User login

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever Presenting as Febrile Pancytopenia

Cover

Tres Pasitos: "Three Little Steps" to Aldicarb Poisoning

Rhabdomyolysis: Evaluation and Emergent Management

2012 Update on Obstetrics

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

The year that has followed our inaugural “Update on Obstetrics” [OBG Management, January 2011, available at www.obgmanagement.com] saw a resurgence of interest in a number of aspects of obstetric care. We want to highlight four of them in this Update because we think they are particularly important—given the attention they’ve received in the medical literature and in the consumer media:

- the ever-increasing cesarean delivery rate

- home birth

- postpartum hemorrhage

- measurement of cervical length and the use of progesterone.

Taming the cesarean delivery rate—how can we

accomplish this?

No one should be surprised to learn that the cesarean delivery rate increased nearly sevenfold from 1970 to 2011—from a rate of approximately 5% in 1970 to nearly 35%. Recall that, in the 1990s, the US Public Health Service proposed, as part of Healthy People 2010, a target cesarean rate of 15%, with a vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) rate of 60%. Today, the cesarean delivery rate is, as we said, nearly 35% and the VBAC rate is less than 10%.

Many factors have been cited for the rise, including:

- the obesity pandemic

- delaying childbearing

- increasing use of assisted reproduction

- multiple gestation (although the incidence of higher-order multiple gestations is now decreasing, the rate of twin births remains quite high relative to past decades).

So, how did this happen? And what can we do?

For one, VBAC is not likely to gain in popularity. More than 60% of US hospitals that provide OB services handle a volume of fewer than 1,000 deliveries a year. Such low volumes generally will not be able to support (either with dollars or staffing) the resources needed to safely provide VBAC.

Other options have been proposed: Loosen the guidelines for VBAC, change the personnel requirements, gather community groups of doctors, attorneys, and patients to agree on guidelines that, if followed, would protect physicians from being sued1—and so on. The medicolegal reality, however, is that these options have not been shown to be viable. We have concluded that increasing VBAC utilization is not the answer. Rather, addressing ways to prevent primary cesarean delivery holds the most promise for, ultimately, reducing the current rising trend.

On a positive note: The most recent data available from the National Center for Health Statistics suggest that the cesarean delivery rate has dropped slightly: from 32.9% in 2009 to 32.8% in 2010. The drop is truly slight; we’ll watch with interest to see if a trend has begun.

Considering that the cesarean delivery rate in 1970 was 5%, and that the dictum at the time was “once a section, always a section,” it seems clear (to us, at least) that the solution to this problem lies in preventing first cesarean deliveries. How can the specialty and, in some ways, you, in your practice, work toward this goal? Here are possible strategies:

- Eliminate elective inductions of labor when the modified Bishop score is less than 8

- Return to defining “post-term” as 42—not 41—completed weeks’ gestation

- Eliminate all elective inductions before 39 weeks’ gestation

- Provide better and more standardized training of physicians in the interpretation of fetal heart-rate tracings

- Improve communication between obstetricians and anesthesiologists in regard to managing pain during labor

- Institute mandatory review of all cesarean deliveries that are performed in the latent phase of labor and all so-called “stat cesareans”

- Readjust the compensation scale for physicians and hospitals in such a way that successful vaginal delivery is rewarded.

Even if all these measures were implemented, we think it’s unlikely that we will ever see a 5% cesarean delivery rate again—although probably for good reason. But even a return to a more manageable 20% rate seems a reasonable goal.

Home birth: Consider where you stand

We suppose that one way to avoid cesarean delivery would be to deliver at home. The topic, and practice, of home birth has mushroomed in the past few years—for a number of social and economic reasons, probably. It seems to us that there are a few basic issues that must be addressed, however, before it’s possible to come to grips with home birth in the 21st century in an enlightened way:

- In 1935, the maternal mortality rate approached 500 to 600 for every 100,000 births; most of those deaths occurred at home. In 2009, the maternal mortality rate was approximately 8 for every 100,000 births. Both rates are very low, but the difference would be significant to the 492 to 592 women who met a potentially preventable death.

- Methods of identifying who might be an appropriate candidate for a home birth are, at best, imprecise.

- Infrastructure for rapidly transporting mother and baby to a hospital if matters go awry is inadequate.

Although evidence is limited, what data there are suggest that one significant outcome—neonatal death—occurs with higher frequency among home births than among hospital births, even after correcting for anomalies (odds ratio, 2.9 [95% confidence interval, 1.3–6.2]).2 Although women who delivered at home did have fewer episiotomies, fewer third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations, fewer operative deliveries (vaginal and cesarean) and a lower rate of infection, those reductions seem inconsequential compared to the death of a newborn….

Bottom line? Home birth is legal; home birth may be appropriate for some women who are at low risk and willing to accept a legitimate amount of personal risk; and you, as an OB, are in no way required to participate in or endorse the practice.

Many institutions have addressed this matter by developing a family-centered health care model for obstetrics—so-called hospitals within hospitals—that allow for a less interventionist approach to childbirth within the safety net of a hospital facility, should unforeseeable complications arise. Consider your interest in affiliating with such a facility, based on your acceptance of the practice of home birth and your comfort with being part of this approach.

Formal, systematic planning is key to managing

postpartum hemorrhage

A question for mothers-to-be: What could be worse than having a cesarean delivery in your home?

Answer: Having an associated postpartum bleed.

Perhaps that isn’t the most elegant segue, but postpartum hemorrhage is a significant problem that remains a major contributor to maternal mortality in the United States. And, in fact, a prolonged and unsuccessful labor—the kind that could present to your hospital from an outside birthing facility or home—necessitating a cesarean delivery is a set-up for postpartum hemorrhage.

One of the tenets of emergency management in obstetrics is the three-pronged preparedness of 1) risk identification, 2) foreseeability, and 3) having a plan for taking action. Of late, many institutions have begun to develop a formal plan for managing OB emergencies—in particular, postpartum hemorrhage.

(A note about the potential role of interventional radiology in the management of postpartum hemorrhage: Our experience is limited, but we conjecture that, in most US hospitals that provide OB services, mobilizing an interventional radiology group in an emergency isn’t feasible. That makes it essential to have established medical and surgical management guidelines for such cases.)

To establish a plan on labor and delivery for managing postpartum bleeds, we recommend the following steps and direct you to ACOG’s “Practice Bulletin#76” for more specific information3:

- Establish a list of conditions that predispose a woman to postpartum hemorrhage and post that list throughout labor and delivery to heighten the awareness of team members

- Establish protocols for pharmacotherapeutic intervention—including oxytocin, methylergonovine, misoprostol, and prostaglandin F2a, with dosage and frequency guidelines and algorithms for use—and have those protocols readily available on labor and delivery, either on-line or posted

- Establish an “all-hands-on-deck” protocol for surgical emergencies—actual or potential—that includes what personnel to call and in what order to call them

- Use simulation to practice the all-hands-on-deck protocol and evaluate team and individual performance in managing hemorrhage

- Establish blood product replacement protocols, including order sets for products that are linked to particular diagnoses (e.g., typing and cross-matching for patients coming in to deliver who have a diagnosis of placenta previa; adding products such as fresh frozen plasma and platelets for patients who have complicating diagnoses, such as suspected placenta accreta or severe preeclampsia).

To prevent preterm birth: Cervical length screening

and progesterone

Preterm birth accounts for almost 13% of births in the United States, with spontaneous preterm labor and preterm rupture of membranes accounting for approximately 80% of those cases.4 Once preterm labor has begun, little in the way of successful intervention is possible, beyond short-term prolongation of pregnancy with tocolytic agents to allow for corticosteroid administration. Studies in recent years have, therefore, moved the focus back on prevention, using the same treatments that were used 60 years ago—progesterone supplementation and cerclage—with the addition of transvaginal ultrasonography (US) screening for cervical length.

