User login

Insulinoma Presenting as an Unusual Cause of Marital Discord

Watch Out for Drug List Discrepancies and MDAPEs

Necrotizing Fasciitis: Timing is Critical

Grand Rounds: Man, 60, With Abdominal Pain

A 60-year-old white man with a history of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and anxiety presented with complaints of abdominal pain, localized to an area left of the umbilicus. He described the pain as constant and rated it 6 on a scale of 1 to 10. He said the pain had been present for longer than three weeks.

The man said he had been seen by another health care provider shortly after the pain began, but he did not think the provider took his complaint seriously. At that visit, antacids were prescribed, blood work was ordered, and the man was told to return if there was no improvement. He felt that because he was being treated for anxiety, the provider believed he was just imagining the pain.

At the current visit, the review of systems revealed additional complaints of shakiness and nausea without vomiting, with other findings unremarkable. The persistent pain did not seem related to eating, and the patient had no history of any surgeries that might help explain his current complaints. He had smoked a pack of cigarettes daily for 40 years and had a history of heavy alcohol use, although he denied having consumed any alcohol during the previous five years.

His prescribed medications included gemfibrozil 600 mg per day, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg each morning, and diazepam 5 mg twice daily, with an OTC antacid.

The patient’s recent laboratory results were normal; they included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, liver enzyme levels, and a serum amylase level. The patient weighed 280 lb and his height was 5’10”; his BMI was 40. His temperature was 97.7°F, with a regular heart rate of 88 beats/min; blood pressure, 140/90 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min.

The patient did not appear to be in acute distress. A bruit was heard in the indicated area of pain. No mass was palpated, and the width of his aorta could not be determined because of his obesity. His physical exam was otherwise normal.

Abdominal ultrasonography (US) revealed a 5.5-cm abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), and the man was referred for immediate surgery. The aneurysm was repaired in an open abdominal procedure with a polyester prosthetic graft. The surgery was successful.

Discussion

AAA is a permanent bulging area of the aorta that exceeds 3.0 cm in diameter (see Figure 1). It is a potentially life-threatening condition due to the possibility of rupture. Often an aneurysm is asymptomatic until it ruptures, making this a difficult illness to diagnose.1

Each year, an estimated 10,000 deaths result from a ruptured AAA, making this condition the 14th leading cause of death in the United States.2,3 Incidence of AAA appears to have increased over the past two decades. Causes for this may include the aging of the US population, an increase in the number of smokers, and a trend toward diets that are higher in fat.

Prognosis among patients with AAA can be improved with increased awareness of the disease among health care providers, earlier detection of AAAs at risk for rupture, and timely, effective interventions.

Symptomatology

In about one-third of patients with a ruptured AAA, a clinical triad of symptoms is present: abdominal and/or back pain, a pulsatile abdominal mass, and hypotension.4,5 In these cases, according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA),4 immediate surgical evaluation is indicated.

Prior to the rupture of an AAA, the patient may feel a pulsing sensation in the abdomen or may experience no symptoms at all. Some patients report vague complaints, such as back, flank, groin, or abdominal pain. Syncope may be the chief complaint as the aneurysm expands, so it is important for primary care providers to be alert to progressive symptoms, including this signal that an aneurysm may exist and may be expanding.6

Pain may also be abrupt and severe in the lower abdomen and back, including tenderness in the area over the aneurysm. Shock can develop rapidly and symptoms such as cyanosis, mottling, altered mental status, tachycardia, and hypotension may be present.1,4

Since symptoms may be vague, the differential diagnosis can be broad (see Table 14,7,8), necessitating a detailed patient history and a careful physical examination. In an elderly patient, low back pain should be evaluated for AAA.9 In addition, acute abdominal pain in a patient older than 50 should be presumed to be a ruptured AAA.8

Risk Factors

A clinician should be familiar with the risk factors for AAA so that diagnosis can be made before a rupture occurs. Male gender and age greater than 65 are important risk factors for AAA, but one of the most important environmental risks is cigarette smoking.9,10 Current smokers are more than seven times more likely than nonsmokers to have an aneurysm.10 Atherosclerosis, which weakens the wall of the aorta, is also believed to contribute to the risk for AAA.11

Other contributing factors include hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia, and family history. Chronic infection, inflammatory illnesses, and connective tissue disorders (eg, Marfan syndrome) can also increase the risk for aneurysm. Less frequent causes of AAA are trauma and infectious diseases, such as syphilis.1,12

In 85% of patients with femoral aneurysms, AAA has been found to coexist, as it has in 62% of patients with popliteal aneurysms. Patients previously diagnosed with these conditions should be screened for AAA.4,13,14

Diagnosis

An abdominal bruit or a pulsating mass may be found on palpation, but the sensitivity for detection of AAA is related to its size. An aneurysm greater than 5.0 cm has an 82% chance of detection by palpation.15 To assess for the presence of an abdominal aneurysm, the examiner should press the midline between the xiphoid and umbilicus bimanually, firmly but gently.12 There is no evidence to suggest that palpating the abdomen can cause an aneurysm to rupture.

The most useful tests for diagnosis of AAA are US, CT, and MRI.6 US is the simplest and least costly of these diagnostic procedures; it is noninvasive and has a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of nearly 100%. Bedside US can provide a rapid diagnosis in an unstable patient.16

CT is nearly 100% effective in diagnosing AAA and is usually used to help decide on appropriate treatment, as it can determine the size and shape of the aneurysm.17 However, CT should not be used for unstable patients.

MRI is useful in diagnosing AAA, but it is expensive, and inappropriate for unstable patients. Currently, conventional aortography is rarely used for preoperative assessment but may still be used for placement of endovascular devices or in patients with renal complications.1,12

Screening Recommendations

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all men ages 65 to 74 who have a lifelong history of smoking at least 100 cigarettes should be screened for AAA with abdominal US.3,18 Screening is not recommended for those younger than 65 who have never smoked, but this decision must be individualized to the patient, with other risk factors considered.

The ACC/AHA4 advises that men whose parents or siblings have a history of AAA and who are older than 60 should undergo physical examination and screening US for AAA. In addition, patients with a small AAA should receive US surveillance until the aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm in diameter; survival has not been shown to improve if an AAA is repaired before it reaches this size.1,2,19 In consideration of increased comorbidities and decreased life expectancy, screening is not recommended for men older than 75, but this too should be determined individually.3

Screening for women is not recommended by the USPSTF.3,18 The document states that the prevalence of large AAAs in women is low and that screening may lead to an increased number of unnecessary surgeries with associated morbidity and mortality. Clinical judgment must be used in making this decision, however, as several studies have shown that women have an AAA rupture rate that is three times higher than that in men; they also have an increased in-hospital mortality rate when rupture does occur. Thus, women are less likely to experience AAA but have a worse prognosis when AAA does develop.20-22

Management

The size of an AAA is the most important predictor of rupture. According to the ACC/AHA,4 the associated risk for rupture is about 20% for aneurysms that measure 5.0 cm in diameter, 40% for those measuring at least 6.0 cm, and at least 50% for aneurysms exceeding 7.0 cm.4,23,24 Regarding surveillance of known aneurysms, it is recommended that a patient with an aneurysm smaller than 3.0 cm in diameter requires no further testing. If an AAA measures 3.0 to 4.0 cm, US should be performed yearly; if it is 4.0 to 4.9 cm, US should be performed every six months.4,25

If an identified AAA is larger than 4.5 cm, or if any segment of the aorta is more than 1.5 times the diameter of an adjacent section, referral to a vascular surgeon for further evaluation is indicated. The vascular surgeon should be consulted immediately regarding a symptomatic patient with an AAA, or one with an aneurysm that measures 5.5 cm or larger, as the risk for rupture is high.4,26

