User login

Does any antidepressant besides bupropion help smokers quit?

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes, nortriptyline approximately doubles smoking cessation rates, an effect comparable to bupropion. Adding nortriptyline to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) doesn’t improve rates further (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram), venlafaxine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs; moclobemide, selegiline), doxepin, and St. John’s wort don’t improve smoking cessation rates (SOR: A, systematic reviews and RCTs).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Bupropion is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved antidepressant recommended as a first-line pharmacologic agent to assist with smoking cessation, based in part on a meta-analysis of 44 placebo-controlled RCTs (13,728 patients), which found that bupropion had a relative risk (RR) of 1.62 for smoking cessation compared with placebo (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.49-1.76). Bupropion produced quit rates that were approximately double those of placebo rates (18% [range 4%-43%] for bupropion vs 9% [range 0%-18%] for placebo).1

Nortriptyline is also effective, other antidepressants not so much

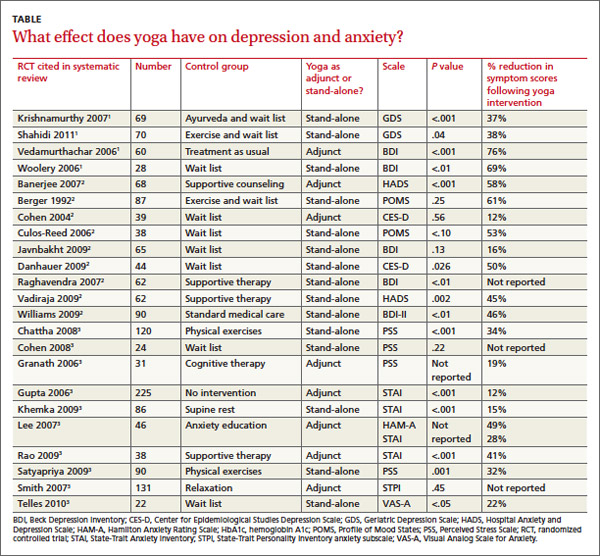

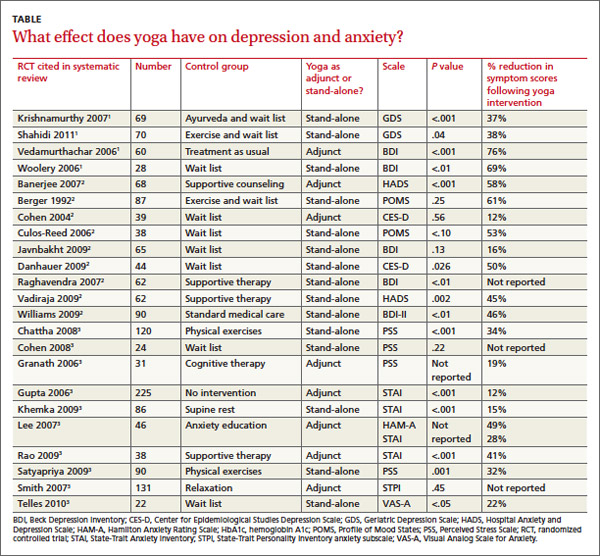

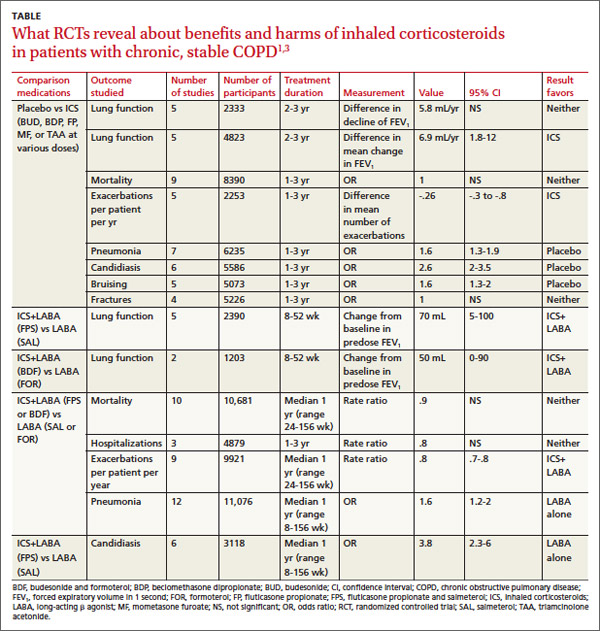

A Cochrane systematic review of 10 antidepressants used for smoking cessation included 64 placebo-controlled trials, measuring at least 6-month abstinence rates as primary outcomes, and monitoring biochemical markers (such as breath carbon monoxide and urinary cotinine) to verify abstinence. Some trials included participants with previous depressive episodes, but most didn’t enroll patients with active major depression.1 The TABLE1 gives an overview of the studies and outcomes.

Nortriptyline, which was evaluated in 6 trials, was the only antidepressant besides bupropion that was superior to placebo.1 Two of the nortriptyline trials included participants with active depression and the other trials had participants with a history of depression. One trial found no difference in quit rates for patients taking nortriptyline with or without a history of major depression, although the subgroups were small. Two trials measured quit rates for 12 months whereas the other 4 trials used 6-month quit rates.

Four additional RCTs with 1644 patients that combined nortriptyline with NRT found no improvement in quit rates compared with NRT alone (RR=1.21; 95% CI, 0.94-1.55).1 Three RCTs with 417 patients compared bupropion with nortriptyline and found no difference (RR=1.3; 95% CI, 0.93-1.8).1

SSRIs. None of the 4 SSRIs investigated in the trials (fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram) improved smoking cessation rates more than placebo.1 The 5 RCTs that studied the drugs followed participants for as long as a year. None of the participants were depressed at the time of the studies, although some had a history of depression.

The sertraline RCT used individual counseling sessions in conjunction with either sertraline or placebo. All participants had a history of major depression.

The paroxetine trial used NRT in all patients randomized to either paroxetine or placebo.

Venlafaxine. The serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine didn’t improve smoking cessation rates over 12 months.1

MAOIs. Neither of the 2 MAOIs increased smoking cessation rates.1 The moclobemide RCT followed participants for 12 months; the 5 selegiline RCTs followed participants for as long as 6 months.

Other antidepressants. An RCT with 19 participants found that doxepin didn’t improve smoking cessation at 2 months.1 One RCT and one open, randomized trial of St. John’s wort found no benefit for smoking cessation.1,2

RECOMMENDATIONS

The United States Public Health Service (USPHS) and the University of Michigan Health System (UMHS) guidelines recommend the following FDA-approved pharmacotherapies as first-line agents for smoking cessation: sustained-release bupropion, NRT (gum, inhaler, lozenge, nasal spray, or patch), and varenicline.3,4 They say that clonidine and nortriptyline are also effective but recommend them as second-line agents because these drugs lack FDA approval for this purpose.

The USPHS also recommends combinations of NRT and bupropion for long-term use. Because of additional cost and limited benefit, UMHS recommends reserving NRT-bupropion combination therapy for highly addicted tobacco users who have several failed quit attempts.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force guideline emphasizes counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use; it doesn’t provide recommendations for pharmacotherapy.5 It does cite the same agents recommended by USPHS and UMHS as effective.

1. Hughes JR, Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, et al. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD000031.

2. Sood A, Ebbert JO, Prasad K, et al. A randomized clinical trial of St. John’s wort for smoking cessation. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:761-767.

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2014.

4. University of Michigan Health System. Tobacco treatment. University of Michigan Health System Web site. Available at: http://www.med.umich.edu/1info/fhp/practiceguides/smoking/smoking.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2014.

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease in adults and pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:551-555.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes, nortriptyline approximately doubles smoking cessation rates, an effect comparable to bupropion. Adding nortriptyline to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) doesn’t improve rates further (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram), venlafaxine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs; moclobemide, selegiline), doxepin, and St. John’s wort don’t improve smoking cessation rates (SOR: A, systematic reviews and RCTs).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Bupropion is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved antidepressant recommended as a first-line pharmacologic agent to assist with smoking cessation, based in part on a meta-analysis of 44 placebo-controlled RCTs (13,728 patients), which found that bupropion had a relative risk (RR) of 1.62 for smoking cessation compared with placebo (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.49-1.76). Bupropion produced quit rates that were approximately double those of placebo rates (18% [range 4%-43%] for bupropion vs 9% [range 0%-18%] for placebo).1

Nortriptyline is also effective, other antidepressants not so much

A Cochrane systematic review of 10 antidepressants used for smoking cessation included 64 placebo-controlled trials, measuring at least 6-month abstinence rates as primary outcomes, and monitoring biochemical markers (such as breath carbon monoxide and urinary cotinine) to verify abstinence. Some trials included participants with previous depressive episodes, but most didn’t enroll patients with active major depression.1 The TABLE1 gives an overview of the studies and outcomes.

