User login

Outcomes of Arthroscopic Versus Open Rotator Cuff Repair: A Systematic Review of the Literature

UPDATE: URINARY INCONTINENCE

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is no small problem. With a prevalence thought to range as high as 30%, the condition challenges us to manage resources in a way that is mindful of cost—both financial expense and cost to the patient in terms of recovery and quality of life.

Although a large percentage of women who have POP also complain of symptomatic incontinence, a substantial number of continent women who have severe POP become incontinent after surgical repair. One reason may be that advanced POP sometimes causes urethral kinking and external urethral compression, fixing a hypermobile urethra in place. Once normal anatomy is restored and the urethra is no longer kinked, the urinary incontinence is “unmasked.”

Women who develop de novo incontinence after POP repair are thought to have “occult” urinary incontinence. Occult stress incontinence is urinary leakage that is prevented by POP and becomes symptomatic only after restoration of pelvic anatomy.1 It has been reported that 36% to 80% of continent women who have POP will develop stress urinary incontinence once the prolapse is reduced, either preoperatively with a pessary or vaginal pack, or after surgical correction.2

This information prompts important questions: If a woman who has POP is continent at the time of her surgical repair, should she undergo a concomitant incontinence procedure “just in case”? Or should she be reevaluated postoperatively for a possible continence procedure at a later time?

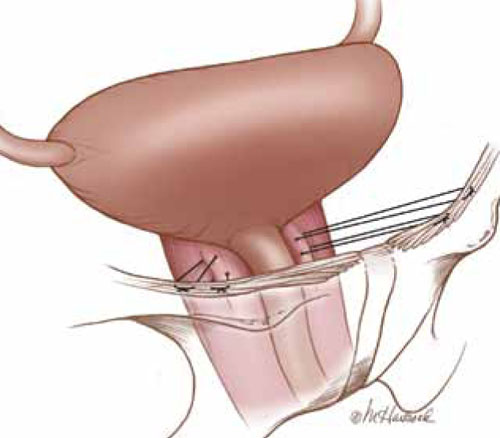

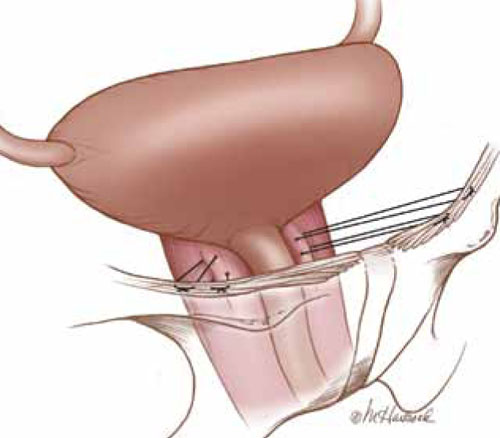

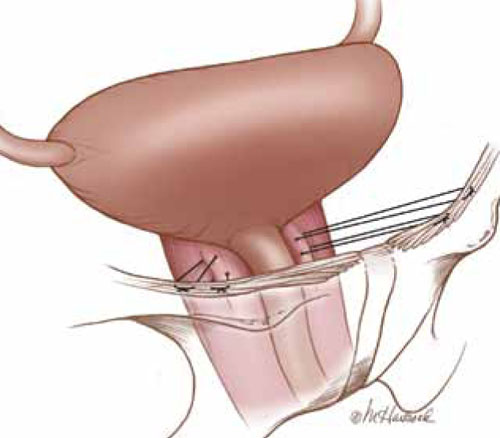

The colpopexy and urinary reduction efforts (CARE) trial concluded that postoperative stress incontinence in continent women is significantly reduced when sacrocolpopexy is combined with Burch urethropexy (FIGURE).3 When women who underwent a concomitant Burch procedure were compared with those who didn’t, de novo stress incontinence after prolapse repair occurred in 24% and 44% of women, respectively.3,4 This finding suggests that Burch urethropexy provides a protective benefit for continent women when it is performed at the time of abdominal sacrocolpopexy, eliminating the need for an additional procedure in the future.

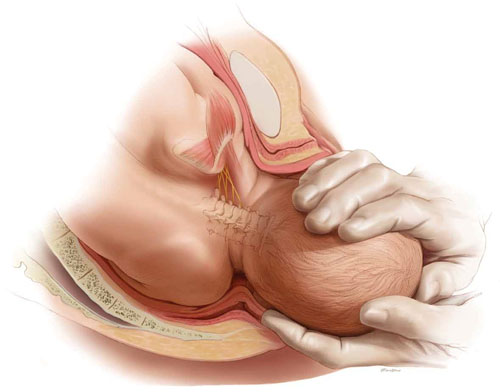

FIGURE: Burch urethropexy

Sutures are placed at the level of the bladder neck and passed through the Cooper’s ligaments to support the urethra and eliminate stress urinary incontinence.

Publication of the CARE findings sparked debate among pelvic surgeons. According to a recent survey of pelvic surgeons, only 50% changed their practice as a result of the CARE trial.5 Some argue that the addition of a continence procedure adds unnecessary surgical risk when the patient lacks subjective or objective evidence of stress incontinence. Besides the surgical risks—which, one might argue, are low—continence surgery may lead to new symptoms of urinary dysfunction, such as urinary obstruction or new-onset urge incontinence. The development of such symptoms can create significant dissatisfaction in a patient who was previously asymptomatic.

This article explores the issue in more depth, focusing on two recent studies:

- analysis of CARE trial data to determine the positive predictive value of preoperative prolapse reduction and urodynamic testing among continent women who have POP

- a retrospective comparison of women who had urodynamically confirmed occult incontinence with those who didn’t, along with their response to different interventions.

What’s the best way to assess women for occult stress incontinence?

Visco AG, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, et al; for Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. The role of preoperative urodynamic testing in stress-continent women undergoing sacrocolpopexy: the Colpopexy and Urinary Reduction Efforts (CARE) randomized surgical trial. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(5):607–614.

Elser DM, Moen MD, Stanford EJ, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy and urinary incontinence: surgical planning based on urodynamics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):375.e1–5.

Preoperative urodynamic testing is often used to evaluate women undergoing pelvic and continence surgery. For adequate evaluation, the prolapse must be reduced sufficiently to simulate the support achieved with the planned surgery. The techniques used to reduce the prolapse during the testing are variable, as is the predictive value of the urodynamic evaluation.

Prolapse may be reduced using a large cotton swab, ring forceps, pessary, or split speculum. When these methods and the utility of urodynamics were evaluated as part of the CARE trial, Visco and colleagues demonstrated that reduction of the prolapse with a large swab yielded the highest positive predictive value. Women who had urodynamically confirmed stress incontinence after the prolapse was reduced with a swab were more likely to develop symptomatic stress incontinence after sacrocolpopexy.

In this study, 35% of women who did not demonstrate occult incontinence during preoperative testing with the swab also went on to develop postoperative incontinence. Overall, urodynamic testing was not helpful in the evaluation of women who had POP. However, asymptomatic women who leaked during preoperative evaluation were more likely to experience incontinence postoperatively, even if they underwent Burch urethropexy.

1. Long CY, Hsu SC, Wu TP, Sun DJ, Su JH, Tsai EM. Urodynamic comparison of continent and incontinent women with severe uterovaginal prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2004;49(1):33-37.

2. Roovers JP, Oelke M. Clinical relevance of urodynamic investigation tests prior to surgical correction of genital prolapse: a literature review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(4):455-460.

3. Brubaker L, Cundiff GW, Fine P, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy with Burch colposuspension to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(15):1557-1566.

4. Brubaker L, Nygaard I, Richter HE, et al. Two-year outcomes after sacrocolpopexy with and without Burch to prevent stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):49-55.

5. Aungst MJ, Mamienski TD, Albright TS, Zahn CM, Fischer JR. Prophylactic Burch colposuspension at the time of abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a survey of current practice patterns. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(8):897-904.

6. Ward KL, Hilton P. Prospective multicentre randomised trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension as primary treatment for stress incontinence. BMJ. 2002;325(735):67-70.

7. Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):611-621.

8. Kennelly MJ, Moore R, Nguyen JN, Lukban JC, Siegel S. Prospective evaluation of a single incision sling for stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2010;184(2):604-609.

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is no small problem. With a prevalence thought to range as high as 30%, the condition challenges us to manage resources in a way that is mindful of cost—both financial expense and cost to the patient in terms of recovery and quality of life.

Although a large percentage of women who have POP also complain of symptomatic incontinence, a substantial number of continent women who have severe POP become incontinent after surgical repair. One reason may be that advanced POP sometimes causes urethral kinking and external urethral compression, fixing a hypermobile urethra in place. Once normal anatomy is restored and the urethra is no longer kinked, the urinary incontinence is “unmasked.”

Women who develop de novo incontinence after POP repair are thought to have “occult” urinary incontinence. Occult stress incontinence is urinary leakage that is prevented by POP and becomes symptomatic only after restoration of pelvic anatomy.1 It has been reported that 36% to 80% of continent women who have POP will develop stress urinary incontinence once the prolapse is reduced, either preoperatively with a pessary or vaginal pack, or after surgical correction.2

This information prompts important questions: If a woman who has POP is continent at the time of her surgical repair, should she undergo a concomitant incontinence procedure “just in case”? Or should she be reevaluated postoperatively for a possible continence procedure at a later time?

