse events than was lower GI delivery (2% vs 6%; P value not given). FMT possibly or probably produced serious infections in 0.7% of patients, and there was one colonoscopy-associated death caused by aspiration (0.1% mortality).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Guidelines published by the American College of Gastroenterology in 2013 listed FMT as a treatment option for patients who have had 3 episodes of CDI and vancomycin therapy (based on moderate quality evidence).6

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

An open-label RCT enrolled 41 immunocompetent older adults who had relapsed CDI after at least one course of antibiotic therapy.1 Investigators randomized patients to 3 treatment groups:

- vancomycin therapy, bowel lavage (with 4 L nasogastric polyethylene glycol solution), and nasogastric-infused fresh donor feces;

- vancomycin with nasogastric bowel lavage without donor feces; or

- vancomycin alone.

Researchers defined cure as the absence of diarrhea or 3 negative stool samples (if patients continued to have persistent diarrhea) at 10 weeks without relapse.

Thirteen of 16 patients (81%) in the donor feces infusion group were cured with the first infusion. Two of the 3 remaining patients were cured after a second donor transplant. FMT produced higher total cure rates than those of vancomycin (94% vs 27%; P<.001; number needed to treat [NNT]=2). Bowel lavage had no effect on outcome.

FMT cures more patients than vancomycin alone

An open-label RCT of 39 patients compared healthy-donor, fresh FMT given via colonoscopy with vancomycin alone for recurrent CDIs.2 Researchers recruited immunocompetent adults who had recurrent CDIs after at least one course of vancomycin or metronidazole.

Patients in the treatment group received a short course of vancomycin, followed by bowel cleansing and fecal transplant via colonoscopy. Clinicians repeated the fecal transplant every 3 days until resolution for patients with pseudomembranous colitis. Patients in the control group were treated with vancomycin for at least 3 weeks. Researchers defined cure as the absence of diarrhea or 2 negative stool samples (if patients continued to have diarrhea) at 10 weeks without relapse.

Thirteen of 20 patients in the FMT group (65%) achieved cure after the first fecal infusion. The 7 remaining patients received multiple infusions; 5 were cured. Overall, FMT cured more patients than vancomycin alone (90% vs 26%; odds ratio=25.2; 99.9% confidence interval [CI], 1.26-502; NNT=2).

Continue to: Fresh and frozen stool are equally effective

Fresh and frozen stool are equally effective

A randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial compared the effectiveness of frozen and thawed FMT with that of fresh FMT in 219 patients ≥18 years of age with recurrent or refractory CDIs.3 Researchers prescribed suppressive antibiotics, which were discontinued within 24 to 48 hours of FMT, and then administered 50 mL of either fresh or frozen stool by enema. They repeated the FMT with the same donor stool if symptoms didn’t improve within 4 days. Any patient still unresponsive was offered repeat FMT or antibiotic therapy.

Researchers defined a 15% difference in outcome as a clinically important effect. Intention-to-treat analysis yielded no significant difference in clinical resolution between groups (75% frozen vs 70.3% fresh; P=.01 for noninferiority).

Nasogastric delivery works as well as colonoscopy

An open-label RCT (not included in the reviews described previously) evaluated the effectiveness of colonoscopically administered FMT compared with that of nasogastric administration in 20 patients with recurrent or refractory CDIs.4 Patients had experienced either a minimum of 3 episodes of mild-to-moderate CDI with a failed 6- to 8-week taper of vancomycin or 2 episodes of severe CDI resulting in hospitalization. Researchers offered patients from both groups a second FMT if symptoms didn’t improve with the initial administration.

Eight patients in the colonoscopy group and 6 in the nasogastric group were cured (all symptoms resolved) after the first FMT. One patient in the nasogastric group refused subsequent administration. All 5 remaining participants chose to have subsequent nasogastric administration (80% cure rate). Both methods of administering FMT produced comparable cure rates (80% in the initial nasogastric group vs 100% in the initial colonoscopy group; P=.53).

Continue to: A third of patients suffer adverse effects, but serious harms are rare

A third of patients suffer adverse effects, but serious harms are rare

A systematic review analyzed 50 trials (16 case series, 9 case reports, 4 RCTs, 21 unreported type; 1089 FMT-treated patients) for adverse effects of FMT.5 Most patients (831) had CDIs, 235 had inflammatory bowel disease, and 106 had both conditions. Donor screening tests for FMT included viral screenings (hepatitis A, B, and C; Epstein-Barr virus; human immunodeficiency virus; Treponema pallidum; and cytomegalovirus), stool tests for C difficile toxin, and routine bacterial culture for enteric pathogens (Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, Campylobacter), ova, and parasites.

Overall, 28.5% of patients receiving FMT experienced adverse events. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) administration resulted in more total adverse events than did lower GI delivery (43.6% vs 20.6%; P value not given), mostly abdominal discomfort. However, upper GI delivery was associated with fewer serious adverse events than was lower GI delivery (2% vs 6%; P value not given). FMT possibly or probably produced serious infections in 0.7% of patients, and there was one colonoscopy-associated death caused by aspiration (0.1% mortality).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Guidelines published by the American College of Gastroenterology in 2013 listed FMT as a treatment option for patients who have had 3 episodes of CDI and vancomycin therapy (based on moderate quality evidence).6

1. van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407-415.

