User login

Man, 54, With Delusions and Seizures

A 54-year-old African-American man was brought by police officers to the emergency department (ED) after he called 911 several times to report seeing a Rottweiler looking into his second-story window. At the scene, the police were unable to confirm his story, thought the man seemed intoxicated, and brought him to the ED for evaluation.

The patient reported that he had been drinking the previous evening but denied current intoxication or illicit drug use. He denied experiencing symptoms of alcohol withdrawal.

Regarding his medical history, the patient admitted to having had seizures, including two episodes that he said required hospitalization. He described these episodes as right-hand “tingling” (paresthesias), accompanied by right-facial numbness and aphasia. The patient said his physician had instructed him to take “a few phenytoin pills” whenever these episodes occurred. He reported that the medication usually helped resolve his symptoms. He said he had taken phenytoin shortly before his current presentation.

According to friends of the patient who were questioned, he had had noticeable memory problems during the previous six to eight months. They said that he often told the same joke, day after day. His speech had become increasingly slurred, even when he was not drinking.

Once the patient’s medical records were retrieved, it was revealed that he had been hospitalized twice for witnessed grand mal seizures about six months before his current admission; he had been drinking alcohol prior to both episodes. He underwent electroencephalography (EEG) during one of these hospitalizations, with results reported as normal. On both occasions, the patient was discharged with phenytoin and was instructed to follow up with his primary care provider and neurologist.

The patient, who reported working in customer service, had no known allergies. He claimed to drink one or two 40-ounce beers twice per week and admitted to occasional cocaine use. Of significance in his family history was a fatal MI in his mother. Although the patient denied any history of rashes or lesions, his current delirium made it impossible to obtain a reliable sexual history; a friend who was questioned, however, described the patient as promiscuous.

On initial physical examination, the man was afebrile, tachycardic, and somewhat combative with the ED staff. He was fully oriented to self but only partially to place and time.

His right pupil was 3+ and his left pupil was 2+, with neither reactive to light. He spoke with tangential speech and his gait was unsteady, but no other significant abnormalities were noted. A full assessment revealed no rashes or other lesions.

Significant laboratory findings included a low level of phenytoin, a negative blood alcohol level, presence of cocaine on urine drug screening, and normal levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), vitamin B12, and folate. The patient’s serum VDRL (venereal disease research laboratory) titer was positive at 1:256.

Electroencephalography showed diffuse slowing, and brain CT performed in the ED showed atrophy that was mild but appropriate for a person of the patient’s age, with no evidence of a cerebrovascular accident (CVA). Aneurysm was ruled out by CT angiography of the brain. MRI revealed persistent increased signal in the subarachnoid space.

The patient was admitted with an initial diagnosis of paranoid delusional psychosis and monitored for alcohol withdrawal. He was given lorazepam as needed for agitation. Consultations were arranged with the psychiatry service regarding his delusions, and with neurology to determine whether to continue phenytoin.

The patient showed little response during the next several days. Based on positive results on serum VDRL with high titer, the presence of Argyll-Robertson pupils on exam, and his history of dementia-like symptoms, a lumbar puncture was performed to rule out neurosyphilis. In the patient’s cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) analysis, the first tube was clear and colorless, with 72 cells (28% neutrophils, 59% lymphocytes); glucose, 64 mg/dL; and total protein, 117 mg/dL. The fourth tube had 34 cells (17% neutrophils, 65% lymphocytes) and a positive VDRL titer at 1:128. Results from a serum syphilis immunoglobulin G (IgG) test were positive, and HIV antibody testing was nonreactive, confirming the diagnosis of neurosyphilis.

The hospital’s infectious disease (ID) team recommended treatment with IV penicillin for 14 days. Once this was completed, the patient was discharged with instructions to follow up at the ID clinic in three months for a repeat CSF VDRL titer to monitor for resolution of the disease. His prescription for phenytoin was discontinued.

At the time of discharge, it was noted that the patient showed no evidence of having regained cognitive function. He was deemed by the psychiatry service to lack decision-making capacity—a likely sequelae of untreated neurosyphilis of unknown duration.

He did return to the ID clinic six months after his discharge. At that visit, a VDRL serum titer was drawn with a result of 1:64, a decrease from 1:128. His syphilis IgG remained positive, however.

Discussion

Definition and Epidemiology

Syphilis is commonly known as a sexually transmitted disease with primary, secondary, and tertiary (early and late latent) stages.1 Neurosyphilis is defined as a manifestation of the inflammatory response to invasion over decades by the Treponema pallidum spirochete in the CSF as a result of untreated primary and/or secondary syphilis.2 About one in 10 patients with untreated syphilis will experience neurologic involvement.3,4 Before 2005, neurosyphilis was required to be reported as a specific stage of syphilis (ie, a manifestation of tertiary syphilis4), but now should be reported as syphilis with neurologic manifestations.5

A reportable infectious disease, syphilis was widespread until the advent of penicillin. According to CDC statistics,6 the number of reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis has declined steadily since 1943. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the number of tertiary cases also began to plateau, likely as a result of earlier diagnosis and more widespread use of penicillin. Recent case reports suggest greater prevalence of syphilis among men than women and increased incidence among men who have sex with men.7

Pathogenesis

Syphilis is most commonly spread by sexual contact or contact with an infected primary lesion (chancre). Less likely routes of transmission are placental passage or blood transfusion. Infectivity is greatest in the early disease stages.8

Primary syphilis is marked by transmission of the spirochete, ending with development of secondary syphilis (usually two to 12 weeks after transmission). A chancre commonly develops but is often missed by patients because it is painless and can heal spontaneously.7 The chancre is also often confused with two other sources of genital lesions, herpes simplex (genital herpes) and Haemophilus ducreyi (chancroid). In two-thirds of cases of untreated primary syphilis, the infection clears spontaneously, but in the remaining one-third, the disease progresses.8

Secondary syphilis, with or without presence of a chancre, manifests with constitutional symptoms, including lymphadenopathy, fever, headache, and malaise. Patients in this disease phase may also present with a generalized, nonpruritic, macular to maculopapular or pustular rash. The rash can affect the skin of the trunk, the proximal extremities, and the palms and soles. Ocular involvement may occur, especially in patients who are coinfected with HIV.8 In either primary or secondary syphilis, infection can invade the central nervous system.1

During latent syphilis, patients show serologic conversion without overt symptoms. Early latent syphilis is defined as infection within the previous year, as demonstrated by conversion from negative to positive testing, or an increase in titers within the previous year. Any case occurring after one year is defined as late or unknown latent syphilis.8

Tertiary syphilis is marked by complications resulting from untreated syphilis; affected patients commonly experience central nervous system and cardiovascular involvement. Gummatous disease is seen in 15% of patients.1

The early stages of neurosyphilis may be asymptomatic, acute meningeal, and meningovascular.1,4,8,9 Only 5% of patients with early neurosyphilis are symptomatic, with the added potential for cranial neuritis or ocular involvement.1 The late stages of neurosyphilis are detailed in the table.1,4,8

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of syphilis is made by testing blood samples or scrapings from a lesion. In patients with suspected syphilis, rapid plasma reagin (RPR) testing or a VDRL titer is commonly ordered. When results are positive, a serum treponemal test is recommended to confirm a diagnosis of syphilis. Options include the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA-ABS) and the microhemagglutinin assay for antibody to T pallidum (MHA-TP).5

If neurologic symptoms are present, a CSF sample should be obtained, followed by the same testing. A confirmed diagnosis of neurosyphilis is defined by the CDC as syphilis at any stage that meets laboratory criteria for neurosyphilis5; these include increased CSF protein or an elevated CSF leukocyte count with no other known cause, and clinical signs or symptoms without other known causes.7

Treatment

Treatment of syphilis generally consists of penicillin, administered intramuscularly (IM) or IV, depending on the stage. According to 2006 guidelines from the CDC,10,11 treatment for adults with primary and secondary syphilis is a single dose of IM penicillin G, 2.4 million units. If neurosyphilis is suspected, recommended treatment is IV penicillin G, 18 to 24 million units per day divided into six doses (ie, 3 to 4 million units every four hours) or continuous pump infusion for 10 to 14 days.10-12 Follow-up is recommended by monitoring CSF titers to ensure clearance of infection; retreatment may be required if CSF abnormalities persist after two years.11

Patients with a penicillin allergy should undergo desensitization, as penicillin is the preferred agent; the potential exists for cross-reactivity with ceftriaxone, a possible alternative for patients with neurosyphilis.11 All patients diagnosed with syphilis should also be tested for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.10-12

The prognosis of patients treated for neurosyphilis is generally good if the condition is diagnosed and treated early. In patients with cerebral atrophy, frontal lesions, dementia, or tabes dorsalis, the potential for recovery decreases.2,13,14

Teaching Points

There are several teaching points to take away from this case:

• Remember to rule out a CVA in any patient who presents with numbness, paresthesias, or slurred speech. In this case, a brain CT and CT angiography of the brain were both obtained in the ED before the patient was admitted. They both yielded negative results; because the patient’s history was consistent with alcohol and drug use and he had a history of seizures, he was monitored closely for signs of withdrawal or further seizure.

