User login

Challenges of Spine Surgery in Obese Patients

Occupational Hazards Facing Orthopedic Surgeons

UPDATE ON CERVICAL DISEASE

Read Dr. Cox’s recommendations onhow to counsel women about their HPV test results in the 2011 Update on Cervical Disease.

Dr. Cox is a consultant to Gen-Probe, OncoHealth, and Roche, and serves on the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMB) for Merck HPV vaccine trials. He is a speaker for Bradley Pharmaceuticals.

The American Cancer Society estimates that approximately 12,700 new cases of invasive cervical cancer were diagnosed in 2011 in the United States; nearly 4,300 of those women will die of the disease, the Society projects.1 Great disparities in prevalence and incidence persist, with the rate of cervical cancer 1) highest in Latino women and 2) about 50% higher in African-American women than in non-Latino white women.

Because approximately 60% of cervical cancers occur in women who don’t undergo any screening for the disease, or who undergo only very infrequent screening, bringing more women in to be screened is most important. For women who are screened very infrequently, providing testing with the longest interval that provides safety should also reduce their risk of cancer.

Two advances have the potential to provide huge benefit in reducing the risk of cervical cancer: 1) increasing utilization of human papillomavirus (HPV) testing with Pap testing (so-called co-testing) for screening women 30 years and older and 2) widespread administration of the HPV vaccine to girls before they begin sexual activity. Regrettably, the promise of the HPV vaccine has not yet been fulfilled: Vaccine uptake (all three doses) among the primary target population hasn’t even reached 40%. And co-testing continues to be underutilized—in part because the best management strategy for women who have a negative Pap test result but a positive HPV test result (written here as “Pap–/HPV+”) has been less than clear.

Disappointments aside, 2011 did bring us a wealth of data on 1) the likely value of co-testing in preventing cervical cancer, and 2) improved management strategies for Pap–/HPV+ women—the areas of practice that I’ve made the focus of this year’s Update. The first question to ask: Does co-testing reduce the risk of cervical cancer more than current screening strategies that employ the Pap test?

Primary cytology (Pap test) screening (above) augmented by HPV testing—so-called co-testing—appears to cut the long-term risk of cervical Ca. Consider making a co-testing stratagem part of your practice, urges author Dr. J. Thomas Cox.

Will co-testing reduce the rate of cervical Ca to a greater degree than Pap screening has?

Kinney W, Fetterman B, Cox JT, Lorey T, Flanagan T, Castle PE. Characteristics of 44 cervical cancers diagnosed following Pap-negative, high risk HPV-positive screening in routine clinical practice. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(2):309–313.

Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(1):78–88.

Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(7):663–672.

Recent studies have brought us closer to answering this question—and data certainly appear to suggest that the answer is “Yes.” Evidence from randomized controlled trials, prospective long-term cohort trials, and a large US screening population show that introducing HPV testing into cervical cancer screening could reduce cervical cancer incidence in women age ≥30—and even cervical cancer mortality.

I discussed one of these trials—the Italian NTCC trial—in the 2011 OBG Management Update on Cervical Disease [read that article in the archive at www.obgmanagement.com]; earlier detection and treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade-3 (CIN 3) lesions in the first screening round in the co-tested group were proposed as the reasons that no cancers were detected in the second screening round (nine cancers were detected in the women having cytology only).2

Similar results were reported in the POBASCAM study from the Netherlands, in which more than 44,000 women were randomized to co-testing or screening with cytology alone, then re-screened 5 years later. As in the NTCC trial, more cases of CIN 3+ were detected and treated at the initial screen by co-testing than by cytology alone (i.e., projected out to 79 additional cases of CIN 3 and 30 additional cancers for every 100,000 women screened), with fewer cases of CIN 3+ detected in the co-tested group in the subsequent 5 years than in the cytology-only group (again, projected out to 24 fewer cases of CIN 3 and 10 fewer cancers for every 100,000 women).

(In a review of these study findings, experts at the National Cancer Institute [NCI] estimated that co-testing in POBASCAM reduced the risk of cervical cancer to only 2.2 cancers for every 100,000 women a year—demonstrating the safety of a 5-year screening interval.3) This means that women testing Pap–/HPV–, who are best screened at 3-year intervals, would be safe with an interval as long as 5 years—providing greater protection for irregularly screened women.

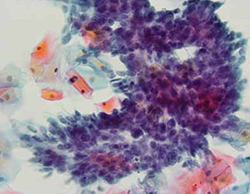

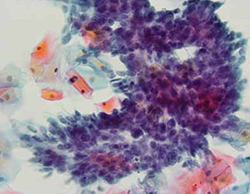

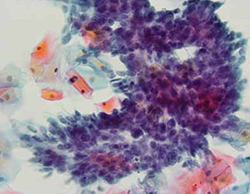

FIGURE 1 Cervical adenocarcinoma in situ

Cervical AIS demonstrated in a cytology specimen. Most studies have shown that cytology is less sensitive than HPV testing for a glandular lesion.

Photo: Courtesy of Dennis O’Conner, MD.

Similar results were described by Katki and coworkers in a large HMO screening population in the United States, in which Pap–/HPV+ women had half the risk of cancer over the subsequent 5 years, compared with women who were negative by Pap testing only (3.2 cases for every 100,000 women, compared with 7.5 cases, respectively). Of the total cases of CIN 3+ found, 35% of cases of CIN 3 and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) (FIGURE 1) were detected in women Pap-/HPV+, as were 29% of cancers. Cytology has been shown, in almost all studies, to be less sensitive for glandular lesions; it isn’t surprising, therefore, that 63% of adenocarcinomas found in this study population were detected by HPV testing only.

These results appear to provide overwhelming evidence of the benefit of including HPV testing in screening programs for cervical cancer.3

Adding HPV testing to primary screening with Pap testing (co-testing) appears to reduce the long-term risk of cervical Ca. Consider making this stratagem part of your practice.

Dilemma: How do we best manage women who are Pap–/HPV+?

Kinney W, Fetterman B, Cox JT, Lorey T, Flanagan T, Castle PE. Characteristics of 44 cervical cancers diagnosed following Pap-negative, high risk HPV-positive screening in routine clinical practice. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(2):309–313.

Although co-testing appears to reduce the risk of cervical cancer—allowing a safer margin for Pap-negative plus HPV-negative (Pap–/HPV–) women if they miss by up to 2 years their 3-year recommended screening—the question remains: What is the best way to manage Pap–/HPV+ women?

The primary recommendation by both the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) and ACOG is to re-screen them in 12 months, rather than send them immediately for colposcopy. Why? Because HPV infection 1) is relatively common among women who do not have CIN 2, 3 or invasive cervical cancer and 2) most often resolves without causing significant disease.

But re-screening these patients in 12 months negates much of the benefit of the high clinical sensitivity of HPV testing because it could lead to significant delay in the diagnosis and treatment of some women who already have either cervical cancer or advanced CIN 3 that might progress to cancer before their next evaluation. This concern is supported by the findings of the studies I discussed earlier.1-3

Although cervical cancer missed at cytology screening is uncommon, 44 cervical cancers were reported by Kinney and coworkers in a large screening population in women who had one or more Pap–/HPV+ co-test results (18 had two or more Pap–/HPV+ results before diagnosis). More than 60% had cervical adenocarcinoma, which is more than three times the normal proportion of glandular cancer to squamous cervical cancer—again highlighting the relative insensitivity of cytology to detect glandular lesions.

Other drawbacks of waiting 12 months for further evaluation include 1) prolonged uncertainty for the patient and 2) the potential for losing her to follow-up, which occurs in as many as 50% of subjects in many studies.

Therefore, finding patients who are at greatest risk of CIN 2+ among the larger group of Pap–/HPV+ women, and referring them immediately for colposcopy, should provide great benefit.

Note that the 2006 ASCCP guidelines included a statement that, once an FDA-approved test for HPV 16, 18 was available, triage of Pap–/HPV+ patients who are positive for HPV 16, 18 could identify a majority at greatest risk of CIN 2,3+ and who would therefore benefit most by referral for colposcopy. In contrast, patients at lower risk (i.e., positive for any of the other 12 HPV types but not for types 16 and 18) would be better managed by repeating co-testing in 12 months—referring for colposcopy only those who are found again to be HPV+ or who have an abnormal Pap test.

In the next section of this Update, I explore recent evidence about the important role played by HPV 16, 18 in cervical carcinogenesis.

ASCCP guidelines provide the option of testing Pap–/HPV+ women for HPV 16, 18 and referring women positive for either of these types to colposcopy.

HPV 16, 18 pose long-term risk for CIN 3+ and cervical Ca

Kjaer SK, Frederiksen K, Munk C, Iftner T. Long-term absolute risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse following human papillomavirus infection: role of persistence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(19):1478–1488.

