User login

UPDATE ON CONTRACEPTION

- An appeal to the FDA: Remove the black-box warning for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate!

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; David A. Grimes, MD (August 2011) - 10 (+1) practical, evidence-based recommendations for you to improve contraceptive care now

Colleen Krajewski, MD; Mark D. Walters, MD (August 2011) - Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other?

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; March 2011) - IUD use in nulliparous and adolescent women

Jennefer A. Russo, MD; Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (Update on Contraception, August 2010)

“Emergency contraception,” “the morning-after pill,” and “Plan B” are all phrases commonly used in most gynecologists’ offices. Regrettably, these phrases are not heard as frequently among patients. With half of all pregnancies unintended and 40% of these pregnancies ending in abortion, there is clearly an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception (EC). Although more women have turned to EC in recent years, this contraceptive approach remains highly underutilized in the US population. Despite some increase in usage, we have not yet realized a lower rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.

Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined oral contraceptives (OCs) for postcoital contraception in 1974. Since then, researchers have been trying to manipulate various hormonal configurations in an attempt to best prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse. For years, we have quoted success rates as high as 85% when EC is initiated within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse1—but early studies may have overestimated the ability of EC to prevent unintended pregnancy. More recent investigations have shown that the magical “morning-after pill” and the physicians recommending it are long overdue for a wake-up call.

This installment of the Update on Contraception will review recent evidence on the efficacy of EC and make recommendations for practice, focusing on:

- the reasons EC has failed to reduce the rate of unintended pregnancy

- the efficacy of oral levonorgestrel (LNG) versus ulipristal acetate

- the impact of overweight and obesity on the efficacy of oral agents

- the overall superiority of the copper intrauterine device (IUD).

Half of all pregnancies are unintended, and 40% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion. These figures reflect an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception, which remains highly underutilized in the United States.

Access to EC is increasing, but women still lack basic information about it

Kavanaugh M, Schwarz EB. Counseling about and use of emergency contraception in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(2):81–86.

Kavanaugh M, Williams S, Schwarz EB. Emergency contraception use and counseling after changes in United States prescription status. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(8):2578–2581.

In 1974, Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined estrogen-progestin OCs for postcoital contraception.2 At the same time, Kesseru and colleagues were evaluating progestin-only regimens for the same purpose.3

For many subsequent years, combinations of common OC pills containing ethinyl estradiol and LNG were used for EC, until 1998, when a progestin-only method containing two 0.75-mg LNG pills was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and marketed in the United States under the brand name Plan B. That approval was based on a double-blind, randomized trial by the World Health Organization that demonstrated an almost threefold higher incidence of pregnancy with use of the Yuzpe regimen, compared with this LNG regimen.1

Access to the LNG-only method in the United States increased when the product was given behind-the-counter status in 2006, making it possible for women 18 years and older to obtain the medication without a prescription. In 2009, access was approved—also without a prescription—for 17-year-old women. The same year, the FDA approved Plan B One-Step, allowing women to take both 0.75-mg tablets together as a single tablet, theoretically improving treatment adherence.

Seeking a way to further increase use of EC, many investigators explored the potential benefits of advance provision. The idea was not new, as it had been proposed even for the Yuzpe method, and utilization increased significantly after 2006. Reviews of data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) showed an increase in EC use among women who had ever had sexual intercourse with a man from 4.2% of women surveyed in 2002 to 9.7% of women surveyed in 2006 to 2008, as reported by Kavanaugh and colleagues. Regrettably, this increase did not reduce the number of unintended pregnancies during the same time periods. Clearly, men and women fail to use EC every time they are at risk of unintended pregnancy.4

One of the biggest barriers to EC use is probably the lack of information patients receive from providers. Only 3% of respondents to the 2006–2008 NSFG indicated that they had received any counseling about EC in the past year, a number relatively unchanged from the 2002 survey. This finding suggests that the increase in EC use is likely due to the publicity surrounding the EC status change in 2006.

Greater availability and less restrictive access to EC has not reduced the rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States. However, improvements in the counseling of women may have an impact on the pregnancy rate. As the National Survey of Family Growth reveals, only about 3% of women receive any counseling about EC in a given year. For utilization of EC to increase, women need to be aware that it exists. Providers must begin to change their practices and discuss EC at all routine appointments before the public health benefit of a decrease in unintended pregnancies can ever be realized.

Ulipristal acetate makes its debut—and demonstrates superiority to LNG

Glasier A, Cameron S, Fine P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:555(9714)–562.

Fine P, Mathe H, Ginde S, et al. Ulipristal acetate taken 48–120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2pt1):257–263.

In 1998, the first-generation antiprogestin mifepristone was approved for use in France in medical abortion. As early as 1991, researchers were already investigating mifepristone as a method of EC, with great success.5,6 Overall, mifepristone was more effective and had fewer side effects than oral LNG, although the onset of menses was delayed with mifepristone.7 Mifepristone is available as EC in Russia and China, but its use in other countries is limited by social and political constraints.

Enter ulipristal acetate (UPA), a second-generation progesterone receptor modulator. Unlike its predecessor mifepristone, UPA (brand name, ella) is not approved for pregnancy termination, and no studies have been performed to evaluate the effects of UPA on an existing pregnancy. Because effects on pregnancy are unknown, the manufacturer states that exclusion of pregnancy is a requirement before UPA can be prescribed for EC.

The data on UPA as emergency contraception

UPA has been evaluated for EC in two large randomized trials.8,9 In the first study, UPA was administered in a 50-mg dose as long as 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. In the second study, conducted by Glasier and colleagues, a 30-mg micronized dose (bioequivalent to the 50-mg nonmicronized dose) was used as long as 120 hours after unprotected intercourse. Participants in both studies were randomized to UPA or oral LNG.

The first study showed UPA to be at least as effective as LNG in preventing pregnancy when taken within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. The efficacy of UPA did not appear to decline even when it was taken 48 to 72 hours after unprotected intercourse, unlike the efficacy of LNG.

The second study similarly found UPA to be non-inferior to LNG. Although neither study was powered to demonstrate superiority, both did show that UPA seemed to prevent more pregnancies than LNG.

Glasier and colleagues then performed a meta-analysis of both studies, demonstrating that UPA almost halved the risk of pregnancy, compared with LNG, in women who received treatment within 120 hours after intercourse, with a reduction of almost two thirds when UPA was taken within 24 hours of unprotected intercourse.

UPA has FDA approval for use within 120 hours after unprotected intercourse and requires a prescription. Although the data leading to this approval are incredibly encouraging, fewer than 200 of more than 2,000 women in three studies performed with UPA took EC 96 to 120 hours after intercourse. With such a small number of women actually tested in this time range, physicians should use caution when counseling patients about the efficacy of UPA when it is taken more than 96 hours after unprotected intercourse.8-10

UPA is more expensive than LNG, which may be a barrier to use by some women. However, because the probability of becoming pregnant when taking UPA within 120 hours of unprotected intercourse is lower than with LNG, the cost differential between drugs is much smaller when total costs—including the cost of unintended pregnancy—are consid-ered.11

Although the LNG-only method is the only EC that is available without a prescription, UPA appears to be more effective, particularly when it is taken more than 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. However, providers should be aware that a relatively small number of women have been studied with UPA beyond 72 hours after unprotected intercourse.

Although LNG-only EC is available behind the counter, the superiority of UPA means that physicians should discuss EC with patients during routine appointments and consider advance provision. For patients, cost and access will be important issues when deciding whether to use LNG or UPA.

EC is more likely to fail in overweight and obese women

Glasier A, Cameron S, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel [published online ahead of print April 2, 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.

Edelman AB, Carlson NE, Cherala G, et al. Impact of obesity on oral contraceptive pharmacokinetics and hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian activity. Contraception. 2009;80(2):119–127.

Westhoff CT, Torgal AL, Mayeda ER, et al. Ovarian suppression in normal-weight and obese women during oral contraceptive use. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 2):275–283.