• Phenytoin is an antiepileptic agent whose use requires proper patient education and drug level monitoring. Appropriate follow-up must be ensured before phenytoin therapy is begun, as toxicity can result in nystagmus, ataxia, slurred speech, decreased coordination, mental confusion, and possibly death.15,16

• For patients with a suspected acute change in mental status, a workup is required and should be tailored appropriately, based on findings. This should include, but not be limited to, a thorough history and physical exam, CT of the brain (to rule out an acute brain injury17), and, if warranted, MRI of the brain. Also, a urine drug screen and alcohol level, a complete blood count, a TSH level (to evaluate for altered thyroid function that may explain mental status changes), comprehensive panel, RPR testing and/or a VDRL titer should be obtained, depending on the facility’s protocol18,19; at some facilities, a treponemal test, rather than VDRL, is being obtained at the outset.20 Levels of vitamin B12 (as part of the dementia workup), folate, thiamine, and ammonia (in patients with suspected liver disease) can also be obtained in patients with change in mental status.18,19 Urinalysis should not be overlooked to check for a urinary tract infection, especially in elderly patients.21

• If primary syphilis is suspected, treatment must be undertaken.20

Conclusion

Despite the decline seen since the 1940s in cases of primary and secondary syphilis, and the effectiveness of penicillin in treating the infection early, patients with late-stage syphilis, including those with neurosyphilis, may still present to the emergency care, urgent care, or primary care setting. Immediate treatment with penicillin is recommended to achieve an optimal prognosis for the affected patient.

1. Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1510-1514.

2. Simon RP. Chapter 20. Neurosyphilis. In: Klausner JD, Hook EW III, eds. Current Diagnosis & Treatment of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. USA: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2007:130-137.

3. Sanchez FM, Zisselman MH. Treatment of psychiatric symptoms associated with neurosyphilis. Psychosomatics. 2007;48:440-445.

4. Marra CM. Neurosyphilis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2004;4(6):435-440.

5. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases surveillance, 2007: STD surveillance case definitions. www.cdc.gov/std/stats07/app-casedef.htm. Accessed March 23, 2011.

6. CDC. 2008 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance: Table 1. Cases of sexually transmitted diseases reported by state health departments and rates per 100,000 population: United States, 1941-2008. www.cdc.gov/std/stats08/tables/1.htm. Accessed March 23, 2011.

7. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs): Syphilis: CDC fact sheet. www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/STDfact-syphilis.htm. Accessed March 23, 2011.

8. Tramont EC. Chapter 238. Treponema pallidum (syphilis). In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

9. Ghanem KG. Neurosyphilis: a historical perspective and review. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010; 16(5):e157-e168.

10. Workowski KA, Berman SM; CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

11. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases: treatment guidelines 2006. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2006/genital-ulcers.htm#genulc6. Accessed March 29, 2011.

12. Drugs for sexually transmitted infections. Treatment Guidelines from the Medical Letter. 2010;95:95a. http://secure.medicalletter.org. Accessed March 23, 2011.

13. Russouw HG, Roberts MC, Emsley RA, et al. Psychiatric manifestations and magnetic resonance imaging in HIV-negative neurosyphilis. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41(4):467-473.

14. Hooshmand H, Escobar MR, Kopf SW. Neurosyphylis: a study of 241 patients. JAMA. 1972;219 (6):726-729.

15. Miller CA, Joyce DM. Toxicity, phenytoin. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/816447-overview. Accessed March 23, 2011.

16. Earnest MP, Marx JA, Drury LR. Complications of intravenous phenytoin for acute treatment of seizures: recommendations for usage. JAMA. 1983; 246(6):762-765.

17. Geschwind MD, Shu H, Haman A, et al. Rapidly progressive dementia. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(1): 97-108.

18. Mechem CC. Chapter 143. Altered mental status and coma. In: Ma J, Cline DM, Tintinalli JE, et al, eds. Emergency Medicine Manual, 6e. www.access emergencymedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=2020. Accessed March 23, 2011.

19. Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, et al; Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review). Neurology. 2001;56(9):1143-1153.

20. CDC. Syphilis testing algorithms using treponemal tests for initial screening—four laboratories, New York City, 2005-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(32):872-875.

21. Anderson CA, Filley CM. Chapter 33. Behavioral presentations of medical and neurologic disorders. In: Jacobson JL, Jacobson AM, eds. Psychiatric Secrets. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Hanley & Belfus; 2001.

A 54-year-old African-American man was brought by police officers to the emergency department (ED) after he called 911 several times to report seeing a Rottweiler looking into his second-story window. At the scene, the police were unable to confirm his story, thought the man seemed intoxicated, and brought him to the ED for evaluation.

The patient reported that he had been drinking the previous evening but denied current intoxication or illicit drug use. He denied experiencing symptoms of alcohol withdrawal.

Regarding his medical history, the patient admitted to having had seizures, including two episodes that he said required hospitalization. He described these episodes as right-hand “tingling” (paresthesias), accompanied by right-facial numbness and aphasia. The patient said his physician had instructed him to take “a few phenytoin pills” whenever these episodes occurred. He reported that the medication usually helped resolve his symptoms. He said he had taken phenytoin shortly before his current presentation.

According to friends of the patient who were questioned, he had had noticeable memory problems during the previous six to eight months. They said that he often told the same joke, day after day. His speech had become increasingly slurred, even when he was not drinking.

Once the patient’s medical records were retrieved, it was revealed that he had been hospitalized twice for witnessed grand mal seizures about six months before his current admission; he had been drinking alcohol prior to both episodes. He underwent electroencephalography (EEG) during one of these hospitalizations, with results reported as normal. On both occasions, the patient was discharged with phenytoin and was instructed to follow up with his primary care provider and neurologist.

The patient, who reported working in customer service, had no known allergies. He claimed to drink one or two 40-ounce beers twice per week and admitted to occasional cocaine use. Of significance in his family history was a fatal MI in his mother. Although the patient denied any history of rashes or lesions, his current delirium made it impossible to obtain a reliable sexual history; a friend who was questioned, however, described the patient as promiscuous.

On initial physical examination, the man was afebrile, tachycardic, and somewhat combative with the ED staff. He was fully oriented to self but only partially to place and time.

His right pupil was 3+ and his left pupil was 2+, with neither reactive to light. He spoke with tangential speech and his gait was unsteady, but no other significant abnormalities were noted. A full assessment revealed no rashes or other lesions.

Significant laboratory findings included a low level of phenytoin, a negative blood alcohol level, presence of cocaine on urine drug screening, and normal levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), vitamin B12, and folate. The patient’s serum VDRL (venereal disease research laboratory) titer was positive at 1:256.

Electroencephalography showed diffuse slowing, and brain CT performed in the ED showed atrophy that was mild but appropriate for a person of the patient’s age, with no evidence of a cerebrovascular accident (CVA). Aneurysm was ruled out by CT angiography of the brain. MRI revealed persistent increased signal in the subarachnoid space.

The patient was admitted with an initial diagnosis of paranoid delusional psychosis and monitored for alcohol withdrawal. He was given lorazepam as needed for agitation. Consultations were arranged with the psychiatry service regarding his delusions, and with neurology to determine whether to continue phenytoin.

The patient showed little response during the next several days. Based on positive results on serum VDRL with high titer, the presence of Argyll-Robertson pupils on exam, and his history of dementia-like symptoms, a lumbar puncture was performed to rule out neurosyphilis. In the patient’s cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) analysis, the first tube was clear and colorless, with 72 cells (28% neutrophils, 59% lymphocytes); glucose, 64 mg/dL; and total protein, 117 mg/dL. The fourth tube had 34 cells (17% neutrophils, 65% lymphocytes) and a positive VDRL titer at 1:128. Results from a serum syphilis immunoglobulin G (IgG) test were positive, and HIV antibody testing was nonreactive, confirming the diagnosis of neurosyphilis.

The hospital’s infectious disease (ID) team recommended treatment with IV penicillin for 14 days. Once this was completed, the patient was discharged with instructions to follow up at the ID clinic in three months for a repeat CSF VDRL titer to monitor for resolution of the disease. His prescription for phenytoin was discontinued.

At the time of discharge, it was noted that the patient showed no evidence of having regained cognitive function. He was deemed by the psychiatry service to lack decision-making capacity—a likely sequelae of untreated neurosyphilis of unknown duration.

He did return to the ID clinic six months after his discharge. At that visit, a VDRL serum titer was drawn with a result of 1:64, a decrease from 1:128. His syphilis IgG remained positive, however.

Discussion

Definition and Epidemiology

Syphilis is commonly known as a sexually transmitted disease with primary, secondary, and tertiary (early and late latent) stages.1 Neurosyphilis is defined as a manifestation of the inflammatory response to invasion over decades by the Treponema pallidum spirochete in the CSF as a result of untreated primary and/or secondary syphilis.2 About one in 10 patients with untreated syphilis will experience neurologic involvement.3,4 Before 2005, neurosyphilis was required to be reported as a specific stage of syphilis (ie, a manifestation of tertiary syphilis4), but now should be reported as syphilis with neurologic manifestations.5

A reportable infectious disease, syphilis was widespread until the advent of penicillin. According to CDC statistics,6 the number of reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis has declined steadily since 1943. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the number of tertiary cases also began to plateau, likely as a result of earlier diagnosis and more widespread use of penicillin. Recent case reports suggest greater prevalence of syphilis among men than women and increased incidence among men who have sex with men.7

Pathogenesis

Syphilis is most commonly spread by sexual contact or contact with an infected primary lesion (chancre). Less likely routes of transmission are placental passage or blood transfusion. Infectivity is greatest in the early disease stages.8

Primary syphilis is marked by transmission of the spirochete, ending with development of secondary syphilis (usually two to 12 weeks after transmission). A chancre commonly develops but is often missed by patients because it is painless and can heal spontaneously.7 The chancre is also often confused with two other sources of genital lesions, herpes simplex (genital herpes) and Haemophilus ducreyi (chancroid). In two-thirds of cases of untreated primary syphilis, the infection clears spontaneously, but in the remaining one-third, the disease progresses.8

Secondary syphilis, with or without presence of a chancre, manifests with constitutional symptoms, including lymphadenopathy, fever, headache, and malaise. Patients in this disease phase may also present with a generalized, nonpruritic, macular to maculopapular or pustular rash. The rash can affect the skin of the trunk, the proximal extremities, and the palms and soles. Ocular involvement may occur, especially in patients who are coinfected with HIV.8 In either primary or secondary syphilis, infection can invade the central nervous system.1

During latent syphilis, patients show serologic conversion without overt symptoms. Early latent syphilis is defined as infection within the previous year, as demonstrated by conversion from negative to positive testing, or an increase in titers within the previous year. Any case occurring after one year is defined as late or unknown latent syphilis.8

Tertiary syphilis is marked by complications resulting from untreated syphilis; affected patients commonly experience central nervous system and cardiovascular involvement. Gummatous disease is seen in 15% of patients.1

The early stages of neurosyphilis may be asymptomatic, acute meningeal, and meningovascular.1,4,8,9 Only 5% of patients with early neurosyphilis are symptomatic, with the added potential for cranial neuritis or ocular involvement.1 The late stages of neurosyphilis are detailed in the table.1,4,8

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of syphilis is made by testing blood samples or scrapings from a lesion. In patients with suspected syphilis, rapid plasma reagin (RPR) testing or a VDRL titer is commonly ordered. When results are positive, a serum treponemal test is recommended to confirm a diagnosis of syphilis. Options include the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA-ABS) and the microhemagglutinin assay for antibody to T pallidum (MHA-TP).5

If neurologic symptoms are present, a CSF sample should be obtained, followed by the same testing. A confirmed diagnosis of neurosyphilis is defined by the CDC as syphilis at any stage that meets laboratory criteria for neurosyphilis5; these include increased CSF protein or an elevated CSF leukocyte count with no other known cause, and clinical signs or symptoms without other known causes.7

Treatment

Treatment of syphilis generally consists of penicillin, administered intramuscularly (IM) or IV, depending on the stage. According to 2006 guidelines from the CDC,10,11 treatment for adults with primary and secondary syphilis is a single dose of IM penicillin G, 2.4 million units. If neurosyphilis is suspected, recommended treatment is IV penicillin G, 18 to 24 million units per day divided into six doses (ie, 3 to 4 million units every four hours) or continuous pump infusion for 10 to 14 days.10-12 Follow-up is recommended by monitoring CSF titers to ensure clearance of infection; retreatment may be required if CSF abnormalities persist after two years.11

Patients with a penicillin allergy should undergo desensitization, as penicillin is the preferred agent; the potential exists for cross-reactivity with ceftriaxone, a possible alternative for patients with neurosyphilis.11 All patients diagnosed with syphilis should also be tested for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.10-12

The prognosis of patients treated for neurosyphilis is generally good if the condition is diagnosed and treated early. In patients with cerebral atrophy, frontal lesions, dementia, or tabes dorsalis, the potential for recovery decreases.2,13,14

Teaching Points

There are several teaching points to take away from this case:

• Remember to rule out a CVA in any patient who presents with numbness, paresthesias, or slurred speech. In this case, a brain CT and CT angiography of the brain were both obtained in the ED before the patient was admitted. They both yielded negative results; because the patient’s history was consistent with alcohol and drug use and he had a history of seizures, he was monitored closely for signs of withdrawal or further seizure.

• Phenytoin is an antiepileptic agent whose use requires proper patient education and drug level monitoring. Appropriate follow-up must be ensured before phenytoin therapy is begun, as toxicity can result in nystagmus, ataxia, slurred speech, decreased coordination, mental confusion, and possibly death.15,16

• For patients with a suspected acute change in mental status, a workup is required and should be tailored appropriately, based on findings. This should include, but not be limited to, a thorough history and physical exam, CT of the brain (to rule out an acute brain injury17), and, if warranted, MRI of the brain. Also, a urine drug screen and alcohol level, a complete blood count, a TSH level (to evaluate for altered thyroid function that may explain mental status changes), comprehensive panel, RPR testing and/or a VDRL titer should be obtained, depending on the facility’s protocol18,19; at some facilities, a treponemal test, rather than VDRL, is being obtained at the outset.20 Levels of vitamin B12 (as part of the dementia workup), folate, thiamine, and ammonia (in patients with suspected liver disease) can also be obtained in patients with change in mental status.18,19 Urinalysis should not be overlooked to check for a urinary tract infection, especially in elderly patients.21

• If primary syphilis is suspected, treatment must be undertaken.20

Conclusion

Despite the decline seen since the 1940s in cases of primary and secondary syphilis, and the effectiveness of penicillin in treating the infection early, patients with late-stage syphilis, including those with neurosyphilis, may still present to the emergency care, urgent care, or primary care setting. Immediate treatment with penicillin is recommended to achieve an optimal prognosis for the affected patient.

A 54-year-old African-American man was brought by police officers to the emergency department (ED) after he called 911 several times to report seeing a Rottweiler looking into his second-story window. At the scene, the police were unable to confirm his story, thought the man seemed intoxicated, and brought him to the ED for evaluation.

The patient reported that he had been drinking the previous evening but denied current intoxication or illicit drug use. He denied experiencing symptoms of alcohol withdrawal.

Regarding his medical history, the patient admitted to having had seizures, including two episodes that he said required hospitalization. He described these episodes as right-hand “tingling” (paresthesias), accompanied by right-facial numbness and aphasia. The patient said his physician had instructed him to take “a few phenytoin pills” whenever these episodes occurred. He reported that the medication usually helped resolve his symptoms. He said he had taken phenytoin shortly before his current presentation.

According to friends of the patient who were questioned, he had had noticeable memory problems during the previous six to eight months. They said that he often told the same joke, day after day. His speech had become increasingly slurred, even when he was not drinking.

Once the patient’s medical records were retrieved, it was revealed that he had been hospitalized twice for witnessed grand mal seizures about six months before his current admission; he had been drinking alcohol prior to both episodes. He underwent electroencephalography (EEG) during one of these hospitalizations, with results reported as normal. On both occasions, the patient was discharged with phenytoin and was instructed to follow up with his primary care provider and neurologist.

The patient, who reported working in customer service, had no known allergies. He claimed to drink one or two 40-ounce beers twice per week and admitted to occasional cocaine use. Of significance in his family history was a fatal MI in his mother. Although the patient denied any history of rashes or lesions, his current delirium made it impossible to obtain a reliable sexual history; a friend who was questioned, however, described the patient as promiscuous.

On initial physical examination, the man was afebrile, tachycardic, and somewhat combative with the ED staff. He was fully oriented to self but only partially to place and time.

His right pupil was 3+ and his left pupil was 2+, with neither reactive to light. He spoke with tangential speech and his gait was unsteady, but no other significant abnormalities were noted. A full assessment revealed no rashes or other lesions.

Significant laboratory findings included a low level of phenytoin, a negative blood alcohol level, presence of cocaine on urine drug screening, and normal levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), vitamin B12, and folate. The patient’s serum VDRL (venereal disease research laboratory) titer was positive at 1:256.

Electroencephalography showed diffuse slowing, and brain CT performed in the ED showed atrophy that was mild but appropriate for a person of the patient’s age, with no evidence of a cerebrovascular accident (CVA). Aneurysm was ruled out by CT angiography of the brain. MRI revealed persistent increased signal in the subarachnoid space.

The patient was admitted with an initial diagnosis of paranoid delusional psychosis and monitored for alcohol withdrawal. He was given lorazepam as needed for agitation. Consultations were arranged with the psychiatry service regarding his delusions, and with neurology to determine whether to continue phenytoin.

The patient showed little response during the next several days. Based on positive results on serum VDRL with high titer, the presence of Argyll-Robertson pupils on exam, and his history of dementia-like symptoms, a lumbar puncture was performed to rule out neurosyphilis. In the patient’s cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) analysis, the first tube was clear and colorless, with 72 cells (28% neutrophils, 59% lymphocytes); glucose, 64 mg/dL; and total protein, 117 mg/dL. The fourth tube had 34 cells (17% neutrophils, 65% lymphocytes) and a positive VDRL titer at 1:128. Results from a serum syphilis immunoglobulin G (IgG) test were positive, and HIV antibody testing was nonreactive, confirming the diagnosis of neurosyphilis.

The hospital’s infectious disease (ID) team recommended treatment with IV penicillin for 14 days. Once this was completed, the patient was discharged with instructions to follow up at the ID clinic in three months for a repeat CSF VDRL titer to monitor for resolution of the disease. His prescription for phenytoin was discontinued.

At the time of discharge, it was noted that the patient showed no evidence of having regained cognitive function. He was deemed by the psychiatry service to lack decision-making capacity—a likely sequelae of untreated neurosyphilis of unknown duration.

He did return to the ID clinic six months after his discharge. At that visit, a VDRL serum titer was drawn with a result of 1:64, a decrease from 1:128. His syphilis IgG remained positive, however.

Discussion

Definition and Epidemiology

Syphilis is commonly known as a sexually transmitted disease with primary, secondary, and tertiary (early and late latent) stages.1 Neurosyphilis is defined as a manifestation of the inflammatory response to invasion over decades by the Treponema pallidum spirochete in the CSF as a result of untreated primary and/or secondary syphilis.2 About one in 10 patients with untreated syphilis will experience neurologic involvement.3,4 Before 2005, neurosyphilis was required to be reported as a specific stage of syphilis (ie, a manifestation of tertiary syphilis4), but now should be reported as syphilis with neurologic manifestations.5

A reportable infectious disease, syphilis was widespread until the advent of penicillin. According to CDC statistics,6 the number of reported cases of primary and secondary syphilis has declined steadily since 1943. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the number of tertiary cases also began to plateau, likely as a result of earlier diagnosis and more widespread use of penicillin. Recent case reports suggest greater prevalence of syphilis among men than women and increased incidence among men who have sex with men.7

Pathogenesis

Syphilis is most commonly spread by sexual contact or contact with an infected primary lesion (chancre). Less likely routes of transmission are placental passage or blood transfusion. Infectivity is greatest in the early disease stages.8

Primary syphilis is marked by transmission of the spirochete, ending with development of secondary syphilis (usually two to 12 weeks after transmission). A chancre commonly develops but is often missed by patients because it is painless and can heal spontaneously.7 The chancre is also often confused with two other sources of genital lesions, herpes simplex (genital herpes) and Haemophilus ducreyi (chancroid). In two-thirds of cases of untreated primary syphilis, the infection clears spontaneously, but in the remaining one-third, the disease progresses.8

Secondary syphilis, with or without presence of a chancre, manifests with constitutional symptoms, including lymphadenopathy, fever, headache, and malaise. Patients in this disease phase may also present with a generalized, nonpruritic, macular to maculopapular or pustular rash. The rash can affect the skin of the trunk, the proximal extremities, and the palms and soles. Ocular involvement may occur, especially in patients who are coinfected with HIV.8 In either primary or secondary syphilis, infection can invade the central nervous system.1

During latent syphilis, patients show serologic conversion without overt symptoms. Early latent syphilis is defined as infection within the previous year, as demonstrated by conversion from negative to positive testing, or an increase in titers within the previous year. Any case occurring after one year is defined as late or unknown latent syphilis.8

Tertiary syphilis is marked by complications resulting from untreated syphilis; affected patients commonly experience central nervous system and cardiovascular involvement. Gummatous disease is seen in 15% of patients.1

The early stages of neurosyphilis may be asymptomatic, acute meningeal, and meningovascular.1,4,8,9 Only 5% of patients with early neurosyphilis are symptomatic, with the added potential for cranial neuritis or ocular involvement.1 The late stages of neurosyphilis are detailed in the table.1,4,8

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of syphilis is made by testing blood samples or scrapings from a lesion. In patients with suspected syphilis, rapid plasma reagin (RPR) testing or a VDRL titer is commonly ordered. When results are positive, a serum treponemal test is recommended to confirm a diagnosis of syphilis. Options include the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test (FTA-ABS) and the microhemagglutinin assay for antibody to T pallidum (MHA-TP).5

If neurologic symptoms are present, a CSF sample should be obtained, followed by the same testing. A confirmed diagnosis of neurosyphilis is defined by the CDC as syphilis at any stage that meets laboratory criteria for neurosyphilis5; these include increased CSF protein or an elevated CSF leukocyte count with no other known cause, and clinical signs or symptoms without other known causes.7

Treatment

Treatment of syphilis generally consists of penicillin, administered intramuscularly (IM) or IV, depending on the stage. According to 2006 guidelines from the CDC,10,11 treatment for adults with primary and secondary syphilis is a single dose of IM penicillin G, 2.4 million units. If neurosyphilis is suspected, recommended treatment is IV penicillin G, 18 to 24 million units per day divided into six doses (ie, 3 to 4 million units every four hours) or continuous pump infusion for 10 to 14 days.10-12 Follow-up is recommended by monitoring CSF titers to ensure clearance of infection; retreatment may be required if CSF abnormalities persist after two years.11

Patients with a penicillin allergy should undergo desensitization, as penicillin is the preferred agent; the potential exists for cross-reactivity with ceftriaxone, a possible alternative for patients with neurosyphilis.11 All patients diagnosed with syphilis should also be tested for HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases.10-12

The prognosis of patients treated for neurosyphilis is generally good if the condition is diagnosed and treated early. In patients with cerebral atrophy, frontal lesions, dementia, or tabes dorsalis, the potential for recovery decreases.2,13,14

Teaching Points

There are several teaching points to take away from this case:

• Remember to rule out a CVA in any patient who presents with numbness, paresthesias, or slurred speech. In this case, a brain CT and CT angiography of the brain were both obtained in the ED before the patient was admitted. They both yielded negative results; because the patient’s history was consistent with alcohol and drug use and he had a history of seizures, he was monitored closely for signs of withdrawal or further seizure.

• Phenytoin is an antiepileptic agent whose use requires proper patient education and drug level monitoring. Appropriate follow-up must be ensured before phenytoin therapy is begun, as toxicity can result in nystagmus, ataxia, slurred speech, decreased coordination, mental confusion, and possibly death.15,16

• For patients with a suspected acute change in mental status, a workup is required and should be tailored appropriately, based on findings. This should include, but not be limited to, a thorough history and physical exam, CT of the brain (to rule out an acute brain injury17), and, if warranted, MRI of the brain. Also, a urine drug screen and alcohol level, a complete blood count, a TSH level (to evaluate for altered thyroid function that may explain mental status changes), comprehensive panel, RPR testing and/or a VDRL titer should be obtained, depending on the facility’s protocol18,19; at some facilities, a treponemal test, rather than VDRL, is being obtained at the outset.20 Levels of vitamin B12 (as part of the dementia workup), folate, thiamine, and ammonia (in patients with suspected liver disease) can also be obtained in patients with change in mental status.18,19 Urinalysis should not be overlooked to check for a urinary tract infection, especially in elderly patients.21

• If primary syphilis is suspected, treatment must be undertaken.20

Conclusion

Despite the decline seen since the 1940s in cases of primary and secondary syphilis, and the effectiveness of penicillin in treating the infection early, patients with late-stage syphilis, including those with neurosyphilis, may still present to the emergency care, urgent care, or primary care setting. Immediate treatment with penicillin is recommended to achieve an optimal prognosis for the affected patient.

1. Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1510-1514.

2. Simon RP. Chapter 20. Neurosyphilis. In: Klausner JD, Hook EW III, eds. Current Diagnosis & Treatment of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. USA: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2007:130-137.

3. Sanchez FM, Zisselman MH. Treatment of psychiatric symptoms associated with neurosyphilis. Psychosomatics. 2007;48:440-445.

4. Marra CM. Neurosyphilis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2004;4(6):435-440.

5. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases surveillance, 2007: STD surveillance case definitions. www.cdc.gov/std/stats07/app-casedef.htm. Accessed March 23, 2011.

6. CDC. 2008 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance: Table 1. Cases of sexually transmitted diseases reported by state health departments and rates per 100,000 population: United States, 1941-2008. www.cdc.gov/std/stats08/tables/1.htm. Accessed March 23, 2011.

7. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs): Syphilis: CDC fact sheet. www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/STDfact-syphilis.htm. Accessed March 23, 2011.

8. Tramont EC. Chapter 238. Treponema pallidum (syphilis). In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

9. Ghanem KG. Neurosyphilis: a historical perspective and review. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010; 16(5):e157-e168.

10. Workowski KA, Berman SM; CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

11. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases: treatment guidelines 2006. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2006/genital-ulcers.htm#genulc6. Accessed March 29, 2011.

12. Drugs for sexually transmitted infections. Treatment Guidelines from the Medical Letter. 2010;95:95a. http://secure.medicalletter.org. Accessed March 23, 2011.

13. Russouw HG, Roberts MC, Emsley RA, et al. Psychiatric manifestations and magnetic resonance imaging in HIV-negative neurosyphilis. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41(4):467-473.

14. Hooshmand H, Escobar MR, Kopf SW. Neurosyphylis: a study of 241 patients. JAMA. 1972;219 (6):726-729.

15. Miller CA, Joyce DM. Toxicity, phenytoin. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/816447-overview. Accessed March 23, 2011.

16. Earnest MP, Marx JA, Drury LR. Complications of intravenous phenytoin for acute treatment of seizures: recommendations for usage. JAMA. 1983; 246(6):762-765.

17. Geschwind MD, Shu H, Haman A, et al. Rapidly progressive dementia. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(1): 97-108.

18. Mechem CC. Chapter 143. Altered mental status and coma. In: Ma J, Cline DM, Tintinalli JE, et al, eds. Emergency Medicine Manual, 6e. www.access emergencymedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=2020. Accessed March 23, 2011.

19. Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, et al; Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review). Neurology. 2001;56(9):1143-1153.

20. CDC. Syphilis testing algorithms using treponemal tests for initial screening—four laboratories, New York City, 2005-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(32):872-875.

21. Anderson CA, Filley CM. Chapter 33. Behavioral presentations of medical and neurologic disorders. In: Jacobson JL, Jacobson AM, eds. Psychiatric Secrets. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Hanley & Belfus; 2001.

1. Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1510-1514.

2. Simon RP. Chapter 20. Neurosyphilis. In: Klausner JD, Hook EW III, eds. Current Diagnosis & Treatment of Sexually Transmitted Diseases. USA: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2007:130-137.

3. Sanchez FM, Zisselman MH. Treatment of psychiatric symptoms associated with neurosyphilis. Psychosomatics. 2007;48:440-445.

4. Marra CM. Neurosyphilis. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2004;4(6):435-440.

5. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases surveillance, 2007: STD surveillance case definitions. www.cdc.gov/std/stats07/app-casedef.htm. Accessed March 23, 2011.

6. CDC. 2008 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance: Table 1. Cases of sexually transmitted diseases reported by state health departments and rates per 100,000 population: United States, 1941-2008. www.cdc.gov/std/stats08/tables/1.htm. Accessed March 23, 2011.

7. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs): Syphilis: CDC fact sheet. www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/STDfact-syphilis.htm. Accessed March 23, 2011.

8. Tramont EC. Chapter 238. Treponema pallidum (syphilis). In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2009.

9. Ghanem KG. Neurosyphilis: a historical perspective and review. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010; 16(5):e157-e168.

10. Workowski KA, Berman SM; CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR-11):1-94.

11. CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases: treatment guidelines 2006. www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2006/genital-ulcers.htm#genulc6. Accessed March 29, 2011.

12. Drugs for sexually transmitted infections. Treatment Guidelines from the Medical Letter. 2010;95:95a. http://secure.medicalletter.org. Accessed March 23, 2011.

13. Russouw HG, Roberts MC, Emsley RA, et al. Psychiatric manifestations and magnetic resonance imaging in HIV-negative neurosyphilis. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41(4):467-473.

14. Hooshmand H, Escobar MR, Kopf SW. Neurosyphylis: a study of 241 patients. JAMA. 1972;219 (6):726-729.

15. Miller CA, Joyce DM. Toxicity, phenytoin. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/816447-overview. Accessed March 23, 2011.

16. Earnest MP, Marx JA, Drury LR. Complications of intravenous phenytoin for acute treatment of seizures: recommendations for usage. JAMA. 1983; 246(6):762-765.

17. Geschwind MD, Shu H, Haman A, et al. Rapidly progressive dementia. Ann Neurol. 2008;64(1): 97-108.

18. Mechem CC. Chapter 143. Altered mental status and coma. In: Ma J, Cline DM, Tintinalli JE, et al, eds. Emergency Medicine Manual, 6e. www.access emergencymedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=2020. Accessed March 23, 2011.

19. Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, et al; Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review). Neurology. 2001;56(9):1143-1153.

20. CDC. Syphilis testing algorithms using treponemal tests for initial screening—four laboratories, New York City, 2005-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(32):872-875.

21. Anderson CA, Filley CM. Chapter 33. Behavioral presentations of medical and neurologic disorders. In: Jacobson JL, Jacobson AM, eds. Psychiatric Secrets. 2nd ed. St. Louis, MO: Hanley & Belfus; 2001.

A Toxic Swimming Pool Hazard

Procedural Sedation and Analgesia in the ED: Focusing on Deep Sedation

Tibial Stress Injuries in Athletes

Women's Musculoskeletal Foot Conditions Exacerbated by Shoe Wear: An Imaging Perspective

Diagnostics in Suspicion of Ankle Syndesmotic Injury

UPDATE ON MINIMALLY INVASIVE SURGERY

- Applying single-incision laparoscopic surgery to gyn practice: What’s involved

Russell P. Atkin, MD; Michael L. Nimaroff, MD; Vrunda Bhavsar, MD (April 2011) - 10 practical, evidence-based suggestions to improve your minimally invasive surgical skills now

Catherine A. Matthews, MD (April 2011)

The uterine leiomyoma is the most common tumor of the female genital tract. Seventy percent of white women and 80% of black women develop one or more of these tumors by the time they reach 50 years, and the myomas are clinically apparent in 25% of patients.1,2 When a fibroid is submucosal, it is often associated with menorrhagia, abnormal uterine bleeding, and infertility.2-4

In this article, I describe three aspects of managing leiomyomata:

- ways of classifying the tumor to better predict the blood loss, operative time and morbidity associated with removal

- the indications for hysteroscopic myomectomy and polypectomy

- new tools for the removal of polyps and myomas.

Preoperative assessment of submucosal myomas is essential

Lasmar RB, Barrozo PR, Dias R, Oliveira MA. Submucous myomas: a new presurgical classification to evaluate the viability of hysteroscopic surgical treatment—preliminary report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(4):308–311.

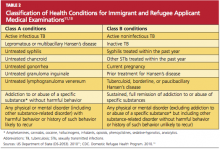

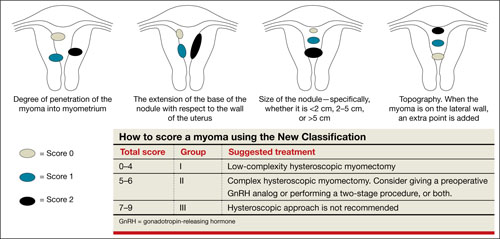

Wamsteker and colleagues were the first to propose a system for classifying myoma position within the uterine cavity as a means of estimating the degree of difficulty of resectoscopic removal.5 The European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE) later adopted this system, which is now known by its acronym. According to the ESGE system, myomas that lie entirely within the uterine cavity (Type 0) are easier to remove, require less operative time, and involve less fluid deficit and blood loss than myomas that invade the myometrium to varying degrees (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1 ESGE classification

Submucosal myomas are classified as Type 0, Type I, or Type II, according to the degree of myometrial penetration.When more than 50% of a tumor penetrates the myometrium (Type II), the risk of excessive intraoperative fluid absorption is elevated, along with the risk of bleeding and the likelihood of electrolyte abnormalities with the use of non-electrolyte fluid media. Type II tumors also increase operative time and the likelihood that additional procedures will be needed because of incomplete resection—even in the hands of expert hysteroscopic surgeons.5

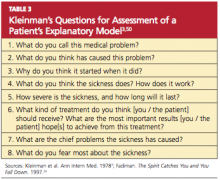

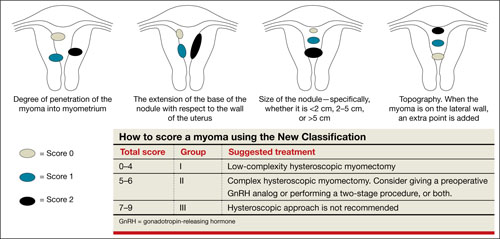

FIGURE 2 New classification

New classification system increases accuracy

Lasmar and colleagues devised a new system for preoperative assessment of submucosal myomas, hoping to estimate more precisely the likelihood of successful removal via resectoscopy. They call their system the New Classification (NC). Besides taking into account the degree of penetration into the myometrium, they consider the percentage of uterine wall encompassed by the myoma and the location of the myoma within the uterus (i.e., fundus, body, or lower segment) (FIGURE 2). The total score is used to categorize the tumor into Group I, II, or III to estimate the likelihood of successful removal.

In devising the system, Lasmar and colleagues used the NC and ESGE systems to analyze 55 myomectomy cases involving 57 myomas. They found that the NC more accurately predicts differences between Groups I and II in regard to completed procedures, fluid deficit, and operative time.

Preoperative hysteroscopic evaluation of submucosal myomas is essential and reliable using the New Classification system.

Hysteroscopic removal of myomas and polyps

yields multiple benefits

Shokeir T, El-Shafei M, Yousef H, Allam AF, Sadek E. Submucous myomas and their implications in the pregnancy rates of patients with otherwise unexplained primary infertility undergoing hysteroscopic myomectomy: a randomized matched control study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(2):724–729.

Rackow BW, Jorgensen E, Taylor HS. Endometrial polyps affect uterine receptivity [published online ahead of print January 24, 2011]. Fertil Steril. doi 10.1016/j. fertnstert.2010.12.034.

Afifi K, Anand S. Nallapeta S, Gelbaya TA. Management of endometrial polyps in subfertile women: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;151(2):117–121.

Studies evaluating the association between infertility and submucosal fibroids have been controversial because the exact mechanism has not been identified. However, new evidence suggests a molecular causal relationship, and Pritts and colleagues demonstrated improved fertility after submucosal myomectomy.3,6

More recently, Shokeir and coworkers conducted a prospective, randomized, age-matched, controlled trial to explore the effects of hysteroscopic myomectomy on otherwise unexplained primary infertility. They enrolled 215 women who had infertility longer than 12 months and who had their fibroids assessed by means of ultrasonography and classified according to the ESGE system.

Women who underwent myomectomy were twice as likely as women in the control group to become pregnant (relative risk = 2.1; 95% confidence interval = 1.5–2.9). Women who had Type 0 and Type I myomas removed had significantly higher pregnancy rates than women in the control group (P < .001). No statistically significant difference in the pregnancy rate between groups was found for Type II myomas.

Polyps may also affect fertility

Rackow and coworkers demonstrated that endometrial polyps affect uterine receptivity on the molecular level, suggesting a relationship between endometrial polyps and infertility. And after a systematic review of endometrial polyps in women who had subfertility, Afifi and colleagues concluded that polypectomy can improve fertility, especially when assisted reproductive technologies are planned.

Myomas, polyps also contribute to bleeding abnormalities

Submucosal myomas have been associated with bleeding abnormalities, such as heavy menstrual bleeding and menopausal bleeding. Although the precise mechanism is unknown by which these bleeding abnormalities arise in the presence of submucosal fibroids, abnormalities within the endometrium or myometrium may play a role at the genetic and molecular level.7,8 There is clear evidence supporting hysteroscopic removal of submucosal fibroids to improve bleeding abnormalities.9,10

Hysteroscopic removal of eSge type 0 and type i submucosal myomas improves the pregnancy rate for patients who have otherwise unexplained primary infertility. Removal of endometrial polyps is also recommended to improve fertility.

Besides improving fertility, hysteroscopic removal of submucosal myomas and endometrial polyps improves menorrhagia and irregular and abnormal uterine bleeding.

Hysteroscopic morcellators offer advantages over traditional resectoscopy, making hysteroscopic myomectomy of Type 0 and Type I myomas safer and more feasible for gynecologic surgeons. They allow resection using saline, operate without electrical energy, and utilize vacuum suction to remove tissue fragments from the uterine cavity.

Hysteroscopic morcellators ease the task of myomectomy

Hysteroscopic removal of submucosal myomas and polyps is an effective treatment for women who experience bleeding abnormalities or infertility, but the potential for complications deters many gynecologists from performing resectoscopic myomectomy.

Use of a monopolar loop electrode (VIDEO 1) requires an electrolyte-free distention medium, such as 1.5% glycine or 3% sorbitol, and intravasation of these fluids must be limited to minimize the risk of complications such as hyponatremia, cardiovascular compromise, cerebral edema, and, even, death.12 Although the use of normal saline with bipolar resectoscopic instrumentation (VIDEO 2) and automated fluid-management systems reduces the risk of fluid overload, it does not eliminate it entirely, and fluid balance must be carefully scrutinized.13

Intrauterine electrosurgery can burn pelvic organs if an activated electrode perforates the uterine wall and makes contact with bowel or other organs. Burns to the cervix, vagina, and vulva have also been reported when monopolar resectoscopic insulation fails or monopolar electrical current is inadvertently diverted.12

In addition, unless one uses tissue-vaporizing electrodes (VIDEO 3) or is equipped

with newer instrumentation that allows tissue to be removed through the operative sheath of the resectoscope, the myoma must be extracted in pieces, often with repeated removal and reinsertion of the resectoscope and grasping instruments, increasing the risk of cervical injury or uterine perforation with each placement.

Another variable that deters hysteroscopic myomectomy is the lack of training at the residency level. The typical ObGyn resident graduating between 2002 and 2007 had performed a median of only 40 to 51 operative hysteroscopic procedures by the time of graduation.14 This statistic suggests that few residency programs provide adequate training for more demanding hysteroscopic surgeries.

Mechanical morcellators facilitate tissue removal

Hysteroscopic morcellators offer advantages over traditional resectoscopy, making hysteroscopic myomectomy of Type 0 and Type I myomas safer and more feasible for gynecologic surgeons. These morcellators allow resection of a myoma using saline, minimizing the hazards of fluid overload. Because they are mechanical devices that do not require electrical energy, the potential for thermal injury is eliminated.

Mechanical morcellators utilize vacuum suction to remove tissue fragments from the uterine cavity, maintaining a tissue-free operative environment and eliminating the need for repeated manual removal. This feature also reduces the risks of perforation, creation of a false passageway, and gas embolus that have been linked to instrument reinsertion and manual removal of tissue fragments.12

Furthermore, mechanical morcellators are easy to use, reducing operative time and fluid deficit.

Removing Type II myomas with a hysteroscopic morcellator may pose a challenge, however, because of significant myometrial penetration. In addition, bleeding is more likely during removal of a Type II myoma than during removal of other types of tumors, necessitating the use of electric current to address it appropriately. Surgeons who are experienced using the morcellator can overcome these challenges by avoiding the myometrial interface and allowing uterine expulsive contractions to push the myoma into the cavity, making it unnecessary to penetrate the myometrium with the instrument. Thorough preoperative evaluation of Type II myomas is recommended, keeping in mind that removal may be safer and more effective using electrosurgical loop resection.

Option 1: TRUCLEAR morcellator

The TRUCLEAR Hysteroscopic Morcellator (Smith & Nephew) was FDA-approved in 2005 as the first intrauterine mechanical morcellator (VIDEO 4). It requires a dedicated fluid pump and has different instrumentation for myomas and polyps. For myomas, the instrument consists of a rotating tube that reciprocates within an outer 4-mm tube. Both tubes have windows at the end with cutting edges. A vacuum connected to the inner tube provides controlled suction that pulls the tissue into the window on the outer tube and cuts it as the inner tube rotates (VIDEO 5).

For polyps, both inner and outer tubes have oscillating serrated edges on each window (VIDEO 6).

Both instruments are used through a 9-mm offset rod-lens continuous-flow hysteroscope.

In a retrospective analysis, the TRUCLEAR morcellator reduced operative time by about two thirds for polyps and one half for Type 0 and Type I myomas, compared with monopolar loop resection.15 A later study of inexperienced ObGyn residents demonstrated shorter operative times and lower total fluid deficits for the TRUCLEAR morcellator, compared with resectoscopic procedures overall, during polypectomy and myomectomy of Type 0 and Type I myomas.16

Smith & Nephew recently introduced a smaller set of instruments, including a 2.9-mm blade for removal of polyps through a 5.6-mm continuous-flow hysteroscope. However, the new instruments have not yet been approved by the FDA and are unavailable within the United States.

Option 2: MyoSure

The MyoSure Tissue Removal System (Hologic) was FDA-approved in 2009. The hand piece is a rotating and reciprocating 2-mm blade within a 3-mm outer tube. The cutter is connected to a vacuum source that aspirates resected tissue through a side-facing cutting window in the outer tube. The system utilizes standard hysteroscopy set-up for fluid inflow and suction. The instrument is placed through an offset lens continuous-flow hysteroscope with an outer diameter of

6.25 mm. The smaller diameter reduces the amount of cervical dilation required, as well as the risk of uterine perforation.

The smaller size of the instrument renders it ideal for an office setting. Miller and colleagues demonstrated its safety and efficacy for office removal of polyps and myomas (VIDEO 7; VIDEO 8).17

Inadequate reimbursement?

Although both morcellators simplify hysteroscopic myomectomy and polypectomy, insurance reimbursement does not yet differentiate between places of service—unlike other in-office procedures that take into account the cost of the procedural device (see “Reimbursement is limited for hysteroscopic myomectomy in an office setting”). Until the relative value unit (RVU) is modified to reflect this cost, office use of the hysteroscopic morcellator for myomectomy and polypectomy will be financially restrictive to the gynecologist in private practice. Nevertheless, both instruments are easy to use and offer improved safety, increasing access to uterine-preserving surgery.

Thanks to Dr. Andrew I. Brill and Dr. William H. Parker for their thoughtful review of this article.

Since the inception of the resource-based relative value scale, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have provided for different levels of payment to physicians, depending on the place of service and the extent of work involved. The relative value units (RVUs) established for each clinical service are based on three components:

- physician work

- practice expense

- malpractice expense.

The practice expense includes supplies, equipment, clinical and administrative staff, and renting and leasing of space.

When a physician provides a service in a hospital setting or outpatient clinic or surgery unit, the practice expense is lower because the hospital or outpatient facility shoulders those costs. In an office setting, however, the physician practice incurs the full expense of providing the service. In most cases, therefore, the practice is reimbursed at a higher total RVU for office procedures.

The “place of service” code required on your claim form lets the payer know whether the service was rendered in your office (code 11) or a facility such as a hospital or outpatient surgery center (codes 21–24). Physicians who work out of a hospital-owned facility—i.e., physicians who are employed by a hospital—would bill for a facility place of service rather than an office.

The difference in RVUs can be significant. For example, hysteroscopic sterilization (CPT code 58565) has two different RVUs, depending on whether the service is performed in a facility or office (TABLE). However, although hysteroscopic myomectomy can now be safely performed in the office setting for small, less invasive myomas, CMS has not yet assigned a place of service differential for this procedure (CPT code 58561). In other words, CMS has determined that hysteroscopic myomectomy—by definition or practice—is rarely or never performed outside a hospital or outpatient facility.

Medicare reimbursement for hysteroscopic procedures

| Procedure | CPT code | Relative value units | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Facility | Office | ||

| Sterilization | 58565 | 12.90 | 56.66 |

| Endometrial ablation | 58563 | 10.23 | 52.05 |

| Cryoablation | 58356 | 10.34 | 58.92 |

| Myomectomy | 58561 | 16.33 | NA |

| Polypectomy (with dilation and curettage, biopsy) | 58558 | 7.95 | 10.60 |

| To determine reimbursement, multiply the RVU by the Medicare conversion factor, which is $33.9764 | |||

When contracting with a private payer, be sure to ask how the payer reimburses for hysteroscopic myomectomy in an office setting. Payers that do not include a place of service differential may be amenable to negotiation if you can demonstrate that extra compensation can actually save them money and maintain high-quality patient care.

—Melanie Witt, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Day Baird D, Dunson DB, Hill MC, Cousins D, Schectman JM. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;188(1):100-107.

2. Lasmar RB, Barrozo PR, Dias R, Oliveira MA. Submucous myomas: A new presurgical classification to evaluate the viability of hysteroscopic surgical treatment—Preliminary report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;12(4):308-311.

3. Pritts EA, Parker WH, Olive DL. Fibroids and infertility: an updated systematic review of the evidence. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4):1215-1223.

4. Shokeir T, El-Shafei M, Yousef H, Allam AF, Sadek E. Submucous myomas and their implications in the pregnancy rates of patients with otherwise unexplained primary infertility undergoing hysteroscopic myomectomy: a randomized matched control study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(2):724-729.

5. Wamsteker K, Emanuel MH, de Kruif JH. Transcervical hysteroscopic resection of submucous fibroids for abnormal uterine bleeding: results regarding the degree of intramural extension. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82(5):736-740.

6. Rackow BW, Taylor HS. Submucosal uterine leiomyomas have a global effect on molecular determinants of endometrial receptivity. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(6):2027-2034.

7. Stewart EA, Nowak RA. Leiomyoma-related bleeding: a classic hypothesis updated for the molecular era. Human Repro Update. 1996;2(4):295-306.

8. Laughlin SK, Stewart EA. Uterine leiomyomas. Individualizing the approach to a heterogeneous condition. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 pt 1):396-403.

9. Loffer FD. Improving results of hysteroscopic submucosal myomectomy for menorrhagia by concomitant endometrial ablation. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(3):254-260.

10. Emanuel MH, Wamsteker K, Hart AA, Metz G, Lammes FB. Long-term results of hysteroscopic myomectomy for abnormal uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93(5 pt 1):743-748.

11. Nathani F, Clark TJ. Uterine polypectomy in the management of abnormal uterine bleeding: a systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13(4):260-268.

12. Munro MG. Complications of hysteroscopic and uterine resectoscopic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2010;37(3):399-425.

13. Kung RC, Vilos GA, Thomas B, Penkin P, Zaltz AP, Stabinsky SA. A new bipolar system for performing operative hysteroscopy in normal saline. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1999;6(3):331-336.

14. Miller CE. Training in minimally iInvasive surgery—you say you want a revolution. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16(2):113-120.

15. Emanuel MH, Wamsteker K. The intra uterine morcellator: a new hysteroscopic moperating technique to remove intrauterine polyps and myomas. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(1):62-66.

16. Van Dongen H, Emanuel MH, Wolterbeek R, Trimbos JB, Jansen FW. Hysteroscopic morcellator for removal of intrauterine polyps and myomas: a randomized controlled pilot study among residents in training. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(4):466-471.

17. Miller CE, Glazerman L, Roy K, Lukes A. Clinical evaluation of a new hysteroscopic morcellator—retrospective case review. J Med. 2009;2(3):163-166.

- Applying single-incision laparoscopic surgery to gyn practice: What’s involved

Russell P. Atkin, MD; Michael L. Nimaroff, MD; Vrunda Bhavsar, MD (April 2011) - 10 practical, evidence-based suggestions to improve your minimally invasive surgical skills now

Catherine A. Matthews, MD (April 2011)

The uterine leiomyoma is the most common tumor of the female genital tract. Seventy percent of white women and 80% of black women develop one or more of these tumors by the time they reach 50 years, and the myomas are clinically apparent in 25% of patients.1,2 When a fibroid is submucosal, it is often associated with menorrhagia, abnormal uterine bleeding, and infertility.2-4

In this article, I describe three aspects of managing leiomyomata:

- ways of classifying the tumor to better predict the blood loss, operative time and morbidity associated with removal

- the indications for hysteroscopic myomectomy and polypectomy

- new tools for the removal of polyps and myomas.

Preoperative assessment of submucosal myomas is essential

Lasmar RB, Barrozo PR, Dias R, Oliveira MA. Submucous myomas: a new presurgical classification to evaluate the viability of hysteroscopic surgical treatment—preliminary report. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(4):308–311.

Wamsteker and colleagues were the first to propose a system for classifying myoma position within the uterine cavity as a means of estimating the degree of difficulty of resectoscopic removal.5 The European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE) later adopted this system, which is now known by its acronym. According to the ESGE system, myomas that lie entirely within the uterine cavity (Type 0) are easier to remove, require less operative time, and involve less fluid deficit and blood loss than myomas that invade the myometrium to varying degrees (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1 ESGE classification

Submucosal myomas are classified as Type 0, Type I, or Type II, according to the degree of myometrial penetration.When more than 50% of a tumor penetrates the myometrium (Type II), the risk of excessive intraoperative fluid absorption is elevated, along with the risk of bleeding and the likelihood of electrolyte abnormalities with the use of non-electrolyte fluid media. Type II tumors also increase operative time and the likelihood that additional procedures will be needed because of incomplete resection—even in the hands of expert hysteroscopic surgeons.5

FIGURE 2 New classification

New classification system increases accuracy

Lasmar and colleagues devised a new system for preoperative assessment of submucosal myomas, hoping to estimate more precisely the likelihood of successful removal via resectoscopy. They call their system the New Classification (NC). Besides taking into account the degree of penetration into the myometrium, they consider the percentage of uterine wall encompassed by the myoma and the location of the myoma within the uterus (i.e., fundus, body, or lower segment) (FIGURE 2). The total score is used to categorize the tumor into Group I, II, or III to estimate the likelihood of successful removal.

In devising the system, Lasmar and colleagues used the NC and ESGE systems to analyze 55 myomectomy cases involving 57 myomas. They found that the NC more accurately predicts differences between Groups I and II in regard to completed procedures, fluid deficit, and operative time.

Preoperative hysteroscopic evaluation of submucosal myomas is essential and reliable using the New Classification system.

Hysteroscopic removal of myomas and polyps

yields multiple benefits

Shokeir T, El-Shafei M, Yousef H, Allam AF, Sadek E. Submucous myomas and their implications in the pregnancy rates of patients with otherwise unexplained primary infertility undergoing hysteroscopic myomectomy: a randomized matched control study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(2):724–729.

Rackow BW, Jorgensen E, Taylor HS. Endometrial polyps affect uterine receptivity [published online ahead of print January 24, 2011]. Fertil Steril. doi 10.1016/j. fertnstert.2010.12.034.

Afifi K, Anand S. Nallapeta S, Gelbaya TA. Management of endometrial polyps in subfertile women: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;151(2):117–121.

Studies evaluating the association between infertility and submucosal fibroids have been controversial because the exact mechanism has not been identified. However, new evidence suggests a molecular causal relationship, and Pritts and colleagues demonstrated improved fertility after submucosal myomectomy.3,6

More recently, Shokeir and coworkers conducted a prospective, randomized, age-matched, controlled trial to explore the effects of hysteroscopic myomectomy on otherwise unexplained primary infertility. They enrolled 215 women who had infertility longer than 12 months and who had their fibroids assessed by means of ultrasonography and classified according to the ESGE system.

Women who underwent myomectomy were twice as likely as women in the control group to become pregnant (relative risk = 2.1; 95% confidence interval = 1.5–2.9). Women who had Type 0 and Type I myomas removed had significantly higher pregnancy rates than women in the control group (P < .001). No statistically significant difference in the pregnancy rate between groups was found for Type II myomas.

Polyps may also affect fertility

Rackow and coworkers demonstrated that endometrial polyps affect uterine receptivity on the molecular level, suggesting a relationship between endometrial polyps and infertility. And after a systematic review of endometrial polyps in women who had subfertility, Afifi and colleagues concluded that polypectomy can improve fertility, especially when assisted reproductive technologies are planned.

Myomas, polyps also contribute to bleeding abnormalities

Submucosal myomas have been associated with bleeding abnormalities, such as heavy menstrual bleeding and menopausal bleeding. Although the precise mechanism is unknown by which these bleeding abnormalities arise in the presence of submucosal fibroids, abnormalities within the endometrium or myometrium may play a role at the genetic and molecular level.7,8 There is clear evidence supporting hysteroscopic removal of submucosal fibroids to improve bleeding abnormalities.9,10

Hysteroscopic removal of eSge type 0 and type i submucosal myomas improves the pregnancy rate for patients who have otherwise unexplained primary infertility. Removal of endometrial polyps is also recommended to improve fertility.

Besides improving fertility, hysteroscopic removal of submucosal myomas and endometrial polyps improves menorrhagia and irregular and abnormal uterine bleeding.

Hysteroscopic morcellators offer advantages over traditional resectoscopy, making hysteroscopic myomectomy of Type 0 and Type I myomas safer and more feasible for gynecologic surgeons. They allow resection using saline, operate without electrical energy, and utilize vacuum suction to remove tissue fragments from the uterine cavity.

Hysteroscopic morcellators ease the task of myomectomy

Hysteroscopic removal of submucosal myomas and polyps is an effective treatment for women who experience bleeding abnormalities or infertility, but the potential for complications deters many gynecologists from performing resectoscopic myomectomy.

Use of a monopolar loop electrode (VIDEO 1) requires an electrolyte-free distention medium, such as 1.5% glycine or 3% sorbitol, and intravasation of these fluids must be limited to minimize the risk of complications such as hyponatremia, cardiovascular compromise, cerebral edema, and, even, death.12 Although the use of normal saline with bipolar resectoscopic instrumentation (VIDEO 2) and automated fluid-management systems reduces the risk of fluid overload, it does not eliminate it entirely, and fluid balance must be carefully scrutinized.13

Intrauterine electrosurgery can burn pelvic organs if an activated electrode perforates the uterine wall and makes contact with bowel or other organs. Burns to the cervix, vagina, and vulva have also been reported when monopolar resectoscopic insulation fails or monopolar electrical current is inadvertently diverted.12

In addition, unless one uses tissue-vaporizing electrodes (VIDEO 3) or is equipped

with newer instrumentation that allows tissue to be removed through the operative sheath of the resectoscope, the myoma must be extracted in pieces, often with repeated removal and reinsertion of the resectoscope and grasping instruments, increasing the risk of cervical injury or uterine perforation with each placement.