Nortriptyline, which was evaluated in 6 trials, was the only antidepressant besides bupropion that was superior to placebo.1 Two of the nortriptyline trials included participants with active depression and the other trials had participants with a history of depression. One trial found no difference in quit rates for patients taking nortriptyline with or without a history of major depression, although the subgroups were small. Two trials measured quit rates for 12 months whereas the other 4 trials used 6-month quit rates.

Four additional RCTs with 1644 patients that combined nortriptyline with NRT found no improvement in quit rates compared with NRT alone (RR=1.21; 95% CI, 0.94-1.55).1 Three RCTs with 417 patients compared bupropion with nortriptyline and found no difference (RR=1.3; 95% CI, 0.93-1.8).1

SSRIs. None of the 4 SSRIs investigated in the trials (fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram) improved smoking cessation rates more than placebo.1 The 5 RCTs that studied the drugs followed participants for as long as a year. None of the participants were depressed at the time of the studies, although some had a history of depression.

The sertraline RCT used individual counseling sessions in conjunction with either sertraline or placebo. All participants had a history of major depression.

The paroxetine trial used NRT in all patients randomized to either paroxetine or placebo.

Venlafaxine. The serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine didn’t improve smoking cessation rates over 12 months.1

MAOIs. Neither of the 2 MAOIs increased smoking cessation rates.1 The moclobemide RCT followed participants for 12 months; the 5 selegiline RCTs followed participants for as long as 6 months.

Other antidepressants. An RCT with 19 participants found that doxepin didn’t improve smoking cessation at 2 months.1 One RCT and one open, randomized trial of St. John’s wort found no benefit for smoking cessation.1,2

RECOMMENDATIONS

The United States Public Health Service (USPHS) and the University of Michigan Health System (UMHS) guidelines recommend the following FDA-approved pharmacotherapies as first-line agents for smoking cessation: sustained-release bupropion, NRT (gum, inhaler, lozenge, nasal spray, or patch), and varenicline.3,4 They say that clonidine and nortriptyline are also effective but recommend them as second-line agents because these drugs lack FDA approval for this purpose.

The USPHS also recommends combinations of NRT and bupropion for long-term use. Because of additional cost and limited benefit, UMHS recommends reserving NRT-bupropion combination therapy for highly addicted tobacco users who have several failed quit attempts.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force guideline emphasizes counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use; it doesn’t provide recommendations for pharmacotherapy.5 It does cite the same agents recommended by USPHS and UMHS as effective.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes, nortriptyline approximately doubles smoking cessation rates, an effect comparable to bupropion. Adding nortriptyline to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) doesn’t improve rates further (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram), venlafaxine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs; moclobemide, selegiline), doxepin, and St. John’s wort don’t improve smoking cessation rates (SOR: A, systematic reviews and RCTs).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Bupropion is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved antidepressant recommended as a first-line pharmacologic agent to assist with smoking cessation, based in part on a meta-analysis of 44 placebo-controlled RCTs (13,728 patients), which found that bupropion had a relative risk (RR) of 1.62 for smoking cessation compared with placebo (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.49-1.76). Bupropion produced quit rates that were approximately double those of placebo rates (18% [range 4%-43%] for bupropion vs 9% [range 0%-18%] for placebo).1

Nortriptyline is also effective, other antidepressants not so much

A Cochrane systematic review of 10 antidepressants used for smoking cessation included 64 placebo-controlled trials, measuring at least 6-month abstinence rates as primary outcomes, and monitoring biochemical markers (such as breath carbon monoxide and urinary cotinine) to verify abstinence. Some trials included participants with previous depressive episodes, but most didn’t enroll patients with active major depression.1 The TABLE1 gives an overview of the studies and outcomes.

Nortriptyline, which was evaluated in 6 trials, was the only antidepressant besides bupropion that was superior to placebo.1 Two of the nortriptyline trials included participants with active depression and the other trials had participants with a history of depression. One trial found no difference in quit rates for patients taking nortriptyline with or without a history of major depression, although the subgroups were small. Two trials measured quit rates for 12 months whereas the other 4 trials used 6-month quit rates.

Four additional RCTs with 1644 patients that combined nortriptyline with NRT found no improvement in quit rates compared with NRT alone (RR=1.21; 95% CI, 0.94-1.55).1 Three RCTs with 417 patients compared bupropion with nortriptyline and found no difference (RR=1.3; 95% CI, 0.93-1.8).1

SSRIs. None of the 4 SSRIs investigated in the trials (fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram) improved smoking cessation rates more than placebo.1 The 5 RCTs that studied the drugs followed participants for as long as a year. None of the participants were depressed at the time of the studies, although some had a history of depression.

The sertraline RCT used individual counseling sessions in conjunction with either sertraline or placebo. All participants had a history of major depression.

The paroxetine trial used NRT in all patients randomized to either paroxetine or placebo.

Venlafaxine. The serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine didn’t improve smoking cessation rates over 12 months.1

MAOIs. Neither of the 2 MAOIs increased smoking cessation rates.1 The moclobemide RCT followed participants for 12 months; the 5 selegiline RCTs followed participants for as long as 6 months.

Other antidepressants. An RCT with 19 participants found that doxepin didn’t improve smoking cessation at 2 months.1 One RCT and one open, randomized trial of St. John’s wort found no benefit for smoking cessation.1,2

RECOMMENDATIONS

The United States Public Health Service (USPHS) and the University of Michigan Health System (UMHS) guidelines recommend the following FDA-approved pharmacotherapies as first-line agents for smoking cessation: sustained-release bupropion, NRT (gum, inhaler, lozenge, nasal spray, or patch), and varenicline.3,4 They say that clonidine and nortriptyline are also effective but recommend them as second-line agents because these drugs lack FDA approval for this purpose.

The USPHS also recommends combinations of NRT and bupropion for long-term use. Because of additional cost and limited benefit, UMHS recommends reserving NRT-bupropion combination therapy for highly addicted tobacco users who have several failed quit attempts.

The United States Preventive Services Task Force guideline emphasizes counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use; it doesn’t provide recommendations for pharmacotherapy.5 It does cite the same agents recommended by USPHS and UMHS as effective.

1. Hughes JR, Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, et al. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD000031.

2. Sood A, Ebbert JO, Prasad K, et al. A randomized clinical trial of St. John’s wort for smoking cessation. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:761-767.

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2014.

4. University of Michigan Health System. Tobacco treatment. University of Michigan Health System Web site. Available at: http://www.med.umich.edu/1info/fhp/practiceguides/smoking/smoking.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2014.

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease in adults and pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:551-555.

1. Hughes JR, Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, et al. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD000031.

2. Sood A, Ebbert JO, Prasad K, et al. A randomized clinical trial of St. John’s wort for smoking cessation. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16:761-767.

3. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/update/treating_tobacco_use08.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2014.

4. University of Michigan Health System. Tobacco treatment. University of Michigan Health System Web site. Available at: http://www.med.umich.edu/1info/fhp/practiceguides/smoking/smoking.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2014.

5. US Preventive Services Task Force. Counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease in adults and pregnant women: US Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:551-555.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

What treatments relieve arthritis and fatigue associated with systemic lupus erythematosus?

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine improve the arthritis associated with mild systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)—producing a 50% reduction in arthritis flares and articular involvement—and have few adverse effects (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Methotrexate reduces arthralgias by as much as 79%, but produces adverse effects in up to 70% of patients (SOR: B, systematic review of RCTs with limited patient-oriented evidence).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids are often used for SLE joint pain (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Omega-3 fatty acids may reduce arthritis symptoms by about 35% (SOR: B, RCTs with inconsistent evidence).

Abatacept and dehydroepiandrosterone don’t produce clinically meaningful improvements in fatigue associated with SLE, and abatacept causes significant adverse effects (SOR: B, posthoc analysis of a single RCT).

