User login

The case for chemoprevention as a tool to avert breast cancer

The author reports that he is a consultant to Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Wyeth, and a speaker for Eli Lilly and Wyeth.

CASE 1: Premenopausal woman

at high risk of breast cancer

R. J. is a 43-year-old, nulliparous woman who reached menarche at age 11. She has undergone two breast biopsies, the most recent of which revealed ductal hyperplasia with marked atypia.

R. J.’s sister had breast cancer at 49 years of age; her mother had breast cancer at 66 years. Because of R. J.’s family history, she underwent testing for a BRCA mutation. The result was negative.

R. J. has come to your office today to find out if she can do anything to reduce her risk of breast cancer. What options can you offer?

The most common method of “prevention” of breast cancer involves early detection and assessment of abnormalities through frequent surveillance with mammography. Some women who have dense breasts, a history of breast biopsy, or other risk factors for breast cancer may benefit from intensive surveillance with both mammography and ultrasonography—and, in some cases, magnetic resonance imaging.

More aggressive options include:

- the use of a chemopreventive agent such as tamoxifen or raloxifene

- in rare cases—usually when a BRCA mutation is present—prophylactic mastectomy.

Before it is possible to determine the optimal approach for a particular woman, it is necessary to conduct an individualized assessment of her risk—that is, to estimate the probability that she will develop breast cancer over a defined period of time. Such an estimate is also useful for designing prevention trials in high-risk subsets of the population. (Prevention trials differ from therapeutic clinical trials in that asymptomatic healthy women are exposed to potentially toxic interventions for prolonged periods to reduce their risk of breast cancer.)

This article describes chemopreventive options for women at high risk, based on individualized risk assessment using the Gail model.

(Editor’s note: For additional discussion of the important role ObGyns play in the fight against breast cancer, see Editor in Chief Dr. Robert L. Barbieri’s Editorial.)

You can estimate the likelihood that a woman like your patient may develop breast cancer using various individual risk factors ( TABLE 1 ), but estimates for combinations of risk factors are preferable. The Gail model takes into account some nongenetic factors, such as parity and age at menarche, but also genetic factors, such as family history. The model calculates a woman’s individualized breast cancer probability and yields a numerical risk (a percentage) that she will develop invasive breast cancer over the next 5 years; it also yields an estimate of her risk of developing the malignancy over the remainder of her life.1,2

A Gail-model 5-year estimate of 1.66% or higher denotes a high risk of developing breast cancer. That benchmark was the one employed in the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT), conducted as part of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP).3

TABLE 1

What are the risk factors for breast cancer?

And what degree of relative risk do they confer?

| Relative risk | ||

|---|---|---|

| <2 | 2–4 | >4 |

| • Age 25–34 years at first live birth • Early menarche • Late menopause • Benign proliferative disease • Postmenopausal obesity • Alcohol use • Hormone replacement therapy | • Age >35 years at first live birth • First-degree relative with breast cancer • Nulliparity • Radiation exposure • Personal history of breast cancer | • Gene mutation (BRCA 1 or 2) • Lobular carcinoma in situ • Ductal carcinoma in situ • Atypical hyperplasia |

| Adapted from Bilimoria and Morrow23 | ||

Weaknesses of the Gail model

The Gail model’s approach to estimating risk has some limitations. The model uses the number of prior breast biopsies in its assessment—but the relative risk associated with prior biopsy is smaller for women older than 50 years than it is for younger women.

Furthermore, data on which Gail bases its estimates were collected in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Since then, the increasing ease of breast histopathologic assessment—through fine-needle aspiration and outpatient core-needle biopsy—has confused the issue of just what constitutes a breast “biopsy.” (Most patients surveyed consider it to be any histologic sampling of the breast.)

As a result, the 1.66% cutoff becomes somewhat difficult to interpret in light of current practice.

Consider the following example. A 50-year-old nulliparous Caucasian woman reached menarche when she was 11 years old, has never had a biopsy, and has no first-degree relatives with breast cancer. According to the Gail model, her risk of developing breast cancer is 1.2% over the next 5 years and 10.8% in her lifetime. Therefore, she is not considered at high risk. If she were to give a history of three previous breast biopsies, however, none of them showing hyperplasia, her 5-year risk would rise to 1.8% and push her over the line into the high-risk category.

Compare her situation to that of R. J., the nulliparous woman described in Case 1. R. J. also reached menarche at 11 years, but she has had two breast biopsies (one of which showed atypical hyperplasia) and has two first-degree relatives who have had breast cancer. Her Gail score shows a 5-year risk of breast cancer of 13.5% (the norm for a 43-year-old woman is 0.8%), and a lifetime risk of 69.2%. Clearly, she has a high risk of breast cancer.

How do we improve an imperfect science?

We need to identify objective findings that are patient-specific but highly correlative with the development of breast cancer. Patient-specific biomarkers have been proposed, such as ultrasensitive measurement of the serum estradiol level in postmenopausal women. In the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation, also known as the MORE trial, women who experienced the greatest reduction in the rate of breast cancer during treatment with raloxifene were a subgroup who had the highest baseline level of serum estradiol—although, overall, all patients had an estradiol level well within the postmenopausal range (≤20 pmol/L).4,5

How tamoxifen became a chemopreventive agent

Tamoxifen inhibits mammary tumors in mice and rats and suppresses hormone-dependent breast cancer cell lines in vitro.6 Clinical data from the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group yielded additional motivation for prevention trials with tamoxifen: Besides reducing the rate of recurrent breast cancer, tamoxifen reduced the risk of contralateral new-onset breast cancer by 47% after 5 years of adjuvant treatment.7 Preclinical findings in vitro and in animal models, coupled with clinical data and evidence of tamoxifen’s favorable effects on skeleton remodeling and lipid levels, led to a series of chemoprevention trials in the United States and Europe using tamoxifen.

In the aforementioned BCPT, launched in 1992, 13,388 women 35 years and older who were deemed to be at high risk of developing breast cancer were enrolled at numerous sites throughout the United States and Canada.3 The Gail model was used to select women for the trial—only those who had a 5-year risk of 1.66% or higher were included. Participants were randomly assigned to receive tamoxifen 20 mg or placebo daily for 5 years. The trial was terminated early because of the dramatic reduction in new-onset breast cancer with tamoxifen, compared with placebo.

The overall incidence of breast cancer in the tamoxifen group was 3.4 cases for every 1,000 women, compared with 6.8 cases for every 1,000 women receiving placebo.3 Overall, the reduction in invasive breast cancer with tamoxifen was 49% (P<.00001). When broken down by age group, the reduction was:

- 44% in women 35 to 49 years old

- 51% in women 50 to 59 years old

- 55% in women 60 years and older.

Even noninvasive breast cancer was reduced with tamoxifen

Tamoxifen decreased the incidence of noninvasive breast cancer (ductal carcinoma in situ [DCIS]) by 50%. Expanded use of mammography has increased the detection of DCIS. Most DCIS lesions appear to be estrogen-receptor positive.8

In addition, tamoxifen reduced breast cancer risk in women who had a history of lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), a precancer, by 56%, and it reduced the risk of breast cancer in women who had a history of atypical hyperplasia by 86%. Overall, tamoxifen reduced the occurrence of estrogen-positive tumors by 69%, but had no impact on the incidence of estrogen-receptor–negative tumors.

The BCPT was stopped 14 months before planned because the Data and Safety Monitoring Board felt it was unethical to continue to allow one half of such high-risk participants to take placebo in light of the dramatic reduction in both invasive and noninvasive breast cancer among women who took tamoxifen.

In postmenopausal women, tamoxifen increases some risks

Two secondary endpoints of the BCPT are worthy of consideration:

- The overall relative risk (RR) of endometrial cancer associated with tamoxifen therapy in healthy women was 2.53 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.35, 4.97). However, further analysis by age yielded a RR of 4.01 in women who were older than 50 years (95% CI, 1.70, 10.90), compared with a RR of 1.21 in women 49 years and younger (95% CI, 0.41, 3.60).

- The same age distinction held true for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolus, with no statistically significant increases in either in women 49 years and younger, but a RR of 1.71 and 3.19, respectively, in women 50 years and older. It is unclear whether the trial was sufficiently powered for this particular secondary endpoint.