The colpopexy and urinary reduction efforts (CARE) trial concluded that postoperative stress incontinence in continent women is significantly reduced when sacrocolpopexy is combined with Burch urethropexy (FIGURE).3 When women who underwent a concomitant Burch procedure were compared with those who didn’t, de novo stress incontinence after prolapse repair occurred in 24% and 44% of women, respectively.3,4 This finding suggests that Burch urethropexy provides a protective benefit for continent women when it is performed at the time of abdominal sacrocolpopexy, eliminating the need for an additional procedure in the future.

FIGURE: Burch urethropexy

Sutures are placed at the level of the bladder neck and passed through the Cooper’s ligaments to support the urethra and eliminate stress urinary incontinence.

Publication of the CARE findings sparked debate among pelvic surgeons. According to a recent survey of pelvic surgeons, only 50% changed their practice as a result of the CARE trial.5 Some argue that the addition of a continence procedure adds unnecessary surgical risk when the patient lacks subjective or objective evidence of stress incontinence. Besides the surgical risks—which, one might argue, are low—continence surgery may lead to new symptoms of urinary dysfunction, such as urinary obstruction or new-onset urge incontinence. The development of such symptoms can create significant dissatisfaction in a patient who was previously asymptomatic.

This article explores the issue in more depth, focusing on two recent studies:

- analysis of CARE trial data to determine the positive predictive value of preoperative prolapse reduction and urodynamic testing among continent women who have POP

- a retrospective comparison of women who had urodynamically confirmed occult incontinence with those who didn’t, along with their response to different interventions.

What’s the best way to assess women for occult stress incontinence?

Visco AG, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, et al; for Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. The role of preoperative urodynamic testing in stress-continent women undergoing sacrocolpopexy: the Colpopexy and Urinary Reduction Efforts (CARE) randomized surgical trial. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(5):607–614.

Elser DM, Moen MD, Stanford EJ, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy and urinary incontinence: surgical planning based on urodynamics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):375.e1–5.

Preoperative urodynamic testing is often used to evaluate women undergoing pelvic and continence surgery. For adequate evaluation, the prolapse must be reduced sufficiently to simulate the support achieved with the planned surgery. The techniques used to reduce the prolapse during the testing are variable, as is the predictive value of the urodynamic evaluation.

Prolapse may be reduced using a large cotton swab, ring forceps, pessary, or split speculum. When these methods and the utility of urodynamics were evaluated as part of the CARE trial, Visco and colleagues demonstrated that reduction of the prolapse with a large swab yielded the highest positive predictive value. Women who had urodynamically confirmed stress incontinence after the prolapse was reduced with a swab were more likely to develop symptomatic stress incontinence after sacrocolpopexy.

In this study, 35% of women who did not demonstrate occult incontinence during preoperative testing with the swab also went on to develop postoperative incontinence. Overall, urodynamic testing was not helpful in the evaluation of women who had POP. However, asymptomatic women who leaked during preoperative evaluation were more likely to experience incontinence postoperatively, even if they underwent Burch urethropexy.

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is no small problem. With a prevalence thought to range as high as 30%, the condition challenges us to manage resources in a way that is mindful of cost—both financial expense and cost to the patient in terms of recovery and quality of life.

Although a large percentage of women who have POP also complain of symptomatic incontinence, a substantial number of continent women who have severe POP become incontinent after surgical repair. One reason may be that advanced POP sometimes causes urethral kinking and external urethral compression, fixing a hypermobile urethra in place. Once normal anatomy is restored and the urethra is no longer kinked, the urinary incontinence is “unmasked.”

Women who develop de novo incontinence after POP repair are thought to have “occult” urinary incontinence. Occult stress incontinence is urinary leakage that is prevented by POP and becomes symptomatic only after restoration of pelvic anatomy.1 It has been reported that 36% to 80% of continent women who have POP will develop stress urinary incontinence once the prolapse is reduced, either preoperatively with a pessary or vaginal pack, or after surgical correction.2

This information prompts important questions: If a woman who has POP is continent at the time of her surgical repair, should she undergo a concomitant incontinence procedure “just in case”? Or should she be reevaluated postoperatively for a possible continence procedure at a later time?

The colpopexy and urinary reduction efforts (CARE) trial concluded that postoperative stress incontinence in continent women is significantly reduced when sacrocolpopexy is combined with Burch urethropexy (FIGURE).3 When women who underwent a concomitant Burch procedure were compared with those who didn’t, de novo stress incontinence after prolapse repair occurred in 24% and 44% of women, respectively.3,4 This finding suggests that Burch urethropexy provides a protective benefit for continent women when it is performed at the time of abdominal sacrocolpopexy, eliminating the need for an additional procedure in the future.

FIGURE: Burch urethropexy

Sutures are placed at the level of the bladder neck and passed through the Cooper’s ligaments to support the urethra and eliminate stress urinary incontinence.

Publication of the CARE findings sparked debate among pelvic surgeons. According to a recent survey of pelvic surgeons, only 50% changed their practice as a result of the CARE trial.5 Some argue that the addition of a continence procedure adds unnecessary surgical risk when the patient lacks subjective or objective evidence of stress incontinence. Besides the surgical risks—which, one might argue, are low—continence surgery may lead to new symptoms of urinary dysfunction, such as urinary obstruction or new-onset urge incontinence. The development of such symptoms can create significant dissatisfaction in a patient who was previously asymptomatic.

This article explores the issue in more depth, focusing on two recent studies:

- analysis of CARE trial data to determine the positive predictive value of preoperative prolapse reduction and urodynamic testing among continent women who have POP

- a retrospective comparison of women who had urodynamically confirmed occult incontinence with those who didn’t, along with their response to different interventions.

What’s the best way to assess women for occult stress incontinence?

Visco AG, Brubaker L, Nygaard I, et al; for Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. The role of preoperative urodynamic testing in stress-continent women undergoing sacrocolpopexy: the Colpopexy and Urinary Reduction Efforts (CARE) randomized surgical trial. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(5):607–614.

Elser DM, Moen MD, Stanford EJ, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy and urinary incontinence: surgical planning based on urodynamics. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(4):375.e1–5.

Preoperative urodynamic testing is often used to evaluate women undergoing pelvic and continence surgery. For adequate evaluation, the prolapse must be reduced sufficiently to simulate the support achieved with the planned surgery. The techniques used to reduce the prolapse during the testing are variable, as is the predictive value of the urodynamic evaluation.

Prolapse may be reduced using a large cotton swab, ring forceps, pessary, or split speculum. When these methods and the utility of urodynamics were evaluated as part of the CARE trial, Visco and colleagues demonstrated that reduction of the prolapse with a large swab yielded the highest positive predictive value. Women who had urodynamically confirmed stress incontinence after the prolapse was reduced with a swab were more likely to develop symptomatic stress incontinence after sacrocolpopexy.

In this study, 35% of women who did not demonstrate occult incontinence during preoperative testing with the swab also went on to develop postoperative incontinence. Overall, urodynamic testing was not helpful in the evaluation of women who had POP. However, asymptomatic women who leaked during preoperative evaluation were more likely to experience incontinence postoperatively, even if they underwent Burch urethropexy.

1. Long CY, Hsu SC, Wu TP, Sun DJ, Su JH, Tsai EM. Urodynamic comparison of continent and incontinent women with severe uterovaginal prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2004;49(1):33-37.

2. Roovers JP, Oelke M. Clinical relevance of urodynamic investigation tests prior to surgical correction of genital prolapse: a literature review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(4):455-460.

3. Brubaker L, Cundiff GW, Fine P, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy with Burch colposuspension to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(15):1557-1566.

4. Brubaker L, Nygaard I, Richter HE, et al. Two-year outcomes after sacrocolpopexy with and without Burch to prevent stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):49-55.

5. Aungst MJ, Mamienski TD, Albright TS, Zahn CM, Fischer JR. Prophylactic Burch colposuspension at the time of abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a survey of current practice patterns. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(8):897-904.

6. Ward KL, Hilton P. Prospective multicentre randomised trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension as primary treatment for stress incontinence. BMJ. 2002;325(735):67-70.

7. Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):611-621.

8. Kennelly MJ, Moore R, Nguyen JN, Lukban JC, Siegel S. Prospective evaluation of a single incision sling for stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2010;184(2):604-609.

1. Long CY, Hsu SC, Wu TP, Sun DJ, Su JH, Tsai EM. Urodynamic comparison of continent and incontinent women with severe uterovaginal prolapse. J Reprod Med. 2004;49(1):33-37.

2. Roovers JP, Oelke M. Clinical relevance of urodynamic investigation tests prior to surgical correction of genital prolapse: a literature review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(4):455-460.

3. Brubaker L, Cundiff GW, Fine P, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy with Burch colposuspension to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(15):1557-1566.

4. Brubaker L, Nygaard I, Richter HE, et al. Two-year outcomes after sacrocolpopexy with and without Burch to prevent stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):49-55.

5. Aungst MJ, Mamienski TD, Albright TS, Zahn CM, Fischer JR. Prophylactic Burch colposuspension at the time of abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a survey of current practice patterns. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(8):897-904.

6. Ward KL, Hilton P. Prospective multicentre randomised trial of tension-free vaginal tape and colposuspension as primary treatment for stress incontinence. BMJ. 2002;325(735):67-70.

7. Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):611-621.