Aerobic exercise may help fatigue (SOR: B, systematic review with inconsistent evidence).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

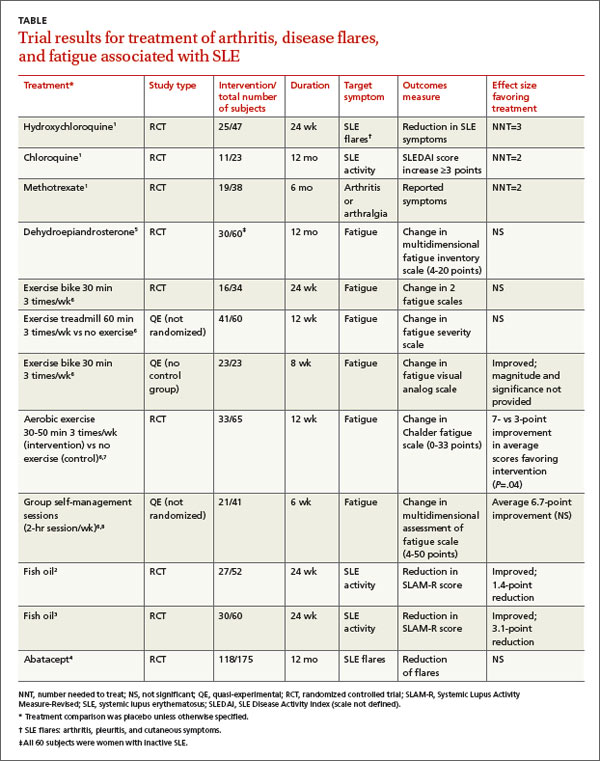

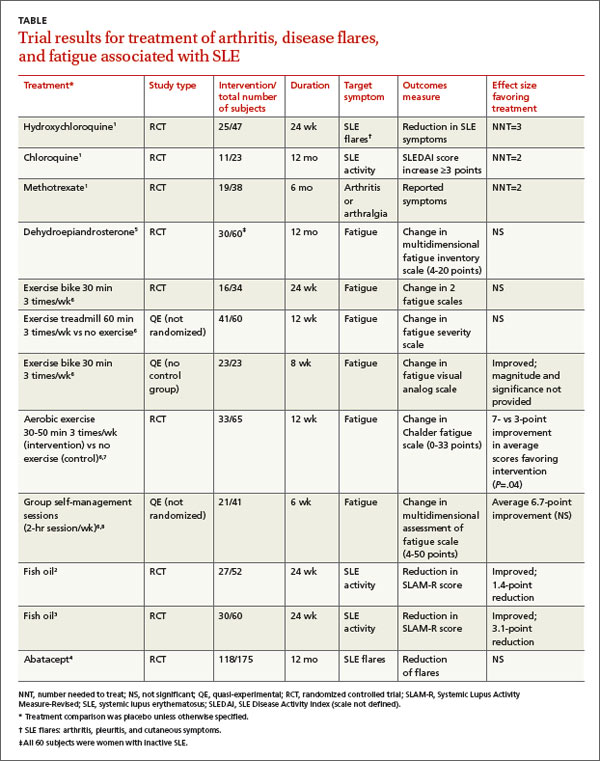

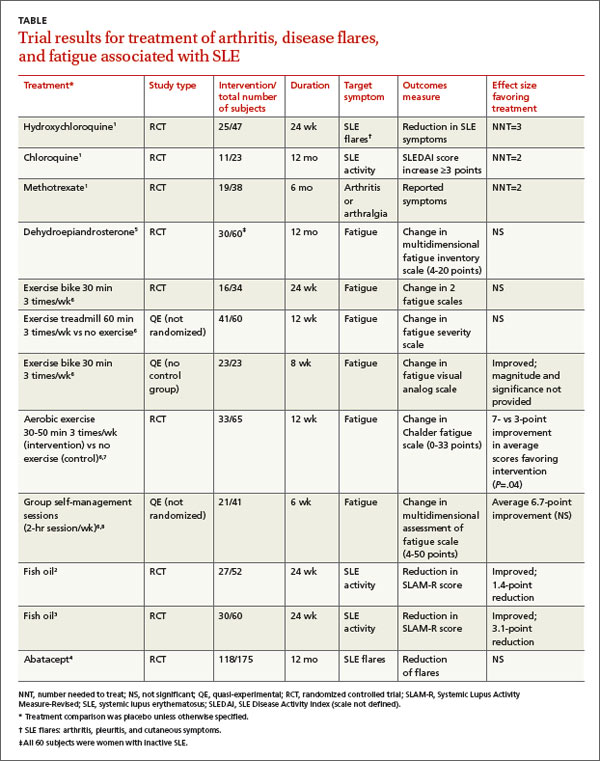

A systematic review of pharmacotherapy for joint pain in patients with SLE found 4 poor-quality RCTs that evaluated hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and methotrexate.1 Of the 2 studies that examined the effect of hydroxychloroquine, one (47 patients) showed a statistically significant 50% reduction in SLE flares (including arthritis, pleuritis, and cutaneous symptoms) over 24 weeks in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine compared with placebo (TABLE1-8). The second study (71 subjects) found a nonquantified decrease in self-reported pain when hydroxychloroquine was compared with placebo, although some of the patients were also taking prednisone (10 mg/d).

An RCT that evaluated the effect of chloroquine showed a statistically significant reduction in unspecified “articular involvement” compared with placebo.

The fourth RCT, assessing methotrexate, found a statistically significant reduction by as much as 79% in patients with residual arthritis or arthralgia at 6 months compared with placebo, although 70% of patients taking methotrexate developed significant adverse effects, including infections, gastrointestinal symptoms, and elevated transaminases compared with 14% on placebo (number needed to harm [NNH]=2).

The authors of the review noted that consensus opinion holds that oral corticosteroids and NSAIDs reduce SLE-associated joint pain, but they found no studies that objectively evaluated either of these interventions.1

Fish oil also helps arthritis

Two RCTs on the effects of 3 g/d of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (fish oil) for 24 weeks in SLE patients with mild disease found a reduction in Systemic Lupus Activity Measure-Revised (SLAM-R) scores.2,3 SLAM-R is a validated measure of SLE disease activity, rated on a scale from 0 to 81, including 23 clinical and 7 laboratory manifestations of disease.

In the first study (52 subjects), disease activity decreased from an average SLAM-R score of 6.1 at baseline to 4.7 (P<.05). The second study (60 subjects) found a similar reduction in mean SLAM-R scores from 9.4 to 6.3 (P<.001) and joint pain scores from 1.27 to 0.83 (P=.047).

Drug treatments don’t significantly relieve fatigue

An industry-sponsored RCT that compared abatacept with placebo found improvements in fatigue that weren’t clinically meaningful in posthoc analysis (-9.45 points difference on a self-reported 0-to-100 visual analog scale; 95% confidence interval, -17.65 to -1.25, with a 10-point reduction considered to be clinically meaningful). Abatacept also had a high rate of serious adverse events, including facial edema, polyneuropathy, and serious infections (24/121 with abatacept vs 4/59 placebo; NNH=8).4

Another RCT found no effect of dehydroepiandrosterone on fatigue in women with inactive SLE.5

Nondrug treatments for fatigue produce mixed results

Studies of nondrug treatment of SLE-associated fatigue show inconsistent results. A systematic review of nonpharmacologic interventions for fatigue in several chronic diseases found 2 RCTs and 4 quasi-experimental studies that included 324 patients with SLE.6 Of 4 studies that evaluated the effect of exercise, 2 showed improvement and 2 didn’t. Neither group self-management nor relaxation therapy and telephone counseling significantly relieved fatigue.6-8 A small RCT (24 patients) found no benefit for acupuncture over sham needling in treating pain and fatigue in SLE.9

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Rheumatology guideline for referral and management of SLE states that “NSAIDs are sometimes helpful for control of fever, arthritis, and mild serositis. Antimalarial agents (eg, hydroxychloroquine) are useful for skin and joint manifestations of SLE, for preventing flares, and for other constitutional symptoms of the disease. They may also reduce fatigue.”10

The European League Against Rheumatism recommends antimalarials or glucocorticoids to treat patients with SLE without major organ manifestations. They also say clinicians may try NSAIDs for limited periods of time in patients at low risk for the drugs’ complications.11

1. Madhok R, Wu O. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Evid. 2009;7:1123.

2. Duffy EM, Meenagh GK, McMillan SA, et al. The clinical effect of dietary supplementation with omega-3 fish oils and/ or copper in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1551-1556.

3. Wright SA, O’Prey FM, McHenry MT, et al. A randomised interventional trial of omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids on endothelial function and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:841-848.

4. Merrill JT, Burgos-Vargas R, Westhovens R, et al. The efficacy and safety of abatacept in patients with non-life-threatening manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a twelve-month, multicenter, exploratory, phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3077-3087.

5. Hartkamp A, Geenen R, Godaert GL, et al. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone on fatigue and well-being in women with quiescent systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1144-1147.

6. Neill J, Belan I, Reid K. Effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for fatigue in adults with multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or systemic lupus erythematosis: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56:617-635.

7. Tench CM, McCarthy J, McCurdie I, et al. Fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial of exercise. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:1050-1054.

8. Sohng KY. Effects of a self-management course for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42:479-486.

9. Greco CM, Kao AH, Maksimowicz-McKinnon K, et al. Acupuncture for systemic lupus erythematosus: a pilot RCT feasibility and safety study. Lupus. 2008;17:1108-1116.

10. American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Guidelines. Guidelines for referral and management of systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1785-1796.

11. Bertsias G, Ioannidis JP, Boletis J, et al; Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:195-205.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine improve the arthritis associated with mild systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)—producing a 50% reduction in arthritis flares and articular involvement—and have few adverse effects (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Methotrexate reduces arthralgias by as much as 79%, but produces adverse effects in up to 70% of patients (SOR: B, systematic review of RCTs with limited patient-oriented evidence).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids are often used for SLE joint pain (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Omega-3 fatty acids may reduce arthritis symptoms by about 35% (SOR: B, RCTs with inconsistent evidence).

Abatacept and dehydroepiandrosterone don’t produce clinically meaningful improvements in fatigue associated with SLE, and abatacept causes significant adverse effects (SOR: B, posthoc analysis of a single RCT).

Aerobic exercise may help fatigue (SOR: B, systematic review with inconsistent evidence).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of pharmacotherapy for joint pain in patients with SLE found 4 poor-quality RCTs that evaluated hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and methotrexate.1 Of the 2 studies that examined the effect of hydroxychloroquine, one (47 patients) showed a statistically significant 50% reduction in SLE flares (including arthritis, pleuritis, and cutaneous symptoms) over 24 weeks in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine compared with placebo (TABLE1-8). The second study (71 subjects) found a nonquantified decrease in self-reported pain when hydroxychloroquine was compared with placebo, although some of the patients were also taking prednisone (10 mg/d).

An RCT that evaluated the effect of chloroquine showed a statistically significant reduction in unspecified “articular involvement” compared with placebo.

The fourth RCT, assessing methotrexate, found a statistically significant reduction by as much as 79% in patients with residual arthritis or arthralgia at 6 months compared with placebo, although 70% of patients taking methotrexate developed significant adverse effects, including infections, gastrointestinal symptoms, and elevated transaminases compared with 14% on placebo (number needed to harm [NNH]=2).

The authors of the review noted that consensus opinion holds that oral corticosteroids and NSAIDs reduce SLE-associated joint pain, but they found no studies that objectively evaluated either of these interventions.1

Fish oil also helps arthritis

Two RCTs on the effects of 3 g/d of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (fish oil) for 24 weeks in SLE patients with mild disease found a reduction in Systemic Lupus Activity Measure-Revised (SLAM-R) scores.2,3 SLAM-R is a validated measure of SLE disease activity, rated on a scale from 0 to 81, including 23 clinical and 7 laboratory manifestations of disease.

In the first study (52 subjects), disease activity decreased from an average SLAM-R score of 6.1 at baseline to 4.7 (P<.05). The second study (60 subjects) found a similar reduction in mean SLAM-R scores from 9.4 to 6.3 (P<.001) and joint pain scores from 1.27 to 0.83 (P=.047).

Drug treatments don’t significantly relieve fatigue

An industry-sponsored RCT that compared abatacept with placebo found improvements in fatigue that weren’t clinically meaningful in posthoc analysis (-9.45 points difference on a self-reported 0-to-100 visual analog scale; 95% confidence interval, -17.65 to -1.25, with a 10-point reduction considered to be clinically meaningful). Abatacept also had a high rate of serious adverse events, including facial edema, polyneuropathy, and serious infections (24/121 with abatacept vs 4/59 placebo; NNH=8).4

Another RCT found no effect of dehydroepiandrosterone on fatigue in women with inactive SLE.5

Nondrug treatments for fatigue produce mixed results

Studies of nondrug treatment of SLE-associated fatigue show inconsistent results. A systematic review of nonpharmacologic interventions for fatigue in several chronic diseases found 2 RCTs and 4 quasi-experimental studies that included 324 patients with SLE.6 Of 4 studies that evaluated the effect of exercise, 2 showed improvement and 2 didn’t. Neither group self-management nor relaxation therapy and telephone counseling significantly relieved fatigue.6-8 A small RCT (24 patients) found no benefit for acupuncture over sham needling in treating pain and fatigue in SLE.9

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Rheumatology guideline for referral and management of SLE states that “NSAIDs are sometimes helpful for control of fever, arthritis, and mild serositis. Antimalarial agents (eg, hydroxychloroquine) are useful for skin and joint manifestations of SLE, for preventing flares, and for other constitutional symptoms of the disease. They may also reduce fatigue.”10

The European League Against Rheumatism recommends antimalarials or glucocorticoids to treat patients with SLE without major organ manifestations. They also say clinicians may try NSAIDs for limited periods of time in patients at low risk for the drugs’ complications.11

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine improve the arthritis associated with mild systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)—producing a 50% reduction in arthritis flares and articular involvement—and have few adverse effects (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Methotrexate reduces arthralgias by as much as 79%, but produces adverse effects in up to 70% of patients (SOR: B, systematic review of RCTs with limited patient-oriented evidence).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids are often used for SLE joint pain (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Omega-3 fatty acids may reduce arthritis symptoms by about 35% (SOR: B, RCTs with inconsistent evidence).

Abatacept and dehydroepiandrosterone don’t produce clinically meaningful improvements in fatigue associated with SLE, and abatacept causes significant adverse effects (SOR: B, posthoc analysis of a single RCT).

Aerobic exercise may help fatigue (SOR: B, systematic review with inconsistent evidence).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of pharmacotherapy for joint pain in patients with SLE found 4 poor-quality RCTs that evaluated hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and methotrexate.1 Of the 2 studies that examined the effect of hydroxychloroquine, one (47 patients) showed a statistically significant 50% reduction in SLE flares (including arthritis, pleuritis, and cutaneous symptoms) over 24 weeks in patients treated with hydroxychloroquine compared with placebo (TABLE1-8). The second study (71 subjects) found a nonquantified decrease in self-reported pain when hydroxychloroquine was compared with placebo, although some of the patients were also taking prednisone (10 mg/d).

An RCT that evaluated the effect of chloroquine showed a statistically significant reduction in unspecified “articular involvement” compared with placebo.

The fourth RCT, assessing methotrexate, found a statistically significant reduction by as much as 79% in patients with residual arthritis or arthralgia at 6 months compared with placebo, although 70% of patients taking methotrexate developed significant adverse effects, including infections, gastrointestinal symptoms, and elevated transaminases compared with 14% on placebo (number needed to harm [NNH]=2).

The authors of the review noted that consensus opinion holds that oral corticosteroids and NSAIDs reduce SLE-associated joint pain, but they found no studies that objectively evaluated either of these interventions.1

Fish oil also helps arthritis

Two RCTs on the effects of 3 g/d of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (fish oil) for 24 weeks in SLE patients with mild disease found a reduction in Systemic Lupus Activity Measure-Revised (SLAM-R) scores.2,3 SLAM-R is a validated measure of SLE disease activity, rated on a scale from 0 to 81, including 23 clinical and 7 laboratory manifestations of disease.

In the first study (52 subjects), disease activity decreased from an average SLAM-R score of 6.1 at baseline to 4.7 (P<.05). The second study (60 subjects) found a similar reduction in mean SLAM-R scores from 9.4 to 6.3 (P<.001) and joint pain scores from 1.27 to 0.83 (P=.047).

Drug treatments don’t significantly relieve fatigue

An industry-sponsored RCT that compared abatacept with placebo found improvements in fatigue that weren’t clinically meaningful in posthoc analysis (-9.45 points difference on a self-reported 0-to-100 visual analog scale; 95% confidence interval, -17.65 to -1.25, with a 10-point reduction considered to be clinically meaningful). Abatacept also had a high rate of serious adverse events, including facial edema, polyneuropathy, and serious infections (24/121 with abatacept vs 4/59 placebo; NNH=8).4

Another RCT found no effect of dehydroepiandrosterone on fatigue in women with inactive SLE.5

Nondrug treatments for fatigue produce mixed results

Studies of nondrug treatment of SLE-associated fatigue show inconsistent results. A systematic review of nonpharmacologic interventions for fatigue in several chronic diseases found 2 RCTs and 4 quasi-experimental studies that included 324 patients with SLE.6 Of 4 studies that evaluated the effect of exercise, 2 showed improvement and 2 didn’t. Neither group self-management nor relaxation therapy and telephone counseling significantly relieved fatigue.6-8 A small RCT (24 patients) found no benefit for acupuncture over sham needling in treating pain and fatigue in SLE.9

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Rheumatology guideline for referral and management of SLE states that “NSAIDs are sometimes helpful for control of fever, arthritis, and mild serositis. Antimalarial agents (eg, hydroxychloroquine) are useful for skin and joint manifestations of SLE, for preventing flares, and for other constitutional symptoms of the disease. They may also reduce fatigue.”10

The European League Against Rheumatism recommends antimalarials or glucocorticoids to treat patients with SLE without major organ manifestations. They also say clinicians may try NSAIDs for limited periods of time in patients at low risk for the drugs’ complications.11

1. Madhok R, Wu O. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Evid. 2009;7:1123.

2. Duffy EM, Meenagh GK, McMillan SA, et al. The clinical effect of dietary supplementation with omega-3 fish oils and/ or copper in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1551-1556.

