User login

Postpartum hemorrhage: 11 critical questions, answered by an expert

We know the potentially tragic outcome of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH): Worldwide, more than 140,000 women die every year as a result of PPH—one death every 4 minutes! Lest you dismiss PPH as a concern largely for developing countries, where it accounts for 25% of maternal deaths, consider this: In our highly developed nation, it accounts for nearly 8% of maternal deaths—a troubling statistic, to say the least.

The significant maternal death rate associated with PPH, and questions about how to reduce it, prompted the editors of OBG Management to talk with Haywood L. Brown, MD. Dr. Brown is Roy T. Parker Professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC. He is also a nationally recognized specialist in maternal-fetal medicine. In this interview, he discusses the full spectrum of management of PPH, from proactive assessment of a woman’s risk to determination of the cause to the tactic of last resort, emergent hysterectomy.

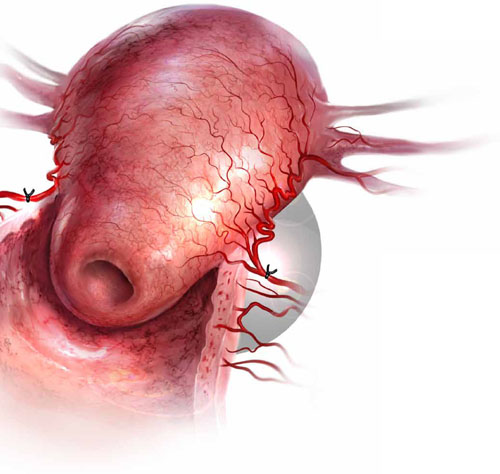

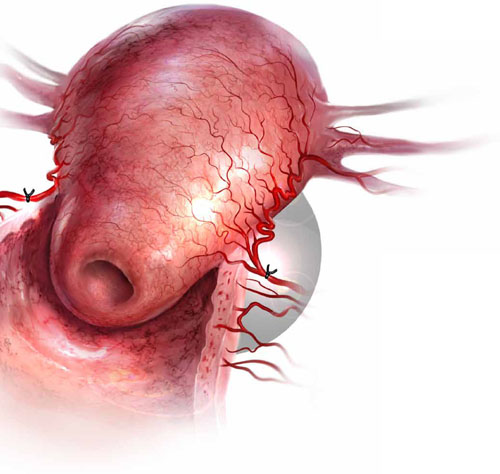

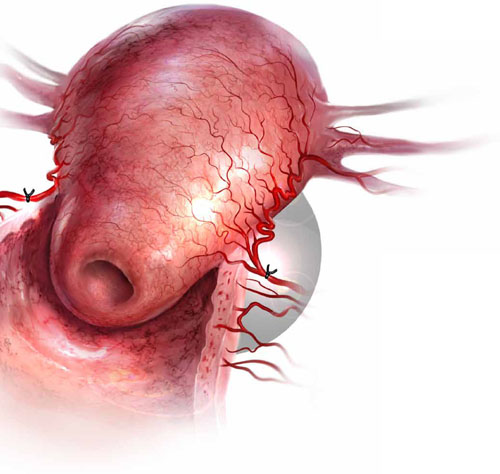

Uterine atony is the leading cause of postpartum hemorrhage. When medical management fails to stanch the bleeding, bilateral uterine artery ligation is one surgical option.

1. What is PPH?

OBG Management: Dr. Brown, let’s start with a simple but important aspect of PPH—how do you define it?

Dr. Brown: Obstetric hemorrhage is excessive bleeding that occurs during the intrapartum or postpartum period—specifically, estimated blood loss of 500 mL or more after vaginal delivery or 1,000 mL or more after cesarean delivery.

PPH is characterized as early or late, depending on whether the bleeding occurs within 24 hours of delivery (early, or primary) or between 24 hours and 6 to 12 weeks postpartum (late, or secondary). Primary PPH occurs in 4% to 6% of pregnancies.

Another way to define PPH: a decline of 10% or more in the baseline hematocrit level.

OBG Management: How do you measure blood loss?

Dr. Brown: The estimation of blood loss after delivery is an inexact science and typically yields an underestimation. Most clinicians rely on visual inspection to estimate the amount of blood collected in the drapes after vaginal delivery and in the suction bottles after cesarean delivery. Some facilities weigh lap pads or drapes to get a more accurate assessment of blood loss. In a routine delivery, no specific calorimetric measuring devices are used to estimate blood loss.

At my institution, we make an attempt to estimate blood loss at every delivery—vaginal or cesarean—and record the estimate. By doing this routinely, the clinician improves in accuracy and becomes more adept at identifying excessive bleeding.

OBG Management: Is blood loss the only variable that arouses concern about possible hemorrhage?

Dr. Brown: Because pregnant women experience an increase in blood volume and physiologic cardiovascular changes, the usual sign of significant bleeding can sometimes be masked. Therefore, any changes in maternal vital signs, such as a drop in blood pressure, tachycardia, or sensorial changes, may suggest that more blood has been lost than has been estimated.

Hypotension, dizziness, tachycardia or palpitations, and decreasing urine output will typically occur when more than 10% of maternal blood volume has been lost. In this situation, the patient should be given additional fluids, and a second intravenous line should be started using large-bore, 14-gauge access. In addition, the patient’s hemoglobin and hematocrit levels should be measured. All these actions constitute a first-line strategy to prevent shock and potential irreversible renal failure and cardiovascular collapse.

Low: 500 to 1,000 mL

This level of hemorrhage should be anticipated and can usually be managed with uterine massage and administration of a uterotonic agent, such as oxytocin. Intravenous fluids and careful monitoring of maternal vital signs are also warranted.

Active management of the third stage of labor has been shown to reduce the risk of significant postpartum hemorrhage (PPH). Active management includes:

- administration of a uterotonic agent immediately after delivery of the infant

- early cord clamping and cutting

- gentle cord traction with uterine counter-traction when the uterus is well contracted

- uterine massage.2

If these methods are unsuccessful in correcting the atony, uterotonics such as a prostaglandin (rectally administered misoprostol [800 mg] or intramuscular carboprost tromethamine [Hemabate; 250 μg/mL]) will usually succeed.

Medium: 1,000 to 1,500 mL

Blood loss of this volume is usually accompanied by cardiovascular signs, such as a fall in blood pressure, diaphoresis, and tachycardia. Women with this level of hemorrhage exhibit mild signs of shock.

It is important to correct maternal hypotension with fluids, restabilize vital signs, and resolve the bleeding expeditiously. If uterotonics and massage fail to stanch the bleeding, consider placing a balloon (e.g., Bakri balloon). Once the balloon is placed and inflated, it can be left for as long as 24 hours or until the uterus regains its tone.

Be sure to check hemoglobin and hematocrit levels and transfuse the patient, if necessary, especially if vital signs have not stabilized.

High: 1,500 to 2,000 mL, or greater

This is a medical emergency that must be managed aggressively to prevent morbidity and death. Blood loss of this volume will usually bring significant cardiovascular changes, such as hypotension, tachycardia, restlessness, pallor, oliguria, and cardiovascular collapse from hemorrhagic shock. this degree of blood loss means that the patient has lost 25% to 35% of her blood volume and will need blood-product replacement to prevent coagulation and the cascade of hemorrhage.

If conservative measures are unsuccessful, timely surgical intervention with B-Lynch suture, uterine vessel ligation, or hysterectomy is lifesaving.—HAYWOOD L. BROWN, MD

2. What causes PPH?

OBG Management: Why does PPH occur?

Dr. Brown: The leading cause is uterine atony, a failure of the uterus to contract and undergo resolution following delivery of an infant. Approximately 80% of cases of early PPH are related to uterine atony.

There are other causes of PPH:

- lacerations of the genital tract (perineum, vagina, cervix, or uterus)

- retained fragments of placental tissue

- uterine rupture

- blood clotting abnormalities

- uterine inversion.

3. Is it possible to prepare for PPH?

OBG Management: What is the starting point for management of PPH?

Dr. Brown: Prevention of, and preparation for, hemorrhage begin well before delivery. During the prenatal period, for example, it is important to assess the woman’s level of risk for PPH. Among the variables that increase her risk:

- any situation that leads to overstretching of the uterus, including multiple gestation, whether delivery is vaginal or cesarean

- a history of PPH.

It is important that women with these characteristics maintain adequate hemoglobin and hematocrit levels by taking vitamin and iron supplements in the antepartum period.