The most compelling prediction of the risk of CIN 3+ in cases of either single (incident) or persistent high-risk HPV detection comes from a 13-year follow-up study out of Denmark. More than 8,600 Danish women, 20 to 29 years old at enrollment, were tested twice, 2 years apart, for HPV by the Hybrid Capture 2 High-Risk (HC2 HR) HPV DNA Test (Qiagen) and by line-blot assays for type-specific HPV.

Subjects were followed subsequently with routine screening; data on their overall long-term risk of CIN 3+ was obtained from the national Danish Pathology Data Bank. Among those who tested positive for HPV 16, absolute risk of CIN 3+ within 12 years of incident detection was 26.7%; for HPV 18, it was 19.1%—both percentages markedly higher than the 6% risk for women who tested positive for a panel of 10 other high-risk HPV types (also not including HPV 31, 33).

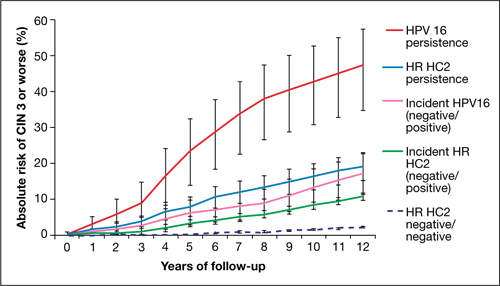

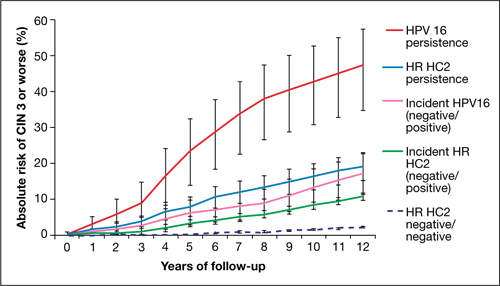

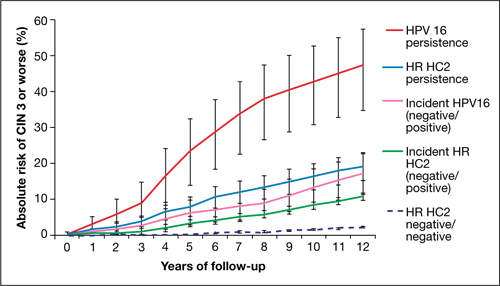

FIGURE 2 Over time, risk of CIN 3+ rises in all subpopulations infected by high-risk HPV

Shown is the absolute risk for CIN 3+ during follow-up among women who have HPV 16 persistence (red line), Hybrid Capture 2 High-Risk HPV DNA Test (HC2 HR) persistence for a panel of 13 high-risk HPV types (blue), incident or newly detected HPV 16 infection (i.e., HPV 16-negative at first examination and HPV 16-positive at second examination) (pink), and women with an incident high-risk HPV infection (i.e., negative for high-risk HPV by HC2 HR at first examination and positive at second examination) (green). For comparison, the dashed purple line shows the nearly flat absolute risk of CIN 3+ for women who are negative for high-risk HPV by HC2 HR at both examinations.

Source: Kjaer et al, 2010. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Oxford University Press.

Risk associated with HPV 16. The most successfully persistent viral type was 16; just under 30% of subjects who were HPV 16+ on the first test remained HPV 16+ on the second test 2 years later. For this 30% subset, the risk of CIN 3+ was 8.9% at 3 years; 23.8% at 5 years; and an astonishing 47.4% at 12 years (FIGURE 2). In other words, almost half of subjects who had persistent HPV 16 in their 20s developed CIN 3 or cancer within 12 years. In contrast, the absolute risk for developing CIN 3+ within 12 years of a single negative HPV test was only 3%.

HPV 18. Viral type 18 was nearly as likely to persist as HPV 16; when persistent, it resulted in CIN 3+ in just under 30% of subjects within 12 years and tended to result in CIN 3+ that was detected later.

The long-term risk of CIN 3+ and cervical cancer that comes with testing positive for HPV 16 or 18 is very high—particularly when either of these viral types are detected twice over a 2-year period. Even one-time detection of either of these types in the context of a Pap–/HPV+ co-test result is important enough to refer to colposcopy.

Using HPV 16, 18 testing to improve the management of Pap–/HPV+ women

Two more HPV tests are now FDA-approved for clinical use

In the 2006 Update on Cervical Disease [available in the archive at www.obgmanagement.com], I noted the importance of HPV 16, 18 in cervical carcinogenesis and observed that a test for these two viral types was on the horizon. It wasn’t until 2009 approval of the Cervista HPV DNA HR Test (Hologic), however, that such a test became available.

In 2011, two more tests were approved:

- cobas 4800 HPV DNA

- Aptima mRNA HPV.

Like Cervista, the cobas 4800 (Roche) is FDA-approved to detect HPV DNA types 16 and 18 individually; Gen-Probe’s Aptima HPV test is the first HPV E6,E7 mRNA test approved in the US; the company plans to add an HPV 16, 18 mRNA test. The addition of one, perhaps two, new HPV 16, 18 genotyping tests expands the opportunity for you to improve the management of Pap–/HPV+ patients.

Let’s look at new data that support testing of Pap–/HPV+ women for HPV 16, 18.

Wright TC Jr, Stoler MH, Sharma A, Zhang G, Behrens C, Wright TL; ATHENA (Addressing THE Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics) Study Group. Evaluation of HPV-16 and HPV-18 genotyping for the triage of women with high-risk HPV+ cytology-negative results. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136(4):578–586.

Castle PE, Stoler MH, Wright TC Jr, Sharma A, Wright TL, Behrens CM. Performance of carcinogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and HPV16 or HPV18 genotyping for cervical cancer screening of women aged 25 years and older: a subanalysis of the ATHENA study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(9):880–890.

Data to support the application to the FDA for approval of the cobas 4800 was provided by the ATHENA Trial, the largest (47,208 women) cervical screening trial of US women to assess the performance of HPV DNA testing with individual genotyping for HPV 16, 18, compared with the Pap.

Wright and co-workers. These investigators evaluated the subset of 32,260 women 30 years and older who had negative cytology. The overall prevalence of Pap–/HPV+ was 6.7%. Just over one quarter of the Pap–/HPV+ women (1.5% of the subset population) were positive for HPV 16 or 18, or both.

As has been shown in other studies, the overall prevalence of HPV declined with age, as did the prevalence of HPV 16, 18. The estimated absolute risk of CIN 3+ at colposcopy for women who were Pap–/HPV+ was only 4.1%, but their relative risk—that is, compared with women in whom both tests were negative—was 14.4%. The absolute risk for CIN 3+ increased to 9.8% for Pap-negative women who tested positive for HPV 16 or 18, or both, and to 11.7% in women who tested positive for HPV 16 only.

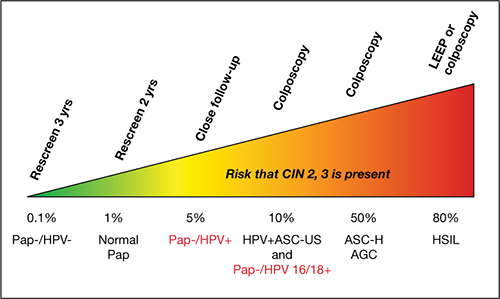

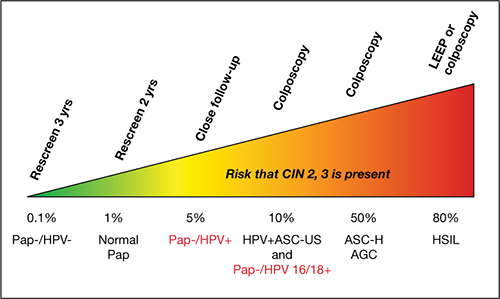

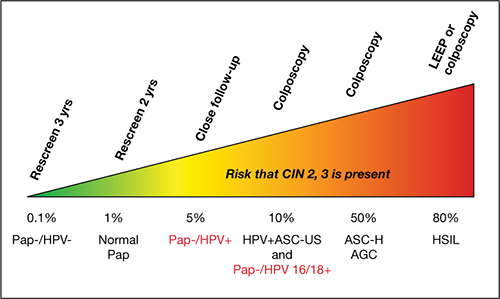

Ongoing work by Castle and colleagues. In a seminal 2007 article on risk management, Castle and colleagues proposed that women who had an absolute risk of CIN 3+ of ≥10% across 2–3 years of follow-up should have colposcopy.4 These data, therefore, clearly support the recommendation of ASCCP that Pap–/HPV 16+ and (or) HPV 18+ women should be referred for colposcopy (FIGURE 3).

FIGURE 3 Managing risk of CIN 3+ across 2 years of follow-up

This stratagem is based on 2006 ASCCP Consensus Guidelines, 2010 ACOG guidelines, and Castle and colleagues’ proposal in their 2007 article, “Risk assessment to guide the prevention of cervical cancer.”4

Figure courtesy of Thomas C. Wright, MD.