3. Wright SA, O’Prey FM, McHenry MT, et al. A randomised interventional trial of omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids on endothelial function and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:841-848.

4. Merrill JT, Burgos-Vargas R, Westhovens R, et al. The efficacy and safety of abatacept in patients with non-life-threatening manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a twelve-month, multicenter, exploratory, phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3077-3087.

5. Hartkamp A, Geenen R, Godaert GL, et al. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone on fatigue and well-being in women with quiescent systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1144-1147.

6. Neill J, Belan I, Reid K. Effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for fatigue in adults with multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or systemic lupus erythematosis: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56:617-635.

7. Tench CM, McCarthy J, McCurdie I, et al. Fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial of exercise. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:1050-1054.

8. Sohng KY. Effects of a self-management course for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42:479-486.

9. Greco CM, Kao AH, Maksimowicz-McKinnon K, et al. Acupuncture for systemic lupus erythematosus: a pilot RCT feasibility and safety study. Lupus. 2008;17:1108-1116.

10. American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Guidelines. Guidelines for referral and management of systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1785-1796.

11. Bertsias G, Ioannidis JP, Boletis J, et al; Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:195-205.

1. Madhok R, Wu O. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Evid. 2009;7:1123.

2. Duffy EM, Meenagh GK, McMillan SA, et al. The clinical effect of dietary supplementation with omega-3 fish oils and/ or copper in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:1551-1556.

3. Wright SA, O’Prey FM, McHenry MT, et al. A randomised interventional trial of omega-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids on endothelial function and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:841-848.

4. Merrill JT, Burgos-Vargas R, Westhovens R, et al. The efficacy and safety of abatacept in patients with non-life-threatening manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: results of a twelve-month, multicenter, exploratory, phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3077-3087.

5. Hartkamp A, Geenen R, Godaert GL, et al. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone on fatigue and well-being in women with quiescent systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1144-1147.

6. Neill J, Belan I, Reid K. Effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for fatigue in adults with multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or systemic lupus erythematosis: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56:617-635.

7. Tench CM, McCarthy J, McCurdie I, et al. Fatigue in systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomized controlled trial of exercise. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42:1050-1054.

8. Sohng KY. Effects of a self-management course for patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42:479-486.

9. Greco CM, Kao AH, Maksimowicz-McKinnon K, et al. Acupuncture for systemic lupus erythematosus: a pilot RCT feasibility and safety study. Lupus. 2008;17:1108-1116.

10. American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Guidelines. Guidelines for referral and management of systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1785-1796.

11. Bertsias G, Ioannidis JP, Boletis J, et al; Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:195-205.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Do oral contraceptives put women with a family history of breast cancer at increased risk?

No. Modern combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) don’t increase breast cancer risk in women with a family history (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of cohort, case-control studies). However, older, higher-dose OCPs (in use before 1975) did increase breast cancer risk in these women (SOR: C, case-control study).

Similarly, modern OCPs don’t raise breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1/2 mutations, although higher-dose, pre-1975 OCPs did (SOR: B and C, a meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of the effect of combined OCPs on women with a family history of breast cancer found no additional increase in risk.1 Investigators identified 3 retrospective cohort studies (N=66,500, with 8500 cases) and 7 case-control studies (total 10,500 cases) from the past 40 years, most including women from the United States and Canada, but one including women from 5 continents.

In most trials, women of reproductive age using combined OCPs had 1 or more first-degree female relatives with breast cancer, although a few trials also included second-degree relatives. Women ranged in age from 20 to 79 years at diagnosis, and most trials controlled for age, parity, menstrual and menopausal history, duration of OCP exposure, and age at first use. Follow-up intervals for the retrospective cohort studies ranged from 5 to 16 years. Investigators were unable to combine results because of heterogenous populations.

Three of the cohort studies found no significant difference in breast cancer risk between OCP users and nonusers, regardless of age or duration of use. One cohort study found an increased risk in women taking older, higher-dose OCPs from before 1975 (relative risk [RR]=3.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-7.2). All of the case-control studies found no significant difference in breast cancer risk for any age of starting, duration of OCP use, or degree of relative with breast cancer.

A meta-analysis of 54 case-control studies (6757 cases), comprising approximately 90% of the epidemiologic information on this topic, also found no significant difference in breast cancer risk related to OCP use among women with one or more first-degree relatives with breast cancer.2 Investigators found that neither recent OCP use (<10 years, RR=0.77; 95% CI, 0.54-1.11) nor past OCP use (>10 years, RR=1.01; 95% CI, 0.80-1.28) affected risk of developing breast cancer.

Three additional case-control studies involving women with a family history of breast cancer also found no significant association for breast cancer incidence among OCP users compared with nonusers.3-5

Modern combined OCPs don’t raise risk in women with BRCA1/2 mutations

A meta-analysis of 5 studies (one retrospective cohort, 4 case-control, with a total of 2855 breast cancer cases and 2944 controls) evaluated whether combined OCPs increased the risk of breast cancer in women, all of whom were carrying BRCA1/2 mutations.6

Using modern combined OCPs didn’t raise the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1/2 carriers overall (RR=1.13; 95% CI, 0.88-1.45) or separately in BRCA1 carriers (5 studies, RR=1.09; 95% CI, 0.77-1.54) or BRCA2 carriers (3 studies, RR=1.15; 95% CI, 0.88-1.45).

However, pre-1975 (higher dose) combined OCPs produced significantly increased risk (RR=1.47; 95% CI, 1.06-2.04). Similarly, women who had used combined OCPs >10 years before the study (older women, likely to have been using pre-1975 OCPs) also had significantly increased risk (RR=1.46; 95% CI, 1.07-2.07).

A bit of good news: Combined OCPs reduce ovarian cancer risk

The analysis also determined that combined OCPs significantly reduced the risk of ovarian cancer in women carrying BRCA1/2 mutations (RR=0.50; 95% CI, 0.33-0.75), with an additional linear decrease in risk for each 10 years of OCP use (RR=0.64; 95% CI, 0.53-0.78).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The World Health Organization guidelines outlining criteria for contraceptive use state that OCPs don’t alter the risk of breast cancer among women with either a family history of breast cancer or breast cancer susceptibility genes.7

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) says that a positive family history of breast cancer shouldn’t be regarded as a contraindication to OCP use.8 ACOG also says that women with the BRCA1 mutation have an increased risk of breast cancer if they used OCPs for longer than 5 years before age 30, but this risk may be more than balanced by the benefit of a greatly reduced risk of ovarian cancer.

1. Gaffield ME, Culwell KR, Ravi A. Oral contraceptives and family history of breast cancer. Contraception. 2009;80:372-380.

2. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative re-analysis of individual data on 53,297 women with breast cancer and 100,239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 1996;347:1713-1727.

3. Jernström H, Loman N, Johannsson OT, et al. Impact of teenage oral contraceptive use in a population-based series of early-onset breast cancer cases who have undergone BRCA mutation testing. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2312-2320.

4. Cibula D, Gompel A, Mueck AO, et al. Hormonal contraception and risk of cancer. Human Reprod Update. 2010;16: 631-650.

5. Long-term oral contraceptive use and the risk of breast cancer. The Centers for Disease Control Cancer and Steroid Hormone Study. JAMA. 1983;249:1591-1595.

6. Iodice S, Barile M, Rotmensz N, et al. Oral contraceptive use and breast or ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1/2 carriers: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2275-2284.

7. World Health Organization. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. World Health Organization Web site. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241563888_eng.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2013.

8. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin. No. 73: Use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1453-1472.

No. Modern combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) don’t increase breast cancer risk in women with a family history (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of cohort, case-control studies). However, older, higher-dose OCPs (in use before 1975) did increase breast cancer risk in these women (SOR: C, case-control study).

Similarly, modern OCPs don’t raise breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1/2 mutations, although higher-dose, pre-1975 OCPs did (SOR: B and C, a meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of the effect of combined OCPs on women with a family history of breast cancer found no additional increase in risk.1 Investigators identified 3 retrospective cohort studies (N=66,500, with 8500 cases) and 7 case-control studies (total 10,500 cases) from the past 40 years, most including women from the United States and Canada, but one including women from 5 continents.

In most trials, women of reproductive age using combined OCPs had 1 or more first-degree female relatives with breast cancer, although a few trials also included second-degree relatives. Women ranged in age from 20 to 79 years at diagnosis, and most trials controlled for age, parity, menstrual and menopausal history, duration of OCP exposure, and age at first use. Follow-up intervals for the retrospective cohort studies ranged from 5 to 16 years. Investigators were unable to combine results because of heterogenous populations.

Three of the cohort studies found no significant difference in breast cancer risk between OCP users and nonusers, regardless of age or duration of use. One cohort study found an increased risk in women taking older, higher-dose OCPs from before 1975 (relative risk [RR]=3.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-7.2). All of the case-control studies found no significant difference in breast cancer risk for any age of starting, duration of OCP use, or degree of relative with breast cancer.

A meta-analysis of 54 case-control studies (6757 cases), comprising approximately 90% of the epidemiologic information on this topic, also found no significant difference in breast cancer risk related to OCP use among women with one or more first-degree relatives with breast cancer.2 Investigators found that neither recent OCP use (<10 years, RR=0.77; 95% CI, 0.54-1.11) nor past OCP use (>10 years, RR=1.01; 95% CI, 0.80-1.28) affected risk of developing breast cancer.

Three additional case-control studies involving women with a family history of breast cancer also found no significant association for breast cancer incidence among OCP users compared with nonusers.3-5

Modern combined OCPs don’t raise risk in women with BRCA1/2 mutations

A meta-analysis of 5 studies (one retrospective cohort, 4 case-control, with a total of 2855 breast cancer cases and 2944 controls) evaluated whether combined OCPs increased the risk of breast cancer in women, all of whom were carrying BRCA1/2 mutations.6

Using modern combined OCPs didn’t raise the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1/2 carriers overall (RR=1.13; 95% CI, 0.88-1.45) or separately in BRCA1 carriers (5 studies, RR=1.09; 95% CI, 0.77-1.54) or BRCA2 carriers (3 studies, RR=1.15; 95% CI, 0.88-1.45).

However, pre-1975 (higher dose) combined OCPs produced significantly increased risk (RR=1.47; 95% CI, 1.06-2.04). Similarly, women who had used combined OCPs >10 years before the study (older women, likely to have been using pre-1975 OCPs) also had significantly increased risk (RR=1.46; 95% CI, 1.07-2.07).

A bit of good news: Combined OCPs reduce ovarian cancer risk

The analysis also determined that combined OCPs significantly reduced the risk of ovarian cancer in women carrying BRCA1/2 mutations (RR=0.50; 95% CI, 0.33-0.75), with an additional linear decrease in risk for each 10 years of OCP use (RR=0.64; 95% CI, 0.53-0.78).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The World Health Organization guidelines outlining criteria for contraceptive use state that OCPs don’t alter the risk of breast cancer among women with either a family history of breast cancer or breast cancer susceptibility genes.7

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) says that a positive family history of breast cancer shouldn’t be regarded as a contraindication to OCP use.8 ACOG also says that women with the BRCA1 mutation have an increased risk of breast cancer if they used OCPs for longer than 5 years before age 30, but this risk may be more than balanced by the benefit of a greatly reduced risk of ovarian cancer.

No. Modern combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) don’t increase breast cancer risk in women with a family history (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic review of cohort, case-control studies). However, older, higher-dose OCPs (in use before 1975) did increase breast cancer risk in these women (SOR: C, case-control study).

Similarly, modern OCPs don’t raise breast cancer risk in women with BRCA1/2 mutations, although higher-dose, pre-1975 OCPs did (SOR: B and C, a meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review of the effect of combined OCPs on women with a family history of breast cancer found no additional increase in risk.1 Investigators identified 3 retrospective cohort studies (N=66,500, with 8500 cases) and 7 case-control studies (total 10,500 cases) from the past 40 years, most including women from the United States and Canada, but one including women from 5 continents.

In most trials, women of reproductive age using combined OCPs had 1 or more first-degree female relatives with breast cancer, although a few trials also included second-degree relatives. Women ranged in age from 20 to 79 years at diagnosis, and most trials controlled for age, parity, menstrual and menopausal history, duration of OCP exposure, and age at first use. Follow-up intervals for the retrospective cohort studies ranged from 5 to 16 years. Investigators were unable to combine results because of heterogenous populations.

Three of the cohort studies found no significant difference in breast cancer risk between OCP users and nonusers, regardless of age or duration of use. One cohort study found an increased risk in women taking older, higher-dose OCPs from before 1975 (relative risk [RR]=3.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5-7.2). All of the case-control studies found no significant difference in breast cancer risk for any age of starting, duration of OCP use, or degree of relative with breast cancer.

A meta-analysis of 54 case-control studies (6757 cases), comprising approximately 90% of the epidemiologic information on this topic, also found no significant difference in breast cancer risk related to OCP use among women with one or more first-degree relatives with breast cancer.2 Investigators found that neither recent OCP use (<10 years, RR=0.77; 95% CI, 0.54-1.11) nor past OCP use (>10 years, RR=1.01; 95% CI, 0.80-1.28) affected risk of developing breast cancer.

Three additional case-control studies involving women with a family history of breast cancer also found no significant association for breast cancer incidence among OCP users compared with nonusers.3-5

Modern combined OCPs don’t raise risk in women with BRCA1/2 mutations

A meta-analysis of 5 studies (one retrospective cohort, 4 case-control, with a total of 2855 breast cancer cases and 2944 controls) evaluated whether combined OCPs increased the risk of breast cancer in women, all of whom were carrying BRCA1/2 mutations.6

Using modern combined OCPs didn’t raise the risk of breast cancer in BRCA1/2 carriers overall (RR=1.13; 95% CI, 0.88-1.45) or separately in BRCA1 carriers (5 studies, RR=1.09; 95% CI, 0.77-1.54) or BRCA2 carriers (3 studies, RR=1.15; 95% CI, 0.88-1.45).

However, pre-1975 (higher dose) combined OCPs produced significantly increased risk (RR=1.47; 95% CI, 1.06-2.04). Similarly, women who had used combined OCPs >10 years before the study (older women, likely to have been using pre-1975 OCPs) also had significantly increased risk (RR=1.46; 95% CI, 1.07-2.07).

A bit of good news: Combined OCPs reduce ovarian cancer risk

The analysis also determined that combined OCPs significantly reduced the risk of ovarian cancer in women carrying BRCA1/2 mutations (RR=0.50; 95% CI, 0.33-0.75), with an additional linear decrease in risk for each 10 years of OCP use (RR=0.64; 95% CI, 0.53-0.78).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The World Health Organization guidelines outlining criteria for contraceptive use state that OCPs don’t alter the risk of breast cancer among women with either a family history of breast cancer or breast cancer susceptibility genes.7

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) says that a positive family history of breast cancer shouldn’t be regarded as a contraindication to OCP use.8 ACOG also says that women with the BRCA1 mutation have an increased risk of breast cancer if they used OCPs for longer than 5 years before age 30, but this risk may be more than balanced by the benefit of a greatly reduced risk of ovarian cancer.

1. Gaffield ME, Culwell KR, Ravi A. Oral contraceptives and family history of breast cancer. Contraception. 2009;80:372-380.

2. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative re-analysis of individual data on 53,297 women with breast cancer and 100,239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 1996;347:1713-1727.

3. Jernström H, Loman N, Johannsson OT, et al. Impact of teenage oral contraceptive use in a population-based series of early-onset breast cancer cases who have undergone BRCA mutation testing. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2312-2320.

4. Cibula D, Gompel A, Mueck AO, et al. Hormonal contraception and risk of cancer. Human Reprod Update. 2010;16: 631-650.

5. Long-term oral contraceptive use and the risk of breast cancer. The Centers for Disease Control Cancer and Steroid Hormone Study. JAMA. 1983;249:1591-1595.

6. Iodice S, Barile M, Rotmensz N, et al. Oral contraceptive use and breast or ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1/2 carriers: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2275-2284.

7. World Health Organization. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. World Health Organization Web site. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241563888_eng.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2013.

8. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin. No. 73: Use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1453-1472.

1. Gaffield ME, Culwell KR, Ravi A. Oral contraceptives and family history of breast cancer. Contraception. 2009;80:372-380.

2. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative re-analysis of individual data on 53,297 women with breast cancer and 100,239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 1996;347:1713-1727.

3. Jernström H, Loman N, Johannsson OT, et al. Impact of teenage oral contraceptive use in a population-based series of early-onset breast cancer cases who have undergone BRCA mutation testing. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:2312-2320.

4. Cibula D, Gompel A, Mueck AO, et al. Hormonal contraception and risk of cancer. Human Reprod Update. 2010;16: 631-650.

5. Long-term oral contraceptive use and the risk of breast cancer. The Centers for Disease Control Cancer and Steroid Hormone Study. JAMA. 1983;249:1591-1595.

6. Iodice S, Barile M, Rotmensz N, et al. Oral contraceptive use and breast or ovarian cancer risk in BRCA1/2 carriers: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2275-2284.

7. World Health Organization. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. 4th ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. World Health Organization Web site. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241563888_eng.pdf. Accessed September 24, 2013.

8. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin. No. 73: Use of hormonal contraception in women with coexisting medical conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:1453-1472.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

What is the best nonsurgical therapy for pelvic organ prolapse?

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and pessaries are equally effective in treating symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse (POP). PFMT transiently improves patient satisfaction and reduces urinary incontinence more than pessaries do (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, a randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

PFMT moderately improves prolapse symptoms and severity, especially following 6 months of supervised intervention (SOR: B, a systematic review of randomized trials with some methodologic flaws).

Two pessaries (ring with support and Gellhorn) reduce symptoms in as many as 60% of patients (SOR: B, a systematic review of randomized trials).

Untreated postmenopausal women with mild grades of uterine prolapse are unlikely to develop more severe prolapse; 25% to 50% improve spontaneously (SOR: C, a prospective cohort study with methodologic flaws).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2010 multicenter RCT with 445 women (mean age 49.8 years) compared PFMT, pessary use, and combined treatment.1 Investigators used the Patient Global Impression of Improvement and the stress incontinence subscale of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory to measure patient satisfaction and urinary incontinence symptoms.

At 3 months, equivalent numbers of women using PFMT and a pessary (49% and 40%, respectively; P=.09) reported they were “much better” or “very much better.” More women in the PFMT cohort than women using a pessary reported resolution of incontinence symptoms at 3 months (49% vs 33%; P=.006), and satisfaction with treatment (75% vs 63%; P=.02), but these differences disappeared at 12 months. Combination therapy wasn’t superior to PFMT alone.

Pelvic floor muscle training improves symptoms, especially with perseverance

A 2011 Cochrane review that compared women receiving PFMT with a control group (observed but not treated) found that PFMT moderately improved prolapse symptoms and severity, especially following 6 months of supervised intervention.2 Investigators evalu-ated 4 trials, (N=857), including 3 with fewer than 25 women per arm.

Three studies found that PFMT improved symptom severity and manometric measures. Although the authors couldn’t pool the data because of different symptom scoring instruments, typical improvements ranged from 20% to 30%. Two trials found that PFMT increased the chance of improvement in POP stage by 17% (pooled data, relative risk=.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], .71-.96). PFMT also improved urinary outcomes (approximately 30% reduction in urinary frequency and stress incontinence symptoms) in 2 of 3 trials and improved bowel symptoms in one trial (approximately 25% to 30% reduction).

Pessaries also relieve symptoms

A 2013 Cochrane Review seeking to determine the effectiveness of pessaries in POP, identified one RCT (crossover, 3 month, multicenter, United States) that compared symptom relief and change in life impact over baseline for 134 women (parous, mean age 61 years, range 30-89 years) with POP stage II or greater who were treated with ring with support or Gellhorn pessaries.3 Sixty percent of patients who completed the study (the dropout rate was 37%) reported symptom relief with both types of pessary. Outcomes were measured by multiple questionnaires and Likert scales.

Patients reported improved symptoms on both the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory (POPDI) and Pelvic Organ Prolapse Impact Questionnaire (POPIQ) scales (P<.05 for difference from baseline on each scale, actual scores not reported). The ring with support and Gellhorn pessaries didn’t produce different scores on either scale (POPDI, P=.99; POPIQ, P=.29).

Untreated mild prolapse postmenopause usually doesn’t progress and may regress

A cohort of 412 postmenopausal women (ages ≥50 years) with POP who were observed, but not treated, found that mild POP was unlikely to progress and sometimes improved spontaneously.4 Over a mean follow-up of 5.7 years, few women with grade 1 POP (prolapsed pelvic organs remaining within the vagina) progressed to grade 2 or 3 (probability of progression for women with cystoceles=.095, 95% CI, .07-.13; women with rectoceles=.135, 95% CI, .09-.19; and women with uterine prolapse=.019, 95% CI, .0005-.099).

Some women with grade 1 POP regressed to grade 0 (probability of regression for women with cystoceles=.235, 95% CI, .19- .28; women with rectoceles=.22, 95% CI, .16-.28; and women with uterine prolapse=.48, 95% CI, 0.34-.62). Women with grades 2 and 3 POP were less likely to regress to grade 0 (probability of regression for women with cystoceles=.093, 95% CI, .05-.14; women with rectoceles=.033, 95% CI, .011-.075; and women with uterine prolapse=0, 95% CI, 0-.37).

One flaw of this study was that the women received hormone replacement therapy, which the investigators didn’t evaluate independently. However, a 2010 Cochrane review (2 small trials, one meta-analysis) found insufficient data to determine whether hormone replacement therapy alters POP.5

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin on POP recommends the following:6

- Pessaries can be fitted in most women with prolapse, regardless of prolapse stage (equivalent to grade) or site of predominant prolapse.

- Pessary use should be considered before surgical intervention in women with symptomatic prolapse.

- Women with prolapse who are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic can be observed at regular intervals, unless new bothersome symptoms develop.

1. Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al;Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609-617.

2. Hagen S, Stark D. Conservative prevention and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD003882.

3. Bugge C, Adams EJ, Gopinath D, et al. Pessaries (mechanical devices) for pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD004010.

4. Handa VL, Garrett E, Hendrix S, et al. Progression and remission of pelvic organ prolapse: a longitudinal study of menopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:27-32.

5. Ismail SI, Bain C, Hagen S. Oestrogens for treatment or prevention of pelvic organ prolapse in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;9:CD007063.

6. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 85: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:717-729.

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and pessaries are equally effective in treating symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse (POP). PFMT transiently improves patient satisfaction and reduces urinary incontinence more than pessaries do (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, a randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

PFMT moderately improves prolapse symptoms and severity, especially following 6 months of supervised intervention (SOR: B, a systematic review of randomized trials with some methodologic flaws).

Two pessaries (ring with support and Gellhorn) reduce symptoms in as many as 60% of patients (SOR: B, a systematic review of randomized trials).

Untreated postmenopausal women with mild grades of uterine prolapse are unlikely to develop more severe prolapse; 25% to 50% improve spontaneously (SOR: C, a prospective cohort study with methodologic flaws).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2010 multicenter RCT with 445 women (mean age 49.8 years) compared PFMT, pessary use, and combined treatment.1 Investigators used the Patient Global Impression of Improvement and the stress incontinence subscale of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory to measure patient satisfaction and urinary incontinence symptoms.

At 3 months, equivalent numbers of women using PFMT and a pessary (49% and 40%, respectively; P=.09) reported they were “much better” or “very much better.” More women in the PFMT cohort than women using a pessary reported resolution of incontinence symptoms at 3 months (49% vs 33%; P=.006), and satisfaction with treatment (75% vs 63%; P=.02), but these differences disappeared at 12 months. Combination therapy wasn’t superior to PFMT alone.

Pelvic floor muscle training improves symptoms, especially with perseverance

A 2011 Cochrane review that compared women receiving PFMT with a control group (observed but not treated) found that PFMT moderately improved prolapse symptoms and severity, especially following 6 months of supervised intervention.2 Investigators evalu-ated 4 trials, (N=857), including 3 with fewer than 25 women per arm.

Three studies found that PFMT improved symptom severity and manometric measures. Although the authors couldn’t pool the data because of different symptom scoring instruments, typical improvements ranged from 20% to 30%. Two trials found that PFMT increased the chance of improvement in POP stage by 17% (pooled data, relative risk=.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], .71-.96). PFMT also improved urinary outcomes (approximately 30% reduction in urinary frequency and stress incontinence symptoms) in 2 of 3 trials and improved bowel symptoms in one trial (approximately 25% to 30% reduction).