2. Cammarota G, Masucci L, Ianiro G, et al. Randomised clinical trial: faecal microbiota transplantation by colonoscopy vs. vancomycin for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:835-843.

3. Lee CH, Steiner T, Petrof EO, et al. Frozen vs fresh fecal microbiota transplantation and clinical resolution of diarrhea in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. JAMA. 2016;315:142-149.

4. Youngster I, Sauk J, Pindar C, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection using a frozen inoculum from unrelated donors: a randomized, open-label, controlled pilot study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1515-1522.

5. Wang S, Xu M, Wang W, et al. Systematic review: adverse events of fecal microbiota transplantation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161174.

6. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:478-498.

1. van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:407-415.

2. Cammarota G, Masucci L, Ianiro G, et al. Randomised clinical trial: faecal microbiota transplantation by colonoscopy vs. vancomycin for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:835-843.

3. Lee CH, Steiner T, Petrof EO, et al. Frozen vs fresh fecal microbiota transplantation and clinical resolution of diarrhea in patients with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. JAMA. 2016;315:142-149.

4. Youngster I, Sauk J, Pindar C, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant for relapsing Clostridium difficile infection using a frozen inoculum from unrelated donors: a randomized, open-label, controlled pilot study. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1515-1522.

5. Wang S, Xu M, Wang W, et al. Systematic review: adverse events of fecal microbiota transplantation. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161174.

6. Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:478-498.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Fecal microbial transplant (FMT) is reasonably safe and effective. In patients who have had multiple Clostridium difficile infections (CDIs), FMT results in a 65% to 80% cure rate with one treatment and 90% to 95% cure rate with repeated treatments compared with a 25% to 27% cure rate for antibiotics (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, small open-label randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Fresh and frozen donor feces, administered by either nasogastric tube or colonoscope, produce equal results (SOR B, RCTs).

FMT has an overall adverse event rate of 30%, primarily involving abdominal discomfort, but also, rarely, severe infections (0.7%) and death (0.1%) (SOR: B, systematic review not limited to RCTs).

Does niacin decrease cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in CVD patients?