Now, in another review of the ATHENA results, expanded to a subset of women 25 years and older, Castle and co-workers reported that triage of Pap–/HPV+ women by testing for HPV 16, 18 detected 72% of all CIN 3+ that was missed by cytology alone. Because only 18% of Pap–/HPV+ women were positive for HPV 16, 18, the majority (i.e., 82% who were ≥25 years and 78% who were ≥30 years) could be reassured that their risk was sufficiently low that it could be best managed by repeating co-testing in 1 year. This avoids delaying the diagnosis of nearly three quarters of the Pap–/HPV+ women who have CIN 3+, without overburdening colposcopy services.

The ATHENA trial is ongoing; eventually, results from 3 years of follow-up of these women will be evaluated. The findings should add important information about the total burden of cervical precancer detected over a longer period after a Pap–/HPV+ result, with or without testing positive for HPV 16, 18.

Among your patients who are Pap–/HPV+, testing for HPV 16, 18 allows you to identify most of those who are at highest risk of CIN 3+ (i.e., HPV 16+ or HPV 18+, or both)—and who will, therefore, be most likely to benefit from immediate colposcopy.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. American Cancer Society. Cervical cancer. What are the key statistics about cervical cancer? http://www.cancer.org/Cancer/CervicalCancer/DetailedGuide/cervical-cancer-key-statistics. Revised October 26 2011. Accessed February 15, 2012.

2. Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al; New Technologies for Cervical Cancer Screening (NTCC) Working Group. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(3):249-257.

3. Katki HA, Wentzensen N. How might HPV testing be integrated into cervical screening? Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(1):8-10.

4. Castle PE, Sideri M, Jeronimo J, Solomon D, Schiffman M. Risk assessment to guide the prevention of cervical cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(4):356.e1-6.

Read Dr. Cox’s recommendations onhow to counsel women about their HPV test results in the 2011 Update on Cervical Disease.

Dr. Cox is a consultant to Gen-Probe, OncoHealth, and Roche, and serves on the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMB) for Merck HPV vaccine trials. He is a speaker for Bradley Pharmaceuticals.

The American Cancer Society estimates that approximately 12,700 new cases of invasive cervical cancer were diagnosed in 2011 in the United States; nearly 4,300 of those women will die of the disease, the Society projects.1 Great disparities in prevalence and incidence persist, with the rate of cervical cancer 1) highest in Latino women and 2) about 50% higher in African-American women than in non-Latino white women.

Because approximately 60% of cervical cancers occur in women who don’t undergo any screening for the disease, or who undergo only very infrequent screening, bringing more women in to be screened is most important. For women who are screened very infrequently, providing testing with the longest interval that provides safety should also reduce their risk of cancer.

Two advances have the potential to provide huge benefit in reducing the risk of cervical cancer: 1) increasing utilization of human papillomavirus (HPV) testing with Pap testing (so-called co-testing) for screening women 30 years and older and 2) widespread administration of the HPV vaccine to girls before they begin sexual activity. Regrettably, the promise of the HPV vaccine has not yet been fulfilled: Vaccine uptake (all three doses) among the primary target population hasn’t even reached 40%. And co-testing continues to be underutilized—in part because the best management strategy for women who have a negative Pap test result but a positive HPV test result (written here as “Pap–/HPV+”) has been less than clear.

Disappointments aside, 2011 did bring us a wealth of data on 1) the likely value of co-testing in preventing cervical cancer, and 2) improved management strategies for Pap–/HPV+ women—the areas of practice that I’ve made the focus of this year’s Update. The first question to ask: Does co-testing reduce the risk of cervical cancer more than current screening strategies that employ the Pap test?

Primary cytology (Pap test) screening (above) augmented by HPV testing—so-called co-testing—appears to cut the long-term risk of cervical Ca. Consider making a co-testing stratagem part of your practice, urges author Dr. J. Thomas Cox.

Will co-testing reduce the rate of cervical Ca to a greater degree than Pap screening has?

Kinney W, Fetterman B, Cox JT, Lorey T, Flanagan T, Castle PE. Characteristics of 44 cervical cancers diagnosed following Pap-negative, high risk HPV-positive screening in routine clinical practice. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(2):309–313.

Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(1):78–88.

Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(7):663–672.

Recent studies have brought us closer to answering this question—and data certainly appear to suggest that the answer is “Yes.” Evidence from randomized controlled trials, prospective long-term cohort trials, and a large US screening population show that introducing HPV testing into cervical cancer screening could reduce cervical cancer incidence in women age ≥30—and even cervical cancer mortality.

I discussed one of these trials—the Italian NTCC trial—in the 2011 OBG Management Update on Cervical Disease [read that article in the archive at www.obgmanagement.com]; earlier detection and treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade-3 (CIN 3) lesions in the first screening round in the co-tested group were proposed as the reasons that no cancers were detected in the second screening round (nine cancers were detected in the women having cytology only).2

Similar results were reported in the POBASCAM study from the Netherlands, in which more than 44,000 women were randomized to co-testing or screening with cytology alone, then re-screened 5 years later. As in the NTCC trial, more cases of CIN 3+ were detected and treated at the initial screen by co-testing than by cytology alone (i.e., projected out to 79 additional cases of CIN 3 and 30 additional cancers for every 100,000 women screened), with fewer cases of CIN 3+ detected in the co-tested group in the subsequent 5 years than in the cytology-only group (again, projected out to 24 fewer cases of CIN 3 and 10 fewer cancers for every 100,000 women).

(In a review of these study findings, experts at the National Cancer Institute [NCI] estimated that co-testing in POBASCAM reduced the risk of cervical cancer to only 2.2 cancers for every 100,000 women a year—demonstrating the safety of a 5-year screening interval.3) This means that women testing Pap–/HPV–, who are best screened at 3-year intervals, would be safe with an interval as long as 5 years—providing greater protection for irregularly screened women.

FIGURE 1 Cervical adenocarcinoma in situ

Cervical AIS demonstrated in a cytology specimen. Most studies have shown that cytology is less sensitive than HPV testing for a glandular lesion.

Photo: Courtesy of Dennis O’Conner, MD.

Similar results were described by Katki and coworkers in a large HMO screening population in the United States, in which Pap–/HPV+ women had half the risk of cancer over the subsequent 5 years, compared with women who were negative by Pap testing only (3.2 cases for every 100,000 women, compared with 7.5 cases, respectively). Of the total cases of CIN 3+ found, 35% of cases of CIN 3 and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) (FIGURE 1) were detected in women Pap-/HPV+, as were 29% of cancers. Cytology has been shown, in almost all studies, to be less sensitive for glandular lesions; it isn’t surprising, therefore, that 63% of adenocarcinomas found in this study population were detected by HPV testing only.

These results appear to provide overwhelming evidence of the benefit of including HPV testing in screening programs for cervical cancer.3

Adding HPV testing to primary screening with Pap testing (co-testing) appears to reduce the long-term risk of cervical Ca. Consider making this stratagem part of your practice.

Dilemma: How do we best manage women who are Pap–/HPV+?

Kinney W, Fetterman B, Cox JT, Lorey T, Flanagan T, Castle PE. Characteristics of 44 cervical cancers diagnosed following Pap-negative, high risk HPV-positive screening in routine clinical practice. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(2):309–313.

Although co-testing appears to reduce the risk of cervical cancer—allowing a safer margin for Pap-negative plus HPV-negative (Pap–/HPV–) women if they miss by up to 2 years their 3-year recommended screening—the question remains: What is the best way to manage Pap–/HPV+ women?

The primary recommendation by both the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) and ACOG is to re-screen them in 12 months, rather than send them immediately for colposcopy. Why? Because HPV infection 1) is relatively common among women who do not have CIN 2, 3 or invasive cervical cancer and 2) most often resolves without causing significant disease.

But re-screening these patients in 12 months negates much of the benefit of the high clinical sensitivity of HPV testing because it could lead to significant delay in the diagnosis and treatment of some women who already have either cervical cancer or advanced CIN 3 that might progress to cancer before their next evaluation. This concern is supported by the findings of the studies I discussed earlier.1-3

Although cervical cancer missed at cytology screening is uncommon, 44 cervical cancers were reported by Kinney and coworkers in a large screening population in women who had one or more Pap–/HPV+ co-test results (18 had two or more Pap–/HPV+ results before diagnosis). More than 60% had cervical adenocarcinoma, which is more than three times the normal proportion of glandular cancer to squamous cervical cancer—again highlighting the relative insensitivity of cytology to detect glandular lesions.

Other drawbacks of waiting 12 months for further evaluation include 1) prolonged uncertainty for the patient and 2) the potential for losing her to follow-up, which occurs in as many as 50% of subjects in many studies.

Therefore, finding patients who are at greatest risk of CIN 2+ among the larger group of Pap–/HPV+ women, and referring them immediately for colposcopy, should provide great benefit.