In addition, women who have abnormal placental implantation, such as placenta previa, are at risk for bleeding during the antepartum period and during cesarean delivery. They should maintain a hematocrit in the mid-30s because of expected blood loss during delivery.

OBG Management: What preparatory steps should be taken at the time of hospital admission if a woman has an elevated risk of bleeding?

Dr. Brown: When the patient is hospitalized in anticipation of delivery—whether vaginal or cesarean—the team should assess her hemoglobin and hematocrit levels and type and screen for possible transfusion. The patient should also be apprised of her risk and the potential for transfusion.

Last, the anesthesia team should be alerted to her risk factors for postpartum bleeding.

4. What intrapartum variables signal an increased risk of PPH?

OBG Management: During labor and delivery, what variables signal an elevated risk of bleeding?

Dr. Brown: Risk factors for hemorrhage become more apparent during this period. They include prolonged or rapid labor, prolonged use of oxytocin, operative delivery, infections such as chorioamnionitis, and vaginal birth after cesarean delivery (VBAC).

Bleeding with VBAC merits special attention because it could signal uterine rupture. Women who have a low transverse uterine scar and who undergo VBAC have a risk of uterine scar separation during labor of 0.5% to 1%.

OBG Management: What about retained placenta or a placenta that requires manual removal?

Dr. Brown: These intrapartum variables are not as easy to anticipate. They may suggest a condition such as placenta accreta, especially if the patient is undergoing VBAC.

Uterine inversion can also lead to hemorrhage and is a medical emergency.

OBG Management: What steps should be taken at the time of labor to ensure a safe outcome?

Dr. Brown: A type and screen should be available for all women on labor and delivery, and the team should anticipate the need to cross-match for blood if there is a high potential for transfusion. For example, a woman known to have anemia (hematocrit <30%) should have a cross-match performed so that blood can be prepared for transfusion.

In addition, women who are undergoing planned delivery for placental implantation disorders should have blood in the operating room ready for transfusion when cesarean is performed. These women are at great risk of hemorrhage and peripartum hysterectomy.

5. What first-line strategies do you recommend?

OBG Management: Do you recommend oxytocin administration and fundal massage for every patient after delivery of the infant?

Dr. Brown: Yes. These strategies lessen the risk of uterine atony and excessive bleeding after vaginal delivery. At the time of cesarean delivery, expression of the placenta and uterine massage, along with oxytocin administration, reduce the risk of excessive blood loss.

If bleeding continues even after the uterus begins to contract, look for other causes of the bleeding, such as uterine laceration or retained placental fragments.

OBG Management: What uterotonic agents do you use besides oxytocin, and when?

Dr. Brown: Oxytocin is the first-line agent for control of hemorrhage. I give a dosage of 10 to 40 U/L of normal saline or lactated Ringer solution, infused continuously. Alternatively, 10 U can be given intramuscularly (IM). Second-line drugs and their dosages are listed in the TABLE.

Uterotonic agents and how to administer them

| Drug | Dosage and route | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| FIRST-LINE | ||

| Oxytocin | 10–40 U/L of saline or lactated ringer solution, infused continuously, Or 10 U IM | The preferred drug—often the only one needed |

| SECOND-LINE | ||

| Misoprostol (Cytotec, Prostaglandin e1) | 800–1,000 μg can be given rectally | Often, the second-line drug that is given just after oxytocin because it is easy to administer |

| Methylergonovine (Methergine) | 0.2 mg IM every 2–4 hr | Contraindicated in hypertension |

| Carboprost tromethamine (Hemabate) | 0.25 mg IM every 15–90 minutes (maximum of 8 doses) | Avoid in patients who have asthma. Contra-indicated in hepatic, renal, and cardiac disease |

| Dinoprostone (Prostin e2) | 20 mg suppository can be given vaginally or rectally every 2 hours | Avoid in hypotension |

6. How do you assess the patient once PPH is identified?

OBG Management: How do you assess the patient after hemorrhage begins?

Dr. Brown: We recheck the hemoglobin and hematocrit levels and monitor vital signs for hypotension and tachycardia. We also begin fluid resuscitation and type and cross-match blood and blood products.

A delayed response to hemorrhage raises the risk of maternal morbidity and death.

We notify the anesthesia team when it seems likely that a surgical approach to the hemorrhage will be needed. And we notify interventional radiology if the bleeding may respond to uterine artery embolization.

7. Why is it important to replace blood products?

OBG Management: You’ve been known to say, “The more blood a patient loses, the more blood she loses.” What do you mean by that?

Dr. Brown: Excessive bleeding leads to a loss of critical clotting factors that are made in the liver. Once the clotting factors are depleted, the woman is at risk of coagulopathy or disseminated intravascular coagulation. This depletion potentiates the cycle of hemorrhage. When that occurs, the hemorrhage can be controlled only with transfusion of red blood cells (RBCs) and replacement of clotting factors with fresh frozen plasma, platelets, and cryoprecipitate, along with prompt correction of the process that is causing the bleeding.

OBG Management: What blood products do you administer to a patient with hemorrhage, and when?

Dr. Brown: The first line of defense for blood loss requiring transfusion is packed RBCs. Each unit of packed cells increases the hematocrit by 3% and hemoglobin by 1 g/dL, assuming bleeding is under control. After that, consider:

- Platelets. Depending on the severity of the hemorrhage and the level of platelets once the coagulation status is checked, platelets can be given. A 50-mL unit can raise the platelet count 5,000–10,000/mm3. Platelets should be considered if the count is below 50,000/mm3.

- Fresh frozen plasma should be given to replace clotting factors. Fresh frozen plasma contains fibrinogen, antithrombin III, factor V, and factor VIII. Each unit of fresh frozen plasma increases the fibrinogen level by 10 mg/dL.

- Cryoprecipitate contains fibrinogen, factors VIII and XIII, and von Willebrand factor. Each unit of cryoprecipitate increases fibrinogen by 10 mg/dL.

- Factor VII can be given if the hemorrhage is still active, but it should only be given after fresh frozen plasma and cryo-precipitate have been given to replace clotting factors. Factor VII is ineffective without clotting factor replacement prior to its administration. This medication is associated with a high risk of thromboembolism. It is also expensive.

- Synthetic fibrinogen (RiaSTAP) is available for use in the United States, but it has FDA approval only for the treatment of acute bleeding in patients who have congenital fibrinogen deficiency. It may have potential for use during PPH when essential clotting factors have been depleted.

A woman who is obese has additional risk factors for hemorrhage. Obesity itself is associated with prolonged labor and large-for-gestational-age infants, which, in turn, lead to poor contractility of the uterus and the potential for early postpartum hemorrhage.

Begin by ensuring that the obese or morbidly obese woman has appropriate intravenous access at the time of labor and receives early regional anesthesia (epidural). also alert anesthesia to the risk and assess baseline hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, including a type and screen.

An obese woman undergoing cesarean delivery has a heightened risk of uterine laceration, difficult extraction of the fetus, and uterine atony, especially if prolonged labor preceded the cesarean. Second-stage arrest and prolonged pushing before the cesarean may make extraction of the infant difficult and lead to poor uterine contractility once the placenta is removed.

All obese women, as well as other women at risk of postpartum uterine atony, should have oxytocin infused before the placenta is removed, especially at the time of cesarean delivery. Expressing the placenta at the time of cesarean delivery—as opposed to manual removal—is associated with lower blood loss and allows the uterus to begin contracting before the placenta is removed.—HAYWOOD L. BROWN, MD

8. When do you use the intrauterine balloon?

OBG Management: When is the intrauterine balloon a management option?

Dr. Brown: The balloon offers a way to actively manage hemorrhage and has been associated with decreasing morbidity and a reduced need for surgical intervention, including hysterectomy. It works through a tamponade effect. Once the balloon is inflated with 300 to 500 mL of saline, it compresses the uterine cavity until the uterus develops predelivery tone. It can be left in place as long as 24 hours, need be.

Several balloons are available for use, with the Bakri balloon being the prototype. The balloon may cut off uterine blood flow as a mechanism of action.

Before the advent of manufactured balloons, uterine tamponade was attempted using packing with gauze and a large-bore Foley catheter.

9. How do you proceed when surgery is necessary?

OBG Management: What surgical techniques—aside from hysterectomy—may be useful in stanching hemorrhage?

Dr. Brown: The first-line surgical approach after vaginal delivery is uterine exploration to evacuate uterine clots and check for retained placental fragments. This act alone may impart improved uterine contractility. If retained placental fragments are suspected, a gentle curettage of the uterine cavity, using a large curette, is appropriate.

When it is obvious that atony is the cause of the hemorrhage, and medical management has failed, these surgical steps are appropriate:

- Uterine artery ligation, using the “O’Leary” technique, can be performed bilaterally. The utero-ovarian vessels can also be ligated (but not cut!)

- B-Lynch suture as a technique to compress the uterus. This strategy uses outside, draping, absorbable suture to collapse the uterine cavity. It can be quite successful when combined with the use of uterotonics. One study reported more than 1,000 B-Lynch procedures, with only seven failures.1 Hemostatic multiple-square compression is a surgical technique that works according to a similar principle

- Hypogastric artery ligation can be performed by an experienced surgeon but is rarely employed in severe hemorrhage owing to the risk of complications and lengthy procedure time.

OBG Management: When does hysterectomy become an option?

Dr. Brown: Hysterectomy is the last defense against morbidity and maternal death from hemorrhage due to atony.

Clearly, when hysterectomy is performed, sooner is better than later, especially if uterine artery ligation and B-Lynch suture do not appear to be controlling the hemorrhage and the patient is hemodynamically unstable.

If the patient is a young woman with low parity, the uterus should be preserved, if at all possible, unless the hemorrhage cannot be controlled and the woman’s life is jeopardized.

When a uterine rupture has occurred, usually after a VBAC attempt, it may be prudent to proceed to hysterectomy, especially if the uterus appears to be difficult to repair.

10. When do you call for help?

OBG Management: When do you call in extra help?

Dr. Brown: As soon as hemorrhage occurs, the team should be assembled. It is critical that anesthesia be notified immediately, in the event that the patient requires surgical management. The blood bank should be notified that blood and blood products are likely to be required.

We designate a nursing leader to monitor the patient and another to keep the staff and unit on alert for potential surgical intervention. If uterine rupture or an invasive placental abnormality is suspected, we assemble the surgical team, including any potential consultant surgeon. We also notify the best available surgeons so that they can be ready to perform the necessary techniques. In addition, we notify the OR and surgical intensive care unit, in case they are needed.

OBG Management: How can obstetricians and obstetric units practice the response to OB hemorrhage so that, when a hemorrhage occurs, they are at the top of their game?

Dr. Brown: Obstetric units prepare by performing drills and simulations. These drills are now considered part of most units’ quality and safety programs.

Because obstetric hemorrhage can occur on any unit at any time, the team must be prepared to respond around the clock promptly and effectively to reduce the risk of morbidity and death.

After emergent surgical management of obstetric hemorrhage, the team should be assembled again to discuss what occurred and how they performed or could have performed more effectively as a team.

OBG Management: Should all obstetricians who perform repeat cesarean delivery be able to perform a cesarean hysterectomy in the event that uncontrollable hemorrhage is encountered?

Dr. Brown: It is an absolute must that any clinician who allows VBAC be capable of performing peripartum cesarean hysterectomy and know the indications for hysterectomy, as we have discussed. In fact, any obstetrician who performs cesarean delivery should be capable of performing a cesarean hysterectomy.

11. What do you recommend for practice?

OBG Management: How would you summarize the main points of management of postpartum hemorrhage?

Dr. Brown: I would suggest that the first step is organizing the team (obstetricians, nurses, anesthesiologist), followed by:

- resuscitation of the mother with oxygen and fluids through large-bore intravenous access sites

- notification of the blood bank (with typing and cross-matching) of the possible need for 4 to 6 U of blood for trans-fusion

- liberal assessment of laboratory values, especially coagulation status (International Normalized Ratio [INR], prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time) and blood counts (hemoglobin and hematocrit). Values may be lower if there has been significant blood loss and aggressive fluid resuscitation. Blood products such as fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate are indicated, in addition to packed RBCs, if the patient has or is developing a coagulopathy. Also give platelets if the count is low. Once it becomes apparent that surgical intervention will be necessary, begin transfusion and replace clotting factors before beginning the procedure

- monitoring of vital signs and urine output throughout resuscitation and medical and surgical intervention

- elimination of the cause of bleeding as soon as possible by whatever means necessary to prevent maternal death, beginning with conservative medical management and, if necessary, followed by surgical intervention.

Tell us about a challenging case of postpartum hemorrhage and how you managed it.

Go to Send Us Your Letters. Please include your name, city, and state. We’ll publish intriguing “pearls” in an upcoming issue.

1. Allam MS, B-Lynch C. The B-Lynch and other uterine compression techniques. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;89(3):236-241.

2. Prendiville WJ, Elbourne D, McDonald S. Active versus expectant management in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(3):CD000007.-

- Activated factor VII proves to be a lifesaver in postpartum hemorrhage

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (February 2007) - Postpartum hemorrhage: Solutions to 2 intractable cases

Michael L. Stitely, MD, and Robert B. Gherman, MD (April 2007) - Give a uterotonic routinely during the third stage of labor

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (May 2007) - Consider retroperitoneal packing for postpartum hemorrhage

Maj. William R. Fulton, DO (July 2008) - You should add the Bakri balloon to your treatments for OB bleeds

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (February 2009) - Planning reduces the risk of maternal death. This tool helps.

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (August 2009) - What you can do to optimize blood conservation in ObGyn practice

Eric J. Bieber, MD, Linda Scott, RN, Corinna Muller, DO, Nancy Nuss, RN, and Edie L. Derian, MD (February 2010)

We know the potentially tragic outcome of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH): Worldwide, more than 140,000 women die every year as a result of PPH—one death every 4 minutes! Lest you dismiss PPH as a concern largely for developing countries, where it accounts for 25% of maternal deaths, consider this: In our highly developed nation, it accounts for nearly 8% of maternal deaths—a troubling statistic, to say the least.

The significant maternal death rate associated with PPH, and questions about how to reduce it, prompted the editors of OBG Management to talk with Haywood L. Brown, MD. Dr. Brown is Roy T. Parker Professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC. He is also a nationally recognized specialist in maternal-fetal medicine. In this interview, he discusses the full spectrum of management of PPH, from proactive assessment of a woman’s risk to determination of the cause to the tactic of last resort, emergent hysterectomy.

Uterine atony is the leading cause of postpartum hemorrhage. When medical management fails to stanch the bleeding, bilateral uterine artery ligation is one surgical option.

1. What is PPH?

OBG Management: Dr. Brown, let’s start with a simple but important aspect of PPH—how do you define it?

Dr. Brown: Obstetric hemorrhage is excessive bleeding that occurs during the intrapartum or postpartum period—specifically, estimated blood loss of 500 mL or more after vaginal delivery or 1,000 mL or more after cesarean delivery.

PPH is characterized as early or late, depending on whether the bleeding occurs within 24 hours of delivery (early, or primary) or between 24 hours and 6 to 12 weeks postpartum (late, or secondary). Primary PPH occurs in 4% to 6% of pregnancies.

Another way to define PPH: a decline of 10% or more in the baseline hematocrit level.

OBG Management: How do you measure blood loss?

Dr. Brown: The estimation of blood loss after delivery is an inexact science and typically yields an underestimation. Most clinicians rely on visual inspection to estimate the amount of blood collected in the drapes after vaginal delivery and in the suction bottles after cesarean delivery. Some facilities weigh lap pads or drapes to get a more accurate assessment of blood loss. In a routine delivery, no specific calorimetric measuring devices are used to estimate blood loss.

At my institution, we make an attempt to estimate blood loss at every delivery—vaginal or cesarean—and record the estimate. By doing this routinely, the clinician improves in accuracy and becomes more adept at identifying excessive bleeding.

OBG Management: Is blood loss the only variable that arouses concern about possible hemorrhage?

Dr. Brown: Because pregnant women experience an increase in blood volume and physiologic cardiovascular changes, the usual sign of significant bleeding can sometimes be masked. Therefore, any changes in maternal vital signs, such as a drop in blood pressure, tachycardia, or sensorial changes, may suggest that more blood has been lost than has been estimated.

Hypotension, dizziness, tachycardia or palpitations, and decreasing urine output will typically occur when more than 10% of maternal blood volume has been lost. In this situation, the patient should be given additional fluids, and a second intravenous line should be started using large-bore, 14-gauge access. In addition, the patient’s hemoglobin and hematocrit levels should be measured. All these actions constitute a first-line strategy to prevent shock and potential irreversible renal failure and cardiovascular collapse.

Low: 500 to 1,000 mL

This level of hemorrhage should be anticipated and can usually be managed with uterine massage and administration of a uterotonic agent, such as oxytocin. Intravenous fluids and careful monitoring of maternal vital signs are also warranted.

Active management of the third stage of labor has been shown to reduce the risk of significant postpartum hemorrhage (PPH). Active management includes:

- administration of a uterotonic agent immediately after delivery of the infant

- early cord clamping and cutting

- gentle cord traction with uterine counter-traction when the uterus is well contracted

- uterine massage.2

If these methods are unsuccessful in correcting the atony, uterotonics such as a prostaglandin (rectally administered misoprostol [800 mg] or intramuscular carboprost tromethamine [Hemabate; 250 μg/mL]) will usually succeed.

Medium: 1,000 to 1,500 mL

Blood loss of this volume is usually accompanied by cardiovascular signs, such as a fall in blood pressure, diaphoresis, and tachycardia. Women with this level of hemorrhage exhibit mild signs of shock.

It is important to correct maternal hypotension with fluids, restabilize vital signs, and resolve the bleeding expeditiously. If uterotonics and massage fail to stanch the bleeding, consider placing a balloon (e.g., Bakri balloon). Once the balloon is placed and inflated, it can be left for as long as 24 hours or until the uterus regains its tone.

Be sure to check hemoglobin and hematocrit levels and transfuse the patient, if necessary, especially if vital signs have not stabilized.

High: 1,500 to 2,000 mL, or greater

This is a medical emergency that must be managed aggressively to prevent morbidity and death. Blood loss of this volume will usually bring significant cardiovascular changes, such as hypotension, tachycardia, restlessness, pallor, oliguria, and cardiovascular collapse from hemorrhagic shock. this degree of blood loss means that the patient has lost 25% to 35% of her blood volume and will need blood-product replacement to prevent coagulation and the cascade of hemorrhage.

If conservative measures are unsuccessful, timely surgical intervention with B-Lynch suture, uterine vessel ligation, or hysterectomy is lifesaving.—HAYWOOD L. BROWN, MD

2. What causes PPH?

OBG Management: Why does PPH occur?

Dr. Brown: The leading cause is uterine atony, a failure of the uterus to contract and undergo resolution following delivery of an infant. Approximately 80% of cases of early PPH are related to uterine atony.

There are other causes of PPH:

- lacerations of the genital tract (perineum, vagina, cervix, or uterus)

- retained fragments of placental tissue

- uterine rupture

- blood clotting abnormalities

- uterine inversion.

3. Is it possible to prepare for PPH?

OBG Management: What is the starting point for management of PPH?

Dr. Brown: Prevention of, and preparation for, hemorrhage begin well before delivery. During the prenatal period, for example, it is important to assess the woman’s level of risk for PPH. Among the variables that increase her risk:

- any situation that leads to overstretching of the uterus, including multiple gestation, whether delivery is vaginal or cesarean

- a history of PPH.

It is important that women with these characteristics maintain adequate hemoglobin and hematocrit levels by taking vitamin and iron supplements in the antepartum period.

In addition, women who have abnormal placental implantation, such as placenta previa, are at risk for bleeding during the antepartum period and during cesarean delivery. They should maintain a hematocrit in the mid-30s because of expected blood loss during delivery.

OBG Management: What preparatory steps should be taken at the time of hospital admission if a woman has an elevated risk of bleeding?

Dr. Brown: When the patient is hospitalized in anticipation of delivery—whether vaginal or cesarean—the team should assess her hemoglobin and hematocrit levels and type and screen for possible transfusion. The patient should also be apprised of her risk and the potential for transfusion.

Last, the anesthesia team should be alerted to her risk factors for postpartum bleeding.

4. What intrapartum variables signal an increased risk of PPH?

OBG Management: During labor and delivery, what variables signal an elevated risk of bleeding?

Dr. Brown: Risk factors for hemorrhage become more apparent during this period. They include prolonged or rapid labor, prolonged use of oxytocin, operative delivery, infections such as chorioamnionitis, and vaginal birth after cesarean delivery (VBAC).

Bleeding with VBAC merits special attention because it could signal uterine rupture. Women who have a low transverse uterine scar and who undergo VBAC have a risk of uterine scar separation during labor of 0.5% to 1%.

OBG Management: What about retained placenta or a placenta that requires manual removal?

Dr. Brown: These intrapartum variables are not as easy to anticipate. They may suggest a condition such as placenta accreta, especially if the patient is undergoing VBAC.

Uterine inversion can also lead to hemorrhage and is a medical emergency.

OBG Management: What steps should be taken at the time of labor to ensure a safe outcome?

Dr. Brown: A type and screen should be available for all women on labor and delivery, and the team should anticipate the need to cross-match for blood if there is a high potential for transfusion. For example, a woman known to have anemia (hematocrit <30%) should have a cross-match performed so that blood can be prepared for transfusion.

In addition, women who are undergoing planned delivery for placental implantation disorders should have blood in the operating room ready for transfusion when cesarean is performed. These women are at great risk of hemorrhage and peripartum hysterectomy.

5. What first-line strategies do you recommend?

OBG Management: Do you recommend oxytocin administration and fundal massage for every patient after delivery of the infant?

Dr. Brown: Yes. These strategies lessen the risk of uterine atony and excessive bleeding after vaginal delivery. At the time of cesarean delivery, expression of the placenta and uterine massage, along with oxytocin administration, reduce the risk of excessive blood loss.

If bleeding continues even after the uterus begins to contract, look for other causes of the bleeding, such as uterine laceration or retained placental fragments.

OBG Management: What uterotonic agents do you use besides oxytocin, and when?

Dr. Brown: Oxytocin is the first-line agent for control of hemorrhage. I give a dosage of 10 to 40 U/L of normal saline or lactated Ringer solution, infused continuously. Alternatively, 10 U can be given intramuscularly (IM). Second-line drugs and their dosages are listed in the TABLE.

Uterotonic agents and how to administer them

| Drug | Dosage and route | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| FIRST-LINE | ||

| Oxytocin | 10–40 U/L of saline or lactated ringer solution, infused continuously, Or 10 U IM | The preferred drug—often the only one needed |

| SECOND-LINE | ||

| Misoprostol (Cytotec, Prostaglandin e1) | 800–1,000 μg can be given rectally | Often, the second-line drug that is given just after oxytocin because it is easy to administer |

| Methylergonovine (Methergine) | 0.2 mg IM every 2–4 hr | Contraindicated in hypertension |

| Carboprost tromethamine (Hemabate) | 0.25 mg IM every 15–90 minutes (maximum of 8 doses) | Avoid in patients who have asthma. Contra-indicated in hepatic, renal, and cardiac disease |

| Dinoprostone (Prostin e2) | 20 mg suppository can be given vaginally or rectally every 2 hours | Avoid in hypotension |

6. How do you assess the patient once PPH is identified?

OBG Management: How do you assess the patient after hemorrhage begins?

Dr. Brown: We recheck the hemoglobin and hematocrit levels and monitor vital signs for hypotension and tachycardia. We also begin fluid resuscitation and type and cross-match blood and blood products.

A delayed response to hemorrhage raises the risk of maternal morbidity and death.

We notify the anesthesia team when it seems likely that a surgical approach to the hemorrhage will be needed. And we notify interventional radiology if the bleeding may respond to uterine artery embolization.

7. Why is it important to replace blood products?

OBG Management: You’ve been known to say, “The more blood a patient loses, the more blood she loses.” What do you mean by that?

Dr. Brown: Excessive bleeding leads to a loss of critical clotting factors that are made in the liver. Once the clotting factors are depleted, the woman is at risk of coagulopathy or disseminated intravascular coagulation. This depletion potentiates the cycle of hemorrhage. When that occurs, the hemorrhage can be controlled only with transfusion of red blood cells (RBCs) and replacement of clotting factors with fresh frozen plasma, platelets, and cryoprecipitate, along with prompt correction of the process that is causing the bleeding.

OBG Management: What blood products do you administer to a patient with hemorrhage, and when?

Dr. Brown: The first line of defense for blood loss requiring transfusion is packed RBCs. Each unit of packed cells increases the hematocrit by 3% and hemoglobin by 1 g/dL, assuming bleeding is under control. After that, consider:

- Platelets. Depending on the severity of the hemorrhage and the level of platelets once the coagulation status is checked, platelets can be given. A 50-mL unit can raise the platelet count 5,000–10,000/mm3. Platelets should be considered if the count is below 50,000/mm3.

- Fresh frozen plasma should be given to replace clotting factors. Fresh frozen plasma contains fibrinogen, antithrombin III, factor V, and factor VIII. Each unit of fresh frozen plasma increases the fibrinogen level by 10 mg/dL.

- Cryoprecipitate contains fibrinogen, factors VIII and XIII, and von Willebrand factor. Each unit of cryoprecipitate increases fibrinogen by 10 mg/dL.

- Factor VII can be given if the hemorrhage is still active, but it should only be given after fresh frozen plasma and cryo-precipitate have been given to replace clotting factors. Factor VII is ineffective without clotting factor replacement prior to its administration. This medication is associated with a high risk of thromboembolism. It is also expensive.

- Synthetic fibrinogen (RiaSTAP) is available for use in the United States, but it has FDA approval only for the treatment of acute bleeding in patients who have congenital fibrinogen deficiency. It may have potential for use during PPH when essential clotting factors have been depleted.

A woman who is obese has additional risk factors for hemorrhage. Obesity itself is associated with prolonged labor and large-for-gestational-age infants, which, in turn, lead to poor contractility of the uterus and the potential for early postpartum hemorrhage.

Begin by ensuring that the obese or morbidly obese woman has appropriate intravenous access at the time of labor and receives early regional anesthesia (epidural). also alert anesthesia to the risk and assess baseline hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, including a type and screen.

An obese woman undergoing cesarean delivery has a heightened risk of uterine laceration, difficult extraction of the fetus, and uterine atony, especially if prolonged labor preceded the cesarean. Second-stage arrest and prolonged pushing before the cesarean may make extraction of the infant difficult and lead to poor uterine contractility once the placenta is removed.

All obese women, as well as other women at risk of postpartum uterine atony, should have oxytocin infused before the placenta is removed, especially at the time of cesarean delivery. Expressing the placenta at the time of cesarean delivery—as opposed to manual removal—is associated with lower blood loss and allows the uterus to begin contracting before the placenta is removed.—HAYWOOD L. BROWN, MD

8. When do you use the intrauterine balloon?

OBG Management: When is the intrauterine balloon a management option?

Dr. Brown: The balloon offers a way to actively manage hemorrhage and has been associated with decreasing morbidity and a reduced need for surgical intervention, including hysterectomy. It works through a tamponade effect. Once the balloon is inflated with 300 to 500 mL of saline, it compresses the uterine cavity until the uterus develops predelivery tone. It can be left in place as long as 24 hours, need be.

Several balloons are available for use, with the Bakri balloon being the prototype. The balloon may cut off uterine blood flow as a mechanism of action.

Before the advent of manufactured balloons, uterine tamponade was attempted using packing with gauze and a large-bore Foley catheter.

9. How do you proceed when surgery is necessary?

OBG Management: What surgical techniques—aside from hysterectomy—may be useful in stanching hemorrhage?

Dr. Brown: The first-line surgical approach after vaginal delivery is uterine exploration to evacuate uterine clots and check for retained placental fragments. This act alone may impart improved uterine contractility. If retained placental fragments are suspected, a gentle curettage of the uterine cavity, using a large curette, is appropriate.

When it is obvious that atony is the cause of the hemorrhage, and medical management has failed, these surgical steps are appropriate:

- Uterine artery ligation, using the “O’Leary” technique, can be performed bilaterally. The utero-ovarian vessels can also be ligated (but not cut!)

- B-Lynch suture as a technique to compress the uterus. This strategy uses outside, draping, absorbable suture to collapse the uterine cavity. It can be quite successful when combined with the use of uterotonics. One study reported more than 1,000 B-Lynch procedures, with only seven failures.1 Hemostatic multiple-square compression is a surgical technique that works according to a similar principle

- Hypogastric artery ligation can be performed by an experienced surgeon but is rarely employed in severe hemorrhage owing to the risk of complications and lengthy procedure time.

OBG Management: When does hysterectomy become an option?

Dr. Brown: Hysterectomy is the last defense against morbidity and maternal death from hemorrhage due to atony.

Clearly, when hysterectomy is performed, sooner is better than later, especially if uterine artery ligation and B-Lynch suture do not appear to be controlling the hemorrhage and the patient is hemodynamically unstable.

If the patient is a young woman with low parity, the uterus should be preserved, if at all possible, unless the hemorrhage cannot be controlled and the woman’s life is jeopardized.

When a uterine rupture has occurred, usually after a VBAC attempt, it may be prudent to proceed to hysterectomy, especially if the uterus appears to be difficult to repair.

10. When do you call for help?

OBG Management: When do you call in extra help?

Dr. Brown: As soon as hemorrhage occurs, the team should be assembled. It is critical that anesthesia be notified immediately, in the event that the patient requires surgical management. The blood bank should be notified that blood and blood products are likely to be required.

We designate a nursing leader to monitor the patient and another to keep the staff and unit on alert for potential surgical intervention. If uterine rupture or an invasive placental abnormality is suspected, we assemble the surgical team, including any potential consultant surgeon. We also notify the best available surgeons so that they can be ready to perform the necessary techniques. In addition, we notify the OR and surgical intensive care unit, in case they are needed.

OBG Management: How can obstetricians and obstetric units practice the response to OB hemorrhage so that, when a hemorrhage occurs, they are at the top of their game?

Dr. Brown: Obstetric units prepare by performing drills and simulations. These drills are now considered part of most units’ quality and safety programs.

Because obstetric hemorrhage can occur on any unit at any time, the team must be prepared to respond around the clock promptly and effectively to reduce the risk of morbidity and death.

After emergent surgical management of obstetric hemorrhage, the team should be assembled again to discuss what occurred and how they performed or could have performed more effectively as a team.

OBG Management: Should all obstetricians who perform repeat cesarean delivery be able to perform a cesarean hysterectomy in the event that uncontrollable hemorrhage is encountered?

Dr. Brown: It is an absolute must that any clinician who allows VBAC be capable of performing peripartum cesarean hysterectomy and know the indications for hysterectomy, as we have discussed. In fact, any obstetrician who performs cesarean delivery should be capable of performing a cesarean hysterectomy.

11. What do you recommend for practice?

OBG Management: How would you summarize the main points of management of postpartum hemorrhage?

Dr. Brown: I would suggest that the first step is organizing the team (obstetricians, nurses, anesthesiologist), followed by:

- resuscitation of the mother with oxygen and fluids through large-bore intravenous access sites

- notification of the blood bank (with typing and cross-matching) of the possible need for 4 to 6 U of blood for trans-fusion

- liberal assessment of laboratory values, especially coagulation status (International Normalized Ratio [INR], prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time) and blood counts (hemoglobin and hematocrit). Values may be lower if there has been significant blood loss and aggressive fluid resuscitation. Blood products such as fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate are indicated, in addition to packed RBCs, if the patient has or is developing a coagulopathy. Also give platelets if the count is low. Once it becomes apparent that surgical intervention will be necessary, begin transfusion and replace clotting factors before beginning the procedure

- monitoring of vital signs and urine output throughout resuscitation and medical and surgical intervention

- elimination of the cause of bleeding as soon as possible by whatever means necessary to prevent maternal death, beginning with conservative medical management and, if necessary, followed by surgical intervention.

Tell us about a challenging case of postpartum hemorrhage and how you managed it.

Go to Send Us Your Letters. Please include your name, city, and state. We’ll publish intriguing “pearls” in an upcoming issue.

We know the potentially tragic outcome of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH): Worldwide, more than 140,000 women die every year as a result of PPH—one death every 4 minutes! Lest you dismiss PPH as a concern largely for developing countries, where it accounts for 25% of maternal deaths, consider this: In our highly developed nation, it accounts for nearly 8% of maternal deaths—a troubling statistic, to say the least.

The significant maternal death rate associated with PPH, and questions about how to reduce it, prompted the editors of OBG Management to talk with Haywood L. Brown, MD. Dr. Brown is Roy T. Parker Professor and chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC. He is also a nationally recognized specialist in maternal-fetal medicine. In this interview, he discusses the full spectrum of management of PPH, from proactive assessment of a woman’s risk to determination of the cause to the tactic of last resort, emergent hysterectomy.

Uterine atony is the leading cause of postpartum hemorrhage. When medical management fails to stanch the bleeding, bilateral uterine artery ligation is one surgical option.

1. What is PPH?

OBG Management: Dr. Brown, let’s start with a simple but important aspect of PPH—how do you define it?

Dr. Brown: Obstetric hemorrhage is excessive bleeding that occurs during the intrapartum or postpartum period—specifically, estimated blood loss of 500 mL or more after vaginal delivery or 1,000 mL or more after cesarean delivery.

PPH is characterized as early or late, depending on whether the bleeding occurs within 24 hours of delivery (early, or primary) or between 24 hours and 6 to 12 weeks postpartum (late, or secondary). Primary PPH occurs in 4% to 6% of pregnancies.

Another way to define PPH: a decline of 10% or more in the baseline hematocrit level.

OBG Management: How do you measure blood loss?

Dr. Brown: The estimation of blood loss after delivery is an inexact science and typically yields an underestimation. Most clinicians rely on visual inspection to estimate the amount of blood collected in the drapes after vaginal delivery and in the suction bottles after cesarean delivery. Some facilities weigh lap pads or drapes to get a more accurate assessment of blood loss. In a routine delivery, no specific calorimetric measuring devices are used to estimate blood loss.

At my institution, we make an attempt to estimate blood loss at every delivery—vaginal or cesarean—and record the estimate. By doing this routinely, the clinician improves in accuracy and becomes more adept at identifying excessive bleeding.

OBG Management: Is blood loss the only variable that arouses concern about possible hemorrhage?

Dr. Brown: Because pregnant women experience an increase in blood volume and physiologic cardiovascular changes, the usual sign of significant bleeding can sometimes be masked. Therefore, any changes in maternal vital signs, such as a drop in blood pressure, tachycardia, or sensorial changes, may suggest that more blood has been lost than has been estimated.

Hypotension, dizziness, tachycardia or palpitations, and decreasing urine output will typically occur when more than 10% of maternal blood volume has been lost. In this situation, the patient should be given additional fluids, and a second intravenous line should be started using large-bore, 14-gauge access. In addition, the patient’s hemoglobin and hematocrit levels should be measured. All these actions constitute a first-line strategy to prevent shock and potential irreversible renal failure and cardiovascular collapse.

Low: 500 to 1,000 mL

This level of hemorrhage should be anticipated and can usually be managed with uterine massage and administration of a uterotonic agent, such as oxytocin. Intravenous fluids and careful monitoring of maternal vital signs are also warranted.

Active management of the third stage of labor has been shown to reduce the risk of significant postpartum hemorrhage (PPH). Active management includes:

- administration of a uterotonic agent immediately after delivery of the infant

- early cord clamping and cutting

- gentle cord traction with uterine counter-traction when the uterus is well contracted

- uterine massage.2

If these methods are unsuccessful in correcting the atony, uterotonics such as a prostaglandin (rectally administered misoprostol [800 mg] or intramuscular carboprost tromethamine [Hemabate; 250 μg/mL]) will usually succeed.

Medium: 1,000 to 1,500 mL

Blood loss of this volume is usually accompanied by cardiovascular signs, such as a fall in blood pressure, diaphoresis, and tachycardia. Women with this level of hemorrhage exhibit mild signs of shock.

It is important to correct maternal hypotension with fluids, restabilize vital signs, and resolve the bleeding expeditiously. If uterotonics and massage fail to stanch the bleeding, consider placing a balloon (e.g., Bakri balloon). Once the balloon is placed and inflated, it can be left for as long as 24 hours or until the uterus regains its tone.

Be sure to check hemoglobin and hematocrit levels and transfuse the patient, if necessary, especially if vital signs have not stabilized.

High: 1,500 to 2,000 mL, or greater

This is a medical emergency that must be managed aggressively to prevent morbidity and death. Blood loss of this volume will usually bring significant cardiovascular changes, such as hypotension, tachycardia, restlessness, pallor, oliguria, and cardiovascular collapse from hemorrhagic shock. this degree of blood loss means that the patient has lost 25% to 35% of her blood volume and will need blood-product replacement to prevent coagulation and the cascade of hemorrhage.

If conservative measures are unsuccessful, timely surgical intervention with B-Lynch suture, uterine vessel ligation, or hysterectomy is lifesaving.—HAYWOOD L. BROWN, MD

2. What causes PPH?

OBG Management: Why does PPH occur?

Dr. Brown: The leading cause is uterine atony, a failure of the uterus to contract and undergo resolution following delivery of an infant. Approximately 80% of cases of early PPH are related to uterine atony.

There are other causes of PPH:

- lacerations of the genital tract (perineum, vagina, cervix, or uterus)

- retained fragments of placental tissue

- uterine rupture

- blood clotting abnormalities

- uterine inversion.

3. Is it possible to prepare for PPH?

OBG Management: What is the starting point for management of PPH?

Dr. Brown: Prevention of, and preparation for, hemorrhage begin well before delivery. During the prenatal period, for example, it is important to assess the woman’s level of risk for PPH. Among the variables that increase her risk:

- any situation that leads to overstretching of the uterus, including multiple gestation, whether delivery is vaginal or cesarean

- a history of PPH.

It is important that women with these characteristics maintain adequate hemoglobin and hematocrit levels by taking vitamin and iron supplements in the antepartum period.

In addition, women who have abnormal placental implantation, such as placenta previa, are at risk for bleeding during the antepartum period and during cesarean delivery. They should maintain a hematocrit in the mid-30s because of expected blood loss during delivery.

OBG Management: What preparatory steps should be taken at the time of hospital admission if a woman has an elevated risk of bleeding?

Dr. Brown: When the patient is hospitalized in anticipation of delivery—whether vaginal or cesarean—the team should assess her hemoglobin and hematocrit levels and type and screen for possible transfusion. The patient should also be apprised of her risk and the potential for transfusion.

Last, the anesthesia team should be alerted to her risk factors for postpartum bleeding.

4. What intrapartum variables signal an increased risk of PPH?

OBG Management: During labor and delivery, what variables signal an elevated risk of bleeding?

Dr. Brown: Risk factors for hemorrhage become more apparent during this period. They include prolonged or rapid labor, prolonged use of oxytocin, operative delivery, infections such as chorioamnionitis, and vaginal birth after cesarean delivery (VBAC).

Bleeding with VBAC merits special attention because it could signal uterine rupture. Women who have a low transverse uterine scar and who undergo VBAC have a risk of uterine scar separation during labor of 0.5% to 1%.

OBG Management: What about retained placenta or a placenta that requires manual removal?

Dr. Brown: These intrapartum variables are not as easy to anticipate. They may suggest a condition such as placenta accreta, especially if the patient is undergoing VBAC.

Uterine inversion can also lead to hemorrhage and is a medical emergency.

OBG Management: What steps should be taken at the time of labor to ensure a safe outcome?

Dr. Brown: A type and screen should be available for all women on labor and delivery, and the team should anticipate the need to cross-match for blood if there is a high potential for transfusion. For example, a woman known to have anemia (hematocrit <30%) should have a cross-match performed so that blood can be prepared for transfusion.

In addition, women who are undergoing planned delivery for placental implantation disorders should have blood in the operating room ready for transfusion when cesarean is performed. These women are at great risk of hemorrhage and peripartum hysterectomy.

5. What first-line strategies do you recommend?

OBG Management: Do you recommend oxytocin administration and fundal massage for every patient after delivery of the infant?

Dr. Brown: Yes. These strategies lessen the risk of uterine atony and excessive bleeding after vaginal delivery. At the time of cesarean delivery, expression of the placenta and uterine massage, along with oxytocin administration, reduce the risk of excessive blood loss.

If bleeding continues even after the uterus begins to contract, look for other causes of the bleeding, such as uterine laceration or retained placental fragments.

OBG Management: What uterotonic agents do you use besides oxytocin, and when?

Dr. Brown: Oxytocin is the first-line agent for control of hemorrhage. I give a dosage of 10 to 40 U/L of normal saline or lactated Ringer solution, infused continuously. Alternatively, 10 U can be given intramuscularly (IM). Second-line drugs and their dosages are listed in the TABLE.

Uterotonic agents and how to administer them

| Drug | Dosage and route | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| FIRST-LINE | ||

| Oxytocin | 10–40 U/L of saline or lactated ringer solution, infused continuously, Or 10 U IM | The preferred drug—often the only one needed |

| SECOND-LINE | ||

| Misoprostol (Cytotec, Prostaglandin e1) | 800–1,000 μg can be given rectally | Often, the second-line drug that is given just after oxytocin because it is easy to administer |

| Methylergonovine (Methergine) | 0.2 mg IM every 2–4 hr | Contraindicated in hypertension |

| Carboprost tromethamine (Hemabate) | 0.25 mg IM every 15–90 minutes (maximum of 8 doses) | Avoid in patients who have asthma. Contra-indicated in hepatic, renal, and cardiac disease |

| Dinoprostone (Prostin e2) | 20 mg suppository can be given vaginally or rectally every 2 hours | Avoid in hypotension |

6. How do you assess the patient once PPH is identified?

OBG Management: How do you assess the patient after hemorrhage begins?

Dr. Brown: We recheck the hemoglobin and hematocrit levels and monitor vital signs for hypotension and tachycardia. We also begin fluid resuscitation and type and cross-match blood and blood products.

A delayed response to hemorrhage raises the risk of maternal morbidity and death.

We notify the anesthesia team when it seems likely that a surgical approach to the hemorrhage will be needed. And we notify interventional radiology if the bleeding may respond to uterine artery embolization.

7. Why is it important to replace blood products?

OBG Management: You’ve been known to say, “The more blood a patient loses, the more blood she loses.” What do you mean by that?

Dr. Brown: Excessive bleeding leads to a loss of critical clotting factors that are made in the liver. Once the clotting factors are depleted, the woman is at risk of coagulopathy or disseminated intravascular coagulation. This depletion potentiates the cycle of hemorrhage. When that occurs, the hemorrhage can be controlled only with transfusion of red blood cells (RBCs) and replacement of clotting factors with fresh frozen plasma, platelets, and cryoprecipitate, along with prompt correction of the process that is causing the bleeding.

OBG Management: What blood products do you administer to a patient with hemorrhage, and when?

Dr. Brown: The first line of defense for blood loss requiring transfusion is packed RBCs. Each unit of packed cells increases the hematocrit by 3% and hemoglobin by 1 g/dL, assuming bleeding is under control. After that, consider:

- Platelets. Depending on the severity of the hemorrhage and the level of platelets once the coagulation status is checked, platelets can be given. A 50-mL unit can raise the platelet count 5,000–10,000/mm3. Platelets should be considered if the count is below 50,000/mm3.

- Fresh frozen plasma should be given to replace clotting factors. Fresh frozen plasma contains fibrinogen, antithrombin III, factor V, and factor VIII. Each unit of fresh frozen plasma increases the fibrinogen level by 10 mg/dL.

- Cryoprecipitate contains fibrinogen, factors VIII and XIII, and von Willebrand factor. Each unit of cryoprecipitate increases fibrinogen by 10 mg/dL.

- Factor VII can be given if the hemorrhage is still active, but it should only be given after fresh frozen plasma and cryo-precipitate have been given to replace clotting factors. Factor VII is ineffective without clotting factor replacement prior to its administration. This medication is associated with a high risk of thromboembolism. It is also expensive.

- Synthetic fibrinogen (RiaSTAP) is available for use in the United States, but it has FDA approval only for the treatment of acute bleeding in patients who have congenital fibrinogen deficiency. It may have potential for use during PPH when essential clotting factors have been depleted.

A woman who is obese has additional risk factors for hemorrhage. Obesity itself is associated with prolonged labor and large-for-gestational-age infants, which, in turn, lead to poor contractility of the uterus and the potential for early postpartum hemorrhage.

Begin by ensuring that the obese or morbidly obese woman has appropriate intravenous access at the time of labor and receives early regional anesthesia (epidural). also alert anesthesia to the risk and assess baseline hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, including a type and screen.

An obese woman undergoing cesarean delivery has a heightened risk of uterine laceration, difficult extraction of the fetus, and uterine atony, especially if prolonged labor preceded the cesarean. Second-stage arrest and prolonged pushing before the cesarean may make extraction of the infant difficult and lead to poor uterine contractility once the placenta is removed.

All obese women, as well as other women at risk of postpartum uterine atony, should have oxytocin infused before the placenta is removed, especially at the time of cesarean delivery. Expressing the placenta at the time of cesarean delivery—as opposed to manual removal—is associated with lower blood loss and allows the uterus to begin contracting before the placenta is removed.—HAYWOOD L. BROWN, MD

8. When do you use the intrauterine balloon?

OBG Management: When is the intrauterine balloon a management option?

Dr. Brown: The balloon offers a way to actively manage hemorrhage and has been associated with decreasing morbidity and a reduced need for surgical intervention, including hysterectomy. It works through a tamponade effect. Once the balloon is inflated with 300 to 500 mL of saline, it compresses the uterine cavity until the uterus develops predelivery tone. It can be left in place as long as 24 hours, need be.

Several balloons are available for use, with the Bakri balloon being the prototype. The balloon may cut off uterine blood flow as a mechanism of action.

Before the advent of manufactured balloons, uterine tamponade was attempted using packing with gauze and a large-bore Foley catheter.

9. How do you proceed when surgery is necessary?

OBG Management: What surgical techniques—aside from hysterectomy—may be useful in stanching hemorrhage?

Dr. Brown: The first-line surgical approach after vaginal delivery is uterine exploration to evacuate uterine clots and check for retained placental fragments. This act alone may impart improved uterine contractility. If retained placental fragments are suspected, a gentle curettage of the uterine cavity, using a large curette, is appropriate.

When it is obvious that atony is the cause of the hemorrhage, and medical management has failed, these surgical steps are appropriate:

- Uterine artery ligation, using the “O’Leary” technique, can be performed bilaterally. The utero-ovarian vessels can also be ligated (but not cut!)

- B-Lynch suture as a technique to compress the uterus. This strategy uses outside, draping, absorbable suture to collapse the uterine cavity. It can be quite successful when combined with the use of uterotonics. One study reported more than 1,000 B-Lynch procedures, with only seven failures.1 Hemostatic multiple-square compression is a surgical technique that works according to a similar principle

- Hypogastric artery ligation can be performed by an experienced surgeon but is rarely employed in severe hemorrhage owing to the risk of complications and lengthy procedure time.

OBG Management: When does hysterectomy become an option?

Dr. Brown: Hysterectomy is the last defense against morbidity and maternal death from hemorrhage due to atony.

Clearly, when hysterectomy is performed, sooner is better than later, especially if uterine artery ligation and B-Lynch suture do not appear to be controlling the hemorrhage and the patient is hemodynamically unstable.

If the patient is a young woman with low parity, the uterus should be preserved, if at all possible, unless the hemorrhage cannot be controlled and the woman’s life is jeopardized.

When a uterine rupture has occurred, usually after a VBAC attempt, it may be prudent to proceed to hysterectomy, especially if the uterus appears to be difficult to repair.

10. When do you call for help?

OBG Management: When do you call in extra help?

Dr. Brown: As soon as hemorrhage occurs, the team should be assembled. It is critical that anesthesia be notified immediately, in the event that the patient requires surgical management. The blood bank should be notified that blood and blood products are likely to be required.

We designate a nursing leader to monitor the patient and another to keep the staff and unit on alert for potential surgical intervention. If uterine rupture or an invasive placental abnormality is suspected, we assemble the surgical team, including any potential consultant surgeon. We also notify the best available surgeons so that they can be ready to perform the necessary techniques. In addition, we notify the OR and surgical intensive care unit, in case they are needed.

OBG Management: How can obstetricians and obstetric units practice the response to OB hemorrhage so that, when a hemorrhage occurs, they are at the top of their game?

Dr. Brown: Obstetric units prepare by performing drills and simulations. These drills are now considered part of most units’ quality and safety programs.

Because obstetric hemorrhage can occur on any unit at any time, the team must be prepared to respond around the clock promptly and effectively to reduce the risk of morbidity and death.

After emergent surgical management of obstetric hemorrhage, the team should be assembled again to discuss what occurred and how they performed or could have performed more effectively as a team.

OBG Management: Should all obstetricians who perform repeat cesarean delivery be able to perform a cesarean hysterectomy in the event that uncontrollable hemorrhage is encountered?

Dr. Brown: It is an absolute must that any clinician who allows VBAC be capable of performing peripartum cesarean hysterectomy and know the indications for hysterectomy, as we have discussed. In fact, any obstetrician who performs cesarean delivery should be capable of performing a cesarean hysterectomy.

11. What do you recommend for practice?

OBG Management: How would you summarize the main points of management of postpartum hemorrhage?

Dr. Brown: I would suggest that the first step is organizing the team (obstetricians, nurses, anesthesiologist), followed by:

- resuscitation of the mother with oxygen and fluids through large-bore intravenous access sites

- notification of the blood bank (with typing and cross-matching) of the possible need for 4 to 6 U of blood for trans-fusion

- liberal assessment of laboratory values, especially coagulation status (International Normalized Ratio [INR], prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time) and blood counts (hemoglobin and hematocrit). Values may be lower if there has been significant blood loss and aggressive fluid resuscitation. Blood products such as fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate are indicated, in addition to packed RBCs, if the patient has or is developing a coagulopathy. Also give platelets if the count is low. Once it becomes apparent that surgical intervention will be necessary, begin transfusion and replace clotting factors before beginning the procedure

- monitoring of vital signs and urine output throughout resuscitation and medical and surgical intervention

- elimination of the cause of bleeding as soon as possible by whatever means necessary to prevent maternal death, beginning with conservative medical management and, if necessary, followed by surgical intervention.

Tell us about a challenging case of postpartum hemorrhage and how you managed it.

Go to Send Us Your Letters. Please include your name, city, and state. We’ll publish intriguing “pearls” in an upcoming issue.

1. Allam MS, B-Lynch C. The B-Lynch and other uterine compression techniques. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;89(3):236-241.

2. Prendiville WJ, Elbourne D, McDonald S. Active versus expectant management in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(3):CD000007.-

- Activated factor VII proves to be a lifesaver in postpartum hemorrhage

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (February 2007) - Postpartum hemorrhage: Solutions to 2 intractable cases

Michael L. Stitely, MD, and Robert B. Gherman, MD (April 2007) - Give a uterotonic routinely during the third stage of labor

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (May 2007) - Consider retroperitoneal packing for postpartum hemorrhage

Maj. William R. Fulton, DO (July 2008) - You should add the Bakri balloon to your treatments for OB bleeds

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (February 2009) - Planning reduces the risk of maternal death. This tool helps.

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (August 2009) - What you can do to optimize blood conservation in ObGyn practice

Eric J. Bieber, MD, Linda Scott, RN, Corinna Muller, DO, Nancy Nuss, RN, and Edie L. Derian, MD (February 2010)

1. Allam MS, B-Lynch C. The B-Lynch and other uterine compression techniques. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2005;89(3):236-241.

2. Prendiville WJ, Elbourne D, McDonald S. Active versus expectant management in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(3):CD000007.-

- Activated factor VII proves to be a lifesaver in postpartum hemorrhage

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (February 2007) - Postpartum hemorrhage: Solutions to 2 intractable cases

Michael L. Stitely, MD, and Robert B. Gherman, MD (April 2007) - Give a uterotonic routinely during the third stage of labor

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (May 2007) - Consider retroperitoneal packing for postpartum hemorrhage

Maj. William R. Fulton, DO (July 2008) - You should add the Bakri balloon to your treatments for OB bleeds

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (February 2009) - Planning reduces the risk of maternal death. This tool helps.

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (August 2009) - What you can do to optimize blood conservation in ObGyn practice

Eric J. Bieber, MD, Linda Scott, RN, Corinna Muller, DO, Nancy Nuss, RN, and Edie L. Derian, MD (February 2010)

Extra Swabs Make a Difference

Activated Macrophage Suspension for Hard-to-Heal Pressure Ulcers

Patient-Centered Foot Care for Veterans Receiving Dialysis

Adjunctive Treatment for a Nonhealing Pressure Ulcer in a Patient with Spinal Cord Injury

Stroke and Preventable Hospitalization: Who Is Most At Risk?

Bite of the Brown Recluse Spider

The brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) is a small arachnid with great potential to inflict physical harm. More potent than a rattlesnake’s venom, the toxin emitted by the brown recluse has the ability to rupture cell membranes and destroy regional nerves, blood vessels, and fatty tissue. Envenomation by the brown recluse can lead to severe necrosis of the cutaneous tissues.1,2

In the United States, L reclusa is one of 13 species of Loxosceles—five of which have been associated with necrotic lesions resulting from bites and envenomation.3 Though rare, and virtually nonexistent across significant portions of North America,4 the brown recluse is often cited as the offending creature in reported bites involving envenomation5 (with reports sometimes outnumbering estimated numbers of specimens in a given area6). Considering the limited range within which the spider is considered endemic, any patient who presents reporting a possible brown recluse spider bite (or who presents with a wound suspected of being such a bite) must be questioned quickly and carefully. The first and foremost question: where, geographically, was the patient bitten?

Endemic Areas

Brown recluse spiders are known to be present in the subtropical areas of North America—but not in areas with high humidity. According to arachnologists in the southeastern United States, the closer one is to the Gulf of Mexico, the less likely one is to encounter a brown recluse.7 This spider is most commonly found in eastern Texas, Arkansas, areas west of the Appalachian Mountains, and northern areas of the Gulf Coast states (see Figure 18). They are virtually nonexistent along the Atlantic seaboard and the Gulf Coast,4 although lone specimens of Loxosceles species have been reported in numerous nonendemic areas, suggesting possible transport through commerce or family relocation.9 One suspected case of brown recluse envenomation was recently reported in New York State.10

If it is determined that the geographic area in question is indeed populated by brown recluse spiders, more detailed history must then be elicited from the patient regarding recent activities. The brown recluse may reside indoors and often hides in bed sheets, blankets, and stored clothing. This spider also may be found behind furniture, in basements and cupboards, or in other small, tight areas. It is commonly found in cardboard boxes stored in a closet or an attic,11 and boxes with folded flaps are a preferred dwelling place.7 (Thus, a remote chance that L reclusa can be inadvertently transported to a nonendemic area9 does exist.)

In the outdoors, the brown recluse may be found in woodpiles, piles of leaves or other natural debris, in outdoor sheds or garages, under rocks, and in other places that are relatively dark and seldom used.12

Patient Presentation/Patient History

Initially, patients with a brown recluse spider bite may present to a primary care provider with complaints of mild pain and itching, presumably around the bite site. Within eight hours, the pain becomes stabbing and penetrating and may give way to a burning sensation.7

Patients with a positive pertinent history who are at increased risk for a bite are those who live in areas where these spiders are endemic and who have been performing tasks in areas where these spiders might reside. Not wearing long pants and long-sleeved shirts contributes to the probability that a patient has sustained a bite.

Physical Examination

The site of the suspected bite and surrounding skin should be examined carefully. A pustule, generally small and white, may appear, surrounded by erythema. For as long as 24 hours following the time of the initial bite, a volcano-like lesion may be present, with a sunken central “crater” that has raised edges. While the center of the lesion is free of inflammation, the surrounding skin is typically red and inflamed.12

Pathologically, a specified sequence occurs following a bite with envenomation. Initially, platelets aggregate, followed by endothelial swelling and destruction (see Figure 2a). Gradually, this leads to the blocking of capillaries with white blood cells, which results in ischemia and ultimately necrosis.1

The clinical manifestations of the brown recluse spider bite may vary, based on the amount of venom injected and the age and overall health of the patient. One who has been bitten with minimal envenomation may experience little more than mild erythema, localized urticaria, and generalized discomfort that resolves spontaneously in three to five days.1

In patients who experience more significant envenomation, a “bull’s-eye” lesion may appear. The center of the wound may be bluish in hue, with concentric rings—an inner pale ring, and an outer reddened ring. The center of the wound subsequently forms a hemorrhagic bleb that will typically become necrotic. Eventually, as the eschar matures, the necrotic tissue will slough off, and an area of granulation will develop. Full healing of the wound may take from four weeks to as long as six months.1

Laboratory Workup

A complete blood count, including platelet count and differential, will allow the provider to observe for disseminated intravascular coagulation, hemolysis, and thrombocytopenia. The abnormal results most commonly found in patients who have sustained a brown recluse spider bite are leukocytosis and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. A skin biopsy of the site may reveal the presence of eosinophils, neutrophils, and thrombosis, all of which support the diagnosis of a brown recluse spider bite.2

A valid, reliable test to detect Loxosceles venom is needed in the clinical setting; the differential diagnosis for brown recluse spider bites is broad (see the table1,6,11,13-15 below), and diagnostic error can occur, delaying appropriate treatment for the actual presenting condition—which could be debilitating or in rare cases, fatal.16 One test for Loxosceles venom, though not currently marketed for use in humans, shows potential. It is a polyclonal enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with a demonstrated ability to detect venom in rabbits for as long as seven days after injection.7 Further refinement of the polyclonal ELISA is under way in efforts to increase its sensitivity and specificity.17

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of a brown recluse spider bite is difficult at best. Other potential causes of the associated presenting symptoms should be excluded before a brown recluse spider bite is considered confirmed.

Several factors add to the difficulty of diagnosing a brown recluse bite. Oftentimes it may take the patients days or weeks after the bite to see a health care provider, and they rarely present with the spider that bit them (or that they believe bit them).1 Currently, the only true standard for proof of envenomation by a brown recluse is to collect the spider and have its identify verified by an entomologist or other expert—not necessarily the health care provider.