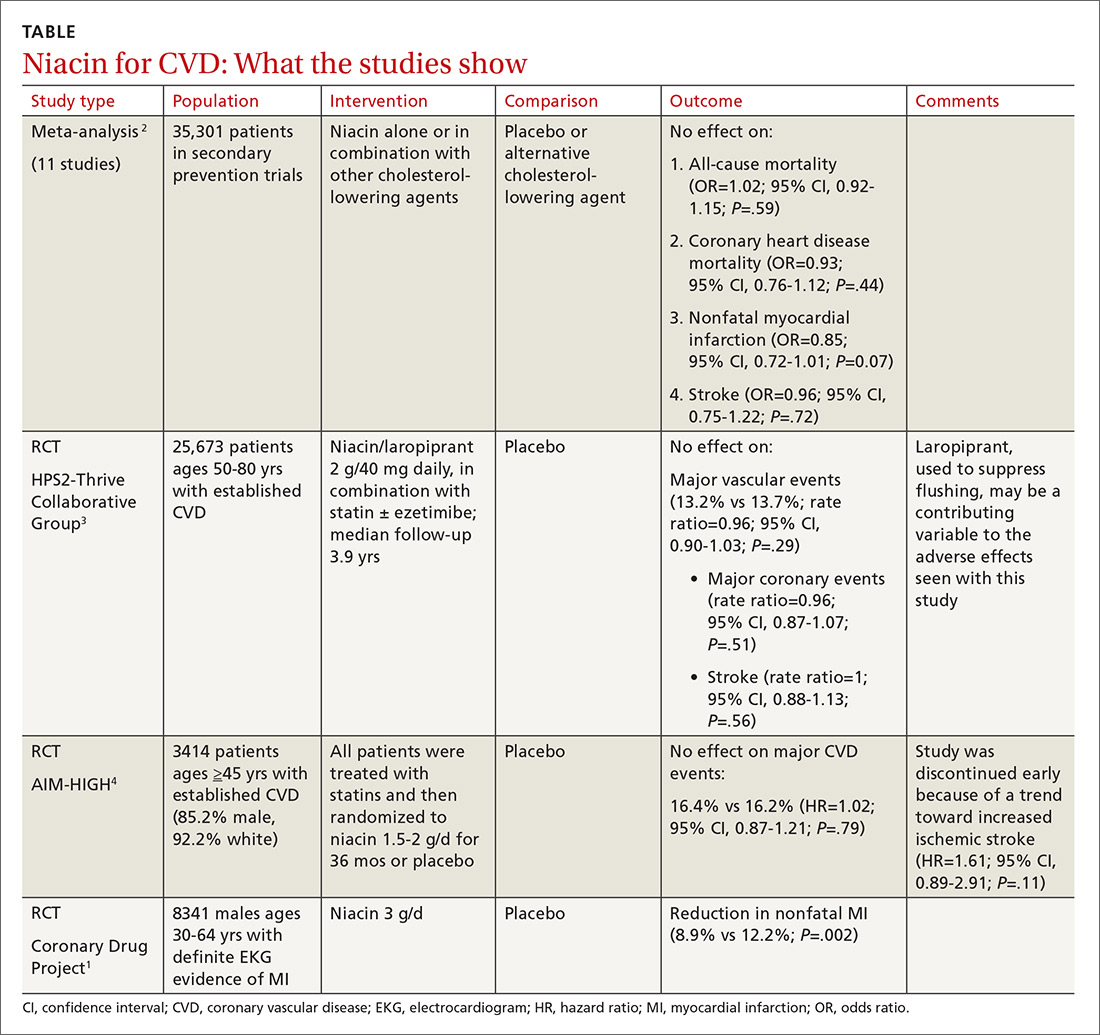

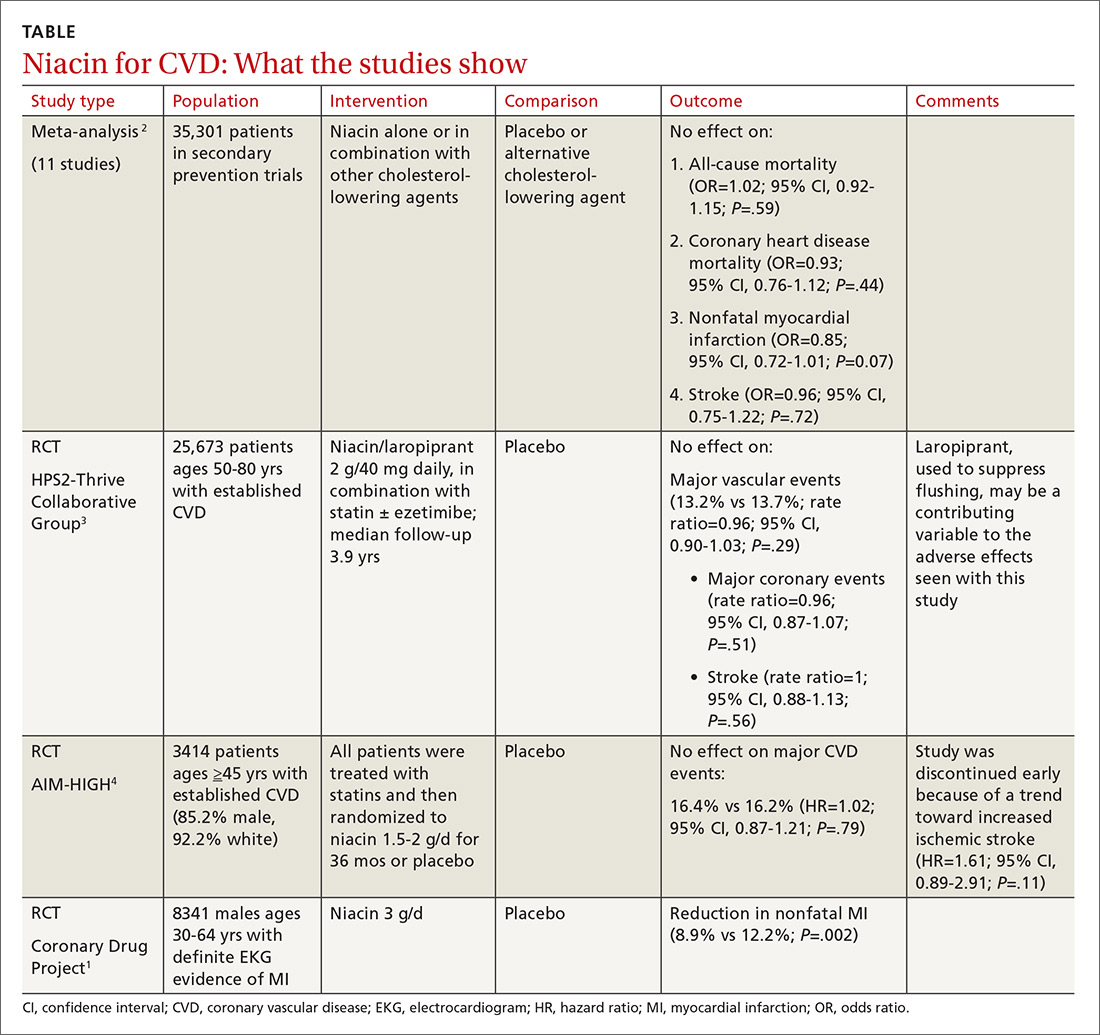

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

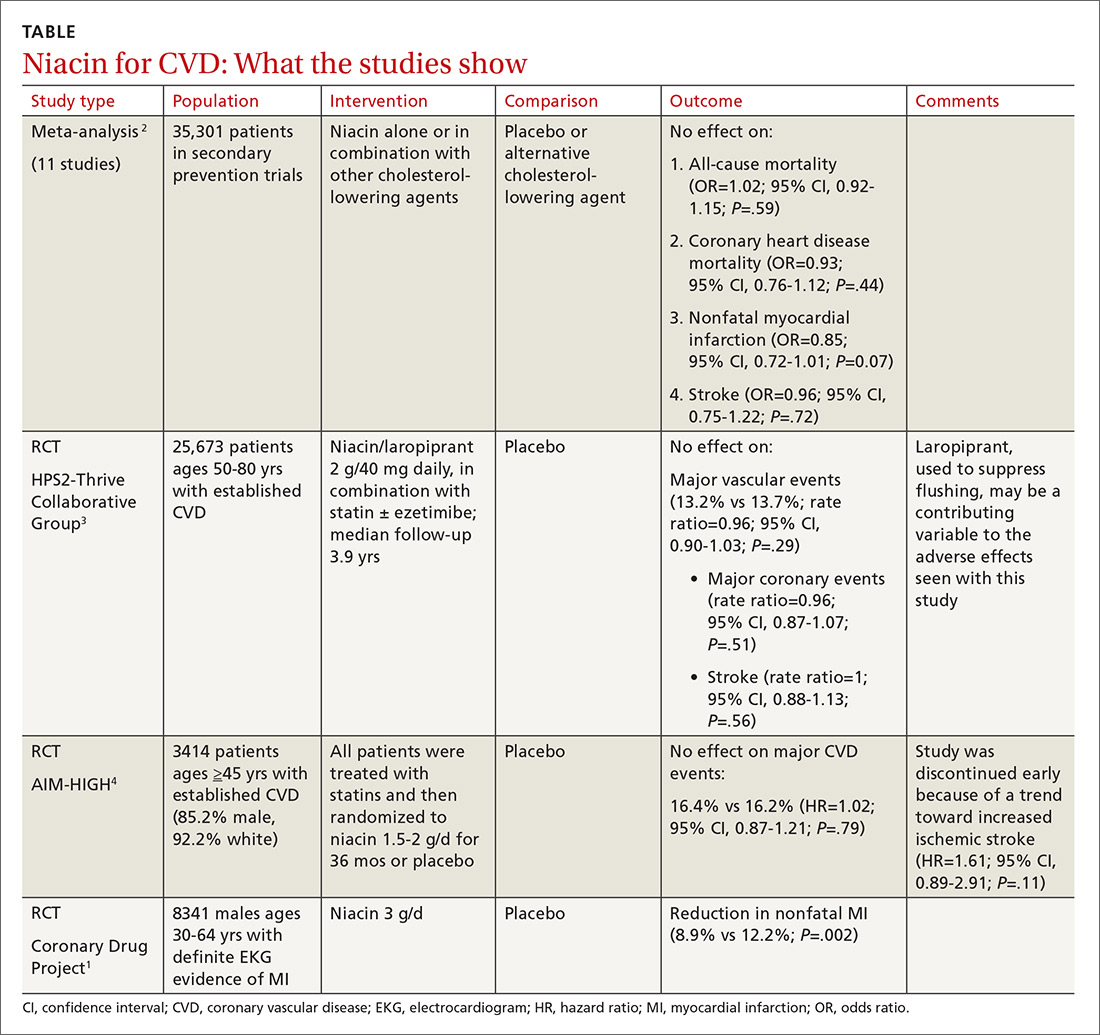

Before the statin era, the Coronary Drug Project RCT (8341 patients) showed that niacin monotherapy in patients with definite electrocardiographic evidence of previous myocardial infarction (MI) reduced nonfatal MI to 8.9% compared with 12.2% for placebo (P=.002).1 (See TABLE.1-4) It also decreased long-term mortality by 11% compared with placebo (P=.0004).5

Adverse effects such as flushing, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal disturbance, and elevated liver enzymes interfered with adherence to niacin treatment (66.3% of patients were adherent to treatment with niacin vs 77.8% for placebo). The study was limited by the fact that flushing essentially unblinded participants and physicians.

But adding niacin to a statin has no effect

A 2014 meta-analysis driven by the power of the large HPS2-Thrive study evaluated data from 35,301 patients primarily in secondary prevention trials.2,3 It found that adding niacin to statins had no effect on all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease mortality, nonfatal MI, or stroke. The subset of 6 trials (N=4991) assessing niacin monotherapy did show a reduction in cardiovascular events (odds ratio [OR]=0.62; confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.82), whereas the 5 studies (30,310 patients) involving niacin with a statin demonstrated no effect (OR=0.94; CI, 0.83-1.06).

No benefit from niacin/statin therapy despite an improved lipid profile

A 2011 RCT included 3414 patients with coronary heart disease on simvastatin who were randomized to niacin or placebo.4 All patients received simvastatin 40 to 80 mg ± ezetimibe 10 mg/d to achieve low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels of 40 to 80 mg/dL.

At 3 years, no benefit was seen in the composite CVD primary endpoint (hazard ratio=1.02; 95% CI, 0.87-1.21; P=.79) even though the niacin group had significantly increased median high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol compared with placebo and lower triglycerides and LDL cholesterol compared with baseline.

A nonsignificant trend toward increased stroke in the niacin group compared with placebo led to early termination of the study. However, multivariate analysis showed independent associations between ischemic stroke risk and age older than 65 years, history of stroke/transient ischemic attack/carotid artery disease, and elevated baseline cholesterol.6

Niacin combined with a statin increases the risk of adverse events

The largest RCT in the 2014 meta-analysis (HPS2-Thrive) evaluated 25,673 patients with established CVD receiving cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe who were randomized to niacin or placebo for a median follow-up period of 3.9 years.3 A pre-randomization run-in phase established effective cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe.