Note that the 2006 ASCCP guidelines included a statement that, once an FDA-approved test for HPV 16, 18 was available, triage of Pap–/HPV+ patients who are positive for HPV 16, 18 could identify a majority at greatest risk of CIN 2,3+ and who would therefore benefit most by referral for colposcopy. In contrast, patients at lower risk (i.e., positive for any of the other 12 HPV types but not for types 16 and 18) would be better managed by repeating co-testing in 12 months—referring for colposcopy only those who are found again to be HPV+ or who have an abnormal Pap test.

In the next section of this Update, I explore recent evidence about the important role played by HPV 16, 18 in cervical carcinogenesis.

ASCCP guidelines provide the option of testing Pap–/HPV+ women for HPV 16, 18 and referring women positive for either of these types to colposcopy.

HPV 16, 18 pose long-term risk for CIN 3+ and cervical Ca

Kjaer SK, Frederiksen K, Munk C, Iftner T. Long-term absolute risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse following human papillomavirus infection: role of persistence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(19):1478–1488.

The most compelling prediction of the risk of CIN 3+ in cases of either single (incident) or persistent high-risk HPV detection comes from a 13-year follow-up study out of Denmark. More than 8,600 Danish women, 20 to 29 years old at enrollment, were tested twice, 2 years apart, for HPV by the Hybrid Capture 2 High-Risk (HC2 HR) HPV DNA Test (Qiagen) and by line-blot assays for type-specific HPV.

Subjects were followed subsequently with routine screening; data on their overall long-term risk of CIN 3+ was obtained from the national Danish Pathology Data Bank. Among those who tested positive for HPV 16, absolute risk of CIN 3+ within 12 years of incident detection was 26.7%; for HPV 18, it was 19.1%—both percentages markedly higher than the 6% risk for women who tested positive for a panel of 10 other high-risk HPV types (also not including HPV 31, 33).

FIGURE 2 Over time, risk of CIN 3+ rises in all subpopulations infected by high-risk HPV

Shown is the absolute risk for CIN 3+ during follow-up among women who have HPV 16 persistence (red line), Hybrid Capture 2 High-Risk HPV DNA Test (HC2 HR) persistence for a panel of 13 high-risk HPV types (blue), incident or newly detected HPV 16 infection (i.e., HPV 16-negative at first examination and HPV 16-positive at second examination) (pink), and women with an incident high-risk HPV infection (i.e., negative for high-risk HPV by HC2 HR at first examination and positive at second examination) (green). For comparison, the dashed purple line shows the nearly flat absolute risk of CIN 3+ for women who are negative for high-risk HPV by HC2 HR at both examinations.

Source: Kjaer et al, 2010. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Oxford University Press.

Risk associated with HPV 16. The most successfully persistent viral type was 16; just under 30% of subjects who were HPV 16+ on the first test remained HPV 16+ on the second test 2 years later. For this 30% subset, the risk of CIN 3+ was 8.9% at 3 years; 23.8% at 5 years; and an astonishing 47.4% at 12 years (FIGURE 2). In other words, almost half of subjects who had persistent HPV 16 in their 20s developed CIN 3 or cancer within 12 years. In contrast, the absolute risk for developing CIN 3+ within 12 years of a single negative HPV test was only 3%.

HPV 18. Viral type 18 was nearly as likely to persist as HPV 16; when persistent, it resulted in CIN 3+ in just under 30% of subjects within 12 years and tended to result in CIN 3+ that was detected later.

The long-term risk of CIN 3+ and cervical cancer that comes with testing positive for HPV 16 or 18 is very high—particularly when either of these viral types are detected twice over a 2-year period. Even one-time detection of either of these types in the context of a Pap–/HPV+ co-test result is important enough to refer to colposcopy.

Using HPV 16, 18 testing to improve the management of Pap–/HPV+ women

Two more HPV tests are now FDA-approved for clinical use

In the 2006 Update on Cervical Disease [available in the archive at www.obgmanagement.com], I noted the importance of HPV 16, 18 in cervical carcinogenesis and observed that a test for these two viral types was on the horizon. It wasn’t until 2009 approval of the Cervista HPV DNA HR Test (Hologic), however, that such a test became available.

In 2011, two more tests were approved:

- cobas 4800 HPV DNA

- Aptima mRNA HPV.

Like Cervista, the cobas 4800 (Roche) is FDA-approved to detect HPV DNA types 16 and 18 individually; Gen-Probe’s Aptima HPV test is the first HPV E6,E7 mRNA test approved in the US; the company plans to add an HPV 16, 18 mRNA test. The addition of one, perhaps two, new HPV 16, 18 genotyping tests expands the opportunity for you to improve the management of Pap–/HPV+ patients.

Let’s look at new data that support testing of Pap–/HPV+ women for HPV 16, 18.

Wright TC Jr, Stoler MH, Sharma A, Zhang G, Behrens C, Wright TL; ATHENA (Addressing THE Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics) Study Group. Evaluation of HPV-16 and HPV-18 genotyping for the triage of women with high-risk HPV+ cytology-negative results. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136(4):578–586.

Castle PE, Stoler MH, Wright TC Jr, Sharma A, Wright TL, Behrens CM. Performance of carcinogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and HPV16 or HPV18 genotyping for cervical cancer screening of women aged 25 years and older: a subanalysis of the ATHENA study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(9):880–890.

Data to support the application to the FDA for approval of the cobas 4800 was provided by the ATHENA Trial, the largest (47,208 women) cervical screening trial of US women to assess the performance of HPV DNA testing with individual genotyping for HPV 16, 18, compared with the Pap.

Wright and co-workers. These investigators evaluated the subset of 32,260 women 30 years and older who had negative cytology. The overall prevalence of Pap–/HPV+ was 6.7%. Just over one quarter of the Pap–/HPV+ women (1.5% of the subset population) were positive for HPV 16 or 18, or both.

As has been shown in other studies, the overall prevalence of HPV declined with age, as did the prevalence of HPV 16, 18. The estimated absolute risk of CIN 3+ at colposcopy for women who were Pap–/HPV+ was only 4.1%, but their relative risk—that is, compared with women in whom both tests were negative—was 14.4%. The absolute risk for CIN 3+ increased to 9.8% for Pap-negative women who tested positive for HPV 16 or 18, or both, and to 11.7% in women who tested positive for HPV 16 only.

Ongoing work by Castle and colleagues. In a seminal 2007 article on risk management, Castle and colleagues proposed that women who had an absolute risk of CIN 3+ of ≥10% across 2–3 years of follow-up should have colposcopy.4 These data, therefore, clearly support the recommendation of ASCCP that Pap–/HPV 16+ and (or) HPV 18+ women should be referred for colposcopy (FIGURE 3).

FIGURE 3 Managing risk of CIN 3+ across 2 years of follow-up

This stratagem is based on 2006 ASCCP Consensus Guidelines, 2010 ACOG guidelines, and Castle and colleagues’ proposal in their 2007 article, “Risk assessment to guide the prevention of cervical cancer.”4

Figure courtesy of Thomas C. Wright, MD.

Now, in another review of the ATHENA results, expanded to a subset of women 25 years and older, Castle and co-workers reported that triage of Pap–/HPV+ women by testing for HPV 16, 18 detected 72% of all CIN 3+ that was missed by cytology alone. Because only 18% of Pap–/HPV+ women were positive for HPV 16, 18, the majority (i.e., 82% who were ≥25 years and 78% who were ≥30 years) could be reassured that their risk was sufficiently low that it could be best managed by repeating co-testing in 1 year. This avoids delaying the diagnosis of nearly three quarters of the Pap–/HPV+ women who have CIN 3+, without overburdening colposcopy services.

The ATHENA trial is ongoing; eventually, results from 3 years of follow-up of these women will be evaluated. The findings should add important information about the total burden of cervical precancer detected over a longer period after a Pap–/HPV+ result, with or without testing positive for HPV 16, 18.

Among your patients who are Pap–/HPV+, testing for HPV 16, 18 allows you to identify most of those who are at highest risk of CIN 3+ (i.e., HPV 16+ or HPV 18+, or both)—and who will, therefore, be most likely to benefit from immediate colposcopy.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Read Dr. Cox’s recommendations onhow to counsel women about their HPV test results in the 2011 Update on Cervical Disease.

Dr. Cox is a consultant to Gen-Probe, OncoHealth, and Roche, and serves on the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (DSMB) for Merck HPV vaccine trials. He is a speaker for Bradley Pharmaceuticals.

The American Cancer Society estimates that approximately 12,700 new cases of invasive cervical cancer were diagnosed in 2011 in the United States; nearly 4,300 of those women will die of the disease, the Society projects.1 Great disparities in prevalence and incidence persist, with the rate of cervical cancer 1) highest in Latino women and 2) about 50% higher in African-American women than in non-Latino white women.

Because approximately 60% of cervical cancers occur in women who don’t undergo any screening for the disease, or who undergo only very infrequent screening, bringing more women in to be screened is most important. For women who are screened very infrequently, providing testing with the longest interval that provides safety should also reduce their risk of cancer.

Two advances have the potential to provide huge benefit in reducing the risk of cervical cancer: 1) increasing utilization of human papillomavirus (HPV) testing with Pap testing (so-called co-testing) for screening women 30 years and older and 2) widespread administration of the HPV vaccine to girls before they begin sexual activity. Regrettably, the promise of the HPV vaccine has not yet been fulfilled: Vaccine uptake (all three doses) among the primary target population hasn’t even reached 40%. And co-testing continues to be underutilized—in part because the best management strategy for women who have a negative Pap test result but a positive HPV test result (written here as “Pap–/HPV+”) has been less than clear.

Disappointments aside, 2011 did bring us a wealth of data on 1) the likely value of co-testing in preventing cervical cancer, and 2) improved management strategies for Pap–/HPV+ women—the areas of practice that I’ve made the focus of this year’s Update. The first question to ask: Does co-testing reduce the risk of cervical cancer more than current screening strategies that employ the Pap test?

Primary cytology (Pap test) screening (above) augmented by HPV testing—so-called co-testing—appears to cut the long-term risk of cervical Ca. Consider making a co-testing stratagem part of your practice, urges author Dr. J. Thomas Cox.

Will co-testing reduce the rate of cervical Ca to a greater degree than Pap screening has?

Kinney W, Fetterman B, Cox JT, Lorey T, Flanagan T, Castle PE. Characteristics of 44 cervical cancers diagnosed following Pap-negative, high risk HPV-positive screening in routine clinical practice. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(2):309–313.

Rijkaart DC, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus testing for the detection of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer: final results of the POBASCAM randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(1):78–88.

Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(7):663–672.

Recent studies have brought us closer to answering this question—and data certainly appear to suggest that the answer is “Yes.” Evidence from randomized controlled trials, prospective long-term cohort trials, and a large US screening population show that introducing HPV testing into cervical cancer screening could reduce cervical cancer incidence in women age ≥30—and even cervical cancer mortality.

I discussed one of these trials—the Italian NTCC trial—in the 2011 OBG Management Update on Cervical Disease [read that article in the archive at www.obgmanagement.com]; earlier detection and treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade-3 (CIN 3) lesions in the first screening round in the co-tested group were proposed as the reasons that no cancers were detected in the second screening round (nine cancers were detected in the women having cytology only).2

Similar results were reported in the POBASCAM study from the Netherlands, in which more than 44,000 women were randomized to co-testing or screening with cytology alone, then re-screened 5 years later. As in the NTCC trial, more cases of CIN 3+ were detected and treated at the initial screen by co-testing than by cytology alone (i.e., projected out to 79 additional cases of CIN 3 and 30 additional cancers for every 100,000 women screened), with fewer cases of CIN 3+ detected in the co-tested group in the subsequent 5 years than in the cytology-only group (again, projected out to 24 fewer cases of CIN 3 and 10 fewer cancers for every 100,000 women).

(In a review of these study findings, experts at the National Cancer Institute [NCI] estimated that co-testing in POBASCAM reduced the risk of cervical cancer to only 2.2 cancers for every 100,000 women a year—demonstrating the safety of a 5-year screening interval.3) This means that women testing Pap–/HPV–, who are best screened at 3-year intervals, would be safe with an interval as long as 5 years—providing greater protection for irregularly screened women.

FIGURE 1 Cervical adenocarcinoma in situ

Cervical AIS demonstrated in a cytology specimen. Most studies have shown that cytology is less sensitive than HPV testing for a glandular lesion.

Photo: Courtesy of Dennis O’Conner, MD.

Similar results were described by Katki and coworkers in a large HMO screening population in the United States, in which Pap–/HPV+ women had half the risk of cancer over the subsequent 5 years, compared with women who were negative by Pap testing only (3.2 cases for every 100,000 women, compared with 7.5 cases, respectively). Of the total cases of CIN 3+ found, 35% of cases of CIN 3 and adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) (FIGURE 1) were detected in women Pap-/HPV+, as were 29% of cancers. Cytology has been shown, in almost all studies, to be less sensitive for glandular lesions; it isn’t surprising, therefore, that 63% of adenocarcinomas found in this study population were detected by HPV testing only.

These results appear to provide overwhelming evidence of the benefit of including HPV testing in screening programs for cervical cancer.3

Adding HPV testing to primary screening with Pap testing (co-testing) appears to reduce the long-term risk of cervical Ca. Consider making this stratagem part of your practice.

Dilemma: How do we best manage women who are Pap–/HPV+?

Kinney W, Fetterman B, Cox JT, Lorey T, Flanagan T, Castle PE. Characteristics of 44 cervical cancers diagnosed following Pap-negative, high risk HPV-positive screening in routine clinical practice. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(2):309–313.

Although co-testing appears to reduce the risk of cervical cancer—allowing a safer margin for Pap-negative plus HPV-negative (Pap–/HPV–) women if they miss by up to 2 years their 3-year recommended screening—the question remains: What is the best way to manage Pap–/HPV+ women?

The primary recommendation by both the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) and ACOG is to re-screen them in 12 months, rather than send them immediately for colposcopy. Why? Because HPV infection 1) is relatively common among women who do not have CIN 2, 3 or invasive cervical cancer and 2) most often resolves without causing significant disease.

But re-screening these patients in 12 months negates much of the benefit of the high clinical sensitivity of HPV testing because it could lead to significant delay in the diagnosis and treatment of some women who already have either cervical cancer or advanced CIN 3 that might progress to cancer before their next evaluation. This concern is supported by the findings of the studies I discussed earlier.1-3

Although cervical cancer missed at cytology screening is uncommon, 44 cervical cancers were reported by Kinney and coworkers in a large screening population in women who had one or more Pap–/HPV+ co-test results (18 had two or more Pap–/HPV+ results before diagnosis). More than 60% had cervical adenocarcinoma, which is more than three times the normal proportion of glandular cancer to squamous cervical cancer—again highlighting the relative insensitivity of cytology to detect glandular lesions.

Other drawbacks of waiting 12 months for further evaluation include 1) prolonged uncertainty for the patient and 2) the potential for losing her to follow-up, which occurs in as many as 50% of subjects in many studies.

Therefore, finding patients who are at greatest risk of CIN 2+ among the larger group of Pap–/HPV+ women, and referring them immediately for colposcopy, should provide great benefit.

Note that the 2006 ASCCP guidelines included a statement that, once an FDA-approved test for HPV 16, 18 was available, triage of Pap–/HPV+ patients who are positive for HPV 16, 18 could identify a majority at greatest risk of CIN 2,3+ and who would therefore benefit most by referral for colposcopy. In contrast, patients at lower risk (i.e., positive for any of the other 12 HPV types but not for types 16 and 18) would be better managed by repeating co-testing in 12 months—referring for colposcopy only those who are found again to be HPV+ or who have an abnormal Pap test.

In the next section of this Update, I explore recent evidence about the important role played by HPV 16, 18 in cervical carcinogenesis.

ASCCP guidelines provide the option of testing Pap–/HPV+ women for HPV 16, 18 and referring women positive for either of these types to colposcopy.

HPV 16, 18 pose long-term risk for CIN 3+ and cervical Ca

Kjaer SK, Frederiksen K, Munk C, Iftner T. Long-term absolute risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse following human papillomavirus infection: role of persistence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(19):1478–1488.

The most compelling prediction of the risk of CIN 3+ in cases of either single (incident) or persistent high-risk HPV detection comes from a 13-year follow-up study out of Denmark. More than 8,600 Danish women, 20 to 29 years old at enrollment, were tested twice, 2 years apart, for HPV by the Hybrid Capture 2 High-Risk (HC2 HR) HPV DNA Test (Qiagen) and by line-blot assays for type-specific HPV.

Subjects were followed subsequently with routine screening; data on their overall long-term risk of CIN 3+ was obtained from the national Danish Pathology Data Bank. Among those who tested positive for HPV 16, absolute risk of CIN 3+ within 12 years of incident detection was 26.7%; for HPV 18, it was 19.1%—both percentages markedly higher than the 6% risk for women who tested positive for a panel of 10 other high-risk HPV types (also not including HPV 31, 33).

FIGURE 2 Over time, risk of CIN 3+ rises in all subpopulations infected by high-risk HPV

Shown is the absolute risk for CIN 3+ during follow-up among women who have HPV 16 persistence (red line), Hybrid Capture 2 High-Risk HPV DNA Test (HC2 HR) persistence for a panel of 13 high-risk HPV types (blue), incident or newly detected HPV 16 infection (i.e., HPV 16-negative at first examination and HPV 16-positive at second examination) (pink), and women with an incident high-risk HPV infection (i.e., negative for high-risk HPV by HC2 HR at first examination and positive at second examination) (green). For comparison, the dashed purple line shows the nearly flat absolute risk of CIN 3+ for women who are negative for high-risk HPV by HC2 HR at both examinations.

Source: Kjaer et al, 2010. Reproduced by permission of the publisher, Oxford University Press.

Risk associated with HPV 16. The most successfully persistent viral type was 16; just under 30% of subjects who were HPV 16+ on the first test remained HPV 16+ on the second test 2 years later. For this 30% subset, the risk of CIN 3+ was 8.9% at 3 years; 23.8% at 5 years; and an astonishing 47.4% at 12 years (FIGURE 2). In other words, almost half of subjects who had persistent HPV 16 in their 20s developed CIN 3 or cancer within 12 years. In contrast, the absolute risk for developing CIN 3+ within 12 years of a single negative HPV test was only 3%.

HPV 18. Viral type 18 was nearly as likely to persist as HPV 16; when persistent, it resulted in CIN 3+ in just under 30% of subjects within 12 years and tended to result in CIN 3+ that was detected later.

The long-term risk of CIN 3+ and cervical cancer that comes with testing positive for HPV 16 or 18 is very high—particularly when either of these viral types are detected twice over a 2-year period. Even one-time detection of either of these types in the context of a Pap–/HPV+ co-test result is important enough to refer to colposcopy.

Using HPV 16, 18 testing to improve the management of Pap–/HPV+ women

Two more HPV tests are now FDA-approved for clinical use

In the 2006 Update on Cervical Disease [available in the archive at www.obgmanagement.com], I noted the importance of HPV 16, 18 in cervical carcinogenesis and observed that a test for these two viral types was on the horizon. It wasn’t until 2009 approval of the Cervista HPV DNA HR Test (Hologic), however, that such a test became available.

In 2011, two more tests were approved:

- cobas 4800 HPV DNA

- Aptima mRNA HPV.

Like Cervista, the cobas 4800 (Roche) is FDA-approved to detect HPV DNA types 16 and 18 individually; Gen-Probe’s Aptima HPV test is the first HPV E6,E7 mRNA test approved in the US; the company plans to add an HPV 16, 18 mRNA test. The addition of one, perhaps two, new HPV 16, 18 genotyping tests expands the opportunity for you to improve the management of Pap–/HPV+ patients.

Let’s look at new data that support testing of Pap–/HPV+ women for HPV 16, 18.

Wright TC Jr, Stoler MH, Sharma A, Zhang G, Behrens C, Wright TL; ATHENA (Addressing THE Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics) Study Group. Evaluation of HPV-16 and HPV-18 genotyping for the triage of women with high-risk HPV+ cytology-negative results. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136(4):578–586.

Castle PE, Stoler MH, Wright TC Jr, Sharma A, Wright TL, Behrens CM. Performance of carcinogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and HPV16 or HPV18 genotyping for cervical cancer screening of women aged 25 years and older: a subanalysis of the ATHENA study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(9):880–890.

Data to support the application to the FDA for approval of the cobas 4800 was provided by the ATHENA Trial, the largest (47,208 women) cervical screening trial of US women to assess the performance of HPV DNA testing with individual genotyping for HPV 16, 18, compared with the Pap.

Wright and co-workers. These investigators evaluated the subset of 32,260 women 30 years and older who had negative cytology. The overall prevalence of Pap–/HPV+ was 6.7%. Just over one quarter of the Pap–/HPV+ women (1.5% of the subset population) were positive for HPV 16 or 18, or both.

As has been shown in other studies, the overall prevalence of HPV declined with age, as did the prevalence of HPV 16, 18. The estimated absolute risk of CIN 3+ at colposcopy for women who were Pap–/HPV+ was only 4.1%, but their relative risk—that is, compared with women in whom both tests were negative—was 14.4%. The absolute risk for CIN 3+ increased to 9.8% for Pap-negative women who tested positive for HPV 16 or 18, or both, and to 11.7% in women who tested positive for HPV 16 only.

Ongoing work by Castle and colleagues. In a seminal 2007 article on risk management, Castle and colleagues proposed that women who had an absolute risk of CIN 3+ of ≥10% across 2–3 years of follow-up should have colposcopy.4 These data, therefore, clearly support the recommendation of ASCCP that Pap–/HPV 16+ and (or) HPV 18+ women should be referred for colposcopy (FIGURE 3).

FIGURE 3 Managing risk of CIN 3+ across 2 years of follow-up

This stratagem is based on 2006 ASCCP Consensus Guidelines, 2010 ACOG guidelines, and Castle and colleagues’ proposal in their 2007 article, “Risk assessment to guide the prevention of cervical cancer.”4

Figure courtesy of Thomas C. Wright, MD.

Now, in another review of the ATHENA results, expanded to a subset of women 25 years and older, Castle and co-workers reported that triage of Pap–/HPV+ women by testing for HPV 16, 18 detected 72% of all CIN 3+ that was missed by cytology alone. Because only 18% of Pap–/HPV+ women were positive for HPV 16, 18, the majority (i.e., 82% who were ≥25 years and 78% who were ≥30 years) could be reassured that their risk was sufficiently low that it could be best managed by repeating co-testing in 1 year. This avoids delaying the diagnosis of nearly three quarters of the Pap–/HPV+ women who have CIN 3+, without overburdening colposcopy services.

The ATHENA trial is ongoing; eventually, results from 3 years of follow-up of these women will be evaluated. The findings should add important information about the total burden of cervical precancer detected over a longer period after a Pap–/HPV+ result, with or without testing positive for HPV 16, 18.

Among your patients who are Pap–/HPV+, testing for HPV 16, 18 allows you to identify most of those who are at highest risk of CIN 3+ (i.e., HPV 16+ or HPV 18+, or both)—and who will, therefore, be most likely to benefit from immediate colposcopy.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. American Cancer Society. Cervical cancer. What are the key statistics about cervical cancer? http://www.cancer.org/Cancer/CervicalCancer/DetailedGuide/cervical-cancer-key-statistics. Revised October 26 2011. Accessed February 15, 2012.

2. Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al; New Technologies for Cervical Cancer Screening (NTCC) Working Group. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(3):249-257.

3. Katki HA, Wentzensen N. How might HPV testing be integrated into cervical screening? Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(1):8-10.

4. Castle PE, Sideri M, Jeronimo J, Solomon D, Schiffman M. Risk assessment to guide the prevention of cervical cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(4):356.e1-6.

1. American Cancer Society. Cervical cancer. What are the key statistics about cervical cancer? http://www.cancer.org/Cancer/CervicalCancer/DetailedGuide/cervical-cancer-key-statistics. Revised October 26 2011. Accessed February 15, 2012.

2. Ronco G, Giorgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al; New Technologies for Cervical Cancer Screening (NTCC) Working Group. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(3):249-257.

3. Katki HA, Wentzensen N. How might HPV testing be integrated into cervical screening? Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(1):8-10.

4. Castle PE, Sideri M, Jeronimo J, Solomon D, Schiffman M. Risk assessment to guide the prevention of cervical cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(4):356.e1-6.

How to choose a contraceptive for your postpartum patient

“How to prepare your patient for the many nuances of postpartum sexuality”

Roya Rezaee, MD; Sheryl Kingsberg, PhD (January 2012)

“Not all contraceptives are suitable immediately postpartum”

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, September 2011)

What’s a vital aspect of the care we provide to postpartum patients?

Optimal timing of evaluation for contraception.

Good timing minimizes the likelihood that postpartum contraception will be initiated too early or too late to be effective.

The choice of a contraceptive method for a postpartum woman also requires a careful balancing act. On one side: the risks of contraception to the mother and her new-born. On the other: the risks of unintended pregnancy. Among the concerns that need to be addressed in contraceptive decision-making are:

- whether the woman has resumed sexual intercourse

- infant feeding practices

- risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE)

- logistics of various long-acting reversible contraceptives and tubal sterilization.

In this article, we outline the components of effective contraceptive counseling and decision-making. We also summarize recent recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on the use of various contraceptive methods during the postpartum period.

First: Start at 3 weeks

The traditional 6-week postpartum visit was timed to take place after complete involution of the uterus following vaginal delivery. However, involution occurs too late to prevent unintended pregnancy because ovulation can—and often does—occur as early as the fourth postpartum week among nonbreastfeeding women.

In the past, when it was more common to fit a contraceptive diaphragm after pregnancy, 6 weeks may have been the best timing for the visit. Today, given the high safety and efficacy of modern contraceptive methods (even when initiated before complete involution), as well as the importance of safe birth spacing, the routine postpartum visit is more appropriately scheduled at 3 weeks for women who have had an uneventful delivery.

In some cases, of course, it may be appropriate to schedule a visit even earlier, depending on the medical needs of the mother, which may include staple removal after cesarean delivery, follow-up blood pressure assessment for patients who have gestational hypertension, and so on. That said, the first postpartum visit should be routinely scheduled for no later than 3 weeks for healthy women who have had an uncomplicated delivery.1

The data support this approach. In one study, 57% of women reported the resumption of intercourse by the sixth postpartum week.2 A routine 3-week postpartum visit instead of a visit at 6 weeks would reduce unmet contraceptive need among this group of women.

How infant feeding practices come into play

Both the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding because of recognized health benefits for both the mother and her infant. Exclusive breastfeeding is also a requirement if a woman desires to use breastfeeding as a contraceptive method.

Healthy People 2010 is a set of US health objectives that includes goals for breastfeeding rates. Although the percentage of infants who were ever breastfed has reached the 75% target of Healthy People 2010, according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the percentage of infants who were breastfed at 6 months of age has changed only minimally.3 For Mexican-American infants, that rate is 40%, compared with 35% for non-Hispanic whites and 20% for non-Hispanic black infants.3 Rates of exclusive breastfeeding are even lower, highlighting the importance of early breastfeeding support and contraceptive guidance during the postpartum period—support and guidance that can be offered at a 3-week postpartum visit.

Extent of breastfeeding needs to be assessed

Full or nearly full breastfeeding should be encouraged, along with frequent feeding of the infant. In addition, the contraceptive effect of lactation during the first 6 months of breastfeeding should be emphasized (see the sidebar on the lactational amenorrhea method [LAM] of contraception). Keep in mind, however, that a substantial number of nursing mothers who are not breastfeeding exclusively will ovulate before the 6-week postpartum visit. Data suggest that approximately 50% of all nonbreastfeeding women will ovulate before the 6-week visit, with some ovulating as early as postpartum day 25.4

For this reason, you need to determine the extent of breastfeeding at the 3-week visit to determine whether LAM is a contraceptive option for your patient. “Full or nearly full” breastfeeding means that the vast majority of feeding is breastfeeding and that breastfeeding is not replaced by any other kind of feeding. “Frequent feeding” means that the infant is breastfed when hungry, be it day or night, which implies at least one night-time feeding. If evaluation at the 3-week visit indicates that breastfeeding is no longer full or nearly full and frequent, another form of contraception should be initiated.5

For most women, the benefits of initiating a progestin-only or nonhormonal method of contraception at this time outweigh the risks, regardless of breastfeeding status, according to the CDC’s medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use.6

the patient knows how to use it

The lactational amenorrhea method (LAM) of contraception requires fertility awareness, exclusive breastfeeding, and an ability to recognize the physiologic signs and circumstances that suggest that ovulation is resuming.

How does it work?

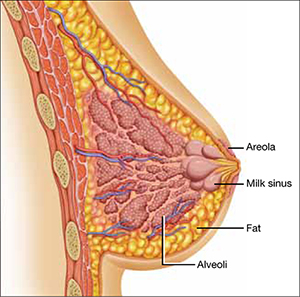

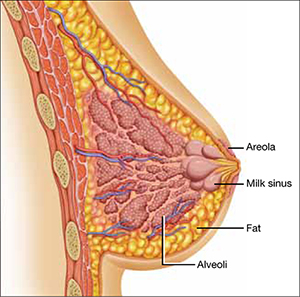

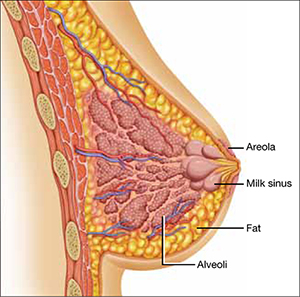

Elevated prolactin levels in breastfeeding women inhibit the normal pulsatile secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), suppressing the secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) from the pituitary, thereby inhibiting ovulation (FIGURE).9

Nipple stimulation from breastfeeding causes the pituitary gland to release prolactin—the hormone that acts at the alveolar secretory cells of the breast to stimulate lactogenesis and at the hypothalamus to decrease the pulsatile release of GnRH. Suckling increases the plasma level of prolactin markedly within 10 minutes of its initiation.

There are three rules for effective use of LAM:

- The infant must be fully or nearly fully breastfed. Prolactin remains elevated for approximately 3 hours, which is about the time it takes for hunger to resume after a feeding of breast milk. Clearly, this level of breastfeeding requires at least one night-time feeding. If cow’s milk formula is given to supplement breastfeeding, its greater fat content slows transit time and prolongs the feeding interval. The result is a decreased prolactin level that may allow FSH and LH to rise and eventually trigger ovulation.

- The woman should be alert for vaginal bleeding after postpartum day 56, which could signal the return of menstruation. The duration of lochia is variable and can make it difficult to detect the onset of menstrual bleeding. In a study by the World Health Organization (WHO), postpartum lochia was present from a minimum of 2 days to a maximum of 90 days, with an average duration of 27 days.10 Most women with LAM will not experience true menstrual bleeding before postpartum day 56 (8 weeks). The frequency of breastfeeding has no effect on the duration of postpartum lochia.

- LAM should be used as contraception only during the first 6 months postpartum. After 6 months, even fully breastfeeding mothers begin to ovulate.

Breast pumping might not maintain an adequate prolactin level

When a woman is separated from her infant, breast pumping has been shown to stimulate the release of prolactin at a level comparable to actual breastfeeding.11 However, women separated from their infant tend to pump less often than they would breastfeed, which can lead to an increased frequency of ovulation and conception.11 Because it is difficult for women to pump at a sufficient frequency to reliably suppress ovulation, the increased risk of pregnancy should be anticipated, and another form of contraception should be encouraged.

What the data show

The WHO conducted a large prospective study examining the relationship between infant feeding and amenorrhea, as well as the rate of pregnancy during LAM. Women who were still breastfeeding and remained amenorrheic had a pregnancy rate of 0.8% at 6 months.10

How the risk of VTE affects the choice of contraceptive

The hematologic changes of normal pregnancy shift coagulability and fibrinolytic systems toward a state of hypercoagulability. This physiologic process reduces the risk of puerperal hemorrhage; however, it also predisposes women to VTE during pregnancy and into the postpartum period. Studies assessing the risk of VTE in postpartum women indicate that it increases by a factor of 22 to 84 during the first 6 weeks, compared with the risk in nonpregnant, nonpostpartum women of reproductive age.7 This heightened risk is most pronounced immediately after delivery, declining rapidly over the first 21 days after delivery and returning to a near-baseline level by 42 days postpartum.

By the time of the recommended 3-week postpartum visit, the period of highest VTE risk has passed. For women who are no longer breastfeeding, the benefits of all hormonal contraceptive methods, including those that contain estrogen, outweigh their risks, according to a newly released update to recommendations from the CDC (TABLE).6 Although combined oral contraceptives are known to increase the risk of VTE by a factor of 3 to 7, data suggest that healthy women who do not have additional risk factors for VTE (e.g., thrombophilia, obesity, smoking, or age of 35 years or older) can use them safely.6

The updated recommendations discourage the use of estrogen-containing contraceptives before 21 days postpartum because they present an unacceptable level of risk (regardless of breastfeeding status), but they allow the use of combined hormonal contraceptives among otherwise healthy breastfeeding women after 30 days postpartum. For women who have additional risk factors for VTE, the risks of combined hormonal contraceptives outweigh the benefits until 6 weeks postpartum, regardless of breastfeeding status.6

In contrast, progestin-only and nonhormonal contraceptive methods can be safely initiated by both breastfeeding and nonbreastfeeding women before 21 days postpartum, which means that women can begin using them before discharge from the hospital.

Updated recommendations for use of combined hormonal contraceptives during the postpartum period*

| Time since delivery | Recommendation | Clarification |

|---|---|---|

| Nonbreastfeeding women | ||

| <21 days | Combined hormonal contraception not recommended | Presents an unacceptable health risk |

| 21–42 days | Not recommended for women who have other risk factors for VTE (e.g., age ≥35 years, previous VTE, thrombophilia, immobility, transfusion at delivery, BMI ≥30, postpartum hemorrhage, cesarean delivery, preeclampsia or smoking) Acceptable for women who do not have other risk factors for VTE | Theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh advantages in women who have risk factors for VTE Advantages generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks in women who do not have other risk factors for VTE |

| >42 days | Recommended | No restrictions |

| Breastfeeding women | ||

| <21 days | Not recommended | Presents an unacceptable health risk |

| 21–29 days | Not recommended for women who have other risk factors for VTE (e.g., age ≥35 years, previous VTE, thrombophilia, immobility, transfusion at delivery, BMI ≥30, postpartum hemorrhage, cesarean delivery, preeclampsia or smoking) Not recommended for women who do not have other risk factors for VTE | Theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh advantages |

| 30–42 days | Not recommended for women who have other risk factors for VTE (e.g., age ≥35 years, previous VTE, thrombophilia, immobility, transfusion at delivery, BMI ≥30, postpartum hemorrhage, cesarean delivery, preeclampsia or smoking) Acceptable for women who do not have other risk factors for VTE | Theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh advantages in women who have risk factors for VTE Advantages generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks in women who do not have other risk factors for VTE |

| >42 days | Acceptable | Advantages generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks |

| VTE = venous thromboembolism, BMI = body mass index * Includes combined oral contraceptives, combined hormonal patch, and combined vaginal ring SOURCE: Adapted from CDC6 | ||

When to consider LARC or sterilization

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC) are an important postpartum contraceptive option because they offer highly effective protection against pregnancy that can begin as soon as the placenta is delivered. LARC methods include contraceptive implants and intrauterine devices (IUDs).

According to the CDC’s medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, contraceptive implants can be placed immediately after delivery of the placenta without restriction.8

The copper IUD can be placed within 10 minutes after delivery of the placenta without restriction. If this window is missed, the benefits of inserting the IUD still outweigh the risks. Because 4 weeks postpartum is another time when the copper IUD can be inserted without restriction, the 3-week visit is a reasonable time to screen and schedule a patient for insertion.

The benefits of insertion of the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) are also believed to outweigh the risks before 4 weeks postpartum. Like the copper IUD, the LNG-IUS can be inserted without restriction at 4 weeks postpartum or later.

There is no need for a pelvic exam at the 3-week postpartum visit among women who undergo immediate postplacental insertion of the copper IUD or LNG-IUS. In fact, women can delay the exam until involution is complete.

Sterilization is best after complete involution

Interval tubal sterilization by laparoscopic, bilateral tubal fulguration or hysteroscopic microinsert placement is one of the most effective ways to prevent pregnancy. Both methods are best performed after the completion of involution and the return of normal coagulation; scheduling can take place at the 3-week postpartum visit.

Given the benefit of depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) in endometrial suppression before hysteroscopic sterilization, it is reasonable to consider administering DMPA at the 3-week postpartum visit in anticipation of surgery after involution is complete.

The bottom line

Because most contraceptive methods can be safely initiated at or shortly after a 3-weeks’ postpartum visit, there is no longer any reason to time the routine postpartum visit to coincide with the completion of involution. For healthy women who have had an uneventful delivery, the routine postpartum visit should occur at 3 weeks.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Speroff L, Mishell DR. The postpartum visit: it’s time for a change in order to optimally initiate contraception. Contraception. 2008;78(2):90-98.

2. Connolly A, Thorp J, Pahel L. Effects of pregnancy and childbirth on postpartum sexual function: a longitudinal prospective study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16(4):263-267.

3. McDowell MA, Wang C-Y, Kennedy-Stephenson J. Breastfeeding in the United States: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys 1999–2006. NCHS Data Briefs. 2008;5:1-8.

4. Jackson E, Glasier A. Return of ovulation and menses in postpartum nonlactatinglactating women: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):657-662.

5. Kennedy K, Rivera R, McNeilly A. Consensus statement on the use of breastfeeding as a family planning method. Contraception. 1988;39(5):477-496.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update to CDC’s US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use 2010: Revised recommendations for the use of contraceptive methods during the postpartum period. MMWR. 2011;60(26):878-883.

7. Jackson E, Curtis K, Gaffield M. Risk of venous thromboembolism during the postpartum period: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):691-703.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use 2010. MMWR. 2010;59(No. RR-4):1-86.

9. Kletzky OA, Marrs RP, Howard WF, McCormick W, Mishell DR Jr. Prolactin synthesis and release during pregnancy and puerperium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980;136(4):545-550.

10. Labbok MH, Hight-Laukaran V, Peterson AE, Fletcher V, von Hertzen H, Van Look PF. Multicenter study of the Lactional Amenorrhea Method (LAM): I. Efficacy duration, and implications for clinical application. Contraception. 1997;55(6):327-336.

11. Valdes V, Labbok MH, Pugin E, Perez A. The efficacy of the Lactational Amenorrhea Method (LAM) among working women. Contraception. 2000;62(5):217-219.

“How to prepare your patient for the many nuances of postpartum sexuality”

Roya Rezaee, MD; Sheryl Kingsberg, PhD (January 2012)

“Not all contraceptives are suitable immediately postpartum”

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, September 2011)

What’s a vital aspect of the care we provide to postpartum patients?

Optimal timing of evaluation for contraception.

Good timing minimizes the likelihood that postpartum contraception will be initiated too early or too late to be effective.

The choice of a contraceptive method for a postpartum woman also requires a careful balancing act. On one side: the risks of contraception to the mother and her new-born. On the other: the risks of unintended pregnancy. Among the concerns that need to be addressed in contraceptive decision-making are:

- whether the woman has resumed sexual intercourse

- infant feeding practices

- risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE)

- logistics of various long-acting reversible contraceptives and tubal sterilization.

In this article, we outline the components of effective contraceptive counseling and decision-making. We also summarize recent recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on the use of various contraceptive methods during the postpartum period.

First: Start at 3 weeks

The traditional 6-week postpartum visit was timed to take place after complete involution of the uterus following vaginal delivery. However, involution occurs too late to prevent unintended pregnancy because ovulation can—and often does—occur as early as the fourth postpartum week among nonbreastfeeding women.

In the past, when it was more common to fit a contraceptive diaphragm after pregnancy, 6 weeks may have been the best timing for the visit. Today, given the high safety and efficacy of modern contraceptive methods (even when initiated before complete involution), as well as the importance of safe birth spacing, the routine postpartum visit is more appropriately scheduled at 3 weeks for women who have had an uneventful delivery.

In some cases, of course, it may be appropriate to schedule a visit even earlier, depending on the medical needs of the mother, which may include staple removal after cesarean delivery, follow-up blood pressure assessment for patients who have gestational hypertension, and so on. That said, the first postpartum visit should be routinely scheduled for no later than 3 weeks for healthy women who have had an uncomplicated delivery.1

The data support this approach. In one study, 57% of women reported the resumption of intercourse by the sixth postpartum week.2 A routine 3-week postpartum visit instead of a visit at 6 weeks would reduce unmet contraceptive need among this group of women.

How infant feeding practices come into play

Both the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding because of recognized health benefits for both the mother and her infant. Exclusive breastfeeding is also a requirement if a woman desires to use breastfeeding as a contraceptive method.

Healthy People 2010 is a set of US health objectives that includes goals for breastfeeding rates. Although the percentage of infants who were ever breastfed has reached the 75% target of Healthy People 2010, according to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), the percentage of infants who were breastfed at 6 months of age has changed only minimally.3 For Mexican-American infants, that rate is 40%, compared with 35% for non-Hispanic whites and 20% for non-Hispanic black infants.3 Rates of exclusive breastfeeding are even lower, highlighting the importance of early breastfeeding support and contraceptive guidance during the postpartum period—support and guidance that can be offered at a 3-week postpartum visit.

Extent of breastfeeding needs to be assessed

Full or nearly full breastfeeding should be encouraged, along with frequent feeding of the infant. In addition, the contraceptive effect of lactation during the first 6 months of breastfeeding should be emphasized (see the sidebar on the lactational amenorrhea method [LAM] of contraception). Keep in mind, however, that a substantial number of nursing mothers who are not breastfeeding exclusively will ovulate before the 6-week postpartum visit. Data suggest that approximately 50% of all nonbreastfeeding women will ovulate before the 6-week visit, with some ovulating as early as postpartum day 25.4

For this reason, you need to determine the extent of breastfeeding at the 3-week visit to determine whether LAM is a contraceptive option for your patient. “Full or nearly full” breastfeeding means that the vast majority of feeding is breastfeeding and that breastfeeding is not replaced by any other kind of feeding. “Frequent feeding” means that the infant is breastfed when hungry, be it day or night, which implies at least one night-time feeding. If evaluation at the 3-week visit indicates that breastfeeding is no longer full or nearly full and frequent, another form of contraception should be initiated.5

For most women, the benefits of initiating a progestin-only or nonhormonal method of contraception at this time outweigh the risks, regardless of breastfeeding status, according to the CDC’s medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use.6

the patient knows how to use it

The lactational amenorrhea method (LAM) of contraception requires fertility awareness, exclusive breastfeeding, and an ability to recognize the physiologic signs and circumstances that suggest that ovulation is resuming.

How does it work?

Elevated prolactin levels in breastfeeding women inhibit the normal pulsatile secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), suppressing the secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) from the pituitary, thereby inhibiting ovulation (FIGURE).9

Nipple stimulation from breastfeeding causes the pituitary gland to release prolactin—the hormone that acts at the alveolar secretory cells of the breast to stimulate lactogenesis and at the hypothalamus to decrease the pulsatile release of GnRH. Suckling increases the plasma level of prolactin markedly within 10 minutes of its initiation.

There are three rules for effective use of LAM: