User login

Which prophylactic therapies best prevent gout attacks?

Allopurinol and febuxostat reduce the frequency of gout attacks equally after 8 weeks of treatment (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, multiple randomized control trials [RCTs] with limitations).

Intravenous pegloticase decreases serum uric acid and gout attacks and improves quality of life (QOL) (SOR: A, 2 RCTs).

Colchicine reduces gout attacks when combined with probenecid or allopurinol at the start of urate-lowering therapy (SOR: B, 1 high-quality and 1 low-quality RCT).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 28-week RCT compared the effects of placebo, allopurinol (300 mg/d), and febuxostat (80 mg, 120 mg, and 240 mg) on serum uric acid levels (sUA) and gout attacks in 1067 patients with gout and hyperuricemia (94% male, 78% white, 18 to 85 years of age with mean age ranging from 51 to 54 years ± 12 years in each group).1 Patients also received prophylaxis with either colchicine or naproxen during the first 8 weeks of the study.

During Weeks 1 through 8, investigators found no statistically significant differences in the percentage of patients requiring treatment for gout attacks between the febuxostat 80 mg, allopurinol, and placebo groups (28%, 23%, and 20%, respectively). During Weeks 8 through 28, no statistically significant differences in gout attack rates occurred between the allopurinol and febuxostat groups, although the study didn’t report specific attack rates for this period.

Both allopurinol and all doses of febuxostat reduced sUA to <6 mg/dL more effectively than placebo; more patients treated with febuxostat than allopurinol achieved a uric acid level of less than <6 mg/dL.

Another RCT of 762 mostly white, male patients (mean age 52 years) with gout and sUA >8 mg/dL—35% of whom had renal impairment, defined as creatinine clearance <80 mL/min/1.73m2—also concluded that febuxostat and allopurinol are equally effective in reducing gout attacks (incidence of gout flares during Weeks 9 to 52 was 64% with both febuxostat 80 mg and allopurinol 300 mg).2 The percentage of patients with sUA <6 mg/dL at the last 3 monthly visits was 53% in the febuxostat 80 mg group compared with 21% in the allopurinol 300 mg group (P<.001; number needed to treat [NNT]=4]).

One significant limitation of both RCTs was the fixed dose of allopurinol (300 mg/d). US Food and Drug Administration-approved dosing for allopurinol allows for titration to a maximum of 800 mg/d to achieve serum uric acid <6 mg/dL.

IV pegloticase decreases gout attacks after 3 months, improves quality of life

Pegloticase is an intravenously administered, recombinant form of uricase, the natural enzyme that converts uric acid to more soluble allantoin. Two RCTs compared pegloticase with placebo in a total of 212 patients with gout (mean age 54 to 59 years; 70% to 90% male) intolerant or refractory to allopurinol (defined as baseline sUA of ≥8 mg/dL and at least one of the following: ≥3 self-reported gout flares during the previous 18 months, ≥1 tophi, or gouty arthropathy.

These trials found that treatment with 8 mg of pegloticase every 2 weeks for 6 months initially increased gout flares during Months 1 to 3 (75% with pegloticase, 53% with placebo; P=.02; number needed to harm [NNH]=5) but then decreased the incidence of acute gout attacks during Months 4 to 6 (41% with pegloticase, 67% with placebo; P=.007; NNT=4).3 In addition, pegloticase resulted in statistically significant improvements in QOL measured at the final visit using the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) pain scale, the HAQ-Disability Index, and the 36-item Short Form Health Survey.

Colchicine plus probenecid or allopurinol reduces gout attacks

One small, low-quality RCT (N=38) found that colchicine 0.5 mg administered 3 times daily effectively prevented gout attacks when administered concomitantly with probenecid initiated to lower urate (gout attacks per month in colchicine and placebo-treated patients, respectively, were 0.19±0.05 and 0.48±0.12; P<.05).4

Another RCT that compared allopurinol with and without colchicine showed that coadministration of colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily reduced gout attacks: 33% of patients treated with colchicine experienced a gout flare compared with 77% of placebo-treated patients (P=.008; NNT=3 over 6 months).5

We identified no RCTs that evaluated the uricosuric agent probenecid and no studies that assessed the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to prevent recurrent gout attacks.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines on managing gout recommend allopurinol or febuxostat as first-line pharmacologic urate-lowering therapy, with a goal of reducing sUA to <6 mg/dL. They recommend probenecid as an alternative if contraindications exist or the patient is intolerant to allopurinol and febuxostat.6 The guidelines note that allopurinol doses may exceed 300 mg/d, even in patients with chronic kidney disease.

The ACR recommends anti-inflammatory prophylaxis with colchicine or NSAIDs upon initiation of urate-lowering therapy. Anti-inflammatory prophylaxis should be continued as long as clinical evidence of continuing gout disease exists and until the sUA target has been acheived.7

1. Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Wortmann RL, et al. Effects of febuxostat versus allopurinol and placebo in reducing serum urate in subjects with hyperuricemia and gout: a 28-week, phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1540-1548.

2. Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2450-2461.

3. Sundy JS, Baraf HSB, Yood RA, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pegloticase for the treatment of chronic gout in patients refractory to conventional treatment: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2011;306:711-720.

4. Paulus HE, Schlosstein LH, Godfrey RG, et al. Prophylactic colchicine therapy of intercritical gout: a placebo-controlled study of probenecid-treated patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1974;17:609-614.

5. Borstad GC, Bryant LR, Abel MP, et al. Colchicine for prophylaxis of acute flares when initiating allopurinol for chronic gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2429-2432.

6. Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al; American College of Rheumatology. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1431-1446.

7. Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al; American College of Rheumatology. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1447-1461.

Allopurinol and febuxostat reduce the frequency of gout attacks equally after 8 weeks of treatment (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, multiple randomized control trials [RCTs] with limitations).

Intravenous pegloticase decreases serum uric acid and gout attacks and improves quality of life (QOL) (SOR: A, 2 RCTs).

Colchicine reduces gout attacks when combined with probenecid or allopurinol at the start of urate-lowering therapy (SOR: B, 1 high-quality and 1 low-quality RCT).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 28-week RCT compared the effects of placebo, allopurinol (300 mg/d), and febuxostat (80 mg, 120 mg, and 240 mg) on serum uric acid levels (sUA) and gout attacks in 1067 patients with gout and hyperuricemia (94% male, 78% white, 18 to 85 years of age with mean age ranging from 51 to 54 years ± 12 years in each group).1 Patients also received prophylaxis with either colchicine or naproxen during the first 8 weeks of the study.

During Weeks 1 through 8, investigators found no statistically significant differences in the percentage of patients requiring treatment for gout attacks between the febuxostat 80 mg, allopurinol, and placebo groups (28%, 23%, and 20%, respectively). During Weeks 8 through 28, no statistically significant differences in gout attack rates occurred between the allopurinol and febuxostat groups, although the study didn’t report specific attack rates for this period.

Both allopurinol and all doses of febuxostat reduced sUA to <6 mg/dL more effectively than placebo; more patients treated with febuxostat than allopurinol achieved a uric acid level of less than <6 mg/dL.

Another RCT of 762 mostly white, male patients (mean age 52 years) with gout and sUA >8 mg/dL—35% of whom had renal impairment, defined as creatinine clearance <80 mL/min/1.73m2—also concluded that febuxostat and allopurinol are equally effective in reducing gout attacks (incidence of gout flares during Weeks 9 to 52 was 64% with both febuxostat 80 mg and allopurinol 300 mg).2 The percentage of patients with sUA <6 mg/dL at the last 3 monthly visits was 53% in the febuxostat 80 mg group compared with 21% in the allopurinol 300 mg group (P<.001; number needed to treat [NNT]=4]).

One significant limitation of both RCTs was the fixed dose of allopurinol (300 mg/d). US Food and Drug Administration-approved dosing for allopurinol allows for titration to a maximum of 800 mg/d to achieve serum uric acid <6 mg/dL.