Niacin didn’t reduce the incidence of major vascular events even though, once again, it decreased LDL and increased HDL more than placebo. Niacin increased the risk of serious adverse events 56% vs 53% (risk ratio [RR]=6; 95% CI, 3-8; number needed to harm [NNH]=35; 95% CI, 25-60), such as new onset diabetes (5.7% vs 4.3%; P<.001; NNH=71) and gastrointestinal bleeding/ulceration and other gastrointestinal disorders (4.8% vs 3.8%; P<.001; NNH=100).

A subsequent 2014 study examined the adverse events recorded in the AIM-HIGH4 study and found that niacin caused more gastrointestinal disorders (7.4% vs 5.5%; P=.02; NNH=53) and infections and infestations (8.1% vs 5.8%; P=.008; NNH=43) than placebo.7 The overall observed rate of serious hemorrhagic adverse events was low, however, showing no significant difference between the 2 groups (3.4% vs 2.9%; P=.36).

RECOMMENDATIONS

As of November 2013, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends against using niacin in combination with statins because of the increased risk of adverse events without a reduction in CVD outcomes. Niacin may be considered as monotherapy in patients who can’t tolerate statins or fibrates based on results of the Coronary Drug Project and other studies completed before the era of widespread statin use.8

Similarly, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines state that patients who are completely statin intolerant may use nonstatin cholesterol-lowering drugs, including niacin, that have been shown to reduce CVD events in RCTs if the CVD risk-reduction benefits outweigh the potential for adverse effects.9

1. Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Colofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231:360-81.

2. Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379.

3. HPS2-Thrive Collaborative Group. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203-212.

4. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267.

5. Canner PL, Berge KG, Wender NK, et al. Fifteen-year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245-1255.

6. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Extended-release niacin therapy and risk of ischemic stroke in patients with cardiovascular disease: the Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcome (AIM-HIGH) trial. Stroke. 2013;44:2688-2693.

7. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Safety profile of extended-release niacin in the AIM-HIGH trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:288-290.

8. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guideline summary: Lipid management in adults. National Guideline Clearinghouse. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov. Accessed July 20, 2015.

9. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;25 (suppl 2):S1-S45.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Before the statin era, the Coronary Drug Project RCT (8341 patients) showed that niacin monotherapy in patients with definite electrocardiographic evidence of previous myocardial infarction (MI) reduced nonfatal MI to 8.9% compared with 12.2% for placebo (P=.002).1 (See TABLE.1-4) It also decreased long-term mortality by 11% compared with placebo (P=.0004).5

Adverse effects such as flushing, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal disturbance, and elevated liver enzymes interfered with adherence to niacin treatment (66.3% of patients were adherent to treatment with niacin vs 77.8% for placebo). The study was limited by the fact that flushing essentially unblinded participants and physicians.

But adding niacin to a statin has no effect

A 2014 meta-analysis driven by the power of the large HPS2-Thrive study evaluated data from 35,301 patients primarily in secondary prevention trials.2,3 It found that adding niacin to statins had no effect on all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease mortality, nonfatal MI, or stroke. The subset of 6 trials (N=4991) assessing niacin monotherapy did show a reduction in cardiovascular events (odds ratio [OR]=0.62; confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.82), whereas the 5 studies (30,310 patients) involving niacin with a statin demonstrated no effect (OR=0.94; CI, 0.83-1.06).

No benefit from niacin/statin therapy despite an improved lipid profile

A 2011 RCT included 3414 patients with coronary heart disease on simvastatin who were randomized to niacin or placebo.4 All patients received simvastatin 40 to 80 mg ± ezetimibe 10 mg/d to achieve low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels of 40 to 80 mg/dL.

At 3 years, no benefit was seen in the composite CVD primary endpoint (hazard ratio=1.02; 95% CI, 0.87-1.21; P=.79) even though the niacin group had significantly increased median high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol compared with placebo and lower triglycerides and LDL cholesterol compared with baseline.

A nonsignificant trend toward increased stroke in the niacin group compared with placebo led to early termination of the study. However, multivariate analysis showed independent associations between ischemic stroke risk and age older than 65 years, history of stroke/transient ischemic attack/carotid artery disease, and elevated baseline cholesterol.6

Niacin combined with a statin increases the risk of adverse events

The largest RCT in the 2014 meta-analysis (HPS2-Thrive) evaluated 25,673 patients with established CVD receiving cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe who were randomized to niacin or placebo for a median follow-up period of 3.9 years.3 A pre-randomization run-in phase established effective cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe.

Niacin didn’t reduce the incidence of major vascular events even though, once again, it decreased LDL and increased HDL more than placebo. Niacin increased the risk of serious adverse events 56% vs 53% (risk ratio [RR]=6; 95% CI, 3-8; number needed to harm [NNH]=35; 95% CI, 25-60), such as new onset diabetes (5.7% vs 4.3%; P<.001; NNH=71) and gastrointestinal bleeding/ulceration and other gastrointestinal disorders (4.8% vs 3.8%; P<.001; NNH=100).