8. Kennelly MJ, Moore R, Nguyen JN, Lukban JC, Siegel S. Prospective evaluation of a single incision sling for stress urinary incontinence. J Urol. 2010;184(2):604-609.

Sound strategies to avoid malpractice hazards on labor and delivery

CASE: Is TOLAC feasible?

Your patient is a 33-year-old gravida 3, para 2002, with a previous cesarean delivery who was admitted to labor and delivery with premature ruptured membranes at term. She is not contracting. Fetal status is reassuring.

Her obstetric history is of one normal, spontaneous delivery followed by one cesarean delivery, both occurring at term.

She wants to know if she can safely undergo a trial of labor, or if she must have a repeat cesarean delivery. How should you counsel her?

At the start of any discussion about how to reduce your risk of being sued for malpractice because of your work as an obstetrician, in particular during labor and delivery, two distinct, underlying avenues of concern need to be addressed. Before moving on to discuss strategy, then, let’s consider what they are and how they arise: Allegation (perception). You are at risk of an allegation of malpractice (or of a perception of malpractice) because of an unexpected event or outcome for mother or baby. Allegation and perception can arise apart from any specific clinical action you undertook, or did not undertake. An example? Counseling about options for care that falls short of full understanding by the patient.

Allegation and perception are the subjects of this first installment of our two-part article on strategies for avoiding claims of malpractice in L & D that begin with the first prenatal visit.

Causation. Your actions—what you do in the course of providing prenatal care and delivering a baby—put you at risk of a charge of malpractice when you have provided medical care that 1) is inconsistent with current medical practice and thus 2) harmed the mother or newborn.

For a medical malpractice case to go forward, it must meet a well-defined paradigm that teases apart components of causation, beginning with your duty to the patient (TABLE 1).

TABLE 1 Signposts in the medical malpractice paradigm

| When the clinical issue at hand is … | … Then the legal term is … |

|---|---|

| A health-care professional’s obligation to provide care | “Duty” |

| A deviation in the care that was provided | “Standard of care” |

| An allegation that a breach in the standard of care resulted in injury | “Proximate cause” |

| An assertion or finding that an injury is “compensable” | “Damages” |

| Source: Yale New Haven Medical Center, 1997.5 | |

Allegation of malpractice arises from a range of sources, as we’ll discuss, but it is causation that reflects the actual, hands-on practice of medicine. We’ll examine strategies for avoiding charges of causation in the second part of this article.

(For now, we’ll just note that a recent excellent review of intrapartum interventions and their basis in evidence1 offers a model for evaluating a number of widely utilized practices in obstetrics. The goal, of course, is to minimize bad outcomes that follow from causation. Regrettably, that evidence-based approach is a limited one, because of a paucity of adequately controlled studies about OB practice.)

CASE: Continued

You consider your patient’s comment that she would like to avoid a repeat cesarean delivery, and advise her that she may safely attempt vaginal birth.

When spontaneous labor does not occur in 6 hours, oxytocin is administered. She dilates to 9 cm and begins to push spontaneously.

The fetal heart rate then drops to 70/min; fetal station, which had been +2, is now -1. A Stat cesarean delivery is performed. Uterine rupture with partial fetal expulsion is found. Apgar scores are 1, 3, and 5 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes.

Your patient requires a hysterectomy to control bleeding.

Some broad considerations for the physician arising from this CASE

- The counseling that you provide to a patient should be nondirective; it should include your opinion, however, about the best option available to her. Insert yourself into this hypothetical case, for discussion’s sake: Did you provide that important opinion to her?

- You must make certain that she clearly understands the risks and benefits of a procedure or other action, and the available alternatives. Did you undertake a check of her comprehension, given the anxiety and confusion of the moment?

- When an adverse outcome ensues—however unlikely it was to occur—it is necessary for you to review the circumstances with the patient as soon as clinically possible. Did you “debrief” and counsel her before and after the hysterectomy?

No more “perfect outcomes”: Our role changed, so did our risk

From the moment an OB patient enters triage, until her arrival home with her infant, this crucial period of her life is colored by concern, curiosity, myth, and fear.

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy infant. In an earlier era, the patient and her family relied on the sage advice of their physician to ensure this outcome. To an extent, physicians themselves reinforced this reliance, embracing the notion that they were, in fact, able to provide such a perfect outcome.

With advances that have been made in reproductive medicine, pregnancy has become more readily available to women with increasingly advanced disease; this has made labor and delivery more challenging to them and to their physicians. Realistically, our role as physicians is now better expressed as providing advice to help a woman achieve the best possible outcome, recognizing her individual clinical circumstances, instead of ensuring a perfect outcome.

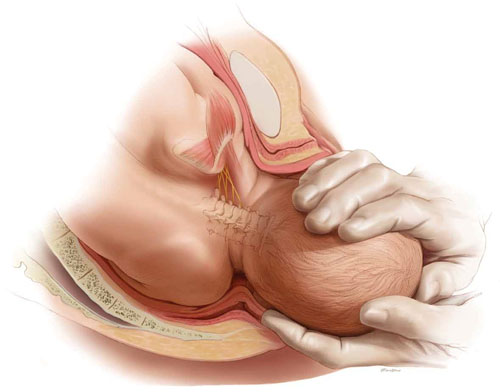

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy baby. But the role of the OB is better expressed as helping her achieve the best possible outcome, not a perfect outcome. ABOVE: Shoulder dystocia is one of the most treacherous and frightening—and litigated—complications of childbirth, yet it is, for the most part, unpredictable and unpreventable in the course of even routine delivery.

Key concept #1

COMMUNICATION

Communication is central to patients’ comprehension about the care that you provide to them. But to enter a genuine dialogue with a patient under your care, and with her family, can challenge your communication skills.

First, you need written and verbal skills. Second, you need to know how to read visual cues.

Third, the messages that you deliver to the patient are influenced by:

- your style of communication

- your cultural background

- the setting in which you’re providing care (office, hospital).

Where are such skills developed? For one, biopsychosocial models that are employed in medical student education and resident training aid the physician in developing appropriate communication skills.

But training alone cannot overcome the fact that communication is a double-sided activity: Patients bring many of their own variables to a dialogue. How patients understand and interact with you—and with other providers and the health-care system—is not, therefore, directly or strictly within your sphere of influence.

Yet your sensitivity to a patient’s issues can go a long way toward ameliorating her misconceptions and prejudices. Here are several suggestions, developed by others, to optimize patients’ understanding of their care2,3:

- Apply what’s known as flip default. Assume the patient does not understand the information that you’re providing. Ask her to repeat your instructions back to you (as is done with a verbal order in the hospital).

- Manage face-to-face time effectively. Don’t attempt to teach a patient everything about her care at once. Focus on the critical aspects of her case and on providing understanding; use a strategy of sequential learning.

- Reduce the “overwhelm” factor. Periodically, stop and ask the patient if she has questions. Don’t wait until the end of the appointment to do this.

- Eliminate jargon. When you notify a patient about the results of testing, for example, clarify what the results say about her health and mean for her care. Do so in plain language.

- Recognize her preconceptions. Discuss any psychosocial issues head on with the patient. Use an interpreter or a social worker, or counselors from other fields, as appropriate.

Remember: All health-care personnel need to understand the importance of making the patient comfortable in the often foreign, and sometimes sterile, milieu of the medical office and hospital.

Key concept #2

TRUST

Trust between patient and clinician is, we believe, the most basic necessity for ameliorating allegations of malpractice—secondary only, perhaps, to your knowledge of medicine.

Trust can be enhanced by interactions that demonstrate to both parties the advisability of working together to resolve a problem. Any aspect of the physician-patient interaction that is potentially adversarial does not serve the interests of either.

We encourage you to construct a communication bridge, so to speak, with your patient. Begin by:

- introducing yourself to her and explaining your role in her care

- making appropriate eye contact with her

- maintaining a positive attitude

- dressing appropriately

- making her feel that she is your No. 1 priority.

There is more.

Recognize the duality of respect

- Ask the patient how she wishes to be addressed

- Ask about her belief system

- Explain the specifics of her care without arrogance.

Engender trust

- Be honest with her

- Be on her side

- Take time with her

- Allow her the right that she has to select from the options or to refuse treatment

- Disclose to the patient your status as a student or resident, if that is your rank.

Recognize the benefits of partnership

Forging a partnership with the patient:

- improves the accuracy of information

- eases ongoing communication

- facilitates informed consent

- provides an opportunity for you to educate her.

TABLE 2 When building trust, both patient and physician

are charged with responsibilities

| In regard to … | The patient’s responsibility is to … | The physician’s responsibility is to … |

|---|---|---|

| Gathering an honest and complete medical history | Know and report | Question completely |

| Being adherent to prescribed care | Follow through | Make reasonable demands |

| Making decisions about care | Ask questions and actively participate in choices Make realistic requests | Be knowledgeable about available alternatives Individualize options |

Key concept #3

SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

Patient and physician both have responsibilities that are important to achieving an optimal outcome; so does the hospital (TABLE 2 and TABLE 3). Both patient and physician should practice full disclosure throughout the course of care; this will benefit both of you.4 Here are a few select examples.

TABLE 3 Relative degrees of responsibility for a good outcome

vary across interested parties, but none are exempt

| Area of emphasis | Hospital’s responsibility | Physician’s responsibility | Patient’s responsibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creating a positive environment for care | 3+ | 2+ | 1+ |

| Providing clear communication | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Obtaining informed consent | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Making reasonable requests | 1+ | 1+ | 3+ |

| Compliance | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Key to the relative scale: 1+: at the least, minimally responsible; 2+: at the least, somewhat responsible; 3+, responsible to the greatest degree. | |||

The importance of the intake form

At the outset of OB care, in most practices, the patient provides the initial detailed medical history by completing a form in the waiting room. In reviewing and completing this survey with her during the appointment, pay particular attention to those questions for which the response has been left blank.

Patients need to understand that key recommendations about their care, and a proper analysis of their concerns, are based on the information that they provide on this survey. In our practices, we find that patients answer most of these early questions without difficulty—even inquiries of a personal nature, such as the number of prior pregnancies, or drug, alcohol, and smoking habits—as long as they understand why it’s in their best interests for you to have this information. If they leave a question blank and you do not follow up verbally, you may have lost invaluable information that can affect the outcome of her pregnancy.

What should you do when, occasionally, a patient refuses to answer one of your questions? We recommend that you record her refusal on the form itself, where the note remains part of the record.

Keep in mind that all necessary and useful information about a patient may not be available, or may not be appropriate to consider, at the initial prenatal visit. In that case, you have an ongoing opportunity—at subsequent visits during the pregnancy—to develop her full medical profile and algorithm.

The necessity of adherence

It almost goes without saying: To provide the care that our patients need, we sometimes require the unpleasant of them—to undergo evaluations, or testing, or to take medications that may be inconvenient or costly.

After you explain the specific course of care to a patient—whether you’re ordering a test or writing a prescription—your follow-up must include notation in the record of adherence. The fact is that both of you share responsibility for having her understand the importance of adherence to your instructions and the consequences of limited adherence or nonadherence.

Recall one of the lessons from the case that introduced this article: For the patient to make an informed decision about her care, the clinician must have thorough knowledge of 1) the risks and benefits of whatever intervention is being proposed in the particular clinical scenario and 2) the available alternatives. It is key that you communicate your risk-benefit assessment accurately to the patient.

Follow-up

Sometimes, new medical problems arise during subsequent prenatal visits. Follow-up appointments also provide an opportunity for you to expand your attention to problems identified earlier. Regardless of what the patient reported about her history and current health at the initial prenatal visit, listen for her to bring new issues to light for resolution later in the pregnancy that will have an impact on L & D. Again, it goes without saying but needs to be said: The OB clinician needs to have whatever skills are necessary to 1) fully evaluate the progress of a pregnancy and 2) make recommendations for care in light of changes in the status of mother and fetus along the way.

TABLE 4 Examples of the cardinal rule of “Be specific”

when you document care

| Instead of noting … | … Use alternative wording |

|---|---|

| “Mild vaginal bleeding” | “Vaginal bleeding requiring two pads an hour” |

| “Gentle traction” | “The shoulders were rotated before assisting the patient’s expulsive efforts” |

| “Patient refuses…” [or “declines…”] | “Patient voiced the nature of the problem and the alternatives that i have explained to her” |

| “Expedited cesarean section” | “The time from decision to incision was 35 minutes” |

Basic principles of documentation

The medical record is the best witness to interactions between a physician and a patient. In the record, we’re required to write a “5-C” description of events—namely, one that is:

- correct

- comprehensive

- conscientious

- clear

- contemporaneous.

Avoid medical jargon in the record. Be careful not to use vague terminology or descriptions, such as “mild vaginal bleeding,” “gentle traction,” or “patient refuses and accepts the consequences.” Specificity is the key to accuracy with respect to documentation (TABLE 4).

Editor’s note: Part 2 of this article will appear in the January 2011 issue of OBG Management. The authors’ analysis of L & D malpractice claims moves to a discussion of causation—by way of 4 troubling cases.

You’ll find a rich, useful archive of expert analysis of your professional liability and malpractice risk, at www.obgmanagement.com

• 10 keys to defending (or, better, keeping clear of) a shoulder dystocia suit

Andrew K. Worek, Esq (March 2008)

• After a patient’s unexpected death, First Aid for the emotionally wounded

Ronald A. Chez, MD, and Wayne Fortin, MS (April 2010)

• Afraid of getting sued? A plaintiff attorney offers counsel (but no sympathy)

Janelle Yates, Senior Editor, with Lewis Laska, JD, PhD (October 2009)

• Can a change in practice patterns reduce the number of OB malpractice claims?

Jason K. Baxter, MD, MSCP, and Louis Weinstein, MD (April 2009)

• Strategies for breaking bad news to patients

Barry Bub, MD (September 2008)

• Stuff of nightmares: Criminal prosecution for malpractice

Gary Steinman, MD, PhD (August 2008)

• Deposition Dos and Don’ts: How to answer 8 tricky questions

James L. Knoll, IV, MD, and Phillip J. Resnick, MD (May 2008)

• Playing high-stakes poker: Do you fight—or settle—that malpractice lawsuit?

Jeffrey Segal, MD (April 2008)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based labor and delivery management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(5):445-454.

2. Paasche-Orlow MK, Riekert KA, Bilderback A, et al. Tailored education may reduce health literacy disparities in asthma self-management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:980-986.

3. Huvane K. Health literacy: reading is just the beginning. Focus on multicultural healthcare. 2007;3(4):16-19.

4. Giordano K. Legal Principles. In: O’Grady JP, Gimovsky ML, Bayer-Zwirello L, Giordano K, eds. Operative Obstetrics. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

5. The Four Elements of Medical Malpractice Yale New Haven Medical Center: Issues in Risk Management. 1997.

CASE: Is TOLAC feasible?

Your patient is a 33-year-old gravida 3, para 2002, with a previous cesarean delivery who was admitted to labor and delivery with premature ruptured membranes at term. She is not contracting. Fetal status is reassuring.

Her obstetric history is of one normal, spontaneous delivery followed by one cesarean delivery, both occurring at term.

She wants to know if she can safely undergo a trial of labor, or if she must have a repeat cesarean delivery. How should you counsel her?

At the start of any discussion about how to reduce your risk of being sued for malpractice because of your work as an obstetrician, in particular during labor and delivery, two distinct, underlying avenues of concern need to be addressed. Before moving on to discuss strategy, then, let’s consider what they are and how they arise: Allegation (perception). You are at risk of an allegation of malpractice (or of a perception of malpractice) because of an unexpected event or outcome for mother or baby. Allegation and perception can arise apart from any specific clinical action you undertook, or did not undertake. An example? Counseling about options for care that falls short of full understanding by the patient.

Allegation and perception are the subjects of this first installment of our two-part article on strategies for avoiding claims of malpractice in L & D that begin with the first prenatal visit.

Causation. Your actions—what you do in the course of providing prenatal care and delivering a baby—put you at risk of a charge of malpractice when you have provided medical care that 1) is inconsistent with current medical practice and thus 2) harmed the mother or newborn.

For a medical malpractice case to go forward, it must meet a well-defined paradigm that teases apart components of causation, beginning with your duty to the patient (TABLE 1).

TABLE 1 Signposts in the medical malpractice paradigm

| When the clinical issue at hand is … | … Then the legal term is … |

|---|---|

| A health-care professional’s obligation to provide care | “Duty” |

| A deviation in the care that was provided | “Standard of care” |

| An allegation that a breach in the standard of care resulted in injury | “Proximate cause” |

| An assertion or finding that an injury is “compensable” | “Damages” |

| Source: Yale New Haven Medical Center, 1997.5 | |

Allegation of malpractice arises from a range of sources, as we’ll discuss, but it is causation that reflects the actual, hands-on practice of medicine. We’ll examine strategies for avoiding charges of causation in the second part of this article.

(For now, we’ll just note that a recent excellent review of intrapartum interventions and their basis in evidence1 offers a model for evaluating a number of widely utilized practices in obstetrics. The goal, of course, is to minimize bad outcomes that follow from causation. Regrettably, that evidence-based approach is a limited one, because of a paucity of adequately controlled studies about OB practice.)

CASE: Continued

You consider your patient’s comment that she would like to avoid a repeat cesarean delivery, and advise her that she may safely attempt vaginal birth.

When spontaneous labor does not occur in 6 hours, oxytocin is administered. She dilates to 9 cm and begins to push spontaneously.

The fetal heart rate then drops to 70/min; fetal station, which had been +2, is now -1. A Stat cesarean delivery is performed. Uterine rupture with partial fetal expulsion is found. Apgar scores are 1, 3, and 5 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes.

Your patient requires a hysterectomy to control bleeding.

Some broad considerations for the physician arising from this CASE

- The counseling that you provide to a patient should be nondirective; it should include your opinion, however, about the best option available to her. Insert yourself into this hypothetical case, for discussion’s sake: Did you provide that important opinion to her?

- You must make certain that she clearly understands the risks and benefits of a procedure or other action, and the available alternatives. Did you undertake a check of her comprehension, given the anxiety and confusion of the moment?

- When an adverse outcome ensues—however unlikely it was to occur—it is necessary for you to review the circumstances with the patient as soon as clinically possible. Did you “debrief” and counsel her before and after the hysterectomy?

No more “perfect outcomes”: Our role changed, so did our risk

From the moment an OB patient enters triage, until her arrival home with her infant, this crucial period of her life is colored by concern, curiosity, myth, and fear.

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy infant. In an earlier era, the patient and her family relied on the sage advice of their physician to ensure this outcome. To an extent, physicians themselves reinforced this reliance, embracing the notion that they were, in fact, able to provide such a perfect outcome.

With advances that have been made in reproductive medicine, pregnancy has become more readily available to women with increasingly advanced disease; this has made labor and delivery more challenging to them and to their physicians. Realistically, our role as physicians is now better expressed as providing advice to help a woman achieve the best possible outcome, recognizing her individual clinical circumstances, instead of ensuring a perfect outcome.

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy baby. But the role of the OB is better expressed as helping her achieve the best possible outcome, not a perfect outcome. ABOVE: Shoulder dystocia is one of the most treacherous and frightening—and litigated—complications of childbirth, yet it is, for the most part, unpredictable and unpreventable in the course of even routine delivery.

Key concept #1

COMMUNICATION

Communication is central to patients’ comprehension about the care that you provide to them. But to enter a genuine dialogue with a patient under your care, and with her family, can challenge your communication skills.

First, you need written and verbal skills. Second, you need to know how to read visual cues.

Third, the messages that you deliver to the patient are influenced by:

- your style of communication

- your cultural background

- the setting in which you’re providing care (office, hospital).

Where are such skills developed? For one, biopsychosocial models that are employed in medical student education and resident training aid the physician in developing appropriate communication skills.

But training alone cannot overcome the fact that communication is a double-sided activity: Patients bring many of their own variables to a dialogue. How patients understand and interact with you—and with other providers and the health-care system—is not, therefore, directly or strictly within your sphere of influence.

Yet your sensitivity to a patient’s issues can go a long way toward ameliorating her misconceptions and prejudices. Here are several suggestions, developed by others, to optimize patients’ understanding of their care2,3:

- Apply what’s known as flip default. Assume the patient does not understand the information that you’re providing. Ask her to repeat your instructions back to you (as is done with a verbal order in the hospital).

- Manage face-to-face time effectively. Don’t attempt to teach a patient everything about her care at once. Focus on the critical aspects of her case and on providing understanding; use a strategy of sequential learning.

- Reduce the “overwhelm” factor. Periodically, stop and ask the patient if she has questions. Don’t wait until the end of the appointment to do this.

- Eliminate jargon. When you notify a patient about the results of testing, for example, clarify what the results say about her health and mean for her care. Do so in plain language.

- Recognize her preconceptions. Discuss any psychosocial issues head on with the patient. Use an interpreter or a social worker, or counselors from other fields, as appropriate.

Remember: All health-care personnel need to understand the importance of making the patient comfortable in the often foreign, and sometimes sterile, milieu of the medical office and hospital.

Key concept #2

TRUST

Trust between patient and clinician is, we believe, the most basic necessity for ameliorating allegations of malpractice—secondary only, perhaps, to your knowledge of medicine.

Trust can be enhanced by interactions that demonstrate to both parties the advisability of working together to resolve a problem. Any aspect of the physician-patient interaction that is potentially adversarial does not serve the interests of either.

We encourage you to construct a communication bridge, so to speak, with your patient. Begin by:

- introducing yourself to her and explaining your role in her care

- making appropriate eye contact with her

- maintaining a positive attitude

- dressing appropriately

- making her feel that she is your No. 1 priority.

There is more.

Recognize the duality of respect

- Ask the patient how she wishes to be addressed

- Ask about her belief system

- Explain the specifics of her care without arrogance.

Engender trust

- Be honest with her

- Be on her side

- Take time with her

- Allow her the right that she has to select from the options or to refuse treatment

- Disclose to the patient your status as a student or resident, if that is your rank.

Recognize the benefits of partnership

Forging a partnership with the patient:

- improves the accuracy of information

- eases ongoing communication

- facilitates informed consent

- provides an opportunity for you to educate her.

TABLE 2 When building trust, both patient and physician

are charged with responsibilities

| In regard to … | The patient’s responsibility is to … | The physician’s responsibility is to … |

|---|---|---|

| Gathering an honest and complete medical history | Know and report | Question completely |

| Being adherent to prescribed care | Follow through | Make reasonable demands |

| Making decisions about care | Ask questions and actively participate in choices Make realistic requests | Be knowledgeable about available alternatives Individualize options |

Key concept #3

SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

Patient and physician both have responsibilities that are important to achieving an optimal outcome; so does the hospital (TABLE 2 and TABLE 3). Both patient and physician should practice full disclosure throughout the course of care; this will benefit both of you.4 Here are a few select examples.

TABLE 3 Relative degrees of responsibility for a good outcome

vary across interested parties, but none are exempt

| Area of emphasis | Hospital’s responsibility | Physician’s responsibility | Patient’s responsibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creating a positive environment for care | 3+ | 2+ | 1+ |

| Providing clear communication | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Obtaining informed consent | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Making reasonable requests | 1+ | 1+ | 3+ |

| Compliance | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Key to the relative scale: 1+: at the least, minimally responsible; 2+: at the least, somewhat responsible; 3+, responsible to the greatest degree. | |||

The importance of the intake form

At the outset of OB care, in most practices, the patient provides the initial detailed medical history by completing a form in the waiting room. In reviewing and completing this survey with her during the appointment, pay particular attention to those questions for which the response has been left blank.

Patients need to understand that key recommendations about their care, and a proper analysis of their concerns, are based on the information that they provide on this survey. In our practices, we find that patients answer most of these early questions without difficulty—even inquiries of a personal nature, such as the number of prior pregnancies, or drug, alcohol, and smoking habits—as long as they understand why it’s in their best interests for you to have this information. If they leave a question blank and you do not follow up verbally, you may have lost invaluable information that can affect the outcome of her pregnancy.

What should you do when, occasionally, a patient refuses to answer one of your questions? We recommend that you record her refusal on the form itself, where the note remains part of the record.

Keep in mind that all necessary and useful information about a patient may not be available, or may not be appropriate to consider, at the initial prenatal visit. In that case, you have an ongoing opportunity—at subsequent visits during the pregnancy—to develop her full medical profile and algorithm.

The necessity of adherence

It almost goes without saying: To provide the care that our patients need, we sometimes require the unpleasant of them—to undergo evaluations, or testing, or to take medications that may be inconvenient or costly.

After you explain the specific course of care to a patient—whether you’re ordering a test or writing a prescription—your follow-up must include notation in the record of adherence. The fact is that both of you share responsibility for having her understand the importance of adherence to your instructions and the consequences of limited adherence or nonadherence.

Recall one of the lessons from the case that introduced this article: For the patient to make an informed decision about her care, the clinician must have thorough knowledge of 1) the risks and benefits of whatever intervention is being proposed in the particular clinical scenario and 2) the available alternatives. It is key that you communicate your risk-benefit assessment accurately to the patient.

Follow-up

Sometimes, new medical problems arise during subsequent prenatal visits. Follow-up appointments also provide an opportunity for you to expand your attention to problems identified earlier. Regardless of what the patient reported about her history and current health at the initial prenatal visit, listen for her to bring new issues to light for resolution later in the pregnancy that will have an impact on L & D. Again, it goes without saying but needs to be said: The OB clinician needs to have whatever skills are necessary to 1) fully evaluate the progress of a pregnancy and 2) make recommendations for care in light of changes in the status of mother and fetus along the way.

TABLE 4 Examples of the cardinal rule of “Be specific”

when you document care

| Instead of noting … | … Use alternative wording |

|---|---|

| “Mild vaginal bleeding” | “Vaginal bleeding requiring two pads an hour” |

| “Gentle traction” | “The shoulders were rotated before assisting the patient’s expulsive efforts” |

| “Patient refuses…” [or “declines…”] | “Patient voiced the nature of the problem and the alternatives that i have explained to her” |

| “Expedited cesarean section” | “The time from decision to incision was 35 minutes” |

Basic principles of documentation

The medical record is the best witness to interactions between a physician and a patient. In the record, we’re required to write a “5-C” description of events—namely, one that is:

- correct

- comprehensive

- conscientious

- clear

- contemporaneous.

Avoid medical jargon in the record. Be careful not to use vague terminology or descriptions, such as “mild vaginal bleeding,” “gentle traction,” or “patient refuses and accepts the consequences.” Specificity is the key to accuracy with respect to documentation (TABLE 4).

Editor’s note: Part 2 of this article will appear in the January 2011 issue of OBG Management. The authors’ analysis of L & D malpractice claims moves to a discussion of causation—by way of 4 troubling cases.

You’ll find a rich, useful archive of expert analysis of your professional liability and malpractice risk, at www.obgmanagement.com

• 10 keys to defending (or, better, keeping clear of) a shoulder dystocia suit

Andrew K. Worek, Esq (March 2008)

• After a patient’s unexpected death, First Aid for the emotionally wounded

Ronald A. Chez, MD, and Wayne Fortin, MS (April 2010)

• Afraid of getting sued? A plaintiff attorney offers counsel (but no sympathy)

Janelle Yates, Senior Editor, with Lewis Laska, JD, PhD (October 2009)

• Can a change in practice patterns reduce the number of OB malpractice claims?

Jason K. Baxter, MD, MSCP, and Louis Weinstein, MD (April 2009)

• Strategies for breaking bad news to patients

Barry Bub, MD (September 2008)

• Stuff of nightmares: Criminal prosecution for malpractice

Gary Steinman, MD, PhD (August 2008)

• Deposition Dos and Don’ts: How to answer 8 tricky questions

James L. Knoll, IV, MD, and Phillip J. Resnick, MD (May 2008)

• Playing high-stakes poker: Do you fight—or settle—that malpractice lawsuit?

Jeffrey Segal, MD (April 2008)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

CASE: Is TOLAC feasible?

Your patient is a 33-year-old gravida 3, para 2002, with a previous cesarean delivery who was admitted to labor and delivery with premature ruptured membranes at term. She is not contracting. Fetal status is reassuring.

Her obstetric history is of one normal, spontaneous delivery followed by one cesarean delivery, both occurring at term.

She wants to know if she can safely undergo a trial of labor, or if she must have a repeat cesarean delivery. How should you counsel her?

At the start of any discussion about how to reduce your risk of being sued for malpractice because of your work as an obstetrician, in particular during labor and delivery, two distinct, underlying avenues of concern need to be addressed. Before moving on to discuss strategy, then, let’s consider what they are and how they arise: Allegation (perception). You are at risk of an allegation of malpractice (or of a perception of malpractice) because of an unexpected event or outcome for mother or baby. Allegation and perception can arise apart from any specific clinical action you undertook, or did not undertake. An example? Counseling about options for care that falls short of full understanding by the patient.

Allegation and perception are the subjects of this first installment of our two-part article on strategies for avoiding claims of malpractice in L & D that begin with the first prenatal visit.

Causation. Your actions—what you do in the course of providing prenatal care and delivering a baby—put you at risk of a charge of malpractice when you have provided medical care that 1) is inconsistent with current medical practice and thus 2) harmed the mother or newborn.

For a medical malpractice case to go forward, it must meet a well-defined paradigm that teases apart components of causation, beginning with your duty to the patient (TABLE 1).

TABLE 1 Signposts in the medical malpractice paradigm

| When the clinical issue at hand is … | … Then the legal term is … |

|---|---|

| A health-care professional’s obligation to provide care | “Duty” |

| A deviation in the care that was provided | “Standard of care” |

| An allegation that a breach in the standard of care resulted in injury | “Proximate cause” |

| An assertion or finding that an injury is “compensable” | “Damages” |

| Source: Yale New Haven Medical Center, 1997.5 | |

Allegation of malpractice arises from a range of sources, as we’ll discuss, but it is causation that reflects the actual, hands-on practice of medicine. We’ll examine strategies for avoiding charges of causation in the second part of this article.

(For now, we’ll just note that a recent excellent review of intrapartum interventions and their basis in evidence1 offers a model for evaluating a number of widely utilized practices in obstetrics. The goal, of course, is to minimize bad outcomes that follow from causation. Regrettably, that evidence-based approach is a limited one, because of a paucity of adequately controlled studies about OB practice.)

CASE: Continued

You consider your patient’s comment that she would like to avoid a repeat cesarean delivery, and advise her that she may safely attempt vaginal birth.

When spontaneous labor does not occur in 6 hours, oxytocin is administered. She dilates to 9 cm and begins to push spontaneously.

The fetal heart rate then drops to 70/min; fetal station, which had been +2, is now -1. A Stat cesarean delivery is performed. Uterine rupture with partial fetal expulsion is found. Apgar scores are 1, 3, and 5 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes.

Your patient requires a hysterectomy to control bleeding.

Some broad considerations for the physician arising from this CASE

- The counseling that you provide to a patient should be nondirective; it should include your opinion, however, about the best option available to her. Insert yourself into this hypothetical case, for discussion’s sake: Did you provide that important opinion to her?

- You must make certain that she clearly understands the risks and benefits of a procedure or other action, and the available alternatives. Did you undertake a check of her comprehension, given the anxiety and confusion of the moment?

- When an adverse outcome ensues—however unlikely it was to occur—it is necessary for you to review the circumstances with the patient as soon as clinically possible. Did you “debrief” and counsel her before and after the hysterectomy?

No more “perfect outcomes”: Our role changed, so did our risk

From the moment an OB patient enters triage, until her arrival home with her infant, this crucial period of her life is colored by concern, curiosity, myth, and fear.

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy infant. In an earlier era, the patient and her family relied on the sage advice of their physician to ensure this outcome. To an extent, physicians themselves reinforced this reliance, embracing the notion that they were, in fact, able to provide such a perfect outcome.

With advances that have been made in reproductive medicine, pregnancy has become more readily available to women with increasingly advanced disease; this has made labor and delivery more challenging to them and to their physicians. Realistically, our role as physicians is now better expressed as providing advice to help a woman achieve the best possible outcome, recognizing her individual clinical circumstances, instead of ensuring a perfect outcome.

Every woman anticipates the birth of a healthy baby. But the role of the OB is better expressed as helping her achieve the best possible outcome, not a perfect outcome. ABOVE: Shoulder dystocia is one of the most treacherous and frightening—and litigated—complications of childbirth, yet it is, for the most part, unpredictable and unpreventable in the course of even routine delivery.

Key concept #1

COMMUNICATION

Communication is central to patients’ comprehension about the care that you provide to them. But to enter a genuine dialogue with a patient under your care, and with her family, can challenge your communication skills.

First, you need written and verbal skills. Second, you need to know how to read visual cues.

Third, the messages that you deliver to the patient are influenced by:

- your style of communication

- your cultural background

- the setting in which you’re providing care (office, hospital).

Where are such skills developed? For one, biopsychosocial models that are employed in medical student education and resident training aid the physician in developing appropriate communication skills.

But training alone cannot overcome the fact that communication is a double-sided activity: Patients bring many of their own variables to a dialogue. How patients understand and interact with you—and with other providers and the health-care system—is not, therefore, directly or strictly within your sphere of influence.

Yet your sensitivity to a patient’s issues can go a long way toward ameliorating her misconceptions and prejudices. Here are several suggestions, developed by others, to optimize patients’ understanding of their care2,3:

- Apply what’s known as flip default. Assume the patient does not understand the information that you’re providing. Ask her to repeat your instructions back to you (as is done with a verbal order in the hospital).

- Manage face-to-face time effectively. Don’t attempt to teach a patient everything about her care at once. Focus on the critical aspects of her case and on providing understanding; use a strategy of sequential learning.

- Reduce the “overwhelm” factor. Periodically, stop and ask the patient if she has questions. Don’t wait until the end of the appointment to do this.

- Eliminate jargon. When you notify a patient about the results of testing, for example, clarify what the results say about her health and mean for her care. Do so in plain language.

- Recognize her preconceptions. Discuss any psychosocial issues head on with the patient. Use an interpreter or a social worker, or counselors from other fields, as appropriate.

Remember: All health-care personnel need to understand the importance of making the patient comfortable in the often foreign, and sometimes sterile, milieu of the medical office and hospital.

Key concept #2

TRUST

Trust between patient and clinician is, we believe, the most basic necessity for ameliorating allegations of malpractice—secondary only, perhaps, to your knowledge of medicine.

Trust can be enhanced by interactions that demonstrate to both parties the advisability of working together to resolve a problem. Any aspect of the physician-patient interaction that is potentially adversarial does not serve the interests of either.

We encourage you to construct a communication bridge, so to speak, with your patient. Begin by:

- introducing yourself to her and explaining your role in her care

- making appropriate eye contact with her

- maintaining a positive attitude

- dressing appropriately

- making her feel that she is your No. 1 priority.

There is more.

Recognize the duality of respect

- Ask the patient how she wishes to be addressed

- Ask about her belief system

- Explain the specifics of her care without arrogance.

Engender trust

- Be honest with her

- Be on her side

- Take time with her

- Allow her the right that she has to select from the options or to refuse treatment

- Disclose to the patient your status as a student or resident, if that is your rank.

Recognize the benefits of partnership

Forging a partnership with the patient:

- improves the accuracy of information

- eases ongoing communication

- facilitates informed consent

- provides an opportunity for you to educate her.

TABLE 2 When building trust, both patient and physician

are charged with responsibilities

| In regard to … | The patient’s responsibility is to … | The physician’s responsibility is to … |

|---|---|---|

| Gathering an honest and complete medical history | Know and report | Question completely |

| Being adherent to prescribed care | Follow through | Make reasonable demands |

| Making decisions about care | Ask questions and actively participate in choices Make realistic requests | Be knowledgeable about available alternatives Individualize options |

Key concept #3

SHARED RESPONSIBILITY

Patient and physician both have responsibilities that are important to achieving an optimal outcome; so does the hospital (TABLE 2 and TABLE 3). Both patient and physician should practice full disclosure throughout the course of care; this will benefit both of you.4 Here are a few select examples.

TABLE 3 Relative degrees of responsibility for a good outcome

vary across interested parties, but none are exempt

| Area of emphasis | Hospital’s responsibility | Physician’s responsibility | Patient’s responsibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creating a positive environment for care | 3+ | 2+ | 1+ |

| Providing clear communication | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Obtaining informed consent | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Making reasonable requests | 1+ | 1+ | 3+ |

| Compliance | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ |

| Key to the relative scale: 1+: at the least, minimally responsible; 2+: at the least, somewhat responsible; 3+, responsible to the greatest degree. | |||

The importance of the intake form

At the outset of OB care, in most practices, the patient provides the initial detailed medical history by completing a form in the waiting room. In reviewing and completing this survey with her during the appointment, pay particular attention to those questions for which the response has been left blank.

Patients need to understand that key recommendations about their care, and a proper analysis of their concerns, are based on the information that they provide on this survey. In our practices, we find that patients answer most of these early questions without difficulty—even inquiries of a personal nature, such as the number of prior pregnancies, or drug, alcohol, and smoking habits—as long as they understand why it’s in their best interests for you to have this information. If they leave a question blank and you do not follow up verbally, you may have lost invaluable information that can affect the outcome of her pregnancy.

What should you do when, occasionally, a patient refuses to answer one of your questions? We recommend that you record her refusal on the form itself, where the note remains part of the record.

Keep in mind that all necessary and useful information about a patient may not be available, or may not be appropriate to consider, at the initial prenatal visit. In that case, you have an ongoing opportunity—at subsequent visits during the pregnancy—to develop her full medical profile and algorithm.

The necessity of adherence

It almost goes without saying: To provide the care that our patients need, we sometimes require the unpleasant of them—to undergo evaluations, or testing, or to take medications that may be inconvenient or costly.

After you explain the specific course of care to a patient—whether you’re ordering a test or writing a prescription—your follow-up must include notation in the record of adherence. The fact is that both of you share responsibility for having her understand the importance of adherence to your instructions and the consequences of limited adherence or nonadherence.

Recall one of the lessons from the case that introduced this article: For the patient to make an informed decision about her care, the clinician must have thorough knowledge of 1) the risks and benefits of whatever intervention is being proposed in the particular clinical scenario and 2) the available alternatives. It is key that you communicate your risk-benefit assessment accurately to the patient.

Follow-up

Sometimes, new medical problems arise during subsequent prenatal visits. Follow-up appointments also provide an opportunity for you to expand your attention to problems identified earlier. Regardless of what the patient reported about her history and current health at the initial prenatal visit, listen for her to bring new issues to light for resolution later in the pregnancy that will have an impact on L & D. Again, it goes without saying but needs to be said: The OB clinician needs to have whatever skills are necessary to 1) fully evaluate the progress of a pregnancy and 2) make recommendations for care in light of changes in the status of mother and fetus along the way.

TABLE 4 Examples of the cardinal rule of “Be specific”

when you document care

| Instead of noting … | … Use alternative wording |

|---|---|

| “Mild vaginal bleeding” | “Vaginal bleeding requiring two pads an hour” |

| “Gentle traction” | “The shoulders were rotated before assisting the patient’s expulsive efforts” |

| “Patient refuses…” [or “declines…”] | “Patient voiced the nature of the problem and the alternatives that i have explained to her” |

| “Expedited cesarean section” | “The time from decision to incision was 35 minutes” |

Basic principles of documentation

The medical record is the best witness to interactions between a physician and a patient. In the record, we’re required to write a “5-C” description of events—namely, one that is:

- correct

- comprehensive

- conscientious

- clear

- contemporaneous.

Avoid medical jargon in the record. Be careful not to use vague terminology or descriptions, such as “mild vaginal bleeding,” “gentle traction,” or “patient refuses and accepts the consequences.” Specificity is the key to accuracy with respect to documentation (TABLE 4).

Editor’s note: Part 2 of this article will appear in the January 2011 issue of OBG Management. The authors’ analysis of L & D malpractice claims moves to a discussion of causation—by way of 4 troubling cases.

You’ll find a rich, useful archive of expert analysis of your professional liability and malpractice risk, at www.obgmanagement.com

• 10 keys to defending (or, better, keeping clear of) a shoulder dystocia suit

Andrew K. Worek, Esq (March 2008)

• After a patient’s unexpected death, First Aid for the emotionally wounded

Ronald A. Chez, MD, and Wayne Fortin, MS (April 2010)

• Afraid of getting sued? A plaintiff attorney offers counsel (but no sympathy)

Janelle Yates, Senior Editor, with Lewis Laska, JD, PhD (October 2009)

• Can a change in practice patterns reduce the number of OB malpractice claims?

Jason K. Baxter, MD, MSCP, and Louis Weinstein, MD (April 2009)

• Strategies for breaking bad news to patients

Barry Bub, MD (September 2008)

• Stuff of nightmares: Criminal prosecution for malpractice

Gary Steinman, MD, PhD (August 2008)

• Deposition Dos and Don’ts: How to answer 8 tricky questions

James L. Knoll, IV, MD, and Phillip J. Resnick, MD (May 2008)

• Playing high-stakes poker: Do you fight—or settle—that malpractice lawsuit?

Jeffrey Segal, MD (April 2008)

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based labor and delivery management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(5):445-454.

2. Paasche-Orlow MK, Riekert KA, Bilderback A, et al. Tailored education may reduce health literacy disparities in asthma self-management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:980-986.

3. Huvane K. Health literacy: reading is just the beginning. Focus on multicultural healthcare. 2007;3(4):16-19.

4. Giordano K. Legal Principles. In: O’Grady JP, Gimovsky ML, Bayer-Zwirello L, Giordano K, eds. Operative Obstetrics. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

5. The Four Elements of Medical Malpractice Yale New Haven Medical Center: Issues in Risk Management. 1997.

1. Berghella V, Baxter JK, Chauhan SP. Evidence-based labor and delivery management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(5):445-454.

2. Paasche-Orlow MK, Riekert KA, Bilderback A, et al. Tailored education may reduce health literacy disparities in asthma self-management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:980-986.

3. Huvane K. Health literacy: reading is just the beginning. Focus on multicultural healthcare. 2007;3(4):16-19.

4. Giordano K. Legal Principles. In: O’Grady JP, Gimovsky ML, Bayer-Zwirello L, Giordano K, eds. Operative Obstetrics. 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2008.

5. The Four Elements of Medical Malpractice Yale New Haven Medical Center: Issues in Risk Management. 1997.

Skilled US imaging of the adnexae: The fallopian tubes

Part 1 A Starting Point (September 2010)

Part 2 The non-neoplastic ovarian mass (October 2010)

Part 3 Ovarian neoplasms (November 2010)

An imaging study of the adnexae would not be complete without thorough assessment of the fallopian tubes. Among the pathologies that may be identified or confirmed by ultrasonography are:

- ectopic pregnancy

- tubal inflammatory disease, or salpingitis

- chronic tubal disease, or hydrosalpinx

- tubo-ovarian complex

- tubo-ovarian abscess

- tubal and ovarian torsion

- cancer.

In this final installment of our four-part series on ultrasonographic (US) imaging of the adnexae, we take these entities as our focus.

Suspect ectopic pregnancy even if the hCG level is not yet available

A detailed discussion of ectopic pregnancy far exceeds the framework of this article. Suffice it to say that ectopic pregnancy should always be considered in a woman of reproductive age, especially one who complains of abdominal or pelvic pain, vaginal bleeding, or both. However, these signs and symptoms are present in only about 25% of women who have this condition. When these signs and symptoms are present, it is wise to be suspicious even if the results of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) measurement are not yet available.

A complete history is important in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Risk factors include a history of ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), or tubal surgery, or use of an intrauterine device.

Unequivocal US diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy is possible in only about 20% of cases, and depends on identification of an extrauterine pregnancy, which may not be visible in the early days of gestation. However, some grayscale ultrasonographic findings that may suggest ectopic pregnancy include:

- an empty uterus in a woman who has an hCG level above 1,000 to 1,500 mIu/mL (the discriminatory level)

- a thick, hyperechoic endometrial echo (decidualization)

- an adnexal mass other than a simple cyst

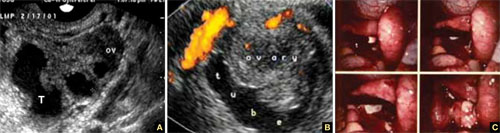

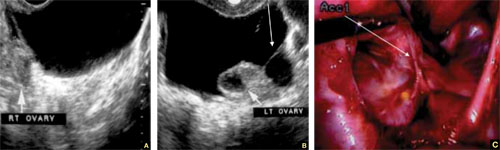

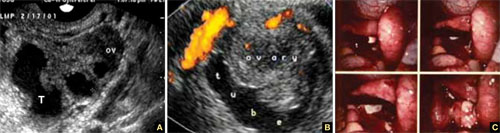

- echogenic fluid in the cul-de-sac (FIGURE 1A–1D).

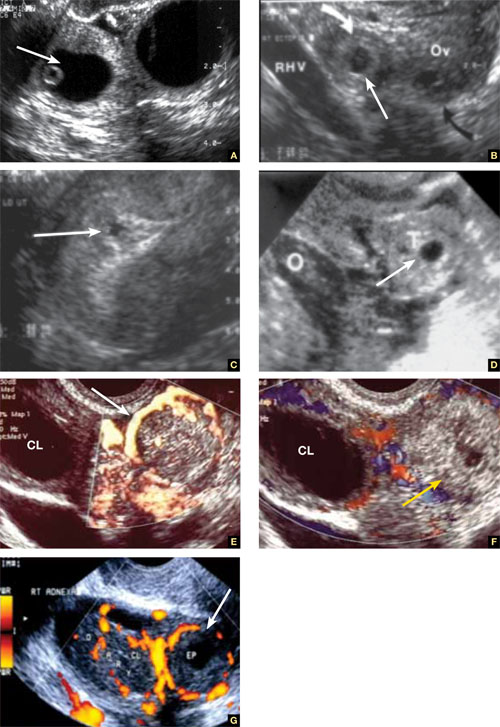

Power Doppler can help the sonographer localize the ectopic pregnancy in the tubes by demonstrating the circular vascularization of the more or less typical “tubal ring” (FIGURE 1E–1G).