Pessaries also relieve symptoms

A 2013 Cochrane Review seeking to determine the effectiveness of pessaries in POP, identified one RCT (crossover, 3 month, multicenter, United States) that compared symptom relief and change in life impact over baseline for 134 women (parous, mean age 61 years, range 30-89 years) with POP stage II or greater who were treated with ring with support or Gellhorn pessaries.3 Sixty percent of patients who completed the study (the dropout rate was 37%) reported symptom relief with both types of pessary. Outcomes were measured by multiple questionnaires and Likert scales.

Patients reported improved symptoms on both the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory (POPDI) and Pelvic Organ Prolapse Impact Questionnaire (POPIQ) scales (P<.05 for difference from baseline on each scale, actual scores not reported). The ring with support and Gellhorn pessaries didn’t produce different scores on either scale (POPDI, P=.99; POPIQ, P=.29).

Untreated mild prolapse postmenopause usually doesn’t progress and may regress

A cohort of 412 postmenopausal women (ages ≥50 years) with POP who were observed, but not treated, found that mild POP was unlikely to progress and sometimes improved spontaneously.4 Over a mean follow-up of 5.7 years, few women with grade 1 POP (prolapsed pelvic organs remaining within the vagina) progressed to grade 2 or 3 (probability of progression for women with cystoceles=.095, 95% CI, .07-.13; women with rectoceles=.135, 95% CI, .09-.19; and women with uterine prolapse=.019, 95% CI, .0005-.099).

Some women with grade 1 POP regressed to grade 0 (probability of regression for women with cystoceles=.235, 95% CI, .19- .28; women with rectoceles=.22, 95% CI, .16-.28; and women with uterine prolapse=.48, 95% CI, 0.34-.62). Women with grades 2 and 3 POP were less likely to regress to grade 0 (probability of regression for women with cystoceles=.093, 95% CI, .05-.14; women with rectoceles=.033, 95% CI, .011-.075; and women with uterine prolapse=0, 95% CI, 0-.37).

One flaw of this study was that the women received hormone replacement therapy, which the investigators didn’t evaluate independently. However, a 2010 Cochrane review (2 small trials, one meta-analysis) found insufficient data to determine whether hormone replacement therapy alters POP.5

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin on POP recommends the following:6

- Pessaries can be fitted in most women with prolapse, regardless of prolapse stage (equivalent to grade) or site of predominant prolapse.

- Pessary use should be considered before surgical intervention in women with symptomatic prolapse.

- Women with prolapse who are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic can be observed at regular intervals, unless new bothersome symptoms develop.

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and pessaries are equally effective in treating symptoms of pelvic organ prolapse (POP). PFMT transiently improves patient satisfaction and reduces urinary incontinence more than pessaries do (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, a randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

PFMT moderately improves prolapse symptoms and severity, especially following 6 months of supervised intervention (SOR: B, a systematic review of randomized trials with some methodologic flaws).

Two pessaries (ring with support and Gellhorn) reduce symptoms in as many as 60% of patients (SOR: B, a systematic review of randomized trials).

Untreated postmenopausal women with mild grades of uterine prolapse are unlikely to develop more severe prolapse; 25% to 50% improve spontaneously (SOR: C, a prospective cohort study with methodologic flaws).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2010 multicenter RCT with 445 women (mean age 49.8 years) compared PFMT, pessary use, and combined treatment.1 Investigators used the Patient Global Impression of Improvement and the stress incontinence subscale of the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory to measure patient satisfaction and urinary incontinence symptoms.

At 3 months, equivalent numbers of women using PFMT and a pessary (49% and 40%, respectively; P=.09) reported they were “much better” or “very much better.” More women in the PFMT cohort than women using a pessary reported resolution of incontinence symptoms at 3 months (49% vs 33%; P=.006), and satisfaction with treatment (75% vs 63%; P=.02), but these differences disappeared at 12 months. Combination therapy wasn’t superior to PFMT alone.

Pelvic floor muscle training improves symptoms, especially with perseverance

A 2011 Cochrane review that compared women receiving PFMT with a control group (observed but not treated) found that PFMT moderately improved prolapse symptoms and severity, especially following 6 months of supervised intervention.2 Investigators evalu-ated 4 trials, (N=857), including 3 with fewer than 25 women per arm.

Three studies found that PFMT improved symptom severity and manometric measures. Although the authors couldn’t pool the data because of different symptom scoring instruments, typical improvements ranged from 20% to 30%. Two trials found that PFMT increased the chance of improvement in POP stage by 17% (pooled data, relative risk=.83; 95% confidence interval [CI], .71-.96). PFMT also improved urinary outcomes (approximately 30% reduction in urinary frequency and stress incontinence symptoms) in 2 of 3 trials and improved bowel symptoms in one trial (approximately 25% to 30% reduction).

Pessaries also relieve symptoms

A 2013 Cochrane Review seeking to determine the effectiveness of pessaries in POP, identified one RCT (crossover, 3 month, multicenter, United States) that compared symptom relief and change in life impact over baseline for 134 women (parous, mean age 61 years, range 30-89 years) with POP stage II or greater who were treated with ring with support or Gellhorn pessaries.3 Sixty percent of patients who completed the study (the dropout rate was 37%) reported symptom relief with both types of pessary. Outcomes were measured by multiple questionnaires and Likert scales.

Patients reported improved symptoms on both the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Distress Inventory (POPDI) and Pelvic Organ Prolapse Impact Questionnaire (POPIQ) scales (P<.05 for difference from baseline on each scale, actual scores not reported). The ring with support and Gellhorn pessaries didn’t produce different scores on either scale (POPDI, P=.99; POPIQ, P=.29).

Untreated mild prolapse postmenopause usually doesn’t progress and may regress

A cohort of 412 postmenopausal women (ages ≥50 years) with POP who were observed, but not treated, found that mild POP was unlikely to progress and sometimes improved spontaneously.4 Over a mean follow-up of 5.7 years, few women with grade 1 POP (prolapsed pelvic organs remaining within the vagina) progressed to grade 2 or 3 (probability of progression for women with cystoceles=.095, 95% CI, .07-.13; women with rectoceles=.135, 95% CI, .09-.19; and women with uterine prolapse=.019, 95% CI, .0005-.099).

Some women with grade 1 POP regressed to grade 0 (probability of regression for women with cystoceles=.235, 95% CI, .19- .28; women with rectoceles=.22, 95% CI, .16-.28; and women with uterine prolapse=.48, 95% CI, 0.34-.62). Women with grades 2 and 3 POP were less likely to regress to grade 0 (probability of regression for women with cystoceles=.093, 95% CI, .05-.14; women with rectoceles=.033, 95% CI, .011-.075; and women with uterine prolapse=0, 95% CI, 0-.37).

One flaw of this study was that the women received hormone replacement therapy, which the investigators didn’t evaluate independently. However, a 2010 Cochrane review (2 small trials, one meta-analysis) found insufficient data to determine whether hormone replacement therapy alters POP.5

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin on POP recommends the following:6

- Pessaries can be fitted in most women with prolapse, regardless of prolapse stage (equivalent to grade) or site of predominant prolapse.

- Pessary use should be considered before surgical intervention in women with symptomatic prolapse.

- Women with prolapse who are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic can be observed at regular intervals, unless new bothersome symptoms develop.

1. Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al;Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609-617.

2. Hagen S, Stark D. Conservative prevention and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD003882.

3. Bugge C, Adams EJ, Gopinath D, et al. Pessaries (mechanical devices) for pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD004010.

4. Handa VL, Garrett E, Hendrix S, et al. Progression and remission of pelvic organ prolapse: a longitudinal study of menopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:27-32.

5. Ismail SI, Bain C, Hagen S. Oestrogens for treatment or prevention of pelvic organ prolapse in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;9:CD007063.

6. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 85: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:717-729.

1. Richter HE, Burgio KL, Brubaker L, et al;Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Continence pessary compared with behavioral therapy or combined therapy for stress incontinence: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:609-617.

2. Hagen S, Stark D. Conservative prevention and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD003882.

3. Bugge C, Adams EJ, Gopinath D, et al. Pessaries (mechanical devices) for pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD004010.

4. Handa VL, Garrett E, Hendrix S, et al. Progression and remission of pelvic organ prolapse: a longitudinal study of menopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:27-32.

5. Ismail SI, Bain C, Hagen S. Oestrogens for treatment or prevention of pelvic organ prolapse in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;9:CD007063.

6. ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 85: Pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:717-729.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Are topical nitrates safe and effective for upper extremity tendinopathies?