A subsequent 2014 study examined the adverse events recorded in the AIM-HIGH4 study and found that niacin caused more gastrointestinal disorders (7.4% vs 5.5%; P=.02; NNH=53) and infections and infestations (8.1% vs 5.8%; P=.008; NNH=43) than placebo.7 The overall observed rate of serious hemorrhagic adverse events was low, however, showing no significant difference between the 2 groups (3.4% vs 2.9%; P=.36).

RECOMMENDATIONS

As of November 2013, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends against using niacin in combination with statins because of the increased risk of adverse events without a reduction in CVD outcomes. Niacin may be considered as monotherapy in patients who can’t tolerate statins or fibrates based on results of the Coronary Drug Project and other studies completed before the era of widespread statin use.8

Similarly, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines state that patients who are completely statin intolerant may use nonstatin cholesterol-lowering drugs, including niacin, that have been shown to reduce CVD events in RCTs if the CVD risk-reduction benefits outweigh the potential for adverse effects.9

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Before the statin era, the Coronary Drug Project RCT (8341 patients) showed that niacin monotherapy in patients with definite electrocardiographic evidence of previous myocardial infarction (MI) reduced nonfatal MI to 8.9% compared with 12.2% for placebo (P=.002).1 (See TABLE.1-4) It also decreased long-term mortality by 11% compared with placebo (P=.0004).5

Adverse effects such as flushing, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal disturbance, and elevated liver enzymes interfered with adherence to niacin treatment (66.3% of patients were adherent to treatment with niacin vs 77.8% for placebo). The study was limited by the fact that flushing essentially unblinded participants and physicians.

But adding niacin to a statin has no effect

A 2014 meta-analysis driven by the power of the large HPS2-Thrive study evaluated data from 35,301 patients primarily in secondary prevention trials.2,3 It found that adding niacin to statins had no effect on all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease mortality, nonfatal MI, or stroke. The subset of 6 trials (N=4991) assessing niacin monotherapy did show a reduction in cardiovascular events (odds ratio [OR]=0.62; confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.82), whereas the 5 studies (30,310 patients) involving niacin with a statin demonstrated no effect (OR=0.94; CI, 0.83-1.06).

No benefit from niacin/statin therapy despite an improved lipid profile

A 2011 RCT included 3414 patients with coronary heart disease on simvastatin who were randomized to niacin or placebo.4 All patients received simvastatin 40 to 80 mg ± ezetimibe 10 mg/d to achieve low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels of 40 to 80 mg/dL.

At 3 years, no benefit was seen in the composite CVD primary endpoint (hazard ratio=1.02; 95% CI, 0.87-1.21; P=.79) even though the niacin group had significantly increased median high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol compared with placebo and lower triglycerides and LDL cholesterol compared with baseline.

A nonsignificant trend toward increased stroke in the niacin group compared with placebo led to early termination of the study. However, multivariate analysis showed independent associations between ischemic stroke risk and age older than 65 years, history of stroke/transient ischemic attack/carotid artery disease, and elevated baseline cholesterol.6

Niacin combined with a statin increases the risk of adverse events

The largest RCT in the 2014 meta-analysis (HPS2-Thrive) evaluated 25,673 patients with established CVD receiving cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe who were randomized to niacin or placebo for a median follow-up period of 3.9 years.3 A pre-randomization run-in phase established effective cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe.

Niacin didn’t reduce the incidence of major vascular events even though, once again, it decreased LDL and increased HDL more than placebo. Niacin increased the risk of serious adverse events 56% vs 53% (risk ratio [RR]=6; 95% CI, 3-8; number needed to harm [NNH]=35; 95% CI, 25-60), such as new onset diabetes (5.7% vs 4.3%; P<.001; NNH=71) and gastrointestinal bleeding/ulceration and other gastrointestinal disorders (4.8% vs 3.8%; P<.001; NNH=100).

A subsequent 2014 study examined the adverse events recorded in the AIM-HIGH4 study and found that niacin caused more gastrointestinal disorders (7.4% vs 5.5%; P=.02; NNH=53) and infections and infestations (8.1% vs 5.8%; P=.008; NNH=43) than placebo.7 The overall observed rate of serious hemorrhagic adverse events was low, however, showing no significant difference between the 2 groups (3.4% vs 2.9%; P=.36).

RECOMMENDATIONS

As of November 2013, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends against using niacin in combination with statins because of the increased risk of adverse events without a reduction in CVD outcomes. Niacin may be considered as monotherapy in patients who can’t tolerate statins or fibrates based on results of the Coronary Drug Project and other studies completed before the era of widespread statin use.8

Similarly, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines state that patients who are completely statin intolerant may use nonstatin cholesterol-lowering drugs, including niacin, that have been shown to reduce CVD events in RCTs if the CVD risk-reduction benefits outweigh the potential for adverse effects.9

1. Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Colofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231:360-81.

2. Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379.

3. HPS2-Thrive Collaborative Group. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203-212.

4. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267.

5. Canner PL, Berge KG, Wender NK, et al. Fifteen-year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245-1255.

6. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Extended-release niacin therapy and risk of ischemic stroke in patients with cardiovascular disease: the Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcome (AIM-HIGH) trial. Stroke. 2013;44:2688-2693.

7. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Safety profile of extended-release niacin in the AIM-HIGH trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:288-290.

8. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guideline summary: Lipid management in adults. National Guideline Clearinghouse. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov. Accessed July 20, 2015.

9. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;25 (suppl 2):S1-S45.

1. Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Colofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231:360-81.

2. Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379.

3. HPS2-Thrive Collaborative Group. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203-212.

4. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267.

5. Canner PL, Berge KG, Wender NK, et al. Fifteen-year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245-1255.

6. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Extended-release niacin therapy and risk of ischemic stroke in patients with cardiovascular disease: the Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcome (AIM-HIGH) trial. Stroke. 2013;44:2688-2693.

7. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Safety profile of extended-release niacin in the AIM-HIGH trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:288-290.

8. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guideline summary: Lipid management in adults. National Guideline Clearinghouse. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov. Accessed July 20, 2015.

9. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;25 (suppl 2):S1-S45.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE BASED ANSWER:

No. Niacin doesn’t reduce cardiovascular disease (CVD) morbidity or mortality in patients with established disease (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and subsequent large RCTs).

Niacin may be considered as monotherapy for patients intolerant of statins (SOR: B, one well-done RCT).

How well do POLST forms assure that patients get the end-of-life care they requested?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The POLST form offers choices within 4 treatment areas: “attempt CPR” or “allow natural death” if the patient is in cardiopulmonary arrest; “comfort,” “limited,” or “full” medical interventions if pulse or breathing is present; choices of additional orders, including intravenous fluids, feeding tubes, and antibiotics; and additional written orders. Most POLST studies used cross-sectional and retrospective cohort designs and assessed whether CPR was attempted. Fewer studies also evaluated adherence to orders in the other treatment areas.

Community settings: Patients with POLST more likely to die out of hospital

The largest study of POLST use in community settings evaluated deaths in Oregon over one year.1 It found that patients who indicated “do not attempt CPR” on a POLST form were 6 times more likely to die a natural, out-of-hospital death than those who had no POLST form (TABLE1-10).

A West Virginia study found that patients with POLST forms had 30% higher out-of-hospital death rates than those with traditional advanced directives and no POLST.2 In a Wisconsin study, no decedents who indicated DNR on their POLST forms received CPR.3

One study that evaluated the consistency of actual medical interventions with POLST orders in all 4 treatment areas found it to be good in most areas (“feeding tubes,” “attempting CPR.” “antibiotics,” and “IV fluids”) except “additional written orders.4

Skilled nursing facilities: Generally high adherence to POLST orders

The largest study to evaluate the consistency of treatments with POLST orders among nursing home residents found high adherence overall (94%).5 Caregivers performed CPR on none of 299 residents who selected “DNR.” However, they did not administer CPR to 6 of 7 who chose “attempt CPR” and administered antibiotics to 32% of patients who specified “no antibiotics” on their POLST forms.5

A second study of nursing home residents who selected “comfort measures only” also found high consistency for attempting CPR, intensive care admission, and ventilator support, although physicians hospitalized 2% of patients to extend life.6 Similarly, treatments matched POLST orders well overall in a Washington state study, although one patient got a feeding tube against orders.7

POLST adherence is good, but can EMS workers find the form?

A study comparing emergency medical services (EMS) management with POLST orders in an Oregon registry found good consistency.8 EMS providers didn’t attempt or halted CPR in most patients with DNR orders who were found in cardiac arrest and initiated CPR in most patients who chose “attempt CPR.” EMS providers initiated CPR in the field on 11 patients (22%) with a DNR order but discontinued resuscitation en route to the hospital.

In a smaller study, EMS providers never located paper POLST forms at the scene in most cases.9

Hospice: POLST orders prevent unwanted Tx, except maybe antibiotics

A study evaluating management in hospice programs in 3 states found that care providers followed POLST orders for limited treatment in 98% of cases.10 No patients received unwanted CPR, intubation, or feeding tubes. POLST orders didn’t predict whether patients were treated with antibiotics, however.

1. Fromme EK, Zive D, Schmidt TA, et al. Association between physician orders for life-sustaining treatment for scope of treatment and in-hospital death in Oregon. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1246-1251.

2. Pedraza SL, Culp S, Falkenstine EC, et al. POST forms more than advance directives associated with out-of-hospital death: insights from a state registry. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016; 51:240-246.

3. Hammes B, Rooney BL, Gundrum JD, et al. The POLST program: a retrospective review of the demographics of use and outcomes in one community where advance directives are prevalent. J Palliative Med. 2012;15:77-85.

4. Lee MA, Brummel-Smith K, Meyer J, et al. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST): outcomes in a PACE program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:1219-1225.

5. Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, et al. The consistency between treatments provided to nursing facility residents and orders on the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2091-2099.

6. Tolle SW, Tilden VP, Nelson CA, et al. A prospective study of the efficacy of the physician order form for life sustaining treatment. J Am Ger Soc.1998;46:1097-1102.

7. Meyers J, Moore C, McGrory A, et al. Physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form: honoring end-of-life directives for nursing home residents. J Geron Nursing. 2004;30:37-46.