IV pegloticase decreases gout attacks after 3 months, improves quality of life

Pegloticase is an intravenously administered, recombinant form of uricase, the natural enzyme that converts uric acid to more soluble allantoin. Two RCTs compared pegloticase with placebo in a total of 212 patients with gout (mean age 54 to 59 years; 70% to 90% male) intolerant or refractory to allopurinol (defined as baseline sUA of ≥8 mg/dL and at least one of the following: ≥3 self-reported gout flares during the previous 18 months, ≥1 tophi, or gouty arthropathy.

These trials found that treatment with 8 mg of pegloticase every 2 weeks for 6 months initially increased gout flares during Months 1 to 3 (75% with pegloticase, 53% with placebo; P=.02; number needed to harm [NNH]=5) but then decreased the incidence of acute gout attacks during Months 4 to 6 (41% with pegloticase, 67% with placebo; P=.007; NNT=4).3 In addition, pegloticase resulted in statistically significant improvements in QOL measured at the final visit using the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) pain scale, the HAQ-Disability Index, and the 36-item Short Form Health Survey.

Colchicine plus probenecid or allopurinol reduces gout attacks

One small, low-quality RCT (N=38) found that colchicine 0.5 mg administered 3 times daily effectively prevented gout attacks when administered concomitantly with probenecid initiated to lower urate (gout attacks per month in colchicine and placebo-treated patients, respectively, were 0.19±0.05 and 0.48±0.12; P<.05).4

Another RCT that compared allopurinol with and without colchicine showed that coadministration of colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily reduced gout attacks: 33% of patients treated with colchicine experienced a gout flare compared with 77% of placebo-treated patients (P=.008; NNT=3 over 6 months).5

We identified no RCTs that evaluated the uricosuric agent probenecid and no studies that assessed the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to prevent recurrent gout attacks.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines on managing gout recommend allopurinol or febuxostat as first-line pharmacologic urate-lowering therapy, with a goal of reducing sUA to <6 mg/dL. They recommend probenecid as an alternative if contraindications exist or the patient is intolerant to allopurinol and febuxostat.6 The guidelines note that allopurinol doses may exceed 300 mg/d, even in patients with chronic kidney disease.

The ACR recommends anti-inflammatory prophylaxis with colchicine or NSAIDs upon initiation of urate-lowering therapy. Anti-inflammatory prophylaxis should be continued as long as clinical evidence of continuing gout disease exists and until the sUA target has been acheived.7

Allopurinol and febuxostat reduce the frequency of gout attacks equally after 8 weeks of treatment (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, multiple randomized control trials [RCTs] with limitations).

Intravenous pegloticase decreases serum uric acid and gout attacks and improves quality of life (QOL) (SOR: A, 2 RCTs).

Colchicine reduces gout attacks when combined with probenecid or allopurinol at the start of urate-lowering therapy (SOR: B, 1 high-quality and 1 low-quality RCT).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 28-week RCT compared the effects of placebo, allopurinol (300 mg/d), and febuxostat (80 mg, 120 mg, and 240 mg) on serum uric acid levels (sUA) and gout attacks in 1067 patients with gout and hyperuricemia (94% male, 78% white, 18 to 85 years of age with mean age ranging from 51 to 54 years ± 12 years in each group).1 Patients also received prophylaxis with either colchicine or naproxen during the first 8 weeks of the study.

During Weeks 1 through 8, investigators found no statistically significant differences in the percentage of patients requiring treatment for gout attacks between the febuxostat 80 mg, allopurinol, and placebo groups (28%, 23%, and 20%, respectively). During Weeks 8 through 28, no statistically significant differences in gout attack rates occurred between the allopurinol and febuxostat groups, although the study didn’t report specific attack rates for this period.

Both allopurinol and all doses of febuxostat reduced sUA to <6 mg/dL more effectively than placebo; more patients treated with febuxostat than allopurinol achieved a uric acid level of less than <6 mg/dL.

Another RCT of 762 mostly white, male patients (mean age 52 years) with gout and sUA >8 mg/dL—35% of whom had renal impairment, defined as creatinine clearance <80 mL/min/1.73m2—also concluded that febuxostat and allopurinol are equally effective in reducing gout attacks (incidence of gout flares during Weeks 9 to 52 was 64% with both febuxostat 80 mg and allopurinol 300 mg).2 The percentage of patients with sUA <6 mg/dL at the last 3 monthly visits was 53% in the febuxostat 80 mg group compared with 21% in the allopurinol 300 mg group (P<.001; number needed to treat [NNT]=4]).

One significant limitation of both RCTs was the fixed dose of allopurinol (300 mg/d). US Food and Drug Administration-approved dosing for allopurinol allows for titration to a maximum of 800 mg/d to achieve serum uric acid <6 mg/dL.

IV pegloticase decreases gout attacks after 3 months, improves quality of life

Pegloticase is an intravenously administered, recombinant form of uricase, the natural enzyme that converts uric acid to more soluble allantoin. Two RCTs compared pegloticase with placebo in a total of 212 patients with gout (mean age 54 to 59 years; 70% to 90% male) intolerant or refractory to allopurinol (defined as baseline sUA of ≥8 mg/dL and at least one of the following: ≥3 self-reported gout flares during the previous 18 months, ≥1 tophi, or gouty arthropathy.

These trials found that treatment with 8 mg of pegloticase every 2 weeks for 6 months initially increased gout flares during Months 1 to 3 (75% with pegloticase, 53% with placebo; P=.02; number needed to harm [NNH]=5) but then decreased the incidence of acute gout attacks during Months 4 to 6 (41% with pegloticase, 67% with placebo; P=.007; NNT=4).3 In addition, pegloticase resulted in statistically significant improvements in QOL measured at the final visit using the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) pain scale, the HAQ-Disability Index, and the 36-item Short Form Health Survey.

Colchicine plus probenecid or allopurinol reduces gout attacks

One small, low-quality RCT (N=38) found that colchicine 0.5 mg administered 3 times daily effectively prevented gout attacks when administered concomitantly with probenecid initiated to lower urate (gout attacks per month in colchicine and placebo-treated patients, respectively, were 0.19±0.05 and 0.48±0.12; P<.05).4

Another RCT that compared allopurinol with and without colchicine showed that coadministration of colchicine 0.6 mg twice daily reduced gout attacks: 33% of patients treated with colchicine experienced a gout flare compared with 77% of placebo-treated patients (P=.008; NNT=3 over 6 months).5

We identified no RCTs that evaluated the uricosuric agent probenecid and no studies that assessed the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to prevent recurrent gout attacks.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines on managing gout recommend allopurinol or febuxostat as first-line pharmacologic urate-lowering therapy, with a goal of reducing sUA to <6 mg/dL. They recommend probenecid as an alternative if contraindications exist or the patient is intolerant to allopurinol and febuxostat.6 The guidelines note that allopurinol doses may exceed 300 mg/d, even in patients with chronic kidney disease.

The ACR recommends anti-inflammatory prophylaxis with colchicine or NSAIDs upon initiation of urate-lowering therapy. Anti-inflammatory prophylaxis should be continued as long as clinical evidence of continuing gout disease exists and until the sUA target has been acheived.7

1. Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Wortmann RL, et al. Effects of febuxostat versus allopurinol and placebo in reducing serum urate in subjects with hyperuricemia and gout: a 28-week, phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1540-1548.

2. Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2450-2461.

3. Sundy JS, Baraf HSB, Yood RA, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pegloticase for the treatment of chronic gout in patients refractory to conventional treatment: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2011;306:711-720.

4. Paulus HE, Schlosstein LH, Godfrey RG, et al. Prophylactic colchicine therapy of intercritical gout: a placebo-controlled study of probenecid-treated patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1974;17:609-614.

5. Borstad GC, Bryant LR, Abel MP, et al. Colchicine for prophylaxis of acute flares when initiating allopurinol for chronic gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2429-2432.

6. Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al; American College of Rheumatology. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1431-1446.

7. Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al; American College of Rheumatology. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1447-1461.

1. Schumacher HR Jr, Becker MA, Wortmann RL, et al. Effects of febuxostat versus allopurinol and placebo in reducing serum urate in subjects with hyperuricemia and gout: a 28-week, phase III, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1540-1548.

2. Becker MA, Schumacher HR Jr, Wortmann RL, et al. Febuxostat compared with allopurinol in patients with hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2450-2461.