As we observed, despite more widespread use of EC after the LNG-only method was made available without a prescription, we have not realized the public health benefit of a decreased rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.4 Studies have shown that, despite taking EC, women who have further acts of intercourse in the same cycle of EC use are more likely to conceive.12,13

We now have clear information about another specific population in which EC is more likely to fail: overweight and obese women. Compared with women of normal weight (body mass index [BMI] <25), overweight women (BMI 25–30) had a risk of pregnancy 1.5 times greater, and obese women (BMI ≥30) had a risk of pregnancy more than three times greater.13

Pregnancy rate among obese women using LNG was the same as the background rate

Obese women who used LNG as EC had a pregnancy rate of 5.8%, which is approximately equivalent to the overall pregnancy rate expected in the absence of EC. Overweight women in the LNG group had a relative risk of pregnancy that was double that of normal or underweight women, whereas overweight women taking UPA had the same risk as normal or underweight women taking the same medication.

When researchers compared pregnancy rates by weight instead of BMI, differences persisted between the two treatment options, with a limit of efficacy reached at a weight of 70 kg (154 lb) for LNG, compared with 88 kg (194 lb) for UPA.

OC hormone absorption is slower in obesity

Two recent studies—by Edelman and colleagues and Westhoff and coworkers—have demonstrated that OC hormone absorption is slower in obese women than it is in women of normal weight. With EC, immediate absorption is important; this delay could explain the lower efficacy in obese women. No studies have evaluated whether a higher or double dose of LNG would improve efficacy. Like women who experience repeated acts of unprotected intercourse, overweight and obese women are at high risk of EC failure and should be counseled about this risk.

As the incidence of obesity continues to increase exponentially in the United States, the efficacy of our commonly used methods of EC will continue to decline. At a minimum, overweight and obese women should be counseled to take UPA rather than LNG because of its increased efficacy in this population. We also need to inform overweight patients that their risk of pregnancy is higher than is commonly quoted.

Have we overlooked the best available emergency contraceptive?

Wu S, Godfrey EM, Wojdyla D, et al. Copper T380A intrauterine device for emergency contraception: a prospective, multicentre, cohort clinical trial. BJOG. 2010;117(10):1205–1210.

Turok D, Gurtcheff S, Handley E, et al. A pilot study of the Copper T380A IUD and levonorgestral for emergency contraception. Contraception. 2010;82(6):520–525.

The copper IUD has always been the most effective EC available. Not only does it prevent pregnancy when inserted as EC, but it continues to provide long-term, reversible contraception for 10 years or longer. Two large studies—one of them published within the past year—found efficacy rates of 96.9% and 100%, much higher than those associated with oral EC, with only two pregnancies occurring in more than 2,000 women.14,15

Although use of the IUD as EC was described as early as 1976, adoption of this method has been minimal in the United States.16 One reason may be the need for a clinician to insert the device, but many providers undoubtedly dismiss the IUD as an option for EC, believing that American women are unwilling to accept it. Some providers maintain the longstanding opinion that the IUD is an option only for parous women, although this notion has been cast aside by layers of medical evidence, as reviewed by current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) medical eligibility criteria for contraception.17

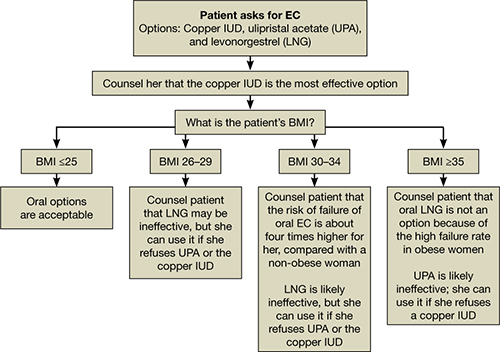

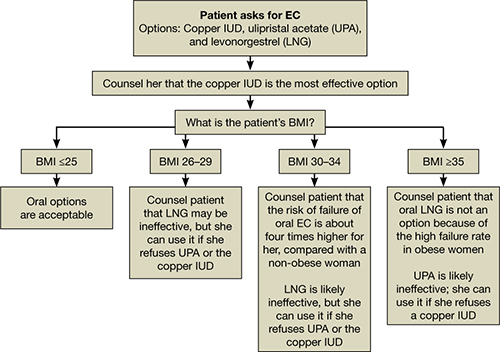

All women should be counseled about the long-term benefits of the copper IUD, the most reliable method of EC. The copper IUD not only provides effective emergency contraception but also long-term contraception for 10 years or more. Therefore, we should offer the copper IUD as first-line treatment for women seeking EC (FIGURE). This method is likely to be much more acceptable to patients than previously assumed.

Women are more accepting of the IUD than we thought

Schwarz and colleagues surveyed 412 women in Pittsburgh family planning clinics who were seeking EC or pregnancy testing and found that 15% of these women would be interested in same-day insertion of an IUD.18 This number increased if the IUD was free among women who reported difficulty with access to contraception.

In an observational study, Turok and colleagues offered women who were seeking EC a choice between the copper IUD and oral LNG and followed them for 6 months. Both methods were offered free of charge. They had assumed that, for every 20 women choosing oral LNG, one would choose the copper IUD. What they found was quite different: For every 1.5 women who chose oral LNG, one chose the copper IUD. Even more impressive was the number of women still using highly effective contraception (IUD, implant, or sterilization) 6 months later—4.5% in the oral LNG group and 61.5% in the IUD group. By the end of the 6-month period, two pregnancies had occurred in the oral LNG group and none in the IUD group.

How to counsel a patient seeking emergency contraceptionWe want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Lancet. 1998;352(9126):428-433.

2. Yuzpe A, Thurlow H, Ramzy I, Leyshon J. Post coital contraception–A pilot study. J Reprod Med. 1974;13(2):53-58.

3. Kesseru E, Garmendia F, Westphal N, Parada J. The hormonal and peripheral effects of d-norgestrel in postcoital contraception. Contraception. 1974;10(4):411-424.

4. Polis CB, Schaffer K, Banchard K, et al. Advance provision of emergency contraception for pregnancy prevention (full review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005497.-

5. Glasier A, Thong KJ, Dewar M, Mackie M, Baird DT. Postcoital contraception with mifepristone. Lancet. 1991;337(8754):1414-1415.

6. Webb AM. Alternative treatments in oral postcoital contraception: interim results. Adv Contracept. 1991;7(2–3):271-279.

7. Cheng L, Gülmezoglu AM, Piaggio G, Ezcurra E, Van Look PF. Interventions for emergency contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD001324.-

8. Creinin MD, Schlaff W, Archer D, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator for emergency contraception: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1089-1097.

9. Glasier A, Cameron S, Fine P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9714):555-562.

10. Fine P, Mathe H, Ginde S, et al. Ulipristal acetate taken 48-120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):257-263.

11. Thomas CM, Schmid R, Cameron S. Is it worth paying more for emergency hormonal contraception? The cost-effectiveness of ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2010;36(4):197-201.

12. von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Ding J, et al. Low dose mifepris-tone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9348):1803-1810.

13. Glasier A, Cameron S, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel [published online ahead of print April 2 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.

14. Zhou LY, Xiao BL. Emergency contraception with Multiload Cu-375 SL IUD: A multicenter clinical trial. Contraception. 2001;64(2):107-112.

15. Wu S, Godfrey EM, Wojdyla D, et al. Copper T380A intrauterine device for emergency contraception: a prospective, multicentre, cohort clinical trial. BJOG. 2010;117(10):1205-1210.

16. Lippes J, Malik T, Tatum HJ. The postcoital copper-T. Adv Plan Parent. 1976;11(1):24-29.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria contraceptive use 2010. MMWR. 2010;59 (RR04):1-6.

18. Schwarz EB, Kavanaugh M, Douglas E, Dubowitz T, Creinin MD. Interest in intrauterine contraception among seekers of emergency contraception and pregnancy testing. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(4):833-839.

- An appeal to the FDA: Remove the black-box warning for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate!

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; David A. Grimes, MD (August 2011) - 10 (+1) practical, evidence-based recommendations for you to improve contraceptive care now

Colleen Krajewski, MD; Mark D. Walters, MD (August 2011) - Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other?