8. Richardson DK, Fromme E, Zive D, et al. Concordance of out-of-hospital and emergency department cardiac arrest resuscitation with documented end-of-life choices in Oregon. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;63:375-383.

9. Schmidt T, Olszewski EA, Zive D, et al. The Oregon physician orders for life-sustaining treatment registry: a preliminary study of emergency medical services utilization. J Emerg Med. 2013;44:796-805.

10. Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, et al. Use of the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST) paradigm program in the hospice setting. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:133-141.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The POLST form offers choices within 4 treatment areas: “attempt CPR” or “allow natural death” if the patient is in cardiopulmonary arrest; “comfort,” “limited,” or “full” medical interventions if pulse or breathing is present; choices of additional orders, including intravenous fluids, feeding tubes, and antibiotics; and additional written orders. Most POLST studies used cross-sectional and retrospective cohort designs and assessed whether CPR was attempted. Fewer studies also evaluated adherence to orders in the other treatment areas.

Community settings: Patients with POLST more likely to die out of hospital

The largest study of POLST use in community settings evaluated deaths in Oregon over one year.1 It found that patients who indicated “do not attempt CPR” on a POLST form were 6 times more likely to die a natural, out-of-hospital death than those who had no POLST form (TABLE1-10).

A West Virginia study found that patients with POLST forms had 30% higher out-of-hospital death rates than those with traditional advanced directives and no POLST.2 In a Wisconsin study, no decedents who indicated DNR on their POLST forms received CPR.3

One study that evaluated the consistency of actual medical interventions with POLST orders in all 4 treatment areas found it to be good in most areas (“feeding tubes,” “attempting CPR.” “antibiotics,” and “IV fluids”) except “additional written orders.4

Skilled nursing facilities: Generally high adherence to POLST orders

The largest study to evaluate the consistency of treatments with POLST orders among nursing home residents found high adherence overall (94%).5 Caregivers performed CPR on none of 299 residents who selected “DNR.” However, they did not administer CPR to 6 of 7 who chose “attempt CPR” and administered antibiotics to 32% of patients who specified “no antibiotics” on their POLST forms.5

A second study of nursing home residents who selected “comfort measures only” also found high consistency for attempting CPR, intensive care admission, and ventilator support, although physicians hospitalized 2% of patients to extend life.6 Similarly, treatments matched POLST orders well overall in a Washington state study, although one patient got a feeding tube against orders.7

POLST adherence is good, but can EMS workers find the form?

A study comparing emergency medical services (EMS) management with POLST orders in an Oregon registry found good consistency.8 EMS providers didn’t attempt or halted CPR in most patients with DNR orders who were found in cardiac arrest and initiated CPR in most patients who chose “attempt CPR.” EMS providers initiated CPR in the field on 11 patients (22%) with a DNR order but discontinued resuscitation en route to the hospital.

In a smaller study, EMS providers never located paper POLST forms at the scene in most cases.9

Hospice: POLST orders prevent unwanted Tx, except maybe antibiotics

A study evaluating management in hospice programs in 3 states found that care providers followed POLST orders for limited treatment in 98% of cases.10 No patients received unwanted CPR, intubation, or feeding tubes. POLST orders didn’t predict whether patients were treated with antibiotics, however.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The POLST form offers choices within 4 treatment areas: “attempt CPR” or “allow natural death” if the patient is in cardiopulmonary arrest; “comfort,” “limited,” or “full” medical interventions if pulse or breathing is present; choices of additional orders, including intravenous fluids, feeding tubes, and antibiotics; and additional written orders. Most POLST studies used cross-sectional and retrospective cohort designs and assessed whether CPR was attempted. Fewer studies also evaluated adherence to orders in the other treatment areas.

Community settings: Patients with POLST more likely to die out of hospital

The largest study of POLST use in community settings evaluated deaths in Oregon over one year.1 It found that patients who indicated “do not attempt CPR” on a POLST form were 6 times more likely to die a natural, out-of-hospital death than those who had no POLST form (TABLE1-10).

A West Virginia study found that patients with POLST forms had 30% higher out-of-hospital death rates than those with traditional advanced directives and no POLST.2 In a Wisconsin study, no decedents who indicated DNR on their POLST forms received CPR.3

One study that evaluated the consistency of actual medical interventions with POLST orders in all 4 treatment areas found it to be good in most areas (“feeding tubes,” “attempting CPR.” “antibiotics,” and “IV fluids”) except “additional written orders.4

Skilled nursing facilities: Generally high adherence to POLST orders

The largest study to evaluate the consistency of treatments with POLST orders among nursing home residents found high adherence overall (94%).5 Caregivers performed CPR on none of 299 residents who selected “DNR.” However, they did not administer CPR to 6 of 7 who chose “attempt CPR” and administered antibiotics to 32% of patients who specified “no antibiotics” on their POLST forms.5

A second study of nursing home residents who selected “comfort measures only” also found high consistency for attempting CPR, intensive care admission, and ventilator support, although physicians hospitalized 2% of patients to extend life.6 Similarly, treatments matched POLST orders well overall in a Washington state study, although one patient got a feeding tube against orders.7

POLST adherence is good, but can EMS workers find the form?