3. Sundy JS, Baraf HSB, Yood RA, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pegloticase for the treatment of chronic gout in patients refractory to conventional treatment: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2011;306:711-720.

4. Paulus HE, Schlosstein LH, Godfrey RG, et al. Prophylactic colchicine therapy of intercritical gout: a placebo-controlled study of probenecid-treated patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1974;17:609-614.

5. Borstad GC, Bryant LR, Abel MP, et al. Colchicine for prophylaxis of acute flares when initiating allopurinol for chronic gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2429-2432.

6. Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al; American College of Rheumatology. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1431-1446.

7. Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al; American College of Rheumatology. 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and anti-inflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1447-1461.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

How can we effectively treat stress urinary incontinence without drugs or surgery?

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and intravaginal electrical stimulation seem to be the best bets. PFMT increases urinary continence and improves symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review or randomized, controlled trials [RCTs]). PFMT also improves quality of life (QOL) (activity and psychological impact) (SOR: B, 1 RCT).

Intravaginal electrical stimulation increases urinary continence and improves SUI symptoms; percutaneous electrical stimulation also improves SUI symptoms and likely improves QOL measures (SOR: A, systematic review).

Magnetic stimulation doesn’t increase continence, has mixed effects on SUI symptoms, and produces no clinically meaningful improvement in QOL (SOR: B, heterogeneous RCTs with conflicting results). Vaginal cones don’t increase continence or QOL (SOR: B, 2 RCTs with methodologic flaws).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

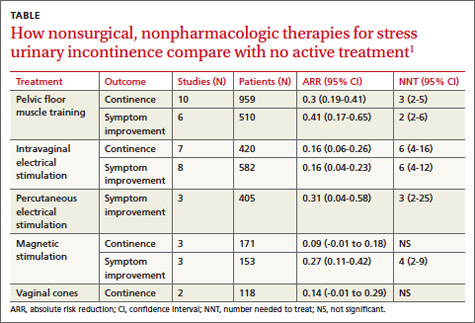

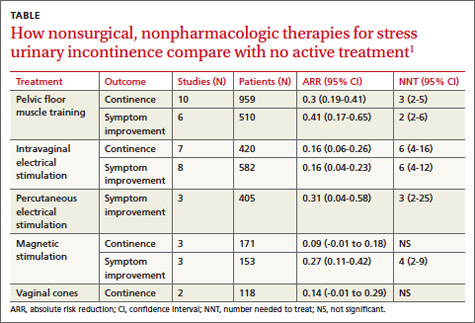

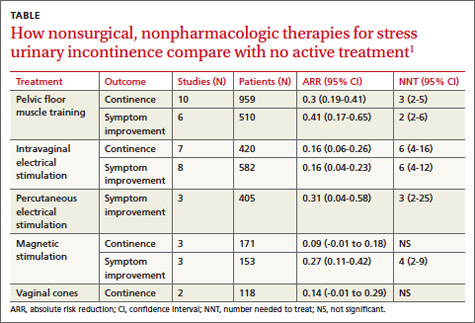

A systematic review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of adult female outpatients with SUI examined the effectiveness of PFMT, electrical stimulation, magnetic stimulation, and vaginal cones compared with no active treatment or sham treatment to produce continence (90% to 100% symptom reduction) or improve symptoms (at least 50% patient-reported symptom reduction).1 The TABLE summarizes the results.1 Investigators also assessed improvement in patient-reported QOL.

Pelvic floor muscle training improves continence, quality of life

A meta-analysis of 10 RCTs demonstrated that PFMT produced continence more often than placebo, and a meta-analysis of 6 RCTs found that PFMT improved SUI symptoms.1 PFMT regimens ranged in duration from 8 weeks to 6 months, including unsupervised treatment (8 to 12 repetitions, 3 to 10 times a day) and supervised treatment (as long as an hour, as often as 3 times a week).1

Both unsupervised and supervised PFMT produced similar results. One RCT evaluating QOL measures found that PFMT improved activity and reduced psychological impact (number needed to treat [NNT]=1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1-2).1

Intravaginal electrical stimulation improves continence and symptoms

A meta-analysis of 7 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation increased continence compared with sham treatment.1 A meta-analysis of 8 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation also improved SUI symptoms.1 All of the trials used electrical stimulation at frequencies between 4 and 50 Hz for 15 to 20 minutes, 1 to 3 times daily for 4 to 15 weeks.

Percutaneous electrical stimulation improves symptoms

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that percutaneous electrical stimulation improved SUI symptoms compared with no active treatment. Four RCTs found that electrical stimulation improved QOL, although a meta-analysis couldn’t be performed because of clinical heterogeneity.1

Magnetic stimulation produces conflicting results

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that magnetic stimulation at frequencies of 10 to 18.5 Hz given over 1 to 8 weeks didn’t increase continence. A meta-analysis of an additional 3 RCTs concluded that magnetic stimulation improved continence, but the individual studies reported conflicting results and were heterogenous.1

Two RCTs evaluating QOL scores found conflicting results. One study found a mean difference of 3.9 points on the 100-point Incontinence Quality of Life Questionnaire (95% CI, 2.08-5.72; minimal clinically important difference rated 2-5 points).1

Vaginal cones are ineffective and not well-tolerated

Two RCTs found that vaginal cones didn’t improve continence or QOL compared with no treatment. Investigators reported high discontinuation rates and adverse effects with the cones, which weighed 20 to 70 g and were worn for 20 minutes a day for as long as 24 weeks.1

RECOMMENDATIONS

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends PFMT comprising at least 8 contractions 3 times daily for at least 3 months as first-line therapy for women with SUI.2 They don’t recommend electrical stimulation or intravaginal devices for women who can actively contract their pelvic floor muscles. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends PFMT as first-line therapy for women with SUI and states that PFMT is more effective than electrical stimulation or vaginal cones.3

1. Nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in adult women: Diagnosis and comparative effectiveness. Executive summary. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/169/1021/CER36_Urinary-Incontinence_execsumm.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2014.

2. Urinary Incontinence: The management of urinary incontinence in women. NICE Clinical Guideline 171. London: NICE; 2006. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/CG171. Accessed March 19, 2014.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1533-1545.

AHIP; stress urinary incontinence; SUI; pelvic floor muscle training; PFMT; intravaginal electrical stimulation

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and intravaginal electrical stimulation seem to be the best bets. PFMT increases urinary continence and improves symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review or randomized, controlled trials [RCTs]). PFMT also improves quality of life (QOL) (activity and psychological impact) (SOR: B, 1 RCT).

Intravaginal electrical stimulation increases urinary continence and improves SUI symptoms; percutaneous electrical stimulation also improves SUI symptoms and likely improves QOL measures (SOR: A, systematic review).

Magnetic stimulation doesn’t increase continence, has mixed effects on SUI symptoms, and produces no clinically meaningful improvement in QOL (SOR: B, heterogeneous RCTs with conflicting results). Vaginal cones don’t increase continence or QOL (SOR: B, 2 RCTs with methodologic flaws).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of adult female outpatients with SUI examined the effectiveness of PFMT, electrical stimulation, magnetic stimulation, and vaginal cones compared with no active treatment or sham treatment to produce continence (90% to 100% symptom reduction) or improve symptoms (at least 50% patient-reported symptom reduction).1 The TABLE summarizes the results.1 Investigators also assessed improvement in patient-reported QOL.

Pelvic floor muscle training improves continence, quality of life

A meta-analysis of 10 RCTs demonstrated that PFMT produced continence more often than placebo, and a meta-analysis of 6 RCTs found that PFMT improved SUI symptoms.1 PFMT regimens ranged in duration from 8 weeks to 6 months, including unsupervised treatment (8 to 12 repetitions, 3 to 10 times a day) and supervised treatment (as long as an hour, as often as 3 times a week).1

Both unsupervised and supervised PFMT produced similar results. One RCT evaluating QOL measures found that PFMT improved activity and reduced psychological impact (number needed to treat [NNT]=1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1-2).1

Intravaginal electrical stimulation improves continence and symptoms

A meta-analysis of 7 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation increased continence compared with sham treatment.1 A meta-analysis of 8 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation also improved SUI symptoms.1 All of the trials used electrical stimulation at frequencies between 4 and 50 Hz for 15 to 20 minutes, 1 to 3 times daily for 4 to 15 weeks.