These findings suggest that serious adverse events do not occur at the same magnitude in women younger than 50 years that they do in women 50 and older. The difference in the risk–benefit profile between younger and older women has significant clinical implications for the care of perimenopausal patients.

Risk of other malignancies was not affected by tamoxifen

Overall, invasive cancers other than those of the breast and uterus occurred at the same rate in the tamoxifen and placebo groups of the BCPT. The RR of death from any cause was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.56–1.16). There was a slight increase in the risk of myocardial infarction (RR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.65–1.92) and a slight decrease in the risk of severe angina (RR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.40–2.14) in tamoxifen users, although neither of these risks was statistically significant.

The overall RR of fracture of the hip, spine, or radius was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.63–1.05). There was a statistically significant increase in the number of women who had cataracts who then underwent cataract surgery in the tamoxifen group (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.16–2.14).

Tamoxifen is approved as a preventive for high-risk women only

Based on the results of the BCPT, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved tamoxifen in October 1998 for the primary prevention of breast cancer in women who are at high risk of the disease. The FDA recommends that use of tamoxifen be limited to women at high risk because of the potentially serious side effects seen in clinical trials, including the BCPT.

The FDA did not define “high risk,” but it did recommend that the decision to use tamoxifen as chemopreventive therapy be based on thorough evaluation of the patient’s personal, family, and medical histories; her age; and her understanding of the risks and benefits of treatment.

The FDA also required the following language in the package insert:

- You should not take tamoxifen to reduce the risk of breast cancer unless you are at high risk of breast cancer. Certain conditions put women at high risk, and it is possible to calculate this risk for any woman. Breast cancer risk-assessment tools to help calculate your risk of breast cancer have been developed and are available to your health-care professional. You should discuss your risk with your healthcare professional.

CASE 1 RESOLVED

You determine that R. J. is an excellent candidate for tamoxifen by virtue of her significant risk of breast cancer. You are able to reassure her that, as the BCPT demonstrated, tamoxifen should not increase the risk of uterine cancer, DVT, or pulmonary embolism in a woman her age.

Raloxifene

CASE 2: Patient worries about breasts and bones

S. T. is a 58-year-old Caucasian mother of two whose own mother had breast cancer when she was 74 years old, and whose older sister was given a diagnosis of the malignancy 4 years ago.

S. T. had her first period when she was 11 years old, delivered her first child when she was 31, and entered menopause when she was 52. She is 5 ft 5 in tall and weighs 144 lb.

Her main reason for visiting you today is a breast Mammotome biopsy that showed ductal hyperplasia with atypia. She has been tested for a BRCA mutation, but the result was negative. Her Gail-model score is a 9.7% risk of developing breast cancer over the next 5 years, and a lifetime risk of 44.2%.

She also asks about osteoporosis prevention, given that a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan 1 year ago yielded a T-score of –1.3 for her hip and –1.1 for her spine. Her World Health Organization FRAX 10-year risk of hip fracture is 0.7%, and her risk of major osteoporotic fracture is 8.6%.

How do you respond to her concerns?

This patient has a high risk of invasive breast cancer but does not meet criteria for pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis prevention. A good option for her would be raloxifene, a selective estrogen-receptor modulator (SERM) that has been shown to reduce the risk of breast cancer as well as osteoporosis. S. T. would benefit from it on the basis of its breast benefit alone.

The genesis of a drug with multiple benefits

Raloxifene is a benzothiophene derivative, unlike the triphenylethylene family from which tamoxifen is derived. Like tamoxifen, raloxifene was originally investigated as a treatment for advanced breast cancer.

Preclinical studies indicated that raloxifene had an antiproliferative effect on both estrogen-receptor–positive mammary tumors and estrogen-receptor–positive human breast cancer cell lines.9 In the 1980s, however, a small, phase-II trial revealed that raloxifene had no further antitumor effects in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer in whom tamoxifen had failed.10 After information surfaced about the neoplastic effect of tamoxifen on the uteri of postmenopausal women, interest in raloxifene revived.11

Raloxifene has estrogen-agonistic activity on bone remodeling and lipid metabolism and was approved by the FDA for prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women in December 1997. Its indication was extended to treatment of osteoporosis 2 years later.

Raloxifene appears to have no effect on the endometrium of postmenopausal women, compared with placebo. In a 12-month comparative trial, there was no difference in endometrial thickness, endoluminal masses, proliferation, or hyperplasia between the raloxifene and placebo groups.12 This finding corroborates earlier evidence that raloxifene does not cause endometrial hyperplasia or cancer and is not associated with vaginal bleeding or increased endometrial thickness, as measured by transvaginal ultrasonography.

A big difference between raloxifene and tamoxifen, therefore, is their varying effect on the uterus of postmenopausal women.

Additional clinical trials confirm anticancer action of raloxifene

Preclinical data in animal models suggested that, like tamoxifen, raloxifene has potent antiestrogenic effects on breast tissue.9 The MORE trial involved 7,705 postmenopausal women up to 80 years old who had established osteoporosis.13 In that trial, participants were randomized to raloxifene or placebo. Bone mineral density (BMD) and fracture incidence were the primary endpoints; breast cancer was a secondary endpoint.

Over the 4 years of the trial, raloxifene significantly reduced the incidence of all invasive breast cancers by 72%, compared with placebo (RR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.17–0.46). Raloxifene also significantly reduced the incidence of invasive estrogen-receptor–positive tumors by 84%, compared with placebo (RR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.09–0.30), but had no effect on estrogen-receptor–negative tumors. The incidence of vaginal bleeding, breast pain, and endometrial cancer in the raloxifene group did not differ significantly from that of the placebo group.

Like tamoxifen, raloxifene appeared to be associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic disease, including DVT and pulmonary embolism, which developed in 1.1% of women taking raloxifene, compared with 0.5% of women in the placebo group (P=.003).

In a 4-year continuation of the MORE trial, known as the Continuing Outcomes Relevant to Evista, or CORE, trial, 5,231 women were randomized to continue raloxifene or placebo.14 Over the 8 years of the combined trials, the incidence of invasive breast cancer was reduced by 66% in the raloxifene group (RR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.22–0.50). The 8-year data are extremely clinically relevant, in that raloxifene has no time limit, whereas tamoxifen is usually prescribed for no longer than 5 years.

Raloxifene is not approved for use in premenopausal women. SERM compounds, which are structurally similar to clomiphene citrate, seem to have different effects in premenopausal and postmenopausal women, as evidenced by tamoxifen’s differing effects by age in the BCPT.

Other investigations of raloxifene confirm its value in high-risk women

To compare the clinical safety and efficacy of tamoxifen and raloxifene in reducing the risk of breast cancer among healthy women, the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) was initiated in 1999.15 In that trial, 19,747 postmenopausal women older than 35 years were blindly assigned to raloxifene 60 mg or tamoxifen 20 mg daily.

Baseline characteristics of subjects in STAR are summarized in TABLE 2 . Mean age was 58.5 years. All women had a 5-year risk of developing breast cancer that exceeded 1.66%, according to the Gail model. The average Gail score was 4.03% (standard deviation, ±2.17%). Because it would have been unethical to subject high-risk women to a placebo group in light of the findings of the BCPT, there was no placebo control.

TABLE 2

Baseline characteristics of women

in the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 58.5 years |

| Caucasian | 93% |

| Hysterectomy | 51% |

| At least one first-degree relative with breast cancer | 71% |

| Lobular carcinoma in situ | 9% |

| Atypical hyperplasia | 23% |

| 5-year risk of invasive breast cancer (mean)* | 4.03% |

| *As estimated with the Gail model Risk Calculator. | |

Here are noteworthy findings of the STAR trial:

- 163 cases of invasive breast cancer occurred in the tamoxifen group, compared with 168 among women taking raloxifene (RR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.82–1.28).

- 36 cases of uterine cancer occurred in the tamoxifen group, compared with 23 among women taking raloxifene (RR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.35–1.08). Earlier studies had shown a marked difference in the rate of uterine cancer between these agents. Although the difference here is not statistically significant, uterine cancer was not an endpoint of the study; nor was the study powered to explore this difference.

- The number of hysterectomies among women who were diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia with or without atypia was, proportionally, significantly higher among women taking tamoxifen ( TABLE 3 ).

