User login

Vulvar pain syndromes: Making the correct diagnosis

Although the incidence of vulvar pain has increased over the past decade—thanks to both greater awareness and increasing numbers of affected women—the phenomenon is not a recent development. As early as 1874, T. Galliard Thomas wrote, “[T]his disorder, although fortunately not very frequent, is by no means very rare.”1 He went on to express “surprise” that it had not been “more generally and fully described.”

Despite the focus Thomas directed to the issue, vulvar pain did not get much attention until the 21st century, when a number of studies began to gauge its prevalence. For example, in a study in Boston of about 5,000 women, the lifetime prevalence of chronic vulvar pain was 16%.2 And in a study in Texas, the prevalence of vulvar pain in an urban, largely minority population was estimated to be 11%.3 The Boston study also reported that “nearly 40% of women chose not to seek treatment, and, of those who did, 60% saw three or more doctors, many of whom could not provide a diagnosis.”2

Clearly, there is a need for comprehensive information on vulvar pain and its causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. To address the lack of guidance, OBG Management Contributing Editor Neal M. Lonky, MD, assembled a panel of experts on vulvar pain syndromes and invited them to share their considerable knowledge. The ensuing discussion, presented in three parts, offers a gold mine of information.

In this opening article, the panel focuses on causes, symptomatology, and diagnosis of this common complaint. In Part 2, which will appear in the October issue of this journal, the focus is the bounty of treatment options. Part 3 follows in November, when the discussion shifts to vestibulodynia.

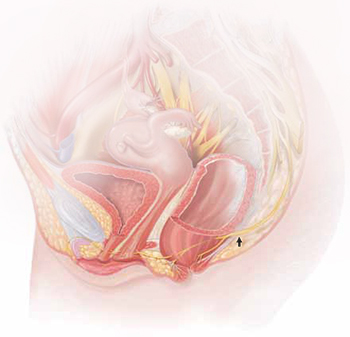

The lower vagina and vulva are richly supplied with peripheral nerves and are, therefore, sensitive to pain, particularly the region of the hymeneal ring. Although the pudendal nerve (arrow) courses through the area, it is an uncommon source of vulvar pain.

Common diagnoses—and misdiagnoses

Dr. Lonky: What are the most common diagnoses when vulvar pain is the complaint?

Dr. Gunter: The most common cause of chronic vulvar pain is vulvodynia, although lichen simplex chronicus, chronic yeast infections, and non-neoplastic epithelial disorders, such as lichen sclerosus and lichen planus, can also produce irritation and pain. In postmenopausal women, atrophic vaginitis can also cause a burning pain, although symptoms are typically more vaginal than vulvar. Yeast and lichen simplex chronicus typically produce itching, although sometimes they can present with irritation and pain, so they must be considered in the differential diagnosis. It is important to remember that many women with vulvodynia have used multiple topical agents and may have developed complex hygiene rituals in an attempt to treat their symptoms, which can result in a secondary lichen simplex chronicus.

That said, there is a high frequency of misdiagnosis with yeast. For example, in a study by Nyirjesy and colleagues, two thirds of women who were referred to a tertiary clinic for chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis were found to have a noninfectious entity instead—most commonly lichen simplex chronicus and vulvodynia.4

Dr. Edwards: The most common “diagnosis” for vulvar pain is vulvodynia. However, the definition of vulvodynia is pain—i.e., burning, rawness, irritation, soreness, aching, or stabbing or stinging sensations—in the absence of skin disease, infection, or specific neurologic disease. Therefore, even though the usual cause of vulvar pain is vulvodynia, it is a diagnosis of exclusion, and skin disease, infection, and neurologic disease must be ruled out.

In regard to infection, Candida albicans and bacterial vaginosis (BV) are usually the first conditions that are considered when a patient complains of vulvar pain, but they are not common causes of vulvar pain and are never causes of chronic vulvar pain. Very rarely they may cause recurrent pain that clears, at least briefly, with treatment.

Candida albicans is usually primarily pruritic, and BV produces discharge and odor, sometimes with minor symptoms. Non-albicans Candida (e.g., Candida glabrata) is nearly always asymptomatic, but it occasionally causes irritation and burning.

Group B streptococcus is another infectious entity that very, very occasionally causes irritation and dyspareunia but is usually only a colonizer.

Herpes simplex virus is a cause of recurrent but not chronic pain.

Chronic pain is more likely to be caused by skin disease than by infection. Lichen simplex chronicus causes itching; any pain is due to erosions from scratching.

Dr. Haefner: Several other infectious conditions or their treatments can cause vulvar pain. For example, herpes (particularly primary herpes infection) is classically associated with vulvar pain. The pain is so great that, at times, the patient requires admission for pain control. Surprisingly, despite the known pain of herpes, approximately 80% of patients who have it are unaware of their diagnosis.

Although condyloma is generally a painless condition, many patients complain of pain following treatment for it, whether treatment involves topical medications or laser surgery.

Chancroid is a painful vulvar ulcer. Trichomonas can sometimes be associated with vulvar pain.

Dr. Lonky: What terminology do we use when we discuss vulvar pain?

Dr. Haefner: The current terminology used to describe vulvar pain was published in 2004, after years of debate over nomenclature within the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease.5 The terminology lists two major categories of vulvar pain:

- pain related to a specific disorder. This category encompasses numerous conditions that feature an abnormal appearance of the vulva (Table 1).

TABLE 1

Terminology and classification of vulvar pain from the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease

|

| SOURCE: Moyal-Barracco and Lynch.5 Reproduced with permission from the Journal of Reproductive Medicine. |

- vulvodynia, in which the vulva appears normal, other than occasional erythema, which is most prominent at the duct openings (vestibular ducts—Bartholin’s and Skene’s).

As for vulvar pain, there are two major forms:

- hyperalgesia (a low threshold for pain)

- allodynia (pain in response to light touch).

Some diseases that are associated with vulvar pain do not qualify for the diagnosis of vulvodynia (Table 2) because they are associated with an abnormal appearance of the vulva.

TABLE 2

Conditions other than vulvodynia that are associated with vulvar pain

| Acute irritant contact dermatitis (e.g., erosion due to podofilox, imiquimod, cantharidin, fluorouracil, or podophyllin toxin) |

| Aphthous ulcer |

| Atrophy |

| Bartholin’s abscess |

| Candidiasis |

| Carcinoma |

| Chronic irritant contact dermatitis |

| Endometriosis |

| Herpes (simplex and zoster) |

| Immunobullous diseases (including cicatricial pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, linear immunoglobulin A disease, etc.) |

| Lichen planus |

| Lichen sclerosus |

| Podophyllin overdose (see above) |

| Prolapsed urethra |

| Sjögren’s syndrome |

| Trauma |

| Trichomoniasis |

| Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia |

What needs to be ruled out for a diagnosis of vulvodynia?

Dr. Lonky: What skin diseases need to be ruled out before vulvodynia can be diagnosed?

Dr. Edwards: Skin diseases that affect the vulva are usually pruritic—pain is a later sign. Lichen simplex chronicus (also known as eczema) is pruritus caused by any irritant; any pain that arises is produced by visible excoriations from scratching.

Lichen sclerosus manifests as white epithelium that has a crinkling, shiny, or waxy texture. It can produce pain, especially dyspareunia. The pain is caused by erosions that arise from fragility and introital narrowing and inelasticity.

Vulvovaginal lichen planus is usually erosive and preferentially affects mucous membranes, especially the vestibule; it sometimes affects the vagina and mouth, as well.

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis is most likely a skin disease that affects only the vagina. It involves introital redness and a clinically and microscopically purulent vaginal discharge that also reveals parabasal cells and absent lactobacilli.

Dr. Lonky: You mentioned that neurologic diseases can sometimes cause vulvar pain. Which ones?

Dr. Edwards: Pudendal neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy, and post-herpetic neuralgia are the most common specific neurologic causes of vulvar pain. Multiple sclerosis can also produce pain syndromes. Post-herpetic neuralgia follows herpes zoster—not herpes simplex—virus infection.

Dr. Lonky: Any other conditions that can cause vulvar pain?

Dr. Haefner: Aphthous ulcers are common and are often flared by stress.

Non-neoplastic epithelial disorders are also seen frequently in health-care providers’ offices; many patients who experience them report pain on the vulva.

It is always important to consider cancer when a patient has an abnormal vulvar appearance and pain that has persisted despite treatment.

What are the most common vulvar pain syndromes?

Dr. Lonky: If you were to rank vulvar pain syndromes according to their prevalence, what would the most common syndromes be?