Percutaneous electrical stimulation improves symptoms

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that percutaneous electrical stimulation improved SUI symptoms compared with no active treatment. Four RCTs found that electrical stimulation improved QOL, although a meta-analysis couldn’t be performed because of clinical heterogeneity.1

Magnetic stimulation produces conflicting results

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that magnetic stimulation at frequencies of 10 to 18.5 Hz given over 1 to 8 weeks didn’t increase continence. A meta-analysis of an additional 3 RCTs concluded that magnetic stimulation improved continence, but the individual studies reported conflicting results and were heterogenous.1

Two RCTs evaluating QOL scores found conflicting results. One study found a mean difference of 3.9 points on the 100-point Incontinence Quality of Life Questionnaire (95% CI, 2.08-5.72; minimal clinically important difference rated 2-5 points).1

Vaginal cones are ineffective and not well-tolerated

Two RCTs found that vaginal cones didn’t improve continence or QOL compared with no treatment. Investigators reported high discontinuation rates and adverse effects with the cones, which weighed 20 to 70 g and were worn for 20 minutes a day for as long as 24 weeks.1

RECOMMENDATIONS

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends PFMT comprising at least 8 contractions 3 times daily for at least 3 months as first-line therapy for women with SUI.2 They don’t recommend electrical stimulation or intravaginal devices for women who can actively contract their pelvic floor muscles. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends PFMT as first-line therapy for women with SUI and states that PFMT is more effective than electrical stimulation or vaginal cones.3

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and intravaginal electrical stimulation seem to be the best bets. PFMT increases urinary continence and improves symptoms of stress urinary incontinence (SUI) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review or randomized, controlled trials [RCTs]). PFMT also improves quality of life (QOL) (activity and psychological impact) (SOR: B, 1 RCT).

Intravaginal electrical stimulation increases urinary continence and improves SUI symptoms; percutaneous electrical stimulation also improves SUI symptoms and likely improves QOL measures (SOR: A, systematic review).

Magnetic stimulation doesn’t increase continence, has mixed effects on SUI symptoms, and produces no clinically meaningful improvement in QOL (SOR: B, heterogeneous RCTs with conflicting results). Vaginal cones don’t increase continence or QOL (SOR: B, 2 RCTs with methodologic flaws).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality of adult female outpatients with SUI examined the effectiveness of PFMT, electrical stimulation, magnetic stimulation, and vaginal cones compared with no active treatment or sham treatment to produce continence (90% to 100% symptom reduction) or improve symptoms (at least 50% patient-reported symptom reduction).1 The TABLE summarizes the results.1 Investigators also assessed improvement in patient-reported QOL.

Pelvic floor muscle training improves continence, quality of life

A meta-analysis of 10 RCTs demonstrated that PFMT produced continence more often than placebo, and a meta-analysis of 6 RCTs found that PFMT improved SUI symptoms.1 PFMT regimens ranged in duration from 8 weeks to 6 months, including unsupervised treatment (8 to 12 repetitions, 3 to 10 times a day) and supervised treatment (as long as an hour, as often as 3 times a week).1

Both unsupervised and supervised PFMT produced similar results. One RCT evaluating QOL measures found that PFMT improved activity and reduced psychological impact (number needed to treat [NNT]=1; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1-2).1

Intravaginal electrical stimulation improves continence and symptoms

A meta-analysis of 7 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation increased continence compared with sham treatment.1 A meta-analysis of 8 RCTs found that intravaginal electrical stimulation also improved SUI symptoms.1 All of the trials used electrical stimulation at frequencies between 4 and 50 Hz for 15 to 20 minutes, 1 to 3 times daily for 4 to 15 weeks.

Percutaneous electrical stimulation improves symptoms

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that percutaneous electrical stimulation improved SUI symptoms compared with no active treatment. Four RCTs found that electrical stimulation improved QOL, although a meta-analysis couldn’t be performed because of clinical heterogeneity.1

Magnetic stimulation produces conflicting results

A meta-analysis of 3 RCTs found that magnetic stimulation at frequencies of 10 to 18.5 Hz given over 1 to 8 weeks didn’t increase continence. A meta-analysis of an additional 3 RCTs concluded that magnetic stimulation improved continence, but the individual studies reported conflicting results and were heterogenous.1

Two RCTs evaluating QOL scores found conflicting results. One study found a mean difference of 3.9 points on the 100-point Incontinence Quality of Life Questionnaire (95% CI, 2.08-5.72; minimal clinically important difference rated 2-5 points).1

Vaginal cones are ineffective and not well-tolerated

Two RCTs found that vaginal cones didn’t improve continence or QOL compared with no treatment. Investigators reported high discontinuation rates and adverse effects with the cones, which weighed 20 to 70 g and were worn for 20 minutes a day for as long as 24 weeks.1

RECOMMENDATIONS

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends PFMT comprising at least 8 contractions 3 times daily for at least 3 months as first-line therapy for women with SUI.2 They don’t recommend electrical stimulation or intravaginal devices for women who can actively contract their pelvic floor muscles. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends PFMT as first-line therapy for women with SUI and states that PFMT is more effective than electrical stimulation or vaginal cones.3

1. Nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in adult women: Diagnosis and comparative effectiveness. Executive summary. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/169/1021/CER36_Urinary-Incontinence_execsumm.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2014.

2. Urinary Incontinence: The management of urinary incontinence in women. NICE Clinical Guideline 171. London: NICE; 2006. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/CG171. Accessed March 19, 2014.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1533-1545.

1. Nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in adult women: Diagnosis and comparative effectiveness. Executive summary. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/169/1021/CER36_Urinary-Incontinence_execsumm.pdf. Accessed March 19, 2014.

2. Urinary Incontinence: The management of urinary incontinence in women. NICE Clinical Guideline 171. London: NICE; 2006. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Web site. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/CG171. Accessed March 19, 2014.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Urinary incontinence in women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1533-1545.

AHIP; stress urinary incontinence; SUI; pelvic floor muscle training; PFMT; intravaginal electrical stimulation

AHIP; stress urinary incontinence; SUI; pelvic floor muscle training; PFMT; intravaginal electrical stimulation

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Is there a primary care tool to detect aberrant drug-related behaviors in patients on opioids?

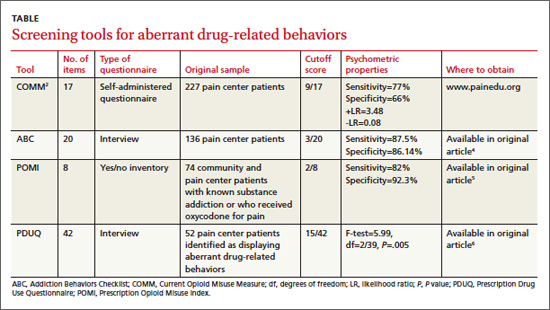

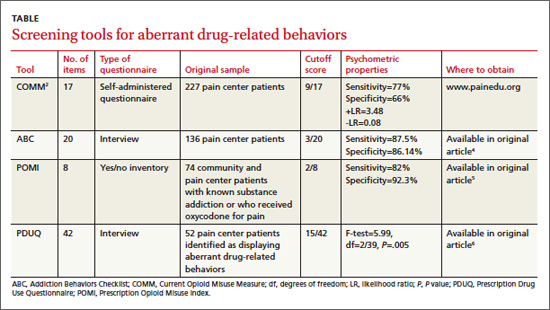

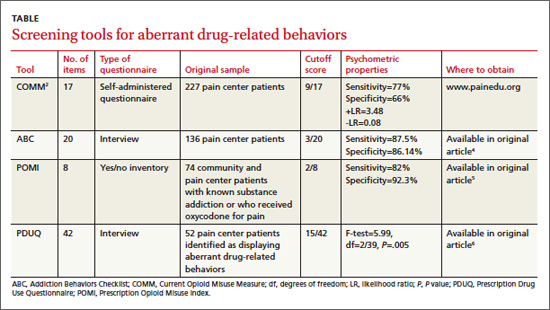

Yes. Of the several screening instruments developed and originally validated in patients in a pain center population (TABLE), one also has been validated in primary care. The Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) predicts aberrant drug-related behaviors in primary care patients who have been prescribed opioids within the past 12 months with a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 77% (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, cohort studies).