- No difference between groups was found for other invasive cancers, ischemic heart events, or stroke.

- Thromboembolic events occurred less frequently in the raloxifene group (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.54–0.91). However, both raloxifene and tamoxifen have consistently been associated with a twofold to threefold increase in the risk of thromboembolic events, compared with placebo.

- Vasomotor symptoms and leg cramps increased in frequency and severity among women in both groups of the trial. These symptoms appear to be less common and less severe among women who are older and more remote from the onset of menopause.

TABLE 3

Relative risk of hysterectomy and uterine hyperplasia during STAR

| Characteristic | Women who took tamoxifen | Women who took raloxifene | Relative risk (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy during study | 246 | 92 | 0.37 (0.28, 0.47) |

| Hyperplasia • with atypia • without atypia | 100 15 85 | 17 2 15 | 0.17 (0.09, 0.28) 0.13 (0.01, 0.56) 0.17 (0.09, 0.30) |

What is raloxifene’s effect on the heart?

The Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH) trial explored the primary endpoints of coronary artery disease (CAD) and breast cancer in more than 10,000 women who had CAD or multiple risk factors for it.16 This study began prior to the Women’s Health Initiative, at a time when hormone replacement therapy was widely believed to reduce CAD.

In the double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled RUTH trial, raloxifene had no significant effect on primary coronary events (533 vs 553; hazard ratio [HR], 0.95; 95% CI, 0.84–1.07). Even in this population, however, there was a 44% reduction in invasive breast cancer (40 vs 70 events; HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.38–0.83).

Based on these results, the FDA approved raloxifene for the “reduction in risk of invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women at high risk for breast cancer,” as well as for the “reduction in risk of invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis” ( FIGURE ).

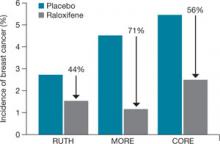

FIGURE How raloxifene reduced invasive breast cancer in three trials

Raloxifene significantly reduced the risk of cancer, compared with placebo, in the Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH), Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE), and Continuing Outcomes Relevant to Evista (CORE) trials.

CASE 2 RESOLVED

S. T. begins taking raloxifene 60 mg daily to lower her risk of invasive breast cancer. Although she temporarily experienced hot flashes after initiating the drug, they are only mildly bothersome, and she continues raloxifene therapy. She says she is grateful that there is an agent that can help her reduce the likelihood that she will develop breast cancer, and protection of her BMD is an added benefit.

CASE 3: At risk for both breast cancer and bone fracture

A. N., 63, is a nulliparous Caucasian woman who weighs 134 lb and stands 5 ft 4 in tall. She reached menarche when she was 12 years old and entered menopause at 49.

Although A. N. has never had a breast abnormality, her 59-year-old sister was just given a diagnosis of breast cancer. Her Gail score reveals that she has a 3.1% risk of developing breast cancer over the next 5 years.

In addition to her concerns about breast cancer, A. N. is worried about hip fracture—because her mother suffered one after menopause and because her T-score is –1.9 at the hip and –2.1 at the spine. A. N. has used steroids off and on for much of her life for asthma. Her FRAX score indicates that she has a 2.8% risk of hip fracture and a 25% risk of major osteoporotic fracture over the next 10 years.

What do you offer her?

Because of new FRAX criteria, this osteopenic woman is now a candidate for medication to reduce her risk of major osteoporotic fracture, and raloxifene is a good option. Her Gail score of 3.1% also makes her a good candidate for breast cancer risk reduction with raloxifene.

CASE 3 RESOLVED

Because A. N. needs an agent that benefits both breast and bone, you prescribe raloxifene. The drug should significantly reduce her risk of both invasive breast cancer and bone fracture, without increasing her risk of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer, both of which are associated with tamoxifen in her age group.

Aromatase inhibitors

A fairly new class of drugs being explored for their ability to reduce the risk of breast cancer is aromatase inhibitors. Substantial evidence suggests that estrogens facilitate the development of breast cancer in animals and in women, although the precise mechanism remains unknown.17 The most commonly held theory is that estrogen stimulates proliferation of breast cells and thereby increases the risk of genetic mutation that could lead to cancer.

Aromatase inhibitors block peripheral conversion of androstenedione to estrogens. In premenopausal women, the primary site of this action is in the ovary. In postmenopausal women, this conversion occurs primarily in extraovarian sites, including the adrenal glands, adipose tissue, liver, muscle, and skin.

Aromatase inhibitors may be more effective than SERMs in preventing breast cancer because of their dual role: blocking both the initiation and promotion of breast cancer.18 These agents reduce levels of the genotoxic metabolites of estradiol by lowering estradiol concentration in tissue. At the same time, aromatase inhibitors also block tumor promotion by lowering tissue levels of estrogen and preventing cell proliferation.

The main drawback of these agents—besides the fact that they are not FDA-approved for reducing risk—is their antiestrogenic effect on bone and lipid metabolism. They also induce vasomotor symptoms.

Studies of third-generation aromatase inhibitors in the prevention of breast cancer are under way in high-risk women. These agents include anastrozole, exemestane, and letrozole.

1. Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1879-1886.

2. Breast Cancer Assessment Tool. Available at: www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/Default.aspx. Accessed June 5, 2009.

3. Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1371-1388.

4. Ruffin MT, 4th, August DA, Kelloff GJ, Boone CW, Weber BL, Brenner DE. Selection criteria for breast cancer chemoprevention subjects. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1993;17G:234-241.

5. Cummings SR, Duong T, Kenyon E, Cauley JA, Whitehead M, Krueger KA. For the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Trial. Serum estradiol level and risk of breast cancer during treatment with raloxifene. JAMA. 2002;287:216-220.

6. Jordan VC, Allen KE. Evaluation of the antitumor activity of the non-steroidal antioestrogen monohydroxytamoxifen in the DMBA-induced rat mammary carcinoma mode. Eur J Cancer. 1980;16:239-251.

7. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group. Effects of adjuvant tamoxifen and of cytotoxic therapy on mortality in early breast cancer. An overview of 61 randomized trials among 28,896 women. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1681-1692.

8. Bur ME, Zimarowski MJ, Schnitt SJ, Baker S, Lew R. Estrogen receptor immunohistochemistry in carcinoma in situ of the breast. Cancer. 1992;69:1174-1181.

9. Hol T, Cox MB, Bryant HU, Draper MW. Selective estrogen receptor modulators and postmenopausal women’s health. J Womens Health. 1997;6:523-531.

10. Buzdar AU, Marcus C, Holmes F, Hug V, Hortobagyi G. Phase II evaluation of LY156758 in metastatic breast cancer. Oncology. 1988;45:344-345.

11. Neven P, De Muylder X, Van Belle Y, Vanderick G, De Muylder E. Hysteroscopic follow-up during tamoxifen treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1990;35:235-238.

12. Goldstein SR, Scheele WH, Rajagopalan SK, Wilkie JL, Walsh BW, Parsons AK. A 12-month comparative study of raloxifene, estrogen, and placebo on the postmenopausal endometrium. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:95-103.

13. Cauley JA, Norton L, Lippman ME, et al. Continued breast cancer risk reduction in postmenopausal women treated with raloxifene: 4-year results from the MORE trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;65:125-134.

14. Martino S, Cauley JA, Barrett-Connor E, et al. For the CORE Investigators. Continuing outcomes relevant to Evista: breast cancer incidence in postmenopausal osteoporotic women in a randomized trial of raloxifene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1751-1761.

15. Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. For the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP). Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 Trial. JAMA. 2006;21:2727-2741.

16. Barrett-Connor E, Mosca L, Collins P, et al. For the Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH) Trial Investigators. Effects of raloxifene on cardiovascular events and breast cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:125-137.

17. Santen RJ, Yue W, Naftolin F, Mor G, Berstein L. The potential of aromatase inhibitors in breast cancer prevention. Endocr Relat Cancer. 1999;6:235-243.

18. Goss PE, Strasser K. Aromatase inhibitors in the treatment and prevention of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:881-894.

19. Bryant HU, Dere WH. Selective estrogen receptor modulators: an alternative to hormone replacement therapy. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1998;217:45-52.

20. Grady D, Gebretsadik T, Kerlikowske K, Ernster V, Petitti D. Hormone replacement therapy and endometrial cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:304-313.

21. Miller BA, Feuer EJ, Hankey BF. The significance of the rising incidence of breast cancer in the United States. In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, eds. Important Advances in Oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1994:193-207.

22. Spicer DV, Pike MC. Risk factors in breast cancer. In: Roses DF, ed. Breast Cancer. New York: Churchill Livingston; 1944.

23. Bilimoria MM, Morrow M. The woman at increased risk for breast cancer: evaluation and management strategies. CA Cancer J Clin. 1995;45:263-278.

The author reports that he is a consultant to Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Wyeth, and a speaker for Eli Lilly and Wyeth.

CASE 1: Premenopausal woman

at high risk of breast cancer

R. J. is a 43-year-old, nulliparous woman who reached menarche at age 11. She has undergone two breast biopsies, the most recent of which revealed ductal hyperplasia with marked atypia.

R. J.’s sister had breast cancer at 49 years of age; her mother had breast cancer at 66 years. Because of R. J.’s family history, she underwent testing for a BRCA mutation. The result was negative.

R. J. has come to your office today to find out if she can do anything to reduce her risk of breast cancer. What options can you offer?

The most common method of “prevention” of breast cancer involves early detection and assessment of abnormalities through frequent surveillance with mammography. Some women who have dense breasts, a history of breast biopsy, or other risk factors for breast cancer may benefit from intensive surveillance with both mammography and ultrasonography—and, in some cases, magnetic resonance imaging.

More aggressive options include:

- the use of a chemopreventive agent such as tamoxifen or raloxifene

- in rare cases—usually when a BRCA mutation is present—prophylactic mastectomy.

Before it is possible to determine the optimal approach for a particular woman, it is necessary to conduct an individualized assessment of her risk—that is, to estimate the probability that she will develop breast cancer over a defined period of time. Such an estimate is also useful for designing prevention trials in high-risk subsets of the population. (Prevention trials differ from therapeutic clinical trials in that asymptomatic healthy women are exposed to potentially toxic interventions for prolonged periods to reduce their risk of breast cancer.)

This article describes chemopreventive options for women at high risk, based on individualized risk assessment using the Gail model.

(Editor’s note: For additional discussion of the important role ObGyns play in the fight against breast cancer, see Editor in Chief Dr. Robert L. Barbieri’s Editorial.)

You can estimate the likelihood that a woman like your patient may develop breast cancer using various individual risk factors ( TABLE 1 ), but estimates for combinations of risk factors are preferable. The Gail model takes into account some nongenetic factors, such as parity and age at menarche, but also genetic factors, such as family history. The model calculates a woman’s individualized breast cancer probability and yields a numerical risk (a percentage) that she will develop invasive breast cancer over the next 5 years; it also yields an estimate of her risk of developing the malignancy over the remainder of her life.1,2

A Gail-model 5-year estimate of 1.66% or higher denotes a high risk of developing breast cancer. That benchmark was the one employed in the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT), conducted as part of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP).3

TABLE 1

What are the risk factors for breast cancer?

And what degree of relative risk do they confer?

| Relative risk | ||

|---|---|---|

| <2 | 2–4 | >4 |

| • Age 25–34 years at first live birth • Early menarche • Late menopause • Benign proliferative disease • Postmenopausal obesity • Alcohol use • Hormone replacement therapy | • Age >35 years at first live birth • First-degree relative with breast cancer • Nulliparity • Radiation exposure • Personal history of breast cancer | • Gene mutation (BRCA 1 or 2) • Lobular carcinoma in situ • Ductal carcinoma in situ • Atypical hyperplasia |

| Adapted from Bilimoria and Morrow23 | ||

Weaknesses of the Gail model

The Gail model’s approach to estimating risk has some limitations. The model uses the number of prior breast biopsies in its assessment—but the relative risk associated with prior biopsy is smaller for women older than 50 years than it is for younger women.

Furthermore, data on which Gail bases its estimates were collected in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Since then, the increasing ease of breast histopathologic assessment—through fine-needle aspiration and outpatient core-needle biopsy—has confused the issue of just what constitutes a breast “biopsy.” (Most patients surveyed consider it to be any histologic sampling of the breast.)

As a result, the 1.66% cutoff becomes somewhat difficult to interpret in light of current practice.

Consider the following example. A 50-year-old nulliparous Caucasian woman reached menarche when she was 11 years old, has never had a biopsy, and has no first-degree relatives with breast cancer. According to the Gail model, her risk of developing breast cancer is 1.2% over the next 5 years and 10.8% in her lifetime. Therefore, she is not considered at high risk. If she were to give a history of three previous breast biopsies, however, none of them showing hyperplasia, her 5-year risk would rise to 1.8% and push her over the line into the high-risk category.

Compare her situation to that of R. J., the nulliparous woman described in Case 1. R. J. also reached menarche at 11 years, but she has had two breast biopsies (one of which showed atypical hyperplasia) and has two first-degree relatives who have had breast cancer. Her Gail score shows a 5-year risk of breast cancer of 13.5% (the norm for a 43-year-old woman is 0.8%), and a lifetime risk of 69.2%. Clearly, she has a high risk of breast cancer.

How do we improve an imperfect science?

We need to identify objective findings that are patient-specific but highly correlative with the development of breast cancer. Patient-specific biomarkers have been proposed, such as ultrasensitive measurement of the serum estradiol level in postmenopausal women. In the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation, also known as the MORE trial, women who experienced the greatest reduction in the rate of breast cancer during treatment with raloxifene were a subgroup who had the highest baseline level of serum estradiol—although, overall, all patients had an estradiol level well within the postmenopausal range (≤20 pmol/L).4,5

How tamoxifen became a chemopreventive agent

Tamoxifen inhibits mammary tumors in mice and rats and suppresses hormone-dependent breast cancer cell lines in vitro.6 Clinical data from the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group yielded additional motivation for prevention trials with tamoxifen: Besides reducing the rate of recurrent breast cancer, tamoxifen reduced the risk of contralateral new-onset breast cancer by 47% after 5 years of adjuvant treatment.7 Preclinical findings in vitro and in animal models, coupled with clinical data and evidence of tamoxifen’s favorable effects on skeleton remodeling and lipid levels, led to a series of chemoprevention trials in the United States and Europe using tamoxifen.

In the aforementioned BCPT, launched in 1992, 13,388 women 35 years and older who were deemed to be at high risk of developing breast cancer were enrolled at numerous sites throughout the United States and Canada.3 The Gail model was used to select women for the trial—only those who had a 5-year risk of 1.66% or higher were included. Participants were randomly assigned to receive tamoxifen 20 mg or placebo daily for 5 years. The trial was terminated early because of the dramatic reduction in new-onset breast cancer with tamoxifen, compared with placebo.

The overall incidence of breast cancer in the tamoxifen group was 3.4 cases for every 1,000 women, compared with 6.8 cases for every 1,000 women receiving placebo.3 Overall, the reduction in invasive breast cancer with tamoxifen was 49% (P<.00001). When broken down by age group, the reduction was:

- 44% in women 35 to 49 years old

- 51% in women 50 to 59 years old

- 55% in women 60 years and older.

Even noninvasive breast cancer was reduced with tamoxifen

Tamoxifen decreased the incidence of noninvasive breast cancer (ductal carcinoma in situ [DCIS]) by 50%. Expanded use of mammography has increased the detection of DCIS. Most DCIS lesions appear to be estrogen-receptor positive.8

In addition, tamoxifen reduced breast cancer risk in women who had a history of lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), a precancer, by 56%, and it reduced the risk of breast cancer in women who had a history of atypical hyperplasia by 86%. Overall, tamoxifen reduced the occurrence of estrogen-positive tumors by 69%, but had no impact on the incidence of estrogen-receptor–negative tumors.

The BCPT was stopped 14 months before planned because the Data and Safety Monitoring Board felt it was unethical to continue to allow one half of such high-risk participants to take placebo in light of the dramatic reduction in both invasive and noninvasive breast cancer among women who took tamoxifen.

In postmenopausal women, tamoxifen increases some risks

Two secondary endpoints of the BCPT are worthy of consideration:

- The overall relative risk (RR) of endometrial cancer associated with tamoxifen therapy in healthy women was 2.53 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.35, 4.97). However, further analysis by age yielded a RR of 4.01 in women who were older than 50 years (95% CI, 1.70, 10.90), compared with a RR of 1.21 in women 49 years and younger (95% CI, 0.41, 3.60).

- The same age distinction held true for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolus, with no statistically significant increases in either in women 49 years and younger, but a RR of 1.71 and 3.19, respectively, in women 50 years and older. It is unclear whether the trial was sufficiently powered for this particular secondary endpoint.

These findings suggest that serious adverse events do not occur at the same magnitude in women younger than 50 years that they do in women 50 and older. The difference in the risk–benefit profile between younger and older women has significant clinical implications for the care of perimenopausal patients.

Risk of other malignancies was not affected by tamoxifen

Overall, invasive cancers other than those of the breast and uterus occurred at the same rate in the tamoxifen and placebo groups of the BCPT. The RR of death from any cause was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.56–1.16). There was a slight increase in the risk of myocardial infarction (RR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.65–1.92) and a slight decrease in the risk of severe angina (RR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.40–2.14) in tamoxifen users, although neither of these risks was statistically significant.

The overall RR of fracture of the hip, spine, or radius was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.63–1.05). There was a statistically significant increase in the number of women who had cataracts who then underwent cataract surgery in the tamoxifen group (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.16–2.14).

Tamoxifen is approved as a preventive for high-risk women only

Based on the results of the BCPT, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved tamoxifen in October 1998 for the primary prevention of breast cancer in women who are at high risk of the disease. The FDA recommends that use of tamoxifen be limited to women at high risk because of the potentially serious side effects seen in clinical trials, including the BCPT.

The FDA did not define “high risk,” but it did recommend that the decision to use tamoxifen as chemopreventive therapy be based on thorough evaluation of the patient’s personal, family, and medical histories; her age; and her understanding of the risks and benefits of treatment.

The FDA also required the following language in the package insert:

- You should not take tamoxifen to reduce the risk of breast cancer unless you are at high risk of breast cancer. Certain conditions put women at high risk, and it is possible to calculate this risk for any woman. Breast cancer risk-assessment tools to help calculate your risk of breast cancer have been developed and are available to your health-care professional. You should discuss your risk with your healthcare professional.

CASE 1 RESOLVED

You determine that R. J. is an excellent candidate for tamoxifen by virtue of her significant risk of breast cancer. You are able to reassure her that, as the BCPT demonstrated, tamoxifen should not increase the risk of uterine cancer, DVT, or pulmonary embolism in a woman her age.

Raloxifene

CASE 2: Patient worries about breasts and bones

S. T. is a 58-year-old Caucasian mother of two whose own mother had breast cancer when she was 74 years old, and whose older sister was given a diagnosis of the malignancy 4 years ago.

S. T. had her first period when she was 11 years old, delivered her first child when she was 31, and entered menopause when she was 52. She is 5 ft 5 in tall and weighs 144 lb.

Her main reason for visiting you today is a breast Mammotome biopsy that showed ductal hyperplasia with atypia. She has been tested for a BRCA mutation, but the result was negative. Her Gail-model score is a 9.7% risk of developing breast cancer over the next 5 years, and a lifetime risk of 44.2%.

She also asks about osteoporosis prevention, given that a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan 1 year ago yielded a T-score of –1.3 for her hip and –1.1 for her spine. Her World Health Organization FRAX 10-year risk of hip fracture is 0.7%, and her risk of major osteoporotic fracture is 8.6%.

How do you respond to her concerns?

This patient has a high risk of invasive breast cancer but does not meet criteria for pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis prevention. A good option for her would be raloxifene, a selective estrogen-receptor modulator (SERM) that has been shown to reduce the risk of breast cancer as well as osteoporosis. S. T. would benefit from it on the basis of its breast benefit alone.

The genesis of a drug with multiple benefits

Raloxifene is a benzothiophene derivative, unlike the triphenylethylene family from which tamoxifen is derived. Like tamoxifen, raloxifene was originally investigated as a treatment for advanced breast cancer.

Preclinical studies indicated that raloxifene had an antiproliferative effect on both estrogen-receptor–positive mammary tumors and estrogen-receptor–positive human breast cancer cell lines.9 In the 1980s, however, a small, phase-II trial revealed that raloxifene had no further antitumor effects in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer in whom tamoxifen had failed.10 After information surfaced about the neoplastic effect of tamoxifen on the uteri of postmenopausal women, interest in raloxifene revived.11

Raloxifene has estrogen-agonistic activity on bone remodeling and lipid metabolism and was approved by the FDA for prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women in December 1997. Its indication was extended to treatment of osteoporosis 2 years later.

Raloxifene appears to have no effect on the endometrium of postmenopausal women, compared with placebo. In a 12-month comparative trial, there was no difference in endometrial thickness, endoluminal masses, proliferation, or hyperplasia between the raloxifene and placebo groups.12 This finding corroborates earlier evidence that raloxifene does not cause endometrial hyperplasia or cancer and is not associated with vaginal bleeding or increased endometrial thickness, as measured by transvaginal ultrasonography.

A big difference between raloxifene and tamoxifen, therefore, is their varying effect on the uterus of postmenopausal women.

Additional clinical trials confirm anticancer action of raloxifene

Preclinical data in animal models suggested that, like tamoxifen, raloxifene has potent antiestrogenic effects on breast tissue.9 The MORE trial involved 7,705 postmenopausal women up to 80 years old who had established osteoporosis.13 In that trial, participants were randomized to raloxifene or placebo. Bone mineral density (BMD) and fracture incidence were the primary endpoints; breast cancer was a secondary endpoint.

Over the 4 years of the trial, raloxifene significantly reduced the incidence of all invasive breast cancers by 72%, compared with placebo (RR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.17–0.46). Raloxifene also significantly reduced the incidence of invasive estrogen-receptor–positive tumors by 84%, compared with placebo (RR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.09–0.30), but had no effect on estrogen-receptor–negative tumors. The incidence of vaginal bleeding, breast pain, and endometrial cancer in the raloxifene group did not differ significantly from that of the placebo group.

Like tamoxifen, raloxifene appeared to be associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic disease, including DVT and pulmonary embolism, which developed in 1.1% of women taking raloxifene, compared with 0.5% of women in the placebo group (P=.003).

In a 4-year continuation of the MORE trial, known as the Continuing Outcomes Relevant to Evista, or CORE, trial, 5,231 women were randomized to continue raloxifene or placebo.14 Over the 8 years of the combined trials, the incidence of invasive breast cancer was reduced by 66% in the raloxifene group (RR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.22–0.50). The 8-year data are extremely clinically relevant, in that raloxifene has no time limit, whereas tamoxifen is usually prescribed for no longer than 5 years.

Raloxifene is not approved for use in premenopausal women. SERM compounds, which are structurally similar to clomiphene citrate, seem to have different effects in premenopausal and postmenopausal women, as evidenced by tamoxifen’s differing effects by age in the BCPT.

Other investigations of raloxifene confirm its value in high-risk women

To compare the clinical safety and efficacy of tamoxifen and raloxifene in reducing the risk of breast cancer among healthy women, the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) was initiated in 1999.15 In that trial, 19,747 postmenopausal women older than 35 years were blindly assigned to raloxifene 60 mg or tamoxifen 20 mg daily.

Baseline characteristics of subjects in STAR are summarized in TABLE 2 . Mean age was 58.5 years. All women had a 5-year risk of developing breast cancer that exceeded 1.66%, according to the Gail model. The average Gail score was 4.03% (standard deviation, ±2.17%). Because it would have been unethical to subject high-risk women to a placebo group in light of the findings of the BCPT, there was no placebo control.

TABLE 2

Baseline characteristics of women

in the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 58.5 years |

| Caucasian | 93% |

| Hysterectomy | 51% |

| At least one first-degree relative with breast cancer | 71% |

| Lobular carcinoma in situ | 9% |

| Atypical hyperplasia | 23% |

| 5-year risk of invasive breast cancer (mean)* | 4.03% |

| *As estimated with the Gail model Risk Calculator. | |

Here are noteworthy findings of the STAR trial:

- 163 cases of invasive breast cancer occurred in the tamoxifen group, compared with 168 among women taking raloxifene (RR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.82–1.28).

- 36 cases of uterine cancer occurred in the tamoxifen group, compared with 23 among women taking raloxifene (RR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.35–1.08). Earlier studies had shown a marked difference in the rate of uterine cancer between these agents. Although the difference here is not statistically significant, uterine cancer was not an endpoint of the study; nor was the study powered to explore this difference.

- The number of hysterectomies among women who were diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia with or without atypia was, proportionally, significantly higher among women taking tamoxifen ( TABLE 3 ).

- No difference between groups was found for other invasive cancers, ischemic heart events, or stroke.

- Thromboembolic events occurred less frequently in the raloxifene group (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.54–0.91). However, both raloxifene and tamoxifen have consistently been associated with a twofold to threefold increase in the risk of thromboembolic events, compared with placebo.

- Vasomotor symptoms and leg cramps increased in frequency and severity among women in both groups of the trial. These symptoms appear to be less common and less severe among women who are older and more remote from the onset of menopause.

TABLE 3

Relative risk of hysterectomy and uterine hyperplasia during STAR

| Characteristic | Women who took tamoxifen | Women who took raloxifene | Relative risk (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy during study | 246 | 92 | 0.37 (0.28, 0.47) |

| Hyperplasia • with atypia • without atypia | 100 15 85 | 17 2 15 | 0.17 (0.09, 0.28) 0.13 (0.01, 0.56) 0.17 (0.09, 0.30) |

What is raloxifene’s effect on the heart?

The Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH) trial explored the primary endpoints of coronary artery disease (CAD) and breast cancer in more than 10,000 women who had CAD or multiple risk factors for it.16 This study began prior to the Women’s Health Initiative, at a time when hormone replacement therapy was widely believed to reduce CAD.

In the double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled RUTH trial, raloxifene had no significant effect on primary coronary events (533 vs 553; hazard ratio [HR], 0.95; 95% CI, 0.84–1.07). Even in this population, however, there was a 44% reduction in invasive breast cancer (40 vs 70 events; HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.38–0.83).

Based on these results, the FDA approved raloxifene for the “reduction in risk of invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women at high risk for breast cancer,” as well as for the “reduction in risk of invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis” ( FIGURE ).

FIGURE How raloxifene reduced invasive breast cancer in three trials

Raloxifene significantly reduced the risk of cancer, compared with placebo, in the Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH), Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE), and Continuing Outcomes Relevant to Evista (CORE) trials.

CASE 2 RESOLVED

S. T. begins taking raloxifene 60 mg daily to lower her risk of invasive breast cancer. Although she temporarily experienced hot flashes after initiating the drug, they are only mildly bothersome, and she continues raloxifene therapy. She says she is grateful that there is an agent that can help her reduce the likelihood that she will develop breast cancer, and protection of her BMD is an added benefit.

CASE 3: At risk for both breast cancer and bone fracture

A. N., 63, is a nulliparous Caucasian woman who weighs 134 lb and stands 5 ft 4 in tall. She reached menarche when she was 12 years old and entered menopause at 49.

Although A. N. has never had a breast abnormality, her 59-year-old sister was just given a diagnosis of breast cancer. Her Gail score reveals that she has a 3.1% risk of developing breast cancer over the next 5 years.

In addition to her concerns about breast cancer, A. N. is worried about hip fracture—because her mother suffered one after menopause and because her T-score is –1.9 at the hip and –2.1 at the spine. A. N. has used steroids off and on for much of her life for asthma. Her FRAX score indicates that she has a 2.8% risk of hip fracture and a 25% risk of major osteoporotic fracture over the next 10 years.

What do you offer her?

Because of new FRAX criteria, this osteopenic woman is now a candidate for medication to reduce her risk of major osteoporotic fracture, and raloxifene is a good option. Her Gail score of 3.1% also makes her a good candidate for breast cancer risk reduction with raloxifene.

CASE 3 RESOLVED

Because A. N. needs an agent that benefits both breast and bone, you prescribe raloxifene. The drug should significantly reduce her risk of both invasive breast cancer and bone fracture, without increasing her risk of endometrial hyperplasia and cancer, both of which are associated with tamoxifen in her age group.

Aromatase inhibitors

A fairly new class of drugs being explored for their ability to reduce the risk of breast cancer is aromatase inhibitors. Substantial evidence suggests that estrogens facilitate the development of breast cancer in animals and in women, although the precise mechanism remains unknown.17 The most commonly held theory is that estrogen stimulates proliferation of breast cells and thereby increases the risk of genetic mutation that could lead to cancer.

Aromatase inhibitors block peripheral conversion of androstenedione to estrogens. In premenopausal women, the primary site of this action is in the ovary. In postmenopausal women, this conversion occurs primarily in extraovarian sites, including the adrenal glands, adipose tissue, liver, muscle, and skin.

Aromatase inhibitors may be more effective than SERMs in preventing breast cancer because of their dual role: blocking both the initiation and promotion of breast cancer.18 These agents reduce levels of the genotoxic metabolites of estradiol by lowering estradiol concentration in tissue. At the same time, aromatase inhibitors also block tumor promotion by lowering tissue levels of estrogen and preventing cell proliferation.

The main drawback of these agents—besides the fact that they are not FDA-approved for reducing risk—is their antiestrogenic effect on bone and lipid metabolism. They also induce vasomotor symptoms.

Studies of third-generation aromatase inhibitors in the prevention of breast cancer are under way in high-risk women. These agents include anastrozole, exemestane, and letrozole.

The author reports that he is a consultant to Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and Wyeth, and a speaker for Eli Lilly and Wyeth.

CASE 1: Premenopausal woman

at high risk of breast cancer

R. J. is a 43-year-old, nulliparous woman who reached menarche at age 11. She has undergone two breast biopsies, the most recent of which revealed ductal hyperplasia with marked atypia.

R. J.’s sister had breast cancer at 49 years of age; her mother had breast cancer at 66 years. Because of R. J.’s family history, she underwent testing for a BRCA mutation. The result was negative.

R. J. has come to your office today to find out if she can do anything to reduce her risk of breast cancer. What options can you offer?

The most common method of “prevention” of breast cancer involves early detection and assessment of abnormalities through frequent surveillance with mammography. Some women who have dense breasts, a history of breast biopsy, or other risk factors for breast cancer may benefit from intensive surveillance with both mammography and ultrasonography—and, in some cases, magnetic resonance imaging.

More aggressive options include:

- the use of a chemopreventive agent such as tamoxifen or raloxifene

- in rare cases—usually when a BRCA mutation is present—prophylactic mastectomy.

Before it is possible to determine the optimal approach for a particular woman, it is necessary to conduct an individualized assessment of her risk—that is, to estimate the probability that she will develop breast cancer over a defined period of time. Such an estimate is also useful for designing prevention trials in high-risk subsets of the population. (Prevention trials differ from therapeutic clinical trials in that asymptomatic healthy women are exposed to potentially toxic interventions for prolonged periods to reduce their risk of breast cancer.)

This article describes chemopreventive options for women at high risk, based on individualized risk assessment using the Gail model.

(Editor’s note: For additional discussion of the important role ObGyns play in the fight against breast cancer, see Editor in Chief Dr. Robert L. Barbieri’s Editorial.)

You can estimate the likelihood that a woman like your patient may develop breast cancer using various individual risk factors ( TABLE 1 ), but estimates for combinations of risk factors are preferable. The Gail model takes into account some nongenetic factors, such as parity and age at menarche, but also genetic factors, such as family history. The model calculates a woman’s individualized breast cancer probability and yields a numerical risk (a percentage) that she will develop invasive breast cancer over the next 5 years; it also yields an estimate of her risk of developing the malignancy over the remainder of her life.1,2

A Gail-model 5-year estimate of 1.66% or higher denotes a high risk of developing breast cancer. That benchmark was the one employed in the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT), conducted as part of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP).3

TABLE 1

What are the risk factors for breast cancer?

And what degree of relative risk do they confer?

| Relative risk | ||

|---|---|---|

| <2 | 2–4 | >4 |

| • Age 25–34 years at first live birth • Early menarche • Late menopause • Benign proliferative disease • Postmenopausal obesity • Alcohol use • Hormone replacement therapy | • Age >35 years at first live birth • First-degree relative with breast cancer • Nulliparity • Radiation exposure • Personal history of breast cancer | • Gene mutation (BRCA 1 or 2) • Lobular carcinoma in situ • Ductal carcinoma in situ • Atypical hyperplasia |

| Adapted from Bilimoria and Morrow23 | ||

Weaknesses of the Gail model

The Gail model’s approach to estimating risk has some limitations. The model uses the number of prior breast biopsies in its assessment—but the relative risk associated with prior biopsy is smaller for women older than 50 years than it is for younger women.

Furthermore, data on which Gail bases its estimates were collected in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Since then, the increasing ease of breast histopathologic assessment—through fine-needle aspiration and outpatient core-needle biopsy—has confused the issue of just what constitutes a breast “biopsy.” (Most patients surveyed consider it to be any histologic sampling of the breast.)

As a result, the 1.66% cutoff becomes somewhat difficult to interpret in light of current practice.

Consider the following example. A 50-year-old nulliparous Caucasian woman reached menarche when she was 11 years old, has never had a biopsy, and has no first-degree relatives with breast cancer. According to the Gail model, her risk of developing breast cancer is 1.2% over the next 5 years and 10.8% in her lifetime. Therefore, she is not considered at high risk. If she were to give a history of three previous breast biopsies, however, none of them showing hyperplasia, her 5-year risk would rise to 1.8% and push her over the line into the high-risk category.

Compare her situation to that of R. J., the nulliparous woman described in Case 1. R. J. also reached menarche at 11 years, but she has had two breast biopsies (one of which showed atypical hyperplasia) and has two first-degree relatives who have had breast cancer. Her Gail score shows a 5-year risk of breast cancer of 13.5% (the norm for a 43-year-old woman is 0.8%), and a lifetime risk of 69.2%. Clearly, she has a high risk of breast cancer.

How do we improve an imperfect science?

We need to identify objective findings that are patient-specific but highly correlative with the development of breast cancer. Patient-specific biomarkers have been proposed, such as ultrasensitive measurement of the serum estradiol level in postmenopausal women. In the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation, also known as the MORE trial, women who experienced the greatest reduction in the rate of breast cancer during treatment with raloxifene were a subgroup who had the highest baseline level of serum estradiol—although, overall, all patients had an estradiol level well within the postmenopausal range (≤20 pmol/L).4,5

How tamoxifen became a chemopreventive agent

Tamoxifen inhibits mammary tumors in mice and rats and suppresses hormone-dependent breast cancer cell lines in vitro.6 Clinical data from the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group yielded additional motivation for prevention trials with tamoxifen: Besides reducing the rate of recurrent breast cancer, tamoxifen reduced the risk of contralateral new-onset breast cancer by 47% after 5 years of adjuvant treatment.7 Preclinical findings in vitro and in animal models, coupled with clinical data and evidence of tamoxifen’s favorable effects on skeleton remodeling and lipid levels, led to a series of chemoprevention trials in the United States and Europe using tamoxifen.

In the aforementioned BCPT, launched in 1992, 13,388 women 35 years and older who were deemed to be at high risk of developing breast cancer were enrolled at numerous sites throughout the United States and Canada.3 The Gail model was used to select women for the trial—only those who had a 5-year risk of 1.66% or higher were included. Participants were randomly assigned to receive tamoxifen 20 mg or placebo daily for 5 years. The trial was terminated early because of the dramatic reduction in new-onset breast cancer with tamoxifen, compared with placebo.

The overall incidence of breast cancer in the tamoxifen group was 3.4 cases for every 1,000 women, compared with 6.8 cases for every 1,000 women receiving placebo.3 Overall, the reduction in invasive breast cancer with tamoxifen was 49% (P<.00001). When broken down by age group, the reduction was:

- 44% in women 35 to 49 years old

- 51% in women 50 to 59 years old

- 55% in women 60 years and older.

Even noninvasive breast cancer was reduced with tamoxifen

Tamoxifen decreased the incidence of noninvasive breast cancer (ductal carcinoma in situ [DCIS]) by 50%. Expanded use of mammography has increased the detection of DCIS. Most DCIS lesions appear to be estrogen-receptor positive.8

In addition, tamoxifen reduced breast cancer risk in women who had a history of lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), a precancer, by 56%, and it reduced the risk of breast cancer in women who had a history of atypical hyperplasia by 86%. Overall, tamoxifen reduced the occurrence of estrogen-positive tumors by 69%, but had no impact on the incidence of estrogen-receptor–negative tumors.

The BCPT was stopped 14 months before planned because the Data and Safety Monitoring Board felt it was unethical to continue to allow one half of such high-risk participants to take placebo in light of the dramatic reduction in both invasive and noninvasive breast cancer among women who took tamoxifen.

In postmenopausal women, tamoxifen increases some risks

Two secondary endpoints of the BCPT are worthy of consideration:

- The overall relative risk (RR) of endometrial cancer associated with tamoxifen therapy in healthy women was 2.53 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.35, 4.97). However, further analysis by age yielded a RR of 4.01 in women who were older than 50 years (95% CI, 1.70, 10.90), compared with a RR of 1.21 in women 49 years and younger (95% CI, 0.41, 3.60).

- The same age distinction held true for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolus, with no statistically significant increases in either in women 49 years and younger, but a RR of 1.71 and 3.19, respectively, in women 50 years and older. It is unclear whether the trial was sufficiently powered for this particular secondary endpoint.

These findings suggest that serious adverse events do not occur at the same magnitude in women younger than 50 years that they do in women 50 and older. The difference in the risk–benefit profile between younger and older women has significant clinical implications for the care of perimenopausal patients.

Risk of other malignancies was not affected by tamoxifen

Overall, invasive cancers other than those of the breast and uterus occurred at the same rate in the tamoxifen and placebo groups of the BCPT. The RR of death from any cause was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.56–1.16). There was a slight increase in the risk of myocardial infarction (RR, 1.11; 95% CI, 0.65–1.92) and a slight decrease in the risk of severe angina (RR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.40–2.14) in tamoxifen users, although neither of these risks was statistically significant.

The overall RR of fracture of the hip, spine, or radius was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.63–1.05). There was a statistically significant increase in the number of women who had cataracts who then underwent cataract surgery in the tamoxifen group (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.16–2.14).

Tamoxifen is approved as a preventive for high-risk women only

Based on the results of the BCPT, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved tamoxifen in October 1998 for the primary prevention of breast cancer in women who are at high risk of the disease. The FDA recommends that use of tamoxifen be limited to women at high risk because of the potentially serious side effects seen in clinical trials, including the BCPT.

The FDA did not define “high risk,” but it did recommend that the decision to use tamoxifen as chemopreventive therapy be based on thorough evaluation of the patient’s personal, family, and medical histories; her age; and her understanding of the risks and benefits of treatment.

The FDA also required the following language in the package insert:

- You should not take tamoxifen to reduce the risk of breast cancer unless you are at high risk of breast cancer. Certain conditions put women at high risk, and it is possible to calculate this risk for any woman. Breast cancer risk-assessment tools to help calculate your risk of breast cancer have been developed and are available to your health-care professional. You should discuss your risk with your healthcare professional.

CASE 1 RESOLVED

You determine that R. J. is an excellent candidate for tamoxifen by virtue of her significant risk of breast cancer. You are able to reassure her that, as the BCPT demonstrated, tamoxifen should not increase the risk of uterine cancer, DVT, or pulmonary embolism in a woman her age.

Raloxifene

CASE 2: Patient worries about breasts and bones

S. T. is a 58-year-old Caucasian mother of two whose own mother had breast cancer when she was 74 years old, and whose older sister was given a diagnosis of the malignancy 4 years ago.

S. T. had her first period when she was 11 years old, delivered her first child when she was 31, and entered menopause when she was 52. She is 5 ft 5 in tall and weighs 144 lb.

Her main reason for visiting you today is a breast Mammotome biopsy that showed ductal hyperplasia with atypia. She has been tested for a BRCA mutation, but the result was negative. Her Gail-model score is a 9.7% risk of developing breast cancer over the next 5 years, and a lifetime risk of 44.2%.

She also asks about osteoporosis prevention, given that a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan 1 year ago yielded a T-score of –1.3 for her hip and –1.1 for her spine. Her World Health Organization FRAX 10-year risk of hip fracture is 0.7%, and her risk of major osteoporotic fracture is 8.6%.

How do you respond to her concerns?

This patient has a high risk of invasive breast cancer but does not meet criteria for pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis prevention. A good option for her would be raloxifene, a selective estrogen-receptor modulator (SERM) that has been shown to reduce the risk of breast cancer as well as osteoporosis. S. T. would benefit from it on the basis of its breast benefit alone.

The genesis of a drug with multiple benefits

Raloxifene is a benzothiophene derivative, unlike the triphenylethylene family from which tamoxifen is derived. Like tamoxifen, raloxifene was originally investigated as a treatment for advanced breast cancer.

Preclinical studies indicated that raloxifene had an antiproliferative effect on both estrogen-receptor–positive mammary tumors and estrogen-receptor–positive human breast cancer cell lines.9 In the 1980s, however, a small, phase-II trial revealed that raloxifene had no further antitumor effects in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer in whom tamoxifen had failed.10 After information surfaced about the neoplastic effect of tamoxifen on the uteri of postmenopausal women, interest in raloxifene revived.11

Raloxifene has estrogen-agonistic activity on bone remodeling and lipid metabolism and was approved by the FDA for prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women in December 1997. Its indication was extended to treatment of osteoporosis 2 years later.

Raloxifene appears to have no effect on the endometrium of postmenopausal women, compared with placebo. In a 12-month comparative trial, there was no difference in endometrial thickness, endoluminal masses, proliferation, or hyperplasia between the raloxifene and placebo groups.12 This finding corroborates earlier evidence that raloxifene does not cause endometrial hyperplasia or cancer and is not associated with vaginal bleeding or increased endometrial thickness, as measured by transvaginal ultrasonography.

A big difference between raloxifene and tamoxifen, therefore, is their varying effect on the uterus of postmenopausal women.

Additional clinical trials confirm anticancer action of raloxifene

Preclinical data in animal models suggested that, like tamoxifen, raloxifene has potent antiestrogenic effects on breast tissue.9 The MORE trial involved 7,705 postmenopausal women up to 80 years old who had established osteoporosis.13 In that trial, participants were randomized to raloxifene or placebo. Bone mineral density (BMD) and fracture incidence were the primary endpoints; breast cancer was a secondary endpoint.

Over the 4 years of the trial, raloxifene significantly reduced the incidence of all invasive breast cancers by 72%, compared with placebo (RR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.17–0.46). Raloxifene also significantly reduced the incidence of invasive estrogen-receptor–positive tumors by 84%, compared with placebo (RR, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.09–0.30), but had no effect on estrogen-receptor–negative tumors. The incidence of vaginal bleeding, breast pain, and endometrial cancer in the raloxifene group did not differ significantly from that of the placebo group.

Like tamoxifen, raloxifene appeared to be associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic disease, including DVT and pulmonary embolism, which developed in 1.1% of women taking raloxifene, compared with 0.5% of women in the placebo group (P=.003).

In a 4-year continuation of the MORE trial, known as the Continuing Outcomes Relevant to Evista, or CORE, trial, 5,231 women were randomized to continue raloxifene or placebo.14 Over the 8 years of the combined trials, the incidence of invasive breast cancer was reduced by 66% in the raloxifene group (RR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.22–0.50). The 8-year data are extremely clinically relevant, in that raloxifene has no time limit, whereas tamoxifen is usually prescribed for no longer than 5 years.

Raloxifene is not approved for use in premenopausal women. SERM compounds, which are structurally similar to clomiphene citrate, seem to have different effects in premenopausal and postmenopausal women, as evidenced by tamoxifen’s differing effects by age in the BCPT.

Other investigations of raloxifene confirm its value in high-risk women

To compare the clinical safety and efficacy of tamoxifen and raloxifene in reducing the risk of breast cancer among healthy women, the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) was initiated in 1999.15 In that trial, 19,747 postmenopausal women older than 35 years were blindly assigned to raloxifene 60 mg or tamoxifen 20 mg daily.

Baseline characteristics of subjects in STAR are summarized in TABLE 2 . Mean age was 58.5 years. All women had a 5-year risk of developing breast cancer that exceeded 1.66%, according to the Gail model. The average Gail score was 4.03% (standard deviation, ±2.17%). Because it would have been unethical to subject high-risk women to a placebo group in light of the findings of the BCPT, there was no placebo control.

TABLE 2

Baseline characteristics of women

in the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 58.5 years |

| Caucasian | 93% |

| Hysterectomy | 51% |

| At least one first-degree relative with breast cancer | 71% |

| Lobular carcinoma in situ | 9% |

| Atypical hyperplasia | 23% |

| 5-year risk of invasive breast cancer (mean)* | 4.03% |

| *As estimated with the Gail model Risk Calculator. | |

Here are noteworthy findings of the STAR trial:

- 163 cases of invasive breast cancer occurred in the tamoxifen group, compared with 168 among women taking raloxifene (RR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.82–1.28).

- 36 cases of uterine cancer occurred in the tamoxifen group, compared with 23 among women taking raloxifene (RR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.35–1.08). Earlier studies had shown a marked difference in the rate of uterine cancer between these agents. Although the difference here is not statistically significant, uterine cancer was not an endpoint of the study; nor was the study powered to explore this difference.

- The number of hysterectomies among women who were diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia with or without atypia was, proportionally, significantly higher among women taking tamoxifen ( TABLE 3 ).

- No difference between groups was found for other invasive cancers, ischemic heart events, or stroke.

- Thromboembolic events occurred less frequently in the raloxifene group (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.54–0.91). However, both raloxifene and tamoxifen have consistently been associated with a twofold to threefold increase in the risk of thromboembolic events, compared with placebo.

- Vasomotor symptoms and leg cramps increased in frequency and severity among women in both groups of the trial. These symptoms appear to be less common and less severe among women who are older and more remote from the onset of menopause.

TABLE 3

Relative risk of hysterectomy and uterine hyperplasia during STAR

| Characteristic | Women who took tamoxifen | Women who took raloxifene | Relative risk (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hysterectomy during study | 246 | 92 | 0.37 (0.28, 0.47) |

| Hyperplasia • with atypia • without atypia | 100 15 85 | 17 2 15 | 0.17 (0.09, 0.28) 0.13 (0.01, 0.56) 0.17 (0.09, 0.30) |

What is raloxifene’s effect on the heart?

The Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH) trial explored the primary endpoints of coronary artery disease (CAD) and breast cancer in more than 10,000 women who had CAD or multiple risk factors for it.16 This study began prior to the Women’s Health Initiative, at a time when hormone replacement therapy was widely believed to reduce CAD.

In the double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled RUTH trial, raloxifene had no significant effect on primary coronary events (533 vs 553; hazard ratio [HR], 0.95; 95% CI, 0.84–1.07). Even in this population, however, there was a 44% reduction in invasive breast cancer (40 vs 70 events; HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.38–0.83).

Based on these results, the FDA approved raloxifene for the “reduction in risk of invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women at high risk for breast cancer,” as well as for the “reduction in risk of invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis” ( FIGURE ).

FIGURE How raloxifene reduced invasive breast cancer in three trials

Raloxifene significantly reduced the risk of cancer, compared with placebo, in the Raloxifene Use for The Heart (RUTH), Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE), and Continuing Outcomes Relevant to Evista (CORE) trials.

CASE 2 RESOLVED

S. T. begins taking raloxifene 60 mg daily to lower her risk of invasive breast cancer. Although she temporarily experienced hot flashes after initiating the drug, they are only mildly bothersome, and she continues raloxifene therapy. She says she is grateful that there is an agent that can help her reduce the likelihood that she will develop breast cancer, and protection of her BMD is an added benefit.

CASE 3: At risk for both breast cancer and bone fracture

A. N., 63, is a nulliparous Caucasian woman who weighs 134 lb and stands 5 ft 4 in tall. She reached menarche when she was 12 years old and entered menopause at 49.

Although A. N. has never had a breast abnormality, her 59-year-old sister was just given a diagnosis of breast cancer. Her Gail score reveals that she has a 3.1% risk of developing breast cancer over the next 5 years.