Preventing rupture of an AAA is the primary aim in management. Beta-blockers may be used to reduce systolic hypertension in cardiac patients, thus slowing the rate of expansion in those with aortic aneurysms. Patients with a known AAA should undergo frequent monitoring for blood pressure and lipid levels and be advised to stop smoking. Smoking cessation interventions such as behavior modification, nicotine replacement, or bupropion should be offered.27,28

There is evidence that statin use may reduce the size of aneurysms, even in patients without hypercholesterolemia, possibly due to statins’ anti-inflammatory properties.22,29 ACE inhibitors may also be beneficial in reducing AAA growth and in lowering blood pressure. Antiplatelet medications are important in general cardiovascular risk reduction in the patient with AAA. Aspirin is the drug of choice.27,29

Surgical Repair

AAAs are usually repaired by one of two types of surgery: endovascular repair (EVR) or open surgery. Open surgical repair, the more traditional method, involves an incision into the abdomen from the breastbone to below the navel. The weakened area is replaced with a graft made of synthetic material. Open repair of an intact AAA, performed under general anesthesia, takes from three to six hours, and the patient must be hospitalized for five to eight days.30

In EVR, the patient is given epidural anesthesia and an incision is made in the right groin, allowing a synthetic stent graft to be threaded by way of a catheter through the femoral artery to repair the lesion (see Figure 2). EVR generally takes two to five hours, followed by a two- to five-day hospital stay. EVR is usually recommended for patients who are at high risk for complications from open operations because of severe cardiopulmonary disease or other risk factors, such as advanced age, morbid obesity, or a history of multiple abdominal operations.1,2,4,19

Prognosis

Patients with a ruptured AAA have a survival rate of less than 50%, with most deaths occurring before surgical repair has been attempted.3,31 In patients with kidney failure resulting from AAA (whether ruptured or unruptured, an AAA can disrupt renal blood flow), the chance for survival is poor. By contrast, the risk for death during surgical graft repair of an AAA is only about 2% to 8%.1,12

In a systematic review, EVR was associated with a lower 30-day mortality rate compared with open surgical repair (1.6% vs 4.7%, respectively), but this reduction did not persist over two years’ follow-up; neither did EVR improve overall survival or quality of life, compared with open surgery.1 Additionally, EVR requires periodic imaging throughout the patient’s life, which is associated with more reinterventions.1,19

Patient Education

Clinicians should encourage all patients to stop smoking, follow a low-cholesterol diet, control hypertension, and exercise regularly to lower the risk for AAAs. Screening recommendations should be explained to patients at risk, as should the signs and symptoms of an aneurysm. These patients should be instructed to call their health care provider immediately if they suspect a problem.

Conclusion

The incidence of AAA is increasing, and primary care providers must be prepared to act promptly in any case of suspected AAA to ensure a safe outcome. For aneurysms measuring greater than 5.5 cm in diameter, open or endovascular surgical repair should be considered. Patients with smaller aneurysms or contraindications for surgery should receive careful medical management and education to reduce the risks of AAA expansion leading to possible rupture.

1. Wilt TJ, Lederle FA, MacDonald R, et al; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Comparison of Endovascular and Open Surgical Repairs for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. AHRQ publication 06-E107. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment 144. www.ahrq.gov/CLINIC/tp/aaareptp.htm. Accessed June 23, 2009.

2. Birkmeyer JD, Upchurch GR Jr. Evidence-based screening and management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):749-750.

3. Fleming C, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Lederle FA. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a best-evidence systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(3):203-211.

4. Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease) endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(6):1239-1312.

5. Kiell CS, Ernst CB. Advances in management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Adv Surg. 1993;26:73–98.

6. O’Connor RE. Aneurysm, abdominal. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/756735-overview. Accessed June 23, 2009.

7. Lederle FA, Parenti CM, Chute EP. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: the internist as diagnostician. Am J Med. 1994;96:163-167.

8. Cartwright SL, Knudson MP. Evaluation of acute abdominal pain in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(7): 971-978.

9. Lyon C, Clark DC. Diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in older patients. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(9):1537-1544.

10. Wilmink TB, Quick CR, Day NE. The association between cigarette smoking and abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(6):1099-1105.

11. Palazzuoli P, Gallotta M, Guerrieri G, et al. Prevalence of risk factors, coronary and systemic atherosclerosis in abdominal aortic aneurysm: comparison with high cardiovascular risk population. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4(4):877-883.

12. Sakalihasan N, Limet R, Defawe OD. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Lancet. 2005;365(9470):1577-1589.

13. Graham LM, Zelenock GB, Whitehouse WM Jr, et al. Clinical significance of arteriosclerotic femoral artery aneurysms. Arch Surg. 1980;115(4):502–507.

14. Whitehouse WM Jr, Wakefield TW, Graham LM, et al. Limb-threatening potential of arteriosclerotic popliteal artery aneurysms. Surgery. 1983;93(5):694–699.

15. Fink HA, Lederle FA, Roth CS, et al. The accuracy of physical examination to detect abdominal aortic aneurysm. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:833-836.

16. Bentz S, Jones J. Accuracy of emergency department ultrasound scanning in detecting abdominal aortic aneurysm. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(10):803-804.

17. Kvilekval KH, Best IM, Mason RA, et al. The value of computed tomography in the management of symptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 1990;12(1):28-33.

18. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(3):198-202.

19. Lederle FA, Kane RL, MacDonald R, Wilt TJ. Systematic review: repair of unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):735-741.

20. McPhee JT, Hill JS, Elami MH. The impact of gender on presentation, therapy, and mortality of abdominal aortic aneurysm in the United States, 2001-2004. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(5):891-899.

21. Mofidi R, Goldie VJ, Kelman J, et al. Influence of sex on expansion rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg. 2007;94(3):310-314.

22. Norman PE, Powell JT. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: the prognosis in women is worse than in men. Circulation. 2007;115(22):2865-2869.

23. Englund R, Hudson P, Hanel K, Stanton A. Expansion rates of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68(1):21–24.

24. Conway KP, Byrne J, Townsend M, Lane IF. Prognosis of patients turned down for conventional abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in the endovascular and sonographic era: Szilagyi revisited? J Vasc Surg. 2001;33(4):752–757.

25. Cook TA, Galland RB. A prospective study to define the optimum rescreening interval for small abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;4(4):441–444.

26. Kent KC, Zwolak RM, Jaff MR, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery; American Association of Vascular Surgery; Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39(1):267-269.

27. Golledge J, Powell JT. Medical management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;4(3):267-273.

28. Sule S, Aronow WS. Management of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Compr Ther. 2009;35(1):3-8.

29. Powell JT. Non-operative or medical management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Scand J Surg. 2008;97(2): 121-124.

30. Huber TS, Wang JG, Derrow AE, et al. Experience in the United States with intact abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33(2):304-310.

31. Adam DJ, Mohan IV, Stuart WP, et al. Community and hospital outcome from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm within the catchment area of a regional vascular surgical service. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(5):922-928.

A 60-year-old white man with a history of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and anxiety presented with complaints of abdominal pain, localized to an area left of the umbilicus. He described the pain as constant and rated it 6 on a scale of 1 to 10. He said the pain had been present for longer than three weeks.

The man said he had been seen by another health care provider shortly after the pain began, but he did not think the provider took his complaint seriously. At that visit, antacids were prescribed, blood work was ordered, and the man was told to return if there was no improvement. He felt that because he was being treated for anxiety, the provider believed he was just imagining the pain.

At the current visit, the review of systems revealed additional complaints of shakiness and nausea without vomiting, with other findings unremarkable. The persistent pain did not seem related to eating, and the patient had no history of any surgeries that might help explain his current complaints. He had smoked a pack of cigarettes daily for 40 years and had a history of heavy alcohol use, although he denied having consumed any alcohol during the previous five years.

His prescribed medications included gemfibrozil 600 mg per day, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg each morning, and diazepam 5 mg twice daily, with an OTC antacid.

The patient’s recent laboratory results were normal; they included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, liver enzyme levels, and a serum amylase level. The patient weighed 280 lb and his height was 5’10”; his BMI was 40. His temperature was 97.7°F, with a regular heart rate of 88 beats/min; blood pressure, 140/90 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min.

The patient did not appear to be in acute distress. A bruit was heard in the indicated area of pain. No mass was palpated, and the width of his aorta could not be determined because of his obesity. His physical exam was otherwise normal.

Abdominal ultrasonography (US) revealed a 5.5-cm abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), and the man was referred for immediate surgery. The aneurysm was repaired in an open abdominal procedure with a polyester prosthetic graft. The surgery was successful.

Discussion

AAA is a permanent bulging area of the aorta that exceeds 3.0 cm in diameter (see Figure 1). It is a potentially life-threatening condition due to the possibility of rupture. Often an aneurysm is asymptomatic until it ruptures, making this a difficult illness to diagnose.1

Each year, an estimated 10,000 deaths result from a ruptured AAA, making this condition the 14th leading cause of death in the United States.2,3 Incidence of AAA appears to have increased over the past two decades. Causes for this may include the aging of the US population, an increase in the number of smokers, and a trend toward diets that are higher in fat.

Prognosis among patients with AAA can be improved with increased awareness of the disease among health care providers, earlier detection of AAAs at risk for rupture, and timely, effective interventions.

Symptomatology

In about one-third of patients with a ruptured AAA, a clinical triad of symptoms is present: abdominal and/or back pain, a pulsatile abdominal mass, and hypotension.4,5 In these cases, according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA),4 immediate surgical evaluation is indicated.

Prior to the rupture of an AAA, the patient may feel a pulsing sensation in the abdomen or may experience no symptoms at all. Some patients report vague complaints, such as back, flank, groin, or abdominal pain. Syncope may be the chief complaint as the aneurysm expands, so it is important for primary care providers to be alert to progressive symptoms, including this signal that an aneurysm may exist and may be expanding.6

Pain may also be abrupt and severe in the lower abdomen and back, including tenderness in the area over the aneurysm. Shock can develop rapidly and symptoms such as cyanosis, mottling, altered mental status, tachycardia, and hypotension may be present.1,4

Since symptoms may be vague, the differential diagnosis can be broad (see Table 14,7,8), necessitating a detailed patient history and a careful physical examination. In an elderly patient, low back pain should be evaluated for AAA.9 In addition, acute abdominal pain in a patient older than 50 should be presumed to be a ruptured AAA.8

Risk Factors

A clinician should be familiar with the risk factors for AAA so that diagnosis can be made before a rupture occurs. Male gender and age greater than 65 are important risk factors for AAA, but one of the most important environmental risks is cigarette smoking.9,10 Current smokers are more than seven times more likely than nonsmokers to have an aneurysm.10 Atherosclerosis, which weakens the wall of the aorta, is also believed to contribute to the risk for AAA.11

Other contributing factors include hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia, and family history. Chronic infection, inflammatory illnesses, and connective tissue disorders (eg, Marfan syndrome) can also increase the risk for aneurysm. Less frequent causes of AAA are trauma and infectious diseases, such as syphilis.1,12

In 85% of patients with femoral aneurysms, AAA has been found to coexist, as it has in 62% of patients with popliteal aneurysms. Patients previously diagnosed with these conditions should be screened for AAA.4,13,14

Diagnosis

An abdominal bruit or a pulsating mass may be found on palpation, but the sensitivity for detection of AAA is related to its size. An aneurysm greater than 5.0 cm has an 82% chance of detection by palpation.15 To assess for the presence of an abdominal aneurysm, the examiner should press the midline between the xiphoid and umbilicus bimanually, firmly but gently.12 There is no evidence to suggest that palpating the abdomen can cause an aneurysm to rupture.

The most useful tests for diagnosis of AAA are US, CT, and MRI.6 US is the simplest and least costly of these diagnostic procedures; it is noninvasive and has a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of nearly 100%. Bedside US can provide a rapid diagnosis in an unstable patient.16

CT is nearly 100% effective in diagnosing AAA and is usually used to help decide on appropriate treatment, as it can determine the size and shape of the aneurysm.17 However, CT should not be used for unstable patients.

MRI is useful in diagnosing AAA, but it is expensive, and inappropriate for unstable patients. Currently, conventional aortography is rarely used for preoperative assessment but may still be used for placement of endovascular devices or in patients with renal complications.1,12

Screening Recommendations

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all men ages 65 to 74 who have a lifelong history of smoking at least 100 cigarettes should be screened for AAA with abdominal US.3,18 Screening is not recommended for those younger than 65 who have never smoked, but this decision must be individualized to the patient, with other risk factors considered.

The ACC/AHA4 advises that men whose parents or siblings have a history of AAA and who are older than 60 should undergo physical examination and screening US for AAA. In addition, patients with a small AAA should receive US surveillance until the aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm in diameter; survival has not been shown to improve if an AAA is repaired before it reaches this size.1,2,19 In consideration of increased comorbidities and decreased life expectancy, screening is not recommended for men older than 75, but this too should be determined individually.3

Screening for women is not recommended by the USPSTF.3,18 The document states that the prevalence of large AAAs in women is low and that screening may lead to an increased number of unnecessary surgeries with associated morbidity and mortality. Clinical judgment must be used in making this decision, however, as several studies have shown that women have an AAA rupture rate that is three times higher than that in men; they also have an increased in-hospital mortality rate when rupture does occur. Thus, women are less likely to experience AAA but have a worse prognosis when AAA does develop.20-22

Management

The size of an AAA is the most important predictor of rupture. According to the ACC/AHA,4 the associated risk for rupture is about 20% for aneurysms that measure 5.0 cm in diameter, 40% for those measuring at least 6.0 cm, and at least 50% for aneurysms exceeding 7.0 cm.4,23,24 Regarding surveillance of known aneurysms, it is recommended that a patient with an aneurysm smaller than 3.0 cm in diameter requires no further testing. If an AAA measures 3.0 to 4.0 cm, US should be performed yearly; if it is 4.0 to 4.9 cm, US should be performed every six months.4,25

If an identified AAA is larger than 4.5 cm, or if any segment of the aorta is more than 1.5 times the diameter of an adjacent section, referral to a vascular surgeon for further evaluation is indicated. The vascular surgeon should be consulted immediately regarding a symptomatic patient with an AAA, or one with an aneurysm that measures 5.5 cm or larger, as the risk for rupture is high.4,26

Preventing rupture of an AAA is the primary aim in management. Beta-blockers may be used to reduce systolic hypertension in cardiac patients, thus slowing the rate of expansion in those with aortic aneurysms. Patients with a known AAA should undergo frequent monitoring for blood pressure and lipid levels and be advised to stop smoking. Smoking cessation interventions such as behavior modification, nicotine replacement, or bupropion should be offered.27,28

There is evidence that statin use may reduce the size of aneurysms, even in patients without hypercholesterolemia, possibly due to statins’ anti-inflammatory properties.22,29 ACE inhibitors may also be beneficial in reducing AAA growth and in lowering blood pressure. Antiplatelet medications are important in general cardiovascular risk reduction in the patient with AAA. Aspirin is the drug of choice.27,29

Surgical Repair

AAAs are usually repaired by one of two types of surgery: endovascular repair (EVR) or open surgery. Open surgical repair, the more traditional method, involves an incision into the abdomen from the breastbone to below the navel. The weakened area is replaced with a graft made of synthetic material. Open repair of an intact AAA, performed under general anesthesia, takes from three to six hours, and the patient must be hospitalized for five to eight days.30

In EVR, the patient is given epidural anesthesia and an incision is made in the right groin, allowing a synthetic stent graft to be threaded by way of a catheter through the femoral artery to repair the lesion (see Figure 2). EVR generally takes two to five hours, followed by a two- to five-day hospital stay. EVR is usually recommended for patients who are at high risk for complications from open operations because of severe cardiopulmonary disease or other risk factors, such as advanced age, morbid obesity, or a history of multiple abdominal operations.1,2,4,19

Prognosis

Patients with a ruptured AAA have a survival rate of less than 50%, with most deaths occurring before surgical repair has been attempted.3,31 In patients with kidney failure resulting from AAA (whether ruptured or unruptured, an AAA can disrupt renal blood flow), the chance for survival is poor. By contrast, the risk for death during surgical graft repair of an AAA is only about 2% to 8%.1,12

In a systematic review, EVR was associated with a lower 30-day mortality rate compared with open surgical repair (1.6% vs 4.7%, respectively), but this reduction did not persist over two years’ follow-up; neither did EVR improve overall survival or quality of life, compared with open surgery.1 Additionally, EVR requires periodic imaging throughout the patient’s life, which is associated with more reinterventions.1,19

Patient Education

Clinicians should encourage all patients to stop smoking, follow a low-cholesterol diet, control hypertension, and exercise regularly to lower the risk for AAAs. Screening recommendations should be explained to patients at risk, as should the signs and symptoms of an aneurysm. These patients should be instructed to call their health care provider immediately if they suspect a problem.

Conclusion

The incidence of AAA is increasing, and primary care providers must be prepared to act promptly in any case of suspected AAA to ensure a safe outcome. For aneurysms measuring greater than 5.5 cm in diameter, open or endovascular surgical repair should be considered. Patients with smaller aneurysms or contraindications for surgery should receive careful medical management and education to reduce the risks of AAA expansion leading to possible rupture.

A 60-year-old white man with a history of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and anxiety presented with complaints of abdominal pain, localized to an area left of the umbilicus. He described the pain as constant and rated it 6 on a scale of 1 to 10. He said the pain had been present for longer than three weeks.

The man said he had been seen by another health care provider shortly after the pain began, but he did not think the provider took his complaint seriously. At that visit, antacids were prescribed, blood work was ordered, and the man was told to return if there was no improvement. He felt that because he was being treated for anxiety, the provider believed he was just imagining the pain.

At the current visit, the review of systems revealed additional complaints of shakiness and nausea without vomiting, with other findings unremarkable. The persistent pain did not seem related to eating, and the patient had no history of any surgeries that might help explain his current complaints. He had smoked a pack of cigarettes daily for 40 years and had a history of heavy alcohol use, although he denied having consumed any alcohol during the previous five years.

His prescribed medications included gemfibrozil 600 mg per day, hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg each morning, and diazepam 5 mg twice daily, with an OTC antacid.

The patient’s recent laboratory results were normal; they included a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, liver enzyme levels, and a serum amylase level. The patient weighed 280 lb and his height was 5’10”; his BMI was 40. His temperature was 97.7°F, with a regular heart rate of 88 beats/min; blood pressure, 140/90 mm Hg; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min.

The patient did not appear to be in acute distress. A bruit was heard in the indicated area of pain. No mass was palpated, and the width of his aorta could not be determined because of his obesity. His physical exam was otherwise normal.

Abdominal ultrasonography (US) revealed a 5.5-cm abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), and the man was referred for immediate surgery. The aneurysm was repaired in an open abdominal procedure with a polyester prosthetic graft. The surgery was successful.

Discussion

AAA is a permanent bulging area of the aorta that exceeds 3.0 cm in diameter (see Figure 1). It is a potentially life-threatening condition due to the possibility of rupture. Often an aneurysm is asymptomatic until it ruptures, making this a difficult illness to diagnose.1

Each year, an estimated 10,000 deaths result from a ruptured AAA, making this condition the 14th leading cause of death in the United States.2,3 Incidence of AAA appears to have increased over the past two decades. Causes for this may include the aging of the US population, an increase in the number of smokers, and a trend toward diets that are higher in fat.

Prognosis among patients with AAA can be improved with increased awareness of the disease among health care providers, earlier detection of AAAs at risk for rupture, and timely, effective interventions.

Symptomatology

In about one-third of patients with a ruptured AAA, a clinical triad of symptoms is present: abdominal and/or back pain, a pulsatile abdominal mass, and hypotension.4,5 In these cases, according to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA),4 immediate surgical evaluation is indicated.

Prior to the rupture of an AAA, the patient may feel a pulsing sensation in the abdomen or may experience no symptoms at all. Some patients report vague complaints, such as back, flank, groin, or abdominal pain. Syncope may be the chief complaint as the aneurysm expands, so it is important for primary care providers to be alert to progressive symptoms, including this signal that an aneurysm may exist and may be expanding.6

Pain may also be abrupt and severe in the lower abdomen and back, including tenderness in the area over the aneurysm. Shock can develop rapidly and symptoms such as cyanosis, mottling, altered mental status, tachycardia, and hypotension may be present.1,4

Since symptoms may be vague, the differential diagnosis can be broad (see Table 14,7,8), necessitating a detailed patient history and a careful physical examination. In an elderly patient, low back pain should be evaluated for AAA.9 In addition, acute abdominal pain in a patient older than 50 should be presumed to be a ruptured AAA.8

Risk Factors

A clinician should be familiar with the risk factors for AAA so that diagnosis can be made before a rupture occurs. Male gender and age greater than 65 are important risk factors for AAA, but one of the most important environmental risks is cigarette smoking.9,10 Current smokers are more than seven times more likely than nonsmokers to have an aneurysm.10 Atherosclerosis, which weakens the wall of the aorta, is also believed to contribute to the risk for AAA.11

Other contributing factors include hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperlipidemia, and family history. Chronic infection, inflammatory illnesses, and connective tissue disorders (eg, Marfan syndrome) can also increase the risk for aneurysm. Less frequent causes of AAA are trauma and infectious diseases, such as syphilis.1,12

In 85% of patients with femoral aneurysms, AAA has been found to coexist, as it has in 62% of patients with popliteal aneurysms. Patients previously diagnosed with these conditions should be screened for AAA.4,13,14

Diagnosis

An abdominal bruit or a pulsating mass may be found on palpation, but the sensitivity for detection of AAA is related to its size. An aneurysm greater than 5.0 cm has an 82% chance of detection by palpation.15 To assess for the presence of an abdominal aneurysm, the examiner should press the midline between the xiphoid and umbilicus bimanually, firmly but gently.12 There is no evidence to suggest that palpating the abdomen can cause an aneurysm to rupture.

The most useful tests for diagnosis of AAA are US, CT, and MRI.6 US is the simplest and least costly of these diagnostic procedures; it is noninvasive and has a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of nearly 100%. Bedside US can provide a rapid diagnosis in an unstable patient.16

CT is nearly 100% effective in diagnosing AAA and is usually used to help decide on appropriate treatment, as it can determine the size and shape of the aneurysm.17 However, CT should not be used for unstable patients.

MRI is useful in diagnosing AAA, but it is expensive, and inappropriate for unstable patients. Currently, conventional aortography is rarely used for preoperative assessment but may still be used for placement of endovascular devices or in patients with renal complications.1,12

Screening Recommendations

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that all men ages 65 to 74 who have a lifelong history of smoking at least 100 cigarettes should be screened for AAA with abdominal US.3,18 Screening is not recommended for those younger than 65 who have never smoked, but this decision must be individualized to the patient, with other risk factors considered.

The ACC/AHA4 advises that men whose parents or siblings have a history of AAA and who are older than 60 should undergo physical examination and screening US for AAA. In addition, patients with a small AAA should receive US surveillance until the aneurysm reaches 5.5 cm in diameter; survival has not been shown to improve if an AAA is repaired before it reaches this size.1,2,19 In consideration of increased comorbidities and decreased life expectancy, screening is not recommended for men older than 75, but this too should be determined individually.3

Screening for women is not recommended by the USPSTF.3,18 The document states that the prevalence of large AAAs in women is low and that screening may lead to an increased number of unnecessary surgeries with associated morbidity and mortality. Clinical judgment must be used in making this decision, however, as several studies have shown that women have an AAA rupture rate that is three times higher than that in men; they also have an increased in-hospital mortality rate when rupture does occur. Thus, women are less likely to experience AAA but have a worse prognosis when AAA does develop.20-22

Management

The size of an AAA is the most important predictor of rupture. According to the ACC/AHA,4 the associated risk for rupture is about 20% for aneurysms that measure 5.0 cm in diameter, 40% for those measuring at least 6.0 cm, and at least 50% for aneurysms exceeding 7.0 cm.4,23,24 Regarding surveillance of known aneurysms, it is recommended that a patient with an aneurysm smaller than 3.0 cm in diameter requires no further testing. If an AAA measures 3.0 to 4.0 cm, US should be performed yearly; if it is 4.0 to 4.9 cm, US should be performed every six months.4,25

If an identified AAA is larger than 4.5 cm, or if any segment of the aorta is more than 1.5 times the diameter of an adjacent section, referral to a vascular surgeon for further evaluation is indicated. The vascular surgeon should be consulted immediately regarding a symptomatic patient with an AAA, or one with an aneurysm that measures 5.5 cm or larger, as the risk for rupture is high.4,26

Preventing rupture of an AAA is the primary aim in management. Beta-blockers may be used to reduce systolic hypertension in cardiac patients, thus slowing the rate of expansion in those with aortic aneurysms. Patients with a known AAA should undergo frequent monitoring for blood pressure and lipid levels and be advised to stop smoking. Smoking cessation interventions such as behavior modification, nicotine replacement, or bupropion should be offered.27,28

There is evidence that statin use may reduce the size of aneurysms, even in patients without hypercholesterolemia, possibly due to statins’ anti-inflammatory properties.22,29 ACE inhibitors may also be beneficial in reducing AAA growth and in lowering blood pressure. Antiplatelet medications are important in general cardiovascular risk reduction in the patient with AAA. Aspirin is the drug of choice.27,29

Surgical Repair

AAAs are usually repaired by one of two types of surgery: endovascular repair (EVR) or open surgery. Open surgical repair, the more traditional method, involves an incision into the abdomen from the breastbone to below the navel. The weakened area is replaced with a graft made of synthetic material. Open repair of an intact AAA, performed under general anesthesia, takes from three to six hours, and the patient must be hospitalized for five to eight days.30

In EVR, the patient is given epidural anesthesia and an incision is made in the right groin, allowing a synthetic stent graft to be threaded by way of a catheter through the femoral artery to repair the lesion (see Figure 2). EVR generally takes two to five hours, followed by a two- to five-day hospital stay. EVR is usually recommended for patients who are at high risk for complications from open operations because of severe cardiopulmonary disease or other risk factors, such as advanced age, morbid obesity, or a history of multiple abdominal operations.1,2,4,19

Prognosis

Patients with a ruptured AAA have a survival rate of less than 50%, with most deaths occurring before surgical repair has been attempted.3,31 In patients with kidney failure resulting from AAA (whether ruptured or unruptured, an AAA can disrupt renal blood flow), the chance for survival is poor. By contrast, the risk for death during surgical graft repair of an AAA is only about 2% to 8%.1,12

In a systematic review, EVR was associated with a lower 30-day mortality rate compared with open surgical repair (1.6% vs 4.7%, respectively), but this reduction did not persist over two years’ follow-up; neither did EVR improve overall survival or quality of life, compared with open surgery.1 Additionally, EVR requires periodic imaging throughout the patient’s life, which is associated with more reinterventions.1,19

Patient Education

Clinicians should encourage all patients to stop smoking, follow a low-cholesterol diet, control hypertension, and exercise regularly to lower the risk for AAAs. Screening recommendations should be explained to patients at risk, as should the signs and symptoms of an aneurysm. These patients should be instructed to call their health care provider immediately if they suspect a problem.

Conclusion

The incidence of AAA is increasing, and primary care providers must be prepared to act promptly in any case of suspected AAA to ensure a safe outcome. For aneurysms measuring greater than 5.5 cm in diameter, open or endovascular surgical repair should be considered. Patients with smaller aneurysms or contraindications for surgery should receive careful medical management and education to reduce the risks of AAA expansion leading to possible rupture.

1. Wilt TJ, Lederle FA, MacDonald R, et al; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Comparison of Endovascular and Open Surgical Repairs for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. AHRQ publication 06-E107. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment 144. www.ahrq.gov/CLINIC/tp/aaareptp.htm. Accessed June 23, 2009.

2. Birkmeyer JD, Upchurch GR Jr. Evidence-based screening and management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):749-750.

3. Fleming C, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Lederle FA. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a best-evidence systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(3):203-211.

4. Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease) endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(6):1239-1312.

5. Kiell CS, Ernst CB. Advances in management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Adv Surg. 1993;26:73–98.

6. O’Connor RE. Aneurysm, abdominal. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/756735-overview. Accessed June 23, 2009.

7. Lederle FA, Parenti CM, Chute EP. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: the internist as diagnostician. Am J Med. 1994;96:163-167.

8. Cartwright SL, Knudson MP. Evaluation of acute abdominal pain in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(7): 971-978.

9. Lyon C, Clark DC. Diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in older patients. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(9):1537-1544.

10. Wilmink TB, Quick CR, Day NE. The association between cigarette smoking and abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(6):1099-1105.

11. Palazzuoli P, Gallotta M, Guerrieri G, et al. Prevalence of risk factors, coronary and systemic atherosclerosis in abdominal aortic aneurysm: comparison with high cardiovascular risk population. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4(4):877-883.

12. Sakalihasan N, Limet R, Defawe OD. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Lancet. 2005;365(9470):1577-1589.

13. Graham LM, Zelenock GB, Whitehouse WM Jr, et al. Clinical significance of arteriosclerotic femoral artery aneurysms. Arch Surg. 1980;115(4):502–507.

14. Whitehouse WM Jr, Wakefield TW, Graham LM, et al. Limb-threatening potential of arteriosclerotic popliteal artery aneurysms. Surgery. 1983;93(5):694–699.

15. Fink HA, Lederle FA, Roth CS, et al. The accuracy of physical examination to detect abdominal aortic aneurysm. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:833-836.

16. Bentz S, Jones J. Accuracy of emergency department ultrasound scanning in detecting abdominal aortic aneurysm. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(10):803-804.

17. Kvilekval KH, Best IM, Mason RA, et al. The value of computed tomography in the management of symptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 1990;12(1):28-33.

18. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(3):198-202.

19. Lederle FA, Kane RL, MacDonald R, Wilt TJ. Systematic review: repair of unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):735-741.

20. McPhee JT, Hill JS, Elami MH. The impact of gender on presentation, therapy, and mortality of abdominal aortic aneurysm in the United States, 2001-2004. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(5):891-899.

21. Mofidi R, Goldie VJ, Kelman J, et al. Influence of sex on expansion rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg. 2007;94(3):310-314.

22. Norman PE, Powell JT. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: the prognosis in women is worse than in men. Circulation. 2007;115(22):2865-2869.

23. Englund R, Hudson P, Hanel K, Stanton A. Expansion rates of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68(1):21–24.

24. Conway KP, Byrne J, Townsend M, Lane IF. Prognosis of patients turned down for conventional abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in the endovascular and sonographic era: Szilagyi revisited? J Vasc Surg. 2001;33(4):752–757.

25. Cook TA, Galland RB. A prospective study to define the optimum rescreening interval for small abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;4(4):441–444.

26. Kent KC, Zwolak RM, Jaff MR, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery; American Association of Vascular Surgery; Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39(1):267-269.

27. Golledge J, Powell JT. Medical management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;4(3):267-273.

28. Sule S, Aronow WS. Management of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Compr Ther. 2009;35(1):3-8.

29. Powell JT. Non-operative or medical management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Scand J Surg. 2008;97(2): 121-124.

30. Huber TS, Wang JG, Derrow AE, et al. Experience in the United States with intact abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33(2):304-310.

31. Adam DJ, Mohan IV, Stuart WP, et al. Community and hospital outcome from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm within the catchment area of a regional vascular surgical service. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(5):922-928.

1. Wilt TJ, Lederle FA, MacDonald R, et al; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Comparison of Endovascular and Open Surgical Repairs for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. AHRQ publication 06-E107. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment 144. www.ahrq.gov/CLINIC/tp/aaareptp.htm. Accessed June 23, 2009.

2. Birkmeyer JD, Upchurch GR Jr. Evidence-based screening and management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):749-750.

3. Fleming C, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Lederle FA. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a best-evidence systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(3):203-211.

4. Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): executive summary a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease) endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(6):1239-1312.

5. Kiell CS, Ernst CB. Advances in management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Adv Surg. 1993;26:73–98.

6. O’Connor RE. Aneurysm, abdominal. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/756735-overview. Accessed June 23, 2009.

7. Lederle FA, Parenti CM, Chute EP. Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm: the internist as diagnostician. Am J Med. 1994;96:163-167.

8. Cartwright SL, Knudson MP. Evaluation of acute abdominal pain in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(7): 971-978.

9. Lyon C, Clark DC. Diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in older patients. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(9):1537-1544.

10. Wilmink TB, Quick CR, Day NE. The association between cigarette smoking and abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(6):1099-1105.

11. Palazzuoli P, Gallotta M, Guerrieri G, et al. Prevalence of risk factors, coronary and systemic atherosclerosis in abdominal aortic aneurysm: comparison with high cardiovascular risk population. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4(4):877-883.

12. Sakalihasan N, Limet R, Defawe OD. Abdominal aortic aneurysm. Lancet. 2005;365(9470):1577-1589.

13. Graham LM, Zelenock GB, Whitehouse WM Jr, et al. Clinical significance of arteriosclerotic femoral artery aneurysms. Arch Surg. 1980;115(4):502–507.

14. Whitehouse WM Jr, Wakefield TW, Graham LM, et al. Limb-threatening potential of arteriosclerotic popliteal artery aneurysms. Surgery. 1983;93(5):694–699.

15. Fink HA, Lederle FA, Roth CS, et al. The accuracy of physical examination to detect abdominal aortic aneurysm. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:833-836.

16. Bentz S, Jones J. Accuracy of emergency department ultrasound scanning in detecting abdominal aortic aneurysm. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(10):803-804.

17. Kvilekval KH, Best IM, Mason RA, et al. The value of computed tomography in the management of symptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 1990;12(1):28-33.

18. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(3):198-202.

19. Lederle FA, Kane RL, MacDonald R, Wilt TJ. Systematic review: repair of unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(10):735-741.

20. McPhee JT, Hill JS, Elami MH. The impact of gender on presentation, therapy, and mortality of abdominal aortic aneurysm in the United States, 2001-2004. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(5):891-899.

21. Mofidi R, Goldie VJ, Kelman J, et al. Influence of sex on expansion rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg. 2007;94(3):310-314.

22. Norman PE, Powell JT. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: the prognosis in women is worse than in men. Circulation. 2007;115(22):2865-2869.

23. Englund R, Hudson P, Hanel K, Stanton A. Expansion rates of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. Aust N Z J Surg. 1998;68(1):21–24.

24. Conway KP, Byrne J, Townsend M, Lane IF. Prognosis of patients turned down for conventional abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in the endovascular and sonographic era: Szilagyi revisited? J Vasc Surg. 2001;33(4):752–757.

25. Cook TA, Galland RB. A prospective study to define the optimum rescreening interval for small abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;4(4):441–444.

26. Kent KC, Zwolak RM, Jaff MR, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery; American Association of Vascular Surgery; Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39(1):267-269.

27. Golledge J, Powell JT. Medical management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;4(3):267-273.

28. Sule S, Aronow WS. Management of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Compr Ther. 2009;35(1):3-8.

29. Powell JT. Non-operative or medical management of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Scand J Surg. 2008;97(2): 121-124.

30. Huber TS, Wang JG, Derrow AE, et al. Experience in the United States with intact abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg. 2001;33(2):304-310.

31. Adam DJ, Mohan IV, Stuart WP, et al. Community and hospital outcome from ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm within the catchment area of a regional vascular surgical service. J Vasc Surg. 1999;30(5):922-928.

Transient Ischemic Attack: What You Need to Know

Emergency Department Evaluation of Patients With Intrathecal Pumps

When to Suspect Ischemic Colitis

Managing Peripartum Emergencies

Melorheostosis

UPDATE: ENDOMETRIAL CANCER

Dr. Mutch reports that he has received grant or research support from Lilly and Genentech. He serves as a speaker for GSK, Lilly, and Merck. Dr. Rimel reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Endometrial cancer is a great concern in industrialized nations, where it is the most common gynecologic cancer—with incidence increasing every year. Survival is generally very good for women who have low-grade disease confined to the uterus. However, for patients who have high-grade disease, an aggressive histologic type, or other features that suggest a poor prognosis, the cure rate approaches 75%.1

Primary surgery is the mainstay of initial treatment and basis of FIGO staging ( TABLE ), which requires:

- total hysterectomy

- bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

- complete examination of the abdomen

- pelvic washings

- lymph-adenectomy (anatomic boundaries and node counts aren’t specified).

Controversy clouds our understanding of the optimal type of surgery, utility of pelvic lymphadenectomy, and possible benefit of adjuvant radiation therapy. During the past year, fuel has been added to this debate:

- Two randomized, controlled trials of surgery with and without pelvic lymphadenectomy in early-stage patients demonstrated no survival benefit. Earlier studies investigating the benefits of lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer have been largely retrospective, and results have varied.

- A concurrent randomized, controlled trial of external-beam radiotherapy for women who have intermediate- or high-risk disease showed no improvement in overall survival, although local control increased by 3%.

TABLE

FIGO surgical staging for endometrial cancer

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Tumor is confined to uterine fundus |

| IA | Tumor is limited to endometrium |

| IB | Tumor invades less than half of the myometrial thickness |

| IC | Tumor invades more than half of the myometrial thickness |

| II | Tumor extends to cervix |

| IIA | Cervical extension is limited to endocervical glands |

| IIB | Tumor invades cervical stroma |

| III | There is regional tumor spread |

| IIIA | Tumor invades uterine serosa or adnexa, or cells in the peritoneum show signs of cancer |

| IIIB | Vaginal metastases are present |

| IIIC | Tumor has spread to lymph nodes near the uterus |

| IV | There is bulky pelvic disease or distant spread |

| IVA | Tumor has spread to bladder or rectum |

| IVB | Distant metastases are present |

No survival advantage to pelvic lymphadenectomy—but it has other benefits

ASTEC study group, Kitchener H, Swart AM, Qian Q, Amos C, Parmar MK. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomised study. Lancet. 2009;373:125–136.

Benedetti Panici P, Basile S, Maneschi F, et al. Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs. no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1707–1716.

Among the arguments for lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer staging are:

- It aids in the selection of women for radiation or other adjuvant treatment

- It may have a direct survival benefit, as suggested by retrospective studies.

But lymphadenectomy is time-consuming, requires a specialized gynecologic surgeon, and is associated with some increase in the risk of morbidity—namely, lymphedema, lymphocyst formation, deep-vein thrombosis (DVT), and blood loss.

The much-anticipated report of the 85-center, multinational ASTEC trial [ A S urgical T rial of E ndometrial C ancer], published earlier this year, offers further insight into the practice of lymphadenectomy. ASTEC involved two randomizations: The first, to pelvic lymphadenectomy; the second, to radiation therapy.

The ASTEC trial enrolled 1,408 women who had histologically confirmed endometrial carcinoma that was believed to be confined to the uterus. How this determination was made was not specified. Patients who had enlarged lymph nodes corroborated by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging were not excluded.

Participants were randomized to either of the following treatment groups:

- traditional surgery with total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic washings, and palpation of para-aortic nodes

- the same surgery plus systematic lymphadenectomy of the iliac and obturator nodes.

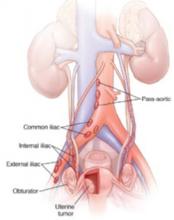

If any para-aortic nodes were suspicious, biopsy or lymphadenectomy was performed at the discretion of the surgeon ( FIGURE ).

FIGURE Nodes reveal when cancer has spread

Women in the ASTEC trial were randomized to traditional surgery (total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy), pelvic washings, and palpation of para-aortic nodes or to the same surgery plus lymphadenectomy of the iliac and obturator nodes.

Operative findings determined a patient’s level of risk

After surgery, patients were categorized as having one of the following:

- low-risk, early-stage disease. This group included patients who had disease classified as stage IA or IB, grade 1 or 2. They were deemed to have a suitably low risk of recurrence to be offered further treatment according to their physician’s standard practice.

- intermediate- or high-risk, early-stage disease. These patients were randomized to the ASTEC radiation-therapy trial, which compared external-beam radiotherapy with no external-beam radiotherapy. The authors assert that this second randomization was necessary to prevent over- or undertreatment of patients who had unknown node status, which might alter survival outcomes.

- advanced disease. These patients were referred to their physician for further treatment.

In both surgical groups (with and without lymphadenectomy), approximately 80% of patients had disease confined to the uterus. Nodes were harvested in 91% of the patients in the lymphadenectomy group, compared with 5% of patients in the traditional-surgery group. Nine percent of women in the lymphadenectomy group had positive nodes.

The authors observe that more women had deeply invasive disease and adverse histologic types in the group that underwent lymphadenectomy. There were no differences between the two groups in overall survival; disease-specific survival; recurrence-free survival; or recurrence-free, disease-specific survival, after adjustment for baseline differences. Subgroup analysis for low-risk, high-risk, and advanced disease also failed to demonstrate differences in overall survival and recurrence-free survival.

Study from Italy produces similar findings

An independent randomized, controlled trial examining survival outcomes for endometrial cancer patients with and without lymphadenectomy was released by the Italian group in late 2008. In this study, 537 patients who had histologically confirmed endometrial carcinoma believed to be confined to the uterus were randomized to total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with or without pelvic lymphadenectomy.

Anatomic boundaries of the pelvic lymph-node dissection were clearly defined, and a minimum lymph-node count of 20 was specified for inclusion. Intraoperative frozen section was utilized to exclude patients who had grade-1 disease that was less than 50% invasive. The option of para-aortic lymph-node dissection or sampling was left to the discretion of the surgeon. If pelvic nodes were larger than 1 cm, they were removed or sampled regardless of randomization.

Unlike the ASTEC trial, this study did not attempt to control adjuvant treatment. Patients were treated according to the discretion of the physician. Most patients received no further therapy; only 20% underwent radiation therapy, and 7% received chemotherapy.

Given the findings of these two, large, multi-institutional trials with strikingly similar results but major problems, what is a gynecologist to do? Can lymphadenectomy be avoided in patients whose disease is believed to be confined to the uterus?

For now, the answer is a tentative “No.”

There appears to be no survival advantage to removal of lymph nodes when disease is confined to the uterus, but that is not to say there is no benefit to systematic lymphadenectomy—just that there is no survival benefit afforded by the procedure. Benefits of lymphadenectomy, which include more precise definition of the extent of disease, minimization of over- or undertreatment, and a reduction in overall treatment and cost, still remain. The concept of surgical debulking put forward by Bristow and coworkers still has merit, and any gross disease should be removed, if feasible.2

Lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer remains controversial and complex, especially as we lack a precise method for determining which patients will have nodal disease. Our practice remains to remove the lymph nodes whenever possible to better tailor any adjuvant treatment.—DAVID G. MUTCH, MD; B. J. RIMEL, MD

Women in the lymphadenectomy group were more likely to have stage-IIIC disease, which is directly attributable to histologic evaluation of the lymph nodes in this group. The authors point out that these patients had more accurate assessment of their prognosis, allowing for the tailoring of adjuvant treatment.

The overall survival and disease-free survival curves for the two experimental groups were similar, consistent with data from the ASTEC trial. This proved to be true for both the intention-to-treat and according-to-protocol groups. The authors note that their results are similar to those of the ASTEC trial, despite the significant difference in the number of nodes removed in each trial.

Some aspects of the trials hamper interpretation and comparison

Outcomes are improved when surgery is performed by a trained gynecologic oncologist. In the ASTEC trial, each lymphadenectomy was performed by a specialized gynecologic surgeon who was “skilled in the procedure.” In the Italian study, the type of surgeon was not specified, but the specific anatomic boundaries of the dissection and the minimum node count were. More specific data are needed before any conclusions can be drawn about the effect of surgical skill on outcome in these trials.

In the ASTEC trial, 9% of patients in the lymphadenectomy group had no nodes removed, and more than 60% of patients would not have met criteria for inclusion in the lymphadenectomy arm of the Italian study—suggesting that the majority of women in the ASTEC trial had inadequate lymphadenectomy. Para-aortic lymphadenectomy was left to the discretion of the attending surgeon, and some patients did have resection of these nodes. The data do not include information about whether these patients were treated in the para-aortic region based on the histology of these nodes.

Randomization in a prospective study is supposed to equalize the risks between groups. In the ASTEC trial, despite randomization, there were 10% more patients who had deeply invasive disease in the lymphadenectomy group, along with 3% more adverse histologies and high-grade (grade-3) tumors. Given the higher incidence of positive nodes and poorer outcome in these cases, this difference may have had a significant impact on the evaluation of the groups for overall or disease-specific survival.

External-beam radiotherapy reduces local recurrence of endometrial Ca but does not improve survival

ASTEC/EN.5 Study Group, Blake P, Swart AM, Orton J, et al. Adjuvant external beam radiotherapy in the treatment of endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC and NCIC CTG EN.5 randomised trials): pooled trial results, systematic review, and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:137–146.

Radiation therapy has been a standard treatment for endometrial cancer when there is high risk of recurrence. This report combines two independent randomized, controlled trials investigating the benefit of postoperative adjuvant pelvic radiation in women who had early-stage disease and who met histologic criteria for high risk of recurrence and death. The trials are the EN.5 trial from Canada, and the radiation-therapy randomization of the ASTEC trial). Neither found a benefit in terms of overall survival, disease-specific survival, or recurrence-free survival, although local recurrence was reduced by 2.9% The authors also provide a review of the literature and a meta-analysis of other randomized, controlled trials on this subject.

Details of the EN.5 and ASTEC radiation-therapy trials

Criteria for enrollment were similar for the two trials, which focused on women who had histologically confirmed endometrial cancer and an intermediate or high risk of recurrence. This included women who had FIGO stage IA or stage IB (grade 3), stage IC (all grades), or papillary serous or clear-cell histology (all stages).

Survival is the primary goal of cancer treatment. External-beam radiotherapy does not improve survival, but does provide a small but real increase in local control. Regrettably, this improvement in local control comes at a cost: 3% of patients experience acute severe or life-threatening toxicity from treatment. The absolute difference in local recurrence between women who received external-beam radiotherapy and those who did not was only 2.9%. Local recurrences are largely salvageable in women who have not been irradiated.

Therefore, external-beam radiotherapy, as delivered in this trial, regardless of node status, should not be the standard of care. Improvement in technology with intensity-modulated radiotherapy, and the further evaluation of vaginal brachytherapy alone, may provide new ways to apply this kind of treatment in endometrial cancer.

This aspect of endometrial cancer treatment clearly needs further investigation. Trials are under way that may determine the role of radiation therapy in women who have endometrial cancer.—DAVID G. MUTCH, MD; B. J. RIMEL, MD

Lymphadenectomy was not required for patients enrolled in EN.5, but was part of the surgical randomization for ASTEC. This distinction could confound the results of the combined trials, as the investigators were trying to answer two questions within one patient population.

In both the EN.5 and ASTEC trials, women were randomized to observation or external-beam radiotherapy, with these parameters:

- Radiation therapy was to begin no later than 12 weeks after surgery (most patients began radiation therapy 6 to 8 weeks after surgery)

- For ASTEC, the target dosage was 40–46 Gy in 20–26 daily fractions to the pelvis, with treatment five times each week. For EN.5, the dosage and timing were very similar: 45 Gy, 25 daily fractions, five times weekly

- In both trials, vaginal brachytherapy was allowed if it was the local practice or the center’s policy

- Women were classified as being at intermediate risk or high risk, based on the likelihood of distant recurrence, as defined by GOG99 and PORTEC1 studies. Intermediate risk included all patients who had stage-IA or -IB (grade-3) or stage-IC or -IIA (grade-1 or -2) disease. Women who had papillary serous or clear-cell histology, stage-IC or -IIA (grade-3) disease, or any stage-IIB disease were considered at high risk.

The primary outcome evaluated for both trials was overall survival. Secondary endpoints were:

- disease-specific survival

- recurrence-free survival

- locoregional recurrence

- treatment toxicity.

A total of 905 women were enrolled in the ASTEC and EN.5 trials, with most patients having endometrial histology (83%) and being categorized as at intermediate risk (75%). Approximately half the patients in both trials received brachytherapy, which was allowed according to local practice. Only 47% of the observation group actually received no treatment.

Findings were remarkably similar in EN.5 and ASTEC

Here are the main findings:

- no difference between groups in overall survival, disease-specific survival, and recurrence-free survival

- significantly fewer isolated vaginal or pelvic initial recurrences in the external-beam radiotherapy group, with an absolute difference of 2.9%. (Only 35% of all recurrences were isolated recurrences)

- no significant difference between groups in distant or local and distant recurrences

- as expected, higher toxicity in the group receiving external-beam radiotherapy, including life-threatening toxicity (acute toxicity, 3% vs <1%; late toxicity, 1% vs 0%).

Subgroup analysis comparing overall survival in intermediate- and high-risk patients demonstrated no improvement with external-beam radiotherapy. Nor was overall survival altered by lymphadenectomy. The authors performed a meta-analysis using data from GOG99, PORTEC1, and this combined trial, and found no significant difference in overall survival or disease-specific survival, regardless of histologic risk group.

Trial has notable strengths and weaknesses

This large prospective trial has significant strengths: its size and its multi-institutional nature. The authors also evaluated their data in combination with other randomized, controlled trials to further investigate the effect of external-beam radiotherapy on survival. However, allowing brachytherapy somewhat confounds the true effect of external-beam radiotherapy on local recurrence. (There were few local recurrences, and the authors did not evaluate whether women who had an isolated vaginal recurrence received vaginal brachytherapy.) Moreover, 15% of women who were randomized to external-beam radiotherapy did not complete it.

In addition, secondary randomization of patients in the intermediate-risk and high-risk categories to external-beam radiotherapy versus no treatment may have significantly confounded the results of the entire ASTEC trial. Because women were, or were not, randomized to treatment regardless of node status, some patients who had positive nodes failed to receive adjuvant treatment. This may have had a significant effect on overall survival, as positive lymph nodes are a negative prognostic factor.

1. Keys HM, Roberts JA, Brunetto VL, et al. Gynecologic Oncology Group. A phase III trial of surgery with or without adjunctive external pelvic radiation therapy in intermediate risk endometrial adenocarcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92:744-751.

2. Bristow RE, Zahurak ML, Alexander CJ, Zellars RC, Montz FJ. FIGO stage IIIC endometrial carcinoma: resection of macroscopic nodal disease and other determinants of survival. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2003;13:664-672.

Dr. Mutch reports that he has received grant or research support from Lilly and Genentech. He serves as a speaker for GSK, Lilly, and Merck. Dr. Rimel reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Endometrial cancer is a great concern in industrialized nations, where it is the most common gynecologic cancer—with incidence increasing every year. Survival is generally very good for women who have low-grade disease confined to the uterus. However, for patients who have high-grade disease, an aggressive histologic type, or other features that suggest a poor prognosis, the cure rate approaches 75%.1

Primary surgery is the mainstay of initial treatment and basis of FIGO staging ( TABLE ), which requires:

- total hysterectomy

- bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

- complete examination of the abdomen

- pelvic washings

- lymph-adenectomy (anatomic boundaries and node counts aren’t specified).

Controversy clouds our understanding of the optimal type of surgery, utility of pelvic lymphadenectomy, and possible benefit of adjuvant radiation therapy. During the past year, fuel has been added to this debate:

- Two randomized, controlled trials of surgery with and without pelvic lymphadenectomy in early-stage patients demonstrated no survival benefit. Earlier studies investigating the benefits of lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer have been largely retrospective, and results have varied.

- A concurrent randomized, controlled trial of external-beam radiotherapy for women who have intermediate- or high-risk disease showed no improvement in overall survival, although local control increased by 3%.

TABLE

FIGO surgical staging for endometrial cancer

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Tumor is confined to uterine fundus |

| IA | Tumor is limited to endometrium |

| IB | Tumor invades less than half of the myometrial thickness |

| IC | Tumor invades more than half of the myometrial thickness |

| II | Tumor extends to cervix |

| IIA | Cervical extension is limited to endocervical glands |

| IIB | Tumor invades cervical stroma |

| III | There is regional tumor spread |

| IIIA | Tumor invades uterine serosa or adnexa, or cells in the peritoneum show signs of cancer |

| IIIB | Vaginal metastases are present |

| IIIC | Tumor has spread to lymph nodes near the uterus |

| IV | There is bulky pelvic disease or distant spread |

| IVA | Tumor has spread to bladder or rectum |

| IVB | Distant metastases are present |

No survival advantage to pelvic lymphadenectomy—but it has other benefits

ASTEC study group, Kitchener H, Swart AM, Qian Q, Amos C, Parmar MK. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomised study. Lancet. 2009;373:125–136.

Benedetti Panici P, Basile S, Maneschi F, et al. Systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy vs. no lymphadenectomy in early-stage endometrial carcinoma: randomized clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1707–1716.

Among the arguments for lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer staging are:

- It aids in the selection of women for radiation or other adjuvant treatment

- It may have a direct survival benefit, as suggested by retrospective studies.

But lymphadenectomy is time-consuming, requires a specialized gynecologic surgeon, and is associated with some increase in the risk of morbidity—namely, lymphedema, lymphocyst formation, deep-vein thrombosis (DVT), and blood loss.

The much-anticipated report of the 85-center, multinational ASTEC trial [ A S urgical T rial of E ndometrial C ancer], published earlier this year, offers further insight into the practice of lymphadenectomy. ASTEC involved two randomizations: The first, to pelvic lymphadenectomy; the second, to radiation therapy.