Although not validated in primary care populations, 3 other instruments (the Addiction Behaviors Checklist [ABC], Prescription Opioid Misuse Index [POMI], and Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire [PDUQ]) detect aberrant drug-related behaviors in pain center patients with chronic pain with sensitivities of 82% to 87.5% and specificities of 86.14% to 92.3% (SOR: B, cohort studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The COMM—originally designed to detect recent aberrant drug-related behaviors in pain center patients—was validated by a cross-sectional study involving 238 primary care patients who had been prescribed an opioid within the previous 12 months.1

The study authors defined aberrant drug-related behaviors as meeting the criteria for prescription drug use disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV). High COMM scores significantly predicted this diagnosis (P<.001). A COMM cutoff score >13 yielded a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 77% (positive predictive value=0.30; negative predictive value=0.96).

Development of the COMM. The authors of the COMM developed questions by expert consensus for use in a population of patients in a pain center. They established the validity of the questions by correlating COMM results from a cohort of pain center patients with 2 previously validated instruments: The Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale and the Aberrant Drug Behavior Index. They also tested COMM’s validity for monitoring changes in aberrant drug-related behaviors in a second cohort (sensitivity=94%; specificity=73%).2 They later cross-validated COMM with another group of 226 patients treated at pain management clinics, achieving similar results.3

Three additional tools have been validated only among pain clinic patients

The ABC was developed based on literature review and validated against the PDUQ and clinician judgment of opioid misuse. Scores on the ABC differed significantly between patients who were discontinued from opioid therapy (based on urine toxicology, for example) and patients who weren’t (P=.021).4

The authors of the POMI determined sensitivity and specificity by comparing the POMI with DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for opiate addiction. One weakness of this index is that it is based on a small, homogenous sample.5

Items in the PDUQ were based on a literature review and extracts from the charts of patients with chronic pain.6

Additional reviews

Two systematic reviews of screening tools used to predict aberrant behaviors in pain center populations included several studies with methodologic limitations.7,8

RECOMMENDATIONS

A guideline from the American Pain Society based on a systematic review concluded that the most predictive factor for aberrant drug-related behaviors is a personal or family history of drug or alcohol abuse.9,10 In 2009, APS and American Academy of Pain Medicine developed guidelines to assist in selecting, risk-stratifying, and monitoring patients on chronic pain medication.9,10 The American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians recommends evaluation of misuse risk, but considers screening tools an optional measure during initial assessment for opioid prescribing.11

1. Meltzer EC, Rybin D, Saitz R, et al. Identifying prescription opioid use disorder in primary care: diagnostic characteristics of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM). Pain. 2011;152:397-402.

2. Butler SF, Budham SH, Fernandez KC, et al. Development and validation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure. Pain. 2007;130:144-156.

3. Butler SF, Budman SH, Fanciullo GJ, et al. Cross validation of the current opioid misuse measure (COMM) to monitor chronic pain patients on opioid therapy. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:770-776.

4. Wu SM, Compton P, Bolus R, et. al. The addiction behaviors checklist: validation of a new clinician-based measure of inappropriate opioid use in chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:342-351.

5. Knisely JS, Wunsch MJ, Cropsey KL, et al. Prescription Opioid Misuse Index: A brief questionnaire to assess misuse. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35:380-386.

6. Compton P, Darakjian J, Miotto K. Screening for addiction in patients with chronic pain and “problematic” substance use: evaluation of a pilot assessment tool. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;16:355-363.

7. Sehgal N, Manchikanti L, Smith HS. Prescription opioid abuse in chronic pain: a review of opioid abuse predictors and strategies to curb opioid abuse. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3 suppl):ES67-ES92.

8. Solanki DR, Koyyalagunta D, Shah RV, et al. Monitoring opioid adherence in chronic pain patients: assessment of risk of substance misuse. Pain Physician. 2011;14:E119-E131.

9. Chou R. 2009 Clinical guidelines from the American Pain Society and the American Academy of Pain Medicine on the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain: what are the key messages for clinical practice? Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119:469-477.

10. Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10:113-130.

11. Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Alturi S, et al; American Pain Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for responsible opioid prescribing in chronic non-cancer pain: Part 2—guidance. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3 suppl):S67-S116.

Yes. Of the several screening instruments developed and originally validated in patients in a pain center population (TABLE), one also has been validated in primary care. The Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) predicts aberrant drug-related behaviors in primary care patients who have been prescribed opioids within the past 12 months with a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 77% (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, cohort studies).

Although not validated in primary care populations, 3 other instruments (the Addiction Behaviors Checklist [ABC], Prescription Opioid Misuse Index [POMI], and Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire [PDUQ]) detect aberrant drug-related behaviors in pain center patients with chronic pain with sensitivities of 82% to 87.5% and specificities of 86.14% to 92.3% (SOR: B, cohort studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The COMM—originally designed to detect recent aberrant drug-related behaviors in pain center patients—was validated by a cross-sectional study involving 238 primary care patients who had been prescribed an opioid within the previous 12 months.1

The study authors defined aberrant drug-related behaviors as meeting the criteria for prescription drug use disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV). High COMM scores significantly predicted this diagnosis (P<.001). A COMM cutoff score >13 yielded a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 77% (positive predictive value=0.30; negative predictive value=0.96).

Development of the COMM. The authors of the COMM developed questions by expert consensus for use in a population of patients in a pain center. They established the validity of the questions by correlating COMM results from a cohort of pain center patients with 2 previously validated instruments: The Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale and the Aberrant Drug Behavior Index. They also tested COMM’s validity for monitoring changes in aberrant drug-related behaviors in a second cohort (sensitivity=94%; specificity=73%).2 They later cross-validated COMM with another group of 226 patients treated at pain management clinics, achieving similar results.3

Three additional tools have been validated only among pain clinic patients

The ABC was developed based on literature review and validated against the PDUQ and clinician judgment of opioid misuse. Scores on the ABC differed significantly between patients who were discontinued from opioid therapy (based on urine toxicology, for example) and patients who weren’t (P=.021).4

The authors of the POMI determined sensitivity and specificity by comparing the POMI with DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for opiate addiction. One weakness of this index is that it is based on a small, homogenous sample.5

Items in the PDUQ were based on a literature review and extracts from the charts of patients with chronic pain.6

Additional reviews

Two systematic reviews of screening tools used to predict aberrant behaviors in pain center populations included several studies with methodologic limitations.7,8

RECOMMENDATIONS

A guideline from the American Pain Society based on a systematic review concluded that the most predictive factor for aberrant drug-related behaviors is a personal or family history of drug or alcohol abuse.9,10 In 2009, APS and American Academy of Pain Medicine developed guidelines to assist in selecting, risk-stratifying, and monitoring patients on chronic pain medication.9,10 The American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians recommends evaluation of misuse risk, but considers screening tools an optional measure during initial assessment for opioid prescribing.11

Yes. Of the several screening instruments developed and originally validated in patients in a pain center population (TABLE), one also has been validated in primary care. The Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) predicts aberrant drug-related behaviors in primary care patients who have been prescribed opioids within the past 12 months with a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 77% (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, cohort studies).

Although not validated in primary care populations, 3 other instruments (the Addiction Behaviors Checklist [ABC], Prescription Opioid Misuse Index [POMI], and Prescription Drug Use Questionnaire [PDUQ]) detect aberrant drug-related behaviors in pain center patients with chronic pain with sensitivities of 82% to 87.5% and specificities of 86.14% to 92.3% (SOR: B, cohort studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The COMM—originally designed to detect recent aberrant drug-related behaviors in pain center patients—was validated by a cross-sectional study involving 238 primary care patients who had been prescribed an opioid within the previous 12 months.1

The study authors defined aberrant drug-related behaviors as meeting the criteria for prescription drug use disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV). High COMM scores significantly predicted this diagnosis (P<.001). A COMM cutoff score >13 yielded a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 77% (positive predictive value=0.30; negative predictive value=0.96).