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; March 2011) - IUD use in nulliparous and adolescent women

Jennefer A. Russo, MD; Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (Update on Contraception, August 2010)

“Emergency contraception,” “the morning-after pill,” and “Plan B” are all phrases commonly used in most gynecologists’ offices. Regrettably, these phrases are not heard as frequently among patients. With half of all pregnancies unintended and 40% of these pregnancies ending in abortion, there is clearly an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception (EC). Although more women have turned to EC in recent years, this contraceptive approach remains highly underutilized in the US population. Despite some increase in usage, we have not yet realized a lower rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.

Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined oral contraceptives (OCs) for postcoital contraception in 1974. Since then, researchers have been trying to manipulate various hormonal configurations in an attempt to best prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse. For years, we have quoted success rates as high as 85% when EC is initiated within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse1—but early studies may have overestimated the ability of EC to prevent unintended pregnancy. More recent investigations have shown that the magical “morning-after pill” and the physicians recommending it are long overdue for a wake-up call.

This installment of the Update on Contraception will review recent evidence on the efficacy of EC and make recommendations for practice, focusing on:

- the reasons EC has failed to reduce the rate of unintended pregnancy

- the efficacy of oral levonorgestrel (LNG) versus ulipristal acetate

- the impact of overweight and obesity on the efficacy of oral agents

- the overall superiority of the copper intrauterine device (IUD).

Half of all pregnancies are unintended, and 40% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion. These figures reflect an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception, which remains highly underutilized in the United States.

Access to EC is increasing, but women still lack basic information about it

Kavanaugh M, Schwarz EB. Counseling about and use of emergency contraception in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(2):81–86.

Kavanaugh M, Williams S, Schwarz EB. Emergency contraception use and counseling after changes in United States prescription status. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(8):2578–2581.

In 1974, Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined estrogen-progestin OCs for postcoital contraception.2 At the same time, Kesseru and colleagues were evaluating progestin-only regimens for the same purpose.3

For many subsequent years, combinations of common OC pills containing ethinyl estradiol and LNG were used for EC, until 1998, when a progestin-only method containing two 0.75-mg LNG pills was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and marketed in the United States under the brand name Plan B. That approval was based on a double-blind, randomized trial by the World Health Organization that demonstrated an almost threefold higher incidence of pregnancy with use of the Yuzpe regimen, compared with this LNG regimen.1

Access to the LNG-only method in the United States increased when the product was given behind-the-counter status in 2006, making it possible for women 18 years and older to obtain the medication without a prescription. In 2009, access was approved—also without a prescription—for 17-year-old women. The same year, the FDA approved Plan B One-Step, allowing women to take both 0.75-mg tablets together as a single tablet, theoretically improving treatment adherence.

Seeking a way to further increase use of EC, many investigators explored the potential benefits of advance provision. The idea was not new, as it had been proposed even for the Yuzpe method, and utilization increased significantly after 2006. Reviews of data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) showed an increase in EC use among women who had ever had sexual intercourse with a man from 4.2% of women surveyed in 2002 to 9.7% of women surveyed in 2006 to 2008, as reported by Kavanaugh and colleagues. Regrettably, this increase did not reduce the number of unintended pregnancies during the same time periods. Clearly, men and women fail to use EC every time they are at risk of unintended pregnancy.4

One of the biggest barriers to EC use is probably the lack of information patients receive from providers. Only 3% of respondents to the 2006–2008 NSFG indicated that they had received any counseling about EC in the past year, a number relatively unchanged from the 2002 survey. This finding suggests that the increase in EC use is likely due to the publicity surrounding the EC status change in 2006.

Greater availability and less restrictive access to EC has not reduced the rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States. However, improvements in the counseling of women may have an impact on the pregnancy rate. As the National Survey of Family Growth reveals, only about 3% of women receive any counseling about EC in a given year. For utilization of EC to increase, women need to be aware that it exists. Providers must begin to change their practices and discuss EC at all routine appointments before the public health benefit of a decrease in unintended pregnancies can ever be realized.

Ulipristal acetate makes its debut—and demonstrates superiority to LNG

Glasier A, Cameron S, Fine P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:555(9714)–562.

Fine P, Mathe H, Ginde S, et al. Ulipristal acetate taken 48–120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2pt1):257–263.

In 1998, the first-generation antiprogestin mifepristone was approved for use in France in medical abortion. As early as 1991, researchers were already investigating mifepristone as a method of EC, with great success.5,6 Overall, mifepristone was more effective and had fewer side effects than oral LNG, although the onset of menses was delayed with mifepristone.7 Mifepristone is available as EC in Russia and China, but its use in other countries is limited by social and political constraints.

Enter ulipristal acetate (UPA), a second-generation progesterone receptor modulator. Unlike its predecessor mifepristone, UPA (brand name, ella) is not approved for pregnancy termination, and no studies have been performed to evaluate the effects of UPA on an existing pregnancy. Because effects on pregnancy are unknown, the manufacturer states that exclusion of pregnancy is a requirement before UPA can be prescribed for EC.

The data on UPA as emergency contraception

UPA has been evaluated for EC in two large randomized trials.8,9 In the first study, UPA was administered in a 50-mg dose as long as 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. In the second study, conducted by Glasier and colleagues, a 30-mg micronized dose (bioequivalent to the 50-mg nonmicronized dose) was used as long as 120 hours after unprotected intercourse. Participants in both studies were randomized to UPA or oral LNG.

The first study showed UPA to be at least as effective as LNG in preventing pregnancy when taken within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. The efficacy of UPA did not appear to decline even when it was taken 48 to 72 hours after unprotected intercourse, unlike the efficacy of LNG.

The second study similarly found UPA to be non-inferior to LNG. Although neither study was powered to demonstrate superiority, both did show that UPA seemed to prevent more pregnancies than LNG.

Glasier and colleagues then performed a meta-analysis of both studies, demonstrating that UPA almost halved the risk of pregnancy, compared with LNG, in women who received treatment within 120 hours after intercourse, with a reduction of almost two thirds when UPA was taken within 24 hours of unprotected intercourse.

UPA has FDA approval for use within 120 hours after unprotected intercourse and requires a prescription. Although the data leading to this approval are incredibly encouraging, fewer than 200 of more than 2,000 women in three studies performed with UPA took EC 96 to 120 hours after intercourse. With such a small number of women actually tested in this time range, physicians should use caution when counseling patients about the efficacy of UPA when it is taken more than 96 hours after unprotected intercourse.8-10

UPA is more expensive than LNG, which may be a barrier to use by some women. However, because the probability of becoming pregnant when taking UPA within 120 hours of unprotected intercourse is lower than with LNG, the cost differential between drugs is much smaller when total costs—including the cost of unintended pregnancy—are consid-ered.11

Although the LNG-only method is the only EC that is available without a prescription, UPA appears to be more effective, particularly when it is taken more than 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. However, providers should be aware that a relatively small number of women have been studied with UPA beyond 72 hours after unprotected intercourse.

Although LNG-only EC is available behind the counter, the superiority of UPA means that physicians should discuss EC with patients during routine appointments and consider advance provision. For patients, cost and access will be important issues when deciding whether to use LNG or UPA.

EC is more likely to fail in overweight and obese women

Glasier A, Cameron S, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel [published online ahead of print April 2, 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.

Edelman AB, Carlson NE, Cherala G, et al. Impact of obesity on oral contraceptive pharmacokinetics and hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian activity. Contraception. 2009;80(2):119–127.

Westhoff CT, Torgal AL, Mayeda ER, et al. Ovarian suppression in normal-weight and obese women during oral contraceptive use. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 2):275–283.

As we observed, despite more widespread use of EC after the LNG-only method was made available without a prescription, we have not realized the public health benefit of a decreased rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.4 Studies have shown that, despite taking EC, women who have further acts of intercourse in the same cycle of EC use are more likely to conceive.12,13

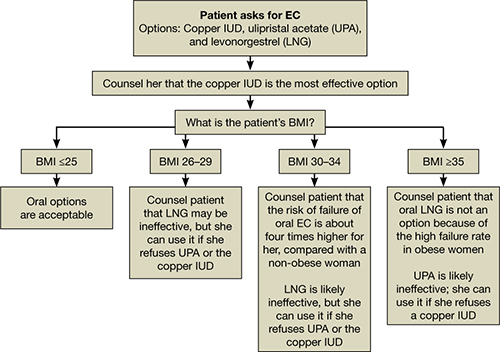

We now have clear information about another specific population in which EC is more likely to fail: overweight and obese women. Compared with women of normal weight (body mass index [BMI] <25), overweight women (BMI 25–30) had a risk of pregnancy 1.5 times greater, and obese women (BMI ≥30) had a risk of pregnancy more than three times greater.13

Pregnancy rate among obese women using LNG was the same as the background rate

Obese women who used LNG as EC had a pregnancy rate of 5.8%, which is approximately equivalent to the overall pregnancy rate expected in the absence of EC. Overweight women in the LNG group had a relative risk of pregnancy that was double that of normal or underweight women, whereas overweight women taking UPA had the same risk as normal or underweight women taking the same medication.

When researchers compared pregnancy rates by weight instead of BMI, differences persisted between the two treatment options, with a limit of efficacy reached at a weight of 70 kg (154 lb) for LNG, compared with 88 kg (194 lb) for UPA.

OC hormone absorption is slower in obesity

Two recent studies—by Edelman and colleagues and Westhoff and coworkers—have demonstrated that OC hormone absorption is slower in obese women than it is in women of normal weight. With EC, immediate absorption is important; this delay could explain the lower efficacy in obese women. No studies have evaluated whether a higher or double dose of LNG would improve efficacy. Like women who experience repeated acts of unprotected intercourse, overweight and obese women are at high risk of EC failure and should be counseled about this risk.

As the incidence of obesity continues to increase exponentially in the United States, the efficacy of our commonly used methods of EC will continue to decline. At a minimum, overweight and obese women should be counseled to take UPA rather than LNG because of its increased efficacy in this population. We also need to inform overweight patients that their risk of pregnancy is higher than is commonly quoted.

Have we overlooked the best available emergency contraceptive?

Wu S, Godfrey EM, Wojdyla D, et al. Copper T380A intrauterine device for emergency contraception: a prospective, multicentre, cohort clinical trial. BJOG. 2010;117(10):1205–1210.

Turok D, Gurtcheff S, Handley E, et al. A pilot study of the Copper T380A IUD and levonorgestral for emergency contraception. Contraception. 2010;82(6):520–525.

The copper IUD has always been the most effective EC available. Not only does it prevent pregnancy when inserted as EC, but it continues to provide long-term, reversible contraception for 10 years or longer. Two large studies—one of them published within the past year—found efficacy rates of 96.9% and 100%, much higher than those associated with oral EC, with only two pregnancies occurring in more than 2,000 women.14,15

Although use of the IUD as EC was described as early as 1976, adoption of this method has been minimal in the United States.16 One reason may be the need for a clinician to insert the device, but many providers undoubtedly dismiss the IUD as an option for EC, believing that American women are unwilling to accept it. Some providers maintain the longstanding opinion that the IUD is an option only for parous women, although this notion has been cast aside by layers of medical evidence, as reviewed by current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) medical eligibility criteria for contraception.17

All women should be counseled about the long-term benefits of the copper IUD, the most reliable method of EC. The copper IUD not only provides effective emergency contraception but also long-term contraception for 10 years or more. Therefore, we should offer the copper IUD as first-line treatment for women seeking EC (FIGURE). This method is likely to be much more acceptable to patients than previously assumed.

Women are more accepting of the IUD than we thought

Schwarz and colleagues surveyed 412 women in Pittsburgh family planning clinics who were seeking EC or pregnancy testing and found that 15% of these women would be interested in same-day insertion of an IUD.18 This number increased if the IUD was free among women who reported difficulty with access to contraception.

In an observational study, Turok and colleagues offered women who were seeking EC a choice between the copper IUD and oral LNG and followed them for 6 months. Both methods were offered free of charge. They had assumed that, for every 20 women choosing oral LNG, one would choose the copper IUD. What they found was quite different: For every 1.5 women who chose oral LNG, one chose the copper IUD. Even more impressive was the number of women still using highly effective contraception (IUD, implant, or sterilization) 6 months later—4.5% in the oral LNG group and 61.5% in the IUD group. By the end of the 6-month period, two pregnancies had occurred in the oral LNG group and none in the IUD group.

How to counsel a patient seeking emergency contraceptionWe want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- An appeal to the FDA: Remove the black-box warning for depot medroxyprogesterone acetate!

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD; David A. Grimes, MD (August 2011) - 10 (+1) practical, evidence-based recommendations for you to improve contraceptive care now

Colleen Krajewski, MD; Mark D. Walters, MD (August 2011) - Levonorgestrel or ulipristal: Is one a better emergency contraceptive than the other?

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial; March 2011) - IUD use in nulliparous and adolescent women

Jennefer A. Russo, MD; Mitchell D. Creinin, MD (Update on Contraception, August 2010)

“Emergency contraception,” “the morning-after pill,” and “Plan B” are all phrases commonly used in most gynecologists’ offices. Regrettably, these phrases are not heard as frequently among patients. With half of all pregnancies unintended and 40% of these pregnancies ending in abortion, there is clearly an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception (EC). Although more women have turned to EC in recent years, this contraceptive approach remains highly underutilized in the US population. Despite some increase in usage, we have not yet realized a lower rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.

Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined oral contraceptives (OCs) for postcoital contraception in 1974. Since then, researchers have been trying to manipulate various hormonal configurations in an attempt to best prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse. For years, we have quoted success rates as high as 85% when EC is initiated within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse1—but early studies may have overestimated the ability of EC to prevent unintended pregnancy. More recent investigations have shown that the magical “morning-after pill” and the physicians recommending it are long overdue for a wake-up call.

This installment of the Update on Contraception will review recent evidence on the efficacy of EC and make recommendations for practice, focusing on:

- the reasons EC has failed to reduce the rate of unintended pregnancy

- the efficacy of oral levonorgestrel (LNG) versus ulipristal acetate

- the impact of overweight and obesity on the efficacy of oral agents

- the overall superiority of the copper intrauterine device (IUD).

Half of all pregnancies are unintended, and 40% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion. These figures reflect an unmet need for both contraception and emergency contraception, which remains highly underutilized in the United States.

Access to EC is increasing, but women still lack basic information about it

Kavanaugh M, Schwarz EB. Counseling about and use of emergency contraception in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2008;40(2):81–86.

Kavanaugh M, Williams S, Schwarz EB. Emergency contraception use and counseling after changes in United States prescription status. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(8):2578–2581.

In 1974, Yuzpe and colleagues first published findings on the use of combined estrogen-progestin OCs for postcoital contraception.2 At the same time, Kesseru and colleagues were evaluating progestin-only regimens for the same purpose.3

For many subsequent years, combinations of common OC pills containing ethinyl estradiol and LNG were used for EC, until 1998, when a progestin-only method containing two 0.75-mg LNG pills was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and marketed in the United States under the brand name Plan B. That approval was based on a double-blind, randomized trial by the World Health Organization that demonstrated an almost threefold higher incidence of pregnancy with use of the Yuzpe regimen, compared with this LNG regimen.1

Access to the LNG-only method in the United States increased when the product was given behind-the-counter status in 2006, making it possible for women 18 years and older to obtain the medication without a prescription. In 2009, access was approved—also without a prescription—for 17-year-old women. The same year, the FDA approved Plan B One-Step, allowing women to take both 0.75-mg tablets together as a single tablet, theoretically improving treatment adherence.

Seeking a way to further increase use of EC, many investigators explored the potential benefits of advance provision. The idea was not new, as it had been proposed even for the Yuzpe method, and utilization increased significantly after 2006. Reviews of data from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) showed an increase in EC use among women who had ever had sexual intercourse with a man from 4.2% of women surveyed in 2002 to 9.7% of women surveyed in 2006 to 2008, as reported by Kavanaugh and colleagues. Regrettably, this increase did not reduce the number of unintended pregnancies during the same time periods. Clearly, men and women fail to use EC every time they are at risk of unintended pregnancy.4

One of the biggest barriers to EC use is probably the lack of information patients receive from providers. Only 3% of respondents to the 2006–2008 NSFG indicated that they had received any counseling about EC in the past year, a number relatively unchanged from the 2002 survey. This finding suggests that the increase in EC use is likely due to the publicity surrounding the EC status change in 2006.

Greater availability and less restrictive access to EC has not reduced the rate of unintended pregnancy in the United States. However, improvements in the counseling of women may have an impact on the pregnancy rate. As the National Survey of Family Growth reveals, only about 3% of women receive any counseling about EC in a given year. For utilization of EC to increase, women need to be aware that it exists. Providers must begin to change their practices and discuss EC at all routine appointments before the public health benefit of a decrease in unintended pregnancies can ever be realized.

Ulipristal acetate makes its debut—and demonstrates superiority to LNG

Glasier A, Cameron S, Fine P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:555(9714)–562.

Fine P, Mathe H, Ginde S, et al. Ulipristal acetate taken 48–120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2pt1):257–263.

In 1998, the first-generation antiprogestin mifepristone was approved for use in France in medical abortion. As early as 1991, researchers were already investigating mifepristone as a method of EC, with great success.5,6 Overall, mifepristone was more effective and had fewer side effects than oral LNG, although the onset of menses was delayed with mifepristone.7 Mifepristone is available as EC in Russia and China, but its use in other countries is limited by social and political constraints.

Enter ulipristal acetate (UPA), a second-generation progesterone receptor modulator. Unlike its predecessor mifepristone, UPA (brand name, ella) is not approved for pregnancy termination, and no studies have been performed to evaluate the effects of UPA on an existing pregnancy. Because effects on pregnancy are unknown, the manufacturer states that exclusion of pregnancy is a requirement before UPA can be prescribed for EC.

The data on UPA as emergency contraception

UPA has been evaluated for EC in two large randomized trials.8,9 In the first study, UPA was administered in a 50-mg dose as long as 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. In the second study, conducted by Glasier and colleagues, a 30-mg micronized dose (bioequivalent to the 50-mg nonmicronized dose) was used as long as 120 hours after unprotected intercourse. Participants in both studies were randomized to UPA or oral LNG.

The first study showed UPA to be at least as effective as LNG in preventing pregnancy when taken within 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. The efficacy of UPA did not appear to decline even when it was taken 48 to 72 hours after unprotected intercourse, unlike the efficacy of LNG.

The second study similarly found UPA to be non-inferior to LNG. Although neither study was powered to demonstrate superiority, both did show that UPA seemed to prevent more pregnancies than LNG.

Glasier and colleagues then performed a meta-analysis of both studies, demonstrating that UPA almost halved the risk of pregnancy, compared with LNG, in women who received treatment within 120 hours after intercourse, with a reduction of almost two thirds when UPA was taken within 24 hours of unprotected intercourse.

UPA has FDA approval for use within 120 hours after unprotected intercourse and requires a prescription. Although the data leading to this approval are incredibly encouraging, fewer than 200 of more than 2,000 women in three studies performed with UPA took EC 96 to 120 hours after intercourse. With such a small number of women actually tested in this time range, physicians should use caution when counseling patients about the efficacy of UPA when it is taken more than 96 hours after unprotected intercourse.8-10

UPA is more expensive than LNG, which may be a barrier to use by some women. However, because the probability of becoming pregnant when taking UPA within 120 hours of unprotected intercourse is lower than with LNG, the cost differential between drugs is much smaller when total costs—including the cost of unintended pregnancy—are consid-ered.11

Although the LNG-only method is the only EC that is available without a prescription, UPA appears to be more effective, particularly when it is taken more than 72 hours after unprotected intercourse. However, providers should be aware that a relatively small number of women have been studied with UPA beyond 72 hours after unprotected intercourse.

Although LNG-only EC is available behind the counter, the superiority of UPA means that physicians should discuss EC with patients during routine appointments and consider advance provision. For patients, cost and access will be important issues when deciding whether to use LNG or UPA.

EC is more likely to fail in overweight and obese women

Glasier A, Cameron S, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel [published online ahead of print April 2, 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.

Edelman AB, Carlson NE, Cherala G, et al. Impact of obesity on oral contraceptive pharmacokinetics and hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian activity. Contraception. 2009;80(2):119–127.

Westhoff CT, Torgal AL, Mayeda ER, et al. Ovarian suppression in normal-weight and obese women during oral contraceptive use. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 2):275–283.

As we observed, despite more widespread use of EC after the LNG-only method was made available without a prescription, we have not realized the public health benefit of a decreased rate of unintended pregnancy or abortion.4 Studies have shown that, despite taking EC, women who have further acts of intercourse in the same cycle of EC use are more likely to conceive.12,13

We now have clear information about another specific population in which EC is more likely to fail: overweight and obese women. Compared with women of normal weight (body mass index [BMI] <25), overweight women (BMI 25–30) had a risk of pregnancy 1.5 times greater, and obese women (BMI ≥30) had a risk of pregnancy more than three times greater.13

Pregnancy rate among obese women using LNG was the same as the background rate

Obese women who used LNG as EC had a pregnancy rate of 5.8%, which is approximately equivalent to the overall pregnancy rate expected in the absence of EC. Overweight women in the LNG group had a relative risk of pregnancy that was double that of normal or underweight women, whereas overweight women taking UPA had the same risk as normal or underweight women taking the same medication.

When researchers compared pregnancy rates by weight instead of BMI, differences persisted between the two treatment options, with a limit of efficacy reached at a weight of 70 kg (154 lb) for LNG, compared with 88 kg (194 lb) for UPA.

OC hormone absorption is slower in obesity

Two recent studies—by Edelman and colleagues and Westhoff and coworkers—have demonstrated that OC hormone absorption is slower in obese women than it is in women of normal weight. With EC, immediate absorption is important; this delay could explain the lower efficacy in obese women. No studies have evaluated whether a higher or double dose of LNG would improve efficacy. Like women who experience repeated acts of unprotected intercourse, overweight and obese women are at high risk of EC failure and should be counseled about this risk.

As the incidence of obesity continues to increase exponentially in the United States, the efficacy of our commonly used methods of EC will continue to decline. At a minimum, overweight and obese women should be counseled to take UPA rather than LNG because of its increased efficacy in this population. We also need to inform overweight patients that their risk of pregnancy is higher than is commonly quoted.

Have we overlooked the best available emergency contraceptive?

Wu S, Godfrey EM, Wojdyla D, et al. Copper T380A intrauterine device for emergency contraception: a prospective, multicentre, cohort clinical trial. BJOG. 2010;117(10):1205–1210.

Turok D, Gurtcheff S, Handley E, et al. A pilot study of the Copper T380A IUD and levonorgestral for emergency contraception. Contraception. 2010;82(6):520–525.

The copper IUD has always been the most effective EC available. Not only does it prevent pregnancy when inserted as EC, but it continues to provide long-term, reversible contraception for 10 years or longer. Two large studies—one of them published within the past year—found efficacy rates of 96.9% and 100%, much higher than those associated with oral EC, with only two pregnancies occurring in more than 2,000 women.14,15

Although use of the IUD as EC was described as early as 1976, adoption of this method has been minimal in the United States.16 One reason may be the need for a clinician to insert the device, but many providers undoubtedly dismiss the IUD as an option for EC, believing that American women are unwilling to accept it. Some providers maintain the longstanding opinion that the IUD is an option only for parous women, although this notion has been cast aside by layers of medical evidence, as reviewed by current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) medical eligibility criteria for contraception.17

All women should be counseled about the long-term benefits of the copper IUD, the most reliable method of EC. The copper IUD not only provides effective emergency contraception but also long-term contraception for 10 years or more. Therefore, we should offer the copper IUD as first-line treatment for women seeking EC (FIGURE). This method is likely to be much more acceptable to patients than previously assumed.

Women are more accepting of the IUD than we thought

Schwarz and colleagues surveyed 412 women in Pittsburgh family planning clinics who were seeking EC or pregnancy testing and found that 15% of these women would be interested in same-day insertion of an IUD.18 This number increased if the IUD was free among women who reported difficulty with access to contraception.

In an observational study, Turok and colleagues offered women who were seeking EC a choice between the copper IUD and oral LNG and followed them for 6 months. Both methods were offered free of charge. They had assumed that, for every 20 women choosing oral LNG, one would choose the copper IUD. What they found was quite different: For every 1.5 women who chose oral LNG, one chose the copper IUD. Even more impressive was the number of women still using highly effective contraception (IUD, implant, or sterilization) 6 months later—4.5% in the oral LNG group and 61.5% in the IUD group. By the end of the 6-month period, two pregnancies had occurred in the oral LNG group and none in the IUD group.

How to counsel a patient seeking emergency contraceptionWe want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Lancet. 1998;352(9126):428-433.

2. Yuzpe A, Thurlow H, Ramzy I, Leyshon J. Post coital contraception–A pilot study. J Reprod Med. 1974;13(2):53-58.

3. Kesseru E, Garmendia F, Westphal N, Parada J. The hormonal and peripheral effects of d-norgestrel in postcoital contraception. Contraception. 1974;10(4):411-424.

4. Polis CB, Schaffer K, Banchard K, et al. Advance provision of emergency contraception for pregnancy prevention (full review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005497.-

5. Glasier A, Thong KJ, Dewar M, Mackie M, Baird DT. Postcoital contraception with mifepristone. Lancet. 1991;337(8754):1414-1415.

6. Webb AM. Alternative treatments in oral postcoital contraception: interim results. Adv Contracept. 1991;7(2–3):271-279.

7. Cheng L, Gülmezoglu AM, Piaggio G, Ezcurra E, Van Look PF. Interventions for emergency contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD001324.-

8. Creinin MD, Schlaff W, Archer D, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator for emergency contraception: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1089-1097.

9. Glasier A, Cameron S, Fine P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9714):555-562.

10. Fine P, Mathe H, Ginde S, et al. Ulipristal acetate taken 48-120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):257-263.

11. Thomas CM, Schmid R, Cameron S. Is it worth paying more for emergency hormonal contraception? The cost-effectiveness of ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2010;36(4):197-201.

12. von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Ding J, et al. Low dose mifepris-tone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9348):1803-1810.

13. Glasier A, Cameron S, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel [published online ahead of print April 2 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.

14. Zhou LY, Xiao BL. Emergency contraception with Multiload Cu-375 SL IUD: A multicenter clinical trial. Contraception. 2001;64(2):107-112.

15. Wu S, Godfrey EM, Wojdyla D, et al. Copper T380A intrauterine device for emergency contraception: a prospective, multicentre, cohort clinical trial. BJOG. 2010;117(10):1205-1210.

16. Lippes J, Malik T, Tatum HJ. The postcoital copper-T. Adv Plan Parent. 1976;11(1):24-29.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria contraceptive use 2010. MMWR. 2010;59 (RR04):1-6.

18. Schwarz EB, Kavanaugh M, Douglas E, Dubowitz T, Creinin MD. Interest in intrauterine contraception among seekers of emergency contraception and pregnancy testing. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(4):833-839.

1. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Lancet. 1998;352(9126):428-433.

2. Yuzpe A, Thurlow H, Ramzy I, Leyshon J. Post coital contraception–A pilot study. J Reprod Med. 1974;13(2):53-58.

3. Kesseru E, Garmendia F, Westphal N, Parada J. The hormonal and peripheral effects of d-norgestrel in postcoital contraception. Contraception. 1974;10(4):411-424.

4. Polis CB, Schaffer K, Banchard K, et al. Advance provision of emergency contraception for pregnancy prevention (full review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD005497.-

5. Glasier A, Thong KJ, Dewar M, Mackie M, Baird DT. Postcoital contraception with mifepristone. Lancet. 1991;337(8754):1414-1415.

6. Webb AM. Alternative treatments in oral postcoital contraception: interim results. Adv Contracept. 1991;7(2–3):271-279.

7. Cheng L, Gülmezoglu AM, Piaggio G, Ezcurra E, Van Look PF. Interventions for emergency contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD001324.-

8. Creinin MD, Schlaff W, Archer D, et al. Progesterone receptor modulator for emergency contraception: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108(5):1089-1097.

9. Glasier A, Cameron S, Fine P, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomized non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9714):555-562.

10. Fine P, Mathe H, Ginde S, et al. Ulipristal acetate taken 48-120 hours after intercourse for emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 1):257-263.

11. Thomas CM, Schmid R, Cameron S. Is it worth paying more for emergency hormonal contraception? The cost-effectiveness of ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel 1.5 mg. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2010;36(4):197-201.

12. von Hertzen H, Piaggio G, Ding J, et al. Low dose mifepris-tone and two regimens of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a WHO multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9348):1803-1810.

13. Glasier A, Cameron S, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel [published online ahead of print April 2 2011]. Contraception. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.02.009.

14. Zhou LY, Xiao BL. Emergency contraception with Multiload Cu-375 SL IUD: A multicenter clinical trial. Contraception. 2001;64(2):107-112.

15. Wu S, Godfrey EM, Wojdyla D, et al. Copper T380A intrauterine device for emergency contraception: a prospective, multicentre, cohort clinical trial. BJOG. 2010;117(10):1205-1210.

16. Lippes J, Malik T, Tatum HJ. The postcoital copper-T. Adv Plan Parent. 1976;11(1):24-29.

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria contraceptive use 2010. MMWR. 2010;59 (RR04):1-6.

18. Schwarz EB, Kavanaugh M, Douglas E, Dubowitz T, Creinin MD. Interest in intrauterine contraception among seekers of emergency contraception and pregnancy testing. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(4):833-839.

Vitamin D and pregnancy: 9 things you need to know

- How much vitamin D should you recommend to your nonpregnant patients?

Emily D. Szmuilowicz, MD, MS; JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH (July 2011)

With all the publicity surrounding vitamin D lately, it’s no surprise that you have lots of questions. Should you test your patients for deficiency? When? What numbers should you use? And how do you treat a low vitamin D level?

In pregnancy, these issues become critical because there are not one but two patients to consider. Despite the lack of clear guidelines, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that you should at least consider monitoring the vitamin D status of your pregnant patients.

Fetal needs for vitamin D increase during the latter half of pregnancy, when bone growth and ossification are most prominent. Vitamin D travels to the fetus by passive transfer, and the fetus is entirely dependent on maternal stores.1 Therefore, maternal status is a direct reflection of fetal nutritional status.

The vitamin D level in breast milk also correlates with the maternal serum level, and a low vitamin D level in breast milk can exert a harmful effect on a newborn.

In this article, I address nine questions regarding vitamin D and pregnancy:

- Is vitamin D really a vitamin?

- Why do the numbers vary?

- Does the vitamin D level affect pregnancy outcomes?

- Can’t people get enough vitamin D through their diet?

- What level signals deficiency?

- How many women are deficient?

- Should you test all pregnant patients?

- How should you treat vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy?

- Can a person get too much vitamin D?

1. Is vitamin D really a vitamin?

For years, vitamin D was discussed solely in relation to bone metabolism and absorption, and deficiency states were the purview of endocrinologists and gynecologists who treated menopausal patients at risk of osteoporosis. Recent studies demonstrate that vitamin D plays a role in multiple endocrine systems. Indeed, vitamin D may be more correctly considered a hormone because it is a substance produced by one organ (skin) that travels through the bloodstream to target end organs. Vitamin D receptors have been found in bone, breast, brain, colon, muscle, and pancreatic tissues. Not only does vitamin D affect bone metabolism, it also modulates immune responses and even glucose metabolism.2 Vitamin D receptors have also been found in the placenta; their role in that organ remains to be elucidated.

2. Why do the numbers vary?

Some of the confusion surrounding vitamin D concerns the units used to measure and discuss it. Vitamin D can be measured in nanograms per milliliter (ng/mL) or in nanomoles per liter (nmol/L). A measurement of 1 ng/mL equals approximately 2.44 nmol/L. Therefore, deficiency in some articles is described as a vitamin D level below 20 ng/mL and in other articles as a level below 50 nmol/L. As for normal range, it may be listed as a level above 32 ng/mL or as a level above 75 nmol/L.

Compounding the confusion, vitamin D in supplement form can be written in two different measurements—using micrograms or international units. A measurement of 1 μg equals 40 IU, so a supplement of 150 μg/day is the same as one of 6,000 IU/day.

3. Does the vitamin D level affect pregnancy outcomes?

Vitamin D’s role in pregnancy outcomes has yet to be fully described, making it an exciting field to explore. Research into vitamin D and its effects on pregnancy is still in its infancy, but many intriguing associations have been noted. For example, lower levels of vitamin D have been associated with increased rates of cesarean delivery,3 bacterial vaginosis,4 and preeclampsia,5 as well as less efficient glucose metabolism.6

There is biological plausibility for vitamin D to play a role in pregnancy outcomes, given the presence of receptors in gestational tissues. Vitamin D receptors in uterine muscle could affect contractile strength, and vitamin D has been shown to have immunomodulatory effects, thereby potentially protecting the host from infection.

As I mentioned, placental vitamin D receptors and their role need further exploration.

4. Can’t people get enough vitamin D through their diet?

Very few foods contain a large amount of vitamin D, and the few that do (herring, cod liver oil) are not standard fare. Even fortified foods such as milk lack a substantial amount. TABLE 1 lists the amount of vitamin D in various foods.7

TABLE 1

In food, the vitamin D level is generally low

| Source | Amount of vitamin D (IU) |

|---|---|

| Egg yolk | 25 |

| Cereal, fortified with vitamin D, 1 cup | 40–50 |

| Cow’s milk, fortified with vitamin D, 8 oz | 98 |

| Soy milk, fortified with vitamin D, 8 oz | 100 |

| Orange juice, fortified with vitamin D, 8 oz | 100 |

| Quaker Nutrition for Women instant oatmeal, 1 packet | 154 |

| Tuna, canned in oil, 3 oz | 200 |

| Sardines, canned, 3 oz | 231 |

| Mackerel, 3 oz | 306 |

| Most multivitamins | 400 |

| Tri-Vi-Sol infant supplements, 1 drop | 400 |

| Prenatal vitamins | 400 |

| Catfish, 3 oz | 425 |

| Pink salmon, canned, 3 oz | 530 |

| Cod liver oil, 1 tablespoon | 1,360 |

| Herring, 3 oz | 1,383 |

| Over-the-counter vitamin D3 supplements | 2,000 (maximum) |

| Typical prescription of vitamin D2 for deficiency | 50,000 (given weekly until replete) |

5. What level signals deficiency?

Experts disagree about the level of vitamin D that signals deficiency. Many labs report a reference range of 32 to 100 ng/mL as normal. However, in November 2010, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) weighed in on the matter. After examining the data, the IOM suggested that a vitamin D level of 20 ng/mL is sufficient to prevent bone loss and changes seen in rickets and osteoporosis.

This level is hotly contested by experts in other fields, who argue that, although 20 ng/mL may be considered the bare minimum level to prevent negative bone resorption changes, it can hardly be construed as a normal level.

Nor did the IOM recommendation take pregnancy into consideration. Therefore, the IOM made no comment as to whether a level of 20 ng/mL is sufficient for a pregnant woman, given that the fetus will be actively soliciting maternal vitamin D for its own development. Indeed, some researchers have indicated that the actual daily recommended intake for pregnancy and lactation may be as high as 6,000 IU/day.8

6. How many women are deficient?

The rate of deficiency varies, but studies have documented rates as high as 97% in some pregnant populations; the rates vary by race and latitude.9-11

The high prevalence of deficiency in the population is due, in large part, to vitamin D’s mode of production and changes in human lifestyle and culture. Vitamin D is produced primarily through direct exposure of the skin to the sun. Over the past 50 years, as more and more people have come to spend their days in an office or factory instead of on a farm, the opportunity to produce vitamin D has greatly diminished.

Other entities or practices that reduce the production of vitamin D:

- Sunscreen SPF 50 may prevent skin cancer, but it also blocks vitamin D production.

- Fat cells Obese patients produce vitamin D less rapidly than patients of normal weight.

- Melanin Darker-skinned people produce vitamin D at a slower rate than those who have fair skin.

- Cultural practices Some religious and cultural practices mandate full skin coverage in public, particularly for women, leading to minimal sun exposure.

- Age Older people also produce vitamin D more slowly. Among the population of reproductive age, however, the effect of age is minimal.

- Latitude Northern latitudes, with their longer winters and shorter summers, provide less opportunity for sun exposure.

Because vitamin D is, in essence, a “seasonal” vitamin, it makes evolutionary sense that the human body has developed a wide normal range to “store up” vitamin D when sunshine is plentiful and then use its stores during times of scarcity, such as winter. This seasonal variability is another reason why the rate of deficiency can vary, depending on the time and location of study.

Because vitamin D deficiency is clinically silent until severe events such as rickets occur, the best way to check for it is to measure total levels of the two forms of vitamin D found in the body—D2 and D3. The recommended test is total 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25-OHD). Measurement of the activated form of vitamin D—1,25-OHD—will not tell you whether a person’s overall stores are lacking, because the body maintains a normal 1,25-OHD level over a wide range until severe deficiency occurs.

7. Should you test all pregnant patients for deficiency?

ACOG does not recommend that vitamin D be measured routinely in pregnant women.12 In a Committee Opinion published in July 2011, ACOG determined that “there is insufficient evidence to support a recommendation for screening all pregnant women for vitamin D deficiency.”12

Many experts disagree, however, citing the increased rate of rickets being found in the United States.6,8 Pediatricians in the United States have found such a high rate of deficiency in the neonatal population that the American Academy of Pediatricians now recommends that all exclusively breastfed babies be given a supplement of 400 IU of vitamin D daily, beginning in the first few days of life.13

ACOG acknowledged that, for pregnant patients “thought to be at increased risk, measurement of total levels can be considered with “high-risk groups” that have many of the risk factors cited earlier.12

If you want to test your patients, no single plan is recommended. A sample algorithm includes the following steps:

- Measure total 25-OHD at the time of prenatal registration labs

- Select a level of supplementation, based on the findings (see TABLE 2)

- Recheck the 25-OHD level after 3 months. For most patients, this would be around the time of a standard glucose screening test

- Adjust the supplementation level, as needed

- Measure 25-OHD at admission to labor and delivery.

TABLE 2

When (and with how much “D”) to treat pregnant patients

| If the 25-OHD level is… | …then supplement with* |

|---|---|

| <20 ng/mL | 50,000 IU oral vitamin D weekly for 12 weeks |

| 20–32 ng/mL | 2,000–4,000 IU oral vitamin D daily (~15,000–30,000 IU weekly) |

| >32 ng/mL | No action needed |

| *Assuming that the patient will continue taking a prenatal vitamin containing 400 IU/tablet. | |

8. How should you treat vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy?

Here, again, there is a lack of solid evidence. No guidelines exist for pregnant patients. In its Commitee Opinion, ACOG points out that higher-dose regimens have not been studied in pregnancy, but cites studies using up to 4,000 IU daily.12 The question becomes: Can guidelines that have been established for nonpregnant patients be used safely in pregnancy?

Although there is no evidence-based consensus, physiology and previous studies suggest that they can.

In one study, pregnant women were given doses as high as 200,000 IU in the third trimester to treat vitamin D deficiency.14 That investigation produced two key findings:

- There were no signs or symptoms of toxicity in patients or newborns, demonstrating that a single dose of a large amount of vitamin D can be administered safely.

- Despite the treatment, many of the women in this study remained deficient, indicating that continued supplementation would be required beyond the initial dose.

Although the dosage administered in this study seems like a large amount, it should be viewed in context: a Caucasian female can produce 50,000 IU of vitamin D from 30 minutes of sun exposure at midday.14

The IOM acknowledged that it underestimated the amount of vitamin D that can be taken safely and increased its upper limit of normal to 4,000 IU daily. Note that this upper limit is for people who are presumed to have a normal level to begin with. Therefore, it would be expected that a deficiency would require a greater amount for treatment.

As for treatment, both daily and weekly regimens are acceptable. Because vitamin D is fat-soluble, a daily dose of 1,000 IU is equivalent to a weekly dose of 7,000 IU. Many patients prefer the convenience of weekly dosing, which can also improve compliance.

See TABLE 2 for a proposed guideline on how to treat a pregnant patient, based on the 25-OHD level.

9. Can a person get too much vitamin D?

Vitamin D is fat-soluble. Should you worry about toxicity?

Because there is such a wide normal range for vitamin D, a person would have to be taking massive amounts of the nutrient for a substantial time before hypervitaminosis and a potential impact on calcium metabolism occur. Pharmacokinetic data demonstrate that toxicity may not occur until a vitamin D level of 300 ng/mL or higher is reached, which is three times the upper limit of normal for most reference ranges.15 A 2007 review found no cases of toxicity reported in the literature at a total serum level below 200 ng/mL (twice the normal limit) or a dose of less than 30,000 IU/day.16

Last words

Many questions and research opportunities remain regarding optimal vitamin D levels and supplementation in pregnancy, as well as the impact of vitamin D not only on pregnancy-related outcomes but on neonatal and infant health. One thing is certain: No one can argue that a nutritionally deficient state is preferred in pregnancy for maternal or fetal health. As advocates for women’s health, it behooves us to address this situation for the benefit of our patients and their children.

How do you manage the vitamin D requirements of pregnant and nonpregnant patients? Do you agree with the IOM that a vitamin D level of 20 ng/mL is sufficient for most individuals? Do you routinely measure the vitamin D level of your patients? Do you recommend vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy?

To tell us, click here

Study finds vitamin D supplementation in pregnancy to be safe and effective

Daily 4,000-IU vitamin D supplementation from 12 to 16 weeks of gestation is safe and effective in achieving vitamin D sufficiency in pregnant women and their neonates, according to a study published in the July 2011 issue of the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

Bruce W. Hollis, PhD, from the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, and colleagues assessed the need, safety, and effectiveness of vitamin D supplementation in 350 women with singleton pregnancies at 12 to 16 weeks of gestation. Participants were randomly assigned to receive 400 IU, 2,000 IU, or 4,000 IU vitamin D3 daily until delivery. The outcomes studied included maternal/neonatal circulating serum vitamin D (25-OHD) levels at delivery, achieving 25-OHD of 80 nmol/L or more, and achieving 25-OHD concentration for maximal 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol (1,25-OH2D) production.

The investigators found that the percentage of participants who achieved vitamin D sufficiency was significantly different between groups, with the 4,000-IU group having the highest percentage. Within 1 month of delivery, the relative risk (RR) of achieving 25-OHD of 80 nmol/L or more differed significantly between the 2,000-IU versus 400-IU groups and 4,000-IU versus 400-IU groups (RR, 1.52 and 1.60, respectively). There was no significant difference between the 2,000-IU and 4,000-IU groups. Circulatory 25-OHD directly influenced 1,25-OH2D levels throughout pregnancy, with maximal production of 1,25-OH2D in the 4,000-IU group. Vitamin D supplementation was not associated with adverse events, and safety measures were similar between the groups.

“A daily vitamin D dose of 4,000 IU was associated with improved vitamin D status throughout pregnancy, one month prior, and at delivery in both mother and neonate,” the authors write.

One of the study authors disclosed financial ties with the Diasorin Corporation.

Copyright © 2011 HealthDay. All rights reserved.

1. Dror DK, Allen LH. Vitamin D inadequacy in pregnancy: biology outcomes, and interventions. Nutr Rev. 2010;68(8):465-477.

2. Verstuyf A, Carmeliet G, Bouillon R, Mathieu C. Vitamin D: a pleiotropic hormone. Kidney Int. 2010;78(2):140-145.

3. Merewood A, Mehta SD, Chen TC, Bauchner H, Holick MF. Association between vitamin D deficiency and primary cesarean section. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(3):940-945.

4. Bodnar LM, Krohn MA, Simhan HN. Maternal vitamin D deficiency is associated with bacterial vaginosis in the first trimester of pregnancy. J Nutr. 2009;139(6):1157-1161.

5. Robinson CJ, Alanis MC, Wagner CL, Hollis BW, Johnson DD. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in early-onset severe preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):366.e1-6.

6. Lau SL, Gunton JE, Athayde NP, Byth K, Cheung NW. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and glycated haemoglobin levels in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Med J Aust. 2011;194(7):334-337.

7. Mulligan ML, Felton SK, Riek AE, Bernal-Mizrachi C. Implications of vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy and lactation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(5):429.e1-9.

8. Hollis BW. Vitamin D requirement during pregnancy and lactation. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22 (suppl 2):V39-44.

9. Johnson DD, Wagner CL, Hulsey TC, McNeil RB, Ebeling M, Hollis BW. Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency is common during pregnancy. Am J Perinatol. 2010;28(1):7-12.

10. Bodnar LM, Simhan HN, Powers RW, Frank MP, Cooperstein E, Roberts JM. High prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in black and white pregnant women residing in the northern United States and their neonates. J Nutr. 2007;137(2):447-452.

11. Ginde AA, Sullivan AF, Mansbach JM, Camargo CA, Jr. Vitamin D insufficiency in pregnant and nonpregnant women of childbearing age in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(5):436.e1-8.

12. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 495: Vitamin D: Screening and supplementation during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(1):197-198.

13. Wagner CL, Greer FR. American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;122(5):1142-1152.

14. Yu CK, Sykes L, Sethi M, Teoh TG, Robinson S. Vitamin D deficiency and supplementation during pregnancy. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2009;70(5):685-690.

15. Jones G. Pharmacokinetics of vitamin D toxicity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(2):582S-586S.

16. Hathcock JN, Shao A, Vieth R, Heaney R. Risk assessment for vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(1):6-18.

17. Hollis BW. Vitamin D requirement during pregnancy and lactation. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22 (suppl 2):V39-44.

- How much vitamin D should you recommend to your nonpregnant patients?

Emily D. Szmuilowicz, MD, MS; JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH (July 2011)

With all the publicity surrounding vitamin D lately, it’s no surprise that you have lots of questions. Should you test your patients for deficiency? When? What numbers should you use? And how do you treat a low vitamin D level?

In pregnancy, these issues become critical because there are not one but two patients to consider. Despite the lack of clear guidelines, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that you should at least consider monitoring the vitamin D status of your pregnant patients.

Fetal needs for vitamin D increase during the latter half of pregnancy, when bone growth and ossification are most prominent. Vitamin D travels to the fetus by passive transfer, and the fetus is entirely dependent on maternal stores.1 Therefore, maternal status is a direct reflection of fetal nutritional status.

The vitamin D level in breast milk also correlates with the maternal serum level, and a low vitamin D level in breast milk can exert a harmful effect on a newborn.

In this article, I address nine questions regarding vitamin D and pregnancy:

- Is vitamin D really a vitamin?

- Why do the numbers vary?

- Does the vitamin D level affect pregnancy outcomes?

- Can’t people get enough vitamin D through their diet?

- What level signals deficiency?

- How many women are deficient?

- Should you test all pregnant patients?

- How should you treat vitamin D deficiency in pregnancy?

- Can a person get too much vitamin D?

1. Is vitamin D really a vitamin?