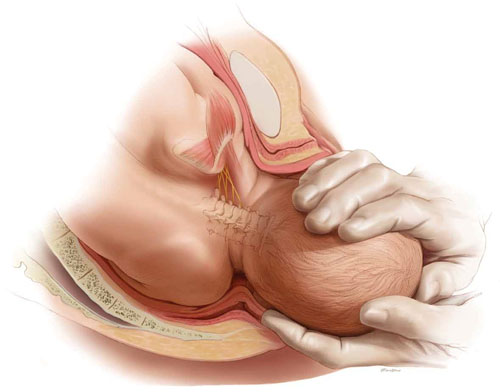

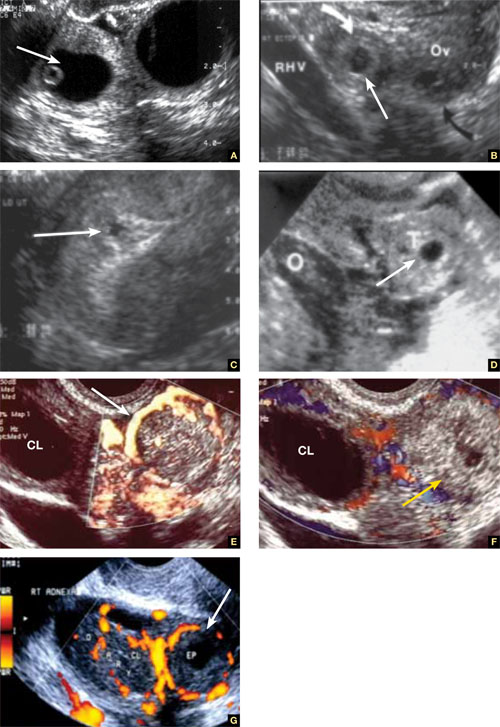

FIGURE 1 Ectopic pregnancy

A–D. Various cases of tubal ectopic gestation (arrows point to each gestation). E–G. Power Doppler localizes the ectopic pregnancy (arrows), side by side with the corpus luteum (CL).

A patient’s history may yield clues to tubal inflammatory disease

The diagnosis of acute salpingitis begins with a thorough patient history. Look for any report of PID, unexplained fever, foul vaginal discharge, sexually transmitted infection, or recent intrauterine procedures such as hysteroscopy, IUD insertion, endometrial biopsy, or saline infusion sonohysterography.

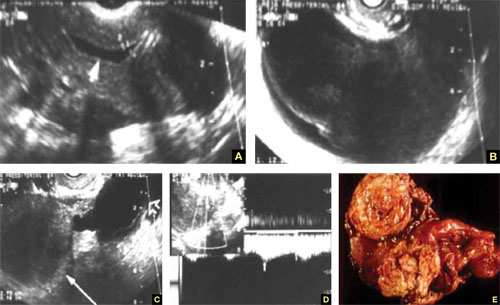

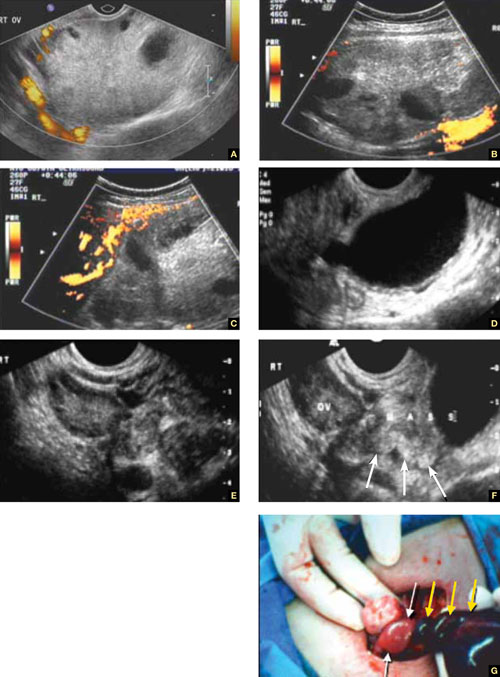

US diagnosis is based on the findings of a slightly dilated fallopian tube with low-level echogenic fluid content, thick tubal walls, and tenderness to the touch of the transvaginal probe.1

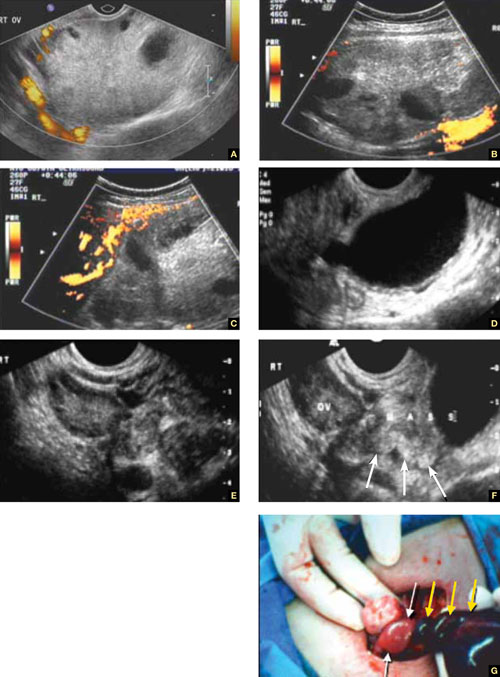

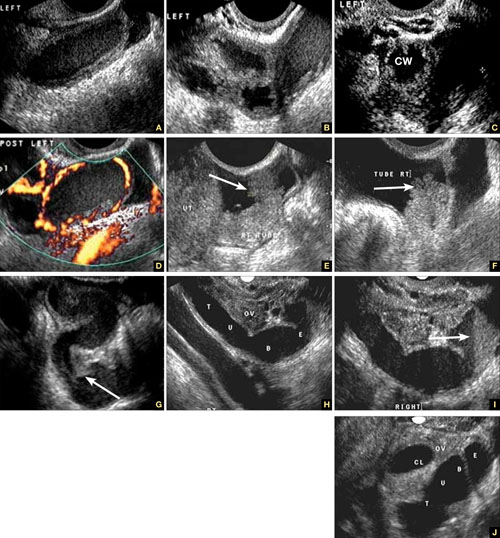

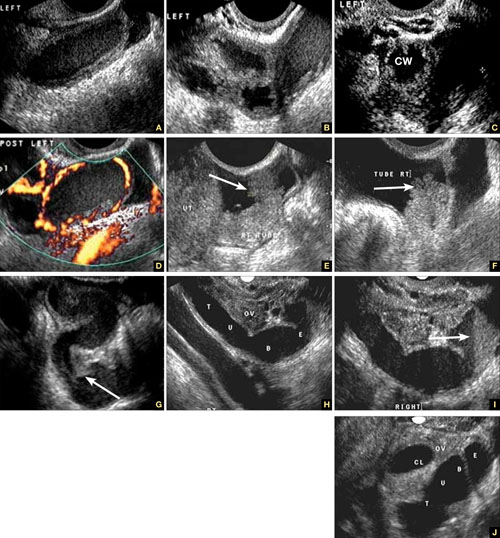

In cross section, the tube forms the “cogwheel sign” (FIGURE 2C). Power Doppler shows the subserosal blood vessels characteristic of this entity (FIGURE 2D).

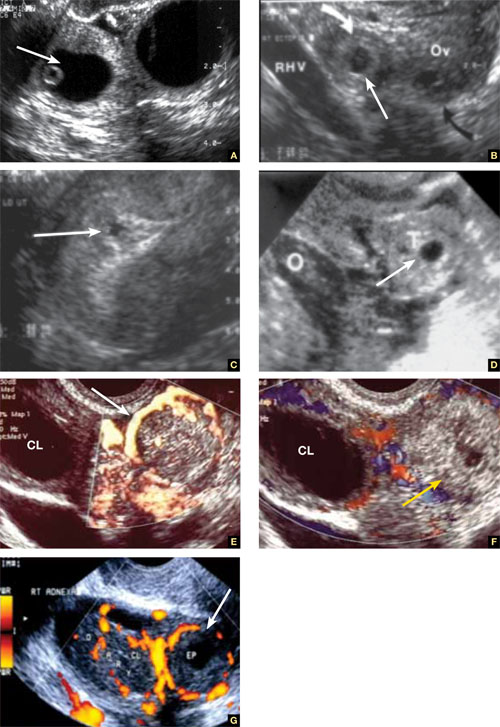

FIGURE 2 Tubal disease

A–C. Grayscale images showing thick walls, low-level echoic fluid (pus?) and the “cogwheel sign” (CW). D. Subserosal vascularization typical of an inflammatory response in hollow abdominal viscera. E,F. Edematous fimbrial end (arrow) of the inflamed tubes, floating in a small amount of free pelvic fluid. G. Low-level echoic, fluid-filled, thick-walled tubes with incomplete septae (arrow) are the hallmarks of hydrosalpinx. H–J. Bilateral hydrosalpinx. Note the thin walls and anechoic fluid-filled forms (sausage-shaped) (CL = corpus luteum; OV = ovary; UT = uterus).

Look for fluid dilating the tube in chronic tubal disease