Development of the COMM. The authors of the COMM developed questions by expert consensus for use in a population of patients in a pain center. They established the validity of the questions by correlating COMM results from a cohort of pain center patients with 2 previously validated instruments: The Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale and the Aberrant Drug Behavior Index. They also tested COMM’s validity for monitoring changes in aberrant drug-related behaviors in a second cohort (sensitivity=94%; specificity=73%).2 They later cross-validated COMM with another group of 226 patients treated at pain management clinics, achieving similar results.3

Three additional tools have been validated only among pain clinic patients

The ABC was developed based on literature review and validated against the PDUQ and clinician judgment of opioid misuse. Scores on the ABC differed significantly between patients who were discontinued from opioid therapy (based on urine toxicology, for example) and patients who weren’t (P=.021).4

The authors of the POMI determined sensitivity and specificity by comparing the POMI with DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for opiate addiction. One weakness of this index is that it is based on a small, homogenous sample.5

Items in the PDUQ were based on a literature review and extracts from the charts of patients with chronic pain.6

Additional reviews

Two systematic reviews of screening tools used to predict aberrant behaviors in pain center populations included several studies with methodologic limitations.7,8

RECOMMENDATIONS

A guideline from the American Pain Society based on a systematic review concluded that the most predictive factor for aberrant drug-related behaviors is a personal or family history of drug or alcohol abuse.9,10 In 2009, APS and American Academy of Pain Medicine developed guidelines to assist in selecting, risk-stratifying, and monitoring patients on chronic pain medication.9,10 The American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians recommends evaluation of misuse risk, but considers screening tools an optional measure during initial assessment for opioid prescribing.11

1. Meltzer EC, Rybin D, Saitz R, et al. Identifying prescription opioid use disorder in primary care: diagnostic characteristics of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM). Pain. 2011;152:397-402.

2. Butler SF, Budham SH, Fernandez KC, et al. Development and validation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure. Pain. 2007;130:144-156.

3. Butler SF, Budman SH, Fanciullo GJ, et al. Cross validation of the current opioid misuse measure (COMM) to monitor chronic pain patients on opioid therapy. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:770-776.

4. Wu SM, Compton P, Bolus R, et. al. The addiction behaviors checklist: validation of a new clinician-based measure of inappropriate opioid use in chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:342-351.

5. Knisely JS, Wunsch MJ, Cropsey KL, et al. Prescription Opioid Misuse Index: A brief questionnaire to assess misuse. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35:380-386.

6. Compton P, Darakjian J, Miotto K. Screening for addiction in patients with chronic pain and “problematic” substance use: evaluation of a pilot assessment tool. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;16:355-363.

7. Sehgal N, Manchikanti L, Smith HS. Prescription opioid abuse in chronic pain: a review of opioid abuse predictors and strategies to curb opioid abuse. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3 suppl):ES67-ES92.

8. Solanki DR, Koyyalagunta D, Shah RV, et al. Monitoring opioid adherence in chronic pain patients: assessment of risk of substance misuse. Pain Physician. 2011;14:E119-E131.

9. Chou R. 2009 Clinical guidelines from the American Pain Society and the American Academy of Pain Medicine on the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain: what are the key messages for clinical practice? Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119:469-477.

10. Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10:113-130.

11. Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Alturi S, et al; American Pain Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for responsible opioid prescribing in chronic non-cancer pain: Part 2—guidance. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3 suppl):S67-S116.

1. Meltzer EC, Rybin D, Saitz R, et al. Identifying prescription opioid use disorder in primary care: diagnostic characteristics of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM). Pain. 2011;152:397-402.

2. Butler SF, Budham SH, Fernandez KC, et al. Development and validation of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure. Pain. 2007;130:144-156.

3. Butler SF, Budman SH, Fanciullo GJ, et al. Cross validation of the current opioid misuse measure (COMM) to monitor chronic pain patients on opioid therapy. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:770-776.

4. Wu SM, Compton P, Bolus R, et. al. The addiction behaviors checklist: validation of a new clinician-based measure of inappropriate opioid use in chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:342-351.

5. Knisely JS, Wunsch MJ, Cropsey KL, et al. Prescription Opioid Misuse Index: A brief questionnaire to assess misuse. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35:380-386.

6. Compton P, Darakjian J, Miotto K. Screening for addiction in patients with chronic pain and “problematic” substance use: evaluation of a pilot assessment tool. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1998;16:355-363.

7. Sehgal N, Manchikanti L, Smith HS. Prescription opioid abuse in chronic pain: a review of opioid abuse predictors and strategies to curb opioid abuse. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3 suppl):ES67-ES92.

8. Solanki DR, Koyyalagunta D, Shah RV, et al. Monitoring opioid adherence in chronic pain patients: assessment of risk of substance misuse. Pain Physician. 2011;14:E119-E131.

9. Chou R. 2009 Clinical guidelines from the American Pain Society and the American Academy of Pain Medicine on the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain: what are the key messages for clinical practice? Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2009;119:469-477.

10. Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain. 2009;10:113-130.

11. Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Alturi S, et al; American Pain Society-American Academy of Pain Medicine Opioids Guidelines Panel. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for responsible opioid prescribing in chronic non-cancer pain: Part 2—guidance. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3 suppl):S67-S116.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

When you suspect ACS, which serologic marker is best?

Measurement of troponin levels provides the most sensitive and accurate serologic information in evaluating a patient with acute coronary syndrome (ACS); troponin elevations are more sensitive than elevations of creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB). Isolated elevation of troponin levels increases the likelihood of myocardial infarction (MI) or death, whereas isolated elevation of CK-MB levels doesn’t. (Strength of recommendation [SOR] for all statements: A, multiple, large prospective cohort studies.)

Repeated measurement of troponin levels at presentation and then 3 and 6 hours afterward increases the diagnostic sensitivity for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (SOR: A, multiple, small prospective studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Troponin I and T proteins are specific to cardiac myocytes and, unlike CK-MB, aren’t elevated by damage to skeletal muscle.

Measuring troponin levels increased the number of patients diagnosed with AMI

A multinational prospective cohort study of patients with suspected ACS (N=10,719) found that measuring troponin levels in addition to CK-MB levels improved the diagnosis of AMI.1 Investigators used elevation of any biomarker (CK, CK-MB, or troponin I or T) above the upper limit of normal as their diagnostic criterion. They found that measuring troponin increased the number of patients diagnosed with AMI by 10.4% over patients diagnosed using CK and CK-MB levels. Elevated troponin levels were associated with an inpatient mortality rate 1.5 to 3 times higher, regardless of the patient’s CK-MB status.

Troponin levels are more sensitive and specific than CK-MB

A prospective cohort study of 718 patients with suspected AMI calculated the area under curve (AUC) of the receiver operator curve—a measure of diagnostic accuracy in which an AUC value of 1 indicates 100% sensitivity and specificity—for troponin and CK-MB levels at initial presentation.2 Two independent cardiologists reviewed all available medical records and made the final diagnosis. The AUCs for troponin levels ranged from 0.94 to 0.96 compared with 0.88 for CK-MB.

Troponin levels and odds of MI or death

A prospective study of 1852 patients with suspected ACS from 3 trial populations evaluated the prognostic value of increased troponin levels vs CK-MB levels at initial presentation, compared with a reference group with normal troponin and CK-MB levels.3 Patients with isolated troponin elevation had an increased odds of MI or death at 24 hours (odds ratio [OR]=5.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.2-11.9) and 30 days (OR=2.1; 95% CI, 1.4-3.0), whereas patients with isolated CK-MB elevations didn't. At 30 days, patients with isolated CK-MB elevations equaled the reference group odds for MI and death (OR=1.0; 95% CI, 0.6-1.6).