Dr. Gunter: Given the misdiagnosis of many women, who are told they have chronic yeast infection, as I mentioned, it’s hard to know which vulvar pain syndromes are most prevalent. I suspect that lichen simplex chronicus is most common, followed by vulvodynia, with chronic yeast infection a distant third.

My experience reflects what Nyirjesy and colleagues4 found: 65% to 75% of women referred to my clinic with chronic yeast actually have lichen simplex chronicus or vulvodynia. In postmenopausal women, atrophic vaginitis is also a consideration; it’s becoming more common now that the use of systemic hormone replacement therapy is decreasing.

Dr. Lonky: What about subsets of vulvodynia? Which ones are most common?

Dr. Edwards: There is good evidence of marked overlap among subsets of vulvodynia. The vast majority of women who have vulvodynia experience primarily provoked vestibular pain, regardless of age. However, I find that almost all patients also report pain that extends beyond the vestibule at times, as well as occasional unprovoked pain.

The diagnosis requires the exclusion of other causes of vulvar pain, and the subset is identified by the location of pain (that is, is it strictly localized or generalized or even migratory?) and its provoked or unprovoked nature.

Localized clitoral pain and vulvar pain localized to one side of the vulva are extremely uncommon, but they do occur. And although I rarely encounter teenagers and prepubertal children who have vulvodynia, I do have patients in both age groups who have vulvodynia.

Dr. Lonky: Are there racial differences in the prevalence of vulvodynia?

Dr. Edwards: Although several good studies show that women of African descent and white patients are equally likely to experience vulvodynia, the vast majority (99%) of my patients who have vulvodynia are white. My patients of African descent consult me primarily for itching or discharge.

My local demographics prevent me from judging the likelihood of Asians having vulvodynia, and our Hispanic population has limited access to health care.

In general, I don’t think that demographics are useful in making the diagnosis of vulvodynia.

Do women who have vulvar pain tend to have comorbidities?

Dr. Lonky: Do your patients who have vulvodynia or another vulvar pain syndrome tend to have comorbidities? If so, is this information helpful in establishing the diagnosis and planning therapy?

Dr. Haefner: Women who have vulvodynia often have other medical problems as well. In my practice, when new patients who have vulvodynia complete their intake survey, they often report a history of headache, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, fibromyalgia,6 chronic fatigue syndrome, back pain, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder. These comorbidities are not particularly helpful in establishing the diagnosis of vulvodynia, but they are an important consideration when choosing therapy for the patient. Often, the medications chosen to treat one condition will also benefit another condition. However, it’s important to check for potential interactions between drugs before prescribing a new treatment.

Dr. Gunter: A significant number of women who have vulvodynia also have other chronic pain syndromes. For example, the incidence of bladder pain syndrome–interstitial cystitis is 68% to 82% among women who have vulvodynia, compared with a baseline rate among all women of 6% to 11%.7-10 The rate of irritable bowel syndrome is more than doubled among women who have vulvodynia, compared with the general population (27% versus 12%).8 Another common comorbidity, hypertonic somatic dysfunction of the pelvic floor, is identified in 10% to 90% of women who have chronic vulvar pain.8,11,12 These women also have a higher incidence of nongenital pain syndromes, such as fibromyalgia, migraine, and TMJ dysfunction, than the general population, as Dr. Haefner noted.8,12,13

Many studies have evaluated psychological and emotional contributions to chronic vulvar pain. Pain and depression are intimately related—the incidence of depression among all people who experience chronic pain ranges from 27% to 54%, compared with 5% to 17% among the general population.14-16 The relationship is complex because chronic illness in general is associated with depression. Nevertheless, several studies have noted an increase in anxiety, stress, and depression among women who have vulvodynia.17-19

I screen every patient for depression using a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9); I also screen for anxiety. I find that a significant percentage of patients in my clinic are depressed or have an anxiety disorder. Failure to address these comorbidities makes treatment very difficult. I typically prescribe citalopram (Celexa), although there is some question whether it can safely be combined with a tricyclic antidepressant. We also offer stress-reduction classes, teach every patient the value of diaphragmatic breathing, offer mind-body classes for anxiety and stress, and provide intensive programs where the patient can learn important self-care skills, such as pacing (spacing activities throughout the day in a manner that avoids aggravating the pain), and address her anxiety and stress in a more guided manner. We also have a psychologist who specializes in pain for any patient who may need one-on-one counseling.

Dr. Edwards: The presence of comorbidities is somewhat useful in making the diagnosis of vulvodynia. I question my diagnosis, in fact, when a patient who has vulvodynia does not have headaches, low energy, depression, anxiety, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, sensitivity to medications, TMJ dysfunction, or urinary symptoms.

How common is pudendal neuralgia?

Dr. Lonky: How prevalent is a finding of pudendal neuralgia?

Dr. Edwards: The prevalence and incidence of pudendal neuralgia are not known. Those who specialize in this condition think it is relatively common. I do not identify or suspect it very often. Its definitive diagnosis and management are outside the purview of the general gynecologist, but the general gynecologist should recognize the symptoms of pudendal neuralgia and refer the patient for evaluation and therapy.

Dr. Lonky: What are those symptoms?

Dr. Haefner: Pudendal neuralgia often occurs following trauma to the pudendal nerve. The pudendal nerve arises from sacral nerves, generally sacral nerves 2 to 4. Several tests can be utilized to diagnose this condition, including quantitative sensor tests, pudendal nerve motor latency tests, electromyography (EMG), and pudendal nerve blocks.20

Nantes Criteria allow for making a diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia (Table 3).21

TABLE 3

Nantes Criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment

Essential criteria

|

Complementary diagnostic criteria

|

Exclusion criteria

|

Associated signs not excluding the diagnosis

|

| SOURCE: Labat et al.21 Reproduced with permission from Neurology and Urodynamics. |

Initial treatments for pudendal neuralgia should be conservative. Treatments consist of lifestyle changes to prevent flare of disease. Physical therapy, medical management, nerve blocks, and alternative treatments may be beneficial.

Pudendal nerve entrapment is often exacerbated by sitting (not on a toilet seat, however) and is reduced in a standing position. It tends to increase in intensity throughout the day.22 The final treatment for pudendal nerve entrapment is surgery if the nerve is compressed. By this time, the generalist is not generally the provider who performs the surgery.

Dr. Gunter: I believe pudendal neuralgia is sometimes overdiagnosed. EMG studies of the pudendal nerve, often touted as a diagnostic tool, are unreliable (they can be abnormal after vaginal delivery or vaginal hysterectomy, for example). In my experience, bilateral pain is less likely to be pudendal neuralgia; spontaneous bilateral compression neuropathy at exactly the same level is not a common phenomenon in chronic pain.

I reserve the diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia for women who have allodynia in the distribution of the pudendal nerve with severe pain on sitting, and who have exquisite tenderness when pressure is applied over the pudendal nerve (at the level of the ischial spine on vaginal examination). Typically, the vaginal sidewall on the affected side is very sensitive to light touch. I do see pudendal nerve pain after vaginal surgery when there has been some compromise of the pudendal nerve or the sacral plexus. This is typically unilateral pain.

Dr. Lonky: Thank you all. We’ll continue our discussion, with a focus on treatment, in the October 2011 issue.

- Part 2: A bounty of treatment options

(October 2011) - Part 3: Vestibulodynia

(November 2011)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Thomas TG. Practical Treatise on the Diseases of Women. Philadelphia Pa: Henry C. Lea; 1874.

2. Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58(2):82-88.

3. Lavy RJ, Hynan LS, Haley RW. Prevalence of vulvar pain in an urban minority population. J Reprod Med. 2007;52(1):59-62.

4. Nyirjesy P, Peyton C, Weitz MV, Mathew L, Culhane JF. Causes of chronic vaginitis: analysis of a prospective database of affected women. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1185-1191.

5. Moyal-Barracco M, Lynch PJ. 2003 ISSVD terminology and classification of vulvodynia: a historical perspective. J Reprod Med. 2004;49(10):772-777.

6. Yunas MB. Fibromyalgia and overlapping disorders: the unifying concept of central sensitivity syndromes. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36(6):339-356.

7. Kahn BS, Tatro C, Parsons CL, Willems JJ. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in vulvodynia patients detected by bladder potassium sensitivity. J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 Pt 2):996-1002.

8. Arnold JD, Bachman GS, Rosen R, Kelly S, Rhoads GG. Vulvodynia: characteristics and associations with comorbidities and quality of life. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(3):617-624.

9. Parsons CL, Dell J, Stanford EJ, et al. The prevalence of interstitial cystitis in gynecologic patients with pelvic pain, as detected by intravesical potassium sensitivity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(5):1395-1400.

10. Clemens JQ, Meenan RT, O’Keefe Rosetti MC, et al. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis symptoms in a managed care population. J Urol. 2005;174(2):576-580.

11. Engman M, Lindehammar H, Wijma B. Surface electromyography diagnostics in women with partial vaginismus with or without vulvar vestibulitis and in asymptomatic women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2004;25(3-4):281-294.

12. Gunter J. Vulvodynia: new thoughts on a devastating condition. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(12):812-819.

13. Gordon AS, Panahlan-Jand M, McComb F, Melegari C, Sharp S. Characteristics of women with vulvar pain disorders: a Web-based survey. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003;29(suppl 1):45.-

14. Whitten CE, Cristobal K. Chronic pain is a chronic condition not just a symptom. Permanente J. 2005;9(3):43.-

15. Manchikanti L, Fellows B, Pampati V, et al. Comparison of psychological status of chronic pain patients and the general population. Pain Physician. 2002;5(1):40-48.

16. Banks SM, Kerns RD. Explaining the high rates of depression in chronic pain: a diathesis-stress framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119(1):95-110.

17. Sadownik LA. Clinical correlates of vulvodynia patients. A prospective study of 300 patients. J Reprod Med. 2000;5:40-48.Editor found in PubMed: Sadownik LA. Clinical profile of vulvodynia patients. A prospective study of 300 patients. J Reprod Med. 2000;45(8):679–684. Could not find the citation listed. Please confirm.

18. Reed BD, Haefner HK, Punch MR, Roth RS, Gorenflo DW, Gillespie BW. Psychosocial and sexual functioning in women with vulvodynia and chronic pelvic pain. A comparative evaluation. J Reprod Med. 2000;45(8):624-632.

19. Landry T, Bergeron S. Biopsychosocial factors associated with dyspareunia in a community sample of adolescent girls. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;June 22.

20. Goldstein A, Pukall C, Goldstein I. When Sex Hurts: A Woman’s Guide to Banishing Sexual Pain. Cambridge Mass: Da Capo Lifelong Books; 2011;117-126.

21. Labat JJ, Riant T, Robert R, Amarenco G, Lefaucheur JP, Rigaud J. Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria). Neurol Urodyn. 2008;27(4):306-310.

22. Popeney C, Answell V, Renney K. Pudendal entrapment as an etiology of chronic perineal pain: Diagnosis and treatment. Neurol Urodyn. 2007;26(6):820-827.

Although the incidence of vulvar pain has increased over the past decade—thanks to both greater awareness and increasing numbers of affected women—the phenomenon is not a recent development. As early as 1874, T. Galliard Thomas wrote, “[T]his disorder, although fortunately not very frequent, is by no means very rare.”1 He went on to express “surprise” that it had not been “more generally and fully described.”

Despite the focus Thomas directed to the issue, vulvar pain did not get much attention until the 21st century, when a number of studies began to gauge its prevalence. For example, in a study in Boston of about 5,000 women, the lifetime prevalence of chronic vulvar pain was 16%.2 And in a study in Texas, the prevalence of vulvar pain in an urban, largely minority population was estimated to be 11%.3 The Boston study also reported that “nearly 40% of women chose not to seek treatment, and, of those who did, 60% saw three or more doctors, many of whom could not provide a diagnosis.”2

Clearly, there is a need for comprehensive information on vulvar pain and its causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. To address the lack of guidance, OBG Management Contributing Editor Neal M. Lonky, MD, assembled a panel of experts on vulvar pain syndromes and invited them to share their considerable knowledge. The ensuing discussion, presented in three parts, offers a gold mine of information.

In this opening article, the panel focuses on causes, symptomatology, and diagnosis of this common complaint. In Part 2, which will appear in the October issue of this journal, the focus is the bounty of treatment options. Part 3 follows in November, when the discussion shifts to vestibulodynia.

The lower vagina and vulva are richly supplied with peripheral nerves and are, therefore, sensitive to pain, particularly the region of the hymeneal ring. Although the pudendal nerve (arrow) courses through the area, it is an uncommon source of vulvar pain.

Common diagnoses—and misdiagnoses

Dr. Lonky: What are the most common diagnoses when vulvar pain is the complaint?

Dr. Gunter: The most common cause of chronic vulvar pain is vulvodynia, although lichen simplex chronicus, chronic yeast infections, and non-neoplastic epithelial disorders, such as lichen sclerosus and lichen planus, can also produce irritation and pain. In postmenopausal women, atrophic vaginitis can also cause a burning pain, although symptoms are typically more vaginal than vulvar. Yeast and lichen simplex chronicus typically produce itching, although sometimes they can present with irritation and pain, so they must be considered in the differential diagnosis. It is important to remember that many women with vulvodynia have used multiple topical agents and may have developed complex hygiene rituals in an attempt to treat their symptoms, which can result in a secondary lichen simplex chronicus.

That said, there is a high frequency of misdiagnosis with yeast. For example, in a study by Nyirjesy and colleagues, two thirds of women who were referred to a tertiary clinic for chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis were found to have a noninfectious entity instead—most commonly lichen simplex chronicus and vulvodynia.4

Dr. Edwards: The most common “diagnosis” for vulvar pain is vulvodynia. However, the definition of vulvodynia is pain—i.e., burning, rawness, irritation, soreness, aching, or stabbing or stinging sensations—in the absence of skin disease, infection, or specific neurologic disease. Therefore, even though the usual cause of vulvar pain is vulvodynia, it is a diagnosis of exclusion, and skin disease, infection, and neurologic disease must be ruled out.

In regard to infection, Candida albicans and bacterial vaginosis (BV) are usually the first conditions that are considered when a patient complains of vulvar pain, but they are not common causes of vulvar pain and are never causes of chronic vulvar pain. Very rarely they may cause recurrent pain that clears, at least briefly, with treatment.

Candida albicans is usually primarily pruritic, and BV produces discharge and odor, sometimes with minor symptoms. Non-albicans Candida (e.g., Candida glabrata) is nearly always asymptomatic, but it occasionally causes irritation and burning.

Group B streptococcus is another infectious entity that very, very occasionally causes irritation and dyspareunia but is usually only a colonizer.

Herpes simplex virus is a cause of recurrent but not chronic pain.

Chronic pain is more likely to be caused by skin disease than by infection. Lichen simplex chronicus causes itching; any pain is due to erosions from scratching.

Dr. Haefner: Several other infectious conditions or their treatments can cause vulvar pain. For example, herpes (particularly primary herpes infection) is classically associated with vulvar pain. The pain is so great that, at times, the patient requires admission for pain control. Surprisingly, despite the known pain of herpes, approximately 80% of patients who have it are unaware of their diagnosis.

Although condyloma is generally a painless condition, many patients complain of pain following treatment for it, whether treatment involves topical medications or laser surgery.

Chancroid is a painful vulvar ulcer. Trichomonas can sometimes be associated with vulvar pain.

Dr. Lonky: What terminology do we use when we discuss vulvar pain?

Dr. Haefner: The current terminology used to describe vulvar pain was published in 2004, after years of debate over nomenclature within the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease.5 The terminology lists two major categories of vulvar pain:

- pain related to a specific disorder. This category encompasses numerous conditions that feature an abnormal appearance of the vulva (Table 1).

TABLE 1

Terminology and classification of vulvar pain from the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease

|

| SOURCE: Moyal-Barracco and Lynch.5 Reproduced with permission from the Journal of Reproductive Medicine. |

- vulvodynia, in which the vulva appears normal, other than occasional erythema, which is most prominent at the duct openings (vestibular ducts—Bartholin’s and Skene’s).

As for vulvar pain, there are two major forms:

- hyperalgesia (a low threshold for pain)

- allodynia (pain in response to light touch).

Some diseases that are associated with vulvar pain do not qualify for the diagnosis of vulvodynia (Table 2) because they are associated with an abnormal appearance of the vulva.

TABLE 2

Conditions other than vulvodynia that are associated with vulvar pain

| Acute irritant contact dermatitis (e.g., erosion due to podofilox, imiquimod, cantharidin, fluorouracil, or podophyllin toxin) |

| Aphthous ulcer |

| Atrophy |

| Bartholin’s abscess |

| Candidiasis |

| Carcinoma |

| Chronic irritant contact dermatitis |

| Endometriosis |

| Herpes (simplex and zoster) |

| Immunobullous diseases (including cicatricial pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, linear immunoglobulin A disease, etc.) |

| Lichen planus |

| Lichen sclerosus |

| Podophyllin overdose (see above) |

| Prolapsed urethra |

| Sjögren’s syndrome |

| Trauma |

| Trichomoniasis |

| Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia |

What needs to be ruled out for a diagnosis of vulvodynia?

Dr. Lonky: What skin diseases need to be ruled out before vulvodynia can be diagnosed?

Dr. Edwards: Skin diseases that affect the vulva are usually pruritic—pain is a later sign. Lichen simplex chronicus (also known as eczema) is pruritus caused by any irritant; any pain that arises is produced by visible excoriations from scratching.

Lichen sclerosus manifests as white epithelium that has a crinkling, shiny, or waxy texture. It can produce pain, especially dyspareunia. The pain is caused by erosions that arise from fragility and introital narrowing and inelasticity.

Vulvovaginal lichen planus is usually erosive and preferentially affects mucous membranes, especially the vestibule; it sometimes affects the vagina and mouth, as well.

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis is most likely a skin disease that affects only the vagina. It involves introital redness and a clinically and microscopically purulent vaginal discharge that also reveals parabasal cells and absent lactobacilli.

Dr. Lonky: You mentioned that neurologic diseases can sometimes cause vulvar pain. Which ones?

Dr. Edwards: Pudendal neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy, and post-herpetic neuralgia are the most common specific neurologic causes of vulvar pain. Multiple sclerosis can also produce pain syndromes. Post-herpetic neuralgia follows herpes zoster—not herpes simplex—virus infection.

Dr. Lonky: Any other conditions that can cause vulvar pain?

Dr. Haefner: Aphthous ulcers are common and are often flared by stress.

Non-neoplastic epithelial disorders are also seen frequently in health-care providers’ offices; many patients who experience them report pain on the vulva.

It is always important to consider cancer when a patient has an abnormal vulvar appearance and pain that has persisted despite treatment.

What are the most common vulvar pain syndromes?

Dr. Lonky: If you were to rank vulvar pain syndromes according to their prevalence, what would the most common syndromes be?

Dr. Gunter: Given the misdiagnosis of many women, who are told they have chronic yeast infection, as I mentioned, it’s hard to know which vulvar pain syndromes are most prevalent. I suspect that lichen simplex chronicus is most common, followed by vulvodynia, with chronic yeast infection a distant third.

My experience reflects what Nyirjesy and colleagues4 found: 65% to 75% of women referred to my clinic with chronic yeast actually have lichen simplex chronicus or vulvodynia. In postmenopausal women, atrophic vaginitis is also a consideration; it’s becoming more common now that the use of systemic hormone replacement therapy is decreasing.

Dr. Lonky: What about subsets of vulvodynia? Which ones are most common?

Dr. Edwards: There is good evidence of marked overlap among subsets of vulvodynia. The vast majority of women who have vulvodynia experience primarily provoked vestibular pain, regardless of age. However, I find that almost all patients also report pain that extends beyond the vestibule at times, as well as occasional unprovoked pain.

The diagnosis requires the exclusion of other causes of vulvar pain, and the subset is identified by the location of pain (that is, is it strictly localized or generalized or even migratory?) and its provoked or unprovoked nature.

Localized clitoral pain and vulvar pain localized to one side of the vulva are extremely uncommon, but they do occur. And although I rarely encounter teenagers and prepubertal children who have vulvodynia, I do have patients in both age groups who have vulvodynia.

Dr. Lonky: Are there racial differences in the prevalence of vulvodynia?

Dr. Edwards: Although several good studies show that women of African descent and white patients are equally likely to experience vulvodynia, the vast majority (99%) of my patients who have vulvodynia are white. My patients of African descent consult me primarily for itching or discharge.

My local demographics prevent me from judging the likelihood of Asians having vulvodynia, and our Hispanic population has limited access to health care.

In general, I don’t think that demographics are useful in making the diagnosis of vulvodynia.

Do women who have vulvar pain tend to have comorbidities?

Dr. Lonky: Do your patients who have vulvodynia or another vulvar pain syndrome tend to have comorbidities? If so, is this information helpful in establishing the diagnosis and planning therapy?

Dr. Haefner: Women who have vulvodynia often have other medical problems as well. In my practice, when new patients who have vulvodynia complete their intake survey, they often report a history of headache, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, fibromyalgia,6 chronic fatigue syndrome, back pain, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder. These comorbidities are not particularly helpful in establishing the diagnosis of vulvodynia, but they are an important consideration when choosing therapy for the patient. Often, the medications chosen to treat one condition will also benefit another condition. However, it’s important to check for potential interactions between drugs before prescribing a new treatment.

Dr. Gunter: A significant number of women who have vulvodynia also have other chronic pain syndromes. For example, the incidence of bladder pain syndrome–interstitial cystitis is 68% to 82% among women who have vulvodynia, compared with a baseline rate among all women of 6% to 11%.7-10 The rate of irritable bowel syndrome is more than doubled among women who have vulvodynia, compared with the general population (27% versus 12%).8 Another common comorbidity, hypertonic somatic dysfunction of the pelvic floor, is identified in 10% to 90% of women who have chronic vulvar pain.8,11,12 These women also have a higher incidence of nongenital pain syndromes, such as fibromyalgia, migraine, and TMJ dysfunction, than the general population, as Dr. Haefner noted.8,12,13

Many studies have evaluated psychological and emotional contributions to chronic vulvar pain. Pain and depression are intimately related—the incidence of depression among all people who experience chronic pain ranges from 27% to 54%, compared with 5% to 17% among the general population.14-16 The relationship is complex because chronic illness in general is associated with depression. Nevertheless, several studies have noted an increase in anxiety, stress, and depression among women who have vulvodynia.17-19

I screen every patient for depression using a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9); I also screen for anxiety. I find that a significant percentage of patients in my clinic are depressed or have an anxiety disorder. Failure to address these comorbidities makes treatment very difficult. I typically prescribe citalopram (Celexa), although there is some question whether it can safely be combined with a tricyclic antidepressant. We also offer stress-reduction classes, teach every patient the value of diaphragmatic breathing, offer mind-body classes for anxiety and stress, and provide intensive programs where the patient can learn important self-care skills, such as pacing (spacing activities throughout the day in a manner that avoids aggravating the pain), and address her anxiety and stress in a more guided manner. We also have a psychologist who specializes in pain for any patient who may need one-on-one counseling.

Dr. Edwards: The presence of comorbidities is somewhat useful in making the diagnosis of vulvodynia. I question my diagnosis, in fact, when a patient who has vulvodynia does not have headaches, low energy, depression, anxiety, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, sensitivity to medications, TMJ dysfunction, or urinary symptoms.

How common is pudendal neuralgia?

Dr. Lonky: How prevalent is a finding of pudendal neuralgia?

Dr. Edwards: The prevalence and incidence of pudendal neuralgia are not known. Those who specialize in this condition think it is relatively common. I do not identify or suspect it very often. Its definitive diagnosis and management are outside the purview of the general gynecologist, but the general gynecologist should recognize the symptoms of pudendal neuralgia and refer the patient for evaluation and therapy.

Dr. Lonky: What are those symptoms?

Dr. Haefner: Pudendal neuralgia often occurs following trauma to the pudendal nerve. The pudendal nerve arises from sacral nerves, generally sacral nerves 2 to 4. Several tests can be utilized to diagnose this condition, including quantitative sensor tests, pudendal nerve motor latency tests, electromyography (EMG), and pudendal nerve blocks.20

Nantes Criteria allow for making a diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia (Table 3).21

TABLE 3

Nantes Criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment

Essential criteria

|

Complementary diagnostic criteria

|

Exclusion criteria

|

Associated signs not excluding the diagnosis

|

| SOURCE: Labat et al.21 Reproduced with permission from Neurology and Urodynamics. |

Initial treatments for pudendal neuralgia should be conservative. Treatments consist of lifestyle changes to prevent flare of disease. Physical therapy, medical management, nerve blocks, and alternative treatments may be beneficial.

Pudendal nerve entrapment is often exacerbated by sitting (not on a toilet seat, however) and is reduced in a standing position. It tends to increase in intensity throughout the day.22 The final treatment for pudendal nerve entrapment is surgery if the nerve is compressed. By this time, the generalist is not generally the provider who performs the surgery.

Dr. Gunter: I believe pudendal neuralgia is sometimes overdiagnosed. EMG studies of the pudendal nerve, often touted as a diagnostic tool, are unreliable (they can be abnormal after vaginal delivery or vaginal hysterectomy, for example). In my experience, bilateral pain is less likely to be pudendal neuralgia; spontaneous bilateral compression neuropathy at exactly the same level is not a common phenomenon in chronic pain.

I reserve the diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia for women who have allodynia in the distribution of the pudendal nerve with severe pain on sitting, and who have exquisite tenderness when pressure is applied over the pudendal nerve (at the level of the ischial spine on vaginal examination). Typically, the vaginal sidewall on the affected side is very sensitive to light touch. I do see pudendal nerve pain after vaginal surgery when there has been some compromise of the pudendal nerve or the sacral plexus. This is typically unilateral pain.

Dr. Lonky: Thank you all. We’ll continue our discussion, with a focus on treatment, in the October 2011 issue.

- Part 2: A bounty of treatment options

(October 2011) - Part 3: Vestibulodynia

(November 2011)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Although the incidence of vulvar pain has increased over the past decade—thanks to both greater awareness and increasing numbers of affected women—the phenomenon is not a recent development. As early as 1874, T. Galliard Thomas wrote, “[T]his disorder, although fortunately not very frequent, is by no means very rare.”1 He went on to express “surprise” that it had not been “more generally and fully described.”

Despite the focus Thomas directed to the issue, vulvar pain did not get much attention until the 21st century, when a number of studies began to gauge its prevalence. For example, in a study in Boston of about 5,000 women, the lifetime prevalence of chronic vulvar pain was 16%.2 And in a study in Texas, the prevalence of vulvar pain in an urban, largely minority population was estimated to be 11%.3 The Boston study also reported that “nearly 40% of women chose not to seek treatment, and, of those who did, 60% saw three or more doctors, many of whom could not provide a diagnosis.”2

Clearly, there is a need for comprehensive information on vulvar pain and its causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment. To address the lack of guidance, OBG Management Contributing Editor Neal M. Lonky, MD, assembled a panel of experts on vulvar pain syndromes and invited them to share their considerable knowledge. The ensuing discussion, presented in three parts, offers a gold mine of information.

In this opening article, the panel focuses on causes, symptomatology, and diagnosis of this common complaint. In Part 2, which will appear in the October issue of this journal, the focus is the bounty of treatment options. Part 3 follows in November, when the discussion shifts to vestibulodynia.

The lower vagina and vulva are richly supplied with peripheral nerves and are, therefore, sensitive to pain, particularly the region of the hymeneal ring. Although the pudendal nerve (arrow) courses through the area, it is an uncommon source of vulvar pain.

Common diagnoses—and misdiagnoses

Dr. Lonky: What are the most common diagnoses when vulvar pain is the complaint?

Dr. Gunter: The most common cause of chronic vulvar pain is vulvodynia, although lichen simplex chronicus, chronic yeast infections, and non-neoplastic epithelial disorders, such as lichen sclerosus and lichen planus, can also produce irritation and pain. In postmenopausal women, atrophic vaginitis can also cause a burning pain, although symptoms are typically more vaginal than vulvar. Yeast and lichen simplex chronicus typically produce itching, although sometimes they can present with irritation and pain, so they must be considered in the differential diagnosis. It is important to remember that many women with vulvodynia have used multiple topical agents and may have developed complex hygiene rituals in an attempt to treat their symptoms, which can result in a secondary lichen simplex chronicus.

That said, there is a high frequency of misdiagnosis with yeast. For example, in a study by Nyirjesy and colleagues, two thirds of women who were referred to a tertiary clinic for chronic vulvovaginal candidiasis were found to have a noninfectious entity instead—most commonly lichen simplex chronicus and vulvodynia.4

Dr. Edwards: The most common “diagnosis” for vulvar pain is vulvodynia. However, the definition of vulvodynia is pain—i.e., burning, rawness, irritation, soreness, aching, or stabbing or stinging sensations—in the absence of skin disease, infection, or specific neurologic disease. Therefore, even though the usual cause of vulvar pain is vulvodynia, it is a diagnosis of exclusion, and skin disease, infection, and neurologic disease must be ruled out.

In regard to infection, Candida albicans and bacterial vaginosis (BV) are usually the first conditions that are considered when a patient complains of vulvar pain, but they are not common causes of vulvar pain and are never causes of chronic vulvar pain. Very rarely they may cause recurrent pain that clears, at least briefly, with treatment.

Candida albicans is usually primarily pruritic, and BV produces discharge and odor, sometimes with minor symptoms. Non-albicans Candida (e.g., Candida glabrata) is nearly always asymptomatic, but it occasionally causes irritation and burning.

Group B streptococcus is another infectious entity that very, very occasionally causes irritation and dyspareunia but is usually only a colonizer.

Herpes simplex virus is a cause of recurrent but not chronic pain.

Chronic pain is more likely to be caused by skin disease than by infection. Lichen simplex chronicus causes itching; any pain is due to erosions from scratching.

Dr. Haefner: Several other infectious conditions or their treatments can cause vulvar pain. For example, herpes (particularly primary herpes infection) is classically associated with vulvar pain. The pain is so great that, at times, the patient requires admission for pain control. Surprisingly, despite the known pain of herpes, approximately 80% of patients who have it are unaware of their diagnosis.

Although condyloma is generally a painless condition, many patients complain of pain following treatment for it, whether treatment involves topical medications or laser surgery.

Chancroid is a painful vulvar ulcer. Trichomonas can sometimes be associated with vulvar pain.

Dr. Lonky: What terminology do we use when we discuss vulvar pain?

Dr. Haefner: The current terminology used to describe vulvar pain was published in 2004, after years of debate over nomenclature within the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease.5 The terminology lists two major categories of vulvar pain:

- pain related to a specific disorder. This category encompasses numerous conditions that feature an abnormal appearance of the vulva (Table 1).

TABLE 1

Terminology and classification of vulvar pain from the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease

|

| SOURCE: Moyal-Barracco and Lynch.5 Reproduced with permission from the Journal of Reproductive Medicine. |

- vulvodynia, in which the vulva appears normal, other than occasional erythema, which is most prominent at the duct openings (vestibular ducts—Bartholin’s and Skene’s).

As for vulvar pain, there are two major forms:

- hyperalgesia (a low threshold for pain)

- allodynia (pain in response to light touch).

Some diseases that are associated with vulvar pain do not qualify for the diagnosis of vulvodynia (Table 2) because they are associated with an abnormal appearance of the vulva.

TABLE 2

Conditions other than vulvodynia that are associated with vulvar pain

| Acute irritant contact dermatitis (e.g., erosion due to podofilox, imiquimod, cantharidin, fluorouracil, or podophyllin toxin) |

| Aphthous ulcer |

| Atrophy |

| Bartholin’s abscess |

| Candidiasis |

| Carcinoma |

| Chronic irritant contact dermatitis |

| Endometriosis |

| Herpes (simplex and zoster) |

| Immunobullous diseases (including cicatricial pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, linear immunoglobulin A disease, etc.) |

| Lichen planus |

| Lichen sclerosus |

| Podophyllin overdose (see above) |

| Prolapsed urethra |

| Sjögren’s syndrome |

| Trauma |

| Trichomoniasis |

| Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia |

What needs to be ruled out for a diagnosis of vulvodynia?

Dr. Lonky: What skin diseases need to be ruled out before vulvodynia can be diagnosed?

Dr. Edwards: Skin diseases that affect the vulva are usually pruritic—pain is a later sign. Lichen simplex chronicus (also known as eczema) is pruritus caused by any irritant; any pain that arises is produced by visible excoriations from scratching.

Lichen sclerosus manifests as white epithelium that has a crinkling, shiny, or waxy texture. It can produce pain, especially dyspareunia. The pain is caused by erosions that arise from fragility and introital narrowing and inelasticity.

Vulvovaginal lichen planus is usually erosive and preferentially affects mucous membranes, especially the vestibule; it sometimes affects the vagina and mouth, as well.

Desquamative inflammatory vaginitis is most likely a skin disease that affects only the vagina. It involves introital redness and a clinically and microscopically purulent vaginal discharge that also reveals parabasal cells and absent lactobacilli.

Dr. Lonky: You mentioned that neurologic diseases can sometimes cause vulvar pain. Which ones?

Dr. Edwards: Pudendal neuralgia, diabetic neuropathy, and post-herpetic neuralgia are the most common specific neurologic causes of vulvar pain. Multiple sclerosis can also produce pain syndromes. Post-herpetic neuralgia follows herpes zoster—not herpes simplex—virus infection.

Dr. Lonky: Any other conditions that can cause vulvar pain?

Dr. Haefner: Aphthous ulcers are common and are often flared by stress.

Non-neoplastic epithelial disorders are also seen frequently in health-care providers’ offices; many patients who experience them report pain on the vulva.

It is always important to consider cancer when a patient has an abnormal vulvar appearance and pain that has persisted despite treatment.

What are the most common vulvar pain syndromes?

Dr. Lonky: If you were to rank vulvar pain syndromes according to their prevalence, what would the most common syndromes be?

Dr. Gunter: Given the misdiagnosis of many women, who are told they have chronic yeast infection, as I mentioned, it’s hard to know which vulvar pain syndromes are most prevalent. I suspect that lichen simplex chronicus is most common, followed by vulvodynia, with chronic yeast infection a distant third.

My experience reflects what Nyirjesy and colleagues4 found: 65% to 75% of women referred to my clinic with chronic yeast actually have lichen simplex chronicus or vulvodynia. In postmenopausal women, atrophic vaginitis is also a consideration; it’s becoming more common now that the use of systemic hormone replacement therapy is decreasing.

Dr. Lonky: What about subsets of vulvodynia? Which ones are most common?

Dr. Edwards: There is good evidence of marked overlap among subsets of vulvodynia. The vast majority of women who have vulvodynia experience primarily provoked vestibular pain, regardless of age. However, I find that almost all patients also report pain that extends beyond the vestibule at times, as well as occasional unprovoked pain.

The diagnosis requires the exclusion of other causes of vulvar pain, and the subset is identified by the location of pain (that is, is it strictly localized or generalized or even migratory?) and its provoked or unprovoked nature.

Localized clitoral pain and vulvar pain localized to one side of the vulva are extremely uncommon, but they do occur. And although I rarely encounter teenagers and prepubertal children who have vulvodynia, I do have patients in both age groups who have vulvodynia.

Dr. Lonky: Are there racial differences in the prevalence of vulvodynia?

Dr. Edwards: Although several good studies show that women of African descent and white patients are equally likely to experience vulvodynia, the vast majority (99%) of my patients who have vulvodynia are white. My patients of African descent consult me primarily for itching or discharge.

My local demographics prevent me from judging the likelihood of Asians having vulvodynia, and our Hispanic population has limited access to health care.

In general, I don’t think that demographics are useful in making the diagnosis of vulvodynia.

Do women who have vulvar pain tend to have comorbidities?

Dr. Lonky: Do your patients who have vulvodynia or another vulvar pain syndrome tend to have comorbidities? If so, is this information helpful in establishing the diagnosis and planning therapy?

Dr. Haefner: Women who have vulvodynia often have other medical problems as well. In my practice, when new patients who have vulvodynia complete their intake survey, they often report a history of headache, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, fibromyalgia,6 chronic fatigue syndrome, back pain, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder. These comorbidities are not particularly helpful in establishing the diagnosis of vulvodynia, but they are an important consideration when choosing therapy for the patient. Often, the medications chosen to treat one condition will also benefit another condition. However, it’s important to check for potential interactions between drugs before prescribing a new treatment.

Dr. Gunter: A significant number of women who have vulvodynia also have other chronic pain syndromes. For example, the incidence of bladder pain syndrome–interstitial cystitis is 68% to 82% among women who have vulvodynia, compared with a baseline rate among all women of 6% to 11%.7-10 The rate of irritable bowel syndrome is more than doubled among women who have vulvodynia, compared with the general population (27% versus 12%).8 Another common comorbidity, hypertonic somatic dysfunction of the pelvic floor, is identified in 10% to 90% of women who have chronic vulvar pain.8,11,12 These women also have a higher incidence of nongenital pain syndromes, such as fibromyalgia, migraine, and TMJ dysfunction, than the general population, as Dr. Haefner noted.8,12,13

Many studies have evaluated psychological and emotional contributions to chronic vulvar pain. Pain and depression are intimately related—the incidence of depression among all people who experience chronic pain ranges from 27% to 54%, compared with 5% to 17% among the general population.14-16 The relationship is complex because chronic illness in general is associated with depression. Nevertheless, several studies have noted an increase in anxiety, stress, and depression among women who have vulvodynia.17-19

I screen every patient for depression using a Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9); I also screen for anxiety. I find that a significant percentage of patients in my clinic are depressed or have an anxiety disorder. Failure to address these comorbidities makes treatment very difficult. I typically prescribe citalopram (Celexa), although there is some question whether it can safely be combined with a tricyclic antidepressant. We also offer stress-reduction classes, teach every patient the value of diaphragmatic breathing, offer mind-body classes for anxiety and stress, and provide intensive programs where the patient can learn important self-care skills, such as pacing (spacing activities throughout the day in a manner that avoids aggravating the pain), and address her anxiety and stress in a more guided manner. We also have a psychologist who specializes in pain for any patient who may need one-on-one counseling.

Dr. Edwards: The presence of comorbidities is somewhat useful in making the diagnosis of vulvodynia. I question my diagnosis, in fact, when a patient who has vulvodynia does not have headaches, low energy, depression, anxiety, irritable bowel syndrome, constipation, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, sensitivity to medications, TMJ dysfunction, or urinary symptoms.

How common is pudendal neuralgia?

Dr. Lonky: How prevalent is a finding of pudendal neuralgia?

Dr. Edwards: The prevalence and incidence of pudendal neuralgia are not known. Those who specialize in this condition think it is relatively common. I do not identify or suspect it very often. Its definitive diagnosis and management are outside the purview of the general gynecologist, but the general gynecologist should recognize the symptoms of pudendal neuralgia and refer the patient for evaluation and therapy.

Dr. Lonky: What are those symptoms?

Dr. Haefner: Pudendal neuralgia often occurs following trauma to the pudendal nerve. The pudendal nerve arises from sacral nerves, generally sacral nerves 2 to 4. Several tests can be utilized to diagnose this condition, including quantitative sensor tests, pudendal nerve motor latency tests, electromyography (EMG), and pudendal nerve blocks.20

Nantes Criteria allow for making a diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia (Table 3).21

TABLE 3

Nantes Criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment

Essential criteria

|

Complementary diagnostic criteria

|

Exclusion criteria

|

Associated signs not excluding the diagnosis

|

| SOURCE: Labat et al.21 Reproduced with permission from Neurology and Urodynamics. |

Initial treatments for pudendal neuralgia should be conservative. Treatments consist of lifestyle changes to prevent flare of disease. Physical therapy, medical management, nerve blocks, and alternative treatments may be beneficial.

Pudendal nerve entrapment is often exacerbated by sitting (not on a toilet seat, however) and is reduced in a standing position. It tends to increase in intensity throughout the day.22 The final treatment for pudendal nerve entrapment is surgery if the nerve is compressed. By this time, the generalist is not generally the provider who performs the surgery.

Dr. Gunter: I believe pudendal neuralgia is sometimes overdiagnosed. EMG studies of the pudendal nerve, often touted as a diagnostic tool, are unreliable (they can be abnormal after vaginal delivery or vaginal hysterectomy, for example). In my experience, bilateral pain is less likely to be pudendal neuralgia; spontaneous bilateral compression neuropathy at exactly the same level is not a common phenomenon in chronic pain.

I reserve the diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia for women who have allodynia in the distribution of the pudendal nerve with severe pain on sitting, and who have exquisite tenderness when pressure is applied over the pudendal nerve (at the level of the ischial spine on vaginal examination). Typically, the vaginal sidewall on the affected side is very sensitive to light touch. I do see pudendal nerve pain after vaginal surgery when there has been some compromise of the pudendal nerve or the sacral plexus. This is typically unilateral pain.

Dr. Lonky: Thank you all. We’ll continue our discussion, with a focus on treatment, in the October 2011 issue.

- Part 2: A bounty of treatment options

(October 2011) - Part 3: Vestibulodynia

(November 2011)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Thomas TG. Practical Treatise on the Diseases of Women. Philadelphia Pa: Henry C. Lea; 1874.

2. Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58(2):82-88.

3. Lavy RJ, Hynan LS, Haley RW. Prevalence of vulvar pain in an urban minority population. J Reprod Med. 2007;52(1):59-62.

4. Nyirjesy P, Peyton C, Weitz MV, Mathew L, Culhane JF. Causes of chronic vaginitis: analysis of a prospective database of affected women. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1185-1191.

5. Moyal-Barracco M, Lynch PJ. 2003 ISSVD terminology and classification of vulvodynia: a historical perspective. J Reprod Med. 2004;49(10):772-777.

6. Yunas MB. Fibromyalgia and overlapping disorders: the unifying concept of central sensitivity syndromes. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36(6):339-356.

7. Kahn BS, Tatro C, Parsons CL, Willems JJ. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in vulvodynia patients detected by bladder potassium sensitivity. J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 Pt 2):996-1002.

8. Arnold JD, Bachman GS, Rosen R, Kelly S, Rhoads GG. Vulvodynia: characteristics and associations with comorbidities and quality of life. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(3):617-624.

9. Parsons CL, Dell J, Stanford EJ, et al. The prevalence of interstitial cystitis in gynecologic patients with pelvic pain, as detected by intravesical potassium sensitivity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(5):1395-1400.

10. Clemens JQ, Meenan RT, O’Keefe Rosetti MC, et al. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis symptoms in a managed care population. J Urol. 2005;174(2):576-580.

11. Engman M, Lindehammar H, Wijma B. Surface electromyography diagnostics in women with partial vaginismus with or without vulvar vestibulitis and in asymptomatic women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2004;25(3-4):281-294.

12. Gunter J. Vulvodynia: new thoughts on a devastating condition. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(12):812-819.

13. Gordon AS, Panahlan-Jand M, McComb F, Melegari C, Sharp S. Characteristics of women with vulvar pain disorders: a Web-based survey. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003;29(suppl 1):45.-

14. Whitten CE, Cristobal K. Chronic pain is a chronic condition not just a symptom. Permanente J. 2005;9(3):43.-

15. Manchikanti L, Fellows B, Pampati V, et al. Comparison of psychological status of chronic pain patients and the general population. Pain Physician. 2002;5(1):40-48.

16. Banks SM, Kerns RD. Explaining the high rates of depression in chronic pain: a diathesis-stress framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119(1):95-110.

17. Sadownik LA. Clinical correlates of vulvodynia patients. A prospective study of 300 patients. J Reprod Med. 2000;5:40-48.Editor found in PubMed: Sadownik LA. Clinical profile of vulvodynia patients. A prospective study of 300 patients. J Reprod Med. 2000;45(8):679–684. Could not find the citation listed. Please confirm.

18. Reed BD, Haefner HK, Punch MR, Roth RS, Gorenflo DW, Gillespie BW. Psychosocial and sexual functioning in women with vulvodynia and chronic pelvic pain. A comparative evaluation. J Reprod Med. 2000;45(8):624-632.

19. Landry T, Bergeron S. Biopsychosocial factors associated with dyspareunia in a community sample of adolescent girls. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;June 22.

20. Goldstein A, Pukall C, Goldstein I. When Sex Hurts: A Woman’s Guide to Banishing Sexual Pain. Cambridge Mass: Da Capo Lifelong Books; 2011;117-126.

21. Labat JJ, Riant T, Robert R, Amarenco G, Lefaucheur JP, Rigaud J. Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria). Neurol Urodyn. 2008;27(4):306-310.

22. Popeney C, Answell V, Renney K. Pudendal entrapment as an etiology of chronic perineal pain: Diagnosis and treatment. Neurol Urodyn. 2007;26(6):820-827.

1. Thomas TG. Practical Treatise on the Diseases of Women. Philadelphia Pa: Henry C. Lea; 1874.

2. Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2003;58(2):82-88.

3. Lavy RJ, Hynan LS, Haley RW. Prevalence of vulvar pain in an urban minority population. J Reprod Med. 2007;52(1):59-62.

4. Nyirjesy P, Peyton C, Weitz MV, Mathew L, Culhane JF. Causes of chronic vaginitis: analysis of a prospective database of affected women. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1185-1191.

5. Moyal-Barracco M, Lynch PJ. 2003 ISSVD terminology and classification of vulvodynia: a historical perspective. J Reprod Med. 2004;49(10):772-777.

6. Yunas MB. Fibromyalgia and overlapping disorders: the unifying concept of central sensitivity syndromes. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36(6):339-356.

7. Kahn BS, Tatro C, Parsons CL, Willems JJ. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis in vulvodynia patients detected by bladder potassium sensitivity. J Sex Med. 2010;7(2 Pt 2):996-1002.

8. Arnold JD, Bachman GS, Rosen R, Kelly S, Rhoads GG. Vulvodynia: characteristics and associations with comorbidities and quality of life. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(3):617-624.

9. Parsons CL, Dell J, Stanford EJ, et al. The prevalence of interstitial cystitis in gynecologic patients with pelvic pain, as detected by intravesical potassium sensitivity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(5):1395-1400.

10. Clemens JQ, Meenan RT, O’Keefe Rosetti MC, et al. Prevalence of interstitial cystitis symptoms in a managed care population. J Urol. 2005;174(2):576-580.

11. Engman M, Lindehammar H, Wijma B. Surface electromyography diagnostics in women with partial vaginismus with or without vulvar vestibulitis and in asymptomatic women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2004;25(3-4):281-294.

12. Gunter J. Vulvodynia: new thoughts on a devastating condition. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62(12):812-819.

13. Gordon AS, Panahlan-Jand M, McComb F, Melegari C, Sharp S. Characteristics of women with vulvar pain disorders: a Web-based survey. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003;29(suppl 1):45.-

14. Whitten CE, Cristobal K. Chronic pain is a chronic condition not just a symptom. Permanente J. 2005;9(3):43.-

15. Manchikanti L, Fellows B, Pampati V, et al. Comparison of psychological status of chronic pain patients and the general population. Pain Physician. 2002;5(1):40-48.

16. Banks SM, Kerns RD. Explaining the high rates of depression in chronic pain: a diathesis-stress framework. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;119(1):95-110.

17. Sadownik LA. Clinical correlates of vulvodynia patients. A prospective study of 300 patients. J Reprod Med. 2000;5:40-48.Editor found in PubMed: Sadownik LA. Clinical profile of vulvodynia patients. A prospective study of 300 patients. J Reprod Med. 2000;45(8):679–684. Could not find the citation listed. Please confirm.

18. Reed BD, Haefner HK, Punch MR, Roth RS, Gorenflo DW, Gillespie BW. Psychosocial and sexual functioning in women with vulvodynia and chronic pelvic pain. A comparative evaluation. J Reprod Med. 2000;45(8):624-632.

19. Landry T, Bergeron S. Biopsychosocial factors associated with dyspareunia in a community sample of adolescent girls. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;June 22.

20. Goldstein A, Pukall C, Goldstein I. When Sex Hurts: A Woman’s Guide to Banishing Sexual Pain. Cambridge Mass: Da Capo Lifelong Books; 2011;117-126.

21. Labat JJ, Riant T, Robert R, Amarenco G, Lefaucheur JP, Rigaud J. Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria). Neurol Urodyn. 2008;27(4):306-310.

22. Popeney C, Answell V, Renney K. Pudendal entrapment as an etiology of chronic perineal pain: Diagnosis and treatment. Neurol Urodyn. 2007;26(6):820-827.

IN THIS ARTICLE

Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease

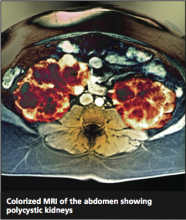

Twice as common as autism and half as well-known,1 autosomal polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) occurs in one in 400 to one in 1,000 people.2 It is an inherited progressive genetic disorder that causes hypertension and decreased renal function and, over time, can lead to kidney failure. Two polycstin genes that code for ADPKD, PKD1 and PKD2, were identified in 1994 and 1996, respectively.3,4 Awareness and understanding of the genes responsible for ADPKD have increased clinicians’ ability to identify at-risk patients and to slow or alter the course of the disease.

Case Presentation

A 45-year-old black man presents to your office with severe, nonradiating back pain and new-onset hypertension. Regarding the pain, he stated, “I turned around to see who kicked me, but no one was there.” When the pain began, he went to see the nurse at the school where he is employed, and she found that his blood pressure was high at 162/90 mm Hg. Although the patient’s back pain is resolving, he is very concerned about his blood pressure, since he has never had a high reading before.

He is the baseball coach and physical education teacher at the local high school and is in excellent physical condition as a result of his professional interaction with teenagers every day. He does not smoke or use any illicit drugs but does admit to occasional alcohol consumption. His medical history is significant only for occasional broken fingers and twisted ankles, all occurring while he was engaged in sports.

His family history includes one brother without medical problems, a brother and a sister with hypertension, a sister with diabetes and obesity, and a brother with a congenital abnormality that required a living donor kidney transplant at age 17 (the father served as donor). No family-wide workup has ever been done because no one practitioner has ever made a connection among these conditions and considered a diagnosis of ADPKD.

The patient’s blood pressure in the office is 172/92 mm Hg while sitting and 166/88 mm Hg while standing. He is somewhat sore with a localized spasm in the lumbar-sacral area but no radiation of pain. The patient has trouble touching his toes but reports that he can never touch his toes. His straight leg lift is negative. The rest of his physical exam is noncontributory.

What should be the next step in this patient’s workup?

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

ADPKD is a progressive expansion of numerous fluid-filled cysts that result in massive enlargement of the kidneys.5 Less than 5% of all nephrons become cystic; however, the average volume of a polycystic kidney is 1,000 mL (normal, 300 mL), that is, the volume of a standard-sized pineapple. Even with this significant enlargement, a decline in the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is not usually seen initially. Each cyst is derived from a single hyperproliferative epithelial cell. Increased cellular proliferation, followed by fluid secretion and alterations in the extracellular matrix, cause an outpouching from the parent nephron, which eventually detaches from the parent nephron and continues to enlarge and autonomously secrete fluid.6,7

PKD1 and PKD2 are two genes responsible for ADPKD that have been isolated so far. Since there are families carrying neither the PKD1 nor the PKD2 gene that still have an inherited type of ADPKD, there is suspicion that at least one more PKD gene, not yet isolated, exists.8 It is also possible that other genetic or environmental factors may be at play.9,10

In 1994, the PKD1 gene was isolated on chromosome 16,3 and it was found to code for polycystin 1. A lack of polycystin 1 causes an abnormality in the Na+/K(+)-ATPase pumps, leading to abnormal sodium reabsorption.11 How and why this happens is not quite clear. However, the hypertension that is a key objective finding in patients with ADPKD is thought to result from this pump abnormality.

PKD2 is found on the long arm of chromosome 4 and codes for polycystin 2.4 Polycystin 2 is an amino acid that is responsible for voltage-activated cellular calcium channels,5 again explaining the hypertension so commonly seen in the course of ADPKD. ADPKD-associated hypertension may be present as early as the teenage years.12

EPIDEMIOLOGY

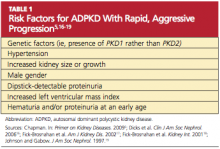

More than 85% of ADPKD cases are associated with PKD1, and this form is called polycystic kidney disease 1 (PKD 1), the more aggressive form of the disease.13,14 PKD 2 (the form associated with the gene PKD2), though less common, is also likely to progress to end-stage renal disease (ESRD), but at a later age (median age of 74 years, compared with 54 in patients with PKD 1).14 ADPKD accounts for about 5% of cases of ESRD in North America,9 but for most patients, presentation and decreased renal function do not occur until the 40s.15 However, patients with the risk factors listed in Table 15,16-19 are likely to experience a more rapid and aggressive form of the disease.

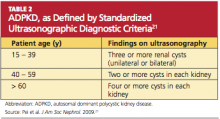

Even with the same germline mutation in a family with this inherited disease, the severity of ADPKD among family members is quite variable; this is true even in the case of twins.9,10,20 Since the age and symptoms at presentation can vary so greatly, a uniform method of identifying patients with ADPKD, along with staging, was needed. Most patients do not undergo genetic testing (ie, DNA linkage or gene-based direct sequencing9) for a diagnosis of ADPKD or to differentiate between the PKD 1 and PKD 2 disease forms unless they are participating in a research study. Diagnostic criteria were needed that were applicable for any type of ADPKD.

In 2009, the University of Toronto’s Division of Nephrology convened experts in the fields of nephrology and radiology to reach a consensus on standardized ultrasonographic diagnostic criteria.21 They formulated definitions based on a study of 948 individuals who were at risk for either PKD 1 or PKD 2 (see Table 221). The specificity and sensitivity of the resulting criteria range from 82% to 100%, making it possible to standardize the care and classification of renal patients worldwide.

Since family members with the same genotypes can experience very divergent disease manifestations, the two-hit hypothesis has been developed.22 In simple terms, it proposes that after the germline mutation (PKD1 or PKD2), there is a second somatic mutation that leads to progressive cyst formation; when the number and size of cysts increase, the patient starts to experience symptoms of ADPKD.22

Age at presentation can be quite variable, as can the presenting symptoms. Most patients with PKD 1 present in their 50s, with 54 being the average age in US patients.14 The most common presenting symptom is flank or back pain.2,5 The pain is due to the massive enlargement of the kidneys, causing a stretching of the kidney capsule and leading to a chronic, dull and persistent pain in the low back. Severe pain, sharp and cutting, occurs when one of the cysts hemorrhages; to some patients, the pain resembles a quick, powerful “kick in the back.” Hematuria can occur following cyst hemorrhage; depending on the location of the cyst that burst within the kidney (ie, how close it is to the collecting system) and how large it is, the amount and color of the hematuria can be impressive.

ADPKD is more common in men than women, and cyst rupture can be precipitated by trauma or lifting heavy objects. Cyst hemorrhage can turn the urine bright red, which is especially frightening to the male patient. Hematuria is often the key presenting symptom in patients who will be diagnosed with ADPKD-induced hypertension.

Besides hematuria, other common manifestations of ADPKD include:

• Hypertension (60% of affected patients, which increases to 100% by the time ESRD develops)

• Extrarenal cysts (100% of affected patients)

• Urinary tract infections

• Nephrolithiasis (20% of affected patients)

• Proteinuria, occasionally (18% of affected patients).2,5,23

Among these manifestations, those most commonly attributed to a diagnosis of ADPKD are hypertension, kidney stones, and urinary tract or kidney infections. Since isolated proteinuria is unusual in patients with ADPKD, it is recommended that another cause of kidney disease be explored in patients with this presentation.24

Extrarenal manifestations of cyst development are common, eventually occurring in all patients as they age. Hepatic cysts are universal in patients with ADPKD by age 30, although hepatic function is preserved. There may be a mild elevation in the alkaline phosphatase level in patients with ADPKD, resulting from the presence of hepatic cysts. Cysts may also be found in the pancreas, spleen, thyroid, and epididymis.5,25 Some patients may complain of dyspnea, pain, early satiety, or lower extremity edema as a result of enlarged cyst.

The Case Patient

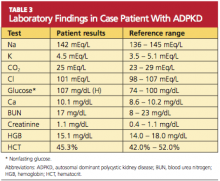

Because you recently attended a lecture about ADPKD, you are aware that flank pain in men with hypertension is indicative of ADPKD until proven otherwise. Believing that this patient’s hypertension is renal in origin, you order an abdominal ultrasound. You also order a comprehensive metabolic panel and a complete blood count. The patient’s GFR is measured at 89 mL/min (indicative of stage 2 kidney disease). Other results are shown in Table 3.

The very broad differential includes essential hypertension, hypertension resulting from intake of “power drinks” or salt in an athlete, illicit use of medications (including steroids), herniated disc leading to transient hypertension, and urinary tract infection or sexually transmitted disease. All of this is moot when the ultrasound shows both kidneys measuring greater than 15 cm, with four distinct cysts on the right kidney and three distinct cysts on the left.

You explain to the patient that ADPKD is a genetic disease and that he and his siblings each had a certain chance of inheriting it. Although different presentations may occur (“congenital” polycystic kidney disease, hypertension, or obesity), they all must undergo ultrasonographic screening for ADPKD. You add that although ADPKD is a genetic disease, it can also be diagnosed in different members of the same family at different ages.

TREATMENT

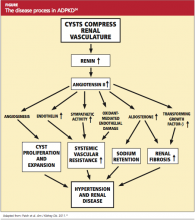

The goal of treatment for the patient with ADPKD is to slow cyst development and the natural course of the disease. If this can be achieved, the need for dialysis or kidney transplantation may be postponed for a number of years. Because cyst growth causes an elevation in renin and activates the angiotensin II renin system26 (see figure,24), an ACE inhibitor is the most effective treatment to lower blood pressure and thus slow the progression of ADPKD. Most patients with ADPKD are started on an ACE inhibitor at an early age to slow the rate of disease progression.27,28 Several studies are under way to determine the best antihypertensive medication and the optimal age for initiating treatment.29,30

Lipid screening and treatment for dyslipidemia are important23 because ADPKD can lead to a reduction in kidney function, resulting in chronic kidney disease (CKD). CKD is considered a coronary heart disease risk equivalent, and most professionals will treat the patient with ADPKD for hyperlipidemia.23,31 While there are no data showing that statin use will reduce the incidence of ESRD or delay the need for dialysis or kidney transplantation in patients with ADPKD, the beneficial effects of good renal blood flow and endothelial function have been noted.32,33

One of the most common and significant complications in ADPKD is intracranial hemorrhage resulting from a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. In the younger adult, the incidence of cerebral aneurysm is 4%, but incidence increases to 10% in patients older than 65.34-36 Family clusters of aneurysms have been reported.37 If an intracranial aneurysm is found in the family history, the risk of an aneurysm in another family member increases to 22%.38