Several large, randomized trials have examined the use of intramuscular injection or vaginal delivery of progesterone to prevent preterm birth in patients who are at high risk of preterm birth based on their obstetric history.5,6 Both 17a-hydroxyprogesterone caproate and vaginal progesterone suppositories are associated with a significant reduction in the risk of preterm birth in singleton pregnancies. ACOG reconfirmed the value of this finding in a 2011 Committee Opinion, which recommended the use of progesterone supplementation in singleton pregnancies in which there is a history of preterm labor or preterm rupture of membranes.7

There is mounting evidence that cervical length is inversely related to risk of preterm birth.The real question, however, is: What should be done about transvaginal cervical length: Should we be screening, or not? As recently as 2009, a Cochrane Review did not advocate universal screening for cervical length as a predictor for preterm birth4—despite mounting evidence that cervical length is inversely related to risk of preterm birth, with progressively shorter length (starting at <25 mm) associated with significantly higher risk of preterm birth.8,9 Keeping in mind that the decision to screen depends on your ability to treat the condition for which you are screening, what was needed was proof that intervention works.

2011 brought two studies that recommend screening for cervical length based on a successful reduction in preterm birth with a specific intervention. A large, randomized trial of vaginal progesterone gel for the prevention of preterm birth used universal screening for shortened cervical length (10 to 20 mm) as the criterion for randomization to treatment or placebo. The investigators demonstrated a 45% reduction in preterm birth of less than 33 weeks in the treatment arm.10

An interesting aspect of this study: The reduction in preterm birth was not, in fact, seen in patients who had a history of preterm birth, suggesting that this may be a different patient population that benefits from vaginal progesterone.

On the other hand, a recent meta-analysis concluded that patients who meet the criteria of 1) cervical length less than 25 mm and 2) a history of prior spontaneous preterm birth experience a significant reduction in preterm birth and a reduction in perinatal morbidity and mortality if they have cervical cerclage placed.11

Although these publications lead us to hope that there may be some benefit from preventive intervention for preterm birth, the question of how to screen for, and prevent, spontaneous preterm birth remains somewhat nebulous: It hasn’t been determined which patient population will benefit from which combination of screening and intervention. Larger trials for specific populations are still needed.

This is what we know, for now:

- Women who have a history of spontaneous preterm birth should have a thorough evaluation of their OB history to determine possible modifiable risk factors (e.g., smoking, short inter-pregnancy interval) and to determine, as definitively as possible, the likely cause of that preterm birth

- Women who have a singleton pregnancy and a history of either spontaneous preterm labor or preterm rupture of membranes can be offered progesterone supplementation as intramuscular 17a-hydroxyprogesterone or a vaginal preparation to reduce their risk of preterm birth

- Women who have an asymptomatic shortening of the cervix, as measured on transvaginal US at 18 to 24 weeks’ gestation, can be offered vaginal progesterone to reduce their risk of preterm birth

- Women who have a history of preterm birth and cervical shortening may see a reduction in their risk of preterm birth from cerclage placement

- The use of screening for cervical length or progesterone supplementation, or both, in a multiple gestation pregnancy are not recommended because their benefit in this population has not been demonstrated.

Until we fully understand the various etiologic pathways of spontaneous preterm birth, we won’t have a one-size-fits-all solution to this major cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Scott JR. Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery; a common sense approach. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 Pt 1):342-350.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 476: Planned home birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 Pt 1):425-428.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 76: Postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(4):1039-1047.

4. Berghella V, Baxter JK, Hendrix NW. Cervical assessment by ultrasound for preventing preterm delivery (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD007235.-

5. da Fonseca EB, Bittar RE, Carvalho MH, Zugaib M. Prophylactic administration of progesterone by vaginal suppository to reduce the incidence of spontaneous preterm birth in women at increased risk: a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(2):419-424.

6. Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(24):2379-2385.

7. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 419: Use of progesterone to reduce preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(4):963-935.

8. Owen J, Yost N, Berghella V, et al:. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Mid-trimester endovaginal sonography in women at high risk for spontaneous preterm birth. JAMA. 2001;286(11):1340-1348.

9. Durnwald CP, Walker H, Lundy JC, Iams JD. Rates of recurrent preterm birth by obstetrical history and cervical length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3):1170-1174.

10. Hassan SS, Romero R, Vidyadhari D, et al. PREGNANT Trial. Vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: a multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(1):18-31.

11. Berghella V, Rafael TJ, Szychowski M, Rust OA, Owen J. Cerclage for short cervix on ultrasonography in women with singleton gestations and previous preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):663-771

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

The year that has followed our inaugural “Update on Obstetrics” [OBG Management, January 2011, available at www.obgmanagement.com] saw a resurgence of interest in a number of aspects of obstetric care. We want to highlight four of them in this Update because we think they are particularly important—given the attention they’ve received in the medical literature and in the consumer media:

- the ever-increasing cesarean delivery rate

- home birth

- postpartum hemorrhage

- measurement of cervical length and the use of progesterone.

Taming the cesarean delivery rate—how can we

accomplish this?

No one should be surprised to learn that the cesarean delivery rate increased nearly sevenfold from 1970 to 2011—from a rate of approximately 5% in 1970 to nearly 35%. Recall that, in the 1990s, the US Public Health Service proposed, as part of Healthy People 2010, a target cesarean rate of 15%, with a vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) rate of 60%. Today, the cesarean delivery rate is, as we said, nearly 35% and the VBAC rate is less than 10%.

Many factors have been cited for the rise, including:

- the obesity pandemic

- delaying childbearing

- increasing use of assisted reproduction

- multiple gestation (although the incidence of higher-order multiple gestations is now decreasing, the rate of twin births remains quite high relative to past decades).

So, how did this happen? And what can we do?

For one, VBAC is not likely to gain in popularity. More than 60% of US hospitals that provide OB services handle a volume of fewer than 1,000 deliveries a year. Such low volumes generally will not be able to support (either with dollars or staffing) the resources needed to safely provide VBAC.

Other options have been proposed: Loosen the guidelines for VBAC, change the personnel requirements, gather community groups of doctors, attorneys, and patients to agree on guidelines that, if followed, would protect physicians from being sued1—and so on. The medicolegal reality, however, is that these options have not been shown to be viable. We have concluded that increasing VBAC utilization is not the answer. Rather, addressing ways to prevent primary cesarean delivery holds the most promise for, ultimately, reducing the current rising trend.

On a positive note: The most recent data available from the National Center for Health Statistics suggest that the cesarean delivery rate has dropped slightly: from 32.9% in 2009 to 32.8% in 2010. The drop is truly slight; we’ll watch with interest to see if a trend has begun.

Considering that the cesarean delivery rate in 1970 was 5%, and that the dictum at the time was “once a section, always a section,” it seems clear (to us, at least) that the solution to this problem lies in preventing first cesarean deliveries. How can the specialty and, in some ways, you, in your practice, work toward this goal? Here are possible strategies:

- Eliminate elective inductions of labor when the modified Bishop score is less than 8

- Return to defining “post-term” as 42—not 41—completed weeks’ gestation

- Eliminate all elective inductions before 39 weeks’ gestation

- Provide better and more standardized training of physicians in the interpretation of fetal heart-rate tracings

- Improve communication between obstetricians and anesthesiologists in regard to managing pain during labor

- Institute mandatory review of all cesarean deliveries that are performed in the latent phase of labor and all so-called “stat cesareans”

- Readjust the compensation scale for physicians and hospitals in such a way that successful vaginal delivery is rewarded.

Even if all these measures were implemented, we think it’s unlikely that we will ever see a 5% cesarean delivery rate again—although probably for good reason. But even a return to a more manageable 20% rate seems a reasonable goal.

Home birth: Consider where you stand

We suppose that one way to avoid cesarean delivery would be to deliver at home. The topic, and practice, of home birth has mushroomed in the past few years—for a number of social and economic reasons, probably. It seems to us that there are a few basic issues that must be addressed, however, before it’s possible to come to grips with home birth in the 21st century in an enlightened way:

- In 1935, the maternal mortality rate approached 500 to 600 for every 100,000 births; most of those deaths occurred at home. In 2009, the maternal mortality rate was approximately 8 for every 100,000 births. Both rates are very low, but the difference would be significant to the 492 to 592 women who met a potentially preventable death.

- Methods of identifying who might be an appropriate candidate for a home birth are, at best, imprecise.

- Infrastructure for rapidly transporting mother and baby to a hospital if matters go awry is inadequate.

Although evidence is limited, what data there are suggest that one significant outcome—neonatal death—occurs with higher frequency among home births than among hospital births, even after correcting for anomalies (odds ratio, 2.9 [95% confidence interval, 1.3–6.2]).2 Although women who delivered at home did have fewer episiotomies, fewer third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations, fewer operative deliveries (vaginal and cesarean) and a lower rate of infection, those reductions seem inconsequential compared to the death of a newborn….

Bottom line? Home birth is legal; home birth may be appropriate for some women who are at low risk and willing to accept a legitimate amount of personal risk; and you, as an OB, are in no way required to participate in or endorse the practice.

Many institutions have addressed this matter by developing a family-centered health care model for obstetrics—so-called hospitals within hospitals—that allow for a less interventionist approach to childbirth within the safety net of a hospital facility, should unforeseeable complications arise. Consider your interest in affiliating with such a facility, based on your acceptance of the practice of home birth and your comfort with being part of this approach.

Formal, systematic planning is key to managing

postpartum hemorrhage

A question for mothers-to-be: What could be worse than having a cesarean delivery in your home?

Answer: Having an associated postpartum bleed.

Perhaps that isn’t the most elegant segue, but postpartum hemorrhage is a significant problem that remains a major contributor to maternal mortality in the United States. And, in fact, a prolonged and unsuccessful labor—the kind that could present to your hospital from an outside birthing facility or home—necessitating a cesarean delivery is a set-up for postpartum hemorrhage.

One of the tenets of emergency management in obstetrics is the three-pronged preparedness of 1) risk identification, 2) foreseeability, and 3) having a plan for taking action. Of late, many institutions have begun to develop a formal plan for managing OB emergencies—in particular, postpartum hemorrhage.

(A note about the potential role of interventional radiology in the management of postpartum hemorrhage: Our experience is limited, but we conjecture that, in most US hospitals that provide OB services, mobilizing an interventional radiology group in an emergency isn’t feasible. That makes it essential to have established medical and surgical management guidelines for such cases.)

To establish a plan on labor and delivery for managing postpartum bleeds, we recommend the following steps and direct you to ACOG’s “Practice Bulletin#76” for more specific information3:

- Establish a list of conditions that predispose a woman to postpartum hemorrhage and post that list throughout labor and delivery to heighten the awareness of team members

- Establish protocols for pharmacotherapeutic intervention—including oxytocin, methylergonovine, misoprostol, and prostaglandin F2a, with dosage and frequency guidelines and algorithms for use—and have those protocols readily available on labor and delivery, either on-line or posted

- Establish an “all-hands-on-deck” protocol for surgical emergencies—actual or potential—that includes what personnel to call and in what order to call them

- Use simulation to practice the all-hands-on-deck protocol and evaluate team and individual performance in managing hemorrhage

- Establish blood product replacement protocols, including order sets for products that are linked to particular diagnoses (e.g., typing and cross-matching for patients coming in to deliver who have a diagnosis of placenta previa; adding products such as fresh frozen plasma and platelets for patients who have complicating diagnoses, such as suspected placenta accreta or severe preeclampsia).

To prevent preterm birth: Cervical length screening

and progesterone

Preterm birth accounts for almost 13% of births in the United States, with spontaneous preterm labor and preterm rupture of membranes accounting for approximately 80% of those cases.4 Once preterm labor has begun, little in the way of successful intervention is possible, beyond short-term prolongation of pregnancy with tocolytic agents to allow for corticosteroid administration. Studies in recent years have, therefore, moved the focus back on prevention, using the same treatments that were used 60 years ago—progesterone supplementation and cerclage—with the addition of transvaginal ultrasonography (US) screening for cervical length.

Several large, randomized trials have examined the use of intramuscular injection or vaginal delivery of progesterone to prevent preterm birth in patients who are at high risk of preterm birth based on their obstetric history.5,6 Both 17a-hydroxyprogesterone caproate and vaginal progesterone suppositories are associated with a significant reduction in the risk of preterm birth in singleton pregnancies. ACOG reconfirmed the value of this finding in a 2011 Committee Opinion, which recommended the use of progesterone supplementation in singleton pregnancies in which there is a history of preterm labor or preterm rupture of membranes.7

There is mounting evidence that cervical length is inversely related to risk of preterm birth.The real question, however, is: What should be done about transvaginal cervical length: Should we be screening, or not? As recently as 2009, a Cochrane Review did not advocate universal screening for cervical length as a predictor for preterm birth4—despite mounting evidence that cervical length is inversely related to risk of preterm birth, with progressively shorter length (starting at <25 mm) associated with significantly higher risk of preterm birth.8,9 Keeping in mind that the decision to screen depends on your ability to treat the condition for which you are screening, what was needed was proof that intervention works.

2011 brought two studies that recommend screening for cervical length based on a successful reduction in preterm birth with a specific intervention. A large, randomized trial of vaginal progesterone gel for the prevention of preterm birth used universal screening for shortened cervical length (10 to 20 mm) as the criterion for randomization to treatment or placebo. The investigators demonstrated a 45% reduction in preterm birth of less than 33 weeks in the treatment arm.10

An interesting aspect of this study: The reduction in preterm birth was not, in fact, seen in patients who had a history of preterm birth, suggesting that this may be a different patient population that benefits from vaginal progesterone.

On the other hand, a recent meta-analysis concluded that patients who meet the criteria of 1) cervical length less than 25 mm and 2) a history of prior spontaneous preterm birth experience a significant reduction in preterm birth and a reduction in perinatal morbidity and mortality if they have cervical cerclage placed.11

Although these publications lead us to hope that there may be some benefit from preventive intervention for preterm birth, the question of how to screen for, and prevent, spontaneous preterm birth remains somewhat nebulous: It hasn’t been determined which patient population will benefit from which combination of screening and intervention. Larger trials for specific populations are still needed.

This is what we know, for now:

- Women who have a history of spontaneous preterm birth should have a thorough evaluation of their OB history to determine possible modifiable risk factors (e.g., smoking, short inter-pregnancy interval) and to determine, as definitively as possible, the likely cause of that preterm birth

- Women who have a singleton pregnancy and a history of either spontaneous preterm labor or preterm rupture of membranes can be offered progesterone supplementation as intramuscular 17a-hydroxyprogesterone or a vaginal preparation to reduce their risk of preterm birth

- Women who have an asymptomatic shortening of the cervix, as measured on transvaginal US at 18 to 24 weeks’ gestation, can be offered vaginal progesterone to reduce their risk of preterm birth

- Women who have a history of preterm birth and cervical shortening may see a reduction in their risk of preterm birth from cerclage placement

- The use of screening for cervical length or progesterone supplementation, or both, in a multiple gestation pregnancy are not recommended because their benefit in this population has not been demonstrated.

Until we fully understand the various etiologic pathways of spontaneous preterm birth, we won’t have a one-size-fits-all solution to this major cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

The authors report no financial relationships relevant to this article.

The year that has followed our inaugural “Update on Obstetrics” [OBG Management, January 2011, available at www.obgmanagement.com] saw a resurgence of interest in a number of aspects of obstetric care. We want to highlight four of them in this Update because we think they are particularly important—given the attention they’ve received in the medical literature and in the consumer media:

- the ever-increasing cesarean delivery rate

- home birth

- postpartum hemorrhage

- measurement of cervical length and the use of progesterone.

Taming the cesarean delivery rate—how can we

accomplish this?

No one should be surprised to learn that the cesarean delivery rate increased nearly sevenfold from 1970 to 2011—from a rate of approximately 5% in 1970 to nearly 35%. Recall that, in the 1990s, the US Public Health Service proposed, as part of Healthy People 2010, a target cesarean rate of 15%, with a vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC) rate of 60%. Today, the cesarean delivery rate is, as we said, nearly 35% and the VBAC rate is less than 10%.

Many factors have been cited for the rise, including:

- the obesity pandemic

- delaying childbearing

- increasing use of assisted reproduction

- multiple gestation (although the incidence of higher-order multiple gestations is now decreasing, the rate of twin births remains quite high relative to past decades).

So, how did this happen? And what can we do?

For one, VBAC is not likely to gain in popularity. More than 60% of US hospitals that provide OB services handle a volume of fewer than 1,000 deliveries a year. Such low volumes generally will not be able to support (either with dollars or staffing) the resources needed to safely provide VBAC.

Other options have been proposed: Loosen the guidelines for VBAC, change the personnel requirements, gather community groups of doctors, attorneys, and patients to agree on guidelines that, if followed, would protect physicians from being sued1—and so on. The medicolegal reality, however, is that these options have not been shown to be viable. We have concluded that increasing VBAC utilization is not the answer. Rather, addressing ways to prevent primary cesarean delivery holds the most promise for, ultimately, reducing the current rising trend.

On a positive note: The most recent data available from the National Center for Health Statistics suggest that the cesarean delivery rate has dropped slightly: from 32.9% in 2009 to 32.8% in 2010. The drop is truly slight; we’ll watch with interest to see if a trend has begun.

Considering that the cesarean delivery rate in 1970 was 5%, and that the dictum at the time was “once a section, always a section,” it seems clear (to us, at least) that the solution to this problem lies in preventing first cesarean deliveries. How can the specialty and, in some ways, you, in your practice, work toward this goal? Here are possible strategies:

- Eliminate elective inductions of labor when the modified Bishop score is less than 8

- Return to defining “post-term” as 42—not 41—completed weeks’ gestation

- Eliminate all elective inductions before 39 weeks’ gestation

- Provide better and more standardized training of physicians in the interpretation of fetal heart-rate tracings

- Improve communication between obstetricians and anesthesiologists in regard to managing pain during labor

- Institute mandatory review of all cesarean deliveries that are performed in the latent phase of labor and all so-called “stat cesareans”

- Readjust the compensation scale for physicians and hospitals in such a way that successful vaginal delivery is rewarded.

Even if all these measures were implemented, we think it’s unlikely that we will ever see a 5% cesarean delivery rate again—although probably for good reason. But even a return to a more manageable 20% rate seems a reasonable goal.

Home birth: Consider where you stand

We suppose that one way to avoid cesarean delivery would be to deliver at home. The topic, and practice, of home birth has mushroomed in the past few years—for a number of social and economic reasons, probably. It seems to us that there are a few basic issues that must be addressed, however, before it’s possible to come to grips with home birth in the 21st century in an enlightened way:

- In 1935, the maternal mortality rate approached 500 to 600 for every 100,000 births; most of those deaths occurred at home. In 2009, the maternal mortality rate was approximately 8 for every 100,000 births. Both rates are very low, but the difference would be significant to the 492 to 592 women who met a potentially preventable death.

- Methods of identifying who might be an appropriate candidate for a home birth are, at best, imprecise.

- Infrastructure for rapidly transporting mother and baby to a hospital if matters go awry is inadequate.

Although evidence is limited, what data there are suggest that one significant outcome—neonatal death—occurs with higher frequency among home births than among hospital births, even after correcting for anomalies (odds ratio, 2.9 [95% confidence interval, 1.3–6.2]).2 Although women who delivered at home did have fewer episiotomies, fewer third- and fourth-degree perineal lacerations, fewer operative deliveries (vaginal and cesarean) and a lower rate of infection, those reductions seem inconsequential compared to the death of a newborn….

Bottom line? Home birth is legal; home birth may be appropriate for some women who are at low risk and willing to accept a legitimate amount of personal risk; and you, as an OB, are in no way required to participate in or endorse the practice.

Many institutions have addressed this matter by developing a family-centered health care model for obstetrics—so-called hospitals within hospitals—that allow for a less interventionist approach to childbirth within the safety net of a hospital facility, should unforeseeable complications arise. Consider your interest in affiliating with such a facility, based on your acceptance of the practice of home birth and your comfort with being part of this approach.

Formal, systematic planning is key to managing

postpartum hemorrhage

A question for mothers-to-be: What could be worse than having a cesarean delivery in your home?

Answer: Having an associated postpartum bleed.

Perhaps that isn’t the most elegant segue, but postpartum hemorrhage is a significant problem that remains a major contributor to maternal mortality in the United States. And, in fact, a prolonged and unsuccessful labor—the kind that could present to your hospital from an outside birthing facility or home—necessitating a cesarean delivery is a set-up for postpartum hemorrhage.

One of the tenets of emergency management in obstetrics is the three-pronged preparedness of 1) risk identification, 2) foreseeability, and 3) having a plan for taking action. Of late, many institutions have begun to develop a formal plan for managing OB emergencies—in particular, postpartum hemorrhage.

(A note about the potential role of interventional radiology in the management of postpartum hemorrhage: Our experience is limited, but we conjecture that, in most US hospitals that provide OB services, mobilizing an interventional radiology group in an emergency isn’t feasible. That makes it essential to have established medical and surgical management guidelines for such cases.)

To establish a plan on labor and delivery for managing postpartum bleeds, we recommend the following steps and direct you to ACOG’s “Practice Bulletin#76” for more specific information3:

- Establish a list of conditions that predispose a woman to postpartum hemorrhage and post that list throughout labor and delivery to heighten the awareness of team members

- Establish protocols for pharmacotherapeutic intervention—including oxytocin, methylergonovine, misoprostol, and prostaglandin F2a, with dosage and frequency guidelines and algorithms for use—and have those protocols readily available on labor and delivery, either on-line or posted

- Establish an “all-hands-on-deck” protocol for surgical emergencies—actual or potential—that includes what personnel to call and in what order to call them

- Use simulation to practice the all-hands-on-deck protocol and evaluate team and individual performance in managing hemorrhage

- Establish blood product replacement protocols, including order sets for products that are linked to particular diagnoses (e.g., typing and cross-matching for patients coming in to deliver who have a diagnosis of placenta previa; adding products such as fresh frozen plasma and platelets for patients who have complicating diagnoses, such as suspected placenta accreta or severe preeclampsia).

To prevent preterm birth: Cervical length screening

and progesterone

Preterm birth accounts for almost 13% of births in the United States, with spontaneous preterm labor and preterm rupture of membranes accounting for approximately 80% of those cases.4 Once preterm labor has begun, little in the way of successful intervention is possible, beyond short-term prolongation of pregnancy with tocolytic agents to allow for corticosteroid administration. Studies in recent years have, therefore, moved the focus back on prevention, using the same treatments that were used 60 years ago—progesterone supplementation and cerclage—with the addition of transvaginal ultrasonography (US) screening for cervical length.

Several large, randomized trials have examined the use of intramuscular injection or vaginal delivery of progesterone to prevent preterm birth in patients who are at high risk of preterm birth based on their obstetric history.5,6 Both 17a-hydroxyprogesterone caproate and vaginal progesterone suppositories are associated with a significant reduction in the risk of preterm birth in singleton pregnancies. ACOG reconfirmed the value of this finding in a 2011 Committee Opinion, which recommended the use of progesterone supplementation in singleton pregnancies in which there is a history of preterm labor or preterm rupture of membranes.7

There is mounting evidence that cervical length is inversely related to risk of preterm birth.The real question, however, is: What should be done about transvaginal cervical length: Should we be screening, or not? As recently as 2009, a Cochrane Review did not advocate universal screening for cervical length as a predictor for preterm birth4—despite mounting evidence that cervical length is inversely related to risk of preterm birth, with progressively shorter length (starting at <25 mm) associated with significantly higher risk of preterm birth.8,9 Keeping in mind that the decision to screen depends on your ability to treat the condition for which you are screening, what was needed was proof that intervention works.

2011 brought two studies that recommend screening for cervical length based on a successful reduction in preterm birth with a specific intervention. A large, randomized trial of vaginal progesterone gel for the prevention of preterm birth used universal screening for shortened cervical length (10 to 20 mm) as the criterion for randomization to treatment or placebo. The investigators demonstrated a 45% reduction in preterm birth of less than 33 weeks in the treatment arm.10

An interesting aspect of this study: The reduction in preterm birth was not, in fact, seen in patients who had a history of preterm birth, suggesting that this may be a different patient population that benefits from vaginal progesterone.

On the other hand, a recent meta-analysis concluded that patients who meet the criteria of 1) cervical length less than 25 mm and 2) a history of prior spontaneous preterm birth experience a significant reduction in preterm birth and a reduction in perinatal morbidity and mortality if they have cervical cerclage placed.11

Although these publications lead us to hope that there may be some benefit from preventive intervention for preterm birth, the question of how to screen for, and prevent, spontaneous preterm birth remains somewhat nebulous: It hasn’t been determined which patient population will benefit from which combination of screening and intervention. Larger trials for specific populations are still needed.

This is what we know, for now:

- Women who have a history of spontaneous preterm birth should have a thorough evaluation of their OB history to determine possible modifiable risk factors (e.g., smoking, short inter-pregnancy interval) and to determine, as definitively as possible, the likely cause of that preterm birth

- Women who have a singleton pregnancy and a history of either spontaneous preterm labor or preterm rupture of membranes can be offered progesterone supplementation as intramuscular 17a-hydroxyprogesterone or a vaginal preparation to reduce their risk of preterm birth

- Women who have an asymptomatic shortening of the cervix, as measured on transvaginal US at 18 to 24 weeks’ gestation, can be offered vaginal progesterone to reduce their risk of preterm birth

- Women who have a history of preterm birth and cervical shortening may see a reduction in their risk of preterm birth from cerclage placement

- The use of screening for cervical length or progesterone supplementation, or both, in a multiple gestation pregnancy are not recommended because their benefit in this population has not been demonstrated.

Until we fully understand the various etiologic pathways of spontaneous preterm birth, we won’t have a one-size-fits-all solution to this major cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Scott JR. Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery; a common sense approach. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 Pt 1):342-350.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 476: Planned home birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 Pt 1):425-428.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 76: Postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(4):1039-1047.

4. Berghella V, Baxter JK, Hendrix NW. Cervical assessment by ultrasound for preventing preterm delivery (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD007235.-

5. da Fonseca EB, Bittar RE, Carvalho MH, Zugaib M. Prophylactic administration of progesterone by vaginal suppository to reduce the incidence of spontaneous preterm birth in women at increased risk: a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(2):419-424.

6. Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(24):2379-2385.

7. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 419: Use of progesterone to reduce preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(4):963-935.

8. Owen J, Yost N, Berghella V, et al:. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Mid-trimester endovaginal sonography in women at high risk for spontaneous preterm birth. JAMA. 2001;286(11):1340-1348.

9. Durnwald CP, Walker H, Lundy JC, Iams JD. Rates of recurrent preterm birth by obstetrical history and cervical length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3):1170-1174.

10. Hassan SS, Romero R, Vidyadhari D, et al. PREGNANT Trial. Vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: a multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(1):18-31.

11. Berghella V, Rafael TJ, Szychowski M, Rust OA, Owen J. Cerclage for short cervix on ultrasonography in women with singleton gestations and previous preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):663-771

1. Scott JR. Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery; a common sense approach. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 Pt 1):342-350.

2. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 476: Planned home birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 Pt 1):425-428.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 76: Postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(4):1039-1047.

4. Berghella V, Baxter JK, Hendrix NW. Cervical assessment by ultrasound for preventing preterm delivery (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD007235.-

5. da Fonseca EB, Bittar RE, Carvalho MH, Zugaib M. Prophylactic administration of progesterone by vaginal suppository to reduce the incidence of spontaneous preterm birth in women at increased risk: a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188(2):419-424.

6. Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E, et al. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(24):2379-2385.

7. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 419: Use of progesterone to reduce preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(4):963-935.

8. Owen J, Yost N, Berghella V, et al:. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Mid-trimester endovaginal sonography in women at high risk for spontaneous preterm birth. JAMA. 2001;286(11):1340-1348.

9. Durnwald CP, Walker H, Lundy JC, Iams JD. Rates of recurrent preterm birth by obstetrical history and cervical length. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3):1170-1174.

10. Hassan SS, Romero R, Vidyadhari D, et al. PREGNANT Trial. Vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: a multicenter randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(1):18-31.

11. Berghella V, Rafael TJ, Szychowski M, Rust OA, Owen J. Cerclage for short cervix on ultrasonography in women with singleton gestations and previous preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):663-771

Be vigilant for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia— here is why

How should you evaluate a patient who has a cytologic diagnosis of atypical glandular cells (AGC)?

Charles J. Dunton, MD (Examining the Evidence; August 2011)

What is optimal surveillance after treatment for high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)?

Alan G. Waxman, MD, MPH (Examining the Evidence; June 2011)

2 HPV vaccines, 7 questions that you need answered

Neal M. Lonky, MD, MPH, and an expert panel (August 2010)

Dr. Massad reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

The societal shifts of the 1960s generated many changes—among them, permanently altered sexual mores. That may be a primary reason why the incidence of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) increased more than 400% between 1973 and 2000, says L. Stewart Massad, Jr, MD, chairman of the Practice Committee of the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) and member of the ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice—and one of the authors of a new joint Committee Opinion on the management of VIN.1 This precancer is often associated with carcinogenic types of human papillomavirus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted disease in the nation.

The 400% statistic caught the attention of OBG Management. The editors invited Dr. Massad to discuss the subject of VIN at length, elaborating on key issues such as its prevention, identification, treatment, and surveillance.

How to identify a VIN lesion

OBG Management: What is VIN? What does it look like?

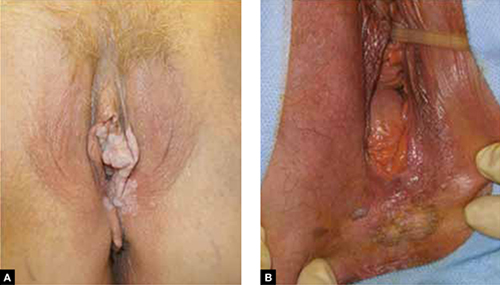

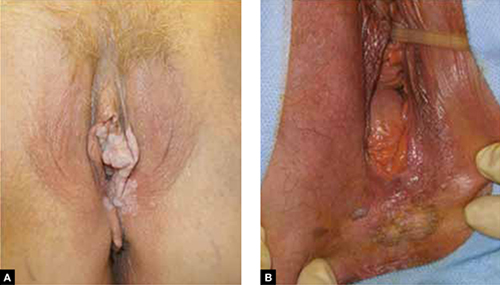

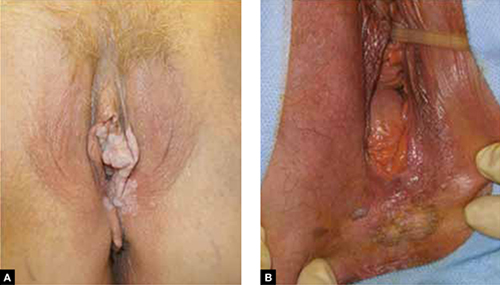

Dr. Massad: VIN is a premalignant condition of the vulva that may present as unifocal or multifocal lesions. These lesions may be flesh-colored, hypopigmented, or hyperpigmented (FIGURE). They also may be erythematous, flat, or raised. They can be found on any part of the vulva. The dysplastic cells may extend into hair shafts or sweat glands; they don’t penetrate the basement membrane, however, so, by definition, they aren’t invasive.

Usual-type VIN

A. This warty lesion is hyperpigmented around the periphery, hypopigmented in the center. B. Another warty lesion. Both images reflect the application of acetic acid.OBG Management: Why has the incidence increased so considerably?

Dr. Massad: The data we have on incidence comes from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute, as reported by Judson and colleagues.2 Although better reporting of findings of VIN may play a role, the rising incidence seems to be attributable to changes in sexual behavior over the past half century. The incidence of vulvar cancer rose during the same period—about 20%.3 The much slower growth in the incidence of vulvar cancer suggests that treatment of VIN has blunted the risk of cancer.

OBG Management: Is VIN associated with any particular type of HPV?

Dr. Massad: Yes, more than 80% of VIN lesions are associated with HPV 16.

OBG Management: One study from 2005 noted that the mean age of women with VIN decreased from 50 years before 1980 to 39 years in subsequent years.4 Why are more younger women developing VIN?

Dr. Massad: The study that showed that age shift was from New Zealand. The authors speculated that the change was due to earlier sexual activity among women who smoke: HPV, especially HPV 16, and smoking are important risk factors for VIN. The question hasn’t been definitively answered.

OBG Management: What are the risk factors for VIN?

Dr. Massad: Smoking is a big one. More than 50% of women who have VIN are smokers. Thirty percent have concurrent or prior cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN). The risk of invasion rises with age at the time of the initial diagnosis and with longer follow-up. I can talk about surveillance a little later.

Are some lesions more worrisome than others?

OBG Management: Are VIN lesions categorized similarly to CIN lesions—that is, using three different grades of severity?

Dr. Massad: Until recently, that was the case, but it is no longer so. Broadly, there are now two classes of VIN, according to the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD): usual-type VIN and differentiated VIN.

ACOG and ASCCP have embraced this classification system, although not all pathologists have done so, and clinicians may still see reports using the old three-tier system.

Usual-type VIN is associated with infection with high-risk types of HPV—most notably, HPV 16, as I mentioned. Histologically, usual-type VIN can mimic common genital warts, and the warty subtype shows keratosis at the surface, a spiky or undulating surface, and vertical maturation of cells in the lesion but with pleomorphic cells filling half or more of the epithelial thickness. The basaloid subtype of usual VIN shows little maturation.

Differentiated VIN exhibits more subtle atypia, with keratin pearls and an eosinophilic cytoplasm.

Biologically, usual-type VIN is associated with HPV and linked to smoking and sexual activity, as we discussed. As its name suggests, it is found more frequently than differentiated VIN. It is most common in women in their late 30s to early 50s.

In contrast, differentiated VIN is not associated with HPV and is more common in postmenopausal women; it is frequently seen with lichen sclerosus.

OBG Management: When did this new way of classifying VIN—as usual-type and differentiated—originate?

Dr. Massad: The ISVVD classification system changed in 2004. Before then, it paralleled the CIN classification system, with three grades of intraepithelial neoplasia corresponding to the thickness of the epithelium filled by dysplastic cells: VIN 1, 2, and 3. However, VIN 1 was not really neoplastic. It reflected infection with HPV, and although it might progress to higher-grade dysplasia or cancer, the risk was minimal. So the ISVVD revised the classification system to include only high-grade VIN—the old VIN 2 and VIN 3. HPV-associated lesions with dysplastic cells confined to the lower third of the epithelium are managed like genital warts, with observation for spontaneous regression or treatment with topical therapy or surgery.

How to screen for VIN

OBG Management: What screening strategy is recommended for VIN?

Dr. Massad: There is no such recommendation. Screening for VIN hasn’t been implemented for several reasons. Most important, other than inspection of the vulva by a clinician, there is no good screening test. VIN isn’t very common, so mass inspection for lesions is unlikely to be cost-effective. The sensitivity and specificity of inspection by a clinician aren’t known. Most lesions are found by women, their partners, or clinicians before cancer develops. And most disease is treated before cancer arises.

OBG Management: Isn’t there a need for heightened scrutiny of the vulva?

Dr. Massad: Yes. Women should examine their genitalia several times a year and seek attention if anything changes. That’s especially true for women who have risk factors, such as smoking, immunosuppression, and a history of being treated for cervical dysplasia. It’s the same concept we employ when teaching women to identify early breast lesions through self-examination.

The biggest challenges in detecting VIN are educating women to report vulvar skin changes to their clinicians for assessment and educating clinicians to examine the vulva before inserting the speculum for cervical screening and vaginal inspection.

OBG Management: Is another challenge distinguishing some forms of VIN from genital warts?

Dr. Massad: It can be a challenge, but clinicians should recall that warts are most common among women around the time of the onset of sexual activity. Older women sometimes develop warts with a new sexual partner. However, when women in their 40s and older develop new warty lesions, always suspect VIN. A woman in her 60s or older who has a new, warty-appearing vulvar lesion should be assumed to have VIN or cancer.

OBG Management: Does VIN ever regress spontaneously?

Dr. Massad: Yes. There have been reports of spontaneous regression of VIN, especially in young women. Regrettably, there are also reports of progression to cancer during observation. There are no characteristics that allow us to distinguish lesions that are going to progress from those that will regress. The ACOG-ASCCP Committee Opinion recommends treatment of all VIN.1

Can VIN be prevented?

OBG Management: The Committee Opinion recommends that the quadrivalent HPV vaccine be offered to women “in target populations” because it can decrease the risk of VIN. What are those target populations?

Dr. Massad: The target population for HPV vaccination is 11- and 12-year-old girls, but catch-up vaccination is acceptable in patients as old as 26 years.

OBG Management: Why isn’t the bivalent vaccine recommended?

Dr. Massad: Only the quadrivalent vaccine has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for prevention of VIN, although, in theory, the bivalent vaccine ought to be effective as well.

When to biopsy

OBG Management: Do you recommend that any suspect lesion on the vulva be biopsied?

Dr. Massad: The decision to biopsy should be individualized. However, women who have apparent warts that fail to respond to topical therapy should undergo biopsy, as should older women with warty lesions. Keep in mind that older women may develop verrucous carcinomas and may benefit from excision of enlarging warty lesions even if a biopsy is reported as only condylomata. Clinicians should not biopsy varicosities or obvious flat nevi.

OBG Management: Is colposcopy ever helpful in assessing vulvar lesions?

Dr. Massad: Most vulvar lesions can be identified without colposcopy, but colposcopy is useful in determining the extent of lesions. It often reveals subclinical disease not evident at the time of vulvar inspection.

OBG Management: When colposcopy is used, is the procedure the same as for cervical examination?

Dr. Massad: Not exactly. The clinician should apply 5% acetic acid for 5 minutes using a gauze sponge, but the magnification should be 63 to 103—not 153, as it is for cervical examination. It’s important to distinguish hyperplasia from VIN. In general, hyperplastic lesions are faint, gray, diffuse, and flat, whereas VIN lesions are raised and irregular in shape, with sharp borders.

OBG Management: What about toluidine blue? Is it useful in inspection of lesions?

Dr. Massad: Toluidine blue stains skin that is irritated. It isn’t very specific for VIN or vulvar cancer, and it can make colposcopy difficult, so experts no longer recommend it.

OBG Management: What are the treatment options for VIN?

Dr. Massad: They include surgical excision, laser ablation, and topical therapy with 5% imiquimod. All are potentially effective. The Committee Opinion doesn’t specify a preference, except to say that excision is advised when there is any suspicion of cancer to preserve a sample for pathologic analysis. Ablation destroys the lesion, making assessment of possible invasion impossible, and imiquimod may allow disease to progress during observation.

OBG Management: The Committee Opinion recommends wide local excision when cancer is suspected. What size of margin is optimal?

Dr. Massad: In general, a margin of 5 to 10 mm around the lesion is recommended. Vulvectomy isn’t needed because close follow-up usually identifies recurrence before invasion occurs.

OBG Management: When is laser ablation a good choice?

Dr. Massad: Whenever a biopsy shows VIN and cancer is not suspected. Laser ablation is ideal when lesions are multifocal or extensive, although repeated treatments may be required to resolve small foci of residual disease. Done with careful attention to power density and depth of ablation, laser therapy can be less disfiguring than excision.

OBG Management: You mentioned 5% imiquimod. Is there evidence that it’s effective in the treatment of VIN?

Dr. Massad: Multiple randomized, controlled trials have shown 5% imiquimod to be effective against VIN, although the agent does not have approval from the FDA for that indication.5,6 Lower concentrations of imiquimod have not been studied in the treatment of VIN. Women treated with this topical therapy should be followed every 4 weeks with colposcopy because progression to cancer has been reported during imiquimod therapy. Lesions that fail to respond completely after a full course of imiquimod should be treated with excision or laser ablation.

Surveillance is critical

OBG Management: According to the Committee Opinion, the recurrence rate of VIN can reach 30% to 50%.7 Why so high?

Dr. Massad: Usual-type VIN reflects exposure to carcinogenic HPV, and differentiated VIN arises from a vulvar dystrophy. In both situations, treatments destroy VIN and arrest progress to cancer, but the entire vulvar skin remains subject to the inciting condition.

OBG Management: Would skinning vulvectomy eliminate the risk of recurrence?

Dr. Massad: Full vulvectomy is crippling and usually unnecessary. Most patients and clinicians accept the risk of recurrence of VIN to avoid the side effects of radical treatment.

OBG Management: What kind of surveillance is recommended after treatment?

Dr. Massad: Patients should perform vulvar self-examination every few months. They should also be examined 6 and 12 months after initial treatment and annually thereafter because the risk of recurrence may persist for years.

Because VIN is associated with carcinogenic HPV, women with VIN should undergo an annual Pap test.

OBG Management: Thank you, Dr. Massad. Let’s hope the incidence of this precancer begins to decline.

- Recommend the quadrivalent HPV vaccine for girls in the target age range (11 and 12 years old) to reduce the risk of VIN.

- Encourage smoking cessation.

- Make it a practice to inspect the vulva before inserting the speculum for cervical examination.

- Biopsy most pigmented lesions on the vulva. Biopsy all warty lesions in postmenopausal women and in women who fail topical treatment for genital warts.

- Treat all VIN lesions. When cancer is suspected, use wide local excision with a margin of 5 to 10 mm.

- Keep in mind that dysplastic cells can extend into hair follicles and sweat glands.

- Closely follow up all women treated for VIN (6 and 12 months after treatment and annually thereafter) and encourage them to examine their vulva several times every year. Perform an annual Pap test for any woman found to have VIN.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Committee on Gynecologic Practice; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion #509: Management of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1192-1194.

2. Judson PL, Habermann EB, Baxter NN, Durham SB, Virnig BA. Trends in the incidence of invasive and in situ vulvar carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(5):1018-1022.

3. Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, Lawson HW, Chesson H, Unger ER. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-2):1-24.

4. Jones RW, Rowan DM, Stewart AW. Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: aspects of the natural history and outcome in 405 women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(6):1319-1326.

5. Van Seters M, van Beurden M, ten Kate FJW, et al. Treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia with topical imiquimod. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(14):1465-1473.

6. Terlou A, van Seters M, Ewing PC, et al. Treatment of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia with topical imiquimod: seven years median follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121(1):157-162.

7. Hillemanns P, Wang X, Staehle S, Michels W, Dannecker C. Evaluation of different treatment modalities for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN): CO2 laser vaporization, photodynamic therapy, excision and vulvectomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;100(2):271-275.

How should you evaluate a patient who has a cytologic diagnosis of atypical glandular cells (AGC)?

Charles J. Dunton, MD (Examining the Evidence; August 2011)

What is optimal surveillance after treatment for high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)?

Alan G. Waxman, MD, MPH (Examining the Evidence; June 2011)

2 HPV vaccines, 7 questions that you need answered

Neal M. Lonky, MD, MPH, and an expert panel (August 2010)

Dr. Massad reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

The societal shifts of the 1960s generated many changes—among them, permanently altered sexual mores. That may be a primary reason why the incidence of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) increased more than 400% between 1973 and 2000, says L. Stewart Massad, Jr, MD, chairman of the Practice Committee of the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) and member of the ACOG Committee on Gynecologic Practice—and one of the authors of a new joint Committee Opinion on the management of VIN.1 This precancer is often associated with carcinogenic types of human papillomavirus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted disease in the nation.

The 400% statistic caught the attention of OBG Management. The editors invited Dr. Massad to discuss the subject of VIN at length, elaborating on key issues such as its prevention, identification, treatment, and surveillance.

How to identify a VIN lesion

OBG Management: What is VIN? What does it look like?

Dr. Massad: VIN is a premalignant condition of the vulva that may present as unifocal or multifocal lesions. These lesions may be flesh-colored, hypopigmented, or hyperpigmented (FIGURE). They also may be erythematous, flat, or raised. They can be found on any part of the vulva. The dysplastic cells may extend into hair shafts or sweat glands; they don’t penetrate the basement membrane, however, so, by definition, they aren’t invasive.

Usual-type VIN

A. This warty lesion is hyperpigmented around the periphery, hypopigmented in the center. B. Another warty lesion. Both images reflect the application of acetic acid.OBG Management: Why has the incidence increased so considerably?

Dr. Massad: The data we have on incidence comes from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute, as reported by Judson and colleagues.2 Although better reporting of findings of VIN may play a role, the rising incidence seems to be attributable to changes in sexual behavior over the past half century. The incidence of vulvar cancer rose during the same period—about 20%.3 The much slower growth in the incidence of vulvar cancer suggests that treatment of VIN has blunted the risk of cancer.

OBG Management: Is VIN associated with any particular type of HPV?

Dr. Massad: Yes, more than 80% of VIN lesions are associated with HPV 16.

OBG Management: One study from 2005 noted that the mean age of women with VIN decreased from 50 years before 1980 to 39 years in subsequent years.4 Why are more younger women developing VIN?

Dr. Massad: The study that showed that age shift was from New Zealand. The authors speculated that the change was due to earlier sexual activity among women who smoke: HPV, especially HPV 16, and smoking are important risk factors for VIN. The question hasn’t been definitively answered.

OBG Management: What are the risk factors for VIN?

Dr. Massad: Smoking is a big one. More than 50% of women who have VIN are smokers. Thirty percent have concurrent or prior cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VAIN). The risk of invasion rises with age at the time of the initial diagnosis and with longer follow-up. I can talk about surveillance a little later.

Are some lesions more worrisome than others?

OBG Management: Are VIN lesions categorized similarly to CIN lesions—that is, using three different grades of severity?

Dr. Massad: Until recently, that was the case, but it is no longer so. Broadly, there are now two classes of VIN, according to the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD): usual-type VIN and differentiated VIN.

ACOG and ASCCP have embraced this classification system, although not all pathologists have done so, and clinicians may still see reports using the old three-tier system.

Usual-type VIN is associated with infection with high-risk types of HPV—most notably, HPV 16, as I mentioned. Histologically, usual-type VIN can mimic common genital warts, and the warty subtype shows keratosis at the surface, a spiky or undulating surface, and vertical maturation of cells in the lesion but with pleomorphic cells filling half or more of the epithelial thickness. The basaloid subtype of usual VIN shows little maturation.

Differentiated VIN exhibits more subtle atypia, with keratin pearls and an eosinophilic cytoplasm.

Biologically, usual-type VIN is associated with HPV and linked to smoking and sexual activity, as we discussed. As its name suggests, it is found more frequently than differentiated VIN. It is most common in women in their late 30s to early 50s.

In contrast, differentiated VIN is not associated with HPV and is more common in postmenopausal women; it is frequently seen with lichen sclerosus.

OBG Management: When did this new way of classifying VIN—as usual-type and differentiated—originate?

Dr. Massad: The ISVVD classification system changed in 2004. Before then, it paralleled the CIN classification system, with three grades of intraepithelial neoplasia corresponding to the thickness of the epithelium filled by dysplastic cells: VIN 1, 2, and 3. However, VIN 1 was not really neoplastic. It reflected infection with HPV, and although it might progress to higher-grade dysplasia or cancer, the risk was minimal. So the ISVVD revised the classification system to include only high-grade VIN—the old VIN 2 and VIN 3. HPV-associated lesions with dysplastic cells confined to the lower third of the epithelium are managed like genital warts, with observation for spontaneous regression or treatment with topical therapy or surgery.

How to screen for VIN

OBG Management: What screening strategy is recommended for VIN?

Dr. Massad: There is no such recommendation. Screening for VIN hasn’t been implemented for several reasons. Most important, other than inspection of the vulva by a clinician, there is no good screening test. VIN isn’t very common, so mass inspection for lesions is unlikely to be cost-effective. The sensitivity and specificity of inspection by a clinician aren’t known. Most lesions are found by women, their partners, or clinicians before cancer develops. And most disease is treated before cancer arises.

OBG Management: Isn’t there a need for heightened scrutiny of the vulva?

Dr. Massad: Yes. Women should examine their genitalia several times a year and seek attention if anything changes. That’s especially true for women who have risk factors, such as smoking, immunosuppression, and a history of being treated for cervical dysplasia. It’s the same concept we employ when teaching women to identify early breast lesions through self-examination.

The biggest challenges in detecting VIN are educating women to report vulvar skin changes to their clinicians for assessment and educating clinicians to examine the vulva before inserting the speculum for cervical screening and vaginal inspection.

OBG Management: Is another challenge distinguishing some forms of VIN from genital warts?

Dr. Massad: It can be a challenge, but clinicians should recall that warts are most common among women around the time of the onset of sexual activity. Older women sometimes develop warts with a new sexual partner. However, when women in their 40s and older develop new warty lesions, always suspect VIN. A woman in her 60s or older who has a new, warty-appearing vulvar lesion should be assumed to have VIN or cancer.

OBG Management: Does VIN ever regress spontaneously?

Dr. Massad: Yes. There have been reports of spontaneous regression of VIN, especially in young women. Regrettably, there are also reports of progression to cancer during observation. There are no characteristics that allow us to distinguish lesions that are going to progress from those that will regress. The ACOG-ASCCP Committee Opinion recommends treatment of all VIN.1

Can VIN be prevented?

OBG Management: The Committee Opinion recommends that the quadrivalent HPV vaccine be offered to women “in target populations” because it can decrease the risk of VIN. What are those target populations?

Dr. Massad: The target population for HPV vaccination is 11- and 12-year-old girls, but catch-up vaccination is acceptable in patients as old as 26 years.

OBG Management: Why isn’t the bivalent vaccine recommended?

Dr. Massad: Only the quadrivalent vaccine has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for prevention of VIN, although, in theory, the bivalent vaccine ought to be effective as well.

When to biopsy

OBG Management: Do you recommend that any suspect lesion on the vulva be biopsied?

Dr. Massad: The decision to biopsy should be individualized. However, women who have apparent warts that fail to respond to topical therapy should undergo biopsy, as should older women with warty lesions. Keep in mind that older women may develop verrucous carcinomas and may benefit from excision of enlarging warty lesions even if a biopsy is reported as only condylomata. Clinicians should not biopsy varicosities or obvious flat nevi.

OBG Management: Is colposcopy ever helpful in assessing vulvar lesions?

Dr. Massad: Most vulvar lesions can be identified without colposcopy, but colposcopy is useful in determining the extent of lesions. It often reveals subclinical disease not evident at the time of vulvar inspection.

OBG Management: When colposcopy is used, is the procedure the same as for cervical examination?

Dr. Massad: Not exactly. The clinician should apply 5% acetic acid for 5 minutes using a gauze sponge, but the magnification should be 63 to 103—not 153, as it is for cervical examination. It’s important to distinguish hyperplasia from VIN. In general, hyperplastic lesions are faint, gray, diffuse, and flat, whereas VIN lesions are raised and irregular in shape, with sharp borders.

OBG Management: What about toluidine blue? Is it useful in inspection of lesions?

Dr. Massad: Toluidine blue stains skin that is irritated. It isn’t very specific for VIN or vulvar cancer, and it can make colposcopy difficult, so experts no longer recommend it.

OBG Management: What are the treatment options for VIN?

Dr. Massad: They include surgical excision, laser ablation, and topical therapy with 5% imiquimod. All are potentially effective. The Committee Opinion doesn’t specify a preference, except to say that excision is advised when there is any suspicion of cancer to preserve a sample for pathologic analysis. Ablation destroys the lesion, making assessment of possible invasion impossible, and imiquimod may allow disease to progress during observation.

OBG Management: The Committee Opinion recommends wide local excision when cancer is suspected. What size of margin is optimal?

Dr. Massad: In general, a margin of 5 to 10 mm around the lesion is recommended. Vulvectomy isn’t needed because close follow-up usually identifies recurrence before invasion occurs.

OBG Management: When is laser ablation a good choice?

Dr. Massad: Whenever a biopsy shows VIN and cancer is not suspected. Laser ablation is ideal when lesions are multifocal or extensive, although repeated treatments may be required to resolve small foci of residual disease. Done with careful attention to power density and depth of ablation, laser therapy can be less disfiguring than excision.

OBG Management: You mentioned 5% imiquimod. Is there evidence that it’s effective in the treatment of VIN?

Dr. Massad: Multiple randomized, controlled trials have shown 5% imiquimod to be effective against VIN, although the agent does not have approval from the FDA for that indication.5,6 Lower concentrations of imiquimod have not been studied in the treatment of VIN. Women treated with this topical therapy should be followed every 4 weeks with colposcopy because progression to cancer has been reported during imiquimod therapy. Lesions that fail to respond completely after a full course of imiquimod should be treated with excision or laser ablation.

Surveillance is critical

OBG Management: According to the Committee Opinion, the recurrence rate of VIN can reach 30% to 50%.7 Why so high?

Dr. Massad: Usual-type VIN reflects exposure to carcinogenic HPV, and differentiated VIN arises from a vulvar dystrophy. In both situations, treatments destroy VIN and arrest progress to cancer, but the entire vulvar skin remains subject to the inciting condition.

OBG Management: Would skinning vulvectomy eliminate the risk of recurrence?

Dr. Massad: Full vulvectomy is crippling and usually unnecessary. Most patients and clinicians accept the risk of recurrence of VIN to avoid the side effects of radical treatment.

OBG Management: What kind of surveillance is recommended after treatment?

Dr. Massad: Patients should perform vulvar self-examination every few months. They should also be examined 6 and 12 months after initial treatment and annually thereafter because the risk of recurrence may persist for years.

Because VIN is associated with carcinogenic HPV, women with VIN should undergo an annual Pap test.

OBG Management: Thank you, Dr. Massad. Let’s hope the incidence of this precancer begins to decline.

- Recommend the quadrivalent HPV vaccine for girls in the target age range (11 and 12 years old) to reduce the risk of VIN.

- Encourage smoking cessation.

- Make it a practice to inspect the vulva before inserting the speculum for cervical examination.