Serial troponin assessment boosts diagnostic sensitivity

A prospective cohort study found that serial measurements of troponin increased the diagnostic sensitivity for AMI.4 Investigators evaluated 1818 consecutive patients with new onset chest pain in 3 German chest-pain units with troponin levels on admission and at 3 and 6 hours later. The gold standard was diagnosis of AMI by 2 independent cardiologists. Troponin measurement produced an AUC of 0.96 at admission, increasing to 0.98 and 0.99 at 3 and 6 hours after admission, respectively.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend measuring biomarkers of cardiac injury in all patients who present with chest discomfort consistent with ACS.5 A cardiac-specific troponin is the preferred marker and should be measured in all patients. If troponin is not available, CK-MB is the best alternative. Cardiac biomarkers should be repeated 6 to 9 hours after presentation and, in patients with a high clinical suspicion of AMI, at 12 to 24 hours.6,7

1. Goodman SG, Steg PG, Eagle KA, et al; GRACE Investigators. The diagnostic and prognostic impact of the redefinition of acute myocardial infarction: lessons from the global registry of acute coronary events (GRACE). Am Heart J. 2006;151:654-660.

2. Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Bassetti S, et al. Early diagnosis of myocardial infarction with sensitive cardiac troponin assays. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:858-867.

3. Rao SV, Ohman EM, Granger CB, et al. Prognostic value of isolated troponin elevation across the spectrum of chest pain syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:936-940.

4. Keller T, Zeller T, Peetz D, et al. Sensitive troponin I assay in early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:868-877.

5. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee, American College of Emergency Physicians, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine). ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:e1-e157.

6. Morrow DA, Cannon CP, Jesse RL, et al; National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory Medicine practice guidelines: clinical characteristics and utilization of biochemical markers in acute coronary syndromes. Clin Chem. 2007;53:552-574.

7. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, et al. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:2634-2653.

Measurement of troponin levels provides the most sensitive and accurate serologic information in evaluating a patient with acute coronary syndrome (ACS); troponin elevations are more sensitive than elevations of creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB). Isolated elevation of troponin levels increases the likelihood of myocardial infarction (MI) or death, whereas isolated elevation of CK-MB levels doesn’t. (Strength of recommendation [SOR] for all statements: A, multiple, large prospective cohort studies.)

Repeated measurement of troponin levels at presentation and then 3 and 6 hours afterward increases the diagnostic sensitivity for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (SOR: A, multiple, small prospective studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Troponin I and T proteins are specific to cardiac myocytes and, unlike CK-MB, aren’t elevated by damage to skeletal muscle.

Measuring troponin levels increased the number of patients diagnosed with AMI

A multinational prospective cohort study of patients with suspected ACS (N=10,719) found that measuring troponin levels in addition to CK-MB levels improved the diagnosis of AMI.1 Investigators used elevation of any biomarker (CK, CK-MB, or troponin I or T) above the upper limit of normal as their diagnostic criterion. They found that measuring troponin increased the number of patients diagnosed with AMI by 10.4% over patients diagnosed using CK and CK-MB levels. Elevated troponin levels were associated with an inpatient mortality rate 1.5 to 3 times higher, regardless of the patient’s CK-MB status.

Troponin levels are more sensitive and specific than CK-MB

A prospective cohort study of 718 patients with suspected AMI calculated the area under curve (AUC) of the receiver operator curve—a measure of diagnostic accuracy in which an AUC value of 1 indicates 100% sensitivity and specificity—for troponin and CK-MB levels at initial presentation.2 Two independent cardiologists reviewed all available medical records and made the final diagnosis. The AUCs for troponin levels ranged from 0.94 to 0.96 compared with 0.88 for CK-MB.

Troponin levels and odds of MI or death

A prospective study of 1852 patients with suspected ACS from 3 trial populations evaluated the prognostic value of increased troponin levels vs CK-MB levels at initial presentation, compared with a reference group with normal troponin and CK-MB levels.3 Patients with isolated troponin elevation had an increased odds of MI or death at 24 hours (odds ratio [OR]=5.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.2-11.9) and 30 days (OR=2.1; 95% CI, 1.4-3.0), whereas patients with isolated CK-MB elevations didn't. At 30 days, patients with isolated CK-MB elevations equaled the reference group odds for MI and death (OR=1.0; 95% CI, 0.6-1.6).

Serial troponin assessment boosts diagnostic sensitivity

A prospective cohort study found that serial measurements of troponin increased the diagnostic sensitivity for AMI.4 Investigators evaluated 1818 consecutive patients with new onset chest pain in 3 German chest-pain units with troponin levels on admission and at 3 and 6 hours later. The gold standard was diagnosis of AMI by 2 independent cardiologists. Troponin measurement produced an AUC of 0.96 at admission, increasing to 0.98 and 0.99 at 3 and 6 hours after admission, respectively.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend measuring biomarkers of cardiac injury in all patients who present with chest discomfort consistent with ACS.5 A cardiac-specific troponin is the preferred marker and should be measured in all patients. If troponin is not available, CK-MB is the best alternative. Cardiac biomarkers should be repeated 6 to 9 hours after presentation and, in patients with a high clinical suspicion of AMI, at 12 to 24 hours.6,7

Measurement of troponin levels provides the most sensitive and accurate serologic information in evaluating a patient with acute coronary syndrome (ACS); troponin elevations are more sensitive than elevations of creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB). Isolated elevation of troponin levels increases the likelihood of myocardial infarction (MI) or death, whereas isolated elevation of CK-MB levels doesn’t. (Strength of recommendation [SOR] for all statements: A, multiple, large prospective cohort studies.)

Repeated measurement of troponin levels at presentation and then 3 and 6 hours afterward increases the diagnostic sensitivity for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (SOR: A, multiple, small prospective studies).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Troponin I and T proteins are specific to cardiac myocytes and, unlike CK-MB, aren’t elevated by damage to skeletal muscle.

Measuring troponin levels increased the number of patients diagnosed with AMI

A multinational prospective cohort study of patients with suspected ACS (N=10,719) found that measuring troponin levels in addition to CK-MB levels improved the diagnosis of AMI.1 Investigators used elevation of any biomarker (CK, CK-MB, or troponin I or T) above the upper limit of normal as their diagnostic criterion. They found that measuring troponin increased the number of patients diagnosed with AMI by 10.4% over patients diagnosed using CK and CK-MB levels. Elevated troponin levels were associated with an inpatient mortality rate 1.5 to 3 times higher, regardless of the patient’s CK-MB status.

Troponin levels are more sensitive and specific than CK-MB

A prospective cohort study of 718 patients with suspected AMI calculated the area under curve (AUC) of the receiver operator curve—a measure of diagnostic accuracy in which an AUC value of 1 indicates 100% sensitivity and specificity—for troponin and CK-MB levels at initial presentation.2 Two independent cardiologists reviewed all available medical records and made the final diagnosis. The AUCs for troponin levels ranged from 0.94 to 0.96 compared with 0.88 for CK-MB.

Troponin levels and odds of MI or death

A prospective study of 1852 patients with suspected ACS from 3 trial populations evaluated the prognostic value of increased troponin levels vs CK-MB levels at initial presentation, compared with a reference group with normal troponin and CK-MB levels.3 Patients with isolated troponin elevation had an increased odds of MI or death at 24 hours (odds ratio [OR]=5.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.2-11.9) and 30 days (OR=2.1; 95% CI, 1.4-3.0), whereas patients with isolated CK-MB elevations didn't. At 30 days, patients with isolated CK-MB elevations equaled the reference group odds for MI and death (OR=1.0; 95% CI, 0.6-1.6).

Serial troponin assessment boosts diagnostic sensitivity

A prospective cohort study found that serial measurements of troponin increased the diagnostic sensitivity for AMI.4 Investigators evaluated 1818 consecutive patients with new onset chest pain in 3 German chest-pain units with troponin levels on admission and at 3 and 6 hours later. The gold standard was diagnosis of AMI by 2 independent cardiologists. Troponin measurement produced an AUC of 0.96 at admission, increasing to 0.98 and 0.99 at 3 and 6 hours after admission, respectively.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend measuring biomarkers of cardiac injury in all patients who present with chest discomfort consistent with ACS.5 A cardiac-specific troponin is the preferred marker and should be measured in all patients. If troponin is not available, CK-MB is the best alternative. Cardiac biomarkers should be repeated 6 to 9 hours after presentation and, in patients with a high clinical suspicion of AMI, at 12 to 24 hours.6,7

1. Goodman SG, Steg PG, Eagle KA, et al; GRACE Investigators. The diagnostic and prognostic impact of the redefinition of acute myocardial infarction: lessons from the global registry of acute coronary events (GRACE). Am Heart J. 2006;151:654-660.

2. Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Bassetti S, et al. Early diagnosis of myocardial infarction with sensitive cardiac troponin assays. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:858-867.

3. Rao SV, Ohman EM, Granger CB, et al. Prognostic value of isolated troponin elevation across the spectrum of chest pain syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:936-940.

4. Keller T, Zeller T, Peetz D, et al. Sensitive troponin I assay in early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:868-877.

5. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee, American College of Emergency Physicians, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine). ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:e1-e157.

6. Morrow DA, Cannon CP, Jesse RL, et al; National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory Medicine practice guidelines: clinical characteristics and utilization of biochemical markers in acute coronary syndromes. Clin Chem. 2007;53:552-574.

7. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, et al. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:2634-2653.

1. Goodman SG, Steg PG, Eagle KA, et al; GRACE Investigators. The diagnostic and prognostic impact of the redefinition of acute myocardial infarction: lessons from the global registry of acute coronary events (GRACE). Am Heart J. 2006;151:654-660.

2. Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Bassetti S, et al. Early diagnosis of myocardial infarction with sensitive cardiac troponin assays. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:858-867.

3. Rao SV, Ohman EM, Granger CB, et al. Prognostic value of isolated troponin elevation across the spectrum of chest pain syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:936-940.

4. Keller T, Zeller T, Peetz D, et al. Sensitive troponin I assay in early diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:868-877.

5. Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, et al. American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee, American College of Emergency Physicians, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation, Society for Academic Emergency Medicine). ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:e1-e157.

6. Morrow DA, Cannon CP, Jesse RL, et al; National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry. National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry Laboratory Medicine practice guidelines: clinical characteristics and utilization of biochemical markers in acute coronary syndromes. Clin Chem. 2007;53:552-574.

7. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, White HD, et al. Universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2007;116:2634-2653.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Which drugs are most effective for recurrent herpes labialis?

Daily oral acyclovir or valacyclovir may help prevent herpes simplex labialis (HSL) recurrences (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with heterogeneous results).

No trials compare oral or topical treatments for HSL outbreaks against each other. Oral antivirals modestly reduce healing time and duration of pain, varying according to the agent used: valacyclovir reduces both healing time and duration of pain, famciclovir reduces both in one dosage form but not another, and acyclovir reduces only pain duration (SOR: B, single RCTs).

Several topical medications (acyclovir, penciclovir, docosanol) modestly decrease healing time and pain duration—typically by less than a day—and require multiple doses per day (SOR: B, multiple RCTs).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of oral and topical nucleoside antiviral agents to prevent recurrent HSL in immunocompetent people found 11 RCTs with a total of 1250 patients that compared an active drug against placebo.1 The medications were topical 5% acyclovir, topical 1% penciclovir, and oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir in various doses. The primary outcome was recurrence of herpes simplex virus type 1 lesions during the treatment period. The relative risk (RR) of recurrence ranged from 0.22 to 1.22. Pooled results found a benefit favoring antiviral agents (RR of recurrence=0.70; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.55-0.89).

Seven of the trials looked at acyclovir (5 oral, 2 topical). A subgroup analysis demonstrated that oral acyclovir (800-1000 mg/d) was more effective than placebo (RR=0.51; 95% CI, 0.29-0.88), whereas topical acyclovir wasn’t. Oral valacyclovir (2 studies; 500 mg/d for 4 months) also reduced recurrence (RR=0.65; 95% CI, 0.43-0.91). The authors of the meta-analysis noted that although 9 studies favored the use of an antiviral drug, only 4 showed statistically significant differences when compared with placebo, and none of them had a low risk of bias. They concluded that the review supported using oral acyclovir and valacyclovir to prevent recurrent HSL.1

Oral antivirals produce variable treatment results

Three RCTs evaluated oral antiviral medications against placebo to treat recurrent HSL, with mixed results. The largest RCT found that valacyclovir (2000 mg twice in 24 hours, with or without an additional 1000 mg twice in another 24 hours) modestly but significantly reduced both healing time and duration of pain (by 0.5-0.8 day).2 The second RCT showed that a higher, single dose of famciclovir (1500 mg) reduced healing time (by 1.8 days) and pain duration (by 1.2 days) and that a smaller, repeated dose (750 mg twice in 24 hours) reduced healing time alone (by 2.2 days).3

The third RCT demonstrated that acyclovir (400 mg 5 times a day for 5 days) reduced pain duration (by 0.9 day) but didn’t shorten healing time. If acyclovir was started during the prodrome, it decreased the time to disappearance of the lesion’s hard crust (2.1 days’ less time; P=.03), but the clinical significance of this finding is unclear.4

Topical treatment shows modest success

Two trials demonstrated that topical acyclovir (5% cream) modestly improved healing time and duration of pain (by as much as half a day). Patients in the first trial (paired RCTs reported together) began treatment within an hour of prodromal symptoms or signs, applying the medication 5 times daily for 4 days.5

Patients in the second trial used ME-609 cream (5% acyclovir plus 1% hydrocortisone), 5% acyclovir cream, or placebo, all applied 5 times daily for 5 days.6 Although the cream with acyclovir and hydrocortisone showed a slight benefit compared with placebo (lessening healing time by 0.8 day and pain duration by 1 day), it didn’t improve healing more than acyclovir alone. Other topical agents (penciclovir 1%; docosanol 10%) produced results similar to topical acyclovir.7,8

RECOMMENDATIONS

No national guidelines on this topic exist. An online resource notes that most patients don’t require treatment for mild self-limited HSL.9 For patients with prodromal symptoms, the authors recommend episodic oral antiviral therapy. Patients who have no prodome but multiple painful or disfiguring lesions may choose to use chronic suppressive therapy with an oral antiviral drug.

1. Rahimi H, Mara T, Costella J, et al. Effectiveness of antiviral agents for the prevention of recurrent herpes labialis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2012;113:618-627.

2. Spruance SL, Jones TM, Blatter MM, et al. High-dose, short-duration, early valacyclovir therapy for episodic treatment of cold sores: results of two randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1072-1080.

3. Spruance SL, Bodsworth N, Resnick H, et al. Single-dose, patient-initiated famciclovir: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial for episodic treatment of herpes labialis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:47-53.

4. Spruance SL, Stewart JC, Rowe NH, et al. Treatment of recurrent herpes simplex labialis with oral acyclovir. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:185-190.

5. Spruance SL, Nett R, Marbury T, et al. Acyclovir cream for treatment of herpes simplex labialis: results of two randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, multicenter clinical trials. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:2238-2243.

6. Hull CM, Harmenberg J, Arlander E, et al; ME-609 Studt Group. Early treatment of cold sores with topical ME-609 decreases the frequency of ulcerative lesions: a randomized, doubleblind, placebo-controlled, patient-initiated clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:696.e1-696.e11.

7. Raborn GW, Martel AY, Lassonde M, et al; Worldwide Topical Penciclovir Collaborative Study Group. Effective treatment of herpes simplex labialis with penciclovir cream: combined results of two trials. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:303-309.

8. Sacks SL, Thisted RA, Jones TM, et al; Docosanol 10% Cream Study Group. Clinical efficacy of topical docosanol 10% cream for herpes simplex labialis: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:222-230.

9. Klein RS. Treatment of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection in immunocompetent patients. Waltham, MA: UpToDate; 2012. Available at: www.uptodate.com/contents/treatment-of-herpessimplex-virus-type-1-infection-in-immunocompetentpatients. Accessed January 19, 2012.

Daily oral acyclovir or valacyclovir may help prevent herpes simplex labialis (HSL) recurrences (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with heterogeneous results).

No trials compare oral or topical treatments for HSL outbreaks against each other. Oral antivirals modestly reduce healing time and duration of pain, varying according to the agent used: valacyclovir reduces both healing time and duration of pain, famciclovir reduces both in one dosage form but not another, and acyclovir reduces only pain duration (SOR: B, single RCTs).

Several topical medications (acyclovir, penciclovir, docosanol) modestly decrease healing time and pain duration—typically by less than a day—and require multiple doses per day (SOR: B, multiple RCTs).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY